User login

A Retrospective Analysis of Hemostatic Techniques in Primary Total Knee Arthroplasty: Traditional Electrocautery, Bipolar Sealer, and Argon Beam Coagulation

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is a reliable and successful treatment for end-stage degenerative joint disease of the knee. Given the reproducibility of its generally excellent outcomes, TKA is increasingly being performed.1 However, the potential complications of this procedure can be devastating.2-4 The arthroplasty literature has shed light on the detrimental effects of postoperative blood loss and anemia.5,6 In addition, the increase in transfusion burden among patients is not without risk.7 Given these concerns, surgeons have been tasked with determining the ideal methods for minimizing blood transfusions and postoperative hematomas and anemia. Several strategies have been described.8-11 Hemostasis can be achieved with use of intravenous medications, intra-articular agents, or electrocautery devices. Electrocautery technologies include traditional electrocautery (TE), saline-coupled bipolar sealer (BS), and argon beam coagulation (ABC). There is controversy as to whether outcomes are better with one hemostasis method over another and whether these methods are worth the additional cost.

In traditional (Bovie) electrocautery, a unipolar device delivers an electrical current to tissues through a pencil-like instrument. Intraoperative tissue temperatures can exceed 400°C.12 In BS, radiofrequency energy is delivered through a saline medium, which increases the contact area, acts as an electrode, and maintains a cooler environment during electrocautery. Proposed advantages are reduced tissue destruction and absence of smoke.12 There is evidence both for10,12-16 and against17-20 use of BS in total joint arthroplasty. ABC, a novel hemostasis method, has been studied in the context of orthopedics21,22 but not TKA specifically. ABC establishes a monopolar electric circuit between a handheld device and the target tissues by channeling electrons through ionized argon gas. Hemostasis is achieved through thermal coagulation. Tissue penetration can be adjusted by changing power, probe-to-target distance, and duration of use.23 We conducted a study to assess the efficacy of all 3 electrocautery methods during TKA. We hypothesized the 3 methods would be clinically equivalent with respect to estimated blood loss (EBL), 48-hour wound drainage, operative time, and change from preoperative hemoglobin (Hb) level.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of consecutive primary TKAs performed by Dr. Levine between October 2010 and November 2011. Patients were identified by querying an internal database. Exclusion criteria were prior ipsilateral open knee procedure, prior fracture, nonuse of our standard hemostatic protocol, and either tourniquet time under 40 minutes or intraoperative documentation of tourniquet failure. As only 9 patients were initially identified for the TE cohort, the same database was used to add 32 patients treated between April 2009 and October 2009 (before our institution began using BS and ABC).

Clinical charts were reviewed, and baseline demographics (age, body mass index [BMI], preoperative Hb level) were abstracted, as were outcome metrics (EBL, 48-hour wound drainage, operative time, postoperative transfusions, adverse events (AEs) before discharge, and change in Hb level from before surgery to after surgery, in recovery room and on discharge). Statistical analyses were performed with JMP Version 10.0.0 (SAS Institute). Given the hypothesis that the 3 hemostasis methods would be clinically equivalent, 2 one-sided tests (TOSTs) of equivalence were performed with an α of 0.05. With TOST, the traditional null and alternative hypotheses are reversed; thus, P < .05 identifies statistical equivalence. The advantage of this study design is that equivalence can be identified, whereas traditional study designs can identify only a lack of statistical difference.24 We used our consensus opinions to set clinical insignificance thresholds for EBL (150 mL), wound drainage (150 mL), decrease from postoperative Hb level (1 g/dL), and operative time (10 minutes). Patients who received a blood transfusion were subsequently excluded from analysis in order to avoid skewing Hb-level depreciation calculations. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and χ2 tests were used to compare preoperative variables, transfusion requirements, hospital length of stay, and AE rates by hemostasis type.

Cautery Technique

In all cases, TE was used for surgical dissection, which followed a standard midvastus approach. Then, for meniscal excision, the capsule and meniscal attachment sites were treated with TE, BS, or ABC. During cement hardening, an available supplemental cautery option was used to achieve hemostasis of the suprapatellar fat pad and visible meniscal attachment sites. All other aspects of the procedure and the postoperative protocols—including the anticoagulation and rapid rehabilitation (early ambulation and therapy) protocols—were similar for all patients. The standard anticoagulation protocol was to use low-molecular-weight heparin, unless contraindicated. Tranexamic acid was not used at our institution during the study period.

Results

For the study period, 280 cases (41 TE, 203 BS, 36 ABC) met the inclusion criteria. Of the 280 TKAs, 261 (93.21%) were performed for degenerative arthritis. There was no statistically significant difference among cohorts in indication (χ2 = 1.841, P = .398) or sex (χ2 = 1.176, P= .555).

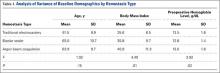

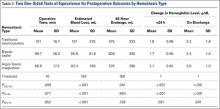

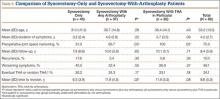

Table 1 lists the cohorts’ baseline demographics (mean age, BMI, preoperative Hb level) and comparative ANOVA results. TOSTs of equivalence were performed to compare operative time, EBL, 48-hour wound drainage, and postoperative Hb-level depreciation among hemostasis types. Changes in Hb level were calculated for the immediate postoperative period and time of discharge (Table 2). ANOVA of hospital length of stay demonstrated no significant difference in means among groups (P = .09).

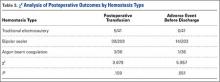

The cohorts were compared with respect to use of postoperative transfusions and incidence of postoperative AEs (Table 3). The TE cohort did not have any AEs. Of the 203 BS patients, 14 (7%) had 1 or more AEs, which included acute kidney injury (3 cases), electrolyte disturbance (3), urinary tract infection (2), oxygen desaturation (2), altered mental status (1), pneumonia (1), arrhythmia (1), congestive heart failure exacerbation (1), dehiscence (1), pulmonary embolism (2), and hypotension (1). Of the 36 ABC patients, 1 (3%) had arrhythmia, pneumonia, sepsis, and altered mental status.

Discussion

With the population aging, the demand for TKA is greater than ever.1 As surgical volume increases, the ability to minimize the rates of intraoperative bleeding, postoperative anemia, and transfusion is becoming increasingly important to patients and the healthcare system. There is no consensus as to which cautery method is ideal. Other investigators have identified differences in clinical outcomes between cautery systems, but reported results are largely conflicting.10,12-20 In addition, no one has studied the utility of ABC in TKA. In the present retrospective cohort analysis, we hypothesized that TE, BS, and ABC would be clinically equivalent in primary TKA with respect to EBL, 48-hour wound drainage, operative time, and change from preoperative Hb level.

The data on hemostatic technology in primary TKA are inconclusive. In an age- and sex-matched study comparing TE and BS in primary TKA, BS used with shed blood autotransfusion reduced homologous blood transfusions by a factor of 5.16 In addition, BS patients lost significantly less total visible blood (intraoperative EBL, postoperative drain output), and their magnitude of postoperative Hb-level depreciations at time of discharge was significantly lower. In a multicenter, prospective randomized trial comparing TE with BS, adjusted blood loss and need for autologous blood transfusions were lower in BS patients,10 though there was no significant difference in Knee Society Scale scores between the 2 treatment arms. However, analysis was potentially biased in that multiple authors had financial ties to Salient Surgical Technologies, the manufacturer of the BS device used in the study. Other prospective randomized trials of patients who had primary TKA with either TE or BS did not find any significant difference in postoperative Hb level, postoperative drainage, or transfusion requirements.19 ABC has been studied in the context of orthopedics but not joint arthroplasty specifically. This technology was anecdotally identified as a means of attaining hemostasis in foot and ankle surgery after failure of TE and other conventional means.22 ABC has also been identified as a successful adjuvant to curettage in the treatment of aneurysmal bone cysts.21 However, ABC has not been compared with TE or BS in the orthopedic literature.

In the present study, analysis of preoperative variables revealed a statistically but not clinically significant difference in BMI among cohorts. Mean (SD) BMI was 35.6 (6.5) for TE patients, 35.8 (9.7) for BS patients, and 40.9 (11.3) for ABC patients. (Previously, BMI did not correlate with intraoperative blood loss in TKA.25) Analysis also revealed a statistically significant but clinically insignificant and inconsequential difference in Hb level among cohorts. Mean (SD) preoperative Hb level was 13.5 (1.6) g/dL for TE patients, 12.8 (1.4) g/dL for BS patients, and 13.0 (1.6) g/dL for ABC patients. As decreases from preoperative baseline Hb levels were the intended focus of analysis—not absolute Hb levels—this finding does not refute postoperative analyses.

Our results suggest that, though TE may have relatively longer operative times in primary TKA, it is clinically equivalent to BS and ABC with respect to EBL and postoperative change in Hb levels. In addition, postoperative drainage was lower in TE than in BS and ABC, which were equivalent. No significant differences were found among hemostasis types with respect to postoperative transfusion requirements.

The prevalence distribution of predischarge AEs trended toward significance (χ2 = 5.957, P = .051), despite not meeting the predetermined α level. Rates of predischarge AEs were 0% (0/41) for TE patients, 7% (14/203) for BS patients, and 3% (1/36) for ABC patients. AEs included acute kidney injuries, electrolyte disturbances, urinary tract infections, oxygen desaturation, altered mental status, sepsis/infections, arrhythmias, congestive heart failure exacerbation, dehiscence, pulmonary embolism, and hypotension. Clearly, many of these AEs are not attributable to the hemostasis system used.

Limitations of this study include its retrospective design, documentation inadequate to account for drainage amount reinfused, and limited data on which clinical insignificance thresholds were based. In addition, reliance on historical data may have introduced bias into the analysis. The historical data used to increase the size of the TE cohort may reflect a period of relative inexperience and may have contributed to the longer operative times relative to those of the ABC cohort (Dr. Levine used ABC later in his career).

Traditional electrocautery remains a viable option in primary TKA. With its low cost and hemostasis equivalent to that of BS and ABC, TE deserves consideration equal to that given to these more modern hemostasis technologies. Cost per case is about $10 for TE versus $500 for BS and $110 for ABC.17 Soaring healthcare expenditures may warrant returning to TE or combining cautery techniques and other agents in primary TKA in order to reduce the number of transfusions and associated surgical costs.

1. Cram P, Lu X, Kates SL, Singh JA, Li Y, Wolf BR. Total knee arthroplasty volume, utilization, and outcomes among Medicare beneficiaries, 1991-2010. JAMA. 2012;308(12):1227-1236.

2. Leijtens B, Kremers van de Hei K, Jansen J, Koëter S. High complication rate after total knee and hip replacement due to perioperative bridging of anticoagulant therapy based on the 2012 ACCP guideline. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2014;134(9):1335-1341.

3. Park CH, Lee SH, Kang DG, Cho KY, Lee SH, Kim KI. Compartment syndrome following total knee arthroplasty: clinical results of late fasciotomy. Knee Surg Relat Res. 2014;26(3):177-181.

4. Pedersen AB, Mehnert F, Sorensen HT, Emmeluth C, Overgaard S, Johnsen SP. The risk of venous thromboembolism, myocardial infarction, stroke, major bleeding and death in patients undergoing total hip and knee replacement: a 15-year retrospective cohort study of routine clinical practice. Bone Joint J. 2014;96-B(4):479-485.

5. Carson JL, Poses RM, Spence RK, Bonavita G. Severity of anaemia and operative mortality and morbidity. Lancet. 1988;1(8588):727-729.

6. Carson JL, Duff A, Poses RM, et al. Effect of anaemia and cardiovascular disease on surgical mortality and morbidity. Lancet. 1996;348(9034):1055-1060.

7. Dodd RY. Current risk for transfusion transmitted infections. Curr Opin Hematol. 2007;14(6):671-676.

8. Kang DG, Khurana S, Baek JH, Park YS, Lee SH, Kim KI. Efficacy and safety using autotransfusion system with postoperative shed blood following total knee arthroplasty in haemophilia. Haemophilia. 2014;20(1):129-132.

9. Aguilera X, Martinez-Zapata MJ, Bosch A, et al. Efficacy and safety of fibrin glue and tranexamic acid to prevent postoperative blood loss in total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(22):2001-2007.

10. Marulanda GA, Krebs VE, Bierbaum BE, et al. Hemostasis using a bipolar sealer in primary unilateral total knee arthroplasty. Am J Orthop. 2009;38(12):E179-E183.

11. Katkhouda N, Friedlander M, Darehzereshki A, et al. Argon beam coagulation versus fibrin sealant for hemostasis following liver resection: a randomized study in a porcine model. Hepatogastroenterology. 2013;60(125):1110-1116.

12. Marulanda GA, Ulrich SD, Seyler TM, Delanois RE, Mont MA. Reductions in blood loss with a bipolar sealer in total hip arthroplasty. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2008;5(2):125-131.

13. Morris MJ, Berend KR, Lombardi AV Jr. Hemostasis in anterior supine intermuscular total hip arthroplasty: pilot study comparing standard electrocautery and a bipolar sealer. Surg Technol Int. 2010;20:352-356.

14. Clement RC, Kamath AF, Derman PB, Garino JP, Lee GC. Bipolar sealing in revision total hip arthroplasty for infection: efficacy and cost analysis. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(7):1376-1381.

15. Rosenberg AG. Reducing blood loss in total joint surgery with a saline-coupled bipolar sealing technology. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22(4 suppl 1):82-85.

16. Pfeiffer M, Bräutigam H, Draws D, Sigg A. A new bipolar blood sealing system embedded in perioperative strategies vs. a conventional regimen for total knee arthroplasty: results of a matched-pair study. Ger Med Sci. 2005;3:Doc10.

17. Morris MJ, Barrett M, Lombardi AV Jr, Tucker TL, Berend KR. Randomized blinded study comparing a bipolar sealer and standard electrocautery in reducing transfusion requirements in anterior supine intermuscular total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(9):1614-1617.

18. Barsoum WK, Klika AK, Murray TG, Higuera C, Lee HH, Krebs VE. Prospective randomized evaluation of the need for blood transfusion during primary total hip arthroplasty with use of a bipolar sealer. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(6):513-518.

19. Plymale MF, Capogna BM, Lovy AJ, Adler ML, Hirsh DM, Kim SJ. Unipolar vs bipolar hemostasis in total knee arthroplasty: a prospective randomized trial. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(6):1133-1137.e1.

20. Zeh A, Messer J, Davis J, Vasarhelyi A, Wohlrab D. The Aquamantys system—an alternative to reduce blood loss in primary total hip arthroplasty? J Arthroplasty. 2010;25(7):1072-1077.

21. Cummings JE, Smith RA, Heck RK Jr. Argon beam coagulation as adjuvant treatment after curettage of aneurysmal bone cysts: a preliminary study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(1):231-237.

22. Adams ML, Steinberg JS. Argon beam coagulation in foot and ankle surgery. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2011;50(6):780-782.

23. Neumayer L, Vargo D. Principles of preoperative and operative surgery. In: Townsend CM Jr, Beauchamp RD, Evers BM, Mattox KL, eds. Sabiston Textbook of Surgery. 19th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:211-239.

24. Walker E, Nowacki AS. Understanding equivalence and noninferiority testing. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(2):192-196.

25. Hrnack SA, Skeen N, Xu T, Rosenstein AD. Correlation of body mass index and blood loss during total knee and total hip arthroplasty. Am J Orthop. 2012;41(10):467-471.

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is a reliable and successful treatment for end-stage degenerative joint disease of the knee. Given the reproducibility of its generally excellent outcomes, TKA is increasingly being performed.1 However, the potential complications of this procedure can be devastating.2-4 The arthroplasty literature has shed light on the detrimental effects of postoperative blood loss and anemia.5,6 In addition, the increase in transfusion burden among patients is not without risk.7 Given these concerns, surgeons have been tasked with determining the ideal methods for minimizing blood transfusions and postoperative hematomas and anemia. Several strategies have been described.8-11 Hemostasis can be achieved with use of intravenous medications, intra-articular agents, or electrocautery devices. Electrocautery technologies include traditional electrocautery (TE), saline-coupled bipolar sealer (BS), and argon beam coagulation (ABC). There is controversy as to whether outcomes are better with one hemostasis method over another and whether these methods are worth the additional cost.

In traditional (Bovie) electrocautery, a unipolar device delivers an electrical current to tissues through a pencil-like instrument. Intraoperative tissue temperatures can exceed 400°C.12 In BS, radiofrequency energy is delivered through a saline medium, which increases the contact area, acts as an electrode, and maintains a cooler environment during electrocautery. Proposed advantages are reduced tissue destruction and absence of smoke.12 There is evidence both for10,12-16 and against17-20 use of BS in total joint arthroplasty. ABC, a novel hemostasis method, has been studied in the context of orthopedics21,22 but not TKA specifically. ABC establishes a monopolar electric circuit between a handheld device and the target tissues by channeling electrons through ionized argon gas. Hemostasis is achieved through thermal coagulation. Tissue penetration can be adjusted by changing power, probe-to-target distance, and duration of use.23 We conducted a study to assess the efficacy of all 3 electrocautery methods during TKA. We hypothesized the 3 methods would be clinically equivalent with respect to estimated blood loss (EBL), 48-hour wound drainage, operative time, and change from preoperative hemoglobin (Hb) level.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of consecutive primary TKAs performed by Dr. Levine between October 2010 and November 2011. Patients were identified by querying an internal database. Exclusion criteria were prior ipsilateral open knee procedure, prior fracture, nonuse of our standard hemostatic protocol, and either tourniquet time under 40 minutes or intraoperative documentation of tourniquet failure. As only 9 patients were initially identified for the TE cohort, the same database was used to add 32 patients treated between April 2009 and October 2009 (before our institution began using BS and ABC).

Clinical charts were reviewed, and baseline demographics (age, body mass index [BMI], preoperative Hb level) were abstracted, as were outcome metrics (EBL, 48-hour wound drainage, operative time, postoperative transfusions, adverse events (AEs) before discharge, and change in Hb level from before surgery to after surgery, in recovery room and on discharge). Statistical analyses were performed with JMP Version 10.0.0 (SAS Institute). Given the hypothesis that the 3 hemostasis methods would be clinically equivalent, 2 one-sided tests (TOSTs) of equivalence were performed with an α of 0.05. With TOST, the traditional null and alternative hypotheses are reversed; thus, P < .05 identifies statistical equivalence. The advantage of this study design is that equivalence can be identified, whereas traditional study designs can identify only a lack of statistical difference.24 We used our consensus opinions to set clinical insignificance thresholds for EBL (150 mL), wound drainage (150 mL), decrease from postoperative Hb level (1 g/dL), and operative time (10 minutes). Patients who received a blood transfusion were subsequently excluded from analysis in order to avoid skewing Hb-level depreciation calculations. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and χ2 tests were used to compare preoperative variables, transfusion requirements, hospital length of stay, and AE rates by hemostasis type.

Cautery Technique

In all cases, TE was used for surgical dissection, which followed a standard midvastus approach. Then, for meniscal excision, the capsule and meniscal attachment sites were treated with TE, BS, or ABC. During cement hardening, an available supplemental cautery option was used to achieve hemostasis of the suprapatellar fat pad and visible meniscal attachment sites. All other aspects of the procedure and the postoperative protocols—including the anticoagulation and rapid rehabilitation (early ambulation and therapy) protocols—were similar for all patients. The standard anticoagulation protocol was to use low-molecular-weight heparin, unless contraindicated. Tranexamic acid was not used at our institution during the study period.

Results

For the study period, 280 cases (41 TE, 203 BS, 36 ABC) met the inclusion criteria. Of the 280 TKAs, 261 (93.21%) were performed for degenerative arthritis. There was no statistically significant difference among cohorts in indication (χ2 = 1.841, P = .398) or sex (χ2 = 1.176, P= .555).

Table 1 lists the cohorts’ baseline demographics (mean age, BMI, preoperative Hb level) and comparative ANOVA results. TOSTs of equivalence were performed to compare operative time, EBL, 48-hour wound drainage, and postoperative Hb-level depreciation among hemostasis types. Changes in Hb level were calculated for the immediate postoperative period and time of discharge (Table 2). ANOVA of hospital length of stay demonstrated no significant difference in means among groups (P = .09).

The cohorts were compared with respect to use of postoperative transfusions and incidence of postoperative AEs (Table 3). The TE cohort did not have any AEs. Of the 203 BS patients, 14 (7%) had 1 or more AEs, which included acute kidney injury (3 cases), electrolyte disturbance (3), urinary tract infection (2), oxygen desaturation (2), altered mental status (1), pneumonia (1), arrhythmia (1), congestive heart failure exacerbation (1), dehiscence (1), pulmonary embolism (2), and hypotension (1). Of the 36 ABC patients, 1 (3%) had arrhythmia, pneumonia, sepsis, and altered mental status.

Discussion

With the population aging, the demand for TKA is greater than ever.1 As surgical volume increases, the ability to minimize the rates of intraoperative bleeding, postoperative anemia, and transfusion is becoming increasingly important to patients and the healthcare system. There is no consensus as to which cautery method is ideal. Other investigators have identified differences in clinical outcomes between cautery systems, but reported results are largely conflicting.10,12-20 In addition, no one has studied the utility of ABC in TKA. In the present retrospective cohort analysis, we hypothesized that TE, BS, and ABC would be clinically equivalent in primary TKA with respect to EBL, 48-hour wound drainage, operative time, and change from preoperative Hb level.

The data on hemostatic technology in primary TKA are inconclusive. In an age- and sex-matched study comparing TE and BS in primary TKA, BS used with shed blood autotransfusion reduced homologous blood transfusions by a factor of 5.16 In addition, BS patients lost significantly less total visible blood (intraoperative EBL, postoperative drain output), and their magnitude of postoperative Hb-level depreciations at time of discharge was significantly lower. In a multicenter, prospective randomized trial comparing TE with BS, adjusted blood loss and need for autologous blood transfusions were lower in BS patients,10 though there was no significant difference in Knee Society Scale scores between the 2 treatment arms. However, analysis was potentially biased in that multiple authors had financial ties to Salient Surgical Technologies, the manufacturer of the BS device used in the study. Other prospective randomized trials of patients who had primary TKA with either TE or BS did not find any significant difference in postoperative Hb level, postoperative drainage, or transfusion requirements.19 ABC has been studied in the context of orthopedics but not joint arthroplasty specifically. This technology was anecdotally identified as a means of attaining hemostasis in foot and ankle surgery after failure of TE and other conventional means.22 ABC has also been identified as a successful adjuvant to curettage in the treatment of aneurysmal bone cysts.21 However, ABC has not been compared with TE or BS in the orthopedic literature.

In the present study, analysis of preoperative variables revealed a statistically but not clinically significant difference in BMI among cohorts. Mean (SD) BMI was 35.6 (6.5) for TE patients, 35.8 (9.7) for BS patients, and 40.9 (11.3) for ABC patients. (Previously, BMI did not correlate with intraoperative blood loss in TKA.25) Analysis also revealed a statistically significant but clinically insignificant and inconsequential difference in Hb level among cohorts. Mean (SD) preoperative Hb level was 13.5 (1.6) g/dL for TE patients, 12.8 (1.4) g/dL for BS patients, and 13.0 (1.6) g/dL for ABC patients. As decreases from preoperative baseline Hb levels were the intended focus of analysis—not absolute Hb levels—this finding does not refute postoperative analyses.

Our results suggest that, though TE may have relatively longer operative times in primary TKA, it is clinically equivalent to BS and ABC with respect to EBL and postoperative change in Hb levels. In addition, postoperative drainage was lower in TE than in BS and ABC, which were equivalent. No significant differences were found among hemostasis types with respect to postoperative transfusion requirements.

The prevalence distribution of predischarge AEs trended toward significance (χ2 = 5.957, P = .051), despite not meeting the predetermined α level. Rates of predischarge AEs were 0% (0/41) for TE patients, 7% (14/203) for BS patients, and 3% (1/36) for ABC patients. AEs included acute kidney injuries, electrolyte disturbances, urinary tract infections, oxygen desaturation, altered mental status, sepsis/infections, arrhythmias, congestive heart failure exacerbation, dehiscence, pulmonary embolism, and hypotension. Clearly, many of these AEs are not attributable to the hemostasis system used.

Limitations of this study include its retrospective design, documentation inadequate to account for drainage amount reinfused, and limited data on which clinical insignificance thresholds were based. In addition, reliance on historical data may have introduced bias into the analysis. The historical data used to increase the size of the TE cohort may reflect a period of relative inexperience and may have contributed to the longer operative times relative to those of the ABC cohort (Dr. Levine used ABC later in his career).

Traditional electrocautery remains a viable option in primary TKA. With its low cost and hemostasis equivalent to that of BS and ABC, TE deserves consideration equal to that given to these more modern hemostasis technologies. Cost per case is about $10 for TE versus $500 for BS and $110 for ABC.17 Soaring healthcare expenditures may warrant returning to TE or combining cautery techniques and other agents in primary TKA in order to reduce the number of transfusions and associated surgical costs.

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is a reliable and successful treatment for end-stage degenerative joint disease of the knee. Given the reproducibility of its generally excellent outcomes, TKA is increasingly being performed.1 However, the potential complications of this procedure can be devastating.2-4 The arthroplasty literature has shed light on the detrimental effects of postoperative blood loss and anemia.5,6 In addition, the increase in transfusion burden among patients is not without risk.7 Given these concerns, surgeons have been tasked with determining the ideal methods for minimizing blood transfusions and postoperative hematomas and anemia. Several strategies have been described.8-11 Hemostasis can be achieved with use of intravenous medications, intra-articular agents, or electrocautery devices. Electrocautery technologies include traditional electrocautery (TE), saline-coupled bipolar sealer (BS), and argon beam coagulation (ABC). There is controversy as to whether outcomes are better with one hemostasis method over another and whether these methods are worth the additional cost.

In traditional (Bovie) electrocautery, a unipolar device delivers an electrical current to tissues through a pencil-like instrument. Intraoperative tissue temperatures can exceed 400°C.12 In BS, radiofrequency energy is delivered through a saline medium, which increases the contact area, acts as an electrode, and maintains a cooler environment during electrocautery. Proposed advantages are reduced tissue destruction and absence of smoke.12 There is evidence both for10,12-16 and against17-20 use of BS in total joint arthroplasty. ABC, a novel hemostasis method, has been studied in the context of orthopedics21,22 but not TKA specifically. ABC establishes a monopolar electric circuit between a handheld device and the target tissues by channeling electrons through ionized argon gas. Hemostasis is achieved through thermal coagulation. Tissue penetration can be adjusted by changing power, probe-to-target distance, and duration of use.23 We conducted a study to assess the efficacy of all 3 electrocautery methods during TKA. We hypothesized the 3 methods would be clinically equivalent with respect to estimated blood loss (EBL), 48-hour wound drainage, operative time, and change from preoperative hemoglobin (Hb) level.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of consecutive primary TKAs performed by Dr. Levine between October 2010 and November 2011. Patients were identified by querying an internal database. Exclusion criteria were prior ipsilateral open knee procedure, prior fracture, nonuse of our standard hemostatic protocol, and either tourniquet time under 40 minutes or intraoperative documentation of tourniquet failure. As only 9 patients were initially identified for the TE cohort, the same database was used to add 32 patients treated between April 2009 and October 2009 (before our institution began using BS and ABC).

Clinical charts were reviewed, and baseline demographics (age, body mass index [BMI], preoperative Hb level) were abstracted, as were outcome metrics (EBL, 48-hour wound drainage, operative time, postoperative transfusions, adverse events (AEs) before discharge, and change in Hb level from before surgery to after surgery, in recovery room and on discharge). Statistical analyses were performed with JMP Version 10.0.0 (SAS Institute). Given the hypothesis that the 3 hemostasis methods would be clinically equivalent, 2 one-sided tests (TOSTs) of equivalence were performed with an α of 0.05. With TOST, the traditional null and alternative hypotheses are reversed; thus, P < .05 identifies statistical equivalence. The advantage of this study design is that equivalence can be identified, whereas traditional study designs can identify only a lack of statistical difference.24 We used our consensus opinions to set clinical insignificance thresholds for EBL (150 mL), wound drainage (150 mL), decrease from postoperative Hb level (1 g/dL), and operative time (10 minutes). Patients who received a blood transfusion were subsequently excluded from analysis in order to avoid skewing Hb-level depreciation calculations. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and χ2 tests were used to compare preoperative variables, transfusion requirements, hospital length of stay, and AE rates by hemostasis type.

Cautery Technique

In all cases, TE was used for surgical dissection, which followed a standard midvastus approach. Then, for meniscal excision, the capsule and meniscal attachment sites were treated with TE, BS, or ABC. During cement hardening, an available supplemental cautery option was used to achieve hemostasis of the suprapatellar fat pad and visible meniscal attachment sites. All other aspects of the procedure and the postoperative protocols—including the anticoagulation and rapid rehabilitation (early ambulation and therapy) protocols—were similar for all patients. The standard anticoagulation protocol was to use low-molecular-weight heparin, unless contraindicated. Tranexamic acid was not used at our institution during the study period.

Results

For the study period, 280 cases (41 TE, 203 BS, 36 ABC) met the inclusion criteria. Of the 280 TKAs, 261 (93.21%) were performed for degenerative arthritis. There was no statistically significant difference among cohorts in indication (χ2 = 1.841, P = .398) or sex (χ2 = 1.176, P= .555).

Table 1 lists the cohorts’ baseline demographics (mean age, BMI, preoperative Hb level) and comparative ANOVA results. TOSTs of equivalence were performed to compare operative time, EBL, 48-hour wound drainage, and postoperative Hb-level depreciation among hemostasis types. Changes in Hb level were calculated for the immediate postoperative period and time of discharge (Table 2). ANOVA of hospital length of stay demonstrated no significant difference in means among groups (P = .09).

The cohorts were compared with respect to use of postoperative transfusions and incidence of postoperative AEs (Table 3). The TE cohort did not have any AEs. Of the 203 BS patients, 14 (7%) had 1 or more AEs, which included acute kidney injury (3 cases), electrolyte disturbance (3), urinary tract infection (2), oxygen desaturation (2), altered mental status (1), pneumonia (1), arrhythmia (1), congestive heart failure exacerbation (1), dehiscence (1), pulmonary embolism (2), and hypotension (1). Of the 36 ABC patients, 1 (3%) had arrhythmia, pneumonia, sepsis, and altered mental status.

Discussion

With the population aging, the demand for TKA is greater than ever.1 As surgical volume increases, the ability to minimize the rates of intraoperative bleeding, postoperative anemia, and transfusion is becoming increasingly important to patients and the healthcare system. There is no consensus as to which cautery method is ideal. Other investigators have identified differences in clinical outcomes between cautery systems, but reported results are largely conflicting.10,12-20 In addition, no one has studied the utility of ABC in TKA. In the present retrospective cohort analysis, we hypothesized that TE, BS, and ABC would be clinically equivalent in primary TKA with respect to EBL, 48-hour wound drainage, operative time, and change from preoperative Hb level.

The data on hemostatic technology in primary TKA are inconclusive. In an age- and sex-matched study comparing TE and BS in primary TKA, BS used with shed blood autotransfusion reduced homologous blood transfusions by a factor of 5.16 In addition, BS patients lost significantly less total visible blood (intraoperative EBL, postoperative drain output), and their magnitude of postoperative Hb-level depreciations at time of discharge was significantly lower. In a multicenter, prospective randomized trial comparing TE with BS, adjusted blood loss and need for autologous blood transfusions were lower in BS patients,10 though there was no significant difference in Knee Society Scale scores between the 2 treatment arms. However, analysis was potentially biased in that multiple authors had financial ties to Salient Surgical Technologies, the manufacturer of the BS device used in the study. Other prospective randomized trials of patients who had primary TKA with either TE or BS did not find any significant difference in postoperative Hb level, postoperative drainage, or transfusion requirements.19 ABC has been studied in the context of orthopedics but not joint arthroplasty specifically. This technology was anecdotally identified as a means of attaining hemostasis in foot and ankle surgery after failure of TE and other conventional means.22 ABC has also been identified as a successful adjuvant to curettage in the treatment of aneurysmal bone cysts.21 However, ABC has not been compared with TE or BS in the orthopedic literature.

In the present study, analysis of preoperative variables revealed a statistically but not clinically significant difference in BMI among cohorts. Mean (SD) BMI was 35.6 (6.5) for TE patients, 35.8 (9.7) for BS patients, and 40.9 (11.3) for ABC patients. (Previously, BMI did not correlate with intraoperative blood loss in TKA.25) Analysis also revealed a statistically significant but clinically insignificant and inconsequential difference in Hb level among cohorts. Mean (SD) preoperative Hb level was 13.5 (1.6) g/dL for TE patients, 12.8 (1.4) g/dL for BS patients, and 13.0 (1.6) g/dL for ABC patients. As decreases from preoperative baseline Hb levels were the intended focus of analysis—not absolute Hb levels—this finding does not refute postoperative analyses.

Our results suggest that, though TE may have relatively longer operative times in primary TKA, it is clinically equivalent to BS and ABC with respect to EBL and postoperative change in Hb levels. In addition, postoperative drainage was lower in TE than in BS and ABC, which were equivalent. No significant differences were found among hemostasis types with respect to postoperative transfusion requirements.

The prevalence distribution of predischarge AEs trended toward significance (χ2 = 5.957, P = .051), despite not meeting the predetermined α level. Rates of predischarge AEs were 0% (0/41) for TE patients, 7% (14/203) for BS patients, and 3% (1/36) for ABC patients. AEs included acute kidney injuries, electrolyte disturbances, urinary tract infections, oxygen desaturation, altered mental status, sepsis/infections, arrhythmias, congestive heart failure exacerbation, dehiscence, pulmonary embolism, and hypotension. Clearly, many of these AEs are not attributable to the hemostasis system used.

Limitations of this study include its retrospective design, documentation inadequate to account for drainage amount reinfused, and limited data on which clinical insignificance thresholds were based. In addition, reliance on historical data may have introduced bias into the analysis. The historical data used to increase the size of the TE cohort may reflect a period of relative inexperience and may have contributed to the longer operative times relative to those of the ABC cohort (Dr. Levine used ABC later in his career).

Traditional electrocautery remains a viable option in primary TKA. With its low cost and hemostasis equivalent to that of BS and ABC, TE deserves consideration equal to that given to these more modern hemostasis technologies. Cost per case is about $10 for TE versus $500 for BS and $110 for ABC.17 Soaring healthcare expenditures may warrant returning to TE or combining cautery techniques and other agents in primary TKA in order to reduce the number of transfusions and associated surgical costs.

1. Cram P, Lu X, Kates SL, Singh JA, Li Y, Wolf BR. Total knee arthroplasty volume, utilization, and outcomes among Medicare beneficiaries, 1991-2010. JAMA. 2012;308(12):1227-1236.

2. Leijtens B, Kremers van de Hei K, Jansen J, Koëter S. High complication rate after total knee and hip replacement due to perioperative bridging of anticoagulant therapy based on the 2012 ACCP guideline. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2014;134(9):1335-1341.

3. Park CH, Lee SH, Kang DG, Cho KY, Lee SH, Kim KI. Compartment syndrome following total knee arthroplasty: clinical results of late fasciotomy. Knee Surg Relat Res. 2014;26(3):177-181.

4. Pedersen AB, Mehnert F, Sorensen HT, Emmeluth C, Overgaard S, Johnsen SP. The risk of venous thromboembolism, myocardial infarction, stroke, major bleeding and death in patients undergoing total hip and knee replacement: a 15-year retrospective cohort study of routine clinical practice. Bone Joint J. 2014;96-B(4):479-485.

5. Carson JL, Poses RM, Spence RK, Bonavita G. Severity of anaemia and operative mortality and morbidity. Lancet. 1988;1(8588):727-729.

6. Carson JL, Duff A, Poses RM, et al. Effect of anaemia and cardiovascular disease on surgical mortality and morbidity. Lancet. 1996;348(9034):1055-1060.

7. Dodd RY. Current risk for transfusion transmitted infections. Curr Opin Hematol. 2007;14(6):671-676.

8. Kang DG, Khurana S, Baek JH, Park YS, Lee SH, Kim KI. Efficacy and safety using autotransfusion system with postoperative shed blood following total knee arthroplasty in haemophilia. Haemophilia. 2014;20(1):129-132.

9. Aguilera X, Martinez-Zapata MJ, Bosch A, et al. Efficacy and safety of fibrin glue and tranexamic acid to prevent postoperative blood loss in total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(22):2001-2007.

10. Marulanda GA, Krebs VE, Bierbaum BE, et al. Hemostasis using a bipolar sealer in primary unilateral total knee arthroplasty. Am J Orthop. 2009;38(12):E179-E183.

11. Katkhouda N, Friedlander M, Darehzereshki A, et al. Argon beam coagulation versus fibrin sealant for hemostasis following liver resection: a randomized study in a porcine model. Hepatogastroenterology. 2013;60(125):1110-1116.

12. Marulanda GA, Ulrich SD, Seyler TM, Delanois RE, Mont MA. Reductions in blood loss with a bipolar sealer in total hip arthroplasty. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2008;5(2):125-131.

13. Morris MJ, Berend KR, Lombardi AV Jr. Hemostasis in anterior supine intermuscular total hip arthroplasty: pilot study comparing standard electrocautery and a bipolar sealer. Surg Technol Int. 2010;20:352-356.

14. Clement RC, Kamath AF, Derman PB, Garino JP, Lee GC. Bipolar sealing in revision total hip arthroplasty for infection: efficacy and cost analysis. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(7):1376-1381.

15. Rosenberg AG. Reducing blood loss in total joint surgery with a saline-coupled bipolar sealing technology. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22(4 suppl 1):82-85.

16. Pfeiffer M, Bräutigam H, Draws D, Sigg A. A new bipolar blood sealing system embedded in perioperative strategies vs. a conventional regimen for total knee arthroplasty: results of a matched-pair study. Ger Med Sci. 2005;3:Doc10.

17. Morris MJ, Barrett M, Lombardi AV Jr, Tucker TL, Berend KR. Randomized blinded study comparing a bipolar sealer and standard electrocautery in reducing transfusion requirements in anterior supine intermuscular total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(9):1614-1617.

18. Barsoum WK, Klika AK, Murray TG, Higuera C, Lee HH, Krebs VE. Prospective randomized evaluation of the need for blood transfusion during primary total hip arthroplasty with use of a bipolar sealer. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(6):513-518.

19. Plymale MF, Capogna BM, Lovy AJ, Adler ML, Hirsh DM, Kim SJ. Unipolar vs bipolar hemostasis in total knee arthroplasty: a prospective randomized trial. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(6):1133-1137.e1.

20. Zeh A, Messer J, Davis J, Vasarhelyi A, Wohlrab D. The Aquamantys system—an alternative to reduce blood loss in primary total hip arthroplasty? J Arthroplasty. 2010;25(7):1072-1077.

21. Cummings JE, Smith RA, Heck RK Jr. Argon beam coagulation as adjuvant treatment after curettage of aneurysmal bone cysts: a preliminary study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(1):231-237.

22. Adams ML, Steinberg JS. Argon beam coagulation in foot and ankle surgery. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2011;50(6):780-782.

23. Neumayer L, Vargo D. Principles of preoperative and operative surgery. In: Townsend CM Jr, Beauchamp RD, Evers BM, Mattox KL, eds. Sabiston Textbook of Surgery. 19th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:211-239.

24. Walker E, Nowacki AS. Understanding equivalence and noninferiority testing. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(2):192-196.

25. Hrnack SA, Skeen N, Xu T, Rosenstein AD. Correlation of body mass index and blood loss during total knee and total hip arthroplasty. Am J Orthop. 2012;41(10):467-471.

1. Cram P, Lu X, Kates SL, Singh JA, Li Y, Wolf BR. Total knee arthroplasty volume, utilization, and outcomes among Medicare beneficiaries, 1991-2010. JAMA. 2012;308(12):1227-1236.

2. Leijtens B, Kremers van de Hei K, Jansen J, Koëter S. High complication rate after total knee and hip replacement due to perioperative bridging of anticoagulant therapy based on the 2012 ACCP guideline. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2014;134(9):1335-1341.

3. Park CH, Lee SH, Kang DG, Cho KY, Lee SH, Kim KI. Compartment syndrome following total knee arthroplasty: clinical results of late fasciotomy. Knee Surg Relat Res. 2014;26(3):177-181.

4. Pedersen AB, Mehnert F, Sorensen HT, Emmeluth C, Overgaard S, Johnsen SP. The risk of venous thromboembolism, myocardial infarction, stroke, major bleeding and death in patients undergoing total hip and knee replacement: a 15-year retrospective cohort study of routine clinical practice. Bone Joint J. 2014;96-B(4):479-485.

5. Carson JL, Poses RM, Spence RK, Bonavita G. Severity of anaemia and operative mortality and morbidity. Lancet. 1988;1(8588):727-729.

6. Carson JL, Duff A, Poses RM, et al. Effect of anaemia and cardiovascular disease on surgical mortality and morbidity. Lancet. 1996;348(9034):1055-1060.

7. Dodd RY. Current risk for transfusion transmitted infections. Curr Opin Hematol. 2007;14(6):671-676.

8. Kang DG, Khurana S, Baek JH, Park YS, Lee SH, Kim KI. Efficacy and safety using autotransfusion system with postoperative shed blood following total knee arthroplasty in haemophilia. Haemophilia. 2014;20(1):129-132.

9. Aguilera X, Martinez-Zapata MJ, Bosch A, et al. Efficacy and safety of fibrin glue and tranexamic acid to prevent postoperative blood loss in total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(22):2001-2007.

10. Marulanda GA, Krebs VE, Bierbaum BE, et al. Hemostasis using a bipolar sealer in primary unilateral total knee arthroplasty. Am J Orthop. 2009;38(12):E179-E183.

11. Katkhouda N, Friedlander M, Darehzereshki A, et al. Argon beam coagulation versus fibrin sealant for hemostasis following liver resection: a randomized study in a porcine model. Hepatogastroenterology. 2013;60(125):1110-1116.

12. Marulanda GA, Ulrich SD, Seyler TM, Delanois RE, Mont MA. Reductions in blood loss with a bipolar sealer in total hip arthroplasty. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2008;5(2):125-131.

13. Morris MJ, Berend KR, Lombardi AV Jr. Hemostasis in anterior supine intermuscular total hip arthroplasty: pilot study comparing standard electrocautery and a bipolar sealer. Surg Technol Int. 2010;20:352-356.

14. Clement RC, Kamath AF, Derman PB, Garino JP, Lee GC. Bipolar sealing in revision total hip arthroplasty for infection: efficacy and cost analysis. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(7):1376-1381.

15. Rosenberg AG. Reducing blood loss in total joint surgery with a saline-coupled bipolar sealing technology. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22(4 suppl 1):82-85.

16. Pfeiffer M, Bräutigam H, Draws D, Sigg A. A new bipolar blood sealing system embedded in perioperative strategies vs. a conventional regimen for total knee arthroplasty: results of a matched-pair study. Ger Med Sci. 2005;3:Doc10.

17. Morris MJ, Barrett M, Lombardi AV Jr, Tucker TL, Berend KR. Randomized blinded study comparing a bipolar sealer and standard electrocautery in reducing transfusion requirements in anterior supine intermuscular total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(9):1614-1617.

18. Barsoum WK, Klika AK, Murray TG, Higuera C, Lee HH, Krebs VE. Prospective randomized evaluation of the need for blood transfusion during primary total hip arthroplasty with use of a bipolar sealer. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(6):513-518.

19. Plymale MF, Capogna BM, Lovy AJ, Adler ML, Hirsh DM, Kim SJ. Unipolar vs bipolar hemostasis in total knee arthroplasty: a prospective randomized trial. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(6):1133-1137.e1.

20. Zeh A, Messer J, Davis J, Vasarhelyi A, Wohlrab D. The Aquamantys system—an alternative to reduce blood loss in primary total hip arthroplasty? J Arthroplasty. 2010;25(7):1072-1077.

21. Cummings JE, Smith RA, Heck RK Jr. Argon beam coagulation as adjuvant treatment after curettage of aneurysmal bone cysts: a preliminary study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(1):231-237.

22. Adams ML, Steinberg JS. Argon beam coagulation in foot and ankle surgery. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2011;50(6):780-782.

23. Neumayer L, Vargo D. Principles of preoperative and operative surgery. In: Townsend CM Jr, Beauchamp RD, Evers BM, Mattox KL, eds. Sabiston Textbook of Surgery. 19th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:211-239.

24. Walker E, Nowacki AS. Understanding equivalence and noninferiority testing. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(2):192-196.

25. Hrnack SA, Skeen N, Xu T, Rosenstein AD. Correlation of body mass index and blood loss during total knee and total hip arthroplasty. Am J Orthop. 2012;41(10):467-471.

Pigmented Villonodular Synovitis of the Hip: A Systematic Review

Pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS) is a rare monoarticular disorder that affects the joints, bursae, or tendon sheaths of 1.8 per million patients.1,2 PVNS is defined by exuberant proliferation of synovial villi and nodules. Although its etiology is unknown, PVNS behaves much as a neoplastic process does, with occasional chromosomal abnormalities, local tissue invasion, and the potential for malignant transformation.3,4 Radiographs show cystic erosions or joint space narrowing, and magnetic resonance imaging shows characteristic low-signal intensity (on T1- and T2-weighted sequences) because of high hemosiderin content. Biopsy remains the gold standard for diagnosis and reveals hemosiderin-laden macrophages, vascularized villi, mononuclear cell infiltration, and sporadic mitotic figures.5 Diffuse PVNS appears as a thickened synovium with matted villi and synovial folds; localized PVNS presents as a pedunculated, firm yellow nodule.6

PVNS has a predilection for large joints, most commonly the knee (up to 80% of cases) and the hip.1,2,7 Treatment strategies for knee PVNS have been well studied and, as an aggregate, show no superiority of arthroscopic or open techniques.8 The literature on hip PVNS is less abundant and more case-based, making it difficult to reach a consensus on effective treatment. Open synovectomy and arthroplasty have been the mainstays of treatment over the past 60 years, but the advent of hip arthroscopy has introduced a new treatment modality.1,9 As arthroscopic management becomes more readily available, it is important to understand and compare the effectiveness of synovectomy and arthroplasty.

We systematically reviewed the treatment modalities for PVNS of the hip to determine how synovectomy and arthroplasty compare with respect to efficacy and revision rates.

Methods

Search Strategy

We systematically reviewed the literature according to PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines using the PRISMA checklist.10 Searches were completed in July 2014 using the PubMed Medline database and the Cochrane Central Register of Clinical Trials. Keyword selection was designed to capture all level I to V evidence English-language studies that reported clinical and/or radiographic outcomes. This was accomplished with a keyword search of all available titles and manuscript abstracts: (pigmented [Title/Abstract] AND villonodular [Title/Abstract] AND synovitis [Title/Abstract]) AND (hip [Title/Abstract]) AND (English [lang])). Abstracts from the 75 resulting studies were reviewed for exclusion criteria, which consisted of any cadaveric, biomechanical, histologic, and/or kinematic results, as well as a lack of any clinical and/or radiographic data (eg, review or technique articles). Studies were also excluded if they did not have clinical follow-up of at least 2 years. Studies not dedicated to hip PVNS specifically were not immediately excluded but were reviewed for outcomes data specific to the hip PVNS subpopulation. If a specific hip PVNS population could be distinguished from other patients, that study was included for review. If a study could not be deconstructed as such or was entirely devoted to one of our exclusion criteria, that study was excluded from our review. This initial search strategy yielded 16 studies.1,6,7,11-28

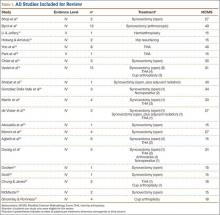

Bibliographical review of these 16 studies yielded several more for review. To ensure that no patients were counted twice, each study’s authors, data collection period, and ethnic population were reviewed and compared with those of the other studies. If there was any overlap in authorship, period, and place, only the study with the most relevant or comprehensive data was included. After accounting for all inclusion and exclusion criteria, we selected a total of 21 studies with 82 patients (86 hips) for inclusion (Figure 1).

Data Extraction

Details of study design, sample size, and patient demographics, including age, sex, and duration of symptoms, were recorded. Use of diagnostic biopsy, joint space narrowing on radiographs, treatment method, and use of radiation therapy were also abstracted. Some studies described multiple treatment methods. If those methods could not be differentiated into distinct outcomes groups, the study would have been excluded for lack of specific clinical data. Studies with sufficient data were deconstructed such that the patients from each treatment group were isolated.

Fewer than 5 studies reported physical examination findings, validated survey scores, and/or radiographic results. Therefore, the primary outcomes reported and compared between treatment groups were disease recurrence, clinical worsening defined as progressive pain or loss of function, and revision surgery. Revision surgery was subdivided into repeat synovectomy and eventual arthroplasty, arthrodesis, or revision arthroplasty. Time to revision surgery was also documented. Each study’s methodologic quality and bias were evaluated with the Modified Coleman Methodology Score (MCMS), described by Cowan and colleagues.29 MCMS is a 15-item instrument that has been used to assess randomized and nonrandomized patient trials.30,31 It has a scaled potential score ranging from 0 to 100, with scores from 85 through 100 indicating excellent, 70 through 84 good, 55 through 69 fair, and under 55 poor.

Statistical Analysis

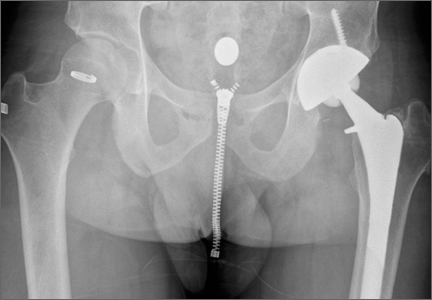

We report our data as weighted means (SDs). A mean was calculated for each study reporting on a respective data point, and each mean was then weighted according to the sample size of that study. We multiplied each study’s individual mean by the number of patients enrolled in that study and divided the sum of all the studies’ weighted data points by the number of eligible patients in all relevant studies. The result is that the nonweighted means from studies with a smaller sample size did not carry as much weight as those from larger studies. We then compared 2 groups of patients: those who had only a synovectomy and those who had a combination of synovectomy and arthroplasty. The synovectomy-only group was also compared with a group that underwent total hip arthroplasty (THA) specifically (Figure 2). Groups were compared with Student t test (SPSS Version 18, IBM), and statistical significance was set at α = 0.05.

Results

Twenty-one studies (82 patients) were included in the final dataset (Table 1). Of these studies, 19 were retrospective case series (level IV evidence) in which the number of eligible hip PVNS patients ranged from 1 to 15. The other 2 studies were case reports (level V evidence). Mean (SD) MCMS was 25.0 (10.9).

Fifty-one patients (59.3%) were female. Mean (SD) age of all patients was 33.2 (12.6) years. Mean (SD) duration of symptoms was 4.2 (2.7) years. The right hip was affected in 59.5% of patients in whom laterality was documented. Sixty-eight patients (79.1%) had biopsy-proven PVNS; presence or absence of a biopsy was not documented for the other 18 patients.

Of the 82 patients in the study, 45 (54.9%) underwent synovectomy without arthroplasty. Staged radiation was used to augment the synovectomy in 2 of these 45 cases. One series in this group consisted of 15 cases of arthroscopic synovectomy.1 The 37 patients (45.1%) in the other treatment group had arthroplasty at time of synovectomy. These patients underwent 22 THAs, 8 cup arthroplasties, 2 metal-on-metal hip resurfacings, and 1 hemiarthroplasty. The remaining 4 patients were treated nonoperatively (3) or with primary arthrodesis (1).

Comparisons between the synovectomy-only and synovectomy-with-arthroplasty groups are listed in Table 2. Synovectomy patients were younger on average than arthroplasty patients, but the difference was not statistically significant (P = .28). Only 6 studies distinguished between local and diffuse PVNS histology, and the diffuse type was detected in 87.0%, with insufficient data to detect a difference between the synovectomy and arthroplasty groups. In studies with documented radiographic findings, 75.0% of patients had evidence of joint space narrowing, which was significantly (P = .03) more common in the arthroplasty group (96.7% vs 31.3%).

Mean (SD) clinical follow-up was 8.4 (5.9) years for all patients. A larger percentage of synovectomy-only patients experienced recurrence and worsened symptoms, but neither trend achieved statistical significance. The rate of eventual THA or arthrodesis after synovectomy alone was almost identical (P = .17) to the rate of revision THA in the synovectomy-with-arthroplasty group (26.2% vs 24.3%). Time to revision surgery, however, was significantly (P = .02) longer in the arthroplasty group. Two additional patients in the synovectomy-with-arthroplasty group underwent repeat synovectomy alone, but no patients in the synovectomy-only group underwent repeat synovectomy without arthroplasty.

One nonoperatively managed patient experienced symptom progression over the course of 10 years. The other 2 patients were stable after 2- and 4-year follow-up. The arthrodesis patient did not experience recurrence or have a revision operation in the 5 years after the index procedure.

Discussion

PVNS is a proliferative disorder of synovial tissue with a high risk of recurrence.15,32 Metastasis is extremely rare; there is only 1 case report of a fatality, which occurred within 42 months.12 Chiari and colleagues15 suggested that the PVNS recurrence rate is highest in the large joints. Therefore, in hip PVNS, early surgical resection is needed to limit articular destruction and the potential for recurrence. The primary treatment modalities are synovectomy alone and synovectomy with arthroplasty, which includes THA, cup arthroplasty, hip resurfacing, and hemiarthroplasty. According to our systematic review, about one-fourth of all patients in both treatment groups ultimately underwent revision surgery. Mean time to revision was significantly longer for synovectomy-with-arthroplasty patients (almost 12 years) than for synovectomy-only patients (6.5 years). One potential explanation is that arthroplasty component fixation may take longer to loosen than an inadequately synovectomized joint takes to recur. The synovectomy-only group did have a higher recurrence rate, though the difference was not statistically significant.

Open synovectomy is the most widely described technique for addressing hip PVNS. The precise pathophysiology of PVNS remains largely unknown, but most authors agree that aggressive débridement is required to halt its locally invasive course. Scott24 described the invasion of vascular foramina from synovium into bone and thought that radical synovectomy was essential to remove the stalks of these synovial villi. Furthermore, PVNS most commonly affects adults in the third through fifth decades of life,7 and many surgeons want to avoid prosthetic components (which may loosen over time) in this age group. Synovectomy, however, has persistently high recurrence rates, and, without removal of the femoral head and neck, it can be difficult to obtain adequate exposure for complete débridement. Although adjuvant external beam radiation has been used by some authors,17,19,33 its utility is unproven, and other authors have cautioned against unnecessary irradiation of reproductive organs.1,24,34

The high rates of bony involvement, joint destruction, and recurrence after synovectomy have prompted many surgeons to turn to arthroplasty. González Della Valle and colleagues18 theorized that joint space narrowing is more common in hip PVNS because of the poor distensibility of the hip capsule compared with that of the knee and other joints. In turn, bony lesions and arthritis present earlier in hip PVNS.14 Yoo and colleagues14 found a statistically significant increase in Harris Hip Scale (HHS) scores and a high rate of return to athletic activity after THA for PVNS. However, they also reported revisions for component loosening and osteolysis in 2 of 8 patients and periprosthetic osteolysis without loosening in another 2 patients. Vastel and colleagues16 similarly reported aseptic loosening of the acetabular component in half their patient cohort. No studies have determined which condition—PVNS recurrence or debris-related osteolysis—causes the accelerated loosening in this demographic.

Byrd and colleagues1 recently described use of hip arthroscopy in the treatment of PVNS. In a cohort of 13 patients, they found statistically significant improvements in HHS scores, no postoperative complications, and only 1 revision (THA 6 years after surgery). Although there is a prevailing perception that nodular (vs diffuse) PVNS is more appropriately treated with arthroscopic excision, no studies have provided data on this effect, and Byrd and colleagues1 in fact showed a trend of slightly better outcomes in diffuse cases than in nodular cases. The main challenges of hip arthroscopy are the steep learning curve and adequate exposure. Recent innovations include additional arthroscopic portals and enlarged T-capsulotomy, which may be contributing to decreased complication rates in hip arthroscopy in general.35

The limitations of this systematic review were largely imposed by the studies analyzed. The primary limitation was the relative paucity of clinical and radiographic data on hip PVNS. To our knowledge, studies on the treatment of hip PVNS have reported evidence levels no higher than IV. In addition, the studies we reviewed often had only 1 or 2 patient cases satisfying our inclusion criteria. For this reason, we included case reports, which further lowered the level of evidence of studies used. There were no consistently reported physical examination, survey, or radiographic findings that could be used to compare studies. All studies with sufficient data on hip PVNS treatment outcomes were rated poorly with the Modified Coleman Methodology Scoring system.29 Selection bias was minimized by the inclusive nature of studies with level I to V evidence, but this led to a study design bias in that most studies consisted of level IV evidence.

Conclusion

Although the hip PVNS literature is limited, our review provides insight into expected outcomes. No matter which surgery is to be performed, surgeons must counsel patients about the high revision rate. One in 4 patients ultimately undergoes a second surgery, which may be required within 6 or 7 years after synovectomy without arthroplasty. Further development and innovation in hip arthroscopy may transform the treatment of PVNS. We encourage other investigators to conduct prospective, comparative trials with higher evidence levels to assess the utility of arthroscopy and other treatment modalities.

1. Byrd JWT, Jones KS, Maiers GP. Two to 10 years’ follow-up of arthroscopic management of pigmented villonodular synovitis in the hip: a case series. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(11):1783-1787.

2. Myers BW, Masi AT. Pigmented villonodular synovitis and tenosynovitis: a clinical epidemiologic study of 166 cases and literature review. Medicine. 1980;59(3):223-238.

3. Sciot R, Rosai J, Dal Cin P, et al. Analysis of 35 cases of localized and diffuse tenosynovial giant cell tumor: a report from the Chromosomes and Morphology (CHAMP) study group. Mod Pathol. 1999;12(6):576-579.

4. Bertoni F, Unni KK, Beabout JW, Sim FH. Malignant giant cell tumor of the tendon sheaths and joints (malignant pigmented villonodular synovitis). Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21(2):153-163.

5. Mankin H, Trahan C, Hornicek F. Pigmented villonodular synovitis of joints. J Surg Oncol. 2011;103(5):386-389.

6. Martin RC, Osborne DL, Edwards MJ, Wrightson W, McMasters KM. Giant cell tumor of tendon sheath, tenosynovial giant cell tumor, and pigmented villonodular synovitis: defining the presentation, surgical therapy and recurrence. Oncol Rep. 2000;7(2):413-419.

7. Danzig LA, Gershuni DH, Resnick D. Diagnosis and treatment of diffuse pigmented villonodular synovitis of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1982;(168):42-47.

8. Aurégan JC, Klouche S, Bohu Y, Lefèvre N, Herman S, Hardy P. Treatment of pigmented villonodular synovitis of the knee. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(10):1327-1341.

9. Gondolph-Zink B, Puhl W, Noack W. Semiarthroscopic synovectomy of the hip. Int Orthop. 1988;12(1):31-35.

10. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):1006-1012.

11. Shoji T, Yasunaga Y, Yamasaki T, et al. Transtrochanteric rotational osteotomy combined with intra-articular procedures for pigmented villonodular synovitis of the hip. J Orthop Sci. 2015;20(5):943-950.

12. Li LM, Jeffery J. Exceptionally aggressive pigmented villonodular synovitis of the hip unresponsive to radiotherapy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93(7):995-997.

13. Hoberg M, Amstutz HC. Metal-on-metal hip resurfacing in patients with pigmented villonodular synovitis: a report of two cases. Orthopedics. 2010;33(1):50-53.

14. Yoo JJ, Kwon YS, Koo KH, Yoon KS, Min BW, Kim HJ. Cementless total hip arthroplasty performed in patients with pigmented villonodular synovitis. J Arthroplasty. 2010;25(4):552-557.

15. Chiari C, Pirich C, Brannath W, Kotz R, Trieb K. What affects the recurrence and clinical outcome of pigmented villonodular synovitis? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;(450):172-178.

16. Vastel L, Lambert P, De Pinieux G, Charrois O, Kerboull M, Courpied JP. Surgical treatment of pigmented villonodular synovitis of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(5):1019-1024.

17. Shabat S, Kollender Y, Merimsky O, et al. The use of surgery and yttrium 90 in the management of extensive and diffuse pigmented villonodular synovitis of large joints. Rheumatology. 2002;41(10):1113-1118.

18. González Della Valle A, Piccaluga F, Potter HG, Salvati EA, Pusso R. Pigmented villonodular synovitis of the hip: 2- to 23-year followup study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;(388):187-199.

19. de Visser E, Veth RP, Pruszczynski M, Wobbes T, Van de Putte LB. Diffuse and localized pigmented villonodular synovitis: evaluation of treatment of 38 patients. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1999;119(7-8):401-404.

20. Aboulafia AJ, Kaplan L, Jelinek J, Benevenia J, Monson DK. Neuropathy secondary to pigmented villonodular synovitis of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;(325):174-180.

21. Moroni A, Innao V, Picci P. Pigmented villonodular synovitis of the hip. Study of 9 cases. Ital J Orthop Traumatol. 1983;9(3):331-337.

22. Aglietti P, Di Muria GV, Salvati EA, Stringa G. Pigmented villonodular synovitis of the hip joint (review of the literature and report of personal case material). Ital J Orthop Traumatol. 1983;9(4):487-496.

23. Docken WP. Pigmented villonodular synovitis: a review with illustrative case reports. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1979;9(1):1-22.

24. Scott PM. Bone lesions in pigmented villonodular synovitis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1968;50(2):306-311.

25. Chung SM, Janes JM. Diffuse pigmented villonodular synovitis of the hip joint. Review of the literature and report of four cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1965;47:293-303.

26. McMaster PE. Pigmented villonodular synovitis with invasion of bone. Report of six cases. Rheumatology. 1960;42(7):1170-1183.

27. Ghormley RK, Romness JO. Pigmented villonodular synovitis (xanthomatosis) of the hip joint. Proc Staff Meet Mayo Clin. 1954;29(6):171-180.

28. Park KS, Diwanji SR, Yang HK, Yoon TR, Seon JK. Pigmented villonodular synovitis of the hip presenting as a buttock mass treated by total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2010;25(2):333.e9-e12.

29. Cowan J, Lozano-Calderón S, Ring D. Quality of prospective controlled randomized trials. Analysis of trials of treatment for lateral epicondylitis as an example. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(8):1693-1699.

30. Harris JD, Siston RA, Pan X, Flanigan DC. Autologous chondrocyte implantation: a systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(12):2220-2233.

31. Harris JD, Siston RA, Brophy RH, Lattermann C, Carey JL, Flanigan DC. Failures, re-operations, and complications after autologous chondrocyte implantation—a systematic review. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2011;19(7):779-791.

32. Rao AS, Vigorita VJ. Pigmented villonodular synovitis (giant-cell tumor of the tendon sheath and synovial membrane). A review of eighty-one cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66(1):76-94.

33. Kat S, Kutz R, Elbracht T, Weseloh G, Kuwert T. Radiosynovectomy in pigmented villonodular synovitis. Nuklearmedizin. 2000;39(7):209-213.

34. Gitelis S, Heligman D, Morton T. The treatment of pigmented villonodular synovitis of the hip. A case report and literature review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;(239):154-160.

35. Harris JD, McCormick FM, Abrams GD, et al. Complications and reoperations during and after hip arthroscopy: a systematic review of 92 studies and more than 6,000 patients. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(3):589-595.

Pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS) is a rare monoarticular disorder that affects the joints, bursae, or tendon sheaths of 1.8 per million patients.1,2 PVNS is defined by exuberant proliferation of synovial villi and nodules. Although its etiology is unknown, PVNS behaves much as a neoplastic process does, with occasional chromosomal abnormalities, local tissue invasion, and the potential for malignant transformation.3,4 Radiographs show cystic erosions or joint space narrowing, and magnetic resonance imaging shows characteristic low-signal intensity (on T1- and T2-weighted sequences) because of high hemosiderin content. Biopsy remains the gold standard for diagnosis and reveals hemosiderin-laden macrophages, vascularized villi, mononuclear cell infiltration, and sporadic mitotic figures.5 Diffuse PVNS appears as a thickened synovium with matted villi and synovial folds; localized PVNS presents as a pedunculated, firm yellow nodule.6

PVNS has a predilection for large joints, most commonly the knee (up to 80% of cases) and the hip.1,2,7 Treatment strategies for knee PVNS have been well studied and, as an aggregate, show no superiority of arthroscopic or open techniques.8 The literature on hip PVNS is less abundant and more case-based, making it difficult to reach a consensus on effective treatment. Open synovectomy and arthroplasty have been the mainstays of treatment over the past 60 years, but the advent of hip arthroscopy has introduced a new treatment modality.1,9 As arthroscopic management becomes more readily available, it is important to understand and compare the effectiveness of synovectomy and arthroplasty.

We systematically reviewed the treatment modalities for PVNS of the hip to determine how synovectomy and arthroplasty compare with respect to efficacy and revision rates.

Methods

Search Strategy

We systematically reviewed the literature according to PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines using the PRISMA checklist.10 Searches were completed in July 2014 using the PubMed Medline database and the Cochrane Central Register of Clinical Trials. Keyword selection was designed to capture all level I to V evidence English-language studies that reported clinical and/or radiographic outcomes. This was accomplished with a keyword search of all available titles and manuscript abstracts: (pigmented [Title/Abstract] AND villonodular [Title/Abstract] AND synovitis [Title/Abstract]) AND (hip [Title/Abstract]) AND (English [lang])). Abstracts from the 75 resulting studies were reviewed for exclusion criteria, which consisted of any cadaveric, biomechanical, histologic, and/or kinematic results, as well as a lack of any clinical and/or radiographic data (eg, review or technique articles). Studies were also excluded if they did not have clinical follow-up of at least 2 years. Studies not dedicated to hip PVNS specifically were not immediately excluded but were reviewed for outcomes data specific to the hip PVNS subpopulation. If a specific hip PVNS population could be distinguished from other patients, that study was included for review. If a study could not be deconstructed as such or was entirely devoted to one of our exclusion criteria, that study was excluded from our review. This initial search strategy yielded 16 studies.1,6,7,11-28

Bibliographical review of these 16 studies yielded several more for review. To ensure that no patients were counted twice, each study’s authors, data collection period, and ethnic population were reviewed and compared with those of the other studies. If there was any overlap in authorship, period, and place, only the study with the most relevant or comprehensive data was included. After accounting for all inclusion and exclusion criteria, we selected a total of 21 studies with 82 patients (86 hips) for inclusion (Figure 1).

Data Extraction

Details of study design, sample size, and patient demographics, including age, sex, and duration of symptoms, were recorded. Use of diagnostic biopsy, joint space narrowing on radiographs, treatment method, and use of radiation therapy were also abstracted. Some studies described multiple treatment methods. If those methods could not be differentiated into distinct outcomes groups, the study would have been excluded for lack of specific clinical data. Studies with sufficient data were deconstructed such that the patients from each treatment group were isolated.

Fewer than 5 studies reported physical examination findings, validated survey scores, and/or radiographic results. Therefore, the primary outcomes reported and compared between treatment groups were disease recurrence, clinical worsening defined as progressive pain or loss of function, and revision surgery. Revision surgery was subdivided into repeat synovectomy and eventual arthroplasty, arthrodesis, or revision arthroplasty. Time to revision surgery was also documented. Each study’s methodologic quality and bias were evaluated with the Modified Coleman Methodology Score (MCMS), described by Cowan and colleagues.29 MCMS is a 15-item instrument that has been used to assess randomized and nonrandomized patient trials.30,31 It has a scaled potential score ranging from 0 to 100, with scores from 85 through 100 indicating excellent, 70 through 84 good, 55 through 69 fair, and under 55 poor.

Statistical Analysis

We report our data as weighted means (SDs). A mean was calculated for each study reporting on a respective data point, and each mean was then weighted according to the sample size of that study. We multiplied each study’s individual mean by the number of patients enrolled in that study and divided the sum of all the studies’ weighted data points by the number of eligible patients in all relevant studies. The result is that the nonweighted means from studies with a smaller sample size did not carry as much weight as those from larger studies. We then compared 2 groups of patients: those who had only a synovectomy and those who had a combination of synovectomy and arthroplasty. The synovectomy-only group was also compared with a group that underwent total hip arthroplasty (THA) specifically (Figure 2). Groups were compared with Student t test (SPSS Version 18, IBM), and statistical significance was set at α = 0.05.

Results

Twenty-one studies (82 patients) were included in the final dataset (Table 1). Of these studies, 19 were retrospective case series (level IV evidence) in which the number of eligible hip PVNS patients ranged from 1 to 15. The other 2 studies were case reports (level V evidence). Mean (SD) MCMS was 25.0 (10.9).

Fifty-one patients (59.3%) were female. Mean (SD) age of all patients was 33.2 (12.6) years. Mean (SD) duration of symptoms was 4.2 (2.7) years. The right hip was affected in 59.5% of patients in whom laterality was documented. Sixty-eight patients (79.1%) had biopsy-proven PVNS; presence or absence of a biopsy was not documented for the other 18 patients.

Of the 82 patients in the study, 45 (54.9%) underwent synovectomy without arthroplasty. Staged radiation was used to augment the synovectomy in 2 of these 45 cases. One series in this group consisted of 15 cases of arthroscopic synovectomy.1 The 37 patients (45.1%) in the other treatment group had arthroplasty at time of synovectomy. These patients underwent 22 THAs, 8 cup arthroplasties, 2 metal-on-metal hip resurfacings, and 1 hemiarthroplasty. The remaining 4 patients were treated nonoperatively (3) or with primary arthrodesis (1).