User login

VHA Practice Guideline Recommendations for Diffuse Gliomas (FULL)

Over the past few decades, our understanding of the molecular underpinning of primary neoplasms of the central nervous system (CNS) has progressed substantially. Thanks in large part to this expansion in our knowledge base, the World Health Organization (WHO) has recently updated its classification of tumors of the CNS.1 One of the key elements of this update was the inclusion of molecular diagnostic criteria for the classification of infiltrating gliomas. While the previous classification system was based upon histologic subtypes of the tumor (astrocytoma, oligodendroglioma, and oligoastrocytoma), the revised classification system incorporates molecular testing to establish the genetic characteristics of the tumor to reach a final integrated diagnosis.

In this article, we present 3 cases to highlight some of these recent changes in the WHO diagnostic categories of primary CNS tumors and to illustrate the role of specific molecular tests in reaching a final integrated diagnosis. We then propose a clinical practice guideline for the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) that recommends use of molecular testing for veterans as part of the diagnostic workup of primary CNS neoplasms.

Purpose

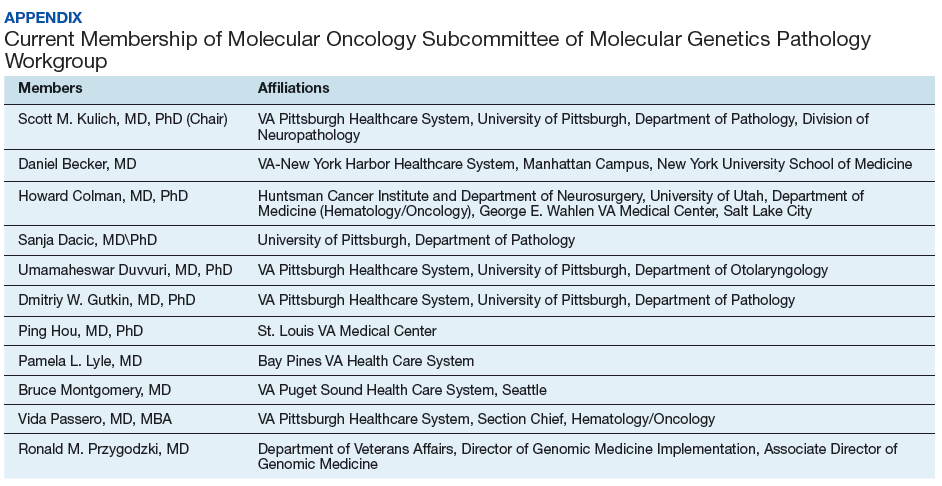

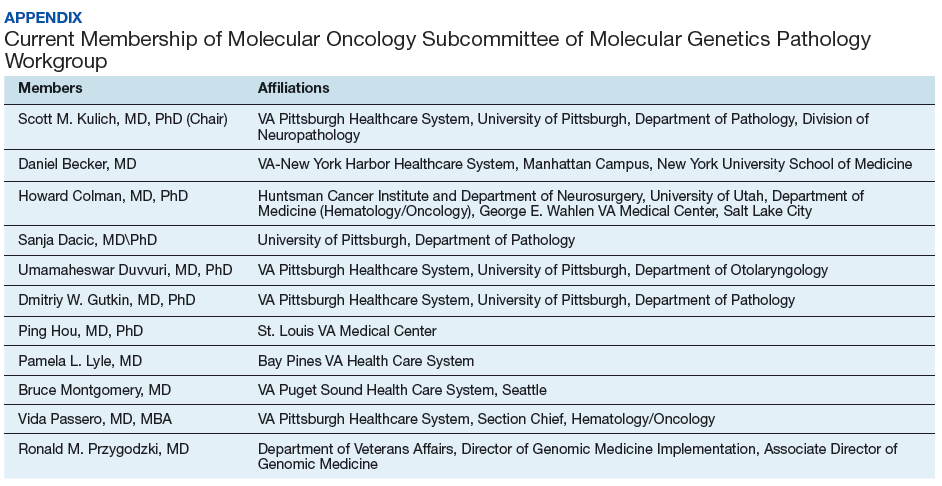

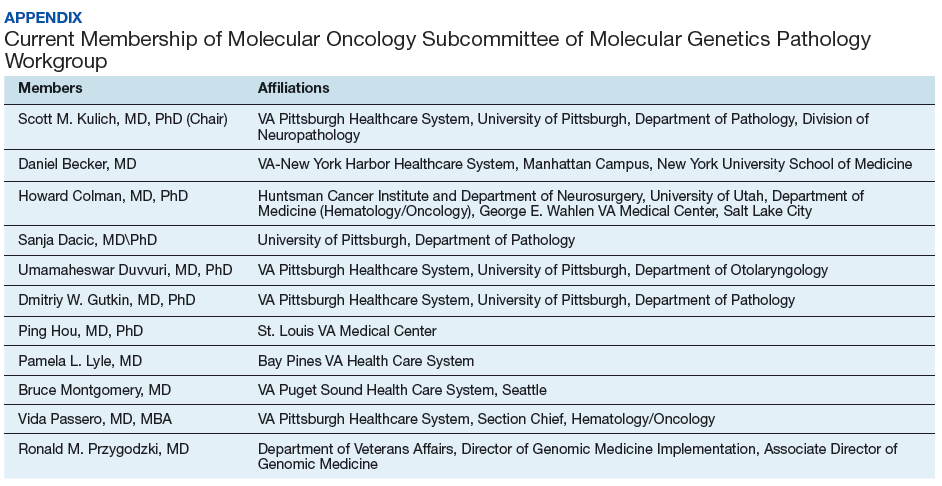

In 2013 the VHA National Director of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine Services (P&LMS) chartered a national molecular genetics pathology workgroup (MGPW) that was charged with 4 specific tasks: (1) Provide recommendations about the effective use of molecular genetic testing for veterans; (2) Promote increased quality and availability of molecular testing within the VHA; (3) Encourage internal referral testing; and (4) Create an organizational structure and policies for molecular genetic testing and laboratory developed tests. The workgroup is currently composed of 4 subcommittees: genetic medicine, hematopathology, pharmacogenomics, and molecular oncology. The molecular oncology subcommittee is focused upon molecular genetic testing for solid tumors.

This article is intended to be the first of several publications from the molecular oncology subcommittee of the MGPW that address some of the aforementioned tasks. Similar to the recent publication from the hematopathology subcommittee of the MGPW, this article focuses on CNS neoplasms.2

Scope of Problem

The incidence of tumors of the CNS in the US population varies among age groups. It is the most common solid tumor in children aged < 14 years and represents a significant cause of mortality across all age groups.3 Of CNS tumors, diffuse gliomas comprise about 20% of the tumors and more than 70% of the primary malignant CNS tumors.3 Analysis of the VA Central Cancer Registry data from 2010 to 2014 identified 1,186 veterans (about 237 veterans per year) who were diagnosed with diffuse gliomas. (Lynch, Kulich, Colman, unpublished data, February 2018). While the majority (nearly 80%) of these cases were glioblastomas (GBMs), unfortunately a majority of these cases did not undergo molecular testing (Lynch, Kulich, Colman, unpublished data, February 2018).

Although this low rate of testing may be in part reflective of the period from which these data were gleaned (ie, prior to the WHO release of their updated the classification of tumors of the CNS), it is important to raise VA practitioners’ awareness of these recent changes to ensure that veterans receive the proper diagnosis and treatment for their disease. Thus, while the number of veterans diagnosed with diffuse gliomas within the VHA is relatively small in comparison to other malignancies, such as prostatic adenocarcinomas and lung carcinomas, the majority of diffuse gliomas do not seem to be receiving the molecular testing that would be necessary for (1) appropriate classification under the recently revised WHO recommendations; and (2) making important treatment decisions.

Case Presentations

Case 1. A veteran of the Gulf War presented with a 3-month history of possible narcoleptic events associated with a motor vehicle accident. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a large left frontal mass lesion with minimal surrounding edema without appreciable contrast enhancement (Figures 1A, 1B, and 1C).

Neither mitotic figures nor endothelial proliferation were identified. Immunohistochemical stains revealed a lack of R132H mutant IDH1 protein expression, a loss of nuclear staining for ATRX protein within a substantial number of cells, and a clonal pattern of p53 protein overexpression (Figures 1E, 1F, and 1G). The lesion demonstrated diffuse glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) immunoreactivity and a low proliferation index (as determined by Ki-67 staining; estimated at less than 5%) (Figures 1H and 1I).

Based upon these results, an initial morphologic diagnosis of diffuse glioma was issued, and tissue was subjected to a variety of nucleic acid-based tests. While fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) studies were negative for 1p/19q codeletion, pyrosequencing analysis revealed the presence of a c.394C>T (R132C) mutation of the IDH1 gene (Figure 1J). The University of Pittsburgh Medical Center’s GlioSeq targeted next-generation sequence (NGS) analysis confirmed the presence of the c.394C > T mutation in IDH1 gene.4 Based upon this additional information, a final integrated morphologic and molecular diagnosis of diffuse astrocytoma, IDH-mutant was rendered.

Case 2. A Vietnam War veteran presented with a 6-week history of new onset falls with associated left lower extremity weakness. A MRI revealed a right frontoparietal mass lesion with surrounding edema without appreciable contrast enhancement (Figures 2A, 2B, and 2C).

Immunohistochemical stains revealed R132H mutant IDH1 protein expression, retention of nuclear staining for ATRX protein, the lack of a clonal pattern of p53 protein overexpression, diffuse GFAP immunoreactivity, and a proliferation index (as determined by Ki-67 staining) focally approaching 20% (Figures 2E, 2F, 2G, 2H and 2I).

Based upon these results, an initial morphologic diagnosis of diffuse (high grade) glioma was issued, and tissue was subjected to a variety of nucleic acid-based tests. The FISH studies were positive for 1p/19q codeletion, and pyrosequencing analysis confirmed the immunohistochemical findings of a c.395G>A (R132H) mutation of the IDH1 gene (Figure 2J). GlioSeq targeted NGS analysis confirmed the presence of the c.395G>A mutation in the IDH1 gene, a mutation in the telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) promoter, and possible decreased copy number of the CIC (chromosome 1p) and FUBP1 (chromosome 19q) genes.

A final integrated morphologic and molecular diagnosis of anaplastic oligodendroglioma, IDH-mutant and 1p/19q-codeleted was rendered based on the additional information. With this final diagnosis, methylation analysis of the MGMT gene promoter, which was performed for prognostic and predictive purposes, was identified in this case.5,6

Case 3. A veteran of the Vietnam War presented with a new onset seizure. A MRI revealed a focally contrast-enhancing mass with surrounding edema within the left frontal lobe (Figures 3A, 3B, and 3C).

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained sections following formalin fixation and paraffin embedding demonstrated similar findings (Figure 3D), and while mitotic figures were readily identified, areas of necrosis were not identified and endothelial proliferation was not a prominent feature. Immunohistochemical stains revealed no evidence of R132H mutant IDH1 protein expression, retention of nuclear staining for ATRX protein, a clonal pattern of p53 protein overexpression, patchy GFAP immunoreactivity, and a proliferation index (as determined by Ki-67 staining) focally approaching 50% (Figures 3E, 3F, 3G, 3H, and 3I).

Based upon these results, an initial morphologic diagnosis of diffuse (high grade) glioma was issued, and the tissue was subjected to a variety of nucleic acid-based tests. The FISH studies were negative for EGFR gene amplification and 1p/19q codeletion, although a gain of the long arm of chromosome 1 was detected. Pyrosequencing analysis for mutations in codon 132 of the IDH1 gene revealed no mutations (Figure 3J). GlioSeq targeted NGS analysis identified mutations within the NF1, TP53, and PIK3CA genes without evidence of mutations in the IDH1, IDH2, ATRX, H3F3A, or EGFR genes or the TERT promoter. Based upon this additional information, a final integrated morphologic and molecular diagnosis of GBM, IDH wild-type was issued. The MGMT gene promoter was negative for methylation, a finding that has prognostic and predictive impact with regard to treatment with temazolamide.7-9

New Diffuse Glioma Classification

Since the issuance of the previous edition of the WHO classification of CNS tumors in 2007, several sentinel discoveries have been made that have advanced our understanding of the underlying biology of primary CNS neoplasms. Since a detailed review of these findings is beyond the scope and purpose of this manuscript and salient reviews on the topic can be found elsewhere, we will focus on the molecular findings that have been incorporated into the recently revised WHO classification.10 The importance of providing such information for proper patient management is illustrated by the recent acknowledgement by the American Academy of Neurology that molecular testing of brain tumors is a specific area in which there is a need for quality improvement.11 Therefore, it is critical that these underlying molecular abnormalities are identified to allow for proper classification and treatment of diffuse gliomas in the veteran population.

As noted previously, based on VA cancer registry data, diffuse gliomas are the most commonly encountered primary CNS cancers in the veteran population. Several of the aforementioned seminal discoveries have been incorporated into the updated classification of diffuse gliomas. While the recently updated WHO classification allows for the assignment of “not otherwise specified (NOS)” diagnostic designation, this category must be limited to cases where there is insufficient data to allow for a more precise classification due to sample limitations and not simply due to a failure of VA pathology laboratories to pursue the appropriate diagnostic testing.

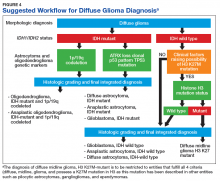

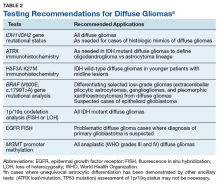

Figure 4 presents the recommended diagnostic workflow for the workup of diffuse gliomas. As illustrated in the above cases, a variety of different methodologies, including immunohistochemical, FISH, loss of heterozygosity analysis, traditional and NGS may be applied when elucidating the status of molecular events at critical diagnostic branch points.

Diagnostic Uses of Molecular Testing

While the case studies in this article demonstrate the use of ancillary testing and provide a suggested strategy for properly subclassifying diffuse gliomas, inherent in this strategy is the assumption that, based upon the initial clinical and pathologic information available, one can accurately categorize the lesion as a diffuse glioma. In reality, such a distinction is not always a straightforward endeavor. It is well recognized that a proportion of low-grade, typically radiologically circumscribed, CNS neoplasms, such as pilocytic astrocytomas and glioneuronal tumors, may infiltrate the surrounding brain parenchyma. In addition, many of these low-grade CNS neoplasms also may have growth patterns that are shared with diffuse gliomas, a diagnostic challenge that often can be further hampered by the inherent limitations involved in obtaining adequate samples for diagnosis from the CNS.

Although there are limitations and caveats, molecular diagnostic testing may be invaluable in properly classifying CNS tumors in such situations. The finding of mutations in the IDH1 or IDH2 genes has been shown to be very valuable in distinguishing low-grade diffuse glioma from both nonneoplastic and low-grade circumscribed neuroepithelial neoplasms that may exhibit growth patterns that can mimic those of diffuse gliomas.15-17 Conversely, finding abnormalities in the BRAF gene in a brain neoplasm that has a low-grade morphology suggests that the lesion may represent one of these low-grade lesions such as a pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma, pilocytic astrocytoma, or mixed neuronal-glial tumor as opposed to a diffuse glioma.18,19

Depending upon the environment in which one practices, small biopsy specimens may be prevalent, and unfortunately, it is not uncommon to obtain a biopsy that exhibits a histologic growth pattern that is discordant from what one would predict based on the clinical context and imaging findings. Molecular testing may be useful in resolving discordances in such situations. If a biopsy of a ring-enhancing lesion demonstrates a diffuse glioma that doesn’t meet WHO grade IV criteria, applying methodologies that look for genetic features commonly encountered in high-grade astrocytomas may identify genetic abnormalities that suggest a more aggressive lesion than is indicated by the histologic findings. The presence of genetic abnormalities such as homozygous deletion of the CDKN2A gene, TERT promoter mutation, loss of heterozygosity of chromosome 10q and/or phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) mutations, EGFR gene amplification or the presence of the EGFR variant III are a few findings that would suggest the aforementioned sample may represent an undersampling of a higher grade diffuse astrocytoma, which would be important information to convey to the treating clinicians.20-26

Testing In the VA

The goals of the MPWG include promoting increased quality and availability of genetic testing within the VHA as well as encouraging internal referral testing. An informal survey of the chiefs of VA Pathology and Laboratory Medicine Services was conducted in November of 2017 in an attempt to identify internal VA pathology laboratories currently conducting testing that may be of use in the workup of diffuse gliomas (Table 1).

The VA currently offers NGS panels for patients with advanced-stage malignancies under the auspices of the Precision Oncology Program, whose reports provide both (1) mutational analyses for genes such as TP53, ATRX, NF1, BRAF, PTEN, TERT IDH1, and IDH2 that may be useful in the proper classifying of high-grade diffuse gliomas; and (2) information regarding clinical trials for which the veteran may be eligible for based on their glioma’s mutational profile. Interested VA providers should visit tinyurl.com/precisiononcology/ for more information about this program. Finally, although internal testing within VA laboratories is recommended to allow for the development of more cost-effective testing, testing may be performed through many nationally contracted reference laboratories.

Conclusion

In light of the recent progress made in our understanding of the molecular events of gliomagenesis, the way we diagnose diffuse gliomas within the CNS has undergone a major paradigm shift. While histology still plays a critical role in the process, we believe that additional ancillary testing is a requirement for all diffuse gliomas diagnosed within VA pathology laboratories. In the context of recently encountered cases, we have provided a recommended workflow highlighting the testing that can be performed to allow for the proper diagnosis of our veterans with diffuse gliomas (Figure 4).

Unless limited by the amount of tissue available for such tests, ancillary testing must be performed on all diffuse gliomas diagnosed within the VA system to ensure proper diagnosis and treatment of our veterans with diffuse gliomas.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Craig M. Horbinski (Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University) and Dr. Geoffrey H. Murdoch (University of Pittsburgh) for their constructive criticism of the manuscript. We also thank the following individuals for past service as members of the molecular oncology subcommittee of the MGPW: Dr. George Ansstas (Washington University School of Medicine), Dr. Osssama Hemadeh (Bay Pines VA Health Care System), Dr. James Herman (VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System), and Dr. Ryan Phan (formerly of the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System) as well as the members of the Veterans Administration pathology and laboratory medicine service molecular genetics pathology workgroup.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the US Government, or any of its agencies.

Dr. Kulich is the Acting Chief of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine Service at VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System and member of the Division of Neuropathology at University of Pittsburgh Department of Pathology, Dr. Duvvuri is an Otolaryngologist at VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System, and Dr. Passero is the Section Chief of Hematology\Oncology at VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System in Pennsylvania. Dr. Becker is an Oncologist at VA-New York Harbor Healthcare System. Dr. Dacic is a Pathologist at University of Pittsburgh Department of Pathology in Pennsylvania. Dr. Ehsan is Chief of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine Services at the South Texas Veterans Healthcare System in San Antonio. Dr. Gutkin is the former Chief of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine Service at VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System. Dr. Hou is a Pathologist at St. Louis VA Medical Center in Missouri. Dr. Icardi is the VA National Director of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine Services. Dr. Lyle is a Pathologist at Bay Pine Health Care System in Florida. Dr. Lynch is an Investigator at VA Salt Lake Health Care System Informatics and Computing Infrastructure. Dr. Montgomery is an Oncologist at VA Puget Sound Health Care System, in Seattle, Washington. Dr. Przygodzki is the Director of Genomic Medicine Implementation and Associate Director of Genomic Medicine for the VA. Dr. Colman is a Neuro-Oncologist at George E. Wahlen VA Medical Center and the Director of Medical Neuro-Oncology at the Huntsman Cancer Institute, Salt Lake City, Utah.

Correspondence: Dr. Kulich ([email protected])

1. Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, et al. The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131(6):803-820.

2. Wang-Rodriguez J, Yunes A, Phan R, et al. The challenges of precision medicine and new advances in molecular diagnostic testing in hematolymphoid malignancies: impact on the VHA. Fed Pract. 2017;34(suppl 5):S38-S49.

3. Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Liao P, et al. CBTRUS statistical report: primary brain and other central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2010-2014. Neuro Oncol. 2017;19(suppl 5):v1-v88.

4. Nikiforova MN, Wald AI, Melan MA, et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing panel (GlioSeq) provides comprehensive genetic profiling of central nervous system tumors. Neuro Oncol. 2016;18(3)379-387.

5. Cairncross JG, Ueki K, Zlatescu MC, et al. Specific genetic predictors of chemotherapeutic response and survival in patients with anaplastic oligodendrogliomas. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90(19):1473-1479.

6. van den Bent MJ, Erdem-Eraslan L, Idbaih A, et al. MGMT-STP27 methylation status as predictive marker for response to PCV in anaplastic oligodendrogliomas and oligoastrocytomas. A report from EORTC study 26951. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(19):5513-5522.

7. Stupp R, Hegi ME, Mason WP, et al; European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Brain Tumour and Radiation Oncology Groups; National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. Effects of radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide versus radiotherapy alone on survival in glioblastoma in a randomised phase III study: 5-year analysis of the EORTC-NCIC trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(5):459-466.

8. Malmstrom A, Gronberg BH, Marosi C, et al. Temozolomide versus standard 6-week radiotherapy versus hypofractionated radiotherapy in patients older than 60 years with glioblastoma: the Nordic randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(9):916-926.

9. van den Bent MJ, Kros JM. Predictive and prognostic markers in neuro-oncology. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2007;66(12):1074-1081.

10. Chen R, Smith-Cohn M, Cohen AL, Colman H. Glioma subclassifications and their clinical significance. Neurotherapeutics. 2017;14(2):284-297.

11. Jordan JT, Sanders AE, Armstrong T, et al. Quality improvement in neurology: neuro-oncology quality measurement set. Neurology. 2018;90(14):652-658.

12. Chen L, Voronovich Z, Clark K, et al. Predicting the likelihood of an isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 or 2 mutation in diagnoses of infiltrative glioma. Neuro Oncol. 2014;16(11):1478-1483.

13. Hegi ME, Diserens AC, Gorlia T, et al. MGMT gene silencing and benefit from temozolomide in glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(10):997-1003.

14. Wick W, Platten M, Meisner C, et al; NOA-08 Study Group of Neuro-oncology Working Group (NOA) of German Cancer Society. Temozolomide chemotherapy alone versus radiotherapy alone for malignant astrocytoma in the elderly: the NOA-08 randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(7):707-715.

15. Horbinski C, Kofler J, Kelly LM, Murdoch GH, Nikiforova MN. Diagnostic use of IDH1/2 mutation analysis in routine clinical testing of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded glioma tissues. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2009;68(12):1319-1325.

16. Camelo-Piragua S, Jansen M, Ganguly A, Kim JC, Louis DN, Nutt CL. Mutant IDH1-specific immunohistochemistry distinguishes diffuse astrocytoma from astrocytosis. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;119(4):509-511.

17. Horbinski C, Kofler J, Yeaney G, et al. Isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 analysis differentiates gangliogliomas from infiltrative gliomas. Brain Pathol. 2011;21(5):564-574.

18. Berghoff AS, Preusser M. BRAF alterations in brain tumours: molecular pathology and therapeutic opportunities. Curr Opin Neurol. 2014;27(6):689-696.

19. Korshunov A, Meyer J, Capper D, et al. Combined molecular analysis of BRAF and IDH1 distinguishes pilocytic astrocytoma from diffuse astrocytoma. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;118(3):401-405.

20. Fuller CE, Schmidt RE, Roth KA, et al. Clinical utility of fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) in morphologically ambiguous gliomas with hybrid oligodendroglial/astrocytic features. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2003;62(11):1118-1128.

21. Horbinski C. Practical molecular diagnostics in neuropathology: making a tough job a little easier. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2010;27(2):105-113.

22. Fuller GN, Bigner SH. Amplified cellular oncogenes in neoplasms of the human central nervous system. Mutat Res. 1992;276(3):299-306.

23. Brennan CW, Verhaak RG, McKenna A, et al; TCGA Research Network. The somatic genomic landscape of glioblastoma. Cell. 2013;155(2):462-477.

24. Aldape K, Zadeh G, Mansouri S, Reifenberger G, von Deimling A. Glioblastoma: pathology, molecular mechanisms and markers. Acta Neuropathol. 2015;129(6):829-848.

25. Killela PJ, Reitman ZJ, Jiao Y, et al. TERT promoter mutations occur frequently in gliomas and a subset of tumors derived from cells with low rates of self-renewal. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(15):6021-6026.

26. Nikiforova MN, Hamilton RL. Molecular diagnostics of gliomas. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135(5):558-568.

Over the past few decades, our understanding of the molecular underpinning of primary neoplasms of the central nervous system (CNS) has progressed substantially. Thanks in large part to this expansion in our knowledge base, the World Health Organization (WHO) has recently updated its classification of tumors of the CNS.1 One of the key elements of this update was the inclusion of molecular diagnostic criteria for the classification of infiltrating gliomas. While the previous classification system was based upon histologic subtypes of the tumor (astrocytoma, oligodendroglioma, and oligoastrocytoma), the revised classification system incorporates molecular testing to establish the genetic characteristics of the tumor to reach a final integrated diagnosis.

In this article, we present 3 cases to highlight some of these recent changes in the WHO diagnostic categories of primary CNS tumors and to illustrate the role of specific molecular tests in reaching a final integrated diagnosis. We then propose a clinical practice guideline for the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) that recommends use of molecular testing for veterans as part of the diagnostic workup of primary CNS neoplasms.

Purpose

In 2013 the VHA National Director of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine Services (P&LMS) chartered a national molecular genetics pathology workgroup (MGPW) that was charged with 4 specific tasks: (1) Provide recommendations about the effective use of molecular genetic testing for veterans; (2) Promote increased quality and availability of molecular testing within the VHA; (3) Encourage internal referral testing; and (4) Create an organizational structure and policies for molecular genetic testing and laboratory developed tests. The workgroup is currently composed of 4 subcommittees: genetic medicine, hematopathology, pharmacogenomics, and molecular oncology. The molecular oncology subcommittee is focused upon molecular genetic testing for solid tumors.

This article is intended to be the first of several publications from the molecular oncology subcommittee of the MGPW that address some of the aforementioned tasks. Similar to the recent publication from the hematopathology subcommittee of the MGPW, this article focuses on CNS neoplasms.2

Scope of Problem

The incidence of tumors of the CNS in the US population varies among age groups. It is the most common solid tumor in children aged < 14 years and represents a significant cause of mortality across all age groups.3 Of CNS tumors, diffuse gliomas comprise about 20% of the tumors and more than 70% of the primary malignant CNS tumors.3 Analysis of the VA Central Cancer Registry data from 2010 to 2014 identified 1,186 veterans (about 237 veterans per year) who were diagnosed with diffuse gliomas. (Lynch, Kulich, Colman, unpublished data, February 2018). While the majority (nearly 80%) of these cases were glioblastomas (GBMs), unfortunately a majority of these cases did not undergo molecular testing (Lynch, Kulich, Colman, unpublished data, February 2018).

Although this low rate of testing may be in part reflective of the period from which these data were gleaned (ie, prior to the WHO release of their updated the classification of tumors of the CNS), it is important to raise VA practitioners’ awareness of these recent changes to ensure that veterans receive the proper diagnosis and treatment for their disease. Thus, while the number of veterans diagnosed with diffuse gliomas within the VHA is relatively small in comparison to other malignancies, such as prostatic adenocarcinomas and lung carcinomas, the majority of diffuse gliomas do not seem to be receiving the molecular testing that would be necessary for (1) appropriate classification under the recently revised WHO recommendations; and (2) making important treatment decisions.

Case Presentations

Case 1. A veteran of the Gulf War presented with a 3-month history of possible narcoleptic events associated with a motor vehicle accident. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a large left frontal mass lesion with minimal surrounding edema without appreciable contrast enhancement (Figures 1A, 1B, and 1C).

Neither mitotic figures nor endothelial proliferation were identified. Immunohistochemical stains revealed a lack of R132H mutant IDH1 protein expression, a loss of nuclear staining for ATRX protein within a substantial number of cells, and a clonal pattern of p53 protein overexpression (Figures 1E, 1F, and 1G). The lesion demonstrated diffuse glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) immunoreactivity and a low proliferation index (as determined by Ki-67 staining; estimated at less than 5%) (Figures 1H and 1I).

Based upon these results, an initial morphologic diagnosis of diffuse glioma was issued, and tissue was subjected to a variety of nucleic acid-based tests. While fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) studies were negative for 1p/19q codeletion, pyrosequencing analysis revealed the presence of a c.394C>T (R132C) mutation of the IDH1 gene (Figure 1J). The University of Pittsburgh Medical Center’s GlioSeq targeted next-generation sequence (NGS) analysis confirmed the presence of the c.394C > T mutation in IDH1 gene.4 Based upon this additional information, a final integrated morphologic and molecular diagnosis of diffuse astrocytoma, IDH-mutant was rendered.

Case 2. A Vietnam War veteran presented with a 6-week history of new onset falls with associated left lower extremity weakness. A MRI revealed a right frontoparietal mass lesion with surrounding edema without appreciable contrast enhancement (Figures 2A, 2B, and 2C).

Immunohistochemical stains revealed R132H mutant IDH1 protein expression, retention of nuclear staining for ATRX protein, the lack of a clonal pattern of p53 protein overexpression, diffuse GFAP immunoreactivity, and a proliferation index (as determined by Ki-67 staining) focally approaching 20% (Figures 2E, 2F, 2G, 2H and 2I).

Based upon these results, an initial morphologic diagnosis of diffuse (high grade) glioma was issued, and tissue was subjected to a variety of nucleic acid-based tests. The FISH studies were positive for 1p/19q codeletion, and pyrosequencing analysis confirmed the immunohistochemical findings of a c.395G>A (R132H) mutation of the IDH1 gene (Figure 2J). GlioSeq targeted NGS analysis confirmed the presence of the c.395G>A mutation in the IDH1 gene, a mutation in the telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) promoter, and possible decreased copy number of the CIC (chromosome 1p) and FUBP1 (chromosome 19q) genes.

A final integrated morphologic and molecular diagnosis of anaplastic oligodendroglioma, IDH-mutant and 1p/19q-codeleted was rendered based on the additional information. With this final diagnosis, methylation analysis of the MGMT gene promoter, which was performed for prognostic and predictive purposes, was identified in this case.5,6

Case 3. A veteran of the Vietnam War presented with a new onset seizure. A MRI revealed a focally contrast-enhancing mass with surrounding edema within the left frontal lobe (Figures 3A, 3B, and 3C).

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained sections following formalin fixation and paraffin embedding demonstrated similar findings (Figure 3D), and while mitotic figures were readily identified, areas of necrosis were not identified and endothelial proliferation was not a prominent feature. Immunohistochemical stains revealed no evidence of R132H mutant IDH1 protein expression, retention of nuclear staining for ATRX protein, a clonal pattern of p53 protein overexpression, patchy GFAP immunoreactivity, and a proliferation index (as determined by Ki-67 staining) focally approaching 50% (Figures 3E, 3F, 3G, 3H, and 3I).

Based upon these results, an initial morphologic diagnosis of diffuse (high grade) glioma was issued, and the tissue was subjected to a variety of nucleic acid-based tests. The FISH studies were negative for EGFR gene amplification and 1p/19q codeletion, although a gain of the long arm of chromosome 1 was detected. Pyrosequencing analysis for mutations in codon 132 of the IDH1 gene revealed no mutations (Figure 3J). GlioSeq targeted NGS analysis identified mutations within the NF1, TP53, and PIK3CA genes without evidence of mutations in the IDH1, IDH2, ATRX, H3F3A, or EGFR genes or the TERT promoter. Based upon this additional information, a final integrated morphologic and molecular diagnosis of GBM, IDH wild-type was issued. The MGMT gene promoter was negative for methylation, a finding that has prognostic and predictive impact with regard to treatment with temazolamide.7-9

New Diffuse Glioma Classification

Since the issuance of the previous edition of the WHO classification of CNS tumors in 2007, several sentinel discoveries have been made that have advanced our understanding of the underlying biology of primary CNS neoplasms. Since a detailed review of these findings is beyond the scope and purpose of this manuscript and salient reviews on the topic can be found elsewhere, we will focus on the molecular findings that have been incorporated into the recently revised WHO classification.10 The importance of providing such information for proper patient management is illustrated by the recent acknowledgement by the American Academy of Neurology that molecular testing of brain tumors is a specific area in which there is a need for quality improvement.11 Therefore, it is critical that these underlying molecular abnormalities are identified to allow for proper classification and treatment of diffuse gliomas in the veteran population.

As noted previously, based on VA cancer registry data, diffuse gliomas are the most commonly encountered primary CNS cancers in the veteran population. Several of the aforementioned seminal discoveries have been incorporated into the updated classification of diffuse gliomas. While the recently updated WHO classification allows for the assignment of “not otherwise specified (NOS)” diagnostic designation, this category must be limited to cases where there is insufficient data to allow for a more precise classification due to sample limitations and not simply due to a failure of VA pathology laboratories to pursue the appropriate diagnostic testing.

Figure 4 presents the recommended diagnostic workflow for the workup of diffuse gliomas. As illustrated in the above cases, a variety of different methodologies, including immunohistochemical, FISH, loss of heterozygosity analysis, traditional and NGS may be applied when elucidating the status of molecular events at critical diagnostic branch points.

Diagnostic Uses of Molecular Testing

While the case studies in this article demonstrate the use of ancillary testing and provide a suggested strategy for properly subclassifying diffuse gliomas, inherent in this strategy is the assumption that, based upon the initial clinical and pathologic information available, one can accurately categorize the lesion as a diffuse glioma. In reality, such a distinction is not always a straightforward endeavor. It is well recognized that a proportion of low-grade, typically radiologically circumscribed, CNS neoplasms, such as pilocytic astrocytomas and glioneuronal tumors, may infiltrate the surrounding brain parenchyma. In addition, many of these low-grade CNS neoplasms also may have growth patterns that are shared with diffuse gliomas, a diagnostic challenge that often can be further hampered by the inherent limitations involved in obtaining adequate samples for diagnosis from the CNS.

Although there are limitations and caveats, molecular diagnostic testing may be invaluable in properly classifying CNS tumors in such situations. The finding of mutations in the IDH1 or IDH2 genes has been shown to be very valuable in distinguishing low-grade diffuse glioma from both nonneoplastic and low-grade circumscribed neuroepithelial neoplasms that may exhibit growth patterns that can mimic those of diffuse gliomas.15-17 Conversely, finding abnormalities in the BRAF gene in a brain neoplasm that has a low-grade morphology suggests that the lesion may represent one of these low-grade lesions such as a pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma, pilocytic astrocytoma, or mixed neuronal-glial tumor as opposed to a diffuse glioma.18,19

Depending upon the environment in which one practices, small biopsy specimens may be prevalent, and unfortunately, it is not uncommon to obtain a biopsy that exhibits a histologic growth pattern that is discordant from what one would predict based on the clinical context and imaging findings. Molecular testing may be useful in resolving discordances in such situations. If a biopsy of a ring-enhancing lesion demonstrates a diffuse glioma that doesn’t meet WHO grade IV criteria, applying methodologies that look for genetic features commonly encountered in high-grade astrocytomas may identify genetic abnormalities that suggest a more aggressive lesion than is indicated by the histologic findings. The presence of genetic abnormalities such as homozygous deletion of the CDKN2A gene, TERT promoter mutation, loss of heterozygosity of chromosome 10q and/or phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) mutations, EGFR gene amplification or the presence of the EGFR variant III are a few findings that would suggest the aforementioned sample may represent an undersampling of a higher grade diffuse astrocytoma, which would be important information to convey to the treating clinicians.20-26

Testing In the VA

The goals of the MPWG include promoting increased quality and availability of genetic testing within the VHA as well as encouraging internal referral testing. An informal survey of the chiefs of VA Pathology and Laboratory Medicine Services was conducted in November of 2017 in an attempt to identify internal VA pathology laboratories currently conducting testing that may be of use in the workup of diffuse gliomas (Table 1).

The VA currently offers NGS panels for patients with advanced-stage malignancies under the auspices of the Precision Oncology Program, whose reports provide both (1) mutational analyses for genes such as TP53, ATRX, NF1, BRAF, PTEN, TERT IDH1, and IDH2 that may be useful in the proper classifying of high-grade diffuse gliomas; and (2) information regarding clinical trials for which the veteran may be eligible for based on their glioma’s mutational profile. Interested VA providers should visit tinyurl.com/precisiononcology/ for more information about this program. Finally, although internal testing within VA laboratories is recommended to allow for the development of more cost-effective testing, testing may be performed through many nationally contracted reference laboratories.

Conclusion

In light of the recent progress made in our understanding of the molecular events of gliomagenesis, the way we diagnose diffuse gliomas within the CNS has undergone a major paradigm shift. While histology still plays a critical role in the process, we believe that additional ancillary testing is a requirement for all diffuse gliomas diagnosed within VA pathology laboratories. In the context of recently encountered cases, we have provided a recommended workflow highlighting the testing that can be performed to allow for the proper diagnosis of our veterans with diffuse gliomas (Figure 4).

Unless limited by the amount of tissue available for such tests, ancillary testing must be performed on all diffuse gliomas diagnosed within the VA system to ensure proper diagnosis and treatment of our veterans with diffuse gliomas.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Craig M. Horbinski (Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University) and Dr. Geoffrey H. Murdoch (University of Pittsburgh) for their constructive criticism of the manuscript. We also thank the following individuals for past service as members of the molecular oncology subcommittee of the MGPW: Dr. George Ansstas (Washington University School of Medicine), Dr. Osssama Hemadeh (Bay Pines VA Health Care System), Dr. James Herman (VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System), and Dr. Ryan Phan (formerly of the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System) as well as the members of the Veterans Administration pathology and laboratory medicine service molecular genetics pathology workgroup.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the US Government, or any of its agencies.

Dr. Kulich is the Acting Chief of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine Service at VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System and member of the Division of Neuropathology at University of Pittsburgh Department of Pathology, Dr. Duvvuri is an Otolaryngologist at VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System, and Dr. Passero is the Section Chief of Hematology\Oncology at VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System in Pennsylvania. Dr. Becker is an Oncologist at VA-New York Harbor Healthcare System. Dr. Dacic is a Pathologist at University of Pittsburgh Department of Pathology in Pennsylvania. Dr. Ehsan is Chief of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine Services at the South Texas Veterans Healthcare System in San Antonio. Dr. Gutkin is the former Chief of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine Service at VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System. Dr. Hou is a Pathologist at St. Louis VA Medical Center in Missouri. Dr. Icardi is the VA National Director of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine Services. Dr. Lyle is a Pathologist at Bay Pine Health Care System in Florida. Dr. Lynch is an Investigator at VA Salt Lake Health Care System Informatics and Computing Infrastructure. Dr. Montgomery is an Oncologist at VA Puget Sound Health Care System, in Seattle, Washington. Dr. Przygodzki is the Director of Genomic Medicine Implementation and Associate Director of Genomic Medicine for the VA. Dr. Colman is a Neuro-Oncologist at George E. Wahlen VA Medical Center and the Director of Medical Neuro-Oncology at the Huntsman Cancer Institute, Salt Lake City, Utah.

Correspondence: Dr. Kulich ([email protected])

Over the past few decades, our understanding of the molecular underpinning of primary neoplasms of the central nervous system (CNS) has progressed substantially. Thanks in large part to this expansion in our knowledge base, the World Health Organization (WHO) has recently updated its classification of tumors of the CNS.1 One of the key elements of this update was the inclusion of molecular diagnostic criteria for the classification of infiltrating gliomas. While the previous classification system was based upon histologic subtypes of the tumor (astrocytoma, oligodendroglioma, and oligoastrocytoma), the revised classification system incorporates molecular testing to establish the genetic characteristics of the tumor to reach a final integrated diagnosis.

In this article, we present 3 cases to highlight some of these recent changes in the WHO diagnostic categories of primary CNS tumors and to illustrate the role of specific molecular tests in reaching a final integrated diagnosis. We then propose a clinical practice guideline for the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) that recommends use of molecular testing for veterans as part of the diagnostic workup of primary CNS neoplasms.

Purpose

In 2013 the VHA National Director of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine Services (P&LMS) chartered a national molecular genetics pathology workgroup (MGPW) that was charged with 4 specific tasks: (1) Provide recommendations about the effective use of molecular genetic testing for veterans; (2) Promote increased quality and availability of molecular testing within the VHA; (3) Encourage internal referral testing; and (4) Create an organizational structure and policies for molecular genetic testing and laboratory developed tests. The workgroup is currently composed of 4 subcommittees: genetic medicine, hematopathology, pharmacogenomics, and molecular oncology. The molecular oncology subcommittee is focused upon molecular genetic testing for solid tumors.

This article is intended to be the first of several publications from the molecular oncology subcommittee of the MGPW that address some of the aforementioned tasks. Similar to the recent publication from the hematopathology subcommittee of the MGPW, this article focuses on CNS neoplasms.2

Scope of Problem

The incidence of tumors of the CNS in the US population varies among age groups. It is the most common solid tumor in children aged < 14 years and represents a significant cause of mortality across all age groups.3 Of CNS tumors, diffuse gliomas comprise about 20% of the tumors and more than 70% of the primary malignant CNS tumors.3 Analysis of the VA Central Cancer Registry data from 2010 to 2014 identified 1,186 veterans (about 237 veterans per year) who were diagnosed with diffuse gliomas. (Lynch, Kulich, Colman, unpublished data, February 2018). While the majority (nearly 80%) of these cases were glioblastomas (GBMs), unfortunately a majority of these cases did not undergo molecular testing (Lynch, Kulich, Colman, unpublished data, February 2018).

Although this low rate of testing may be in part reflective of the period from which these data were gleaned (ie, prior to the WHO release of their updated the classification of tumors of the CNS), it is important to raise VA practitioners’ awareness of these recent changes to ensure that veterans receive the proper diagnosis and treatment for their disease. Thus, while the number of veterans diagnosed with diffuse gliomas within the VHA is relatively small in comparison to other malignancies, such as prostatic adenocarcinomas and lung carcinomas, the majority of diffuse gliomas do not seem to be receiving the molecular testing that would be necessary for (1) appropriate classification under the recently revised WHO recommendations; and (2) making important treatment decisions.

Case Presentations

Case 1. A veteran of the Gulf War presented with a 3-month history of possible narcoleptic events associated with a motor vehicle accident. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a large left frontal mass lesion with minimal surrounding edema without appreciable contrast enhancement (Figures 1A, 1B, and 1C).

Neither mitotic figures nor endothelial proliferation were identified. Immunohistochemical stains revealed a lack of R132H mutant IDH1 protein expression, a loss of nuclear staining for ATRX protein within a substantial number of cells, and a clonal pattern of p53 protein overexpression (Figures 1E, 1F, and 1G). The lesion demonstrated diffuse glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) immunoreactivity and a low proliferation index (as determined by Ki-67 staining; estimated at less than 5%) (Figures 1H and 1I).

Based upon these results, an initial morphologic diagnosis of diffuse glioma was issued, and tissue was subjected to a variety of nucleic acid-based tests. While fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) studies were negative for 1p/19q codeletion, pyrosequencing analysis revealed the presence of a c.394C>T (R132C) mutation of the IDH1 gene (Figure 1J). The University of Pittsburgh Medical Center’s GlioSeq targeted next-generation sequence (NGS) analysis confirmed the presence of the c.394C > T mutation in IDH1 gene.4 Based upon this additional information, a final integrated morphologic and molecular diagnosis of diffuse astrocytoma, IDH-mutant was rendered.

Case 2. A Vietnam War veteran presented with a 6-week history of new onset falls with associated left lower extremity weakness. A MRI revealed a right frontoparietal mass lesion with surrounding edema without appreciable contrast enhancement (Figures 2A, 2B, and 2C).

Immunohistochemical stains revealed R132H mutant IDH1 protein expression, retention of nuclear staining for ATRX protein, the lack of a clonal pattern of p53 protein overexpression, diffuse GFAP immunoreactivity, and a proliferation index (as determined by Ki-67 staining) focally approaching 20% (Figures 2E, 2F, 2G, 2H and 2I).

Based upon these results, an initial morphologic diagnosis of diffuse (high grade) glioma was issued, and tissue was subjected to a variety of nucleic acid-based tests. The FISH studies were positive for 1p/19q codeletion, and pyrosequencing analysis confirmed the immunohistochemical findings of a c.395G>A (R132H) mutation of the IDH1 gene (Figure 2J). GlioSeq targeted NGS analysis confirmed the presence of the c.395G>A mutation in the IDH1 gene, a mutation in the telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) promoter, and possible decreased copy number of the CIC (chromosome 1p) and FUBP1 (chromosome 19q) genes.

A final integrated morphologic and molecular diagnosis of anaplastic oligodendroglioma, IDH-mutant and 1p/19q-codeleted was rendered based on the additional information. With this final diagnosis, methylation analysis of the MGMT gene promoter, which was performed for prognostic and predictive purposes, was identified in this case.5,6

Case 3. A veteran of the Vietnam War presented with a new onset seizure. A MRI revealed a focally contrast-enhancing mass with surrounding edema within the left frontal lobe (Figures 3A, 3B, and 3C).

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained sections following formalin fixation and paraffin embedding demonstrated similar findings (Figure 3D), and while mitotic figures were readily identified, areas of necrosis were not identified and endothelial proliferation was not a prominent feature. Immunohistochemical stains revealed no evidence of R132H mutant IDH1 protein expression, retention of nuclear staining for ATRX protein, a clonal pattern of p53 protein overexpression, patchy GFAP immunoreactivity, and a proliferation index (as determined by Ki-67 staining) focally approaching 50% (Figures 3E, 3F, 3G, 3H, and 3I).

Based upon these results, an initial morphologic diagnosis of diffuse (high grade) glioma was issued, and the tissue was subjected to a variety of nucleic acid-based tests. The FISH studies were negative for EGFR gene amplification and 1p/19q codeletion, although a gain of the long arm of chromosome 1 was detected. Pyrosequencing analysis for mutations in codon 132 of the IDH1 gene revealed no mutations (Figure 3J). GlioSeq targeted NGS analysis identified mutations within the NF1, TP53, and PIK3CA genes without evidence of mutations in the IDH1, IDH2, ATRX, H3F3A, or EGFR genes or the TERT promoter. Based upon this additional information, a final integrated morphologic and molecular diagnosis of GBM, IDH wild-type was issued. The MGMT gene promoter was negative for methylation, a finding that has prognostic and predictive impact with regard to treatment with temazolamide.7-9

New Diffuse Glioma Classification

Since the issuance of the previous edition of the WHO classification of CNS tumors in 2007, several sentinel discoveries have been made that have advanced our understanding of the underlying biology of primary CNS neoplasms. Since a detailed review of these findings is beyond the scope and purpose of this manuscript and salient reviews on the topic can be found elsewhere, we will focus on the molecular findings that have been incorporated into the recently revised WHO classification.10 The importance of providing such information for proper patient management is illustrated by the recent acknowledgement by the American Academy of Neurology that molecular testing of brain tumors is a specific area in which there is a need for quality improvement.11 Therefore, it is critical that these underlying molecular abnormalities are identified to allow for proper classification and treatment of diffuse gliomas in the veteran population.

As noted previously, based on VA cancer registry data, diffuse gliomas are the most commonly encountered primary CNS cancers in the veteran population. Several of the aforementioned seminal discoveries have been incorporated into the updated classification of diffuse gliomas. While the recently updated WHO classification allows for the assignment of “not otherwise specified (NOS)” diagnostic designation, this category must be limited to cases where there is insufficient data to allow for a more precise classification due to sample limitations and not simply due to a failure of VA pathology laboratories to pursue the appropriate diagnostic testing.

Figure 4 presents the recommended diagnostic workflow for the workup of diffuse gliomas. As illustrated in the above cases, a variety of different methodologies, including immunohistochemical, FISH, loss of heterozygosity analysis, traditional and NGS may be applied when elucidating the status of molecular events at critical diagnostic branch points.

Diagnostic Uses of Molecular Testing

While the case studies in this article demonstrate the use of ancillary testing and provide a suggested strategy for properly subclassifying diffuse gliomas, inherent in this strategy is the assumption that, based upon the initial clinical and pathologic information available, one can accurately categorize the lesion as a diffuse glioma. In reality, such a distinction is not always a straightforward endeavor. It is well recognized that a proportion of low-grade, typically radiologically circumscribed, CNS neoplasms, such as pilocytic astrocytomas and glioneuronal tumors, may infiltrate the surrounding brain parenchyma. In addition, many of these low-grade CNS neoplasms also may have growth patterns that are shared with diffuse gliomas, a diagnostic challenge that often can be further hampered by the inherent limitations involved in obtaining adequate samples for diagnosis from the CNS.

Although there are limitations and caveats, molecular diagnostic testing may be invaluable in properly classifying CNS tumors in such situations. The finding of mutations in the IDH1 or IDH2 genes has been shown to be very valuable in distinguishing low-grade diffuse glioma from both nonneoplastic and low-grade circumscribed neuroepithelial neoplasms that may exhibit growth patterns that can mimic those of diffuse gliomas.15-17 Conversely, finding abnormalities in the BRAF gene in a brain neoplasm that has a low-grade morphology suggests that the lesion may represent one of these low-grade lesions such as a pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma, pilocytic astrocytoma, or mixed neuronal-glial tumor as opposed to a diffuse glioma.18,19

Depending upon the environment in which one practices, small biopsy specimens may be prevalent, and unfortunately, it is not uncommon to obtain a biopsy that exhibits a histologic growth pattern that is discordant from what one would predict based on the clinical context and imaging findings. Molecular testing may be useful in resolving discordances in such situations. If a biopsy of a ring-enhancing lesion demonstrates a diffuse glioma that doesn’t meet WHO grade IV criteria, applying methodologies that look for genetic features commonly encountered in high-grade astrocytomas may identify genetic abnormalities that suggest a more aggressive lesion than is indicated by the histologic findings. The presence of genetic abnormalities such as homozygous deletion of the CDKN2A gene, TERT promoter mutation, loss of heterozygosity of chromosome 10q and/or phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) mutations, EGFR gene amplification or the presence of the EGFR variant III are a few findings that would suggest the aforementioned sample may represent an undersampling of a higher grade diffuse astrocytoma, which would be important information to convey to the treating clinicians.20-26

Testing In the VA

The goals of the MPWG include promoting increased quality and availability of genetic testing within the VHA as well as encouraging internal referral testing. An informal survey of the chiefs of VA Pathology and Laboratory Medicine Services was conducted in November of 2017 in an attempt to identify internal VA pathology laboratories currently conducting testing that may be of use in the workup of diffuse gliomas (Table 1).

The VA currently offers NGS panels for patients with advanced-stage malignancies under the auspices of the Precision Oncology Program, whose reports provide both (1) mutational analyses for genes such as TP53, ATRX, NF1, BRAF, PTEN, TERT IDH1, and IDH2 that may be useful in the proper classifying of high-grade diffuse gliomas; and (2) information regarding clinical trials for which the veteran may be eligible for based on their glioma’s mutational profile. Interested VA providers should visit tinyurl.com/precisiononcology/ for more information about this program. Finally, although internal testing within VA laboratories is recommended to allow for the development of more cost-effective testing, testing may be performed through many nationally contracted reference laboratories.

Conclusion

In light of the recent progress made in our understanding of the molecular events of gliomagenesis, the way we diagnose diffuse gliomas within the CNS has undergone a major paradigm shift. While histology still plays a critical role in the process, we believe that additional ancillary testing is a requirement for all diffuse gliomas diagnosed within VA pathology laboratories. In the context of recently encountered cases, we have provided a recommended workflow highlighting the testing that can be performed to allow for the proper diagnosis of our veterans with diffuse gliomas (Figure 4).

Unless limited by the amount of tissue available for such tests, ancillary testing must be performed on all diffuse gliomas diagnosed within the VA system to ensure proper diagnosis and treatment of our veterans with diffuse gliomas.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Craig M. Horbinski (Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University) and Dr. Geoffrey H. Murdoch (University of Pittsburgh) for their constructive criticism of the manuscript. We also thank the following individuals for past service as members of the molecular oncology subcommittee of the MGPW: Dr. George Ansstas (Washington University School of Medicine), Dr. Osssama Hemadeh (Bay Pines VA Health Care System), Dr. James Herman (VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System), and Dr. Ryan Phan (formerly of the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System) as well as the members of the Veterans Administration pathology and laboratory medicine service molecular genetics pathology workgroup.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the US Government, or any of its agencies.

Dr. Kulich is the Acting Chief of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine Service at VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System and member of the Division of Neuropathology at University of Pittsburgh Department of Pathology, Dr. Duvvuri is an Otolaryngologist at VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System, and Dr. Passero is the Section Chief of Hematology\Oncology at VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System in Pennsylvania. Dr. Becker is an Oncologist at VA-New York Harbor Healthcare System. Dr. Dacic is a Pathologist at University of Pittsburgh Department of Pathology in Pennsylvania. Dr. Ehsan is Chief of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine Services at the South Texas Veterans Healthcare System in San Antonio. Dr. Gutkin is the former Chief of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine Service at VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System. Dr. Hou is a Pathologist at St. Louis VA Medical Center in Missouri. Dr. Icardi is the VA National Director of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine Services. Dr. Lyle is a Pathologist at Bay Pine Health Care System in Florida. Dr. Lynch is an Investigator at VA Salt Lake Health Care System Informatics and Computing Infrastructure. Dr. Montgomery is an Oncologist at VA Puget Sound Health Care System, in Seattle, Washington. Dr. Przygodzki is the Director of Genomic Medicine Implementation and Associate Director of Genomic Medicine for the VA. Dr. Colman is a Neuro-Oncologist at George E. Wahlen VA Medical Center and the Director of Medical Neuro-Oncology at the Huntsman Cancer Institute, Salt Lake City, Utah.

Correspondence: Dr. Kulich ([email protected])

1. Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, et al. The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131(6):803-820.

2. Wang-Rodriguez J, Yunes A, Phan R, et al. The challenges of precision medicine and new advances in molecular diagnostic testing in hematolymphoid malignancies: impact on the VHA. Fed Pract. 2017;34(suppl 5):S38-S49.

3. Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Liao P, et al. CBTRUS statistical report: primary brain and other central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2010-2014. Neuro Oncol. 2017;19(suppl 5):v1-v88.

4. Nikiforova MN, Wald AI, Melan MA, et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing panel (GlioSeq) provides comprehensive genetic profiling of central nervous system tumors. Neuro Oncol. 2016;18(3)379-387.

5. Cairncross JG, Ueki K, Zlatescu MC, et al. Specific genetic predictors of chemotherapeutic response and survival in patients with anaplastic oligodendrogliomas. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90(19):1473-1479.

6. van den Bent MJ, Erdem-Eraslan L, Idbaih A, et al. MGMT-STP27 methylation status as predictive marker for response to PCV in anaplastic oligodendrogliomas and oligoastrocytomas. A report from EORTC study 26951. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(19):5513-5522.

7. Stupp R, Hegi ME, Mason WP, et al; European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Brain Tumour and Radiation Oncology Groups; National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. Effects of radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide versus radiotherapy alone on survival in glioblastoma in a randomised phase III study: 5-year analysis of the EORTC-NCIC trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(5):459-466.

8. Malmstrom A, Gronberg BH, Marosi C, et al. Temozolomide versus standard 6-week radiotherapy versus hypofractionated radiotherapy in patients older than 60 years with glioblastoma: the Nordic randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(9):916-926.

9. van den Bent MJ, Kros JM. Predictive and prognostic markers in neuro-oncology. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2007;66(12):1074-1081.

10. Chen R, Smith-Cohn M, Cohen AL, Colman H. Glioma subclassifications and their clinical significance. Neurotherapeutics. 2017;14(2):284-297.

11. Jordan JT, Sanders AE, Armstrong T, et al. Quality improvement in neurology: neuro-oncology quality measurement set. Neurology. 2018;90(14):652-658.

12. Chen L, Voronovich Z, Clark K, et al. Predicting the likelihood of an isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 or 2 mutation in diagnoses of infiltrative glioma. Neuro Oncol. 2014;16(11):1478-1483.

13. Hegi ME, Diserens AC, Gorlia T, et al. MGMT gene silencing and benefit from temozolomide in glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(10):997-1003.

14. Wick W, Platten M, Meisner C, et al; NOA-08 Study Group of Neuro-oncology Working Group (NOA) of German Cancer Society. Temozolomide chemotherapy alone versus radiotherapy alone for malignant astrocytoma in the elderly: the NOA-08 randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(7):707-715.

15. Horbinski C, Kofler J, Kelly LM, Murdoch GH, Nikiforova MN. Diagnostic use of IDH1/2 mutation analysis in routine clinical testing of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded glioma tissues. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2009;68(12):1319-1325.

16. Camelo-Piragua S, Jansen M, Ganguly A, Kim JC, Louis DN, Nutt CL. Mutant IDH1-specific immunohistochemistry distinguishes diffuse astrocytoma from astrocytosis. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;119(4):509-511.

17. Horbinski C, Kofler J, Yeaney G, et al. Isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 analysis differentiates gangliogliomas from infiltrative gliomas. Brain Pathol. 2011;21(5):564-574.

18. Berghoff AS, Preusser M. BRAF alterations in brain tumours: molecular pathology and therapeutic opportunities. Curr Opin Neurol. 2014;27(6):689-696.

19. Korshunov A, Meyer J, Capper D, et al. Combined molecular analysis of BRAF and IDH1 distinguishes pilocytic astrocytoma from diffuse astrocytoma. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;118(3):401-405.

20. Fuller CE, Schmidt RE, Roth KA, et al. Clinical utility of fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) in morphologically ambiguous gliomas with hybrid oligodendroglial/astrocytic features. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2003;62(11):1118-1128.

21. Horbinski C. Practical molecular diagnostics in neuropathology: making a tough job a little easier. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2010;27(2):105-113.

22. Fuller GN, Bigner SH. Amplified cellular oncogenes in neoplasms of the human central nervous system. Mutat Res. 1992;276(3):299-306.

23. Brennan CW, Verhaak RG, McKenna A, et al; TCGA Research Network. The somatic genomic landscape of glioblastoma. Cell. 2013;155(2):462-477.

24. Aldape K, Zadeh G, Mansouri S, Reifenberger G, von Deimling A. Glioblastoma: pathology, molecular mechanisms and markers. Acta Neuropathol. 2015;129(6):829-848.

25. Killela PJ, Reitman ZJ, Jiao Y, et al. TERT promoter mutations occur frequently in gliomas and a subset of tumors derived from cells with low rates of self-renewal. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(15):6021-6026.

26. Nikiforova MN, Hamilton RL. Molecular diagnostics of gliomas. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135(5):558-568.

1. Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, et al. The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131(6):803-820.

2. Wang-Rodriguez J, Yunes A, Phan R, et al. The challenges of precision medicine and new advances in molecular diagnostic testing in hematolymphoid malignancies: impact on the VHA. Fed Pract. 2017;34(suppl 5):S38-S49.

3. Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Liao P, et al. CBTRUS statistical report: primary brain and other central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2010-2014. Neuro Oncol. 2017;19(suppl 5):v1-v88.

4. Nikiforova MN, Wald AI, Melan MA, et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing panel (GlioSeq) provides comprehensive genetic profiling of central nervous system tumors. Neuro Oncol. 2016;18(3)379-387.

5. Cairncross JG, Ueki K, Zlatescu MC, et al. Specific genetic predictors of chemotherapeutic response and survival in patients with anaplastic oligodendrogliomas. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90(19):1473-1479.

6. van den Bent MJ, Erdem-Eraslan L, Idbaih A, et al. MGMT-STP27 methylation status as predictive marker for response to PCV in anaplastic oligodendrogliomas and oligoastrocytomas. A report from EORTC study 26951. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(19):5513-5522.

7. Stupp R, Hegi ME, Mason WP, et al; European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Brain Tumour and Radiation Oncology Groups; National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. Effects of radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide versus radiotherapy alone on survival in glioblastoma in a randomised phase III study: 5-year analysis of the EORTC-NCIC trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(5):459-466.

8. Malmstrom A, Gronberg BH, Marosi C, et al. Temozolomide versus standard 6-week radiotherapy versus hypofractionated radiotherapy in patients older than 60 years with glioblastoma: the Nordic randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(9):916-926.

9. van den Bent MJ, Kros JM. Predictive and prognostic markers in neuro-oncology. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2007;66(12):1074-1081.

10. Chen R, Smith-Cohn M, Cohen AL, Colman H. Glioma subclassifications and their clinical significance. Neurotherapeutics. 2017;14(2):284-297.

11. Jordan JT, Sanders AE, Armstrong T, et al. Quality improvement in neurology: neuro-oncology quality measurement set. Neurology. 2018;90(14):652-658.

12. Chen L, Voronovich Z, Clark K, et al. Predicting the likelihood of an isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 or 2 mutation in diagnoses of infiltrative glioma. Neuro Oncol. 2014;16(11):1478-1483.

13. Hegi ME, Diserens AC, Gorlia T, et al. MGMT gene silencing and benefit from temozolomide in glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(10):997-1003.

14. Wick W, Platten M, Meisner C, et al; NOA-08 Study Group of Neuro-oncology Working Group (NOA) of German Cancer Society. Temozolomide chemotherapy alone versus radiotherapy alone for malignant astrocytoma in the elderly: the NOA-08 randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(7):707-715.

15. Horbinski C, Kofler J, Kelly LM, Murdoch GH, Nikiforova MN. Diagnostic use of IDH1/2 mutation analysis in routine clinical testing of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded glioma tissues. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2009;68(12):1319-1325.

16. Camelo-Piragua S, Jansen M, Ganguly A, Kim JC, Louis DN, Nutt CL. Mutant IDH1-specific immunohistochemistry distinguishes diffuse astrocytoma from astrocytosis. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;119(4):509-511.

17. Horbinski C, Kofler J, Yeaney G, et al. Isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 analysis differentiates gangliogliomas from infiltrative gliomas. Brain Pathol. 2011;21(5):564-574.

18. Berghoff AS, Preusser M. BRAF alterations in brain tumours: molecular pathology and therapeutic opportunities. Curr Opin Neurol. 2014;27(6):689-696.

19. Korshunov A, Meyer J, Capper D, et al. Combined molecular analysis of BRAF and IDH1 distinguishes pilocytic astrocytoma from diffuse astrocytoma. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;118(3):401-405.

20. Fuller CE, Schmidt RE, Roth KA, et al. Clinical utility of fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) in morphologically ambiguous gliomas with hybrid oligodendroglial/astrocytic features. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2003;62(11):1118-1128.

21. Horbinski C. Practical molecular diagnostics in neuropathology: making a tough job a little easier. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2010;27(2):105-113.

22. Fuller GN, Bigner SH. Amplified cellular oncogenes in neoplasms of the human central nervous system. Mutat Res. 1992;276(3):299-306.

23. Brennan CW, Verhaak RG, McKenna A, et al; TCGA Research Network. The somatic genomic landscape of glioblastoma. Cell. 2013;155(2):462-477.

24. Aldape K, Zadeh G, Mansouri S, Reifenberger G, von Deimling A. Glioblastoma: pathology, molecular mechanisms and markers. Acta Neuropathol. 2015;129(6):829-848.

25. Killela PJ, Reitman ZJ, Jiao Y, et al. TERT promoter mutations occur frequently in gliomas and a subset of tumors derived from cells with low rates of self-renewal. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(15):6021-6026.

26. Nikiforova MN, Hamilton RL. Molecular diagnostics of gliomas. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135(5):558-568.

Complex Malignancies: A Diagnostic and Therapeutic Trilemma

Mr. F. is a 67-year-old man with a medical history significant for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, gastroesophageal reflux disease, abdominal aortic aneurysm repair, and lung nodules (8-mm nodules in his right lower lobe and left upper lobe) since 2009 for which he had been followed in the pulmonary clinic. His last radiologic imaging had been performed in November 2010. The patient had failed to show for a serial scan and follow-up pulmonary appointments. He had seen his primary care practitioner annually. He reporteded a 60 pack-year smoking history and drank up to 10 to 15 beers a day, 3 days a week. He also reported exposure to asbestos while in the U.S. Navy as well as having worked in a sheet metal yard. He reported no family history of lung cancer.

In January 2014, Mr. F. presented to his primary care doctor with a nonpainful neck lump noted by the patient for a few months. On physical examination, the patient appeared healthy and without change in weight, loss of appetite, dysphagia, hemoptysis, or any other remarkable symptoms except for the pain in the left-sided neck mass. On oral examination, the patient did not have any oral lesions but was noted to have poor dentition. He had decreased breath sounds on the right side but no adventitious breath sounds. His cardiac status was within normal limits with a regular heart rate, warm skin, and well-perfused extremities. His abdomen was soft and nontender with good bowel sounds.

A neck computed tomography (CT) done on January 17, 2014, showed 2 left neck masses in the tail of the parotid gland or in level 2 adjacent to the parotid gland. The ear, nose, and throat (ENT) clinic noted that he had a 3-cm level 2 mass, which was mobile and nontender. A fine needle aspiration biopsy showed poorly differentiated rare malignant cells, but the small size of the biopsy precluded identification of the cells. For that reason, the patient was scheduled for an operative laryngoscopy.

A combined positron emission tomography and CT (PET/CT) scan on February 5, 2014, showed multiple areas of hypermetabolic activity. A highly metabolic 2.6 x 1.9-cm mass was noted in the left neck inseparable from the inferior border of the left parotid gland; whether this represented a parotid neoplasm or neoplastic lymph node could not be determined. Positive level 5 neck lymph nodes were suggestive of metastatic disease. There were also 2 foci of mild nonspecific metabolic activity in the right parotid gland. A spiculated mass in the right lower lung, measuring 2.3 x 3.5 cm, demonstrated intense fludeoxyglucose F 18 (FDG) uptake with maximum standardized uptake value (SUV) of 12.7, which was consistent with neoplasm. Thickening of the middistal esophageal wall with intense FDG uptake (SUV of 7.9) was suggestive of esophageal carcinoma.

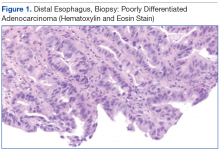

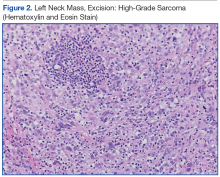

The patient underwent an endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) esophageal biopsy, which demonstrated poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma (Figure 1). The tumor seemed to have originated at this site, as the biopsy fragments also contained foci of Barrett’s metaplasia and in situ carcinoma. He was presented in the hospital tumor board about whether he should undergo a high-risk lung biopsy due to the location of the mass or have his left neck mass rebiopsied, assuming that he had metastatic esophageal cancer in both the lung and neck. The safer procedure of redoing the neck biopsy in the Ear, Nose, and Throat clinic was pursued, and the patient underwent a biopsy and surgical excision of his left neck mass with positive pathology of highgrade sarcoma (Figure 2).

The tumor consisted of spindle and epithelioid cell proliferation within a lymph node. The neoplastic cells exhibited prominent nuclear atypia, multinucleation, frequent mitoses, and focal necrosis. By immunohistochemistry, the tumor cells were diffusely positive for vimentin, CD68, and CD34 and were negative for pankeratin, CK7, CAM 5.2, CD30, CD15, tyrosine, melan-a, HMB-45, epithelial membrane antigen, keratin 903, desmin protein, CD56, CD99, actin protein, and CD1a. A differential diagnosis included malignant fibrous histiocytoma and histiocytic sarcoma.

Knowing the patient had 2 tumors, a percutaneous lung biopsy was scheduled. It was assumed that the lung mass would be metastatic from esophagus vs sarcoma, but the biopsy showed small cell cancer (Figure 3). The tumor was composed of small cells with finely granular chromatin and a sparse amount of cytoplasm. By immunohistochemistry, the tumor cells were positive for TTF-1, CK7, CAM 5.2, CD56, and synaptophysin and were negative for CK5, CK6, and p63. The patient was represented at the tumor board with diagnostic recommendations to undergo a magnetic resonance imaging of the brain (negative for metastasis) and a PET/CT scan (stable disease).

A lengthy discussion ensued regarding treatment for the 3 cancers. The AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 7th edition, was used as the framework for all staging.1 The patient had a stage IIA (T1bN0MX), grade 3 sarcoma, which could be removed by neck dissection. He had a stage IIIB esophageal carcinoma (T3N2MX), which would require concurrent chemoradiation. His limited stage small cell lung cancer might have been amenable to a lobectomy if a mediastinoscopy was negative. The standard of care for limited stage small cell lung cancer is that if the cancer is precisely staged and the patient is a good surgical candidate, then surgery can be considered. The rationale for considering resection in this case was that if his other cancers could be cured, then surgery would be an excellent option.2 These options were presented to the patient, who opted for chemotherapy. The oncologist treating the patient elected to target the small cell cancer initially, because it was likely the fastest growing cancer. The patient started treatment with etoposide/carboplatin shortly thereafter. Mr. F. was also referred to palliative care.

Discussion

When a patient presents with several tumor masses detected either clinically or radiologically, it is reasonable to assume, at least initially, that all the lesions can be attributed to the same disease (ie, a primary neoplasm and distant metastases). Based on this assumption, it is rational to establish a tissue diagnosis by sampling the most accessible lesion. In the correct clinical context, this may be sufficient to initiate an appropriate therapy. However, health care providers should be aware that unrelated neoplasms can develop simultaneously, and about 8% of patients have > 1 malignancy at presentation.3

This patient presented with 3 different malignant neoplasms: esophageal adenocarcinoma, pulmonary small-cell carcinoma, and high-grade sarcoma. These types of tumors have completely different histogenesis. Esophageal adenocarcinoma develops from glandular cells of Barrett’s esophagus, small-cell carcinoma develops from neuroendocrine Kulchitsky cells, and sarcoma arises from mesenchymal cells. This constellation of neoplasms does not represent any known multicancer syndrome, such as Li-Fraumeni syndrome or Lynch syndrome. Whether these concomitant tumors represent coincidental neoplasms or have common underlying molecular alterations remains unknown.

The treatment for each of this patient’s cancers was very different and required a multidisciplinary, staged approach for management. This could have been arranged for him had he wanted to pursue multiple resections of the neck and lung plus have chemotherapy and radiation for the esophageal cancer. The patient opted for chemotherapy for the most aggressive cancer, but other options would have been possible had he wanted to pursue them.

Conclusion

This complex case demonstrates the role for careful review of all data and the importance of not making assumptions when analyzing images and history despite all the procedures and time to diagnosis.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Edge S, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 2010.

2. Koletsis EN, Prokakis C, Karanikolas M, Apostolakis E, Dougenis D. Current role of surgery in small cell lung carcinoma. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2009;4:30.