User login

Angiolymphoid Hyperplasia with Eosinophilia in a Patient With Coccidioidomycosis

Angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia (ALHE) is a rare nodular unencapsulated mass that is characterized by benign anomalous vascular hyperplasia of epithelioidlike endothelial cells attached to dilated blood vessels. The mass is surrounded by lymphocytes and eosinophils that can present clinically as papules, plaques, or nodules.1 The etiology of ALHE is unknown; it is hypothesized that it is a vascular neoplasm or a lymphoproliferative disorder.

Coccidioidomycosis (CM) is a prevalent deep fungal infection endemic to the southwestern United States caused by Coccidioides immitis and Coccidioides posadasii. Infection can occur from direct inoculation through abrasions or direct trauma but usually occurs through the inhalation of spores and can result in a reactive rash (eg, Sweet syndrome, erythema nodosum, interstitial granulomatous dermatitis).2 Coccidioidomycosis also can result in respiratory pneumonia and dissemination from pulmonary infection of the skin. As such, it is important to distinguish CM and its immunologically mediated eruptions for accurate diagnosis and treatment.

We report a novel case of ALHE as a reactive dermatologic presentation in a patient with CM.

Case Report

A 72-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic with itchy papules and plaques on the arms and legs of 17 years’ duration. Her medical history included coronary artery disease and hypercholesterolemia as well as a remote history of cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of the nose, which was confirmed by histology and treated more than 10 years prior and has remained in remission for 6 years. Her current medications included aspirin, atorvastatin, lisinopril, and metoprolol succinate.

Our patient first presented to our dermatology clinic for itchy nodules and papules on the legs and arms. The patient previously had been seen by another dermatologist 2 months prior for the same condition. At that time, biopsies of the lesions were reported as prurigo nodules. Physical examination at the current presentation revealed round, pink to flesh-colored, raised papules and plaques scattered on the arms and legs (Figure 1). The differential diagnosis included lymphomatoid papulosis, cutaneous B-cell lymphoma, pseudolymphoma, cutaneous CM, and papular mucinosis.

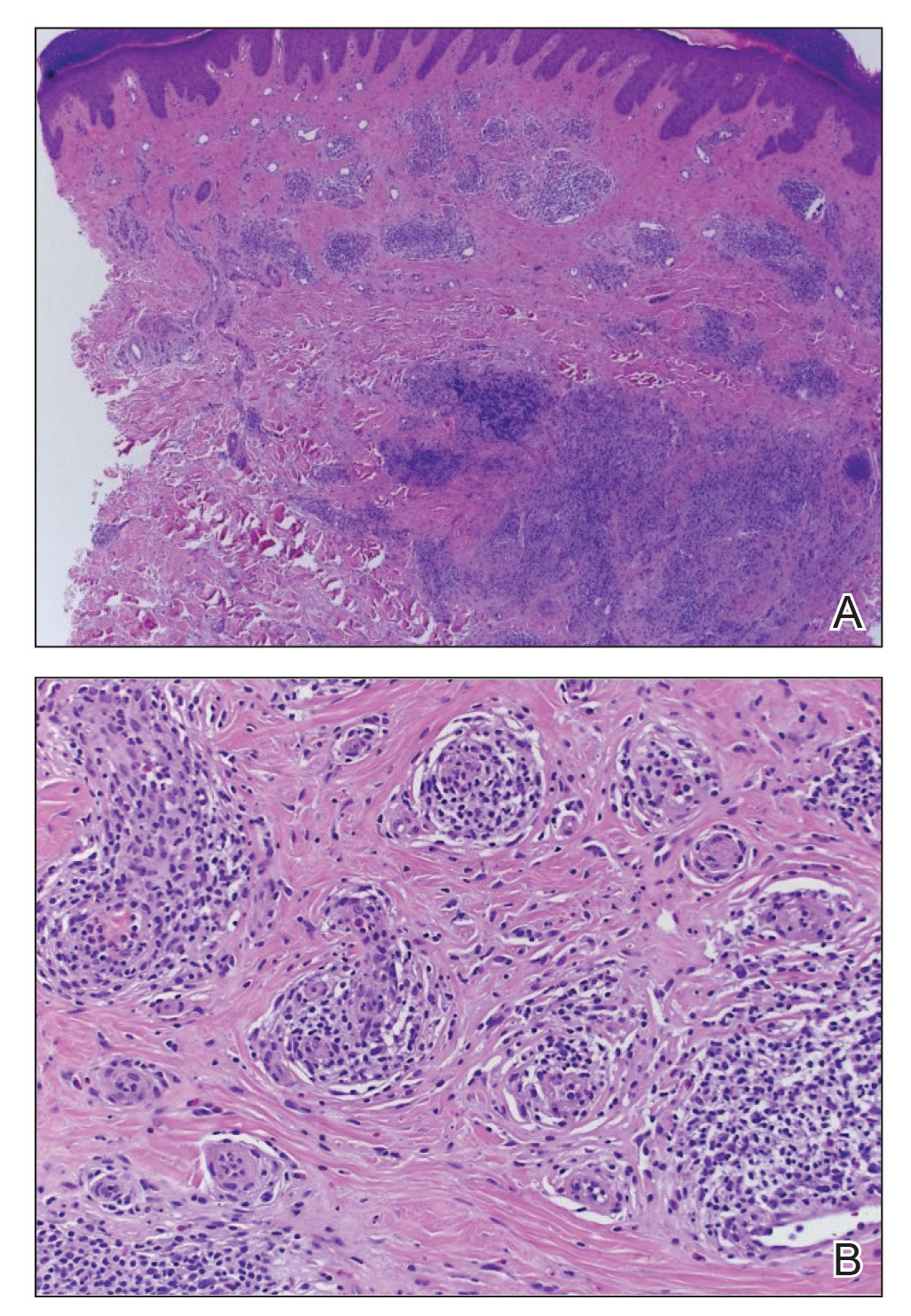

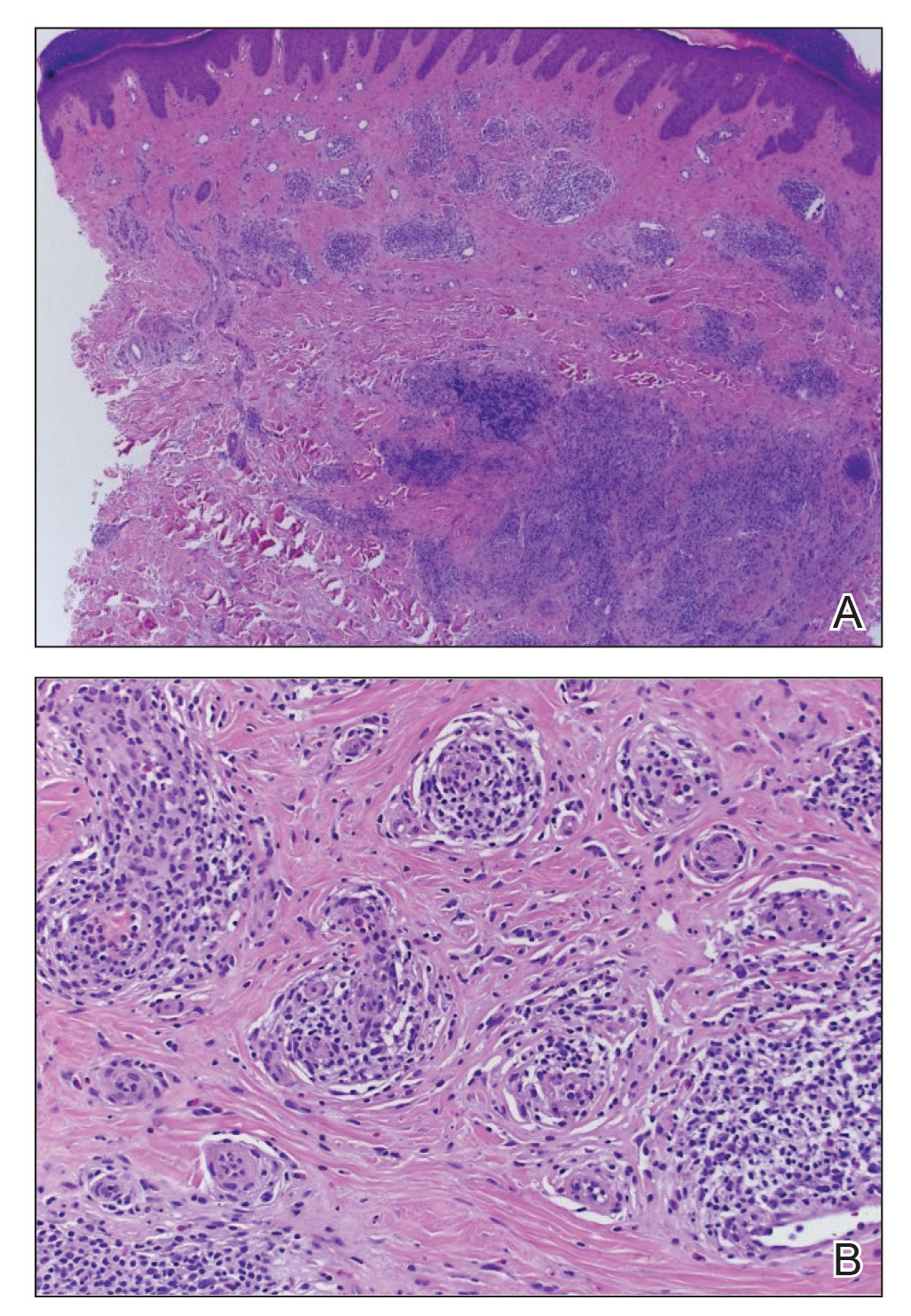

Four-mm punch biopsies of the right proximal pretibial region and left knee region were taken and sent for histologic analysis, direct immunofluorescence testing, and tissue culture. Testing for atypical mycobacteria and deep fungal infection was negative; bacterial cultures and sensitivity testing were negative. Direct immunofluorescence testing was negative. Microscopic examination of material from the right proximal pretibial region showed widely dilated, variously shaped, large blood vessels in a multinodular pattern; the vessels also were surrounded by an inflammatory cell infiltrate containing eosinophils. Histologic findings were consistent with ALHE.

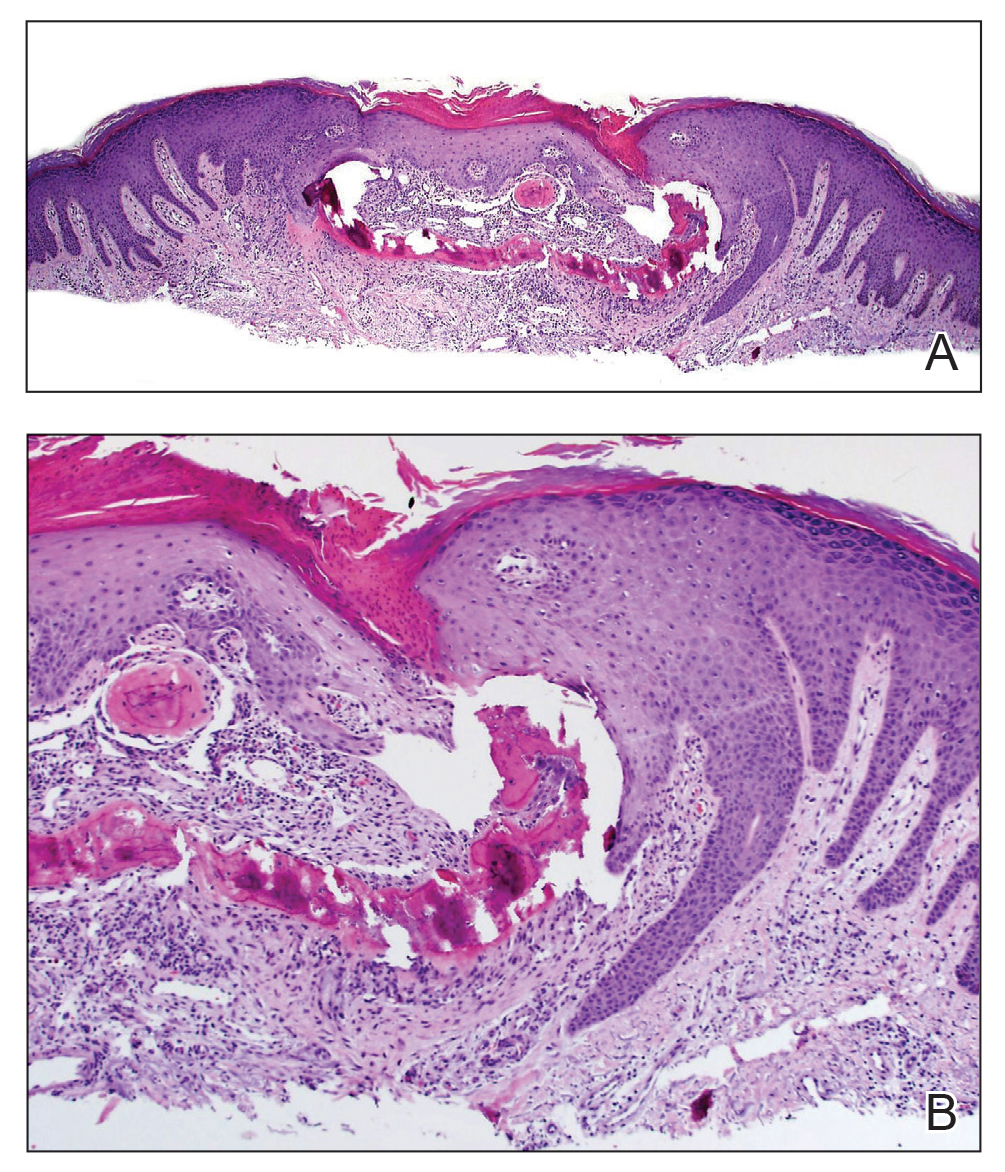

Subsequent biopsies were completed 2 weeks and 1 month from the initial presentation. Both histology reports—from 2 different histopathology laboratories—were consistent with ALHE (Figure 2). Additional work-up during the patient’s initial visit to our clinic for the rash included CM serologic testing, which demonstrated IgM and IgG antibodies. Subsequently, chest radiography revealed a 2.2×2.3-cm mass in the right lower lobe of the lung. Follow-up computed tomography 1 month later confirmed the nodule in the same area to be 2.3×2.1×1.8 cm.

The patient was referred to pulmonology and was treated for pulmonary CM with oral fluconazole 200 mg twice daily for 4 months. Initial treatment also included clobetasol cream 0.05% applied twice daily, which did not produce marked improvement in pruritus. Narrowband UVB phototherapy was attempted, but the patient could not complete the course because of travel time to the office; however, the patient’s ALHE improved considerably with the fluconazole treatment for pulmonary CM.

Oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily was added to the fluconazole 2 months after her initial visit to our office, which kept the ALHE at bay and helped with the pruritus (Figure 3). Pulmonology and primary care comanaged the pulmonary CM with oral fluconazole 200 mg twice daily. Repeat serologic testing for CM was negative for IgG and IgM after 14 months since the initial visit to the office.

Comment

Pulmonary CM infection has varying dermatologic manifestations. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms ALHE and coccidioidomycosis yielded no case reports; in fact, there have been few reported cases of ALHE at all. Notable conditions associated with ALHE include membranous nephropathy and arteriovenous malformations treated with corticosteroids and surgery, respectively.3,4 Our case is a rare presentation of CM infection manifesting with ALHE. Following treatment and remission for our patient’s CM infection, the ALHE lesion decreased in size.

Standard treatment of uncomplicated CM involves azole antifungals, typically oral fluconazole or itraconazole 400 to 600 mg/d. In more severe cases (eg, immunocompromised patients) amphotericin B can be used.5 Our patient was treated with oral fluconazole 200 mg twice daily for 4 months.

In the literature, treatment via surgical excision, steroid injection, pulsed-dye laser therapy, and radiotherapy also has been described.6-8 Antibiotics including clindamycin, doxycycline, and amoxicillin-clavulanate also have been shown to be effective.9

In our patient, ALHE improved when oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily was added to the oral fluconazole. In fact, after 4 months of treatment, the CM infection and ALHE lesions both improved to a point at which the lesions were not visible. When those lesions recurred 15 months later, they responded with another course of doxycycline and fluconazole.

Upon recurrence, the patient was asked to have her care transferred to her pulmonologist, who then managed the fluconazole regimen. During the pulmonologist’s workup, no peripheral eosinophilia was found. This is important because eosinophils can be a marker for CM infection; in this case, however, the ALHE lesion was a reactive process to the infection. Classically known to play a reactive role in fungal infection, these white blood cells demonstrate reactivity to the environmental fungus Alternaria alternata by contact-dependent killing, utilizing β2 integrins and CD11b to recognize and adhere to β-glucan. Eosinophils react through contact-dependent killing, releasing cytotoxic granule proteins and proinflammatory mediators, and have been documented to occur in CM and Paracoccidioides brasiliensis infection, in which they deposit major basic protein on the organism.10 Most pertinent to our case with ALHE and CM is the ability of eosinophils to communicate with other immune cells. Eosinophils play a role in the active inflammation of CM through cytokine signaling, which may propagate formation of ALHE.

The function of eosinophils in ALHE is poorly understood; it is unclear whether they act as a primary driver of pathogenesis or are simply indicators of secondary infiltration or infection. Our review of the current literature suggests that eosinophils are unnecessary for progression of ALHE but might be involved at its onset. As reported, even monoclonal antibody therapy (eg, mepolizumab and benralizumab) that effectively depletes eosinophil levels by negating IL-5 signaling do not slow progression of ALHE.11 Symptomatic changes are modest at best (ie, simply softening the ALHE nodules).

Our patient had no peripheral eosinophilia, suggesting that the onset of ALHE might not be caused by eosinophilia but a different inflammatory process—in this patient, by CM. Because peripheral eosinophilia was not seen in our patient, the presence of eosinophils in the ALHE lesion likely is unnecessary for its onset or progression but is a secondary process that exacerbates the lesion. The pathogenesis is unknown but could be directed toward lymphocytes and plasma cells, with eosinophils as part of the dynamic process.11

Conclusion

Because reports of an association between CM and ALHE are limited, our case is distinguished by a unique clinical presentation of ALHE. When a patient is given a diagnosis of ALHE, it therefore is important to consider exposure to CM as a cause, especially in patients who reside in or travel to a region where CM is endemic.

- Wells GC, Whimster IW. Subcutaneous angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia. Br J Dermatol. 1969;81:1-14. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1969.tb15914.x

- DiCaudo D. Coccidioidomycosis. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2014;33:140-145. doi:10.12788/j.sder.0111

- Onishi Y, Ohara K. Angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia associated with arteriovenous malformation: a clinicopathological correlation with angiography and serial estimation of serum levels of renin, eosinophil cationic protein and interleukin 5. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:1153-1156. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.02880.x

- Matsumoto A, Matsui I, Namba T, et al. VEGF-A links angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia (ALHE) to THSD7A membranous nephropathy: a report of 2 cases. Am J Kidney Dis. 2019;73:880-885. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2018.10.009

- Bercovitch RS, Catanzaro A, Schwartz BS, et al. Coccidioidomycosis during pregnancy: a review and recommendations for management. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:363-368. doi:10.1093/cid/cir410

- Youssef A, Hasan AR, Youssef Y, et al. Angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2018;12:89. doi:10.1186/s13256-018-1599-x

- Abrahamson TG, Davis DA. Angiolymphoid hyperplasia witheosinophilia responsive to pulsed dye laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(2 suppl case reports):S195-S196. doi:10.1067/mjd.2003.314

- Lembo S, Balato A, Cirillo T, et al. A long-term follow-up of angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia treated by corticosteroids: when a traditional therapy is still up-to-date. Case Rep Dermatol. 2011;3:64-67. doi:10.1159/000323182

- Cleveland E. Atypical presentation of angiolymphomatous hyperplasia with eosinophilia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79(3 suppl 1):AB53. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.05.249

- Ravin KA, Loy M. The eosinophil in infection. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2015;50:214-227. doi:10.1007/s12016-015-8525-4

- Grünewald M, Stölzl D, Wehkamp U, et al. Role of eosinophils in angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:1241-1243. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.2732

Angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia (ALHE) is a rare nodular unencapsulated mass that is characterized by benign anomalous vascular hyperplasia of epithelioidlike endothelial cells attached to dilated blood vessels. The mass is surrounded by lymphocytes and eosinophils that can present clinically as papules, plaques, or nodules.1 The etiology of ALHE is unknown; it is hypothesized that it is a vascular neoplasm or a lymphoproliferative disorder.

Coccidioidomycosis (CM) is a prevalent deep fungal infection endemic to the southwestern United States caused by Coccidioides immitis and Coccidioides posadasii. Infection can occur from direct inoculation through abrasions or direct trauma but usually occurs through the inhalation of spores and can result in a reactive rash (eg, Sweet syndrome, erythema nodosum, interstitial granulomatous dermatitis).2 Coccidioidomycosis also can result in respiratory pneumonia and dissemination from pulmonary infection of the skin. As such, it is important to distinguish CM and its immunologically mediated eruptions for accurate diagnosis and treatment.

We report a novel case of ALHE as a reactive dermatologic presentation in a patient with CM.

Case Report

A 72-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic with itchy papules and plaques on the arms and legs of 17 years’ duration. Her medical history included coronary artery disease and hypercholesterolemia as well as a remote history of cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of the nose, which was confirmed by histology and treated more than 10 years prior and has remained in remission for 6 years. Her current medications included aspirin, atorvastatin, lisinopril, and metoprolol succinate.

Our patient first presented to our dermatology clinic for itchy nodules and papules on the legs and arms. The patient previously had been seen by another dermatologist 2 months prior for the same condition. At that time, biopsies of the lesions were reported as prurigo nodules. Physical examination at the current presentation revealed round, pink to flesh-colored, raised papules and plaques scattered on the arms and legs (Figure 1). The differential diagnosis included lymphomatoid papulosis, cutaneous B-cell lymphoma, pseudolymphoma, cutaneous CM, and papular mucinosis.

Four-mm punch biopsies of the right proximal pretibial region and left knee region were taken and sent for histologic analysis, direct immunofluorescence testing, and tissue culture. Testing for atypical mycobacteria and deep fungal infection was negative; bacterial cultures and sensitivity testing were negative. Direct immunofluorescence testing was negative. Microscopic examination of material from the right proximal pretibial region showed widely dilated, variously shaped, large blood vessels in a multinodular pattern; the vessels also were surrounded by an inflammatory cell infiltrate containing eosinophils. Histologic findings were consistent with ALHE.

Subsequent biopsies were completed 2 weeks and 1 month from the initial presentation. Both histology reports—from 2 different histopathology laboratories—were consistent with ALHE (Figure 2). Additional work-up during the patient’s initial visit to our clinic for the rash included CM serologic testing, which demonstrated IgM and IgG antibodies. Subsequently, chest radiography revealed a 2.2×2.3-cm mass in the right lower lobe of the lung. Follow-up computed tomography 1 month later confirmed the nodule in the same area to be 2.3×2.1×1.8 cm.

The patient was referred to pulmonology and was treated for pulmonary CM with oral fluconazole 200 mg twice daily for 4 months. Initial treatment also included clobetasol cream 0.05% applied twice daily, which did not produce marked improvement in pruritus. Narrowband UVB phototherapy was attempted, but the patient could not complete the course because of travel time to the office; however, the patient’s ALHE improved considerably with the fluconazole treatment for pulmonary CM.

Oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily was added to the fluconazole 2 months after her initial visit to our office, which kept the ALHE at bay and helped with the pruritus (Figure 3). Pulmonology and primary care comanaged the pulmonary CM with oral fluconazole 200 mg twice daily. Repeat serologic testing for CM was negative for IgG and IgM after 14 months since the initial visit to the office.

Comment

Pulmonary CM infection has varying dermatologic manifestations. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms ALHE and coccidioidomycosis yielded no case reports; in fact, there have been few reported cases of ALHE at all. Notable conditions associated with ALHE include membranous nephropathy and arteriovenous malformations treated with corticosteroids and surgery, respectively.3,4 Our case is a rare presentation of CM infection manifesting with ALHE. Following treatment and remission for our patient’s CM infection, the ALHE lesion decreased in size.

Standard treatment of uncomplicated CM involves azole antifungals, typically oral fluconazole or itraconazole 400 to 600 mg/d. In more severe cases (eg, immunocompromised patients) amphotericin B can be used.5 Our patient was treated with oral fluconazole 200 mg twice daily for 4 months.

In the literature, treatment via surgical excision, steroid injection, pulsed-dye laser therapy, and radiotherapy also has been described.6-8 Antibiotics including clindamycin, doxycycline, and amoxicillin-clavulanate also have been shown to be effective.9

In our patient, ALHE improved when oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily was added to the oral fluconazole. In fact, after 4 months of treatment, the CM infection and ALHE lesions both improved to a point at which the lesions were not visible. When those lesions recurred 15 months later, they responded with another course of doxycycline and fluconazole.

Upon recurrence, the patient was asked to have her care transferred to her pulmonologist, who then managed the fluconazole regimen. During the pulmonologist’s workup, no peripheral eosinophilia was found. This is important because eosinophils can be a marker for CM infection; in this case, however, the ALHE lesion was a reactive process to the infection. Classically known to play a reactive role in fungal infection, these white blood cells demonstrate reactivity to the environmental fungus Alternaria alternata by contact-dependent killing, utilizing β2 integrins and CD11b to recognize and adhere to β-glucan. Eosinophils react through contact-dependent killing, releasing cytotoxic granule proteins and proinflammatory mediators, and have been documented to occur in CM and Paracoccidioides brasiliensis infection, in which they deposit major basic protein on the organism.10 Most pertinent to our case with ALHE and CM is the ability of eosinophils to communicate with other immune cells. Eosinophils play a role in the active inflammation of CM through cytokine signaling, which may propagate formation of ALHE.

The function of eosinophils in ALHE is poorly understood; it is unclear whether they act as a primary driver of pathogenesis or are simply indicators of secondary infiltration or infection. Our review of the current literature suggests that eosinophils are unnecessary for progression of ALHE but might be involved at its onset. As reported, even monoclonal antibody therapy (eg, mepolizumab and benralizumab) that effectively depletes eosinophil levels by negating IL-5 signaling do not slow progression of ALHE.11 Symptomatic changes are modest at best (ie, simply softening the ALHE nodules).

Our patient had no peripheral eosinophilia, suggesting that the onset of ALHE might not be caused by eosinophilia but a different inflammatory process—in this patient, by CM. Because peripheral eosinophilia was not seen in our patient, the presence of eosinophils in the ALHE lesion likely is unnecessary for its onset or progression but is a secondary process that exacerbates the lesion. The pathogenesis is unknown but could be directed toward lymphocytes and plasma cells, with eosinophils as part of the dynamic process.11

Conclusion

Because reports of an association between CM and ALHE are limited, our case is distinguished by a unique clinical presentation of ALHE. When a patient is given a diagnosis of ALHE, it therefore is important to consider exposure to CM as a cause, especially in patients who reside in or travel to a region where CM is endemic.

Angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia (ALHE) is a rare nodular unencapsulated mass that is characterized by benign anomalous vascular hyperplasia of epithelioidlike endothelial cells attached to dilated blood vessels. The mass is surrounded by lymphocytes and eosinophils that can present clinically as papules, plaques, or nodules.1 The etiology of ALHE is unknown; it is hypothesized that it is a vascular neoplasm or a lymphoproliferative disorder.

Coccidioidomycosis (CM) is a prevalent deep fungal infection endemic to the southwestern United States caused by Coccidioides immitis and Coccidioides posadasii. Infection can occur from direct inoculation through abrasions or direct trauma but usually occurs through the inhalation of spores and can result in a reactive rash (eg, Sweet syndrome, erythema nodosum, interstitial granulomatous dermatitis).2 Coccidioidomycosis also can result in respiratory pneumonia and dissemination from pulmonary infection of the skin. As such, it is important to distinguish CM and its immunologically mediated eruptions for accurate diagnosis and treatment.

We report a novel case of ALHE as a reactive dermatologic presentation in a patient with CM.

Case Report

A 72-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic with itchy papules and plaques on the arms and legs of 17 years’ duration. Her medical history included coronary artery disease and hypercholesterolemia as well as a remote history of cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of the nose, which was confirmed by histology and treated more than 10 years prior and has remained in remission for 6 years. Her current medications included aspirin, atorvastatin, lisinopril, and metoprolol succinate.

Our patient first presented to our dermatology clinic for itchy nodules and papules on the legs and arms. The patient previously had been seen by another dermatologist 2 months prior for the same condition. At that time, biopsies of the lesions were reported as prurigo nodules. Physical examination at the current presentation revealed round, pink to flesh-colored, raised papules and plaques scattered on the arms and legs (Figure 1). The differential diagnosis included lymphomatoid papulosis, cutaneous B-cell lymphoma, pseudolymphoma, cutaneous CM, and papular mucinosis.

Four-mm punch biopsies of the right proximal pretibial region and left knee region were taken and sent for histologic analysis, direct immunofluorescence testing, and tissue culture. Testing for atypical mycobacteria and deep fungal infection was negative; bacterial cultures and sensitivity testing were negative. Direct immunofluorescence testing was negative. Microscopic examination of material from the right proximal pretibial region showed widely dilated, variously shaped, large blood vessels in a multinodular pattern; the vessels also were surrounded by an inflammatory cell infiltrate containing eosinophils. Histologic findings were consistent with ALHE.

Subsequent biopsies were completed 2 weeks and 1 month from the initial presentation. Both histology reports—from 2 different histopathology laboratories—were consistent with ALHE (Figure 2). Additional work-up during the patient’s initial visit to our clinic for the rash included CM serologic testing, which demonstrated IgM and IgG antibodies. Subsequently, chest radiography revealed a 2.2×2.3-cm mass in the right lower lobe of the lung. Follow-up computed tomography 1 month later confirmed the nodule in the same area to be 2.3×2.1×1.8 cm.

The patient was referred to pulmonology and was treated for pulmonary CM with oral fluconazole 200 mg twice daily for 4 months. Initial treatment also included clobetasol cream 0.05% applied twice daily, which did not produce marked improvement in pruritus. Narrowband UVB phototherapy was attempted, but the patient could not complete the course because of travel time to the office; however, the patient’s ALHE improved considerably with the fluconazole treatment for pulmonary CM.

Oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily was added to the fluconazole 2 months after her initial visit to our office, which kept the ALHE at bay and helped with the pruritus (Figure 3). Pulmonology and primary care comanaged the pulmonary CM with oral fluconazole 200 mg twice daily. Repeat serologic testing for CM was negative for IgG and IgM after 14 months since the initial visit to the office.

Comment

Pulmonary CM infection has varying dermatologic manifestations. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms ALHE and coccidioidomycosis yielded no case reports; in fact, there have been few reported cases of ALHE at all. Notable conditions associated with ALHE include membranous nephropathy and arteriovenous malformations treated with corticosteroids and surgery, respectively.3,4 Our case is a rare presentation of CM infection manifesting with ALHE. Following treatment and remission for our patient’s CM infection, the ALHE lesion decreased in size.

Standard treatment of uncomplicated CM involves azole antifungals, typically oral fluconazole or itraconazole 400 to 600 mg/d. In more severe cases (eg, immunocompromised patients) amphotericin B can be used.5 Our patient was treated with oral fluconazole 200 mg twice daily for 4 months.

In the literature, treatment via surgical excision, steroid injection, pulsed-dye laser therapy, and radiotherapy also has been described.6-8 Antibiotics including clindamycin, doxycycline, and amoxicillin-clavulanate also have been shown to be effective.9

In our patient, ALHE improved when oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily was added to the oral fluconazole. In fact, after 4 months of treatment, the CM infection and ALHE lesions both improved to a point at which the lesions were not visible. When those lesions recurred 15 months later, they responded with another course of doxycycline and fluconazole.

Upon recurrence, the patient was asked to have her care transferred to her pulmonologist, who then managed the fluconazole regimen. During the pulmonologist’s workup, no peripheral eosinophilia was found. This is important because eosinophils can be a marker for CM infection; in this case, however, the ALHE lesion was a reactive process to the infection. Classically known to play a reactive role in fungal infection, these white blood cells demonstrate reactivity to the environmental fungus Alternaria alternata by contact-dependent killing, utilizing β2 integrins and CD11b to recognize and adhere to β-glucan. Eosinophils react through contact-dependent killing, releasing cytotoxic granule proteins and proinflammatory mediators, and have been documented to occur in CM and Paracoccidioides brasiliensis infection, in which they deposit major basic protein on the organism.10 Most pertinent to our case with ALHE and CM is the ability of eosinophils to communicate with other immune cells. Eosinophils play a role in the active inflammation of CM through cytokine signaling, which may propagate formation of ALHE.

The function of eosinophils in ALHE is poorly understood; it is unclear whether they act as a primary driver of pathogenesis or are simply indicators of secondary infiltration or infection. Our review of the current literature suggests that eosinophils are unnecessary for progression of ALHE but might be involved at its onset. As reported, even monoclonal antibody therapy (eg, mepolizumab and benralizumab) that effectively depletes eosinophil levels by negating IL-5 signaling do not slow progression of ALHE.11 Symptomatic changes are modest at best (ie, simply softening the ALHE nodules).

Our patient had no peripheral eosinophilia, suggesting that the onset of ALHE might not be caused by eosinophilia but a different inflammatory process—in this patient, by CM. Because peripheral eosinophilia was not seen in our patient, the presence of eosinophils in the ALHE lesion likely is unnecessary for its onset or progression but is a secondary process that exacerbates the lesion. The pathogenesis is unknown but could be directed toward lymphocytes and plasma cells, with eosinophils as part of the dynamic process.11

Conclusion

Because reports of an association between CM and ALHE are limited, our case is distinguished by a unique clinical presentation of ALHE. When a patient is given a diagnosis of ALHE, it therefore is important to consider exposure to CM as a cause, especially in patients who reside in or travel to a region where CM is endemic.

- Wells GC, Whimster IW. Subcutaneous angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia. Br J Dermatol. 1969;81:1-14. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1969.tb15914.x

- DiCaudo D. Coccidioidomycosis. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2014;33:140-145. doi:10.12788/j.sder.0111

- Onishi Y, Ohara K. Angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia associated with arteriovenous malformation: a clinicopathological correlation with angiography and serial estimation of serum levels of renin, eosinophil cationic protein and interleukin 5. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:1153-1156. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.02880.x

- Matsumoto A, Matsui I, Namba T, et al. VEGF-A links angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia (ALHE) to THSD7A membranous nephropathy: a report of 2 cases. Am J Kidney Dis. 2019;73:880-885. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2018.10.009

- Bercovitch RS, Catanzaro A, Schwartz BS, et al. Coccidioidomycosis during pregnancy: a review and recommendations for management. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:363-368. doi:10.1093/cid/cir410

- Youssef A, Hasan AR, Youssef Y, et al. Angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2018;12:89. doi:10.1186/s13256-018-1599-x

- Abrahamson TG, Davis DA. Angiolymphoid hyperplasia witheosinophilia responsive to pulsed dye laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(2 suppl case reports):S195-S196. doi:10.1067/mjd.2003.314

- Lembo S, Balato A, Cirillo T, et al. A long-term follow-up of angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia treated by corticosteroids: when a traditional therapy is still up-to-date. Case Rep Dermatol. 2011;3:64-67. doi:10.1159/000323182

- Cleveland E. Atypical presentation of angiolymphomatous hyperplasia with eosinophilia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79(3 suppl 1):AB53. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.05.249

- Ravin KA, Loy M. The eosinophil in infection. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2015;50:214-227. doi:10.1007/s12016-015-8525-4

- Grünewald M, Stölzl D, Wehkamp U, et al. Role of eosinophils in angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:1241-1243. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.2732

- Wells GC, Whimster IW. Subcutaneous angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia. Br J Dermatol. 1969;81:1-14. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1969.tb15914.x

- DiCaudo D. Coccidioidomycosis. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2014;33:140-145. doi:10.12788/j.sder.0111

- Onishi Y, Ohara K. Angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia associated with arteriovenous malformation: a clinicopathological correlation with angiography and serial estimation of serum levels of renin, eosinophil cationic protein and interleukin 5. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:1153-1156. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.02880.x

- Matsumoto A, Matsui I, Namba T, et al. VEGF-A links angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia (ALHE) to THSD7A membranous nephropathy: a report of 2 cases. Am J Kidney Dis. 2019;73:880-885. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2018.10.009

- Bercovitch RS, Catanzaro A, Schwartz BS, et al. Coccidioidomycosis during pregnancy: a review and recommendations for management. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:363-368. doi:10.1093/cid/cir410

- Youssef A, Hasan AR, Youssef Y, et al. Angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2018;12:89. doi:10.1186/s13256-018-1599-x

- Abrahamson TG, Davis DA. Angiolymphoid hyperplasia witheosinophilia responsive to pulsed dye laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(2 suppl case reports):S195-S196. doi:10.1067/mjd.2003.314

- Lembo S, Balato A, Cirillo T, et al. A long-term follow-up of angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia treated by corticosteroids: when a traditional therapy is still up-to-date. Case Rep Dermatol. 2011;3:64-67. doi:10.1159/000323182

- Cleveland E. Atypical presentation of angiolymphomatous hyperplasia with eosinophilia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79(3 suppl 1):AB53. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.05.249

- Ravin KA, Loy M. The eosinophil in infection. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2015;50:214-227. doi:10.1007/s12016-015-8525-4

- Grünewald M, Stölzl D, Wehkamp U, et al. Role of eosinophils in angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:1241-1243. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.2732

Practice Points

- Angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia (ALHE) is a rare entity of unknown etiology.

- There is an association between ALHE and coccidioidomycosis (CM). Patients who present with ALHE and reside in a CM-endemic region should be examined for CM.

Erythematous Nodule With Central Erosions on the Calf

The Diagnosis: Osteoma Cutis

Osteoma cutis is the heterotopic development of cutaneous ossifications in the dermis or subcutaneous fat and presents as plaquelike, stony, hard nodules. It can manifest as either a primary or secondary condition based on the presence or absence of a prior skin insult at the lesion site. Primary osteoma cutis occurs in 15% of patients and arises either de novo or in association with any of several inflammatory, neoplastic, and metabolic diseases that provide a favorable environment for abnormal mesenchymal stem cell commitment to osteoid,1 including Albright hereditary osteodystrophy, myositis ossificans progressiva, and progressive osseous heteroplasia, which are all associated with mutations in the heterotrimeric G-protein alpha subunit encoding gene, GNAS. 1,2 It is suggested that an insufficiency of Gsα leads to uncontrolled negative regulation of nonosseous connective tissue differentiation, forming osteoid.3 Additionally, diseases involving gain-of-function mutations in the activin A receptor type 1 encoding gene, ACVR1, such as fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva, have been associated with osteoma cutis.4 These mutations lead to decreased receptor affinity to molecular safeguards of bone morphogenetic protein signaling, ultimately contributing to progressive ectopic bone formation.5 Secondary osteoma cutis occurs in 85% of patients and develops at the site of prior skin damage due to inflammation, neoplasm, or trauma.6 It is believed that tissue damage and degeneration lead to mesenchymal stem cell proliferation and skeletogenicinducing factor recruitment forming cartilaginous tissue, later replaced by bone through endochondral ossification.7

Although osteoma cutis previously was believed to be rare, more recent radiologic studies suggest otherwise, detecting cutaneous osteomas in up to 42.1% of patients.8 Consequently, it is likely that osteoma cutis is underdiagnosed due to its subclinical nature. Our patient, however, presented with a solitary osteoma cutis with perforation of the epidermis, a rare phenomenon.9-12

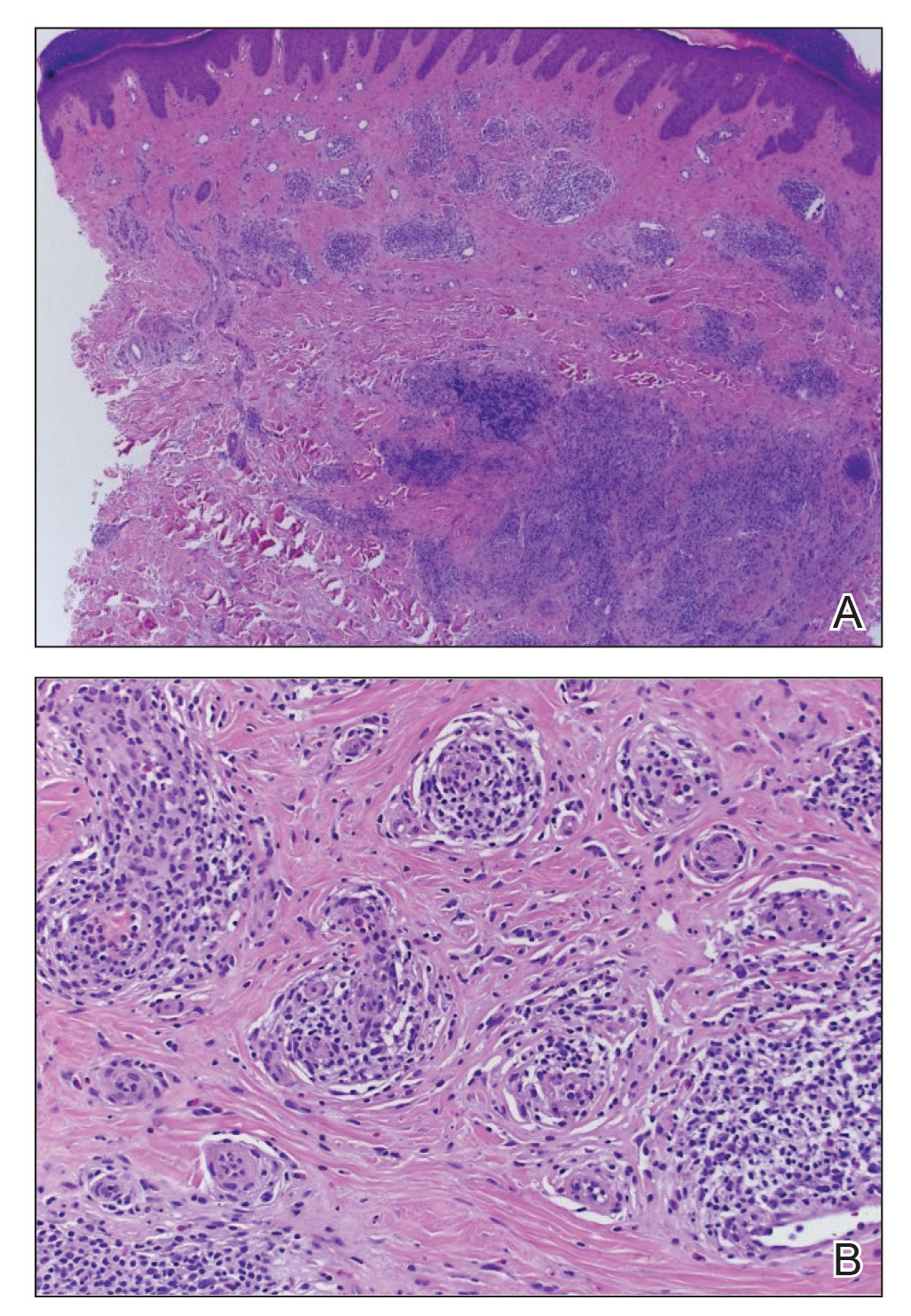

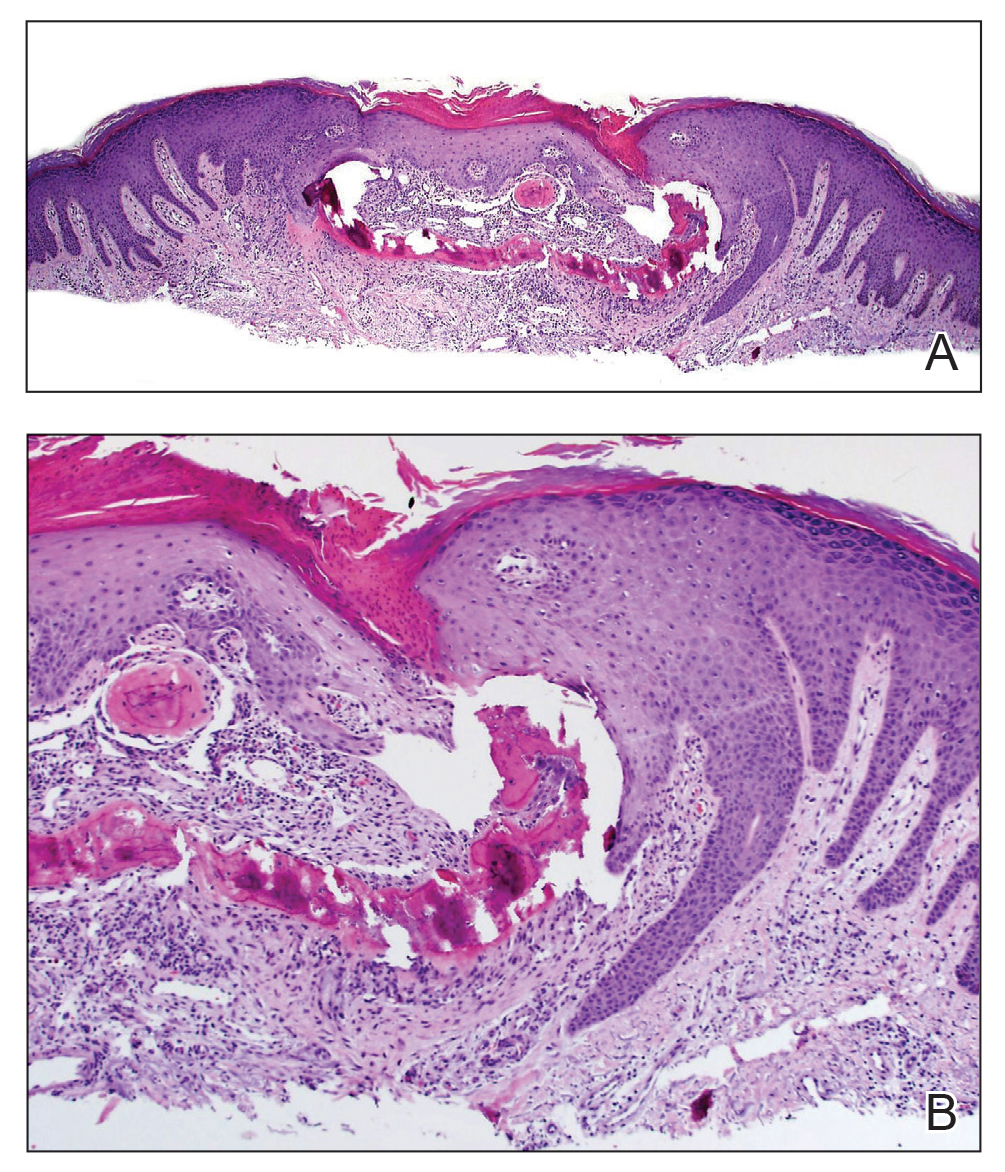

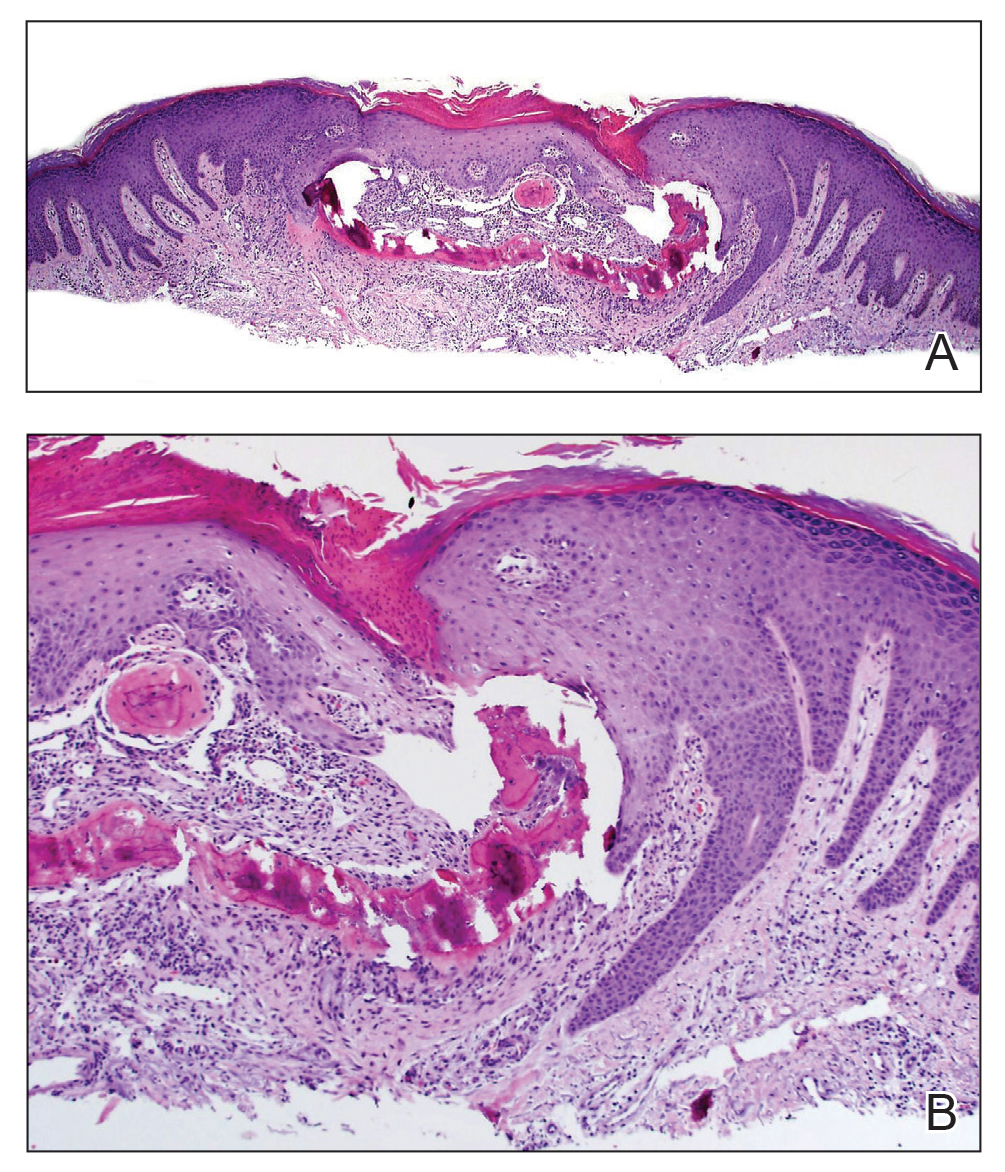

A shave biopsy in our patient revealed moderate to focally marked, irregular epidermal hyperplasia with a large focus of moderate, compact, parakeratotic crust overlying the epidermis in the center of the specimen. The papillary dermis in the center of the specimen revealed large foci of dark pink to purple bone fragments surrounded by moderate lymphocytic infiltrate with few foci perforating through the overlying epidermis (Figure, A). These findings were characteristic of osteoma cutis with perforation through the overlying epidermis.

The diagnosis of osteoma cutis at the age of 62 years suggested that the lesion was not primary in association with previously described diseases. Furthermore, the lack of phenotypic features of these diseases including obesity, developmental disability, and high parathyroid hormone levels essentially excluded this possibility. The presence of the lesion on the lower extremities initially may have suggested osteoma cutis secondary to chronic venous insufficiency13; however, the absence of visible varicose veins or obvious signs of stasis disease made this unlikely. No further cutaneous disorders at or around the lesion site clinically and histologically suggested that our patient’s lesion was primary and of idiopathic nature. Dermatofibroma can present similarly in appearance but would characteristically dimple centrally when pinched. Keratoacanthoma presents with central ulceration and keratin plugging. Pilomatricoma more commonly presents on the head and neck and less frequently as a firm nodule. Lastly, prurigo nodularis more commonly presents as a symmetrically diffuse rash compared to an isolated nodule.

Osteoma cutis is a cutaneous ossification that may be primary or secondary in nature and less rare than originally thought. Workup for potentially associated inflammatory, neoplastic, and metabolic diseases should be considered in patients with this condition. Perforating osteoma cutis is a rare variant that presents as solitary or multiple nodules with central erosion and crust. The mechanism of transepidermal elimination leading to skin perforation is hypothesized to involve epidermal hyperproliferation leading to upward movement.14 Shave biopsy establishes a definitive histopathologic diagnosis and often is curative. Given that lesions of osteoma cutis themselves are benign, removal may not be necessary.

- Falsey RR, Ackerman L. Eruptive, hard cutaneous nodules in a 61-yearold woman. osteoma cutis in a patient with Albright hereditary osteodystrophy (AHO). JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:975-976.

- Martin J, Tucker M, Browning JC. Infantile osteoma cutis as a presentation of a GNAS mutation. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:483-484.

- Shore EM, Ahn J, de Beur SJ, et al. Paternally inherited inactivating mutations of the GNAS1 gene in progressive osseous heteroplasia. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:99-106.

- Kaplan FS, Le Merrer M, Glaser DL, et al. Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2008;22:191-205.

- Song GA, Kim HJ, Woo KM, et al. Molecular consequences of the ACVR1(R206H) mutation of fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:22542-22553.

- Roth SI, Stowell RE, Helwig EB, et al. Cutaneous ossification. report of 120 cases and review of the literature. Arch Pathol. 1963;76:44-54.

- Shimono K, Uchibe K, Kuboki T, et al. The pathophysiology of heterotopic ossification: current treatment considerations in dentistry. Japanese Dental Science Review. 2014;50:1-8.

- Kim D, Franco GA, Shigehara H, et al. Benign miliary osteoma cutis of the face: a common incidental CT finding. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2017;38:789-794.

- Basu P, Erickson CP, Calame A, et al. Osteoma cutis: an adverse event following tattoo placement. Cureus. 2019;11:E4323.

- Cohen PR. Perforating osteoma cutis: case report and literature review of patients with a solitary perforating osteoma cutis lesion. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:13030/qt6kt5n92w.

- Hong SH, Kang HY. A case of perforating osteoma cutis. Ann Dermatol. 2003;15:153-155.

- Kim BK, Ahn SK. Acquired perforating osteoma cutis. Ann Dermatol. 2015;27:452-453.

- Lippmann HI, Goldin RR. Subcutaneous ossification of the legs in chronic venous insufficiency. Radiology. 1960;74:279-288.

- Haro R, Revelles JM, Angulo J, et al. Plaque-like osteoma cutis with transepidermal elimination. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:591-593.

The Diagnosis: Osteoma Cutis

Osteoma cutis is the heterotopic development of cutaneous ossifications in the dermis or subcutaneous fat and presents as plaquelike, stony, hard nodules. It can manifest as either a primary or secondary condition based on the presence or absence of a prior skin insult at the lesion site. Primary osteoma cutis occurs in 15% of patients and arises either de novo or in association with any of several inflammatory, neoplastic, and metabolic diseases that provide a favorable environment for abnormal mesenchymal stem cell commitment to osteoid,1 including Albright hereditary osteodystrophy, myositis ossificans progressiva, and progressive osseous heteroplasia, which are all associated with mutations in the heterotrimeric G-protein alpha subunit encoding gene, GNAS. 1,2 It is suggested that an insufficiency of Gsα leads to uncontrolled negative regulation of nonosseous connective tissue differentiation, forming osteoid.3 Additionally, diseases involving gain-of-function mutations in the activin A receptor type 1 encoding gene, ACVR1, such as fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva, have been associated with osteoma cutis.4 These mutations lead to decreased receptor affinity to molecular safeguards of bone morphogenetic protein signaling, ultimately contributing to progressive ectopic bone formation.5 Secondary osteoma cutis occurs in 85% of patients and develops at the site of prior skin damage due to inflammation, neoplasm, or trauma.6 It is believed that tissue damage and degeneration lead to mesenchymal stem cell proliferation and skeletogenicinducing factor recruitment forming cartilaginous tissue, later replaced by bone through endochondral ossification.7

Although osteoma cutis previously was believed to be rare, more recent radiologic studies suggest otherwise, detecting cutaneous osteomas in up to 42.1% of patients.8 Consequently, it is likely that osteoma cutis is underdiagnosed due to its subclinical nature. Our patient, however, presented with a solitary osteoma cutis with perforation of the epidermis, a rare phenomenon.9-12

A shave biopsy in our patient revealed moderate to focally marked, irregular epidermal hyperplasia with a large focus of moderate, compact, parakeratotic crust overlying the epidermis in the center of the specimen. The papillary dermis in the center of the specimen revealed large foci of dark pink to purple bone fragments surrounded by moderate lymphocytic infiltrate with few foci perforating through the overlying epidermis (Figure, A). These findings were characteristic of osteoma cutis with perforation through the overlying epidermis.

The diagnosis of osteoma cutis at the age of 62 years suggested that the lesion was not primary in association with previously described diseases. Furthermore, the lack of phenotypic features of these diseases including obesity, developmental disability, and high parathyroid hormone levels essentially excluded this possibility. The presence of the lesion on the lower extremities initially may have suggested osteoma cutis secondary to chronic venous insufficiency13; however, the absence of visible varicose veins or obvious signs of stasis disease made this unlikely. No further cutaneous disorders at or around the lesion site clinically and histologically suggested that our patient’s lesion was primary and of idiopathic nature. Dermatofibroma can present similarly in appearance but would characteristically dimple centrally when pinched. Keratoacanthoma presents with central ulceration and keratin plugging. Pilomatricoma more commonly presents on the head and neck and less frequently as a firm nodule. Lastly, prurigo nodularis more commonly presents as a symmetrically diffuse rash compared to an isolated nodule.

Osteoma cutis is a cutaneous ossification that may be primary or secondary in nature and less rare than originally thought. Workup for potentially associated inflammatory, neoplastic, and metabolic diseases should be considered in patients with this condition. Perforating osteoma cutis is a rare variant that presents as solitary or multiple nodules with central erosion and crust. The mechanism of transepidermal elimination leading to skin perforation is hypothesized to involve epidermal hyperproliferation leading to upward movement.14 Shave biopsy establishes a definitive histopathologic diagnosis and often is curative. Given that lesions of osteoma cutis themselves are benign, removal may not be necessary.

The Diagnosis: Osteoma Cutis

Osteoma cutis is the heterotopic development of cutaneous ossifications in the dermis or subcutaneous fat and presents as plaquelike, stony, hard nodules. It can manifest as either a primary or secondary condition based on the presence or absence of a prior skin insult at the lesion site. Primary osteoma cutis occurs in 15% of patients and arises either de novo or in association with any of several inflammatory, neoplastic, and metabolic diseases that provide a favorable environment for abnormal mesenchymal stem cell commitment to osteoid,1 including Albright hereditary osteodystrophy, myositis ossificans progressiva, and progressive osseous heteroplasia, which are all associated with mutations in the heterotrimeric G-protein alpha subunit encoding gene, GNAS. 1,2 It is suggested that an insufficiency of Gsα leads to uncontrolled negative regulation of nonosseous connective tissue differentiation, forming osteoid.3 Additionally, diseases involving gain-of-function mutations in the activin A receptor type 1 encoding gene, ACVR1, such as fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva, have been associated with osteoma cutis.4 These mutations lead to decreased receptor affinity to molecular safeguards of bone morphogenetic protein signaling, ultimately contributing to progressive ectopic bone formation.5 Secondary osteoma cutis occurs in 85% of patients and develops at the site of prior skin damage due to inflammation, neoplasm, or trauma.6 It is believed that tissue damage and degeneration lead to mesenchymal stem cell proliferation and skeletogenicinducing factor recruitment forming cartilaginous tissue, later replaced by bone through endochondral ossification.7

Although osteoma cutis previously was believed to be rare, more recent radiologic studies suggest otherwise, detecting cutaneous osteomas in up to 42.1% of patients.8 Consequently, it is likely that osteoma cutis is underdiagnosed due to its subclinical nature. Our patient, however, presented with a solitary osteoma cutis with perforation of the epidermis, a rare phenomenon.9-12

A shave biopsy in our patient revealed moderate to focally marked, irregular epidermal hyperplasia with a large focus of moderate, compact, parakeratotic crust overlying the epidermis in the center of the specimen. The papillary dermis in the center of the specimen revealed large foci of dark pink to purple bone fragments surrounded by moderate lymphocytic infiltrate with few foci perforating through the overlying epidermis (Figure, A). These findings were characteristic of osteoma cutis with perforation through the overlying epidermis.

The diagnosis of osteoma cutis at the age of 62 years suggested that the lesion was not primary in association with previously described diseases. Furthermore, the lack of phenotypic features of these diseases including obesity, developmental disability, and high parathyroid hormone levels essentially excluded this possibility. The presence of the lesion on the lower extremities initially may have suggested osteoma cutis secondary to chronic venous insufficiency13; however, the absence of visible varicose veins or obvious signs of stasis disease made this unlikely. No further cutaneous disorders at or around the lesion site clinically and histologically suggested that our patient’s lesion was primary and of idiopathic nature. Dermatofibroma can present similarly in appearance but would characteristically dimple centrally when pinched. Keratoacanthoma presents with central ulceration and keratin plugging. Pilomatricoma more commonly presents on the head and neck and less frequently as a firm nodule. Lastly, prurigo nodularis more commonly presents as a symmetrically diffuse rash compared to an isolated nodule.

Osteoma cutis is a cutaneous ossification that may be primary or secondary in nature and less rare than originally thought. Workup for potentially associated inflammatory, neoplastic, and metabolic diseases should be considered in patients with this condition. Perforating osteoma cutis is a rare variant that presents as solitary or multiple nodules with central erosion and crust. The mechanism of transepidermal elimination leading to skin perforation is hypothesized to involve epidermal hyperproliferation leading to upward movement.14 Shave biopsy establishes a definitive histopathologic diagnosis and often is curative. Given that lesions of osteoma cutis themselves are benign, removal may not be necessary.

- Falsey RR, Ackerman L. Eruptive, hard cutaneous nodules in a 61-yearold woman. osteoma cutis in a patient with Albright hereditary osteodystrophy (AHO). JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:975-976.

- Martin J, Tucker M, Browning JC. Infantile osteoma cutis as a presentation of a GNAS mutation. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:483-484.

- Shore EM, Ahn J, de Beur SJ, et al. Paternally inherited inactivating mutations of the GNAS1 gene in progressive osseous heteroplasia. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:99-106.

- Kaplan FS, Le Merrer M, Glaser DL, et al. Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2008;22:191-205.

- Song GA, Kim HJ, Woo KM, et al. Molecular consequences of the ACVR1(R206H) mutation of fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:22542-22553.

- Roth SI, Stowell RE, Helwig EB, et al. Cutaneous ossification. report of 120 cases and review of the literature. Arch Pathol. 1963;76:44-54.

- Shimono K, Uchibe K, Kuboki T, et al. The pathophysiology of heterotopic ossification: current treatment considerations in dentistry. Japanese Dental Science Review. 2014;50:1-8.

- Kim D, Franco GA, Shigehara H, et al. Benign miliary osteoma cutis of the face: a common incidental CT finding. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2017;38:789-794.

- Basu P, Erickson CP, Calame A, et al. Osteoma cutis: an adverse event following tattoo placement. Cureus. 2019;11:E4323.

- Cohen PR. Perforating osteoma cutis: case report and literature review of patients with a solitary perforating osteoma cutis lesion. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:13030/qt6kt5n92w.

- Hong SH, Kang HY. A case of perforating osteoma cutis. Ann Dermatol. 2003;15:153-155.

- Kim BK, Ahn SK. Acquired perforating osteoma cutis. Ann Dermatol. 2015;27:452-453.

- Lippmann HI, Goldin RR. Subcutaneous ossification of the legs in chronic venous insufficiency. Radiology. 1960;74:279-288.

- Haro R, Revelles JM, Angulo J, et al. Plaque-like osteoma cutis with transepidermal elimination. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:591-593.

- Falsey RR, Ackerman L. Eruptive, hard cutaneous nodules in a 61-yearold woman. osteoma cutis in a patient with Albright hereditary osteodystrophy (AHO). JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:975-976.

- Martin J, Tucker M, Browning JC. Infantile osteoma cutis as a presentation of a GNAS mutation. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:483-484.

- Shore EM, Ahn J, de Beur SJ, et al. Paternally inherited inactivating mutations of the GNAS1 gene in progressive osseous heteroplasia. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:99-106.

- Kaplan FS, Le Merrer M, Glaser DL, et al. Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2008;22:191-205.

- Song GA, Kim HJ, Woo KM, et al. Molecular consequences of the ACVR1(R206H) mutation of fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:22542-22553.

- Roth SI, Stowell RE, Helwig EB, et al. Cutaneous ossification. report of 120 cases and review of the literature. Arch Pathol. 1963;76:44-54.

- Shimono K, Uchibe K, Kuboki T, et al. The pathophysiology of heterotopic ossification: current treatment considerations in dentistry. Japanese Dental Science Review. 2014;50:1-8.

- Kim D, Franco GA, Shigehara H, et al. Benign miliary osteoma cutis of the face: a common incidental CT finding. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2017;38:789-794.

- Basu P, Erickson CP, Calame A, et al. Osteoma cutis: an adverse event following tattoo placement. Cureus. 2019;11:E4323.

- Cohen PR. Perforating osteoma cutis: case report and literature review of patients with a solitary perforating osteoma cutis lesion. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:13030/qt6kt5n92w.

- Hong SH, Kang HY. A case of perforating osteoma cutis. Ann Dermatol. 2003;15:153-155.

- Kim BK, Ahn SK. Acquired perforating osteoma cutis. Ann Dermatol. 2015;27:452-453.

- Lippmann HI, Goldin RR. Subcutaneous ossification of the legs in chronic venous insufficiency. Radiology. 1960;74:279-288.

- Haro R, Revelles JM, Angulo J, et al. Plaque-like osteoma cutis with transepidermal elimination. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:591-593.

A 62-year-old woman presented with an irregular, erythematous, 4-mm nodule with central erosions on the left proximal calf of 2 months’ duration. The patient had a history of actinic keratoses and dysplastic nevi. She had no other notable medical history. She was not taking any medications and reported no history of trauma to the area. A shave biopsy of the lesion (encircled by black ink) was performed.