User login

New-Onset Pemphigoid Gestationis Following COVID-19 Vaccination

To the Editor:

Pemphigoid gestationis (PG), or gestational pemphigoid, is a rare autoimmune bullous disease (AIBD) occurring in 1 in 50,000 pregnancies. It is characterized by abrupt development of intensely pruritic papules and urticarial plaques, followed by an eruption of blisters.1 We present a case of new-onset PG that erupted 10 days following SARs-CoV-2 messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccination with BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech).

A 36-year-old pregnant woman (gravida 1, para 0, aborta 0) at 37 weeks’ gestation presented to our AIBD clinic with a pruritic dermatitis of 6 weeks’ duration that developed 10 days after receiving the second dose of BNT162b2. Multiple intensely pruritic, red bumps presented first on the forearms and within days spread to the thighs, hands, and abdomen, followed by progression to the ankles, feet, and back 2 weeks later. An initial biopsy was consistent with subacute spongiotic dermatitis with rare eosinophils. She found minimal relief from diphenhydramine or topical steroids. She denied oral, nasal, ocular, or genital involvement or history of any other skin disease. The pregnancy had been otherwise uneventful.

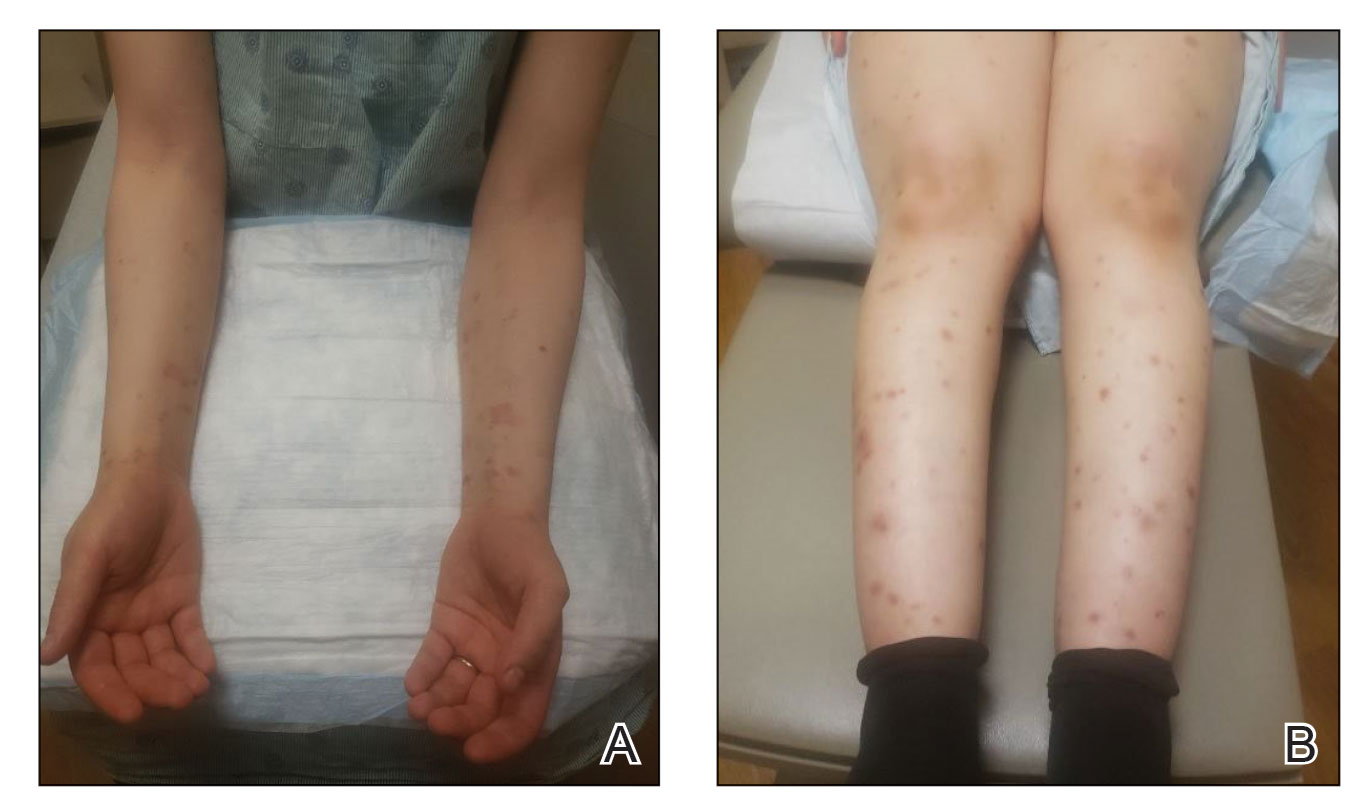

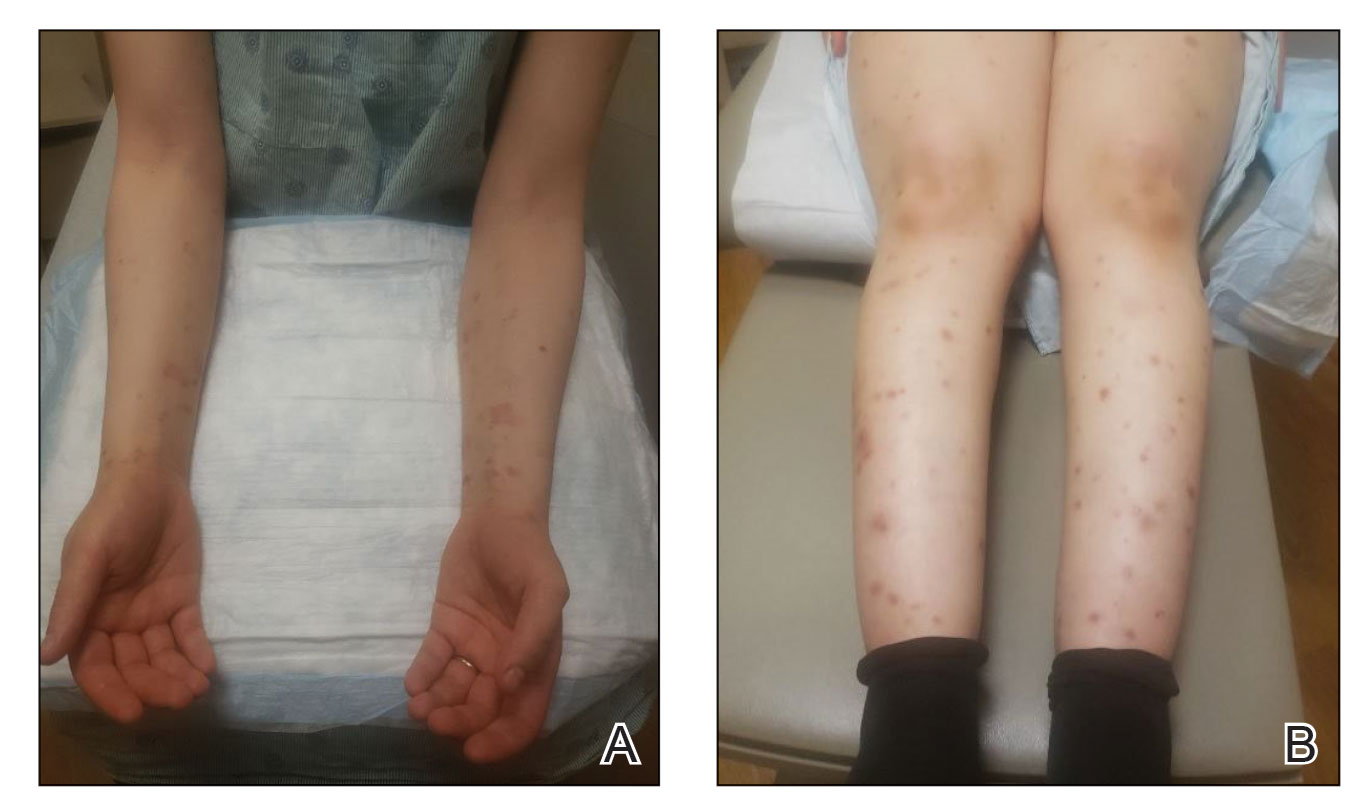

Physical examination revealed annular edematous plaques on the trunk and buttocks; excoriated and erythematous papules on the neck, trunk, arms, and legs; and scattered vesicles along the fingers, arms, hands, abdomen, back, legs, and feet (Figure 1). The Bullous Pemphigoid Disease Area Index (BPDAI) total skin activity score was 25.3, corresponding to moderate disease activity (validated at 20–56).2 The BPDAI total pruritus component score was 20. A repeat biopsy for direct immunofluorescence showed faint linear deposits of IgG and bright linear deposits of C3 along the basement membrane zone. Indirect immunofluorescence showed linear deposits of IgG localized to the blister roof of salt-split skin at a dilution of 1:40. An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for anti-BP180 was 62 U/mL (negative, <9 U/mL; positive, ≥9 U/mL), and anti-BP230 autoantibodies were less than 9 U/mL (negative <9 U/mL; positive, ≥9 U/mL). Given these clinical and histopathologic findings, PG was diagnosed.

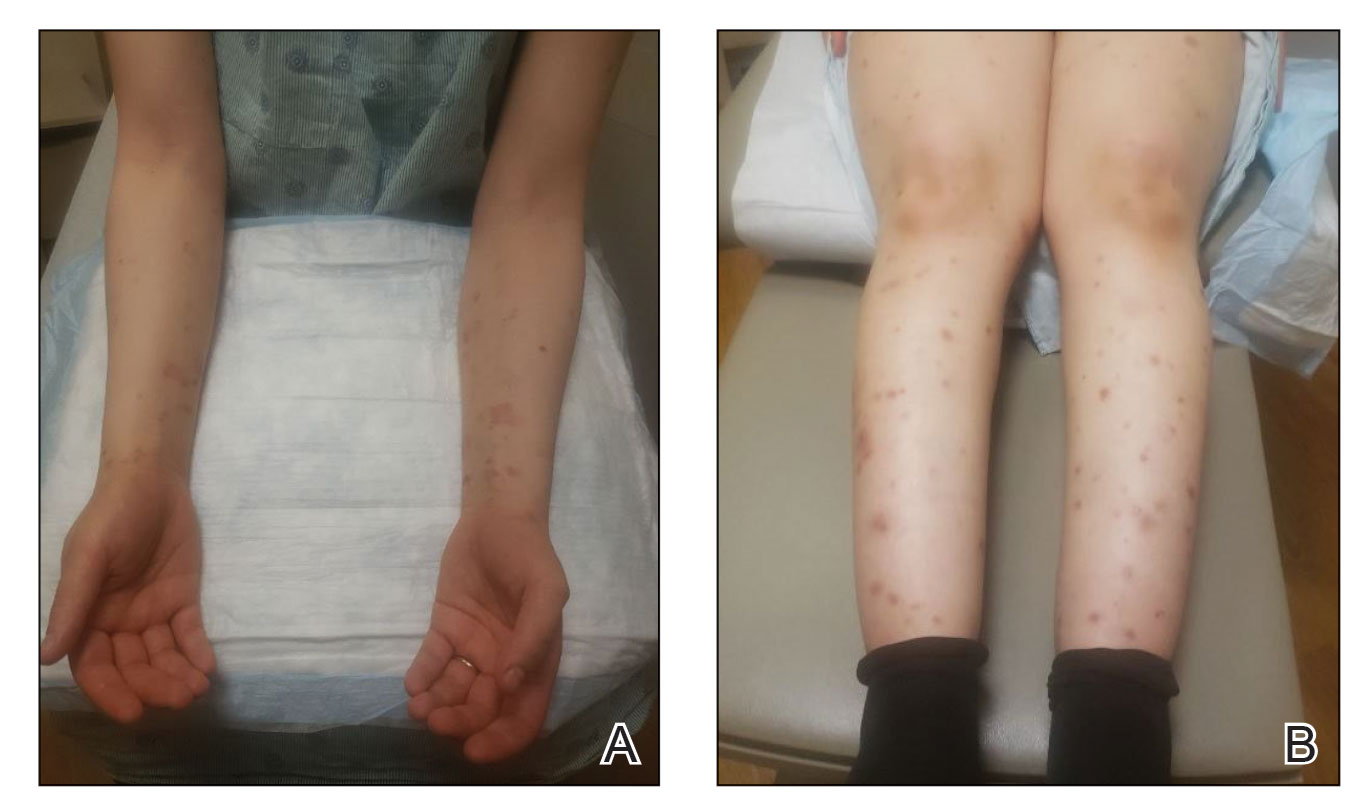

The patient was started on prednisone 20 mg and antihistamines while continuing topical steroids. Pruritus and blistering improved close to delivery. Fetal monitoring with regular biophysical profiles remained normal. The patient delivered a healthy neonate without skin lesions at 40 weeks’ gestation. The disease flared 2 days after delivery, and prednisone was increased to 40 mg and slowly tapered. Two months after delivery, the patient remained on prednisone 10 mg daily with ongoing but reduced blistering and pruritus (Figure 2). The BPDAI total skin activity and pruritus component scores remained elevated at 20.3 and 14, respectively, and anti-BP180 was 44 U/mL. After a discussion with the patient on safe systemic therapy while breastfeeding, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) was initiated. The patient received 3 monthly infusions at 2 g/kg and was able to taper the prednisone to 5 mg every other day without new lesions. Four months after completion of IVIG therapy, she achieved complete remission off all therapy.

Management of PG begins with topical corticosteroids, but most patients require systemic steroid therapy.1 Remission commonly occurs close to delivery, and 75% of patients flare post partum, though the disease typically resolves 6 months following delivery.1,3,4 For persistent intrapartum cases requiring more than prednisone 20 mg daily, therapy can include dapsone, IVIG, azathioprine, rituximab, or plasmapheresis.4,5 Dapsone and IVIG are compatible with breastfeeding postpartum, but if dapsone is selected, the infant must be monitored for hemolytic anemia.5 Pemphigoid gestationis increases the risk for a premature or small-for-gestational-age neonate, necessitating regular fetal monitoring until delivery.1 Cutaneous lesions may affect the newborn, though this occurrence is rare and self-limiting.6 Pemphigoid gestationis may recur in subsequent pregnancies at a rate of 33% to 55%, with earlier and more severe presentations.4

Clinically and histologically, PG closely resembles bullous pemphigoid (BP), but the exact pathogenesis is not fully understood. Recently, another case of what was termed pseudo-PG has been described 3 days following administration of the second dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine.7 Since the introduction of COVID-19 mRNA vaccines, cases of postvaccination BP, BP-like eruptions, and pemphigus vulgaris have been described.8-11 Tomayko et al10 reported 12 cases of subepidermal eruptions, including BP, in which 7 patients developed blisters after the second dose of either the Pfizer-BioNTech or Moderna mRNA vaccine. Three patients who developed BP after the first dose of the vaccine and chose to receive the second dose tolerated it well, with a mild flare observed in 1 patient.10 Similarly, subsequent vaccine doses in reports of vaccine-associated AIBD resulted in increased disease activity in 21% of cases.12 COVID-19 vaccine–associated BP, similar to drug-induced BP, seemingly displays a milder course of disease compared to the classic form of BP.10,13 More follow-up is needed to better understand these reactions and inform appropriate discussions on the administration of booster doses. Currently, completion of the vaccination series against COVID-19 is advisable given the paucity of reports of postvaccination AIBD and the risk for COVID-19 infection, but careful discussions on a case-by-case basis are warranted related to the risk for disease exacerbation following subsequent vaccinations.

The clinical presentation and diagnostic evaluation of our patient’s rash were consistent with PG. The temporal relationship between vaccine administration and PG lesion onset suggests the mRNA vaccine triggered AIBD in our patient. Interestingly, AIBD associated with COVID-19 is not unique to only the vaccines and has been observed following infection with the virus itself.14 The high rate of vaccination against COVID-19 in contrast with the low number of reported cases of AIBD after vaccination supports the overall safety of COVID-19 vaccines but identifies a need for further understanding of the processes that lead to the development of autoimmune conditions in at-risk populations.

- Wiznia LE, Pomeranz MK. Skin changes and diseases in pregnancy. In: Kang S, Amagai M, Bruckner AL, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology. 9th ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2019.

- Masmoudi W, Vaillant M, Vassileva S, et al. International validation of the Bullous Pemphigoid Disease Area Index severity score and calculation of cut-off values for defining mild, moderate and severe types of bullous pemphigoid. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184:1106-1112. doi:10.1111/bjd.19611

- Semkova K, Black M. Pemphigoid gestationis: current insights into pathogenesis and treatment. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;145:138-144.

- Savervall C, Sand FL, Thomsen SF. Pemphigoid gestationis: current perspectives. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2017;10:441-449.

- Braunstein I, Werth V. Treatment of dermatologic connective tissue disease and autoimmune blistering disorders in pregnancy. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26:354-363.

- Lipozencic J, Ljubojevic S, Bukvic-Mokos Z. Pemphigoid gestationis. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:51-55.

- de Lorenzi C, Kaya G, Toutous Trellu L. Pseudo-pemphigoid gestationis eruption following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination with mRNA vaccine. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2022;9:203-206. doi:10.3390/dermatopathology9030025

- McMahon DE, Kovarik CL, Damsky W, et al. Clinical and pathologic correlation of cutaneous COVID-19 vaccine reactions including V-REPP: a registry-based study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:113-121.

- Solimani F, Mansour Y, Didona D, et al. Development of severe pemphigus vulgaris following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination with BNT162b2. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:E649-E651.

- Tomayko MM, Damsky W, Fathy R, et al. Subepidermal blistering eruptions, including bullous pemphigoid, following COVID-19 vaccination. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;148:750-751.

- Coto-Segura P, Fernandez-Prada M, Mir-Bonafe M, et al. Vesiculobullous skin reactions induced by COVID-19 mRNA vaccine: report of four cases and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:141-143.

- Kasperkiewicz M, Woodley DT. Association between vaccination and autoimmune bullous diseases: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1160-1164.

- Stavropoulos PG, Soura E, Antoniou C. Drug-induced pemphigoid: a review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:1133-1140.

- Olson N, Eckhardt D, Delano A. New-onset bullous pemphigoid in a COVID-19 patient. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2021;2021:5575111.

To the Editor:

Pemphigoid gestationis (PG), or gestational pemphigoid, is a rare autoimmune bullous disease (AIBD) occurring in 1 in 50,000 pregnancies. It is characterized by abrupt development of intensely pruritic papules and urticarial plaques, followed by an eruption of blisters.1 We present a case of new-onset PG that erupted 10 days following SARs-CoV-2 messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccination with BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech).

A 36-year-old pregnant woman (gravida 1, para 0, aborta 0) at 37 weeks’ gestation presented to our AIBD clinic with a pruritic dermatitis of 6 weeks’ duration that developed 10 days after receiving the second dose of BNT162b2. Multiple intensely pruritic, red bumps presented first on the forearms and within days spread to the thighs, hands, and abdomen, followed by progression to the ankles, feet, and back 2 weeks later. An initial biopsy was consistent with subacute spongiotic dermatitis with rare eosinophils. She found minimal relief from diphenhydramine or topical steroids. She denied oral, nasal, ocular, or genital involvement or history of any other skin disease. The pregnancy had been otherwise uneventful.

Physical examination revealed annular edematous plaques on the trunk and buttocks; excoriated and erythematous papules on the neck, trunk, arms, and legs; and scattered vesicles along the fingers, arms, hands, abdomen, back, legs, and feet (Figure 1). The Bullous Pemphigoid Disease Area Index (BPDAI) total skin activity score was 25.3, corresponding to moderate disease activity (validated at 20–56).2 The BPDAI total pruritus component score was 20. A repeat biopsy for direct immunofluorescence showed faint linear deposits of IgG and bright linear deposits of C3 along the basement membrane zone. Indirect immunofluorescence showed linear deposits of IgG localized to the blister roof of salt-split skin at a dilution of 1:40. An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for anti-BP180 was 62 U/mL (negative, <9 U/mL; positive, ≥9 U/mL), and anti-BP230 autoantibodies were less than 9 U/mL (negative <9 U/mL; positive, ≥9 U/mL). Given these clinical and histopathologic findings, PG was diagnosed.

The patient was started on prednisone 20 mg and antihistamines while continuing topical steroids. Pruritus and blistering improved close to delivery. Fetal monitoring with regular biophysical profiles remained normal. The patient delivered a healthy neonate without skin lesions at 40 weeks’ gestation. The disease flared 2 days after delivery, and prednisone was increased to 40 mg and slowly tapered. Two months after delivery, the patient remained on prednisone 10 mg daily with ongoing but reduced blistering and pruritus (Figure 2). The BPDAI total skin activity and pruritus component scores remained elevated at 20.3 and 14, respectively, and anti-BP180 was 44 U/mL. After a discussion with the patient on safe systemic therapy while breastfeeding, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) was initiated. The patient received 3 monthly infusions at 2 g/kg and was able to taper the prednisone to 5 mg every other day without new lesions. Four months after completion of IVIG therapy, she achieved complete remission off all therapy.

Management of PG begins with topical corticosteroids, but most patients require systemic steroid therapy.1 Remission commonly occurs close to delivery, and 75% of patients flare post partum, though the disease typically resolves 6 months following delivery.1,3,4 For persistent intrapartum cases requiring more than prednisone 20 mg daily, therapy can include dapsone, IVIG, azathioprine, rituximab, or plasmapheresis.4,5 Dapsone and IVIG are compatible with breastfeeding postpartum, but if dapsone is selected, the infant must be monitored for hemolytic anemia.5 Pemphigoid gestationis increases the risk for a premature or small-for-gestational-age neonate, necessitating regular fetal monitoring until delivery.1 Cutaneous lesions may affect the newborn, though this occurrence is rare and self-limiting.6 Pemphigoid gestationis may recur in subsequent pregnancies at a rate of 33% to 55%, with earlier and more severe presentations.4

Clinically and histologically, PG closely resembles bullous pemphigoid (BP), but the exact pathogenesis is not fully understood. Recently, another case of what was termed pseudo-PG has been described 3 days following administration of the second dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine.7 Since the introduction of COVID-19 mRNA vaccines, cases of postvaccination BP, BP-like eruptions, and pemphigus vulgaris have been described.8-11 Tomayko et al10 reported 12 cases of subepidermal eruptions, including BP, in which 7 patients developed blisters after the second dose of either the Pfizer-BioNTech or Moderna mRNA vaccine. Three patients who developed BP after the first dose of the vaccine and chose to receive the second dose tolerated it well, with a mild flare observed in 1 patient.10 Similarly, subsequent vaccine doses in reports of vaccine-associated AIBD resulted in increased disease activity in 21% of cases.12 COVID-19 vaccine–associated BP, similar to drug-induced BP, seemingly displays a milder course of disease compared to the classic form of BP.10,13 More follow-up is needed to better understand these reactions and inform appropriate discussions on the administration of booster doses. Currently, completion of the vaccination series against COVID-19 is advisable given the paucity of reports of postvaccination AIBD and the risk for COVID-19 infection, but careful discussions on a case-by-case basis are warranted related to the risk for disease exacerbation following subsequent vaccinations.

The clinical presentation and diagnostic evaluation of our patient’s rash were consistent with PG. The temporal relationship between vaccine administration and PG lesion onset suggests the mRNA vaccine triggered AIBD in our patient. Interestingly, AIBD associated with COVID-19 is not unique to only the vaccines and has been observed following infection with the virus itself.14 The high rate of vaccination against COVID-19 in contrast with the low number of reported cases of AIBD after vaccination supports the overall safety of COVID-19 vaccines but identifies a need for further understanding of the processes that lead to the development of autoimmune conditions in at-risk populations.

To the Editor:

Pemphigoid gestationis (PG), or gestational pemphigoid, is a rare autoimmune bullous disease (AIBD) occurring in 1 in 50,000 pregnancies. It is characterized by abrupt development of intensely pruritic papules and urticarial plaques, followed by an eruption of blisters.1 We present a case of new-onset PG that erupted 10 days following SARs-CoV-2 messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccination with BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech).

A 36-year-old pregnant woman (gravida 1, para 0, aborta 0) at 37 weeks’ gestation presented to our AIBD clinic with a pruritic dermatitis of 6 weeks’ duration that developed 10 days after receiving the second dose of BNT162b2. Multiple intensely pruritic, red bumps presented first on the forearms and within days spread to the thighs, hands, and abdomen, followed by progression to the ankles, feet, and back 2 weeks later. An initial biopsy was consistent with subacute spongiotic dermatitis with rare eosinophils. She found minimal relief from diphenhydramine or topical steroids. She denied oral, nasal, ocular, or genital involvement or history of any other skin disease. The pregnancy had been otherwise uneventful.

Physical examination revealed annular edematous plaques on the trunk and buttocks; excoriated and erythematous papules on the neck, trunk, arms, and legs; and scattered vesicles along the fingers, arms, hands, abdomen, back, legs, and feet (Figure 1). The Bullous Pemphigoid Disease Area Index (BPDAI) total skin activity score was 25.3, corresponding to moderate disease activity (validated at 20–56).2 The BPDAI total pruritus component score was 20. A repeat biopsy for direct immunofluorescence showed faint linear deposits of IgG and bright linear deposits of C3 along the basement membrane zone. Indirect immunofluorescence showed linear deposits of IgG localized to the blister roof of salt-split skin at a dilution of 1:40. An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for anti-BP180 was 62 U/mL (negative, <9 U/mL; positive, ≥9 U/mL), and anti-BP230 autoantibodies were less than 9 U/mL (negative <9 U/mL; positive, ≥9 U/mL). Given these clinical and histopathologic findings, PG was diagnosed.

The patient was started on prednisone 20 mg and antihistamines while continuing topical steroids. Pruritus and blistering improved close to delivery. Fetal monitoring with regular biophysical profiles remained normal. The patient delivered a healthy neonate without skin lesions at 40 weeks’ gestation. The disease flared 2 days after delivery, and prednisone was increased to 40 mg and slowly tapered. Two months after delivery, the patient remained on prednisone 10 mg daily with ongoing but reduced blistering and pruritus (Figure 2). The BPDAI total skin activity and pruritus component scores remained elevated at 20.3 and 14, respectively, and anti-BP180 was 44 U/mL. After a discussion with the patient on safe systemic therapy while breastfeeding, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) was initiated. The patient received 3 monthly infusions at 2 g/kg and was able to taper the prednisone to 5 mg every other day without new lesions. Four months after completion of IVIG therapy, she achieved complete remission off all therapy.

Management of PG begins with topical corticosteroids, but most patients require systemic steroid therapy.1 Remission commonly occurs close to delivery, and 75% of patients flare post partum, though the disease typically resolves 6 months following delivery.1,3,4 For persistent intrapartum cases requiring more than prednisone 20 mg daily, therapy can include dapsone, IVIG, azathioprine, rituximab, or plasmapheresis.4,5 Dapsone and IVIG are compatible with breastfeeding postpartum, but if dapsone is selected, the infant must be monitored for hemolytic anemia.5 Pemphigoid gestationis increases the risk for a premature or small-for-gestational-age neonate, necessitating regular fetal monitoring until delivery.1 Cutaneous lesions may affect the newborn, though this occurrence is rare and self-limiting.6 Pemphigoid gestationis may recur in subsequent pregnancies at a rate of 33% to 55%, with earlier and more severe presentations.4

Clinically and histologically, PG closely resembles bullous pemphigoid (BP), but the exact pathogenesis is not fully understood. Recently, another case of what was termed pseudo-PG has been described 3 days following administration of the second dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine.7 Since the introduction of COVID-19 mRNA vaccines, cases of postvaccination BP, BP-like eruptions, and pemphigus vulgaris have been described.8-11 Tomayko et al10 reported 12 cases of subepidermal eruptions, including BP, in which 7 patients developed blisters after the second dose of either the Pfizer-BioNTech or Moderna mRNA vaccine. Three patients who developed BP after the first dose of the vaccine and chose to receive the second dose tolerated it well, with a mild flare observed in 1 patient.10 Similarly, subsequent vaccine doses in reports of vaccine-associated AIBD resulted in increased disease activity in 21% of cases.12 COVID-19 vaccine–associated BP, similar to drug-induced BP, seemingly displays a milder course of disease compared to the classic form of BP.10,13 More follow-up is needed to better understand these reactions and inform appropriate discussions on the administration of booster doses. Currently, completion of the vaccination series against COVID-19 is advisable given the paucity of reports of postvaccination AIBD and the risk for COVID-19 infection, but careful discussions on a case-by-case basis are warranted related to the risk for disease exacerbation following subsequent vaccinations.

The clinical presentation and diagnostic evaluation of our patient’s rash were consistent with PG. The temporal relationship between vaccine administration and PG lesion onset suggests the mRNA vaccine triggered AIBD in our patient. Interestingly, AIBD associated with COVID-19 is not unique to only the vaccines and has been observed following infection with the virus itself.14 The high rate of vaccination against COVID-19 in contrast with the low number of reported cases of AIBD after vaccination supports the overall safety of COVID-19 vaccines but identifies a need for further understanding of the processes that lead to the development of autoimmune conditions in at-risk populations.

- Wiznia LE, Pomeranz MK. Skin changes and diseases in pregnancy. In: Kang S, Amagai M, Bruckner AL, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology. 9th ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2019.

- Masmoudi W, Vaillant M, Vassileva S, et al. International validation of the Bullous Pemphigoid Disease Area Index severity score and calculation of cut-off values for defining mild, moderate and severe types of bullous pemphigoid. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184:1106-1112. doi:10.1111/bjd.19611

- Semkova K, Black M. Pemphigoid gestationis: current insights into pathogenesis and treatment. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;145:138-144.

- Savervall C, Sand FL, Thomsen SF. Pemphigoid gestationis: current perspectives. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2017;10:441-449.

- Braunstein I, Werth V. Treatment of dermatologic connective tissue disease and autoimmune blistering disorders in pregnancy. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26:354-363.

- Lipozencic J, Ljubojevic S, Bukvic-Mokos Z. Pemphigoid gestationis. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:51-55.

- de Lorenzi C, Kaya G, Toutous Trellu L. Pseudo-pemphigoid gestationis eruption following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination with mRNA vaccine. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2022;9:203-206. doi:10.3390/dermatopathology9030025

- McMahon DE, Kovarik CL, Damsky W, et al. Clinical and pathologic correlation of cutaneous COVID-19 vaccine reactions including V-REPP: a registry-based study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:113-121.

- Solimani F, Mansour Y, Didona D, et al. Development of severe pemphigus vulgaris following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination with BNT162b2. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:E649-E651.

- Tomayko MM, Damsky W, Fathy R, et al. Subepidermal blistering eruptions, including bullous pemphigoid, following COVID-19 vaccination. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;148:750-751.

- Coto-Segura P, Fernandez-Prada M, Mir-Bonafe M, et al. Vesiculobullous skin reactions induced by COVID-19 mRNA vaccine: report of four cases and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:141-143.

- Kasperkiewicz M, Woodley DT. Association between vaccination and autoimmune bullous diseases: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1160-1164.

- Stavropoulos PG, Soura E, Antoniou C. Drug-induced pemphigoid: a review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:1133-1140.

- Olson N, Eckhardt D, Delano A. New-onset bullous pemphigoid in a COVID-19 patient. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2021;2021:5575111.

- Wiznia LE, Pomeranz MK. Skin changes and diseases in pregnancy. In: Kang S, Amagai M, Bruckner AL, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology. 9th ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2019.

- Masmoudi W, Vaillant M, Vassileva S, et al. International validation of the Bullous Pemphigoid Disease Area Index severity score and calculation of cut-off values for defining mild, moderate and severe types of bullous pemphigoid. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184:1106-1112. doi:10.1111/bjd.19611

- Semkova K, Black M. Pemphigoid gestationis: current insights into pathogenesis and treatment. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;145:138-144.

- Savervall C, Sand FL, Thomsen SF. Pemphigoid gestationis: current perspectives. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2017;10:441-449.

- Braunstein I, Werth V. Treatment of dermatologic connective tissue disease and autoimmune blistering disorders in pregnancy. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26:354-363.

- Lipozencic J, Ljubojevic S, Bukvic-Mokos Z. Pemphigoid gestationis. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:51-55.

- de Lorenzi C, Kaya G, Toutous Trellu L. Pseudo-pemphigoid gestationis eruption following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination with mRNA vaccine. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2022;9:203-206. doi:10.3390/dermatopathology9030025

- McMahon DE, Kovarik CL, Damsky W, et al. Clinical and pathologic correlation of cutaneous COVID-19 vaccine reactions including V-REPP: a registry-based study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:113-121.

- Solimani F, Mansour Y, Didona D, et al. Development of severe pemphigus vulgaris following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination with BNT162b2. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:E649-E651.

- Tomayko MM, Damsky W, Fathy R, et al. Subepidermal blistering eruptions, including bullous pemphigoid, following COVID-19 vaccination. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;148:750-751.

- Coto-Segura P, Fernandez-Prada M, Mir-Bonafe M, et al. Vesiculobullous skin reactions induced by COVID-19 mRNA vaccine: report of four cases and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:141-143.

- Kasperkiewicz M, Woodley DT. Association between vaccination and autoimmune bullous diseases: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1160-1164.

- Stavropoulos PG, Soura E, Antoniou C. Drug-induced pemphigoid: a review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:1133-1140.

- Olson N, Eckhardt D, Delano A. New-onset bullous pemphigoid in a COVID-19 patient. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2021;2021:5575111.

Practice Points

- Dermatologists should be aware that COVID-19 messenger RNA vaccinations may present with various cutaneous complications.

- Pemphigoid gestationis should be considered in a pregnant or postpartum woman with an unexplained eruption of persistent, pruritic, urticarial lesions and blisters occurring postvaccination. Treatments include high-potency topical steroids and frequently systemic corticosteroids, along with steroid-sparing agents in severe cases.