User login

Poor diet causes 70% of type 2 diabetes, says new study

Poor diets account for most newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes cases worldwide, a new analysis has found.

More specifically, the modeling study showed that roughly 14 million cases of type 2 diabetes – or 70% of total type 2 diabetes diagnoses in 2018 – were linked with a poor diet, found Meghan O’Hearn, a doctoral student at the Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy, Tufts University, Boston, and colleagues. The study was published online in Nature Medicine.

The results also indicate that the greatest burdens of type 2 diabetes were accounted for by excess wheat intake and refined rice (24.6%), excess processed meat consumption (20.3%), and inadequate whole-grain consumption (26.1%). Factors such as drinking too much fruit juice and not eating enough nonstarchy vegetables, nuts, or seeds, had less of an impact on new cases of the disease, the researchers determined.

“These findings can help inform nutritional priorities for clinicians, policymakers, and private sector actors as they encourage healthier dietary choices that address this global epidemic,” Ms. O’Hearn said in a press release.

Prior research has suggested that poor diet contributes to about 40% of type 2 diabetes cases worldwide, the researchers note.

The team attributes their finding of a 70% contribution to the new information in their analysis, such as the first-ever inclusion of refined grains, which was one of the top contributors to diabetes burden, and updated data on dietary habits based on national individual-level dietary surveys rather than agricultural estimates.

“Our study suggests poor carbohydrate quality is a leading driver of diet-attributable type 2 diabetes globally and with important variation by nation and over time,” said senior author Dariush Mozaffarian, MD, DrPh, MPH, who is the Jean Mayer Professor of Nutrition at the Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy.

“These new findings reveal critical areas for national and global focus to improve nutrition and reduce devastating burdens of diabetes,” he noted.

“Left unchecked and with incidence only projected to rise, type 2 diabetes will continue to impact population health, economic productivity, [and] health care system capacity, [as well as] drive health inequities worldwide,” Ms. O’Hearn said.

It’s about reducing harmful dietary components

Ms. O’Hearn and colleagues set out to fill information gaps in knowledge about how the global burden of diet-associated type 2 diabetes is impacted by disparities and other factors known to influence risk, including dietary components.

They used information from the Global Dietary Database to study dietary intake in 184 nations from 1990 to 2018. They also studied demographics from multiple sources, estimates of type 2 diabetes incidence around the world, and data on food choices, including the effect of 11 dietary factors, from prior research.

They found that there were 8.6 million more cases of type 2 diabetes in 2018 than in 1990 because of poor diet.

Regionally, Central and Eastern Europe and Central Asia had the greatest number of type 2 diabetes cases linked to diet, particularly Poland and Russia, where diets tend to be rich in red meat, processed meat, and potatoes. Incidence was also high in Latin America and the Caribbean, especially in Colombia and Mexico, which was attributed to high consumption of sugary drinks and processed meat and low intake of whole grains.

Regions where diet had less of an impact on type 2 diabetes cases included South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, although the largest increases in type 2 diabetes due to poor diet between 1990 and 2018 were observed in sub-Saharan Africa.

Diet-attributable type 2 diabetes was generally larger among urban versus rural residents and higher versus lower educated individuals, except in high-income countries, Central and Eastern Europe, and Central Asia, where burdens were larger in rural residents and in lower educated individuals.

Notably, women had lower proportions of diet-related type 2 diabetes, compared with men, and these proportions were inversely related to age.

Excess intake of harmful dietary factors contributed a greater percentage of the burden of type 2 diabetes globally (60.8%) than did insufficient intake of protective dietary factors (39.2%).

“Future research should address whether more complex diet–type 2 diabetes dose–response relationships exist,” the authors conclude.

Ms. O’Hearn has reported receiving research funding from the Gates Foundation, as well as the National Institutes of Health and Vail Innovative Global Research and employment with Food Systems for the Future. Dr. Mozaffarian has reported receiving funding from the National Institutes of Health, the Gates Foundation, the Rockefeller Foundation, Vail Innovative Global Research, and the Kaiser Permanente Fund at East Bay Community Foundation; personal fees from Acasti Pharma, Barilla, Danone, and Motif FoodWorks; is on the scientific advisory board for Beren Therapeutics, Brightseed, Calibrate, DiscernDx, Elysium Health, Filtricine, HumanCo, January, Perfect Day, Tiny Organics and (ended) Day Two and Season Health; has stock ownership in Calibrate and HumanCo; and receives chapter royalties from UpToDate.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Poor diets account for most newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes cases worldwide, a new analysis has found.

More specifically, the modeling study showed that roughly 14 million cases of type 2 diabetes – or 70% of total type 2 diabetes diagnoses in 2018 – were linked with a poor diet, found Meghan O’Hearn, a doctoral student at the Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy, Tufts University, Boston, and colleagues. The study was published online in Nature Medicine.

The results also indicate that the greatest burdens of type 2 diabetes were accounted for by excess wheat intake and refined rice (24.6%), excess processed meat consumption (20.3%), and inadequate whole-grain consumption (26.1%). Factors such as drinking too much fruit juice and not eating enough nonstarchy vegetables, nuts, or seeds, had less of an impact on new cases of the disease, the researchers determined.

“These findings can help inform nutritional priorities for clinicians, policymakers, and private sector actors as they encourage healthier dietary choices that address this global epidemic,” Ms. O’Hearn said in a press release.

Prior research has suggested that poor diet contributes to about 40% of type 2 diabetes cases worldwide, the researchers note.

The team attributes their finding of a 70% contribution to the new information in their analysis, such as the first-ever inclusion of refined grains, which was one of the top contributors to diabetes burden, and updated data on dietary habits based on national individual-level dietary surveys rather than agricultural estimates.

“Our study suggests poor carbohydrate quality is a leading driver of diet-attributable type 2 diabetes globally and with important variation by nation and over time,” said senior author Dariush Mozaffarian, MD, DrPh, MPH, who is the Jean Mayer Professor of Nutrition at the Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy.

“These new findings reveal critical areas for national and global focus to improve nutrition and reduce devastating burdens of diabetes,” he noted.

“Left unchecked and with incidence only projected to rise, type 2 diabetes will continue to impact population health, economic productivity, [and] health care system capacity, [as well as] drive health inequities worldwide,” Ms. O’Hearn said.

It’s about reducing harmful dietary components

Ms. O’Hearn and colleagues set out to fill information gaps in knowledge about how the global burden of diet-associated type 2 diabetes is impacted by disparities and other factors known to influence risk, including dietary components.

They used information from the Global Dietary Database to study dietary intake in 184 nations from 1990 to 2018. They also studied demographics from multiple sources, estimates of type 2 diabetes incidence around the world, and data on food choices, including the effect of 11 dietary factors, from prior research.

They found that there were 8.6 million more cases of type 2 diabetes in 2018 than in 1990 because of poor diet.

Regionally, Central and Eastern Europe and Central Asia had the greatest number of type 2 diabetes cases linked to diet, particularly Poland and Russia, where diets tend to be rich in red meat, processed meat, and potatoes. Incidence was also high in Latin America and the Caribbean, especially in Colombia and Mexico, which was attributed to high consumption of sugary drinks and processed meat and low intake of whole grains.

Regions where diet had less of an impact on type 2 diabetes cases included South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, although the largest increases in type 2 diabetes due to poor diet between 1990 and 2018 were observed in sub-Saharan Africa.

Diet-attributable type 2 diabetes was generally larger among urban versus rural residents and higher versus lower educated individuals, except in high-income countries, Central and Eastern Europe, and Central Asia, where burdens were larger in rural residents and in lower educated individuals.

Notably, women had lower proportions of diet-related type 2 diabetes, compared with men, and these proportions were inversely related to age.

Excess intake of harmful dietary factors contributed a greater percentage of the burden of type 2 diabetes globally (60.8%) than did insufficient intake of protective dietary factors (39.2%).

“Future research should address whether more complex diet–type 2 diabetes dose–response relationships exist,” the authors conclude.

Ms. O’Hearn has reported receiving research funding from the Gates Foundation, as well as the National Institutes of Health and Vail Innovative Global Research and employment with Food Systems for the Future. Dr. Mozaffarian has reported receiving funding from the National Institutes of Health, the Gates Foundation, the Rockefeller Foundation, Vail Innovative Global Research, and the Kaiser Permanente Fund at East Bay Community Foundation; personal fees from Acasti Pharma, Barilla, Danone, and Motif FoodWorks; is on the scientific advisory board for Beren Therapeutics, Brightseed, Calibrate, DiscernDx, Elysium Health, Filtricine, HumanCo, January, Perfect Day, Tiny Organics and (ended) Day Two and Season Health; has stock ownership in Calibrate and HumanCo; and receives chapter royalties from UpToDate.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Poor diets account for most newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes cases worldwide, a new analysis has found.

More specifically, the modeling study showed that roughly 14 million cases of type 2 diabetes – or 70% of total type 2 diabetes diagnoses in 2018 – were linked with a poor diet, found Meghan O’Hearn, a doctoral student at the Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy, Tufts University, Boston, and colleagues. The study was published online in Nature Medicine.

The results also indicate that the greatest burdens of type 2 diabetes were accounted for by excess wheat intake and refined rice (24.6%), excess processed meat consumption (20.3%), and inadequate whole-grain consumption (26.1%). Factors such as drinking too much fruit juice and not eating enough nonstarchy vegetables, nuts, or seeds, had less of an impact on new cases of the disease, the researchers determined.

“These findings can help inform nutritional priorities for clinicians, policymakers, and private sector actors as they encourage healthier dietary choices that address this global epidemic,” Ms. O’Hearn said in a press release.

Prior research has suggested that poor diet contributes to about 40% of type 2 diabetes cases worldwide, the researchers note.

The team attributes their finding of a 70% contribution to the new information in their analysis, such as the first-ever inclusion of refined grains, which was one of the top contributors to diabetes burden, and updated data on dietary habits based on national individual-level dietary surveys rather than agricultural estimates.

“Our study suggests poor carbohydrate quality is a leading driver of diet-attributable type 2 diabetes globally and with important variation by nation and over time,” said senior author Dariush Mozaffarian, MD, DrPh, MPH, who is the Jean Mayer Professor of Nutrition at the Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy.

“These new findings reveal critical areas for national and global focus to improve nutrition and reduce devastating burdens of diabetes,” he noted.

“Left unchecked and with incidence only projected to rise, type 2 diabetes will continue to impact population health, economic productivity, [and] health care system capacity, [as well as] drive health inequities worldwide,” Ms. O’Hearn said.

It’s about reducing harmful dietary components

Ms. O’Hearn and colleagues set out to fill information gaps in knowledge about how the global burden of diet-associated type 2 diabetes is impacted by disparities and other factors known to influence risk, including dietary components.

They used information from the Global Dietary Database to study dietary intake in 184 nations from 1990 to 2018. They also studied demographics from multiple sources, estimates of type 2 diabetes incidence around the world, and data on food choices, including the effect of 11 dietary factors, from prior research.

They found that there were 8.6 million more cases of type 2 diabetes in 2018 than in 1990 because of poor diet.

Regionally, Central and Eastern Europe and Central Asia had the greatest number of type 2 diabetes cases linked to diet, particularly Poland and Russia, where diets tend to be rich in red meat, processed meat, and potatoes. Incidence was also high in Latin America and the Caribbean, especially in Colombia and Mexico, which was attributed to high consumption of sugary drinks and processed meat and low intake of whole grains.

Regions where diet had less of an impact on type 2 diabetes cases included South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, although the largest increases in type 2 diabetes due to poor diet between 1990 and 2018 were observed in sub-Saharan Africa.

Diet-attributable type 2 diabetes was generally larger among urban versus rural residents and higher versus lower educated individuals, except in high-income countries, Central and Eastern Europe, and Central Asia, where burdens were larger in rural residents and in lower educated individuals.

Notably, women had lower proportions of diet-related type 2 diabetes, compared with men, and these proportions were inversely related to age.

Excess intake of harmful dietary factors contributed a greater percentage of the burden of type 2 diabetes globally (60.8%) than did insufficient intake of protective dietary factors (39.2%).

“Future research should address whether more complex diet–type 2 diabetes dose–response relationships exist,” the authors conclude.

Ms. O’Hearn has reported receiving research funding from the Gates Foundation, as well as the National Institutes of Health and Vail Innovative Global Research and employment with Food Systems for the Future. Dr. Mozaffarian has reported receiving funding from the National Institutes of Health, the Gates Foundation, the Rockefeller Foundation, Vail Innovative Global Research, and the Kaiser Permanente Fund at East Bay Community Foundation; personal fees from Acasti Pharma, Barilla, Danone, and Motif FoodWorks; is on the scientific advisory board for Beren Therapeutics, Brightseed, Calibrate, DiscernDx, Elysium Health, Filtricine, HumanCo, January, Perfect Day, Tiny Organics and (ended) Day Two and Season Health; has stock ownership in Calibrate and HumanCo; and receives chapter royalties from UpToDate.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM NATURE MEDICINE

Optimal time period for weight loss drugs: Debate continues

After bariatric surgery in 2014, Kristal Hartman still struggled to manage her weight long term. It took her over a year to lose 100 pounds, a loss she initially maintained, but then gradually her body mass index (BMI) started creeping up again.

“The body kind of has a set point, and you have to constantly trick it because it is going to start to gain weight again,” Ms. Hartman, who is on the national board of directors for the Obesity Action Coalition, said in an interview.

So, 2.5 years after her surgery, Ms. Hartman began weekly subcutaneous injections of the glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1) agonist semaglutide, a medication that is now almost infamous because of its popularity among celebrities and social media influencers.

Branded as Ozempic for type 2 diabetes and Wegovy for obesity, both contain semaglutide but in slightly different doses. The popularity of the medication has led to shortages for those living with type 2 diabetes and/or obesity. And other medications are waiting in the wings that work on GLP-1 and other hormones that regulate appetite, such as the twincretin tirzepatide (Mounjaro), another weekly injection, approved by the Food and Drug Administration in May 2022 for type 2 diabetes and awaiting approval for obesity.

Ms. Hartman said taking semaglutide helped her not only lose weight but also “curb [her] obsessive thoughts over food.” To maintain a BMI within the healthy range, as well as taking the GLP-1 agonist, Ms. Hartman relies on other strategies, including exercise, and mental health support.

“Physicians really need to be open to these FDA-approved medications as one of many tools in the toolbox for patients with obesity. It’s just like any other chronic disease state, when they are thinking of using these, they need to think about long-term use ... in patients who have obesity, not just [among those people] who just want to lose 5-10 pounds. That’s not what these drugs are designed for. They are for people who are actually living with the chronic disease of obesity every day of their lives,” she emphasized.

On average, patients lose 25%-40% of their total body weight following bariatric surgery, said Teresa LeMasters, MD, president of the American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery. However, there typically is a “small” weight regain after surgery.

“For most patients, it is a small 5-10 pounds, but for some others, it can be significant,” said Dr. LeMasters, a bariatric surgeon at UnityPoint Clinic, Des Moines, Iowa.

“We do still see some patients– anywhere from 10% to 30% – who will have some [significant] weight regain, and so then we will look at that,” she noted. In those cases, the disease of obesity “is definitely still present.”

Medications can counter weight regain after surgery

For patients who don’t reach their weight loss goals after bariatric surgery, Dr. LeMasters said it’s appropriate to consider adding an anti-obesity medication. The newer GLP-1 agonists can lead to a loss of around 15% of body weight in some patients.

or even just to optimize their initial response to surgery if they are starting at a very, very severe point of disease,” she explained.

She noted, however, that some patients shouldn’t be prescribed GLP-1 agonists, including those with a history of thyroid cancer or pancreatitis.

Caroline M. Apovian, MD, codirector of the center for weight management and wellness and professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an interview that the physiology behind bariatric surgery and that of the newer obesity medications is somewhat aligned.

“In order to reduce ... body weight permanently you need adjustments. We learned that you need the adjustments of the hormones [that affect appetite, such as GLP-1], and that’s why bariatric surgery works because ... [it] provides the most durable and the most effective treatment for obesity ... because [with surgery] you are adjusting the secretion and timing of many of the hormones that regulate body weight,” she explained.

So, when people are taking GLP-1 agonists for obesity, with or without surgery, these medications “are meant and were approved by the FDA to be taken indefinitely. They are not [for the] short term,” Dr. Apovian noted.

Benjamin O’Donnell, MD, an associate professor at Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, agreed that the newer anti-obesity medications can be very effective; however, he expressed uncertainty about prescribing these medications for years and years.

“If somebody has obesity, they need medicine to help them manage appetite and maintain a lower, healthier weight. It would make sense that they would just stay on the medicine,” he noted.

But he qualified: “I have a hard time committing to saying that someone should take this medication for the rest of their life. Part of my hesitation is that the medications are expensive, so we’ve had a hard time with people staying on them, mostly because of insurance formulary changes.”

Why stop the medications? Side effects and lack of insurance coverage

Many people have to discontinue these newer medications for that exact reason.

When Ms. Hartman’s insurance coverage lapsed, she had to go without semaglutide for a while.

“At that time, I absolutely gained weight back up into an abnormal BMI range,” Ms. Hartman said. When she was able to resume the medication, she lost weight again and her BMI returned to normal range.

These medications currently cost around $1,400 per month in the United States, unless patients can access initiatives such as company coupons. Some insurers, including state-subsidized Medicare and Medicaid, don’t cover the new medications.

Dr. O’Donnell said, “More accessibility for more people would help in the big picture.”

Other patients stop taking GLP-1 agonists because they experience side effects, such as nausea.

“Gastrointestinal complaints ... are the number one reason for people to come off the medication,” said Disha Narang, MD, an endocrinologist and obesity medicine specialist at Northwestern Medicine Lake Forest (Ill.) Hospital.

“It is an elective therapy, so it is not mandatory that someone take it. So if they are not feeling well or they are sick, then that’s a major reason for coming off of it,” she said.

Dan Bessesen, MD, professor of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and chief of endocrinology, agreed.

Patients are unlikely to stay on these medications if they feel nauseous or experience vomiting, he said. Although he noted there are options to try to counter this, such as starting patients on a very low dose of the drug and up-titrating slowly. This method requires good coordination between the patient and physician.

Goutham Rao, MD, a professor of medicine at Case Western Reserve University and head of the weight-loss initiative Fitter Me at University Hospitals, both in Cleveland, said that prior to prescribing GLP-1 agonists for weight loss, he sets four basic, nonnegotiable goals for patients: “to have breakfast within 30 minutes of getting up, to drink just water, no food or drink after 7:00 p.m. except for water, and 30 minutes of continuous exercise per day, which is typically, for older clientele, walking.”

This, he said, can help establish good habits because if “patients are not engaged psychologically in weight loss ... they expect the medication to do [all] the work.”

Most regain weight after stopping obesity medications

As Ms. Hartman’s story illustrates, discontinuing the medications often leads to weight regain.

“Without the medicine, there are a variety of things that will happen. Appetite will tend to increase, and so [patients] will gradually tend to eat more over time,” Dr. Bessesen noted.

“So it may take a long time for the weight regain to happen, but in every study where an obesity medicine has been used, and then it is stopped, the weight goes back to where it was on lifestyle alone,” he added.

In the STEP 1 trial, almost 2,000 patients who were either overweight or living with obesity were randomized 2:1 to semaglutide, titrated up to 2.4 mg each week by week 16, or placebo in addition to lifestyle modification. After 68 weeks, those in the semaglutide group had a mean weight loss of 14.9%, compared with 2.4% in the placebo group.

Patients were also followed in a 1-year extension of the trial, published in Diabetes, Obesity, and Metabolism.

Within 1 year of stopping treatment, participants regained two thirds of the weight they had initially lost.

Hence, Dr. Bessesen stressed that a total rethink of how obesity is approached is needed among most physicians.

“I think in the future treating obesity with medications should be like treating hypertension and diabetes, something most primary care doctors are comfortable doing, but that’s going to take a little work and practice on the part of clinicians to really have a comfortable conversation about risks, and benefits, with patients,” he said.

“I would encourage primary care doctors to learn more about the treatment of obesity, and learn more about bias and stigma, and think about how they can deliver care that is compassionate and competent,” he concluded.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

After bariatric surgery in 2014, Kristal Hartman still struggled to manage her weight long term. It took her over a year to lose 100 pounds, a loss she initially maintained, but then gradually her body mass index (BMI) started creeping up again.

“The body kind of has a set point, and you have to constantly trick it because it is going to start to gain weight again,” Ms. Hartman, who is on the national board of directors for the Obesity Action Coalition, said in an interview.

So, 2.5 years after her surgery, Ms. Hartman began weekly subcutaneous injections of the glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1) agonist semaglutide, a medication that is now almost infamous because of its popularity among celebrities and social media influencers.

Branded as Ozempic for type 2 diabetes and Wegovy for obesity, both contain semaglutide but in slightly different doses. The popularity of the medication has led to shortages for those living with type 2 diabetes and/or obesity. And other medications are waiting in the wings that work on GLP-1 and other hormones that regulate appetite, such as the twincretin tirzepatide (Mounjaro), another weekly injection, approved by the Food and Drug Administration in May 2022 for type 2 diabetes and awaiting approval for obesity.

Ms. Hartman said taking semaglutide helped her not only lose weight but also “curb [her] obsessive thoughts over food.” To maintain a BMI within the healthy range, as well as taking the GLP-1 agonist, Ms. Hartman relies on other strategies, including exercise, and mental health support.

“Physicians really need to be open to these FDA-approved medications as one of many tools in the toolbox for patients with obesity. It’s just like any other chronic disease state, when they are thinking of using these, they need to think about long-term use ... in patients who have obesity, not just [among those people] who just want to lose 5-10 pounds. That’s not what these drugs are designed for. They are for people who are actually living with the chronic disease of obesity every day of their lives,” she emphasized.

On average, patients lose 25%-40% of their total body weight following bariatric surgery, said Teresa LeMasters, MD, president of the American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery. However, there typically is a “small” weight regain after surgery.

“For most patients, it is a small 5-10 pounds, but for some others, it can be significant,” said Dr. LeMasters, a bariatric surgeon at UnityPoint Clinic, Des Moines, Iowa.

“We do still see some patients– anywhere from 10% to 30% – who will have some [significant] weight regain, and so then we will look at that,” she noted. In those cases, the disease of obesity “is definitely still present.”

Medications can counter weight regain after surgery

For patients who don’t reach their weight loss goals after bariatric surgery, Dr. LeMasters said it’s appropriate to consider adding an anti-obesity medication. The newer GLP-1 agonists can lead to a loss of around 15% of body weight in some patients.

or even just to optimize their initial response to surgery if they are starting at a very, very severe point of disease,” she explained.

She noted, however, that some patients shouldn’t be prescribed GLP-1 agonists, including those with a history of thyroid cancer or pancreatitis.

Caroline M. Apovian, MD, codirector of the center for weight management and wellness and professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an interview that the physiology behind bariatric surgery and that of the newer obesity medications is somewhat aligned.

“In order to reduce ... body weight permanently you need adjustments. We learned that you need the adjustments of the hormones [that affect appetite, such as GLP-1], and that’s why bariatric surgery works because ... [it] provides the most durable and the most effective treatment for obesity ... because [with surgery] you are adjusting the secretion and timing of many of the hormones that regulate body weight,” she explained.

So, when people are taking GLP-1 agonists for obesity, with or without surgery, these medications “are meant and were approved by the FDA to be taken indefinitely. They are not [for the] short term,” Dr. Apovian noted.

Benjamin O’Donnell, MD, an associate professor at Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, agreed that the newer anti-obesity medications can be very effective; however, he expressed uncertainty about prescribing these medications for years and years.

“If somebody has obesity, they need medicine to help them manage appetite and maintain a lower, healthier weight. It would make sense that they would just stay on the medicine,” he noted.

But he qualified: “I have a hard time committing to saying that someone should take this medication for the rest of their life. Part of my hesitation is that the medications are expensive, so we’ve had a hard time with people staying on them, mostly because of insurance formulary changes.”

Why stop the medications? Side effects and lack of insurance coverage

Many people have to discontinue these newer medications for that exact reason.

When Ms. Hartman’s insurance coverage lapsed, she had to go without semaglutide for a while.

“At that time, I absolutely gained weight back up into an abnormal BMI range,” Ms. Hartman said. When she was able to resume the medication, she lost weight again and her BMI returned to normal range.

These medications currently cost around $1,400 per month in the United States, unless patients can access initiatives such as company coupons. Some insurers, including state-subsidized Medicare and Medicaid, don’t cover the new medications.

Dr. O’Donnell said, “More accessibility for more people would help in the big picture.”

Other patients stop taking GLP-1 agonists because they experience side effects, such as nausea.

“Gastrointestinal complaints ... are the number one reason for people to come off the medication,” said Disha Narang, MD, an endocrinologist and obesity medicine specialist at Northwestern Medicine Lake Forest (Ill.) Hospital.

“It is an elective therapy, so it is not mandatory that someone take it. So if they are not feeling well or they are sick, then that’s a major reason for coming off of it,” she said.

Dan Bessesen, MD, professor of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and chief of endocrinology, agreed.

Patients are unlikely to stay on these medications if they feel nauseous or experience vomiting, he said. Although he noted there are options to try to counter this, such as starting patients on a very low dose of the drug and up-titrating slowly. This method requires good coordination between the patient and physician.

Goutham Rao, MD, a professor of medicine at Case Western Reserve University and head of the weight-loss initiative Fitter Me at University Hospitals, both in Cleveland, said that prior to prescribing GLP-1 agonists for weight loss, he sets four basic, nonnegotiable goals for patients: “to have breakfast within 30 minutes of getting up, to drink just water, no food or drink after 7:00 p.m. except for water, and 30 minutes of continuous exercise per day, which is typically, for older clientele, walking.”

This, he said, can help establish good habits because if “patients are not engaged psychologically in weight loss ... they expect the medication to do [all] the work.”

Most regain weight after stopping obesity medications

As Ms. Hartman’s story illustrates, discontinuing the medications often leads to weight regain.

“Without the medicine, there are a variety of things that will happen. Appetite will tend to increase, and so [patients] will gradually tend to eat more over time,” Dr. Bessesen noted.

“So it may take a long time for the weight regain to happen, but in every study where an obesity medicine has been used, and then it is stopped, the weight goes back to where it was on lifestyle alone,” he added.

In the STEP 1 trial, almost 2,000 patients who were either overweight or living with obesity were randomized 2:1 to semaglutide, titrated up to 2.4 mg each week by week 16, or placebo in addition to lifestyle modification. After 68 weeks, those in the semaglutide group had a mean weight loss of 14.9%, compared with 2.4% in the placebo group.

Patients were also followed in a 1-year extension of the trial, published in Diabetes, Obesity, and Metabolism.

Within 1 year of stopping treatment, participants regained two thirds of the weight they had initially lost.

Hence, Dr. Bessesen stressed that a total rethink of how obesity is approached is needed among most physicians.

“I think in the future treating obesity with medications should be like treating hypertension and diabetes, something most primary care doctors are comfortable doing, but that’s going to take a little work and practice on the part of clinicians to really have a comfortable conversation about risks, and benefits, with patients,” he said.

“I would encourage primary care doctors to learn more about the treatment of obesity, and learn more about bias and stigma, and think about how they can deliver care that is compassionate and competent,” he concluded.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

After bariatric surgery in 2014, Kristal Hartman still struggled to manage her weight long term. It took her over a year to lose 100 pounds, a loss she initially maintained, but then gradually her body mass index (BMI) started creeping up again.

“The body kind of has a set point, and you have to constantly trick it because it is going to start to gain weight again,” Ms. Hartman, who is on the national board of directors for the Obesity Action Coalition, said in an interview.

So, 2.5 years after her surgery, Ms. Hartman began weekly subcutaneous injections of the glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1) agonist semaglutide, a medication that is now almost infamous because of its popularity among celebrities and social media influencers.

Branded as Ozempic for type 2 diabetes and Wegovy for obesity, both contain semaglutide but in slightly different doses. The popularity of the medication has led to shortages for those living with type 2 diabetes and/or obesity. And other medications are waiting in the wings that work on GLP-1 and other hormones that regulate appetite, such as the twincretin tirzepatide (Mounjaro), another weekly injection, approved by the Food and Drug Administration in May 2022 for type 2 diabetes and awaiting approval for obesity.

Ms. Hartman said taking semaglutide helped her not only lose weight but also “curb [her] obsessive thoughts over food.” To maintain a BMI within the healthy range, as well as taking the GLP-1 agonist, Ms. Hartman relies on other strategies, including exercise, and mental health support.

“Physicians really need to be open to these FDA-approved medications as one of many tools in the toolbox for patients with obesity. It’s just like any other chronic disease state, when they are thinking of using these, they need to think about long-term use ... in patients who have obesity, not just [among those people] who just want to lose 5-10 pounds. That’s not what these drugs are designed for. They are for people who are actually living with the chronic disease of obesity every day of their lives,” she emphasized.

On average, patients lose 25%-40% of their total body weight following bariatric surgery, said Teresa LeMasters, MD, president of the American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery. However, there typically is a “small” weight regain after surgery.

“For most patients, it is a small 5-10 pounds, but for some others, it can be significant,” said Dr. LeMasters, a bariatric surgeon at UnityPoint Clinic, Des Moines, Iowa.

“We do still see some patients– anywhere from 10% to 30% – who will have some [significant] weight regain, and so then we will look at that,” she noted. In those cases, the disease of obesity “is definitely still present.”

Medications can counter weight regain after surgery

For patients who don’t reach their weight loss goals after bariatric surgery, Dr. LeMasters said it’s appropriate to consider adding an anti-obesity medication. The newer GLP-1 agonists can lead to a loss of around 15% of body weight in some patients.

or even just to optimize their initial response to surgery if they are starting at a very, very severe point of disease,” she explained.

She noted, however, that some patients shouldn’t be prescribed GLP-1 agonists, including those with a history of thyroid cancer or pancreatitis.

Caroline M. Apovian, MD, codirector of the center for weight management and wellness and professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an interview that the physiology behind bariatric surgery and that of the newer obesity medications is somewhat aligned.

“In order to reduce ... body weight permanently you need adjustments. We learned that you need the adjustments of the hormones [that affect appetite, such as GLP-1], and that’s why bariatric surgery works because ... [it] provides the most durable and the most effective treatment for obesity ... because [with surgery] you are adjusting the secretion and timing of many of the hormones that regulate body weight,” she explained.

So, when people are taking GLP-1 agonists for obesity, with or without surgery, these medications “are meant and were approved by the FDA to be taken indefinitely. They are not [for the] short term,” Dr. Apovian noted.

Benjamin O’Donnell, MD, an associate professor at Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, agreed that the newer anti-obesity medications can be very effective; however, he expressed uncertainty about prescribing these medications for years and years.

“If somebody has obesity, they need medicine to help them manage appetite and maintain a lower, healthier weight. It would make sense that they would just stay on the medicine,” he noted.

But he qualified: “I have a hard time committing to saying that someone should take this medication for the rest of their life. Part of my hesitation is that the medications are expensive, so we’ve had a hard time with people staying on them, mostly because of insurance formulary changes.”

Why stop the medications? Side effects and lack of insurance coverage

Many people have to discontinue these newer medications for that exact reason.

When Ms. Hartman’s insurance coverage lapsed, she had to go without semaglutide for a while.

“At that time, I absolutely gained weight back up into an abnormal BMI range,” Ms. Hartman said. When she was able to resume the medication, she lost weight again and her BMI returned to normal range.

These medications currently cost around $1,400 per month in the United States, unless patients can access initiatives such as company coupons. Some insurers, including state-subsidized Medicare and Medicaid, don’t cover the new medications.

Dr. O’Donnell said, “More accessibility for more people would help in the big picture.”

Other patients stop taking GLP-1 agonists because they experience side effects, such as nausea.

“Gastrointestinal complaints ... are the number one reason for people to come off the medication,” said Disha Narang, MD, an endocrinologist and obesity medicine specialist at Northwestern Medicine Lake Forest (Ill.) Hospital.

“It is an elective therapy, so it is not mandatory that someone take it. So if they are not feeling well or they are sick, then that’s a major reason for coming off of it,” she said.

Dan Bessesen, MD, professor of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and chief of endocrinology, agreed.

Patients are unlikely to stay on these medications if they feel nauseous or experience vomiting, he said. Although he noted there are options to try to counter this, such as starting patients on a very low dose of the drug and up-titrating slowly. This method requires good coordination between the patient and physician.

Goutham Rao, MD, a professor of medicine at Case Western Reserve University and head of the weight-loss initiative Fitter Me at University Hospitals, both in Cleveland, said that prior to prescribing GLP-1 agonists for weight loss, he sets four basic, nonnegotiable goals for patients: “to have breakfast within 30 minutes of getting up, to drink just water, no food or drink after 7:00 p.m. except for water, and 30 minutes of continuous exercise per day, which is typically, for older clientele, walking.”

This, he said, can help establish good habits because if “patients are not engaged psychologically in weight loss ... they expect the medication to do [all] the work.”

Most regain weight after stopping obesity medications

As Ms. Hartman’s story illustrates, discontinuing the medications often leads to weight regain.

“Without the medicine, there are a variety of things that will happen. Appetite will tend to increase, and so [patients] will gradually tend to eat more over time,” Dr. Bessesen noted.

“So it may take a long time for the weight regain to happen, but in every study where an obesity medicine has been used, and then it is stopped, the weight goes back to where it was on lifestyle alone,” he added.

In the STEP 1 trial, almost 2,000 patients who were either overweight or living with obesity were randomized 2:1 to semaglutide, titrated up to 2.4 mg each week by week 16, or placebo in addition to lifestyle modification. After 68 weeks, those in the semaglutide group had a mean weight loss of 14.9%, compared with 2.4% in the placebo group.

Patients were also followed in a 1-year extension of the trial, published in Diabetes, Obesity, and Metabolism.

Within 1 year of stopping treatment, participants regained two thirds of the weight they had initially lost.

Hence, Dr. Bessesen stressed that a total rethink of how obesity is approached is needed among most physicians.

“I think in the future treating obesity with medications should be like treating hypertension and diabetes, something most primary care doctors are comfortable doing, but that’s going to take a little work and practice on the part of clinicians to really have a comfortable conversation about risks, and benefits, with patients,” he said.

“I would encourage primary care doctors to learn more about the treatment of obesity, and learn more about bias and stigma, and think about how they can deliver care that is compassionate and competent,” he concluded.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

STEMI times to treatment usually miss established goals

Therapy initiated within national treatment-time goals set a decade ago for patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) remains associated with improved survival in recent years. But for many such patients, time from first symptoms to initiation of reperfusion therapy still fails to meet those goals, suggests a cross-sectional registry analysis.

For example, patients initially transported to centers with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) capability had a median treatment time of 148 minutes, in the analysis spanning the second quarter (Q2) of 2018 to the third quarter (Q3) of 2021. But the goal for centers called for treatment initiation within 90 minutes for at least 75% of such STEMI patients.

Moreover, overall STEMI treatment times and in-hospital mortality rose in tandem significantly from Q2 2018 through the first quarter (Q1) of 2021, which included the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Median time to treatment went from 86 minutes to 91 minutes during that period. Meanwhile, in-hospital mortality went from 5.6% to 8.7%, report the study authors led by James G. Jollis, MD, Duke University, Durham, N.C.

Their report, based on 114,871 STEMI patients at 601 US hospitals contributing to the Get With The Guidelines – Coronary Artery Disease registry, was published online in JAMA.

Of those patients, 25,085 had been transferred from non-PCI hospitals, 32,483 were walk-ins, and 57,303 arrived via emergency medical services (EMS). Their median times from symptom onset to PCI were 240, 195, and 148 minutes, respectively.

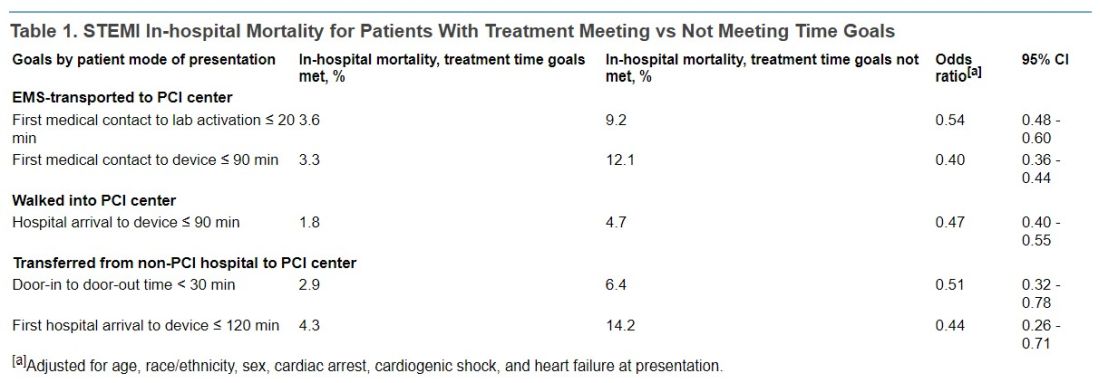

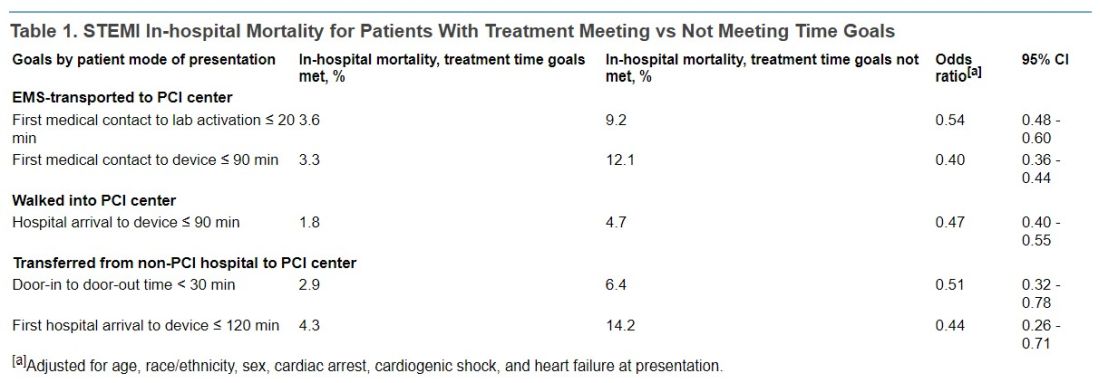

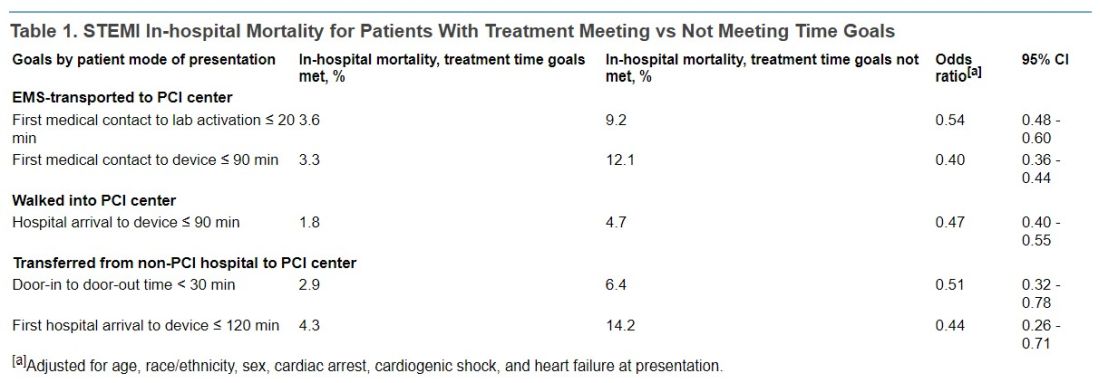

In-hospital mortality was significantly reduced in an adjusted analysis for patients treated within target times, compared with those whose treatment missed the time goals, regardless of whether they were transported by EMS, walked into a hospital with on-site PCI, or were transferred from a non-PCI center (Table 1).

Regardless of mode of patient presentation, treatment time goals were not met most of the time, the group reports. Patients who required interhospital transfer experienced the longest system delays; only 17% were treated within 120 minutes.

Among patients who received primary PCI, 20% had a registry-defined hospital-specified reason for delay, including cardiac arrest and/or need for intubation in 6.8%, “difficulty crossing the culprit lesion” in 3.8%, and “other reasons” in 5.8%, the group reports.

“In 2020, a new reason for delay was added to the registry, ‘need for additional personal protective equipment for suspected/confirmed infectious disease.’ This reason was most commonly used in the second quarter of 2020 (6%) and then declined over time to 1% in the final 2 quarters,” they write.

“Thus, active SARS-CoV-2 infection appeared to have a smaller direct role in longer treatment times or worse outcomes.” Rather, they continue, “the pandemic potentially had a significant indirect role as hospitals were overwhelmed with patients, EMS and hospitals were challenged in maintaining paramedic and nurse staffing and intensive care bed availability, and patients experienced delayed care due to barriers to access or perceived fear of becoming entangled in an overwhelmed medical system.”

Still an important quality metric

STEMI treatment times remain an important quality metric to which hospitals should continue to pay attention because shorter times improve patient care, Deepak Bhatt, MD, MPH, told this news organization.

“Having said that, as with all metrics, one needs to be thoughtful and realize that a difference of a couple of minutes is probably not a crucial thing,” said Dr. Bhatt, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, who was not involved with the current study.

Interhospital transfers indeed involve longer delays, he observed, suggesting that regional integrated health systems should develop methods for optimizing STEMI care – even, for example, if they involve bypassing non-PCI centers or stopping patients briefly for stabilization followed by rapid transport to a PCI-capable facility.

“That, of course, requires cooperation among hospitals. Sometimes that requires hospitals putting aside economic considerations and just focusing on doing the right thing for that individual patient,” Dr. Bhatt said.

Transfer delays are common for patients presenting with STEMI at hospitals without PCI capability, he noted. “Having clear protocols in place that expedite that type of transfer, I think, could go a long way in reducing the time to treatment in patients that are presenting to the hospital without cath labs. That’s an important message that these data provide.”

The onset of COVID-19 led to widespread delays in STEMI time to treatment early in the pandemic. There were concerns about exposing cath lab personnel to SARS-CoV-2 and potential adverse consequences of sick personnel being unable to provide patient care in the subsequent weeks and months, Dr. Bhatt observed.

However, “All of that seems to have quieted down, and I don’t think COVID is impacting time to treatment right now.”

‘Suboptimal compliance’ with standards

The current findings of “suboptimal compliance with national targets underscore why reassessing quality metrics, in light of changing practice patterns and other secular trends, is critical,” write Andrew S. Oseran, MD, MBA, and Robert W. Yeh, MD, both of Harvard Medical School, in an accompanying editorial.

“While the importance of coordinated and expeditious care for this high-risk patient population is undeniable, the specific actions that hospitals can – or should – take to further improve overall STEMI outcomes are less clear,” they say.

“As physicians contemplate the optimal path forward in managing the care of STEMI patients, they must recognize the clinical and operational nuance that exists in caring for this diverse population and acknowledge the trade-offs associated with uniform quality metrics,” write the editorialists.

“Global reductions in time to treatment for STEMI patients has been one of health care’s great success stories. As we move forward, it may be time to consider whether efforts to achieve additional improvement in target treatment times will result in substantive benefits, or whether we have reached the point of diminishing returns.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Therapy initiated within national treatment-time goals set a decade ago for patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) remains associated with improved survival in recent years. But for many such patients, time from first symptoms to initiation of reperfusion therapy still fails to meet those goals, suggests a cross-sectional registry analysis.

For example, patients initially transported to centers with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) capability had a median treatment time of 148 minutes, in the analysis spanning the second quarter (Q2) of 2018 to the third quarter (Q3) of 2021. But the goal for centers called for treatment initiation within 90 minutes for at least 75% of such STEMI patients.

Moreover, overall STEMI treatment times and in-hospital mortality rose in tandem significantly from Q2 2018 through the first quarter (Q1) of 2021, which included the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Median time to treatment went from 86 minutes to 91 minutes during that period. Meanwhile, in-hospital mortality went from 5.6% to 8.7%, report the study authors led by James G. Jollis, MD, Duke University, Durham, N.C.

Their report, based on 114,871 STEMI patients at 601 US hospitals contributing to the Get With The Guidelines – Coronary Artery Disease registry, was published online in JAMA.

Of those patients, 25,085 had been transferred from non-PCI hospitals, 32,483 were walk-ins, and 57,303 arrived via emergency medical services (EMS). Their median times from symptom onset to PCI were 240, 195, and 148 minutes, respectively.

In-hospital mortality was significantly reduced in an adjusted analysis for patients treated within target times, compared with those whose treatment missed the time goals, regardless of whether they were transported by EMS, walked into a hospital with on-site PCI, or were transferred from a non-PCI center (Table 1).

Regardless of mode of patient presentation, treatment time goals were not met most of the time, the group reports. Patients who required interhospital transfer experienced the longest system delays; only 17% were treated within 120 minutes.

Among patients who received primary PCI, 20% had a registry-defined hospital-specified reason for delay, including cardiac arrest and/or need for intubation in 6.8%, “difficulty crossing the culprit lesion” in 3.8%, and “other reasons” in 5.8%, the group reports.

“In 2020, a new reason for delay was added to the registry, ‘need for additional personal protective equipment for suspected/confirmed infectious disease.’ This reason was most commonly used in the second quarter of 2020 (6%) and then declined over time to 1% in the final 2 quarters,” they write.

“Thus, active SARS-CoV-2 infection appeared to have a smaller direct role in longer treatment times or worse outcomes.” Rather, they continue, “the pandemic potentially had a significant indirect role as hospitals were overwhelmed with patients, EMS and hospitals were challenged in maintaining paramedic and nurse staffing and intensive care bed availability, and patients experienced delayed care due to barriers to access or perceived fear of becoming entangled in an overwhelmed medical system.”

Still an important quality metric

STEMI treatment times remain an important quality metric to which hospitals should continue to pay attention because shorter times improve patient care, Deepak Bhatt, MD, MPH, told this news organization.

“Having said that, as with all metrics, one needs to be thoughtful and realize that a difference of a couple of minutes is probably not a crucial thing,” said Dr. Bhatt, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, who was not involved with the current study.

Interhospital transfers indeed involve longer delays, he observed, suggesting that regional integrated health systems should develop methods for optimizing STEMI care – even, for example, if they involve bypassing non-PCI centers or stopping patients briefly for stabilization followed by rapid transport to a PCI-capable facility.

“That, of course, requires cooperation among hospitals. Sometimes that requires hospitals putting aside economic considerations and just focusing on doing the right thing for that individual patient,” Dr. Bhatt said.

Transfer delays are common for patients presenting with STEMI at hospitals without PCI capability, he noted. “Having clear protocols in place that expedite that type of transfer, I think, could go a long way in reducing the time to treatment in patients that are presenting to the hospital without cath labs. That’s an important message that these data provide.”

The onset of COVID-19 led to widespread delays in STEMI time to treatment early in the pandemic. There were concerns about exposing cath lab personnel to SARS-CoV-2 and potential adverse consequences of sick personnel being unable to provide patient care in the subsequent weeks and months, Dr. Bhatt observed.

However, “All of that seems to have quieted down, and I don’t think COVID is impacting time to treatment right now.”

‘Suboptimal compliance’ with standards

The current findings of “suboptimal compliance with national targets underscore why reassessing quality metrics, in light of changing practice patterns and other secular trends, is critical,” write Andrew S. Oseran, MD, MBA, and Robert W. Yeh, MD, both of Harvard Medical School, in an accompanying editorial.

“While the importance of coordinated and expeditious care for this high-risk patient population is undeniable, the specific actions that hospitals can – or should – take to further improve overall STEMI outcomes are less clear,” they say.

“As physicians contemplate the optimal path forward in managing the care of STEMI patients, they must recognize the clinical and operational nuance that exists in caring for this diverse population and acknowledge the trade-offs associated with uniform quality metrics,” write the editorialists.

“Global reductions in time to treatment for STEMI patients has been one of health care’s great success stories. As we move forward, it may be time to consider whether efforts to achieve additional improvement in target treatment times will result in substantive benefits, or whether we have reached the point of diminishing returns.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Therapy initiated within national treatment-time goals set a decade ago for patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) remains associated with improved survival in recent years. But for many such patients, time from first symptoms to initiation of reperfusion therapy still fails to meet those goals, suggests a cross-sectional registry analysis.

For example, patients initially transported to centers with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) capability had a median treatment time of 148 minutes, in the analysis spanning the second quarter (Q2) of 2018 to the third quarter (Q3) of 2021. But the goal for centers called for treatment initiation within 90 minutes for at least 75% of such STEMI patients.

Moreover, overall STEMI treatment times and in-hospital mortality rose in tandem significantly from Q2 2018 through the first quarter (Q1) of 2021, which included the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Median time to treatment went from 86 minutes to 91 minutes during that period. Meanwhile, in-hospital mortality went from 5.6% to 8.7%, report the study authors led by James G. Jollis, MD, Duke University, Durham, N.C.

Their report, based on 114,871 STEMI patients at 601 US hospitals contributing to the Get With The Guidelines – Coronary Artery Disease registry, was published online in JAMA.

Of those patients, 25,085 had been transferred from non-PCI hospitals, 32,483 were walk-ins, and 57,303 arrived via emergency medical services (EMS). Their median times from symptom onset to PCI were 240, 195, and 148 minutes, respectively.

In-hospital mortality was significantly reduced in an adjusted analysis for patients treated within target times, compared with those whose treatment missed the time goals, regardless of whether they were transported by EMS, walked into a hospital with on-site PCI, or were transferred from a non-PCI center (Table 1).

Regardless of mode of patient presentation, treatment time goals were not met most of the time, the group reports. Patients who required interhospital transfer experienced the longest system delays; only 17% were treated within 120 minutes.

Among patients who received primary PCI, 20% had a registry-defined hospital-specified reason for delay, including cardiac arrest and/or need for intubation in 6.8%, “difficulty crossing the culprit lesion” in 3.8%, and “other reasons” in 5.8%, the group reports.

“In 2020, a new reason for delay was added to the registry, ‘need for additional personal protective equipment for suspected/confirmed infectious disease.’ This reason was most commonly used in the second quarter of 2020 (6%) and then declined over time to 1% in the final 2 quarters,” they write.

“Thus, active SARS-CoV-2 infection appeared to have a smaller direct role in longer treatment times or worse outcomes.” Rather, they continue, “the pandemic potentially had a significant indirect role as hospitals were overwhelmed with patients, EMS and hospitals were challenged in maintaining paramedic and nurse staffing and intensive care bed availability, and patients experienced delayed care due to barriers to access or perceived fear of becoming entangled in an overwhelmed medical system.”

Still an important quality metric

STEMI treatment times remain an important quality metric to which hospitals should continue to pay attention because shorter times improve patient care, Deepak Bhatt, MD, MPH, told this news organization.

“Having said that, as with all metrics, one needs to be thoughtful and realize that a difference of a couple of minutes is probably not a crucial thing,” said Dr. Bhatt, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, who was not involved with the current study.

Interhospital transfers indeed involve longer delays, he observed, suggesting that regional integrated health systems should develop methods for optimizing STEMI care – even, for example, if they involve bypassing non-PCI centers or stopping patients briefly for stabilization followed by rapid transport to a PCI-capable facility.

“That, of course, requires cooperation among hospitals. Sometimes that requires hospitals putting aside economic considerations and just focusing on doing the right thing for that individual patient,” Dr. Bhatt said.

Transfer delays are common for patients presenting with STEMI at hospitals without PCI capability, he noted. “Having clear protocols in place that expedite that type of transfer, I think, could go a long way in reducing the time to treatment in patients that are presenting to the hospital without cath labs. That’s an important message that these data provide.”

The onset of COVID-19 led to widespread delays in STEMI time to treatment early in the pandemic. There were concerns about exposing cath lab personnel to SARS-CoV-2 and potential adverse consequences of sick personnel being unable to provide patient care in the subsequent weeks and months, Dr. Bhatt observed.

However, “All of that seems to have quieted down, and I don’t think COVID is impacting time to treatment right now.”

‘Suboptimal compliance’ with standards

The current findings of “suboptimal compliance with national targets underscore why reassessing quality metrics, in light of changing practice patterns and other secular trends, is critical,” write Andrew S. Oseran, MD, MBA, and Robert W. Yeh, MD, both of Harvard Medical School, in an accompanying editorial.

“While the importance of coordinated and expeditious care for this high-risk patient population is undeniable, the specific actions that hospitals can – or should – take to further improve overall STEMI outcomes are less clear,” they say.

“As physicians contemplate the optimal path forward in managing the care of STEMI patients, they must recognize the clinical and operational nuance that exists in caring for this diverse population and acknowledge the trade-offs associated with uniform quality metrics,” write the editorialists.

“Global reductions in time to treatment for STEMI patients has been one of health care’s great success stories. As we move forward, it may be time to consider whether efforts to achieve additional improvement in target treatment times will result in substantive benefits, or whether we have reached the point of diminishing returns.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA

‘The Whale’: Is this new movie fat-phobic or fat-friendly?

“I could relate to many, many, many of the experiences and emotions that Charlie, which is Brendan Fraser’s character, was portraying,” Patricia Nece recalls after watching a preview copy of the new film “The Whale.”

Much of the movie “rang true and hit home for me as things that I, too, had experienced,” Ms. Nece, the board of directors’ chair of the Obesity Action Coalition (OAC) and a person living with obesity, shares with this news organization.

In theaters as of December 9, The Whale chronicles the experience of a 600-lb, middle-aged man named Charlie. Throughout the film, Charlie seeks to rebuild his relationship with his estranged teenage daughter. Charlie had left his daughter and family to pursue a relationship with a man, who eventually died. As he navigates the pain surrounding his partner’s death and his lack of community, Charlie turns to food for comfort.

When the movie premiered at the Venice Film Festival, Mr. Fraser received a 6-minute standing ovation. However, activists criticized the movie for casting Fraser over an actor with obesity as well as its depiction of people with obesity.

Representatives from the National Association to Advance Fat Acceptance contend that casting an actor without obesity only contributes to ongoing bias against people of size. “Medical weight stigma and other socio-political determinants of health for people of all sizes cause far more harm to fat people than body fat does. Bias endangers fat people’s health. Anti-obesity organizations, such as those consulted with for this movie, contribute to stigma rather than reducing it as they claim,” NAAFA wrote in a statement to this news organization.

And they added that though the fat suit used in the movie may be superior to previous ones, it is still not an accurate depiction: “The creators of The Whale consider its CGI-generated fat suit to be superior to tactile fat suits, but we don’t. The issue with fat suits in Hollywood is not that they aren’t realistic enough. The issue is that they are used rather than using performers who actually live in bodies like the ones being depicted. If there is a 600-pound character in a movie, there should be a 600-pound human in that role. Rather than concentrate on the hype around the fake fat body created for The Whale, we want to see Hollywood create more opportunities for fat people across the size spectrum, both in front of the camera and behind the scenes.”

Prosthetics vs. reality?

Ms. Nece says she understands the controversy surrounding the use of fat suits but believes that it was not done in poor taste.

“OAC got involved with the movie after Brendan was already chosen for the part, and we never would have gotten involved with it had the prosthetics or fat suit been used to ridicule or make fun of people with obesity, which is usually the case,” she explains.

“But we knew from the start that that was never the intent of anyone involved with The Whale. And I think that’s shown by the fact that Brendan and Darren Aronofsky, the director, reached out to people who live with obesity on a daily basis to find out and learn more about it and to educate themselves about it,” Ms. Nece continues.

In a Daily Mail article, Mr. Fraser credited his son Griffin, who is autistic and obese, with helping him understand the struggles that people with obesity face.

Rachel Goldman, PhD, a clinical psychologist in private practice in New York and a professor in the psychology department at New York University, notes that there are other considerations that played into casting. “I know there was some pushback in terms of could, a say 600-lb individual, even be able to go to be on set every day and do this kind of work, and the answer is we don’t know.”

“I’m sure Darren chose Brendan for many reasons above and beyond just his body. I think that’s very important to keep in mind that just as much as representation is very important, I think it is also about finding the right person for the right role,” adds Dr. Goldman, who served as a consultant to the film.

Fat suits, extreme weight gains all to play a role

About 42% of adults in the United States have obesity, according to the 2017-2020 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, but that reality is not reflected in films or television.

A study of 1018 major television characters found that 24% of men and 14% of women had either overweight or obesity – far below the national average. And when characters with obesity are portrayed, actors often wear prosthetics, like Gwyneth Paltrow in Shallow Hal or Eddie Murphy in the Nutty Professor.

But unlike Mr. Fraser, some actors gain weight quickly instead.

This practice is unhealthy, says Jaime Almandoz, MD, an associate professor at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, and a nonsurgical weight management expert. In interviews, actors have shared how they increased calorie intake by drinking two milkshakes per day, going to fast food places regularly, or, in Mark Walhberg’s case, consuming 7,000 calories per day to gain 30 pounds for his role as boxer-turned-priest in the movie Father Stu.

This method provides their bodies with excess calories they are unable to burn off. “Then the amount of sugar and fat that streams into the blood as a result creates problems both directly and indirectly as your body tries to store it. It basically ends up using overflow warehouses for fat storage, like the liver for example, so we can create a condition called fatty liver, or in the muscle and other places, and this excess sugar and fat in the bloodstream cause several factors that are both insulin resistance causing,” Dr. Almandoz explains.

Though gaining weight helps the actor understand the character’s life experience, it may also be risky.

“To have an actor deliberately put his own health at risk and gain a certain amount of weight and whatever that might entail, one – that’s not necessarily the safest thing for that actor – but two, it’s also important to highlight the authentic experience of someone who has dealt with this chronic disease as well,” says Disha Narang, MD, a quadruple-board certified endocrinologist, obesity medicine, and culinary medicine specialist at Northwestern Medicine Lake Forest Hospital, Chicago.

These extreme fluctuations in weight may create problems. “It is typically not something we recommend because there could be metabolic damages as well as health concerns when patients are trying to gain weight quickly, just as we don’t want patients to lose weight quickly,” says Kurt Hong, MD, PhD, board-certified in internal medicine and clinical nutrition at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

Dr. Hong notes that it may be difficult for individuals to experience sudden weight gain because the body works hard to maintain a state of homeostasis.

“Similarly, to someone trying to gain weight you overeat, initially your body will try to again, maybe enhance its metabolic efficiency to hold the body stable,” Dr. Hong adds.

Dietary choices that may contribute to insulin resistance or promote high blood sugar can contribute to inflammation and a number of other adverse health outcomes, notes Dr. Almandoz. “The things that actors need to do in order to gain this magnitude of weight and they want to do it in the most time-effective manner is often not helpful for our bodies, it can be very problematic, the same thing goes for weight loss when actors need to lose significant amounts of weight for roles,” says Dr. Almandoz.

And Dr. Hong explained that for patients trying to lose weight, they may cut calories, but the body will try to compensate by slowing down the metabolism to keep their weight the same.

‘Your own worst bully’

In “The Whale,” Charlie appears to suffer from internalized weight bias, which is common to many people living with obesity, Ms. Nece says.

“Internalized weight bias is when the person of size takes all that negativity and turns it on themselves. The easiest way to describe that is to tell you that I became my own worst bully because I started believing all the negative things people said to me about my weight,” Ms. Nece adds.

Her hope is that the film will bring attention to the harm that this bias creates, especially when it derives from other people. “There’s no telling whether it will, but what Charlie experiences in bias and stigma from others clearly happens. It’s realistic. Those of us in large bodies have experienced what he is experiencing, so some people have said the movie is fat-phobic, but I see it as I can relate to those experiences because I have them too, so they are very realistic.”

Ms. Nece notes that it is important for clinicians to understand that obesity is a multifaceted and sensitive topic. “For those medical professionals who do not already know that obesity is complex, I hope the film will begin to open their eyes to the many different facets involved in obesity and their patients with obesity, I hope it will help them empathize and show compassion to their patients with obesity,” she concludes.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“I could relate to many, many, many of the experiences and emotions that Charlie, which is Brendan Fraser’s character, was portraying,” Patricia Nece recalls after watching a preview copy of the new film “The Whale.”

Much of the movie “rang true and hit home for me as things that I, too, had experienced,” Ms. Nece, the board of directors’ chair of the Obesity Action Coalition (OAC) and a person living with obesity, shares with this news organization.

In theaters as of December 9, The Whale chronicles the experience of a 600-lb, middle-aged man named Charlie. Throughout the film, Charlie seeks to rebuild his relationship with his estranged teenage daughter. Charlie had left his daughter and family to pursue a relationship with a man, who eventually died. As he navigates the pain surrounding his partner’s death and his lack of community, Charlie turns to food for comfort.

When the movie premiered at the Venice Film Festival, Mr. Fraser received a 6-minute standing ovation. However, activists criticized the movie for casting Fraser over an actor with obesity as well as its depiction of people with obesity.

Representatives from the National Association to Advance Fat Acceptance contend that casting an actor without obesity only contributes to ongoing bias against people of size. “Medical weight stigma and other socio-political determinants of health for people of all sizes cause far more harm to fat people than body fat does. Bias endangers fat people’s health. Anti-obesity organizations, such as those consulted with for this movie, contribute to stigma rather than reducing it as they claim,” NAAFA wrote in a statement to this news organization.

And they added that though the fat suit used in the movie may be superior to previous ones, it is still not an accurate depiction: “The creators of The Whale consider its CGI-generated fat suit to be superior to tactile fat suits, but we don’t. The issue with fat suits in Hollywood is not that they aren’t realistic enough. The issue is that they are used rather than using performers who actually live in bodies like the ones being depicted. If there is a 600-pound character in a movie, there should be a 600-pound human in that role. Rather than concentrate on the hype around the fake fat body created for The Whale, we want to see Hollywood create more opportunities for fat people across the size spectrum, both in front of the camera and behind the scenes.”

Prosthetics vs. reality?

Ms. Nece says she understands the controversy surrounding the use of fat suits but believes that it was not done in poor taste.

“OAC got involved with the movie after Brendan was already chosen for the part, and we never would have gotten involved with it had the prosthetics or fat suit been used to ridicule or make fun of people with obesity, which is usually the case,” she explains.

“But we knew from the start that that was never the intent of anyone involved with The Whale. And I think that’s shown by the fact that Brendan and Darren Aronofsky, the director, reached out to people who live with obesity on a daily basis to find out and learn more about it and to educate themselves about it,” Ms. Nece continues.

In a Daily Mail article, Mr. Fraser credited his son Griffin, who is autistic and obese, with helping him understand the struggles that people with obesity face.

Rachel Goldman, PhD, a clinical psychologist in private practice in New York and a professor in the psychology department at New York University, notes that there are other considerations that played into casting. “I know there was some pushback in terms of could, a say 600-lb individual, even be able to go to be on set every day and do this kind of work, and the answer is we don’t know.”

“I’m sure Darren chose Brendan for many reasons above and beyond just his body. I think that’s very important to keep in mind that just as much as representation is very important, I think it is also about finding the right person for the right role,” adds Dr. Goldman, who served as a consultant to the film.

Fat suits, extreme weight gains all to play a role

About 42% of adults in the United States have obesity, according to the 2017-2020 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, but that reality is not reflected in films or television.

A study of 1018 major television characters found that 24% of men and 14% of women had either overweight or obesity – far below the national average. And when characters with obesity are portrayed, actors often wear prosthetics, like Gwyneth Paltrow in Shallow Hal or Eddie Murphy in the Nutty Professor.

But unlike Mr. Fraser, some actors gain weight quickly instead.

This practice is unhealthy, says Jaime Almandoz, MD, an associate professor at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, and a nonsurgical weight management expert. In interviews, actors have shared how they increased calorie intake by drinking two milkshakes per day, going to fast food places regularly, or, in Mark Walhberg’s case, consuming 7,000 calories per day to gain 30 pounds for his role as boxer-turned-priest in the movie Father Stu.

This method provides their bodies with excess calories they are unable to burn off. “Then the amount of sugar and fat that streams into the blood as a result creates problems both directly and indirectly as your body tries to store it. It basically ends up using overflow warehouses for fat storage, like the liver for example, so we can create a condition called fatty liver, or in the muscle and other places, and this excess sugar and fat in the bloodstream cause several factors that are both insulin resistance causing,” Dr. Almandoz explains.

Though gaining weight helps the actor understand the character’s life experience, it may also be risky.