User login

Hepatitis vaccination update

One of the most important commitments family physicians can undertake in protecting the health of their patients and communities is to ensure that their patients are fully vaccinated. This task is increasingly complicated as new vaccines are approved every year and recommendations change regarding new and established vaccines. To assist primary care providers, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) annually updates 2 immunization schedules—one for children and adolescents, and one for adults. These schedules are available on the CDC Web site (https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/index.html).

These updates originate from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), which meets 3 times a year to consider and adopt changes to the schedules. During 2018, relatively few new recommendations were adopted. The September 2018 Practice Alert1 in this journal covered the updated recommendations for influenza immunization, which included reinstating live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) to the active list of influenza vaccines.

This current Practice Alert reviews 3 additional updates: 1) a new hepatitis B (HepB) vaccine; 2) updated recommendations for the use of hepatitis A (HepA) vaccine for post-exposure prevention and before travel; and 3) inclusion of the homeless among those who should be routinely vaccinated with HepA vaccine.

Hepatitis B: New 2-dose product

As of 2015, the annual incidence of new hepatitis B cases had declined by 88.5% since the first HepB vaccine was licensed in 1981 and recommendations for its routine use were issued in 1982.2 The HepB vaccine products available in the United States are 2 single-antigen products, Engerix-B (GlaxoSmithKline) and Recombivax HB (Merck & Co.). Both can be used in all age groups, starting at birth, in a 3-dose series. HepB vaccine is also available in 2 combination products: Pediarix, containing HepB, diphtheria and tetanus toxoids, acellular pertussis, and inactivated poliovirus (GlaxoSmithKline), approved for use in children 6 weeks to 6 years old; and Twinrix (GlaxoSmithKline), which contains both HepB and HepA and is approved for use in adults 18 years and older.

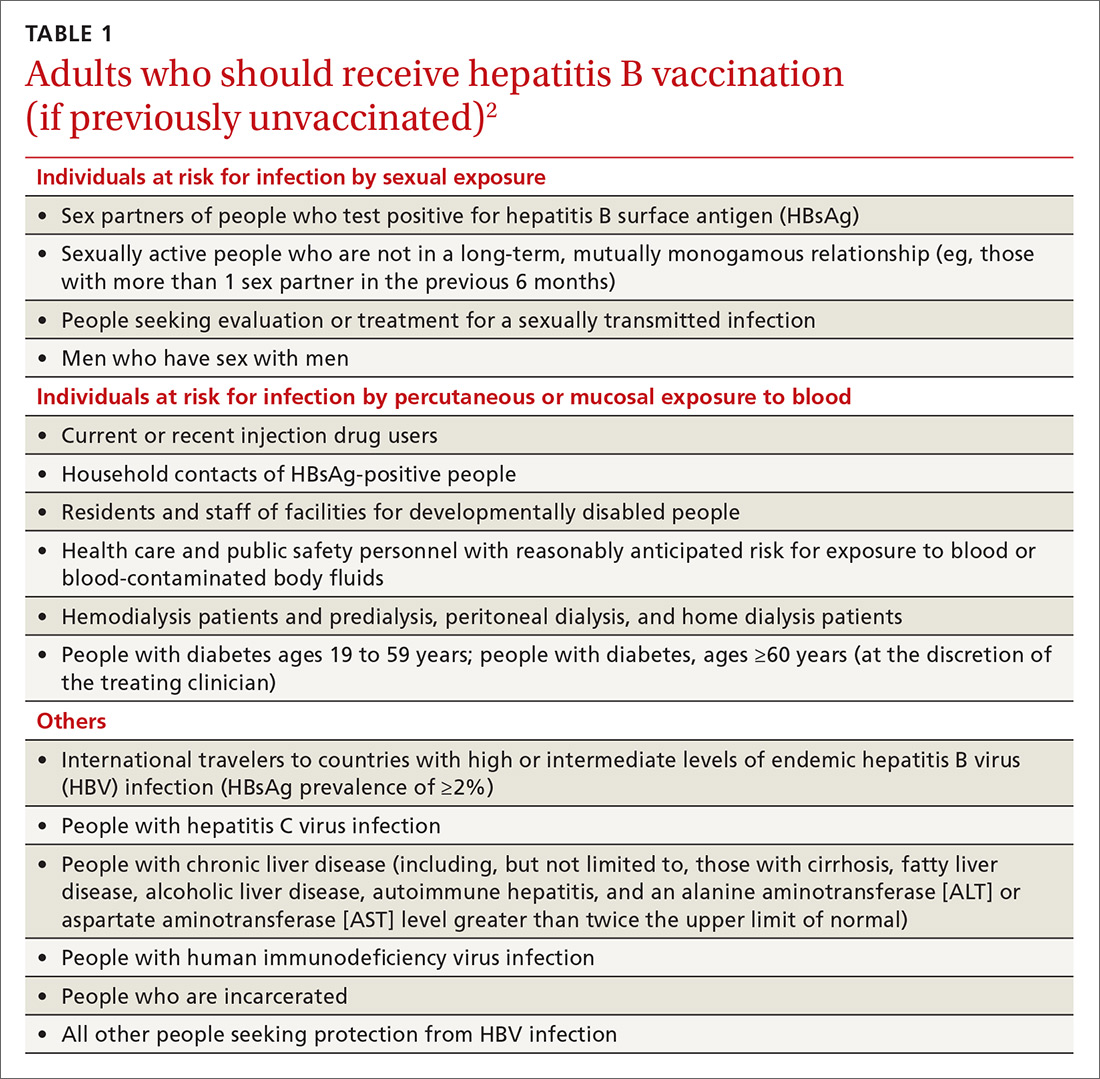

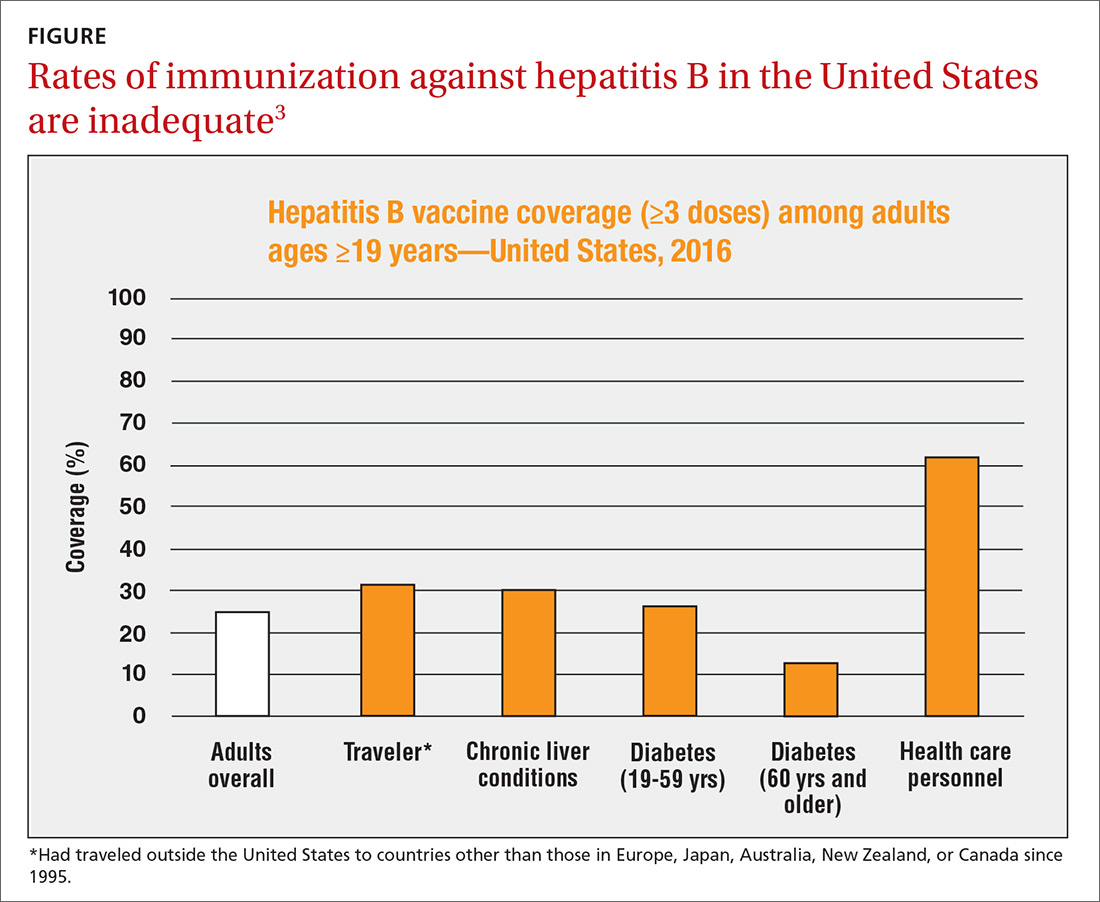

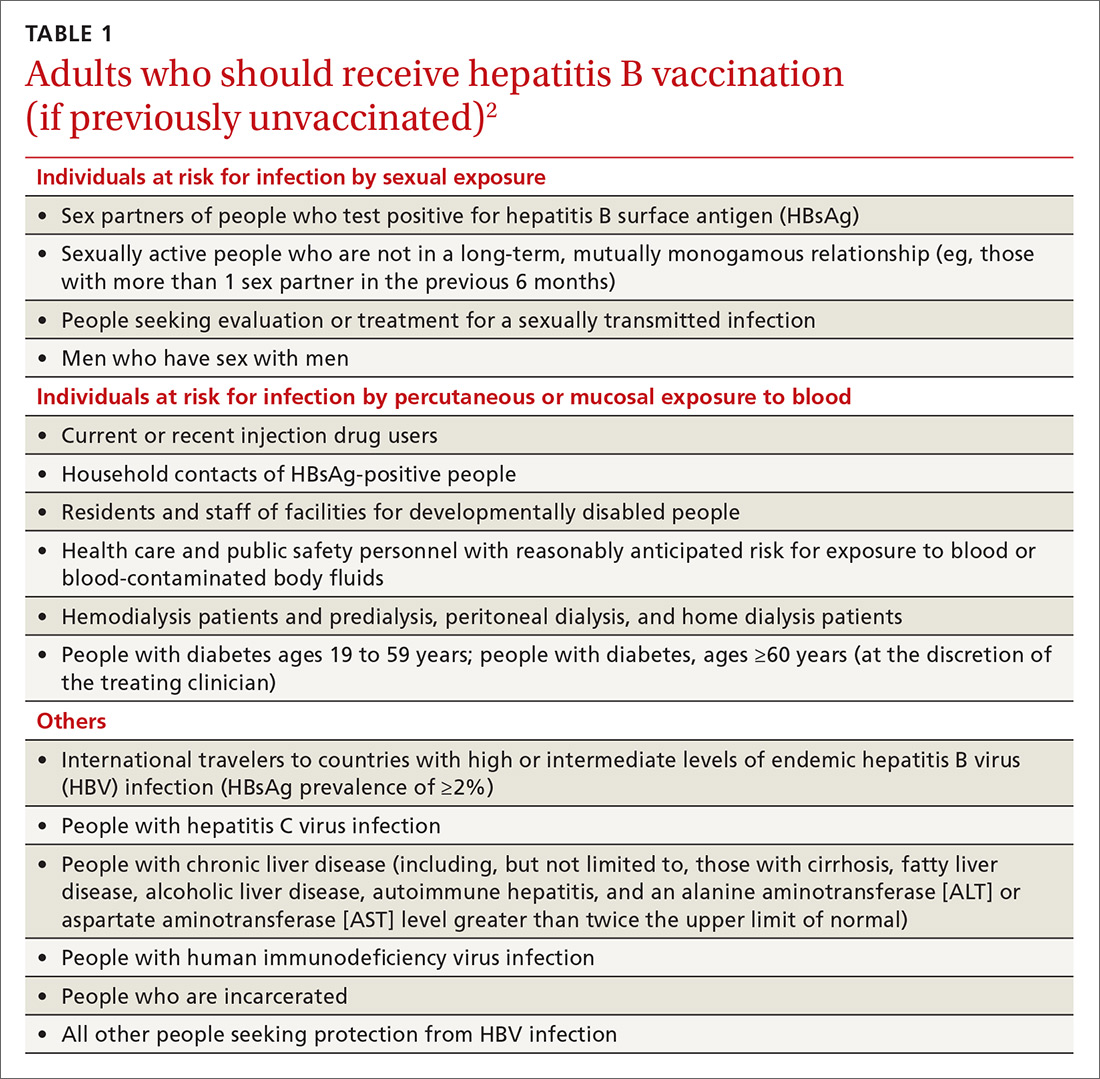

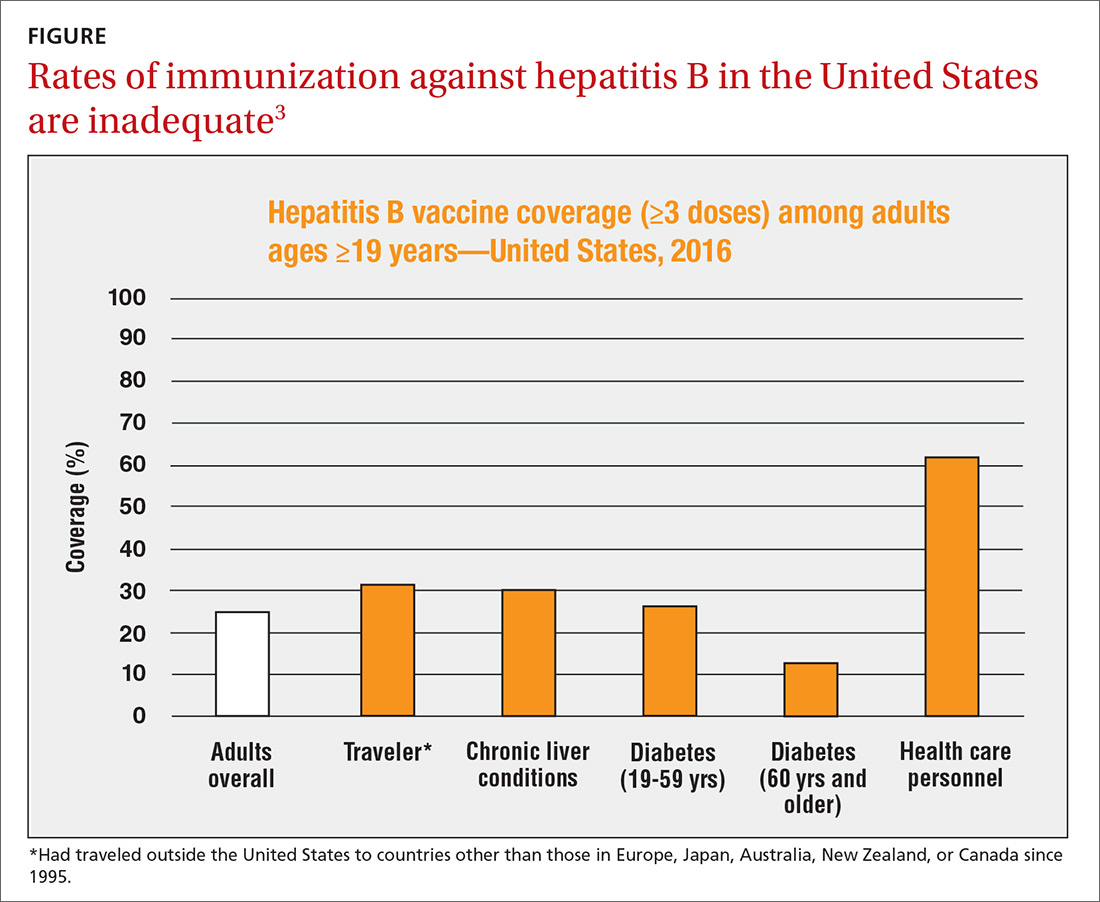

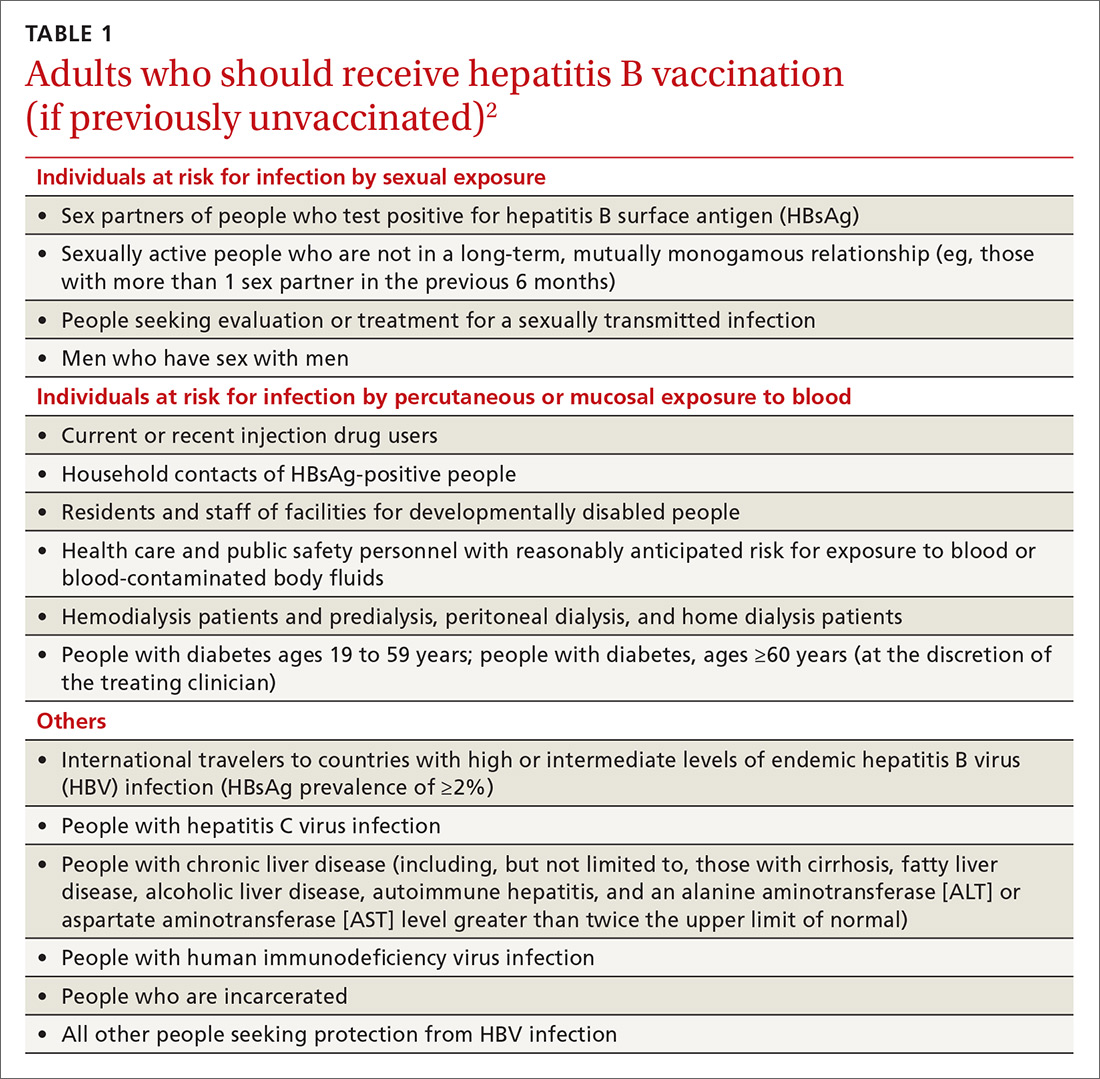

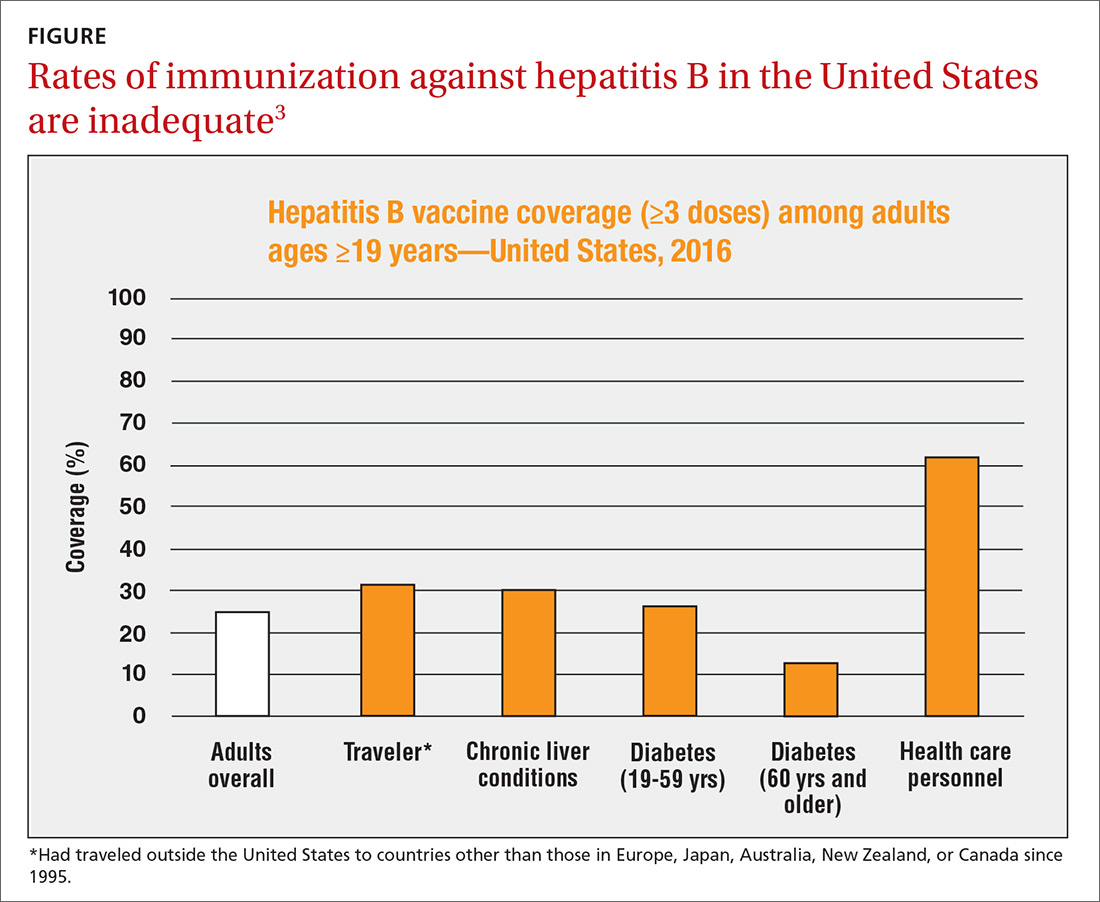

The HepB vaccine is recommended for all children and unvaccinated adolescents as part of the routine vaccination schedule. It is also recommended for unvaccinated adults with specific risks (TABLE 12). However, the rate of HepB vaccination in adults for whom it is recommended is suboptimal (FIGURE),3 and just a little more than half of adults who start a 3-dose series of HepB complete it.4A new vaccine against hepatitis B, HEPLISAV-B (Dynavax Technologies), was licensed by the US Food and Drug Administration in late 2017. ACIP now recommends it as an option along with other available HepB products. HEPLISAV-B is given in 2 doses separated by 1 month. It is hoped that this shortened 2-dose series will increase the number of adults who achieve full vaccination. In addition, it appears that HEPLISAV-B provides higher levels of protection in some high-risk groups—those with type 2 diabetes or chronic kidney disease.3 However, initial safety studies have shown a small absolute increase in cardiac events after vaccination with HEPLISAV-B. Post-marketing surveillance will be needed to show whether this is causal or coincidental.3

As with other HepB products, use of HEPLISAV-B should follow the latest CDC directives on who to test serologically for prior immunity, and on post-vaccination testing to ensure protective antibody levels were achieved.2 It is best to complete a HepB series with the same product, but, if necessary, a combination of products at different doses can be used to complete the HepB series. Any such combination should include 3 doses, even if one of the doses is HEPLISAV-B.

Hepatitis A: Vaccination assumes greater importance for more people

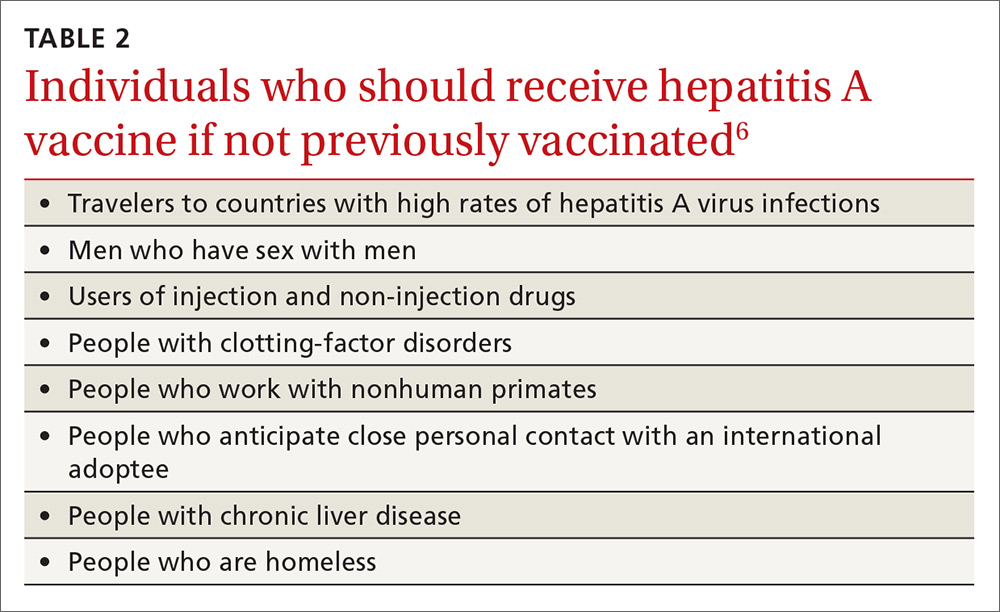

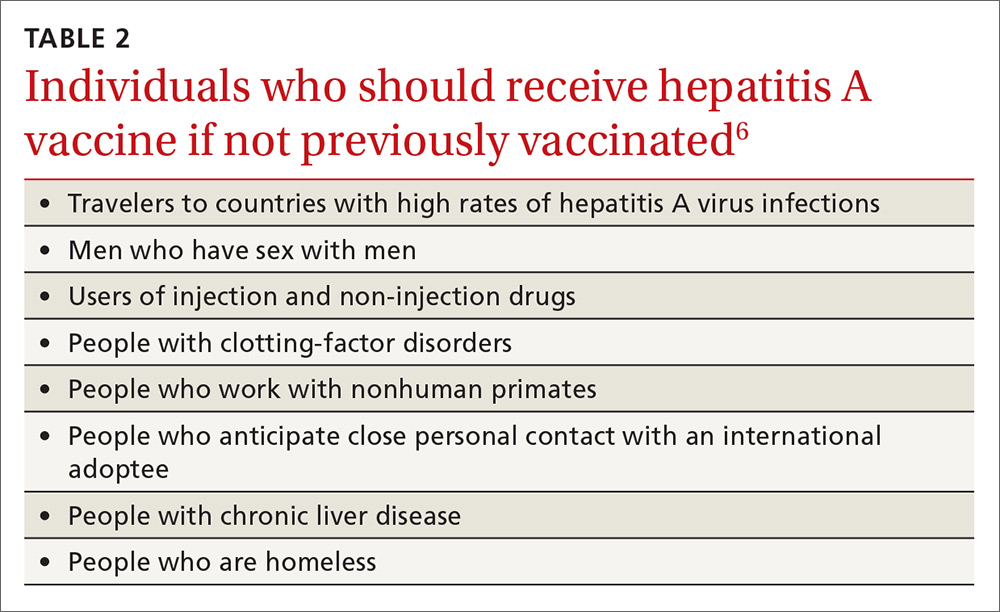

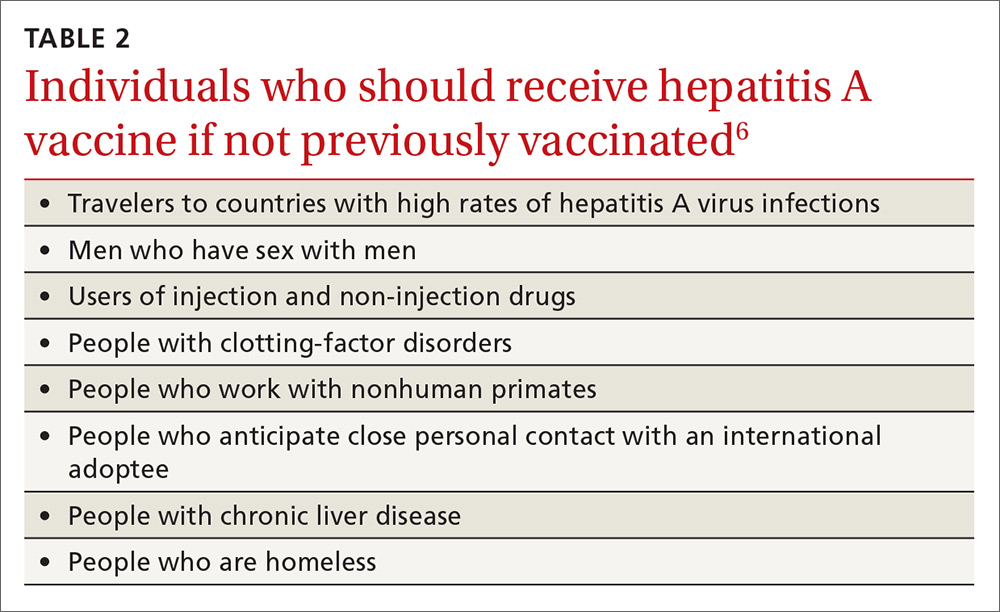

A Practice Alert in early 2018 described a series of outbreaks of hepatitis A around the country and the high rates of associated hospitalizations.5 These outbreaks have occurred primarily among the homeless and their contacts and those who use illicit drugs. This nationwide outbreak has now spread, resulting in more than 7500 cases since July 1, 2016.6 The progress of this epidemic can be viewed on the CDC Web site

Continue to: Remember that the current recommendation...

Remember that the current recommendation is to vaccinate all children 12 to 23 months old with HepA, in 2 separate doses. Two single-antigen HepA products are available: Havrix (GSK) and Vaqta (Merck). For the 2-dose sequence, Havrix is given at 0 and 6 to 12 months; Vaqta at 0 and 6 to 18 months. Even a single dose will provide protection for up to 11 years. In addition to these vaccines, there is the combination HepA and HepB vaccine (Twinrix) mentioned earlier.

Previous recommendations for preventing hepatitis A after exposure, made in 2007, stated that HepA vaccine was preferred for healthy individuals ages 12 months through 40 years, while immune globulin (IG) was preferred for adults older than 40, infants before their first birthday, immunocompromised individuals, those with chronic liver disease, and those for whom HepA vaccine is contraindicated.8 The 2007 recommendations also advised vaccinating individuals traveling to countries with intermediate to high hepatitis A endemicity.

A single dose of HepA vaccine was recommended for all those 12 months or older, although older adults, immunocompromised individuals, and those with chronic liver disease or other chronic medical conditions planning to visit an endemic area in ≤ 2 weeks were supposed to receive the initial dose of vaccine and could also receive IG (0.02 mL/kg) if their provider advised it. Travelers who declined vaccination, those younger than 12 months, or those allergic to a vaccine component could receive a single dose of IG (0.02 mL/kg), which provides protection up to 3 months.

Several factors influenced ACIP to reconsider both the pre- and post-exposure recommendations. Regarding IG, evidence of its decreased potency over time led the committee to increase the recommended dose (see below). IG also must be re-administered every 2 months, the supply of the product is questionable, and many health care facilities do not stock it. By comparison, HepA vaccine offers the advantages of easier administration, inducing active immunity, and providing longer protection. Another issue involved infants ages 6 to 11 months traveling to an area with endemic measles transmission and who must therefore receive the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine. MMR and IG should not be co-administered, and, for infants, the health risk from measles outweighs that from hepatitis A.

Updated recommendations. After considering all this information, ACIP made the following changes to its hepatitis A virus (HAV) prevention recommendations (in addition to adding homeless people to the list of HepA vaccine recipients)9:

- Administer HepA vaccine as post-exposure prophylaxis to all individuals 12 months and older.

- IG may be administered, in addition to HepA vaccine, to those older than 40 years, depending on the provider’s risk assessment (degree of exposure and medical conditions that might lead to severe complications from HAV infection). The recommended IG dose is now 0.1 mL/kg for post-exposure prevention; it is 0.1 to 0.2 mL/kg for pre-exposure prophylaxis for travelers, depending on the length of planned travel.

- Administer HepA vaccine alone to infants ages 6 to 11 months traveling outside the United States when protection against hepatitis A is recommended.

These recommendations have been published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.9

1. Campos-Outcalt D. CDC recommendations for the 2018-2019 influenza season. J Fam Pract. 2018;67:550-553.

2. Schillie S, Vellozzi C, Reingold A, et al. Prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2018;67:1-31.

3. CDC. Schillie S. HEPLISAV-B: considerations and proposed recommendations, vote. Presented at: meeting of the Hepatitis Work Group, Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; February 21, 2018; Atlanta, Ga. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2018-02/Hepatitis-03-Schillie-508.pdf. Accessed January 19, 2019.

4. Nelson JC, Bittner RC, Bounds L, et al. Compliance with multiple-dose vaccine schedules among older children, adolescents, and adults: results from a vaccine safety datalink study. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(Suppl 2):S389-S397.

5. Campos-Outcalt D. CDC provides advice on recent hepatitis A outbreaks. J Fam Pract. 2018;67:30-32.

6. CDC. Nelson N. Background – hepatitis A among the homeless. Presented at: meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; October 24, 2018; Atlanta, Ga. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2018-10/Hepatitis-02-Nelson-508.pdf. Accessed January 19, 2019.

7. CDC. 2017 – Outbreaks of hepatitis A in multiple states among people who use drugs and/or people who are homeless. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/outbreaks/2017March-HepatitisA.htm. Accessed January 19, 2019.

8. CDC. Update: Prevention of hepatitis A after exposure to hepatitis A virus and in international travelers. Updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56:1080-1084. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5641a3.htm. Accessed February 9, 2019.

9. Nelson NP, Link-Gelles R, Hofmeister MG, et al. Update: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for use of hepatitis A vaccine for postexposure prophylaxis and for preexposure prophylaxis for international travel. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1216-1220.

One of the most important commitments family physicians can undertake in protecting the health of their patients and communities is to ensure that their patients are fully vaccinated. This task is increasingly complicated as new vaccines are approved every year and recommendations change regarding new and established vaccines. To assist primary care providers, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) annually updates 2 immunization schedules—one for children and adolescents, and one for adults. These schedules are available on the CDC Web site (https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/index.html).

These updates originate from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), which meets 3 times a year to consider and adopt changes to the schedules. During 2018, relatively few new recommendations were adopted. The September 2018 Practice Alert1 in this journal covered the updated recommendations for influenza immunization, which included reinstating live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) to the active list of influenza vaccines.

This current Practice Alert reviews 3 additional updates: 1) a new hepatitis B (HepB) vaccine; 2) updated recommendations for the use of hepatitis A (HepA) vaccine for post-exposure prevention and before travel; and 3) inclusion of the homeless among those who should be routinely vaccinated with HepA vaccine.

Hepatitis B: New 2-dose product

As of 2015, the annual incidence of new hepatitis B cases had declined by 88.5% since the first HepB vaccine was licensed in 1981 and recommendations for its routine use were issued in 1982.2 The HepB vaccine products available in the United States are 2 single-antigen products, Engerix-B (GlaxoSmithKline) and Recombivax HB (Merck & Co.). Both can be used in all age groups, starting at birth, in a 3-dose series. HepB vaccine is also available in 2 combination products: Pediarix, containing HepB, diphtheria and tetanus toxoids, acellular pertussis, and inactivated poliovirus (GlaxoSmithKline), approved for use in children 6 weeks to 6 years old; and Twinrix (GlaxoSmithKline), which contains both HepB and HepA and is approved for use in adults 18 years and older.

The HepB vaccine is recommended for all children and unvaccinated adolescents as part of the routine vaccination schedule. It is also recommended for unvaccinated adults with specific risks (TABLE 12). However, the rate of HepB vaccination in adults for whom it is recommended is suboptimal (FIGURE),3 and just a little more than half of adults who start a 3-dose series of HepB complete it.4A new vaccine against hepatitis B, HEPLISAV-B (Dynavax Technologies), was licensed by the US Food and Drug Administration in late 2017. ACIP now recommends it as an option along with other available HepB products. HEPLISAV-B is given in 2 doses separated by 1 month. It is hoped that this shortened 2-dose series will increase the number of adults who achieve full vaccination. In addition, it appears that HEPLISAV-B provides higher levels of protection in some high-risk groups—those with type 2 diabetes or chronic kidney disease.3 However, initial safety studies have shown a small absolute increase in cardiac events after vaccination with HEPLISAV-B. Post-marketing surveillance will be needed to show whether this is causal or coincidental.3

As with other HepB products, use of HEPLISAV-B should follow the latest CDC directives on who to test serologically for prior immunity, and on post-vaccination testing to ensure protective antibody levels were achieved.2 It is best to complete a HepB series with the same product, but, if necessary, a combination of products at different doses can be used to complete the HepB series. Any such combination should include 3 doses, even if one of the doses is HEPLISAV-B.

Hepatitis A: Vaccination assumes greater importance for more people

A Practice Alert in early 2018 described a series of outbreaks of hepatitis A around the country and the high rates of associated hospitalizations.5 These outbreaks have occurred primarily among the homeless and their contacts and those who use illicit drugs. This nationwide outbreak has now spread, resulting in more than 7500 cases since July 1, 2016.6 The progress of this epidemic can be viewed on the CDC Web site

Continue to: Remember that the current recommendation...

Remember that the current recommendation is to vaccinate all children 12 to 23 months old with HepA, in 2 separate doses. Two single-antigen HepA products are available: Havrix (GSK) and Vaqta (Merck). For the 2-dose sequence, Havrix is given at 0 and 6 to 12 months; Vaqta at 0 and 6 to 18 months. Even a single dose will provide protection for up to 11 years. In addition to these vaccines, there is the combination HepA and HepB vaccine (Twinrix) mentioned earlier.

Previous recommendations for preventing hepatitis A after exposure, made in 2007, stated that HepA vaccine was preferred for healthy individuals ages 12 months through 40 years, while immune globulin (IG) was preferred for adults older than 40, infants before their first birthday, immunocompromised individuals, those with chronic liver disease, and those for whom HepA vaccine is contraindicated.8 The 2007 recommendations also advised vaccinating individuals traveling to countries with intermediate to high hepatitis A endemicity.

A single dose of HepA vaccine was recommended for all those 12 months or older, although older adults, immunocompromised individuals, and those with chronic liver disease or other chronic medical conditions planning to visit an endemic area in ≤ 2 weeks were supposed to receive the initial dose of vaccine and could also receive IG (0.02 mL/kg) if their provider advised it. Travelers who declined vaccination, those younger than 12 months, or those allergic to a vaccine component could receive a single dose of IG (0.02 mL/kg), which provides protection up to 3 months.

Several factors influenced ACIP to reconsider both the pre- and post-exposure recommendations. Regarding IG, evidence of its decreased potency over time led the committee to increase the recommended dose (see below). IG also must be re-administered every 2 months, the supply of the product is questionable, and many health care facilities do not stock it. By comparison, HepA vaccine offers the advantages of easier administration, inducing active immunity, and providing longer protection. Another issue involved infants ages 6 to 11 months traveling to an area with endemic measles transmission and who must therefore receive the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine. MMR and IG should not be co-administered, and, for infants, the health risk from measles outweighs that from hepatitis A.

Updated recommendations. After considering all this information, ACIP made the following changes to its hepatitis A virus (HAV) prevention recommendations (in addition to adding homeless people to the list of HepA vaccine recipients)9:

- Administer HepA vaccine as post-exposure prophylaxis to all individuals 12 months and older.

- IG may be administered, in addition to HepA vaccine, to those older than 40 years, depending on the provider’s risk assessment (degree of exposure and medical conditions that might lead to severe complications from HAV infection). The recommended IG dose is now 0.1 mL/kg for post-exposure prevention; it is 0.1 to 0.2 mL/kg for pre-exposure prophylaxis for travelers, depending on the length of planned travel.

- Administer HepA vaccine alone to infants ages 6 to 11 months traveling outside the United States when protection against hepatitis A is recommended.

These recommendations have been published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.9

One of the most important commitments family physicians can undertake in protecting the health of their patients and communities is to ensure that their patients are fully vaccinated. This task is increasingly complicated as new vaccines are approved every year and recommendations change regarding new and established vaccines. To assist primary care providers, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) annually updates 2 immunization schedules—one for children and adolescents, and one for adults. These schedules are available on the CDC Web site (https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/index.html).

These updates originate from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), which meets 3 times a year to consider and adopt changes to the schedules. During 2018, relatively few new recommendations were adopted. The September 2018 Practice Alert1 in this journal covered the updated recommendations for influenza immunization, which included reinstating live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) to the active list of influenza vaccines.

This current Practice Alert reviews 3 additional updates: 1) a new hepatitis B (HepB) vaccine; 2) updated recommendations for the use of hepatitis A (HepA) vaccine for post-exposure prevention and before travel; and 3) inclusion of the homeless among those who should be routinely vaccinated with HepA vaccine.

Hepatitis B: New 2-dose product

As of 2015, the annual incidence of new hepatitis B cases had declined by 88.5% since the first HepB vaccine was licensed in 1981 and recommendations for its routine use were issued in 1982.2 The HepB vaccine products available in the United States are 2 single-antigen products, Engerix-B (GlaxoSmithKline) and Recombivax HB (Merck & Co.). Both can be used in all age groups, starting at birth, in a 3-dose series. HepB vaccine is also available in 2 combination products: Pediarix, containing HepB, diphtheria and tetanus toxoids, acellular pertussis, and inactivated poliovirus (GlaxoSmithKline), approved for use in children 6 weeks to 6 years old; and Twinrix (GlaxoSmithKline), which contains both HepB and HepA and is approved for use in adults 18 years and older.

The HepB vaccine is recommended for all children and unvaccinated adolescents as part of the routine vaccination schedule. It is also recommended for unvaccinated adults with specific risks (TABLE 12). However, the rate of HepB vaccination in adults for whom it is recommended is suboptimal (FIGURE),3 and just a little more than half of adults who start a 3-dose series of HepB complete it.4A new vaccine against hepatitis B, HEPLISAV-B (Dynavax Technologies), was licensed by the US Food and Drug Administration in late 2017. ACIP now recommends it as an option along with other available HepB products. HEPLISAV-B is given in 2 doses separated by 1 month. It is hoped that this shortened 2-dose series will increase the number of adults who achieve full vaccination. In addition, it appears that HEPLISAV-B provides higher levels of protection in some high-risk groups—those with type 2 diabetes or chronic kidney disease.3 However, initial safety studies have shown a small absolute increase in cardiac events after vaccination with HEPLISAV-B. Post-marketing surveillance will be needed to show whether this is causal or coincidental.3

As with other HepB products, use of HEPLISAV-B should follow the latest CDC directives on who to test serologically for prior immunity, and on post-vaccination testing to ensure protective antibody levels were achieved.2 It is best to complete a HepB series with the same product, but, if necessary, a combination of products at different doses can be used to complete the HepB series. Any such combination should include 3 doses, even if one of the doses is HEPLISAV-B.

Hepatitis A: Vaccination assumes greater importance for more people

A Practice Alert in early 2018 described a series of outbreaks of hepatitis A around the country and the high rates of associated hospitalizations.5 These outbreaks have occurred primarily among the homeless and their contacts and those who use illicit drugs. This nationwide outbreak has now spread, resulting in more than 7500 cases since July 1, 2016.6 The progress of this epidemic can be viewed on the CDC Web site

Continue to: Remember that the current recommendation...

Remember that the current recommendation is to vaccinate all children 12 to 23 months old with HepA, in 2 separate doses. Two single-antigen HepA products are available: Havrix (GSK) and Vaqta (Merck). For the 2-dose sequence, Havrix is given at 0 and 6 to 12 months; Vaqta at 0 and 6 to 18 months. Even a single dose will provide protection for up to 11 years. In addition to these vaccines, there is the combination HepA and HepB vaccine (Twinrix) mentioned earlier.

Previous recommendations for preventing hepatitis A after exposure, made in 2007, stated that HepA vaccine was preferred for healthy individuals ages 12 months through 40 years, while immune globulin (IG) was preferred for adults older than 40, infants before their first birthday, immunocompromised individuals, those with chronic liver disease, and those for whom HepA vaccine is contraindicated.8 The 2007 recommendations also advised vaccinating individuals traveling to countries with intermediate to high hepatitis A endemicity.

A single dose of HepA vaccine was recommended for all those 12 months or older, although older adults, immunocompromised individuals, and those with chronic liver disease or other chronic medical conditions planning to visit an endemic area in ≤ 2 weeks were supposed to receive the initial dose of vaccine and could also receive IG (0.02 mL/kg) if their provider advised it. Travelers who declined vaccination, those younger than 12 months, or those allergic to a vaccine component could receive a single dose of IG (0.02 mL/kg), which provides protection up to 3 months.

Several factors influenced ACIP to reconsider both the pre- and post-exposure recommendations. Regarding IG, evidence of its decreased potency over time led the committee to increase the recommended dose (see below). IG also must be re-administered every 2 months, the supply of the product is questionable, and many health care facilities do not stock it. By comparison, HepA vaccine offers the advantages of easier administration, inducing active immunity, and providing longer protection. Another issue involved infants ages 6 to 11 months traveling to an area with endemic measles transmission and who must therefore receive the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine. MMR and IG should not be co-administered, and, for infants, the health risk from measles outweighs that from hepatitis A.

Updated recommendations. After considering all this information, ACIP made the following changes to its hepatitis A virus (HAV) prevention recommendations (in addition to adding homeless people to the list of HepA vaccine recipients)9:

- Administer HepA vaccine as post-exposure prophylaxis to all individuals 12 months and older.

- IG may be administered, in addition to HepA vaccine, to those older than 40 years, depending on the provider’s risk assessment (degree of exposure and medical conditions that might lead to severe complications from HAV infection). The recommended IG dose is now 0.1 mL/kg for post-exposure prevention; it is 0.1 to 0.2 mL/kg for pre-exposure prophylaxis for travelers, depending on the length of planned travel.

- Administer HepA vaccine alone to infants ages 6 to 11 months traveling outside the United States when protection against hepatitis A is recommended.

These recommendations have been published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.9

1. Campos-Outcalt D. CDC recommendations for the 2018-2019 influenza season. J Fam Pract. 2018;67:550-553.

2. Schillie S, Vellozzi C, Reingold A, et al. Prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2018;67:1-31.

3. CDC. Schillie S. HEPLISAV-B: considerations and proposed recommendations, vote. Presented at: meeting of the Hepatitis Work Group, Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; February 21, 2018; Atlanta, Ga. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2018-02/Hepatitis-03-Schillie-508.pdf. Accessed January 19, 2019.

4. Nelson JC, Bittner RC, Bounds L, et al. Compliance with multiple-dose vaccine schedules among older children, adolescents, and adults: results from a vaccine safety datalink study. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(Suppl 2):S389-S397.

5. Campos-Outcalt D. CDC provides advice on recent hepatitis A outbreaks. J Fam Pract. 2018;67:30-32.

6. CDC. Nelson N. Background – hepatitis A among the homeless. Presented at: meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; October 24, 2018; Atlanta, Ga. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2018-10/Hepatitis-02-Nelson-508.pdf. Accessed January 19, 2019.

7. CDC. 2017 – Outbreaks of hepatitis A in multiple states among people who use drugs and/or people who are homeless. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/outbreaks/2017March-HepatitisA.htm. Accessed January 19, 2019.

8. CDC. Update: Prevention of hepatitis A after exposure to hepatitis A virus and in international travelers. Updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56:1080-1084. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5641a3.htm. Accessed February 9, 2019.

9. Nelson NP, Link-Gelles R, Hofmeister MG, et al. Update: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for use of hepatitis A vaccine for postexposure prophylaxis and for preexposure prophylaxis for international travel. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1216-1220.

1. Campos-Outcalt D. CDC recommendations for the 2018-2019 influenza season. J Fam Pract. 2018;67:550-553.

2. Schillie S, Vellozzi C, Reingold A, et al. Prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2018;67:1-31.

3. CDC. Schillie S. HEPLISAV-B: considerations and proposed recommendations, vote. Presented at: meeting of the Hepatitis Work Group, Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; February 21, 2018; Atlanta, Ga. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2018-02/Hepatitis-03-Schillie-508.pdf. Accessed January 19, 2019.

4. Nelson JC, Bittner RC, Bounds L, et al. Compliance with multiple-dose vaccine schedules among older children, adolescents, and adults: results from a vaccine safety datalink study. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(Suppl 2):S389-S397.

5. Campos-Outcalt D. CDC provides advice on recent hepatitis A outbreaks. J Fam Pract. 2018;67:30-32.

6. CDC. Nelson N. Background – hepatitis A among the homeless. Presented at: meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; October 24, 2018; Atlanta, Ga. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2018-10/Hepatitis-02-Nelson-508.pdf. Accessed January 19, 2019.

7. CDC. 2017 – Outbreaks of hepatitis A in multiple states among people who use drugs and/or people who are homeless. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/outbreaks/2017March-HepatitisA.htm. Accessed January 19, 2019.

8. CDC. Update: Prevention of hepatitis A after exposure to hepatitis A virus and in international travelers. Updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56:1080-1084. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5641a3.htm. Accessed February 9, 2019.

9. Nelson NP, Link-Gelles R, Hofmeister MG, et al. Update: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for use of hepatitis A vaccine for postexposure prophylaxis and for preexposure prophylaxis for international travel. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1216-1220.

Don’t overlook this step in combatting the rise in STIs

Resources

1. Kuehn BM. A proactive approach needed to combat rising STIs. JAMA. 2019;321:330-332.

2. Screening Recommendations and Considerations Referenced in Treatment Guidelines and Original Sources. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/screening-recommendations.htm. Updated June 4, 2015. Accessed February 27, 2019.

3. STD Clinical Consultation Network. National STD Curriculum. https://www.std.uw.edu/page/site/clinical-consultation. Accessed February 27, 2019.

4. National STD Curriculum. https://www.std.uw.edu/. Accessed February 27, 2019.

5. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2017. Syphilis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats17/syphilis.htm. Reviewed July 24, 2018. Accessed February 27, 2019.

Resources

1. Kuehn BM. A proactive approach needed to combat rising STIs. JAMA. 2019;321:330-332.

2. Screening Recommendations and Considerations Referenced in Treatment Guidelines and Original Sources. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/screening-recommendations.htm. Updated June 4, 2015. Accessed February 27, 2019.

3. STD Clinical Consultation Network. National STD Curriculum. https://www.std.uw.edu/page/site/clinical-consultation. Accessed February 27, 2019.

4. National STD Curriculum. https://www.std.uw.edu/. Accessed February 27, 2019.

5. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2017. Syphilis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats17/syphilis.htm. Reviewed July 24, 2018. Accessed February 27, 2019.

Resources

1. Kuehn BM. A proactive approach needed to combat rising STIs. JAMA. 2019;321:330-332.

2. Screening Recommendations and Considerations Referenced in Treatment Guidelines and Original Sources. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/screening-recommendations.htm. Updated June 4, 2015. Accessed February 27, 2019.

3. STD Clinical Consultation Network. National STD Curriculum. https://www.std.uw.edu/page/site/clinical-consultation. Accessed February 27, 2019.

4. National STD Curriculum. https://www.std.uw.edu/. Accessed February 27, 2019.

5. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2017. Syphilis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats17/syphilis.htm. Reviewed July 24, 2018. Accessed February 27, 2019.

Flu activity & measles outbreaks: Where we stand, steps we can take

Resources

Measles (Robeola). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. https://www.cdc.gov/measles/index.html. Updated January 28, 2019. Accessed January 31, 2019.

Influenza (Flu). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/index.htm. Updated January 25, 2019. Accessed January 31, 2019.

Resources

Measles (Robeola). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. https://www.cdc.gov/measles/index.html. Updated January 28, 2019. Accessed January 31, 2019.

Influenza (Flu). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/index.htm. Updated January 25, 2019. Accessed January 31, 2019.

Resources

Measles (Robeola). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. https://www.cdc.gov/measles/index.html. Updated January 28, 2019. Accessed January 31, 2019.

Influenza (Flu). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/index.htm. Updated January 25, 2019. Accessed January 31, 2019.

“The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans”— a summary with tips

Resources

US Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. 2nd ed. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Web site. Published 2018. https://health.gov/paguidelines/second-edition/. Accessed January 7, 2019.

Piercy KL, Troiano RP, Ballard RM, et al. The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. JAMA. 2018;320:2020-2028.

Resources

US Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. 2nd ed. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Web site. Published 2018. https://health.gov/paguidelines/second-edition/. Accessed January 7, 2019.

Piercy KL, Troiano RP, Ballard RM, et al. The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. JAMA. 2018;320:2020-2028.

Resources

US Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. 2nd ed. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Web site. Published 2018. https://health.gov/paguidelines/second-edition/. Accessed January 7, 2019.

Piercy KL, Troiano RP, Ballard RM, et al. The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. JAMA. 2018;320:2020-2028.

A look at new guidelines for HIV treatment and prevention

An International Antiviral Society-USA Panel recently published an updated set of recommendations on using antiviral drugs to treat and prevent human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection1—a rapidly changing and complex topic. This new guideline updates the society’s 2016 publication.2 It contains recommendations on when to start antiretroviral therapy for those who are HIV positive and advice on suitable combinations of antiretroviral drugs. It also details pre- and post-exposure prophylaxis strategies for preventing HIV infection in those at risk.

This Practice Alert highlights the most important recommendations on treating those newly diagnosed as HIV positive and on preventing infection. Physicians who provide care for those who are HIV positive should familiarize themselves with the entire guideline.

Initiating treatment in those newly diagnosed as HIV positive

The panel now recommends starting antiretroviral therapy (ART) as soon as possible after HIV infection is confirmed; immediately if a patient is ready to commit to starting and continuing treatment. Any patient with an opportunistic infection should begin ART within 2 weeks of its diagnosis. Patients being treated for tuberculosis (TB) should begin ART within 2 weeks of starting TB treatment if their CD4 cell count is <50/mcL; those whose count is ≥50/mcL should begin ART within 2 to 8 weeks.

The panel recommends one of 3 ART combinations (TABLE 11), all of which contain an integrase strand transfer inhibitor (INSTI). ART started immediately should not include a nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) because of possible viral resistance. The guideline recommends 6 other ART combinations if none of the first 3 options can be used.1

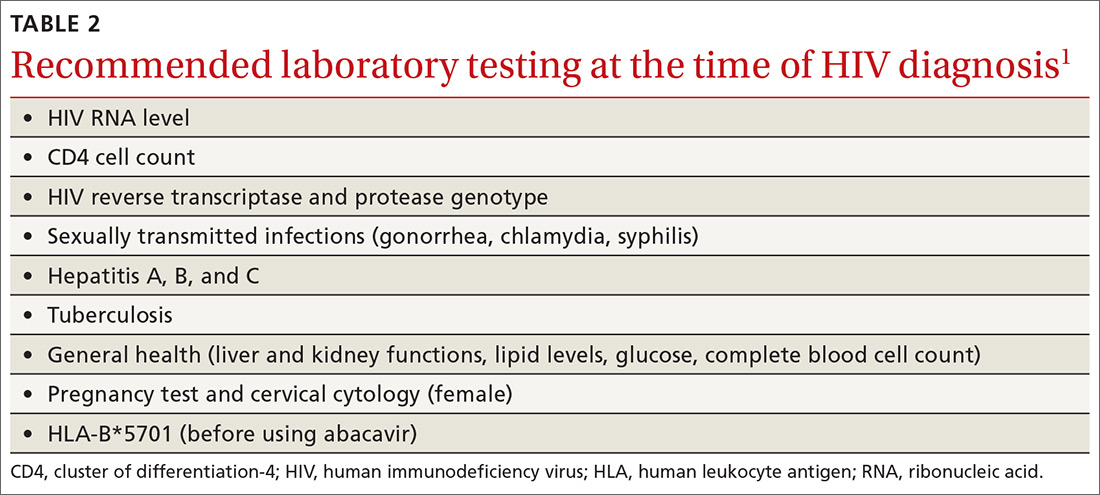

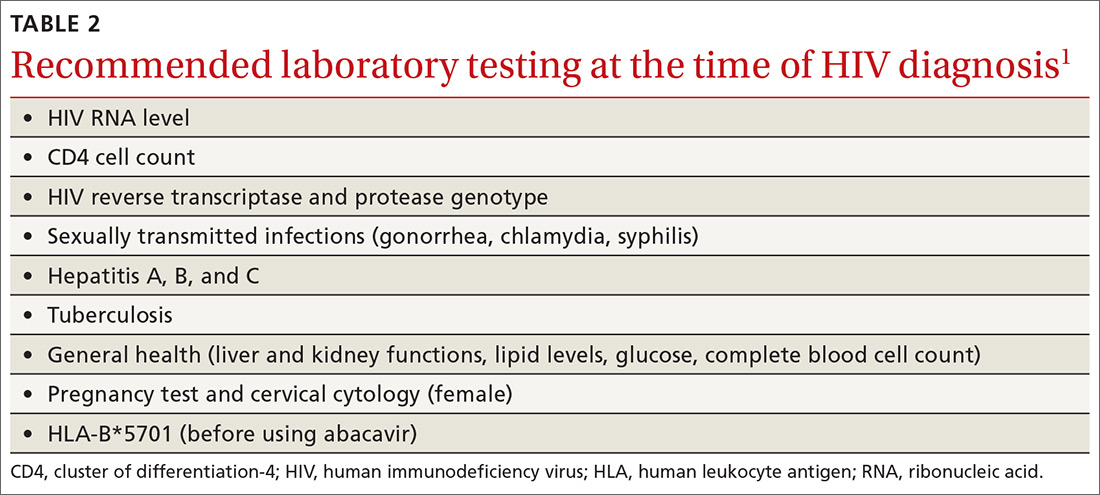

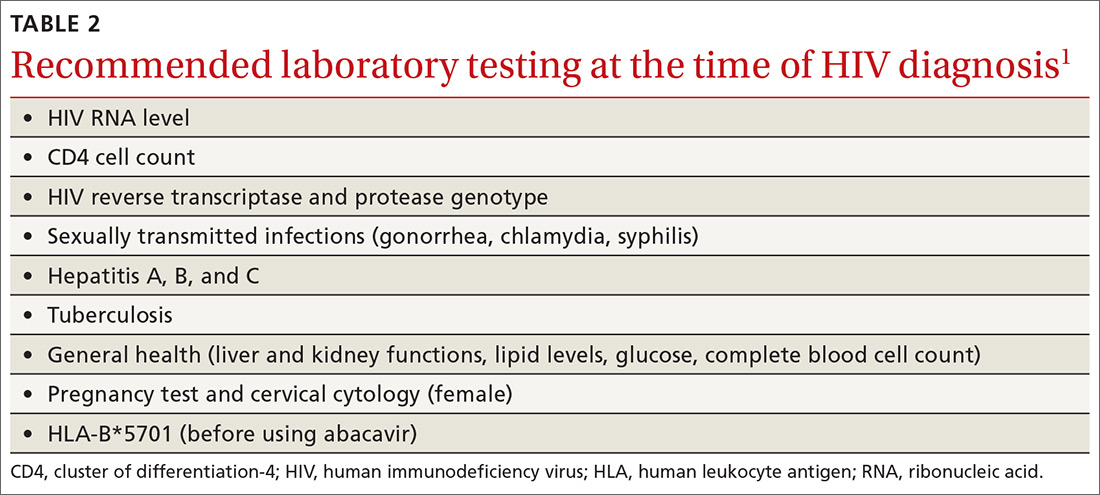

An initial set of laboratory tests (TABLE 21) should be conducted on each individual receiving ART, although treatment can start before the results are returned. Ongoing laboratory monitoring, described in detail in the guideline, depends on the ART regimen chosen and the patient’s response to therapy. The only routinely recommended prophylaxis for opportunistic infections is for Pneumocystis pneumonia if the CD4 count is <200/mcL.

Preventing HIV with prEP

Consider prescribing daily pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (Truvada) for men and women who are at risk from sexual exposure to HIV or who inject illicit drugs. It takes about 1 week for protective tissue levels to be achieved. Testing to rule out HIV infection is recommended before starting PrEP, as is testing for serum creatinine level, estimated glomerular filtration rate, and hepatitis B surface antigen. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate is not recommended for those with creatinine clearance of less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. For patients taking PrEP, emphasize other preventive measures such as using condoms to protect against both HIV and other sexually-transmitted diseases (STDs), using clean needles and syringes when injecting drugs, or entering a drug rehabilitation program. After initiating PrEP, schedule the first follow-up visit for 30 days later to repeat the HIV test and to assess adverse reactions and PrEP adherence.

For men who have sex with men (MSM), there is an alternative form of PrEP when sexual exposure is infrequent. “On-demand” or “event-driven” PrEP involves 4 doses of emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate; 2 doses given with food 2 to 24 hours before sex (the closer to 24 the better), one dose 24 hours after the first and one 24 hours after the second. This is referred to as 2-1-1 dosing. This option has only been tested in MSM with sexual exposure. It is not recommended at this time for others at risk for HIV or for MSM with chronic or active hepatitis B infection.

Continue to: Preventing HIV infection with post-exposure prophylaxis

Preventing HIV infection with post-exposure prophylaxis

Post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) for HIV infection is divided into 2 categories: occupational PEP (oPEP) and non-occupational PEP (nPEP). Recommendations for oPEP are described elsewhere3 and are not covered in this Practice Alert. Summarized below are the recommendations for nPEP after sex, injection drug use, and other nonoccupational exposures, which are also described on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Web site.4

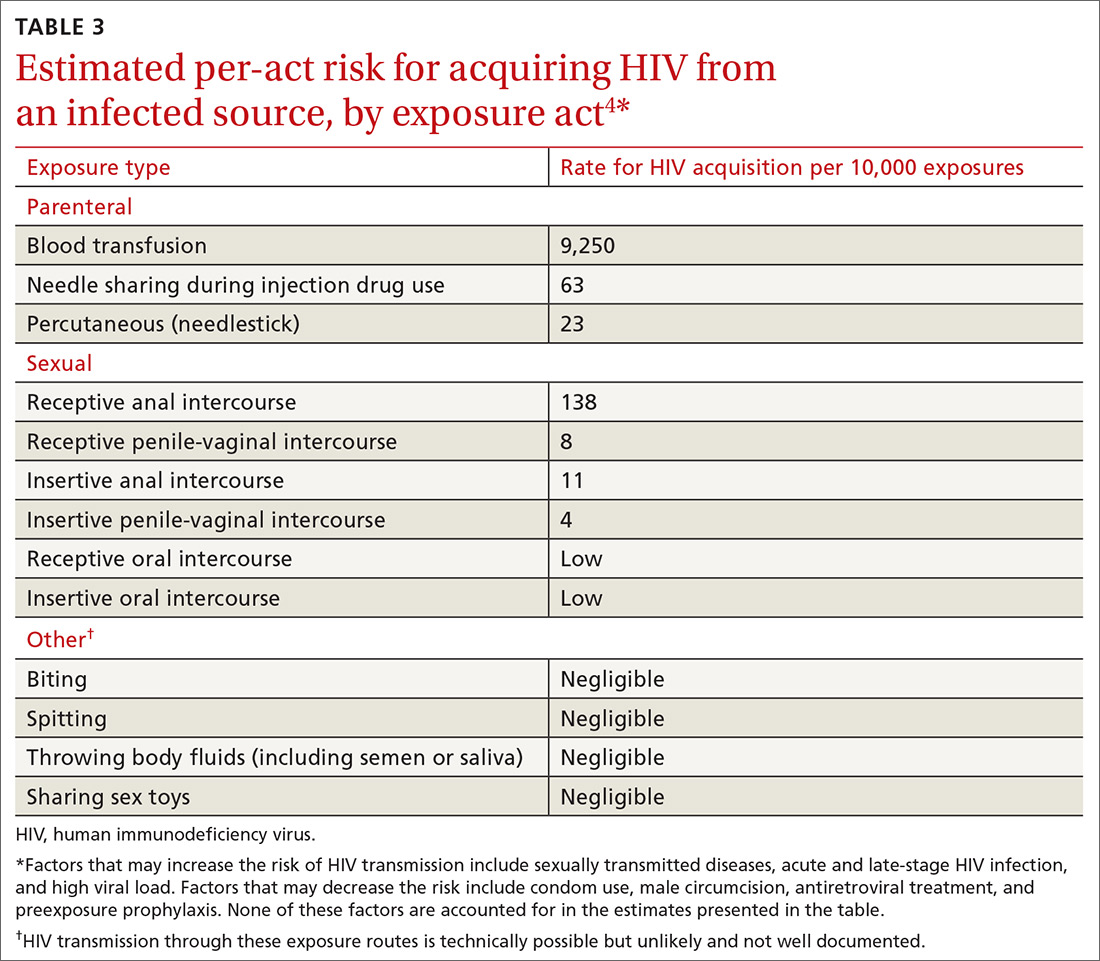

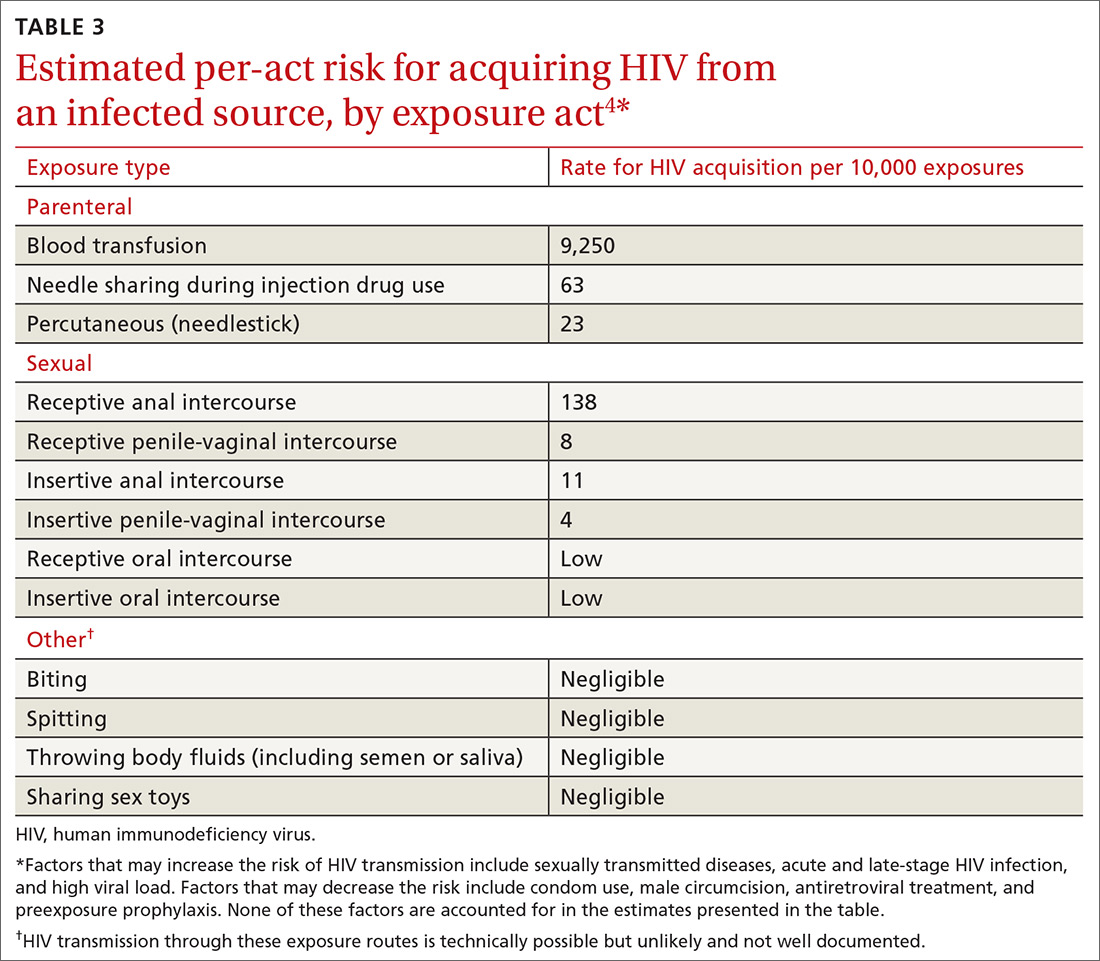

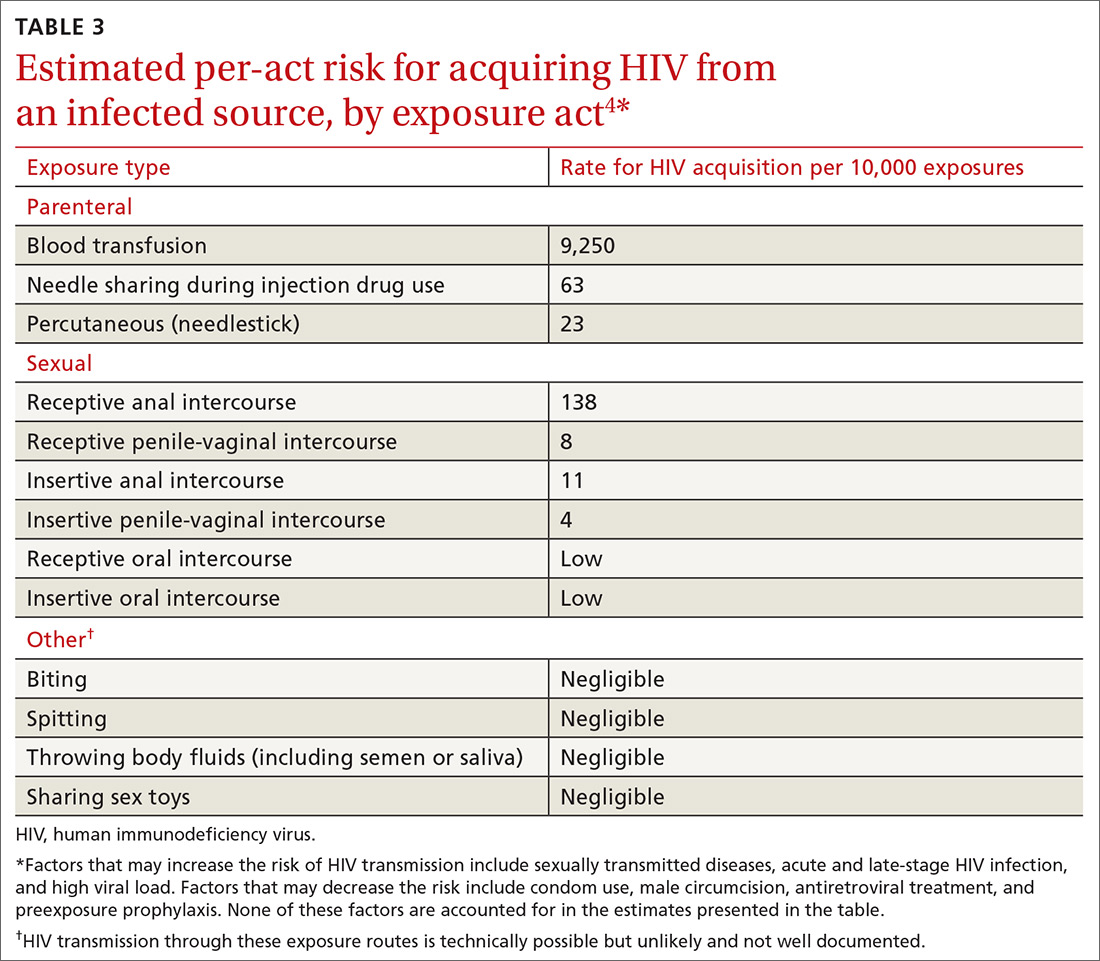

Assess the need for nPEP if high-risk exposure (TABLE 34) occurred ≤72 hours earlier. Before starting nPEP, perform a rapid HIV blood test. If rapid testing is unavailable, start nPEP, which can be discontinued if the patient is later determined to have HIV infection. Repeat HIV testing at 4 to 6 weeks and 3 months following initiation of nPEP. Approved HIV tests are described on the CDC Web site at http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/testing/laboratorytests.html. Oral HIV tests are not recommended for HIV testing before initiating nPEP.

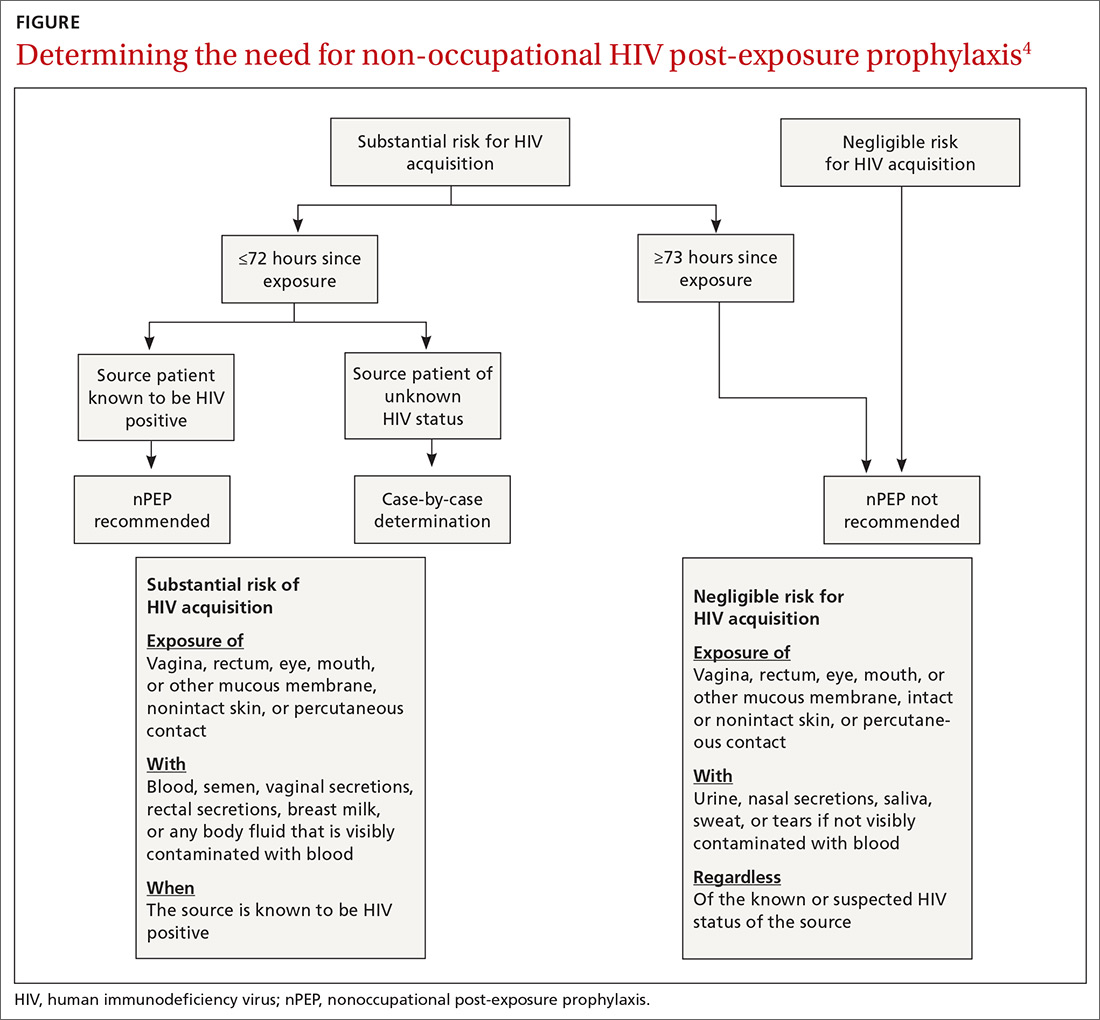

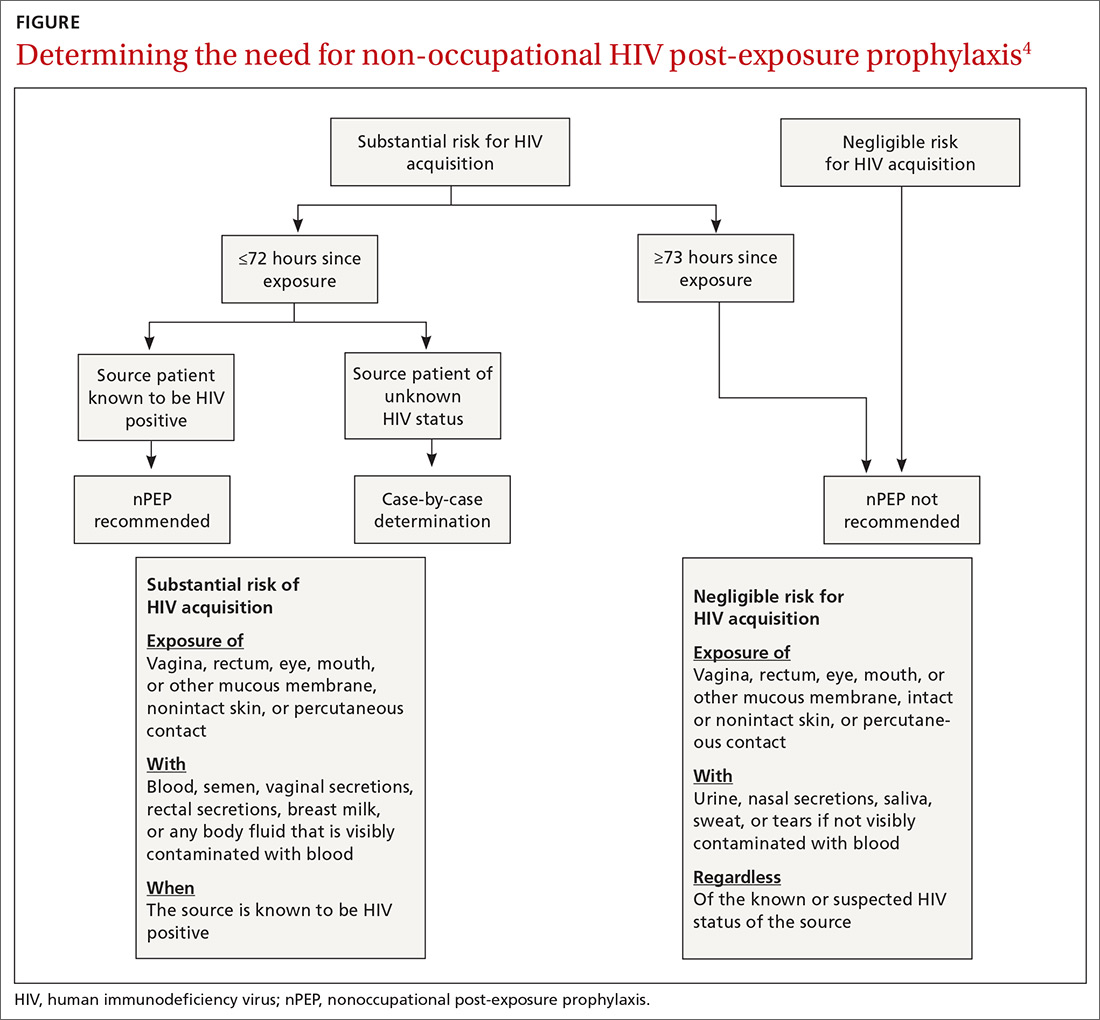

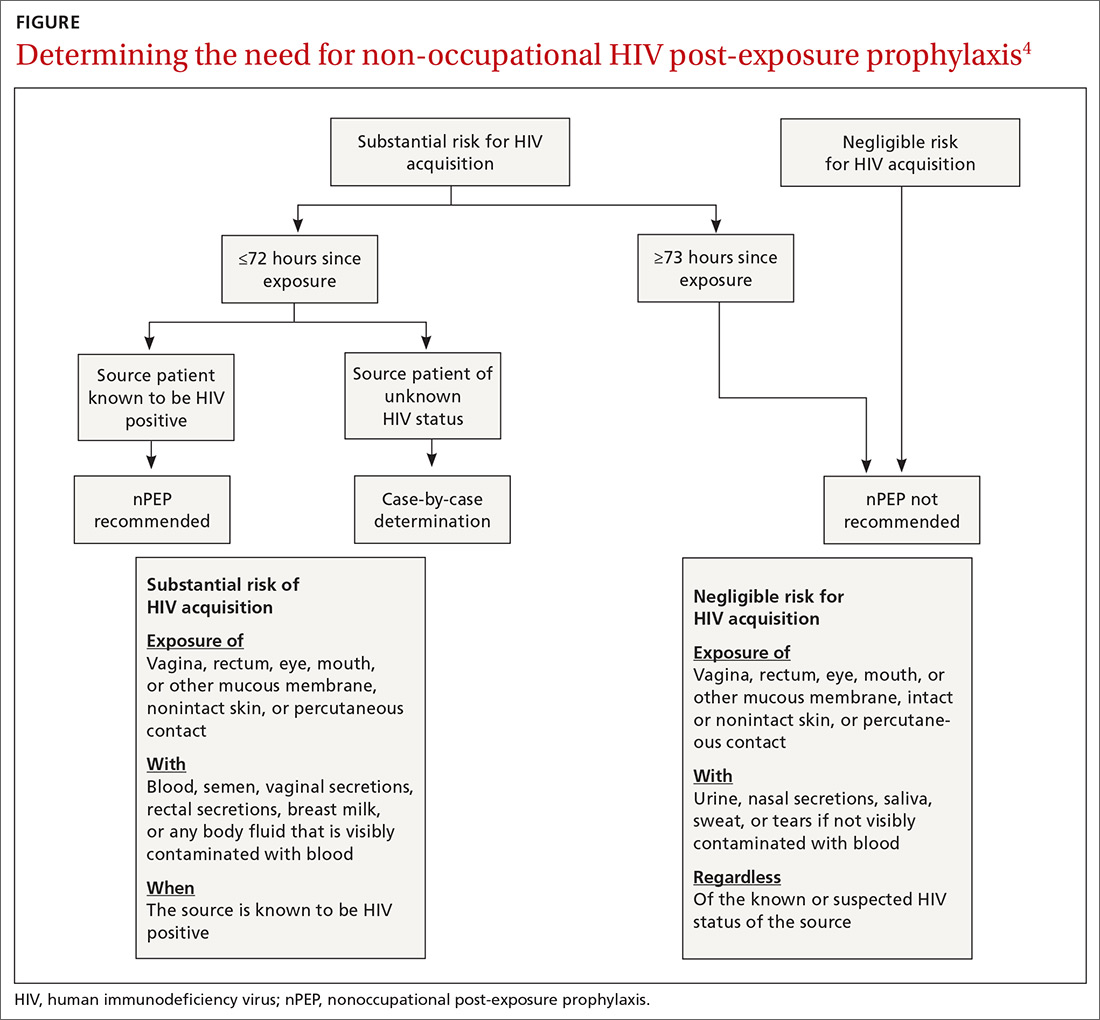

nPEP is not recommended when an individual’s risk of exposure to HIV is not high, or if the exposure occurred more than 72 hours before presentation. An algorithm is available to assist with assessing whether nPEP is recommended (FIGURE4).

Specific nPEP regimens. For otherwise healthy adults and adolescents, preferred nPEP consists of a 28-day course of a 3-drug combination: tenofovir disoproxil fumarate 300 mg once daily; emtricitabine 200 mg once daily; and raltegravir, 400 mg twice daily, or dolutegravir 50 mg once daily. Alternative regimens for adults and adolescents are described in the guideline, as are options for children, those with decreased renal function, and pregnant women. Those who receive more than one course of nPEP within a 12-month period should consider PrEP.

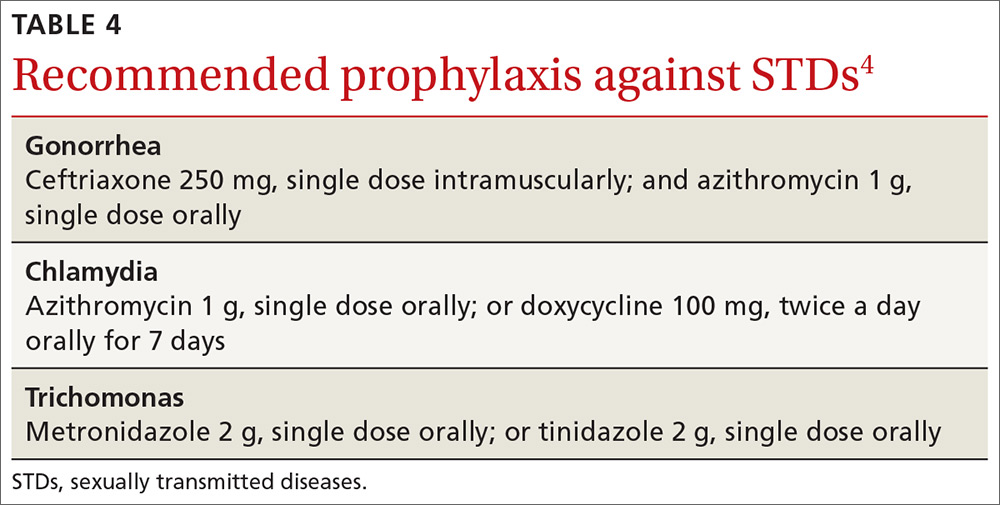

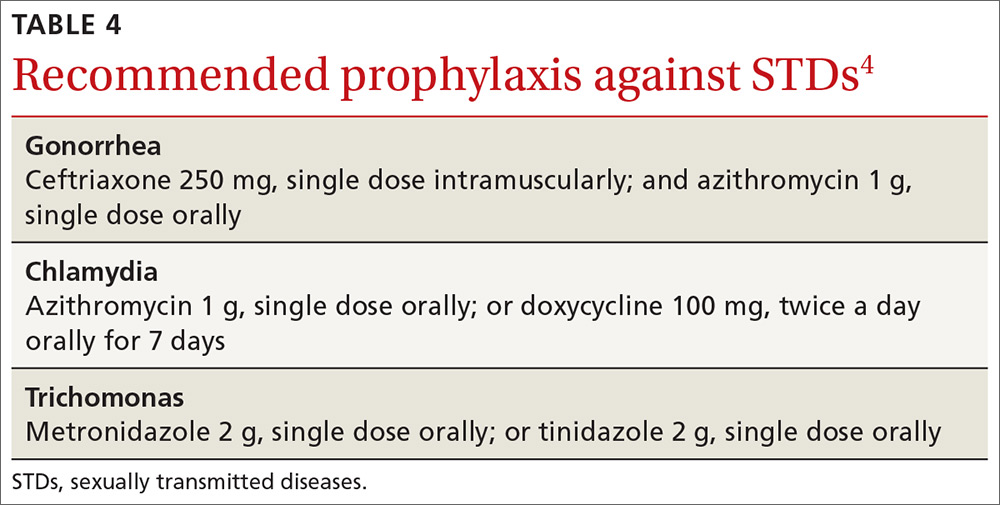

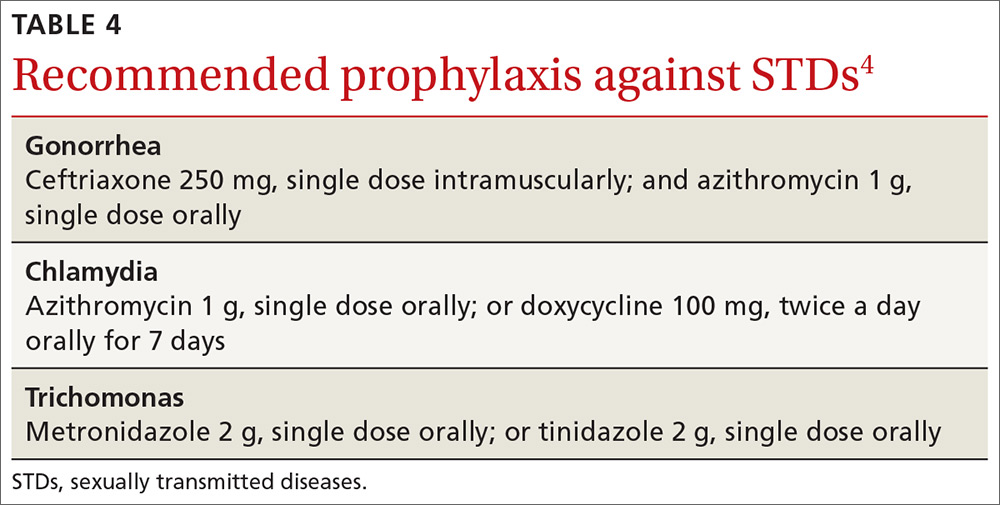

When additional vaccination is needed. For victims of sexual assault, offer prophylaxis against STD (TABLE 44) and hepatitis B virus (HBV). Those who have not been vaccinated against HBV should receive the first dose at the initial visit. If the exposure source is known to be HBsAg-positive, give the unvaccinated patient both hepatitis B vaccine and hepatitis B immune globulin at the first visit. The full hepatitis B vaccine series should then be completed according to the recommended schedule and the vaccine product used. Those who have completed hepatitis B vaccination but who were not tested with a post-vaccine titer should receive a single dose of hepatitis B vaccine.

Continue to: Victims of sexual assault...

Victims of sexual assault can benefit from referral to professionals with expertise in post-assault counseling. Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner programs are listed at http://www.sane-sart.com.

Financial assistance for patients. Anti-retroviral drugs are expensive, and those who need nPEP may not have a payer source. Many pharmaceutical manufacturers offer medication assistance programs, and processes are set up to handle time-sensitive requests. Information for specific medications can be found at http://www.pparx.org/en/prescription_assistance_programs/list_of_participating_programs. Those who are prescribed nPEP after a sexual assault can receive reimbursement for medications and health care costs through state Crime Victim Compensation Programs funded by the Department of Justice. State-specific contact information is available at http://www.nacvcb.org/index.asp?sid=6.

1. Saag MS, Benson CA, Gandhi RT, et al. Antiretroviral drugs for treatment and prevention of HIV infection in adults: 2018 recommendations of the International Antiviral Society-USA Panel. JAMA. 2018;320:379-396.

2. Günthard HF, Saag MS, Benson CA, et al. Antiretroviral drugs for treatment and prevention of HIV infection in adults: 2016 recommendations of the International Antiviral Society-USA Panel. JAMA. 2016;316:191-210.

3. Kuhar DT, Henderson DK, Struble KA, et al; US Public Health Service Working Group. Updated US Public Health Service guidelines for the management of occupational exposures to human immunodeficiency virus and recommendations for postexposure prophylaxis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34:875-892.

4. CDC. Updated guidelines for antiretroviral postexposure prophylaxis after sexual, injection drug use, or other nonoccupational exposure to HIV—United States, 2016. https://www-cdc-gov.ezproxy3.library.arizona.edu/hiv/pdf/programresources/cdc-hiv-npep-guidelines.pdf. Accessed October 11, 2018.

An International Antiviral Society-USA Panel recently published an updated set of recommendations on using antiviral drugs to treat and prevent human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection1—a rapidly changing and complex topic. This new guideline updates the society’s 2016 publication.2 It contains recommendations on when to start antiretroviral therapy for those who are HIV positive and advice on suitable combinations of antiretroviral drugs. It also details pre- and post-exposure prophylaxis strategies for preventing HIV infection in those at risk.

This Practice Alert highlights the most important recommendations on treating those newly diagnosed as HIV positive and on preventing infection. Physicians who provide care for those who are HIV positive should familiarize themselves with the entire guideline.

Initiating treatment in those newly diagnosed as HIV positive

The panel now recommends starting antiretroviral therapy (ART) as soon as possible after HIV infection is confirmed; immediately if a patient is ready to commit to starting and continuing treatment. Any patient with an opportunistic infection should begin ART within 2 weeks of its diagnosis. Patients being treated for tuberculosis (TB) should begin ART within 2 weeks of starting TB treatment if their CD4 cell count is <50/mcL; those whose count is ≥50/mcL should begin ART within 2 to 8 weeks.

The panel recommends one of 3 ART combinations (TABLE 11), all of which contain an integrase strand transfer inhibitor (INSTI). ART started immediately should not include a nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) because of possible viral resistance. The guideline recommends 6 other ART combinations if none of the first 3 options can be used.1

An initial set of laboratory tests (TABLE 21) should be conducted on each individual receiving ART, although treatment can start before the results are returned. Ongoing laboratory monitoring, described in detail in the guideline, depends on the ART regimen chosen and the patient’s response to therapy. The only routinely recommended prophylaxis for opportunistic infections is for Pneumocystis pneumonia if the CD4 count is <200/mcL.

Preventing HIV with prEP

Consider prescribing daily pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (Truvada) for men and women who are at risk from sexual exposure to HIV or who inject illicit drugs. It takes about 1 week for protective tissue levels to be achieved. Testing to rule out HIV infection is recommended before starting PrEP, as is testing for serum creatinine level, estimated glomerular filtration rate, and hepatitis B surface antigen. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate is not recommended for those with creatinine clearance of less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. For patients taking PrEP, emphasize other preventive measures such as using condoms to protect against both HIV and other sexually-transmitted diseases (STDs), using clean needles and syringes when injecting drugs, or entering a drug rehabilitation program. After initiating PrEP, schedule the first follow-up visit for 30 days later to repeat the HIV test and to assess adverse reactions and PrEP adherence.

For men who have sex with men (MSM), there is an alternative form of PrEP when sexual exposure is infrequent. “On-demand” or “event-driven” PrEP involves 4 doses of emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate; 2 doses given with food 2 to 24 hours before sex (the closer to 24 the better), one dose 24 hours after the first and one 24 hours after the second. This is referred to as 2-1-1 dosing. This option has only been tested in MSM with sexual exposure. It is not recommended at this time for others at risk for HIV or for MSM with chronic or active hepatitis B infection.

Continue to: Preventing HIV infection with post-exposure prophylaxis

Preventing HIV infection with post-exposure prophylaxis

Post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) for HIV infection is divided into 2 categories: occupational PEP (oPEP) and non-occupational PEP (nPEP). Recommendations for oPEP are described elsewhere3 and are not covered in this Practice Alert. Summarized below are the recommendations for nPEP after sex, injection drug use, and other nonoccupational exposures, which are also described on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Web site.4

Assess the need for nPEP if high-risk exposure (TABLE 34) occurred ≤72 hours earlier. Before starting nPEP, perform a rapid HIV blood test. If rapid testing is unavailable, start nPEP, which can be discontinued if the patient is later determined to have HIV infection. Repeat HIV testing at 4 to 6 weeks and 3 months following initiation of nPEP. Approved HIV tests are described on the CDC Web site at http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/testing/laboratorytests.html. Oral HIV tests are not recommended for HIV testing before initiating nPEP.

nPEP is not recommended when an individual’s risk of exposure to HIV is not high, or if the exposure occurred more than 72 hours before presentation. An algorithm is available to assist with assessing whether nPEP is recommended (FIGURE4).

Specific nPEP regimens. For otherwise healthy adults and adolescents, preferred nPEP consists of a 28-day course of a 3-drug combination: tenofovir disoproxil fumarate 300 mg once daily; emtricitabine 200 mg once daily; and raltegravir, 400 mg twice daily, or dolutegravir 50 mg once daily. Alternative regimens for adults and adolescents are described in the guideline, as are options for children, those with decreased renal function, and pregnant women. Those who receive more than one course of nPEP within a 12-month period should consider PrEP.

When additional vaccination is needed. For victims of sexual assault, offer prophylaxis against STD (TABLE 44) and hepatitis B virus (HBV). Those who have not been vaccinated against HBV should receive the first dose at the initial visit. If the exposure source is known to be HBsAg-positive, give the unvaccinated patient both hepatitis B vaccine and hepatitis B immune globulin at the first visit. The full hepatitis B vaccine series should then be completed according to the recommended schedule and the vaccine product used. Those who have completed hepatitis B vaccination but who were not tested with a post-vaccine titer should receive a single dose of hepatitis B vaccine.

Continue to: Victims of sexual assault...

Victims of sexual assault can benefit from referral to professionals with expertise in post-assault counseling. Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner programs are listed at http://www.sane-sart.com.

Financial assistance for patients. Anti-retroviral drugs are expensive, and those who need nPEP may not have a payer source. Many pharmaceutical manufacturers offer medication assistance programs, and processes are set up to handle time-sensitive requests. Information for specific medications can be found at http://www.pparx.org/en/prescription_assistance_programs/list_of_participating_programs. Those who are prescribed nPEP after a sexual assault can receive reimbursement for medications and health care costs through state Crime Victim Compensation Programs funded by the Department of Justice. State-specific contact information is available at http://www.nacvcb.org/index.asp?sid=6.

An International Antiviral Society-USA Panel recently published an updated set of recommendations on using antiviral drugs to treat and prevent human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection1—a rapidly changing and complex topic. This new guideline updates the society’s 2016 publication.2 It contains recommendations on when to start antiretroviral therapy for those who are HIV positive and advice on suitable combinations of antiretroviral drugs. It also details pre- and post-exposure prophylaxis strategies for preventing HIV infection in those at risk.

This Practice Alert highlights the most important recommendations on treating those newly diagnosed as HIV positive and on preventing infection. Physicians who provide care for those who are HIV positive should familiarize themselves with the entire guideline.

Initiating treatment in those newly diagnosed as HIV positive

The panel now recommends starting antiretroviral therapy (ART) as soon as possible after HIV infection is confirmed; immediately if a patient is ready to commit to starting and continuing treatment. Any patient with an opportunistic infection should begin ART within 2 weeks of its diagnosis. Patients being treated for tuberculosis (TB) should begin ART within 2 weeks of starting TB treatment if their CD4 cell count is <50/mcL; those whose count is ≥50/mcL should begin ART within 2 to 8 weeks.

The panel recommends one of 3 ART combinations (TABLE 11), all of which contain an integrase strand transfer inhibitor (INSTI). ART started immediately should not include a nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) because of possible viral resistance. The guideline recommends 6 other ART combinations if none of the first 3 options can be used.1

An initial set of laboratory tests (TABLE 21) should be conducted on each individual receiving ART, although treatment can start before the results are returned. Ongoing laboratory monitoring, described in detail in the guideline, depends on the ART regimen chosen and the patient’s response to therapy. The only routinely recommended prophylaxis for opportunistic infections is for Pneumocystis pneumonia if the CD4 count is <200/mcL.

Preventing HIV with prEP

Consider prescribing daily pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (Truvada) for men and women who are at risk from sexual exposure to HIV or who inject illicit drugs. It takes about 1 week for protective tissue levels to be achieved. Testing to rule out HIV infection is recommended before starting PrEP, as is testing for serum creatinine level, estimated glomerular filtration rate, and hepatitis B surface antigen. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate is not recommended for those with creatinine clearance of less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. For patients taking PrEP, emphasize other preventive measures such as using condoms to protect against both HIV and other sexually-transmitted diseases (STDs), using clean needles and syringes when injecting drugs, or entering a drug rehabilitation program. After initiating PrEP, schedule the first follow-up visit for 30 days later to repeat the HIV test and to assess adverse reactions and PrEP adherence.

For men who have sex with men (MSM), there is an alternative form of PrEP when sexual exposure is infrequent. “On-demand” or “event-driven” PrEP involves 4 doses of emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate; 2 doses given with food 2 to 24 hours before sex (the closer to 24 the better), one dose 24 hours after the first and one 24 hours after the second. This is referred to as 2-1-1 dosing. This option has only been tested in MSM with sexual exposure. It is not recommended at this time for others at risk for HIV or for MSM with chronic or active hepatitis B infection.

Continue to: Preventing HIV infection with post-exposure prophylaxis

Preventing HIV infection with post-exposure prophylaxis

Post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) for HIV infection is divided into 2 categories: occupational PEP (oPEP) and non-occupational PEP (nPEP). Recommendations for oPEP are described elsewhere3 and are not covered in this Practice Alert. Summarized below are the recommendations for nPEP after sex, injection drug use, and other nonoccupational exposures, which are also described on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Web site.4

Assess the need for nPEP if high-risk exposure (TABLE 34) occurred ≤72 hours earlier. Before starting nPEP, perform a rapid HIV blood test. If rapid testing is unavailable, start nPEP, which can be discontinued if the patient is later determined to have HIV infection. Repeat HIV testing at 4 to 6 weeks and 3 months following initiation of nPEP. Approved HIV tests are described on the CDC Web site at http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/testing/laboratorytests.html. Oral HIV tests are not recommended for HIV testing before initiating nPEP.

nPEP is not recommended when an individual’s risk of exposure to HIV is not high, or if the exposure occurred more than 72 hours before presentation. An algorithm is available to assist with assessing whether nPEP is recommended (FIGURE4).

Specific nPEP regimens. For otherwise healthy adults and adolescents, preferred nPEP consists of a 28-day course of a 3-drug combination: tenofovir disoproxil fumarate 300 mg once daily; emtricitabine 200 mg once daily; and raltegravir, 400 mg twice daily, or dolutegravir 50 mg once daily. Alternative regimens for adults and adolescents are described in the guideline, as are options for children, those with decreased renal function, and pregnant women. Those who receive more than one course of nPEP within a 12-month period should consider PrEP.

When additional vaccination is needed. For victims of sexual assault, offer prophylaxis against STD (TABLE 44) and hepatitis B virus (HBV). Those who have not been vaccinated against HBV should receive the first dose at the initial visit. If the exposure source is known to be HBsAg-positive, give the unvaccinated patient both hepatitis B vaccine and hepatitis B immune globulin at the first visit. The full hepatitis B vaccine series should then be completed according to the recommended schedule and the vaccine product used. Those who have completed hepatitis B vaccination but who were not tested with a post-vaccine titer should receive a single dose of hepatitis B vaccine.

Continue to: Victims of sexual assault...

Victims of sexual assault can benefit from referral to professionals with expertise in post-assault counseling. Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner programs are listed at http://www.sane-sart.com.

Financial assistance for patients. Anti-retroviral drugs are expensive, and those who need nPEP may not have a payer source. Many pharmaceutical manufacturers offer medication assistance programs, and processes are set up to handle time-sensitive requests. Information for specific medications can be found at http://www.pparx.org/en/prescription_assistance_programs/list_of_participating_programs. Those who are prescribed nPEP after a sexual assault can receive reimbursement for medications and health care costs through state Crime Victim Compensation Programs funded by the Department of Justice. State-specific contact information is available at http://www.nacvcb.org/index.asp?sid=6.

1. Saag MS, Benson CA, Gandhi RT, et al. Antiretroviral drugs for treatment and prevention of HIV infection in adults: 2018 recommendations of the International Antiviral Society-USA Panel. JAMA. 2018;320:379-396.

2. Günthard HF, Saag MS, Benson CA, et al. Antiretroviral drugs for treatment and prevention of HIV infection in adults: 2016 recommendations of the International Antiviral Society-USA Panel. JAMA. 2016;316:191-210.

3. Kuhar DT, Henderson DK, Struble KA, et al; US Public Health Service Working Group. Updated US Public Health Service guidelines for the management of occupational exposures to human immunodeficiency virus and recommendations for postexposure prophylaxis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34:875-892.

4. CDC. Updated guidelines for antiretroviral postexposure prophylaxis after sexual, injection drug use, or other nonoccupational exposure to HIV—United States, 2016. https://www-cdc-gov.ezproxy3.library.arizona.edu/hiv/pdf/programresources/cdc-hiv-npep-guidelines.pdf. Accessed October 11, 2018.

1. Saag MS, Benson CA, Gandhi RT, et al. Antiretroviral drugs for treatment and prevention of HIV infection in adults: 2018 recommendations of the International Antiviral Society-USA Panel. JAMA. 2018;320:379-396.

2. Günthard HF, Saag MS, Benson CA, et al. Antiretroviral drugs for treatment and prevention of HIV infection in adults: 2016 recommendations of the International Antiviral Society-USA Panel. JAMA. 2016;316:191-210.

3. Kuhar DT, Henderson DK, Struble KA, et al; US Public Health Service Working Group. Updated US Public Health Service guidelines for the management of occupational exposures to human immunodeficiency virus and recommendations for postexposure prophylaxis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34:875-892.

4. CDC. Updated guidelines for antiretroviral postexposure prophylaxis after sexual, injection drug use, or other nonoccupational exposure to HIV—United States, 2016. https://www-cdc-gov.ezproxy3.library.arizona.edu/hiv/pdf/programresources/cdc-hiv-npep-guidelines.pdf. Accessed October 11, 2018.

Aspirin as CVD prevention in seniors? Think twice

Resources

US Preventive Services Task Force. Final recommendation statement: Aspirin use to prevent cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancer: preventive medication.

https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/aspirin-to-prevent-cardiovascular-disease-and-cancer.

Published April 2016. Accessed September 14, 2018.

McNeil JJ, Woods RL, Nelson MR, et al. Effect of aspirin on disability-free survival in the healthy elderly. 2018;379:1499-1508.

https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1800722. Accessed November 7, 2018.

McNeil JJ, Nelson MR, Woods JE, et al. Effect of aspirin on all-cause mortality in the healthy elderly. 2018;379:1519-1528.

https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1803955. Accessed November 7, 2018.

Resources

US Preventive Services Task Force. Final recommendation statement: Aspirin use to prevent cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancer: preventive medication.

https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/aspirin-to-prevent-cardiovascular-disease-and-cancer.

Published April 2016. Accessed September 14, 2018.

McNeil JJ, Woods RL, Nelson MR, et al. Effect of aspirin on disability-free survival in the healthy elderly. 2018;379:1499-1508.

https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1800722. Accessed November 7, 2018.

McNeil JJ, Nelson MR, Woods JE, et al. Effect of aspirin on all-cause mortality in the healthy elderly. 2018;379:1519-1528.

https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1803955. Accessed November 7, 2018.

Resources

US Preventive Services Task Force. Final recommendation statement: Aspirin use to prevent cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancer: preventive medication.

https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/aspirin-to-prevent-cardiovascular-disease-and-cancer.

Published April 2016. Accessed September 14, 2018.

McNeil JJ, Woods RL, Nelson MR, et al. Effect of aspirin on disability-free survival in the healthy elderly. 2018;379:1499-1508.

https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1800722. Accessed November 7, 2018.

McNeil JJ, Nelson MR, Woods JE, et al. Effect of aspirin on all-cause mortality in the healthy elderly. 2018;379:1519-1528.

https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1803955. Accessed November 7, 2018.

ECG to screen asymptomatic adults? Not so fast, says USPSTF

Resources

US Preventive Services Task Force. Final recommendation statement: Cardiovascular disease risk: screening with electrocardiography.

https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/cardiovascular-disease-risk-screening-with-electrocardiography. Published June 2018. Accessed October 23, 2018.

US Preventive Services Task Force. Final recommendation statement: Atrial fibrillation: screening with electrocardiography.

https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/atrial-fibrillation-screening-with-electrocardiography. Published August 2018. Accessed October 23, 2018.

Resources

US Preventive Services Task Force. Final recommendation statement: Cardiovascular disease risk: screening with electrocardiography.

https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/cardiovascular-disease-risk-screening-with-electrocardiography. Published June 2018. Accessed October 23, 2018.

US Preventive Services Task Force. Final recommendation statement: Atrial fibrillation: screening with electrocardiography.

https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/atrial-fibrillation-screening-with-electrocardiography. Published August 2018. Accessed October 23, 2018.

Resources

US Preventive Services Task Force. Final recommendation statement: Cardiovascular disease risk: screening with electrocardiography.

https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/cardiovascular-disease-risk-screening-with-electrocardiography. Published June 2018. Accessed October 23, 2018.

US Preventive Services Task Force. Final recommendation statement: Atrial fibrillation: screening with electrocardiography.

https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/atrial-fibrillation-screening-with-electrocardiography. Published August 2018. Accessed October 23, 2018.

Cervical cancer: Who should you screen?

Resource

US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for cervical cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320:674-686. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2697704. Accessed September 14, 2018.

Resource

US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for cervical cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320:674-686. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2697704. Accessed September 14, 2018.

Resource

US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for cervical cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320:674-686. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2697704. Accessed September 14, 2018.

CDC recommendations for the 2018-2019 influenza season

The 2017-2018 influenza season was one of the most severe in this century, according to every indicator measured by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The proportion of outpatient visits due to influenza-like illness (ILI) was elevated nationally above a baseline of 2.2% for 19 straight weeks, and for 3 weeks it was over 7%.1 High ILI activity was widespread and included all 50 states in January.

From October 2017 through April 2018, the CDC estimates that the influenza-related hospitalization rate was 106.6 per 100,000 population, with the highest rates among children 0 to 4 years (74.3/100,000), adults 50 to 64 years (115.7/100,000), and adults 65 years and older (460.9/100,000). More than 90% of adults hospitalized had a chronic condition, such as heart or lung disease, diabetes, or obesity, placing them at high risk for influenza complications.1

Influenza severity is also measured as the proportion of deaths due to pneumonia and influenza, which was above the epidemic threshold for 16 weeks in 2017-2018 and was above 10% for 4 weeks in January.1 Based on all of these indicators, the 2017-2018 influenza season was classified as high severity overall and for all age groups, the first time this has happened since the 2003-2004 season. There were 171 pediatric deaths attributed to influenza, and more than three-quarters of vaccine-eligible children who died from influenza this season had not received influenza vaccine.1

The type of influenza predominating last season was influenza A from early- through mid-season, and was influenza B later in the season (see https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/54974).1 For the entire season, 71.2% of specimens that tested positive for influenza in public health labs were Influenza A and 84.9% of these were H3N2.1

Effectiveness of influenza vaccine last season. As measured by preventing respiratory illness needing medical attention, vaccine effectiveness was 36% overall: 25% against influenza A (H3N2), 67% against influenza A (H1N1), and 42% against influenza B.1 Effectiveness varied by age, being the highest in those 8 years and younger.2 Effectiveness was questionable in those older than 65, with an estimated effectiveness of 23% but confidence intervals including 0.2

While the effectiveness of influenza vaccines remains suboptimal, the morbidity and mortality they prevent is still considerable. The CDC estimates that in 2016-2017, more than 5 million influenza illnesses, 2.6 million medical visits, and 84,700 hospitalizations were prevented.3 And effectiveness last season was similar to, or better than, what has been seen in each of the past 10 years (FIGURE).4

Three drugs were recommended for use to treat influenza in 2017-1018 (oseltamivir, peramivir, and zanamivir), and no resistance was found except in 1% of influenza A (H1N1) tested.1 No resistance was found in other A or any B viruses tested.1

Continue to: Safety

Safety

The safety of influenza vaccines is studied each year by both the CDC and US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). This past year, studies were conducted using the CDC-supported Safety Datalink System, looking for increased rates of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, anaphylaxis, Bell’s palsy, encephalitis, Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS), seizures, and transverse myelitis.5 No safety signals were detected. However, for some of the newer vaccines, the numbers of vaccinated individuals studied were small. The FDA studied the incidence of GBS using Medicare data and found no increased rates in those vaccinated.5

2018-2019 Recommendations

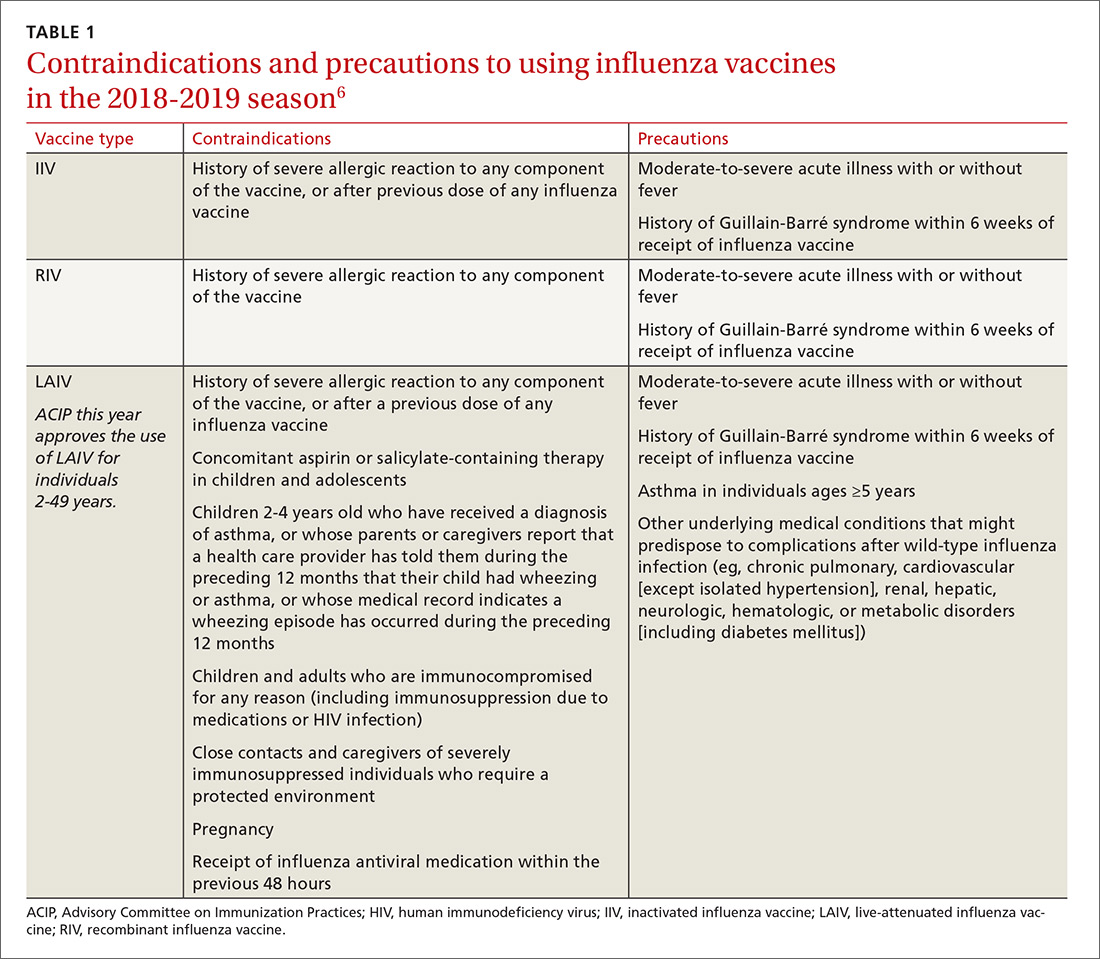

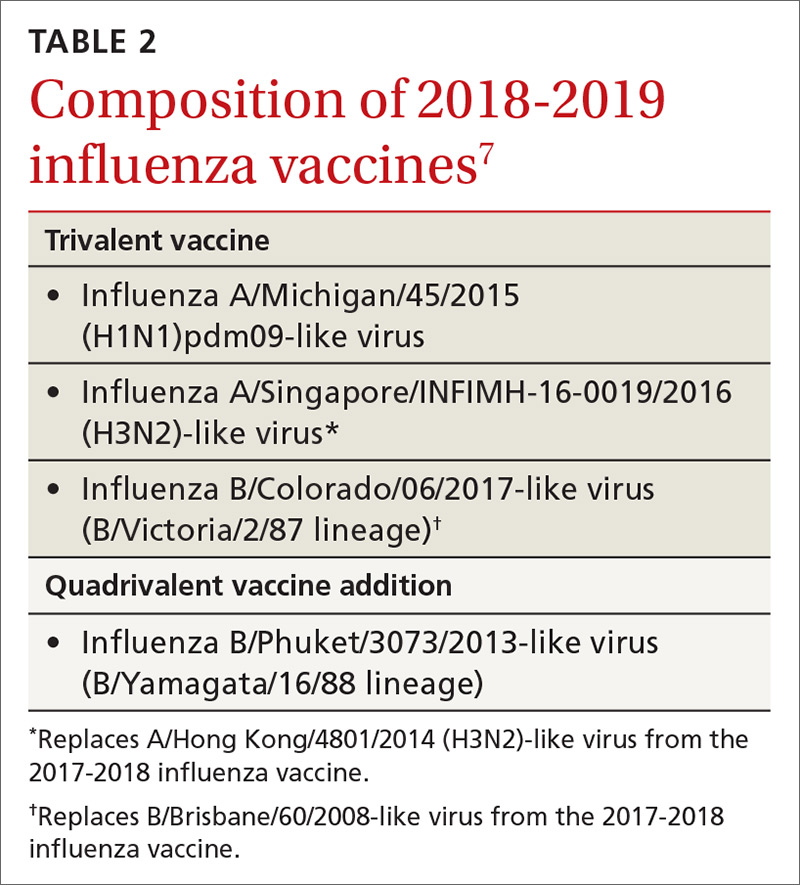

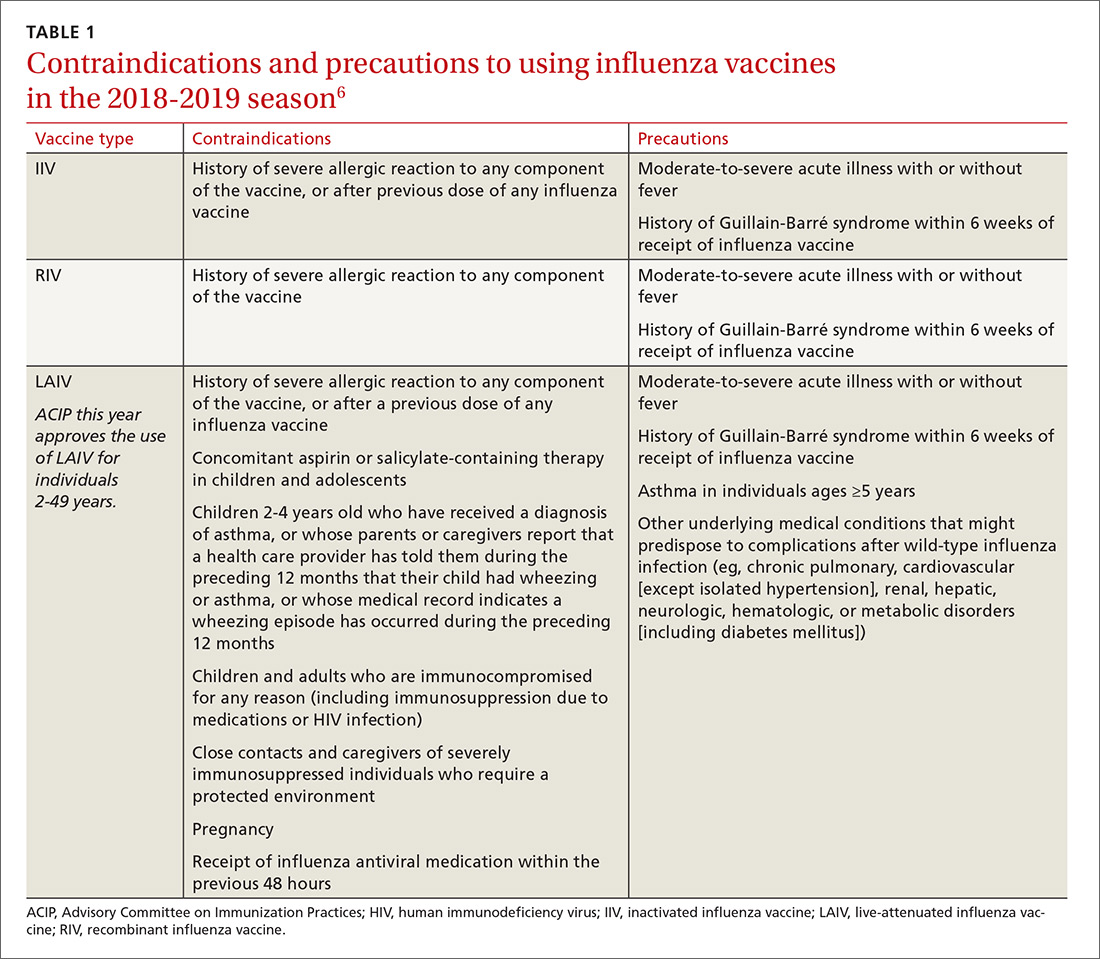

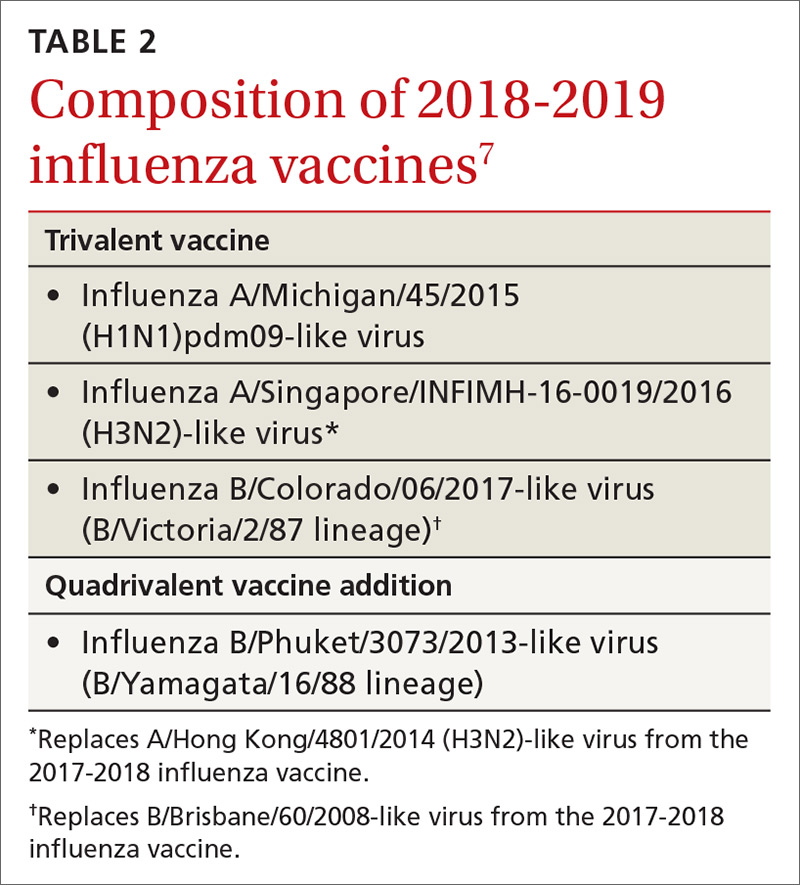

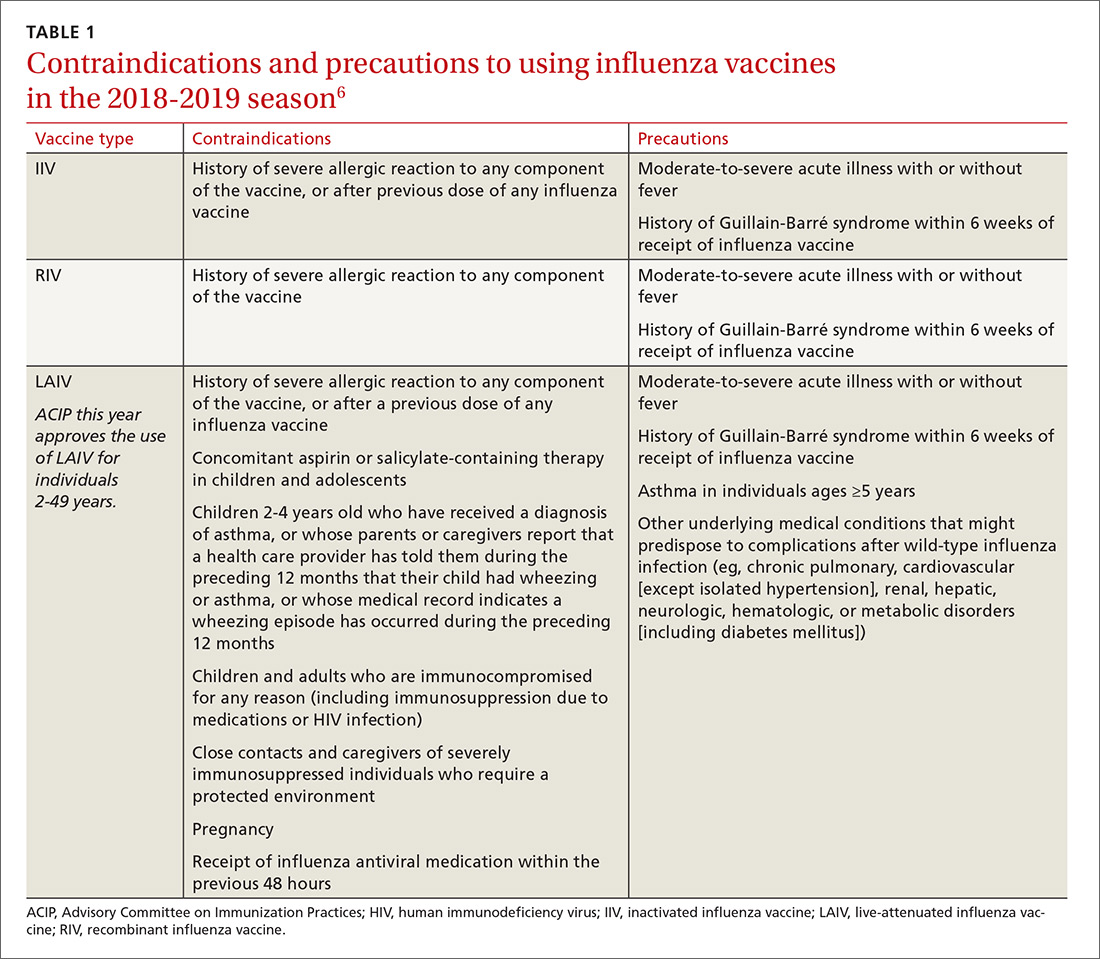

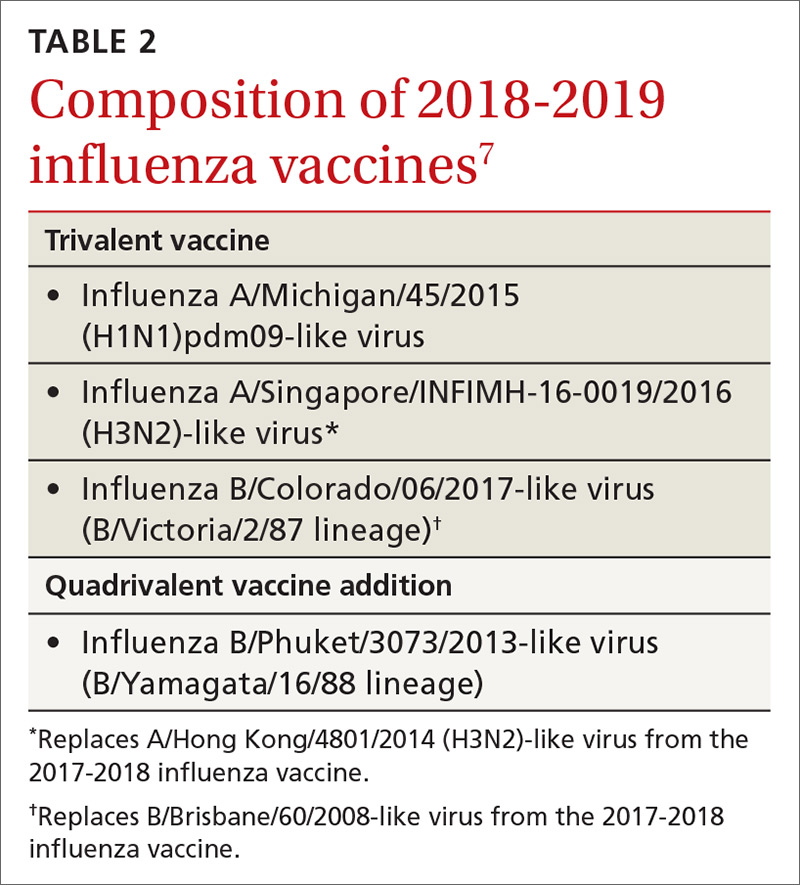

There are only a few changes to the recommendations for the upcoming influenza season. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) still recommends universal vaccination for anyone age 6 months and older who does not have a contraindication (TABLE 16). Two of the antigens in the vaccines for this coming season are slightly different from last season (TABLE 27).

After 2 years of recommending against the use of live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) because of its low effectiveness in children against influenza A (H1N1), ACIP now includes it as an option for the upcoming season in individuals ages 2 through 49 years.8 The basis of this revised recommendation was 2-fold: 1) evidence of LAIV effectiveness comparable to that of inactivated products against A (H3N2) and B viruses; and 2) evidence that a new strain of A (H1N1) now used to produce the vaccine (A/Slovenia) produces a significantly higher antibody response than the strain (A/Bolivia) used in the years when the vaccine was not effective against A (H1N1).

However, the new formulation’s clinical effectiveness against A (H1N1) has not been demonstrated, leading the American Academy of Pediatrics to recommend that LAIV should be used in children only if other options are not available or if injectable vaccine is refused.9 Contraindications to the use of LAIV remain the same as the previous version of the vaccine (TABLE 16).

Individuals with non-severe egg allergies can receive any licensed, recommended age-appropriate influenza vaccine and no longer have to be monitored for 30 minutes after receiving the vaccine. People who have severe egg allergies should be vaccinated with an egg-free product or in a medical setting and be supervised by a health care provider who is able to recognize and manage severe allergic conditions.

Continue to: Children 6 months through 8 years...

Children 6 months through 8 years who have previously received an influenza vaccine, either trivalent or quadrivalent, need only 1 dose; those who have not received vaccination need 2 doses separated by at least 4 weeks.

Available vaccine products

A table found on the CDC influenza Web site lists the vaccine products available in the United States and the ages for which they are approved.6 The options now include 2 standard-dose trivalent inactivated influenza vaccines (IIV3), 4 standard-dose quadrivalent inactivated influenza vaccines (IIV4), one cell culture-based IIV4 (ccIIV4), one standard dose IIV4 intradermal option, a trivalent and a quadrivalent recombinant influenza vaccine (RIV3, RIV4), one LAIV, and 2 products for those 65 years and older—an adjuvanted IIV3 (aIIV3) and a high dose IIV3. Three of these products do not depend on egg-based technology: RIV3, RIV4, and ccIIV4.

Comparative effectiveness studies of these vaccine options, including those available for the elderly, are being conducted. Studies presented at the June 2018 ACIP meeting show comparable effectiveness of egg-based and non–egg-based products.6 At this time, ACIP does not make a preferential recommendation for any influenza vaccine product for any age group.

1. Garten R, Blanton L, Elal AIA, eta al. Update: Influenza activity in the United States during the 2017-18 season and composition of the 2018-2019 influenza vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67;634-642.

2. Flannery B, Chung JR, Belongia EA, et al. Interim estimates of 2017-18 seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness – United States, February 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:180-185.

3. Flannery B, Chung J, Ferdinands J. Preliminary estimates of 2017-2018 seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness against laboratory-confirmed influenza from the US Flu VE and HAIVEN network. Meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; June 20, 2018; Atlanta, Ga. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2018-06/flu-02-Flannery-508.pdf. Accessed August 11, 2018.

4. CDC. Seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness, 2005-2018. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/vaccination/effectiveness-studies.htm. Accessed July 27, 2018.

5. Shimabukuro T. End-of-season update: 2017-2018 influenza vaccine safety monitoring. Presented at: meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; June 20, 2018; Atlanta, Ga. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2018-06/flu-04-Shimabukuro-508.pdf. Accessed August 11, 2018.

6. CDC. Prevention and Control of Seasonal Influenza with Vaccines: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2018–19 Influenza Season. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/67/rr/rr6703a1.htm?s_cid=rr6703a1_w. Accessed August 23, 2018.

7. CDC. Update: Influenza activity in the United States during the 2017-18 season and composition of the 2018-19 influenza vaccine. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/67/wr/mm6722a4.htm. Accessed July 27, 2018.

8. Grohskopf LA, Sokolow LZ, Fry AM, et al. Update: ACIP recommendations for the use of quadrivalent live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV4) — United States, 2018–19 influenza season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:643-645.

9. Jenco M. AAP: Give children IIV flu shot; use LAIV as last resort. Available at: http://www.aappublications.org/news/2018/05/21/fluvaccine051818. Accessed August 1, 2018.

The 2017-2018 influenza season was one of the most severe in this century, according to every indicator measured by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The proportion of outpatient visits due to influenza-like illness (ILI) was elevated nationally above a baseline of 2.2% for 19 straight weeks, and for 3 weeks it was over 7%.1 High ILI activity was widespread and included all 50 states in January.

From October 2017 through April 2018, the CDC estimates that the influenza-related hospitalization rate was 106.6 per 100,000 population, with the highest rates among children 0 to 4 years (74.3/100,000), adults 50 to 64 years (115.7/100,000), and adults 65 years and older (460.9/100,000). More than 90% of adults hospitalized had a chronic condition, such as heart or lung disease, diabetes, or obesity, placing them at high risk for influenza complications.1

Influenza severity is also measured as the proportion of deaths due to pneumonia and influenza, which was above the epidemic threshold for 16 weeks in 2017-2018 and was above 10% for 4 weeks in January.1 Based on all of these indicators, the 2017-2018 influenza season was classified as high severity overall and for all age groups, the first time this has happened since the 2003-2004 season. There were 171 pediatric deaths attributed to influenza, and more than three-quarters of vaccine-eligible children who died from influenza this season had not received influenza vaccine.1

The type of influenza predominating last season was influenza A from early- through mid-season, and was influenza B later in the season (see https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/54974).1 For the entire season, 71.2% of specimens that tested positive for influenza in public health labs were Influenza A and 84.9% of these were H3N2.1

Effectiveness of influenza vaccine last season. As measured by preventing respiratory illness needing medical attention, vaccine effectiveness was 36% overall: 25% against influenza A (H3N2), 67% against influenza A (H1N1), and 42% against influenza B.1 Effectiveness varied by age, being the highest in those 8 years and younger.2 Effectiveness was questionable in those older than 65, with an estimated effectiveness of 23% but confidence intervals including 0.2

While the effectiveness of influenza vaccines remains suboptimal, the morbidity and mortality they prevent is still considerable. The CDC estimates that in 2016-2017, more than 5 million influenza illnesses, 2.6 million medical visits, and 84,700 hospitalizations were prevented.3 And effectiveness last season was similar to, or better than, what has been seen in each of the past 10 years (FIGURE).4

Three drugs were recommended for use to treat influenza in 2017-1018 (oseltamivir, peramivir, and zanamivir), and no resistance was found except in 1% of influenza A (H1N1) tested.1 No resistance was found in other A or any B viruses tested.1

Continue to: Safety

Safety

The safety of influenza vaccines is studied each year by both the CDC and US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). This past year, studies were conducted using the CDC-supported Safety Datalink System, looking for increased rates of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, anaphylaxis, Bell’s palsy, encephalitis, Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS), seizures, and transverse myelitis.5 No safety signals were detected. However, for some of the newer vaccines, the numbers of vaccinated individuals studied were small. The FDA studied the incidence of GBS using Medicare data and found no increased rates in those vaccinated.5

2018-2019 Recommendations

There are only a few changes to the recommendations for the upcoming influenza season. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) still recommends universal vaccination for anyone age 6 months and older who does not have a contraindication (TABLE 16). Two of the antigens in the vaccines for this coming season are slightly different from last season (TABLE 27).

After 2 years of recommending against the use of live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) because of its low effectiveness in children against influenza A (H1N1), ACIP now includes it as an option for the upcoming season in individuals ages 2 through 49 years.8 The basis of this revised recommendation was 2-fold: 1) evidence of LAIV effectiveness comparable to that of inactivated products against A (H3N2) and B viruses; and 2) evidence that a new strain of A (H1N1) now used to produce the vaccine (A/Slovenia) produces a significantly higher antibody response than the strain (A/Bolivia) used in the years when the vaccine was not effective against A (H1N1).

However, the new formulation’s clinical effectiveness against A (H1N1) has not been demonstrated, leading the American Academy of Pediatrics to recommend that LAIV should be used in children only if other options are not available or if injectable vaccine is refused.9 Contraindications to the use of LAIV remain the same as the previous version of the vaccine (TABLE 16).