User login

Ear-worn device helps Parkinson’s patients to improve their voice

PORTLAND, ORE. – A new device worn on one ear may help individuals with Parkinson’s disease to overcome speech deficits associated with the disease. When triggered by the wearer’s voice, the device, SpeechVive, provides a simulated room crowd noise or “babble” only when they are talking. Because it capitalizes on natural reflexes to this simulated background noise, improvement can occur independent of speech training.

Researchers led by Jessica Huber, PhD, a professor of speech, language, and hearing sciences at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Ind., investigated changes to speech after 3 months of daily use of the SpeechVive device by 16 individuals. The cohort had a mean age of 64.5 years (range: 56-78 years) and a mean disease duration of 8.1 years (range: 2-17 years). Six participants had previously had speech therapy (five with LSVT [Lee Silverman Voice Treatment] LOUD speech training exercises), and two had deep brain stimulation implants.

Similar to an earlier study of 39 participants, “We found a nice increase in loudness, that they just can wear the device, and they’re louder in their everyday communication,” Dr. Huber said in an interview during a poster session at the World Parkinson Congress. New to this study was a finding that the melody of speech was a little better, “so their questions are more like questions, and their statements are more like statements, so are the rising intonation on questions and the falling intonation on a statement.” Participants were also able to say more on one breath and to sound more natural with appropriate pauses because of the longer utterances.

After 3 months of use, participants as a group increased their sound pressure level (loudness) from 76.6 dB to 78.8 dB (a gain of 2.2 dB) from having the device OFF to ON. When it was then turned off, they had an intermediate sound pressure level of 77.7 dB (both P less than .0001 vs. pretest OFF). Intonation variability and intonation range also showed significant improvements for both statements and questions with the use of the device (all P less than or equal to .01). There were also improvements in a correct statement or question being produced, pausing patterns, and utterance length. No adverse events occurred in the study.

Dr. Huber said patients in the study were quite variable in their responses to SpeechVive for the different measures of speech. In general, she has found that about 75% of users get louder with the device, and some have clearer articulation or slower speech. Another 10%-15% have slower speech or better articulation without an increase in loudness.

A total of 50% of the users have a “carry-over” effect after using the device when they are not wearing it. “After about 8 weeks, they don’t need to keep wearing the device every day,” Dr. Huber noted. Others may wear it in the morning and have a lasting effect for the rest of the day, and some lose any benefit as soon as taking the device off. Not all patients reach a normal speech loudness, “but they’re going to get way better” than where they started, she said.

Available speech therapies

People with Parkinson’s disease (PD) often have reduced vocal loudness, increased speech rate, and slurred articulation. Available speech therapies have included adduction exercises, vocal function exercises, and LSVT LOUD speech training exercises. For some individuals with PD, these behavioral treatments may not carry over into daily life.

The SpeechVive consists of a piece placed into the ear canal and a piece that sits behind the ear, similar to a slightly larger version of a modern hearing aid. It is designed large enough that many patients, who have motor deficits, can don it themselves. Because it is on just one ear, users can hear other people talking and what is going on around them.

Dr. Huber noted several strengths of the device. First, it does not impose any cognitive load on the user because its effect is based on an automatic reflex. Second, little training is necessary. It is easy for the user to put on the device, and many of its beneficial effects occur as soon as it is activated. Third, compliance can be tracked using data stored by the device itself.

In a previous study, she saw that after using the device for 8 weeks, participants used more effective patterns with their respiratory and laryngeal mechanisms to produce louder speech. “It’s not like they’re working super hard after 8 weeks.” She thinks they are just not usually using their speech apparatus in the most efficient manner, and they become more efficient after using the device. They may also not sense how loud they are without it, so it helps patients “recalibrate” a sense of their own voices, something the LSVT LOUD training also does.

Jori Fleisher, MD, a movement disorders neurologist at the New York University Langone Medical Center, commented that the study shows an interesting approach to the common and difficult problem of hypophonia and dysphonia in people with Parkinson’s disease. “It can be very difficult to speak loud enough to be heard, and it often leads to people withdrawing socially and not speaking as much in conversation as they normally would,” she said. “LSVT LOUD works in practice when you’re actually doing the exercises, but often when people stop doing the exercises, their voice goes back toward their normal. So this is something that you can keep with you and sort of have constant prompting to overcome that tendency toward quieter voice. It has a lot of promise.”

She said she would like to see the data on compliance or adherence with using the device “because it seems like a great idea, but how much are people actually using it? ... Having more long-term follow-up to see whether this is something that people want to put into practice in their daily life would be very useful.” She also said she would like to see how long the carry-over effect lasts once people take off the device to be able to compare it with sessions of speech therapy or doing speech exercises.

SpeechVive is $2,495, which includes the device, a charger, and earpiece fittings. It is available only in the United States, but the company now has clearance to market it in Canada.

The research was funded by a grant from SpeechVive. Dr. Huber is the inventor of SpeechVive, has a patent on it, has a financial interest in the SpeechVive company, and sits on its board of directors. Dr. Fleisher reported having no financial conflicts.

PORTLAND, ORE. – A new device worn on one ear may help individuals with Parkinson’s disease to overcome speech deficits associated with the disease. When triggered by the wearer’s voice, the device, SpeechVive, provides a simulated room crowd noise or “babble” only when they are talking. Because it capitalizes on natural reflexes to this simulated background noise, improvement can occur independent of speech training.

Researchers led by Jessica Huber, PhD, a professor of speech, language, and hearing sciences at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Ind., investigated changes to speech after 3 months of daily use of the SpeechVive device by 16 individuals. The cohort had a mean age of 64.5 years (range: 56-78 years) and a mean disease duration of 8.1 years (range: 2-17 years). Six participants had previously had speech therapy (five with LSVT [Lee Silverman Voice Treatment] LOUD speech training exercises), and two had deep brain stimulation implants.

Similar to an earlier study of 39 participants, “We found a nice increase in loudness, that they just can wear the device, and they’re louder in their everyday communication,” Dr. Huber said in an interview during a poster session at the World Parkinson Congress. New to this study was a finding that the melody of speech was a little better, “so their questions are more like questions, and their statements are more like statements, so are the rising intonation on questions and the falling intonation on a statement.” Participants were also able to say more on one breath and to sound more natural with appropriate pauses because of the longer utterances.

After 3 months of use, participants as a group increased their sound pressure level (loudness) from 76.6 dB to 78.8 dB (a gain of 2.2 dB) from having the device OFF to ON. When it was then turned off, they had an intermediate sound pressure level of 77.7 dB (both P less than .0001 vs. pretest OFF). Intonation variability and intonation range also showed significant improvements for both statements and questions with the use of the device (all P less than or equal to .01). There were also improvements in a correct statement or question being produced, pausing patterns, and utterance length. No adverse events occurred in the study.

Dr. Huber said patients in the study were quite variable in their responses to SpeechVive for the different measures of speech. In general, she has found that about 75% of users get louder with the device, and some have clearer articulation or slower speech. Another 10%-15% have slower speech or better articulation without an increase in loudness.

A total of 50% of the users have a “carry-over” effect after using the device when they are not wearing it. “After about 8 weeks, they don’t need to keep wearing the device every day,” Dr. Huber noted. Others may wear it in the morning and have a lasting effect for the rest of the day, and some lose any benefit as soon as taking the device off. Not all patients reach a normal speech loudness, “but they’re going to get way better” than where they started, she said.

Available speech therapies

People with Parkinson’s disease (PD) often have reduced vocal loudness, increased speech rate, and slurred articulation. Available speech therapies have included adduction exercises, vocal function exercises, and LSVT LOUD speech training exercises. For some individuals with PD, these behavioral treatments may not carry over into daily life.

The SpeechVive consists of a piece placed into the ear canal and a piece that sits behind the ear, similar to a slightly larger version of a modern hearing aid. It is designed large enough that many patients, who have motor deficits, can don it themselves. Because it is on just one ear, users can hear other people talking and what is going on around them.

Dr. Huber noted several strengths of the device. First, it does not impose any cognitive load on the user because its effect is based on an automatic reflex. Second, little training is necessary. It is easy for the user to put on the device, and many of its beneficial effects occur as soon as it is activated. Third, compliance can be tracked using data stored by the device itself.

In a previous study, she saw that after using the device for 8 weeks, participants used more effective patterns with their respiratory and laryngeal mechanisms to produce louder speech. “It’s not like they’re working super hard after 8 weeks.” She thinks they are just not usually using their speech apparatus in the most efficient manner, and they become more efficient after using the device. They may also not sense how loud they are without it, so it helps patients “recalibrate” a sense of their own voices, something the LSVT LOUD training also does.

Jori Fleisher, MD, a movement disorders neurologist at the New York University Langone Medical Center, commented that the study shows an interesting approach to the common and difficult problem of hypophonia and dysphonia in people with Parkinson’s disease. “It can be very difficult to speak loud enough to be heard, and it often leads to people withdrawing socially and not speaking as much in conversation as they normally would,” she said. “LSVT LOUD works in practice when you’re actually doing the exercises, but often when people stop doing the exercises, their voice goes back toward their normal. So this is something that you can keep with you and sort of have constant prompting to overcome that tendency toward quieter voice. It has a lot of promise.”

She said she would like to see the data on compliance or adherence with using the device “because it seems like a great idea, but how much are people actually using it? ... Having more long-term follow-up to see whether this is something that people want to put into practice in their daily life would be very useful.” She also said she would like to see how long the carry-over effect lasts once people take off the device to be able to compare it with sessions of speech therapy or doing speech exercises.

SpeechVive is $2,495, which includes the device, a charger, and earpiece fittings. It is available only in the United States, but the company now has clearance to market it in Canada.

The research was funded by a grant from SpeechVive. Dr. Huber is the inventor of SpeechVive, has a patent on it, has a financial interest in the SpeechVive company, and sits on its board of directors. Dr. Fleisher reported having no financial conflicts.

PORTLAND, ORE. – A new device worn on one ear may help individuals with Parkinson’s disease to overcome speech deficits associated with the disease. When triggered by the wearer’s voice, the device, SpeechVive, provides a simulated room crowd noise or “babble” only when they are talking. Because it capitalizes on natural reflexes to this simulated background noise, improvement can occur independent of speech training.

Researchers led by Jessica Huber, PhD, a professor of speech, language, and hearing sciences at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Ind., investigated changes to speech after 3 months of daily use of the SpeechVive device by 16 individuals. The cohort had a mean age of 64.5 years (range: 56-78 years) and a mean disease duration of 8.1 years (range: 2-17 years). Six participants had previously had speech therapy (five with LSVT [Lee Silverman Voice Treatment] LOUD speech training exercises), and two had deep brain stimulation implants.

Similar to an earlier study of 39 participants, “We found a nice increase in loudness, that they just can wear the device, and they’re louder in their everyday communication,” Dr. Huber said in an interview during a poster session at the World Parkinson Congress. New to this study was a finding that the melody of speech was a little better, “so their questions are more like questions, and their statements are more like statements, so are the rising intonation on questions and the falling intonation on a statement.” Participants were also able to say more on one breath and to sound more natural with appropriate pauses because of the longer utterances.

After 3 months of use, participants as a group increased their sound pressure level (loudness) from 76.6 dB to 78.8 dB (a gain of 2.2 dB) from having the device OFF to ON. When it was then turned off, they had an intermediate sound pressure level of 77.7 dB (both P less than .0001 vs. pretest OFF). Intonation variability and intonation range also showed significant improvements for both statements and questions with the use of the device (all P less than or equal to .01). There were also improvements in a correct statement or question being produced, pausing patterns, and utterance length. No adverse events occurred in the study.

Dr. Huber said patients in the study were quite variable in their responses to SpeechVive for the different measures of speech. In general, she has found that about 75% of users get louder with the device, and some have clearer articulation or slower speech. Another 10%-15% have slower speech or better articulation without an increase in loudness.

A total of 50% of the users have a “carry-over” effect after using the device when they are not wearing it. “After about 8 weeks, they don’t need to keep wearing the device every day,” Dr. Huber noted. Others may wear it in the morning and have a lasting effect for the rest of the day, and some lose any benefit as soon as taking the device off. Not all patients reach a normal speech loudness, “but they’re going to get way better” than where they started, she said.

Available speech therapies

People with Parkinson’s disease (PD) often have reduced vocal loudness, increased speech rate, and slurred articulation. Available speech therapies have included adduction exercises, vocal function exercises, and LSVT LOUD speech training exercises. For some individuals with PD, these behavioral treatments may not carry over into daily life.

The SpeechVive consists of a piece placed into the ear canal and a piece that sits behind the ear, similar to a slightly larger version of a modern hearing aid. It is designed large enough that many patients, who have motor deficits, can don it themselves. Because it is on just one ear, users can hear other people talking and what is going on around them.

Dr. Huber noted several strengths of the device. First, it does not impose any cognitive load on the user because its effect is based on an automatic reflex. Second, little training is necessary. It is easy for the user to put on the device, and many of its beneficial effects occur as soon as it is activated. Third, compliance can be tracked using data stored by the device itself.

In a previous study, she saw that after using the device for 8 weeks, participants used more effective patterns with their respiratory and laryngeal mechanisms to produce louder speech. “It’s not like they’re working super hard after 8 weeks.” She thinks they are just not usually using their speech apparatus in the most efficient manner, and they become more efficient after using the device. They may also not sense how loud they are without it, so it helps patients “recalibrate” a sense of their own voices, something the LSVT LOUD training also does.

Jori Fleisher, MD, a movement disorders neurologist at the New York University Langone Medical Center, commented that the study shows an interesting approach to the common and difficult problem of hypophonia and dysphonia in people with Parkinson’s disease. “It can be very difficult to speak loud enough to be heard, and it often leads to people withdrawing socially and not speaking as much in conversation as they normally would,” she said. “LSVT LOUD works in practice when you’re actually doing the exercises, but often when people stop doing the exercises, their voice goes back toward their normal. So this is something that you can keep with you and sort of have constant prompting to overcome that tendency toward quieter voice. It has a lot of promise.”

She said she would like to see the data on compliance or adherence with using the device “because it seems like a great idea, but how much are people actually using it? ... Having more long-term follow-up to see whether this is something that people want to put into practice in their daily life would be very useful.” She also said she would like to see how long the carry-over effect lasts once people take off the device to be able to compare it with sessions of speech therapy or doing speech exercises.

SpeechVive is $2,495, which includes the device, a charger, and earpiece fittings. It is available only in the United States, but the company now has clearance to market it in Canada.

The research was funded by a grant from SpeechVive. Dr. Huber is the inventor of SpeechVive, has a patent on it, has a financial interest in the SpeechVive company, and sits on its board of directors. Dr. Fleisher reported having no financial conflicts.

AT WPC 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Loudness increased 2.2 dB from 76.6 dB to 78.8 dB after 3 months of use. Intonation also improved.

Data source: A prospective study of 16 participants with hypophonia comparing speech parameters with and without the device after 3 months of use.

Disclosures: The research was funded by a grant from SpeechVive. Dr. Huber is the inventor of SpeechVive, has a patent on it, has a financial interest in the SpeechVive company, and sits on its board of directors. Dr. Fleisher reported having no financial conflicts.

Biopsy scalp area for alopecia diagnosis

BOSTON – Getting a proper scalp biopsy and providing the dermatopathologist with a good supporting history are important elements in diagnosing a patient with hair loss, according to Eleanor Knopp, MD, a dermatologist and dermatopathologist with Group Health Permanente, Seattle.

The keys to a good scalp biopsy in a patient with alopecia are to take an adequate sample of scalp in both size and degree of involvement. With regard to where to biopsy, “it’s important ... to select an area of advanced thinning if you’re doing a biopsy of a nonscarring alopecia,” Dr. Knopp said at the American Academy of Dermatology summer meeting. She advised being “generous” with an anesthetic, preferably one containing epinephrine, to help keep the wound dry and to help with visualization during the procedure.

Evaluating for the presence or absence of follicular ostia with a dermatoscope helps distinguish scarring from nonscarring alopecia. Scarring alopecias typically show loss of follicular ostia, she noted.

While this method is effective at identifying nonscarring areas in white patients, it can be difficult to appreciate the disappearance of follicular ostia with a dermatoscope in patients of African descent or patients with darkly pigmented skin. In these patients, eccrine ostia appear as white pinpoint dots under a dermatoscope and mimic the appearance of follicular ostia, despite the presence of scarring alopecia, she noted.

In this situation, Dr. Knopp said the threshold for biopsying patients with darkly pigmented skin should be lower to rule out an early cicatricial alopecia.

For any specimen sent to the dermatopathologist, it is important to note patient characteristics, including age and race, duration of the condition, and clinical pattern. Not only is race helpful for interpreting what is seen in the specimen, but certain racial groups have higher predilections for certain diseases. There are also differences in normal hair densities depending on race although there can be a wide range even within a race, she added. Providing a photo of the involved area of the scalp is also a good idea, she added.

When biopsying a scarring alopecia, Dr. Knopp said that her preference is to find an area of relatively early thinning with visible erythema, and scale if it is present, “so that you know you have active inflammatory disease, but it’s not so advanced that you’re just seeing end-stage changes of scarring.”

It is worth having a discussion with the dermatopathologist about sectioning specimens, Dr. Knopp said. The consensus among most dermatopathologists is that horizontal sections are “absolutely the way to go for nonscarring alopecias,” but some dermatopathologists strongly prefer vertical sections, especially in cicatricial alopecias. Clinicians can always choose among the many reference laboratories to obtain the type of sections they prefer.

In cases of cicatricial alopecia, Dr. Knopp cautioned that clinicians may see “juicy pustules or fluctuant nodules” and consider these findings indicative of a highly active area of disease, but these changes may obscure early findings that are helpful to a pathologist. A better choice for a biopsy site is an area of early involvement that is not too inflamed and not so advanced that it is just scar, she noted.

Another potential pitfall is the temptation to biopsy a tuft of hairs. If there is polytrichia or compounding of follicles, it may be tempting to fit the punch tool over what are also sometimes called “doll’s hairs.” But those structures are nonspecific, end-stage features of many different cicatricial alopecias, including lichen planopilaris, central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia, and even lupus. Instead, Dr. Knopp recommended taking a specimen at the periphery where compounding is not present but where there is thinning and active inflammation.

Dr. Knopp, also with the University of Washington, Seattle, reported no financial relationships.

BOSTON – Getting a proper scalp biopsy and providing the dermatopathologist with a good supporting history are important elements in diagnosing a patient with hair loss, according to Eleanor Knopp, MD, a dermatologist and dermatopathologist with Group Health Permanente, Seattle.

The keys to a good scalp biopsy in a patient with alopecia are to take an adequate sample of scalp in both size and degree of involvement. With regard to where to biopsy, “it’s important ... to select an area of advanced thinning if you’re doing a biopsy of a nonscarring alopecia,” Dr. Knopp said at the American Academy of Dermatology summer meeting. She advised being “generous” with an anesthetic, preferably one containing epinephrine, to help keep the wound dry and to help with visualization during the procedure.

Evaluating for the presence or absence of follicular ostia with a dermatoscope helps distinguish scarring from nonscarring alopecia. Scarring alopecias typically show loss of follicular ostia, she noted.

While this method is effective at identifying nonscarring areas in white patients, it can be difficult to appreciate the disappearance of follicular ostia with a dermatoscope in patients of African descent or patients with darkly pigmented skin. In these patients, eccrine ostia appear as white pinpoint dots under a dermatoscope and mimic the appearance of follicular ostia, despite the presence of scarring alopecia, she noted.

In this situation, Dr. Knopp said the threshold for biopsying patients with darkly pigmented skin should be lower to rule out an early cicatricial alopecia.

For any specimen sent to the dermatopathologist, it is important to note patient characteristics, including age and race, duration of the condition, and clinical pattern. Not only is race helpful for interpreting what is seen in the specimen, but certain racial groups have higher predilections for certain diseases. There are also differences in normal hair densities depending on race although there can be a wide range even within a race, she added. Providing a photo of the involved area of the scalp is also a good idea, she added.

When biopsying a scarring alopecia, Dr. Knopp said that her preference is to find an area of relatively early thinning with visible erythema, and scale if it is present, “so that you know you have active inflammatory disease, but it’s not so advanced that you’re just seeing end-stage changes of scarring.”

It is worth having a discussion with the dermatopathologist about sectioning specimens, Dr. Knopp said. The consensus among most dermatopathologists is that horizontal sections are “absolutely the way to go for nonscarring alopecias,” but some dermatopathologists strongly prefer vertical sections, especially in cicatricial alopecias. Clinicians can always choose among the many reference laboratories to obtain the type of sections they prefer.

In cases of cicatricial alopecia, Dr. Knopp cautioned that clinicians may see “juicy pustules or fluctuant nodules” and consider these findings indicative of a highly active area of disease, but these changes may obscure early findings that are helpful to a pathologist. A better choice for a biopsy site is an area of early involvement that is not too inflamed and not so advanced that it is just scar, she noted.

Another potential pitfall is the temptation to biopsy a tuft of hairs. If there is polytrichia or compounding of follicles, it may be tempting to fit the punch tool over what are also sometimes called “doll’s hairs.” But those structures are nonspecific, end-stage features of many different cicatricial alopecias, including lichen planopilaris, central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia, and even lupus. Instead, Dr. Knopp recommended taking a specimen at the periphery where compounding is not present but where there is thinning and active inflammation.

Dr. Knopp, also with the University of Washington, Seattle, reported no financial relationships.

BOSTON – Getting a proper scalp biopsy and providing the dermatopathologist with a good supporting history are important elements in diagnosing a patient with hair loss, according to Eleanor Knopp, MD, a dermatologist and dermatopathologist with Group Health Permanente, Seattle.

The keys to a good scalp biopsy in a patient with alopecia are to take an adequate sample of scalp in both size and degree of involvement. With regard to where to biopsy, “it’s important ... to select an area of advanced thinning if you’re doing a biopsy of a nonscarring alopecia,” Dr. Knopp said at the American Academy of Dermatology summer meeting. She advised being “generous” with an anesthetic, preferably one containing epinephrine, to help keep the wound dry and to help with visualization during the procedure.

Evaluating for the presence or absence of follicular ostia with a dermatoscope helps distinguish scarring from nonscarring alopecia. Scarring alopecias typically show loss of follicular ostia, she noted.

While this method is effective at identifying nonscarring areas in white patients, it can be difficult to appreciate the disappearance of follicular ostia with a dermatoscope in patients of African descent or patients with darkly pigmented skin. In these patients, eccrine ostia appear as white pinpoint dots under a dermatoscope and mimic the appearance of follicular ostia, despite the presence of scarring alopecia, she noted.

In this situation, Dr. Knopp said the threshold for biopsying patients with darkly pigmented skin should be lower to rule out an early cicatricial alopecia.

For any specimen sent to the dermatopathologist, it is important to note patient characteristics, including age and race, duration of the condition, and clinical pattern. Not only is race helpful for interpreting what is seen in the specimen, but certain racial groups have higher predilections for certain diseases. There are also differences in normal hair densities depending on race although there can be a wide range even within a race, she added. Providing a photo of the involved area of the scalp is also a good idea, she added.

When biopsying a scarring alopecia, Dr. Knopp said that her preference is to find an area of relatively early thinning with visible erythema, and scale if it is present, “so that you know you have active inflammatory disease, but it’s not so advanced that you’re just seeing end-stage changes of scarring.”

It is worth having a discussion with the dermatopathologist about sectioning specimens, Dr. Knopp said. The consensus among most dermatopathologists is that horizontal sections are “absolutely the way to go for nonscarring alopecias,” but some dermatopathologists strongly prefer vertical sections, especially in cicatricial alopecias. Clinicians can always choose among the many reference laboratories to obtain the type of sections they prefer.

In cases of cicatricial alopecia, Dr. Knopp cautioned that clinicians may see “juicy pustules or fluctuant nodules” and consider these findings indicative of a highly active area of disease, but these changes may obscure early findings that are helpful to a pathologist. A better choice for a biopsy site is an area of early involvement that is not too inflamed and not so advanced that it is just scar, she noted.

Another potential pitfall is the temptation to biopsy a tuft of hairs. If there is polytrichia or compounding of follicles, it may be tempting to fit the punch tool over what are also sometimes called “doll’s hairs.” But those structures are nonspecific, end-stage features of many different cicatricial alopecias, including lichen planopilaris, central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia, and even lupus. Instead, Dr. Knopp recommended taking a specimen at the periphery where compounding is not present but where there is thinning and active inflammation.

Dr. Knopp, also with the University of Washington, Seattle, reported no financial relationships.

Many overweight Parkinson’s patients have insulin resistance

PORTLAND, ORE. – More than half of overweight, nondiabetic people with Parkinson’s disease were insulin resistant even though most had normal fasting glucose and insulin levels in a prospective, observational study, raising concerns about the potential role of insulin resistance in accelerating the progression of neurodegenerative diseases, including certain features of Parkinson’s disease.

Researchers at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles tested 93 patients with Parkinson’s disease to determine the prevalence of undiagnosed insulin resistance (IR). They used the homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) formula, with a HOMA-IR index of 2.0 as a cut-off for abnormal insulin sensitivity. The index is a measure of how much insulin is needed to control blood sugar and uses just blood fasting insulin and glucose levels for the calculation.

Of the 93 patients (71 men), with an average age of 66 years, 9 were diabetic. Of the 84 nondiabetic patients, 49 (58%) had an abnormal HOMA-IR index, ranging from 2.01 to 9.92, which is consistent with IR. Of the 84, 63 were overweight (body mass index [BMI] greater than 25 kg/m2), and 60.3% had IR. Among the 27 nondiabetic, obese patients (BMI greater than 30 kg/m2), 96% had IR. Only 19% of patients with normal BMI had IR. All the nondiabetic subjects with abnormal HOMA-IR who had values available (n = 22) had normal fasting glucose and glycated hemoglobin levels.

The vast majority of subjects with IR had normal fasting glucose and insulin levels. “They’re using too much insulin to control the amount of glucose that they have even though their glucose itself is not abnormal,” Dr. Hogg said. “The relevance of this could be that this may promote some of the degenerative processes that are inherent to Parkinson’s and, more importantly, could potentially offer a reversible target, because if you can identify patients who are insulin resistant, you could, through diet and exercise and lifestyle changes or medications, potentially reverse this and potentially change their path from heading to Parkinson’s or worsening Parkinson’s to something else. That would be the ultimate hope for this research.”

Although overweight is a well known risk factor for insulin resistance, it may be particularly relevant in Parkinson’s disease “because it seems to promote aspects of the disease that could impact not just the motor features of Parkinson’s but also the nonmotor features. We’re most concerned about cognition. ... one of the most feared complications of Parkinson’s and something that we have very little to offer for right now,” Dr. Hogg explained.

He said he plans to look at brain glucose metabolism in Parkinson’s patients without insulin resistance and compare it to similar patients with insulin resistance using PET scanning to see if “these brains are potentially starved of energy.” He cited a British study that showed that exenatide, a glucagonlike peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonist used in diabetes, improved cognition in a treated group. He plans to test liraglutide, another GLP-1 agonist, to see if it will improve or at least stabilize motor or nonmotor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease in insulin-resistant patients.

He suggested that physicians may want to look at insulin and not just measures of blood glucose in appropriate patients.

Jori Fleisher, MD, a movement disorders neurologist at New York University Langone Medical Center in New York, commented that the study indicates that there may be a cohort of patients who are seen routinely but have an undiagnosed risk factor. “Potentially, if we could address it and get their insulin resistance under control, perhaps with weight loss, then we might be able to potentially affect the progression of the Parkinson’s disease,” she said.

As for a mechanism of the effect, she said it is known that there is a “huge role of oxidative stress and apoptosis in the progression of Parkinson’s disease,” and insulin resistance may contribute to it.

She said she would like to see the study replicated in a much larger cohort before routinely adopting insulin measures in clinical practice. If the findings are sufficiently validated, “this is something that seems fairly easy and innocuous to test for.”

Richard Smeyne, PhD, director of the Jefferson Comprehensive Parkinson’s Center at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, speculated that insulin may also have functions in the brain aside from its metabolic effects, specifically, promoting or maintaining neurons through neurotropic effects mediated through the insulinlike growth factor-1 receptors. Still, he cautioned that he would be “hesitant to look at insulin resistance peripherally and make some sort of comment about its relationship to Parkinson’s disease.”

The study was investigator initiated and had no commercial support. Dr. Hogg, Dr. Fleisher, and Dr. Smeyne reported having no financial disclosures.

PORTLAND, ORE. – More than half of overweight, nondiabetic people with Parkinson’s disease were insulin resistant even though most had normal fasting glucose and insulin levels in a prospective, observational study, raising concerns about the potential role of insulin resistance in accelerating the progression of neurodegenerative diseases, including certain features of Parkinson’s disease.

Researchers at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles tested 93 patients with Parkinson’s disease to determine the prevalence of undiagnosed insulin resistance (IR). They used the homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) formula, with a HOMA-IR index of 2.0 as a cut-off for abnormal insulin sensitivity. The index is a measure of how much insulin is needed to control blood sugar and uses just blood fasting insulin and glucose levels for the calculation.

Of the 93 patients (71 men), with an average age of 66 years, 9 were diabetic. Of the 84 nondiabetic patients, 49 (58%) had an abnormal HOMA-IR index, ranging from 2.01 to 9.92, which is consistent with IR. Of the 84, 63 were overweight (body mass index [BMI] greater than 25 kg/m2), and 60.3% had IR. Among the 27 nondiabetic, obese patients (BMI greater than 30 kg/m2), 96% had IR. Only 19% of patients with normal BMI had IR. All the nondiabetic subjects with abnormal HOMA-IR who had values available (n = 22) had normal fasting glucose and glycated hemoglobin levels.

The vast majority of subjects with IR had normal fasting glucose and insulin levels. “They’re using too much insulin to control the amount of glucose that they have even though their glucose itself is not abnormal,” Dr. Hogg said. “The relevance of this could be that this may promote some of the degenerative processes that are inherent to Parkinson’s and, more importantly, could potentially offer a reversible target, because if you can identify patients who are insulin resistant, you could, through diet and exercise and lifestyle changes or medications, potentially reverse this and potentially change their path from heading to Parkinson’s or worsening Parkinson’s to something else. That would be the ultimate hope for this research.”

Although overweight is a well known risk factor for insulin resistance, it may be particularly relevant in Parkinson’s disease “because it seems to promote aspects of the disease that could impact not just the motor features of Parkinson’s but also the nonmotor features. We’re most concerned about cognition. ... one of the most feared complications of Parkinson’s and something that we have very little to offer for right now,” Dr. Hogg explained.

He said he plans to look at brain glucose metabolism in Parkinson’s patients without insulin resistance and compare it to similar patients with insulin resistance using PET scanning to see if “these brains are potentially starved of energy.” He cited a British study that showed that exenatide, a glucagonlike peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonist used in diabetes, improved cognition in a treated group. He plans to test liraglutide, another GLP-1 agonist, to see if it will improve or at least stabilize motor or nonmotor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease in insulin-resistant patients.

He suggested that physicians may want to look at insulin and not just measures of blood glucose in appropriate patients.

Jori Fleisher, MD, a movement disorders neurologist at New York University Langone Medical Center in New York, commented that the study indicates that there may be a cohort of patients who are seen routinely but have an undiagnosed risk factor. “Potentially, if we could address it and get their insulin resistance under control, perhaps with weight loss, then we might be able to potentially affect the progression of the Parkinson’s disease,” she said.

As for a mechanism of the effect, she said it is known that there is a “huge role of oxidative stress and apoptosis in the progression of Parkinson’s disease,” and insulin resistance may contribute to it.

She said she would like to see the study replicated in a much larger cohort before routinely adopting insulin measures in clinical practice. If the findings are sufficiently validated, “this is something that seems fairly easy and innocuous to test for.”

Richard Smeyne, PhD, director of the Jefferson Comprehensive Parkinson’s Center at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, speculated that insulin may also have functions in the brain aside from its metabolic effects, specifically, promoting or maintaining neurons through neurotropic effects mediated through the insulinlike growth factor-1 receptors. Still, he cautioned that he would be “hesitant to look at insulin resistance peripherally and make some sort of comment about its relationship to Parkinson’s disease.”

The study was investigator initiated and had no commercial support. Dr. Hogg, Dr. Fleisher, and Dr. Smeyne reported having no financial disclosures.

PORTLAND, ORE. – More than half of overweight, nondiabetic people with Parkinson’s disease were insulin resistant even though most had normal fasting glucose and insulin levels in a prospective, observational study, raising concerns about the potential role of insulin resistance in accelerating the progression of neurodegenerative diseases, including certain features of Parkinson’s disease.

Researchers at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles tested 93 patients with Parkinson’s disease to determine the prevalence of undiagnosed insulin resistance (IR). They used the homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) formula, with a HOMA-IR index of 2.0 as a cut-off for abnormal insulin sensitivity. The index is a measure of how much insulin is needed to control blood sugar and uses just blood fasting insulin and glucose levels for the calculation.

Of the 93 patients (71 men), with an average age of 66 years, 9 were diabetic. Of the 84 nondiabetic patients, 49 (58%) had an abnormal HOMA-IR index, ranging from 2.01 to 9.92, which is consistent with IR. Of the 84, 63 were overweight (body mass index [BMI] greater than 25 kg/m2), and 60.3% had IR. Among the 27 nondiabetic, obese patients (BMI greater than 30 kg/m2), 96% had IR. Only 19% of patients with normal BMI had IR. All the nondiabetic subjects with abnormal HOMA-IR who had values available (n = 22) had normal fasting glucose and glycated hemoglobin levels.

The vast majority of subjects with IR had normal fasting glucose and insulin levels. “They’re using too much insulin to control the amount of glucose that they have even though their glucose itself is not abnormal,” Dr. Hogg said. “The relevance of this could be that this may promote some of the degenerative processes that are inherent to Parkinson’s and, more importantly, could potentially offer a reversible target, because if you can identify patients who are insulin resistant, you could, through diet and exercise and lifestyle changes or medications, potentially reverse this and potentially change their path from heading to Parkinson’s or worsening Parkinson’s to something else. That would be the ultimate hope for this research.”

Although overweight is a well known risk factor for insulin resistance, it may be particularly relevant in Parkinson’s disease “because it seems to promote aspects of the disease that could impact not just the motor features of Parkinson’s but also the nonmotor features. We’re most concerned about cognition. ... one of the most feared complications of Parkinson’s and something that we have very little to offer for right now,” Dr. Hogg explained.

He said he plans to look at brain glucose metabolism in Parkinson’s patients without insulin resistance and compare it to similar patients with insulin resistance using PET scanning to see if “these brains are potentially starved of energy.” He cited a British study that showed that exenatide, a glucagonlike peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonist used in diabetes, improved cognition in a treated group. He plans to test liraglutide, another GLP-1 agonist, to see if it will improve or at least stabilize motor or nonmotor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease in insulin-resistant patients.

He suggested that physicians may want to look at insulin and not just measures of blood glucose in appropriate patients.

Jori Fleisher, MD, a movement disorders neurologist at New York University Langone Medical Center in New York, commented that the study indicates that there may be a cohort of patients who are seen routinely but have an undiagnosed risk factor. “Potentially, if we could address it and get their insulin resistance under control, perhaps with weight loss, then we might be able to potentially affect the progression of the Parkinson’s disease,” she said.

As for a mechanism of the effect, she said it is known that there is a “huge role of oxidative stress and apoptosis in the progression of Parkinson’s disease,” and insulin resistance may contribute to it.

She said she would like to see the study replicated in a much larger cohort before routinely adopting insulin measures in clinical practice. If the findings are sufficiently validated, “this is something that seems fairly easy and innocuous to test for.”

Richard Smeyne, PhD, director of the Jefferson Comprehensive Parkinson’s Center at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, speculated that insulin may also have functions in the brain aside from its metabolic effects, specifically, promoting or maintaining neurons through neurotropic effects mediated through the insulinlike growth factor-1 receptors. Still, he cautioned that he would be “hesitant to look at insulin resistance peripherally and make some sort of comment about its relationship to Parkinson’s disease.”

The study was investigator initiated and had no commercial support. Dr. Hogg, Dr. Fleisher, and Dr. Smeyne reported having no financial disclosures.

AT WPC 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Among 84 nondiabetic, Parkinson’s patients, 58% had insulin resistance, although their blood glucose and insulin levels were not abnormal.

Data source: Prospective, observational study of a total of 93 Parkinson’s patients.

Disclosures: The study was investigator initiated and had no commercial support. Dr. Hogg, Dr. Fleisher, and Dr. Smeyne reported having no financial disclosures.

Biomarkers predict Parkinson’s among high-risk individuals

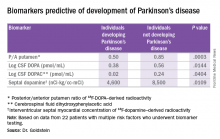

PORTLAND, ORE. – The presence of at least three out of four chemical biomarkers can predict the development of Parkinson’s disease at 3 years of follow-up in people with multiple risk factors for the disease, according to David Goldstein, MD.

These biomarkers, found in the cerebrospinal fluid and in the heart, represent catecholaminergic neurodegeneration.

The PDRisk study of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) is investigating whether individuals with at least three out of four statistical risk factors for Parkinson’s disease (PD) develop the disease, based on chemical biomarkers of neurodegeneration. The risk factors are family history of the disease, olfactory dysfunction, dream enactment behavior, and orthostatic hypotension. The biomarkers are PET neuroimaging or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) neurochemical indicators of catecholamine deficiency in the brain or heart. All the biomarkers are related to dopamine, its precursor, or its metabolites.

Four individuals out of the 22 reached the primary endpoint, which was a diagnosis of PD by a neurologist unaware of the biomarker data. Two of the four individuals with PD also had Lewy body dementia.

“All of the people who went on to convert [to PD], all of them, had at least three of those biomarkers positive. And among the 18 who so far haven’t developed Parkinson’s, none of them had three or more biomarkers. Most of them had none,” said Dr. Goldstein, director of the clinical neurocardiology section at the NINDS. He presented this first look at the PDRisk Study outcome data at the World Parkinson Congress.

Among 10 healthy control subjects without any risk factors for PD, 1 had two positive biomarkers, and the rest had none. Individuals who converted to PD could be distinguished from those who did not by low values for the posterior/anterior ratio of putamen 18F-DOPA–derived radioactivity, CSF DOPA, CSF 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC, a metabolite of dopamine), and septal myocardial 18F-dopamine-derived radioactivity. Almost 20 years ago, Dr. Goldstein found that there is a substantial loss of sympathetic noradrenergic nerves in the heart in PD.

He has weighted all the biomarkers as if they had equal contributions, which “is not fair,” he said. All four biomarkers were predictive on their own, but some were more potent than others, notably the ratio of DOPA in the anterior to posterior putamen and low values for DOPA in the CSF. He noted that this finding is the first time CSF DOPA has been documented as a biomarker for the development of PD.

The question remains about what to do with these predictors of PD if they are validated. Dr. Goldstein said they could be used to track the efficacy of any intervention to slow the decline to PD.

The study was run by the NINDS and had no outside support. Dr. Goldstein is a U.S. government employee and reported having no financial disclosures.

PORTLAND, ORE. – The presence of at least three out of four chemical biomarkers can predict the development of Parkinson’s disease at 3 years of follow-up in people with multiple risk factors for the disease, according to David Goldstein, MD.

These biomarkers, found in the cerebrospinal fluid and in the heart, represent catecholaminergic neurodegeneration.

The PDRisk study of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) is investigating whether individuals with at least three out of four statistical risk factors for Parkinson’s disease (PD) develop the disease, based on chemical biomarkers of neurodegeneration. The risk factors are family history of the disease, olfactory dysfunction, dream enactment behavior, and orthostatic hypotension. The biomarkers are PET neuroimaging or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) neurochemical indicators of catecholamine deficiency in the brain or heart. All the biomarkers are related to dopamine, its precursor, or its metabolites.

Four individuals out of the 22 reached the primary endpoint, which was a diagnosis of PD by a neurologist unaware of the biomarker data. Two of the four individuals with PD also had Lewy body dementia.

“All of the people who went on to convert [to PD], all of them, had at least three of those biomarkers positive. And among the 18 who so far haven’t developed Parkinson’s, none of them had three or more biomarkers. Most of them had none,” said Dr. Goldstein, director of the clinical neurocardiology section at the NINDS. He presented this first look at the PDRisk Study outcome data at the World Parkinson Congress.

Among 10 healthy control subjects without any risk factors for PD, 1 had two positive biomarkers, and the rest had none. Individuals who converted to PD could be distinguished from those who did not by low values for the posterior/anterior ratio of putamen 18F-DOPA–derived radioactivity, CSF DOPA, CSF 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC, a metabolite of dopamine), and septal myocardial 18F-dopamine-derived radioactivity. Almost 20 years ago, Dr. Goldstein found that there is a substantial loss of sympathetic noradrenergic nerves in the heart in PD.

He has weighted all the biomarkers as if they had equal contributions, which “is not fair,” he said. All four biomarkers were predictive on their own, but some were more potent than others, notably the ratio of DOPA in the anterior to posterior putamen and low values for DOPA in the CSF. He noted that this finding is the first time CSF DOPA has been documented as a biomarker for the development of PD.

The question remains about what to do with these predictors of PD if they are validated. Dr. Goldstein said they could be used to track the efficacy of any intervention to slow the decline to PD.

The study was run by the NINDS and had no outside support. Dr. Goldstein is a U.S. government employee and reported having no financial disclosures.

PORTLAND, ORE. – The presence of at least three out of four chemical biomarkers can predict the development of Parkinson’s disease at 3 years of follow-up in people with multiple risk factors for the disease, according to David Goldstein, MD.

These biomarkers, found in the cerebrospinal fluid and in the heart, represent catecholaminergic neurodegeneration.

The PDRisk study of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) is investigating whether individuals with at least three out of four statistical risk factors for Parkinson’s disease (PD) develop the disease, based on chemical biomarkers of neurodegeneration. The risk factors are family history of the disease, olfactory dysfunction, dream enactment behavior, and orthostatic hypotension. The biomarkers are PET neuroimaging or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) neurochemical indicators of catecholamine deficiency in the brain or heart. All the biomarkers are related to dopamine, its precursor, or its metabolites.

Four individuals out of the 22 reached the primary endpoint, which was a diagnosis of PD by a neurologist unaware of the biomarker data. Two of the four individuals with PD also had Lewy body dementia.

“All of the people who went on to convert [to PD], all of them, had at least three of those biomarkers positive. And among the 18 who so far haven’t developed Parkinson’s, none of them had three or more biomarkers. Most of them had none,” said Dr. Goldstein, director of the clinical neurocardiology section at the NINDS. He presented this first look at the PDRisk Study outcome data at the World Parkinson Congress.

Among 10 healthy control subjects without any risk factors for PD, 1 had two positive biomarkers, and the rest had none. Individuals who converted to PD could be distinguished from those who did not by low values for the posterior/anterior ratio of putamen 18F-DOPA–derived radioactivity, CSF DOPA, CSF 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC, a metabolite of dopamine), and septal myocardial 18F-dopamine-derived radioactivity. Almost 20 years ago, Dr. Goldstein found that there is a substantial loss of sympathetic noradrenergic nerves in the heart in PD.

He has weighted all the biomarkers as if they had equal contributions, which “is not fair,” he said. All four biomarkers were predictive on their own, but some were more potent than others, notably the ratio of DOPA in the anterior to posterior putamen and low values for DOPA in the CSF. He noted that this finding is the first time CSF DOPA has been documented as a biomarker for the development of PD.

The question remains about what to do with these predictors of PD if they are validated. Dr. Goldstein said they could be used to track the efficacy of any intervention to slow the decline to PD.

The study was run by the NINDS and had no outside support. Dr. Goldstein is a U.S. government employee and reported having no financial disclosures.

AT WPC 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Among 22 individuals followed for at least 3 years, biomarkers were 100% positively or negatively predictive of developing Parkinson’s disease.

Data source: A prospective cohort study of 3,176 individuals supplying risk factor data, of whom 31 had three or more risk factors and biomarkers testing, and of whom 22 were followed for at least 3 years.

Disclosures: The study was run by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and had no outside support. Dr. Goldstein is a U.S. government employee and reported having no financial disclosures.

Asleep deep brain stimulation placement offers advantages in Parkinson’s

PORTLAND, ORE. – Performing deep brain stimulation surgery for Parkinson’s disease using intraoperative CT imaging while the patient is under general anesthesia had clinical advantages and no disadvantages over surgery using microelectrode recording for lead placement with the patient awake, in a prospective, open-label study of 64 patients.

Regarding motor outcomes after asleep surgery, “We found that it was noninferior, so in other words, the change in scores following surgery were the same for asleep and awake patients,” physician assistant and study coauthor Shannon Anderson said during a poster session at the World Parkinson Congress. “What was surprising to us was that verbal fluency ... the ability to come up with the right word, actually improved in our asleep DBS [deep brain stimulation] group, which is a huge complication for patients [and] has a really negative impact on their life.”

Patients with Parkinson’s disease and motor complications (n = 64) were enrolled prospectively at the Oregon Health & Science University in Portland. Thirty received asleep procedures under general anesthesia with ICT guidance for lead targeting to the globus pallidus pars interna (GPi; n = 21) or to the subthalamic nucleus (STN; n = 9). Thirty-four patients received DBS devices with MER guidance (15 STN; 19 GPi). At baseline, the two groups were similar in age (mean 61.1-62.7 years) and off-medication motor subscale scores of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (mUPDRS; mean 43.0-43.5). The university investigators optimized the DBS parameters at 1, 2, 3, and 6 months after implantation. The same surgeon performed all the procedures at the same medical center.

Motor improvements were similar between the asleep and awake cohorts. At 6 months, the ICT (asleep) group experienced a mean improvement in motor abilities of 14.3 (plus or minus 10.88) on the mUPDRS off-medication and on DBS, compared with an improvement of 17.6 (plus or minus 12.26) for the MER (awake) group (P = .25).

Better language measures with asleep DBS

Asleep DBS with ICT resulted in improvements in aspects of language, whereas awake patients lost language abilities. The asleep group showed a 0.8-point increase in phonemic fluency and a 1.0-point increase in semantic fluency at 6 months versus a worsening on both language measures (–3.5 points and –4.7 points, respectively; both P less than .001) if DBS was performed via MER on awake patients.

Although both cohorts showed significant improvements on the 39-item Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire at 6 months, the cohorts did not differ in their degrees of improvement. Similarly, both had improvements on scores of activities of daily living, and both cohorts had a 4-4.5 hours/day increase in “on” time without dyskinesia and a 2.6-3.5 hours/day decrease in “on” time with dyskinesia.

Patients tolerated asleep DBS well, and there were no serious complications.

The sleep surgery is much shorter, “so it’s about 2 hours long as opposed to 4, 5, sometimes 8, 10 hours with the awake. There [are fewer] complications, so less risk of hemorrhage or seizures or things like that,” Ms. Anderson said. “In a separate study, we found that it’s a much more accurate placement of the electrodes so the target is much more accurate. So, all of those things considered, we feel the asleep version is definitely the superior choice between the two.”

Being asleep is much more comfortable for the patient, added study leader Matthew Brodsky, MD. “But the biggest advantage is that it’s a single pass into the brain as opposed to multiple passes.” The average number of passes using MER is two to three per side of the brain, and in some centers, four or more. “Problems such as speech prosody are related to pokes in the brain, if you will, rather than stimulation,” he said.

Ms. Anderson said MER “is a fantastic research tool, and it gives us a lot of information on the electrophysiology, but really, there’s no need for it in the clinical application of DBS.”

Based on the asleep procedure’s accuracy, lower rate of complications, shorter operating room time, and noninferiority in terms of motor outcomes, she said, “Our recommendation is that more centers, more neurosurgeons be trained in this technique ... We’d like to see the clinical field move toward that area and really reserve microelectrode recording for the research side of things.”

“If you talk to folks who are considering brain surgery for their Parkinson’s, for some of them, the idea of being awake in the operating room and undergoing this is a barrier that they can’t quite overcome,” Dr. Brodsky said. “So, having this as an option makes it easier for them to sign up for the process.”

Richard Smeyne, PhD, director of the Jefferson Comprehensive Parkinson’s Center at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, said that the asleep procedure is the newer one and can target either the GPi or the STN. “The asleep DBS seems to have a little bit better improvement on speech afterwards than the awake DBS, and there could be several causes of this,” he said. “Some might be operative in that you can make smaller holes, you can get really nice guidance, you don’t have to sort of move around as in the awake DBS.”

In addition, CT scanning with the patients asleep in the operating room allows more time in the scanner and greater precision in anatomical placement of the DBS leads.

“If I had to choose, looking at this particular study, it would suggest that the asleep DBS is actually a better overall way to go,” Dr. Smeyne said. However, he had no objection to awake procedures “if the neurosurgeon has a record of good results with it ... But if you have the option ... that becomes an individual choice that you should discuss with the neurosurgeon.”

Some of the work presented in the study was supported by a research grant from Medtronic. Ms. Anderson and Dr. Brodsky reported having no other financial disclosures. Dr. Smeyne reported having no financial disclosures.

PORTLAND, ORE. – Performing deep brain stimulation surgery for Parkinson’s disease using intraoperative CT imaging while the patient is under general anesthesia had clinical advantages and no disadvantages over surgery using microelectrode recording for lead placement with the patient awake, in a prospective, open-label study of 64 patients.

Regarding motor outcomes after asleep surgery, “We found that it was noninferior, so in other words, the change in scores following surgery were the same for asleep and awake patients,” physician assistant and study coauthor Shannon Anderson said during a poster session at the World Parkinson Congress. “What was surprising to us was that verbal fluency ... the ability to come up with the right word, actually improved in our asleep DBS [deep brain stimulation] group, which is a huge complication for patients [and] has a really negative impact on their life.”

Patients with Parkinson’s disease and motor complications (n = 64) were enrolled prospectively at the Oregon Health & Science University in Portland. Thirty received asleep procedures under general anesthesia with ICT guidance for lead targeting to the globus pallidus pars interna (GPi; n = 21) or to the subthalamic nucleus (STN; n = 9). Thirty-four patients received DBS devices with MER guidance (15 STN; 19 GPi). At baseline, the two groups were similar in age (mean 61.1-62.7 years) and off-medication motor subscale scores of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (mUPDRS; mean 43.0-43.5). The university investigators optimized the DBS parameters at 1, 2, 3, and 6 months after implantation. The same surgeon performed all the procedures at the same medical center.

Motor improvements were similar between the asleep and awake cohorts. At 6 months, the ICT (asleep) group experienced a mean improvement in motor abilities of 14.3 (plus or minus 10.88) on the mUPDRS off-medication and on DBS, compared with an improvement of 17.6 (plus or minus 12.26) for the MER (awake) group (P = .25).

Better language measures with asleep DBS

Asleep DBS with ICT resulted in improvements in aspects of language, whereas awake patients lost language abilities. The asleep group showed a 0.8-point increase in phonemic fluency and a 1.0-point increase in semantic fluency at 6 months versus a worsening on both language measures (–3.5 points and –4.7 points, respectively; both P less than .001) if DBS was performed via MER on awake patients.

Although both cohorts showed significant improvements on the 39-item Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire at 6 months, the cohorts did not differ in their degrees of improvement. Similarly, both had improvements on scores of activities of daily living, and both cohorts had a 4-4.5 hours/day increase in “on” time without dyskinesia and a 2.6-3.5 hours/day decrease in “on” time with dyskinesia.

Patients tolerated asleep DBS well, and there were no serious complications.

The sleep surgery is much shorter, “so it’s about 2 hours long as opposed to 4, 5, sometimes 8, 10 hours with the awake. There [are fewer] complications, so less risk of hemorrhage or seizures or things like that,” Ms. Anderson said. “In a separate study, we found that it’s a much more accurate placement of the electrodes so the target is much more accurate. So, all of those things considered, we feel the asleep version is definitely the superior choice between the two.”

Being asleep is much more comfortable for the patient, added study leader Matthew Brodsky, MD. “But the biggest advantage is that it’s a single pass into the brain as opposed to multiple passes.” The average number of passes using MER is two to three per side of the brain, and in some centers, four or more. “Problems such as speech prosody are related to pokes in the brain, if you will, rather than stimulation,” he said.

Ms. Anderson said MER “is a fantastic research tool, and it gives us a lot of information on the electrophysiology, but really, there’s no need for it in the clinical application of DBS.”

Based on the asleep procedure’s accuracy, lower rate of complications, shorter operating room time, and noninferiority in terms of motor outcomes, she said, “Our recommendation is that more centers, more neurosurgeons be trained in this technique ... We’d like to see the clinical field move toward that area and really reserve microelectrode recording for the research side of things.”

“If you talk to folks who are considering brain surgery for their Parkinson’s, for some of them, the idea of being awake in the operating room and undergoing this is a barrier that they can’t quite overcome,” Dr. Brodsky said. “So, having this as an option makes it easier for them to sign up for the process.”

Richard Smeyne, PhD, director of the Jefferson Comprehensive Parkinson’s Center at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, said that the asleep procedure is the newer one and can target either the GPi or the STN. “The asleep DBS seems to have a little bit better improvement on speech afterwards than the awake DBS, and there could be several causes of this,” he said. “Some might be operative in that you can make smaller holes, you can get really nice guidance, you don’t have to sort of move around as in the awake DBS.”

In addition, CT scanning with the patients asleep in the operating room allows more time in the scanner and greater precision in anatomical placement of the DBS leads.

“If I had to choose, looking at this particular study, it would suggest that the asleep DBS is actually a better overall way to go,” Dr. Smeyne said. However, he had no objection to awake procedures “if the neurosurgeon has a record of good results with it ... But if you have the option ... that becomes an individual choice that you should discuss with the neurosurgeon.”

Some of the work presented in the study was supported by a research grant from Medtronic. Ms. Anderson and Dr. Brodsky reported having no other financial disclosures. Dr. Smeyne reported having no financial disclosures.

PORTLAND, ORE. – Performing deep brain stimulation surgery for Parkinson’s disease using intraoperative CT imaging while the patient is under general anesthesia had clinical advantages and no disadvantages over surgery using microelectrode recording for lead placement with the patient awake, in a prospective, open-label study of 64 patients.

Regarding motor outcomes after asleep surgery, “We found that it was noninferior, so in other words, the change in scores following surgery were the same for asleep and awake patients,” physician assistant and study coauthor Shannon Anderson said during a poster session at the World Parkinson Congress. “What was surprising to us was that verbal fluency ... the ability to come up with the right word, actually improved in our asleep DBS [deep brain stimulation] group, which is a huge complication for patients [and] has a really negative impact on their life.”

Patients with Parkinson’s disease and motor complications (n = 64) were enrolled prospectively at the Oregon Health & Science University in Portland. Thirty received asleep procedures under general anesthesia with ICT guidance for lead targeting to the globus pallidus pars interna (GPi; n = 21) or to the subthalamic nucleus (STN; n = 9). Thirty-four patients received DBS devices with MER guidance (15 STN; 19 GPi). At baseline, the two groups were similar in age (mean 61.1-62.7 years) and off-medication motor subscale scores of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (mUPDRS; mean 43.0-43.5). The university investigators optimized the DBS parameters at 1, 2, 3, and 6 months after implantation. The same surgeon performed all the procedures at the same medical center.

Motor improvements were similar between the asleep and awake cohorts. At 6 months, the ICT (asleep) group experienced a mean improvement in motor abilities of 14.3 (plus or minus 10.88) on the mUPDRS off-medication and on DBS, compared with an improvement of 17.6 (plus or minus 12.26) for the MER (awake) group (P = .25).

Better language measures with asleep DBS

Asleep DBS with ICT resulted in improvements in aspects of language, whereas awake patients lost language abilities. The asleep group showed a 0.8-point increase in phonemic fluency and a 1.0-point increase in semantic fluency at 6 months versus a worsening on both language measures (–3.5 points and –4.7 points, respectively; both P less than .001) if DBS was performed via MER on awake patients.

Although both cohorts showed significant improvements on the 39-item Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire at 6 months, the cohorts did not differ in their degrees of improvement. Similarly, both had improvements on scores of activities of daily living, and both cohorts had a 4-4.5 hours/day increase in “on” time without dyskinesia and a 2.6-3.5 hours/day decrease in “on” time with dyskinesia.

Patients tolerated asleep DBS well, and there were no serious complications.

The sleep surgery is much shorter, “so it’s about 2 hours long as opposed to 4, 5, sometimes 8, 10 hours with the awake. There [are fewer] complications, so less risk of hemorrhage or seizures or things like that,” Ms. Anderson said. “In a separate study, we found that it’s a much more accurate placement of the electrodes so the target is much more accurate. So, all of those things considered, we feel the asleep version is definitely the superior choice between the two.”

Being asleep is much more comfortable for the patient, added study leader Matthew Brodsky, MD. “But the biggest advantage is that it’s a single pass into the brain as opposed to multiple passes.” The average number of passes using MER is two to three per side of the brain, and in some centers, four or more. “Problems such as speech prosody are related to pokes in the brain, if you will, rather than stimulation,” he said.

Ms. Anderson said MER “is a fantastic research tool, and it gives us a lot of information on the electrophysiology, but really, there’s no need for it in the clinical application of DBS.”

Based on the asleep procedure’s accuracy, lower rate of complications, shorter operating room time, and noninferiority in terms of motor outcomes, she said, “Our recommendation is that more centers, more neurosurgeons be trained in this technique ... We’d like to see the clinical field move toward that area and really reserve microelectrode recording for the research side of things.”

“If you talk to folks who are considering brain surgery for their Parkinson’s, for some of them, the idea of being awake in the operating room and undergoing this is a barrier that they can’t quite overcome,” Dr. Brodsky said. “So, having this as an option makes it easier for them to sign up for the process.”

Richard Smeyne, PhD, director of the Jefferson Comprehensive Parkinson’s Center at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, said that the asleep procedure is the newer one and can target either the GPi or the STN. “The asleep DBS seems to have a little bit better improvement on speech afterwards than the awake DBS, and there could be several causes of this,” he said. “Some might be operative in that you can make smaller holes, you can get really nice guidance, you don’t have to sort of move around as in the awake DBS.”

In addition, CT scanning with the patients asleep in the operating room allows more time in the scanner and greater precision in anatomical placement of the DBS leads.

“If I had to choose, looking at this particular study, it would suggest that the asleep DBS is actually a better overall way to go,” Dr. Smeyne said. However, he had no objection to awake procedures “if the neurosurgeon has a record of good results with it ... But if you have the option ... that becomes an individual choice that you should discuss with the neurosurgeon.”

Some of the work presented in the study was supported by a research grant from Medtronic. Ms. Anderson and Dr. Brodsky reported having no other financial disclosures. Dr. Smeyne reported having no financial disclosures.

AT WPC 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The asleep group showed a 0.8-point increase in phonemic fluency and a 1.0-point increase in semantic fluency at 6 months versus a worsening on both language measures (–3.5 points and –4.7 points, respectively; both P less than .001) if DBS was performed via MER on awake patients.

Data source: Prospective, open-label study of 64 patients receiving either awake or asleep deep brain stimulation placement.

Disclosures: Some of the work presented in the study was supported by a research grant from Medtronic. Ms. Anderson and Dr. Brodsky reported having no other financial disclosures. Dr. Smeyne reported having no financial disclosures.

Acne and diet: Still no solid basis for dietary recommendations

BOSTON – For years, much of the information that has circulated about the relationship of diet to acne has been inconsistent. And while recent studies have pointed to two aggravating factors – foods with a high glycemic index and skim milk – whether dietary changes can help control acne remains up in the air, according to Andrea Zaenglein, MD.

At the American Academy of Dermatology summer meeting, Dr. Zaenglein, professor of dermatology and pediatrics, Penn State University, Hershey, reviewed information about diet and acne dating back to the early 1930s, when reports suggested an increased risk of acne in people who were glucose intolerant. Subsequent studies looked at the role of dairy, carbohydrate, chloride, saturated and total fats, sugar, and chocolate in acne. Researchers found no acne in a study of natives of Kitava, an island in Papua New Guinea, whose diet consisted mostly of roots, coconut, fruit, and fish (Arch Dermatol. 2002;138[12]:1584-90). But genetics certainly appears to play a dominant role in acne, Dr. Zaenglein said, referring to a large twin study that found that in 81% of the population with acne, it was due to genetic factors, and in 19% it was due to environmental factors (J Invest Dermatol. 2002 Dec;119[6]:1317-22).

For now, Dr. Zaenglein’s advice is to recommend a low glycemic index diet mainly of fruits and vegetables and low in saturated fats and sugars, which may ameliorate acne by decreasing weight and insulin resistance – especially in patients who already have abnormal metabolic parameters. Patients should also be advised to limit processed foods, meat, and dairy, she added.

As far as dairy and acne, it is too early to say what the impact of intervention would be “because we don’t have any great interventional studies that have been done,” she said. Moreover, it is unclear how early dietary interventions would need to be started to reduce an individual’s risk of acne, she added.“It could go all the way back to things that happened when you were born that influence your outcome,” Dr. Zaenglein said. For example, babies born prematurely are at greater risk for endocrine stressors, which lead to premature adrenarche, increasing their risk for acne, she noted.

“We really need new, better intervention studies to be able to give advice to our patients,” she said. However, conducting such studies is challenging because it is difficult for people to eliminate dairy or other types of food from their diets for a prolonged period. To date, the majority of dietary studies have been observational and have relied on subjects’ recall of what they consumed, so these studies have their own inherent problems, she added.Dr. Zaenglein’s disclosures include serving as an adviser to Anacor Pharmaceuticals and Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, and serving as an investigator and receiving grants/research funding from Anacor, Astellas Pharma US, Ranbaxy Laboratories Limited, and Stiefel, a GSK company.

BOSTON – For years, much of the information that has circulated about the relationship of diet to acne has been inconsistent. And while recent studies have pointed to two aggravating factors – foods with a high glycemic index and skim milk – whether dietary changes can help control acne remains up in the air, according to Andrea Zaenglein, MD.