User login

Sniffing Out Skin Disease: Odors in Dermatologic Conditions

Sniffing Out Skin Disease: Odors in Dermatologic Conditions

Humans possess the ability to recognize and distinguish a large range of odors that can be utilized in a wide range of applications. For example, sommeliers can classify more than 88 smells specific to the roughly 800 volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in wine. Thorough physical examination is essential in dermatology, and although sight and touch play the most important diagnostic roles, the sense of smell often is overlooked. Dermatologists are rigorously trained on the many visual aspects of skin disease and have a plethora of terms to describe these features while there is minimal characterization of odors. Research on odors and the role of olfaction in dermatologic practice is limited.1,2 We conducted a literature review of PubMed and Google Scholar for peer-reviewed articles discussing the role of odors in dermatologic diseases. Keywords included odor + dermatology, smell + dermatology, cutaneous odor, odor + diagnosis, and disease odor. Relevant studies were identified by screening their abstracts, followed by a full-text review. A total of 38 articles written in English that presented information on the odor associated with dermatologic diseases were included. Articles that were unrelated to the topic or written in a language other than English were excluded.

Common Skin Odors

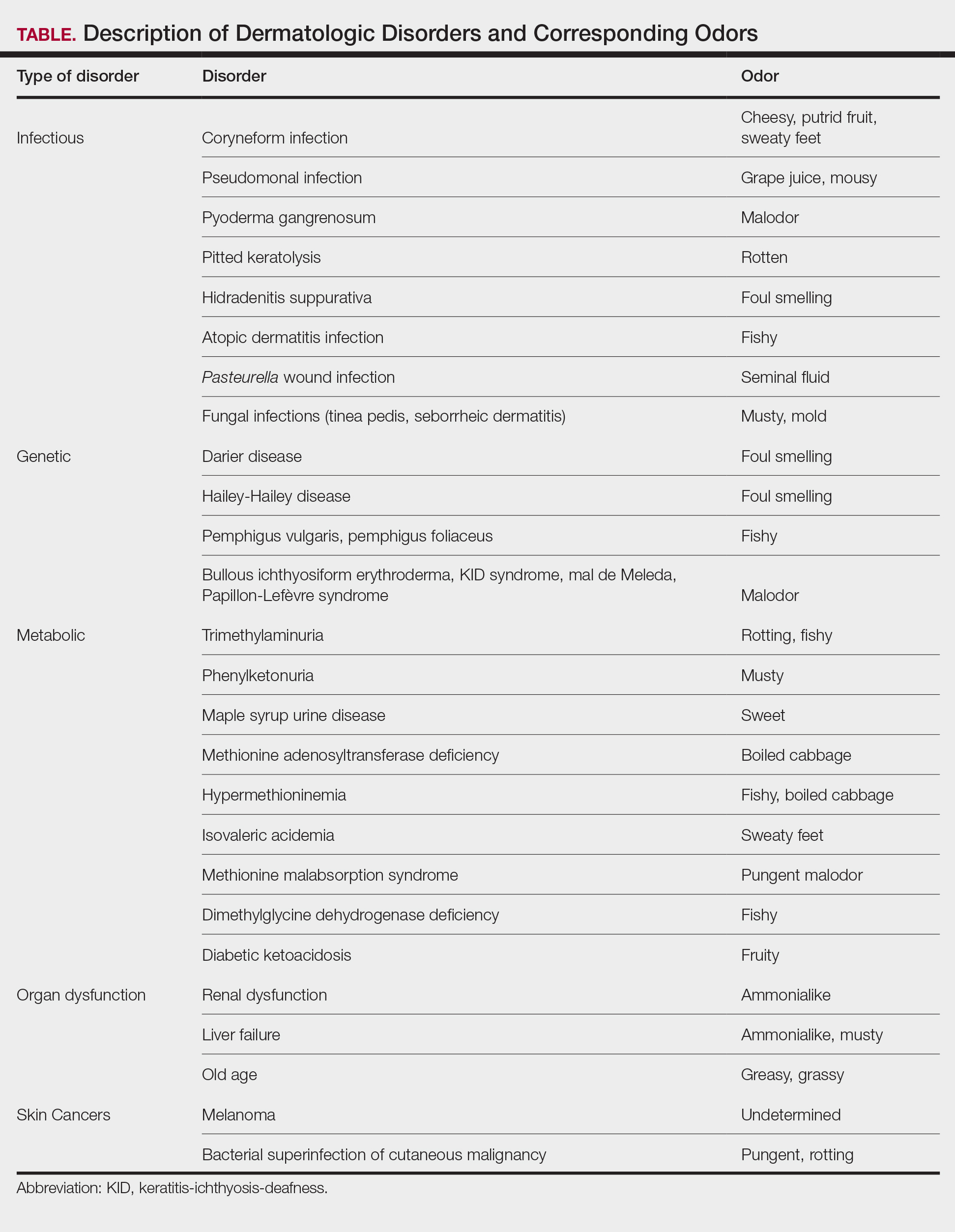

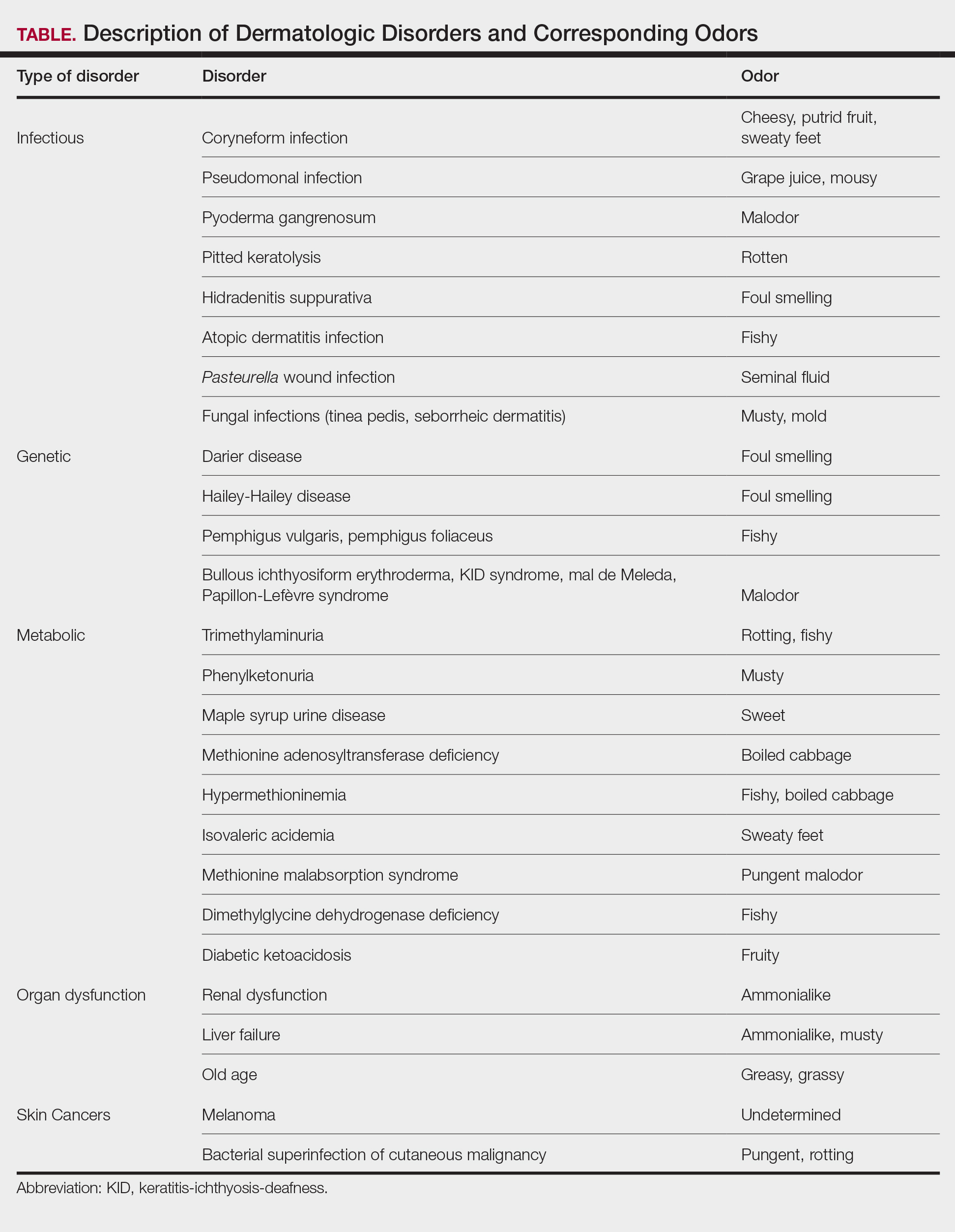

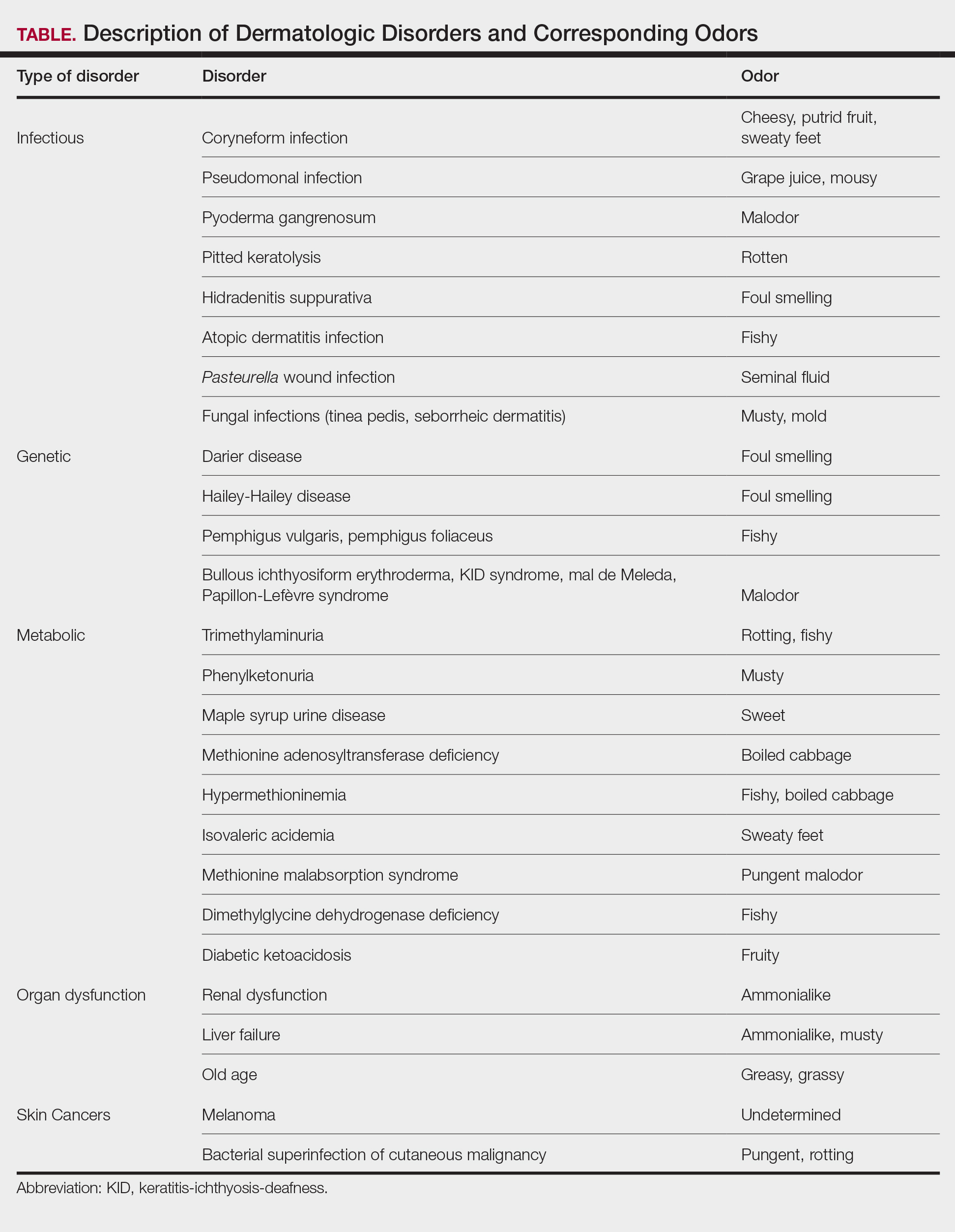

The human body emits odorants—small VOCs—in various forms (skin/sweat, breath, urine, reproductive fluids). Human odor originates from the oxidation and bacterial metabolism of sweat and sebum on the skin.3 While many odors are physiologic and not cause for concern, others can signal underlying dermatologic pathologies.4 Odor-producing conditions can be categorized broadly into infectious diseases, disorders of keratinization and acantholysis, metabolic disorders, and organ dysfunction (Table). Infectious causes include bacterial infections and chronic wounds, which commonly emit characteristic offensive odors. For example, coryneform infections produce methanethiol, causing a cheesy odor of putrid fruit, and pseudomonal pyoderma infections emit a grape juice–like or mousy odor.

Bacterial and Fungal Infections

Bacterial and fungal infections often have distinct smells. Coryneform infections emit an odor of sweaty feet, pseudomonal infections emit a grape juice–like or mousy odor, and trichomycosis infections (caused by Corynebacterium tenuis) present with malodor.5 Pseudomonas can infect pyoderma gangrenosum lesions, producing a characteristic malodor.5 These smells can be clues for infectious etiology and guide further workup.

Pitted keratolysis, a malodorous pitted rash characterized by infection of the stratum corneum by Kytococcus sedentarius, Dermatophilus congolensis, or Corynebacterium species, is associated with a rotten smell. Its pungent odor, clinical location, and characteristic appearance often are enough to make a diagnosis. The amount of bacteria maintained in the stratum corneum is correlated with the extent of the lesion. Controlling excessive moisture in footwear, aluminum chloride, and topical microbial agents work together to eliminate the skin eruption.6

Hidradenitis suppurativa, a chronic inflammatory disease of apocrine gland–containing skin, can manifest with abscesses, draining sinuses, and nodules that produce a foul-smelling, purulent discharge. The disease can be debilitating, largely impacting patients’ quality of life, making early diagnosis and treatment critical.7,8 Therapy is dependent on disease severity and includes topical antibiotics, systemic therapies, and biologics.8

Patients with atopic dermatitis often experience bacterial superinfection with Staphylococcus aureus. A case report described a patient who developed a fishy odor in this setting that resolved with antibiotic treatment, implicating S aureus in the etiology of the smell.9

A seminal fluid odor has been reported in cases of Pasteurella wound infection. In such cases, Pasteurella multocida subspecies septica was identified in the wounds caused by a dog scratch and a cat bite. The seminal fluid–like odor was apparent hours after the inciting incident and resolved after treatment with antibiotics.10

Fungal infections frequently emit musty or moldy odors. Tinea pedis (athlete’s foot) is the most prevalent cutaneous fungal infection. The presence of tinea pedis is associated with an intense foul-smelling odor, itching, fissuring, scaling, or maceration of the interdigital regions. The rash and odor resolve with use of topical antifungal agents.11,12 Seborrheic dermatitis, a prevalent and chronic dermatosis, is characterized by yellow greasy scaling on an erythematous base. In severe cases, a greasy crust with an offensive odor can cover the entire scalp.13 The specific cause of this odor is unclear, but it is thought that sebum production and the immunological response to specific Malassezia yeast species may play a role.14

Genetic and Metabolic Disorders

An array of disorders of keratinization and acantholysis can manifest with distinctive smells that dermatologists frequently encounter. For example, Darier disease, characterized by keratotic papules progressing to crusted plaques, has a signature foul-smelling odor associated with cutaneous bacterial colonization.15 Similarly, Hailey-Hailey disease, an autosomal-dominant disorder with crusted erosions in skinfold areas, produces a distinct foul smell.16 Disorders such as pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus emit a peculiar fishy odor that can be helpful in making a diagnosis.17 Additionally, bullous ichthyosiform erythroderma, keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness syndrome, mal de Meleda, and Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome are all associated with malodor.5

Certain metabolic disorders can manifest and present initially with identifiable odors. Trimethylaminuria is a psychologically disabling disease known for its rotting fishy smell due to high amounts of trimethylamine appearing in affected individuals’ sweat, urine, and breath. Previously considered to be very rare, Messenger et al18 reported the disorder is likely underdiagnosed in those with idiopathic malodor production. Detection and treatment can greatly improve patient quality of life.

Phenylketonuria is an autosomal-recessive inborn error of phenylalanine metabolism that produces a musty body and urine odor as well as other neurologic and dermatologic symptoms.19,20 Patients can present with eczematous rashes, fair skin, and blue eyes. Phenylacetic acid produces the characteristic odor in the bodily fluids, and the disease is treated with a phenylalanine-free diet.21

Maple syrup urine disease is a disorder of the oxidative decarboxylation of valine, leucine, and isoleucine (branched-chain amino acids) characterized by urine that smells sweet, resembling maple syrup, in afflicted individuals. The odor also can be present in other bodily secretions, such as sweat. Patients present early in infancy with poor feeding and vomiting as well as neurologic symptoms, eventually leading to intellectual disability. These individuals must avoid the branched-chain amino acids in their diets.21

Other metabolic storage disorders linked with specific odors are methionine adenosyltransferase deficiency (boiled cabbage), hypermethioninemia (fishy, boiled cabbage), isovaleric acidemia (sweaty feet), methionine malabsorption syndrome (pungent malodor), and dimethylglycine dehydrogenase deficiency (fishy).5,21,22

In diabetic ketoacidosis, a life-threatening complication of diabetes, the excess of ketone bodies produced causes patients to have a distinct fruity breath and urine odor, as well as fatigue, polyuria, polydipsia, nausea, and vomiting.22 Although patients with type 1 diabetes typically comprise the cohort of patients presenting with diabetic ketoacidosis, patients with type 2 diabetes can exhibit cutaneous manifestations such as infection, xerosis, and inflammatory skin diseases.23,24

Organ Dysfunction

A peculiar body odor can be a sign of organ dysfunction. Renal dysfunction may present with both an odor and dermatologic manifestations. Patients with end-stage renal disease can have an ammonialike uremic breath odor as the result of excessive nitrogenous waste products and increased concentrations of urea in their saliva.4,22 These patients also can exhibit pruritus, xerosis, pigmentation changes, nail changes, other dermatoses, and rarely uremic frost with white urate crystals present on the skin.25,26

Liver failure has been associated with an ammonialike musty breath odor termed fetor hepaticus. Shimamoto et al27 reported notably higher levels of breath ammonia levels in patients with hepatic encephalopathy, indicating that excess ammonia is responsible for the odor. Fetor hepaticus has unique characteristics that can permit a diagnosis of liver disease, though it has been reported in cases in which a liver injury could not be identified.28

Aging patients typically have a distinctive smell. Haze et al29 analyzed the body odor of patients aged 26 to 75 years and discovered the compound 2-nonenal—an unsaturated aldehyde with a smell described as greasy and grassy—was found only in patients older than 40 years. The researchers’ analysis of skin-surface lipids also revealed that the presence of ω7 unsaturated fatty acids and lipid peroxides increased with age. They concluded that 2-nonenal is generated from the oxidative degradation of ω7 unsaturated fatty acids by lipid peroxides, suggesting that 2-nonenal may be a cause of the odor of old age.29

Cutaneous Malignancies

Research shows that the profiles of the body’s continuously released VOCs change in the presence of malignancy. Some studies suggest that melanoma may have a unique odor. Willis et al30 reported that after a 13-month training period, a dog was able to correctly identify melanoma and distinguish it from basal cell carcinoma, benign nevi, and healthy skin based on olfaction alone. Additional cases have been reported in which dogs have been able to identify melanoma based on smell, suggesting that canine olfactory detection of melanoma could possibly aid in the diagnosis of skin cancer, which warrants further investigation.31,32 There is limited evidence on the specific odors of other cutaneous malignancies, such as basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma.

Bacterial superinfection of cutaneous malignancy can secrete pungent odors. An offensive rotting odor has been associated with necrotic malignant ulcers of the vagina. This malodor likely is a result of the formation of putrescine, cadaverine, short-chain fatty acids (isovaleric and butyric acids) and sulfur-containing compounds by bacteria.33 Recognition of similar smells may aid in management of these infections.

Diagnostic Techniques

Evaluating human skin odor is challenging, as the components of VOCs are complicated and typically found at trace levels. Studies indicate that gas chromatography–mass spectrometry is the most effective way to analyze human odor. This method separates, quantifies, and analyzes VOCs from samples containing odors.34 Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry, however, has limitations, as the time for analysis is lengthy, the equipment is large, and the process is expensive.3 Research supports the usefulness and validity of quantitative gas chromatography–olfactometry to detect odorants and evaluate odor activity of VOCs in various samples.35 With this technique, human assessors act in place of more conventional detectors, such as mass spectrometers. This method has been used to evaluate odorants in human urine with the goal of increasing understanding of metabolization and excretion processes.36 However, gas chromatography–olfactometry typically is used in the analysis of food and drink, and future research should be aimed at applying this method to medicine.

Zheng et al3 proposed a wearable electronic nose as a tool to identify human odor to emulate the odor recognition of a canine’s nose. They developed a sensor array based on the composites of carbon nanotubes and polymers able to examine and identify odors in the air. Study participants wore the electronic nose on the arm with the sensory array facing the armpits while they walked on a treadmill. Although many issues regarding odor measurement were not addressed in this study, the research suggests further studies are warranted to improve analysis of odor.3

Clinical Cases

Patient 1—Arseculeratne et al37 described a 41-year-old man who presented with a fishy odor that others had noticed since the age of 13 years but that the patient could not smell himself. Based on his presentation, he was worked up for trimethylaminuria and found to have elevated levels of urinary trimethylamine (TMA) with a raised TMA/TMA-oxidase ratio. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of primary trimethylaminuria, and the patient was referred to a dietician for counseling on foods that contain low amounts of choline and lecithin. Initially his urinary TMA level fell but then rose again, indicating possible relaxation of his diet. He then took a 10-day course of metronidazole, which helped reduce some of the malodor. The authors reported that the most impactful therapy for the patient was being able to discuss the disorder with his friends and family members.37 This case highlighted the importance of confirming the diagnosis and early initiation of dietary and pharmacologic interventions in patients with trimethylaminuria. In patients reporting a persistent fishy body odor, trimethylaminuria should be on the differential.

Patient 2—In 1999, Schissel et al6 described a 20-year-old active-duty soldier who presented to the dermatology department with smelly trench foot and tinea pedis. The soldier reported having this malodorous pitted rash for more than 10 years. He also reported occasional interdigital burning and itching and noted no improvement despite using various topical antifungals. Physical examination revealed an “overpowering pungent odor” when the patient removed his shoes. He had many tender, white, and wet plaques with scalloped borders coalescing into shallow pits on the plantar surface of the feet and great toes. Potassium hydroxide preparation of the great toe plaques and interdigital web spaces were positive for fungal elements, and bacterial cultures isolated moderate coagulase-negative staphylococcal and Corynebacterium species. Additionally, fungal cultures identified Acremonium species. The patient was started on clotrimazole cream twice daily, clindamycin solution twice daily, and topical ammonium chloride nightly. Two weeks later, the patient reported resolution of symptoms, including the malodor.6 In pitted keratolysis, warm and wet environments within boots or shoes allow for the growth of bacteria and fungi. The extent of the lesions is related to the amount of bacteria within the stratum corneum. The diagnosis often is made based on odor, location, and appearance of the rash alone. The most common organisms implicated as causal agents in the condition are Kytococcus sedentarius, Dermatophilus congolensis, and species of Corynebacterium and Actinomyces. It is thought that these organisms release proteolytic enzymes that degrade the horny layer, releasing a mixture of thiols, thioesters, and sulfides, which cause the pungent odor. Familiarity with the characteristic odor aids in prompt diagnosis and treatment, which will ultimately heal the skin eruption.

Patient 3—Srivastava et al32 described a 43-year-old woman who presented with a nevus on the back since childhood. She noticed that it had changed and grown over the past few years and reported that her dog would often sniff the lesion and try to scratch and bite the lesion. This reaction from her dog led the patient to seek out evaluation from a dermatologist. The patient had no personal history of skin cancer, bad sunburns, tanning bed use, or use of immunosuppressants. She reported that her father had a history of basal cell carcinoma. Physical examination revealed a 1.2×1.5-cm brown patch with an ulcerated nodule located on the lower aspect of the lesion. The patient underwent a wide local excision and sentinel lymph node biopsy with pathology showing a 4-mm-thick melanoma with positive lymph nodes. She then underwent a right axillary lymphadenectomy and was diagnosed with stage IIIB malignant melanoma. Following the surgery, the patient’s dog would sniff the back and calmly rest his head in her lap. She has not had a recurrence and credits her dog for saving her life.32 Canine olfaction may play a role in detecting skin cancers, as evidenced by this case. Patients and dermatologists should pay attention to the behavior of dogs toward skin lesions. Harnessing this sense into a method to noninvasively screen for melanoma in humans should be further investigated.

Patient 4—Matthews et al38 described a 32-year-old woman who presented to an emergency eye clinic with a white “lump” on the left upper eyelid of 6 months’ duration. Physical examination revealed 3 nodular and cystic lesions oozing a thick yellow-white discharge. Cultures were taken, and the patient was started on chloramphenicol ointment once daily to the skin. At follow-up, the lesions had not changed, and the cultures were negative. The patient reported an intermittent malodorous discharge and noted multiple similar lesions on her body. Excisional biopsy demonstrated histologic findings including dyskeratosis, papillomatosis, and suprabasal acantholysis associated with focal underlying chronic inflammatory infiltrate. She was referred to a dermatologist and was diagnosed with Darier disease. She was started on clobetasone butyrate when necessary and adapalene nocte. Understanding the smell associated with Darier disease in conjunction with the cutaneous findings may aid in earlier diagnosis, improving outcomes for affected patients.38

Conclusion

The sense of smell may be an overlooked diagnostic tool that dermatologists innately possess. Odors detected when examining patients should be considered, as these odors may help guide a diagnosis. Early diagnosis and treatment are important in many dermatologic diseases, so it is imperative to consider all diagnostic clues. Although physician olfaction may aid in diagnosis, its utility remains challenging, as there is a lack of consensus and terminology regarding odor in disease. A limitation of training to identify disease-specific odors is the requirement of engaging in often unpleasant odors. Methods to objectively measure odor are expensive and still in the early stages of development. Further research and exploration of olfactory-based diagnostic techniques is warranted to potentially improve dermatologic diagnosis.

- Stitt WZ, Goldsmith A. Scratch and sniff: the dynamic duo. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:997-999.

- Delahunty CM, Eyres G, Dufour JP. Gas chromatography-olfactometry. J Sep Sci. 2006;29:2107-2125.

- Zheng Y, Li H, Shen W, et al. Wearable electronic nose for human skin odor identification: a preliminary study. Sens Actuators A Phys. 2019;285:395-405.

- Mogilnicka I, Bogucki P, Ufnal M. Microbiota and malodor—etiology and management. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:2886. doi:10.3390/ijms21082886

- Ravindra K, Gandhi S, Sivuni A. Olfactory diagnosis in skin. Clin Derm Rev. 2018;2:38-40.

- Schissel DJ, Aydelotte J, Keller R. Road rash with a rotten odor. Mil Med. 1999;164:65-67.

- Buyukasik O, Osmanoglu CG, Polat Y, et al. A life-threatening multilocalized hidradenitis suppurativa case. MedGenMed. 2005;7:19.

- Napolitano M, Megna M, Timoshchuk EA, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa: from pathogenesis to diagnosis and treatment. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2017;10:105-115.

- Hon KLE, Leung AKC, Kong AYF, et al. Atopic dermatitis complicated by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100:797-800.

- Arashima Y, Kumasaka K, Tutchiya T, et al. Two cases of pasteurellosis accompanied by exudate with semen-like odor from the wound. Article in Japanese. Kansenshogaku Zasshi. 1999;73:623-625.

- Goldstein AO, Smith KM, Ives TJ, et al. Mycotic infections. Effective management of conditions involving the skin, hair, and nails. Geriatrics. 2000;55:40-42, 45-47, 51-52.

- Kircik LH. Observational evaluation of sertaconazole nitrate cream 2% in the treatment of pruritus related to tinea pedis. Cutis. 2009;84:279-283.

- James WD, Elston DM, Treat JR, et al. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2019.

- Sameen K. A clinical study on the efficacy of homoeopathic medicines in the treatment of seborrhiec eczema. Int J Hom Sci. 2022;6:209-212.

- Burge S. Management of Darier’s disease. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1999;24:53-56.

- Nanda KB, Saldanha CS, Jacintha M, et al. Hailey-Hailey disease responding to thalidomide. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:190-192.

- Kanwar AJ, Ghosh S, Dhar S, et al. Odor in pemphigus. Dermatology. 1992;185:215.

- Messenger J, Clark S, Massick S, et al. A review of trimethylaminuria: (fish odor syndrome). J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:45-48.

- Stone WL, Basit H, Los E. Phenylketonuria. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated August 8, 2023. Accessed August 12, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535378/

- Williams RA, Mamotte CDS, Burnett JR. Phenylketonuria: an inborn error of phenylalanine metabolism. Clin Biochem Rev. 2008;29:31-41.

- Cone TE Jr. Diagnosis and treatment: some diseases, syndromes, and conditions associated with an unusual odor. Pediatrics. 1968;41:993-995.

- Shirasu M, Touhara K. The scent of disease: volatile organic compounds of the human body related to disease and disorder. J Biochem. 2011;150:257-266.

- Ghimire P, Dhamoon AS. Ketoacidosis. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated August 8, 2023. Accessed August 12, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534848/

- Duff M, Demidova O, Blackburn S, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of diabetes mellitus. Clin Diabetes. 2015;33:40-48.

- Raina S, Chauhan V, Sharma R, et al. Uremic frost. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5(suppl 1):S58.

- Blaha T, Nigwekar S, Combs S, et al. Dermatologic manifestations in end stage renal disease. Hemodial Int. 2019;23:3-18.

- Shimamoto C, Hirata I, Katsu K. Breath and blood ammonia in liver cirrhosis. Hepatogastroenterology. 2000;47:443-445.

- Butt HR, Mason HL. Fetor hepaticus: its clinical significance and attempts at chemical isolation. Gastroenterology. 1954;26:829-845.

- Haze S, Gozu Y, Nakamura S, et al. 2-nonenal newly found in human body odor tends to increase with aging. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;116:520-524.

- Willis CM, Britton LE, Swindells MA, et al. Invasive melanoma in vivo can be distinguished from basal cell carcinoma, benign naevi and healthy skin by canine olfaction: a proof-of-principle study of differential volatile organic compound emission. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:1020-1029.

- Campbell LF, Farmery L, George SMC, et al. Canine olfactory detection of malignant melanoma. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:bcr2013008566. doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-008566

- Srivastava R, John JJ, Reilly C, et al. Sniffing out malignant melanoma: a case of canine olfactory detection. Cutis. 2019;104:E4-E6.

- Fleck CA. Fighting odor in wounds. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2006;19:242-244.

- Gallagher M, Wysocki CJ, Leyden JJ, et al. Analyses of volatile organic compounds from human skin. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:780-791.

- Campo E, Ferreira V, Escudero A, et al. Quantitative gas chromatography–olfactometry and chemical quantitative study of the aroma of four Madeira wines. Anal Chim Acta. 2006;563:180-187.

- Wagenstaller M, Buettner A. Characterization of odorants in human urine using a combined chemo-analytical and human-sensory approach: a potential diagnostic strategy. Metabolomics. 2012;9:9-20.

- Arseculeratne G, Wong AKC, Goudie DR, et al. Trimethylaminuria (fish-odor syndrome): a case report. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:81-84.

- Mathews D, Perera LP, Irion LD, et al. Darier disease: beware the cyst that smells. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;26:206-207.

Humans possess the ability to recognize and distinguish a large range of odors that can be utilized in a wide range of applications. For example, sommeliers can classify more than 88 smells specific to the roughly 800 volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in wine. Thorough physical examination is essential in dermatology, and although sight and touch play the most important diagnostic roles, the sense of smell often is overlooked. Dermatologists are rigorously trained on the many visual aspects of skin disease and have a plethora of terms to describe these features while there is minimal characterization of odors. Research on odors and the role of olfaction in dermatologic practice is limited.1,2 We conducted a literature review of PubMed and Google Scholar for peer-reviewed articles discussing the role of odors in dermatologic diseases. Keywords included odor + dermatology, smell + dermatology, cutaneous odor, odor + diagnosis, and disease odor. Relevant studies were identified by screening their abstracts, followed by a full-text review. A total of 38 articles written in English that presented information on the odor associated with dermatologic diseases were included. Articles that were unrelated to the topic or written in a language other than English were excluded.

Common Skin Odors

The human body emits odorants—small VOCs—in various forms (skin/sweat, breath, urine, reproductive fluids). Human odor originates from the oxidation and bacterial metabolism of sweat and sebum on the skin.3 While many odors are physiologic and not cause for concern, others can signal underlying dermatologic pathologies.4 Odor-producing conditions can be categorized broadly into infectious diseases, disorders of keratinization and acantholysis, metabolic disorders, and organ dysfunction (Table). Infectious causes include bacterial infections and chronic wounds, which commonly emit characteristic offensive odors. For example, coryneform infections produce methanethiol, causing a cheesy odor of putrid fruit, and pseudomonal pyoderma infections emit a grape juice–like or mousy odor.

Bacterial and Fungal Infections

Bacterial and fungal infections often have distinct smells. Coryneform infections emit an odor of sweaty feet, pseudomonal infections emit a grape juice–like or mousy odor, and trichomycosis infections (caused by Corynebacterium tenuis) present with malodor.5 Pseudomonas can infect pyoderma gangrenosum lesions, producing a characteristic malodor.5 These smells can be clues for infectious etiology and guide further workup.

Pitted keratolysis, a malodorous pitted rash characterized by infection of the stratum corneum by Kytococcus sedentarius, Dermatophilus congolensis, or Corynebacterium species, is associated with a rotten smell. Its pungent odor, clinical location, and characteristic appearance often are enough to make a diagnosis. The amount of bacteria maintained in the stratum corneum is correlated with the extent of the lesion. Controlling excessive moisture in footwear, aluminum chloride, and topical microbial agents work together to eliminate the skin eruption.6

Hidradenitis suppurativa, a chronic inflammatory disease of apocrine gland–containing skin, can manifest with abscesses, draining sinuses, and nodules that produce a foul-smelling, purulent discharge. The disease can be debilitating, largely impacting patients’ quality of life, making early diagnosis and treatment critical.7,8 Therapy is dependent on disease severity and includes topical antibiotics, systemic therapies, and biologics.8

Patients with atopic dermatitis often experience bacterial superinfection with Staphylococcus aureus. A case report described a patient who developed a fishy odor in this setting that resolved with antibiotic treatment, implicating S aureus in the etiology of the smell.9

A seminal fluid odor has been reported in cases of Pasteurella wound infection. In such cases, Pasteurella multocida subspecies septica was identified in the wounds caused by a dog scratch and a cat bite. The seminal fluid–like odor was apparent hours after the inciting incident and resolved after treatment with antibiotics.10

Fungal infections frequently emit musty or moldy odors. Tinea pedis (athlete’s foot) is the most prevalent cutaneous fungal infection. The presence of tinea pedis is associated with an intense foul-smelling odor, itching, fissuring, scaling, or maceration of the interdigital regions. The rash and odor resolve with use of topical antifungal agents.11,12 Seborrheic dermatitis, a prevalent and chronic dermatosis, is characterized by yellow greasy scaling on an erythematous base. In severe cases, a greasy crust with an offensive odor can cover the entire scalp.13 The specific cause of this odor is unclear, but it is thought that sebum production and the immunological response to specific Malassezia yeast species may play a role.14

Genetic and Metabolic Disorders

An array of disorders of keratinization and acantholysis can manifest with distinctive smells that dermatologists frequently encounter. For example, Darier disease, characterized by keratotic papules progressing to crusted plaques, has a signature foul-smelling odor associated with cutaneous bacterial colonization.15 Similarly, Hailey-Hailey disease, an autosomal-dominant disorder with crusted erosions in skinfold areas, produces a distinct foul smell.16 Disorders such as pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus emit a peculiar fishy odor that can be helpful in making a diagnosis.17 Additionally, bullous ichthyosiform erythroderma, keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness syndrome, mal de Meleda, and Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome are all associated with malodor.5

Certain metabolic disorders can manifest and present initially with identifiable odors. Trimethylaminuria is a psychologically disabling disease known for its rotting fishy smell due to high amounts of trimethylamine appearing in affected individuals’ sweat, urine, and breath. Previously considered to be very rare, Messenger et al18 reported the disorder is likely underdiagnosed in those with idiopathic malodor production. Detection and treatment can greatly improve patient quality of life.

Phenylketonuria is an autosomal-recessive inborn error of phenylalanine metabolism that produces a musty body and urine odor as well as other neurologic and dermatologic symptoms.19,20 Patients can present with eczematous rashes, fair skin, and blue eyes. Phenylacetic acid produces the characteristic odor in the bodily fluids, and the disease is treated with a phenylalanine-free diet.21

Maple syrup urine disease is a disorder of the oxidative decarboxylation of valine, leucine, and isoleucine (branched-chain amino acids) characterized by urine that smells sweet, resembling maple syrup, in afflicted individuals. The odor also can be present in other bodily secretions, such as sweat. Patients present early in infancy with poor feeding and vomiting as well as neurologic symptoms, eventually leading to intellectual disability. These individuals must avoid the branched-chain amino acids in their diets.21

Other metabolic storage disorders linked with specific odors are methionine adenosyltransferase deficiency (boiled cabbage), hypermethioninemia (fishy, boiled cabbage), isovaleric acidemia (sweaty feet), methionine malabsorption syndrome (pungent malodor), and dimethylglycine dehydrogenase deficiency (fishy).5,21,22

In diabetic ketoacidosis, a life-threatening complication of diabetes, the excess of ketone bodies produced causes patients to have a distinct fruity breath and urine odor, as well as fatigue, polyuria, polydipsia, nausea, and vomiting.22 Although patients with type 1 diabetes typically comprise the cohort of patients presenting with diabetic ketoacidosis, patients with type 2 diabetes can exhibit cutaneous manifestations such as infection, xerosis, and inflammatory skin diseases.23,24

Organ Dysfunction

A peculiar body odor can be a sign of organ dysfunction. Renal dysfunction may present with both an odor and dermatologic manifestations. Patients with end-stage renal disease can have an ammonialike uremic breath odor as the result of excessive nitrogenous waste products and increased concentrations of urea in their saliva.4,22 These patients also can exhibit pruritus, xerosis, pigmentation changes, nail changes, other dermatoses, and rarely uremic frost with white urate crystals present on the skin.25,26

Liver failure has been associated with an ammonialike musty breath odor termed fetor hepaticus. Shimamoto et al27 reported notably higher levels of breath ammonia levels in patients with hepatic encephalopathy, indicating that excess ammonia is responsible for the odor. Fetor hepaticus has unique characteristics that can permit a diagnosis of liver disease, though it has been reported in cases in which a liver injury could not be identified.28

Aging patients typically have a distinctive smell. Haze et al29 analyzed the body odor of patients aged 26 to 75 years and discovered the compound 2-nonenal—an unsaturated aldehyde with a smell described as greasy and grassy—was found only in patients older than 40 years. The researchers’ analysis of skin-surface lipids also revealed that the presence of ω7 unsaturated fatty acids and lipid peroxides increased with age. They concluded that 2-nonenal is generated from the oxidative degradation of ω7 unsaturated fatty acids by lipid peroxides, suggesting that 2-nonenal may be a cause of the odor of old age.29

Cutaneous Malignancies

Research shows that the profiles of the body’s continuously released VOCs change in the presence of malignancy. Some studies suggest that melanoma may have a unique odor. Willis et al30 reported that after a 13-month training period, a dog was able to correctly identify melanoma and distinguish it from basal cell carcinoma, benign nevi, and healthy skin based on olfaction alone. Additional cases have been reported in which dogs have been able to identify melanoma based on smell, suggesting that canine olfactory detection of melanoma could possibly aid in the diagnosis of skin cancer, which warrants further investigation.31,32 There is limited evidence on the specific odors of other cutaneous malignancies, such as basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma.

Bacterial superinfection of cutaneous malignancy can secrete pungent odors. An offensive rotting odor has been associated with necrotic malignant ulcers of the vagina. This malodor likely is a result of the formation of putrescine, cadaverine, short-chain fatty acids (isovaleric and butyric acids) and sulfur-containing compounds by bacteria.33 Recognition of similar smells may aid in management of these infections.

Diagnostic Techniques

Evaluating human skin odor is challenging, as the components of VOCs are complicated and typically found at trace levels. Studies indicate that gas chromatography–mass spectrometry is the most effective way to analyze human odor. This method separates, quantifies, and analyzes VOCs from samples containing odors.34 Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry, however, has limitations, as the time for analysis is lengthy, the equipment is large, and the process is expensive.3 Research supports the usefulness and validity of quantitative gas chromatography–olfactometry to detect odorants and evaluate odor activity of VOCs in various samples.35 With this technique, human assessors act in place of more conventional detectors, such as mass spectrometers. This method has been used to evaluate odorants in human urine with the goal of increasing understanding of metabolization and excretion processes.36 However, gas chromatography–olfactometry typically is used in the analysis of food and drink, and future research should be aimed at applying this method to medicine.

Zheng et al3 proposed a wearable electronic nose as a tool to identify human odor to emulate the odor recognition of a canine’s nose. They developed a sensor array based on the composites of carbon nanotubes and polymers able to examine and identify odors in the air. Study participants wore the electronic nose on the arm with the sensory array facing the armpits while they walked on a treadmill. Although many issues regarding odor measurement were not addressed in this study, the research suggests further studies are warranted to improve analysis of odor.3

Clinical Cases

Patient 1—Arseculeratne et al37 described a 41-year-old man who presented with a fishy odor that others had noticed since the age of 13 years but that the patient could not smell himself. Based on his presentation, he was worked up for trimethylaminuria and found to have elevated levels of urinary trimethylamine (TMA) with a raised TMA/TMA-oxidase ratio. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of primary trimethylaminuria, and the patient was referred to a dietician for counseling on foods that contain low amounts of choline and lecithin. Initially his urinary TMA level fell but then rose again, indicating possible relaxation of his diet. He then took a 10-day course of metronidazole, which helped reduce some of the malodor. The authors reported that the most impactful therapy for the patient was being able to discuss the disorder with his friends and family members.37 This case highlighted the importance of confirming the diagnosis and early initiation of dietary and pharmacologic interventions in patients with trimethylaminuria. In patients reporting a persistent fishy body odor, trimethylaminuria should be on the differential.

Patient 2—In 1999, Schissel et al6 described a 20-year-old active-duty soldier who presented to the dermatology department with smelly trench foot and tinea pedis. The soldier reported having this malodorous pitted rash for more than 10 years. He also reported occasional interdigital burning and itching and noted no improvement despite using various topical antifungals. Physical examination revealed an “overpowering pungent odor” when the patient removed his shoes. He had many tender, white, and wet plaques with scalloped borders coalescing into shallow pits on the plantar surface of the feet and great toes. Potassium hydroxide preparation of the great toe plaques and interdigital web spaces were positive for fungal elements, and bacterial cultures isolated moderate coagulase-negative staphylococcal and Corynebacterium species. Additionally, fungal cultures identified Acremonium species. The patient was started on clotrimazole cream twice daily, clindamycin solution twice daily, and topical ammonium chloride nightly. Two weeks later, the patient reported resolution of symptoms, including the malodor.6 In pitted keratolysis, warm and wet environments within boots or shoes allow for the growth of bacteria and fungi. The extent of the lesions is related to the amount of bacteria within the stratum corneum. The diagnosis often is made based on odor, location, and appearance of the rash alone. The most common organisms implicated as causal agents in the condition are Kytococcus sedentarius, Dermatophilus congolensis, and species of Corynebacterium and Actinomyces. It is thought that these organisms release proteolytic enzymes that degrade the horny layer, releasing a mixture of thiols, thioesters, and sulfides, which cause the pungent odor. Familiarity with the characteristic odor aids in prompt diagnosis and treatment, which will ultimately heal the skin eruption.

Patient 3—Srivastava et al32 described a 43-year-old woman who presented with a nevus on the back since childhood. She noticed that it had changed and grown over the past few years and reported that her dog would often sniff the lesion and try to scratch and bite the lesion. This reaction from her dog led the patient to seek out evaluation from a dermatologist. The patient had no personal history of skin cancer, bad sunburns, tanning bed use, or use of immunosuppressants. She reported that her father had a history of basal cell carcinoma. Physical examination revealed a 1.2×1.5-cm brown patch with an ulcerated nodule located on the lower aspect of the lesion. The patient underwent a wide local excision and sentinel lymph node biopsy with pathology showing a 4-mm-thick melanoma with positive lymph nodes. She then underwent a right axillary lymphadenectomy and was diagnosed with stage IIIB malignant melanoma. Following the surgery, the patient’s dog would sniff the back and calmly rest his head in her lap. She has not had a recurrence and credits her dog for saving her life.32 Canine olfaction may play a role in detecting skin cancers, as evidenced by this case. Patients and dermatologists should pay attention to the behavior of dogs toward skin lesions. Harnessing this sense into a method to noninvasively screen for melanoma in humans should be further investigated.

Patient 4—Matthews et al38 described a 32-year-old woman who presented to an emergency eye clinic with a white “lump” on the left upper eyelid of 6 months’ duration. Physical examination revealed 3 nodular and cystic lesions oozing a thick yellow-white discharge. Cultures were taken, and the patient was started on chloramphenicol ointment once daily to the skin. At follow-up, the lesions had not changed, and the cultures were negative. The patient reported an intermittent malodorous discharge and noted multiple similar lesions on her body. Excisional biopsy demonstrated histologic findings including dyskeratosis, papillomatosis, and suprabasal acantholysis associated with focal underlying chronic inflammatory infiltrate. She was referred to a dermatologist and was diagnosed with Darier disease. She was started on clobetasone butyrate when necessary and adapalene nocte. Understanding the smell associated with Darier disease in conjunction with the cutaneous findings may aid in earlier diagnosis, improving outcomes for affected patients.38

Conclusion

The sense of smell may be an overlooked diagnostic tool that dermatologists innately possess. Odors detected when examining patients should be considered, as these odors may help guide a diagnosis. Early diagnosis and treatment are important in many dermatologic diseases, so it is imperative to consider all diagnostic clues. Although physician olfaction may aid in diagnosis, its utility remains challenging, as there is a lack of consensus and terminology regarding odor in disease. A limitation of training to identify disease-specific odors is the requirement of engaging in often unpleasant odors. Methods to objectively measure odor are expensive and still in the early stages of development. Further research and exploration of olfactory-based diagnostic techniques is warranted to potentially improve dermatologic diagnosis.

Humans possess the ability to recognize and distinguish a large range of odors that can be utilized in a wide range of applications. For example, sommeliers can classify more than 88 smells specific to the roughly 800 volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in wine. Thorough physical examination is essential in dermatology, and although sight and touch play the most important diagnostic roles, the sense of smell often is overlooked. Dermatologists are rigorously trained on the many visual aspects of skin disease and have a plethora of terms to describe these features while there is minimal characterization of odors. Research on odors and the role of olfaction in dermatologic practice is limited.1,2 We conducted a literature review of PubMed and Google Scholar for peer-reviewed articles discussing the role of odors in dermatologic diseases. Keywords included odor + dermatology, smell + dermatology, cutaneous odor, odor + diagnosis, and disease odor. Relevant studies were identified by screening their abstracts, followed by a full-text review. A total of 38 articles written in English that presented information on the odor associated with dermatologic diseases were included. Articles that were unrelated to the topic or written in a language other than English were excluded.

Common Skin Odors

The human body emits odorants—small VOCs—in various forms (skin/sweat, breath, urine, reproductive fluids). Human odor originates from the oxidation and bacterial metabolism of sweat and sebum on the skin.3 While many odors are physiologic and not cause for concern, others can signal underlying dermatologic pathologies.4 Odor-producing conditions can be categorized broadly into infectious diseases, disorders of keratinization and acantholysis, metabolic disorders, and organ dysfunction (Table). Infectious causes include bacterial infections and chronic wounds, which commonly emit characteristic offensive odors. For example, coryneform infections produce methanethiol, causing a cheesy odor of putrid fruit, and pseudomonal pyoderma infections emit a grape juice–like or mousy odor.

Bacterial and Fungal Infections

Bacterial and fungal infections often have distinct smells. Coryneform infections emit an odor of sweaty feet, pseudomonal infections emit a grape juice–like or mousy odor, and trichomycosis infections (caused by Corynebacterium tenuis) present with malodor.5 Pseudomonas can infect pyoderma gangrenosum lesions, producing a characteristic malodor.5 These smells can be clues for infectious etiology and guide further workup.

Pitted keratolysis, a malodorous pitted rash characterized by infection of the stratum corneum by Kytococcus sedentarius, Dermatophilus congolensis, or Corynebacterium species, is associated with a rotten smell. Its pungent odor, clinical location, and characteristic appearance often are enough to make a diagnosis. The amount of bacteria maintained in the stratum corneum is correlated with the extent of the lesion. Controlling excessive moisture in footwear, aluminum chloride, and topical microbial agents work together to eliminate the skin eruption.6

Hidradenitis suppurativa, a chronic inflammatory disease of apocrine gland–containing skin, can manifest with abscesses, draining sinuses, and nodules that produce a foul-smelling, purulent discharge. The disease can be debilitating, largely impacting patients’ quality of life, making early diagnosis and treatment critical.7,8 Therapy is dependent on disease severity and includes topical antibiotics, systemic therapies, and biologics.8

Patients with atopic dermatitis often experience bacterial superinfection with Staphylococcus aureus. A case report described a patient who developed a fishy odor in this setting that resolved with antibiotic treatment, implicating S aureus in the etiology of the smell.9

A seminal fluid odor has been reported in cases of Pasteurella wound infection. In such cases, Pasteurella multocida subspecies septica was identified in the wounds caused by a dog scratch and a cat bite. The seminal fluid–like odor was apparent hours after the inciting incident and resolved after treatment with antibiotics.10

Fungal infections frequently emit musty or moldy odors. Tinea pedis (athlete’s foot) is the most prevalent cutaneous fungal infection. The presence of tinea pedis is associated with an intense foul-smelling odor, itching, fissuring, scaling, or maceration of the interdigital regions. The rash and odor resolve with use of topical antifungal agents.11,12 Seborrheic dermatitis, a prevalent and chronic dermatosis, is characterized by yellow greasy scaling on an erythematous base. In severe cases, a greasy crust with an offensive odor can cover the entire scalp.13 The specific cause of this odor is unclear, but it is thought that sebum production and the immunological response to specific Malassezia yeast species may play a role.14

Genetic and Metabolic Disorders

An array of disorders of keratinization and acantholysis can manifest with distinctive smells that dermatologists frequently encounter. For example, Darier disease, characterized by keratotic papules progressing to crusted plaques, has a signature foul-smelling odor associated with cutaneous bacterial colonization.15 Similarly, Hailey-Hailey disease, an autosomal-dominant disorder with crusted erosions in skinfold areas, produces a distinct foul smell.16 Disorders such as pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus emit a peculiar fishy odor that can be helpful in making a diagnosis.17 Additionally, bullous ichthyosiform erythroderma, keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness syndrome, mal de Meleda, and Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome are all associated with malodor.5

Certain metabolic disorders can manifest and present initially with identifiable odors. Trimethylaminuria is a psychologically disabling disease known for its rotting fishy smell due to high amounts of trimethylamine appearing in affected individuals’ sweat, urine, and breath. Previously considered to be very rare, Messenger et al18 reported the disorder is likely underdiagnosed in those with idiopathic malodor production. Detection and treatment can greatly improve patient quality of life.

Phenylketonuria is an autosomal-recessive inborn error of phenylalanine metabolism that produces a musty body and urine odor as well as other neurologic and dermatologic symptoms.19,20 Patients can present with eczematous rashes, fair skin, and blue eyes. Phenylacetic acid produces the characteristic odor in the bodily fluids, and the disease is treated with a phenylalanine-free diet.21

Maple syrup urine disease is a disorder of the oxidative decarboxylation of valine, leucine, and isoleucine (branched-chain amino acids) characterized by urine that smells sweet, resembling maple syrup, in afflicted individuals. The odor also can be present in other bodily secretions, such as sweat. Patients present early in infancy with poor feeding and vomiting as well as neurologic symptoms, eventually leading to intellectual disability. These individuals must avoid the branched-chain amino acids in their diets.21

Other metabolic storage disorders linked with specific odors are methionine adenosyltransferase deficiency (boiled cabbage), hypermethioninemia (fishy, boiled cabbage), isovaleric acidemia (sweaty feet), methionine malabsorption syndrome (pungent malodor), and dimethylglycine dehydrogenase deficiency (fishy).5,21,22

In diabetic ketoacidosis, a life-threatening complication of diabetes, the excess of ketone bodies produced causes patients to have a distinct fruity breath and urine odor, as well as fatigue, polyuria, polydipsia, nausea, and vomiting.22 Although patients with type 1 diabetes typically comprise the cohort of patients presenting with diabetic ketoacidosis, patients with type 2 diabetes can exhibit cutaneous manifestations such as infection, xerosis, and inflammatory skin diseases.23,24

Organ Dysfunction

A peculiar body odor can be a sign of organ dysfunction. Renal dysfunction may present with both an odor and dermatologic manifestations. Patients with end-stage renal disease can have an ammonialike uremic breath odor as the result of excessive nitrogenous waste products and increased concentrations of urea in their saliva.4,22 These patients also can exhibit pruritus, xerosis, pigmentation changes, nail changes, other dermatoses, and rarely uremic frost with white urate crystals present on the skin.25,26

Liver failure has been associated with an ammonialike musty breath odor termed fetor hepaticus. Shimamoto et al27 reported notably higher levels of breath ammonia levels in patients with hepatic encephalopathy, indicating that excess ammonia is responsible for the odor. Fetor hepaticus has unique characteristics that can permit a diagnosis of liver disease, though it has been reported in cases in which a liver injury could not be identified.28

Aging patients typically have a distinctive smell. Haze et al29 analyzed the body odor of patients aged 26 to 75 years and discovered the compound 2-nonenal—an unsaturated aldehyde with a smell described as greasy and grassy—was found only in patients older than 40 years. The researchers’ analysis of skin-surface lipids also revealed that the presence of ω7 unsaturated fatty acids and lipid peroxides increased with age. They concluded that 2-nonenal is generated from the oxidative degradation of ω7 unsaturated fatty acids by lipid peroxides, suggesting that 2-nonenal may be a cause of the odor of old age.29

Cutaneous Malignancies

Research shows that the profiles of the body’s continuously released VOCs change in the presence of malignancy. Some studies suggest that melanoma may have a unique odor. Willis et al30 reported that after a 13-month training period, a dog was able to correctly identify melanoma and distinguish it from basal cell carcinoma, benign nevi, and healthy skin based on olfaction alone. Additional cases have been reported in which dogs have been able to identify melanoma based on smell, suggesting that canine olfactory detection of melanoma could possibly aid in the diagnosis of skin cancer, which warrants further investigation.31,32 There is limited evidence on the specific odors of other cutaneous malignancies, such as basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma.

Bacterial superinfection of cutaneous malignancy can secrete pungent odors. An offensive rotting odor has been associated with necrotic malignant ulcers of the vagina. This malodor likely is a result of the formation of putrescine, cadaverine, short-chain fatty acids (isovaleric and butyric acids) and sulfur-containing compounds by bacteria.33 Recognition of similar smells may aid in management of these infections.

Diagnostic Techniques

Evaluating human skin odor is challenging, as the components of VOCs are complicated and typically found at trace levels. Studies indicate that gas chromatography–mass spectrometry is the most effective way to analyze human odor. This method separates, quantifies, and analyzes VOCs from samples containing odors.34 Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry, however, has limitations, as the time for analysis is lengthy, the equipment is large, and the process is expensive.3 Research supports the usefulness and validity of quantitative gas chromatography–olfactometry to detect odorants and evaluate odor activity of VOCs in various samples.35 With this technique, human assessors act in place of more conventional detectors, such as mass spectrometers. This method has been used to evaluate odorants in human urine with the goal of increasing understanding of metabolization and excretion processes.36 However, gas chromatography–olfactometry typically is used in the analysis of food and drink, and future research should be aimed at applying this method to medicine.

Zheng et al3 proposed a wearable electronic nose as a tool to identify human odor to emulate the odor recognition of a canine’s nose. They developed a sensor array based on the composites of carbon nanotubes and polymers able to examine and identify odors in the air. Study participants wore the electronic nose on the arm with the sensory array facing the armpits while they walked on a treadmill. Although many issues regarding odor measurement were not addressed in this study, the research suggests further studies are warranted to improve analysis of odor.3

Clinical Cases

Patient 1—Arseculeratne et al37 described a 41-year-old man who presented with a fishy odor that others had noticed since the age of 13 years but that the patient could not smell himself. Based on his presentation, he was worked up for trimethylaminuria and found to have elevated levels of urinary trimethylamine (TMA) with a raised TMA/TMA-oxidase ratio. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of primary trimethylaminuria, and the patient was referred to a dietician for counseling on foods that contain low amounts of choline and lecithin. Initially his urinary TMA level fell but then rose again, indicating possible relaxation of his diet. He then took a 10-day course of metronidazole, which helped reduce some of the malodor. The authors reported that the most impactful therapy for the patient was being able to discuss the disorder with his friends and family members.37 This case highlighted the importance of confirming the diagnosis and early initiation of dietary and pharmacologic interventions in patients with trimethylaminuria. In patients reporting a persistent fishy body odor, trimethylaminuria should be on the differential.

Patient 2—In 1999, Schissel et al6 described a 20-year-old active-duty soldier who presented to the dermatology department with smelly trench foot and tinea pedis. The soldier reported having this malodorous pitted rash for more than 10 years. He also reported occasional interdigital burning and itching and noted no improvement despite using various topical antifungals. Physical examination revealed an “overpowering pungent odor” when the patient removed his shoes. He had many tender, white, and wet plaques with scalloped borders coalescing into shallow pits on the plantar surface of the feet and great toes. Potassium hydroxide preparation of the great toe plaques and interdigital web spaces were positive for fungal elements, and bacterial cultures isolated moderate coagulase-negative staphylococcal and Corynebacterium species. Additionally, fungal cultures identified Acremonium species. The patient was started on clotrimazole cream twice daily, clindamycin solution twice daily, and topical ammonium chloride nightly. Two weeks later, the patient reported resolution of symptoms, including the malodor.6 In pitted keratolysis, warm and wet environments within boots or shoes allow for the growth of bacteria and fungi. The extent of the lesions is related to the amount of bacteria within the stratum corneum. The diagnosis often is made based on odor, location, and appearance of the rash alone. The most common organisms implicated as causal agents in the condition are Kytococcus sedentarius, Dermatophilus congolensis, and species of Corynebacterium and Actinomyces. It is thought that these organisms release proteolytic enzymes that degrade the horny layer, releasing a mixture of thiols, thioesters, and sulfides, which cause the pungent odor. Familiarity with the characteristic odor aids in prompt diagnosis and treatment, which will ultimately heal the skin eruption.

Patient 3—Srivastava et al32 described a 43-year-old woman who presented with a nevus on the back since childhood. She noticed that it had changed and grown over the past few years and reported that her dog would often sniff the lesion and try to scratch and bite the lesion. This reaction from her dog led the patient to seek out evaluation from a dermatologist. The patient had no personal history of skin cancer, bad sunburns, tanning bed use, or use of immunosuppressants. She reported that her father had a history of basal cell carcinoma. Physical examination revealed a 1.2×1.5-cm brown patch with an ulcerated nodule located on the lower aspect of the lesion. The patient underwent a wide local excision and sentinel lymph node biopsy with pathology showing a 4-mm-thick melanoma with positive lymph nodes. She then underwent a right axillary lymphadenectomy and was diagnosed with stage IIIB malignant melanoma. Following the surgery, the patient’s dog would sniff the back and calmly rest his head in her lap. She has not had a recurrence and credits her dog for saving her life.32 Canine olfaction may play a role in detecting skin cancers, as evidenced by this case. Patients and dermatologists should pay attention to the behavior of dogs toward skin lesions. Harnessing this sense into a method to noninvasively screen for melanoma in humans should be further investigated.

Patient 4—Matthews et al38 described a 32-year-old woman who presented to an emergency eye clinic with a white “lump” on the left upper eyelid of 6 months’ duration. Physical examination revealed 3 nodular and cystic lesions oozing a thick yellow-white discharge. Cultures were taken, and the patient was started on chloramphenicol ointment once daily to the skin. At follow-up, the lesions had not changed, and the cultures were negative. The patient reported an intermittent malodorous discharge and noted multiple similar lesions on her body. Excisional biopsy demonstrated histologic findings including dyskeratosis, papillomatosis, and suprabasal acantholysis associated with focal underlying chronic inflammatory infiltrate. She was referred to a dermatologist and was diagnosed with Darier disease. She was started on clobetasone butyrate when necessary and adapalene nocte. Understanding the smell associated with Darier disease in conjunction with the cutaneous findings may aid in earlier diagnosis, improving outcomes for affected patients.38

Conclusion

The sense of smell may be an overlooked diagnostic tool that dermatologists innately possess. Odors detected when examining patients should be considered, as these odors may help guide a diagnosis. Early diagnosis and treatment are important in many dermatologic diseases, so it is imperative to consider all diagnostic clues. Although physician olfaction may aid in diagnosis, its utility remains challenging, as there is a lack of consensus and terminology regarding odor in disease. A limitation of training to identify disease-specific odors is the requirement of engaging in often unpleasant odors. Methods to objectively measure odor are expensive and still in the early stages of development. Further research and exploration of olfactory-based diagnostic techniques is warranted to potentially improve dermatologic diagnosis.

- Stitt WZ, Goldsmith A. Scratch and sniff: the dynamic duo. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:997-999.

- Delahunty CM, Eyres G, Dufour JP. Gas chromatography-olfactometry. J Sep Sci. 2006;29:2107-2125.

- Zheng Y, Li H, Shen W, et al. Wearable electronic nose for human skin odor identification: a preliminary study. Sens Actuators A Phys. 2019;285:395-405.

- Mogilnicka I, Bogucki P, Ufnal M. Microbiota and malodor—etiology and management. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:2886. doi:10.3390/ijms21082886

- Ravindra K, Gandhi S, Sivuni A. Olfactory diagnosis in skin. Clin Derm Rev. 2018;2:38-40.

- Schissel DJ, Aydelotte J, Keller R. Road rash with a rotten odor. Mil Med. 1999;164:65-67.

- Buyukasik O, Osmanoglu CG, Polat Y, et al. A life-threatening multilocalized hidradenitis suppurativa case. MedGenMed. 2005;7:19.

- Napolitano M, Megna M, Timoshchuk EA, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa: from pathogenesis to diagnosis and treatment. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2017;10:105-115.

- Hon KLE, Leung AKC, Kong AYF, et al. Atopic dermatitis complicated by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100:797-800.

- Arashima Y, Kumasaka K, Tutchiya T, et al. Two cases of pasteurellosis accompanied by exudate with semen-like odor from the wound. Article in Japanese. Kansenshogaku Zasshi. 1999;73:623-625.

- Goldstein AO, Smith KM, Ives TJ, et al. Mycotic infections. Effective management of conditions involving the skin, hair, and nails. Geriatrics. 2000;55:40-42, 45-47, 51-52.

- Kircik LH. Observational evaluation of sertaconazole nitrate cream 2% in the treatment of pruritus related to tinea pedis. Cutis. 2009;84:279-283.

- James WD, Elston DM, Treat JR, et al. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2019.

- Sameen K. A clinical study on the efficacy of homoeopathic medicines in the treatment of seborrhiec eczema. Int J Hom Sci. 2022;6:209-212.

- Burge S. Management of Darier’s disease. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1999;24:53-56.

- Nanda KB, Saldanha CS, Jacintha M, et al. Hailey-Hailey disease responding to thalidomide. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:190-192.

- Kanwar AJ, Ghosh S, Dhar S, et al. Odor in pemphigus. Dermatology. 1992;185:215.

- Messenger J, Clark S, Massick S, et al. A review of trimethylaminuria: (fish odor syndrome). J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:45-48.

- Stone WL, Basit H, Los E. Phenylketonuria. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated August 8, 2023. Accessed August 12, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535378/

- Williams RA, Mamotte CDS, Burnett JR. Phenylketonuria: an inborn error of phenylalanine metabolism. Clin Biochem Rev. 2008;29:31-41.

- Cone TE Jr. Diagnosis and treatment: some diseases, syndromes, and conditions associated with an unusual odor. Pediatrics. 1968;41:993-995.

- Shirasu M, Touhara K. The scent of disease: volatile organic compounds of the human body related to disease and disorder. J Biochem. 2011;150:257-266.

- Ghimire P, Dhamoon AS. Ketoacidosis. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated August 8, 2023. Accessed August 12, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534848/

- Duff M, Demidova O, Blackburn S, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of diabetes mellitus. Clin Diabetes. 2015;33:40-48.

- Raina S, Chauhan V, Sharma R, et al. Uremic frost. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5(suppl 1):S58.

- Blaha T, Nigwekar S, Combs S, et al. Dermatologic manifestations in end stage renal disease. Hemodial Int. 2019;23:3-18.

- Shimamoto C, Hirata I, Katsu K. Breath and blood ammonia in liver cirrhosis. Hepatogastroenterology. 2000;47:443-445.

- Butt HR, Mason HL. Fetor hepaticus: its clinical significance and attempts at chemical isolation. Gastroenterology. 1954;26:829-845.

- Haze S, Gozu Y, Nakamura S, et al. 2-nonenal newly found in human body odor tends to increase with aging. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;116:520-524.

- Willis CM, Britton LE, Swindells MA, et al. Invasive melanoma in vivo can be distinguished from basal cell carcinoma, benign naevi and healthy skin by canine olfaction: a proof-of-principle study of differential volatile organic compound emission. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:1020-1029.

- Campbell LF, Farmery L, George SMC, et al. Canine olfactory detection of malignant melanoma. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:bcr2013008566. doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-008566

- Srivastava R, John JJ, Reilly C, et al. Sniffing out malignant melanoma: a case of canine olfactory detection. Cutis. 2019;104:E4-E6.

- Fleck CA. Fighting odor in wounds. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2006;19:242-244.

- Gallagher M, Wysocki CJ, Leyden JJ, et al. Analyses of volatile organic compounds from human skin. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:780-791.

- Campo E, Ferreira V, Escudero A, et al. Quantitative gas chromatography–olfactometry and chemical quantitative study of the aroma of four Madeira wines. Anal Chim Acta. 2006;563:180-187.

- Wagenstaller M, Buettner A. Characterization of odorants in human urine using a combined chemo-analytical and human-sensory approach: a potential diagnostic strategy. Metabolomics. 2012;9:9-20.

- Arseculeratne G, Wong AKC, Goudie DR, et al. Trimethylaminuria (fish-odor syndrome): a case report. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:81-84.

- Mathews D, Perera LP, Irion LD, et al. Darier disease: beware the cyst that smells. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;26:206-207.

- Stitt WZ, Goldsmith A. Scratch and sniff: the dynamic duo. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:997-999.

- Delahunty CM, Eyres G, Dufour JP. Gas chromatography-olfactometry. J Sep Sci. 2006;29:2107-2125.

- Zheng Y, Li H, Shen W, et al. Wearable electronic nose for human skin odor identification: a preliminary study. Sens Actuators A Phys. 2019;285:395-405.

- Mogilnicka I, Bogucki P, Ufnal M. Microbiota and malodor—etiology and management. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:2886. doi:10.3390/ijms21082886

- Ravindra K, Gandhi S, Sivuni A. Olfactory diagnosis in skin. Clin Derm Rev. 2018;2:38-40.

- Schissel DJ, Aydelotte J, Keller R. Road rash with a rotten odor. Mil Med. 1999;164:65-67.

- Buyukasik O, Osmanoglu CG, Polat Y, et al. A life-threatening multilocalized hidradenitis suppurativa case. MedGenMed. 2005;7:19.

- Napolitano M, Megna M, Timoshchuk EA, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa: from pathogenesis to diagnosis and treatment. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2017;10:105-115.

- Hon KLE, Leung AKC, Kong AYF, et al. Atopic dermatitis complicated by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100:797-800.

- Arashima Y, Kumasaka K, Tutchiya T, et al. Two cases of pasteurellosis accompanied by exudate with semen-like odor from the wound. Article in Japanese. Kansenshogaku Zasshi. 1999;73:623-625.

- Goldstein AO, Smith KM, Ives TJ, et al. Mycotic infections. Effective management of conditions involving the skin, hair, and nails. Geriatrics. 2000;55:40-42, 45-47, 51-52.

- Kircik LH. Observational evaluation of sertaconazole nitrate cream 2% in the treatment of pruritus related to tinea pedis. Cutis. 2009;84:279-283.

- James WD, Elston DM, Treat JR, et al. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2019.

- Sameen K. A clinical study on the efficacy of homoeopathic medicines in the treatment of seborrhiec eczema. Int J Hom Sci. 2022;6:209-212.

- Burge S. Management of Darier’s disease. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1999;24:53-56.

- Nanda KB, Saldanha CS, Jacintha M, et al. Hailey-Hailey disease responding to thalidomide. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:190-192.

- Kanwar AJ, Ghosh S, Dhar S, et al. Odor in pemphigus. Dermatology. 1992;185:215.

- Messenger J, Clark S, Massick S, et al. A review of trimethylaminuria: (fish odor syndrome). J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:45-48.

- Stone WL, Basit H, Los E. Phenylketonuria. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated August 8, 2023. Accessed August 12, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535378/

- Williams RA, Mamotte CDS, Burnett JR. Phenylketonuria: an inborn error of phenylalanine metabolism. Clin Biochem Rev. 2008;29:31-41.

- Cone TE Jr. Diagnosis and treatment: some diseases, syndromes, and conditions associated with an unusual odor. Pediatrics. 1968;41:993-995.

- Shirasu M, Touhara K. The scent of disease: volatile organic compounds of the human body related to disease and disorder. J Biochem. 2011;150:257-266.

- Ghimire P, Dhamoon AS. Ketoacidosis. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated August 8, 2023. Accessed August 12, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534848/

- Duff M, Demidova O, Blackburn S, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of diabetes mellitus. Clin Diabetes. 2015;33:40-48.

- Raina S, Chauhan V, Sharma R, et al. Uremic frost. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5(suppl 1):S58.

- Blaha T, Nigwekar S, Combs S, et al. Dermatologic manifestations in end stage renal disease. Hemodial Int. 2019;23:3-18.

- Shimamoto C, Hirata I, Katsu K. Breath and blood ammonia in liver cirrhosis. Hepatogastroenterology. 2000;47:443-445.

- Butt HR, Mason HL. Fetor hepaticus: its clinical significance and attempts at chemical isolation. Gastroenterology. 1954;26:829-845.

- Haze S, Gozu Y, Nakamura S, et al. 2-nonenal newly found in human body odor tends to increase with aging. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;116:520-524.

- Willis CM, Britton LE, Swindells MA, et al. Invasive melanoma in vivo can be distinguished from basal cell carcinoma, benign naevi and healthy skin by canine olfaction: a proof-of-principle study of differential volatile organic compound emission. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:1020-1029.

- Campbell LF, Farmery L, George SMC, et al. Canine olfactory detection of malignant melanoma. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:bcr2013008566. doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-008566

- Srivastava R, John JJ, Reilly C, et al. Sniffing out malignant melanoma: a case of canine olfactory detection. Cutis. 2019;104:E4-E6.

- Fleck CA. Fighting odor in wounds. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2006;19:242-244.

- Gallagher M, Wysocki CJ, Leyden JJ, et al. Analyses of volatile organic compounds from human skin. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:780-791.

- Campo E, Ferreira V, Escudero A, et al. Quantitative gas chromatography–olfactometry and chemical quantitative study of the aroma of four Madeira wines. Anal Chim Acta. 2006;563:180-187.

- Wagenstaller M, Buettner A. Characterization of odorants in human urine using a combined chemo-analytical and human-sensory approach: a potential diagnostic strategy. Metabolomics. 2012;9:9-20.

- Arseculeratne G, Wong AKC, Goudie DR, et al. Trimethylaminuria (fish-odor syndrome): a case report. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:81-84.

- Mathews D, Perera LP, Irion LD, et al. Darier disease: beware the cyst that smells. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;26:206-207.

Sniffing Out Skin Disease: Odors in Dermatologic Conditions

Sniffing Out Skin Disease: Odors in Dermatologic Conditions

PRACTICE POINTS

- Olfaction may be underutilized in making dermatologic diagnoses. Clinicians should include smell in their physical examination, as characteristic odors are associated with infectious disorders, disorders of keratinization and acantholysis, and metabolic disorders.

- Recognizing distinctive smells can help narrow the differential diagnosis and prompt targeted testing in dermatology.

- Canines and electronic noses have demonstrated the potential to detect certain malignancies, including melanoma, based on unique volatile organic compound profiles.

Severe rash after COVID-19 vaccination

A 41-year-old man presented for evaluation of an extensive skin rash that had erupted more than a month earlier. The patient had received 2 doses of the Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine 3 weeks apart. Ten days after his second dose, the patient developed a rash all over his body. He described the rash as burning, itchy, and uncomfortable. The patient denied any triggers such as recent or previous infections, stressors, or drugs. The patient had no personal or family history of dermatologic disorders; his general medical history was unremarkable. The patient smoked and drank alcohol occasionally.

On physical exam, the patient had a diffuse rash, which initially had manifested on both of his hands, including the palms, and then spread to 60% to 70% of his total body surface area, including his face, ears, anterior and posterior chest, upper and lower extremities, and buttocks. The rash consisted of 10- to 15-mm white scaly plaques that did not bleed.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Guttate psoriasis

Punch biopsies were obtained, and histopathology revealed diffuse compact hyperkeratosis with broad zones of parakeratosis. There was attenuation of the granular layer and regular elongation of the rete ridges associated with thinning of the suprapapillary epidermis and mild spongiosis. These pathologic findings were consistent with a diagnosis of psoriasis. There were no drug-related skin eruption features, such as apoptotic keratinocytes, eosinophils, or interface dermatitis. Periodic acid-Schiff stains for fungal organisms were negative. The combined clinical presentation (itchy, teardrop-shaped, scaly lesions) and histologic impression were consistent with guttate psoriasis.

Psoriasis can be seen in various forms. Subtypes of psoriasis include guttate psoriasis, inverse psoriasis, erythrodermic psoriasis, nail psoriasis, and pustular psoriasis.1 Guttate psoriasis accounts for about 2% of psoriasis cases and usually is seen in patients younger than 30 years.2 Guttate psoriasis is characterized by 1- to 10-mm teardrop-shaped pink papules with fine scaling.3

Triggers for psoriasis. Vaccinations, medications, and infections (eg, group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal upper respiratory infections) can trigger guttate psoriasis.3 MRNA vaccines (eg, Moderna and Pfizer/BioNTech COVID-19 vaccines) have been associated with psoriasis episodes.1 Other vaccines such as influenza, rubella, bacillus Calmette-Guerin, tetanus-diphtheria, and pneumococcal polysaccharide also have been known to trigger psoriasis.4 Medications that can trigger psoriasis include beta-blockers, lithium, antimalarial drugs, and (in some cases) nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.5

The impact of COVID-19 vaccine. We are still learning about the incidence and prevalence of adverse effects (such as psoriasis) that can follow COVID-19 vaccination.

Psoriasis following vaccination. The pathologic mechanism for the new onset or flare of psoriasis after COVID-19 vaccination is unknown. What is known is that the dysregulation of Th-1 and Th-17 plays an important role in the pathogenesis of psoriasis.7 Previously, it was found that psoriasis can manifest after tetanus-diphtheria vaccines due to an increase in the production of Th-17 cells.7 Th-1 and Th-17 production also increases after influenza vaccine and can cause an onset or flare-up of psoriasis.8

Continue to: The differential includes syphilis and exfoliative dermatitis

The differential includes syphilis and exfoliative dermatitis

The differential diagnosis includes various forms of psoriasiform dermatitis, such as secondary syphilis, chronic spongiotic dermatitis, psoriasiform drug eruption, exfoliative dermatitis, and pityriasis rubra pilaris. A combination of clinical and histopathologic findings is used to zero in on the diagnosis. The summary below highlights the clinical findings.

Secondary syphilis manifests with symmetric papular eruptions primarily on the trunk and extremities with involvement on the palms and soles. Lesions are red or reddish brown, can be smooth, and are rarely pustular.

Chronic spongiotic dermatitis manifests with a shiny, glazed, cracked appearance and itchy reddish lesions on the soles.

Psoriasiform drug eruption manifests after drug administration with a psoriasis-like rash with erythematous, squamous, thick, dry, and plaque-type lesions.

Exfoliative dermatitis manifests with erythematous single or multiple pruritic patches on the trunk, head, and genitals.

Continue to: Pityriasis rubra pilaris

Pityriasis rubra pilaris manifests in various ways. Patients may have plaques that are erythematous, scaly, or follicular. Sometimes, it may manifest as erythroderma with an “island of sparing,” which is normal-looking skin in the affected areas.

How to make the diagnosis

Psoriasis can be diagnosed by physical examination. A skin biopsy is not usually necessary but can be helpful for complex cases.

There are no laboratory or genetic tests to confirm the diagnosis of psoriasis. Depending on the case, routine bloodwork (eg, complete blood count and metabolic panel) and infectious disease tests (eg, HIV, hepatitis panel, and

Starting with a low- to medium-potency steroid, such as betamethasone valerate 0.1% cream twice per day or triamcinolone acetonide 0.1% cream twice per day for 2 weeks, provides high safety and efficacy for localized disease.9 An appropriate-potency steroid should be chosen based on the disease severity, location, and patient’s preference and age. Topical vitamin D analogues often are used in conjunction with topical steroids to treat psoriasis.9