User login

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

To the Editor: We read with interest the article by Young et al on hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM)1 and would like to raise a few important points.

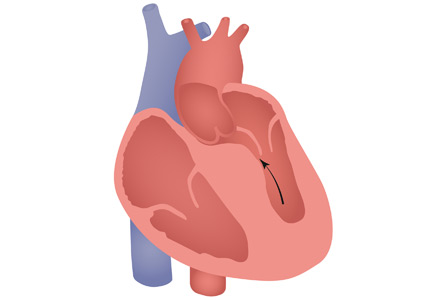

HCM has a complex phenotypic expression and doesn’t necessarily involve left ventricular outflow obstruction. Midventricular obstruction is a unique subtype of HCM, with increased risk of left ventricular apical aneurysm (LVAA) formation. We reported that 25% of HCM patients with midventricular obstruction progress to LVAA compared with 0.3% of patients with other HCM subtypes.2 Magnetic resonance imaging plays a pivotal role in assessing midventricular obstruction, owing to asymmetric geometry of the left ventricle and the shortcomings of echocardiography in assessing the apical aneurysm.2

Anticoagulation remains one of the cornerstones in treating midventricular obstruction with LVAA. We performed a systematic review and found a high prevalence of atrial arrhythmia, apical thrombus, and stroke, which necessitated anticoagulation in one-fifth of patients.2

Ventricular arrhythmias are prevalent in midventricular obstruction with LVAA, mainly from increased fibrosis formation at the apical rim.3 In our review, 25.7% of patients with midventricular obstruction with LVAA and an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) experienced appropriate shocks.2 Our finding was in line with those of Rowin et al,3 who showed appropriate ICD shocks in one-third of HCM patients with apical aneurysm. Apical aneurysm is currently considered an independent risk factor for sudden cardiac death in HCM, with an increased rate of sudden death of up to 5% every year.3,4

It is imperative to distinguish midventricular obstruction with LVAA as a unique disease imposing a higher risk of thromboembolism, ventricular arrhythmia, and progression to end-stage heart failure.3 We suggest that those patients be evaluated early in the course of disease for anticoagulation, ICD implantation, and early surgical intervention.2

- Young L, Smedira NG, Tower-Rader A, Lever H, Desai MY. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a complex disease. Cleve Clin J Med 2018; 85(5):399–411. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a.17076

- Elsheshtawy MO, Mahmoud AN, Abdelghany M, Suen IH, Sadiq A, Shani J. Left ventricular aneurysms in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with midventricular obstruction: a systematic review of literature. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2018 May 22. doi:10.1111/pace.13380. [Epub ahead of print].

- Rowin EJ, Maron BJ, Haas TS, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with left ventricular apical aneurysm: implications for risk stratification and management. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69(7):761–773. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.11.063

- Spirito P. Saving more lives. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69(7): 774–776. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.12.010

To the Editor: We read with interest the article by Young et al on hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM)1 and would like to raise a few important points.

HCM has a complex phenotypic expression and doesn’t necessarily involve left ventricular outflow obstruction. Midventricular obstruction is a unique subtype of HCM, with increased risk of left ventricular apical aneurysm (LVAA) formation. We reported that 25% of HCM patients with midventricular obstruction progress to LVAA compared with 0.3% of patients with other HCM subtypes.2 Magnetic resonance imaging plays a pivotal role in assessing midventricular obstruction, owing to asymmetric geometry of the left ventricle and the shortcomings of echocardiography in assessing the apical aneurysm.2

Anticoagulation remains one of the cornerstones in treating midventricular obstruction with LVAA. We performed a systematic review and found a high prevalence of atrial arrhythmia, apical thrombus, and stroke, which necessitated anticoagulation in one-fifth of patients.2

Ventricular arrhythmias are prevalent in midventricular obstruction with LVAA, mainly from increased fibrosis formation at the apical rim.3 In our review, 25.7% of patients with midventricular obstruction with LVAA and an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) experienced appropriate shocks.2 Our finding was in line with those of Rowin et al,3 who showed appropriate ICD shocks in one-third of HCM patients with apical aneurysm. Apical aneurysm is currently considered an independent risk factor for sudden cardiac death in HCM, with an increased rate of sudden death of up to 5% every year.3,4

It is imperative to distinguish midventricular obstruction with LVAA as a unique disease imposing a higher risk of thromboembolism, ventricular arrhythmia, and progression to end-stage heart failure.3 We suggest that those patients be evaluated early in the course of disease for anticoagulation, ICD implantation, and early surgical intervention.2

To the Editor: We read with interest the article by Young et al on hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM)1 and would like to raise a few important points.

HCM has a complex phenotypic expression and doesn’t necessarily involve left ventricular outflow obstruction. Midventricular obstruction is a unique subtype of HCM, with increased risk of left ventricular apical aneurysm (LVAA) formation. We reported that 25% of HCM patients with midventricular obstruction progress to LVAA compared with 0.3% of patients with other HCM subtypes.2 Magnetic resonance imaging plays a pivotal role in assessing midventricular obstruction, owing to asymmetric geometry of the left ventricle and the shortcomings of echocardiography in assessing the apical aneurysm.2

Anticoagulation remains one of the cornerstones in treating midventricular obstruction with LVAA. We performed a systematic review and found a high prevalence of atrial arrhythmia, apical thrombus, and stroke, which necessitated anticoagulation in one-fifth of patients.2

Ventricular arrhythmias are prevalent in midventricular obstruction with LVAA, mainly from increased fibrosis formation at the apical rim.3 In our review, 25.7% of patients with midventricular obstruction with LVAA and an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) experienced appropriate shocks.2 Our finding was in line with those of Rowin et al,3 who showed appropriate ICD shocks in one-third of HCM patients with apical aneurysm. Apical aneurysm is currently considered an independent risk factor for sudden cardiac death in HCM, with an increased rate of sudden death of up to 5% every year.3,4

It is imperative to distinguish midventricular obstruction with LVAA as a unique disease imposing a higher risk of thromboembolism, ventricular arrhythmia, and progression to end-stage heart failure.3 We suggest that those patients be evaluated early in the course of disease for anticoagulation, ICD implantation, and early surgical intervention.2

- Young L, Smedira NG, Tower-Rader A, Lever H, Desai MY. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a complex disease. Cleve Clin J Med 2018; 85(5):399–411. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a.17076

- Elsheshtawy MO, Mahmoud AN, Abdelghany M, Suen IH, Sadiq A, Shani J. Left ventricular aneurysms in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with midventricular obstruction: a systematic review of literature. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2018 May 22. doi:10.1111/pace.13380. [Epub ahead of print].

- Rowin EJ, Maron BJ, Haas TS, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with left ventricular apical aneurysm: implications for risk stratification and management. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69(7):761–773. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.11.063

- Spirito P. Saving more lives. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69(7): 774–776. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.12.010

- Young L, Smedira NG, Tower-Rader A, Lever H, Desai MY. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a complex disease. Cleve Clin J Med 2018; 85(5):399–411. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a.17076

- Elsheshtawy MO, Mahmoud AN, Abdelghany M, Suen IH, Sadiq A, Shani J. Left ventricular aneurysms in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with midventricular obstruction: a systematic review of literature. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2018 May 22. doi:10.1111/pace.13380. [Epub ahead of print].

- Rowin EJ, Maron BJ, Haas TS, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with left ventricular apical aneurysm: implications for risk stratification and management. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69(7):761–773. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.11.063

- Spirito P. Saving more lives. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69(7): 774–776. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.12.010

Osborn waves of hypothermia

A 40-year-old man was brought to the emergency department with altered mental status. His roommate had found him lying unconscious in snow on the lawn outside his residence. When the emergency medical services team arrived, they recorded a core body temperature of 28.3°C (82.9°F) and instituted advanced cardiac life support.

During transit to the hospital, the patient’s heart rhythm changed from asystole to ventricular fibrillation, and defibrillation was performed twice.

Upon his arrival at the emergency room, advanced life support was continued, resulting in return of spontaneous circulation, with slow, wide-complex QRS rhythm noted on electrocardiography (ECG).

On examination, the patient’s pupils were fixed and dilated. The extremities were cold to palpation. The core body temperature dropped to 27.7°C (81.9°F).

Laboratory test results showed severe acidemia (arterial pH 6.8), elevated aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase levels, and elevated creatinine and troponin. The troponin was measured 3 times and rose from 0.8 ng/mL to 0.9 ng/mL. A urine toxicology screen was positive for cannabinoids and cocaine.

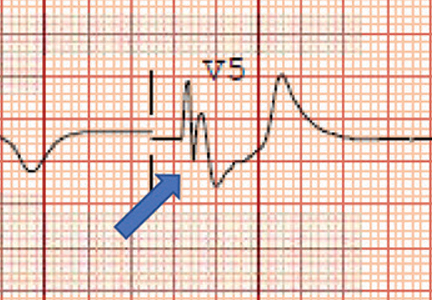

ECG revealed J-point elevation (Osborn waves) in the precordial leads (Figure 1). A baseline electrocardiogram in the medical record from a previous admission had been normal.

An aggressive hypothermia protocol was initiated, but the patient died despite resuscitation efforts.

HYPOTHERMIA AND HEART RHYTHMS

Hypothermia—a core body temperature below 35°C (95°F)—causes generalized slowing of impulse conduction through cardiac tissues, shown on ECG as a prolongation of the PR, RR, QRS, and QT intervals.1

A characteristic feature is elevation of the J point, also called the J wave or Osborn wave, most prominent in precordial leads V2 to V5 and caused by abnormal membrane repolarization in the early phase. The degree of hypothermia correlates linearly with the amplitude of the Osborn wave.2,3

Laboratory tests can identify complications such as rhabdomyolysis, spontaneous bleeding, and lactic acidosis. Moderate to severe hypothermia may cause prolongation of all ECG intervals. Management requires resuscitation and rewarming.

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis are Brugada syndrome, hypercalcemia, and early repolarization syndrome.

- Doshi HH, Giudici MC. The EKG in hypothermia and hyperthermia. J Electrocardiol 2015; 48:203–208.

- Alsafwah S. Electrocardiographic changes in hypothermia. Heart Lung 2001; 30:161–163.

- Graham CA, McNaughton GW, Wyatt JP. The electrocardiogram in hypothermia. Wilderness Environ Med 2001; 12:232–235.

A 40-year-old man was brought to the emergency department with altered mental status. His roommate had found him lying unconscious in snow on the lawn outside his residence. When the emergency medical services team arrived, they recorded a core body temperature of 28.3°C (82.9°F) and instituted advanced cardiac life support.

During transit to the hospital, the patient’s heart rhythm changed from asystole to ventricular fibrillation, and defibrillation was performed twice.

Upon his arrival at the emergency room, advanced life support was continued, resulting in return of spontaneous circulation, with slow, wide-complex QRS rhythm noted on electrocardiography (ECG).

On examination, the patient’s pupils were fixed and dilated. The extremities were cold to palpation. The core body temperature dropped to 27.7°C (81.9°F).

Laboratory test results showed severe acidemia (arterial pH 6.8), elevated aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase levels, and elevated creatinine and troponin. The troponin was measured 3 times and rose from 0.8 ng/mL to 0.9 ng/mL. A urine toxicology screen was positive for cannabinoids and cocaine.

ECG revealed J-point elevation (Osborn waves) in the precordial leads (Figure 1). A baseline electrocardiogram in the medical record from a previous admission had been normal.

An aggressive hypothermia protocol was initiated, but the patient died despite resuscitation efforts.

HYPOTHERMIA AND HEART RHYTHMS

Hypothermia—a core body temperature below 35°C (95°F)—causes generalized slowing of impulse conduction through cardiac tissues, shown on ECG as a prolongation of the PR, RR, QRS, and QT intervals.1

A characteristic feature is elevation of the J point, also called the J wave or Osborn wave, most prominent in precordial leads V2 to V5 and caused by abnormal membrane repolarization in the early phase. The degree of hypothermia correlates linearly with the amplitude of the Osborn wave.2,3

Laboratory tests can identify complications such as rhabdomyolysis, spontaneous bleeding, and lactic acidosis. Moderate to severe hypothermia may cause prolongation of all ECG intervals. Management requires resuscitation and rewarming.

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis are Brugada syndrome, hypercalcemia, and early repolarization syndrome.

A 40-year-old man was brought to the emergency department with altered mental status. His roommate had found him lying unconscious in snow on the lawn outside his residence. When the emergency medical services team arrived, they recorded a core body temperature of 28.3°C (82.9°F) and instituted advanced cardiac life support.

During transit to the hospital, the patient’s heart rhythm changed from asystole to ventricular fibrillation, and defibrillation was performed twice.

Upon his arrival at the emergency room, advanced life support was continued, resulting in return of spontaneous circulation, with slow, wide-complex QRS rhythm noted on electrocardiography (ECG).

On examination, the patient’s pupils were fixed and dilated. The extremities were cold to palpation. The core body temperature dropped to 27.7°C (81.9°F).

Laboratory test results showed severe acidemia (arterial pH 6.8), elevated aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase levels, and elevated creatinine and troponin. The troponin was measured 3 times and rose from 0.8 ng/mL to 0.9 ng/mL. A urine toxicology screen was positive for cannabinoids and cocaine.

ECG revealed J-point elevation (Osborn waves) in the precordial leads (Figure 1). A baseline electrocardiogram in the medical record from a previous admission had been normal.

An aggressive hypothermia protocol was initiated, but the patient died despite resuscitation efforts.

HYPOTHERMIA AND HEART RHYTHMS

Hypothermia—a core body temperature below 35°C (95°F)—causes generalized slowing of impulse conduction through cardiac tissues, shown on ECG as a prolongation of the PR, RR, QRS, and QT intervals.1

A characteristic feature is elevation of the J point, also called the J wave or Osborn wave, most prominent in precordial leads V2 to V5 and caused by abnormal membrane repolarization in the early phase. The degree of hypothermia correlates linearly with the amplitude of the Osborn wave.2,3

Laboratory tests can identify complications such as rhabdomyolysis, spontaneous bleeding, and lactic acidosis. Moderate to severe hypothermia may cause prolongation of all ECG intervals. Management requires resuscitation and rewarming.

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis are Brugada syndrome, hypercalcemia, and early repolarization syndrome.

- Doshi HH, Giudici MC. The EKG in hypothermia and hyperthermia. J Electrocardiol 2015; 48:203–208.

- Alsafwah S. Electrocardiographic changes in hypothermia. Heart Lung 2001; 30:161–163.

- Graham CA, McNaughton GW, Wyatt JP. The electrocardiogram in hypothermia. Wilderness Environ Med 2001; 12:232–235.

- Doshi HH, Giudici MC. The EKG in hypothermia and hyperthermia. J Electrocardiol 2015; 48:203–208.

- Alsafwah S. Electrocardiographic changes in hypothermia. Heart Lung 2001; 30:161–163.

- Graham CA, McNaughton GW, Wyatt JP. The electrocardiogram in hypothermia. Wilderness Environ Med 2001; 12:232–235.