User login

Vandetanib Photoinduced Cutaneous Toxicities

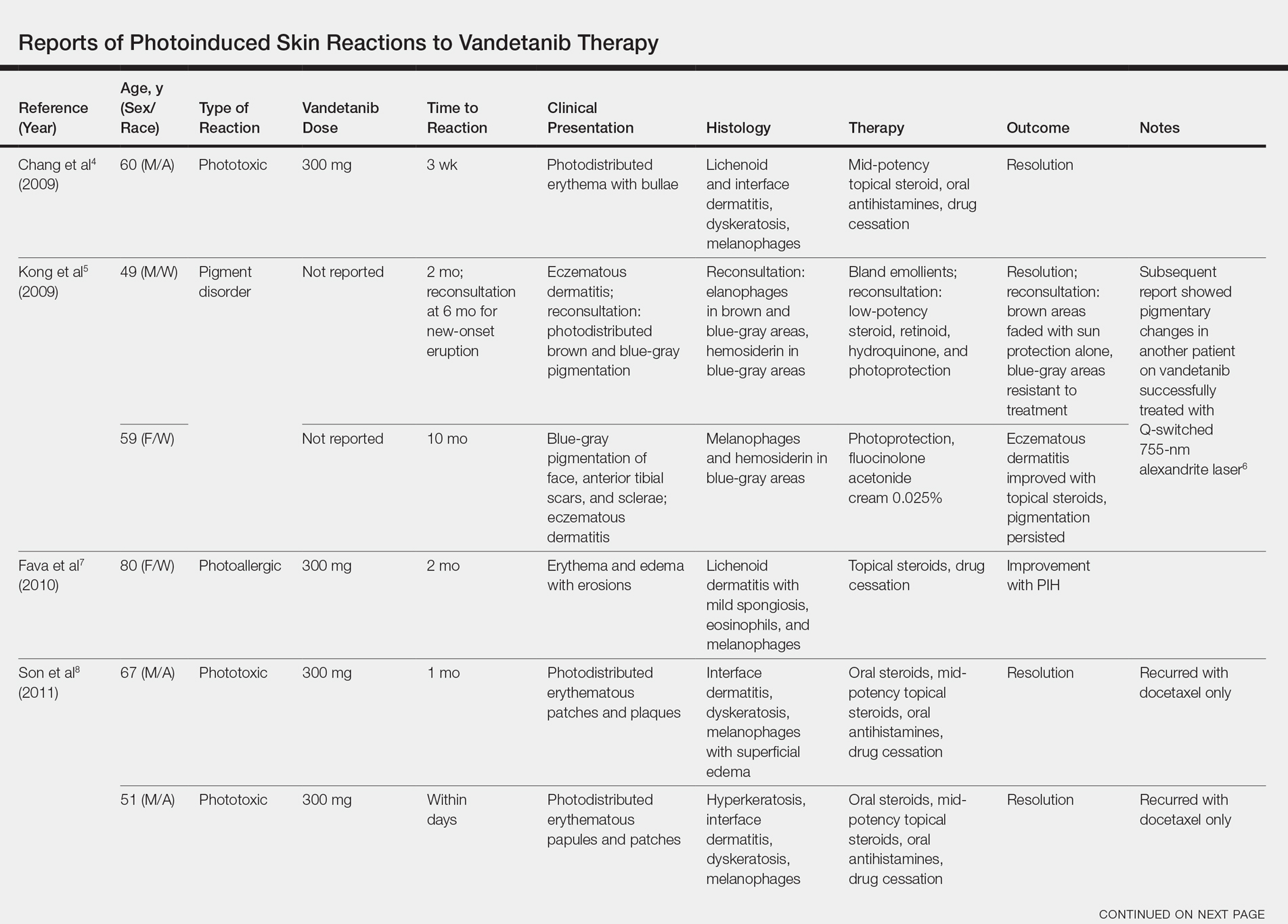

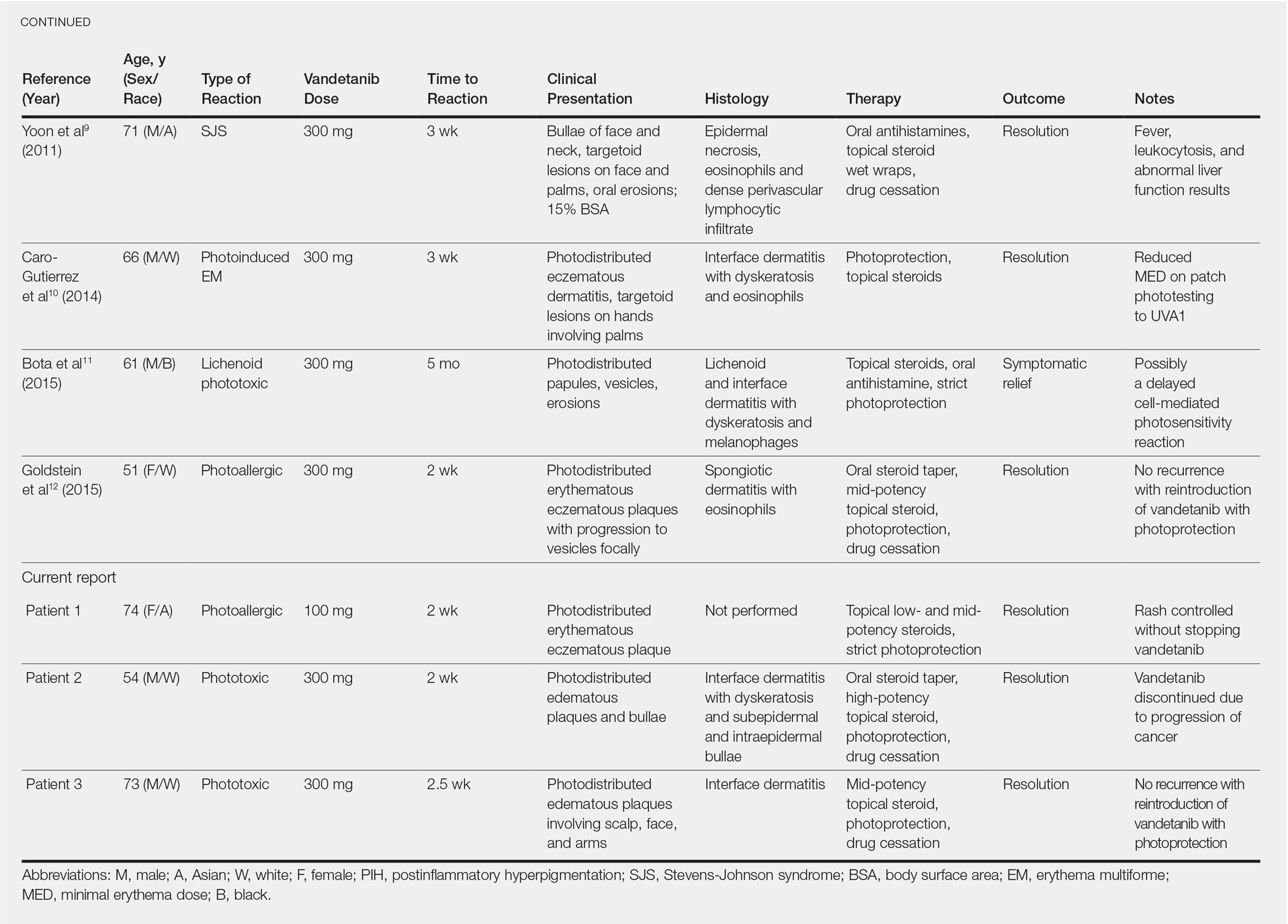

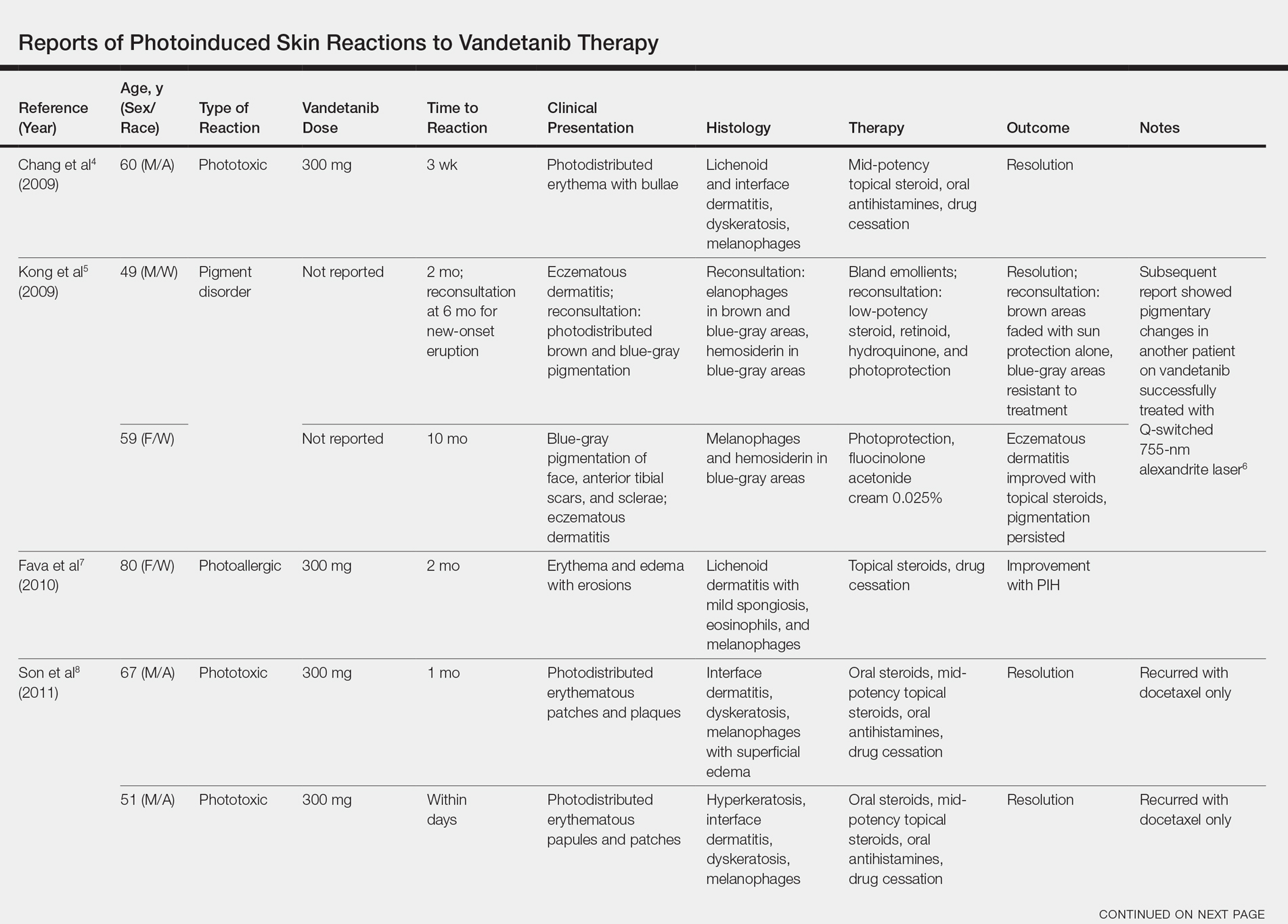

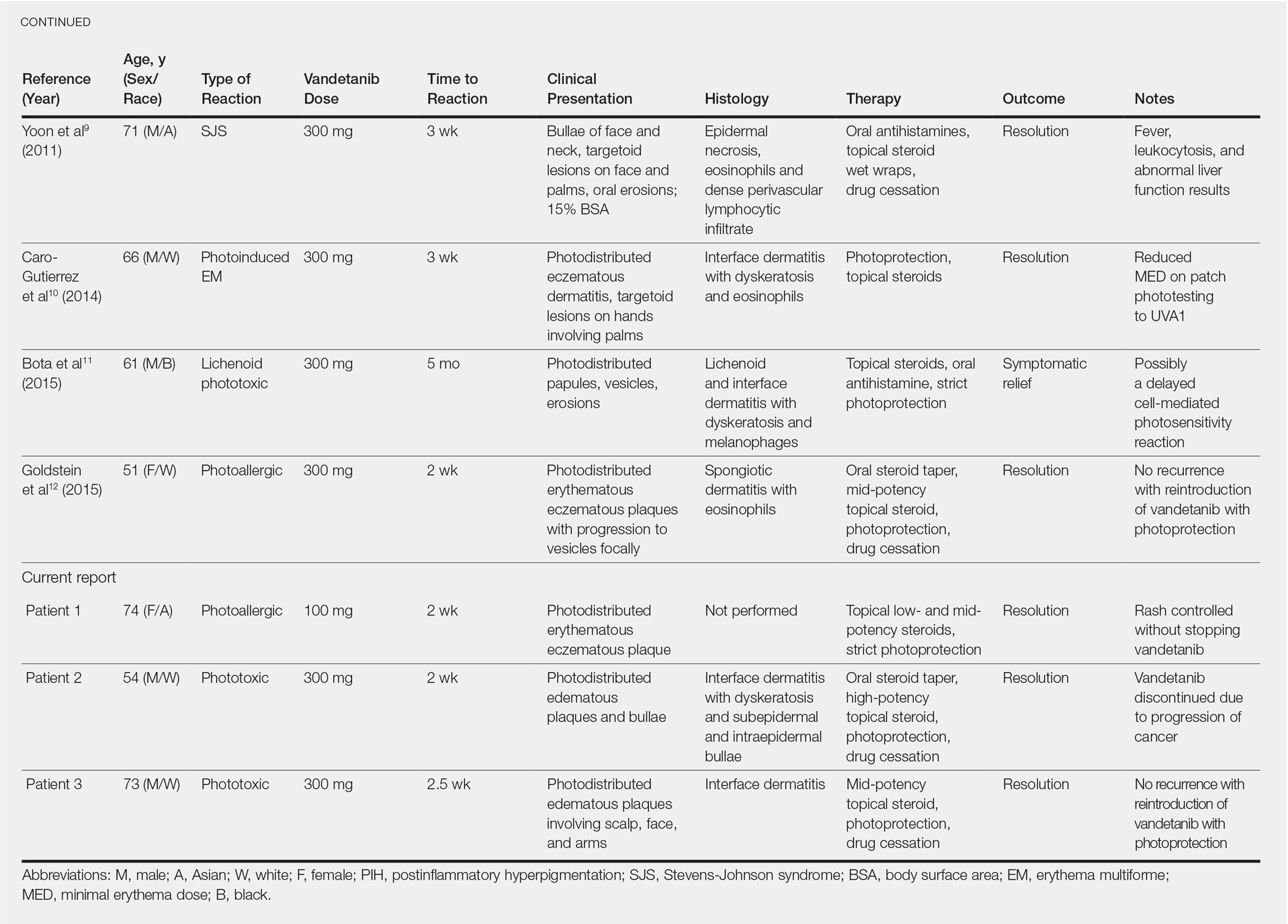

Vandetanib is a once-daily oral multikinase inhibitor that targets the rearranged during transfection (RET) tyrosine kinase, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor, and epidermal growth factor receptor. It has shown efficacy at doses of 300 mg daily in the treatment of progressive medullary thyroid cancer and has shown promise in non–small cell lung cancer and breast cancer. Vandetanib’s toxicity profile includes QT prolongation, diarrhea, and rash.1-3 Cutaneous involvement has been described in the literature as a photodistributed drug reaction with both erythema multiforme (EM) and Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS)–like eruptions, phototoxicity, and photoallergy (Table).4-12 Photoinduction is the common thread, but various mechanisms have been proposed, including drug deposition within the dermis and direct toxicity to keratinocytes; however, an understanding of the varied presentation is lacking.

We present 3 cases of vandetanib photoinduced cutaneous toxicities and review the literature on this novel kinase inhibitor. This discussion highlights the spectrum of photosensitivity reactions to vandetanib among patients with varying histologic and clinical presentations.

Case Reports

Patient 1A

74-year-old woman with a history of recurrent metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix and Fitzpatrick skin type III presented with erythematous, well-demarcated, photodistributed, eczematous papules that were coalescing into plaques on the scalp, hands, and face. The rash appeared sharply demarcated at the wrists bilaterally and principally involved the dorsal sun-exposed areas of her hands (Figure 1). The rash also involved the face and the V of the neck with sharp demarcation. Two weeks prior to onset, she initiated a phase 1 trial of oral vandetanib 100 mg twice daily and oral everolimus 5 mg daily. She did not recall practicing sun protection or experiencing increased sun exposure after starting that trial. The patient demonstrated symptom improvement with desonide cream, hydrocortisone cream 2.5%, and over-the-counter analgesic cream while continuing with the study drugs. However, she developed new, warm, painful papules on the hands and face. Phototesting and biopsy were not performed, and the etiology of the photosensitivity was unknown.

The patient was counseled about regular sun protection and was prescribed triamcinolone cream 0.1% for the arms and hydrocortisone cream 2.5% for the affected facial areas. Therapy with vandetanib and everolimus was continued without dose reduction or further cutaneous eruptions.

Patient 2

A 54-year-old man with a history of progressive medullary thyroid carcinoma and Fitzpatrick skin type II presented with erythematous, well-demarcated, photodistributed, edematous plaques and bullae of the head and neck, bilateral dorsal hands, and bilateral palms of 2 weeks’ duration. The rash spared the upper back and chest with a well-demarcated border (Figure 2A). There were ulcerations and erosions at the base of the neck and the dorsal hands (Figure 2B). He also had conjunctivitis but uninvolved oral and genital mucosae.

Two weeks before the rash appeared, oral vandetanib 300 mg daily was initiated. The patient initially noted some dry skin, which progressed to an eruption involving the face and neck and later the hands with palmar blistering and desquamation. Medication cessation for 1 month led to moderate improvement of the rash on the face and neck. He had not been practicing sun protection but did wear a baseball cap when outside. The patient did not recall an incidence of increased sun exposure. He underwent a skin biopsy of the right dorsal hand, which revealed interface dermatitis with dyskeratosis and subepidermal and intraepidermal bullae (Figure 3). The biopsy findings were most consistent with a phototoxic eruption. Phototesting was not performed.

The patient then initiated sun-protective measures, a prednisone taper, and high-potency steroid ointments. As he tapered his prednisone, he noted continued improvement in the rash. His disease progressed, however, and he did not restart vandetanib.

Patient 3

A 73-year-old man with a history of metastatic lung carcinoma and Fitzpatrick skin type II presented with a rash on the scalp, face, and arms of 2.5 weeks’ duration. There was sharp demarcation at the edges of sun-exposed skin, and no bullae were noted (Figure 4). Prior to presentation, the patient started a 4-week phase 1 trial with vandetanib 300 mg daily and everolimus 10 mg daily. He did not recall any episodes of increased sun exposure. A punch biopsy of the arm showed an interface dermatitis suggestive of a phototoxic reaction. Phototesting was not performed to further clarify if there was a diminished minimal erythema dose with UVA or UVB radiation. Both drugs were discontinued, strict photoprotection was practiced, and triamcinolone cream 0.1% was initiated with resolution of rash. Vandetanib and everolimus were resumed at initial doses with strict photoprotection, and the rash has not recurred.

Comment

Adverse Events Associated With Vandetanib

Vandetanib is a novel multikinase inhibitor that targets RET tyrosine kinase, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor, and epidermal growth factor receptor.1,2 It currently is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of progressive medullary thyroid cancer and is being used in clinical trials for non–small cell lung cancer, glioma, advanced biliary tract cancer, breast cancer, and other advanced solid malignancies. Frequently reported adverse events (AEs) include QT prolongation, diarrhea, and rash.1-3 In a large phase 3 trial, 45% of patients had a rash; of these, 4% were grade 3 and above.3 The most common reasons for dose decrease or cessation were diarrhea and rash (1% and 1.3%, respectively).13 Outside of a trial setting, 75% (45/60) of patients in one French study reported a cutaneous AE, with photosensitivity noted in 22% (13/60). Thus, cutaneous reactions tend to be a common occurrence for patients on this drug, requiring diligent dermatologic examinations.14 In one meta-analysis comprising 9 studies with a total of 2961 patients, the incidence of all-grade rash was 46.1% (95% CI, 40.6%-51.8%), and it was concluded that vandetanib has the highest association of all-grade rash among the anti–vascular endothelial growth factor tyrosine kinase inhibitors. In this meta-analysis, the specific diagnosis of AEs was not further classified.15 In another cohort of vandetanib-treated patients, as many as 37% (28/63) of patients had photosensitivity, with no clarification of the etiology.16

Photoallergic vs Phototoxic Reactions

Photosensitivity reactions are cutaneous reactions that occur from UV light exposure, typically in conjunction with a photosensitizing agent. Photosensitivity reactions can be further classified into phototoxic and photoallergic reactions, which can be distinguished by histopathologic evaluation and history. Although phototoxic reactions will cause keratinocyte necrosis similar to a sunburn, photoallergic reactions will cause epidermal spongiosis similar to allergic contact dermatitis or eczema. Also, phototoxic reactions appear within 1 to 2 days of UV exposure and often are painful, whereas photoallergic reactions can be delayed for 2 to 3 weeks and usually are pruritic. Photosensitivity reactions related to vandetanib have been reported and are summarized in the Table.4-12

Although reported cutaneous reactions to vandetanib thus far in the literature were reported as photoinduced reactions, there have been isolated case reports of other eruptions including cutaneous pigmentation5 and one case of SJS.9 According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms vandetanib and rash, we found that there are a variety of clinical findings, but most of the reported photosensitivity cases were phototoxic. Fava et al7 and Goldstein et al12 both reported 1 photoallergic reaction each, plus patient 1 in our case series was noted to have a photoallergic reaction. Phototoxic reactions were reported in 4 patients (including our patient 2) who had dyskeratotic keratinocytes and vacuolar degeneration of the basal layer on histopathology.4,8 Fava et al7 described a lichenoid infiltrate with spongiosis consistent with a photoallergic reaction, but Chang et al4 and Bota et al11 described a lichenoid infiltrate with dyskeratotic cells. Also, Giacchero et al16 described a photosensitivity reaction in 28 of 63 patients. Although only 6 patients had biopsies performed, the range of photosensitivity reactions was demonstrated with lichenoid, dyskeratotic, and spongiotic reactions. However, the cases were not further defined as photoallergic or phototoxic.16 Vandetanib also has been associated with cutaneous blue pigmentation after likely phototoxic reactions. Pigment changes occurred after photosensitivity, but the clinical presentation of photosensitivity was not further characterized.5,16

Classic Drug Eruptions

Two patients were described as having classic drug eruptions—EM10 and SJS9—in photodistributed locations. Histologically, these entities are identical to phototoxic reactions, resulting in epidermal necrosis and an interface dermatitis, but the presence of targetoid lesions on the palms prompted the diagnosis of photodistributed EM and SJS in both cases.9,10 Unique to the SJS case was oral involvement.9

Distinguishing between a phototoxic reaction and photodistributed EM or SJS may be inconsequential if both can be prevented with photoprotection. Rechallenging patients with vandetanib while practicing photoprotection would help to clarify the mechanism, though this course is not always practical.

Mechanism of Action

As seen in our case series, cutaneous reactions occurred only on sun-exposed surfaces, and patients presented with sharp cutoff points that spared non–sun-exposed areas. Although clinically organized as a subtype of photosensitivity, the phototoxicity mechanism of action is considered a direct toxic effect on keratinocytes, which explains the histopathologic finding of dyskeratotic cells and the clinical spectrum of sunburn reaction, phototoxic EM, and SJS. UVA1 induces 2 photoproducts of vandetanib via a UVA1-mediated debromination process,17 but these photoproducts are not responsible for epidermal dyskeratosis.18 It was subsequently demonstrated that keratinocyte death was induced by apoptosis through photoinduced DNA cleavage and the formation of an aryl radical, which can induce further DNA damage.18 Caro-Gutierrez et al10 demonstrated a lowered minimal erythema dose in their patient with vandetanib-induced phototoxic EM.

Conversely, photoallergic reactions are considered immune-mediated delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions.4,7,11 Although the mechanism of a photoallergic reaction remains unclear, it is possible that vandetanib or a metabolite (in susceptible patients) induces an immune-mediated delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction with repeated exposure to the compound, which may explain the varied timing of photoallergic onset, including the events featured in the Bota et al11 case that occurred several months after drug initiation.

Conclusion

Considering the high prevalence of cutaneous AEs, especially varied photosensitivity reactions, these cases emphasize the importance of sun protection to help prevent dose reduction or drug cessation among patients taking vandetanib therapy.

- Carlomagno F, Vitagliano D, Guida T, et al. ZD6474, an orally available inhibitor of KDR tyrosine kinase activity, efficiently blocks oncogenic RET kinases. Cancer Res. 2002;62:7284-7290.

- Wedge SR, Ogilvie DJ, Dukes M, et al. ZD6474 inhibits vascular endothelial growth factor signaling, angiogenesis, and tumor growth following oral administration. Cancer Res. 2002;62:4645-4655.

- Wells SA Jr, Robinson BG, Gagel RF, et al. Vandetanib in patients with locally advanced or metastatic medullary thyroid cancer: a randomized, double-blind phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:134-141.

- Chang CH, Chang JW, Hui CY, et al. Severe photosensitivity reaction to vandetanib. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:E114-E115.

- Kong HH, Fine HA, Stern JB, et al. Cutaneous pigmentation after photosensitivity induced by vandetanib therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:923-925.

- Brooks S, Linehan WM, Srinivasan R, et al. Successful laser treatment of vandetanib-associated cutaneous pigmentation. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:364-365.

- Fava P, Quaglino P, Fierro MT, et al. Therapeutic hotline. a rare vandetanib-induced photo-allergic drug eruption. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:553-555.

- Son YM, Roh JY, Cho EK, et al. Photosensitivity reactions to vandetanib: redevelopment after sequential treatment with docetaxel. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23(suppl 3):S314-S318.

- Yoon J, Oh CW, Kim CY. Stevens-Johnson syndrome induced by vandetanib. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23(suppl 3):S343-S345.

- Caro-Gutierrez D, Floristan Muruzabal MU, Gomez de la Fuente E, et al. Photo-induced erythema multiforme associated with vandetanib administration. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:E142-E144.11.

- Bota J, Harvey V, Ferguson C, et al. A rare case of late-onset lichenoid photodermatitis after vandetanib therapy. JAAD Case Rep. 2015;1:141-143.

- Goldstein J, Patel AB, Curry JL, et al. Photoallergic reaction in a patient receiving vandetanib for metastatic follicular thyroid carcinoma: a case report. BMC Dermatol. 2015;15:2.

- Thornton K, Kim G, Maher VE, et al. Vandetanib for the treatment of symptomatic or progressive medullary thyroid cancer in patients with unresectable locally advanced or metastatic disease: US Food and Drug Administration drug approval summary. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:3722-3730.

- Chougnet CN, Borget I, Leboulleux S, et al. Vandetanib for the treatment of advanced medullary thyroid cancer outside a clinical trial: results from a French cohort. Thyroid. 2015;25:386-391.

- Rosen AC, Wu S, Damse A, et al. Risk of rash in cancer patients treated with vandetanib: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:1125-1133.

- Giacchero D, Ramacciotti C, Arnault JP, et al. A new spectrum of skin toxic effects associated with the multikinase inhibitor vandetanib. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1418-1420.

- Dall’acqua S, Vedaldi D, Salvador A. Isolation and structure elucidation of the main UV-A photoproducts of vandetanib. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2013;84:196-200.

- Salvador A, Vedaldi D, Brun P, et al. Vandetanib-induced phototoxicity in human keratinocytes NCTC-2544. Toxicol In Vitro. 2014;28:803-811.

Vandetanib is a once-daily oral multikinase inhibitor that targets the rearranged during transfection (RET) tyrosine kinase, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor, and epidermal growth factor receptor. It has shown efficacy at doses of 300 mg daily in the treatment of progressive medullary thyroid cancer and has shown promise in non–small cell lung cancer and breast cancer. Vandetanib’s toxicity profile includes QT prolongation, diarrhea, and rash.1-3 Cutaneous involvement has been described in the literature as a photodistributed drug reaction with both erythema multiforme (EM) and Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS)–like eruptions, phototoxicity, and photoallergy (Table).4-12 Photoinduction is the common thread, but various mechanisms have been proposed, including drug deposition within the dermis and direct toxicity to keratinocytes; however, an understanding of the varied presentation is lacking.

We present 3 cases of vandetanib photoinduced cutaneous toxicities and review the literature on this novel kinase inhibitor. This discussion highlights the spectrum of photosensitivity reactions to vandetanib among patients with varying histologic and clinical presentations.

Case Reports

Patient 1A

74-year-old woman with a history of recurrent metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix and Fitzpatrick skin type III presented with erythematous, well-demarcated, photodistributed, eczematous papules that were coalescing into plaques on the scalp, hands, and face. The rash appeared sharply demarcated at the wrists bilaterally and principally involved the dorsal sun-exposed areas of her hands (Figure 1). The rash also involved the face and the V of the neck with sharp demarcation. Two weeks prior to onset, she initiated a phase 1 trial of oral vandetanib 100 mg twice daily and oral everolimus 5 mg daily. She did not recall practicing sun protection or experiencing increased sun exposure after starting that trial. The patient demonstrated symptom improvement with desonide cream, hydrocortisone cream 2.5%, and over-the-counter analgesic cream while continuing with the study drugs. However, she developed new, warm, painful papules on the hands and face. Phototesting and biopsy were not performed, and the etiology of the photosensitivity was unknown.

The patient was counseled about regular sun protection and was prescribed triamcinolone cream 0.1% for the arms and hydrocortisone cream 2.5% for the affected facial areas. Therapy with vandetanib and everolimus was continued without dose reduction or further cutaneous eruptions.

Patient 2

A 54-year-old man with a history of progressive medullary thyroid carcinoma and Fitzpatrick skin type II presented with erythematous, well-demarcated, photodistributed, edematous plaques and bullae of the head and neck, bilateral dorsal hands, and bilateral palms of 2 weeks’ duration. The rash spared the upper back and chest with a well-demarcated border (Figure 2A). There were ulcerations and erosions at the base of the neck and the dorsal hands (Figure 2B). He also had conjunctivitis but uninvolved oral and genital mucosae.

Two weeks before the rash appeared, oral vandetanib 300 mg daily was initiated. The patient initially noted some dry skin, which progressed to an eruption involving the face and neck and later the hands with palmar blistering and desquamation. Medication cessation for 1 month led to moderate improvement of the rash on the face and neck. He had not been practicing sun protection but did wear a baseball cap when outside. The patient did not recall an incidence of increased sun exposure. He underwent a skin biopsy of the right dorsal hand, which revealed interface dermatitis with dyskeratosis and subepidermal and intraepidermal bullae (Figure 3). The biopsy findings were most consistent with a phototoxic eruption. Phototesting was not performed.

The patient then initiated sun-protective measures, a prednisone taper, and high-potency steroid ointments. As he tapered his prednisone, he noted continued improvement in the rash. His disease progressed, however, and he did not restart vandetanib.

Patient 3

A 73-year-old man with a history of metastatic lung carcinoma and Fitzpatrick skin type II presented with a rash on the scalp, face, and arms of 2.5 weeks’ duration. There was sharp demarcation at the edges of sun-exposed skin, and no bullae were noted (Figure 4). Prior to presentation, the patient started a 4-week phase 1 trial with vandetanib 300 mg daily and everolimus 10 mg daily. He did not recall any episodes of increased sun exposure. A punch biopsy of the arm showed an interface dermatitis suggestive of a phototoxic reaction. Phototesting was not performed to further clarify if there was a diminished minimal erythema dose with UVA or UVB radiation. Both drugs were discontinued, strict photoprotection was practiced, and triamcinolone cream 0.1% was initiated with resolution of rash. Vandetanib and everolimus were resumed at initial doses with strict photoprotection, and the rash has not recurred.

Comment

Adverse Events Associated With Vandetanib

Vandetanib is a novel multikinase inhibitor that targets RET tyrosine kinase, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor, and epidermal growth factor receptor.1,2 It currently is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of progressive medullary thyroid cancer and is being used in clinical trials for non–small cell lung cancer, glioma, advanced biliary tract cancer, breast cancer, and other advanced solid malignancies. Frequently reported adverse events (AEs) include QT prolongation, diarrhea, and rash.1-3 In a large phase 3 trial, 45% of patients had a rash; of these, 4% were grade 3 and above.3 The most common reasons for dose decrease or cessation were diarrhea and rash (1% and 1.3%, respectively).13 Outside of a trial setting, 75% (45/60) of patients in one French study reported a cutaneous AE, with photosensitivity noted in 22% (13/60). Thus, cutaneous reactions tend to be a common occurrence for patients on this drug, requiring diligent dermatologic examinations.14 In one meta-analysis comprising 9 studies with a total of 2961 patients, the incidence of all-grade rash was 46.1% (95% CI, 40.6%-51.8%), and it was concluded that vandetanib has the highest association of all-grade rash among the anti–vascular endothelial growth factor tyrosine kinase inhibitors. In this meta-analysis, the specific diagnosis of AEs was not further classified.15 In another cohort of vandetanib-treated patients, as many as 37% (28/63) of patients had photosensitivity, with no clarification of the etiology.16

Photoallergic vs Phototoxic Reactions

Photosensitivity reactions are cutaneous reactions that occur from UV light exposure, typically in conjunction with a photosensitizing agent. Photosensitivity reactions can be further classified into phototoxic and photoallergic reactions, which can be distinguished by histopathologic evaluation and history. Although phototoxic reactions will cause keratinocyte necrosis similar to a sunburn, photoallergic reactions will cause epidermal spongiosis similar to allergic contact dermatitis or eczema. Also, phototoxic reactions appear within 1 to 2 days of UV exposure and often are painful, whereas photoallergic reactions can be delayed for 2 to 3 weeks and usually are pruritic. Photosensitivity reactions related to vandetanib have been reported and are summarized in the Table.4-12

Although reported cutaneous reactions to vandetanib thus far in the literature were reported as photoinduced reactions, there have been isolated case reports of other eruptions including cutaneous pigmentation5 and one case of SJS.9 According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms vandetanib and rash, we found that there are a variety of clinical findings, but most of the reported photosensitivity cases were phototoxic. Fava et al7 and Goldstein et al12 both reported 1 photoallergic reaction each, plus patient 1 in our case series was noted to have a photoallergic reaction. Phototoxic reactions were reported in 4 patients (including our patient 2) who had dyskeratotic keratinocytes and vacuolar degeneration of the basal layer on histopathology.4,8 Fava et al7 described a lichenoid infiltrate with spongiosis consistent with a photoallergic reaction, but Chang et al4 and Bota et al11 described a lichenoid infiltrate with dyskeratotic cells. Also, Giacchero et al16 described a photosensitivity reaction in 28 of 63 patients. Although only 6 patients had biopsies performed, the range of photosensitivity reactions was demonstrated with lichenoid, dyskeratotic, and spongiotic reactions. However, the cases were not further defined as photoallergic or phototoxic.16 Vandetanib also has been associated with cutaneous blue pigmentation after likely phototoxic reactions. Pigment changes occurred after photosensitivity, but the clinical presentation of photosensitivity was not further characterized.5,16

Classic Drug Eruptions

Two patients were described as having classic drug eruptions—EM10 and SJS9—in photodistributed locations. Histologically, these entities are identical to phototoxic reactions, resulting in epidermal necrosis and an interface dermatitis, but the presence of targetoid lesions on the palms prompted the diagnosis of photodistributed EM and SJS in both cases.9,10 Unique to the SJS case was oral involvement.9

Distinguishing between a phototoxic reaction and photodistributed EM or SJS may be inconsequential if both can be prevented with photoprotection. Rechallenging patients with vandetanib while practicing photoprotection would help to clarify the mechanism, though this course is not always practical.

Mechanism of Action

As seen in our case series, cutaneous reactions occurred only on sun-exposed surfaces, and patients presented with sharp cutoff points that spared non–sun-exposed areas. Although clinically organized as a subtype of photosensitivity, the phototoxicity mechanism of action is considered a direct toxic effect on keratinocytes, which explains the histopathologic finding of dyskeratotic cells and the clinical spectrum of sunburn reaction, phototoxic EM, and SJS. UVA1 induces 2 photoproducts of vandetanib via a UVA1-mediated debromination process,17 but these photoproducts are not responsible for epidermal dyskeratosis.18 It was subsequently demonstrated that keratinocyte death was induced by apoptosis through photoinduced DNA cleavage and the formation of an aryl radical, which can induce further DNA damage.18 Caro-Gutierrez et al10 demonstrated a lowered minimal erythema dose in their patient with vandetanib-induced phototoxic EM.

Conversely, photoallergic reactions are considered immune-mediated delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions.4,7,11 Although the mechanism of a photoallergic reaction remains unclear, it is possible that vandetanib or a metabolite (in susceptible patients) induces an immune-mediated delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction with repeated exposure to the compound, which may explain the varied timing of photoallergic onset, including the events featured in the Bota et al11 case that occurred several months after drug initiation.

Conclusion

Considering the high prevalence of cutaneous AEs, especially varied photosensitivity reactions, these cases emphasize the importance of sun protection to help prevent dose reduction or drug cessation among patients taking vandetanib therapy.

Vandetanib is a once-daily oral multikinase inhibitor that targets the rearranged during transfection (RET) tyrosine kinase, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor, and epidermal growth factor receptor. It has shown efficacy at doses of 300 mg daily in the treatment of progressive medullary thyroid cancer and has shown promise in non–small cell lung cancer and breast cancer. Vandetanib’s toxicity profile includes QT prolongation, diarrhea, and rash.1-3 Cutaneous involvement has been described in the literature as a photodistributed drug reaction with both erythema multiforme (EM) and Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS)–like eruptions, phototoxicity, and photoallergy (Table).4-12 Photoinduction is the common thread, but various mechanisms have been proposed, including drug deposition within the dermis and direct toxicity to keratinocytes; however, an understanding of the varied presentation is lacking.

We present 3 cases of vandetanib photoinduced cutaneous toxicities and review the literature on this novel kinase inhibitor. This discussion highlights the spectrum of photosensitivity reactions to vandetanib among patients with varying histologic and clinical presentations.

Case Reports

Patient 1A

74-year-old woman with a history of recurrent metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix and Fitzpatrick skin type III presented with erythematous, well-demarcated, photodistributed, eczematous papules that were coalescing into plaques on the scalp, hands, and face. The rash appeared sharply demarcated at the wrists bilaterally and principally involved the dorsal sun-exposed areas of her hands (Figure 1). The rash also involved the face and the V of the neck with sharp demarcation. Two weeks prior to onset, she initiated a phase 1 trial of oral vandetanib 100 mg twice daily and oral everolimus 5 mg daily. She did not recall practicing sun protection or experiencing increased sun exposure after starting that trial. The patient demonstrated symptom improvement with desonide cream, hydrocortisone cream 2.5%, and over-the-counter analgesic cream while continuing with the study drugs. However, she developed new, warm, painful papules on the hands and face. Phototesting and biopsy were not performed, and the etiology of the photosensitivity was unknown.

The patient was counseled about regular sun protection and was prescribed triamcinolone cream 0.1% for the arms and hydrocortisone cream 2.5% for the affected facial areas. Therapy with vandetanib and everolimus was continued without dose reduction or further cutaneous eruptions.

Patient 2

A 54-year-old man with a history of progressive medullary thyroid carcinoma and Fitzpatrick skin type II presented with erythematous, well-demarcated, photodistributed, edematous plaques and bullae of the head and neck, bilateral dorsal hands, and bilateral palms of 2 weeks’ duration. The rash spared the upper back and chest with a well-demarcated border (Figure 2A). There were ulcerations and erosions at the base of the neck and the dorsal hands (Figure 2B). He also had conjunctivitis but uninvolved oral and genital mucosae.

Two weeks before the rash appeared, oral vandetanib 300 mg daily was initiated. The patient initially noted some dry skin, which progressed to an eruption involving the face and neck and later the hands with palmar blistering and desquamation. Medication cessation for 1 month led to moderate improvement of the rash on the face and neck. He had not been practicing sun protection but did wear a baseball cap when outside. The patient did not recall an incidence of increased sun exposure. He underwent a skin biopsy of the right dorsal hand, which revealed interface dermatitis with dyskeratosis and subepidermal and intraepidermal bullae (Figure 3). The biopsy findings were most consistent with a phototoxic eruption. Phototesting was not performed.

The patient then initiated sun-protective measures, a prednisone taper, and high-potency steroid ointments. As he tapered his prednisone, he noted continued improvement in the rash. His disease progressed, however, and he did not restart vandetanib.

Patient 3

A 73-year-old man with a history of metastatic lung carcinoma and Fitzpatrick skin type II presented with a rash on the scalp, face, and arms of 2.5 weeks’ duration. There was sharp demarcation at the edges of sun-exposed skin, and no bullae were noted (Figure 4). Prior to presentation, the patient started a 4-week phase 1 trial with vandetanib 300 mg daily and everolimus 10 mg daily. He did not recall any episodes of increased sun exposure. A punch biopsy of the arm showed an interface dermatitis suggestive of a phototoxic reaction. Phototesting was not performed to further clarify if there was a diminished minimal erythema dose with UVA or UVB radiation. Both drugs were discontinued, strict photoprotection was practiced, and triamcinolone cream 0.1% was initiated with resolution of rash. Vandetanib and everolimus were resumed at initial doses with strict photoprotection, and the rash has not recurred.

Comment

Adverse Events Associated With Vandetanib

Vandetanib is a novel multikinase inhibitor that targets RET tyrosine kinase, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor, and epidermal growth factor receptor.1,2 It currently is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of progressive medullary thyroid cancer and is being used in clinical trials for non–small cell lung cancer, glioma, advanced biliary tract cancer, breast cancer, and other advanced solid malignancies. Frequently reported adverse events (AEs) include QT prolongation, diarrhea, and rash.1-3 In a large phase 3 trial, 45% of patients had a rash; of these, 4% were grade 3 and above.3 The most common reasons for dose decrease or cessation were diarrhea and rash (1% and 1.3%, respectively).13 Outside of a trial setting, 75% (45/60) of patients in one French study reported a cutaneous AE, with photosensitivity noted in 22% (13/60). Thus, cutaneous reactions tend to be a common occurrence for patients on this drug, requiring diligent dermatologic examinations.14 In one meta-analysis comprising 9 studies with a total of 2961 patients, the incidence of all-grade rash was 46.1% (95% CI, 40.6%-51.8%), and it was concluded that vandetanib has the highest association of all-grade rash among the anti–vascular endothelial growth factor tyrosine kinase inhibitors. In this meta-analysis, the specific diagnosis of AEs was not further classified.15 In another cohort of vandetanib-treated patients, as many as 37% (28/63) of patients had photosensitivity, with no clarification of the etiology.16

Photoallergic vs Phototoxic Reactions

Photosensitivity reactions are cutaneous reactions that occur from UV light exposure, typically in conjunction with a photosensitizing agent. Photosensitivity reactions can be further classified into phototoxic and photoallergic reactions, which can be distinguished by histopathologic evaluation and history. Although phototoxic reactions will cause keratinocyte necrosis similar to a sunburn, photoallergic reactions will cause epidermal spongiosis similar to allergic contact dermatitis or eczema. Also, phototoxic reactions appear within 1 to 2 days of UV exposure and often are painful, whereas photoallergic reactions can be delayed for 2 to 3 weeks and usually are pruritic. Photosensitivity reactions related to vandetanib have been reported and are summarized in the Table.4-12

Although reported cutaneous reactions to vandetanib thus far in the literature were reported as photoinduced reactions, there have been isolated case reports of other eruptions including cutaneous pigmentation5 and one case of SJS.9 According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms vandetanib and rash, we found that there are a variety of clinical findings, but most of the reported photosensitivity cases were phototoxic. Fava et al7 and Goldstein et al12 both reported 1 photoallergic reaction each, plus patient 1 in our case series was noted to have a photoallergic reaction. Phototoxic reactions were reported in 4 patients (including our patient 2) who had dyskeratotic keratinocytes and vacuolar degeneration of the basal layer on histopathology.4,8 Fava et al7 described a lichenoid infiltrate with spongiosis consistent with a photoallergic reaction, but Chang et al4 and Bota et al11 described a lichenoid infiltrate with dyskeratotic cells. Also, Giacchero et al16 described a photosensitivity reaction in 28 of 63 patients. Although only 6 patients had biopsies performed, the range of photosensitivity reactions was demonstrated with lichenoid, dyskeratotic, and spongiotic reactions. However, the cases were not further defined as photoallergic or phototoxic.16 Vandetanib also has been associated with cutaneous blue pigmentation after likely phototoxic reactions. Pigment changes occurred after photosensitivity, but the clinical presentation of photosensitivity was not further characterized.5,16

Classic Drug Eruptions

Two patients were described as having classic drug eruptions—EM10 and SJS9—in photodistributed locations. Histologically, these entities are identical to phototoxic reactions, resulting in epidermal necrosis and an interface dermatitis, but the presence of targetoid lesions on the palms prompted the diagnosis of photodistributed EM and SJS in both cases.9,10 Unique to the SJS case was oral involvement.9

Distinguishing between a phototoxic reaction and photodistributed EM or SJS may be inconsequential if both can be prevented with photoprotection. Rechallenging patients with vandetanib while practicing photoprotection would help to clarify the mechanism, though this course is not always practical.

Mechanism of Action

As seen in our case series, cutaneous reactions occurred only on sun-exposed surfaces, and patients presented with sharp cutoff points that spared non–sun-exposed areas. Although clinically organized as a subtype of photosensitivity, the phototoxicity mechanism of action is considered a direct toxic effect on keratinocytes, which explains the histopathologic finding of dyskeratotic cells and the clinical spectrum of sunburn reaction, phototoxic EM, and SJS. UVA1 induces 2 photoproducts of vandetanib via a UVA1-mediated debromination process,17 but these photoproducts are not responsible for epidermal dyskeratosis.18 It was subsequently demonstrated that keratinocyte death was induced by apoptosis through photoinduced DNA cleavage and the formation of an aryl radical, which can induce further DNA damage.18 Caro-Gutierrez et al10 demonstrated a lowered minimal erythema dose in their patient with vandetanib-induced phototoxic EM.

Conversely, photoallergic reactions are considered immune-mediated delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions.4,7,11 Although the mechanism of a photoallergic reaction remains unclear, it is possible that vandetanib or a metabolite (in susceptible patients) induces an immune-mediated delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction with repeated exposure to the compound, which may explain the varied timing of photoallergic onset, including the events featured in the Bota et al11 case that occurred several months after drug initiation.

Conclusion

Considering the high prevalence of cutaneous AEs, especially varied photosensitivity reactions, these cases emphasize the importance of sun protection to help prevent dose reduction or drug cessation among patients taking vandetanib therapy.

- Carlomagno F, Vitagliano D, Guida T, et al. ZD6474, an orally available inhibitor of KDR tyrosine kinase activity, efficiently blocks oncogenic RET kinases. Cancer Res. 2002;62:7284-7290.

- Wedge SR, Ogilvie DJ, Dukes M, et al. ZD6474 inhibits vascular endothelial growth factor signaling, angiogenesis, and tumor growth following oral administration. Cancer Res. 2002;62:4645-4655.

- Wells SA Jr, Robinson BG, Gagel RF, et al. Vandetanib in patients with locally advanced or metastatic medullary thyroid cancer: a randomized, double-blind phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:134-141.

- Chang CH, Chang JW, Hui CY, et al. Severe photosensitivity reaction to vandetanib. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:E114-E115.

- Kong HH, Fine HA, Stern JB, et al. Cutaneous pigmentation after photosensitivity induced by vandetanib therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:923-925.

- Brooks S, Linehan WM, Srinivasan R, et al. Successful laser treatment of vandetanib-associated cutaneous pigmentation. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:364-365.

- Fava P, Quaglino P, Fierro MT, et al. Therapeutic hotline. a rare vandetanib-induced photo-allergic drug eruption. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:553-555.

- Son YM, Roh JY, Cho EK, et al. Photosensitivity reactions to vandetanib: redevelopment after sequential treatment with docetaxel. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23(suppl 3):S314-S318.

- Yoon J, Oh CW, Kim CY. Stevens-Johnson syndrome induced by vandetanib. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23(suppl 3):S343-S345.

- Caro-Gutierrez D, Floristan Muruzabal MU, Gomez de la Fuente E, et al. Photo-induced erythema multiforme associated with vandetanib administration. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:E142-E144.11.

- Bota J, Harvey V, Ferguson C, et al. A rare case of late-onset lichenoid photodermatitis after vandetanib therapy. JAAD Case Rep. 2015;1:141-143.

- Goldstein J, Patel AB, Curry JL, et al. Photoallergic reaction in a patient receiving vandetanib for metastatic follicular thyroid carcinoma: a case report. BMC Dermatol. 2015;15:2.

- Thornton K, Kim G, Maher VE, et al. Vandetanib for the treatment of symptomatic or progressive medullary thyroid cancer in patients with unresectable locally advanced or metastatic disease: US Food and Drug Administration drug approval summary. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:3722-3730.

- Chougnet CN, Borget I, Leboulleux S, et al. Vandetanib for the treatment of advanced medullary thyroid cancer outside a clinical trial: results from a French cohort. Thyroid. 2015;25:386-391.

- Rosen AC, Wu S, Damse A, et al. Risk of rash in cancer patients treated with vandetanib: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:1125-1133.

- Giacchero D, Ramacciotti C, Arnault JP, et al. A new spectrum of skin toxic effects associated with the multikinase inhibitor vandetanib. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1418-1420.

- Dall’acqua S, Vedaldi D, Salvador A. Isolation and structure elucidation of the main UV-A photoproducts of vandetanib. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2013;84:196-200.

- Salvador A, Vedaldi D, Brun P, et al. Vandetanib-induced phototoxicity in human keratinocytes NCTC-2544. Toxicol In Vitro. 2014;28:803-811.

- Carlomagno F, Vitagliano D, Guida T, et al. ZD6474, an orally available inhibitor of KDR tyrosine kinase activity, efficiently blocks oncogenic RET kinases. Cancer Res. 2002;62:7284-7290.

- Wedge SR, Ogilvie DJ, Dukes M, et al. ZD6474 inhibits vascular endothelial growth factor signaling, angiogenesis, and tumor growth following oral administration. Cancer Res. 2002;62:4645-4655.

- Wells SA Jr, Robinson BG, Gagel RF, et al. Vandetanib in patients with locally advanced or metastatic medullary thyroid cancer: a randomized, double-blind phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:134-141.

- Chang CH, Chang JW, Hui CY, et al. Severe photosensitivity reaction to vandetanib. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:E114-E115.

- Kong HH, Fine HA, Stern JB, et al. Cutaneous pigmentation after photosensitivity induced by vandetanib therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:923-925.

- Brooks S, Linehan WM, Srinivasan R, et al. Successful laser treatment of vandetanib-associated cutaneous pigmentation. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:364-365.

- Fava P, Quaglino P, Fierro MT, et al. Therapeutic hotline. a rare vandetanib-induced photo-allergic drug eruption. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:553-555.

- Son YM, Roh JY, Cho EK, et al. Photosensitivity reactions to vandetanib: redevelopment after sequential treatment with docetaxel. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23(suppl 3):S314-S318.

- Yoon J, Oh CW, Kim CY. Stevens-Johnson syndrome induced by vandetanib. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23(suppl 3):S343-S345.

- Caro-Gutierrez D, Floristan Muruzabal MU, Gomez de la Fuente E, et al. Photo-induced erythema multiforme associated with vandetanib administration. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:E142-E144.11.

- Bota J, Harvey V, Ferguson C, et al. A rare case of late-onset lichenoid photodermatitis after vandetanib therapy. JAAD Case Rep. 2015;1:141-143.

- Goldstein J, Patel AB, Curry JL, et al. Photoallergic reaction in a patient receiving vandetanib for metastatic follicular thyroid carcinoma: a case report. BMC Dermatol. 2015;15:2.

- Thornton K, Kim G, Maher VE, et al. Vandetanib for the treatment of symptomatic or progressive medullary thyroid cancer in patients with unresectable locally advanced or metastatic disease: US Food and Drug Administration drug approval summary. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:3722-3730.

- Chougnet CN, Borget I, Leboulleux S, et al. Vandetanib for the treatment of advanced medullary thyroid cancer outside a clinical trial: results from a French cohort. Thyroid. 2015;25:386-391.

- Rosen AC, Wu S, Damse A, et al. Risk of rash in cancer patients treated with vandetanib: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:1125-1133.

- Giacchero D, Ramacciotti C, Arnault JP, et al. A new spectrum of skin toxic effects associated with the multikinase inhibitor vandetanib. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1418-1420.

- Dall’acqua S, Vedaldi D, Salvador A. Isolation and structure elucidation of the main UV-A photoproducts of vandetanib. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2013;84:196-200.

- Salvador A, Vedaldi D, Brun P, et al. Vandetanib-induced phototoxicity in human keratinocytes NCTC-2544. Toxicol In Vitro. 2014;28:803-811.

Practice Points

- Vandetanib is a US Food and Drug Administration– approved once-daily oral multikinase inhibitor for patients with progressive medullary thyroid cancer with a high incidence of cutaneous toxicities including phototoxicity. Early recognition of such cutaneous toxicities leads to early intervention and may allow greater compliance with treatment.

- The most common toxicity is phototoxicity. Diligent interventions include photoprotection such as sunscreen, sun-protective clothing, and avoiding peak hours of sun exposure.

- Topical steroids as well as bland emollients are the mainstay of therapy for symptomatic lesions.

- Extensive cutaneous involvement may include blistering, pain, and pruritus and necessitate dose reduction or even drug cessation.

Primary Cutaneous Follicle Center Lymphoma Mimicking Folliculitis

The 2008 World Health Organization and European Organization for Treatment of Cancer joint classification has distinguished 3 categories of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma (PCFCL), primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, and primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma.1-3 Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma is the most common type of cutaneous B-cell lymphoma, accounting for approximately 60% of cases worldwide.4 The median age at diagnosis is 60 years, and most lesions are located on the scalp, forehead, neck, and trunk.5 Histologically, PCFCL is characterized by dermal proliferation of centrocytes and centroblasts derived from germinal center B cells that are arranged in either a follicular, diffuse, or mixed growth pattern.1 The cutaneous manifestations of PCFCL include solitary erythematous or violaceous plaques, nodules, or tumors of varying sizes.4 Grouped lesions also may be observed, but multifocal disease is rare.1 We report a rare presentation of PCFCL mimicking folliculitis with multiple multifocal papules on the back.

Case Report

A 54-year-old woman presented with fever and leukocytosis of 4 days’ duration and was admitted to the hospital for presumed sepsis. She had a history of mastectomy for treatment of ductal carcinoma in situ of the right breast 5 years prior to the current presentation and endocrine therapy with tamoxifen. Her symptoms were thought to be a complication from a surgery for implantation of a tissue expander in the right breast 5 years prior to presentation.

During her hospital admission, she developed a papular and cystic eruption on the back that was clinically suggestive of folliculitis, transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover disease), or miliaria rubra (Figure 1). This papular and cystic eruption initially was managed conservatively with observation as she recovered from an occult infection. Due to the persistent nature of the eruption on the back, an excisional biopsy of the cystic component was performed 2 months after her discharge from the hospital. Histologic studies showed a dense infiltrate of lymphocytes, which expanded into the deep dermis in a nodular and diffuse growth pattern that was accentuated in the periadnexal areas. The B lymphocytes were small and hyperchromatic with few scattered centroblasts (Figure 2). Further immunohistochemical studies demonstrated that the neoplastic cells were positive for CD20, CD79a, BCL-2, and BCL-6; CD3, CD5, and cyclin D1 were negative. Staining for antigen Ki-67 revealed a proliferation index of 15% to 20% among the neoplastic cells (Figure 3). These findings were consistent with either PCFCL or secondary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma.

Further evaluation for systemic disease was unremarkable. Positron emission tomography–computed tomography revealed no evidence of nodal lymphoma, and a bone marrow biopsy was negative. Other laboratory studies including lactate dehydrogenase were within reference range, which conferred a diagnosis of PCFCL. The patient was treated with localized electron beam radiation therapy to the skin of the mid back for a total dose of 24 Gy in 12 fractions at 2 Gy per fraction once daily over a 12-day period. She tolerated the treatment well and has remained clinically and radiographically without evidence of disease for more than 3 years.

Comment

Because the incidence of cutaneous B-cell lymphomas has been increasing, especially among males, non-Hispanic whites, and adults older than 50 years,1 it is important for clinicians to have a high index of suspicion for this entity. In our patient, the clinical findings of a papular, largely asymptomatic eruption on the back with acute onset were initially thought to be consistent with folliculitis; the differential diagnosis included transient acantholytic dermatosis and miliaria rubra. Lymphoma was not in the initial clinical differential, and we only arrived at this diagnosis based on histopathologic evaluation.

The neoplastic cells typically are positive for CD20, CD79a, and BCL-6, and negative for BCL-2.4 Most cases of PCFCL do not express the t(14;18) translocation involving the BCL-2 locus, in contrast to systemic follicular lymphoma.1 Systemic imaging and evaluation is needed to definitively differentiate PCFCL from systemic lymphoma with cutaneous involvement. Our patient was unusual in that BCL-2 was strongly staining in the setting of a negative systemic workup.

With regard to treatment of PCFCL, electron beam radiation therapy is highly effective and safe in patients with solitary lesions, as the remission rate is close to 100%.1 For patients with multiple lesions confined to one area, electron beam radiation therapy also can be helpful, as in our patient. In patients with more extensive skin involvement, rituximab therapy may be preferable. Relapse following treatment with either radiation or rituximab occurs in approximately one-third of patients, but these relapses generally are limited to the skin.1 The International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group has noted that elevated lactate dehydrogenase, presence of more than 2 skin lesions, and presence of nodular lesions are negative prognostic factors in patients with PCFCL6; however, PCFCL has an excellent prognosis overall with a 5-year survival rate of 95%.1

Other rare heterogeneous presentations of PCFCL have been reported in the literature. A large multinodular mass on the scalp with multifocal facial lesions has been described in a patient with essential thrombocytopenia.7 Another report identified a variant of PCFCL characterized by multiple erythematous firm papules that were distributed in a miliary pattern, predominantly on the forehead and cheeks.8 Barzilai et al9 described 4 patients with PCFCL who developed lesions that were clinically similar to rosacea or rhinophyma, including papulonodular eruptions on the cheeks; infiltrated erythematous nasal plaques; and small flesh-colored to erythematous papules on the cheeks, nose, helices, and upper back. Hodak et al10 identified 2 cases of PCFCL that manifested as anetoderma, a condition characterized by the focal loss of elastic tissue. In the setting of chronic lymphocytic leukemia, PCFCL has been observed as a red or violaceous nodule with a centrally depressed scar on the legs.11 In one case, PCFCL manifested as recurrent episodes of extraorbital swelling and a multifocal red-blue macular lesion that extended from the inferior orbital rim to the nasojugal fold.12 An interesting presentation of PCFCL was noted as a small, recurring, blood-filled blister on the cheek with perineural spread of the tumor along cranial nerves V2, V3, VII, and VIII.13 In the pediatric literature, PCFCL has been reported to present as an erythematous nodule with a smooth surface and a hard elastic consistency that appeared on the nose and nasolabial fold and spread to the ipsilateral cheek, maxillary sinus, and soft palate.14 In many of these unusual cases, the diagnosis of PCFCL was made after treatment with topical or systemic anti-inflammatory therapies failed.

Increased recognition of anomalous presentations of PCFCL among dermatologists can lead to more timely diagnoses and treatment. Based on our experience with this patient, we recommend considering biopsy for histopathologic evaluation when treating patients with presumed folliculitis or transient acantholytic dermatosis that does not improve with routine treatment or is accompanied by systemic symptoms.

- Wilcox RA. Cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: 2015 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2015;90:73-76.

- Kim YH, Willemze R, Pimpinelli N, et al. TNM classification system for primary cutaneous lymphomas other than mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: a proposal of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas (ISCL) and the Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Blood. 2007;110:479-484.

- World Health Organization. WHO Classification of Tumors of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon, France: World Health Organization; 2008: 227.

- Dilly M, Ben-Rejeb H, Vergier B, et al. Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma with Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg-like cells: a new histopathologic variant. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:797-801.

- Suárez AL, Pulitzer M, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: part I. clinical features, diagnosis, and classification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:329.e1-13; quiz 341-342.

- Mian M, Marcheselli L, Luminari S, et al. CLIPI: a new prognostic index for indolent cutaneous B cell lymphoma proposed by the International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group (IELSG 11) [published online September 25, 2010]. Ann Hematol. 2011;90:401-408.

- Tirefort Y, Pham XC, Ibrahim YL, et al. A rare case of primary cutaneous follicle centre lymphoma presenting as a giant tumour of the scalp and combined with JAK2V617F positive essential thrombocythaemia. Biomark Res. 2014;2:7.

- Massone C, Fink-Puches R, Laimer M, et al. Miliary and agminated-type primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma: report of 18 cases.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:749-755.

- Barzilai A, Feuerman H, Quaglino P, et al. Cutaneous B-cell neoplasms mimicking granulomatous rosacea or rhinophyma. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:824-831.

- Hodak E, Feuerman H, Barzilai A, et al. Anetodermic primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma: a unique clinicopathological presentation of lymphoma possibly associated with antiphospholipid antibodies. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:175-182.

- Konda S, Beckford A, Demierre MF, et al. Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma in the setting of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:314-317.

- Pandya VB, Conway RM, Taylor SF. Primary cutaneous B cell lymphoma presenting as recurrent eyelid swelling. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2008;36:672-674.

- Buda-Okreglak EM, Walden MJ, Brissette MD. Perineural CNS invasion in primary cutaneous follicular center lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4684-4686.

- Ghislanzoni M, Gambini D, Perrone T, et al. Primary cutaneous follicular center cell lymphoma of the nose with maxillary sinus involvement in a pediatric patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52(5 suppl 1):S73-S75.

The 2008 World Health Organization and European Organization for Treatment of Cancer joint classification has distinguished 3 categories of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma (PCFCL), primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, and primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma.1-3 Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma is the most common type of cutaneous B-cell lymphoma, accounting for approximately 60% of cases worldwide.4 The median age at diagnosis is 60 years, and most lesions are located on the scalp, forehead, neck, and trunk.5 Histologically, PCFCL is characterized by dermal proliferation of centrocytes and centroblasts derived from germinal center B cells that are arranged in either a follicular, diffuse, or mixed growth pattern.1 The cutaneous manifestations of PCFCL include solitary erythematous or violaceous plaques, nodules, or tumors of varying sizes.4 Grouped lesions also may be observed, but multifocal disease is rare.1 We report a rare presentation of PCFCL mimicking folliculitis with multiple multifocal papules on the back.

Case Report

A 54-year-old woman presented with fever and leukocytosis of 4 days’ duration and was admitted to the hospital for presumed sepsis. She had a history of mastectomy for treatment of ductal carcinoma in situ of the right breast 5 years prior to the current presentation and endocrine therapy with tamoxifen. Her symptoms were thought to be a complication from a surgery for implantation of a tissue expander in the right breast 5 years prior to presentation.

During her hospital admission, she developed a papular and cystic eruption on the back that was clinically suggestive of folliculitis, transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover disease), or miliaria rubra (Figure 1). This papular and cystic eruption initially was managed conservatively with observation as she recovered from an occult infection. Due to the persistent nature of the eruption on the back, an excisional biopsy of the cystic component was performed 2 months after her discharge from the hospital. Histologic studies showed a dense infiltrate of lymphocytes, which expanded into the deep dermis in a nodular and diffuse growth pattern that was accentuated in the periadnexal areas. The B lymphocytes were small and hyperchromatic with few scattered centroblasts (Figure 2). Further immunohistochemical studies demonstrated that the neoplastic cells were positive for CD20, CD79a, BCL-2, and BCL-6; CD3, CD5, and cyclin D1 were negative. Staining for antigen Ki-67 revealed a proliferation index of 15% to 20% among the neoplastic cells (Figure 3). These findings were consistent with either PCFCL or secondary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma.

Further evaluation for systemic disease was unremarkable. Positron emission tomography–computed tomography revealed no evidence of nodal lymphoma, and a bone marrow biopsy was negative. Other laboratory studies including lactate dehydrogenase were within reference range, which conferred a diagnosis of PCFCL. The patient was treated with localized electron beam radiation therapy to the skin of the mid back for a total dose of 24 Gy in 12 fractions at 2 Gy per fraction once daily over a 12-day period. She tolerated the treatment well and has remained clinically and radiographically without evidence of disease for more than 3 years.

Comment

Because the incidence of cutaneous B-cell lymphomas has been increasing, especially among males, non-Hispanic whites, and adults older than 50 years,1 it is important for clinicians to have a high index of suspicion for this entity. In our patient, the clinical findings of a papular, largely asymptomatic eruption on the back with acute onset were initially thought to be consistent with folliculitis; the differential diagnosis included transient acantholytic dermatosis and miliaria rubra. Lymphoma was not in the initial clinical differential, and we only arrived at this diagnosis based on histopathologic evaluation.

The neoplastic cells typically are positive for CD20, CD79a, and BCL-6, and negative for BCL-2.4 Most cases of PCFCL do not express the t(14;18) translocation involving the BCL-2 locus, in contrast to systemic follicular lymphoma.1 Systemic imaging and evaluation is needed to definitively differentiate PCFCL from systemic lymphoma with cutaneous involvement. Our patient was unusual in that BCL-2 was strongly staining in the setting of a negative systemic workup.

With regard to treatment of PCFCL, electron beam radiation therapy is highly effective and safe in patients with solitary lesions, as the remission rate is close to 100%.1 For patients with multiple lesions confined to one area, electron beam radiation therapy also can be helpful, as in our patient. In patients with more extensive skin involvement, rituximab therapy may be preferable. Relapse following treatment with either radiation or rituximab occurs in approximately one-third of patients, but these relapses generally are limited to the skin.1 The International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group has noted that elevated lactate dehydrogenase, presence of more than 2 skin lesions, and presence of nodular lesions are negative prognostic factors in patients with PCFCL6; however, PCFCL has an excellent prognosis overall with a 5-year survival rate of 95%.1

Other rare heterogeneous presentations of PCFCL have been reported in the literature. A large multinodular mass on the scalp with multifocal facial lesions has been described in a patient with essential thrombocytopenia.7 Another report identified a variant of PCFCL characterized by multiple erythematous firm papules that were distributed in a miliary pattern, predominantly on the forehead and cheeks.8 Barzilai et al9 described 4 patients with PCFCL who developed lesions that were clinically similar to rosacea or rhinophyma, including papulonodular eruptions on the cheeks; infiltrated erythematous nasal plaques; and small flesh-colored to erythematous papules on the cheeks, nose, helices, and upper back. Hodak et al10 identified 2 cases of PCFCL that manifested as anetoderma, a condition characterized by the focal loss of elastic tissue. In the setting of chronic lymphocytic leukemia, PCFCL has been observed as a red or violaceous nodule with a centrally depressed scar on the legs.11 In one case, PCFCL manifested as recurrent episodes of extraorbital swelling and a multifocal red-blue macular lesion that extended from the inferior orbital rim to the nasojugal fold.12 An interesting presentation of PCFCL was noted as a small, recurring, blood-filled blister on the cheek with perineural spread of the tumor along cranial nerves V2, V3, VII, and VIII.13 In the pediatric literature, PCFCL has been reported to present as an erythematous nodule with a smooth surface and a hard elastic consistency that appeared on the nose and nasolabial fold and spread to the ipsilateral cheek, maxillary sinus, and soft palate.14 In many of these unusual cases, the diagnosis of PCFCL was made after treatment with topical or systemic anti-inflammatory therapies failed.

Increased recognition of anomalous presentations of PCFCL among dermatologists can lead to more timely diagnoses and treatment. Based on our experience with this patient, we recommend considering biopsy for histopathologic evaluation when treating patients with presumed folliculitis or transient acantholytic dermatosis that does not improve with routine treatment or is accompanied by systemic symptoms.

The 2008 World Health Organization and European Organization for Treatment of Cancer joint classification has distinguished 3 categories of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma (PCFCL), primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, and primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma.1-3 Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma is the most common type of cutaneous B-cell lymphoma, accounting for approximately 60% of cases worldwide.4 The median age at diagnosis is 60 years, and most lesions are located on the scalp, forehead, neck, and trunk.5 Histologically, PCFCL is characterized by dermal proliferation of centrocytes and centroblasts derived from germinal center B cells that are arranged in either a follicular, diffuse, or mixed growth pattern.1 The cutaneous manifestations of PCFCL include solitary erythematous or violaceous plaques, nodules, or tumors of varying sizes.4 Grouped lesions also may be observed, but multifocal disease is rare.1 We report a rare presentation of PCFCL mimicking folliculitis with multiple multifocal papules on the back.

Case Report

A 54-year-old woman presented with fever and leukocytosis of 4 days’ duration and was admitted to the hospital for presumed sepsis. She had a history of mastectomy for treatment of ductal carcinoma in situ of the right breast 5 years prior to the current presentation and endocrine therapy with tamoxifen. Her symptoms were thought to be a complication from a surgery for implantation of a tissue expander in the right breast 5 years prior to presentation.

During her hospital admission, she developed a papular and cystic eruption on the back that was clinically suggestive of folliculitis, transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover disease), or miliaria rubra (Figure 1). This papular and cystic eruption initially was managed conservatively with observation as she recovered from an occult infection. Due to the persistent nature of the eruption on the back, an excisional biopsy of the cystic component was performed 2 months after her discharge from the hospital. Histologic studies showed a dense infiltrate of lymphocytes, which expanded into the deep dermis in a nodular and diffuse growth pattern that was accentuated in the periadnexal areas. The B lymphocytes were small and hyperchromatic with few scattered centroblasts (Figure 2). Further immunohistochemical studies demonstrated that the neoplastic cells were positive for CD20, CD79a, BCL-2, and BCL-6; CD3, CD5, and cyclin D1 were negative. Staining for antigen Ki-67 revealed a proliferation index of 15% to 20% among the neoplastic cells (Figure 3). These findings were consistent with either PCFCL or secondary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma.

Further evaluation for systemic disease was unremarkable. Positron emission tomography–computed tomography revealed no evidence of nodal lymphoma, and a bone marrow biopsy was negative. Other laboratory studies including lactate dehydrogenase were within reference range, which conferred a diagnosis of PCFCL. The patient was treated with localized electron beam radiation therapy to the skin of the mid back for a total dose of 24 Gy in 12 fractions at 2 Gy per fraction once daily over a 12-day period. She tolerated the treatment well and has remained clinically and radiographically without evidence of disease for more than 3 years.

Comment

Because the incidence of cutaneous B-cell lymphomas has been increasing, especially among males, non-Hispanic whites, and adults older than 50 years,1 it is important for clinicians to have a high index of suspicion for this entity. In our patient, the clinical findings of a papular, largely asymptomatic eruption on the back with acute onset were initially thought to be consistent with folliculitis; the differential diagnosis included transient acantholytic dermatosis and miliaria rubra. Lymphoma was not in the initial clinical differential, and we only arrived at this diagnosis based on histopathologic evaluation.

The neoplastic cells typically are positive for CD20, CD79a, and BCL-6, and negative for BCL-2.4 Most cases of PCFCL do not express the t(14;18) translocation involving the BCL-2 locus, in contrast to systemic follicular lymphoma.1 Systemic imaging and evaluation is needed to definitively differentiate PCFCL from systemic lymphoma with cutaneous involvement. Our patient was unusual in that BCL-2 was strongly staining in the setting of a negative systemic workup.

With regard to treatment of PCFCL, electron beam radiation therapy is highly effective and safe in patients with solitary lesions, as the remission rate is close to 100%.1 For patients with multiple lesions confined to one area, electron beam radiation therapy also can be helpful, as in our patient. In patients with more extensive skin involvement, rituximab therapy may be preferable. Relapse following treatment with either radiation or rituximab occurs in approximately one-third of patients, but these relapses generally are limited to the skin.1 The International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group has noted that elevated lactate dehydrogenase, presence of more than 2 skin lesions, and presence of nodular lesions are negative prognostic factors in patients with PCFCL6; however, PCFCL has an excellent prognosis overall with a 5-year survival rate of 95%.1

Other rare heterogeneous presentations of PCFCL have been reported in the literature. A large multinodular mass on the scalp with multifocal facial lesions has been described in a patient with essential thrombocytopenia.7 Another report identified a variant of PCFCL characterized by multiple erythematous firm papules that were distributed in a miliary pattern, predominantly on the forehead and cheeks.8 Barzilai et al9 described 4 patients with PCFCL who developed lesions that were clinically similar to rosacea or rhinophyma, including papulonodular eruptions on the cheeks; infiltrated erythematous nasal plaques; and small flesh-colored to erythematous papules on the cheeks, nose, helices, and upper back. Hodak et al10 identified 2 cases of PCFCL that manifested as anetoderma, a condition characterized by the focal loss of elastic tissue. In the setting of chronic lymphocytic leukemia, PCFCL has been observed as a red or violaceous nodule with a centrally depressed scar on the legs.11 In one case, PCFCL manifested as recurrent episodes of extraorbital swelling and a multifocal red-blue macular lesion that extended from the inferior orbital rim to the nasojugal fold.12 An interesting presentation of PCFCL was noted as a small, recurring, blood-filled blister on the cheek with perineural spread of the tumor along cranial nerves V2, V3, VII, and VIII.13 In the pediatric literature, PCFCL has been reported to present as an erythematous nodule with a smooth surface and a hard elastic consistency that appeared on the nose and nasolabial fold and spread to the ipsilateral cheek, maxillary sinus, and soft palate.14 In many of these unusual cases, the diagnosis of PCFCL was made after treatment with topical or systemic anti-inflammatory therapies failed.

Increased recognition of anomalous presentations of PCFCL among dermatologists can lead to more timely diagnoses and treatment. Based on our experience with this patient, we recommend considering biopsy for histopathologic evaluation when treating patients with presumed folliculitis or transient acantholytic dermatosis that does not improve with routine treatment or is accompanied by systemic symptoms.

- Wilcox RA. Cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: 2015 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2015;90:73-76.

- Kim YH, Willemze R, Pimpinelli N, et al. TNM classification system for primary cutaneous lymphomas other than mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: a proposal of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas (ISCL) and the Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Blood. 2007;110:479-484.

- World Health Organization. WHO Classification of Tumors of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon, France: World Health Organization; 2008: 227.

- Dilly M, Ben-Rejeb H, Vergier B, et al. Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma with Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg-like cells: a new histopathologic variant. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:797-801.

- Suárez AL, Pulitzer M, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: part I. clinical features, diagnosis, and classification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:329.e1-13; quiz 341-342.

- Mian M, Marcheselli L, Luminari S, et al. CLIPI: a new prognostic index for indolent cutaneous B cell lymphoma proposed by the International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group (IELSG 11) [published online September 25, 2010]. Ann Hematol. 2011;90:401-408.

- Tirefort Y, Pham XC, Ibrahim YL, et al. A rare case of primary cutaneous follicle centre lymphoma presenting as a giant tumour of the scalp and combined with JAK2V617F positive essential thrombocythaemia. Biomark Res. 2014;2:7.

- Massone C, Fink-Puches R, Laimer M, et al. Miliary and agminated-type primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma: report of 18 cases.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:749-755.

- Barzilai A, Feuerman H, Quaglino P, et al. Cutaneous B-cell neoplasms mimicking granulomatous rosacea or rhinophyma. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:824-831.

- Hodak E, Feuerman H, Barzilai A, et al. Anetodermic primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma: a unique clinicopathological presentation of lymphoma possibly associated with antiphospholipid antibodies. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:175-182.

- Konda S, Beckford A, Demierre MF, et al. Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma in the setting of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:314-317.

- Pandya VB, Conway RM, Taylor SF. Primary cutaneous B cell lymphoma presenting as recurrent eyelid swelling. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2008;36:672-674.

- Buda-Okreglak EM, Walden MJ, Brissette MD. Perineural CNS invasion in primary cutaneous follicular center lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4684-4686.

- Ghislanzoni M, Gambini D, Perrone T, et al. Primary cutaneous follicular center cell lymphoma of the nose with maxillary sinus involvement in a pediatric patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52(5 suppl 1):S73-S75.

- Wilcox RA. Cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: 2015 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2015;90:73-76.

- Kim YH, Willemze R, Pimpinelli N, et al. TNM classification system for primary cutaneous lymphomas other than mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: a proposal of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas (ISCL) and the Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Blood. 2007;110:479-484.

- World Health Organization. WHO Classification of Tumors of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon, France: World Health Organization; 2008: 227.

- Dilly M, Ben-Rejeb H, Vergier B, et al. Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma with Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg-like cells: a new histopathologic variant. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:797-801.

- Suárez AL, Pulitzer M, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: part I. clinical features, diagnosis, and classification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:329.e1-13; quiz 341-342.

- Mian M, Marcheselli L, Luminari S, et al. CLIPI: a new prognostic index for indolent cutaneous B cell lymphoma proposed by the International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group (IELSG 11) [published online September 25, 2010]. Ann Hematol. 2011;90:401-408.

- Tirefort Y, Pham XC, Ibrahim YL, et al. A rare case of primary cutaneous follicle centre lymphoma presenting as a giant tumour of the scalp and combined with JAK2V617F positive essential thrombocythaemia. Biomark Res. 2014;2:7.

- Massone C, Fink-Puches R, Laimer M, et al. Miliary and agminated-type primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma: report of 18 cases.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:749-755.

- Barzilai A, Feuerman H, Quaglino P, et al. Cutaneous B-cell neoplasms mimicking granulomatous rosacea or rhinophyma. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:824-831.

- Hodak E, Feuerman H, Barzilai A, et al. Anetodermic primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma: a unique clinicopathological presentation of lymphoma possibly associated with antiphospholipid antibodies. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:175-182.

- Konda S, Beckford A, Demierre MF, et al. Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma in the setting of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:314-317.

- Pandya VB, Conway RM, Taylor SF. Primary cutaneous B cell lymphoma presenting as recurrent eyelid swelling. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2008;36:672-674.

- Buda-Okreglak EM, Walden MJ, Brissette MD. Perineural CNS invasion in primary cutaneous follicular center lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4684-4686.

- Ghislanzoni M, Gambini D, Perrone T, et al. Primary cutaneous follicular center cell lymphoma of the nose with maxillary sinus involvement in a pediatric patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52(5 suppl 1):S73-S75.

Practice Points

- Atypical or unresponsive folliculitis should be biopsied.

- Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma can mimic folliculitis or Grover disease.