User login

Training Lifeguards to Assist in Skin Cancer Prevention

Training Lifeguards to Assist in Skin Cancer Prevention

Lifeguards play a crucial role in ensuring water safety, but they also are uniquely positioned to promote skin cancer prevention and proper sunscreen use.1,2 There are several benefits and challenges to offering skin cancer prevention training for lifeguards.3 We examine the advantages of training, highlight the role lifeguards can play in larger public skin cancer prevention efforts, and address practical techniques for developing lifeguardfocused skin cancer education programs. By providing this knowledge to lifeguards, we can improve community health outcomes and encourage sun-safe behaviors in high-risk outdoor locations.

Benefits of Skin Cancer Prevention Training for Lifeguards

Research has shown that lifeguards are at an elevated risk for basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and melanoma due to frequent prolonged occupational sun exposure.1,2,4-6 Therefore, comprehensive education on skin cancer prevention—including instruction on proper sunscreen application techniques and the importance of regular reapplication as well as how to recognize suspicious skin lesions—should be incorporated into lifeguard certification programs. One study evaluating the effectiveness of a skin cancer prevention program for lifeguards found that many of the participants lacked a thorough understanding of the different types of skin cancer.5 Another study found that lifeguards at pools in areas where societal norms supporting sun safety are stronger exhibited noticeably more sun protection practices, with regression estimates of 0.22 (95% CI, 0.17-0.26).7 Empowering lifeguards with valuable health knowledge during their regular training could potentially reduce their risk for skin cancer,4 as they may be more inclined to use sunscreen appropriately and reach out to a dermatologist for regular skin checks and evaluation of suspicious lesions.

Role of Lifeguards in Public Skin Cancer Prevention Efforts

Once trained on skin cancer prevention, lifeguards also can play a pivotal role in promoting sunscreen use among the public. Despite the widespread availability of high-quality sunscreens, many swimmers and beachgoers neglect to regularly apply or reapply sunscreen, especially on commonly exposed areas such as the back, shoulders, and face.8 Educating lifeguards on skin cancer prevention could enhance health outcomes by increasing early detection rates and promoting sun-safe behaviors among the general public.9 However, additional training requirements might increase the cost and time commitment for lifeguard certification, potentially leading to staffing shortages.3,7 There also is a risk of lifeguards overstepping their role and providing inaccurate medical advice, which could cause distress or even lead to liability issues.7 Balancing these factors will be crucial in developing effective and sustainable skin cancer prevention programs for lifeguards.

Implementing Lifeguard Skin Cancer Training

Implementing skin cancer prevention training programs for lifeguards requires strategic collaboration between dermatologists, and lifeguard training organizations to ensure that the participants receive consistent and comprehensive training.10 Additionally, public health campaigns can support these efforts by raising awareness about the importance of sun safety and regular skin checks.6 Tailored training modules/materials, ongoing technical assistance, and active, multicomponent approaches that account for both individual and environmental factors can increase program implementation in a variety of community settings.

Final Thoughts

Through effective education, lifeguards can potentially have a substantial impact on skin cancer prevention, both among lifeguards themselves and the general public. By promoting proper sunscreen use, lifeguards can help reduce the incidence and mortality associated with skin cancers. Future studies should focus on developing and implementing targeted education initiatives for lifeguards, fostering collaboration between relevant stakeholders, and raising public awareness about the importance of sun safety and early skin cancer detection. These efforts ultimately could lead to improved public health outcomes and reduced skin cancer rates, particularly in high-risk populations that frequently are exposed to UV radiation.

- Enos CW, Rey S, Slocum J, et al. Sun-protection behaviors among active members of the United States Lifesaving Association. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14:14-20.

- Verma K, Lewis DJ, Siddiqui FS, et al. Mohs micrographic surgery management of melanoma and melanoma in situ. StatPearls. Updated August 28, 2024. Accessed April 15, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK606123/

- Verma KK, Joshi TP, Lewis DJ, et al. Nail technicians as partners in early melanoma detection: bridging the knowledge gap. Arch Dermatol Res. 2024;316:586. doi:10.1007/s00403-024-03342-0

- Geller AC, Glanz K, Shigaki D, et al. Impact of skin cancer prevention on outdoor aquatics staff: the Pool Cool program in Hawaii and Massachusetts. Prev Med. 2001;33:155-161. doi:10.1006/pmed.2001.0870

- Hiemstra M, Glanz K, Nehl E. Changes in sunburn and tanning attitudes among lifeguards over a summer season. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:430-437. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.11.050

- Verma KK, Ahmad N, Friedmann DP, et al. Melanoma in tattooed skin: diagnostic challenges and the potential for tattoo artists in early detection. Arch Dermatol Res. 2024;316:690. doi:10.1007/s00403-024-03415-0

- Hall DM, McCarty F, Elliott T, et al. Lifeguards’ sun protection habits and sunburns: association with sun-safe environments and skin cancer prevention program participation. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:139-144. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2008.553

- Emmons KM, Geller AC, Puleo E, et al. Skin cancer education and early detection at the beach: a randomized trial of dermatologist examination and biometric feedback. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:282-289. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.01.040

- Rabin BA, Nehl E, Elliott T, et al. Individual and setting level predictors of the implementation of a skin cancer prevention program: a multilevel analysis. Implement Sci. 2010;5:40. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-5-40

- Walkosz BJ, Buller D, Buller M, et al. Sun safe workplaces: effect of an occupational skin cancer prevention program on employee sun safety practices. J Occup Environ Med. 2018;60:900-997. doi:10.1097 /JOM.0000000000001427

Lifeguards play a crucial role in ensuring water safety, but they also are uniquely positioned to promote skin cancer prevention and proper sunscreen use.1,2 There are several benefits and challenges to offering skin cancer prevention training for lifeguards.3 We examine the advantages of training, highlight the role lifeguards can play in larger public skin cancer prevention efforts, and address practical techniques for developing lifeguardfocused skin cancer education programs. By providing this knowledge to lifeguards, we can improve community health outcomes and encourage sun-safe behaviors in high-risk outdoor locations.

Benefits of Skin Cancer Prevention Training for Lifeguards

Research has shown that lifeguards are at an elevated risk for basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and melanoma due to frequent prolonged occupational sun exposure.1,2,4-6 Therefore, comprehensive education on skin cancer prevention—including instruction on proper sunscreen application techniques and the importance of regular reapplication as well as how to recognize suspicious skin lesions—should be incorporated into lifeguard certification programs. One study evaluating the effectiveness of a skin cancer prevention program for lifeguards found that many of the participants lacked a thorough understanding of the different types of skin cancer.5 Another study found that lifeguards at pools in areas where societal norms supporting sun safety are stronger exhibited noticeably more sun protection practices, with regression estimates of 0.22 (95% CI, 0.17-0.26).7 Empowering lifeguards with valuable health knowledge during their regular training could potentially reduce their risk for skin cancer,4 as they may be more inclined to use sunscreen appropriately and reach out to a dermatologist for regular skin checks and evaluation of suspicious lesions.

Role of Lifeguards in Public Skin Cancer Prevention Efforts

Once trained on skin cancer prevention, lifeguards also can play a pivotal role in promoting sunscreen use among the public. Despite the widespread availability of high-quality sunscreens, many swimmers and beachgoers neglect to regularly apply or reapply sunscreen, especially on commonly exposed areas such as the back, shoulders, and face.8 Educating lifeguards on skin cancer prevention could enhance health outcomes by increasing early detection rates and promoting sun-safe behaviors among the general public.9 However, additional training requirements might increase the cost and time commitment for lifeguard certification, potentially leading to staffing shortages.3,7 There also is a risk of lifeguards overstepping their role and providing inaccurate medical advice, which could cause distress or even lead to liability issues.7 Balancing these factors will be crucial in developing effective and sustainable skin cancer prevention programs for lifeguards.

Implementing Lifeguard Skin Cancer Training

Implementing skin cancer prevention training programs for lifeguards requires strategic collaboration between dermatologists, and lifeguard training organizations to ensure that the participants receive consistent and comprehensive training.10 Additionally, public health campaigns can support these efforts by raising awareness about the importance of sun safety and regular skin checks.6 Tailored training modules/materials, ongoing technical assistance, and active, multicomponent approaches that account for both individual and environmental factors can increase program implementation in a variety of community settings.

Final Thoughts

Through effective education, lifeguards can potentially have a substantial impact on skin cancer prevention, both among lifeguards themselves and the general public. By promoting proper sunscreen use, lifeguards can help reduce the incidence and mortality associated with skin cancers. Future studies should focus on developing and implementing targeted education initiatives for lifeguards, fostering collaboration between relevant stakeholders, and raising public awareness about the importance of sun safety and early skin cancer detection. These efforts ultimately could lead to improved public health outcomes and reduced skin cancer rates, particularly in high-risk populations that frequently are exposed to UV radiation.

Lifeguards play a crucial role in ensuring water safety, but they also are uniquely positioned to promote skin cancer prevention and proper sunscreen use.1,2 There are several benefits and challenges to offering skin cancer prevention training for lifeguards.3 We examine the advantages of training, highlight the role lifeguards can play in larger public skin cancer prevention efforts, and address practical techniques for developing lifeguardfocused skin cancer education programs. By providing this knowledge to lifeguards, we can improve community health outcomes and encourage sun-safe behaviors in high-risk outdoor locations.

Benefits of Skin Cancer Prevention Training for Lifeguards

Research has shown that lifeguards are at an elevated risk for basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and melanoma due to frequent prolonged occupational sun exposure.1,2,4-6 Therefore, comprehensive education on skin cancer prevention—including instruction on proper sunscreen application techniques and the importance of regular reapplication as well as how to recognize suspicious skin lesions—should be incorporated into lifeguard certification programs. One study evaluating the effectiveness of a skin cancer prevention program for lifeguards found that many of the participants lacked a thorough understanding of the different types of skin cancer.5 Another study found that lifeguards at pools in areas where societal norms supporting sun safety are stronger exhibited noticeably more sun protection practices, with regression estimates of 0.22 (95% CI, 0.17-0.26).7 Empowering lifeguards with valuable health knowledge during their regular training could potentially reduce their risk for skin cancer,4 as they may be more inclined to use sunscreen appropriately and reach out to a dermatologist for regular skin checks and evaluation of suspicious lesions.

Role of Lifeguards in Public Skin Cancer Prevention Efforts

Once trained on skin cancer prevention, lifeguards also can play a pivotal role in promoting sunscreen use among the public. Despite the widespread availability of high-quality sunscreens, many swimmers and beachgoers neglect to regularly apply or reapply sunscreen, especially on commonly exposed areas such as the back, shoulders, and face.8 Educating lifeguards on skin cancer prevention could enhance health outcomes by increasing early detection rates and promoting sun-safe behaviors among the general public.9 However, additional training requirements might increase the cost and time commitment for lifeguard certification, potentially leading to staffing shortages.3,7 There also is a risk of lifeguards overstepping their role and providing inaccurate medical advice, which could cause distress or even lead to liability issues.7 Balancing these factors will be crucial in developing effective and sustainable skin cancer prevention programs for lifeguards.

Implementing Lifeguard Skin Cancer Training

Implementing skin cancer prevention training programs for lifeguards requires strategic collaboration between dermatologists, and lifeguard training organizations to ensure that the participants receive consistent and comprehensive training.10 Additionally, public health campaigns can support these efforts by raising awareness about the importance of sun safety and regular skin checks.6 Tailored training modules/materials, ongoing technical assistance, and active, multicomponent approaches that account for both individual and environmental factors can increase program implementation in a variety of community settings.

Final Thoughts

Through effective education, lifeguards can potentially have a substantial impact on skin cancer prevention, both among lifeguards themselves and the general public. By promoting proper sunscreen use, lifeguards can help reduce the incidence and mortality associated with skin cancers. Future studies should focus on developing and implementing targeted education initiatives for lifeguards, fostering collaboration between relevant stakeholders, and raising public awareness about the importance of sun safety and early skin cancer detection. These efforts ultimately could lead to improved public health outcomes and reduced skin cancer rates, particularly in high-risk populations that frequently are exposed to UV radiation.

- Enos CW, Rey S, Slocum J, et al. Sun-protection behaviors among active members of the United States Lifesaving Association. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14:14-20.

- Verma K, Lewis DJ, Siddiqui FS, et al. Mohs micrographic surgery management of melanoma and melanoma in situ. StatPearls. Updated August 28, 2024. Accessed April 15, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK606123/

- Verma KK, Joshi TP, Lewis DJ, et al. Nail technicians as partners in early melanoma detection: bridging the knowledge gap. Arch Dermatol Res. 2024;316:586. doi:10.1007/s00403-024-03342-0

- Geller AC, Glanz K, Shigaki D, et al. Impact of skin cancer prevention on outdoor aquatics staff: the Pool Cool program in Hawaii and Massachusetts. Prev Med. 2001;33:155-161. doi:10.1006/pmed.2001.0870

- Hiemstra M, Glanz K, Nehl E. Changes in sunburn and tanning attitudes among lifeguards over a summer season. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:430-437. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.11.050

- Verma KK, Ahmad N, Friedmann DP, et al. Melanoma in tattooed skin: diagnostic challenges and the potential for tattoo artists in early detection. Arch Dermatol Res. 2024;316:690. doi:10.1007/s00403-024-03415-0

- Hall DM, McCarty F, Elliott T, et al. Lifeguards’ sun protection habits and sunburns: association with sun-safe environments and skin cancer prevention program participation. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:139-144. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2008.553

- Emmons KM, Geller AC, Puleo E, et al. Skin cancer education and early detection at the beach: a randomized trial of dermatologist examination and biometric feedback. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:282-289. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.01.040

- Rabin BA, Nehl E, Elliott T, et al. Individual and setting level predictors of the implementation of a skin cancer prevention program: a multilevel analysis. Implement Sci. 2010;5:40. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-5-40

- Walkosz BJ, Buller D, Buller M, et al. Sun safe workplaces: effect of an occupational skin cancer prevention program on employee sun safety practices. J Occup Environ Med. 2018;60:900-997. doi:10.1097 /JOM.0000000000001427

- Enos CW, Rey S, Slocum J, et al. Sun-protection behaviors among active members of the United States Lifesaving Association. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14:14-20.

- Verma K, Lewis DJ, Siddiqui FS, et al. Mohs micrographic surgery management of melanoma and melanoma in situ. StatPearls. Updated August 28, 2024. Accessed April 15, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK606123/

- Verma KK, Joshi TP, Lewis DJ, et al. Nail technicians as partners in early melanoma detection: bridging the knowledge gap. Arch Dermatol Res. 2024;316:586. doi:10.1007/s00403-024-03342-0

- Geller AC, Glanz K, Shigaki D, et al. Impact of skin cancer prevention on outdoor aquatics staff: the Pool Cool program in Hawaii and Massachusetts. Prev Med. 2001;33:155-161. doi:10.1006/pmed.2001.0870

- Hiemstra M, Glanz K, Nehl E. Changes in sunburn and tanning attitudes among lifeguards over a summer season. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:430-437. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.11.050

- Verma KK, Ahmad N, Friedmann DP, et al. Melanoma in tattooed skin: diagnostic challenges and the potential for tattoo artists in early detection. Arch Dermatol Res. 2024;316:690. doi:10.1007/s00403-024-03415-0

- Hall DM, McCarty F, Elliott T, et al. Lifeguards’ sun protection habits and sunburns: association with sun-safe environments and skin cancer prevention program participation. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:139-144. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2008.553

- Emmons KM, Geller AC, Puleo E, et al. Skin cancer education and early detection at the beach: a randomized trial of dermatologist examination and biometric feedback. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:282-289. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.01.040

- Rabin BA, Nehl E, Elliott T, et al. Individual and setting level predictors of the implementation of a skin cancer prevention program: a multilevel analysis. Implement Sci. 2010;5:40. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-5-40

- Walkosz BJ, Buller D, Buller M, et al. Sun safe workplaces: effect of an occupational skin cancer prevention program on employee sun safety practices. J Occup Environ Med. 2018;60:900-997. doi:10.1097 /JOM.0000000000001427

Training Lifeguards to Assist in Skin Cancer Prevention

Training Lifeguards to Assist in Skin Cancer Prevention

Cutaneous Manifestation as Initial Presentation of Metastatic Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review

Breast cancer is the second most common malignancy in women (after primary skin cancer) and is the second leading cause of cancer-related death in this population. In 2020, the American Cancer Society reported an estimated 276,480 new breast cancer diagnoses and 42,170 breast cancer–related deaths.1 Despite the fact that routine screening with mammography and sonography is standard, the incidence of advanced breast cancer at the time of diagnosis has remained stable over time, suggesting that life-threatening breast cancers are not being caught at an earlier stage. The number of breast cancers with distant metastases at the time of diagnosis also has not decreased.2 Therefore, although screening tests are valuable, they are imperfect and not without limitations.

Cutaneous metastasis is defined as the spread of malignant cells from an internal neoplasm to the skin, which can occur either by contiguous invasion or by distant metastasis through hematogenous or lymphatic routes.3 The diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis requires a high index of suspicion on the part of the clinician.4 Of the various internal malignancies in women, breast cancer most frequently results in metastasis to the skin,5 with up to 24% of patients with metastatic breast cancer developing cutaneous lesions.6

In recent years, there have been multiple reports of skin lesions prompting the diagnosis of a previously unknown breast cancer. In a study by Lookingbill et al,6 6.3% of patients with breast cancer presented with cutaneous involvement at the time of diagnosis, with 3.5% having skin symptoms as the presenting sign. Although there have been studies analyzing cutaneous metastasis from various internal malignancies, none thus far have focused on cutaneous metastasis as a presenting sign of breast cancer. This systematic review aimed to highlight the diverse clinical presentations of cutaneous metastatic breast cancer and their clinical implications.

Methods

Study Selection

This study utilized the PRISMA guidelines for systematic reviews.7 A review of the literature was conducted using the following databases: MEDLINE/PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane library, CINAHL, and EBSCO.

Search Strategy and Analysis

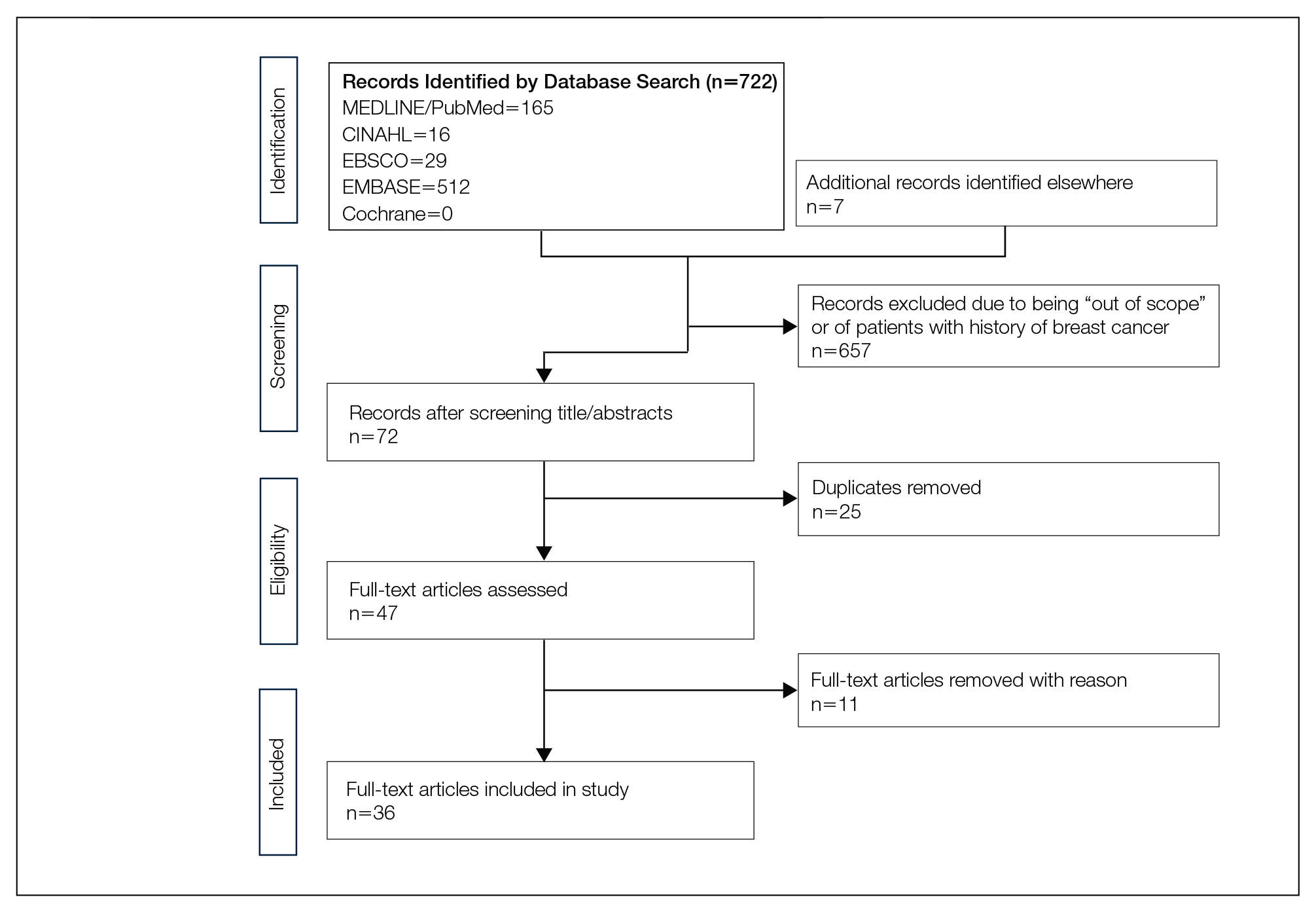

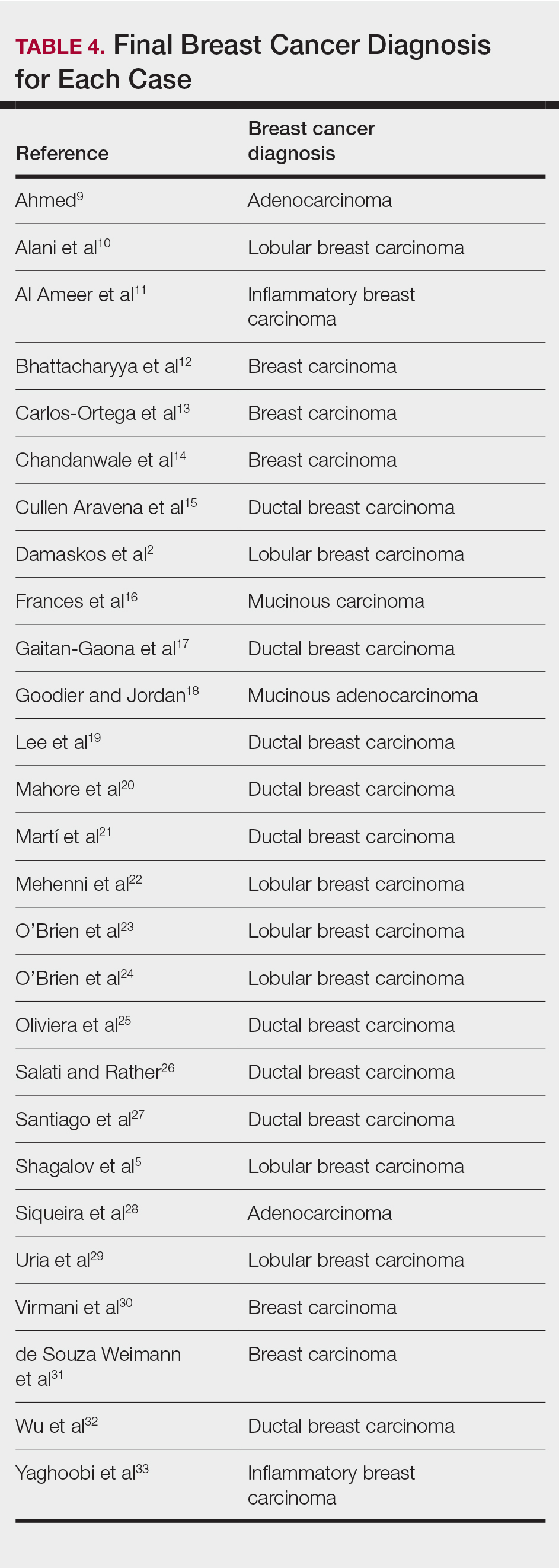

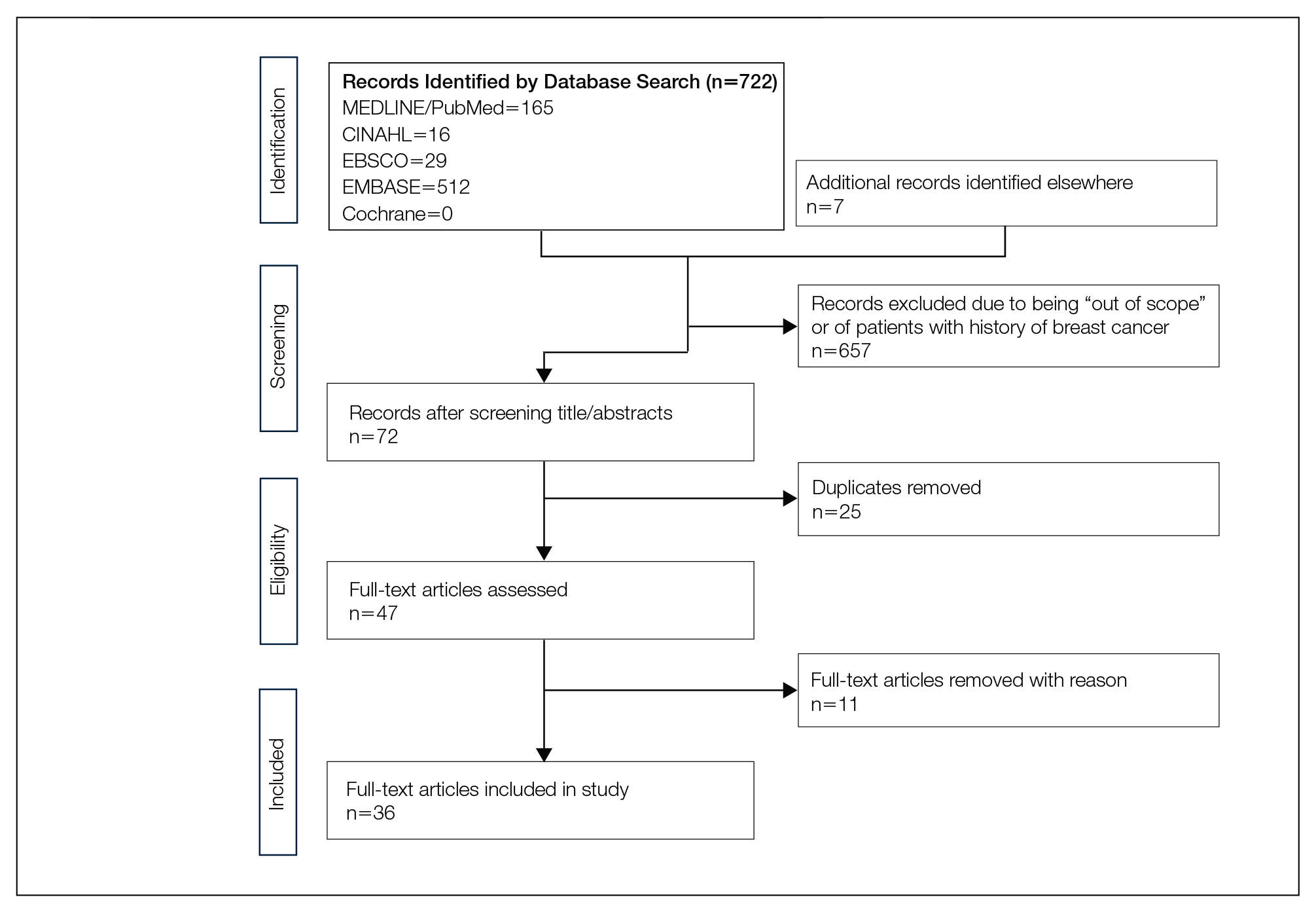

We completed our search of each of the databases on December 16, 2017, using the phrases cutaneous metastasis and breast cancer to find relevant case reports and retrospective studies. Three authors (C.J., S.R., and M.A.) manually reviewed the resulting abstracts. If an abstract did not include enough information to determine inclusion, the full-text version was reviewed by 2 of the authors (C.J. and S.R.). Two of the authors (C.J. and M.A.) also assessed each source for relevancy and included the articles deemed eligible (Figure 1).

Inclusion criteria were the following: case reports and retrospective studies published in the prior 10 years (January 1, 2007, to December 16, 2017) with human female patients who developed metastatic cutaneous lesions due to a previously unknown primary breast malignancy. Studies published in other languages were included; these articles were translated into English using a human translator or computer translation program (Google Translate). Exclusion criteria were the following: male patients, patients with a known diagnosis of primary breast malignancy prior to the appearance of a metastatic cutaneous lesion, articles focusing on the treatment of breast cancer, and articles without enough details to draw meaningful conclusions.

For a retrospective review to be included, it must have specified the number of breast cancer cases and the number of cutaneous metastases presenting initially or simultaneously to the breast cancer diagnosis. Bansal et al8 defined a simultaneous diagnosis as a skin lesion presenting with other concerns associated with the primary malignancy.

Results

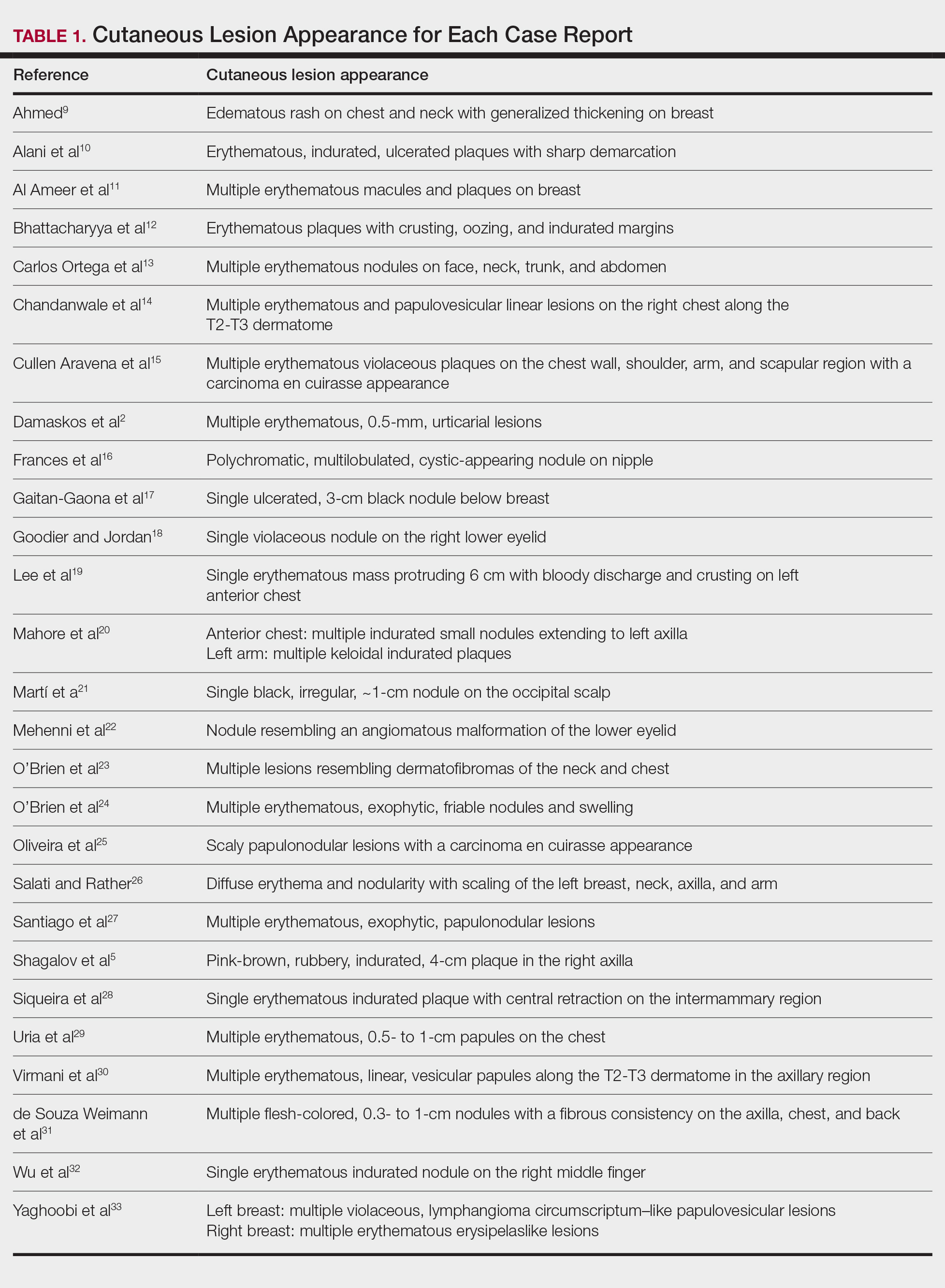

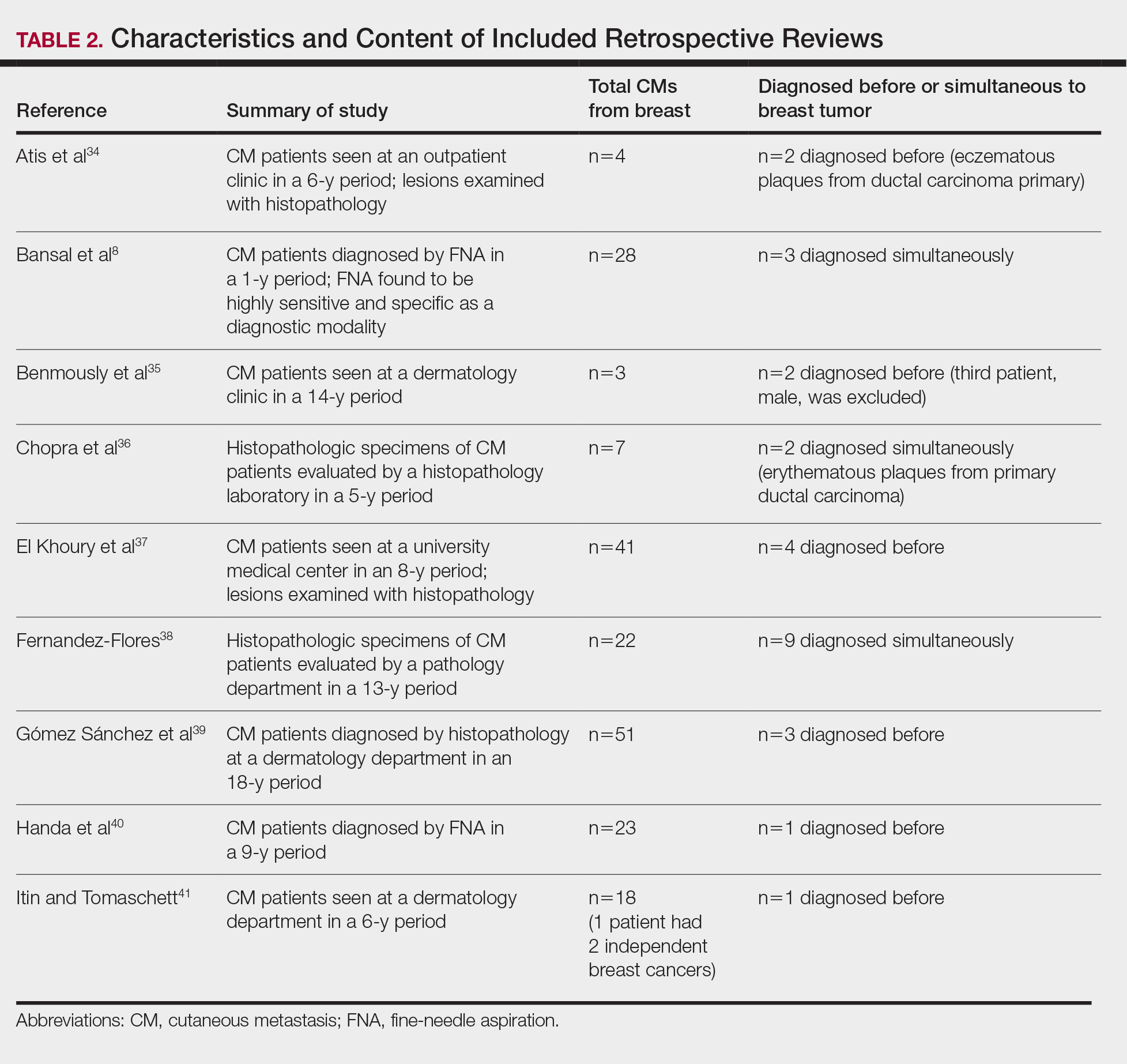

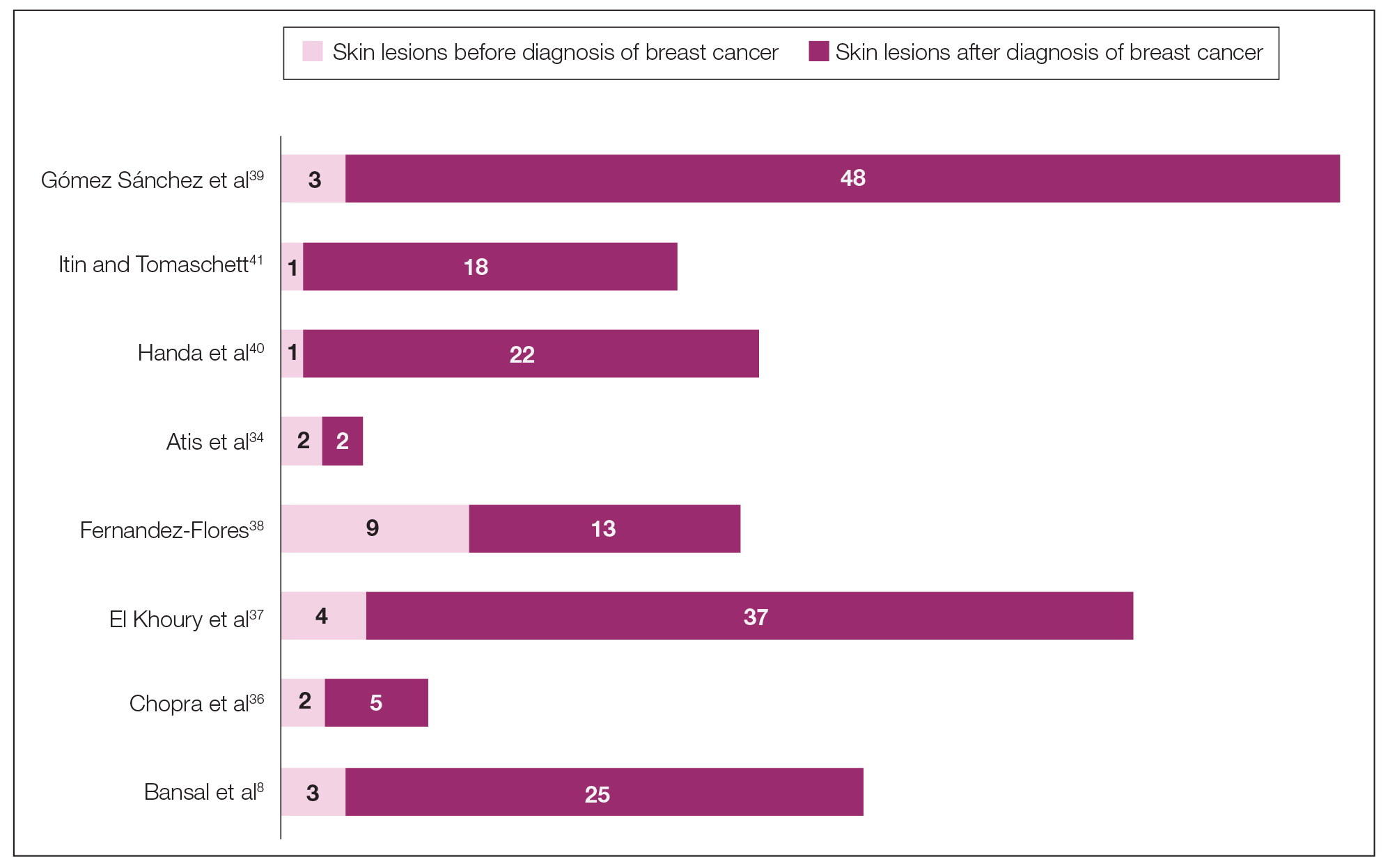

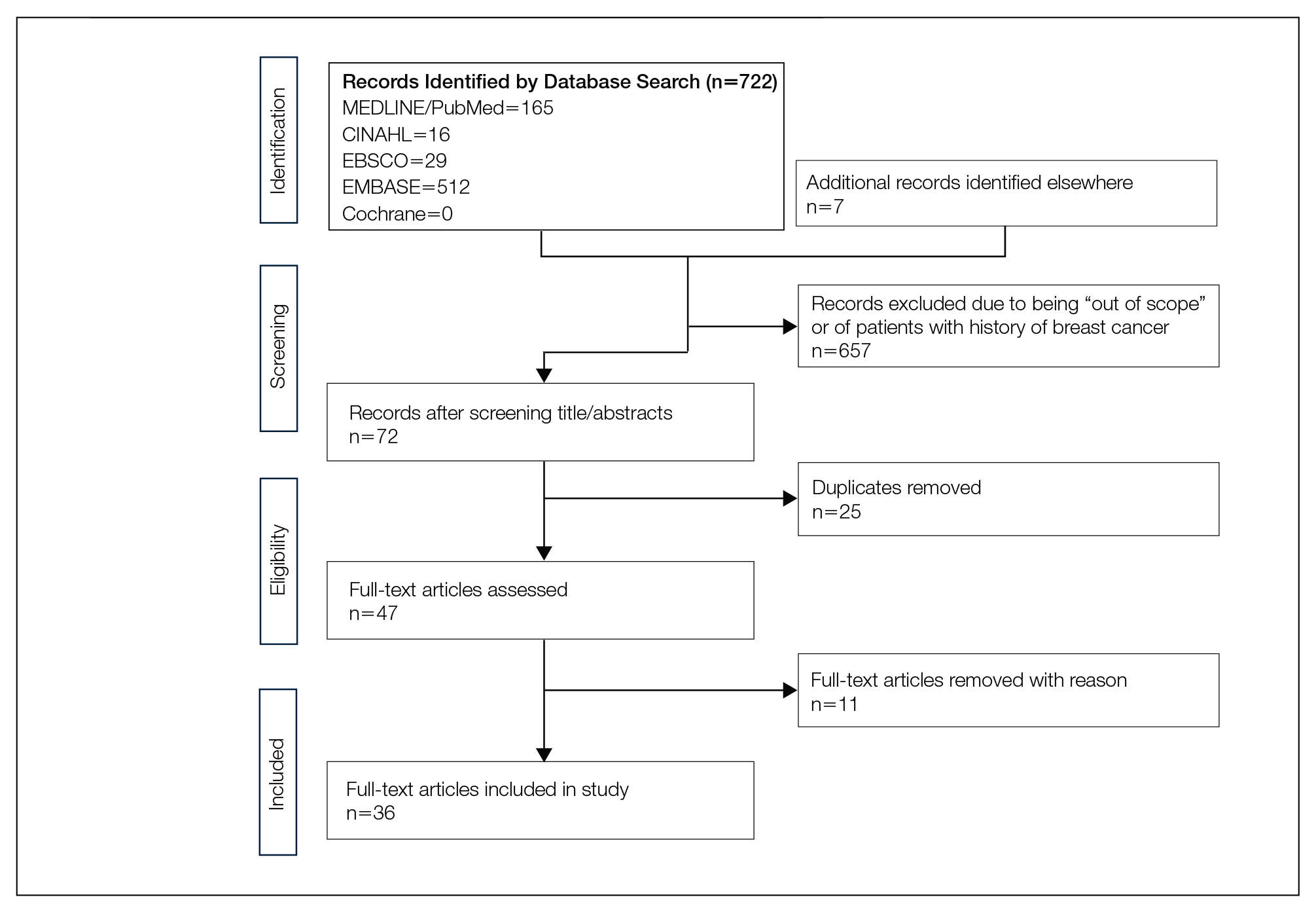

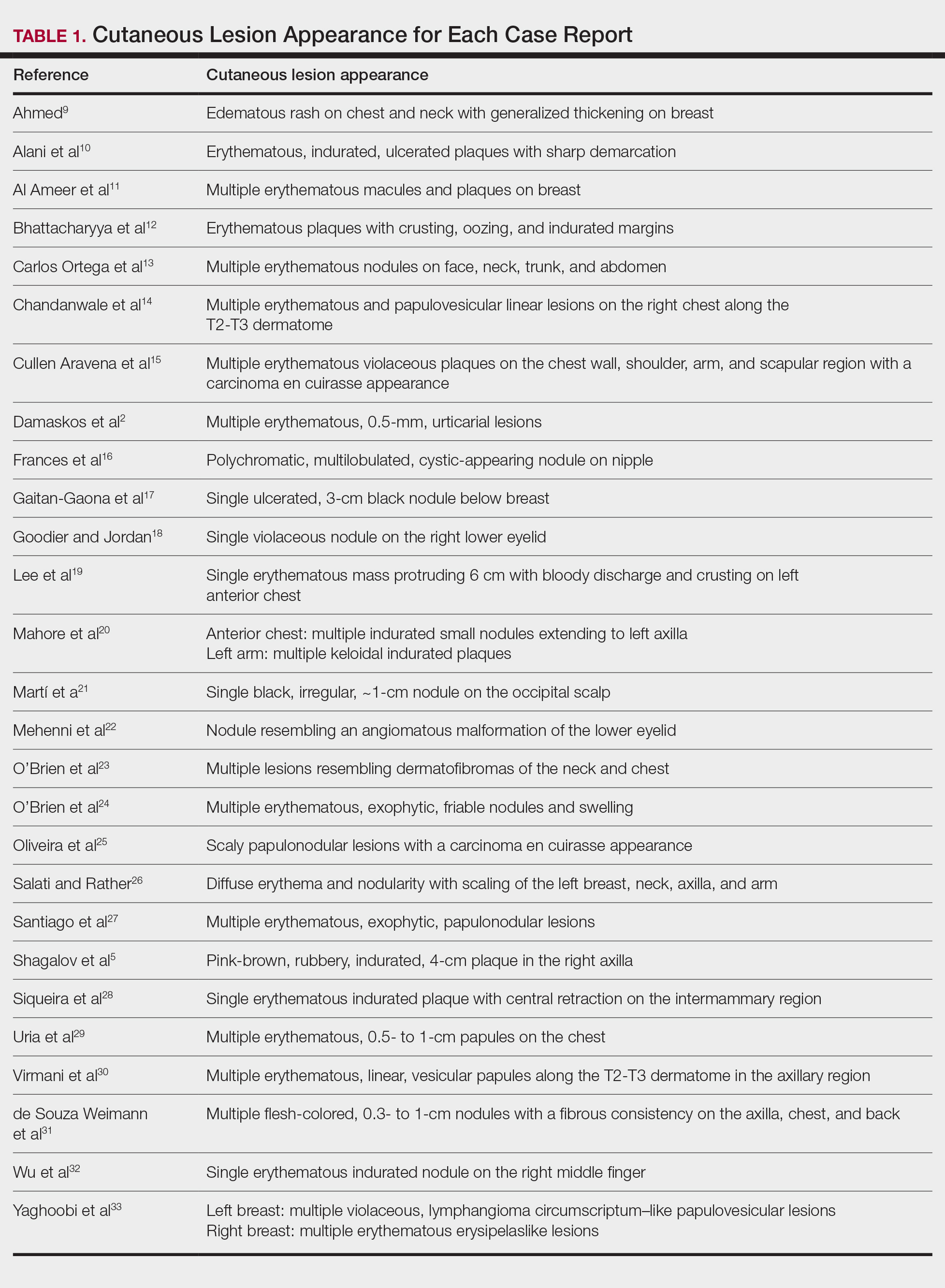

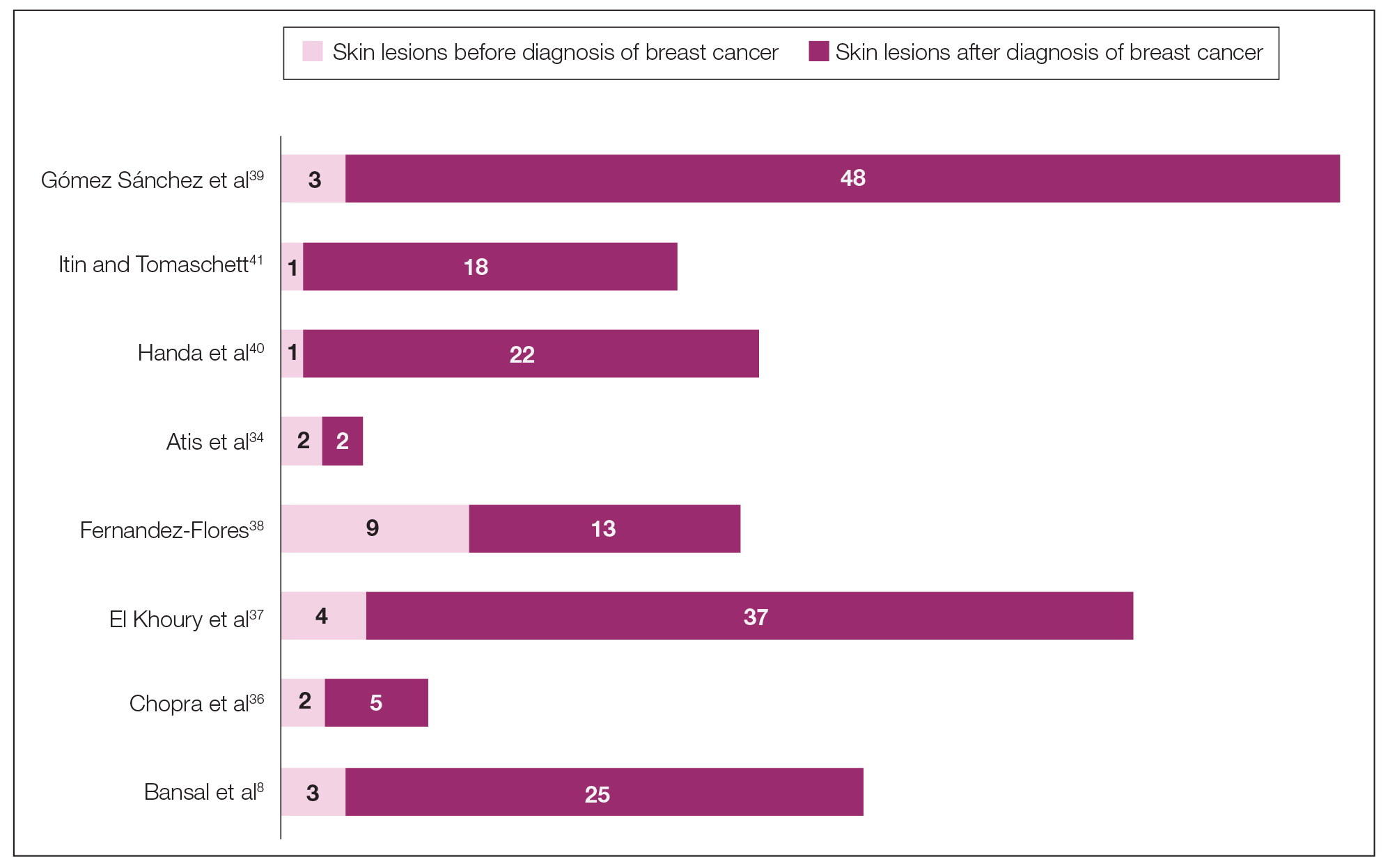

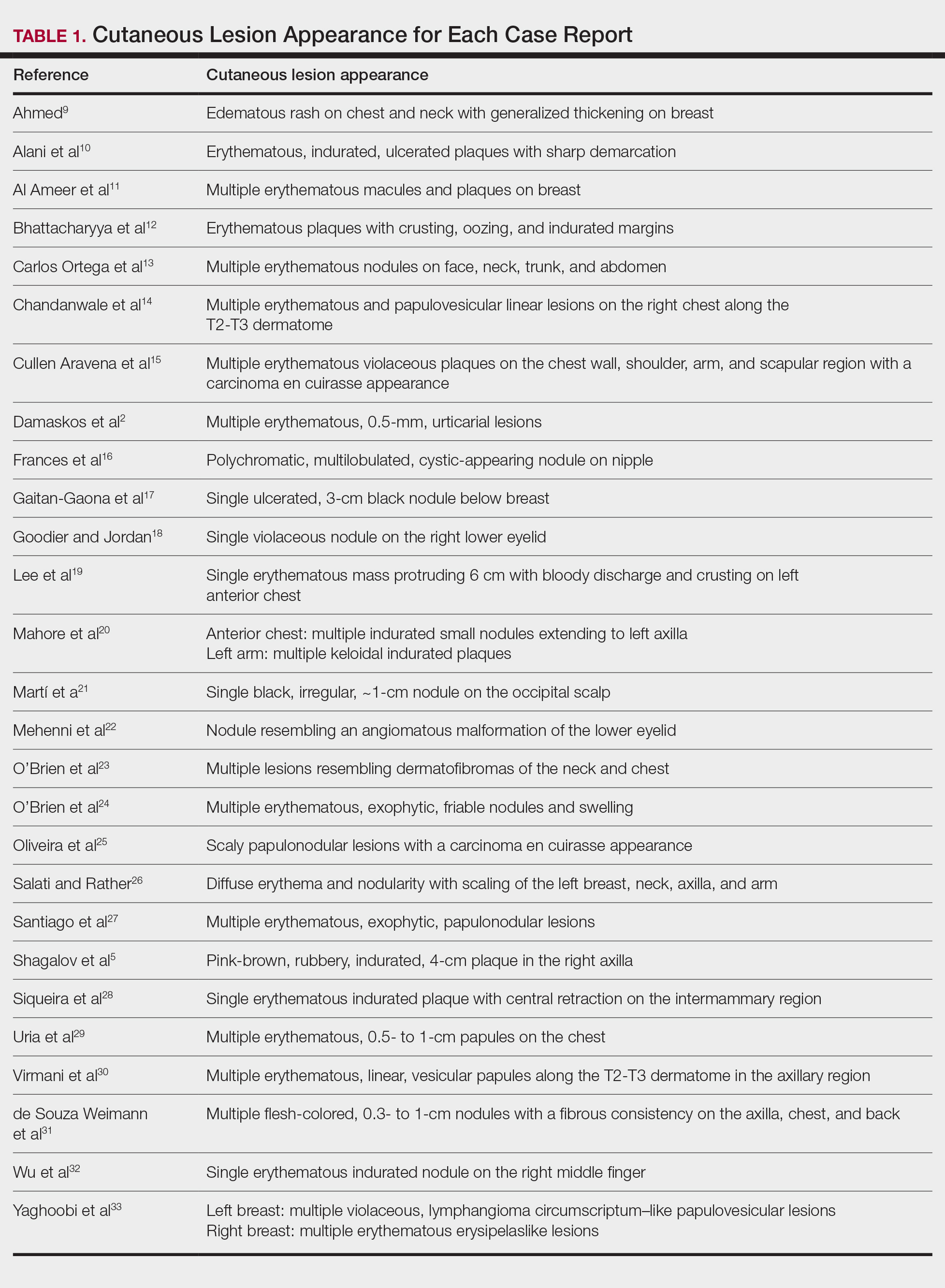

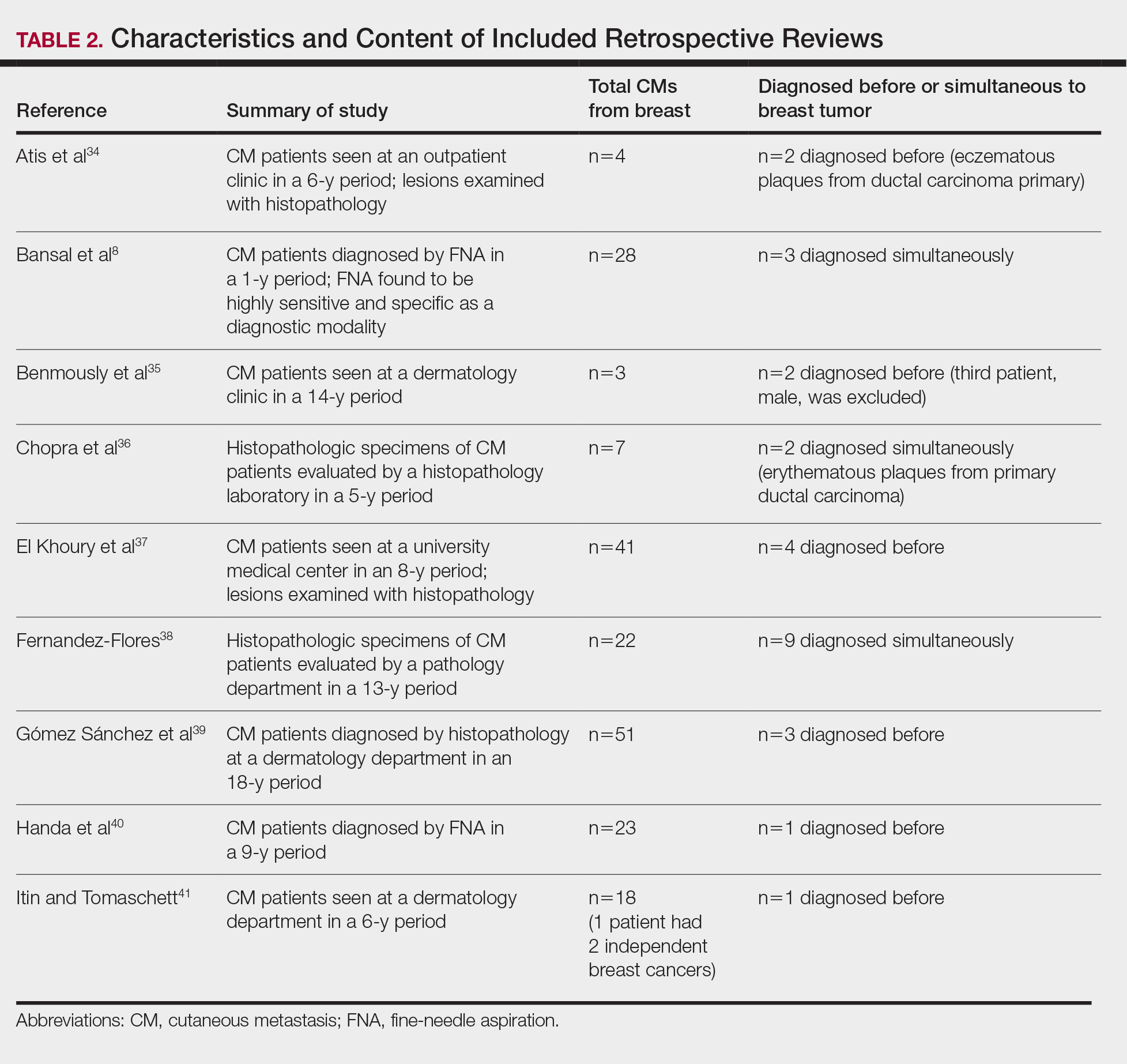

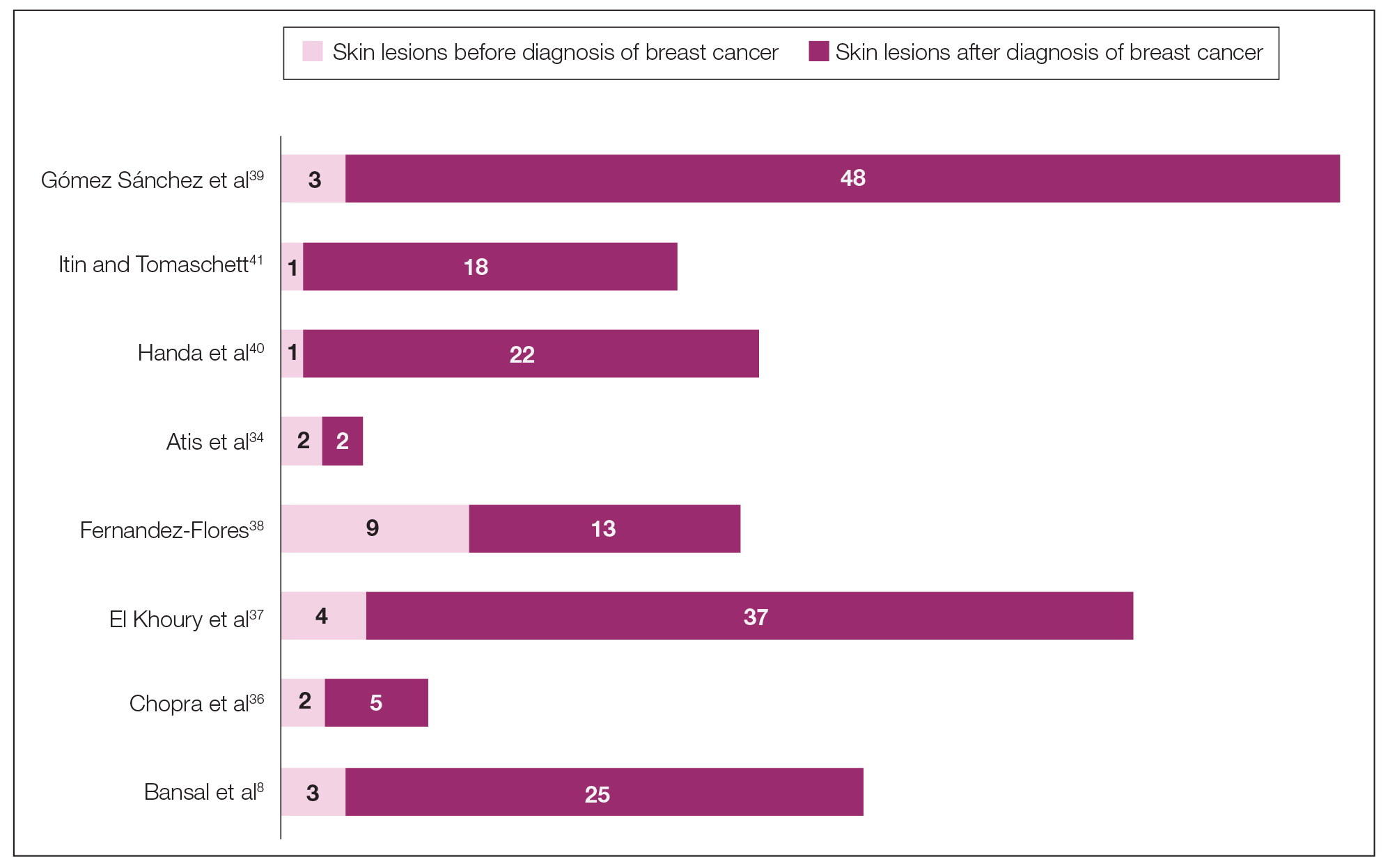

The initial search of MEDLINE/PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane library, CINAHL, and EBSCO yielded a total of 722 articles. Seven other articles found separately while undergoing our initial research were added to this total. Abstracts were manually screened, with 657 articles discarded after failing to meet the predetermined inclusion criteria. After removal of 25 duplicate articles, the full text of the remaining 47 articles were reviewed, leading to the elimination of an additional 11 articles that did not meet the necessary criteria. This resulted in 36 articles (Figure 1), including 27 individual case reports (Table 1) and 9 retrospective reviews (Table 2). Approximately 13.7% of patients in the 9 retrospective reviews presented with a skin lesion before or simultaneous to the diagnosis of breast cancer (Figure 2).

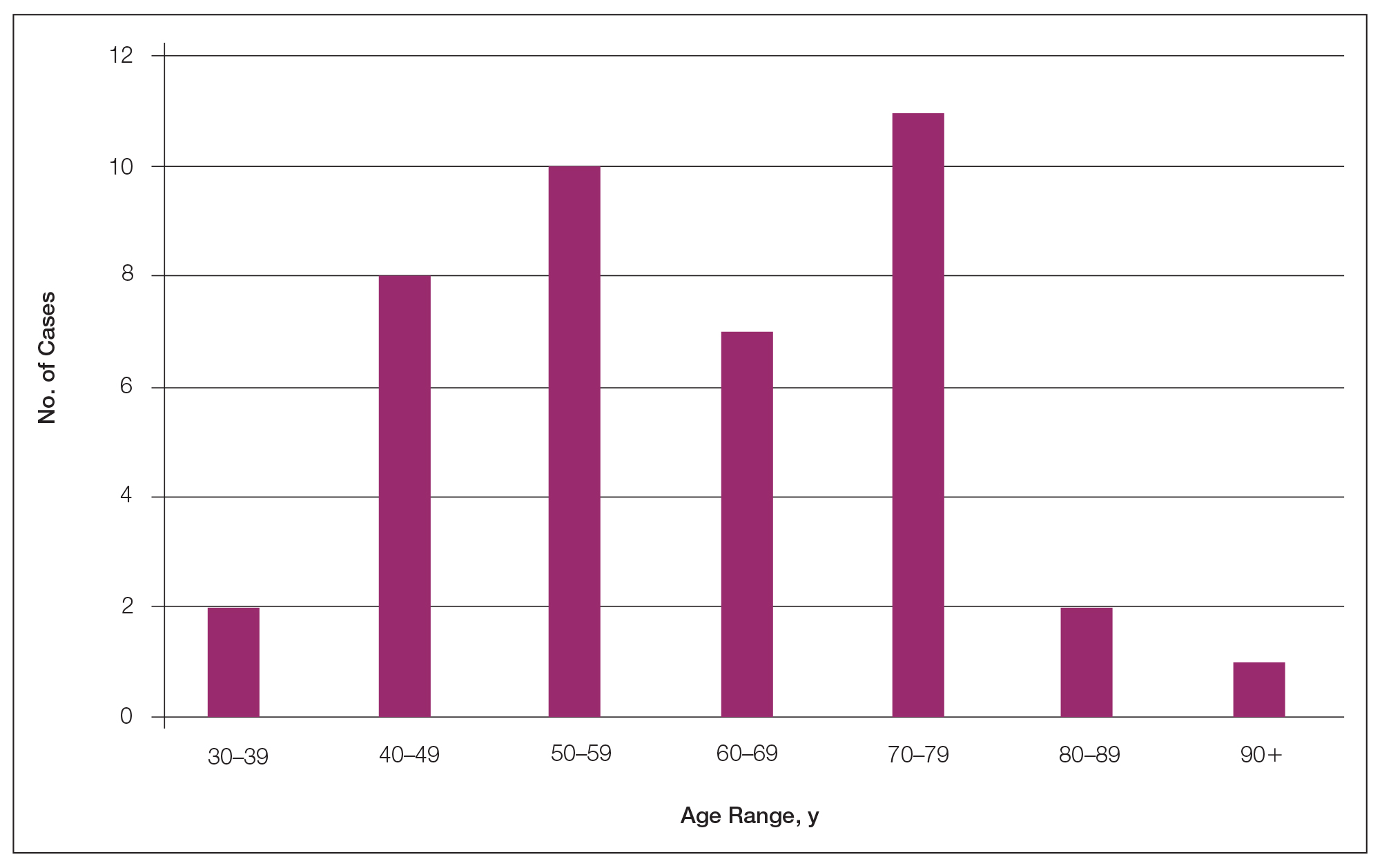

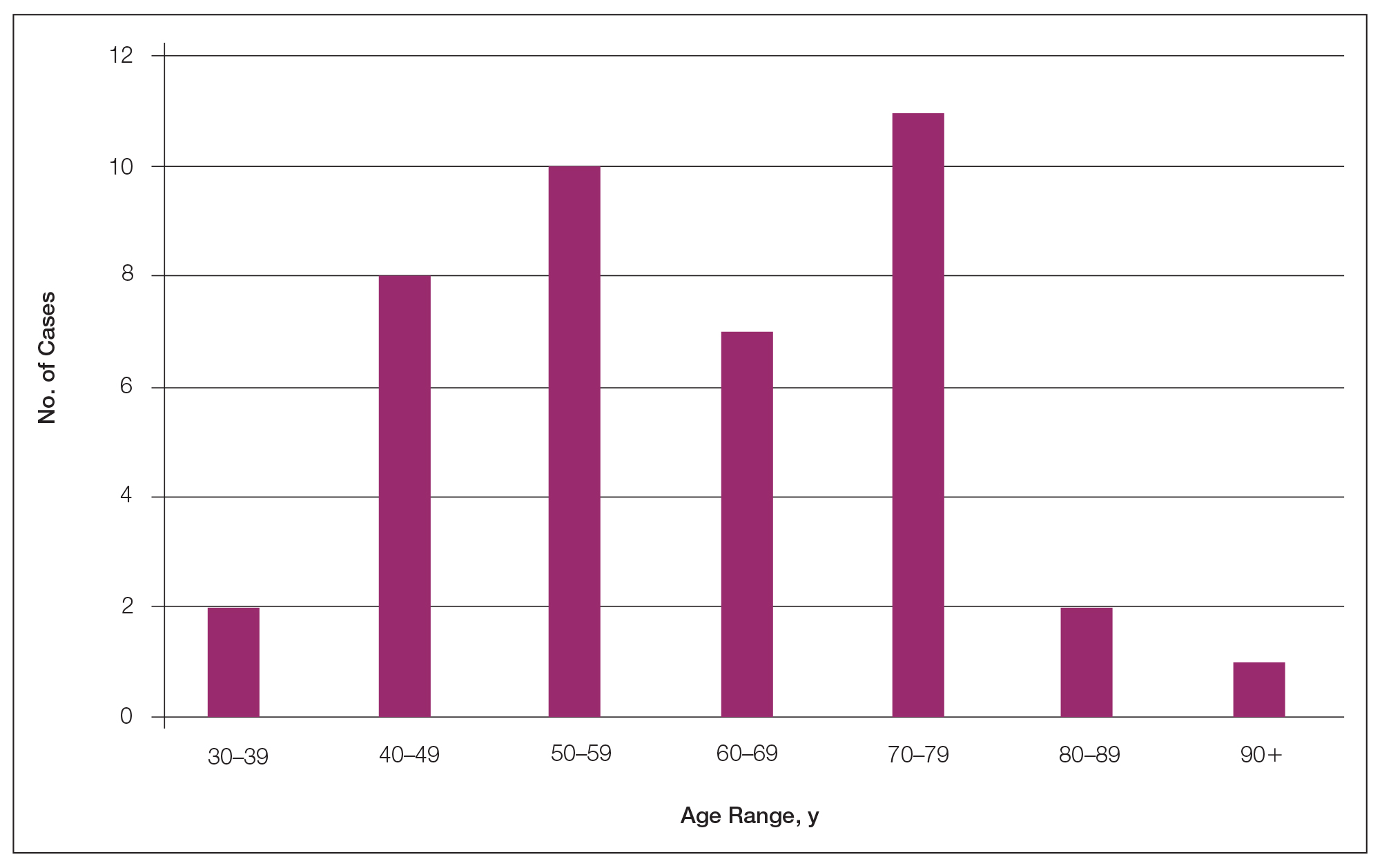

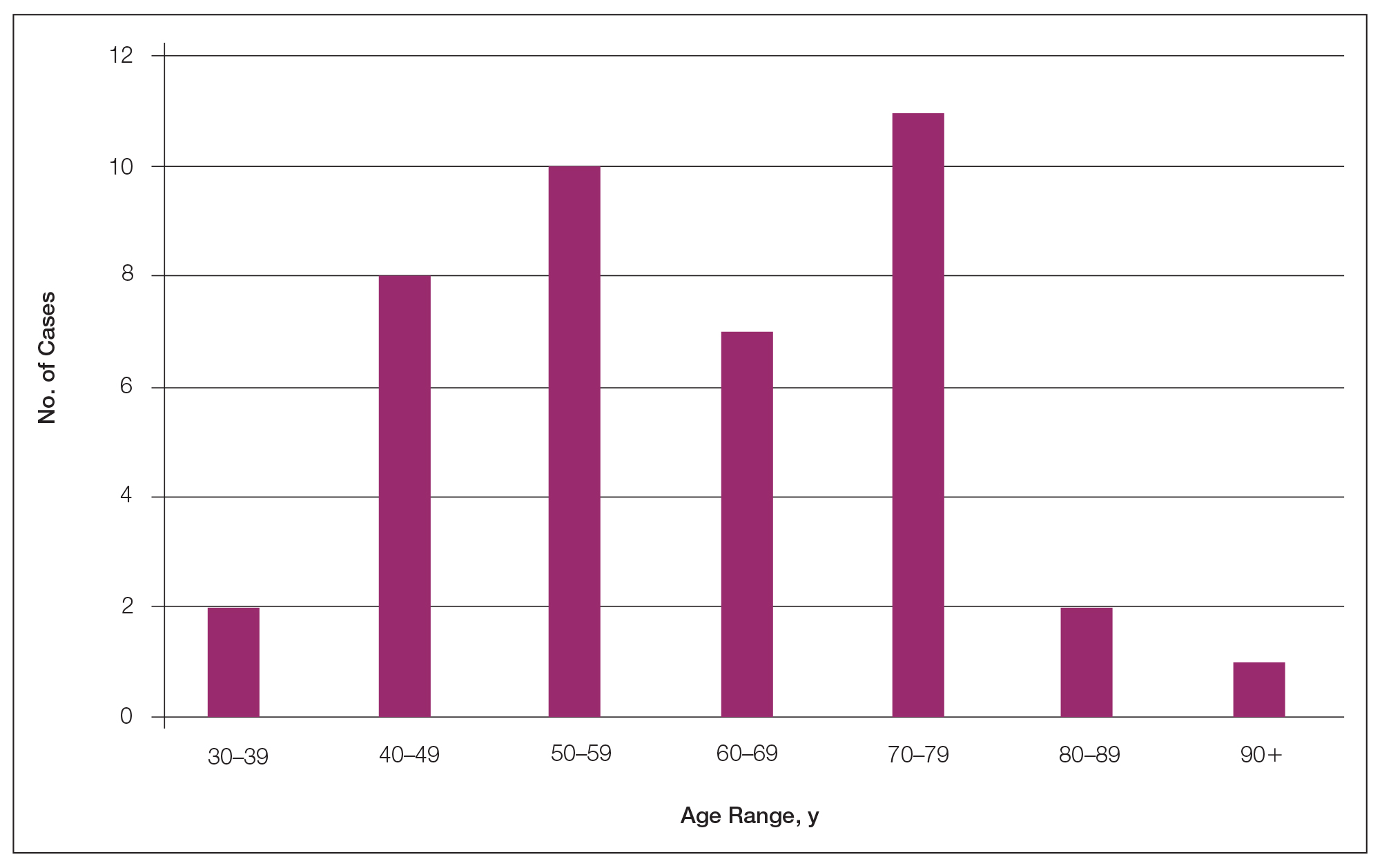

Forty-one percent (17/41) of the patients with cutaneous metastasis as a presenting feature of their breast cancer fell outside the age range for breast cancer screening recommended by the US Preventive Services Task Force,42 with 24% of the patients younger than 50 years and 17% older than 74 years (Figure 3).

Lesion Characteristics

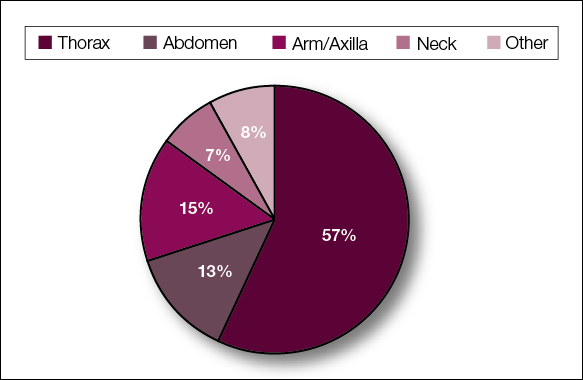

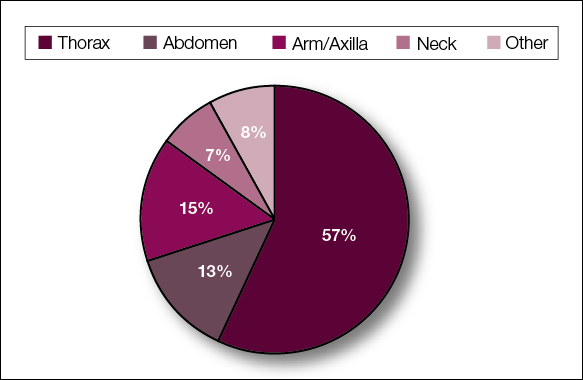

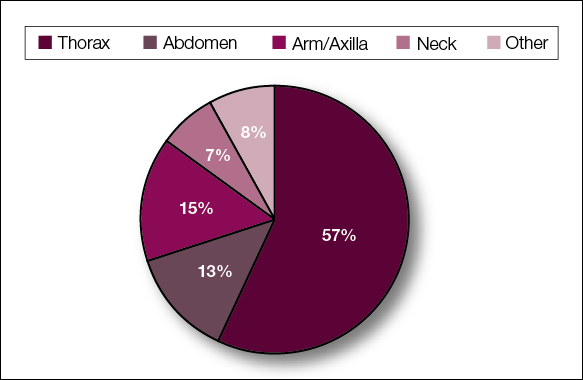

The most common cutaneous lesions were erythematous nodules and plaques, with a few reports of black17,21 or flesh-colored5,20,31 lesions, as well as ulceration.8,17,32 The most common location for skin lesions was on the thorax (chest or breast), accounting for 57% of the cutaneous metastases, with the arms and axillae being second most commonly involved (15%)(Figure 4). Some cases presented with skin lesions extending to multiple regions. In these cases, each location of the lesion was recorded separately when analyzing the data. An additional 5 cases, shown as “Other” in Figure 4, included the eyelids, occiput, and finger. Eight case reports described symptoms associated with the cutaneous lesions, with painful or tender lesions reported in 7 cases5,9,14,17,20,30,32 and pruritus in 2 cases.12,20 Moreover, 6 case reports presented patients denying any systemic or associated symptoms with their skin lesions.2,5,9,16,17,28 Multiple cases were initially treated as other conditions due to misdiagnosis, including herpes zoster14,30 and dermatitis.11,12

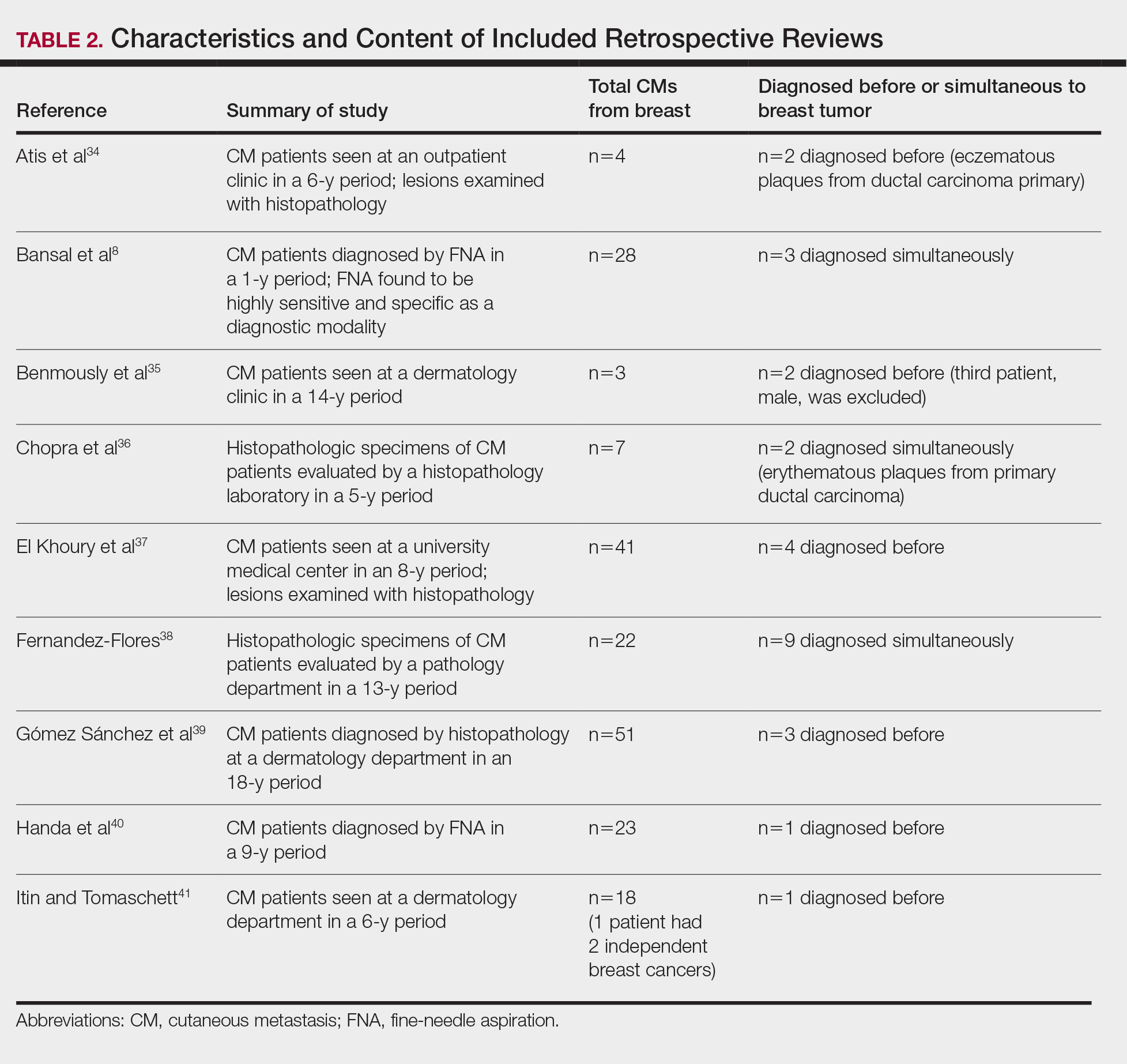

Diagnostic Data

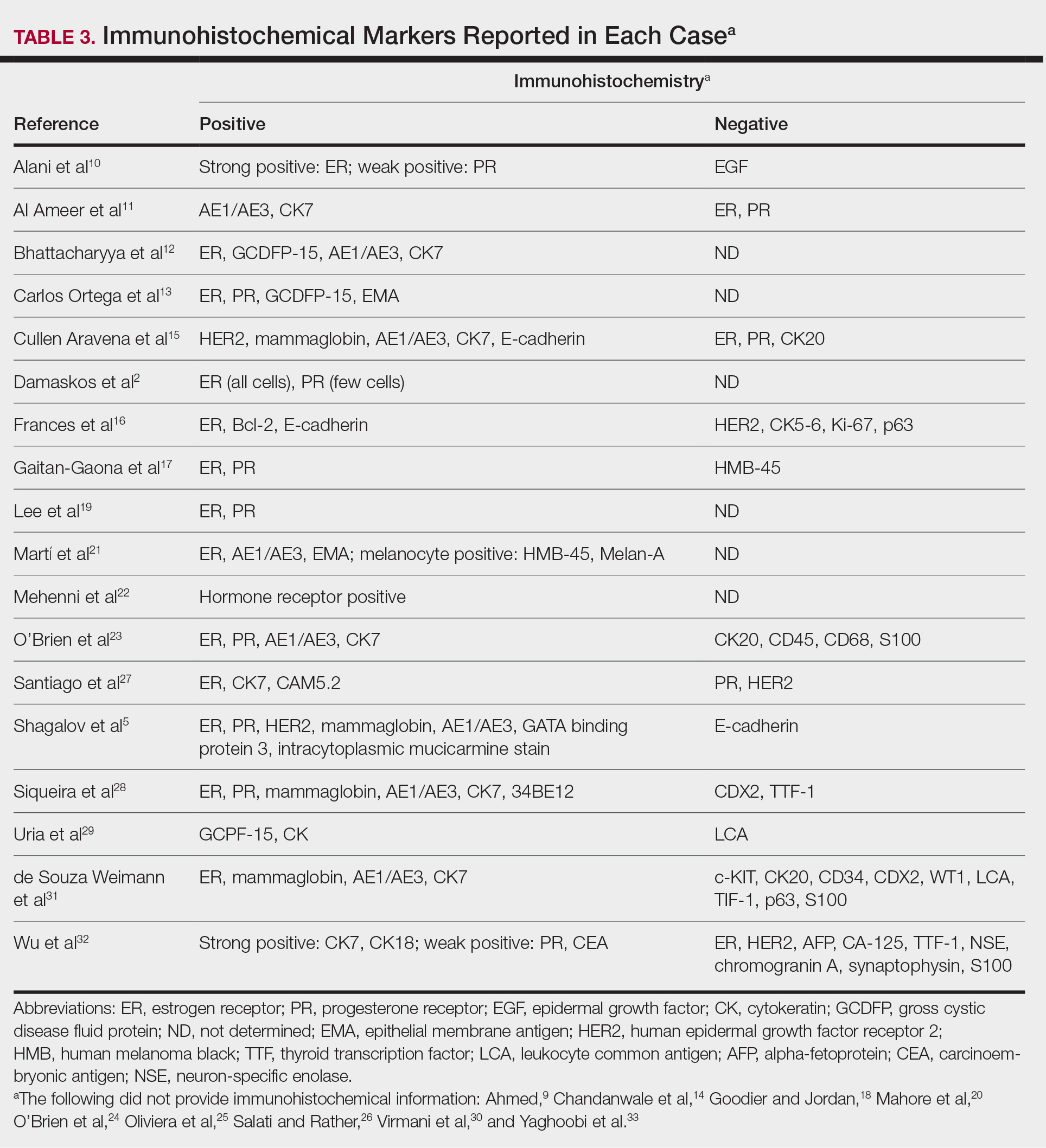

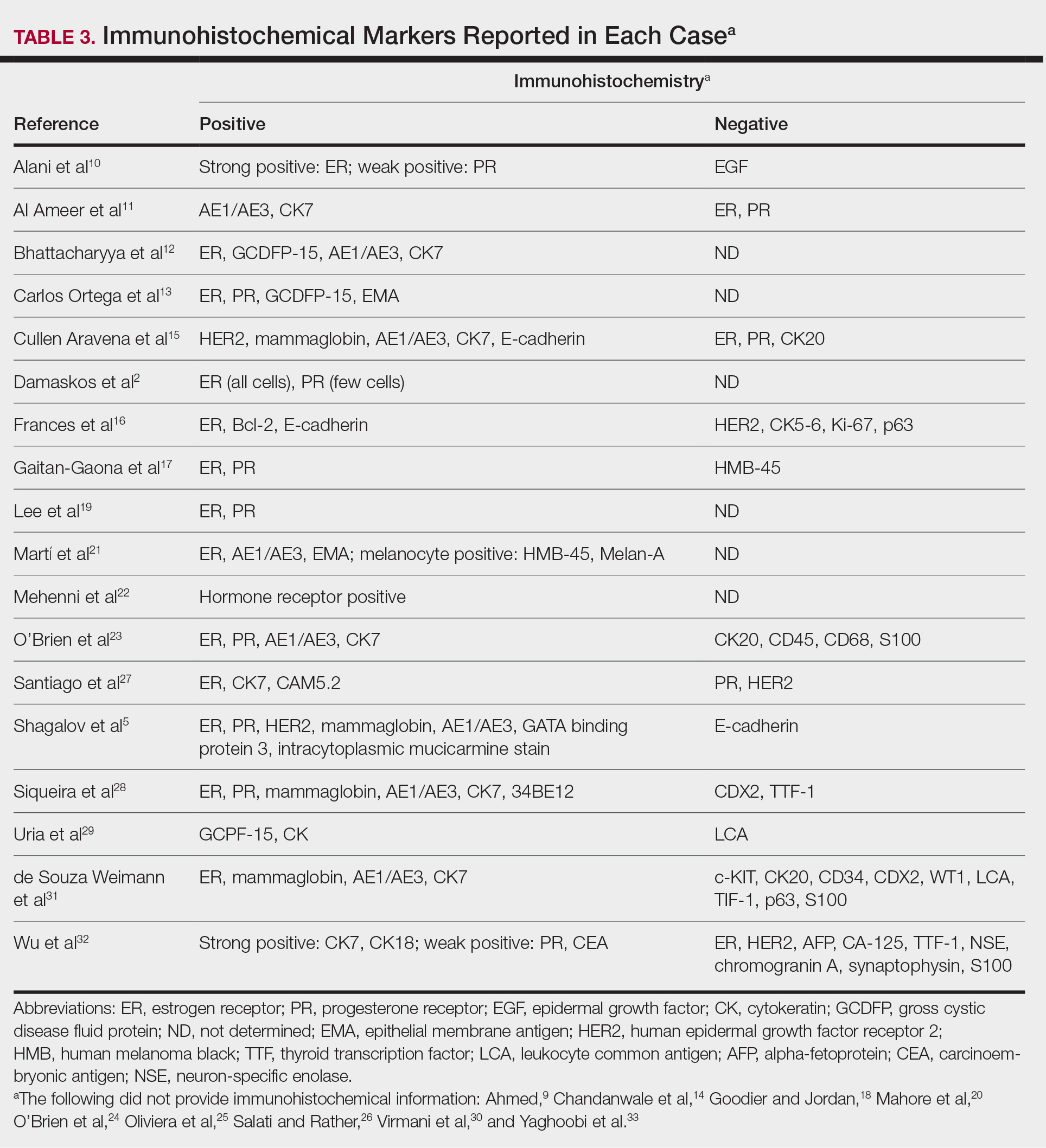

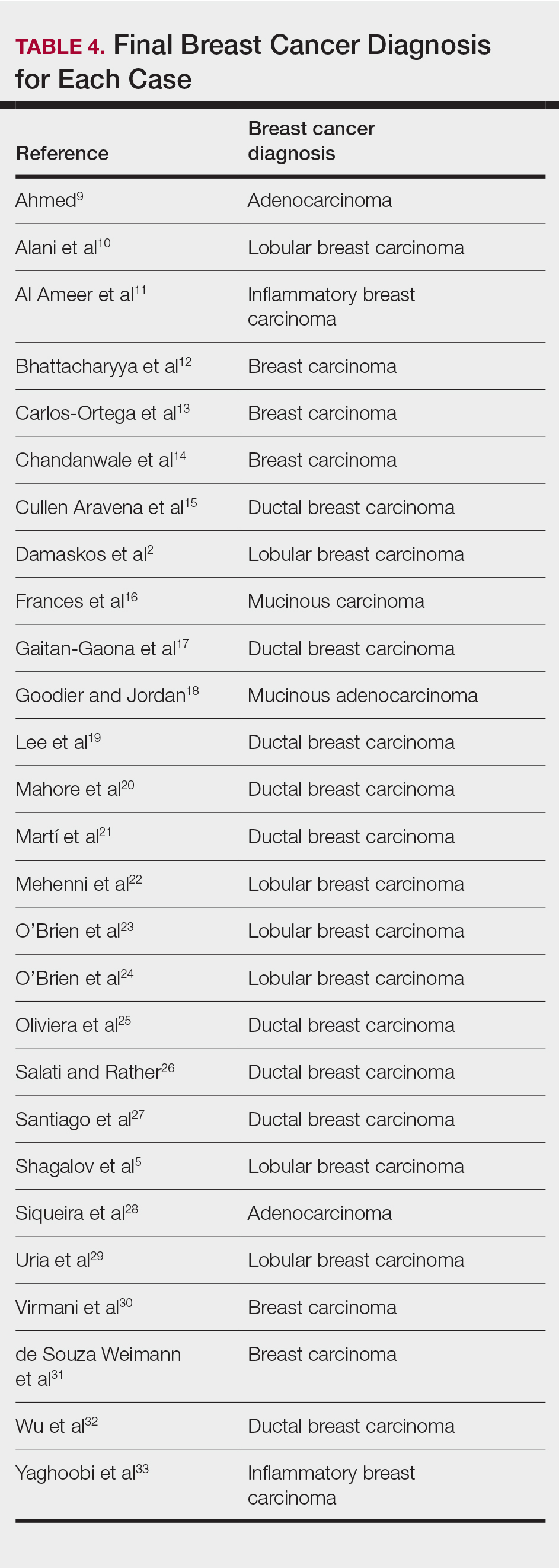

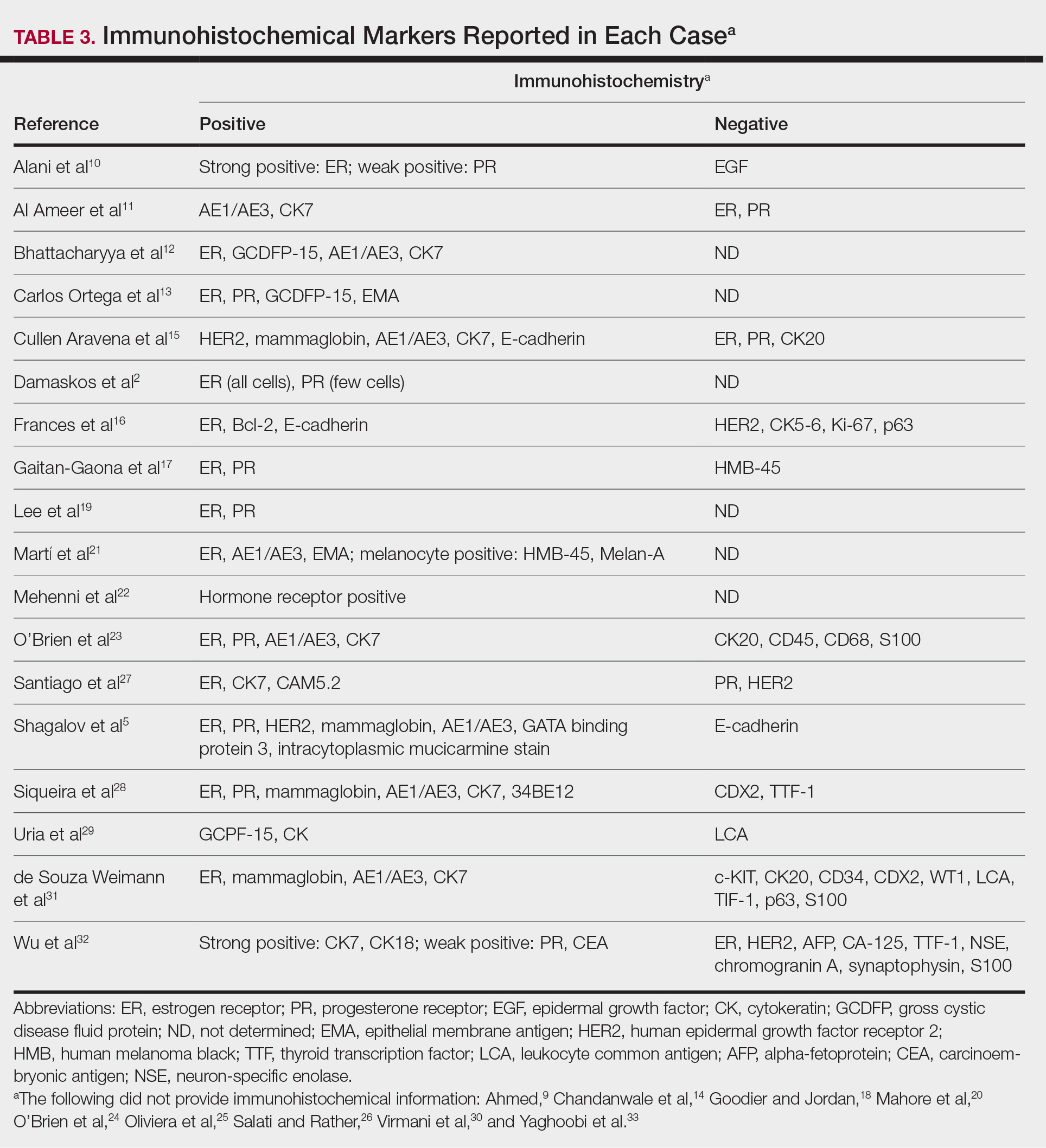

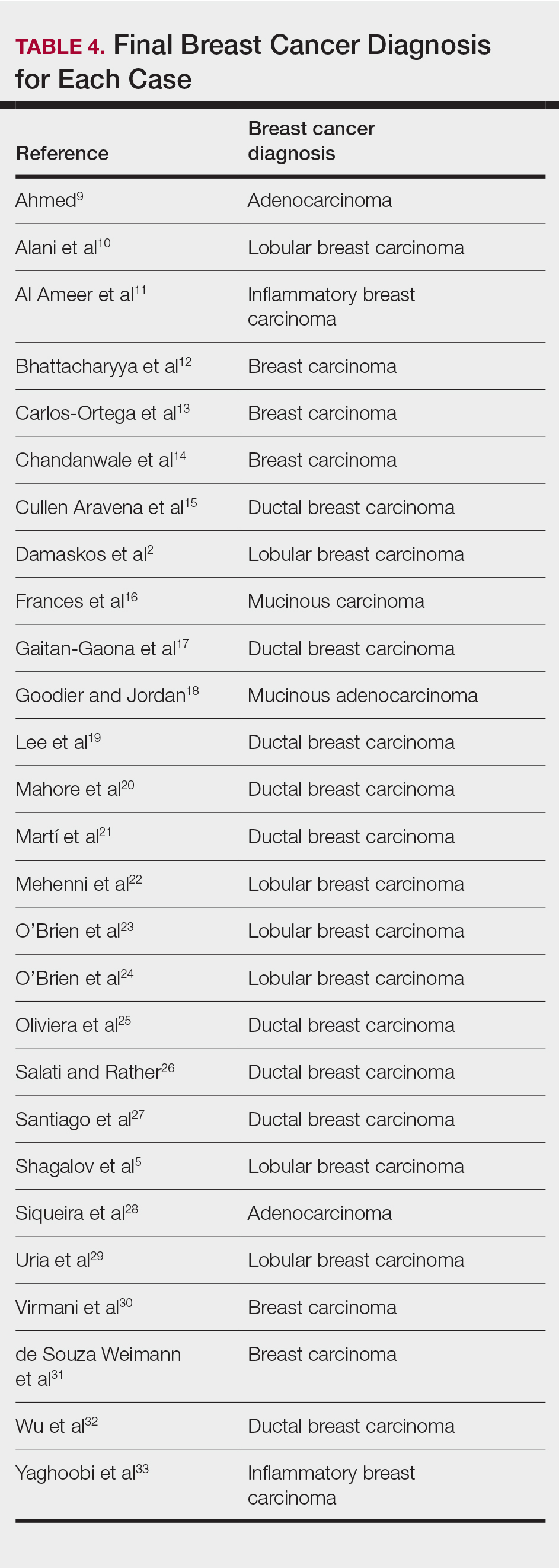

Eighteen cases reported positive immunohistochemistry from cutaneous biopsy (Table 3), given its high specificity in determining the origin of cutaneous metastases, while 8 case reports only performed hematoxylin and eosin staining. One case did not report hematoxylin and eosin or immunohistochemical staining. Table 4 lists the final breast cancer diagnosis for each case.

As per the standard of care, patients were evaluated with mammography or ultrasonography, combined with fine-needle aspiration of a suspected primary tumor, to give a definitive diagnosis of breast cancer. However, 4 cases reported negative mammography and ultrasonography.13,22,28,31 In 3 of these cases, no primary tumor was ever found.13,22,31

Comment

Our systematic review demonstrated that cutaneous lesions may be the first clinical manifestation of an undetected primary malignancy.40 These lesions often occur on the chest but may involve the face, abdomen, or extremities. Although asymptomatic erythematous nodules and plaques are the most common clinical presentations, lesions may be tender or pruritic or may even resemble benign skin conditions, including dermatitis, cellulitis, urticaria, and papulovesicular eruptions, causing them to go unrecognized.

Nevertheless, cutaneous metastasis of a visceral malignancy generally is observed late in the disease course, often following the diagnosis of a primary malignancy.14 Breast cancer is the most common internal malignancy to feature cutaneous spread, with the largest case series revealing a 23.9% rate of cutaneous metastases in females with breast carcinoma.6 Because of its proximity, the chest wall is the most common location for cutaneous lesions of metastatic breast cancer.

Malignant cells from a primary breast tumor may spread to the skin via lymphatic, hematogenous, or contiguous tissue dissemination, as well as iatrogenically through direct implantation during surgical procedures.3 The mechanism of neoplasm spread may likewise influence the clinical appearance of the resulting lesions. The localized lymphedema with a peau d’orange appearance of inflammatory metastatic breast carcinoma or the erythematous plaques of carcinoma erysipeloides are caused by embolized tumor cells obstructing dermal lymphatic vessels.3,11 On the other hand, the indurated erythematous plaques of carcinoma en cuirasse are caused by diffuse cutaneous and subcutaneous infiltration of tumor cells that also may be associated with marked reduction in breast volume.3

A primary breast cancer is classically diagnosed with a combination of clinical breast examination, radiologic imaging (ultrasound, mammogram, breast magnetic resonance imaging, or computed tomography), and fine-needle aspiration or lesional biopsy with histopathology.9 Given that in 20% of metastasized breast cancers the primary tumor may not be identified, a negative breast examination and imaging do not rule out breast cancer, especially if cutaneous biopsy reveals a primary malignancy.43 Histopathology and immunohistochemistry can thereby confirm the presence of metastatic cutaneous lesions and help characterize the breast cancer type involved, with adenocarcinomas being most commonly implicated.28 Although both ductal and lobular adenocarcinomas stain positive for cytokeratin 7, estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, gross cystic disease fluid protein 15, carcinoembryonic antigen, and mammaglobin, only the former shows positivity for e-cadherin markers.3 Conversely, inflammatory carcinoma stains positive for CD31 and podoplanin, telangiectatic carcinoma stains positive for CD31, and mammary Paget disease stains positive for cytokeratin 7 and mucin 1, cell surface associated.3 Apart from cutaneous biopsy, fine-needle aspiration cytology can likewise provide a simple and rapid method of diagnosis with high sensitivity and specificity.14

Conclusion

Although cutaneous metastasis as the presenting sign of a breast malignancy is rare, a high index of suspicion should be exercised when encountering rapid-onset, out-of-place nodules or plaques in female patients, particularly nodules or plaques presenting on the chest.

- Siegel R, Miller K, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020 [published online January 8, 2020]. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:7-30.

- Damaskos C, Dimitroulis D, Pergialiotis V, et al. An unexpected metastasis of breast cancer mimicking wheal rush. G Chir. 2016;37:136-138.

- Alcaraz I, Cerroni L, Rütten A, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393.

- Wong CYB, Helm MA, Kalb RE, et al. The presentation, pathology, and current management strategies of cutaneous metastasis. N Am J Med Sci. 2013;5:499-504.

- Shagalov D, Xu M, Liebman T, et al. Unilateral indurated plaque in the axilla: a case of metastatic breast carcinoma. Dermatol Online J. 2016;22:13030/qt8vw382nx.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Helm KF. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:228-236.

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:e1-e34.

- Bansal R, Patel T, Sarin J, et al. Cutaneous and subcutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: an analysis of cases diagnosed by fine needle aspiration. Diagn Cytopathol. 2011;39:882-887.

- Ahmed M. Cutaneous metastases from breast carcinoma. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011:bcr0620114398.

- Alani A, Roberts G, Kerr O. Carcinoma en cuirasse. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017:bcr2017222121.

- Al Ameer A, Imran M, Kaliyadan F, et al. Carcinoma erysipeloides as a presenting feature of breast carcinoma: a case report and brief review of literature. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:396-398.

- Bhattacharyya A, Gangopadhyay M, Ghosh K, et al. Wolf in sheep’s clothing: a case of carcinoma erysipeloides. Oxf Med Case Rep. 2016;2016:97-100.

- Carlos Ortega B, Alfaro Mejia A, Gómez-Campos G, et al. Metástasis de carcinoma de mama que simula prototecosis. Dermatol Rev Mex. 2012;56:55-61.

- Chandanwale SS, Gore CR, Buch AC, et al. Zosteriform cutaneous metastasis: a primary manifestation of carcinoma breast, rare case report. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2011;54:863-864.

- Cullen Aravena R, Cullen Aravena D, Velasco MJ, et al. Carcinoma hemorrhagiectoides: case report of an uncommon presentation of cutaneous metastatic breast carcinoma. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt3hm3z850.

- Frances L, Cuesta L, Leiva-Salinas M, et al. Secondary mucinous carcinoma of the skin. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:22361.

- Gaitan-Gaona F, Said MC, Valdes-Rodriguez R. Cutaneous metastatic pigmented breast carcinoma. Dermatol Online J. 2016;22:13030/qt0sv018ck.

- Goodier MA, Jordan JR. Metastatic breast cancer to the lower eyelid. Laryngoscope. 2010;120(suppl 4):S129.

- Lee H-J, Kim J-M, Kim G-W, et al. A unique cutaneous presentation of breast cancer: a red apple stuck in the breast. Ann Dermatol. 2016;28:499-501.

- Mahore SD, Bothale KA, Patrikar AD, et al. Carcinoma en cuirasse : a rare presentation of breast cancer. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2010;53:351-358.

- Martí N, Molina I, Monteagudo C, et al. Cutaneous metastasis of breast carcinoma mimicking malignant melanoma in scalp. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:12.

- Mehenni NN, Gamaz-Bensaou M, Bouzid K. Metastatic breast carcinoma to the gallbladder and the lower eyelid with no malignant lesion in the breast: an unusual case report with a short review of the literature [abstract]. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(suppl 3):iii49.

- O’Brien OA, AboGhaly E, Heffron C. An unusual presentation of a common malignancy [abstract]. J Pathol. 2013;231:S33.

- O’Brien R, Porto DA, Friedman BJ, et al. Elderly female with swelling of the right breast. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;67:e25-e26.

- Oliveira GM de, Zachetti DBC, Barros HR, et al. Breast carcinoma en Cuirasse—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:608-610.

- Salati SA, Rather AA. Carcinoma en cuirasse. J Pak Assoc Derma. 2013;23:452-454.

- Santiago F, Saleiro S, Brites MM, et al. A remarkable case of cutaneous metastatic breast carcinoma. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:10.

- Siqueira VR, Frota AS, Maia IL, et al. Cutaneous involvement as the initial presentation of metastatic breast adenocarcinoma - case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:960-963.

- Uria M, Chirino C, Rivas D. Inusual clinical presentation of cutaneous metastasis from breast carcinoma. A case report. Rev Argent Dermatol. 2009;90:230-236.

- Virmani NC, Sharma YK, Panicker NK, et al. Zosteriform skin metastases: clue to an undiagnosed breast cancer. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:726-727.

- de Souza Weimann ET, Botero EB, Mendes C, et al. Cutaneous metastasis as the first manifestation of occult malignant breast neoplasia. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91(5 suppl 1):105-107.

- Wu CY, Gao HW, Huang WH, et al. Infection-like acral cutaneous metastasis as the presenting sign of an occult breast cancer. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:e409-e410.

- Yaghoobi R, Talaizade A, Lal K, et al. Inflammatory breast carcinoma presenting with two different patterns of cutaneous metastases: carcinoma telangiectaticum and carcinoma erysipeloides. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:47-51.

- Atis G, Demirci GT, Atunay IK, et al. The clinical characteristics and the frequency of metastatic cutaneous tumors among primary skin tumors. Turkderm. 2013;47:166-169.

- Benmously R, Souissi A, Badri T, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal cancers. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2008;17:167-170.

- Chopra R, Chhabra S, Samra SG, et al. Cutaneous metastases of internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:125-131.

- El Khoury J, Khalifeh I, Kibbi AG, et al. Cutaneous metastasis: clinicopathological study of 72 patients from a tertiary care center in Lebanon. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:147-158.

- Fernandez-Flores A. Cutaneous metastases: a study of 78 biopsies from 69 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:222-239.

- Gómez Sánchez ME, Martinez Martinez ML, Martín De Hijas MC, et al. Metástasis cutáneas de tumores sólidos. Estudio descriptivo retrospectivo. Piel. 2014;29:207-212

- Handa U, Kundu R, Dimri K. Cutaneous metastasis: a study of 138 cases diagnosed by fine-needle aspiration cytology. Acta Cytol. 2017;61:47-54.

- Itin P, Tomaschett S. Cutaneous metastases from malignancies which do not originate from the skin. An epidemiological study. Article in German. Internist (Berl). 2009;50:179-186.

- Siu AL, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for breast cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:279-296.

- Torres HA, Bodey GP, Tarrand JJ, et al. Protothecosis in patients with cancer: case series and literature review. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2003;9:786-792.

Breast cancer is the second most common malignancy in women (after primary skin cancer) and is the second leading cause of cancer-related death in this population. In 2020, the American Cancer Society reported an estimated 276,480 new breast cancer diagnoses and 42,170 breast cancer–related deaths.1 Despite the fact that routine screening with mammography and sonography is standard, the incidence of advanced breast cancer at the time of diagnosis has remained stable over time, suggesting that life-threatening breast cancers are not being caught at an earlier stage. The number of breast cancers with distant metastases at the time of diagnosis also has not decreased.2 Therefore, although screening tests are valuable, they are imperfect and not without limitations.

Cutaneous metastasis is defined as the spread of malignant cells from an internal neoplasm to the skin, which can occur either by contiguous invasion or by distant metastasis through hematogenous or lymphatic routes.3 The diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis requires a high index of suspicion on the part of the clinician.4 Of the various internal malignancies in women, breast cancer most frequently results in metastasis to the skin,5 with up to 24% of patients with metastatic breast cancer developing cutaneous lesions.6

In recent years, there have been multiple reports of skin lesions prompting the diagnosis of a previously unknown breast cancer. In a study by Lookingbill et al,6 6.3% of patients with breast cancer presented with cutaneous involvement at the time of diagnosis, with 3.5% having skin symptoms as the presenting sign. Although there have been studies analyzing cutaneous metastasis from various internal malignancies, none thus far have focused on cutaneous metastasis as a presenting sign of breast cancer. This systematic review aimed to highlight the diverse clinical presentations of cutaneous metastatic breast cancer and their clinical implications.

Methods

Study Selection

This study utilized the PRISMA guidelines for systematic reviews.7 A review of the literature was conducted using the following databases: MEDLINE/PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane library, CINAHL, and EBSCO.

Search Strategy and Analysis

We completed our search of each of the databases on December 16, 2017, using the phrases cutaneous metastasis and breast cancer to find relevant case reports and retrospective studies. Three authors (C.J., S.R., and M.A.) manually reviewed the resulting abstracts. If an abstract did not include enough information to determine inclusion, the full-text version was reviewed by 2 of the authors (C.J. and S.R.). Two of the authors (C.J. and M.A.) also assessed each source for relevancy and included the articles deemed eligible (Figure 1).

Inclusion criteria were the following: case reports and retrospective studies published in the prior 10 years (January 1, 2007, to December 16, 2017) with human female patients who developed metastatic cutaneous lesions due to a previously unknown primary breast malignancy. Studies published in other languages were included; these articles were translated into English using a human translator or computer translation program (Google Translate). Exclusion criteria were the following: male patients, patients with a known diagnosis of primary breast malignancy prior to the appearance of a metastatic cutaneous lesion, articles focusing on the treatment of breast cancer, and articles without enough details to draw meaningful conclusions.

For a retrospective review to be included, it must have specified the number of breast cancer cases and the number of cutaneous metastases presenting initially or simultaneously to the breast cancer diagnosis. Bansal et al8 defined a simultaneous diagnosis as a skin lesion presenting with other concerns associated with the primary malignancy.

Results

The initial search of MEDLINE/PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane library, CINAHL, and EBSCO yielded a total of 722 articles. Seven other articles found separately while undergoing our initial research were added to this total. Abstracts were manually screened, with 657 articles discarded after failing to meet the predetermined inclusion criteria. After removal of 25 duplicate articles, the full text of the remaining 47 articles were reviewed, leading to the elimination of an additional 11 articles that did not meet the necessary criteria. This resulted in 36 articles (Figure 1), including 27 individual case reports (Table 1) and 9 retrospective reviews (Table 2). Approximately 13.7% of patients in the 9 retrospective reviews presented with a skin lesion before or simultaneous to the diagnosis of breast cancer (Figure 2).

Forty-one percent (17/41) of the patients with cutaneous metastasis as a presenting feature of their breast cancer fell outside the age range for breast cancer screening recommended by the US Preventive Services Task Force,42 with 24% of the patients younger than 50 years and 17% older than 74 years (Figure 3).

Lesion Characteristics

The most common cutaneous lesions were erythematous nodules and plaques, with a few reports of black17,21 or flesh-colored5,20,31 lesions, as well as ulceration.8,17,32 The most common location for skin lesions was on the thorax (chest or breast), accounting for 57% of the cutaneous metastases, with the arms and axillae being second most commonly involved (15%)(Figure 4). Some cases presented with skin lesions extending to multiple regions. In these cases, each location of the lesion was recorded separately when analyzing the data. An additional 5 cases, shown as “Other” in Figure 4, included the eyelids, occiput, and finger. Eight case reports described symptoms associated with the cutaneous lesions, with painful or tender lesions reported in 7 cases5,9,14,17,20,30,32 and pruritus in 2 cases.12,20 Moreover, 6 case reports presented patients denying any systemic or associated symptoms with their skin lesions.2,5,9,16,17,28 Multiple cases were initially treated as other conditions due to misdiagnosis, including herpes zoster14,30 and dermatitis.11,12

Diagnostic Data

Eighteen cases reported positive immunohistochemistry from cutaneous biopsy (Table 3), given its high specificity in determining the origin of cutaneous metastases, while 8 case reports only performed hematoxylin and eosin staining. One case did not report hematoxylin and eosin or immunohistochemical staining. Table 4 lists the final breast cancer diagnosis for each case.

As per the standard of care, patients were evaluated with mammography or ultrasonography, combined with fine-needle aspiration of a suspected primary tumor, to give a definitive diagnosis of breast cancer. However, 4 cases reported negative mammography and ultrasonography.13,22,28,31 In 3 of these cases, no primary tumor was ever found.13,22,31

Comment

Our systematic review demonstrated that cutaneous lesions may be the first clinical manifestation of an undetected primary malignancy.40 These lesions often occur on the chest but may involve the face, abdomen, or extremities. Although asymptomatic erythematous nodules and plaques are the most common clinical presentations, lesions may be tender or pruritic or may even resemble benign skin conditions, including dermatitis, cellulitis, urticaria, and papulovesicular eruptions, causing them to go unrecognized.

Nevertheless, cutaneous metastasis of a visceral malignancy generally is observed late in the disease course, often following the diagnosis of a primary malignancy.14 Breast cancer is the most common internal malignancy to feature cutaneous spread, with the largest case series revealing a 23.9% rate of cutaneous metastases in females with breast carcinoma.6 Because of its proximity, the chest wall is the most common location for cutaneous lesions of metastatic breast cancer.

Malignant cells from a primary breast tumor may spread to the skin via lymphatic, hematogenous, or contiguous tissue dissemination, as well as iatrogenically through direct implantation during surgical procedures.3 The mechanism of neoplasm spread may likewise influence the clinical appearance of the resulting lesions. The localized lymphedema with a peau d’orange appearance of inflammatory metastatic breast carcinoma or the erythematous plaques of carcinoma erysipeloides are caused by embolized tumor cells obstructing dermal lymphatic vessels.3,11 On the other hand, the indurated erythematous plaques of carcinoma en cuirasse are caused by diffuse cutaneous and subcutaneous infiltration of tumor cells that also may be associated with marked reduction in breast volume.3

A primary breast cancer is classically diagnosed with a combination of clinical breast examination, radiologic imaging (ultrasound, mammogram, breast magnetic resonance imaging, or computed tomography), and fine-needle aspiration or lesional biopsy with histopathology.9 Given that in 20% of metastasized breast cancers the primary tumor may not be identified, a negative breast examination and imaging do not rule out breast cancer, especially if cutaneous biopsy reveals a primary malignancy.43 Histopathology and immunohistochemistry can thereby confirm the presence of metastatic cutaneous lesions and help characterize the breast cancer type involved, with adenocarcinomas being most commonly implicated.28 Although both ductal and lobular adenocarcinomas stain positive for cytokeratin 7, estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, gross cystic disease fluid protein 15, carcinoembryonic antigen, and mammaglobin, only the former shows positivity for e-cadherin markers.3 Conversely, inflammatory carcinoma stains positive for CD31 and podoplanin, telangiectatic carcinoma stains positive for CD31, and mammary Paget disease stains positive for cytokeratin 7 and mucin 1, cell surface associated.3 Apart from cutaneous biopsy, fine-needle aspiration cytology can likewise provide a simple and rapid method of diagnosis with high sensitivity and specificity.14

Conclusion

Although cutaneous metastasis as the presenting sign of a breast malignancy is rare, a high index of suspicion should be exercised when encountering rapid-onset, out-of-place nodules or plaques in female patients, particularly nodules or plaques presenting on the chest.

Breast cancer is the second most common malignancy in women (after primary skin cancer) and is the second leading cause of cancer-related death in this population. In 2020, the American Cancer Society reported an estimated 276,480 new breast cancer diagnoses and 42,170 breast cancer–related deaths.1 Despite the fact that routine screening with mammography and sonography is standard, the incidence of advanced breast cancer at the time of diagnosis has remained stable over time, suggesting that life-threatening breast cancers are not being caught at an earlier stage. The number of breast cancers with distant metastases at the time of diagnosis also has not decreased.2 Therefore, although screening tests are valuable, they are imperfect and not without limitations.

Cutaneous metastasis is defined as the spread of malignant cells from an internal neoplasm to the skin, which can occur either by contiguous invasion or by distant metastasis through hematogenous or lymphatic routes.3 The diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis requires a high index of suspicion on the part of the clinician.4 Of the various internal malignancies in women, breast cancer most frequently results in metastasis to the skin,5 with up to 24% of patients with metastatic breast cancer developing cutaneous lesions.6

In recent years, there have been multiple reports of skin lesions prompting the diagnosis of a previously unknown breast cancer. In a study by Lookingbill et al,6 6.3% of patients with breast cancer presented with cutaneous involvement at the time of diagnosis, with 3.5% having skin symptoms as the presenting sign. Although there have been studies analyzing cutaneous metastasis from various internal malignancies, none thus far have focused on cutaneous metastasis as a presenting sign of breast cancer. This systematic review aimed to highlight the diverse clinical presentations of cutaneous metastatic breast cancer and their clinical implications.

Methods

Study Selection

This study utilized the PRISMA guidelines for systematic reviews.7 A review of the literature was conducted using the following databases: MEDLINE/PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane library, CINAHL, and EBSCO.

Search Strategy and Analysis

We completed our search of each of the databases on December 16, 2017, using the phrases cutaneous metastasis and breast cancer to find relevant case reports and retrospective studies. Three authors (C.J., S.R., and M.A.) manually reviewed the resulting abstracts. If an abstract did not include enough information to determine inclusion, the full-text version was reviewed by 2 of the authors (C.J. and S.R.). Two of the authors (C.J. and M.A.) also assessed each source for relevancy and included the articles deemed eligible (Figure 1).

Inclusion criteria were the following: case reports and retrospective studies published in the prior 10 years (January 1, 2007, to December 16, 2017) with human female patients who developed metastatic cutaneous lesions due to a previously unknown primary breast malignancy. Studies published in other languages were included; these articles were translated into English using a human translator or computer translation program (Google Translate). Exclusion criteria were the following: male patients, patients with a known diagnosis of primary breast malignancy prior to the appearance of a metastatic cutaneous lesion, articles focusing on the treatment of breast cancer, and articles without enough details to draw meaningful conclusions.

For a retrospective review to be included, it must have specified the number of breast cancer cases and the number of cutaneous metastases presenting initially or simultaneously to the breast cancer diagnosis. Bansal et al8 defined a simultaneous diagnosis as a skin lesion presenting with other concerns associated with the primary malignancy.

Results

The initial search of MEDLINE/PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane library, CINAHL, and EBSCO yielded a total of 722 articles. Seven other articles found separately while undergoing our initial research were added to this total. Abstracts were manually screened, with 657 articles discarded after failing to meet the predetermined inclusion criteria. After removal of 25 duplicate articles, the full text of the remaining 47 articles were reviewed, leading to the elimination of an additional 11 articles that did not meet the necessary criteria. This resulted in 36 articles (Figure 1), including 27 individual case reports (Table 1) and 9 retrospective reviews (Table 2). Approximately 13.7% of patients in the 9 retrospective reviews presented with a skin lesion before or simultaneous to the diagnosis of breast cancer (Figure 2).

Forty-one percent (17/41) of the patients with cutaneous metastasis as a presenting feature of their breast cancer fell outside the age range for breast cancer screening recommended by the US Preventive Services Task Force,42 with 24% of the patients younger than 50 years and 17% older than 74 years (Figure 3).

Lesion Characteristics

The most common cutaneous lesions were erythematous nodules and plaques, with a few reports of black17,21 or flesh-colored5,20,31 lesions, as well as ulceration.8,17,32 The most common location for skin lesions was on the thorax (chest or breast), accounting for 57% of the cutaneous metastases, with the arms and axillae being second most commonly involved (15%)(Figure 4). Some cases presented with skin lesions extending to multiple regions. In these cases, each location of the lesion was recorded separately when analyzing the data. An additional 5 cases, shown as “Other” in Figure 4, included the eyelids, occiput, and finger. Eight case reports described symptoms associated with the cutaneous lesions, with painful or tender lesions reported in 7 cases5,9,14,17,20,30,32 and pruritus in 2 cases.12,20 Moreover, 6 case reports presented patients denying any systemic or associated symptoms with their skin lesions.2,5,9,16,17,28 Multiple cases were initially treated as other conditions due to misdiagnosis, including herpes zoster14,30 and dermatitis.11,12

Diagnostic Data

Eighteen cases reported positive immunohistochemistry from cutaneous biopsy (Table 3), given its high specificity in determining the origin of cutaneous metastases, while 8 case reports only performed hematoxylin and eosin staining. One case did not report hematoxylin and eosin or immunohistochemical staining. Table 4 lists the final breast cancer diagnosis for each case.

As per the standard of care, patients were evaluated with mammography or ultrasonography, combined with fine-needle aspiration of a suspected primary tumor, to give a definitive diagnosis of breast cancer. However, 4 cases reported negative mammography and ultrasonography.13,22,28,31 In 3 of these cases, no primary tumor was ever found.13,22,31

Comment

Our systematic review demonstrated that cutaneous lesions may be the first clinical manifestation of an undetected primary malignancy.40 These lesions often occur on the chest but may involve the face, abdomen, or extremities. Although asymptomatic erythematous nodules and plaques are the most common clinical presentations, lesions may be tender or pruritic or may even resemble benign skin conditions, including dermatitis, cellulitis, urticaria, and papulovesicular eruptions, causing them to go unrecognized.

Nevertheless, cutaneous metastasis of a visceral malignancy generally is observed late in the disease course, often following the diagnosis of a primary malignancy.14 Breast cancer is the most common internal malignancy to feature cutaneous spread, with the largest case series revealing a 23.9% rate of cutaneous metastases in females with breast carcinoma.6 Because of its proximity, the chest wall is the most common location for cutaneous lesions of metastatic breast cancer.

Malignant cells from a primary breast tumor may spread to the skin via lymphatic, hematogenous, or contiguous tissue dissemination, as well as iatrogenically through direct implantation during surgical procedures.3 The mechanism of neoplasm spread may likewise influence the clinical appearance of the resulting lesions. The localized lymphedema with a peau d’orange appearance of inflammatory metastatic breast carcinoma or the erythematous plaques of carcinoma erysipeloides are caused by embolized tumor cells obstructing dermal lymphatic vessels.3,11 On the other hand, the indurated erythematous plaques of carcinoma en cuirasse are caused by diffuse cutaneous and subcutaneous infiltration of tumor cells that also may be associated with marked reduction in breast volume.3

A primary breast cancer is classically diagnosed with a combination of clinical breast examination, radiologic imaging (ultrasound, mammogram, breast magnetic resonance imaging, or computed tomography), and fine-needle aspiration or lesional biopsy with histopathology.9 Given that in 20% of metastasized breast cancers the primary tumor may not be identified, a negative breast examination and imaging do not rule out breast cancer, especially if cutaneous biopsy reveals a primary malignancy.43 Histopathology and immunohistochemistry can thereby confirm the presence of metastatic cutaneous lesions and help characterize the breast cancer type involved, with adenocarcinomas being most commonly implicated.28 Although both ductal and lobular adenocarcinomas stain positive for cytokeratin 7, estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, gross cystic disease fluid protein 15, carcinoembryonic antigen, and mammaglobin, only the former shows positivity for e-cadherin markers.3 Conversely, inflammatory carcinoma stains positive for CD31 and podoplanin, telangiectatic carcinoma stains positive for CD31, and mammary Paget disease stains positive for cytokeratin 7 and mucin 1, cell surface associated.3 Apart from cutaneous biopsy, fine-needle aspiration cytology can likewise provide a simple and rapid method of diagnosis with high sensitivity and specificity.14

Conclusion

Although cutaneous metastasis as the presenting sign of a breast malignancy is rare, a high index of suspicion should be exercised when encountering rapid-onset, out-of-place nodules or plaques in female patients, particularly nodules or plaques presenting on the chest.

- Siegel R, Miller K, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020 [published online January 8, 2020]. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:7-30.

- Damaskos C, Dimitroulis D, Pergialiotis V, et al. An unexpected metastasis of breast cancer mimicking wheal rush. G Chir. 2016;37:136-138.

- Alcaraz I, Cerroni L, Rütten A, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393.

- Wong CYB, Helm MA, Kalb RE, et al. The presentation, pathology, and current management strategies of cutaneous metastasis. N Am J Med Sci. 2013;5:499-504.

- Shagalov D, Xu M, Liebman T, et al. Unilateral indurated plaque in the axilla: a case of metastatic breast carcinoma. Dermatol Online J. 2016;22:13030/qt8vw382nx.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Helm KF. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:228-236.

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:e1-e34.

- Bansal R, Patel T, Sarin J, et al. Cutaneous and subcutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: an analysis of cases diagnosed by fine needle aspiration. Diagn Cytopathol. 2011;39:882-887.

- Ahmed M. Cutaneous metastases from breast carcinoma. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011:bcr0620114398.

- Alani A, Roberts G, Kerr O. Carcinoma en cuirasse. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017:bcr2017222121.

- Al Ameer A, Imran M, Kaliyadan F, et al. Carcinoma erysipeloides as a presenting feature of breast carcinoma: a case report and brief review of literature. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:396-398.

- Bhattacharyya A, Gangopadhyay M, Ghosh K, et al. Wolf in sheep’s clothing: a case of carcinoma erysipeloides. Oxf Med Case Rep. 2016;2016:97-100.

- Carlos Ortega B, Alfaro Mejia A, Gómez-Campos G, et al. Metástasis de carcinoma de mama que simula prototecosis. Dermatol Rev Mex. 2012;56:55-61.

- Chandanwale SS, Gore CR, Buch AC, et al. Zosteriform cutaneous metastasis: a primary manifestation of carcinoma breast, rare case report. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2011;54:863-864.

- Cullen Aravena R, Cullen Aravena D, Velasco MJ, et al. Carcinoma hemorrhagiectoides: case report of an uncommon presentation of cutaneous metastatic breast carcinoma. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt3hm3z850.

- Frances L, Cuesta L, Leiva-Salinas M, et al. Secondary mucinous carcinoma of the skin. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:22361.

- Gaitan-Gaona F, Said MC, Valdes-Rodriguez R. Cutaneous metastatic pigmented breast carcinoma. Dermatol Online J. 2016;22:13030/qt0sv018ck.

- Goodier MA, Jordan JR. Metastatic breast cancer to the lower eyelid. Laryngoscope. 2010;120(suppl 4):S129.

- Lee H-J, Kim J-M, Kim G-W, et al. A unique cutaneous presentation of breast cancer: a red apple stuck in the breast. Ann Dermatol. 2016;28:499-501.

- Mahore SD, Bothale KA, Patrikar AD, et al. Carcinoma en cuirasse : a rare presentation of breast cancer. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2010;53:351-358.

- Martí N, Molina I, Monteagudo C, et al. Cutaneous metastasis of breast carcinoma mimicking malignant melanoma in scalp. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:12.

- Mehenni NN, Gamaz-Bensaou M, Bouzid K. Metastatic breast carcinoma to the gallbladder and the lower eyelid with no malignant lesion in the breast: an unusual case report with a short review of the literature [abstract]. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(suppl 3):iii49.

- O’Brien OA, AboGhaly E, Heffron C. An unusual presentation of a common malignancy [abstract]. J Pathol. 2013;231:S33.

- O’Brien R, Porto DA, Friedman BJ, et al. Elderly female with swelling of the right breast. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;67:e25-e26.

- Oliveira GM de, Zachetti DBC, Barros HR, et al. Breast carcinoma en Cuirasse—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:608-610.

- Salati SA, Rather AA. Carcinoma en cuirasse. J Pak Assoc Derma. 2013;23:452-454.

- Santiago F, Saleiro S, Brites MM, et al. A remarkable case of cutaneous metastatic breast carcinoma. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:10.

- Siqueira VR, Frota AS, Maia IL, et al. Cutaneous involvement as the initial presentation of metastatic breast adenocarcinoma - case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:960-963.

- Uria M, Chirino C, Rivas D. Inusual clinical presentation of cutaneous metastasis from breast carcinoma. A case report. Rev Argent Dermatol. 2009;90:230-236.

- Virmani NC, Sharma YK, Panicker NK, et al. Zosteriform skin metastases: clue to an undiagnosed breast cancer. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:726-727.

- de Souza Weimann ET, Botero EB, Mendes C, et al. Cutaneous metastasis as the first manifestation of occult malignant breast neoplasia. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91(5 suppl 1):105-107.

- Wu CY, Gao HW, Huang WH, et al. Infection-like acral cutaneous metastasis as the presenting sign of an occult breast cancer. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:e409-e410.

- Yaghoobi R, Talaizade A, Lal K, et al. Inflammatory breast carcinoma presenting with two different patterns of cutaneous metastases: carcinoma telangiectaticum and carcinoma erysipeloides. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:47-51.

- Atis G, Demirci GT, Atunay IK, et al. The clinical characteristics and the frequency of metastatic cutaneous tumors among primary skin tumors. Turkderm. 2013;47:166-169.

- Benmously R, Souissi A, Badri T, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal cancers. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2008;17:167-170.

- Chopra R, Chhabra S, Samra SG, et al. Cutaneous metastases of internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:125-131.

- El Khoury J, Khalifeh I, Kibbi AG, et al. Cutaneous metastasis: clinicopathological study of 72 patients from a tertiary care center in Lebanon. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:147-158.

- Fernandez-Flores A. Cutaneous metastases: a study of 78 biopsies from 69 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:222-239.

- Gómez Sánchez ME, Martinez Martinez ML, Martín De Hijas MC, et al. Metástasis cutáneas de tumores sólidos. Estudio descriptivo retrospectivo. Piel. 2014;29:207-212

- Handa U, Kundu R, Dimri K. Cutaneous metastasis: a study of 138 cases diagnosed by fine-needle aspiration cytology. Acta Cytol. 2017;61:47-54.

- Itin P, Tomaschett S. Cutaneous metastases from malignancies which do not originate from the skin. An epidemiological study. Article in German. Internist (Berl). 2009;50:179-186.

- Siu AL, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for breast cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:279-296.

- Torres HA, Bodey GP, Tarrand JJ, et al. Protothecosis in patients with cancer: case series and literature review. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2003;9:786-792.

- Siegel R, Miller K, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020 [published online January 8, 2020]. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:7-30.

- Damaskos C, Dimitroulis D, Pergialiotis V, et al. An unexpected metastasis of breast cancer mimicking wheal rush. G Chir. 2016;37:136-138.

- Alcaraz I, Cerroni L, Rütten A, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393.

- Wong CYB, Helm MA, Kalb RE, et al. The presentation, pathology, and current management strategies of cutaneous metastasis. N Am J Med Sci. 2013;5:499-504.

- Shagalov D, Xu M, Liebman T, et al. Unilateral indurated plaque in the axilla: a case of metastatic breast carcinoma. Dermatol Online J. 2016;22:13030/qt8vw382nx.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Helm KF. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:228-236.

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:e1-e34.

- Bansal R, Patel T, Sarin J, et al. Cutaneous and subcutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: an analysis of cases diagnosed by fine needle aspiration. Diagn Cytopathol. 2011;39:882-887.

- Ahmed M. Cutaneous metastases from breast carcinoma. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011:bcr0620114398.

- Alani A, Roberts G, Kerr O. Carcinoma en cuirasse. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017:bcr2017222121.

- Al Ameer A, Imran M, Kaliyadan F, et al. Carcinoma erysipeloides as a presenting feature of breast carcinoma: a case report and brief review of literature. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:396-398.

- Bhattacharyya A, Gangopadhyay M, Ghosh K, et al. Wolf in sheep’s clothing: a case of carcinoma erysipeloides. Oxf Med Case Rep. 2016;2016:97-100.

- Carlos Ortega B, Alfaro Mejia A, Gómez-Campos G, et al. Metástasis de carcinoma de mama que simula prototecosis. Dermatol Rev Mex. 2012;56:55-61.

- Chandanwale SS, Gore CR, Buch AC, et al. Zosteriform cutaneous metastasis: a primary manifestation of carcinoma breast, rare case report. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2011;54:863-864.

- Cullen Aravena R, Cullen Aravena D, Velasco MJ, et al. Carcinoma hemorrhagiectoides: case report of an uncommon presentation of cutaneous metastatic breast carcinoma. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt3hm3z850.

- Frances L, Cuesta L, Leiva-Salinas M, et al. Secondary mucinous carcinoma of the skin. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:22361.

- Gaitan-Gaona F, Said MC, Valdes-Rodriguez R. Cutaneous metastatic pigmented breast carcinoma. Dermatol Online J. 2016;22:13030/qt0sv018ck.

- Goodier MA, Jordan JR. Metastatic breast cancer to the lower eyelid. Laryngoscope. 2010;120(suppl 4):S129.

- Lee H-J, Kim J-M, Kim G-W, et al. A unique cutaneous presentation of breast cancer: a red apple stuck in the breast. Ann Dermatol. 2016;28:499-501.

- Mahore SD, Bothale KA, Patrikar AD, et al. Carcinoma en cuirasse : a rare presentation of breast cancer. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2010;53:351-358.

- Martí N, Molina I, Monteagudo C, et al. Cutaneous metastasis of breast carcinoma mimicking malignant melanoma in scalp. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:12.

- Mehenni NN, Gamaz-Bensaou M, Bouzid K. Metastatic breast carcinoma to the gallbladder and the lower eyelid with no malignant lesion in the breast: an unusual case report with a short review of the literature [abstract]. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(suppl 3):iii49.

- O’Brien OA, AboGhaly E, Heffron C. An unusual presentation of a common malignancy [abstract]. J Pathol. 2013;231:S33.

- O’Brien R, Porto DA, Friedman BJ, et al. Elderly female with swelling of the right breast. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;67:e25-e26.

- Oliveira GM de, Zachetti DBC, Barros HR, et al. Breast carcinoma en Cuirasse—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:608-610.

- Salati SA, Rather AA. Carcinoma en cuirasse. J Pak Assoc Derma. 2013;23:452-454.

- Santiago F, Saleiro S, Brites MM, et al. A remarkable case of cutaneous metastatic breast carcinoma. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:10.

- Siqueira VR, Frota AS, Maia IL, et al. Cutaneous involvement as the initial presentation of metastatic breast adenocarcinoma - case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:960-963.

- Uria M, Chirino C, Rivas D. Inusual clinical presentation of cutaneous metastasis from breast carcinoma. A case report. Rev Argent Dermatol. 2009;90:230-236.

- Virmani NC, Sharma YK, Panicker NK, et al. Zosteriform skin metastases: clue to an undiagnosed breast cancer. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:726-727.

- de Souza Weimann ET, Botero EB, Mendes C, et al. Cutaneous metastasis as the first manifestation of occult malignant breast neoplasia. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91(5 suppl 1):105-107.

- Wu CY, Gao HW, Huang WH, et al. Infection-like acral cutaneous metastasis as the presenting sign of an occult breast cancer. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:e409-e410.

- Yaghoobi R, Talaizade A, Lal K, et al. Inflammatory breast carcinoma presenting with two different patterns of cutaneous metastases: carcinoma telangiectaticum and carcinoma erysipeloides. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:47-51.

- Atis G, Demirci GT, Atunay IK, et al. The clinical characteristics and the frequency of metastatic cutaneous tumors among primary skin tumors. Turkderm. 2013;47:166-169.

- Benmously R, Souissi A, Badri T, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal cancers. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2008;17:167-170.

- Chopra R, Chhabra S, Samra SG, et al. Cutaneous metastases of internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:125-131.

- El Khoury J, Khalifeh I, Kibbi AG, et al. Cutaneous metastasis: clinicopathological study of 72 patients from a tertiary care center in Lebanon. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:147-158.

- Fernandez-Flores A. Cutaneous metastases: a study of 78 biopsies from 69 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:222-239.

- Gómez Sánchez ME, Martinez Martinez ML, Martín De Hijas MC, et al. Metástasis cutáneas de tumores sólidos. Estudio descriptivo retrospectivo. Piel. 2014;29:207-212

- Handa U, Kundu R, Dimri K. Cutaneous metastasis: a study of 138 cases diagnosed by fine-needle aspiration cytology. Acta Cytol. 2017;61:47-54.

- Itin P, Tomaschett S. Cutaneous metastases from malignancies which do not originate from the skin. An epidemiological study. Article in German. Internist (Berl). 2009;50:179-186.

- Siu AL, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for breast cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:279-296.

- Torres HA, Bodey GP, Tarrand JJ, et al. Protothecosis in patients with cancer: case series and literature review. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2003;9:786-792.

PRACTICE POINTS

- Dermatologists may play a role in diagnosing breast cancer through cutaneous metastasis, even in patients without a history of breast cancer.

- Clinicians should consider breast cancer metastasis in the differential for any erythematous lesion on the trunk.

Herpes Esophagitis in the Setting of Immunosuppression From Pemphigus Vulgaris Therapy

Pemphigus vulgaris (PV) is a chronic autoimmune intraepithelial bullous disease caused by pathogenic IgG antibodies at the intraepidermal cell-surface proteins desmoglein 1 (DSG1) and desmoglein 3 (DSG3), which are members of the cadherin superfamily of desmosomal proteins and are involved in keratinocyte adhesion. Autoantibody binding to these molecules leads to the loss of cell-cell adhesion in the epithelial suprabasilar layer, producing flaccid blisters on an erythematous base with a positive Nikolsky sign.1 The blisters frequently rupture, leaving painful nonscarring erosions with the potential for secondary infection.

The clinical phenotype of PV is directly related to the autoantibody profile. Clinically, PV often is mucosal dominant on presentation with painful oropharyngeal involvement and associated IgG antibodies against DSG3. Progression to cutaneous disease, such as on the scalp or axillae, is accompanied by a shift in IgG antibodies against both DSG1 and DSG3.2,3

Combination therapy with prednisone and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) has proven to be an effective method of controlling the signs and symptoms of PV4; however, the immunosuppressive effects of these medications put the patient at risk for a host of opportunistic infections. Herpes simplex virus (HSV) has been associated with PV lesions of the oral mucosa, though a clear-cut relationship between these 2 entities has yet to be established.5 Herpes simplex virus has likewise been confirmed in therapy-resistant exacerbations of PV.6 Herpes esophagitis is a rare consequence of treatment with prednisone and MMF that is primarily encountered in patients with a history of solid organ transplantation7 and rarely has been reported in PV patients undergoing therapeutic immunosuppression.

Acute odynophagia in patients undergoing systemic treatment of active PV warrants prompt endoscopic evaluation to rule out esophageal pemphigus or superinfection. We report the case of a 35-year-old man with stable but poorly controlled PV who was undergoing systemic treatment and experienced rapid deterioration due to herpes esophagitis from immunosuppression.

Case Report

A 35-year-old man was referred to our clinic for evaluation of blisters on the scalp, oral mucosa, and proximal upper and lower extremities of 4 months’ duration. A biopsy performed by his primary care physician within a month of onset of symptoms was reportedly suggestive of PV; although no direct immunofluorescence had been performed, serum indirect immunofluorescence was highly positive for IgG antibodies toward DSG3 and to a lesser extent DSG1. The blisters failed to improve with a 2-week prednisone taper completed 1 month prior to presentation. The patient was not currently taking any other medications. He had a remote history of fever blisters but no other dermatologic issues.

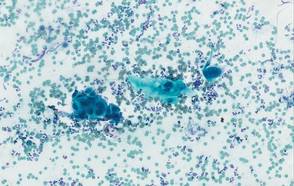

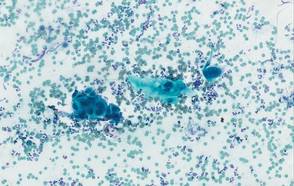

Initial examination revealed flaccid bullae on an erythematous base involving the posterior scalp as well as tender white erosions to shallow ulcers on the tongue and hard and soft palates. A Tzanck smear (modified Wright-Giemsa stain) of these erosions confirmed acantholytic mucosal cells. Punch biopsies of lesional and perilesional skin from the scalp were obtained for histopathologic confirmation and immunofluorescence. An acantholytic dermatosis with a tombstone pattern along the basement membrane was present on hematoxylin and eosin staining, and direct immunofluorescence was positive for IgG and C3 in an intraepidermal lacelike pattern, confirming a diagnosis of PV.

Despite starting an oral regimen of high-dose corticosteroids (prednisone 80 mg once daily), no improvement was noted at 2-week follow-up. He had developed flaccid blisters on the left axillae and mildly worsened oral erosions. He also reported moderate difficulty eating due to pain with swallowing. Mycophenolate mofetil (500 mg twice daily) was added as combination therapy with the prednisone.

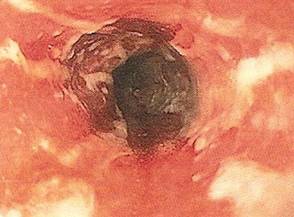

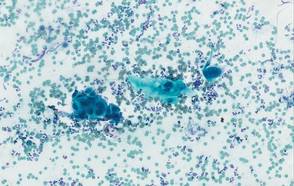

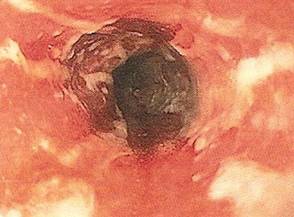

One week later, the patient was unable to eat or drink due to worsening odynophagia. He was admitted as an inpatient for treatment with intravenous methylprednisolone (120 mg every 8 hours) and MMF (1000 mg daily). The gastroenterology department was consulted and an esophagogastroduodenoscopy revealed diffuse areas of denuded and friable mucosa with an overlay of white exudate (Figure 1). Cytology performed on esophageal brushings revealed viral cytopathic changes confirming herpes esophagitis (Figure 2). No esophageal viral cultures were taken. The patient was started on intravenous acyclovir (800 mg 4 times daily), leading to rapid resolution of the odynophagia. He was discharged after 4 days with a course of oral acyclovir (400 mg 4 times daily for 14 days). Tzanck smears and HSV cultures of oral lesions performed immediately following discharge were negative. Combination therapy with MMF (500 mg twice daily) and a slow taper of prednisone (down to 5 mg once daily) was continued past 1 year without flare of his cutaneous disease.

Comment

Although PV may have been considered a fatal disease at one time, treatment with systemic steroids has made it a manageable, albeit relapsing, condition. The development of corticosteroid-sparing, adjuvant immunosuppressives such as MMF has allowed for the more aggressive treatment of this disease with fewer steroid-related side effects.4,8,9 As seen in solid organ transplant recipients who often utilize combination therapy, the use of adjuvant immunosuppressives is associated with potential complications including bone marrow suppression and an increased risk for infections.7,10

Odynophagia is among the potential complications in patients with PV and has a wide differential diagnosis. Mucosal lesions of PV previously have been associated with HSV colonization, though a causal relationship has not been corroborated.5 Herpes simplex virus is more often detected in PV patients being treated with immunosuppressive agents than in nontreated patient groups.11 Recalcitrant or suddenly exacerbated oral mucosal lesions of PV under appropriate therapy may therefore be the result of HSV superinfection, which has been deferentially referred to as pemphigus herpeticum.12 Esophageal mucosal involvement by PV also may be more common than previously thought and should be suspected in patients with active oral disease.13 Esophagitis secondary to medications or various opportunistic organisms such as Candida, cytomegalovirus, or HSV also should be ruled out in patients taking immunosuppressives.5,10