User login

Volunteer surgeon describes working at a New York hospital

In an April 18 Twitter post, Dr. Salles wrote that her unit had experienced three code blues and two deaths in a single night.

“I don’t know how many times I’ve called to tell someone their loved one has died,” she wrote in the post. “I had to do it again last night. ... Of the five patients I’ve personally been responsible for in the past two nights, two have come so close to dying that we called a code blue. That means 40% of my patients have coded. Never in my life has anything close to that happened,” she continued in the thread.

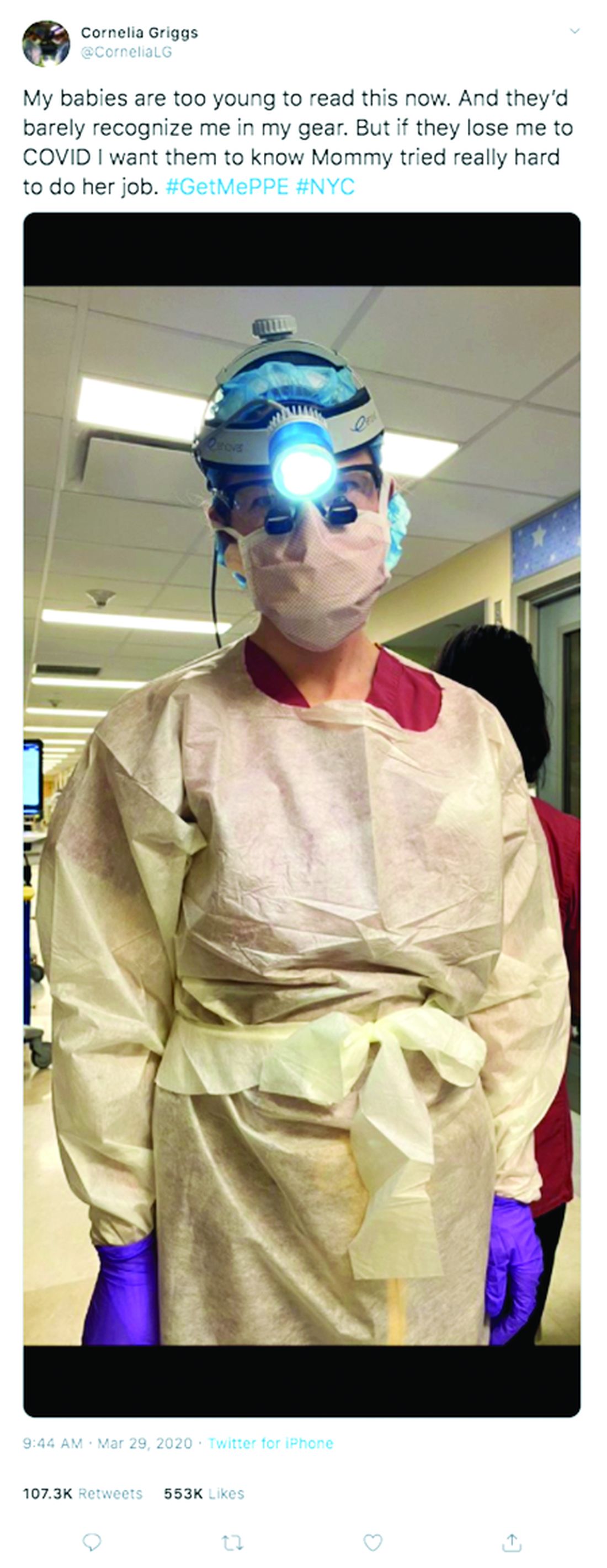

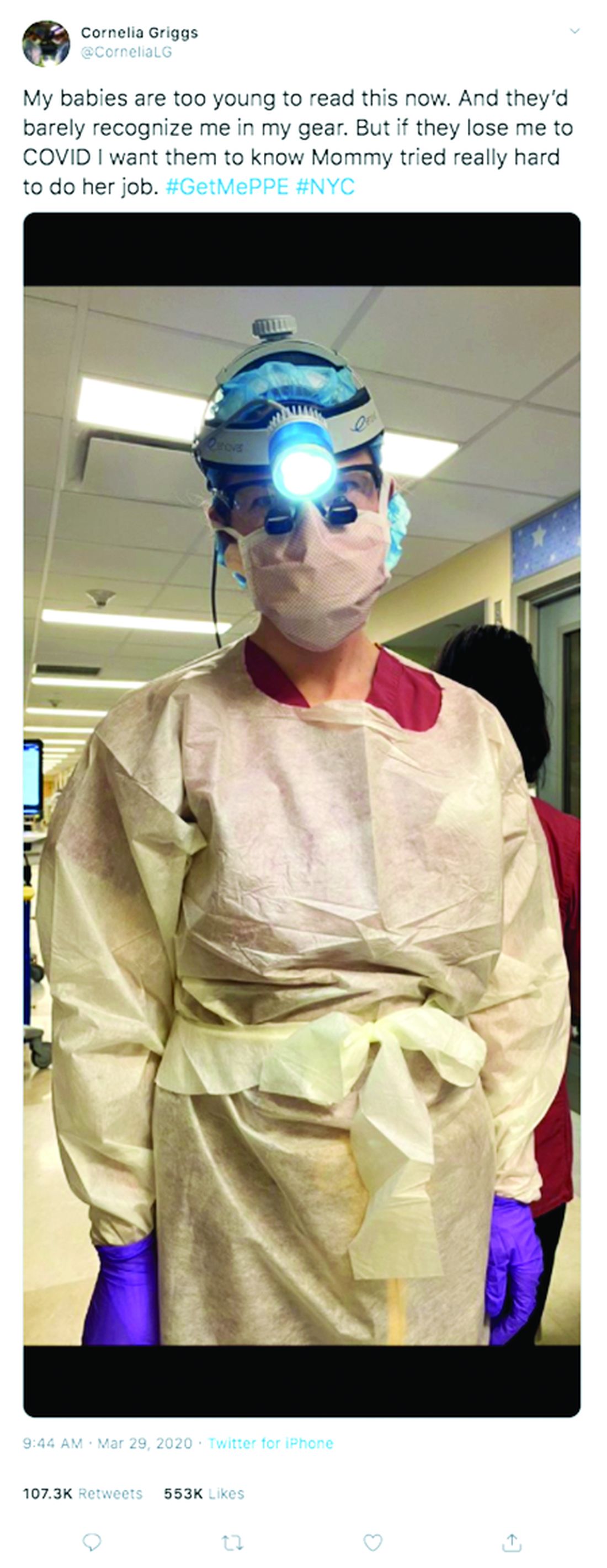

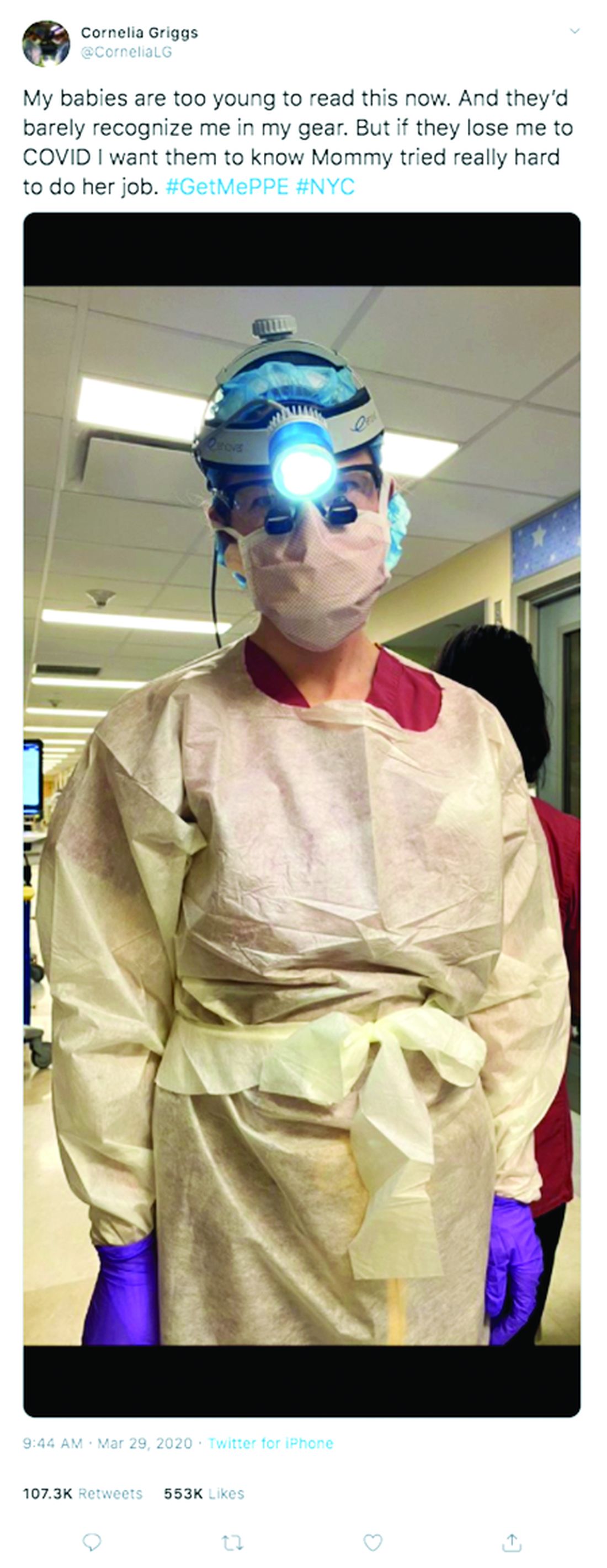

Dr. Salles, a minimally invasive and bariatric surgeon and scholar in residence at Stanford (Calif.) University, headed to New York in mid-April to assist with COVID-19 treatment efforts. Before the trip, she collected as many supplies and as much personal protective equipment as she could acquire, some of which were donated by Good Samaritans. On her first day as a volunteer, Dr. Salles recounted the stark differences between what she is used to seeing and her new environment and the novel challenges she has encountered in New York.

“Things that were not normal now seem normal,” she wrote in an April 15 Twitter post. “ICU patients in [a postanesthesia care unit] and Preop is the new normal. Patients satting in the 70s and 80s seems normal. ICU docs managing [continuous veno-venous hemodialysis] seems normal. Working with strangers seems normal. ... Obviously everyone walking around with barely any skin exposed is also the new normal.”

Similar to a “normal” ICU, new patients are admitted daily, Dr. Salles noted. However, the majority of those who leave the ICU do not go home, she wrote.

“Almost all of the ones who leave are doing so because they’ve died rather than getting better,” she wrote in the same April 19 Twitter thread. “There is a pervasive feeling of helplessness. ... The tools we are working with seem insufficient. For the sickest patients, there are no ventilator settings that seem to work, there are no medications that seem to help. I am not used to this.”

When patients are close to dying, health care workers do their best to connect the patient to loved ones through video calls, watching as family members say their last goodbyes through a screen, Dr. Salles detailed in a later post.

“Their voices cracked, and though they weren’t speaking English, I could hear their pain,” she wrote in an April 20 Twitter post. “For a moment, I imagined having to say goodbye to my mother this way. To not be able to be there, to not be able to hold her hand, to not be able to hug her. And I watched my colleague, who amazingly kept her composure until they had said everything they wanted to say. It was only after they hung up that I saw the tears well up in her eyes.”

But amid the dark days and bleak outcomes, Dr. Salles has found silver linings, humor, and gifts for which to be thankful.

“People are really generous,” she wrote in an April 15 post. “So many have offered to pay for transportation. Other docs in NY have offered to help me with supplies (and I am paying it forward). Grateful to you all!”

In another post, Dr. Salles joked that her “small head” makes it difficult to wear PPE.

“Wearing an N95 for hours really sucks,” she wrote. “It rides up, I pull it down. It digs into my cheeks, I pull it up. Repeat.”

The volunteer experience thus far has also made Dr. Salles question the future and worry about the mental health of her fellow health care professionals.

“The people who have been in NYC since the beginning of this, and those who work in Lombardy, Italy, and in Wuhan, China have faced loss for weeks to months,” she wrote in an April 18 Twitter post. “Not only do we not know when this will end, but it is likely that after it fades, it will come back in a second wave. I am lucky. I’m just a visitor here. I have the privilege to observe and learn and hopefully help, knowing I will be able to walk away. But what about those who can’t walk away? Social distancing is starting to work. But for healthcare workers, the ongoing devastation is very real. What is our long term plan?”

Dr. Salles expressed concern for health care workers who are witnessing “horrible things” with little time to process the experiences.

“It may be especially hard for those who are now working in specialties they are not used to, having to provide care they are not familiar with. They are all doing their best, but inevitably mistakes will be made, and they will likely blame themselves,” she wrote. “How do we best support them?”

Stay tuned for upcoming commentaries from Dr. Salles on her COVID-19 volunteer experience in New York City.

In an April 18 Twitter post, Dr. Salles wrote that her unit had experienced three code blues and two deaths in a single night.

“I don’t know how many times I’ve called to tell someone their loved one has died,” she wrote in the post. “I had to do it again last night. ... Of the five patients I’ve personally been responsible for in the past two nights, two have come so close to dying that we called a code blue. That means 40% of my patients have coded. Never in my life has anything close to that happened,” she continued in the thread.

Dr. Salles, a minimally invasive and bariatric surgeon and scholar in residence at Stanford (Calif.) University, headed to New York in mid-April to assist with COVID-19 treatment efforts. Before the trip, she collected as many supplies and as much personal protective equipment as she could acquire, some of which were donated by Good Samaritans. On her first day as a volunteer, Dr. Salles recounted the stark differences between what she is used to seeing and her new environment and the novel challenges she has encountered in New York.

“Things that were not normal now seem normal,” she wrote in an April 15 Twitter post. “ICU patients in [a postanesthesia care unit] and Preop is the new normal. Patients satting in the 70s and 80s seems normal. ICU docs managing [continuous veno-venous hemodialysis] seems normal. Working with strangers seems normal. ... Obviously everyone walking around with barely any skin exposed is also the new normal.”

Similar to a “normal” ICU, new patients are admitted daily, Dr. Salles noted. However, the majority of those who leave the ICU do not go home, she wrote.

“Almost all of the ones who leave are doing so because they’ve died rather than getting better,” she wrote in the same April 19 Twitter thread. “There is a pervasive feeling of helplessness. ... The tools we are working with seem insufficient. For the sickest patients, there are no ventilator settings that seem to work, there are no medications that seem to help. I am not used to this.”

When patients are close to dying, health care workers do their best to connect the patient to loved ones through video calls, watching as family members say their last goodbyes through a screen, Dr. Salles detailed in a later post.

“Their voices cracked, and though they weren’t speaking English, I could hear their pain,” she wrote in an April 20 Twitter post. “For a moment, I imagined having to say goodbye to my mother this way. To not be able to be there, to not be able to hold her hand, to not be able to hug her. And I watched my colleague, who amazingly kept her composure until they had said everything they wanted to say. It was only after they hung up that I saw the tears well up in her eyes.”

But amid the dark days and bleak outcomes, Dr. Salles has found silver linings, humor, and gifts for which to be thankful.

“People are really generous,” she wrote in an April 15 post. “So many have offered to pay for transportation. Other docs in NY have offered to help me with supplies (and I am paying it forward). Grateful to you all!”

In another post, Dr. Salles joked that her “small head” makes it difficult to wear PPE.

“Wearing an N95 for hours really sucks,” she wrote. “It rides up, I pull it down. It digs into my cheeks, I pull it up. Repeat.”

The volunteer experience thus far has also made Dr. Salles question the future and worry about the mental health of her fellow health care professionals.

“The people who have been in NYC since the beginning of this, and those who work in Lombardy, Italy, and in Wuhan, China have faced loss for weeks to months,” she wrote in an April 18 Twitter post. “Not only do we not know when this will end, but it is likely that after it fades, it will come back in a second wave. I am lucky. I’m just a visitor here. I have the privilege to observe and learn and hopefully help, knowing I will be able to walk away. But what about those who can’t walk away? Social distancing is starting to work. But for healthcare workers, the ongoing devastation is very real. What is our long term plan?”

Dr. Salles expressed concern for health care workers who are witnessing “horrible things” with little time to process the experiences.

“It may be especially hard for those who are now working in specialties they are not used to, having to provide care they are not familiar with. They are all doing their best, but inevitably mistakes will be made, and they will likely blame themselves,” she wrote. “How do we best support them?”

Stay tuned for upcoming commentaries from Dr. Salles on her COVID-19 volunteer experience in New York City.

In an April 18 Twitter post, Dr. Salles wrote that her unit had experienced three code blues and two deaths in a single night.

“I don’t know how many times I’ve called to tell someone their loved one has died,” she wrote in the post. “I had to do it again last night. ... Of the five patients I’ve personally been responsible for in the past two nights, two have come so close to dying that we called a code blue. That means 40% of my patients have coded. Never in my life has anything close to that happened,” she continued in the thread.

Dr. Salles, a minimally invasive and bariatric surgeon and scholar in residence at Stanford (Calif.) University, headed to New York in mid-April to assist with COVID-19 treatment efforts. Before the trip, she collected as many supplies and as much personal protective equipment as she could acquire, some of which were donated by Good Samaritans. On her first day as a volunteer, Dr. Salles recounted the stark differences between what she is used to seeing and her new environment and the novel challenges she has encountered in New York.

“Things that were not normal now seem normal,” she wrote in an April 15 Twitter post. “ICU patients in [a postanesthesia care unit] and Preop is the new normal. Patients satting in the 70s and 80s seems normal. ICU docs managing [continuous veno-venous hemodialysis] seems normal. Working with strangers seems normal. ... Obviously everyone walking around with barely any skin exposed is also the new normal.”

Similar to a “normal” ICU, new patients are admitted daily, Dr. Salles noted. However, the majority of those who leave the ICU do not go home, she wrote.

“Almost all of the ones who leave are doing so because they’ve died rather than getting better,” she wrote in the same April 19 Twitter thread. “There is a pervasive feeling of helplessness. ... The tools we are working with seem insufficient. For the sickest patients, there are no ventilator settings that seem to work, there are no medications that seem to help. I am not used to this.”

When patients are close to dying, health care workers do their best to connect the patient to loved ones through video calls, watching as family members say their last goodbyes through a screen, Dr. Salles detailed in a later post.

“Their voices cracked, and though they weren’t speaking English, I could hear their pain,” she wrote in an April 20 Twitter post. “For a moment, I imagined having to say goodbye to my mother this way. To not be able to be there, to not be able to hold her hand, to not be able to hug her. And I watched my colleague, who amazingly kept her composure until they had said everything they wanted to say. It was only after they hung up that I saw the tears well up in her eyes.”

But amid the dark days and bleak outcomes, Dr. Salles has found silver linings, humor, and gifts for which to be thankful.

“People are really generous,” she wrote in an April 15 post. “So many have offered to pay for transportation. Other docs in NY have offered to help me with supplies (and I am paying it forward). Grateful to you all!”

In another post, Dr. Salles joked that her “small head” makes it difficult to wear PPE.

“Wearing an N95 for hours really sucks,” she wrote. “It rides up, I pull it down. It digs into my cheeks, I pull it up. Repeat.”

The volunteer experience thus far has also made Dr. Salles question the future and worry about the mental health of her fellow health care professionals.

“The people who have been in NYC since the beginning of this, and those who work in Lombardy, Italy, and in Wuhan, China have faced loss for weeks to months,” she wrote in an April 18 Twitter post. “Not only do we not know when this will end, but it is likely that after it fades, it will come back in a second wave. I am lucky. I’m just a visitor here. I have the privilege to observe and learn and hopefully help, knowing I will be able to walk away. But what about those who can’t walk away? Social distancing is starting to work. But for healthcare workers, the ongoing devastation is very real. What is our long term plan?”

Dr. Salles expressed concern for health care workers who are witnessing “horrible things” with little time to process the experiences.

“It may be especially hard for those who are now working in specialties they are not used to, having to provide care they are not familiar with. They are all doing their best, but inevitably mistakes will be made, and they will likely blame themselves,” she wrote. “How do we best support them?”

Stay tuned for upcoming commentaries from Dr. Salles on her COVID-19 volunteer experience in New York City.

Supreme Court: Government owes more than $12 billion to health plans

The federal government owes billions of dollars to health insurers under an Affordable Care Act provision intended to help insurers mitigate risk, the U.S. Supreme Court has ruled.

In an 8-to-1 vote announced April 27, justices sided with the plaintiff health plans in Maine Community Health Options v. United States, ruling that the risk corridors statute created a government obligation to pay insurers the full amount originally calculated and that appropriation measures later passed by Congress did not repeal this obligation.

“In establishing the temporary risk corridors program, Congress created a rare money-mandating obligation requiring the federal government to make payments under [Section 1342 of the Affordable Care Act’s] formula,” Associate Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote in the majority opinion. “Lacking other statutory paths to relief ... petitioners may seek to collect payment through a damages action in the Court of Federal Claims.”

Maine Community Health Options v. United States, which consolidates several lawsuits against the government, centers on the ACA’s risk corridor program, which required the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services to collect funds from profitable insurers that offered qualified health plans under the exchanges and distribute the funds to insurers with excessive losses. Collections from profitable insurers under the program fell short in 2014, 2015, and 2016, while losses steadily grew, resulting in the HHS paying about 12 cents on the dollar in payments to insurers. More than 150 insurers now allege they were shortchanged by more than $12 billion all together.

The U.S. Department of Justice countered that the government is not required to pay the plans because of measures passed by Congress in 2014 and later years that limited the funding available to compensate insurers for their losses.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit decided in favor of the government, ruling that while the ACA required the government to compensate the insurers for their losses, the appropriations measures repealed or suspended that requirement.

The U.S. Supreme Court disagreed. Justices noted that even after Congress enacted the first rider, HHS and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services reiterated that the ACA requires the Secretary to make full payments to issuers and that “HHS [would] record risk corridors payments due as an obligation of the United States government for which full payment is required,” according to the Supreme Court opinion.

“They understood that profitable insurers’ payments to the government would not dispel the Secretary’s obligation to pay unprofitable insurers, even ‘in the event of a shortfall,’ ” Justice Sotomayor wrote in the majority opinion.

Associate Justice Samuel Alito Jr. however, took issue with his fellow justices’ decision. In his dissenting opinion, Justice Alito wrote that under the ruling, billions of taxpayer dollars will be turned over to insurance companies that bet unsuccessfully on the success of the program in question.

“This money will have to be paid even though Congress has pointedly declined to appropriate money for that purpose,” he wrote. “Not only will today’s decision have a massive immediate impact, its potential consequences go much further.”

The high court remanded the consolidated cases to the lower court for further proceedings on details of the disbursement.

The federal government owes billions of dollars to health insurers under an Affordable Care Act provision intended to help insurers mitigate risk, the U.S. Supreme Court has ruled.

In an 8-to-1 vote announced April 27, justices sided with the plaintiff health plans in Maine Community Health Options v. United States, ruling that the risk corridors statute created a government obligation to pay insurers the full amount originally calculated and that appropriation measures later passed by Congress did not repeal this obligation.

“In establishing the temporary risk corridors program, Congress created a rare money-mandating obligation requiring the federal government to make payments under [Section 1342 of the Affordable Care Act’s] formula,” Associate Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote in the majority opinion. “Lacking other statutory paths to relief ... petitioners may seek to collect payment through a damages action in the Court of Federal Claims.”

Maine Community Health Options v. United States, which consolidates several lawsuits against the government, centers on the ACA’s risk corridor program, which required the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services to collect funds from profitable insurers that offered qualified health plans under the exchanges and distribute the funds to insurers with excessive losses. Collections from profitable insurers under the program fell short in 2014, 2015, and 2016, while losses steadily grew, resulting in the HHS paying about 12 cents on the dollar in payments to insurers. More than 150 insurers now allege they were shortchanged by more than $12 billion all together.

The U.S. Department of Justice countered that the government is not required to pay the plans because of measures passed by Congress in 2014 and later years that limited the funding available to compensate insurers for their losses.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit decided in favor of the government, ruling that while the ACA required the government to compensate the insurers for their losses, the appropriations measures repealed or suspended that requirement.

The U.S. Supreme Court disagreed. Justices noted that even after Congress enacted the first rider, HHS and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services reiterated that the ACA requires the Secretary to make full payments to issuers and that “HHS [would] record risk corridors payments due as an obligation of the United States government for which full payment is required,” according to the Supreme Court opinion.

“They understood that profitable insurers’ payments to the government would not dispel the Secretary’s obligation to pay unprofitable insurers, even ‘in the event of a shortfall,’ ” Justice Sotomayor wrote in the majority opinion.

Associate Justice Samuel Alito Jr. however, took issue with his fellow justices’ decision. In his dissenting opinion, Justice Alito wrote that under the ruling, billions of taxpayer dollars will be turned over to insurance companies that bet unsuccessfully on the success of the program in question.

“This money will have to be paid even though Congress has pointedly declined to appropriate money for that purpose,” he wrote. “Not only will today’s decision have a massive immediate impact, its potential consequences go much further.”

The high court remanded the consolidated cases to the lower court for further proceedings on details of the disbursement.

The federal government owes billions of dollars to health insurers under an Affordable Care Act provision intended to help insurers mitigate risk, the U.S. Supreme Court has ruled.

In an 8-to-1 vote announced April 27, justices sided with the plaintiff health plans in Maine Community Health Options v. United States, ruling that the risk corridors statute created a government obligation to pay insurers the full amount originally calculated and that appropriation measures later passed by Congress did not repeal this obligation.

“In establishing the temporary risk corridors program, Congress created a rare money-mandating obligation requiring the federal government to make payments under [Section 1342 of the Affordable Care Act’s] formula,” Associate Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote in the majority opinion. “Lacking other statutory paths to relief ... petitioners may seek to collect payment through a damages action in the Court of Federal Claims.”

Maine Community Health Options v. United States, which consolidates several lawsuits against the government, centers on the ACA’s risk corridor program, which required the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services to collect funds from profitable insurers that offered qualified health plans under the exchanges and distribute the funds to insurers with excessive losses. Collections from profitable insurers under the program fell short in 2014, 2015, and 2016, while losses steadily grew, resulting in the HHS paying about 12 cents on the dollar in payments to insurers. More than 150 insurers now allege they were shortchanged by more than $12 billion all together.

The U.S. Department of Justice countered that the government is not required to pay the plans because of measures passed by Congress in 2014 and later years that limited the funding available to compensate insurers for their losses.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit decided in favor of the government, ruling that while the ACA required the government to compensate the insurers for their losses, the appropriations measures repealed or suspended that requirement.

The U.S. Supreme Court disagreed. Justices noted that even after Congress enacted the first rider, HHS and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services reiterated that the ACA requires the Secretary to make full payments to issuers and that “HHS [would] record risk corridors payments due as an obligation of the United States government for which full payment is required,” according to the Supreme Court opinion.

“They understood that profitable insurers’ payments to the government would not dispel the Secretary’s obligation to pay unprofitable insurers, even ‘in the event of a shortfall,’ ” Justice Sotomayor wrote in the majority opinion.

Associate Justice Samuel Alito Jr. however, took issue with his fellow justices’ decision. In his dissenting opinion, Justice Alito wrote that under the ruling, billions of taxpayer dollars will be turned over to insurance companies that bet unsuccessfully on the success of the program in question.

“This money will have to be paid even though Congress has pointedly declined to appropriate money for that purpose,” he wrote. “Not only will today’s decision have a massive immediate impact, its potential consequences go much further.”

The high court remanded the consolidated cases to the lower court for further proceedings on details of the disbursement.

More doctors used digital tools in 2019

The use of digital tools among physicians has markedly risen since 2016, with telehealth visits and remote patient monitoring making the greatest strides in usage, an American Medical Association report shows.

In 2019, 28% of physicians used televisits/virtual visits, up from 14% in 2016, while remote monitoring and management for improved care rose to 22% in 2019, an increase from 13% in 2016, according to the AMA report, released in February 2020. The report, which surveyed 1,359 doctors, includes responses from 672 primary care physicians and 687 specialists.

Remote monitoring for efficiency, meanwhile, grew to 16% in 2019 from 12% in 2016. Remote monitoring for efficiency pertains to smart versions of common clinical devices such as thermometers, blood pressure cuffs, and scales that automatically enter readings in the record. Remote monitoring for improved care refers to mobile applications and devices used for daily measurement of vital signs such as weight, blood pressure, blood glucose.

Adoption of other digital tools by physicians have also grown, including clinical decision support, which climbed to 37% in 2019 from 28% in 2016 and patient engagement tools, which rose to 33% in 2019, up from 26% in 2016. Clinical decision support tools pertain to modules used in conjunction with the electronic health record (EHR), or mobile applications integrated with an EHR that can signify changes in patient data, such as weight gain/loss, or change in blood chemistry. Patient engagement tools, meanwhile, refer to solutions that promote patient wellness and active patient participation in their care.

Tools that encompass use of point of care/workflow enhancement increased to 47% in 2019, from 42% in 2016. This area includes communication and sharing of electronic clinical data to consult with specialists, make referrals and/or transitions of care. Tools that address consumer access to their clinical data, meanwhile, rose to 58% in 2019 from 53% in 2016, the highest adoption rate among the digital health tool categories.

Overall, more physicians see an advantage to digital health solutions than did 3 years ago. More primary care physicians and specialists in 2019 reported a “definite advantage” to digital tools enhancing care of patients than in 2016. Doctors who see no advantage to such tools are trending downward and are concentrated to those age 50 and older, according to the report.

Solo-practice physicians are slowly increasing their use of digital health tools. In 2016, solo physicians reported using an average of 1.5 digital tools, which in 2019 increased to an average of 2.2 digital tools. Small practices with between one and three doctors used an average of 1.4 tools in 2016, which rose to an average of 2.2 tools in 2019, the report found. PCPs used slightly more digital tools, compared with specialists, in both 2016 and 2019.

Female doctors are slightly ahead of their male counterparts when it comes to digital health tools. In 2019, female physicians used an average of 2.6 digital tools, up from 1.9 in 2016. Male doctors used an average of 2.4 tools in 2019, compared with 1.9 tools in 2016.

For the physicians surveyed, the most important factor associated with usage was that digital tools were covered by malpractice insurance, followed by the importance of data privacy/security ensured by the EHR vendor, and that the tools were well integrated with the EHR. Other important factors included that data security was ensured by the practice or hospital, that doctors were reimbursed for their time spent using digital tools, and that the tools were supported by the EHR vendor.

Regarding the top motivator for doctors to use digital tools, 51% of physicians in 2019 said improved efficiency was “very important,” up from 48% in 2016. Other top motivators included that digital tools increased safety, improved diagnostic ability, and addressed physician burnout.

In 2019, the demonstration of safety and efficacy in peer-reviewed publications as it relates to digital tools also grew in importance. Of the physicians surveyed, 36% reported that safety and efficacy demonstrated in peer-reviewed publications was “very important,” an increase from 32% in 2016. Other “very important” factors for physicians are that digital tools used are proven to be as good/superior to traditional care, that they are intuitive/require no special training, that they align with the standard of care, and that their safety and efficacy is validated by the Food and Drug Administration.

“The rise of the digital-native physician will have a profound impact on health care and patient outcomes, and will place digital health technologies under pressure to perform according to higher expectations,” AMA board chair Jesse M. Ehrenfeld, MD, PhD, said in a statement. “The AMA survey provides deep insight into the emerging requirements that physicians expect from digital technologies and sets an industry guidepost for understanding what a growing number of physicians require to adopt new technology.”

The survey was derived from the same physician panel used in 2016, provided by WebMD. For the 2019 survey, the basic 2016 survey was followed in wording and question order, with a few variations to remove some questions no longer relevant. The 2019 sample used careful quotas to ensure a sample composition similar to that of 2016, according to the report.

SOURCE: AMA Digital Health Research: Physicians’ motivations and requirements for adopting digital health – Adoption and attitudinal shifts from 2016 to 2019. American Medical Association. February 2020.

The use of digital tools among physicians has markedly risen since 2016, with telehealth visits and remote patient monitoring making the greatest strides in usage, an American Medical Association report shows.

In 2019, 28% of physicians used televisits/virtual visits, up from 14% in 2016, while remote monitoring and management for improved care rose to 22% in 2019, an increase from 13% in 2016, according to the AMA report, released in February 2020. The report, which surveyed 1,359 doctors, includes responses from 672 primary care physicians and 687 specialists.

Remote monitoring for efficiency, meanwhile, grew to 16% in 2019 from 12% in 2016. Remote monitoring for efficiency pertains to smart versions of common clinical devices such as thermometers, blood pressure cuffs, and scales that automatically enter readings in the record. Remote monitoring for improved care refers to mobile applications and devices used for daily measurement of vital signs such as weight, blood pressure, blood glucose.

Adoption of other digital tools by physicians have also grown, including clinical decision support, which climbed to 37% in 2019 from 28% in 2016 and patient engagement tools, which rose to 33% in 2019, up from 26% in 2016. Clinical decision support tools pertain to modules used in conjunction with the electronic health record (EHR), or mobile applications integrated with an EHR that can signify changes in patient data, such as weight gain/loss, or change in blood chemistry. Patient engagement tools, meanwhile, refer to solutions that promote patient wellness and active patient participation in their care.

Tools that encompass use of point of care/workflow enhancement increased to 47% in 2019, from 42% in 2016. This area includes communication and sharing of electronic clinical data to consult with specialists, make referrals and/or transitions of care. Tools that address consumer access to their clinical data, meanwhile, rose to 58% in 2019 from 53% in 2016, the highest adoption rate among the digital health tool categories.

Overall, more physicians see an advantage to digital health solutions than did 3 years ago. More primary care physicians and specialists in 2019 reported a “definite advantage” to digital tools enhancing care of patients than in 2016. Doctors who see no advantage to such tools are trending downward and are concentrated to those age 50 and older, according to the report.

Solo-practice physicians are slowly increasing their use of digital health tools. In 2016, solo physicians reported using an average of 1.5 digital tools, which in 2019 increased to an average of 2.2 digital tools. Small practices with between one and three doctors used an average of 1.4 tools in 2016, which rose to an average of 2.2 tools in 2019, the report found. PCPs used slightly more digital tools, compared with specialists, in both 2016 and 2019.

Female doctors are slightly ahead of their male counterparts when it comes to digital health tools. In 2019, female physicians used an average of 2.6 digital tools, up from 1.9 in 2016. Male doctors used an average of 2.4 tools in 2019, compared with 1.9 tools in 2016.

For the physicians surveyed, the most important factor associated with usage was that digital tools were covered by malpractice insurance, followed by the importance of data privacy/security ensured by the EHR vendor, and that the tools were well integrated with the EHR. Other important factors included that data security was ensured by the practice or hospital, that doctors were reimbursed for their time spent using digital tools, and that the tools were supported by the EHR vendor.

Regarding the top motivator for doctors to use digital tools, 51% of physicians in 2019 said improved efficiency was “very important,” up from 48% in 2016. Other top motivators included that digital tools increased safety, improved diagnostic ability, and addressed physician burnout.

In 2019, the demonstration of safety and efficacy in peer-reviewed publications as it relates to digital tools also grew in importance. Of the physicians surveyed, 36% reported that safety and efficacy demonstrated in peer-reviewed publications was “very important,” an increase from 32% in 2016. Other “very important” factors for physicians are that digital tools used are proven to be as good/superior to traditional care, that they are intuitive/require no special training, that they align with the standard of care, and that their safety and efficacy is validated by the Food and Drug Administration.

“The rise of the digital-native physician will have a profound impact on health care and patient outcomes, and will place digital health technologies under pressure to perform according to higher expectations,” AMA board chair Jesse M. Ehrenfeld, MD, PhD, said in a statement. “The AMA survey provides deep insight into the emerging requirements that physicians expect from digital technologies and sets an industry guidepost for understanding what a growing number of physicians require to adopt new technology.”

The survey was derived from the same physician panel used in 2016, provided by WebMD. For the 2019 survey, the basic 2016 survey was followed in wording and question order, with a few variations to remove some questions no longer relevant. The 2019 sample used careful quotas to ensure a sample composition similar to that of 2016, according to the report.

SOURCE: AMA Digital Health Research: Physicians’ motivations and requirements for adopting digital health – Adoption and attitudinal shifts from 2016 to 2019. American Medical Association. February 2020.

The use of digital tools among physicians has markedly risen since 2016, with telehealth visits and remote patient monitoring making the greatest strides in usage, an American Medical Association report shows.

In 2019, 28% of physicians used televisits/virtual visits, up from 14% in 2016, while remote monitoring and management for improved care rose to 22% in 2019, an increase from 13% in 2016, according to the AMA report, released in February 2020. The report, which surveyed 1,359 doctors, includes responses from 672 primary care physicians and 687 specialists.

Remote monitoring for efficiency, meanwhile, grew to 16% in 2019 from 12% in 2016. Remote monitoring for efficiency pertains to smart versions of common clinical devices such as thermometers, blood pressure cuffs, and scales that automatically enter readings in the record. Remote monitoring for improved care refers to mobile applications and devices used for daily measurement of vital signs such as weight, blood pressure, blood glucose.

Adoption of other digital tools by physicians have also grown, including clinical decision support, which climbed to 37% in 2019 from 28% in 2016 and patient engagement tools, which rose to 33% in 2019, up from 26% in 2016. Clinical decision support tools pertain to modules used in conjunction with the electronic health record (EHR), or mobile applications integrated with an EHR that can signify changes in patient data, such as weight gain/loss, or change in blood chemistry. Patient engagement tools, meanwhile, refer to solutions that promote patient wellness and active patient participation in their care.

Tools that encompass use of point of care/workflow enhancement increased to 47% in 2019, from 42% in 2016. This area includes communication and sharing of electronic clinical data to consult with specialists, make referrals and/or transitions of care. Tools that address consumer access to their clinical data, meanwhile, rose to 58% in 2019 from 53% in 2016, the highest adoption rate among the digital health tool categories.

Overall, more physicians see an advantage to digital health solutions than did 3 years ago. More primary care physicians and specialists in 2019 reported a “definite advantage” to digital tools enhancing care of patients than in 2016. Doctors who see no advantage to such tools are trending downward and are concentrated to those age 50 and older, according to the report.

Solo-practice physicians are slowly increasing their use of digital health tools. In 2016, solo physicians reported using an average of 1.5 digital tools, which in 2019 increased to an average of 2.2 digital tools. Small practices with between one and three doctors used an average of 1.4 tools in 2016, which rose to an average of 2.2 tools in 2019, the report found. PCPs used slightly more digital tools, compared with specialists, in both 2016 and 2019.

Female doctors are slightly ahead of their male counterparts when it comes to digital health tools. In 2019, female physicians used an average of 2.6 digital tools, up from 1.9 in 2016. Male doctors used an average of 2.4 tools in 2019, compared with 1.9 tools in 2016.

For the physicians surveyed, the most important factor associated with usage was that digital tools were covered by malpractice insurance, followed by the importance of data privacy/security ensured by the EHR vendor, and that the tools were well integrated with the EHR. Other important factors included that data security was ensured by the practice or hospital, that doctors were reimbursed for their time spent using digital tools, and that the tools were supported by the EHR vendor.

Regarding the top motivator for doctors to use digital tools, 51% of physicians in 2019 said improved efficiency was “very important,” up from 48% in 2016. Other top motivators included that digital tools increased safety, improved diagnostic ability, and addressed physician burnout.

In 2019, the demonstration of safety and efficacy in peer-reviewed publications as it relates to digital tools also grew in importance. Of the physicians surveyed, 36% reported that safety and efficacy demonstrated in peer-reviewed publications was “very important,” an increase from 32% in 2016. Other “very important” factors for physicians are that digital tools used are proven to be as good/superior to traditional care, that they are intuitive/require no special training, that they align with the standard of care, and that their safety and efficacy is validated by the Food and Drug Administration.

“The rise of the digital-native physician will have a profound impact on health care and patient outcomes, and will place digital health technologies under pressure to perform according to higher expectations,” AMA board chair Jesse M. Ehrenfeld, MD, PhD, said in a statement. “The AMA survey provides deep insight into the emerging requirements that physicians expect from digital technologies and sets an industry guidepost for understanding what a growing number of physicians require to adopt new technology.”

The survey was derived from the same physician panel used in 2016, provided by WebMD. For the 2019 survey, the basic 2016 survey was followed in wording and question order, with a few variations to remove some questions no longer relevant. The 2019 sample used careful quotas to ensure a sample composition similar to that of 2016, according to the report.

SOURCE: AMA Digital Health Research: Physicians’ motivations and requirements for adopting digital health – Adoption and attitudinal shifts from 2016 to 2019. American Medical Association. February 2020.

COVID-19 causes financial woes for GI practices

On a typical clinic day, Will Bulsiewicz, MD, a Charleston, S.C.–based gastroenterologist, used to see 22 patients, while other days were filled with up to 16 procedures.

Since COVID-19 however, things have vastly changed. Dr. Bulsiewicz now visits with all clinic patients through telehealth, and the volume has dipped to between zero and six patients per day. His three-doctor practice has also experienced a more than 90% reduction in endoscopy volume.

“Naturally, this has been devastating,” Dr. Bulsiewicz said in an interview. “Our practice was started in 1984, and we had a business model that we used for the history of our practice. That practice model was upended in a matter of 2 weeks.”

Dr. Bulsiewicz is far from alone. Community GI practices across the country are experiencing similar financial distress in the face of COVID-19. In addition to a decrease in patient referrals, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has requested that all elective esophagogastroduodenoscopies, colonoscopies, endoscopies, surgeries, and procedures be delayed during the coronavirus outbreak to conserve critical equipment and limit virus exposure. The guidance aligns with recent recommendations issued by American Gastroenterological Association, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, American College of Gastroenterology, and American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. The lack of patients has led to plummeting revenue for many GI practices and resulted in layoffs, reduced hours, and limited salaries in order to keep practices afloat.

“We’ve had to make drastic changes in the way we work,” said Rajeev Jain, MD, AGAF, a Dallas-based gastroenterologist. “The way private practices are economically set up, they don’t have large reserves of capital or liquidity. We’re not like Apple or these big companies that have these massive cushions. It’s one thing when you have a downturn in the economy and less people come to get care, but when you have a complete shutdown, your revenue stream to pay your bills is literally dried up.”

Dr. Jain’s practice is part of Texas Digestive Disease Consultants (TDDC), which provides GI care for patients in Texas and Louisiana. TDDC is part of GI Alliance, a private equity–based consolidation of practices that includes several states and more than 350 GIs. The management services organization is a collaboration between the PE firm and the partner physicians. Since the COVID-19 outbreak, Dr. Jain said his practice has seen a dramatic drop in patients. Normally, Dr. Jain would perform between 25 and 30 outpatient scopes over the course of 2 days, he said. On a recent Monday, he performed two procedures. To preserve cash flow, Dr. Jain said he and his senior partners are not taking an income right now. Some employees were recently furloughed and laid off.

“I never in my life thought that I would have to lay off people because of an economic issue,” Dr. Jain said. “That’s psychological strain that as a physician owner you feel because these are people that you work with on a day-to-day basis and you don’t want them suffering either. That’s been a tough thing.

James S. Leavitt, MD, said his 17-physician center in Miami, Fla., has furloughed about half its staff. The center is part of Gastro Health, a private equity firm–based medical group with more than 250 providers in four states. Dr. Leavitt, president and chief clinical officer for Gastro Health, said his center has gone from about 150 patients per day to 5 or fewer, while procedures have dropped from more than 100 a day to maybe 5.

Having partnered with a private equity firm, however, Dr. Leavitt believes his practice is bettered situated to manage the health crisis and address financial challenges.

“It’s made us better prepared to weather the storm. We have a very high-powered, sophisticated administration and much broader base and access to capital. [For example,] we had a lot of depth in management so that we could roll out a robust televisit program in a week in four states with over 250 doctors.”

From a business standpoint, however, certain goals for the company are on hold, he said, such as closing on potential acquisitions.

Telemedicine works well for many patients, particularly for follow-up patients and for patients who have an established relationship with Dr. Leavitt, he said. There are limitations of course, he noted.

“If I were a dermatologist, maybe I could see the skin rash, but you can’t examine the patient,” he said. “There are certain things you can’t do. If a patient has significant abdominal pain, a televisit isn’t the greatest.”

That’s why Dr. Leavitt’s care center remains open for the handful of patients who must be seen in-person, he said. Those patients are screened beforehand and their temperatures taken before treatment.

Dr. Bulsiewicz’s practice made the transition to telehealth after never having used the modality before COVID-19.

“This was a scramble,” said Dr. Bulsiewicz, who posts about COVID-19 on social media. “We started from zero knowledge to implementation in less than a week.”

Overall, the switch went smoothly, but Dr. Bulsiewicz said reimbursement challenges come with telehealth.

“The billing is not the same,” he said. “You’re doing the same work or more, and you’re taking a reduced fee because of the antiquated fee structure that is forcing you to apply the typical rules of an office encounter.”

He hopes CMS will alter the reimbursement schedule to temporarily pay on par with traditional evaluation and management codes based on medical complexity as opposed to documentation of physical exam. CMS has already expanded Medicare telehealth coverage to cover a wider range of health care services in light of the COVID-19 crisis and also broadened the range of communication tools that can be used, according to a March announcement.

In the meantime, many practices have applied for financial assistance programs. The AGA recently pushed the government for additional assistance to help struggling practices.

Dr. Jain hopes these assistance programs roll out quickly.

“If these don’t get out there quick enough and big enough, we are going to see a massive wave of loss of independent practices and/or consolidation,” he said. “I fear a death to small, independent practices because they’re not going to have the financial wherewithal to tolerate this for too long.”

On a typical clinic day, Will Bulsiewicz, MD, a Charleston, S.C.–based gastroenterologist, used to see 22 patients, while other days were filled with up to 16 procedures.

Since COVID-19 however, things have vastly changed. Dr. Bulsiewicz now visits with all clinic patients through telehealth, and the volume has dipped to between zero and six patients per day. His three-doctor practice has also experienced a more than 90% reduction in endoscopy volume.

“Naturally, this has been devastating,” Dr. Bulsiewicz said in an interview. “Our practice was started in 1984, and we had a business model that we used for the history of our practice. That practice model was upended in a matter of 2 weeks.”

Dr. Bulsiewicz is far from alone. Community GI practices across the country are experiencing similar financial distress in the face of COVID-19. In addition to a decrease in patient referrals, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has requested that all elective esophagogastroduodenoscopies, colonoscopies, endoscopies, surgeries, and procedures be delayed during the coronavirus outbreak to conserve critical equipment and limit virus exposure. The guidance aligns with recent recommendations issued by American Gastroenterological Association, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, American College of Gastroenterology, and American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. The lack of patients has led to plummeting revenue for many GI practices and resulted in layoffs, reduced hours, and limited salaries in order to keep practices afloat.

“We’ve had to make drastic changes in the way we work,” said Rajeev Jain, MD, AGAF, a Dallas-based gastroenterologist. “The way private practices are economically set up, they don’t have large reserves of capital or liquidity. We’re not like Apple or these big companies that have these massive cushions. It’s one thing when you have a downturn in the economy and less people come to get care, but when you have a complete shutdown, your revenue stream to pay your bills is literally dried up.”

Dr. Jain’s practice is part of Texas Digestive Disease Consultants (TDDC), which provides GI care for patients in Texas and Louisiana. TDDC is part of GI Alliance, a private equity–based consolidation of practices that includes several states and more than 350 GIs. The management services organization is a collaboration between the PE firm and the partner physicians. Since the COVID-19 outbreak, Dr. Jain said his practice has seen a dramatic drop in patients. Normally, Dr. Jain would perform between 25 and 30 outpatient scopes over the course of 2 days, he said. On a recent Monday, he performed two procedures. To preserve cash flow, Dr. Jain said he and his senior partners are not taking an income right now. Some employees were recently furloughed and laid off.

“I never in my life thought that I would have to lay off people because of an economic issue,” Dr. Jain said. “That’s psychological strain that as a physician owner you feel because these are people that you work with on a day-to-day basis and you don’t want them suffering either. That’s been a tough thing.

James S. Leavitt, MD, said his 17-physician center in Miami, Fla., has furloughed about half its staff. The center is part of Gastro Health, a private equity firm–based medical group with more than 250 providers in four states. Dr. Leavitt, president and chief clinical officer for Gastro Health, said his center has gone from about 150 patients per day to 5 or fewer, while procedures have dropped from more than 100 a day to maybe 5.

Having partnered with a private equity firm, however, Dr. Leavitt believes his practice is bettered situated to manage the health crisis and address financial challenges.

“It’s made us better prepared to weather the storm. We have a very high-powered, sophisticated administration and much broader base and access to capital. [For example,] we had a lot of depth in management so that we could roll out a robust televisit program in a week in four states with over 250 doctors.”

From a business standpoint, however, certain goals for the company are on hold, he said, such as closing on potential acquisitions.

Telemedicine works well for many patients, particularly for follow-up patients and for patients who have an established relationship with Dr. Leavitt, he said. There are limitations of course, he noted.

“If I were a dermatologist, maybe I could see the skin rash, but you can’t examine the patient,” he said. “There are certain things you can’t do. If a patient has significant abdominal pain, a televisit isn’t the greatest.”

That’s why Dr. Leavitt’s care center remains open for the handful of patients who must be seen in-person, he said. Those patients are screened beforehand and their temperatures taken before treatment.

Dr. Bulsiewicz’s practice made the transition to telehealth after never having used the modality before COVID-19.

“This was a scramble,” said Dr. Bulsiewicz, who posts about COVID-19 on social media. “We started from zero knowledge to implementation in less than a week.”

Overall, the switch went smoothly, but Dr. Bulsiewicz said reimbursement challenges come with telehealth.

“The billing is not the same,” he said. “You’re doing the same work or more, and you’re taking a reduced fee because of the antiquated fee structure that is forcing you to apply the typical rules of an office encounter.”

He hopes CMS will alter the reimbursement schedule to temporarily pay on par with traditional evaluation and management codes based on medical complexity as opposed to documentation of physical exam. CMS has already expanded Medicare telehealth coverage to cover a wider range of health care services in light of the COVID-19 crisis and also broadened the range of communication tools that can be used, according to a March announcement.

In the meantime, many practices have applied for financial assistance programs. The AGA recently pushed the government for additional assistance to help struggling practices.

Dr. Jain hopes these assistance programs roll out quickly.

“If these don’t get out there quick enough and big enough, we are going to see a massive wave of loss of independent practices and/or consolidation,” he said. “I fear a death to small, independent practices because they’re not going to have the financial wherewithal to tolerate this for too long.”

On a typical clinic day, Will Bulsiewicz, MD, a Charleston, S.C.–based gastroenterologist, used to see 22 patients, while other days were filled with up to 16 procedures.

Since COVID-19 however, things have vastly changed. Dr. Bulsiewicz now visits with all clinic patients through telehealth, and the volume has dipped to between zero and six patients per day. His three-doctor practice has also experienced a more than 90% reduction in endoscopy volume.

“Naturally, this has been devastating,” Dr. Bulsiewicz said in an interview. “Our practice was started in 1984, and we had a business model that we used for the history of our practice. That practice model was upended in a matter of 2 weeks.”

Dr. Bulsiewicz is far from alone. Community GI practices across the country are experiencing similar financial distress in the face of COVID-19. In addition to a decrease in patient referrals, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has requested that all elective esophagogastroduodenoscopies, colonoscopies, endoscopies, surgeries, and procedures be delayed during the coronavirus outbreak to conserve critical equipment and limit virus exposure. The guidance aligns with recent recommendations issued by American Gastroenterological Association, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, American College of Gastroenterology, and American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. The lack of patients has led to plummeting revenue for many GI practices and resulted in layoffs, reduced hours, and limited salaries in order to keep practices afloat.

“We’ve had to make drastic changes in the way we work,” said Rajeev Jain, MD, AGAF, a Dallas-based gastroenterologist. “The way private practices are economically set up, they don’t have large reserves of capital or liquidity. We’re not like Apple or these big companies that have these massive cushions. It’s one thing when you have a downturn in the economy and less people come to get care, but when you have a complete shutdown, your revenue stream to pay your bills is literally dried up.”

Dr. Jain’s practice is part of Texas Digestive Disease Consultants (TDDC), which provides GI care for patients in Texas and Louisiana. TDDC is part of GI Alliance, a private equity–based consolidation of practices that includes several states and more than 350 GIs. The management services organization is a collaboration between the PE firm and the partner physicians. Since the COVID-19 outbreak, Dr. Jain said his practice has seen a dramatic drop in patients. Normally, Dr. Jain would perform between 25 and 30 outpatient scopes over the course of 2 days, he said. On a recent Monday, he performed two procedures. To preserve cash flow, Dr. Jain said he and his senior partners are not taking an income right now. Some employees were recently furloughed and laid off.

“I never in my life thought that I would have to lay off people because of an economic issue,” Dr. Jain said. “That’s psychological strain that as a physician owner you feel because these are people that you work with on a day-to-day basis and you don’t want them suffering either. That’s been a tough thing.

James S. Leavitt, MD, said his 17-physician center in Miami, Fla., has furloughed about half its staff. The center is part of Gastro Health, a private equity firm–based medical group with more than 250 providers in four states. Dr. Leavitt, president and chief clinical officer for Gastro Health, said his center has gone from about 150 patients per day to 5 or fewer, while procedures have dropped from more than 100 a day to maybe 5.

Having partnered with a private equity firm, however, Dr. Leavitt believes his practice is bettered situated to manage the health crisis and address financial challenges.

“It’s made us better prepared to weather the storm. We have a very high-powered, sophisticated administration and much broader base and access to capital. [For example,] we had a lot of depth in management so that we could roll out a robust televisit program in a week in four states with over 250 doctors.”

From a business standpoint, however, certain goals for the company are on hold, he said, such as closing on potential acquisitions.

Telemedicine works well for many patients, particularly for follow-up patients and for patients who have an established relationship with Dr. Leavitt, he said. There are limitations of course, he noted.

“If I were a dermatologist, maybe I could see the skin rash, but you can’t examine the patient,” he said. “There are certain things you can’t do. If a patient has significant abdominal pain, a televisit isn’t the greatest.”

That’s why Dr. Leavitt’s care center remains open for the handful of patients who must be seen in-person, he said. Those patients are screened beforehand and their temperatures taken before treatment.

Dr. Bulsiewicz’s practice made the transition to telehealth after never having used the modality before COVID-19.

“This was a scramble,” said Dr. Bulsiewicz, who posts about COVID-19 on social media. “We started from zero knowledge to implementation in less than a week.”

Overall, the switch went smoothly, but Dr. Bulsiewicz said reimbursement challenges come with telehealth.

“The billing is not the same,” he said. “You’re doing the same work or more, and you’re taking a reduced fee because of the antiquated fee structure that is forcing you to apply the typical rules of an office encounter.”

He hopes CMS will alter the reimbursement schedule to temporarily pay on par with traditional evaluation and management codes based on medical complexity as opposed to documentation of physical exam. CMS has already expanded Medicare telehealth coverage to cover a wider range of health care services in light of the COVID-19 crisis and also broadened the range of communication tools that can be used, according to a March announcement.

In the meantime, many practices have applied for financial assistance programs. The AGA recently pushed the government for additional assistance to help struggling practices.

Dr. Jain hopes these assistance programs roll out quickly.

“If these don’t get out there quick enough and big enough, we are going to see a massive wave of loss of independent practices and/or consolidation,” he said. “I fear a death to small, independent practices because they’re not going to have the financial wherewithal to tolerate this for too long.”

Concerns for clinicians over 65 grow in the face of COVID-19

When Judith Salerno, MD, heard that New York was calling for volunteer clinicians to assist with the COVID-19 response, she didn’t hesitate to sign up.

Although Dr. Salerno, 68, has held administrative, research, and policy roles for 25 years, she has kept her medical license active and always found ways to squeeze some clinical work into her busy schedule.

“I have what I could consider ‘rusty’ clinical skills, but pretty good clinical judgment,” said Dr. Salerno, president of the New York Academy of Medicine. “I thought in this situation that I could resurrect and hone those skills, even if it was just taking care of routine patients and working on a team, there was a lot of good I can do.”

Dr. Salerno is among 80,000 health care professionals who have volunteered to work temporarily in New York during the COVID-19 pandemic as of March 31, 2020, according to New York state officials. In mid-March, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo (D) issued a plea for retired physicians and nurses to help the state by signing up for on-call work. Other states have made similar appeals for retired health care professionals to return to medicine in an effort to relieve overwhelmed hospital staffs and aid capacity if health care workers become ill. Such redeployments, however, are raising concerns about exposing senior physicians to a virus that causes more severe illness in individuals aged over 65 years and kills them at a higher rate.

At the same time, a significant portion of the current health care workforce is aged 55 years and older, placing them at higher risk for serious illness, hospitalization, and death from COVID-19, said Douglas O. Staiger, PhD, a researcher and economics professor at Dartmouth College, Hanover, N.H. Dr. Staiger recently coauthored a viewpoint in JAMA called “Older clinicians and the surge in novel coronavirus disease 2019,” which outlines the risks and mortality rates from the novel coronavirus among patients aged 55 years and older.

Among the 1.2 million practicing physicians in the United States, about 20% are aged 55-64 years and an estimated 9% are 65 years or older, according to the paper. Of the nation’s nearly 2 million registered nurses employed in hospitals, about 19% are aged 55-64 years, and an estimated 3% are aged 65 years or older.

“In some metro areas, this proportion is even higher,” Dr. Staiger said in an interview. “Hospitals and other health care providers should consider ways of utilizing older clinicians’ skills and experience in a way that minimizes their risk of exposure to COVID-19, such as transferring them from jobs interacting with patients to more supervisory, administrative, or telehealth roles. This is increasingly important as retired physicians and nurses are being asked to return to the workforce.”

Protecting staff, screening volunteers

Hematologist-oncologist David H. Henry, MD, said his eight-physician group practice at Pennsylvania Hospital, Philadelphia, has already taken steps to protect him from COVID exposure.

At the request of his younger colleagues, Dr. Henry, 69, said he is no longer seeing patients in the hospital where there is increased exposure risk to the virus. He and the staff also limit their time in the office to 2-3 days a week and practice telemedicine the rest of the week, Dr. Henry said in an interview.

“Whether you’re a person trying to stay at home because you’re quote ‘nonessential,’ or you’re a health care worker and you have to keep seeing patients to some extent, the less we’re face to face with others the better,” said Dr. Henry, who hosts the Blood & Cancer podcast for MDedge News. “There’s an extreme and a middle ground. If they told me just to stay home that wouldn’t help anybody. If they said, ‘business as usual,’ that would be wrong. This is a middle strategy, which is reasonable, rational, and will help dial this dangerous time down as fast as possible.”

On a recent weekend when Dr. Henry would normally have been on call in the hospital, he took phone calls for his colleagues at home while they saw patients in the hospital. This included calls with patients who had questions and consultation calls with other physicians.

“They are helping me and I am helping them,” Dr. Henry said. “Taking those calls makes it easier for my partners to see all those patients. We all want to help and be there, within reason. You want to step up an do your job, but you want to be safe.”

Peter D. Quinn, DMD, MD, chief executive physician of the Penn Medicine Medical Group, said safeguarding the health of its workforce is a top priority as Penn Medicine works to fight the COVID-19 pandemic.

“This includes ensuring that all employees adhere to Centers for Disease Control and Penn Medicine infection prevention guidance as they continue their normal clinical work,” Dr. Quinn said in an interview. “Though age alone is not a criterion to remove frontline staff from direct clinical care during the COVID-19 outbreak, certain conditions such as cardiac or lung disease may be, and clinicians who have concerns are urged to speak with their leadership about options to fill clinical or support roles remotely.”

Meanwhile, for states calling on retired health professionals to assist during the pandemic, thorough screenings that identify high-risk volunteers are essential to protect vulnerable clinicians, said Nathaniel Hibbs, DO, president of the Colorado chapter of the American College of Emergency Physicians.

After Colorado issued a statewide request for retired clinicians to help, Dr. Hibbs became concerned that the state’s website initially included only a basic set of questions for interested volunteers.

“It didn’t have screening questions for prior health problems, comorbidities, or things like high blood pressure, heart disease, lung disease – the high-risk factors that we associate with bad outcomes if people get infected with COVID,” Dr. Hibbs said in an interview.

To address this, Dr. Hibbs and associates recently provided recommendations to the state about its screening process that advised collecting more health information from volunteers and considering lower-risk assignments for high-risk individuals. State officials indicated they would strongly consider the recommendations, Dr. Hibbs said.

The Colorado Department of Public Health & Environment did not respond to messages seeking comment. Officials at the New York State Department of Health declined to be interviewed for this article but confirmed that they are reviewing the age and background of all volunteers, and individual hospitals will also review each volunteer to find suitable jobs.

The American Medical Association on March 30 issued guidance for retired physicians about rejoining the workforce to help with the COVID response. The guidance outlines license considerations, contribution options, professional liability considerations, and questions to ask volunteer coordinators.

“Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, many physicians over the age of 65 will provide care to patients,” AMA President Patrice A. Harris, MD, said in a statement. “Whether ‘senior’ physicians should be on the front line of patient care at this time is a complex issue that must balance several factors against the benefit these physicians can provide. As with all people in high-risk age groups, careful consideration must be given to the health and safety of retired physicians and their immediate family members, especially those with chronic medical conditions.”

Tapping talent, sharing knowledge

When Barbara L. Schuster, MD, 69, filled out paperwork to join the Georgia Medical Reserve Corps, she answered a range of questions, including inquiries about her age, specialty, licensing, and whether she had any major medical conditions.

“They sent out instructions that said, if you are over the age of 60, we really don’t want you to be doing inpatient or ambulatory with active patients,” said Dr. Schuster, a retired medical school dean in the Athens, Ga., area. “Unless they get to a point where it’s going to be you or nobody, I think that they try to protect us for both our sake and also theirs.”

Dr. Schuster opted for telehealth or administrative duties, but has not yet been called upon to help. The Athens area has not seen high numbers of COVID-19 patients, compared with other parts of the country, and there have not been many volunteer opportunities for physicians thus far, she said. In the meantime, Dr. Schuster has found other ways to give her time, such as answering questions from community members on both COVID-19 and non–COVID-19 topics, and offering guidance to medical students.

“I’ve spent an increasing number of hours on Zoom, Skype, or FaceTime meeting with them to talk about various issues,” Dr. Schuster said.

As hospitals and organizations ramp up pandemic preparation, now is the time to consider roles for older clinicians and how they can best contribute, said Peter I. Buerhaus, PhD, RN, a nurse and director of the Center for Interdisciplinary Health Workforce Studies at Montana State University, Bozeman, Mont. Dr. Buerhaus was the first author of the recent JAMA viewpoint “Older clinicians and the surge in novel coronavirus 2019.”

“It’s important for hospitals that are anticipating a surge of critically ill patients to assess their workforce’s capability, including the proportion of older clinicians,” he said. “Is there something organizations can do differently to lessen older physicians’ and nurses’ direct patient contact and reduce their risk of infection?”

Dr. Buerhaus’ JAMA piece offers a range of ideas and assignments for older clinicians during the pandemic, including consulting with younger staff, advising on resources, assisting with clinical and organizational problem solving, aiding clinicians and managers with challenging decisions, consulting with patient families, advising managers and executives, being public spokespersons, and working with public and community health organizations.

“Older clinicians are at increased risk of becoming seriously ill if infected, but yet they’re also the ones who perhaps some of the best minds and experiences to help organizations combat the pandemic,” Dr. Buerhaus said. “These clinicians have great backgrounds and skills and 20, 30, 40 years of experience to draw on, including dealing with prior medical emergencies. I would hope that organizations, if they can, use the time before becoming a hotspot as an opportunity where the younger workforce could be teamed up with some of the older clinicians and learn as much as possible. It’s a great opportunity to share this wealth of knowledge with the workforce that will carry on after the pandemic.”

Since responding to New York’s call for volunteers, Dr. Salerno has been assigned to a palliative care inpatient team at a Manhattan hospital where she is working with large numbers of ICU patients and their families.

“My experience as a geriatrician helps me in talking with anxious and concerned families, especially when they are unable to see or communicate with their critically ill loved ones,” she said.

Before she was assigned the post, Dr. Salerno said she heard concerns from her adult children, who would prefer their mom take on a volunteer telehealth role. At the time, Dr. Salerno said she was not opposed to a telehealth assignment, but stressed to her family that she would go where she was needed.

“I’m healthy enough to run an organization, work long hours, long weeks; I have the stamina. The only thing working against me is age,” she said. “To say I’m not concerned is not honest. Of course I’m concerned. Am I afraid? No. I’m hoping that we can all be kept safe.”

When Judith Salerno, MD, heard that New York was calling for volunteer clinicians to assist with the COVID-19 response, she didn’t hesitate to sign up.

Although Dr. Salerno, 68, has held administrative, research, and policy roles for 25 years, she has kept her medical license active and always found ways to squeeze some clinical work into her busy schedule.

“I have what I could consider ‘rusty’ clinical skills, but pretty good clinical judgment,” said Dr. Salerno, president of the New York Academy of Medicine. “I thought in this situation that I could resurrect and hone those skills, even if it was just taking care of routine patients and working on a team, there was a lot of good I can do.”

Dr. Salerno is among 80,000 health care professionals who have volunteered to work temporarily in New York during the COVID-19 pandemic as of March 31, 2020, according to New York state officials. In mid-March, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo (D) issued a plea for retired physicians and nurses to help the state by signing up for on-call work. Other states have made similar appeals for retired health care professionals to return to medicine in an effort to relieve overwhelmed hospital staffs and aid capacity if health care workers become ill. Such redeployments, however, are raising concerns about exposing senior physicians to a virus that causes more severe illness in individuals aged over 65 years and kills them at a higher rate.

At the same time, a significant portion of the current health care workforce is aged 55 years and older, placing them at higher risk for serious illness, hospitalization, and death from COVID-19, said Douglas O. Staiger, PhD, a researcher and economics professor at Dartmouth College, Hanover, N.H. Dr. Staiger recently coauthored a viewpoint in JAMA called “Older clinicians and the surge in novel coronavirus disease 2019,” which outlines the risks and mortality rates from the novel coronavirus among patients aged 55 years and older.

Among the 1.2 million practicing physicians in the United States, about 20% are aged 55-64 years and an estimated 9% are 65 years or older, according to the paper. Of the nation’s nearly 2 million registered nurses employed in hospitals, about 19% are aged 55-64 years, and an estimated 3% are aged 65 years or older.

“In some metro areas, this proportion is even higher,” Dr. Staiger said in an interview. “Hospitals and other health care providers should consider ways of utilizing older clinicians’ skills and experience in a way that minimizes their risk of exposure to COVID-19, such as transferring them from jobs interacting with patients to more supervisory, administrative, or telehealth roles. This is increasingly important as retired physicians and nurses are being asked to return to the workforce.”

Protecting staff, screening volunteers

Hematologist-oncologist David H. Henry, MD, said his eight-physician group practice at Pennsylvania Hospital, Philadelphia, has already taken steps to protect him from COVID exposure.

At the request of his younger colleagues, Dr. Henry, 69, said he is no longer seeing patients in the hospital where there is increased exposure risk to the virus. He and the staff also limit their time in the office to 2-3 days a week and practice telemedicine the rest of the week, Dr. Henry said in an interview.

“Whether you’re a person trying to stay at home because you’re quote ‘nonessential,’ or you’re a health care worker and you have to keep seeing patients to some extent, the less we’re face to face with others the better,” said Dr. Henry, who hosts the Blood & Cancer podcast for MDedge News. “There’s an extreme and a middle ground. If they told me just to stay home that wouldn’t help anybody. If they said, ‘business as usual,’ that would be wrong. This is a middle strategy, which is reasonable, rational, and will help dial this dangerous time down as fast as possible.”

On a recent weekend when Dr. Henry would normally have been on call in the hospital, he took phone calls for his colleagues at home while they saw patients in the hospital. This included calls with patients who had questions and consultation calls with other physicians.

“They are helping me and I am helping them,” Dr. Henry said. “Taking those calls makes it easier for my partners to see all those patients. We all want to help and be there, within reason. You want to step up an do your job, but you want to be safe.”

Peter D. Quinn, DMD, MD, chief executive physician of the Penn Medicine Medical Group, said safeguarding the health of its workforce is a top priority as Penn Medicine works to fight the COVID-19 pandemic.

“This includes ensuring that all employees adhere to Centers for Disease Control and Penn Medicine infection prevention guidance as they continue their normal clinical work,” Dr. Quinn said in an interview. “Though age alone is not a criterion to remove frontline staff from direct clinical care during the COVID-19 outbreak, certain conditions such as cardiac or lung disease may be, and clinicians who have concerns are urged to speak with their leadership about options to fill clinical or support roles remotely.”

Meanwhile, for states calling on retired health professionals to assist during the pandemic, thorough screenings that identify high-risk volunteers are essential to protect vulnerable clinicians, said Nathaniel Hibbs, DO, president of the Colorado chapter of the American College of Emergency Physicians.

After Colorado issued a statewide request for retired clinicians to help, Dr. Hibbs became concerned that the state’s website initially included only a basic set of questions for interested volunteers.

“It didn’t have screening questions for prior health problems, comorbidities, or things like high blood pressure, heart disease, lung disease – the high-risk factors that we associate with bad outcomes if people get infected with COVID,” Dr. Hibbs said in an interview.

To address this, Dr. Hibbs and associates recently provided recommendations to the state about its screening process that advised collecting more health information from volunteers and considering lower-risk assignments for high-risk individuals. State officials indicated they would strongly consider the recommendations, Dr. Hibbs said.