User login

New guidelines provide standardized hypoglycemia values for clinical evaluation

, joining with the European Association for the Study of Diabetes to specify that a level of less than 3 mmol/L (54 mg/dL) should be considered “clinically important hypoglycemia.”

“A single glucose level should be agreed to that has serious clinical and health-economic consequences,” the ADA and EASD stated in the new guidelines. “This would enable the diabetes and regulatory communities to compare the effectiveness of interventions in reducing hypoglycemia, be they pharmacological, technological, or educational. It would also permit the use of meta-analysis as a statistical tool to increase power when comparing interventions.”

An international, multidisciplinary group – the International Hypoglycemia Study Group – was formed to create distinct definitions of the various levels of severity that hypoglycemia can have. The new guidelines contain three levels, which should be used by clinicians to determine what amounts of blood glucose are significant enough to be clinically reported.

“Currently, there is no uniform agreement to what constitutes reportable hypoglycemia in clinical trials,” she said. “In some studies, it is defined as a blood glucose level of less than 70 mg/dL, whereas in others it is defined as a blood glucose level less than 54 mg/dL.”

The guidelines define first-level hypoglycemia as any glucose level of 3.9 mmol/L (70 mg/dL) or less. This is not considered low enough to be reported on a consistent basis in clinical studies; however, that determination must ultimately be made by the investigators, as the parameters for what is significant often vary from study to study.

The second level is the 3 mmol/L (54 mg/dL), which now is deemed to be a clinically significant level of hypoglycemia. Because it is “sufficiently low to indicate serious, clinically important hypoglycemia,” it should be reported as part of any clinical studies. Finally, the third level, less than 2.8 mmol/L (50 mg/dL), indicates severe hypoglycemia and is classified as any individual with “severe cognitive impairment requiring external assistance for recovery,” according to the guidelines (Diabetes Care. 2016 Dec 1. doi: 10.2337/dc16-2215).

With a new standard of hypoglycemic values that are deemed clinically significant, the ADA and EASD hope that comparing different insulins, medications, technologies, and educational interventions will now become easier and more standardized, leading to better care worldwide.

Although there is general agreement as to where severe hypoglycemia really begins, the newly defined glucose levels are “a step in the right direction,” according to Dr. Rodbard.

The International Hypoglycaemia Study Group developed these guidelines through a grant from Novo Nordisk, awarded to the Six Degrees Academy of Toronto. Dr. Heller has received advisory or consultation fees from Lilly, Novo Nordisk, Takeda, Merck, Sharp & Dohme, and Becton Dickinson; has served as a speaker for AstraZeneca, Lilly, Novo Nordisk, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Takeda; and has received research support from Medtronic U.K. Dr. Rodbard did not report any financial disclosures.

, joining with the European Association for the Study of Diabetes to specify that a level of less than 3 mmol/L (54 mg/dL) should be considered “clinically important hypoglycemia.”

“A single glucose level should be agreed to that has serious clinical and health-economic consequences,” the ADA and EASD stated in the new guidelines. “This would enable the diabetes and regulatory communities to compare the effectiveness of interventions in reducing hypoglycemia, be they pharmacological, technological, or educational. It would also permit the use of meta-analysis as a statistical tool to increase power when comparing interventions.”

An international, multidisciplinary group – the International Hypoglycemia Study Group – was formed to create distinct definitions of the various levels of severity that hypoglycemia can have. The new guidelines contain three levels, which should be used by clinicians to determine what amounts of blood glucose are significant enough to be clinically reported.

“Currently, there is no uniform agreement to what constitutes reportable hypoglycemia in clinical trials,” she said. “In some studies, it is defined as a blood glucose level of less than 70 mg/dL, whereas in others it is defined as a blood glucose level less than 54 mg/dL.”

The guidelines define first-level hypoglycemia as any glucose level of 3.9 mmol/L (70 mg/dL) or less. This is not considered low enough to be reported on a consistent basis in clinical studies; however, that determination must ultimately be made by the investigators, as the parameters for what is significant often vary from study to study.

The second level is the 3 mmol/L (54 mg/dL), which now is deemed to be a clinically significant level of hypoglycemia. Because it is “sufficiently low to indicate serious, clinically important hypoglycemia,” it should be reported as part of any clinical studies. Finally, the third level, less than 2.8 mmol/L (50 mg/dL), indicates severe hypoglycemia and is classified as any individual with “severe cognitive impairment requiring external assistance for recovery,” according to the guidelines (Diabetes Care. 2016 Dec 1. doi: 10.2337/dc16-2215).

With a new standard of hypoglycemic values that are deemed clinically significant, the ADA and EASD hope that comparing different insulins, medications, technologies, and educational interventions will now become easier and more standardized, leading to better care worldwide.

Although there is general agreement as to where severe hypoglycemia really begins, the newly defined glucose levels are “a step in the right direction,” according to Dr. Rodbard.

The International Hypoglycaemia Study Group developed these guidelines through a grant from Novo Nordisk, awarded to the Six Degrees Academy of Toronto. Dr. Heller has received advisory or consultation fees from Lilly, Novo Nordisk, Takeda, Merck, Sharp & Dohme, and Becton Dickinson; has served as a speaker for AstraZeneca, Lilly, Novo Nordisk, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Takeda; and has received research support from Medtronic U.K. Dr. Rodbard did not report any financial disclosures.

, joining with the European Association for the Study of Diabetes to specify that a level of less than 3 mmol/L (54 mg/dL) should be considered “clinically important hypoglycemia.”

“A single glucose level should be agreed to that has serious clinical and health-economic consequences,” the ADA and EASD stated in the new guidelines. “This would enable the diabetes and regulatory communities to compare the effectiveness of interventions in reducing hypoglycemia, be they pharmacological, technological, or educational. It would also permit the use of meta-analysis as a statistical tool to increase power when comparing interventions.”

An international, multidisciplinary group – the International Hypoglycemia Study Group – was formed to create distinct definitions of the various levels of severity that hypoglycemia can have. The new guidelines contain three levels, which should be used by clinicians to determine what amounts of blood glucose are significant enough to be clinically reported.

“Currently, there is no uniform agreement to what constitutes reportable hypoglycemia in clinical trials,” she said. “In some studies, it is defined as a blood glucose level of less than 70 mg/dL, whereas in others it is defined as a blood glucose level less than 54 mg/dL.”

The guidelines define first-level hypoglycemia as any glucose level of 3.9 mmol/L (70 mg/dL) or less. This is not considered low enough to be reported on a consistent basis in clinical studies; however, that determination must ultimately be made by the investigators, as the parameters for what is significant often vary from study to study.

The second level is the 3 mmol/L (54 mg/dL), which now is deemed to be a clinically significant level of hypoglycemia. Because it is “sufficiently low to indicate serious, clinically important hypoglycemia,” it should be reported as part of any clinical studies. Finally, the third level, less than 2.8 mmol/L (50 mg/dL), indicates severe hypoglycemia and is classified as any individual with “severe cognitive impairment requiring external assistance for recovery,” according to the guidelines (Diabetes Care. 2016 Dec 1. doi: 10.2337/dc16-2215).

With a new standard of hypoglycemic values that are deemed clinically significant, the ADA and EASD hope that comparing different insulins, medications, technologies, and educational interventions will now become easier and more standardized, leading to better care worldwide.

Although there is general agreement as to where severe hypoglycemia really begins, the newly defined glucose levels are “a step in the right direction,” according to Dr. Rodbard.

The International Hypoglycaemia Study Group developed these guidelines through a grant from Novo Nordisk, awarded to the Six Degrees Academy of Toronto. Dr. Heller has received advisory or consultation fees from Lilly, Novo Nordisk, Takeda, Merck, Sharp & Dohme, and Becton Dickinson; has served as a speaker for AstraZeneca, Lilly, Novo Nordisk, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Takeda; and has received research support from Medtronic U.K. Dr. Rodbard did not report any financial disclosures.

Infants with congenital Zika born without microcephaly still can still develop it

Infants born with laboratory-confirmed congenital Zika virus but who show no signs of microcephaly at birth may still experience a reduction in cranial size as they grow older, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s latest Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

“These findings demonstrate the importance of early neuroimaging for infants exposed to Zika virus prenatally and the need for comprehensive medical and developmental follow-up,” wrote Vanessa van der Linden, MD, of the Association for Assistance of Disabled Children in Recife, Brazil, and her coauthors.

Dr. van der Linden and her coinvestigators examined 13 infants, all of whom were born in Brazil between October 2015 and January 2016, who had confirmed brain abnormalities at birth despite having a normal head size. These abnormalities included ventriculomegaly, subcortical calcifications, cortical malformations, and decreased brain volume. Investigators defined microcephaly as being “head circumference (HC) [that’s] more than 2 [standard deviations] below the mean for gestational age and sex.”

Nine of the infants were male, four were female. Eleven of the infants were born within 37-41 weeks’ of gestation. The remaining two were born at 35-36 weeks’ of gestation, considered “preterm” by the investigators. All infants tested positive for Zika via immunoglobulin M testing of cerebrospinal fluid, serum, or both. Only six of the mothers reported having a rash while pregnant; four reported experiencing it during the first trimester, while the other two said it occurred in the second.

All 13 infants showed a decrease in HC to what was defined as microcephaly within 1 year of birth (October 2016). Neuroimaging showed that all but one had decreased brain volume, all had malformations of cortical development, four had cerebellum or brain-stem hypoplasia, ten had ventriculomegaly, and three had increased extra-axial CSF space.

“More than 60% of infants in this series had epilepsy (likely related to the cortical malformations), and all had significant motor disabilities consistent with mixed cerebral palsy,” the authors noted, adding that the “pathogenesis of postnatal microcephaly from congenital Zika virus infections is [still] not known.”

Infants born with laboratory-confirmed congenital Zika virus but who show no signs of microcephaly at birth may still experience a reduction in cranial size as they grow older, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s latest Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

“These findings demonstrate the importance of early neuroimaging for infants exposed to Zika virus prenatally and the need for comprehensive medical and developmental follow-up,” wrote Vanessa van der Linden, MD, of the Association for Assistance of Disabled Children in Recife, Brazil, and her coauthors.

Dr. van der Linden and her coinvestigators examined 13 infants, all of whom were born in Brazil between October 2015 and January 2016, who had confirmed brain abnormalities at birth despite having a normal head size. These abnormalities included ventriculomegaly, subcortical calcifications, cortical malformations, and decreased brain volume. Investigators defined microcephaly as being “head circumference (HC) [that’s] more than 2 [standard deviations] below the mean for gestational age and sex.”

Nine of the infants were male, four were female. Eleven of the infants were born within 37-41 weeks’ of gestation. The remaining two were born at 35-36 weeks’ of gestation, considered “preterm” by the investigators. All infants tested positive for Zika via immunoglobulin M testing of cerebrospinal fluid, serum, or both. Only six of the mothers reported having a rash while pregnant; four reported experiencing it during the first trimester, while the other two said it occurred in the second.

All 13 infants showed a decrease in HC to what was defined as microcephaly within 1 year of birth (October 2016). Neuroimaging showed that all but one had decreased brain volume, all had malformations of cortical development, four had cerebellum or brain-stem hypoplasia, ten had ventriculomegaly, and three had increased extra-axial CSF space.

“More than 60% of infants in this series had epilepsy (likely related to the cortical malformations), and all had significant motor disabilities consistent with mixed cerebral palsy,” the authors noted, adding that the “pathogenesis of postnatal microcephaly from congenital Zika virus infections is [still] not known.”

Infants born with laboratory-confirmed congenital Zika virus but who show no signs of microcephaly at birth may still experience a reduction in cranial size as they grow older, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s latest Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

“These findings demonstrate the importance of early neuroimaging for infants exposed to Zika virus prenatally and the need for comprehensive medical and developmental follow-up,” wrote Vanessa van der Linden, MD, of the Association for Assistance of Disabled Children in Recife, Brazil, and her coauthors.

Dr. van der Linden and her coinvestigators examined 13 infants, all of whom were born in Brazil between October 2015 and January 2016, who had confirmed brain abnormalities at birth despite having a normal head size. These abnormalities included ventriculomegaly, subcortical calcifications, cortical malformations, and decreased brain volume. Investigators defined microcephaly as being “head circumference (HC) [that’s] more than 2 [standard deviations] below the mean for gestational age and sex.”

Nine of the infants were male, four were female. Eleven of the infants were born within 37-41 weeks’ of gestation. The remaining two were born at 35-36 weeks’ of gestation, considered “preterm” by the investigators. All infants tested positive for Zika via immunoglobulin M testing of cerebrospinal fluid, serum, or both. Only six of the mothers reported having a rash while pregnant; four reported experiencing it during the first trimester, while the other two said it occurred in the second.

All 13 infants showed a decrease in HC to what was defined as microcephaly within 1 year of birth (October 2016). Neuroimaging showed that all but one had decreased brain volume, all had malformations of cortical development, four had cerebellum or brain-stem hypoplasia, ten had ventriculomegaly, and three had increased extra-axial CSF space.

“More than 60% of infants in this series had epilepsy (likely related to the cortical malformations), and all had significant motor disabilities consistent with mixed cerebral palsy,” the authors noted, adding that the “pathogenesis of postnatal microcephaly from congenital Zika virus infections is [still] not known.”

FROM THE MMWR

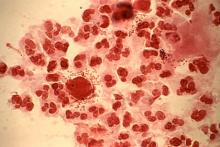

Multidose metronidazole may be better option for trichomoniasis treatment

ATLANTA – A multidose regimen of metronidazole was found to have a lower likelihood of treatment failure than a single-dose regimen in treating trichomoniasis in a meta-analysis presented at a conference on STD prevention sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In its 2015 STD treatment guidelines, the CDC recommends that women with HIV infection who receive a diagnosis of Trichomonas vaginalis infection should be treated with metronidazole 500 mg orally twice daily for 7 days, rather than with a 2-g single dose of metronidazole. However, it recommends a 2-g single dose of either metronidazole or tinidazole for other women with trichomoniasis as first-line treatment.

“[Trichomoniasis] is the most prevalent nonviral sexually transmitted infection in the U.S.; there are estimates of anywhere between 3.7 to 7 million [cases]. It eclipses gonorrhea, chlamydia, and syphilis in its prevalence, and there are about 276 million [cases] worldwide,” she said.

While single-dose therapy is inexpensive and has excellent adherence, recurrence has been a problem.

To compare the effectiveness of single- versus multidose treatment strategies, Dr. Kissinger and her coinvestigators searched Embase, Medline, and clinicaltrials.gov for any studies published before Jan. 25, 2016, that were English-language clinical trials evaluating trichomoniasis and metronidazole, and that compared single with multidose treatment regimens. Nearly 500 articles were identified and reviewed, but only six studies were included for analysis based on relevance and quality. Of those, one study included only HIV-positive women.

The primary endpoint was the pooled relative risk (RR) across all included studies of treatment failure in single- and multidose regimens.

Results showed that women who received single-dose metronidazole were 1.87 times more likely to experience treatment failure than those who received multidose therapy (95% confidence interval, 1.23-2.82; P less than .01). When the investigators excluded the one study involving HIV-positive women, the findings were similar, with those on single-dose therapy being 1.80 times more likely than those on a multidose regimen to experience treatment failure (95% CI, 1.07-3.02; P less than .03).

“Limitations [include] that the quality of the studies were not at the same level as we’d be doing in this decade,” Dr. Kissinger said. “There’s a scarcity of studies that evaluate this topic, [and] clinical trial methods have improved substantially since the 1980s, when most of these studies were done.”

Dr. Kissinger did not report information on financial disclosures.

ATLANTA – A multidose regimen of metronidazole was found to have a lower likelihood of treatment failure than a single-dose regimen in treating trichomoniasis in a meta-analysis presented at a conference on STD prevention sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In its 2015 STD treatment guidelines, the CDC recommends that women with HIV infection who receive a diagnosis of Trichomonas vaginalis infection should be treated with metronidazole 500 mg orally twice daily for 7 days, rather than with a 2-g single dose of metronidazole. However, it recommends a 2-g single dose of either metronidazole or tinidazole for other women with trichomoniasis as first-line treatment.

“[Trichomoniasis] is the most prevalent nonviral sexually transmitted infection in the U.S.; there are estimates of anywhere between 3.7 to 7 million [cases]. It eclipses gonorrhea, chlamydia, and syphilis in its prevalence, and there are about 276 million [cases] worldwide,” she said.

While single-dose therapy is inexpensive and has excellent adherence, recurrence has been a problem.

To compare the effectiveness of single- versus multidose treatment strategies, Dr. Kissinger and her coinvestigators searched Embase, Medline, and clinicaltrials.gov for any studies published before Jan. 25, 2016, that were English-language clinical trials evaluating trichomoniasis and metronidazole, and that compared single with multidose treatment regimens. Nearly 500 articles were identified and reviewed, but only six studies were included for analysis based on relevance and quality. Of those, one study included only HIV-positive women.

The primary endpoint was the pooled relative risk (RR) across all included studies of treatment failure in single- and multidose regimens.

Results showed that women who received single-dose metronidazole were 1.87 times more likely to experience treatment failure than those who received multidose therapy (95% confidence interval, 1.23-2.82; P less than .01). When the investigators excluded the one study involving HIV-positive women, the findings were similar, with those on single-dose therapy being 1.80 times more likely than those on a multidose regimen to experience treatment failure (95% CI, 1.07-3.02; P less than .03).

“Limitations [include] that the quality of the studies were not at the same level as we’d be doing in this decade,” Dr. Kissinger said. “There’s a scarcity of studies that evaluate this topic, [and] clinical trial methods have improved substantially since the 1980s, when most of these studies were done.”

Dr. Kissinger did not report information on financial disclosures.

ATLANTA – A multidose regimen of metronidazole was found to have a lower likelihood of treatment failure than a single-dose regimen in treating trichomoniasis in a meta-analysis presented at a conference on STD prevention sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In its 2015 STD treatment guidelines, the CDC recommends that women with HIV infection who receive a diagnosis of Trichomonas vaginalis infection should be treated with metronidazole 500 mg orally twice daily for 7 days, rather than with a 2-g single dose of metronidazole. However, it recommends a 2-g single dose of either metronidazole or tinidazole for other women with trichomoniasis as first-line treatment.

“[Trichomoniasis] is the most prevalent nonviral sexually transmitted infection in the U.S.; there are estimates of anywhere between 3.7 to 7 million [cases]. It eclipses gonorrhea, chlamydia, and syphilis in its prevalence, and there are about 276 million [cases] worldwide,” she said.

While single-dose therapy is inexpensive and has excellent adherence, recurrence has been a problem.

To compare the effectiveness of single- versus multidose treatment strategies, Dr. Kissinger and her coinvestigators searched Embase, Medline, and clinicaltrials.gov for any studies published before Jan. 25, 2016, that were English-language clinical trials evaluating trichomoniasis and metronidazole, and that compared single with multidose treatment regimens. Nearly 500 articles were identified and reviewed, but only six studies were included for analysis based on relevance and quality. Of those, one study included only HIV-positive women.

The primary endpoint was the pooled relative risk (RR) across all included studies of treatment failure in single- and multidose regimens.

Results showed that women who received single-dose metronidazole were 1.87 times more likely to experience treatment failure than those who received multidose therapy (95% confidence interval, 1.23-2.82; P less than .01). When the investigators excluded the one study involving HIV-positive women, the findings were similar, with those on single-dose therapy being 1.80 times more likely than those on a multidose regimen to experience treatment failure (95% CI, 1.07-3.02; P less than .03).

“Limitations [include] that the quality of the studies were not at the same level as we’d be doing in this decade,” Dr. Kissinger said. “There’s a scarcity of studies that evaluate this topic, [and] clinical trial methods have improved substantially since the 1980s, when most of these studies were done.”

Dr. Kissinger did not report information on financial disclosures.

AT THE 2016 STD PREVENTION CONFERENCE

Key clinical point:

Major finding: A single-dose regimen of metronidazole was more likely to fail, compared with a multidose regimen, with a pooled risk ratio of 1.87 (95% CI, 1.23-2.82; P less than .01).

Data source: Meta-analysis of six studies that evaluated single- and multidose metronidazole in treating T. vaginalis infections.

Disclosures: Dr. Kissinger did not report information on financial disclosures.

Thyroid disease does not affect primary biliary cholangitis complications

While associations are known to exist between primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) and many different types of thyroid disease (TD), a new study shows that the mere presence of thyroid disease does not have any bearing on the hepatic complications or progression of PBC.

“The prevalence of TD in PBC reportedly ranges between 7.24% and 14.4%, the most often encountered thyroid dysfunction being Hashimoto’s thyroiditis,” wrote the study’s authors, led by Annarosa Floreani, MD, of the University of Padua (Italy).

Of the 921 total patients enrolled, 150 (16.3%) had TD. The most common TD patients had were Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, which 94 (10.2%) individuals had; Graves’ disease, found in 15 (1.6%) patients; multinodular goiter, which 22 (2.4%) patients had; thyroid cancer, which was found in 7 (0.8%); and “other thyroid conditions,” which affected 12 (1.3%) patients. Patients from Padua had significantly more Graves’ disease and thyroid cancer than those from Barcelona: 11 (15.7%) versus 4 (5.0%) for Graves’ (P = .03), and 6 (8.6%) versus 1 (1.3%) for thyroid cancer (P = .03), respectively. However, no significant differences were found in PBC patients who had TD and those who did not, when it came to comparing the histologic stages at which they were diagnosed with PBC, hepatic decompensation events, occurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma, or liver transplantation rate. Furthermore, TD was not found to affect PBC survival rates, either positively or negatively.

“The results of our study confirm that TDs are often associated with PBC, especially Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, which shares an autoimmune etiology with PBC,” the authors concluded, adding that “More importantly … the clinical characteristics and natural history of PBC were much the same in the two cohorts, as demonstrated by the absence of significant differences regarding histological stage at diagnosis (the only exception being more patients in stage III in the Italian cohort); biochemical data; response to UDCA [ursodeoxycholic acid]; the association with other extrahepatic autoimmune disorders; the occurrence of clinical events; and survival.”

No funding source was reported for this study. Dr. Floreani and her coauthors did not report any financial disclosures relevant to this study.

While associations are known to exist between primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) and many different types of thyroid disease (TD), a new study shows that the mere presence of thyroid disease does not have any bearing on the hepatic complications or progression of PBC.

“The prevalence of TD in PBC reportedly ranges between 7.24% and 14.4%, the most often encountered thyroid dysfunction being Hashimoto’s thyroiditis,” wrote the study’s authors, led by Annarosa Floreani, MD, of the University of Padua (Italy).

Of the 921 total patients enrolled, 150 (16.3%) had TD. The most common TD patients had were Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, which 94 (10.2%) individuals had; Graves’ disease, found in 15 (1.6%) patients; multinodular goiter, which 22 (2.4%) patients had; thyroid cancer, which was found in 7 (0.8%); and “other thyroid conditions,” which affected 12 (1.3%) patients. Patients from Padua had significantly more Graves’ disease and thyroid cancer than those from Barcelona: 11 (15.7%) versus 4 (5.0%) for Graves’ (P = .03), and 6 (8.6%) versus 1 (1.3%) for thyroid cancer (P = .03), respectively. However, no significant differences were found in PBC patients who had TD and those who did not, when it came to comparing the histologic stages at which they were diagnosed with PBC, hepatic decompensation events, occurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma, or liver transplantation rate. Furthermore, TD was not found to affect PBC survival rates, either positively or negatively.

“The results of our study confirm that TDs are often associated with PBC, especially Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, which shares an autoimmune etiology with PBC,” the authors concluded, adding that “More importantly … the clinical characteristics and natural history of PBC were much the same in the two cohorts, as demonstrated by the absence of significant differences regarding histological stage at diagnosis (the only exception being more patients in stage III in the Italian cohort); biochemical data; response to UDCA [ursodeoxycholic acid]; the association with other extrahepatic autoimmune disorders; the occurrence of clinical events; and survival.”

No funding source was reported for this study. Dr. Floreani and her coauthors did not report any financial disclosures relevant to this study.

While associations are known to exist between primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) and many different types of thyroid disease (TD), a new study shows that the mere presence of thyroid disease does not have any bearing on the hepatic complications or progression of PBC.

“The prevalence of TD in PBC reportedly ranges between 7.24% and 14.4%, the most often encountered thyroid dysfunction being Hashimoto’s thyroiditis,” wrote the study’s authors, led by Annarosa Floreani, MD, of the University of Padua (Italy).

Of the 921 total patients enrolled, 150 (16.3%) had TD. The most common TD patients had were Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, which 94 (10.2%) individuals had; Graves’ disease, found in 15 (1.6%) patients; multinodular goiter, which 22 (2.4%) patients had; thyroid cancer, which was found in 7 (0.8%); and “other thyroid conditions,” which affected 12 (1.3%) patients. Patients from Padua had significantly more Graves’ disease and thyroid cancer than those from Barcelona: 11 (15.7%) versus 4 (5.0%) for Graves’ (P = .03), and 6 (8.6%) versus 1 (1.3%) for thyroid cancer (P = .03), respectively. However, no significant differences were found in PBC patients who had TD and those who did not, when it came to comparing the histologic stages at which they were diagnosed with PBC, hepatic decompensation events, occurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma, or liver transplantation rate. Furthermore, TD was not found to affect PBC survival rates, either positively or negatively.

“The results of our study confirm that TDs are often associated with PBC, especially Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, which shares an autoimmune etiology with PBC,” the authors concluded, adding that “More importantly … the clinical characteristics and natural history of PBC were much the same in the two cohorts, as demonstrated by the absence of significant differences regarding histological stage at diagnosis (the only exception being more patients in stage III in the Italian cohort); biochemical data; response to UDCA [ursodeoxycholic acid]; the association with other extrahepatic autoimmune disorders; the occurrence of clinical events; and survival.”

No funding source was reported for this study. Dr. Floreani and her coauthors did not report any financial disclosures relevant to this study.

Key clinical point:

Major finding: 150 of 921 PBC patients had TD (16.3%), but there was no correlation between PBC patients who had TD and their histologic stage either at diagnosis, hepatic decompensation events, occurrence of hepatocelluler carcinoma, or liver transplantation rates.

Data source: Prospective study of 921 PBC patients in Padua and Barcelona from 1975 to 2015.

Disclosures: No funding source was disclosed; authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Another Zika vaccine heads to Phase I trials

Scientists with the U.S. Department of Defense have launched a Phase I clinical trial to test an investigational Zika vaccine that relies on inactivated virus.

The candidate vaccine is known as the Zika Purified Inactivated Virus (ZPIV) vaccine and contains whole but inactivated Zika virus particles to stimulate an immune system response without replicating and causing illness.

“We urgently need a safe and effective vaccine to protect people from Zika virus infection as the virus continues to spread and cause serious public health consequences, particularly for pregnant women and their babies,” Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), said in a statement. “We are pleased to be part of the collaborative effort to advance this promising candidate vaccine into clinical trials.”

The NIAID helped support the preclinical development of the vaccine candidate and is part of a joint research agreement with the Department of Defense and other federal agencies to develop the vaccine for use in humans.

The trial at Walter Reed will enroll 75 individuals, ranging in age from 18-49 years, all of whom should have no history of a flavivirus infection. Twenty-five subjects will be given a pair of either intramuscular ZPIV injections, or a placebo (saline), with 28 days between injections.

The remaining 50 subjects will be divided into two groups of 25, with one group receiving two doses of a Japanese encephalitis virus vaccine and the other getting one dose of a yellow fever vaccine, before they both receive the two-dose ZPIV vaccine regimen.

A subgroup of 30 patients will then receive a third ZPIV dose 1 year later. Across all cohorts, the ZPIV dosage will be 5 micrograms.

In addition to the testing of the ZPIV vaccine, there are Phase I trials of a DNA-based Zika vaccine ongoing at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center in Bethesda, Md., the Center for Vaccine Development at the University of Maryland in Baltimore, Md., and at Emory University in Atlanta, Ga. Those trials were launched in August 2016.

Scientists with the U.S. Department of Defense have launched a Phase I clinical trial to test an investigational Zika vaccine that relies on inactivated virus.

The candidate vaccine is known as the Zika Purified Inactivated Virus (ZPIV) vaccine and contains whole but inactivated Zika virus particles to stimulate an immune system response without replicating and causing illness.

“We urgently need a safe and effective vaccine to protect people from Zika virus infection as the virus continues to spread and cause serious public health consequences, particularly for pregnant women and their babies,” Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), said in a statement. “We are pleased to be part of the collaborative effort to advance this promising candidate vaccine into clinical trials.”

The NIAID helped support the preclinical development of the vaccine candidate and is part of a joint research agreement with the Department of Defense and other federal agencies to develop the vaccine for use in humans.

The trial at Walter Reed will enroll 75 individuals, ranging in age from 18-49 years, all of whom should have no history of a flavivirus infection. Twenty-five subjects will be given a pair of either intramuscular ZPIV injections, or a placebo (saline), with 28 days between injections.

The remaining 50 subjects will be divided into two groups of 25, with one group receiving two doses of a Japanese encephalitis virus vaccine and the other getting one dose of a yellow fever vaccine, before they both receive the two-dose ZPIV vaccine regimen.

A subgroup of 30 patients will then receive a third ZPIV dose 1 year later. Across all cohorts, the ZPIV dosage will be 5 micrograms.

In addition to the testing of the ZPIV vaccine, there are Phase I trials of a DNA-based Zika vaccine ongoing at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center in Bethesda, Md., the Center for Vaccine Development at the University of Maryland in Baltimore, Md., and at Emory University in Atlanta, Ga. Those trials were launched in August 2016.

Scientists with the U.S. Department of Defense have launched a Phase I clinical trial to test an investigational Zika vaccine that relies on inactivated virus.

The candidate vaccine is known as the Zika Purified Inactivated Virus (ZPIV) vaccine and contains whole but inactivated Zika virus particles to stimulate an immune system response without replicating and causing illness.

“We urgently need a safe and effective vaccine to protect people from Zika virus infection as the virus continues to spread and cause serious public health consequences, particularly for pregnant women and their babies,” Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), said in a statement. “We are pleased to be part of the collaborative effort to advance this promising candidate vaccine into clinical trials.”

The NIAID helped support the preclinical development of the vaccine candidate and is part of a joint research agreement with the Department of Defense and other federal agencies to develop the vaccine for use in humans.

The trial at Walter Reed will enroll 75 individuals, ranging in age from 18-49 years, all of whom should have no history of a flavivirus infection. Twenty-five subjects will be given a pair of either intramuscular ZPIV injections, or a placebo (saline), with 28 days between injections.

The remaining 50 subjects will be divided into two groups of 25, with one group receiving two doses of a Japanese encephalitis virus vaccine and the other getting one dose of a yellow fever vaccine, before they both receive the two-dose ZPIV vaccine regimen.

A subgroup of 30 patients will then receive a third ZPIV dose 1 year later. Across all cohorts, the ZPIV dosage will be 5 micrograms.

In addition to the testing of the ZPIV vaccine, there are Phase I trials of a DNA-based Zika vaccine ongoing at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center in Bethesda, Md., the Center for Vaccine Development at the University of Maryland in Baltimore, Md., and at Emory University in Atlanta, Ga. Those trials were launched in August 2016.

Treating upper GI diseases: Where do we go from here?

WASHINGTON – The American Gastroenterological Association, the Food and Drug Administration, pharmaceutical companies, and patient advocacy groups came together for a first-of-its-kind meeting, a program of the AGA Center for Diagnostics and Therapeutics, to discuss new and emerging drugs for the treatment of four key GI diseases, highlighting the promise that these treatments show and the hurdles they face to gain approval.

“If we look at the AGA’s Burden of GI Disease Survey, published a few years ago in Gastroenterology, [you] can see that there are millions of visits to primary care and specialists for a variety of upper gastrointestinal symptoms, so clearly upper GI disorders still pose a major burden to our health care environment,” explained Colin W. Howden, MD, AGAF, chair of the AGA Center for Diagnostics and Therapeutics from the University of Tennessee in Memphis.

While proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) continue to be the first line of management for GERD, severe cases often require a stronger approach. Alternatives that are being investigated include potassium-competitive acid blockers, for which there have been clinical trials. However, no advantage over PPIs was demonstrated in any trials. Another alternative is bile salt binders, for which at least one trial is currently underway. Dr. Vela was unable to say when findings are expected to be published.

Another approach to managing GERD is to treat the acid pocket itself by using alginate. A randomized study by Rohof et al. investigated this in 2013, comparing Gaviscon and antacid; although the population size was small (n = 16), investigators concluded that “alginate-antacid raft localizes to the postprandial acid pocket and displaces it below the diaphragm to reduce postprandial acid reflux [making it] an appropriate therapy for postprandial acid reflux.”

Another new drug is lesogaberan, a GABA-B agonist that was examined in a 2010 randomized, double-blind crossover study by Boeckxstaens et al. While also a small trial (n = 21), the findings indicated that the drug is a good option for those with only partial response to PPIs, as it decreased the number of transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations (TLESRs) and reflux episodes, and increased LES pressure [in] patients with reflux symptoms. Work to inhibit transient LES relaxations also is being done, but so far lesogaberan, arbaclofen, and ADX 10059 (an mGluR5 modulator) programs have all been halted because of side effects or insufficient efficacy findings.

Prokinetics are also being looked at, with drugs such as metoclopramide being examined for efficacy, although to this point, the drug has shown “no improvement in acid exposure or esophageal clearance [when] compared to placebo,” according to Dr. Vela. Other drugs that are available outside the United States include domperidone, itopride, and mosapride, but Dr. Vela, who led a 2014 report on these therapies, stated that benefits offered by these are modest, and studies investigating them are limited in number.

Also being looked at are rebamipide, which can be used a cytoprotective agent that increases prostaglandin production. A 2010 study by Yoshida et al. found that lansoprazole (15 mg/day), combined with 300 mg/day of rebamipide, was significantly better at preventing relapse within a year than was just the former medication taken on its own. Additionally, there are conceptual studies examining topical protection to maintain mucosal integrity, nociceptor blockades, and imipramine.

Regarding trials for GERD, Robyn Carson, director of health economics & outcomes research at Allergan stated that the company recently redefined what constitutes GERD in order to help refocus what its drugs were trying to do.

“I think we’ve operationalized it very recently in terms of exclusion and GERD,” she explained. “The way we define it is ‘active GERD’ with two or more episodes a week of heartburn, so it was very much focused on the heartburn and PPI use was acceptable.”

Following the GERD discussion, panelists talked about what’s coming up in the realm of EoE. Stuart J. Spechler, MD, of the University of Texas Southwestern in Dallas, discussed ongoing research into treating EoE as an antigen-driven disorder, noting that about half of all EoE patients have a history of atopic disease – such as rhinitis, asthma, and atopic dermatitis – and exhibit sensitization to food or other aeroallergens. Furthermore, about 3% of patients who undergo oral immunotherapy to treat a food allergy develop EoE.

But in terms of what to take EoE research forward, Dr. Spechler called for a shift away from trying to distinguish between EoE and GERD, arguing that GERD contributes to EoE pathogenesis, and vice versa. PPIs can and should be used in EoE for the same reasons that they’re used to treat GERD, he explained.

“We need a shift in focus [because] I don’t think it’s likely to be that productive a line of research,” Dr. Spechler said. “The two diseases often coexist.”

To attack gastroparesis, P. Jay Pasricha, MD explained that a number of trials examining several drugs have shown that they are either ineffective or “do not correlate with improvement in gastric emptying.” These drugs include cisapride, tegaserod, botulinum toxin, mitemcinal, camcinal, TZP 102, and relamorelin.

“I’m not going to talk about emerging biomarkers because there isn’t a lot to talk about with biomarkers that hasn’t already been said,” stated Dr. Pasricha of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore adding that his focus would largely be focused on emerging therapies and treatment targets.

A 2013 study by Parkman et al. investigated the effects of nortriptyline on mitigating idiopathic gastroparesis symptoms, finding that there was no significant difference in symptoms among patients who took the drug, versus those who took a placebo. In terms of using antinauseants to alleviate symptoms, dopamine receptor antagonists continue to be commonly prescribed, but they have their limitations. Metoclopramide, though approved since 1986, can be used for only 12 weeks, has acute and chronic side effects such as mood and irreversible movement disorders, and a black box warning imposed on it by the FDA in 2009 for tardive dyskinesia. One drug approved in India, though not by the FDA, is domperidone, which has no side effects to the central nervous system but does raise cardiovascular concerns in patients with “mild hERG affinity.”

Currently, the APRON trial is investigating the efficacy of aprepitant to relieve chronic nausea and vomiting in gastroparesis patients. Those enrolled in the study are all at least 18 years old, have undergone gastric-emptying scintigraphy, and either a normal upper endoscopy or an upper GI series within the 2 years prior to enrollment, have symptoms of chronic nausea or vomiting consistent with a functional gastric disorder for at least 6 months before enrollment, and nausea defined as “significant” by a visual analog scale score of at least 25 mm.

“Continuing to focus solely on accelerating gastric emptying is a failed strategy,” said Dr. Pasricha, adding that research needs to focus on the unique aspects of the disease’s biology, including pathogenic similarities with functional dyspepsia.

To that end, the final disease covered was functional dyspepsia. In terms of ongoing or planned clinical studies, Jan Tack, MD, from the University of Leuven (Belgium), mentioned three. Two of them are multicenter controlled trials investigating acotiamide, one in Europe and the other in India, for the management of functional dyspepsia and postprandial distress syndrome, while the other is a multicenter study examining rikkunshito, a traditional Japanese medicine. Additionally, ongoing or planned mechanistic studies include single-center controlled trials in Belgium on the efficacy of acotiamide and rikkunshito for intragastric pressure, as well as another Belgian study analyzing the impact of monoacylglycerol lipase inhibitors on intragastric pressure in patients that have functional dyspepsia with “impaired accommodation.”

Meal-related symptoms, nutrient challenge tests, and intragastric pressure measurements should all become short-term pathophysiology and efficacy markers, said Dr. Tack, adding that it’s also important for new therapeutic targets to include gastric emptying, hypersensitivity, and duodenal alterations, if necessary.

Hurdles persist in getting drugs through the approval process, however. Juli Tomaino, MD, of the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, explained where many proposed drugs run into issues in the regulatory process.

“We really have to know what we’re diagnosing, so the regulatory pathway to any of these approvals will really depend on the independent patient population, it will depend on the mechanism of action of the drug, what the drug is able to do and not do, and how you’re going to design that trial to target whatever that drug can do,” Dr. Tomaino said.

The issue of labeling also factors in, according to her. “We know that patients with acid-mediated heartburn do well on PPIs, but if they’re having different symptoms due to different mechanisms of action, then you have to design that drug with that patient population in mind, and that’s what the labeling would look like,” she explained. “So I’m not saying that it would necessarily have to list all the enrollment criteria, all the enrichment techniques that we use in that trial, but it would be a description of the intended patient population and what the drug would do.”

Mrs. Carson also chimed in on the topic of trial difficulties, saying that “[Irritable bowel syndrome] and [chronic idiopathic constipation] became quite an impediment to recruitment, and I think as we get farther away from the complete overlapping conditions, I think that’s where in discussions with the [Qualification Review Team] at FDA, they recognize that [we should] track that and let this evidence drive the next step,” adding that “we’ll have data on that shortly.”

The AGA Center for Diagnostics and Therapeutics will be issuing white papers on each of the four upper GI disorders discussed at the meeting.

Dr. Howden disclosed that he is a consultant for Aralez, Ironwood, Allergan, Otsuka, and SynteractHCR; an expert witness for Allergan; and coeditor of Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. Dr. Spechler disclosed that he is a consultant for Interpace Diagnostics, Takeda Pharmaceuticals, and Ironwood Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Pasricha disclosed that he is the cofounder of Neurogastrx, OrphoMed, and ETX Pharma, and is a consultant for Vanda and Allergan. Dr. Tack disclosed that he is a consultant for Abide, Allergan, AstraZeneca, Danone, El Pharma, Menarini, Novartis, Ono, Shire, Takeda, Theravance, Tsumura, and Zeria, as well as being on several of their advisory boards and speakers bureaus. Dr. Vela is a consultant for Medtronic and Torax.*

*Additions were made to the story on 11/8/2016 and 11/18/2016.

WASHINGTON – The American Gastroenterological Association, the Food and Drug Administration, pharmaceutical companies, and patient advocacy groups came together for a first-of-its-kind meeting, a program of the AGA Center for Diagnostics and Therapeutics, to discuss new and emerging drugs for the treatment of four key GI diseases, highlighting the promise that these treatments show and the hurdles they face to gain approval.

“If we look at the AGA’s Burden of GI Disease Survey, published a few years ago in Gastroenterology, [you] can see that there are millions of visits to primary care and specialists for a variety of upper gastrointestinal symptoms, so clearly upper GI disorders still pose a major burden to our health care environment,” explained Colin W. Howden, MD, AGAF, chair of the AGA Center for Diagnostics and Therapeutics from the University of Tennessee in Memphis.

While proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) continue to be the first line of management for GERD, severe cases often require a stronger approach. Alternatives that are being investigated include potassium-competitive acid blockers, for which there have been clinical trials. However, no advantage over PPIs was demonstrated in any trials. Another alternative is bile salt binders, for which at least one trial is currently underway. Dr. Vela was unable to say when findings are expected to be published.

Another approach to managing GERD is to treat the acid pocket itself by using alginate. A randomized study by Rohof et al. investigated this in 2013, comparing Gaviscon and antacid; although the population size was small (n = 16), investigators concluded that “alginate-antacid raft localizes to the postprandial acid pocket and displaces it below the diaphragm to reduce postprandial acid reflux [making it] an appropriate therapy for postprandial acid reflux.”

Another new drug is lesogaberan, a GABA-B agonist that was examined in a 2010 randomized, double-blind crossover study by Boeckxstaens et al. While also a small trial (n = 21), the findings indicated that the drug is a good option for those with only partial response to PPIs, as it decreased the number of transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations (TLESRs) and reflux episodes, and increased LES pressure [in] patients with reflux symptoms. Work to inhibit transient LES relaxations also is being done, but so far lesogaberan, arbaclofen, and ADX 10059 (an mGluR5 modulator) programs have all been halted because of side effects or insufficient efficacy findings.

Prokinetics are also being looked at, with drugs such as metoclopramide being examined for efficacy, although to this point, the drug has shown “no improvement in acid exposure or esophageal clearance [when] compared to placebo,” according to Dr. Vela. Other drugs that are available outside the United States include domperidone, itopride, and mosapride, but Dr. Vela, who led a 2014 report on these therapies, stated that benefits offered by these are modest, and studies investigating them are limited in number.

Also being looked at are rebamipide, which can be used a cytoprotective agent that increases prostaglandin production. A 2010 study by Yoshida et al. found that lansoprazole (15 mg/day), combined with 300 mg/day of rebamipide, was significantly better at preventing relapse within a year than was just the former medication taken on its own. Additionally, there are conceptual studies examining topical protection to maintain mucosal integrity, nociceptor blockades, and imipramine.

Regarding trials for GERD, Robyn Carson, director of health economics & outcomes research at Allergan stated that the company recently redefined what constitutes GERD in order to help refocus what its drugs were trying to do.

“I think we’ve operationalized it very recently in terms of exclusion and GERD,” she explained. “The way we define it is ‘active GERD’ with two or more episodes a week of heartburn, so it was very much focused on the heartburn and PPI use was acceptable.”

Following the GERD discussion, panelists talked about what’s coming up in the realm of EoE. Stuart J. Spechler, MD, of the University of Texas Southwestern in Dallas, discussed ongoing research into treating EoE as an antigen-driven disorder, noting that about half of all EoE patients have a history of atopic disease – such as rhinitis, asthma, and atopic dermatitis – and exhibit sensitization to food or other aeroallergens. Furthermore, about 3% of patients who undergo oral immunotherapy to treat a food allergy develop EoE.

But in terms of what to take EoE research forward, Dr. Spechler called for a shift away from trying to distinguish between EoE and GERD, arguing that GERD contributes to EoE pathogenesis, and vice versa. PPIs can and should be used in EoE for the same reasons that they’re used to treat GERD, he explained.

“We need a shift in focus [because] I don’t think it’s likely to be that productive a line of research,” Dr. Spechler said. “The two diseases often coexist.”

To attack gastroparesis, P. Jay Pasricha, MD explained that a number of trials examining several drugs have shown that they are either ineffective or “do not correlate with improvement in gastric emptying.” These drugs include cisapride, tegaserod, botulinum toxin, mitemcinal, camcinal, TZP 102, and relamorelin.

“I’m not going to talk about emerging biomarkers because there isn’t a lot to talk about with biomarkers that hasn’t already been said,” stated Dr. Pasricha of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore adding that his focus would largely be focused on emerging therapies and treatment targets.

A 2013 study by Parkman et al. investigated the effects of nortriptyline on mitigating idiopathic gastroparesis symptoms, finding that there was no significant difference in symptoms among patients who took the drug, versus those who took a placebo. In terms of using antinauseants to alleviate symptoms, dopamine receptor antagonists continue to be commonly prescribed, but they have their limitations. Metoclopramide, though approved since 1986, can be used for only 12 weeks, has acute and chronic side effects such as mood and irreversible movement disorders, and a black box warning imposed on it by the FDA in 2009 for tardive dyskinesia. One drug approved in India, though not by the FDA, is domperidone, which has no side effects to the central nervous system but does raise cardiovascular concerns in patients with “mild hERG affinity.”

Currently, the APRON trial is investigating the efficacy of aprepitant to relieve chronic nausea and vomiting in gastroparesis patients. Those enrolled in the study are all at least 18 years old, have undergone gastric-emptying scintigraphy, and either a normal upper endoscopy or an upper GI series within the 2 years prior to enrollment, have symptoms of chronic nausea or vomiting consistent with a functional gastric disorder for at least 6 months before enrollment, and nausea defined as “significant” by a visual analog scale score of at least 25 mm.

“Continuing to focus solely on accelerating gastric emptying is a failed strategy,” said Dr. Pasricha, adding that research needs to focus on the unique aspects of the disease’s biology, including pathogenic similarities with functional dyspepsia.

To that end, the final disease covered was functional dyspepsia. In terms of ongoing or planned clinical studies, Jan Tack, MD, from the University of Leuven (Belgium), mentioned three. Two of them are multicenter controlled trials investigating acotiamide, one in Europe and the other in India, for the management of functional dyspepsia and postprandial distress syndrome, while the other is a multicenter study examining rikkunshito, a traditional Japanese medicine. Additionally, ongoing or planned mechanistic studies include single-center controlled trials in Belgium on the efficacy of acotiamide and rikkunshito for intragastric pressure, as well as another Belgian study analyzing the impact of monoacylglycerol lipase inhibitors on intragastric pressure in patients that have functional dyspepsia with “impaired accommodation.”

Meal-related symptoms, nutrient challenge tests, and intragastric pressure measurements should all become short-term pathophysiology and efficacy markers, said Dr. Tack, adding that it’s also important for new therapeutic targets to include gastric emptying, hypersensitivity, and duodenal alterations, if necessary.

Hurdles persist in getting drugs through the approval process, however. Juli Tomaino, MD, of the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, explained where many proposed drugs run into issues in the regulatory process.

“We really have to know what we’re diagnosing, so the regulatory pathway to any of these approvals will really depend on the independent patient population, it will depend on the mechanism of action of the drug, what the drug is able to do and not do, and how you’re going to design that trial to target whatever that drug can do,” Dr. Tomaino said.

The issue of labeling also factors in, according to her. “We know that patients with acid-mediated heartburn do well on PPIs, but if they’re having different symptoms due to different mechanisms of action, then you have to design that drug with that patient population in mind, and that’s what the labeling would look like,” she explained. “So I’m not saying that it would necessarily have to list all the enrollment criteria, all the enrichment techniques that we use in that trial, but it would be a description of the intended patient population and what the drug would do.”

Mrs. Carson also chimed in on the topic of trial difficulties, saying that “[Irritable bowel syndrome] and [chronic idiopathic constipation] became quite an impediment to recruitment, and I think as we get farther away from the complete overlapping conditions, I think that’s where in discussions with the [Qualification Review Team] at FDA, they recognize that [we should] track that and let this evidence drive the next step,” adding that “we’ll have data on that shortly.”

The AGA Center for Diagnostics and Therapeutics will be issuing white papers on each of the four upper GI disorders discussed at the meeting.

Dr. Howden disclosed that he is a consultant for Aralez, Ironwood, Allergan, Otsuka, and SynteractHCR; an expert witness for Allergan; and coeditor of Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. Dr. Spechler disclosed that he is a consultant for Interpace Diagnostics, Takeda Pharmaceuticals, and Ironwood Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Pasricha disclosed that he is the cofounder of Neurogastrx, OrphoMed, and ETX Pharma, and is a consultant for Vanda and Allergan. Dr. Tack disclosed that he is a consultant for Abide, Allergan, AstraZeneca, Danone, El Pharma, Menarini, Novartis, Ono, Shire, Takeda, Theravance, Tsumura, and Zeria, as well as being on several of their advisory boards and speakers bureaus. Dr. Vela is a consultant for Medtronic and Torax.*

*Additions were made to the story on 11/8/2016 and 11/18/2016.

WASHINGTON – The American Gastroenterological Association, the Food and Drug Administration, pharmaceutical companies, and patient advocacy groups came together for a first-of-its-kind meeting, a program of the AGA Center for Diagnostics and Therapeutics, to discuss new and emerging drugs for the treatment of four key GI diseases, highlighting the promise that these treatments show and the hurdles they face to gain approval.

“If we look at the AGA’s Burden of GI Disease Survey, published a few years ago in Gastroenterology, [you] can see that there are millions of visits to primary care and specialists for a variety of upper gastrointestinal symptoms, so clearly upper GI disorders still pose a major burden to our health care environment,” explained Colin W. Howden, MD, AGAF, chair of the AGA Center for Diagnostics and Therapeutics from the University of Tennessee in Memphis.

While proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) continue to be the first line of management for GERD, severe cases often require a stronger approach. Alternatives that are being investigated include potassium-competitive acid blockers, for which there have been clinical trials. However, no advantage over PPIs was demonstrated in any trials. Another alternative is bile salt binders, for which at least one trial is currently underway. Dr. Vela was unable to say when findings are expected to be published.

Another approach to managing GERD is to treat the acid pocket itself by using alginate. A randomized study by Rohof et al. investigated this in 2013, comparing Gaviscon and antacid; although the population size was small (n = 16), investigators concluded that “alginate-antacid raft localizes to the postprandial acid pocket and displaces it below the diaphragm to reduce postprandial acid reflux [making it] an appropriate therapy for postprandial acid reflux.”

Another new drug is lesogaberan, a GABA-B agonist that was examined in a 2010 randomized, double-blind crossover study by Boeckxstaens et al. While also a small trial (n = 21), the findings indicated that the drug is a good option for those with only partial response to PPIs, as it decreased the number of transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations (TLESRs) and reflux episodes, and increased LES pressure [in] patients with reflux symptoms. Work to inhibit transient LES relaxations also is being done, but so far lesogaberan, arbaclofen, and ADX 10059 (an mGluR5 modulator) programs have all been halted because of side effects or insufficient efficacy findings.

Prokinetics are also being looked at, with drugs such as metoclopramide being examined for efficacy, although to this point, the drug has shown “no improvement in acid exposure or esophageal clearance [when] compared to placebo,” according to Dr. Vela. Other drugs that are available outside the United States include domperidone, itopride, and mosapride, but Dr. Vela, who led a 2014 report on these therapies, stated that benefits offered by these are modest, and studies investigating them are limited in number.

Also being looked at are rebamipide, which can be used a cytoprotective agent that increases prostaglandin production. A 2010 study by Yoshida et al. found that lansoprazole (15 mg/day), combined with 300 mg/day of rebamipide, was significantly better at preventing relapse within a year than was just the former medication taken on its own. Additionally, there are conceptual studies examining topical protection to maintain mucosal integrity, nociceptor blockades, and imipramine.

Regarding trials for GERD, Robyn Carson, director of health economics & outcomes research at Allergan stated that the company recently redefined what constitutes GERD in order to help refocus what its drugs were trying to do.

“I think we’ve operationalized it very recently in terms of exclusion and GERD,” she explained. “The way we define it is ‘active GERD’ with two or more episodes a week of heartburn, so it was very much focused on the heartburn and PPI use was acceptable.”

Following the GERD discussion, panelists talked about what’s coming up in the realm of EoE. Stuart J. Spechler, MD, of the University of Texas Southwestern in Dallas, discussed ongoing research into treating EoE as an antigen-driven disorder, noting that about half of all EoE patients have a history of atopic disease – such as rhinitis, asthma, and atopic dermatitis – and exhibit sensitization to food or other aeroallergens. Furthermore, about 3% of patients who undergo oral immunotherapy to treat a food allergy develop EoE.

But in terms of what to take EoE research forward, Dr. Spechler called for a shift away from trying to distinguish between EoE and GERD, arguing that GERD contributes to EoE pathogenesis, and vice versa. PPIs can and should be used in EoE for the same reasons that they’re used to treat GERD, he explained.

“We need a shift in focus [because] I don’t think it’s likely to be that productive a line of research,” Dr. Spechler said. “The two diseases often coexist.”

To attack gastroparesis, P. Jay Pasricha, MD explained that a number of trials examining several drugs have shown that they are either ineffective or “do not correlate with improvement in gastric emptying.” These drugs include cisapride, tegaserod, botulinum toxin, mitemcinal, camcinal, TZP 102, and relamorelin.

“I’m not going to talk about emerging biomarkers because there isn’t a lot to talk about with biomarkers that hasn’t already been said,” stated Dr. Pasricha of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore adding that his focus would largely be focused on emerging therapies and treatment targets.

A 2013 study by Parkman et al. investigated the effects of nortriptyline on mitigating idiopathic gastroparesis symptoms, finding that there was no significant difference in symptoms among patients who took the drug, versus those who took a placebo. In terms of using antinauseants to alleviate symptoms, dopamine receptor antagonists continue to be commonly prescribed, but they have their limitations. Metoclopramide, though approved since 1986, can be used for only 12 weeks, has acute and chronic side effects such as mood and irreversible movement disorders, and a black box warning imposed on it by the FDA in 2009 for tardive dyskinesia. One drug approved in India, though not by the FDA, is domperidone, which has no side effects to the central nervous system but does raise cardiovascular concerns in patients with “mild hERG affinity.”

Currently, the APRON trial is investigating the efficacy of aprepitant to relieve chronic nausea and vomiting in gastroparesis patients. Those enrolled in the study are all at least 18 years old, have undergone gastric-emptying scintigraphy, and either a normal upper endoscopy or an upper GI series within the 2 years prior to enrollment, have symptoms of chronic nausea or vomiting consistent with a functional gastric disorder for at least 6 months before enrollment, and nausea defined as “significant” by a visual analog scale score of at least 25 mm.

“Continuing to focus solely on accelerating gastric emptying is a failed strategy,” said Dr. Pasricha, adding that research needs to focus on the unique aspects of the disease’s biology, including pathogenic similarities with functional dyspepsia.

To that end, the final disease covered was functional dyspepsia. In terms of ongoing or planned clinical studies, Jan Tack, MD, from the University of Leuven (Belgium), mentioned three. Two of them are multicenter controlled trials investigating acotiamide, one in Europe and the other in India, for the management of functional dyspepsia and postprandial distress syndrome, while the other is a multicenter study examining rikkunshito, a traditional Japanese medicine. Additionally, ongoing or planned mechanistic studies include single-center controlled trials in Belgium on the efficacy of acotiamide and rikkunshito for intragastric pressure, as well as another Belgian study analyzing the impact of monoacylglycerol lipase inhibitors on intragastric pressure in patients that have functional dyspepsia with “impaired accommodation.”

Meal-related symptoms, nutrient challenge tests, and intragastric pressure measurements should all become short-term pathophysiology and efficacy markers, said Dr. Tack, adding that it’s also important for new therapeutic targets to include gastric emptying, hypersensitivity, and duodenal alterations, if necessary.

Hurdles persist in getting drugs through the approval process, however. Juli Tomaino, MD, of the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, explained where many proposed drugs run into issues in the regulatory process.

“We really have to know what we’re diagnosing, so the regulatory pathway to any of these approvals will really depend on the independent patient population, it will depend on the mechanism of action of the drug, what the drug is able to do and not do, and how you’re going to design that trial to target whatever that drug can do,” Dr. Tomaino said.

The issue of labeling also factors in, according to her. “We know that patients with acid-mediated heartburn do well on PPIs, but if they’re having different symptoms due to different mechanisms of action, then you have to design that drug with that patient population in mind, and that’s what the labeling would look like,” she explained. “So I’m not saying that it would necessarily have to list all the enrollment criteria, all the enrichment techniques that we use in that trial, but it would be a description of the intended patient population and what the drug would do.”

Mrs. Carson also chimed in on the topic of trial difficulties, saying that “[Irritable bowel syndrome] and [chronic idiopathic constipation] became quite an impediment to recruitment, and I think as we get farther away from the complete overlapping conditions, I think that’s where in discussions with the [Qualification Review Team] at FDA, they recognize that [we should] track that and let this evidence drive the next step,” adding that “we’ll have data on that shortly.”

The AGA Center for Diagnostics and Therapeutics will be issuing white papers on each of the four upper GI disorders discussed at the meeting.

Dr. Howden disclosed that he is a consultant for Aralez, Ironwood, Allergan, Otsuka, and SynteractHCR; an expert witness for Allergan; and coeditor of Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. Dr. Spechler disclosed that he is a consultant for Interpace Diagnostics, Takeda Pharmaceuticals, and Ironwood Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Pasricha disclosed that he is the cofounder of Neurogastrx, OrphoMed, and ETX Pharma, and is a consultant for Vanda and Allergan. Dr. Tack disclosed that he is a consultant for Abide, Allergan, AstraZeneca, Danone, El Pharma, Menarini, Novartis, Ono, Shire, Takeda, Theravance, Tsumura, and Zeria, as well as being on several of their advisory boards and speakers bureaus. Dr. Vela is a consultant for Medtronic and Torax.*

*Additions were made to the story on 11/8/2016 and 11/18/2016.

AT THE AGA DRUG DEVELOPMENT CONFERENCE

Syphilis testing before and after stillbirth is suboptimal

ATLANTA – Physicians are falling short on syphilis testing in both the prenatal period and at the time of delivery, suggest the findings of a study examining insurance claims from nearly 10,000 women who experienced stillbirths.

Overall, less than 10% of women in the study were tested for syphilis following a stillbirth delivery, while less than two-thirds of women who experienced a stillbirth had received prenatal syphilis testing.

Dr. Patel and his coinvestigators examined data from the Truven Health MarketScan Medicaid and commercial claims database to evaluate the proportion of women who had syphilis testing within at least 1 week before and 1 week after a stillbirth delivery.

The investigators identified women aged 15-44 years who had a stillbirth delivery in 2013. Stillbirths were identified via ICD-9 codes and these codes were also used to track prenatal syphilis testing, as well as syphilis testing, placental examination and complete blood count (CBC) performed at the time of delivery.

In total, there were 3,731 women enrolled in Medicaid and 6,096 commercially-insured women who experienced stillbirths and were included in the study. Of these women, 65.5% of Medicaid-covered women and 56.6% of commercially-insured women received prenatal syphilis testing. At delivery, 6.5% of Medicaid-insured women and 9.3% of commercially-insured women received syphilis testing.

Most women in the study were receiving prenatal care. In all, 73.2% of Medicaid-covered women and 76.5% of commercially-insured women received it. Placental examination at the time of delivery occurred for 61.5% of Medicaid-covered women and 58.0% of commercially-insured women, while CBC was performed in 31.2% and 35.8% of women, respectively.

“Overall, prenatal syphilis testing was significantly higher than syphilis testing at the time of delivery,” Dr. Patel said. “Women with prenatal syphilis testing were more likely to be tested for syphilis at delivery than those not tested, regardless of [their] insurance.”

Dr. Patel did not report information on financial disclosures.

ATLANTA – Physicians are falling short on syphilis testing in both the prenatal period and at the time of delivery, suggest the findings of a study examining insurance claims from nearly 10,000 women who experienced stillbirths.

Overall, less than 10% of women in the study were tested for syphilis following a stillbirth delivery, while less than two-thirds of women who experienced a stillbirth had received prenatal syphilis testing.

Dr. Patel and his coinvestigators examined data from the Truven Health MarketScan Medicaid and commercial claims database to evaluate the proportion of women who had syphilis testing within at least 1 week before and 1 week after a stillbirth delivery.

The investigators identified women aged 15-44 years who had a stillbirth delivery in 2013. Stillbirths were identified via ICD-9 codes and these codes were also used to track prenatal syphilis testing, as well as syphilis testing, placental examination and complete blood count (CBC) performed at the time of delivery.

In total, there were 3,731 women enrolled in Medicaid and 6,096 commercially-insured women who experienced stillbirths and were included in the study. Of these women, 65.5% of Medicaid-covered women and 56.6% of commercially-insured women received prenatal syphilis testing. At delivery, 6.5% of Medicaid-insured women and 9.3% of commercially-insured women received syphilis testing.

Most women in the study were receiving prenatal care. In all, 73.2% of Medicaid-covered women and 76.5% of commercially-insured women received it. Placental examination at the time of delivery occurred for 61.5% of Medicaid-covered women and 58.0% of commercially-insured women, while CBC was performed in 31.2% and 35.8% of women, respectively.

“Overall, prenatal syphilis testing was significantly higher than syphilis testing at the time of delivery,” Dr. Patel said. “Women with prenatal syphilis testing were more likely to be tested for syphilis at delivery than those not tested, regardless of [their] insurance.”

Dr. Patel did not report information on financial disclosures.

ATLANTA – Physicians are falling short on syphilis testing in both the prenatal period and at the time of delivery, suggest the findings of a study examining insurance claims from nearly 10,000 women who experienced stillbirths.

Overall, less than 10% of women in the study were tested for syphilis following a stillbirth delivery, while less than two-thirds of women who experienced a stillbirth had received prenatal syphilis testing.

Dr. Patel and his coinvestigators examined data from the Truven Health MarketScan Medicaid and commercial claims database to evaluate the proportion of women who had syphilis testing within at least 1 week before and 1 week after a stillbirth delivery.

The investigators identified women aged 15-44 years who had a stillbirth delivery in 2013. Stillbirths were identified via ICD-9 codes and these codes were also used to track prenatal syphilis testing, as well as syphilis testing, placental examination and complete blood count (CBC) performed at the time of delivery.

In total, there were 3,731 women enrolled in Medicaid and 6,096 commercially-insured women who experienced stillbirths and were included in the study. Of these women, 65.5% of Medicaid-covered women and 56.6% of commercially-insured women received prenatal syphilis testing. At delivery, 6.5% of Medicaid-insured women and 9.3% of commercially-insured women received syphilis testing.

Most women in the study were receiving prenatal care. In all, 73.2% of Medicaid-covered women and 76.5% of commercially-insured women received it. Placental examination at the time of delivery occurred for 61.5% of Medicaid-covered women and 58.0% of commercially-insured women, while CBC was performed in 31.2% and 35.8% of women, respectively.

“Overall, prenatal syphilis testing was significantly higher than syphilis testing at the time of delivery,” Dr. Patel said. “Women with prenatal syphilis testing were more likely to be tested for syphilis at delivery than those not tested, regardless of [their] insurance.”

Dr. Patel did not report information on financial disclosures.

AT THE 2016 STD PREVENTION CONFERENCE

Key clinical point:

Major finding: A total of 65.5% of Medicaid-covered women and 56.6% of commercially-insured women received prenatal syphilis testing. At delivery, 6.5% of Medicaid-covered women and 9.3% of commercially-insured women received syphilis testing.

Data source: Review of claims data from 3,731 women enrolled in Medicaid and 6,096 commercially-insured women who had stillbirth deliveries in 2013.

Disclosures: Dr. Patel did not report information on financial disclosures.

ACIP approves changes to HPV, Tdap, DTaP, MenB vaccination guidance

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices approved a series of minor changes to the current guidance for meningococcal, Tdap, DTaP, and human papillomavirus vaccination schedules.