User login

Patient Preferences for Physician Attire: A Multicenter Study in Japan

The patient-physician relationship is critical for ensuring the delivery of high-quality healthcare. Successful patient-physician relationships arise from shared trust, knowledge, mutual respect, and effective verbal and nonverbal communication. The ways in which patients experience healthcare and their satisfaction with physicians affect a myriad of important health outcomes, such as adherence to treatment and outcomes for conditions such as hypertension and diabetes mellitus.1-5 One method for potentially enhancing patient satisfaction is through understanding how patients wish their physicians to dress6-8 and tailoring attire to match these expectations. In addition to our systematic review,9 a recent large-scale, multicenter study in the United States revealed that most patients perceive physician attire as important, but that preferences for specific types of attire are contextual.9,10 For example, elderly patients preferred physicians in formal attire and white coat, while scrubs with white coat or scrubs alone were preferred for emergency department (ED) physicians and surgeons, respectively. Moreover, regional variation regarding attire preference was also observed in the US, with preferences for more formal attire in the South and less formal in the Midwest.

Geographic variation, regarding patient preferences for physician dress, is perhaps even more relevant internationally. In particular, Japan is considered to have a highly contextualized culture that relies on nonverbal and implicit communication. However, medical professionals have no specific dress code and, thus, don many different kinds of attire. In part, this may be because it is not clear whether or how physician attire impacts patient satisfaction and perceived healthcare quality in Japan.11-13 Although previous studies in Japan have suggested that physician attire has a considerable influence on patient satisfaction, these studies either involved a single department in one hospital or a small number of respondents.14-17 Therefore, we performed a multicenter, cross-sectional study to understand patients’ preferences for physician attire in different clinical settings and in different geographic regions in Japan.

METHODS

Study Population

We conducted a cross-sectional, questionnaire-based study from 2015 to 2017, in four geographically diverse hospitals in Japan. Two of these hospitals, Tokyo Joto Hospital and Juntendo University Hospital, are located in eastern Japan whereas the others, Kurashiki Central Hospital and Akashi Medical Center, are in western Japan.

Questionnaires were printed and randomly distributed by research staff to outpatients in waiting rooms and inpatients in medical wards who were 20 years of age or older. We placed no restriction on ward site or time of questionnaire distribution. Research staff, including physicians, nurses, and medical clerks, were instructed to avoid guiding or influencing participants’ responses. Informed consent was obtained by the staff; only those who provided informed consent participated in the study. Respondents could request assistance with form completion from persons accompanying them if they had difficulties, such as physical, visual, or hearing impairments. All responses were collected anonymously. The study was approved by the ethics committees of all four hospitals.

Questionnaire

We used a modified version of the survey instrument from a prior study.10 The first section of the survey showed photographs of either a male or female physician with 7 unique forms of attire, including casual, casual with white coat, scrubs, scrubs with white coat, formal, formal with white coat, and business suit (Figure 1). Given the Japanese context of this study, the language was translated to Japanese and photographs of physicians of Japanese descent were used. Photographs were taken with attention paid to achieving constant facial expressions on the physicians as well as in other visual cues (eg, lighting, background, pose). The physician’s gender and attire in the first photograph seen by each respondent were randomized to prevent bias in ordering, priming, and anchoring; all other sections of the survey were identical.

Respondents were first asked to rate the standalone, randomized physician photograph using a 1-10 scale across five domains (ie, how knowledgeable, trustworthy, caring, and approachable the physician appeared and how comfortable the physician’s appearance made the respondent feel), with a score of 10 representing the highest rating. Respondents were subsequently given 7 photographs of the same physician wearing various forms of attire. Questions were asked regarding preference of attire in varied clinical settings (ie, primary care, ED, hospital, surgery, overall preference). To identify the influence of and respondent preferences for physician dress and white coats, a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) was employed. The scale was trichotomized into “disagree” (1, 2), “neither agree nor disagree” (3), and “agree” (4, 5) for analysis. Demographic data, including age, gender, education level, nationality (Japanese or non-Japanese), and number of physicians seen in the past year were collected.

Outcomes and Sample Size Calculation

The primary outcome of attire preference was calculated as the mean composite score of the five individual rating domains (ie, knowledgeable, trustworthy, caring, approachable, and comfortable), with the highest score representing the most preferred form of attire. We also assessed variation in preferences for physician attire by respondent characteristics, such as age and gender.

Sample size estimation was based on previous survey methodology.10 The Likert scale range for identifying influence of and respondent preferences for physician dress and white coats was 1-5 (“strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”). The scale range for measuring preferences for the randomized attire photograph was 1-10. An assumption of normality was made regarding responses on the 1-10 scale. An estimated standard deviation of 2.2 was assumed, based on prior findings.10 Based on these assumptions and the inclusion of at least 816 respondents (assuming a two-sided alpha error of 0.05), we expected to have 90% capacity to detect differences for effect sizes of 0.50 on the 1-10 scale.

Statistical Analyses

Paper-based survey data were entered independently and in duplicate by the study team. Respondents were not required to answer all questions; therefore, the denominator for each question varied. Data were reported as mean and standard deviation (SD) or percentages, where appropriate. Differences in the mean composite rating scores were assessed using one-way ANOVA with the Tukey method for pairwise comparisons. Differences in proportions for categorical data were compared using the Z-test. Chi-squared tests were used for bivariate comparisons between respondent age, gender, and level of education and corresponding respondent preferences. All analyses were performed using Stata 14 MP/SE (Stata Corp., College Station, Texas, USA).

RESULTS

Characteristics of Participants

Between December 1, 2015 and October 30, 2017, a total of 2,020 surveys were completed by patients across four academic hospitals in Japan. Of those, 1,960 patients (97.0%) completed the survey in its entirety. Approximately half of the respondents were 65 years of age or older (49%), of female gender (52%), and reported receiving care in the outpatient setting (53%). Regarding use of healthcare, 91% had seen more than one physician in the year preceding the time of survey completion (Table 1).

Ratings of Physician Attire

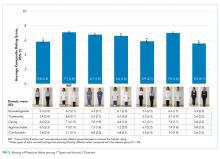

Compared with all forms of attire depicted in the survey’s first standalone photograph, respondents rated “casual attire with white coat” the highest (Figure 2). The mean composite score for “casual attire with white coat” was 7.1 (standard deviation [SD] = 1.8), and this attire was set as the referent group. Cronbach’s alpha, for the five items included in the composite score, was 0.95. However, “formal attire with white coat” was rated almost as highly as “casual attire with white coat” with an overall mean composite score of 7.0 (SD = 1.6).

Variation in Preference for Physician Attire by Clinical Setting

Preferences for physician attire varied by clinical care setting. Most respondents preferred “casual attire with white coat” or “formal attire with white coat” in both primary care and hospital settings, with a slight preference for “casual attire with white coat.” In contrast, respondents preferred “scrubs without white coat” in the ED and surgical settings. When asked about their overall preference, respondents reported they felt their physician should wear “formal attire with white coat” (35%) or “casual attire with white coat” (30%; Table 2). When comparing the group of photographs of physicians with white coats to the group without white coats (Figure 1), respondents preferred physicians wearing white coats overall and specifically when providing care in primary care and hospital settings. However, they preferred physicians without white coats when providing care in the ED (P < .001). With respect to surgeons, there was no statistically significant difference between preference for white coats and no white coats. These results were similar for photographs of both male and female physicians.

When asked whether physician dress was important to them and if physician attire influenced their satisfaction with the care received, 61% of participants agreed that physician dress was important, and 47% agreed that physician attire influenced satisfaction (Appendix Table 1). With respect to appropriateness of physicians dressing casually over the weekend in clinical settings, 52% responded that casual wear was inappropriate, while 31% had a neutral opinion.

Participants were asked whether physicians should wear a white coat in different clinical settings. Nearly two-thirds indicated a preference for white coats in the office and hospital (65% and 64%, respectively). Responses regarding whether emergency physicians should wear white coats were nearly equally divided (Agree, 37%; Disagree, 32%; Neither Agree nor Disagree, 31%). However, “scrubs without white coat” was most preferred (56%) when patients were given photographs of various attire and asked, “Which physician would you prefer to see when visiting the ER?” Responses to the question “Physicians should always wear a white coat when seeing patients in any setting” varied equally (Agree, 32%; Disagree, 34%; Neither Agree nor Disagree, 34%).

Variation in Preference for Physician Attire by Respondent Demographics

When comparing respondents by age, those 65 years or older preferred “formal attire with white coat” more so than respondents younger than 65 years (Appendix Table 2). This finding was identified in both primary care (36% vs 31%, P < .001) and hospital settings (37% vs 30%, P < .001). Additionally, physician attire had a greater impact on older respondents’ satisfaction and experience (Appendix Table 3). For example, 67% of respondents 65 years and older agreed that physician attire was important, and 54% agreed that attire influenced satisfaction. Conversely, for respondents younger than 65 years, the proportion agreeing with these statements was lower (56% and 41%, both P < .001). When comparing older and younger respondents, those 65 years and older more often preferred physicians wearing white coats in any setting (39% vs 26%, P < .001) and specifically in their office (68% vs 61%, P = .002), the ED (40% vs 34%, P < .001), and the hospital (69% vs 60%, P < .001).

When comparing male and female respondents, male respondents more often stated that physician dress was important to them (men, 64%; women, 58%; P = .002). When comparing responses to the question “Overall, which clothes do you feel a doctor should wear?”, between the eastern and western Japanese hospitals, preferences for physician attire varied.

Variation in Expectations Between Male and Female Physicians

When comparing the ratings of male and female physicians, female physicians were rated higher in how caring (P = .005) and approachable (P < .001) they appeared. However, there were no significant differences in the ratings of the three remaining domains (ie, knowledgeable, trustworthy, and comfortable) or the composite score.

DISCUSSION

Since we employed the same methodology as previous studies conducted in the US10 and Switzerland,18 a notable strength of our approach is that comparisons among these countries can be drawn. For example, physician attire appears to hold greater importance in Japan than in the US and Switzerland. Among Japanese participants, 61% agreed that physician dress is important (US, 53%; Switzerland, 36%), and 47% agreed that physician dress influenced how satisfied they were with their care (US, 36%; Switzerland, 23%).10 This result supports the notion that nonverbal and implicit communications (such as physician dress) may carry more importance among Japanese people.11-13

Regarding preference ratings for type of dress among respondents in Japan, “casual attire with white coat” received the highest mean composite score rating, with “formal attire with white coat” rated second overall. In contrast, US respondents rated “formal attire with white coat” highest and “scrubs with white coat” second.10 Our result runs counter to our expectation in that we expected Japanese respondents to prefer formal attire, since Japan is one of the most formal cultures in the world. One potential explanation for this difference is that the casual style chosen for this study was close to the smart casual style (slightly casual). Most hospitals and clinics in Japan do not allow physicians to wear jeans or polo shirts, which were chosen as the casual attire in the previous US study.

When examining various care settings and physician types, both Japanese and US respondents were more likely to prefer physicians wearing a white coat in the office or hospital.10 However, Japanese participants preferred both “casual attire with white coat” and “formal attire with white coat” equally in primary care or hospital settings. A smaller proportion of US respondents preferred “casual attire with white coat” in primary care (11%) and hospital settings (9%), but more preferred “formal attire with white coat” for primary care (44%) and hospital physicians (39%). In the ED setting, 32% of participants in Japan and 18% in the US disagreed with the idea that physicians should wear a white coat. Among Japanese participants, “scrubs without white coat” was rated highest for emergency physicians (56%) and surgeons (47%), while US preferences were 40% and 42%, respectively.10 One potential explanation is that scrubs-based attire became popular among Japanese ED and surgical contexts as a result of cultural influence and spread from western countries.19, 20

With respect to perceptions regarding physician attire on weekends, 52% of participants considered it inappropriate for a physician to dress casually over the weekend, compared with only 30% in Switzerland and 21% in the US.11,12 Given Japan’s level of formality and the fact that most Japanese physicians continue to work over the weekend,21-23 Japanese patients tend to expect their physicians to dress in more formal attire during these times.

Previous studies in Japan have demonstrated that older patients gave low ratings to scrubs and high ratings to white coat with any attire,15,17 and this was also the case in our study. Perhaps elderly patients reflect conservative values in their preferences of physician dress. Their perceptions may be less influenced by scenes portraying physicians in popular media when compared with the perceptions of younger patients. Though a 2015 systematic review and studies in other countries revealed white coats were preferred regardless of exact dress,9,24-26 they also showed variation in preferences for physician attire. For example, patients in Saudi Arabia preferred white coat and traditional ethnic dress,25 whereas mothers of pediatric patients in Saudi Arabia preferred scrubs for their pediatricians.27 Therefore, it is recommended for internationally mobile physicians to choose their dress depending on a variety of factors including country, context, and patient age group.

Our study has limitations. First, because some physicians presented the surveys to the patients, participants may have responded differently. Second, participants may have identified photographs of the male physician model as their personal healthcare provider (one author, K.K.). To avoid this possible bias, we randomly distributed 14 different versions of physician photographs in the questionnaire. Third, although physician photographs were strictly controlled, the “formal attire and white coat” and “casual attire and white coat” photographs appeared similar, especially given that the white coats were buttoned. Also, the female physician depicted in the photographs did not have the scrub shirt tucked in, while the male physician did. These nuances may have affected participant ratings between groups. Fourth,

In conclusion, patient preferences for physician attire were examined using a multicenter survey with a large sample size and robust survey methodology, thus overcoming weaknesses of previous studies into Japanese attire. Japanese patients perceive that physician attire is important and influences satisfaction with their care, more so than patients in other countries, like the US and Switzerland. Geography, settings of care, and patient age play a role in preferences. As a result, hospitals and health systems may use these findings to inform dress code policy based on patient population and context, recognizing that the appearance of their providers affects the patient-physician relationship. Future research should focus on better understanding the various cultural and societal customs that lead to patient expectations of physician attire.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Fumi Takemoto, Masayuki Ueno, Kazuya Sakai, Saori Kinami, and Toshio Naito for their assistance with data collection at their respective sites. Additionally, the authors thank Dr. Yoko Kanamitsu for serving as a model for photographs.

1. Manary MP, Boulding W, Staelin R, Glickman SW. The patient experience and health outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(3):201-203. https://doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMp1211775.

2. Boulding W, Glickman SW, Manary MP, Schulman KA, Staelin R. Relationship between patient satisfaction with inpatient care and hospital readmission within 30 days. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17(1):41-48.

3. Barbosa CD, Balp MM, Kulich K, Germain N, Rofail D. A literature review to explore the link between treatment satisfaction and adherence, compliance, and persistence. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2012;6:39-48. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S24752.

4. Jha AK, Orav EJ, Zheng J, Epstein AM. Patients’ perception of hospital care in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(18):1921-31. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa080411.

5. O’Malley AS, Forrest CB, Mandelblatt J. Adherence of low-income women to cancer screening recommendations. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(2):144-54. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10431.x.

6. Chung H, Lee H, Chang DS, Kim HS, Park HJ, Chae Y. Doctor’s attire influences perceived empathy in the patient-doctor relationship. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;89(3):387-391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2012.02.017.

7. Bianchi MT. Desiderata or dogma: what the evidence reveals about physician attire. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(5):641-643. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0546-8.

8. Brandt LJ. On the value of an old dress code in the new millennium. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(11):1277-1281. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.163.11.1277.

9. Petrilli CM, Mack M, Petrilli JJ, Hickner A, Saint S, Chopra V. Understanding the role of physician attire on patient perceptions: a systematic review of the literature--targeting attire to improve likelihood of rapport (TAILOR) investigators. BMJ Open. 2015;5(1):e006578. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006578.

10. Petrilli CM, Saint S, Jennings JJ, et al. Understanding patient preference for physician attire: a cross-sectional observational study of 10 academic medical centres in the USA. BMJ Open. 2018;8(5):e021239. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-021239.

11. Rowbury R. The need for more proactive communications. Low trust and changing values mean Japan can no longer fall back on its homogeneity. The Japan Times. 2017, Oct 15;Sect. Opinion. https://www.japantimes.co.jp/opinion/2017/10/15/commentary/japan-commentary/need-proactive-communications/#.Xej7lC3MzUI. Accessed December 5, 2019.

12. Shoji Nishimura ANaST. Communication Style and Cultural Features in High/Low Context Communication Cultures: A Case Study of Finland, Japan and India. Nov 22nd, 2009.

13. Smith RMRSW. The influence of high/low-context culture and power distance on choice of communication media: Students’ media choice to communicate with Professors in Japan and America. Int J Intercultural Relations. 2007;31(4):479-501.

14. Yamada Y, Takahashi O, Ohde S, Deshpande GA, Fukui T. Patients’ preferences for doctors’ attire in Japan. Intern Med. 2010;49(15):1521-1526. https://doi.org/10.2169/internalmedicine.49.3572.

15. Ikusaka M, Kamegai M, Sunaga T, et al. Patients’ attitude toward consultations by a physician without a white coat in Japan. Intern Med. 1999;38(7):533-536. https://doi.org/10.2169/internalmedicine.38.533.

16. Lefor AK, Ohnuma T, Nunomiya S, Yokota S, Makino J, Sanui M. Physician attire in the intensive care unit in Japan influences visitors’ perception of care. J Crit Care. 2018;43:288-293.

17. Kurihara H, Maeno T. Importance of physicians’ attire: factors influencing the impression it makes on patients, a cross-sectional study. Asia Pac Fam Med. 2014;13(1):2. https://doi.org/10.1186/1447-056X-13-2.

18. Zollinger M, Houchens N, Chopra V, et al. Understanding patient preference for physician attire in ambulatory clinics: a cross-sectional observational study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(5):e026009. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026009.

19. Chung JE. Medical Dramas and Viewer Perception of Health: Testing Cultivation Effects. Hum Commun Res. 2014;40(3):333-349.

20. Michael Pfau LJM, Kirsten Garrow. The influence of television viewing on public perceptions of physicians. J Broadcast Electron Media. 1995;39(4):441-458.

21. Suzuki S. Exhausting physicians employed in hospitals in Japan assessed by a health questionnaire [in Japanese]. Sangyo Eiseigaku Zasshi. 2017;59(4):107-118. https://doi.org/10.1539/sangyoeisei.

22. Ogawa R, Seo E, Maeno T, Ito M, Sanuki M. The relationship between long working hours and depression among first-year residents in Japan. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):50. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-018-1171-9.

23. Saijo Y, Chiba S, Yoshioka E, et al. Effects of work burden, job strain and support on depressive symptoms and burnout among Japanese physicians. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2014;27(6):980-992. https://doi.org/10.2478/s13382-014-0324-2.

24. Tiang KW, Razack AH, Ng KL. The ‘auxiliary’ white coat effect in hospitals: perceptions of patients and doctors. Singapore Med J. 2017;58(10):574-575. https://doi.org/10.11622/smedj.2017023.

25. Al Amry KM, Al Farrah M, Ur Rahman S, Abdulmajeed I. Patient perceptions and preferences of physicians’ attire in Saudi primary healthcare setting. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2018;8(6):326-330. https://doi.org/10.1080/20009666.2018.1551026.

26. Healy WL. Letter to the editor: editor’s spotlight/take 5: physicians’ attire influences patients’ perceptions in the urban outpatient orthopaedic surgery setting. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474(11):2545-2546. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-016-5049-z.

27. Aldrees T, Alsuhaibani R, Alqaryan S, et al. Physicians’ attire. Parents preferences in a tertiary hospital. Saudi Med J. 2017;38(4):435-439. https://doi.org/10.15537/smj.2017.4.15853.

The patient-physician relationship is critical for ensuring the delivery of high-quality healthcare. Successful patient-physician relationships arise from shared trust, knowledge, mutual respect, and effective verbal and nonverbal communication. The ways in which patients experience healthcare and their satisfaction with physicians affect a myriad of important health outcomes, such as adherence to treatment and outcomes for conditions such as hypertension and diabetes mellitus.1-5 One method for potentially enhancing patient satisfaction is through understanding how patients wish their physicians to dress6-8 and tailoring attire to match these expectations. In addition to our systematic review,9 a recent large-scale, multicenter study in the United States revealed that most patients perceive physician attire as important, but that preferences for specific types of attire are contextual.9,10 For example, elderly patients preferred physicians in formal attire and white coat, while scrubs with white coat or scrubs alone were preferred for emergency department (ED) physicians and surgeons, respectively. Moreover, regional variation regarding attire preference was also observed in the US, with preferences for more formal attire in the South and less formal in the Midwest.

Geographic variation, regarding patient preferences for physician dress, is perhaps even more relevant internationally. In particular, Japan is considered to have a highly contextualized culture that relies on nonverbal and implicit communication. However, medical professionals have no specific dress code and, thus, don many different kinds of attire. In part, this may be because it is not clear whether or how physician attire impacts patient satisfaction and perceived healthcare quality in Japan.11-13 Although previous studies in Japan have suggested that physician attire has a considerable influence on patient satisfaction, these studies either involved a single department in one hospital or a small number of respondents.14-17 Therefore, we performed a multicenter, cross-sectional study to understand patients’ preferences for physician attire in different clinical settings and in different geographic regions in Japan.

METHODS

Study Population

We conducted a cross-sectional, questionnaire-based study from 2015 to 2017, in four geographically diverse hospitals in Japan. Two of these hospitals, Tokyo Joto Hospital and Juntendo University Hospital, are located in eastern Japan whereas the others, Kurashiki Central Hospital and Akashi Medical Center, are in western Japan.

Questionnaires were printed and randomly distributed by research staff to outpatients in waiting rooms and inpatients in medical wards who were 20 years of age or older. We placed no restriction on ward site or time of questionnaire distribution. Research staff, including physicians, nurses, and medical clerks, were instructed to avoid guiding or influencing participants’ responses. Informed consent was obtained by the staff; only those who provided informed consent participated in the study. Respondents could request assistance with form completion from persons accompanying them if they had difficulties, such as physical, visual, or hearing impairments. All responses were collected anonymously. The study was approved by the ethics committees of all four hospitals.

Questionnaire

We used a modified version of the survey instrument from a prior study.10 The first section of the survey showed photographs of either a male or female physician with 7 unique forms of attire, including casual, casual with white coat, scrubs, scrubs with white coat, formal, formal with white coat, and business suit (Figure 1). Given the Japanese context of this study, the language was translated to Japanese and photographs of physicians of Japanese descent were used. Photographs were taken with attention paid to achieving constant facial expressions on the physicians as well as in other visual cues (eg, lighting, background, pose). The physician’s gender and attire in the first photograph seen by each respondent were randomized to prevent bias in ordering, priming, and anchoring; all other sections of the survey were identical.

Respondents were first asked to rate the standalone, randomized physician photograph using a 1-10 scale across five domains (ie, how knowledgeable, trustworthy, caring, and approachable the physician appeared and how comfortable the physician’s appearance made the respondent feel), with a score of 10 representing the highest rating. Respondents were subsequently given 7 photographs of the same physician wearing various forms of attire. Questions were asked regarding preference of attire in varied clinical settings (ie, primary care, ED, hospital, surgery, overall preference). To identify the influence of and respondent preferences for physician dress and white coats, a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) was employed. The scale was trichotomized into “disagree” (1, 2), “neither agree nor disagree” (3), and “agree” (4, 5) for analysis. Demographic data, including age, gender, education level, nationality (Japanese or non-Japanese), and number of physicians seen in the past year were collected.

Outcomes and Sample Size Calculation

The primary outcome of attire preference was calculated as the mean composite score of the five individual rating domains (ie, knowledgeable, trustworthy, caring, approachable, and comfortable), with the highest score representing the most preferred form of attire. We also assessed variation in preferences for physician attire by respondent characteristics, such as age and gender.

Sample size estimation was based on previous survey methodology.10 The Likert scale range for identifying influence of and respondent preferences for physician dress and white coats was 1-5 (“strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”). The scale range for measuring preferences for the randomized attire photograph was 1-10. An assumption of normality was made regarding responses on the 1-10 scale. An estimated standard deviation of 2.2 was assumed, based on prior findings.10 Based on these assumptions and the inclusion of at least 816 respondents (assuming a two-sided alpha error of 0.05), we expected to have 90% capacity to detect differences for effect sizes of 0.50 on the 1-10 scale.

Statistical Analyses

Paper-based survey data were entered independently and in duplicate by the study team. Respondents were not required to answer all questions; therefore, the denominator for each question varied. Data were reported as mean and standard deviation (SD) or percentages, where appropriate. Differences in the mean composite rating scores were assessed using one-way ANOVA with the Tukey method for pairwise comparisons. Differences in proportions for categorical data were compared using the Z-test. Chi-squared tests were used for bivariate comparisons between respondent age, gender, and level of education and corresponding respondent preferences. All analyses were performed using Stata 14 MP/SE (Stata Corp., College Station, Texas, USA).

RESULTS

Characteristics of Participants

Between December 1, 2015 and October 30, 2017, a total of 2,020 surveys were completed by patients across four academic hospitals in Japan. Of those, 1,960 patients (97.0%) completed the survey in its entirety. Approximately half of the respondents were 65 years of age or older (49%), of female gender (52%), and reported receiving care in the outpatient setting (53%). Regarding use of healthcare, 91% had seen more than one physician in the year preceding the time of survey completion (Table 1).

Ratings of Physician Attire

Compared with all forms of attire depicted in the survey’s first standalone photograph, respondents rated “casual attire with white coat” the highest (Figure 2). The mean composite score for “casual attire with white coat” was 7.1 (standard deviation [SD] = 1.8), and this attire was set as the referent group. Cronbach’s alpha, for the five items included in the composite score, was 0.95. However, “formal attire with white coat” was rated almost as highly as “casual attire with white coat” with an overall mean composite score of 7.0 (SD = 1.6).

Variation in Preference for Physician Attire by Clinical Setting

Preferences for physician attire varied by clinical care setting. Most respondents preferred “casual attire with white coat” or “formal attire with white coat” in both primary care and hospital settings, with a slight preference for “casual attire with white coat.” In contrast, respondents preferred “scrubs without white coat” in the ED and surgical settings. When asked about their overall preference, respondents reported they felt their physician should wear “formal attire with white coat” (35%) or “casual attire with white coat” (30%; Table 2). When comparing the group of photographs of physicians with white coats to the group without white coats (Figure 1), respondents preferred physicians wearing white coats overall and specifically when providing care in primary care and hospital settings. However, they preferred physicians without white coats when providing care in the ED (P < .001). With respect to surgeons, there was no statistically significant difference between preference for white coats and no white coats. These results were similar for photographs of both male and female physicians.

When asked whether physician dress was important to them and if physician attire influenced their satisfaction with the care received, 61% of participants agreed that physician dress was important, and 47% agreed that physician attire influenced satisfaction (Appendix Table 1). With respect to appropriateness of physicians dressing casually over the weekend in clinical settings, 52% responded that casual wear was inappropriate, while 31% had a neutral opinion.

Participants were asked whether physicians should wear a white coat in different clinical settings. Nearly two-thirds indicated a preference for white coats in the office and hospital (65% and 64%, respectively). Responses regarding whether emergency physicians should wear white coats were nearly equally divided (Agree, 37%; Disagree, 32%; Neither Agree nor Disagree, 31%). However, “scrubs without white coat” was most preferred (56%) when patients were given photographs of various attire and asked, “Which physician would you prefer to see when visiting the ER?” Responses to the question “Physicians should always wear a white coat when seeing patients in any setting” varied equally (Agree, 32%; Disagree, 34%; Neither Agree nor Disagree, 34%).

Variation in Preference for Physician Attire by Respondent Demographics

When comparing respondents by age, those 65 years or older preferred “formal attire with white coat” more so than respondents younger than 65 years (Appendix Table 2). This finding was identified in both primary care (36% vs 31%, P < .001) and hospital settings (37% vs 30%, P < .001). Additionally, physician attire had a greater impact on older respondents’ satisfaction and experience (Appendix Table 3). For example, 67% of respondents 65 years and older agreed that physician attire was important, and 54% agreed that attire influenced satisfaction. Conversely, for respondents younger than 65 years, the proportion agreeing with these statements was lower (56% and 41%, both P < .001). When comparing older and younger respondents, those 65 years and older more often preferred physicians wearing white coats in any setting (39% vs 26%, P < .001) and specifically in their office (68% vs 61%, P = .002), the ED (40% vs 34%, P < .001), and the hospital (69% vs 60%, P < .001).

When comparing male and female respondents, male respondents more often stated that physician dress was important to them (men, 64%; women, 58%; P = .002). When comparing responses to the question “Overall, which clothes do you feel a doctor should wear?”, between the eastern and western Japanese hospitals, preferences for physician attire varied.

Variation in Expectations Between Male and Female Physicians

When comparing the ratings of male and female physicians, female physicians were rated higher in how caring (P = .005) and approachable (P < .001) they appeared. However, there were no significant differences in the ratings of the three remaining domains (ie, knowledgeable, trustworthy, and comfortable) or the composite score.

DISCUSSION

Since we employed the same methodology as previous studies conducted in the US10 and Switzerland,18 a notable strength of our approach is that comparisons among these countries can be drawn. For example, physician attire appears to hold greater importance in Japan than in the US and Switzerland. Among Japanese participants, 61% agreed that physician dress is important (US, 53%; Switzerland, 36%), and 47% agreed that physician dress influenced how satisfied they were with their care (US, 36%; Switzerland, 23%).10 This result supports the notion that nonverbal and implicit communications (such as physician dress) may carry more importance among Japanese people.11-13

Regarding preference ratings for type of dress among respondents in Japan, “casual attire with white coat” received the highest mean composite score rating, with “formal attire with white coat” rated second overall. In contrast, US respondents rated “formal attire with white coat” highest and “scrubs with white coat” second.10 Our result runs counter to our expectation in that we expected Japanese respondents to prefer formal attire, since Japan is one of the most formal cultures in the world. One potential explanation for this difference is that the casual style chosen for this study was close to the smart casual style (slightly casual). Most hospitals and clinics in Japan do not allow physicians to wear jeans or polo shirts, which were chosen as the casual attire in the previous US study.

When examining various care settings and physician types, both Japanese and US respondents were more likely to prefer physicians wearing a white coat in the office or hospital.10 However, Japanese participants preferred both “casual attire with white coat” and “formal attire with white coat” equally in primary care or hospital settings. A smaller proportion of US respondents preferred “casual attire with white coat” in primary care (11%) and hospital settings (9%), but more preferred “formal attire with white coat” for primary care (44%) and hospital physicians (39%). In the ED setting, 32% of participants in Japan and 18% in the US disagreed with the idea that physicians should wear a white coat. Among Japanese participants, “scrubs without white coat” was rated highest for emergency physicians (56%) and surgeons (47%), while US preferences were 40% and 42%, respectively.10 One potential explanation is that scrubs-based attire became popular among Japanese ED and surgical contexts as a result of cultural influence and spread from western countries.19, 20

With respect to perceptions regarding physician attire on weekends, 52% of participants considered it inappropriate for a physician to dress casually over the weekend, compared with only 30% in Switzerland and 21% in the US.11,12 Given Japan’s level of formality and the fact that most Japanese physicians continue to work over the weekend,21-23 Japanese patients tend to expect their physicians to dress in more formal attire during these times.

Previous studies in Japan have demonstrated that older patients gave low ratings to scrubs and high ratings to white coat with any attire,15,17 and this was also the case in our study. Perhaps elderly patients reflect conservative values in their preferences of physician dress. Their perceptions may be less influenced by scenes portraying physicians in popular media when compared with the perceptions of younger patients. Though a 2015 systematic review and studies in other countries revealed white coats were preferred regardless of exact dress,9,24-26 they also showed variation in preferences for physician attire. For example, patients in Saudi Arabia preferred white coat and traditional ethnic dress,25 whereas mothers of pediatric patients in Saudi Arabia preferred scrubs for their pediatricians.27 Therefore, it is recommended for internationally mobile physicians to choose their dress depending on a variety of factors including country, context, and patient age group.

Our study has limitations. First, because some physicians presented the surveys to the patients, participants may have responded differently. Second, participants may have identified photographs of the male physician model as their personal healthcare provider (one author, K.K.). To avoid this possible bias, we randomly distributed 14 different versions of physician photographs in the questionnaire. Third, although physician photographs were strictly controlled, the “formal attire and white coat” and “casual attire and white coat” photographs appeared similar, especially given that the white coats were buttoned. Also, the female physician depicted in the photographs did not have the scrub shirt tucked in, while the male physician did. These nuances may have affected participant ratings between groups. Fourth,

In conclusion, patient preferences for physician attire were examined using a multicenter survey with a large sample size and robust survey methodology, thus overcoming weaknesses of previous studies into Japanese attire. Japanese patients perceive that physician attire is important and influences satisfaction with their care, more so than patients in other countries, like the US and Switzerland. Geography, settings of care, and patient age play a role in preferences. As a result, hospitals and health systems may use these findings to inform dress code policy based on patient population and context, recognizing that the appearance of their providers affects the patient-physician relationship. Future research should focus on better understanding the various cultural and societal customs that lead to patient expectations of physician attire.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Fumi Takemoto, Masayuki Ueno, Kazuya Sakai, Saori Kinami, and Toshio Naito for their assistance with data collection at their respective sites. Additionally, the authors thank Dr. Yoko Kanamitsu for serving as a model for photographs.

The patient-physician relationship is critical for ensuring the delivery of high-quality healthcare. Successful patient-physician relationships arise from shared trust, knowledge, mutual respect, and effective verbal and nonverbal communication. The ways in which patients experience healthcare and their satisfaction with physicians affect a myriad of important health outcomes, such as adherence to treatment and outcomes for conditions such as hypertension and diabetes mellitus.1-5 One method for potentially enhancing patient satisfaction is through understanding how patients wish their physicians to dress6-8 and tailoring attire to match these expectations. In addition to our systematic review,9 a recent large-scale, multicenter study in the United States revealed that most patients perceive physician attire as important, but that preferences for specific types of attire are contextual.9,10 For example, elderly patients preferred physicians in formal attire and white coat, while scrubs with white coat or scrubs alone were preferred for emergency department (ED) physicians and surgeons, respectively. Moreover, regional variation regarding attire preference was also observed in the US, with preferences for more formal attire in the South and less formal in the Midwest.

Geographic variation, regarding patient preferences for physician dress, is perhaps even more relevant internationally. In particular, Japan is considered to have a highly contextualized culture that relies on nonverbal and implicit communication. However, medical professionals have no specific dress code and, thus, don many different kinds of attire. In part, this may be because it is not clear whether or how physician attire impacts patient satisfaction and perceived healthcare quality in Japan.11-13 Although previous studies in Japan have suggested that physician attire has a considerable influence on patient satisfaction, these studies either involved a single department in one hospital or a small number of respondents.14-17 Therefore, we performed a multicenter, cross-sectional study to understand patients’ preferences for physician attire in different clinical settings and in different geographic regions in Japan.

METHODS

Study Population

We conducted a cross-sectional, questionnaire-based study from 2015 to 2017, in four geographically diverse hospitals in Japan. Two of these hospitals, Tokyo Joto Hospital and Juntendo University Hospital, are located in eastern Japan whereas the others, Kurashiki Central Hospital and Akashi Medical Center, are in western Japan.

Questionnaires were printed and randomly distributed by research staff to outpatients in waiting rooms and inpatients in medical wards who were 20 years of age or older. We placed no restriction on ward site or time of questionnaire distribution. Research staff, including physicians, nurses, and medical clerks, were instructed to avoid guiding or influencing participants’ responses. Informed consent was obtained by the staff; only those who provided informed consent participated in the study. Respondents could request assistance with form completion from persons accompanying them if they had difficulties, such as physical, visual, or hearing impairments. All responses were collected anonymously. The study was approved by the ethics committees of all four hospitals.

Questionnaire

We used a modified version of the survey instrument from a prior study.10 The first section of the survey showed photographs of either a male or female physician with 7 unique forms of attire, including casual, casual with white coat, scrubs, scrubs with white coat, formal, formal with white coat, and business suit (Figure 1). Given the Japanese context of this study, the language was translated to Japanese and photographs of physicians of Japanese descent were used. Photographs were taken with attention paid to achieving constant facial expressions on the physicians as well as in other visual cues (eg, lighting, background, pose). The physician’s gender and attire in the first photograph seen by each respondent were randomized to prevent bias in ordering, priming, and anchoring; all other sections of the survey were identical.

Respondents were first asked to rate the standalone, randomized physician photograph using a 1-10 scale across five domains (ie, how knowledgeable, trustworthy, caring, and approachable the physician appeared and how comfortable the physician’s appearance made the respondent feel), with a score of 10 representing the highest rating. Respondents were subsequently given 7 photographs of the same physician wearing various forms of attire. Questions were asked regarding preference of attire in varied clinical settings (ie, primary care, ED, hospital, surgery, overall preference). To identify the influence of and respondent preferences for physician dress and white coats, a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) was employed. The scale was trichotomized into “disagree” (1, 2), “neither agree nor disagree” (3), and “agree” (4, 5) for analysis. Demographic data, including age, gender, education level, nationality (Japanese or non-Japanese), and number of physicians seen in the past year were collected.

Outcomes and Sample Size Calculation

The primary outcome of attire preference was calculated as the mean composite score of the five individual rating domains (ie, knowledgeable, trustworthy, caring, approachable, and comfortable), with the highest score representing the most preferred form of attire. We also assessed variation in preferences for physician attire by respondent characteristics, such as age and gender.

Sample size estimation was based on previous survey methodology.10 The Likert scale range for identifying influence of and respondent preferences for physician dress and white coats was 1-5 (“strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”). The scale range for measuring preferences for the randomized attire photograph was 1-10. An assumption of normality was made regarding responses on the 1-10 scale. An estimated standard deviation of 2.2 was assumed, based on prior findings.10 Based on these assumptions and the inclusion of at least 816 respondents (assuming a two-sided alpha error of 0.05), we expected to have 90% capacity to detect differences for effect sizes of 0.50 on the 1-10 scale.

Statistical Analyses

Paper-based survey data were entered independently and in duplicate by the study team. Respondents were not required to answer all questions; therefore, the denominator for each question varied. Data were reported as mean and standard deviation (SD) or percentages, where appropriate. Differences in the mean composite rating scores were assessed using one-way ANOVA with the Tukey method for pairwise comparisons. Differences in proportions for categorical data were compared using the Z-test. Chi-squared tests were used for bivariate comparisons between respondent age, gender, and level of education and corresponding respondent preferences. All analyses were performed using Stata 14 MP/SE (Stata Corp., College Station, Texas, USA).

RESULTS

Characteristics of Participants

Between December 1, 2015 and October 30, 2017, a total of 2,020 surveys were completed by patients across four academic hospitals in Japan. Of those, 1,960 patients (97.0%) completed the survey in its entirety. Approximately half of the respondents were 65 years of age or older (49%), of female gender (52%), and reported receiving care in the outpatient setting (53%). Regarding use of healthcare, 91% had seen more than one physician in the year preceding the time of survey completion (Table 1).

Ratings of Physician Attire

Compared with all forms of attire depicted in the survey’s first standalone photograph, respondents rated “casual attire with white coat” the highest (Figure 2). The mean composite score for “casual attire with white coat” was 7.1 (standard deviation [SD] = 1.8), and this attire was set as the referent group. Cronbach’s alpha, for the five items included in the composite score, was 0.95. However, “formal attire with white coat” was rated almost as highly as “casual attire with white coat” with an overall mean composite score of 7.0 (SD = 1.6).

Variation in Preference for Physician Attire by Clinical Setting

Preferences for physician attire varied by clinical care setting. Most respondents preferred “casual attire with white coat” or “formal attire with white coat” in both primary care and hospital settings, with a slight preference for “casual attire with white coat.” In contrast, respondents preferred “scrubs without white coat” in the ED and surgical settings. When asked about their overall preference, respondents reported they felt their physician should wear “formal attire with white coat” (35%) or “casual attire with white coat” (30%; Table 2). When comparing the group of photographs of physicians with white coats to the group without white coats (Figure 1), respondents preferred physicians wearing white coats overall and specifically when providing care in primary care and hospital settings. However, they preferred physicians without white coats when providing care in the ED (P < .001). With respect to surgeons, there was no statistically significant difference between preference for white coats and no white coats. These results were similar for photographs of both male and female physicians.

When asked whether physician dress was important to them and if physician attire influenced their satisfaction with the care received, 61% of participants agreed that physician dress was important, and 47% agreed that physician attire influenced satisfaction (Appendix Table 1). With respect to appropriateness of physicians dressing casually over the weekend in clinical settings, 52% responded that casual wear was inappropriate, while 31% had a neutral opinion.

Participants were asked whether physicians should wear a white coat in different clinical settings. Nearly two-thirds indicated a preference for white coats in the office and hospital (65% and 64%, respectively). Responses regarding whether emergency physicians should wear white coats were nearly equally divided (Agree, 37%; Disagree, 32%; Neither Agree nor Disagree, 31%). However, “scrubs without white coat” was most preferred (56%) when patients were given photographs of various attire and asked, “Which physician would you prefer to see when visiting the ER?” Responses to the question “Physicians should always wear a white coat when seeing patients in any setting” varied equally (Agree, 32%; Disagree, 34%; Neither Agree nor Disagree, 34%).

Variation in Preference for Physician Attire by Respondent Demographics

When comparing respondents by age, those 65 years or older preferred “formal attire with white coat” more so than respondents younger than 65 years (Appendix Table 2). This finding was identified in both primary care (36% vs 31%, P < .001) and hospital settings (37% vs 30%, P < .001). Additionally, physician attire had a greater impact on older respondents’ satisfaction and experience (Appendix Table 3). For example, 67% of respondents 65 years and older agreed that physician attire was important, and 54% agreed that attire influenced satisfaction. Conversely, for respondents younger than 65 years, the proportion agreeing with these statements was lower (56% and 41%, both P < .001). When comparing older and younger respondents, those 65 years and older more often preferred physicians wearing white coats in any setting (39% vs 26%, P < .001) and specifically in their office (68% vs 61%, P = .002), the ED (40% vs 34%, P < .001), and the hospital (69% vs 60%, P < .001).

When comparing male and female respondents, male respondents more often stated that physician dress was important to them (men, 64%; women, 58%; P = .002). When comparing responses to the question “Overall, which clothes do you feel a doctor should wear?”, between the eastern and western Japanese hospitals, preferences for physician attire varied.

Variation in Expectations Between Male and Female Physicians

When comparing the ratings of male and female physicians, female physicians were rated higher in how caring (P = .005) and approachable (P < .001) they appeared. However, there were no significant differences in the ratings of the three remaining domains (ie, knowledgeable, trustworthy, and comfortable) or the composite score.

DISCUSSION

Since we employed the same methodology as previous studies conducted in the US10 and Switzerland,18 a notable strength of our approach is that comparisons among these countries can be drawn. For example, physician attire appears to hold greater importance in Japan than in the US and Switzerland. Among Japanese participants, 61% agreed that physician dress is important (US, 53%; Switzerland, 36%), and 47% agreed that physician dress influenced how satisfied they were with their care (US, 36%; Switzerland, 23%).10 This result supports the notion that nonverbal and implicit communications (such as physician dress) may carry more importance among Japanese people.11-13

Regarding preference ratings for type of dress among respondents in Japan, “casual attire with white coat” received the highest mean composite score rating, with “formal attire with white coat” rated second overall. In contrast, US respondents rated “formal attire with white coat” highest and “scrubs with white coat” second.10 Our result runs counter to our expectation in that we expected Japanese respondents to prefer formal attire, since Japan is one of the most formal cultures in the world. One potential explanation for this difference is that the casual style chosen for this study was close to the smart casual style (slightly casual). Most hospitals and clinics in Japan do not allow physicians to wear jeans or polo shirts, which were chosen as the casual attire in the previous US study.

When examining various care settings and physician types, both Japanese and US respondents were more likely to prefer physicians wearing a white coat in the office or hospital.10 However, Japanese participants preferred both “casual attire with white coat” and “formal attire with white coat” equally in primary care or hospital settings. A smaller proportion of US respondents preferred “casual attire with white coat” in primary care (11%) and hospital settings (9%), but more preferred “formal attire with white coat” for primary care (44%) and hospital physicians (39%). In the ED setting, 32% of participants in Japan and 18% in the US disagreed with the idea that physicians should wear a white coat. Among Japanese participants, “scrubs without white coat” was rated highest for emergency physicians (56%) and surgeons (47%), while US preferences were 40% and 42%, respectively.10 One potential explanation is that scrubs-based attire became popular among Japanese ED and surgical contexts as a result of cultural influence and spread from western countries.19, 20

With respect to perceptions regarding physician attire on weekends, 52% of participants considered it inappropriate for a physician to dress casually over the weekend, compared with only 30% in Switzerland and 21% in the US.11,12 Given Japan’s level of formality and the fact that most Japanese physicians continue to work over the weekend,21-23 Japanese patients tend to expect their physicians to dress in more formal attire during these times.

Previous studies in Japan have demonstrated that older patients gave low ratings to scrubs and high ratings to white coat with any attire,15,17 and this was also the case in our study. Perhaps elderly patients reflect conservative values in their preferences of physician dress. Their perceptions may be less influenced by scenes portraying physicians in popular media when compared with the perceptions of younger patients. Though a 2015 systematic review and studies in other countries revealed white coats were preferred regardless of exact dress,9,24-26 they also showed variation in preferences for physician attire. For example, patients in Saudi Arabia preferred white coat and traditional ethnic dress,25 whereas mothers of pediatric patients in Saudi Arabia preferred scrubs for their pediatricians.27 Therefore, it is recommended for internationally mobile physicians to choose their dress depending on a variety of factors including country, context, and patient age group.

Our study has limitations. First, because some physicians presented the surveys to the patients, participants may have responded differently. Second, participants may have identified photographs of the male physician model as their personal healthcare provider (one author, K.K.). To avoid this possible bias, we randomly distributed 14 different versions of physician photographs in the questionnaire. Third, although physician photographs were strictly controlled, the “formal attire and white coat” and “casual attire and white coat” photographs appeared similar, especially given that the white coats were buttoned. Also, the female physician depicted in the photographs did not have the scrub shirt tucked in, while the male physician did. These nuances may have affected participant ratings between groups. Fourth,

In conclusion, patient preferences for physician attire were examined using a multicenter survey with a large sample size and robust survey methodology, thus overcoming weaknesses of previous studies into Japanese attire. Japanese patients perceive that physician attire is important and influences satisfaction with their care, more so than patients in other countries, like the US and Switzerland. Geography, settings of care, and patient age play a role in preferences. As a result, hospitals and health systems may use these findings to inform dress code policy based on patient population and context, recognizing that the appearance of their providers affects the patient-physician relationship. Future research should focus on better understanding the various cultural and societal customs that lead to patient expectations of physician attire.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Fumi Takemoto, Masayuki Ueno, Kazuya Sakai, Saori Kinami, and Toshio Naito for their assistance with data collection at their respective sites. Additionally, the authors thank Dr. Yoko Kanamitsu for serving as a model for photographs.

1. Manary MP, Boulding W, Staelin R, Glickman SW. The patient experience and health outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(3):201-203. https://doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMp1211775.

2. Boulding W, Glickman SW, Manary MP, Schulman KA, Staelin R. Relationship between patient satisfaction with inpatient care and hospital readmission within 30 days. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17(1):41-48.

3. Barbosa CD, Balp MM, Kulich K, Germain N, Rofail D. A literature review to explore the link between treatment satisfaction and adherence, compliance, and persistence. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2012;6:39-48. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S24752.

4. Jha AK, Orav EJ, Zheng J, Epstein AM. Patients’ perception of hospital care in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(18):1921-31. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa080411.

5. O’Malley AS, Forrest CB, Mandelblatt J. Adherence of low-income women to cancer screening recommendations. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(2):144-54. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10431.x.

6. Chung H, Lee H, Chang DS, Kim HS, Park HJ, Chae Y. Doctor’s attire influences perceived empathy in the patient-doctor relationship. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;89(3):387-391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2012.02.017.

7. Bianchi MT. Desiderata or dogma: what the evidence reveals about physician attire. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(5):641-643. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0546-8.

8. Brandt LJ. On the value of an old dress code in the new millennium. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(11):1277-1281. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.163.11.1277.

9. Petrilli CM, Mack M, Petrilli JJ, Hickner A, Saint S, Chopra V. Understanding the role of physician attire on patient perceptions: a systematic review of the literature--targeting attire to improve likelihood of rapport (TAILOR) investigators. BMJ Open. 2015;5(1):e006578. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006578.

10. Petrilli CM, Saint S, Jennings JJ, et al. Understanding patient preference for physician attire: a cross-sectional observational study of 10 academic medical centres in the USA. BMJ Open. 2018;8(5):e021239. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-021239.

11. Rowbury R. The need for more proactive communications. Low trust and changing values mean Japan can no longer fall back on its homogeneity. The Japan Times. 2017, Oct 15;Sect. Opinion. https://www.japantimes.co.jp/opinion/2017/10/15/commentary/japan-commentary/need-proactive-communications/#.Xej7lC3MzUI. Accessed December 5, 2019.

12. Shoji Nishimura ANaST. Communication Style and Cultural Features in High/Low Context Communication Cultures: A Case Study of Finland, Japan and India. Nov 22nd, 2009.

13. Smith RMRSW. The influence of high/low-context culture and power distance on choice of communication media: Students’ media choice to communicate with Professors in Japan and America. Int J Intercultural Relations. 2007;31(4):479-501.

14. Yamada Y, Takahashi O, Ohde S, Deshpande GA, Fukui T. Patients’ preferences for doctors’ attire in Japan. Intern Med. 2010;49(15):1521-1526. https://doi.org/10.2169/internalmedicine.49.3572.

15. Ikusaka M, Kamegai M, Sunaga T, et al. Patients’ attitude toward consultations by a physician without a white coat in Japan. Intern Med. 1999;38(7):533-536. https://doi.org/10.2169/internalmedicine.38.533.

16. Lefor AK, Ohnuma T, Nunomiya S, Yokota S, Makino J, Sanui M. Physician attire in the intensive care unit in Japan influences visitors’ perception of care. J Crit Care. 2018;43:288-293.

17. Kurihara H, Maeno T. Importance of physicians’ attire: factors influencing the impression it makes on patients, a cross-sectional study. Asia Pac Fam Med. 2014;13(1):2. https://doi.org/10.1186/1447-056X-13-2.

18. Zollinger M, Houchens N, Chopra V, et al. Understanding patient preference for physician attire in ambulatory clinics: a cross-sectional observational study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(5):e026009. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026009.

19. Chung JE. Medical Dramas and Viewer Perception of Health: Testing Cultivation Effects. Hum Commun Res. 2014;40(3):333-349.

20. Michael Pfau LJM, Kirsten Garrow. The influence of television viewing on public perceptions of physicians. J Broadcast Electron Media. 1995;39(4):441-458.

21. Suzuki S. Exhausting physicians employed in hospitals in Japan assessed by a health questionnaire [in Japanese]. Sangyo Eiseigaku Zasshi. 2017;59(4):107-118. https://doi.org/10.1539/sangyoeisei.

22. Ogawa R, Seo E, Maeno T, Ito M, Sanuki M. The relationship between long working hours and depression among first-year residents in Japan. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):50. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-018-1171-9.

23. Saijo Y, Chiba S, Yoshioka E, et al. Effects of work burden, job strain and support on depressive symptoms and burnout among Japanese physicians. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2014;27(6):980-992. https://doi.org/10.2478/s13382-014-0324-2.

24. Tiang KW, Razack AH, Ng KL. The ‘auxiliary’ white coat effect in hospitals: perceptions of patients and doctors. Singapore Med J. 2017;58(10):574-575. https://doi.org/10.11622/smedj.2017023.

25. Al Amry KM, Al Farrah M, Ur Rahman S, Abdulmajeed I. Patient perceptions and preferences of physicians’ attire in Saudi primary healthcare setting. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2018;8(6):326-330. https://doi.org/10.1080/20009666.2018.1551026.

26. Healy WL. Letter to the editor: editor’s spotlight/take 5: physicians’ attire influences patients’ perceptions in the urban outpatient orthopaedic surgery setting. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474(11):2545-2546. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-016-5049-z.

27. Aldrees T, Alsuhaibani R, Alqaryan S, et al. Physicians’ attire. Parents preferences in a tertiary hospital. Saudi Med J. 2017;38(4):435-439. https://doi.org/10.15537/smj.2017.4.15853.

1. Manary MP, Boulding W, Staelin R, Glickman SW. The patient experience and health outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(3):201-203. https://doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMp1211775.

2. Boulding W, Glickman SW, Manary MP, Schulman KA, Staelin R. Relationship between patient satisfaction with inpatient care and hospital readmission within 30 days. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17(1):41-48.

3. Barbosa CD, Balp MM, Kulich K, Germain N, Rofail D. A literature review to explore the link between treatment satisfaction and adherence, compliance, and persistence. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2012;6:39-48. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S24752.

4. Jha AK, Orav EJ, Zheng J, Epstein AM. Patients’ perception of hospital care in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(18):1921-31. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa080411.

5. O’Malley AS, Forrest CB, Mandelblatt J. Adherence of low-income women to cancer screening recommendations. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(2):144-54. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10431.x.

6. Chung H, Lee H, Chang DS, Kim HS, Park HJ, Chae Y. Doctor’s attire influences perceived empathy in the patient-doctor relationship. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;89(3):387-391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2012.02.017.

7. Bianchi MT. Desiderata or dogma: what the evidence reveals about physician attire. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(5):641-643. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0546-8.

8. Brandt LJ. On the value of an old dress code in the new millennium. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(11):1277-1281. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.163.11.1277.

9. Petrilli CM, Mack M, Petrilli JJ, Hickner A, Saint S, Chopra V. Understanding the role of physician attire on patient perceptions: a systematic review of the literature--targeting attire to improve likelihood of rapport (TAILOR) investigators. BMJ Open. 2015;5(1):e006578. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006578.

10. Petrilli CM, Saint S, Jennings JJ, et al. Understanding patient preference for physician attire: a cross-sectional observational study of 10 academic medical centres in the USA. BMJ Open. 2018;8(5):e021239. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-021239.

11. Rowbury R. The need for more proactive communications. Low trust and changing values mean Japan can no longer fall back on its homogeneity. The Japan Times. 2017, Oct 15;Sect. Opinion. https://www.japantimes.co.jp/opinion/2017/10/15/commentary/japan-commentary/need-proactive-communications/#.Xej7lC3MzUI. Accessed December 5, 2019.

12. Shoji Nishimura ANaST. Communication Style and Cultural Features in High/Low Context Communication Cultures: A Case Study of Finland, Japan and India. Nov 22nd, 2009.

13. Smith RMRSW. The influence of high/low-context culture and power distance on choice of communication media: Students’ media choice to communicate with Professors in Japan and America. Int J Intercultural Relations. 2007;31(4):479-501.

14. Yamada Y, Takahashi O, Ohde S, Deshpande GA, Fukui T. Patients’ preferences for doctors’ attire in Japan. Intern Med. 2010;49(15):1521-1526. https://doi.org/10.2169/internalmedicine.49.3572.

15. Ikusaka M, Kamegai M, Sunaga T, et al. Patients’ attitude toward consultations by a physician without a white coat in Japan. Intern Med. 1999;38(7):533-536. https://doi.org/10.2169/internalmedicine.38.533.

16. Lefor AK, Ohnuma T, Nunomiya S, Yokota S, Makino J, Sanui M. Physician attire in the intensive care unit in Japan influences visitors’ perception of care. J Crit Care. 2018;43:288-293.

17. Kurihara H, Maeno T. Importance of physicians’ attire: factors influencing the impression it makes on patients, a cross-sectional study. Asia Pac Fam Med. 2014;13(1):2. https://doi.org/10.1186/1447-056X-13-2.

18. Zollinger M, Houchens N, Chopra V, et al. Understanding patient preference for physician attire in ambulatory clinics: a cross-sectional observational study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(5):e026009. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026009.

19. Chung JE. Medical Dramas and Viewer Perception of Health: Testing Cultivation Effects. Hum Commun Res. 2014;40(3):333-349.

20. Michael Pfau LJM, Kirsten Garrow. The influence of television viewing on public perceptions of physicians. J Broadcast Electron Media. 1995;39(4):441-458.

21. Suzuki S. Exhausting physicians employed in hospitals in Japan assessed by a health questionnaire [in Japanese]. Sangyo Eiseigaku Zasshi. 2017;59(4):107-118. https://doi.org/10.1539/sangyoeisei.

22. Ogawa R, Seo E, Maeno T, Ito M, Sanuki M. The relationship between long working hours and depression among first-year residents in Japan. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):50. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-018-1171-9.

23. Saijo Y, Chiba S, Yoshioka E, et al. Effects of work burden, job strain and support on depressive symptoms and burnout among Japanese physicians. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2014;27(6):980-992. https://doi.org/10.2478/s13382-014-0324-2.

24. Tiang KW, Razack AH, Ng KL. The ‘auxiliary’ white coat effect in hospitals: perceptions of patients and doctors. Singapore Med J. 2017;58(10):574-575. https://doi.org/10.11622/smedj.2017023.

25. Al Amry KM, Al Farrah M, Ur Rahman S, Abdulmajeed I. Patient perceptions and preferences of physicians’ attire in Saudi primary healthcare setting. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2018;8(6):326-330. https://doi.org/10.1080/20009666.2018.1551026.

26. Healy WL. Letter to the editor: editor’s spotlight/take 5: physicians’ attire influences patients’ perceptions in the urban outpatient orthopaedic surgery setting. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474(11):2545-2546. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-016-5049-z.

27. Aldrees T, Alsuhaibani R, Alqaryan S, et al. Physicians’ attire. Parents preferences in a tertiary hospital. Saudi Med J. 2017;38(4):435-439. https://doi.org/10.15537/smj.2017.4.15853.

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine