User login

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

To the Editor: We read with interest the article by Young et al on hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM)1 and would like to raise a few important points.

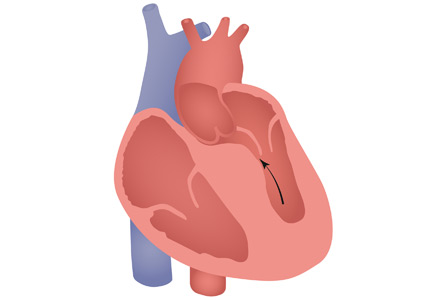

HCM has a complex phenotypic expression and doesn’t necessarily involve left ventricular outflow obstruction. Midventricular obstruction is a unique subtype of HCM, with increased risk of left ventricular apical aneurysm (LVAA) formation. We reported that 25% of HCM patients with midventricular obstruction progress to LVAA compared with 0.3% of patients with other HCM subtypes.2 Magnetic resonance imaging plays a pivotal role in assessing midventricular obstruction, owing to asymmetric geometry of the left ventricle and the shortcomings of echocardiography in assessing the apical aneurysm.2

Anticoagulation remains one of the cornerstones in treating midventricular obstruction with LVAA. We performed a systematic review and found a high prevalence of atrial arrhythmia, apical thrombus, and stroke, which necessitated anticoagulation in one-fifth of patients.2

Ventricular arrhythmias are prevalent in midventricular obstruction with LVAA, mainly from increased fibrosis formation at the apical rim.3 In our review, 25.7% of patients with midventricular obstruction with LVAA and an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) experienced appropriate shocks.2 Our finding was in line with those of Rowin et al,3 who showed appropriate ICD shocks in one-third of HCM patients with apical aneurysm. Apical aneurysm is currently considered an independent risk factor for sudden cardiac death in HCM, with an increased rate of sudden death of up to 5% every year.3,4

It is imperative to distinguish midventricular obstruction with LVAA as a unique disease imposing a higher risk of thromboembolism, ventricular arrhythmia, and progression to end-stage heart failure.3 We suggest that those patients be evaluated early in the course of disease for anticoagulation, ICD implantation, and early surgical intervention.2

- Young L, Smedira NG, Tower-Rader A, Lever H, Desai MY. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a complex disease. Cleve Clin J Med 2018; 85(5):399–411. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a.17076

- Elsheshtawy MO, Mahmoud AN, Abdelghany M, Suen IH, Sadiq A, Shani J. Left ventricular aneurysms in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with midventricular obstruction: a systematic review of literature. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2018 May 22. doi:10.1111/pace.13380. [Epub ahead of print].

- Rowin EJ, Maron BJ, Haas TS, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with left ventricular apical aneurysm: implications for risk stratification and management. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69(7):761–773. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.11.063

- Spirito P. Saving more lives. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69(7): 774–776. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.12.010

To the Editor: We read with interest the article by Young et al on hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM)1 and would like to raise a few important points.

HCM has a complex phenotypic expression and doesn’t necessarily involve left ventricular outflow obstruction. Midventricular obstruction is a unique subtype of HCM, with increased risk of left ventricular apical aneurysm (LVAA) formation. We reported that 25% of HCM patients with midventricular obstruction progress to LVAA compared with 0.3% of patients with other HCM subtypes.2 Magnetic resonance imaging plays a pivotal role in assessing midventricular obstruction, owing to asymmetric geometry of the left ventricle and the shortcomings of echocardiography in assessing the apical aneurysm.2

Anticoagulation remains one of the cornerstones in treating midventricular obstruction with LVAA. We performed a systematic review and found a high prevalence of atrial arrhythmia, apical thrombus, and stroke, which necessitated anticoagulation in one-fifth of patients.2

Ventricular arrhythmias are prevalent in midventricular obstruction with LVAA, mainly from increased fibrosis formation at the apical rim.3 In our review, 25.7% of patients with midventricular obstruction with LVAA and an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) experienced appropriate shocks.2 Our finding was in line with those of Rowin et al,3 who showed appropriate ICD shocks in one-third of HCM patients with apical aneurysm. Apical aneurysm is currently considered an independent risk factor for sudden cardiac death in HCM, with an increased rate of sudden death of up to 5% every year.3,4

It is imperative to distinguish midventricular obstruction with LVAA as a unique disease imposing a higher risk of thromboembolism, ventricular arrhythmia, and progression to end-stage heart failure.3 We suggest that those patients be evaluated early in the course of disease for anticoagulation, ICD implantation, and early surgical intervention.2

To the Editor: We read with interest the article by Young et al on hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM)1 and would like to raise a few important points.

HCM has a complex phenotypic expression and doesn’t necessarily involve left ventricular outflow obstruction. Midventricular obstruction is a unique subtype of HCM, with increased risk of left ventricular apical aneurysm (LVAA) formation. We reported that 25% of HCM patients with midventricular obstruction progress to LVAA compared with 0.3% of patients with other HCM subtypes.2 Magnetic resonance imaging plays a pivotal role in assessing midventricular obstruction, owing to asymmetric geometry of the left ventricle and the shortcomings of echocardiography in assessing the apical aneurysm.2

Anticoagulation remains one of the cornerstones in treating midventricular obstruction with LVAA. We performed a systematic review and found a high prevalence of atrial arrhythmia, apical thrombus, and stroke, which necessitated anticoagulation in one-fifth of patients.2

Ventricular arrhythmias are prevalent in midventricular obstruction with LVAA, mainly from increased fibrosis formation at the apical rim.3 In our review, 25.7% of patients with midventricular obstruction with LVAA and an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) experienced appropriate shocks.2 Our finding was in line with those of Rowin et al,3 who showed appropriate ICD shocks in one-third of HCM patients with apical aneurysm. Apical aneurysm is currently considered an independent risk factor for sudden cardiac death in HCM, with an increased rate of sudden death of up to 5% every year.3,4

It is imperative to distinguish midventricular obstruction with LVAA as a unique disease imposing a higher risk of thromboembolism, ventricular arrhythmia, and progression to end-stage heart failure.3 We suggest that those patients be evaluated early in the course of disease for anticoagulation, ICD implantation, and early surgical intervention.2

- Young L, Smedira NG, Tower-Rader A, Lever H, Desai MY. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a complex disease. Cleve Clin J Med 2018; 85(5):399–411. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a.17076

- Elsheshtawy MO, Mahmoud AN, Abdelghany M, Suen IH, Sadiq A, Shani J. Left ventricular aneurysms in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with midventricular obstruction: a systematic review of literature. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2018 May 22. doi:10.1111/pace.13380. [Epub ahead of print].

- Rowin EJ, Maron BJ, Haas TS, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with left ventricular apical aneurysm: implications for risk stratification and management. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69(7):761–773. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.11.063

- Spirito P. Saving more lives. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69(7): 774–776. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.12.010

- Young L, Smedira NG, Tower-Rader A, Lever H, Desai MY. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a complex disease. Cleve Clin J Med 2018; 85(5):399–411. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a.17076

- Elsheshtawy MO, Mahmoud AN, Abdelghany M, Suen IH, Sadiq A, Shani J. Left ventricular aneurysms in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with midventricular obstruction: a systematic review of literature. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2018 May 22. doi:10.1111/pace.13380. [Epub ahead of print].

- Rowin EJ, Maron BJ, Haas TS, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with left ventricular apical aneurysm: implications for risk stratification and management. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69(7):761–773. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.11.063

- Spirito P. Saving more lives. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69(7): 774–776. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.12.010

Cardiac mass: Tumor or thrombus?

To the Editor: We read with great interest the article by Patnaik et al1 about a patient who had a cardiac metastasis of ovarian cancer, and we would like to raise a few points.

It is important to clarify that metastatic cardiac tumors are not necessary malignant. Intravenous leiomyomatosis is a benign small-muscle tumor that can spread to the heart, causing various cardiac symptoms.2 Even with extensive disease, patients with intravenous leiomyomatosis may remain asymptomatic until cardiac involvement occurs. The most common cardiac symptoms are dyspnea, syncope, and lower-extremity edema.

Cardiac involvement in intravenous leiomyomatosis may occur via direct invasion or hematogenous or lymphatic spread of the tumor. In leiomyoma and leiomyosarcoma, cardiac invasion usually occurs via direct spread through the inferior vena cava into the right atrium and ventricle. Thus, cardiac involvement with these tumors (except for nephroma) was reported to exclusively involve the right side of the heart.

In 2014, we reported a unique case of intravenous leiomyomatosis that extended from the right side into the left side of the heart and the aorta via an atrial septal defect.2 Intracardiac extension of intravenous leiomyomatosis may result in pulmonary embolism, systemic embolization if involving the left side, and, rarely, sudden death.2

In patients with malignancy, differentiating between thrombosis and tumor is critical. These patients have a hypercoagulable state and a fourfold increase in thrombosis risk, and chemotherapy increases this risk even more.3 Although tissue pathology examination is important for differentiating thrombosis from tumor, visualization of the direct extension of the mass from the primary source into the heart through the inferior vena cava by ultrasonography, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging may help in making this distinction.2

- Patnaik S, Shah M, Sharma S, Ram P, Rammohan HS, Rubin A. A large mass in the right ventricle: tumor or thrombus? Cleve Clin J Med 2017; 84:517–519.

- Abdelghany M, Sodagam A, Patel P, Goldblatt C, Patel R. Intracardiac atypical leiomyoma involving all four cardiac chambers and the aorta. Rev Cardiovasc Med 2014; 15:271–275.

- Khorana AA, Kuderer NM, Culakova E, Lyman GH, Francis CW. Development and validation of a predictive model for chemotherapy-associated thrombosis. Blood 2008; 111:4902–4907.

To the Editor: We read with great interest the article by Patnaik et al1 about a patient who had a cardiac metastasis of ovarian cancer, and we would like to raise a few points.

It is important to clarify that metastatic cardiac tumors are not necessary malignant. Intravenous leiomyomatosis is a benign small-muscle tumor that can spread to the heart, causing various cardiac symptoms.2 Even with extensive disease, patients with intravenous leiomyomatosis may remain asymptomatic until cardiac involvement occurs. The most common cardiac symptoms are dyspnea, syncope, and lower-extremity edema.

Cardiac involvement in intravenous leiomyomatosis may occur via direct invasion or hematogenous or lymphatic spread of the tumor. In leiomyoma and leiomyosarcoma, cardiac invasion usually occurs via direct spread through the inferior vena cava into the right atrium and ventricle. Thus, cardiac involvement with these tumors (except for nephroma) was reported to exclusively involve the right side of the heart.

In 2014, we reported a unique case of intravenous leiomyomatosis that extended from the right side into the left side of the heart and the aorta via an atrial septal defect.2 Intracardiac extension of intravenous leiomyomatosis may result in pulmonary embolism, systemic embolization if involving the left side, and, rarely, sudden death.2

In patients with malignancy, differentiating between thrombosis and tumor is critical. These patients have a hypercoagulable state and a fourfold increase in thrombosis risk, and chemotherapy increases this risk even more.3 Although tissue pathology examination is important for differentiating thrombosis from tumor, visualization of the direct extension of the mass from the primary source into the heart through the inferior vena cava by ultrasonography, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging may help in making this distinction.2

To the Editor: We read with great interest the article by Patnaik et al1 about a patient who had a cardiac metastasis of ovarian cancer, and we would like to raise a few points.

It is important to clarify that metastatic cardiac tumors are not necessary malignant. Intravenous leiomyomatosis is a benign small-muscle tumor that can spread to the heart, causing various cardiac symptoms.2 Even with extensive disease, patients with intravenous leiomyomatosis may remain asymptomatic until cardiac involvement occurs. The most common cardiac symptoms are dyspnea, syncope, and lower-extremity edema.

Cardiac involvement in intravenous leiomyomatosis may occur via direct invasion or hematogenous or lymphatic spread of the tumor. In leiomyoma and leiomyosarcoma, cardiac invasion usually occurs via direct spread through the inferior vena cava into the right atrium and ventricle. Thus, cardiac involvement with these tumors (except for nephroma) was reported to exclusively involve the right side of the heart.

In 2014, we reported a unique case of intravenous leiomyomatosis that extended from the right side into the left side of the heart and the aorta via an atrial septal defect.2 Intracardiac extension of intravenous leiomyomatosis may result in pulmonary embolism, systemic embolization if involving the left side, and, rarely, sudden death.2

In patients with malignancy, differentiating between thrombosis and tumor is critical. These patients have a hypercoagulable state and a fourfold increase in thrombosis risk, and chemotherapy increases this risk even more.3 Although tissue pathology examination is important for differentiating thrombosis from tumor, visualization of the direct extension of the mass from the primary source into the heart through the inferior vena cava by ultrasonography, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging may help in making this distinction.2

- Patnaik S, Shah M, Sharma S, Ram P, Rammohan HS, Rubin A. A large mass in the right ventricle: tumor or thrombus? Cleve Clin J Med 2017; 84:517–519.

- Abdelghany M, Sodagam A, Patel P, Goldblatt C, Patel R. Intracardiac atypical leiomyoma involving all four cardiac chambers and the aorta. Rev Cardiovasc Med 2014; 15:271–275.

- Khorana AA, Kuderer NM, Culakova E, Lyman GH, Francis CW. Development and validation of a predictive model for chemotherapy-associated thrombosis. Blood 2008; 111:4902–4907.

- Patnaik S, Shah M, Sharma S, Ram P, Rammohan HS, Rubin A. A large mass in the right ventricle: tumor or thrombus? Cleve Clin J Med 2017; 84:517–519.

- Abdelghany M, Sodagam A, Patel P, Goldblatt C, Patel R. Intracardiac atypical leiomyoma involving all four cardiac chambers and the aorta. Rev Cardiovasc Med 2014; 15:271–275.

- Khorana AA, Kuderer NM, Culakova E, Lyman GH, Francis CW. Development and validation of a predictive model for chemotherapy-associated thrombosis. Blood 2008; 111:4902–4907.