User login

Insulin rationing common, ‘surprising’ even among privately insured

Insulin rationing due to cost in the United States is common even among people with diabetes who have private health insurance, new data show.

The findings from the 2021 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) suggest that about one in six people with insulin-treated diabetes in the United States practice insulin rationing – skipping doses, taking less insulin than needed, or delaying the purchase of insulin – because of the price.

Not surprisingly, those without insurance had the highest rationing rate, at nearly a third. However, those with private insurance also had higher rates, at nearly one in five, than those of the overall diabetes population. And those with public insurance – Medicare and Medicaid – had lower rates.

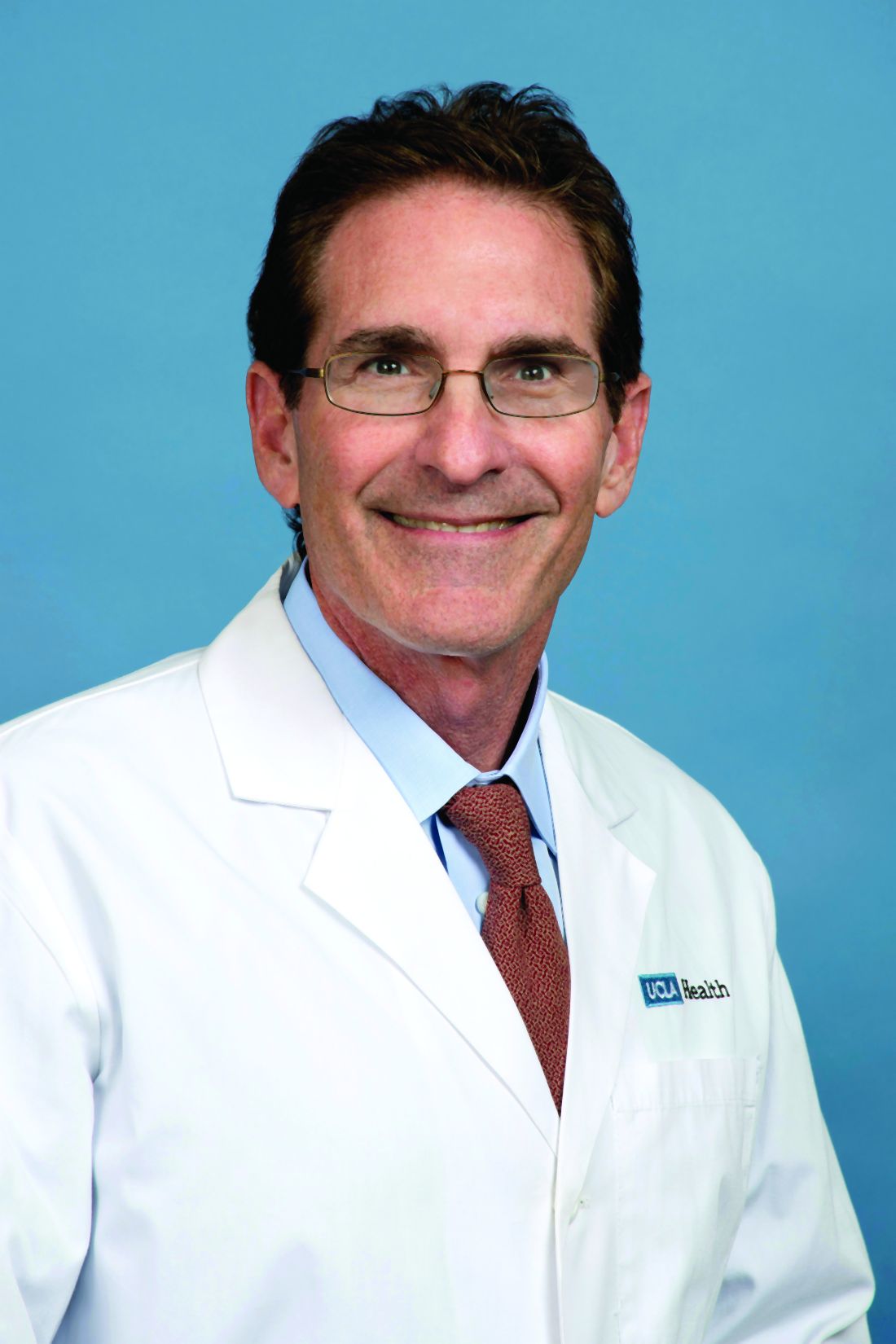

The finding regarding privately insured individuals was “somewhat surprising,” lead author Adam Gaffney, MD, told this news organization. But he noted that the finding likely reflects issues such as copays and deductibles, along with other barriers patients experience within the private health insurance system.

The authors pointed out that the $35 copay cap on insulin included in the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 might improve insulin access for Medicare beneficiaries but a similar cap for privately insured people was removed from the bill. Moreover, copay caps don’t help people who are uninsured.

And, although some states have also passed insulin copay caps that apply to privately insured people, “even a monthly cost of $35 can be a lot of money for people with low incomes. That isn’t negligible. It’s important to keep that in mind,” said Dr. Gaffney, a pulmonary and critical care physician at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and Cambridge (Mass.) Health Alliance.

“Insulin rationing is frequently harmful and sometimes deadly. In the ICU, I have cared for patients who have life-threatening complications of diabetes because they couldn’t afford this life-saving drug. Universal access to insulin, without cost barriers, is urgently needed,” Dr. Gaffney said in a Public Citizen statement.

Senior author Steffie Woolhandler, MD, agrees. “Drug companies have ramped up prices on insulin year after year, even for products that remain completely unchanged,” she noted.

“Drug firms are making vast profits at the expense of the health, and even the lives, of patients,” noted Dr. Woolhandler, a distinguished professor at Hunter College, City University of New York, a lecturer in medicine at Harvard, and a research associate at Public Citizen.

Uninsured, privately insured, and younger people more likely to ration

Dr. Gaffney and colleagues’ findings were published online in Annals of Internal Medicine.

The study is the first to examine insulin rationing across the United States among people with all diabetes types treated with insulin using the nationally representative NHIS data.

The results are consistent with those of previous studies, which have found similar rates of insulin rationing at a single U.S. institution and internationally among just those with type 1 diabetes, Dr. Gaffney noted.

In 2021, questions about insulin rationing were added to the NHIS for the first time.

The sample included 982 insulin users with diabetes, representing about 1.4 million U.S. adults with type 1 diabetes, 5.8 million with type 2 diabetes, and 0.4 million with other/unknown types.

Overall, 16.5% of participants – 1.3 million nationwide – reported skipping or reducing insulin doses or delaying the purchase of it in the past year. Delaying purchase was the most common type of rationing, reported by 14.2%, while taking less than needed was the most common practice among those with type 1 diabetes (16.5%).

Age made a difference, with 11.2% of adults aged 65 or older versus 20.4% of younger people reporting rationing. And by income level, even among those at the top level examined – 400% or higher of the federal poverty line – 10.8% reported rationing.

“The high-income group is not necessarily rich. Many would be considered middle-income,” Dr. Gaffney pointed out.

By race, 23.2% of Black participants reported rationing compared with 16.0% of White and Hispanic individuals.

People without insurance had the highest rationing rate (29.2%), followed by those with private insurance (18.8%), other coverage (16.1%), Medicare (13.5%), and Medicaid (11.6%).

‘It’s a complicated system’

Dr. Gaffney noted that even when the patient has private insurance, it’s challenging for the clinician to know in advance whether there are formulary restrictions on what type of insulin can be prescribed or what the patient’s copay or deductible will be.

“Often the prescription gets written without clear knowledge of coverage beforehand ... Coverage differs from patient to patient, from insurance to insurance. It’s a complicated system.”

He added, though, that some electronic health records (EHRs) incorporate this information. “Currently, some EHRs give real-time feedback. I see no reason why, for all the money we plug into these EHRs, there couldn’t be real-time feedback for every patient so you know what the copay is and whether it’s covered at the time you’re prescribing it. To me that’s a very straightforward technological fix that we could achieve. We have the information, but it’s hard to act on it.”

But beyond the EHR, “there are also problems when the patient’s insurance changes or their network changes, and what insulin is covered changes. And they don’t necessarily get that new prescription in time. And suddenly they have a gap. Gaps can be dangerous.”

What’s more, Dr. Gaffney noted: “The study raises concerning questions about what happens when the public health emergency ends and millions of people with Medicaid lose their coverage. Where are they going to get insulin? That’s another population we have to be worried about.”

All of this puts clinicians in a difficult spot, he said.

“They want the best for their patients but they’re working in a system that’s not letting them focus on practicing medicine and instead is forcing them to think about these economic issues that are in large part out of their control.”

Dr. Gaffney is a member of Physicians for a National Health Program, which advocates for a single-payer health system in the United States.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Insulin rationing due to cost in the United States is common even among people with diabetes who have private health insurance, new data show.

The findings from the 2021 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) suggest that about one in six people with insulin-treated diabetes in the United States practice insulin rationing – skipping doses, taking less insulin than needed, or delaying the purchase of insulin – because of the price.

Not surprisingly, those without insurance had the highest rationing rate, at nearly a third. However, those with private insurance also had higher rates, at nearly one in five, than those of the overall diabetes population. And those with public insurance – Medicare and Medicaid – had lower rates.

The finding regarding privately insured individuals was “somewhat surprising,” lead author Adam Gaffney, MD, told this news organization. But he noted that the finding likely reflects issues such as copays and deductibles, along with other barriers patients experience within the private health insurance system.

The authors pointed out that the $35 copay cap on insulin included in the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 might improve insulin access for Medicare beneficiaries but a similar cap for privately insured people was removed from the bill. Moreover, copay caps don’t help people who are uninsured.

And, although some states have also passed insulin copay caps that apply to privately insured people, “even a monthly cost of $35 can be a lot of money for people with low incomes. That isn’t negligible. It’s important to keep that in mind,” said Dr. Gaffney, a pulmonary and critical care physician at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and Cambridge (Mass.) Health Alliance.

“Insulin rationing is frequently harmful and sometimes deadly. In the ICU, I have cared for patients who have life-threatening complications of diabetes because they couldn’t afford this life-saving drug. Universal access to insulin, without cost barriers, is urgently needed,” Dr. Gaffney said in a Public Citizen statement.

Senior author Steffie Woolhandler, MD, agrees. “Drug companies have ramped up prices on insulin year after year, even for products that remain completely unchanged,” she noted.

“Drug firms are making vast profits at the expense of the health, and even the lives, of patients,” noted Dr. Woolhandler, a distinguished professor at Hunter College, City University of New York, a lecturer in medicine at Harvard, and a research associate at Public Citizen.

Uninsured, privately insured, and younger people more likely to ration

Dr. Gaffney and colleagues’ findings were published online in Annals of Internal Medicine.

The study is the first to examine insulin rationing across the United States among people with all diabetes types treated with insulin using the nationally representative NHIS data.

The results are consistent with those of previous studies, which have found similar rates of insulin rationing at a single U.S. institution and internationally among just those with type 1 diabetes, Dr. Gaffney noted.

In 2021, questions about insulin rationing were added to the NHIS for the first time.

The sample included 982 insulin users with diabetes, representing about 1.4 million U.S. adults with type 1 diabetes, 5.8 million with type 2 diabetes, and 0.4 million with other/unknown types.

Overall, 16.5% of participants – 1.3 million nationwide – reported skipping or reducing insulin doses or delaying the purchase of it in the past year. Delaying purchase was the most common type of rationing, reported by 14.2%, while taking less than needed was the most common practice among those with type 1 diabetes (16.5%).

Age made a difference, with 11.2% of adults aged 65 or older versus 20.4% of younger people reporting rationing. And by income level, even among those at the top level examined – 400% or higher of the federal poverty line – 10.8% reported rationing.

“The high-income group is not necessarily rich. Many would be considered middle-income,” Dr. Gaffney pointed out.

By race, 23.2% of Black participants reported rationing compared with 16.0% of White and Hispanic individuals.

People without insurance had the highest rationing rate (29.2%), followed by those with private insurance (18.8%), other coverage (16.1%), Medicare (13.5%), and Medicaid (11.6%).

‘It’s a complicated system’

Dr. Gaffney noted that even when the patient has private insurance, it’s challenging for the clinician to know in advance whether there are formulary restrictions on what type of insulin can be prescribed or what the patient’s copay or deductible will be.

“Often the prescription gets written without clear knowledge of coverage beforehand ... Coverage differs from patient to patient, from insurance to insurance. It’s a complicated system.”

He added, though, that some electronic health records (EHRs) incorporate this information. “Currently, some EHRs give real-time feedback. I see no reason why, for all the money we plug into these EHRs, there couldn’t be real-time feedback for every patient so you know what the copay is and whether it’s covered at the time you’re prescribing it. To me that’s a very straightforward technological fix that we could achieve. We have the information, but it’s hard to act on it.”

But beyond the EHR, “there are also problems when the patient’s insurance changes or their network changes, and what insulin is covered changes. And they don’t necessarily get that new prescription in time. And suddenly they have a gap. Gaps can be dangerous.”

What’s more, Dr. Gaffney noted: “The study raises concerning questions about what happens when the public health emergency ends and millions of people with Medicaid lose their coverage. Where are they going to get insulin? That’s another population we have to be worried about.”

All of this puts clinicians in a difficult spot, he said.

“They want the best for their patients but they’re working in a system that’s not letting them focus on practicing medicine and instead is forcing them to think about these economic issues that are in large part out of their control.”

Dr. Gaffney is a member of Physicians for a National Health Program, which advocates for a single-payer health system in the United States.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Insulin rationing due to cost in the United States is common even among people with diabetes who have private health insurance, new data show.

The findings from the 2021 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) suggest that about one in six people with insulin-treated diabetes in the United States practice insulin rationing – skipping doses, taking less insulin than needed, or delaying the purchase of insulin – because of the price.

Not surprisingly, those without insurance had the highest rationing rate, at nearly a third. However, those with private insurance also had higher rates, at nearly one in five, than those of the overall diabetes population. And those with public insurance – Medicare and Medicaid – had lower rates.

The finding regarding privately insured individuals was “somewhat surprising,” lead author Adam Gaffney, MD, told this news organization. But he noted that the finding likely reflects issues such as copays and deductibles, along with other barriers patients experience within the private health insurance system.

The authors pointed out that the $35 copay cap on insulin included in the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 might improve insulin access for Medicare beneficiaries but a similar cap for privately insured people was removed from the bill. Moreover, copay caps don’t help people who are uninsured.

And, although some states have also passed insulin copay caps that apply to privately insured people, “even a monthly cost of $35 can be a lot of money for people with low incomes. That isn’t negligible. It’s important to keep that in mind,” said Dr. Gaffney, a pulmonary and critical care physician at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and Cambridge (Mass.) Health Alliance.

“Insulin rationing is frequently harmful and sometimes deadly. In the ICU, I have cared for patients who have life-threatening complications of diabetes because they couldn’t afford this life-saving drug. Universal access to insulin, without cost barriers, is urgently needed,” Dr. Gaffney said in a Public Citizen statement.

Senior author Steffie Woolhandler, MD, agrees. “Drug companies have ramped up prices on insulin year after year, even for products that remain completely unchanged,” she noted.

“Drug firms are making vast profits at the expense of the health, and even the lives, of patients,” noted Dr. Woolhandler, a distinguished professor at Hunter College, City University of New York, a lecturer in medicine at Harvard, and a research associate at Public Citizen.

Uninsured, privately insured, and younger people more likely to ration

Dr. Gaffney and colleagues’ findings were published online in Annals of Internal Medicine.

The study is the first to examine insulin rationing across the United States among people with all diabetes types treated with insulin using the nationally representative NHIS data.

The results are consistent with those of previous studies, which have found similar rates of insulin rationing at a single U.S. institution and internationally among just those with type 1 diabetes, Dr. Gaffney noted.

In 2021, questions about insulin rationing were added to the NHIS for the first time.

The sample included 982 insulin users with diabetes, representing about 1.4 million U.S. adults with type 1 diabetes, 5.8 million with type 2 diabetes, and 0.4 million with other/unknown types.

Overall, 16.5% of participants – 1.3 million nationwide – reported skipping or reducing insulin doses or delaying the purchase of it in the past year. Delaying purchase was the most common type of rationing, reported by 14.2%, while taking less than needed was the most common practice among those with type 1 diabetes (16.5%).

Age made a difference, with 11.2% of adults aged 65 or older versus 20.4% of younger people reporting rationing. And by income level, even among those at the top level examined – 400% or higher of the federal poverty line – 10.8% reported rationing.

“The high-income group is not necessarily rich. Many would be considered middle-income,” Dr. Gaffney pointed out.

By race, 23.2% of Black participants reported rationing compared with 16.0% of White and Hispanic individuals.

People without insurance had the highest rationing rate (29.2%), followed by those with private insurance (18.8%), other coverage (16.1%), Medicare (13.5%), and Medicaid (11.6%).

‘It’s a complicated system’

Dr. Gaffney noted that even when the patient has private insurance, it’s challenging for the clinician to know in advance whether there are formulary restrictions on what type of insulin can be prescribed or what the patient’s copay or deductible will be.

“Often the prescription gets written without clear knowledge of coverage beforehand ... Coverage differs from patient to patient, from insurance to insurance. It’s a complicated system.”

He added, though, that some electronic health records (EHRs) incorporate this information. “Currently, some EHRs give real-time feedback. I see no reason why, for all the money we plug into these EHRs, there couldn’t be real-time feedback for every patient so you know what the copay is and whether it’s covered at the time you’re prescribing it. To me that’s a very straightforward technological fix that we could achieve. We have the information, but it’s hard to act on it.”

But beyond the EHR, “there are also problems when the patient’s insurance changes or their network changes, and what insulin is covered changes. And they don’t necessarily get that new prescription in time. And suddenly they have a gap. Gaps can be dangerous.”

What’s more, Dr. Gaffney noted: “The study raises concerning questions about what happens when the public health emergency ends and millions of people with Medicaid lose their coverage. Where are they going to get insulin? That’s another population we have to be worried about.”

All of this puts clinicians in a difficult spot, he said.

“They want the best for their patients but they’re working in a system that’s not letting them focus on practicing medicine and instead is forcing them to think about these economic issues that are in large part out of their control.”

Dr. Gaffney is a member of Physicians for a National Health Program, which advocates for a single-payer health system in the United States.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Diabetes becoming less potent risk factor for CVD events

Diabetes persists as a risk factor for cardiovascular events, but where it once meant the same risk of heart attack or stroke as cardiovascular disease itself, a large Canadian population study reports that’s no longer the case. Thanks to advances in diabetes management over the past quarter century, diabetes is no longer considered equivalent to CVD as a risk factor for cardiovascular events, researchers from the University of Toronto reported.

The retrospective, population-based study used administrative data from Ontario’s provincial universal health care system. The researchers created five population-based cohorts of adults at 5-year intervals from 1994 to 2014, consisting of 1.87 million adults in the first cohort and 1.5 million in the last. In that 20-year span, the prevalence of diabetes in this population tripled, from 3.1% to 9%.

“In the last 25 years we’ve seen wholesale changes in the way people approach diabetes,” lead study author Calvin Ke, MD, PhD, an endocrinologist and assistant professor at the University of Toronto, said in an interview. “Part of the findings show that diabetes and cardiovascular disease were equivalent for risk of cardiovascular events in 1994, but by 2014 that was not the case.”

However, Dr. Ke added, “Diabetes is still a very strong cardiovascular risk factor.”

The investigators for the study, reported as a research letter in JAMA, analyzed the risk of cardiovascular events in four subgroups: those who had both diabetes and CVD, CVD only, diabetes only, and no CVD or diabetes.

Between 1994 and 2014, the cardiovascular event rates declined significantly among people with diabetes alone, compared with people with no disease: from 28.4 to 12.7 per 1,000 person-years, or an absolute risk increase (ARI) of 4.4% and a relative risk (RR) more than double (2.06), in 1994 to 14 vs. 8 per 1,000 person-years, and an ARI of 2% and RR less than double (1.58) 20 years later.

Among people with CVD only, those values shifted from 36.1 per 1,000 person-years, ARI of 5.1% and RR of 2.16 in 1994 to 23.9, ARI of 3.7% and RR still more than double (2.06) in 2014.

People with both CVD and diabetes had the highest CVD event rates across all 5-year cohorts: 74 per 1,000 person-years, ARI of 12% and RR almost four times greater (3.81) in 1994 than people with no disease. By 2014, the ARI in this group was 7.6% and the RR 3.10.

The investigators calculated that event rates from 1994 to 2014 declined across all four subgroups, with rate ratios of 0.49 for diabetes only, 0.66 for CVD only, 0.60 for both diabetes and CVD, and 0.63 for neither disease.

Shift in practice

The study noted that the shift in diabetes as a risk factor for heart attack and stroke is “a change that likely reflects the use of modern, multifactorial approaches to diabetes.”

“A number of changes have occurred in practice that really focus on this idea of a multifactorial approach to diabetes: more aggressive management of blood sugar, blood pressure, and lipids,” Dr. Ke said. “We know from the statin trials that statins can reduce the risk of heart disease significantly, and the use of statins increased from 28.4% in 1999 to 56.3% in 2018 in the United States,” Dr. Ke said. He added that statin use in Canada in adults ages 40 and older went from 1.2% in 1994 to 58.4% in 2010-2015. Use of ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers for hypertension followed similar trends, contributing further to reducing risks for heart attack and stroke, Dr. Ke said.

Dr. Ke also noted that the evolution of guidelines and advances in treatments for both CVD and diabetes since 1994 have contributed to improving risks for people with diabetes. SGLT2 inhibitors have been linked to a 2%-6% reduction in hemoglobin A1c, he said. “All of these factors combined have had a major effect on the reduced risk of cardiovascular events.”

Prakash Deedwania, MD, professor at the University of California, San Francisco, Fresno, said that this study confirms a trend that others have reported regarding the risk of CVD in diabetes. The large database covering millions of adults is a study strength, he said.

And the findings, Dr. Deedwania added, underscore what’s been published in clinical guidelines, notably the American Heart Association scientific statement for managing CVD risk in patients with diabetes. “This means that, from observations made 20-plus years ago, when most people were not being treated for diabetes or heart disease, the pendulum has swung,” he said.

However, he added, “The authors state clearly that it does not mean that diabetes is not associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular events; it just means it is no longer equivalent to CVD.”

Managing diabetes continues to be “particularly important,” Dr. Deedwania said, because the prevalence of diabetes continues to rise. “This is a phenomenal risk, and it emphasizes that, to really conquer or control diabetes, we should make every effort to prevent diabetes,” he said.

Dr. Ke and Dr. Deedwania have no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Diabetes persists as a risk factor for cardiovascular events, but where it once meant the same risk of heart attack or stroke as cardiovascular disease itself, a large Canadian population study reports that’s no longer the case. Thanks to advances in diabetes management over the past quarter century, diabetes is no longer considered equivalent to CVD as a risk factor for cardiovascular events, researchers from the University of Toronto reported.

The retrospective, population-based study used administrative data from Ontario’s provincial universal health care system. The researchers created five population-based cohorts of adults at 5-year intervals from 1994 to 2014, consisting of 1.87 million adults in the first cohort and 1.5 million in the last. In that 20-year span, the prevalence of diabetes in this population tripled, from 3.1% to 9%.

“In the last 25 years we’ve seen wholesale changes in the way people approach diabetes,” lead study author Calvin Ke, MD, PhD, an endocrinologist and assistant professor at the University of Toronto, said in an interview. “Part of the findings show that diabetes and cardiovascular disease were equivalent for risk of cardiovascular events in 1994, but by 2014 that was not the case.”

However, Dr. Ke added, “Diabetes is still a very strong cardiovascular risk factor.”

The investigators for the study, reported as a research letter in JAMA, analyzed the risk of cardiovascular events in four subgroups: those who had both diabetes and CVD, CVD only, diabetes only, and no CVD or diabetes.

Between 1994 and 2014, the cardiovascular event rates declined significantly among people with diabetes alone, compared with people with no disease: from 28.4 to 12.7 per 1,000 person-years, or an absolute risk increase (ARI) of 4.4% and a relative risk (RR) more than double (2.06), in 1994 to 14 vs. 8 per 1,000 person-years, and an ARI of 2% and RR less than double (1.58) 20 years later.

Among people with CVD only, those values shifted from 36.1 per 1,000 person-years, ARI of 5.1% and RR of 2.16 in 1994 to 23.9, ARI of 3.7% and RR still more than double (2.06) in 2014.

People with both CVD and diabetes had the highest CVD event rates across all 5-year cohorts: 74 per 1,000 person-years, ARI of 12% and RR almost four times greater (3.81) in 1994 than people with no disease. By 2014, the ARI in this group was 7.6% and the RR 3.10.

The investigators calculated that event rates from 1994 to 2014 declined across all four subgroups, with rate ratios of 0.49 for diabetes only, 0.66 for CVD only, 0.60 for both diabetes and CVD, and 0.63 for neither disease.

Shift in practice

The study noted that the shift in diabetes as a risk factor for heart attack and stroke is “a change that likely reflects the use of modern, multifactorial approaches to diabetes.”

“A number of changes have occurred in practice that really focus on this idea of a multifactorial approach to diabetes: more aggressive management of blood sugar, blood pressure, and lipids,” Dr. Ke said. “We know from the statin trials that statins can reduce the risk of heart disease significantly, and the use of statins increased from 28.4% in 1999 to 56.3% in 2018 in the United States,” Dr. Ke said. He added that statin use in Canada in adults ages 40 and older went from 1.2% in 1994 to 58.4% in 2010-2015. Use of ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers for hypertension followed similar trends, contributing further to reducing risks for heart attack and stroke, Dr. Ke said.

Dr. Ke also noted that the evolution of guidelines and advances in treatments for both CVD and diabetes since 1994 have contributed to improving risks for people with diabetes. SGLT2 inhibitors have been linked to a 2%-6% reduction in hemoglobin A1c, he said. “All of these factors combined have had a major effect on the reduced risk of cardiovascular events.”

Prakash Deedwania, MD, professor at the University of California, San Francisco, Fresno, said that this study confirms a trend that others have reported regarding the risk of CVD in diabetes. The large database covering millions of adults is a study strength, he said.

And the findings, Dr. Deedwania added, underscore what’s been published in clinical guidelines, notably the American Heart Association scientific statement for managing CVD risk in patients with diabetes. “This means that, from observations made 20-plus years ago, when most people were not being treated for diabetes or heart disease, the pendulum has swung,” he said.

However, he added, “The authors state clearly that it does not mean that diabetes is not associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular events; it just means it is no longer equivalent to CVD.”

Managing diabetes continues to be “particularly important,” Dr. Deedwania said, because the prevalence of diabetes continues to rise. “This is a phenomenal risk, and it emphasizes that, to really conquer or control diabetes, we should make every effort to prevent diabetes,” he said.

Dr. Ke and Dr. Deedwania have no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Diabetes persists as a risk factor for cardiovascular events, but where it once meant the same risk of heart attack or stroke as cardiovascular disease itself, a large Canadian population study reports that’s no longer the case. Thanks to advances in diabetes management over the past quarter century, diabetes is no longer considered equivalent to CVD as a risk factor for cardiovascular events, researchers from the University of Toronto reported.

The retrospective, population-based study used administrative data from Ontario’s provincial universal health care system. The researchers created five population-based cohorts of adults at 5-year intervals from 1994 to 2014, consisting of 1.87 million adults in the first cohort and 1.5 million in the last. In that 20-year span, the prevalence of diabetes in this population tripled, from 3.1% to 9%.

“In the last 25 years we’ve seen wholesale changes in the way people approach diabetes,” lead study author Calvin Ke, MD, PhD, an endocrinologist and assistant professor at the University of Toronto, said in an interview. “Part of the findings show that diabetes and cardiovascular disease were equivalent for risk of cardiovascular events in 1994, but by 2014 that was not the case.”

However, Dr. Ke added, “Diabetes is still a very strong cardiovascular risk factor.”

The investigators for the study, reported as a research letter in JAMA, analyzed the risk of cardiovascular events in four subgroups: those who had both diabetes and CVD, CVD only, diabetes only, and no CVD or diabetes.

Between 1994 and 2014, the cardiovascular event rates declined significantly among people with diabetes alone, compared with people with no disease: from 28.4 to 12.7 per 1,000 person-years, or an absolute risk increase (ARI) of 4.4% and a relative risk (RR) more than double (2.06), in 1994 to 14 vs. 8 per 1,000 person-years, and an ARI of 2% and RR less than double (1.58) 20 years later.

Among people with CVD only, those values shifted from 36.1 per 1,000 person-years, ARI of 5.1% and RR of 2.16 in 1994 to 23.9, ARI of 3.7% and RR still more than double (2.06) in 2014.

People with both CVD and diabetes had the highest CVD event rates across all 5-year cohorts: 74 per 1,000 person-years, ARI of 12% and RR almost four times greater (3.81) in 1994 than people with no disease. By 2014, the ARI in this group was 7.6% and the RR 3.10.

The investigators calculated that event rates from 1994 to 2014 declined across all four subgroups, with rate ratios of 0.49 for diabetes only, 0.66 for CVD only, 0.60 for both diabetes and CVD, and 0.63 for neither disease.

Shift in practice

The study noted that the shift in diabetes as a risk factor for heart attack and stroke is “a change that likely reflects the use of modern, multifactorial approaches to diabetes.”

“A number of changes have occurred in practice that really focus on this idea of a multifactorial approach to diabetes: more aggressive management of blood sugar, blood pressure, and lipids,” Dr. Ke said. “We know from the statin trials that statins can reduce the risk of heart disease significantly, and the use of statins increased from 28.4% in 1999 to 56.3% in 2018 in the United States,” Dr. Ke said. He added that statin use in Canada in adults ages 40 and older went from 1.2% in 1994 to 58.4% in 2010-2015. Use of ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers for hypertension followed similar trends, contributing further to reducing risks for heart attack and stroke, Dr. Ke said.

Dr. Ke also noted that the evolution of guidelines and advances in treatments for both CVD and diabetes since 1994 have contributed to improving risks for people with diabetes. SGLT2 inhibitors have been linked to a 2%-6% reduction in hemoglobin A1c, he said. “All of these factors combined have had a major effect on the reduced risk of cardiovascular events.”

Prakash Deedwania, MD, professor at the University of California, San Francisco, Fresno, said that this study confirms a trend that others have reported regarding the risk of CVD in diabetes. The large database covering millions of adults is a study strength, he said.

And the findings, Dr. Deedwania added, underscore what’s been published in clinical guidelines, notably the American Heart Association scientific statement for managing CVD risk in patients with diabetes. “This means that, from observations made 20-plus years ago, when most people were not being treated for diabetes or heart disease, the pendulum has swung,” he said.

However, he added, “The authors state clearly that it does not mean that diabetes is not associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular events; it just means it is no longer equivalent to CVD.”

Managing diabetes continues to be “particularly important,” Dr. Deedwania said, because the prevalence of diabetes continues to rise. “This is a phenomenal risk, and it emphasizes that, to really conquer or control diabetes, we should make every effort to prevent diabetes,” he said.

Dr. Ke and Dr. Deedwania have no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

FROM JAMA

Finerenone benefits T2D across spectrum of renal function

Treatment with finerenone produced roughly similar reductions in heart failure–related outcomes in people with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease (CKD) across the spectrum of kidney function, compared with placebo, including those who had albuminuria but a preserved estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), in a post hoc analysis of pooled data from more than 13,000 people.

The findings, from the two pivotal trials for the agent, “reinforce the importance of routine eGFR and UACR [urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio] screening” in people with type 2 diabetes to identify new candidates for treatment with finerenone (Kerendia), Gerasimos Filippatos, MD, and coauthors said in a report published online in JACC: Heart Failure.

Among the 13,026 patients in the two combined trials, 40% had a preserved eGFR of greater than 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 despite also having albuminuria with a UACR of at least 30 mg/g, showing how often this combination occurs. But many clinicians “do not follow the guidelines” and fail to measure the UACR in these patients in routine practice, noted Dr. Filippatos at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology in August.

“We now have something to do for these patients,” treat them with finerenone, said Dr. Filippatos, professor and director of heart failure at the Attikon University Hospital, Athens.

The availability of finerenone following its U.S. approval in 2021 means clinicians “must get used to measuring UACR” in people with type 2 diabetes even when their eGFR is normal, especially people with type 2 diabetes plus high cardiovascular disease risk, he said.

The Food and Drug Administration approved finerenone, a nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, for treating people with type 2 diabetes and CKD in July 2021, but its uptake has been slow, experts say. In a talk in September 2022 during the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes, Jennifer B. Green, MD, estimated that U.S. uptake of finerenone for appropriate people with type 2 diabetes had not advanced beyond 10%.

A recent review also noted that uptake of screening for elevated UACR in U.S. patients with type 2 diabetes was in the range of 10%-40% during 2017-2019, a “shockingly low rate,” said Dr. Green, a professor and diabetes specialist at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

A new reason to screen for albuminuria

“It’s an extremely important message,” Johann Bauersachs, MD, commented in an interview. Results from “many studies have shown that albuminuria is an excellent additional marker for cardiovascular disease risk. But measurement of albuminuria is not widely done, despite guidelines that recommend annual albuminuria testing in people with type 2 diabetes,” said Dr. Bauersachs, professor and head of the department of cardiology at Hannover (Germany) Medical School.

“Even before there was finerenone, there were reasons to measure UACR, but I hope adding finerenone will help, and more clinicians will incorporate UACR into their routine practice,” said Dr. Bauersachs, who was not involved with the finerenone studies.

The analyses reported by Dr. Filippatos and coauthors used data from two related trials of finerenone, FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD, combined by prespecified design into a single dataset, FIDELITY, with a total of 13,026 participants eligible for analysis and followed for a median of 3 years. All had type 2 diabetes and CKD based on having a UACR of at least 30 mg/g. Their eGFR levels could run as high as 74 mL/min per 1.73 m2 in FIDELIO-DKD, and as high as 90 mL/min/1.73m2 in FIGARO-DKD. The two trials excluded people with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, and those with a serum potassium greater than 4.8 mmol/L.

In the FIDELITY dataset treatment with finerenone led to a significant 17% reduction in the combined incidence of cardiovascular death or first hospitalization for heart failure relative to those who received placebo. This relative risk reduction was not affected by either eGFR or UACR values at baseline, the new analysis showed.

The analysis also demonstrated a nonsignificant trend toward greater reductions in heart failure–related outcomes among study participants who began with an eGFR in the normal range of at least 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2. The researchers also found a nonsignificant trend to a greater reduction in heart failure–related events among those with a UACR of less than 300 mg/g.

Finerenone favors patients with less advanced CKD

In short “the magnitude of the treatment benefit tended to favor patients with less advanced CKD,” concluded the researchers, suggesting that “earlier intervention [with finerenone] in the CKD course is likely to provide the greatest long-term benefit on heart failure–related outcomes.” This led them to further infer “the importance of not only routine assessing eGFR, but also perhaps more importantly, routinely screening for UACR to facilitate early diagnosis and early intervention in patients with type 2 diabetes.”

Findings from FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD led to recent guideline additions for finerenone by several medical groups. In August 2022, the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists released an update to its guideline for managing people with diabetes that recommended treating people with type 2 diabetes with finerenone when they have a UACR of at least 30 mg/g if they are already treated with a maximum-tolerated dose of a renin-angiotensin system inhibitor, have a normal serum potassium level, and have an eGFR of at least 25 mL/min per 1.73 m2. The identical recommendation also appeared in a Consensus Report from the American Diabetes Association and KDIGO, an international organization promoting evidence-based management of patients with CKD.

“Finerenone provides a very important contribution because it improves prognosis even in very well managed patients” with type 2 diabetes, commented Lars Rydén, MD, professor of cardiology at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, as designated discussant for the report by Dr. Filippatos at the ESC congress.

The findings from the FIDELITY analysis are “trustworthy, and clinically important,” Dr. Rydén said. When left untreated, diabetic kidney disease “reduces life expectancy by an average of 16 years.”

The finerenone trials were sponsored by Bayer, which markets finerenone (Kerendia). Dr. Filippatos has received lecture fees from Bayer as well as from Amgen, Medtronic, Novartis, Servier, and Vifor. Dr. Green has financial ties to Bayer as well as to Anji, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim/Lilly, Hawthorne Effect/Omada, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi/Lexicon, and Valo. Dr. Bauersachs has been a consultant to Bayer as well as to Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cardior, Cervia, CVRx, Novartis, Pfizer, and Vifor, and he has received research funding from Abiomed. Dr. Rydén has financial ties to Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, and Novo Nordisk.

Treatment with finerenone produced roughly similar reductions in heart failure–related outcomes in people with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease (CKD) across the spectrum of kidney function, compared with placebo, including those who had albuminuria but a preserved estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), in a post hoc analysis of pooled data from more than 13,000 people.

The findings, from the two pivotal trials for the agent, “reinforce the importance of routine eGFR and UACR [urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio] screening” in people with type 2 diabetes to identify new candidates for treatment with finerenone (Kerendia), Gerasimos Filippatos, MD, and coauthors said in a report published online in JACC: Heart Failure.

Among the 13,026 patients in the two combined trials, 40% had a preserved eGFR of greater than 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 despite also having albuminuria with a UACR of at least 30 mg/g, showing how often this combination occurs. But many clinicians “do not follow the guidelines” and fail to measure the UACR in these patients in routine practice, noted Dr. Filippatos at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology in August.

“We now have something to do for these patients,” treat them with finerenone, said Dr. Filippatos, professor and director of heart failure at the Attikon University Hospital, Athens.

The availability of finerenone following its U.S. approval in 2021 means clinicians “must get used to measuring UACR” in people with type 2 diabetes even when their eGFR is normal, especially people with type 2 diabetes plus high cardiovascular disease risk, he said.

The Food and Drug Administration approved finerenone, a nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, for treating people with type 2 diabetes and CKD in July 2021, but its uptake has been slow, experts say. In a talk in September 2022 during the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes, Jennifer B. Green, MD, estimated that U.S. uptake of finerenone for appropriate people with type 2 diabetes had not advanced beyond 10%.

A recent review also noted that uptake of screening for elevated UACR in U.S. patients with type 2 diabetes was in the range of 10%-40% during 2017-2019, a “shockingly low rate,” said Dr. Green, a professor and diabetes specialist at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

A new reason to screen for albuminuria

“It’s an extremely important message,” Johann Bauersachs, MD, commented in an interview. Results from “many studies have shown that albuminuria is an excellent additional marker for cardiovascular disease risk. But measurement of albuminuria is not widely done, despite guidelines that recommend annual albuminuria testing in people with type 2 diabetes,” said Dr. Bauersachs, professor and head of the department of cardiology at Hannover (Germany) Medical School.

“Even before there was finerenone, there were reasons to measure UACR, but I hope adding finerenone will help, and more clinicians will incorporate UACR into their routine practice,” said Dr. Bauersachs, who was not involved with the finerenone studies.

The analyses reported by Dr. Filippatos and coauthors used data from two related trials of finerenone, FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD, combined by prespecified design into a single dataset, FIDELITY, with a total of 13,026 participants eligible for analysis and followed for a median of 3 years. All had type 2 diabetes and CKD based on having a UACR of at least 30 mg/g. Their eGFR levels could run as high as 74 mL/min per 1.73 m2 in FIDELIO-DKD, and as high as 90 mL/min/1.73m2 in FIGARO-DKD. The two trials excluded people with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, and those with a serum potassium greater than 4.8 mmol/L.

In the FIDELITY dataset treatment with finerenone led to a significant 17% reduction in the combined incidence of cardiovascular death or first hospitalization for heart failure relative to those who received placebo. This relative risk reduction was not affected by either eGFR or UACR values at baseline, the new analysis showed.

The analysis also demonstrated a nonsignificant trend toward greater reductions in heart failure–related outcomes among study participants who began with an eGFR in the normal range of at least 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2. The researchers also found a nonsignificant trend to a greater reduction in heart failure–related events among those with a UACR of less than 300 mg/g.

Finerenone favors patients with less advanced CKD

In short “the magnitude of the treatment benefit tended to favor patients with less advanced CKD,” concluded the researchers, suggesting that “earlier intervention [with finerenone] in the CKD course is likely to provide the greatest long-term benefit on heart failure–related outcomes.” This led them to further infer “the importance of not only routine assessing eGFR, but also perhaps more importantly, routinely screening for UACR to facilitate early diagnosis and early intervention in patients with type 2 diabetes.”

Findings from FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD led to recent guideline additions for finerenone by several medical groups. In August 2022, the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists released an update to its guideline for managing people with diabetes that recommended treating people with type 2 diabetes with finerenone when they have a UACR of at least 30 mg/g if they are already treated with a maximum-tolerated dose of a renin-angiotensin system inhibitor, have a normal serum potassium level, and have an eGFR of at least 25 mL/min per 1.73 m2. The identical recommendation also appeared in a Consensus Report from the American Diabetes Association and KDIGO, an international organization promoting evidence-based management of patients with CKD.

“Finerenone provides a very important contribution because it improves prognosis even in very well managed patients” with type 2 diabetes, commented Lars Rydén, MD, professor of cardiology at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, as designated discussant for the report by Dr. Filippatos at the ESC congress.

The findings from the FIDELITY analysis are “trustworthy, and clinically important,” Dr. Rydén said. When left untreated, diabetic kidney disease “reduces life expectancy by an average of 16 years.”

The finerenone trials were sponsored by Bayer, which markets finerenone (Kerendia). Dr. Filippatos has received lecture fees from Bayer as well as from Amgen, Medtronic, Novartis, Servier, and Vifor. Dr. Green has financial ties to Bayer as well as to Anji, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim/Lilly, Hawthorne Effect/Omada, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi/Lexicon, and Valo. Dr. Bauersachs has been a consultant to Bayer as well as to Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cardior, Cervia, CVRx, Novartis, Pfizer, and Vifor, and he has received research funding from Abiomed. Dr. Rydén has financial ties to Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, and Novo Nordisk.

Treatment with finerenone produced roughly similar reductions in heart failure–related outcomes in people with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease (CKD) across the spectrum of kidney function, compared with placebo, including those who had albuminuria but a preserved estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), in a post hoc analysis of pooled data from more than 13,000 people.

The findings, from the two pivotal trials for the agent, “reinforce the importance of routine eGFR and UACR [urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio] screening” in people with type 2 diabetes to identify new candidates for treatment with finerenone (Kerendia), Gerasimos Filippatos, MD, and coauthors said in a report published online in JACC: Heart Failure.

Among the 13,026 patients in the two combined trials, 40% had a preserved eGFR of greater than 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 despite also having albuminuria with a UACR of at least 30 mg/g, showing how often this combination occurs. But many clinicians “do not follow the guidelines” and fail to measure the UACR in these patients in routine practice, noted Dr. Filippatos at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology in August.

“We now have something to do for these patients,” treat them with finerenone, said Dr. Filippatos, professor and director of heart failure at the Attikon University Hospital, Athens.

The availability of finerenone following its U.S. approval in 2021 means clinicians “must get used to measuring UACR” in people with type 2 diabetes even when their eGFR is normal, especially people with type 2 diabetes plus high cardiovascular disease risk, he said.

The Food and Drug Administration approved finerenone, a nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, for treating people with type 2 diabetes and CKD in July 2021, but its uptake has been slow, experts say. In a talk in September 2022 during the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes, Jennifer B. Green, MD, estimated that U.S. uptake of finerenone for appropriate people with type 2 diabetes had not advanced beyond 10%.

A recent review also noted that uptake of screening for elevated UACR in U.S. patients with type 2 diabetes was in the range of 10%-40% during 2017-2019, a “shockingly low rate,” said Dr. Green, a professor and diabetes specialist at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

A new reason to screen for albuminuria

“It’s an extremely important message,” Johann Bauersachs, MD, commented in an interview. Results from “many studies have shown that albuminuria is an excellent additional marker for cardiovascular disease risk. But measurement of albuminuria is not widely done, despite guidelines that recommend annual albuminuria testing in people with type 2 diabetes,” said Dr. Bauersachs, professor and head of the department of cardiology at Hannover (Germany) Medical School.

“Even before there was finerenone, there were reasons to measure UACR, but I hope adding finerenone will help, and more clinicians will incorporate UACR into their routine practice,” said Dr. Bauersachs, who was not involved with the finerenone studies.

The analyses reported by Dr. Filippatos and coauthors used data from two related trials of finerenone, FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD, combined by prespecified design into a single dataset, FIDELITY, with a total of 13,026 participants eligible for analysis and followed for a median of 3 years. All had type 2 diabetes and CKD based on having a UACR of at least 30 mg/g. Their eGFR levels could run as high as 74 mL/min per 1.73 m2 in FIDELIO-DKD, and as high as 90 mL/min/1.73m2 in FIGARO-DKD. The two trials excluded people with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, and those with a serum potassium greater than 4.8 mmol/L.

In the FIDELITY dataset treatment with finerenone led to a significant 17% reduction in the combined incidence of cardiovascular death or first hospitalization for heart failure relative to those who received placebo. This relative risk reduction was not affected by either eGFR or UACR values at baseline, the new analysis showed.

The analysis also demonstrated a nonsignificant trend toward greater reductions in heart failure–related outcomes among study participants who began with an eGFR in the normal range of at least 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2. The researchers also found a nonsignificant trend to a greater reduction in heart failure–related events among those with a UACR of less than 300 mg/g.

Finerenone favors patients with less advanced CKD

In short “the magnitude of the treatment benefit tended to favor patients with less advanced CKD,” concluded the researchers, suggesting that “earlier intervention [with finerenone] in the CKD course is likely to provide the greatest long-term benefit on heart failure–related outcomes.” This led them to further infer “the importance of not only routine assessing eGFR, but also perhaps more importantly, routinely screening for UACR to facilitate early diagnosis and early intervention in patients with type 2 diabetes.”

Findings from FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD led to recent guideline additions for finerenone by several medical groups. In August 2022, the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists released an update to its guideline for managing people with diabetes that recommended treating people with type 2 diabetes with finerenone when they have a UACR of at least 30 mg/g if they are already treated with a maximum-tolerated dose of a renin-angiotensin system inhibitor, have a normal serum potassium level, and have an eGFR of at least 25 mL/min per 1.73 m2. The identical recommendation also appeared in a Consensus Report from the American Diabetes Association and KDIGO, an international organization promoting evidence-based management of patients with CKD.

“Finerenone provides a very important contribution because it improves prognosis even in very well managed patients” with type 2 diabetes, commented Lars Rydén, MD, professor of cardiology at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, as designated discussant for the report by Dr. Filippatos at the ESC congress.

The findings from the FIDELITY analysis are “trustworthy, and clinically important,” Dr. Rydén said. When left untreated, diabetic kidney disease “reduces life expectancy by an average of 16 years.”

The finerenone trials were sponsored by Bayer, which markets finerenone (Kerendia). Dr. Filippatos has received lecture fees from Bayer as well as from Amgen, Medtronic, Novartis, Servier, and Vifor. Dr. Green has financial ties to Bayer as well as to Anji, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim/Lilly, Hawthorne Effect/Omada, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi/Lexicon, and Valo. Dr. Bauersachs has been a consultant to Bayer as well as to Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cardior, Cervia, CVRx, Novartis, Pfizer, and Vifor, and he has received research funding from Abiomed. Dr. Rydén has financial ties to Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, and Novo Nordisk.

FROM JACC: HEART FAILURE

Tirzepatide’s benefits expand: Lean mass up, serum lipids down

STOCKHOLM – New insights into the benefits of treatment with the “twincretin” tirzepatide for people with overweight or obesity – with or without diabetes – come from new findings reported at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

Additional results from the SURMOUNT-1 trial, which matched tirzepatide against placebo in people with overweight or obesity, provide further details on the favorable changes produced by 72 weeks of tirzepatide treatment on outcomes that included fat and lean mass, insulin sensitivity, and patient-reported outcomes related to functional health and well being, reported Ania M. Jastreboff, MD, PhD.

And results from a meta-analysis of six trials that compared tirzepatide (Mounjaro) against several different comparators in patients with type 2 diabetes further confirm the drug’s ability to reliably produce positive changes in blood lipids, especially by significantly lowering levels of triglycerides, LDL cholesterol, and very LDL (VLDL) cholesterol, said Thomas Karagiannis, MD, PhD, in a separate report at the meeting.

Tirzepatide works as an agonist on receptors for both the glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1), and for the glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide, and received Food and Drug Administration approval for treating people with type 2 diabetes in May 2022. On the basis of results from SURMOUNT-1, the FDA on Oct. 6 granted tirzepatide fast-track designation for a proposed labeling of the agent for treating people with overweight or obesity. This FDA decision will likely remain pending at least until results from a second trial in people with overweight or obesity but without diabetes, SURMOUNT-2, become available in 2023.

SURMOUNT-1 randomized 2,539 people with obesity or overweight and at least one weight-related complication to a weekly injection of tirzepatide or placebo for 72 weeks. The study’s primary efficacy endpoints were the average reduction in weight from baseline, and the percentage of people in each treatment arm achieving weight loss of at least 5% from baseline.

For both endpoints, the outcomes with tirzepatide significantly surpassed placebo effects. Average weight loss ranged from 15%-21% from baseline, depending on dose, compared with 3% on placebo. The rate of participants with at least a 5% weight loss ranged from 85% to 91%, compared with 35% with placebo, as reported in July 2022 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Cutting fat mass, boosting lean mass

New results from the trial reported by Dr. Jastreboff included a cut in fat mass from 46.2% of total body mass at baseline to 38.5% after 72 weeks, compared with a change from 46.8% at baseline to 44.7% after 72 weeks in the placebo group. Concurrently, lean mass increased with tirzepatide treatment from 51.0% at baseline to 58.1% after 72 weeks.

Participants who received tirzepatide, compared with those who received placebo, had “proportionately greater decrease in fat mass and proportionately greater increase in lean mass” compared with those who received placebo, said Dr. Jastreboff, an endocrinologist and obesity medicine specialist with Yale Medicine in New Haven, Conn. “I was impressed by the amount of visceral fat lost.”

These effects translated into a significant reduction in fat mass-to-lean mass ratio among the people treated with tirzepatide, with the greatest reduction in those who lost at least 15% of their starting weight. In that subgroup the fat-to-lean mass ratio dropped from 0.94 at baseline to 0.64 after 72 weeks of treatment, she said.

Focus on diet quality

People treated with tirzepatide “eat so little food that we need to improve the quality of what they eat to protect their muscle,” commented Carel le Roux, MBChB, PhD, a professor in the Diabetes Complications Research Centre of University College Dublin. “You no longer need a dietitian to help people lose weight, because the drug does that. You need dietitians to look after the nutritional health of patients while they lose weight,” Dr. le Roux said in a separate session at the meeting.

Additional tests showed that blood glucose and insulin levels were all significantly lower among trial participants on all three doses of tirzepatide compared with those on placebo, and the tirzepatide-treated subjects also had significant, roughly twofold elevations in their insulin sensitivity measured by the Matsuda Index.

The impact of tirzepatide on glucose and insulin levels and on insulin sensitivity was similar regardless of whether study participants had normoglycemia or prediabetes at entry. By design, no study participants had diabetes.

The trial assessed patient-reported quality-of-life outcomes using the 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36). Participants had significant increases in all eight domains within the SF-36 at all three tirzepatide doses, compared with placebo, at 72 weeks, Dr. Jastreboff reported. Improvements in the physical function domain increased most notably among study participants on tirzepatide who had functional limitations at baseline. Heart rate rose among participants who received either of the two highest tirzepatide doses by 2.3-2.5 beats/min, comparable with the effect of other injected incretin-based treatments.

Lipids improve in those with type 2 diabetes

Tirzepatide treatment also results in a “secondary effect” of improving levels of several lipids in people with type 2 diabetes, according to a meta-analysis of findings from six randomized trials. The meta-analysis collectively involved 4,502 participants treated for numerous weeks with one of three doses of tirzepatide and 2,144 people in comparator groups, reported Dr. Karagiannis, a diabetes researcher at Aristotle University of Thessaloniki (Greece).

Among the significant lipid changes linked with tirzepatide treatment, compared with placebo, were an average 13 mg/dL decrease in LDL cholesterol, an average 6 mg/dL decrease in VLDL cholesterol, and an average 50 mg/dL decrease in triglycerides. In comparison to a GLP-1 receptor agonist, an average 25 mg/dL decrease in triglycerides and an average 4 mg/dL reduction in VLDL cholesterol were seen. And trials comparing tirzepatide with basal insulin saw average reductions of 7% in LDL cholesterol, 15% in VLDL cholesterol, 15% in triglycerides, and an 8% increase in HDL cholesterol.

Dr. Karagiannis highlighted that the clinical impact of these effects is unclear, although he noted that the average reduction in LDL cholesterol relative to placebo is of a magnitude that could have a modest effect on long-term outcomes.

These lipid effects of tirzepatide “should be considered alongside” tirzepatide’s “key metabolic effects” on weight and hemoglobin A1c as well as the drug’s safety, concluded Dr. Karagiannis.

The tirzepatide trials were all funded by Eli Lilly, which markets tirzepatide (Mounjaro). Dr. Jastreboff has been an adviser and consultant to Eli Lilly, as well as to Intellihealth, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Rhythm Scholars, Roche, and Weight Watchers, and she has received research funding from Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk. Dr. Karagiannis had no disclosures. Dr. le Roux has had financial relationships with Eli Lilly, as well as with Boehringer Ingelheim, Consilient Health, Covidion, Fractyl, GL Dynamics, Herbalife, Johnson & Johnson, Keyron, and Novo Nordisk.

STOCKHOLM – New insights into the benefits of treatment with the “twincretin” tirzepatide for people with overweight or obesity – with or without diabetes – come from new findings reported at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

Additional results from the SURMOUNT-1 trial, which matched tirzepatide against placebo in people with overweight or obesity, provide further details on the favorable changes produced by 72 weeks of tirzepatide treatment on outcomes that included fat and lean mass, insulin sensitivity, and patient-reported outcomes related to functional health and well being, reported Ania M. Jastreboff, MD, PhD.

And results from a meta-analysis of six trials that compared tirzepatide (Mounjaro) against several different comparators in patients with type 2 diabetes further confirm the drug’s ability to reliably produce positive changes in blood lipids, especially by significantly lowering levels of triglycerides, LDL cholesterol, and very LDL (VLDL) cholesterol, said Thomas Karagiannis, MD, PhD, in a separate report at the meeting.

Tirzepatide works as an agonist on receptors for both the glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1), and for the glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide, and received Food and Drug Administration approval for treating people with type 2 diabetes in May 2022. On the basis of results from SURMOUNT-1, the FDA on Oct. 6 granted tirzepatide fast-track designation for a proposed labeling of the agent for treating people with overweight or obesity. This FDA decision will likely remain pending at least until results from a second trial in people with overweight or obesity but without diabetes, SURMOUNT-2, become available in 2023.

SURMOUNT-1 randomized 2,539 people with obesity or overweight and at least one weight-related complication to a weekly injection of tirzepatide or placebo for 72 weeks. The study’s primary efficacy endpoints were the average reduction in weight from baseline, and the percentage of people in each treatment arm achieving weight loss of at least 5% from baseline.

For both endpoints, the outcomes with tirzepatide significantly surpassed placebo effects. Average weight loss ranged from 15%-21% from baseline, depending on dose, compared with 3% on placebo. The rate of participants with at least a 5% weight loss ranged from 85% to 91%, compared with 35% with placebo, as reported in July 2022 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Cutting fat mass, boosting lean mass

New results from the trial reported by Dr. Jastreboff included a cut in fat mass from 46.2% of total body mass at baseline to 38.5% after 72 weeks, compared with a change from 46.8% at baseline to 44.7% after 72 weeks in the placebo group. Concurrently, lean mass increased with tirzepatide treatment from 51.0% at baseline to 58.1% after 72 weeks.

Participants who received tirzepatide, compared with those who received placebo, had “proportionately greater decrease in fat mass and proportionately greater increase in lean mass” compared with those who received placebo, said Dr. Jastreboff, an endocrinologist and obesity medicine specialist with Yale Medicine in New Haven, Conn. “I was impressed by the amount of visceral fat lost.”

These effects translated into a significant reduction in fat mass-to-lean mass ratio among the people treated with tirzepatide, with the greatest reduction in those who lost at least 15% of their starting weight. In that subgroup the fat-to-lean mass ratio dropped from 0.94 at baseline to 0.64 after 72 weeks of treatment, she said.

Focus on diet quality

People treated with tirzepatide “eat so little food that we need to improve the quality of what they eat to protect their muscle,” commented Carel le Roux, MBChB, PhD, a professor in the Diabetes Complications Research Centre of University College Dublin. “You no longer need a dietitian to help people lose weight, because the drug does that. You need dietitians to look after the nutritional health of patients while they lose weight,” Dr. le Roux said in a separate session at the meeting.

Additional tests showed that blood glucose and insulin levels were all significantly lower among trial participants on all three doses of tirzepatide compared with those on placebo, and the tirzepatide-treated subjects also had significant, roughly twofold elevations in their insulin sensitivity measured by the Matsuda Index.

The impact of tirzepatide on glucose and insulin levels and on insulin sensitivity was similar regardless of whether study participants had normoglycemia or prediabetes at entry. By design, no study participants had diabetes.

The trial assessed patient-reported quality-of-life outcomes using the 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36). Participants had significant increases in all eight domains within the SF-36 at all three tirzepatide doses, compared with placebo, at 72 weeks, Dr. Jastreboff reported. Improvements in the physical function domain increased most notably among study participants on tirzepatide who had functional limitations at baseline. Heart rate rose among participants who received either of the two highest tirzepatide doses by 2.3-2.5 beats/min, comparable with the effect of other injected incretin-based treatments.

Lipids improve in those with type 2 diabetes

Tirzepatide treatment also results in a “secondary effect” of improving levels of several lipids in people with type 2 diabetes, according to a meta-analysis of findings from six randomized trials. The meta-analysis collectively involved 4,502 participants treated for numerous weeks with one of three doses of tirzepatide and 2,144 people in comparator groups, reported Dr. Karagiannis, a diabetes researcher at Aristotle University of Thessaloniki (Greece).

Among the significant lipid changes linked with tirzepatide treatment, compared with placebo, were an average 13 mg/dL decrease in LDL cholesterol, an average 6 mg/dL decrease in VLDL cholesterol, and an average 50 mg/dL decrease in triglycerides. In comparison to a GLP-1 receptor agonist, an average 25 mg/dL decrease in triglycerides and an average 4 mg/dL reduction in VLDL cholesterol were seen. And trials comparing tirzepatide with basal insulin saw average reductions of 7% in LDL cholesterol, 15% in VLDL cholesterol, 15% in triglycerides, and an 8% increase in HDL cholesterol.

Dr. Karagiannis highlighted that the clinical impact of these effects is unclear, although he noted that the average reduction in LDL cholesterol relative to placebo is of a magnitude that could have a modest effect on long-term outcomes.

These lipid effects of tirzepatide “should be considered alongside” tirzepatide’s “key metabolic effects” on weight and hemoglobin A1c as well as the drug’s safety, concluded Dr. Karagiannis.

The tirzepatide trials were all funded by Eli Lilly, which markets tirzepatide (Mounjaro). Dr. Jastreboff has been an adviser and consultant to Eli Lilly, as well as to Intellihealth, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Rhythm Scholars, Roche, and Weight Watchers, and she has received research funding from Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk. Dr. Karagiannis had no disclosures. Dr. le Roux has had financial relationships with Eli Lilly, as well as with Boehringer Ingelheim, Consilient Health, Covidion, Fractyl, GL Dynamics, Herbalife, Johnson & Johnson, Keyron, and Novo Nordisk.

STOCKHOLM – New insights into the benefits of treatment with the “twincretin” tirzepatide for people with overweight or obesity – with or without diabetes – come from new findings reported at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

Additional results from the SURMOUNT-1 trial, which matched tirzepatide against placebo in people with overweight or obesity, provide further details on the favorable changes produced by 72 weeks of tirzepatide treatment on outcomes that included fat and lean mass, insulin sensitivity, and patient-reported outcomes related to functional health and well being, reported Ania M. Jastreboff, MD, PhD.

And results from a meta-analysis of six trials that compared tirzepatide (Mounjaro) against several different comparators in patients with type 2 diabetes further confirm the drug’s ability to reliably produce positive changes in blood lipids, especially by significantly lowering levels of triglycerides, LDL cholesterol, and very LDL (VLDL) cholesterol, said Thomas Karagiannis, MD, PhD, in a separate report at the meeting.

Tirzepatide works as an agonist on receptors for both the glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1), and for the glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide, and received Food and Drug Administration approval for treating people with type 2 diabetes in May 2022. On the basis of results from SURMOUNT-1, the FDA on Oct. 6 granted tirzepatide fast-track designation for a proposed labeling of the agent for treating people with overweight or obesity. This FDA decision will likely remain pending at least until results from a second trial in people with overweight or obesity but without diabetes, SURMOUNT-2, become available in 2023.

SURMOUNT-1 randomized 2,539 people with obesity or overweight and at least one weight-related complication to a weekly injection of tirzepatide or placebo for 72 weeks. The study’s primary efficacy endpoints were the average reduction in weight from baseline, and the percentage of people in each treatment arm achieving weight loss of at least 5% from baseline.

For both endpoints, the outcomes with tirzepatide significantly surpassed placebo effects. Average weight loss ranged from 15%-21% from baseline, depending on dose, compared with 3% on placebo. The rate of participants with at least a 5% weight loss ranged from 85% to 91%, compared with 35% with placebo, as reported in July 2022 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Cutting fat mass, boosting lean mass

New results from the trial reported by Dr. Jastreboff included a cut in fat mass from 46.2% of total body mass at baseline to 38.5% after 72 weeks, compared with a change from 46.8% at baseline to 44.7% after 72 weeks in the placebo group. Concurrently, lean mass increased with tirzepatide treatment from 51.0% at baseline to 58.1% after 72 weeks.

Participants who received tirzepatide, compared with those who received placebo, had “proportionately greater decrease in fat mass and proportionately greater increase in lean mass” compared with those who received placebo, said Dr. Jastreboff, an endocrinologist and obesity medicine specialist with Yale Medicine in New Haven, Conn. “I was impressed by the amount of visceral fat lost.”

These effects translated into a significant reduction in fat mass-to-lean mass ratio among the people treated with tirzepatide, with the greatest reduction in those who lost at least 15% of their starting weight. In that subgroup the fat-to-lean mass ratio dropped from 0.94 at baseline to 0.64 after 72 weeks of treatment, she said.

Focus on diet quality

People treated with tirzepatide “eat so little food that we need to improve the quality of what they eat to protect their muscle,” commented Carel le Roux, MBChB, PhD, a professor in the Diabetes Complications Research Centre of University College Dublin. “You no longer need a dietitian to help people lose weight, because the drug does that. You need dietitians to look after the nutritional health of patients while they lose weight,” Dr. le Roux said in a separate session at the meeting.

Additional tests showed that blood glucose and insulin levels were all significantly lower among trial participants on all three doses of tirzepatide compared with those on placebo, and the tirzepatide-treated subjects also had significant, roughly twofold elevations in their insulin sensitivity measured by the Matsuda Index.

The impact of tirzepatide on glucose and insulin levels and on insulin sensitivity was similar regardless of whether study participants had normoglycemia or prediabetes at entry. By design, no study participants had diabetes.

The trial assessed patient-reported quality-of-life outcomes using the 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36). Participants had significant increases in all eight domains within the SF-36 at all three tirzepatide doses, compared with placebo, at 72 weeks, Dr. Jastreboff reported. Improvements in the physical function domain increased most notably among study participants on tirzepatide who had functional limitations at baseline. Heart rate rose among participants who received either of the two highest tirzepatide doses by 2.3-2.5 beats/min, comparable with the effect of other injected incretin-based treatments.

Lipids improve in those with type 2 diabetes

Tirzepatide treatment also results in a “secondary effect” of improving levels of several lipids in people with type 2 diabetes, according to a meta-analysis of findings from six randomized trials. The meta-analysis collectively involved 4,502 participants treated for numerous weeks with one of three doses of tirzepatide and 2,144 people in comparator groups, reported Dr. Karagiannis, a diabetes researcher at Aristotle University of Thessaloniki (Greece).

Among the significant lipid changes linked with tirzepatide treatment, compared with placebo, were an average 13 mg/dL decrease in LDL cholesterol, an average 6 mg/dL decrease in VLDL cholesterol, and an average 50 mg/dL decrease in triglycerides. In comparison to a GLP-1 receptor agonist, an average 25 mg/dL decrease in triglycerides and an average 4 mg/dL reduction in VLDL cholesterol were seen. And trials comparing tirzepatide with basal insulin saw average reductions of 7% in LDL cholesterol, 15% in VLDL cholesterol, 15% in triglycerides, and an 8% increase in HDL cholesterol.

Dr. Karagiannis highlighted that the clinical impact of these effects is unclear, although he noted that the average reduction in LDL cholesterol relative to placebo is of a magnitude that could have a modest effect on long-term outcomes.

These lipid effects of tirzepatide “should be considered alongside” tirzepatide’s “key metabolic effects” on weight and hemoglobin A1c as well as the drug’s safety, concluded Dr. Karagiannis.

The tirzepatide trials were all funded by Eli Lilly, which markets tirzepatide (Mounjaro). Dr. Jastreboff has been an adviser and consultant to Eli Lilly, as well as to Intellihealth, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Rhythm Scholars, Roche, and Weight Watchers, and she has received research funding from Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk. Dr. Karagiannis had no disclosures. Dr. le Roux has had financial relationships with Eli Lilly, as well as with Boehringer Ingelheim, Consilient Health, Covidion, Fractyl, GL Dynamics, Herbalife, Johnson & Johnson, Keyron, and Novo Nordisk.

AT EASD 2022

New advice on artificial pancreas insulin delivery systems

A new consensus statement summarizes the benefits, limitations, and challenges of using automated insulin delivery (AID) systems and provides recommendations for use by people with diabetes.

“Automated insulin delivery systems” is becoming the standard terminology – including by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration – to refer to systems that integrate data from a continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) system via a control algorithm into an insulin pump in order to automate subcutaneous insulin delivery. “Hybrid AID” or “hybrid closed-loop” refers to the current status of these systems, which still require some degree of user input to control glucose levels.

The term “artificial pancreas” was used interchangeably with AID in the past, but it doesn’t take into account exocrine pancreatic function. The term “bionic pancreas” refers to a specific system in development that would ultimately include glucagon along with insulin.