User login

Granuloma Annulare: A Retrospective Series of 133 Patients

Granuloma annulare (GA) is a granulomatous skin disorder of uncertain etiology. A number of clinical variants exist, most commonly localized annular plaques on the hands or feet, generalized lesions, or subcutaneous nodules in children. Histologically, GA exhibits granulomatous inflammation with either interstitial or palisading lymphocytes and histiocytes with mucin deposition.

Few data exist regarding the epidemiology of GA. Although the pathogenesis of GA is unknown, associations between GA and underlying systemic processes, such as diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, thyroid disease, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), have been suggested.

The purpose of this retrospective study was to determine the number of cases of GA seen annually at the Department of Dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) from 2008 to 2014. Additionally, we reviewed all cases of biopsy-proven GA from 2010 to 2014 and reported the demographics, underlying medical comorbidities, medications, treatments, and outcomes seen in this patient population.

Methods

We identified the number of outpatients presenting with GA annually using PennSeek, a tool developed by the Penn Medicine Data Analytics Center to search electronic medical records (EMRs). We queried the EMR database to determine the number of discrete patients seen at the Department of Dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania annually from 2008 (the year the EMR was established) to 2014. We then used PennSeek to determine the number of patients given a diagnosis of GA annually from 2008 to 2014 based on the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9).

After using PennSeek to identify all patients given the ICD-9 diagnosis of GA from 2008 to 2014, we reviewed the EMRs of these patients to identify cases that were biopsy proven. For the biopsy-proven cases of GA seen at the University of Pennsylvania from 2010 to 2014, we reviewed the EMRs of these patients for clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes. For each case, we recorded the patient’s age, sex, medical comorbidities, GA subtype, and medications.

This study was approved by the University of Pennsylvania’s institutional review board.

Results

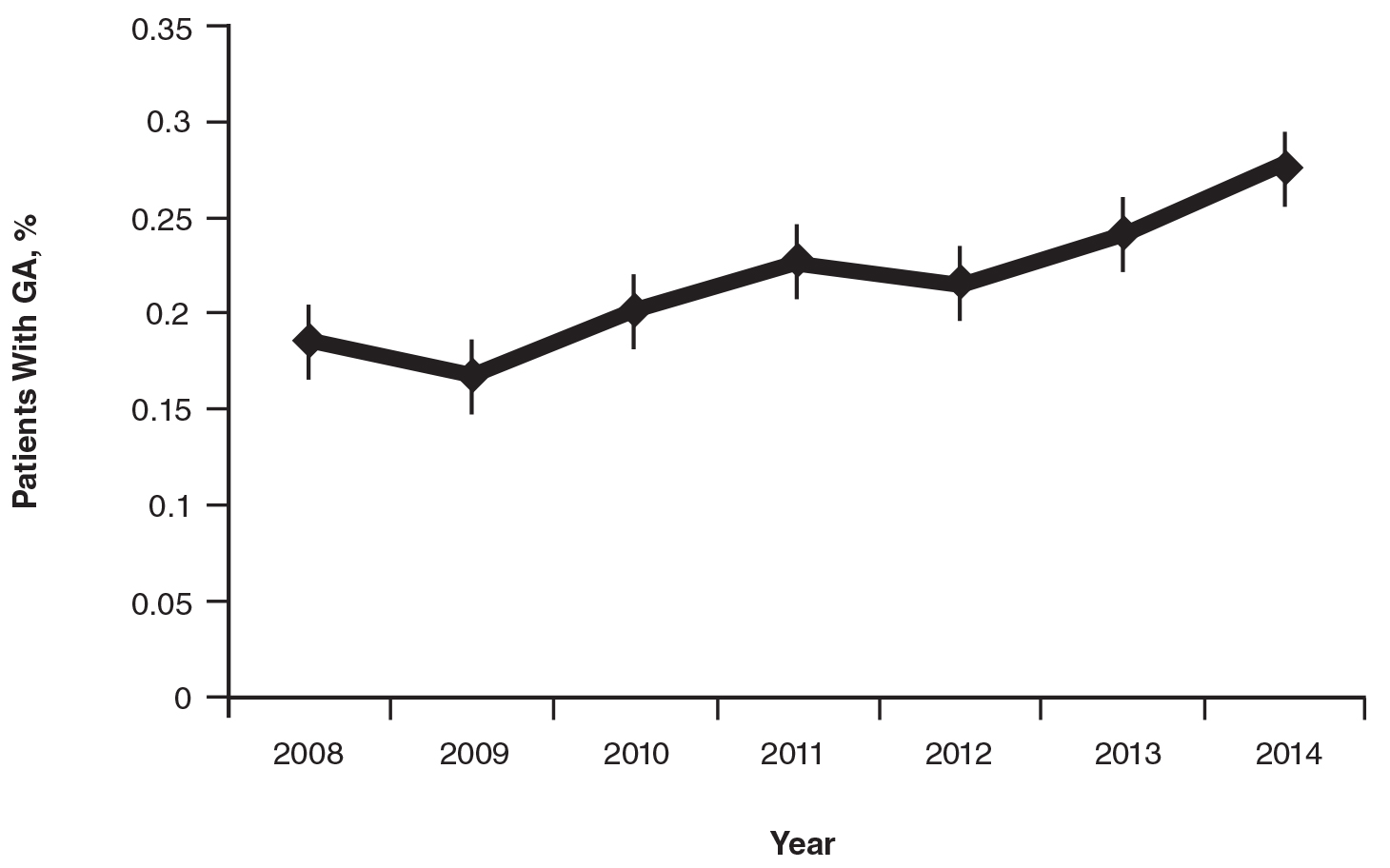

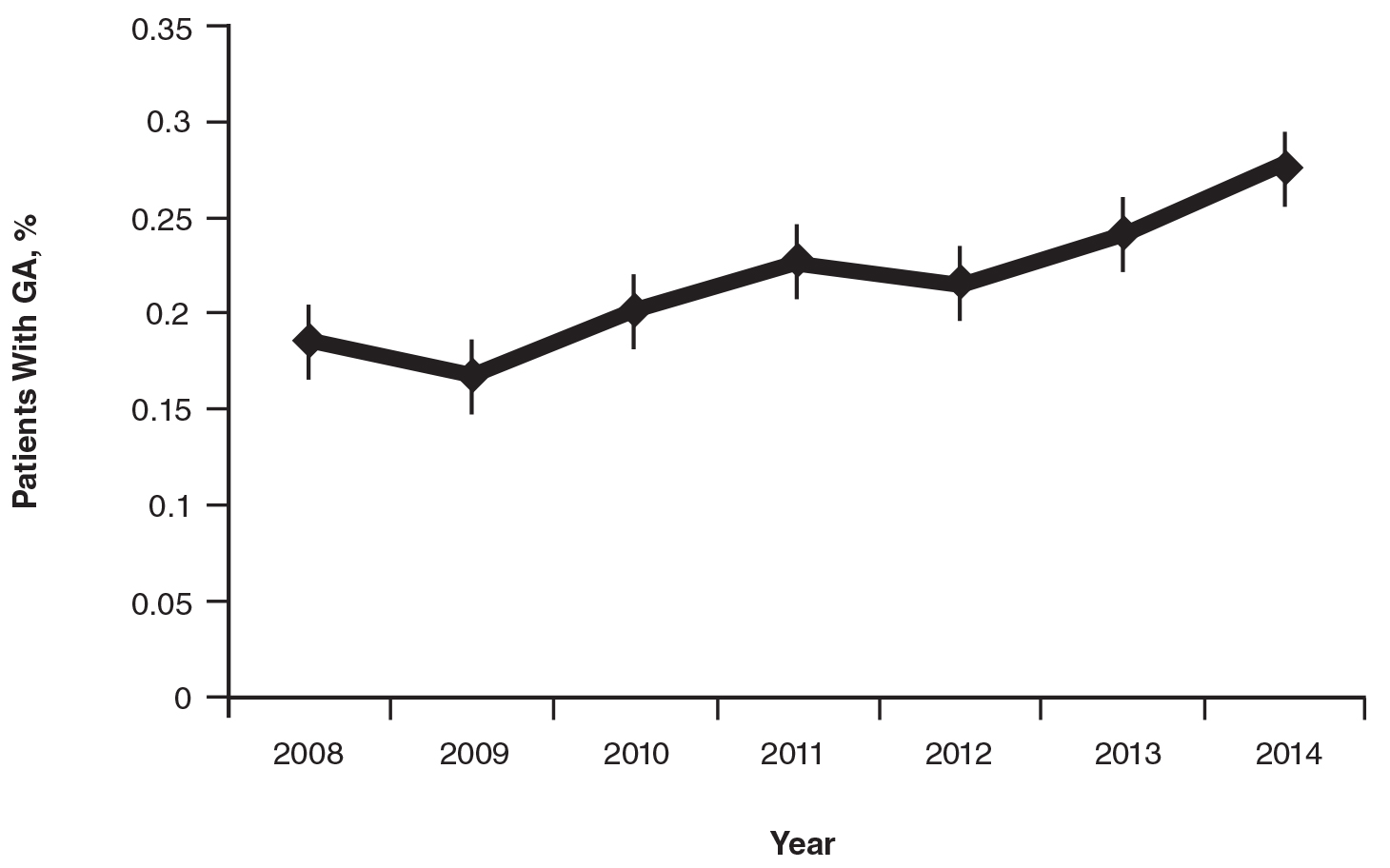

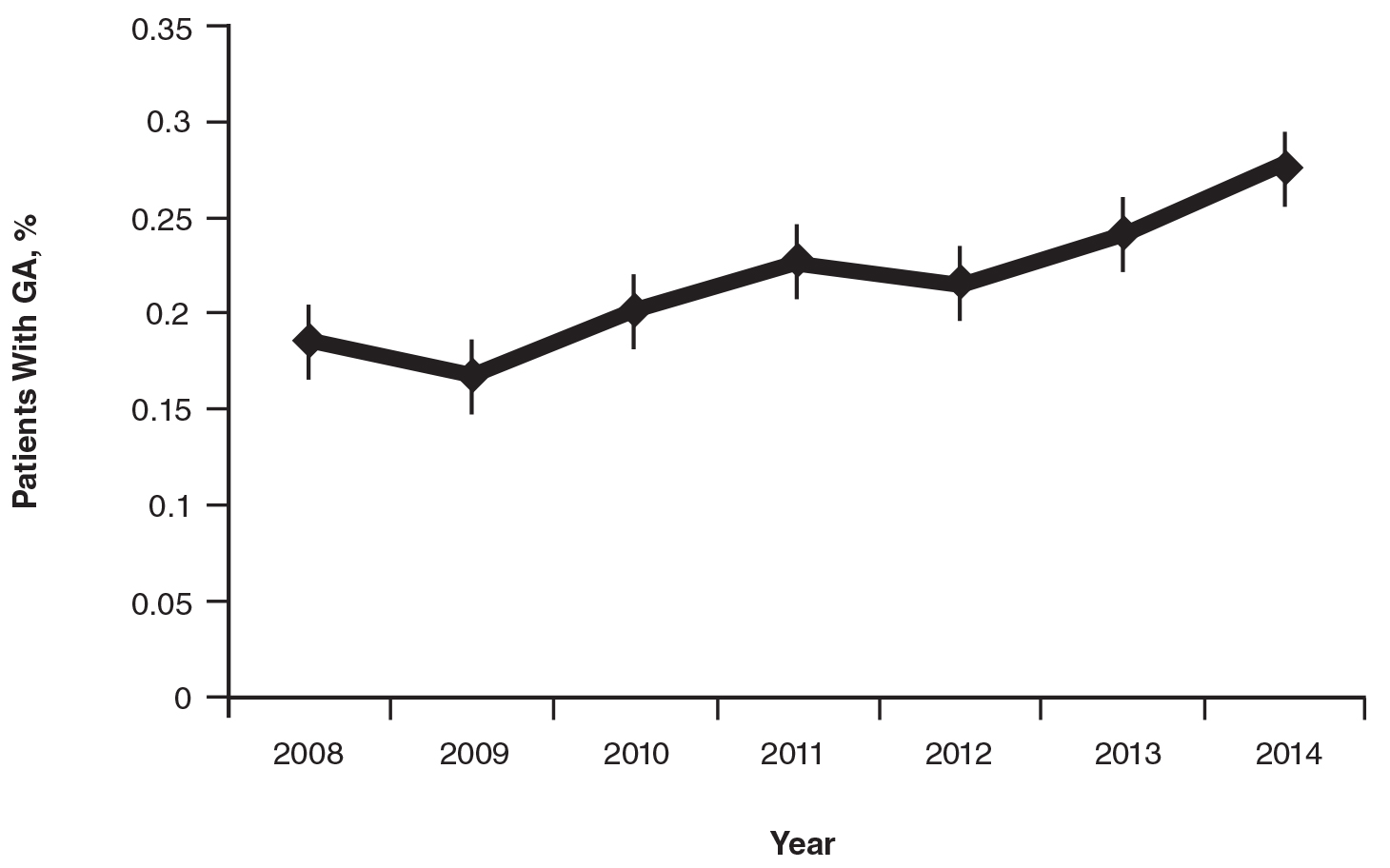

On average, the percentage of patients given a diagnosis of GA annually was 0.22% (95% CI, 0.19%-0.24%). A Pearson χ2 test was used to determine if any single annual percentage was significantly different from the others. We found a P value of .321, which suggests that the percentage of patients with GA seen annually has been stable from 2008 to 2014 (Figure).

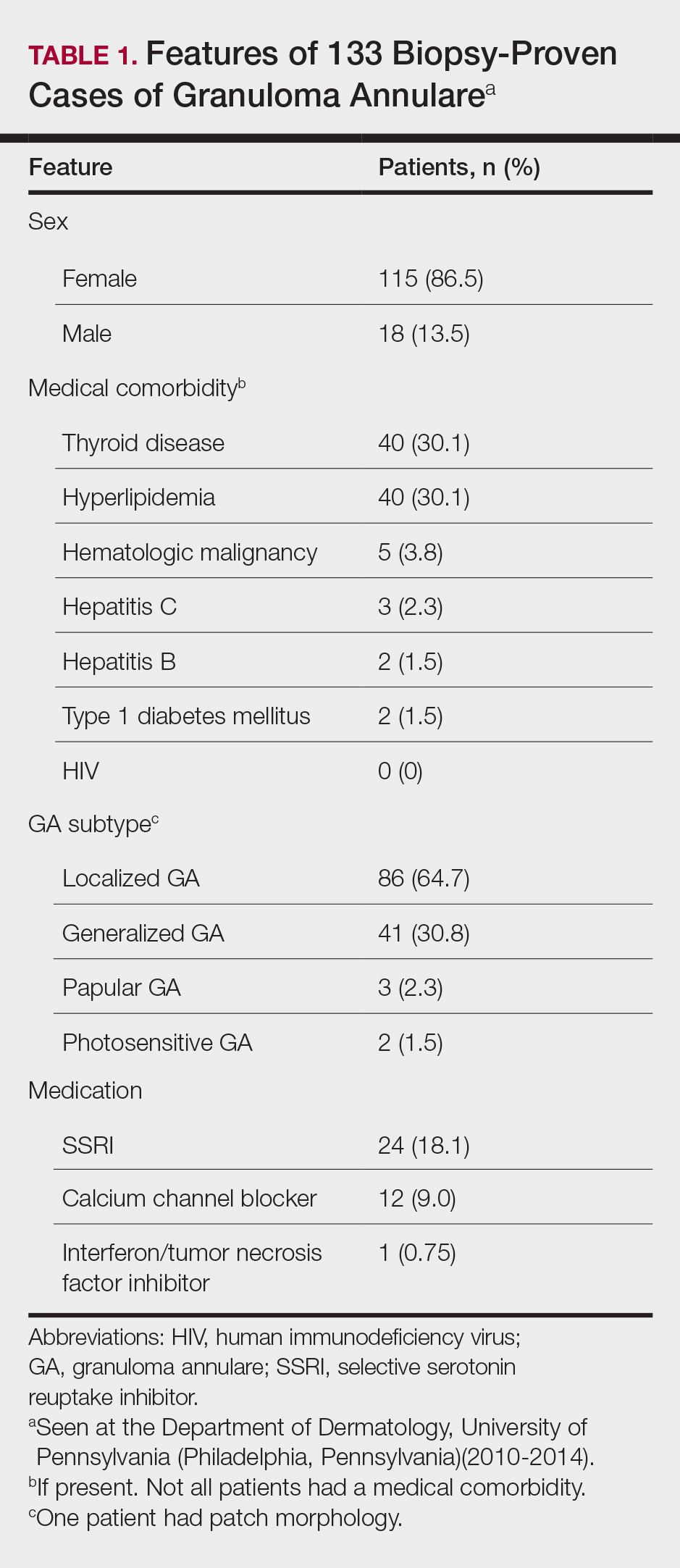

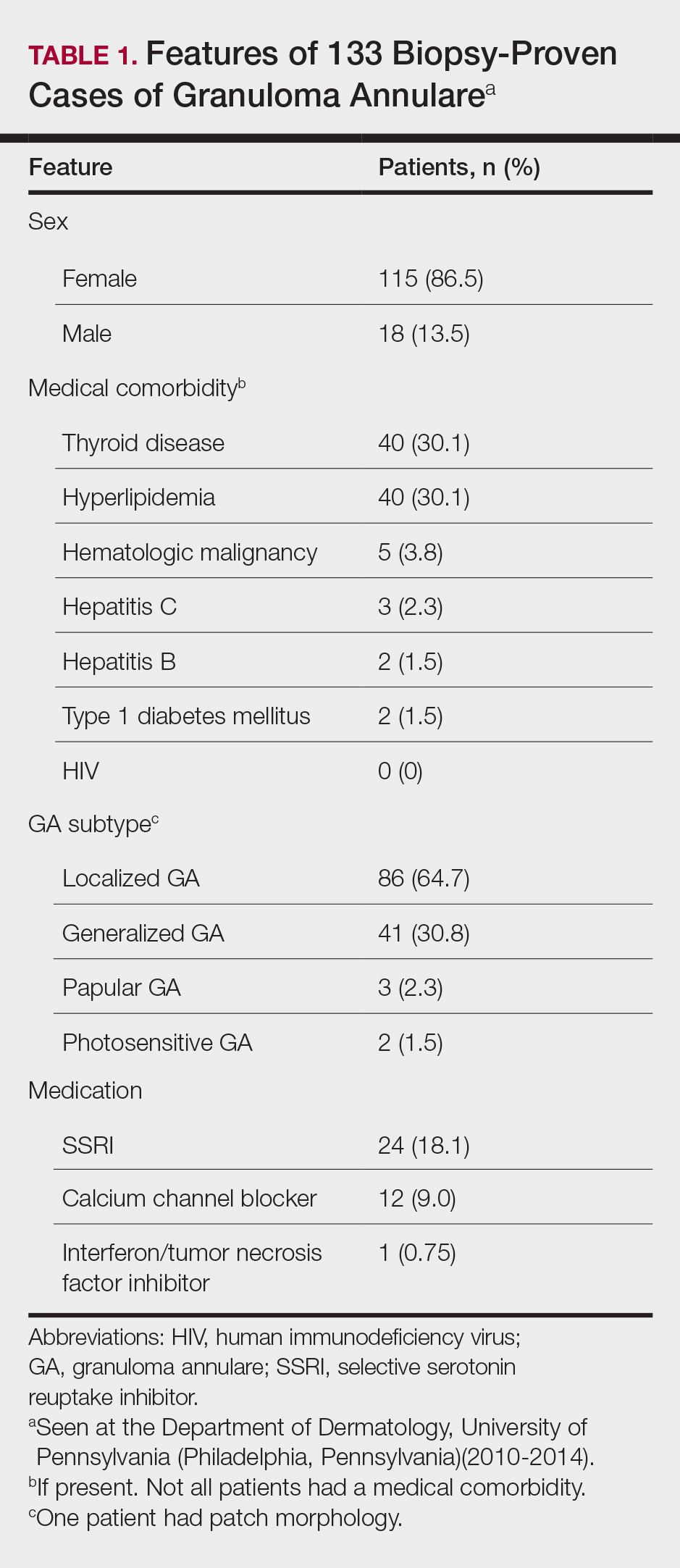

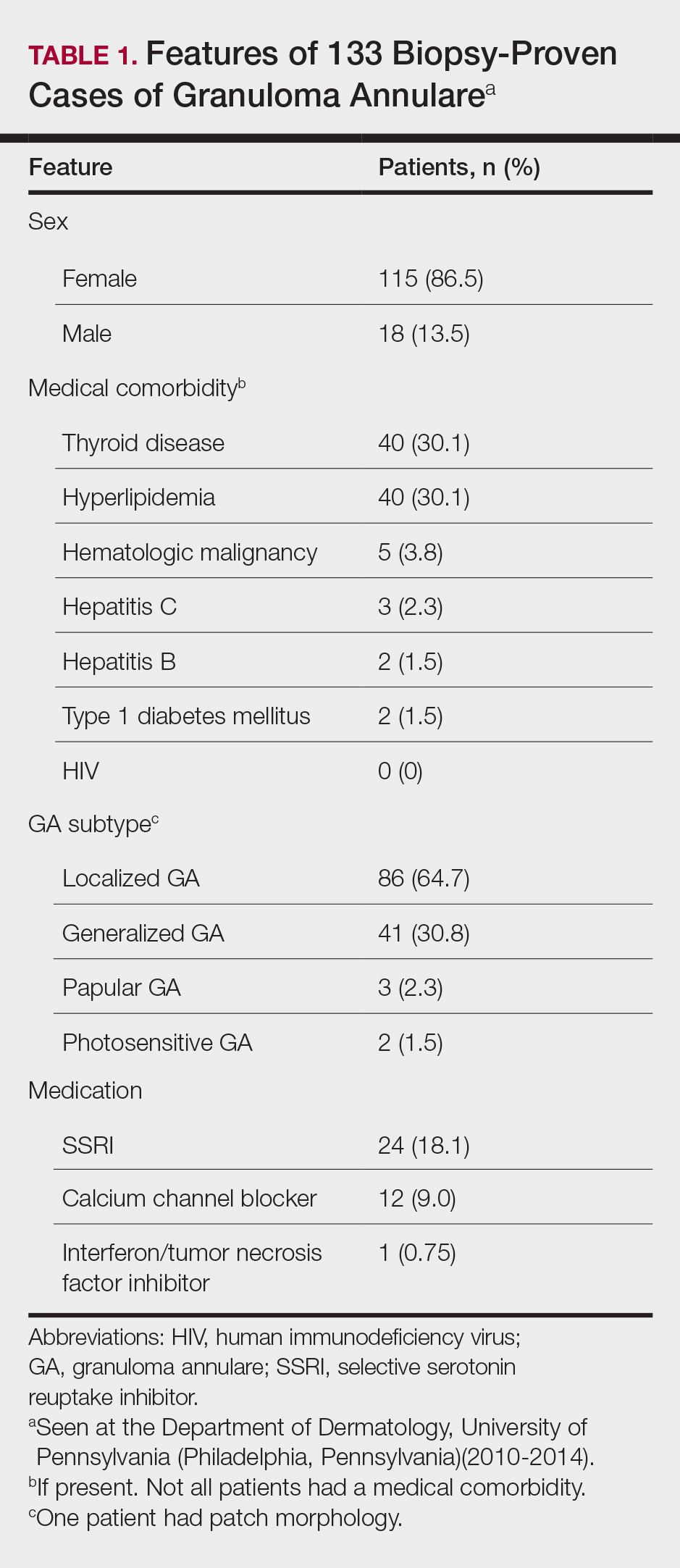

There were 133 cases of biopsy-proven GA that were reviewed for clinical characteristics; of them, 86.5% were female. Thyroid disease was noted in 30.1% of patients, hyperlipidemia in 30.1%, and hematologic malignancies in 3.8%. Type 1 diabetes mellitus was noted in 1.5% of patients. None of the patients were HIV-positive, 1.5% were hepatitis B–positive, and 2.3% were hepatitis C–positive. Of the 133 cases, 64.7% had localized GA and 30.8% had generalized GA. Photosensitive and papular GA were rarer (1.5% and 2.3% of cases, respectively). Use of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) was noted in 18.1% of patients; use of a calcium channel blocker was noted in 9.0% (Table 1).

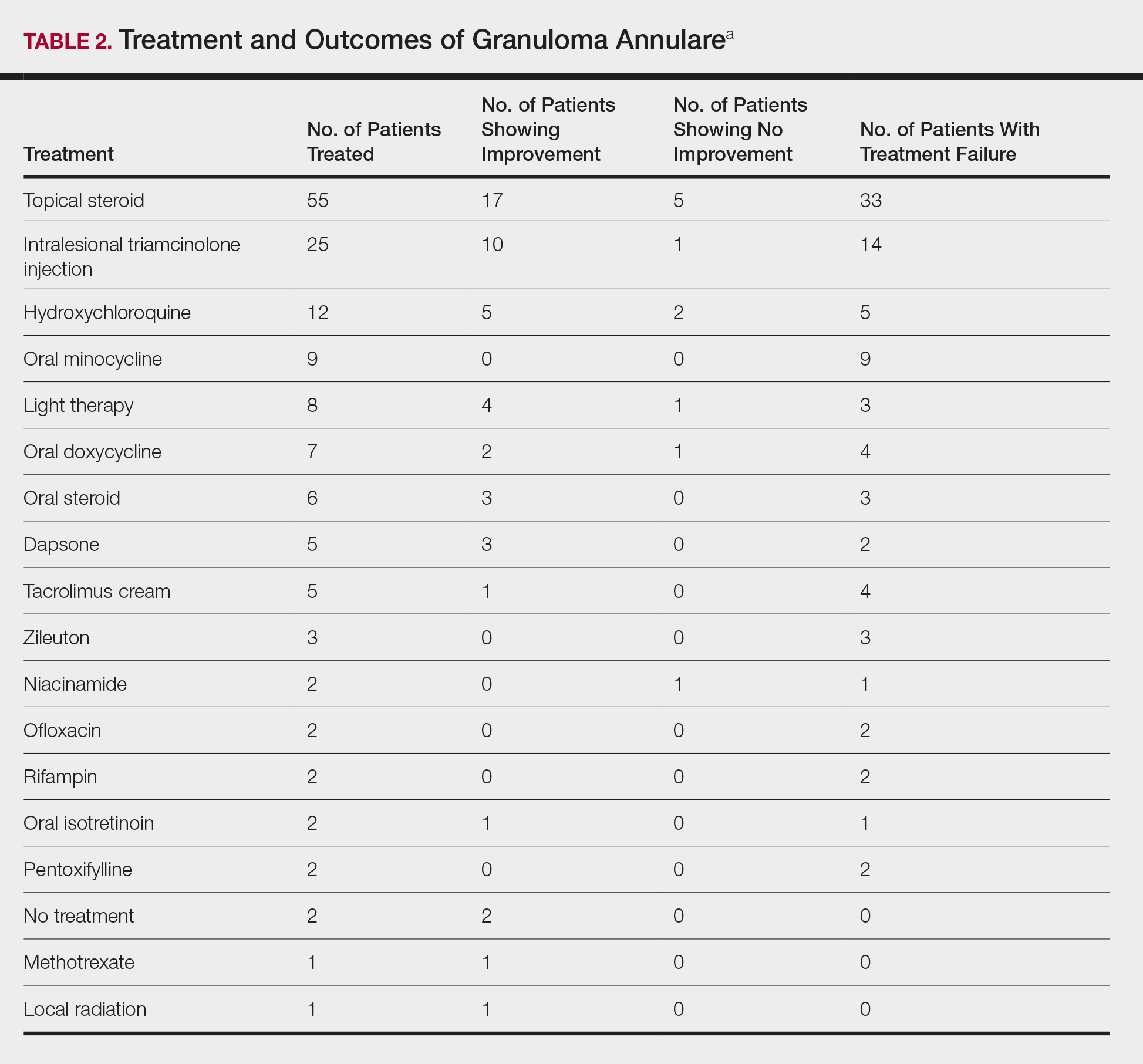

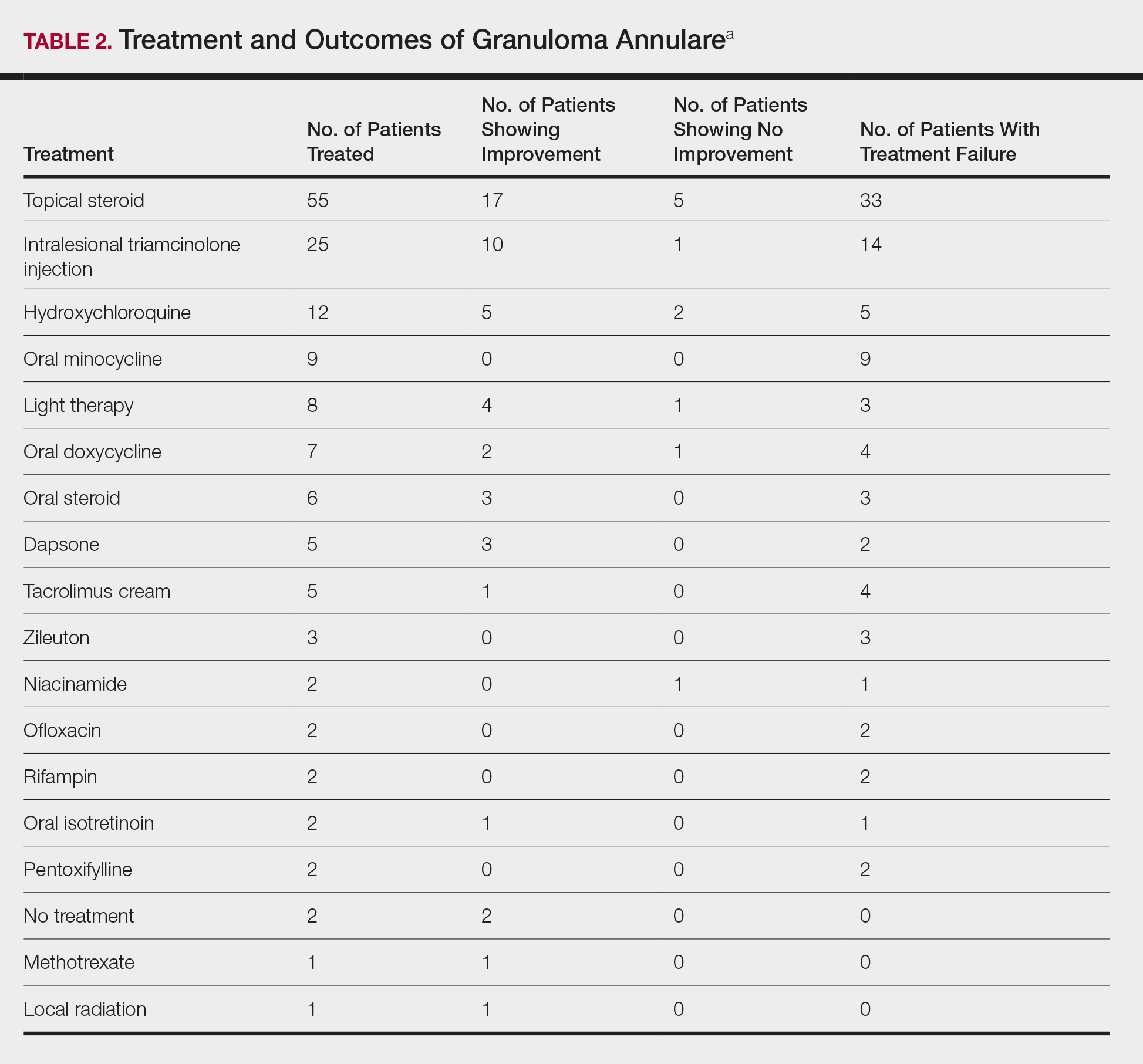

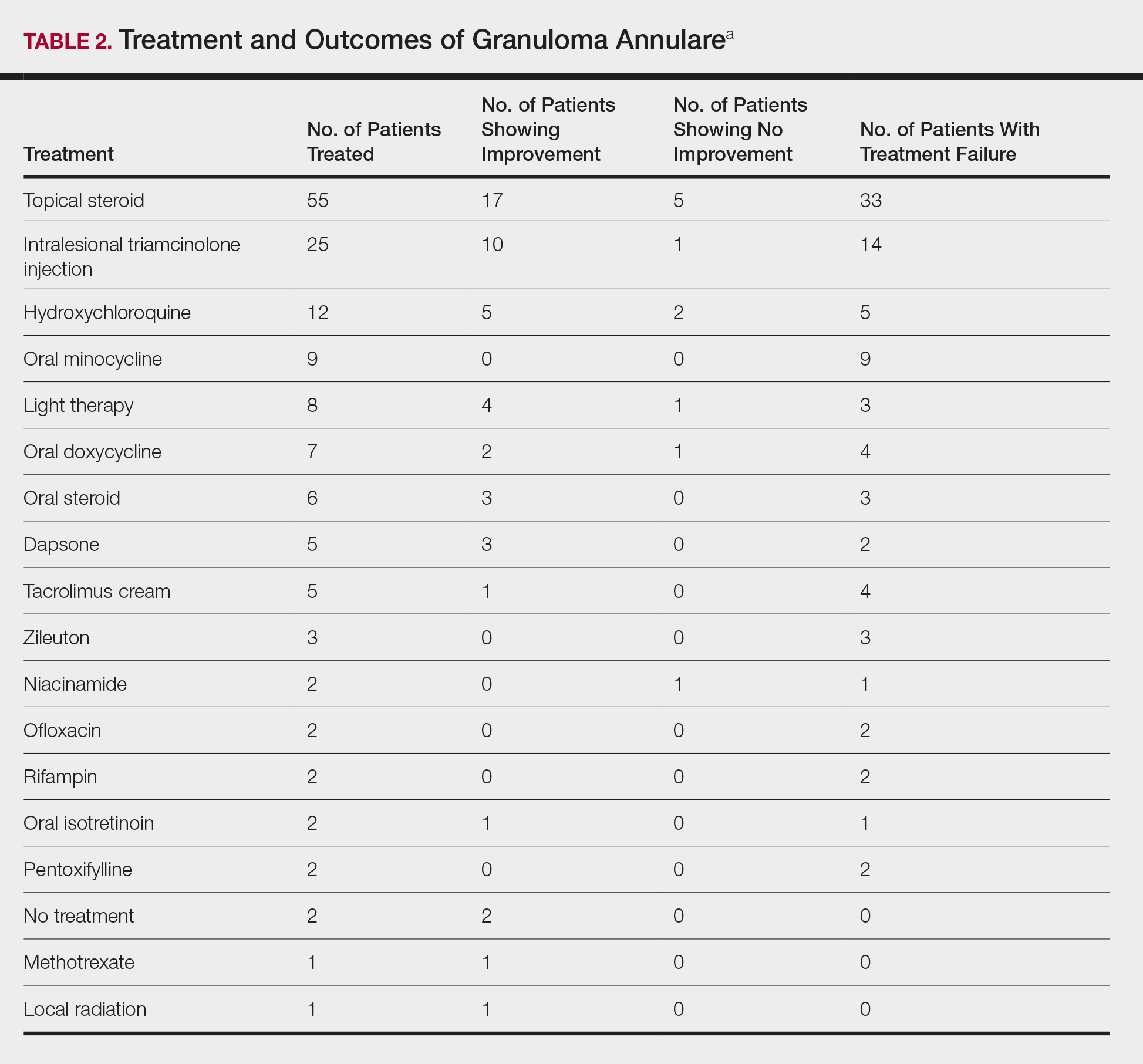

The most commonly prescribed treatment of GA was topical steroids; 30.9% of patients who were prescribed a topical steroid experienced improvement of their condition. Intralesional triamcinolone was the second most prescribed treatment of GA, with an improvement rate of 40.0% (Table 2).

Comment

We attempted to determine the period of prevalence of GA in a tertiary care, university-based referral practice and evaluate disease associations, treatments, and outcomes of patients with biopsy-proven GA. Our calculated period prevalence of GA of 0.22% to 0.27% is consistent with another review, which reported that 0.1% to 0.4% of new patients presenting to a dermatology practice were given a diagnosis of GA.1 More than 85% of the cases we reviewed were seen in females, a finding that is more heavily skewed compared to prior reports that have suggested a female to male ratio of approximately 1:1 to 2:1.1-7 Our findings suggest that GA is a female-predominant condition, or women may be more likely to seek evaluation for the condition.

More than 95% of the cases we reviewed were localized (64.7%) or generalized (30.8%) GA, making these variants the most common forms of GA, which is consistent with prior reports.1-3,8,9 Other varieties of GA—drug induced, patch, perforating, photosensitive, palmar, and papular—appear rare. Because this study was conducted at an adult hospital, subcutaneous GA, which often is seen in children, may be underrepresented. As a retrospective chart review, it is possible that documentation is insufficient to capture each rare variant.

Concomitant Disorders and Unrelated Medical Therapy

Hypothyroidism is statistically significantly overrepresented in our patient population (30.1%) compared with an average prevalence of 1% to 2% in iodine-replete populations (Fisher exact test, P<.001).10 This finding is consistent with prior small studies and cases series, which have suggested an association between autoimmune thyroiditis and GA.11-14

Despite prior reports of a possible association between HIV and GA,15-24 none of our patients had a diagnosis of HIV. However, many of our patients were not tested for HIV, which confounds our results and may represent a practice gap in the field.

At 1.5%, the prevalence of type 1 diabetes mellitus in our patients is slightly higher than the national average of 0.3%.25 However, based on a Fisher exact test of analysis of proportions, this difference is not statistically significant (P=.106).

At 1.5% and 2.3%, the prevalence of hepatitis B and hepatitis C, respectively, in our patients is slightly higher than the national average of 0.5% and 1%, respectively.26 However, based on a Fisher exact test of analysis of proportions, these differences are not statistically significant (P=.142 and P=.146, respectively).

Given the high prevalence of hyperlipidemia in the United States (31.7%), this disease is not overrepresented in our sample (30.1%), though others have suggested there may be a connection.27,28 Based on a Fisher exact test, this difference of proportions is not statistically significant (P=.780).

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use is common in the United States; approximately 11% of Americans older than 12 years use an SSRI.29 At 18.1%, the use of SSRIs in our patient group was statistically significantly higher than the national average (Fisher exact test, P=.017), suggesting a possible association between SSRI use and development of GA, warranting further investigation.

The use of calcium channel blockers, interferon, and tumor necrosis factor inhibitors was not significantly associated with GA in our series.

GA Therapy

The most commonly used treatments for GA in our study were topical steroids and intralesional triamcinolone, followed by hydroxychloroquine; all treatments employed exhibited a widely variable response. Assessing treatment response via retrospective chart review is challenging and response rates may not be accurately captured.

Study Limitations

Our study had several limitations. In calculating the period prevalence of GA, our query was limited by the number of years that the EMR has been in place. The number of cases we reviewed for clinical characteristics was limited to 133, as many cases with the ICD-9 diagnosis of GA were not biopsy proven and therefore were not included in our review. Many of the cases we reviewed were lost to follow-up, which prevented us from determining treatment outcomes.

Another weakness of our study was that our query did not provide an estimate of incidence or prevalence of GA overall, as this analysis was not a population-based study. The power of our study was limited by the number of cases of GA seen annually and the number of patients lost to follow-up. Additionally, our study population may only be generalizable to other large academic centers.

Conclusion

This study further solidifies our understanding of the epidemiology of GA and diseases that can be associated with GA. We identified a higher female to male ratio than previous reports, and consistent with prior reports, we noted potential associations with conditions such as thyroid disease and hyperlipidemia. Our population demonstrated higher rates of SSRI use than expected, warranting further investigation. Dermatologists should be aware of potential disease associations with GA, but as a whole we need better data and larger studies to determine the appropriate evaluation and treatment for patients with GA.

- Muhlbauer JE. Granuloma annulare. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:217-230.

- Thornsberry LA, English JC 3rd. Etiology, diagnosis, and therapeutic management of granuloma annulare: an update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:279-290.

- Wells RS, Smith MA. The natural history of granuloma annulare. Br J Dermatol. 1963;75:199-205.

- Wallet-Faber N, Farhi D, Gorin I, et al. Outcome of granuloma annulare: shorter duration is associated with younger age and recent onset. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:103-104.

- Dahl MV. Granuloma annulare: long-term follow-up. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:946-947.

- Yun JH, Lee JY, Kim MK, et al. Clinical and pathological features of generalized granuloma annulare with their correlation: a retrospective multicenter study in Korea. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:113-119.

- Tan HH, Goh CL. Granuloma annulare: a review of 41 cases at the National Skin Centre. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2000;29:714-718.

- Cyr PR. Diagnosis and management of granuloma annulare. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74:1729-1734.

- Smith MD, Downie JB, DiCostanzo D. Granuloma annulare. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:326-333.

- Vanderpump MPJ. The epidemiology of thyroid diseases. In: Braverman LE, Utiger RD, eds. Werner and Ingbar’s The Thyroid: A Fundamental and Clinical Text. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005:398-496.

- Vázquez-López F, Pereiro M Jr, Manjón Haces JA, et al. Localized granuloma annulare and autoimmune thyroiditis in adult women: a case-control study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:517-520.

- Vázquez-López F, González-López MA, Raya-Aguado C, et al. Localized granuloma annulare and autoimmune thyroiditis: a new case report. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(5, pt 2):943-945.

- Kappeler D, Troendle A, Mueller B. Localized granuloma annulare associated with autoimmune thyroid disease in a patient with a positive family history for autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type II. Eur J Endocrinol. 2001;145:101-102.

- Maschio M, Marigliano M, Sabbion A, et al. A rare case of granuloma annulare in a 5-year-old child with type 1 diabetes and autoimmune thyroiditis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:385-387.

- Smith NP. AIDS, Kaposi’s sarcoma and the dermatologist. J R Soc Med. 1985;78:97-99.

- Huerter CJ, Bass J, Bergfeld WF, et al. Perforating granuloma annulare in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Immunohistologic evaluation of the cellular infiltrate. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:1217-1220.

- Jones SK, Harman RR. Atypical granuloma annulare in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20(2 pt 1):299-300.

- Devesa Parente JA, Dores JA, Aranha JM. Generalized perforating granuloma annulare: case report. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2012;20:260-262.

- Ghadially R, Sibbald RG, Walter JB, et al. Granuloma annulare in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infections. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20(2, pt 1):232-235.

- Toro JR, Chu P, Yen TS, et al. Granuloma annulare and human immunodeficiency virus infection. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1341-1346.

- Cohen PR. Granuloma annulare: a mucocutaneous condition in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1404-1407.

- O’Moore EJ, Nandawni R, Uthayakumar S, et al. HIV-associated granuloma annulare (HAGA): a report of six cases. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:1054-1056.

- Kapembwa MS, Goolamali SK, Price A, et al. Granuloma annulare masquerading as molluscum contagiosum-like eruption in an HIV-positive African woman. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(suppl 2):S184-S186.

- Morris SD, Cerio R, Paige DG. An unusual presentation of diffuse granuloma annulare in an HIV-positive patient—immunohistochemical evidence of predominant CD8 lymphocytes. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:205-208.

- Maahs DM, West NA, Lawrence JM, et al. Epidemiology of type 1 diabetes. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2010;39:481-497.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Viral hepatitis surveillance—United States, 2010. www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2010surveillance/commentary.htm. Accessed November 10, 2018.

- Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2015 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;131:E29-E322.

- Wu W, Robinson-Bostom L, Kokkotou E, et al. Dyslipidemia in granuloma annulare: a case-control study. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1131-1136.

- Pratt LA, Brody DJ, Gu Q. Antidepressant Use in Persons Aged 12 and Over: United States, 2005-2008. NCHS Data Brief, No. 76. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2011. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db76.htm. Updated October 19, 2011. Accessed June 1, 2014.

Granuloma annulare (GA) is a granulomatous skin disorder of uncertain etiology. A number of clinical variants exist, most commonly localized annular plaques on the hands or feet, generalized lesions, or subcutaneous nodules in children. Histologically, GA exhibits granulomatous inflammation with either interstitial or palisading lymphocytes and histiocytes with mucin deposition.

Few data exist regarding the epidemiology of GA. Although the pathogenesis of GA is unknown, associations between GA and underlying systemic processes, such as diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, thyroid disease, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), have been suggested.

The purpose of this retrospective study was to determine the number of cases of GA seen annually at the Department of Dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) from 2008 to 2014. Additionally, we reviewed all cases of biopsy-proven GA from 2010 to 2014 and reported the demographics, underlying medical comorbidities, medications, treatments, and outcomes seen in this patient population.

Methods

We identified the number of outpatients presenting with GA annually using PennSeek, a tool developed by the Penn Medicine Data Analytics Center to search electronic medical records (EMRs). We queried the EMR database to determine the number of discrete patients seen at the Department of Dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania annually from 2008 (the year the EMR was established) to 2014. We then used PennSeek to determine the number of patients given a diagnosis of GA annually from 2008 to 2014 based on the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9).

After using PennSeek to identify all patients given the ICD-9 diagnosis of GA from 2008 to 2014, we reviewed the EMRs of these patients to identify cases that were biopsy proven. For the biopsy-proven cases of GA seen at the University of Pennsylvania from 2010 to 2014, we reviewed the EMRs of these patients for clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes. For each case, we recorded the patient’s age, sex, medical comorbidities, GA subtype, and medications.

This study was approved by the University of Pennsylvania’s institutional review board.

Results

On average, the percentage of patients given a diagnosis of GA annually was 0.22% (95% CI, 0.19%-0.24%). A Pearson χ2 test was used to determine if any single annual percentage was significantly different from the others. We found a P value of .321, which suggests that the percentage of patients with GA seen annually has been stable from 2008 to 2014 (Figure).

There were 133 cases of biopsy-proven GA that were reviewed for clinical characteristics; of them, 86.5% were female. Thyroid disease was noted in 30.1% of patients, hyperlipidemia in 30.1%, and hematologic malignancies in 3.8%. Type 1 diabetes mellitus was noted in 1.5% of patients. None of the patients were HIV-positive, 1.5% were hepatitis B–positive, and 2.3% were hepatitis C–positive. Of the 133 cases, 64.7% had localized GA and 30.8% had generalized GA. Photosensitive and papular GA were rarer (1.5% and 2.3% of cases, respectively). Use of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) was noted in 18.1% of patients; use of a calcium channel blocker was noted in 9.0% (Table 1).

The most commonly prescribed treatment of GA was topical steroids; 30.9% of patients who were prescribed a topical steroid experienced improvement of their condition. Intralesional triamcinolone was the second most prescribed treatment of GA, with an improvement rate of 40.0% (Table 2).

Comment

We attempted to determine the period of prevalence of GA in a tertiary care, university-based referral practice and evaluate disease associations, treatments, and outcomes of patients with biopsy-proven GA. Our calculated period prevalence of GA of 0.22% to 0.27% is consistent with another review, which reported that 0.1% to 0.4% of new patients presenting to a dermatology practice were given a diagnosis of GA.1 More than 85% of the cases we reviewed were seen in females, a finding that is more heavily skewed compared to prior reports that have suggested a female to male ratio of approximately 1:1 to 2:1.1-7 Our findings suggest that GA is a female-predominant condition, or women may be more likely to seek evaluation for the condition.

More than 95% of the cases we reviewed were localized (64.7%) or generalized (30.8%) GA, making these variants the most common forms of GA, which is consistent with prior reports.1-3,8,9 Other varieties of GA—drug induced, patch, perforating, photosensitive, palmar, and papular—appear rare. Because this study was conducted at an adult hospital, subcutaneous GA, which often is seen in children, may be underrepresented. As a retrospective chart review, it is possible that documentation is insufficient to capture each rare variant.

Concomitant Disorders and Unrelated Medical Therapy

Hypothyroidism is statistically significantly overrepresented in our patient population (30.1%) compared with an average prevalence of 1% to 2% in iodine-replete populations (Fisher exact test, P<.001).10 This finding is consistent with prior small studies and cases series, which have suggested an association between autoimmune thyroiditis and GA.11-14

Despite prior reports of a possible association between HIV and GA,15-24 none of our patients had a diagnosis of HIV. However, many of our patients were not tested for HIV, which confounds our results and may represent a practice gap in the field.

At 1.5%, the prevalence of type 1 diabetes mellitus in our patients is slightly higher than the national average of 0.3%.25 However, based on a Fisher exact test of analysis of proportions, this difference is not statistically significant (P=.106).

At 1.5% and 2.3%, the prevalence of hepatitis B and hepatitis C, respectively, in our patients is slightly higher than the national average of 0.5% and 1%, respectively.26 However, based on a Fisher exact test of analysis of proportions, these differences are not statistically significant (P=.142 and P=.146, respectively).

Given the high prevalence of hyperlipidemia in the United States (31.7%), this disease is not overrepresented in our sample (30.1%), though others have suggested there may be a connection.27,28 Based on a Fisher exact test, this difference of proportions is not statistically significant (P=.780).

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use is common in the United States; approximately 11% of Americans older than 12 years use an SSRI.29 At 18.1%, the use of SSRIs in our patient group was statistically significantly higher than the national average (Fisher exact test, P=.017), suggesting a possible association between SSRI use and development of GA, warranting further investigation.

The use of calcium channel blockers, interferon, and tumor necrosis factor inhibitors was not significantly associated with GA in our series.

GA Therapy

The most commonly used treatments for GA in our study were topical steroids and intralesional triamcinolone, followed by hydroxychloroquine; all treatments employed exhibited a widely variable response. Assessing treatment response via retrospective chart review is challenging and response rates may not be accurately captured.

Study Limitations

Our study had several limitations. In calculating the period prevalence of GA, our query was limited by the number of years that the EMR has been in place. The number of cases we reviewed for clinical characteristics was limited to 133, as many cases with the ICD-9 diagnosis of GA were not biopsy proven and therefore were not included in our review. Many of the cases we reviewed were lost to follow-up, which prevented us from determining treatment outcomes.

Another weakness of our study was that our query did not provide an estimate of incidence or prevalence of GA overall, as this analysis was not a population-based study. The power of our study was limited by the number of cases of GA seen annually and the number of patients lost to follow-up. Additionally, our study population may only be generalizable to other large academic centers.

Conclusion

This study further solidifies our understanding of the epidemiology of GA and diseases that can be associated with GA. We identified a higher female to male ratio than previous reports, and consistent with prior reports, we noted potential associations with conditions such as thyroid disease and hyperlipidemia. Our population demonstrated higher rates of SSRI use than expected, warranting further investigation. Dermatologists should be aware of potential disease associations with GA, but as a whole we need better data and larger studies to determine the appropriate evaluation and treatment for patients with GA.

Granuloma annulare (GA) is a granulomatous skin disorder of uncertain etiology. A number of clinical variants exist, most commonly localized annular plaques on the hands or feet, generalized lesions, or subcutaneous nodules in children. Histologically, GA exhibits granulomatous inflammation with either interstitial or palisading lymphocytes and histiocytes with mucin deposition.

Few data exist regarding the epidemiology of GA. Although the pathogenesis of GA is unknown, associations between GA and underlying systemic processes, such as diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, thyroid disease, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), have been suggested.

The purpose of this retrospective study was to determine the number of cases of GA seen annually at the Department of Dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) from 2008 to 2014. Additionally, we reviewed all cases of biopsy-proven GA from 2010 to 2014 and reported the demographics, underlying medical comorbidities, medications, treatments, and outcomes seen in this patient population.

Methods

We identified the number of outpatients presenting with GA annually using PennSeek, a tool developed by the Penn Medicine Data Analytics Center to search electronic medical records (EMRs). We queried the EMR database to determine the number of discrete patients seen at the Department of Dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania annually from 2008 (the year the EMR was established) to 2014. We then used PennSeek to determine the number of patients given a diagnosis of GA annually from 2008 to 2014 based on the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9).

After using PennSeek to identify all patients given the ICD-9 diagnosis of GA from 2008 to 2014, we reviewed the EMRs of these patients to identify cases that were biopsy proven. For the biopsy-proven cases of GA seen at the University of Pennsylvania from 2010 to 2014, we reviewed the EMRs of these patients for clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes. For each case, we recorded the patient’s age, sex, medical comorbidities, GA subtype, and medications.

This study was approved by the University of Pennsylvania’s institutional review board.

Results

On average, the percentage of patients given a diagnosis of GA annually was 0.22% (95% CI, 0.19%-0.24%). A Pearson χ2 test was used to determine if any single annual percentage was significantly different from the others. We found a P value of .321, which suggests that the percentage of patients with GA seen annually has been stable from 2008 to 2014 (Figure).

There were 133 cases of biopsy-proven GA that were reviewed for clinical characteristics; of them, 86.5% were female. Thyroid disease was noted in 30.1% of patients, hyperlipidemia in 30.1%, and hematologic malignancies in 3.8%. Type 1 diabetes mellitus was noted in 1.5% of patients. None of the patients were HIV-positive, 1.5% were hepatitis B–positive, and 2.3% were hepatitis C–positive. Of the 133 cases, 64.7% had localized GA and 30.8% had generalized GA. Photosensitive and papular GA were rarer (1.5% and 2.3% of cases, respectively). Use of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) was noted in 18.1% of patients; use of a calcium channel blocker was noted in 9.0% (Table 1).

The most commonly prescribed treatment of GA was topical steroids; 30.9% of patients who were prescribed a topical steroid experienced improvement of their condition. Intralesional triamcinolone was the second most prescribed treatment of GA, with an improvement rate of 40.0% (Table 2).

Comment

We attempted to determine the period of prevalence of GA in a tertiary care, university-based referral practice and evaluate disease associations, treatments, and outcomes of patients with biopsy-proven GA. Our calculated period prevalence of GA of 0.22% to 0.27% is consistent with another review, which reported that 0.1% to 0.4% of new patients presenting to a dermatology practice were given a diagnosis of GA.1 More than 85% of the cases we reviewed were seen in females, a finding that is more heavily skewed compared to prior reports that have suggested a female to male ratio of approximately 1:1 to 2:1.1-7 Our findings suggest that GA is a female-predominant condition, or women may be more likely to seek evaluation for the condition.

More than 95% of the cases we reviewed were localized (64.7%) or generalized (30.8%) GA, making these variants the most common forms of GA, which is consistent with prior reports.1-3,8,9 Other varieties of GA—drug induced, patch, perforating, photosensitive, palmar, and papular—appear rare. Because this study was conducted at an adult hospital, subcutaneous GA, which often is seen in children, may be underrepresented. As a retrospective chart review, it is possible that documentation is insufficient to capture each rare variant.

Concomitant Disorders and Unrelated Medical Therapy

Hypothyroidism is statistically significantly overrepresented in our patient population (30.1%) compared with an average prevalence of 1% to 2% in iodine-replete populations (Fisher exact test, P<.001).10 This finding is consistent with prior small studies and cases series, which have suggested an association between autoimmune thyroiditis and GA.11-14

Despite prior reports of a possible association between HIV and GA,15-24 none of our patients had a diagnosis of HIV. However, many of our patients were not tested for HIV, which confounds our results and may represent a practice gap in the field.

At 1.5%, the prevalence of type 1 diabetes mellitus in our patients is slightly higher than the national average of 0.3%.25 However, based on a Fisher exact test of analysis of proportions, this difference is not statistically significant (P=.106).

At 1.5% and 2.3%, the prevalence of hepatitis B and hepatitis C, respectively, in our patients is slightly higher than the national average of 0.5% and 1%, respectively.26 However, based on a Fisher exact test of analysis of proportions, these differences are not statistically significant (P=.142 and P=.146, respectively).

Given the high prevalence of hyperlipidemia in the United States (31.7%), this disease is not overrepresented in our sample (30.1%), though others have suggested there may be a connection.27,28 Based on a Fisher exact test, this difference of proportions is not statistically significant (P=.780).

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use is common in the United States; approximately 11% of Americans older than 12 years use an SSRI.29 At 18.1%, the use of SSRIs in our patient group was statistically significantly higher than the national average (Fisher exact test, P=.017), suggesting a possible association between SSRI use and development of GA, warranting further investigation.

The use of calcium channel blockers, interferon, and tumor necrosis factor inhibitors was not significantly associated with GA in our series.

GA Therapy

The most commonly used treatments for GA in our study were topical steroids and intralesional triamcinolone, followed by hydroxychloroquine; all treatments employed exhibited a widely variable response. Assessing treatment response via retrospective chart review is challenging and response rates may not be accurately captured.

Study Limitations

Our study had several limitations. In calculating the period prevalence of GA, our query was limited by the number of years that the EMR has been in place. The number of cases we reviewed for clinical characteristics was limited to 133, as many cases with the ICD-9 diagnosis of GA were not biopsy proven and therefore were not included in our review. Many of the cases we reviewed were lost to follow-up, which prevented us from determining treatment outcomes.

Another weakness of our study was that our query did not provide an estimate of incidence or prevalence of GA overall, as this analysis was not a population-based study. The power of our study was limited by the number of cases of GA seen annually and the number of patients lost to follow-up. Additionally, our study population may only be generalizable to other large academic centers.

Conclusion

This study further solidifies our understanding of the epidemiology of GA and diseases that can be associated with GA. We identified a higher female to male ratio than previous reports, and consistent with prior reports, we noted potential associations with conditions such as thyroid disease and hyperlipidemia. Our population demonstrated higher rates of SSRI use than expected, warranting further investigation. Dermatologists should be aware of potential disease associations with GA, but as a whole we need better data and larger studies to determine the appropriate evaluation and treatment for patients with GA.

- Muhlbauer JE. Granuloma annulare. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:217-230.

- Thornsberry LA, English JC 3rd. Etiology, diagnosis, and therapeutic management of granuloma annulare: an update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:279-290.

- Wells RS, Smith MA. The natural history of granuloma annulare. Br J Dermatol. 1963;75:199-205.

- Wallet-Faber N, Farhi D, Gorin I, et al. Outcome of granuloma annulare: shorter duration is associated with younger age and recent onset. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:103-104.

- Dahl MV. Granuloma annulare: long-term follow-up. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:946-947.

- Yun JH, Lee JY, Kim MK, et al. Clinical and pathological features of generalized granuloma annulare with their correlation: a retrospective multicenter study in Korea. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:113-119.

- Tan HH, Goh CL. Granuloma annulare: a review of 41 cases at the National Skin Centre. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2000;29:714-718.

- Cyr PR. Diagnosis and management of granuloma annulare. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74:1729-1734.

- Smith MD, Downie JB, DiCostanzo D. Granuloma annulare. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:326-333.

- Vanderpump MPJ. The epidemiology of thyroid diseases. In: Braverman LE, Utiger RD, eds. Werner and Ingbar’s The Thyroid: A Fundamental and Clinical Text. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005:398-496.

- Vázquez-López F, Pereiro M Jr, Manjón Haces JA, et al. Localized granuloma annulare and autoimmune thyroiditis in adult women: a case-control study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:517-520.

- Vázquez-López F, González-López MA, Raya-Aguado C, et al. Localized granuloma annulare and autoimmune thyroiditis: a new case report. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(5, pt 2):943-945.

- Kappeler D, Troendle A, Mueller B. Localized granuloma annulare associated with autoimmune thyroid disease in a patient with a positive family history for autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type II. Eur J Endocrinol. 2001;145:101-102.

- Maschio M, Marigliano M, Sabbion A, et al. A rare case of granuloma annulare in a 5-year-old child with type 1 diabetes and autoimmune thyroiditis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:385-387.

- Smith NP. AIDS, Kaposi’s sarcoma and the dermatologist. J R Soc Med. 1985;78:97-99.

- Huerter CJ, Bass J, Bergfeld WF, et al. Perforating granuloma annulare in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Immunohistologic evaluation of the cellular infiltrate. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:1217-1220.

- Jones SK, Harman RR. Atypical granuloma annulare in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20(2 pt 1):299-300.

- Devesa Parente JA, Dores JA, Aranha JM. Generalized perforating granuloma annulare: case report. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2012;20:260-262.

- Ghadially R, Sibbald RG, Walter JB, et al. Granuloma annulare in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infections. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20(2, pt 1):232-235.

- Toro JR, Chu P, Yen TS, et al. Granuloma annulare and human immunodeficiency virus infection. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1341-1346.

- Cohen PR. Granuloma annulare: a mucocutaneous condition in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1404-1407.

- O’Moore EJ, Nandawni R, Uthayakumar S, et al. HIV-associated granuloma annulare (HAGA): a report of six cases. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:1054-1056.

- Kapembwa MS, Goolamali SK, Price A, et al. Granuloma annulare masquerading as molluscum contagiosum-like eruption in an HIV-positive African woman. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(suppl 2):S184-S186.

- Morris SD, Cerio R, Paige DG. An unusual presentation of diffuse granuloma annulare in an HIV-positive patient—immunohistochemical evidence of predominant CD8 lymphocytes. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:205-208.

- Maahs DM, West NA, Lawrence JM, et al. Epidemiology of type 1 diabetes. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2010;39:481-497.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Viral hepatitis surveillance—United States, 2010. www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2010surveillance/commentary.htm. Accessed November 10, 2018.

- Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2015 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;131:E29-E322.

- Wu W, Robinson-Bostom L, Kokkotou E, et al. Dyslipidemia in granuloma annulare: a case-control study. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1131-1136.

- Pratt LA, Brody DJ, Gu Q. Antidepressant Use in Persons Aged 12 and Over: United States, 2005-2008. NCHS Data Brief, No. 76. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2011. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db76.htm. Updated October 19, 2011. Accessed June 1, 2014.

- Muhlbauer JE. Granuloma annulare. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:217-230.

- Thornsberry LA, English JC 3rd. Etiology, diagnosis, and therapeutic management of granuloma annulare: an update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:279-290.

- Wells RS, Smith MA. The natural history of granuloma annulare. Br J Dermatol. 1963;75:199-205.

- Wallet-Faber N, Farhi D, Gorin I, et al. Outcome of granuloma annulare: shorter duration is associated with younger age and recent onset. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:103-104.

- Dahl MV. Granuloma annulare: long-term follow-up. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:946-947.

- Yun JH, Lee JY, Kim MK, et al. Clinical and pathological features of generalized granuloma annulare with their correlation: a retrospective multicenter study in Korea. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:113-119.

- Tan HH, Goh CL. Granuloma annulare: a review of 41 cases at the National Skin Centre. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2000;29:714-718.

- Cyr PR. Diagnosis and management of granuloma annulare. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74:1729-1734.

- Smith MD, Downie JB, DiCostanzo D. Granuloma annulare. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:326-333.

- Vanderpump MPJ. The epidemiology of thyroid diseases. In: Braverman LE, Utiger RD, eds. Werner and Ingbar’s The Thyroid: A Fundamental and Clinical Text. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005:398-496.

- Vázquez-López F, Pereiro M Jr, Manjón Haces JA, et al. Localized granuloma annulare and autoimmune thyroiditis in adult women: a case-control study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:517-520.

- Vázquez-López F, González-López MA, Raya-Aguado C, et al. Localized granuloma annulare and autoimmune thyroiditis: a new case report. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(5, pt 2):943-945.

- Kappeler D, Troendle A, Mueller B. Localized granuloma annulare associated with autoimmune thyroid disease in a patient with a positive family history for autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type II. Eur J Endocrinol. 2001;145:101-102.

- Maschio M, Marigliano M, Sabbion A, et al. A rare case of granuloma annulare in a 5-year-old child with type 1 diabetes and autoimmune thyroiditis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:385-387.

- Smith NP. AIDS, Kaposi’s sarcoma and the dermatologist. J R Soc Med. 1985;78:97-99.

- Huerter CJ, Bass J, Bergfeld WF, et al. Perforating granuloma annulare in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Immunohistologic evaluation of the cellular infiltrate. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:1217-1220.

- Jones SK, Harman RR. Atypical granuloma annulare in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20(2 pt 1):299-300.

- Devesa Parente JA, Dores JA, Aranha JM. Generalized perforating granuloma annulare: case report. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2012;20:260-262.

- Ghadially R, Sibbald RG, Walter JB, et al. Granuloma annulare in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infections. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20(2, pt 1):232-235.

- Toro JR, Chu P, Yen TS, et al. Granuloma annulare and human immunodeficiency virus infection. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1341-1346.

- Cohen PR. Granuloma annulare: a mucocutaneous condition in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1404-1407.

- O’Moore EJ, Nandawni R, Uthayakumar S, et al. HIV-associated granuloma annulare (HAGA): a report of six cases. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:1054-1056.

- Kapembwa MS, Goolamali SK, Price A, et al. Granuloma annulare masquerading as molluscum contagiosum-like eruption in an HIV-positive African woman. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(suppl 2):S184-S186.

- Morris SD, Cerio R, Paige DG. An unusual presentation of diffuse granuloma annulare in an HIV-positive patient—immunohistochemical evidence of predominant CD8 lymphocytes. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:205-208.

- Maahs DM, West NA, Lawrence JM, et al. Epidemiology of type 1 diabetes. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2010;39:481-497.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Viral hepatitis surveillance—United States, 2010. www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2010surveillance/commentary.htm. Accessed November 10, 2018.

- Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2015 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;131:E29-E322.

- Wu W, Robinson-Bostom L, Kokkotou E, et al. Dyslipidemia in granuloma annulare: a case-control study. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1131-1136.

- Pratt LA, Brody DJ, Gu Q. Antidepressant Use in Persons Aged 12 and Over: United States, 2005-2008. NCHS Data Brief, No. 76. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2011. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db76.htm. Updated October 19, 2011. Accessed June 1, 2014.

Practice Points

- Although the pathogenesis of granuloma annulare (GA) is unknown, associations between the disorder and underlying systemic processes (eg, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, thyroid disease, human immunodeficiency virus) have been proposed.

- This study elicited a period prevalence of GA of 0.22% to 0.27%.

- The most commonly used treatments of GA were topical steroids and intralesional triamcinolone, followed by hydroxychloroquine.