User login

Harlequin Syndrome: Discovery of an Ancient Schwannoma

To the Editor:

A 52-year-old man who was otherwise healthy and a long-distance runner presented with the sudden onset of diminished sweating on the left side of the body of 6 weeks’ duration. While training for a marathon, he reported that he perspired only on the right side of the body during runs of 12 to 15 miles; he observed a lack of sweating on the left side of the face, left side of the trunk, left arm, and left leg. This absence of sweating was accompanied by intense flushing on the right side of the face and trunk.

The patient did not take any medications. He reported no history of trauma and exhibited no neurologic deficits. A chest radiograph was negative. Thyroid function testing and a comprehensive metabolic panel were normal. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the chest and abdomen revealed a 4.3-cm soft-tissue mass in the left superior mediastinum that was superior to the aortic arch, posterior to the left subclavian artery in proximity to the sympathetic chain, and lateral to the trachea. The patient was diagnosed with Harlequin syndrome (HS).

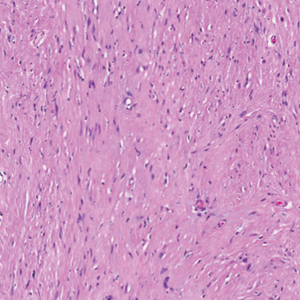

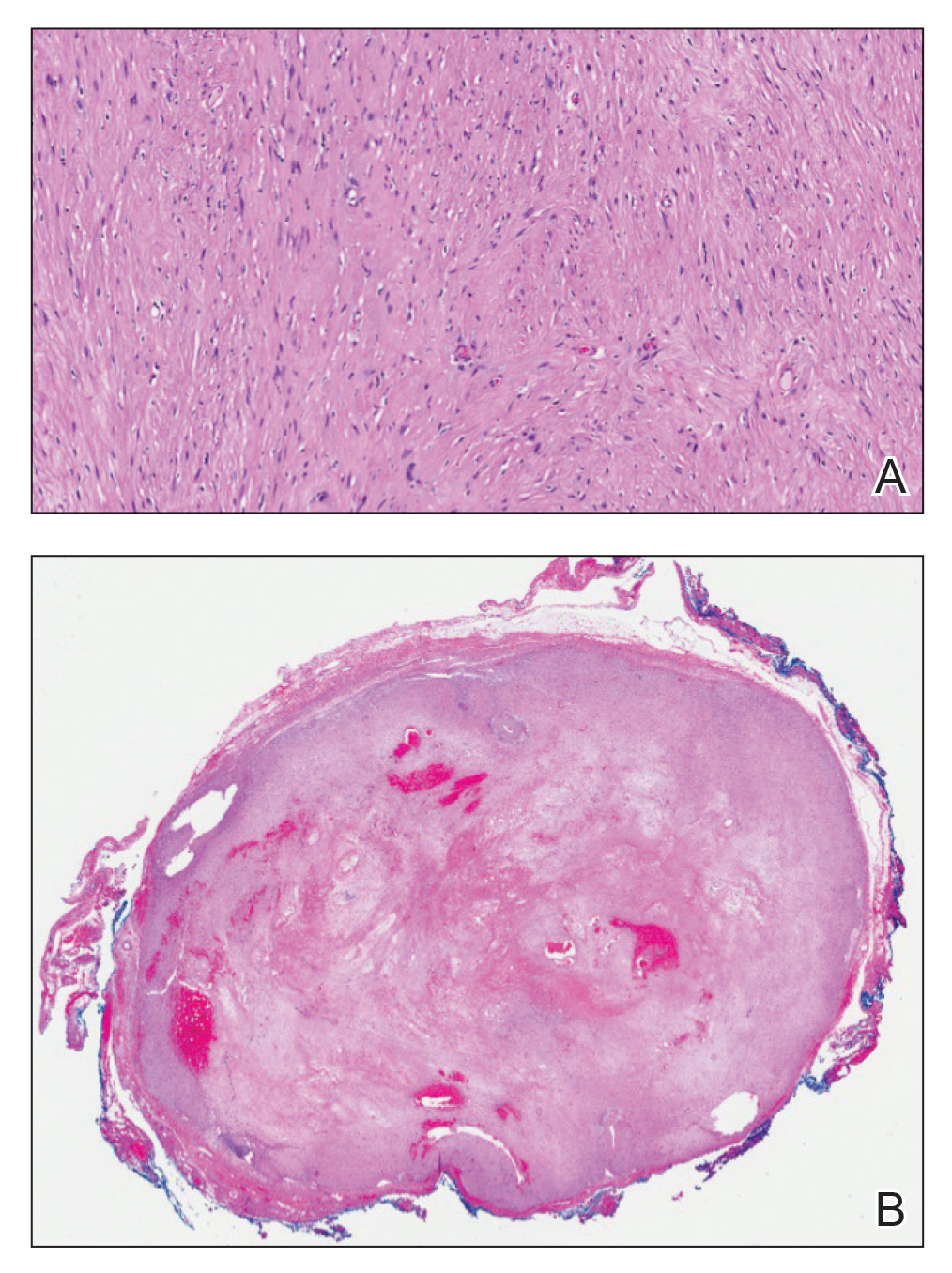

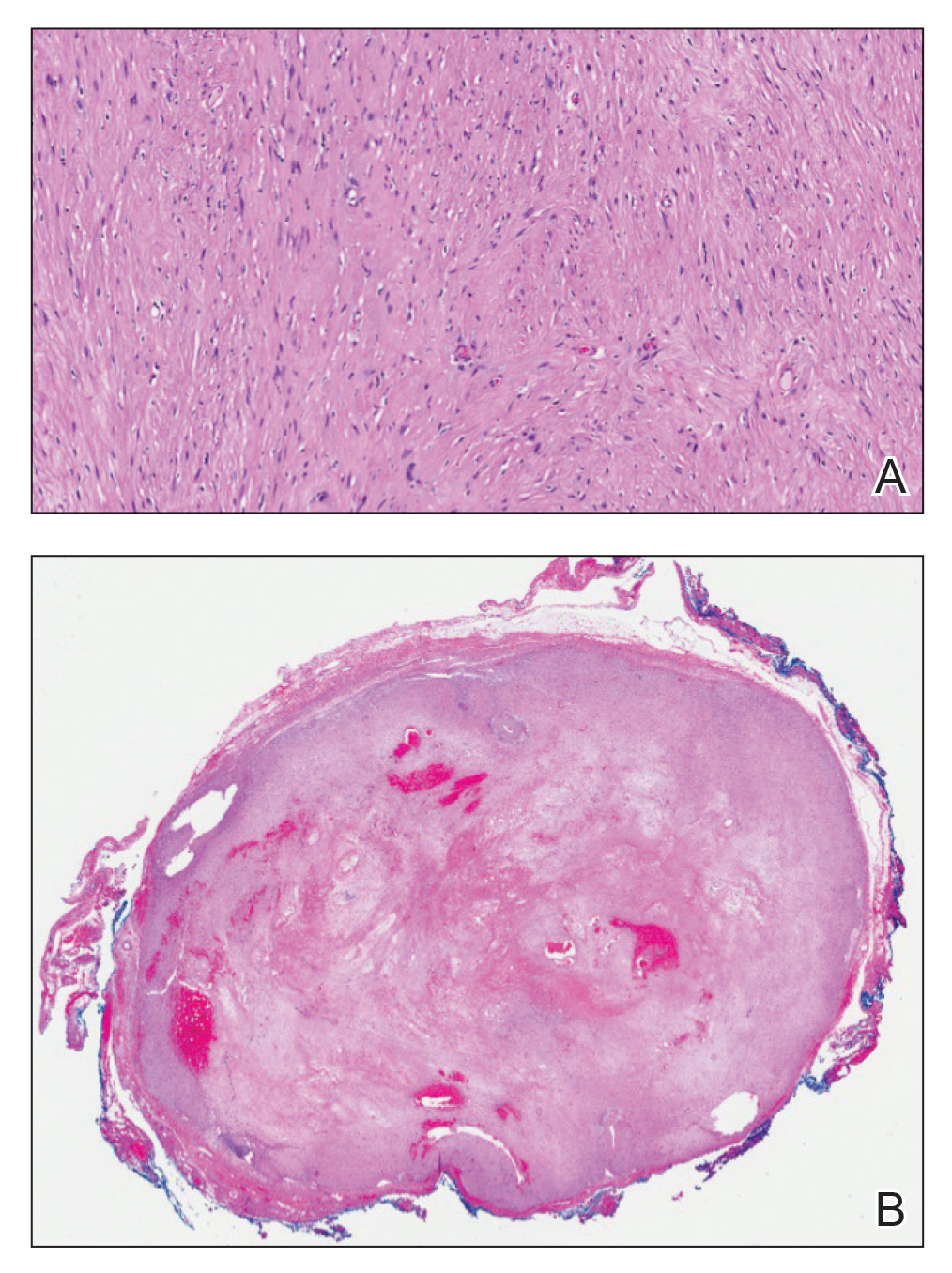

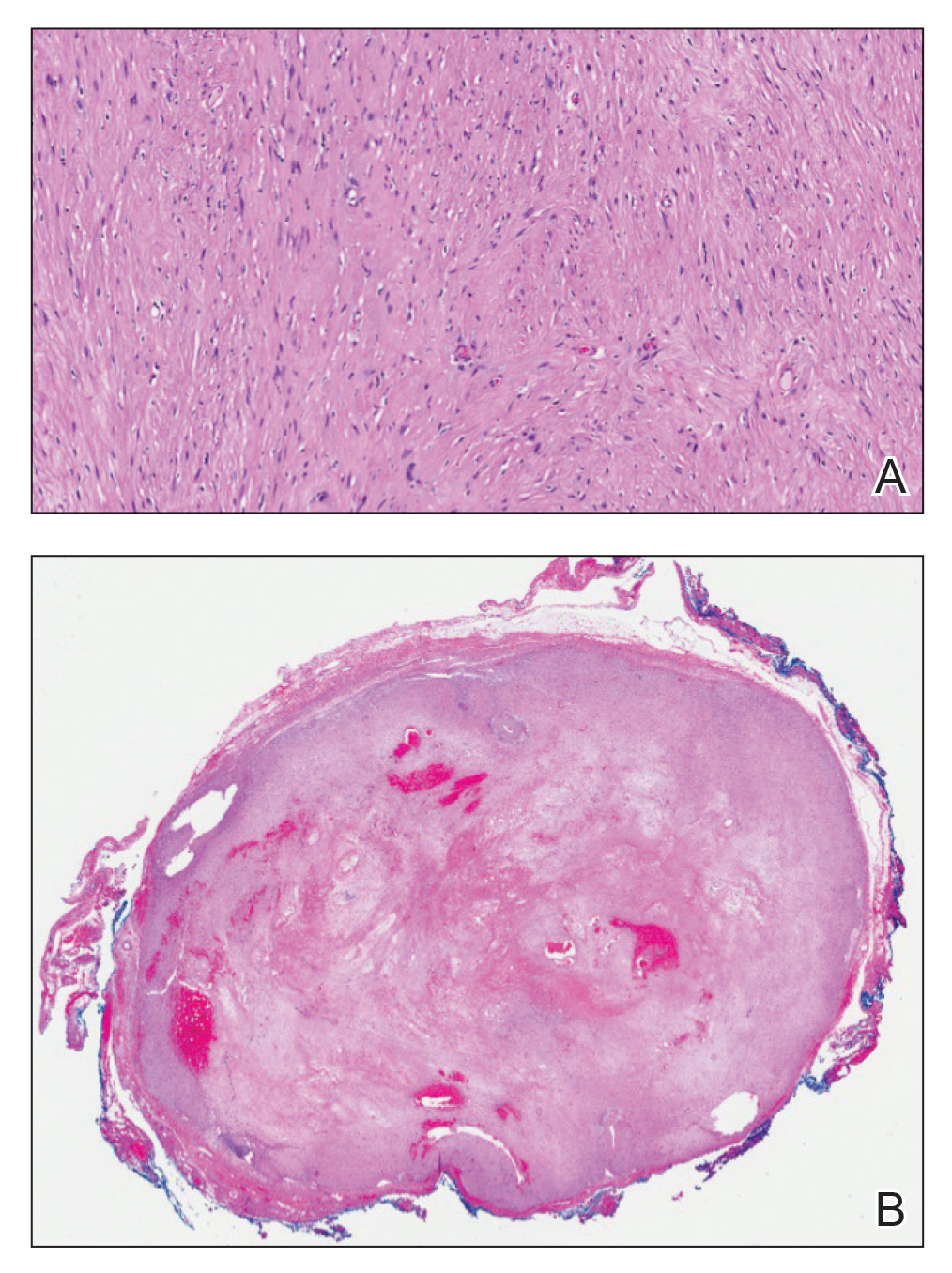

Open thoracotomy was performed to remove the lesion. Analysis of the mass showed cystic areas, areas of hemorrhage (Figure 1A), and alternating zones of compact Antoni A spindle cells admixed with areas of less orderly Antoni B spindle cells within a hypocellular stroma (Figure 1B). Individual cells were characterized by eosinophilic cytoplasm and tapered nuclei. The mass appeared to be completely encapsulated. No mitotic figures were seen on multiple slides. The cells stained diffusely positive for S-100 proteins. At 6-month follow-up, the patient reported that he did not notice any return of normal sweating on the left side. However, the right-sided flushing had resolved.

Harlequin syndrome (also called the Harlequin sign) is a rare disorder of the sympathetic nervous system and should not be confused with lethal harlequin-type ichthyosis, an autosomal-recessive congenital disorder in which the affected newborn’s skin is hard and thickened over most of the body.1 Harlequin syndrome usually is characterized by unilateral flushing and sweating that can affect the face, trunk, and extremities.2 Physical stimuli, such as exercising (as in our patient), high body temperature, and the consumption of spicy or pungent food, or an emotional response can unmask or exacerbate symptoms of HS. The syndrome also can present with cluster headache.3 Harlequin syndrome is more common in females (66% of cases).4 Originally, the side of the face marked by increased sweating and flushing was perceived to be the pathologic side; now it is recognized that the anhidrotic side is affected by the causative pathology. The side of the face characterized by flushing might gradually darken as it compensates for lack of thermal regulation on the other side.2,5

Usually, HS is an idiopathic condition associated with localized failure of upper thoracic sympathetic chain ganglia.5 A theory is that HS is part of a spectrum of autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy.6 Typically, the syndrome is asymptomatic at rest, but testing can reveal an underlying sympathetic lesion.7 Structural lesions have been reported as a cause of the syndrome,6 similar to our patient.

Disrupted thermoregulatory vasodilation in HS is caused by an ipsilateral lesion of the sympathetic vasodilator neurons that innervate the face. Hemifacial anhidrosis also occurs because sudomotor neurons travel within the same pathways as vasodilator neurons.4

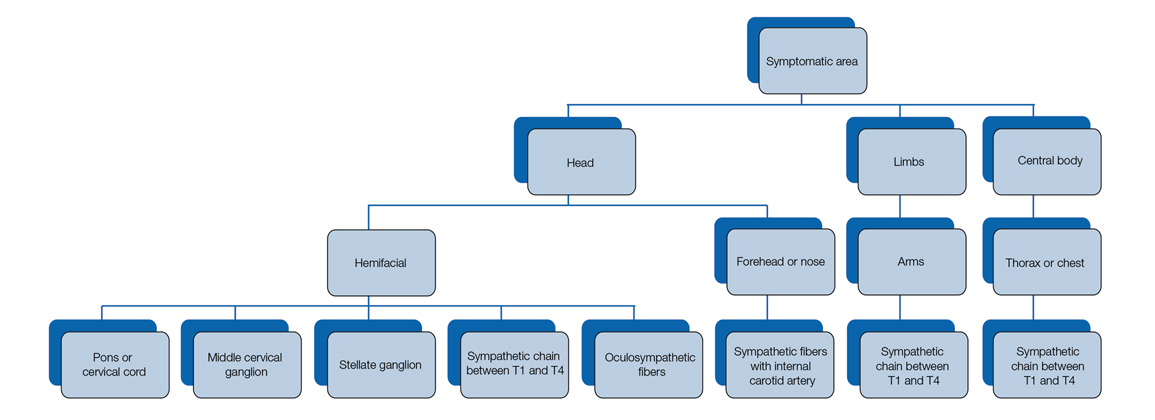

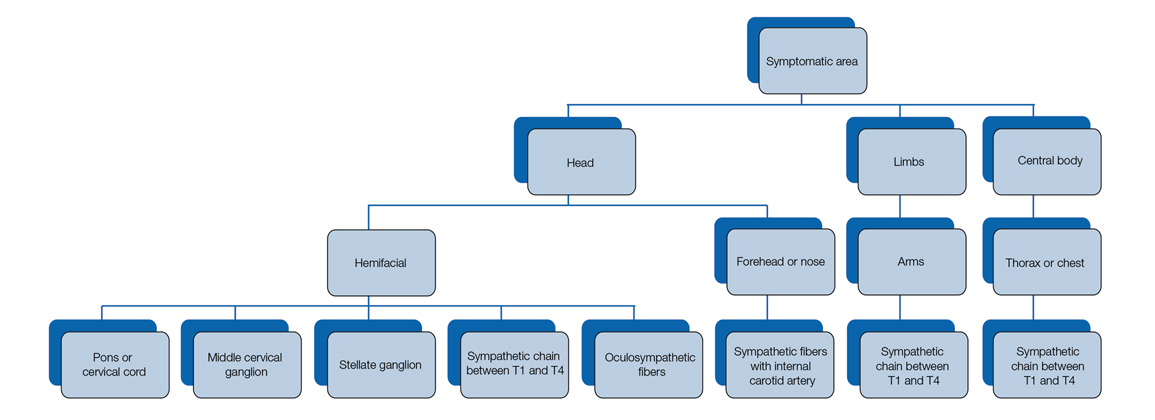

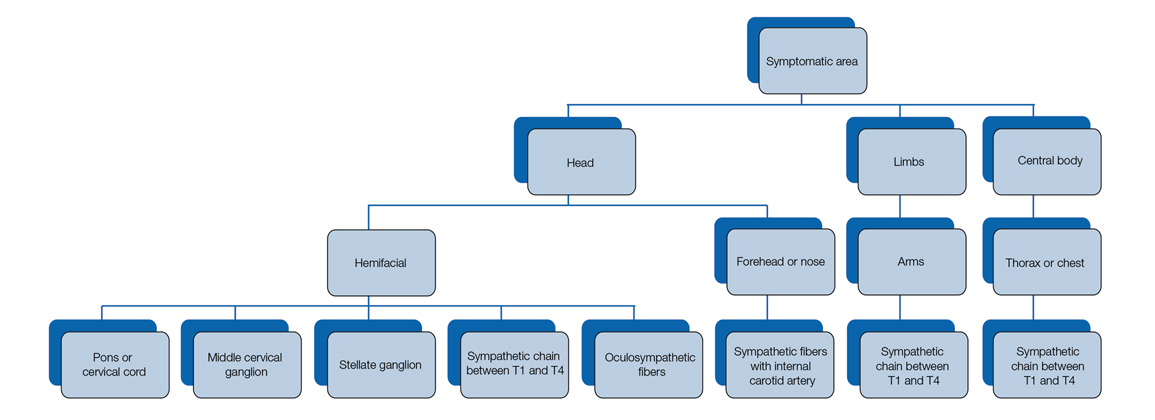

Our patient had a posterior mediastinal ancient schwannoma to the left of the subclavian artery, lateral to the trachea, with ipsilateral anhidrosis of the forehead, cheek, chin, and torso. In the medical literature, the forehead, cheek, and chin are described as being affected in HS when the lesion is located under the bifurcation of the carotid artery.3,5 Most of the sudomotor and vasomotor fibers that innervate the face leave the spinal cord through ventral roots T2-T34 (symptomatic areas are described in Figure 2), which correlates with the hypothesis that HS results from a deficit originating in the third thoracic nerve that is caused by a peripheral lesion affecting sympathetic outflow through the third thoracic root.2 The location of our patient’s lesion supports this claim.

Harlequin syndrome can present simultaneously with ipsilateral Horner, Adie, and Ross syndromes.8 There are varying clinical presentations of Horner syndrome. Some patients with HS show autonomic ocular signs, such as miosis and ptosis, exhibiting Horner syndrome as an additional feature.5 Adie syndrome is characterized by tonic pupils with hyporeflexia and is unilateral in most cases. Ross syndrome is similar to Adie syndrome—including tonic pupils with hyporeflexia—in addition to a finding of segmental anhidrosis; it is bilateral in most cases.4

In some cases, Horner syndrome and HS originate from unilateral pharmaceutical sympathetic denervation (ie, as a consequence of paravertebral spread of local anesthetic to ipsilateral stellate ganglion).9 Facial nonflushing areas in HS typically are identical with anhidrotic areas10; Horner syndrome often is ipsilateral to the affected sympathetic region.11

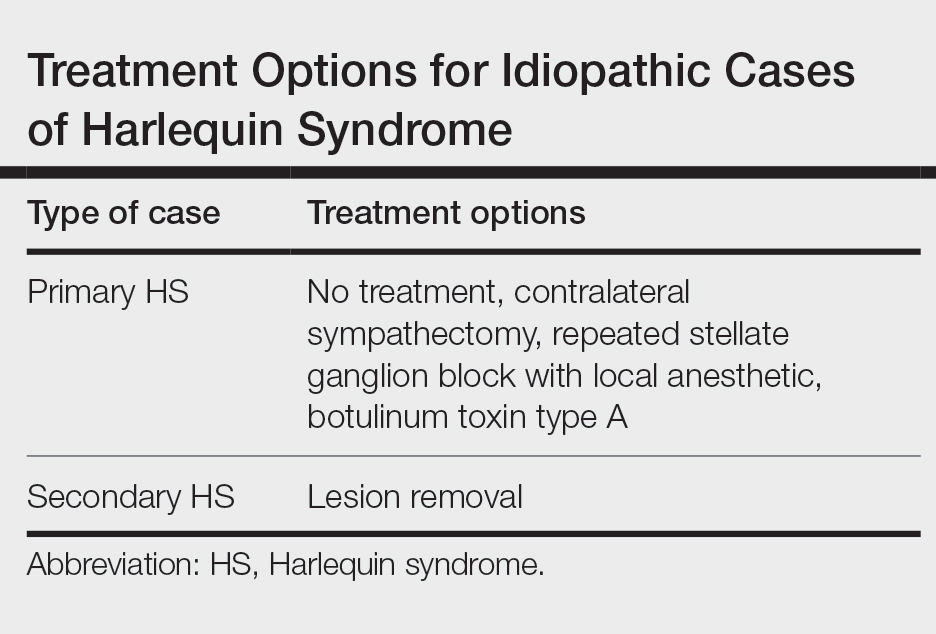

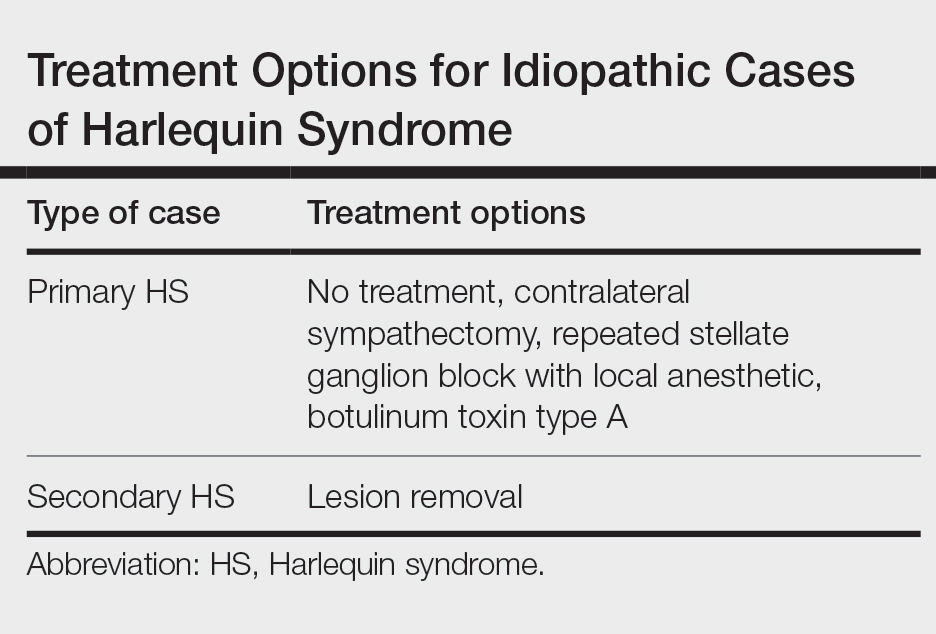

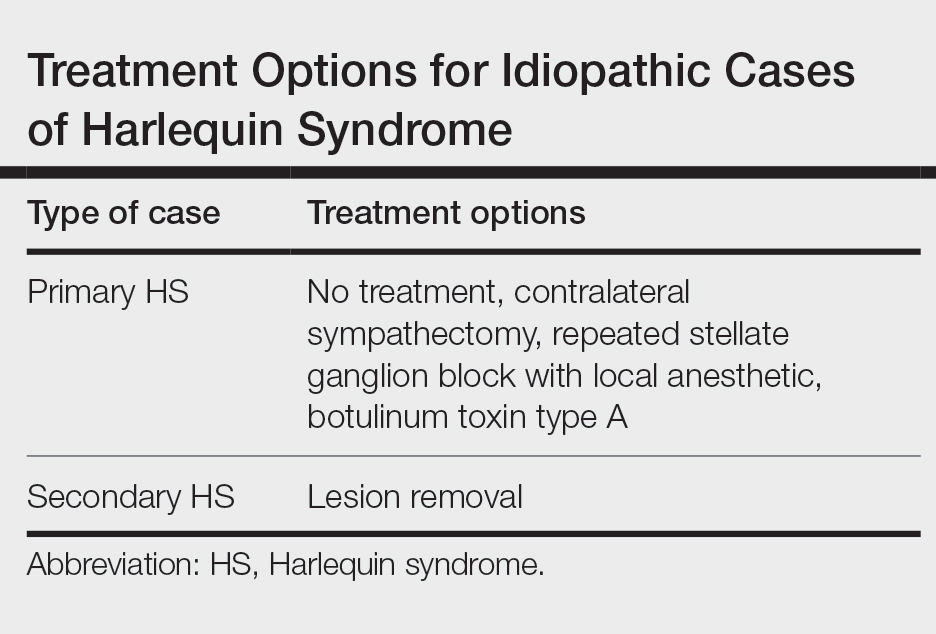

Our patient exhibited secondary HS from a tumor effect; however, an underlying tumor or infarct is absent in many cases. In primary (idiopathic) cases of HS, treatment is not recommended because the syndrome is benign.10,11

If symptoms of HS cause notable social embarrassment, contralateral sympathectomy can be considered.5,12 Repeated stellate ganglion block with a local anesthetic could be a less invasive treatment option.13 When considered on a case-by-case-basis, botulinum toxin type A has been effective as a treatment of compensatory hyperhidrosis on the unaffected side.14

In cases of secondary HS, surgical removal of the lesion may alleviate symptoms, though thoracotomy in our patient to remove the schwannoma did not alleviate anhidrosis. The Table lists treatment options for primary and secondary HS.4,5,11

- Harlequin ichthyosis. MedlinePlus. National Library of Medicine [Internet]. Updated January 7, 2022. Accessed April 5, 2022. https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/harlequin-ichthyosis

- Lance JW, Drummond PD, Gandevia SC, et al. Harlequin syndrome: the sudden onset of unilateral flushing and sweating. J Neurol Neurosurg Psych. 1988;51:635-642. doi:10.1136/jnnp.51.5.635

- Lehman K, Kumar N, Vu Q, et al. Harlequin syndrome in cluster headache. Headache. 2016;56:1053-1054. doi:10.1111/head.12852

- Willaert WIM, Scheltinga MRM, Steenhuisen SF, et al. Harlequin syndrome: two new cases and a management proposal. Acta Neurol Belg. 2009;109:214-220.

- Duddy ME, Baker MR. Images in clinical medicine. Harlequin’s darker side. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:E22. doi:10.1056/NEJMicm067851

- Karam C. Harlequin syndrome in a patient with putative autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy. Auton Neurosci. 2016;194:58-59. doi:10.1016/j.autneu.2015.12.004

- Wasner G, Maag R, Ludwig J, et al. Harlequin syndrome—one face of many etiologies. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2005;1:54-59. doi:10.1038/ncpneuro0040

- Guilloton L, Demarquay G, Quesnel L, et al. Dysautonomic syndrome of the face with Harlequin sign and syndrome: three new cases and a review of the literature. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2013;169:884-891. doi:10.1016/j.neurol.2013.01.628

- Burlacu CL, Buggy DJ. Coexisting Harlequin and Horner syndromes after high thoracic paravertebral anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 2005;95:822-824. doi:10.1093/bja/aei258

- Morrison DA, Bibby K, Woodruff G. The “Harlequin” sign and congenital Horner’s syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psych. 1997;62:626-628. doi:10.1136/jnnp.62.6.626

- Bremner F, Smith S. Pupillographic findings in 39 consecutive cases of Harlequin syndrome. J Neuroophthalmol. 2008;28:171-177. doi:10.1097/WNO.0b013e318183c885

- Kaur S, Aggarwal P, Jindal N, et al. Harlequin syndrome: a mask of rare dysautonomic syndromes. Dermatol Online J. 2015;21:13030/qt3q39d7mz.

- Reddy H, Fatah S, Gulve A, et al. Novel management of Harlequin syndrome with stellate ganglion block. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:954-956. doi:10.1111/bjd.12561

- ManhRKJV, Spitz M, Vasconcellos LF. Botulinum toxin for treatment of Harlequin syndrome. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2016;23:112-113. doi:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2015.11.030

To the Editor:

A 52-year-old man who was otherwise healthy and a long-distance runner presented with the sudden onset of diminished sweating on the left side of the body of 6 weeks’ duration. While training for a marathon, he reported that he perspired only on the right side of the body during runs of 12 to 15 miles; he observed a lack of sweating on the left side of the face, left side of the trunk, left arm, and left leg. This absence of sweating was accompanied by intense flushing on the right side of the face and trunk.

The patient did not take any medications. He reported no history of trauma and exhibited no neurologic deficits. A chest radiograph was negative. Thyroid function testing and a comprehensive metabolic panel were normal. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the chest and abdomen revealed a 4.3-cm soft-tissue mass in the left superior mediastinum that was superior to the aortic arch, posterior to the left subclavian artery in proximity to the sympathetic chain, and lateral to the trachea. The patient was diagnosed with Harlequin syndrome (HS).

Open thoracotomy was performed to remove the lesion. Analysis of the mass showed cystic areas, areas of hemorrhage (Figure 1A), and alternating zones of compact Antoni A spindle cells admixed with areas of less orderly Antoni B spindle cells within a hypocellular stroma (Figure 1B). Individual cells were characterized by eosinophilic cytoplasm and tapered nuclei. The mass appeared to be completely encapsulated. No mitotic figures were seen on multiple slides. The cells stained diffusely positive for S-100 proteins. At 6-month follow-up, the patient reported that he did not notice any return of normal sweating on the left side. However, the right-sided flushing had resolved.

Harlequin syndrome (also called the Harlequin sign) is a rare disorder of the sympathetic nervous system and should not be confused with lethal harlequin-type ichthyosis, an autosomal-recessive congenital disorder in which the affected newborn’s skin is hard and thickened over most of the body.1 Harlequin syndrome usually is characterized by unilateral flushing and sweating that can affect the face, trunk, and extremities.2 Physical stimuli, such as exercising (as in our patient), high body temperature, and the consumption of spicy or pungent food, or an emotional response can unmask or exacerbate symptoms of HS. The syndrome also can present with cluster headache.3 Harlequin syndrome is more common in females (66% of cases).4 Originally, the side of the face marked by increased sweating and flushing was perceived to be the pathologic side; now it is recognized that the anhidrotic side is affected by the causative pathology. The side of the face characterized by flushing might gradually darken as it compensates for lack of thermal regulation on the other side.2,5

Usually, HS is an idiopathic condition associated with localized failure of upper thoracic sympathetic chain ganglia.5 A theory is that HS is part of a spectrum of autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy.6 Typically, the syndrome is asymptomatic at rest, but testing can reveal an underlying sympathetic lesion.7 Structural lesions have been reported as a cause of the syndrome,6 similar to our patient.

Disrupted thermoregulatory vasodilation in HS is caused by an ipsilateral lesion of the sympathetic vasodilator neurons that innervate the face. Hemifacial anhidrosis also occurs because sudomotor neurons travel within the same pathways as vasodilator neurons.4

Our patient had a posterior mediastinal ancient schwannoma to the left of the subclavian artery, lateral to the trachea, with ipsilateral anhidrosis of the forehead, cheek, chin, and torso. In the medical literature, the forehead, cheek, and chin are described as being affected in HS when the lesion is located under the bifurcation of the carotid artery.3,5 Most of the sudomotor and vasomotor fibers that innervate the face leave the spinal cord through ventral roots T2-T34 (symptomatic areas are described in Figure 2), which correlates with the hypothesis that HS results from a deficit originating in the third thoracic nerve that is caused by a peripheral lesion affecting sympathetic outflow through the third thoracic root.2 The location of our patient’s lesion supports this claim.

Harlequin syndrome can present simultaneously with ipsilateral Horner, Adie, and Ross syndromes.8 There are varying clinical presentations of Horner syndrome. Some patients with HS show autonomic ocular signs, such as miosis and ptosis, exhibiting Horner syndrome as an additional feature.5 Adie syndrome is characterized by tonic pupils with hyporeflexia and is unilateral in most cases. Ross syndrome is similar to Adie syndrome—including tonic pupils with hyporeflexia—in addition to a finding of segmental anhidrosis; it is bilateral in most cases.4

In some cases, Horner syndrome and HS originate from unilateral pharmaceutical sympathetic denervation (ie, as a consequence of paravertebral spread of local anesthetic to ipsilateral stellate ganglion).9 Facial nonflushing areas in HS typically are identical with anhidrotic areas10; Horner syndrome often is ipsilateral to the affected sympathetic region.11

Our patient exhibited secondary HS from a tumor effect; however, an underlying tumor or infarct is absent in many cases. In primary (idiopathic) cases of HS, treatment is not recommended because the syndrome is benign.10,11

If symptoms of HS cause notable social embarrassment, contralateral sympathectomy can be considered.5,12 Repeated stellate ganglion block with a local anesthetic could be a less invasive treatment option.13 When considered on a case-by-case-basis, botulinum toxin type A has been effective as a treatment of compensatory hyperhidrosis on the unaffected side.14

In cases of secondary HS, surgical removal of the lesion may alleviate symptoms, though thoracotomy in our patient to remove the schwannoma did not alleviate anhidrosis. The Table lists treatment options for primary and secondary HS.4,5,11

To the Editor:

A 52-year-old man who was otherwise healthy and a long-distance runner presented with the sudden onset of diminished sweating on the left side of the body of 6 weeks’ duration. While training for a marathon, he reported that he perspired only on the right side of the body during runs of 12 to 15 miles; he observed a lack of sweating on the left side of the face, left side of the trunk, left arm, and left leg. This absence of sweating was accompanied by intense flushing on the right side of the face and trunk.

The patient did not take any medications. He reported no history of trauma and exhibited no neurologic deficits. A chest radiograph was negative. Thyroid function testing and a comprehensive metabolic panel were normal. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the chest and abdomen revealed a 4.3-cm soft-tissue mass in the left superior mediastinum that was superior to the aortic arch, posterior to the left subclavian artery in proximity to the sympathetic chain, and lateral to the trachea. The patient was diagnosed with Harlequin syndrome (HS).

Open thoracotomy was performed to remove the lesion. Analysis of the mass showed cystic areas, areas of hemorrhage (Figure 1A), and alternating zones of compact Antoni A spindle cells admixed with areas of less orderly Antoni B spindle cells within a hypocellular stroma (Figure 1B). Individual cells were characterized by eosinophilic cytoplasm and tapered nuclei. The mass appeared to be completely encapsulated. No mitotic figures were seen on multiple slides. The cells stained diffusely positive for S-100 proteins. At 6-month follow-up, the patient reported that he did not notice any return of normal sweating on the left side. However, the right-sided flushing had resolved.

Harlequin syndrome (also called the Harlequin sign) is a rare disorder of the sympathetic nervous system and should not be confused with lethal harlequin-type ichthyosis, an autosomal-recessive congenital disorder in which the affected newborn’s skin is hard and thickened over most of the body.1 Harlequin syndrome usually is characterized by unilateral flushing and sweating that can affect the face, trunk, and extremities.2 Physical stimuli, such as exercising (as in our patient), high body temperature, and the consumption of spicy or pungent food, or an emotional response can unmask or exacerbate symptoms of HS. The syndrome also can present with cluster headache.3 Harlequin syndrome is more common in females (66% of cases).4 Originally, the side of the face marked by increased sweating and flushing was perceived to be the pathologic side; now it is recognized that the anhidrotic side is affected by the causative pathology. The side of the face characterized by flushing might gradually darken as it compensates for lack of thermal regulation on the other side.2,5

Usually, HS is an idiopathic condition associated with localized failure of upper thoracic sympathetic chain ganglia.5 A theory is that HS is part of a spectrum of autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy.6 Typically, the syndrome is asymptomatic at rest, but testing can reveal an underlying sympathetic lesion.7 Structural lesions have been reported as a cause of the syndrome,6 similar to our patient.

Disrupted thermoregulatory vasodilation in HS is caused by an ipsilateral lesion of the sympathetic vasodilator neurons that innervate the face. Hemifacial anhidrosis also occurs because sudomotor neurons travel within the same pathways as vasodilator neurons.4

Our patient had a posterior mediastinal ancient schwannoma to the left of the subclavian artery, lateral to the trachea, with ipsilateral anhidrosis of the forehead, cheek, chin, and torso. In the medical literature, the forehead, cheek, and chin are described as being affected in HS when the lesion is located under the bifurcation of the carotid artery.3,5 Most of the sudomotor and vasomotor fibers that innervate the face leave the spinal cord through ventral roots T2-T34 (symptomatic areas are described in Figure 2), which correlates with the hypothesis that HS results from a deficit originating in the third thoracic nerve that is caused by a peripheral lesion affecting sympathetic outflow through the third thoracic root.2 The location of our patient’s lesion supports this claim.

Harlequin syndrome can present simultaneously with ipsilateral Horner, Adie, and Ross syndromes.8 There are varying clinical presentations of Horner syndrome. Some patients with HS show autonomic ocular signs, such as miosis and ptosis, exhibiting Horner syndrome as an additional feature.5 Adie syndrome is characterized by tonic pupils with hyporeflexia and is unilateral in most cases. Ross syndrome is similar to Adie syndrome—including tonic pupils with hyporeflexia—in addition to a finding of segmental anhidrosis; it is bilateral in most cases.4

In some cases, Horner syndrome and HS originate from unilateral pharmaceutical sympathetic denervation (ie, as a consequence of paravertebral spread of local anesthetic to ipsilateral stellate ganglion).9 Facial nonflushing areas in HS typically are identical with anhidrotic areas10; Horner syndrome often is ipsilateral to the affected sympathetic region.11

Our patient exhibited secondary HS from a tumor effect; however, an underlying tumor or infarct is absent in many cases. In primary (idiopathic) cases of HS, treatment is not recommended because the syndrome is benign.10,11

If symptoms of HS cause notable social embarrassment, contralateral sympathectomy can be considered.5,12 Repeated stellate ganglion block with a local anesthetic could be a less invasive treatment option.13 When considered on a case-by-case-basis, botulinum toxin type A has been effective as a treatment of compensatory hyperhidrosis on the unaffected side.14

In cases of secondary HS, surgical removal of the lesion may alleviate symptoms, though thoracotomy in our patient to remove the schwannoma did not alleviate anhidrosis. The Table lists treatment options for primary and secondary HS.4,5,11

- Harlequin ichthyosis. MedlinePlus. National Library of Medicine [Internet]. Updated January 7, 2022. Accessed April 5, 2022. https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/harlequin-ichthyosis

- Lance JW, Drummond PD, Gandevia SC, et al. Harlequin syndrome: the sudden onset of unilateral flushing and sweating. J Neurol Neurosurg Psych. 1988;51:635-642. doi:10.1136/jnnp.51.5.635

- Lehman K, Kumar N, Vu Q, et al. Harlequin syndrome in cluster headache. Headache. 2016;56:1053-1054. doi:10.1111/head.12852

- Willaert WIM, Scheltinga MRM, Steenhuisen SF, et al. Harlequin syndrome: two new cases and a management proposal. Acta Neurol Belg. 2009;109:214-220.

- Duddy ME, Baker MR. Images in clinical medicine. Harlequin’s darker side. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:E22. doi:10.1056/NEJMicm067851

- Karam C. Harlequin syndrome in a patient with putative autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy. Auton Neurosci. 2016;194:58-59. doi:10.1016/j.autneu.2015.12.004

- Wasner G, Maag R, Ludwig J, et al. Harlequin syndrome—one face of many etiologies. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2005;1:54-59. doi:10.1038/ncpneuro0040

- Guilloton L, Demarquay G, Quesnel L, et al. Dysautonomic syndrome of the face with Harlequin sign and syndrome: three new cases and a review of the literature. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2013;169:884-891. doi:10.1016/j.neurol.2013.01.628

- Burlacu CL, Buggy DJ. Coexisting Harlequin and Horner syndromes after high thoracic paravertebral anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 2005;95:822-824. doi:10.1093/bja/aei258

- Morrison DA, Bibby K, Woodruff G. The “Harlequin” sign and congenital Horner’s syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psych. 1997;62:626-628. doi:10.1136/jnnp.62.6.626

- Bremner F, Smith S. Pupillographic findings in 39 consecutive cases of Harlequin syndrome. J Neuroophthalmol. 2008;28:171-177. doi:10.1097/WNO.0b013e318183c885

- Kaur S, Aggarwal P, Jindal N, et al. Harlequin syndrome: a mask of rare dysautonomic syndromes. Dermatol Online J. 2015;21:13030/qt3q39d7mz.

- Reddy H, Fatah S, Gulve A, et al. Novel management of Harlequin syndrome with stellate ganglion block. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:954-956. doi:10.1111/bjd.12561

- ManhRKJV, Spitz M, Vasconcellos LF. Botulinum toxin for treatment of Harlequin syndrome. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2016;23:112-113. doi:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2015.11.030

- Harlequin ichthyosis. MedlinePlus. National Library of Medicine [Internet]. Updated January 7, 2022. Accessed April 5, 2022. https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/harlequin-ichthyosis

- Lance JW, Drummond PD, Gandevia SC, et al. Harlequin syndrome: the sudden onset of unilateral flushing and sweating. J Neurol Neurosurg Psych. 1988;51:635-642. doi:10.1136/jnnp.51.5.635

- Lehman K, Kumar N, Vu Q, et al. Harlequin syndrome in cluster headache. Headache. 2016;56:1053-1054. doi:10.1111/head.12852

- Willaert WIM, Scheltinga MRM, Steenhuisen SF, et al. Harlequin syndrome: two new cases and a management proposal. Acta Neurol Belg. 2009;109:214-220.

- Duddy ME, Baker MR. Images in clinical medicine. Harlequin’s darker side. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:E22. doi:10.1056/NEJMicm067851

- Karam C. Harlequin syndrome in a patient with putative autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy. Auton Neurosci. 2016;194:58-59. doi:10.1016/j.autneu.2015.12.004

- Wasner G, Maag R, Ludwig J, et al. Harlequin syndrome—one face of many etiologies. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2005;1:54-59. doi:10.1038/ncpneuro0040

- Guilloton L, Demarquay G, Quesnel L, et al. Dysautonomic syndrome of the face with Harlequin sign and syndrome: three new cases and a review of the literature. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2013;169:884-891. doi:10.1016/j.neurol.2013.01.628

- Burlacu CL, Buggy DJ. Coexisting Harlequin and Horner syndromes after high thoracic paravertebral anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 2005;95:822-824. doi:10.1093/bja/aei258

- Morrison DA, Bibby K, Woodruff G. The “Harlequin” sign and congenital Horner’s syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psych. 1997;62:626-628. doi:10.1136/jnnp.62.6.626

- Bremner F, Smith S. Pupillographic findings in 39 consecutive cases of Harlequin syndrome. J Neuroophthalmol. 2008;28:171-177. doi:10.1097/WNO.0b013e318183c885

- Kaur S, Aggarwal P, Jindal N, et al. Harlequin syndrome: a mask of rare dysautonomic syndromes. Dermatol Online J. 2015;21:13030/qt3q39d7mz.

- Reddy H, Fatah S, Gulve A, et al. Novel management of Harlequin syndrome with stellate ganglion block. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:954-956. doi:10.1111/bjd.12561

- ManhRKJV, Spitz M, Vasconcellos LF. Botulinum toxin for treatment of Harlequin syndrome. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2016;23:112-113. doi:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2015.11.030

Practice Points

- Harlequin syndrome is a rare disorder of the sympathetic nervous system that is characterized by unilateral flushing and sweating that can affect the face, trunk, and extremities.

- Secondary causes can be from schwannomas in the cervical chain ganglion.