User login

Hospitalists Can Improve Healthcare Value

As the nation considers how to reduce healthcare costs, hospitalists can play a crucial role in this effort because they control many healthcare services through routine clinical decisions at the point of care. In fact, the government, payers, and the public now look to hospitalists as essential partners for reining in healthcare costs.[1, 2] The role of hospitalists is even more critical as payers, including Medicare, seek to shift reimbursements from volume to value.[1] Medicare's Value‐Based Purchasing program has already tied a percentage of hospital payments to metrics of quality, patient satisfaction, and cost,[1, 3] and Health and Human Services Secretary Sylvia Burwell announced that by the end of 2018, the goal is to have 50% of Medicare payments tied to quality or value through alternative payment models.[4]

Major opportunities for cost savings exist across the care continuum, particularly in postacute and transitional care, and hospitalist groups are leading innovative models that show promise for coordinating care and improving value.[5] Individual hospitalists are also in a unique position to provide high‐value care for their patients through advocating for appropriate care and leading local initiatives to improve value of care.[6, 7, 8] This commentary article aims to provide practicing hospitalists with a framework to incorporate these strategies into their daily work.

DESIGN STRATEGIES TO COORDINATE CARE

As delivery systems undertake the task of population health management, hospitalists will inevitably play a critical role in facilitating coordination between community, acute, and postacute care. During admission, discharge, and the hospitalization itself, standardizing care pathways for common hospital conditions such as pneumonia and cellulitis can be effective in decreasing utilization and improving clinical outcomes.[9, 10] Intermountain Healthcare in Utah has applied evidence‐based protocols to more than 60 clinical processes, re‐engineering roughly 80% of all care that they deliver.[11] These types of care redesigns and standardization promise to provide better, more efficient, and often safer care for more patients. Hospitalists can play important roles in developing and delivering on these pathways.

In addition, hospital physician discontinuity during admissions may lead to increased resource utilization, costs, and lower patient satisfaction.[12] Therefore, ensuring clear handoffs between inpatient providers, as well as with outpatient providers during transitions in care, is a vital component of delivering high‐value care. Of particular importance is the population of patients frequently readmitted to the hospital. Hospitalists are often well acquainted with these patients, and the myriad of psychosocial, economic, and environmental challenges this vulnerable population faces. Although care coordination programs are increasing in prevalence, data on their cost‐effectiveness are mixed, highlighting the need for testing innovations.[13] Certainly, hospitalists can be leaders adopting and documenting the effectiveness of spreading interventions that have been shown to be promising in improving care transitions at discharge, such as the Care Transitions Intervention, Project RED (Re‐Engineered Discharge), or the Transitional Care Model.[14, 15, 16]

The University of Chicago, through funding from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation, is testing the use of a single physician who cares for frequently admitted patients both in and out of the hospital, thereby reducing the costs of coordination.[5] This comprehensivist model depends on physicians seeing patients in the hospital and then in a clinic located in or near the hospital for the subset of patients who stand to benefit most from this continuity. This differs from the old model of having primary care providers (PCPs) see inpatients and outpatients because the comprehensivist's patient panel is enriched with only patients who are at high risk for hospitalization, and thus these physicians have a more direct focus on hospital‐related care and higher daily hospitalized patient censuses, whereas PCPs were seeing fewer and fewer of their patients in the hospital on a daily basis. Evidence concerning the effectiveness of this model is expected by 2016. Hospitalists have also ventured out of the hospital into skilled nursing facilities, specializing in long‐term care.[17] These physicians are helping provide care to the roughly 1.6 million residents of US nursing homes.[17, 18] Preliminary evidence suggests increased physician staffing is associated with decreased hospitalization of nursing home residents.[18]

ADVOCATE FOR APPROPRIATE CARE

Hospitalists can advocate for appropriate care through avoiding low‐value services at the point of care, as well as learning and teaching about value.

Avoiding Low‐Value Services at the Point of Care

The largest contributor to the approximately $750 billion in annual healthcare waste is unnecessary services, which includes overuse, discretionary use beyond benchmarks, and unnecessary choice of higher‐cost services.[19] Drivers of overuse include medical culture, fee‐for‐service payments, patient expectations, and fear of malpractice litigation.[20] For practicing hospitalists, the most substantial motivation for overuse may be a desire to reassure patients and themselves.[21] Unfortunately, patients commonly overestimate the benefits and underestimate the potential harms of testing and treatments.[22] However, clear communication with patients can reduce overuse, underuse, and misuse.[23]

Specific targets for improving appropriate resource utilization may be identified from resources such as Choosing Wisely lists, guidelines, and appropriateness criteria. The Choosing Wisely campaign has brought together an unprecedented number of medical specialty societies to issue top five lists of things that physicians and patients should question (

| Adult Hospital Medicine Recommendations | Pediatric Hospital Medicine Recommendations |

|---|---|

| 1. Do not place, or leave in place, urinary catheters for incontinence or convenience, or monitoring of output for noncritically ill patients (acceptable indications: critical illness, obstruction, hospice, perioperatively for <2 days or urologic procedures; use weights instead to monitor diuresis). | 1. Do not order chest radiographs in children with uncomplicated asthma or bronchiolitis. |

| 2. Do not prescribe medications for stress ulcer prophylaxis to medical inpatients unless at high risk for gastrointestinal complication. | 2. Do not routinely use bronchodilators in children with bronchiolitis. |

| 3. Avoid transfusing red blood cells just because hemoglobin levels are below arbitrary thresholds such as 10, 9, or even 8 mg/dL in the absence of symptoms. | 3. Do not use systemic corticosteroids in children under 2 years of age with an uncomplicated lower respiratory tract infection. |

| 4. Avoid overuse/unnecessary use of telemetry monitoring in the hospital, particularly for patients at low risk for adverse cardiac outcomes. | 4. Do not treat gastroesophageal reflux in infants routinely with acid suppression therapy. |

| 5. Do not perform repetitive complete blood count and chemistry testing in the face of clinical and lab stability. | 5. Do not use continuous pulse oximetry routinely in children with acute respiratory illness unless they are on supplemental oxygen. |

As an example of this strategy, 1 multi‐institutional group has started training medical students to augment the traditional subjective‐objective‐assessment‐plan (SOAP) daily template with a value section (SOAP‐V), creating a cognitive forcing function to promote discussion of high‐value care delivery.[28] Physicians could include brief thoughts in this section about why they chose a specific intervention, their consideration of the potential benefits and harms compared to alternatives, how it may incorporate the patient's goals and values, and the known and potential costs of the intervention. Similarly, Flanders and Saint recommend that daily progress notes and sign‐outs include the indication, day of administration, and expected duration of therapy for all antimicrobial treatments, as a mechanism for curbing antimicrobial overuse in hospitalized patients.[29] Likewise, hospitalists can also document whether or not a patient needs routine labs, telemetry, continuous pulse oximetry, or other interventions or monitoring. It is not yet clear how effective this type of strategy will be, and drawbacks include creating longer progress notes and requiring more time for documentation. Another approach would be to work with the electronic health record to flag patients who are scheduled for telemetry or other potentially wasteful practices to inspire a daily practice audit to question whether the patient still meets criteria for such care. This approach acknowledges that patient's clinical status changes, and overcomes the inertia that results in so many therapies being continued despite a need or indication.

Communicating With Patients Who Want Everything

Some patients may be more worried about not getting every possible test, rather than concerns regarding associated costs. This may oftentimes be related to patients routinely overestimating the benefits of testing and treatments while not realizing the many potential downstream harms.[22] The perception is that patient demands frequently drive overtesting, but studies suggest the demanding patient is actually much less common than most physicians think.[30]

The Choosing Wisely campaign features video modules that provide a framework and specific examples for physician‐patient communication around some of the Choosing Wisely recommendations (available at:

Clinicians can explain why they do not believe that a test will help a patient and can share their concerns about the potential harms and downstream consequences of a given test. In addition, Consumer Reports and other groups have created trusted resources for patients that provide clear information for the public about unnecessary testing and services.

Learn and Teach Value

Traditionally, healthcare costs have largely remained hidden from both the public and medical professionals.[31, 32] As a result, hospitalists are generally not aware of the costs associated with their care.[33, 34] Although medical education has historically avoided the topic of healthcare costs,[35] recent calls to teach healthcare value have led to new educational efforts.[35, 36, 37] Future generations of medical professionals will be trained in these skills, but current hospitalists should seek opportunities to improve their knowledge of healthcare value and costs.

Fortunately, several resources can fill this gap. In addition to Choosing Wisely and ACR appropriateness criteria discussed above, newer tools focus on how to operationalize these recommendations with patients. The American College of Physicians (ACP) has launched a high‐value care educational platform that includes clinical recommendations, physician resources, curricula and public policy recommendations, and patient resources to help them understand the benefits, harms, and costs of tests and treatments for common clinical issues (

In an effort to provide frontline clinicians with the knowledge and tools necessary to address healthcare value, we have authored a textbook, Understanding Value‐Based Healthcare.[38] To identify the most promising ways of teaching these concepts, we also host the annual Teaching Value & Choosing Wisely Challenge and convene the Teaching Value in Healthcare Learning Network (bit.ly/teachingvaluenetwork) through our nonprofit, Costs of Care.[39]

In addition, hospitalists can also advocate for greater price transparency to help improve cost awareness and drive more appropriate care. The evidence on the effect of transparent costs in the electronic ordering system is evolving. Historically, efforts to provide diagnostic test prices at time of order led to mixed results,[40] but recent studies show clear benefits in resource utilization related to some form of cost display.[41, 42] This may be because physicians care more about healthcare costs and resource utilization than before. Feldman and colleagues found in a controlled clinical trial at Johns Hopkins that providing the costs of lab tests resulted in substantial decreases of certain lab tests and yielded a net cost reduction (based on 2011 Medicare Allowable Rate) of more than $400,000 at the hospital level during the 6‐month intervention period.[41] A recent systematic review concluded that charge information changed ordering and prescribing behavior in the majority of studies.[42] Some hospitalist programs are developing dashboards for various quality and utilization metrics. Sharing ratings or metrics internally or publically is a powerful way to motivate behavior change.[43]

LEAD LOCAL VALUE INITIATIVES

Hospitalists are ideal leaders of local value initiatives, whether it be through running value‐improvement projects or launching formal high‐value care programs.

Conduct Value‐Improvement Projects

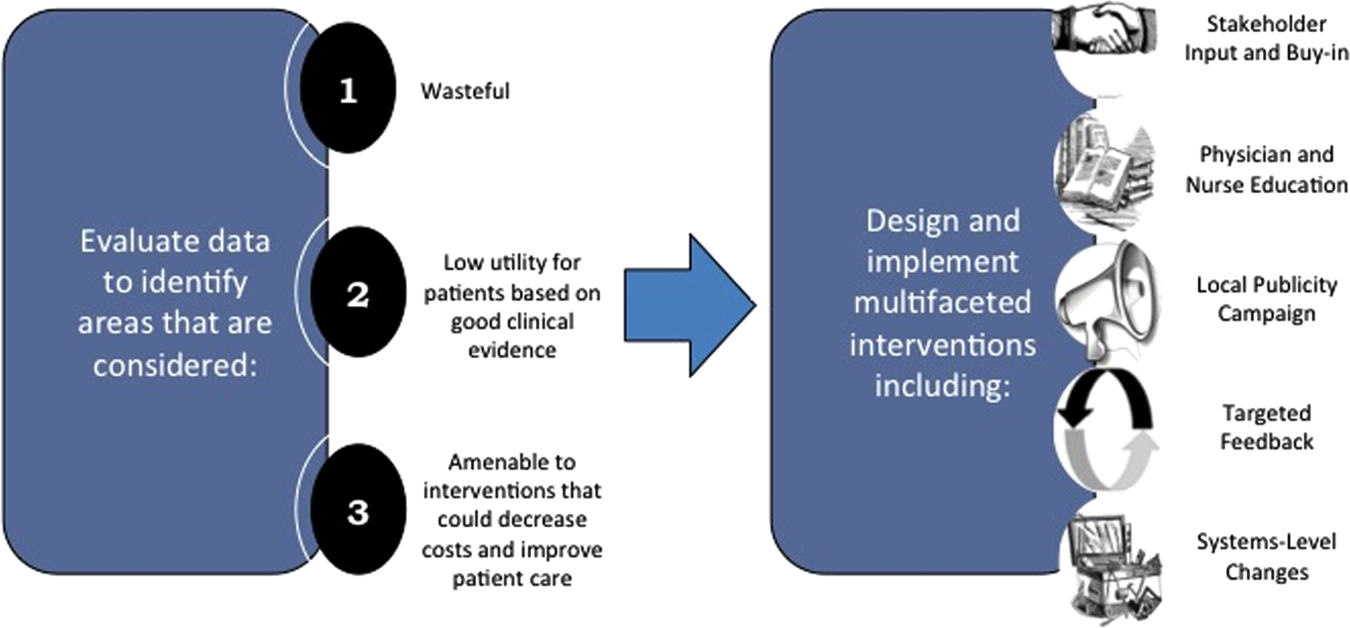

Hospitalists across the country have largely taken the lead on designing value‐improvement pilots, programs, and groups within hospitals. Although value‐improvement projects may be built upon the established structures and techniques for quality improvement, importantly these programs should also include expertise in cost analyses.[8] Furthermore, some traditional quality‐improvement programs have failed to result in actual cost savings[44]; thus, it is not enough to simply rebrand quality improvement with a banner of value. Value‐improvement efforts must overcome the cultural hurdle of more care as better care, as well as pay careful attention to the diplomacy required with value improvement, because reducing costs may result in decreased revenue for certain departments or even decreases in individuals' wages.

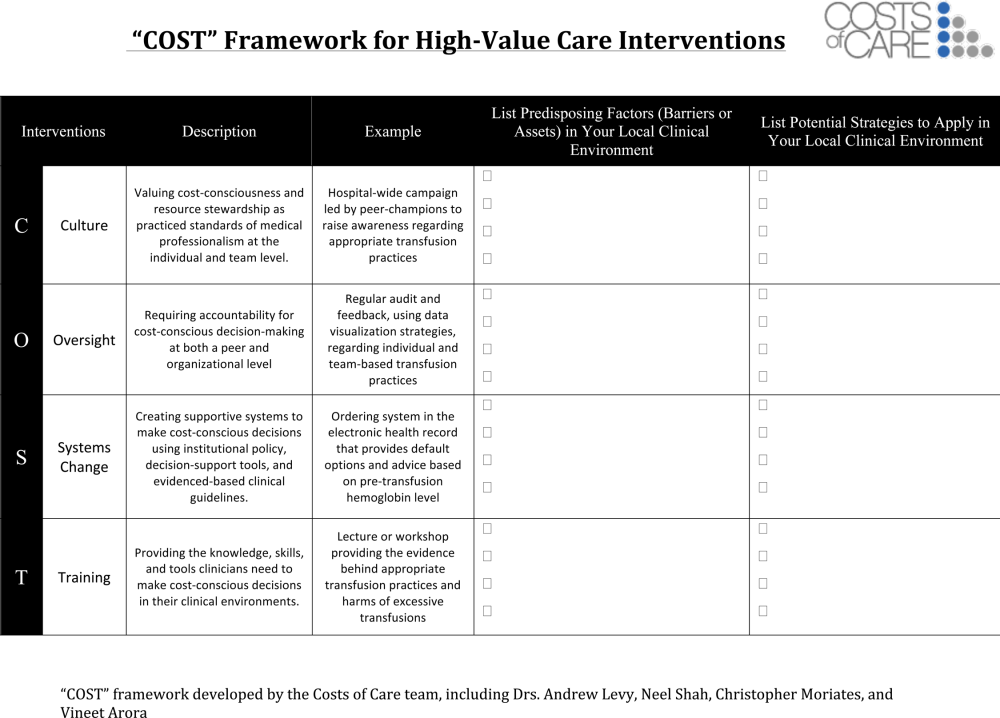

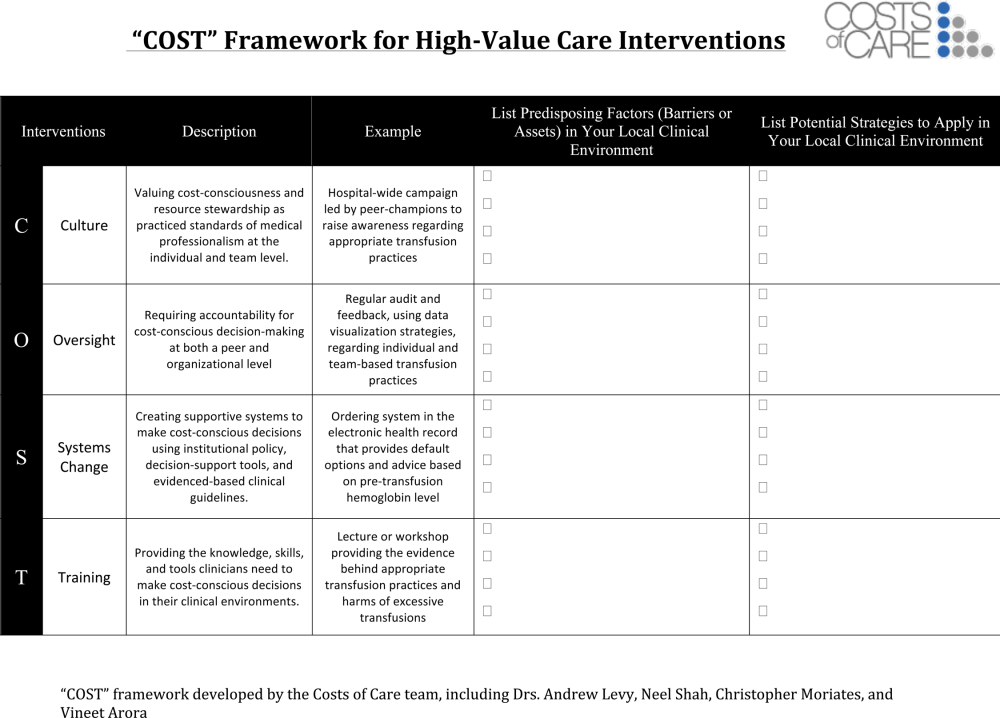

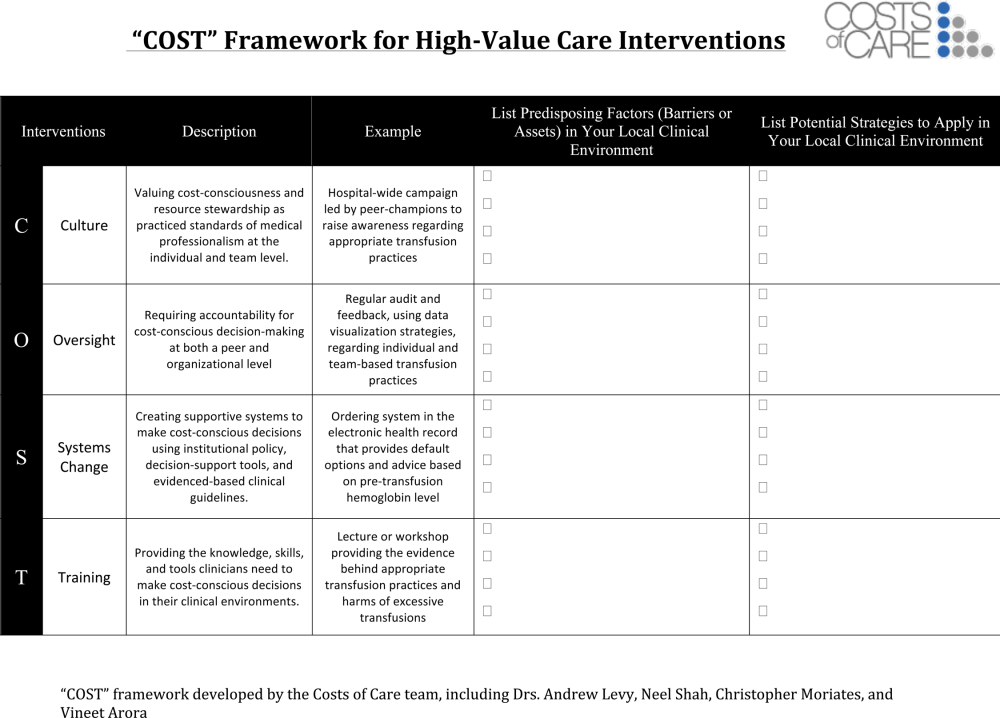

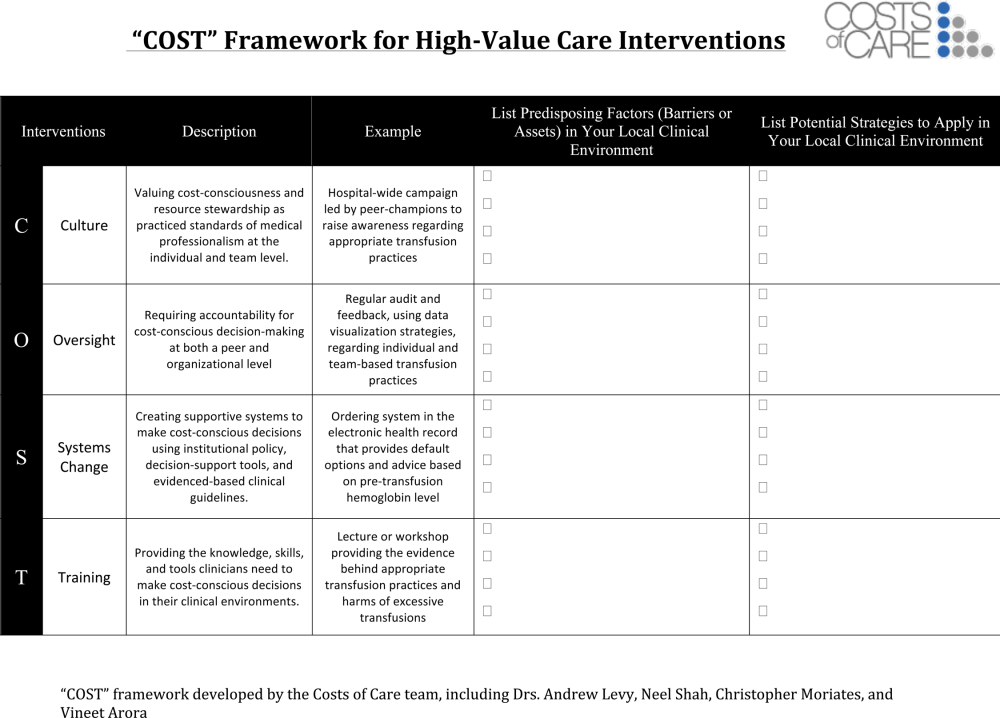

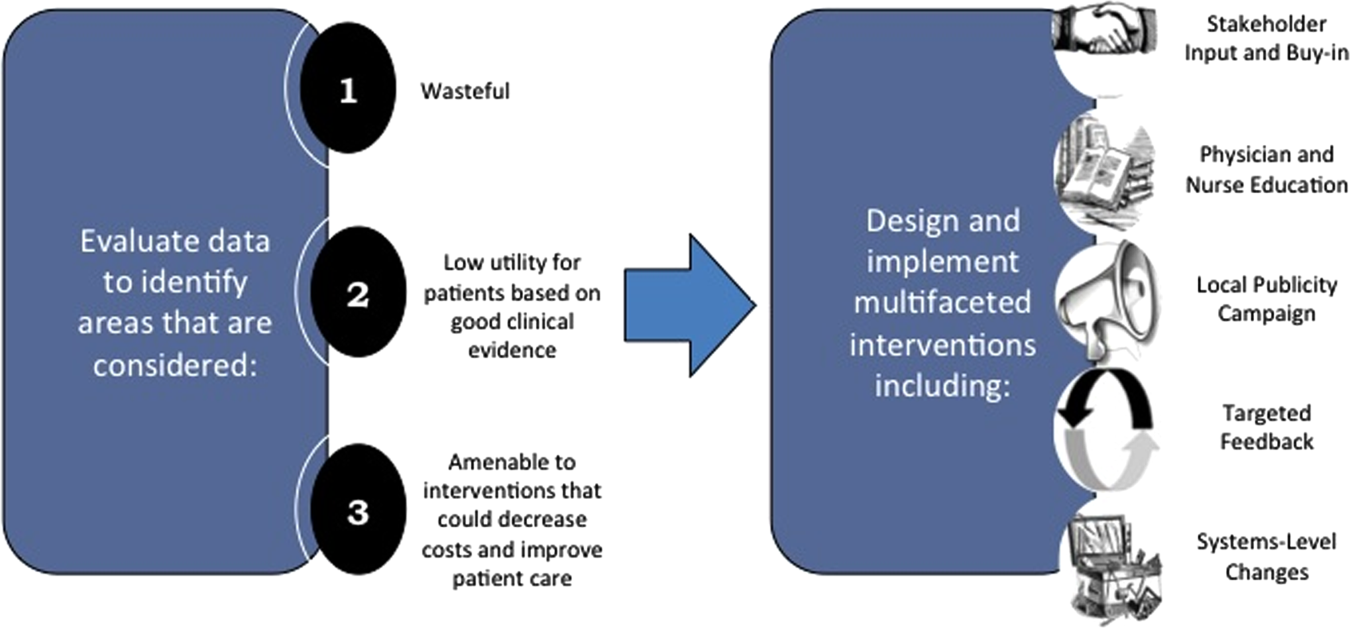

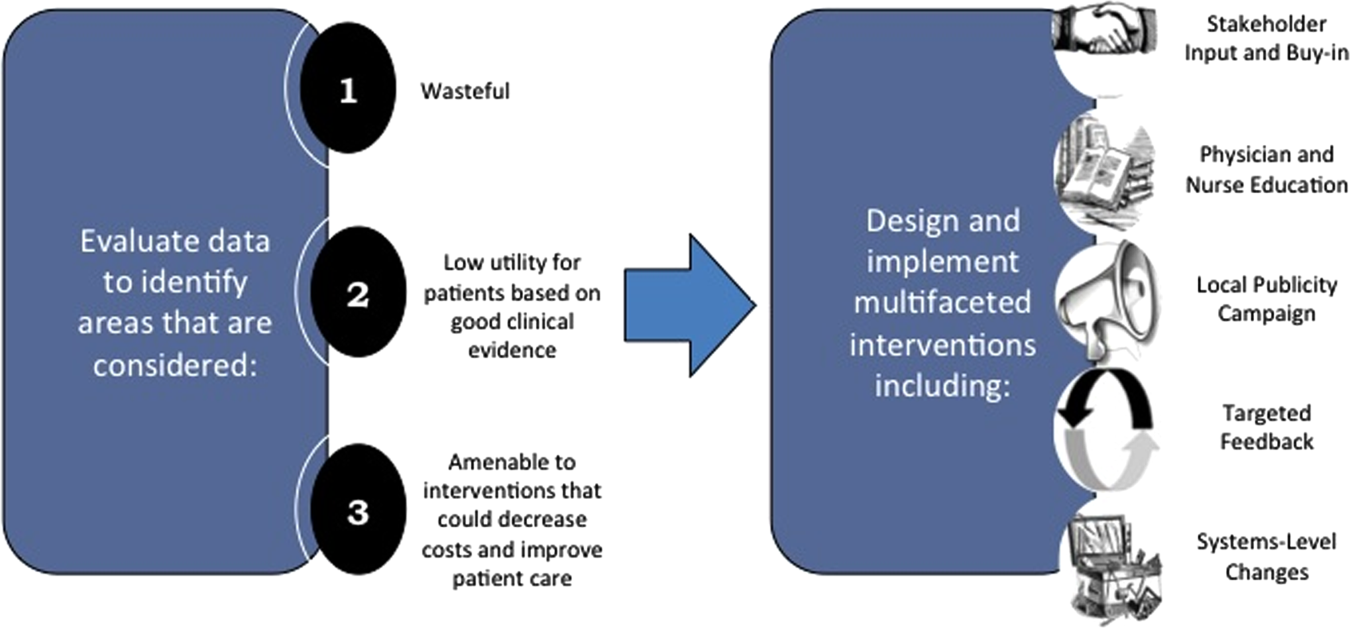

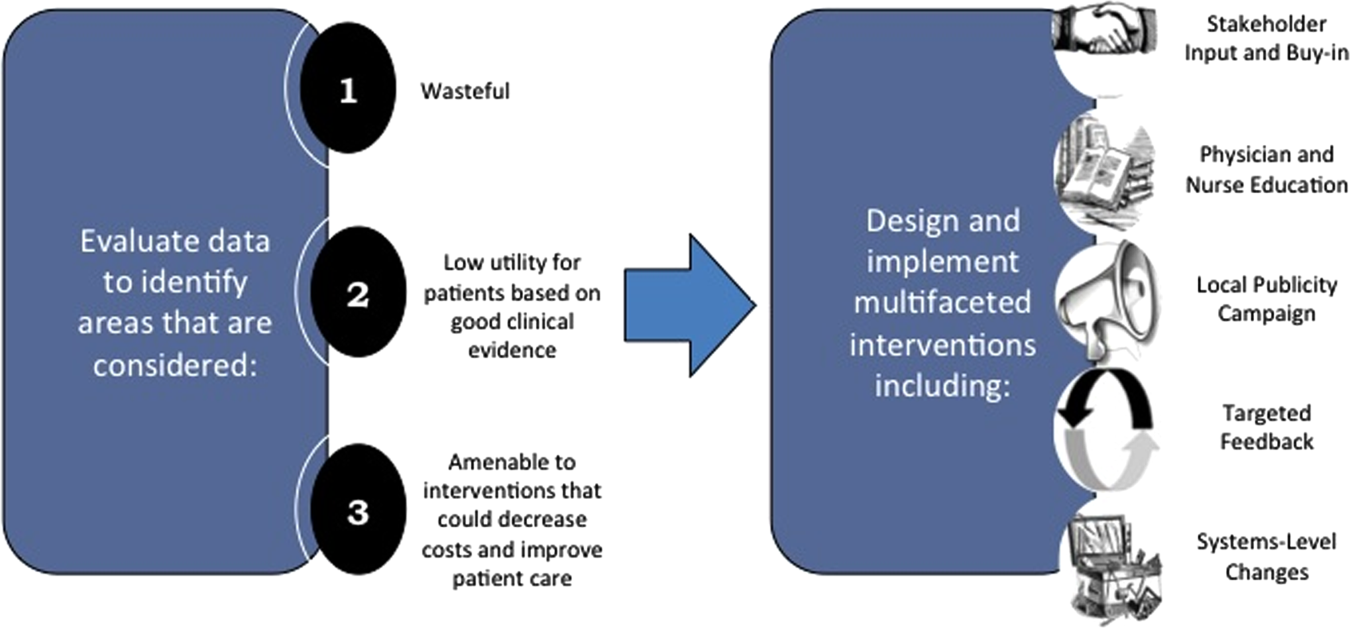

One framework that we have used to guide value‐improvement project design is COST: culture, oversight accountability, system support, and training.[45] This approach leverages principles from implementation science to ensure that value‐improvement projects successfully provide multipronged tactics for overcoming the many barriers to high‐value care delivery. Figure 1 includes a worksheet for individual clinicians or teams to use when initially planning value‐improvement project interventions.[46] The examples in this worksheet come from a successful project at the University of California, San Francisco aimed at improving blood utilization stewardship by supporting adherence to a restrictive transfusion strategy. To address culture, a hospital‐wide campaign was led by physician peer champions to raise awareness about appropriate transfusion practices. This included posters that featured prominent local physician leaders displaying their support for the program. Oversight was provided through regular audit and feedback. Each month the number of patients on the medicine service who received transfusion with a pretransfusion hemoglobin above 8 grams per deciliter was shared at a faculty lunch meeting and shown on a graph included in the quality newsletter that was widely distributed in the hospital. The ordering system in the electronic medical record was eventually modified to include the patient's pretransfusion hemoglobin level at time of transfusion order and to provide default options and advice based on whether or not guidelines would generally recommend transfusion. Hospitalists and resident physicians were trained through multiple lectures and informal teaching settings about the rationale behind the changes and the evidence that supported a restrictive transfusion strategy.

Launch High‐Value Care Programs

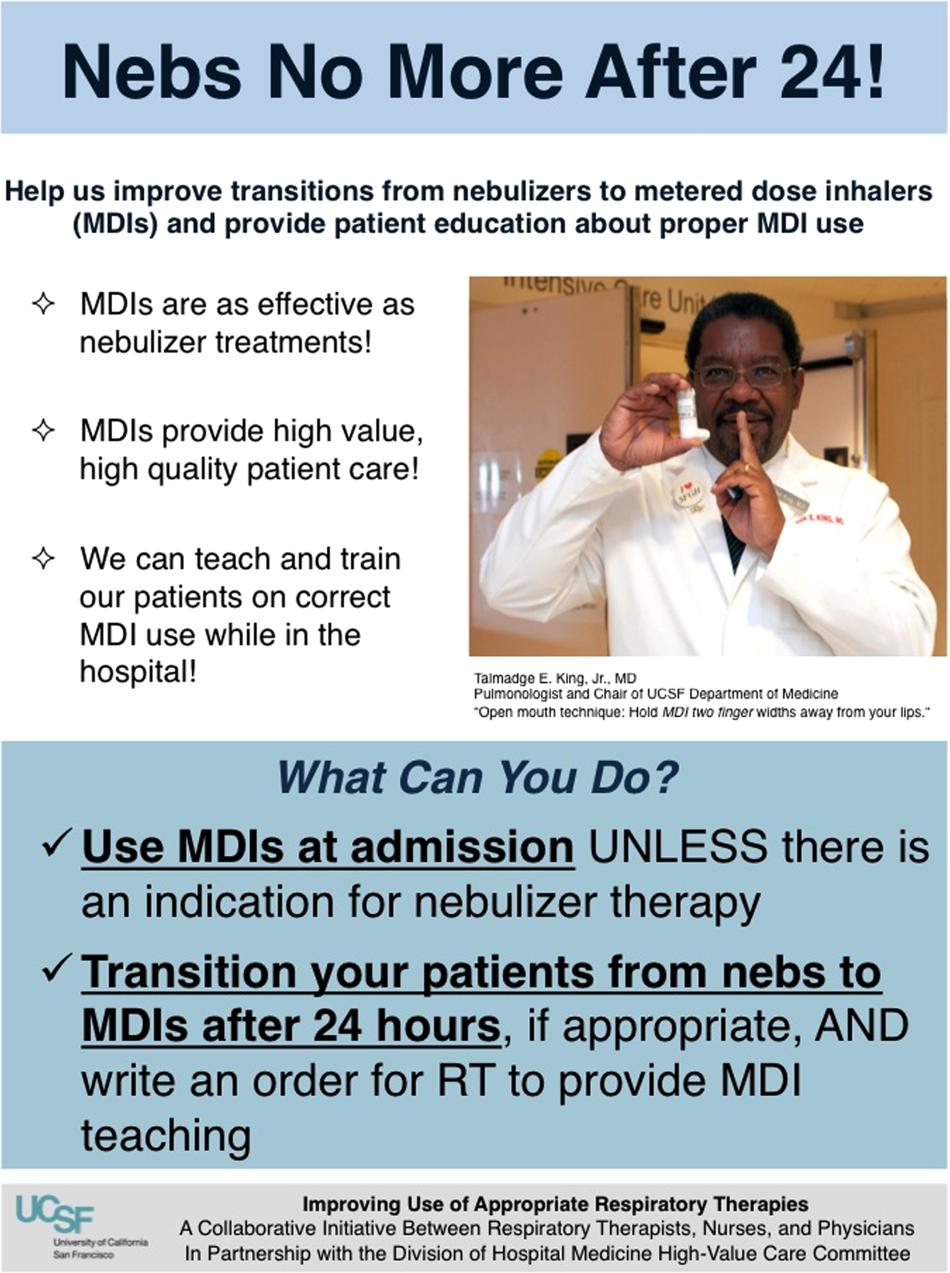

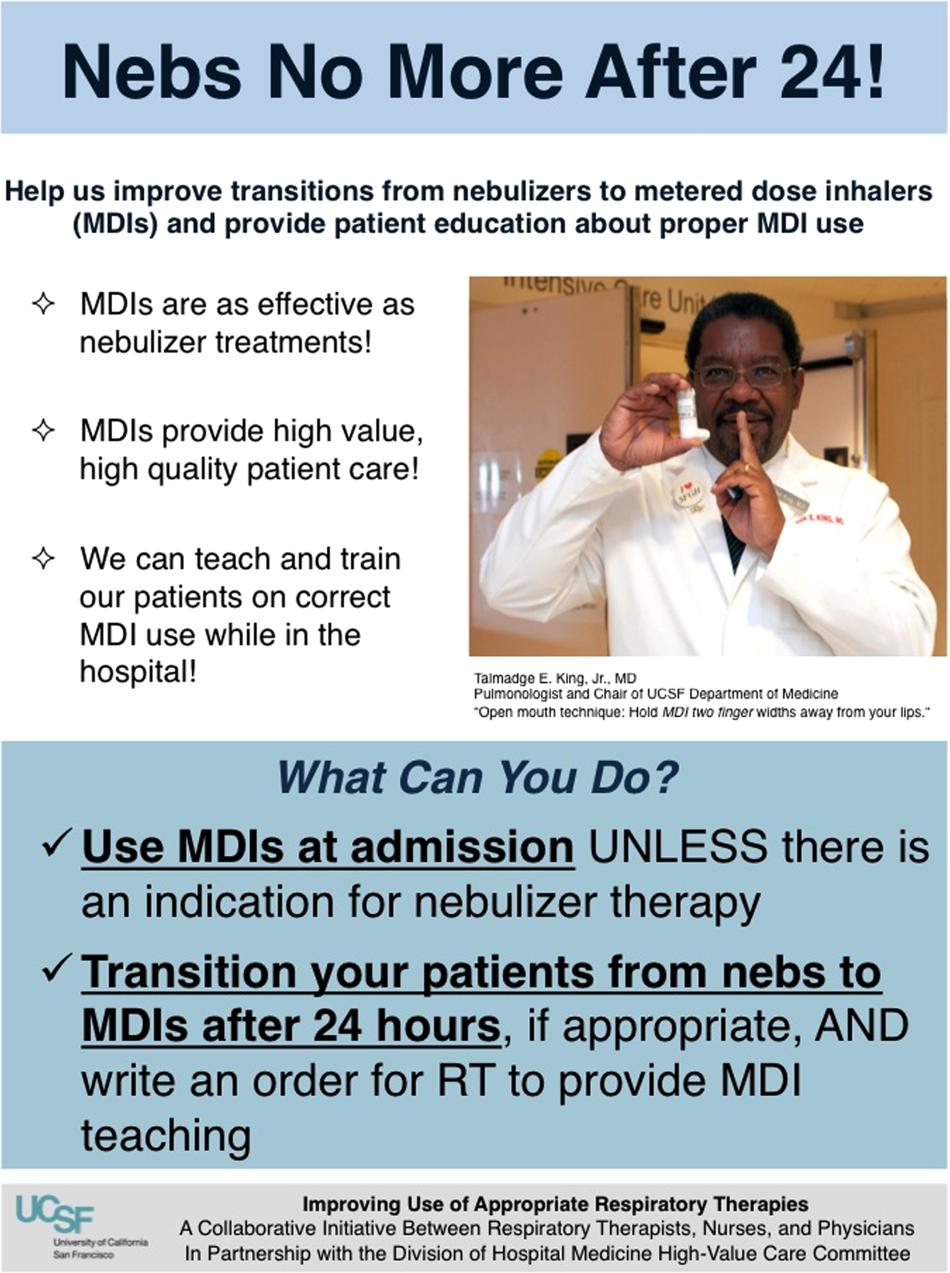

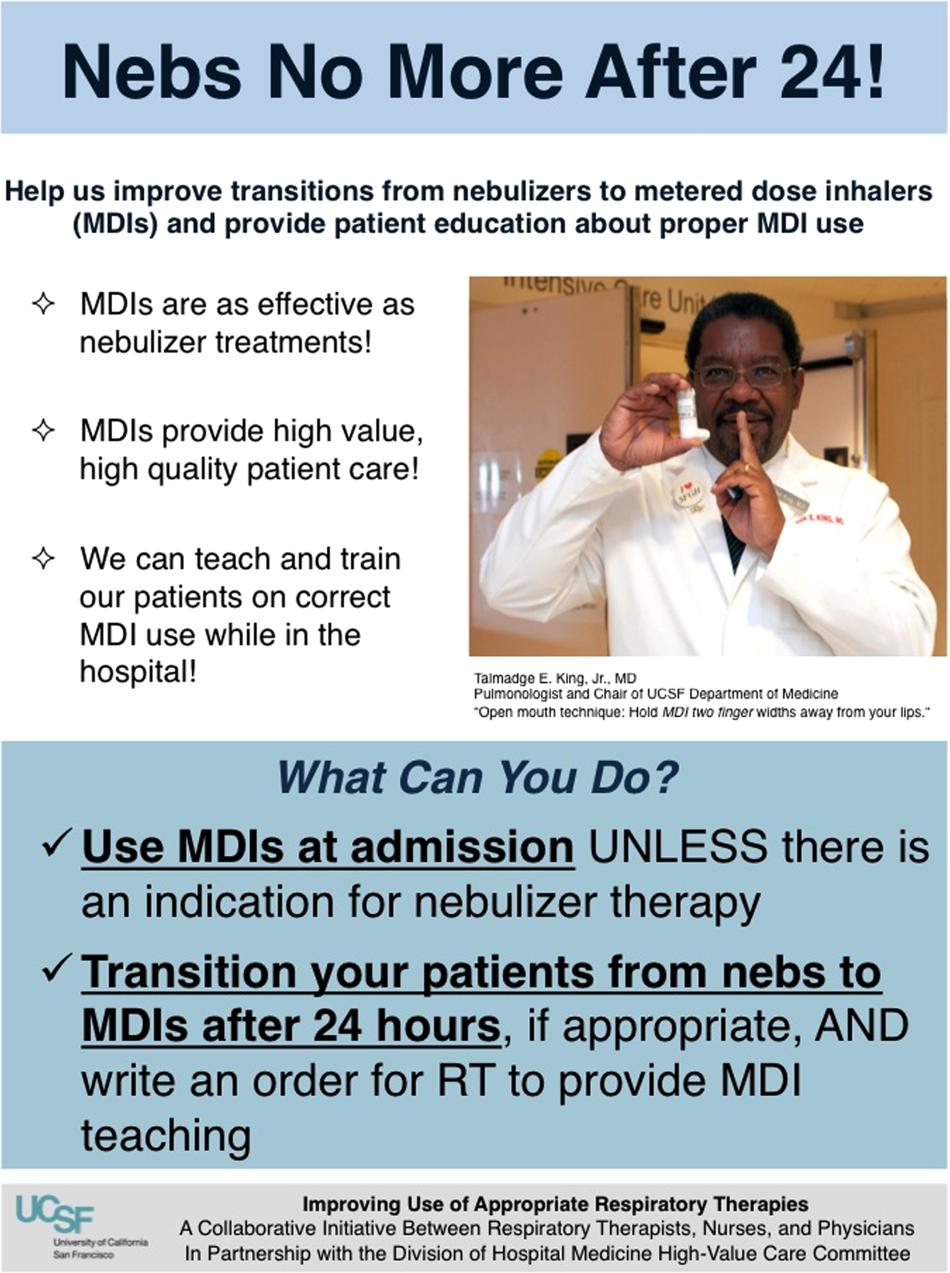

As value‐improvement projects grow, some institutions have created high‐value care programs and infrastructure. In March 2012, the University of California, San Francisco Division of Hospital Medicine launched a high‐value care program to promote healthcare value and clinician engagement.[8] The program was led by clinical hospitalists alongside a financial administrator, and aimed to use financial data to identify areas with clear evidence of waste, create evidence‐based interventions that would simultaneously improve quality while cutting costs, and pair interventions with cost awareness education and culture change efforts. In the first year of this program, 6 projects were launched targeting: (1) nebulizer to inhaler transitions,[47] (2) overuse of proton pump inhibitor stress ulcer prophlaxis,[48] (3) transfusions, (4) telemetry, (5) ionized calcium lab ordering, and (6) repeat inpatient echocardiograms.[8]

Similar hospitalist‐led groups have now formed across the country including the Johns Hopkins High‐Value Care Committee, Johns Hopkins Bayview Physicians for Responsible Ordering, and High‐Value Carolina. These groups are relatively new, and best practices and early lessons are still emerging, but all focus on engaging frontline clinicians in choosing targets and leading multipronged intervention efforts.

What About Financial Incentives?

Hospitalist high‐value care groups thus far have mostly focused on intrinsic motivations for decreasing waste by appealing to hospitalists' sense of professionalism and their commitment to improve patient affordability. When financial incentives are used, it is important that they are well aligned with internal motivations for clinicians to provide the best possible care to their patients. The Institute of Medicine recommends that payments are structured in a way to reward continuous learning and improvement in the provision of best care at lower cost.[19] In the Geisinger Health System in Pennsylvania, physician incentives are designed to reward teamwork and collaboration. For example, endocrinologists' goals are based on good control of glucose levels for all diabetes patients in the system, not just those they see.[49] Moreover, a collaborative approach is encouraged by bringing clinicians together across disciplinary service lines to plan, budget, and evaluate one another's performance. These efforts are partly credited with a 43% reduction in hospitalized days and $100 per member per month in savings among diabetic patients.[50]

Healthcare leaders, Drs. Tom Lee and Toby Cosgrove, have made a number of recommendations for creating incentives that lead to sustainable changes in care delivery[49]: avoid attaching large sums to any single target, watch for conflicts of interest, reward collaboration, and communicate the incentive program and goals clearly to clinicians.

In general, when appropriate extrinsic motivators align or interact synergistically with intrinsic motivation, it can promote high levels of performance and satisfaction.[51]

CONCLUSIONS

Hospitalists are now faced with a responsibility to reduce financial harm and provide high‐value care. To achieve this goal, hospitalist groups are developing innovative models for care across the continuum from hospital to home, and individual hospitalists can advocate for appropriate care and lead value‐improvement initiatives in hospitals. Through existing knowledge and new frameworks and tools that specifically address value, hospitalists can champion value at the bedside and ensure their patients get the best possible care at lower costs.

Disclosures: Drs. Moriates, Shah, and Arora have received grant funding from the ABIM Foundation, and royalties from McGraw‐Hill for the textbook Understanding Value‐Based Healthcare. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- , . Value‐based purchasing—national programs to move from volume to value. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(4):292–295.

- . Value‐driven health care: implications for hospitals and hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(8):507–511.

- , . Hospital value‐based purchasing. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(5):271–277.

- . Setting value‐based payment goals—HHS efforts to improve U.S. health care. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(10):897–899.

- , . Redesigning care for patients at increased hospitalization risk: the Comprehensive Care Physician model. Health Aff Proj Hope. 2014;33(5):770–777.

- , , , et al. Choosing wisely in adult hospital medicine: five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):486–492.

- , , . First, do no (financial) harm. JAMA. 2013;310(6):577–578.

- , , , . Development of a hospital‐based program focused on improving healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(10):671–677.

- , , , et al. A controlled trial of a critical pathway for treatment of community‐acquired pneumonia. JAMA. 2000;283(6):749–755.

- , , , , . Evidence‐based care pathway for cellulitis improves process, clinical, and cost outcomes [published online July 28, 2015]. J Hosp Med. doi:10.1002/jhm.2433.

- . The Lean approach to health care: safety, quality, and cost. Institute of Medicine. Available at: http://nam.edu/perspectives‐2012‐the‐lean‐approach‐to‐health‐care‐safety‐quality‐and‐cost/. Accessed September 22, 2015.

- , , , et al. The impact of hospitalist discontinuity on hospital cost, readmissions, and patient satisfaction. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(7):1004–1008.

- Congressional Budget Office. Lessons from Medicare's Demonstration Projects on Disease Management, Care Coordination, and Value‐Based Payment. Available at: https://www.cbo.gov/publication/42860. Accessed April 26, 2015.

- , , , et al. A reengineered hospital discharge program to decrease rehospitalization: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(3):178–187.

- , , , . The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(17):1822–1828.

- , , , et al. Comprehensive discharge planning and home follow‐up of hospitalized elders: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 1999;281(7):613–620.

- . “SNFists” at work: nursing home docs patterned after hospitalists. Mod Healthc. 2012;42(13):32–33.

- , , , . Nursing home physician specialists: a response to the workforce crisis in long‐term care. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(6):411–413.

- Institute of Medicine. Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2012.

- , . The perfect storm of overutilization. JAMA. 2008;299(23):2789–2791.

- , , , et al. Overuse of testing in preoperative evaluation and syncope: a survey of hospitalists. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(2):100–108.

- , . Patients' expectations of the benefits and harms of treatments, screening, and tests: a systematic review. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(2):274–286.

- , , , et al. Enhancing the Use and Quality of Colorectal Cancer Screening. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2010. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK44526. Accessed September 30, 2013.

- , , , et al. Choosing wisely in pediatric hospital medicine: five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):479–485.

- . Teaching Choosing Wisely in medical education and training: the story of a pioneer. The Medical Professionalism Blog. Available at: http://blog.abimfoundation.org/teaching‐choosing‐wisely‐in‐meded. Accessed March 29, 2014.

- American College of Radiology. ACR appropriateness criteria overview. November 2013. Available at: http://www.acr.org/∼/media/ACR/Documents/AppCriteria/Overview.pdf. Accessed March 4, 2014.

- American College of Cardiology Foundation. Appropriate use criteria: what you need to know. Available at: http://www.cardiosource.org/∼/media/Files/Science%20and%20Quality/Quality%20Programs/FOCUS/E1302_AUC_Primer_Update.ashx. Accessed March 4, 2014.

- , , , , . SOAP‐V: applying high‐value care during patient care. The Medical Professionalism Blog. Available at: http://blog.abimfoundation.org/soap‐v‐applying‐high‐value‐care‐during‐patient‐care. Accessed April 3, 2015.

- , . Why does antimicrobial overuse in hospitalized patients persist? JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(5):661–662.

- . The myth of the demanding patient. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(1):18–19.

- . The disruptive innovation of price transparency in health care. JAMA. 2013;310(18):1927–1928.

- United States Government Accountability Office. Health Care Price Transparency—Meaningful Price Information Is Difficult for Consumers to Obtain Prior to Receiving Care. Washington, DC: United States Government Accountability Office; 2011:43.

- , , . General pediatric attending physicians' and residents' knowledge of inpatient hospital finances. Pediatrics. 2013;131(6):1072–1080.

- , , . Hospitalists' awareness of patient charges associated with inpatient care. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(5):295–297.

- . Cost consciousness in patient care—what is medical education's responsibility? N Engl J Med. 2010;362(14):1253–1255.

- . Providing high‐value, cost‐conscious care: a critical seventh general competency for physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(6):386–388.

- , , , . Defining competencies for education in health care value: recommendations from the University of California, San Francisco Center for Healthcare Value Training Initiative. Acad Med. 2015;90(4):421–424.

- , , . Understanding Value‐Based Healthcare. New York: McGraw‐Hill; 2015.

- , , , . Wisdom of the crowd: bright ideas and innovations from the teaching value and choosing wisely challenge. Acad Med. 2015;90(5):624–628.

- , , , et al. Does the computerized display of charges affect inpatient ancillary test utilization? Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(21):2501–2508.

- , , , et al. Impact of providing fee data on laboratory test ordering: a controlled clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(10):903–908.

- , , , . The effect of charge display on cost of care and physician practice behaviors: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(6):835–842.

- , , , , , . Closing the Quality Gap: Revisiting the State of the Science. Vol. 5. Public Reporting as a Quality Improvement Strategy. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2012.

- , , , . The savings illusion—why clinical quality improvement fails to deliver bottom‐line results. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(26):e48.

- , , , . Fostering value in clinical practice among future physicians: time to consider COST. Acad Med. 2014;89(11):1440.

- , , , , , . The Teaching Value Workshop. MedEdPORTAL Publications; 2014. Available at: https://www.mededportal.org/publication/9859. Accessed September 22, 2015.

- , , , , . “Nebs no more after 24”: a pilot program to improve the use of appropriate respiratory therapies. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(17):1647–1648.

- , , , et al. The development and implementation of a bundled quality improvement initiative to reduce inappropriate stress ulcer prophylaxis. ICU Dir. 2013;4(6):322–325.

- , . Engaging doctors in the health care revolution. Harvard Business Review. June 2014. Available at: http://hbr.org/2014/06/engaging‐doctors‐in‐the‐health‐care‐revolution/ar/1. Accessed July 30, 2014.

- , , . Geisinger Health System: achieving the potential of system integration through innovation, leadership, measurement, and incentives. June 2009. Available at: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/case‐studies/2009/jun/geisinger‐health‐system‐achieving‐the‐potential‐of‐system‐integration. Accessed September 22, 2015.

- Motivational synergy: toward new conceptualizations of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation in the workplace. Hum Resource Manag 1993;3(3):185–201. Available at: http://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=2500. Accessed July 31, 2014.

As the nation considers how to reduce healthcare costs, hospitalists can play a crucial role in this effort because they control many healthcare services through routine clinical decisions at the point of care. In fact, the government, payers, and the public now look to hospitalists as essential partners for reining in healthcare costs.[1, 2] The role of hospitalists is even more critical as payers, including Medicare, seek to shift reimbursements from volume to value.[1] Medicare's Value‐Based Purchasing program has already tied a percentage of hospital payments to metrics of quality, patient satisfaction, and cost,[1, 3] and Health and Human Services Secretary Sylvia Burwell announced that by the end of 2018, the goal is to have 50% of Medicare payments tied to quality or value through alternative payment models.[4]

Major opportunities for cost savings exist across the care continuum, particularly in postacute and transitional care, and hospitalist groups are leading innovative models that show promise for coordinating care and improving value.[5] Individual hospitalists are also in a unique position to provide high‐value care for their patients through advocating for appropriate care and leading local initiatives to improve value of care.[6, 7, 8] This commentary article aims to provide practicing hospitalists with a framework to incorporate these strategies into their daily work.

DESIGN STRATEGIES TO COORDINATE CARE

As delivery systems undertake the task of population health management, hospitalists will inevitably play a critical role in facilitating coordination between community, acute, and postacute care. During admission, discharge, and the hospitalization itself, standardizing care pathways for common hospital conditions such as pneumonia and cellulitis can be effective in decreasing utilization and improving clinical outcomes.[9, 10] Intermountain Healthcare in Utah has applied evidence‐based protocols to more than 60 clinical processes, re‐engineering roughly 80% of all care that they deliver.[11] These types of care redesigns and standardization promise to provide better, more efficient, and often safer care for more patients. Hospitalists can play important roles in developing and delivering on these pathways.

In addition, hospital physician discontinuity during admissions may lead to increased resource utilization, costs, and lower patient satisfaction.[12] Therefore, ensuring clear handoffs between inpatient providers, as well as with outpatient providers during transitions in care, is a vital component of delivering high‐value care. Of particular importance is the population of patients frequently readmitted to the hospital. Hospitalists are often well acquainted with these patients, and the myriad of psychosocial, economic, and environmental challenges this vulnerable population faces. Although care coordination programs are increasing in prevalence, data on their cost‐effectiveness are mixed, highlighting the need for testing innovations.[13] Certainly, hospitalists can be leaders adopting and documenting the effectiveness of spreading interventions that have been shown to be promising in improving care transitions at discharge, such as the Care Transitions Intervention, Project RED (Re‐Engineered Discharge), or the Transitional Care Model.[14, 15, 16]

The University of Chicago, through funding from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation, is testing the use of a single physician who cares for frequently admitted patients both in and out of the hospital, thereby reducing the costs of coordination.[5] This comprehensivist model depends on physicians seeing patients in the hospital and then in a clinic located in or near the hospital for the subset of patients who stand to benefit most from this continuity. This differs from the old model of having primary care providers (PCPs) see inpatients and outpatients because the comprehensivist's patient panel is enriched with only patients who are at high risk for hospitalization, and thus these physicians have a more direct focus on hospital‐related care and higher daily hospitalized patient censuses, whereas PCPs were seeing fewer and fewer of their patients in the hospital on a daily basis. Evidence concerning the effectiveness of this model is expected by 2016. Hospitalists have also ventured out of the hospital into skilled nursing facilities, specializing in long‐term care.[17] These physicians are helping provide care to the roughly 1.6 million residents of US nursing homes.[17, 18] Preliminary evidence suggests increased physician staffing is associated with decreased hospitalization of nursing home residents.[18]

ADVOCATE FOR APPROPRIATE CARE

Hospitalists can advocate for appropriate care through avoiding low‐value services at the point of care, as well as learning and teaching about value.

Avoiding Low‐Value Services at the Point of Care

The largest contributor to the approximately $750 billion in annual healthcare waste is unnecessary services, which includes overuse, discretionary use beyond benchmarks, and unnecessary choice of higher‐cost services.[19] Drivers of overuse include medical culture, fee‐for‐service payments, patient expectations, and fear of malpractice litigation.[20] For practicing hospitalists, the most substantial motivation for overuse may be a desire to reassure patients and themselves.[21] Unfortunately, patients commonly overestimate the benefits and underestimate the potential harms of testing and treatments.[22] However, clear communication with patients can reduce overuse, underuse, and misuse.[23]

Specific targets for improving appropriate resource utilization may be identified from resources such as Choosing Wisely lists, guidelines, and appropriateness criteria. The Choosing Wisely campaign has brought together an unprecedented number of medical specialty societies to issue top five lists of things that physicians and patients should question (

| Adult Hospital Medicine Recommendations | Pediatric Hospital Medicine Recommendations |

|---|---|

| 1. Do not place, or leave in place, urinary catheters for incontinence or convenience, or monitoring of output for noncritically ill patients (acceptable indications: critical illness, obstruction, hospice, perioperatively for <2 days or urologic procedures; use weights instead to monitor diuresis). | 1. Do not order chest radiographs in children with uncomplicated asthma or bronchiolitis. |

| 2. Do not prescribe medications for stress ulcer prophylaxis to medical inpatients unless at high risk for gastrointestinal complication. | 2. Do not routinely use bronchodilators in children with bronchiolitis. |

| 3. Avoid transfusing red blood cells just because hemoglobin levels are below arbitrary thresholds such as 10, 9, or even 8 mg/dL in the absence of symptoms. | 3. Do not use systemic corticosteroids in children under 2 years of age with an uncomplicated lower respiratory tract infection. |

| 4. Avoid overuse/unnecessary use of telemetry monitoring in the hospital, particularly for patients at low risk for adverse cardiac outcomes. | 4. Do not treat gastroesophageal reflux in infants routinely with acid suppression therapy. |

| 5. Do not perform repetitive complete blood count and chemistry testing in the face of clinical and lab stability. | 5. Do not use continuous pulse oximetry routinely in children with acute respiratory illness unless they are on supplemental oxygen. |

As an example of this strategy, 1 multi‐institutional group has started training medical students to augment the traditional subjective‐objective‐assessment‐plan (SOAP) daily template with a value section (SOAP‐V), creating a cognitive forcing function to promote discussion of high‐value care delivery.[28] Physicians could include brief thoughts in this section about why they chose a specific intervention, their consideration of the potential benefits and harms compared to alternatives, how it may incorporate the patient's goals and values, and the known and potential costs of the intervention. Similarly, Flanders and Saint recommend that daily progress notes and sign‐outs include the indication, day of administration, and expected duration of therapy for all antimicrobial treatments, as a mechanism for curbing antimicrobial overuse in hospitalized patients.[29] Likewise, hospitalists can also document whether or not a patient needs routine labs, telemetry, continuous pulse oximetry, or other interventions or monitoring. It is not yet clear how effective this type of strategy will be, and drawbacks include creating longer progress notes and requiring more time for documentation. Another approach would be to work with the electronic health record to flag patients who are scheduled for telemetry or other potentially wasteful practices to inspire a daily practice audit to question whether the patient still meets criteria for such care. This approach acknowledges that patient's clinical status changes, and overcomes the inertia that results in so many therapies being continued despite a need or indication.

Communicating With Patients Who Want Everything

Some patients may be more worried about not getting every possible test, rather than concerns regarding associated costs. This may oftentimes be related to patients routinely overestimating the benefits of testing and treatments while not realizing the many potential downstream harms.[22] The perception is that patient demands frequently drive overtesting, but studies suggest the demanding patient is actually much less common than most physicians think.[30]

The Choosing Wisely campaign features video modules that provide a framework and specific examples for physician‐patient communication around some of the Choosing Wisely recommendations (available at:

Clinicians can explain why they do not believe that a test will help a patient and can share their concerns about the potential harms and downstream consequences of a given test. In addition, Consumer Reports and other groups have created trusted resources for patients that provide clear information for the public about unnecessary testing and services.

Learn and Teach Value

Traditionally, healthcare costs have largely remained hidden from both the public and medical professionals.[31, 32] As a result, hospitalists are generally not aware of the costs associated with their care.[33, 34] Although medical education has historically avoided the topic of healthcare costs,[35] recent calls to teach healthcare value have led to new educational efforts.[35, 36, 37] Future generations of medical professionals will be trained in these skills, but current hospitalists should seek opportunities to improve their knowledge of healthcare value and costs.

Fortunately, several resources can fill this gap. In addition to Choosing Wisely and ACR appropriateness criteria discussed above, newer tools focus on how to operationalize these recommendations with patients. The American College of Physicians (ACP) has launched a high‐value care educational platform that includes clinical recommendations, physician resources, curricula and public policy recommendations, and patient resources to help them understand the benefits, harms, and costs of tests and treatments for common clinical issues (

In an effort to provide frontline clinicians with the knowledge and tools necessary to address healthcare value, we have authored a textbook, Understanding Value‐Based Healthcare.[38] To identify the most promising ways of teaching these concepts, we also host the annual Teaching Value & Choosing Wisely Challenge and convene the Teaching Value in Healthcare Learning Network (bit.ly/teachingvaluenetwork) through our nonprofit, Costs of Care.[39]

In addition, hospitalists can also advocate for greater price transparency to help improve cost awareness and drive more appropriate care. The evidence on the effect of transparent costs in the electronic ordering system is evolving. Historically, efforts to provide diagnostic test prices at time of order led to mixed results,[40] but recent studies show clear benefits in resource utilization related to some form of cost display.[41, 42] This may be because physicians care more about healthcare costs and resource utilization than before. Feldman and colleagues found in a controlled clinical trial at Johns Hopkins that providing the costs of lab tests resulted in substantial decreases of certain lab tests and yielded a net cost reduction (based on 2011 Medicare Allowable Rate) of more than $400,000 at the hospital level during the 6‐month intervention period.[41] A recent systematic review concluded that charge information changed ordering and prescribing behavior in the majority of studies.[42] Some hospitalist programs are developing dashboards for various quality and utilization metrics. Sharing ratings or metrics internally or publically is a powerful way to motivate behavior change.[43]

LEAD LOCAL VALUE INITIATIVES

Hospitalists are ideal leaders of local value initiatives, whether it be through running value‐improvement projects or launching formal high‐value care programs.

Conduct Value‐Improvement Projects

Hospitalists across the country have largely taken the lead on designing value‐improvement pilots, programs, and groups within hospitals. Although value‐improvement projects may be built upon the established structures and techniques for quality improvement, importantly these programs should also include expertise in cost analyses.[8] Furthermore, some traditional quality‐improvement programs have failed to result in actual cost savings[44]; thus, it is not enough to simply rebrand quality improvement with a banner of value. Value‐improvement efforts must overcome the cultural hurdle of more care as better care, as well as pay careful attention to the diplomacy required with value improvement, because reducing costs may result in decreased revenue for certain departments or even decreases in individuals' wages.

One framework that we have used to guide value‐improvement project design is COST: culture, oversight accountability, system support, and training.[45] This approach leverages principles from implementation science to ensure that value‐improvement projects successfully provide multipronged tactics for overcoming the many barriers to high‐value care delivery. Figure 1 includes a worksheet for individual clinicians or teams to use when initially planning value‐improvement project interventions.[46] The examples in this worksheet come from a successful project at the University of California, San Francisco aimed at improving blood utilization stewardship by supporting adherence to a restrictive transfusion strategy. To address culture, a hospital‐wide campaign was led by physician peer champions to raise awareness about appropriate transfusion practices. This included posters that featured prominent local physician leaders displaying their support for the program. Oversight was provided through regular audit and feedback. Each month the number of patients on the medicine service who received transfusion with a pretransfusion hemoglobin above 8 grams per deciliter was shared at a faculty lunch meeting and shown on a graph included in the quality newsletter that was widely distributed in the hospital. The ordering system in the electronic medical record was eventually modified to include the patient's pretransfusion hemoglobin level at time of transfusion order and to provide default options and advice based on whether or not guidelines would generally recommend transfusion. Hospitalists and resident physicians were trained through multiple lectures and informal teaching settings about the rationale behind the changes and the evidence that supported a restrictive transfusion strategy.

Launch High‐Value Care Programs

As value‐improvement projects grow, some institutions have created high‐value care programs and infrastructure. In March 2012, the University of California, San Francisco Division of Hospital Medicine launched a high‐value care program to promote healthcare value and clinician engagement.[8] The program was led by clinical hospitalists alongside a financial administrator, and aimed to use financial data to identify areas with clear evidence of waste, create evidence‐based interventions that would simultaneously improve quality while cutting costs, and pair interventions with cost awareness education and culture change efforts. In the first year of this program, 6 projects were launched targeting: (1) nebulizer to inhaler transitions,[47] (2) overuse of proton pump inhibitor stress ulcer prophlaxis,[48] (3) transfusions, (4) telemetry, (5) ionized calcium lab ordering, and (6) repeat inpatient echocardiograms.[8]

Similar hospitalist‐led groups have now formed across the country including the Johns Hopkins High‐Value Care Committee, Johns Hopkins Bayview Physicians for Responsible Ordering, and High‐Value Carolina. These groups are relatively new, and best practices and early lessons are still emerging, but all focus on engaging frontline clinicians in choosing targets and leading multipronged intervention efforts.

What About Financial Incentives?

Hospitalist high‐value care groups thus far have mostly focused on intrinsic motivations for decreasing waste by appealing to hospitalists' sense of professionalism and their commitment to improve patient affordability. When financial incentives are used, it is important that they are well aligned with internal motivations for clinicians to provide the best possible care to their patients. The Institute of Medicine recommends that payments are structured in a way to reward continuous learning and improvement in the provision of best care at lower cost.[19] In the Geisinger Health System in Pennsylvania, physician incentives are designed to reward teamwork and collaboration. For example, endocrinologists' goals are based on good control of glucose levels for all diabetes patients in the system, not just those they see.[49] Moreover, a collaborative approach is encouraged by bringing clinicians together across disciplinary service lines to plan, budget, and evaluate one another's performance. These efforts are partly credited with a 43% reduction in hospitalized days and $100 per member per month in savings among diabetic patients.[50]

Healthcare leaders, Drs. Tom Lee and Toby Cosgrove, have made a number of recommendations for creating incentives that lead to sustainable changes in care delivery[49]: avoid attaching large sums to any single target, watch for conflicts of interest, reward collaboration, and communicate the incentive program and goals clearly to clinicians.

In general, when appropriate extrinsic motivators align or interact synergistically with intrinsic motivation, it can promote high levels of performance and satisfaction.[51]

CONCLUSIONS

Hospitalists are now faced with a responsibility to reduce financial harm and provide high‐value care. To achieve this goal, hospitalist groups are developing innovative models for care across the continuum from hospital to home, and individual hospitalists can advocate for appropriate care and lead value‐improvement initiatives in hospitals. Through existing knowledge and new frameworks and tools that specifically address value, hospitalists can champion value at the bedside and ensure their patients get the best possible care at lower costs.

Disclosures: Drs. Moriates, Shah, and Arora have received grant funding from the ABIM Foundation, and royalties from McGraw‐Hill for the textbook Understanding Value‐Based Healthcare. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

As the nation considers how to reduce healthcare costs, hospitalists can play a crucial role in this effort because they control many healthcare services through routine clinical decisions at the point of care. In fact, the government, payers, and the public now look to hospitalists as essential partners for reining in healthcare costs.[1, 2] The role of hospitalists is even more critical as payers, including Medicare, seek to shift reimbursements from volume to value.[1] Medicare's Value‐Based Purchasing program has already tied a percentage of hospital payments to metrics of quality, patient satisfaction, and cost,[1, 3] and Health and Human Services Secretary Sylvia Burwell announced that by the end of 2018, the goal is to have 50% of Medicare payments tied to quality or value through alternative payment models.[4]

Major opportunities for cost savings exist across the care continuum, particularly in postacute and transitional care, and hospitalist groups are leading innovative models that show promise for coordinating care and improving value.[5] Individual hospitalists are also in a unique position to provide high‐value care for their patients through advocating for appropriate care and leading local initiatives to improve value of care.[6, 7, 8] This commentary article aims to provide practicing hospitalists with a framework to incorporate these strategies into their daily work.

DESIGN STRATEGIES TO COORDINATE CARE

As delivery systems undertake the task of population health management, hospitalists will inevitably play a critical role in facilitating coordination between community, acute, and postacute care. During admission, discharge, and the hospitalization itself, standardizing care pathways for common hospital conditions such as pneumonia and cellulitis can be effective in decreasing utilization and improving clinical outcomes.[9, 10] Intermountain Healthcare in Utah has applied evidence‐based protocols to more than 60 clinical processes, re‐engineering roughly 80% of all care that they deliver.[11] These types of care redesigns and standardization promise to provide better, more efficient, and often safer care for more patients. Hospitalists can play important roles in developing and delivering on these pathways.

In addition, hospital physician discontinuity during admissions may lead to increased resource utilization, costs, and lower patient satisfaction.[12] Therefore, ensuring clear handoffs between inpatient providers, as well as with outpatient providers during transitions in care, is a vital component of delivering high‐value care. Of particular importance is the population of patients frequently readmitted to the hospital. Hospitalists are often well acquainted with these patients, and the myriad of psychosocial, economic, and environmental challenges this vulnerable population faces. Although care coordination programs are increasing in prevalence, data on their cost‐effectiveness are mixed, highlighting the need for testing innovations.[13] Certainly, hospitalists can be leaders adopting and documenting the effectiveness of spreading interventions that have been shown to be promising in improving care transitions at discharge, such as the Care Transitions Intervention, Project RED (Re‐Engineered Discharge), or the Transitional Care Model.[14, 15, 16]

The University of Chicago, through funding from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation, is testing the use of a single physician who cares for frequently admitted patients both in and out of the hospital, thereby reducing the costs of coordination.[5] This comprehensivist model depends on physicians seeing patients in the hospital and then in a clinic located in or near the hospital for the subset of patients who stand to benefit most from this continuity. This differs from the old model of having primary care providers (PCPs) see inpatients and outpatients because the comprehensivist's patient panel is enriched with only patients who are at high risk for hospitalization, and thus these physicians have a more direct focus on hospital‐related care and higher daily hospitalized patient censuses, whereas PCPs were seeing fewer and fewer of their patients in the hospital on a daily basis. Evidence concerning the effectiveness of this model is expected by 2016. Hospitalists have also ventured out of the hospital into skilled nursing facilities, specializing in long‐term care.[17] These physicians are helping provide care to the roughly 1.6 million residents of US nursing homes.[17, 18] Preliminary evidence suggests increased physician staffing is associated with decreased hospitalization of nursing home residents.[18]

ADVOCATE FOR APPROPRIATE CARE

Hospitalists can advocate for appropriate care through avoiding low‐value services at the point of care, as well as learning and teaching about value.

Avoiding Low‐Value Services at the Point of Care

The largest contributor to the approximately $750 billion in annual healthcare waste is unnecessary services, which includes overuse, discretionary use beyond benchmarks, and unnecessary choice of higher‐cost services.[19] Drivers of overuse include medical culture, fee‐for‐service payments, patient expectations, and fear of malpractice litigation.[20] For practicing hospitalists, the most substantial motivation for overuse may be a desire to reassure patients and themselves.[21] Unfortunately, patients commonly overestimate the benefits and underestimate the potential harms of testing and treatments.[22] However, clear communication with patients can reduce overuse, underuse, and misuse.[23]

Specific targets for improving appropriate resource utilization may be identified from resources such as Choosing Wisely lists, guidelines, and appropriateness criteria. The Choosing Wisely campaign has brought together an unprecedented number of medical specialty societies to issue top five lists of things that physicians and patients should question (

| Adult Hospital Medicine Recommendations | Pediatric Hospital Medicine Recommendations |

|---|---|

| 1. Do not place, or leave in place, urinary catheters for incontinence or convenience, or monitoring of output for noncritically ill patients (acceptable indications: critical illness, obstruction, hospice, perioperatively for <2 days or urologic procedures; use weights instead to monitor diuresis). | 1. Do not order chest radiographs in children with uncomplicated asthma or bronchiolitis. |

| 2. Do not prescribe medications for stress ulcer prophylaxis to medical inpatients unless at high risk for gastrointestinal complication. | 2. Do not routinely use bronchodilators in children with bronchiolitis. |

| 3. Avoid transfusing red blood cells just because hemoglobin levels are below arbitrary thresholds such as 10, 9, or even 8 mg/dL in the absence of symptoms. | 3. Do not use systemic corticosteroids in children under 2 years of age with an uncomplicated lower respiratory tract infection. |

| 4. Avoid overuse/unnecessary use of telemetry monitoring in the hospital, particularly for patients at low risk for adverse cardiac outcomes. | 4. Do not treat gastroesophageal reflux in infants routinely with acid suppression therapy. |

| 5. Do not perform repetitive complete blood count and chemistry testing in the face of clinical and lab stability. | 5. Do not use continuous pulse oximetry routinely in children with acute respiratory illness unless they are on supplemental oxygen. |

As an example of this strategy, 1 multi‐institutional group has started training medical students to augment the traditional subjective‐objective‐assessment‐plan (SOAP) daily template with a value section (SOAP‐V), creating a cognitive forcing function to promote discussion of high‐value care delivery.[28] Physicians could include brief thoughts in this section about why they chose a specific intervention, their consideration of the potential benefits and harms compared to alternatives, how it may incorporate the patient's goals and values, and the known and potential costs of the intervention. Similarly, Flanders and Saint recommend that daily progress notes and sign‐outs include the indication, day of administration, and expected duration of therapy for all antimicrobial treatments, as a mechanism for curbing antimicrobial overuse in hospitalized patients.[29] Likewise, hospitalists can also document whether or not a patient needs routine labs, telemetry, continuous pulse oximetry, or other interventions or monitoring. It is not yet clear how effective this type of strategy will be, and drawbacks include creating longer progress notes and requiring more time for documentation. Another approach would be to work with the electronic health record to flag patients who are scheduled for telemetry or other potentially wasteful practices to inspire a daily practice audit to question whether the patient still meets criteria for such care. This approach acknowledges that patient's clinical status changes, and overcomes the inertia that results in so many therapies being continued despite a need or indication.

Communicating With Patients Who Want Everything

Some patients may be more worried about not getting every possible test, rather than concerns regarding associated costs. This may oftentimes be related to patients routinely overestimating the benefits of testing and treatments while not realizing the many potential downstream harms.[22] The perception is that patient demands frequently drive overtesting, but studies suggest the demanding patient is actually much less common than most physicians think.[30]

The Choosing Wisely campaign features video modules that provide a framework and specific examples for physician‐patient communication around some of the Choosing Wisely recommendations (available at:

Clinicians can explain why they do not believe that a test will help a patient and can share their concerns about the potential harms and downstream consequences of a given test. In addition, Consumer Reports and other groups have created trusted resources for patients that provide clear information for the public about unnecessary testing and services.

Learn and Teach Value

Traditionally, healthcare costs have largely remained hidden from both the public and medical professionals.[31, 32] As a result, hospitalists are generally not aware of the costs associated with their care.[33, 34] Although medical education has historically avoided the topic of healthcare costs,[35] recent calls to teach healthcare value have led to new educational efforts.[35, 36, 37] Future generations of medical professionals will be trained in these skills, but current hospitalists should seek opportunities to improve their knowledge of healthcare value and costs.

Fortunately, several resources can fill this gap. In addition to Choosing Wisely and ACR appropriateness criteria discussed above, newer tools focus on how to operationalize these recommendations with patients. The American College of Physicians (ACP) has launched a high‐value care educational platform that includes clinical recommendations, physician resources, curricula and public policy recommendations, and patient resources to help them understand the benefits, harms, and costs of tests and treatments for common clinical issues (

In an effort to provide frontline clinicians with the knowledge and tools necessary to address healthcare value, we have authored a textbook, Understanding Value‐Based Healthcare.[38] To identify the most promising ways of teaching these concepts, we also host the annual Teaching Value & Choosing Wisely Challenge and convene the Teaching Value in Healthcare Learning Network (bit.ly/teachingvaluenetwork) through our nonprofit, Costs of Care.[39]

In addition, hospitalists can also advocate for greater price transparency to help improve cost awareness and drive more appropriate care. The evidence on the effect of transparent costs in the electronic ordering system is evolving. Historically, efforts to provide diagnostic test prices at time of order led to mixed results,[40] but recent studies show clear benefits in resource utilization related to some form of cost display.[41, 42] This may be because physicians care more about healthcare costs and resource utilization than before. Feldman and colleagues found in a controlled clinical trial at Johns Hopkins that providing the costs of lab tests resulted in substantial decreases of certain lab tests and yielded a net cost reduction (based on 2011 Medicare Allowable Rate) of more than $400,000 at the hospital level during the 6‐month intervention period.[41] A recent systematic review concluded that charge information changed ordering and prescribing behavior in the majority of studies.[42] Some hospitalist programs are developing dashboards for various quality and utilization metrics. Sharing ratings or metrics internally or publically is a powerful way to motivate behavior change.[43]

LEAD LOCAL VALUE INITIATIVES

Hospitalists are ideal leaders of local value initiatives, whether it be through running value‐improvement projects or launching formal high‐value care programs.

Conduct Value‐Improvement Projects

Hospitalists across the country have largely taken the lead on designing value‐improvement pilots, programs, and groups within hospitals. Although value‐improvement projects may be built upon the established structures and techniques for quality improvement, importantly these programs should also include expertise in cost analyses.[8] Furthermore, some traditional quality‐improvement programs have failed to result in actual cost savings[44]; thus, it is not enough to simply rebrand quality improvement with a banner of value. Value‐improvement efforts must overcome the cultural hurdle of more care as better care, as well as pay careful attention to the diplomacy required with value improvement, because reducing costs may result in decreased revenue for certain departments or even decreases in individuals' wages.

One framework that we have used to guide value‐improvement project design is COST: culture, oversight accountability, system support, and training.[45] This approach leverages principles from implementation science to ensure that value‐improvement projects successfully provide multipronged tactics for overcoming the many barriers to high‐value care delivery. Figure 1 includes a worksheet for individual clinicians or teams to use when initially planning value‐improvement project interventions.[46] The examples in this worksheet come from a successful project at the University of California, San Francisco aimed at improving blood utilization stewardship by supporting adherence to a restrictive transfusion strategy. To address culture, a hospital‐wide campaign was led by physician peer champions to raise awareness about appropriate transfusion practices. This included posters that featured prominent local physician leaders displaying their support for the program. Oversight was provided through regular audit and feedback. Each month the number of patients on the medicine service who received transfusion with a pretransfusion hemoglobin above 8 grams per deciliter was shared at a faculty lunch meeting and shown on a graph included in the quality newsletter that was widely distributed in the hospital. The ordering system in the electronic medical record was eventually modified to include the patient's pretransfusion hemoglobin level at time of transfusion order and to provide default options and advice based on whether or not guidelines would generally recommend transfusion. Hospitalists and resident physicians were trained through multiple lectures and informal teaching settings about the rationale behind the changes and the evidence that supported a restrictive transfusion strategy.

Launch High‐Value Care Programs

As value‐improvement projects grow, some institutions have created high‐value care programs and infrastructure. In March 2012, the University of California, San Francisco Division of Hospital Medicine launched a high‐value care program to promote healthcare value and clinician engagement.[8] The program was led by clinical hospitalists alongside a financial administrator, and aimed to use financial data to identify areas with clear evidence of waste, create evidence‐based interventions that would simultaneously improve quality while cutting costs, and pair interventions with cost awareness education and culture change efforts. In the first year of this program, 6 projects were launched targeting: (1) nebulizer to inhaler transitions,[47] (2) overuse of proton pump inhibitor stress ulcer prophlaxis,[48] (3) transfusions, (4) telemetry, (5) ionized calcium lab ordering, and (6) repeat inpatient echocardiograms.[8]

Similar hospitalist‐led groups have now formed across the country including the Johns Hopkins High‐Value Care Committee, Johns Hopkins Bayview Physicians for Responsible Ordering, and High‐Value Carolina. These groups are relatively new, and best practices and early lessons are still emerging, but all focus on engaging frontline clinicians in choosing targets and leading multipronged intervention efforts.

What About Financial Incentives?

Hospitalist high‐value care groups thus far have mostly focused on intrinsic motivations for decreasing waste by appealing to hospitalists' sense of professionalism and their commitment to improve patient affordability. When financial incentives are used, it is important that they are well aligned with internal motivations for clinicians to provide the best possible care to their patients. The Institute of Medicine recommends that payments are structured in a way to reward continuous learning and improvement in the provision of best care at lower cost.[19] In the Geisinger Health System in Pennsylvania, physician incentives are designed to reward teamwork and collaboration. For example, endocrinologists' goals are based on good control of glucose levels for all diabetes patients in the system, not just those they see.[49] Moreover, a collaborative approach is encouraged by bringing clinicians together across disciplinary service lines to plan, budget, and evaluate one another's performance. These efforts are partly credited with a 43% reduction in hospitalized days and $100 per member per month in savings among diabetic patients.[50]

Healthcare leaders, Drs. Tom Lee and Toby Cosgrove, have made a number of recommendations for creating incentives that lead to sustainable changes in care delivery[49]: avoid attaching large sums to any single target, watch for conflicts of interest, reward collaboration, and communicate the incentive program and goals clearly to clinicians.

In general, when appropriate extrinsic motivators align or interact synergistically with intrinsic motivation, it can promote high levels of performance and satisfaction.[51]

CONCLUSIONS

Hospitalists are now faced with a responsibility to reduce financial harm and provide high‐value care. To achieve this goal, hospitalist groups are developing innovative models for care across the continuum from hospital to home, and individual hospitalists can advocate for appropriate care and lead value‐improvement initiatives in hospitals. Through existing knowledge and new frameworks and tools that specifically address value, hospitalists can champion value at the bedside and ensure their patients get the best possible care at lower costs.

Disclosures: Drs. Moriates, Shah, and Arora have received grant funding from the ABIM Foundation, and royalties from McGraw‐Hill for the textbook Understanding Value‐Based Healthcare. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- , . Value‐based purchasing—national programs to move from volume to value. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(4):292–295.

- . Value‐driven health care: implications for hospitals and hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(8):507–511.

- , . Hospital value‐based purchasing. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(5):271–277.

- . Setting value‐based payment goals—HHS efforts to improve U.S. health care. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(10):897–899.

- , . Redesigning care for patients at increased hospitalization risk: the Comprehensive Care Physician model. Health Aff Proj Hope. 2014;33(5):770–777.

- , , , et al. Choosing wisely in adult hospital medicine: five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):486–492.

- , , . First, do no (financial) harm. JAMA. 2013;310(6):577–578.

- , , , . Development of a hospital‐based program focused on improving healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(10):671–677.

- , , , et al. A controlled trial of a critical pathway for treatment of community‐acquired pneumonia. JAMA. 2000;283(6):749–755.

- , , , , . Evidence‐based care pathway for cellulitis improves process, clinical, and cost outcomes [published online July 28, 2015]. J Hosp Med. doi:10.1002/jhm.2433.

- . The Lean approach to health care: safety, quality, and cost. Institute of Medicine. Available at: http://nam.edu/perspectives‐2012‐the‐lean‐approach‐to‐health‐care‐safety‐quality‐and‐cost/. Accessed September 22, 2015.

- , , , et al. The impact of hospitalist discontinuity on hospital cost, readmissions, and patient satisfaction. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(7):1004–1008.

- Congressional Budget Office. Lessons from Medicare's Demonstration Projects on Disease Management, Care Coordination, and Value‐Based Payment. Available at: https://www.cbo.gov/publication/42860. Accessed April 26, 2015.

- , , , et al. A reengineered hospital discharge program to decrease rehospitalization: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(3):178–187.

- , , , . The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(17):1822–1828.

- , , , et al. Comprehensive discharge planning and home follow‐up of hospitalized elders: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 1999;281(7):613–620.

- . “SNFists” at work: nursing home docs patterned after hospitalists. Mod Healthc. 2012;42(13):32–33.

- , , , . Nursing home physician specialists: a response to the workforce crisis in long‐term care. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(6):411–413.

- Institute of Medicine. Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2012.

- , . The perfect storm of overutilization. JAMA. 2008;299(23):2789–2791.

- , , , et al. Overuse of testing in preoperative evaluation and syncope: a survey of hospitalists. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(2):100–108.

- , . Patients' expectations of the benefits and harms of treatments, screening, and tests: a systematic review. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(2):274–286.

- , , , et al. Enhancing the Use and Quality of Colorectal Cancer Screening. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2010. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK44526. Accessed September 30, 2013.

- , , , et al. Choosing wisely in pediatric hospital medicine: five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):479–485.

- . Teaching Choosing Wisely in medical education and training: the story of a pioneer. The Medical Professionalism Blog. Available at: http://blog.abimfoundation.org/teaching‐choosing‐wisely‐in‐meded. Accessed March 29, 2014.

- American College of Radiology. ACR appropriateness criteria overview. November 2013. Available at: http://www.acr.org/∼/media/ACR/Documents/AppCriteria/Overview.pdf. Accessed March 4, 2014.

- American College of Cardiology Foundation. Appropriate use criteria: what you need to know. Available at: http://www.cardiosource.org/∼/media/Files/Science%20and%20Quality/Quality%20Programs/FOCUS/E1302_AUC_Primer_Update.ashx. Accessed March 4, 2014.

- , , , , . SOAP‐V: applying high‐value care during patient care. The Medical Professionalism Blog. Available at: http://blog.abimfoundation.org/soap‐v‐applying‐high‐value‐care‐during‐patient‐care. Accessed April 3, 2015.

- , . Why does antimicrobial overuse in hospitalized patients persist? JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(5):661–662.

- . The myth of the demanding patient. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(1):18–19.

- . The disruptive innovation of price transparency in health care. JAMA. 2013;310(18):1927–1928.

- United States Government Accountability Office. Health Care Price Transparency—Meaningful Price Information Is Difficult for Consumers to Obtain Prior to Receiving Care. Washington, DC: United States Government Accountability Office; 2011:43.

- , , . General pediatric attending physicians' and residents' knowledge of inpatient hospital finances. Pediatrics. 2013;131(6):1072–1080.

- , , . Hospitalists' awareness of patient charges associated with inpatient care. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(5):295–297.

- . Cost consciousness in patient care—what is medical education's responsibility? N Engl J Med. 2010;362(14):1253–1255.

- . Providing high‐value, cost‐conscious care: a critical seventh general competency for physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(6):386–388.

- , , , . Defining competencies for education in health care value: recommendations from the University of California, San Francisco Center for Healthcare Value Training Initiative. Acad Med. 2015;90(4):421–424.

- , , . Understanding Value‐Based Healthcare. New York: McGraw‐Hill; 2015.

- , , , . Wisdom of the crowd: bright ideas and innovations from the teaching value and choosing wisely challenge. Acad Med. 2015;90(5):624–628.

- , , , et al. Does the computerized display of charges affect inpatient ancillary test utilization? Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(21):2501–2508.

- , , , et al. Impact of providing fee data on laboratory test ordering: a controlled clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(10):903–908.

- , , , . The effect of charge display on cost of care and physician practice behaviors: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(6):835–842.

- , , , , , . Closing the Quality Gap: Revisiting the State of the Science. Vol. 5. Public Reporting as a Quality Improvement Strategy. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2012.

- , , , . The savings illusion—why clinical quality improvement fails to deliver bottom‐line results. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(26):e48.

- , , , . Fostering value in clinical practice among future physicians: time to consider COST. Acad Med. 2014;89(11):1440.

- , , , , , . The Teaching Value Workshop. MedEdPORTAL Publications; 2014. Available at: https://www.mededportal.org/publication/9859. Accessed September 22, 2015.

- , , , , . “Nebs no more after 24”: a pilot program to improve the use of appropriate respiratory therapies. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(17):1647–1648.

- , , , et al. The development and implementation of a bundled quality improvement initiative to reduce inappropriate stress ulcer prophylaxis. ICU Dir. 2013;4(6):322–325.

- , . Engaging doctors in the health care revolution. Harvard Business Review. June 2014. Available at: http://hbr.org/2014/06/engaging‐doctors‐in‐the‐health‐care‐revolution/ar/1. Accessed July 30, 2014.

- , , . Geisinger Health System: achieving the potential of system integration through innovation, leadership, measurement, and incentives. June 2009. Available at: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/case‐studies/2009/jun/geisinger‐health‐system‐achieving‐the‐potential‐of‐system‐integration. Accessed September 22, 2015.

- Motivational synergy: toward new conceptualizations of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation in the workplace. Hum Resource Manag 1993;3(3):185–201. Available at: http://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=2500. Accessed July 31, 2014.

- , . Value‐based purchasing—national programs to move from volume to value. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(4):292–295.

- . Value‐driven health care: implications for hospitals and hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(8):507–511.

- , . Hospital value‐based purchasing. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(5):271–277.

- . Setting value‐based payment goals—HHS efforts to improve U.S. health care. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(10):897–899.

- , . Redesigning care for patients at increased hospitalization risk: the Comprehensive Care Physician model. Health Aff Proj Hope. 2014;33(5):770–777.

- , , , et al. Choosing wisely in adult hospital medicine: five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):486–492.

- , , . First, do no (financial) harm. JAMA. 2013;310(6):577–578.

- , , , . Development of a hospital‐based program focused on improving healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(10):671–677.

- , , , et al. A controlled trial of a critical pathway for treatment of community‐acquired pneumonia. JAMA. 2000;283(6):749–755.

- , , , , . Evidence‐based care pathway for cellulitis improves process, clinical, and cost outcomes [published online July 28, 2015]. J Hosp Med. doi:10.1002/jhm.2433.

- . The Lean approach to health care: safety, quality, and cost. Institute of Medicine. Available at: http://nam.edu/perspectives‐2012‐the‐lean‐approach‐to‐health‐care‐safety‐quality‐and‐cost/. Accessed September 22, 2015.

- , , , et al. The impact of hospitalist discontinuity on hospital cost, readmissions, and patient satisfaction. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(7):1004–1008.

- Congressional Budget Office. Lessons from Medicare's Demonstration Projects on Disease Management, Care Coordination, and Value‐Based Payment. Available at: https://www.cbo.gov/publication/42860. Accessed April 26, 2015.

- , , , et al. A reengineered hospital discharge program to decrease rehospitalization: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(3):178–187.

- , , , . The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(17):1822–1828.

- , , , et al. Comprehensive discharge planning and home follow‐up of hospitalized elders: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 1999;281(7):613–620.

- . “SNFists” at work: nursing home docs patterned after hospitalists. Mod Healthc. 2012;42(13):32–33.

- , , , . Nursing home physician specialists: a response to the workforce crisis in long‐term care. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(6):411–413.

- Institute of Medicine. Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2012.

- , . The perfect storm of overutilization. JAMA. 2008;299(23):2789–2791.

- , , , et al. Overuse of testing in preoperative evaluation and syncope: a survey of hospitalists. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(2):100–108.

- , . Patients' expectations of the benefits and harms of treatments, screening, and tests: a systematic review. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(2):274–286.

- , , , et al. Enhancing the Use and Quality of Colorectal Cancer Screening. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2010. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK44526. Accessed September 30, 2013.

- , , , et al. Choosing wisely in pediatric hospital medicine: five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):479–485.

- . Teaching Choosing Wisely in medical education and training: the story of a pioneer. The Medical Professionalism Blog. Available at: http://blog.abimfoundation.org/teaching‐choosing‐wisely‐in‐meded. Accessed March 29, 2014.

- American College of Radiology. ACR appropriateness criteria overview. November 2013. Available at: http://www.acr.org/∼/media/ACR/Documents/AppCriteria/Overview.pdf. Accessed March 4, 2014.