User login

Trends in hospital medicine program operations during COVID-19

Staffing was a challenge for most groups

What a year it has been in the world of hospital medicine with all the changes, challenges, and uncertainties surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic. Some hospitalist programs were hit hard early on with an early surge, when little was known about COVID-19, and other programs have had more time to plan and adapt to later surges.

As many readers of The Hospitalist know, the Society of Hospital Medicine publishes a biennial State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) Report – last published in September 2020 using data from 2019. The SoHM Report contains a wealth of information that many groups find useful in evaluating their programs, with topics ranging from compensation to staffing to scheduling. As some prior months’ Survey Insights columns have alluded to, with the rapid pace of change in 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Society of Hospital Medicine made the decision to publish an addendum highlighting the myriad of adjustments and adaptations that have occurred in such a short period of time. The COVID-19 Addendum is available to all purchasers of the SoHM Report and contains data from survey responses submitted in September 2020.

Let’s take a look at what transpired in 2020, starting with staffing – no doubt a challenge for many groups. During some periods of time, patient volumes may have fallen below historical averages with stay-at-home orders, canceled procedures, and a reluctance by patients to seek medical care. In contrast, for many groups, other parts of the year were all-hands-on-deck scenarios to care for extraordinary surges in patient volume. To compound this, many hospitalist groups had physicians and staff facing quarantine or isolation requirements because of exposures or contracting COVID-19, and locums positions may have been difficult to fill because of travel restrictions and extreme demand.

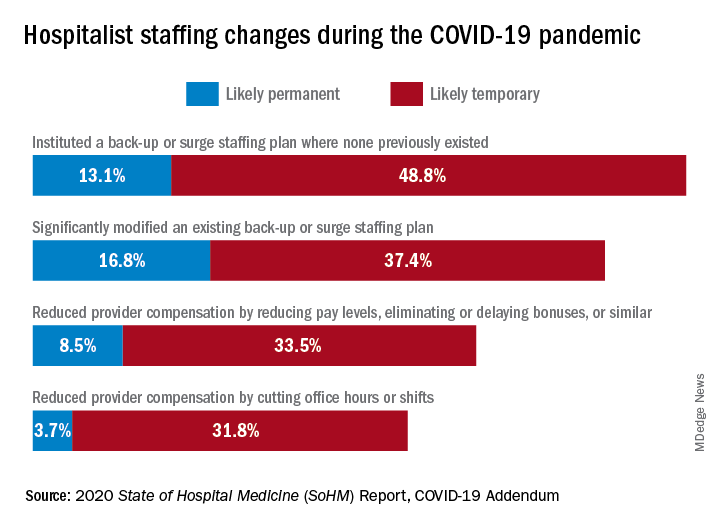

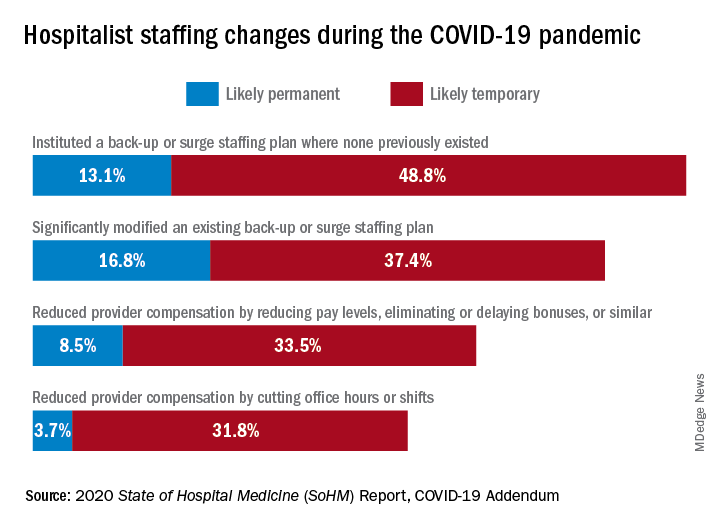

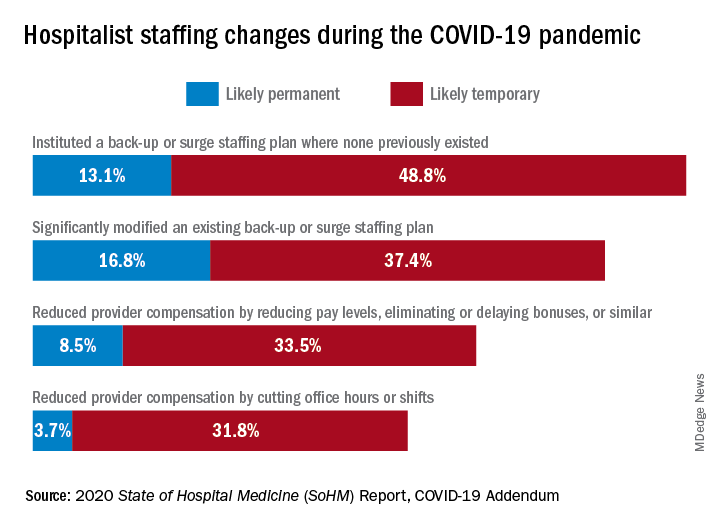

What operational changes were made in response to these staffing challenges? Perhaps one notable finding from the COVID-19 Addendum was the need for contingency planning and backup systems. From the 2020 SoHM, prior to the pandemic, 47.4% of adult hospital medicine groups had backup systems in place. In our recently published addendum, we found that 61.9% of groups instituted a backup system where none previously existed. In addition, 54.2% of groups modified their existing backup system. Some 39.6% of hospital medicine groups also utilized clinicians from other service lines to help cover service needs.

Aside from staffing, hospitals faced unprecedented financial challenges, and these effects rippled through to hospitalists. Our addendum found that 42.0% of hospitalist groups faced reductions in salary or bonuses, and 35.5% of hospital medicine groups reduced provider compensation by a reduction of work hours or shifts. I’ve personally been struck by these findings – that many hospitalists at the front-lines of COVID-19 received salary reductions, albeit temporary for many groups, during one of the most challenging years of their professional careers. Our addendum, interestingly, also found that a smaller 10.7% of groups instituted hazard pay for clinicians caring for COVID-19 patients.

So, are the changes and challenges your group faced similar to what was experienced by other hospital medicine programs? These findings and many more interesting and useful pieces of data are available in the full COVID-19 Addendum. Perhaps my biggest takeaway is that hospitalists have been perhaps the most uniquely positioned specialty to tackle the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic. We have always been a dynamic, changing field, ready to lead and tackle change – and while change may have happened more quickly and in ways that were unforeseen just a year ago, hospitalists have undoubtedly demonstrated their strengths as leaders ready to adapt and rise to the occasion.

I am optimistic that, as we move beyond the pandemic in the coming months and years, the value that hospitalists have proven yet again will yield long-term recognition and benefits to our programs and our specialty.

Dr. Huang is a physician adviser and clinical professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at the University of California, San Diego. He is a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Staffing was a challenge for most groups

Staffing was a challenge for most groups

What a year it has been in the world of hospital medicine with all the changes, challenges, and uncertainties surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic. Some hospitalist programs were hit hard early on with an early surge, when little was known about COVID-19, and other programs have had more time to plan and adapt to later surges.

As many readers of The Hospitalist know, the Society of Hospital Medicine publishes a biennial State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) Report – last published in September 2020 using data from 2019. The SoHM Report contains a wealth of information that many groups find useful in evaluating their programs, with topics ranging from compensation to staffing to scheduling. As some prior months’ Survey Insights columns have alluded to, with the rapid pace of change in 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Society of Hospital Medicine made the decision to publish an addendum highlighting the myriad of adjustments and adaptations that have occurred in such a short period of time. The COVID-19 Addendum is available to all purchasers of the SoHM Report and contains data from survey responses submitted in September 2020.

Let’s take a look at what transpired in 2020, starting with staffing – no doubt a challenge for many groups. During some periods of time, patient volumes may have fallen below historical averages with stay-at-home orders, canceled procedures, and a reluctance by patients to seek medical care. In contrast, for many groups, other parts of the year were all-hands-on-deck scenarios to care for extraordinary surges in patient volume. To compound this, many hospitalist groups had physicians and staff facing quarantine or isolation requirements because of exposures or contracting COVID-19, and locums positions may have been difficult to fill because of travel restrictions and extreme demand.

What operational changes were made in response to these staffing challenges? Perhaps one notable finding from the COVID-19 Addendum was the need for contingency planning and backup systems. From the 2020 SoHM, prior to the pandemic, 47.4% of adult hospital medicine groups had backup systems in place. In our recently published addendum, we found that 61.9% of groups instituted a backup system where none previously existed. In addition, 54.2% of groups modified their existing backup system. Some 39.6% of hospital medicine groups also utilized clinicians from other service lines to help cover service needs.

Aside from staffing, hospitals faced unprecedented financial challenges, and these effects rippled through to hospitalists. Our addendum found that 42.0% of hospitalist groups faced reductions in salary or bonuses, and 35.5% of hospital medicine groups reduced provider compensation by a reduction of work hours or shifts. I’ve personally been struck by these findings – that many hospitalists at the front-lines of COVID-19 received salary reductions, albeit temporary for many groups, during one of the most challenging years of their professional careers. Our addendum, interestingly, also found that a smaller 10.7% of groups instituted hazard pay for clinicians caring for COVID-19 patients.

So, are the changes and challenges your group faced similar to what was experienced by other hospital medicine programs? These findings and many more interesting and useful pieces of data are available in the full COVID-19 Addendum. Perhaps my biggest takeaway is that hospitalists have been perhaps the most uniquely positioned specialty to tackle the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic. We have always been a dynamic, changing field, ready to lead and tackle change – and while change may have happened more quickly and in ways that were unforeseen just a year ago, hospitalists have undoubtedly demonstrated their strengths as leaders ready to adapt and rise to the occasion.

I am optimistic that, as we move beyond the pandemic in the coming months and years, the value that hospitalists have proven yet again will yield long-term recognition and benefits to our programs and our specialty.

Dr. Huang is a physician adviser and clinical professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at the University of California, San Diego. He is a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

What a year it has been in the world of hospital medicine with all the changes, challenges, and uncertainties surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic. Some hospitalist programs were hit hard early on with an early surge, when little was known about COVID-19, and other programs have had more time to plan and adapt to later surges.

As many readers of The Hospitalist know, the Society of Hospital Medicine publishes a biennial State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) Report – last published in September 2020 using data from 2019. The SoHM Report contains a wealth of information that many groups find useful in evaluating their programs, with topics ranging from compensation to staffing to scheduling. As some prior months’ Survey Insights columns have alluded to, with the rapid pace of change in 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Society of Hospital Medicine made the decision to publish an addendum highlighting the myriad of adjustments and adaptations that have occurred in such a short period of time. The COVID-19 Addendum is available to all purchasers of the SoHM Report and contains data from survey responses submitted in September 2020.

Let’s take a look at what transpired in 2020, starting with staffing – no doubt a challenge for many groups. During some periods of time, patient volumes may have fallen below historical averages with stay-at-home orders, canceled procedures, and a reluctance by patients to seek medical care. In contrast, for many groups, other parts of the year were all-hands-on-deck scenarios to care for extraordinary surges in patient volume. To compound this, many hospitalist groups had physicians and staff facing quarantine or isolation requirements because of exposures or contracting COVID-19, and locums positions may have been difficult to fill because of travel restrictions and extreme demand.

What operational changes were made in response to these staffing challenges? Perhaps one notable finding from the COVID-19 Addendum was the need for contingency planning and backup systems. From the 2020 SoHM, prior to the pandemic, 47.4% of adult hospital medicine groups had backup systems in place. In our recently published addendum, we found that 61.9% of groups instituted a backup system where none previously existed. In addition, 54.2% of groups modified their existing backup system. Some 39.6% of hospital medicine groups also utilized clinicians from other service lines to help cover service needs.

Aside from staffing, hospitals faced unprecedented financial challenges, and these effects rippled through to hospitalists. Our addendum found that 42.0% of hospitalist groups faced reductions in salary or bonuses, and 35.5% of hospital medicine groups reduced provider compensation by a reduction of work hours or shifts. I’ve personally been struck by these findings – that many hospitalists at the front-lines of COVID-19 received salary reductions, albeit temporary for many groups, during one of the most challenging years of their professional careers. Our addendum, interestingly, also found that a smaller 10.7% of groups instituted hazard pay for clinicians caring for COVID-19 patients.

So, are the changes and challenges your group faced similar to what was experienced by other hospital medicine programs? These findings and many more interesting and useful pieces of data are available in the full COVID-19 Addendum. Perhaps my biggest takeaway is that hospitalists have been perhaps the most uniquely positioned specialty to tackle the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic. We have always been a dynamic, changing field, ready to lead and tackle change – and while change may have happened more quickly and in ways that were unforeseen just a year ago, hospitalists have undoubtedly demonstrated their strengths as leaders ready to adapt and rise to the occasion.

I am optimistic that, as we move beyond the pandemic in the coming months and years, the value that hospitalists have proven yet again will yield long-term recognition and benefits to our programs and our specialty.

Dr. Huang is a physician adviser and clinical professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at the University of California, San Diego. He is a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Productivity-based salary structure not associated with value-based culture

Background: Although new payment models have been implemented by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) for hospital reimbursement, little is known about the effects of reimbursement models on the culture of providing value-based care among individual hospitalists. The concern is that productivity-based models increase pressure on hospitalists to maximize volume and billing, as opposed to focusing on value.

Study design: Observational, cross-sectional, survey-based study.

Setting: A total of 12 hospitals in California, which represented university, community, and safety-net settings.

Synopsis: Hospitalists were asked to complete the High-Value Care Culture Survey (HVCCS), a validated tool that assesses value-based decision making. Components of the survey assessed leadership and health system messaging, data transparency and access, comfort with cost conversations, and blame-free environments. Hospitalists were also asked to self-report their reimbursement structure: salary alone, salary plus productivity, or salary plus value-based adjustments.

A total of 255 hospitalists completed the survey. The mean HVCCS score was 50.2 on a 0-100 scale. Hospitalists who reported reimbursement with salary plus productivity adjustments had a lower mean HVCCS score (beta = –6.2; 95% confidence interval, –9.9 to –2.5) when compared with hospitalists paid with salary alone. An association was not found between HVCCS score and reimbursement with salary plus value-based adjustments when compared with salary alone, though this finding may have been limited by sample size.

Bottom line: A hospitalist reimbursement model of salary plus productivity was associated with lower measures of value-based care culture.

Citation: Gupta R et al. Association between hospitalist productivity payments and high-value care culture. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(1):16-21.

Dr. Huang is a physician adviser and associate clinical professor in the division of hospital medicine at the University of California, San Diego.

Background: Although new payment models have been implemented by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) for hospital reimbursement, little is known about the effects of reimbursement models on the culture of providing value-based care among individual hospitalists. The concern is that productivity-based models increase pressure on hospitalists to maximize volume and billing, as opposed to focusing on value.

Study design: Observational, cross-sectional, survey-based study.

Setting: A total of 12 hospitals in California, which represented university, community, and safety-net settings.

Synopsis: Hospitalists were asked to complete the High-Value Care Culture Survey (HVCCS), a validated tool that assesses value-based decision making. Components of the survey assessed leadership and health system messaging, data transparency and access, comfort with cost conversations, and blame-free environments. Hospitalists were also asked to self-report their reimbursement structure: salary alone, salary plus productivity, or salary plus value-based adjustments.

A total of 255 hospitalists completed the survey. The mean HVCCS score was 50.2 on a 0-100 scale. Hospitalists who reported reimbursement with salary plus productivity adjustments had a lower mean HVCCS score (beta = –6.2; 95% confidence interval, –9.9 to –2.5) when compared with hospitalists paid with salary alone. An association was not found between HVCCS score and reimbursement with salary plus value-based adjustments when compared with salary alone, though this finding may have been limited by sample size.

Bottom line: A hospitalist reimbursement model of salary plus productivity was associated with lower measures of value-based care culture.

Citation: Gupta R et al. Association between hospitalist productivity payments and high-value care culture. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(1):16-21.

Dr. Huang is a physician adviser and associate clinical professor in the division of hospital medicine at the University of California, San Diego.

Background: Although new payment models have been implemented by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) for hospital reimbursement, little is known about the effects of reimbursement models on the culture of providing value-based care among individual hospitalists. The concern is that productivity-based models increase pressure on hospitalists to maximize volume and billing, as opposed to focusing on value.

Study design: Observational, cross-sectional, survey-based study.

Setting: A total of 12 hospitals in California, which represented university, community, and safety-net settings.

Synopsis: Hospitalists were asked to complete the High-Value Care Culture Survey (HVCCS), a validated tool that assesses value-based decision making. Components of the survey assessed leadership and health system messaging, data transparency and access, comfort with cost conversations, and blame-free environments. Hospitalists were also asked to self-report their reimbursement structure: salary alone, salary plus productivity, or salary plus value-based adjustments.

A total of 255 hospitalists completed the survey. The mean HVCCS score was 50.2 on a 0-100 scale. Hospitalists who reported reimbursement with salary plus productivity adjustments had a lower mean HVCCS score (beta = –6.2; 95% confidence interval, –9.9 to –2.5) when compared with hospitalists paid with salary alone. An association was not found between HVCCS score and reimbursement with salary plus value-based adjustments when compared with salary alone, though this finding may have been limited by sample size.

Bottom line: A hospitalist reimbursement model of salary plus productivity was associated with lower measures of value-based care culture.

Citation: Gupta R et al. Association between hospitalist productivity payments and high-value care culture. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(1):16-21.

Dr. Huang is a physician adviser and associate clinical professor in the division of hospital medicine at the University of California, San Diego.

Additional physical therapy decreases length of stay

Background: The optimal quantity of physical therapy provided to hospitalized patients is unknown. It has been hypothesized that the costs of additional physical therapy might be outweighed by a decrease in length of stay. A prior meta-analysis done by the same authors was inconclusive; subsequently, additional large trials were published, prompting the authors to repeat their meta-analysis.

Study design: Meta-analysis.

Setting: Literature review of English-language studies conducted worldwide.

Synopsis: A total of 24 randomized controlled trials with a total of 3,262 participants was included in this meta-analysis. The primary finding was that additional physical therapy was associated with a 3-day reduction in length of stay in subacute settings (95% confidence interval, –4.6 to –0.9) and a 0.6-day reduction in acute care settings (95% CI, –1.1 to 0.0). Furthermore, additional physical therapy was associated with small improvements in self-care and activities of daily living. One trial included an economic analysis that suggested additional physical therapy was cost effective.

Of note, there was no standard definition of “additional physical therapy” across the heterogeneous group of trials analyzed in this meta-analysis. In all studies, the experimental group received more physical therapy than the control group, either by increased frequency or duration of sessions. Nonetheless, hospitals may consider increasing physical therapy services as a cost-effective means of reducing length of stay.

Bottom line: Additional physical therapy in acute and subacute care settings results in a decreased length of stay and may be cost effective.

Citation: Peiris CL et al. Additional physical therapy services reduce length of stay and improve health outcomes in people with acute and subacute conditions: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 2018;99(11):2299-312.

Dr. Huang is a physician adviser and associate clinical professor in the division of hospital medicine at the University of California, San Diego.

Background: The optimal quantity of physical therapy provided to hospitalized patients is unknown. It has been hypothesized that the costs of additional physical therapy might be outweighed by a decrease in length of stay. A prior meta-analysis done by the same authors was inconclusive; subsequently, additional large trials were published, prompting the authors to repeat their meta-analysis.

Study design: Meta-analysis.

Setting: Literature review of English-language studies conducted worldwide.

Synopsis: A total of 24 randomized controlled trials with a total of 3,262 participants was included in this meta-analysis. The primary finding was that additional physical therapy was associated with a 3-day reduction in length of stay in subacute settings (95% confidence interval, –4.6 to –0.9) and a 0.6-day reduction in acute care settings (95% CI, –1.1 to 0.0). Furthermore, additional physical therapy was associated with small improvements in self-care and activities of daily living. One trial included an economic analysis that suggested additional physical therapy was cost effective.

Of note, there was no standard definition of “additional physical therapy” across the heterogeneous group of trials analyzed in this meta-analysis. In all studies, the experimental group received more physical therapy than the control group, either by increased frequency or duration of sessions. Nonetheless, hospitals may consider increasing physical therapy services as a cost-effective means of reducing length of stay.

Bottom line: Additional physical therapy in acute and subacute care settings results in a decreased length of stay and may be cost effective.

Citation: Peiris CL et al. Additional physical therapy services reduce length of stay and improve health outcomes in people with acute and subacute conditions: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 2018;99(11):2299-312.

Dr. Huang is a physician adviser and associate clinical professor in the division of hospital medicine at the University of California, San Diego.

Background: The optimal quantity of physical therapy provided to hospitalized patients is unknown. It has been hypothesized that the costs of additional physical therapy might be outweighed by a decrease in length of stay. A prior meta-analysis done by the same authors was inconclusive; subsequently, additional large trials were published, prompting the authors to repeat their meta-analysis.

Study design: Meta-analysis.

Setting: Literature review of English-language studies conducted worldwide.

Synopsis: A total of 24 randomized controlled trials with a total of 3,262 participants was included in this meta-analysis. The primary finding was that additional physical therapy was associated with a 3-day reduction in length of stay in subacute settings (95% confidence interval, –4.6 to –0.9) and a 0.6-day reduction in acute care settings (95% CI, –1.1 to 0.0). Furthermore, additional physical therapy was associated with small improvements in self-care and activities of daily living. One trial included an economic analysis that suggested additional physical therapy was cost effective.

Of note, there was no standard definition of “additional physical therapy” across the heterogeneous group of trials analyzed in this meta-analysis. In all studies, the experimental group received more physical therapy than the control group, either by increased frequency or duration of sessions. Nonetheless, hospitals may consider increasing physical therapy services as a cost-effective means of reducing length of stay.

Bottom line: Additional physical therapy in acute and subacute care settings results in a decreased length of stay and may be cost effective.

Citation: Peiris CL et al. Additional physical therapy services reduce length of stay and improve health outcomes in people with acute and subacute conditions: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 2018;99(11):2299-312.

Dr. Huang is a physician adviser and associate clinical professor in the division of hospital medicine at the University of California, San Diego.

Unit-based assignments: Pros and cons

Geographic cohorting shows ‘varying success’

A relatively recent practice catching on in many different hospitalist groups is geographic cohorting, or unit-based assignments. Traditionally, most hospitalists have had patients assigned on multiple different units. Unit-based assignments have been touted as a way of improving interdisciplinary communication and provider and patient satisfaction.1

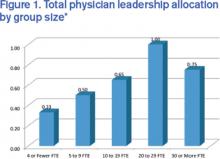

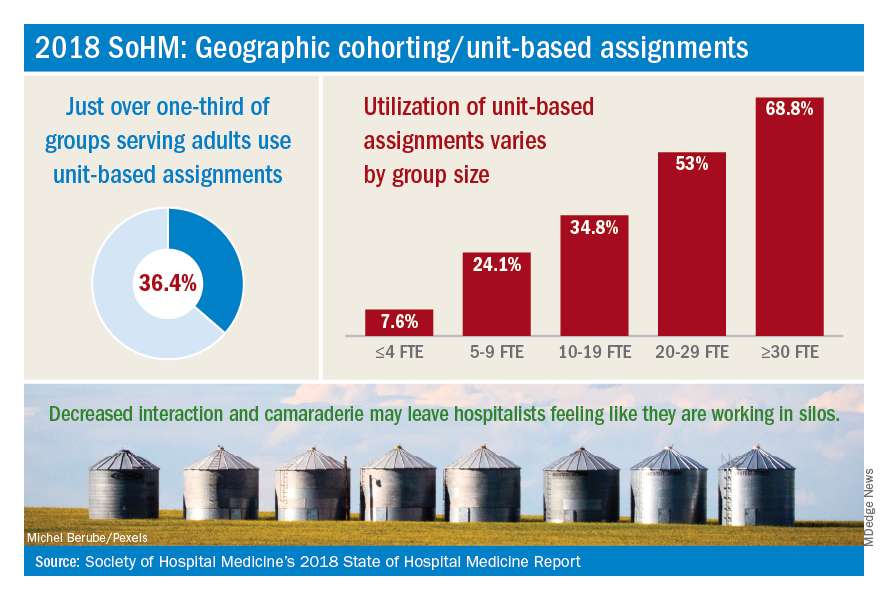

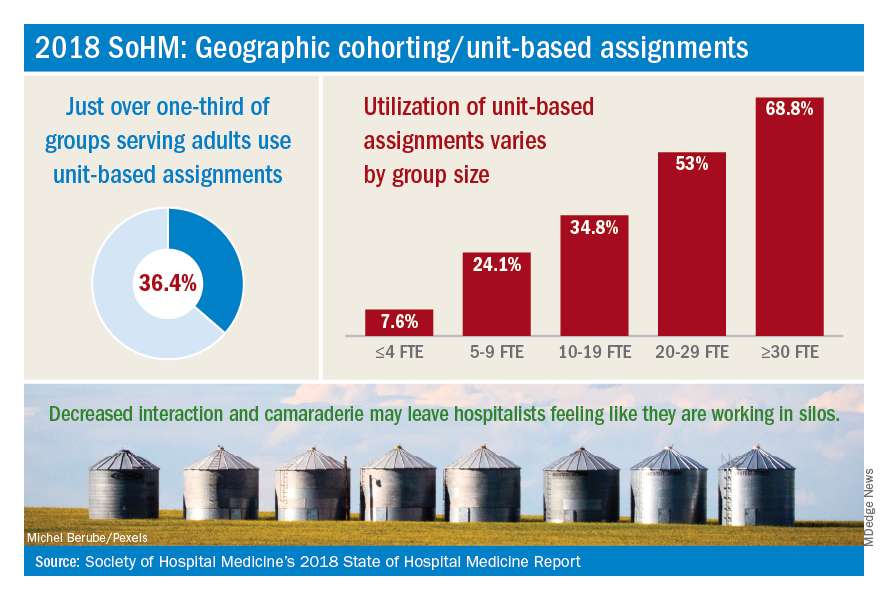

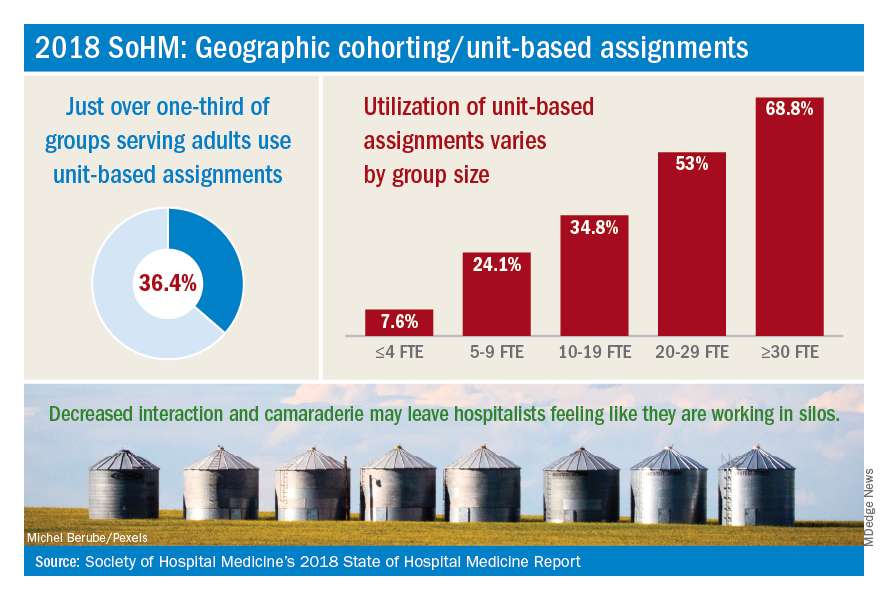

How frequently are hospital medicine groups using unit-based assignments? SHM sought to quantify this trend in the recently published 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report. Overall, among hospital medicine groups serving adults only, a little over one-third (36.4%) of groups reported utilizing unit-based assignments. However, there was significant variation, particularly dependent on group size. Geographic cohorting was used only in 7.6% of groups with 4 or fewer full-time equivalents, and in 68.8% of groups with 30 or more FTE. These data seem logical, as the potential gains from cohorting likely increase with group/hospital size, where physicians would otherwise round on an increasingly large number of units.

As has been shared in the hospital medicine literature, groups have experienced variable success with geographic cohorting. Improvements have been achieved in interprofessional collaboration, efficiency, nursing satisfaction,2 and, in some instances, length of stay. Unit-based assignments have allowed some groups to pilot other interventions, such as interdisciplinary rounds.

But geographic cohorting comes with its implementation challenges, too. For example, in many hospitals, some units have differing telemetry or nursing capabilities. And, in other institutions, there are units providing specialized care, such as care for neurology or oncology patients. The workload for hospitalists caring for particular types of patients may vary, and with specialty units, it may be more difficult to keep a similar census assigned to each hospitalist.

While some groups have noted increased professional satisfaction, others have noted decreases in satisfaction. One reason is that, while the frequency of paging may decrease, this is replaced by an increase in face-to-face interruptions. Also, unit-based assignments in some groups have resulted in hospitalists perceiving they are working in silos because of a decrease in interactions and camaraderie among providers in the same hospital medicine group.

At my home institution, University of California, San Diego, geographic cohorting has largely been a successful and positively perceived change. Our efforts have been particularly successful at one of our two campuses where most units have telemetry capabilities and where we have a dedicated daytime admitter (there are data on this in the Report as well, and a dedicated daytime admitter is the topic of a future Survey Insights column). Unit-based assignments have allowed the implementation of what we’ve termed focused interdisciplinary rounds.

Our unit-based assignments are not perfect – we re-cohort each week when new hospitalists come on service, and some hospitalists are assigned a small number of patients off their home unit. Our internal data have shown a significant increase in patient satisfaction scores, but we have not realized a decrease in length of stay. Despite an overall positive perception, hospitalists have sometimes noted an imbalanced workload – we have a particularly challenging oncology/palliative unit and a daytime admitter that is at times very busy. Our system also requires the use of physician time to assign patients each morning and each week.

In contrast, while we’ve aimed to achieve the same success with unit-based assignments at our other campus, we’ve faced more challenges there. Our other facility is older, and fewer units have telemetry capabilities. A more traditional teaching structure also means that teams take turns with on-call admitting days, as opposed to a daytime admitter structure, and there may not be beds available in the unit assigned to the admitting team of the day.

Overall, geographic cohorting is likely to be considered or implemented in many hospital medicine groups, and efforts have met with varying success. There are certainly pros and cons to every model, and if your group is looking at redesigning services to include unit-based assignments, it’s worth examining the intended outcomes. While unit-based assignments are not for every group, there’s no doubt that this trend has been driven by our specialty’s commitment to outcome-driven process improvement.

Addendum added Feb. 15, 2019: The impact of UC San Diego's efforts discussed in this article are the author's own opinions through limited participation in focused interdisciplinary rounds, and have not been validated with formal data analysis. More study is in progress on the impact of focused interdiscplinary rounds on communication, utilization, and quality metrics. Sarah Horman, MD ([email protected]), Daniel Bouland, MD ([email protected]), and William Frederick, MD ([email protected]), have led efforts at UC San Diego to develop and implement focused interdisciplinary rounds, and may be contacted for further information.

Dr. Huang is physician advisor for care management and associate clinical professor in the division of hospital medicine at the University of California, San Diego. He is a member of SHM’s practice analysis subcommittee.

References

1. O’Leary KJ et al. Interdisciplinary teamwork in hospitals: A review and practical recommendations for improvement. J Hosp Med. 2012 Jan;7(1):48-54.

2. Kara A et al. Hospital-based clinicians’ perceptions of geographic cohorting: Identifying opportunities for improvement. Am J Med Qual. 2018 May/Jun;33(3):303-12.

Geographic cohorting shows ‘varying success’

Geographic cohorting shows ‘varying success’

A relatively recent practice catching on in many different hospitalist groups is geographic cohorting, or unit-based assignments. Traditionally, most hospitalists have had patients assigned on multiple different units. Unit-based assignments have been touted as a way of improving interdisciplinary communication and provider and patient satisfaction.1

How frequently are hospital medicine groups using unit-based assignments? SHM sought to quantify this trend in the recently published 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report. Overall, among hospital medicine groups serving adults only, a little over one-third (36.4%) of groups reported utilizing unit-based assignments. However, there was significant variation, particularly dependent on group size. Geographic cohorting was used only in 7.6% of groups with 4 or fewer full-time equivalents, and in 68.8% of groups with 30 or more FTE. These data seem logical, as the potential gains from cohorting likely increase with group/hospital size, where physicians would otherwise round on an increasingly large number of units.

As has been shared in the hospital medicine literature, groups have experienced variable success with geographic cohorting. Improvements have been achieved in interprofessional collaboration, efficiency, nursing satisfaction,2 and, in some instances, length of stay. Unit-based assignments have allowed some groups to pilot other interventions, such as interdisciplinary rounds.

But geographic cohorting comes with its implementation challenges, too. For example, in many hospitals, some units have differing telemetry or nursing capabilities. And, in other institutions, there are units providing specialized care, such as care for neurology or oncology patients. The workload for hospitalists caring for particular types of patients may vary, and with specialty units, it may be more difficult to keep a similar census assigned to each hospitalist.

While some groups have noted increased professional satisfaction, others have noted decreases in satisfaction. One reason is that, while the frequency of paging may decrease, this is replaced by an increase in face-to-face interruptions. Also, unit-based assignments in some groups have resulted in hospitalists perceiving they are working in silos because of a decrease in interactions and camaraderie among providers in the same hospital medicine group.

At my home institution, University of California, San Diego, geographic cohorting has largely been a successful and positively perceived change. Our efforts have been particularly successful at one of our two campuses where most units have telemetry capabilities and where we have a dedicated daytime admitter (there are data on this in the Report as well, and a dedicated daytime admitter is the topic of a future Survey Insights column). Unit-based assignments have allowed the implementation of what we’ve termed focused interdisciplinary rounds.

Our unit-based assignments are not perfect – we re-cohort each week when new hospitalists come on service, and some hospitalists are assigned a small number of patients off their home unit. Our internal data have shown a significant increase in patient satisfaction scores, but we have not realized a decrease in length of stay. Despite an overall positive perception, hospitalists have sometimes noted an imbalanced workload – we have a particularly challenging oncology/palliative unit and a daytime admitter that is at times very busy. Our system also requires the use of physician time to assign patients each morning and each week.

In contrast, while we’ve aimed to achieve the same success with unit-based assignments at our other campus, we’ve faced more challenges there. Our other facility is older, and fewer units have telemetry capabilities. A more traditional teaching structure also means that teams take turns with on-call admitting days, as opposed to a daytime admitter structure, and there may not be beds available in the unit assigned to the admitting team of the day.

Overall, geographic cohorting is likely to be considered or implemented in many hospital medicine groups, and efforts have met with varying success. There are certainly pros and cons to every model, and if your group is looking at redesigning services to include unit-based assignments, it’s worth examining the intended outcomes. While unit-based assignments are not for every group, there’s no doubt that this trend has been driven by our specialty’s commitment to outcome-driven process improvement.

Addendum added Feb. 15, 2019: The impact of UC San Diego's efforts discussed in this article are the author's own opinions through limited participation in focused interdisciplinary rounds, and have not been validated with formal data analysis. More study is in progress on the impact of focused interdiscplinary rounds on communication, utilization, and quality metrics. Sarah Horman, MD ([email protected]), Daniel Bouland, MD ([email protected]), and William Frederick, MD ([email protected]), have led efforts at UC San Diego to develop and implement focused interdisciplinary rounds, and may be contacted for further information.

Dr. Huang is physician advisor for care management and associate clinical professor in the division of hospital medicine at the University of California, San Diego. He is a member of SHM’s practice analysis subcommittee.

References

1. O’Leary KJ et al. Interdisciplinary teamwork in hospitals: A review and practical recommendations for improvement. J Hosp Med. 2012 Jan;7(1):48-54.

2. Kara A et al. Hospital-based clinicians’ perceptions of geographic cohorting: Identifying opportunities for improvement. Am J Med Qual. 2018 May/Jun;33(3):303-12.

A relatively recent practice catching on in many different hospitalist groups is geographic cohorting, or unit-based assignments. Traditionally, most hospitalists have had patients assigned on multiple different units. Unit-based assignments have been touted as a way of improving interdisciplinary communication and provider and patient satisfaction.1

How frequently are hospital medicine groups using unit-based assignments? SHM sought to quantify this trend in the recently published 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report. Overall, among hospital medicine groups serving adults only, a little over one-third (36.4%) of groups reported utilizing unit-based assignments. However, there was significant variation, particularly dependent on group size. Geographic cohorting was used only in 7.6% of groups with 4 or fewer full-time equivalents, and in 68.8% of groups with 30 or more FTE. These data seem logical, as the potential gains from cohorting likely increase with group/hospital size, where physicians would otherwise round on an increasingly large number of units.

As has been shared in the hospital medicine literature, groups have experienced variable success with geographic cohorting. Improvements have been achieved in interprofessional collaboration, efficiency, nursing satisfaction,2 and, in some instances, length of stay. Unit-based assignments have allowed some groups to pilot other interventions, such as interdisciplinary rounds.

But geographic cohorting comes with its implementation challenges, too. For example, in many hospitals, some units have differing telemetry or nursing capabilities. And, in other institutions, there are units providing specialized care, such as care for neurology or oncology patients. The workload for hospitalists caring for particular types of patients may vary, and with specialty units, it may be more difficult to keep a similar census assigned to each hospitalist.

While some groups have noted increased professional satisfaction, others have noted decreases in satisfaction. One reason is that, while the frequency of paging may decrease, this is replaced by an increase in face-to-face interruptions. Also, unit-based assignments in some groups have resulted in hospitalists perceiving they are working in silos because of a decrease in interactions and camaraderie among providers in the same hospital medicine group.

At my home institution, University of California, San Diego, geographic cohorting has largely been a successful and positively perceived change. Our efforts have been particularly successful at one of our two campuses where most units have telemetry capabilities and where we have a dedicated daytime admitter (there are data on this in the Report as well, and a dedicated daytime admitter is the topic of a future Survey Insights column). Unit-based assignments have allowed the implementation of what we’ve termed focused interdisciplinary rounds.

Our unit-based assignments are not perfect – we re-cohort each week when new hospitalists come on service, and some hospitalists are assigned a small number of patients off their home unit. Our internal data have shown a significant increase in patient satisfaction scores, but we have not realized a decrease in length of stay. Despite an overall positive perception, hospitalists have sometimes noted an imbalanced workload – we have a particularly challenging oncology/palliative unit and a daytime admitter that is at times very busy. Our system also requires the use of physician time to assign patients each morning and each week.

In contrast, while we’ve aimed to achieve the same success with unit-based assignments at our other campus, we’ve faced more challenges there. Our other facility is older, and fewer units have telemetry capabilities. A more traditional teaching structure also means that teams take turns with on-call admitting days, as opposed to a daytime admitter structure, and there may not be beds available in the unit assigned to the admitting team of the day.

Overall, geographic cohorting is likely to be considered or implemented in many hospital medicine groups, and efforts have met with varying success. There are certainly pros and cons to every model, and if your group is looking at redesigning services to include unit-based assignments, it’s worth examining the intended outcomes. While unit-based assignments are not for every group, there’s no doubt that this trend has been driven by our specialty’s commitment to outcome-driven process improvement.

Addendum added Feb. 15, 2019: The impact of UC San Diego's efforts discussed in this article are the author's own opinions through limited participation in focused interdisciplinary rounds, and have not been validated with formal data analysis. More study is in progress on the impact of focused interdiscplinary rounds on communication, utilization, and quality metrics. Sarah Horman, MD ([email protected]), Daniel Bouland, MD ([email protected]), and William Frederick, MD ([email protected]), have led efforts at UC San Diego to develop and implement focused interdisciplinary rounds, and may be contacted for further information.

Dr. Huang is physician advisor for care management and associate clinical professor in the division of hospital medicine at the University of California, San Diego. He is a member of SHM’s practice analysis subcommittee.

References

1. O’Leary KJ et al. Interdisciplinary teamwork in hospitals: A review and practical recommendations for improvement. J Hosp Med. 2012 Jan;7(1):48-54.

2. Kara A et al. Hospital-based clinicians’ perceptions of geographic cohorting: Identifying opportunities for improvement. Am J Med Qual. 2018 May/Jun;33(3):303-12.

How Hospitalist Groups Make Time for Leadership

Negotiating salaries. Improving patient flow. Increasing patient satisfaction. Reducing readmissions. Championing quality improvement efforts. Planning strategically. Handling schedule issues. Dealing with coverage issues. Working on Ebola preparation. Being on call 24 hours a day for an urgent concern from hospital administration or a hospitalist.

Hospitalist group leaders often feel they are pulled in multiple directions all at once and find that a day off really is not a day off. Leaders often are asked to take on additional responsibilities and might wonder whether they are given sufficient protected time. Leaders of larger HM groups might ask whether adding an associate chief would help cover the administrative workload. Or they may be asking whether hospitalist group leaders should receive a premium in salary, above that of other hospitalists in the group.

These are questions the State of Hospital Medicine Report (SOHM) attempts to answer. Although there is significant variation that is dependent on many factors (i.e., group size, academic status, and whether or not the practice is part of a larger multi-site group), the 2014 SOHM found that the median total full-time equivalent (FTE) allocation for physician administration/leadership for HMGs serving adults was just 0.60. The highest-ranking physician leader most commonly had 0.25 to 0.35 FTE protected for administrative responsibilities. And the median compensation premium for group leaders was 15%.

One leadership challenge is that administrative work never stops. Group leaders often find themselves having to come in for meetings before or after night shifts. Leaders sometimes feel that the 0.30 FTE allocated for administrative responsibilities actually requires the workload of a full-time position. Yet, like other hospitalists, leaders typically work a significant number of consecutive clinical shifts to ensure continuity of care for patients, which can make juggling administrative work challenging.

Additionally, group leaders often carry a significant clinical workload. (Read about Team Hospitalist’s newest member and her split leadership-clinical roles) I would argue that this is a good thing, important for many reasons, including maintaining clinical skills, understanding the nature of work and challenges on the front lines, and being able to facilitate quality improvement efforts. Further, group leaders often are perceived to be team players by other hospitalists when they work a wide variety of shifts on all days of the week. Many programs face staffing challenges, and leaders might work extra shifts when other hospitalists are unable to fill them.

Certainly group leaders face significant challenges, but the position also comes with many rewards. Satisfaction comes from improving the program for all hospitalists in a group, from gains in hospital efficiency or flow, from systems improvements to ensure patient safety or improve patient outcomes, and from being respected by hospital administration as well as other hospitalists in the group. With a good understanding of hospital finances and patient flow, some hospitalist group leaders advance to other roles in hospital administration, such as CMO or CEO.

Although there may be no one-size-fits-all answer for the right amount of protected time or salary for group leaders, leaders clearly play a challenging but essential role in bringing value to both hospitals and hospitalist groups.

For more data from the 2014 State of Hospital Medicine Report, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey.

Dr. Huang is associate chief of the division of hospital medicine and associate clinical professor at the University of California San Diego. He is a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Negotiating salaries. Improving patient flow. Increasing patient satisfaction. Reducing readmissions. Championing quality improvement efforts. Planning strategically. Handling schedule issues. Dealing with coverage issues. Working on Ebola preparation. Being on call 24 hours a day for an urgent concern from hospital administration or a hospitalist.

Hospitalist group leaders often feel they are pulled in multiple directions all at once and find that a day off really is not a day off. Leaders often are asked to take on additional responsibilities and might wonder whether they are given sufficient protected time. Leaders of larger HM groups might ask whether adding an associate chief would help cover the administrative workload. Or they may be asking whether hospitalist group leaders should receive a premium in salary, above that of other hospitalists in the group.

These are questions the State of Hospital Medicine Report (SOHM) attempts to answer. Although there is significant variation that is dependent on many factors (i.e., group size, academic status, and whether or not the practice is part of a larger multi-site group), the 2014 SOHM found that the median total full-time equivalent (FTE) allocation for physician administration/leadership for HMGs serving adults was just 0.60. The highest-ranking physician leader most commonly had 0.25 to 0.35 FTE protected for administrative responsibilities. And the median compensation premium for group leaders was 15%.

One leadership challenge is that administrative work never stops. Group leaders often find themselves having to come in for meetings before or after night shifts. Leaders sometimes feel that the 0.30 FTE allocated for administrative responsibilities actually requires the workload of a full-time position. Yet, like other hospitalists, leaders typically work a significant number of consecutive clinical shifts to ensure continuity of care for patients, which can make juggling administrative work challenging.

Additionally, group leaders often carry a significant clinical workload. (Read about Team Hospitalist’s newest member and her split leadership-clinical roles) I would argue that this is a good thing, important for many reasons, including maintaining clinical skills, understanding the nature of work and challenges on the front lines, and being able to facilitate quality improvement efforts. Further, group leaders often are perceived to be team players by other hospitalists when they work a wide variety of shifts on all days of the week. Many programs face staffing challenges, and leaders might work extra shifts when other hospitalists are unable to fill them.

Certainly group leaders face significant challenges, but the position also comes with many rewards. Satisfaction comes from improving the program for all hospitalists in a group, from gains in hospital efficiency or flow, from systems improvements to ensure patient safety or improve patient outcomes, and from being respected by hospital administration as well as other hospitalists in the group. With a good understanding of hospital finances and patient flow, some hospitalist group leaders advance to other roles in hospital administration, such as CMO or CEO.

Although there may be no one-size-fits-all answer for the right amount of protected time or salary for group leaders, leaders clearly play a challenging but essential role in bringing value to both hospitals and hospitalist groups.

For more data from the 2014 State of Hospital Medicine Report, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey.

Dr. Huang is associate chief of the division of hospital medicine and associate clinical professor at the University of California San Diego. He is a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Negotiating salaries. Improving patient flow. Increasing patient satisfaction. Reducing readmissions. Championing quality improvement efforts. Planning strategically. Handling schedule issues. Dealing with coverage issues. Working on Ebola preparation. Being on call 24 hours a day for an urgent concern from hospital administration or a hospitalist.

Hospitalist group leaders often feel they are pulled in multiple directions all at once and find that a day off really is not a day off. Leaders often are asked to take on additional responsibilities and might wonder whether they are given sufficient protected time. Leaders of larger HM groups might ask whether adding an associate chief would help cover the administrative workload. Or they may be asking whether hospitalist group leaders should receive a premium in salary, above that of other hospitalists in the group.

These are questions the State of Hospital Medicine Report (SOHM) attempts to answer. Although there is significant variation that is dependent on many factors (i.e., group size, academic status, and whether or not the practice is part of a larger multi-site group), the 2014 SOHM found that the median total full-time equivalent (FTE) allocation for physician administration/leadership for HMGs serving adults was just 0.60. The highest-ranking physician leader most commonly had 0.25 to 0.35 FTE protected for administrative responsibilities. And the median compensation premium for group leaders was 15%.

One leadership challenge is that administrative work never stops. Group leaders often find themselves having to come in for meetings before or after night shifts. Leaders sometimes feel that the 0.30 FTE allocated for administrative responsibilities actually requires the workload of a full-time position. Yet, like other hospitalists, leaders typically work a significant number of consecutive clinical shifts to ensure continuity of care for patients, which can make juggling administrative work challenging.

Additionally, group leaders often carry a significant clinical workload. (Read about Team Hospitalist’s newest member and her split leadership-clinical roles) I would argue that this is a good thing, important for many reasons, including maintaining clinical skills, understanding the nature of work and challenges on the front lines, and being able to facilitate quality improvement efforts. Further, group leaders often are perceived to be team players by other hospitalists when they work a wide variety of shifts on all days of the week. Many programs face staffing challenges, and leaders might work extra shifts when other hospitalists are unable to fill them.

Certainly group leaders face significant challenges, but the position also comes with many rewards. Satisfaction comes from improving the program for all hospitalists in a group, from gains in hospital efficiency or flow, from systems improvements to ensure patient safety or improve patient outcomes, and from being respected by hospital administration as well as other hospitalists in the group. With a good understanding of hospital finances and patient flow, some hospitalist group leaders advance to other roles in hospital administration, such as CMO or CEO.

Although there may be no one-size-fits-all answer for the right amount of protected time or salary for group leaders, leaders clearly play a challenging but essential role in bringing value to both hospitals and hospitalist groups.

For more data from the 2014 State of Hospital Medicine Report, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey.

Dr. Huang is associate chief of the division of hospital medicine and associate clinical professor at the University of California San Diego. He is a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.