User login

Official Newspaper of the American College of Surgeons

PSA screens could be cost effective if low-risk cases went untreated

Given current treatment practices, prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening is not cost effective unless performed every 4 years in men aged 55-69 years, and with a biopsy threshold of 10.0 ng/mL, researchers reported online in JAMA Oncology.

But several less conservative testing strategies could be cost effective if patients with Gleason scores under 7 and clinical T2a stage cancer or lower are not treated unless they clinically progress, said Joshua A. Roth, Ph.D., of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle and his associates.

The study has “clear implications for the future of PSA screening in the United States,” the investigators wrote (JAMA Oncol. Mar 24. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.6275). “Rather than stopping PSA screening, as recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, implementation of strategies that extend the screening interval and/or use higher PSA biopsy thresholds have the potential to preserve substantial benefit, while controlling harm and costs.”

The investigators constructed a hypothetical group of men in the United States who underwent 18 different PSA screening strategies starting at age 40. Under the current treatment paradigm, PSA screening increased years of life by 3%-6%, with a cost of $7,335-$21,649 for each extra year of life. Quality years of life rose only if the strategy included a narrower age range for testing or a biopsy threshold of 10.0 ng/mL.

If the more selective treatment model was used, screening 55- to 69-year-old men every 4 years and using a PSA biopsy threshold of 3.0 ng/mL was not only potentially cost effective, but also increased quality years of life. The same was true for quadrennial screening of men aged 50-74 years with a biopsy threshold of 4.0 ng/mL.

“Our work adds to a growing consensus that highly conservative use of the PSA test and biopsy referral is necessary if PSA screening is to be cost effective,” the researchers concluded. Less frequent screening and stricter biopsy criteria for biopsy were most likely to make screening cost effective, especially if physicians do not immediately treat low-risk cases, they added.

The study was supported by the National Cancer Institute, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The investigators had no disclosures.

This study forces us to change the debate from “Should we screen?” to “How can we get physicians to follow best practice?” I have heard it said that the professional, financial, and malpractice incentives to screen and then treat low-risk cancer are too overwhelming to allow for significant practice change. But this is clearly disconfirmed by the literature. Use of active surveillance for low-risk prostate cancer has increased fourfold in the past few years; PSA testing in older men has also fallen recently. Rates of unnecessary treatment still remain much too high (about 60%) as does screening of older men (about 35% for those aged 75 years and older). More work needs to be done, and much more change needs to happen.

|

Andrew J. Vickers, Ph.D. |

Based on these results, if we follow the literature on how to screen with PSA and which screen-detected prostate cancers to treat, we will likely do more good than harm. If we simply carry on with common practice – screening older men, aggressively treating low-risk disease – then we should call for PSA screening to end.

Andrew J. Vickers, Ph.D., is at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York. He reported being named on a patent application for a statistical method to detect prostate cancer; receiving royalties from sales of the test; and having stock options in OPKO Health, which commercialized the test. These comments are from his editorial (JAMA Oncol. 2016 Mar 24 doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.6276).

This study forces us to change the debate from “Should we screen?” to “How can we get physicians to follow best practice?” I have heard it said that the professional, financial, and malpractice incentives to screen and then treat low-risk cancer are too overwhelming to allow for significant practice change. But this is clearly disconfirmed by the literature. Use of active surveillance for low-risk prostate cancer has increased fourfold in the past few years; PSA testing in older men has also fallen recently. Rates of unnecessary treatment still remain much too high (about 60%) as does screening of older men (about 35% for those aged 75 years and older). More work needs to be done, and much more change needs to happen.

|

Andrew J. Vickers, Ph.D. |

Based on these results, if we follow the literature on how to screen with PSA and which screen-detected prostate cancers to treat, we will likely do more good than harm. If we simply carry on with common practice – screening older men, aggressively treating low-risk disease – then we should call for PSA screening to end.

Andrew J. Vickers, Ph.D., is at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York. He reported being named on a patent application for a statistical method to detect prostate cancer; receiving royalties from sales of the test; and having stock options in OPKO Health, which commercialized the test. These comments are from his editorial (JAMA Oncol. 2016 Mar 24 doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.6276).

This study forces us to change the debate from “Should we screen?” to “How can we get physicians to follow best practice?” I have heard it said that the professional, financial, and malpractice incentives to screen and then treat low-risk cancer are too overwhelming to allow for significant practice change. But this is clearly disconfirmed by the literature. Use of active surveillance for low-risk prostate cancer has increased fourfold in the past few years; PSA testing in older men has also fallen recently. Rates of unnecessary treatment still remain much too high (about 60%) as does screening of older men (about 35% for those aged 75 years and older). More work needs to be done, and much more change needs to happen.

|

Andrew J. Vickers, Ph.D. |

Based on these results, if we follow the literature on how to screen with PSA and which screen-detected prostate cancers to treat, we will likely do more good than harm. If we simply carry on with common practice – screening older men, aggressively treating low-risk disease – then we should call for PSA screening to end.

Andrew J. Vickers, Ph.D., is at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York. He reported being named on a patent application for a statistical method to detect prostate cancer; receiving royalties from sales of the test; and having stock options in OPKO Health, which commercialized the test. These comments are from his editorial (JAMA Oncol. 2016 Mar 24 doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.6276).

Given current treatment practices, prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening is not cost effective unless performed every 4 years in men aged 55-69 years, and with a biopsy threshold of 10.0 ng/mL, researchers reported online in JAMA Oncology.

But several less conservative testing strategies could be cost effective if patients with Gleason scores under 7 and clinical T2a stage cancer or lower are not treated unless they clinically progress, said Joshua A. Roth, Ph.D., of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle and his associates.

The study has “clear implications for the future of PSA screening in the United States,” the investigators wrote (JAMA Oncol. Mar 24. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.6275). “Rather than stopping PSA screening, as recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, implementation of strategies that extend the screening interval and/or use higher PSA biopsy thresholds have the potential to preserve substantial benefit, while controlling harm and costs.”

The investigators constructed a hypothetical group of men in the United States who underwent 18 different PSA screening strategies starting at age 40. Under the current treatment paradigm, PSA screening increased years of life by 3%-6%, with a cost of $7,335-$21,649 for each extra year of life. Quality years of life rose only if the strategy included a narrower age range for testing or a biopsy threshold of 10.0 ng/mL.

If the more selective treatment model was used, screening 55- to 69-year-old men every 4 years and using a PSA biopsy threshold of 3.0 ng/mL was not only potentially cost effective, but also increased quality years of life. The same was true for quadrennial screening of men aged 50-74 years with a biopsy threshold of 4.0 ng/mL.

“Our work adds to a growing consensus that highly conservative use of the PSA test and biopsy referral is necessary if PSA screening is to be cost effective,” the researchers concluded. Less frequent screening and stricter biopsy criteria for biopsy were most likely to make screening cost effective, especially if physicians do not immediately treat low-risk cases, they added.

The study was supported by the National Cancer Institute, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The investigators had no disclosures.

Given current treatment practices, prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening is not cost effective unless performed every 4 years in men aged 55-69 years, and with a biopsy threshold of 10.0 ng/mL, researchers reported online in JAMA Oncology.

But several less conservative testing strategies could be cost effective if patients with Gleason scores under 7 and clinical T2a stage cancer or lower are not treated unless they clinically progress, said Joshua A. Roth, Ph.D., of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle and his associates.

The study has “clear implications for the future of PSA screening in the United States,” the investigators wrote (JAMA Oncol. Mar 24. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.6275). “Rather than stopping PSA screening, as recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, implementation of strategies that extend the screening interval and/or use higher PSA biopsy thresholds have the potential to preserve substantial benefit, while controlling harm and costs.”

The investigators constructed a hypothetical group of men in the United States who underwent 18 different PSA screening strategies starting at age 40. Under the current treatment paradigm, PSA screening increased years of life by 3%-6%, with a cost of $7,335-$21,649 for each extra year of life. Quality years of life rose only if the strategy included a narrower age range for testing or a biopsy threshold of 10.0 ng/mL.

If the more selective treatment model was used, screening 55- to 69-year-old men every 4 years and using a PSA biopsy threshold of 3.0 ng/mL was not only potentially cost effective, but also increased quality years of life. The same was true for quadrennial screening of men aged 50-74 years with a biopsy threshold of 4.0 ng/mL.

“Our work adds to a growing consensus that highly conservative use of the PSA test and biopsy referral is necessary if PSA screening is to be cost effective,” the researchers concluded. Less frequent screening and stricter biopsy criteria for biopsy were most likely to make screening cost effective, especially if physicians do not immediately treat low-risk cases, they added.

The study was supported by the National Cancer Institute, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The investigators had no disclosures.

FROM JAMA ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: A modeling study found that screening for prostate-specific antigen could be cost effective if low-risk cases are not treated unless they progress.

Major finding: Screening 55- to 69-year-old men every 4 years and using a PSA biopsy threshold of 3.0 ng/mL was potentially cost effective and also increased quality years of life. The same was true for quadrennial screening of men aged 50-74 years with a biopsy threshold of 4.0 ng/mL.

Data source: A microsimulation model of prostate cancer incidence and mortality.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the National Cancer Institute, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The investigators had no disclosures.

FDA investigates Boston Scientific’s surgical mesh

The Food and Drug Administration is investigating allegations that Boston Scientific is using counterfeit raw materials in its urogynecologic surgical mesh.

For women who already have the Boston Scientific mesh implanted, the FDA is not recommending removal. The available data do not suggest any decreased benefit with the device and the risk of mesh removal outweighs any potential risk from mesh manufactured from alleged counterfeit raw materials, according to the FDA.

The investigation, announced by the FDA on April 1, 2016, comes after the agency received a citizen’s petition alleging that Boston Scientific was using a resin manufactured in China rather than the authentic Marlex HGX-030-01 resin.

Teresa Stevens, who is also involved in a federal class action lawsuit against Boston Scientific, submitted the citizen’s petition asking the FDA to begin an immediate Class I recall of all Boston Scientific mesh products made with the alleged counterfeit resin.

Boston Scientific is denying the allegations made in the petition.

“Boston Scientific does not use ‘counterfeit’ or ‘adulterated’ materials in our medical devices,” company officials wrote in an April 1 statement. “We have the highest confidence in the safety of our mesh devices. We have shared our test data with the Food and Drug Administration and are fully cooperating with the agency’s requests for information as part of our ongoing discussions. Additionally, we have offered to conduct further biocompatibility and chemical characterization testing to complement the results from existing tests.”

Company officials said they located a new supplier of Marlex resin in 2011 and put samples of the materials through a battery of tests to demonstrate equivalency.

The FDA acknowledged that it is not uncommon for companies to change the source of their raw materials after a device has been cleared for marketing and that the change often does not require premarket review by the agency. But due to the allegations in the citizen’s petition, the FDA will evaluate the results of new testing conducted by the company, including chemical characterization and toxicologic risk assessment of the raw material alleged to be counterfeit, as well as chemical characterization and biocompatibility of the final finished urogynecologic surgical mesh.

“The additional testing should be sufficient for the FDA to determine whether or not the urogynecologic surgical mesh manufactured from the alleged counterfeit raw material are equivalent to the urogynecologic surgical mesh manufactured from the original raw material supplier,” FDA officials wrote. “We expect that this testing will take several months to complete.”

On Twitter @maryellenny

The Food and Drug Administration is investigating allegations that Boston Scientific is using counterfeit raw materials in its urogynecologic surgical mesh.

For women who already have the Boston Scientific mesh implanted, the FDA is not recommending removal. The available data do not suggest any decreased benefit with the device and the risk of mesh removal outweighs any potential risk from mesh manufactured from alleged counterfeit raw materials, according to the FDA.

The investigation, announced by the FDA on April 1, 2016, comes after the agency received a citizen’s petition alleging that Boston Scientific was using a resin manufactured in China rather than the authentic Marlex HGX-030-01 resin.

Teresa Stevens, who is also involved in a federal class action lawsuit against Boston Scientific, submitted the citizen’s petition asking the FDA to begin an immediate Class I recall of all Boston Scientific mesh products made with the alleged counterfeit resin.

Boston Scientific is denying the allegations made in the petition.

“Boston Scientific does not use ‘counterfeit’ or ‘adulterated’ materials in our medical devices,” company officials wrote in an April 1 statement. “We have the highest confidence in the safety of our mesh devices. We have shared our test data with the Food and Drug Administration and are fully cooperating with the agency’s requests for information as part of our ongoing discussions. Additionally, we have offered to conduct further biocompatibility and chemical characterization testing to complement the results from existing tests.”

Company officials said they located a new supplier of Marlex resin in 2011 and put samples of the materials through a battery of tests to demonstrate equivalency.

The FDA acknowledged that it is not uncommon for companies to change the source of their raw materials after a device has been cleared for marketing and that the change often does not require premarket review by the agency. But due to the allegations in the citizen’s petition, the FDA will evaluate the results of new testing conducted by the company, including chemical characterization and toxicologic risk assessment of the raw material alleged to be counterfeit, as well as chemical characterization and biocompatibility of the final finished urogynecologic surgical mesh.

“The additional testing should be sufficient for the FDA to determine whether or not the urogynecologic surgical mesh manufactured from the alleged counterfeit raw material are equivalent to the urogynecologic surgical mesh manufactured from the original raw material supplier,” FDA officials wrote. “We expect that this testing will take several months to complete.”

On Twitter @maryellenny

The Food and Drug Administration is investigating allegations that Boston Scientific is using counterfeit raw materials in its urogynecologic surgical mesh.

For women who already have the Boston Scientific mesh implanted, the FDA is not recommending removal. The available data do not suggest any decreased benefit with the device and the risk of mesh removal outweighs any potential risk from mesh manufactured from alleged counterfeit raw materials, according to the FDA.

The investigation, announced by the FDA on April 1, 2016, comes after the agency received a citizen’s petition alleging that Boston Scientific was using a resin manufactured in China rather than the authentic Marlex HGX-030-01 resin.

Teresa Stevens, who is also involved in a federal class action lawsuit against Boston Scientific, submitted the citizen’s petition asking the FDA to begin an immediate Class I recall of all Boston Scientific mesh products made with the alleged counterfeit resin.

Boston Scientific is denying the allegations made in the petition.

“Boston Scientific does not use ‘counterfeit’ or ‘adulterated’ materials in our medical devices,” company officials wrote in an April 1 statement. “We have the highest confidence in the safety of our mesh devices. We have shared our test data with the Food and Drug Administration and are fully cooperating with the agency’s requests for information as part of our ongoing discussions. Additionally, we have offered to conduct further biocompatibility and chemical characterization testing to complement the results from existing tests.”

Company officials said they located a new supplier of Marlex resin in 2011 and put samples of the materials through a battery of tests to demonstrate equivalency.

The FDA acknowledged that it is not uncommon for companies to change the source of their raw materials after a device has been cleared for marketing and that the change often does not require premarket review by the agency. But due to the allegations in the citizen’s petition, the FDA will evaluate the results of new testing conducted by the company, including chemical characterization and toxicologic risk assessment of the raw material alleged to be counterfeit, as well as chemical characterization and biocompatibility of the final finished urogynecologic surgical mesh.

“The additional testing should be sufficient for the FDA to determine whether or not the urogynecologic surgical mesh manufactured from the alleged counterfeit raw material are equivalent to the urogynecologic surgical mesh manufactured from the original raw material supplier,” FDA officials wrote. “We expect that this testing will take several months to complete.”

On Twitter @maryellenny

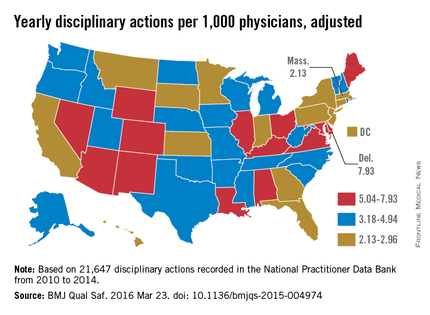

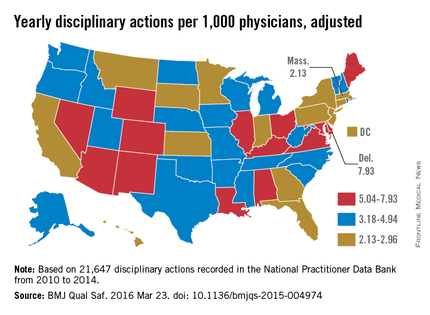

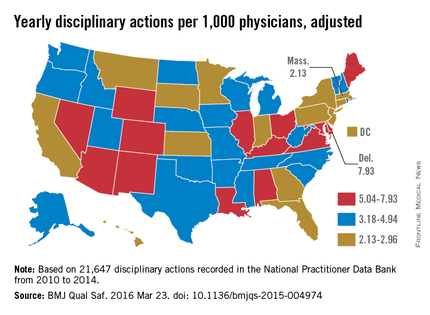

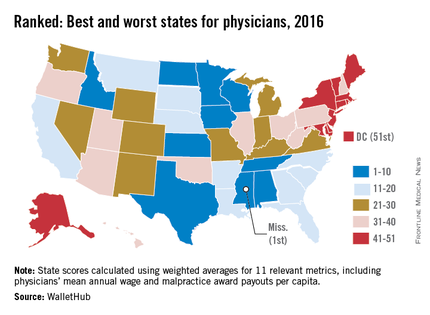

State board discipline of physicians varies widely by state

The rate at which medical boards discipline physicians varies widely by state, with Delaware doctors facing four times more disciplinary actions that Massachusetts physicians, according to a review of physicians in all 50 states.

Dr. John Alexander Harris of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues reviewed 21,647 physician disciplinary actions recorded in the National Practitioner Data Bank from 2010 to 2014 across all 50 states and the District of Columbia (BMJ Qual Saf. 2016 Mar 23; doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004974).

Investigators evaluated American Medical Association demographic data from the same time frame to estimate rates of disciplinary actions while controlling for the number of physicians in each state. Of the actions studied, 24% were major disciplinary actions involving revocation, suspension, or license surrender. Researchers also controlled for data reliability, year to year variation, physician labor supply, and malpractice climate in each state.

Delaware experienced the highest rate of medical board discipline with eight actions per 1,000 physicians, while Massachusetts had the lowest rate with two actions per 1,000 physicians, the investigators found. Kentucky and Ohio were among the states with the highest rates of disciplinary actions. New York, Connecticut, and Pennsylvania doctors experienced among the lowest rates of medical board disciplinary actions.

Researchers presumed there would be differences in the level of medical board disciplinary actions, but they were surprised at the fourfold gap between states, Dr. Harris said in an interview.

“The biggest takeaway is that there is a large, unexplained variation between the rate at which medical boards discipline physicians from state to state,” he said. “We should focus more on understanding what’s causing this variation.”

Investigators found no significant connection between state medical malpractice climate and the rate of medical board disciplinary actions. They also found no marked association between the rate of disciplinary actions and physician supply or the year of the discipline. No correlation was found between the rate of major and minor disciplinary action. In other words, states that had higher rates of major actions did not necessarily have higher rates of minor actions.

Potential reasons behind the state differences could include variations in the volume of physician misconduct per state, differences in the reporting of misconduct, or disparities in how often medical boards investigate incidents, Dr. Harris said.

“The process of physician disciplinary actions is complex,” he noted. “There are several different steps where the system can change the outcome significantly.”

For more than one-third of actions studied, the basis for the disciplinary action was classified as “unspecified” (38%). Specified reasons included negligence (9%), illegal activity (8%), license action (7%), failure to comply with medical board (6%), fraud (6%), unprofessional conduct (4%), substance abuse (4%), sexual or boundary misconduct (2%), failure to maintain adequate records (2%), immediate threat to public health and safety (1%), and “other” (14%). A total of 5,242 actions had no information regarding the reason for the action.

State medical boards should consider policies aimed at “improving standardization and coordination to provide consistent supervision to physicians and ensure public safety,” the authors wrote. In the meantime, more research is needed in the area, Dr. Harris said.

On Twitter @legal_med

The rate at which medical boards discipline physicians varies widely by state, with Delaware doctors facing four times more disciplinary actions that Massachusetts physicians, according to a review of physicians in all 50 states.

Dr. John Alexander Harris of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues reviewed 21,647 physician disciplinary actions recorded in the National Practitioner Data Bank from 2010 to 2014 across all 50 states and the District of Columbia (BMJ Qual Saf. 2016 Mar 23; doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004974).

Investigators evaluated American Medical Association demographic data from the same time frame to estimate rates of disciplinary actions while controlling for the number of physicians in each state. Of the actions studied, 24% were major disciplinary actions involving revocation, suspension, or license surrender. Researchers also controlled for data reliability, year to year variation, physician labor supply, and malpractice climate in each state.

Delaware experienced the highest rate of medical board discipline with eight actions per 1,000 physicians, while Massachusetts had the lowest rate with two actions per 1,000 physicians, the investigators found. Kentucky and Ohio were among the states with the highest rates of disciplinary actions. New York, Connecticut, and Pennsylvania doctors experienced among the lowest rates of medical board disciplinary actions.

Researchers presumed there would be differences in the level of medical board disciplinary actions, but they were surprised at the fourfold gap between states, Dr. Harris said in an interview.

“The biggest takeaway is that there is a large, unexplained variation between the rate at which medical boards discipline physicians from state to state,” he said. “We should focus more on understanding what’s causing this variation.”

Investigators found no significant connection between state medical malpractice climate and the rate of medical board disciplinary actions. They also found no marked association between the rate of disciplinary actions and physician supply or the year of the discipline. No correlation was found between the rate of major and minor disciplinary action. In other words, states that had higher rates of major actions did not necessarily have higher rates of minor actions.

Potential reasons behind the state differences could include variations in the volume of physician misconduct per state, differences in the reporting of misconduct, or disparities in how often medical boards investigate incidents, Dr. Harris said.

“The process of physician disciplinary actions is complex,” he noted. “There are several different steps where the system can change the outcome significantly.”

For more than one-third of actions studied, the basis for the disciplinary action was classified as “unspecified” (38%). Specified reasons included negligence (9%), illegal activity (8%), license action (7%), failure to comply with medical board (6%), fraud (6%), unprofessional conduct (4%), substance abuse (4%), sexual or boundary misconduct (2%), failure to maintain adequate records (2%), immediate threat to public health and safety (1%), and “other” (14%). A total of 5,242 actions had no information regarding the reason for the action.

State medical boards should consider policies aimed at “improving standardization and coordination to provide consistent supervision to physicians and ensure public safety,” the authors wrote. In the meantime, more research is needed in the area, Dr. Harris said.

On Twitter @legal_med

The rate at which medical boards discipline physicians varies widely by state, with Delaware doctors facing four times more disciplinary actions that Massachusetts physicians, according to a review of physicians in all 50 states.

Dr. John Alexander Harris of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues reviewed 21,647 physician disciplinary actions recorded in the National Practitioner Data Bank from 2010 to 2014 across all 50 states and the District of Columbia (BMJ Qual Saf. 2016 Mar 23; doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004974).

Investigators evaluated American Medical Association demographic data from the same time frame to estimate rates of disciplinary actions while controlling for the number of physicians in each state. Of the actions studied, 24% were major disciplinary actions involving revocation, suspension, or license surrender. Researchers also controlled for data reliability, year to year variation, physician labor supply, and malpractice climate in each state.

Delaware experienced the highest rate of medical board discipline with eight actions per 1,000 physicians, while Massachusetts had the lowest rate with two actions per 1,000 physicians, the investigators found. Kentucky and Ohio were among the states with the highest rates of disciplinary actions. New York, Connecticut, and Pennsylvania doctors experienced among the lowest rates of medical board disciplinary actions.

Researchers presumed there would be differences in the level of medical board disciplinary actions, but they were surprised at the fourfold gap between states, Dr. Harris said in an interview.

“The biggest takeaway is that there is a large, unexplained variation between the rate at which medical boards discipline physicians from state to state,” he said. “We should focus more on understanding what’s causing this variation.”

Investigators found no significant connection between state medical malpractice climate and the rate of medical board disciplinary actions. They also found no marked association between the rate of disciplinary actions and physician supply or the year of the discipline. No correlation was found between the rate of major and minor disciplinary action. In other words, states that had higher rates of major actions did not necessarily have higher rates of minor actions.

Potential reasons behind the state differences could include variations in the volume of physician misconduct per state, differences in the reporting of misconduct, or disparities in how often medical boards investigate incidents, Dr. Harris said.

“The process of physician disciplinary actions is complex,” he noted. “There are several different steps where the system can change the outcome significantly.”

For more than one-third of actions studied, the basis for the disciplinary action was classified as “unspecified” (38%). Specified reasons included negligence (9%), illegal activity (8%), license action (7%), failure to comply with medical board (6%), fraud (6%), unprofessional conduct (4%), substance abuse (4%), sexual or boundary misconduct (2%), failure to maintain adequate records (2%), immediate threat to public health and safety (1%), and “other” (14%). A total of 5,242 actions had no information regarding the reason for the action.

State medical boards should consider policies aimed at “improving standardization and coordination to provide consistent supervision to physicians and ensure public safety,” the authors wrote. In the meantime, more research is needed in the area, Dr. Harris said.

On Twitter @legal_med

Hospital scoring model predicts high-quality surgical outcomes in low-volume centers

MONTREAL – A “hospital ecosystem score” derived from examining high-volume, high-quality hospitals has good specificity in predicting which hospitals will have high-quality outcomes, though these hospitals have low surgical volume for a given procedure.

“What we’re talking about is a care delivery macro-environment,” said Dr. Anai Kothari, presenting results of a retrospective study of surgical outcomes at the Central Surgical Association’s annual meeting.

The study built on previous work that had identified “hospital system factors that actually equipped hospitals to provide high quality care,” said Dr. Kothari, a surgical research resident at Loyola University Medical Center in Maywood, Ill. “These high-volume ecosystems do exist at low-volume hospitals,” he said.

The study was designed as a retrospective review of 24,784 patient encounters over a 5-year period from 302 hospitals; data were taken from the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Services (HCAHPS) databases in California and Florida, with hospital resources data taken from the American Hospital Association (AHA) Annual Survey Database.

Adult patients were included if they had a malignancy of the esophagus, pancreas, or rectum, and had a surgical resection of the malignancy.

Dr. Kothari and his coinvestigators used patient mortality as a marker of quality, and analyzed the relationship between quality and case volume for each of the three procedures. “We used very strict definitions for high and low-volume” of surgical procedures, based on criteria set by the “Take the Volume Pledge” campaign that discourages surgeons from performing certain complex procedures unless they do them frequently, he said.

When procedural volume was mapped against risk-adjusted patient mortality in the data, the results could be divided into quadrants: high-volume/high-quality, high-volume/low-quality, low-volume/high-quality, and low-volume/low-quality.

Dr. Kothari said that an interesting pattern emerged, where a significant number of hospitals had low case volume but high quality outcomes. “In some cases … there are actually more low-volume/high-quality centers than high-volume/high-quality centers,” he said.

The researchers then looked at centers that performed at least two of the three surgical procedures at a high volume, to tease out some of the hospital system factors at play. They settled on examining 13 hospitals of over 300 initially studied, looking at more than 30 hospital characteristics that fell into five broad categories. These included infrastructure, size, staffing, perioperative services, and support intensity.

Within these categories, infrastructure characteristics associated with better outcomes included the facility’s being a level 1 trauma center and having transplant services. Size characteristics associated with better outcomes included total number of hospital admissions and total inpatient surgical volume. In terms of staffing, higher resident-to-bed and nurse-to-bed ratio (but not a higher physician-to-bed ratio) were both linked to better outcomes.

The perioperative services that mattered for outcomes were patient rehabilitation, geriatric services, speech and language pathology, and inpatient palliative care. Patients in facilities with a high level of oncology support also fared better.

Using different analytic models, Dr. Kothari and his colleagues attempted to determine whether these factors were predictive of a high-volume ecosystem that would result in better outcomes, even if volume for a particular procedure was low.

They found that their model, which assigned one point for each hospital ecosystem characteristic present at a given hospital, was very specific for identifying low-volume, high-quality care centers. “So a score of 7 and above has a specificity for low volume/high quality of care of over 70%” in esophageal resection, said Dr. Kothari.

Dr. Kothari noted how few high-volume centers were identified for this study, a finding that points to the practical importance for hospital administrators of knowing what factors may contribute to better surgical outcomes in smaller facilities.

Dr. Luke Funk, director of minimally invasive surgery research at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and a sometime collaborator of Dr. Kothari’s, had some suggestions for next steps. “Perhaps you could drill down qualitatively, going into some of these centers and talking to folks. Then you could take aspects from these programs and apply them to lower volume centers.” Dr. Kothari agreed, saying this would be a “very natural next step.”

Dr. Kothari reported no relevant disclosures; he is supported by an NIH training grant.

On Twitter @karioakes

MONTREAL – A “hospital ecosystem score” derived from examining high-volume, high-quality hospitals has good specificity in predicting which hospitals will have high-quality outcomes, though these hospitals have low surgical volume for a given procedure.

“What we’re talking about is a care delivery macro-environment,” said Dr. Anai Kothari, presenting results of a retrospective study of surgical outcomes at the Central Surgical Association’s annual meeting.

The study built on previous work that had identified “hospital system factors that actually equipped hospitals to provide high quality care,” said Dr. Kothari, a surgical research resident at Loyola University Medical Center in Maywood, Ill. “These high-volume ecosystems do exist at low-volume hospitals,” he said.

The study was designed as a retrospective review of 24,784 patient encounters over a 5-year period from 302 hospitals; data were taken from the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Services (HCAHPS) databases in California and Florida, with hospital resources data taken from the American Hospital Association (AHA) Annual Survey Database.

Adult patients were included if they had a malignancy of the esophagus, pancreas, or rectum, and had a surgical resection of the malignancy.

Dr. Kothari and his coinvestigators used patient mortality as a marker of quality, and analyzed the relationship between quality and case volume for each of the three procedures. “We used very strict definitions for high and low-volume” of surgical procedures, based on criteria set by the “Take the Volume Pledge” campaign that discourages surgeons from performing certain complex procedures unless they do them frequently, he said.

When procedural volume was mapped against risk-adjusted patient mortality in the data, the results could be divided into quadrants: high-volume/high-quality, high-volume/low-quality, low-volume/high-quality, and low-volume/low-quality.

Dr. Kothari said that an interesting pattern emerged, where a significant number of hospitals had low case volume but high quality outcomes. “In some cases … there are actually more low-volume/high-quality centers than high-volume/high-quality centers,” he said.

The researchers then looked at centers that performed at least two of the three surgical procedures at a high volume, to tease out some of the hospital system factors at play. They settled on examining 13 hospitals of over 300 initially studied, looking at more than 30 hospital characteristics that fell into five broad categories. These included infrastructure, size, staffing, perioperative services, and support intensity.

Within these categories, infrastructure characteristics associated with better outcomes included the facility’s being a level 1 trauma center and having transplant services. Size characteristics associated with better outcomes included total number of hospital admissions and total inpatient surgical volume. In terms of staffing, higher resident-to-bed and nurse-to-bed ratio (but not a higher physician-to-bed ratio) were both linked to better outcomes.

The perioperative services that mattered for outcomes were patient rehabilitation, geriatric services, speech and language pathology, and inpatient palliative care. Patients in facilities with a high level of oncology support also fared better.

Using different analytic models, Dr. Kothari and his colleagues attempted to determine whether these factors were predictive of a high-volume ecosystem that would result in better outcomes, even if volume for a particular procedure was low.

They found that their model, which assigned one point for each hospital ecosystem characteristic present at a given hospital, was very specific for identifying low-volume, high-quality care centers. “So a score of 7 and above has a specificity for low volume/high quality of care of over 70%” in esophageal resection, said Dr. Kothari.

Dr. Kothari noted how few high-volume centers were identified for this study, a finding that points to the practical importance for hospital administrators of knowing what factors may contribute to better surgical outcomes in smaller facilities.

Dr. Luke Funk, director of minimally invasive surgery research at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and a sometime collaborator of Dr. Kothari’s, had some suggestions for next steps. “Perhaps you could drill down qualitatively, going into some of these centers and talking to folks. Then you could take aspects from these programs and apply them to lower volume centers.” Dr. Kothari agreed, saying this would be a “very natural next step.”

Dr. Kothari reported no relevant disclosures; he is supported by an NIH training grant.

On Twitter @karioakes

MONTREAL – A “hospital ecosystem score” derived from examining high-volume, high-quality hospitals has good specificity in predicting which hospitals will have high-quality outcomes, though these hospitals have low surgical volume for a given procedure.

“What we’re talking about is a care delivery macro-environment,” said Dr. Anai Kothari, presenting results of a retrospective study of surgical outcomes at the Central Surgical Association’s annual meeting.

The study built on previous work that had identified “hospital system factors that actually equipped hospitals to provide high quality care,” said Dr. Kothari, a surgical research resident at Loyola University Medical Center in Maywood, Ill. “These high-volume ecosystems do exist at low-volume hospitals,” he said.

The study was designed as a retrospective review of 24,784 patient encounters over a 5-year period from 302 hospitals; data were taken from the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Services (HCAHPS) databases in California and Florida, with hospital resources data taken from the American Hospital Association (AHA) Annual Survey Database.

Adult patients were included if they had a malignancy of the esophagus, pancreas, or rectum, and had a surgical resection of the malignancy.

Dr. Kothari and his coinvestigators used patient mortality as a marker of quality, and analyzed the relationship between quality and case volume for each of the three procedures. “We used very strict definitions for high and low-volume” of surgical procedures, based on criteria set by the “Take the Volume Pledge” campaign that discourages surgeons from performing certain complex procedures unless they do them frequently, he said.

When procedural volume was mapped against risk-adjusted patient mortality in the data, the results could be divided into quadrants: high-volume/high-quality, high-volume/low-quality, low-volume/high-quality, and low-volume/low-quality.

Dr. Kothari said that an interesting pattern emerged, where a significant number of hospitals had low case volume but high quality outcomes. “In some cases … there are actually more low-volume/high-quality centers than high-volume/high-quality centers,” he said.

The researchers then looked at centers that performed at least two of the three surgical procedures at a high volume, to tease out some of the hospital system factors at play. They settled on examining 13 hospitals of over 300 initially studied, looking at more than 30 hospital characteristics that fell into five broad categories. These included infrastructure, size, staffing, perioperative services, and support intensity.

Within these categories, infrastructure characteristics associated with better outcomes included the facility’s being a level 1 trauma center and having transplant services. Size characteristics associated with better outcomes included total number of hospital admissions and total inpatient surgical volume. In terms of staffing, higher resident-to-bed and nurse-to-bed ratio (but not a higher physician-to-bed ratio) were both linked to better outcomes.

The perioperative services that mattered for outcomes were patient rehabilitation, geriatric services, speech and language pathology, and inpatient palliative care. Patients in facilities with a high level of oncology support also fared better.

Using different analytic models, Dr. Kothari and his colleagues attempted to determine whether these factors were predictive of a high-volume ecosystem that would result in better outcomes, even if volume for a particular procedure was low.

They found that their model, which assigned one point for each hospital ecosystem characteristic present at a given hospital, was very specific for identifying low-volume, high-quality care centers. “So a score of 7 and above has a specificity for low volume/high quality of care of over 70%” in esophageal resection, said Dr. Kothari.

Dr. Kothari noted how few high-volume centers were identified for this study, a finding that points to the practical importance for hospital administrators of knowing what factors may contribute to better surgical outcomes in smaller facilities.

Dr. Luke Funk, director of minimally invasive surgery research at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and a sometime collaborator of Dr. Kothari’s, had some suggestions for next steps. “Perhaps you could drill down qualitatively, going into some of these centers and talking to folks. Then you could take aspects from these programs and apply them to lower volume centers.” Dr. Kothari agreed, saying this would be a “very natural next step.”

Dr. Kothari reported no relevant disclosures; he is supported by an NIH training grant.

On Twitter @karioakes

AT THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE CENTRAL SURGICAL ASSOCIATION

Key clinical point: Hospital macro-environment factors can predict good outcomes even with low procedural volume.

Major finding: A “hospital ecosystem score” can predict which low-volume centers will have high-quality outcomes for some surgeries.

Data source: Retrospective review of 5 years of patient-level data, yielding 24,784 encounters from 302 hospitals from the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Services (HCAHPS) database; hospital resource data taken from the American Hospital Association (AHA) Annual Survey Database.

Disclosures: The study authors reported no relevant disclosures.

Coronary bypass shows compelling advantages in ischemic cardiomyopathy

CHICAGO – Coronary artery bypass grafting plus guideline-directed medical therapy resulted in significantly lower all-cause mortality than did optimal medical therapy alone at 10 years of follow-up in the Surgical Treatment for Ischemic Heart Failure Extension Study (STICHES), Dr. Eric J. Velazquez reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

“We believe these results have the immediate clinical implications that the presence of severe left ventricular dysfunction should prompt an evaluation for the extent and severity of angiographic CAD, and that among patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy, CABG should be strongly considered in order to improve long-term survival,” declared Dr. Velazquez, professor of medicine in the division of cardiology at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

STICHES included 1,212 patients in 22 countries, all with heart failure and an ejection fraction of 35% or less along with CAD deemed suitable for surgical revascularization. They were randomized to CABG plus guideline-directed medical therapy or to the medical therapy alone. The 98% successful follow-up rate over the course of 10 years in this trial drew audience praise as a herculean effort.

At a median 9.8 years of follow-up, all-cause mortality – the primary study endpoint – had occurred in 58.9% of the CABG group and 66.1% of medically managed patients. That translates to a 16% relative risk reduction and an absolute 8% difference in favor of CABG. The median survival extension conferred by CABG was 1.4 years. The number of patients needed to treat with CABG in order to prevent one death from any cause was 14.

The CABG group also did significantly better in terms of secondary endpoints. The cardiovascular mortality rate was 40.5% in the CABG group versus 49.3% with medical therapy, for a 21% relative risk reduction favoring CABG and a number needed to treat of 11. The composite endpoint of all-cause mortality or cardiovascular hospitalization occurred in 76.6% of the CABG group and 87% of the medically treated patients.

In an earlier analysis based upon 56 months of follow-up, there was a trend favoring CABG in terms of all-cause mortality, but it didn’t reach statistical significance (N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1607-16). With an additional 5 years of prospective follow-up, however, the divergence in outcome between the two study arms increased sufficiently that the difference achieved statistical significance. But the more impressive study finding, in Dr. Velazquez’s view, was the durability of the CABG benefits out to 10 years.

Discussant Dr. Jeroean J. Bax of Leiden (the Netherlands) University commented that while the solid advantage in outcomes displayed by the CABG group was noteworthy, he finds it sobering that even though the STICHES participants averaged only 60 years of age at entry, the majority were dead at 10 years’ follow-up. What, he asked, is the likely mechanism for the very high mortality seen in this population?

“My take-home after many years working with our team is that I believe these patients have very low reserve, and they are at risk any time they take a hit. I don’t believe just one mechanism is involved. In our previous analysis of the 5-year follow-up data, we showed the results can’t be explained solely by viability, ischemia, or functional recovery. I think the issue of arrhythmia reduction and substrate reduction is important. But for me, it’s a combination of many factors. Any additional hit for this high-risk population is not well tolerated; that’s what leads to death,” Dr. Velazquez replied.

Asked how he thinks multivessel percutaneous coronary intervention would perform as an alternative to CABG in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy, Dr. Velazquez responded that he has no idea because it hasn’t been studied.

“I can picture reasons for and against PCI providing benefits similar to CABG,” he added.

Simultaneous with Dr. Velazquez’s presentation at ACC 16, the STICHES results were published online (N Engl J Med. 2016 April 3. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1602001).

In an accompanying editorial, Dr. Robert A. Guyton and Dr. Andrew L. Smith of Emory University in Atlanta asserted that these strong results from STICHES make a compelling case that CABG for patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy should be upgraded in the ACC/AHA heart failure management guidelines from its current status as a class IIb recommendation that “might be considered” to class IIa, indicating it is “probably beneficial” (N Engl J Med. 2016 April 3. doi:10.1056/NEJMe1603615).

STICHES was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The study presenter reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study.

CHICAGO – Coronary artery bypass grafting plus guideline-directed medical therapy resulted in significantly lower all-cause mortality than did optimal medical therapy alone at 10 years of follow-up in the Surgical Treatment for Ischemic Heart Failure Extension Study (STICHES), Dr. Eric J. Velazquez reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

“We believe these results have the immediate clinical implications that the presence of severe left ventricular dysfunction should prompt an evaluation for the extent and severity of angiographic CAD, and that among patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy, CABG should be strongly considered in order to improve long-term survival,” declared Dr. Velazquez, professor of medicine in the division of cardiology at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

STICHES included 1,212 patients in 22 countries, all with heart failure and an ejection fraction of 35% or less along with CAD deemed suitable for surgical revascularization. They were randomized to CABG plus guideline-directed medical therapy or to the medical therapy alone. The 98% successful follow-up rate over the course of 10 years in this trial drew audience praise as a herculean effort.

At a median 9.8 years of follow-up, all-cause mortality – the primary study endpoint – had occurred in 58.9% of the CABG group and 66.1% of medically managed patients. That translates to a 16% relative risk reduction and an absolute 8% difference in favor of CABG. The median survival extension conferred by CABG was 1.4 years. The number of patients needed to treat with CABG in order to prevent one death from any cause was 14.

The CABG group also did significantly better in terms of secondary endpoints. The cardiovascular mortality rate was 40.5% in the CABG group versus 49.3% with medical therapy, for a 21% relative risk reduction favoring CABG and a number needed to treat of 11. The composite endpoint of all-cause mortality or cardiovascular hospitalization occurred in 76.6% of the CABG group and 87% of the medically treated patients.

In an earlier analysis based upon 56 months of follow-up, there was a trend favoring CABG in terms of all-cause mortality, but it didn’t reach statistical significance (N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1607-16). With an additional 5 years of prospective follow-up, however, the divergence in outcome between the two study arms increased sufficiently that the difference achieved statistical significance. But the more impressive study finding, in Dr. Velazquez’s view, was the durability of the CABG benefits out to 10 years.

Discussant Dr. Jeroean J. Bax of Leiden (the Netherlands) University commented that while the solid advantage in outcomes displayed by the CABG group was noteworthy, he finds it sobering that even though the STICHES participants averaged only 60 years of age at entry, the majority were dead at 10 years’ follow-up. What, he asked, is the likely mechanism for the very high mortality seen in this population?

“My take-home after many years working with our team is that I believe these patients have very low reserve, and they are at risk any time they take a hit. I don’t believe just one mechanism is involved. In our previous analysis of the 5-year follow-up data, we showed the results can’t be explained solely by viability, ischemia, or functional recovery. I think the issue of arrhythmia reduction and substrate reduction is important. But for me, it’s a combination of many factors. Any additional hit for this high-risk population is not well tolerated; that’s what leads to death,” Dr. Velazquez replied.

Asked how he thinks multivessel percutaneous coronary intervention would perform as an alternative to CABG in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy, Dr. Velazquez responded that he has no idea because it hasn’t been studied.

“I can picture reasons for and against PCI providing benefits similar to CABG,” he added.

Simultaneous with Dr. Velazquez’s presentation at ACC 16, the STICHES results were published online (N Engl J Med. 2016 April 3. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1602001).

In an accompanying editorial, Dr. Robert A. Guyton and Dr. Andrew L. Smith of Emory University in Atlanta asserted that these strong results from STICHES make a compelling case that CABG for patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy should be upgraded in the ACC/AHA heart failure management guidelines from its current status as a class IIb recommendation that “might be considered” to class IIa, indicating it is “probably beneficial” (N Engl J Med. 2016 April 3. doi:10.1056/NEJMe1603615).

STICHES was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The study presenter reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study.

CHICAGO – Coronary artery bypass grafting plus guideline-directed medical therapy resulted in significantly lower all-cause mortality than did optimal medical therapy alone at 10 years of follow-up in the Surgical Treatment for Ischemic Heart Failure Extension Study (STICHES), Dr. Eric J. Velazquez reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

“We believe these results have the immediate clinical implications that the presence of severe left ventricular dysfunction should prompt an evaluation for the extent and severity of angiographic CAD, and that among patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy, CABG should be strongly considered in order to improve long-term survival,” declared Dr. Velazquez, professor of medicine in the division of cardiology at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

STICHES included 1,212 patients in 22 countries, all with heart failure and an ejection fraction of 35% or less along with CAD deemed suitable for surgical revascularization. They were randomized to CABG plus guideline-directed medical therapy or to the medical therapy alone. The 98% successful follow-up rate over the course of 10 years in this trial drew audience praise as a herculean effort.

At a median 9.8 years of follow-up, all-cause mortality – the primary study endpoint – had occurred in 58.9% of the CABG group and 66.1% of medically managed patients. That translates to a 16% relative risk reduction and an absolute 8% difference in favor of CABG. The median survival extension conferred by CABG was 1.4 years. The number of patients needed to treat with CABG in order to prevent one death from any cause was 14.

The CABG group also did significantly better in terms of secondary endpoints. The cardiovascular mortality rate was 40.5% in the CABG group versus 49.3% with medical therapy, for a 21% relative risk reduction favoring CABG and a number needed to treat of 11. The composite endpoint of all-cause mortality or cardiovascular hospitalization occurred in 76.6% of the CABG group and 87% of the medically treated patients.

In an earlier analysis based upon 56 months of follow-up, there was a trend favoring CABG in terms of all-cause mortality, but it didn’t reach statistical significance (N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1607-16). With an additional 5 years of prospective follow-up, however, the divergence in outcome between the two study arms increased sufficiently that the difference achieved statistical significance. But the more impressive study finding, in Dr. Velazquez’s view, was the durability of the CABG benefits out to 10 years.

Discussant Dr. Jeroean J. Bax of Leiden (the Netherlands) University commented that while the solid advantage in outcomes displayed by the CABG group was noteworthy, he finds it sobering that even though the STICHES participants averaged only 60 years of age at entry, the majority were dead at 10 years’ follow-up. What, he asked, is the likely mechanism for the very high mortality seen in this population?

“My take-home after many years working with our team is that I believe these patients have very low reserve, and they are at risk any time they take a hit. I don’t believe just one mechanism is involved. In our previous analysis of the 5-year follow-up data, we showed the results can’t be explained solely by viability, ischemia, or functional recovery. I think the issue of arrhythmia reduction and substrate reduction is important. But for me, it’s a combination of many factors. Any additional hit for this high-risk population is not well tolerated; that’s what leads to death,” Dr. Velazquez replied.

Asked how he thinks multivessel percutaneous coronary intervention would perform as an alternative to CABG in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy, Dr. Velazquez responded that he has no idea because it hasn’t been studied.

“I can picture reasons for and against PCI providing benefits similar to CABG,” he added.

Simultaneous with Dr. Velazquez’s presentation at ACC 16, the STICHES results were published online (N Engl J Med. 2016 April 3. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1602001).

In an accompanying editorial, Dr. Robert A. Guyton and Dr. Andrew L. Smith of Emory University in Atlanta asserted that these strong results from STICHES make a compelling case that CABG for patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy should be upgraded in the ACC/AHA heart failure management guidelines from its current status as a class IIb recommendation that “might be considered” to class IIa, indicating it is “probably beneficial” (N Engl J Med. 2016 April 3. doi:10.1056/NEJMe1603615).

STICHES was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The study presenter reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study.

AT ACC 16

Key clinical point: CABG plus optimal medical therapy is the treatment of choice in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy.

Major finding: The number of patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy who need to be treated with CABG plus optimal medical therapy instead of medical therapy alone in order to prevent one additional death due to any cause is 14.

Data source: This was a randomized, unblinded clinical trial involving 1,212 patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy in 22 countries.

Disclosures: STICHES was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The study presenter reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study.

Trauma checklist in ED can increase discharge rates

MONTREAL – A trauma checklist may help increase the proportion of trauma patients who are discharged home from an emergency department, according to a single-center study that tracked trauma admissions before and after institution of a trauma checklist.

Dr. Amani Jambhekar, a surgery resident at New York Methodist Hospital, Brooklyn, presented the study findings at the Central Surgical Association’s annual meeting. Discharges in July and August of 2015, after the checklist had been implemented, increased significantly, from a 6.5% rate in the first study month, before the checklist was implemented, to a 23.4% and 16.7% rate for the last two study months (P = .004).

However, the injury severity score decreased over the period of the study, from a mean of 7.27 in the first month of the study to 4.60 in the last month of the study (P = .019), and the injury severity level was generally low.

When a trauma patient is admitted who might fare well at home, not only does the admission represent a potentially avoidable cost, it also exposes patients, particularly elderly patients, to infection risk, increased immobility, and other negative effects of hospitalization.

“Why don’t we discharge patients from the emergency department more? Well, there’s a significant fear of ‘bounce-backs,’ ” Dr. Jambhekar said. The bounce-back phenomenon, where patients who are discharged and then present again and are admitted, had not been well studied among trauma patients discharged from the emergency department, he added.

Risk factors for readmission after a hospital discharge had been studied, and may include low socioeconomic status, no insurance or publicly provided insurance, long initial inpatient stay, and higher Injury Severity Score (ISS). “But none of this had been evaluated in patients who were initially discharged from the emergency department,” said Dr. Jambhekar.

New York Methodist, the study site, is a 651-bed urban community hospital. It sees approximately 100,000 emergency department (ED) visits per year, with 8,000 trauma patients coming through the door of the ED in the first 11 months of the hospital’s designation as a level II trauma center.

Dr. Jambhekar and her colleagues evaluated 376 trauma patients, divided into two groups. The first group of 198 patients was seen in the 3 months before the checklist was put in place. The second group of 178 patients was seen in the 60 days after the trauma checklist was mandated. Patients were included in the study if they had been evaluated by the trauma surgery service.

The trauma checklist contained basic demographic and history information, as well as information about the patients’ ED course – for example, what imaging studied were obtained, lab values, what consults they received. The ISS was calculated prior to patient disposition.

“We wanted to present a template to all of our providers to use, in order to correctly document patients’ injuries. If they knew the extent of every patient’s injuries, they could correctly identify patients who were safe to discharge from the emergency department.” One limitation of the study, said Dr. Jambhekar, is overtriage of patients to the trauma center. This is evidenced by the relatively low ISS scores. “As our trauma center became more popular in Brooklyn and in New York City, more patients were brought to our trauma center, even when they could have adequately been treated elsewhere.”

The study didn’t have long-term follow-up of patients to see if they were satisfied with their care, and if they had recovered from their injuries. The exact cost of outpatient follow-up is also uncertain, said Dr. Jambhekar.

Dr. Jambhekar and her colleagues plan to investigate safety and cost outcomes for discharge of trauma patients from the ED; they also will look at the bounce-back phenomenon, and long-term outcomes for outpatient care of trauma patients.

They reported no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @karioakes

MONTREAL – A trauma checklist may help increase the proportion of trauma patients who are discharged home from an emergency department, according to a single-center study that tracked trauma admissions before and after institution of a trauma checklist.

Dr. Amani Jambhekar, a surgery resident at New York Methodist Hospital, Brooklyn, presented the study findings at the Central Surgical Association’s annual meeting. Discharges in July and August of 2015, after the checklist had been implemented, increased significantly, from a 6.5% rate in the first study month, before the checklist was implemented, to a 23.4% and 16.7% rate for the last two study months (P = .004).

However, the injury severity score decreased over the period of the study, from a mean of 7.27 in the first month of the study to 4.60 in the last month of the study (P = .019), and the injury severity level was generally low.

When a trauma patient is admitted who might fare well at home, not only does the admission represent a potentially avoidable cost, it also exposes patients, particularly elderly patients, to infection risk, increased immobility, and other negative effects of hospitalization.

“Why don’t we discharge patients from the emergency department more? Well, there’s a significant fear of ‘bounce-backs,’ ” Dr. Jambhekar said. The bounce-back phenomenon, where patients who are discharged and then present again and are admitted, had not been well studied among trauma patients discharged from the emergency department, he added.

Risk factors for readmission after a hospital discharge had been studied, and may include low socioeconomic status, no insurance or publicly provided insurance, long initial inpatient stay, and higher Injury Severity Score (ISS). “But none of this had been evaluated in patients who were initially discharged from the emergency department,” said Dr. Jambhekar.

New York Methodist, the study site, is a 651-bed urban community hospital. It sees approximately 100,000 emergency department (ED) visits per year, with 8,000 trauma patients coming through the door of the ED in the first 11 months of the hospital’s designation as a level II trauma center.

Dr. Jambhekar and her colleagues evaluated 376 trauma patients, divided into two groups. The first group of 198 patients was seen in the 3 months before the checklist was put in place. The second group of 178 patients was seen in the 60 days after the trauma checklist was mandated. Patients were included in the study if they had been evaluated by the trauma surgery service.

The trauma checklist contained basic demographic and history information, as well as information about the patients’ ED course – for example, what imaging studied were obtained, lab values, what consults they received. The ISS was calculated prior to patient disposition.

“We wanted to present a template to all of our providers to use, in order to correctly document patients’ injuries. If they knew the extent of every patient’s injuries, they could correctly identify patients who were safe to discharge from the emergency department.” One limitation of the study, said Dr. Jambhekar, is overtriage of patients to the trauma center. This is evidenced by the relatively low ISS scores. “As our trauma center became more popular in Brooklyn and in New York City, more patients were brought to our trauma center, even when they could have adequately been treated elsewhere.”

The study didn’t have long-term follow-up of patients to see if they were satisfied with their care, and if they had recovered from their injuries. The exact cost of outpatient follow-up is also uncertain, said Dr. Jambhekar.

Dr. Jambhekar and her colleagues plan to investigate safety and cost outcomes for discharge of trauma patients from the ED; they also will look at the bounce-back phenomenon, and long-term outcomes for outpatient care of trauma patients.

They reported no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @karioakes

MONTREAL – A trauma checklist may help increase the proportion of trauma patients who are discharged home from an emergency department, according to a single-center study that tracked trauma admissions before and after institution of a trauma checklist.

Dr. Amani Jambhekar, a surgery resident at New York Methodist Hospital, Brooklyn, presented the study findings at the Central Surgical Association’s annual meeting. Discharges in July and August of 2015, after the checklist had been implemented, increased significantly, from a 6.5% rate in the first study month, before the checklist was implemented, to a 23.4% and 16.7% rate for the last two study months (P = .004).

However, the injury severity score decreased over the period of the study, from a mean of 7.27 in the first month of the study to 4.60 in the last month of the study (P = .019), and the injury severity level was generally low.

When a trauma patient is admitted who might fare well at home, not only does the admission represent a potentially avoidable cost, it also exposes patients, particularly elderly patients, to infection risk, increased immobility, and other negative effects of hospitalization.

“Why don’t we discharge patients from the emergency department more? Well, there’s a significant fear of ‘bounce-backs,’ ” Dr. Jambhekar said. The bounce-back phenomenon, where patients who are discharged and then present again and are admitted, had not been well studied among trauma patients discharged from the emergency department, he added.

Risk factors for readmission after a hospital discharge had been studied, and may include low socioeconomic status, no insurance or publicly provided insurance, long initial inpatient stay, and higher Injury Severity Score (ISS). “But none of this had been evaluated in patients who were initially discharged from the emergency department,” said Dr. Jambhekar.

New York Methodist, the study site, is a 651-bed urban community hospital. It sees approximately 100,000 emergency department (ED) visits per year, with 8,000 trauma patients coming through the door of the ED in the first 11 months of the hospital’s designation as a level II trauma center.

Dr. Jambhekar and her colleagues evaluated 376 trauma patients, divided into two groups. The first group of 198 patients was seen in the 3 months before the checklist was put in place. The second group of 178 patients was seen in the 60 days after the trauma checklist was mandated. Patients were included in the study if they had been evaluated by the trauma surgery service.

The trauma checklist contained basic demographic and history information, as well as information about the patients’ ED course – for example, what imaging studied were obtained, lab values, what consults they received. The ISS was calculated prior to patient disposition.

“We wanted to present a template to all of our providers to use, in order to correctly document patients’ injuries. If they knew the extent of every patient’s injuries, they could correctly identify patients who were safe to discharge from the emergency department.” One limitation of the study, said Dr. Jambhekar, is overtriage of patients to the trauma center. This is evidenced by the relatively low ISS scores. “As our trauma center became more popular in Brooklyn and in New York City, more patients were brought to our trauma center, even when they could have adequately been treated elsewhere.”

The study didn’t have long-term follow-up of patients to see if they were satisfied with their care, and if they had recovered from their injuries. The exact cost of outpatient follow-up is also uncertain, said Dr. Jambhekar.

Dr. Jambhekar and her colleagues plan to investigate safety and cost outcomes for discharge of trauma patients from the ED; they also will look at the bounce-back phenomenon, and long-term outcomes for outpatient care of trauma patients.

They reported no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @karioakes

AT THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE CENTRAL SURGICAL ASSOCIATION

Key clinical point: Use of a standardized trauma checklist in the emergency department (ED) may increase discharge rates.

Major finding: Discharge rates increased significantly after implementation of a trauma checklist.

Data source: Single-center study comparing discharge rates before and after implementation of a trauma checklist.

Disclosures: Dr. Ambhekar and her colleagues reported no disclosures.

Pump-delivered anesthetic reduces pain post-hernia repair

MONTREAL – An elastomeric pump delivering local anesthetic to the site of a ventral hernia repair can significantly reduce postoperative pain, according to a small, single-center study.

The prospective, randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trial of the use of an elastomeric bupivacaine-containing pump for pain management after laparoscopic ventral hernia repair (LVHR) found that patients receiving bupivacaine reported significantly less postoperative pain than did those receiving saline through the pump.

“The idea is that the use of this technology, in combination with standard postoperative pain medication, would do two things: It would maintain the same level of postoperative pain control, as well as reducing the amount of narcotic and non-narcotic pain medication used,” said Francis DeAsis, a medical student at Midwestern University, Chicago.

“For our project, we focused on the specific anatomic location of the catheter,” Mr. DeAsis said in a presentation at the annual meeting of the Central Surgical Association. A previous study, he said, had shown no efficacy for pump-delivered bupivacaine when it was delivered directly into the hernia sac.

In the present study, the cannula for the pump was placed inferior to the costochondral margin, with catheters tunnelled bilaterally between the transversalis fascia and the parietal peritoneum. “The idea behind this was to knock out as many pain receptors as possible,” said Mr. DeAsis.

Primary outcome measures were the self-reported level of postoperative pain and the amount of postoperative medication use. Adult patients at a single site who were undergoing nonemergent ventral hernia repair and who had no history of opioid abuse or adverse reactions to opioids or local anesthetics were enrolled.

Patients were then prospectively randomized to the placebo arm, where they received 400 mL of saline via pump, or to the intervention arm, where they received 400 mL of 0.5% bupivacaine following LVHR. The pump delivered the study drug for a period of 4 days after placement in both groups.

Patients completed a pain diary and medication log for the 7 days after discharge. They rated their current pain level, reported how frequently they had pain, and reported satisfaction with pain control.

In-hospital use of opioid pain medication did not differ significantly between groups, but patients receiving bupivacaine through their pumps used significantly less ketorolac as inpatients (mean 30 mg, compared with 53 mg in the saline group, P = .01).

“Ketorolac is our first-line; we try to avoid narcotics for many different reasons ... Ketorolac PRN was ordered for everybody,” said Dr. Michael Ujiki, a general surgeon at NorthShore University HealthSystem, Evanston, Ill., and senior investigator for the study.

The median pain score on a 1-10 Likert scale at discharge was 2.0 (interquartile range, 0.0-3.0) for the bupivacaine group and 4.0 (interquartile range, 2.0-5.0) for the saline group (P = .06).

Once patients were discharged from the hospital, patients receiving bupivacaine had significantly less postoperative pain through postoperative day 4 and significantly less frequent pain through postoperative day 4. Finally, they reported being significantly more satisfied with their pain management scores on postoperative days 1-3.

The study was limited by the small cohort size. “The primary reason behind this was that during recruitment, we had a lot of patients voice concern about potentially receiving placebo,” thereby forgoing the chance for additional pain relief, said Mr. DeAsis. “A well-powered study should be conducted in the future.”

The investigators reported no relevant financial disclosures, but all study pumps were provided by the manufacturer, On-Q.

On Twitter @karioakes

MONTREAL – An elastomeric pump delivering local anesthetic to the site of a ventral hernia repair can significantly reduce postoperative pain, according to a small, single-center study.

The prospective, randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trial of the use of an elastomeric bupivacaine-containing pump for pain management after laparoscopic ventral hernia repair (LVHR) found that patients receiving bupivacaine reported significantly less postoperative pain than did those receiving saline through the pump.

“The idea is that the use of this technology, in combination with standard postoperative pain medication, would do two things: It would maintain the same level of postoperative pain control, as well as reducing the amount of narcotic and non-narcotic pain medication used,” said Francis DeAsis, a medical student at Midwestern University, Chicago.

“For our project, we focused on the specific anatomic location of the catheter,” Mr. DeAsis said in a presentation at the annual meeting of the Central Surgical Association. A previous study, he said, had shown no efficacy for pump-delivered bupivacaine when it was delivered directly into the hernia sac.