User login

Liraglutide Prevents Ketogenesis in Type 1 Diabetes

ORLANDO – A single injection of liraglutide can prevent ketogenesis in fasting patients with type 1 diabetes who were on basal insulin, findings from a small study have shown.

Husam Ghanim, Ph.D., research associate professor at the State University of New York at Buffalo, presented the results in a late-breaking oral presentation session at the annual meeting of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.

In a previous trial (Diabetes Care. 2016;39:1027-35) of patients with type 1 diabetes who took liraglutide, which does not have Food and Drug Administration approval for use in type 1 diabetes, for 12 weeks, investigators observed decreases in blood glucose levels compared with placebo and decreases in glucagon concentrations following a meal compared with before starting liraglutide. When patients already taking liraglutide and insulin were put on dapagliflozin for 12 weeks, glucagon levels rose more with dapagliflozin compared to placebo, and urinary acetoacetate and beta-hydroxybutyrate (adjusted to creatinine) rose over baseline levels.

Some researchers have hypothesized that liraglutide might stimulate residual beta cells (or beta cell stem cells) in patients with type 1 diabetes to produce insulin, thereby reducing the need for exogenous insulin. Promising data from animal studies suggesting that the drug stimulated residual beta cells were not duplicated in human studies. But some evidence shows it may reduce insulin doses anyway, even in cases of patients with no C-peptide, which means they are not producing any insulin on their own (Diabetes Care 2011. 34:1463-8).

In their study, Dr. Ghanim and his associates therefore wanted to test the effect on glucagon, free fatty acid, and ketone levels of acute administration of liraglutide to patients with type 1 diabetes in an insulinopenic condition. They randomly assigned patients with type 1 diabetes, aged 18-75 years, with undetectable C-peptide and hemoglobin A1c less than 8.5%, to receive an injection of 1.8 mg of liraglutide (n = 8) or placebo (n = 8) the morning after an overnight fast, which continued for the 5 hours of the study.

Patients had their basal insulin dose from the night before but no further insulin unless they were on an infusion pump, which they continued. Subjects were excluded if they were taking a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist or a sodium/glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitor, if they had renal impairment, had type 1 diabetes for less than 1 year, or had various other comorbidities.

The liraglutide group was slightly older than the placebo group (46 vs. 43 years), had a higher HbA1c (7.7% vs. 7.6%), and higher systolic but lower diastolic blood pressure (130/73 vs. 121/78 mm Hg). Body mass index was around 30 kg/m2 for both groups.

In the placebo group, there was no change in the blood glucose concentrations during the study period, whereas the liraglutide group showed a decrease from a baseline of 175 mg/dL to 135 mg/dL at 5 hours (P less than .05). Glucagon levels were maintained in the placebo group but showed significant suppression from 82 ng/L to 65 ng/L in the liraglutide arm (P less than .05).

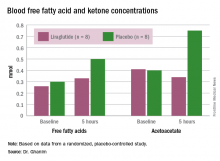

“Free fatty acid increased in both groups, but the increase in the placebo arm was significantly higher than that in the liraglutide group,” Dr. Ghanim said. Ketones increased in the placebo group but actually dropped in the liraglutide arm. Ghrelin levels rose by 20% in the placebo group and fell by 10% with liraglutide. Hormone-sensitive lipase decreased about 10% in both arms over the study period.

Dr. Ghanim proposed that since ghrelin is a mediator of lipolysis, possibly the suppression of ghrelin, as well as glucagon, by liraglutide “could contribute to the lower free fatty acid levels, which therefore leads to a lower ketogenic process and reduced ketone bodies.

“With the significant risk of DKA [diabetic ketoacidosis] in type 1 diabetics, especially when you have a drug like an SGLT2 inhibitor, which has been shown to be ketogenic, it is very important to know that liraglutide actually attenuates that response and reduces ketogenesis and therefore reduces the risk of DKA,” he said.

He suggested that these study results should lead to larger randomized trials of GLP-1 receptor agonists and SGLT2 inhibitors, also not approved for use in type 1 diabetes, for use in this population because most of them are not presently well controlled and need additional agents.

Dr. John Miles, professor of both medicine and endocrinology, diabetes, and metabolism at the University of Kansas Medical Center in Kansas City, Kansas, asked Dr. Ghanim why the study subjects did not vomit when receiving the dose of liraglutide. Dr. Ghanim responded that the subjects were not naive to it and had been on it previously.

Session moderator Dr. David Lieb, associate professor of medicine at Eastern Virginia Medical School in Norfolk, said that liraglutide may be a good option for type 1 diabetes patients who are obese and want to lose weight. “I think if there is a drug that can potentially help with glucose control, because liraglutide is not all about causing insulin secretion by the pancreas – it also affects glucagon levels, and it affects appetite and satiety – [so] it may also help with weight loss. I think there’s a role for those sorts of medications in type 1 diabetics on a case-by-case, individual basis,” he said.

However, he wondered if there are any negative effects of suppressing glucagon because patients with type 1 diabetes may be at increased risk for hypoglycemia because of their insulin use, their activities, and their sensitivity to insulin. “Glucagon … allows glucose to be released by the liver,” he said, so (hypothetically) suppressing glucose release may exacerbate hypoglycemia. He said he looks forward to further studies of these drugs for type 1 diabetes and seeing the rate of occurrence of hypoglycemic episodes and how patients respond to them.

There was no funding for the study. Dr. Ghanim and Dr. Lieb reported having no financial disclosures.

ORLANDO – A single injection of liraglutide can prevent ketogenesis in fasting patients with type 1 diabetes who were on basal insulin, findings from a small study have shown.

Husam Ghanim, Ph.D., research associate professor at the State University of New York at Buffalo, presented the results in a late-breaking oral presentation session at the annual meeting of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.

In a previous trial (Diabetes Care. 2016;39:1027-35) of patients with type 1 diabetes who took liraglutide, which does not have Food and Drug Administration approval for use in type 1 diabetes, for 12 weeks, investigators observed decreases in blood glucose levels compared with placebo and decreases in glucagon concentrations following a meal compared with before starting liraglutide. When patients already taking liraglutide and insulin were put on dapagliflozin for 12 weeks, glucagon levels rose more with dapagliflozin compared to placebo, and urinary acetoacetate and beta-hydroxybutyrate (adjusted to creatinine) rose over baseline levels.

Some researchers have hypothesized that liraglutide might stimulate residual beta cells (or beta cell stem cells) in patients with type 1 diabetes to produce insulin, thereby reducing the need for exogenous insulin. Promising data from animal studies suggesting that the drug stimulated residual beta cells were not duplicated in human studies. But some evidence shows it may reduce insulin doses anyway, even in cases of patients with no C-peptide, which means they are not producing any insulin on their own (Diabetes Care 2011. 34:1463-8).

In their study, Dr. Ghanim and his associates therefore wanted to test the effect on glucagon, free fatty acid, and ketone levels of acute administration of liraglutide to patients with type 1 diabetes in an insulinopenic condition. They randomly assigned patients with type 1 diabetes, aged 18-75 years, with undetectable C-peptide and hemoglobin A1c less than 8.5%, to receive an injection of 1.8 mg of liraglutide (n = 8) or placebo (n = 8) the morning after an overnight fast, which continued for the 5 hours of the study.

Patients had their basal insulin dose from the night before but no further insulin unless they were on an infusion pump, which they continued. Subjects were excluded if they were taking a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist or a sodium/glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitor, if they had renal impairment, had type 1 diabetes for less than 1 year, or had various other comorbidities.

The liraglutide group was slightly older than the placebo group (46 vs. 43 years), had a higher HbA1c (7.7% vs. 7.6%), and higher systolic but lower diastolic blood pressure (130/73 vs. 121/78 mm Hg). Body mass index was around 30 kg/m2 for both groups.

In the placebo group, there was no change in the blood glucose concentrations during the study period, whereas the liraglutide group showed a decrease from a baseline of 175 mg/dL to 135 mg/dL at 5 hours (P less than .05). Glucagon levels were maintained in the placebo group but showed significant suppression from 82 ng/L to 65 ng/L in the liraglutide arm (P less than .05).

“Free fatty acid increased in both groups, but the increase in the placebo arm was significantly higher than that in the liraglutide group,” Dr. Ghanim said. Ketones increased in the placebo group but actually dropped in the liraglutide arm. Ghrelin levels rose by 20% in the placebo group and fell by 10% with liraglutide. Hormone-sensitive lipase decreased about 10% in both arms over the study period.

Dr. Ghanim proposed that since ghrelin is a mediator of lipolysis, possibly the suppression of ghrelin, as well as glucagon, by liraglutide “could contribute to the lower free fatty acid levels, which therefore leads to a lower ketogenic process and reduced ketone bodies.

“With the significant risk of DKA [diabetic ketoacidosis] in type 1 diabetics, especially when you have a drug like an SGLT2 inhibitor, which has been shown to be ketogenic, it is very important to know that liraglutide actually attenuates that response and reduces ketogenesis and therefore reduces the risk of DKA,” he said.

He suggested that these study results should lead to larger randomized trials of GLP-1 receptor agonists and SGLT2 inhibitors, also not approved for use in type 1 diabetes, for use in this population because most of them are not presently well controlled and need additional agents.

Dr. John Miles, professor of both medicine and endocrinology, diabetes, and metabolism at the University of Kansas Medical Center in Kansas City, Kansas, asked Dr. Ghanim why the study subjects did not vomit when receiving the dose of liraglutide. Dr. Ghanim responded that the subjects were not naive to it and had been on it previously.

Session moderator Dr. David Lieb, associate professor of medicine at Eastern Virginia Medical School in Norfolk, said that liraglutide may be a good option for type 1 diabetes patients who are obese and want to lose weight. “I think if there is a drug that can potentially help with glucose control, because liraglutide is not all about causing insulin secretion by the pancreas – it also affects glucagon levels, and it affects appetite and satiety – [so] it may also help with weight loss. I think there’s a role for those sorts of medications in type 1 diabetics on a case-by-case, individual basis,” he said.

However, he wondered if there are any negative effects of suppressing glucagon because patients with type 1 diabetes may be at increased risk for hypoglycemia because of their insulin use, their activities, and their sensitivity to insulin. “Glucagon … allows glucose to be released by the liver,” he said, so (hypothetically) suppressing glucose release may exacerbate hypoglycemia. He said he looks forward to further studies of these drugs for type 1 diabetes and seeing the rate of occurrence of hypoglycemic episodes and how patients respond to them.

There was no funding for the study. Dr. Ghanim and Dr. Lieb reported having no financial disclosures.

ORLANDO – A single injection of liraglutide can prevent ketogenesis in fasting patients with type 1 diabetes who were on basal insulin, findings from a small study have shown.

Husam Ghanim, Ph.D., research associate professor at the State University of New York at Buffalo, presented the results in a late-breaking oral presentation session at the annual meeting of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.

In a previous trial (Diabetes Care. 2016;39:1027-35) of patients with type 1 diabetes who took liraglutide, which does not have Food and Drug Administration approval for use in type 1 diabetes, for 12 weeks, investigators observed decreases in blood glucose levels compared with placebo and decreases in glucagon concentrations following a meal compared with before starting liraglutide. When patients already taking liraglutide and insulin were put on dapagliflozin for 12 weeks, glucagon levels rose more with dapagliflozin compared to placebo, and urinary acetoacetate and beta-hydroxybutyrate (adjusted to creatinine) rose over baseline levels.

Some researchers have hypothesized that liraglutide might stimulate residual beta cells (or beta cell stem cells) in patients with type 1 diabetes to produce insulin, thereby reducing the need for exogenous insulin. Promising data from animal studies suggesting that the drug stimulated residual beta cells were not duplicated in human studies. But some evidence shows it may reduce insulin doses anyway, even in cases of patients with no C-peptide, which means they are not producing any insulin on their own (Diabetes Care 2011. 34:1463-8).

In their study, Dr. Ghanim and his associates therefore wanted to test the effect on glucagon, free fatty acid, and ketone levels of acute administration of liraglutide to patients with type 1 diabetes in an insulinopenic condition. They randomly assigned patients with type 1 diabetes, aged 18-75 years, with undetectable C-peptide and hemoglobin A1c less than 8.5%, to receive an injection of 1.8 mg of liraglutide (n = 8) or placebo (n = 8) the morning after an overnight fast, which continued for the 5 hours of the study.

Patients had their basal insulin dose from the night before but no further insulin unless they were on an infusion pump, which they continued. Subjects were excluded if they were taking a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist or a sodium/glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitor, if they had renal impairment, had type 1 diabetes for less than 1 year, or had various other comorbidities.

The liraglutide group was slightly older than the placebo group (46 vs. 43 years), had a higher HbA1c (7.7% vs. 7.6%), and higher systolic but lower diastolic blood pressure (130/73 vs. 121/78 mm Hg). Body mass index was around 30 kg/m2 for both groups.

In the placebo group, there was no change in the blood glucose concentrations during the study period, whereas the liraglutide group showed a decrease from a baseline of 175 mg/dL to 135 mg/dL at 5 hours (P less than .05). Glucagon levels were maintained in the placebo group but showed significant suppression from 82 ng/L to 65 ng/L in the liraglutide arm (P less than .05).

“Free fatty acid increased in both groups, but the increase in the placebo arm was significantly higher than that in the liraglutide group,” Dr. Ghanim said. Ketones increased in the placebo group but actually dropped in the liraglutide arm. Ghrelin levels rose by 20% in the placebo group and fell by 10% with liraglutide. Hormone-sensitive lipase decreased about 10% in both arms over the study period.

Dr. Ghanim proposed that since ghrelin is a mediator of lipolysis, possibly the suppression of ghrelin, as well as glucagon, by liraglutide “could contribute to the lower free fatty acid levels, which therefore leads to a lower ketogenic process and reduced ketone bodies.

“With the significant risk of DKA [diabetic ketoacidosis] in type 1 diabetics, especially when you have a drug like an SGLT2 inhibitor, which has been shown to be ketogenic, it is very important to know that liraglutide actually attenuates that response and reduces ketogenesis and therefore reduces the risk of DKA,” he said.

He suggested that these study results should lead to larger randomized trials of GLP-1 receptor agonists and SGLT2 inhibitors, also not approved for use in type 1 diabetes, for use in this population because most of them are not presently well controlled and need additional agents.

Dr. John Miles, professor of both medicine and endocrinology, diabetes, and metabolism at the University of Kansas Medical Center in Kansas City, Kansas, asked Dr. Ghanim why the study subjects did not vomit when receiving the dose of liraglutide. Dr. Ghanim responded that the subjects were not naive to it and had been on it previously.

Session moderator Dr. David Lieb, associate professor of medicine at Eastern Virginia Medical School in Norfolk, said that liraglutide may be a good option for type 1 diabetes patients who are obese and want to lose weight. “I think if there is a drug that can potentially help with glucose control, because liraglutide is not all about causing insulin secretion by the pancreas – it also affects glucagon levels, and it affects appetite and satiety – [so] it may also help with weight loss. I think there’s a role for those sorts of medications in type 1 diabetics on a case-by-case, individual basis,” he said.

However, he wondered if there are any negative effects of suppressing glucagon because patients with type 1 diabetes may be at increased risk for hypoglycemia because of their insulin use, their activities, and their sensitivity to insulin. “Glucagon … allows glucose to be released by the liver,” he said, so (hypothetically) suppressing glucose release may exacerbate hypoglycemia. He said he looks forward to further studies of these drugs for type 1 diabetes and seeing the rate of occurrence of hypoglycemic episodes and how patients respond to them.

There was no funding for the study. Dr. Ghanim and Dr. Lieb reported having no financial disclosures.

AT AACE 2016

Liraglutide prevents ketogenesis in type 1 diabetes

ORLANDO – A single injection of liraglutide can prevent ketogenesis in fasting patients with type 1 diabetes who were on basal insulin, findings from a small study have shown.

Husam Ghanim, Ph.D., research associate professor at the State University of New York at Buffalo, presented the results in a late-breaking oral presentation session at the annual meeting of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.

In a previous trial (Diabetes Care. 2016;39:1027-35) of patients with type 1 diabetes who took liraglutide, which does not have Food and Drug Administration approval for use in type 1 diabetes, for 12 weeks, investigators observed decreases in blood glucose levels compared with placebo and decreases in glucagon concentrations following a meal compared with before starting liraglutide. When patients already taking liraglutide and insulin were put on dapagliflozin for 12 weeks, glucagon levels rose more with dapagliflozin compared to placebo, and urinary acetoacetate and beta-hydroxybutyrate (adjusted to creatinine) rose over baseline levels.

Some researchers have hypothesized that liraglutide might stimulate residual beta cells (or beta cell stem cells) in patients with type 1 diabetes to produce insulin, thereby reducing the need for exogenous insulin. Promising data from animal studies suggesting that the drug stimulated residual beta cells were not duplicated in human studies. But some evidence shows it may reduce insulin doses anyway, even in cases of patients with no C-peptide, which means they are not producing any insulin on their own (Diabetes Care 2011. 34:1463-8).

In their study, Dr. Ghanim and his associates therefore wanted to test the effect on glucagon, free fatty acid, and ketone levels of acute administration of liraglutide to patients with type 1 diabetes in an insulinopenic condition. They randomly assigned patients with type 1 diabetes, aged 18-75 years, with undetectable C-peptide and hemoglobin A1c less than 8.5%, to receive an injection of 1.8 mg of liraglutide (n = 8) or placebo (n = 8) the morning after an overnight fast, which continued for the 5 hours of the study.

Patients had their basal insulin dose from the night before but no further insulin unless they were on an infusion pump, which they continued. Subjects were excluded if they were taking a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist or a sodium/glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitor, if they had renal impairment, had type 1 diabetes for less than 1 year, or had various other comorbidities.

The liraglutide group was slightly older than the placebo group (46 vs. 43 years), had a higher HbA1c (7.7% vs. 7.6%), and higher systolic but lower diastolic blood pressure (130/73 vs. 121/78 mm Hg). Body mass index was around 30 kg/m2 for both groups.

In the placebo group, there was no change in the blood glucose concentrations during the study period, whereas the liraglutide group showed a decrease from a baseline of 175 mg/dL to 135 mg/dL at 5 hours (P less than .05). Glucagon levels were maintained in the placebo group but showed significant suppression from 82 ng/L to 65 ng/L in the liraglutide arm (P less than .05).

“Free fatty acid increased in both groups, but the increase in the placebo arm was significantly higher than that in the liraglutide group,” Dr. Ghanim said. Ketones increased in the placebo group but actually dropped in the liraglutide arm. Ghrelin levels rose by 20% in the placebo group and fell by 10% with liraglutide. Hormone-sensitive lipase decreased about 10% in both arms over the study period.

Dr. Ghanim proposed that since ghrelin is a mediator of lipolysis, possibly the suppression of ghrelin, as well as glucagon, by liraglutide “could contribute to the lower free fatty acid levels, which therefore leads to a lower ketogenic process and reduced ketone bodies.

“With the significant risk of DKA [diabetic ketoacidosis] in type 1 diabetics, especially when you have a drug like an SGLT2 inhibitor, which has been shown to be ketogenic, it is very important to know that liraglutide actually attenuates that response and reduces ketogenesis and therefore reduces the risk of DKA,” he said.

He suggested that these study results should lead to larger randomized trials of GLP-1 receptor agonists and SGLT2 inhibitors, also not approved for use in type 1 diabetes, for use in this population because most of them are not presently well controlled and need additional agents.

Dr. John Miles, professor of both medicine and endocrinology, diabetes, and metabolism at the University of Kansas Medical Center in Kansas City, Kansas, asked Dr. Ghanim why the study subjects did not vomit when receiving the dose of liraglutide. Dr. Ghanim responded that the subjects were not naive to it and had been on it previously.

Session moderator Dr. David Lieb, associate professor of medicine at Eastern Virginia Medical School in Norfolk, said that liraglutide may be a good option for type 1 diabetes patients who are obese and want to lose weight. “I think if there is a drug that can potentially help with glucose control, because liraglutide is not all about causing insulin secretion by the pancreas – it also affects glucagon levels, and it affects appetite and satiety – [so] it may also help with weight loss. I think there’s a role for those sorts of medications in type 1 diabetics on a case-by-case, individual basis,” he said.

However, he wondered if there are any negative effects of suppressing glucagon because patients with type 1 diabetes may be at increased risk for hypoglycemia because of their insulin use, their activities, and their sensitivity to insulin. “Glucagon … allows glucose to be released by the liver,” he said, so (hypothetically) suppressing glucose release may exacerbate hypoglycemia. He said he looks forward to further studies of these drugs for type 1 diabetes and seeing the rate of occurrence of hypoglycemic episodes and how patients respond to them.

There was no funding for the study. Dr. Ghanim and Dr. Lieb reported having no financial disclosures.

ORLANDO – A single injection of liraglutide can prevent ketogenesis in fasting patients with type 1 diabetes who were on basal insulin, findings from a small study have shown.

Husam Ghanim, Ph.D., research associate professor at the State University of New York at Buffalo, presented the results in a late-breaking oral presentation session at the annual meeting of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.

In a previous trial (Diabetes Care. 2016;39:1027-35) of patients with type 1 diabetes who took liraglutide, which does not have Food and Drug Administration approval for use in type 1 diabetes, for 12 weeks, investigators observed decreases in blood glucose levels compared with placebo and decreases in glucagon concentrations following a meal compared with before starting liraglutide. When patients already taking liraglutide and insulin were put on dapagliflozin for 12 weeks, glucagon levels rose more with dapagliflozin compared to placebo, and urinary acetoacetate and beta-hydroxybutyrate (adjusted to creatinine) rose over baseline levels.

Some researchers have hypothesized that liraglutide might stimulate residual beta cells (or beta cell stem cells) in patients with type 1 diabetes to produce insulin, thereby reducing the need for exogenous insulin. Promising data from animal studies suggesting that the drug stimulated residual beta cells were not duplicated in human studies. But some evidence shows it may reduce insulin doses anyway, even in cases of patients with no C-peptide, which means they are not producing any insulin on their own (Diabetes Care 2011. 34:1463-8).

In their study, Dr. Ghanim and his associates therefore wanted to test the effect on glucagon, free fatty acid, and ketone levels of acute administration of liraglutide to patients with type 1 diabetes in an insulinopenic condition. They randomly assigned patients with type 1 diabetes, aged 18-75 years, with undetectable C-peptide and hemoglobin A1c less than 8.5%, to receive an injection of 1.8 mg of liraglutide (n = 8) or placebo (n = 8) the morning after an overnight fast, which continued for the 5 hours of the study.

Patients had their basal insulin dose from the night before but no further insulin unless they were on an infusion pump, which they continued. Subjects were excluded if they were taking a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist or a sodium/glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitor, if they had renal impairment, had type 1 diabetes for less than 1 year, or had various other comorbidities.

The liraglutide group was slightly older than the placebo group (46 vs. 43 years), had a higher HbA1c (7.7% vs. 7.6%), and higher systolic but lower diastolic blood pressure (130/73 vs. 121/78 mm Hg). Body mass index was around 30 kg/m2 for both groups.

In the placebo group, there was no change in the blood glucose concentrations during the study period, whereas the liraglutide group showed a decrease from a baseline of 175 mg/dL to 135 mg/dL at 5 hours (P less than .05). Glucagon levels were maintained in the placebo group but showed significant suppression from 82 ng/L to 65 ng/L in the liraglutide arm (P less than .05).

“Free fatty acid increased in both groups, but the increase in the placebo arm was significantly higher than that in the liraglutide group,” Dr. Ghanim said. Ketones increased in the placebo group but actually dropped in the liraglutide arm. Ghrelin levels rose by 20% in the placebo group and fell by 10% with liraglutide. Hormone-sensitive lipase decreased about 10% in both arms over the study period.

Dr. Ghanim proposed that since ghrelin is a mediator of lipolysis, possibly the suppression of ghrelin, as well as glucagon, by liraglutide “could contribute to the lower free fatty acid levels, which therefore leads to a lower ketogenic process and reduced ketone bodies.

“With the significant risk of DKA [diabetic ketoacidosis] in type 1 diabetics, especially when you have a drug like an SGLT2 inhibitor, which has been shown to be ketogenic, it is very important to know that liraglutide actually attenuates that response and reduces ketogenesis and therefore reduces the risk of DKA,” he said.

He suggested that these study results should lead to larger randomized trials of GLP-1 receptor agonists and SGLT2 inhibitors, also not approved for use in type 1 diabetes, for use in this population because most of them are not presently well controlled and need additional agents.

Dr. John Miles, professor of both medicine and endocrinology, diabetes, and metabolism at the University of Kansas Medical Center in Kansas City, Kansas, asked Dr. Ghanim why the study subjects did not vomit when receiving the dose of liraglutide. Dr. Ghanim responded that the subjects were not naive to it and had been on it previously.

Session moderator Dr. David Lieb, associate professor of medicine at Eastern Virginia Medical School in Norfolk, said that liraglutide may be a good option for type 1 diabetes patients who are obese and want to lose weight. “I think if there is a drug that can potentially help with glucose control, because liraglutide is not all about causing insulin secretion by the pancreas – it also affects glucagon levels, and it affects appetite and satiety – [so] it may also help with weight loss. I think there’s a role for those sorts of medications in type 1 diabetics on a case-by-case, individual basis,” he said.

However, he wondered if there are any negative effects of suppressing glucagon because patients with type 1 diabetes may be at increased risk for hypoglycemia because of their insulin use, their activities, and their sensitivity to insulin. “Glucagon … allows glucose to be released by the liver,” he said, so (hypothetically) suppressing glucose release may exacerbate hypoglycemia. He said he looks forward to further studies of these drugs for type 1 diabetes and seeing the rate of occurrence of hypoglycemic episodes and how patients respond to them.

There was no funding for the study. Dr. Ghanim and Dr. Lieb reported having no financial disclosures.

ORLANDO – A single injection of liraglutide can prevent ketogenesis in fasting patients with type 1 diabetes who were on basal insulin, findings from a small study have shown.

Husam Ghanim, Ph.D., research associate professor at the State University of New York at Buffalo, presented the results in a late-breaking oral presentation session at the annual meeting of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.

In a previous trial (Diabetes Care. 2016;39:1027-35) of patients with type 1 diabetes who took liraglutide, which does not have Food and Drug Administration approval for use in type 1 diabetes, for 12 weeks, investigators observed decreases in blood glucose levels compared with placebo and decreases in glucagon concentrations following a meal compared with before starting liraglutide. When patients already taking liraglutide and insulin were put on dapagliflozin for 12 weeks, glucagon levels rose more with dapagliflozin compared to placebo, and urinary acetoacetate and beta-hydroxybutyrate (adjusted to creatinine) rose over baseline levels.

Some researchers have hypothesized that liraglutide might stimulate residual beta cells (or beta cell stem cells) in patients with type 1 diabetes to produce insulin, thereby reducing the need for exogenous insulin. Promising data from animal studies suggesting that the drug stimulated residual beta cells were not duplicated in human studies. But some evidence shows it may reduce insulin doses anyway, even in cases of patients with no C-peptide, which means they are not producing any insulin on their own (Diabetes Care 2011. 34:1463-8).

In their study, Dr. Ghanim and his associates therefore wanted to test the effect on glucagon, free fatty acid, and ketone levels of acute administration of liraglutide to patients with type 1 diabetes in an insulinopenic condition. They randomly assigned patients with type 1 diabetes, aged 18-75 years, with undetectable C-peptide and hemoglobin A1c less than 8.5%, to receive an injection of 1.8 mg of liraglutide (n = 8) or placebo (n = 8) the morning after an overnight fast, which continued for the 5 hours of the study.

Patients had their basal insulin dose from the night before but no further insulin unless they were on an infusion pump, which they continued. Subjects were excluded if they were taking a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist or a sodium/glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitor, if they had renal impairment, had type 1 diabetes for less than 1 year, or had various other comorbidities.

The liraglutide group was slightly older than the placebo group (46 vs. 43 years), had a higher HbA1c (7.7% vs. 7.6%), and higher systolic but lower diastolic blood pressure (130/73 vs. 121/78 mm Hg). Body mass index was around 30 kg/m2 for both groups.

In the placebo group, there was no change in the blood glucose concentrations during the study period, whereas the liraglutide group showed a decrease from a baseline of 175 mg/dL to 135 mg/dL at 5 hours (P less than .05). Glucagon levels were maintained in the placebo group but showed significant suppression from 82 ng/L to 65 ng/L in the liraglutide arm (P less than .05).

“Free fatty acid increased in both groups, but the increase in the placebo arm was significantly higher than that in the liraglutide group,” Dr. Ghanim said. Ketones increased in the placebo group but actually dropped in the liraglutide arm. Ghrelin levels rose by 20% in the placebo group and fell by 10% with liraglutide. Hormone-sensitive lipase decreased about 10% in both arms over the study period.

Dr. Ghanim proposed that since ghrelin is a mediator of lipolysis, possibly the suppression of ghrelin, as well as glucagon, by liraglutide “could contribute to the lower free fatty acid levels, which therefore leads to a lower ketogenic process and reduced ketone bodies.

“With the significant risk of DKA [diabetic ketoacidosis] in type 1 diabetics, especially when you have a drug like an SGLT2 inhibitor, which has been shown to be ketogenic, it is very important to know that liraglutide actually attenuates that response and reduces ketogenesis and therefore reduces the risk of DKA,” he said.

He suggested that these study results should lead to larger randomized trials of GLP-1 receptor agonists and SGLT2 inhibitors, also not approved for use in type 1 diabetes, for use in this population because most of them are not presently well controlled and need additional agents.

Dr. John Miles, professor of both medicine and endocrinology, diabetes, and metabolism at the University of Kansas Medical Center in Kansas City, Kansas, asked Dr. Ghanim why the study subjects did not vomit when receiving the dose of liraglutide. Dr. Ghanim responded that the subjects were not naive to it and had been on it previously.

Session moderator Dr. David Lieb, associate professor of medicine at Eastern Virginia Medical School in Norfolk, said that liraglutide may be a good option for type 1 diabetes patients who are obese and want to lose weight. “I think if there is a drug that can potentially help with glucose control, because liraglutide is not all about causing insulin secretion by the pancreas – it also affects glucagon levels, and it affects appetite and satiety – [so] it may also help with weight loss. I think there’s a role for those sorts of medications in type 1 diabetics on a case-by-case, individual basis,” he said.

However, he wondered if there are any negative effects of suppressing glucagon because patients with type 1 diabetes may be at increased risk for hypoglycemia because of their insulin use, their activities, and their sensitivity to insulin. “Glucagon … allows glucose to be released by the liver,” he said, so (hypothetically) suppressing glucose release may exacerbate hypoglycemia. He said he looks forward to further studies of these drugs for type 1 diabetes and seeing the rate of occurrence of hypoglycemic episodes and how patients respond to them.

There was no funding for the study. Dr. Ghanim and Dr. Lieb reported having no financial disclosures.

AT AACE 2016

Key clinical point: Liraglutide suppresses glucagon and ketogenesis in fasting patients with type 1 diabetes.

Major finding: FFA increase was 60% lower on liraglutide than on placebo.

Data source: Randomized, placebo controlled study involving 16 patients.

Disclosures: There was no funding for the study. Dr. Ghanim and Dr. Lieb reported having no financial disclosures.

Starting With Combination Diabetes Therapy Beats Initial Monotherapy

ORLANDO – Whether to start a patient with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus on combination therapy or monotherapy should be based on experimentation and observation rather than expert opinion, according to Dr. Alan Garber, president of the American College of Endocrinology and professor of medicine, biochemistry, and molecular and cellular biology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston.

Monotherapy for type 2 diabetes with stepwise addition of other antihyperglycemic agents has long been the accepted way to initiate therapy in this population. Beginning in the 1990s, investigators began to compare the efficacy of monotherapy with combination therapy, first with metformin and glyburide alone or together, and then testing metformin in combination with glipizide, rosiglitazone, and sitagliptin, he said.

For metformin and glyburide, each agent alone lowered glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), compared with placebo, but adding one to the other enhanced lowering. Combining the two drugs had the greatest benefit for higher HbA1c entry levels (e.g., HbA1c strata of 9%-9.9% or 10% or greater vs. less than 8%). At the highest-entry HbA1c levels, half doses of each of metformin and glyburide (250 mg/1.25 mg, respectively) were more efficacious than full doses of each (500 mg/2.5 mg). “This is called drug sparing,” he said.

In a trial of metformin and rosiglitazone, the combination was superior to either alone, producing significantly greater mean reductions in HbA1c and in fasting plasma glucose (FPG) at 32 weeks from their respective baselines, again, with greater reductions for higher-entry HbA1c levels. The combination was also better than either drug alone in the speed of reducing HbA1c or FPG, and in the final attained levels.

The combination of metformin and a sulfonylurea presents a risk of hypoglycemia, but Dr. Garber said the results are “much cleaner” using combinations of metformin with agents such as a thiazolidinedione, a dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor, or a sodium/glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor.

Also noteworthy are findings from the EDICT (Efficacy and Durability of Initial Combination Therapy for Type 2 Diabetes) trial using insulin-sensitizing and insulin-secreting agents metformin/pioglitazone/exenatide in combination vs. escalating doses of metformin with sequential addition of a sulfonylurea and glargine insulin to treat patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes. Over 2 years, the subjects receiving combination therapy had lower HbA1c, a mean weight loss, compared with weight gain, in the sequential therapy group, and a 7.5-fold lower rate of hypoglycemia, compared with the sequential treatment group (Diabetes Obes Metab. 2015;17:268-75).

Although the agents used in the two treatment strategies were not strictly equivalent, “it’s clear that testing multiple therapeutic mechanisms tends to produce better outcomes than fewer therapeutic mechanisms,” Dr. Garber said. The conclusions are fairly straightforward. “Look for evidence to support what strategies you want to use for your patients’ care.”

Using the Kaiser Permanente database, investigators found that the mean time of having an HbA1c above 8% was 3 years before a second agent was added, and the mean HbA1c was 9%. Many people have ascribed this sort of delay to a problem with the physician. But Dr. Garber said it is more related to patients, who often resist prescriptions for more drugs. So starting with two drugs may produce better efficacy faster as well as overcome the psychological issues of trying to add another one later (Am J Manag Care. 2003;9:213-7).

Session moderator Dr. Daniel Einhorn, medical director of the Scripps Whittier Diabetes Institute in La Jolla, California, raised the possibility of “subtraction therapy, where you start with three agents no matter what, and then if things go well, you subtract. And so you reverse the situation that Alan discussed.” In the patient’s view, “you have a celebration that night instead of a wake,” he said.

Dr. Garber has received honoraria or consulting fees as a member of the advisory boards of Novo Nordisk, Janssen, and Merck. Dr. Einhorn is on the scientific advisory boards of Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, Janssen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi, and Adocia, is a consultant for Halozyme, Glysens, Freedom-Meditech, and Epitracker, and has research funding from Lilly, Novo, Janssen, AstraZeneca, Mannkind, Freedom-Meditech, Merck, Sanofi, and Boehringer Ingelheim.

ORLANDO – Whether to start a patient with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus on combination therapy or monotherapy should be based on experimentation and observation rather than expert opinion, according to Dr. Alan Garber, president of the American College of Endocrinology and professor of medicine, biochemistry, and molecular and cellular biology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston.

Monotherapy for type 2 diabetes with stepwise addition of other antihyperglycemic agents has long been the accepted way to initiate therapy in this population. Beginning in the 1990s, investigators began to compare the efficacy of monotherapy with combination therapy, first with metformin and glyburide alone or together, and then testing metformin in combination with glipizide, rosiglitazone, and sitagliptin, he said.

For metformin and glyburide, each agent alone lowered glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), compared with placebo, but adding one to the other enhanced lowering. Combining the two drugs had the greatest benefit for higher HbA1c entry levels (e.g., HbA1c strata of 9%-9.9% or 10% or greater vs. less than 8%). At the highest-entry HbA1c levels, half doses of each of metformin and glyburide (250 mg/1.25 mg, respectively) were more efficacious than full doses of each (500 mg/2.5 mg). “This is called drug sparing,” he said.

In a trial of metformin and rosiglitazone, the combination was superior to either alone, producing significantly greater mean reductions in HbA1c and in fasting plasma glucose (FPG) at 32 weeks from their respective baselines, again, with greater reductions for higher-entry HbA1c levels. The combination was also better than either drug alone in the speed of reducing HbA1c or FPG, and in the final attained levels.

The combination of metformin and a sulfonylurea presents a risk of hypoglycemia, but Dr. Garber said the results are “much cleaner” using combinations of metformin with agents such as a thiazolidinedione, a dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor, or a sodium/glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor.

Also noteworthy are findings from the EDICT (Efficacy and Durability of Initial Combination Therapy for Type 2 Diabetes) trial using insulin-sensitizing and insulin-secreting agents metformin/pioglitazone/exenatide in combination vs. escalating doses of metformin with sequential addition of a sulfonylurea and glargine insulin to treat patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes. Over 2 years, the subjects receiving combination therapy had lower HbA1c, a mean weight loss, compared with weight gain, in the sequential therapy group, and a 7.5-fold lower rate of hypoglycemia, compared with the sequential treatment group (Diabetes Obes Metab. 2015;17:268-75).

Although the agents used in the two treatment strategies were not strictly equivalent, “it’s clear that testing multiple therapeutic mechanisms tends to produce better outcomes than fewer therapeutic mechanisms,” Dr. Garber said. The conclusions are fairly straightforward. “Look for evidence to support what strategies you want to use for your patients’ care.”

Using the Kaiser Permanente database, investigators found that the mean time of having an HbA1c above 8% was 3 years before a second agent was added, and the mean HbA1c was 9%. Many people have ascribed this sort of delay to a problem with the physician. But Dr. Garber said it is more related to patients, who often resist prescriptions for more drugs. So starting with two drugs may produce better efficacy faster as well as overcome the psychological issues of trying to add another one later (Am J Manag Care. 2003;9:213-7).

Session moderator Dr. Daniel Einhorn, medical director of the Scripps Whittier Diabetes Institute in La Jolla, California, raised the possibility of “subtraction therapy, where you start with three agents no matter what, and then if things go well, you subtract. And so you reverse the situation that Alan discussed.” In the patient’s view, “you have a celebration that night instead of a wake,” he said.

Dr. Garber has received honoraria or consulting fees as a member of the advisory boards of Novo Nordisk, Janssen, and Merck. Dr. Einhorn is on the scientific advisory boards of Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, Janssen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi, and Adocia, is a consultant for Halozyme, Glysens, Freedom-Meditech, and Epitracker, and has research funding from Lilly, Novo, Janssen, AstraZeneca, Mannkind, Freedom-Meditech, Merck, Sanofi, and Boehringer Ingelheim.

ORLANDO – Whether to start a patient with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus on combination therapy or monotherapy should be based on experimentation and observation rather than expert opinion, according to Dr. Alan Garber, president of the American College of Endocrinology and professor of medicine, biochemistry, and molecular and cellular biology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston.

Monotherapy for type 2 diabetes with stepwise addition of other antihyperglycemic agents has long been the accepted way to initiate therapy in this population. Beginning in the 1990s, investigators began to compare the efficacy of monotherapy with combination therapy, first with metformin and glyburide alone or together, and then testing metformin in combination with glipizide, rosiglitazone, and sitagliptin, he said.

For metformin and glyburide, each agent alone lowered glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), compared with placebo, but adding one to the other enhanced lowering. Combining the two drugs had the greatest benefit for higher HbA1c entry levels (e.g., HbA1c strata of 9%-9.9% or 10% or greater vs. less than 8%). At the highest-entry HbA1c levels, half doses of each of metformin and glyburide (250 mg/1.25 mg, respectively) were more efficacious than full doses of each (500 mg/2.5 mg). “This is called drug sparing,” he said.

In a trial of metformin and rosiglitazone, the combination was superior to either alone, producing significantly greater mean reductions in HbA1c and in fasting plasma glucose (FPG) at 32 weeks from their respective baselines, again, with greater reductions for higher-entry HbA1c levels. The combination was also better than either drug alone in the speed of reducing HbA1c or FPG, and in the final attained levels.

The combination of metformin and a sulfonylurea presents a risk of hypoglycemia, but Dr. Garber said the results are “much cleaner” using combinations of metformin with agents such as a thiazolidinedione, a dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor, or a sodium/glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor.

Also noteworthy are findings from the EDICT (Efficacy and Durability of Initial Combination Therapy for Type 2 Diabetes) trial using insulin-sensitizing and insulin-secreting agents metformin/pioglitazone/exenatide in combination vs. escalating doses of metformin with sequential addition of a sulfonylurea and glargine insulin to treat patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes. Over 2 years, the subjects receiving combination therapy had lower HbA1c, a mean weight loss, compared with weight gain, in the sequential therapy group, and a 7.5-fold lower rate of hypoglycemia, compared with the sequential treatment group (Diabetes Obes Metab. 2015;17:268-75).

Although the agents used in the two treatment strategies were not strictly equivalent, “it’s clear that testing multiple therapeutic mechanisms tends to produce better outcomes than fewer therapeutic mechanisms,” Dr. Garber said. The conclusions are fairly straightforward. “Look for evidence to support what strategies you want to use for your patients’ care.”

Using the Kaiser Permanente database, investigators found that the mean time of having an HbA1c above 8% was 3 years before a second agent was added, and the mean HbA1c was 9%. Many people have ascribed this sort of delay to a problem with the physician. But Dr. Garber said it is more related to patients, who often resist prescriptions for more drugs. So starting with two drugs may produce better efficacy faster as well as overcome the psychological issues of trying to add another one later (Am J Manag Care. 2003;9:213-7).

Session moderator Dr. Daniel Einhorn, medical director of the Scripps Whittier Diabetes Institute in La Jolla, California, raised the possibility of “subtraction therapy, where you start with three agents no matter what, and then if things go well, you subtract. And so you reverse the situation that Alan discussed.” In the patient’s view, “you have a celebration that night instead of a wake,” he said.

Dr. Garber has received honoraria or consulting fees as a member of the advisory boards of Novo Nordisk, Janssen, and Merck. Dr. Einhorn is on the scientific advisory boards of Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, Janssen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi, and Adocia, is a consultant for Halozyme, Glysens, Freedom-Meditech, and Epitracker, and has research funding from Lilly, Novo, Janssen, AstraZeneca, Mannkind, Freedom-Meditech, Merck, Sanofi, and Boehringer Ingelheim.

EXPERT ANALYSIS AT AACE 2016

Starting with combination diabetes therapy beats initial monotherapy

ORLANDO – Whether to start a patient with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus on combination therapy or monotherapy should be based on experimentation and observation rather than expert opinion, according to Dr. Alan Garber, president of the American College of Endocrinology and professor of medicine, biochemistry, and molecular and cellular biology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston.

Monotherapy for type 2 diabetes with stepwise addition of other antihyperglycemic agents has long been the accepted way to initiate therapy in this population. Beginning in the 1990s, investigators began to compare the efficacy of monotherapy with combination therapy, first with metformin and glyburide alone or together, and then testing metformin in combination with glipizide, rosiglitazone, and sitagliptin, he said.

For metformin and glyburide, each agent alone lowered glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), compared with placebo, but adding one to the other enhanced lowering. Combining the two drugs had the greatest benefit for higher HbA1c entry levels (e.g., HbA1c strata of 9%-9.9% or 10% or greater vs. less than 8%). At the highest-entry HbA1c levels, half doses of each of metformin and glyburide (250 mg/1.25 mg, respectively) were more efficacious than full doses of each (500 mg/2.5 mg). “This is called drug sparing,” he said.

In a trial of metformin and rosiglitazone, the combination was superior to either alone, producing significantly greater mean reductions in HbA1c and in fasting plasma glucose (FPG) at 32 weeks from their respective baselines, again, with greater reductions for higher-entry HbA1c levels. The combination was also better than either drug alone in the speed of reducing HbA1c or FPG, and in the final attained levels.

The combination of metformin and a sulfonylurea presents a risk of hypoglycemia, but Dr. Garber said the results are “much cleaner” using combinations of metformin with agents such as a thiazolidinedione, a dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor, or a sodium/glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor.

Also noteworthy are findings from the EDICT (Efficacy and Durability of Initial Combination Therapy for Type 2 Diabetes) trial using insulin-sensitizing and insulin-secreting agents metformin/pioglitazone/exenatide in combination vs. escalating doses of metformin with sequential addition of a sulfonylurea and glargine insulin to treat patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes. Over 2 years, the subjects receiving combination therapy had lower HbA1c, a mean weight loss, compared with weight gain, in the sequential therapy group, and a 7.5-fold lower rate of hypoglycemia, compared with the sequential treatment group (Diabetes Obes Metab. 2015;17:268-75).

Although the agents used in the two treatment strategies were not strictly equivalent, “it’s clear that testing multiple therapeutic mechanisms tends to produce better outcomes than fewer therapeutic mechanisms,” Dr. Garber said. The conclusions are fairly straightforward. “Look for evidence to support what strategies you want to use for your patients’ care.”

Using the Kaiser Permanente database, investigators found that the mean time of having an HbA1c above 8% was 3 years before a second agent was added, and the mean HbA1c was 9%. Many people have ascribed this sort of delay to a problem with the physician. But Dr. Garber said it is more related to patients, who often resist prescriptions for more drugs. So starting with two drugs may produce better efficacy faster as well as overcome the psychological issues of trying to add another one later (Am J Manag Care. 2003;9:213-7).

Session moderator Dr. Daniel Einhorn, medical director of the Scripps Whittier Diabetes Institute in La Jolla, California, raised the possibility of “subtraction therapy, where you start with three agents no matter what, and then if things go well, you subtract. And so you reverse the situation that Alan discussed.” In the patient’s view, “you have a celebration that night instead of a wake,” he said.

Dr. Garber has received honoraria or consulting fees as a member of the advisory boards of Novo Nordisk, Janssen, and Merck. Dr. Einhorn is on the scientific advisory boards of Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, Janssen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi, and Adocia, is a consultant for Halozyme, Glysens, Freedom-Meditech, and Epitracker, and has research funding from Lilly, Novo, Janssen, AstraZeneca, Mannkind, Freedom-Meditech, Merck, Sanofi, and Boehringer Ingelheim.

ORLANDO – Whether to start a patient with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus on combination therapy or monotherapy should be based on experimentation and observation rather than expert opinion, according to Dr. Alan Garber, president of the American College of Endocrinology and professor of medicine, biochemistry, and molecular and cellular biology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston.

Monotherapy for type 2 diabetes with stepwise addition of other antihyperglycemic agents has long been the accepted way to initiate therapy in this population. Beginning in the 1990s, investigators began to compare the efficacy of monotherapy with combination therapy, first with metformin and glyburide alone or together, and then testing metformin in combination with glipizide, rosiglitazone, and sitagliptin, he said.

For metformin and glyburide, each agent alone lowered glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), compared with placebo, but adding one to the other enhanced lowering. Combining the two drugs had the greatest benefit for higher HbA1c entry levels (e.g., HbA1c strata of 9%-9.9% or 10% or greater vs. less than 8%). At the highest-entry HbA1c levels, half doses of each of metformin and glyburide (250 mg/1.25 mg, respectively) were more efficacious than full doses of each (500 mg/2.5 mg). “This is called drug sparing,” he said.

In a trial of metformin and rosiglitazone, the combination was superior to either alone, producing significantly greater mean reductions in HbA1c and in fasting plasma glucose (FPG) at 32 weeks from their respective baselines, again, with greater reductions for higher-entry HbA1c levels. The combination was also better than either drug alone in the speed of reducing HbA1c or FPG, and in the final attained levels.

The combination of metformin and a sulfonylurea presents a risk of hypoglycemia, but Dr. Garber said the results are “much cleaner” using combinations of metformin with agents such as a thiazolidinedione, a dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor, or a sodium/glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor.

Also noteworthy are findings from the EDICT (Efficacy and Durability of Initial Combination Therapy for Type 2 Diabetes) trial using insulin-sensitizing and insulin-secreting agents metformin/pioglitazone/exenatide in combination vs. escalating doses of metformin with sequential addition of a sulfonylurea and glargine insulin to treat patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes. Over 2 years, the subjects receiving combination therapy had lower HbA1c, a mean weight loss, compared with weight gain, in the sequential therapy group, and a 7.5-fold lower rate of hypoglycemia, compared with the sequential treatment group (Diabetes Obes Metab. 2015;17:268-75).

Although the agents used in the two treatment strategies were not strictly equivalent, “it’s clear that testing multiple therapeutic mechanisms tends to produce better outcomes than fewer therapeutic mechanisms,” Dr. Garber said. The conclusions are fairly straightforward. “Look for evidence to support what strategies you want to use for your patients’ care.”

Using the Kaiser Permanente database, investigators found that the mean time of having an HbA1c above 8% was 3 years before a second agent was added, and the mean HbA1c was 9%. Many people have ascribed this sort of delay to a problem with the physician. But Dr. Garber said it is more related to patients, who often resist prescriptions for more drugs. So starting with two drugs may produce better efficacy faster as well as overcome the psychological issues of trying to add another one later (Am J Manag Care. 2003;9:213-7).

Session moderator Dr. Daniel Einhorn, medical director of the Scripps Whittier Diabetes Institute in La Jolla, California, raised the possibility of “subtraction therapy, where you start with three agents no matter what, and then if things go well, you subtract. And so you reverse the situation that Alan discussed.” In the patient’s view, “you have a celebration that night instead of a wake,” he said.

Dr. Garber has received honoraria or consulting fees as a member of the advisory boards of Novo Nordisk, Janssen, and Merck. Dr. Einhorn is on the scientific advisory boards of Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, Janssen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi, and Adocia, is a consultant for Halozyme, Glysens, Freedom-Meditech, and Epitracker, and has research funding from Lilly, Novo, Janssen, AstraZeneca, Mannkind, Freedom-Meditech, Merck, Sanofi, and Boehringer Ingelheim.

ORLANDO – Whether to start a patient with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus on combination therapy or monotherapy should be based on experimentation and observation rather than expert opinion, according to Dr. Alan Garber, president of the American College of Endocrinology and professor of medicine, biochemistry, and molecular and cellular biology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston.

Monotherapy for type 2 diabetes with stepwise addition of other antihyperglycemic agents has long been the accepted way to initiate therapy in this population. Beginning in the 1990s, investigators began to compare the efficacy of monotherapy with combination therapy, first with metformin and glyburide alone or together, and then testing metformin in combination with glipizide, rosiglitazone, and sitagliptin, he said.

For metformin and glyburide, each agent alone lowered glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), compared with placebo, but adding one to the other enhanced lowering. Combining the two drugs had the greatest benefit for higher HbA1c entry levels (e.g., HbA1c strata of 9%-9.9% or 10% or greater vs. less than 8%). At the highest-entry HbA1c levels, half doses of each of metformin and glyburide (250 mg/1.25 mg, respectively) were more efficacious than full doses of each (500 mg/2.5 mg). “This is called drug sparing,” he said.

In a trial of metformin and rosiglitazone, the combination was superior to either alone, producing significantly greater mean reductions in HbA1c and in fasting plasma glucose (FPG) at 32 weeks from their respective baselines, again, with greater reductions for higher-entry HbA1c levels. The combination was also better than either drug alone in the speed of reducing HbA1c or FPG, and in the final attained levels.

The combination of metformin and a sulfonylurea presents a risk of hypoglycemia, but Dr. Garber said the results are “much cleaner” using combinations of metformin with agents such as a thiazolidinedione, a dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor, or a sodium/glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor.

Also noteworthy are findings from the EDICT (Efficacy and Durability of Initial Combination Therapy for Type 2 Diabetes) trial using insulin-sensitizing and insulin-secreting agents metformin/pioglitazone/exenatide in combination vs. escalating doses of metformin with sequential addition of a sulfonylurea and glargine insulin to treat patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes. Over 2 years, the subjects receiving combination therapy had lower HbA1c, a mean weight loss, compared with weight gain, in the sequential therapy group, and a 7.5-fold lower rate of hypoglycemia, compared with the sequential treatment group (Diabetes Obes Metab. 2015;17:268-75).

Although the agents used in the two treatment strategies were not strictly equivalent, “it’s clear that testing multiple therapeutic mechanisms tends to produce better outcomes than fewer therapeutic mechanisms,” Dr. Garber said. The conclusions are fairly straightforward. “Look for evidence to support what strategies you want to use for your patients’ care.”

Using the Kaiser Permanente database, investigators found that the mean time of having an HbA1c above 8% was 3 years before a second agent was added, and the mean HbA1c was 9%. Many people have ascribed this sort of delay to a problem with the physician. But Dr. Garber said it is more related to patients, who often resist prescriptions for more drugs. So starting with two drugs may produce better efficacy faster as well as overcome the psychological issues of trying to add another one later (Am J Manag Care. 2003;9:213-7).

Session moderator Dr. Daniel Einhorn, medical director of the Scripps Whittier Diabetes Institute in La Jolla, California, raised the possibility of “subtraction therapy, where you start with three agents no matter what, and then if things go well, you subtract. And so you reverse the situation that Alan discussed.” In the patient’s view, “you have a celebration that night instead of a wake,” he said.

Dr. Garber has received honoraria or consulting fees as a member of the advisory boards of Novo Nordisk, Janssen, and Merck. Dr. Einhorn is on the scientific advisory boards of Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, Janssen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi, and Adocia, is a consultant for Halozyme, Glysens, Freedom-Meditech, and Epitracker, and has research funding from Lilly, Novo, Janssen, AstraZeneca, Mannkind, Freedom-Meditech, Merck, Sanofi, and Boehringer Ingelheim.

EXPERT ANALYSIS AT AACE 2016

RF ablation successfully treats focal adrenal tumors

ORLANDO – Radiofrequency (RF) ablation is a safe and effective procedure for treating focal adrenal tumors in patients who are poor surgical candidates or who refuse adrenalectomy. With a short treatment time and minimal hospital stay, RF ablation can provide rapid clinical and biochemical improvement.

Dr. Lima Lawrence, an internal medicine resident at the University of Illinois at Chicago/Advocate Christ Medical Center in Oak Lawn, presented a case report and a review of the literature during an oral abstract session at the annual meeting of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. The patient was a 65-year-old woman who presented with weight gain, decreased energy, and muscle weakness. On physical exam, she was hypertensive, anxious, obese, and had prominent supraclavicular fat pads. Salivary cortisol and overnight dexamethasone suppression tests were both elevated, and ACTH levels were depressed, confirming the diagnosis of a cortisol-secreting tumor causing adrenal Cushing’s syndrome. Computed tomography (CT) surveillance showed a progressively enlarging right-sided adrenal mass. A peritoneal biopsy revealed a low-grade serous neoplasm of peritoneal origin.

Her medical history included type 2 diabetes, uncontrolled hypertension, mixed connective tissue disease, depression, and total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy for ovarian cancer.

Dr. Lawrence said the patient had been scheduled for adrenalectomy, but it was not performed because of an intraoperative finding of peritoneal studding from what turned out to be metastatic ovarian cancer. Therefore, she underwent CT-guided RF ablation of the adrenal mass using a 14-gauge probe that heated a 3.5-cm ablation zone to 50-60 C for 8-10 minutes to achieve complete tumor necrosis.

The patient showed dramatic “clinical and biochemical improvement,” Dr. Lawrence said. The patient had no procedural complications and no blood loss and was observed for 23 hours before being discharged to home. A CT scan 8 weeks later showed a slightly decreased mass with marked decreased radiographic attenuation post-contrast from 30.2 Hounsfield Units (HU) preoperatively to 17 HU on follow-up.

Potential adverse outcomes using RF ablation include a risk of pneumothorax, hemothorax, and tumor seeding along the catheter track, but this last possibility can be mitigated by continuing to heat the RF probe as it is withdrawn.

Published evidence supports use of RF ablation. “To date there have been no randomized clinical trials comparing the safety, efficacy, and survival benefits of adrenalectomy vs. radio frequency ablation,” she said. It may not be feasible to do a randomized trial. But a review of the literature generally supports the efficacy of the technique although the publications each involved a small series of patients, Dr. Lawrence said in an interview.

A 2003 series (Cancer. 2003;97:554-60) of 15 primary or metastatic adrenal cell carcinomas that were unresectable or were in patients who were not surgical candidates showed nonenhancement and no growth in 8 (53%) at a mean follow-up of 10.3 months. Eight of the 12 tumors of 5 cm or smaller had complete loss of radiographic enhancement and a decrease in size.

From a retrospective series of 13 patients with functional adrenal neoplasms over 7 years, there was 100% resolution of biochemical abnormalities and clinical symptoms at a mean follow-up of 21.2 months. One small pneumothorax and one limited hemothorax occurred, neither of which required hospital admission. There were two instances of transient, self-remitting hypertension associated with the procedures (Radiology. 2011;258:308-16).

In 2015, one group of investigators followed 11 patients for 12 weeks postprocedure. Eight of nine patients with Conn’s syndrome attained normal serum aldosterone levels. One with a nodule close to the inferior vena cava had incomplete ablation. Two of two Cushing’s patients had normal cortisol levels after the procedure (J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2015;26:1459-64).

A retrospective analysis of 16 adrenal metastases showed that 13 (81%) had no local progression over 14 months after ablation. In two of three functional adrenal neoplasms, clinical and biochemical abnormalities resolved (Eur J Radiol. 2012.81:1717-23).

A retrospective series of 10 adrenal metastases showed that one recurred at 7 months after image-guided thermal ablation, with no recurrence of the rest at 26.6 months. There was no tumor recurrence for any of the cases of metastatic disease localized to the RF ablation site (J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2014;25:593-8).

Results were somewhat less good in a retrospective evaluation of 35 patients with unresectable adrenal masses over 9 years. Although 33 of 35 (94%) lost tumor enhancement after the initial adrenal RF ablation, there was local tumor progression in 8 of 35 (23%) patients at a mean follow-up of 30.1 months (Radiology. 2015;277:584-93).

Finally, Dr. Lawrence discussed a systematic literature review on adrenalectomy vs. stereotactic ablative body radiotherapy (SABR) and percutaneous catheter ablation (PCA) in the treatment of adrenal metastases: 30 papers on adrenalectomy on 818 patients; 9 papers on SABR on 178 patients; and 6 papers on PCA, including RF ablation, on 51 patients. The authors concluded that there was “insufficient evidence to determine the best local treatment modality for isolated or limited adrenal metastases.” Adrenalectomy appeared to be a reasonable treatment for suitable patients. SABR was a valid alternative for nonsurgical candidates, but they did not recommend PCA until more long-term outcomes were available (Cancer Treat Rev. 2014;40:838-46).

Dr. Lawrence concurred, based on her case study and literature review. She said RF ablation “offers patients a minimally invasive option for treating focal adrenal tumors” and is a “safe and effective procedure … in patients who are poor surgical candidates or refuse adrenalectomy.” More long-term follow-up studies are needed before RF ablation could replace adrenalectomy, she noted.

ORLANDO – Radiofrequency (RF) ablation is a safe and effective procedure for treating focal adrenal tumors in patients who are poor surgical candidates or who refuse adrenalectomy. With a short treatment time and minimal hospital stay, RF ablation can provide rapid clinical and biochemical improvement.

Dr. Lima Lawrence, an internal medicine resident at the University of Illinois at Chicago/Advocate Christ Medical Center in Oak Lawn, presented a case report and a review of the literature during an oral abstract session at the annual meeting of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. The patient was a 65-year-old woman who presented with weight gain, decreased energy, and muscle weakness. On physical exam, she was hypertensive, anxious, obese, and had prominent supraclavicular fat pads. Salivary cortisol and overnight dexamethasone suppression tests were both elevated, and ACTH levels were depressed, confirming the diagnosis of a cortisol-secreting tumor causing adrenal Cushing’s syndrome. Computed tomography (CT) surveillance showed a progressively enlarging right-sided adrenal mass. A peritoneal biopsy revealed a low-grade serous neoplasm of peritoneal origin.

Her medical history included type 2 diabetes, uncontrolled hypertension, mixed connective tissue disease, depression, and total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy for ovarian cancer.

Dr. Lawrence said the patient had been scheduled for adrenalectomy, but it was not performed because of an intraoperative finding of peritoneal studding from what turned out to be metastatic ovarian cancer. Therefore, she underwent CT-guided RF ablation of the adrenal mass using a 14-gauge probe that heated a 3.5-cm ablation zone to 50-60 C for 8-10 minutes to achieve complete tumor necrosis.

The patient showed dramatic “clinical and biochemical improvement,” Dr. Lawrence said. The patient had no procedural complications and no blood loss and was observed for 23 hours before being discharged to home. A CT scan 8 weeks later showed a slightly decreased mass with marked decreased radiographic attenuation post-contrast from 30.2 Hounsfield Units (HU) preoperatively to 17 HU on follow-up.

Potential adverse outcomes using RF ablation include a risk of pneumothorax, hemothorax, and tumor seeding along the catheter track, but this last possibility can be mitigated by continuing to heat the RF probe as it is withdrawn.

Published evidence supports use of RF ablation. “To date there have been no randomized clinical trials comparing the safety, efficacy, and survival benefits of adrenalectomy vs. radio frequency ablation,” she said. It may not be feasible to do a randomized trial. But a review of the literature generally supports the efficacy of the technique although the publications each involved a small series of patients, Dr. Lawrence said in an interview.

A 2003 series (Cancer. 2003;97:554-60) of 15 primary or metastatic adrenal cell carcinomas that were unresectable or were in patients who were not surgical candidates showed nonenhancement and no growth in 8 (53%) at a mean follow-up of 10.3 months. Eight of the 12 tumors of 5 cm or smaller had complete loss of radiographic enhancement and a decrease in size.

From a retrospective series of 13 patients with functional adrenal neoplasms over 7 years, there was 100% resolution of biochemical abnormalities and clinical symptoms at a mean follow-up of 21.2 months. One small pneumothorax and one limited hemothorax occurred, neither of which required hospital admission. There were two instances of transient, self-remitting hypertension associated with the procedures (Radiology. 2011;258:308-16).

In 2015, one group of investigators followed 11 patients for 12 weeks postprocedure. Eight of nine patients with Conn’s syndrome attained normal serum aldosterone levels. One with a nodule close to the inferior vena cava had incomplete ablation. Two of two Cushing’s patients had normal cortisol levels after the procedure (J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2015;26:1459-64).

A retrospective analysis of 16 adrenal metastases showed that 13 (81%) had no local progression over 14 months after ablation. In two of three functional adrenal neoplasms, clinical and biochemical abnormalities resolved (Eur J Radiol. 2012.81:1717-23).

A retrospective series of 10 adrenal metastases showed that one recurred at 7 months after image-guided thermal ablation, with no recurrence of the rest at 26.6 months. There was no tumor recurrence for any of the cases of metastatic disease localized to the RF ablation site (J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2014;25:593-8).

Results were somewhat less good in a retrospective evaluation of 35 patients with unresectable adrenal masses over 9 years. Although 33 of 35 (94%) lost tumor enhancement after the initial adrenal RF ablation, there was local tumor progression in 8 of 35 (23%) patients at a mean follow-up of 30.1 months (Radiology. 2015;277:584-93).

Finally, Dr. Lawrence discussed a systematic literature review on adrenalectomy vs. stereotactic ablative body radiotherapy (SABR) and percutaneous catheter ablation (PCA) in the treatment of adrenal metastases: 30 papers on adrenalectomy on 818 patients; 9 papers on SABR on 178 patients; and 6 papers on PCA, including RF ablation, on 51 patients. The authors concluded that there was “insufficient evidence to determine the best local treatment modality for isolated or limited adrenal metastases.” Adrenalectomy appeared to be a reasonable treatment for suitable patients. SABR was a valid alternative for nonsurgical candidates, but they did not recommend PCA until more long-term outcomes were available (Cancer Treat Rev. 2014;40:838-46).

Dr. Lawrence concurred, based on her case study and literature review. She said RF ablation “offers patients a minimally invasive option for treating focal adrenal tumors” and is a “safe and effective procedure … in patients who are poor surgical candidates or refuse adrenalectomy.” More long-term follow-up studies are needed before RF ablation could replace adrenalectomy, she noted.

ORLANDO – Radiofrequency (RF) ablation is a safe and effective procedure for treating focal adrenal tumors in patients who are poor surgical candidates or who refuse adrenalectomy. With a short treatment time and minimal hospital stay, RF ablation can provide rapid clinical and biochemical improvement.

Dr. Lima Lawrence, an internal medicine resident at the University of Illinois at Chicago/Advocate Christ Medical Center in Oak Lawn, presented a case report and a review of the literature during an oral abstract session at the annual meeting of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. The patient was a 65-year-old woman who presented with weight gain, decreased energy, and muscle weakness. On physical exam, she was hypertensive, anxious, obese, and had prominent supraclavicular fat pads. Salivary cortisol and overnight dexamethasone suppression tests were both elevated, and ACTH levels were depressed, confirming the diagnosis of a cortisol-secreting tumor causing adrenal Cushing’s syndrome. Computed tomography (CT) surveillance showed a progressively enlarging right-sided adrenal mass. A peritoneal biopsy revealed a low-grade serous neoplasm of peritoneal origin.

Her medical history included type 2 diabetes, uncontrolled hypertension, mixed connective tissue disease, depression, and total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy for ovarian cancer.

Dr. Lawrence said the patient had been scheduled for adrenalectomy, but it was not performed because of an intraoperative finding of peritoneal studding from what turned out to be metastatic ovarian cancer. Therefore, she underwent CT-guided RF ablation of the adrenal mass using a 14-gauge probe that heated a 3.5-cm ablation zone to 50-60 C for 8-10 minutes to achieve complete tumor necrosis.

The patient showed dramatic “clinical and biochemical improvement,” Dr. Lawrence said. The patient had no procedural complications and no blood loss and was observed for 23 hours before being discharged to home. A CT scan 8 weeks later showed a slightly decreased mass with marked decreased radiographic attenuation post-contrast from 30.2 Hounsfield Units (HU) preoperatively to 17 HU on follow-up.

Potential adverse outcomes using RF ablation include a risk of pneumothorax, hemothorax, and tumor seeding along the catheter track, but this last possibility can be mitigated by continuing to heat the RF probe as it is withdrawn.