User login

Trichoepithelioma and Spiradenoma Collision Tumor

The coexistence of more than one cutaneous adnexal neoplasm in a single biopsy specimen is unusual and is most frequently recognized in the context of a nevus sebaceous or Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, an autosomal-dominant inherited disease characterized by cutaneous adnexal neoplasms, most commonly cylindromas and trichoepitheliomas.1-3 Brooke-Spiegler syndrome is caused by germline mutations in the cylindromatosis gene, CYLD, located on band 16q12; it functions as a tumor suppressor gene and has regulatory roles in development, immunity, and inflammation.1 Weyers et al3 first recognized the tendency for adnexal collision tumors to present in patients with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome; they reported a patient with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome with spiradenomas found in the immediate vicinity of trichoepitheliomas and in continuity with hair follicles.

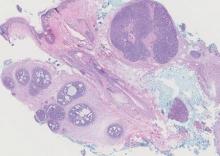

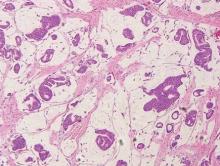

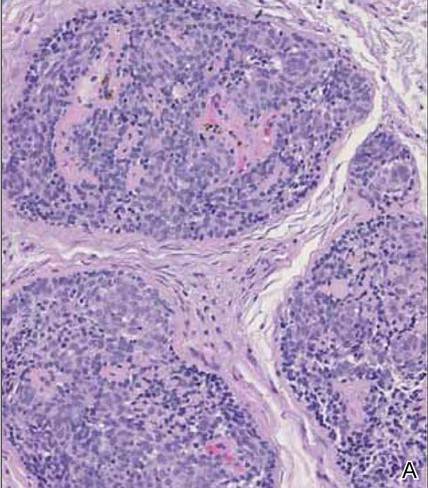

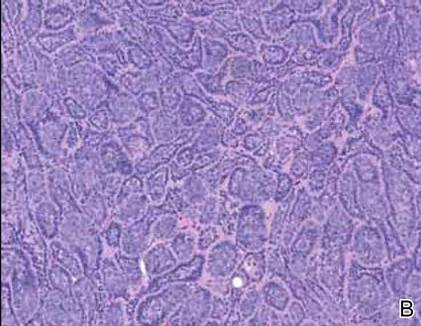

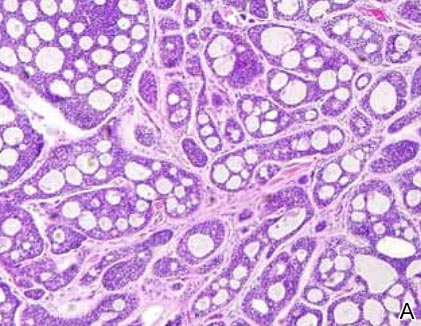

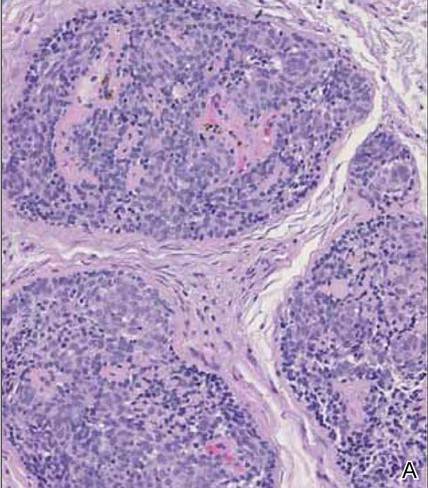

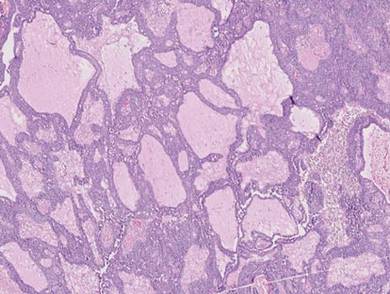

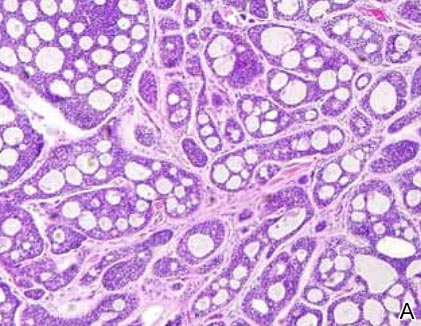

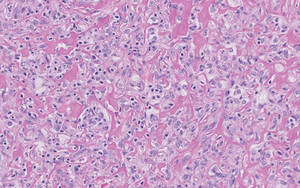

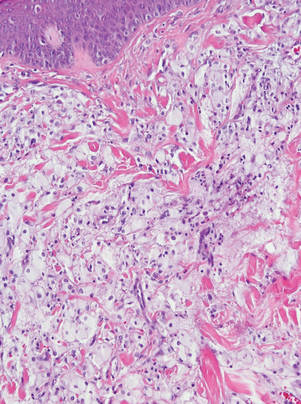

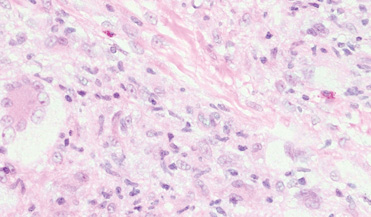

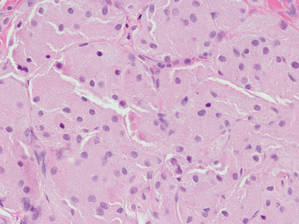

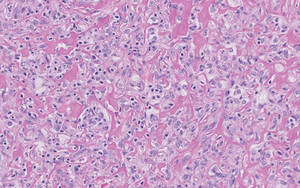

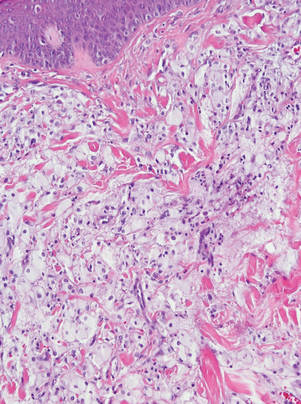

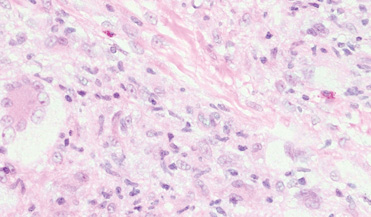

Spiradenomas are composed of large, sharply demarcated, rounded nodules of basaloid cells with little cytoplasm (Figure 1).4 The basaloid nodules may demonstrate a trabecular architecture, and on close inspection 2 cell types—paler cells with more cytoplasm and darker cells with less cytoplasm—are distinguishable (Figure 2A). Lymphocytes often are scattered within the tumor nodules and/or stroma. In Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, collision tumors containing a spiradenomatous component in collision with trichoepithelioma are not uncommon.1 Spiradenomas in Brooke-Spiegler syndrome have been reported to contain sebaceous differentiation or foci with an adenoid cystic carcinoma (ACC)–like pattern and are known to occur as hybrid lesions of spiradenoma and cylindroma or trichoepithelioma (as in this case).

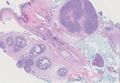

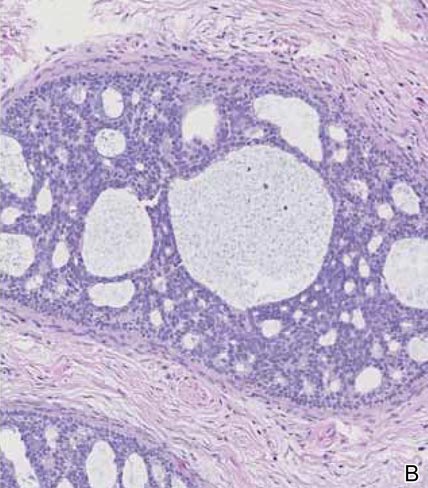

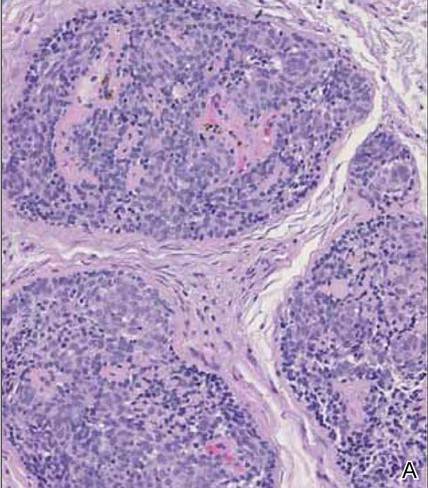

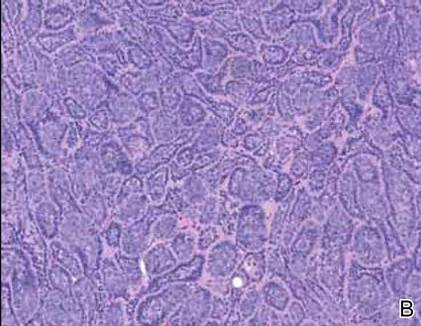

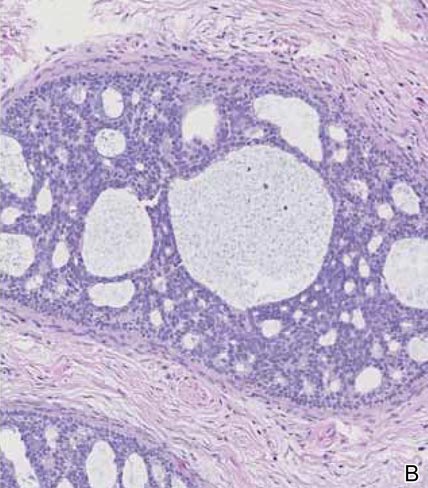

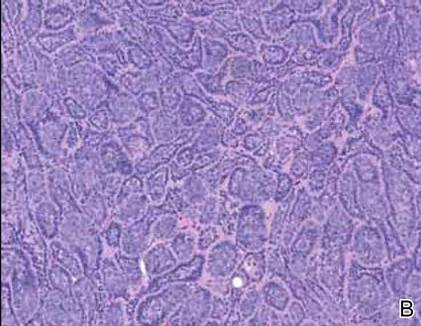

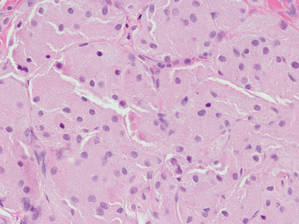

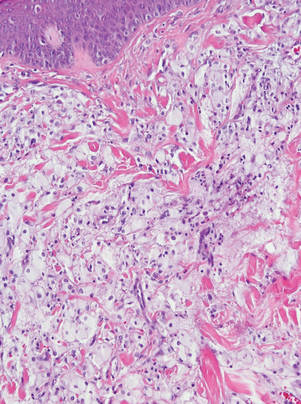

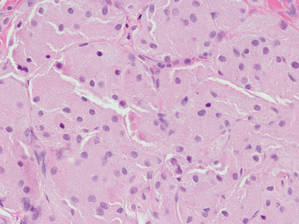

In this case, 2 distinct neoplasms (spiradenoma and trichoepithelioma) are apparent, side by side, with an intervening hair follicle (Figure 1). Trichoepitheliomas, also known as cribriform trichoblastomas,5 are characterized by lobules of basaloid cells resembling basal cell carcinoma surrounded by a fibroblast-rich stroma. They often contain fingerlike projections and adopt a cribriform morphology within the tumor lobules (Figure 2B).4 Numerous horn cysts may be present, but their absence does not preclude the diagnosis. Mucin may be present within the cribriform tumor islands (Figure 2B) but not in the stroma. Characteristically, trichoepitheliomas are distinctly negative for CK7 (Figure 3), and unlike spiradenomas, they lack a myoepithelial component.6 This staining pattern in combination with the tumor’s proximity to an adjacent hair follicle makes a diagnosis of trichoepithelioma and spiradenoma collision tumor most likely and supports a clinical suspicion for Brooke-Spiegler syndrome.

|

Although spiradenomas sometimes contain cystic cavities (microcystic change), they typically are filled with finely granular eosinophilic material, not mucin, that is diastase resistant and periodic acid–Schiff positive (Figure 4).7 Spiradenomas classically stain positive with CK7 (Figure 3), epithelial membrane antigen, and carcinoembryonic antigen, and have a substantial myoepithelial component, as evidenced by the myoepithelial component staining with p63, S-100, and smooth muscle actin (SMA).7-9 The distinct lack of staining with CK7 and SMA in the tumor on the left in Figure 3 confirms that these tumors are of different lineage, rather than representing cystic change within a spiradenoma.

|

|

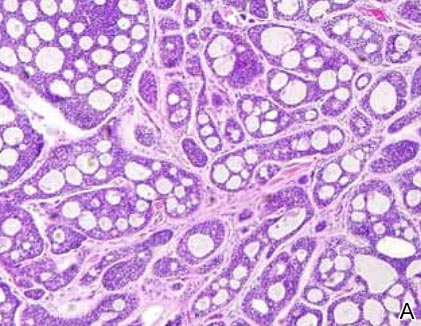

Adenoid cystic carcinoma is a rare neoplasm that may occur in a primary cutaneous form, as a direct extension from an underlying salivary gland neoplasm, or rarely as a focal pattern within spiradenomas occurring both sporadically or in the context of Brooke-Spiegler syndrome.2,7 The tumor is composed of variably sized cribriform islands of basaloid to pink cells concentrically arranged around glandlike spaces filled with mucin (Figure 5A). In contrast to trichoepithelioma, ACC occurs in the mid to deep dermis, often extending into subcutaneous fat with an infiltrative border, and is not often found in close proximity to hair follicles.7 Characteristically, hyaline basement membrane–like material that is periodic acid–Schiff positive is found between the tumor cells and also surrounding the individual lobules. Immunohistochemically, ACC has a myoepithelial component that stains positive with SMA, S-100, and p63; additionally, the tumor cells express low- and high-molecular-weight keratin and demonstrate variable epithelial membrane antigen positivity.10 In the current case, the superficial location, close association with a hair follicle, and lack of staining with both CK7 (Figure 3) and SMA (not shown) make ACC arising within a spiradenoma a less likely diagnosis.

Cylindromas are composed of basaloid islands interconnected in a jigsaw puzzle configuration (Figure 5B).4 Similar to spiradenomas, they also are composed of 2 cell populations. Characteristically, the tumor islands are outlined by a hyalinized eosinophilic basement membrane. Hyalinized droplets of basement membrane zone material also may be noted in the islands. Unlike spiradenomas, they lack both intratumoral lymphocytes and a trabecular growth pattern. Although spiradenocylindromas (cylindroma and spiradenoma collision tumors) are perhaps the most common collision tumor associated with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, there is no evidence suggesting the presence of a cylindroma in the current case.

|

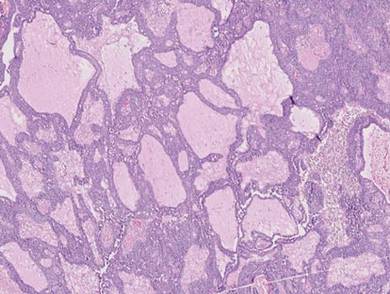

Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma is a rare neoplasm with a predilection for the eyelids; lesions occurring outside of this facial distribution, particularly of the breast, warrant a workup for metastatic disease.7 It typically occurs in the deeper dermis with involvement of the subcutaneous fat and is characterized by delicate fibrous septa enveloping large lakes of mucin, which contain islands of tumor cells (Figure 6). It has not been reported in association with spiradenomas. In addition, the tumor cells typically are CK7 positive.

1. Kazakov DV, Soukup R, Mukensnabl P, et al. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome: report of a case with combined lesions containing cylindromatous, spiradenomatous, trichoblastomatous, and sebaceous differentiation. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:27-33.

2. Petersson F, Kutzner H, Spagnolo DV, et al. Adenoid cystic carcinoma-like pattern in spiradenoma and spiradenocylindroma: a rare feature in sporadic neoplasms and those associated with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:642-648.

3. Weyers W, Nilles M, Eckert F, et al. Spiradenomas in Brooke-Spiegler syndrome. Am J Dermatopathol. 1993;15:156-161.

4. Elston DM, Ferringer T. Dermatopathology. Edinburgh, Scotland: Elsevier Saunders; 2009.

5. Ackerman AB, de Viragh PA, Chongchitnant N. Neoplasms with Follicular Differentiation. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger; 1993.

6. Yamamoto O, Asahi M. Cytokeratin expression in trichoblastic fibroma (small nodular type trichoblastoma), trichoepithelioma and basal cell carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:8-16.

7. Calonje JE, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al. McKee’s Pathology of the Skin with Clinical Correlations. 4th ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

8. Meybehm M, Fischer HP. Spiradenoma and dermal cylindroma: comparative immunohistochemical analysis and histogenetic considerations. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:154-161.

9. Kurokawa I, Nishimura K, Tarumi C, et al. Eccrinespiradenoma: co-expression of cytokeratin and smooth muscle actin suggesting differentiation toward myoepithelial cells. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:121-123.

10. Thompson LD, Penner C, Ho NJ, et al. Sinonasal tract and nasopharyngeal adenoid cystic carcinoma: a clinicopathologic and immunophenotypic study of 86 cases. Head Neck Pathol. 2014;8:88-109.

The coexistence of more than one cutaneous adnexal neoplasm in a single biopsy specimen is unusual and is most frequently recognized in the context of a nevus sebaceous or Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, an autosomal-dominant inherited disease characterized by cutaneous adnexal neoplasms, most commonly cylindromas and trichoepitheliomas.1-3 Brooke-Spiegler syndrome is caused by germline mutations in the cylindromatosis gene, CYLD, located on band 16q12; it functions as a tumor suppressor gene and has regulatory roles in development, immunity, and inflammation.1 Weyers et al3 first recognized the tendency for adnexal collision tumors to present in patients with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome; they reported a patient with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome with spiradenomas found in the immediate vicinity of trichoepitheliomas and in continuity with hair follicles.

Spiradenomas are composed of large, sharply demarcated, rounded nodules of basaloid cells with little cytoplasm (Figure 1).4 The basaloid nodules may demonstrate a trabecular architecture, and on close inspection 2 cell types—paler cells with more cytoplasm and darker cells with less cytoplasm—are distinguishable (Figure 2A). Lymphocytes often are scattered within the tumor nodules and/or stroma. In Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, collision tumors containing a spiradenomatous component in collision with trichoepithelioma are not uncommon.1 Spiradenomas in Brooke-Spiegler syndrome have been reported to contain sebaceous differentiation or foci with an adenoid cystic carcinoma (ACC)–like pattern and are known to occur as hybrid lesions of spiradenoma and cylindroma or trichoepithelioma (as in this case).

In this case, 2 distinct neoplasms (spiradenoma and trichoepithelioma) are apparent, side by side, with an intervening hair follicle (Figure 1). Trichoepitheliomas, also known as cribriform trichoblastomas,5 are characterized by lobules of basaloid cells resembling basal cell carcinoma surrounded by a fibroblast-rich stroma. They often contain fingerlike projections and adopt a cribriform morphology within the tumor lobules (Figure 2B).4 Numerous horn cysts may be present, but their absence does not preclude the diagnosis. Mucin may be present within the cribriform tumor islands (Figure 2B) but not in the stroma. Characteristically, trichoepitheliomas are distinctly negative for CK7 (Figure 3), and unlike spiradenomas, they lack a myoepithelial component.6 This staining pattern in combination with the tumor’s proximity to an adjacent hair follicle makes a diagnosis of trichoepithelioma and spiradenoma collision tumor most likely and supports a clinical suspicion for Brooke-Spiegler syndrome.

|

Although spiradenomas sometimes contain cystic cavities (microcystic change), they typically are filled with finely granular eosinophilic material, not mucin, that is diastase resistant and periodic acid–Schiff positive (Figure 4).7 Spiradenomas classically stain positive with CK7 (Figure 3), epithelial membrane antigen, and carcinoembryonic antigen, and have a substantial myoepithelial component, as evidenced by the myoepithelial component staining with p63, S-100, and smooth muscle actin (SMA).7-9 The distinct lack of staining with CK7 and SMA in the tumor on the left in Figure 3 confirms that these tumors are of different lineage, rather than representing cystic change within a spiradenoma.

|

|

Adenoid cystic carcinoma is a rare neoplasm that may occur in a primary cutaneous form, as a direct extension from an underlying salivary gland neoplasm, or rarely as a focal pattern within spiradenomas occurring both sporadically or in the context of Brooke-Spiegler syndrome.2,7 The tumor is composed of variably sized cribriform islands of basaloid to pink cells concentrically arranged around glandlike spaces filled with mucin (Figure 5A). In contrast to trichoepithelioma, ACC occurs in the mid to deep dermis, often extending into subcutaneous fat with an infiltrative border, and is not often found in close proximity to hair follicles.7 Characteristically, hyaline basement membrane–like material that is periodic acid–Schiff positive is found between the tumor cells and also surrounding the individual lobules. Immunohistochemically, ACC has a myoepithelial component that stains positive with SMA, S-100, and p63; additionally, the tumor cells express low- and high-molecular-weight keratin and demonstrate variable epithelial membrane antigen positivity.10 In the current case, the superficial location, close association with a hair follicle, and lack of staining with both CK7 (Figure 3) and SMA (not shown) make ACC arising within a spiradenoma a less likely diagnosis.

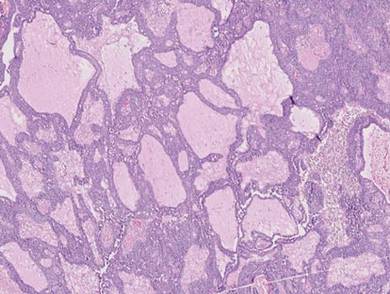

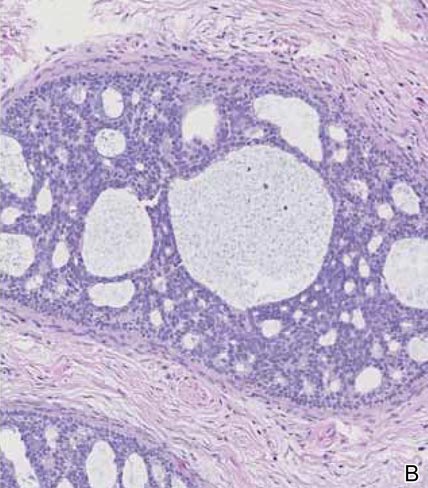

Cylindromas are composed of basaloid islands interconnected in a jigsaw puzzle configuration (Figure 5B).4 Similar to spiradenomas, they also are composed of 2 cell populations. Characteristically, the tumor islands are outlined by a hyalinized eosinophilic basement membrane. Hyalinized droplets of basement membrane zone material also may be noted in the islands. Unlike spiradenomas, they lack both intratumoral lymphocytes and a trabecular growth pattern. Although spiradenocylindromas (cylindroma and spiradenoma collision tumors) are perhaps the most common collision tumor associated with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, there is no evidence suggesting the presence of a cylindroma in the current case.

|

Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma is a rare neoplasm with a predilection for the eyelids; lesions occurring outside of this facial distribution, particularly of the breast, warrant a workup for metastatic disease.7 It typically occurs in the deeper dermis with involvement of the subcutaneous fat and is characterized by delicate fibrous septa enveloping large lakes of mucin, which contain islands of tumor cells (Figure 6). It has not been reported in association with spiradenomas. In addition, the tumor cells typically are CK7 positive.

The coexistence of more than one cutaneous adnexal neoplasm in a single biopsy specimen is unusual and is most frequently recognized in the context of a nevus sebaceous or Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, an autosomal-dominant inherited disease characterized by cutaneous adnexal neoplasms, most commonly cylindromas and trichoepitheliomas.1-3 Brooke-Spiegler syndrome is caused by germline mutations in the cylindromatosis gene, CYLD, located on band 16q12; it functions as a tumor suppressor gene and has regulatory roles in development, immunity, and inflammation.1 Weyers et al3 first recognized the tendency for adnexal collision tumors to present in patients with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome; they reported a patient with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome with spiradenomas found in the immediate vicinity of trichoepitheliomas and in continuity with hair follicles.

Spiradenomas are composed of large, sharply demarcated, rounded nodules of basaloid cells with little cytoplasm (Figure 1).4 The basaloid nodules may demonstrate a trabecular architecture, and on close inspection 2 cell types—paler cells with more cytoplasm and darker cells with less cytoplasm—are distinguishable (Figure 2A). Lymphocytes often are scattered within the tumor nodules and/or stroma. In Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, collision tumors containing a spiradenomatous component in collision with trichoepithelioma are not uncommon.1 Spiradenomas in Brooke-Spiegler syndrome have been reported to contain sebaceous differentiation or foci with an adenoid cystic carcinoma (ACC)–like pattern and are known to occur as hybrid lesions of spiradenoma and cylindroma or trichoepithelioma (as in this case).

In this case, 2 distinct neoplasms (spiradenoma and trichoepithelioma) are apparent, side by side, with an intervening hair follicle (Figure 1). Trichoepitheliomas, also known as cribriform trichoblastomas,5 are characterized by lobules of basaloid cells resembling basal cell carcinoma surrounded by a fibroblast-rich stroma. They often contain fingerlike projections and adopt a cribriform morphology within the tumor lobules (Figure 2B).4 Numerous horn cysts may be present, but their absence does not preclude the diagnosis. Mucin may be present within the cribriform tumor islands (Figure 2B) but not in the stroma. Characteristically, trichoepitheliomas are distinctly negative for CK7 (Figure 3), and unlike spiradenomas, they lack a myoepithelial component.6 This staining pattern in combination with the tumor’s proximity to an adjacent hair follicle makes a diagnosis of trichoepithelioma and spiradenoma collision tumor most likely and supports a clinical suspicion for Brooke-Spiegler syndrome.

|

Although spiradenomas sometimes contain cystic cavities (microcystic change), they typically are filled with finely granular eosinophilic material, not mucin, that is diastase resistant and periodic acid–Schiff positive (Figure 4).7 Spiradenomas classically stain positive with CK7 (Figure 3), epithelial membrane antigen, and carcinoembryonic antigen, and have a substantial myoepithelial component, as evidenced by the myoepithelial component staining with p63, S-100, and smooth muscle actin (SMA).7-9 The distinct lack of staining with CK7 and SMA in the tumor on the left in Figure 3 confirms that these tumors are of different lineage, rather than representing cystic change within a spiradenoma.

|

|

Adenoid cystic carcinoma is a rare neoplasm that may occur in a primary cutaneous form, as a direct extension from an underlying salivary gland neoplasm, or rarely as a focal pattern within spiradenomas occurring both sporadically or in the context of Brooke-Spiegler syndrome.2,7 The tumor is composed of variably sized cribriform islands of basaloid to pink cells concentrically arranged around glandlike spaces filled with mucin (Figure 5A). In contrast to trichoepithelioma, ACC occurs in the mid to deep dermis, often extending into subcutaneous fat with an infiltrative border, and is not often found in close proximity to hair follicles.7 Characteristically, hyaline basement membrane–like material that is periodic acid–Schiff positive is found between the tumor cells and also surrounding the individual lobules. Immunohistochemically, ACC has a myoepithelial component that stains positive with SMA, S-100, and p63; additionally, the tumor cells express low- and high-molecular-weight keratin and demonstrate variable epithelial membrane antigen positivity.10 In the current case, the superficial location, close association with a hair follicle, and lack of staining with both CK7 (Figure 3) and SMA (not shown) make ACC arising within a spiradenoma a less likely diagnosis.

Cylindromas are composed of basaloid islands interconnected in a jigsaw puzzle configuration (Figure 5B).4 Similar to spiradenomas, they also are composed of 2 cell populations. Characteristically, the tumor islands are outlined by a hyalinized eosinophilic basement membrane. Hyalinized droplets of basement membrane zone material also may be noted in the islands. Unlike spiradenomas, they lack both intratumoral lymphocytes and a trabecular growth pattern. Although spiradenocylindromas (cylindroma and spiradenoma collision tumors) are perhaps the most common collision tumor associated with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, there is no evidence suggesting the presence of a cylindroma in the current case.

|

Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma is a rare neoplasm with a predilection for the eyelids; lesions occurring outside of this facial distribution, particularly of the breast, warrant a workup for metastatic disease.7 It typically occurs in the deeper dermis with involvement of the subcutaneous fat and is characterized by delicate fibrous septa enveloping large lakes of mucin, which contain islands of tumor cells (Figure 6). It has not been reported in association with spiradenomas. In addition, the tumor cells typically are CK7 positive.

1. Kazakov DV, Soukup R, Mukensnabl P, et al. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome: report of a case with combined lesions containing cylindromatous, spiradenomatous, trichoblastomatous, and sebaceous differentiation. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:27-33.

2. Petersson F, Kutzner H, Spagnolo DV, et al. Adenoid cystic carcinoma-like pattern in spiradenoma and spiradenocylindroma: a rare feature in sporadic neoplasms and those associated with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:642-648.

3. Weyers W, Nilles M, Eckert F, et al. Spiradenomas in Brooke-Spiegler syndrome. Am J Dermatopathol. 1993;15:156-161.

4. Elston DM, Ferringer T. Dermatopathology. Edinburgh, Scotland: Elsevier Saunders; 2009.

5. Ackerman AB, de Viragh PA, Chongchitnant N. Neoplasms with Follicular Differentiation. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger; 1993.

6. Yamamoto O, Asahi M. Cytokeratin expression in trichoblastic fibroma (small nodular type trichoblastoma), trichoepithelioma and basal cell carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:8-16.

7. Calonje JE, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al. McKee’s Pathology of the Skin with Clinical Correlations. 4th ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

8. Meybehm M, Fischer HP. Spiradenoma and dermal cylindroma: comparative immunohistochemical analysis and histogenetic considerations. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:154-161.

9. Kurokawa I, Nishimura K, Tarumi C, et al. Eccrinespiradenoma: co-expression of cytokeratin and smooth muscle actin suggesting differentiation toward myoepithelial cells. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:121-123.

10. Thompson LD, Penner C, Ho NJ, et al. Sinonasal tract and nasopharyngeal adenoid cystic carcinoma: a clinicopathologic and immunophenotypic study of 86 cases. Head Neck Pathol. 2014;8:88-109.

1. Kazakov DV, Soukup R, Mukensnabl P, et al. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome: report of a case with combined lesions containing cylindromatous, spiradenomatous, trichoblastomatous, and sebaceous differentiation. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:27-33.

2. Petersson F, Kutzner H, Spagnolo DV, et al. Adenoid cystic carcinoma-like pattern in spiradenoma and spiradenocylindroma: a rare feature in sporadic neoplasms and those associated with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:642-648.

3. Weyers W, Nilles M, Eckert F, et al. Spiradenomas in Brooke-Spiegler syndrome. Am J Dermatopathol. 1993;15:156-161.

4. Elston DM, Ferringer T. Dermatopathology. Edinburgh, Scotland: Elsevier Saunders; 2009.

5. Ackerman AB, de Viragh PA, Chongchitnant N. Neoplasms with Follicular Differentiation. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger; 1993.

6. Yamamoto O, Asahi M. Cytokeratin expression in trichoblastic fibroma (small nodular type trichoblastoma), trichoepithelioma and basal cell carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:8-16.

7. Calonje JE, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al. McKee’s Pathology of the Skin with Clinical Correlations. 4th ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

8. Meybehm M, Fischer HP. Spiradenoma and dermal cylindroma: comparative immunohistochemical analysis and histogenetic considerations. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:154-161.

9. Kurokawa I, Nishimura K, Tarumi C, et al. Eccrinespiradenoma: co-expression of cytokeratin and smooth muscle actin suggesting differentiation toward myoepithelial cells. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:121-123.

10. Thompson LD, Penner C, Ho NJ, et al. Sinonasal tract and nasopharyngeal adenoid cystic carcinoma: a clinicopathologic and immunophenotypic study of 86 cases. Head Neck Pathol. 2014;8:88-109.

Lipidized Dermatofibroma

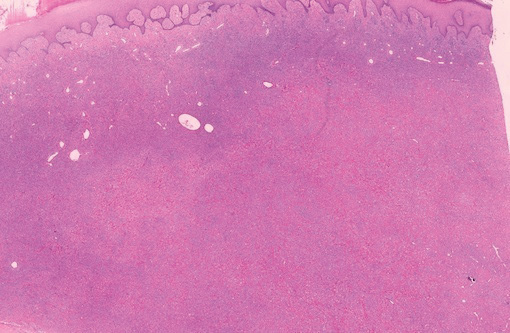

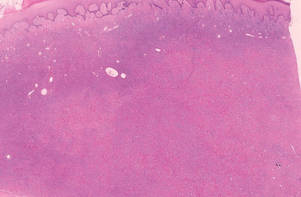

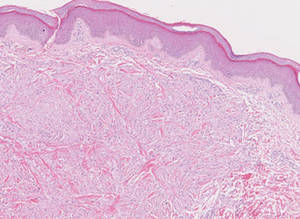

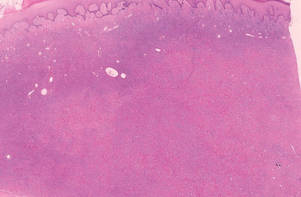

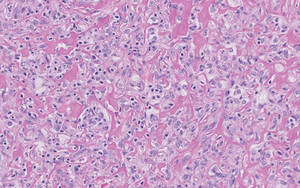

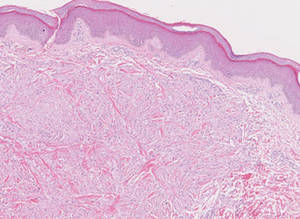

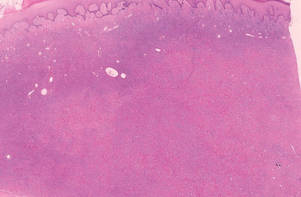

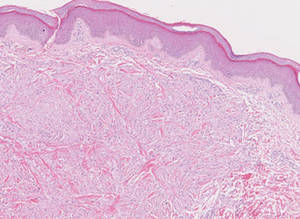

Lipidized dermatofibromas most commonly are found on the ankles, which has led some authors to refer to these lesions as ankle-type fibrous histiocytomas.1 Compared to ordinary dermatofibromas, patients with lipidized dermatofibromas tend to be older, most commonly presenting in the fifth or sixth decades of life, and are predominantly male. Lipidized dermatofibromas typically present as well-circumscribed solitary nodules in the dermis. Characteristic features include numerous xanthomatous cells dissected by distinctive hyalinized wiry collagen fibers (Figures 1 and 2).1 Xanthomatous cells can be round, polygonal, or stellate in shape. These characteristic features in combination with others of dermatofibromas (eg, epidermal acanthosis [Figure 1]) fulfill the criteria for diagnosis of a lipidized dermatofibroma. Additionally, lipidized dermatofibromas tend to be larger than ordinary dermatofibromas, which typically are less than 2 cm in diameter.1

|

Figure 1. Lipidized dermatofibromas are characterized by classic epidermal features of dermatofibromas, such as acanthosis, along with numerous foam cells and extensive stromal hyalinization (H&E, original magnification ×1.5). |

|

Figure 2. Higher-power view of a lipidized dermatofibroma shows the characteristic irregular dissection of hyalinized wiry collagen fibers between the xanthomatous cells (H&E, original magnification ×20). |

Eruptive xanthomas are characterized by a lacelike infiltrate of extravascular lipid deposits between collagen bundles (Figure 3).2 Granular cell tumors are composed of sheets and/or nests of large cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and may be confused with lipidized dermatofibromas, as they also may induce overlying pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia3; however, on closer examination of the cells, the cytoplasm is found to be granular (Figure 4), which contrasts the finely vacuolated cytoplasm of xanthomatous cells found in lipidized dermatofibromas. Giant lysosomal granules (eg, pustulo-ovoid bodies of Milian) are present in some cases.2 Of note, an unusual variant of dermatofibroma exists that features prominent granular cells.4

|

Figure 3. Lacelike deposition of extravascular lipid deposits is seen infiltrating between collagen bundles in an eruptive xanthoma (H&E, original magnification ×20). |

|

Figure 4. An abundant eosinophilic, finely granular cytoplasm is characteristic of granular cell tumor (H&E, original magnification ×40). |

Tuberous xanthomas most commonly occur around the pressure areas, such as the knees, elbows, and buttocks. Foam cells are a main feature of tuberous xanthomas and are arranged in large aggregates throughout the dermis.2 Tuberous xanthomas lack Touton giant cells or inflammatory cells. Older lesions tend to develop substantial fibrosis (Figure 5). Although foam cells can be present in older lesions, they are never as conspicuous as those found in other xanthomas.

Xanthogranulomas commonly occur on the head and neck. Findings noted on low magnification include a well-circumscribed exophytic nodule and an epidermal collarette, which help to easily distinguish xanthogranulomas from lipidized dermatofibromas. Additionally, the presence of a more prominent inflammatory infiltrate, which often includes eosinophils, as well as multinucleated Touton giant cells (Figure 6) and histiocytes with more eosinophilic and less xanthomatous cytoplasm can help distinguish between the lesions.1,5 Notably, Touton giant cells also can be seen in lipidized dermatofibromas,1 but the presence of unique features such as distinctive stromal hyalinization are clues to the correct diagnosis of a lipidized dermatofibroma.

- Iwata J, Fletcher CD. Lipidized fibrous histiocytoma: clinicopathologic analysis of 22 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:126-134.

- Weedon D. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 3rd ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2009.

- Elston DM, Ferringer T. Dermatopathology. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2009.

- Yogesh TL, Sowmya SV. Granules in granular cell lesions of the head and neck: a review. ISRN Pathol. 2011;2011:10.

- Fujita Y, Tsunemi Y, Kadono T, et al. Lipidized fibrous histiocytoma on the left condyle of the tibia. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:634-636.

Lipidized dermatofibromas most commonly are found on the ankles, which has led some authors to refer to these lesions as ankle-type fibrous histiocytomas.1 Compared to ordinary dermatofibromas, patients with lipidized dermatofibromas tend to be older, most commonly presenting in the fifth or sixth decades of life, and are predominantly male. Lipidized dermatofibromas typically present as well-circumscribed solitary nodules in the dermis. Characteristic features include numerous xanthomatous cells dissected by distinctive hyalinized wiry collagen fibers (Figures 1 and 2).1 Xanthomatous cells can be round, polygonal, or stellate in shape. These characteristic features in combination with others of dermatofibromas (eg, epidermal acanthosis [Figure 1]) fulfill the criteria for diagnosis of a lipidized dermatofibroma. Additionally, lipidized dermatofibromas tend to be larger than ordinary dermatofibromas, which typically are less than 2 cm in diameter.1

|

Figure 1. Lipidized dermatofibromas are characterized by classic epidermal features of dermatofibromas, such as acanthosis, along with numerous foam cells and extensive stromal hyalinization (H&E, original magnification ×1.5). |

|

Figure 2. Higher-power view of a lipidized dermatofibroma shows the characteristic irregular dissection of hyalinized wiry collagen fibers between the xanthomatous cells (H&E, original magnification ×20). |

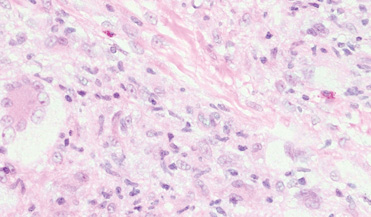

Eruptive xanthomas are characterized by a lacelike infiltrate of extravascular lipid deposits between collagen bundles (Figure 3).2 Granular cell tumors are composed of sheets and/or nests of large cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and may be confused with lipidized dermatofibromas, as they also may induce overlying pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia3; however, on closer examination of the cells, the cytoplasm is found to be granular (Figure 4), which contrasts the finely vacuolated cytoplasm of xanthomatous cells found in lipidized dermatofibromas. Giant lysosomal granules (eg, pustulo-ovoid bodies of Milian) are present in some cases.2 Of note, an unusual variant of dermatofibroma exists that features prominent granular cells.4

|

Figure 3. Lacelike deposition of extravascular lipid deposits is seen infiltrating between collagen bundles in an eruptive xanthoma (H&E, original magnification ×20). |

|

Figure 4. An abundant eosinophilic, finely granular cytoplasm is characteristic of granular cell tumor (H&E, original magnification ×40). |

Tuberous xanthomas most commonly occur around the pressure areas, such as the knees, elbows, and buttocks. Foam cells are a main feature of tuberous xanthomas and are arranged in large aggregates throughout the dermis.2 Tuberous xanthomas lack Touton giant cells or inflammatory cells. Older lesions tend to develop substantial fibrosis (Figure 5). Although foam cells can be present in older lesions, they are never as conspicuous as those found in other xanthomas.

Xanthogranulomas commonly occur on the head and neck. Findings noted on low magnification include a well-circumscribed exophytic nodule and an epidermal collarette, which help to easily distinguish xanthogranulomas from lipidized dermatofibromas. Additionally, the presence of a more prominent inflammatory infiltrate, which often includes eosinophils, as well as multinucleated Touton giant cells (Figure 6) and histiocytes with more eosinophilic and less xanthomatous cytoplasm can help distinguish between the lesions.1,5 Notably, Touton giant cells also can be seen in lipidized dermatofibromas,1 but the presence of unique features such as distinctive stromal hyalinization are clues to the correct diagnosis of a lipidized dermatofibroma.

Lipidized dermatofibromas most commonly are found on the ankles, which has led some authors to refer to these lesions as ankle-type fibrous histiocytomas.1 Compared to ordinary dermatofibromas, patients with lipidized dermatofibromas tend to be older, most commonly presenting in the fifth or sixth decades of life, and are predominantly male. Lipidized dermatofibromas typically present as well-circumscribed solitary nodules in the dermis. Characteristic features include numerous xanthomatous cells dissected by distinctive hyalinized wiry collagen fibers (Figures 1 and 2).1 Xanthomatous cells can be round, polygonal, or stellate in shape. These characteristic features in combination with others of dermatofibromas (eg, epidermal acanthosis [Figure 1]) fulfill the criteria for diagnosis of a lipidized dermatofibroma. Additionally, lipidized dermatofibromas tend to be larger than ordinary dermatofibromas, which typically are less than 2 cm in diameter.1

|

Figure 1. Lipidized dermatofibromas are characterized by classic epidermal features of dermatofibromas, such as acanthosis, along with numerous foam cells and extensive stromal hyalinization (H&E, original magnification ×1.5). |

|

Figure 2. Higher-power view of a lipidized dermatofibroma shows the characteristic irregular dissection of hyalinized wiry collagen fibers between the xanthomatous cells (H&E, original magnification ×20). |

Eruptive xanthomas are characterized by a lacelike infiltrate of extravascular lipid deposits between collagen bundles (Figure 3).2 Granular cell tumors are composed of sheets and/or nests of large cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and may be confused with lipidized dermatofibromas, as they also may induce overlying pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia3; however, on closer examination of the cells, the cytoplasm is found to be granular (Figure 4), which contrasts the finely vacuolated cytoplasm of xanthomatous cells found in lipidized dermatofibromas. Giant lysosomal granules (eg, pustulo-ovoid bodies of Milian) are present in some cases.2 Of note, an unusual variant of dermatofibroma exists that features prominent granular cells.4

|

Figure 3. Lacelike deposition of extravascular lipid deposits is seen infiltrating between collagen bundles in an eruptive xanthoma (H&E, original magnification ×20). |

|

Figure 4. An abundant eosinophilic, finely granular cytoplasm is characteristic of granular cell tumor (H&E, original magnification ×40). |

Tuberous xanthomas most commonly occur around the pressure areas, such as the knees, elbows, and buttocks. Foam cells are a main feature of tuberous xanthomas and are arranged in large aggregates throughout the dermis.2 Tuberous xanthomas lack Touton giant cells or inflammatory cells. Older lesions tend to develop substantial fibrosis (Figure 5). Although foam cells can be present in older lesions, they are never as conspicuous as those found in other xanthomas.

Xanthogranulomas commonly occur on the head and neck. Findings noted on low magnification include a well-circumscribed exophytic nodule and an epidermal collarette, which help to easily distinguish xanthogranulomas from lipidized dermatofibromas. Additionally, the presence of a more prominent inflammatory infiltrate, which often includes eosinophils, as well as multinucleated Touton giant cells (Figure 6) and histiocytes with more eosinophilic and less xanthomatous cytoplasm can help distinguish between the lesions.1,5 Notably, Touton giant cells also can be seen in lipidized dermatofibromas,1 but the presence of unique features such as distinctive stromal hyalinization are clues to the correct diagnosis of a lipidized dermatofibroma.

- Iwata J, Fletcher CD. Lipidized fibrous histiocytoma: clinicopathologic analysis of 22 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:126-134.

- Weedon D. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 3rd ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2009.

- Elston DM, Ferringer T. Dermatopathology. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2009.

- Yogesh TL, Sowmya SV. Granules in granular cell lesions of the head and neck: a review. ISRN Pathol. 2011;2011:10.

- Fujita Y, Tsunemi Y, Kadono T, et al. Lipidized fibrous histiocytoma on the left condyle of the tibia. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:634-636.

- Iwata J, Fletcher CD. Lipidized fibrous histiocytoma: clinicopathologic analysis of 22 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:126-134.

- Weedon D. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 3rd ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2009.

- Elston DM, Ferringer T. Dermatopathology. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2009.

- Yogesh TL, Sowmya SV. Granules in granular cell lesions of the head and neck: a review. ISRN Pathol. 2011;2011:10.

- Fujita Y, Tsunemi Y, Kadono T, et al. Lipidized fibrous histiocytoma on the left condyle of the tibia. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:634-636.