User login

Asteraceae Dermatitis: Everyday Plants With Allergenic Potential

The Asteraceae (formerly Compositae) family of plants is derived from the ancient Greek word aster, meaning “star,” referring to the starlike arrangement of flower petals around a central disc known as a capitulum. What initially appears as a single flower is actually a composite of several smaller flowers, hence the former name Compositae.1 Well-known members of the Asteraceae family include ornamental annuals (eg, sunflowers, marigolds, cosmos), herbaceous perennials (eg, chrysanthemums, dandelions), vegetables (eg, lettuce, chicory, artichokes), herbs (eg, chamomile, tarragon), and weeds (eg, ragweed, horseweed, capeweed)(Figure 1).2

There are more than 25,000 species of Asteraceae plants that thrive in a wide range of climates worldwide. Cases of Asteraceae-induced skin reactions have been reported in North America, Europe, Asia, and Australia.3 Members of the Asteraceae family are ubiquitous in gardens, along roadsides, and in the wilderness. Occupational exposure commonly affects gardeners, florists, farmers, and forestry workers through either direct contact with plants or via airborne pollen. Furthermore, plants of the Asteraceae family are used in various products, including pediculicides (eg, insect repellents), cosmetics (eg, eye creams, body washes), and food products (eg, cooking oils, sweetening agents, coffee substitutes, herbal teas).4-6 These plants have substantial allergic potential, resulting in numerous cutaneous reactions.

Allergic Potential

Asteraceae plants can elicit both immediate and delayed hypersensitivity reactions (HSRs); for instance, exposure to ragweed pollen may cause an IgE-mediated type 1 HSR manifesting as allergic rhinitis or a type IV HSR manifesting as airborne allergic contact dermatitis.7,8 The main contact allergens present in Asteraceae plants are sesquiterpene lactones, which are found in the leaves, stems, flowers, and pollen.9-11 Sesquiterpene lactones consist of an α-methyl group attached to a lactone ring combined with a sesquiterpene.12 Patch testing can be used to diagnose Asteraceae allergy; however, the results are not consistently reliable because there is no perfect screening allergen. Patch test preparations commonly used to detect Asteraceae allergy include Compositae mix (consisting of Anthemis nobilis extract, Chamomilla recutita extract, Achillea millefolium extract, Tanacetum vulgare extract, Arnica montana extract, and parthenolide) and sesquiterpene lactone mix (consisting of alantolactone, dehydrocostus lactone, and costunolide). In North America, the prevalence of positive patch tests to Compositae mix and sesquiterpene lactone mix is approximately 2% and 0.5%, respectively.13 When patch testing is performed, both Compositae mix and sesquiterpene lactone mix should be utilized to minimize the risk of missing Asteraceae allergy, as sesquiterpene lactone mix alone does not detect all Compositae-sensitized patients. Additionally, it may be necessary to test supplemental Asteraceae allergens, including preparations from specific plants to which the patient has been exposed. Exposure to Asteraceae-containing cosmetic products may lead to dermatitis, though this is highly dependent on the particular plant species involved. For instance, the prevalence of sensitization is high in arnica (tincture) and elecampane but low with more commonly used species such as German chamomile.14

Cutaneous Manifestations

Asteraceae dermatitis, which also is known as Australian bush dermatitis, weed dermatitis, and chrysanthemum dermatitis,2 can manifest on any area of the body that directly contacts the plant or is exposed to the pollen. Asteraceae dermatitis historically was reported in older adults with a recent history of plant exposure.6,15 However, recent data have shown a female preponderance and a younger mean age of onset (46–49 years).16

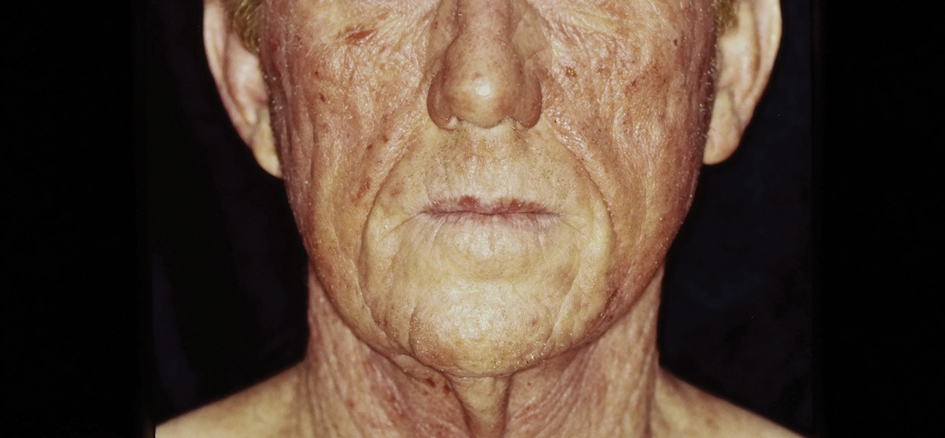

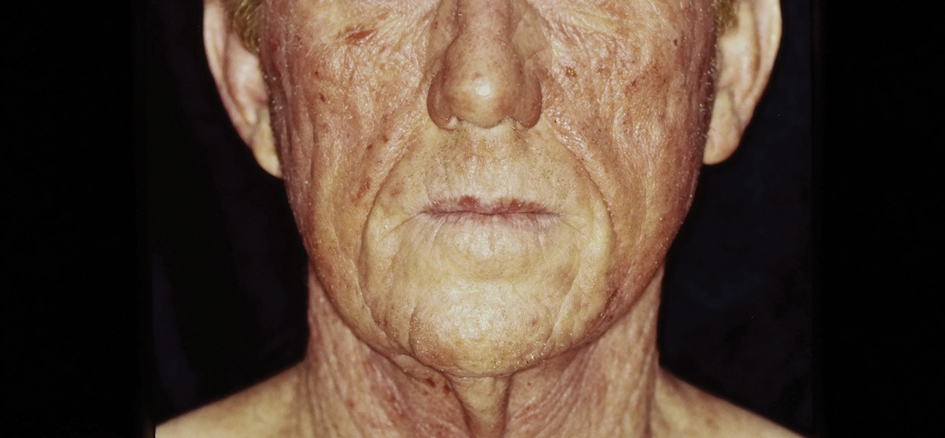

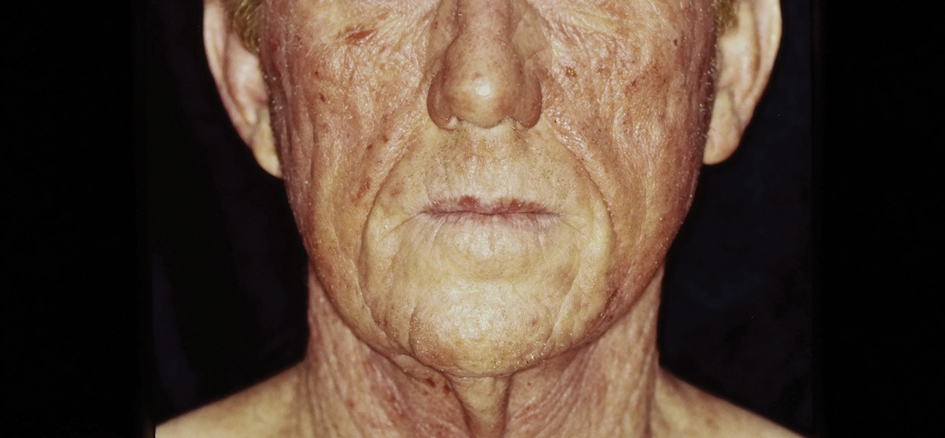

There are multiple distinct clinical manifestations of Asteraceae dermatitis. The most common cutaneous finding is localized vesicular or eczematous patches on the hands or wrists. Other variations include eczematous rashes on the exposed skin of the hands, arms, face, and neck; generalized eczema; and isolated facial eczema.16,17 These variations can be attributed to contact dermatitis caused by airborne pollen, which may mimic photodermatitis. However, airborne Asteraceae dermatitis can be distinguished clinically from photodermatitis by the involvement of sun-protected areas such as the skinfolds of the eyelids, retroauricular sulci, and nasolabial folds (Figure 2).2,9 In rare cases, systemic allergic contact dermatitis can occur if the Asteraceae allergen is ingested.2,18

Other diagnostic clues include dermatitis that flares during the summer, at the peak of the growing season, with remission in the cooler months. Potential risk factors include a childhood history of atopic dermatitis and allergic rhinitis.16 With prolonged exposure, patients may develop chronic actinic dermatitis, an immunologically mediated photodermatosis characterized by lichenified and pruritic eczematous plaques located predominantly on sun-exposed areas with notable sparing of the skin folds.19 The association between Asteraceae dermatitis and chronic actinic dermatitis is highly variable, with some studies reporting a 25% correlation and others finding a stronger association of up to 80%.2,15,20 Asteraceae allergy appears to be a relatively uncommon cause of photoallergy in North America. In one recent study, 16% (3/19) of patients with chronic actinic dermatitis had positive patch or photopatch tests to sesquiterpene lactone mix, but in another large study of photopatch testing it was reported to be a rare photoallergen.21,22

Parthenium dermatitis is an allergic contact dermatitis caused by exposure to Parthenium hysterophorus, a weed of the Asteraceae family that is responsible for 30% of cases of contact dermatitis in India.23,24 Unlike the more classic manifestation of Asteraceae dermatitis, which primarily affects the upper extremities in cases from North America and Europe, Parthenium dermatitis typically occurs in an airborne pattern distribution.24

Management

While complete avoidance of Asteraceae plants is ideal, it often is unrealistic due to their abundance in nature. Therefore, minimizing exposure to the causative plants is recommended. Primary preventive measures such as wearing protective gloves and clothing and applying bentonite clay prior to exposure should be taken when working outdoors. Promptly showering after contact with plants also can reduce the risk for Asteraceae dermatitis.

Symptomatic treatment is appropriate for mild cases and includes topical corticosteroids and calcineurin inhibitors. For severe cases, systemic corticosteroids may be needed for acute flares, with azathioprine, mycophenolate, cyclosporine, or methotrexate available for recalcitrant disease. Verma et al25 found that treatment with azathioprine for 6 months resulted in greater than 60% clearance in all 12 patients, with a majority achieving 80% to 100% clearance. Methotrexate has been used at doses of 15 mg once weekly.26 Narrowband UVB and psoralen plus UVA have been effective in extensive cases; however, care should be exercised in patients with photosensitive dermatitis, who instead should practice strict photoprotection.27-29 Lakshmi et al30 reported the use of cyclosporine during the acute phase of Asteraceae dermatitis at a dose of 2.5 mg/kg daily for 4 to 8 weeks. There have been several case reports of dupilumab treating allergic contact dermatitis; however, there have been 3 cases of patients with atopic dermatitis developing Asteraceae dermatitis while taking dupilumab.31,32 Recently, oral Janus kinase inhibitors have shown success in treating refractory cases of airborne Asteraceae dermatitis.33,34 Further research is needed to determine the safety and efficacy of dupilumab and Janus kinase inhibitors for treatment of Asteraceae dermatitis.

Final Thoughts

The Asteraceae plant family is vast and diverse, with more than 200 species reported to cause allergic contact dermatitis.12 Common modes of contact include gardening, occupational exposure, airborne pollen, and use of pediculicides and cosmetics that contain components of Asteraceae plants. Educating patients on how to minimize contact with Asteraceae plants is the most effective management strategy; topical agents and oral immunosuppressives can be used for symptomatic treatment.

- Morhardt S, Morhardt E. California Desert Flowers: An Introduction to Families, Genera, and Species. University of California Press; 2004.

- Gordon LA. Compositae dermatitis. Australas J Dermatol. 1999;40:123-130. doi:10.1046/j.1440-0960.1999.00341.x

- Denisow-Pietrzyk M, Pietrzyk Ł, Denisow B. Asteraceae species as potential environmental factors of allergy. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2019;26:6290-6300. doi:10.1007/s11356-019-04146-w

- Paulsen E, Chistensen LP, Andersen KE. Cosmetics and herbal remedies with Compositae plant extracts—are they tolerated by Compositae-allergic patients? Contact Dermatitis. 2008;58:15-23. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2007.01250.x

- Burry JN, Reid JG, Kirk J. Australian bush dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 1975;1:263-264. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1975.tb05422.x

- Punchihewa N, Palmer A, Nixon R. Allergic contact dermatitis to Compositae: an Australian case series. Contact Dermatitis. 2022;87:356-362. doi:10.1111/cod.14162

- Chen KW, Marusciac L, Tamas PT, et al. Ragweed pollen allergy: burden, characteristics, and management of an imported allergen source in Europe. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2018;176:163-180. doi:10.1159/000487997

- Schloemer JA, Zirwas MJ, Burkhart CG. Airborne contact dermatitis: common causes in the USA. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:271-274. doi:10.1111/ijd.12692

- Arlette J, Mitchell JC. Compositae dermatitis. current aspects. Contact Dermatitis. 1981;7:129-136. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1981.tb04584.x

- Mitchell JC, Dupuis G. Allergic contact dermatitis from sesquiterpenoids of the Compositae family of plants. Br J Dermatol. 1971;84:139-150. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1971.tb06857.x

- Salapovic H, Geier J, Reznicek G. Quantification of Sesquiterpene lactones in Asteraceae plant extracts: evaluation of their allergenic potential. Sci Pharm. 2013;81:807-818. doi:10.3797/scipharm.1306-17

- Paulsen E. Compositae dermatitis: a survey. Contact Dermatitis. 1992;26:76-86. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1992.tb00888.x. Published correction appears in Contact Dermatitis. 1992;27:208.

- DeKoven JG, Silverberg JI, Warshaw EM, et al. North American Contact Dermatitis Group patch test results: 2017-2018. Dermatitis. 2021;32:111-123. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000729

- Paulsen E. Contact sensitization from Compositae-containing herbal remedies and cosmetics. Contact Dermatitis. 2002;47:189-198. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0536.2002.470401.x

- Frain-Bell W, Johnson BE. Contact allergic sensitivity to plants and the photosensitivity dermatitis and actinic reticuloid syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 1979;101:503-512.

- Paulsen E, Andersen KE. Clinical patterns of Compositae dermatitis in Danish monosensitized patients. Contact Dermatitis. 2018;78:185-193. doi:10.1111/cod.12916

- Jovanovic´ M, Poljacki M. Compositae dermatitis. Med Pregl. 2003;56:43-49. doi:10.2298/mpns0302043j

- Krook G. Occupational dermatitis from Lactuca sativa (lettuce) and Cichorium (endive). simultaneous occurrence of immediate and delayed allergy as a cause of contact dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 1977;3:27-36. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1977.tb03583.x

- Paek SY, Lim HW. Chronic actinic dermatitis. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:355-361, viii-ix. doi:10.1016/j.det.2014.03.007

- du P Menagé H, Hawk JL, White IR. Sesquiterpene lactone mix contact sensitivity and its relationship to chronic actinic dermatitis: a follow-up study. Contact Dermatitis. 1998;39:119-122. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1998.tb05859.x

- Wang CX, Belsito DV. Chronic actinic dermatitis revisited. Dermatitis. 2020;31:68-74. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000531

- DeLeo VA, Adler BL, Warshaw EM, et al. Photopatch test results of the North American contact dermatitis group, 1999-2009. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2022;38:288-291. doi:10.1111/phpp.12742

- McGovern TW, LaWarre S. Botanical briefs: the scourge of India—Parthenium hysterophorus L. Cutis. 2001;67:27-34. Published correction appears in Cutis. 2001;67:154.

- Sharma VK, Verma P, Maharaja K. Parthenium dermatitis. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2013;12:85-94. doi:10.1039/c2pp25186h

- Verma KK, Bansal A, Sethuraman G. Parthenium dermatitis treated with azathioprine weekly pulse doses. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2006;72:24-27. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.19713

- Sharma VK, Bhat R, Sethuraman G, et al. Treatment of Parthenium dermatitis with methotrexate. Contact Dermatitis. 2007;57:118-119. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2006.00950.x

- Burke DA, Corey G, Storrs FJ. Psoralen plus UVA protocol for Compositae photosensitivity. Am J Contact Dermat. 1996;7:171-176.

- Lovell CR. Allergic contact dermatitis due to plants. In: Plants and the Skin. Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1993:96-254.

- Dogra S, Parsad D, Handa S. Narrowband ultraviolet B in airborne contact dermatitis: a ray of hope! Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:373-374. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.05724.x

- Lakshmi C, Srinivas CR, Jayaraman A. Ciclosporin in Parthenium dermatitis—a report of 2 cases. Contact Dermatitis. 2008;59:245-248. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2007.01208.x

- Hendricks AJ, Yosipovitch G, Shi VY. Dupilumab use in dermatologic conditions beyond atopic dermatitis—a systematic review. J Dermatolog Treat. 2021;32:19-28. doi:10.1080/09546634.2019.1689227

- Napolitano M, Fabbrocini G, Patruno C. Allergic contact dermatitis to Compositae: a possible cause of dupilumab-associated facial and neck dermatitis in atopic dermatitis patients? Contact Dermatitis. 2021;85:473-474. doi:10.1111/cod.13898

- Muddebihal A, Sardana K, Sinha S, et al. Tofacitinib in refractory Parthenium-induced airborne allergic contact dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 2023;88:150-152. doi:10.1111/cod.14234

- Baltazar D, Shinamoto SR, Hamann CP, et al. Occupational airborne allergic contact dermatitis to invasive Compositae species treated with abrocitinib: a case report. Contact Dermatitis. 2022;87:542-544. doi:10.1111/cod.14204

The Asteraceae (formerly Compositae) family of plants is derived from the ancient Greek word aster, meaning “star,” referring to the starlike arrangement of flower petals around a central disc known as a capitulum. What initially appears as a single flower is actually a composite of several smaller flowers, hence the former name Compositae.1 Well-known members of the Asteraceae family include ornamental annuals (eg, sunflowers, marigolds, cosmos), herbaceous perennials (eg, chrysanthemums, dandelions), vegetables (eg, lettuce, chicory, artichokes), herbs (eg, chamomile, tarragon), and weeds (eg, ragweed, horseweed, capeweed)(Figure 1).2

There are more than 25,000 species of Asteraceae plants that thrive in a wide range of climates worldwide. Cases of Asteraceae-induced skin reactions have been reported in North America, Europe, Asia, and Australia.3 Members of the Asteraceae family are ubiquitous in gardens, along roadsides, and in the wilderness. Occupational exposure commonly affects gardeners, florists, farmers, and forestry workers through either direct contact with plants or via airborne pollen. Furthermore, plants of the Asteraceae family are used in various products, including pediculicides (eg, insect repellents), cosmetics (eg, eye creams, body washes), and food products (eg, cooking oils, sweetening agents, coffee substitutes, herbal teas).4-6 These plants have substantial allergic potential, resulting in numerous cutaneous reactions.

Allergic Potential

Asteraceae plants can elicit both immediate and delayed hypersensitivity reactions (HSRs); for instance, exposure to ragweed pollen may cause an IgE-mediated type 1 HSR manifesting as allergic rhinitis or a type IV HSR manifesting as airborne allergic contact dermatitis.7,8 The main contact allergens present in Asteraceae plants are sesquiterpene lactones, which are found in the leaves, stems, flowers, and pollen.9-11 Sesquiterpene lactones consist of an α-methyl group attached to a lactone ring combined with a sesquiterpene.12 Patch testing can be used to diagnose Asteraceae allergy; however, the results are not consistently reliable because there is no perfect screening allergen. Patch test preparations commonly used to detect Asteraceae allergy include Compositae mix (consisting of Anthemis nobilis extract, Chamomilla recutita extract, Achillea millefolium extract, Tanacetum vulgare extract, Arnica montana extract, and parthenolide) and sesquiterpene lactone mix (consisting of alantolactone, dehydrocostus lactone, and costunolide). In North America, the prevalence of positive patch tests to Compositae mix and sesquiterpene lactone mix is approximately 2% and 0.5%, respectively.13 When patch testing is performed, both Compositae mix and sesquiterpene lactone mix should be utilized to minimize the risk of missing Asteraceae allergy, as sesquiterpene lactone mix alone does not detect all Compositae-sensitized patients. Additionally, it may be necessary to test supplemental Asteraceae allergens, including preparations from specific plants to which the patient has been exposed. Exposure to Asteraceae-containing cosmetic products may lead to dermatitis, though this is highly dependent on the particular plant species involved. For instance, the prevalence of sensitization is high in arnica (tincture) and elecampane but low with more commonly used species such as German chamomile.14

Cutaneous Manifestations

Asteraceae dermatitis, which also is known as Australian bush dermatitis, weed dermatitis, and chrysanthemum dermatitis,2 can manifest on any area of the body that directly contacts the plant or is exposed to the pollen. Asteraceae dermatitis historically was reported in older adults with a recent history of plant exposure.6,15 However, recent data have shown a female preponderance and a younger mean age of onset (46–49 years).16

There are multiple distinct clinical manifestations of Asteraceae dermatitis. The most common cutaneous finding is localized vesicular or eczematous patches on the hands or wrists. Other variations include eczematous rashes on the exposed skin of the hands, arms, face, and neck; generalized eczema; and isolated facial eczema.16,17 These variations can be attributed to contact dermatitis caused by airborne pollen, which may mimic photodermatitis. However, airborne Asteraceae dermatitis can be distinguished clinically from photodermatitis by the involvement of sun-protected areas such as the skinfolds of the eyelids, retroauricular sulci, and nasolabial folds (Figure 2).2,9 In rare cases, systemic allergic contact dermatitis can occur if the Asteraceae allergen is ingested.2,18

Other diagnostic clues include dermatitis that flares during the summer, at the peak of the growing season, with remission in the cooler months. Potential risk factors include a childhood history of atopic dermatitis and allergic rhinitis.16 With prolonged exposure, patients may develop chronic actinic dermatitis, an immunologically mediated photodermatosis characterized by lichenified and pruritic eczematous plaques located predominantly on sun-exposed areas with notable sparing of the skin folds.19 The association between Asteraceae dermatitis and chronic actinic dermatitis is highly variable, with some studies reporting a 25% correlation and others finding a stronger association of up to 80%.2,15,20 Asteraceae allergy appears to be a relatively uncommon cause of photoallergy in North America. In one recent study, 16% (3/19) of patients with chronic actinic dermatitis had positive patch or photopatch tests to sesquiterpene lactone mix, but in another large study of photopatch testing it was reported to be a rare photoallergen.21,22

Parthenium dermatitis is an allergic contact dermatitis caused by exposure to Parthenium hysterophorus, a weed of the Asteraceae family that is responsible for 30% of cases of contact dermatitis in India.23,24 Unlike the more classic manifestation of Asteraceae dermatitis, which primarily affects the upper extremities in cases from North America and Europe, Parthenium dermatitis typically occurs in an airborne pattern distribution.24

Management

While complete avoidance of Asteraceae plants is ideal, it often is unrealistic due to their abundance in nature. Therefore, minimizing exposure to the causative plants is recommended. Primary preventive measures such as wearing protective gloves and clothing and applying bentonite clay prior to exposure should be taken when working outdoors. Promptly showering after contact with plants also can reduce the risk for Asteraceae dermatitis.

Symptomatic treatment is appropriate for mild cases and includes topical corticosteroids and calcineurin inhibitors. For severe cases, systemic corticosteroids may be needed for acute flares, with azathioprine, mycophenolate, cyclosporine, or methotrexate available for recalcitrant disease. Verma et al25 found that treatment with azathioprine for 6 months resulted in greater than 60% clearance in all 12 patients, with a majority achieving 80% to 100% clearance. Methotrexate has been used at doses of 15 mg once weekly.26 Narrowband UVB and psoralen plus UVA have been effective in extensive cases; however, care should be exercised in patients with photosensitive dermatitis, who instead should practice strict photoprotection.27-29 Lakshmi et al30 reported the use of cyclosporine during the acute phase of Asteraceae dermatitis at a dose of 2.5 mg/kg daily for 4 to 8 weeks. There have been several case reports of dupilumab treating allergic contact dermatitis; however, there have been 3 cases of patients with atopic dermatitis developing Asteraceae dermatitis while taking dupilumab.31,32 Recently, oral Janus kinase inhibitors have shown success in treating refractory cases of airborne Asteraceae dermatitis.33,34 Further research is needed to determine the safety and efficacy of dupilumab and Janus kinase inhibitors for treatment of Asteraceae dermatitis.

Final Thoughts

The Asteraceae plant family is vast and diverse, with more than 200 species reported to cause allergic contact dermatitis.12 Common modes of contact include gardening, occupational exposure, airborne pollen, and use of pediculicides and cosmetics that contain components of Asteraceae plants. Educating patients on how to minimize contact with Asteraceae plants is the most effective management strategy; topical agents and oral immunosuppressives can be used for symptomatic treatment.

The Asteraceae (formerly Compositae) family of plants is derived from the ancient Greek word aster, meaning “star,” referring to the starlike arrangement of flower petals around a central disc known as a capitulum. What initially appears as a single flower is actually a composite of several smaller flowers, hence the former name Compositae.1 Well-known members of the Asteraceae family include ornamental annuals (eg, sunflowers, marigolds, cosmos), herbaceous perennials (eg, chrysanthemums, dandelions), vegetables (eg, lettuce, chicory, artichokes), herbs (eg, chamomile, tarragon), and weeds (eg, ragweed, horseweed, capeweed)(Figure 1).2

There are more than 25,000 species of Asteraceae plants that thrive in a wide range of climates worldwide. Cases of Asteraceae-induced skin reactions have been reported in North America, Europe, Asia, and Australia.3 Members of the Asteraceae family are ubiquitous in gardens, along roadsides, and in the wilderness. Occupational exposure commonly affects gardeners, florists, farmers, and forestry workers through either direct contact with plants or via airborne pollen. Furthermore, plants of the Asteraceae family are used in various products, including pediculicides (eg, insect repellents), cosmetics (eg, eye creams, body washes), and food products (eg, cooking oils, sweetening agents, coffee substitutes, herbal teas).4-6 These plants have substantial allergic potential, resulting in numerous cutaneous reactions.

Allergic Potential

Asteraceae plants can elicit both immediate and delayed hypersensitivity reactions (HSRs); for instance, exposure to ragweed pollen may cause an IgE-mediated type 1 HSR manifesting as allergic rhinitis or a type IV HSR manifesting as airborne allergic contact dermatitis.7,8 The main contact allergens present in Asteraceae plants are sesquiterpene lactones, which are found in the leaves, stems, flowers, and pollen.9-11 Sesquiterpene lactones consist of an α-methyl group attached to a lactone ring combined with a sesquiterpene.12 Patch testing can be used to diagnose Asteraceae allergy; however, the results are not consistently reliable because there is no perfect screening allergen. Patch test preparations commonly used to detect Asteraceae allergy include Compositae mix (consisting of Anthemis nobilis extract, Chamomilla recutita extract, Achillea millefolium extract, Tanacetum vulgare extract, Arnica montana extract, and parthenolide) and sesquiterpene lactone mix (consisting of alantolactone, dehydrocostus lactone, and costunolide). In North America, the prevalence of positive patch tests to Compositae mix and sesquiterpene lactone mix is approximately 2% and 0.5%, respectively.13 When patch testing is performed, both Compositae mix and sesquiterpene lactone mix should be utilized to minimize the risk of missing Asteraceae allergy, as sesquiterpene lactone mix alone does not detect all Compositae-sensitized patients. Additionally, it may be necessary to test supplemental Asteraceae allergens, including preparations from specific plants to which the patient has been exposed. Exposure to Asteraceae-containing cosmetic products may lead to dermatitis, though this is highly dependent on the particular plant species involved. For instance, the prevalence of sensitization is high in arnica (tincture) and elecampane but low with more commonly used species such as German chamomile.14

Cutaneous Manifestations

Asteraceae dermatitis, which also is known as Australian bush dermatitis, weed dermatitis, and chrysanthemum dermatitis,2 can manifest on any area of the body that directly contacts the plant or is exposed to the pollen. Asteraceae dermatitis historically was reported in older adults with a recent history of plant exposure.6,15 However, recent data have shown a female preponderance and a younger mean age of onset (46–49 years).16

There are multiple distinct clinical manifestations of Asteraceae dermatitis. The most common cutaneous finding is localized vesicular or eczematous patches on the hands or wrists. Other variations include eczematous rashes on the exposed skin of the hands, arms, face, and neck; generalized eczema; and isolated facial eczema.16,17 These variations can be attributed to contact dermatitis caused by airborne pollen, which may mimic photodermatitis. However, airborne Asteraceae dermatitis can be distinguished clinically from photodermatitis by the involvement of sun-protected areas such as the skinfolds of the eyelids, retroauricular sulci, and nasolabial folds (Figure 2).2,9 In rare cases, systemic allergic contact dermatitis can occur if the Asteraceae allergen is ingested.2,18

Other diagnostic clues include dermatitis that flares during the summer, at the peak of the growing season, with remission in the cooler months. Potential risk factors include a childhood history of atopic dermatitis and allergic rhinitis.16 With prolonged exposure, patients may develop chronic actinic dermatitis, an immunologically mediated photodermatosis characterized by lichenified and pruritic eczematous plaques located predominantly on sun-exposed areas with notable sparing of the skin folds.19 The association between Asteraceae dermatitis and chronic actinic dermatitis is highly variable, with some studies reporting a 25% correlation and others finding a stronger association of up to 80%.2,15,20 Asteraceae allergy appears to be a relatively uncommon cause of photoallergy in North America. In one recent study, 16% (3/19) of patients with chronic actinic dermatitis had positive patch or photopatch tests to sesquiterpene lactone mix, but in another large study of photopatch testing it was reported to be a rare photoallergen.21,22

Parthenium dermatitis is an allergic contact dermatitis caused by exposure to Parthenium hysterophorus, a weed of the Asteraceae family that is responsible for 30% of cases of contact dermatitis in India.23,24 Unlike the more classic manifestation of Asteraceae dermatitis, which primarily affects the upper extremities in cases from North America and Europe, Parthenium dermatitis typically occurs in an airborne pattern distribution.24

Management

While complete avoidance of Asteraceae plants is ideal, it often is unrealistic due to their abundance in nature. Therefore, minimizing exposure to the causative plants is recommended. Primary preventive measures such as wearing protective gloves and clothing and applying bentonite clay prior to exposure should be taken when working outdoors. Promptly showering after contact with plants also can reduce the risk for Asteraceae dermatitis.

Symptomatic treatment is appropriate for mild cases and includes topical corticosteroids and calcineurin inhibitors. For severe cases, systemic corticosteroids may be needed for acute flares, with azathioprine, mycophenolate, cyclosporine, or methotrexate available for recalcitrant disease. Verma et al25 found that treatment with azathioprine for 6 months resulted in greater than 60% clearance in all 12 patients, with a majority achieving 80% to 100% clearance. Methotrexate has been used at doses of 15 mg once weekly.26 Narrowband UVB and psoralen plus UVA have been effective in extensive cases; however, care should be exercised in patients with photosensitive dermatitis, who instead should practice strict photoprotection.27-29 Lakshmi et al30 reported the use of cyclosporine during the acute phase of Asteraceae dermatitis at a dose of 2.5 mg/kg daily for 4 to 8 weeks. There have been several case reports of dupilumab treating allergic contact dermatitis; however, there have been 3 cases of patients with atopic dermatitis developing Asteraceae dermatitis while taking dupilumab.31,32 Recently, oral Janus kinase inhibitors have shown success in treating refractory cases of airborne Asteraceae dermatitis.33,34 Further research is needed to determine the safety and efficacy of dupilumab and Janus kinase inhibitors for treatment of Asteraceae dermatitis.

Final Thoughts

The Asteraceae plant family is vast and diverse, with more than 200 species reported to cause allergic contact dermatitis.12 Common modes of contact include gardening, occupational exposure, airborne pollen, and use of pediculicides and cosmetics that contain components of Asteraceae plants. Educating patients on how to minimize contact with Asteraceae plants is the most effective management strategy; topical agents and oral immunosuppressives can be used for symptomatic treatment.

- Morhardt S, Morhardt E. California Desert Flowers: An Introduction to Families, Genera, and Species. University of California Press; 2004.

- Gordon LA. Compositae dermatitis. Australas J Dermatol. 1999;40:123-130. doi:10.1046/j.1440-0960.1999.00341.x

- Denisow-Pietrzyk M, Pietrzyk Ł, Denisow B. Asteraceae species as potential environmental factors of allergy. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2019;26:6290-6300. doi:10.1007/s11356-019-04146-w

- Paulsen E, Chistensen LP, Andersen KE. Cosmetics and herbal remedies with Compositae plant extracts—are they tolerated by Compositae-allergic patients? Contact Dermatitis. 2008;58:15-23. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2007.01250.x

- Burry JN, Reid JG, Kirk J. Australian bush dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 1975;1:263-264. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1975.tb05422.x

- Punchihewa N, Palmer A, Nixon R. Allergic contact dermatitis to Compositae: an Australian case series. Contact Dermatitis. 2022;87:356-362. doi:10.1111/cod.14162

- Chen KW, Marusciac L, Tamas PT, et al. Ragweed pollen allergy: burden, characteristics, and management of an imported allergen source in Europe. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2018;176:163-180. doi:10.1159/000487997

- Schloemer JA, Zirwas MJ, Burkhart CG. Airborne contact dermatitis: common causes in the USA. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:271-274. doi:10.1111/ijd.12692

- Arlette J, Mitchell JC. Compositae dermatitis. current aspects. Contact Dermatitis. 1981;7:129-136. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1981.tb04584.x

- Mitchell JC, Dupuis G. Allergic contact dermatitis from sesquiterpenoids of the Compositae family of plants. Br J Dermatol. 1971;84:139-150. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1971.tb06857.x

- Salapovic H, Geier J, Reznicek G. Quantification of Sesquiterpene lactones in Asteraceae plant extracts: evaluation of their allergenic potential. Sci Pharm. 2013;81:807-818. doi:10.3797/scipharm.1306-17

- Paulsen E. Compositae dermatitis: a survey. Contact Dermatitis. 1992;26:76-86. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1992.tb00888.x. Published correction appears in Contact Dermatitis. 1992;27:208.

- DeKoven JG, Silverberg JI, Warshaw EM, et al. North American Contact Dermatitis Group patch test results: 2017-2018. Dermatitis. 2021;32:111-123. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000729

- Paulsen E. Contact sensitization from Compositae-containing herbal remedies and cosmetics. Contact Dermatitis. 2002;47:189-198. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0536.2002.470401.x

- Frain-Bell W, Johnson BE. Contact allergic sensitivity to plants and the photosensitivity dermatitis and actinic reticuloid syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 1979;101:503-512.

- Paulsen E, Andersen KE. Clinical patterns of Compositae dermatitis in Danish monosensitized patients. Contact Dermatitis. 2018;78:185-193. doi:10.1111/cod.12916

- Jovanovic´ M, Poljacki M. Compositae dermatitis. Med Pregl. 2003;56:43-49. doi:10.2298/mpns0302043j

- Krook G. Occupational dermatitis from Lactuca sativa (lettuce) and Cichorium (endive). simultaneous occurrence of immediate and delayed allergy as a cause of contact dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 1977;3:27-36. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1977.tb03583.x

- Paek SY, Lim HW. Chronic actinic dermatitis. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:355-361, viii-ix. doi:10.1016/j.det.2014.03.007

- du P Menagé H, Hawk JL, White IR. Sesquiterpene lactone mix contact sensitivity and its relationship to chronic actinic dermatitis: a follow-up study. Contact Dermatitis. 1998;39:119-122. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1998.tb05859.x

- Wang CX, Belsito DV. Chronic actinic dermatitis revisited. Dermatitis. 2020;31:68-74. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000531

- DeLeo VA, Adler BL, Warshaw EM, et al. Photopatch test results of the North American contact dermatitis group, 1999-2009. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2022;38:288-291. doi:10.1111/phpp.12742

- McGovern TW, LaWarre S. Botanical briefs: the scourge of India—Parthenium hysterophorus L. Cutis. 2001;67:27-34. Published correction appears in Cutis. 2001;67:154.

- Sharma VK, Verma P, Maharaja K. Parthenium dermatitis. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2013;12:85-94. doi:10.1039/c2pp25186h

- Verma KK, Bansal A, Sethuraman G. Parthenium dermatitis treated with azathioprine weekly pulse doses. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2006;72:24-27. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.19713

- Sharma VK, Bhat R, Sethuraman G, et al. Treatment of Parthenium dermatitis with methotrexate. Contact Dermatitis. 2007;57:118-119. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2006.00950.x

- Burke DA, Corey G, Storrs FJ. Psoralen plus UVA protocol for Compositae photosensitivity. Am J Contact Dermat. 1996;7:171-176.

- Lovell CR. Allergic contact dermatitis due to plants. In: Plants and the Skin. Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1993:96-254.

- Dogra S, Parsad D, Handa S. Narrowband ultraviolet B in airborne contact dermatitis: a ray of hope! Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:373-374. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.05724.x

- Lakshmi C, Srinivas CR, Jayaraman A. Ciclosporin in Parthenium dermatitis—a report of 2 cases. Contact Dermatitis. 2008;59:245-248. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2007.01208.x

- Hendricks AJ, Yosipovitch G, Shi VY. Dupilumab use in dermatologic conditions beyond atopic dermatitis—a systematic review. J Dermatolog Treat. 2021;32:19-28. doi:10.1080/09546634.2019.1689227

- Napolitano M, Fabbrocini G, Patruno C. Allergic contact dermatitis to Compositae: a possible cause of dupilumab-associated facial and neck dermatitis in atopic dermatitis patients? Contact Dermatitis. 2021;85:473-474. doi:10.1111/cod.13898

- Muddebihal A, Sardana K, Sinha S, et al. Tofacitinib in refractory Parthenium-induced airborne allergic contact dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 2023;88:150-152. doi:10.1111/cod.14234

- Baltazar D, Shinamoto SR, Hamann CP, et al. Occupational airborne allergic contact dermatitis to invasive Compositae species treated with abrocitinib: a case report. Contact Dermatitis. 2022;87:542-544. doi:10.1111/cod.14204

- Morhardt S, Morhardt E. California Desert Flowers: An Introduction to Families, Genera, and Species. University of California Press; 2004.

- Gordon LA. Compositae dermatitis. Australas J Dermatol. 1999;40:123-130. doi:10.1046/j.1440-0960.1999.00341.x

- Denisow-Pietrzyk M, Pietrzyk Ł, Denisow B. Asteraceae species as potential environmental factors of allergy. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2019;26:6290-6300. doi:10.1007/s11356-019-04146-w

- Paulsen E, Chistensen LP, Andersen KE. Cosmetics and herbal remedies with Compositae plant extracts—are they tolerated by Compositae-allergic patients? Contact Dermatitis. 2008;58:15-23. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2007.01250.x

- Burry JN, Reid JG, Kirk J. Australian bush dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 1975;1:263-264. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1975.tb05422.x

- Punchihewa N, Palmer A, Nixon R. Allergic contact dermatitis to Compositae: an Australian case series. Contact Dermatitis. 2022;87:356-362. doi:10.1111/cod.14162

- Chen KW, Marusciac L, Tamas PT, et al. Ragweed pollen allergy: burden, characteristics, and management of an imported allergen source in Europe. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2018;176:163-180. doi:10.1159/000487997

- Schloemer JA, Zirwas MJ, Burkhart CG. Airborne contact dermatitis: common causes in the USA. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:271-274. doi:10.1111/ijd.12692

- Arlette J, Mitchell JC. Compositae dermatitis. current aspects. Contact Dermatitis. 1981;7:129-136. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1981.tb04584.x

- Mitchell JC, Dupuis G. Allergic contact dermatitis from sesquiterpenoids of the Compositae family of plants. Br J Dermatol. 1971;84:139-150. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1971.tb06857.x

- Salapovic H, Geier J, Reznicek G. Quantification of Sesquiterpene lactones in Asteraceae plant extracts: evaluation of their allergenic potential. Sci Pharm. 2013;81:807-818. doi:10.3797/scipharm.1306-17

- Paulsen E. Compositae dermatitis: a survey. Contact Dermatitis. 1992;26:76-86. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1992.tb00888.x. Published correction appears in Contact Dermatitis. 1992;27:208.

- DeKoven JG, Silverberg JI, Warshaw EM, et al. North American Contact Dermatitis Group patch test results: 2017-2018. Dermatitis. 2021;32:111-123. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000729

- Paulsen E. Contact sensitization from Compositae-containing herbal remedies and cosmetics. Contact Dermatitis. 2002;47:189-198. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0536.2002.470401.x

- Frain-Bell W, Johnson BE. Contact allergic sensitivity to plants and the photosensitivity dermatitis and actinic reticuloid syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 1979;101:503-512.

- Paulsen E, Andersen KE. Clinical patterns of Compositae dermatitis in Danish monosensitized patients. Contact Dermatitis. 2018;78:185-193. doi:10.1111/cod.12916

- Jovanovic´ M, Poljacki M. Compositae dermatitis. Med Pregl. 2003;56:43-49. doi:10.2298/mpns0302043j

- Krook G. Occupational dermatitis from Lactuca sativa (lettuce) and Cichorium (endive). simultaneous occurrence of immediate and delayed allergy as a cause of contact dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 1977;3:27-36. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1977.tb03583.x

- Paek SY, Lim HW. Chronic actinic dermatitis. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:355-361, viii-ix. doi:10.1016/j.det.2014.03.007

- du P Menagé H, Hawk JL, White IR. Sesquiterpene lactone mix contact sensitivity and its relationship to chronic actinic dermatitis: a follow-up study. Contact Dermatitis. 1998;39:119-122. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1998.tb05859.x

- Wang CX, Belsito DV. Chronic actinic dermatitis revisited. Dermatitis. 2020;31:68-74. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000531

- DeLeo VA, Adler BL, Warshaw EM, et al. Photopatch test results of the North American contact dermatitis group, 1999-2009. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2022;38:288-291. doi:10.1111/phpp.12742

- McGovern TW, LaWarre S. Botanical briefs: the scourge of India—Parthenium hysterophorus L. Cutis. 2001;67:27-34. Published correction appears in Cutis. 2001;67:154.

- Sharma VK, Verma P, Maharaja K. Parthenium dermatitis. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2013;12:85-94. doi:10.1039/c2pp25186h

- Verma KK, Bansal A, Sethuraman G. Parthenium dermatitis treated with azathioprine weekly pulse doses. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2006;72:24-27. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.19713

- Sharma VK, Bhat R, Sethuraman G, et al. Treatment of Parthenium dermatitis with methotrexate. Contact Dermatitis. 2007;57:118-119. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2006.00950.x

- Burke DA, Corey G, Storrs FJ. Psoralen plus UVA protocol for Compositae photosensitivity. Am J Contact Dermat. 1996;7:171-176.

- Lovell CR. Allergic contact dermatitis due to plants. In: Plants and the Skin. Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1993:96-254.

- Dogra S, Parsad D, Handa S. Narrowband ultraviolet B in airborne contact dermatitis: a ray of hope! Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:373-374. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.05724.x

- Lakshmi C, Srinivas CR, Jayaraman A. Ciclosporin in Parthenium dermatitis—a report of 2 cases. Contact Dermatitis. 2008;59:245-248. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2007.01208.x

- Hendricks AJ, Yosipovitch G, Shi VY. Dupilumab use in dermatologic conditions beyond atopic dermatitis—a systematic review. J Dermatolog Treat. 2021;32:19-28. doi:10.1080/09546634.2019.1689227

- Napolitano M, Fabbrocini G, Patruno C. Allergic contact dermatitis to Compositae: a possible cause of dupilumab-associated facial and neck dermatitis in atopic dermatitis patients? Contact Dermatitis. 2021;85:473-474. doi:10.1111/cod.13898

- Muddebihal A, Sardana K, Sinha S, et al. Tofacitinib in refractory Parthenium-induced airborne allergic contact dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 2023;88:150-152. doi:10.1111/cod.14234

- Baltazar D, Shinamoto SR, Hamann CP, et al. Occupational airborne allergic contact dermatitis to invasive Compositae species treated with abrocitinib: a case report. Contact Dermatitis. 2022;87:542-544. doi:10.1111/cod.14204

Practice Points

- Asteraceae dermatitis can occur from direct contact with plants of the Asteraceae family; through airborne pollen; or from exposure to topical medications, cooking products, and cosmetics.

- Patient education on primary prevention, especially protective clothing, is crucial, as these plants are ubiquitous outdoors and have diverse phenotypes.

- Management of mild Asteraceae dermatitis consists primarily of topical corticosteroids and calcineurin inhibitors, while systemic corticosteroids and other immunosuppressive agents are utilized for severe or recalcitrant cases.

Cyclosporine for Recalcitrant Bullous Pemphigoid Induced by Nivolumab Therapy for Malignant Melanoma

To the Editor:

Immune checkpoint inhibitors have revolutionized the treatment of advanced-stage melanoma, with remarkably improved progression-free survival.1 Anti–programmed death receptor 1 (anti–PD-1) therapies, such as nivolumab and pembrolizumab, are a class of checkpoint inhibitors that have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for unresectable metastatic melanoma. Anti–PD-1 agents block the interaction of programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) found on tumor cells with the PD-1 receptor on T cells, facilitating a positive immune response.2

Although these therapies have demonstrated notable antitumor efficacy, they also give rise to numerous immune-related adverse events (irAEs). As many as 70% of patients treated with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors experience some type of organ system irAE, of which 30% to 40% are cutaneous.3-6 Dermatologic adverse events are the most common irAEs, specifically spongiotic dermatitis, lichenoid dermatitis, pruritus, and vitiligo.7 Bullous pemphigoid (BP), an autoimmune bullous skin disorder caused by autoantibodies to basement membrane zone antigens, is a rare but potentially serious cutaneous irAE.8 Systemic corticosteroids commonly are used to treat immune checkpoint inhibitor–induced BP; other options include tetracyclines for maintenance therapy and rituximab for corticosteroid-refractory BP associated with anti-PD-1.9 We present a case of recalcitrant BP secondary to nivolumab therapy in a patient with metastatic melanoma who had near-complete resolution of BP following 2 months of cyclosporine.

A 41-year-old man presented with a generalized papular skin eruption of 1 month’s duration. He had a history of stage IIIC malignant melanoma of the lower right leg with positive sentinel lymph node biopsy. The largest lymph node deposit was 0.03 mm without extracapsular extension. Whole-body positron emission tomography–computed tomography showed no evidence of distant disease. The patient was treated with wide local excision with clear surgical margins plus 12 cycles of nivolumab, which was discontinued due to colitis. Four months after the final cycle of nivolumab, the patient developed widespread erythematous papules with hemorrhagic yellow crusting and no mucosal involvement. He was referred to dermatology by his primary oncologist for further evaluation.

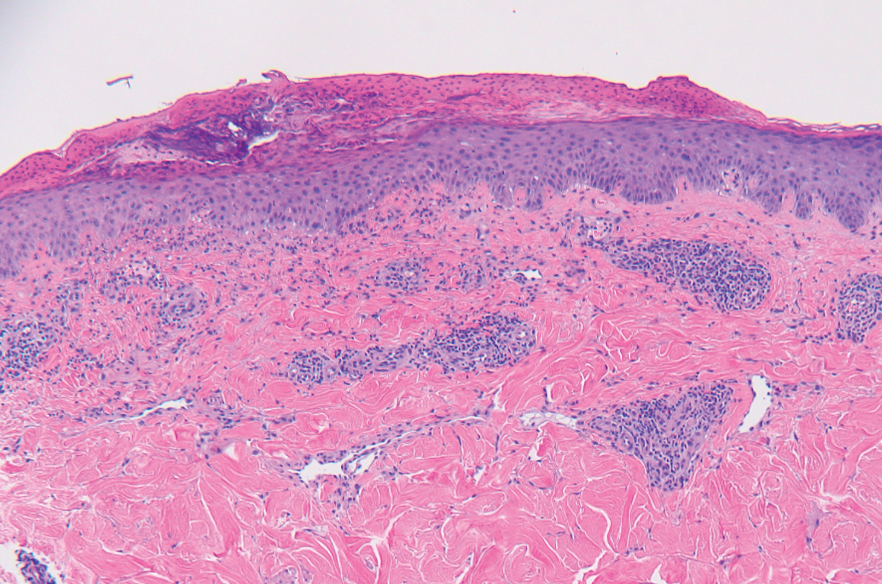

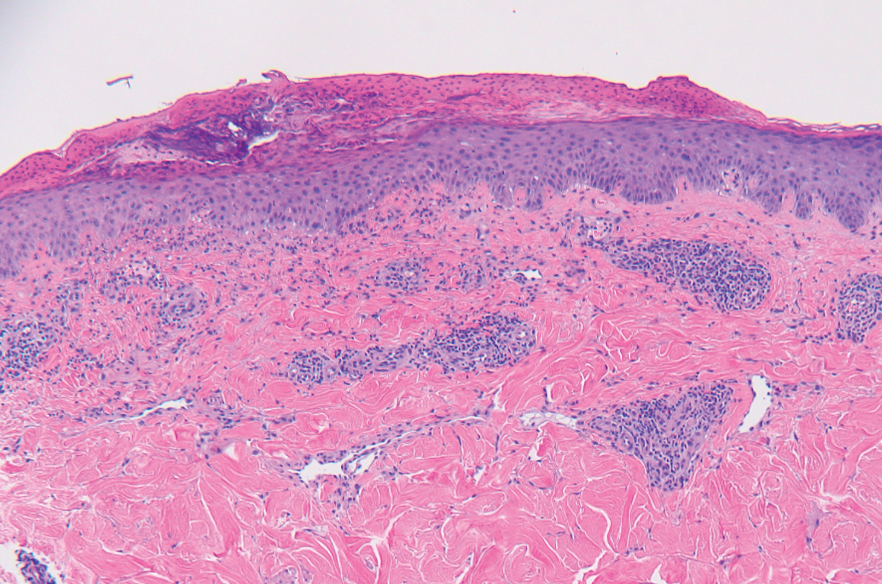

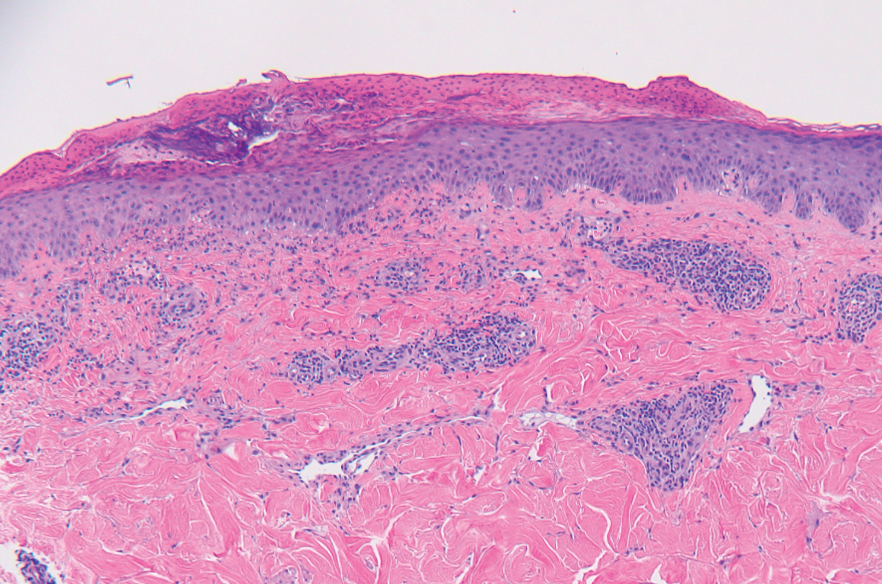

A punch biopsy from the abdomen showed parakeratosis with leukocytoclasis and a superficial dermal infiltrate of neutrophils and eosinophils (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence revealed linear basement membrane deposits of IgG and C3, consistent with subepidermal blistering disease. Indirect immunofluorescence demonstrated trace IgG and IgG4 antibodies localized to the epidermal roof of salt-split skin and was negative for IgA antibodies. An enzyme-linked immunoassay was positive for BP antigen 2 (BP180) antibodies (98.4 U/mL [positive, ≥9 U/mL]) and negative for BP antigen 1 (BP230) antibodies (4.3 U/mL [positive, ≥9 U/mL]). Overall, these findings were consistent with a diagnosis of BP.

The patient was treated with prednisone 60 mg daily with initial response; however, there was disease recurrence with tapering. Doxycycline 100 mg twice daily and nicotinamide 500 mg twice daily were added as steroid-sparing agents, as prednisone was discontinued due to mood changes. Three months after the prednisone taper, the patient continued to develop new blisters. He completed treatment with doxycycline and nicotinamide. Rituximab 375 mg weekly was then initiated for 4 weeks.

At 2-week follow-up after completing the rituximab course, the patient reported worsening symptoms and presented with new bullae on the abdomen and upper extremities (Figure 2). Because of the recent history of mood changes while taking prednisone, a trial of cyclosporine 100 mg twice daily (1.37 mg/kg/d) was initiated, with notable improvement within 2 weeks of treatment. After 2 months of cyclosporine, approximately 90% of the rash had resolved with a few tense bullae remaining on the left frontal scalp but no new flares (Figure 3). One month after treatment ended, the patient remained clear of lesions without relapse.

Programmed death receptor 1 inhibitors have shown dramatic efficacy for a growing number of solid and hematologic malignancies, especially malignant melanoma. However, their use is accompanied by nonspecific activation of the immune system, resulting in a variety of adverse events, many manifesting on the skin. Several cases of BP in patients treated with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors have been reported.9 Cutaneous irAEs usually manifest within 3 weeks of initiation of PD-1 inhibitor therapy; however, the onset of BP typically occurs later at approximately 21 weeks.4,9 Our patient developed cutaneous manifestations 4 months after cessation of nivolumab.

Bullous pemphigoid classically manifests with pruritus and tense bullae. Notably, our patient’s clinical presentation included a widespread eruption of papules without bullae, which was similar to a review by Tsiogka et al,9 which reported that one-third of patients first present with a nonspecific cutaneous eruption. Bullous pemphigoid induced by anti–PD-1 may manifest differently than traditional BP, illuminating the importance of a thorough diagnostic workup.

Although the pathogenesis of immune checkpoint inhibitor–induced BP has not been fully elucidated, it is hypothesized to be caused by increased T cell cytotoxic activity leading to tumor lysis and release of numerous autoantigens. These autoantigens cause priming of abnormal T cells that can lead to further tissue damage in peripheral tissue and to generation of aberrant B cells and subsequent autoantibodies such as BP180 in germinal centers.4,10,11

Cyclosporine is a calcineurin inhibitor that reduces synthesis of IL-2, resulting in reduced cell activation.12 Therefore, cyclosporine may alleviate BP in patients who are being treated, or were previously treated, with an immune checkpoint inhibitor by suppressing T cell–mediated immune reaction and may be a rapid alternative for patients who cannot tolerate systemic steroids.

Treatment options for mild to moderate cases of BP include topical corticosteroids and antihistamines, while severe cases may require high-dose systemic corticosteroids. In recalcitrant cases, rituximab infusion with or without intravenous immunoglobulin often is utilized.8,13 The use of cyclosporine for various bullous disorders, including pemphigus vulgaris and epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, has been described.14 In recent years there has been a shift away from the use of cyclosporine for these conditions following the introduction of rituximab, a monoclonal antibody directed against the CD20 antigen on B lymphocytes. We utilized cyclosporine in our patient after he experienced worsening symptoms 1 month after completing treatment with rituximab.

Improvement from rituximab therapy may be delayed because it can take months to deplete CD20+ B lymphocytes from circulation, which may necessitate additional immunosuppressants or re-treatment with rituximab.15,16 In these instances, cyclosporine may be beneficial as a low-cost alternative in patients who are unable to tolerate systemic steroids, with a relatively good safety profile. The dosage of cyclosporine prescribed to the patient was chosen based on Joint American Academy of Dermatology–National Psoriasis Foundation management guidelines for psoriasis with systemic nonbiologic therapies, which recommends an initial dosage of 1 to 3 mg/kg/d in 2 divided doses.17

As immunotherapy for treating various cancers gains popularity, the frequency of dermatologic irAEs will increase. Therefore, dermatologists must be aware of the array of cutaneous manifestations, such as BP, and potential treatment options. When first-line and second-line therapies are contraindicated or do not provide notable improvement, cyclosporine may be an effective alternative for immune checkpoint inhibitor–induced BP.

- Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, et al. Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab or monotherapy in untreated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:23-34. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1504030

- Alsaab HO, Sau S, Alzhrani R, et al. PD-1 and PD-L1 checkpoint signaling inhibition for cancer immunotherapy: mechanism, combinations, and clinical outcome. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:561. doi:10.3389/fphar.2017.00561

- Puzanov I, Diab A, Abdallah K, et al; . Managing toxicities associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: consensus recommendations from the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC) Toxicity Management Working Group. J Immunother Cancer. 2017;5:95. doi:10.1186/s40425-017-0300-z

- Geisler AN, Phillips GS, Barrios DM, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-related dermatologic adverse events. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1255-1268. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.132

- Villadolid J, Amin A. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in clinical practice: update on management of immune-related toxicities. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2015;4:560-575. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2218-6751.2015.06.06

- Kumar V, Chaudhary N, Garg M, et al. Current diagnosis and management of immune related adverse events (irAEs) induced by immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:49. doi:10.3389/fphar.2017.00049

- Belum VR, Benhuri B, Postow MA, et al. Characterisation and management of dermatologic adverse events to agents targeting the PD-1 receptor. Eur J Cancer. 2016;60:12-25. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2016.02.010

- Schauer F, Rafei-Shamsabadi D, Mai S, et al. Hemidesmosomal reactivity and treatment recommendations in immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced bullous pemphigoid—a retrospective, monocentric study. Front Immunol. 2022;13:953546. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.953546

- Tsiogka A, Bauer JW, Patsatsi A. Bullous pemphigoid associated with anti-programmed cell death protein 1 and anti-programmed cell death ligand 1 therapy: a review of the literature. Acta Derm Venereol. 2021;101:adv00377. doi:10.2340/00015555-3740

- Lopez AT, Khanna T, Antonov N, et al. A review of bullous pemphigoid associated with PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:664-669. doi:10.1111/ijd.13984

- Yang H, Yao Z, Zhou X, et al. Immune-related adverse events of checkpoint inhibitors: insights into immunological dysregulation. Clin Immunol. 2020;213:108377. doi:10.1016/j.clim.2020.108377

- Russell G, Graveley R, Seid J, et al. Mechanisms of action of cyclosporine and effects on connective tissues. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1992;21(6 suppl 3):16-22. doi:10.1016/0049-0172(92)90009-3

- Ahmed AR, Shetty S, Kaveri S, et al. Treatment of recalcitrant bullous pemphigoid (BP) with a novel protocol: a retrospective study with a 6-year follow-up. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:700-708.e3. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.11.030

- Amor KT, Ryan C, Menter A. The use of cyclosporine in dermatology: part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:925-946. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.02.063

- Schmidt E, Hunzelmann N, Zillikens D, et al. Rituximab in refractory autoimmune bullous diseases. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31:503-508. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2006.02151.x

- Kasperkiewicz M, Shimanovich I, Ludwig RJ, et al. Rituximab for treatment-refractory pemphigus and pemphigoid: a case series of 17 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:552-558.

- Menter A, Gelfand JM, Connor C, et al. Joint American Academy of Dermatology–National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis with systemic nonbiologic therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1445-1486. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.02.044

To the Editor:

Immune checkpoint inhibitors have revolutionized the treatment of advanced-stage melanoma, with remarkably improved progression-free survival.1 Anti–programmed death receptor 1 (anti–PD-1) therapies, such as nivolumab and pembrolizumab, are a class of checkpoint inhibitors that have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for unresectable metastatic melanoma. Anti–PD-1 agents block the interaction of programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) found on tumor cells with the PD-1 receptor on T cells, facilitating a positive immune response.2

Although these therapies have demonstrated notable antitumor efficacy, they also give rise to numerous immune-related adverse events (irAEs). As many as 70% of patients treated with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors experience some type of organ system irAE, of which 30% to 40% are cutaneous.3-6 Dermatologic adverse events are the most common irAEs, specifically spongiotic dermatitis, lichenoid dermatitis, pruritus, and vitiligo.7 Bullous pemphigoid (BP), an autoimmune bullous skin disorder caused by autoantibodies to basement membrane zone antigens, is a rare but potentially serious cutaneous irAE.8 Systemic corticosteroids commonly are used to treat immune checkpoint inhibitor–induced BP; other options include tetracyclines for maintenance therapy and rituximab for corticosteroid-refractory BP associated with anti-PD-1.9 We present a case of recalcitrant BP secondary to nivolumab therapy in a patient with metastatic melanoma who had near-complete resolution of BP following 2 months of cyclosporine.

A 41-year-old man presented with a generalized papular skin eruption of 1 month’s duration. He had a history of stage IIIC malignant melanoma of the lower right leg with positive sentinel lymph node biopsy. The largest lymph node deposit was 0.03 mm without extracapsular extension. Whole-body positron emission tomography–computed tomography showed no evidence of distant disease. The patient was treated with wide local excision with clear surgical margins plus 12 cycles of nivolumab, which was discontinued due to colitis. Four months after the final cycle of nivolumab, the patient developed widespread erythematous papules with hemorrhagic yellow crusting and no mucosal involvement. He was referred to dermatology by his primary oncologist for further evaluation.

A punch biopsy from the abdomen showed parakeratosis with leukocytoclasis and a superficial dermal infiltrate of neutrophils and eosinophils (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence revealed linear basement membrane deposits of IgG and C3, consistent with subepidermal blistering disease. Indirect immunofluorescence demonstrated trace IgG and IgG4 antibodies localized to the epidermal roof of salt-split skin and was negative for IgA antibodies. An enzyme-linked immunoassay was positive for BP antigen 2 (BP180) antibodies (98.4 U/mL [positive, ≥9 U/mL]) and negative for BP antigen 1 (BP230) antibodies (4.3 U/mL [positive, ≥9 U/mL]). Overall, these findings were consistent with a diagnosis of BP.

The patient was treated with prednisone 60 mg daily with initial response; however, there was disease recurrence with tapering. Doxycycline 100 mg twice daily and nicotinamide 500 mg twice daily were added as steroid-sparing agents, as prednisone was discontinued due to mood changes. Three months after the prednisone taper, the patient continued to develop new blisters. He completed treatment with doxycycline and nicotinamide. Rituximab 375 mg weekly was then initiated for 4 weeks.

At 2-week follow-up after completing the rituximab course, the patient reported worsening symptoms and presented with new bullae on the abdomen and upper extremities (Figure 2). Because of the recent history of mood changes while taking prednisone, a trial of cyclosporine 100 mg twice daily (1.37 mg/kg/d) was initiated, with notable improvement within 2 weeks of treatment. After 2 months of cyclosporine, approximately 90% of the rash had resolved with a few tense bullae remaining on the left frontal scalp but no new flares (Figure 3). One month after treatment ended, the patient remained clear of lesions without relapse.

Programmed death receptor 1 inhibitors have shown dramatic efficacy for a growing number of solid and hematologic malignancies, especially malignant melanoma. However, their use is accompanied by nonspecific activation of the immune system, resulting in a variety of adverse events, many manifesting on the skin. Several cases of BP in patients treated with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors have been reported.9 Cutaneous irAEs usually manifest within 3 weeks of initiation of PD-1 inhibitor therapy; however, the onset of BP typically occurs later at approximately 21 weeks.4,9 Our patient developed cutaneous manifestations 4 months after cessation of nivolumab.

Bullous pemphigoid classically manifests with pruritus and tense bullae. Notably, our patient’s clinical presentation included a widespread eruption of papules without bullae, which was similar to a review by Tsiogka et al,9 which reported that one-third of patients first present with a nonspecific cutaneous eruption. Bullous pemphigoid induced by anti–PD-1 may manifest differently than traditional BP, illuminating the importance of a thorough diagnostic workup.

Although the pathogenesis of immune checkpoint inhibitor–induced BP has not been fully elucidated, it is hypothesized to be caused by increased T cell cytotoxic activity leading to tumor lysis and release of numerous autoantigens. These autoantigens cause priming of abnormal T cells that can lead to further tissue damage in peripheral tissue and to generation of aberrant B cells and subsequent autoantibodies such as BP180 in germinal centers.4,10,11

Cyclosporine is a calcineurin inhibitor that reduces synthesis of IL-2, resulting in reduced cell activation.12 Therefore, cyclosporine may alleviate BP in patients who are being treated, or were previously treated, with an immune checkpoint inhibitor by suppressing T cell–mediated immune reaction and may be a rapid alternative for patients who cannot tolerate systemic steroids.

Treatment options for mild to moderate cases of BP include topical corticosteroids and antihistamines, while severe cases may require high-dose systemic corticosteroids. In recalcitrant cases, rituximab infusion with or without intravenous immunoglobulin often is utilized.8,13 The use of cyclosporine for various bullous disorders, including pemphigus vulgaris and epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, has been described.14 In recent years there has been a shift away from the use of cyclosporine for these conditions following the introduction of rituximab, a monoclonal antibody directed against the CD20 antigen on B lymphocytes. We utilized cyclosporine in our patient after he experienced worsening symptoms 1 month after completing treatment with rituximab.

Improvement from rituximab therapy may be delayed because it can take months to deplete CD20+ B lymphocytes from circulation, which may necessitate additional immunosuppressants or re-treatment with rituximab.15,16 In these instances, cyclosporine may be beneficial as a low-cost alternative in patients who are unable to tolerate systemic steroids, with a relatively good safety profile. The dosage of cyclosporine prescribed to the patient was chosen based on Joint American Academy of Dermatology–National Psoriasis Foundation management guidelines for psoriasis with systemic nonbiologic therapies, which recommends an initial dosage of 1 to 3 mg/kg/d in 2 divided doses.17

As immunotherapy for treating various cancers gains popularity, the frequency of dermatologic irAEs will increase. Therefore, dermatologists must be aware of the array of cutaneous manifestations, such as BP, and potential treatment options. When first-line and second-line therapies are contraindicated or do not provide notable improvement, cyclosporine may be an effective alternative for immune checkpoint inhibitor–induced BP.

To the Editor:

Immune checkpoint inhibitors have revolutionized the treatment of advanced-stage melanoma, with remarkably improved progression-free survival.1 Anti–programmed death receptor 1 (anti–PD-1) therapies, such as nivolumab and pembrolizumab, are a class of checkpoint inhibitors that have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for unresectable metastatic melanoma. Anti–PD-1 agents block the interaction of programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) found on tumor cells with the PD-1 receptor on T cells, facilitating a positive immune response.2

Although these therapies have demonstrated notable antitumor efficacy, they also give rise to numerous immune-related adverse events (irAEs). As many as 70% of patients treated with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors experience some type of organ system irAE, of which 30% to 40% are cutaneous.3-6 Dermatologic adverse events are the most common irAEs, specifically spongiotic dermatitis, lichenoid dermatitis, pruritus, and vitiligo.7 Bullous pemphigoid (BP), an autoimmune bullous skin disorder caused by autoantibodies to basement membrane zone antigens, is a rare but potentially serious cutaneous irAE.8 Systemic corticosteroids commonly are used to treat immune checkpoint inhibitor–induced BP; other options include tetracyclines for maintenance therapy and rituximab for corticosteroid-refractory BP associated with anti-PD-1.9 We present a case of recalcitrant BP secondary to nivolumab therapy in a patient with metastatic melanoma who had near-complete resolution of BP following 2 months of cyclosporine.

A 41-year-old man presented with a generalized papular skin eruption of 1 month’s duration. He had a history of stage IIIC malignant melanoma of the lower right leg with positive sentinel lymph node biopsy. The largest lymph node deposit was 0.03 mm without extracapsular extension. Whole-body positron emission tomography–computed tomography showed no evidence of distant disease. The patient was treated with wide local excision with clear surgical margins plus 12 cycles of nivolumab, which was discontinued due to colitis. Four months after the final cycle of nivolumab, the patient developed widespread erythematous papules with hemorrhagic yellow crusting and no mucosal involvement. He was referred to dermatology by his primary oncologist for further evaluation.

A punch biopsy from the abdomen showed parakeratosis with leukocytoclasis and a superficial dermal infiltrate of neutrophils and eosinophils (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence revealed linear basement membrane deposits of IgG and C3, consistent with subepidermal blistering disease. Indirect immunofluorescence demonstrated trace IgG and IgG4 antibodies localized to the epidermal roof of salt-split skin and was negative for IgA antibodies. An enzyme-linked immunoassay was positive for BP antigen 2 (BP180) antibodies (98.4 U/mL [positive, ≥9 U/mL]) and negative for BP antigen 1 (BP230) antibodies (4.3 U/mL [positive, ≥9 U/mL]). Overall, these findings were consistent with a diagnosis of BP.

The patient was treated with prednisone 60 mg daily with initial response; however, there was disease recurrence with tapering. Doxycycline 100 mg twice daily and nicotinamide 500 mg twice daily were added as steroid-sparing agents, as prednisone was discontinued due to mood changes. Three months after the prednisone taper, the patient continued to develop new blisters. He completed treatment with doxycycline and nicotinamide. Rituximab 375 mg weekly was then initiated for 4 weeks.

At 2-week follow-up after completing the rituximab course, the patient reported worsening symptoms and presented with new bullae on the abdomen and upper extremities (Figure 2). Because of the recent history of mood changes while taking prednisone, a trial of cyclosporine 100 mg twice daily (1.37 mg/kg/d) was initiated, with notable improvement within 2 weeks of treatment. After 2 months of cyclosporine, approximately 90% of the rash had resolved with a few tense bullae remaining on the left frontal scalp but no new flares (Figure 3). One month after treatment ended, the patient remained clear of lesions without relapse.

Programmed death receptor 1 inhibitors have shown dramatic efficacy for a growing number of solid and hematologic malignancies, especially malignant melanoma. However, their use is accompanied by nonspecific activation of the immune system, resulting in a variety of adverse events, many manifesting on the skin. Several cases of BP in patients treated with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors have been reported.9 Cutaneous irAEs usually manifest within 3 weeks of initiation of PD-1 inhibitor therapy; however, the onset of BP typically occurs later at approximately 21 weeks.4,9 Our patient developed cutaneous manifestations 4 months after cessation of nivolumab.

Bullous pemphigoid classically manifests with pruritus and tense bullae. Notably, our patient’s clinical presentation included a widespread eruption of papules without bullae, which was similar to a review by Tsiogka et al,9 which reported that one-third of patients first present with a nonspecific cutaneous eruption. Bullous pemphigoid induced by anti–PD-1 may manifest differently than traditional BP, illuminating the importance of a thorough diagnostic workup.

Although the pathogenesis of immune checkpoint inhibitor–induced BP has not been fully elucidated, it is hypothesized to be caused by increased T cell cytotoxic activity leading to tumor lysis and release of numerous autoantigens. These autoantigens cause priming of abnormal T cells that can lead to further tissue damage in peripheral tissue and to generation of aberrant B cells and subsequent autoantibodies such as BP180 in germinal centers.4,10,11

Cyclosporine is a calcineurin inhibitor that reduces synthesis of IL-2, resulting in reduced cell activation.12 Therefore, cyclosporine may alleviate BP in patients who are being treated, or were previously treated, with an immune checkpoint inhibitor by suppressing T cell–mediated immune reaction and may be a rapid alternative for patients who cannot tolerate systemic steroids.

Treatment options for mild to moderate cases of BP include topical corticosteroids and antihistamines, while severe cases may require high-dose systemic corticosteroids. In recalcitrant cases, rituximab infusion with or without intravenous immunoglobulin often is utilized.8,13 The use of cyclosporine for various bullous disorders, including pemphigus vulgaris and epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, has been described.14 In recent years there has been a shift away from the use of cyclosporine for these conditions following the introduction of rituximab, a monoclonal antibody directed against the CD20 antigen on B lymphocytes. We utilized cyclosporine in our patient after he experienced worsening symptoms 1 month after completing treatment with rituximab.

Improvement from rituximab therapy may be delayed because it can take months to deplete CD20+ B lymphocytes from circulation, which may necessitate additional immunosuppressants or re-treatment with rituximab.15,16 In these instances, cyclosporine may be beneficial as a low-cost alternative in patients who are unable to tolerate systemic steroids, with a relatively good safety profile. The dosage of cyclosporine prescribed to the patient was chosen based on Joint American Academy of Dermatology–National Psoriasis Foundation management guidelines for psoriasis with systemic nonbiologic therapies, which recommends an initial dosage of 1 to 3 mg/kg/d in 2 divided doses.17

As immunotherapy for treating various cancers gains popularity, the frequency of dermatologic irAEs will increase. Therefore, dermatologists must be aware of the array of cutaneous manifestations, such as BP, and potential treatment options. When first-line and second-line therapies are contraindicated or do not provide notable improvement, cyclosporine may be an effective alternative for immune checkpoint inhibitor–induced BP.

- Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, et al. Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab or monotherapy in untreated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:23-34. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1504030

- Alsaab HO, Sau S, Alzhrani R, et al. PD-1 and PD-L1 checkpoint signaling inhibition for cancer immunotherapy: mechanism, combinations, and clinical outcome. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:561. doi:10.3389/fphar.2017.00561

- Puzanov I, Diab A, Abdallah K, et al; . Managing toxicities associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: consensus recommendations from the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC) Toxicity Management Working Group. J Immunother Cancer. 2017;5:95. doi:10.1186/s40425-017-0300-z

- Geisler AN, Phillips GS, Barrios DM, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-related dermatologic adverse events. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1255-1268. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.132

- Villadolid J, Amin A. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in clinical practice: update on management of immune-related toxicities. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2015;4:560-575. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2218-6751.2015.06.06

- Kumar V, Chaudhary N, Garg M, et al. Current diagnosis and management of immune related adverse events (irAEs) induced by immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:49. doi:10.3389/fphar.2017.00049

- Belum VR, Benhuri B, Postow MA, et al. Characterisation and management of dermatologic adverse events to agents targeting the PD-1 receptor. Eur J Cancer. 2016;60:12-25. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2016.02.010

- Schauer F, Rafei-Shamsabadi D, Mai S, et al. Hemidesmosomal reactivity and treatment recommendations in immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced bullous pemphigoid—a retrospective, monocentric study. Front Immunol. 2022;13:953546. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.953546

- Tsiogka A, Bauer JW, Patsatsi A. Bullous pemphigoid associated with anti-programmed cell death protein 1 and anti-programmed cell death ligand 1 therapy: a review of the literature. Acta Derm Venereol. 2021;101:adv00377. doi:10.2340/00015555-3740

- Lopez AT, Khanna T, Antonov N, et al. A review of bullous pemphigoid associated with PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:664-669. doi:10.1111/ijd.13984

- Yang H, Yao Z, Zhou X, et al. Immune-related adverse events of checkpoint inhibitors: insights into immunological dysregulation. Clin Immunol. 2020;213:108377. doi:10.1016/j.clim.2020.108377

- Russell G, Graveley R, Seid J, et al. Mechanisms of action of cyclosporine and effects on connective tissues. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1992;21(6 suppl 3):16-22. doi:10.1016/0049-0172(92)90009-3

- Ahmed AR, Shetty S, Kaveri S, et al. Treatment of recalcitrant bullous pemphigoid (BP) with a novel protocol: a retrospective study with a 6-year follow-up. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:700-708.e3. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.11.030

- Amor KT, Ryan C, Menter A. The use of cyclosporine in dermatology: part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:925-946. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.02.063

- Schmidt E, Hunzelmann N, Zillikens D, et al. Rituximab in refractory autoimmune bullous diseases. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31:503-508. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2006.02151.x

- Kasperkiewicz M, Shimanovich I, Ludwig RJ, et al. Rituximab for treatment-refractory pemphigus and pemphigoid: a case series of 17 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:552-558.

- Menter A, Gelfand JM, Connor C, et al. Joint American Academy of Dermatology–National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis with systemic nonbiologic therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1445-1486. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.02.044

- Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, et al. Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab or monotherapy in untreated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:23-34. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1504030

- Alsaab HO, Sau S, Alzhrani R, et al. PD-1 and PD-L1 checkpoint signaling inhibition for cancer immunotherapy: mechanism, combinations, and clinical outcome. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:561. doi:10.3389/fphar.2017.00561

- Puzanov I, Diab A, Abdallah K, et al; . Managing toxicities associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: consensus recommendations from the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC) Toxicity Management Working Group. J Immunother Cancer. 2017;5:95. doi:10.1186/s40425-017-0300-z

- Geisler AN, Phillips GS, Barrios DM, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-related dermatologic adverse events. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1255-1268. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.132

- Villadolid J, Amin A. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in clinical practice: update on management of immune-related toxicities. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2015;4:560-575. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2218-6751.2015.06.06

- Kumar V, Chaudhary N, Garg M, et al. Current diagnosis and management of immune related adverse events (irAEs) induced by immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:49. doi:10.3389/fphar.2017.00049

- Belum VR, Benhuri B, Postow MA, et al. Characterisation and management of dermatologic adverse events to agents targeting the PD-1 receptor. Eur J Cancer. 2016;60:12-25. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2016.02.010

- Schauer F, Rafei-Shamsabadi D, Mai S, et al. Hemidesmosomal reactivity and treatment recommendations in immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced bullous pemphigoid—a retrospective, monocentric study. Front Immunol. 2022;13:953546. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.953546

- Tsiogka A, Bauer JW, Patsatsi A. Bullous pemphigoid associated with anti-programmed cell death protein 1 and anti-programmed cell death ligand 1 therapy: a review of the literature. Acta Derm Venereol. 2021;101:adv00377. doi:10.2340/00015555-3740

- Lopez AT, Khanna T, Antonov N, et al. A review of bullous pemphigoid associated with PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:664-669. doi:10.1111/ijd.13984

- Yang H, Yao Z, Zhou X, et al. Immune-related adverse events of checkpoint inhibitors: insights into immunological dysregulation. Clin Immunol. 2020;213:108377. doi:10.1016/j.clim.2020.108377

- Russell G, Graveley R, Seid J, et al. Mechanisms of action of cyclosporine and effects on connective tissues. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1992;21(6 suppl 3):16-22. doi:10.1016/0049-0172(92)90009-3

- Ahmed AR, Shetty S, Kaveri S, et al. Treatment of recalcitrant bullous pemphigoid (BP) with a novel protocol: a retrospective study with a 6-year follow-up. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:700-708.e3. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.11.030

- Amor KT, Ryan C, Menter A. The use of cyclosporine in dermatology: part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:925-946. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.02.063

- Schmidt E, Hunzelmann N, Zillikens D, et al. Rituximab in refractory autoimmune bullous diseases. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31:503-508. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2006.02151.x

- Kasperkiewicz M, Shimanovich I, Ludwig RJ, et al. Rituximab for treatment-refractory pemphigus and pemphigoid: a case series of 17 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:552-558.

- Menter A, Gelfand JM, Connor C, et al. Joint American Academy of Dermatology–National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis with systemic nonbiologic therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1445-1486. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.02.044

Practice Points

- Bullous pemphigoid is a rare dermatologic immune-related adverse event that can occur secondary to anti–programmed death receptor 1 therapy.

- For cases of immune checkpoint inhibitor–induced bullous pemphigoid that are recalcitrant to corticosteroids and rituximab, cyclosporine might be an effective alternative.