User login

Methotrexate as a Treatment of Palmoplantar Lichen Planus

To the Editor:

Palmoplantar lichen planus (LP) is an uncommon variant of LP that involves the palms and soles. The prevalence of LP is approximately 0.1% to 2% in the general population. It can affect both mucosal and cutaneous surfaces.1 A study of 36 patients with LP showed that 25% (9/36) had palmar and/or plantar involvement.2 Palmoplantar LP is more commonly found in men than women, with an average age of onset of 38 to 65 years.3 It tends to affect the soles more often than the palms, with the most common site being the plantar arch. Itching generally is the most common symptom reported. Lesions often resolve over a few months, but relapses can occur in 10% to 29% of patients.2 The clinical morphology commonly is characterized as erythematous scaly plaques, hyperkeratotic plaques, or ulcerations.4 Due to its rare occurrence, palmoplantar LP often is misdiagnosed as psoriasis, eczematous dermatitis, tinea nigra, or secondary syphilis, making pathology extremely helpful in making the diagnosis.1 Darker skin types can obscure defining characteristics, further impeding a timely diagnosis. We describe a novel case of palmoplantar LP that was successfully treated with methotrexate.

A 38-year-old man with no notable medical history presented for dermatologic evaluation of a palmar and plantar rash of 4 months' duration. The rash was accompanied by intense burning pain and pruritus. Prior to presentation, he had been treated with multiple prednisone tapers starting at 40 mg daily as well as combination therapy of a 2-week course of minocycline 100 mg twice daily and clobetasol ointment twice daily for 4 months, with no notable improvement. Workup prior to presentation included a negative potassium hydroxide fungal preparation and a normal antinuclear antibody titer. A review of symptoms was negative for arthralgia, myalgia, photosensitivity, malar rash, Raynaud phenomenon, pleuritic pain, seizures, and psychosis.

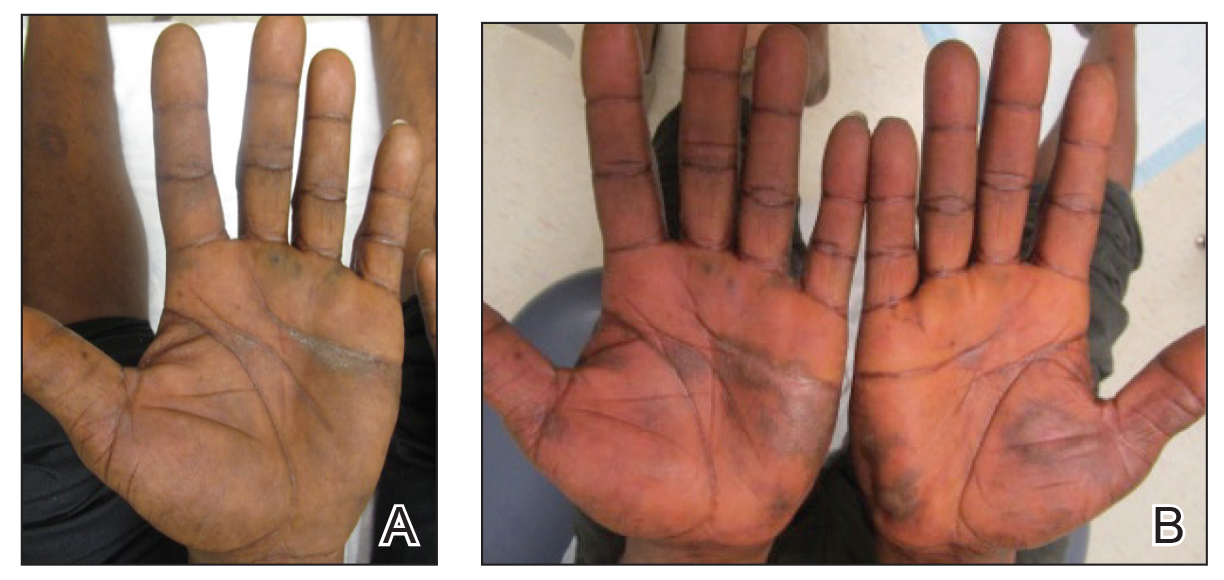

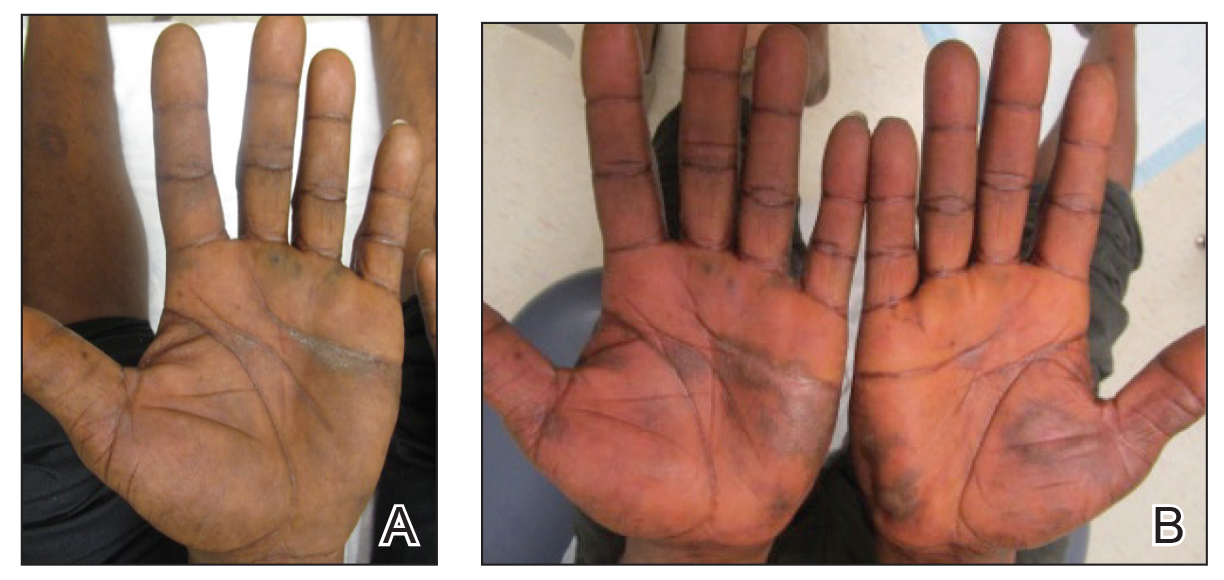

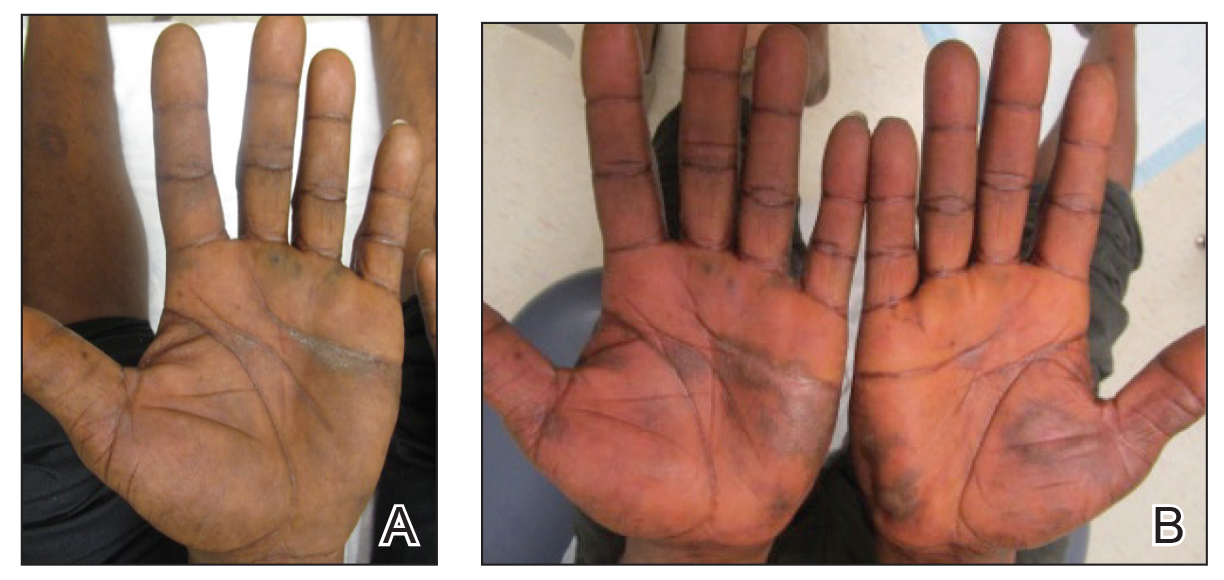

Physical examination revealed focal areas of mildly thick, hyperkeratotic scale with desquamation on the plantar and palmar surfaces of the feet and hands. The underlying skin of the feet consisted of dyspigmented patches of dark brown and hypopigmented skin with erythema, profound scaling, and sparing of the internal plantar arches (Figure 1A). On the palms, thin hyperkeratotic plaques with desquamation and erythematous maceration of the surrounding skin were observed (Figure 2A). Thin white plaques of the posterior bilateral buccal mucosa were appreciated as well as an erosion that extended to the lower lip.

The differential diagnosis included LP, psoriasis, acquired palmoplantar keratoderma, and discoid lupus erythematosus. Tinea pedis and tinea manuum were less likely in the setting of a negative potassium hydroxide fungal preparation.

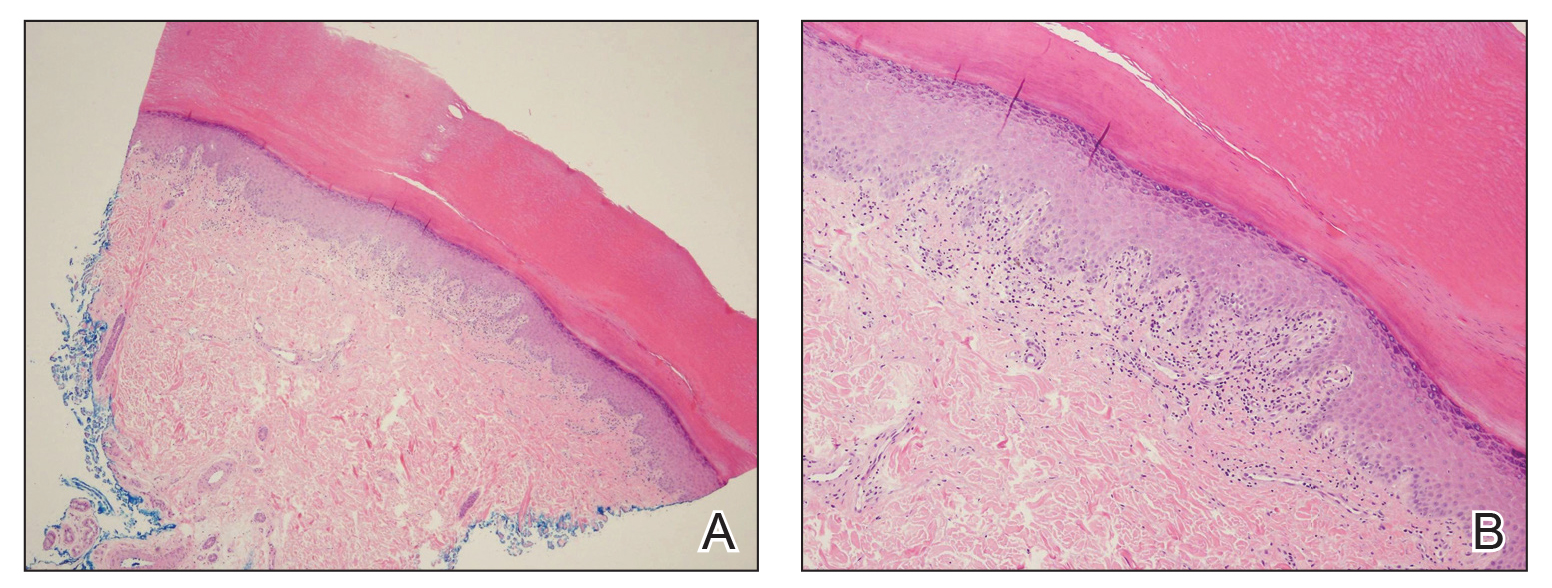

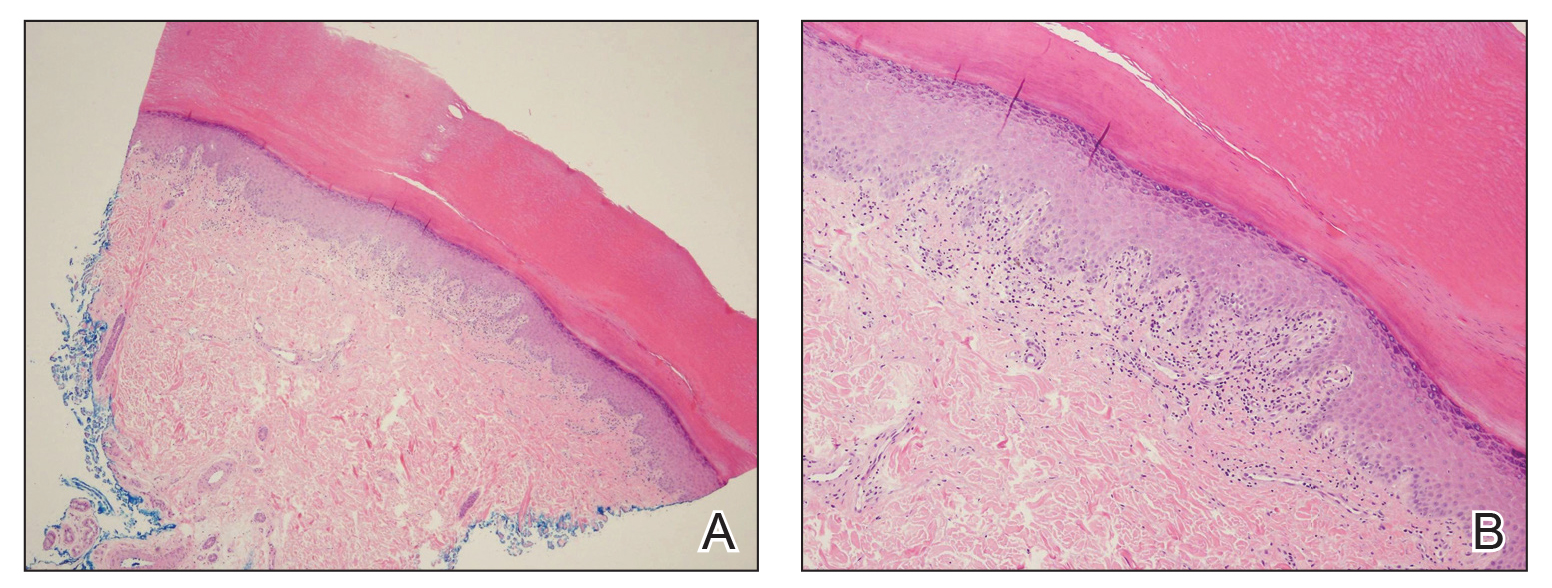

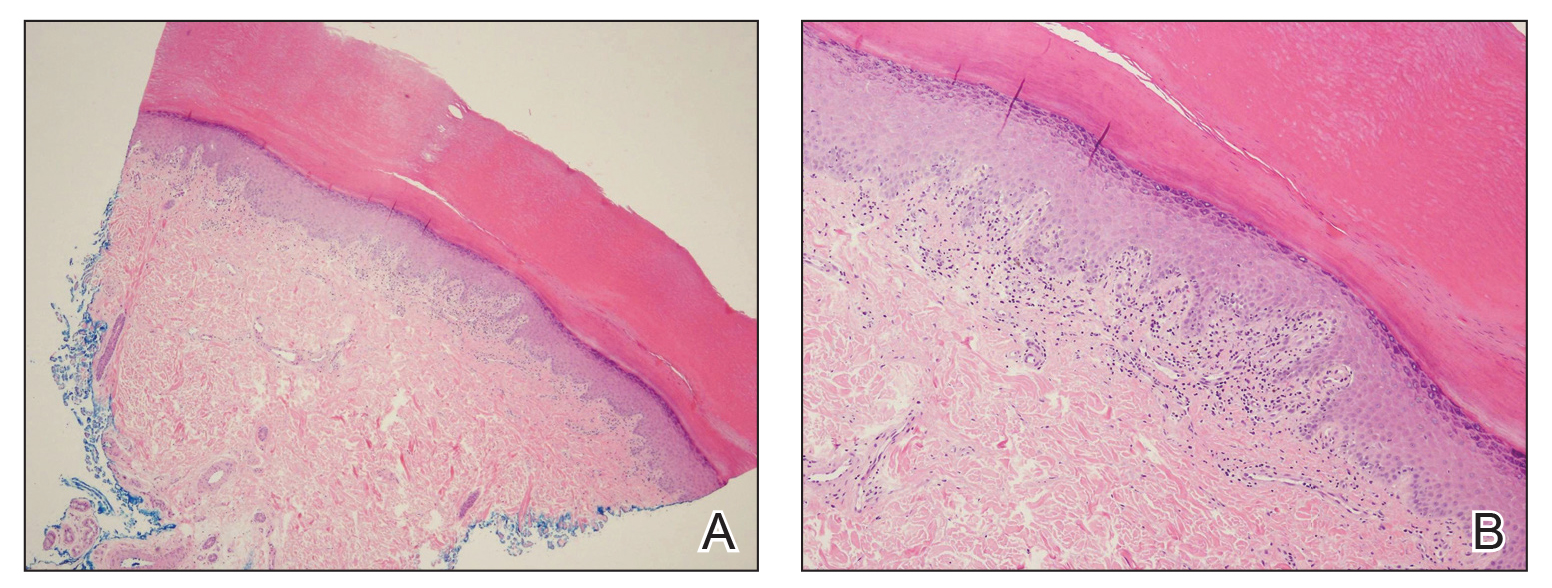

A biopsy of the lateral aspect of the left foot showed a cell-poor interface dermatitis that could resemble partially treated LP or a lichenoid hypersensitivity reaction (Figure 3). Given the clinical and pathologic findings, a diagnosis of palmoplantar LP was favored. The patient was on no medications or over-the-counter supplements prior to the appearance of the rash, making a lichenoid hypersensitivity rash less likely. The histology findings likely were muted, as they were done at the end of the prednisone taper.

Minocycline and clobetasol ointment were discontinued, and the prednisone taper was completed as originally prescribed. The patient was started on 25 mg daily of acitretin for 4 weeks, then increased to 35 mg daily. Notable improvement in the palmar and plantar lesions was noted after the initial 4 weeks of therapy; however, acitretin treatment was discontinued due to lack of adequate insurance coverage for the medication. The patient became symptomatic several weeks following acitretin cessation and was started on methotrexate 15 mg weekly with triamcinolone acetonide paste 0.1% for the oral lesions. Once again, improvement was seen on both the palmar and plantar surfaces after 4 weeks of therapy (Figures 1B and 2B).

Evidence for treatment of palmoplantar LP is limited to a few case reports and case series. Documented treatments for palmoplantar LP include topical and systemic steroids, tazarotene, acitretin, and immunosuppressive medications.4 One case report described a patient who responded well to prednisone therapy (1 mg/kg daily for 3 weeks, then reduced to 5 mg daily).5 Another report described a patient who responded favorably to cyclosporine 3.5 mg/kg daily for 4 weeks, then tapered over another 4 weeks for a total of 8 weeks of treatment.4 Although the most common treatments described in the literature consist of acitretin as well as topical and systemic steroids, few have discussed the efficacy of methotrexate. In one study, acitretin did not result in clearance, but the patient saw profound improvement with methotrexate (titrated up to 25 mg weekly) over 2 months.1

In our case, treatment with methotrexate was proven successful in a patient who responded to acitretin but was unable to afford treatment. This case highlights a rare variant of a common disease and the possibility of methotrexate as a cost-effective and useful treatment option for LP.

- Rieder E, Hale CS, Meehan SA, et al. Palmoplantar lichen planus. Dermatol Online J. 2015;20:13030/qt1vn9s55z.

- Sánchez-Pérez J, Rios Buceta L, Fraga J, et al. Lichen planus with lesions on the palms and/or soles: prevalence and clinicopathological study of 36 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:310-314.

- Gutte R, Khopkar U. Predominant palmoplantar lichen planus: a diagnostic challenge. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:343-347.

- Karakatsanis G, Patsatsi A, Kastoridou C, et al Palmoplantar lichen planus with umbilicated papules: an atypical case with rapid therapeutic response to cyclosporin. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:1006-1007.

- Goucha S, Khaled A, Bennani Z, et al. Erosive lichen planus of the soles: Effective response to prednisone. Dermatol Ther. 2011;1:20-24.

To the Editor:

Palmoplantar lichen planus (LP) is an uncommon variant of LP that involves the palms and soles. The prevalence of LP is approximately 0.1% to 2% in the general population. It can affect both mucosal and cutaneous surfaces.1 A study of 36 patients with LP showed that 25% (9/36) had palmar and/or plantar involvement.2 Palmoplantar LP is more commonly found in men than women, with an average age of onset of 38 to 65 years.3 It tends to affect the soles more often than the palms, with the most common site being the plantar arch. Itching generally is the most common symptom reported. Lesions often resolve over a few months, but relapses can occur in 10% to 29% of patients.2 The clinical morphology commonly is characterized as erythematous scaly plaques, hyperkeratotic plaques, or ulcerations.4 Due to its rare occurrence, palmoplantar LP often is misdiagnosed as psoriasis, eczematous dermatitis, tinea nigra, or secondary syphilis, making pathology extremely helpful in making the diagnosis.1 Darker skin types can obscure defining characteristics, further impeding a timely diagnosis. We describe a novel case of palmoplantar LP that was successfully treated with methotrexate.

A 38-year-old man with no notable medical history presented for dermatologic evaluation of a palmar and plantar rash of 4 months' duration. The rash was accompanied by intense burning pain and pruritus. Prior to presentation, he had been treated with multiple prednisone tapers starting at 40 mg daily as well as combination therapy of a 2-week course of minocycline 100 mg twice daily and clobetasol ointment twice daily for 4 months, with no notable improvement. Workup prior to presentation included a negative potassium hydroxide fungal preparation and a normal antinuclear antibody titer. A review of symptoms was negative for arthralgia, myalgia, photosensitivity, malar rash, Raynaud phenomenon, pleuritic pain, seizures, and psychosis.

Physical examination revealed focal areas of mildly thick, hyperkeratotic scale with desquamation on the plantar and palmar surfaces of the feet and hands. The underlying skin of the feet consisted of dyspigmented patches of dark brown and hypopigmented skin with erythema, profound scaling, and sparing of the internal plantar arches (Figure 1A). On the palms, thin hyperkeratotic plaques with desquamation and erythematous maceration of the surrounding skin were observed (Figure 2A). Thin white plaques of the posterior bilateral buccal mucosa were appreciated as well as an erosion that extended to the lower lip.

The differential diagnosis included LP, psoriasis, acquired palmoplantar keratoderma, and discoid lupus erythematosus. Tinea pedis and tinea manuum were less likely in the setting of a negative potassium hydroxide fungal preparation.

A biopsy of the lateral aspect of the left foot showed a cell-poor interface dermatitis that could resemble partially treated LP or a lichenoid hypersensitivity reaction (Figure 3). Given the clinical and pathologic findings, a diagnosis of palmoplantar LP was favored. The patient was on no medications or over-the-counter supplements prior to the appearance of the rash, making a lichenoid hypersensitivity rash less likely. The histology findings likely were muted, as they were done at the end of the prednisone taper.

Minocycline and clobetasol ointment were discontinued, and the prednisone taper was completed as originally prescribed. The patient was started on 25 mg daily of acitretin for 4 weeks, then increased to 35 mg daily. Notable improvement in the palmar and plantar lesions was noted after the initial 4 weeks of therapy; however, acitretin treatment was discontinued due to lack of adequate insurance coverage for the medication. The patient became symptomatic several weeks following acitretin cessation and was started on methotrexate 15 mg weekly with triamcinolone acetonide paste 0.1% for the oral lesions. Once again, improvement was seen on both the palmar and plantar surfaces after 4 weeks of therapy (Figures 1B and 2B).

Evidence for treatment of palmoplantar LP is limited to a few case reports and case series. Documented treatments for palmoplantar LP include topical and systemic steroids, tazarotene, acitretin, and immunosuppressive medications.4 One case report described a patient who responded well to prednisone therapy (1 mg/kg daily for 3 weeks, then reduced to 5 mg daily).5 Another report described a patient who responded favorably to cyclosporine 3.5 mg/kg daily for 4 weeks, then tapered over another 4 weeks for a total of 8 weeks of treatment.4 Although the most common treatments described in the literature consist of acitretin as well as topical and systemic steroids, few have discussed the efficacy of methotrexate. In one study, acitretin did not result in clearance, but the patient saw profound improvement with methotrexate (titrated up to 25 mg weekly) over 2 months.1

In our case, treatment with methotrexate was proven successful in a patient who responded to acitretin but was unable to afford treatment. This case highlights a rare variant of a common disease and the possibility of methotrexate as a cost-effective and useful treatment option for LP.

To the Editor:

Palmoplantar lichen planus (LP) is an uncommon variant of LP that involves the palms and soles. The prevalence of LP is approximately 0.1% to 2% in the general population. It can affect both mucosal and cutaneous surfaces.1 A study of 36 patients with LP showed that 25% (9/36) had palmar and/or plantar involvement.2 Palmoplantar LP is more commonly found in men than women, with an average age of onset of 38 to 65 years.3 It tends to affect the soles more often than the palms, with the most common site being the plantar arch. Itching generally is the most common symptom reported. Lesions often resolve over a few months, but relapses can occur in 10% to 29% of patients.2 The clinical morphology commonly is characterized as erythematous scaly plaques, hyperkeratotic plaques, or ulcerations.4 Due to its rare occurrence, palmoplantar LP often is misdiagnosed as psoriasis, eczematous dermatitis, tinea nigra, or secondary syphilis, making pathology extremely helpful in making the diagnosis.1 Darker skin types can obscure defining characteristics, further impeding a timely diagnosis. We describe a novel case of palmoplantar LP that was successfully treated with methotrexate.

A 38-year-old man with no notable medical history presented for dermatologic evaluation of a palmar and plantar rash of 4 months' duration. The rash was accompanied by intense burning pain and pruritus. Prior to presentation, he had been treated with multiple prednisone tapers starting at 40 mg daily as well as combination therapy of a 2-week course of minocycline 100 mg twice daily and clobetasol ointment twice daily for 4 months, with no notable improvement. Workup prior to presentation included a negative potassium hydroxide fungal preparation and a normal antinuclear antibody titer. A review of symptoms was negative for arthralgia, myalgia, photosensitivity, malar rash, Raynaud phenomenon, pleuritic pain, seizures, and psychosis.

Physical examination revealed focal areas of mildly thick, hyperkeratotic scale with desquamation on the plantar and palmar surfaces of the feet and hands. The underlying skin of the feet consisted of dyspigmented patches of dark brown and hypopigmented skin with erythema, profound scaling, and sparing of the internal plantar arches (Figure 1A). On the palms, thin hyperkeratotic plaques with desquamation and erythematous maceration of the surrounding skin were observed (Figure 2A). Thin white plaques of the posterior bilateral buccal mucosa were appreciated as well as an erosion that extended to the lower lip.

The differential diagnosis included LP, psoriasis, acquired palmoplantar keratoderma, and discoid lupus erythematosus. Tinea pedis and tinea manuum were less likely in the setting of a negative potassium hydroxide fungal preparation.

A biopsy of the lateral aspect of the left foot showed a cell-poor interface dermatitis that could resemble partially treated LP or a lichenoid hypersensitivity reaction (Figure 3). Given the clinical and pathologic findings, a diagnosis of palmoplantar LP was favored. The patient was on no medications or over-the-counter supplements prior to the appearance of the rash, making a lichenoid hypersensitivity rash less likely. The histology findings likely were muted, as they were done at the end of the prednisone taper.

Minocycline and clobetasol ointment were discontinued, and the prednisone taper was completed as originally prescribed. The patient was started on 25 mg daily of acitretin for 4 weeks, then increased to 35 mg daily. Notable improvement in the palmar and plantar lesions was noted after the initial 4 weeks of therapy; however, acitretin treatment was discontinued due to lack of adequate insurance coverage for the medication. The patient became symptomatic several weeks following acitretin cessation and was started on methotrexate 15 mg weekly with triamcinolone acetonide paste 0.1% for the oral lesions. Once again, improvement was seen on both the palmar and plantar surfaces after 4 weeks of therapy (Figures 1B and 2B).

Evidence for treatment of palmoplantar LP is limited to a few case reports and case series. Documented treatments for palmoplantar LP include topical and systemic steroids, tazarotene, acitretin, and immunosuppressive medications.4 One case report described a patient who responded well to prednisone therapy (1 mg/kg daily for 3 weeks, then reduced to 5 mg daily).5 Another report described a patient who responded favorably to cyclosporine 3.5 mg/kg daily for 4 weeks, then tapered over another 4 weeks for a total of 8 weeks of treatment.4 Although the most common treatments described in the literature consist of acitretin as well as topical and systemic steroids, few have discussed the efficacy of methotrexate. In one study, acitretin did not result in clearance, but the patient saw profound improvement with methotrexate (titrated up to 25 mg weekly) over 2 months.1

In our case, treatment with methotrexate was proven successful in a patient who responded to acitretin but was unable to afford treatment. This case highlights a rare variant of a common disease and the possibility of methotrexate as a cost-effective and useful treatment option for LP.

- Rieder E, Hale CS, Meehan SA, et al. Palmoplantar lichen planus. Dermatol Online J. 2015;20:13030/qt1vn9s55z.

- Sánchez-Pérez J, Rios Buceta L, Fraga J, et al. Lichen planus with lesions on the palms and/or soles: prevalence and clinicopathological study of 36 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:310-314.

- Gutte R, Khopkar U. Predominant palmoplantar lichen planus: a diagnostic challenge. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:343-347.

- Karakatsanis G, Patsatsi A, Kastoridou C, et al Palmoplantar lichen planus with umbilicated papules: an atypical case with rapid therapeutic response to cyclosporin. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:1006-1007.

- Goucha S, Khaled A, Bennani Z, et al. Erosive lichen planus of the soles: Effective response to prednisone. Dermatol Ther. 2011;1:20-24.

- Rieder E, Hale CS, Meehan SA, et al. Palmoplantar lichen planus. Dermatol Online J. 2015;20:13030/qt1vn9s55z.

- Sánchez-Pérez J, Rios Buceta L, Fraga J, et al. Lichen planus with lesions on the palms and/or soles: prevalence and clinicopathological study of 36 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:310-314.

- Gutte R, Khopkar U. Predominant palmoplantar lichen planus: a diagnostic challenge. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:343-347.

- Karakatsanis G, Patsatsi A, Kastoridou C, et al Palmoplantar lichen planus with umbilicated papules: an atypical case with rapid therapeutic response to cyclosporin. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:1006-1007.

- Goucha S, Khaled A, Bennani Z, et al. Erosive lichen planus of the soles: Effective response to prednisone. Dermatol Ther. 2011;1:20-24.

Practice Points

- Palmoplantar lichen planus (LP) is a rare variant of LP that is resistant to most treatments.

- Methotrexate may be a cost-effective option in patients who cannot tolerate systemic retinoids.

Non–HIV-Related Kaposi Sarcoma in 2 Hispanic Patients Arising in the Setting of Chronic Venous Insufficiency

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is a vascular neoplasm associated with human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) infection that is conventionally divided into 4 clinical variants: classic, African, transplant associated, and AIDS related. In the United States, classic KS predominantly is observed in elderly white men of Ashkenazi Jewish or Mediterranean descent.1

The clinical and histological changes seen in KS can be confused with those from chronic venous insufficiency. Both conditions tend to present with purple-colored patches, plaques, or nodules on the lower extremities. Histologically, both KS and chronic venous insufficiency are characterized by blood vessel and endothelial cell proliferation in the papillary dermis, red blood cell extravasation, and hemosiderin deposition.2 Nevertheless, KS can be diagnosed based on the presence of neoplastic spindle-shaped cells and positive immunostaining for HHV-8 antigen.3

We describe the cases of 2 elderly Hispanic patients in the United States with no history of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), immunosuppression, or travel to the Mediterranean region who presented with erythematous to violaceous papules, plaques, and nodules on the distal lower extremities in the setting of chronic venous insufficiency. We review the relationship between KS and chronic venous insufficiency and suggest that these presentations may represent a distinct clinical variant of KS.

Case Reports

Patient 1

An 83-year-old Hispanic woman with a history of hypertension, atrial fibrillation, and chronic venous insufficiency presented with a chronic painful violaceous eruption on the lower legs of 3 years’ duration. The patient reported that the erythematous patches, which she described as bruiselike, originally developed 3 years prior after starting warfarin therapy for atrial fibrillation. At that time, a biopsy indicated findings of pigmented purpuric dermatosis and negative immunostaining for HHV-8. Her condition had worsened over the last 6 months with the development of tender eroded plaques on the dorsal aspects of the feet (Figure 1) and purple-brown patches and plaques on the legs. Prior treatment with topical corticosteroids and a short course of prednisone was unsuccessful. Of note, the patient had no history of immunosuppression or HIV and was not of Mediterranean or African descent.

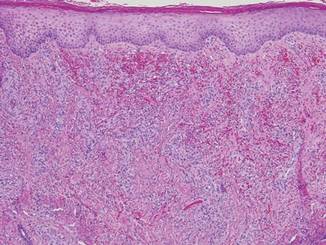

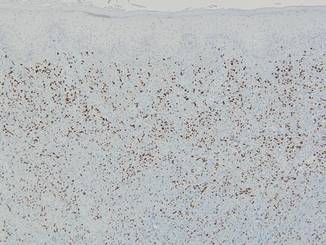

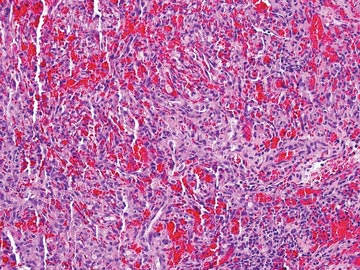

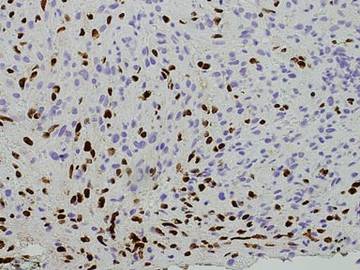

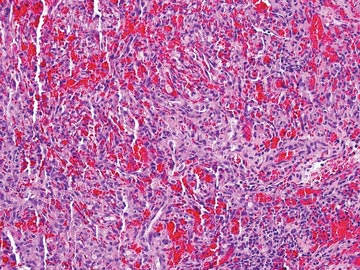

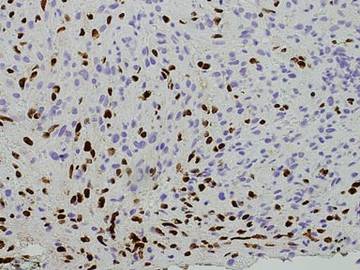

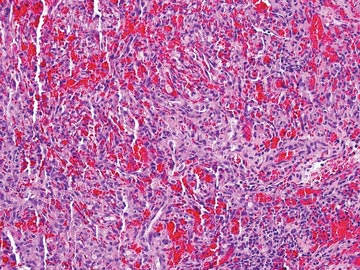

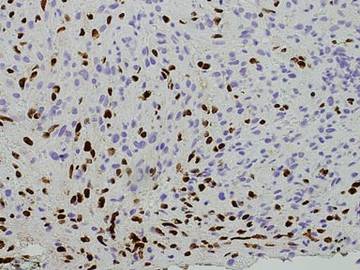

Punch biopsies from the left dorsal foot and left lower leg revealed dermal fibrosis, a proliferation of small blood vessels with plump endothelial cells, and foci of spindled endothelial cells with narrow slitlike spaces containing erythrocytes (Figure 2). There also were extravasated erythrocytes and a sparse inflammatory cell infiltrate comprised of lymphocytes, eosinophils, neutrophils, and plasma cells. Perls Prussian blue stain highlighted numerous siderophages scattered in the dermis. Based on these findings, immunostaining for HHV-8 was performed and highlighted reactivity of the spindled cells (Figure 3). The patient was diagnosed with KS in the setting of chronic venous insufficiency.

|

Patient 2

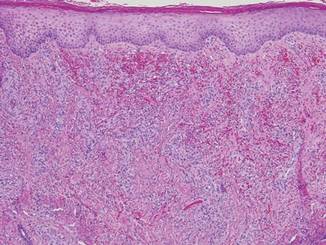

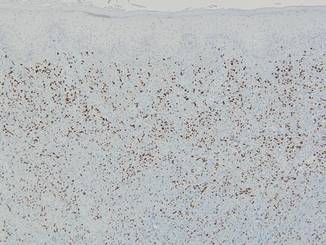

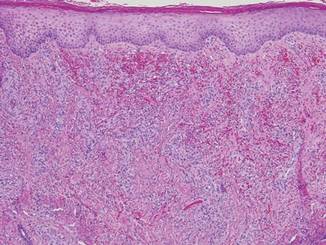

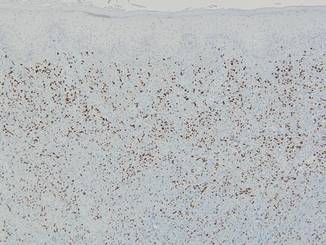

A 67-year-old Hispanic man with a history of diabetes mellitus presented with 10 asymptomatic purple papules and hyperkeratotic and hyperpigmented plaques on the distal aspect of the legs of 1 year’s duration in the setting of chronic venous insufficiency (Figure 4). The patient had no history of immunosuppression or HIV and was not of Mediterranean or African descent. An excisional biopsy from the left fourth toe revealed a cellular dermal vascular proliferation associated with numerous small slitlike vessels and scattered dilated blood vessels with prominent hemorrhage and surrounding dermal fibrosis (Figure 5). The lesion was markedly cellular with nuclear atypia. Many cells showed enlarged oval- to spindle-shaped hyperchromatic nuclei, some with prominent nucleoli and scant amounts of eosinophilic cytoplasm. Although the differential diagnosis included an unusual cellular pyogenic granuloma with atypia in the setting of chronic venous insufficiency, the degree of cellularity and presence of spindled cells associated with slitlike vessels were more consistent with a pyogenic granulomalike variant of KS. This variant is rare but has previously been reported.4 Many of the tumor nucleoli stained strongly for HHV-8, which is a diagnostic finding of KS (Figure 6). The patient subsequently was diagnosed with KS.

Comment

These 2 cases represent unusual clinical presentations of KS in Hispanic patients with no known risk factors for KS. In patient 1, an initial skin biopsy prompted HHV-8 testing due to suspicion for KS. At that time, HHV-8 was negative, perhaps because of technical deficiencies in the staining protocol; alternatively, the patient may have subsequently developed KS. Both patients had known chronic venous insufficiency. However, biopsies revealed spindle-shaped cells forming clefts and positivity for HHV-8. We propose that these cases may represent an additional clinical variant of KS, chronic venous insufficiency–associated KS.

If similar presentations of KS are identified, studies will need to be done to uncover the specific risk factors involved. Human herpesvirus 8 is not sufficient for the development of KS on its own, as oncogenesis of KS requires immunodeficiency or an additional environmental factor such as diabetes mellitus.5 Through impaired microvascular circulation and the release of hypoxia-inducible factor 1a, diabetes can promote KS-herpesvirus replication. Therefore, the risk for KS is increased in individuals with diabetes regardless of a negative history of immunodeficiency, which may have been the case in patient 2.

Our cases suggest that chronic venous insufficiency may be another factor that predisposes immunocompetent individuals to KS. Chronic venous insufficiency can cause hypoxia, promoting the release of cytokines and angiogenic factors responsible for the formation of vascular tumors such as KS.6 Once present, KS can worsen preexisting stasis dermatitis by compressing the external lymphatics and exacerbating lymphedema.7 Stasis dermatitis and KS may be part of a self-perpetuating cycle that involves obstruction due to secondary lymphadenopathy, the development of lymphedema, and the release of cytokines and growth factors that lead to further vascular proliferation.8

|

|

In summary, we present 2 cases of non–HIV-related KS that may represent an additional clinical variant of KS that mimics and/or arises in chronic venous insufficiency and appears as papules and plaques in elderly patients who are Hispanic, immunocompetent, and HIV negative. We suggest including KS in the differential diagnosis for chronic venous insufficiency, especially in cases with an unusual clinical appearance or course. In these cases, skin biopsy with HHV-8 testing may be warranted.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to acknowledge William Putnam, BFA, New York, New York, for his assistance with the figures.

1. Hiatt KM, Nelson AM, Lichy JH, et al. Classic Kaposi sarcoma in the United States over the last two decades: a clinicopathologic and molecular study of 438 non-HIV-related Kaposi Sarcoma patients with comparison to HIV-related Kaposi Sarcoma [published online ahead of print March 28, 2008]. Mod Pathol. 2008;21:572-582.

2. Weaver J, Billings SD. Initial presentation of stasis dermatitis mimicking solitary lesions: a previously unrecognized clinical scenario. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:1028-1032.

3. Bulat V, Lugovic´ L, Šitum M, et al. Acroangiodermatitis (pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma) as part of chronic venous insufficiency. Acta Clin Croat. 2007;46:273-277.

4. Urquhart JL, Uzieblo A, Kohler S. Detection of HHV-8 in pyogenic granuloma-like Kaposi sarcoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:317-321.

5. Anderson LA, Lauria C, Romano N, et al. Risk factors for classical Kaposi sarcoma in a population-based case-control study in Sicily. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:3435-3443.

6. Lunardi-Iskandar Y, Bryant JL, Zeman RA, et al. Tumorigenesis and metastasis of neoplastic Kaposi’s sarcoma cell line in immunodeficient mice blocked by a human pregnancy hormone. Nature. 1995;375:64-68.

7. Allen PJ, Gillespie DL, Redfield RR, et al. Lower extremity lymphedema caused by acquired immune deficiency syndrome-related Kaposi’s sarcoma: case report and review of the literature. J Vasc Surg. 1995;22:178-181.

8. Ramdial PK, Chetty R, Singh B, et al. Lymphedematous HIV-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:474-481.

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is a vascular neoplasm associated with human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) infection that is conventionally divided into 4 clinical variants: classic, African, transplant associated, and AIDS related. In the United States, classic KS predominantly is observed in elderly white men of Ashkenazi Jewish or Mediterranean descent.1

The clinical and histological changes seen in KS can be confused with those from chronic venous insufficiency. Both conditions tend to present with purple-colored patches, plaques, or nodules on the lower extremities. Histologically, both KS and chronic venous insufficiency are characterized by blood vessel and endothelial cell proliferation in the papillary dermis, red blood cell extravasation, and hemosiderin deposition.2 Nevertheless, KS can be diagnosed based on the presence of neoplastic spindle-shaped cells and positive immunostaining for HHV-8 antigen.3

We describe the cases of 2 elderly Hispanic patients in the United States with no history of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), immunosuppression, or travel to the Mediterranean region who presented with erythematous to violaceous papules, plaques, and nodules on the distal lower extremities in the setting of chronic venous insufficiency. We review the relationship between KS and chronic venous insufficiency and suggest that these presentations may represent a distinct clinical variant of KS.

Case Reports

Patient 1

An 83-year-old Hispanic woman with a history of hypertension, atrial fibrillation, and chronic venous insufficiency presented with a chronic painful violaceous eruption on the lower legs of 3 years’ duration. The patient reported that the erythematous patches, which she described as bruiselike, originally developed 3 years prior after starting warfarin therapy for atrial fibrillation. At that time, a biopsy indicated findings of pigmented purpuric dermatosis and negative immunostaining for HHV-8. Her condition had worsened over the last 6 months with the development of tender eroded plaques on the dorsal aspects of the feet (Figure 1) and purple-brown patches and plaques on the legs. Prior treatment with topical corticosteroids and a short course of prednisone was unsuccessful. Of note, the patient had no history of immunosuppression or HIV and was not of Mediterranean or African descent.

Punch biopsies from the left dorsal foot and left lower leg revealed dermal fibrosis, a proliferation of small blood vessels with plump endothelial cells, and foci of spindled endothelial cells with narrow slitlike spaces containing erythrocytes (Figure 2). There also were extravasated erythrocytes and a sparse inflammatory cell infiltrate comprised of lymphocytes, eosinophils, neutrophils, and plasma cells. Perls Prussian blue stain highlighted numerous siderophages scattered in the dermis. Based on these findings, immunostaining for HHV-8 was performed and highlighted reactivity of the spindled cells (Figure 3). The patient was diagnosed with KS in the setting of chronic venous insufficiency.

|

Patient 2

A 67-year-old Hispanic man with a history of diabetes mellitus presented with 10 asymptomatic purple papules and hyperkeratotic and hyperpigmented plaques on the distal aspect of the legs of 1 year’s duration in the setting of chronic venous insufficiency (Figure 4). The patient had no history of immunosuppression or HIV and was not of Mediterranean or African descent. An excisional biopsy from the left fourth toe revealed a cellular dermal vascular proliferation associated with numerous small slitlike vessels and scattered dilated blood vessels with prominent hemorrhage and surrounding dermal fibrosis (Figure 5). The lesion was markedly cellular with nuclear atypia. Many cells showed enlarged oval- to spindle-shaped hyperchromatic nuclei, some with prominent nucleoli and scant amounts of eosinophilic cytoplasm. Although the differential diagnosis included an unusual cellular pyogenic granuloma with atypia in the setting of chronic venous insufficiency, the degree of cellularity and presence of spindled cells associated with slitlike vessels were more consistent with a pyogenic granulomalike variant of KS. This variant is rare but has previously been reported.4 Many of the tumor nucleoli stained strongly for HHV-8, which is a diagnostic finding of KS (Figure 6). The patient subsequently was diagnosed with KS.

Comment

These 2 cases represent unusual clinical presentations of KS in Hispanic patients with no known risk factors for KS. In patient 1, an initial skin biopsy prompted HHV-8 testing due to suspicion for KS. At that time, HHV-8 was negative, perhaps because of technical deficiencies in the staining protocol; alternatively, the patient may have subsequently developed KS. Both patients had known chronic venous insufficiency. However, biopsies revealed spindle-shaped cells forming clefts and positivity for HHV-8. We propose that these cases may represent an additional clinical variant of KS, chronic venous insufficiency–associated KS.

If similar presentations of KS are identified, studies will need to be done to uncover the specific risk factors involved. Human herpesvirus 8 is not sufficient for the development of KS on its own, as oncogenesis of KS requires immunodeficiency or an additional environmental factor such as diabetes mellitus.5 Through impaired microvascular circulation and the release of hypoxia-inducible factor 1a, diabetes can promote KS-herpesvirus replication. Therefore, the risk for KS is increased in individuals with diabetes regardless of a negative history of immunodeficiency, which may have been the case in patient 2.

Our cases suggest that chronic venous insufficiency may be another factor that predisposes immunocompetent individuals to KS. Chronic venous insufficiency can cause hypoxia, promoting the release of cytokines and angiogenic factors responsible for the formation of vascular tumors such as KS.6 Once present, KS can worsen preexisting stasis dermatitis by compressing the external lymphatics and exacerbating lymphedema.7 Stasis dermatitis and KS may be part of a self-perpetuating cycle that involves obstruction due to secondary lymphadenopathy, the development of lymphedema, and the release of cytokines and growth factors that lead to further vascular proliferation.8

|

|

In summary, we present 2 cases of non–HIV-related KS that may represent an additional clinical variant of KS that mimics and/or arises in chronic venous insufficiency and appears as papules and plaques in elderly patients who are Hispanic, immunocompetent, and HIV negative. We suggest including KS in the differential diagnosis for chronic venous insufficiency, especially in cases with an unusual clinical appearance or course. In these cases, skin biopsy with HHV-8 testing may be warranted.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to acknowledge William Putnam, BFA, New York, New York, for his assistance with the figures.

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is a vascular neoplasm associated with human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) infection that is conventionally divided into 4 clinical variants: classic, African, transplant associated, and AIDS related. In the United States, classic KS predominantly is observed in elderly white men of Ashkenazi Jewish or Mediterranean descent.1

The clinical and histological changes seen in KS can be confused with those from chronic venous insufficiency. Both conditions tend to present with purple-colored patches, plaques, or nodules on the lower extremities. Histologically, both KS and chronic venous insufficiency are characterized by blood vessel and endothelial cell proliferation in the papillary dermis, red blood cell extravasation, and hemosiderin deposition.2 Nevertheless, KS can be diagnosed based on the presence of neoplastic spindle-shaped cells and positive immunostaining for HHV-8 antigen.3

We describe the cases of 2 elderly Hispanic patients in the United States with no history of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), immunosuppression, or travel to the Mediterranean region who presented with erythematous to violaceous papules, plaques, and nodules on the distal lower extremities in the setting of chronic venous insufficiency. We review the relationship between KS and chronic venous insufficiency and suggest that these presentations may represent a distinct clinical variant of KS.

Case Reports

Patient 1

An 83-year-old Hispanic woman with a history of hypertension, atrial fibrillation, and chronic venous insufficiency presented with a chronic painful violaceous eruption on the lower legs of 3 years’ duration. The patient reported that the erythematous patches, which she described as bruiselike, originally developed 3 years prior after starting warfarin therapy for atrial fibrillation. At that time, a biopsy indicated findings of pigmented purpuric dermatosis and negative immunostaining for HHV-8. Her condition had worsened over the last 6 months with the development of tender eroded plaques on the dorsal aspects of the feet (Figure 1) and purple-brown patches and plaques on the legs. Prior treatment with topical corticosteroids and a short course of prednisone was unsuccessful. Of note, the patient had no history of immunosuppression or HIV and was not of Mediterranean or African descent.

Punch biopsies from the left dorsal foot and left lower leg revealed dermal fibrosis, a proliferation of small blood vessels with plump endothelial cells, and foci of spindled endothelial cells with narrow slitlike spaces containing erythrocytes (Figure 2). There also were extravasated erythrocytes and a sparse inflammatory cell infiltrate comprised of lymphocytes, eosinophils, neutrophils, and plasma cells. Perls Prussian blue stain highlighted numerous siderophages scattered in the dermis. Based on these findings, immunostaining for HHV-8 was performed and highlighted reactivity of the spindled cells (Figure 3). The patient was diagnosed with KS in the setting of chronic venous insufficiency.

|

Patient 2

A 67-year-old Hispanic man with a history of diabetes mellitus presented with 10 asymptomatic purple papules and hyperkeratotic and hyperpigmented plaques on the distal aspect of the legs of 1 year’s duration in the setting of chronic venous insufficiency (Figure 4). The patient had no history of immunosuppression or HIV and was not of Mediterranean or African descent. An excisional biopsy from the left fourth toe revealed a cellular dermal vascular proliferation associated with numerous small slitlike vessels and scattered dilated blood vessels with prominent hemorrhage and surrounding dermal fibrosis (Figure 5). The lesion was markedly cellular with nuclear atypia. Many cells showed enlarged oval- to spindle-shaped hyperchromatic nuclei, some with prominent nucleoli and scant amounts of eosinophilic cytoplasm. Although the differential diagnosis included an unusual cellular pyogenic granuloma with atypia in the setting of chronic venous insufficiency, the degree of cellularity and presence of spindled cells associated with slitlike vessels were more consistent with a pyogenic granulomalike variant of KS. This variant is rare but has previously been reported.4 Many of the tumor nucleoli stained strongly for HHV-8, which is a diagnostic finding of KS (Figure 6). The patient subsequently was diagnosed with KS.

Comment

These 2 cases represent unusual clinical presentations of KS in Hispanic patients with no known risk factors for KS. In patient 1, an initial skin biopsy prompted HHV-8 testing due to suspicion for KS. At that time, HHV-8 was negative, perhaps because of technical deficiencies in the staining protocol; alternatively, the patient may have subsequently developed KS. Both patients had known chronic venous insufficiency. However, biopsies revealed spindle-shaped cells forming clefts and positivity for HHV-8. We propose that these cases may represent an additional clinical variant of KS, chronic venous insufficiency–associated KS.

If similar presentations of KS are identified, studies will need to be done to uncover the specific risk factors involved. Human herpesvirus 8 is not sufficient for the development of KS on its own, as oncogenesis of KS requires immunodeficiency or an additional environmental factor such as diabetes mellitus.5 Through impaired microvascular circulation and the release of hypoxia-inducible factor 1a, diabetes can promote KS-herpesvirus replication. Therefore, the risk for KS is increased in individuals with diabetes regardless of a negative history of immunodeficiency, which may have been the case in patient 2.

Our cases suggest that chronic venous insufficiency may be another factor that predisposes immunocompetent individuals to KS. Chronic venous insufficiency can cause hypoxia, promoting the release of cytokines and angiogenic factors responsible for the formation of vascular tumors such as KS.6 Once present, KS can worsen preexisting stasis dermatitis by compressing the external lymphatics and exacerbating lymphedema.7 Stasis dermatitis and KS may be part of a self-perpetuating cycle that involves obstruction due to secondary lymphadenopathy, the development of lymphedema, and the release of cytokines and growth factors that lead to further vascular proliferation.8

|

|

In summary, we present 2 cases of non–HIV-related KS that may represent an additional clinical variant of KS that mimics and/or arises in chronic venous insufficiency and appears as papules and plaques in elderly patients who are Hispanic, immunocompetent, and HIV negative. We suggest including KS in the differential diagnosis for chronic venous insufficiency, especially in cases with an unusual clinical appearance or course. In these cases, skin biopsy with HHV-8 testing may be warranted.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to acknowledge William Putnam, BFA, New York, New York, for his assistance with the figures.

1. Hiatt KM, Nelson AM, Lichy JH, et al. Classic Kaposi sarcoma in the United States over the last two decades: a clinicopathologic and molecular study of 438 non-HIV-related Kaposi Sarcoma patients with comparison to HIV-related Kaposi Sarcoma [published online ahead of print March 28, 2008]. Mod Pathol. 2008;21:572-582.

2. Weaver J, Billings SD. Initial presentation of stasis dermatitis mimicking solitary lesions: a previously unrecognized clinical scenario. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:1028-1032.

3. Bulat V, Lugovic´ L, Šitum M, et al. Acroangiodermatitis (pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma) as part of chronic venous insufficiency. Acta Clin Croat. 2007;46:273-277.

4. Urquhart JL, Uzieblo A, Kohler S. Detection of HHV-8 in pyogenic granuloma-like Kaposi sarcoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:317-321.

5. Anderson LA, Lauria C, Romano N, et al. Risk factors for classical Kaposi sarcoma in a population-based case-control study in Sicily. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:3435-3443.

6. Lunardi-Iskandar Y, Bryant JL, Zeman RA, et al. Tumorigenesis and metastasis of neoplastic Kaposi’s sarcoma cell line in immunodeficient mice blocked by a human pregnancy hormone. Nature. 1995;375:64-68.

7. Allen PJ, Gillespie DL, Redfield RR, et al. Lower extremity lymphedema caused by acquired immune deficiency syndrome-related Kaposi’s sarcoma: case report and review of the literature. J Vasc Surg. 1995;22:178-181.

8. Ramdial PK, Chetty R, Singh B, et al. Lymphedematous HIV-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:474-481.

1. Hiatt KM, Nelson AM, Lichy JH, et al. Classic Kaposi sarcoma in the United States over the last two decades: a clinicopathologic and molecular study of 438 non-HIV-related Kaposi Sarcoma patients with comparison to HIV-related Kaposi Sarcoma [published online ahead of print March 28, 2008]. Mod Pathol. 2008;21:572-582.

2. Weaver J, Billings SD. Initial presentation of stasis dermatitis mimicking solitary lesions: a previously unrecognized clinical scenario. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:1028-1032.

3. Bulat V, Lugovic´ L, Šitum M, et al. Acroangiodermatitis (pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma) as part of chronic venous insufficiency. Acta Clin Croat. 2007;46:273-277.

4. Urquhart JL, Uzieblo A, Kohler S. Detection of HHV-8 in pyogenic granuloma-like Kaposi sarcoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:317-321.

5. Anderson LA, Lauria C, Romano N, et al. Risk factors for classical Kaposi sarcoma in a population-based case-control study in Sicily. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:3435-3443.

6. Lunardi-Iskandar Y, Bryant JL, Zeman RA, et al. Tumorigenesis and metastasis of neoplastic Kaposi’s sarcoma cell line in immunodeficient mice blocked by a human pregnancy hormone. Nature. 1995;375:64-68.

7. Allen PJ, Gillespie DL, Redfield RR, et al. Lower extremity lymphedema caused by acquired immune deficiency syndrome-related Kaposi’s sarcoma: case report and review of the literature. J Vasc Surg. 1995;22:178-181.

8. Ramdial PK, Chetty R, Singh B, et al. Lymphedematous HIV-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:474-481.

Practice Points

- The 4 clinical variants of Kaposi sarcoma (KS) are classic, African, transplant associated, and AIDS related.

- Human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) staining can be used to confirm the presence of KS.

- A subset of patients with chronic venous insufficiency with no other risk factors for KS have been found to have violaceous plaques that test positive for HHV-8.

- Chronic venous insufficiency may be a predisposing factor to KS in immunocompetent individuals and may constitute an additional clinical variant of KS.