User login

Collagenase Enzymatic Fasciotomy for Dupuytren Contracture in Patients on Chronic Immunosuppression

The incidence of Dupuytren disease increases with advancing age,1 as do the medical comorbidities of patients seeking treatment for disabling hand contractures. For patients with significant comorbidities, open surgical fasciectomy, the current standard of treatment for Dupuytren disease,2,3 may be associated with increased perioperative risks.

Collagenase enzymatic fasciotomy has become an accepted nonsurgical treatment alternative to traditional fasciectomy or surgical fasciotomy for significant digital contractures caused by Dupuytren disease.4-6 Clostridium histolyticum collagenase (CHC) is a foreign protein, made up of 2 collagenases isolated from the bacteria C histolyticum.7 The collagenases are zinc-dependent matrix metalloproteinases that cleave the triple helical structure of collagen molecules.8 Also known as Xiaflex (Auxilium Pharmaceuticals), CHC was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in February 2010 for use in patients with Dupuytren contractures.

Enzymatic rupture is safe and efficacious at midterm follow-up and offers the theoretical advantage of avoiding palmar and digital fasciectomy and the associated risks of surgical-site infection and wound-healing complications.6 The risks of surgical wound complications are magnified in immunosuppressed patients, particularly those on chronic steroid therapy; wound-healing complication rates may be increased 2 to 5 times compared with controls.9 In a pooled literature review, wound-healing complications were reported after 22.9% of open primary fasciectomies, with infection occurring in 2.4%.10 A nonsurgical alternative is therefore particularly appealing for a patient cohort that may be at higher risk for a frequently described complication of surgery for Dupuytren contracture.

The exclusion criteria in the trials for FDA approval were extensive and included breast-feeding, pregnancy, bleeding disorder, recent stroke, use of tetracycline derivative within 14 days before start of study, use of anticoagulant within 7 days before start of study, allergy to collagenase, and chronic muscular, neurologic, or neuromuscular disorder affecting the hands.6 Safety and efficacy of collagenase in patients requiring chronic immunosuppressive therapy for medical comorbidities have not been previously documented. Furthermore, although skin tears were reported in 11% of patients after manual cord rupture in the CORD (Collagenase Option for the Reduction of Dupuytren’s) I trial,6 the likelihood of deep and superficial infection and delayed wound healing has not been quantitated.

In this article, we report on outcomes of 13 collagenase enzymatic fasciotomies performed in 8 patients who were on chronic immunosuppressive therapy.

Methods

Institutional review board approval was obtained at both academic hand surgery institutions. We retrospectively reviewed prospectively collected clinical data within our 2 centers’ databases of patients with Dupuytren disease. Eight patients on chronic immunosuppressive therapies treated with collagenase for metacarpophalangeal (MP) or proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint contractures between February 2010 and December 2011 were identified. Three of these patients received collagenase injections into 2 or more separate Dupuytren cords at different encounters, resulting in a total of 13 individual collagenase enzymatic fasciotomies.

Collagenase injections were administered following CORD I trial protocol,6 except we injected Dupuytren cords crossing the PIP joint using a lateral approach to minimize risk of flexor tendon rupture. Manipulation of the treated joint was performed between 24 and 48 hours after collagenase injection under local anesthesia with 3 mL of 1% mepivacaine or lidocaine without epinephrine. After manipulation and cord rupture, patients were placed in a hand-based extension splint to wear at night for up to 3 months. Patients were followed at 1 and 12 months.

Results

Patients’ baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Four patients were maintained on chronic prednisone therapy, 3 on methotrexate, and 1 on azathioprine. Therapy duration, medication dose, and diagnoses requiring immunosuppressant therapy varied among patients.

Outcomes and adverse events are summarized in Table 2. Mean number of joint contractures per hand treated was 2.8 (MP, 1.4; PIP, 1.4). However, not all joints met the intervention criteria. Of the 13 joints treated, 7 were MP joints, and 6 were PIP joints. Mean preinjection contracture of the treated joints was 53.0° (range, 20°-90°). Twelve of the 13 joint contractures improved. At mean follow-up of 6.7 months (range, 1-22 months), mean magnitude of contracture improved to 12.9° (range, 0°-45°). Mean MP joint contracture improved from 42.0° to 4.2° (range, 0°-10°), and mean PIP joint contracture improved from 65.8° to 21.7° (range, 0°-45°).

All 13 collagenase injections were well tolerated, and there were no systemic reactions. Injection-site pain was common. Mild injection-site bruising and edema were reported in all cases. Enzymatic fasciotomy was performed in all patients, and immediate improvement in contracture after manipulation 24 to 48 hours after injection was recorded.

Three of the 13 injections were complicated by skin tears during manipulation and cord rupture. All 3 skin tears were treated with local wound care, which included use of povidone-iodine and wet-to-dry dressings. There was no evidence of subsequent superficial or deep, local or regional infection. In 2 cases, the wound healed within 1 week; in the third case, wound healing was present by 2 weeks. Once the wounds showed early re-epithelialization, hand-based extension splinting in a position of comfort was used at night for up to 3 months after injection. Two of the 13 injections were complicated by small blood blisters. These were treated with observation and resolved spontaneously.

Discussion

Collagenase enzymatic fasciotomy appeared to be a safe and efficacious alternative to surgical treatment of Dupuytren contractures in this cohort of patients maintained on chronic immunosuppressive agents. MP contractures responded more substantially than PIP contractures did, as expected.6 No previously undescribed adverse outcomes were noted in these 8 patients on chronic immunosuppressive therapy beyond those reported in the CORD I trial. Three (23%) of the 13 collagenase injections in our series were complicated by skin tears after manipulation. Skins tears were reported in 22 (11%) of 204 patients after manual cord rupture in the CORD I trial.6 Given the limited numbers in this series, it remains unclear if chronic immunosuppression truly increases the risk of skin tears in this subset of patients. Other common treatment-related adverse events seen in the CORD I trial—injection-site hemorrhage (37%), pruritis (11%) and lymphadenopathy (10%)—were not seen after the 13 injections in our case series. We are prospectively following all patients with Dupuytren disease, and this is an area of ongoing research at our centers.

The immunosuppressive actions of prednisone, azathioprine, and methotrexate are well documented. Prednisone is a glucocorticoid, converted in the liver to prednisolone, which suppresses inflammation and immune responses by regulation of gene expression. Its immunosuppressive actions are multifactorial, relating to inhibition of lymphocytes, neutrophils, and monocytes. These effects are dose- and time-dependent11 and may become evident in patients receiving low doses over prolonged periods. Skin atrophy12 and delayed wound healing9 are side effects of long-term prednisone use. Skin atrophy may make the prednisone-treated patient more susceptible to skin tears after collagenase injection and manipulation. Azathioprine inhibits purine synthesis, which is especially important in the proliferation of immune cells.13 It has been shown to inhibit both cellular immunity at low doses and humoral immunity at higher doses.14 Methotrexate inhibits lymphocyte folic acid metabolism. The immunosuppressive properties of low-dose methotrexate have been linked to the induction of apoptosis in activated T cells.15

A more complex process in immunosuppressed patients is the immunogenicity of injected collagenase. As CHC in current use is a mixture of 2 foreign proteins, an immunologic response is expected in the host after injection. It has been shown that, after 3 injections of CHC into Dupuytren cords, 100% of patients developed antibodies to both enzymes in their serum.6 More than 85% demonstrated anti-CHC antibodies after a single injection. However, no patients showed signs of anaphylaxis or allergic reaction, and there was no correlation between serum levels of anti-CHC and adverse events. It has been hypothesized that there is a potential for cross-reactivity of the anti-CHC antibodies with human matrix metalloproteinases, causing enzymatic dysfunction within the host.16 This has yet to be reported clinically, and Xiaflex is currently under postmarketing surveillance. Immunocompromised people, with suppressed humoral and cellular immune responses, may produce less of an antibody response to the foreign CHC proteins. Whether this conclusively leads to a change in the side effect profile of the medication in these individuals is beyond the scope of this article. However, we identified no new side effects in this small but higher risk cohort. The issue should be continually monitored as collagenase is used in wider clinical settings.

Collagenase enzymatic fasciotomy is a new nonsurgical therapeutic option for Dupuytren disease. Indications and guidelines for use continue to evolve. This case series highlights the use of collagenase in 8 patients who were on long-term immunosuppressive therapy. This study has the limitations inherent to retrospective analyses. It is difficult to generalize results across broader immunosuppressed populations. A larger cohort, with long-term follow-up assessing recurrence of contracture, is needed to make definitive conclusions about use of collagenase in this challenging subset of patients. Based on our observations in this limited cohort, it appears appropriate to pursue further studies on use of collagenase enzymatic fasciotomy. A randomized, prospective or case–control series comparing surgical fasciectomy with enzymatic fasciotomy would yield further meaningful data. As more patients seek nonsurgical treatment for Dupuytren disease, its safety and efficacy in select cohorts of patients should continue to be evaluated.

1. Loos B, Puschkin V, Horch RE. 50 years experience with Dupuytren’s contracture in the Erlangen University Hospital—a retrospective analysis of 2919 operated hands from 1956 to 2006. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2007;8:60.

2. Coert JH, Nérin JP, Meek MF. Results of partial fasciectomy for Dupuytren disease in 261 consecutive patients. Ann Plast Surg. 2006;57(1):13-17.

3. Sennwald GR. Fasciectomy for treatment of Dupuytren’s disease and early complications. J Hand Surg Am. 1990;15(5):755-761.

4. Badalamente MA, Hurst LC. Enzyme injection as nonsurgical treatment of Dupuytren’s disease. J Hand Surg Am. 2000;25(4):629-636.

5. Badalamente MA, Hurst LC, Hentz VR. Collagen as a clinical target: nonoperative treatment of Dupuytren’s disease. J Hand Surg Am. 2002;27(5):788-798.

6. Hurst LC, Badalamente MA, Hentz VR, et al; CORD I Study Group. Injectable collagenase Clostridium histolyticum for Dupuytren’s contracture. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(10):968-979.

7. Mookhtiar KA, Van Wart HE. Clostridium histolyticum collagenases: a new look at some old enzymes. Matrix Suppl. 1992;1:116-126.

8. Watanabe K. Collagenolytic proteases from bacteria. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2004;63(5):520-526.

9. Wang AS, Armstrong EJ, Armstrong AW. Corticosteroids and wound healing: clinical considerations in the perioperative period. Am J Surg. 2013;206(3):410-417.

10. Denkler K. Surgical complications associated with fasciectomy for Dupuytren’s disease: a 20-year review of the English literature. Eplasty. 2010;10:e15.

11. Stuck AE, Minder CE, Frey FJ. Risk of infectious complications in patients taking glucocorticosteroids. Rev Infect Dis. 1989;11(6):954-963.

12. Oikarinen A, Autio P. New aspects of the mechanism of corticosteroid-induced dermal atrophy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1991;16(6):416-419.

13. Makinodan T, Santos GW, Quinn RP. Immunosuppressive drugs. Pharmacol Rev. 1970;22(2):189-247.

14. Röllinghoff M, Schrader J, Wagner H. Effect of azathioprine and cytosine arabinoside on humoral and cellular immunity in vitro. Clin Exp Immunol. 1973;15(2):261-269.

15. Genestier L, Paillot R, Fournel S, Ferraro C, Miossec P, Revillard JP. Immunosuppressive properties of methotrexate: apoptosis and clonal deletion of activated peripheral T cells. J Clin Invest. 1998;102(2):322-328.

16. Desai SS, Hentz VR. Collagenase Clostridium histolyticum for Dupuytren’s contracture. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2010;10(9):1395-1404.

The incidence of Dupuytren disease increases with advancing age,1 as do the medical comorbidities of patients seeking treatment for disabling hand contractures. For patients with significant comorbidities, open surgical fasciectomy, the current standard of treatment for Dupuytren disease,2,3 may be associated with increased perioperative risks.

Collagenase enzymatic fasciotomy has become an accepted nonsurgical treatment alternative to traditional fasciectomy or surgical fasciotomy for significant digital contractures caused by Dupuytren disease.4-6 Clostridium histolyticum collagenase (CHC) is a foreign protein, made up of 2 collagenases isolated from the bacteria C histolyticum.7 The collagenases are zinc-dependent matrix metalloproteinases that cleave the triple helical structure of collagen molecules.8 Also known as Xiaflex (Auxilium Pharmaceuticals), CHC was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in February 2010 for use in patients with Dupuytren contractures.

Enzymatic rupture is safe and efficacious at midterm follow-up and offers the theoretical advantage of avoiding palmar and digital fasciectomy and the associated risks of surgical-site infection and wound-healing complications.6 The risks of surgical wound complications are magnified in immunosuppressed patients, particularly those on chronic steroid therapy; wound-healing complication rates may be increased 2 to 5 times compared with controls.9 In a pooled literature review, wound-healing complications were reported after 22.9% of open primary fasciectomies, with infection occurring in 2.4%.10 A nonsurgical alternative is therefore particularly appealing for a patient cohort that may be at higher risk for a frequently described complication of surgery for Dupuytren contracture.

The exclusion criteria in the trials for FDA approval were extensive and included breast-feeding, pregnancy, bleeding disorder, recent stroke, use of tetracycline derivative within 14 days before start of study, use of anticoagulant within 7 days before start of study, allergy to collagenase, and chronic muscular, neurologic, or neuromuscular disorder affecting the hands.6 Safety and efficacy of collagenase in patients requiring chronic immunosuppressive therapy for medical comorbidities have not been previously documented. Furthermore, although skin tears were reported in 11% of patients after manual cord rupture in the CORD (Collagenase Option for the Reduction of Dupuytren’s) I trial,6 the likelihood of deep and superficial infection and delayed wound healing has not been quantitated.

In this article, we report on outcomes of 13 collagenase enzymatic fasciotomies performed in 8 patients who were on chronic immunosuppressive therapy.

Methods

Institutional review board approval was obtained at both academic hand surgery institutions. We retrospectively reviewed prospectively collected clinical data within our 2 centers’ databases of patients with Dupuytren disease. Eight patients on chronic immunosuppressive therapies treated with collagenase for metacarpophalangeal (MP) or proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint contractures between February 2010 and December 2011 were identified. Three of these patients received collagenase injections into 2 or more separate Dupuytren cords at different encounters, resulting in a total of 13 individual collagenase enzymatic fasciotomies.

Collagenase injections were administered following CORD I trial protocol,6 except we injected Dupuytren cords crossing the PIP joint using a lateral approach to minimize risk of flexor tendon rupture. Manipulation of the treated joint was performed between 24 and 48 hours after collagenase injection under local anesthesia with 3 mL of 1% mepivacaine or lidocaine without epinephrine. After manipulation and cord rupture, patients were placed in a hand-based extension splint to wear at night for up to 3 months. Patients were followed at 1 and 12 months.

Results

Patients’ baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Four patients were maintained on chronic prednisone therapy, 3 on methotrexate, and 1 on azathioprine. Therapy duration, medication dose, and diagnoses requiring immunosuppressant therapy varied among patients.

Outcomes and adverse events are summarized in Table 2. Mean number of joint contractures per hand treated was 2.8 (MP, 1.4; PIP, 1.4). However, not all joints met the intervention criteria. Of the 13 joints treated, 7 were MP joints, and 6 were PIP joints. Mean preinjection contracture of the treated joints was 53.0° (range, 20°-90°). Twelve of the 13 joint contractures improved. At mean follow-up of 6.7 months (range, 1-22 months), mean magnitude of contracture improved to 12.9° (range, 0°-45°). Mean MP joint contracture improved from 42.0° to 4.2° (range, 0°-10°), and mean PIP joint contracture improved from 65.8° to 21.7° (range, 0°-45°).

All 13 collagenase injections were well tolerated, and there were no systemic reactions. Injection-site pain was common. Mild injection-site bruising and edema were reported in all cases. Enzymatic fasciotomy was performed in all patients, and immediate improvement in contracture after manipulation 24 to 48 hours after injection was recorded.

Three of the 13 injections were complicated by skin tears during manipulation and cord rupture. All 3 skin tears were treated with local wound care, which included use of povidone-iodine and wet-to-dry dressings. There was no evidence of subsequent superficial or deep, local or regional infection. In 2 cases, the wound healed within 1 week; in the third case, wound healing was present by 2 weeks. Once the wounds showed early re-epithelialization, hand-based extension splinting in a position of comfort was used at night for up to 3 months after injection. Two of the 13 injections were complicated by small blood blisters. These were treated with observation and resolved spontaneously.

Discussion

Collagenase enzymatic fasciotomy appeared to be a safe and efficacious alternative to surgical treatment of Dupuytren contractures in this cohort of patients maintained on chronic immunosuppressive agents. MP contractures responded more substantially than PIP contractures did, as expected.6 No previously undescribed adverse outcomes were noted in these 8 patients on chronic immunosuppressive therapy beyond those reported in the CORD I trial. Three (23%) of the 13 collagenase injections in our series were complicated by skin tears after manipulation. Skins tears were reported in 22 (11%) of 204 patients after manual cord rupture in the CORD I trial.6 Given the limited numbers in this series, it remains unclear if chronic immunosuppression truly increases the risk of skin tears in this subset of patients. Other common treatment-related adverse events seen in the CORD I trial—injection-site hemorrhage (37%), pruritis (11%) and lymphadenopathy (10%)—were not seen after the 13 injections in our case series. We are prospectively following all patients with Dupuytren disease, and this is an area of ongoing research at our centers.

The immunosuppressive actions of prednisone, azathioprine, and methotrexate are well documented. Prednisone is a glucocorticoid, converted in the liver to prednisolone, which suppresses inflammation and immune responses by regulation of gene expression. Its immunosuppressive actions are multifactorial, relating to inhibition of lymphocytes, neutrophils, and monocytes. These effects are dose- and time-dependent11 and may become evident in patients receiving low doses over prolonged periods. Skin atrophy12 and delayed wound healing9 are side effects of long-term prednisone use. Skin atrophy may make the prednisone-treated patient more susceptible to skin tears after collagenase injection and manipulation. Azathioprine inhibits purine synthesis, which is especially important in the proliferation of immune cells.13 It has been shown to inhibit both cellular immunity at low doses and humoral immunity at higher doses.14 Methotrexate inhibits lymphocyte folic acid metabolism. The immunosuppressive properties of low-dose methotrexate have been linked to the induction of apoptosis in activated T cells.15

A more complex process in immunosuppressed patients is the immunogenicity of injected collagenase. As CHC in current use is a mixture of 2 foreign proteins, an immunologic response is expected in the host after injection. It has been shown that, after 3 injections of CHC into Dupuytren cords, 100% of patients developed antibodies to both enzymes in their serum.6 More than 85% demonstrated anti-CHC antibodies after a single injection. However, no patients showed signs of anaphylaxis or allergic reaction, and there was no correlation between serum levels of anti-CHC and adverse events. It has been hypothesized that there is a potential for cross-reactivity of the anti-CHC antibodies with human matrix metalloproteinases, causing enzymatic dysfunction within the host.16 This has yet to be reported clinically, and Xiaflex is currently under postmarketing surveillance. Immunocompromised people, with suppressed humoral and cellular immune responses, may produce less of an antibody response to the foreign CHC proteins. Whether this conclusively leads to a change in the side effect profile of the medication in these individuals is beyond the scope of this article. However, we identified no new side effects in this small but higher risk cohort. The issue should be continually monitored as collagenase is used in wider clinical settings.

Collagenase enzymatic fasciotomy is a new nonsurgical therapeutic option for Dupuytren disease. Indications and guidelines for use continue to evolve. This case series highlights the use of collagenase in 8 patients who were on long-term immunosuppressive therapy. This study has the limitations inherent to retrospective analyses. It is difficult to generalize results across broader immunosuppressed populations. A larger cohort, with long-term follow-up assessing recurrence of contracture, is needed to make definitive conclusions about use of collagenase in this challenging subset of patients. Based on our observations in this limited cohort, it appears appropriate to pursue further studies on use of collagenase enzymatic fasciotomy. A randomized, prospective or case–control series comparing surgical fasciectomy with enzymatic fasciotomy would yield further meaningful data. As more patients seek nonsurgical treatment for Dupuytren disease, its safety and efficacy in select cohorts of patients should continue to be evaluated.

The incidence of Dupuytren disease increases with advancing age,1 as do the medical comorbidities of patients seeking treatment for disabling hand contractures. For patients with significant comorbidities, open surgical fasciectomy, the current standard of treatment for Dupuytren disease,2,3 may be associated with increased perioperative risks.

Collagenase enzymatic fasciotomy has become an accepted nonsurgical treatment alternative to traditional fasciectomy or surgical fasciotomy for significant digital contractures caused by Dupuytren disease.4-6 Clostridium histolyticum collagenase (CHC) is a foreign protein, made up of 2 collagenases isolated from the bacteria C histolyticum.7 The collagenases are zinc-dependent matrix metalloproteinases that cleave the triple helical structure of collagen molecules.8 Also known as Xiaflex (Auxilium Pharmaceuticals), CHC was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in February 2010 for use in patients with Dupuytren contractures.

Enzymatic rupture is safe and efficacious at midterm follow-up and offers the theoretical advantage of avoiding palmar and digital fasciectomy and the associated risks of surgical-site infection and wound-healing complications.6 The risks of surgical wound complications are magnified in immunosuppressed patients, particularly those on chronic steroid therapy; wound-healing complication rates may be increased 2 to 5 times compared with controls.9 In a pooled literature review, wound-healing complications were reported after 22.9% of open primary fasciectomies, with infection occurring in 2.4%.10 A nonsurgical alternative is therefore particularly appealing for a patient cohort that may be at higher risk for a frequently described complication of surgery for Dupuytren contracture.

The exclusion criteria in the trials for FDA approval were extensive and included breast-feeding, pregnancy, bleeding disorder, recent stroke, use of tetracycline derivative within 14 days before start of study, use of anticoagulant within 7 days before start of study, allergy to collagenase, and chronic muscular, neurologic, or neuromuscular disorder affecting the hands.6 Safety and efficacy of collagenase in patients requiring chronic immunosuppressive therapy for medical comorbidities have not been previously documented. Furthermore, although skin tears were reported in 11% of patients after manual cord rupture in the CORD (Collagenase Option for the Reduction of Dupuytren’s) I trial,6 the likelihood of deep and superficial infection and delayed wound healing has not been quantitated.

In this article, we report on outcomes of 13 collagenase enzymatic fasciotomies performed in 8 patients who were on chronic immunosuppressive therapy.

Methods

Institutional review board approval was obtained at both academic hand surgery institutions. We retrospectively reviewed prospectively collected clinical data within our 2 centers’ databases of patients with Dupuytren disease. Eight patients on chronic immunosuppressive therapies treated with collagenase for metacarpophalangeal (MP) or proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint contractures between February 2010 and December 2011 were identified. Three of these patients received collagenase injections into 2 or more separate Dupuytren cords at different encounters, resulting in a total of 13 individual collagenase enzymatic fasciotomies.

Collagenase injections were administered following CORD I trial protocol,6 except we injected Dupuytren cords crossing the PIP joint using a lateral approach to minimize risk of flexor tendon rupture. Manipulation of the treated joint was performed between 24 and 48 hours after collagenase injection under local anesthesia with 3 mL of 1% mepivacaine or lidocaine without epinephrine. After manipulation and cord rupture, patients were placed in a hand-based extension splint to wear at night for up to 3 months. Patients were followed at 1 and 12 months.

Results

Patients’ baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Four patients were maintained on chronic prednisone therapy, 3 on methotrexate, and 1 on azathioprine. Therapy duration, medication dose, and diagnoses requiring immunosuppressant therapy varied among patients.

Outcomes and adverse events are summarized in Table 2. Mean number of joint contractures per hand treated was 2.8 (MP, 1.4; PIP, 1.4). However, not all joints met the intervention criteria. Of the 13 joints treated, 7 were MP joints, and 6 were PIP joints. Mean preinjection contracture of the treated joints was 53.0° (range, 20°-90°). Twelve of the 13 joint contractures improved. At mean follow-up of 6.7 months (range, 1-22 months), mean magnitude of contracture improved to 12.9° (range, 0°-45°). Mean MP joint contracture improved from 42.0° to 4.2° (range, 0°-10°), and mean PIP joint contracture improved from 65.8° to 21.7° (range, 0°-45°).

All 13 collagenase injections were well tolerated, and there were no systemic reactions. Injection-site pain was common. Mild injection-site bruising and edema were reported in all cases. Enzymatic fasciotomy was performed in all patients, and immediate improvement in contracture after manipulation 24 to 48 hours after injection was recorded.

Three of the 13 injections were complicated by skin tears during manipulation and cord rupture. All 3 skin tears were treated with local wound care, which included use of povidone-iodine and wet-to-dry dressings. There was no evidence of subsequent superficial or deep, local or regional infection. In 2 cases, the wound healed within 1 week; in the third case, wound healing was present by 2 weeks. Once the wounds showed early re-epithelialization, hand-based extension splinting in a position of comfort was used at night for up to 3 months after injection. Two of the 13 injections were complicated by small blood blisters. These were treated with observation and resolved spontaneously.

Discussion

Collagenase enzymatic fasciotomy appeared to be a safe and efficacious alternative to surgical treatment of Dupuytren contractures in this cohort of patients maintained on chronic immunosuppressive agents. MP contractures responded more substantially than PIP contractures did, as expected.6 No previously undescribed adverse outcomes were noted in these 8 patients on chronic immunosuppressive therapy beyond those reported in the CORD I trial. Three (23%) of the 13 collagenase injections in our series were complicated by skin tears after manipulation. Skins tears were reported in 22 (11%) of 204 patients after manual cord rupture in the CORD I trial.6 Given the limited numbers in this series, it remains unclear if chronic immunosuppression truly increases the risk of skin tears in this subset of patients. Other common treatment-related adverse events seen in the CORD I trial—injection-site hemorrhage (37%), pruritis (11%) and lymphadenopathy (10%)—were not seen after the 13 injections in our case series. We are prospectively following all patients with Dupuytren disease, and this is an area of ongoing research at our centers.

The immunosuppressive actions of prednisone, azathioprine, and methotrexate are well documented. Prednisone is a glucocorticoid, converted in the liver to prednisolone, which suppresses inflammation and immune responses by regulation of gene expression. Its immunosuppressive actions are multifactorial, relating to inhibition of lymphocytes, neutrophils, and monocytes. These effects are dose- and time-dependent11 and may become evident in patients receiving low doses over prolonged periods. Skin atrophy12 and delayed wound healing9 are side effects of long-term prednisone use. Skin atrophy may make the prednisone-treated patient more susceptible to skin tears after collagenase injection and manipulation. Azathioprine inhibits purine synthesis, which is especially important in the proliferation of immune cells.13 It has been shown to inhibit both cellular immunity at low doses and humoral immunity at higher doses.14 Methotrexate inhibits lymphocyte folic acid metabolism. The immunosuppressive properties of low-dose methotrexate have been linked to the induction of apoptosis in activated T cells.15

A more complex process in immunosuppressed patients is the immunogenicity of injected collagenase. As CHC in current use is a mixture of 2 foreign proteins, an immunologic response is expected in the host after injection. It has been shown that, after 3 injections of CHC into Dupuytren cords, 100% of patients developed antibodies to both enzymes in their serum.6 More than 85% demonstrated anti-CHC antibodies after a single injection. However, no patients showed signs of anaphylaxis or allergic reaction, and there was no correlation between serum levels of anti-CHC and adverse events. It has been hypothesized that there is a potential for cross-reactivity of the anti-CHC antibodies with human matrix metalloproteinases, causing enzymatic dysfunction within the host.16 This has yet to be reported clinically, and Xiaflex is currently under postmarketing surveillance. Immunocompromised people, with suppressed humoral and cellular immune responses, may produce less of an antibody response to the foreign CHC proteins. Whether this conclusively leads to a change in the side effect profile of the medication in these individuals is beyond the scope of this article. However, we identified no new side effects in this small but higher risk cohort. The issue should be continually monitored as collagenase is used in wider clinical settings.

Collagenase enzymatic fasciotomy is a new nonsurgical therapeutic option for Dupuytren disease. Indications and guidelines for use continue to evolve. This case series highlights the use of collagenase in 8 patients who were on long-term immunosuppressive therapy. This study has the limitations inherent to retrospective analyses. It is difficult to generalize results across broader immunosuppressed populations. A larger cohort, with long-term follow-up assessing recurrence of contracture, is needed to make definitive conclusions about use of collagenase in this challenging subset of patients. Based on our observations in this limited cohort, it appears appropriate to pursue further studies on use of collagenase enzymatic fasciotomy. A randomized, prospective or case–control series comparing surgical fasciectomy with enzymatic fasciotomy would yield further meaningful data. As more patients seek nonsurgical treatment for Dupuytren disease, its safety and efficacy in select cohorts of patients should continue to be evaluated.

1. Loos B, Puschkin V, Horch RE. 50 years experience with Dupuytren’s contracture in the Erlangen University Hospital—a retrospective analysis of 2919 operated hands from 1956 to 2006. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2007;8:60.

2. Coert JH, Nérin JP, Meek MF. Results of partial fasciectomy for Dupuytren disease in 261 consecutive patients. Ann Plast Surg. 2006;57(1):13-17.

3. Sennwald GR. Fasciectomy for treatment of Dupuytren’s disease and early complications. J Hand Surg Am. 1990;15(5):755-761.

4. Badalamente MA, Hurst LC. Enzyme injection as nonsurgical treatment of Dupuytren’s disease. J Hand Surg Am. 2000;25(4):629-636.

5. Badalamente MA, Hurst LC, Hentz VR. Collagen as a clinical target: nonoperative treatment of Dupuytren’s disease. J Hand Surg Am. 2002;27(5):788-798.

6. Hurst LC, Badalamente MA, Hentz VR, et al; CORD I Study Group. Injectable collagenase Clostridium histolyticum for Dupuytren’s contracture. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(10):968-979.

7. Mookhtiar KA, Van Wart HE. Clostridium histolyticum collagenases: a new look at some old enzymes. Matrix Suppl. 1992;1:116-126.

8. Watanabe K. Collagenolytic proteases from bacteria. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2004;63(5):520-526.

9. Wang AS, Armstrong EJ, Armstrong AW. Corticosteroids and wound healing: clinical considerations in the perioperative period. Am J Surg. 2013;206(3):410-417.

10. Denkler K. Surgical complications associated with fasciectomy for Dupuytren’s disease: a 20-year review of the English literature. Eplasty. 2010;10:e15.

11. Stuck AE, Minder CE, Frey FJ. Risk of infectious complications in patients taking glucocorticosteroids. Rev Infect Dis. 1989;11(6):954-963.

12. Oikarinen A, Autio P. New aspects of the mechanism of corticosteroid-induced dermal atrophy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1991;16(6):416-419.

13. Makinodan T, Santos GW, Quinn RP. Immunosuppressive drugs. Pharmacol Rev. 1970;22(2):189-247.

14. Röllinghoff M, Schrader J, Wagner H. Effect of azathioprine and cytosine arabinoside on humoral and cellular immunity in vitro. Clin Exp Immunol. 1973;15(2):261-269.

15. Genestier L, Paillot R, Fournel S, Ferraro C, Miossec P, Revillard JP. Immunosuppressive properties of methotrexate: apoptosis and clonal deletion of activated peripheral T cells. J Clin Invest. 1998;102(2):322-328.

16. Desai SS, Hentz VR. Collagenase Clostridium histolyticum for Dupuytren’s contracture. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2010;10(9):1395-1404.

1. Loos B, Puschkin V, Horch RE. 50 years experience with Dupuytren’s contracture in the Erlangen University Hospital—a retrospective analysis of 2919 operated hands from 1956 to 2006. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2007;8:60.

2. Coert JH, Nérin JP, Meek MF. Results of partial fasciectomy for Dupuytren disease in 261 consecutive patients. Ann Plast Surg. 2006;57(1):13-17.

3. Sennwald GR. Fasciectomy for treatment of Dupuytren’s disease and early complications. J Hand Surg Am. 1990;15(5):755-761.

4. Badalamente MA, Hurst LC. Enzyme injection as nonsurgical treatment of Dupuytren’s disease. J Hand Surg Am. 2000;25(4):629-636.

5. Badalamente MA, Hurst LC, Hentz VR. Collagen as a clinical target: nonoperative treatment of Dupuytren’s disease. J Hand Surg Am. 2002;27(5):788-798.

6. Hurst LC, Badalamente MA, Hentz VR, et al; CORD I Study Group. Injectable collagenase Clostridium histolyticum for Dupuytren’s contracture. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(10):968-979.

7. Mookhtiar KA, Van Wart HE. Clostridium histolyticum collagenases: a new look at some old enzymes. Matrix Suppl. 1992;1:116-126.

8. Watanabe K. Collagenolytic proteases from bacteria. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2004;63(5):520-526.

9. Wang AS, Armstrong EJ, Armstrong AW. Corticosteroids and wound healing: clinical considerations in the perioperative period. Am J Surg. 2013;206(3):410-417.

10. Denkler K. Surgical complications associated with fasciectomy for Dupuytren’s disease: a 20-year review of the English literature. Eplasty. 2010;10:e15.

11. Stuck AE, Minder CE, Frey FJ. Risk of infectious complications in patients taking glucocorticosteroids. Rev Infect Dis. 1989;11(6):954-963.

12. Oikarinen A, Autio P. New aspects of the mechanism of corticosteroid-induced dermal atrophy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1991;16(6):416-419.

13. Makinodan T, Santos GW, Quinn RP. Immunosuppressive drugs. Pharmacol Rev. 1970;22(2):189-247.

14. Röllinghoff M, Schrader J, Wagner H. Effect of azathioprine and cytosine arabinoside on humoral and cellular immunity in vitro. Clin Exp Immunol. 1973;15(2):261-269.

15. Genestier L, Paillot R, Fournel S, Ferraro C, Miossec P, Revillard JP. Immunosuppressive properties of methotrexate: apoptosis and clonal deletion of activated peripheral T cells. J Clin Invest. 1998;102(2):322-328.

16. Desai SS, Hentz VR. Collagenase Clostridium histolyticum for Dupuytren’s contracture. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2010;10(9):1395-1404.

Open Carpal Tunnel Release With Use of a Nasal Turbinate Speculum

Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) is a disorder characterized by entrapment of the median nerve at the wrist, which may lead to symptoms of pain, paresthesia, and, ultimately, thenar muscle atrophy. Surgical intervention is indicated with persistent or progressive symptoms despite nonoperative management. Timely surgical decompression aims to halt progression of this disorder and prevent permanent peripheral nerve injury.

Carpal tunnel release (CTR) is the most common hand and wrist surgery in the United States, with about 400,000 operations performed annually.1,2 Several methods of decompressing the carpal tunnel have been described.3 These include standard open CTR (OCTR), mini-open approaches, and various endoscopic techniques. OCTR was initially described by Sir James Learmonth in 1933,4 and it remains the gold-standard surgical treatment for patients with symptomatic CTS. Uniform excellent results with high patient satisfaction and low complication rates have been reported in several series.5-9 Common to all techniques is complete proximal-to-distal division of the transverse carpal ligament (TCL). Magnetic resonance imaging studies have shown that TCL transection and the resulting diastasis between the radial and ulnar leaflets cause a significant increase in the volume of the carpal tunnel, leading to decreased pressure.10,11

Endoscopic CTR (ECTR) techniques were developed in an effort to reduce complications, scar sensitivity, and pillar pain and facilitate more rapid return to work.12-17 Outcome studies have demonstrated that both open and endoscopic releases yield patient-reported subjective improvements over preoperative symptoms.18-22 A randomized, controlled trial by Trumble and colleagues23 in 2002 found that ECTR led to improved patient outcomes in the early postoperative period (first 3 months), though differences in outcomes were reduced at final follow-up. More recently (2007), a Cochrane review of 33 trials concluded there was no strong evidence favoring use of alternative techniques over OCTR.3 Further, OCTR has been found to be technically less demanding and associated with decreased complications and costs.24

Indications

The benefit of median nerve decompression at the wrist for CTS is clear.6,7 Indications for surgery in patients with CTS include persistent symptoms despite nonoperative treatment, objective sensory disturbance or motor weakness, and thenar atrophy. Symptomatic response to corticosteroid injection is predictive of success after carpal tunnel surgery.25 More than 87% of patients who gain symptomatic relief from corticosteroid injection have an excellent surgical outcome.

Technique

OCTR allows direct visualization of the TCL and the distal volar forearm fascia (DVFF) and evaluation for the presence of anomalous branching patterns of the median nerve. OCTR traditionally was performed through a 4- to 5-cm longitudinal incision extending from the wrist crease proximally to the Kaplan cardinal line distally. The mini-open technique is identical with the exception of incision length. We routinely use a 2.5- to 3-cm incision. Regardless of incision length, each OCTR should proceed through the same reproducible steps.

We perform OCTR under tourniquet control. Choice of anesthesia is surgeon and patient preference. We prefer local anesthesia with conscious sedation. After conscious sedation is administered, we infiltrate the carpal tunnel and surrounding subcutaneous tissue with 10 mL of a 50:50 mixture of 0.5% bupivacaine and 1% lidocaine without epinephrine.

A 2.5- to 3-cm longitudinal incision is made along the axis of the radial border of the ring finger from the Kaplan cardinal line26 and extending about 3 cm proximally toward the wrist flexion crease ulnar to the palmaris longus if present (Figure 1).

After the skin is incised longitudinally, the subcutaneous fat is mobilized and cutaneous sensory branches identified and protected. The underlying superficial palmar fascia is incised in line with the skin incision. The underlying midportion of the TCL is now visualized.

Transverse Carpal Ligament Release

Occasionally, the investing fascia along the ulnar edge of the thenar musculature is mobilized radialward (if the thenar musculature is well developed) to visualize the proximal limb of the TCL. Injury to any anomalous motor branch of the median nerve is avoided by directly visualizing and then incising the TCL (Figure 2). The TCL is incised along its ulnar border just radial to the hook of hamate from distal to proximal in line with the radial border of the ring finger. Staying near the ulnar attachment of the TCL keeps the plane of ligament division farther away from the median nerve and its recurrent motor branches. Although the ulnar neurovascular bundle typically resides ulnar to the hook of hamate in the canal of Guyon, the surgeon must be aware that it can be located radial to the hook in some instances.27,28 In the elderly, the ulnar artery may be tortuous and enter the field and require retraction. The TCL is incised distally until the sentinel fat pad, which marks the superficial palmar arterial arch, is visualized. This bed of adipose tissue marks the distal edge of the TCL.29

Proximally, subcutaneous tissues above the proximal limb of the TCL and DVFF are mobilized to about 2 cm proximal to the wrist flexion crease to create a plane for the fine long nasal turbinate speculum. The nasal turbinate speculum is then inserted into this plane above the proximal limb of the TCL and DVFF (Figure 3). Once inserted to the level of the confluence of the TCL and the DVFF, the speculum is opened.

Topside visualization is now encountered with the ulnar neurovascular bundle protected by the ulnar blade of the speculum. A long-handle scalpel is used to incise the TCL and the DVFF under direct visualization from proximal to distal in line with the previously completed distal release (Figure 4). As the nasal turbinate speculum is stretching the TCL and putting it under tension, the TCL can be heard splitting as it is being incised. Once the TCL and the DVFF are divided, the speculum is slowly closed and removed. Wide diastasis of the radial and ulnar leaflets of the TCL and the DVFF is directly visualized. Complete decompression of the median nerve from the distal forearm fascia to the superficial palmar arch is confirmed.

Adhesions between the undersurface of the radial leaflet and the flexor tendons and median nerve are mobilized. The median nerve is assessed for “hourglass” morphology or atrophy. The flexor tendons can be swept radialward with a free elevator to inspect the floor of the carpal tunnel. Flexor tenosynovectomy is not routinely performed. The incision is closed with interrupted simple sutures using 4-0 nylon.

Study Results

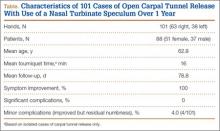

This study was conducted at Hand Surgery PC, Newton-Wellesley Hospital, Tufts University School of Medicine. Over a 10-month interval, 101 consecutive mini-OCTRs (63 right hands, 38 left hands) were performed with this proximal release modification in 88 patients (51 females, 37 males) by Dr. Ruchelsman and Dr. Belsky (Table). CTRs performed in the setting of wrist and/or carpal trauma were excluded. Mean age was 62.8 years. Mean follow-up was 11.3 weeks (~3 months). For isolated cases of CTR, mean tourniquet time was 16 minutes. CTS symptoms were relieved in all patients with a high degree of satisfaction as measured with history and examination findings at follow-up visits. There were no major complications (eg, infection, neural or vascular damage, severe residual pain). Four patients reported minor residual numbness in the fingers at latest follow-up but nevertheless had major improvement over preoperative baseline. These 4 patients had preoperative electromyograms or nerve conduction studies documenting the extent of their disease. There was 1 case of minor wound complication. Three weeks after surgery, the patient had a 1-cm wound opening, which closed with local wound care. The patient did not develop any drainage, infection, bleeding, or neurologic symptoms.

Discussion

Open release of the TCL—the gold standard of surgical treatment for CTS—produces reliable symptom relief in the vast majority of patients.25,30 Given that the most common complication of carpal tunnel surgery is incomplete release of the TCL,31,32 this technique, which uses a nasal turbinate speculum to better visualize the median nerve, could potentially reduce the reoperation rate. The nasal turbinate speculum allows the surgeon to see the confluence of the TCL and the DVFF. In addition, as the complete release can be visualized, there is minimal chance of injury.

The 2007 Cochrane review3 found no strong evidence supporting replacing OCTR with endoscopic techniques. Previous investigators have questioned the utility of ECTR given that it is higher in cost and more resource-intensive than OCTR1,33,34 and is associated with higher rates of certain complications.5,22,35-37 A 2004 meta-analysis of 13 randomized, controlled trials found a higher rate of reversible nerve damage with an odds ratio of 3.1 for ECTR versus OCTR.35 A more recent (2006) review of more than 80 studies found transient neurapraxias in 1.45% of ECTR cases and 0.25% of OCTR cases.5 The same study reported overall complication rates (reversible and major neurovascular structural injuries) of 0.74% for OCTR and 1.63% for ECTR (P < .005). Another limitation of ECTR is that endoscopic techniques require a higher degree of surgical skill, which makes teaching residents and fellows more challenging.

The novel nasal turbinate speculum technique presented here is easily reproducible and allows first-time surgeons to visualize all important structures. Given that this technique does not require an endoscope or an endoscope-viewing tower, it is likely more cost-effective and requires less time for turnover between cases. Patients obtain good relief of their CTS symptoms with this technique, and most return to their daily activities within weeks after operation.

1. Ono S, Clapham PJ, Chung KC. Optimal management of carpal tunnel syndrome. Int J Gen Med. 2010;3(4):255-261.

2. Concannon MJ, Brownfield ML, Puckett CL. The incidence of recurrence after endoscopic carpal tunnel release. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105(5):1662-1665.

3. Scholten RJ, Mink van der Molen A, Uitdehaag BM, Bouter LM, de Vet HC. Surgical treatment options for carpal tunnel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD003905.

4. In memoriam Sir James Learmonth, K.C.V.O., C.B.E., hon. F.R.C.S. (1895-1967). Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1967;41(5):438-439.

5. Benson LS, Bare AA, Nagle DJ, Harder VS, Williams CS, Visotsky JL. Complications of endoscopic and open carpal tunnel release. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(9):919-924, 924.e1-e2.

6. Jarvik JG, Comstock BA, Kliot M, et al. Surgery versus non-surgical therapy for carpal tunnel syndrome: a randomised parallel-group trial. Lancet. 2009;374(9695):1074-1081.

7. Verdugo RJ, Salinas RA, Castillo JL, et al. Surgical versus non-surgical treatment for carpal tunnel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(4):CD001552.

8. Garland H, Langworth EP, Taverner D, et al. Surgical treatment for the carpal tunnel syndrome. Lancet. 1964;1(7343):1129-1130.

9. Gerritsen AA, de Vet HC, Scholten RJ, et al. Splinting vs surgery in the treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288(10):1245-1251.

10. Gelberman RH, Hergenroeder PT, Hargens AR, et al. The carpal tunnel syndrome. A study of carpal canal pressures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1981;63(3):380-383.

11. Sucher BM. Myofascial manipulative release of carpal tunnel syndrome: documentation with magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 1993;93(12):1273-1278.

12. Pereira EE, Miranda DA, Sere I, et al. Endoscopic release of the carpal tunnel: a 2-portal-modified technique. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg. 2010;14(4):263-265.

13. Louis DS, Greene TL, Noellert RC. Complications of carpal tunnel surgery. J Neurosurg. 1985;62(3):352-356.

14. Mirza MA, King ET Jr, Tanveer S. Palmar uniportal extrabursal endoscopic carpal tunnel release. Arthroscopy. 1995;11(1):82-90.

15. Brown MG, Keyser B, Rothenberg ES. Endoscopic carpal tunnel release. J Hand Surg Am. 1992;17(6):1009-1011.

16. Agee JM, McCarroll HR Jr, Tortosa RD, et al. Endoscopic release of the carpal tunnel: a randomized prospective multicenter study. J Hand Surg Am. 1992;17(6):987-995.

17. Okutsu I, Ninomiya S, Takatori Y, et al. Endoscopic management of carpal tunnel syndrome. Arthroscopy. 1989;5(1):11-18.

18. Ghaly RF, Saban KL, Haley DA, et al. Endoscopic carpal tunnel release surgery: report of patient satisfaction. Neurol Res. 2000;22(6):551-555.

19. Lee WP, Plancher KD, Strickland JW. Carpal tunnel release with a small palmar incision. Hand Clin. 1996;12(2):271-284.

20. Biyani A, Downes EM. An open twin incision technique of carpal tunnel decompression with reduced incidence of scar tenderness. J Hand Surg Br. 1993;18(3):331-334.

21. Brown RA, Gelberman RH, Seiler JG 3rd, et al. Carpal tunnel release. A prospective, randomized assessment of open and endoscopic methods. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75(9):1265-1275.

22. Chow JC. Endoscopic release of the carpal ligament for carpal tunnel syndrome: 22-month clinical result. Arthroscopy. 1990;6(4):288-296.

23. Trumble TE, Diao E, Abrams RA, et al. Single-portal endoscopic carpal tunnel release compared with open release: a prospective, randomized trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84(7):1107-1115.

24. Gerritsen AA, Uitdehaag BM, van Geldere D, et al. Systematic review of randomized clinical trials of surgical treatment for carpal tunnel syndrome. Br J Surg. 2001;88(10):1285-1295.

25. Edgell SE, McCabe SJ, Breidenbach WC, et al. Predicting the outcome of carpal tunnel release. J Hand Surg Am. 2003;28(2):255-261.

26. Vella JC, Hartigan BJ, Stern PJ. Kaplan’s cardinal line. J Hand Surg Am. 2006;31(6):912-918.

27. Kwon JY, Kim JY, Hong JT, et al. Position change of the neurovascular structures around the carpal tunnel with dynamic wrist motion. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2011;50(4):377-380.

28. Netscher D, Polsen C, Thornby J, et al. Anatomic delineation of the ulnar nerve and ulnar artery in relation to the carpal tunnel by axial magnetic resonance imaging scanning. J Hand Surg Am. 1996;21(2):273-276.

29. Madhav TJ, To P, Stern PJ. The palmar fat pad is a reliable intraoperative landmark during carpal tunnel release. J Hand Surg Am. 2009;34(7):1204-1209.

30. Kulick MI, Gordillo G, Javidi T, et al. Long-term analysis of patients having surgical treatment for carpal tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg Am. 1986;11(1):59-66.

31. Bland JD. Treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome. Muscle Nerve. 2007;36(2):167-171.

32. MacDonald RI, Lichtman DM, Hanlon JJ, et al. Complications of surgical release for carpal tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg Am. 1978;3(1):70-76.

33. Atroshi I, Larsson GU, Ornstein E, Hofer M, Johnsson R, Ranstam J. Outcomes of endoscopic surgery compared with open surgery for carpal tunnel syndrome among employed patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2006;332(7556):1473.

34. Ferdinand RD, MacLean JG. Endoscopic versus open carpal tunnel release in bilateral carpal tunnel syndrome. A prospective, randomised, blinded assessment. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84(3):375-379.

35. Thoma A, Veltri K, Haines T, et al. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing endoscopic and open carpal tunnel decompression. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114(5):1137-1146.

36. Murphy RX Jr, Jennings JF, Wukich DK. Major neurovascular complications of endoscopic carpal tunnel release. J Hand Surg Am. 1994;19(1):114-118.

37. Palmer DH, Paulson JC, Lane-Larsen CL, et al. Endoscopic carpal tunnel release: a comparison of two techniques with open release. Arthroscopy. 1993;9(5):498-508.

Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) is a disorder characterized by entrapment of the median nerve at the wrist, which may lead to symptoms of pain, paresthesia, and, ultimately, thenar muscle atrophy. Surgical intervention is indicated with persistent or progressive symptoms despite nonoperative management. Timely surgical decompression aims to halt progression of this disorder and prevent permanent peripheral nerve injury.

Carpal tunnel release (CTR) is the most common hand and wrist surgery in the United States, with about 400,000 operations performed annually.1,2 Several methods of decompressing the carpal tunnel have been described.3 These include standard open CTR (OCTR), mini-open approaches, and various endoscopic techniques. OCTR was initially described by Sir James Learmonth in 1933,4 and it remains the gold-standard surgical treatment for patients with symptomatic CTS. Uniform excellent results with high patient satisfaction and low complication rates have been reported in several series.5-9 Common to all techniques is complete proximal-to-distal division of the transverse carpal ligament (TCL). Magnetic resonance imaging studies have shown that TCL transection and the resulting diastasis between the radial and ulnar leaflets cause a significant increase in the volume of the carpal tunnel, leading to decreased pressure.10,11

Endoscopic CTR (ECTR) techniques were developed in an effort to reduce complications, scar sensitivity, and pillar pain and facilitate more rapid return to work.12-17 Outcome studies have demonstrated that both open and endoscopic releases yield patient-reported subjective improvements over preoperative symptoms.18-22 A randomized, controlled trial by Trumble and colleagues23 in 2002 found that ECTR led to improved patient outcomes in the early postoperative period (first 3 months), though differences in outcomes were reduced at final follow-up. More recently (2007), a Cochrane review of 33 trials concluded there was no strong evidence favoring use of alternative techniques over OCTR.3 Further, OCTR has been found to be technically less demanding and associated with decreased complications and costs.24

Indications

The benefit of median nerve decompression at the wrist for CTS is clear.6,7 Indications for surgery in patients with CTS include persistent symptoms despite nonoperative treatment, objective sensory disturbance or motor weakness, and thenar atrophy. Symptomatic response to corticosteroid injection is predictive of success after carpal tunnel surgery.25 More than 87% of patients who gain symptomatic relief from corticosteroid injection have an excellent surgical outcome.

Technique

OCTR allows direct visualization of the TCL and the distal volar forearm fascia (DVFF) and evaluation for the presence of anomalous branching patterns of the median nerve. OCTR traditionally was performed through a 4- to 5-cm longitudinal incision extending from the wrist crease proximally to the Kaplan cardinal line distally. The mini-open technique is identical with the exception of incision length. We routinely use a 2.5- to 3-cm incision. Regardless of incision length, each OCTR should proceed through the same reproducible steps.

We perform OCTR under tourniquet control. Choice of anesthesia is surgeon and patient preference. We prefer local anesthesia with conscious sedation. After conscious sedation is administered, we infiltrate the carpal tunnel and surrounding subcutaneous tissue with 10 mL of a 50:50 mixture of 0.5% bupivacaine and 1% lidocaine without epinephrine.

A 2.5- to 3-cm longitudinal incision is made along the axis of the radial border of the ring finger from the Kaplan cardinal line26 and extending about 3 cm proximally toward the wrist flexion crease ulnar to the palmaris longus if present (Figure 1).

After the skin is incised longitudinally, the subcutaneous fat is mobilized and cutaneous sensory branches identified and protected. The underlying superficial palmar fascia is incised in line with the skin incision. The underlying midportion of the TCL is now visualized.

Transverse Carpal Ligament Release

Occasionally, the investing fascia along the ulnar edge of the thenar musculature is mobilized radialward (if the thenar musculature is well developed) to visualize the proximal limb of the TCL. Injury to any anomalous motor branch of the median nerve is avoided by directly visualizing and then incising the TCL (Figure 2). The TCL is incised along its ulnar border just radial to the hook of hamate from distal to proximal in line with the radial border of the ring finger. Staying near the ulnar attachment of the TCL keeps the plane of ligament division farther away from the median nerve and its recurrent motor branches. Although the ulnar neurovascular bundle typically resides ulnar to the hook of hamate in the canal of Guyon, the surgeon must be aware that it can be located radial to the hook in some instances.27,28 In the elderly, the ulnar artery may be tortuous and enter the field and require retraction. The TCL is incised distally until the sentinel fat pad, which marks the superficial palmar arterial arch, is visualized. This bed of adipose tissue marks the distal edge of the TCL.29

Proximally, subcutaneous tissues above the proximal limb of the TCL and DVFF are mobilized to about 2 cm proximal to the wrist flexion crease to create a plane for the fine long nasal turbinate speculum. The nasal turbinate speculum is then inserted into this plane above the proximal limb of the TCL and DVFF (Figure 3). Once inserted to the level of the confluence of the TCL and the DVFF, the speculum is opened.

Topside visualization is now encountered with the ulnar neurovascular bundle protected by the ulnar blade of the speculum. A long-handle scalpel is used to incise the TCL and the DVFF under direct visualization from proximal to distal in line with the previously completed distal release (Figure 4). As the nasal turbinate speculum is stretching the TCL and putting it under tension, the TCL can be heard splitting as it is being incised. Once the TCL and the DVFF are divided, the speculum is slowly closed and removed. Wide diastasis of the radial and ulnar leaflets of the TCL and the DVFF is directly visualized. Complete decompression of the median nerve from the distal forearm fascia to the superficial palmar arch is confirmed.

Adhesions between the undersurface of the radial leaflet and the flexor tendons and median nerve are mobilized. The median nerve is assessed for “hourglass” morphology or atrophy. The flexor tendons can be swept radialward with a free elevator to inspect the floor of the carpal tunnel. Flexor tenosynovectomy is not routinely performed. The incision is closed with interrupted simple sutures using 4-0 nylon.

Study Results

This study was conducted at Hand Surgery PC, Newton-Wellesley Hospital, Tufts University School of Medicine. Over a 10-month interval, 101 consecutive mini-OCTRs (63 right hands, 38 left hands) were performed with this proximal release modification in 88 patients (51 females, 37 males) by Dr. Ruchelsman and Dr. Belsky (Table). CTRs performed in the setting of wrist and/or carpal trauma were excluded. Mean age was 62.8 years. Mean follow-up was 11.3 weeks (~3 months). For isolated cases of CTR, mean tourniquet time was 16 minutes. CTS symptoms were relieved in all patients with a high degree of satisfaction as measured with history and examination findings at follow-up visits. There were no major complications (eg, infection, neural or vascular damage, severe residual pain). Four patients reported minor residual numbness in the fingers at latest follow-up but nevertheless had major improvement over preoperative baseline. These 4 patients had preoperative electromyograms or nerve conduction studies documenting the extent of their disease. There was 1 case of minor wound complication. Three weeks after surgery, the patient had a 1-cm wound opening, which closed with local wound care. The patient did not develop any drainage, infection, bleeding, or neurologic symptoms.

Discussion

Open release of the TCL—the gold standard of surgical treatment for CTS—produces reliable symptom relief in the vast majority of patients.25,30 Given that the most common complication of carpal tunnel surgery is incomplete release of the TCL,31,32 this technique, which uses a nasal turbinate speculum to better visualize the median nerve, could potentially reduce the reoperation rate. The nasal turbinate speculum allows the surgeon to see the confluence of the TCL and the DVFF. In addition, as the complete release can be visualized, there is minimal chance of injury.

The 2007 Cochrane review3 found no strong evidence supporting replacing OCTR with endoscopic techniques. Previous investigators have questioned the utility of ECTR given that it is higher in cost and more resource-intensive than OCTR1,33,34 and is associated with higher rates of certain complications.5,22,35-37 A 2004 meta-analysis of 13 randomized, controlled trials found a higher rate of reversible nerve damage with an odds ratio of 3.1 for ECTR versus OCTR.35 A more recent (2006) review of more than 80 studies found transient neurapraxias in 1.45% of ECTR cases and 0.25% of OCTR cases.5 The same study reported overall complication rates (reversible and major neurovascular structural injuries) of 0.74% for OCTR and 1.63% for ECTR (P < .005). Another limitation of ECTR is that endoscopic techniques require a higher degree of surgical skill, which makes teaching residents and fellows more challenging.

The novel nasal turbinate speculum technique presented here is easily reproducible and allows first-time surgeons to visualize all important structures. Given that this technique does not require an endoscope or an endoscope-viewing tower, it is likely more cost-effective and requires less time for turnover between cases. Patients obtain good relief of their CTS symptoms with this technique, and most return to their daily activities within weeks after operation.

Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) is a disorder characterized by entrapment of the median nerve at the wrist, which may lead to symptoms of pain, paresthesia, and, ultimately, thenar muscle atrophy. Surgical intervention is indicated with persistent or progressive symptoms despite nonoperative management. Timely surgical decompression aims to halt progression of this disorder and prevent permanent peripheral nerve injury.

Carpal tunnel release (CTR) is the most common hand and wrist surgery in the United States, with about 400,000 operations performed annually.1,2 Several methods of decompressing the carpal tunnel have been described.3 These include standard open CTR (OCTR), mini-open approaches, and various endoscopic techniques. OCTR was initially described by Sir James Learmonth in 1933,4 and it remains the gold-standard surgical treatment for patients with symptomatic CTS. Uniform excellent results with high patient satisfaction and low complication rates have been reported in several series.5-9 Common to all techniques is complete proximal-to-distal division of the transverse carpal ligament (TCL). Magnetic resonance imaging studies have shown that TCL transection and the resulting diastasis between the radial and ulnar leaflets cause a significant increase in the volume of the carpal tunnel, leading to decreased pressure.10,11

Endoscopic CTR (ECTR) techniques were developed in an effort to reduce complications, scar sensitivity, and pillar pain and facilitate more rapid return to work.12-17 Outcome studies have demonstrated that both open and endoscopic releases yield patient-reported subjective improvements over preoperative symptoms.18-22 A randomized, controlled trial by Trumble and colleagues23 in 2002 found that ECTR led to improved patient outcomes in the early postoperative period (first 3 months), though differences in outcomes were reduced at final follow-up. More recently (2007), a Cochrane review of 33 trials concluded there was no strong evidence favoring use of alternative techniques over OCTR.3 Further, OCTR has been found to be technically less demanding and associated with decreased complications and costs.24

Indications

The benefit of median nerve decompression at the wrist for CTS is clear.6,7 Indications for surgery in patients with CTS include persistent symptoms despite nonoperative treatment, objective sensory disturbance or motor weakness, and thenar atrophy. Symptomatic response to corticosteroid injection is predictive of success after carpal tunnel surgery.25 More than 87% of patients who gain symptomatic relief from corticosteroid injection have an excellent surgical outcome.

Technique

OCTR allows direct visualization of the TCL and the distal volar forearm fascia (DVFF) and evaluation for the presence of anomalous branching patterns of the median nerve. OCTR traditionally was performed through a 4- to 5-cm longitudinal incision extending from the wrist crease proximally to the Kaplan cardinal line distally. The mini-open technique is identical with the exception of incision length. We routinely use a 2.5- to 3-cm incision. Regardless of incision length, each OCTR should proceed through the same reproducible steps.

We perform OCTR under tourniquet control. Choice of anesthesia is surgeon and patient preference. We prefer local anesthesia with conscious sedation. After conscious sedation is administered, we infiltrate the carpal tunnel and surrounding subcutaneous tissue with 10 mL of a 50:50 mixture of 0.5% bupivacaine and 1% lidocaine without epinephrine.

A 2.5- to 3-cm longitudinal incision is made along the axis of the radial border of the ring finger from the Kaplan cardinal line26 and extending about 3 cm proximally toward the wrist flexion crease ulnar to the palmaris longus if present (Figure 1).

After the skin is incised longitudinally, the subcutaneous fat is mobilized and cutaneous sensory branches identified and protected. The underlying superficial palmar fascia is incised in line with the skin incision. The underlying midportion of the TCL is now visualized.

Transverse Carpal Ligament Release

Occasionally, the investing fascia along the ulnar edge of the thenar musculature is mobilized radialward (if the thenar musculature is well developed) to visualize the proximal limb of the TCL. Injury to any anomalous motor branch of the median nerve is avoided by directly visualizing and then incising the TCL (Figure 2). The TCL is incised along its ulnar border just radial to the hook of hamate from distal to proximal in line with the radial border of the ring finger. Staying near the ulnar attachment of the TCL keeps the plane of ligament division farther away from the median nerve and its recurrent motor branches. Although the ulnar neurovascular bundle typically resides ulnar to the hook of hamate in the canal of Guyon, the surgeon must be aware that it can be located radial to the hook in some instances.27,28 In the elderly, the ulnar artery may be tortuous and enter the field and require retraction. The TCL is incised distally until the sentinel fat pad, which marks the superficial palmar arterial arch, is visualized. This bed of adipose tissue marks the distal edge of the TCL.29

Proximally, subcutaneous tissues above the proximal limb of the TCL and DVFF are mobilized to about 2 cm proximal to the wrist flexion crease to create a plane for the fine long nasal turbinate speculum. The nasal turbinate speculum is then inserted into this plane above the proximal limb of the TCL and DVFF (Figure 3). Once inserted to the level of the confluence of the TCL and the DVFF, the speculum is opened.

Topside visualization is now encountered with the ulnar neurovascular bundle protected by the ulnar blade of the speculum. A long-handle scalpel is used to incise the TCL and the DVFF under direct visualization from proximal to distal in line with the previously completed distal release (Figure 4). As the nasal turbinate speculum is stretching the TCL and putting it under tension, the TCL can be heard splitting as it is being incised. Once the TCL and the DVFF are divided, the speculum is slowly closed and removed. Wide diastasis of the radial and ulnar leaflets of the TCL and the DVFF is directly visualized. Complete decompression of the median nerve from the distal forearm fascia to the superficial palmar arch is confirmed.

Adhesions between the undersurface of the radial leaflet and the flexor tendons and median nerve are mobilized. The median nerve is assessed for “hourglass” morphology or atrophy. The flexor tendons can be swept radialward with a free elevator to inspect the floor of the carpal tunnel. Flexor tenosynovectomy is not routinely performed. The incision is closed with interrupted simple sutures using 4-0 nylon.

Study Results

This study was conducted at Hand Surgery PC, Newton-Wellesley Hospital, Tufts University School of Medicine. Over a 10-month interval, 101 consecutive mini-OCTRs (63 right hands, 38 left hands) were performed with this proximal release modification in 88 patients (51 females, 37 males) by Dr. Ruchelsman and Dr. Belsky (Table). CTRs performed in the setting of wrist and/or carpal trauma were excluded. Mean age was 62.8 years. Mean follow-up was 11.3 weeks (~3 months). For isolated cases of CTR, mean tourniquet time was 16 minutes. CTS symptoms were relieved in all patients with a high degree of satisfaction as measured with history and examination findings at follow-up visits. There were no major complications (eg, infection, neural or vascular damage, severe residual pain). Four patients reported minor residual numbness in the fingers at latest follow-up but nevertheless had major improvement over preoperative baseline. These 4 patients had preoperative electromyograms or nerve conduction studies documenting the extent of their disease. There was 1 case of minor wound complication. Three weeks after surgery, the patient had a 1-cm wound opening, which closed with local wound care. The patient did not develop any drainage, infection, bleeding, or neurologic symptoms.

Discussion

Open release of the TCL—the gold standard of surgical treatment for CTS—produces reliable symptom relief in the vast majority of patients.25,30 Given that the most common complication of carpal tunnel surgery is incomplete release of the TCL,31,32 this technique, which uses a nasal turbinate speculum to better visualize the median nerve, could potentially reduce the reoperation rate. The nasal turbinate speculum allows the surgeon to see the confluence of the TCL and the DVFF. In addition, as the complete release can be visualized, there is minimal chance of injury.

The 2007 Cochrane review3 found no strong evidence supporting replacing OCTR with endoscopic techniques. Previous investigators have questioned the utility of ECTR given that it is higher in cost and more resource-intensive than OCTR1,33,34 and is associated with higher rates of certain complications.5,22,35-37 A 2004 meta-analysis of 13 randomized, controlled trials found a higher rate of reversible nerve damage with an odds ratio of 3.1 for ECTR versus OCTR.35 A more recent (2006) review of more than 80 studies found transient neurapraxias in 1.45% of ECTR cases and 0.25% of OCTR cases.5 The same study reported overall complication rates (reversible and major neurovascular structural injuries) of 0.74% for OCTR and 1.63% for ECTR (P < .005). Another limitation of ECTR is that endoscopic techniques require a higher degree of surgical skill, which makes teaching residents and fellows more challenging.

The novel nasal turbinate speculum technique presented here is easily reproducible and allows first-time surgeons to visualize all important structures. Given that this technique does not require an endoscope or an endoscope-viewing tower, it is likely more cost-effective and requires less time for turnover between cases. Patients obtain good relief of their CTS symptoms with this technique, and most return to their daily activities within weeks after operation.

1. Ono S, Clapham PJ, Chung KC. Optimal management of carpal tunnel syndrome. Int J Gen Med. 2010;3(4):255-261.

2. Concannon MJ, Brownfield ML, Puckett CL. The incidence of recurrence after endoscopic carpal tunnel release. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105(5):1662-1665.

3. Scholten RJ, Mink van der Molen A, Uitdehaag BM, Bouter LM, de Vet HC. Surgical treatment options for carpal tunnel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD003905.

4. In memoriam Sir James Learmonth, K.C.V.O., C.B.E., hon. F.R.C.S. (1895-1967). Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1967;41(5):438-439.

5. Benson LS, Bare AA, Nagle DJ, Harder VS, Williams CS, Visotsky JL. Complications of endoscopic and open carpal tunnel release. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(9):919-924, 924.e1-e2.

6. Jarvik JG, Comstock BA, Kliot M, et al. Surgery versus non-surgical therapy for carpal tunnel syndrome: a randomised parallel-group trial. Lancet. 2009;374(9695):1074-1081.

7. Verdugo RJ, Salinas RA, Castillo JL, et al. Surgical versus non-surgical treatment for carpal tunnel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(4):CD001552.

8. Garland H, Langworth EP, Taverner D, et al. Surgical treatment for the carpal tunnel syndrome. Lancet. 1964;1(7343):1129-1130.

9. Gerritsen AA, de Vet HC, Scholten RJ, et al. Splinting vs surgery in the treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288(10):1245-1251.

10. Gelberman RH, Hergenroeder PT, Hargens AR, et al. The carpal tunnel syndrome. A study of carpal canal pressures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1981;63(3):380-383.

11. Sucher BM. Myofascial manipulative release of carpal tunnel syndrome: documentation with magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 1993;93(12):1273-1278.

12. Pereira EE, Miranda DA, Sere I, et al. Endoscopic release of the carpal tunnel: a 2-portal-modified technique. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg. 2010;14(4):263-265.

13. Louis DS, Greene TL, Noellert RC. Complications of carpal tunnel surgery. J Neurosurg. 1985;62(3):352-356.

14. Mirza MA, King ET Jr, Tanveer S. Palmar uniportal extrabursal endoscopic carpal tunnel release. Arthroscopy. 1995;11(1):82-90.

15. Brown MG, Keyser B, Rothenberg ES. Endoscopic carpal tunnel release. J Hand Surg Am. 1992;17(6):1009-1011.

16. Agee JM, McCarroll HR Jr, Tortosa RD, et al. Endoscopic release of the carpal tunnel: a randomized prospective multicenter study. J Hand Surg Am. 1992;17(6):987-995.

17. Okutsu I, Ninomiya S, Takatori Y, et al. Endoscopic management of carpal tunnel syndrome. Arthroscopy. 1989;5(1):11-18.

18. Ghaly RF, Saban KL, Haley DA, et al. Endoscopic carpal tunnel release surgery: report of patient satisfaction. Neurol Res. 2000;22(6):551-555.

19. Lee WP, Plancher KD, Strickland JW. Carpal tunnel release with a small palmar incision. Hand Clin. 1996;12(2):271-284.

20. Biyani A, Downes EM. An open twin incision technique of carpal tunnel decompression with reduced incidence of scar tenderness. J Hand Surg Br. 1993;18(3):331-334.

21. Brown RA, Gelberman RH, Seiler JG 3rd, et al. Carpal tunnel release. A prospective, randomized assessment of open and endoscopic methods. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75(9):1265-1275.

22. Chow JC. Endoscopic release of the carpal ligament for carpal tunnel syndrome: 22-month clinical result. Arthroscopy. 1990;6(4):288-296.

23. Trumble TE, Diao E, Abrams RA, et al. Single-portal endoscopic carpal tunnel release compared with open release: a prospective, randomized trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84(7):1107-1115.

24. Gerritsen AA, Uitdehaag BM, van Geldere D, et al. Systematic review of randomized clinical trials of surgical treatment for carpal tunnel syndrome. Br J Surg. 2001;88(10):1285-1295.