User login

Mobile Enlarging Scalp Nodule

The Diagnosis: Hybrid Schwannoma-Perineurioma

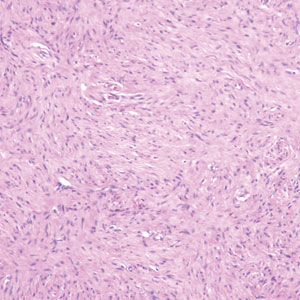

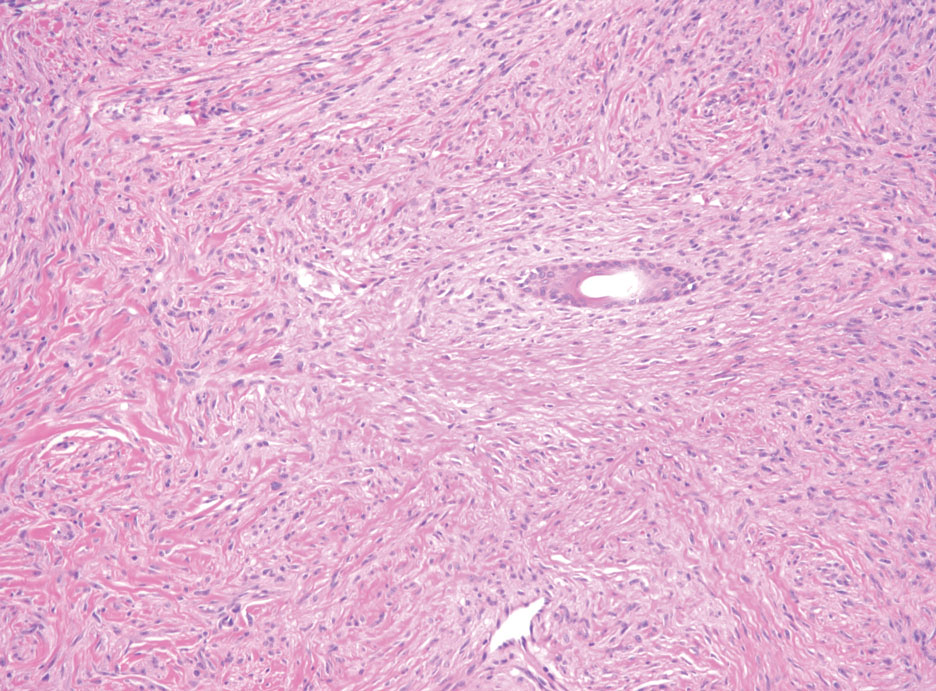

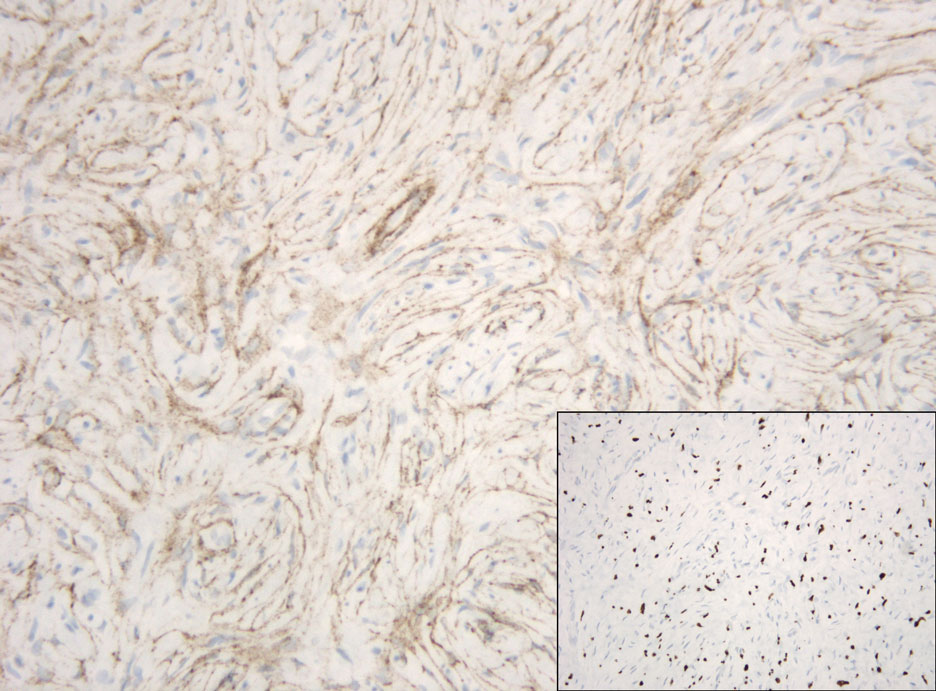

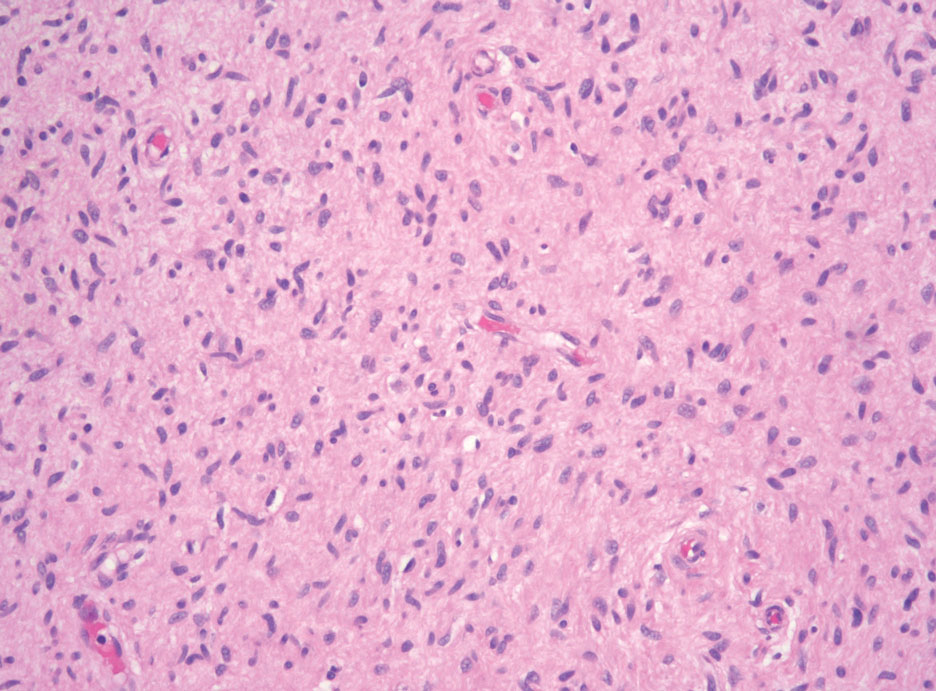

Hybrid nerve sheath tumors are rare entities that display features of more than one nerve sheath tumor such as neurofibromas, schwannomas, and perineuriomas.1 These tumors often are found in the dermis or subcutaneous tissue of the extremities and abdomen2; however, cases of hybrid peripheral nerve sheath tumors have been reported in many anatomical locations without a gender predilection.3 The most common type of hybrid nerve sheath tumor is a schwannoma-perineurioma.3,4 Histologically, they are well-circumscribed lesions composed of both spindled Schwann cells with plump nuclei and spindled perineural cells with more elongated thin nuclei.5 Although the Schwann cell component tends to predominate, the 2 cell populations interdigitate, making it challenging to definitively distinguish them by hematoxylin and eosin staining alone.4 However, immunohistochemical (IHC) staining can be used to help distinguish the 2 separate cell populations. Staining for S-100 and SRY-box transcription factor 10 (SOX-10) will be positive in the Schwann cell component, and staining for epithelial membrane antigen, Claudin-1, or glucose transporter-1 (Figure 1) will be positive in the perineural component. Other hybrid forms of benign nerve sheath tumors include neurofibroma-schwannoma and neurofibromaperineurioma.4 Neurofibroma-schwannomas usually have a schwannoma component containing Antoni A areas with palisading Verocay bodies. The neurofibroma cells typically have wavy elongated nuclei, fibroblasts, and mucinous myxoid material.3 Neurofibroma-perineurioma is the least common hybrid tumor. These hybrid tumors have a plexiform neurofibroma appearance with areas of perineural differentiation, which can be difficult to identify on routine histology and typically will require IHC staining to appreciate. The neurofibroma component will stain positive for S-100 and negative for markers of perineural differentiation, including epithelial membrane antigen, glucose transporter-1, and Claudin-1.3 Although schwannoma-perineuriomas are benign sporadic tumors not associated with neurofibromatosis, neurofibromaschwannomas are associated with neurofibromatosis types 1 and 2 (NF1 and NF2). Neurofibroma-perineurioma tumors usually are associated with only NF1.3,6

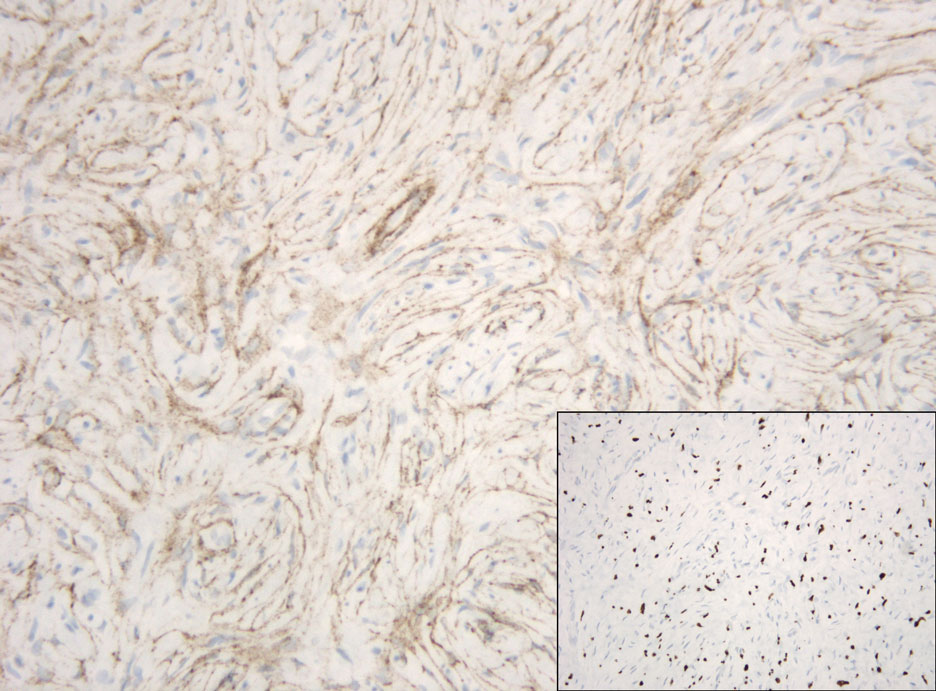

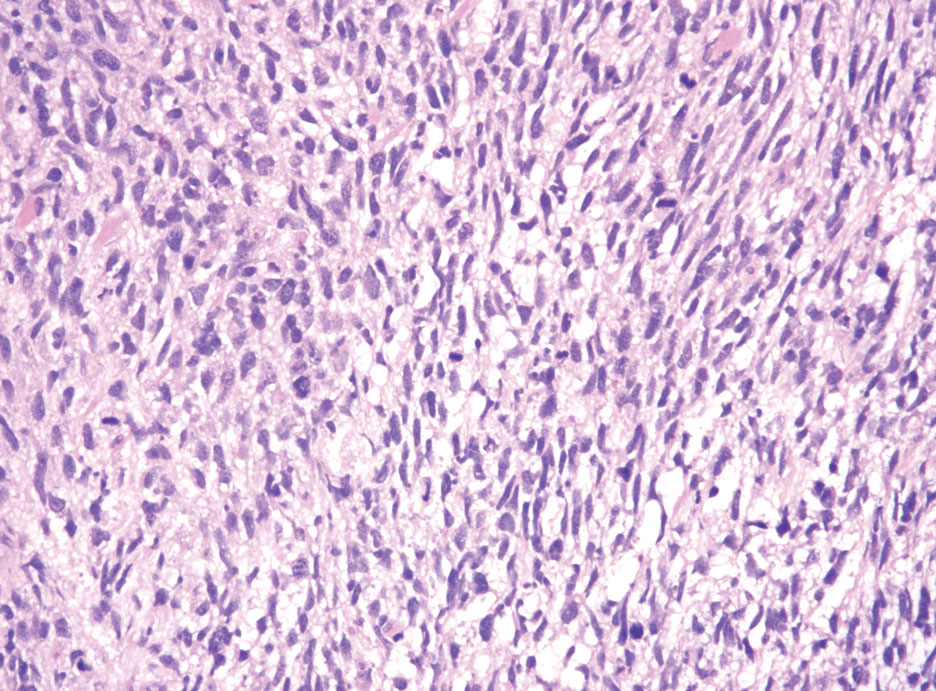

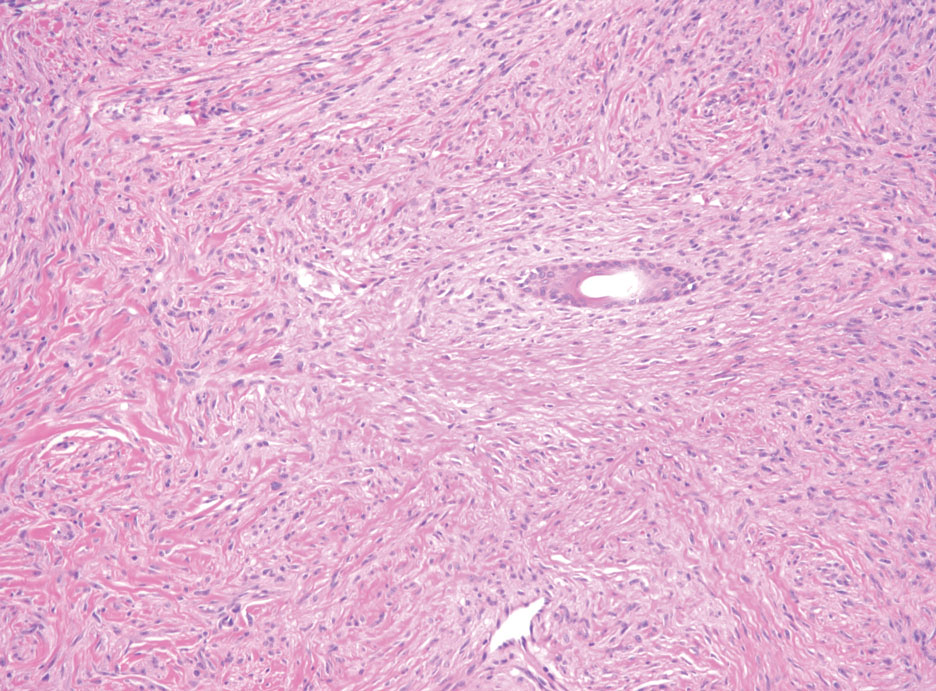

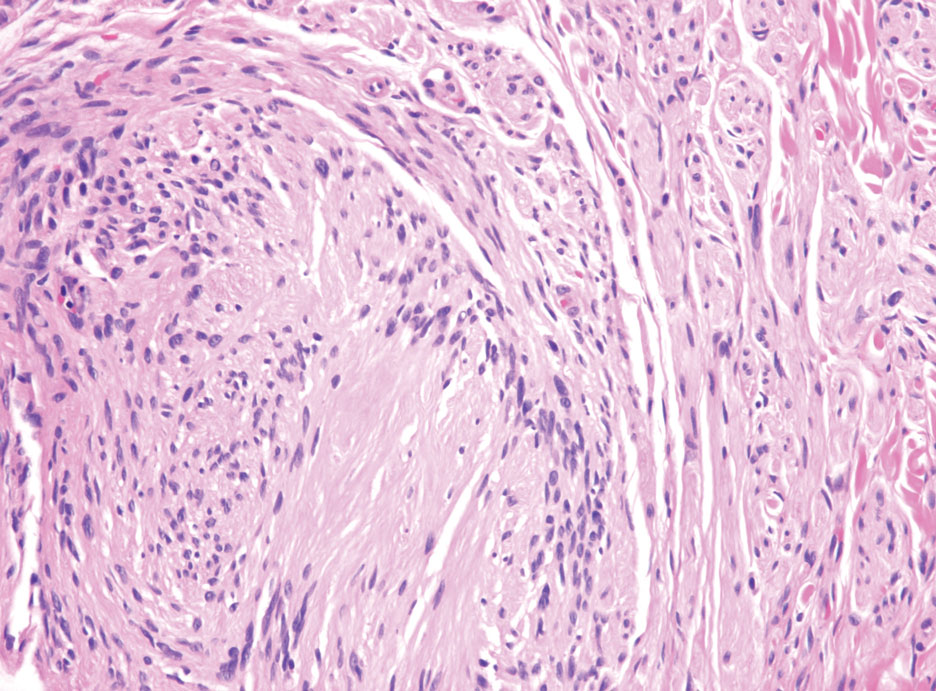

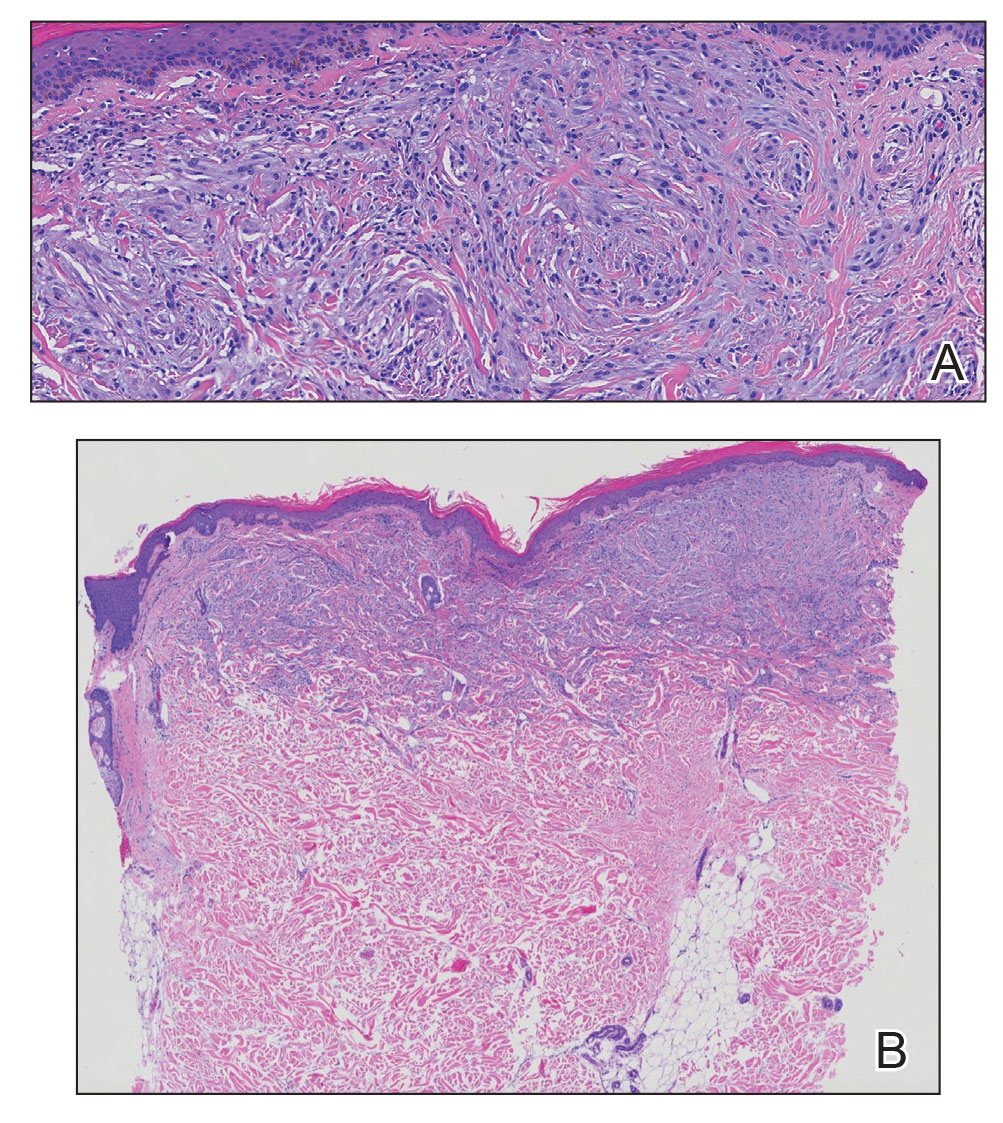

Schwannomas typically present in middle-aged patients as tumors located on flexor surfaces.7 Although perineural cells can be seen at the periphery of a schwannoma forming a capsule, they do not interdigitate between the Schwann cells. Schwannomas are composed almost entirely of well-differentiated Schwann cells.1,4,8 Schwannomas classically are well-circumscribed, encapsulated, biphasic lesions with alternating compact areas (Antoni A) and loosely arranged areas (Antoni B). The spindled cells occasionally may display nuclear palisading within the Antoni A areas, known as Verocay bodies (Figure 2). Antoni B areas are more disorganized and hypocellular with variable macrophage infiltrate.1,4,8 The Schwann cells predominantly will have bland cytologic features, but scattered areas of degenerative nuclear atypia (also known as ancient change) may be present.4 Multiple schwannomas are associated with NF2 gene mutations and loss of merlin protein.8 There are different subtypes of schwannomas, including cellular and plexiform schwannomas.4 Because schwannomas are benign nerve sheath lesions, treatment typically consists of excision with careful dissection around the involved nerve.9

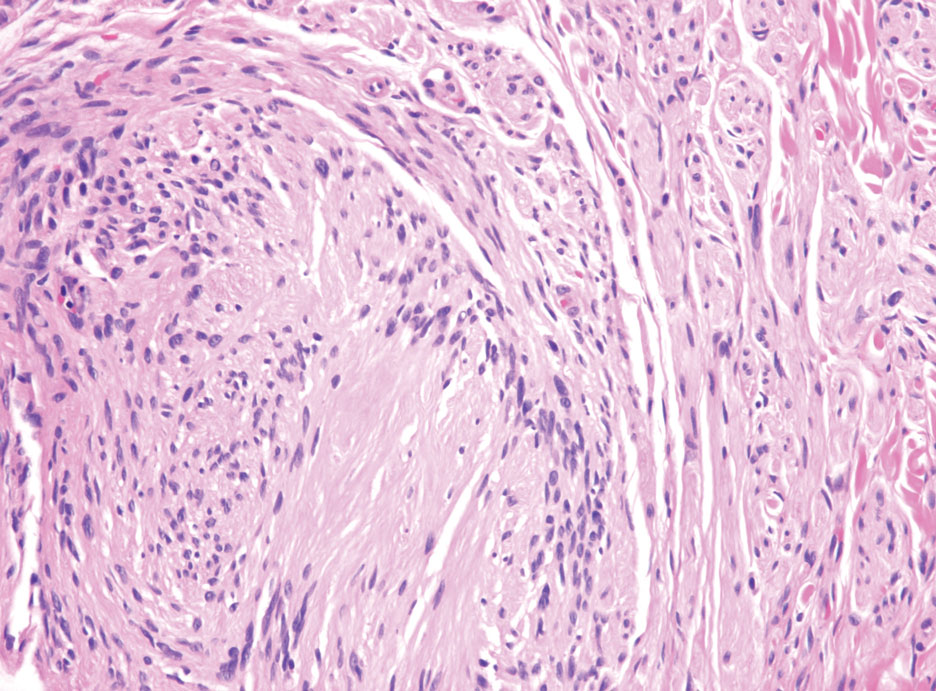

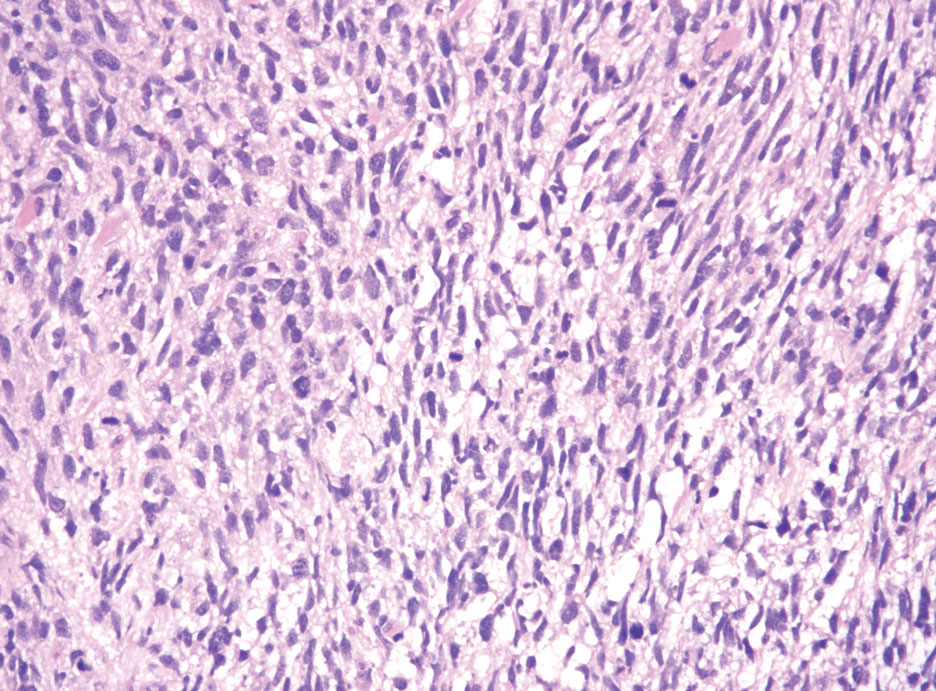

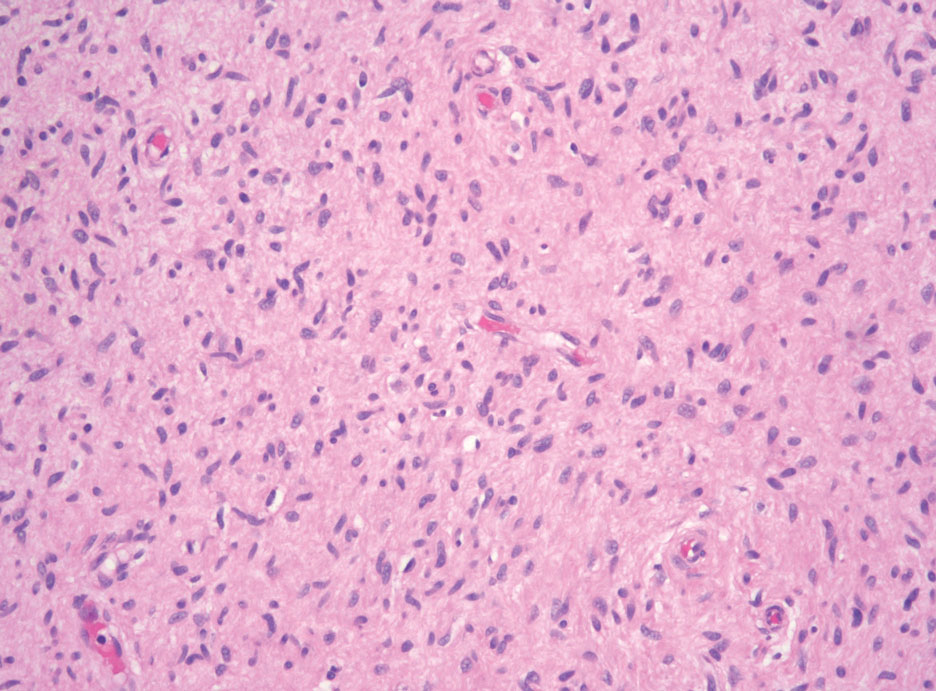

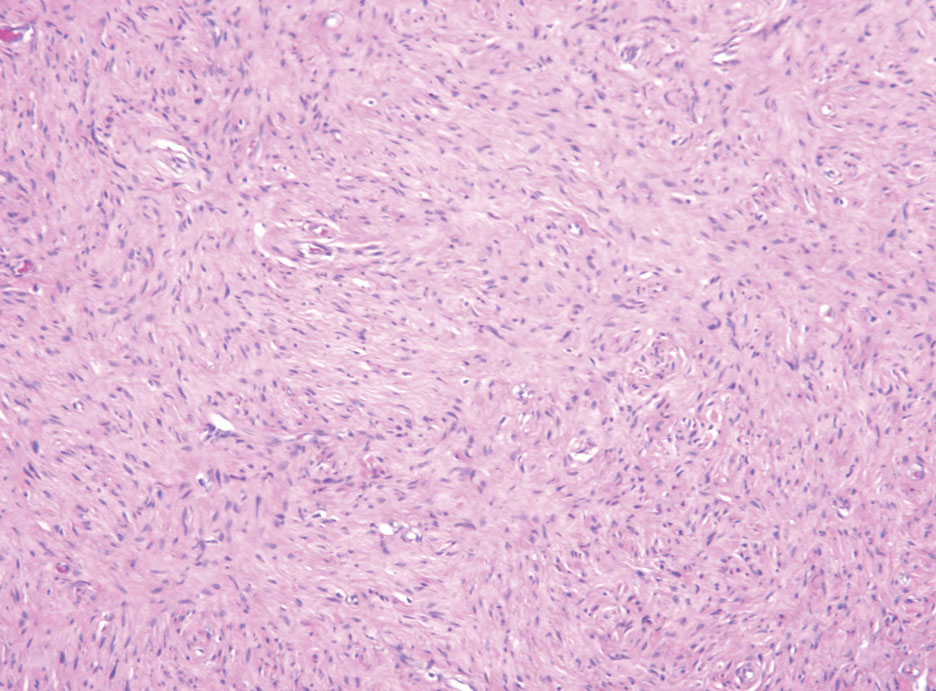

Neurofibromas are the most common peripheral nerve sheath tumors of the skin with no notable anatomic prediction, though one study found them to be more prevalent in the upper extremities.10 They typically present as sporadic solitary lesions, but multiple lesions may appear as superficial pedunculated growths that present in those aged 20 to 30 years.11 Microscopically, neurofibromas typically are not well circumscribed and have an infiltrative growth pattern. Neurofibromas are composed of cytologically bland spindled Schwann cells with thin wavy nuclei in a variable myxoid stroma (Figure 3). In addition to Schwann cells, neurofibromas contain other cell components, including fibroblasts, mast cells, perineurial-like cells, and residual axons.4 Neurofibromas typically are located in the dermis but may extend into the subcutaneous tissue. Clinically, the overlying skin may show hyperpigmentation.8 Neurofibromas can be localized, diffuse, or plexiform, with the majority being localized. Diffuse neurofibromas clinically have a raised plaque appearance. Treatment is unnecessary because these lesions are benign.7

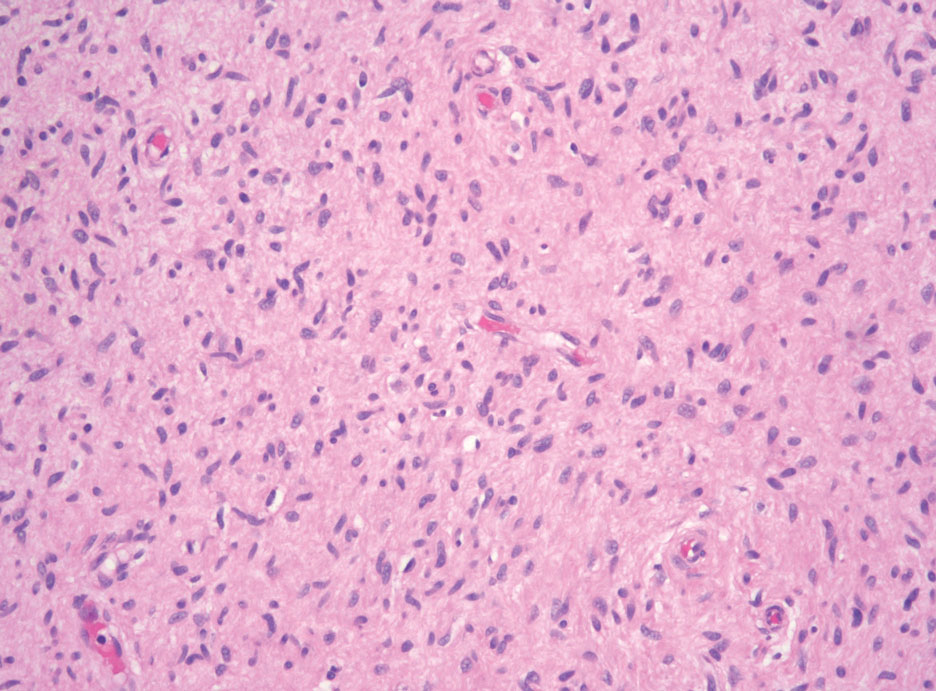

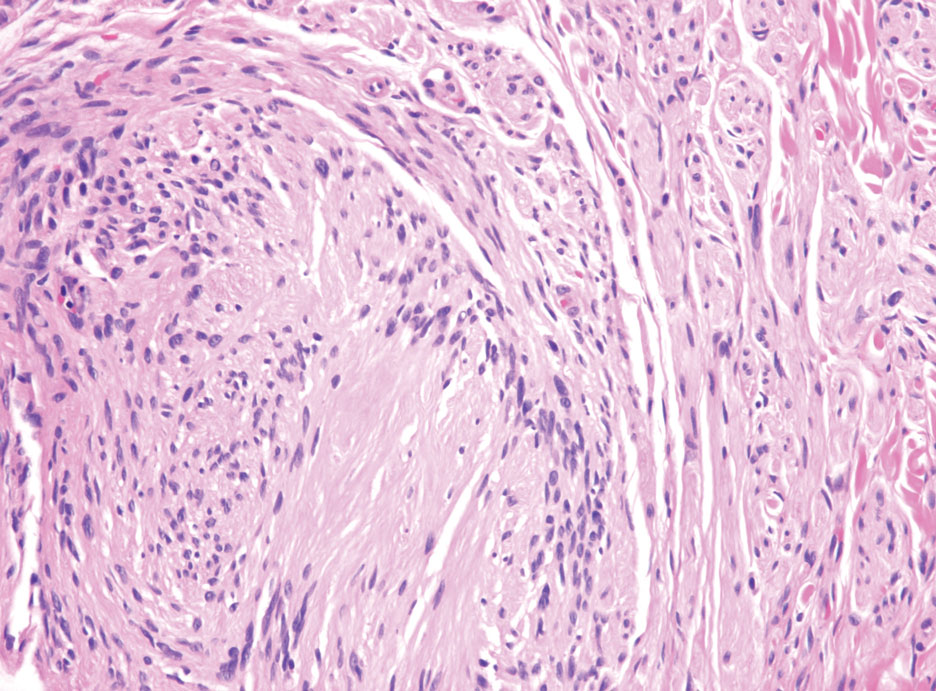

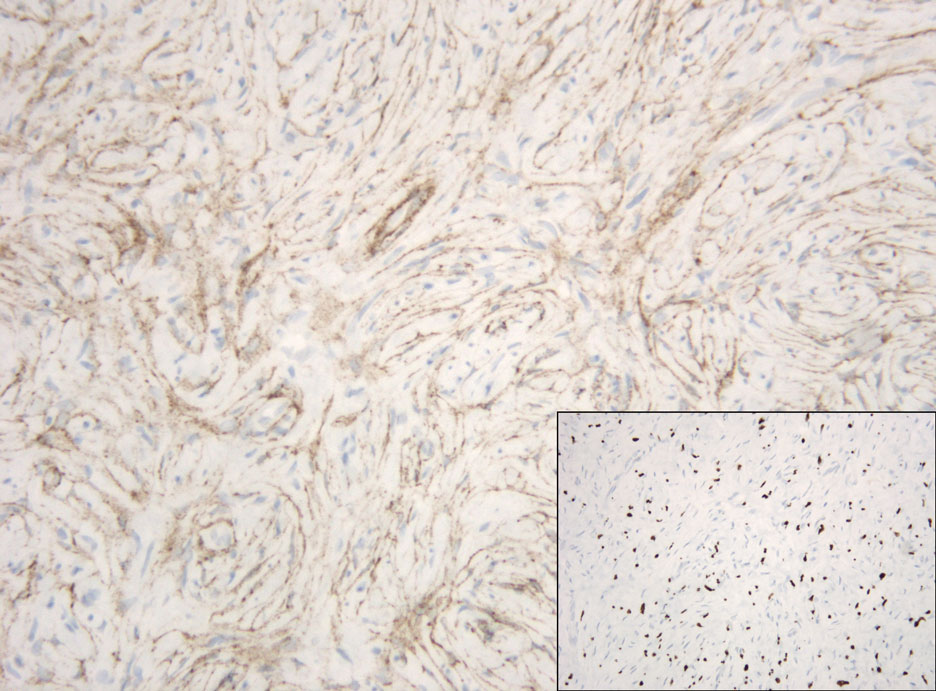

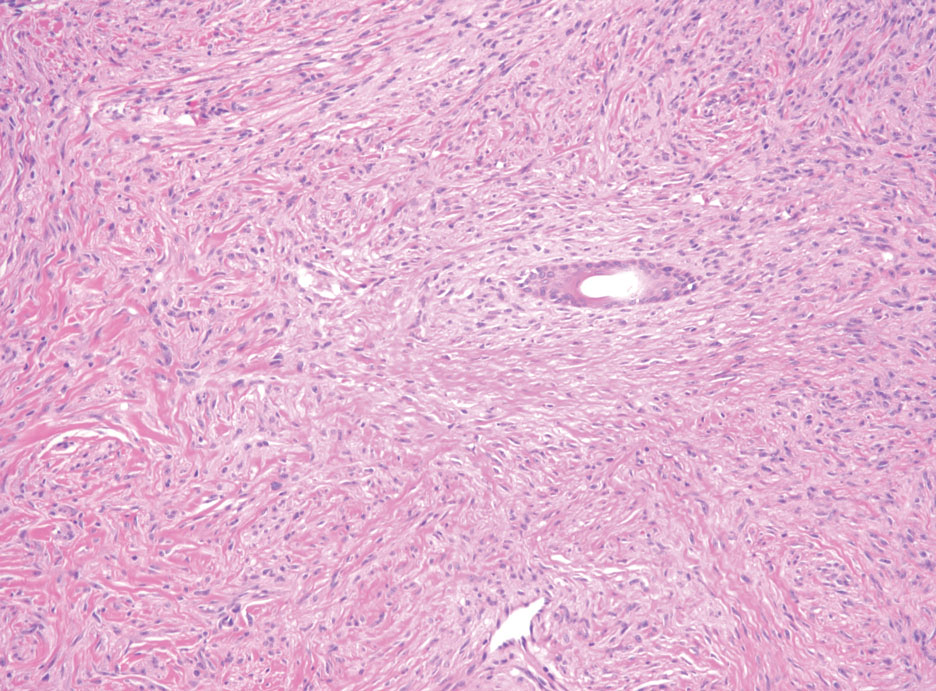

Desmoplastic melanoma (DM) is another diagnosis in the differential for this case. Patients with DM are older compared to non-DM melanoma patients, with a male predilection.12 Desmoplastic melanomas are more likely to be located on the head and neck. In approximately one-third of cases, no in situ component will be identified, leading to confusion of the dermal lesion as a neural lesion or an area of scar formation. Microscopically, DM presents as a variable cellular infiltrative tumor composed of spindle cells with varying degrees of nuclear atypia. The spindled melanocytes are within a collagenous (desmoplastic) stroma (Figure 4).13 Desmoplastic melanoma has been described with a low mitotic index, leading to misdiagnosis with benign spindle cell neoplasms.14 The spindle cells should be positive for S-100 and SOX-10 with IHC staining. Unlike other melanomas, human melanoma black 45 and Melan-A often are negative or only focally positive. Treatment of DM is similar to non-DM in that wide local excision usually is employed. A systematic review evaluating sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) recommended consideration of SLNB in mixed DM but not for pure DM, as rates of positive SLNB were much lower in the latter.15

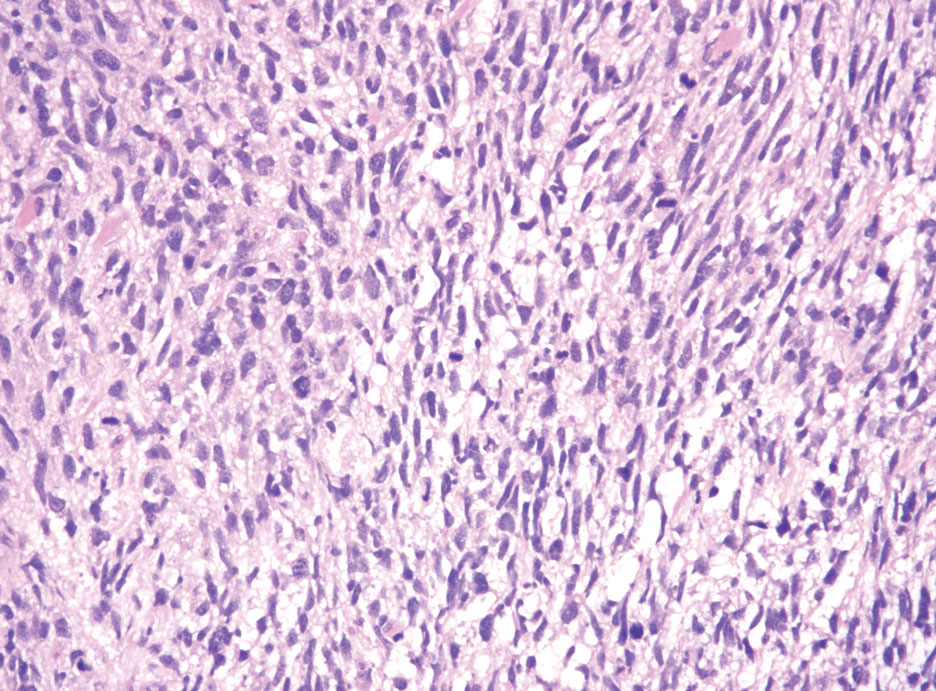

Patients with malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST) usually present with an enlarging mass, pain, or neurologic symptoms. Most cases of MPNST are located on the trunk or extremities.16 Plexiform neurofibromas, especially in adults with NF1, have the potential to transform into an MPNST.4 In fact, MPNST is the most common malignancy in patients with NF1.17 Pediatric cancer survivors also are predisposed to MPNST, with a 40-fold increase in incidence compared to the general population.18 Transformation from schwannoma to MPNST is rare but has been reported.8 Histologically, spindle cells easily can be appreciated with a fasciculated growth pattern (Figure 5). Mitotic activity and tumor necrosis may be present. Diagnosis of these tumors historically has been challenging, though recent research has identified inactivation of polycomb repressive complex 2 in 70% to 90% of MPNSTs. Because of polycomb repressive complex 2 inactivation, there is loss of stone H3K27 trimethylation that can be capitalized on for MPNST diagnosis.19 Negative IHC staining for H3K27 trimethylation has been found to be highly specific for MPNST. Negative staining for different cytokeratin and melanoma markers can be helpful in differentiating it from carcinomas and melanoma. The only curative treatment for MPNST is complete excision, leaving patients with recurrent, refractory, and metastatic cases to be encouraged for enrollment in clinical trials. The 5-year survival rates for patients with MPNST reported in the literature range from 20% to 50%.20

- Hornick JL, Bundock EA, Fletcher CD. Hybrid schwannoma /perineurioma: clinicopathologic analysis of 42 distinctive benign nerve sheath tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1554-1561.

- Leung KCP, Chan E, Ng HYJ, et al. Novel case of hybrid perineuriomaneurofibroma of the orbit. Can J Ophthalmol. 2019;54:E283-E285.

- Ud Din N, Ahmad Z, Abdul-Ghafar J, et al. Hybrid peripheral nerve sheath tumors: report of five cases and detailed review of literature. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:349. doi:10.1186/s12885-017-3350-1

- Belakhoua SM, Rodriguez FJ. Diagnostic pathology of tumors of peripheral nerve. Neurosurgery. 2021;88:443-456.

- Michal M, Kazakov DV, Michal M. Hybrid peripheral nerve sheath tumors: a review. Cesk Patol. 2017;53:81-88.

- Harder A, Wesemann M, Hagel C, et al. Hybrid neurofibroma /schwannoma is overrepresented among schwannomatosis and neurofibromatosis patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:702-709.

- Bhattacharyya AK, Perrin R, Guha A. Peripheral nerve tumors: management strategies and molecular insights. J Neurooncol. 2004;69:335-349.

- Pytel P, Anthony DC. Peripheral nerves and skeletal muscle. In: Kumar V, Abbas AK, Aster JC, eds. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. 10th ed. Elsevier/Saunders; 2015:1218-1239.

- Strike SA, Puhaindran ME. Nerve tumors of the upper extremity. Clin Plast Surg. 2019;46:347-350.

- Kim DH, Murovic JA, Tiel RL, et al. A series of 397 peripheral neural sheath tumors: 30-year experience at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center. J Neurosurg. 2005;102:246-255.

- Pilavaki M, Chourmouzi D, Kiziridou A, et al. Imaging of peripheral nerve sheath tumors with pathologic correlation: pictorial review. Eur J Radiol. 2004;52:229-239.

- Murali R, Shaw HM, Lai K, et al. Prognostic factors in cutaneous desmoplastic melanoma: a study of 252 patients. Cancer. 2010; 116:4130-4138.

- Chen LL, Jaimes N, Barker CA, et al. Desmoplastic melanoma: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:825-833.

- de Almeida LS, Requena L, Rutten A, et al. Desmoplastic malignant melanoma: a clinicopathologic analysis of 113 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:207-215.

- Dunne JA, Wormald JC, Steele J, et al. Is sentinel lymph node biopsy warranted for desmoplastic melanoma? a systematic review. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2017;70:274-280.

- Patel TD, Shaigany K, Fang CH, et al. Comparative analysis of head and neck and non-head and neck malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;154:113-120.

- Prudner BC, Ball T, Rathore R, et al. Diagnosis and management of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors: current practice and future perspectives. Neurooncol Adv. 2020;2(suppl 1):I40-I9.

- Bright CJ, Hawkins MM, Winter DL, et al. Risk of soft-tissue sarcoma among 69,460 five-year survivors of childhood cancer in Europe. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110:649-660.

- Schaefer I-M, Fletcher CD, Hornick JL. Loss of H3K27 trimethylation distinguishes malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors from histologic mimics. Mod Pathol. 2016;29:4-13.

- Kolberg M, Holand M, Agesen TH, et al. Survival meta-analyses for >1800 malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor patients with and without neurofibromatosis type 1. Neuro Oncol. 2013;15:135-147.

The Diagnosis: Hybrid Schwannoma-Perineurioma

Hybrid nerve sheath tumors are rare entities that display features of more than one nerve sheath tumor such as neurofibromas, schwannomas, and perineuriomas.1 These tumors often are found in the dermis or subcutaneous tissue of the extremities and abdomen2; however, cases of hybrid peripheral nerve sheath tumors have been reported in many anatomical locations without a gender predilection.3 The most common type of hybrid nerve sheath tumor is a schwannoma-perineurioma.3,4 Histologically, they are well-circumscribed lesions composed of both spindled Schwann cells with plump nuclei and spindled perineural cells with more elongated thin nuclei.5 Although the Schwann cell component tends to predominate, the 2 cell populations interdigitate, making it challenging to definitively distinguish them by hematoxylin and eosin staining alone.4 However, immunohistochemical (IHC) staining can be used to help distinguish the 2 separate cell populations. Staining for S-100 and SRY-box transcription factor 10 (SOX-10) will be positive in the Schwann cell component, and staining for epithelial membrane antigen, Claudin-1, or glucose transporter-1 (Figure 1) will be positive in the perineural component. Other hybrid forms of benign nerve sheath tumors include neurofibroma-schwannoma and neurofibromaperineurioma.4 Neurofibroma-schwannomas usually have a schwannoma component containing Antoni A areas with palisading Verocay bodies. The neurofibroma cells typically have wavy elongated nuclei, fibroblasts, and mucinous myxoid material.3 Neurofibroma-perineurioma is the least common hybrid tumor. These hybrid tumors have a plexiform neurofibroma appearance with areas of perineural differentiation, which can be difficult to identify on routine histology and typically will require IHC staining to appreciate. The neurofibroma component will stain positive for S-100 and negative for markers of perineural differentiation, including epithelial membrane antigen, glucose transporter-1, and Claudin-1.3 Although schwannoma-perineuriomas are benign sporadic tumors not associated with neurofibromatosis, neurofibromaschwannomas are associated with neurofibromatosis types 1 and 2 (NF1 and NF2). Neurofibroma-perineurioma tumors usually are associated with only NF1.3,6

Schwannomas typically present in middle-aged patients as tumors located on flexor surfaces.7 Although perineural cells can be seen at the periphery of a schwannoma forming a capsule, they do not interdigitate between the Schwann cells. Schwannomas are composed almost entirely of well-differentiated Schwann cells.1,4,8 Schwannomas classically are well-circumscribed, encapsulated, biphasic lesions with alternating compact areas (Antoni A) and loosely arranged areas (Antoni B). The spindled cells occasionally may display nuclear palisading within the Antoni A areas, known as Verocay bodies (Figure 2). Antoni B areas are more disorganized and hypocellular with variable macrophage infiltrate.1,4,8 The Schwann cells predominantly will have bland cytologic features, but scattered areas of degenerative nuclear atypia (also known as ancient change) may be present.4 Multiple schwannomas are associated with NF2 gene mutations and loss of merlin protein.8 There are different subtypes of schwannomas, including cellular and plexiform schwannomas.4 Because schwannomas are benign nerve sheath lesions, treatment typically consists of excision with careful dissection around the involved nerve.9

Neurofibromas are the most common peripheral nerve sheath tumors of the skin with no notable anatomic prediction, though one study found them to be more prevalent in the upper extremities.10 They typically present as sporadic solitary lesions, but multiple lesions may appear as superficial pedunculated growths that present in those aged 20 to 30 years.11 Microscopically, neurofibromas typically are not well circumscribed and have an infiltrative growth pattern. Neurofibromas are composed of cytologically bland spindled Schwann cells with thin wavy nuclei in a variable myxoid stroma (Figure 3). In addition to Schwann cells, neurofibromas contain other cell components, including fibroblasts, mast cells, perineurial-like cells, and residual axons.4 Neurofibromas typically are located in the dermis but may extend into the subcutaneous tissue. Clinically, the overlying skin may show hyperpigmentation.8 Neurofibromas can be localized, diffuse, or plexiform, with the majority being localized. Diffuse neurofibromas clinically have a raised plaque appearance. Treatment is unnecessary because these lesions are benign.7

Desmoplastic melanoma (DM) is another diagnosis in the differential for this case. Patients with DM are older compared to non-DM melanoma patients, with a male predilection.12 Desmoplastic melanomas are more likely to be located on the head and neck. In approximately one-third of cases, no in situ component will be identified, leading to confusion of the dermal lesion as a neural lesion or an area of scar formation. Microscopically, DM presents as a variable cellular infiltrative tumor composed of spindle cells with varying degrees of nuclear atypia. The spindled melanocytes are within a collagenous (desmoplastic) stroma (Figure 4).13 Desmoplastic melanoma has been described with a low mitotic index, leading to misdiagnosis with benign spindle cell neoplasms.14 The spindle cells should be positive for S-100 and SOX-10 with IHC staining. Unlike other melanomas, human melanoma black 45 and Melan-A often are negative or only focally positive. Treatment of DM is similar to non-DM in that wide local excision usually is employed. A systematic review evaluating sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) recommended consideration of SLNB in mixed DM but not for pure DM, as rates of positive SLNB were much lower in the latter.15

Patients with malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST) usually present with an enlarging mass, pain, or neurologic symptoms. Most cases of MPNST are located on the trunk or extremities.16 Plexiform neurofibromas, especially in adults with NF1, have the potential to transform into an MPNST.4 In fact, MPNST is the most common malignancy in patients with NF1.17 Pediatric cancer survivors also are predisposed to MPNST, with a 40-fold increase in incidence compared to the general population.18 Transformation from schwannoma to MPNST is rare but has been reported.8 Histologically, spindle cells easily can be appreciated with a fasciculated growth pattern (Figure 5). Mitotic activity and tumor necrosis may be present. Diagnosis of these tumors historically has been challenging, though recent research has identified inactivation of polycomb repressive complex 2 in 70% to 90% of MPNSTs. Because of polycomb repressive complex 2 inactivation, there is loss of stone H3K27 trimethylation that can be capitalized on for MPNST diagnosis.19 Negative IHC staining for H3K27 trimethylation has been found to be highly specific for MPNST. Negative staining for different cytokeratin and melanoma markers can be helpful in differentiating it from carcinomas and melanoma. The only curative treatment for MPNST is complete excision, leaving patients with recurrent, refractory, and metastatic cases to be encouraged for enrollment in clinical trials. The 5-year survival rates for patients with MPNST reported in the literature range from 20% to 50%.20

The Diagnosis: Hybrid Schwannoma-Perineurioma

Hybrid nerve sheath tumors are rare entities that display features of more than one nerve sheath tumor such as neurofibromas, schwannomas, and perineuriomas.1 These tumors often are found in the dermis or subcutaneous tissue of the extremities and abdomen2; however, cases of hybrid peripheral nerve sheath tumors have been reported in many anatomical locations without a gender predilection.3 The most common type of hybrid nerve sheath tumor is a schwannoma-perineurioma.3,4 Histologically, they are well-circumscribed lesions composed of both spindled Schwann cells with plump nuclei and spindled perineural cells with more elongated thin nuclei.5 Although the Schwann cell component tends to predominate, the 2 cell populations interdigitate, making it challenging to definitively distinguish them by hematoxylin and eosin staining alone.4 However, immunohistochemical (IHC) staining can be used to help distinguish the 2 separate cell populations. Staining for S-100 and SRY-box transcription factor 10 (SOX-10) will be positive in the Schwann cell component, and staining for epithelial membrane antigen, Claudin-1, or glucose transporter-1 (Figure 1) will be positive in the perineural component. Other hybrid forms of benign nerve sheath tumors include neurofibroma-schwannoma and neurofibromaperineurioma.4 Neurofibroma-schwannomas usually have a schwannoma component containing Antoni A areas with palisading Verocay bodies. The neurofibroma cells typically have wavy elongated nuclei, fibroblasts, and mucinous myxoid material.3 Neurofibroma-perineurioma is the least common hybrid tumor. These hybrid tumors have a plexiform neurofibroma appearance with areas of perineural differentiation, which can be difficult to identify on routine histology and typically will require IHC staining to appreciate. The neurofibroma component will stain positive for S-100 and negative for markers of perineural differentiation, including epithelial membrane antigen, glucose transporter-1, and Claudin-1.3 Although schwannoma-perineuriomas are benign sporadic tumors not associated with neurofibromatosis, neurofibromaschwannomas are associated with neurofibromatosis types 1 and 2 (NF1 and NF2). Neurofibroma-perineurioma tumors usually are associated with only NF1.3,6

Schwannomas typically present in middle-aged patients as tumors located on flexor surfaces.7 Although perineural cells can be seen at the periphery of a schwannoma forming a capsule, they do not interdigitate between the Schwann cells. Schwannomas are composed almost entirely of well-differentiated Schwann cells.1,4,8 Schwannomas classically are well-circumscribed, encapsulated, biphasic lesions with alternating compact areas (Antoni A) and loosely arranged areas (Antoni B). The spindled cells occasionally may display nuclear palisading within the Antoni A areas, known as Verocay bodies (Figure 2). Antoni B areas are more disorganized and hypocellular with variable macrophage infiltrate.1,4,8 The Schwann cells predominantly will have bland cytologic features, but scattered areas of degenerative nuclear atypia (also known as ancient change) may be present.4 Multiple schwannomas are associated with NF2 gene mutations and loss of merlin protein.8 There are different subtypes of schwannomas, including cellular and plexiform schwannomas.4 Because schwannomas are benign nerve sheath lesions, treatment typically consists of excision with careful dissection around the involved nerve.9

Neurofibromas are the most common peripheral nerve sheath tumors of the skin with no notable anatomic prediction, though one study found them to be more prevalent in the upper extremities.10 They typically present as sporadic solitary lesions, but multiple lesions may appear as superficial pedunculated growths that present in those aged 20 to 30 years.11 Microscopically, neurofibromas typically are not well circumscribed and have an infiltrative growth pattern. Neurofibromas are composed of cytologically bland spindled Schwann cells with thin wavy nuclei in a variable myxoid stroma (Figure 3). In addition to Schwann cells, neurofibromas contain other cell components, including fibroblasts, mast cells, perineurial-like cells, and residual axons.4 Neurofibromas typically are located in the dermis but may extend into the subcutaneous tissue. Clinically, the overlying skin may show hyperpigmentation.8 Neurofibromas can be localized, diffuse, or plexiform, with the majority being localized. Diffuse neurofibromas clinically have a raised plaque appearance. Treatment is unnecessary because these lesions are benign.7

Desmoplastic melanoma (DM) is another diagnosis in the differential for this case. Patients with DM are older compared to non-DM melanoma patients, with a male predilection.12 Desmoplastic melanomas are more likely to be located on the head and neck. In approximately one-third of cases, no in situ component will be identified, leading to confusion of the dermal lesion as a neural lesion or an area of scar formation. Microscopically, DM presents as a variable cellular infiltrative tumor composed of spindle cells with varying degrees of nuclear atypia. The spindled melanocytes are within a collagenous (desmoplastic) stroma (Figure 4).13 Desmoplastic melanoma has been described with a low mitotic index, leading to misdiagnosis with benign spindle cell neoplasms.14 The spindle cells should be positive for S-100 and SOX-10 with IHC staining. Unlike other melanomas, human melanoma black 45 and Melan-A often are negative or only focally positive. Treatment of DM is similar to non-DM in that wide local excision usually is employed. A systematic review evaluating sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) recommended consideration of SLNB in mixed DM but not for pure DM, as rates of positive SLNB were much lower in the latter.15

Patients with malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST) usually present with an enlarging mass, pain, or neurologic symptoms. Most cases of MPNST are located on the trunk or extremities.16 Plexiform neurofibromas, especially in adults with NF1, have the potential to transform into an MPNST.4 In fact, MPNST is the most common malignancy in patients with NF1.17 Pediatric cancer survivors also are predisposed to MPNST, with a 40-fold increase in incidence compared to the general population.18 Transformation from schwannoma to MPNST is rare but has been reported.8 Histologically, spindle cells easily can be appreciated with a fasciculated growth pattern (Figure 5). Mitotic activity and tumor necrosis may be present. Diagnosis of these tumors historically has been challenging, though recent research has identified inactivation of polycomb repressive complex 2 in 70% to 90% of MPNSTs. Because of polycomb repressive complex 2 inactivation, there is loss of stone H3K27 trimethylation that can be capitalized on for MPNST diagnosis.19 Negative IHC staining for H3K27 trimethylation has been found to be highly specific for MPNST. Negative staining for different cytokeratin and melanoma markers can be helpful in differentiating it from carcinomas and melanoma. The only curative treatment for MPNST is complete excision, leaving patients with recurrent, refractory, and metastatic cases to be encouraged for enrollment in clinical trials. The 5-year survival rates for patients with MPNST reported in the literature range from 20% to 50%.20

- Hornick JL, Bundock EA, Fletcher CD. Hybrid schwannoma /perineurioma: clinicopathologic analysis of 42 distinctive benign nerve sheath tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1554-1561.

- Leung KCP, Chan E, Ng HYJ, et al. Novel case of hybrid perineuriomaneurofibroma of the orbit. Can J Ophthalmol. 2019;54:E283-E285.

- Ud Din N, Ahmad Z, Abdul-Ghafar J, et al. Hybrid peripheral nerve sheath tumors: report of five cases and detailed review of literature. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:349. doi:10.1186/s12885-017-3350-1

- Belakhoua SM, Rodriguez FJ. Diagnostic pathology of tumors of peripheral nerve. Neurosurgery. 2021;88:443-456.

- Michal M, Kazakov DV, Michal M. Hybrid peripheral nerve sheath tumors: a review. Cesk Patol. 2017;53:81-88.

- Harder A, Wesemann M, Hagel C, et al. Hybrid neurofibroma /schwannoma is overrepresented among schwannomatosis and neurofibromatosis patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:702-709.

- Bhattacharyya AK, Perrin R, Guha A. Peripheral nerve tumors: management strategies and molecular insights. J Neurooncol. 2004;69:335-349.

- Pytel P, Anthony DC. Peripheral nerves and skeletal muscle. In: Kumar V, Abbas AK, Aster JC, eds. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. 10th ed. Elsevier/Saunders; 2015:1218-1239.

- Strike SA, Puhaindran ME. Nerve tumors of the upper extremity. Clin Plast Surg. 2019;46:347-350.

- Kim DH, Murovic JA, Tiel RL, et al. A series of 397 peripheral neural sheath tumors: 30-year experience at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center. J Neurosurg. 2005;102:246-255.

- Pilavaki M, Chourmouzi D, Kiziridou A, et al. Imaging of peripheral nerve sheath tumors with pathologic correlation: pictorial review. Eur J Radiol. 2004;52:229-239.

- Murali R, Shaw HM, Lai K, et al. Prognostic factors in cutaneous desmoplastic melanoma: a study of 252 patients. Cancer. 2010; 116:4130-4138.

- Chen LL, Jaimes N, Barker CA, et al. Desmoplastic melanoma: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:825-833.

- de Almeida LS, Requena L, Rutten A, et al. Desmoplastic malignant melanoma: a clinicopathologic analysis of 113 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:207-215.

- Dunne JA, Wormald JC, Steele J, et al. Is sentinel lymph node biopsy warranted for desmoplastic melanoma? a systematic review. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2017;70:274-280.

- Patel TD, Shaigany K, Fang CH, et al. Comparative analysis of head and neck and non-head and neck malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;154:113-120.

- Prudner BC, Ball T, Rathore R, et al. Diagnosis and management of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors: current practice and future perspectives. Neurooncol Adv. 2020;2(suppl 1):I40-I9.

- Bright CJ, Hawkins MM, Winter DL, et al. Risk of soft-tissue sarcoma among 69,460 five-year survivors of childhood cancer in Europe. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110:649-660.

- Schaefer I-M, Fletcher CD, Hornick JL. Loss of H3K27 trimethylation distinguishes malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors from histologic mimics. Mod Pathol. 2016;29:4-13.

- Kolberg M, Holand M, Agesen TH, et al. Survival meta-analyses for >1800 malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor patients with and without neurofibromatosis type 1. Neuro Oncol. 2013;15:135-147.

- Hornick JL, Bundock EA, Fletcher CD. Hybrid schwannoma /perineurioma: clinicopathologic analysis of 42 distinctive benign nerve sheath tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1554-1561.

- Leung KCP, Chan E, Ng HYJ, et al. Novel case of hybrid perineuriomaneurofibroma of the orbit. Can J Ophthalmol. 2019;54:E283-E285.

- Ud Din N, Ahmad Z, Abdul-Ghafar J, et al. Hybrid peripheral nerve sheath tumors: report of five cases and detailed review of literature. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:349. doi:10.1186/s12885-017-3350-1

- Belakhoua SM, Rodriguez FJ. Diagnostic pathology of tumors of peripheral nerve. Neurosurgery. 2021;88:443-456.

- Michal M, Kazakov DV, Michal M. Hybrid peripheral nerve sheath tumors: a review. Cesk Patol. 2017;53:81-88.

- Harder A, Wesemann M, Hagel C, et al. Hybrid neurofibroma /schwannoma is overrepresented among schwannomatosis and neurofibromatosis patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:702-709.

- Bhattacharyya AK, Perrin R, Guha A. Peripheral nerve tumors: management strategies and molecular insights. J Neurooncol. 2004;69:335-349.

- Pytel P, Anthony DC. Peripheral nerves and skeletal muscle. In: Kumar V, Abbas AK, Aster JC, eds. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. 10th ed. Elsevier/Saunders; 2015:1218-1239.

- Strike SA, Puhaindran ME. Nerve tumors of the upper extremity. Clin Plast Surg. 2019;46:347-350.

- Kim DH, Murovic JA, Tiel RL, et al. A series of 397 peripheral neural sheath tumors: 30-year experience at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center. J Neurosurg. 2005;102:246-255.

- Pilavaki M, Chourmouzi D, Kiziridou A, et al. Imaging of peripheral nerve sheath tumors with pathologic correlation: pictorial review. Eur J Radiol. 2004;52:229-239.

- Murali R, Shaw HM, Lai K, et al. Prognostic factors in cutaneous desmoplastic melanoma: a study of 252 patients. Cancer. 2010; 116:4130-4138.

- Chen LL, Jaimes N, Barker CA, et al. Desmoplastic melanoma: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:825-833.

- de Almeida LS, Requena L, Rutten A, et al. Desmoplastic malignant melanoma: a clinicopathologic analysis of 113 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:207-215.

- Dunne JA, Wormald JC, Steele J, et al. Is sentinel lymph node biopsy warranted for desmoplastic melanoma? a systematic review. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2017;70:274-280.

- Patel TD, Shaigany K, Fang CH, et al. Comparative analysis of head and neck and non-head and neck malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;154:113-120.

- Prudner BC, Ball T, Rathore R, et al. Diagnosis and management of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors: current practice and future perspectives. Neurooncol Adv. 2020;2(suppl 1):I40-I9.

- Bright CJ, Hawkins MM, Winter DL, et al. Risk of soft-tissue sarcoma among 69,460 five-year survivors of childhood cancer in Europe. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110:649-660.

- Schaefer I-M, Fletcher CD, Hornick JL. Loss of H3K27 trimethylation distinguishes malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors from histologic mimics. Mod Pathol. 2016;29:4-13.

- Kolberg M, Holand M, Agesen TH, et al. Survival meta-analyses for >1800 malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor patients with and without neurofibromatosis type 1. Neuro Oncol. 2013;15:135-147.

A 50-year-old man presented with a 2.5-cm, subcutaneous, freely mobile nodule on the occipital scalp that first appeared 35 years prior but recently had started enlarging. Histologically the lesion was well circumscribed. Immunohistochemical staining was positive for SRY-box transcription factor 10 in some of the spindle cells, and staining for epithelial membrane antigen was positive in a separate population of intermixed spindle cells.

Scattered Flesh-Colored Papules in a Linear Array in the Setting of Diffuse Skin Thickening

The Diagnosis: Scleromyxedema

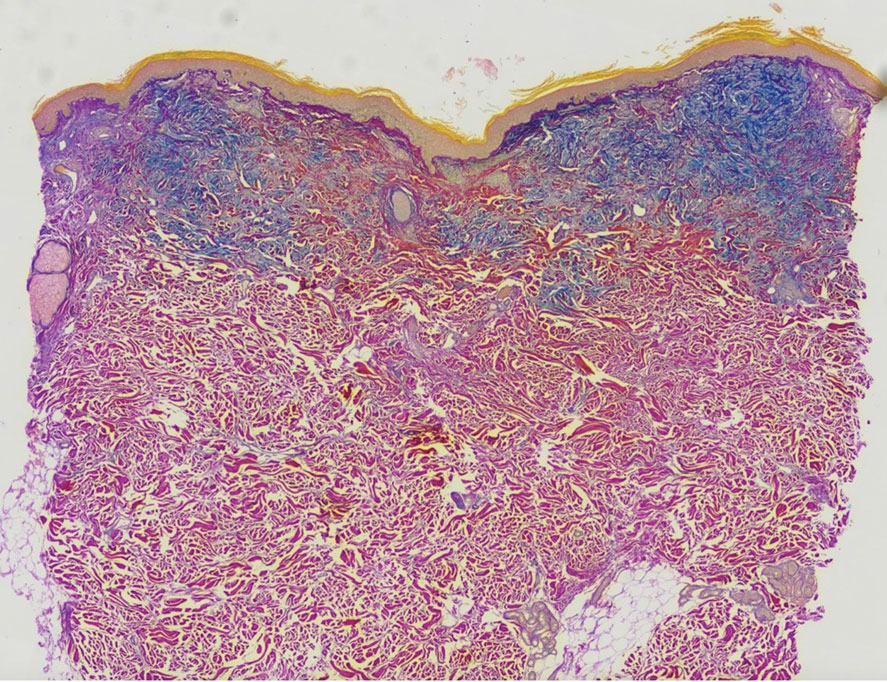

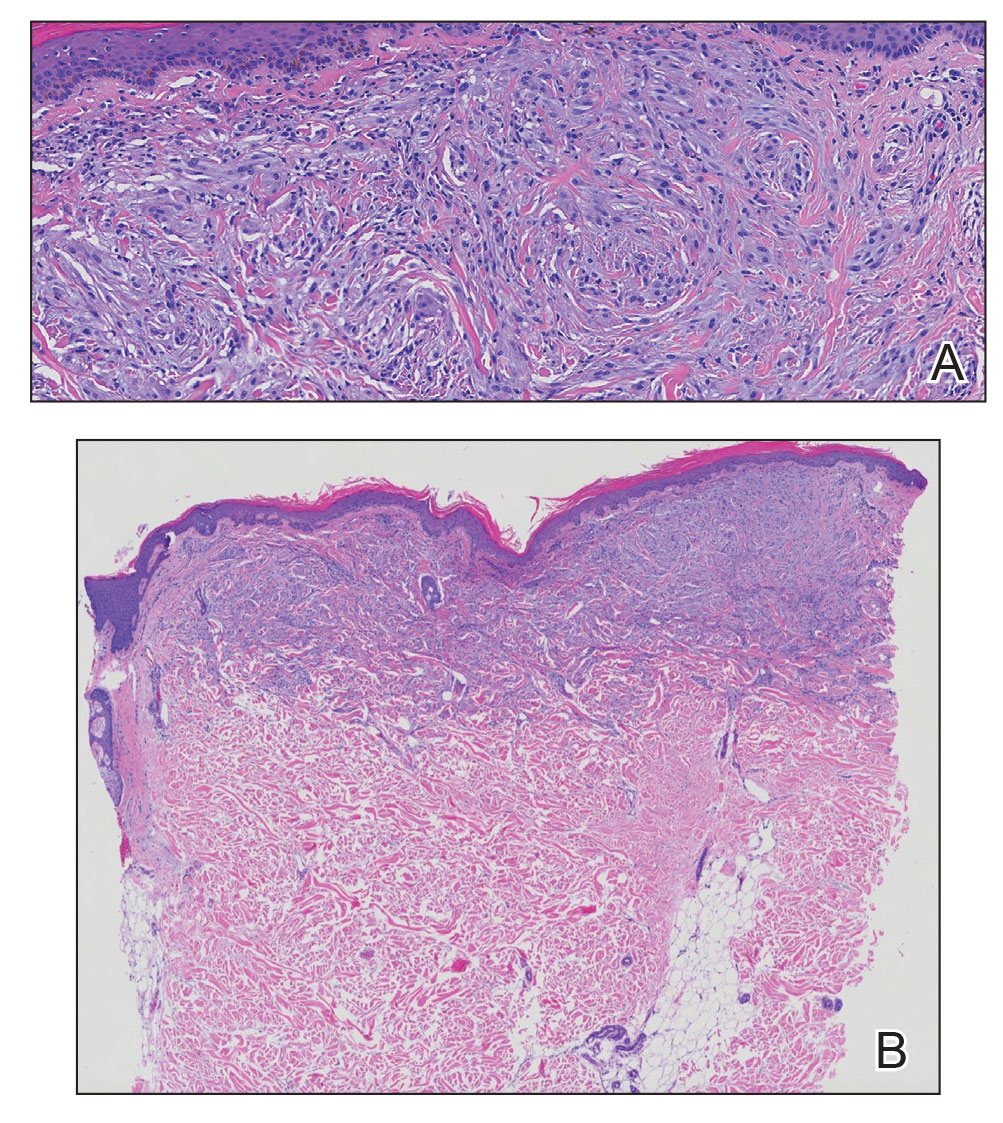

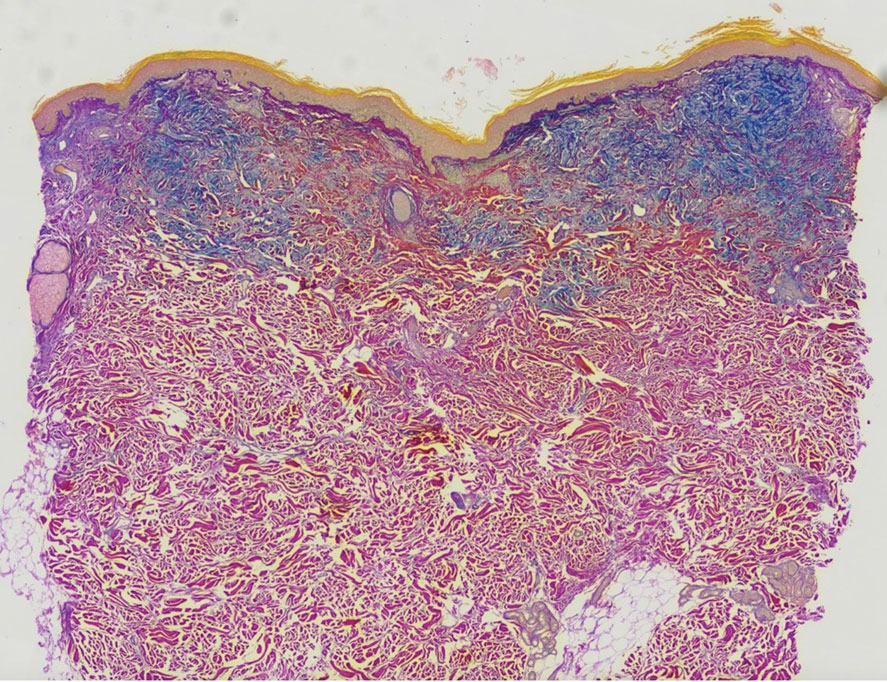

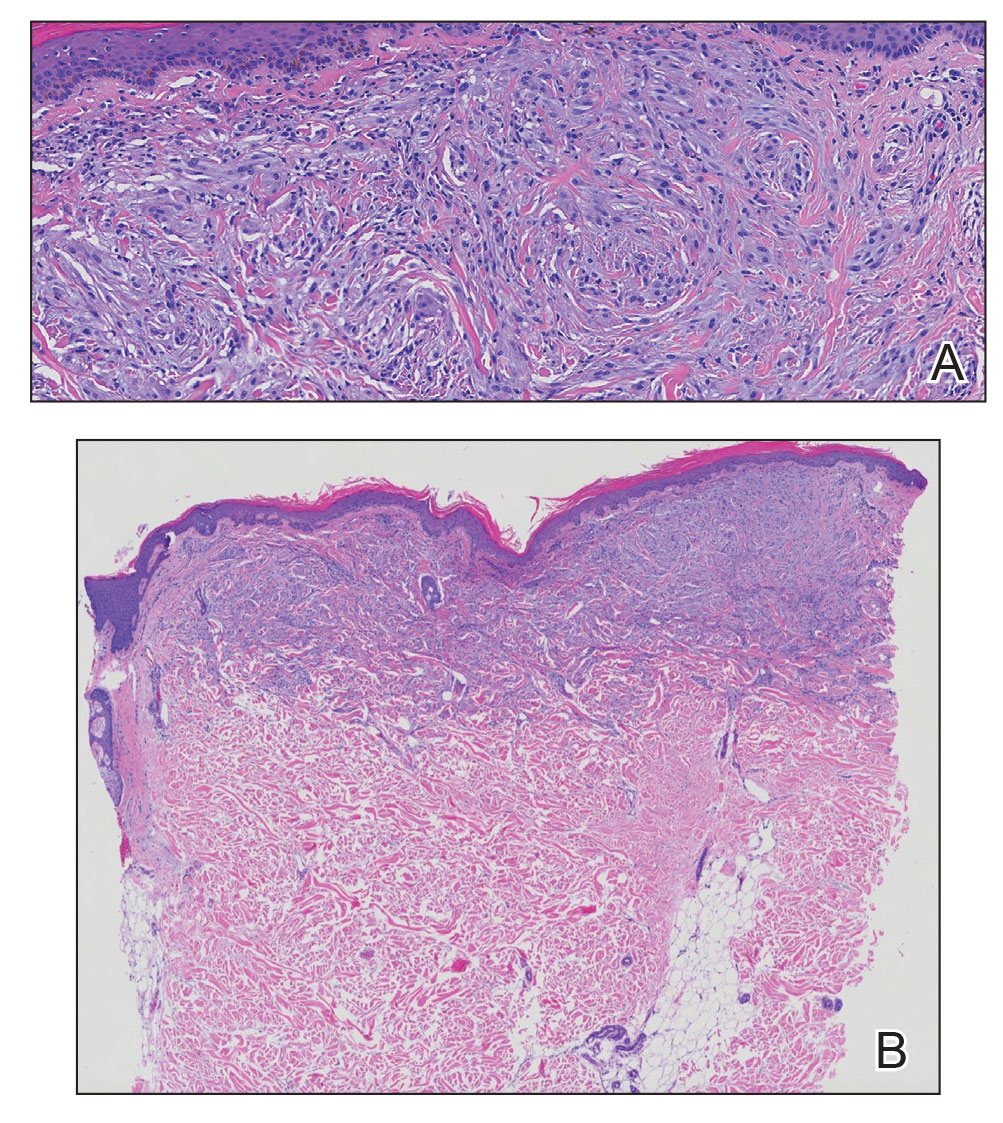

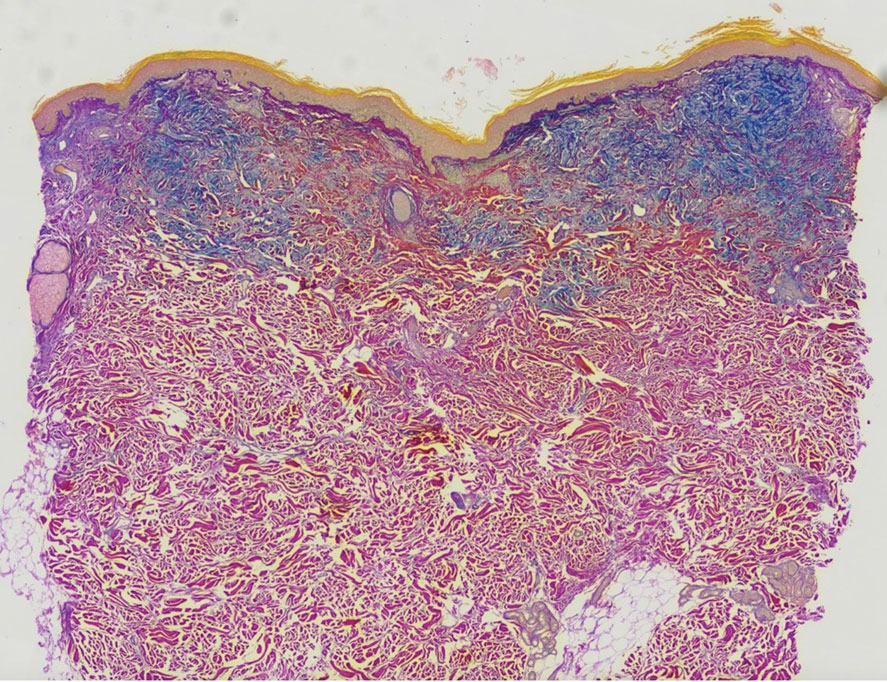

A punch biopsy of the upper back performed at an outside institution revealed increased histiocytes and abundant interstitial mucin confined to the papillary dermis (Figures 1 and 2), consistent with the lichen myxedematosus (LM) papules that may be seen in scleromyxedema. Serum protein electrophoresis revealed the presence of a protein of restricted mobility on the gamma region that occupied 5.3% of the total protein (0.3 g/dL). Urine protein electrophoresis showed free kappa light chain monoclonal protein in the gamma region. Immunofixation electrophoresis revealed the presence of IgG kappa monoclonal protein in the gamma region with 10% monotype kappa cells. The presence of Raynaud phenomenon and positive antinuclear antibody (1:320, speckled) was noted. Laboratory studies for thyroid-stimulating hormone, C-reactive protein, Scl-70 antibody, myositis panel, ribonucleoprotein antibody, Smith antibody, Sjögren syndrome–related antigens A and B antibodies, rheumatoid factor, and RNA polymerase III antibody all were within reference range. Our patient was treated with monthly intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), and he noted substantial improvement in skin findings after 3 months of IVIG.

Localized lichen myxedematosus is a rare idiopathic cutaneous disease that clinically is characterized by waxy indurated papules and histologically is characterized by diffuse mucin deposition and fibroblast proliferation in the upper dermis.1 Scleromyxedema is a diffuse variant of LM in which the papules and plaques of LM are associated with skin thickening involving almost the entire body and associated systemic disease. The exact mechanism of this disease is unknown, but the most widely accepted hypothesis is that immunoglobulins and cytokines contribute to the synthesis of glycosaminoglycans and thereby the deposition of mucin in the dermis.2 Scleromyxedema has a chronic course and generally responds poorly to existing treatments.1 Partial improvement has been demonstrated in treatment with topical calcineurin inhibitors and topical steroids.2

The differential diagnosis in our patient included scleromyxedema, scleredema, scleroderma, LM, and reticular erythematosus mucinosis. He was diagnosed with scleromyxedema with kappa monoclonal gammopathy. Scleromyxedema is a rare disorder involving the deposition of mucinous material in the papillary dermis that causes the formation of infiltrative skin lesions.3 The etiology is unknown, but the presence of a monoclonal protein is an important characteristic of this disorder. It is important to rule out thyroid disease as a possible etiology before concluding that the disease process is driven by the monoclonal gammopathy; this will help determine appropriate therapies.4,5 Usually the monoclonal protein is associated with the IgG lambda subtype. Intravenous immunoglobulin often is considered as a first-line treatment of scleromyxedema and usually is administered at a dosage of 2 g/kg divided over 2 to 5 consecutive days per month.3 Previously, our patient had been treated with IVIG for 3 years for chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy and had stopped 1 to 2 years before his cutaneous symptoms started. Generally, scleromyxedema patients must stay on IVIG long-term to prevent relapse, typically every 6 to 8 weeks. Second-line treatments for scleromyxedema include systemic corticosteroids and thalidomide.6 Scleromyxedema and LM have several clinical and histopathologic features in common. Our patient’s biopsy revealed increased mucin deposition associated with fibroblast proliferation confined to the superficial dermis. These histologic changes can be seen in the setting of either LM or scleromyxedema. Our patient’s diffuse skin thickening and monoclonal gammopathy were more characteristic of scleromyxedema. In contrast, LM is a localized eruption with no internal organ manifestations and no associated systemic disease, such as monoclonal gammopathy and thyroid disease.

Scleredema adultorum of Buschke (also referred to as scleredema) is a rare idiopathic dermatologic condition characterized by thickening and tightening of the skin that leads to firm, nonpitting, woody edema that initially involves the upper back and neck but can spread to the face, scalp, and shoulders; importantly, scleredema spares the hands and feet.7 Scleredema has been associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus, streptococcal upper respiratory tract infections, and monoclonal gammopathy.8 Although our patient did have a monoclonal gammopathy, he also experienced prominent hand involvement with diffuse skin thickening, which is not typical of scleredema. Additionally, biopsy of scleredema would show increased mucin but would not show the proliferation of fibroblasts that was seen in our patient’s biopsy. Furthermore, scleredema has more profound diffuse superficial and deep mucin deposition compared to scleromyxedema. Scleroderma is an autoimmune cutaneous condition that is divided into 2 categories: localized scleroderma and systemic sclerosis (SSc).9 Localized scleroderma (also called morphea) often is characterized by indurated hyperpigmented or hypopigmented lesions. There is an absence of Raynaud phenomenon, telangiectasia, and systemic disease.9 Systemic sclerosis is further divided into 2 categories—limited cutaneous and diffuse cutaneous—which are differentiated by the extent of organ system involvement. Limited cutaneous SSc involves calcinosis, Raynaud phenomenon, esophageal dysmotility, skin sclerosis distal to the elbows and knees, and telangiectasia.9 Diffuse cutaneous SSc is characterized by Raynaud phenomenon; cutaneous sclerosis proximal to the elbows and knees; and fibrosis of the gastrointestinal, pulmonary, renal, and cardiac systems.9 Scl-70 antibodies are specific for diffuse cutaneous SSc, and centromere antibodies are specific for limited cutaneous SSc. Scleromyxedema shares many of the same clinical symptoms as scleroderma; therefore, histopathologic examination is important for differentiating these disorders. Histologically, scleroderma is characterized by thickened collagen bundles associated with a variable degree of perivascular and interstitial lymphoplasmacytic inflammation. No increased dermal mucin is present.9 Our patient did not have the clinical cutaneous features of localized scleroderma and lacked the signs of internal organ involvement that typically are found in SSc. He did have Raynaud phenomenon but did not have matlike telangiectases or Scl-70 or centromere antibodies.

Reticular erythematosus mucinosis (REM) is a rare inflammatory cutaneous disease that is characterized by diffuse reticular erythematous macules or papules that may be asymptomatic or associated with pruritus.10 Reticular erythematosus mucinosis most frequently affects middle-aged women and appears on the trunk.9 Our patient was not part of the demographic group most frequently affected by REM. More importantly, our patient’s lesions were not erythematous or reticular in appearance, making the diagnosis of REM unlikely. Furthermore, REM has no associated cutaneous sclerosis or induration.

- Nofal A, Amer H, Alakad R, et al. Lichen myxedematosus: diagnostic criteria, classification, and severity grading. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:284-290.

- Christman MP, Sukhdeo K, Kim RH, et al. Papular mucinosis, or localized lichen myxedematosus (LM)(discrete papular type). Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:8.

- Haber R, Bachour J, El Gemayel M. Scleromyxedema treatment: a systematic review and update. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:1191-1201.

- Hazan E, Griffin TD Jr, Jabbour SA, et al. Scleromyxedema in a patient with thyroid disease: an atypical case or a case for revised criteria? Cutis. 2020;105:E6-E10.

- Shenoy A, Steixner J, Beltrani V, et al. Discrete papular lichen myxedematosus and scleromyxedema with hypothyroidism: a report of two cases. Case Rep Dermatol. 2019;11:64-70.

- Hoffman JHO, Enk AH. Scleromyxedema. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2020;18:1449-1467.

- Beers WH, Ince AI, Moore TL. Scleredema adultorum of Buschke: a case report and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006;35:355-359.

- Miguel D, Schliemann S, Elsner P. Treatment of scleroderma adultorum Buschke: a systematic review. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98:305-309.

- Rongioletti F, Ferreli C, Atzori L, et al. Scleroderma with an update about clinicopathological correlation. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2018;153:208-215.

- Ocanha-Xavier JP, Cola-Senra CO, Xavier-Junior JCC. Reticular erythematous mucinosis: literature review and case report of a 24-year-old patient with systemic erythematosus lupus. Lupus. 2021;30:325-335.

The Diagnosis: Scleromyxedema

A punch biopsy of the upper back performed at an outside institution revealed increased histiocytes and abundant interstitial mucin confined to the papillary dermis (Figures 1 and 2), consistent with the lichen myxedematosus (LM) papules that may be seen in scleromyxedema. Serum protein electrophoresis revealed the presence of a protein of restricted mobility on the gamma region that occupied 5.3% of the total protein (0.3 g/dL). Urine protein electrophoresis showed free kappa light chain monoclonal protein in the gamma region. Immunofixation electrophoresis revealed the presence of IgG kappa monoclonal protein in the gamma region with 10% monotype kappa cells. The presence of Raynaud phenomenon and positive antinuclear antibody (1:320, speckled) was noted. Laboratory studies for thyroid-stimulating hormone, C-reactive protein, Scl-70 antibody, myositis panel, ribonucleoprotein antibody, Smith antibody, Sjögren syndrome–related antigens A and B antibodies, rheumatoid factor, and RNA polymerase III antibody all were within reference range. Our patient was treated with monthly intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), and he noted substantial improvement in skin findings after 3 months of IVIG.

Localized lichen myxedematosus is a rare idiopathic cutaneous disease that clinically is characterized by waxy indurated papules and histologically is characterized by diffuse mucin deposition and fibroblast proliferation in the upper dermis.1 Scleromyxedema is a diffuse variant of LM in which the papules and plaques of LM are associated with skin thickening involving almost the entire body and associated systemic disease. The exact mechanism of this disease is unknown, but the most widely accepted hypothesis is that immunoglobulins and cytokines contribute to the synthesis of glycosaminoglycans and thereby the deposition of mucin in the dermis.2 Scleromyxedema has a chronic course and generally responds poorly to existing treatments.1 Partial improvement has been demonstrated in treatment with topical calcineurin inhibitors and topical steroids.2

The differential diagnosis in our patient included scleromyxedema, scleredema, scleroderma, LM, and reticular erythematosus mucinosis. He was diagnosed with scleromyxedema with kappa monoclonal gammopathy. Scleromyxedema is a rare disorder involving the deposition of mucinous material in the papillary dermis that causes the formation of infiltrative skin lesions.3 The etiology is unknown, but the presence of a monoclonal protein is an important characteristic of this disorder. It is important to rule out thyroid disease as a possible etiology before concluding that the disease process is driven by the monoclonal gammopathy; this will help determine appropriate therapies.4,5 Usually the monoclonal protein is associated with the IgG lambda subtype. Intravenous immunoglobulin often is considered as a first-line treatment of scleromyxedema and usually is administered at a dosage of 2 g/kg divided over 2 to 5 consecutive days per month.3 Previously, our patient had been treated with IVIG for 3 years for chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy and had stopped 1 to 2 years before his cutaneous symptoms started. Generally, scleromyxedema patients must stay on IVIG long-term to prevent relapse, typically every 6 to 8 weeks. Second-line treatments for scleromyxedema include systemic corticosteroids and thalidomide.6 Scleromyxedema and LM have several clinical and histopathologic features in common. Our patient’s biopsy revealed increased mucin deposition associated with fibroblast proliferation confined to the superficial dermis. These histologic changes can be seen in the setting of either LM or scleromyxedema. Our patient’s diffuse skin thickening and monoclonal gammopathy were more characteristic of scleromyxedema. In contrast, LM is a localized eruption with no internal organ manifestations and no associated systemic disease, such as monoclonal gammopathy and thyroid disease.

Scleredema adultorum of Buschke (also referred to as scleredema) is a rare idiopathic dermatologic condition characterized by thickening and tightening of the skin that leads to firm, nonpitting, woody edema that initially involves the upper back and neck but can spread to the face, scalp, and shoulders; importantly, scleredema spares the hands and feet.7 Scleredema has been associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus, streptococcal upper respiratory tract infections, and monoclonal gammopathy.8 Although our patient did have a monoclonal gammopathy, he also experienced prominent hand involvement with diffuse skin thickening, which is not typical of scleredema. Additionally, biopsy of scleredema would show increased mucin but would not show the proliferation of fibroblasts that was seen in our patient’s biopsy. Furthermore, scleredema has more profound diffuse superficial and deep mucin deposition compared to scleromyxedema. Scleroderma is an autoimmune cutaneous condition that is divided into 2 categories: localized scleroderma and systemic sclerosis (SSc).9 Localized scleroderma (also called morphea) often is characterized by indurated hyperpigmented or hypopigmented lesions. There is an absence of Raynaud phenomenon, telangiectasia, and systemic disease.9 Systemic sclerosis is further divided into 2 categories—limited cutaneous and diffuse cutaneous—which are differentiated by the extent of organ system involvement. Limited cutaneous SSc involves calcinosis, Raynaud phenomenon, esophageal dysmotility, skin sclerosis distal to the elbows and knees, and telangiectasia.9 Diffuse cutaneous SSc is characterized by Raynaud phenomenon; cutaneous sclerosis proximal to the elbows and knees; and fibrosis of the gastrointestinal, pulmonary, renal, and cardiac systems.9 Scl-70 antibodies are specific for diffuse cutaneous SSc, and centromere antibodies are specific for limited cutaneous SSc. Scleromyxedema shares many of the same clinical symptoms as scleroderma; therefore, histopathologic examination is important for differentiating these disorders. Histologically, scleroderma is characterized by thickened collagen bundles associated with a variable degree of perivascular and interstitial lymphoplasmacytic inflammation. No increased dermal mucin is present.9 Our patient did not have the clinical cutaneous features of localized scleroderma and lacked the signs of internal organ involvement that typically are found in SSc. He did have Raynaud phenomenon but did not have matlike telangiectases or Scl-70 or centromere antibodies.

Reticular erythematosus mucinosis (REM) is a rare inflammatory cutaneous disease that is characterized by diffuse reticular erythematous macules or papules that may be asymptomatic or associated with pruritus.10 Reticular erythematosus mucinosis most frequently affects middle-aged women and appears on the trunk.9 Our patient was not part of the demographic group most frequently affected by REM. More importantly, our patient’s lesions were not erythematous or reticular in appearance, making the diagnosis of REM unlikely. Furthermore, REM has no associated cutaneous sclerosis or induration.

The Diagnosis: Scleromyxedema

A punch biopsy of the upper back performed at an outside institution revealed increased histiocytes and abundant interstitial mucin confined to the papillary dermis (Figures 1 and 2), consistent with the lichen myxedematosus (LM) papules that may be seen in scleromyxedema. Serum protein electrophoresis revealed the presence of a protein of restricted mobility on the gamma region that occupied 5.3% of the total protein (0.3 g/dL). Urine protein electrophoresis showed free kappa light chain monoclonal protein in the gamma region. Immunofixation electrophoresis revealed the presence of IgG kappa monoclonal protein in the gamma region with 10% monotype kappa cells. The presence of Raynaud phenomenon and positive antinuclear antibody (1:320, speckled) was noted. Laboratory studies for thyroid-stimulating hormone, C-reactive protein, Scl-70 antibody, myositis panel, ribonucleoprotein antibody, Smith antibody, Sjögren syndrome–related antigens A and B antibodies, rheumatoid factor, and RNA polymerase III antibody all were within reference range. Our patient was treated with monthly intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), and he noted substantial improvement in skin findings after 3 months of IVIG.

Localized lichen myxedematosus is a rare idiopathic cutaneous disease that clinically is characterized by waxy indurated papules and histologically is characterized by diffuse mucin deposition and fibroblast proliferation in the upper dermis.1 Scleromyxedema is a diffuse variant of LM in which the papules and plaques of LM are associated with skin thickening involving almost the entire body and associated systemic disease. The exact mechanism of this disease is unknown, but the most widely accepted hypothesis is that immunoglobulins and cytokines contribute to the synthesis of glycosaminoglycans and thereby the deposition of mucin in the dermis.2 Scleromyxedema has a chronic course and generally responds poorly to existing treatments.1 Partial improvement has been demonstrated in treatment with topical calcineurin inhibitors and topical steroids.2

The differential diagnosis in our patient included scleromyxedema, scleredema, scleroderma, LM, and reticular erythematosus mucinosis. He was diagnosed with scleromyxedema with kappa monoclonal gammopathy. Scleromyxedema is a rare disorder involving the deposition of mucinous material in the papillary dermis that causes the formation of infiltrative skin lesions.3 The etiology is unknown, but the presence of a monoclonal protein is an important characteristic of this disorder. It is important to rule out thyroid disease as a possible etiology before concluding that the disease process is driven by the monoclonal gammopathy; this will help determine appropriate therapies.4,5 Usually the monoclonal protein is associated with the IgG lambda subtype. Intravenous immunoglobulin often is considered as a first-line treatment of scleromyxedema and usually is administered at a dosage of 2 g/kg divided over 2 to 5 consecutive days per month.3 Previously, our patient had been treated with IVIG for 3 years for chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy and had stopped 1 to 2 years before his cutaneous symptoms started. Generally, scleromyxedema patients must stay on IVIG long-term to prevent relapse, typically every 6 to 8 weeks. Second-line treatments for scleromyxedema include systemic corticosteroids and thalidomide.6 Scleromyxedema and LM have several clinical and histopathologic features in common. Our patient’s biopsy revealed increased mucin deposition associated with fibroblast proliferation confined to the superficial dermis. These histologic changes can be seen in the setting of either LM or scleromyxedema. Our patient’s diffuse skin thickening and monoclonal gammopathy were more characteristic of scleromyxedema. In contrast, LM is a localized eruption with no internal organ manifestations and no associated systemic disease, such as monoclonal gammopathy and thyroid disease.

Scleredema adultorum of Buschke (also referred to as scleredema) is a rare idiopathic dermatologic condition characterized by thickening and tightening of the skin that leads to firm, nonpitting, woody edema that initially involves the upper back and neck but can spread to the face, scalp, and shoulders; importantly, scleredema spares the hands and feet.7 Scleredema has been associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus, streptococcal upper respiratory tract infections, and monoclonal gammopathy.8 Although our patient did have a monoclonal gammopathy, he also experienced prominent hand involvement with diffuse skin thickening, which is not typical of scleredema. Additionally, biopsy of scleredema would show increased mucin but would not show the proliferation of fibroblasts that was seen in our patient’s biopsy. Furthermore, scleredema has more profound diffuse superficial and deep mucin deposition compared to scleromyxedema. Scleroderma is an autoimmune cutaneous condition that is divided into 2 categories: localized scleroderma and systemic sclerosis (SSc).9 Localized scleroderma (also called morphea) often is characterized by indurated hyperpigmented or hypopigmented lesions. There is an absence of Raynaud phenomenon, telangiectasia, and systemic disease.9 Systemic sclerosis is further divided into 2 categories—limited cutaneous and diffuse cutaneous—which are differentiated by the extent of organ system involvement. Limited cutaneous SSc involves calcinosis, Raynaud phenomenon, esophageal dysmotility, skin sclerosis distal to the elbows and knees, and telangiectasia.9 Diffuse cutaneous SSc is characterized by Raynaud phenomenon; cutaneous sclerosis proximal to the elbows and knees; and fibrosis of the gastrointestinal, pulmonary, renal, and cardiac systems.9 Scl-70 antibodies are specific for diffuse cutaneous SSc, and centromere antibodies are specific for limited cutaneous SSc. Scleromyxedema shares many of the same clinical symptoms as scleroderma; therefore, histopathologic examination is important for differentiating these disorders. Histologically, scleroderma is characterized by thickened collagen bundles associated with a variable degree of perivascular and interstitial lymphoplasmacytic inflammation. No increased dermal mucin is present.9 Our patient did not have the clinical cutaneous features of localized scleroderma and lacked the signs of internal organ involvement that typically are found in SSc. He did have Raynaud phenomenon but did not have matlike telangiectases or Scl-70 or centromere antibodies.

Reticular erythematosus mucinosis (REM) is a rare inflammatory cutaneous disease that is characterized by diffuse reticular erythematous macules or papules that may be asymptomatic or associated with pruritus.10 Reticular erythematosus mucinosis most frequently affects middle-aged women and appears on the trunk.9 Our patient was not part of the demographic group most frequently affected by REM. More importantly, our patient’s lesions were not erythematous or reticular in appearance, making the diagnosis of REM unlikely. Furthermore, REM has no associated cutaneous sclerosis or induration.

- Nofal A, Amer H, Alakad R, et al. Lichen myxedematosus: diagnostic criteria, classification, and severity grading. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:284-290.

- Christman MP, Sukhdeo K, Kim RH, et al. Papular mucinosis, or localized lichen myxedematosus (LM)(discrete papular type). Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:8.

- Haber R, Bachour J, El Gemayel M. Scleromyxedema treatment: a systematic review and update. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:1191-1201.

- Hazan E, Griffin TD Jr, Jabbour SA, et al. Scleromyxedema in a patient with thyroid disease: an atypical case or a case for revised criteria? Cutis. 2020;105:E6-E10.

- Shenoy A, Steixner J, Beltrani V, et al. Discrete papular lichen myxedematosus and scleromyxedema with hypothyroidism: a report of two cases. Case Rep Dermatol. 2019;11:64-70.

- Hoffman JHO, Enk AH. Scleromyxedema. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2020;18:1449-1467.

- Beers WH, Ince AI, Moore TL. Scleredema adultorum of Buschke: a case report and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006;35:355-359.

- Miguel D, Schliemann S, Elsner P. Treatment of scleroderma adultorum Buschke: a systematic review. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98:305-309.

- Rongioletti F, Ferreli C, Atzori L, et al. Scleroderma with an update about clinicopathological correlation. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2018;153:208-215.

- Ocanha-Xavier JP, Cola-Senra CO, Xavier-Junior JCC. Reticular erythematous mucinosis: literature review and case report of a 24-year-old patient with systemic erythematosus lupus. Lupus. 2021;30:325-335.

- Nofal A, Amer H, Alakad R, et al. Lichen myxedematosus: diagnostic criteria, classification, and severity grading. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:284-290.

- Christman MP, Sukhdeo K, Kim RH, et al. Papular mucinosis, or localized lichen myxedematosus (LM)(discrete papular type). Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:8.

- Haber R, Bachour J, El Gemayel M. Scleromyxedema treatment: a systematic review and update. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:1191-1201.

- Hazan E, Griffin TD Jr, Jabbour SA, et al. Scleromyxedema in a patient with thyroid disease: an atypical case or a case for revised criteria? Cutis. 2020;105:E6-E10.

- Shenoy A, Steixner J, Beltrani V, et al. Discrete papular lichen myxedematosus and scleromyxedema with hypothyroidism: a report of two cases. Case Rep Dermatol. 2019;11:64-70.

- Hoffman JHO, Enk AH. Scleromyxedema. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2020;18:1449-1467.

- Beers WH, Ince AI, Moore TL. Scleredema adultorum of Buschke: a case report and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006;35:355-359.

- Miguel D, Schliemann S, Elsner P. Treatment of scleroderma adultorum Buschke: a systematic review. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98:305-309.

- Rongioletti F, Ferreli C, Atzori L, et al. Scleroderma with an update about clinicopathological correlation. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2018;153:208-215.

- Ocanha-Xavier JP, Cola-Senra CO, Xavier-Junior JCC. Reticular erythematous mucinosis: literature review and case report of a 24-year-old patient with systemic erythematosus lupus. Lupus. 2021;30:325-335.

A 76-year-old man presented to our clinic with diffusely thickened and tightened skin that worsened over the course of 1 year, as well as numerous scattered small, firm, flesh-colored papules arranged in a linear pattern over the face, ears, neck, chest, abdomen, arms, hands, and knees. His symptoms progressed to include substantial skin thickening initially over the thighs followed by the arms, chest, back (top), and face. He developed confluent cobblestonelike plaques over the elbows and hands (bottom) and eventually developed decreased oral aperture limiting oral intake as well as decreased range of motion in the hands. The patient had a deep furrowed appearance of the brow accompanied by discrete, scattered, flesh-colored papules on the forehead and behind the ears. Deep furrows also were present on the back. When the proximal interphalangeal joints of the hands were extended, elevated rings with central depression were seen instead of horizontal folds.