User login

Cutaneous Metastasis of an Undiagnosed Prostatic Adenocarcinoma

Cutaneous Metastasis of an Undiagnosed Prostatic Adenocarcinoma

To the Editor:

Cutaneous metastasis of prostate cancer is rare and portends a bleak prognosis. Diagnosis of the primary cancer can be challenging, as skin metastasis can mimic a variety of conditions. We report a case of metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma confirmed via biopsy of a new skin lesion.

A 97-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic for routine follow-up of psoriasis. During the visit, a family member mentioned a new bleeding lesion on the left shoulder. It was not known how long the lesion had been present. Four months prior, the patient had a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level of 582 ng/mL (reference range, 0-6.5 ng/mL), and computed tomography of the chest had shown innumerable pulmonary nodules in addition to lymphadenopathy of the left axilla, clavicle, and mediastinum. The imaging was ordered by the patient’s urologist as part of routine workup, as he had a history of obstructive renal failure and was being monitored for an indwelling catheter. Two months later, a bone scan ordered by the urologist due to high PSA levels showed extensive osteoblastic metastatic disease throughout the axial and proximal appendicular skeleton. The elevated PSA levels and findings of pulmonary and osteoblastic metastasis suggested a diagnosis of metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma, but no confirmatory biopsy was performed following the imaging because the patient’s family declined additional workup or intervention.

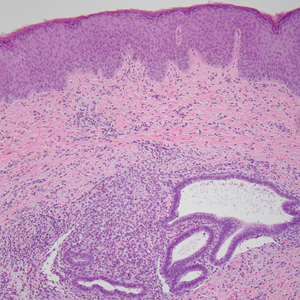

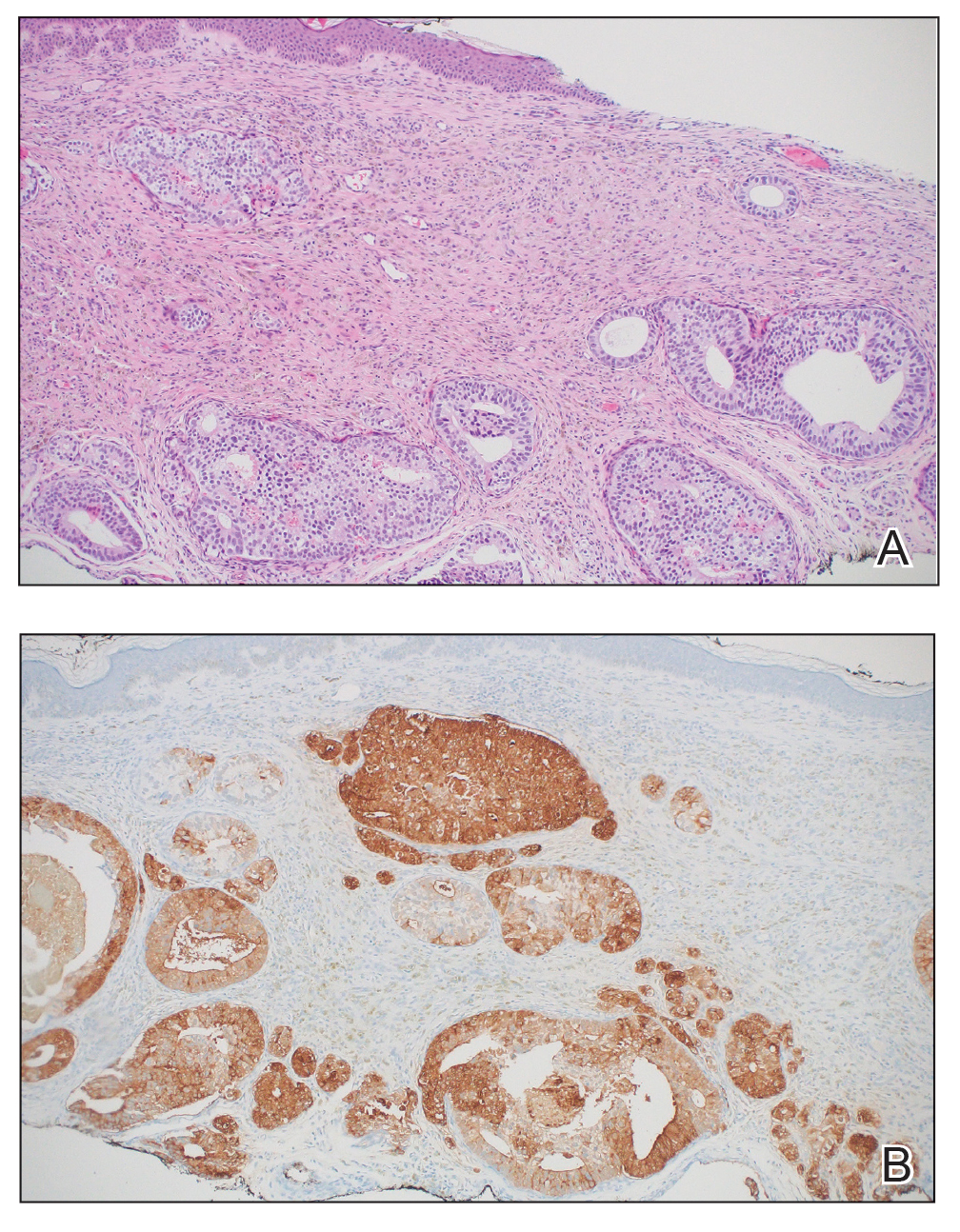

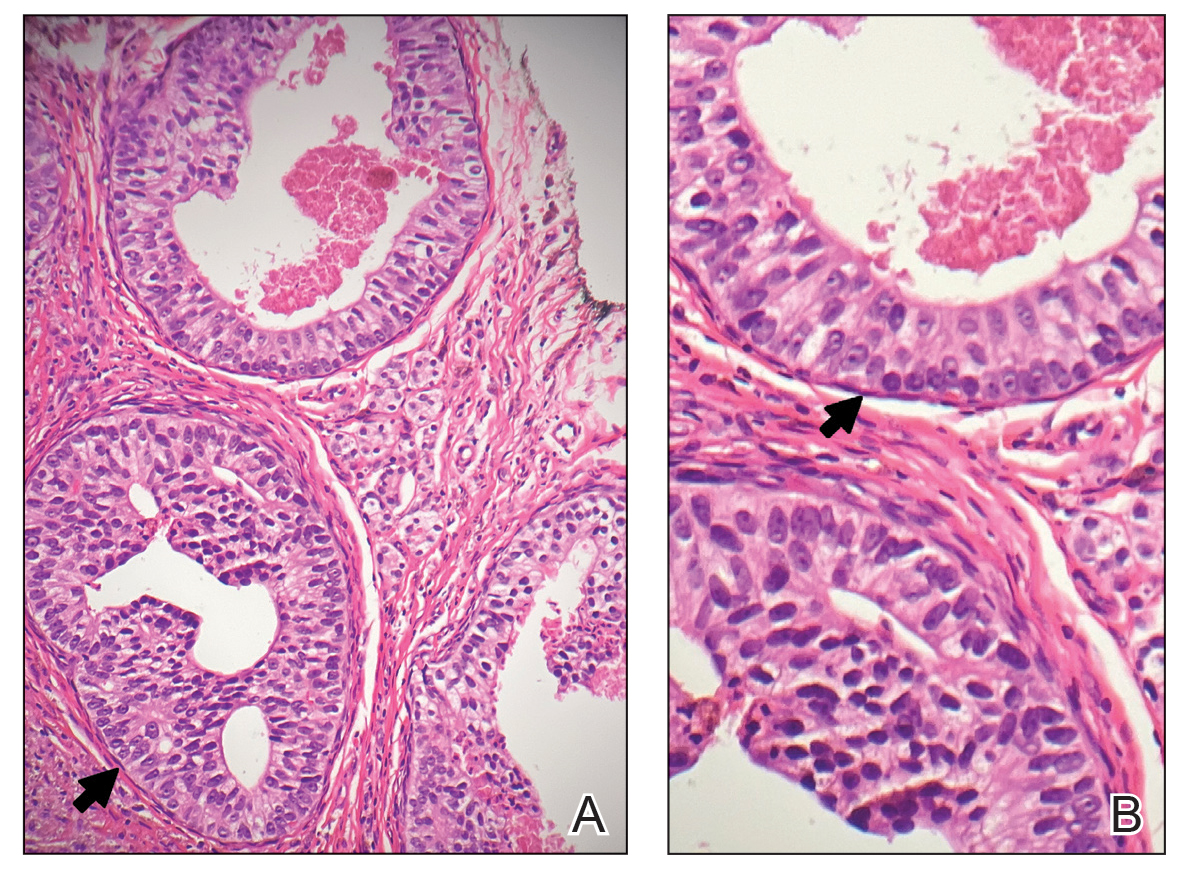

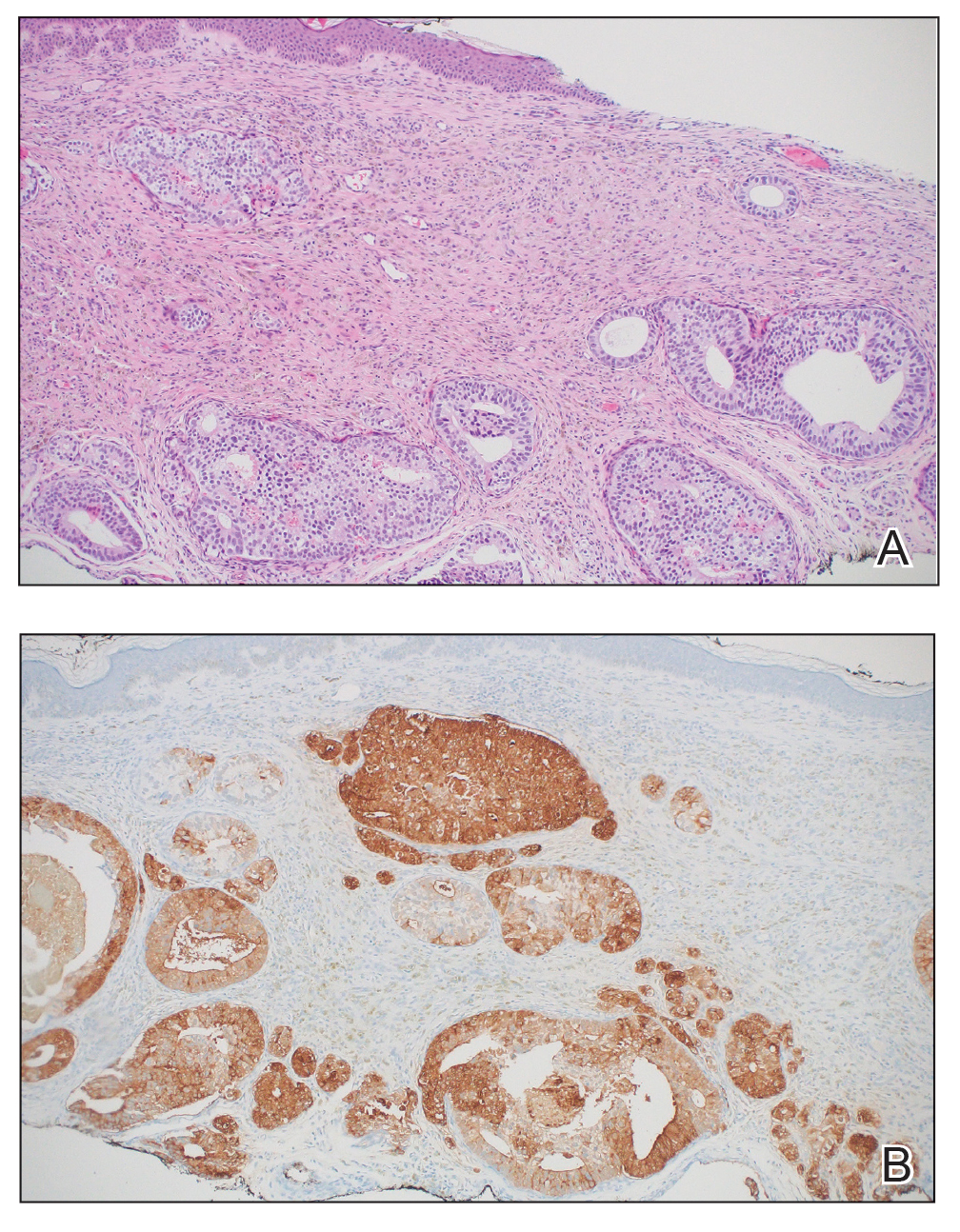

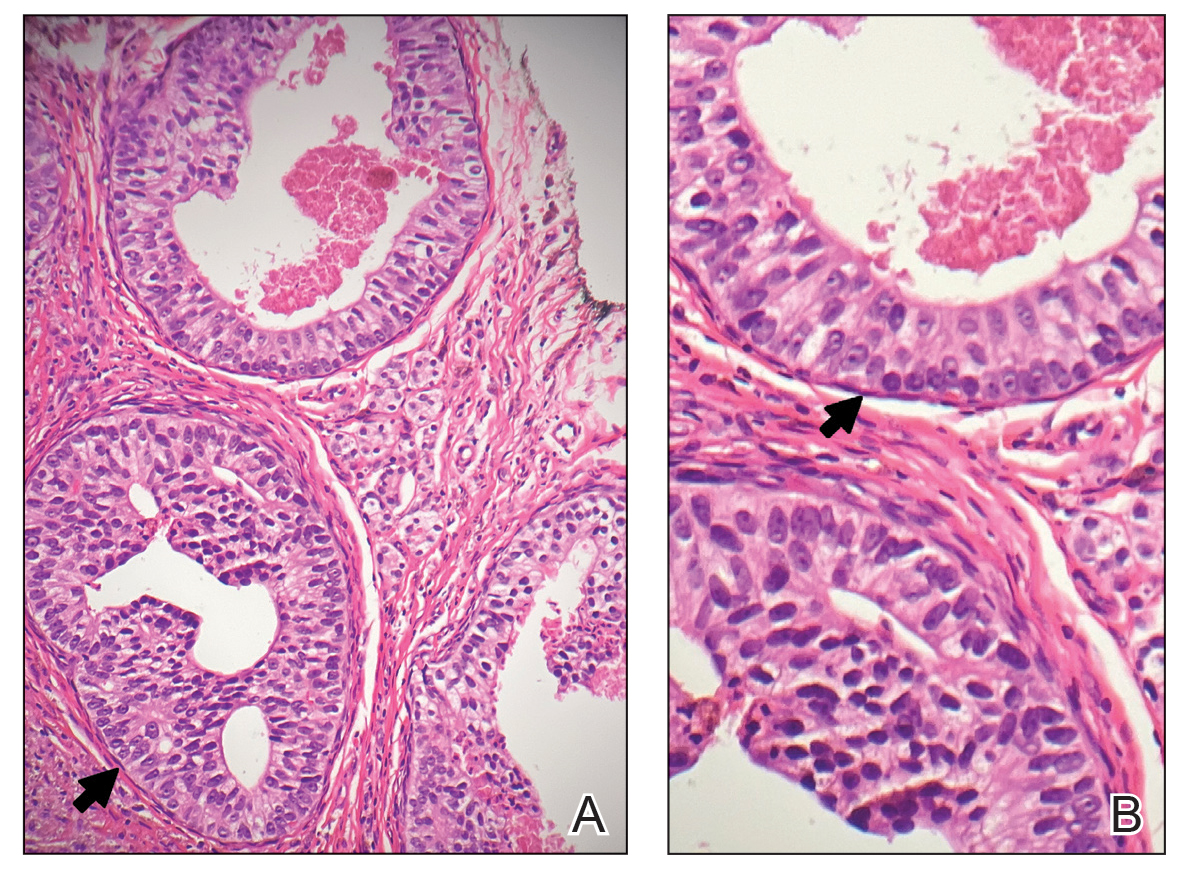

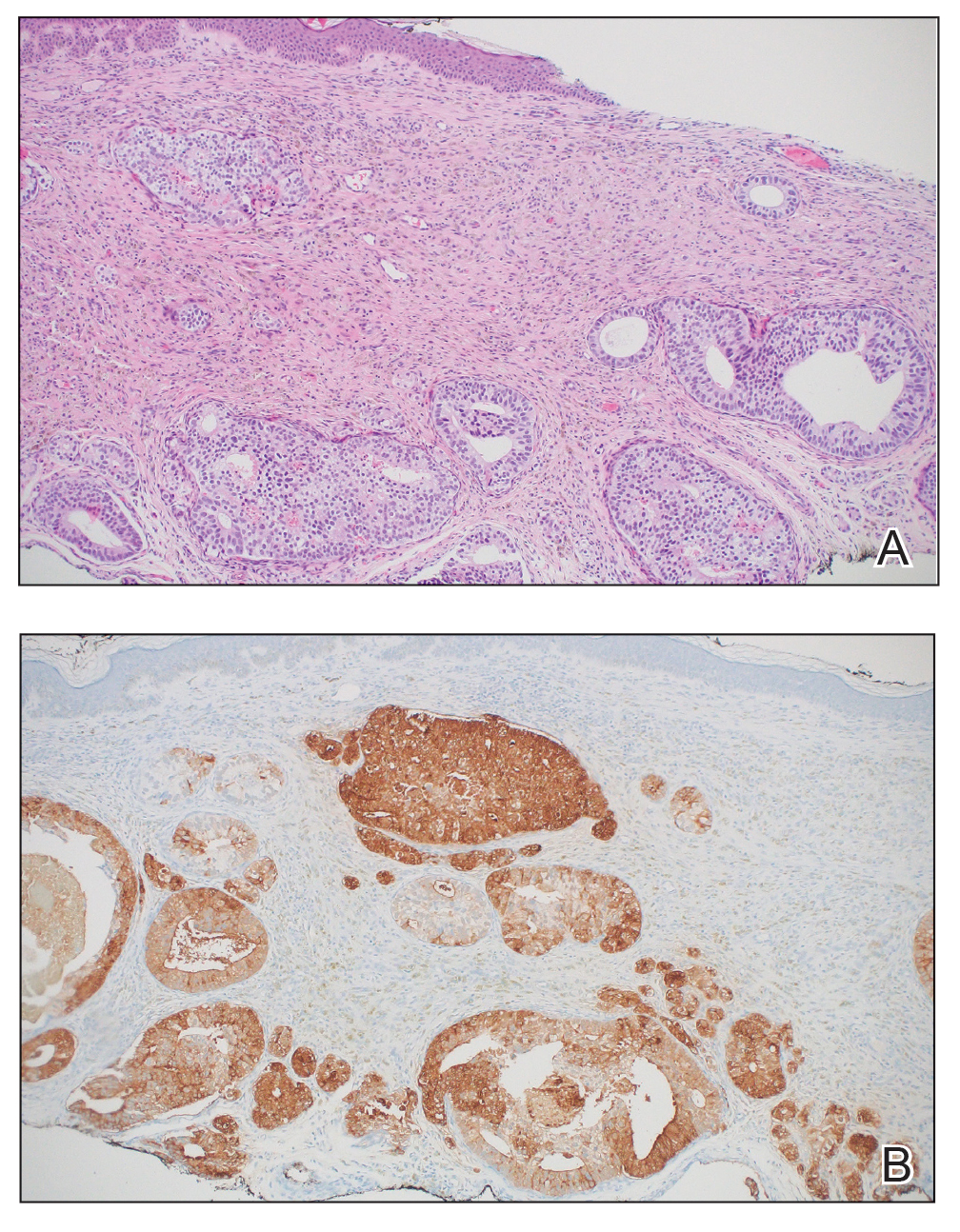

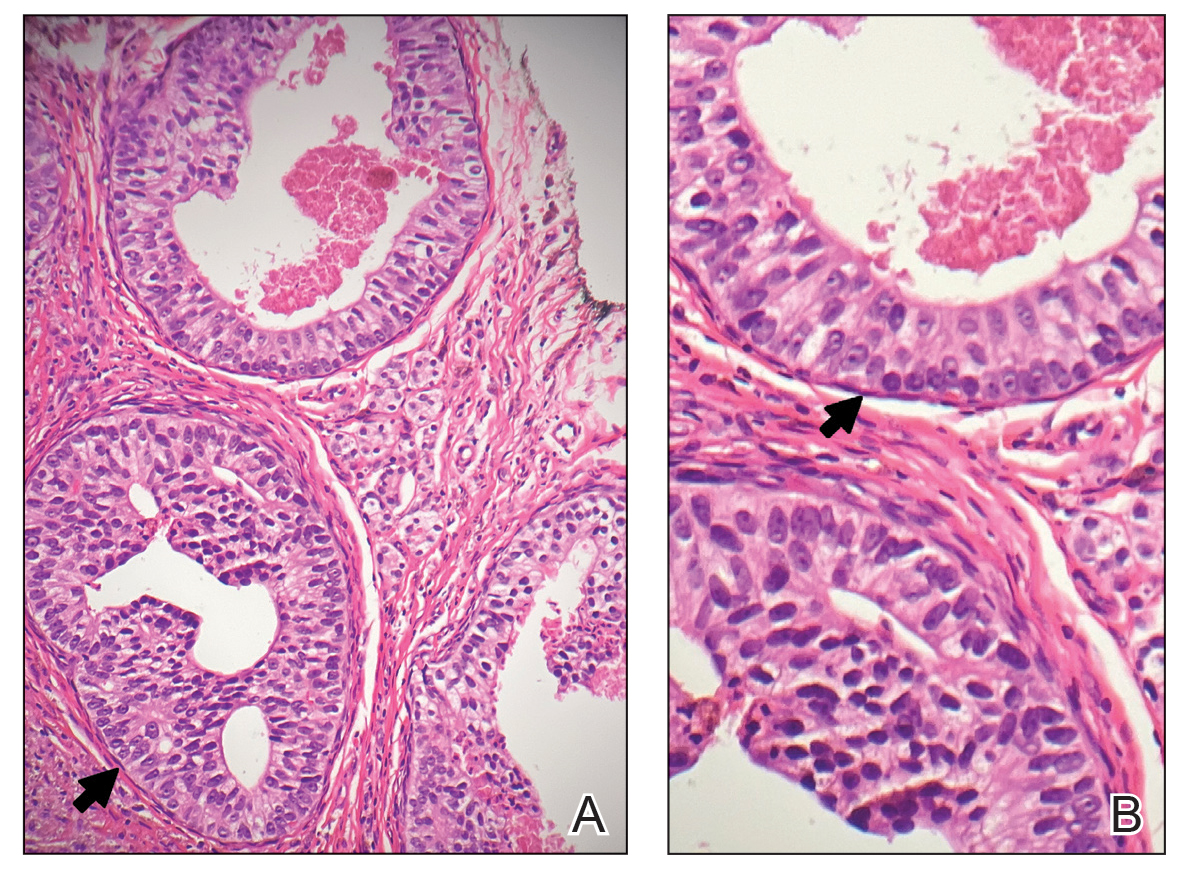

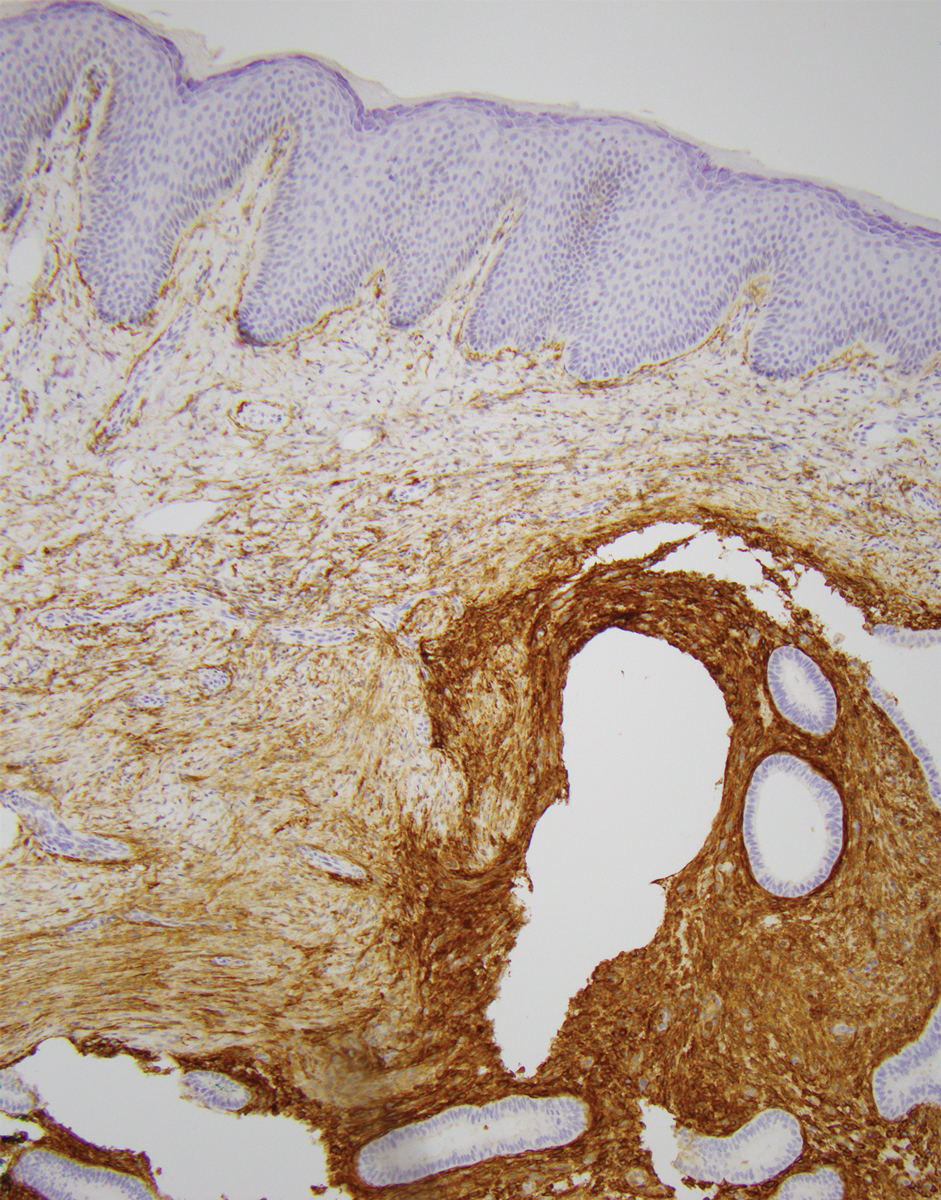

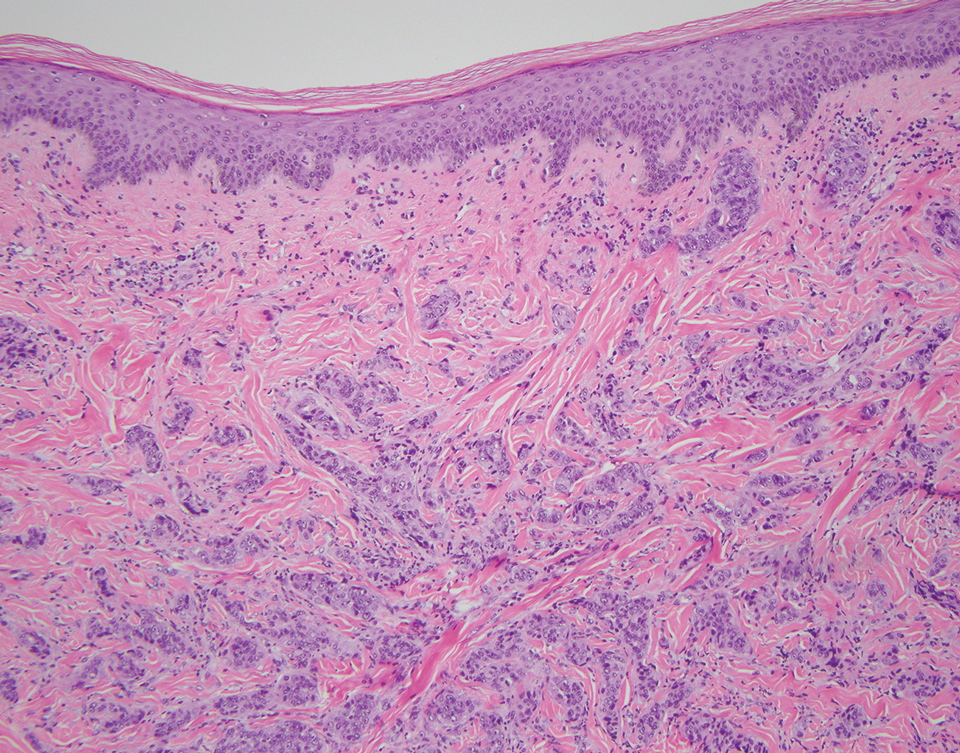

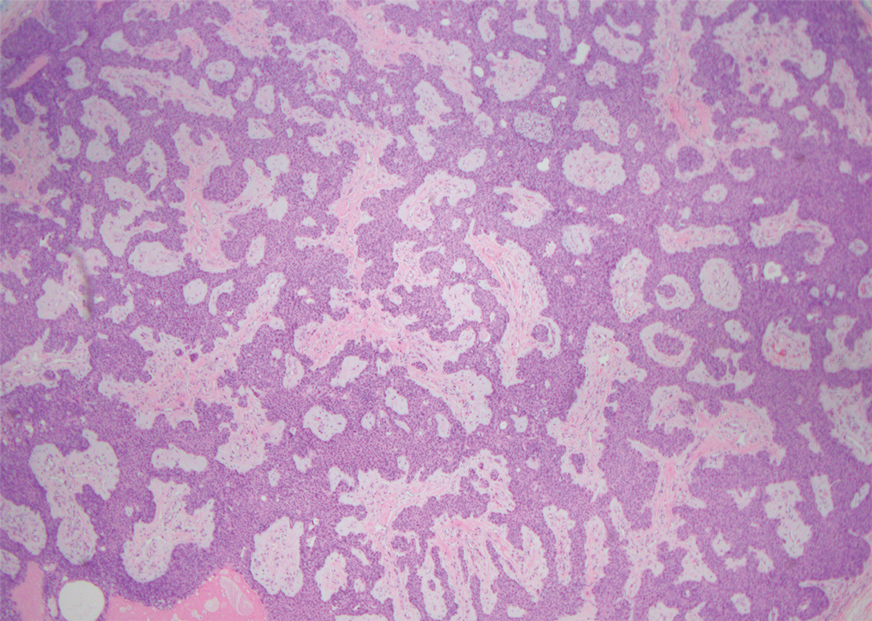

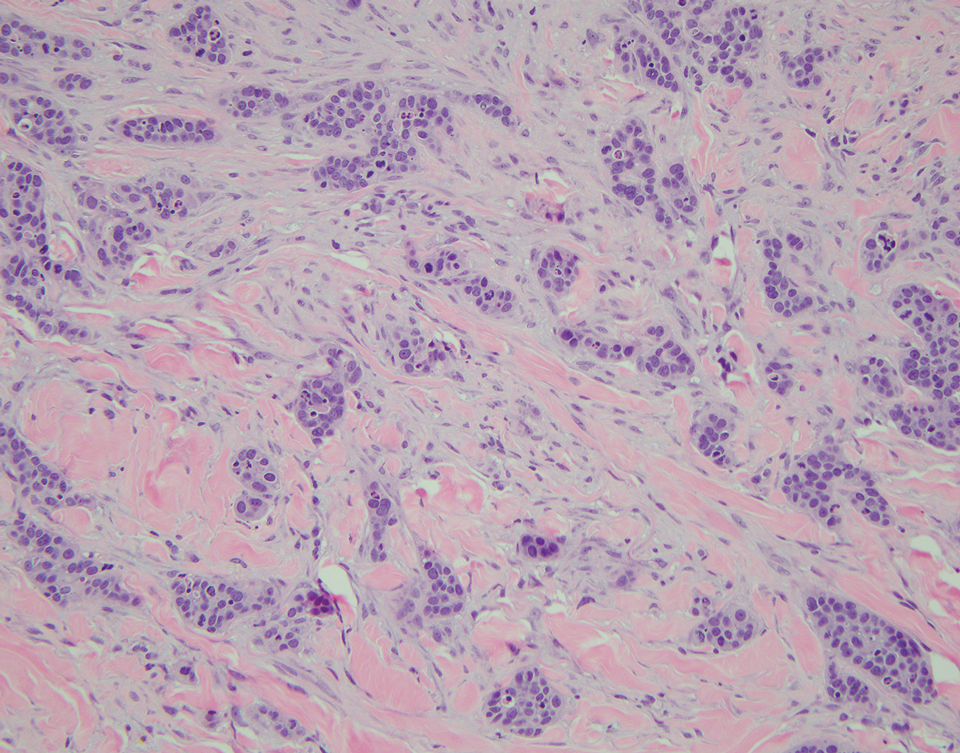

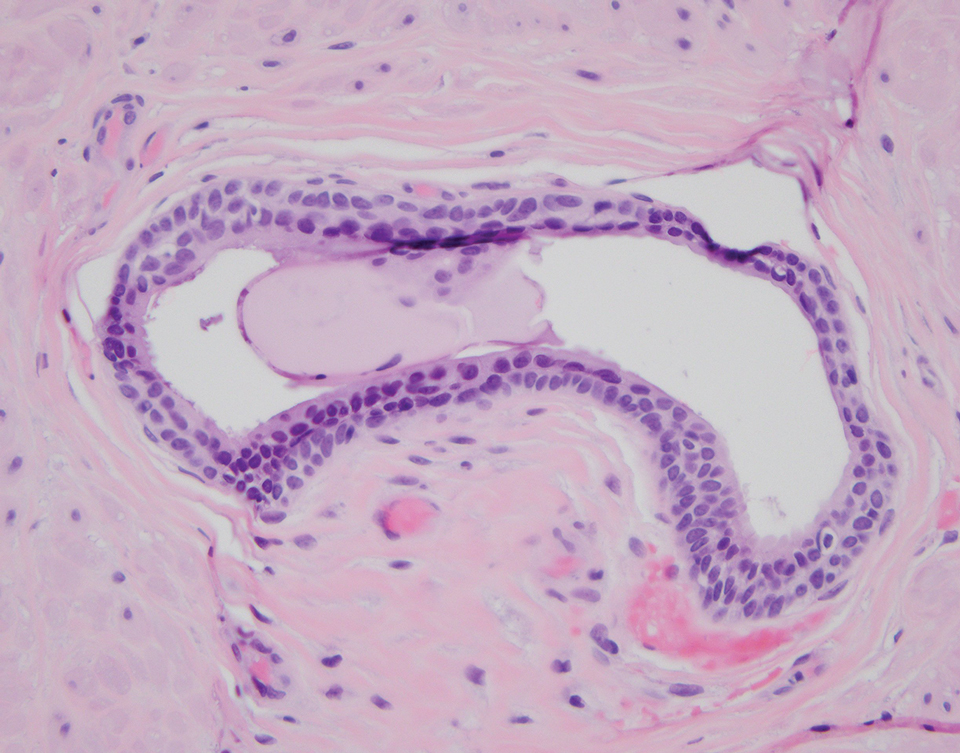

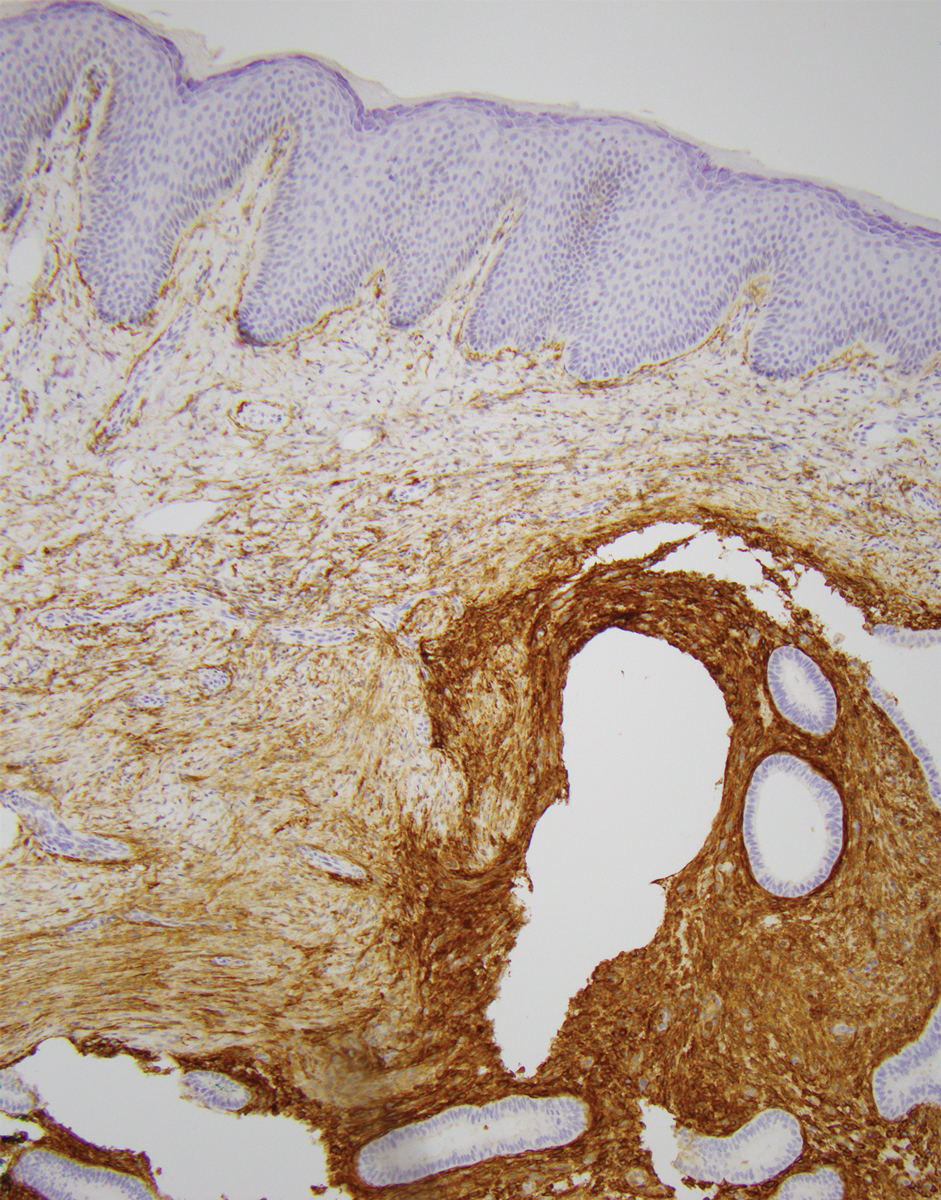

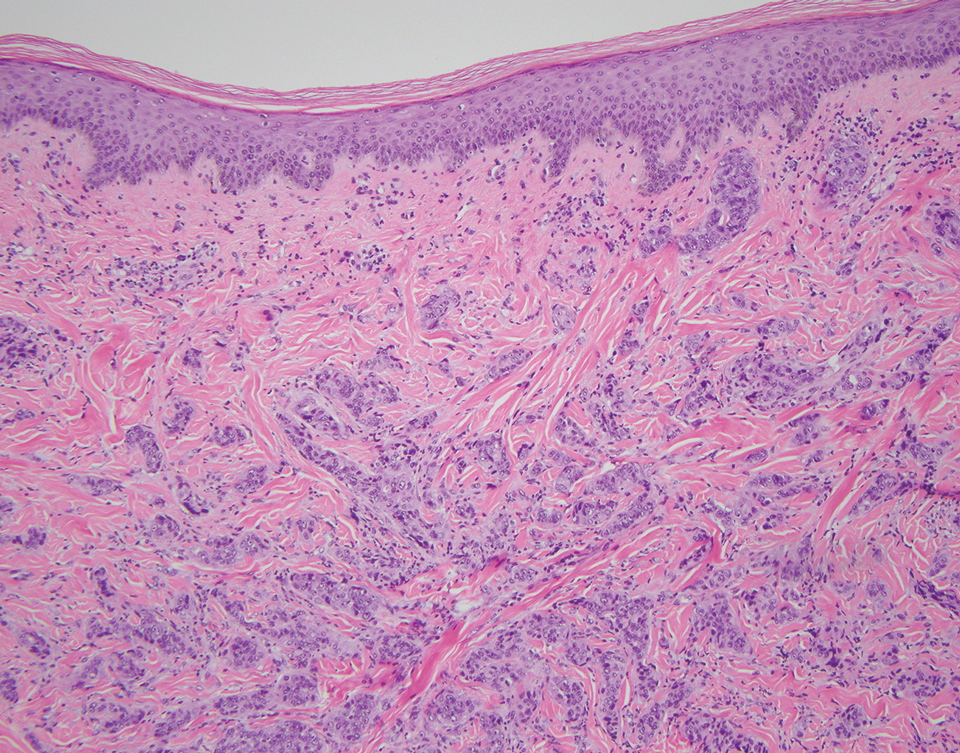

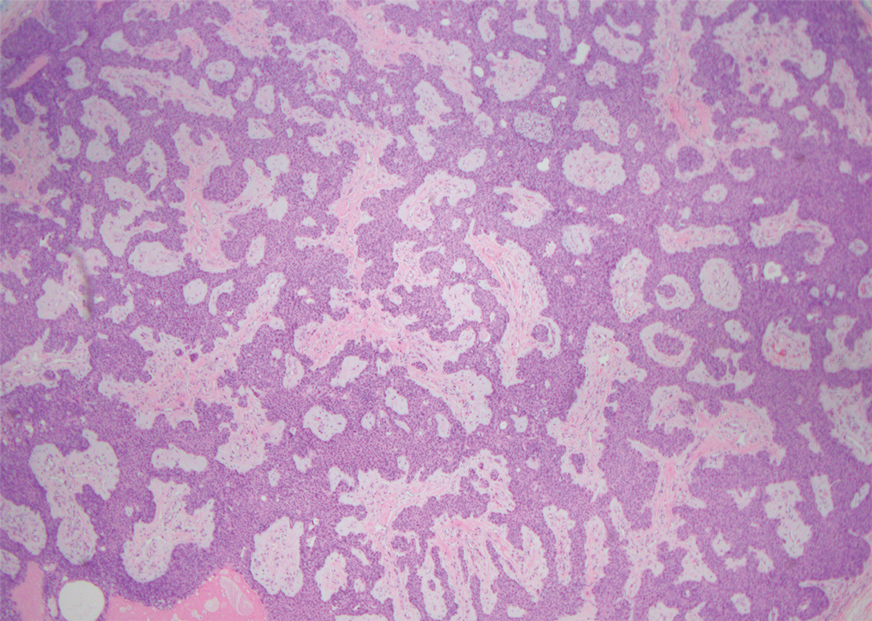

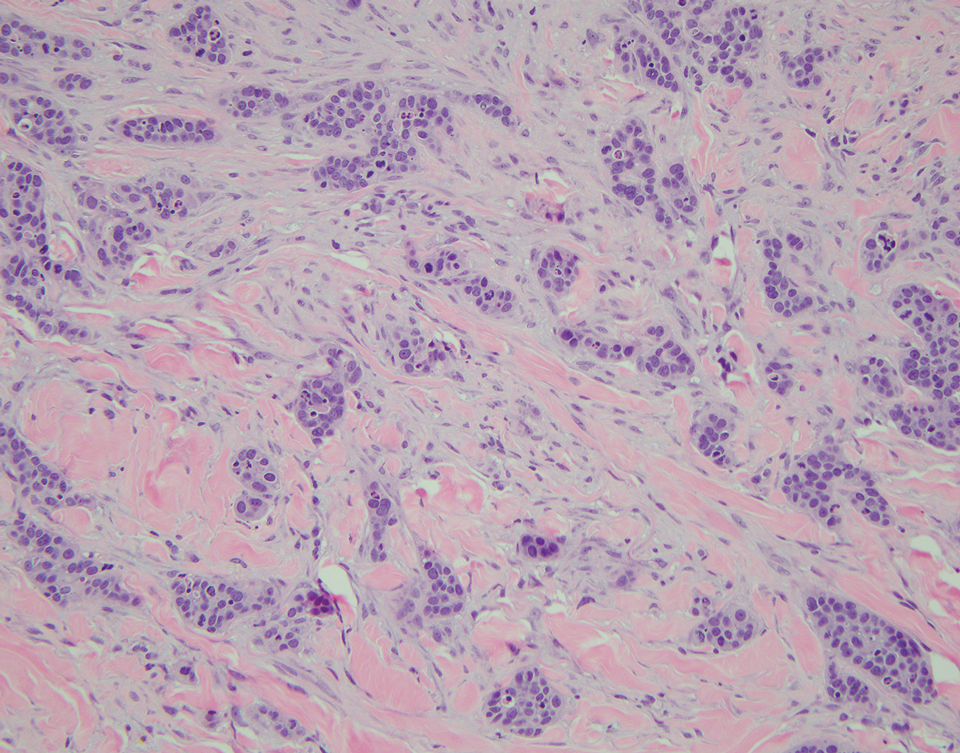

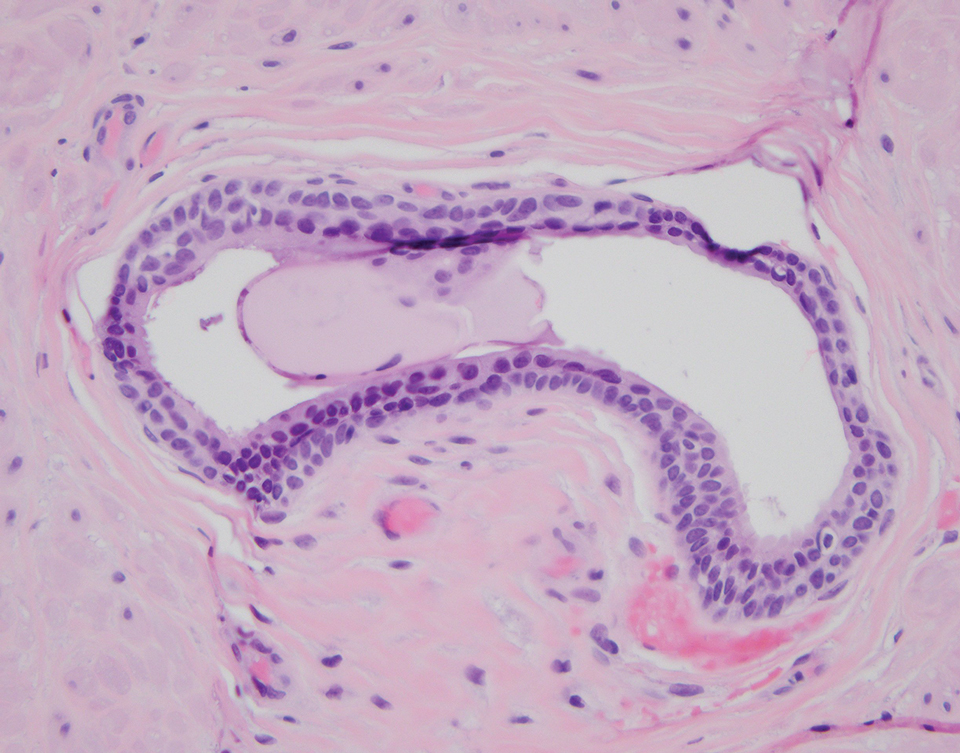

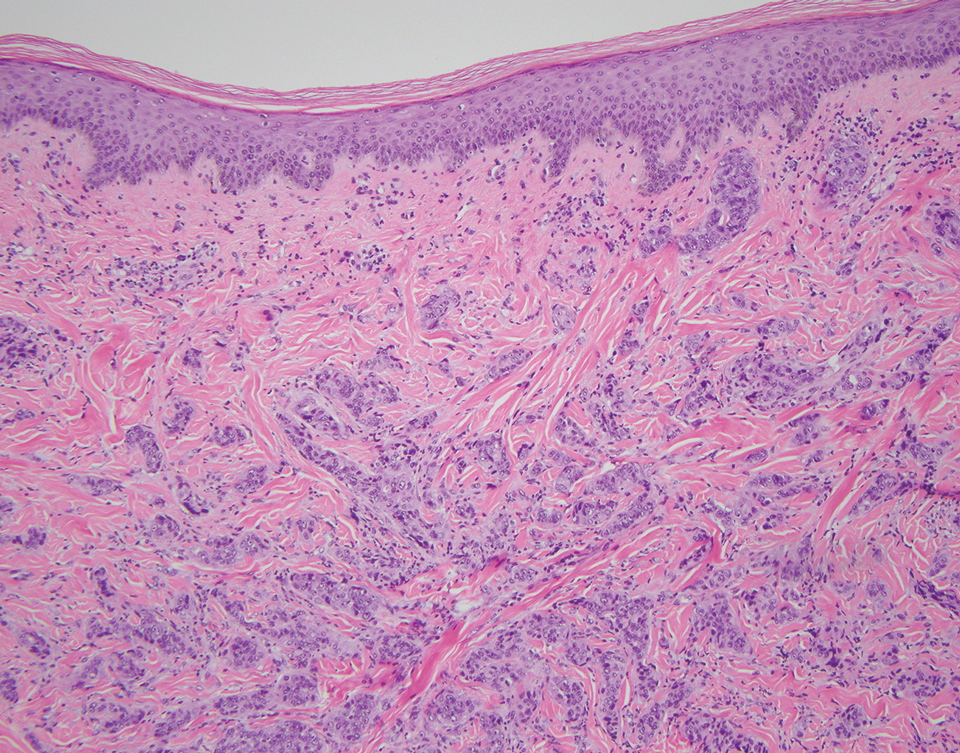

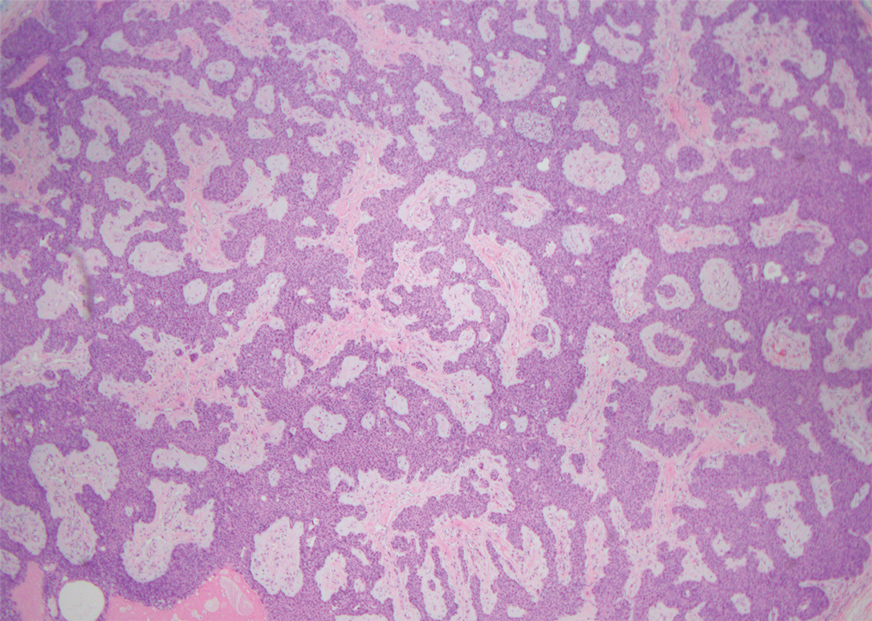

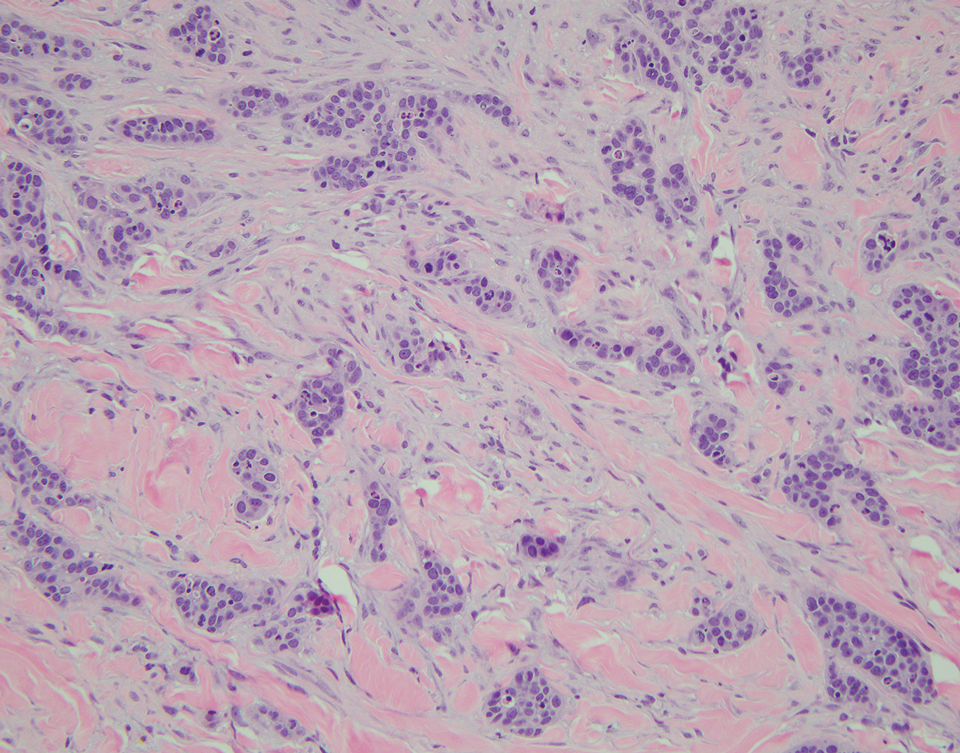

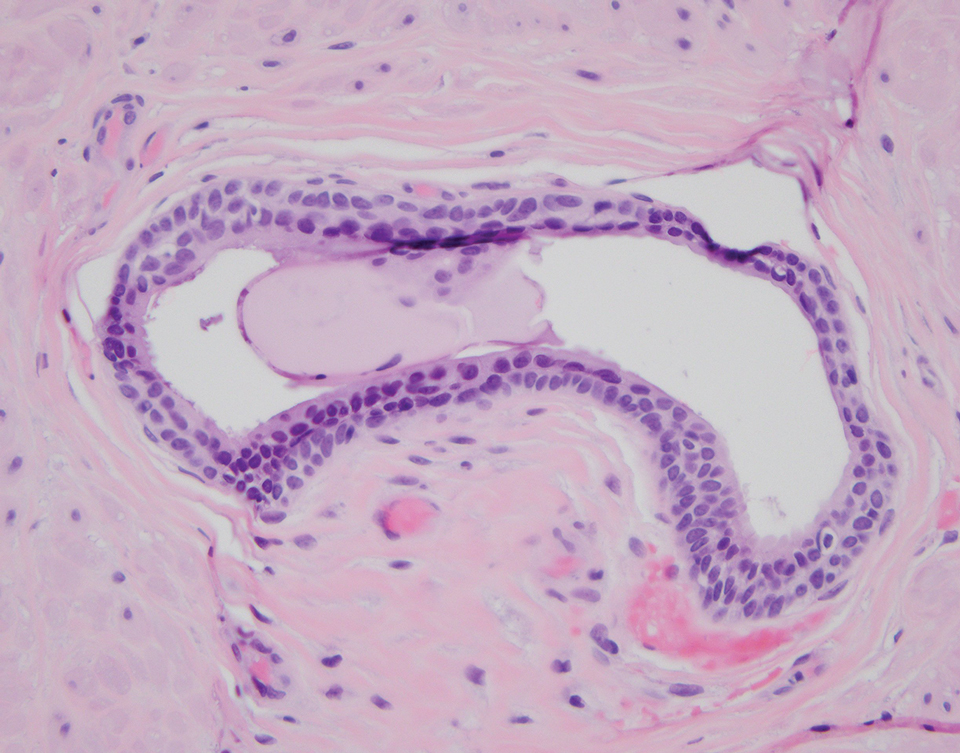

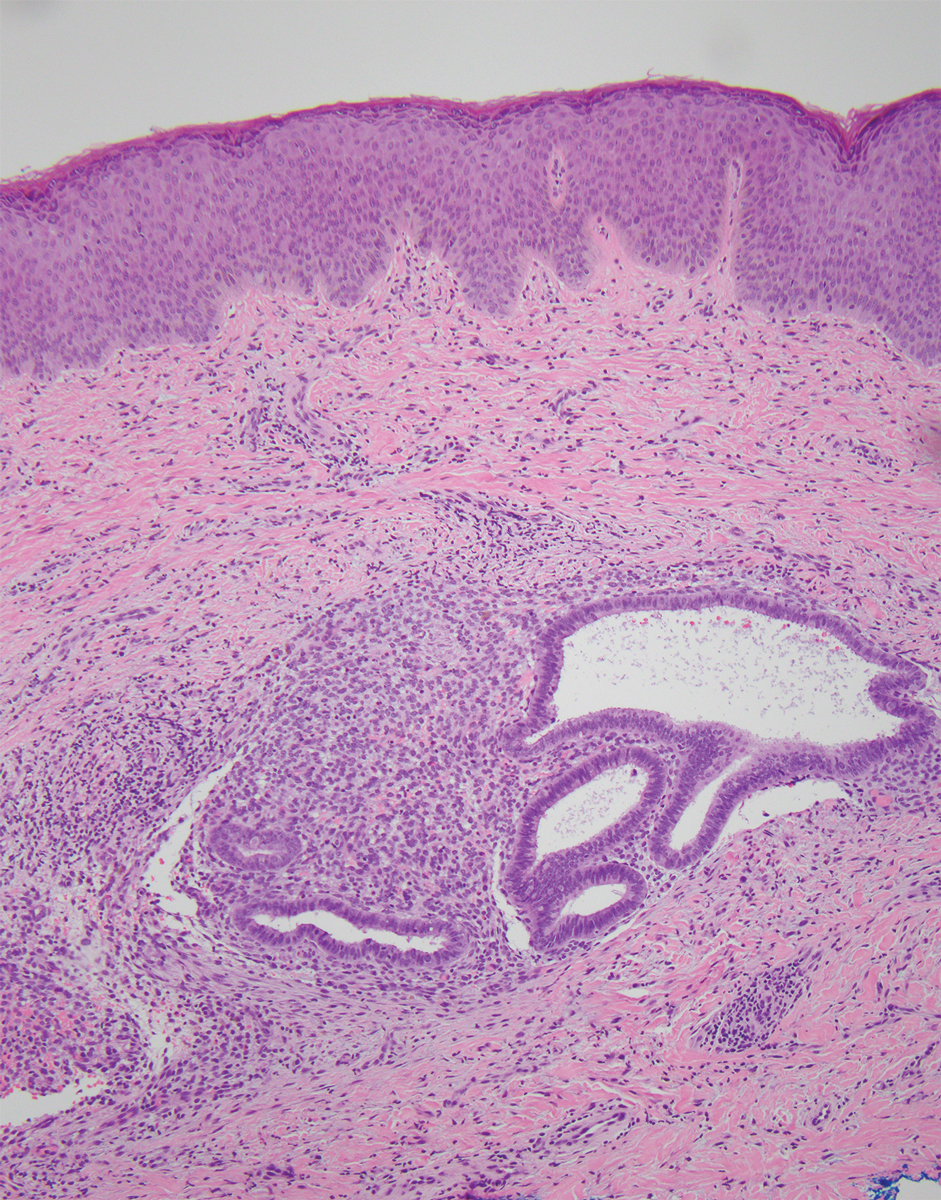

Physical examination at the current presentation revealed an 8-mm brown papule with an overlying blue-white veil (Figure 1). There were no other skin findings. Primary differential diagnoses included metastatic prostate cancer, nodular melanoma, and traumatized seborrheic keratosis. A shave biopsy of the lesion showed multiple glandular structures infiltrating the dermis lined by monomorphic epithelial cells with prominent eosinophilic nucleoli (Figures 2 and 3). Focal cribriform architecture of the glands was present as well as dermal hemorrhage and a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate (Figure 2A). Interestingly, in-transit vascular metastases were confirmed with the support of ERG, CD34, and CD31 immunohistochemical staining of the vessels.

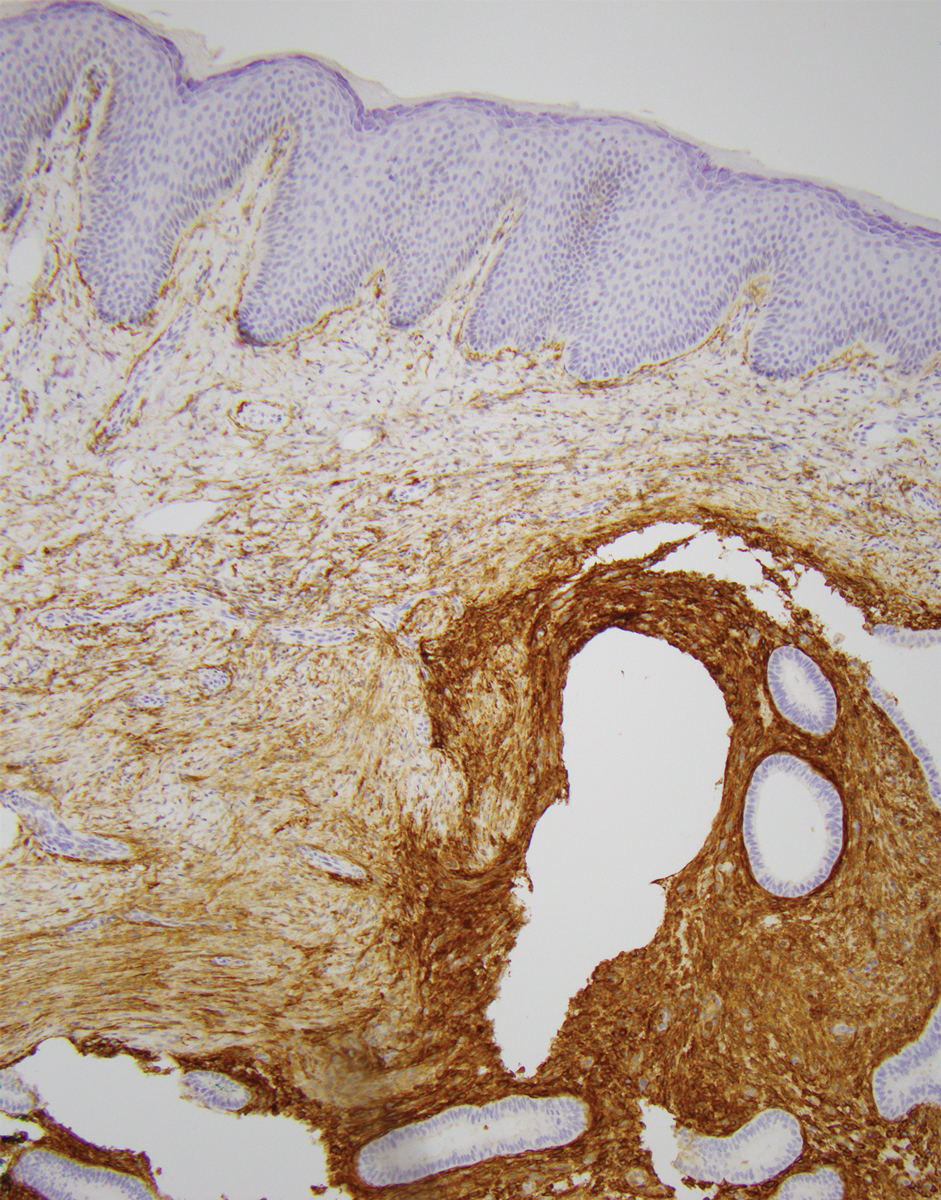

Immunohistochemical staining was positive for PSA (Figure 2B), NKX 3.1, and ERG in the invasive glandular structures, which also displayed patchy weak staining with AMACR. Staining was negative for prostein, cytokeratin (CK) 7, CK20, CK5/6, p63, p40, CDX2, and thyroid transcription factor 1. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma. Next-generation sequencing showed trans-membrane protease serine 2:v-ets erythroblastosis virus E26 oncogene homolog (TMPRSS2-ERG) fusion compatible with the positive ERG immunohistochemical staining. The patient and family declined any treatment due to his age, comorbidities, and rapid decline. He died 2 months after diagnosis of the skin metastasis.

Aside from nonmelanoma skin cancer, prostate cancer is the most common cancer and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths among men in the United States.1 It most commonly metastasizes to the bones, nonregional lymph nodes, liver, and thorax.2 Metastasis to the skin is very rare, with only a 0.36% incidence.3 When prostate cancer does metastasize to the skin, the prognosis is poor, with an estimated mean survival of 7 months after diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis.4 Our patient’s survival time was even shorter—only 2 months after diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis, likely the result of his late diagnosis.

Clinically, cutaneous metastasis of prostate cancer can manifest as a wide variety of lesions; in one report of 78 cases, 56 (72%) were hard nodules, 11 (14%) were single nodules, 5 (7%) were edema or lymphedema, and 5 (7%) were an unspecific rash.4 Diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis of prostate cancer can be challenging, as it often is mistaken for other skin conditions including herpes zoster, basal cell carcinoma, angiosarcoma, cellulitis, mammary Paget disease, telangiectasia, pyoderma, morphea, and trichoepithelioma.5 In our patient, the clinical appearance of the lesion resembled a nodular melanoma. Thus, in patients with a history of prostate cancer, it is important to keep cutaneous metastasis in the differential when examining the skin because of the prognostic implications. Cutaneous metastasis of prostate cancer often indicates a poor prognosis.

In a report of 78 patients, the most common sites of skin metastasis for prostate cancer were the inguinal area and penis (28% [22/78]), abdomen (23% [18/78]), head and neck (16% [12/78]), and chest (14% [11/78]); the extremities and back were less frequently involved (10% [8/78] and 9% [7/78], respectively).4 Generally, cutaneous metastasis of internal malignancies involves the deep dermis and the subcutaneous tissue. It is common for cutaneous metastases to show histologic features of the primary tumor, as we saw in our patient. In a case series with 45 histologic diagnoses of cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies, 75.5% (34/45) of cases showed morphologic features of the primary tumor.6 However, this is not always the case, and the histologic appearance may vary. Metastatic prostate cancer may manifest as sheets, nests, or cords and often may have nuclear pleomorphism with prominent nucleoli.7

Immunohistochemical staining can help make a definitive diagnosis and differentiate the source of the tumor. Prostate cancer metastases often will stain positive for NKX3.1, PSA, AMACR, ERG, PSMA, and prosaposin, with PSA being the most specific marker.7,8 In our patient, no prostate biopsy had been performed, thus the skin biopsy was the diagnostic tissue for the prostatic adenocarcinoma.

Next-generation sequencing showed a TMPRSS2- ERG fusion, which commonly is seen in prostate cancer.9 A search of Google Scholar using the terms next-generation sequencing, cutaneous metastasis, and prostate adenocarcinoma yielded 3 additional cases of cutaneous metastasis of prostate cancer in which next-generation sequencing was performed.10-12 One case showed mutations of the tumor protein 53 (TP53) and phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) genes; one showed just a TP53 mutation; and one showed inactivation of the breast cancer predisposition gene 2 (BRCA2) and amplification of MYC proto-oncogene, BHLH transcription factor (MYC) and fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1).10,11,12 While limited by a small number of reported cases, there does not appear to be a repeating mutation to suggest a genetic mechanism of skin metastasis.

The route of cutaneous metastasis of prostate cancer still is unclear, but hypothesized mechanisms include hematogenous or lymphatic spread, direct infiltration, or implantation from a surgical scar.11 When cutaneous involvement occurs in an area far from the primary tumor, it is thought to be the result of hematogenous spread, which would be consistent with our patient’s findings.13 Given the role of Batson venous plexus as a conduit from the prostate to the vertebral column for metastatic spread and considering the location of the lesion on our patient’s back, we hypothesized that the mechanism of metastasis to the skin was from vascular extension of the metastatic foci involving the vertebrae.

Our case highlights the importance of considering cutaneous involvement of prostatic adenocarcinoma in patients with new skin lesions, particularly in the setting of a known or suspected prostate malignancy. Skin metastasis can have a range of manifestations and provides prognostic information that can help determine the course of treatment.

- US Cancer Statistics Working Group. US cancer statistics data visualizations tool, based on 2022 submission data (1999-2020). US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute. November 2023. Accessed November 11, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/dataviz

- Gandaglia G, Abdollah F, Schiffmann J, et al. Distribution of metastatic sites in patients with prostate cancer: a population-based analysis. Prostate. 2014;74:210-216. doi:10.1002/pros.22742

- Mueller TJ, Wu H, Greenberg RE, et al. Cutaneous metastases from genitourinary malignancies. Urology. 2004;63:1021-1026. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2004.01.014

- Wang SQ, Mecca PS, Myskowski PL, et al. Scrotal and penile papules and plaques as the initial manifestation of a cutaneous metastasis of adenocarcinoma of the prostate: case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:681-684. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2007.00873.x

- Reddy S, Bang RH, Contreras ME. Telangiectatic cutaneous metastasis from carcinoma of the prostate. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:598-600. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07696.x

- Guanziroli E, Coggi A, Venegoni L, et al. Cutaneous metastases of internal malignancies: an experience from a single institution. Eur J Dermatol. 2017;27:609-614. doi:10.1684/ejd.2017.3142

- Onalaja-Underwood AA, Sokumbi O. Eruptive papules as a cutaneous manifestation of metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2023;45:828-830. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000002559

- Oesterling JE. Prostate specific antigen: a critical assessment of the most useful tumor marker for adenocarcinoma of the prostate. J Urol. 1991;145:907-923. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(17)38491-4

- Wang Z, Wang Y, Zhang J, et al. Significance of the TMPRSS2:ERG gene fusion in prostate cancer. Mol Med Rep. 2017;16:5450-5458. doi:10.3892/mmr.2017.7281

- Sharma H, Franklin M, Braunberger R, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from prostate cancer: a case report with literature review. Curr Probl Cancer Case Rep. 2022;7:100175. doi:10.1016/j.cpccr.2022.100175

- Dills A, Obi O, Bustos K, et al. Cutaneous manifestation of prostate adenocarcinoma: a rare presentation of a common disease. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2021;9:2324709621990769. doi:10.1177/2324709621990769

- Fadel CA, Kallab AM. Cutaneous scrotal metastasis secondary to primary prostate adenocarcinoma responding to immunotherapy. Ann Intern Med: Clinical Cases. 2022;1. doi:10.7326/aimcc.2022.0682

- Powell FC, Venencie PY, Winkelmann RK. Metastatic prostate carcinoma manifesting as penile nodules. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:1604- 1606. doi:10.1001/archderm.1984.01650480066022

To the Editor:

Cutaneous metastasis of prostate cancer is rare and portends a bleak prognosis. Diagnosis of the primary cancer can be challenging, as skin metastasis can mimic a variety of conditions. We report a case of metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma confirmed via biopsy of a new skin lesion.

A 97-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic for routine follow-up of psoriasis. During the visit, a family member mentioned a new bleeding lesion on the left shoulder. It was not known how long the lesion had been present. Four months prior, the patient had a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level of 582 ng/mL (reference range, 0-6.5 ng/mL), and computed tomography of the chest had shown innumerable pulmonary nodules in addition to lymphadenopathy of the left axilla, clavicle, and mediastinum. The imaging was ordered by the patient’s urologist as part of routine workup, as he had a history of obstructive renal failure and was being monitored for an indwelling catheter. Two months later, a bone scan ordered by the urologist due to high PSA levels showed extensive osteoblastic metastatic disease throughout the axial and proximal appendicular skeleton. The elevated PSA levels and findings of pulmonary and osteoblastic metastasis suggested a diagnosis of metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma, but no confirmatory biopsy was performed following the imaging because the patient’s family declined additional workup or intervention.

Physical examination at the current presentation revealed an 8-mm brown papule with an overlying blue-white veil (Figure 1). There were no other skin findings. Primary differential diagnoses included metastatic prostate cancer, nodular melanoma, and traumatized seborrheic keratosis. A shave biopsy of the lesion showed multiple glandular structures infiltrating the dermis lined by monomorphic epithelial cells with prominent eosinophilic nucleoli (Figures 2 and 3). Focal cribriform architecture of the glands was present as well as dermal hemorrhage and a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate (Figure 2A). Interestingly, in-transit vascular metastases were confirmed with the support of ERG, CD34, and CD31 immunohistochemical staining of the vessels.

Immunohistochemical staining was positive for PSA (Figure 2B), NKX 3.1, and ERG in the invasive glandular structures, which also displayed patchy weak staining with AMACR. Staining was negative for prostein, cytokeratin (CK) 7, CK20, CK5/6, p63, p40, CDX2, and thyroid transcription factor 1. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma. Next-generation sequencing showed trans-membrane protease serine 2:v-ets erythroblastosis virus E26 oncogene homolog (TMPRSS2-ERG) fusion compatible with the positive ERG immunohistochemical staining. The patient and family declined any treatment due to his age, comorbidities, and rapid decline. He died 2 months after diagnosis of the skin metastasis.

Aside from nonmelanoma skin cancer, prostate cancer is the most common cancer and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths among men in the United States.1 It most commonly metastasizes to the bones, nonregional lymph nodes, liver, and thorax.2 Metastasis to the skin is very rare, with only a 0.36% incidence.3 When prostate cancer does metastasize to the skin, the prognosis is poor, with an estimated mean survival of 7 months after diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis.4 Our patient’s survival time was even shorter—only 2 months after diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis, likely the result of his late diagnosis.

Clinically, cutaneous metastasis of prostate cancer can manifest as a wide variety of lesions; in one report of 78 cases, 56 (72%) were hard nodules, 11 (14%) were single nodules, 5 (7%) were edema or lymphedema, and 5 (7%) were an unspecific rash.4 Diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis of prostate cancer can be challenging, as it often is mistaken for other skin conditions including herpes zoster, basal cell carcinoma, angiosarcoma, cellulitis, mammary Paget disease, telangiectasia, pyoderma, morphea, and trichoepithelioma.5 In our patient, the clinical appearance of the lesion resembled a nodular melanoma. Thus, in patients with a history of prostate cancer, it is important to keep cutaneous metastasis in the differential when examining the skin because of the prognostic implications. Cutaneous metastasis of prostate cancer often indicates a poor prognosis.

In a report of 78 patients, the most common sites of skin metastasis for prostate cancer were the inguinal area and penis (28% [22/78]), abdomen (23% [18/78]), head and neck (16% [12/78]), and chest (14% [11/78]); the extremities and back were less frequently involved (10% [8/78] and 9% [7/78], respectively).4 Generally, cutaneous metastasis of internal malignancies involves the deep dermis and the subcutaneous tissue. It is common for cutaneous metastases to show histologic features of the primary tumor, as we saw in our patient. In a case series with 45 histologic diagnoses of cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies, 75.5% (34/45) of cases showed morphologic features of the primary tumor.6 However, this is not always the case, and the histologic appearance may vary. Metastatic prostate cancer may manifest as sheets, nests, or cords and often may have nuclear pleomorphism with prominent nucleoli.7

Immunohistochemical staining can help make a definitive diagnosis and differentiate the source of the tumor. Prostate cancer metastases often will stain positive for NKX3.1, PSA, AMACR, ERG, PSMA, and prosaposin, with PSA being the most specific marker.7,8 In our patient, no prostate biopsy had been performed, thus the skin biopsy was the diagnostic tissue for the prostatic adenocarcinoma.

Next-generation sequencing showed a TMPRSS2- ERG fusion, which commonly is seen in prostate cancer.9 A search of Google Scholar using the terms next-generation sequencing, cutaneous metastasis, and prostate adenocarcinoma yielded 3 additional cases of cutaneous metastasis of prostate cancer in which next-generation sequencing was performed.10-12 One case showed mutations of the tumor protein 53 (TP53) and phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) genes; one showed just a TP53 mutation; and one showed inactivation of the breast cancer predisposition gene 2 (BRCA2) and amplification of MYC proto-oncogene, BHLH transcription factor (MYC) and fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1).10,11,12 While limited by a small number of reported cases, there does not appear to be a repeating mutation to suggest a genetic mechanism of skin metastasis.

The route of cutaneous metastasis of prostate cancer still is unclear, but hypothesized mechanisms include hematogenous or lymphatic spread, direct infiltration, or implantation from a surgical scar.11 When cutaneous involvement occurs in an area far from the primary tumor, it is thought to be the result of hematogenous spread, which would be consistent with our patient’s findings.13 Given the role of Batson venous plexus as a conduit from the prostate to the vertebral column for metastatic spread and considering the location of the lesion on our patient’s back, we hypothesized that the mechanism of metastasis to the skin was from vascular extension of the metastatic foci involving the vertebrae.

Our case highlights the importance of considering cutaneous involvement of prostatic adenocarcinoma in patients with new skin lesions, particularly in the setting of a known or suspected prostate malignancy. Skin metastasis can have a range of manifestations and provides prognostic information that can help determine the course of treatment.

To the Editor:

Cutaneous metastasis of prostate cancer is rare and portends a bleak prognosis. Diagnosis of the primary cancer can be challenging, as skin metastasis can mimic a variety of conditions. We report a case of metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma confirmed via biopsy of a new skin lesion.

A 97-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic for routine follow-up of psoriasis. During the visit, a family member mentioned a new bleeding lesion on the left shoulder. It was not known how long the lesion had been present. Four months prior, the patient had a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level of 582 ng/mL (reference range, 0-6.5 ng/mL), and computed tomography of the chest had shown innumerable pulmonary nodules in addition to lymphadenopathy of the left axilla, clavicle, and mediastinum. The imaging was ordered by the patient’s urologist as part of routine workup, as he had a history of obstructive renal failure and was being monitored for an indwelling catheter. Two months later, a bone scan ordered by the urologist due to high PSA levels showed extensive osteoblastic metastatic disease throughout the axial and proximal appendicular skeleton. The elevated PSA levels and findings of pulmonary and osteoblastic metastasis suggested a diagnosis of metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma, but no confirmatory biopsy was performed following the imaging because the patient’s family declined additional workup or intervention.

Physical examination at the current presentation revealed an 8-mm brown papule with an overlying blue-white veil (Figure 1). There were no other skin findings. Primary differential diagnoses included metastatic prostate cancer, nodular melanoma, and traumatized seborrheic keratosis. A shave biopsy of the lesion showed multiple glandular structures infiltrating the dermis lined by monomorphic epithelial cells with prominent eosinophilic nucleoli (Figures 2 and 3). Focal cribriform architecture of the glands was present as well as dermal hemorrhage and a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate (Figure 2A). Interestingly, in-transit vascular metastases were confirmed with the support of ERG, CD34, and CD31 immunohistochemical staining of the vessels.

Immunohistochemical staining was positive for PSA (Figure 2B), NKX 3.1, and ERG in the invasive glandular structures, which also displayed patchy weak staining with AMACR. Staining was negative for prostein, cytokeratin (CK) 7, CK20, CK5/6, p63, p40, CDX2, and thyroid transcription factor 1. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma. Next-generation sequencing showed trans-membrane protease serine 2:v-ets erythroblastosis virus E26 oncogene homolog (TMPRSS2-ERG) fusion compatible with the positive ERG immunohistochemical staining. The patient and family declined any treatment due to his age, comorbidities, and rapid decline. He died 2 months after diagnosis of the skin metastasis.

Aside from nonmelanoma skin cancer, prostate cancer is the most common cancer and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths among men in the United States.1 It most commonly metastasizes to the bones, nonregional lymph nodes, liver, and thorax.2 Metastasis to the skin is very rare, with only a 0.36% incidence.3 When prostate cancer does metastasize to the skin, the prognosis is poor, with an estimated mean survival of 7 months after diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis.4 Our patient’s survival time was even shorter—only 2 months after diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis, likely the result of his late diagnosis.

Clinically, cutaneous metastasis of prostate cancer can manifest as a wide variety of lesions; in one report of 78 cases, 56 (72%) were hard nodules, 11 (14%) were single nodules, 5 (7%) were edema or lymphedema, and 5 (7%) were an unspecific rash.4 Diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis of prostate cancer can be challenging, as it often is mistaken for other skin conditions including herpes zoster, basal cell carcinoma, angiosarcoma, cellulitis, mammary Paget disease, telangiectasia, pyoderma, morphea, and trichoepithelioma.5 In our patient, the clinical appearance of the lesion resembled a nodular melanoma. Thus, in patients with a history of prostate cancer, it is important to keep cutaneous metastasis in the differential when examining the skin because of the prognostic implications. Cutaneous metastasis of prostate cancer often indicates a poor prognosis.

In a report of 78 patients, the most common sites of skin metastasis for prostate cancer were the inguinal area and penis (28% [22/78]), abdomen (23% [18/78]), head and neck (16% [12/78]), and chest (14% [11/78]); the extremities and back were less frequently involved (10% [8/78] and 9% [7/78], respectively).4 Generally, cutaneous metastasis of internal malignancies involves the deep dermis and the subcutaneous tissue. It is common for cutaneous metastases to show histologic features of the primary tumor, as we saw in our patient. In a case series with 45 histologic diagnoses of cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies, 75.5% (34/45) of cases showed morphologic features of the primary tumor.6 However, this is not always the case, and the histologic appearance may vary. Metastatic prostate cancer may manifest as sheets, nests, or cords and often may have nuclear pleomorphism with prominent nucleoli.7

Immunohistochemical staining can help make a definitive diagnosis and differentiate the source of the tumor. Prostate cancer metastases often will stain positive for NKX3.1, PSA, AMACR, ERG, PSMA, and prosaposin, with PSA being the most specific marker.7,8 In our patient, no prostate biopsy had been performed, thus the skin biopsy was the diagnostic tissue for the prostatic adenocarcinoma.

Next-generation sequencing showed a TMPRSS2- ERG fusion, which commonly is seen in prostate cancer.9 A search of Google Scholar using the terms next-generation sequencing, cutaneous metastasis, and prostate adenocarcinoma yielded 3 additional cases of cutaneous metastasis of prostate cancer in which next-generation sequencing was performed.10-12 One case showed mutations of the tumor protein 53 (TP53) and phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) genes; one showed just a TP53 mutation; and one showed inactivation of the breast cancer predisposition gene 2 (BRCA2) and amplification of MYC proto-oncogene, BHLH transcription factor (MYC) and fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1).10,11,12 While limited by a small number of reported cases, there does not appear to be a repeating mutation to suggest a genetic mechanism of skin metastasis.

The route of cutaneous metastasis of prostate cancer still is unclear, but hypothesized mechanisms include hematogenous or lymphatic spread, direct infiltration, or implantation from a surgical scar.11 When cutaneous involvement occurs in an area far from the primary tumor, it is thought to be the result of hematogenous spread, which would be consistent with our patient’s findings.13 Given the role of Batson venous plexus as a conduit from the prostate to the vertebral column for metastatic spread and considering the location of the lesion on our patient’s back, we hypothesized that the mechanism of metastasis to the skin was from vascular extension of the metastatic foci involving the vertebrae.

Our case highlights the importance of considering cutaneous involvement of prostatic adenocarcinoma in patients with new skin lesions, particularly in the setting of a known or suspected prostate malignancy. Skin metastasis can have a range of manifestations and provides prognostic information that can help determine the course of treatment.

- US Cancer Statistics Working Group. US cancer statistics data visualizations tool, based on 2022 submission data (1999-2020). US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute. November 2023. Accessed November 11, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/dataviz

- Gandaglia G, Abdollah F, Schiffmann J, et al. Distribution of metastatic sites in patients with prostate cancer: a population-based analysis. Prostate. 2014;74:210-216. doi:10.1002/pros.22742

- Mueller TJ, Wu H, Greenberg RE, et al. Cutaneous metastases from genitourinary malignancies. Urology. 2004;63:1021-1026. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2004.01.014

- Wang SQ, Mecca PS, Myskowski PL, et al. Scrotal and penile papules and plaques as the initial manifestation of a cutaneous metastasis of adenocarcinoma of the prostate: case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:681-684. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2007.00873.x

- Reddy S, Bang RH, Contreras ME. Telangiectatic cutaneous metastasis from carcinoma of the prostate. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:598-600. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07696.x

- Guanziroli E, Coggi A, Venegoni L, et al. Cutaneous metastases of internal malignancies: an experience from a single institution. Eur J Dermatol. 2017;27:609-614. doi:10.1684/ejd.2017.3142

- Onalaja-Underwood AA, Sokumbi O. Eruptive papules as a cutaneous manifestation of metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2023;45:828-830. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000002559

- Oesterling JE. Prostate specific antigen: a critical assessment of the most useful tumor marker for adenocarcinoma of the prostate. J Urol. 1991;145:907-923. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(17)38491-4

- Wang Z, Wang Y, Zhang J, et al. Significance of the TMPRSS2:ERG gene fusion in prostate cancer. Mol Med Rep. 2017;16:5450-5458. doi:10.3892/mmr.2017.7281

- Sharma H, Franklin M, Braunberger R, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from prostate cancer: a case report with literature review. Curr Probl Cancer Case Rep. 2022;7:100175. doi:10.1016/j.cpccr.2022.100175

- Dills A, Obi O, Bustos K, et al. Cutaneous manifestation of prostate adenocarcinoma: a rare presentation of a common disease. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2021;9:2324709621990769. doi:10.1177/2324709621990769

- Fadel CA, Kallab AM. Cutaneous scrotal metastasis secondary to primary prostate adenocarcinoma responding to immunotherapy. Ann Intern Med: Clinical Cases. 2022;1. doi:10.7326/aimcc.2022.0682

- Powell FC, Venencie PY, Winkelmann RK. Metastatic prostate carcinoma manifesting as penile nodules. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:1604- 1606. doi:10.1001/archderm.1984.01650480066022

- US Cancer Statistics Working Group. US cancer statistics data visualizations tool, based on 2022 submission data (1999-2020). US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute. November 2023. Accessed November 11, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/dataviz

- Gandaglia G, Abdollah F, Schiffmann J, et al. Distribution of metastatic sites in patients with prostate cancer: a population-based analysis. Prostate. 2014;74:210-216. doi:10.1002/pros.22742

- Mueller TJ, Wu H, Greenberg RE, et al. Cutaneous metastases from genitourinary malignancies. Urology. 2004;63:1021-1026. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2004.01.014

- Wang SQ, Mecca PS, Myskowski PL, et al. Scrotal and penile papules and plaques as the initial manifestation of a cutaneous metastasis of adenocarcinoma of the prostate: case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:681-684. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2007.00873.x

- Reddy S, Bang RH, Contreras ME. Telangiectatic cutaneous metastasis from carcinoma of the prostate. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:598-600. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07696.x

- Guanziroli E, Coggi A, Venegoni L, et al. Cutaneous metastases of internal malignancies: an experience from a single institution. Eur J Dermatol. 2017;27:609-614. doi:10.1684/ejd.2017.3142

- Onalaja-Underwood AA, Sokumbi O. Eruptive papules as a cutaneous manifestation of metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2023;45:828-830. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000002559

- Oesterling JE. Prostate specific antigen: a critical assessment of the most useful tumor marker for adenocarcinoma of the prostate. J Urol. 1991;145:907-923. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(17)38491-4

- Wang Z, Wang Y, Zhang J, et al. Significance of the TMPRSS2:ERG gene fusion in prostate cancer. Mol Med Rep. 2017;16:5450-5458. doi:10.3892/mmr.2017.7281

- Sharma H, Franklin M, Braunberger R, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from prostate cancer: a case report with literature review. Curr Probl Cancer Case Rep. 2022;7:100175. doi:10.1016/j.cpccr.2022.100175

- Dills A, Obi O, Bustos K, et al. Cutaneous manifestation of prostate adenocarcinoma: a rare presentation of a common disease. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2021;9:2324709621990769. doi:10.1177/2324709621990769

- Fadel CA, Kallab AM. Cutaneous scrotal metastasis secondary to primary prostate adenocarcinoma responding to immunotherapy. Ann Intern Med: Clinical Cases. 2022;1. doi:10.7326/aimcc.2022.0682

- Powell FC, Venencie PY, Winkelmann RK. Metastatic prostate carcinoma manifesting as penile nodules. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:1604- 1606. doi:10.1001/archderm.1984.01650480066022

Cutaneous Metastasis of an Undiagnosed Prostatic Adenocarcinoma

Cutaneous Metastasis of an Undiagnosed Prostatic Adenocarcinoma

PRACTICE POINTS

- Cutaneous metastasis of prostate cancer can have various manifestations and portends a poor prognosis.

- New skin lesions that develop in patients with a high clinical suspicion for prostate cancer warrant consideration of cutaneous metastasis.

Break the Itch-Scratch Cycle to Treat Prurigo Nodularis

Break the Itch-Scratch Cycle to Treat Prurigo Nodularis

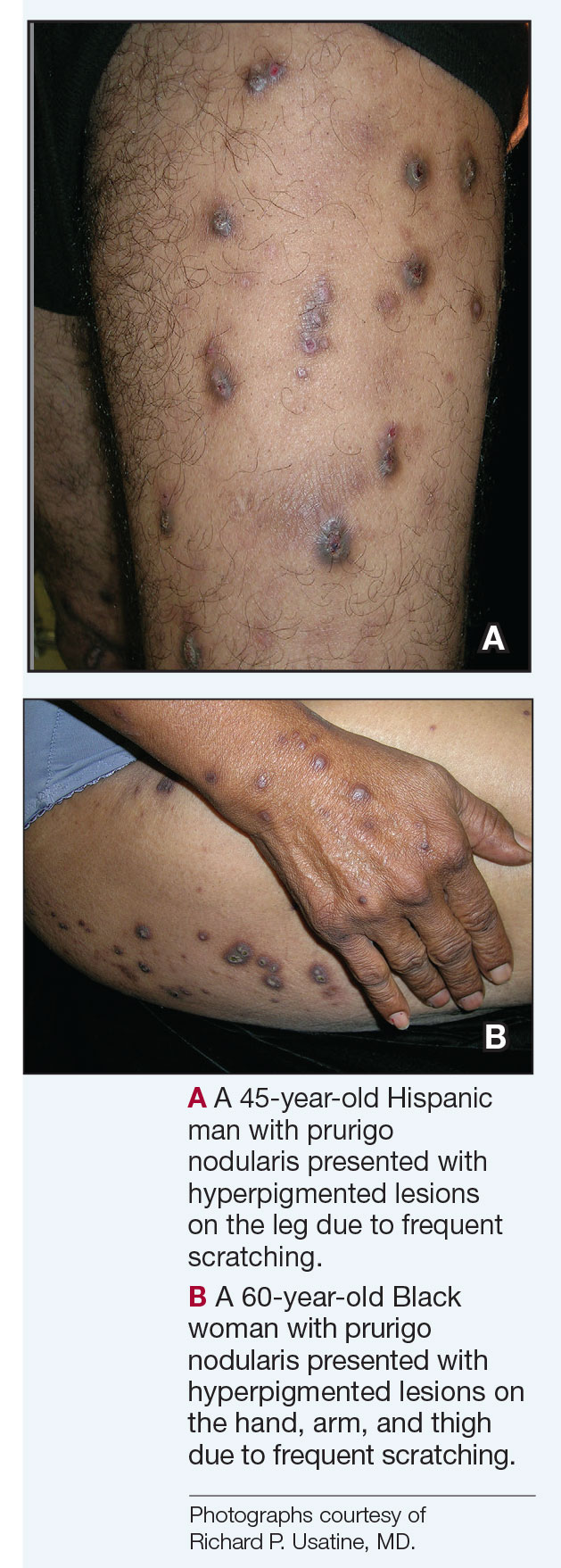

Prurigo nodularis (PN) is a chronic inflammatory skin condition characterized by firm hyperkeratotic nodules that develops when patients persistently scratch or rub intensely itchy areas of the skin. This potent itch-scratch cycle can be traced back to a dysfunctional interplay between cutaneous nerve fibers and the local immune environment.1-3 Pruritis lasting at least 6 weeks is a hallmark symptom of PN and can be accompanied by pain and/or a burning sensation.4 The lesions are symmetrically distributed in areas that are easy to scratch (eg, arms, legs, trunk), typically sparing the face, palms, and soles; however, facial lesions have been reported in pediatric patients with PN, who also are more likely to have back, hand, and foot involvement.5,6

PN can greatly affect patients’ quality of life, leading to increased rates of depression and anxiety.7-9 Patients with severe symptoms also report increased sleep disturbance, distraction from work, selfconsciousness leading to social isolation, and missed days of work/school.9 In one study, patients with PN reported missing at least 1 day of work, school, training, or learning; giving up a leisure activity or sport; or refusing an invitation to dinner or a party in the past 3 months due to the disease.10

Epidemiology

PN has a prevalence of 72 per 100,000 individuals in the United States, most commonly affecting adults aged 51 to 65 years and disproportionately affecting African American and female patients.11-13 Most patients with PN experience a 2-year delay in diagnosis after initial onset of symptoms. 10 Adults with PN have an increased likelihood of having other dermatologic conditions, including atopic dermatitis (AD) and psoriasis.11 Nearly two-thirds of pediatric patients with PN present with AD, and those with AD showed more resistance to first-line treatment options.5

Key Clinical Features

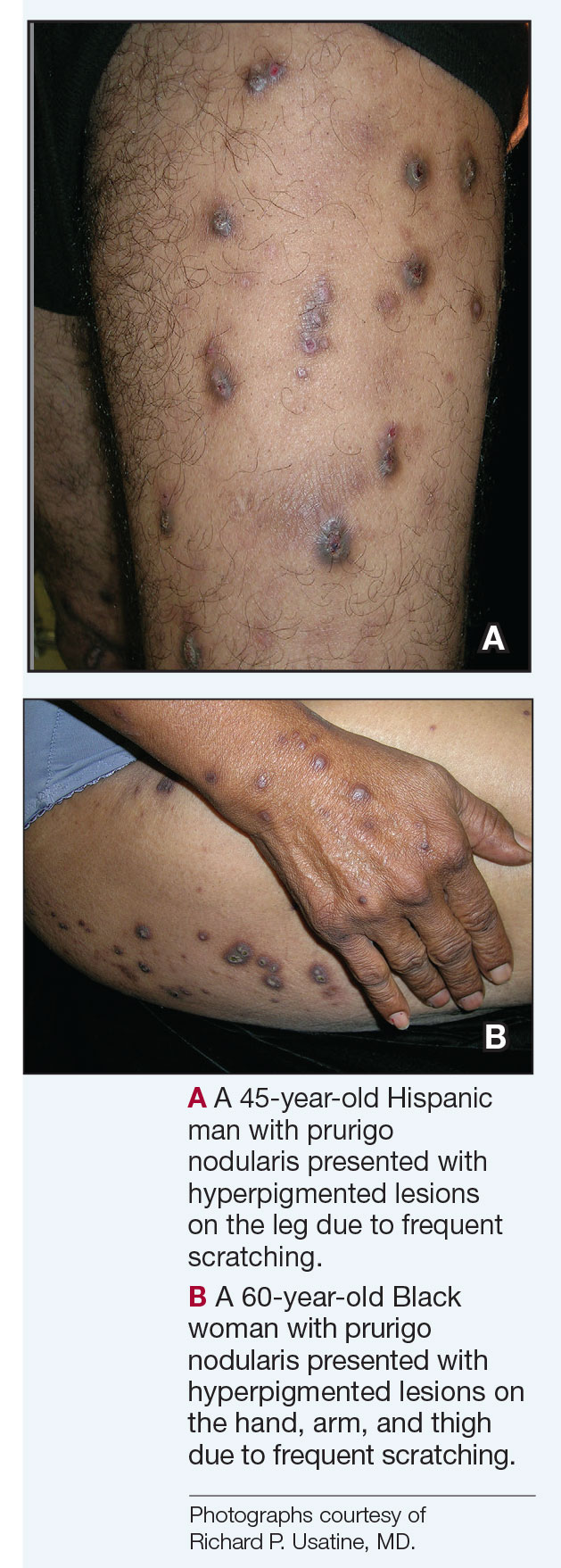

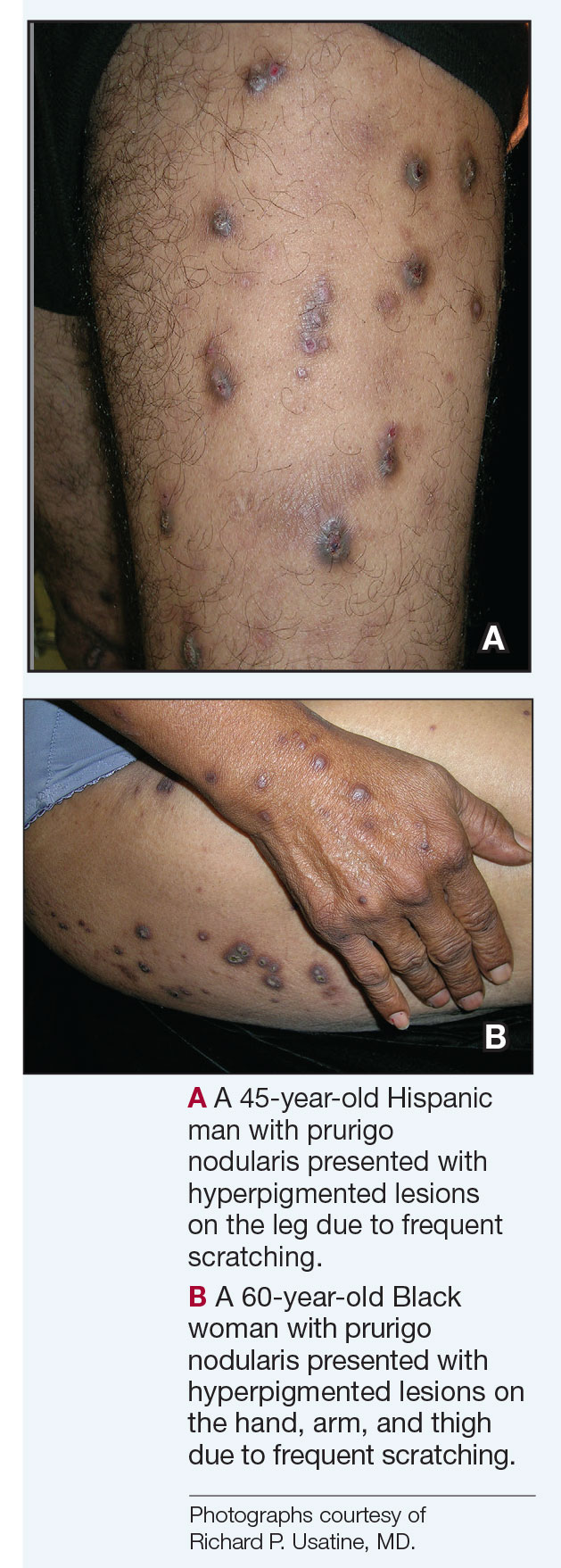

Compared to White patients, who typically present with lesions that appear erythematous or pink, patients with darker skin tones may present with hyperpigmented nodules that are larger and darker.12 The pruritic nodules often show signs of scratching or picking (eg, excoriations, lichenification, and angulated erosions).4

Worth Noting

Diagnosis of PN is made clinically, but skin biopsy may be helpful to rule out alternative diseases. Histologically, the hairy palm sign may be present in addition to other histologic features commonly associated with excessive scratching or rubbing of the skin.

Patients with PN have a high risk for HIV, which is not surprising considering HIV is a known systemic cause of generalized chronic pruritus. Other associations include type 2 diabetes mellitus and thyroid, kidney, and liver disease. 11,13 Workup for patients with PN should include a complete blood count with differential; liver and renal function testing; and testing for C-reactive protein, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and lactate dehydrogenase.4,14 Hemoglobin A1c and HIV testing as well as a hepatitis panel should be considered when appropriate. Because generalized pruritus may be a sign of malignancy, chest radiography and lymph node and abdominal ultrasonography should be performed in patients who have experienced itch for less than 1 year along with B symptoms (fever, night sweats, ≥ 10% weight loss over 6 months, fatigue).14 Frequent scratching can disrupt the skin barrier, contributing to the increased risk for skin infections.13 All patients with a suspected PN diagnosis also should undergo screening for depression and anxiety, as patients with PN are at an increased risk for these conditions.4

Treatment of PN starts with breaking the itch-scratch cycle by addressing the underlying cause of the pruritus. Therapies are focused on addressing the immunologic and neural components of the disease. Topical treatments include moderate to strong corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus or pimecrolimus), capsaicin, and antipruritic emollients. Systemic agents include phototherapy (narrow-band UVB or excimer laser), gabapentin, pregabalin, paroxetine, and amitriptyline to address the neural component of itch. Methotrexate or cyclosporine can be used to address the immunologic component of PN and diminish the itch. That said, methotrexate and cyclosporine often are inadequate to control pruritus. 10 Of note, sedating antihistamines are not effective in treating itch in PN but can be used as an adjuvant therapy for sleep disturbances in these patients.15

The only drugs currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to treat PN are the biologics dupilumab (targeting the IL-4 receptor) approved in 2022 and nemolizumab (targeting the IL-31 receptor) approved in 2024.16-18 The evidence that these injectable biologics work is heartening in a condition that has historically been very challenging to treat.16,18 It should be noted that the high cost of these 2 medications can restrict access to care for patients who are uninsured or underinsured.

Resolution of a prurigo nodule may result in a hyperpigmented macule taking months to years to fade.

Health Disparity Highlight

Patients with PN have a considerable comorbidity burden, negative impact on quality of life, and increased health care utilization rates.12 PN is 3.4 times more common in Black patients than White patients.13 Black patients with PN have increased mortality, higher health care utilization rates, and increased systemic inflammation compared to White patients.12,19,20

- Cevikbas F, Wang X, Akiyama T, et al. A sensory neuron– expressed IL-31 receptor mediates T helper cell–dependent itch: involvement of TRPV1 and TRPA1. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:448-460.

- Lou H, Lu J, Choi EB, et al. Expression of IL-22 in the skin causes Th2-biased immunity, epidermal barrier dysfunction, and pruritus via stimulating epithelial Th2 cytokines and the GRP pathway. J Immunol. 2017;198:2543-2555.

- Sutaria N, Adawi W, Goldberg R, et al. Itch: pathogenesis and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:17-34.

- Elmariah S, Kim B, Berger T, et al. Practical approaches for diagnosis and management of prurigo nodularis: United States expert panel consensus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:747-760.

- Kyvayko R, Fachler-Sharp T, Greenberger S, et al. Characterization of paediatric prurigo nodularis: a multicentre retrospective, observational study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2024;104:adv15771.

- Aggarwal P, Choi J, Sutaria N, et al. Clinical characteristics and disease burden in prurigo nodularis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2021;46:1277-1284.

- Whang KA, Le TK, Khanna R, et al. Health-related quality of life and economic burden of prurigo nodularis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:573-580.

- Jørgensen KM, Egeberg A, Gislason GH, et al. Anxiety, depression and suicide in patients with prurigo nodularis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:E106-E107.

- Rodriguez D, Kwatra SG, Dias-Barbosa C, et al. Patient perspectives on living with severe prurigo nodularis. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159:1205-1212.

- Misery L, Patras de Campaigno C, Taieb C, et al. Impact of chronic prurigo nodularis on daily life and stigmatization. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023;37:E908-E909.

- Huang AH, Canner JK, Khanna R, et al. Real-world prevalence of prurigo nodularis and burden of associated diseases. J Invest Dermatol. 2020;140:480-483.e4.

- Sutaria N, Adawi W, Brown I, et al. Racial disparities in mortality among patients with prurigo nodularis: a multicenter cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;82:487- 490.

- Boozalis E, Tang O, Patel S, et al. Ethnic differences and comorbidities of 909 prurigo nodularis patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:714-719.e3.

- Müller S, Zeidler C, Ständer S. Chronic prurigo including prurigo nodularis: new insights and treatments. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2024;25:15-33.

- Williams KA, Roh YS, Brown I, et al. Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and pharmacological treatment of prurigo nodularis. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2021;14:67-77.

- Kwatra SG, Yosipovitch G, Legat FJ, et al. Phase 3 trial of nemolizumab in patients with prurigo nodularis. N Engl J Med. 2023;389:1579-1589.

- Beck KM, Yang EJ, Sekhon S, et al. Dupilumab treatment for generalized prurigo nodularis. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:118-120.

- Yosipovitch G, Mollanazar N, Ständer S, et al. Dupilumab in patients with prurigo nodularis: two randomized, double- blind, placebo- controlled phase 3 trials. Nat Med. 2023;29:1180-1190.

- Wongvibulsin S, Sutaria N, Williams KA, et al. A nationwide study of prurigo nodularis: disease burden and healthcare utilization in the United States. J Invest Dermatol. 2021;141:2530-2533.e1.

- Sutaria N, Alphonse MP, Marani M, et al. Cluster analysis of circulating plasma biomarkers in prurigo nodularis reveals a distinct systemic inflammatory signature in African Americans. J Invest Dermatol. 2022;142:1300-1308.e3.

Prurigo nodularis (PN) is a chronic inflammatory skin condition characterized by firm hyperkeratotic nodules that develops when patients persistently scratch or rub intensely itchy areas of the skin. This potent itch-scratch cycle can be traced back to a dysfunctional interplay between cutaneous nerve fibers and the local immune environment.1-3 Pruritis lasting at least 6 weeks is a hallmark symptom of PN and can be accompanied by pain and/or a burning sensation.4 The lesions are symmetrically distributed in areas that are easy to scratch (eg, arms, legs, trunk), typically sparing the face, palms, and soles; however, facial lesions have been reported in pediatric patients with PN, who also are more likely to have back, hand, and foot involvement.5,6

PN can greatly affect patients’ quality of life, leading to increased rates of depression and anxiety.7-9 Patients with severe symptoms also report increased sleep disturbance, distraction from work, selfconsciousness leading to social isolation, and missed days of work/school.9 In one study, patients with PN reported missing at least 1 day of work, school, training, or learning; giving up a leisure activity or sport; or refusing an invitation to dinner or a party in the past 3 months due to the disease.10

Epidemiology

PN has a prevalence of 72 per 100,000 individuals in the United States, most commonly affecting adults aged 51 to 65 years and disproportionately affecting African American and female patients.11-13 Most patients with PN experience a 2-year delay in diagnosis after initial onset of symptoms. 10 Adults with PN have an increased likelihood of having other dermatologic conditions, including atopic dermatitis (AD) and psoriasis.11 Nearly two-thirds of pediatric patients with PN present with AD, and those with AD showed more resistance to first-line treatment options.5

Key Clinical Features

Compared to White patients, who typically present with lesions that appear erythematous or pink, patients with darker skin tones may present with hyperpigmented nodules that are larger and darker.12 The pruritic nodules often show signs of scratching or picking (eg, excoriations, lichenification, and angulated erosions).4

Worth Noting

Diagnosis of PN is made clinically, but skin biopsy may be helpful to rule out alternative diseases. Histologically, the hairy palm sign may be present in addition to other histologic features commonly associated with excessive scratching or rubbing of the skin.

Patients with PN have a high risk for HIV, which is not surprising considering HIV is a known systemic cause of generalized chronic pruritus. Other associations include type 2 diabetes mellitus and thyroid, kidney, and liver disease. 11,13 Workup for patients with PN should include a complete blood count with differential; liver and renal function testing; and testing for C-reactive protein, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and lactate dehydrogenase.4,14 Hemoglobin A1c and HIV testing as well as a hepatitis panel should be considered when appropriate. Because generalized pruritus may be a sign of malignancy, chest radiography and lymph node and abdominal ultrasonography should be performed in patients who have experienced itch for less than 1 year along with B symptoms (fever, night sweats, ≥ 10% weight loss over 6 months, fatigue).14 Frequent scratching can disrupt the skin barrier, contributing to the increased risk for skin infections.13 All patients with a suspected PN diagnosis also should undergo screening for depression and anxiety, as patients with PN are at an increased risk for these conditions.4

Treatment of PN starts with breaking the itch-scratch cycle by addressing the underlying cause of the pruritus. Therapies are focused on addressing the immunologic and neural components of the disease. Topical treatments include moderate to strong corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus or pimecrolimus), capsaicin, and antipruritic emollients. Systemic agents include phototherapy (narrow-band UVB or excimer laser), gabapentin, pregabalin, paroxetine, and amitriptyline to address the neural component of itch. Methotrexate or cyclosporine can be used to address the immunologic component of PN and diminish the itch. That said, methotrexate and cyclosporine often are inadequate to control pruritus. 10 Of note, sedating antihistamines are not effective in treating itch in PN but can be used as an adjuvant therapy for sleep disturbances in these patients.15

The only drugs currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to treat PN are the biologics dupilumab (targeting the IL-4 receptor) approved in 2022 and nemolizumab (targeting the IL-31 receptor) approved in 2024.16-18 The evidence that these injectable biologics work is heartening in a condition that has historically been very challenging to treat.16,18 It should be noted that the high cost of these 2 medications can restrict access to care for patients who are uninsured or underinsured.

Resolution of a prurigo nodule may result in a hyperpigmented macule taking months to years to fade.

Health Disparity Highlight

Patients with PN have a considerable comorbidity burden, negative impact on quality of life, and increased health care utilization rates.12 PN is 3.4 times more common in Black patients than White patients.13 Black patients with PN have increased mortality, higher health care utilization rates, and increased systemic inflammation compared to White patients.12,19,20

Prurigo nodularis (PN) is a chronic inflammatory skin condition characterized by firm hyperkeratotic nodules that develops when patients persistently scratch or rub intensely itchy areas of the skin. This potent itch-scratch cycle can be traced back to a dysfunctional interplay between cutaneous nerve fibers and the local immune environment.1-3 Pruritis lasting at least 6 weeks is a hallmark symptom of PN and can be accompanied by pain and/or a burning sensation.4 The lesions are symmetrically distributed in areas that are easy to scratch (eg, arms, legs, trunk), typically sparing the face, palms, and soles; however, facial lesions have been reported in pediatric patients with PN, who also are more likely to have back, hand, and foot involvement.5,6

PN can greatly affect patients’ quality of life, leading to increased rates of depression and anxiety.7-9 Patients with severe symptoms also report increased sleep disturbance, distraction from work, selfconsciousness leading to social isolation, and missed days of work/school.9 In one study, patients with PN reported missing at least 1 day of work, school, training, or learning; giving up a leisure activity or sport; or refusing an invitation to dinner or a party in the past 3 months due to the disease.10

Epidemiology

PN has a prevalence of 72 per 100,000 individuals in the United States, most commonly affecting adults aged 51 to 65 years and disproportionately affecting African American and female patients.11-13 Most patients with PN experience a 2-year delay in diagnosis after initial onset of symptoms. 10 Adults with PN have an increased likelihood of having other dermatologic conditions, including atopic dermatitis (AD) and psoriasis.11 Nearly two-thirds of pediatric patients with PN present with AD, and those with AD showed more resistance to first-line treatment options.5

Key Clinical Features

Compared to White patients, who typically present with lesions that appear erythematous or pink, patients with darker skin tones may present with hyperpigmented nodules that are larger and darker.12 The pruritic nodules often show signs of scratching or picking (eg, excoriations, lichenification, and angulated erosions).4

Worth Noting

Diagnosis of PN is made clinically, but skin biopsy may be helpful to rule out alternative diseases. Histologically, the hairy palm sign may be present in addition to other histologic features commonly associated with excessive scratching or rubbing of the skin.

Patients with PN have a high risk for HIV, which is not surprising considering HIV is a known systemic cause of generalized chronic pruritus. Other associations include type 2 diabetes mellitus and thyroid, kidney, and liver disease. 11,13 Workup for patients with PN should include a complete blood count with differential; liver and renal function testing; and testing for C-reactive protein, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and lactate dehydrogenase.4,14 Hemoglobin A1c and HIV testing as well as a hepatitis panel should be considered when appropriate. Because generalized pruritus may be a sign of malignancy, chest radiography and lymph node and abdominal ultrasonography should be performed in patients who have experienced itch for less than 1 year along with B symptoms (fever, night sweats, ≥ 10% weight loss over 6 months, fatigue).14 Frequent scratching can disrupt the skin barrier, contributing to the increased risk for skin infections.13 All patients with a suspected PN diagnosis also should undergo screening for depression and anxiety, as patients with PN are at an increased risk for these conditions.4

Treatment of PN starts with breaking the itch-scratch cycle by addressing the underlying cause of the pruritus. Therapies are focused on addressing the immunologic and neural components of the disease. Topical treatments include moderate to strong corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus or pimecrolimus), capsaicin, and antipruritic emollients. Systemic agents include phototherapy (narrow-band UVB or excimer laser), gabapentin, pregabalin, paroxetine, and amitriptyline to address the neural component of itch. Methotrexate or cyclosporine can be used to address the immunologic component of PN and diminish the itch. That said, methotrexate and cyclosporine often are inadequate to control pruritus. 10 Of note, sedating antihistamines are not effective in treating itch in PN but can be used as an adjuvant therapy for sleep disturbances in these patients.15

The only drugs currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to treat PN are the biologics dupilumab (targeting the IL-4 receptor) approved in 2022 and nemolizumab (targeting the IL-31 receptor) approved in 2024.16-18 The evidence that these injectable biologics work is heartening in a condition that has historically been very challenging to treat.16,18 It should be noted that the high cost of these 2 medications can restrict access to care for patients who are uninsured or underinsured.

Resolution of a prurigo nodule may result in a hyperpigmented macule taking months to years to fade.

Health Disparity Highlight

Patients with PN have a considerable comorbidity burden, negative impact on quality of life, and increased health care utilization rates.12 PN is 3.4 times more common in Black patients than White patients.13 Black patients with PN have increased mortality, higher health care utilization rates, and increased systemic inflammation compared to White patients.12,19,20

- Cevikbas F, Wang X, Akiyama T, et al. A sensory neuron– expressed IL-31 receptor mediates T helper cell–dependent itch: involvement of TRPV1 and TRPA1. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:448-460.

- Lou H, Lu J, Choi EB, et al. Expression of IL-22 in the skin causes Th2-biased immunity, epidermal barrier dysfunction, and pruritus via stimulating epithelial Th2 cytokines and the GRP pathway. J Immunol. 2017;198:2543-2555.

- Sutaria N, Adawi W, Goldberg R, et al. Itch: pathogenesis and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:17-34.

- Elmariah S, Kim B, Berger T, et al. Practical approaches for diagnosis and management of prurigo nodularis: United States expert panel consensus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:747-760.

- Kyvayko R, Fachler-Sharp T, Greenberger S, et al. Characterization of paediatric prurigo nodularis: a multicentre retrospective, observational study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2024;104:adv15771.

- Aggarwal P, Choi J, Sutaria N, et al. Clinical characteristics and disease burden in prurigo nodularis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2021;46:1277-1284.

- Whang KA, Le TK, Khanna R, et al. Health-related quality of life and economic burden of prurigo nodularis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:573-580.

- Jørgensen KM, Egeberg A, Gislason GH, et al. Anxiety, depression and suicide in patients with prurigo nodularis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:E106-E107.

- Rodriguez D, Kwatra SG, Dias-Barbosa C, et al. Patient perspectives on living with severe prurigo nodularis. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159:1205-1212.

- Misery L, Patras de Campaigno C, Taieb C, et al. Impact of chronic prurigo nodularis on daily life and stigmatization. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023;37:E908-E909.

- Huang AH, Canner JK, Khanna R, et al. Real-world prevalence of prurigo nodularis and burden of associated diseases. J Invest Dermatol. 2020;140:480-483.e4.

- Sutaria N, Adawi W, Brown I, et al. Racial disparities in mortality among patients with prurigo nodularis: a multicenter cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;82:487- 490.

- Boozalis E, Tang O, Patel S, et al. Ethnic differences and comorbidities of 909 prurigo nodularis patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:714-719.e3.

- Müller S, Zeidler C, Ständer S. Chronic prurigo including prurigo nodularis: new insights and treatments. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2024;25:15-33.

- Williams KA, Roh YS, Brown I, et al. Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and pharmacological treatment of prurigo nodularis. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2021;14:67-77.

- Kwatra SG, Yosipovitch G, Legat FJ, et al. Phase 3 trial of nemolizumab in patients with prurigo nodularis. N Engl J Med. 2023;389:1579-1589.

- Beck KM, Yang EJ, Sekhon S, et al. Dupilumab treatment for generalized prurigo nodularis. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:118-120.

- Yosipovitch G, Mollanazar N, Ständer S, et al. Dupilumab in patients with prurigo nodularis: two randomized, double- blind, placebo- controlled phase 3 trials. Nat Med. 2023;29:1180-1190.

- Wongvibulsin S, Sutaria N, Williams KA, et al. A nationwide study of prurigo nodularis: disease burden and healthcare utilization in the United States. J Invest Dermatol. 2021;141:2530-2533.e1.

- Sutaria N, Alphonse MP, Marani M, et al. Cluster analysis of circulating plasma biomarkers in prurigo nodularis reveals a distinct systemic inflammatory signature in African Americans. J Invest Dermatol. 2022;142:1300-1308.e3.

- Cevikbas F, Wang X, Akiyama T, et al. A sensory neuron– expressed IL-31 receptor mediates T helper cell–dependent itch: involvement of TRPV1 and TRPA1. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:448-460.

- Lou H, Lu J, Choi EB, et al. Expression of IL-22 in the skin causes Th2-biased immunity, epidermal barrier dysfunction, and pruritus via stimulating epithelial Th2 cytokines and the GRP pathway. J Immunol. 2017;198:2543-2555.

- Sutaria N, Adawi W, Goldberg R, et al. Itch: pathogenesis and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:17-34.

- Elmariah S, Kim B, Berger T, et al. Practical approaches for diagnosis and management of prurigo nodularis: United States expert panel consensus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:747-760.

- Kyvayko R, Fachler-Sharp T, Greenberger S, et al. Characterization of paediatric prurigo nodularis: a multicentre retrospective, observational study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2024;104:adv15771.

- Aggarwal P, Choi J, Sutaria N, et al. Clinical characteristics and disease burden in prurigo nodularis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2021;46:1277-1284.

- Whang KA, Le TK, Khanna R, et al. Health-related quality of life and economic burden of prurigo nodularis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:573-580.

- Jørgensen KM, Egeberg A, Gislason GH, et al. Anxiety, depression and suicide in patients with prurigo nodularis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:E106-E107.

- Rodriguez D, Kwatra SG, Dias-Barbosa C, et al. Patient perspectives on living with severe prurigo nodularis. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159:1205-1212.

- Misery L, Patras de Campaigno C, Taieb C, et al. Impact of chronic prurigo nodularis on daily life and stigmatization. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023;37:E908-E909.

- Huang AH, Canner JK, Khanna R, et al. Real-world prevalence of prurigo nodularis and burden of associated diseases. J Invest Dermatol. 2020;140:480-483.e4.

- Sutaria N, Adawi W, Brown I, et al. Racial disparities in mortality among patients with prurigo nodularis: a multicenter cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;82:487- 490.

- Boozalis E, Tang O, Patel S, et al. Ethnic differences and comorbidities of 909 prurigo nodularis patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:714-719.e3.

- Müller S, Zeidler C, Ständer S. Chronic prurigo including prurigo nodularis: new insights and treatments. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2024;25:15-33.

- Williams KA, Roh YS, Brown I, et al. Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and pharmacological treatment of prurigo nodularis. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2021;14:67-77.

- Kwatra SG, Yosipovitch G, Legat FJ, et al. Phase 3 trial of nemolizumab in patients with prurigo nodularis. N Engl J Med. 2023;389:1579-1589.

- Beck KM, Yang EJ, Sekhon S, et al. Dupilumab treatment for generalized prurigo nodularis. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:118-120.

- Yosipovitch G, Mollanazar N, Ständer S, et al. Dupilumab in patients with prurigo nodularis: two randomized, double- blind, placebo- controlled phase 3 trials. Nat Med. 2023;29:1180-1190.

- Wongvibulsin S, Sutaria N, Williams KA, et al. A nationwide study of prurigo nodularis: disease burden and healthcare utilization in the United States. J Invest Dermatol. 2021;141:2530-2533.e1.

- Sutaria N, Alphonse MP, Marani M, et al. Cluster analysis of circulating plasma biomarkers in prurigo nodularis reveals a distinct systemic inflammatory signature in African Americans. J Invest Dermatol. 2022;142:1300-1308.e3.

Break the Itch-Scratch Cycle to Treat Prurigo Nodularis

Break the Itch-Scratch Cycle to Treat Prurigo Nodularis

Improving Interprofessional Neurology Training Using Tele-Education

Improving Interprofessional Neurology Training Using Tele-Education

Neurologic disorders are major causes of death and disability. Globally, the burden of neurologic disorders continues to increase. The prevalence of disabling neurologic disorders significantly increases with age. As people live longer, health care systems will face increasing demands for treatment, rehabilitation, and support services for neurologic disorders. The scarcity of established modifiable risks for most of the neurologic burden demonstrates how new knowledge is required to develop effective prevention and treatment strategies.1

A single-center study for chronic headache at a rural institution found that, when combined with public education, clinician education not only can increase access to care but also reduce specialist overuse, hospitalizations, polypharmacy, and emergency department visits.2 A predicted shortage of neurologists has sparked increased interest in the field and individual neurology educators are helping fuel its popularity.3-5

TELE-EDUCATION

Educating the next generation of health professionals is 1 of 4 statutory missions of the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA).6 Tele-education (also known as telelearning and distance learning) deviates from traditional in-person classroom settings, in which the lecture has been a core pedagogic method.7 Audio, video, and online technologies provide health education and can overcome geographic barriers for rural and remote clinicians.8 Recent technological improvements have allowed for inexpensive and efficient dissemination of educational materials, including video lectures, podcasts, online modules, assessment materials, and even entire curricula.9

There has been an increase in the awareness of the parallel curriculum involving self-directed and asynchronous learning opportunities. 10 Several studies report knowledge gained via tele-education is comparable to conventional classroom learning.11-13 A systematic review of e-learning perceptions among health care students suggested benefits (eg, learning flexibility, pedagogical design, online interactions, basic computer skills, and access to technology) and drawbacks (eg, limited acquisition of clinical skills, internet connection problems, and issues with using educational platforms).1

The COVID-19 pandemic forced an abrupt cessation of traditional in-person education, forcing educational institutions and medical organizations to transition to telelearning. Solutions in the education field appeared during the pandemic, such as videoconferencing, social media, and telemedicine, that effectively addressed the sudden cessation of in-person medical education.15

Graduate medical education in neurology residency programs served as an experimental set up for tele-education during the pandemic. Residents from neurology training programs outlined the benefits of a volunteer lecturer-based online didactic program that was established to meet this need, which included exposure to subspeciality topics, access to subspecialist experts not available within the department, exposure to different pedagogic methods, interaction with members of other educational institutions and training programs, career development opportunities, and the potential for forming a community of learning.16

Not all recent educational developments are technology-based. For example, instruction focused on specific patient experiences, and learning processes that emphasize problem solving and personal responsibility over specific knowledge have been successful in neurology.17,18 Departments and institutions must be creative in finding ways to fund continuing education, especially when budgets are limited.19

ANNUAL NEUROLOGY SEMINAR

An annual Veterans Health Administration (VHA) neurology seminar began in 2019 as a 1-day in-person event. Neurologists at the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center in Houston presented in 50-minute sessions. Nonspecialist clinical personnel and neurology clinicians attended the event. Attendees requested making the presentations widely available and regularly repeating the seminar.

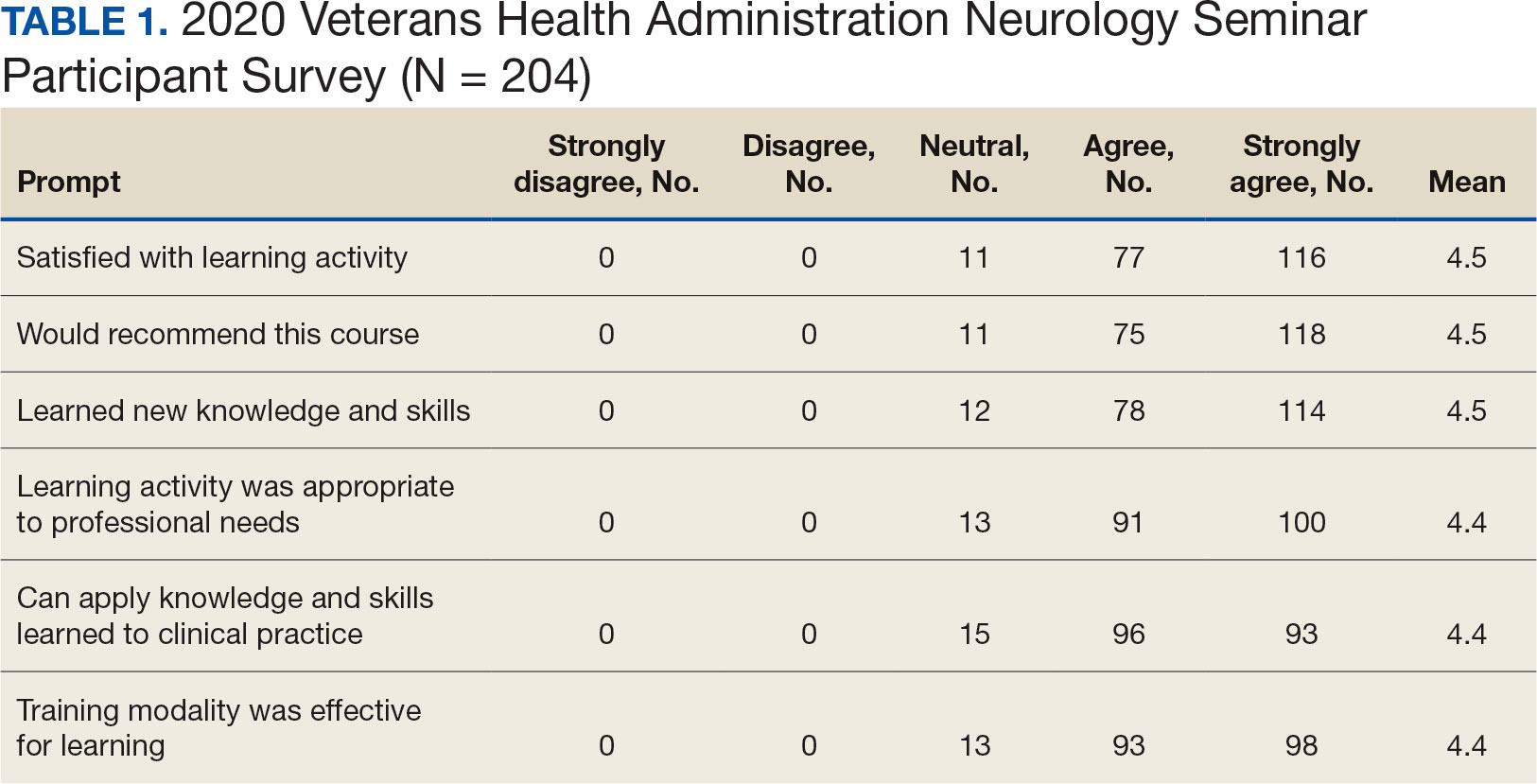

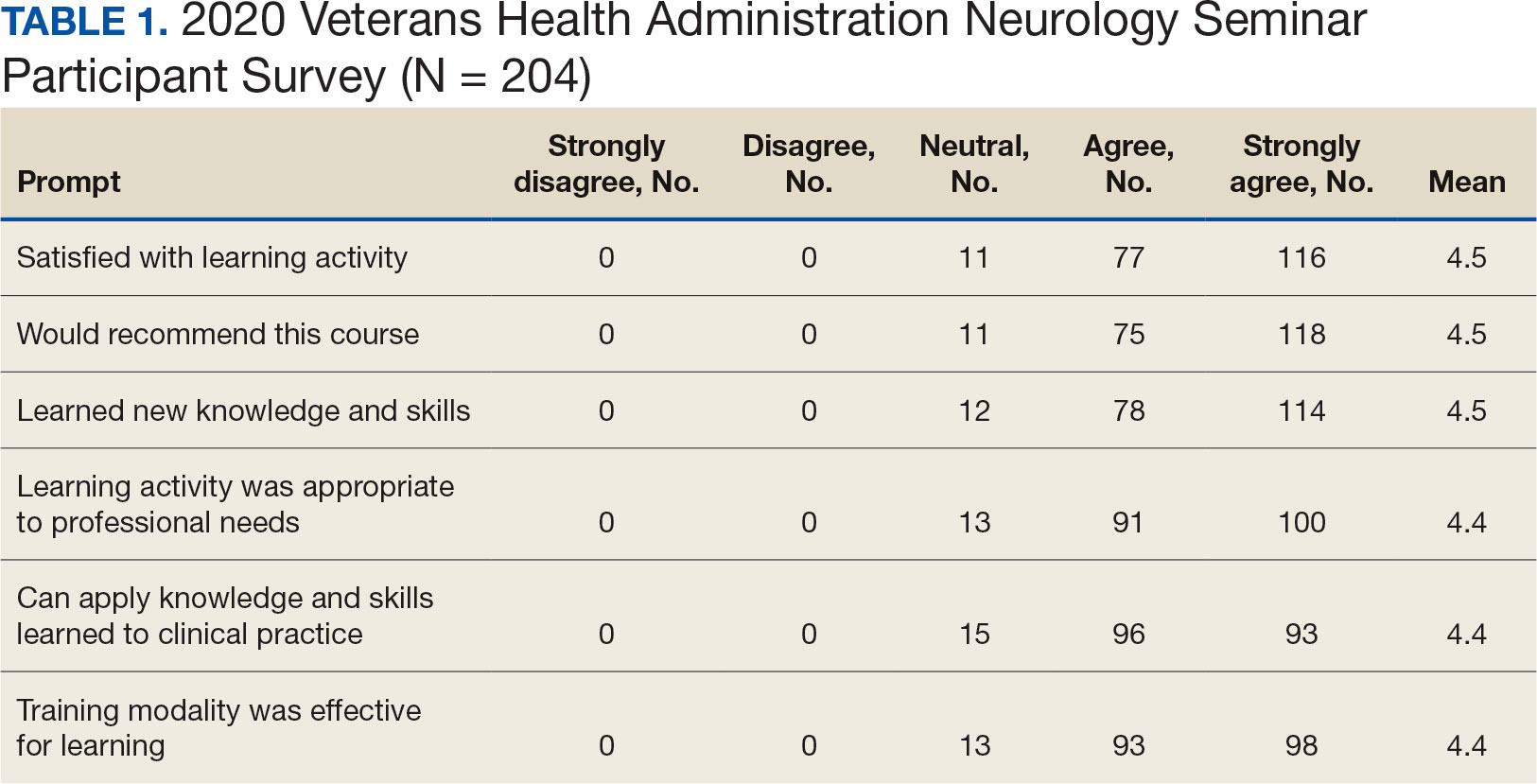

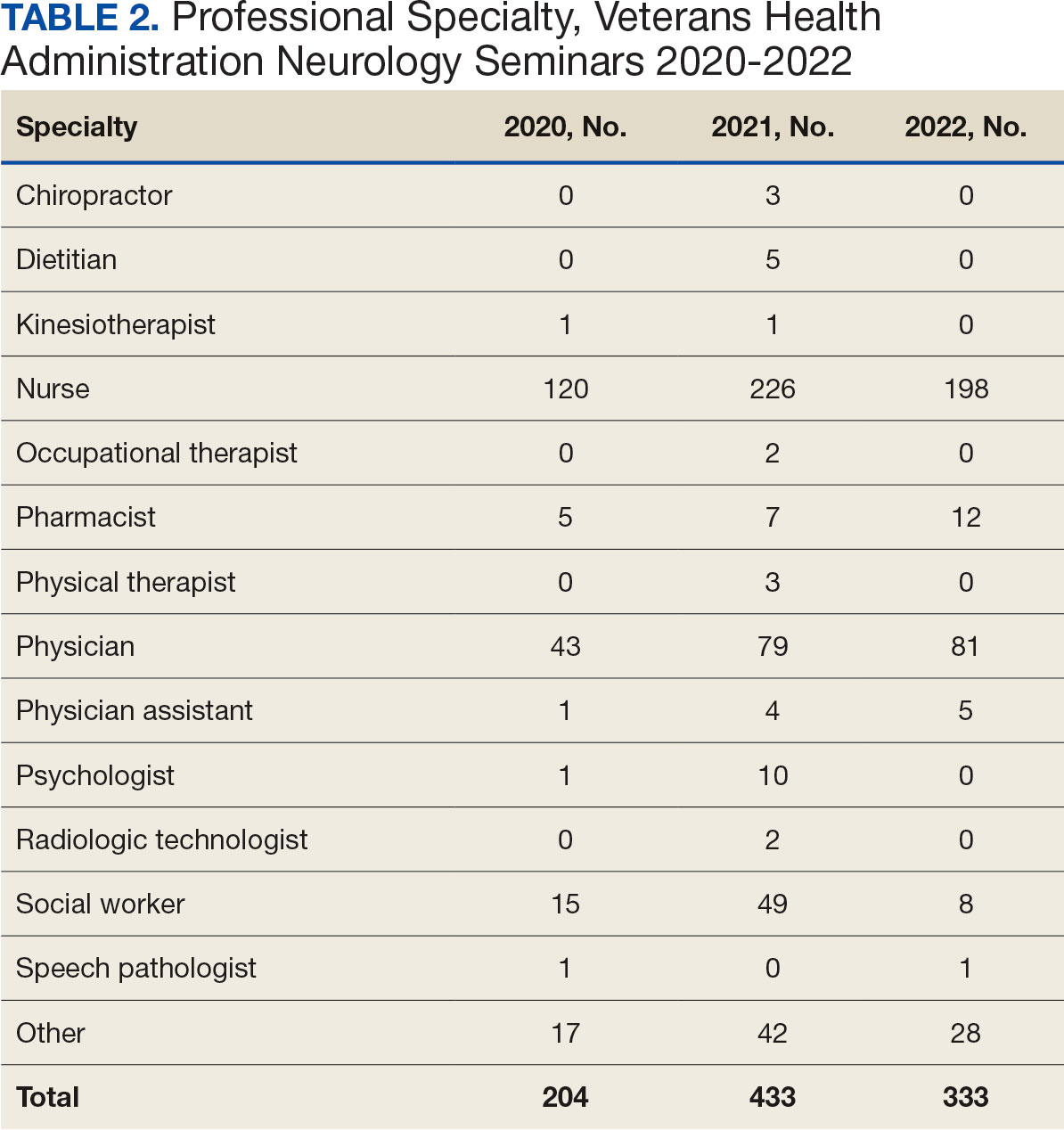

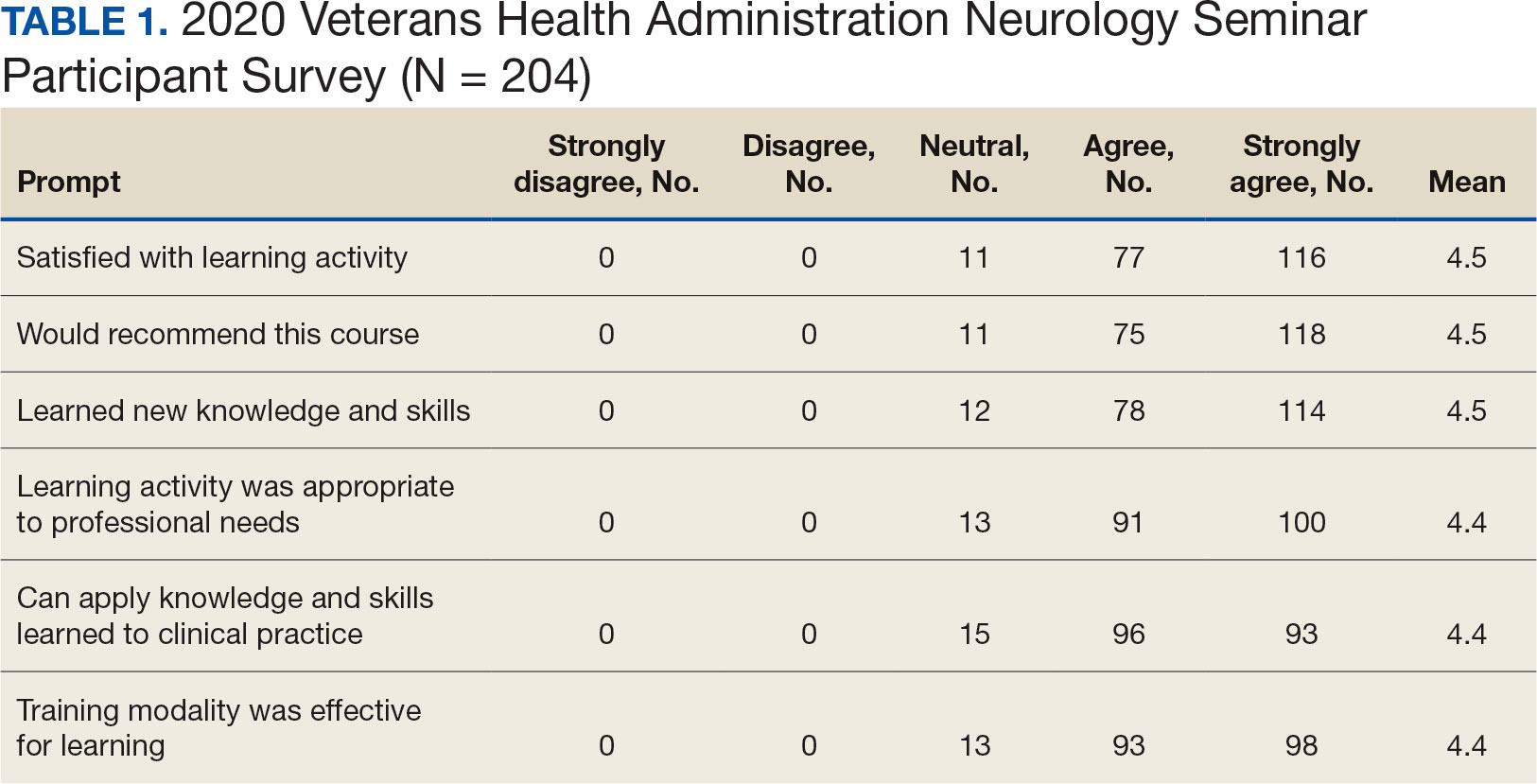

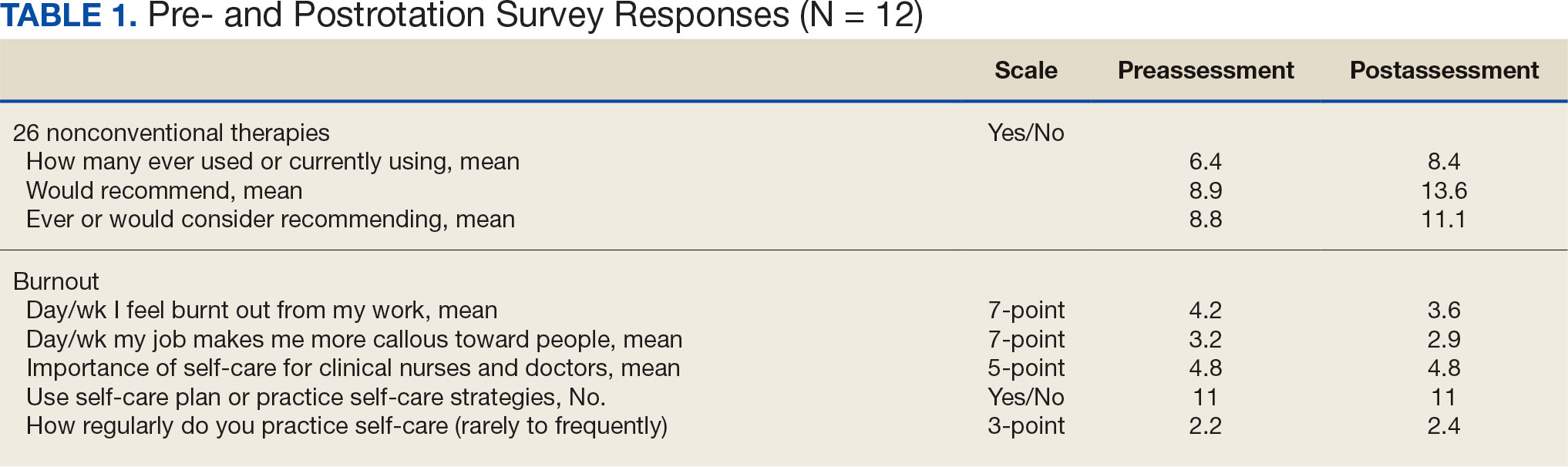

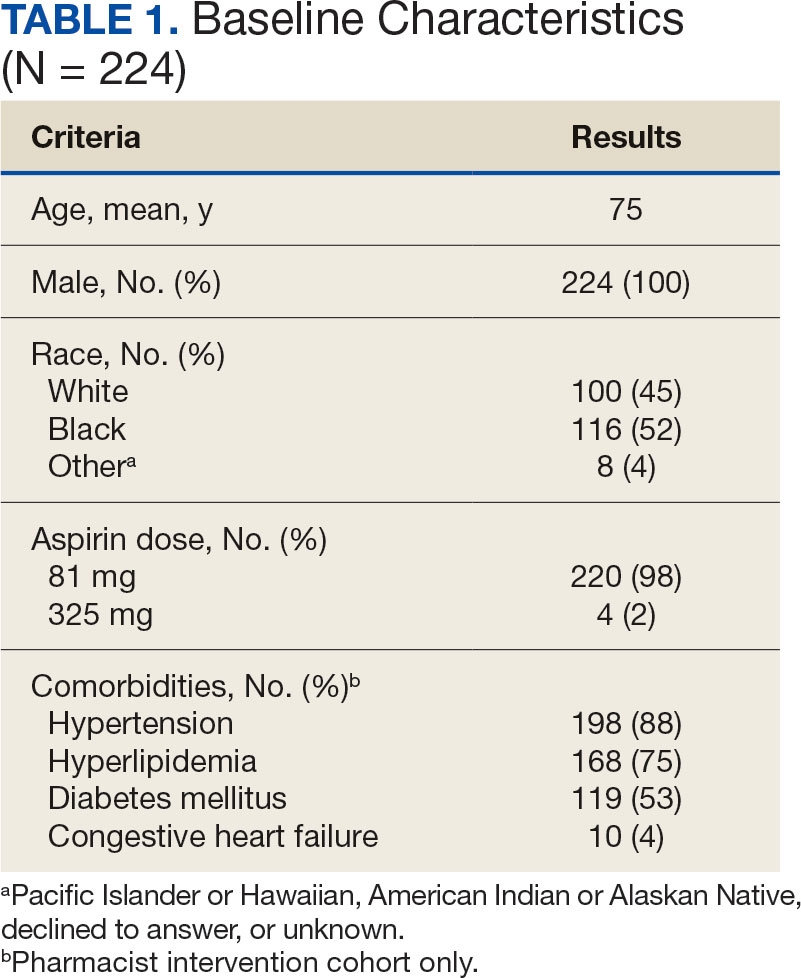

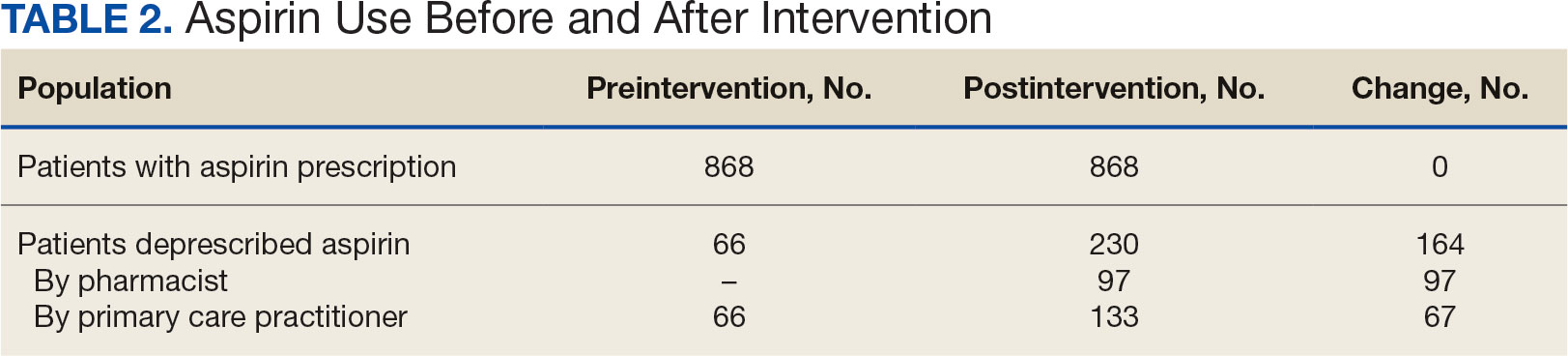

The second neurology seminar took place during the COVID-19 pandemic. It was conducted online and advertised across the Veterans Integrated Services Network (VISN) 16. The 1-day program had 204 participants who were primarily nurses (59%) and physicians (21%); 94% agreed with the program objectives (Table 1). Participants could earn CME credits for the 7 presentations primarily by VHA experts.

Based on feedback and a needs assessment, the program expanded in 2021 and 2022. With support from the national VHA neurology office and VHA Employee Education System (EES), the Institute for Learning, Education, and Development (ILEAD), the feedback identified topics that resonate with VHA clinicians. Neurological disorders in the fields of stroke, dementia, and headache were included since veterans with these disorders regularly visit primary care, geriatrics, mental health, and other clinical offices. Updates provided in the diagnosis and treatment of common neurological disorders were well received. Almost all speakers were VHA clinicians, which allowed them to focus on topics relevant to clinical practice at the VHA.

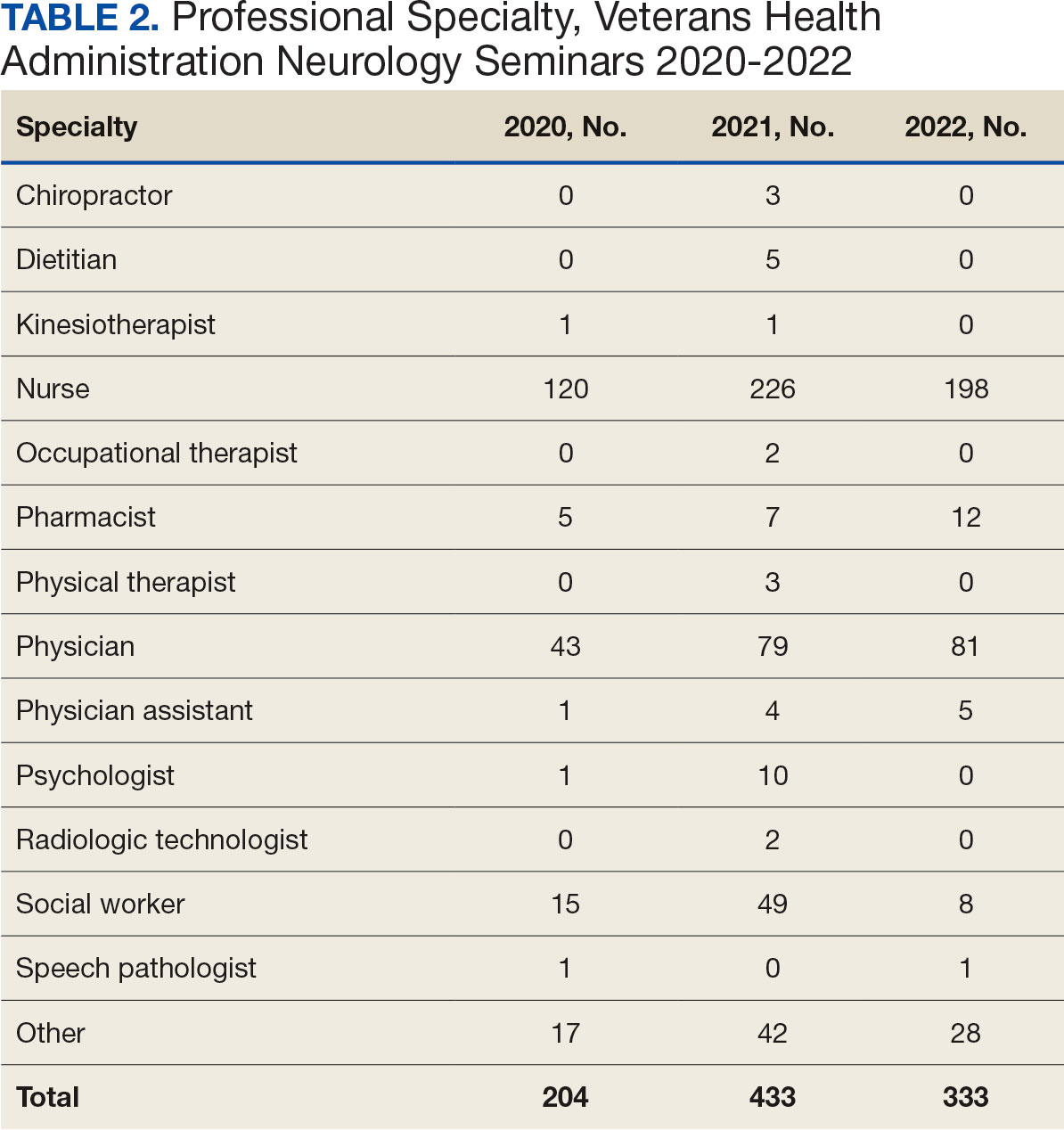

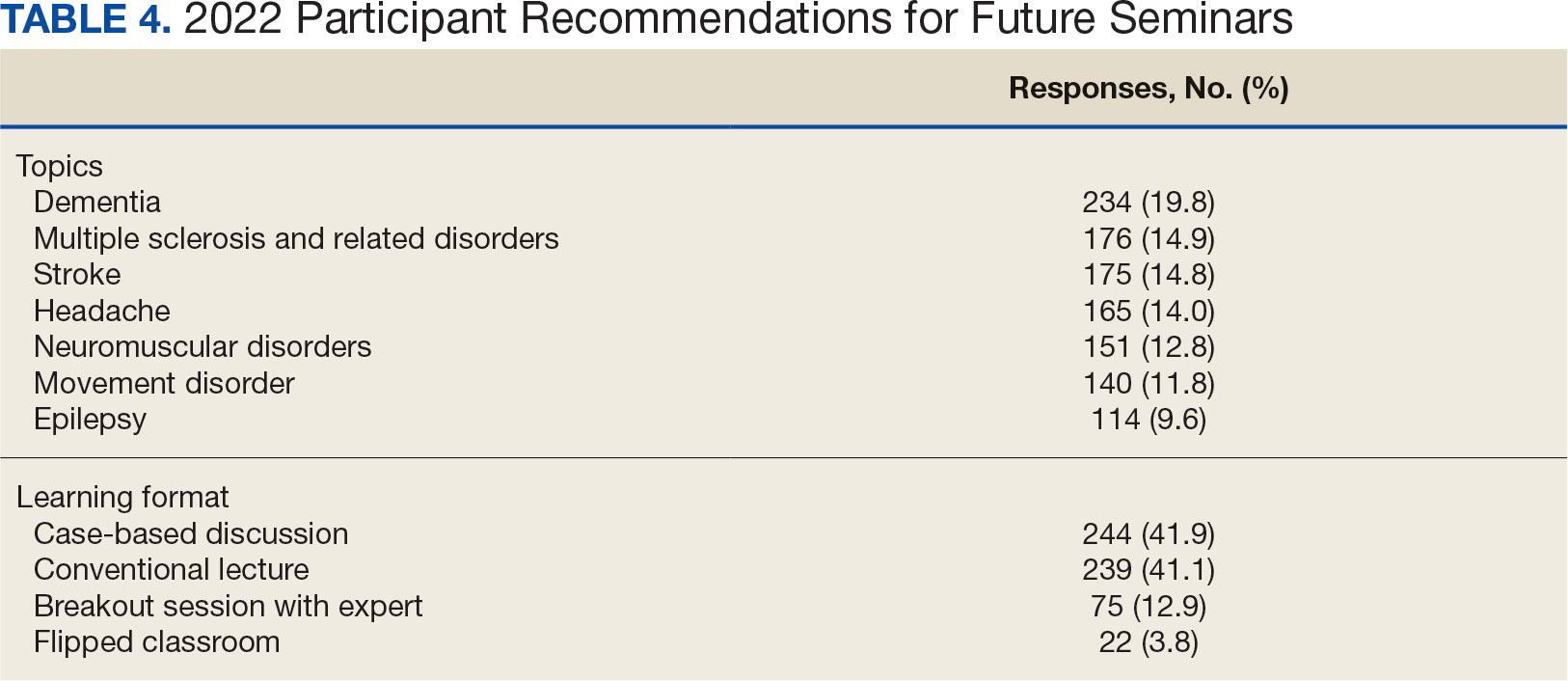

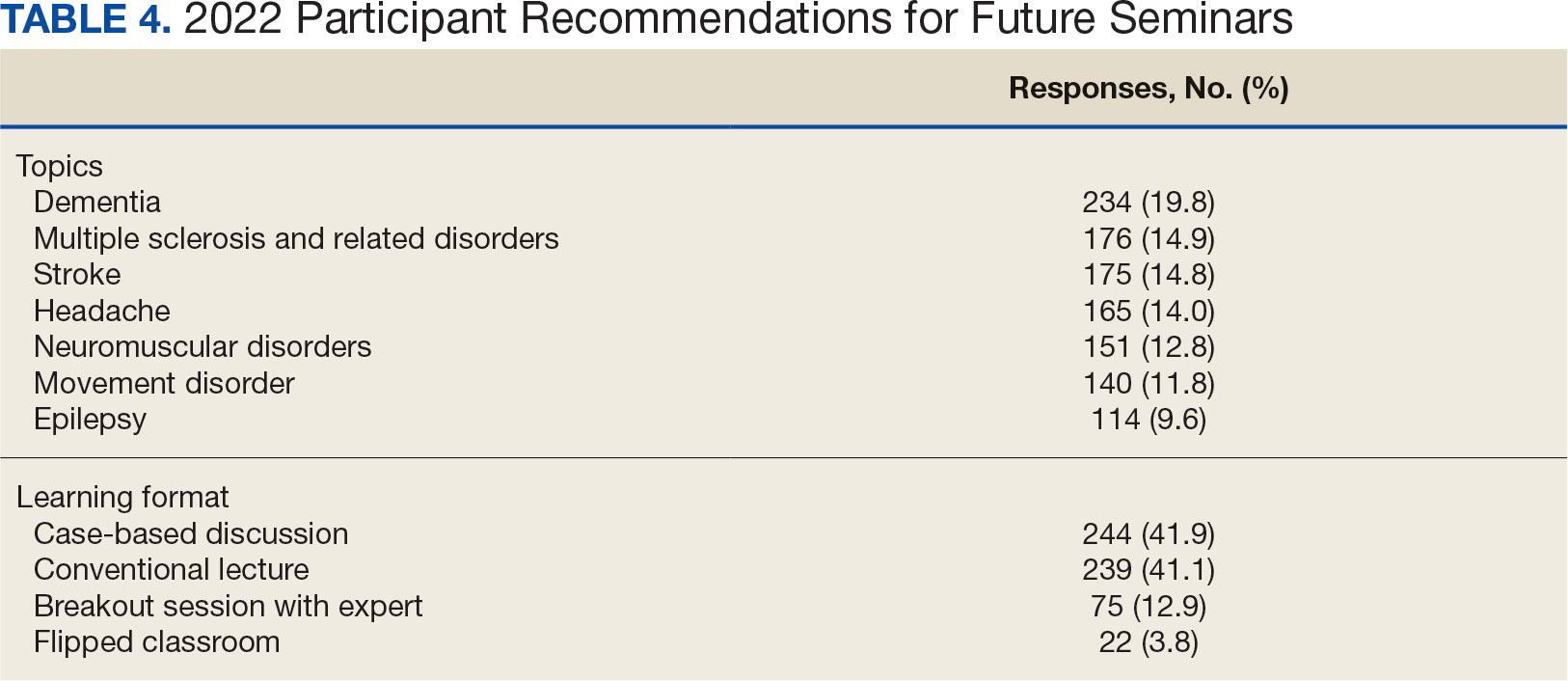

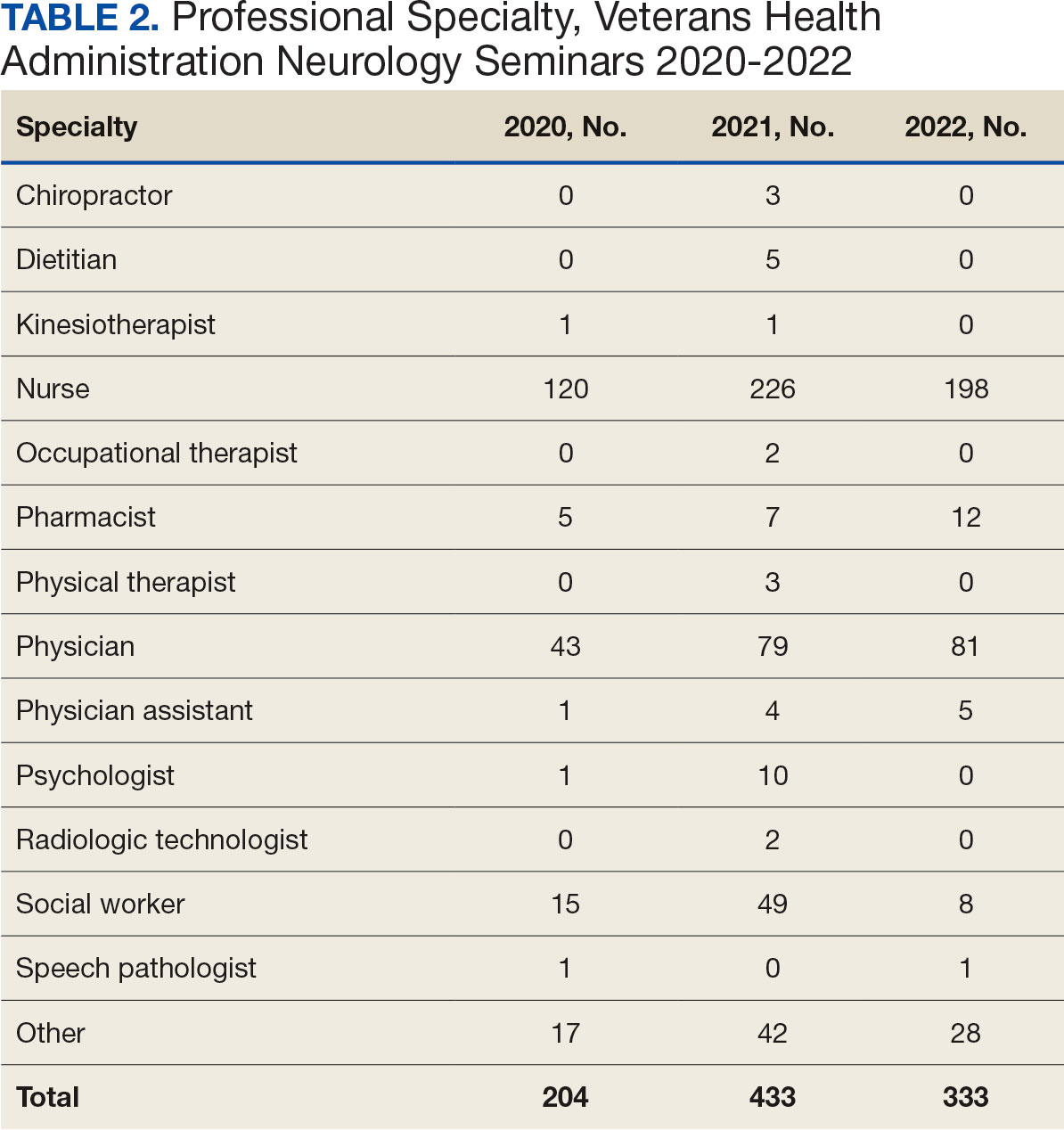

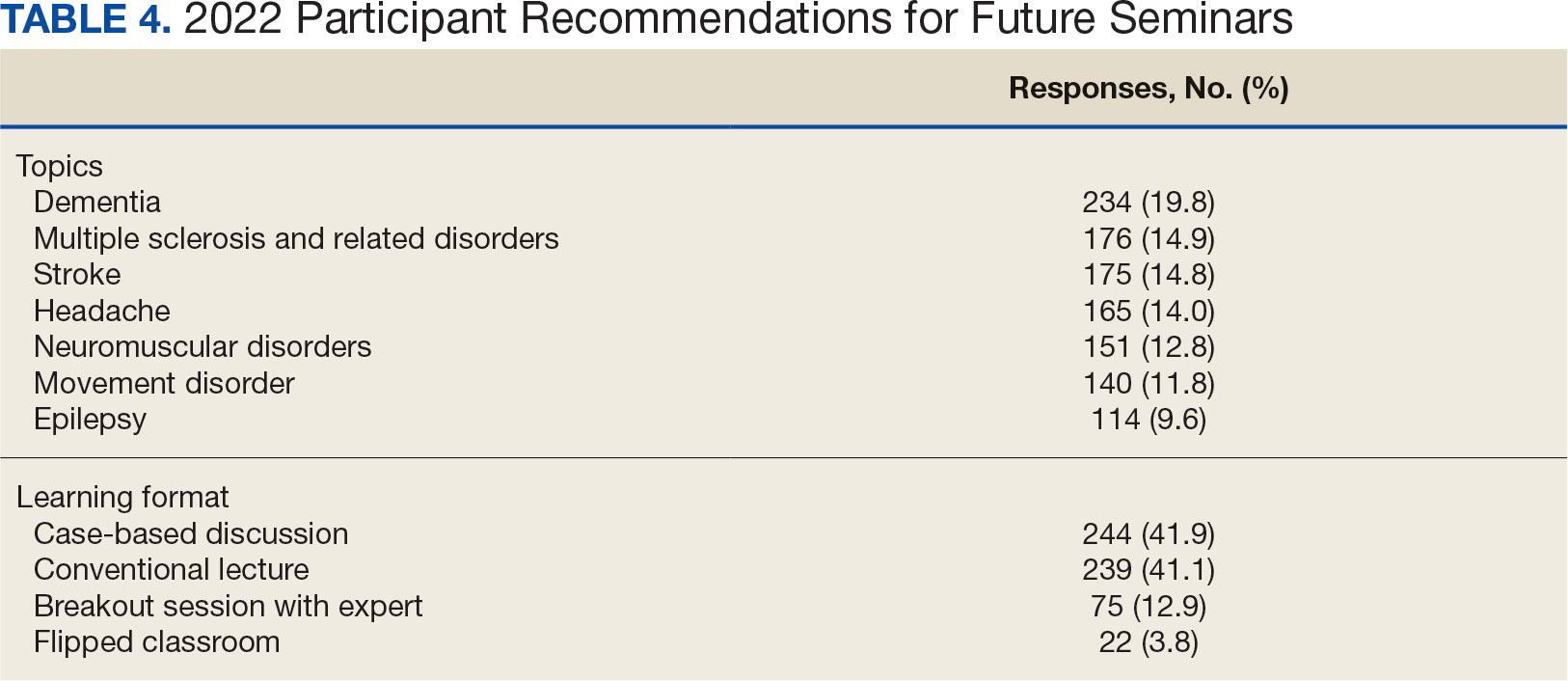

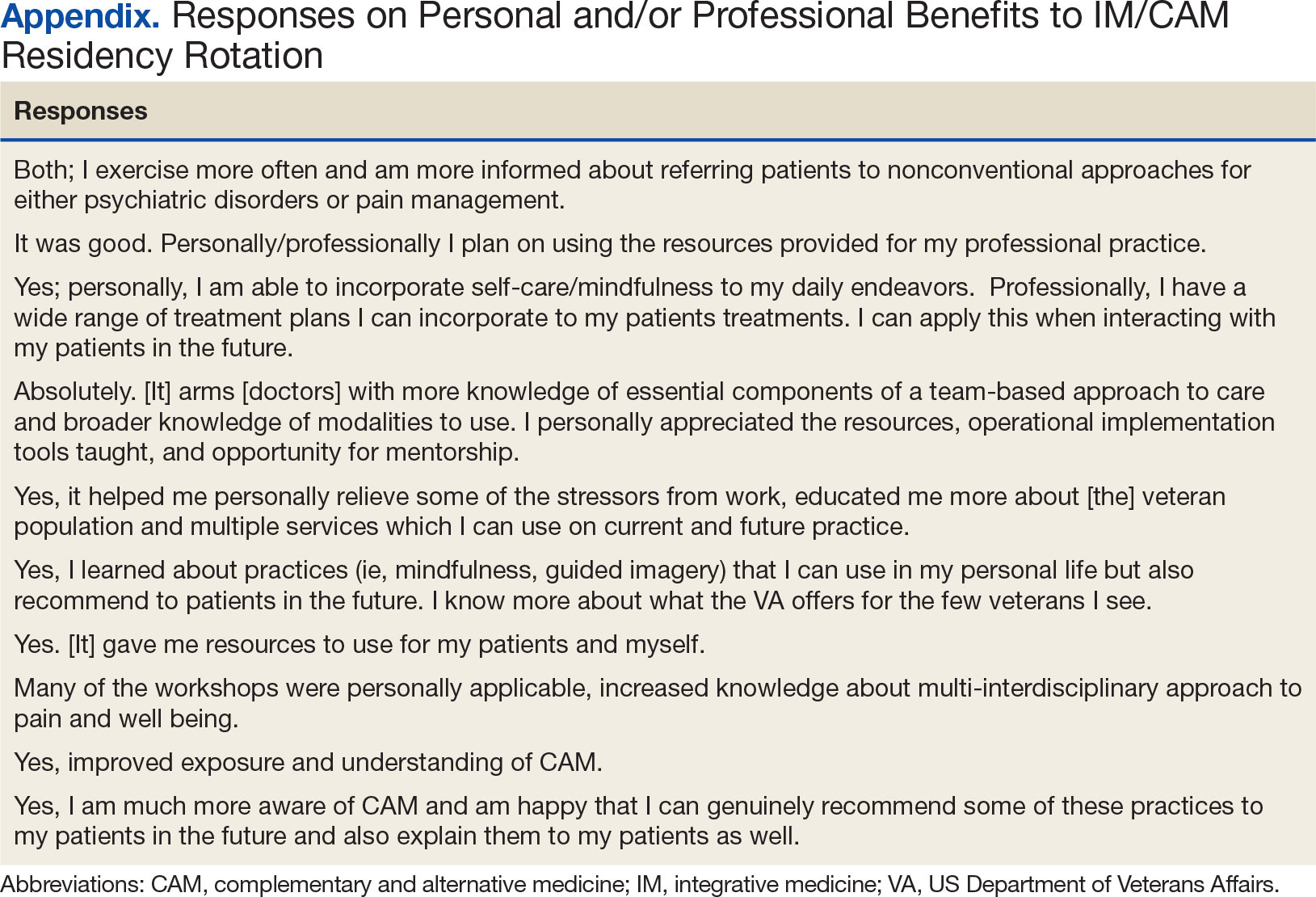

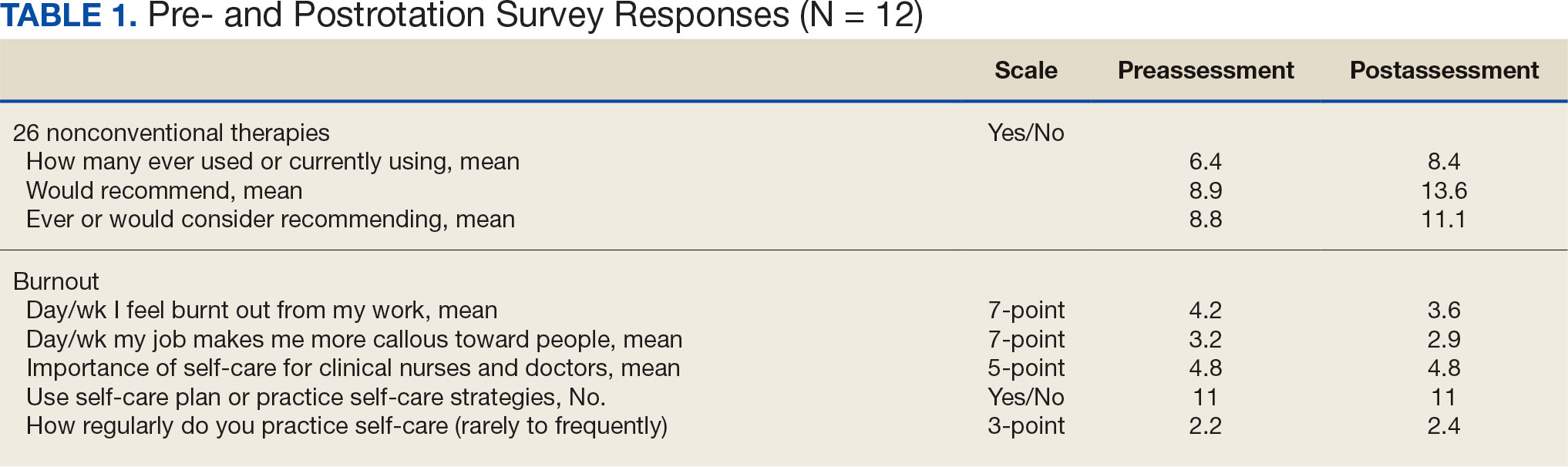

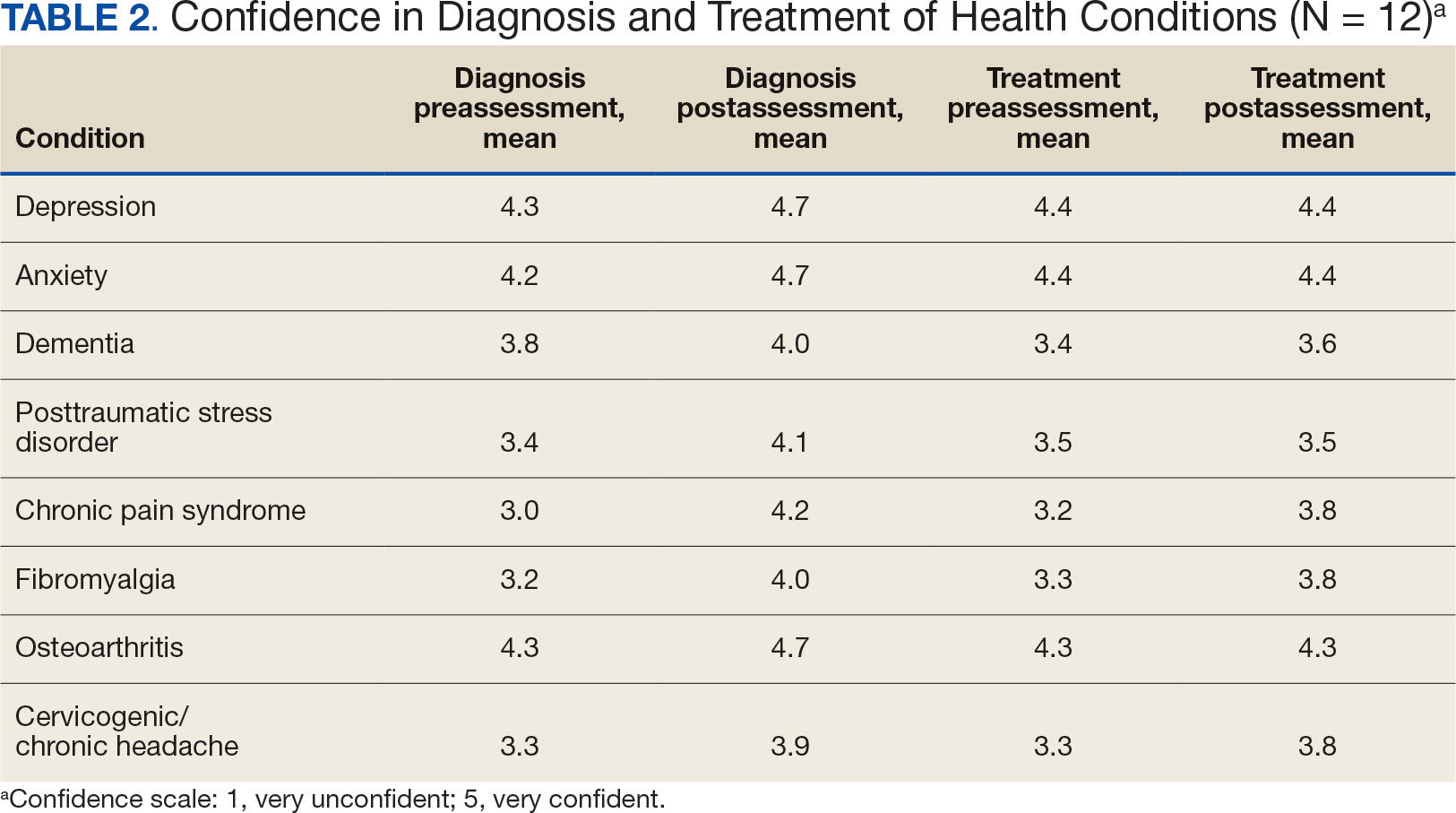

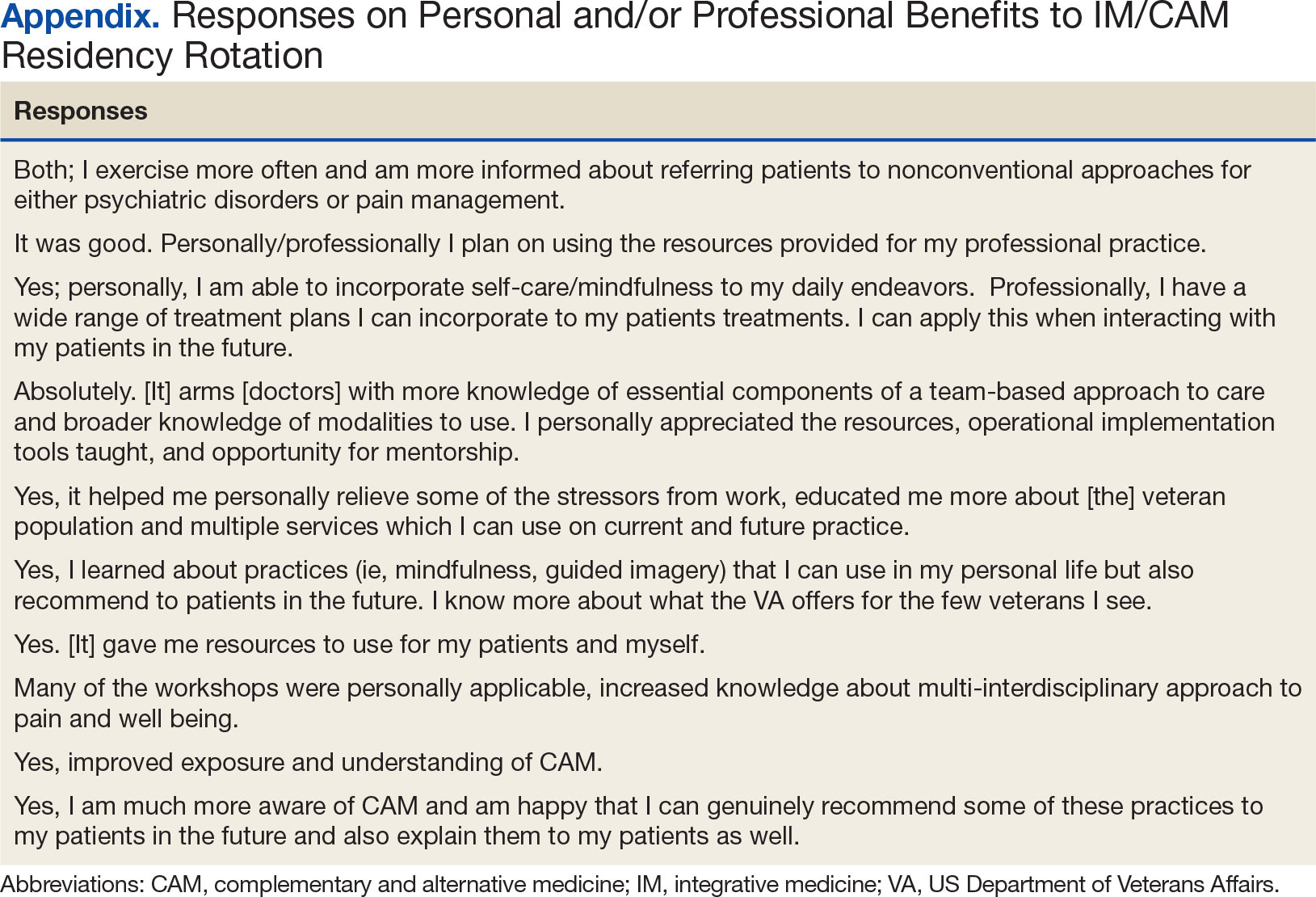

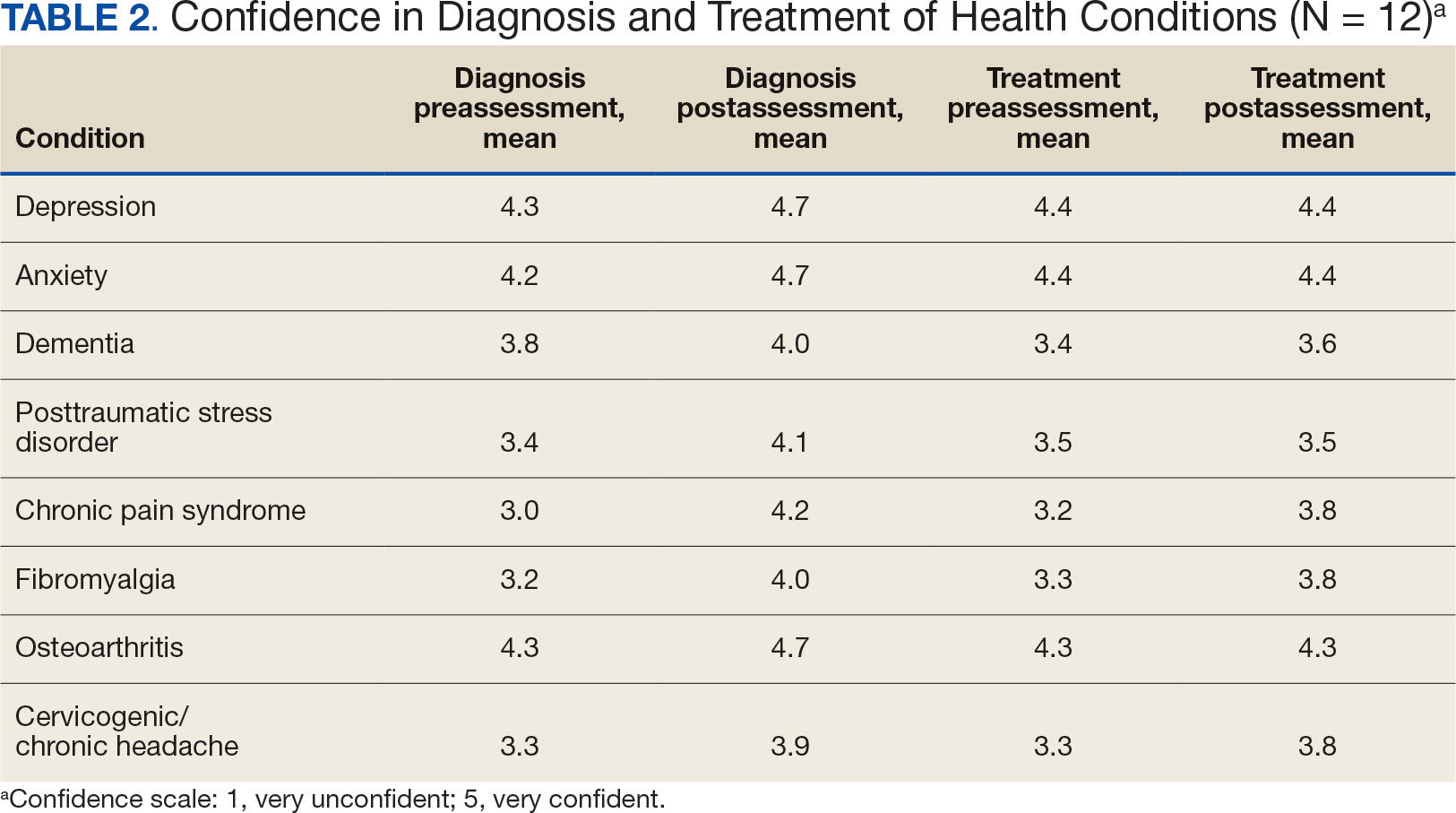

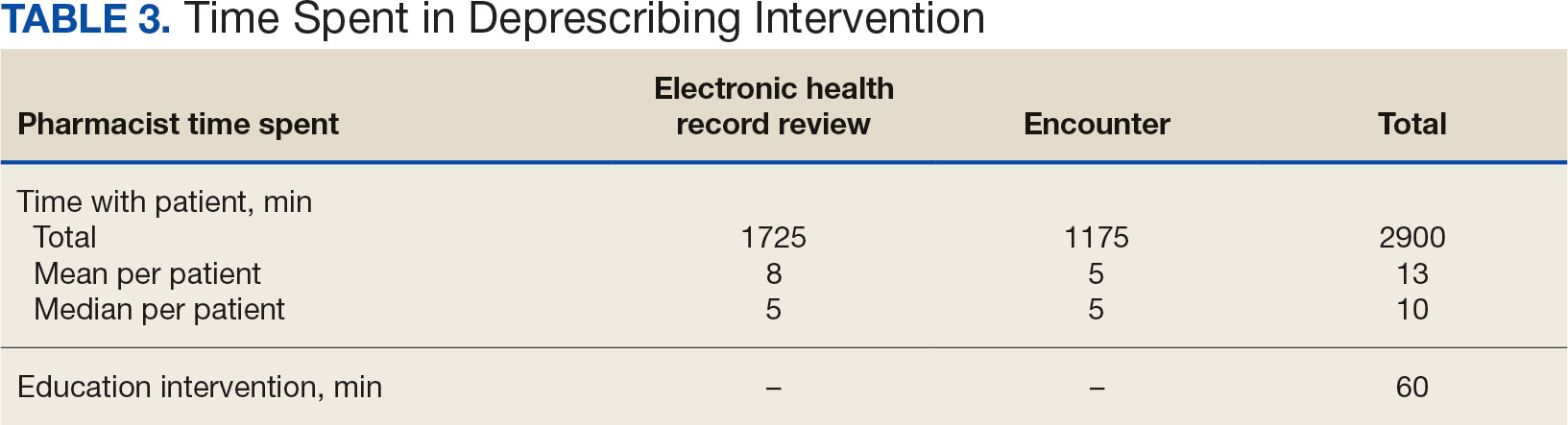

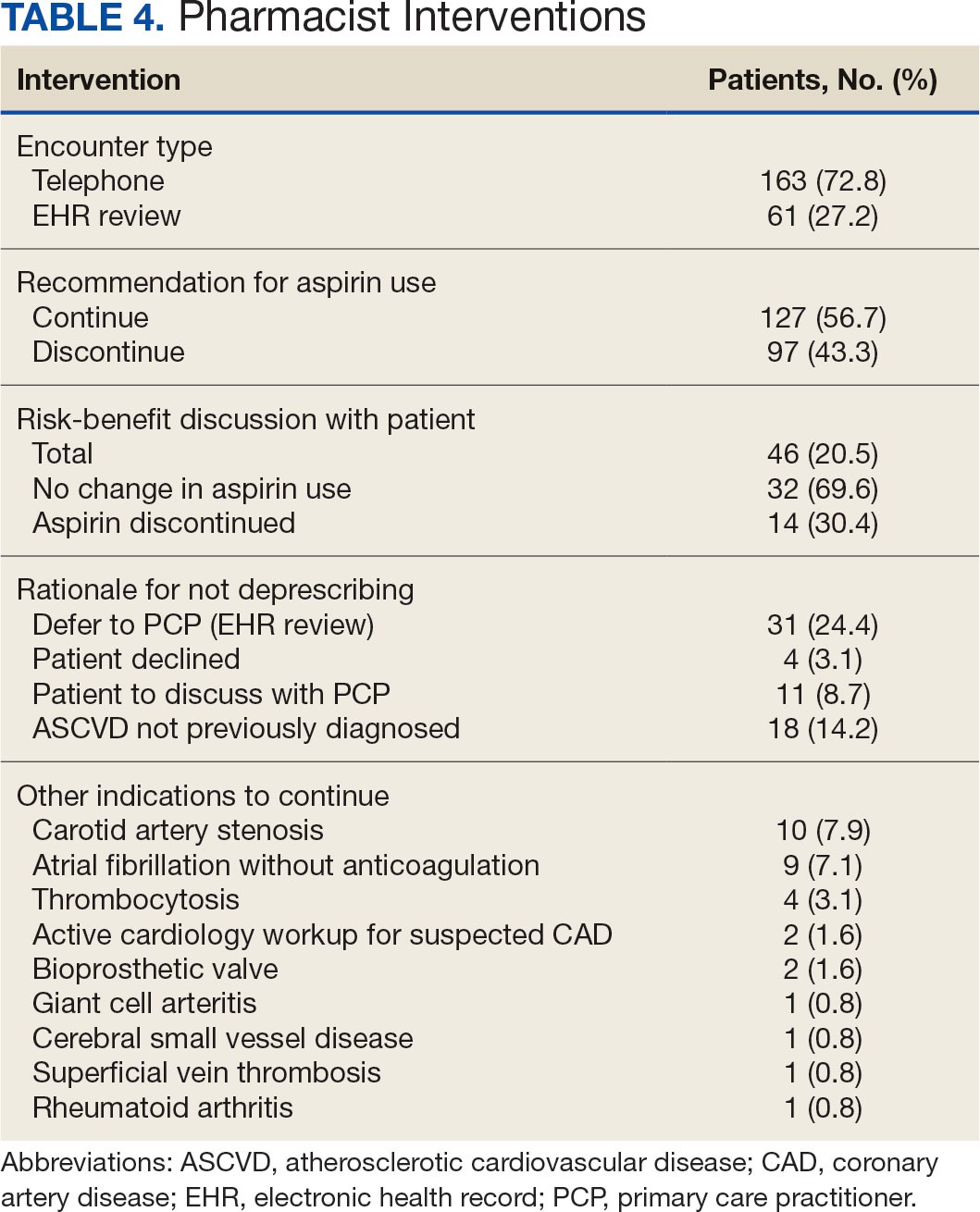

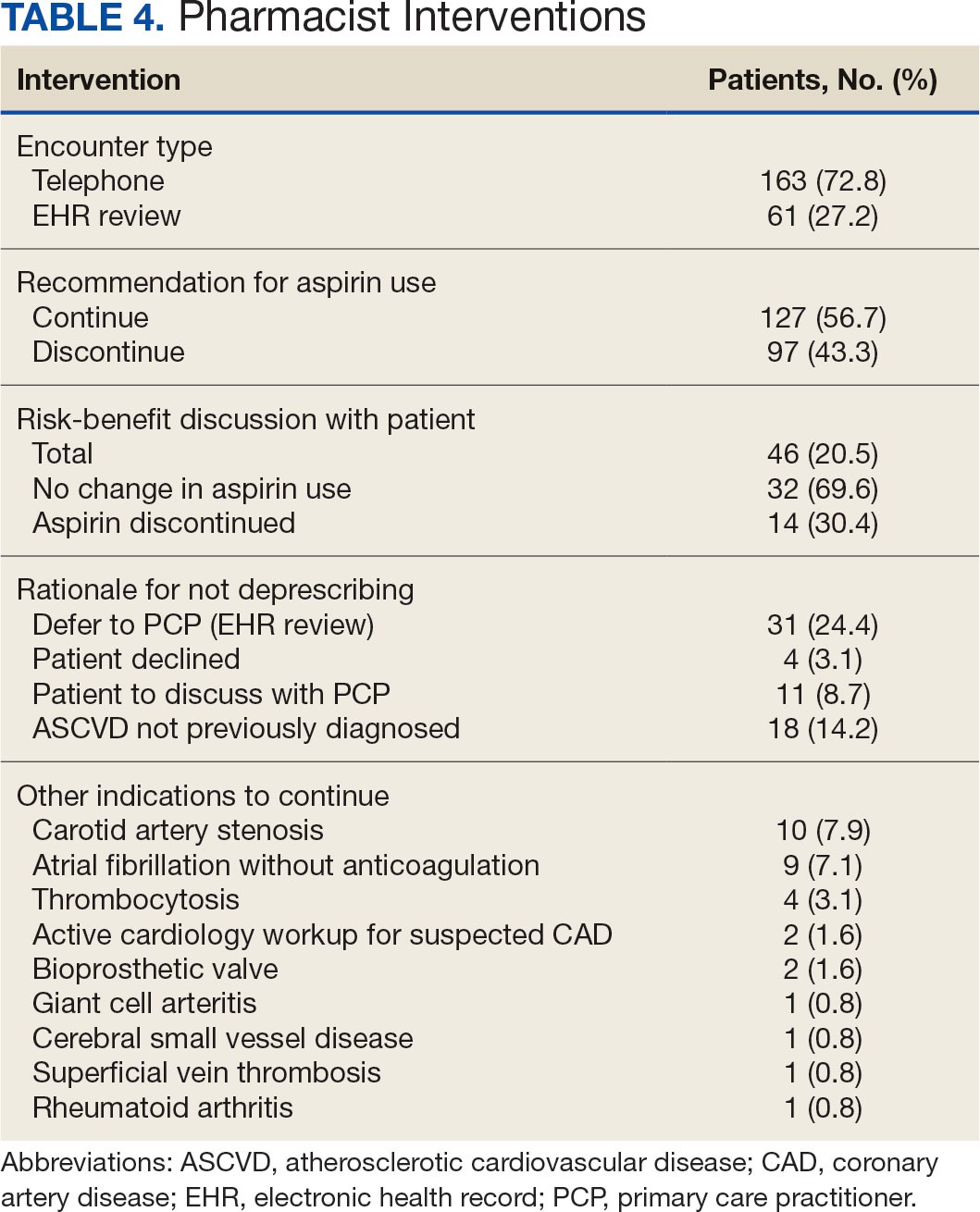

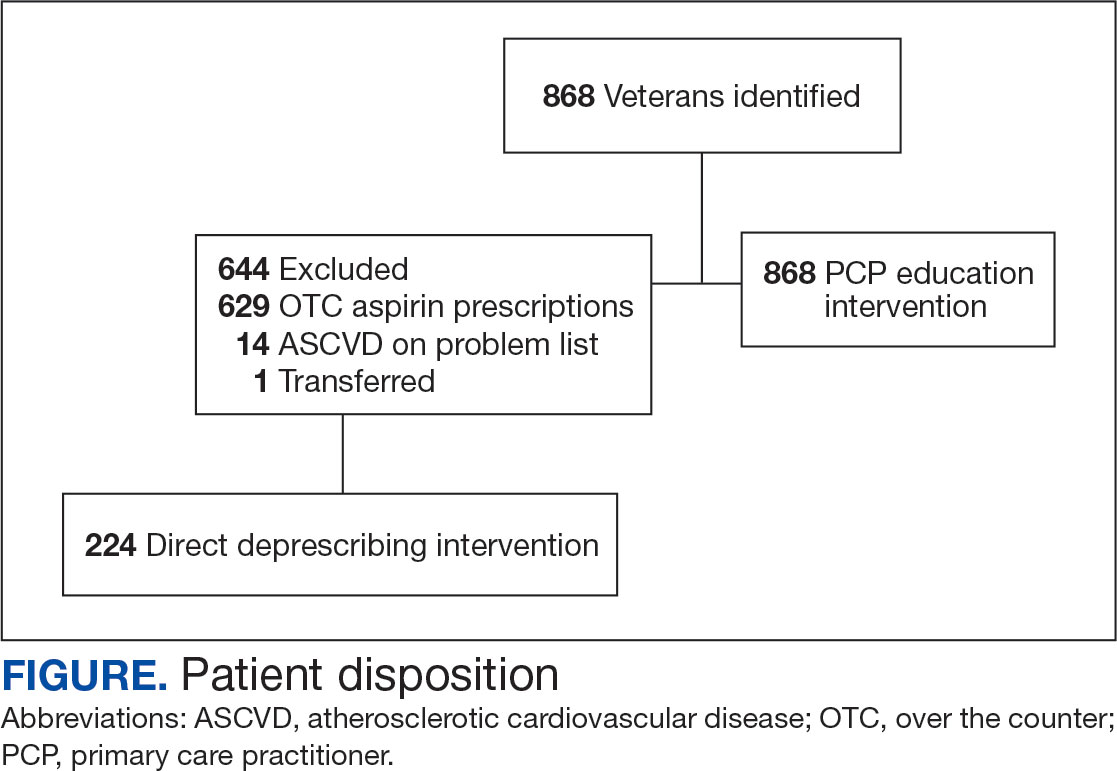

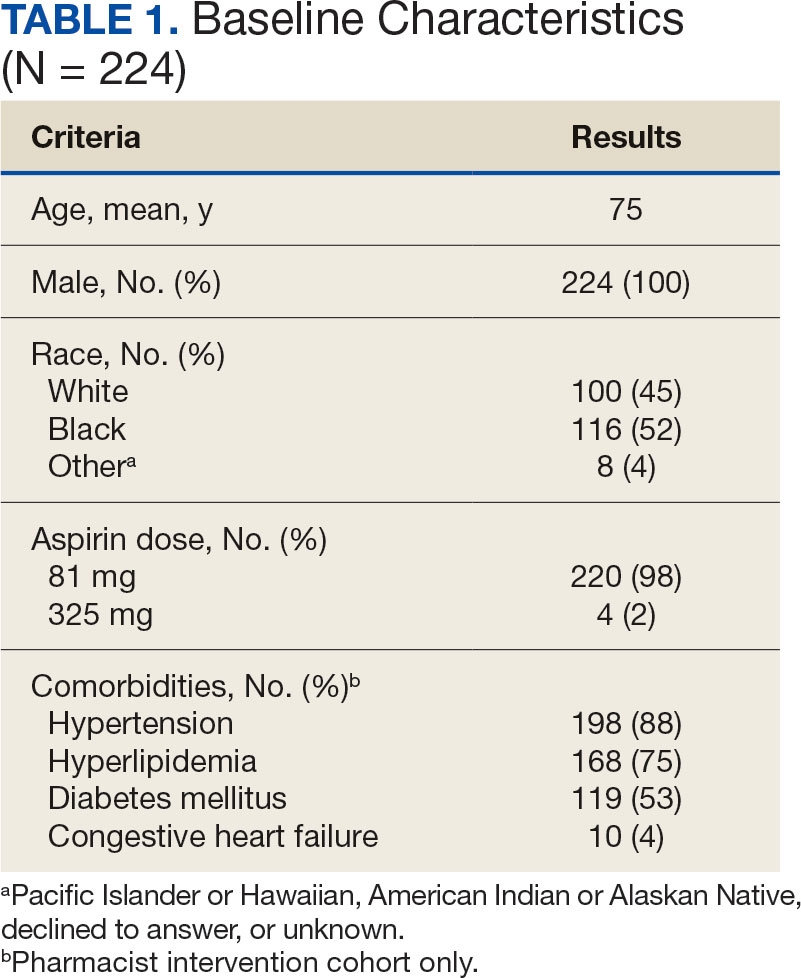

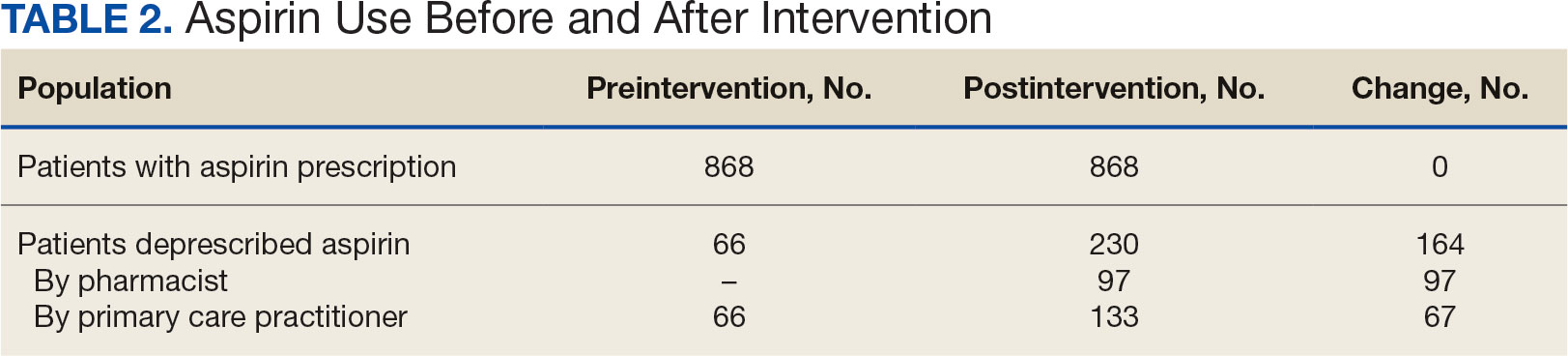

Attendance has increased annually. In 2021, 550 clinicians registered (52% nurses) and 433 completed the postseminar survey (Table 2). In 2022, 635 participants registered and 342 completed evaluations, including attendees from other federal agencies who were invited to participate via EES TRAIN (Training Finder Real-time Affiliate Integrated Network). Forty-seven participants from other federal agencies, including the US Department of Defense, National Institute of Health, and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, completed the feedback evaluation via TRAIN (Table 3). Participants report high levels of satisfaction each year (mean of 4.5 on a 5-point scale). Respondents preferred conventional lecture presentation and case-based discussions for the teaching format and dementia was the most requested topic for future seminars (Table 4).

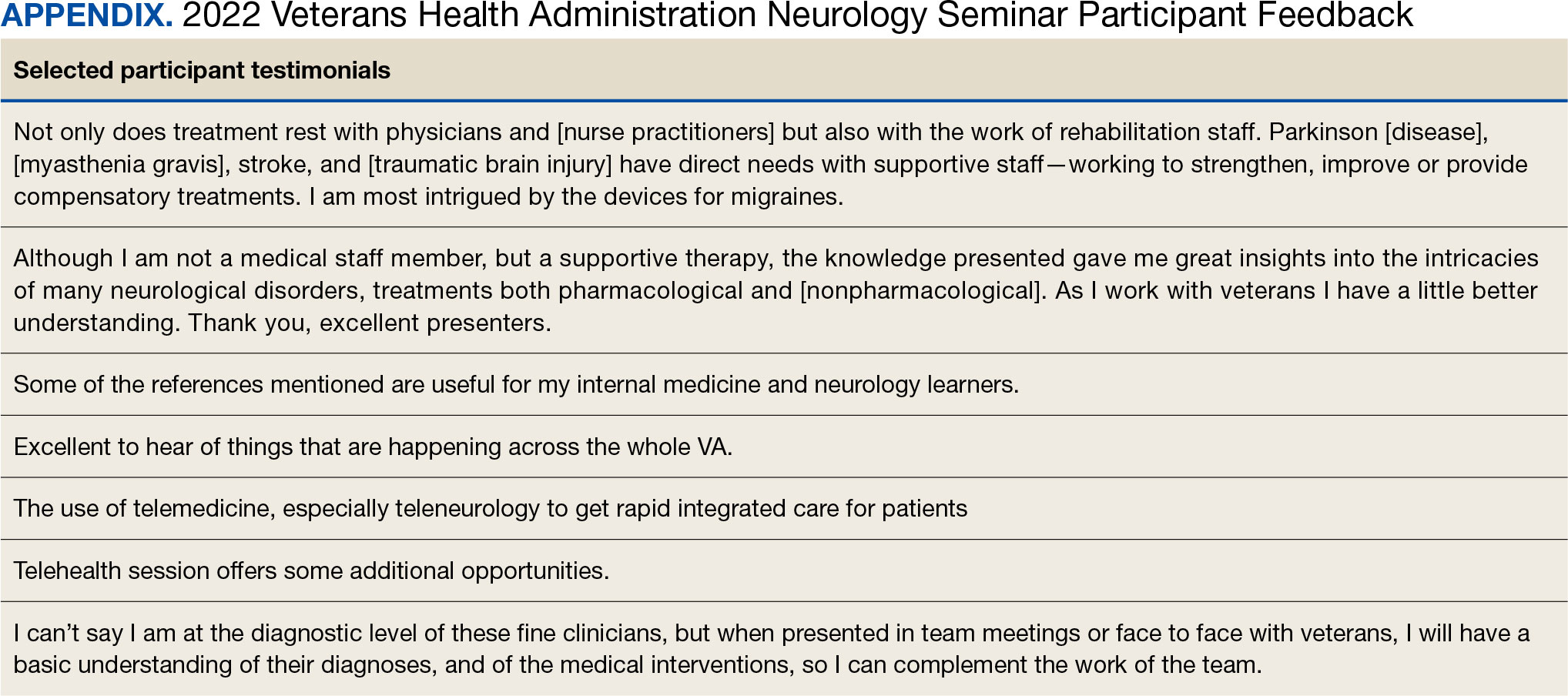

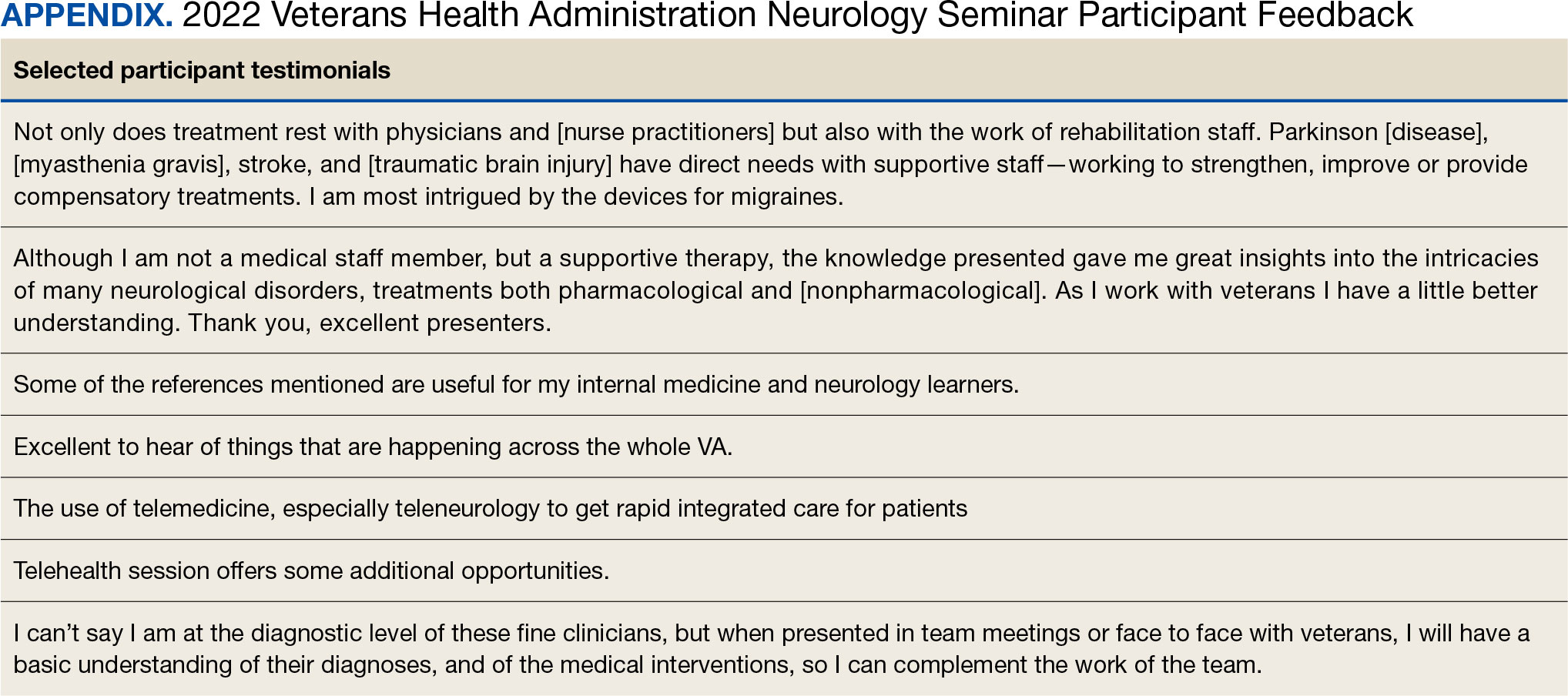

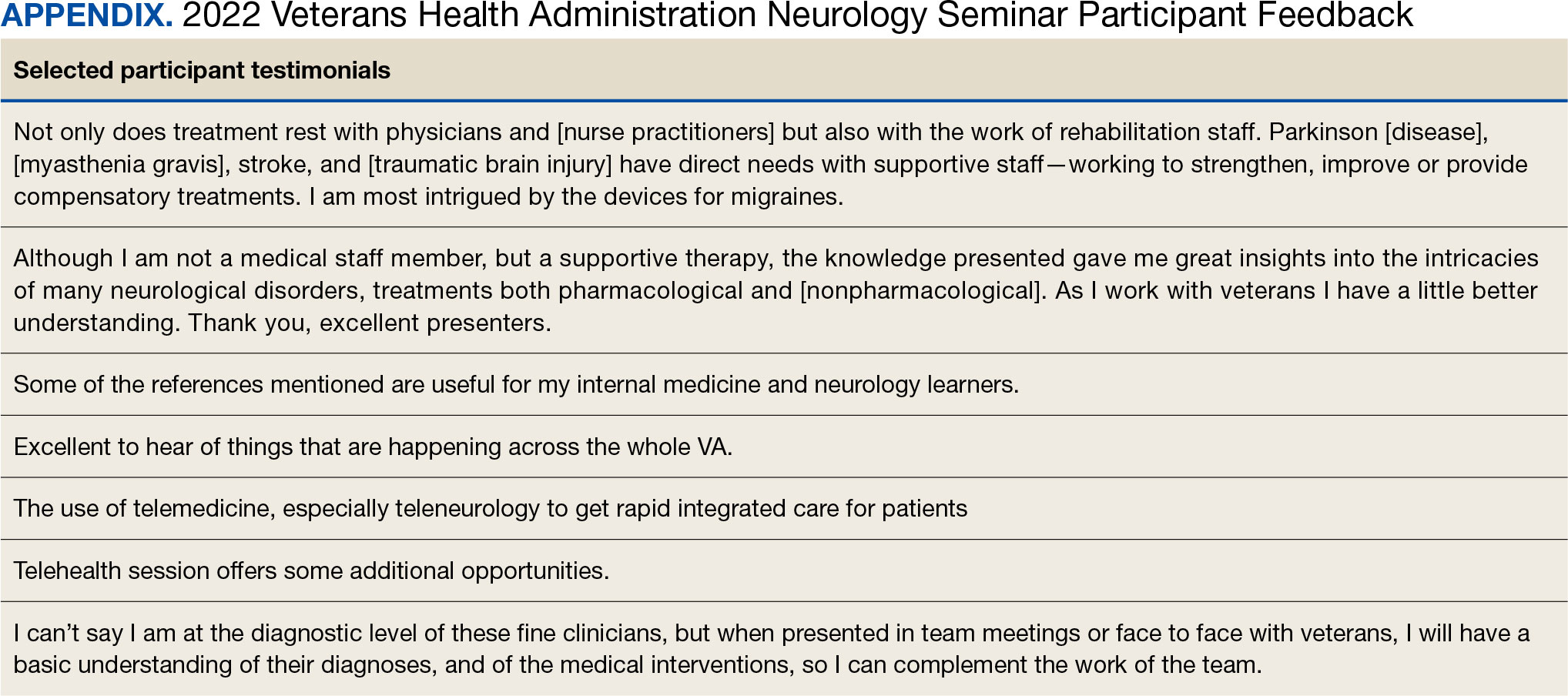

The content of each seminar was designed to include . 1 topic relevant to current clinical practice. The 2020 seminar covered topics of cerebrovascular complications of COVID- 19 and living well with neurodegenerative disease in the COVID-19 era. In 2021, the seminar included COVID-19 and neurologic manifestations. In 2022, topics included trends in stroke rehabilitation. In addition, ≥ 1 session addressed neurologic issues within the VHA. In 2020, the VA Deputy National Director of Neurology presented on the VHA stroke systems of care. In 2021, there was a presentation on traumatic brain injury (TBI) in the military. In 2022, sessions covered long term neurologic consequences of TBI and use of telemedicine for neurologic disorders. Feedback on the sessions were positive (eAppendix, available at doi:10.12788/fp.0545).

At the request of the participants, individual presentations were shared via email by the course director and speakers. In collaboration with the EES, each session was recorded and the 2022 seminar was made available to registrants in TMS and EES TRAIN and via the VHA Neurology SharePoint.

DISCUSSION

The annual VHA neurology seminar is a 1-day neurology conference that provides education to general neurologists and other clinicians caring for patients with neurologic disorders. It is the first of its kind neurology education program in the VHA covering most subspecialties in neurology and aims at improving neurologic patient care and access through education. Sessions have covered stroke, epilepsy, sleep, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, neuropathy, dementia, movement disorders and Parkinson disease, headaches, multiple sclerosis, neurorehabilitation, and telehealth.

The seminar has transitioned from an inperson meeting to a virtual format, making neurology education more convenient and accessible. The virtual format provides the means to increase educational collaborations and share lecture platforms with other federal agencies. The program offers CME credits at no cost to government employees. Recorded lectures can also be asynchronously viewed from the Neurology SharePoint without the ability to earn CME credits. These recordings may be used to educate trainees as well.

The seminar aims to educate all health care professionals caring for patients with neurologic disorders. It aims to eliminate neurophobia, the fear of neural sciences and clinical neurology, and help general practitioners, especially in rural areas, take care of patients with neurologic disorders. The seminars introduce general practitioners to VHA neurology experts; the epilepsy, headache multiple sclerosis, and Parkinson disease centers of excellence; and the national programs for telestroke and teleneurology.

Education Support in the VHA

The EES/ILEAD provides a wide variety of learning opportunities to VHA employees on a broad range of topics, making it one of the largest medical education programs in the country. Pharmacists, social workers, psychologists, therapists, nurses, physician assistants, and physicians have access to certified training opportunities to gain knowledge and skills needed to provide high-quality, veteran-centered care.

A review of geriatrics learning activities through the EES found > 15,000 lectures from 1999 to 2009 for > 300,000 attendees.20 To our knowledge, a review of neurology-related learning activities offered by the EES/ILEAD has not been completed, but the study on geriatrics shows that a similar review would be feasible, given the integrated education system, and helpful in identifying what topics are covered, formats are used, and participants are engaged in neurology education at the VHA. This is a future project planned by the neurology education workgroup.

The EES/ILEAD arranged CME credit for the VHA Neurology Seminar and assisted in organizing an online event with > 500 attendees. Technology support and tools provided by EES during the virtual seminar, such as polling and chat features, kept the audience engaged. Other specialties may similarly value a virtual, all-day seminar format that is efficient and can encourage increased participation from practitioners, nurses, and clinicians.

Future Growth

We plan to increase future participation in the annual neurology seminar with primary care, geriatrics, neurology, and other specialties by instituting an improved and earlier marketing strategy. This includes working with the VHA neurology office to inform neurology practitioners as well as other program offices in the VHA. We intend to host the seminar the same day every year to make it easy for attendees to plan accordingly. In the future we may consider hybrid in-person and virtual modalities if feasible. We plan to focus on reaching out to other government agencies through platforms like TRAIN and the American Academy of Neurology government sections. Securing funding, administrative staff, and protected time in the future may help expand the program further.

Limitations

While a virtual format offers several advantages, using it removes the feel of an in-person meeting, which could be viewed by some attendees as a limitation. The other challenges and drawbacks of transitioning to the virtual platform for a national meeting are similar to those reported in the literature: time zone differences, internet issues, and participants having difficulty using certain online platforms. Attendance could also be limited by scheduling conflicts.16 Despite a large audience attending the seminar, many clinicians do not get protected time from their institutions. Institutional and leadership support at national and local levels will likely improve participation and help participants earn CME credits. While we are still doing a preliminary needs assessment, a formal needs assessment across federal governmental organizations will be helpful.

CONCLUSIONS

The annual VHA neurology seminar promotes interprofessional education, introduces neurology subspecialty centers of excellence, improves access to renowned neurology experts, and provides neurology-related updates through a VHA lens. The program not only provides educational updates to neurology clinicians, but also increases the confidence of non-neurology clinicians called to care for veterans with neurological disorders in their respective clinics.

- GBD 2016 Neurology Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of neurological disorders, 1990- 2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(5):459-480. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30499-X

- Baker V, Hack N. Improving access to care for patients with migraine in a remote Pacific population. Neurol Clin Pract. 2020;10(5):444-448. doi:10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000774

- Gutmann L, Cahill C, Jordan JT, et al. Characteristics of graduating US allopathic medical students pursuing a career in neurology. Neurology. 2019;92(17):e2051-e2063. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000007369

- Jordan JT, Cahill C, Ostendorf T, et al. Attracting neurology’s next generation: a qualitative study of specialty choice and perceptions. Neurology. 2020;95(8):e1080- e1090. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000009461

- Minen MT, Kaplan K, Akter S, et al. Understanding how to strengthen the neurology pipeline with insights from undergraduate neuroscience students. Neurology 2022;98(8):314-323. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000013259

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Academic Affiliations. To Educate for VA and the Nation. Updated August 1, 2024. Accessed August 15, 2024. https://www.va.gov/oaa/

- Schaefer SM, Dominguez M, Moeller JJ. The future of the lecture in neurology education. Semin Neurol. 2018;38(4):418-427. doi:10.1055/s-0038-1667042

- Curran VR. Tele-education. J Telemed Telecare. 2006;12(2):57-63. doi:10.1258/135763306776084400

- Lau KHV, Lakhan SE, Achike F. New media, technology and neurology education. Semin Neurol. 2018;38(4):457- 464. doi:10.1055/s-0038-1666985

- Quirk M, Chumley H. The adaptive medical curriculum: a model for continuous improvement. Med Teach. 2018;40(8):786-790. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2018.1484896

- Brockfeld T, Müller B, de Laffolie J. Video versus live lecture courses: a comparative evaluation of lecture types and results. Med Educ Online. 2018;23(1):1555434. doi:10.1080/10872981.2018.1555434

- Davis J, Crabb S, Rogers E, Zamora J, Khan K. Computer-based teaching is as good as face to face lecture-based teaching of evidence based medicine: a randomized controlled trial. Med Teach. 2008;30(3):302-307. doi:10.1080/01421590701784349

- Markova T, Roth LM, Monsur J. Synchronous distance learning as an effective and feasible method for delivering residency didactics. Fam Med. 2005;37(8):570-575.

- Naciri A, Radid M, Kharbach A, Chemsi G. E-learning in health professions education during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2021;18:27. doi:10.3352/jeehp.2021.18.27

- Dedeilia A, Sotiropoulos MG, Hanrahan JG, Janga D, Dedeilias P, Sideris M. Medical and surgical education challenges and innovations in the COVID-19 era: a systematic review. In Vivo. 2020;34(3 Suppl):1603-1611. doi:10.21873/invivo.11950

- Weber DJ, Albert DVF, Aravamuthan BR, Bernson-Leung ME, Bhatti D, Milligan TA. Training in neurology: rapid implementation of cross-institutional neurology resident education in the time of COVID-19. Neurology. 2020;95(19):883-886. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000010753

- Frey J, Neeley B, Umer A, et al. Training in neurology: neuro day: an innovative curriculum connecting medical students with patients. Neurology. 2021;96(10):e1482- e1486. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000010859

- Schwartzstein RM, Dienstag JL, King RW, et al. The Harvard Medical School Pathways Curriculum: reimagining developmentally appropriate medical education for contemporary learners. Acad Med. 2020;95(11):1687-1695. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003270

- Greer DM, Moeller J, Torres DR, et al. Funding the educational mission in neurology. Neurology. 2021;96(12):574- 582. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000011635

- Thielke S, Tumosa N, Lindenfeld R, Shay K. Geriatric focused educational offerings in the Department of Veterans Affairs from 1999 to 2009. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2011;32(1):38-53. doi:10.1080/02701960.2011.550214

Neurologic disorders are major causes of death and disability. Globally, the burden of neurologic disorders continues to increase. The prevalence of disabling neurologic disorders significantly increases with age. As people live longer, health care systems will face increasing demands for treatment, rehabilitation, and support services for neurologic disorders. The scarcity of established modifiable risks for most of the neurologic burden demonstrates how new knowledge is required to develop effective prevention and treatment strategies.1

A single-center study for chronic headache at a rural institution found that, when combined with public education, clinician education not only can increase access to care but also reduce specialist overuse, hospitalizations, polypharmacy, and emergency department visits.2 A predicted shortage of neurologists has sparked increased interest in the field and individual neurology educators are helping fuel its popularity.3-5

TELE-EDUCATION

Educating the next generation of health professionals is 1 of 4 statutory missions of the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA).6 Tele-education (also known as telelearning and distance learning) deviates from traditional in-person classroom settings, in which the lecture has been a core pedagogic method.7 Audio, video, and online technologies provide health education and can overcome geographic barriers for rural and remote clinicians.8 Recent technological improvements have allowed for inexpensive and efficient dissemination of educational materials, including video lectures, podcasts, online modules, assessment materials, and even entire curricula.9

There has been an increase in the awareness of the parallel curriculum involving self-directed and asynchronous learning opportunities. 10 Several studies report knowledge gained via tele-education is comparable to conventional classroom learning.11-13 A systematic review of e-learning perceptions among health care students suggested benefits (eg, learning flexibility, pedagogical design, online interactions, basic computer skills, and access to technology) and drawbacks (eg, limited acquisition of clinical skills, internet connection problems, and issues with using educational platforms).1

The COVID-19 pandemic forced an abrupt cessation of traditional in-person education, forcing educational institutions and medical organizations to transition to telelearning. Solutions in the education field appeared during the pandemic, such as videoconferencing, social media, and telemedicine, that effectively addressed the sudden cessation of in-person medical education.15

Graduate medical education in neurology residency programs served as an experimental set up for tele-education during the pandemic. Residents from neurology training programs outlined the benefits of a volunteer lecturer-based online didactic program that was established to meet this need, which included exposure to subspeciality topics, access to subspecialist experts not available within the department, exposure to different pedagogic methods, interaction with members of other educational institutions and training programs, career development opportunities, and the potential for forming a community of learning.16

Not all recent educational developments are technology-based. For example, instruction focused on specific patient experiences, and learning processes that emphasize problem solving and personal responsibility over specific knowledge have been successful in neurology.17,18 Departments and institutions must be creative in finding ways to fund continuing education, especially when budgets are limited.19

ANNUAL NEUROLOGY SEMINAR

An annual Veterans Health Administration (VHA) neurology seminar began in 2019 as a 1-day in-person event. Neurologists at the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center in Houston presented in 50-minute sessions. Nonspecialist clinical personnel and neurology clinicians attended the event. Attendees requested making the presentations widely available and regularly repeating the seminar.