User login

The psychiatrist’s role in navigating a toxic news cycle

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I’m Dr. Gregory Scott Brown, an Austin (Tex.)-based psychiatrist and an affiliate faculty member at the University of Texas Dell Medical School.

Recently, a patient of mine told me that, because of the political environment we find ourselves in, he’s avoiding conversations with some of his longtime friends. Because of this, he’s feeling even more isolated than before.

We’re all coming off the heels of a tough year, and many of us expected that when we entered 2021 we’d quickly turn the page and life would get a whole lot easier. Since the reality is that we’re still dealing with deep divisions, social injustices, and the politicization of evidence-based medicine, emotions are naturally running high.

In listening to my patients over the past few weeks, there’s definitely a sense of optimism about coronavirus vaccines and getting back to life as usual. But there’s also a lingering sense of uncertainty and fear, especially when it comes to the possibility of saying the wrong thing, offending our friends, or just having conversations with people we may disagree with. I’m hearing concerns from my patients that 2020 exposed a dormant hatred that was brewing in the underbelly of our society, in our politics, and in our institutions. Patients are telling me that these concerns are making them anxious and some are avoiding interacting with people they may disagree with altogether because they’re afraid of the difficult conversations that may follow.

Since, like many of my patients as well as many of you, I follow the news, including stories of COVID-related deaths, economic hardships, peaceful protests gone bad, and political vitriol, I’ve had to remind myself about the importance of intentional kindness for effective communication and for supporting mental health.

I was reminded of the paper “Hate in the Counter-Transference” by the well-known pediatrician and psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott. He focuses on how to manage and sort through the strong emotions that may be experienced even during an encounter between a therapist and a patient. Although some of what he has to say doesn’t translate well to modern times, his recommendation that we acknowledge and try to normalize some of our feelings does. And this is how I’ve been starting a conversation with my patients – just by normalizing things a bit.

The past year or so has brought with it a range of intense emotions, including frustration, exhaustion, and some degree of sadness for most of us. When we’re self-aware about our feelings, we can make sense of them early on so that they don’t evolve into maladaptive ones like unhinged anger or hatred. My patients and I actively discuss how our feelings don’t have to get in the way of our ability to live and to interact with each other as we’d like to.

Considering the basic tenets of kindness is a good place to start. I recently spoke with Kelli Harding, MD, a psychiatrist and author of The Rabbit Effect: Live Longer, Happier, and Healthier with the Groundbreaking Science of Kindness. She pointed to research suggesting that kindness can benefit multiple areas of our health, from reducing cardiovascular events to improving mood and anxiety. In her book, she notes that

I tell my patients that we can’t always change our environment, but we can definitely change how we respond to it. This doesn’t mean it’s always an easy process, but there are things we can do. First, we have to acknowledge that some degree of conflict or cordial disagreement is inevitable and it doesn’t have to disrupt our mood.

An interesting study on conflict management pointed out that healthy conflict is actually beneficial in some cases. For instance, in the work environment, conflict can help with team development and better group decision-making. But it’s rigid personality differences, poor communication, emotional stress, and lack of candor that may contribute to so-called high-tension events, and this is where conflict can go awry. These are the areas that we can all focus on improving, not only for performance benefits but for our overall health and well-being as well.

The authors also recommend an active style of engagement as a technique to manage conflict, but in a way that feels both natural and safe. Other authors agree that so-called engaged coping is associated with a higher sense of control and overall improved psychological well-being. What this means is that avoidance may be necessary in the short term, but over time it may lead to more emotional stress and anxiety.

Overcoming the tendency to avoid requires both motivation and self-awareness. We need to know about patterns in our own behavior and how the behavior of others can push our buttons and spiral a healthy disagreement into a heated argument.

I like to recommend the hunger, angry, lonely, tired (HALT) model, which is often used as a self-care gauge in addiction treatment and to reduce medication errors. But I think it’s also a useful way to assess personal readiness for having a difficult conversation. I tell my patients to ask themselves in this moment: “Am I hungry, angry, lonely, or tired?” And if they are, perhaps it’s not the best time for the conversation.

Because 2020 brought with it a new set of challenges, it also forced many of us to focus on things that we just didn’t pay as much attention to before, including checking in on our feelings and the feelings of those around us. It also taught us to pay attention to the way and manner in which we communicate. I think that kindness is much easier to carry into difficult conversations if we approach them with a sense of curiosity before judgment. Ultimately, kindness is one of the best tools for balancing the intense emotions that many of us are feeling right now.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I’m Dr. Gregory Scott Brown, an Austin (Tex.)-based psychiatrist and an affiliate faculty member at the University of Texas Dell Medical School.

Recently, a patient of mine told me that, because of the political environment we find ourselves in, he’s avoiding conversations with some of his longtime friends. Because of this, he’s feeling even more isolated than before.

We’re all coming off the heels of a tough year, and many of us expected that when we entered 2021 we’d quickly turn the page and life would get a whole lot easier. Since the reality is that we’re still dealing with deep divisions, social injustices, and the politicization of evidence-based medicine, emotions are naturally running high.

In listening to my patients over the past few weeks, there’s definitely a sense of optimism about coronavirus vaccines and getting back to life as usual. But there’s also a lingering sense of uncertainty and fear, especially when it comes to the possibility of saying the wrong thing, offending our friends, or just having conversations with people we may disagree with. I’m hearing concerns from my patients that 2020 exposed a dormant hatred that was brewing in the underbelly of our society, in our politics, and in our institutions. Patients are telling me that these concerns are making them anxious and some are avoiding interacting with people they may disagree with altogether because they’re afraid of the difficult conversations that may follow.

Since, like many of my patients as well as many of you, I follow the news, including stories of COVID-related deaths, economic hardships, peaceful protests gone bad, and political vitriol, I’ve had to remind myself about the importance of intentional kindness for effective communication and for supporting mental health.

I was reminded of the paper “Hate in the Counter-Transference” by the well-known pediatrician and psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott. He focuses on how to manage and sort through the strong emotions that may be experienced even during an encounter between a therapist and a patient. Although some of what he has to say doesn’t translate well to modern times, his recommendation that we acknowledge and try to normalize some of our feelings does. And this is how I’ve been starting a conversation with my patients – just by normalizing things a bit.

The past year or so has brought with it a range of intense emotions, including frustration, exhaustion, and some degree of sadness for most of us. When we’re self-aware about our feelings, we can make sense of them early on so that they don’t evolve into maladaptive ones like unhinged anger or hatred. My patients and I actively discuss how our feelings don’t have to get in the way of our ability to live and to interact with each other as we’d like to.

Considering the basic tenets of kindness is a good place to start. I recently spoke with Kelli Harding, MD, a psychiatrist and author of The Rabbit Effect: Live Longer, Happier, and Healthier with the Groundbreaking Science of Kindness. She pointed to research suggesting that kindness can benefit multiple areas of our health, from reducing cardiovascular events to improving mood and anxiety. In her book, she notes that

I tell my patients that we can’t always change our environment, but we can definitely change how we respond to it. This doesn’t mean it’s always an easy process, but there are things we can do. First, we have to acknowledge that some degree of conflict or cordial disagreement is inevitable and it doesn’t have to disrupt our mood.

An interesting study on conflict management pointed out that healthy conflict is actually beneficial in some cases. For instance, in the work environment, conflict can help with team development and better group decision-making. But it’s rigid personality differences, poor communication, emotional stress, and lack of candor that may contribute to so-called high-tension events, and this is where conflict can go awry. These are the areas that we can all focus on improving, not only for performance benefits but for our overall health and well-being as well.

The authors also recommend an active style of engagement as a technique to manage conflict, but in a way that feels both natural and safe. Other authors agree that so-called engaged coping is associated with a higher sense of control and overall improved psychological well-being. What this means is that avoidance may be necessary in the short term, but over time it may lead to more emotional stress and anxiety.

Overcoming the tendency to avoid requires both motivation and self-awareness. We need to know about patterns in our own behavior and how the behavior of others can push our buttons and spiral a healthy disagreement into a heated argument.

I like to recommend the hunger, angry, lonely, tired (HALT) model, which is often used as a self-care gauge in addiction treatment and to reduce medication errors. But I think it’s also a useful way to assess personal readiness for having a difficult conversation. I tell my patients to ask themselves in this moment: “Am I hungry, angry, lonely, or tired?” And if they are, perhaps it’s not the best time for the conversation.

Because 2020 brought with it a new set of challenges, it also forced many of us to focus on things that we just didn’t pay as much attention to before, including checking in on our feelings and the feelings of those around us. It also taught us to pay attention to the way and manner in which we communicate. I think that kindness is much easier to carry into difficult conversations if we approach them with a sense of curiosity before judgment. Ultimately, kindness is one of the best tools for balancing the intense emotions that many of us are feeling right now.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I’m Dr. Gregory Scott Brown, an Austin (Tex.)-based psychiatrist and an affiliate faculty member at the University of Texas Dell Medical School.

Recently, a patient of mine told me that, because of the political environment we find ourselves in, he’s avoiding conversations with some of his longtime friends. Because of this, he’s feeling even more isolated than before.

We’re all coming off the heels of a tough year, and many of us expected that when we entered 2021 we’d quickly turn the page and life would get a whole lot easier. Since the reality is that we’re still dealing with deep divisions, social injustices, and the politicization of evidence-based medicine, emotions are naturally running high.

In listening to my patients over the past few weeks, there’s definitely a sense of optimism about coronavirus vaccines and getting back to life as usual. But there’s also a lingering sense of uncertainty and fear, especially when it comes to the possibility of saying the wrong thing, offending our friends, or just having conversations with people we may disagree with. I’m hearing concerns from my patients that 2020 exposed a dormant hatred that was brewing in the underbelly of our society, in our politics, and in our institutions. Patients are telling me that these concerns are making them anxious and some are avoiding interacting with people they may disagree with altogether because they’re afraid of the difficult conversations that may follow.

Since, like many of my patients as well as many of you, I follow the news, including stories of COVID-related deaths, economic hardships, peaceful protests gone bad, and political vitriol, I’ve had to remind myself about the importance of intentional kindness for effective communication and for supporting mental health.

I was reminded of the paper “Hate in the Counter-Transference” by the well-known pediatrician and psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott. He focuses on how to manage and sort through the strong emotions that may be experienced even during an encounter between a therapist and a patient. Although some of what he has to say doesn’t translate well to modern times, his recommendation that we acknowledge and try to normalize some of our feelings does. And this is how I’ve been starting a conversation with my patients – just by normalizing things a bit.

The past year or so has brought with it a range of intense emotions, including frustration, exhaustion, and some degree of sadness for most of us. When we’re self-aware about our feelings, we can make sense of them early on so that they don’t evolve into maladaptive ones like unhinged anger or hatred. My patients and I actively discuss how our feelings don’t have to get in the way of our ability to live and to interact with each other as we’d like to.

Considering the basic tenets of kindness is a good place to start. I recently spoke with Kelli Harding, MD, a psychiatrist and author of The Rabbit Effect: Live Longer, Happier, and Healthier with the Groundbreaking Science of Kindness. She pointed to research suggesting that kindness can benefit multiple areas of our health, from reducing cardiovascular events to improving mood and anxiety. In her book, she notes that

I tell my patients that we can’t always change our environment, but we can definitely change how we respond to it. This doesn’t mean it’s always an easy process, but there are things we can do. First, we have to acknowledge that some degree of conflict or cordial disagreement is inevitable and it doesn’t have to disrupt our mood.

An interesting study on conflict management pointed out that healthy conflict is actually beneficial in some cases. For instance, in the work environment, conflict can help with team development and better group decision-making. But it’s rigid personality differences, poor communication, emotional stress, and lack of candor that may contribute to so-called high-tension events, and this is where conflict can go awry. These are the areas that we can all focus on improving, not only for performance benefits but for our overall health and well-being as well.

The authors also recommend an active style of engagement as a technique to manage conflict, but in a way that feels both natural and safe. Other authors agree that so-called engaged coping is associated with a higher sense of control and overall improved psychological well-being. What this means is that avoidance may be necessary in the short term, but over time it may lead to more emotional stress and anxiety.

Overcoming the tendency to avoid requires both motivation and self-awareness. We need to know about patterns in our own behavior and how the behavior of others can push our buttons and spiral a healthy disagreement into a heated argument.

I like to recommend the hunger, angry, lonely, tired (HALT) model, which is often used as a self-care gauge in addiction treatment and to reduce medication errors. But I think it’s also a useful way to assess personal readiness for having a difficult conversation. I tell my patients to ask themselves in this moment: “Am I hungry, angry, lonely, or tired?” And if they are, perhaps it’s not the best time for the conversation.

Because 2020 brought with it a new set of challenges, it also forced many of us to focus on things that we just didn’t pay as much attention to before, including checking in on our feelings and the feelings of those around us. It also taught us to pay attention to the way and manner in which we communicate. I think that kindness is much easier to carry into difficult conversations if we approach them with a sense of curiosity before judgment. Ultimately, kindness is one of the best tools for balancing the intense emotions that many of us are feeling right now.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The paranoid business executive

CASE Bipolar-like symptoms

Mr. R, age 48, presents to the psychiatric emergency department (ED) for the third time in 4 days after a change in his behavior over the last 2.5 weeks. He exhibits heightened extroversion, pressured speech, and uncharacteristic irritability. Mr. R’s wife reports that her husband normally is reserved.

Mr. R’s wife first became concerned when she noticed he was not sleeping and spending his nights changing the locks on their home. Mr. R, who is a business executive, occupied his time by taking notes on ways to protect his identity from the senior partners at his company.

Three weeks before his first ED visit, Mr. R had been treated for a neck abscess with incision and drainage. He was sent home with a 10-day course of amoxicillin/clavulanate, 875/125 mg by mouth twice daily. There were no reports of steroid use during or after the procedure. Four days after starting the antibiotic, he stopped taking it because he and his wife felt it was contributing to his mood changes and bizarre behavior.

During his first visit to the ED, Mr. R received a 1-time dose of olanzapine, 5 mg by mouth, which helped temporarily reduce his anxiety; however, he returned the following day with the same anxiety symptoms and was discharged with a 30-day prescription for olanzapine, 5 mg/d, to manage symptoms until he could establish care with an outpatient psychiatrist. Two days later, he returned to the ED yet again convinced people were spying on him and that his coworkers were plotting to have him fired. He was not taking his phone to work due to fears that it would be hacked.

Mr. R’s only home medication is clomiphene citrate, 100 mg/d by mouth, which he’s received for the past 7 months to treat low testosterone. He has no personal or family history of psychiatric illness and no prior signs of mania or hypomania.

At the current ED visit, Mr. R’s testosterone level is checked and is within normal limits. His urine drug screen, head CT, and standard laboratory test results are unremarkable, except for mild transaminitis that does not warrant acute management.

The clinicians in the ED establish a diagnosis of mania, unspecified, and psychotic disorder, unspecified. They recommend that Mr. R be admitted for mood stabilization.

[polldaddy:10485725]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Our initial impression was that Mr. R was experiencing a manic episode from undiagnosed bipolar I disorder. The diagnosis was equivocal considering his age, lack of family history, and absence of prior psychiatric symptoms. In most cases, the mean age of onset for mania is late adolescence to early adulthood. It would be less common for a patient to experience a first manic episode at age 48, although mania may emerge at any age. Results from a large British study showed that the incidence of a first manic episode drops from 13.81% in men age 16 to 25 to 2.62% in men age 46 to 55.1 However, some estimates suggest that the prevalence of late-onset mania is much higher than previously expected; medical comorbidities, such as dementia and delirium, may play a significant role in posing as manic-type symptoms in these patients.2

In Mr. R’s case, he remained fully alert and oriented without waxing and waning attentional deficits, which made delirium less likely. His affective symptoms included a reduced need for sleep, anxiety, irritability, rapid speech, and grandiosity lasting at least 2 weeks. He also exhibited psychotic symptoms in the form of paranoia. Altogether, he fit diagnostic criteria for bipolar I disorder well.

At the time of his manic episode, Mr. R was taking clomiphene. Clomiphene-induced mania and psychosis has been reported scarcely in the literature.3 In these cases, behavioral changes occurred within the first month of clomiphene initiation, which is dissimilar from Mr. R’s timeline.4 However, there appeared to be a temporal relationship between Mr. R’s use of amoxicillin/clavulanate and his manic episode.

This led us to consider whether medication-induced bipolar disorder would be a more appropriate diagnosis. There are documented associations between mania and antibiotics5; however, to our knowledge, mania secondary specifically to amoxicillin/clavulanate has not been reported extensively in the American literature. We found 1 case of suspected amoxicillin-induced psychosis,6 as well as a case report from the Netherlands of possible amoxicillin/clavulanate-induced mania.7

EVALUATION Ongoing paranoia

During his psychiatric hospitalization, Mr. R remains cooperative and polite, but exhibits ongoing paranoia, pressured speech, and poor reality testing. He remains convinced that “people are out to get me,” and routinely scans the room for safety during daily evaluations. He reports that he feels safe in the hospital, but does not feel safe to leave. Mr. R does not recall if in the past he had taken any products containing amoxicillin, but he is able to appreciate changes in his mood after being prescribed the antibiotic. He reports that starting the antibiotic made him feel confident in social interactions.

Continue to: During Mr. R's psychiatric hospitalization...

During Mr. R’s psychiatric hospitalization, olanzapine is titrated to 10 mg at bedtime. Clomiphene citrate is discontinued to limit any potential precipitants of mania, and amoxicillin/clavulanate is not restarted.

Mr. R gradually shows improvement in sleep quality and duration and becomes less irritable. His speech returns to a regular rate and rhythm. He eventually begins to question whether his fears were reality-based. After 4 days, Mr. R is ready to be discharged home and return to work.

[polldaddy:10485726]

The authors’ observations

The term “antibiomania” is used to describe manic episodes that coincide with antibiotic usage.8 Clarithromycin and ciprofloxacin are the agents most frequently implicated in antibiomania.9 While numerous reports exist in the literature, antibiomania is still considered a rare or unusual adverse event.

The link between infections and neuropsychiatric symptoms is well documented, which makes it challenging to tease apart the role of the acute infection from the use of antibiotics in precipitating psychiatric symptoms. However, in most reported cases of antibiomania, the onset of manic symptoms typically occurs within the first week of antibiotic initiation and resolves 1 to 3 days after medication discontinuation. The temporal relationship between antibiotic initiation and onset of neuropsychiatric symptoms has been best highlighted in cases where clarithromycin is used to treat a chronic Helicobacter pylori infection.10

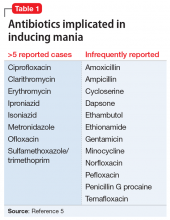

While reports of antibiomania date back more than 6 decades, the exact mechanism by which antibiotics cause psychiatric symptoms is mostly unknown, although there are several hypotheses.5 Many hypotheses suggest some antibiotics play a role in reducing gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) neurotransmission. Quinolones, for example, have been found to cross the blood–brain barrier and can inhibit GABA from binding to the receptor sites. This can result in hyper-excitability in the CNS. Several quinolones have been implicated in antibiomania (Table 15). Penicillins are also thought to interfere with GABA neurotransmission in a similar fashion; however, amoxicillin-clavulanate has poor CNS penetration in the absence of blood–brain barrier disruption,11 which makes this theory a less plausible explanation for Mr. R’s case.

Continue to: Another possible mechanism...

Another possible mechanism of antibiotic-induced CNS excitability is through the glutamatergic system. Cycloserine, an antitubercular agent, is an N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDA) partial agonist and has reported neuropsychiatric adverse effects.12 It has been proposed that quinolones may also have NMDA agonist activity.

The prostaglandin hypothesis suggests that a decrease in GABA may increase concentrations of steroid hormones in the rat CNS.13 Steroids have been implicated in the breakdown of prostaglandin E1 (PGE1).13 A disruption in steroid regulation may prevent PGE1 breakdown. Lithium’s antimanic properties are thought to be caused at least in part by limiting prostaglandin production.14 Thus, a shift in PGE1 may lead to mood dysregulation.

Bipolar disorder has been linked with mitochondrial function abnormalities.15 Antibiotics that target ribosomal RNA may disrupt normal mitochondrial function and increase risk for mania precipitation.15 However, amoxicillin exerts its antibiotic effects through binding to penicillin-binding proteins, which leads to inhibition of the cell wall biosynthesis.

Lastly, research into the microbiome has elucidated the gut-brain axis. In animal studies, the microbiome has been found to play a role in immunity, cognitive function, and behavior. Dysbiosis in the microbiome is currently being investigated for its role in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.16 Both the microbiome and changes in mitochondrial function are thought to develop over time, so while these are plausible explanations, an onset within 4 days of antibiotic initiation is likely too short of an exposure time to produce these changes.

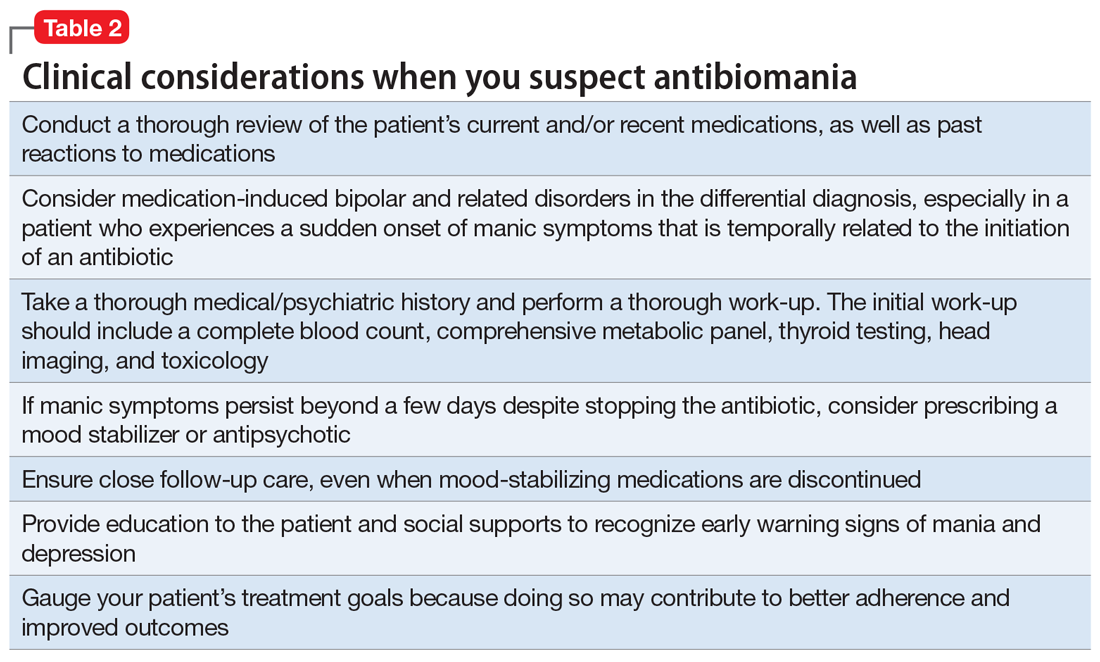

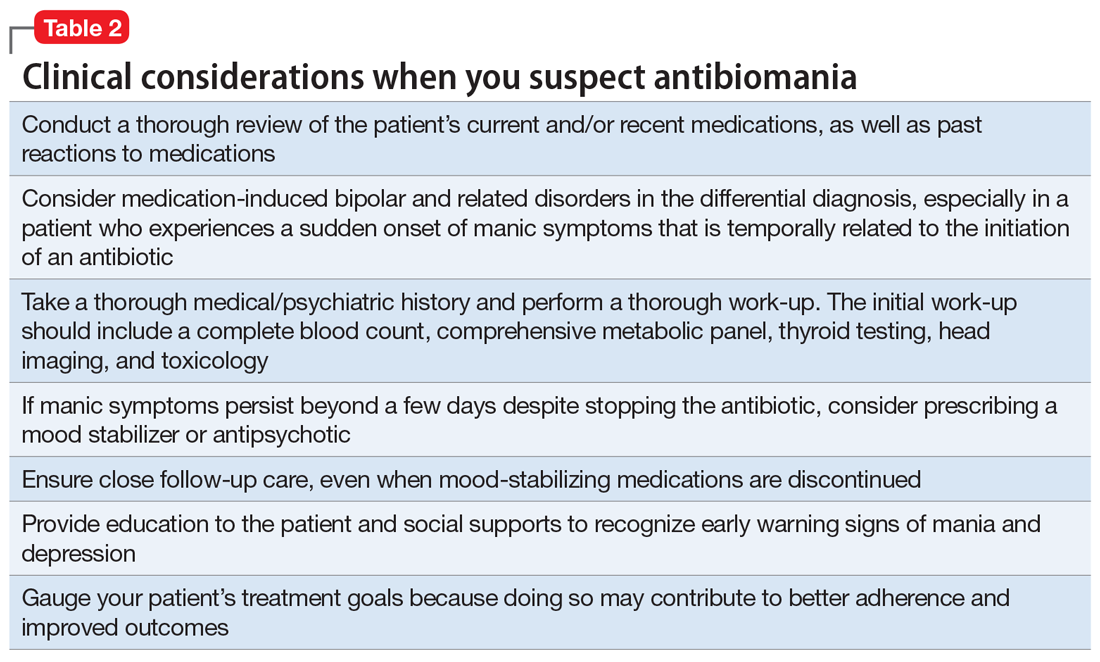

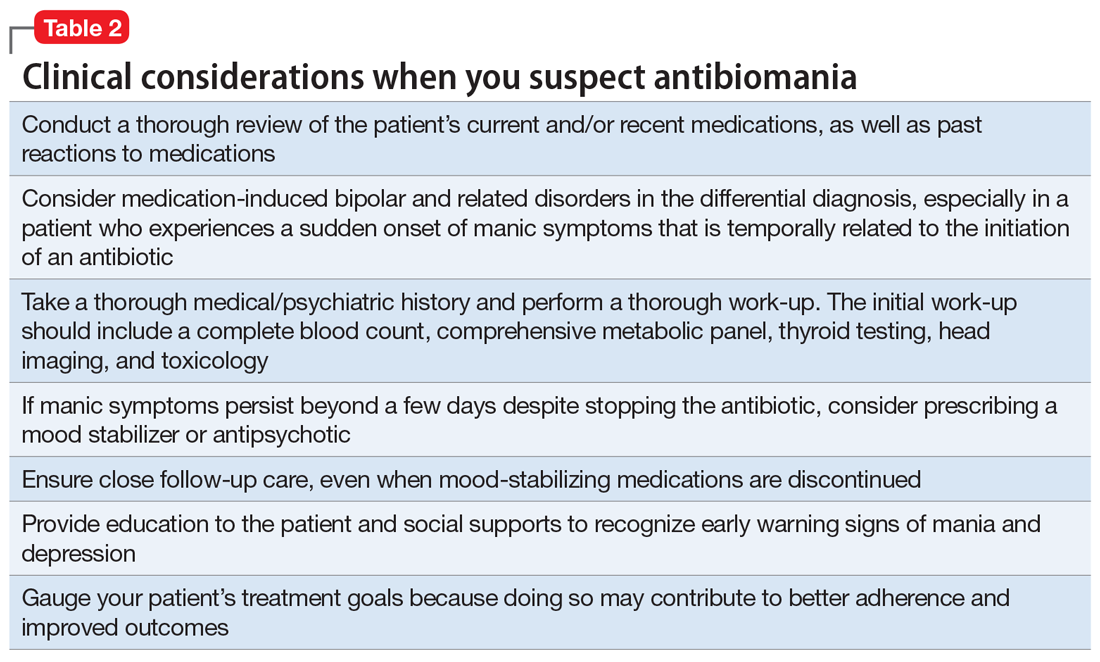

The most likely causes of Mr. R’s manic episode were clomiphene or amoxicillin-clavulanate, and the time course seems to indicate the antibiotic was the most likely culprit. Table 2 lists things to consider if you suspect your patient may be experiencing antibiomania.

Continue to: TREATMENT Stable on olanzapine

TREATMENT Stable on olanzapine

During his first visit to the outpatient clinic 4 weeks after being discharged, Mr. R reports that he has successfully returned to work, and his paranoia has completely resolved. He continues to take olanzapine, 10 mg nightly, and has restarted clomiphene, 100 mg/d.

During this outpatient follow-up visit, Mr. R attributes his manic episode to an adverse reaction to amoxicillin/clavulanate, and requests to be tapered off olanzapine. After he and his psychiatrist discuss the risk of relapse in untreated bipolar disorder, olanzapine is reduced to 7.5 mg at bedtime with a plan to taper to discontinuation.

At his second follow-up visit 1 month later, Mr. R has also stopped clomiphene and is taking a herbal supplement instead, which he reports is helpful for his fatigue.

[polldaddy:10485727]

OUTCOME Lasting euthymic mood

Mr. R agrees to our recommendation of continuing to monitor him every 3 months for at least 1 year. We provide him and his wife with education about early warning signs of mood instability. Eight months after his manic episode, Mr. R no longer receives any psychotropic medications and shows no signs of mood instability. His mood remains euthymic and he is able to function well at work and in his personal life.

Bottom Line

‘Antibiomania’ describes manic episodes that coincide with antibiotic usage. This adverse effect is rare but should be considered in patients who present with unexplained first-episode mania, particularly those with an initial onset of mania after early adulthood.

Continue to: Related Resources

Related Resources

- Rakofsky JJ, Dunlop BW. Nothing to sneeze at: Upper respiratory infections and mood disorders. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(7):29-34.

- Adiba A, Jackson JC, Torrence CL. Older-age bipolar disorder: A case series. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(2):24-29

Drug Brand Names

Amoxicillin • Amoxil

Amoxicillin/clavulanate • Augmentin

Ampicillin • Omnipen-N, Polycillin-N

Ciprofloxacin • Cipro

Clarithromycin • Biaxin

Clomiphene • Clomid

Cycloserine • Seromycin

Dapsone • Dapsone

Erythromycin • Erythrocin, Pediamycin

Ethambutol • Myambutol

Ethionamide • Trecator-SC

Gentamicin • Garamycin

Isoniazid • Hyzyd, Nydrazid

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Metronidazole • Flagyl

Minocycline • Dynacin, Solodyn

Norfloxacin • Noroxin

Ofloxacin • Floxin

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Penicillin G procaine • Duracillin A-S, Pfizerpen

Sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim • Bactrim, Septra

1. Kennedy M, Everitt B, Boydell J, et al. Incidence and distribution of first-episode mania by age: results for a 35-year study. Psychol Med. 2005;35(6):855-863.

2. Dols A, Kupka RW, van Lammeren A, et al. The prevalence of late-life mania: a review. Bipolar Disord. 2014;16:113-118.

3. Siedontopf F, Horstkamp B, Stief G, et al. Clomiphene citrate as a possible cause of a psychotic reaction during infertility treatment. Hum Reprod. 1997;12(4):706-707.

4. Oyffe T, Lerner A, Isaacs G, et al. Clomiphene-induced psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(8):1169-1170.

5. Lambrichts S, Van Oudenhove L, Sienaert P. Antibiotics and mania: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2017;219:149-156.

6. Beal DM, Hudson B, Zaiac M. Amoxicillin-induced psychosis? Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143(2):255-256.

7. Klain V, Timmerman L. Antibiomania, acute manic psychosis following the use of antibiotics. European Psychiatry. 2013;28(suppl 1):1.

8. Abouesh A, Stone C, Hobbs WR. Antimicrobial-induced mania (antibiomania): a review of spontaneous reports. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002;22(1):71-81.

9. Lally L, Mannion L. The potential for antimicrobials to adversely affect mental state. BMJ Case Rep. 2013. pii: bcr2013009659. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-009659.

10. Neufeld NH, Mohamed NS, Grujich N, et al. Acute neuropsychiatric symptoms associated with antibiotic treatment of Helicobactor Pylori infections: a review. J Psychiatr Pract. 2017;23(1):25-35.

11. Sutter R, Rüegg S, Tschudin-Sutter S. Seizures as adverse events of antibiotic drugs: a systematic review. Neurology. 2015;85(15):1332-1341.

12. Bakhla A, Gore P, Srivastava S. Cycloserine induced mania. Ind Psychiatry J. 2013;22(1):69-70.

13. Barbaccia ML, Roscetti G, Trabucchi M, et al. Isoniazid-induced inhibition of GABAergic transmission enhances neurosteroid content in the rat brain. Neuropharmacology. 1996;35(9-10):1299-1305.

14. Murphy D, Donnelly C, Moskowitz J. Inhibition by lithium of prostaglandin E1 and norepinephrine effects on cyclic adenosine monophosphate production in human platelets. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1973;14(5):810-814.

15. Clay H, Sillivan S, Konradi C. Mitochondrial dysfunction and pathology in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2011;29(3):311-324.

16. Dickerson F, Severance E, Yolken R. The microbiome, immunity, and schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Brain Behav Immun. 2017;62:46-52.

CASE Bipolar-like symptoms

Mr. R, age 48, presents to the psychiatric emergency department (ED) for the third time in 4 days after a change in his behavior over the last 2.5 weeks. He exhibits heightened extroversion, pressured speech, and uncharacteristic irritability. Mr. R’s wife reports that her husband normally is reserved.

Mr. R’s wife first became concerned when she noticed he was not sleeping and spending his nights changing the locks on their home. Mr. R, who is a business executive, occupied his time by taking notes on ways to protect his identity from the senior partners at his company.

Three weeks before his first ED visit, Mr. R had been treated for a neck abscess with incision and drainage. He was sent home with a 10-day course of amoxicillin/clavulanate, 875/125 mg by mouth twice daily. There were no reports of steroid use during or after the procedure. Four days after starting the antibiotic, he stopped taking it because he and his wife felt it was contributing to his mood changes and bizarre behavior.

During his first visit to the ED, Mr. R received a 1-time dose of olanzapine, 5 mg by mouth, which helped temporarily reduce his anxiety; however, he returned the following day with the same anxiety symptoms and was discharged with a 30-day prescription for olanzapine, 5 mg/d, to manage symptoms until he could establish care with an outpatient psychiatrist. Two days later, he returned to the ED yet again convinced people were spying on him and that his coworkers were plotting to have him fired. He was not taking his phone to work due to fears that it would be hacked.

Mr. R’s only home medication is clomiphene citrate, 100 mg/d by mouth, which he’s received for the past 7 months to treat low testosterone. He has no personal or family history of psychiatric illness and no prior signs of mania or hypomania.

At the current ED visit, Mr. R’s testosterone level is checked and is within normal limits. His urine drug screen, head CT, and standard laboratory test results are unremarkable, except for mild transaminitis that does not warrant acute management.

The clinicians in the ED establish a diagnosis of mania, unspecified, and psychotic disorder, unspecified. They recommend that Mr. R be admitted for mood stabilization.

[polldaddy:10485725]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Our initial impression was that Mr. R was experiencing a manic episode from undiagnosed bipolar I disorder. The diagnosis was equivocal considering his age, lack of family history, and absence of prior psychiatric symptoms. In most cases, the mean age of onset for mania is late adolescence to early adulthood. It would be less common for a patient to experience a first manic episode at age 48, although mania may emerge at any age. Results from a large British study showed that the incidence of a first manic episode drops from 13.81% in men age 16 to 25 to 2.62% in men age 46 to 55.1 However, some estimates suggest that the prevalence of late-onset mania is much higher than previously expected; medical comorbidities, such as dementia and delirium, may play a significant role in posing as manic-type symptoms in these patients.2

In Mr. R’s case, he remained fully alert and oriented without waxing and waning attentional deficits, which made delirium less likely. His affective symptoms included a reduced need for sleep, anxiety, irritability, rapid speech, and grandiosity lasting at least 2 weeks. He also exhibited psychotic symptoms in the form of paranoia. Altogether, he fit diagnostic criteria for bipolar I disorder well.

At the time of his manic episode, Mr. R was taking clomiphene. Clomiphene-induced mania and psychosis has been reported scarcely in the literature.3 In these cases, behavioral changes occurred within the first month of clomiphene initiation, which is dissimilar from Mr. R’s timeline.4 However, there appeared to be a temporal relationship between Mr. R’s use of amoxicillin/clavulanate and his manic episode.

This led us to consider whether medication-induced bipolar disorder would be a more appropriate diagnosis. There are documented associations between mania and antibiotics5; however, to our knowledge, mania secondary specifically to amoxicillin/clavulanate has not been reported extensively in the American literature. We found 1 case of suspected amoxicillin-induced psychosis,6 as well as a case report from the Netherlands of possible amoxicillin/clavulanate-induced mania.7

EVALUATION Ongoing paranoia

During his psychiatric hospitalization, Mr. R remains cooperative and polite, but exhibits ongoing paranoia, pressured speech, and poor reality testing. He remains convinced that “people are out to get me,” and routinely scans the room for safety during daily evaluations. He reports that he feels safe in the hospital, but does not feel safe to leave. Mr. R does not recall if in the past he had taken any products containing amoxicillin, but he is able to appreciate changes in his mood after being prescribed the antibiotic. He reports that starting the antibiotic made him feel confident in social interactions.

Continue to: During Mr. R's psychiatric hospitalization...

During Mr. R’s psychiatric hospitalization, olanzapine is titrated to 10 mg at bedtime. Clomiphene citrate is discontinued to limit any potential precipitants of mania, and amoxicillin/clavulanate is not restarted.

Mr. R gradually shows improvement in sleep quality and duration and becomes less irritable. His speech returns to a regular rate and rhythm. He eventually begins to question whether his fears were reality-based. After 4 days, Mr. R is ready to be discharged home and return to work.

[polldaddy:10485726]

The authors’ observations

The term “antibiomania” is used to describe manic episodes that coincide with antibiotic usage.8 Clarithromycin and ciprofloxacin are the agents most frequently implicated in antibiomania.9 While numerous reports exist in the literature, antibiomania is still considered a rare or unusual adverse event.

The link between infections and neuropsychiatric symptoms is well documented, which makes it challenging to tease apart the role of the acute infection from the use of antibiotics in precipitating psychiatric symptoms. However, in most reported cases of antibiomania, the onset of manic symptoms typically occurs within the first week of antibiotic initiation and resolves 1 to 3 days after medication discontinuation. The temporal relationship between antibiotic initiation and onset of neuropsychiatric symptoms has been best highlighted in cases where clarithromycin is used to treat a chronic Helicobacter pylori infection.10

While reports of antibiomania date back more than 6 decades, the exact mechanism by which antibiotics cause psychiatric symptoms is mostly unknown, although there are several hypotheses.5 Many hypotheses suggest some antibiotics play a role in reducing gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) neurotransmission. Quinolones, for example, have been found to cross the blood–brain barrier and can inhibit GABA from binding to the receptor sites. This can result in hyper-excitability in the CNS. Several quinolones have been implicated in antibiomania (Table 15). Penicillins are also thought to interfere with GABA neurotransmission in a similar fashion; however, amoxicillin-clavulanate has poor CNS penetration in the absence of blood–brain barrier disruption,11 which makes this theory a less plausible explanation for Mr. R’s case.

Continue to: Another possible mechanism...

Another possible mechanism of antibiotic-induced CNS excitability is through the glutamatergic system. Cycloserine, an antitubercular agent, is an N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDA) partial agonist and has reported neuropsychiatric adverse effects.12 It has been proposed that quinolones may also have NMDA agonist activity.

The prostaglandin hypothesis suggests that a decrease in GABA may increase concentrations of steroid hormones in the rat CNS.13 Steroids have been implicated in the breakdown of prostaglandin E1 (PGE1).13 A disruption in steroid regulation may prevent PGE1 breakdown. Lithium’s antimanic properties are thought to be caused at least in part by limiting prostaglandin production.14 Thus, a shift in PGE1 may lead to mood dysregulation.

Bipolar disorder has been linked with mitochondrial function abnormalities.15 Antibiotics that target ribosomal RNA may disrupt normal mitochondrial function and increase risk for mania precipitation.15 However, amoxicillin exerts its antibiotic effects through binding to penicillin-binding proteins, which leads to inhibition of the cell wall biosynthesis.

Lastly, research into the microbiome has elucidated the gut-brain axis. In animal studies, the microbiome has been found to play a role in immunity, cognitive function, and behavior. Dysbiosis in the microbiome is currently being investigated for its role in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.16 Both the microbiome and changes in mitochondrial function are thought to develop over time, so while these are plausible explanations, an onset within 4 days of antibiotic initiation is likely too short of an exposure time to produce these changes.

The most likely causes of Mr. R’s manic episode were clomiphene or amoxicillin-clavulanate, and the time course seems to indicate the antibiotic was the most likely culprit. Table 2 lists things to consider if you suspect your patient may be experiencing antibiomania.

Continue to: TREATMENT Stable on olanzapine

TREATMENT Stable on olanzapine

During his first visit to the outpatient clinic 4 weeks after being discharged, Mr. R reports that he has successfully returned to work, and his paranoia has completely resolved. He continues to take olanzapine, 10 mg nightly, and has restarted clomiphene, 100 mg/d.

During this outpatient follow-up visit, Mr. R attributes his manic episode to an adverse reaction to amoxicillin/clavulanate, and requests to be tapered off olanzapine. After he and his psychiatrist discuss the risk of relapse in untreated bipolar disorder, olanzapine is reduced to 7.5 mg at bedtime with a plan to taper to discontinuation.

At his second follow-up visit 1 month later, Mr. R has also stopped clomiphene and is taking a herbal supplement instead, which he reports is helpful for his fatigue.

[polldaddy:10485727]

OUTCOME Lasting euthymic mood

Mr. R agrees to our recommendation of continuing to monitor him every 3 months for at least 1 year. We provide him and his wife with education about early warning signs of mood instability. Eight months after his manic episode, Mr. R no longer receives any psychotropic medications and shows no signs of mood instability. His mood remains euthymic and he is able to function well at work and in his personal life.

Bottom Line

‘Antibiomania’ describes manic episodes that coincide with antibiotic usage. This adverse effect is rare but should be considered in patients who present with unexplained first-episode mania, particularly those with an initial onset of mania after early adulthood.

Continue to: Related Resources

Related Resources

- Rakofsky JJ, Dunlop BW. Nothing to sneeze at: Upper respiratory infections and mood disorders. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(7):29-34.

- Adiba A, Jackson JC, Torrence CL. Older-age bipolar disorder: A case series. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(2):24-29

Drug Brand Names

Amoxicillin • Amoxil

Amoxicillin/clavulanate • Augmentin

Ampicillin • Omnipen-N, Polycillin-N

Ciprofloxacin • Cipro

Clarithromycin • Biaxin

Clomiphene • Clomid

Cycloserine • Seromycin

Dapsone • Dapsone

Erythromycin • Erythrocin, Pediamycin

Ethambutol • Myambutol

Ethionamide • Trecator-SC

Gentamicin • Garamycin

Isoniazid • Hyzyd, Nydrazid

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Metronidazole • Flagyl

Minocycline • Dynacin, Solodyn

Norfloxacin • Noroxin

Ofloxacin • Floxin

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Penicillin G procaine • Duracillin A-S, Pfizerpen

Sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim • Bactrim, Septra

CASE Bipolar-like symptoms

Mr. R, age 48, presents to the psychiatric emergency department (ED) for the third time in 4 days after a change in his behavior over the last 2.5 weeks. He exhibits heightened extroversion, pressured speech, and uncharacteristic irritability. Mr. R’s wife reports that her husband normally is reserved.

Mr. R’s wife first became concerned when she noticed he was not sleeping and spending his nights changing the locks on their home. Mr. R, who is a business executive, occupied his time by taking notes on ways to protect his identity from the senior partners at his company.

Three weeks before his first ED visit, Mr. R had been treated for a neck abscess with incision and drainage. He was sent home with a 10-day course of amoxicillin/clavulanate, 875/125 mg by mouth twice daily. There were no reports of steroid use during or after the procedure. Four days after starting the antibiotic, he stopped taking it because he and his wife felt it was contributing to his mood changes and bizarre behavior.

During his first visit to the ED, Mr. R received a 1-time dose of olanzapine, 5 mg by mouth, which helped temporarily reduce his anxiety; however, he returned the following day with the same anxiety symptoms and was discharged with a 30-day prescription for olanzapine, 5 mg/d, to manage symptoms until he could establish care with an outpatient psychiatrist. Two days later, he returned to the ED yet again convinced people were spying on him and that his coworkers were plotting to have him fired. He was not taking his phone to work due to fears that it would be hacked.

Mr. R’s only home medication is clomiphene citrate, 100 mg/d by mouth, which he’s received for the past 7 months to treat low testosterone. He has no personal or family history of psychiatric illness and no prior signs of mania or hypomania.

At the current ED visit, Mr. R’s testosterone level is checked and is within normal limits. His urine drug screen, head CT, and standard laboratory test results are unremarkable, except for mild transaminitis that does not warrant acute management.

The clinicians in the ED establish a diagnosis of mania, unspecified, and psychotic disorder, unspecified. They recommend that Mr. R be admitted for mood stabilization.

[polldaddy:10485725]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Our initial impression was that Mr. R was experiencing a manic episode from undiagnosed bipolar I disorder. The diagnosis was equivocal considering his age, lack of family history, and absence of prior psychiatric symptoms. In most cases, the mean age of onset for mania is late adolescence to early adulthood. It would be less common for a patient to experience a first manic episode at age 48, although mania may emerge at any age. Results from a large British study showed that the incidence of a first manic episode drops from 13.81% in men age 16 to 25 to 2.62% in men age 46 to 55.1 However, some estimates suggest that the prevalence of late-onset mania is much higher than previously expected; medical comorbidities, such as dementia and delirium, may play a significant role in posing as manic-type symptoms in these patients.2

In Mr. R’s case, he remained fully alert and oriented without waxing and waning attentional deficits, which made delirium less likely. His affective symptoms included a reduced need for sleep, anxiety, irritability, rapid speech, and grandiosity lasting at least 2 weeks. He also exhibited psychotic symptoms in the form of paranoia. Altogether, he fit diagnostic criteria for bipolar I disorder well.

At the time of his manic episode, Mr. R was taking clomiphene. Clomiphene-induced mania and psychosis has been reported scarcely in the literature.3 In these cases, behavioral changes occurred within the first month of clomiphene initiation, which is dissimilar from Mr. R’s timeline.4 However, there appeared to be a temporal relationship between Mr. R’s use of amoxicillin/clavulanate and his manic episode.

This led us to consider whether medication-induced bipolar disorder would be a more appropriate diagnosis. There are documented associations between mania and antibiotics5; however, to our knowledge, mania secondary specifically to amoxicillin/clavulanate has not been reported extensively in the American literature. We found 1 case of suspected amoxicillin-induced psychosis,6 as well as a case report from the Netherlands of possible amoxicillin/clavulanate-induced mania.7

EVALUATION Ongoing paranoia

During his psychiatric hospitalization, Mr. R remains cooperative and polite, but exhibits ongoing paranoia, pressured speech, and poor reality testing. He remains convinced that “people are out to get me,” and routinely scans the room for safety during daily evaluations. He reports that he feels safe in the hospital, but does not feel safe to leave. Mr. R does not recall if in the past he had taken any products containing amoxicillin, but he is able to appreciate changes in his mood after being prescribed the antibiotic. He reports that starting the antibiotic made him feel confident in social interactions.

Continue to: During Mr. R's psychiatric hospitalization...

During Mr. R’s psychiatric hospitalization, olanzapine is titrated to 10 mg at bedtime. Clomiphene citrate is discontinued to limit any potential precipitants of mania, and amoxicillin/clavulanate is not restarted.

Mr. R gradually shows improvement in sleep quality and duration and becomes less irritable. His speech returns to a regular rate and rhythm. He eventually begins to question whether his fears were reality-based. After 4 days, Mr. R is ready to be discharged home and return to work.

[polldaddy:10485726]

The authors’ observations

The term “antibiomania” is used to describe manic episodes that coincide with antibiotic usage.8 Clarithromycin and ciprofloxacin are the agents most frequently implicated in antibiomania.9 While numerous reports exist in the literature, antibiomania is still considered a rare or unusual adverse event.

The link between infections and neuropsychiatric symptoms is well documented, which makes it challenging to tease apart the role of the acute infection from the use of antibiotics in precipitating psychiatric symptoms. However, in most reported cases of antibiomania, the onset of manic symptoms typically occurs within the first week of antibiotic initiation and resolves 1 to 3 days after medication discontinuation. The temporal relationship between antibiotic initiation and onset of neuropsychiatric symptoms has been best highlighted in cases where clarithromycin is used to treat a chronic Helicobacter pylori infection.10

While reports of antibiomania date back more than 6 decades, the exact mechanism by which antibiotics cause psychiatric symptoms is mostly unknown, although there are several hypotheses.5 Many hypotheses suggest some antibiotics play a role in reducing gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) neurotransmission. Quinolones, for example, have been found to cross the blood–brain barrier and can inhibit GABA from binding to the receptor sites. This can result in hyper-excitability in the CNS. Several quinolones have been implicated in antibiomania (Table 15). Penicillins are also thought to interfere with GABA neurotransmission in a similar fashion; however, amoxicillin-clavulanate has poor CNS penetration in the absence of blood–brain barrier disruption,11 which makes this theory a less plausible explanation for Mr. R’s case.

Continue to: Another possible mechanism...

Another possible mechanism of antibiotic-induced CNS excitability is through the glutamatergic system. Cycloserine, an antitubercular agent, is an N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDA) partial agonist and has reported neuropsychiatric adverse effects.12 It has been proposed that quinolones may also have NMDA agonist activity.

The prostaglandin hypothesis suggests that a decrease in GABA may increase concentrations of steroid hormones in the rat CNS.13 Steroids have been implicated in the breakdown of prostaglandin E1 (PGE1).13 A disruption in steroid regulation may prevent PGE1 breakdown. Lithium’s antimanic properties are thought to be caused at least in part by limiting prostaglandin production.14 Thus, a shift in PGE1 may lead to mood dysregulation.

Bipolar disorder has been linked with mitochondrial function abnormalities.15 Antibiotics that target ribosomal RNA may disrupt normal mitochondrial function and increase risk for mania precipitation.15 However, amoxicillin exerts its antibiotic effects through binding to penicillin-binding proteins, which leads to inhibition of the cell wall biosynthesis.

Lastly, research into the microbiome has elucidated the gut-brain axis. In animal studies, the microbiome has been found to play a role in immunity, cognitive function, and behavior. Dysbiosis in the microbiome is currently being investigated for its role in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.16 Both the microbiome and changes in mitochondrial function are thought to develop over time, so while these are plausible explanations, an onset within 4 days of antibiotic initiation is likely too short of an exposure time to produce these changes.

The most likely causes of Mr. R’s manic episode were clomiphene or amoxicillin-clavulanate, and the time course seems to indicate the antibiotic was the most likely culprit. Table 2 lists things to consider if you suspect your patient may be experiencing antibiomania.

Continue to: TREATMENT Stable on olanzapine

TREATMENT Stable on olanzapine

During his first visit to the outpatient clinic 4 weeks after being discharged, Mr. R reports that he has successfully returned to work, and his paranoia has completely resolved. He continues to take olanzapine, 10 mg nightly, and has restarted clomiphene, 100 mg/d.

During this outpatient follow-up visit, Mr. R attributes his manic episode to an adverse reaction to amoxicillin/clavulanate, and requests to be tapered off olanzapine. After he and his psychiatrist discuss the risk of relapse in untreated bipolar disorder, olanzapine is reduced to 7.5 mg at bedtime with a plan to taper to discontinuation.

At his second follow-up visit 1 month later, Mr. R has also stopped clomiphene and is taking a herbal supplement instead, which he reports is helpful for his fatigue.

[polldaddy:10485727]

OUTCOME Lasting euthymic mood

Mr. R agrees to our recommendation of continuing to monitor him every 3 months for at least 1 year. We provide him and his wife with education about early warning signs of mood instability. Eight months after his manic episode, Mr. R no longer receives any psychotropic medications and shows no signs of mood instability. His mood remains euthymic and he is able to function well at work and in his personal life.

Bottom Line

‘Antibiomania’ describes manic episodes that coincide with antibiotic usage. This adverse effect is rare but should be considered in patients who present with unexplained first-episode mania, particularly those with an initial onset of mania after early adulthood.

Continue to: Related Resources

Related Resources

- Rakofsky JJ, Dunlop BW. Nothing to sneeze at: Upper respiratory infections and mood disorders. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(7):29-34.

- Adiba A, Jackson JC, Torrence CL. Older-age bipolar disorder: A case series. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(2):24-29

Drug Brand Names

Amoxicillin • Amoxil

Amoxicillin/clavulanate • Augmentin

Ampicillin • Omnipen-N, Polycillin-N

Ciprofloxacin • Cipro

Clarithromycin • Biaxin

Clomiphene • Clomid

Cycloserine • Seromycin

Dapsone • Dapsone

Erythromycin • Erythrocin, Pediamycin

Ethambutol • Myambutol

Ethionamide • Trecator-SC

Gentamicin • Garamycin

Isoniazid • Hyzyd, Nydrazid

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Metronidazole • Flagyl

Minocycline • Dynacin, Solodyn

Norfloxacin • Noroxin

Ofloxacin • Floxin

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Penicillin G procaine • Duracillin A-S, Pfizerpen

Sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim • Bactrim, Septra

1. Kennedy M, Everitt B, Boydell J, et al. Incidence and distribution of first-episode mania by age: results for a 35-year study. Psychol Med. 2005;35(6):855-863.

2. Dols A, Kupka RW, van Lammeren A, et al. The prevalence of late-life mania: a review. Bipolar Disord. 2014;16:113-118.

3. Siedontopf F, Horstkamp B, Stief G, et al. Clomiphene citrate as a possible cause of a psychotic reaction during infertility treatment. Hum Reprod. 1997;12(4):706-707.

4. Oyffe T, Lerner A, Isaacs G, et al. Clomiphene-induced psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(8):1169-1170.

5. Lambrichts S, Van Oudenhove L, Sienaert P. Antibiotics and mania: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2017;219:149-156.

6. Beal DM, Hudson B, Zaiac M. Amoxicillin-induced psychosis? Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143(2):255-256.

7. Klain V, Timmerman L. Antibiomania, acute manic psychosis following the use of antibiotics. European Psychiatry. 2013;28(suppl 1):1.

8. Abouesh A, Stone C, Hobbs WR. Antimicrobial-induced mania (antibiomania): a review of spontaneous reports. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002;22(1):71-81.

9. Lally L, Mannion L. The potential for antimicrobials to adversely affect mental state. BMJ Case Rep. 2013. pii: bcr2013009659. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-009659.

10. Neufeld NH, Mohamed NS, Grujich N, et al. Acute neuropsychiatric symptoms associated with antibiotic treatment of Helicobactor Pylori infections: a review. J Psychiatr Pract. 2017;23(1):25-35.

11. Sutter R, Rüegg S, Tschudin-Sutter S. Seizures as adverse events of antibiotic drugs: a systematic review. Neurology. 2015;85(15):1332-1341.

12. Bakhla A, Gore P, Srivastava S. Cycloserine induced mania. Ind Psychiatry J. 2013;22(1):69-70.

13. Barbaccia ML, Roscetti G, Trabucchi M, et al. Isoniazid-induced inhibition of GABAergic transmission enhances neurosteroid content in the rat brain. Neuropharmacology. 1996;35(9-10):1299-1305.

14. Murphy D, Donnelly C, Moskowitz J. Inhibition by lithium of prostaglandin E1 and norepinephrine effects on cyclic adenosine monophosphate production in human platelets. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1973;14(5):810-814.

15. Clay H, Sillivan S, Konradi C. Mitochondrial dysfunction and pathology in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2011;29(3):311-324.

16. Dickerson F, Severance E, Yolken R. The microbiome, immunity, and schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Brain Behav Immun. 2017;62:46-52.

1. Kennedy M, Everitt B, Boydell J, et al. Incidence and distribution of first-episode mania by age: results for a 35-year study. Psychol Med. 2005;35(6):855-863.

2. Dols A, Kupka RW, van Lammeren A, et al. The prevalence of late-life mania: a review. Bipolar Disord. 2014;16:113-118.

3. Siedontopf F, Horstkamp B, Stief G, et al. Clomiphene citrate as a possible cause of a psychotic reaction during infertility treatment. Hum Reprod. 1997;12(4):706-707.

4. Oyffe T, Lerner A, Isaacs G, et al. Clomiphene-induced psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(8):1169-1170.

5. Lambrichts S, Van Oudenhove L, Sienaert P. Antibiotics and mania: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2017;219:149-156.

6. Beal DM, Hudson B, Zaiac M. Amoxicillin-induced psychosis? Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143(2):255-256.

7. Klain V, Timmerman L. Antibiomania, acute manic psychosis following the use of antibiotics. European Psychiatry. 2013;28(suppl 1):1.

8. Abouesh A, Stone C, Hobbs WR. Antimicrobial-induced mania (antibiomania): a review of spontaneous reports. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002;22(1):71-81.

9. Lally L, Mannion L. The potential for antimicrobials to adversely affect mental state. BMJ Case Rep. 2013. pii: bcr2013009659. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-009659.

10. Neufeld NH, Mohamed NS, Grujich N, et al. Acute neuropsychiatric symptoms associated with antibiotic treatment of Helicobactor Pylori infections: a review. J Psychiatr Pract. 2017;23(1):25-35.

11. Sutter R, Rüegg S, Tschudin-Sutter S. Seizures as adverse events of antibiotic drugs: a systematic review. Neurology. 2015;85(15):1332-1341.

12. Bakhla A, Gore P, Srivastava S. Cycloserine induced mania. Ind Psychiatry J. 2013;22(1):69-70.

13. Barbaccia ML, Roscetti G, Trabucchi M, et al. Isoniazid-induced inhibition of GABAergic transmission enhances neurosteroid content in the rat brain. Neuropharmacology. 1996;35(9-10):1299-1305.

14. Murphy D, Donnelly C, Moskowitz J. Inhibition by lithium of prostaglandin E1 and norepinephrine effects on cyclic adenosine monophosphate production in human platelets. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1973;14(5):810-814.

15. Clay H, Sillivan S, Konradi C. Mitochondrial dysfunction and pathology in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2011;29(3):311-324.

16. Dickerson F, Severance E, Yolken R. The microbiome, immunity, and schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Brain Behav Immun. 2017;62:46-52.

Yoga’s lesson for a young psychiatrist

I have often turned to yoga for my own reprieve; I find the heat, breath, and movement exhilarating. Training to become a yoga teacher has taught me that medicine, not unlike yoga, requires patience and resiliency.

It is 3

4

Let me tell you, when you’re getting certified in Advanced Cardiac Life Support, you go to a class on a Saturday, there are snacks, and your instructor will probably be a paramedic who is earning side cash teaching CPR. You will watch funny videos—we even danced to the Bee Gees’ Stayin’ Alive. But this is not funny, nor is it fun. And my head is spinning so fast, the sound of the Bee Gees smears to silence.

I take off my white coat and trot to the center of the room. The lights are bright, I am hot, and people are moving really fast. I feel like I’m in a vignette. It seems like we’re in the fourth movement of a Shostakovich symphony, the attending is cueing, up and down, like Bernstein conducting the Philharmonic, her arms are flailing; this production is hers and everyone is in sync. The man’s skin is pale, almost gray, he smells like sweat and urine and vomit. His irises are blue, blue like the ocean. His beard is thick and opaque, speckled with premature dots of gray. He looks calm. Listless. Dead. He is looking at me, like the Mona Lisa, as if beckoning me to save him, to give him another chance. At life. I put my hands gently on his sternum and I start my round of chest compressions. His skin is rubbery. I feel like I’m breaking his ribs, am I? This is not like the class. The cardiac monitor flatlines. Was it like that before? I think so, I’m not really sure. The attending stops conducting and runs over. Someone taps me and says it’s time to switch. Shortly thereafter, time of death is pronounced. “Damn it,” I hear the attending exclaim quietly but deliberately. I am hot, and I have a headache. I take off my gloves. Where’s my cell phone? I’m going to check Facebook, maybe ESPN.com. I feel heavy. And then I’m sitting at the computer screen again, after the rain. The attending comes back to her seat. She has a green smoothie, she takes a sip, and is slow to return the oversized cup to the table.

This night 3 years ago remains vivid. I am looking at her now. The unabashed attending. We are all looking at her.

She pulls out a petite makeup case and opens an oval mirror. She applies 2 thin lines of lustrous lip gloss, smacks her lips, grounding herself, then places the mirror back in her bag. She takes one deep breath, pauses briefly, and, letting go, she sits up tall, her dignity restored, then looks at me and claps, “Come on, doctor, we’ve got more patients to see.”

That night in the ER, I experienced how troubling it is losing a life with the burden of responsibility, but also the beauty of Aparigraha, letting go, and moving forward. I learned this lesson, unspoken, from an admirable attending, and was reminded of it 3 years later as I pursued a deeper understanding of yoga.

I have often turned to yoga for my own reprieve; I find the heat, breath, and movement exhilarating. Training to become a yoga teacher has taught me that medicine, not unlike yoga, requires patience and resiliency.

It is 3

4

Let me tell you, when you’re getting certified in Advanced Cardiac Life Support, you go to a class on a Saturday, there are snacks, and your instructor will probably be a paramedic who is earning side cash teaching CPR. You will watch funny videos—we even danced to the Bee Gees’ Stayin’ Alive. But this is not funny, nor is it fun. And my head is spinning so fast, the sound of the Bee Gees smears to silence.

I take off my white coat and trot to the center of the room. The lights are bright, I am hot, and people are moving really fast. I feel like I’m in a vignette. It seems like we’re in the fourth movement of a Shostakovich symphony, the attending is cueing, up and down, like Bernstein conducting the Philharmonic, her arms are flailing; this production is hers and everyone is in sync. The man’s skin is pale, almost gray, he smells like sweat and urine and vomit. His irises are blue, blue like the ocean. His beard is thick and opaque, speckled with premature dots of gray. He looks calm. Listless. Dead. He is looking at me, like the Mona Lisa, as if beckoning me to save him, to give him another chance. At life. I put my hands gently on his sternum and I start my round of chest compressions. His skin is rubbery. I feel like I’m breaking his ribs, am I? This is not like the class. The cardiac monitor flatlines. Was it like that before? I think so, I’m not really sure. The attending stops conducting and runs over. Someone taps me and says it’s time to switch. Shortly thereafter, time of death is pronounced. “Damn it,” I hear the attending exclaim quietly but deliberately. I am hot, and I have a headache. I take off my gloves. Where’s my cell phone? I’m going to check Facebook, maybe ESPN.com. I feel heavy. And then I’m sitting at the computer screen again, after the rain. The attending comes back to her seat. She has a green smoothie, she takes a sip, and is slow to return the oversized cup to the table.

This night 3 years ago remains vivid. I am looking at her now. The unabashed attending. We are all looking at her.

She pulls out a petite makeup case and opens an oval mirror. She applies 2 thin lines of lustrous lip gloss, smacks her lips, grounding herself, then places the mirror back in her bag. She takes one deep breath, pauses briefly, and, letting go, she sits up tall, her dignity restored, then looks at me and claps, “Come on, doctor, we’ve got more patients to see.”

That night in the ER, I experienced how troubling it is losing a life with the burden of responsibility, but also the beauty of Aparigraha, letting go, and moving forward. I learned this lesson, unspoken, from an admirable attending, and was reminded of it 3 years later as I pursued a deeper understanding of yoga.

I have often turned to yoga for my own reprieve; I find the heat, breath, and movement exhilarating. Training to become a yoga teacher has taught me that medicine, not unlike yoga, requires patience and resiliency.

It is 3

4

Let me tell you, when you’re getting certified in Advanced Cardiac Life Support, you go to a class on a Saturday, there are snacks, and your instructor will probably be a paramedic who is earning side cash teaching CPR. You will watch funny videos—we even danced to the Bee Gees’ Stayin’ Alive. But this is not funny, nor is it fun. And my head is spinning so fast, the sound of the Bee Gees smears to silence.

I take off my white coat and trot to the center of the room. The lights are bright, I am hot, and people are moving really fast. I feel like I’m in a vignette. It seems like we’re in the fourth movement of a Shostakovich symphony, the attending is cueing, up and down, like Bernstein conducting the Philharmonic, her arms are flailing; this production is hers and everyone is in sync. The man’s skin is pale, almost gray, he smells like sweat and urine and vomit. His irises are blue, blue like the ocean. His beard is thick and opaque, speckled with premature dots of gray. He looks calm. Listless. Dead. He is looking at me, like the Mona Lisa, as if beckoning me to save him, to give him another chance. At life. I put my hands gently on his sternum and I start my round of chest compressions. His skin is rubbery. I feel like I’m breaking his ribs, am I? This is not like the class. The cardiac monitor flatlines. Was it like that before? I think so, I’m not really sure. The attending stops conducting and runs over. Someone taps me and says it’s time to switch. Shortly thereafter, time of death is pronounced. “Damn it,” I hear the attending exclaim quietly but deliberately. I am hot, and I have a headache. I take off my gloves. Where’s my cell phone? I’m going to check Facebook, maybe ESPN.com. I feel heavy. And then I’m sitting at the computer screen again, after the rain. The attending comes back to her seat. She has a green smoothie, she takes a sip, and is slow to return the oversized cup to the table.

This night 3 years ago remains vivid. I am looking at her now. The unabashed attending. We are all looking at her.

She pulls out a petite makeup case and opens an oval mirror. She applies 2 thin lines of lustrous lip gloss, smacks her lips, grounding herself, then places the mirror back in her bag. She takes one deep breath, pauses briefly, and, letting go, she sits up tall, her dignity restored, then looks at me and claps, “Come on, doctor, we’ve got more patients to see.”

That night in the ER, I experienced how troubling it is losing a life with the burden of responsibility, but also the beauty of Aparigraha, letting go, and moving forward. I learned this lesson, unspoken, from an admirable attending, and was reminded of it 3 years later as I pursued a deeper understanding of yoga.