User login

FDA approves metoclopramide nasal spray for diabetic gastroparesis

The Food and Drug Administration has approved a new formulation of metoclopramide for relief of symptoms of diabetic gastroparesis in adults.

The product, called Gimoti (Evoke Pharma) delivers metoclopramide through nasal administration, offering an advantage over oral administration, which can be impeded because of slowed stomach emptying, the company said in an announcement of the approval. The delivery system provides 15 mg metoclopramide in each 70-mcL spray, which can be taken 30 minutes before each meal and at bedtime for 2-8 weeks, depending on symptomatic response, according to Gimoti’s prescribing information.

Metoclopramide, a dopamine-2 antagonist, has been available for 4 decades in oral and injection formulations. It carries a risk of developing tardive dyskinesia – a serious, often-irreversible movement disorder – that increases with duration of treatment. Therefore, use of the drug should not exceed 12 weeks. Other contraindications include a history of tardive dyskinesia, when stimulation of GI motility might be dangerous, pheochromocytoma and catecholamine-releasing paragangliomas, and epilepsy.

Henry Parkman, MD, who was involved with clinical trials leading to the approval, explained in the Evoke statement that “patients with gastroparesis suffer from characteristic symptoms such as nausea, abdominal pain, bloating, early satiety, as well as vomiting which can be severe and debilitating. These patients often have erratic absorption of orally administered drugs because of delayed gastric emptying.

“Unlike oral medications, Gimoti is administered nasally, bypassing the diseased GI track, allowing the drug to enter the bloodstream directly and therefore may provide predictable delivery of the therapy,” adds Dr. Parkman, chair and director of the Gastroenterology Motility Laboratory at Temple University, Philadelphia.

Gimoti will be available commercially in the fourth quarter of this year, according to Evoke.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved a new formulation of metoclopramide for relief of symptoms of diabetic gastroparesis in adults.

The product, called Gimoti (Evoke Pharma) delivers metoclopramide through nasal administration, offering an advantage over oral administration, which can be impeded because of slowed stomach emptying, the company said in an announcement of the approval. The delivery system provides 15 mg metoclopramide in each 70-mcL spray, which can be taken 30 minutes before each meal and at bedtime for 2-8 weeks, depending on symptomatic response, according to Gimoti’s prescribing information.

Metoclopramide, a dopamine-2 antagonist, has been available for 4 decades in oral and injection formulations. It carries a risk of developing tardive dyskinesia – a serious, often-irreversible movement disorder – that increases with duration of treatment. Therefore, use of the drug should not exceed 12 weeks. Other contraindications include a history of tardive dyskinesia, when stimulation of GI motility might be dangerous, pheochromocytoma and catecholamine-releasing paragangliomas, and epilepsy.

Henry Parkman, MD, who was involved with clinical trials leading to the approval, explained in the Evoke statement that “patients with gastroparesis suffer from characteristic symptoms such as nausea, abdominal pain, bloating, early satiety, as well as vomiting which can be severe and debilitating. These patients often have erratic absorption of orally administered drugs because of delayed gastric emptying.

“Unlike oral medications, Gimoti is administered nasally, bypassing the diseased GI track, allowing the drug to enter the bloodstream directly and therefore may provide predictable delivery of the therapy,” adds Dr. Parkman, chair and director of the Gastroenterology Motility Laboratory at Temple University, Philadelphia.

Gimoti will be available commercially in the fourth quarter of this year, according to Evoke.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved a new formulation of metoclopramide for relief of symptoms of diabetic gastroparesis in adults.

The product, called Gimoti (Evoke Pharma) delivers metoclopramide through nasal administration, offering an advantage over oral administration, which can be impeded because of slowed stomach emptying, the company said in an announcement of the approval. The delivery system provides 15 mg metoclopramide in each 70-mcL spray, which can be taken 30 minutes before each meal and at bedtime for 2-8 weeks, depending on symptomatic response, according to Gimoti’s prescribing information.

Metoclopramide, a dopamine-2 antagonist, has been available for 4 decades in oral and injection formulations. It carries a risk of developing tardive dyskinesia – a serious, often-irreversible movement disorder – that increases with duration of treatment. Therefore, use of the drug should not exceed 12 weeks. Other contraindications include a history of tardive dyskinesia, when stimulation of GI motility might be dangerous, pheochromocytoma and catecholamine-releasing paragangliomas, and epilepsy.

Henry Parkman, MD, who was involved with clinical trials leading to the approval, explained in the Evoke statement that “patients with gastroparesis suffer from characteristic symptoms such as nausea, abdominal pain, bloating, early satiety, as well as vomiting which can be severe and debilitating. These patients often have erratic absorption of orally administered drugs because of delayed gastric emptying.

“Unlike oral medications, Gimoti is administered nasally, bypassing the diseased GI track, allowing the drug to enter the bloodstream directly and therefore may provide predictable delivery of the therapy,” adds Dr. Parkman, chair and director of the Gastroenterology Motility Laboratory at Temple University, Philadelphia.

Gimoti will be available commercially in the fourth quarter of this year, according to Evoke.

AGA Clinical Practice Update: Functional heartburn

Recognizing the presence of functional heartburn is vital to prevent unnecessary acid-suppressive therapy and invasive antireflux treatments, which are ineffective and “might even lead to harm,” cautions a new clinical practice update from the American Gastroenterological Association.

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) “have no therapeutic value in functional heartburn,” unless patients also have gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), Ronnie Fass, MD, of MetroHealth System in Cleveland, and coauthors wrote in Gastroenterology. If clinical work-up finds no clear evidence of GERD, “an attempt to discontinue PPI therapy is warranted,” they added. Likewise, antireflux surgery and endoscopic treatments for GERD “have no therapeutic benefit in functional heartburn and should not be recommended.” However, histamine2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs) “may have an independent benefit in functional heartburn from an esophageal pain modulatory effect.”

Heartburn consists of burning or discomfort that radiates retrosternally from the epigastrium. Patients may report reflux, regurgitation, chest pain or discomfort, fullness, water brash, belching, or a sour and bitter taste in the mouth. Functional heartburn is heartburn that persists after at least 3 months of maximal (double-dose) PPIs taken before meals. Confirming functional heartburn requires high-resolution manometry to rule out major esophageal motor disorders, esophageal endoscopy with biopsy to rule out structural abnormalities and mucosal disorders (e.g., erosive esophagitis, Barrett’s esophagus, and eosinophilic esophagitis), and either pH monitoring while off PPI therapy or pH-impedance monitoring on therapy if patients have proven GERD. According to the clinical practice update, pH studies should document physiological acid exposure in the distal esophagus that is unlinked to symptoms (i.e., both a negative symptom index and a negative symptom association probability).

Functional heartburn resembles GERD, but symptoms are unrelated to acid exposure. Balloon distension studies indicate that patients with functional heartburn experience both esophageal and rectal hypersensitivity. Anxiety and mood disorders also are highly prevalent, and patients “will likely not improve unless esophageal perception and underlying affective disorders are adequately managed,” Dr. Fass and coauthors emphasized.

In keeping with this approach, limited evidence from clinical trials supports the first-line use of neuromodulator therapies, including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, the serotonin 4 receptor antagonist tegaserod, and H2RAs (e.g., cimetidine, famotidine, nizatidine). The only SSRI studied thus far in functional heartburn is fluoxetine. In a placebo-controlled trial of patients with normal endoscopy and heartburn that had not responded to once-daily PPI therapy, 6 weeks of fluoxetine (20 mg daily) significantly outperformed double-dose omeprazole (P < .001) for the primary endpoint of heartburn-free days. “This superior therapeutic effect of fluoxetine was seen only in the subset of patients with a normal pH test,” the experts noted.

In another placebo-controlled trial, the neuromodulator tegaserod (a serotonin 5-HT4 receptor partial agonist) significantly improved tolerance of esophageal pressure during balloon distension and significantly decreased heartburn, regurgitation, and associated distress among patients with functional heartburn. Melatonin, which “also has a pain modulatory effect in the gastrointestinal tract,” significantly improved symptom-related quality of life, compared with nortriptyline and placebo in a randomized, three-arm trial. The patients on melatonin received a 6-mg dose at bedtime for 3 months.

Acupuncture and hypnotherapy also have shown benefit in small studies of functional heartburn patients and may be appropriate as monotherapy or adjunctive treatment, according to the clinical practice update. In a small randomized study, 10 acupuncture sessions delivered over 4 weeks significantly improved daytime and nighttime heartburn and acid regurgitation scores, compared with double-dose PPI. “Mean general health score was significantly improved only in those receiving acupuncture,” the experts noted. Hypnotherapy, the only psychological intervention to have been studied in functional heartburn, was associated with significant improvements in symptoms, visceral anxiety, and quality of life in an uncontrolled study of nine patients.

Although the overall prevalence of functional heartburn is unclear, it has been detected in 21%-39% of PPI-refractory patients evaluated with pH-impedance monitoring, Dr. Fass and associates wrote. Because functional heartburn and GERD can co-occur, some patients with functional heartburn may develop long-term complications of GERD, such as Barrett’s esophagus or peptic stricture. However, the experts noted, “this is anticipated to be rare, and the vast majority of patients with functional heartburn will have compromised quality of life, rather than organic complications over time.

Dr. Fass reported receiving consulting, research, and speaking fees from Ironwood, Takeda, and Salix, among other pharmaceutical companies; Dr. Zerbib received consulting fees from Reckitt Benckiser; and Dr. Gyawali received teaching and consulting fees from Medtronic, Diversatek, and Ironwood.

SOURCE: Fass R et al. Gastroenterology. 2020 Feb 1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.01.034.

This story was updated on 6/11/2020.

Recognizing the presence of functional heartburn is vital to prevent unnecessary acid-suppressive therapy and invasive antireflux treatments, which are ineffective and “might even lead to harm,” cautions a new clinical practice update from the American Gastroenterological Association.

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) “have no therapeutic value in functional heartburn,” unless patients also have gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), Ronnie Fass, MD, of MetroHealth System in Cleveland, and coauthors wrote in Gastroenterology. If clinical work-up finds no clear evidence of GERD, “an attempt to discontinue PPI therapy is warranted,” they added. Likewise, antireflux surgery and endoscopic treatments for GERD “have no therapeutic benefit in functional heartburn and should not be recommended.” However, histamine2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs) “may have an independent benefit in functional heartburn from an esophageal pain modulatory effect.”

Heartburn consists of burning or discomfort that radiates retrosternally from the epigastrium. Patients may report reflux, regurgitation, chest pain or discomfort, fullness, water brash, belching, or a sour and bitter taste in the mouth. Functional heartburn is heartburn that persists after at least 3 months of maximal (double-dose) PPIs taken before meals. Confirming functional heartburn requires high-resolution manometry to rule out major esophageal motor disorders, esophageal endoscopy with biopsy to rule out structural abnormalities and mucosal disorders (e.g., erosive esophagitis, Barrett’s esophagus, and eosinophilic esophagitis), and either pH monitoring while off PPI therapy or pH-impedance monitoring on therapy if patients have proven GERD. According to the clinical practice update, pH studies should document physiological acid exposure in the distal esophagus that is unlinked to symptoms (i.e., both a negative symptom index and a negative symptom association probability).

Functional heartburn resembles GERD, but symptoms are unrelated to acid exposure. Balloon distension studies indicate that patients with functional heartburn experience both esophageal and rectal hypersensitivity. Anxiety and mood disorders also are highly prevalent, and patients “will likely not improve unless esophageal perception and underlying affective disorders are adequately managed,” Dr. Fass and coauthors emphasized.

In keeping with this approach, limited evidence from clinical trials supports the first-line use of neuromodulator therapies, including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, the serotonin 4 receptor antagonist tegaserod, and H2RAs (e.g., cimetidine, famotidine, nizatidine). The only SSRI studied thus far in functional heartburn is fluoxetine. In a placebo-controlled trial of patients with normal endoscopy and heartburn that had not responded to once-daily PPI therapy, 6 weeks of fluoxetine (20 mg daily) significantly outperformed double-dose omeprazole (P < .001) for the primary endpoint of heartburn-free days. “This superior therapeutic effect of fluoxetine was seen only in the subset of patients with a normal pH test,” the experts noted.

In another placebo-controlled trial, the neuromodulator tegaserod (a serotonin 5-HT4 receptor partial agonist) significantly improved tolerance of esophageal pressure during balloon distension and significantly decreased heartburn, regurgitation, and associated distress among patients with functional heartburn. Melatonin, which “also has a pain modulatory effect in the gastrointestinal tract,” significantly improved symptom-related quality of life, compared with nortriptyline and placebo in a randomized, three-arm trial. The patients on melatonin received a 6-mg dose at bedtime for 3 months.

Acupuncture and hypnotherapy also have shown benefit in small studies of functional heartburn patients and may be appropriate as monotherapy or adjunctive treatment, according to the clinical practice update. In a small randomized study, 10 acupuncture sessions delivered over 4 weeks significantly improved daytime and nighttime heartburn and acid regurgitation scores, compared with double-dose PPI. “Mean general health score was significantly improved only in those receiving acupuncture,” the experts noted. Hypnotherapy, the only psychological intervention to have been studied in functional heartburn, was associated with significant improvements in symptoms, visceral anxiety, and quality of life in an uncontrolled study of nine patients.

Although the overall prevalence of functional heartburn is unclear, it has been detected in 21%-39% of PPI-refractory patients evaluated with pH-impedance monitoring, Dr. Fass and associates wrote. Because functional heartburn and GERD can co-occur, some patients with functional heartburn may develop long-term complications of GERD, such as Barrett’s esophagus or peptic stricture. However, the experts noted, “this is anticipated to be rare, and the vast majority of patients with functional heartburn will have compromised quality of life, rather than organic complications over time.

Dr. Fass reported receiving consulting, research, and speaking fees from Ironwood, Takeda, and Salix, among other pharmaceutical companies; Dr. Zerbib received consulting fees from Reckitt Benckiser; and Dr. Gyawali received teaching and consulting fees from Medtronic, Diversatek, and Ironwood.

SOURCE: Fass R et al. Gastroenterology. 2020 Feb 1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.01.034.

This story was updated on 6/11/2020.

Recognizing the presence of functional heartburn is vital to prevent unnecessary acid-suppressive therapy and invasive antireflux treatments, which are ineffective and “might even lead to harm,” cautions a new clinical practice update from the American Gastroenterological Association.

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) “have no therapeutic value in functional heartburn,” unless patients also have gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), Ronnie Fass, MD, of MetroHealth System in Cleveland, and coauthors wrote in Gastroenterology. If clinical work-up finds no clear evidence of GERD, “an attempt to discontinue PPI therapy is warranted,” they added. Likewise, antireflux surgery and endoscopic treatments for GERD “have no therapeutic benefit in functional heartburn and should not be recommended.” However, histamine2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs) “may have an independent benefit in functional heartburn from an esophageal pain modulatory effect.”

Heartburn consists of burning or discomfort that radiates retrosternally from the epigastrium. Patients may report reflux, regurgitation, chest pain or discomfort, fullness, water brash, belching, or a sour and bitter taste in the mouth. Functional heartburn is heartburn that persists after at least 3 months of maximal (double-dose) PPIs taken before meals. Confirming functional heartburn requires high-resolution manometry to rule out major esophageal motor disorders, esophageal endoscopy with biopsy to rule out structural abnormalities and mucosal disorders (e.g., erosive esophagitis, Barrett’s esophagus, and eosinophilic esophagitis), and either pH monitoring while off PPI therapy or pH-impedance monitoring on therapy if patients have proven GERD. According to the clinical practice update, pH studies should document physiological acid exposure in the distal esophagus that is unlinked to symptoms (i.e., both a negative symptom index and a negative symptom association probability).

Functional heartburn resembles GERD, but symptoms are unrelated to acid exposure. Balloon distension studies indicate that patients with functional heartburn experience both esophageal and rectal hypersensitivity. Anxiety and mood disorders also are highly prevalent, and patients “will likely not improve unless esophageal perception and underlying affective disorders are adequately managed,” Dr. Fass and coauthors emphasized.

In keeping with this approach, limited evidence from clinical trials supports the first-line use of neuromodulator therapies, including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, the serotonin 4 receptor antagonist tegaserod, and H2RAs (e.g., cimetidine, famotidine, nizatidine). The only SSRI studied thus far in functional heartburn is fluoxetine. In a placebo-controlled trial of patients with normal endoscopy and heartburn that had not responded to once-daily PPI therapy, 6 weeks of fluoxetine (20 mg daily) significantly outperformed double-dose omeprazole (P < .001) for the primary endpoint of heartburn-free days. “This superior therapeutic effect of fluoxetine was seen only in the subset of patients with a normal pH test,” the experts noted.

In another placebo-controlled trial, the neuromodulator tegaserod (a serotonin 5-HT4 receptor partial agonist) significantly improved tolerance of esophageal pressure during balloon distension and significantly decreased heartburn, regurgitation, and associated distress among patients with functional heartburn. Melatonin, which “also has a pain modulatory effect in the gastrointestinal tract,” significantly improved symptom-related quality of life, compared with nortriptyline and placebo in a randomized, three-arm trial. The patients on melatonin received a 6-mg dose at bedtime for 3 months.

Acupuncture and hypnotherapy also have shown benefit in small studies of functional heartburn patients and may be appropriate as monotherapy or adjunctive treatment, according to the clinical practice update. In a small randomized study, 10 acupuncture sessions delivered over 4 weeks significantly improved daytime and nighttime heartburn and acid regurgitation scores, compared with double-dose PPI. “Mean general health score was significantly improved only in those receiving acupuncture,” the experts noted. Hypnotherapy, the only psychological intervention to have been studied in functional heartburn, was associated with significant improvements in symptoms, visceral anxiety, and quality of life in an uncontrolled study of nine patients.

Although the overall prevalence of functional heartburn is unclear, it has been detected in 21%-39% of PPI-refractory patients evaluated with pH-impedance monitoring, Dr. Fass and associates wrote. Because functional heartburn and GERD can co-occur, some patients with functional heartburn may develop long-term complications of GERD, such as Barrett’s esophagus or peptic stricture. However, the experts noted, “this is anticipated to be rare, and the vast majority of patients with functional heartburn will have compromised quality of life, rather than organic complications over time.

Dr. Fass reported receiving consulting, research, and speaking fees from Ironwood, Takeda, and Salix, among other pharmaceutical companies; Dr. Zerbib received consulting fees from Reckitt Benckiser; and Dr. Gyawali received teaching and consulting fees from Medtronic, Diversatek, and Ironwood.

SOURCE: Fass R et al. Gastroenterology. 2020 Feb 1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.01.034.

This story was updated on 6/11/2020.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

AGA Guideline: Management of eosinophilic esophagitis

Patients with eosinophilic esophagitis should receive topical steroids instead of oral steroids or no treatment, according to new recommendations from the American Gastroenterological Association and the Joint Task Force on Allergy-Immunology Practice Parameters.

In a pooled analysis of eight double-blind clinical trials, monotherapy with topical budesonide or topical fluticasone was about 61% more likely than placebo to produce histologic remissions in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis (relative risk of failure to achieve remission, 0.39; 95% confidence interval, 0.26-0.58), wrote Ikuo Hirano, MD, of Northwestern University, Chicago. Although these trials differed methodologically, the results were robust enough to warrant a strong recommendation for topical steroids, wrote Dr. Hirano and coauthors of the guidelines, published in Gastroenterology (doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.038). “[T]he same inhaled steroid agents are considered very safe for use in children and adults with asthma and are routinely used in [its] primary management,” they noted.

All other recommendations in the guidelines are graded as conditional, reflecting a lack of high-quality supporting evidence. For example, one only study to date has compared topical and oral steroids for patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. In this pediatric trial, children benefited similarly from fluticasone (two puffs four times daily) and oral prednisone (1 mg/kg twice daily), but prednisone caused side effects (weight gain and cushingoid appearance) in 40% of patients, while topical steroids caused oral candidiasis (thrush) in only 15% of patients. Similarities between pediatric and adult eosinophilic esophagitis support the use of topical versus oral steroids in both groups, the guidelines conclude.

Eosinophilic esophagitis tends to be chronic and can progress to recurrent dysphagia, esophageal impactions, and stricture if left untreated. For this reason, the guidelines call for remitted patients to stay on topical steroids as maintenance therapy despite “very low confidence in the estimated benefits of [any type of] long-term therapy.” In a very small trial, 1 year of low-dose budesonide maintenance therapy (0.25 mg twice daily) outperformed placebo, but only 36% of patients maintained less than 5 eosinophils per high power field. Other studies have produced mixed results. Pending more data, the guidelines call maintenance treatment with topical steroids, proton pump inhibitors, and elimination diets “reasonable options” that comprise “a preference-sensitive area of management.”

Dietary interventions for eosinophilic esophagitis include the elemental diet (amino acid–based formulas), the empiric six-food elimination diet, and eliminating foods based on allergy testing. The guidelines cite moderate-quality evidence for the elemental diet, which induced histologic remissions (less than than 15 eosinophils per high power field) in nearly 94% of patients in six single-arm observational studies (in contrast, the rate of histologic failure with placebo is nearly 87%). However, patients may struggle to adhere to both the elemental diet and the six-food elimination diet, which has less supporting evidence. Hence, patients “may reasonably decline” these treatment options and “may prefer alternative medical or dietary therapies” to a diet exclusively based on food allergens, tests for which are potentially inaccurate, the guidelines state.

Esophageal dilation is recommended for patients with stricture based on a systematic review in which 87% of patients improved with this therapy. However, dilation “does not address the esophageal inflammation associated with eosinophilic esophagitis,” and the “assumption that no clinical improvement would occur if dilation was not performed likely overestimates [its] treatment benefit, given the reported symptom-placebo response noted in controlled trials,” according to the guidelines. Moreover, the evidence for dilation “was considered low quality due to the retrospective, single-arm design of all but one of the reports, and the lack of a standard definition for what constitutes clinical improvement.”

Anti-IgE therapy is not recommended – it failed to improve symptoms or esophageal eosinophilia in the only trial conducted to date. Because of a lack of evidence, the guidelines state that patients should receive only montelukast, cromolyn sodium, immunomodulators, anti–tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) therapies, or therapies targeting interleukin (IL)-5, IL-13, or IL-4 in the context of a clinical trial.

Eosinophilic esophagitis is triggered by exposure to food antigens and often overlaps with other atopic conditions, such as asthma, eczema, and allergic rhinitis. It has no approved treatments in the United States, although in 2018, the European Medicines Agency approved a budesonide tablet formulation.

The guideline authors disclosed no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Hirano I et al. Gastroenterology. 2020. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.038.

Patients with eosinophilic esophagitis should receive topical steroids instead of oral steroids or no treatment, according to new recommendations from the American Gastroenterological Association and the Joint Task Force on Allergy-Immunology Practice Parameters.

In a pooled analysis of eight double-blind clinical trials, monotherapy with topical budesonide or topical fluticasone was about 61% more likely than placebo to produce histologic remissions in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis (relative risk of failure to achieve remission, 0.39; 95% confidence interval, 0.26-0.58), wrote Ikuo Hirano, MD, of Northwestern University, Chicago. Although these trials differed methodologically, the results were robust enough to warrant a strong recommendation for topical steroids, wrote Dr. Hirano and coauthors of the guidelines, published in Gastroenterology (doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.038). “[T]he same inhaled steroid agents are considered very safe for use in children and adults with asthma and are routinely used in [its] primary management,” they noted.

All other recommendations in the guidelines are graded as conditional, reflecting a lack of high-quality supporting evidence. For example, one only study to date has compared topical and oral steroids for patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. In this pediatric trial, children benefited similarly from fluticasone (two puffs four times daily) and oral prednisone (1 mg/kg twice daily), but prednisone caused side effects (weight gain and cushingoid appearance) in 40% of patients, while topical steroids caused oral candidiasis (thrush) in only 15% of patients. Similarities between pediatric and adult eosinophilic esophagitis support the use of topical versus oral steroids in both groups, the guidelines conclude.

Eosinophilic esophagitis tends to be chronic and can progress to recurrent dysphagia, esophageal impactions, and stricture if left untreated. For this reason, the guidelines call for remitted patients to stay on topical steroids as maintenance therapy despite “very low confidence in the estimated benefits of [any type of] long-term therapy.” In a very small trial, 1 year of low-dose budesonide maintenance therapy (0.25 mg twice daily) outperformed placebo, but only 36% of patients maintained less than 5 eosinophils per high power field. Other studies have produced mixed results. Pending more data, the guidelines call maintenance treatment with topical steroids, proton pump inhibitors, and elimination diets “reasonable options” that comprise “a preference-sensitive area of management.”

Dietary interventions for eosinophilic esophagitis include the elemental diet (amino acid–based formulas), the empiric six-food elimination diet, and eliminating foods based on allergy testing. The guidelines cite moderate-quality evidence for the elemental diet, which induced histologic remissions (less than than 15 eosinophils per high power field) in nearly 94% of patients in six single-arm observational studies (in contrast, the rate of histologic failure with placebo is nearly 87%). However, patients may struggle to adhere to both the elemental diet and the six-food elimination diet, which has less supporting evidence. Hence, patients “may reasonably decline” these treatment options and “may prefer alternative medical or dietary therapies” to a diet exclusively based on food allergens, tests for which are potentially inaccurate, the guidelines state.

Esophageal dilation is recommended for patients with stricture based on a systematic review in which 87% of patients improved with this therapy. However, dilation “does not address the esophageal inflammation associated with eosinophilic esophagitis,” and the “assumption that no clinical improvement would occur if dilation was not performed likely overestimates [its] treatment benefit, given the reported symptom-placebo response noted in controlled trials,” according to the guidelines. Moreover, the evidence for dilation “was considered low quality due to the retrospective, single-arm design of all but one of the reports, and the lack of a standard definition for what constitutes clinical improvement.”

Anti-IgE therapy is not recommended – it failed to improve symptoms or esophageal eosinophilia in the only trial conducted to date. Because of a lack of evidence, the guidelines state that patients should receive only montelukast, cromolyn sodium, immunomodulators, anti–tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) therapies, or therapies targeting interleukin (IL)-5, IL-13, or IL-4 in the context of a clinical trial.

Eosinophilic esophagitis is triggered by exposure to food antigens and often overlaps with other atopic conditions, such as asthma, eczema, and allergic rhinitis. It has no approved treatments in the United States, although in 2018, the European Medicines Agency approved a budesonide tablet formulation.

The guideline authors disclosed no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Hirano I et al. Gastroenterology. 2020. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.038.

Patients with eosinophilic esophagitis should receive topical steroids instead of oral steroids or no treatment, according to new recommendations from the American Gastroenterological Association and the Joint Task Force on Allergy-Immunology Practice Parameters.

In a pooled analysis of eight double-blind clinical trials, monotherapy with topical budesonide or topical fluticasone was about 61% more likely than placebo to produce histologic remissions in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis (relative risk of failure to achieve remission, 0.39; 95% confidence interval, 0.26-0.58), wrote Ikuo Hirano, MD, of Northwestern University, Chicago. Although these trials differed methodologically, the results were robust enough to warrant a strong recommendation for topical steroids, wrote Dr. Hirano and coauthors of the guidelines, published in Gastroenterology (doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.038). “[T]he same inhaled steroid agents are considered very safe for use in children and adults with asthma and are routinely used in [its] primary management,” they noted.

All other recommendations in the guidelines are graded as conditional, reflecting a lack of high-quality supporting evidence. For example, one only study to date has compared topical and oral steroids for patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. In this pediatric trial, children benefited similarly from fluticasone (two puffs four times daily) and oral prednisone (1 mg/kg twice daily), but prednisone caused side effects (weight gain and cushingoid appearance) in 40% of patients, while topical steroids caused oral candidiasis (thrush) in only 15% of patients. Similarities between pediatric and adult eosinophilic esophagitis support the use of topical versus oral steroids in both groups, the guidelines conclude.

Eosinophilic esophagitis tends to be chronic and can progress to recurrent dysphagia, esophageal impactions, and stricture if left untreated. For this reason, the guidelines call for remitted patients to stay on topical steroids as maintenance therapy despite “very low confidence in the estimated benefits of [any type of] long-term therapy.” In a very small trial, 1 year of low-dose budesonide maintenance therapy (0.25 mg twice daily) outperformed placebo, but only 36% of patients maintained less than 5 eosinophils per high power field. Other studies have produced mixed results. Pending more data, the guidelines call maintenance treatment with topical steroids, proton pump inhibitors, and elimination diets “reasonable options” that comprise “a preference-sensitive area of management.”

Dietary interventions for eosinophilic esophagitis include the elemental diet (amino acid–based formulas), the empiric six-food elimination diet, and eliminating foods based on allergy testing. The guidelines cite moderate-quality evidence for the elemental diet, which induced histologic remissions (less than than 15 eosinophils per high power field) in nearly 94% of patients in six single-arm observational studies (in contrast, the rate of histologic failure with placebo is nearly 87%). However, patients may struggle to adhere to both the elemental diet and the six-food elimination diet, which has less supporting evidence. Hence, patients “may reasonably decline” these treatment options and “may prefer alternative medical or dietary therapies” to a diet exclusively based on food allergens, tests for which are potentially inaccurate, the guidelines state.

Esophageal dilation is recommended for patients with stricture based on a systematic review in which 87% of patients improved with this therapy. However, dilation “does not address the esophageal inflammation associated with eosinophilic esophagitis,” and the “assumption that no clinical improvement would occur if dilation was not performed likely overestimates [its] treatment benefit, given the reported symptom-placebo response noted in controlled trials,” according to the guidelines. Moreover, the evidence for dilation “was considered low quality due to the retrospective, single-arm design of all but one of the reports, and the lack of a standard definition for what constitutes clinical improvement.”

Anti-IgE therapy is not recommended – it failed to improve symptoms or esophageal eosinophilia in the only trial conducted to date. Because of a lack of evidence, the guidelines state that patients should receive only montelukast, cromolyn sodium, immunomodulators, anti–tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) therapies, or therapies targeting interleukin (IL)-5, IL-13, or IL-4 in the context of a clinical trial.

Eosinophilic esophagitis is triggered by exposure to food antigens and often overlaps with other atopic conditions, such as asthma, eczema, and allergic rhinitis. It has no approved treatments in the United States, although in 2018, the European Medicines Agency approved a budesonide tablet formulation.

The guideline authors disclosed no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Hirano I et al. Gastroenterology. 2020. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.038.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Cyclic vomiting syndrome: A GI primer

Introduction

Cyclic vomiting syndrome (CVS) is a chronic disorder of gut-brain interaction (DGBI) and is characterized by recurrent episodes of severe nausea, vomiting, and often, abdominal pain. Patients are usually asymptomatic in between episodes.1 CVS was considered a pediatric disease but is now known to be as common in adults. The prevalence of CVS in adults was 2% in a recent population-based study.2 Patients are predominantly white. Both males and females are affected with some studies showing a female preponderance. The mean age of onset is 5 years in children and 35 years in adults.3

The etiology of CVS is not known, but various hypotheses have been proposed. Zaki et al. showed that two mitochondrial DNA polymorphisms 16519T and 3010A were associated with a 17-fold increased odds of having CVS in children.4 These polymorphisms were not associated with CVS in adults.5 Alterations in the brain-gut axis also have been shown in CVS. Functional neuroimaging studies demonstrate that patients with CVS displayed increased connectivity between insula and salience networks with concomitant decrease in connectivity to somatosensory networks.6 Recent data also indicate that the endocannabinoid system (ECS) and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis are implicated in CVS with an increase in serum endocannabinoid concentration during an episode.7 The same study also showed a significant increase in salivary cortisol in CVS patients who used cannabis. Further, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the gene that encodes for the cannabinoid receptor type 1 (CB1R) are implicated in CVS.8 The CB1R is part of the ECS and is densely expressed in brain areas involved in emesis, such as the dorsal vagal complex consisting of the area postrema (AP), nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS), and also the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus.9 Wasilewski et al. showed an increased risk of CVS among individuals with AG and GG genotypes of CNR1 rs806380 (P less than .01), whereas the CC genotype of CNR1 rs806368 was associated with a decreased risk of CVS (P less than .05).8 CB1R agonists – endocannabinoids and tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) – have acute antiemetic and anxiolytic effects.9-11 The apparent paradoxical effects of cannabis in this patient population are yet to be explained and need further study.

Diagnosis and clinical features of CVS

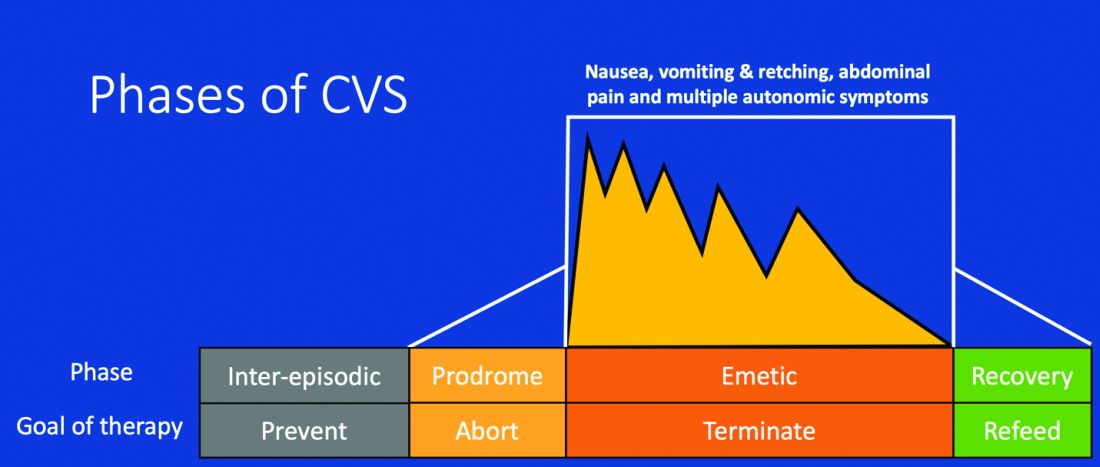

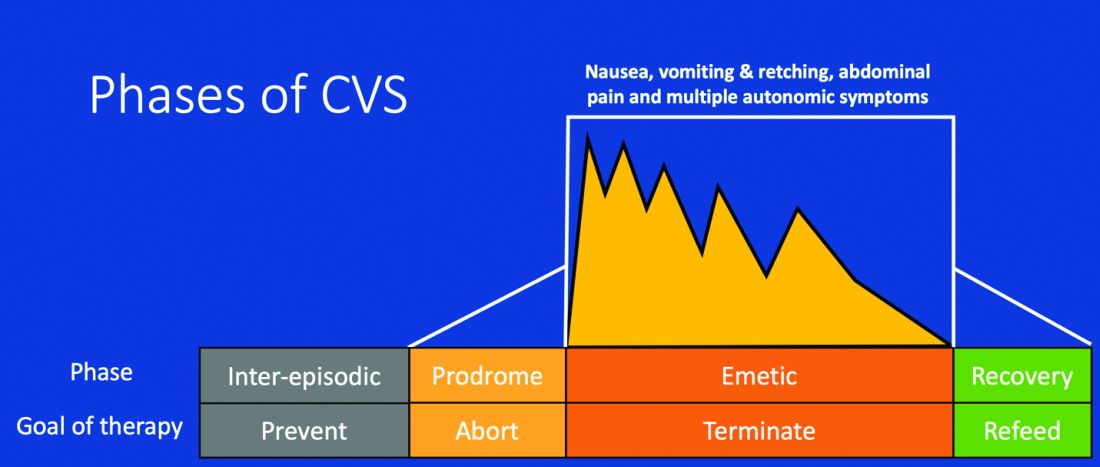

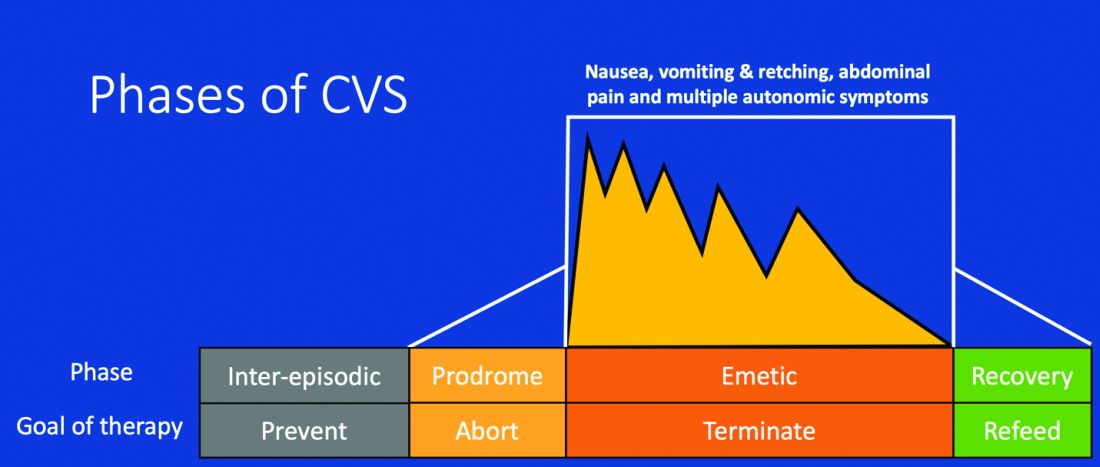

Figure 1: Phases of Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome12

Adapted from Fleisher DR, Gornowicz B, Adams K, Burch R, Feldman EJ. Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome in 41 adults: The illness, the patients, and problems of management. BMC Med 2005;3:20. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, modification, and reproduction in any medium.

CVS consists of four phases which include the a) prodromal phase, b) the episodic phase, c) recovery phase, and d) the interepisodic phase; and was first described by David Fleisher.12 The phases of CVS are important for clinicians and patients alike as they have therapeutic implications. The administration of abortive medications during a prodrome can terminate an episode. The phases of CVS are shown above.

Most patients (~ 93%) have a prodromal phase. Symptoms during this phase can include nausea, abdominal pain, diaphoresis, fatigue, weakness, hot flashes, chills, shivering, increased thirst, loss of appetite, burping, lightheadedness, and paresthesia.13 Some patients report a sense of impending doom and many have symptoms consistent with panic. If untreated, this progresses to the emetic phase and patients have unrelenting nausea, retching, vomiting, and other symptoms. During an episode, patients may vomit up to 20 times per hour and the episode may last several hours to days. During this phase, patients are sometimes described as being in a “conscious coma” and exhibit lethargy, listlessness, withdrawal, and sometimes disorientation.14,15 The emetic phase is followed by the recovery phase, during which symptoms subside and patients are able to resume oral intake. Patients are usually asymptomatic between episodes but ~ 30% can have interepisodic nausea and dyspepsia. In some patients, episodes become progressively longer and the interepisodic phase is considerably shortened and patients have a “coalescence of symptoms.”12 It is important to elicit a thorough history in all patients with vomiting in order to make an accurate diagnosis of CVS since coalescence of symptoms only occurs over a period of time. Episodes often are triggered by psychological stress, both positive and negative. Common triggers can include positive events such as birthdays, holidays, and negative ones like examinations, the death of a loved one, etc. Sleep deprivation and physical exhaustion also can trigger an episode.12

CVS remains a clinical diagnosis since there are no biomarkers. While there is a lack of data on the optimal work-up in these patients, experts recommend an upper endoscopy or upper GI series in order to rule out alternative gastric and intestinal pathology (e.g., malrotation with volvulus).16 Of note, a gastric-emptying study is not recommended as part of the routine work-up as per recent guidelines because of the poor specificity of this test in establishing a diagnosis of CVS.16 Biochemical testing including a complete blood count, serum electrolytes, serum glucose, liver panel, and urinalysis is also warranted. Any additional testing is indicated when clinical features suggest an alternative diagnosis. For instance, neurologic symptoms might warrant a cranial MRI to exclude an intracerebral tumor or other lesions of the brain.

The severity and unpredictable nature of symptoms makes it difficult for some patients to attend school or work; one study found that 32% of patients with CVS were completely disabled.12 Despite increasing awareness of this disorder, patients often are misdiagnosed. The prevalence of CVS in an outpatient gastroenterology clinic in the United Kingdom was 11% and was markedly underdiagnosed in the community.17 Only 5% of patients who were subsequently diagnosed with CVS were initially diagnosed accurately by their referring physician despite meeting criteria for the disorder.17 A subset of patients with CVS even undergo futile surgeries.13 Fleisher et al. noted that 30% of a 41-patient cohort underwent cholecystectomy for CVS symptoms without any improvement in disease.12 Prompt diagnosis and appropriate therapy is essential to improve patient outcomes and improve quality of life.

CVS is associated with various comorbidities such as migraine, anxiety, depression and dysautonomia, which can further impair quality of life.18,19 Approximately 70% of CVS patients report a personal or family history of migraine. Anxiety and depression affects nearly half of patients with CVS.13 Cannabis use is significantly more prevalent among patients with CVS than patients without CVS.20

Role of cannabis in CVS

The role of cannabis in the pathogenesis of symptoms in CVS is controversial. While cannabis has antiemetic properties, there is a strong link between its use and CVS. The use of cannabis has increased over the past decade with increasing legalization.21 Several studies have shown that 40%-80% of patients with CVS use cannabis.22,23 Following this, cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (CHS) was coined as a separate entity based on this statistical association, though there are no data to support the notion that cannabis causes vomiting.24,25 CHS has clinical features that are indistinguishable from CVS except for the chronic heavy cannabis use. A peculiar bathing behavior called “compulsive hot-water bathing” has been described and was thought to be pathognomonic of cannabis use.26 During an episode, patients will take multiple hot showers/baths, which temporarily alleviate their symptoms. Many patients even report running out of hot water and sometimes check into a hotel for a continuous supply of hot water. A small number of patients may sustain burns from the hot-water bathing. However, studies show that this hot-water bathing behavior also is seen in about 50% of patents with CVS who do not use cannabis.22

CHS is now defined by Rome IV criteria, which include episodes of nausea and vomiting similar to CVS preceded by chronic, heavy cannabis use. Patients must have complete resolution of symptoms following cessation.1 A recent systematic review of 376 cases of purported CHS showed that only 59 (15.7%) met Rome IV criteria for this disorder.27 This is because of considerable heterogeneity in how the diagnosis of CHS was made and the lack of standard diagnostic criteria at the time. Some cases of CHS were diagnosed merely based on an association of vomiting, hot-water bathing, and cannabis use.28 Only a minority of patients (71,19%) had a duration of follow-up more than 4 weeks, which would make it impossible to establish a diagnosis of CHS. A period of at least a year or a duration of time that spans at least three episodes is generally recommended to determine if abstinence from cannabis causes a true resolution of symptoms.27 Whether CHS is a separate entity or a subtype of CVS remains to be determined. The paradoxical effects of cannabis may happen because of the use of highly potent cannabis products that are currently in use. A complete discussion of the role of cannabis in CVS is beyond the scope of this article, and the reader is referred to a recent systematic review and discussion.27

Treatment

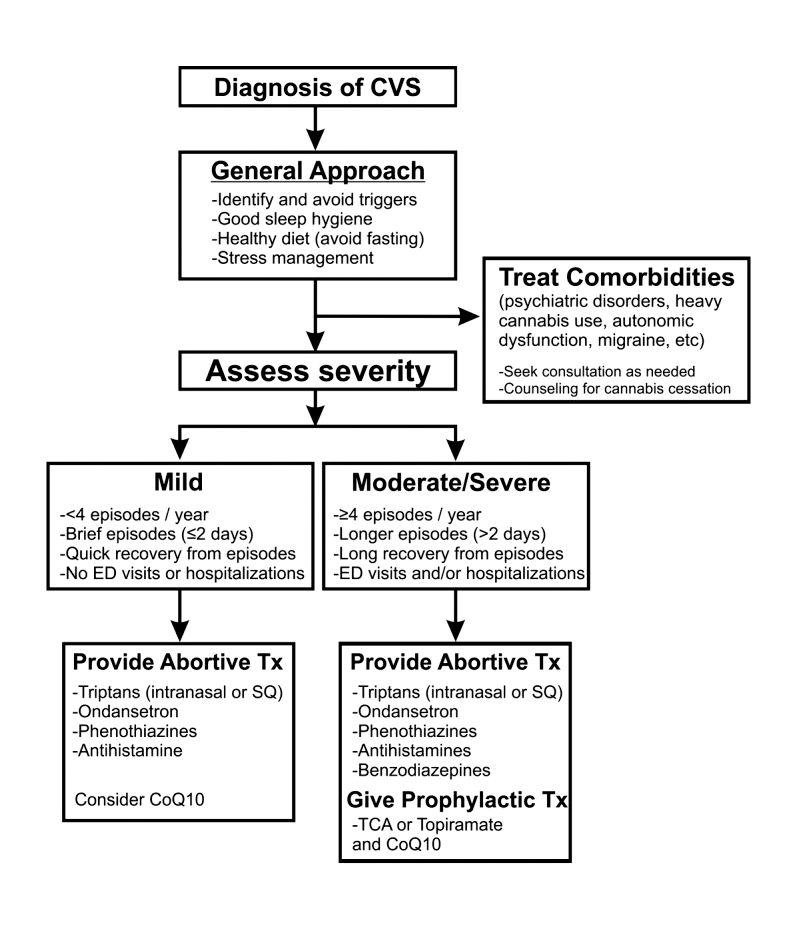

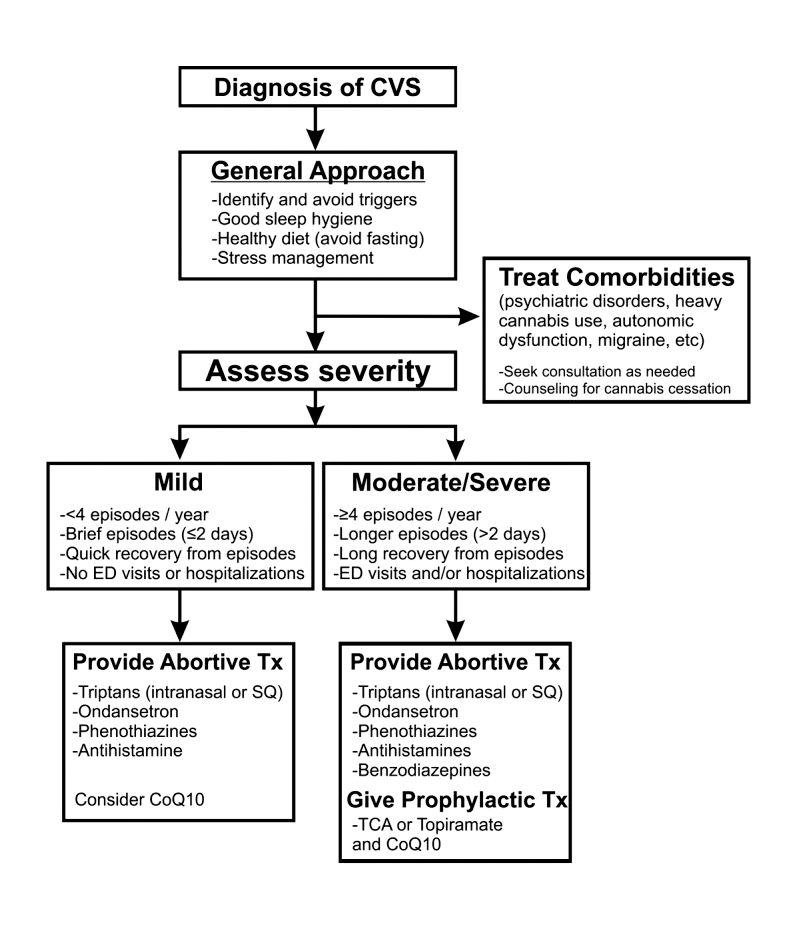

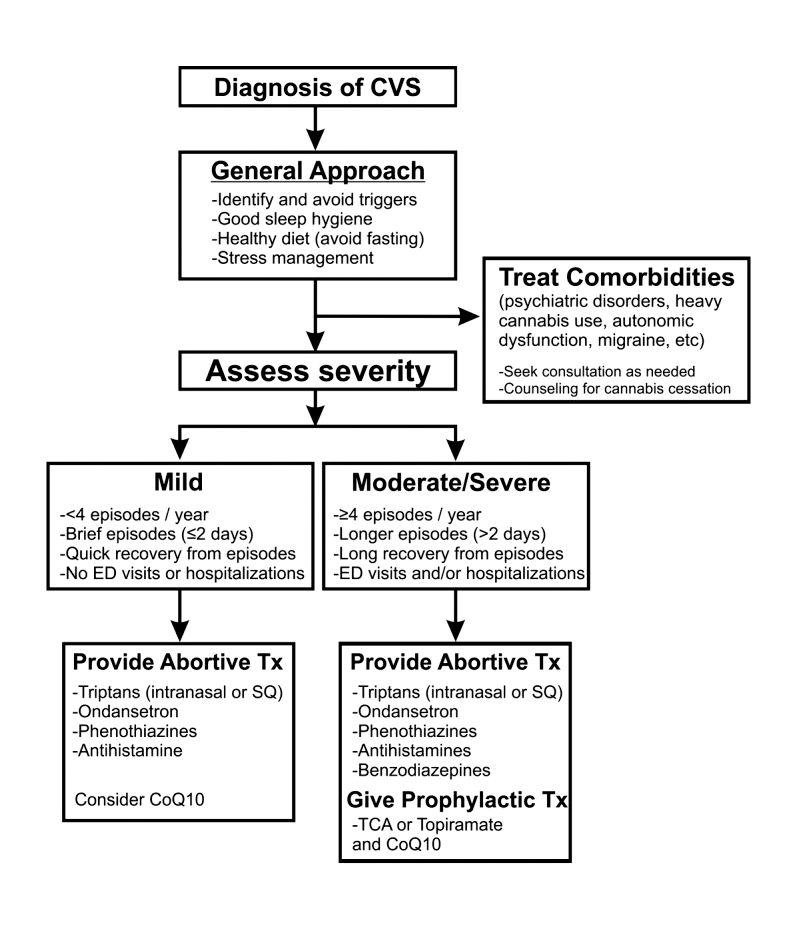

CVS should be treated based on a biopsychosocial model with a multidisciplinary team that includes a gastroenterologist with knowledge of CVS, primary care physician, psychologist, psychiatrist, and sleep specialist if needed.16 Initiating prophylactic treatment is based on the severity of disease. An algorithm for the treatment of CVS based on severity of symptoms is shown below.

Figure 2. Adapted and reprinted by permission from the Licensor: Springer Nature, Current Treatment Options in Gastroenterology, Bhandari S, Venkatesan T. Novel Treatments for Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome: Beyond Ondansetron and Amitriptyline, 14:495-506, Copyright 2016.

Patients who have mild disease (defined as fewer than four episodes/year, episodes lasting up to 2 days, quick recovery from episodes, or episodes not requiring ED care or hospitalization) are usually prescribed abortive medications.16 These medications are best administered during the prodromal phase and can prevent progression to the emetic phase. Medications used for aborting episodes include sumatriptan (20 mg intranasal or 6 mg subcutaneous), ondansetron (8 mg sublingual), and diphenhydramine (25-50 mg).30,31 This combination can help abort symptoms and potentially avoid ED visits or hospitalizations. Patients with moderate-to-severe CVS are offered prophylactic therapy in addition to abortive therapy.16

Recent guidelines recommend tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) as the first-line agent in the prophylaxis of CVS episodes. Data from 14 studies determined that 70% (413/600) of patients responded partially or completely to TCAs.16 An open-label study of 46 patients by Hejazi et al. noted a decline in the number of CVS episodes from 17 to 3, in the duration of a CVS episode from 6 to 2 days, and in the number of ED visits/ hospitalizations from 15 to 3.3.32Amitriptyline should be started at 25 mg at night and titrated up by 10-25 mg each week to minimize emergence of side effects. The mean effective dose is 75-100 mg or 1.0-1.5 mg/kg. An EKG should be checked at baseline and during titration to monitor the QT interval. Unfortunately, side effects from TCAs are quite common and include cognitive impairment, drowsiness, dryness of mouth, weight gain, constipation, and mood changes, which may warrant dose reduction or discontinuation. Antiepileptics such as topiramate, mitochondrial supplements such as Coenzyme Q10 and riboflavin are alternative prophylactic agents in CVS.33 Aprepitant, a newer NK1 receptor antagonist has been found to be effective in refractory CVS.34 In addition to pharmacotherapy, addressing comorbid conditions such as anxiety and depression and counseling patients to abstain from heavy cannabis use is also important to achieve good health care outcomes.

In summary, CVS is a common, chronic functional GI disorder with episodic nausea, vomiting, and often, abdominal pain. Symptoms can be disabling, and prompt diagnosis and therapy is important. CVS is associated with multiple comorbid conditions such as migraine, anxiety and depression, and a biopsychosocial model of care is essential. Medications such as amitriptyline are effective in the prophylaxis of CVS, but side effects hamper their use. Recent recommendations for management of CVS have been published.16 Cannabis is frequently used by patients for symptom relief but use of high potency products may cause worsening of symptoms or unmask symptoms in genetically predisposed individuals.23 Studies to elucidate the pathophysiology of CVS should help in the development of better therapies.

Dr. Mooers is PGY-2, an internal medicine resident in the department of medicine, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee; Dr. Venkatesan is professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, department of medicine, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee. The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

References

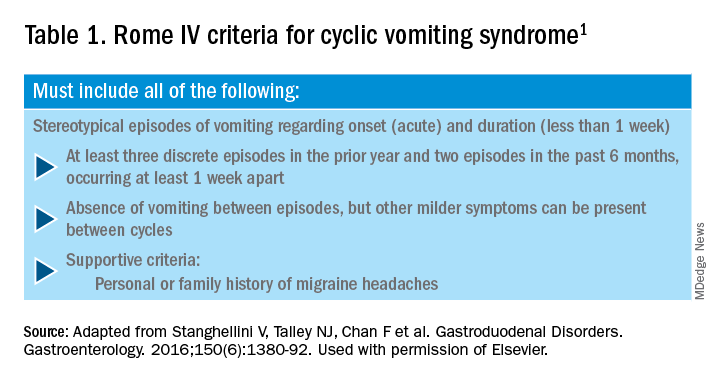

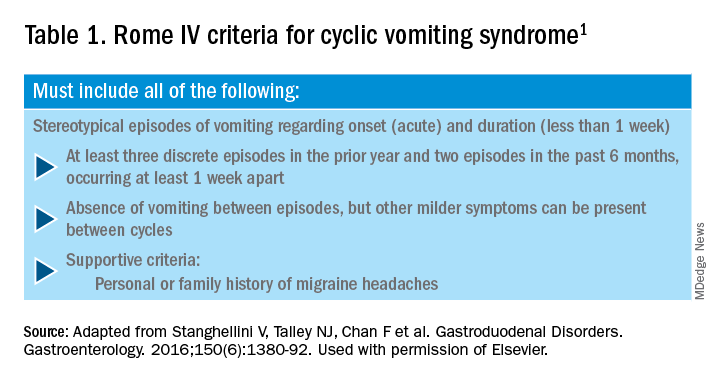

1. Stanghellini V et al. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1380-92.

2. Aziz I et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Apr;17(5):878-86.

3. Kovacic K et al. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2018;20(10):46.

4. Zaki EA et al. Cephalalgia. 2009;29:719-28.

5. Venkatesan T et al. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014;14:181.

6. Ellingsen DM et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;29 (6)e13004 9.

7. Venkatesan T et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;28:1409-18.

8. Wasilewski A et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:933-9.

9. van Sickle MD et al. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2003;285:G566-76.

10. Parker LA et al. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;163:1411-22.

11. van Sickle MD et al. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:767-74.

12. Fleisher DR et al. BMC Med. 2005;3:20.

13. Kumar N et al. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:52.

14. Li BU et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;47:379-93.

15. Bhandari S et al. Clin Auton Res. 2018 Apr;28(2):203-9.

16. Venkatesan T et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019;31 Suppl 2:e13604. doi: 10.1111/nmo.13604.

17. Sagar RC et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018;30. doi: 10.1111/nmo.13174.

18. Taranukha T et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018 Apr;30(4):e13245. doi: 10.1111/nmo.13245.

19. Bhandari S and Venkatesan T. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62:2035-44.

20. Choung RS et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24:20-6, e21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2011.01791.x.

21. Bhandari S et al. Intern Med J. 2019 May;49(5):649-55.

22. Venkatesan T et al. Exp Brain Res. 2014; 232:2563-70.

23. Venkatesan T et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Jul 25. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.07.039.

24. Simonetto DA et al. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:114-9.

25. Wallace EA et al. South Med J. 2011;104:659-64.

26. Allen JH et al. Gut. 2004;53:1566-70.

27. Venkatesan T et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019;31 Suppl 2:e13606. doi: 10.1111/nmo.13606.

28. Habboushe J et al. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2018;122:660-2.

29. Bhandari S and Venkatesan T. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2016;14:495-506.

30. Hikita T et al. Cephalalgia. 2011;31:504-7.

31. Fuseau E et al. Clin Pharmacokinet 2002;41:801-11.

32. Hejazi RA et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:18-21.

33. Sezer OB and Sezer T. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;22:656-60.

34. Cristofori F et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40:309-17.

Introduction

Cyclic vomiting syndrome (CVS) is a chronic disorder of gut-brain interaction (DGBI) and is characterized by recurrent episodes of severe nausea, vomiting, and often, abdominal pain. Patients are usually asymptomatic in between episodes.1 CVS was considered a pediatric disease but is now known to be as common in adults. The prevalence of CVS in adults was 2% in a recent population-based study.2 Patients are predominantly white. Both males and females are affected with some studies showing a female preponderance. The mean age of onset is 5 years in children and 35 years in adults.3

The etiology of CVS is not known, but various hypotheses have been proposed. Zaki et al. showed that two mitochondrial DNA polymorphisms 16519T and 3010A were associated with a 17-fold increased odds of having CVS in children.4 These polymorphisms were not associated with CVS in adults.5 Alterations in the brain-gut axis also have been shown in CVS. Functional neuroimaging studies demonstrate that patients with CVS displayed increased connectivity between insula and salience networks with concomitant decrease in connectivity to somatosensory networks.6 Recent data also indicate that the endocannabinoid system (ECS) and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis are implicated in CVS with an increase in serum endocannabinoid concentration during an episode.7 The same study also showed a significant increase in salivary cortisol in CVS patients who used cannabis. Further, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the gene that encodes for the cannabinoid receptor type 1 (CB1R) are implicated in CVS.8 The CB1R is part of the ECS and is densely expressed in brain areas involved in emesis, such as the dorsal vagal complex consisting of the area postrema (AP), nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS), and also the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus.9 Wasilewski et al. showed an increased risk of CVS among individuals with AG and GG genotypes of CNR1 rs806380 (P less than .01), whereas the CC genotype of CNR1 rs806368 was associated with a decreased risk of CVS (P less than .05).8 CB1R agonists – endocannabinoids and tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) – have acute antiemetic and anxiolytic effects.9-11 The apparent paradoxical effects of cannabis in this patient population are yet to be explained and need further study.

Diagnosis and clinical features of CVS

Figure 1: Phases of Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome12

Adapted from Fleisher DR, Gornowicz B, Adams K, Burch R, Feldman EJ. Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome in 41 adults: The illness, the patients, and problems of management. BMC Med 2005;3:20. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, modification, and reproduction in any medium.

CVS consists of four phases which include the a) prodromal phase, b) the episodic phase, c) recovery phase, and d) the interepisodic phase; and was first described by David Fleisher.12 The phases of CVS are important for clinicians and patients alike as they have therapeutic implications. The administration of abortive medications during a prodrome can terminate an episode. The phases of CVS are shown above.

Most patients (~ 93%) have a prodromal phase. Symptoms during this phase can include nausea, abdominal pain, diaphoresis, fatigue, weakness, hot flashes, chills, shivering, increased thirst, loss of appetite, burping, lightheadedness, and paresthesia.13 Some patients report a sense of impending doom and many have symptoms consistent with panic. If untreated, this progresses to the emetic phase and patients have unrelenting nausea, retching, vomiting, and other symptoms. During an episode, patients may vomit up to 20 times per hour and the episode may last several hours to days. During this phase, patients are sometimes described as being in a “conscious coma” and exhibit lethargy, listlessness, withdrawal, and sometimes disorientation.14,15 The emetic phase is followed by the recovery phase, during which symptoms subside and patients are able to resume oral intake. Patients are usually asymptomatic between episodes but ~ 30% can have interepisodic nausea and dyspepsia. In some patients, episodes become progressively longer and the interepisodic phase is considerably shortened and patients have a “coalescence of symptoms.”12 It is important to elicit a thorough history in all patients with vomiting in order to make an accurate diagnosis of CVS since coalescence of symptoms only occurs over a period of time. Episodes often are triggered by psychological stress, both positive and negative. Common triggers can include positive events such as birthdays, holidays, and negative ones like examinations, the death of a loved one, etc. Sleep deprivation and physical exhaustion also can trigger an episode.12

CVS remains a clinical diagnosis since there are no biomarkers. While there is a lack of data on the optimal work-up in these patients, experts recommend an upper endoscopy or upper GI series in order to rule out alternative gastric and intestinal pathology (e.g., malrotation with volvulus).16 Of note, a gastric-emptying study is not recommended as part of the routine work-up as per recent guidelines because of the poor specificity of this test in establishing a diagnosis of CVS.16 Biochemical testing including a complete blood count, serum electrolytes, serum glucose, liver panel, and urinalysis is also warranted. Any additional testing is indicated when clinical features suggest an alternative diagnosis. For instance, neurologic symptoms might warrant a cranial MRI to exclude an intracerebral tumor or other lesions of the brain.

The severity and unpredictable nature of symptoms makes it difficult for some patients to attend school or work; one study found that 32% of patients with CVS were completely disabled.12 Despite increasing awareness of this disorder, patients often are misdiagnosed. The prevalence of CVS in an outpatient gastroenterology clinic in the United Kingdom was 11% and was markedly underdiagnosed in the community.17 Only 5% of patients who were subsequently diagnosed with CVS were initially diagnosed accurately by their referring physician despite meeting criteria for the disorder.17 A subset of patients with CVS even undergo futile surgeries.13 Fleisher et al. noted that 30% of a 41-patient cohort underwent cholecystectomy for CVS symptoms without any improvement in disease.12 Prompt diagnosis and appropriate therapy is essential to improve patient outcomes and improve quality of life.

CVS is associated with various comorbidities such as migraine, anxiety, depression and dysautonomia, which can further impair quality of life.18,19 Approximately 70% of CVS patients report a personal or family history of migraine. Anxiety and depression affects nearly half of patients with CVS.13 Cannabis use is significantly more prevalent among patients with CVS than patients without CVS.20

Role of cannabis in CVS

The role of cannabis in the pathogenesis of symptoms in CVS is controversial. While cannabis has antiemetic properties, there is a strong link between its use and CVS. The use of cannabis has increased over the past decade with increasing legalization.21 Several studies have shown that 40%-80% of patients with CVS use cannabis.22,23 Following this, cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (CHS) was coined as a separate entity based on this statistical association, though there are no data to support the notion that cannabis causes vomiting.24,25 CHS has clinical features that are indistinguishable from CVS except for the chronic heavy cannabis use. A peculiar bathing behavior called “compulsive hot-water bathing” has been described and was thought to be pathognomonic of cannabis use.26 During an episode, patients will take multiple hot showers/baths, which temporarily alleviate their symptoms. Many patients even report running out of hot water and sometimes check into a hotel for a continuous supply of hot water. A small number of patients may sustain burns from the hot-water bathing. However, studies show that this hot-water bathing behavior also is seen in about 50% of patents with CVS who do not use cannabis.22

CHS is now defined by Rome IV criteria, which include episodes of nausea and vomiting similar to CVS preceded by chronic, heavy cannabis use. Patients must have complete resolution of symptoms following cessation.1 A recent systematic review of 376 cases of purported CHS showed that only 59 (15.7%) met Rome IV criteria for this disorder.27 This is because of considerable heterogeneity in how the diagnosis of CHS was made and the lack of standard diagnostic criteria at the time. Some cases of CHS were diagnosed merely based on an association of vomiting, hot-water bathing, and cannabis use.28 Only a minority of patients (71,19%) had a duration of follow-up more than 4 weeks, which would make it impossible to establish a diagnosis of CHS. A period of at least a year or a duration of time that spans at least three episodes is generally recommended to determine if abstinence from cannabis causes a true resolution of symptoms.27 Whether CHS is a separate entity or a subtype of CVS remains to be determined. The paradoxical effects of cannabis may happen because of the use of highly potent cannabis products that are currently in use. A complete discussion of the role of cannabis in CVS is beyond the scope of this article, and the reader is referred to a recent systematic review and discussion.27

Treatment

CVS should be treated based on a biopsychosocial model with a multidisciplinary team that includes a gastroenterologist with knowledge of CVS, primary care physician, psychologist, psychiatrist, and sleep specialist if needed.16 Initiating prophylactic treatment is based on the severity of disease. An algorithm for the treatment of CVS based on severity of symptoms is shown below.

Figure 2. Adapted and reprinted by permission from the Licensor: Springer Nature, Current Treatment Options in Gastroenterology, Bhandari S, Venkatesan T. Novel Treatments for Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome: Beyond Ondansetron and Amitriptyline, 14:495-506, Copyright 2016.

Patients who have mild disease (defined as fewer than four episodes/year, episodes lasting up to 2 days, quick recovery from episodes, or episodes not requiring ED care or hospitalization) are usually prescribed abortive medications.16 These medications are best administered during the prodromal phase and can prevent progression to the emetic phase. Medications used for aborting episodes include sumatriptan (20 mg intranasal or 6 mg subcutaneous), ondansetron (8 mg sublingual), and diphenhydramine (25-50 mg).30,31 This combination can help abort symptoms and potentially avoid ED visits or hospitalizations. Patients with moderate-to-severe CVS are offered prophylactic therapy in addition to abortive therapy.16

Recent guidelines recommend tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) as the first-line agent in the prophylaxis of CVS episodes. Data from 14 studies determined that 70% (413/600) of patients responded partially or completely to TCAs.16 An open-label study of 46 patients by Hejazi et al. noted a decline in the number of CVS episodes from 17 to 3, in the duration of a CVS episode from 6 to 2 days, and in the number of ED visits/ hospitalizations from 15 to 3.3.32Amitriptyline should be started at 25 mg at night and titrated up by 10-25 mg each week to minimize emergence of side effects. The mean effective dose is 75-100 mg or 1.0-1.5 mg/kg. An EKG should be checked at baseline and during titration to monitor the QT interval. Unfortunately, side effects from TCAs are quite common and include cognitive impairment, drowsiness, dryness of mouth, weight gain, constipation, and mood changes, which may warrant dose reduction or discontinuation. Antiepileptics such as topiramate, mitochondrial supplements such as Coenzyme Q10 and riboflavin are alternative prophylactic agents in CVS.33 Aprepitant, a newer NK1 receptor antagonist has been found to be effective in refractory CVS.34 In addition to pharmacotherapy, addressing comorbid conditions such as anxiety and depression and counseling patients to abstain from heavy cannabis use is also important to achieve good health care outcomes.

In summary, CVS is a common, chronic functional GI disorder with episodic nausea, vomiting, and often, abdominal pain. Symptoms can be disabling, and prompt diagnosis and therapy is important. CVS is associated with multiple comorbid conditions such as migraine, anxiety and depression, and a biopsychosocial model of care is essential. Medications such as amitriptyline are effective in the prophylaxis of CVS, but side effects hamper their use. Recent recommendations for management of CVS have been published.16 Cannabis is frequently used by patients for symptom relief but use of high potency products may cause worsening of symptoms or unmask symptoms in genetically predisposed individuals.23 Studies to elucidate the pathophysiology of CVS should help in the development of better therapies.

Dr. Mooers is PGY-2, an internal medicine resident in the department of medicine, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee; Dr. Venkatesan is professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, department of medicine, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee. The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

References

1. Stanghellini V et al. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1380-92.

2. Aziz I et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Apr;17(5):878-86.

3. Kovacic K et al. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2018;20(10):46.

4. Zaki EA et al. Cephalalgia. 2009;29:719-28.

5. Venkatesan T et al. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014;14:181.

6. Ellingsen DM et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;29 (6)e13004 9.

7. Venkatesan T et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;28:1409-18.

8. Wasilewski A et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:933-9.

9. van Sickle MD et al. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2003;285:G566-76.

10. Parker LA et al. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;163:1411-22.

11. van Sickle MD et al. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:767-74.

12. Fleisher DR et al. BMC Med. 2005;3:20.

13. Kumar N et al. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:52.

14. Li BU et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;47:379-93.

15. Bhandari S et al. Clin Auton Res. 2018 Apr;28(2):203-9.

16. Venkatesan T et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019;31 Suppl 2:e13604. doi: 10.1111/nmo.13604.

17. Sagar RC et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018;30. doi: 10.1111/nmo.13174.

18. Taranukha T et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018 Apr;30(4):e13245. doi: 10.1111/nmo.13245.

19. Bhandari S and Venkatesan T. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62:2035-44.

20. Choung RS et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24:20-6, e21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2011.01791.x.

21. Bhandari S et al. Intern Med J. 2019 May;49(5):649-55.

22. Venkatesan T et al. Exp Brain Res. 2014; 232:2563-70.

23. Venkatesan T et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Jul 25. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.07.039.

24. Simonetto DA et al. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:114-9.

25. Wallace EA et al. South Med J. 2011;104:659-64.

26. Allen JH et al. Gut. 2004;53:1566-70.

27. Venkatesan T et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019;31 Suppl 2:e13606. doi: 10.1111/nmo.13606.

28. Habboushe J et al. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2018;122:660-2.

29. Bhandari S and Venkatesan T. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2016;14:495-506.

30. Hikita T et al. Cephalalgia. 2011;31:504-7.

31. Fuseau E et al. Clin Pharmacokinet 2002;41:801-11.

32. Hejazi RA et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:18-21.

33. Sezer OB and Sezer T. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;22:656-60.

34. Cristofori F et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40:309-17.

Introduction

Cyclic vomiting syndrome (CVS) is a chronic disorder of gut-brain interaction (DGBI) and is characterized by recurrent episodes of severe nausea, vomiting, and often, abdominal pain. Patients are usually asymptomatic in between episodes.1 CVS was considered a pediatric disease but is now known to be as common in adults. The prevalence of CVS in adults was 2% in a recent population-based study.2 Patients are predominantly white. Both males and females are affected with some studies showing a female preponderance. The mean age of onset is 5 years in children and 35 years in adults.3

The etiology of CVS is not known, but various hypotheses have been proposed. Zaki et al. showed that two mitochondrial DNA polymorphisms 16519T and 3010A were associated with a 17-fold increased odds of having CVS in children.4 These polymorphisms were not associated with CVS in adults.5 Alterations in the brain-gut axis also have been shown in CVS. Functional neuroimaging studies demonstrate that patients with CVS displayed increased connectivity between insula and salience networks with concomitant decrease in connectivity to somatosensory networks.6 Recent data also indicate that the endocannabinoid system (ECS) and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis are implicated in CVS with an increase in serum endocannabinoid concentration during an episode.7 The same study also showed a significant increase in salivary cortisol in CVS patients who used cannabis. Further, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the gene that encodes for the cannabinoid receptor type 1 (CB1R) are implicated in CVS.8 The CB1R is part of the ECS and is densely expressed in brain areas involved in emesis, such as the dorsal vagal complex consisting of the area postrema (AP), nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS), and also the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus.9 Wasilewski et al. showed an increased risk of CVS among individuals with AG and GG genotypes of CNR1 rs806380 (P less than .01), whereas the CC genotype of CNR1 rs806368 was associated with a decreased risk of CVS (P less than .05).8 CB1R agonists – endocannabinoids and tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) – have acute antiemetic and anxiolytic effects.9-11 The apparent paradoxical effects of cannabis in this patient population are yet to be explained and need further study.

Diagnosis and clinical features of CVS

Figure 1: Phases of Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome12

Adapted from Fleisher DR, Gornowicz B, Adams K, Burch R, Feldman EJ. Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome in 41 adults: The illness, the patients, and problems of management. BMC Med 2005;3:20. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, modification, and reproduction in any medium.

CVS consists of four phases which include the a) prodromal phase, b) the episodic phase, c) recovery phase, and d) the interepisodic phase; and was first described by David Fleisher.12 The phases of CVS are important for clinicians and patients alike as they have therapeutic implications. The administration of abortive medications during a prodrome can terminate an episode. The phases of CVS are shown above.

Most patients (~ 93%) have a prodromal phase. Symptoms during this phase can include nausea, abdominal pain, diaphoresis, fatigue, weakness, hot flashes, chills, shivering, increased thirst, loss of appetite, burping, lightheadedness, and paresthesia.13 Some patients report a sense of impending doom and many have symptoms consistent with panic. If untreated, this progresses to the emetic phase and patients have unrelenting nausea, retching, vomiting, and other symptoms. During an episode, patients may vomit up to 20 times per hour and the episode may last several hours to days. During this phase, patients are sometimes described as being in a “conscious coma” and exhibit lethargy, listlessness, withdrawal, and sometimes disorientation.14,15 The emetic phase is followed by the recovery phase, during which symptoms subside and patients are able to resume oral intake. Patients are usually asymptomatic between episodes but ~ 30% can have interepisodic nausea and dyspepsia. In some patients, episodes become progressively longer and the interepisodic phase is considerably shortened and patients have a “coalescence of symptoms.”12 It is important to elicit a thorough history in all patients with vomiting in order to make an accurate diagnosis of CVS since coalescence of symptoms only occurs over a period of time. Episodes often are triggered by psychological stress, both positive and negative. Common triggers can include positive events such as birthdays, holidays, and negative ones like examinations, the death of a loved one, etc. Sleep deprivation and physical exhaustion also can trigger an episode.12

CVS remains a clinical diagnosis since there are no biomarkers. While there is a lack of data on the optimal work-up in these patients, experts recommend an upper endoscopy or upper GI series in order to rule out alternative gastric and intestinal pathology (e.g., malrotation with volvulus).16 Of note, a gastric-emptying study is not recommended as part of the routine work-up as per recent guidelines because of the poor specificity of this test in establishing a diagnosis of CVS.16 Biochemical testing including a complete blood count, serum electrolytes, serum glucose, liver panel, and urinalysis is also warranted. Any additional testing is indicated when clinical features suggest an alternative diagnosis. For instance, neurologic symptoms might warrant a cranial MRI to exclude an intracerebral tumor or other lesions of the brain.

The severity and unpredictable nature of symptoms makes it difficult for some patients to attend school or work; one study found that 32% of patients with CVS were completely disabled.12 Despite increasing awareness of this disorder, patients often are misdiagnosed. The prevalence of CVS in an outpatient gastroenterology clinic in the United Kingdom was 11% and was markedly underdiagnosed in the community.17 Only 5% of patients who were subsequently diagnosed with CVS were initially diagnosed accurately by their referring physician despite meeting criteria for the disorder.17 A subset of patients with CVS even undergo futile surgeries.13 Fleisher et al. noted that 30% of a 41-patient cohort underwent cholecystectomy for CVS symptoms without any improvement in disease.12 Prompt diagnosis and appropriate therapy is essential to improve patient outcomes and improve quality of life.

CVS is associated with various comorbidities such as migraine, anxiety, depression and dysautonomia, which can further impair quality of life.18,19 Approximately 70% of CVS patients report a personal or family history of migraine. Anxiety and depression affects nearly half of patients with CVS.13 Cannabis use is significantly more prevalent among patients with CVS than patients without CVS.20

Role of cannabis in CVS

The role of cannabis in the pathogenesis of symptoms in CVS is controversial. While cannabis has antiemetic properties, there is a strong link between its use and CVS. The use of cannabis has increased over the past decade with increasing legalization.21 Several studies have shown that 40%-80% of patients with CVS use cannabis.22,23 Following this, cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (CHS) was coined as a separate entity based on this statistical association, though there are no data to support the notion that cannabis causes vomiting.24,25 CHS has clinical features that are indistinguishable from CVS except for the chronic heavy cannabis use. A peculiar bathing behavior called “compulsive hot-water bathing” has been described and was thought to be pathognomonic of cannabis use.26 During an episode, patients will take multiple hot showers/baths, which temporarily alleviate their symptoms. Many patients even report running out of hot water and sometimes check into a hotel for a continuous supply of hot water. A small number of patients may sustain burns from the hot-water bathing. However, studies show that this hot-water bathing behavior also is seen in about 50% of patents with CVS who do not use cannabis.22

CHS is now defined by Rome IV criteria, which include episodes of nausea and vomiting similar to CVS preceded by chronic, heavy cannabis use. Patients must have complete resolution of symptoms following cessation.1 A recent systematic review of 376 cases of purported CHS showed that only 59 (15.7%) met Rome IV criteria for this disorder.27 This is because of considerable heterogeneity in how the diagnosis of CHS was made and the lack of standard diagnostic criteria at the time. Some cases of CHS were diagnosed merely based on an association of vomiting, hot-water bathing, and cannabis use.28 Only a minority of patients (71,19%) had a duration of follow-up more than 4 weeks, which would make it impossible to establish a diagnosis of CHS. A period of at least a year or a duration of time that spans at least three episodes is generally recommended to determine if abstinence from cannabis causes a true resolution of symptoms.27 Whether CHS is a separate entity or a subtype of CVS remains to be determined. The paradoxical effects of cannabis may happen because of the use of highly potent cannabis products that are currently in use. A complete discussion of the role of cannabis in CVS is beyond the scope of this article, and the reader is referred to a recent systematic review and discussion.27

Treatment