User login

Balanced fat intake links with less type 2 diabetes

Researchers published the study covered in this summary on Preprints with The Lancet as a preprint that has not yet been peer reviewed.

Key takeaways

- Adults in China who consumed a “balanced,” moderate ratio (middle three quintiles) of animal-to-vegetable cooking oil had a lower rate of developing type 2 diabetes during a median follow-up of 8.6 years, compared with those who consumed the lowest ratio (first quintile), after multivariable adjustment using prospectively collected data.

- The results also indicate that increasing animal cooking oil (such as lard, tallow, or butter) and vegetable cooking oil (such as peanut or soybean oil) consumption were each positively associated with a higher rate of developing type 2 diabetes.

- Those who consumed the highest ratio (fifth quintile) of animal-to-vegetable cooking oil had a nonsignificant difference in their rate of developing type 2 diabetes, compared with those in the first quintile.

Why this matters

- The findings suggest that consuming a diet with a “balanced” moderate intake of animal and vegetable oil might lower the risk of type 2 diabetes, which would reduce disease burden and health care expenditures.

- The results imply that using a single source of cooking oil, either animal or vegetable, contributes to the incidence of type 2 diabetes.

- This is the first large epidemiological study showing a relationship between the ratio of animal- and vegetable-derived fats in people’s diets and their risk for incident type 2 diabetes.

Study design

- The researchers used data collected prospectively starting in 2010-2012 from 7,274 adult residents of Guizhou province, China, with follow-up assessment in 2020 after a median of 8.6 years.

- At baseline, participants underwent an oral glucose tolerance test and provided information on demographics, family medical history, and personal medical history, including whether they had been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes or were taking antihyperglycemic medications. The study did not include anyone with a history of diabetes.

- Data on intake of animal and vegetable cooking oil came from a dietary questionnaire.

- The authors calculated hazard ratios for development of type 2 diabetes after adjusting for multiple potential confounders.

Key results

- The study cohort averaged 44 years old, and 53% were women.

- During a median follow-up of 8.6 years, 747 people developed type 2 diabetes.

- Compared with those who had the lowest intake of animal cooking oil (first quintile), those with the highest intake (fifth quintile) had a significant 28% increased relative rate for developing type 2 diabetes after adjustment for several potential confounders.

- Compared with those with the lowest intake of vegetable cooking oil, those with the highest intake had a significant 56% increased rate of developing type 2 diabetes after adjustment.

- Compared with adults with the lowest animal-to-vegetable cooking oil ratio (first quintile), those in the second, third, and fourth quintiles for this ratio had significantly lower adjusted relative rates of developing type 2 diabetes, with adjusted hazard ratios of 0.79, 0.65, and 0.68, respectively. Those in the highest quintile (fifth quintile) did not have a significantly different risk, compared with the first quintile.

- The protective effect of a balanced ratio of animal-to-vegetable cooking oils was stronger in people who lived in rural districts and in those who had obesity.

Limitations

- The dietary information came from participants’ self-reports, which may have produced biased data.

- The study only included information about animal and vegetable cooking oil consumed at home.

- There may have been residual confounding from variables not included in the study.

- The time of diagnosis of type 2 diabetes may have been inaccurate because follow-up occurred only once.

- The study may have underestimated the incidence of type 2 diabetes because of a lack of information about hemoglobin A1c levels at follow-up.

Disclosures

- The study did not receive commercial funding.

- The authors reported no financial disclosures.

This is a summary of a preprint article “The consumption ratio of animal cooking oil to vegetable cooking oil and reduced risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: A prospective cohort study in Southwest China” written by researchers primarily from Zunyi Medical University, China, on Preprints with The Lancet. This study has not yet been peer reviewed. The full text of the study can be found on papers.ssrn.com.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Researchers published the study covered in this summary on Preprints with The Lancet as a preprint that has not yet been peer reviewed.

Key takeaways

- Adults in China who consumed a “balanced,” moderate ratio (middle three quintiles) of animal-to-vegetable cooking oil had a lower rate of developing type 2 diabetes during a median follow-up of 8.6 years, compared with those who consumed the lowest ratio (first quintile), after multivariable adjustment using prospectively collected data.

- The results also indicate that increasing animal cooking oil (such as lard, tallow, or butter) and vegetable cooking oil (such as peanut or soybean oil) consumption were each positively associated with a higher rate of developing type 2 diabetes.

- Those who consumed the highest ratio (fifth quintile) of animal-to-vegetable cooking oil had a nonsignificant difference in their rate of developing type 2 diabetes, compared with those in the first quintile.

Why this matters

- The findings suggest that consuming a diet with a “balanced” moderate intake of animal and vegetable oil might lower the risk of type 2 diabetes, which would reduce disease burden and health care expenditures.

- The results imply that using a single source of cooking oil, either animal or vegetable, contributes to the incidence of type 2 diabetes.

- This is the first large epidemiological study showing a relationship between the ratio of animal- and vegetable-derived fats in people’s diets and their risk for incident type 2 diabetes.

Study design

- The researchers used data collected prospectively starting in 2010-2012 from 7,274 adult residents of Guizhou province, China, with follow-up assessment in 2020 after a median of 8.6 years.

- At baseline, participants underwent an oral glucose tolerance test and provided information on demographics, family medical history, and personal medical history, including whether they had been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes or were taking antihyperglycemic medications. The study did not include anyone with a history of diabetes.

- Data on intake of animal and vegetable cooking oil came from a dietary questionnaire.

- The authors calculated hazard ratios for development of type 2 diabetes after adjusting for multiple potential confounders.

Key results

- The study cohort averaged 44 years old, and 53% were women.

- During a median follow-up of 8.6 years, 747 people developed type 2 diabetes.

- Compared with those who had the lowest intake of animal cooking oil (first quintile), those with the highest intake (fifth quintile) had a significant 28% increased relative rate for developing type 2 diabetes after adjustment for several potential confounders.

- Compared with those with the lowest intake of vegetable cooking oil, those with the highest intake had a significant 56% increased rate of developing type 2 diabetes after adjustment.

- Compared with adults with the lowest animal-to-vegetable cooking oil ratio (first quintile), those in the second, third, and fourth quintiles for this ratio had significantly lower adjusted relative rates of developing type 2 diabetes, with adjusted hazard ratios of 0.79, 0.65, and 0.68, respectively. Those in the highest quintile (fifth quintile) did not have a significantly different risk, compared with the first quintile.

- The protective effect of a balanced ratio of animal-to-vegetable cooking oils was stronger in people who lived in rural districts and in those who had obesity.

Limitations

- The dietary information came from participants’ self-reports, which may have produced biased data.

- The study only included information about animal and vegetable cooking oil consumed at home.

- There may have been residual confounding from variables not included in the study.

- The time of diagnosis of type 2 diabetes may have been inaccurate because follow-up occurred only once.

- The study may have underestimated the incidence of type 2 diabetes because of a lack of information about hemoglobin A1c levels at follow-up.

Disclosures

- The study did not receive commercial funding.

- The authors reported no financial disclosures.

This is a summary of a preprint article “The consumption ratio of animal cooking oil to vegetable cooking oil and reduced risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: A prospective cohort study in Southwest China” written by researchers primarily from Zunyi Medical University, China, on Preprints with The Lancet. This study has not yet been peer reviewed. The full text of the study can be found on papers.ssrn.com.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Researchers published the study covered in this summary on Preprints with The Lancet as a preprint that has not yet been peer reviewed.

Key takeaways

- Adults in China who consumed a “balanced,” moderate ratio (middle three quintiles) of animal-to-vegetable cooking oil had a lower rate of developing type 2 diabetes during a median follow-up of 8.6 years, compared with those who consumed the lowest ratio (first quintile), after multivariable adjustment using prospectively collected data.

- The results also indicate that increasing animal cooking oil (such as lard, tallow, or butter) and vegetable cooking oil (such as peanut or soybean oil) consumption were each positively associated with a higher rate of developing type 2 diabetes.

- Those who consumed the highest ratio (fifth quintile) of animal-to-vegetable cooking oil had a nonsignificant difference in their rate of developing type 2 diabetes, compared with those in the first quintile.

Why this matters

- The findings suggest that consuming a diet with a “balanced” moderate intake of animal and vegetable oil might lower the risk of type 2 diabetes, which would reduce disease burden and health care expenditures.

- The results imply that using a single source of cooking oil, either animal or vegetable, contributes to the incidence of type 2 diabetes.

- This is the first large epidemiological study showing a relationship between the ratio of animal- and vegetable-derived fats in people’s diets and their risk for incident type 2 diabetes.

Study design

- The researchers used data collected prospectively starting in 2010-2012 from 7,274 adult residents of Guizhou province, China, with follow-up assessment in 2020 after a median of 8.6 years.

- At baseline, participants underwent an oral glucose tolerance test and provided information on demographics, family medical history, and personal medical history, including whether they had been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes or were taking antihyperglycemic medications. The study did not include anyone with a history of diabetes.

- Data on intake of animal and vegetable cooking oil came from a dietary questionnaire.

- The authors calculated hazard ratios for development of type 2 diabetes after adjusting for multiple potential confounders.

Key results

- The study cohort averaged 44 years old, and 53% were women.

- During a median follow-up of 8.6 years, 747 people developed type 2 diabetes.

- Compared with those who had the lowest intake of animal cooking oil (first quintile), those with the highest intake (fifth quintile) had a significant 28% increased relative rate for developing type 2 diabetes after adjustment for several potential confounders.

- Compared with those with the lowest intake of vegetable cooking oil, those with the highest intake had a significant 56% increased rate of developing type 2 diabetes after adjustment.

- Compared with adults with the lowest animal-to-vegetable cooking oil ratio (first quintile), those in the second, third, and fourth quintiles for this ratio had significantly lower adjusted relative rates of developing type 2 diabetes, with adjusted hazard ratios of 0.79, 0.65, and 0.68, respectively. Those in the highest quintile (fifth quintile) did not have a significantly different risk, compared with the first quintile.

- The protective effect of a balanced ratio of animal-to-vegetable cooking oils was stronger in people who lived in rural districts and in those who had obesity.

Limitations

- The dietary information came from participants’ self-reports, which may have produced biased data.

- The study only included information about animal and vegetable cooking oil consumed at home.

- There may have been residual confounding from variables not included in the study.

- The time of diagnosis of type 2 diabetes may have been inaccurate because follow-up occurred only once.

- The study may have underestimated the incidence of type 2 diabetes because of a lack of information about hemoglobin A1c levels at follow-up.

Disclosures

- The study did not receive commercial funding.

- The authors reported no financial disclosures.

This is a summary of a preprint article “The consumption ratio of animal cooking oil to vegetable cooking oil and reduced risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: A prospective cohort study in Southwest China” written by researchers primarily from Zunyi Medical University, China, on Preprints with The Lancet. This study has not yet been peer reviewed. The full text of the study can be found on papers.ssrn.com.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

How to improve diagnosis of HFpEF, common in diabetes

STOCKHOLM – Recent study results confirm that two agents from the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor class can significantly cut the incidence of adverse cardiovascular events in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFpEF), a disease especially common in people with type 2 diabetes, obesity, or both.

And findings from secondary analyses of the studies – including one reported at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes – show that these SGLT2 inhibitors work as well for cutting incident adverse events (cardiovascular death or worsening heart failure) in patients with HFpEF and diabetes as they do for people with normal blood glucose levels.

But delivering treatment with these proven agents, dapagliflozin (Farxiga) and empagliflozin (Jardiance), first requires diagnosis of HFpEF, a task that clinicians have historically fallen short in accomplishing.

When in 2021, results from the EMPEROR-Preserved trial with empagliflozin and when in September 2022 results from the DELIVER trial with dapagliflozin established the efficacy of these two SGLT2 inhibitors as the first treatments proven to benefit patients with HFpEF, they also raised the stakes for clinicians to be much more diligent and systematic in evaluating people at high risk for developing HFpEF because of having type 2 diabetes or obesity, two of the most potent risk factors for this form of heart failure.

‘Vigilance ... needs to increase’

“Vigilance for HFpEF needs to increase because we can now help these patients,” declared Lars H. Lund, MD, PhD, speaking at the meeting. “Type 2 diabetes dramatically increases the incidence of HFpEF,” and the mechanisms by which it does this are “especially amenable to treatment with SGLT2 inhibitors,” said Dr. Lund, a cardiologist and heart failure specialist at the Karolinska Institute, Stockholm.

HFpEF has a history of going undetected in people with type 2 diabetes, an ironic situation given its high incidence as well as the elevated rate of adverse cardiovascular events when heart failure occurs in patients with type 2 diabetes compared with patients who do not have diabetes.

The key, say experts, is for clinicians to maintain a high index of suspicion for signs and symptoms of heart failure in people with type 2 diabetes and to regularly assess them, starting with just a few simple questions that probe for the presence of dyspnea, exertional fatigue, or both, an approach not widely employed up to now.

Clinicians who care for people with type 2 diabetes must become “alert to thinking about heart failure and alert to asking questions about signs and symptoms” that flag the presence of HFpEF, advised Naveed Sattar, MBChB, PhD, a professor of metabolic medicine at the University of Glasgow.

Soon, medical groups will issue guidelines for appropriate assessment for the presence of HFpEF in people with type 2 diabetes, Dr. Sattar predicted in an interview.

A need to probe

“You can’t simply ask patients with type 2 diabetes whether they have shortness of breath or exertional fatigue and stop there,” because often their first response will be no.

“Commonly, patients will initially say they have no dyspnea, but when you probe further, you find symptoms,” noted Mikhail N. Kosiborod, MD, codirector of Saint Luke’s Cardiometabolic Center of Excellence in Kansas City, Mo.

These people are often sedentary, so they frequently don’t experience shortness of breath at baseline, Dr. Kosiborod said in an interview. In some cases, they may limit their activity because of their exertional intolerance.

Once a person’s suggestive symptoms become known, the next step is to measure the serum level of N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), a biomarker considered to be a generally reliable signal of existing heart failure when elevated.

Any value above 125 pg/mL is suggestive of prevalent heart failure and should lead to the next diagnostic step of echocardiography, Dr. Sattar said.

Elevated NT-proBNP has such good positive predictive value for identifying heart failure that it is tempting to use it broadly in people with type 2 diabetes. A 2022 consensus report from the American Diabetes Association says that “measurement of a natriuretic peptide [such as NT-proBNP] or high-sensitivity cardiac troponin is recommended on at least a yearly basis to identify the earliest HF [heart failure] stages and implement strategies to prevent transition to symptomatic HF.”

Test costs require targeting

But because of the relatively high current price for an NT-proBNP test, the cost-benefit ratio for widespread annual testing of all people with type 2 diabetes would be poor, some experts caution.

“Screening everyone may not be the right answer. Hundreds of millions of people worldwide” have type 2 diabetes. “You first need to target evaluation to people with symptoms,” advised Dr. Kosiborod.

He also warned that a low NT-proBNP level does not always rule out HFpEF, especially among people with type 2 diabetes who also have overweight or obesity, because NT-proBNP levels can be “artificially low” in people with obesity.

Other potential aids to diagnosis are assessment scores that researchers have developed, such as the H2FPEF score, which relies on variables that include age, obesity, and the presence of atrial fibrillation and hypertension.

However, this score also requires an echocardiography examination, another test that would have a questionable cost-benefit ratio if performed widely for patients with type 2 diabetes without targeting, Dr. Kosiborod said.

SGLT2 inhibitors benefit HFpEF regardless of glucose levels

A prespecified analysis of the DELIVER results that divided the study cohort on the basis of their glycemic status proved the efficacy of the SGLT2 inhibitor dapagliflozin for patients with HFpEF regardless of whether or not they had type 2 diabetes, prediabetes, or were normoglycemic at entry into the study, Silvio E. Inzucchi, MD, reported at the EASD meeting.

Treatment with dapagliflozin cut the incidence of the trial’s primary outcome of cardiovascular death or worsening heart failure by a significant 18% relative to placebo among all enrolled patients.

The new analysis reported by Dr. Inzucchi showed that treatment was associated with a 23% relative risk reduction among those with normoglycemia, a 13% reduction among those with prediabetes, and a 19% reduction among those with type 2 diabetes, with no signal of a significant difference among the three subgroups.

“There was no statistical interaction between categorical glycemic subgrouping and dapagliflozin’s treatment effect,” concluded Dr. Inzucchi, director of the Yale Medicine Diabetes Center, New Haven, Conn.

He also reported that, among the 6,259 people in the trial with HFpEF, 50% had diabetes, 31% had prediabetes, and a scant 19% had normoglycemia. The finding highlights once again the high prevalence of dysglycemia among people with HFpEF.

Previously, a prespecified secondary analysis of data from the EMPEROR-Preserved trial yielded similar findings for empagliflozin that showed the agent’s efficacy for people with HFpEF across the range of glucose levels.

The DELIVER trial was funded by AstraZeneca, the company that markets dapagliflozin (Farxiga). The EMPEROR-Preserved trial was sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim and Eli Lilly, the companies that jointly market empagliflozin (Jardiance). Dr. Lund has been a consultant to AstraZeneca and Boehringer Ingelheim and to numerous other companies, and he is a stockholder in AnaCardio. Dr. Sattar has been a consultant to and has received research support from AstraZeneca and Boehringer Ingelheim, and he has been a consultant with numerous companies. Dr. Kosiborod has been a consultant to and has received research funding from AstraZeneca and Boehringer Ingelheim and has been a consultant to Eli Lilly and numerous other companies. Dr. Inzucchi has been a consultant to, given talks on behalf of, or served on trial committees for Abbott, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Esperion, Lexicon, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, and vTv Therapetics.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

STOCKHOLM – Recent study results confirm that two agents from the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor class can significantly cut the incidence of adverse cardiovascular events in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFpEF), a disease especially common in people with type 2 diabetes, obesity, or both.

And findings from secondary analyses of the studies – including one reported at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes – show that these SGLT2 inhibitors work as well for cutting incident adverse events (cardiovascular death or worsening heart failure) in patients with HFpEF and diabetes as they do for people with normal blood glucose levels.

But delivering treatment with these proven agents, dapagliflozin (Farxiga) and empagliflozin (Jardiance), first requires diagnosis of HFpEF, a task that clinicians have historically fallen short in accomplishing.

When in 2021, results from the EMPEROR-Preserved trial with empagliflozin and when in September 2022 results from the DELIVER trial with dapagliflozin established the efficacy of these two SGLT2 inhibitors as the first treatments proven to benefit patients with HFpEF, they also raised the stakes for clinicians to be much more diligent and systematic in evaluating people at high risk for developing HFpEF because of having type 2 diabetes or obesity, two of the most potent risk factors for this form of heart failure.

‘Vigilance ... needs to increase’

“Vigilance for HFpEF needs to increase because we can now help these patients,” declared Lars H. Lund, MD, PhD, speaking at the meeting. “Type 2 diabetes dramatically increases the incidence of HFpEF,” and the mechanisms by which it does this are “especially amenable to treatment with SGLT2 inhibitors,” said Dr. Lund, a cardiologist and heart failure specialist at the Karolinska Institute, Stockholm.

HFpEF has a history of going undetected in people with type 2 diabetes, an ironic situation given its high incidence as well as the elevated rate of adverse cardiovascular events when heart failure occurs in patients with type 2 diabetes compared with patients who do not have diabetes.

The key, say experts, is for clinicians to maintain a high index of suspicion for signs and symptoms of heart failure in people with type 2 diabetes and to regularly assess them, starting with just a few simple questions that probe for the presence of dyspnea, exertional fatigue, or both, an approach not widely employed up to now.

Clinicians who care for people with type 2 diabetes must become “alert to thinking about heart failure and alert to asking questions about signs and symptoms” that flag the presence of HFpEF, advised Naveed Sattar, MBChB, PhD, a professor of metabolic medicine at the University of Glasgow.

Soon, medical groups will issue guidelines for appropriate assessment for the presence of HFpEF in people with type 2 diabetes, Dr. Sattar predicted in an interview.

A need to probe

“You can’t simply ask patients with type 2 diabetes whether they have shortness of breath or exertional fatigue and stop there,” because often their first response will be no.

“Commonly, patients will initially say they have no dyspnea, but when you probe further, you find symptoms,” noted Mikhail N. Kosiborod, MD, codirector of Saint Luke’s Cardiometabolic Center of Excellence in Kansas City, Mo.

These people are often sedentary, so they frequently don’t experience shortness of breath at baseline, Dr. Kosiborod said in an interview. In some cases, they may limit their activity because of their exertional intolerance.

Once a person’s suggestive symptoms become known, the next step is to measure the serum level of N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), a biomarker considered to be a generally reliable signal of existing heart failure when elevated.

Any value above 125 pg/mL is suggestive of prevalent heart failure and should lead to the next diagnostic step of echocardiography, Dr. Sattar said.

Elevated NT-proBNP has such good positive predictive value for identifying heart failure that it is tempting to use it broadly in people with type 2 diabetes. A 2022 consensus report from the American Diabetes Association says that “measurement of a natriuretic peptide [such as NT-proBNP] or high-sensitivity cardiac troponin is recommended on at least a yearly basis to identify the earliest HF [heart failure] stages and implement strategies to prevent transition to symptomatic HF.”

Test costs require targeting

But because of the relatively high current price for an NT-proBNP test, the cost-benefit ratio for widespread annual testing of all people with type 2 diabetes would be poor, some experts caution.

“Screening everyone may not be the right answer. Hundreds of millions of people worldwide” have type 2 diabetes. “You first need to target evaluation to people with symptoms,” advised Dr. Kosiborod.

He also warned that a low NT-proBNP level does not always rule out HFpEF, especially among people with type 2 diabetes who also have overweight or obesity, because NT-proBNP levels can be “artificially low” in people with obesity.

Other potential aids to diagnosis are assessment scores that researchers have developed, such as the H2FPEF score, which relies on variables that include age, obesity, and the presence of atrial fibrillation and hypertension.

However, this score also requires an echocardiography examination, another test that would have a questionable cost-benefit ratio if performed widely for patients with type 2 diabetes without targeting, Dr. Kosiborod said.

SGLT2 inhibitors benefit HFpEF regardless of glucose levels

A prespecified analysis of the DELIVER results that divided the study cohort on the basis of their glycemic status proved the efficacy of the SGLT2 inhibitor dapagliflozin for patients with HFpEF regardless of whether or not they had type 2 diabetes, prediabetes, or were normoglycemic at entry into the study, Silvio E. Inzucchi, MD, reported at the EASD meeting.

Treatment with dapagliflozin cut the incidence of the trial’s primary outcome of cardiovascular death or worsening heart failure by a significant 18% relative to placebo among all enrolled patients.

The new analysis reported by Dr. Inzucchi showed that treatment was associated with a 23% relative risk reduction among those with normoglycemia, a 13% reduction among those with prediabetes, and a 19% reduction among those with type 2 diabetes, with no signal of a significant difference among the three subgroups.

“There was no statistical interaction between categorical glycemic subgrouping and dapagliflozin’s treatment effect,” concluded Dr. Inzucchi, director of the Yale Medicine Diabetes Center, New Haven, Conn.

He also reported that, among the 6,259 people in the trial with HFpEF, 50% had diabetes, 31% had prediabetes, and a scant 19% had normoglycemia. The finding highlights once again the high prevalence of dysglycemia among people with HFpEF.

Previously, a prespecified secondary analysis of data from the EMPEROR-Preserved trial yielded similar findings for empagliflozin that showed the agent’s efficacy for people with HFpEF across the range of glucose levels.

The DELIVER trial was funded by AstraZeneca, the company that markets dapagliflozin (Farxiga). The EMPEROR-Preserved trial was sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim and Eli Lilly, the companies that jointly market empagliflozin (Jardiance). Dr. Lund has been a consultant to AstraZeneca and Boehringer Ingelheim and to numerous other companies, and he is a stockholder in AnaCardio. Dr. Sattar has been a consultant to and has received research support from AstraZeneca and Boehringer Ingelheim, and he has been a consultant with numerous companies. Dr. Kosiborod has been a consultant to and has received research funding from AstraZeneca and Boehringer Ingelheim and has been a consultant to Eli Lilly and numerous other companies. Dr. Inzucchi has been a consultant to, given talks on behalf of, or served on trial committees for Abbott, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Esperion, Lexicon, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, and vTv Therapetics.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

STOCKHOLM – Recent study results confirm that two agents from the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor class can significantly cut the incidence of adverse cardiovascular events in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFpEF), a disease especially common in people with type 2 diabetes, obesity, or both.

And findings from secondary analyses of the studies – including one reported at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes – show that these SGLT2 inhibitors work as well for cutting incident adverse events (cardiovascular death or worsening heart failure) in patients with HFpEF and diabetes as they do for people with normal blood glucose levels.

But delivering treatment with these proven agents, dapagliflozin (Farxiga) and empagliflozin (Jardiance), first requires diagnosis of HFpEF, a task that clinicians have historically fallen short in accomplishing.

When in 2021, results from the EMPEROR-Preserved trial with empagliflozin and when in September 2022 results from the DELIVER trial with dapagliflozin established the efficacy of these two SGLT2 inhibitors as the first treatments proven to benefit patients with HFpEF, they also raised the stakes for clinicians to be much more diligent and systematic in evaluating people at high risk for developing HFpEF because of having type 2 diabetes or obesity, two of the most potent risk factors for this form of heart failure.

‘Vigilance ... needs to increase’

“Vigilance for HFpEF needs to increase because we can now help these patients,” declared Lars H. Lund, MD, PhD, speaking at the meeting. “Type 2 diabetes dramatically increases the incidence of HFpEF,” and the mechanisms by which it does this are “especially amenable to treatment with SGLT2 inhibitors,” said Dr. Lund, a cardiologist and heart failure specialist at the Karolinska Institute, Stockholm.

HFpEF has a history of going undetected in people with type 2 diabetes, an ironic situation given its high incidence as well as the elevated rate of adverse cardiovascular events when heart failure occurs in patients with type 2 diabetes compared with patients who do not have diabetes.

The key, say experts, is for clinicians to maintain a high index of suspicion for signs and symptoms of heart failure in people with type 2 diabetes and to regularly assess them, starting with just a few simple questions that probe for the presence of dyspnea, exertional fatigue, or both, an approach not widely employed up to now.

Clinicians who care for people with type 2 diabetes must become “alert to thinking about heart failure and alert to asking questions about signs and symptoms” that flag the presence of HFpEF, advised Naveed Sattar, MBChB, PhD, a professor of metabolic medicine at the University of Glasgow.

Soon, medical groups will issue guidelines for appropriate assessment for the presence of HFpEF in people with type 2 diabetes, Dr. Sattar predicted in an interview.

A need to probe

“You can’t simply ask patients with type 2 diabetes whether they have shortness of breath or exertional fatigue and stop there,” because often their first response will be no.

“Commonly, patients will initially say they have no dyspnea, but when you probe further, you find symptoms,” noted Mikhail N. Kosiborod, MD, codirector of Saint Luke’s Cardiometabolic Center of Excellence in Kansas City, Mo.

These people are often sedentary, so they frequently don’t experience shortness of breath at baseline, Dr. Kosiborod said in an interview. In some cases, they may limit their activity because of their exertional intolerance.

Once a person’s suggestive symptoms become known, the next step is to measure the serum level of N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), a biomarker considered to be a generally reliable signal of existing heart failure when elevated.

Any value above 125 pg/mL is suggestive of prevalent heart failure and should lead to the next diagnostic step of echocardiography, Dr. Sattar said.

Elevated NT-proBNP has such good positive predictive value for identifying heart failure that it is tempting to use it broadly in people with type 2 diabetes. A 2022 consensus report from the American Diabetes Association says that “measurement of a natriuretic peptide [such as NT-proBNP] or high-sensitivity cardiac troponin is recommended on at least a yearly basis to identify the earliest HF [heart failure] stages and implement strategies to prevent transition to symptomatic HF.”

Test costs require targeting

But because of the relatively high current price for an NT-proBNP test, the cost-benefit ratio for widespread annual testing of all people with type 2 diabetes would be poor, some experts caution.

“Screening everyone may not be the right answer. Hundreds of millions of people worldwide” have type 2 diabetes. “You first need to target evaluation to people with symptoms,” advised Dr. Kosiborod.

He also warned that a low NT-proBNP level does not always rule out HFpEF, especially among people with type 2 diabetes who also have overweight or obesity, because NT-proBNP levels can be “artificially low” in people with obesity.

Other potential aids to diagnosis are assessment scores that researchers have developed, such as the H2FPEF score, which relies on variables that include age, obesity, and the presence of atrial fibrillation and hypertension.

However, this score also requires an echocardiography examination, another test that would have a questionable cost-benefit ratio if performed widely for patients with type 2 diabetes without targeting, Dr. Kosiborod said.

SGLT2 inhibitors benefit HFpEF regardless of glucose levels

A prespecified analysis of the DELIVER results that divided the study cohort on the basis of their glycemic status proved the efficacy of the SGLT2 inhibitor dapagliflozin for patients with HFpEF regardless of whether or not they had type 2 diabetes, prediabetes, or were normoglycemic at entry into the study, Silvio E. Inzucchi, MD, reported at the EASD meeting.

Treatment with dapagliflozin cut the incidence of the trial’s primary outcome of cardiovascular death or worsening heart failure by a significant 18% relative to placebo among all enrolled patients.

The new analysis reported by Dr. Inzucchi showed that treatment was associated with a 23% relative risk reduction among those with normoglycemia, a 13% reduction among those with prediabetes, and a 19% reduction among those with type 2 diabetes, with no signal of a significant difference among the three subgroups.

“There was no statistical interaction between categorical glycemic subgrouping and dapagliflozin’s treatment effect,” concluded Dr. Inzucchi, director of the Yale Medicine Diabetes Center, New Haven, Conn.

He also reported that, among the 6,259 people in the trial with HFpEF, 50% had diabetes, 31% had prediabetes, and a scant 19% had normoglycemia. The finding highlights once again the high prevalence of dysglycemia among people with HFpEF.

Previously, a prespecified secondary analysis of data from the EMPEROR-Preserved trial yielded similar findings for empagliflozin that showed the agent’s efficacy for people with HFpEF across the range of glucose levels.

The DELIVER trial was funded by AstraZeneca, the company that markets dapagliflozin (Farxiga). The EMPEROR-Preserved trial was sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim and Eli Lilly, the companies that jointly market empagliflozin (Jardiance). Dr. Lund has been a consultant to AstraZeneca and Boehringer Ingelheim and to numerous other companies, and he is a stockholder in AnaCardio. Dr. Sattar has been a consultant to and has received research support from AstraZeneca and Boehringer Ingelheim, and he has been a consultant with numerous companies. Dr. Kosiborod has been a consultant to and has received research funding from AstraZeneca and Boehringer Ingelheim and has been a consultant to Eli Lilly and numerous other companies. Dr. Inzucchi has been a consultant to, given talks on behalf of, or served on trial committees for Abbott, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Esperion, Lexicon, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, and vTv Therapetics.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT EASD 2022

Once-weekly insulin promising in phase 3 trial in type 2 diabetes

STOCKHOLM – The investigational once-weekly insulin icodec (Novo Nordisk) significantly reduces A1c without increasing hypoglycemia in people with type 2 diabetes, the first phase 3 data of such an insulin formulation suggest. The data are from one of six trials in the company’s ONWARDS program.

“Once-weekly insulin may redefine diabetes management,” enthused Athena Philis-Tsimikas, MD, who presented the findings at a session during the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) 2022 Annual Meeting, which also included a summary of previously reported top-line data from other ONWARDS trials as well as phase 2 data for Lilly›s investigational once-weekly Basal Insulin Fc (BIF).

Phase 2 data for icodec were published in 2020 in the New England Journal of Medicine and in 2021 in Diabetes Care, as reported by this news organization.

The capacity for reducing the number of basal insulin injections from at least 365 to just 52 per year means that once-weekly insulin “has the potential to facilitate insulin initiation and improve treatment adherence and persistence in diabetes,” noted Dr. Philis-Tsimikas, corporate vice president of Scripps Whittier Diabetes Institute, San Diego.

Asked to comment, independent diabetes industry consultant Charles Alexander, MD, told this news organization that the new data from ONWARDS 2 of patients switching from daily to once-weekly basal insulin were reassuring with regard to hypoglycemia, at least for people with type 2 diabetes.

“For type 2, I think there’s enough data now to feel comfortable that it’s going to be good, especially for people who are on once-weekly [glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonists].”

However, for type 1 diabetes, the company reported top-line ONWARDS 6 data earlier this year, in which icodec was associated with significantly increased rates of hypoglycemia compared with daily degludec. “In type 1, even the basal needs are [often] changing. That kind of person would want to stay away from once-weekly insulin,” Dr. Alexander said.

And he noted, for any patient who adjusts their insulin dose frequently, “obviously, you’re not going to be able to do that with a once-weekly.”

Similar A1c reduction as daily basal without increased hypoglycemia

In ONWARDS 2, 526 adults with type 2 diabetes were randomized to switch from their current once- or twice-daily basal insulin to either once-weekly icodec or once-daily insulin degludec (Tresiba) for 26 weeks. The study was open-label, with a treat-to-glucose target of 80-130 mg/dL design.

Participants had A1c levels of 7.0%-10.0% and were also taking stable doses of other noninsulin glucose-lowering medications. Over 80% were taking metformin, a third were taking an SGLT2 inhibitor, and about a quarter each were taking a GLP-1 agonist or DPP-4 inhibitor. Those medications were continued, but sulfonylureas were discontinued in the 22% taking those at baseline.

The basal insulin used at baseline was glargine U100 for 42%, degludec for 28%, and glargine U300 for 16%, “so, a very typical presentation of patients we see in our practices today,” Dr. Philis-Tsimikas noted.

The primary endpoint, change in A1c from baseline to week 26, dropped from 8.17% to 7.20% with icodec and from 8.10% to 7.42% with degludec. The estimated treatment difference of –0.22 percentage points met the margins for both noninferiority (P < .0001) and superiority (P = .0028). Those taking icodec were significantly more likely to achieve an A1c under 7% compared with degludec, at 40.3% versus 26.5% (P = .0019).

Continuous glucose monitoring parameters during weeks 22-26 showed time in glucose range of 70-180 mg/dL (3.9-10.0 mmol/L) was 63.1% for icodec and 59.5% for degludec, which was not significantly different, Dr. Philis-Tsimikas reported.

Body weight increased by 1.4 kg (3 lb) with icodec but dropped slightly by 0.30 kg with degludec, which was significantly different (P < .001).

When asked about the body weight results, Dr. Alexander said: “It’s really hard to say. We know that insulin generally causes weight gain. A 1.4-kg weight gain over 6 months isn’t really surprising. Why there wasn’t with degludec, I don’t know.”

There was just one episode of severe hypoglycemia (requiring assistance) in the trial in the degludec group. Rates of combined severe or clinically significant hypoglycemic events (glucose < 54 mg/dL / < 3.0 mmol/L) per patient-year exposed were 0.73 for icodec versus 0.27 for degludec, which was not significantly different (P = .0782). Similar findings were seen for nocturnal hypoglycemia.

Significantly more patients achieved an A1c under 7% without significant hypoglycemia with icodec than degludec, at 36.7% versus 26.8% (P = .0223). Other adverse events were equivalent between the two groups, Dr. Philis-Tsimikas reported.

Scores on the diabetes treatment satisfaction questionnaire, which addresses convenience, flexibility, satisfaction, and willingness to recommend treatment to others, were significantly higher for icodec than degludec, at 4.22 versus 2.96 (P = .0036).

“For me, this is one of the most important outcomes,” she commented.

Benefit in type 2 diabetes, potential concern in type 1 diabetes

Top-line results from ONWARDS 1, a phase 3a 78-week trial in 984 drug-naive people with type 2 diabetes and ONWARDS 6, a 52-week trial in 583 people with type 1 diabetes, were presented earlier this year at the American Diabetes Association 81st Scientific Sessions.

In ONWARDS 1, icodec achieved noninferiority to daily insulin glargine, reducing A1c by 1.55 versus 1.35 percentage points, with superior time in range and no significant differences in hypoglycemia rates.

However, in ONWARDS 6, while noninferiority in A1c lowering compared with daily degludec was achieved, with reductions of 0.47 versus 0.51 percentage points from a baseline A1c of 7.6%, there was a significantly greater rate of severe or clinically significant hypoglycemia with icodec, at 19.93 versus 10.37 events per patient-year with degludec.

Dr. Philis-Tsimikas has reported performing research and serving as an advisor on behalf of her employer for Abbott, Bayer, Dexcom, Eli Lilly, Medtronic, Merck, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi. All reimbursements go to her employer. Dr. Alexander has reported being a nonpaid advisor for diaTribe and a consultant for Kinexum.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

STOCKHOLM – The investigational once-weekly insulin icodec (Novo Nordisk) significantly reduces A1c without increasing hypoglycemia in people with type 2 diabetes, the first phase 3 data of such an insulin formulation suggest. The data are from one of six trials in the company’s ONWARDS program.

“Once-weekly insulin may redefine diabetes management,” enthused Athena Philis-Tsimikas, MD, who presented the findings at a session during the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) 2022 Annual Meeting, which also included a summary of previously reported top-line data from other ONWARDS trials as well as phase 2 data for Lilly›s investigational once-weekly Basal Insulin Fc (BIF).

Phase 2 data for icodec were published in 2020 in the New England Journal of Medicine and in 2021 in Diabetes Care, as reported by this news organization.

The capacity for reducing the number of basal insulin injections from at least 365 to just 52 per year means that once-weekly insulin “has the potential to facilitate insulin initiation and improve treatment adherence and persistence in diabetes,” noted Dr. Philis-Tsimikas, corporate vice president of Scripps Whittier Diabetes Institute, San Diego.

Asked to comment, independent diabetes industry consultant Charles Alexander, MD, told this news organization that the new data from ONWARDS 2 of patients switching from daily to once-weekly basal insulin were reassuring with regard to hypoglycemia, at least for people with type 2 diabetes.

“For type 2, I think there’s enough data now to feel comfortable that it’s going to be good, especially for people who are on once-weekly [glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonists].”

However, for type 1 diabetes, the company reported top-line ONWARDS 6 data earlier this year, in which icodec was associated with significantly increased rates of hypoglycemia compared with daily degludec. “In type 1, even the basal needs are [often] changing. That kind of person would want to stay away from once-weekly insulin,” Dr. Alexander said.

And he noted, for any patient who adjusts their insulin dose frequently, “obviously, you’re not going to be able to do that with a once-weekly.”

Similar A1c reduction as daily basal without increased hypoglycemia

In ONWARDS 2, 526 adults with type 2 diabetes were randomized to switch from their current once- or twice-daily basal insulin to either once-weekly icodec or once-daily insulin degludec (Tresiba) for 26 weeks. The study was open-label, with a treat-to-glucose target of 80-130 mg/dL design.

Participants had A1c levels of 7.0%-10.0% and were also taking stable doses of other noninsulin glucose-lowering medications. Over 80% were taking metformin, a third were taking an SGLT2 inhibitor, and about a quarter each were taking a GLP-1 agonist or DPP-4 inhibitor. Those medications were continued, but sulfonylureas were discontinued in the 22% taking those at baseline.

The basal insulin used at baseline was glargine U100 for 42%, degludec for 28%, and glargine U300 for 16%, “so, a very typical presentation of patients we see in our practices today,” Dr. Philis-Tsimikas noted.

The primary endpoint, change in A1c from baseline to week 26, dropped from 8.17% to 7.20% with icodec and from 8.10% to 7.42% with degludec. The estimated treatment difference of –0.22 percentage points met the margins for both noninferiority (P < .0001) and superiority (P = .0028). Those taking icodec were significantly more likely to achieve an A1c under 7% compared with degludec, at 40.3% versus 26.5% (P = .0019).

Continuous glucose monitoring parameters during weeks 22-26 showed time in glucose range of 70-180 mg/dL (3.9-10.0 mmol/L) was 63.1% for icodec and 59.5% for degludec, which was not significantly different, Dr. Philis-Tsimikas reported.

Body weight increased by 1.4 kg (3 lb) with icodec but dropped slightly by 0.30 kg with degludec, which was significantly different (P < .001).

When asked about the body weight results, Dr. Alexander said: “It’s really hard to say. We know that insulin generally causes weight gain. A 1.4-kg weight gain over 6 months isn’t really surprising. Why there wasn’t with degludec, I don’t know.”

There was just one episode of severe hypoglycemia (requiring assistance) in the trial in the degludec group. Rates of combined severe or clinically significant hypoglycemic events (glucose < 54 mg/dL / < 3.0 mmol/L) per patient-year exposed were 0.73 for icodec versus 0.27 for degludec, which was not significantly different (P = .0782). Similar findings were seen for nocturnal hypoglycemia.

Significantly more patients achieved an A1c under 7% without significant hypoglycemia with icodec than degludec, at 36.7% versus 26.8% (P = .0223). Other adverse events were equivalent between the two groups, Dr. Philis-Tsimikas reported.

Scores on the diabetes treatment satisfaction questionnaire, which addresses convenience, flexibility, satisfaction, and willingness to recommend treatment to others, were significantly higher for icodec than degludec, at 4.22 versus 2.96 (P = .0036).

“For me, this is one of the most important outcomes,” she commented.

Benefit in type 2 diabetes, potential concern in type 1 diabetes

Top-line results from ONWARDS 1, a phase 3a 78-week trial in 984 drug-naive people with type 2 diabetes and ONWARDS 6, a 52-week trial in 583 people with type 1 diabetes, were presented earlier this year at the American Diabetes Association 81st Scientific Sessions.

In ONWARDS 1, icodec achieved noninferiority to daily insulin glargine, reducing A1c by 1.55 versus 1.35 percentage points, with superior time in range and no significant differences in hypoglycemia rates.

However, in ONWARDS 6, while noninferiority in A1c lowering compared with daily degludec was achieved, with reductions of 0.47 versus 0.51 percentage points from a baseline A1c of 7.6%, there was a significantly greater rate of severe or clinically significant hypoglycemia with icodec, at 19.93 versus 10.37 events per patient-year with degludec.

Dr. Philis-Tsimikas has reported performing research and serving as an advisor on behalf of her employer for Abbott, Bayer, Dexcom, Eli Lilly, Medtronic, Merck, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi. All reimbursements go to her employer. Dr. Alexander has reported being a nonpaid advisor for diaTribe and a consultant for Kinexum.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

STOCKHOLM – The investigational once-weekly insulin icodec (Novo Nordisk) significantly reduces A1c without increasing hypoglycemia in people with type 2 diabetes, the first phase 3 data of such an insulin formulation suggest. The data are from one of six trials in the company’s ONWARDS program.

“Once-weekly insulin may redefine diabetes management,” enthused Athena Philis-Tsimikas, MD, who presented the findings at a session during the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) 2022 Annual Meeting, which also included a summary of previously reported top-line data from other ONWARDS trials as well as phase 2 data for Lilly›s investigational once-weekly Basal Insulin Fc (BIF).

Phase 2 data for icodec were published in 2020 in the New England Journal of Medicine and in 2021 in Diabetes Care, as reported by this news organization.

The capacity for reducing the number of basal insulin injections from at least 365 to just 52 per year means that once-weekly insulin “has the potential to facilitate insulin initiation and improve treatment adherence and persistence in diabetes,” noted Dr. Philis-Tsimikas, corporate vice president of Scripps Whittier Diabetes Institute, San Diego.

Asked to comment, independent diabetes industry consultant Charles Alexander, MD, told this news organization that the new data from ONWARDS 2 of patients switching from daily to once-weekly basal insulin were reassuring with regard to hypoglycemia, at least for people with type 2 diabetes.

“For type 2, I think there’s enough data now to feel comfortable that it’s going to be good, especially for people who are on once-weekly [glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonists].”

However, for type 1 diabetes, the company reported top-line ONWARDS 6 data earlier this year, in which icodec was associated with significantly increased rates of hypoglycemia compared with daily degludec. “In type 1, even the basal needs are [often] changing. That kind of person would want to stay away from once-weekly insulin,” Dr. Alexander said.

And he noted, for any patient who adjusts their insulin dose frequently, “obviously, you’re not going to be able to do that with a once-weekly.”

Similar A1c reduction as daily basal without increased hypoglycemia

In ONWARDS 2, 526 adults with type 2 diabetes were randomized to switch from their current once- or twice-daily basal insulin to either once-weekly icodec or once-daily insulin degludec (Tresiba) for 26 weeks. The study was open-label, with a treat-to-glucose target of 80-130 mg/dL design.

Participants had A1c levels of 7.0%-10.0% and were also taking stable doses of other noninsulin glucose-lowering medications. Over 80% were taking metformin, a third were taking an SGLT2 inhibitor, and about a quarter each were taking a GLP-1 agonist or DPP-4 inhibitor. Those medications were continued, but sulfonylureas were discontinued in the 22% taking those at baseline.

The basal insulin used at baseline was glargine U100 for 42%, degludec for 28%, and glargine U300 for 16%, “so, a very typical presentation of patients we see in our practices today,” Dr. Philis-Tsimikas noted.

The primary endpoint, change in A1c from baseline to week 26, dropped from 8.17% to 7.20% with icodec and from 8.10% to 7.42% with degludec. The estimated treatment difference of –0.22 percentage points met the margins for both noninferiority (P < .0001) and superiority (P = .0028). Those taking icodec were significantly more likely to achieve an A1c under 7% compared with degludec, at 40.3% versus 26.5% (P = .0019).

Continuous glucose monitoring parameters during weeks 22-26 showed time in glucose range of 70-180 mg/dL (3.9-10.0 mmol/L) was 63.1% for icodec and 59.5% for degludec, which was not significantly different, Dr. Philis-Tsimikas reported.

Body weight increased by 1.4 kg (3 lb) with icodec but dropped slightly by 0.30 kg with degludec, which was significantly different (P < .001).

When asked about the body weight results, Dr. Alexander said: “It’s really hard to say. We know that insulin generally causes weight gain. A 1.4-kg weight gain over 6 months isn’t really surprising. Why there wasn’t with degludec, I don’t know.”

There was just one episode of severe hypoglycemia (requiring assistance) in the trial in the degludec group. Rates of combined severe or clinically significant hypoglycemic events (glucose < 54 mg/dL / < 3.0 mmol/L) per patient-year exposed were 0.73 for icodec versus 0.27 for degludec, which was not significantly different (P = .0782). Similar findings were seen for nocturnal hypoglycemia.

Significantly more patients achieved an A1c under 7% without significant hypoglycemia with icodec than degludec, at 36.7% versus 26.8% (P = .0223). Other adverse events were equivalent between the two groups, Dr. Philis-Tsimikas reported.

Scores on the diabetes treatment satisfaction questionnaire, which addresses convenience, flexibility, satisfaction, and willingness to recommend treatment to others, were significantly higher for icodec than degludec, at 4.22 versus 2.96 (P = .0036).

“For me, this is one of the most important outcomes,” she commented.

Benefit in type 2 diabetes, potential concern in type 1 diabetes

Top-line results from ONWARDS 1, a phase 3a 78-week trial in 984 drug-naive people with type 2 diabetes and ONWARDS 6, a 52-week trial in 583 people with type 1 diabetes, were presented earlier this year at the American Diabetes Association 81st Scientific Sessions.

In ONWARDS 1, icodec achieved noninferiority to daily insulin glargine, reducing A1c by 1.55 versus 1.35 percentage points, with superior time in range and no significant differences in hypoglycemia rates.

However, in ONWARDS 6, while noninferiority in A1c lowering compared with daily degludec was achieved, with reductions of 0.47 versus 0.51 percentage points from a baseline A1c of 7.6%, there was a significantly greater rate of severe or clinically significant hypoglycemia with icodec, at 19.93 versus 10.37 events per patient-year with degludec.

Dr. Philis-Tsimikas has reported performing research and serving as an advisor on behalf of her employer for Abbott, Bayer, Dexcom, Eli Lilly, Medtronic, Merck, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi. All reimbursements go to her employer. Dr. Alexander has reported being a nonpaid advisor for diaTribe and a consultant for Kinexum.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT EASD 2022

Ezetimibe-statin combo lowers liver fat in open-label trial

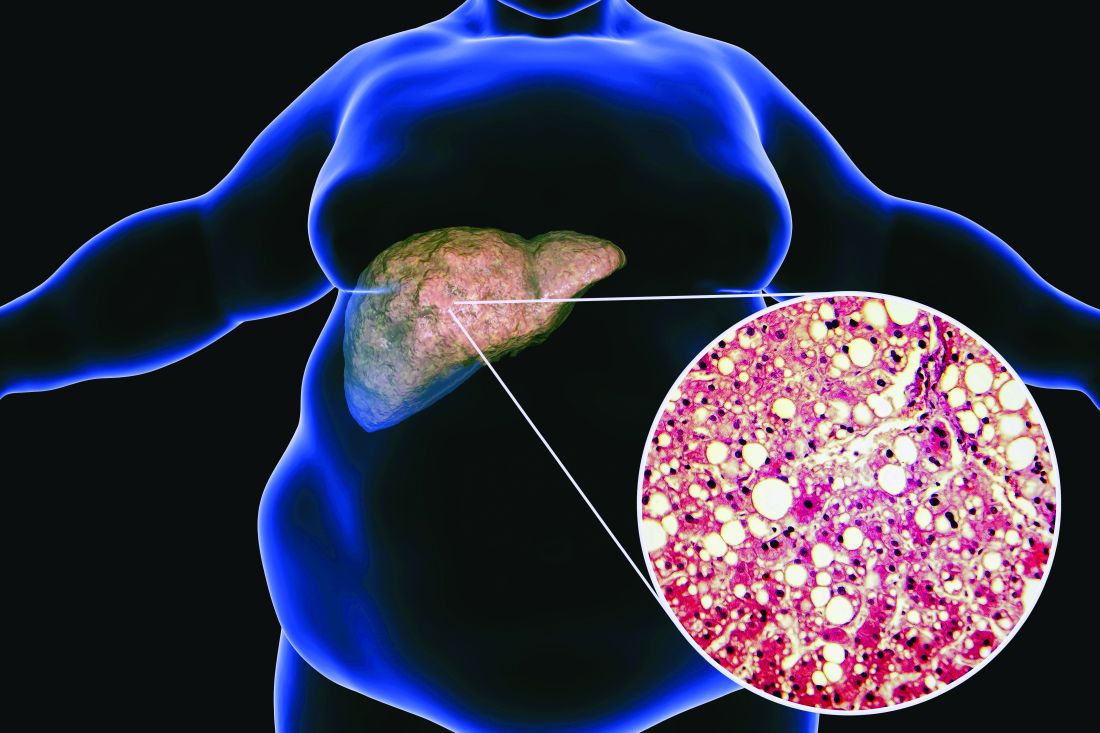

Ezetimibe given in combination with rosuvastatin has a beneficial effect on liver fat in people with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), according results of a randomized, active-controlled trial.

The findings, which come from the investigator-initiated ESSENTIAL trial, are likely to add to the debate over whether or not the lipid-lowering combination could be of benefit beyond its effects in the blood.

“We used magnetic resonance imaging-derived proton density fat fraction [MRI-PDFF], which is highly reliable method of assessing hepatic steatosis,” Youngjoon Kim, PhD, one of the study investigators, said at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes in Barcelona.

“It enables accurate, repeatable and reproducible quantitative assessment of liver fat over the entire liver,” observed Dr. Kim, who works at Severance Hospital, part of Yonsei University in Seoul.

He reported that there was a significant 5.8% decrease in liver fat following 24 weeks’ treatment with ezetimibe and rosuvastatin comparing baseline with end of treatment MRI-PDFF values; a drop that was significant (18.2% vs. 12.3%, P < .001).

Rosuvastatin monotherapy also reduced liver fat from 15.0% at baseline to 12.4% after 24 weeks; this drop of 2.6% was also significant (P = .003).

This gave an absolute mean difference between the two study arms of 3.2% (P = .02).

Rationale for the ESSENTIAL study

Dr. Kim observed during his presentation that NAFLD is burgeoning problem around the world. Ezetimibe plus rosuvastatin was a combination treatment already used widely in clinical practice, and there had been some suggestion that ezetimibe might have an effect on liver fat.

“Although the effect of ezetimibe on hepatic steatosis is still controversial, ezetimibe has been reported to reduce visceral fat and improve insulin resistance in several studies” Dr. Kim said.

“Recently, our group reported that the use of ezetimibe affects autophagy of hepatocytes and the NLRP3 [NOD-like receptors containing pyrin domain 3] inflammasome,” he said.

Moreover, he added, “ezetimibe improved NASH [nonalcoholic steatohepatitis] in an animal model. However, the effects of ezetimibe have not been clearly shown in a human study.”

Dr. Kim also acknowledged a prior randomized control trial that had looked at the role of ezetimibe in 50 patients with NASH, but had not shown a benefit for the drug over placebo in terms of liver fat reduction.

Addressing the Hawthorne effect

“The size of the effect by that might actually be more modest due to the Hawthorne effect,” said session chair Onno Holleboom, MD, PhD, of Amsterdam UMC in the Netherlands.

“What we observe in the large clinical trials is an enormous Hawthorne effect – participating in a NAFLD trial makes people live healthier because they have health checks,” he said.

“That’s a major problem for showing efficacy for the intervention arm,” he added, but of course the open design meant that the trial only had intervention arms; “there was no placebo arm.”

A randomized, active-controlled, clinician-initiated trial

The main objective of the ESSENTIAL trial was therefore to take another look at the potential effect of ezetimibe on hepatic steatosis and doing so in the setting of statin therapy.

In all, 70 patients with NAFLD that had been confirmed via ultrasound were recruited into the prospective, single center, phase 4 trial. Participants were randomized 1:1 to received either ezetimibe 10 mg plus rosuvastatin 5 mg daily or rosuvastatin 5 mg for up to 24 weeks.

Change in liver fat was measured via MRI-PDFF, taking the average values in each of nine liver segments. Magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) was also used to measure liver fibrosis, although results did not show any differences either from baseline to end of treatment values in either group or when the two treatment groups were compared.

Dr. Kim reported that both treatment with the ezetimibe-rosuvastatin combination and rosuvastatin monotherapy reduced parameters that might be associated with a negative outcome in NAFLD, such as body mass index and waist circumference, triglycerides, and LDL cholesterol. There was also a reduction in C-reactive protein levels in the blood, and interleulin-18. There was no change in liver enzymes.

Several subgroup analyses were performed indicating that “individuals with higher BMI, type 2 diabetes, insulin resistance, and severe liver fibrosis were likely to be good responders to ezetimibe treatment,” Dr. Kim said.

“These data indicate that ezetimibe plus rosuvastatin is a safe and effective therapeutic option to treat patients with NAFLD and dyslipidemia,” he concluded.

The results of the ESSENTIAL study have been published in BMC Medicine.

The study was funded by the Yuhan Corporation. Dr. Kim had no conflicts of interest to report. Dr. Holleboom was not involved in the study and had no conflicts of interest.

Ezetimibe given in combination with rosuvastatin has a beneficial effect on liver fat in people with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), according results of a randomized, active-controlled trial.

The findings, which come from the investigator-initiated ESSENTIAL trial, are likely to add to the debate over whether or not the lipid-lowering combination could be of benefit beyond its effects in the blood.

“We used magnetic resonance imaging-derived proton density fat fraction [MRI-PDFF], which is highly reliable method of assessing hepatic steatosis,” Youngjoon Kim, PhD, one of the study investigators, said at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes in Barcelona.

“It enables accurate, repeatable and reproducible quantitative assessment of liver fat over the entire liver,” observed Dr. Kim, who works at Severance Hospital, part of Yonsei University in Seoul.

He reported that there was a significant 5.8% decrease in liver fat following 24 weeks’ treatment with ezetimibe and rosuvastatin comparing baseline with end of treatment MRI-PDFF values; a drop that was significant (18.2% vs. 12.3%, P < .001).

Rosuvastatin monotherapy also reduced liver fat from 15.0% at baseline to 12.4% after 24 weeks; this drop of 2.6% was also significant (P = .003).

This gave an absolute mean difference between the two study arms of 3.2% (P = .02).

Rationale for the ESSENTIAL study

Dr. Kim observed during his presentation that NAFLD is burgeoning problem around the world. Ezetimibe plus rosuvastatin was a combination treatment already used widely in clinical practice, and there had been some suggestion that ezetimibe might have an effect on liver fat.

“Although the effect of ezetimibe on hepatic steatosis is still controversial, ezetimibe has been reported to reduce visceral fat and improve insulin resistance in several studies” Dr. Kim said.

“Recently, our group reported that the use of ezetimibe affects autophagy of hepatocytes and the NLRP3 [NOD-like receptors containing pyrin domain 3] inflammasome,” he said.

Moreover, he added, “ezetimibe improved NASH [nonalcoholic steatohepatitis] in an animal model. However, the effects of ezetimibe have not been clearly shown in a human study.”

Dr. Kim also acknowledged a prior randomized control trial that had looked at the role of ezetimibe in 50 patients with NASH, but had not shown a benefit for the drug over placebo in terms of liver fat reduction.

Addressing the Hawthorne effect

“The size of the effect by that might actually be more modest due to the Hawthorne effect,” said session chair Onno Holleboom, MD, PhD, of Amsterdam UMC in the Netherlands.

“What we observe in the large clinical trials is an enormous Hawthorne effect – participating in a NAFLD trial makes people live healthier because they have health checks,” he said.

“That’s a major problem for showing efficacy for the intervention arm,” he added, but of course the open design meant that the trial only had intervention arms; “there was no placebo arm.”

A randomized, active-controlled, clinician-initiated trial

The main objective of the ESSENTIAL trial was therefore to take another look at the potential effect of ezetimibe on hepatic steatosis and doing so in the setting of statin therapy.

In all, 70 patients with NAFLD that had been confirmed via ultrasound were recruited into the prospective, single center, phase 4 trial. Participants were randomized 1:1 to received either ezetimibe 10 mg plus rosuvastatin 5 mg daily or rosuvastatin 5 mg for up to 24 weeks.

Change in liver fat was measured via MRI-PDFF, taking the average values in each of nine liver segments. Magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) was also used to measure liver fibrosis, although results did not show any differences either from baseline to end of treatment values in either group or when the two treatment groups were compared.

Dr. Kim reported that both treatment with the ezetimibe-rosuvastatin combination and rosuvastatin monotherapy reduced parameters that might be associated with a negative outcome in NAFLD, such as body mass index and waist circumference, triglycerides, and LDL cholesterol. There was also a reduction in C-reactive protein levels in the blood, and interleulin-18. There was no change in liver enzymes.

Several subgroup analyses were performed indicating that “individuals with higher BMI, type 2 diabetes, insulin resistance, and severe liver fibrosis were likely to be good responders to ezetimibe treatment,” Dr. Kim said.

“These data indicate that ezetimibe plus rosuvastatin is a safe and effective therapeutic option to treat patients with NAFLD and dyslipidemia,” he concluded.

The results of the ESSENTIAL study have been published in BMC Medicine.

The study was funded by the Yuhan Corporation. Dr. Kim had no conflicts of interest to report. Dr. Holleboom was not involved in the study and had no conflicts of interest.

Ezetimibe given in combination with rosuvastatin has a beneficial effect on liver fat in people with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), according results of a randomized, active-controlled trial.

The findings, which come from the investigator-initiated ESSENTIAL trial, are likely to add to the debate over whether or not the lipid-lowering combination could be of benefit beyond its effects in the blood.

“We used magnetic resonance imaging-derived proton density fat fraction [MRI-PDFF], which is highly reliable method of assessing hepatic steatosis,” Youngjoon Kim, PhD, one of the study investigators, said at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes in Barcelona.

“It enables accurate, repeatable and reproducible quantitative assessment of liver fat over the entire liver,” observed Dr. Kim, who works at Severance Hospital, part of Yonsei University in Seoul.

He reported that there was a significant 5.8% decrease in liver fat following 24 weeks’ treatment with ezetimibe and rosuvastatin comparing baseline with end of treatment MRI-PDFF values; a drop that was significant (18.2% vs. 12.3%, P < .001).

Rosuvastatin monotherapy also reduced liver fat from 15.0% at baseline to 12.4% after 24 weeks; this drop of 2.6% was also significant (P = .003).

This gave an absolute mean difference between the two study arms of 3.2% (P = .02).

Rationale for the ESSENTIAL study

Dr. Kim observed during his presentation that NAFLD is burgeoning problem around the world. Ezetimibe plus rosuvastatin was a combination treatment already used widely in clinical practice, and there had been some suggestion that ezetimibe might have an effect on liver fat.

“Although the effect of ezetimibe on hepatic steatosis is still controversial, ezetimibe has been reported to reduce visceral fat and improve insulin resistance in several studies” Dr. Kim said.

“Recently, our group reported that the use of ezetimibe affects autophagy of hepatocytes and the NLRP3 [NOD-like receptors containing pyrin domain 3] inflammasome,” he said.

Moreover, he added, “ezetimibe improved NASH [nonalcoholic steatohepatitis] in an animal model. However, the effects of ezetimibe have not been clearly shown in a human study.”

Dr. Kim also acknowledged a prior randomized control trial that had looked at the role of ezetimibe in 50 patients with NASH, but had not shown a benefit for the drug over placebo in terms of liver fat reduction.

Addressing the Hawthorne effect

“The size of the effect by that might actually be more modest due to the Hawthorne effect,” said session chair Onno Holleboom, MD, PhD, of Amsterdam UMC in the Netherlands.

“What we observe in the large clinical trials is an enormous Hawthorne effect – participating in a NAFLD trial makes people live healthier because they have health checks,” he said.

“That’s a major problem for showing efficacy for the intervention arm,” he added, but of course the open design meant that the trial only had intervention arms; “there was no placebo arm.”

A randomized, active-controlled, clinician-initiated trial

The main objective of the ESSENTIAL trial was therefore to take another look at the potential effect of ezetimibe on hepatic steatosis and doing so in the setting of statin therapy.

In all, 70 patients with NAFLD that had been confirmed via ultrasound were recruited into the prospective, single center, phase 4 trial. Participants were randomized 1:1 to received either ezetimibe 10 mg plus rosuvastatin 5 mg daily or rosuvastatin 5 mg for up to 24 weeks.

Change in liver fat was measured via MRI-PDFF, taking the average values in each of nine liver segments. Magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) was also used to measure liver fibrosis, although results did not show any differences either from baseline to end of treatment values in either group or when the two treatment groups were compared.

Dr. Kim reported that both treatment with the ezetimibe-rosuvastatin combination and rosuvastatin monotherapy reduced parameters that might be associated with a negative outcome in NAFLD, such as body mass index and waist circumference, triglycerides, and LDL cholesterol. There was also a reduction in C-reactive protein levels in the blood, and interleulin-18. There was no change in liver enzymes.

Several subgroup analyses were performed indicating that “individuals with higher BMI, type 2 diabetes, insulin resistance, and severe liver fibrosis were likely to be good responders to ezetimibe treatment,” Dr. Kim said.

“These data indicate that ezetimibe plus rosuvastatin is a safe and effective therapeutic option to treat patients with NAFLD and dyslipidemia,” he concluded.

The results of the ESSENTIAL study have been published in BMC Medicine.

The study was funded by the Yuhan Corporation. Dr. Kim had no conflicts of interest to report. Dr. Holleboom was not involved in the study and had no conflicts of interest.

FROM EASD 2022

Cre8 EVO stent loses sweet spot in diabetes at 2 years: SUGAR

BOSTON – Despite a promising start, extended follow-up from the SUGAR trial found that the Cre8 EVO drug-eluting stent could not maintain superiority over the Resolute Onyx DES at 2 years in patients with diabetes undergoing revascularization for coronary artery disease.

The Cre8 EVO stent (Alvimedica) is not available in the United States but, as previously reported, caused a stir last year after demonstrating a 35% relative risk reduction in the primary endpoint of target lesion failure (TLF) at 1 year in a prespecified superiority analysis.

At 2 years, however, the TLF rate was 10.4% with the polymer-free Cre8 EVO amphilimus-eluting stent and 12.1% with the durable polymer Resolute Onyx (Medtronic) zotarolimus-eluting stent, which did not achieve superiority (hazard ratio, 0.84; 95% confidence interval, 0.60-1.19).

Rates were numerically lower with the Cre8 EVO stent for the endpoint’s individual components of cardiac death (3.1% vs. 3.4%), target vessel MI (6.6% vs. 7.6%), and target lesion revascularization (4.3% vs. 4.6%).

Results were also similar between the Cre8 EVO and Resolute Onyx stents for all-cause mortality (7.1% vs. 6.8%), any MI (9.0% vs. 9.2%), target vessel revascularization (5.5% vs. 5.1%), all new revascularizations (7.6% vs. 9.4%), definite stent thrombosis (1.0% vs. 1.2%), and major adverse cardiac events (18.3% vs. 20.8%), Pablo Salinas, MD, PhD, of Hospital Clinico San Carlos, Madrid, reported at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics annual meeting.

He noted that all-cause mortality was 7% in just 2 years in the diabetic cohort, or twice the number of cardiac deaths. “In other words, these patients had the same chance of dying from cardiac causes and noncardiac causes, so we need a more comprehensive approach to the disease. Also, if you look at all new revascularizations, roughly 50% were off target, so there is disease progression at 2 years in this population.”

Among the 586 Cre8 EVO and 589 Resolute Onyx patients who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), roughly half had multivessel coronary artery disease, 83% had hypertension, 81% had dyslipidemia, and 21% were current smokers. Nearly all patients had diabetes type 2 for an average of 10.6 years for Cre8 EVO and 11.4 years for Resolute Onyx, with hemoglobin A1c levels of 7.4% and 7.5%, respectively.

Although there is “insufficient evidence” the Cre8 EVO stent is superior to the Resolute Onyx stent with regard to TLF, Dr. Salinas concluded extended follow-up until 5 years is warranted.

During a discussion of the results, Dr. Salinas said he expects the 5-year results will “probably go parallel” but that it’s worth following this very valuable cohort. “There are not so many trials with 1,000 diabetic patients. We always speak about how complex they are, the results are bad, but we don’t use the diabetic population in trials,” he said at the meeting sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

Asked during a TCT press conference what could have caused the catch-up in TLF at 2 years, Dr. Salinas said there were only 25 primary events from years 1 to 2, driven primarily by periprocedural MI, but that the timing of restenosis was different. Events accrued “drop by drop” with the Cre8 EVO, whereas with the Resolute Onyx there was a “bump in restenosis” after 6 months “but then it is very nice to see it is flat, which means that durable polymers are also safe because we have not seen late events.”

Press conference discussant Carlo Di Mario, MD, from Careggi University Hospital, Florence, Italy, who was not involved in the study, said the reversal of superiority for the Cre8 EVO might be a “bitter note” for the investigators but “maybe it is not bitter for us because overall, the percentage of figures are so low that it’s very difficult to find a difference” between the two stents.

Roxana Mehran, MD, of Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, who previously described the 1-year results as “almost too good to be true,” commented to this news organization, “We just saw in this trial, no benefit whatsoever at 2 years in terms of target lesion failure. So it’s very important for us to evaluate this going forward.”

She continued, “We’ve always been talking about these biodegradable polymers and then going back to the bare metal stent – oh that’s great because polymers aren’t so good – but now we’re seeing durable polymers may be okay, especially with the current technology.”

Asked whether Cre8 EVO, which is CE mark certified in Europe, remains an option in light of the new results, Dr. Mehran said, “I don’t think it kills it. It’s not worse; it’s another stent that’s available.”

Nevertheless, “what we’re looking for is some efficacious benefit for diabetic patients. We don’t have one yet,” observed Dr. Mehran, who is leading the ABILITY Diabetes Global trial, which just finished enrolling 3,000 patients with diabetes and is testing PCI with the Abluminus DES+ sirolimus-eluting stent system vs. the Xience everolimus-eluting stent. The study is estimated to be complete in August 2024.

The study was funded by the Spanish Society of Cardiology. Dr. Salinas reported consulting fees/honoraria from Boston Scientific, Abbott Vascular, Biomenco, and Medtronic.