User login

How should I treat acute agitation in pregnancy?

Acute agitation in the pregnant patient should be treated as an obstetric emergency, as it jeopardizes the safety of the patient and fetus, as well as others in the emergency room. Uncontrolled agitation is associated with obstetric complications such as preterm delivery, placental abnormalities, postnatal death, and spontaneous abortion.1

Current data on the reproductive safety of drugs commonly used to treat acute agitation—benzodiazepines, typical (first-generation) antipsychotics, atypical (second-generation) antipsychotics, and diphenhydramine—suggest no increase in risk beyond the 2% to 3% risk of congenital malformations in the general population when used in the first trimester.2,3

FOCUS OF THE EMERGENCY EVALUATION

Agitation is defined as the physical manifestation of internal distress, due to an underlying medical condition such as delirium or to a psychiatric condition such as acute intoxication or withdrawal, psychosis, mania, or personality disorder.4

For the agitated pregnant woman who is not belligerent at presentation, triage should start with a basic assessment of airways, breathing, and circulation, as well as vital signs and glucose level.5 A thorough medical history and a description of events leading to the presentation, obtained from the patient or the patient’s family or friends, are vital for narrowing the diagnosis and deciding treatment.

The initial evaluation should include consideration of delirium, trauma, intracranial hemorrhage, coagulopathy, thrombocytopenia, amniotic and venous thromboembolism, hypoxia and hypercapnia, and signs and symptoms of intoxication or withdrawal from substances such as alcohol, cocaine, phencyclidine, methamphetamine, and substituted cathinones (“bath salts”). From 20 weeks of gestation to 6 weeks postpartum, eclampsia should also be considered in the differential diagnosis.1 Ruling out these conditions is important since the management of each differs vastly from the protocol for agitation secondary to psychosis, mania, or delirium.

NEW SYSTEM TO DETERMINE RISK DURING PREGNANCY, LACTATION

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has discontinued its pregnancy category labeling system that used the letters A, B, C, D, and X to convey reproductive and lactation safety. The new system, established under the FDA Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule,6 provides descriptive, up-to-date explanations of risk, as well as previously absent context regarding baseline risk for major malformations in the general population to help with informed decision-making.7 This allows the healthcare provider to interpret the risk for an individual patient.

FIRST-GENERATION ANTIPSYCHOTICS SAFE, EFFECTIVE IN PREGNANCY

Reproductive safety of first-generation (ie, typical) neuroleptics such as haloperidol is supported by extensive data accumulated over the past 50 years.2,3,8 No significant teratogenic effect has been documented with this drug class,7 although a 1996 meta-analysis found a small increase in the relative risk of congenital malformations in offspring exposed to low-potency antipsychotics compared with those exposed to high-potency antipsychotics.2

In general, mid- and high-potency antipsychotics (eg, haloperidol, perphenazine) are often recommended because they are less likely to have associated sedative or hypotensive effects than low-potency antipsychotics (eg, chlorpromazine, perphenazine), which may be a significant consideration for a pregnant patient.2,8

There is a theoretical risk of neonatal extrapyramidal symptoms with exposure to first-generation antipsychotics in the third trimester, but the data to support this are from sparse case reports and small observational cohorts.9

NEWER ANTIPSYCHOTICS ALSO SAFE IN PREGNANCY

Newer antipsychotics such as the second-generation antipsychotics, available since the mid-1990s, are increasingly used as primary or adjunctive therapy across a wide range of psychiatric disorders.10 Recent data from large, prospective cohort studies investigating reproductive safety of these agents are reassuring, with no specific patterns of organ malformation.11,12

DIPHENHYDRAMINE

Recent studies of antihistamines such as diphenhydramine have not reported any risk of major malformations with first-trimester exposure to antihistamines.13,14 Dose-dependent anticholinergic adverse effects of antihistamines can induce or exacerbate delirium and agitation, although these effects are classically seen in elderly, nonpregnant patients.15 Thus, given the paucity of adverse effects and the low risk, diphenhydramine is considered safe to use in pregnancy.13

BENZODIAZEPINES

Benzodiazepines are not contraindicated for the treatment of acute agitation in pregnancy.16 Reproductive safety data from meta-analyses and large population-based cohort studies have found no evidence of increased risk of major malformations in neonates born to mothers on prescription benzodiazepines in the first trimester.17,18 While third-trimester exposure to benzodiazepines has been associated with “floppy-baby” syndrome and neonatal withdrawal syndrome,16 these are more likely to occur in women on long-term prescription benzodiazepine therapy. No study has yet assessed the risk of these outcomes with a 1-time acute exposure in the emergency department; however, the risk is likely minimal given the aforementioned data observed in women on long-term prescription benzodiazepine therapy.

STEPWISE MANAGEMENT OF AGITATION IN PREGNANCY

If untreated, agitation in pregnancy is independently associated with outcomes that include premature delivery, low birth weight, growth retardation, postnatal death, and spontaneous abortion.1 The risk of these outcomes greatly outweighs any potential risk from psychotropic medications during pregnancy.

Nevertheless, intervention should progress in a stepwise manner, starting with the least restrictive and progressing toward more restrictive interventions, including pharmacotherapy, use of a seclusion room, and physical restraints (Figure 1).4,19

Before medications are considered, attempts should be made to engage with and “de-escalate” the patient in a safe, nonstimulating environment.19 If this approach is not effective, the patient should be offered oral medications to help with her agitation. However, if the patient’s behavior continues to escalate, presenting a danger to herself or staff, the use of emergency medications is clearly indicated. Providers should succinctly inform the patient of the need for immediate intervention.

If the patient has had a good response in the past to one of these medications or is currently taking one as needed, the same medication should be offered. If the patient has never been treated for agitation, it is important to consider the presenting symptoms, differential diagnosis, and the route and rapidity of administration of medication. If the patient has experienced a fall or other trauma, confirming a viable fetal heart rate between 10 to 22 weeks of gestation with Doppler ultrasonography and obstetric consultation should be considered.

DRUG THERAPY RECOMMENDATIONS

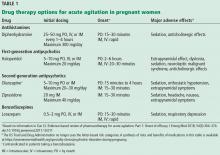

Mild to moderate agitation in pregnancy should be managed conservatively with diphenhydramine. Other options include a benzodiazepine, particularly lorazepam, if alcohol withdrawal is suspected. A second-generation antipsychotic such as olanzapine in a rapidly dissolving form or ziprasidone is another option if a rapid response is required.20 Table 1 provides a summary of pharmacotherapy recommendations.

Severe agitation may require a combination of agents. A commonly used, safe regimen—colloquially called the “B52 bomb”—is haloperidol 5 mg, lorazepam 2 mg, and diphenhydramine 25 to 50 mg for prophylaxis of dystonia.20

The patient’s response should be monitored closely, as dosing may require modification as a result of pregnancy-related changes in drug distribution, metabolism, and clearance.21

Although no study to our knowledge has assessed risk associated with 1-time exposure to any of these classes of medications in pregnant women, the aforementioned data on long-term exposure provide reassurance that single exposure in emergency departments likely has little or no effect for the developing fetus.

PHYSICAL RESTRAINTS FOR AGITATION IN PREGNANCY

Physical restraints along with emergency medications (ie, chemical restraint) may be indicated when the patient poses a danger to herself or others. In some cases, both types of restraint may be required, whether in the emergency room or an inpatient setting.

However, during the second and third trimesters, physical restraints such as 4-point restraints may predispose the patient to inferior vena cava compression syndrome and compromise placental blood flow.4 Therefore, pregnant patients after 20 weeks of gestation should be positioned in the left lateral decubitus position, with the right hip positioned 10 to 12 cm off the bed with pillows or blankets. And when restraints are used in pregnant patients, frequent checking of vital signs and physical assessment is needed to mitigate risks.4

- Aftab A, Shah AA. Behavioral emergencies: special considerations in the pregnant patient. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2017; 40(3):435–448. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2017.05.017

- Altshuler LL, Cohen L, Szuba MP, Burt VK, Gitlin M, Mintz J. Pharmacologic management of psychiatric illness during pregnancy: dilemmas and guidelines. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153(5):592–606. doi:10.1176/ajp.153.5.592

- Einarson A. Safety of psychotropic drug use during pregnancy: a review. MedGenMed 2005; 7(4):3. pmid:16614625

- Wilson MP, Nordstrom K, Shah AA, Vilke GM. Psychiatric emergencies in pregnant women. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2015; 33(4):841–851. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2015.07.010

- Brown HE, Stoklosa J, Freundenreich O. How to stabilize an acutely psychotic patient. Curr Psychiatry 2012; 11(12):10–16.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Pregnancy and lactation labeling (drugs) final rule. www.fda.gov/drugs/developmentapprovalprocess/developmentresources/labeling/ucm093307.htm. Accessed January 8, 2019.

- Brucker MC, King TL. The 2015 US Food and Drug Administration pregnancy and lactation labeling rule. J Midwifery Womens Health 2017; 62(3):308–316. doi:10.1111/jmwh.12611

- Diav-Citrin O, Shechtman S, Ornoy S, et al. Safety of haloperidol and penfluridol in pregnancy: a multicenter, prospective, controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry 2005; 66(3):317–322. pmid:15766297

- Galbally M, Snellen M, Power J. Antipsychotic drugs in pregnancy: a review of their maternal and fetal effects. Ther Adv Drug Saf 2014; 5(2):100–109. doi:10.1177/2042098614522682

- Kulkarni J, Storch A, Baraniuk A, Gilbert H, Gavrilidis E, Worsley R. Antipsychotic use in pregnancy. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2015; 16(9):1335–1345. doi:10.1517/14656566.2015.1041501

- Huybrechts KF, Hernández-Díaz S, Patorno E, et al. Antipsychotic use in pregnancy and the risk for congenital malformations. JAMA Psychiatry 2016; 73(9):938–946. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.1520

- Cohen LS, Viguera AC, McInerney KA, et al. Reproductive safety of second-generation antipsychotics: current data from the Massachusetts General Hospital national pregnancy registry for atypical antipsychotics. Am J Psychiatry 2016; 173(3):263–270. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15040506

- Li Q, Mitchell AA, Werler MM, Yau WP, Hernández-Díaz S. Assessment of antihistamine use in early pregnancy and birth defects. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2013; 1(6):666–674.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2013.07.008

- Gilboa SM, Strickland MJ, Olshan AF, Werler MM, Correa A; National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Use of antihistamine medications during early pregnancy and isolated major malformations. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 2009; 85(2):137–150. doi:10.1002/bdra.20513

- Meuleman JR. Association of diphenhydramine use with adverse effects in hospitalized older patients: possible confounders. Arch Intern Med 2002; 162(6):720–721. pmid:11911733

- Enato E, Moretti M, Koren G. The fetal safety of benzodiazepines: an updated meta-analysis. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2011; 33(1):46–48. doi:10.1016/S1701-2163(16)34772-7

- Dolovich LR, Addis A, Vaillancourt JM, Power JD, Koren G, Einarson TR. Benzodiazepine use in pregnancy and major malformations or oral cleft: meta-analysis of cohort and case-control studies. BMJ 1998; 317(7162):839–843. pmid:9748174

- Bellantuono C, Tofani S, Di Sciascio G, Santone G. Benzodiazepine exposure in pregnancy and risk of major malformations: a critical overview. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2013; 35(1):3–8. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.09.003

- Richmond JS, Berlin JS, Fishkind AB, et al. Verbal de-escalation of the agitated patient: consensus statement of the American Association for Emergency Psychiatry project BETA De-escalation Workgroup. West J Emerg Med 2012; 13(1):17–25. doi:10.5811/westjem.2011.9.6864

- Prager LM, Ivkovic A. Emergency psychiatry. In: Stern TA, Fava M, Wilens TE, Rosenbaum JF, eds. The Massachusetts General Hospital Comprehensive Clinical Psychiatry. 2nd ed. London: Elsevier; 2016:937–949.

- Feghali M, Venkataramanan R, Caritis S. Pharmacokinetics of drugs in pregnancy. Semin Perinatol 2015; 39(7):512–519. doi:10.1053/j.semperi.2015.08.003

Acute agitation in the pregnant patient should be treated as an obstetric emergency, as it jeopardizes the safety of the patient and fetus, as well as others in the emergency room. Uncontrolled agitation is associated with obstetric complications such as preterm delivery, placental abnormalities, postnatal death, and spontaneous abortion.1

Current data on the reproductive safety of drugs commonly used to treat acute agitation—benzodiazepines, typical (first-generation) antipsychotics, atypical (second-generation) antipsychotics, and diphenhydramine—suggest no increase in risk beyond the 2% to 3% risk of congenital malformations in the general population when used in the first trimester.2,3

FOCUS OF THE EMERGENCY EVALUATION

Agitation is defined as the physical manifestation of internal distress, due to an underlying medical condition such as delirium or to a psychiatric condition such as acute intoxication or withdrawal, psychosis, mania, or personality disorder.4

For the agitated pregnant woman who is not belligerent at presentation, triage should start with a basic assessment of airways, breathing, and circulation, as well as vital signs and glucose level.5 A thorough medical history and a description of events leading to the presentation, obtained from the patient or the patient’s family or friends, are vital for narrowing the diagnosis and deciding treatment.

The initial evaluation should include consideration of delirium, trauma, intracranial hemorrhage, coagulopathy, thrombocytopenia, amniotic and venous thromboembolism, hypoxia and hypercapnia, and signs and symptoms of intoxication or withdrawal from substances such as alcohol, cocaine, phencyclidine, methamphetamine, and substituted cathinones (“bath salts”). From 20 weeks of gestation to 6 weeks postpartum, eclampsia should also be considered in the differential diagnosis.1 Ruling out these conditions is important since the management of each differs vastly from the protocol for agitation secondary to psychosis, mania, or delirium.

NEW SYSTEM TO DETERMINE RISK DURING PREGNANCY, LACTATION

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has discontinued its pregnancy category labeling system that used the letters A, B, C, D, and X to convey reproductive and lactation safety. The new system, established under the FDA Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule,6 provides descriptive, up-to-date explanations of risk, as well as previously absent context regarding baseline risk for major malformations in the general population to help with informed decision-making.7 This allows the healthcare provider to interpret the risk for an individual patient.

FIRST-GENERATION ANTIPSYCHOTICS SAFE, EFFECTIVE IN PREGNANCY

Reproductive safety of first-generation (ie, typical) neuroleptics such as haloperidol is supported by extensive data accumulated over the past 50 years.2,3,8 No significant teratogenic effect has been documented with this drug class,7 although a 1996 meta-analysis found a small increase in the relative risk of congenital malformations in offspring exposed to low-potency antipsychotics compared with those exposed to high-potency antipsychotics.2

In general, mid- and high-potency antipsychotics (eg, haloperidol, perphenazine) are often recommended because they are less likely to have associated sedative or hypotensive effects than low-potency antipsychotics (eg, chlorpromazine, perphenazine), which may be a significant consideration for a pregnant patient.2,8

There is a theoretical risk of neonatal extrapyramidal symptoms with exposure to first-generation antipsychotics in the third trimester, but the data to support this are from sparse case reports and small observational cohorts.9

NEWER ANTIPSYCHOTICS ALSO SAFE IN PREGNANCY

Newer antipsychotics such as the second-generation antipsychotics, available since the mid-1990s, are increasingly used as primary or adjunctive therapy across a wide range of psychiatric disorders.10 Recent data from large, prospective cohort studies investigating reproductive safety of these agents are reassuring, with no specific patterns of organ malformation.11,12

DIPHENHYDRAMINE

Recent studies of antihistamines such as diphenhydramine have not reported any risk of major malformations with first-trimester exposure to antihistamines.13,14 Dose-dependent anticholinergic adverse effects of antihistamines can induce or exacerbate delirium and agitation, although these effects are classically seen in elderly, nonpregnant patients.15 Thus, given the paucity of adverse effects and the low risk, diphenhydramine is considered safe to use in pregnancy.13

BENZODIAZEPINES

Benzodiazepines are not contraindicated for the treatment of acute agitation in pregnancy.16 Reproductive safety data from meta-analyses and large population-based cohort studies have found no evidence of increased risk of major malformations in neonates born to mothers on prescription benzodiazepines in the first trimester.17,18 While third-trimester exposure to benzodiazepines has been associated with “floppy-baby” syndrome and neonatal withdrawal syndrome,16 these are more likely to occur in women on long-term prescription benzodiazepine therapy. No study has yet assessed the risk of these outcomes with a 1-time acute exposure in the emergency department; however, the risk is likely minimal given the aforementioned data observed in women on long-term prescription benzodiazepine therapy.

STEPWISE MANAGEMENT OF AGITATION IN PREGNANCY

If untreated, agitation in pregnancy is independently associated with outcomes that include premature delivery, low birth weight, growth retardation, postnatal death, and spontaneous abortion.1 The risk of these outcomes greatly outweighs any potential risk from psychotropic medications during pregnancy.

Nevertheless, intervention should progress in a stepwise manner, starting with the least restrictive and progressing toward more restrictive interventions, including pharmacotherapy, use of a seclusion room, and physical restraints (Figure 1).4,19

Before medications are considered, attempts should be made to engage with and “de-escalate” the patient in a safe, nonstimulating environment.19 If this approach is not effective, the patient should be offered oral medications to help with her agitation. However, if the patient’s behavior continues to escalate, presenting a danger to herself or staff, the use of emergency medications is clearly indicated. Providers should succinctly inform the patient of the need for immediate intervention.

If the patient has had a good response in the past to one of these medications or is currently taking one as needed, the same medication should be offered. If the patient has never been treated for agitation, it is important to consider the presenting symptoms, differential diagnosis, and the route and rapidity of administration of medication. If the patient has experienced a fall or other trauma, confirming a viable fetal heart rate between 10 to 22 weeks of gestation with Doppler ultrasonography and obstetric consultation should be considered.

DRUG THERAPY RECOMMENDATIONS

Mild to moderate agitation in pregnancy should be managed conservatively with diphenhydramine. Other options include a benzodiazepine, particularly lorazepam, if alcohol withdrawal is suspected. A second-generation antipsychotic such as olanzapine in a rapidly dissolving form or ziprasidone is another option if a rapid response is required.20 Table 1 provides a summary of pharmacotherapy recommendations.

Severe agitation may require a combination of agents. A commonly used, safe regimen—colloquially called the “B52 bomb”—is haloperidol 5 mg, lorazepam 2 mg, and diphenhydramine 25 to 50 mg for prophylaxis of dystonia.20

The patient’s response should be monitored closely, as dosing may require modification as a result of pregnancy-related changes in drug distribution, metabolism, and clearance.21

Although no study to our knowledge has assessed risk associated with 1-time exposure to any of these classes of medications in pregnant women, the aforementioned data on long-term exposure provide reassurance that single exposure in emergency departments likely has little or no effect for the developing fetus.

PHYSICAL RESTRAINTS FOR AGITATION IN PREGNANCY

Physical restraints along with emergency medications (ie, chemical restraint) may be indicated when the patient poses a danger to herself or others. In some cases, both types of restraint may be required, whether in the emergency room or an inpatient setting.

However, during the second and third trimesters, physical restraints such as 4-point restraints may predispose the patient to inferior vena cava compression syndrome and compromise placental blood flow.4 Therefore, pregnant patients after 20 weeks of gestation should be positioned in the left lateral decubitus position, with the right hip positioned 10 to 12 cm off the bed with pillows or blankets. And when restraints are used in pregnant patients, frequent checking of vital signs and physical assessment is needed to mitigate risks.4

Acute agitation in the pregnant patient should be treated as an obstetric emergency, as it jeopardizes the safety of the patient and fetus, as well as others in the emergency room. Uncontrolled agitation is associated with obstetric complications such as preterm delivery, placental abnormalities, postnatal death, and spontaneous abortion.1

Current data on the reproductive safety of drugs commonly used to treat acute agitation—benzodiazepines, typical (first-generation) antipsychotics, atypical (second-generation) antipsychotics, and diphenhydramine—suggest no increase in risk beyond the 2% to 3% risk of congenital malformations in the general population when used in the first trimester.2,3

FOCUS OF THE EMERGENCY EVALUATION

Agitation is defined as the physical manifestation of internal distress, due to an underlying medical condition such as delirium or to a psychiatric condition such as acute intoxication or withdrawal, psychosis, mania, or personality disorder.4

For the agitated pregnant woman who is not belligerent at presentation, triage should start with a basic assessment of airways, breathing, and circulation, as well as vital signs and glucose level.5 A thorough medical history and a description of events leading to the presentation, obtained from the patient or the patient’s family or friends, are vital for narrowing the diagnosis and deciding treatment.

The initial evaluation should include consideration of delirium, trauma, intracranial hemorrhage, coagulopathy, thrombocytopenia, amniotic and venous thromboembolism, hypoxia and hypercapnia, and signs and symptoms of intoxication or withdrawal from substances such as alcohol, cocaine, phencyclidine, methamphetamine, and substituted cathinones (“bath salts”). From 20 weeks of gestation to 6 weeks postpartum, eclampsia should also be considered in the differential diagnosis.1 Ruling out these conditions is important since the management of each differs vastly from the protocol for agitation secondary to psychosis, mania, or delirium.

NEW SYSTEM TO DETERMINE RISK DURING PREGNANCY, LACTATION

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has discontinued its pregnancy category labeling system that used the letters A, B, C, D, and X to convey reproductive and lactation safety. The new system, established under the FDA Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule,6 provides descriptive, up-to-date explanations of risk, as well as previously absent context regarding baseline risk for major malformations in the general population to help with informed decision-making.7 This allows the healthcare provider to interpret the risk for an individual patient.

FIRST-GENERATION ANTIPSYCHOTICS SAFE, EFFECTIVE IN PREGNANCY

Reproductive safety of first-generation (ie, typical) neuroleptics such as haloperidol is supported by extensive data accumulated over the past 50 years.2,3,8 No significant teratogenic effect has been documented with this drug class,7 although a 1996 meta-analysis found a small increase in the relative risk of congenital malformations in offspring exposed to low-potency antipsychotics compared with those exposed to high-potency antipsychotics.2

In general, mid- and high-potency antipsychotics (eg, haloperidol, perphenazine) are often recommended because they are less likely to have associated sedative or hypotensive effects than low-potency antipsychotics (eg, chlorpromazine, perphenazine), which may be a significant consideration for a pregnant patient.2,8

There is a theoretical risk of neonatal extrapyramidal symptoms with exposure to first-generation antipsychotics in the third trimester, but the data to support this are from sparse case reports and small observational cohorts.9

NEWER ANTIPSYCHOTICS ALSO SAFE IN PREGNANCY

Newer antipsychotics such as the second-generation antipsychotics, available since the mid-1990s, are increasingly used as primary or adjunctive therapy across a wide range of psychiatric disorders.10 Recent data from large, prospective cohort studies investigating reproductive safety of these agents are reassuring, with no specific patterns of organ malformation.11,12

DIPHENHYDRAMINE

Recent studies of antihistamines such as diphenhydramine have not reported any risk of major malformations with first-trimester exposure to antihistamines.13,14 Dose-dependent anticholinergic adverse effects of antihistamines can induce or exacerbate delirium and agitation, although these effects are classically seen in elderly, nonpregnant patients.15 Thus, given the paucity of adverse effects and the low risk, diphenhydramine is considered safe to use in pregnancy.13

BENZODIAZEPINES

Benzodiazepines are not contraindicated for the treatment of acute agitation in pregnancy.16 Reproductive safety data from meta-analyses and large population-based cohort studies have found no evidence of increased risk of major malformations in neonates born to mothers on prescription benzodiazepines in the first trimester.17,18 While third-trimester exposure to benzodiazepines has been associated with “floppy-baby” syndrome and neonatal withdrawal syndrome,16 these are more likely to occur in women on long-term prescription benzodiazepine therapy. No study has yet assessed the risk of these outcomes with a 1-time acute exposure in the emergency department; however, the risk is likely minimal given the aforementioned data observed in women on long-term prescription benzodiazepine therapy.

STEPWISE MANAGEMENT OF AGITATION IN PREGNANCY

If untreated, agitation in pregnancy is independently associated with outcomes that include premature delivery, low birth weight, growth retardation, postnatal death, and spontaneous abortion.1 The risk of these outcomes greatly outweighs any potential risk from psychotropic medications during pregnancy.

Nevertheless, intervention should progress in a stepwise manner, starting with the least restrictive and progressing toward more restrictive interventions, including pharmacotherapy, use of a seclusion room, and physical restraints (Figure 1).4,19

Before medications are considered, attempts should be made to engage with and “de-escalate” the patient in a safe, nonstimulating environment.19 If this approach is not effective, the patient should be offered oral medications to help with her agitation. However, if the patient’s behavior continues to escalate, presenting a danger to herself or staff, the use of emergency medications is clearly indicated. Providers should succinctly inform the patient of the need for immediate intervention.

If the patient has had a good response in the past to one of these medications or is currently taking one as needed, the same medication should be offered. If the patient has never been treated for agitation, it is important to consider the presenting symptoms, differential diagnosis, and the route and rapidity of administration of medication. If the patient has experienced a fall or other trauma, confirming a viable fetal heart rate between 10 to 22 weeks of gestation with Doppler ultrasonography and obstetric consultation should be considered.

DRUG THERAPY RECOMMENDATIONS

Mild to moderate agitation in pregnancy should be managed conservatively with diphenhydramine. Other options include a benzodiazepine, particularly lorazepam, if alcohol withdrawal is suspected. A second-generation antipsychotic such as olanzapine in a rapidly dissolving form or ziprasidone is another option if a rapid response is required.20 Table 1 provides a summary of pharmacotherapy recommendations.

Severe agitation may require a combination of agents. A commonly used, safe regimen—colloquially called the “B52 bomb”—is haloperidol 5 mg, lorazepam 2 mg, and diphenhydramine 25 to 50 mg for prophylaxis of dystonia.20

The patient’s response should be monitored closely, as dosing may require modification as a result of pregnancy-related changes in drug distribution, metabolism, and clearance.21

Although no study to our knowledge has assessed risk associated with 1-time exposure to any of these classes of medications in pregnant women, the aforementioned data on long-term exposure provide reassurance that single exposure in emergency departments likely has little or no effect for the developing fetus.

PHYSICAL RESTRAINTS FOR AGITATION IN PREGNANCY

Physical restraints along with emergency medications (ie, chemical restraint) may be indicated when the patient poses a danger to herself or others. In some cases, both types of restraint may be required, whether in the emergency room or an inpatient setting.

However, during the second and third trimesters, physical restraints such as 4-point restraints may predispose the patient to inferior vena cava compression syndrome and compromise placental blood flow.4 Therefore, pregnant patients after 20 weeks of gestation should be positioned in the left lateral decubitus position, with the right hip positioned 10 to 12 cm off the bed with pillows or blankets. And when restraints are used in pregnant patients, frequent checking of vital signs and physical assessment is needed to mitigate risks.4

- Aftab A, Shah AA. Behavioral emergencies: special considerations in the pregnant patient. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2017; 40(3):435–448. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2017.05.017

- Altshuler LL, Cohen L, Szuba MP, Burt VK, Gitlin M, Mintz J. Pharmacologic management of psychiatric illness during pregnancy: dilemmas and guidelines. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153(5):592–606. doi:10.1176/ajp.153.5.592

- Einarson A. Safety of psychotropic drug use during pregnancy: a review. MedGenMed 2005; 7(4):3. pmid:16614625

- Wilson MP, Nordstrom K, Shah AA, Vilke GM. Psychiatric emergencies in pregnant women. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2015; 33(4):841–851. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2015.07.010

- Brown HE, Stoklosa J, Freundenreich O. How to stabilize an acutely psychotic patient. Curr Psychiatry 2012; 11(12):10–16.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Pregnancy and lactation labeling (drugs) final rule. www.fda.gov/drugs/developmentapprovalprocess/developmentresources/labeling/ucm093307.htm. Accessed January 8, 2019.

- Brucker MC, King TL. The 2015 US Food and Drug Administration pregnancy and lactation labeling rule. J Midwifery Womens Health 2017; 62(3):308–316. doi:10.1111/jmwh.12611

- Diav-Citrin O, Shechtman S, Ornoy S, et al. Safety of haloperidol and penfluridol in pregnancy: a multicenter, prospective, controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry 2005; 66(3):317–322. pmid:15766297

- Galbally M, Snellen M, Power J. Antipsychotic drugs in pregnancy: a review of their maternal and fetal effects. Ther Adv Drug Saf 2014; 5(2):100–109. doi:10.1177/2042098614522682

- Kulkarni J, Storch A, Baraniuk A, Gilbert H, Gavrilidis E, Worsley R. Antipsychotic use in pregnancy. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2015; 16(9):1335–1345. doi:10.1517/14656566.2015.1041501

- Huybrechts KF, Hernández-Díaz S, Patorno E, et al. Antipsychotic use in pregnancy and the risk for congenital malformations. JAMA Psychiatry 2016; 73(9):938–946. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.1520

- Cohen LS, Viguera AC, McInerney KA, et al. Reproductive safety of second-generation antipsychotics: current data from the Massachusetts General Hospital national pregnancy registry for atypical antipsychotics. Am J Psychiatry 2016; 173(3):263–270. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15040506

- Li Q, Mitchell AA, Werler MM, Yau WP, Hernández-Díaz S. Assessment of antihistamine use in early pregnancy and birth defects. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2013; 1(6):666–674.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2013.07.008

- Gilboa SM, Strickland MJ, Olshan AF, Werler MM, Correa A; National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Use of antihistamine medications during early pregnancy and isolated major malformations. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 2009; 85(2):137–150. doi:10.1002/bdra.20513

- Meuleman JR. Association of diphenhydramine use with adverse effects in hospitalized older patients: possible confounders. Arch Intern Med 2002; 162(6):720–721. pmid:11911733

- Enato E, Moretti M, Koren G. The fetal safety of benzodiazepines: an updated meta-analysis. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2011; 33(1):46–48. doi:10.1016/S1701-2163(16)34772-7

- Dolovich LR, Addis A, Vaillancourt JM, Power JD, Koren G, Einarson TR. Benzodiazepine use in pregnancy and major malformations or oral cleft: meta-analysis of cohort and case-control studies. BMJ 1998; 317(7162):839–843. pmid:9748174

- Bellantuono C, Tofani S, Di Sciascio G, Santone G. Benzodiazepine exposure in pregnancy and risk of major malformations: a critical overview. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2013; 35(1):3–8. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.09.003

- Richmond JS, Berlin JS, Fishkind AB, et al. Verbal de-escalation of the agitated patient: consensus statement of the American Association for Emergency Psychiatry project BETA De-escalation Workgroup. West J Emerg Med 2012; 13(1):17–25. doi:10.5811/westjem.2011.9.6864

- Prager LM, Ivkovic A. Emergency psychiatry. In: Stern TA, Fava M, Wilens TE, Rosenbaum JF, eds. The Massachusetts General Hospital Comprehensive Clinical Psychiatry. 2nd ed. London: Elsevier; 2016:937–949.

- Feghali M, Venkataramanan R, Caritis S. Pharmacokinetics of drugs in pregnancy. Semin Perinatol 2015; 39(7):512–519. doi:10.1053/j.semperi.2015.08.003

- Aftab A, Shah AA. Behavioral emergencies: special considerations in the pregnant patient. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2017; 40(3):435–448. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2017.05.017

- Altshuler LL, Cohen L, Szuba MP, Burt VK, Gitlin M, Mintz J. Pharmacologic management of psychiatric illness during pregnancy: dilemmas and guidelines. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153(5):592–606. doi:10.1176/ajp.153.5.592

- Einarson A. Safety of psychotropic drug use during pregnancy: a review. MedGenMed 2005; 7(4):3. pmid:16614625

- Wilson MP, Nordstrom K, Shah AA, Vilke GM. Psychiatric emergencies in pregnant women. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2015; 33(4):841–851. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2015.07.010

- Brown HE, Stoklosa J, Freundenreich O. How to stabilize an acutely psychotic patient. Curr Psychiatry 2012; 11(12):10–16.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Pregnancy and lactation labeling (drugs) final rule. www.fda.gov/drugs/developmentapprovalprocess/developmentresources/labeling/ucm093307.htm. Accessed January 8, 2019.

- Brucker MC, King TL. The 2015 US Food and Drug Administration pregnancy and lactation labeling rule. J Midwifery Womens Health 2017; 62(3):308–316. doi:10.1111/jmwh.12611

- Diav-Citrin O, Shechtman S, Ornoy S, et al. Safety of haloperidol and penfluridol in pregnancy: a multicenter, prospective, controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry 2005; 66(3):317–322. pmid:15766297

- Galbally M, Snellen M, Power J. Antipsychotic drugs in pregnancy: a review of their maternal and fetal effects. Ther Adv Drug Saf 2014; 5(2):100–109. doi:10.1177/2042098614522682

- Kulkarni J, Storch A, Baraniuk A, Gilbert H, Gavrilidis E, Worsley R. Antipsychotic use in pregnancy. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2015; 16(9):1335–1345. doi:10.1517/14656566.2015.1041501

- Huybrechts KF, Hernández-Díaz S, Patorno E, et al. Antipsychotic use in pregnancy and the risk for congenital malformations. JAMA Psychiatry 2016; 73(9):938–946. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.1520

- Cohen LS, Viguera AC, McInerney KA, et al. Reproductive safety of second-generation antipsychotics: current data from the Massachusetts General Hospital national pregnancy registry for atypical antipsychotics. Am J Psychiatry 2016; 173(3):263–270. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15040506

- Li Q, Mitchell AA, Werler MM, Yau WP, Hernández-Díaz S. Assessment of antihistamine use in early pregnancy and birth defects. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2013; 1(6):666–674.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2013.07.008

- Gilboa SM, Strickland MJ, Olshan AF, Werler MM, Correa A; National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Use of antihistamine medications during early pregnancy and isolated major malformations. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 2009; 85(2):137–150. doi:10.1002/bdra.20513

- Meuleman JR. Association of diphenhydramine use with adverse effects in hospitalized older patients: possible confounders. Arch Intern Med 2002; 162(6):720–721. pmid:11911733

- Enato E, Moretti M, Koren G. The fetal safety of benzodiazepines: an updated meta-analysis. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2011; 33(1):46–48. doi:10.1016/S1701-2163(16)34772-7

- Dolovich LR, Addis A, Vaillancourt JM, Power JD, Koren G, Einarson TR. Benzodiazepine use in pregnancy and major malformations or oral cleft: meta-analysis of cohort and case-control studies. BMJ 1998; 317(7162):839–843. pmid:9748174

- Bellantuono C, Tofani S, Di Sciascio G, Santone G. Benzodiazepine exposure in pregnancy and risk of major malformations: a critical overview. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2013; 35(1):3–8. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.09.003

- Richmond JS, Berlin JS, Fishkind AB, et al. Verbal de-escalation of the agitated patient: consensus statement of the American Association for Emergency Psychiatry project BETA De-escalation Workgroup. West J Emerg Med 2012; 13(1):17–25. doi:10.5811/westjem.2011.9.6864

- Prager LM, Ivkovic A. Emergency psychiatry. In: Stern TA, Fava M, Wilens TE, Rosenbaum JF, eds. The Massachusetts General Hospital Comprehensive Clinical Psychiatry. 2nd ed. London: Elsevier; 2016:937–949.

- Feghali M, Venkataramanan R, Caritis S. Pharmacokinetics of drugs in pregnancy. Semin Perinatol 2015; 39(7):512–519. doi:10.1053/j.semperi.2015.08.003

Pregnant and nursing patients benefit from ‘ambitious’ changes to drug labeling for safety

In December 2014, the FDA issued draft guidance for sweeping changes to labeling of pharmaceutical treatments in regard to pregnancy and lactation information. These changes are now in effect for use in practice.1 The undertaking has been years in the making, and is truly ambitious.

The outdated system of letter categories (A, B, C, D, X) falls short of clinical needs in several ways:

- the quality and volume of data can be lacking

- comparative risk is not described

- using letters can led to oversimplification or, in some cases, exaggeration of risk and safety (Box).

Other drawbacks include infrequent updating of information and omission of information about baseline rates of reproductive-related adverse events, to provide a more meaningful context for risk assessment.

A note before we continue discussion of labeling: Recognize that pregnancy itself is inherently risky; poor outcomes are, regrettably, not uncommon. The rate of birth defects in the United States is approximately 3%, and obstetric complications, such as prematurity, are common.2,3

New system described

The new labeling content has been described in the FDA’s Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule (also called the “final rule”), issued in December 2014. For each medication, there will be subsections in the labeling:

- Pregnancy

- Lactation

- Females and Males of Reproductive Potential.

In addition, FDA instructions now state that labeling:

- must be updated when new information becomes available

- needs to include evaluation of human data that becomes available mainly after the drug is approved

- needs to include information about the background rates of adverse events related to reproduction.

Labeling in pregnancy. As an example, the “Pregnancy” section of every label contains 3 subsections, all of great clinical importance. First is information about pregnancy exposure registries, with a listing of scientifically acceptable registries (if a registry is available for that drug) and contact information; this section focuses on the high value of data that are systematically and prospectively collected. The second summarizes risk associated with the drug during pregnancy, based on available human, animal, and pharmacologic data. Third is a discussion of clinical considerations.

Need for appropriate controls. Psychiatric disorders increase the risk of pregnancy complications, and often are associated with variables that might increase the risk of a poor pregnancy outcome. For example, a patient who has a psychiatric disorder might be less likely to seek prenatal care, take a prenatal vitamin, and sleep and eat well; she also might use alcohol, tobacco, or other substances of abuse.

The medical literature on the reproductive safety of psychotropic medications is fraught with confounding variables other than the medications themselves. These include variables that, taken alone, might confer a poorer outcome on the fetus or newborn of a pregnant or lactating woman who has a psychiatric illness (to the extent that she uses psychotropics during a pregnancy), compared with what would be seen in (1) a healthy woman who is not taking such medication or (2) the general population.

On the new labels, detailed statements on human data include information from clinical trials, pregnancy exposure registries, and epidemiologic studies. Labels are also to include:

- incidence of adverse events

- effect of dosage

- effect of duration of exposure

- effect of gestational timing of exposure.

The labels emphasize quantifying risk relative to the risk of the same outcome in infants born to women who have not been exposed to the particular drug, but who have the disease or condition for which the drug is indicated (ie, appropriate controls).

Clinical considerations are to include information on the following related to the specific medication (when that information is known):

- more information for prescribers, to further risk-benefit counseling

- disease-associated maternal-fetal risks

- dosage adjustments during pregnancy and postpartum

- maternal adverse reactions

- fetal and neonatal adverse reactions

- labor and delivery.

Clearly, this overdue shift in providing information regarding reproductive safety has the potential to inform clinicians and patients in a meaningful way about the risks and benefits of specific treatments during pregnancy and lactation. Translating that information into practice is daunting, however.

Important aspects of implementation

Pregnancy exposure registries will play a crucial role. For most medications, no systematic registry has been established; to do so, rigorous methodology is required to acquire prospective data and account for confounding variables.4 Appropriate control groups also are required to yield data that are useful and interpretable. Primary outcomes require verification, such as review of medical records. Last, registries must be well-conducted and therefore adequately funded, yet labeling changes have not been accompanied by funding requirements set forth by regulators to pharmaceutical manufacturers.

Labeling must be updated continually. Furthermore, it is unclear who will review data for precision and comprehensiveness.

Data need to be understandable to health care providers across disciplines and to patients with varying levels of education for the label to have a meaningful impact on clinical care.

As noted, there is no mandate for funding the meticulous pharmacovigilance required to provide definitive data for labeling. It is unclear if the potential benefits of the new labeling can be reaped without adequate financing of the pharmacovigilance mechanisms required to inform patients adequately.

Role of pregnancy registries

Over the past 2 decades, pregnancy registries have emerged as a rapid, systematic means of collecting important reproductive safety data on the risk for major malformations after prenatal exposure to a medication or a class of medications.5,6 Such registries enhance the rigor of available cohort studies and other analyses of reproductive safety data that have been derived from large administrative databases.

NPRAA and NPRAD. Recently, the National Pregnancy Registry for Atypical Antipsychotics (NPRAA) and the National Pregnancy Registry for Antidepressants (NPRAD) were established in an effort to obtain reproductive safety data about fetal exposure to second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) and to newer antidepressants.7 Based at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, NPRAA and NPRAD systematically and prospectively evaluate the risk of malformations among infants who have been exposed in utero to an SGA or an antidepressant.

The structure of both registries are the same, modeled after the North American Antiepileptic Drug Registry.5,8 Data are collected prospectively from pregnant women, age 18 to 45, by means of 3 telephone interviews conducted proximate to enrollment, at 7 months’ gestation, and at 2 or 3 months’ postpartum.

Participants include (1) pregnant women who have a history of fetal exposure to an SGA or an antidepressant, or both, and (2) a comparison group of non-exposed pregnant women who have a history of a psychiatric illness. Authorization for release of medical records is obtained for obstetric care, labor and delivery, and neonatal care (≤6 months of age).

Information on the presence of major malformations is abstracted from the medical record, along with other data on neonatal and maternal health outcomes. Identified cases of a congenital malformation are sent to a dysmorphologist, who has been blinded to drug exposure, for final adjudication. Release of findings is dictated by a governing Scientific Advisory Board.

Results so far. Results are available from the NPRAA.9 As of December 2014, 487 women were enrolled: 353 who used an SGA and 134 comparison women. Medical records were obtained for 82.2% of participants. A total of 303 women completed the study and were eligible for inclusion in the analysis. Findings include:

- Of 214 live births with first-trimester exposure to an SGA, 3 major malformations were confirmed. In the control group (n = 89), 1 major malformation was confirmed

- The absolute risk of a major malformation was 1.4% for an exposed infant and 1.1% for an unexposed infant

- The odds ratio for a major malformation, comparing exposed infants with unexposed infants, was 1.25 (95% CI, 0.13–12.19).

It is reasonable, therefore, to conclude that, as a class, SGAs are not major teratogens. Although the confidence intervals around the odds ratio estimate remain wide, with the probability for change over the course of the study, it is unlikely that risk will rise to the level of known major teratogens, such as valproate and thalidomide.10,11

Help with decision-making

Given recent FDA guidance about the importance of pregnancy registries (www.fda.gov/pregnancyregistries), such carefully collected data might help clinicians and patients make informed choices about treatment. Future efforts of NPRAA and NPRAD will focus on sustaining growth in enrollment of participants so that the reproductive safety of SGAs and newer antidepressants can be delineated more clearly.

Last, you can refer potential participants to NPRAA and NPRAD by calling 1-866-961-2388. More information is available at www.womensmentalhealth.org.

1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Food and Drug Administration; Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER); Center for Biologic Evaluation and Research (CBER). Pregnancy, lactation, and reproductive potential: labeling for human prescription drug and biological products—content and format: guidance for industry. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM425398.pdf. Published December 2014. Accessed June 7, 2016.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Birth defects. http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/birthdefects/facts.html. Updated September 21, 2005. Accessed June 7, 2016.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preterm birth. http://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pretermbirth.htm. Updated December 4, 2015. Accessed June 7, 2016.

4. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Food and Drug Administration; Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER); Center for Biologic Evaluation and Research (CBER). Guidance for industry: establishing pregnancy exposure registries. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/ScienceResearch/SpecialTopics/WomensHealthResearch/UCM133332.pdf. Published August 2002. Accessed June 7, 2016.

5. Holmes LB, Wyszynski DF. North American antiepileptic drug pregnancy registry. Epilepsia. 2004;45(11):1465.

6. Tomson T, Battino D, Craig J, et al; ILAE Commission on Therapeutic Strategies. Pregnancy registries: differences, similarities, and possible harmonization. Epilepsia. 2010;51(5):909-915.

7. Cohen LS, Viguera AC, McInerney KA, et al. Establishment of the National Pregnancy Registry for Atypical Antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(7):986-989.

8. Holmes LB, Wyszynski DF, Lieberman E. The AED (antiepileptic drug) pregnancy registry: a 6-year experience. Arch Neurol. 2004;61(5):673-678.

9. Cohen LS, Viguera AC, McInerney KA, et al. Reproductive safety of second-generation antipsychotics: current data from the Massachusetts General Hospital National Pregnancy Registry for Atypical Antipsychotics. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(3):263-270.

10. McBride WG. Thalidomide and congenital abnormalities. Lancet. 1961;2(7216):1358.

11. Wyszynski DF, Nambisan M, Surve T, et al; Antiepileptic Drug Pregnancy Registry. Increased rate of major malformations in offspring exposed to valproate during pregnancy. Neurology. 2005;64(6):961-965.

In December 2014, the FDA issued draft guidance for sweeping changes to labeling of pharmaceutical treatments in regard to pregnancy and lactation information. These changes are now in effect for use in practice.1 The undertaking has been years in the making, and is truly ambitious.

The outdated system of letter categories (A, B, C, D, X) falls short of clinical needs in several ways:

- the quality and volume of data can be lacking

- comparative risk is not described

- using letters can led to oversimplification or, in some cases, exaggeration of risk and safety (Box).

Other drawbacks include infrequent updating of information and omission of information about baseline rates of reproductive-related adverse events, to provide a more meaningful context for risk assessment.

A note before we continue discussion of labeling: Recognize that pregnancy itself is inherently risky; poor outcomes are, regrettably, not uncommon. The rate of birth defects in the United States is approximately 3%, and obstetric complications, such as prematurity, are common.2,3

New system described

The new labeling content has been described in the FDA’s Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule (also called the “final rule”), issued in December 2014. For each medication, there will be subsections in the labeling:

- Pregnancy

- Lactation

- Females and Males of Reproductive Potential.

In addition, FDA instructions now state that labeling:

- must be updated when new information becomes available

- needs to include evaluation of human data that becomes available mainly after the drug is approved

- needs to include information about the background rates of adverse events related to reproduction.

Labeling in pregnancy. As an example, the “Pregnancy” section of every label contains 3 subsections, all of great clinical importance. First is information about pregnancy exposure registries, with a listing of scientifically acceptable registries (if a registry is available for that drug) and contact information; this section focuses on the high value of data that are systematically and prospectively collected. The second summarizes risk associated with the drug during pregnancy, based on available human, animal, and pharmacologic data. Third is a discussion of clinical considerations.

Need for appropriate controls. Psychiatric disorders increase the risk of pregnancy complications, and often are associated with variables that might increase the risk of a poor pregnancy outcome. For example, a patient who has a psychiatric disorder might be less likely to seek prenatal care, take a prenatal vitamin, and sleep and eat well; she also might use alcohol, tobacco, or other substances of abuse.

The medical literature on the reproductive safety of psychotropic medications is fraught with confounding variables other than the medications themselves. These include variables that, taken alone, might confer a poorer outcome on the fetus or newborn of a pregnant or lactating woman who has a psychiatric illness (to the extent that she uses psychotropics during a pregnancy), compared with what would be seen in (1) a healthy woman who is not taking such medication or (2) the general population.

On the new labels, detailed statements on human data include information from clinical trials, pregnancy exposure registries, and epidemiologic studies. Labels are also to include:

- incidence of adverse events

- effect of dosage

- effect of duration of exposure

- effect of gestational timing of exposure.

The labels emphasize quantifying risk relative to the risk of the same outcome in infants born to women who have not been exposed to the particular drug, but who have the disease or condition for which the drug is indicated (ie, appropriate controls).

Clinical considerations are to include information on the following related to the specific medication (when that information is known):

- more information for prescribers, to further risk-benefit counseling

- disease-associated maternal-fetal risks

- dosage adjustments during pregnancy and postpartum

- maternal adverse reactions

- fetal and neonatal adverse reactions

- labor and delivery.

Clearly, this overdue shift in providing information regarding reproductive safety has the potential to inform clinicians and patients in a meaningful way about the risks and benefits of specific treatments during pregnancy and lactation. Translating that information into practice is daunting, however.

Important aspects of implementation

Pregnancy exposure registries will play a crucial role. For most medications, no systematic registry has been established; to do so, rigorous methodology is required to acquire prospective data and account for confounding variables.4 Appropriate control groups also are required to yield data that are useful and interpretable. Primary outcomes require verification, such as review of medical records. Last, registries must be well-conducted and therefore adequately funded, yet labeling changes have not been accompanied by funding requirements set forth by regulators to pharmaceutical manufacturers.

Labeling must be updated continually. Furthermore, it is unclear who will review data for precision and comprehensiveness.

Data need to be understandable to health care providers across disciplines and to patients with varying levels of education for the label to have a meaningful impact on clinical care.

As noted, there is no mandate for funding the meticulous pharmacovigilance required to provide definitive data for labeling. It is unclear if the potential benefits of the new labeling can be reaped without adequate financing of the pharmacovigilance mechanisms required to inform patients adequately.

Role of pregnancy registries

Over the past 2 decades, pregnancy registries have emerged as a rapid, systematic means of collecting important reproductive safety data on the risk for major malformations after prenatal exposure to a medication or a class of medications.5,6 Such registries enhance the rigor of available cohort studies and other analyses of reproductive safety data that have been derived from large administrative databases.

NPRAA and NPRAD. Recently, the National Pregnancy Registry for Atypical Antipsychotics (NPRAA) and the National Pregnancy Registry for Antidepressants (NPRAD) were established in an effort to obtain reproductive safety data about fetal exposure to second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) and to newer antidepressants.7 Based at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, NPRAA and NPRAD systematically and prospectively evaluate the risk of malformations among infants who have been exposed in utero to an SGA or an antidepressant.

The structure of both registries are the same, modeled after the North American Antiepileptic Drug Registry.5,8 Data are collected prospectively from pregnant women, age 18 to 45, by means of 3 telephone interviews conducted proximate to enrollment, at 7 months’ gestation, and at 2 or 3 months’ postpartum.

Participants include (1) pregnant women who have a history of fetal exposure to an SGA or an antidepressant, or both, and (2) a comparison group of non-exposed pregnant women who have a history of a psychiatric illness. Authorization for release of medical records is obtained for obstetric care, labor and delivery, and neonatal care (≤6 months of age).

Information on the presence of major malformations is abstracted from the medical record, along with other data on neonatal and maternal health outcomes. Identified cases of a congenital malformation are sent to a dysmorphologist, who has been blinded to drug exposure, for final adjudication. Release of findings is dictated by a governing Scientific Advisory Board.

Results so far. Results are available from the NPRAA.9 As of December 2014, 487 women were enrolled: 353 who used an SGA and 134 comparison women. Medical records were obtained for 82.2% of participants. A total of 303 women completed the study and were eligible for inclusion in the analysis. Findings include:

- Of 214 live births with first-trimester exposure to an SGA, 3 major malformations were confirmed. In the control group (n = 89), 1 major malformation was confirmed

- The absolute risk of a major malformation was 1.4% for an exposed infant and 1.1% for an unexposed infant

- The odds ratio for a major malformation, comparing exposed infants with unexposed infants, was 1.25 (95% CI, 0.13–12.19).

It is reasonable, therefore, to conclude that, as a class, SGAs are not major teratogens. Although the confidence intervals around the odds ratio estimate remain wide, with the probability for change over the course of the study, it is unlikely that risk will rise to the level of known major teratogens, such as valproate and thalidomide.10,11

Help with decision-making

Given recent FDA guidance about the importance of pregnancy registries (www.fda.gov/pregnancyregistries), such carefully collected data might help clinicians and patients make informed choices about treatment. Future efforts of NPRAA and NPRAD will focus on sustaining growth in enrollment of participants so that the reproductive safety of SGAs and newer antidepressants can be delineated more clearly.

Last, you can refer potential participants to NPRAA and NPRAD by calling 1-866-961-2388. More information is available at www.womensmentalhealth.org.

In December 2014, the FDA issued draft guidance for sweeping changes to labeling of pharmaceutical treatments in regard to pregnancy and lactation information. These changes are now in effect for use in practice.1 The undertaking has been years in the making, and is truly ambitious.

The outdated system of letter categories (A, B, C, D, X) falls short of clinical needs in several ways:

- the quality and volume of data can be lacking

- comparative risk is not described

- using letters can led to oversimplification or, in some cases, exaggeration of risk and safety (Box).

Other drawbacks include infrequent updating of information and omission of information about baseline rates of reproductive-related adverse events, to provide a more meaningful context for risk assessment.

A note before we continue discussion of labeling: Recognize that pregnancy itself is inherently risky; poor outcomes are, regrettably, not uncommon. The rate of birth defects in the United States is approximately 3%, and obstetric complications, such as prematurity, are common.2,3

New system described

The new labeling content has been described in the FDA’s Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule (also called the “final rule”), issued in December 2014. For each medication, there will be subsections in the labeling:

- Pregnancy

- Lactation

- Females and Males of Reproductive Potential.

In addition, FDA instructions now state that labeling:

- must be updated when new information becomes available

- needs to include evaluation of human data that becomes available mainly after the drug is approved

- needs to include information about the background rates of adverse events related to reproduction.

Labeling in pregnancy. As an example, the “Pregnancy” section of every label contains 3 subsections, all of great clinical importance. First is information about pregnancy exposure registries, with a listing of scientifically acceptable registries (if a registry is available for that drug) and contact information; this section focuses on the high value of data that are systematically and prospectively collected. The second summarizes risk associated with the drug during pregnancy, based on available human, animal, and pharmacologic data. Third is a discussion of clinical considerations.

Need for appropriate controls. Psychiatric disorders increase the risk of pregnancy complications, and often are associated with variables that might increase the risk of a poor pregnancy outcome. For example, a patient who has a psychiatric disorder might be less likely to seek prenatal care, take a prenatal vitamin, and sleep and eat well; she also might use alcohol, tobacco, or other substances of abuse.

The medical literature on the reproductive safety of psychotropic medications is fraught with confounding variables other than the medications themselves. These include variables that, taken alone, might confer a poorer outcome on the fetus or newborn of a pregnant or lactating woman who has a psychiatric illness (to the extent that she uses psychotropics during a pregnancy), compared with what would be seen in (1) a healthy woman who is not taking such medication or (2) the general population.

On the new labels, detailed statements on human data include information from clinical trials, pregnancy exposure registries, and epidemiologic studies. Labels are also to include:

- incidence of adverse events

- effect of dosage

- effect of duration of exposure

- effect of gestational timing of exposure.

The labels emphasize quantifying risk relative to the risk of the same outcome in infants born to women who have not been exposed to the particular drug, but who have the disease or condition for which the drug is indicated (ie, appropriate controls).

Clinical considerations are to include information on the following related to the specific medication (when that information is known):

- more information for prescribers, to further risk-benefit counseling

- disease-associated maternal-fetal risks

- dosage adjustments during pregnancy and postpartum

- maternal adverse reactions

- fetal and neonatal adverse reactions

- labor and delivery.

Clearly, this overdue shift in providing information regarding reproductive safety has the potential to inform clinicians and patients in a meaningful way about the risks and benefits of specific treatments during pregnancy and lactation. Translating that information into practice is daunting, however.

Important aspects of implementation

Pregnancy exposure registries will play a crucial role. For most medications, no systematic registry has been established; to do so, rigorous methodology is required to acquire prospective data and account for confounding variables.4 Appropriate control groups also are required to yield data that are useful and interpretable. Primary outcomes require verification, such as review of medical records. Last, registries must be well-conducted and therefore adequately funded, yet labeling changes have not been accompanied by funding requirements set forth by regulators to pharmaceutical manufacturers.

Labeling must be updated continually. Furthermore, it is unclear who will review data for precision and comprehensiveness.

Data need to be understandable to health care providers across disciplines and to patients with varying levels of education for the label to have a meaningful impact on clinical care.

As noted, there is no mandate for funding the meticulous pharmacovigilance required to provide definitive data for labeling. It is unclear if the potential benefits of the new labeling can be reaped without adequate financing of the pharmacovigilance mechanisms required to inform patients adequately.

Role of pregnancy registries

Over the past 2 decades, pregnancy registries have emerged as a rapid, systematic means of collecting important reproductive safety data on the risk for major malformations after prenatal exposure to a medication or a class of medications.5,6 Such registries enhance the rigor of available cohort studies and other analyses of reproductive safety data that have been derived from large administrative databases.

NPRAA and NPRAD. Recently, the National Pregnancy Registry for Atypical Antipsychotics (NPRAA) and the National Pregnancy Registry for Antidepressants (NPRAD) were established in an effort to obtain reproductive safety data about fetal exposure to second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) and to newer antidepressants.7 Based at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, NPRAA and NPRAD systematically and prospectively evaluate the risk of malformations among infants who have been exposed in utero to an SGA or an antidepressant.

The structure of both registries are the same, modeled after the North American Antiepileptic Drug Registry.5,8 Data are collected prospectively from pregnant women, age 18 to 45, by means of 3 telephone interviews conducted proximate to enrollment, at 7 months’ gestation, and at 2 or 3 months’ postpartum.

Participants include (1) pregnant women who have a history of fetal exposure to an SGA or an antidepressant, or both, and (2) a comparison group of non-exposed pregnant women who have a history of a psychiatric illness. Authorization for release of medical records is obtained for obstetric care, labor and delivery, and neonatal care (≤6 months of age).

Information on the presence of major malformations is abstracted from the medical record, along with other data on neonatal and maternal health outcomes. Identified cases of a congenital malformation are sent to a dysmorphologist, who has been blinded to drug exposure, for final adjudication. Release of findings is dictated by a governing Scientific Advisory Board.

Results so far. Results are available from the NPRAA.9 As of December 2014, 487 women were enrolled: 353 who used an SGA and 134 comparison women. Medical records were obtained for 82.2% of participants. A total of 303 women completed the study and were eligible for inclusion in the analysis. Findings include:

- Of 214 live births with first-trimester exposure to an SGA, 3 major malformations were confirmed. In the control group (n = 89), 1 major malformation was confirmed

- The absolute risk of a major malformation was 1.4% for an exposed infant and 1.1% for an unexposed infant

- The odds ratio for a major malformation, comparing exposed infants with unexposed infants, was 1.25 (95% CI, 0.13–12.19).

It is reasonable, therefore, to conclude that, as a class, SGAs are not major teratogens. Although the confidence intervals around the odds ratio estimate remain wide, with the probability for change over the course of the study, it is unlikely that risk will rise to the level of known major teratogens, such as valproate and thalidomide.10,11

Help with decision-making

Given recent FDA guidance about the importance of pregnancy registries (www.fda.gov/pregnancyregistries), such carefully collected data might help clinicians and patients make informed choices about treatment. Future efforts of NPRAA and NPRAD will focus on sustaining growth in enrollment of participants so that the reproductive safety of SGAs and newer antidepressants can be delineated more clearly.

Last, you can refer potential participants to NPRAA and NPRAD by calling 1-866-961-2388. More information is available at www.womensmentalhealth.org.

1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Food and Drug Administration; Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER); Center for Biologic Evaluation and Research (CBER). Pregnancy, lactation, and reproductive potential: labeling for human prescription drug and biological products—content and format: guidance for industry. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM425398.pdf. Published December 2014. Accessed June 7, 2016.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Birth defects. http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/birthdefects/facts.html. Updated September 21, 2005. Accessed June 7, 2016.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preterm birth. http://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pretermbirth.htm. Updated December 4, 2015. Accessed June 7, 2016.

4. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Food and Drug Administration; Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER); Center for Biologic Evaluation and Research (CBER). Guidance for industry: establishing pregnancy exposure registries. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/ScienceResearch/SpecialTopics/WomensHealthResearch/UCM133332.pdf. Published August 2002. Accessed June 7, 2016.

5. Holmes LB, Wyszynski DF. North American antiepileptic drug pregnancy registry. Epilepsia. 2004;45(11):1465.

6. Tomson T, Battino D, Craig J, et al; ILAE Commission on Therapeutic Strategies. Pregnancy registries: differences, similarities, and possible harmonization. Epilepsia. 2010;51(5):909-915.

7. Cohen LS, Viguera AC, McInerney KA, et al. Establishment of the National Pregnancy Registry for Atypical Antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(7):986-989.

8. Holmes LB, Wyszynski DF, Lieberman E. The AED (antiepileptic drug) pregnancy registry: a 6-year experience. Arch Neurol. 2004;61(5):673-678.

9. Cohen LS, Viguera AC, McInerney KA, et al. Reproductive safety of second-generation antipsychotics: current data from the Massachusetts General Hospital National Pregnancy Registry for Atypical Antipsychotics. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(3):263-270.

10. McBride WG. Thalidomide and congenital abnormalities. Lancet. 1961;2(7216):1358.

11. Wyszynski DF, Nambisan M, Surve T, et al; Antiepileptic Drug Pregnancy Registry. Increased rate of major malformations in offspring exposed to valproate during pregnancy. Neurology. 2005;64(6):961-965.

1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Food and Drug Administration; Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER); Center for Biologic Evaluation and Research (CBER). Pregnancy, lactation, and reproductive potential: labeling for human prescription drug and biological products—content and format: guidance for industry. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM425398.pdf. Published December 2014. Accessed June 7, 2016.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Birth defects. http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/birthdefects/facts.html. Updated September 21, 2005. Accessed June 7, 2016.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preterm birth. http://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pretermbirth.htm. Updated December 4, 2015. Accessed June 7, 2016.

4. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Food and Drug Administration; Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER); Center for Biologic Evaluation and Research (CBER). Guidance for industry: establishing pregnancy exposure registries. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/ScienceResearch/SpecialTopics/WomensHealthResearch/UCM133332.pdf. Published August 2002. Accessed June 7, 2016.

5. Holmes LB, Wyszynski DF. North American antiepileptic drug pregnancy registry. Epilepsia. 2004;45(11):1465.

6. Tomson T, Battino D, Craig J, et al; ILAE Commission on Therapeutic Strategies. Pregnancy registries: differences, similarities, and possible harmonization. Epilepsia. 2010;51(5):909-915.

7. Cohen LS, Viguera AC, McInerney KA, et al. Establishment of the National Pregnancy Registry for Atypical Antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(7):986-989.

8. Holmes LB, Wyszynski DF, Lieberman E. The AED (antiepileptic drug) pregnancy registry: a 6-year experience. Arch Neurol. 2004;61(5):673-678.

9. Cohen LS, Viguera AC, McInerney KA, et al. Reproductive safety of second-generation antipsychotics: current data from the Massachusetts General Hospital National Pregnancy Registry for Atypical Antipsychotics. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(3):263-270.

10. McBride WG. Thalidomide and congenital abnormalities. Lancet. 1961;2(7216):1358.

11. Wyszynski DF, Nambisan M, Surve T, et al; Antiepileptic Drug Pregnancy Registry. Increased rate of major malformations in offspring exposed to valproate during pregnancy. Neurology. 2005;64(6):961-965.