User login

Can Telehealth Improve Access to Amyloid-Targeting Therapies for Veterans Living With Alzheimer Disease?

Can Telehealth Improve Access to Amyloid-Targeting Therapies for Veterans Living With Alzheimer Disease?

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is the largest US integrated health care system, providing health care to > 9 million veterans annually. Dementia affects > 7.2 million Americans, and an estimated 450,000 veterans live with Alzheimer disease (AD).1,2 Compared with the general population, veterans have a higher burden of chronic medical conditions and are disproportionately affected by AD due to exposure to military-related risk factors (eg, traumatic brain injury and posttraumatic stress disorder) and the high prevalence of nonmilitary risk factors, such as cardiovascular disease. The VHA is a pioneer in dementia care, having established a Dementia System of Care to provide primary and specialty care to veterans with dementia. The VHA also is leading the way in implementing the Institute for Healthcare Improvement Age-Friendly Health Systems (AFHS) framework for providing goal-concordant care in > 100 VHA medical centers. The VHA aims to be the largest AFHS in the country.

AD profoundly affects individuals and their families. The progressive nature of the most common form of dementia diminishes the quality of life for patients as well as their care partners in an ongoing fashion, often leading to emotional, physical, and financial strain. Costs for health and long-term care for people living with AD and other dementias were projected at $360 billion in 2024, largely due to the need for nursing home care.1 Although several oral medications are available, their capacity to effectively mitigate the negative effects of AD is limited. Cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine may offer temporary symptomatic relief, but they do not alter disease progression.3 The use of these agents is relatively low, with about one-third of patients diagnosed with AD receiving these medications.4

Amyloid-Targeting Therapies

Recent advancements in biologics, particularly amyloid-targeting therapies, such as lecanemab and donanemab, offer new hope for managing AD. Older adults treated with these medications show less decline on measures of cognition and function than those receiving a placebo at 18 months.5,6 However, accessing and using these medications is challenging.

Use of amyloid-targeting therapies poses challenges. The medications are expensive, potentially placing a financial burden on patients, families, and health care systems.7 Determining initial eligibility for treatment requires a battery of cognitive assessments, laboratory tests, advanced radiologic studies (eg, magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] of the brain and amyloid positron emission tomography [PET] scans), and possible cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) testing. Frequent ongoing assessments are necessary to monitor safety and efficacy. These treatments carry substantial risks, particularly amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA) such as cerebral edema, microhemorrhages, and superficial siderosis. Therefore, follow-up assessments typically occur around months 2, 3, 4, and 7, depending on which medication is selected. Finally, at present, both agents must be intravenous (IV)-administered in a monitored clinical setting, which requires additional coordination, transportation, and cost.

Ongoing evaluations and in-person administration particularly affect patients and care partners with limitations regarding transportation, time off work, and navigating complex health care systems.8 VHA clinicians at sites that have implemented or are interested in implementing amyloid-targeting therapy programs endorse similar challenges when implementing these therapies in their US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers (VAMCs).9

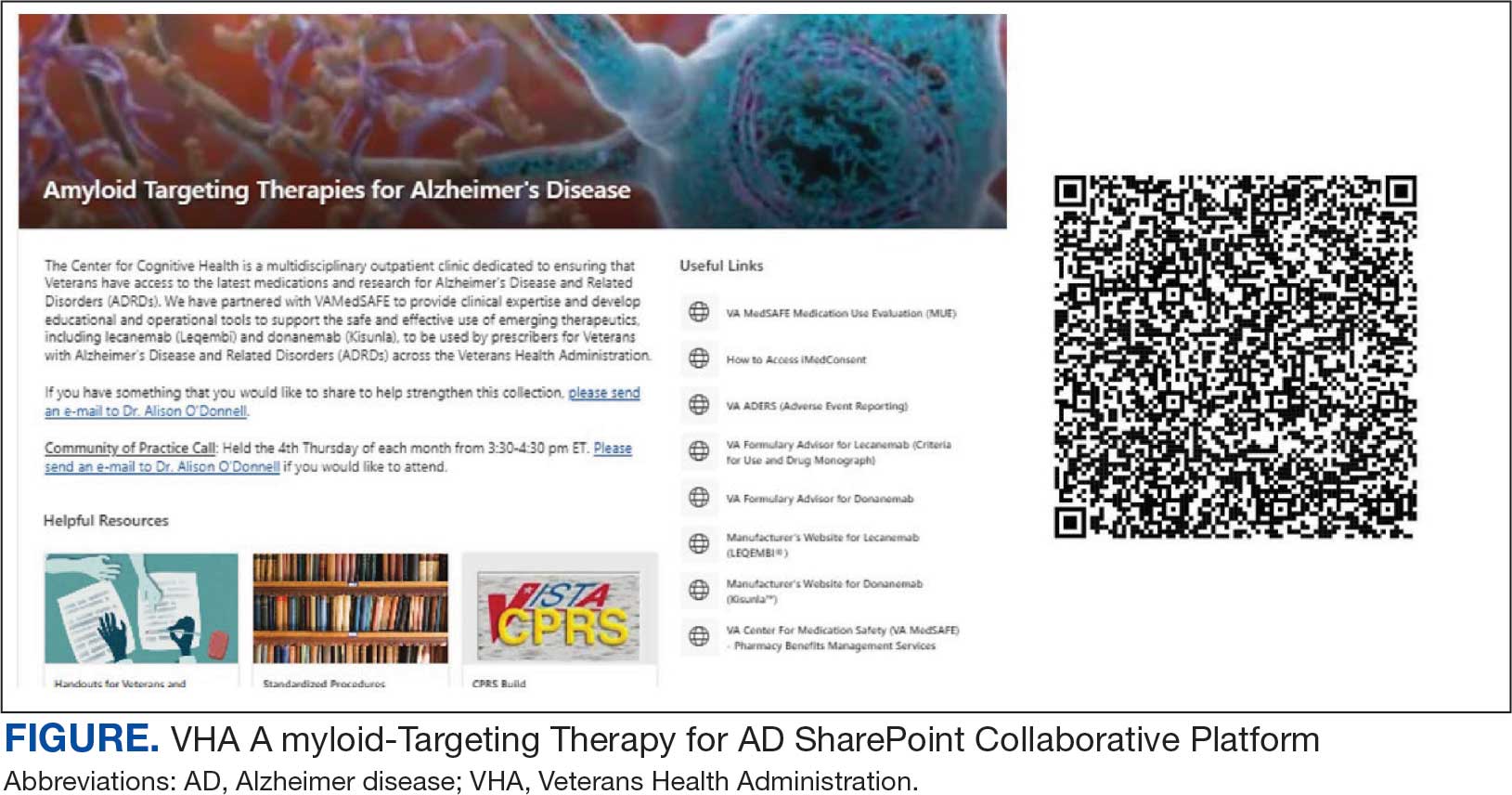

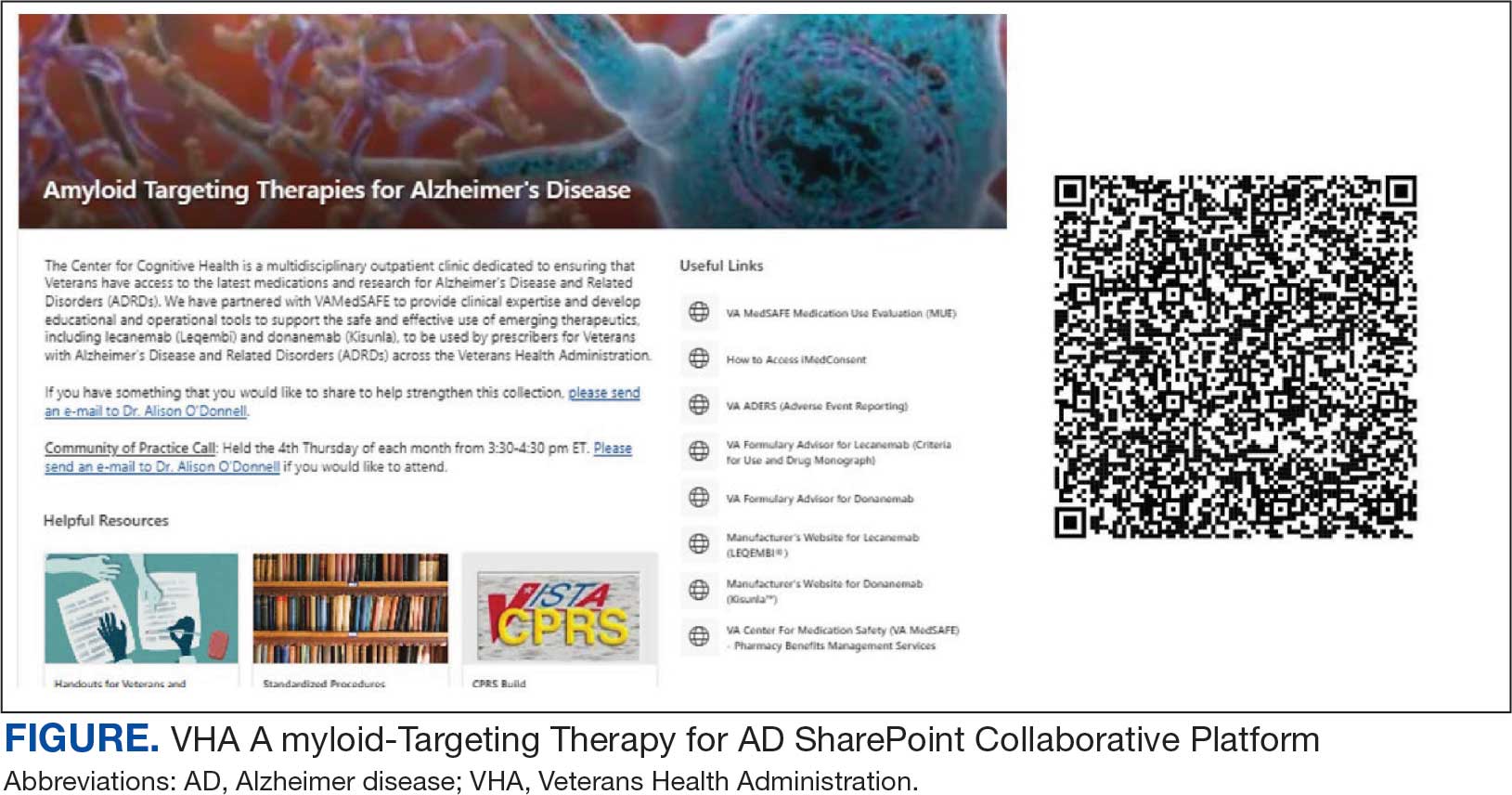

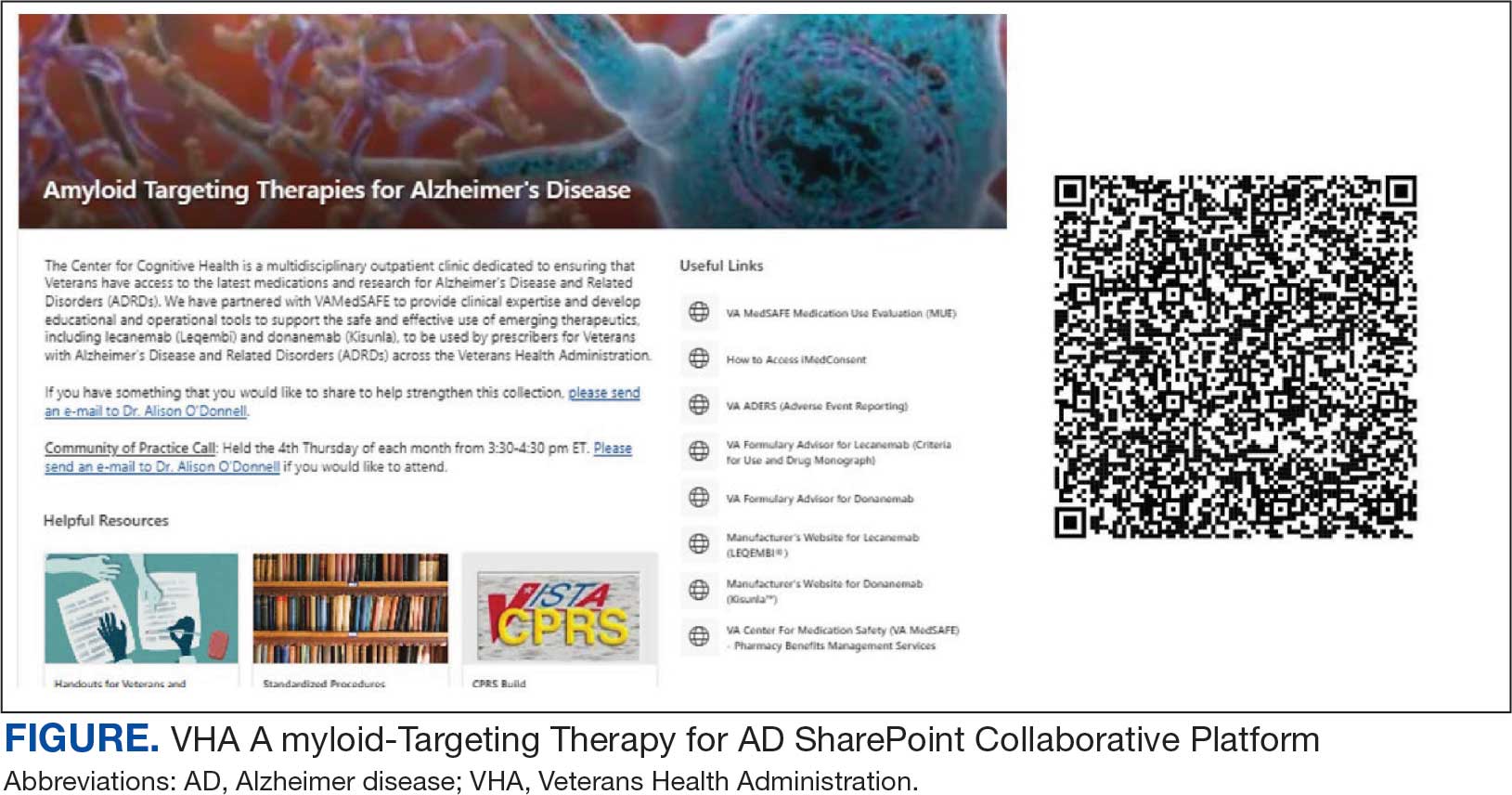

The VHA was one of the first health care systems to use amyloid-targeting therapies, covering the cost of lecanemab and donanemab, in addition to costs associated with concomitant evaluation and testing. However, given the safety concerns with this novel class of medications, the VHA National Formulary Committee developed criteria for use and recommended the VA Center for Medication Safety (VAMedSAFE) conduct a mandatory real-time medication use evaluation (MUE). VAMedSAFE developed the MUE to monitor the safe and appropriate use of amyloid-targeting therapy for AD. Two authors (AJO, SMH) partnered with VAMedSAFE through the VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System Technology Enhancing Cognition and Health–Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Center (TECH-GRECC) to provide clinical expertise, substantive feedback for the development of the MUE, and guidance for VHA sites starting amyloid targeting-therapy programs. We started a VHA Amyloid-Targeting Therapy for AD SharePoint collaborative platform and VHA AD Therapeutics Community of Practice (CoP) for shared learning (Figure). The private SharePoint platform houses an array of implementation materials for VAMCs starting programs: key documents and links; educational materials; sample guidelines; note templates; and electronic health record screenshots. The CoP allows VHAs to share best practices and discuss challenges.

Even with these advantages, we found that ensuring the safe and appropriate use of amyloid-targeting therapies did not overcome the barriers associated with their complexity. This was especially true for veterans living in rural areas. Only 4 VAMCs had administered amyloid-targeting therapies in the first year they were available. Preliminary data demonstrated that 27 (84%) of 32 veterans who initiated lecanemab in the VHA between October 2023 and September 2024 resided in urban areas.10 To address the underutilization of amyloid-targeting therapy, we propose leveraging the strengths of VHA telehealth to facilitate expansion of access to these medications for veterans with early AD. Telehealth may substantially increase access to evaluation for veterans with early dementia and, when medically appropriate, to receive amyloid-targeting therapies by reducing transportation needs and mitigating costs while ensuring appropriate monitoring through ongoing clinical assessments.

Using Telehealth

The VHA is a pioneer in telehealth, with programs dating back to 2003.11 Between October 1, 2018, and September 30, 2019, the VHA served > 900,000 veterans through the provision of > 2.6 million episodes of care via telehealth.12 The COVID-19 pandemic further cemented the role of telemedicine as an essential component of health care. Telehealth has demonstrated success in the assessment and management of individuals living with dementia. At the VHA, the GRECC-Connect Project is a partnership between 9 urban GRECC sites that seek to provide consultative geriatric and dementia care to rural veterans through telehealth.13 Additional evidence supports the potential to leverage telehealth to effectively communicate results of amyloid PET scans.14

This approach is not without limitations such as the digital divide, or the gap that separates technology-enabled individuals and those unprepared to adopt technology due to limited digital literacy levels or access to needed hardware, software, and connectivity. The VHA has taken steps to address these digital divide barriers by broadly providing tools—such as tablets and broadband connectivity—to veterans. Specifically, the VHA has instituted digital divide consults to determine whether telehealth could be a potential solution for appropriate veterans and to provide an iPad (if eligible) to connect with VA clinicians. Complementary to the digital divide consult, a VHA-specific telehealth preparedness assessment tool is under development and being tested by 2 authors (JF, SMH). This telehealth preparedness assessment tool is designed to aid in the seamless integration of telehealth services with the support of tailored education materials specific to gaps in digital literacy that a veteran might experience.

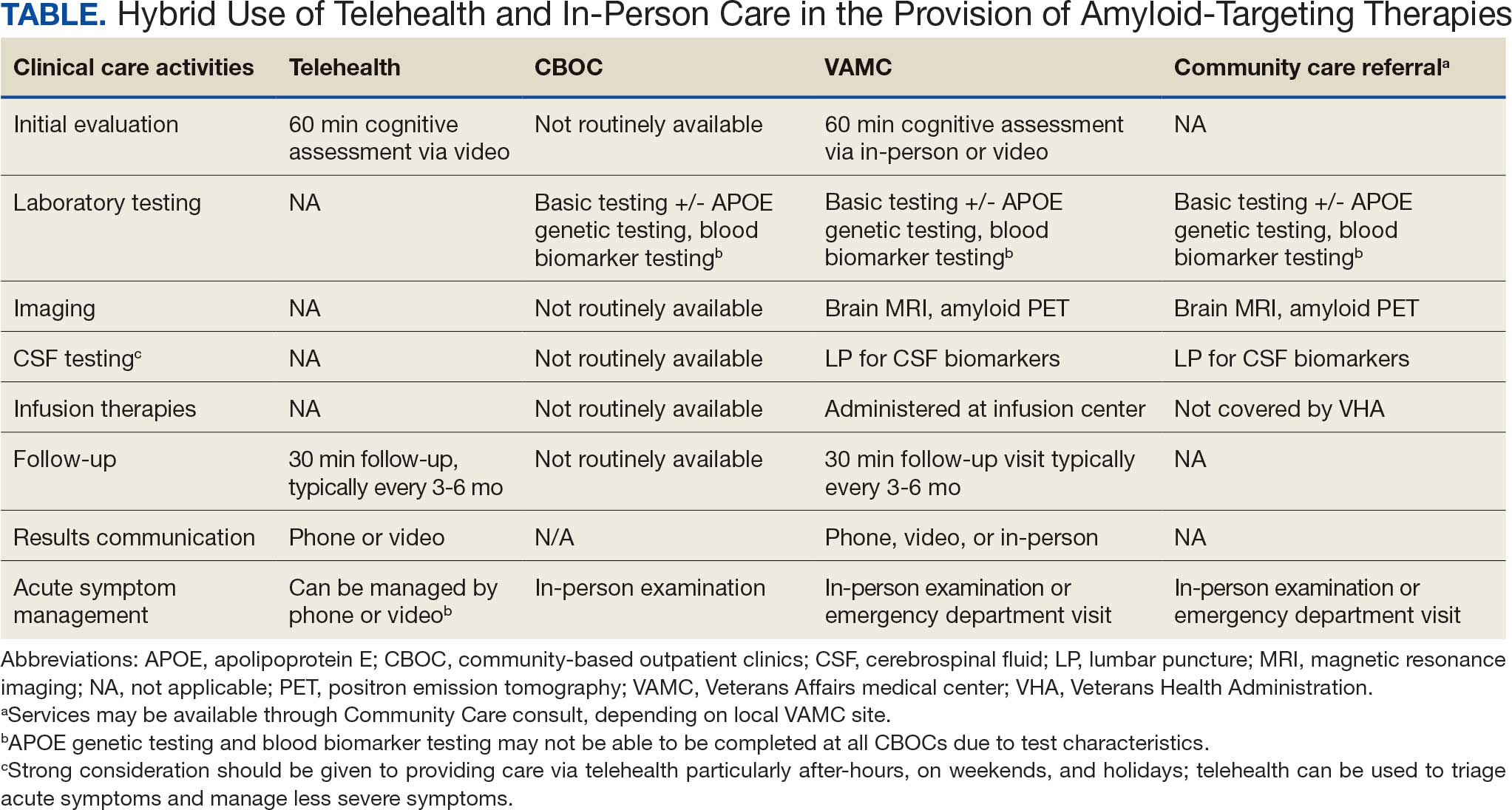

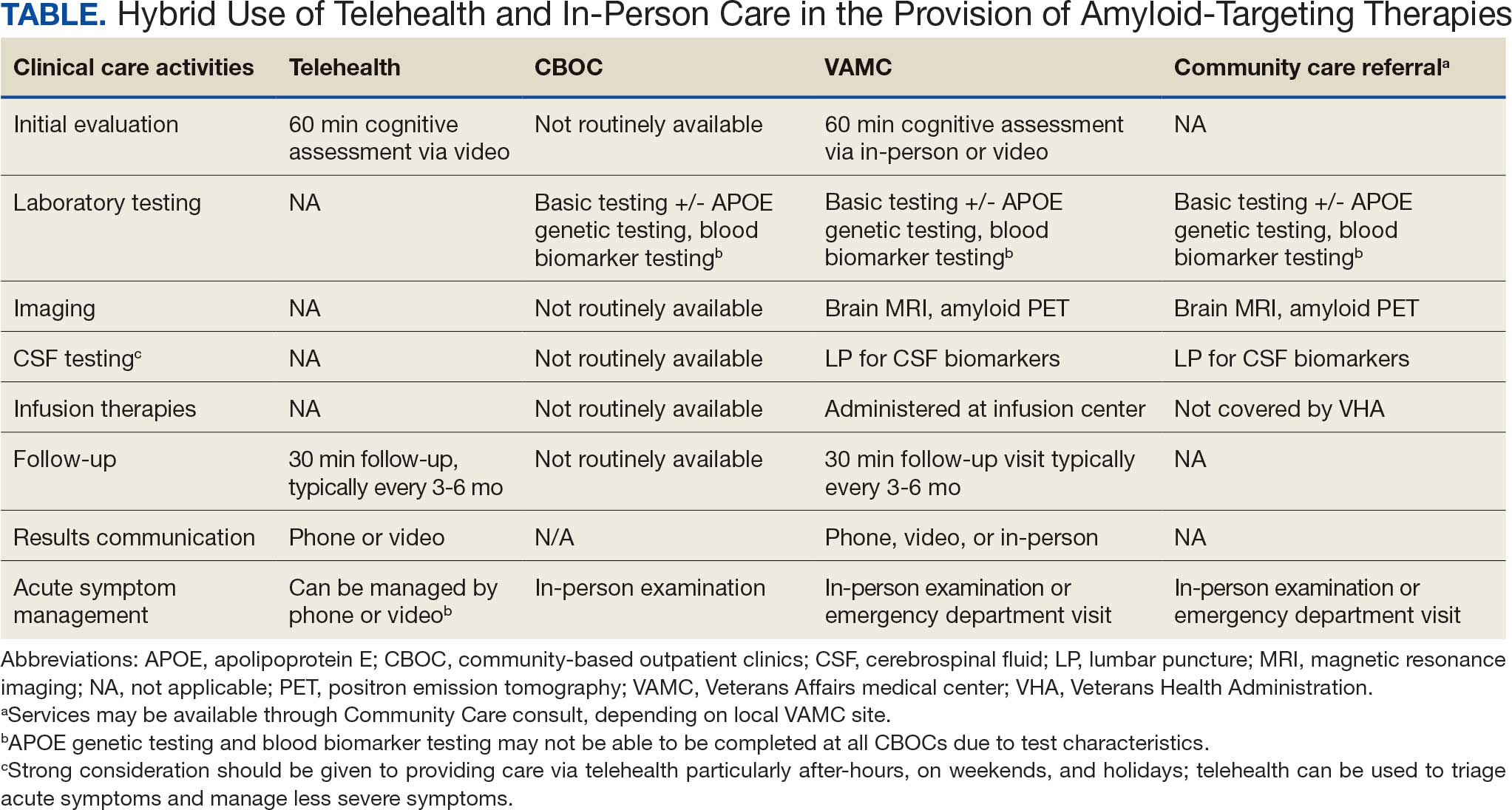

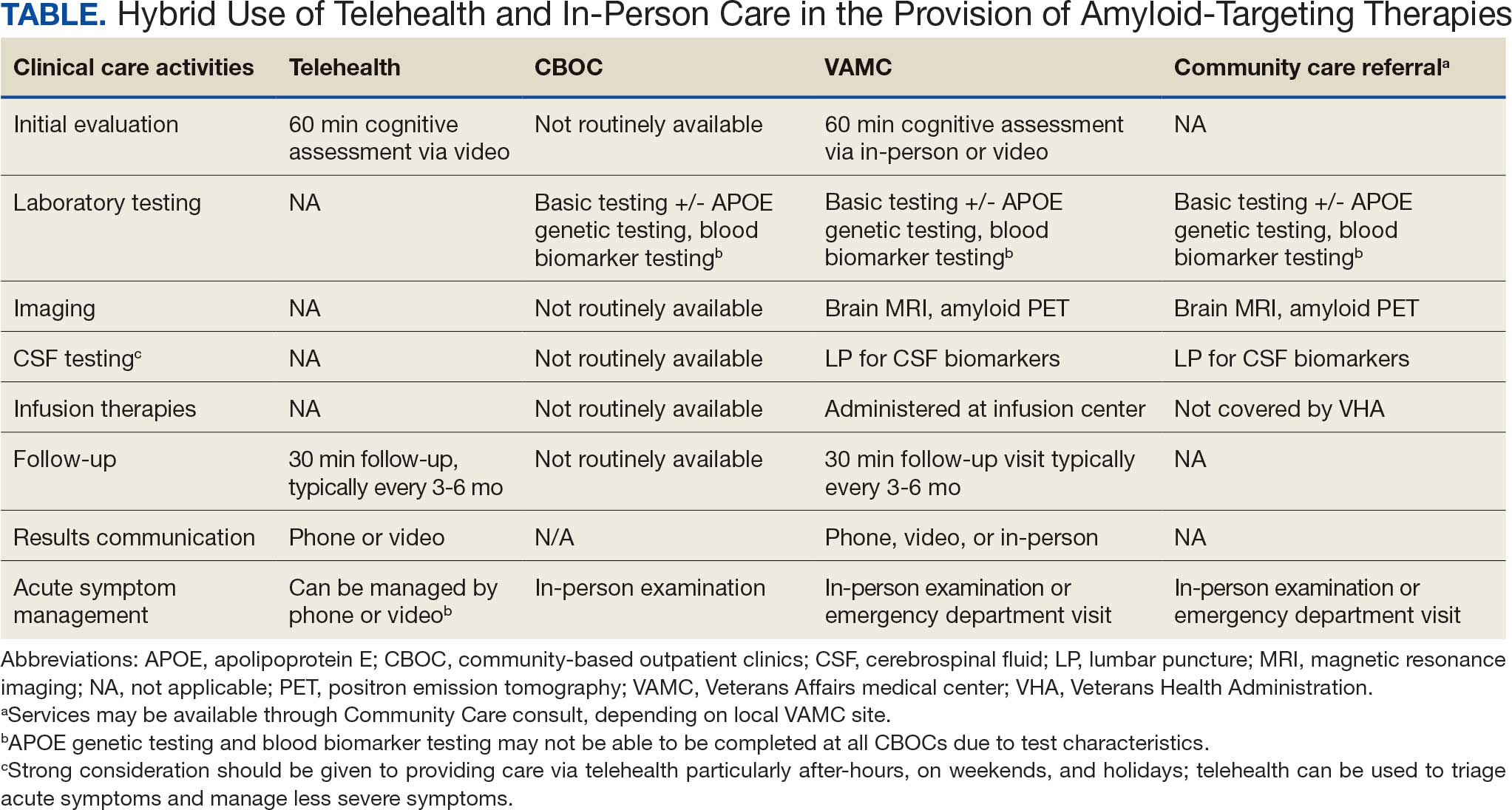

Building on these initiatives, there is an opportunity to expand access to amyloid-targeting therapies, regardless of distance to large VAMCs, by leveraging telehealth as an alternative method of connecting patients with specialty care. Specifically, a hybrid approach could be used to accomplish the myriad initial and follow-up tasks involved in the provision of amyloid-targeting therapies (Table). Not all VHA facilities possess the specialty expertise to prescribe these medications, and local clinicians may not have sufficient knowledge and clinical support to prescribe and monitor these therapies.

The first step is identifying local and regional subject matter experts, followed by the development and expansion of these networks. The National TeleNeurology Program is a good example of a national telehealth program that leverages technology to bring specialty services to rural areas with limited access to care. Although amyloid-targeting therapies often require more complex logistics, such as laboratory tests and imaging, these initial hurdles can be overcome through localized services and collaboration between VAMCs.

While treatment and imaging will most likely need to occur at a VAMC, most basic laboratory studies can be performed at community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs). Some CBOCs may not be able to process more specialized laboratory tests such as apolipoprotein E genetic testing. Samples for these tests can be collected and processed at VAMCs, which usually have contracts with outside laboratories capable of performing these studies. Most, although not all, VAMCs offer advanced imaging, including MRI of the brain and amyloid PETs. VAMCs without those modalities may need to coordinate with other regional VAMCs. Additionally, a pilot program is already underway whereby VAMCs without the ability to quantify the amount of amyloid on PETs are able to leverage technology and collaborations with other VAMCs to obtain these data.

Once the initial phases of evaluation and care are completed, telemedicine can be leveraged for follow-up and ongoing management. Interdisciplinary teams can help facilitate care related to amyloid-targeting therapies, including the close monitoring of veterans for development of ARIA.15 To achieve this monitoring, specialty clinic teams prescribing amyloid-targeting therapies, which may be geographically distant, need to coordinate with local primary care clinical teams and emergency clinicians. All of these health care team members, along with neurologists and neurosurgeons, should be involved in the development and implementation of protocols in the event that patients present to their local primary or specialty care clinics or emergency department with ARIA symptoms.

If amyloid-targeting therapies are to be provided along with other emerging treatments for rural veterans, telehealth must be part of the solution. There is a pressing need to explore innovative evaluation and delivery models for these therapies, particularly as we expect additional diagnostics and therapeutics to be available in the future. With the advent of commercially available blood tests (ie, blood biomarkers) for AD, there is hope for a transition away from PETs and CSF testing given their cost, limited access, and invasiveness for diagnosis and monitoring of AD. These advances will increase the utility of telehealth to help rural veterans access amyloid-targeting therapies.

Additionally, administering the drug at home or at local clinics, supported by a dedicated health care team or home health agency, could further improve accessibility. Telehealth can be leveraged in this scenario, allowing specialty clinics and specialists to connect with patients and clinicians based out of local clinics or even home health agencies. In this scenario, specialists can provide hands-on care guidance and oversight even though they may be geographically distant from care recipients. Transitioning from IV administration to subcutaneous formulations would further enhance convenience and reduce barriers; these formulations may be available soon.16 Addressing logistical challenges to care and access through technology-based solutions will require coordinated efforts and continued VHA investment.

Conclusions

The VHA has a large population of veterans with dementia, and the costs to care for these veterans will only increase. While the current benefits of amyloid-targeting therapies are modest, now is the time to establish care processes that will support future innovations in amyloid-targeting therapies and other treatments and diagnostics. We are developing better ways to detect AD using clinical decision support tools, improving care pathways and the management of AD, and leveraging telehealth to improve access. The VA is conducting research to investigate whether a cognitive screening and laboratory evaluation that includes a telehealth preparedness assessment will be feasible and effective for improving the detection of AD and access to treatment, and we plan to publish the results.

The lessons learned can be extended to non-VHA care settings to help achieve potential benefits for other patients with early AD. Emerging therapies have the potential to improve the quality of life for both patients and care partners, adding life to years and not just years to life. Policymakers and payors must prioritize research funding to evaluate the safety and efficacy of these approaches to the delivery of health services, ensuring that emerging therapies are accessible for all individuals affected by AD.

- Alzheimer’s Association. 2025 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2025;21(4):e70235. doi:10.1002/alz.70235

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Statistical Projections of Alzheimer’s Dementia for VA Patients, VA Enrollees, and US Veterans. December 18, 2020. Accessed November 2, 2025. https://www.va.gov/GERIATRICS/docs/VHA_ALZHEIMERS_DEMENTIA_Statistical_Projections_FY21_and_FY33_sgc121820.pdf

- Casey DA, Antimisiaris D, O’Brien J. Drugs for Alzheimer’s disease: are they effective? P T. 2010;35(4):208-211.

- Barthold D, Joyce G, Ferido P, et al. Pharmaceutical treatment for Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias: utilization and disparities. J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;76(2):579-589. doi:10.3233/JAD-200133

- Sims JR, Zimmer JA, Evans CD, et al. Donanemab in early symptomatic Alzheimer disease: the TRAILBLAZER-ALZ 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2023;330(6):512-527. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.13239

- van Dyck CH, Swanson CJ, Aisen P, et al. Lecanemab in early Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(1):9-21. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2212948

- Tanne JH. Lecanemab: US Veterans Health Administration will cover cost of new Alzheimer’s drug. BMJ. 2023;380:p628. doi:10.1136/bmj.p628

- Nadeau SE. Lecanemab questions. Neurology. 2024;102(7):e209320. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000209320 9. O’Donnell AJ, Fortunato AT, Spitznogle BL, et al. Implementation of lecanemab for Alzheimer’s disease: facilitators and barriers. Presented at: American Geriatrics Society 2025 Annual Scientific Meeting, Chicago. May 2025.

- O’Donnell AJ, Zhao X, Parr A, et al. Use of lecanemab for Alzheimer’s disease within the Veteran’s Health Foundation: early findings. Abstract presented at: Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2025; July 27, 2025; Toronto, Canada.

- O’Donnell AJ, Zhao X, Parr A, et al. Use of lecanemab for Alzheimer’s disease within the Veteran’s Health Foundation: early findings. Abstract presented at: Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2025; July 27, 2025; Toronto, Canada.

- Hopp F, Whitten P, Subramanian U, et al. Perspectives from the Veterans Health Administration about opportunities and barriers in telemedicine. J Telemed Telecare. 2006;12(8):404-409. doi:10.1258/135763306779378717

- VA reports significant increase in veteran use of telehealth services. News release. US Department of Veterans Affairs. November 22, 2019. Accessed November 19, 2025. https://news.va.gov/press-room/va-reports-significant-increase-in-veteran-use-of-telehealth-services/

- Powers BB, Homer MC, Morone N, et al. Creation of an interprofessional teledementia clinic for rural veterans: preliminary data. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(5):1092-1099. doi:10.1111/jgs.14839

- Erickson CM, Chin NA, Rosario HL, et al. Feasibility of virtual Alzheimer’s biomarker disclosure: findings from an observational cohort. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2023;9(3):e12413. doi:10.1002/trc2.12413

- Turk KW, Knobel MD, Nothern A, et al. An interprofessional team for disease-modifying therapy in Alzheimer disease implementation. Neurol Clin Pract. 2024;14(6):e200346. doi:10.1212/CPJ.0000000000200346

- FDA accepts LEQEMBI® (lecanemab-irmb) biologics license application for subcutaneous maintenance dosing for the treatment of early Alzheimer’s disease. News release. Elsai US. January 13, 2025. Accessed November 2, 2025. https://media-us.eisai.com/2025-01-13-FDA-Accepts-LEQEMBI-R-lecanemab-irmb-Biologics-License-Application-for-Subcutaneous-Maintenance-Dosing-for-the-Treatment-of-Early-Alzheimers-Disease

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is the largest US integrated health care system, providing health care to > 9 million veterans annually. Dementia affects > 7.2 million Americans, and an estimated 450,000 veterans live with Alzheimer disease (AD).1,2 Compared with the general population, veterans have a higher burden of chronic medical conditions and are disproportionately affected by AD due to exposure to military-related risk factors (eg, traumatic brain injury and posttraumatic stress disorder) and the high prevalence of nonmilitary risk factors, such as cardiovascular disease. The VHA is a pioneer in dementia care, having established a Dementia System of Care to provide primary and specialty care to veterans with dementia. The VHA also is leading the way in implementing the Institute for Healthcare Improvement Age-Friendly Health Systems (AFHS) framework for providing goal-concordant care in > 100 VHA medical centers. The VHA aims to be the largest AFHS in the country.

AD profoundly affects individuals and their families. The progressive nature of the most common form of dementia diminishes the quality of life for patients as well as their care partners in an ongoing fashion, often leading to emotional, physical, and financial strain. Costs for health and long-term care for people living with AD and other dementias were projected at $360 billion in 2024, largely due to the need for nursing home care.1 Although several oral medications are available, their capacity to effectively mitigate the negative effects of AD is limited. Cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine may offer temporary symptomatic relief, but they do not alter disease progression.3 The use of these agents is relatively low, with about one-third of patients diagnosed with AD receiving these medications.4

Amyloid-Targeting Therapies

Recent advancements in biologics, particularly amyloid-targeting therapies, such as lecanemab and donanemab, offer new hope for managing AD. Older adults treated with these medications show less decline on measures of cognition and function than those receiving a placebo at 18 months.5,6 However, accessing and using these medications is challenging.

Use of amyloid-targeting therapies poses challenges. The medications are expensive, potentially placing a financial burden on patients, families, and health care systems.7 Determining initial eligibility for treatment requires a battery of cognitive assessments, laboratory tests, advanced radiologic studies (eg, magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] of the brain and amyloid positron emission tomography [PET] scans), and possible cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) testing. Frequent ongoing assessments are necessary to monitor safety and efficacy. These treatments carry substantial risks, particularly amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA) such as cerebral edema, microhemorrhages, and superficial siderosis. Therefore, follow-up assessments typically occur around months 2, 3, 4, and 7, depending on which medication is selected. Finally, at present, both agents must be intravenous (IV)-administered in a monitored clinical setting, which requires additional coordination, transportation, and cost.

Ongoing evaluations and in-person administration particularly affect patients and care partners with limitations regarding transportation, time off work, and navigating complex health care systems.8 VHA clinicians at sites that have implemented or are interested in implementing amyloid-targeting therapy programs endorse similar challenges when implementing these therapies in their US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers (VAMCs).9

The VHA was one of the first health care systems to use amyloid-targeting therapies, covering the cost of lecanemab and donanemab, in addition to costs associated with concomitant evaluation and testing. However, given the safety concerns with this novel class of medications, the VHA National Formulary Committee developed criteria for use and recommended the VA Center for Medication Safety (VAMedSAFE) conduct a mandatory real-time medication use evaluation (MUE). VAMedSAFE developed the MUE to monitor the safe and appropriate use of amyloid-targeting therapy for AD. Two authors (AJO, SMH) partnered with VAMedSAFE through the VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System Technology Enhancing Cognition and Health–Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Center (TECH-GRECC) to provide clinical expertise, substantive feedback for the development of the MUE, and guidance for VHA sites starting amyloid targeting-therapy programs. We started a VHA Amyloid-Targeting Therapy for AD SharePoint collaborative platform and VHA AD Therapeutics Community of Practice (CoP) for shared learning (Figure). The private SharePoint platform houses an array of implementation materials for VAMCs starting programs: key documents and links; educational materials; sample guidelines; note templates; and electronic health record screenshots. The CoP allows VHAs to share best practices and discuss challenges.

Even with these advantages, we found that ensuring the safe and appropriate use of amyloid-targeting therapies did not overcome the barriers associated with their complexity. This was especially true for veterans living in rural areas. Only 4 VAMCs had administered amyloid-targeting therapies in the first year they were available. Preliminary data demonstrated that 27 (84%) of 32 veterans who initiated lecanemab in the VHA between October 2023 and September 2024 resided in urban areas.10 To address the underutilization of amyloid-targeting therapy, we propose leveraging the strengths of VHA telehealth to facilitate expansion of access to these medications for veterans with early AD. Telehealth may substantially increase access to evaluation for veterans with early dementia and, when medically appropriate, to receive amyloid-targeting therapies by reducing transportation needs and mitigating costs while ensuring appropriate monitoring through ongoing clinical assessments.

Using Telehealth

The VHA is a pioneer in telehealth, with programs dating back to 2003.11 Between October 1, 2018, and September 30, 2019, the VHA served > 900,000 veterans through the provision of > 2.6 million episodes of care via telehealth.12 The COVID-19 pandemic further cemented the role of telemedicine as an essential component of health care. Telehealth has demonstrated success in the assessment and management of individuals living with dementia. At the VHA, the GRECC-Connect Project is a partnership between 9 urban GRECC sites that seek to provide consultative geriatric and dementia care to rural veterans through telehealth.13 Additional evidence supports the potential to leverage telehealth to effectively communicate results of amyloid PET scans.14

This approach is not without limitations such as the digital divide, or the gap that separates technology-enabled individuals and those unprepared to adopt technology due to limited digital literacy levels or access to needed hardware, software, and connectivity. The VHA has taken steps to address these digital divide barriers by broadly providing tools—such as tablets and broadband connectivity—to veterans. Specifically, the VHA has instituted digital divide consults to determine whether telehealth could be a potential solution for appropriate veterans and to provide an iPad (if eligible) to connect with VA clinicians. Complementary to the digital divide consult, a VHA-specific telehealth preparedness assessment tool is under development and being tested by 2 authors (JF, SMH). This telehealth preparedness assessment tool is designed to aid in the seamless integration of telehealth services with the support of tailored education materials specific to gaps in digital literacy that a veteran might experience.

Building on these initiatives, there is an opportunity to expand access to amyloid-targeting therapies, regardless of distance to large VAMCs, by leveraging telehealth as an alternative method of connecting patients with specialty care. Specifically, a hybrid approach could be used to accomplish the myriad initial and follow-up tasks involved in the provision of amyloid-targeting therapies (Table). Not all VHA facilities possess the specialty expertise to prescribe these medications, and local clinicians may not have sufficient knowledge and clinical support to prescribe and monitor these therapies.

The first step is identifying local and regional subject matter experts, followed by the development and expansion of these networks. The National TeleNeurology Program is a good example of a national telehealth program that leverages technology to bring specialty services to rural areas with limited access to care. Although amyloid-targeting therapies often require more complex logistics, such as laboratory tests and imaging, these initial hurdles can be overcome through localized services and collaboration between VAMCs.

While treatment and imaging will most likely need to occur at a VAMC, most basic laboratory studies can be performed at community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs). Some CBOCs may not be able to process more specialized laboratory tests such as apolipoprotein E genetic testing. Samples for these tests can be collected and processed at VAMCs, which usually have contracts with outside laboratories capable of performing these studies. Most, although not all, VAMCs offer advanced imaging, including MRI of the brain and amyloid PETs. VAMCs without those modalities may need to coordinate with other regional VAMCs. Additionally, a pilot program is already underway whereby VAMCs without the ability to quantify the amount of amyloid on PETs are able to leverage technology and collaborations with other VAMCs to obtain these data.

Once the initial phases of evaluation and care are completed, telemedicine can be leveraged for follow-up and ongoing management. Interdisciplinary teams can help facilitate care related to amyloid-targeting therapies, including the close monitoring of veterans for development of ARIA.15 To achieve this monitoring, specialty clinic teams prescribing amyloid-targeting therapies, which may be geographically distant, need to coordinate with local primary care clinical teams and emergency clinicians. All of these health care team members, along with neurologists and neurosurgeons, should be involved in the development and implementation of protocols in the event that patients present to their local primary or specialty care clinics or emergency department with ARIA symptoms.

If amyloid-targeting therapies are to be provided along with other emerging treatments for rural veterans, telehealth must be part of the solution. There is a pressing need to explore innovative evaluation and delivery models for these therapies, particularly as we expect additional diagnostics and therapeutics to be available in the future. With the advent of commercially available blood tests (ie, blood biomarkers) for AD, there is hope for a transition away from PETs and CSF testing given their cost, limited access, and invasiveness for diagnosis and monitoring of AD. These advances will increase the utility of telehealth to help rural veterans access amyloid-targeting therapies.

Additionally, administering the drug at home or at local clinics, supported by a dedicated health care team or home health agency, could further improve accessibility. Telehealth can be leveraged in this scenario, allowing specialty clinics and specialists to connect with patients and clinicians based out of local clinics or even home health agencies. In this scenario, specialists can provide hands-on care guidance and oversight even though they may be geographically distant from care recipients. Transitioning from IV administration to subcutaneous formulations would further enhance convenience and reduce barriers; these formulations may be available soon.16 Addressing logistical challenges to care and access through technology-based solutions will require coordinated efforts and continued VHA investment.

Conclusions

The VHA has a large population of veterans with dementia, and the costs to care for these veterans will only increase. While the current benefits of amyloid-targeting therapies are modest, now is the time to establish care processes that will support future innovations in amyloid-targeting therapies and other treatments and diagnostics. We are developing better ways to detect AD using clinical decision support tools, improving care pathways and the management of AD, and leveraging telehealth to improve access. The VA is conducting research to investigate whether a cognitive screening and laboratory evaluation that includes a telehealth preparedness assessment will be feasible and effective for improving the detection of AD and access to treatment, and we plan to publish the results.

The lessons learned can be extended to non-VHA care settings to help achieve potential benefits for other patients with early AD. Emerging therapies have the potential to improve the quality of life for both patients and care partners, adding life to years and not just years to life. Policymakers and payors must prioritize research funding to evaluate the safety and efficacy of these approaches to the delivery of health services, ensuring that emerging therapies are accessible for all individuals affected by AD.

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is the largest US integrated health care system, providing health care to > 9 million veterans annually. Dementia affects > 7.2 million Americans, and an estimated 450,000 veterans live with Alzheimer disease (AD).1,2 Compared with the general population, veterans have a higher burden of chronic medical conditions and are disproportionately affected by AD due to exposure to military-related risk factors (eg, traumatic brain injury and posttraumatic stress disorder) and the high prevalence of nonmilitary risk factors, such as cardiovascular disease. The VHA is a pioneer in dementia care, having established a Dementia System of Care to provide primary and specialty care to veterans with dementia. The VHA also is leading the way in implementing the Institute for Healthcare Improvement Age-Friendly Health Systems (AFHS) framework for providing goal-concordant care in > 100 VHA medical centers. The VHA aims to be the largest AFHS in the country.

AD profoundly affects individuals and their families. The progressive nature of the most common form of dementia diminishes the quality of life for patients as well as their care partners in an ongoing fashion, often leading to emotional, physical, and financial strain. Costs for health and long-term care for people living with AD and other dementias were projected at $360 billion in 2024, largely due to the need for nursing home care.1 Although several oral medications are available, their capacity to effectively mitigate the negative effects of AD is limited. Cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine may offer temporary symptomatic relief, but they do not alter disease progression.3 The use of these agents is relatively low, with about one-third of patients diagnosed with AD receiving these medications.4

Amyloid-Targeting Therapies

Recent advancements in biologics, particularly amyloid-targeting therapies, such as lecanemab and donanemab, offer new hope for managing AD. Older adults treated with these medications show less decline on measures of cognition and function than those receiving a placebo at 18 months.5,6 However, accessing and using these medications is challenging.

Use of amyloid-targeting therapies poses challenges. The medications are expensive, potentially placing a financial burden on patients, families, and health care systems.7 Determining initial eligibility for treatment requires a battery of cognitive assessments, laboratory tests, advanced radiologic studies (eg, magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] of the brain and amyloid positron emission tomography [PET] scans), and possible cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) testing. Frequent ongoing assessments are necessary to monitor safety and efficacy. These treatments carry substantial risks, particularly amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA) such as cerebral edema, microhemorrhages, and superficial siderosis. Therefore, follow-up assessments typically occur around months 2, 3, 4, and 7, depending on which medication is selected. Finally, at present, both agents must be intravenous (IV)-administered in a monitored clinical setting, which requires additional coordination, transportation, and cost.

Ongoing evaluations and in-person administration particularly affect patients and care partners with limitations regarding transportation, time off work, and navigating complex health care systems.8 VHA clinicians at sites that have implemented or are interested in implementing amyloid-targeting therapy programs endorse similar challenges when implementing these therapies in their US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers (VAMCs).9

The VHA was one of the first health care systems to use amyloid-targeting therapies, covering the cost of lecanemab and donanemab, in addition to costs associated with concomitant evaluation and testing. However, given the safety concerns with this novel class of medications, the VHA National Formulary Committee developed criteria for use and recommended the VA Center for Medication Safety (VAMedSAFE) conduct a mandatory real-time medication use evaluation (MUE). VAMedSAFE developed the MUE to monitor the safe and appropriate use of amyloid-targeting therapy for AD. Two authors (AJO, SMH) partnered with VAMedSAFE through the VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System Technology Enhancing Cognition and Health–Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Center (TECH-GRECC) to provide clinical expertise, substantive feedback for the development of the MUE, and guidance for VHA sites starting amyloid targeting-therapy programs. We started a VHA Amyloid-Targeting Therapy for AD SharePoint collaborative platform and VHA AD Therapeutics Community of Practice (CoP) for shared learning (Figure). The private SharePoint platform houses an array of implementation materials for VAMCs starting programs: key documents and links; educational materials; sample guidelines; note templates; and electronic health record screenshots. The CoP allows VHAs to share best practices and discuss challenges.

Even with these advantages, we found that ensuring the safe and appropriate use of amyloid-targeting therapies did not overcome the barriers associated with their complexity. This was especially true for veterans living in rural areas. Only 4 VAMCs had administered amyloid-targeting therapies in the first year they were available. Preliminary data demonstrated that 27 (84%) of 32 veterans who initiated lecanemab in the VHA between October 2023 and September 2024 resided in urban areas.10 To address the underutilization of amyloid-targeting therapy, we propose leveraging the strengths of VHA telehealth to facilitate expansion of access to these medications for veterans with early AD. Telehealth may substantially increase access to evaluation for veterans with early dementia and, when medically appropriate, to receive amyloid-targeting therapies by reducing transportation needs and mitigating costs while ensuring appropriate monitoring through ongoing clinical assessments.

Using Telehealth

The VHA is a pioneer in telehealth, with programs dating back to 2003.11 Between October 1, 2018, and September 30, 2019, the VHA served > 900,000 veterans through the provision of > 2.6 million episodes of care via telehealth.12 The COVID-19 pandemic further cemented the role of telemedicine as an essential component of health care. Telehealth has demonstrated success in the assessment and management of individuals living with dementia. At the VHA, the GRECC-Connect Project is a partnership between 9 urban GRECC sites that seek to provide consultative geriatric and dementia care to rural veterans through telehealth.13 Additional evidence supports the potential to leverage telehealth to effectively communicate results of amyloid PET scans.14

This approach is not without limitations such as the digital divide, or the gap that separates technology-enabled individuals and those unprepared to adopt technology due to limited digital literacy levels or access to needed hardware, software, and connectivity. The VHA has taken steps to address these digital divide barriers by broadly providing tools—such as tablets and broadband connectivity—to veterans. Specifically, the VHA has instituted digital divide consults to determine whether telehealth could be a potential solution for appropriate veterans and to provide an iPad (if eligible) to connect with VA clinicians. Complementary to the digital divide consult, a VHA-specific telehealth preparedness assessment tool is under development and being tested by 2 authors (JF, SMH). This telehealth preparedness assessment tool is designed to aid in the seamless integration of telehealth services with the support of tailored education materials specific to gaps in digital literacy that a veteran might experience.

Building on these initiatives, there is an opportunity to expand access to amyloid-targeting therapies, regardless of distance to large VAMCs, by leveraging telehealth as an alternative method of connecting patients with specialty care. Specifically, a hybrid approach could be used to accomplish the myriad initial and follow-up tasks involved in the provision of amyloid-targeting therapies (Table). Not all VHA facilities possess the specialty expertise to prescribe these medications, and local clinicians may not have sufficient knowledge and clinical support to prescribe and monitor these therapies.

The first step is identifying local and regional subject matter experts, followed by the development and expansion of these networks. The National TeleNeurology Program is a good example of a national telehealth program that leverages technology to bring specialty services to rural areas with limited access to care. Although amyloid-targeting therapies often require more complex logistics, such as laboratory tests and imaging, these initial hurdles can be overcome through localized services and collaboration between VAMCs.

While treatment and imaging will most likely need to occur at a VAMC, most basic laboratory studies can be performed at community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs). Some CBOCs may not be able to process more specialized laboratory tests such as apolipoprotein E genetic testing. Samples for these tests can be collected and processed at VAMCs, which usually have contracts with outside laboratories capable of performing these studies. Most, although not all, VAMCs offer advanced imaging, including MRI of the brain and amyloid PETs. VAMCs without those modalities may need to coordinate with other regional VAMCs. Additionally, a pilot program is already underway whereby VAMCs without the ability to quantify the amount of amyloid on PETs are able to leverage technology and collaborations with other VAMCs to obtain these data.

Once the initial phases of evaluation and care are completed, telemedicine can be leveraged for follow-up and ongoing management. Interdisciplinary teams can help facilitate care related to amyloid-targeting therapies, including the close monitoring of veterans for development of ARIA.15 To achieve this monitoring, specialty clinic teams prescribing amyloid-targeting therapies, which may be geographically distant, need to coordinate with local primary care clinical teams and emergency clinicians. All of these health care team members, along with neurologists and neurosurgeons, should be involved in the development and implementation of protocols in the event that patients present to their local primary or specialty care clinics or emergency department with ARIA symptoms.

If amyloid-targeting therapies are to be provided along with other emerging treatments for rural veterans, telehealth must be part of the solution. There is a pressing need to explore innovative evaluation and delivery models for these therapies, particularly as we expect additional diagnostics and therapeutics to be available in the future. With the advent of commercially available blood tests (ie, blood biomarkers) for AD, there is hope for a transition away from PETs and CSF testing given their cost, limited access, and invasiveness for diagnosis and monitoring of AD. These advances will increase the utility of telehealth to help rural veterans access amyloid-targeting therapies.

Additionally, administering the drug at home or at local clinics, supported by a dedicated health care team or home health agency, could further improve accessibility. Telehealth can be leveraged in this scenario, allowing specialty clinics and specialists to connect with patients and clinicians based out of local clinics or even home health agencies. In this scenario, specialists can provide hands-on care guidance and oversight even though they may be geographically distant from care recipients. Transitioning from IV administration to subcutaneous formulations would further enhance convenience and reduce barriers; these formulations may be available soon.16 Addressing logistical challenges to care and access through technology-based solutions will require coordinated efforts and continued VHA investment.

Conclusions

The VHA has a large population of veterans with dementia, and the costs to care for these veterans will only increase. While the current benefits of amyloid-targeting therapies are modest, now is the time to establish care processes that will support future innovations in amyloid-targeting therapies and other treatments and diagnostics. We are developing better ways to detect AD using clinical decision support tools, improving care pathways and the management of AD, and leveraging telehealth to improve access. The VA is conducting research to investigate whether a cognitive screening and laboratory evaluation that includes a telehealth preparedness assessment will be feasible and effective for improving the detection of AD and access to treatment, and we plan to publish the results.

The lessons learned can be extended to non-VHA care settings to help achieve potential benefits for other patients with early AD. Emerging therapies have the potential to improve the quality of life for both patients and care partners, adding life to years and not just years to life. Policymakers and payors must prioritize research funding to evaluate the safety and efficacy of these approaches to the delivery of health services, ensuring that emerging therapies are accessible for all individuals affected by AD.

- Alzheimer’s Association. 2025 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2025;21(4):e70235. doi:10.1002/alz.70235

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Statistical Projections of Alzheimer’s Dementia for VA Patients, VA Enrollees, and US Veterans. December 18, 2020. Accessed November 2, 2025. https://www.va.gov/GERIATRICS/docs/VHA_ALZHEIMERS_DEMENTIA_Statistical_Projections_FY21_and_FY33_sgc121820.pdf

- Casey DA, Antimisiaris D, O’Brien J. Drugs for Alzheimer’s disease: are they effective? P T. 2010;35(4):208-211.

- Barthold D, Joyce G, Ferido P, et al. Pharmaceutical treatment for Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias: utilization and disparities. J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;76(2):579-589. doi:10.3233/JAD-200133

- Sims JR, Zimmer JA, Evans CD, et al. Donanemab in early symptomatic Alzheimer disease: the TRAILBLAZER-ALZ 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2023;330(6):512-527. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.13239

- van Dyck CH, Swanson CJ, Aisen P, et al. Lecanemab in early Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(1):9-21. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2212948

- Tanne JH. Lecanemab: US Veterans Health Administration will cover cost of new Alzheimer’s drug. BMJ. 2023;380:p628. doi:10.1136/bmj.p628

- Nadeau SE. Lecanemab questions. Neurology. 2024;102(7):e209320. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000209320 9. O’Donnell AJ, Fortunato AT, Spitznogle BL, et al. Implementation of lecanemab for Alzheimer’s disease: facilitators and barriers. Presented at: American Geriatrics Society 2025 Annual Scientific Meeting, Chicago. May 2025.

- O’Donnell AJ, Zhao X, Parr A, et al. Use of lecanemab for Alzheimer’s disease within the Veteran’s Health Foundation: early findings. Abstract presented at: Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2025; July 27, 2025; Toronto, Canada.

- O’Donnell AJ, Zhao X, Parr A, et al. Use of lecanemab for Alzheimer’s disease within the Veteran’s Health Foundation: early findings. Abstract presented at: Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2025; July 27, 2025; Toronto, Canada.

- Hopp F, Whitten P, Subramanian U, et al. Perspectives from the Veterans Health Administration about opportunities and barriers in telemedicine. J Telemed Telecare. 2006;12(8):404-409. doi:10.1258/135763306779378717

- VA reports significant increase in veteran use of telehealth services. News release. US Department of Veterans Affairs. November 22, 2019. Accessed November 19, 2025. https://news.va.gov/press-room/va-reports-significant-increase-in-veteran-use-of-telehealth-services/

- Powers BB, Homer MC, Morone N, et al. Creation of an interprofessional teledementia clinic for rural veterans: preliminary data. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(5):1092-1099. doi:10.1111/jgs.14839

- Erickson CM, Chin NA, Rosario HL, et al. Feasibility of virtual Alzheimer’s biomarker disclosure: findings from an observational cohort. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2023;9(3):e12413. doi:10.1002/trc2.12413

- Turk KW, Knobel MD, Nothern A, et al. An interprofessional team for disease-modifying therapy in Alzheimer disease implementation. Neurol Clin Pract. 2024;14(6):e200346. doi:10.1212/CPJ.0000000000200346

- FDA accepts LEQEMBI® (lecanemab-irmb) biologics license application for subcutaneous maintenance dosing for the treatment of early Alzheimer’s disease. News release. Elsai US. January 13, 2025. Accessed November 2, 2025. https://media-us.eisai.com/2025-01-13-FDA-Accepts-LEQEMBI-R-lecanemab-irmb-Biologics-License-Application-for-Subcutaneous-Maintenance-Dosing-for-the-Treatment-of-Early-Alzheimers-Disease

- Alzheimer’s Association. 2025 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2025;21(4):e70235. doi:10.1002/alz.70235

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Statistical Projections of Alzheimer’s Dementia for VA Patients, VA Enrollees, and US Veterans. December 18, 2020. Accessed November 2, 2025. https://www.va.gov/GERIATRICS/docs/VHA_ALZHEIMERS_DEMENTIA_Statistical_Projections_FY21_and_FY33_sgc121820.pdf

- Casey DA, Antimisiaris D, O’Brien J. Drugs for Alzheimer’s disease: are they effective? P T. 2010;35(4):208-211.

- Barthold D, Joyce G, Ferido P, et al. Pharmaceutical treatment for Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias: utilization and disparities. J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;76(2):579-589. doi:10.3233/JAD-200133

- Sims JR, Zimmer JA, Evans CD, et al. Donanemab in early symptomatic Alzheimer disease: the TRAILBLAZER-ALZ 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2023;330(6):512-527. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.13239

- van Dyck CH, Swanson CJ, Aisen P, et al. Lecanemab in early Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(1):9-21. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2212948

- Tanne JH. Lecanemab: US Veterans Health Administration will cover cost of new Alzheimer’s drug. BMJ. 2023;380:p628. doi:10.1136/bmj.p628

- Nadeau SE. Lecanemab questions. Neurology. 2024;102(7):e209320. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000209320 9. O’Donnell AJ, Fortunato AT, Spitznogle BL, et al. Implementation of lecanemab for Alzheimer’s disease: facilitators and barriers. Presented at: American Geriatrics Society 2025 Annual Scientific Meeting, Chicago. May 2025.

- O’Donnell AJ, Zhao X, Parr A, et al. Use of lecanemab for Alzheimer’s disease within the Veteran’s Health Foundation: early findings. Abstract presented at: Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2025; July 27, 2025; Toronto, Canada.

- O’Donnell AJ, Zhao X, Parr A, et al. Use of lecanemab for Alzheimer’s disease within the Veteran’s Health Foundation: early findings. Abstract presented at: Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2025; July 27, 2025; Toronto, Canada.

- Hopp F, Whitten P, Subramanian U, et al. Perspectives from the Veterans Health Administration about opportunities and barriers in telemedicine. J Telemed Telecare. 2006;12(8):404-409. doi:10.1258/135763306779378717

- VA reports significant increase in veteran use of telehealth services. News release. US Department of Veterans Affairs. November 22, 2019. Accessed November 19, 2025. https://news.va.gov/press-room/va-reports-significant-increase-in-veteran-use-of-telehealth-services/

- Powers BB, Homer MC, Morone N, et al. Creation of an interprofessional teledementia clinic for rural veterans: preliminary data. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(5):1092-1099. doi:10.1111/jgs.14839

- Erickson CM, Chin NA, Rosario HL, et al. Feasibility of virtual Alzheimer’s biomarker disclosure: findings from an observational cohort. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2023;9(3):e12413. doi:10.1002/trc2.12413

- Turk KW, Knobel MD, Nothern A, et al. An interprofessional team for disease-modifying therapy in Alzheimer disease implementation. Neurol Clin Pract. 2024;14(6):e200346. doi:10.1212/CPJ.0000000000200346

- FDA accepts LEQEMBI® (lecanemab-irmb) biologics license application for subcutaneous maintenance dosing for the treatment of early Alzheimer’s disease. News release. Elsai US. January 13, 2025. Accessed November 2, 2025. https://media-us.eisai.com/2025-01-13-FDA-Accepts-LEQEMBI-R-lecanemab-irmb-Biologics-License-Application-for-Subcutaneous-Maintenance-Dosing-for-the-Treatment-of-Early-Alzheimers-Disease

Can Telehealth Improve Access to Amyloid-Targeting Therapies for Veterans Living With Alzheimer Disease?

Can Telehealth Improve Access to Amyloid-Targeting Therapies for Veterans Living With Alzheimer Disease?