User login

Leiomyosarcoma of the Penis: A Case Report and Re-Appraisal

Penile cancer is rare with a worldwide incidence of 0.8 cases per 100,000 men.1 The most common type is squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) followed by soft tissue sarcoma (STS) and Kaposi sarcoma.2 Leiomyosarcoma (LMS) is the second most common STS subtype at this location.3 Approximately 50 cases of penile LMS have been reported in the English literature, most as isolated case reports while Fetsch and colleagues reported 14 cases from a single institute.4 We present a case of penile LMS with a review of 31 cases. We also describe presentation, treatment options, and recurrence pattern of this rare malignancy.

Case Presentation

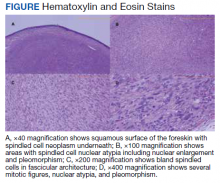

A patient aged 70 years presented to the urology clinic with 1-year history of a slowly enlarging penile mass associated with phimosis. He reported no pain, dysuria, or hesitancy. On examination a 2 × 2-cm smooth, mobile, nonulcerating mass was seen on the tip of his left glans without inguinal lymphadenopathy. He underwent circumcision and excision biopsy that revealed an encapsulated tan-white mass measuring 3 × 2.2 × 1.5 cm under the surface of the foreskin. Histology showed a spindle cell tumor with areas of increased cellularity, prominent atypia, and pleomorphism, focal necrosis, and scattered mitoses, including atypical forms. The tumor stained positive for smooth muscle actin and desmin. Ki-67 staining showed foci with a very high proliferation index (Figure). Resection margins were negative. Final Fédération Nationale des Centres de Lutte Contre Le Cancer score was grade 2 (differentiation, 1; mitotic, 3; necrosis, 1). Computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis did not show evidence of metastasis. The tumor was classified as superficial, stage IIA (pT1cN0cM0). Local excision with negative margins was deemed adequate treatment.

Discussion

Penile LMS is rare and arises from smooth muscles, which in the penis can be from dartos fascia, erector pili in the skin covering the shaft, or from tunica media of the superficial vessels and cavernosa.5 It commonly presents as a nodule or ulcer that might be accompanied by paraphimosis, phimosis, erectile dysfunction, and lower urinary tract symptoms depending on the extent of local tissue involvement. In our review of 31 cases, the age at presentation ranged from 38 to 85 years, with 1 case report of LMS in a 6-year-old. The highest incidence was in the 6th decade. Tumor behavior can be indolent or aggressive. Most patients in our review had asymptomatic, slow-growing lesions for 6 to 24 months before presentation—including our patient—while others had an aggressive tumor with symptoms for a few weeks followed by rapid metastatic spread.6,7

Histology and Staging

Diagnosis requires biopsy followed by histologic examination and immunohistochemistry of the lesion. Typically, LMS shows fascicles of spindle cells with varying degrees of nuclear atypia, pleomorphisms, and necrotic regions. Mitotic rate is variable and usually > 5 per high power field. Cells stain positive for smooth muscle actin, desmin, and h-caldesmon.8 TNM (tumor, nodes, metastasis) stage is determined by the American Joint Committee on Cancer guidelines for STS.

Pratt and colleagues were the first to categorize penile LMS as superficial or deep.9 The former includes all lesions superficial to tunica albuginea while the latter run deep to this layer. Anatomical distinction is an important factor in tumor behavior, treatment selection, and prognosis. In our review, we found 14 cases of superficial and 17 cases of deep LMS.

Treatment

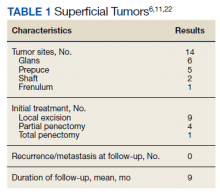

There are no established guidelines on optimum treatment of penile LMS. However, we can extrapolate principles from current guidelines on penile cancer, cutaneous leiomyosarcoma, and limb sarcomas. At present, the first-line treatment for superficial penile LMS is wide local excision to achieve negative margins. Circumcision alone might be sufficient for tumors of the distal prepuce, as in our case.10 Radical resection generally is not required for these early-stage tumors. In our review, no patient in this category developed recurrence or metastasis regardless of initial surgery type (Table 1).6,11,12

For deep lesions, partial—if functional penile stump and negative margins can be achieved—or total penectomy is required.10 In our review, more conservative approaches to deep tumors were associated with local recurrences.7,13,14 Lymphatic spread is rare for LMS. Additionally, involvement of local lymph nodes usually coincides with distant spread. Inguinal lymph node dissection is not indicated if initial negative surgical margins are achieved.

For STS at other sites in the body, radiation therapy is recommended postoperatively for high-grade lesions, which can be extrapolated to penile LMS as well. The benefit of preoperative radiation therapy is less certain. In limb sarcomas, radiation is associated with better local control for large-sized tumors and is used for patients with initial unresectable tumors.15 Similar recommendation could be extended to penile LMS with local spread to inguinal lymph nodes, scrotum, or abdominal wall. In our review, postoperative radiation therapy was used in 3 patients with deep tumors.16-18 Of these, short-term relapse occurred in 1 patient.

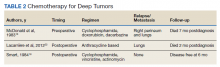

Chemotherapy for LMS remains controversial. The tumor generally is resistant to chemotherapy and systemic therapy, if employed, is for palliative purpose. The most promising results for adjuvant chemotherapy for resectable STS is seen in limb and uterine sarcomas with high-grade, metastatic, or relapsed tumors but improvement in overall survival has been marginal.19,20Single and multidrug regimens based on doxorubicin, ifosfamide, and gemcitabine have been studied with results showing no efficacy or a slight benefit.8,21 Immunotherapy and targeted therapy for penile STS have not been studied. In our review, postoperative chemotherapy was used for 2 patients with deep tumors and 1 patient with a superficial tumor while preoperative chemotherapy was used for 1 patient.16,18,22 Short-term relapse was seen in 2 of 4 of these patients (Table 2).

Metastatic Disease

LMS tends to metastasize hematogenously and lymphatic spread is uncommon. In our review, 7 patients developed metastasis. These patients had deep tumors at presentation with tumor size > 3 cm. Five of 7 patients had involvement of corpora cavernosa at presentation. The lung was the most common site of metastasis, followed by local extension to lower abdominal wall and scrotum. Of the 7 patients, 3 were treated with initial limited excision or partial penectomy and then experienced local recurrence or distant metastasis.7,13,14,23 This supports the use of radical surgery in large, deep tumors. In an additional 4 cases, metastasis occurred despite initial treatment with total penectomy and use of adjuvant chemoradiation therapy.

In most cases penile LMS is a de novo tumor, however, on occasion it could be accompanied by another epithelial malignancy. Similarly, penile LMS might be a site of recurrence for a primary LMS at another site, as seen in 3 of the reviewed cases. In the first, a patient presented with a nodule on the glans suspicious for SCC, second with synchronous SCC and LMS, and a third case where a patient presented with penile LMS 9 years after being treated for similar tumor in the epididymis.17,24,25

Prognosis

Penile LMS prognosis is difficult to ascertain because reported cases are rare. In our review, the longest documented disease-free survival was 3.5 years for a patient with superficial LMS treated with local excision.26 In cases of distant metastasis, average survival was 4.6 months, while the longest survival since initial presentation and last documented local recurrence was 16 years.14 Five-year survival has not been reported.

Conclusions

LMS of the penis is a rare and potentially aggressive malignancy. It can be classified as superficial or deep based on tumor relation to the tunica albuginea. Deep tumors, those > 3 cm, high-grade lesions, and tumors with involvement of corpora cavernosa, tend to spread locally, metastasize to distant areas, and require more radical surgery with or without postoperative radiation therapy. In comparison, superficial lesions can be treated with local excision only. Both superficial and deep tumors require close follow-up.

1. Montes Cardona CE, García-Perdomo HA. Incidence of penile cancer worldwide: systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2017;41:e117. Published 2017 Nov 30. doi:10.26633/RPSP.2017.117

2. Volker HU, Zettl A, Haralambieva E, et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the larynx as a local relapse of squamous cell carcinoma—report of an unusual case. Head Neck. 2010;32(5):679-683. doi:10.1002/hed.21127

3. Wollina U, Steinbach F, Verma S, et al. Penile tumours: a review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28(10):1267-1276. doi:10.1111/jdv.12491

4. Fetsch JF, Davis CJ Jr, Miettinen M, Sesterhenn IA. Leiomyosarcoma of the penis: a clinicopathologic study of 14 cases with review of the literature and discussion of the differential diagnosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28(1):115-125. doi:10.1097/00000478-200401000-00014

5. Sundersingh S, Majhi U, Narayanaswamy K, Balasubramanian S. Primary leiomyosarcoma of the penis. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2009;52(3):447-448. doi:10.4103/0377-4929.55028

6. Mendis D, Bott SR, Davies JH. Subcutaneous leiomyosarcoma of the frenulum. Scientific World J. 2005;5:571-575. doi:10.1100/tsw.2005.76

7. Elem B, Nieslanik J. Leiomyosarcoma of the penis. Br J Urol. 1979;51(1):46. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410x.1979.tb04244.x

8. Serrano C, George S. Leiomyosarcoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2013;27(5):957-974. doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2013.07.002

9. Pratt RM, Ross RT. Leiomyosarcoma of the penis. A report of a case. Br J Surg. 1969;56(11):870-872. doi:10.1002/bjs.1800561122

10. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Penile cancer. NCCN evidence blocks. Version 2.2022 Updated January 26, 2022. Accessed March 16, 2022. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/penile_blocks.pdf

11. Ashley DJ, Edwards EC. Sarcoma of the penis; leiomyosarcoma of the penis: report of a case with a review of the literature on sarcoma of the penis. Br J Surg. 1957;45(190):170-179. doi:10.1002/bjs.18004519011

12. Pow-Sang MR, Orihuela E. Leiomyosarcoma of the penis. J Urol. 1994;151(6):1643-1645. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35328-413. Isa SS, Almaraz R, Magovern J. Leiomyosarcoma of the penis. Case report and review of the literature. Cancer. 1984;54(5):939-942. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19840901)54:5<939::aid-cncr2820540533>3.0.co;2-y

14. Hutcheson JB, Wittaker WW, Fronstin MH. Leiomyosarcoma of the penis: case report and review of literature. J Urol. 1969;101(6):874-875. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(17)62446-7

15. Grimer R, Judson I, Peake D, et al. Guidelines for the management of soft tissue sarcomas. Sarcoma. 2010;2010:506182. doi:10.1155/2010/506182

16. McDonald MW, O’Connell JR, Manning JT, Benjamin RS. Leiomyosarcoma of the penis. J Urol. 1983;130(4):788-789. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(17)51464-0

17. Planz B, Brunner K, Kalem T, Schlick RW, Kind M. Primary leiomyosarcoma of the epididymis and late recurrence on the penis. J Urol. 1998;159(2):508. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(01)63966-1

18. Smart RH. Leiomyosarcoma of the penis. J Urol. 1984;132(2):356-357. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(17)49624-8

19. Patrikidou A, Domont J, Cioffi A, Le Cesne A. Treating soft tissue sarcomas with adjuvant chemotherapy. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2011;12(1):21-31. doi:10.1007/s11864-011-0145-5

20. Italiano A, Delva F, Mathoulin-Pelissier S, et al. Effect of adjuvant chemotherapy on survival in FNCLCC grade 3 soft tissue sarcomas: a multivariate analysis of the French Sarcoma Group Database. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(12):2436-2441. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdq238

21. Pervaiz N, Colterjohn N, Farrokhyar F, Tozer R, Figueredo A, Ghert M. A systematic meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of adjuvant chemotherapy for localized resectable soft-tissue sarcoma. Cancer. 2008;113(3):573-581. doi:10.1002/cncr.23592

22. Lacarrière E, Galliot I, Gobet F, Sibert L. Leiomyosarcoma of the corpus cavernosum mimicking a Peyronie’s plaque. Urology. 2012;79(4):e53-e54. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2011.07.1410

23. Hamal PB. Leiomyosarcoma of penis—case report and review of the literature. Br J Urol. 1975;47(3):319-324. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410x.1975.tb03974.x

24. Greenwood N, Fox H, Edwards EC. Leiomyosarcoma of the penis. Cancer. 1972;29(2):481-483. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(197202)29:2<481::aid -cncr2820290237>3.0.co;2-q

25. Koizumi H, Nagano K, Kosaka S. A case of penile tumor: combination of leiomyosarcoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Hinyokika Kiyo. 1987;33(9):1489-1491.

26. Romero Gonzalez EJ, Marenco Jimenez JL, Mayorga Pineda MP, Martínez Morán A, Castiñeiras Fernández J. Leiomyosarcoma of the penis, an exceptional entity. Urol Case Rep. 2015;3(3):63-64. doi:10.1016/j.eucr.2014.12.007

Penile cancer is rare with a worldwide incidence of 0.8 cases per 100,000 men.1 The most common type is squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) followed by soft tissue sarcoma (STS) and Kaposi sarcoma.2 Leiomyosarcoma (LMS) is the second most common STS subtype at this location.3 Approximately 50 cases of penile LMS have been reported in the English literature, most as isolated case reports while Fetsch and colleagues reported 14 cases from a single institute.4 We present a case of penile LMS with a review of 31 cases. We also describe presentation, treatment options, and recurrence pattern of this rare malignancy.

Case Presentation

A patient aged 70 years presented to the urology clinic with 1-year history of a slowly enlarging penile mass associated with phimosis. He reported no pain, dysuria, or hesitancy. On examination a 2 × 2-cm smooth, mobile, nonulcerating mass was seen on the tip of his left glans without inguinal lymphadenopathy. He underwent circumcision and excision biopsy that revealed an encapsulated tan-white mass measuring 3 × 2.2 × 1.5 cm under the surface of the foreskin. Histology showed a spindle cell tumor with areas of increased cellularity, prominent atypia, and pleomorphism, focal necrosis, and scattered mitoses, including atypical forms. The tumor stained positive for smooth muscle actin and desmin. Ki-67 staining showed foci with a very high proliferation index (Figure). Resection margins were negative. Final Fédération Nationale des Centres de Lutte Contre Le Cancer score was grade 2 (differentiation, 1; mitotic, 3; necrosis, 1). Computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis did not show evidence of metastasis. The tumor was classified as superficial, stage IIA (pT1cN0cM0). Local excision with negative margins was deemed adequate treatment.

Discussion

Penile LMS is rare and arises from smooth muscles, which in the penis can be from dartos fascia, erector pili in the skin covering the shaft, or from tunica media of the superficial vessels and cavernosa.5 It commonly presents as a nodule or ulcer that might be accompanied by paraphimosis, phimosis, erectile dysfunction, and lower urinary tract symptoms depending on the extent of local tissue involvement. In our review of 31 cases, the age at presentation ranged from 38 to 85 years, with 1 case report of LMS in a 6-year-old. The highest incidence was in the 6th decade. Tumor behavior can be indolent or aggressive. Most patients in our review had asymptomatic, slow-growing lesions for 6 to 24 months before presentation—including our patient—while others had an aggressive tumor with symptoms for a few weeks followed by rapid metastatic spread.6,7

Histology and Staging

Diagnosis requires biopsy followed by histologic examination and immunohistochemistry of the lesion. Typically, LMS shows fascicles of spindle cells with varying degrees of nuclear atypia, pleomorphisms, and necrotic regions. Mitotic rate is variable and usually > 5 per high power field. Cells stain positive for smooth muscle actin, desmin, and h-caldesmon.8 TNM (tumor, nodes, metastasis) stage is determined by the American Joint Committee on Cancer guidelines for STS.

Pratt and colleagues were the first to categorize penile LMS as superficial or deep.9 The former includes all lesions superficial to tunica albuginea while the latter run deep to this layer. Anatomical distinction is an important factor in tumor behavior, treatment selection, and prognosis. In our review, we found 14 cases of superficial and 17 cases of deep LMS.

Treatment

There are no established guidelines on optimum treatment of penile LMS. However, we can extrapolate principles from current guidelines on penile cancer, cutaneous leiomyosarcoma, and limb sarcomas. At present, the first-line treatment for superficial penile LMS is wide local excision to achieve negative margins. Circumcision alone might be sufficient for tumors of the distal prepuce, as in our case.10 Radical resection generally is not required for these early-stage tumors. In our review, no patient in this category developed recurrence or metastasis regardless of initial surgery type (Table 1).6,11,12

For deep lesions, partial—if functional penile stump and negative margins can be achieved—or total penectomy is required.10 In our review, more conservative approaches to deep tumors were associated with local recurrences.7,13,14 Lymphatic spread is rare for LMS. Additionally, involvement of local lymph nodes usually coincides with distant spread. Inguinal lymph node dissection is not indicated if initial negative surgical margins are achieved.

For STS at other sites in the body, radiation therapy is recommended postoperatively for high-grade lesions, which can be extrapolated to penile LMS as well. The benefit of preoperative radiation therapy is less certain. In limb sarcomas, radiation is associated with better local control for large-sized tumors and is used for patients with initial unresectable tumors.15 Similar recommendation could be extended to penile LMS with local spread to inguinal lymph nodes, scrotum, or abdominal wall. In our review, postoperative radiation therapy was used in 3 patients with deep tumors.16-18 Of these, short-term relapse occurred in 1 patient.

Chemotherapy for LMS remains controversial. The tumor generally is resistant to chemotherapy and systemic therapy, if employed, is for palliative purpose. The most promising results for adjuvant chemotherapy for resectable STS is seen in limb and uterine sarcomas with high-grade, metastatic, or relapsed tumors but improvement in overall survival has been marginal.19,20Single and multidrug regimens based on doxorubicin, ifosfamide, and gemcitabine have been studied with results showing no efficacy or a slight benefit.8,21 Immunotherapy and targeted therapy for penile STS have not been studied. In our review, postoperative chemotherapy was used for 2 patients with deep tumors and 1 patient with a superficial tumor while preoperative chemotherapy was used for 1 patient.16,18,22 Short-term relapse was seen in 2 of 4 of these patients (Table 2).

Metastatic Disease

LMS tends to metastasize hematogenously and lymphatic spread is uncommon. In our review, 7 patients developed metastasis. These patients had deep tumors at presentation with tumor size > 3 cm. Five of 7 patients had involvement of corpora cavernosa at presentation. The lung was the most common site of metastasis, followed by local extension to lower abdominal wall and scrotum. Of the 7 patients, 3 were treated with initial limited excision or partial penectomy and then experienced local recurrence or distant metastasis.7,13,14,23 This supports the use of radical surgery in large, deep tumors. In an additional 4 cases, metastasis occurred despite initial treatment with total penectomy and use of adjuvant chemoradiation therapy.

In most cases penile LMS is a de novo tumor, however, on occasion it could be accompanied by another epithelial malignancy. Similarly, penile LMS might be a site of recurrence for a primary LMS at another site, as seen in 3 of the reviewed cases. In the first, a patient presented with a nodule on the glans suspicious for SCC, second with synchronous SCC and LMS, and a third case where a patient presented with penile LMS 9 years after being treated for similar tumor in the epididymis.17,24,25

Prognosis

Penile LMS prognosis is difficult to ascertain because reported cases are rare. In our review, the longest documented disease-free survival was 3.5 years for a patient with superficial LMS treated with local excision.26 In cases of distant metastasis, average survival was 4.6 months, while the longest survival since initial presentation and last documented local recurrence was 16 years.14 Five-year survival has not been reported.

Conclusions

LMS of the penis is a rare and potentially aggressive malignancy. It can be classified as superficial or deep based on tumor relation to the tunica albuginea. Deep tumors, those > 3 cm, high-grade lesions, and tumors with involvement of corpora cavernosa, tend to spread locally, metastasize to distant areas, and require more radical surgery with or without postoperative radiation therapy. In comparison, superficial lesions can be treated with local excision only. Both superficial and deep tumors require close follow-up.

Penile cancer is rare with a worldwide incidence of 0.8 cases per 100,000 men.1 The most common type is squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) followed by soft tissue sarcoma (STS) and Kaposi sarcoma.2 Leiomyosarcoma (LMS) is the second most common STS subtype at this location.3 Approximately 50 cases of penile LMS have been reported in the English literature, most as isolated case reports while Fetsch and colleagues reported 14 cases from a single institute.4 We present a case of penile LMS with a review of 31 cases. We also describe presentation, treatment options, and recurrence pattern of this rare malignancy.

Case Presentation

A patient aged 70 years presented to the urology clinic with 1-year history of a slowly enlarging penile mass associated with phimosis. He reported no pain, dysuria, or hesitancy. On examination a 2 × 2-cm smooth, mobile, nonulcerating mass was seen on the tip of his left glans without inguinal lymphadenopathy. He underwent circumcision and excision biopsy that revealed an encapsulated tan-white mass measuring 3 × 2.2 × 1.5 cm under the surface of the foreskin. Histology showed a spindle cell tumor with areas of increased cellularity, prominent atypia, and pleomorphism, focal necrosis, and scattered mitoses, including atypical forms. The tumor stained positive for smooth muscle actin and desmin. Ki-67 staining showed foci with a very high proliferation index (Figure). Resection margins were negative. Final Fédération Nationale des Centres de Lutte Contre Le Cancer score was grade 2 (differentiation, 1; mitotic, 3; necrosis, 1). Computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis did not show evidence of metastasis. The tumor was classified as superficial, stage IIA (pT1cN0cM0). Local excision with negative margins was deemed adequate treatment.

Discussion

Penile LMS is rare and arises from smooth muscles, which in the penis can be from dartos fascia, erector pili in the skin covering the shaft, or from tunica media of the superficial vessels and cavernosa.5 It commonly presents as a nodule or ulcer that might be accompanied by paraphimosis, phimosis, erectile dysfunction, and lower urinary tract symptoms depending on the extent of local tissue involvement. In our review of 31 cases, the age at presentation ranged from 38 to 85 years, with 1 case report of LMS in a 6-year-old. The highest incidence was in the 6th decade. Tumor behavior can be indolent or aggressive. Most patients in our review had asymptomatic, slow-growing lesions for 6 to 24 months before presentation—including our patient—while others had an aggressive tumor with symptoms for a few weeks followed by rapid metastatic spread.6,7

Histology and Staging

Diagnosis requires biopsy followed by histologic examination and immunohistochemistry of the lesion. Typically, LMS shows fascicles of spindle cells with varying degrees of nuclear atypia, pleomorphisms, and necrotic regions. Mitotic rate is variable and usually > 5 per high power field. Cells stain positive for smooth muscle actin, desmin, and h-caldesmon.8 TNM (tumor, nodes, metastasis) stage is determined by the American Joint Committee on Cancer guidelines for STS.

Pratt and colleagues were the first to categorize penile LMS as superficial or deep.9 The former includes all lesions superficial to tunica albuginea while the latter run deep to this layer. Anatomical distinction is an important factor in tumor behavior, treatment selection, and prognosis. In our review, we found 14 cases of superficial and 17 cases of deep LMS.

Treatment

There are no established guidelines on optimum treatment of penile LMS. However, we can extrapolate principles from current guidelines on penile cancer, cutaneous leiomyosarcoma, and limb sarcomas. At present, the first-line treatment for superficial penile LMS is wide local excision to achieve negative margins. Circumcision alone might be sufficient for tumors of the distal prepuce, as in our case.10 Radical resection generally is not required for these early-stage tumors. In our review, no patient in this category developed recurrence or metastasis regardless of initial surgery type (Table 1).6,11,12

For deep lesions, partial—if functional penile stump and negative margins can be achieved—or total penectomy is required.10 In our review, more conservative approaches to deep tumors were associated with local recurrences.7,13,14 Lymphatic spread is rare for LMS. Additionally, involvement of local lymph nodes usually coincides with distant spread. Inguinal lymph node dissection is not indicated if initial negative surgical margins are achieved.

For STS at other sites in the body, radiation therapy is recommended postoperatively for high-grade lesions, which can be extrapolated to penile LMS as well. The benefit of preoperative radiation therapy is less certain. In limb sarcomas, radiation is associated with better local control for large-sized tumors and is used for patients with initial unresectable tumors.15 Similar recommendation could be extended to penile LMS with local spread to inguinal lymph nodes, scrotum, or abdominal wall. In our review, postoperative radiation therapy was used in 3 patients with deep tumors.16-18 Of these, short-term relapse occurred in 1 patient.

Chemotherapy for LMS remains controversial. The tumor generally is resistant to chemotherapy and systemic therapy, if employed, is for palliative purpose. The most promising results for adjuvant chemotherapy for resectable STS is seen in limb and uterine sarcomas with high-grade, metastatic, or relapsed tumors but improvement in overall survival has been marginal.19,20Single and multidrug regimens based on doxorubicin, ifosfamide, and gemcitabine have been studied with results showing no efficacy or a slight benefit.8,21 Immunotherapy and targeted therapy for penile STS have not been studied. In our review, postoperative chemotherapy was used for 2 patients with deep tumors and 1 patient with a superficial tumor while preoperative chemotherapy was used for 1 patient.16,18,22 Short-term relapse was seen in 2 of 4 of these patients (Table 2).

Metastatic Disease

LMS tends to metastasize hematogenously and lymphatic spread is uncommon. In our review, 7 patients developed metastasis. These patients had deep tumors at presentation with tumor size > 3 cm. Five of 7 patients had involvement of corpora cavernosa at presentation. The lung was the most common site of metastasis, followed by local extension to lower abdominal wall and scrotum. Of the 7 patients, 3 were treated with initial limited excision or partial penectomy and then experienced local recurrence or distant metastasis.7,13,14,23 This supports the use of radical surgery in large, deep tumors. In an additional 4 cases, metastasis occurred despite initial treatment with total penectomy and use of adjuvant chemoradiation therapy.

In most cases penile LMS is a de novo tumor, however, on occasion it could be accompanied by another epithelial malignancy. Similarly, penile LMS might be a site of recurrence for a primary LMS at another site, as seen in 3 of the reviewed cases. In the first, a patient presented with a nodule on the glans suspicious for SCC, second with synchronous SCC and LMS, and a third case where a patient presented with penile LMS 9 years after being treated for similar tumor in the epididymis.17,24,25

Prognosis

Penile LMS prognosis is difficult to ascertain because reported cases are rare. In our review, the longest documented disease-free survival was 3.5 years for a patient with superficial LMS treated with local excision.26 In cases of distant metastasis, average survival was 4.6 months, while the longest survival since initial presentation and last documented local recurrence was 16 years.14 Five-year survival has not been reported.

Conclusions

LMS of the penis is a rare and potentially aggressive malignancy. It can be classified as superficial or deep based on tumor relation to the tunica albuginea. Deep tumors, those > 3 cm, high-grade lesions, and tumors with involvement of corpora cavernosa, tend to spread locally, metastasize to distant areas, and require more radical surgery with or without postoperative radiation therapy. In comparison, superficial lesions can be treated with local excision only. Both superficial and deep tumors require close follow-up.

1. Montes Cardona CE, García-Perdomo HA. Incidence of penile cancer worldwide: systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2017;41:e117. Published 2017 Nov 30. doi:10.26633/RPSP.2017.117

2. Volker HU, Zettl A, Haralambieva E, et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the larynx as a local relapse of squamous cell carcinoma—report of an unusual case. Head Neck. 2010;32(5):679-683. doi:10.1002/hed.21127

3. Wollina U, Steinbach F, Verma S, et al. Penile tumours: a review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28(10):1267-1276. doi:10.1111/jdv.12491

4. Fetsch JF, Davis CJ Jr, Miettinen M, Sesterhenn IA. Leiomyosarcoma of the penis: a clinicopathologic study of 14 cases with review of the literature and discussion of the differential diagnosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28(1):115-125. doi:10.1097/00000478-200401000-00014

5. Sundersingh S, Majhi U, Narayanaswamy K, Balasubramanian S. Primary leiomyosarcoma of the penis. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2009;52(3):447-448. doi:10.4103/0377-4929.55028

6. Mendis D, Bott SR, Davies JH. Subcutaneous leiomyosarcoma of the frenulum. Scientific World J. 2005;5:571-575. doi:10.1100/tsw.2005.76

7. Elem B, Nieslanik J. Leiomyosarcoma of the penis. Br J Urol. 1979;51(1):46. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410x.1979.tb04244.x

8. Serrano C, George S. Leiomyosarcoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2013;27(5):957-974. doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2013.07.002

9. Pratt RM, Ross RT. Leiomyosarcoma of the penis. A report of a case. Br J Surg. 1969;56(11):870-872. doi:10.1002/bjs.1800561122

10. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Penile cancer. NCCN evidence blocks. Version 2.2022 Updated January 26, 2022. Accessed March 16, 2022. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/penile_blocks.pdf

11. Ashley DJ, Edwards EC. Sarcoma of the penis; leiomyosarcoma of the penis: report of a case with a review of the literature on sarcoma of the penis. Br J Surg. 1957;45(190):170-179. doi:10.1002/bjs.18004519011

12. Pow-Sang MR, Orihuela E. Leiomyosarcoma of the penis. J Urol. 1994;151(6):1643-1645. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35328-413. Isa SS, Almaraz R, Magovern J. Leiomyosarcoma of the penis. Case report and review of the literature. Cancer. 1984;54(5):939-942. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19840901)54:5<939::aid-cncr2820540533>3.0.co;2-y

14. Hutcheson JB, Wittaker WW, Fronstin MH. Leiomyosarcoma of the penis: case report and review of literature. J Urol. 1969;101(6):874-875. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(17)62446-7

15. Grimer R, Judson I, Peake D, et al. Guidelines for the management of soft tissue sarcomas. Sarcoma. 2010;2010:506182. doi:10.1155/2010/506182

16. McDonald MW, O’Connell JR, Manning JT, Benjamin RS. Leiomyosarcoma of the penis. J Urol. 1983;130(4):788-789. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(17)51464-0

17. Planz B, Brunner K, Kalem T, Schlick RW, Kind M. Primary leiomyosarcoma of the epididymis and late recurrence on the penis. J Urol. 1998;159(2):508. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(01)63966-1

18. Smart RH. Leiomyosarcoma of the penis. J Urol. 1984;132(2):356-357. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(17)49624-8

19. Patrikidou A, Domont J, Cioffi A, Le Cesne A. Treating soft tissue sarcomas with adjuvant chemotherapy. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2011;12(1):21-31. doi:10.1007/s11864-011-0145-5

20. Italiano A, Delva F, Mathoulin-Pelissier S, et al. Effect of adjuvant chemotherapy on survival in FNCLCC grade 3 soft tissue sarcomas: a multivariate analysis of the French Sarcoma Group Database. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(12):2436-2441. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdq238

21. Pervaiz N, Colterjohn N, Farrokhyar F, Tozer R, Figueredo A, Ghert M. A systematic meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of adjuvant chemotherapy for localized resectable soft-tissue sarcoma. Cancer. 2008;113(3):573-581. doi:10.1002/cncr.23592

22. Lacarrière E, Galliot I, Gobet F, Sibert L. Leiomyosarcoma of the corpus cavernosum mimicking a Peyronie’s plaque. Urology. 2012;79(4):e53-e54. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2011.07.1410

23. Hamal PB. Leiomyosarcoma of penis—case report and review of the literature. Br J Urol. 1975;47(3):319-324. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410x.1975.tb03974.x

24. Greenwood N, Fox H, Edwards EC. Leiomyosarcoma of the penis. Cancer. 1972;29(2):481-483. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(197202)29:2<481::aid -cncr2820290237>3.0.co;2-q

25. Koizumi H, Nagano K, Kosaka S. A case of penile tumor: combination of leiomyosarcoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Hinyokika Kiyo. 1987;33(9):1489-1491.

26. Romero Gonzalez EJ, Marenco Jimenez JL, Mayorga Pineda MP, Martínez Morán A, Castiñeiras Fernández J. Leiomyosarcoma of the penis, an exceptional entity. Urol Case Rep. 2015;3(3):63-64. doi:10.1016/j.eucr.2014.12.007

1. Montes Cardona CE, García-Perdomo HA. Incidence of penile cancer worldwide: systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2017;41:e117. Published 2017 Nov 30. doi:10.26633/RPSP.2017.117

2. Volker HU, Zettl A, Haralambieva E, et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the larynx as a local relapse of squamous cell carcinoma—report of an unusual case. Head Neck. 2010;32(5):679-683. doi:10.1002/hed.21127

3. Wollina U, Steinbach F, Verma S, et al. Penile tumours: a review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28(10):1267-1276. doi:10.1111/jdv.12491

4. Fetsch JF, Davis CJ Jr, Miettinen M, Sesterhenn IA. Leiomyosarcoma of the penis: a clinicopathologic study of 14 cases with review of the literature and discussion of the differential diagnosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28(1):115-125. doi:10.1097/00000478-200401000-00014

5. Sundersingh S, Majhi U, Narayanaswamy K, Balasubramanian S. Primary leiomyosarcoma of the penis. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2009;52(3):447-448. doi:10.4103/0377-4929.55028

6. Mendis D, Bott SR, Davies JH. Subcutaneous leiomyosarcoma of the frenulum. Scientific World J. 2005;5:571-575. doi:10.1100/tsw.2005.76

7. Elem B, Nieslanik J. Leiomyosarcoma of the penis. Br J Urol. 1979;51(1):46. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410x.1979.tb04244.x

8. Serrano C, George S. Leiomyosarcoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2013;27(5):957-974. doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2013.07.002

9. Pratt RM, Ross RT. Leiomyosarcoma of the penis. A report of a case. Br J Surg. 1969;56(11):870-872. doi:10.1002/bjs.1800561122

10. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Penile cancer. NCCN evidence blocks. Version 2.2022 Updated January 26, 2022. Accessed March 16, 2022. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/penile_blocks.pdf

11. Ashley DJ, Edwards EC. Sarcoma of the penis; leiomyosarcoma of the penis: report of a case with a review of the literature on sarcoma of the penis. Br J Surg. 1957;45(190):170-179. doi:10.1002/bjs.18004519011

12. Pow-Sang MR, Orihuela E. Leiomyosarcoma of the penis. J Urol. 1994;151(6):1643-1645. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35328-413. Isa SS, Almaraz R, Magovern J. Leiomyosarcoma of the penis. Case report and review of the literature. Cancer. 1984;54(5):939-942. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19840901)54:5<939::aid-cncr2820540533>3.0.co;2-y

14. Hutcheson JB, Wittaker WW, Fronstin MH. Leiomyosarcoma of the penis: case report and review of literature. J Urol. 1969;101(6):874-875. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(17)62446-7

15. Grimer R, Judson I, Peake D, et al. Guidelines for the management of soft tissue sarcomas. Sarcoma. 2010;2010:506182. doi:10.1155/2010/506182

16. McDonald MW, O’Connell JR, Manning JT, Benjamin RS. Leiomyosarcoma of the penis. J Urol. 1983;130(4):788-789. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(17)51464-0

17. Planz B, Brunner K, Kalem T, Schlick RW, Kind M. Primary leiomyosarcoma of the epididymis and late recurrence on the penis. J Urol. 1998;159(2):508. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(01)63966-1

18. Smart RH. Leiomyosarcoma of the penis. J Urol. 1984;132(2):356-357. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(17)49624-8

19. Patrikidou A, Domont J, Cioffi A, Le Cesne A. Treating soft tissue sarcomas with adjuvant chemotherapy. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2011;12(1):21-31. doi:10.1007/s11864-011-0145-5

20. Italiano A, Delva F, Mathoulin-Pelissier S, et al. Effect of adjuvant chemotherapy on survival in FNCLCC grade 3 soft tissue sarcomas: a multivariate analysis of the French Sarcoma Group Database. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(12):2436-2441. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdq238

21. Pervaiz N, Colterjohn N, Farrokhyar F, Tozer R, Figueredo A, Ghert M. A systematic meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of adjuvant chemotherapy for localized resectable soft-tissue sarcoma. Cancer. 2008;113(3):573-581. doi:10.1002/cncr.23592

22. Lacarrière E, Galliot I, Gobet F, Sibert L. Leiomyosarcoma of the corpus cavernosum mimicking a Peyronie’s plaque. Urology. 2012;79(4):e53-e54. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2011.07.1410

23. Hamal PB. Leiomyosarcoma of penis—case report and review of the literature. Br J Urol. 1975;47(3):319-324. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410x.1975.tb03974.x

24. Greenwood N, Fox H, Edwards EC. Leiomyosarcoma of the penis. Cancer. 1972;29(2):481-483. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(197202)29:2<481::aid -cncr2820290237>3.0.co;2-q

25. Koizumi H, Nagano K, Kosaka S. A case of penile tumor: combination of leiomyosarcoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Hinyokika Kiyo. 1987;33(9):1489-1491.

26. Romero Gonzalez EJ, Marenco Jimenez JL, Mayorga Pineda MP, Martínez Morán A, Castiñeiras Fernández J. Leiomyosarcoma of the penis, an exceptional entity. Urol Case Rep. 2015;3(3):63-64. doi:10.1016/j.eucr.2014.12.007

A Single-Center Experience of Cardiac-related Adverse Events from Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors

Introduction

There have been incident reports of cardiac-related adverse events (CrAE) from immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICPI); however, the true incidence and subsequent management of these potential side effects have not been defined. It is therefore important to study ICPI related cardiac dysfunction to assist in monitoring and surveillance of these patients.

Methods

63 patients who received nivolumab and pembrolizumab at Stratton VAMC Albany between January 2015 to December 2018 were studied. Retrospective chart review was done to identify the CrAE up to two-year post-therapy completion or discontinuation. Naranjo score was used to assess drug-related side effect. IRB approval was obtained.

Results

CrAE were defined as new onset arrythmia identified on electrocardiogram, evidence of cardiomyopathy on echocardiogram, an acute coronary event, and hospitalizations from primary cardiac disorder following ICPI administration. Of the 63 patients, 6 patients developed CrAE. Our review showed 3 patients developed new arrythmias including 1 with atrial fibrillation, and 2 with atrial flutter. There was 1 case each of new heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and pericarditis with pericardial tamponade. 1 patient developed acute coronary syndrome in addition to complete heart block. Of the 6 patients, 2 had elevated brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) prior to onset of CrAE. Elevated markers including BNP and troponin-I were also seen in 13 patients with preexisting heart conditions without CrAE. Duration of therapy was variable for all patients with CrAE. Therapy was continued for 3 patients without recurrence of CrAE. Therapy was permanently discontinued in the patient who developed pericardial effusion (grade IV toxicity). The remaining 2 patients had additional concurrent immune-related toxicities that required discontinuation of therapy. Our analysis showed 25/63 patients with pre-existing cardiac conditions (including arrhythmia, heart failure or coronary artery disease) who did not develop new CrAE; however 6 of these patients required hospitalization for exacerbation related to these pre-existing conditions.

Conclusions

CrAE can occur with ICPIs, and vigilance is required in high-risk patient including those with pre-existing cardiac comorbidity. Further studies are required to establish if baseline screening EKG and echocardiogram should be obtained for all patients starting ICPI.

Introduction

There have been incident reports of cardiac-related adverse events (CrAE) from immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICPI); however, the true incidence and subsequent management of these potential side effects have not been defined. It is therefore important to study ICPI related cardiac dysfunction to assist in monitoring and surveillance of these patients.

Methods

63 patients who received nivolumab and pembrolizumab at Stratton VAMC Albany between January 2015 to December 2018 were studied. Retrospective chart review was done to identify the CrAE up to two-year post-therapy completion or discontinuation. Naranjo score was used to assess drug-related side effect. IRB approval was obtained.

Results

CrAE were defined as new onset arrythmia identified on electrocardiogram, evidence of cardiomyopathy on echocardiogram, an acute coronary event, and hospitalizations from primary cardiac disorder following ICPI administration. Of the 63 patients, 6 patients developed CrAE. Our review showed 3 patients developed new arrythmias including 1 with atrial fibrillation, and 2 with atrial flutter. There was 1 case each of new heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and pericarditis with pericardial tamponade. 1 patient developed acute coronary syndrome in addition to complete heart block. Of the 6 patients, 2 had elevated brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) prior to onset of CrAE. Elevated markers including BNP and troponin-I were also seen in 13 patients with preexisting heart conditions without CrAE. Duration of therapy was variable for all patients with CrAE. Therapy was continued for 3 patients without recurrence of CrAE. Therapy was permanently discontinued in the patient who developed pericardial effusion (grade IV toxicity). The remaining 2 patients had additional concurrent immune-related toxicities that required discontinuation of therapy. Our analysis showed 25/63 patients with pre-existing cardiac conditions (including arrhythmia, heart failure or coronary artery disease) who did not develop new CrAE; however 6 of these patients required hospitalization for exacerbation related to these pre-existing conditions.

Conclusions

CrAE can occur with ICPIs, and vigilance is required in high-risk patient including those with pre-existing cardiac comorbidity. Further studies are required to establish if baseline screening EKG and echocardiogram should be obtained for all patients starting ICPI.

Introduction

There have been incident reports of cardiac-related adverse events (CrAE) from immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICPI); however, the true incidence and subsequent management of these potential side effects have not been defined. It is therefore important to study ICPI related cardiac dysfunction to assist in monitoring and surveillance of these patients.

Methods

63 patients who received nivolumab and pembrolizumab at Stratton VAMC Albany between January 2015 to December 2018 were studied. Retrospective chart review was done to identify the CrAE up to two-year post-therapy completion or discontinuation. Naranjo score was used to assess drug-related side effect. IRB approval was obtained.

Results

CrAE were defined as new onset arrythmia identified on electrocardiogram, evidence of cardiomyopathy on echocardiogram, an acute coronary event, and hospitalizations from primary cardiac disorder following ICPI administration. Of the 63 patients, 6 patients developed CrAE. Our review showed 3 patients developed new arrythmias including 1 with atrial fibrillation, and 2 with atrial flutter. There was 1 case each of new heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and pericarditis with pericardial tamponade. 1 patient developed acute coronary syndrome in addition to complete heart block. Of the 6 patients, 2 had elevated brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) prior to onset of CrAE. Elevated markers including BNP and troponin-I were also seen in 13 patients with preexisting heart conditions without CrAE. Duration of therapy was variable for all patients with CrAE. Therapy was continued for 3 patients without recurrence of CrAE. Therapy was permanently discontinued in the patient who developed pericardial effusion (grade IV toxicity). The remaining 2 patients had additional concurrent immune-related toxicities that required discontinuation of therapy. Our analysis showed 25/63 patients with pre-existing cardiac conditions (including arrhythmia, heart failure or coronary artery disease) who did not develop new CrAE; however 6 of these patients required hospitalization for exacerbation related to these pre-existing conditions.

Conclusions

CrAE can occur with ICPIs, and vigilance is required in high-risk patient including those with pre-existing cardiac comorbidity. Further studies are required to establish if baseline screening EKG and echocardiogram should be obtained for all patients starting ICPI.

Racial Disparities in Treatment and Survival for Early-Stage Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Is Equal Access Health Care System the Answer?

Background

Survival for early-stage non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) has dramatically improved with advancement in surgical and radiation techniques over last two decades but there exists a disparity for African Americans (AA) having worse overall survival (OS) in recent studies on the general US population. We studied this racial disparity in Veteran population.

Methods

Data for 2589 AA and 14184 Caucasian Veterans diagnosed with early-stage (I, II) NSCLC between 2011-2017 was obtained from the Cancer Cube Registry (VACCR). IRB approval was obtained.

Results

The distribution of newly diagnosed cases of Stage I (73.92% AA vs 74.71% Caucasians) and Stage II (26.07% vs 25.29%) between the two races was comparable (p = .41). More Caucasians were diagnosed above the age of 60 compared to AA (92.22% vs 84.51%, p < .05). More AA were diagnosed with adenocarcinoma at diagnosis (56.01% vs 45.88% Caucasians, p < .05) for both Stage I and II disease. For the limited number of Veterans with reported performance status (PS), similar proportion of patients had a good PS defined as ECOG 0-2 among the two races (93.70% AA vs 93.97% Caucasians, p = .73). There was no statistically significant difference between 5-year OS for AA and Caucasians (69.81% vs 70.78%, p = .33) for both Stage I and II NSCLC. Both groups had similar rate of receipt of surgery as first line treatment or in combination with other treatments (58.90% AA vs 59.07% Caucasians, p = .90). Similarly, the rate of receiving radiation therapy was comparable between AA and Caucasians (42.4% vs 42.3%, p = .96). Although both races showed improved 5-year OS after surgery, there was no statistical difference in survival benefit between AA and Caucasians (69.8% vs 70.8%, p = .33).

Conclusion

In contrast to the studies assessing general US population trends, there was no racial disparity for 5-year OS in early-stage NSCLC for the Veteran population. This points to the inequities in access to treatment and preventive healthcare services as a possible contributing cause to the increased mortality in AA in general US population and a more equitable healthcare delivery within the VHA system.

Background

Survival for early-stage non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) has dramatically improved with advancement in surgical and radiation techniques over last two decades but there exists a disparity for African Americans (AA) having worse overall survival (OS) in recent studies on the general US population. We studied this racial disparity in Veteran population.

Methods

Data for 2589 AA and 14184 Caucasian Veterans diagnosed with early-stage (I, II) NSCLC between 2011-2017 was obtained from the Cancer Cube Registry (VACCR). IRB approval was obtained.

Results

The distribution of newly diagnosed cases of Stage I (73.92% AA vs 74.71% Caucasians) and Stage II (26.07% vs 25.29%) between the two races was comparable (p = .41). More Caucasians were diagnosed above the age of 60 compared to AA (92.22% vs 84.51%, p < .05). More AA were diagnosed with adenocarcinoma at diagnosis (56.01% vs 45.88% Caucasians, p < .05) for both Stage I and II disease. For the limited number of Veterans with reported performance status (PS), similar proportion of patients had a good PS defined as ECOG 0-2 among the two races (93.70% AA vs 93.97% Caucasians, p = .73). There was no statistically significant difference between 5-year OS for AA and Caucasians (69.81% vs 70.78%, p = .33) for both Stage I and II NSCLC. Both groups had similar rate of receipt of surgery as first line treatment or in combination with other treatments (58.90% AA vs 59.07% Caucasians, p = .90). Similarly, the rate of receiving radiation therapy was comparable between AA and Caucasians (42.4% vs 42.3%, p = .96). Although both races showed improved 5-year OS after surgery, there was no statistical difference in survival benefit between AA and Caucasians (69.8% vs 70.8%, p = .33).

Conclusion

In contrast to the studies assessing general US population trends, there was no racial disparity for 5-year OS in early-stage NSCLC for the Veteran population. This points to the inequities in access to treatment and preventive healthcare services as a possible contributing cause to the increased mortality in AA in general US population and a more equitable healthcare delivery within the VHA system.

Background

Survival for early-stage non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) has dramatically improved with advancement in surgical and radiation techniques over last two decades but there exists a disparity for African Americans (AA) having worse overall survival (OS) in recent studies on the general US population. We studied this racial disparity in Veteran population.

Methods

Data for 2589 AA and 14184 Caucasian Veterans diagnosed with early-stage (I, II) NSCLC between 2011-2017 was obtained from the Cancer Cube Registry (VACCR). IRB approval was obtained.

Results

The distribution of newly diagnosed cases of Stage I (73.92% AA vs 74.71% Caucasians) and Stage II (26.07% vs 25.29%) between the two races was comparable (p = .41). More Caucasians were diagnosed above the age of 60 compared to AA (92.22% vs 84.51%, p < .05). More AA were diagnosed with adenocarcinoma at diagnosis (56.01% vs 45.88% Caucasians, p < .05) for both Stage I and II disease. For the limited number of Veterans with reported performance status (PS), similar proportion of patients had a good PS defined as ECOG 0-2 among the two races (93.70% AA vs 93.97% Caucasians, p = .73). There was no statistically significant difference between 5-year OS for AA and Caucasians (69.81% vs 70.78%, p = .33) for both Stage I and II NSCLC. Both groups had similar rate of receipt of surgery as first line treatment or in combination with other treatments (58.90% AA vs 59.07% Caucasians, p = .90). Similarly, the rate of receiving radiation therapy was comparable between AA and Caucasians (42.4% vs 42.3%, p = .96). Although both races showed improved 5-year OS after surgery, there was no statistical difference in survival benefit between AA and Caucasians (69.8% vs 70.8%, p = .33).

Conclusion

In contrast to the studies assessing general US population trends, there was no racial disparity for 5-year OS in early-stage NSCLC for the Veteran population. This points to the inequities in access to treatment and preventive healthcare services as a possible contributing cause to the increased mortality in AA in general US population and a more equitable healthcare delivery within the VHA system.

Survival Analysis of Untreated Early-Stage Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) in a Veteran Population

Introduction

Veterans with early-stage NSCLC who do not receive any form of treatment have been shown to have a worse overall survival compared to those who receive treatment. Factors that may influence the decision to administer treatment including age, performance status (PS), comorbidities, and racial disparity have not been assessed on a national level in recent years.

Methods

Data for 31,966 veterans diagnosed with early-stage (0, I) NSCLC between 2003-2017 was obtained from the Cancer cube registry (VACCR). IRB approval was obtained.

Results

Patients were divided into treatment (26,833/31,966, 83.16%) and no-treatment group (3096/31966, 9.68%). Of the no-treatment group, 3004 patients were stage I and 92 were stage 0 whereas in the treatment group, the distribution was 26,584 and 249 respectively. Gender, race, and histology distribution were comparable between the two. Patients with poor PS (defined as ECOG III and IV) received less treatment with any modality compared to those with good PS (ECOG I and II) (15.07% in no treatment group vs 4.03% in treatment group, p<0.05). The treatment group had a better 5-year overall survival (OS) as compared to no-treatment group (43.1% vs 14.7%, p<0.05). Regardless of treatment, patients above the age of 60 (41% vs 13.4%, p<0.05) and those with poor PS (19.6% vs 5.8%, p<0.05) had worse 5-year survival, with the effect being greater in the treatment group. Adenocarcinoma had a better 5-year survival compared to squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) in both groups (49.56% vs 39.1% p<0.05). There was no clinically significant OS difference in terms of race (Caucasian or African American) or tumor location (upper, middle, or lower lobe) in between the two groups. Our study was limited by lack of patient- level data including smoking status or reason why no treatment was given.

Conclusion

Patients with early-stage NSCLC who receive no treatment based on poor PS have a worse overall survival compared to the patients that receive treatment. Further investigation is required to assess what other criteria are used to decide treatment eligibility and whether these patients would be candidates for immunotherapy or targeted therapy in the future.

Introduction

Veterans with early-stage NSCLC who do not receive any form of treatment have been shown to have a worse overall survival compared to those who receive treatment. Factors that may influence the decision to administer treatment including age, performance status (PS), comorbidities, and racial disparity have not been assessed on a national level in recent years.

Methods

Data for 31,966 veterans diagnosed with early-stage (0, I) NSCLC between 2003-2017 was obtained from the Cancer cube registry (VACCR). IRB approval was obtained.

Results

Patients were divided into treatment (26,833/31,966, 83.16%) and no-treatment group (3096/31966, 9.68%). Of the no-treatment group, 3004 patients were stage I and 92 were stage 0 whereas in the treatment group, the distribution was 26,584 and 249 respectively. Gender, race, and histology distribution were comparable between the two. Patients with poor PS (defined as ECOG III and IV) received less treatment with any modality compared to those with good PS (ECOG I and II) (15.07% in no treatment group vs 4.03% in treatment group, p<0.05). The treatment group had a better 5-year overall survival (OS) as compared to no-treatment group (43.1% vs 14.7%, p<0.05). Regardless of treatment, patients above the age of 60 (41% vs 13.4%, p<0.05) and those with poor PS (19.6% vs 5.8%, p<0.05) had worse 5-year survival, with the effect being greater in the treatment group. Adenocarcinoma had a better 5-year survival compared to squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) in both groups (49.56% vs 39.1% p<0.05). There was no clinically significant OS difference in terms of race (Caucasian or African American) or tumor location (upper, middle, or lower lobe) in between the two groups. Our study was limited by lack of patient- level data including smoking status or reason why no treatment was given.

Conclusion

Patients with early-stage NSCLC who receive no treatment based on poor PS have a worse overall survival compared to the patients that receive treatment. Further investigation is required to assess what other criteria are used to decide treatment eligibility and whether these patients would be candidates for immunotherapy or targeted therapy in the future.

Introduction

Veterans with early-stage NSCLC who do not receive any form of treatment have been shown to have a worse overall survival compared to those who receive treatment. Factors that may influence the decision to administer treatment including age, performance status (PS), comorbidities, and racial disparity have not been assessed on a national level in recent years.

Methods

Data for 31,966 veterans diagnosed with early-stage (0, I) NSCLC between 2003-2017 was obtained from the Cancer cube registry (VACCR). IRB approval was obtained.

Results

Patients were divided into treatment (26,833/31,966, 83.16%) and no-treatment group (3096/31966, 9.68%). Of the no-treatment group, 3004 patients were stage I and 92 were stage 0 whereas in the treatment group, the distribution was 26,584 and 249 respectively. Gender, race, and histology distribution were comparable between the two. Patients with poor PS (defined as ECOG III and IV) received less treatment with any modality compared to those with good PS (ECOG I and II) (15.07% in no treatment group vs 4.03% in treatment group, p<0.05). The treatment group had a better 5-year overall survival (OS) as compared to no-treatment group (43.1% vs 14.7%, p<0.05). Regardless of treatment, patients above the age of 60 (41% vs 13.4%, p<0.05) and those with poor PS (19.6% vs 5.8%, p<0.05) had worse 5-year survival, with the effect being greater in the treatment group. Adenocarcinoma had a better 5-year survival compared to squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) in both groups (49.56% vs 39.1% p<0.05). There was no clinically significant OS difference in terms of race (Caucasian or African American) or tumor location (upper, middle, or lower lobe) in between the two groups. Our study was limited by lack of patient- level data including smoking status or reason why no treatment was given.

Conclusion

Patients with early-stage NSCLC who receive no treatment based on poor PS have a worse overall survival compared to the patients that receive treatment. Further investigation is required to assess what other criteria are used to decide treatment eligibility and whether these patients would be candidates for immunotherapy or targeted therapy in the future.