User login

Women and Heart Disease: Symptom Recognition and Care

Infant mortality generally unchanged in 2016

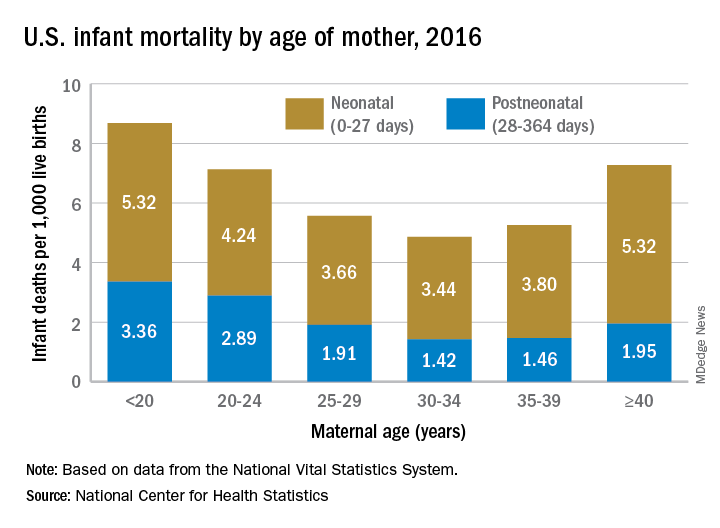

Infant mortality in the United Sates dropped very slightly from 2015 to 2016 and has not changed significantly since 2011, according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

Overall infant mortality was 5.87 per 1,000 live births in 2016, which was not significantly less than the 2015 rate of 5.90 per 1,000 or the rate of 6.07 per 1,000 recorded in 2011, the NCHS said in a recent Data Brief. The rate for 2016 works out to 3.88 per 1,000 for the neonatal period (0-27 days) and 1.99 per 1,000 during the postneonatal period (28-364 days).

The rate was lowest for mothers aged 30-34 years (4.86 per 1,000) and highest for those under 20 years (8.69). All overall rates by maternal age were significantly different from each other, except for those of mothers aged 20-24 years (7.13) and those aged 40 years and over (7.27). Neonatal mortality was highest for the under-20 group and the 40-and-over group at 5.32 per 1,000, with the difference between them coming during the postneonatal period: 3.36 for those under 20 and 1.95 for the 40-and-overs, the NCHS investigators reported based on data from the National Vital Statistics System.

The leading cause of death during the neonatal period in 2016 was low birth weight at 98 per 1,000 live births, with congenital malformations second at 86 per 1,000. The leading cause of death in the postneonatal period was congenital malformations at 36 per 1,000, followed by sudden infant death syndrome (35 per 1,000), unintentional injuries (27 per 1,000), diseases of the circulatory system (9 per 1,000), and homicide (6 per 1,000), they added.

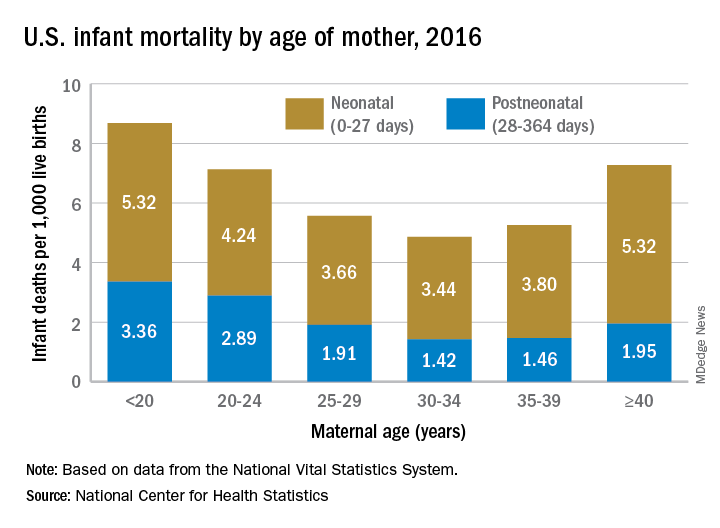

Infant mortality in the United Sates dropped very slightly from 2015 to 2016 and has not changed significantly since 2011, according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

Overall infant mortality was 5.87 per 1,000 live births in 2016, which was not significantly less than the 2015 rate of 5.90 per 1,000 or the rate of 6.07 per 1,000 recorded in 2011, the NCHS said in a recent Data Brief. The rate for 2016 works out to 3.88 per 1,000 for the neonatal period (0-27 days) and 1.99 per 1,000 during the postneonatal period (28-364 days).

The rate was lowest for mothers aged 30-34 years (4.86 per 1,000) and highest for those under 20 years (8.69). All overall rates by maternal age were significantly different from each other, except for those of mothers aged 20-24 years (7.13) and those aged 40 years and over (7.27). Neonatal mortality was highest for the under-20 group and the 40-and-over group at 5.32 per 1,000, with the difference between them coming during the postneonatal period: 3.36 for those under 20 and 1.95 for the 40-and-overs, the NCHS investigators reported based on data from the National Vital Statistics System.

The leading cause of death during the neonatal period in 2016 was low birth weight at 98 per 1,000 live births, with congenital malformations second at 86 per 1,000. The leading cause of death in the postneonatal period was congenital malformations at 36 per 1,000, followed by sudden infant death syndrome (35 per 1,000), unintentional injuries (27 per 1,000), diseases of the circulatory system (9 per 1,000), and homicide (6 per 1,000), they added.

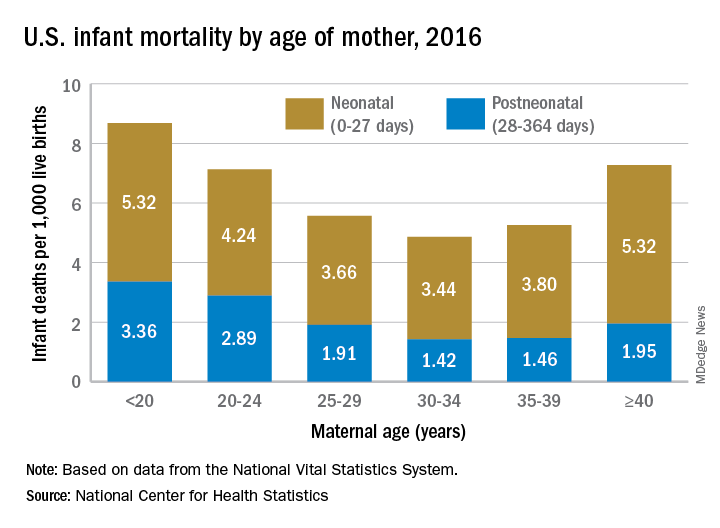

Infant mortality in the United Sates dropped very slightly from 2015 to 2016 and has not changed significantly since 2011, according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

Overall infant mortality was 5.87 per 1,000 live births in 2016, which was not significantly less than the 2015 rate of 5.90 per 1,000 or the rate of 6.07 per 1,000 recorded in 2011, the NCHS said in a recent Data Brief. The rate for 2016 works out to 3.88 per 1,000 for the neonatal period (0-27 days) and 1.99 per 1,000 during the postneonatal period (28-364 days).

The rate was lowest for mothers aged 30-34 years (4.86 per 1,000) and highest for those under 20 years (8.69). All overall rates by maternal age were significantly different from each other, except for those of mothers aged 20-24 years (7.13) and those aged 40 years and over (7.27). Neonatal mortality was highest for the under-20 group and the 40-and-over group at 5.32 per 1,000, with the difference between them coming during the postneonatal period: 3.36 for those under 20 and 1.95 for the 40-and-overs, the NCHS investigators reported based on data from the National Vital Statistics System.

The leading cause of death during the neonatal period in 2016 was low birth weight at 98 per 1,000 live births, with congenital malformations second at 86 per 1,000. The leading cause of death in the postneonatal period was congenital malformations at 36 per 1,000, followed by sudden infant death syndrome (35 per 1,000), unintentional injuries (27 per 1,000), diseases of the circulatory system (9 per 1,000), and homicide (6 per 1,000), they added.

Evidence coming on best preeclampsia treatment threshold

CHICAGO – It’s clear that there’s a dose-dependent relationship between hypertension in pregnancy and poor outcomes, but, even so, treatment usually doesn’t begin until women hit 160/105 mm Hg or higher, according to Mark Santillan, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology – maternal fetal medicine at the University of Iowa, Iowa City.

That might soon change. The National Institutes of Health–funded CHAPS (Chronic Hypertension and Pregnancy) trial is testing whether earlier intervention improves outcomes, and it hopes to define proper treatment targets, which are uncertain at this point. Results are expected as soon as 2020.

What’s already changed is that the old treatment standby – methyldopa – has fallen out of favor for labetalol and nifedipine, which have been shown to work better. “Sometimes, we will throw on hydrochlorothiazide after we max out our beta- and calcium channel blockers,” Dr. Santillan said at the joint scientific sessions of the American Heart Association Council on Hypertension, AHA Council on Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease, and American Society of Hypertension (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 Oct 1;10:CD002252).

For severe hypertension, “most of the time we start off with IV hydralazine or IV labetalol” in the hospital. “You give a dose and check blood pressure in 10 or 20 minutes,” he said. If it hasn’t dropped, “give another dose until you reach your max dose.” When intravenous access is an issue, oral nifedipine is a good option (Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Apr;129[4]:e90-e95).

Delivery date is key; babies exposed to chronic hypertension are more likely to be stillborn. For hypertension without symptoms, delivery is at around 38 weeks. For mild preeclampsia – hypertension with only minor symptoms – it’s at 37 weeks.

In more severe cases – hypertension with pulmonary edema, renal insufficiency, and other problems – “the general gestalt is to stabilize and deliver when you can. See if you can get up to at least 34 weeks,” Dr. Santillan said. However, when women “have full-on HELLP syndrome [hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelet count], we often just deliver [immediately] because there’s not a lot of stabilization” that can be done. “We give magnesium after delivery to help decrease the risk of seizure,” he added.

Guidelines still use 140/90 mm Hg to define hypertension in pregnancy. When that level is reached, “you don’t need proteinuria anymore to diagnose preeclampsia. You need to have hypertension and something that looks like HELLP,” such as impaired liver function or neurologic symptoms, he said. Onset before 34 weeks portends more severe disease.

Daily baby aspirin 81 mg is known to help prevent preeclampsia, if only a little bit, so anyone with a history of preeclampsia or twin pregnancy, chronic hypertension, diabetes, renal disease, or autoimmune disease should automatically be put on aspirin prophylaxis. Women with two or more moderate risk factors – first pregnancy, obesity, preeclamptic family history, or aged 35 years or older – also should also get baby aspirin. Vitamin C, bed rest, and other preventative measures haven’t panned out in trials.

Investigators are looking for better predictors of preeclampsia; uterine artery blood flow is among the promising markers. However, it and other options are “expensive ventures” if you’re just going to end up in the same place, giving baby aspirin, Dr. Santillan said.

Dr. Santillan reported that he holds three patents; two on copeptin to predict preeclampsia and one on vasopressin receptor antagonists to treat it.

CHICAGO – It’s clear that there’s a dose-dependent relationship between hypertension in pregnancy and poor outcomes, but, even so, treatment usually doesn’t begin until women hit 160/105 mm Hg or higher, according to Mark Santillan, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology – maternal fetal medicine at the University of Iowa, Iowa City.

That might soon change. The National Institutes of Health–funded CHAPS (Chronic Hypertension and Pregnancy) trial is testing whether earlier intervention improves outcomes, and it hopes to define proper treatment targets, which are uncertain at this point. Results are expected as soon as 2020.

What’s already changed is that the old treatment standby – methyldopa – has fallen out of favor for labetalol and nifedipine, which have been shown to work better. “Sometimes, we will throw on hydrochlorothiazide after we max out our beta- and calcium channel blockers,” Dr. Santillan said at the joint scientific sessions of the American Heart Association Council on Hypertension, AHA Council on Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease, and American Society of Hypertension (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 Oct 1;10:CD002252).

For severe hypertension, “most of the time we start off with IV hydralazine or IV labetalol” in the hospital. “You give a dose and check blood pressure in 10 or 20 minutes,” he said. If it hasn’t dropped, “give another dose until you reach your max dose.” When intravenous access is an issue, oral nifedipine is a good option (Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Apr;129[4]:e90-e95).

Delivery date is key; babies exposed to chronic hypertension are more likely to be stillborn. For hypertension without symptoms, delivery is at around 38 weeks. For mild preeclampsia – hypertension with only minor symptoms – it’s at 37 weeks.

In more severe cases – hypertension with pulmonary edema, renal insufficiency, and other problems – “the general gestalt is to stabilize and deliver when you can. See if you can get up to at least 34 weeks,” Dr. Santillan said. However, when women “have full-on HELLP syndrome [hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelet count], we often just deliver [immediately] because there’s not a lot of stabilization” that can be done. “We give magnesium after delivery to help decrease the risk of seizure,” he added.

Guidelines still use 140/90 mm Hg to define hypertension in pregnancy. When that level is reached, “you don’t need proteinuria anymore to diagnose preeclampsia. You need to have hypertension and something that looks like HELLP,” such as impaired liver function or neurologic symptoms, he said. Onset before 34 weeks portends more severe disease.

Daily baby aspirin 81 mg is known to help prevent preeclampsia, if only a little bit, so anyone with a history of preeclampsia or twin pregnancy, chronic hypertension, diabetes, renal disease, or autoimmune disease should automatically be put on aspirin prophylaxis. Women with two or more moderate risk factors – first pregnancy, obesity, preeclamptic family history, or aged 35 years or older – also should also get baby aspirin. Vitamin C, bed rest, and other preventative measures haven’t panned out in trials.

Investigators are looking for better predictors of preeclampsia; uterine artery blood flow is among the promising markers. However, it and other options are “expensive ventures” if you’re just going to end up in the same place, giving baby aspirin, Dr. Santillan said.

Dr. Santillan reported that he holds three patents; two on copeptin to predict preeclampsia and one on vasopressin receptor antagonists to treat it.

CHICAGO – It’s clear that there’s a dose-dependent relationship between hypertension in pregnancy and poor outcomes, but, even so, treatment usually doesn’t begin until women hit 160/105 mm Hg or higher, according to Mark Santillan, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology – maternal fetal medicine at the University of Iowa, Iowa City.

That might soon change. The National Institutes of Health–funded CHAPS (Chronic Hypertension and Pregnancy) trial is testing whether earlier intervention improves outcomes, and it hopes to define proper treatment targets, which are uncertain at this point. Results are expected as soon as 2020.

What’s already changed is that the old treatment standby – methyldopa – has fallen out of favor for labetalol and nifedipine, which have been shown to work better. “Sometimes, we will throw on hydrochlorothiazide after we max out our beta- and calcium channel blockers,” Dr. Santillan said at the joint scientific sessions of the American Heart Association Council on Hypertension, AHA Council on Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease, and American Society of Hypertension (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 Oct 1;10:CD002252).

For severe hypertension, “most of the time we start off with IV hydralazine or IV labetalol” in the hospital. “You give a dose and check blood pressure in 10 or 20 minutes,” he said. If it hasn’t dropped, “give another dose until you reach your max dose.” When intravenous access is an issue, oral nifedipine is a good option (Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Apr;129[4]:e90-e95).

Delivery date is key; babies exposed to chronic hypertension are more likely to be stillborn. For hypertension without symptoms, delivery is at around 38 weeks. For mild preeclampsia – hypertension with only minor symptoms – it’s at 37 weeks.

In more severe cases – hypertension with pulmonary edema, renal insufficiency, and other problems – “the general gestalt is to stabilize and deliver when you can. See if you can get up to at least 34 weeks,” Dr. Santillan said. However, when women “have full-on HELLP syndrome [hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelet count], we often just deliver [immediately] because there’s not a lot of stabilization” that can be done. “We give magnesium after delivery to help decrease the risk of seizure,” he added.

Guidelines still use 140/90 mm Hg to define hypertension in pregnancy. When that level is reached, “you don’t need proteinuria anymore to diagnose preeclampsia. You need to have hypertension and something that looks like HELLP,” such as impaired liver function or neurologic symptoms, he said. Onset before 34 weeks portends more severe disease.

Daily baby aspirin 81 mg is known to help prevent preeclampsia, if only a little bit, so anyone with a history of preeclampsia or twin pregnancy, chronic hypertension, diabetes, renal disease, or autoimmune disease should automatically be put on aspirin prophylaxis. Women with two or more moderate risk factors – first pregnancy, obesity, preeclamptic family history, or aged 35 years or older – also should also get baby aspirin. Vitamin C, bed rest, and other preventative measures haven’t panned out in trials.

Investigators are looking for better predictors of preeclampsia; uterine artery blood flow is among the promising markers. However, it and other options are “expensive ventures” if you’re just going to end up in the same place, giving baby aspirin, Dr. Santillan said.

Dr. Santillan reported that he holds three patents; two on copeptin to predict preeclampsia and one on vasopressin receptor antagonists to treat it.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM JOINT HYPERTENSION 2018

NIH director expresses concern over CRISPR-cas9 baby claim

The National Institutes of Health is deeply concerned about the work just presented at the Second International Summit on Human Genome Editing in Hong Kong by Dr. He Jiankui, who described his effort using CRISPR-Cas9 on human embryos to disable the CCR5 gene. He claims that the two embryos were subsequently implanted, and infant twins have been born.

This work represents a deeply disturbing willingness by Dr. He and his team to flout international ethical norms. The project was largely carried out in secret, the medical necessity for inactivation of CCR5 in these infants is utterly unconvincing, the informed consent process appears highly questionable, and the possibility of damaging off-target effects has not been satisfactorily explored. It is profoundly unfortunate that the first apparent application of this powerful technique to the human germline has been carried out so irresponsibly.

The need for development of binding international consensus on setting limits for this kind of research, now being debated in Hong Kong, has never been more apparent. Without such limits, the world will face the serious risk of a deluge of similarly ill-considered and unethical projects.

Should such epic scientific misadventures proceed, a technology with enormous promise for prevention and treatment of disease will be overshadowed by justifiable public outrage, fear, and disgust.

Lest there be any doubt, and as we have stated previously, NIH does not support the use of gene-editing technologies in human embryos.

Francis S. Collins, M.D., Ph.D. is director of the National Institutes of Health. His comments were made in a statement Nov. 28.

The National Institutes of Health is deeply concerned about the work just presented at the Second International Summit on Human Genome Editing in Hong Kong by Dr. He Jiankui, who described his effort using CRISPR-Cas9 on human embryos to disable the CCR5 gene. He claims that the two embryos were subsequently implanted, and infant twins have been born.

This work represents a deeply disturbing willingness by Dr. He and his team to flout international ethical norms. The project was largely carried out in secret, the medical necessity for inactivation of CCR5 in these infants is utterly unconvincing, the informed consent process appears highly questionable, and the possibility of damaging off-target effects has not been satisfactorily explored. It is profoundly unfortunate that the first apparent application of this powerful technique to the human germline has been carried out so irresponsibly.

The need for development of binding international consensus on setting limits for this kind of research, now being debated in Hong Kong, has never been more apparent. Without such limits, the world will face the serious risk of a deluge of similarly ill-considered and unethical projects.

Should such epic scientific misadventures proceed, a technology with enormous promise for prevention and treatment of disease will be overshadowed by justifiable public outrage, fear, and disgust.

Lest there be any doubt, and as we have stated previously, NIH does not support the use of gene-editing technologies in human embryos.

Francis S. Collins, M.D., Ph.D. is director of the National Institutes of Health. His comments were made in a statement Nov. 28.

The National Institutes of Health is deeply concerned about the work just presented at the Second International Summit on Human Genome Editing in Hong Kong by Dr. He Jiankui, who described his effort using CRISPR-Cas9 on human embryos to disable the CCR5 gene. He claims that the two embryos were subsequently implanted, and infant twins have been born.

This work represents a deeply disturbing willingness by Dr. He and his team to flout international ethical norms. The project was largely carried out in secret, the medical necessity for inactivation of CCR5 in these infants is utterly unconvincing, the informed consent process appears highly questionable, and the possibility of damaging off-target effects has not been satisfactorily explored. It is profoundly unfortunate that the first apparent application of this powerful technique to the human germline has been carried out so irresponsibly.

The need for development of binding international consensus on setting limits for this kind of research, now being debated in Hong Kong, has never been more apparent. Without such limits, the world will face the serious risk of a deluge of similarly ill-considered and unethical projects.

Should such epic scientific misadventures proceed, a technology with enormous promise for prevention and treatment of disease will be overshadowed by justifiable public outrage, fear, and disgust.

Lest there be any doubt, and as we have stated previously, NIH does not support the use of gene-editing technologies in human embryos.

Francis S. Collins, M.D., Ph.D. is director of the National Institutes of Health. His comments were made in a statement Nov. 28.

Omega-3 fatty acid supplementation reduces risk of preterm birth

Taking omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids during pregnancy was associated with reduced risk of preterm birth, and also may reduce the risk of babies born at a low birth weight and risk of requiring neonatal intensive care, according to a Cochrane review of 70 randomized controlled trials.

“There are not many options for preventing premature birth, so these new findings are very important for pregnant women, babies, and the health professionals who care for them,” Philippa Middleton, MPH, PhD, of Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group and the South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute, in Adelaide, stated in a press release. “We don’t yet fully understand the causes of premature labor, so predicting and preventing early birth has always been a challenge. This is one of the reasons omega-3 supplementation in pregnancy is of such great interest to researchers around the world.”

Dr. Middleton and her colleagues performed a search of the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth’s Trials Register, ClinicalTrials.gov, and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform and identified 70 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) where 19,927 women at varying levels of risk for preterm birth received omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LCPUFA), placebo, or no omega-3.

“Many pregnant women in the UK are already taking omega-3 supplements by personal choice rather than as a result of advice from health professionals,” Dr. Middleton said in the release. “It’s worth noting though that many supplements currently on the market don’t contain the optimal dose or type of omega-3 for preventing premature birth. Our review found the optimum dose was a daily supplement containing between 500 and 1,000 milligrams of long-chain omega-3 fats (containing at least 500 mg of DHA [docosahexaenoic acid]) starting at 12 weeks of pregnancy.”

In 26 RCTs (10,304 women), the risk of preterm birth under 37 weeks was 11% lower for women who took omega-3 LCPUFA compared with women who did not take omega-3 (relative risk, 0.89; 95% confidence interval, 0.81-0.97), while the risk for preterm birth under 34 weeks in 9 RCTs (5,204 women) was 42% lower for women compared with women who did not take omega-3 (RR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.44-0.77).

With regard to infant health, use of omega-3 LCPUFA during pregnancy was associated in 10 RCTs (7,416 women) with a potential reduced risk of perinatal mortality (RR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.54-1.03) and, in 9 RCTs (6,920 women), a reduced risk of neonatal intensive care admission (RR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.83-1.03). The researchers noted that omega-3 use in 15 trials (8,449 women) was potentially associated with a reduced number of babies with low birth weight (RR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.82-0.99), but an increase in babies who were large for their gestational age in 3,722 women from 6 RCTs (RR, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.97-1.36). There was no significant difference among groups with regard to babies who were born small for their gestational age or in uterine growth restriction, they said.

While maternal outcomes were examined, Dr. Middleton and her colleagues found no significant differences between groups in factors such as postterm induction, serious adverse events, admission to intensive care, and postnatal depression.

“Ultimately, we hope this review will make a real contribution to the evidence base we need to reduce premature births, which continue to be one of the most pressing and intractable maternal and child health problems in every country around the world,” Dr. Middleton said.

The National Institutes of Health funded the review. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Middleton P et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018; doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003402.pub3.

Taking omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids during pregnancy was associated with reduced risk of preterm birth, and also may reduce the risk of babies born at a low birth weight and risk of requiring neonatal intensive care, according to a Cochrane review of 70 randomized controlled trials.

“There are not many options for preventing premature birth, so these new findings are very important for pregnant women, babies, and the health professionals who care for them,” Philippa Middleton, MPH, PhD, of Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group and the South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute, in Adelaide, stated in a press release. “We don’t yet fully understand the causes of premature labor, so predicting and preventing early birth has always been a challenge. This is one of the reasons omega-3 supplementation in pregnancy is of such great interest to researchers around the world.”

Dr. Middleton and her colleagues performed a search of the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth’s Trials Register, ClinicalTrials.gov, and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform and identified 70 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) where 19,927 women at varying levels of risk for preterm birth received omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LCPUFA), placebo, or no omega-3.

“Many pregnant women in the UK are already taking omega-3 supplements by personal choice rather than as a result of advice from health professionals,” Dr. Middleton said in the release. “It’s worth noting though that many supplements currently on the market don’t contain the optimal dose or type of omega-3 for preventing premature birth. Our review found the optimum dose was a daily supplement containing between 500 and 1,000 milligrams of long-chain omega-3 fats (containing at least 500 mg of DHA [docosahexaenoic acid]) starting at 12 weeks of pregnancy.”

In 26 RCTs (10,304 women), the risk of preterm birth under 37 weeks was 11% lower for women who took omega-3 LCPUFA compared with women who did not take omega-3 (relative risk, 0.89; 95% confidence interval, 0.81-0.97), while the risk for preterm birth under 34 weeks in 9 RCTs (5,204 women) was 42% lower for women compared with women who did not take omega-3 (RR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.44-0.77).

With regard to infant health, use of omega-3 LCPUFA during pregnancy was associated in 10 RCTs (7,416 women) with a potential reduced risk of perinatal mortality (RR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.54-1.03) and, in 9 RCTs (6,920 women), a reduced risk of neonatal intensive care admission (RR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.83-1.03). The researchers noted that omega-3 use in 15 trials (8,449 women) was potentially associated with a reduced number of babies with low birth weight (RR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.82-0.99), but an increase in babies who were large for their gestational age in 3,722 women from 6 RCTs (RR, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.97-1.36). There was no significant difference among groups with regard to babies who were born small for their gestational age or in uterine growth restriction, they said.

While maternal outcomes were examined, Dr. Middleton and her colleagues found no significant differences between groups in factors such as postterm induction, serious adverse events, admission to intensive care, and postnatal depression.

“Ultimately, we hope this review will make a real contribution to the evidence base we need to reduce premature births, which continue to be one of the most pressing and intractable maternal and child health problems in every country around the world,” Dr. Middleton said.

The National Institutes of Health funded the review. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Middleton P et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018; doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003402.pub3.

Taking omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids during pregnancy was associated with reduced risk of preterm birth, and also may reduce the risk of babies born at a low birth weight and risk of requiring neonatal intensive care, according to a Cochrane review of 70 randomized controlled trials.

“There are not many options for preventing premature birth, so these new findings are very important for pregnant women, babies, and the health professionals who care for them,” Philippa Middleton, MPH, PhD, of Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group and the South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute, in Adelaide, stated in a press release. “We don’t yet fully understand the causes of premature labor, so predicting and preventing early birth has always been a challenge. This is one of the reasons omega-3 supplementation in pregnancy is of such great interest to researchers around the world.”

Dr. Middleton and her colleagues performed a search of the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth’s Trials Register, ClinicalTrials.gov, and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform and identified 70 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) where 19,927 women at varying levels of risk for preterm birth received omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LCPUFA), placebo, or no omega-3.

“Many pregnant women in the UK are already taking omega-3 supplements by personal choice rather than as a result of advice from health professionals,” Dr. Middleton said in the release. “It’s worth noting though that many supplements currently on the market don’t contain the optimal dose or type of omega-3 for preventing premature birth. Our review found the optimum dose was a daily supplement containing between 500 and 1,000 milligrams of long-chain omega-3 fats (containing at least 500 mg of DHA [docosahexaenoic acid]) starting at 12 weeks of pregnancy.”

In 26 RCTs (10,304 women), the risk of preterm birth under 37 weeks was 11% lower for women who took omega-3 LCPUFA compared with women who did not take omega-3 (relative risk, 0.89; 95% confidence interval, 0.81-0.97), while the risk for preterm birth under 34 weeks in 9 RCTs (5,204 women) was 42% lower for women compared with women who did not take omega-3 (RR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.44-0.77).

With regard to infant health, use of omega-3 LCPUFA during pregnancy was associated in 10 RCTs (7,416 women) with a potential reduced risk of perinatal mortality (RR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.54-1.03) and, in 9 RCTs (6,920 women), a reduced risk of neonatal intensive care admission (RR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.83-1.03). The researchers noted that omega-3 use in 15 trials (8,449 women) was potentially associated with a reduced number of babies with low birth weight (RR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.82-0.99), but an increase in babies who were large for their gestational age in 3,722 women from 6 RCTs (RR, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.97-1.36). There was no significant difference among groups with regard to babies who were born small for their gestational age or in uterine growth restriction, they said.

While maternal outcomes were examined, Dr. Middleton and her colleagues found no significant differences between groups in factors such as postterm induction, serious adverse events, admission to intensive care, and postnatal depression.

“Ultimately, we hope this review will make a real contribution to the evidence base we need to reduce premature births, which continue to be one of the most pressing and intractable maternal and child health problems in every country around the world,” Dr. Middleton said.

The National Institutes of Health funded the review. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Middleton P et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018; doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003402.pub3.

FROM COCHRANE DATABASE OF SYSTEMATIC REVIEWS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: In 26 randomized controlled trials, the risk of preterm birth at 37 weeks (10,304 women) was 11% lower and the risk of preterm birth at 34 weeks (5,204 women) in 9 RCTs was 42% lower for women taking omega-3, compared with women not taking omega-3.

Study details: A Cochrane review of 70 RCTs with a total of 19,927 women at varying levels of risk for preterm birth who received omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids, placebo, or no omega-3.

Disclosures: The National Institutes of Health funded the review. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Source: Middleton P et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003402.pub3.

Healthier lifestyle in midlife women reduces subclinical carotid atherosclerosis

Women who have a healthier lifestyle during the menopausal transition could significantly reduce their risk of cardiovascular disease, new research suggests.

Because women experience a steeper increase in CVD risk during and after the menopausal transition, researchers analyzed data from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN), a prospective longitudinal cohort study of 1,143 women aged 42-52 years. The report is in JAHA: Journal of the American Heart Association.

The analysis revealed that women with the highest average Healthy Lifestyle Score – a composite score of dietary quality, levels of physical activity, and smoking – over 10 years of follow-up had a 0.024-mm smaller common carotid artery intima-media thickness and 0.16-mm smaller adventitial diameter, compared to those with the lowest average score. This was after adjustment for confounders and physiological risk factors such as ethnicity, age, menopausal status, body mass index, and cholesterol levels.

“Smoking, unhealthy diet, and lack of physical activity are three well-known modifiable behavioral risk factors for CVD,” wrote Dongqing Wang of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and his coauthors. “Even after adjusting for the lifestyle-related physiological risk factors, the adherence to a healthy lifestyle composed of abstinence from smoking, healthy diet, and regular engagement in physical activity is inversely associated with atherosclerosis in midlife women.”

Women with higher average health lifestyle score also had lower levels of carotid plaque after adjustment for confounding factors, but this was no longer significant after adjustment for physiological risk factors.

The authors analyzed the three components of the healthy lifestyle score separately, and found that not smoking was strongly and significantly associated with lower scores for all three measures of subclinical atherosclerosis. Women who never smoked across the duration of the study had a 49% lower odds of having a high carotid plaque index compared with women who smoked at some point during the follow-up period.

The analysis showed an inverse association between average Alternate Healthy Eating Index score – a measure of diet quality – and smaller common carotid artery adventitial diameter, although after adjustment for BMI this association was no longer statistically significant. Likewise, the association between dietary quality and intima-media thickness was only marginally significant and lost that significance after adjustment for BMI.

Long-term physical activity was only marginally significantly associated with common carotid artery intima-media thickness, but this was not significant after adjustment for physiological risk factors. No association was found between physical activity and common carotid artery adventitial diameter or carotid plaque.

The authors said that 1.7% of the study population managed to stay in the top category for all three components of healthy lifestyle at all three follow-up time points in the study.

“The low prevalence of a healthy lifestyle in midlife women highlights the potential for lifestyle interventions aimed at this vulnerable population,” they wrote.

In particular, they highlighted abstinence from smoking as having the strongest impact on all three measures of subclinical atherosclerosis, which is known to affect women more than men. However, the outcomes from diet and physical activity weren’t so strong: The authors suggested that BMI could partly mediate the effects of healthier diet and greater levels of physical activity.

One strength of the study was its ethnically diverse population, which included African American, Chinese, and Hispanic women in addition to non-Hispanic white women. However, the study was not powered to examine the impacts ethnicity may have had on outcomes, the researchers wrote.

The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation is supported by the National Institutes of Health. No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Wang D et al. JAHA 2018 Nov. 28.

Women who have a healthier lifestyle during the menopausal transition could significantly reduce their risk of cardiovascular disease, new research suggests.

Because women experience a steeper increase in CVD risk during and after the menopausal transition, researchers analyzed data from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN), a prospective longitudinal cohort study of 1,143 women aged 42-52 years. The report is in JAHA: Journal of the American Heart Association.

The analysis revealed that women with the highest average Healthy Lifestyle Score – a composite score of dietary quality, levels of physical activity, and smoking – over 10 years of follow-up had a 0.024-mm smaller common carotid artery intima-media thickness and 0.16-mm smaller adventitial diameter, compared to those with the lowest average score. This was after adjustment for confounders and physiological risk factors such as ethnicity, age, menopausal status, body mass index, and cholesterol levels.

“Smoking, unhealthy diet, and lack of physical activity are three well-known modifiable behavioral risk factors for CVD,” wrote Dongqing Wang of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and his coauthors. “Even after adjusting for the lifestyle-related physiological risk factors, the adherence to a healthy lifestyle composed of abstinence from smoking, healthy diet, and regular engagement in physical activity is inversely associated with atherosclerosis in midlife women.”

Women with higher average health lifestyle score also had lower levels of carotid plaque after adjustment for confounding factors, but this was no longer significant after adjustment for physiological risk factors.

The authors analyzed the three components of the healthy lifestyle score separately, and found that not smoking was strongly and significantly associated with lower scores for all three measures of subclinical atherosclerosis. Women who never smoked across the duration of the study had a 49% lower odds of having a high carotid plaque index compared with women who smoked at some point during the follow-up period.

The analysis showed an inverse association between average Alternate Healthy Eating Index score – a measure of diet quality – and smaller common carotid artery adventitial diameter, although after adjustment for BMI this association was no longer statistically significant. Likewise, the association between dietary quality and intima-media thickness was only marginally significant and lost that significance after adjustment for BMI.

Long-term physical activity was only marginally significantly associated with common carotid artery intima-media thickness, but this was not significant after adjustment for physiological risk factors. No association was found between physical activity and common carotid artery adventitial diameter or carotid plaque.

The authors said that 1.7% of the study population managed to stay in the top category for all three components of healthy lifestyle at all three follow-up time points in the study.

“The low prevalence of a healthy lifestyle in midlife women highlights the potential for lifestyle interventions aimed at this vulnerable population,” they wrote.

In particular, they highlighted abstinence from smoking as having the strongest impact on all three measures of subclinical atherosclerosis, which is known to affect women more than men. However, the outcomes from diet and physical activity weren’t so strong: The authors suggested that BMI could partly mediate the effects of healthier diet and greater levels of physical activity.

One strength of the study was its ethnically diverse population, which included African American, Chinese, and Hispanic women in addition to non-Hispanic white women. However, the study was not powered to examine the impacts ethnicity may have had on outcomes, the researchers wrote.

The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation is supported by the National Institutes of Health. No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Wang D et al. JAHA 2018 Nov. 28.

Women who have a healthier lifestyle during the menopausal transition could significantly reduce their risk of cardiovascular disease, new research suggests.

Because women experience a steeper increase in CVD risk during and after the menopausal transition, researchers analyzed data from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN), a prospective longitudinal cohort study of 1,143 women aged 42-52 years. The report is in JAHA: Journal of the American Heart Association.

The analysis revealed that women with the highest average Healthy Lifestyle Score – a composite score of dietary quality, levels of physical activity, and smoking – over 10 years of follow-up had a 0.024-mm smaller common carotid artery intima-media thickness and 0.16-mm smaller adventitial diameter, compared to those with the lowest average score. This was after adjustment for confounders and physiological risk factors such as ethnicity, age, menopausal status, body mass index, and cholesterol levels.

“Smoking, unhealthy diet, and lack of physical activity are three well-known modifiable behavioral risk factors for CVD,” wrote Dongqing Wang of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and his coauthors. “Even after adjusting for the lifestyle-related physiological risk factors, the adherence to a healthy lifestyle composed of abstinence from smoking, healthy diet, and regular engagement in physical activity is inversely associated with atherosclerosis in midlife women.”

Women with higher average health lifestyle score also had lower levels of carotid plaque after adjustment for confounding factors, but this was no longer significant after adjustment for physiological risk factors.

The authors analyzed the three components of the healthy lifestyle score separately, and found that not smoking was strongly and significantly associated with lower scores for all three measures of subclinical atherosclerosis. Women who never smoked across the duration of the study had a 49% lower odds of having a high carotid plaque index compared with women who smoked at some point during the follow-up period.

The analysis showed an inverse association between average Alternate Healthy Eating Index score – a measure of diet quality – and smaller common carotid artery adventitial diameter, although after adjustment for BMI this association was no longer statistically significant. Likewise, the association between dietary quality and intima-media thickness was only marginally significant and lost that significance after adjustment for BMI.

Long-term physical activity was only marginally significantly associated with common carotid artery intima-media thickness, but this was not significant after adjustment for physiological risk factors. No association was found between physical activity and common carotid artery adventitial diameter or carotid plaque.

The authors said that 1.7% of the study population managed to stay in the top category for all three components of healthy lifestyle at all three follow-up time points in the study.

“The low prevalence of a healthy lifestyle in midlife women highlights the potential for lifestyle interventions aimed at this vulnerable population,” they wrote.

In particular, they highlighted abstinence from smoking as having the strongest impact on all three measures of subclinical atherosclerosis, which is known to affect women more than men. However, the outcomes from diet and physical activity weren’t so strong: The authors suggested that BMI could partly mediate the effects of healthier diet and greater levels of physical activity.

One strength of the study was its ethnically diverse population, which included African American, Chinese, and Hispanic women in addition to non-Hispanic white women. However, the study was not powered to examine the impacts ethnicity may have had on outcomes, the researchers wrote.

The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation is supported by the National Institutes of Health. No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Wang D et al. JAHA 2018 Nov. 28.

FROM JAHA: JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN HEART ASSOCIATION

Key clinical point: .

Major finding: Following a healthier diet and not smoking were significantly linked with lower subclinical carotid atherosclerosis in menopausal women.

Study details: A prospective, longitudinal cohort study of 1,143 women.

Disclosures: The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation is supported by the National Institutes of Health. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Source: Wang D et al. JAHA 2018 Nov. 28.

Substance use increases likelihood of psychiatric hold in pregnancy

AUSTIN, TEX. – Providers are no more likely to put an involuntary psychiatric hold on someone who is pregnant than not unless she is using substances, recent research shows.

“This raises a question regarding who psychiatrists consider to be their patients: the mother, the unborn child, or both?” Samuel J. House, MD, of the University of Arkansas, Little Rock, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law (AAPL).

Dr. House sent out a survey to members of the AAPL to learn their attitudes toward involuntary psychiatric holds on pregnant women, with and without evidence of substance use, and he presented the results at the meeting.

“We know that the rates of involuntary hospitalizations very widely” across different jurisdictions and practice settings, Dr. House said, but research has shown that age, unmarried status, psychotic symptoms, aggression, and a low level of social function are associated with involuntary commitment. He wanted to explore where pregnancy fit.

Dr. House became interested in clinicians’ perspectives on this issue when he realized how few psychiatric holds he saw among pregnant women during the 4 years he spent at a university hospital’s level 1 trauma center. He included questions about substance use in his survey because of the “recent push to criminalize substance use during pregnancy, mainly in response to the significant impact substance use during pregnancy can have on the fetus or developing child,” he said.

Dr. House received 68 survey responses from AAPL members, most of whom were male with an average age of 47 years. The 7-question survey presented various clinical scenarios and asked what the respondent would do.

The first question concerned being called to the emergency department to evaluate a 28-year-old white woman with clinical signs of depression, history of a suicide attempt, and a mother who had committed suicide when the patient was 15. However, she states during evaluation: “I could never actually kill myself. My family would be too upset, and I would go to hell.”

Two-thirds of respondents (67.6%) said they would admit the woman to an inpatient unit for stabilization, and the others would discharge her with close follow-up.

The second question asked what the clinician would do if the patient declined admission: 41.2% would discharge, and 58.8% would place the woman on a psychiatric hold.

The third question introduced a positive pregnancy test for the woman, but none of the respondents said they would cancel the psychiatric hold. Most were split between proceeding with a hold (42.6%) or proceeding with a discharge (47.1%), though 10.3% would cancel the discharge and place the patient on a hold. Ultimately, respondents were no more likely to put the woman on a hold whether she was pregnant or not.

Then the survey repeated the scenario, but instead of a positive pregnancy test, the question asked what clinicians would do if her drug screen were positive after she had refused admission. In that scenario, the woman reported daily methamphetamine use to the emergency physician.

Among respondents, 48.5% would proceed with a psychiatric hold, 42.6% would proceed with a discharge, and 8.8% would cancel the discharge and put the patient on a hold.

The final question asks clinicians’ course of action if the woman’s pregnancy test were positive after the positive drug screen. Now, only a little over a quarter of respondents (26.5%) would proceed with a discharge and follow-up. More than half (57.4%) would proceed with a hold, and 16.2% would cancel the discharge and place a psychiatric hold.

Therefore, 73.6% of clinicians would place a pregnant woman with a history of substance use on a psychiatric hold, compared with 52.9% if the woman were pregnant but not using methamphetamine.

Laws on pregnancy, substance use

Dr. House considered those findings within the context of current laws governing substance use during pregnancy., with prosecution usually requiring detection of the substance at birth or during pregnancy, or evidence of risk to the child’s health.

Tennessee is unique in considering substance abuse in pregnancy assault if the child is born with dependence or other harm from the drug use. Women in Minnesota, South Dakota, and Wisconsin can be subject to civil commitment, including required inpatient drug treatment, for substance abuse during pregnancy (Am J Psychiatry. 2016 Nov 1;173[11]:1077-80).

Mandatory reporting laws for suspected substance abuse during pregnancy exist in 15 states, mostly in the Southwest, northern Midwest, and states around the District of Columbia. And four states – Kentucky, Iowa, Minnesota, and North Dakota – require pregnant women suspected of substance abuse to be tested.

Yet, most major relevant medical associations oppose criminalization of substance use during pregnancy, including the American Psychiatric Association, the American Academy of Addiction Psychiatry, the American Medical Association, and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

“They are generally for increasing access for people, like voluntary screening, but against criminalization because it creates a barrier to accessing prenatal care,” Dr. House explained.

Aside from the question of whom psychiatrists consider their patients – the woman, her fetus, or both – the results raise another question, Dr. House said: “While studies have shown that criminalizing substance use during pregnancy discourages mothers from seeking prenatal care, does the threat of an involuntary psychiatric admission have a similar consequence?” That’s a question for further research.

No external funding was used. Dr. House was a clinical investigator without compensation for Janssen Pharmaceuticals from 2015 to 2017.

AUSTIN, TEX. – Providers are no more likely to put an involuntary psychiatric hold on someone who is pregnant than not unless she is using substances, recent research shows.

“This raises a question regarding who psychiatrists consider to be their patients: the mother, the unborn child, or both?” Samuel J. House, MD, of the University of Arkansas, Little Rock, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law (AAPL).

Dr. House sent out a survey to members of the AAPL to learn their attitudes toward involuntary psychiatric holds on pregnant women, with and without evidence of substance use, and he presented the results at the meeting.

“We know that the rates of involuntary hospitalizations very widely” across different jurisdictions and practice settings, Dr. House said, but research has shown that age, unmarried status, psychotic symptoms, aggression, and a low level of social function are associated with involuntary commitment. He wanted to explore where pregnancy fit.

Dr. House became interested in clinicians’ perspectives on this issue when he realized how few psychiatric holds he saw among pregnant women during the 4 years he spent at a university hospital’s level 1 trauma center. He included questions about substance use in his survey because of the “recent push to criminalize substance use during pregnancy, mainly in response to the significant impact substance use during pregnancy can have on the fetus or developing child,” he said.

Dr. House received 68 survey responses from AAPL members, most of whom were male with an average age of 47 years. The 7-question survey presented various clinical scenarios and asked what the respondent would do.

The first question concerned being called to the emergency department to evaluate a 28-year-old white woman with clinical signs of depression, history of a suicide attempt, and a mother who had committed suicide when the patient was 15. However, she states during evaluation: “I could never actually kill myself. My family would be too upset, and I would go to hell.”

Two-thirds of respondents (67.6%) said they would admit the woman to an inpatient unit for stabilization, and the others would discharge her with close follow-up.

The second question asked what the clinician would do if the patient declined admission: 41.2% would discharge, and 58.8% would place the woman on a psychiatric hold.

The third question introduced a positive pregnancy test for the woman, but none of the respondents said they would cancel the psychiatric hold. Most were split between proceeding with a hold (42.6%) or proceeding with a discharge (47.1%), though 10.3% would cancel the discharge and place the patient on a hold. Ultimately, respondents were no more likely to put the woman on a hold whether she was pregnant or not.

Then the survey repeated the scenario, but instead of a positive pregnancy test, the question asked what clinicians would do if her drug screen were positive after she had refused admission. In that scenario, the woman reported daily methamphetamine use to the emergency physician.

Among respondents, 48.5% would proceed with a psychiatric hold, 42.6% would proceed with a discharge, and 8.8% would cancel the discharge and put the patient on a hold.

The final question asks clinicians’ course of action if the woman’s pregnancy test were positive after the positive drug screen. Now, only a little over a quarter of respondents (26.5%) would proceed with a discharge and follow-up. More than half (57.4%) would proceed with a hold, and 16.2% would cancel the discharge and place a psychiatric hold.

Therefore, 73.6% of clinicians would place a pregnant woman with a history of substance use on a psychiatric hold, compared with 52.9% if the woman were pregnant but not using methamphetamine.

Laws on pregnancy, substance use

Dr. House considered those findings within the context of current laws governing substance use during pregnancy., with prosecution usually requiring detection of the substance at birth or during pregnancy, or evidence of risk to the child’s health.

Tennessee is unique in considering substance abuse in pregnancy assault if the child is born with dependence or other harm from the drug use. Women in Minnesota, South Dakota, and Wisconsin can be subject to civil commitment, including required inpatient drug treatment, for substance abuse during pregnancy (Am J Psychiatry. 2016 Nov 1;173[11]:1077-80).

Mandatory reporting laws for suspected substance abuse during pregnancy exist in 15 states, mostly in the Southwest, northern Midwest, and states around the District of Columbia. And four states – Kentucky, Iowa, Minnesota, and North Dakota – require pregnant women suspected of substance abuse to be tested.

Yet, most major relevant medical associations oppose criminalization of substance use during pregnancy, including the American Psychiatric Association, the American Academy of Addiction Psychiatry, the American Medical Association, and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

“They are generally for increasing access for people, like voluntary screening, but against criminalization because it creates a barrier to accessing prenatal care,” Dr. House explained.

Aside from the question of whom psychiatrists consider their patients – the woman, her fetus, or both – the results raise another question, Dr. House said: “While studies have shown that criminalizing substance use during pregnancy discourages mothers from seeking prenatal care, does the threat of an involuntary psychiatric admission have a similar consequence?” That’s a question for further research.

No external funding was used. Dr. House was a clinical investigator without compensation for Janssen Pharmaceuticals from 2015 to 2017.

AUSTIN, TEX. – Providers are no more likely to put an involuntary psychiatric hold on someone who is pregnant than not unless she is using substances, recent research shows.

“This raises a question regarding who psychiatrists consider to be their patients: the mother, the unborn child, or both?” Samuel J. House, MD, of the University of Arkansas, Little Rock, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law (AAPL).

Dr. House sent out a survey to members of the AAPL to learn their attitudes toward involuntary psychiatric holds on pregnant women, with and without evidence of substance use, and he presented the results at the meeting.

“We know that the rates of involuntary hospitalizations very widely” across different jurisdictions and practice settings, Dr. House said, but research has shown that age, unmarried status, psychotic symptoms, aggression, and a low level of social function are associated with involuntary commitment. He wanted to explore where pregnancy fit.

Dr. House became interested in clinicians’ perspectives on this issue when he realized how few psychiatric holds he saw among pregnant women during the 4 years he spent at a university hospital’s level 1 trauma center. He included questions about substance use in his survey because of the “recent push to criminalize substance use during pregnancy, mainly in response to the significant impact substance use during pregnancy can have on the fetus or developing child,” he said.

Dr. House received 68 survey responses from AAPL members, most of whom were male with an average age of 47 years. The 7-question survey presented various clinical scenarios and asked what the respondent would do.

The first question concerned being called to the emergency department to evaluate a 28-year-old white woman with clinical signs of depression, history of a suicide attempt, and a mother who had committed suicide when the patient was 15. However, she states during evaluation: “I could never actually kill myself. My family would be too upset, and I would go to hell.”

Two-thirds of respondents (67.6%) said they would admit the woman to an inpatient unit for stabilization, and the others would discharge her with close follow-up.

The second question asked what the clinician would do if the patient declined admission: 41.2% would discharge, and 58.8% would place the woman on a psychiatric hold.

The third question introduced a positive pregnancy test for the woman, but none of the respondents said they would cancel the psychiatric hold. Most were split between proceeding with a hold (42.6%) or proceeding with a discharge (47.1%), though 10.3% would cancel the discharge and place the patient on a hold. Ultimately, respondents were no more likely to put the woman on a hold whether she was pregnant or not.

Then the survey repeated the scenario, but instead of a positive pregnancy test, the question asked what clinicians would do if her drug screen were positive after she had refused admission. In that scenario, the woman reported daily methamphetamine use to the emergency physician.

Among respondents, 48.5% would proceed with a psychiatric hold, 42.6% would proceed with a discharge, and 8.8% would cancel the discharge and put the patient on a hold.

The final question asks clinicians’ course of action if the woman’s pregnancy test were positive after the positive drug screen. Now, only a little over a quarter of respondents (26.5%) would proceed with a discharge and follow-up. More than half (57.4%) would proceed with a hold, and 16.2% would cancel the discharge and place a psychiatric hold.

Therefore, 73.6% of clinicians would place a pregnant woman with a history of substance use on a psychiatric hold, compared with 52.9% if the woman were pregnant but not using methamphetamine.

Laws on pregnancy, substance use

Dr. House considered those findings within the context of current laws governing substance use during pregnancy., with prosecution usually requiring detection of the substance at birth or during pregnancy, or evidence of risk to the child’s health.

Tennessee is unique in considering substance abuse in pregnancy assault if the child is born with dependence or other harm from the drug use. Women in Minnesota, South Dakota, and Wisconsin can be subject to civil commitment, including required inpatient drug treatment, for substance abuse during pregnancy (Am J Psychiatry. 2016 Nov 1;173[11]:1077-80).

Mandatory reporting laws for suspected substance abuse during pregnancy exist in 15 states, mostly in the Southwest, northern Midwest, and states around the District of Columbia. And four states – Kentucky, Iowa, Minnesota, and North Dakota – require pregnant women suspected of substance abuse to be tested.

Yet, most major relevant medical associations oppose criminalization of substance use during pregnancy, including the American Psychiatric Association, the American Academy of Addiction Psychiatry, the American Medical Association, and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

“They are generally for increasing access for people, like voluntary screening, but against criminalization because it creates a barrier to accessing prenatal care,” Dr. House explained.

Aside from the question of whom psychiatrists consider their patients – the woman, her fetus, or both – the results raise another question, Dr. House said: “While studies have shown that criminalizing substance use during pregnancy discourages mothers from seeking prenatal care, does the threat of an involuntary psychiatric admission have a similar consequence?” That’s a question for further research.

No external funding was used. Dr. House was a clinical investigator without compensation for Janssen Pharmaceuticals from 2015 to 2017.

REPORTING FROM THE AAPL ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Women are more likely to receive a psychiatric hold if they are pregnant and using a substance.

Major finding: Almost 53% of clinicians would place a suicidal pregnant woman on a psychiatric hold, but 73.6% would do so if she were using methamphetamines.

Study details: The findings are based on an Internet survey of 68 members of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law.

Disclosures: No external funding was used. Dr. House was a clinical investigator without compensation for Janssen Pharmaceuticals from 2015 to 2017.

Physical activity may count more for women who keep the pounds off

NASHVILLE – , according to new analysis of a small study.

Physical activity is a key component in successful maintenance of weight loss, but differential effects of physical activity between men and women had not been well explored, Ann Caldwell, PhD, said in an interview at Obesity Week 2018, presented by the Obesity Society and the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

Dr. Caldwell and her colleagues at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, conducted a secondary analysis of case-control data of individuals with healthy weight, overweight, or obesity, and those who had successfully maintained weight loss. They compared total daily energy expenditure (TDEE) and physical activity energy expenditure (PAEE), looking at men and women in all three groups separately.

The study included 20 women and 5 men who had successfully maintained a weight loss of at least 13.6 kg for at least 1 year. These were matched with 20 women and 7 men with a body mass index within the healthy range, as controls for the weight loss maintainers at their post–weight loss BMI.

Another group of 22 women and 6 men with BMIs in the overweight or obese category served as controls for the weight loss maintainers at their pre–weight loss BMI.

For all participants, TDEE was measured using the doubly labeled water method for 7 days. This method tracks elimination of a set quantity of ingested water made up of two uncommon isotopes (hydrogen-2 and oxygen-18) to measure energy expenditure. Since the oxygen is lost both as water and carbon dioxide as a result of metabolism, the presence of less oxygen-18 over time indicates a higher total energy expenditure.

Indirect calorimetry was used to measure resting energy expenditure (REE), and energy expenditure related to physical activity was calculated by subtracting REE and a 10% fraction of TDEE (to account for the thermic effect of feeding) from total TDEE.

“There were significant sex-group interactions for TDEE, PAEE, and PAEE/TEE,” said Dr. Caldwell. She explained that the cutoff for statistical significance for the investigators’ analysis was set at P = .1, since sample sizes were so small for men.

For women who were weight-loss maintainers, both PAEE and PAEE/TDEE ratios were higher than for the female healthy-BMI and high-BMI control participants: PAEE was 822 kcal/day for the maintainers, 536 kcal/day for the healthy-BMI, and 669 kcal/day for the high-BMI controls (P less than .01 for both comparisons).

Dr. Caldwell and her colleagues saw no difference when comparing the PAEE/TDEE ratio for women in each of the control groups.

For men, by contrast, PAEE was highest for those with healthy BMIs, at 815 kcal/day, and lowest for those in the high-BMI control group, at 506 kcal/day. Men who were weight loss maintainers fell in the middle, at 772 kcal/day of PAEE. The PAEE/TDEE ratio was significantly higher for both weight loss maintainers and normal-BMI participants than for the high-BMI participants (P less than .07).

“These cross-sectional data suggest potential sex differences in the importance of [physical activity] for successful weight loss maintenance that should be explored further with objective measures,” wrote Dr. Caldwell and her coauthors.

The investigators are planning further work that incorporates objective physical activity data via actigraphy, and that will include a larger sample of men. Through a prospective study that overcomes the limitation of the present study, they hope to develop a clearer picture of sex differences in weight loss maintenance.

The National Institutes of Health supported the study. Dr. Caldwell reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Caldwell A et al. Obesity Week 2018, Abstract TP-3233.

NASHVILLE – , according to new analysis of a small study.

Physical activity is a key component in successful maintenance of weight loss, but differential effects of physical activity between men and women had not been well explored, Ann Caldwell, PhD, said in an interview at Obesity Week 2018, presented by the Obesity Society and the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

Dr. Caldwell and her colleagues at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, conducted a secondary analysis of case-control data of individuals with healthy weight, overweight, or obesity, and those who had successfully maintained weight loss. They compared total daily energy expenditure (TDEE) and physical activity energy expenditure (PAEE), looking at men and women in all three groups separately.

The study included 20 women and 5 men who had successfully maintained a weight loss of at least 13.6 kg for at least 1 year. These were matched with 20 women and 7 men with a body mass index within the healthy range, as controls for the weight loss maintainers at their post–weight loss BMI.

Another group of 22 women and 6 men with BMIs in the overweight or obese category served as controls for the weight loss maintainers at their pre–weight loss BMI.

For all participants, TDEE was measured using the doubly labeled water method for 7 days. This method tracks elimination of a set quantity of ingested water made up of two uncommon isotopes (hydrogen-2 and oxygen-18) to measure energy expenditure. Since the oxygen is lost both as water and carbon dioxide as a result of metabolism, the presence of less oxygen-18 over time indicates a higher total energy expenditure.

Indirect calorimetry was used to measure resting energy expenditure (REE), and energy expenditure related to physical activity was calculated by subtracting REE and a 10% fraction of TDEE (to account for the thermic effect of feeding) from total TDEE.

“There were significant sex-group interactions for TDEE, PAEE, and PAEE/TEE,” said Dr. Caldwell. She explained that the cutoff for statistical significance for the investigators’ analysis was set at P = .1, since sample sizes were so small for men.

For women who were weight-loss maintainers, both PAEE and PAEE/TDEE ratios were higher than for the female healthy-BMI and high-BMI control participants: PAEE was 822 kcal/day for the maintainers, 536 kcal/day for the healthy-BMI, and 669 kcal/day for the high-BMI controls (P less than .01 for both comparisons).

Dr. Caldwell and her colleagues saw no difference when comparing the PAEE/TDEE ratio for women in each of the control groups.

For men, by contrast, PAEE was highest for those with healthy BMIs, at 815 kcal/day, and lowest for those in the high-BMI control group, at 506 kcal/day. Men who were weight loss maintainers fell in the middle, at 772 kcal/day of PAEE. The PAEE/TDEE ratio was significantly higher for both weight loss maintainers and normal-BMI participants than for the high-BMI participants (P less than .07).

“These cross-sectional data suggest potential sex differences in the importance of [physical activity] for successful weight loss maintenance that should be explored further with objective measures,” wrote Dr. Caldwell and her coauthors.

The investigators are planning further work that incorporates objective physical activity data via actigraphy, and that will include a larger sample of men. Through a prospective study that overcomes the limitation of the present study, they hope to develop a clearer picture of sex differences in weight loss maintenance.

The National Institutes of Health supported the study. Dr. Caldwell reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Caldwell A et al. Obesity Week 2018, Abstract TP-3233.

NASHVILLE – , according to new analysis of a small study.

Physical activity is a key component in successful maintenance of weight loss, but differential effects of physical activity between men and women had not been well explored, Ann Caldwell, PhD, said in an interview at Obesity Week 2018, presented by the Obesity Society and the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

Dr. Caldwell and her colleagues at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, conducted a secondary analysis of case-control data of individuals with healthy weight, overweight, or obesity, and those who had successfully maintained weight loss. They compared total daily energy expenditure (TDEE) and physical activity energy expenditure (PAEE), looking at men and women in all three groups separately.

The study included 20 women and 5 men who had successfully maintained a weight loss of at least 13.6 kg for at least 1 year. These were matched with 20 women and 7 men with a body mass index within the healthy range, as controls for the weight loss maintainers at their post–weight loss BMI.

Another group of 22 women and 6 men with BMIs in the overweight or obese category served as controls for the weight loss maintainers at their pre–weight loss BMI.

For all participants, TDEE was measured using the doubly labeled water method for 7 days. This method tracks elimination of a set quantity of ingested water made up of two uncommon isotopes (hydrogen-2 and oxygen-18) to measure energy expenditure. Since the oxygen is lost both as water and carbon dioxide as a result of metabolism, the presence of less oxygen-18 over time indicates a higher total energy expenditure.

Indirect calorimetry was used to measure resting energy expenditure (REE), and energy expenditure related to physical activity was calculated by subtracting REE and a 10% fraction of TDEE (to account for the thermic effect of feeding) from total TDEE.

“There were significant sex-group interactions for TDEE, PAEE, and PAEE/TEE,” said Dr. Caldwell. She explained that the cutoff for statistical significance for the investigators’ analysis was set at P = .1, since sample sizes were so small for men.

For women who were weight-loss maintainers, both PAEE and PAEE/TDEE ratios were higher than for the female healthy-BMI and high-BMI control participants: PAEE was 822 kcal/day for the maintainers, 536 kcal/day for the healthy-BMI, and 669 kcal/day for the high-BMI controls (P less than .01 for both comparisons).

Dr. Caldwell and her colleagues saw no difference when comparing the PAEE/TDEE ratio for women in each of the control groups.

For men, by contrast, PAEE was highest for those with healthy BMIs, at 815 kcal/day, and lowest for those in the high-BMI control group, at 506 kcal/day. Men who were weight loss maintainers fell in the middle, at 772 kcal/day of PAEE. The PAEE/TDEE ratio was significantly higher for both weight loss maintainers and normal-BMI participants than for the high-BMI participants (P less than .07).

“These cross-sectional data suggest potential sex differences in the importance of [physical activity] for successful weight loss maintenance that should be explored further with objective measures,” wrote Dr. Caldwell and her coauthors.

The investigators are planning further work that incorporates objective physical activity data via actigraphy, and that will include a larger sample of men. Through a prospective study that overcomes the limitation of the present study, they hope to develop a clearer picture of sex differences in weight loss maintenance.

The National Institutes of Health supported the study. Dr. Caldwell reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Caldwell A et al. Obesity Week 2018, Abstract TP-3233.

REPORTING FROM OBESITY WEEK 2018

Key clinical point: Women who kept weight off burned more calories in physical activity than did normal or high-BMI controls.

Major finding: In women, the ratio of physical activity energy expenditure to total daily energy expenditure was higher for successful weight-loss maintainers (P less than .01).

Study details: Secondary analysis of case-control study enrolling 80 individuals.

Disclosures: The National Institutes of Health funded the study. Dr. Caldwell reported no conflicts of interest.

Source: Caldwell A et al. Obesity Week 2018, abstract TP-3233.

Abortion measures continue to fall

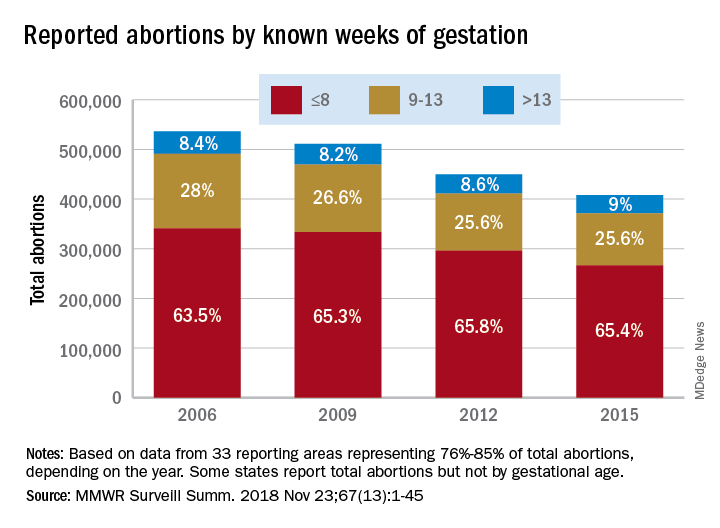

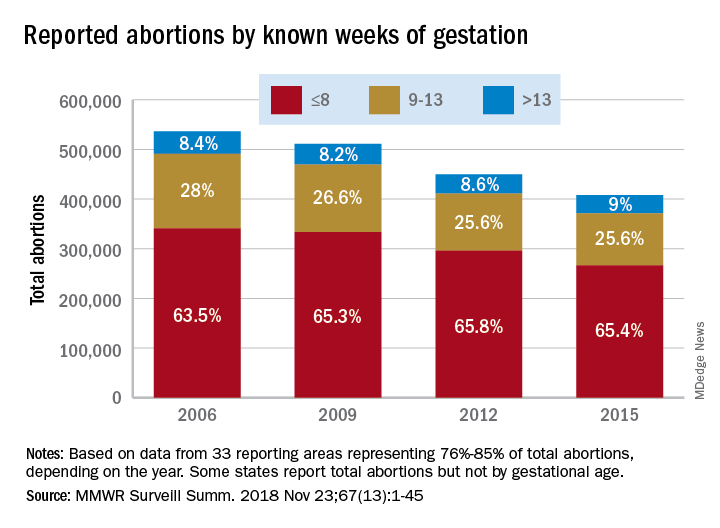

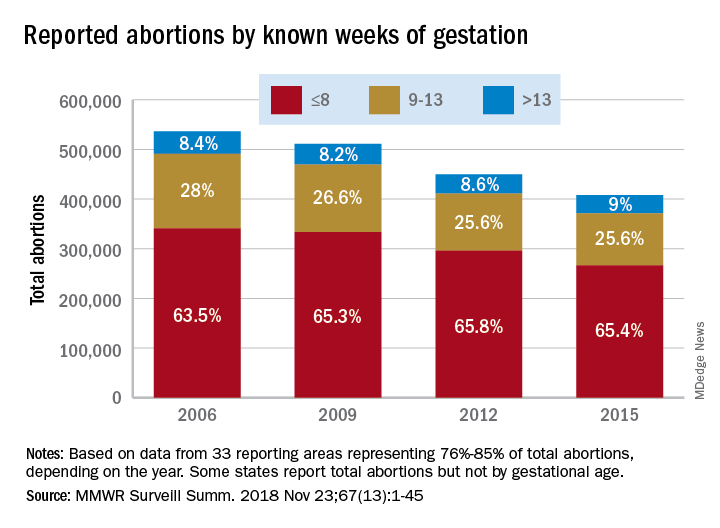

Three important national measures of abortion dropped by at least 19% from 2006 to 2015, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Surgical and medical abortions reported to the CDC dropped by 24%, going from almost 843,000 in 2006 to 638,000 in 2015, with declines occurring every year, Tara C. Jatlaoui, MD, and her associates at the CDC’s National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Atlanta, reported in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Surveillance Summaries.

Over that same time period, the abortion rate fell from 15.9 per 1,000 women aged 15-44 years to 11.8 per 1,000 – a decline of 26%. Abortion ratio – the number of abortions per 1,000 live births within a given population – declined by 19%, dropping from 233 abortions per 1,000 live births in 2006 to 188 abortions per 1,000 live births in 2015, the investigators reported. The findings were based on data from 49 areas that continuously reported over the study period (excludes California, Maryland, and New Hampshire but includes the District of Columbia and New York City).

Abortion rates were highest for women aged 20-29 years for the study period, and this age group accounted for the largest share among the 44 reporting areas that provided data by maternal age each year. Those under age 15 years had the largest drops by age in total number of abortions (40%) and abortion rate (58%) but had the highest, by far, abortion ratio for each year of the study (700 per 1,000 live births in that age group in 2015. The abortion ratio for 15- to 19-year-olds was 289 per 1,000 live births).

The percentage of abortions performed before 14 weeks’ gestation changed little, going from 91.5% in 2006 to 91% in 2015, but “a shift occurred toward earlier gestational ages,” they noted. The percentage of abortions performed before or at 8 weeks increased 3% and those done at 9-13 weeks dropped almost 9% among the 33 areas that reported gestational age every year. Abortions done after 13 weeks gestation represented 9% of all abortions during the study period, with an increase of 7% occurring from 2006 to 2015, Dr. Jatlaoui and her associates said.

Removing barriers such as cost, “insufficient provider reimbursement and training, inadequate client-centered counseling, lack of youth-friendly services, and low client awareness ... might help improve contraceptive use, potentially reducing the number of unintended pregnancies and the number of abortions performed in the United States,” the researchers wrote.

SOURCE: Jatlaoui TC et al. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2018 Nov 23(13):1-45.

Three important national measures of abortion dropped by at least 19% from 2006 to 2015, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.