User login

Verrucous Scalp Plaque and Widespread Eruption

The Diagnosis: Pemphigus Foliaceous

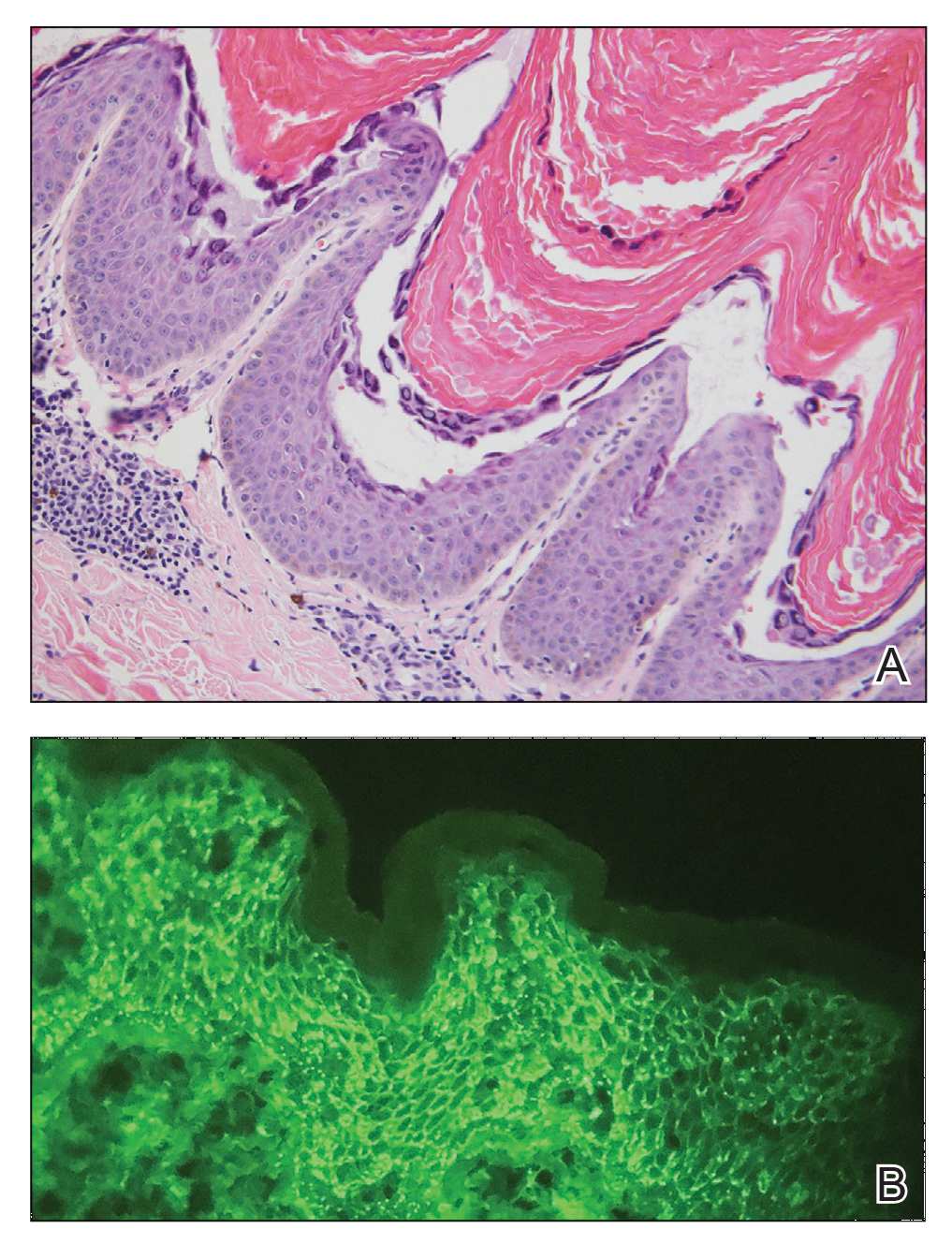

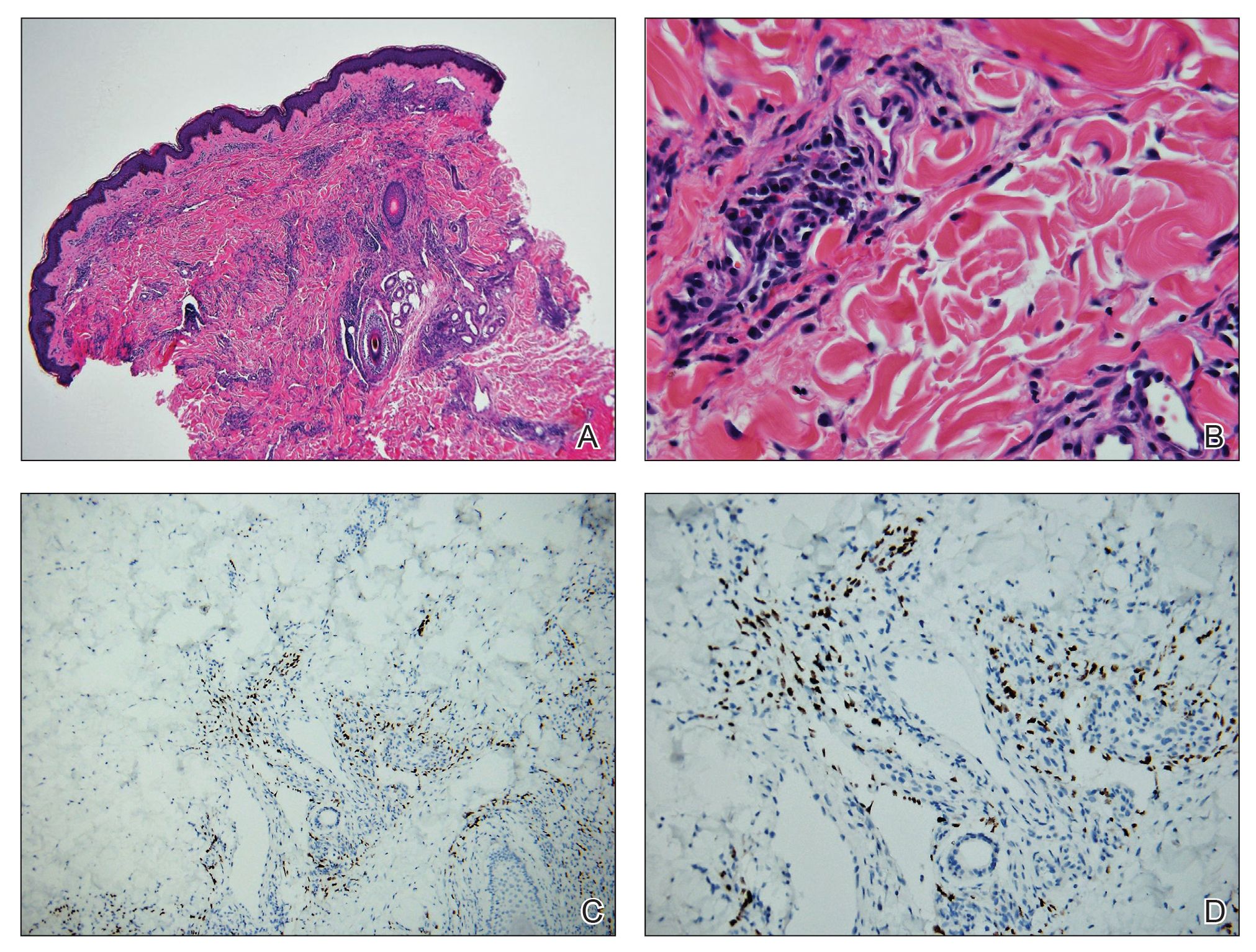

Laboratory workup including a complete blood cell count with differential, comprehensive metabolic panel, antinuclear antibodies, Sjögren syndrome A and B antibodies, hepatitis profile, rapid plasma reagin, HIV screen, aldolase, anti–Jo-1, T-Spot TB test (Quest Diagnostics), and tissue cultures was unremarkable. Two 4-mm punch biopsies were obtained from the left cheek and upper back, both of which demonstrated intragranular acantholysis suggestive of pemphigus foliaceous (Figure 1A). A subsequent punch biopsy from the right lower abdomen sent for direct immunofluorescence demonstrated netlike positivity of IgG and C3 in the upper epidermis (Figure 1B), and serum sent for indirect immunofluorescence demonstrated intercellular IgG antibodies to desmoglein (Dsg) 1 on monkey esophagus and positive Dsg-1 antibodies on enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, confirming the diagnosis.

The patient was started on a 60-mg prednisone taper as well as dapsone 50 mg daily; the dapsone was titrated up to 100 mg daily. After tapering down to 10 mg daily of prednisone over 2 months and continuing dapsone with minimal improvement, he was given 2 infusions of rituximab 1000 mg 2 weeks apart. The scalp plaque was dramatically improved at 3-month follow-up (Figure 2), with partial improvement of the cheek plaques (Figure 3). Dapsone was increased to 150 mg daily, and he was encouraged to use triamcinolone acetonide ointment 0.1% twice daily, which led to further improvement.

Pemphigus foliaceus is an autoimmune blistering disease that most commonly occurs in middle-aged adults. It generally is less common than pemphigus vulgaris, except in Finland, Tunisia, and Brazil, where there is an endemic condition with an identical clinical and histological presentation known as fogo selvagem.1

The pathogenesis of pemphigus foliaceous is characterized by IgG autoantibodies against Dsg-1, a transmembrane glycoprotein involved in the cellular adhesion of keratinocytes, which is preferentially expressed in the superficial epidermis.2-7 Dysfunction of Dsg-1 results in the separation of superficial epidermal cells, resulting in intraepidermal blisters.2,7 In contrast to pemphigus vulgaris, there typically is a lack of oral mucosal involvement due to compensation by Dsg-3 in the mucosa.4 Potential triggers for pemphigus foliaceous include exposure to UV radiation; radiotherapy; pregnancy; physiologic stress; and drugs, most commonly captopril, penicillamine, and thiols.8

Pemphigus foliaceous lesions clinically appear as eroded and crusted lesions on an erythematous base, commonly in a seborrheic distribution on the face, scalp, and trunk with sparing of the oral mucosa,2,6 but lesions can progress to a widespread and more severe exfoliative dermatitis.7 Lesions also can appear as psoriasiform plaques and often are initially misdiagnosed as psoriasis, particularly in patients with skin of color.9,10

Diagnosis of pemphigus foliaceous typically is made using a combination of histology as well as both direct and indirect immunofluorescence. Histologically, pemphigus foliaceus presents with subcorneal acantholysis, which is most prominent in the granular layer and occasionally the presence of neutrophils and eosinophils in the blister cavity.7 Direct immunofluorescence demonstrates netlike intercellular IgG and C3 in the upper portion of the epidermis.11 Indirect immunofluorescence can help detect circulating IgG antibodies to Dsg-1, with guinea pig esophagus being the ideal substrate.11,12

First-line treatment of pemphigus foliaceus consists of systemic glucocorticoid therapy, often administered with azathioprine, methotrexate, or mycophenolate mofetil.2,6,13 Although first-line treatment is effective in 60% to 80% of patients,2 relapsing cases can be treated with cyclophosphamide, intravenous immunoglobulin, immunoadsorption, plasmapheresis, or rituximab.2

Rituximab is a chimeric monoclonal antibody targeting CD20+ B cells, leading to decreased antibody production, which has been shown to be effective in treating severe and refractory cases of pemphigus foliaceus.6,13Rituximab with short-course prednisone has been found to be more effective in achieving complete remission at 24 months than prednisone alone.14 In patients with contraindications to systemic glucocorticoid therapy, rituximab has been shown as an effective first-line therapy.15 One-quarter of patients treated with rituximab relapsed within 2 years of treatment6 (average time to relapse, 6–26 months).16 High-dose rituximab regimens, along with a higher number of rituximab treatment cycles, have been shown to prolong time to relapse.6 Further, higher baseline levels of Dsg-1 antibody have been correlated to earlier relapse and can be used following rituximab therapy to monitor disease progression.6,16

The differential diagnosis for pemphigus foliaceous includes disseminated blastomycosis, hypertrophic lupus erythematosus, sebopsoriasis, and secondary syphilis. Disseminated blastomycosis presents with cutaneous manifestations such as nodules, papules, or pustules evolving over weeks to months into ulcers with subsequent scarring.17 Hypertrophic lupus erythematosus presents with papules and nodules with associated keratotic scaling on the face, palms, and extensor surfaces of the limbs.18 Sebopsoriasis is characterized by well-defined lesions with an overlying scale distributed on the scalp, face, and chest.19 Secondary syphilis presents as early hyperpigmented macules transitioning to acral papulosquamous lesions involving the palms and soles.20

- Hans-Filho G, Aoki V, Hans Bittner NR, et al. Fogo selvagem: endemic pemphigus foliaceus. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:638-650.

- Jenson KK, Burr DM, Edwards BC. Case report: reatment of refractory pemphigus foliaceus with rituximab. Practical Dermatology. February 2016:33-36. Accessed August 27, 2021. https://practicaldermatology.com/articles/2016-feb/case-report -treatment-of-refractory-pemphigus-foliaceus-with-rituximab -financial-matters-aad-asds-resources

- Amagai M, Hashimoto T, Green KJ, et al. Antigen-specific immunoadsorption of pathogenic autoantibodies in pemphigus foliaceus. J Invest Dermatol. 1995;104:895-901.

- Mahoney MG, Wang Z, Rothenberger K, et al. Explanations for the clinical and microscopic localization of lesions in pemphigus foliaceus and vulgaris. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:461-468.

- Oktarina DAM, Sokol E, Kramer D, et al. Endocytosis of IgG, desmoglein 1, and plakoglobin in pemphigus foliaceus patient skin. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1-12.

- Kraft M, Worm M. Pemphigus foliaceus-repeated treatment with rituximab 7 years after initial response: a case report. Front Med. 2018;5:315.

- Hale EK. Pemphigus foliaceous. Dermatol Online J. 2002;8:9.

- Tavakolpour S. Pemphigus trigger factors: special focus on pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus. Arch Dermatol Res. 2018;310:95-106.

- A boobaker J, Morar N, Ramdial PK, et al. Pemphigus in South Africa. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:115-119.

- Austin E, Millsop JW, Ely H, et al. Psoriasiform pemphigus foliaceus in an African American female: an important clinical manifestation. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:471.

- Arbache ST, Nogueira TG, Delgado L, et al. Immunofluorescence testing in the diagnosis of autoimmune blistering diseases: overview of 10-year experience. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:885-889.

- Sabolinski ML, Beutner EH, Krasny S, et al. Substrate specificity of antiepithelial antibodies of pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus sera in immunofluorescence tests on monkey and guinea pig esophagus sections. J Invest Dermatol. 1987;88:545-549.

- Palacios-Álvarez I, Riquelme-McLoughlin C, Curto-Barredo L, et al. Rituximab treatment of pemphigus foliaceus: a retrospective study of 12 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:484-486.

- Murrell DF, Sprecher E. Rituximab and short-course prednisone as the new gold standard for new-onset pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:1143-1144.

- Gregoriou S, Efthymiou O, Stefanaki C, et al. Management of pemphigus vulgaris: challenges and solutions. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2015;8:521-527.

- Saleh MA. A prospective study comparing patients with early and late relapsing pemphigus treated with rituximab. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:97-103.

- Castillo CG, Kauffman CA, Miceli MH. Blastomycosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2016;30:247-264.

- Herzum A, Gasparini G, Emanuele C, et al. Atypical and rare forms of cutaneous lupus erythematosus: the importance of the diagnosis for the best management of patients. Dermatology. 2013;1-10.

- Tull TJ, Noy M, Bunker CB, et al. Sebopsoriasis in patients with HIV: a case series of 20 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2016; 173:813-815.

- Balagula Y, Mattei P, Wisco OJ, et al. The great imitator revised: the spectrum of atypical cutaneous manifestations of secondary syphilis. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1434-1441.

The Diagnosis: Pemphigus Foliaceous

Laboratory workup including a complete blood cell count with differential, comprehensive metabolic panel, antinuclear antibodies, Sjögren syndrome A and B antibodies, hepatitis profile, rapid plasma reagin, HIV screen, aldolase, anti–Jo-1, T-Spot TB test (Quest Diagnostics), and tissue cultures was unremarkable. Two 4-mm punch biopsies were obtained from the left cheek and upper back, both of which demonstrated intragranular acantholysis suggestive of pemphigus foliaceous (Figure 1A). A subsequent punch biopsy from the right lower abdomen sent for direct immunofluorescence demonstrated netlike positivity of IgG and C3 in the upper epidermis (Figure 1B), and serum sent for indirect immunofluorescence demonstrated intercellular IgG antibodies to desmoglein (Dsg) 1 on monkey esophagus and positive Dsg-1 antibodies on enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, confirming the diagnosis.

The patient was started on a 60-mg prednisone taper as well as dapsone 50 mg daily; the dapsone was titrated up to 100 mg daily. After tapering down to 10 mg daily of prednisone over 2 months and continuing dapsone with minimal improvement, he was given 2 infusions of rituximab 1000 mg 2 weeks apart. The scalp plaque was dramatically improved at 3-month follow-up (Figure 2), with partial improvement of the cheek plaques (Figure 3). Dapsone was increased to 150 mg daily, and he was encouraged to use triamcinolone acetonide ointment 0.1% twice daily, which led to further improvement.

Pemphigus foliaceus is an autoimmune blistering disease that most commonly occurs in middle-aged adults. It generally is less common than pemphigus vulgaris, except in Finland, Tunisia, and Brazil, where there is an endemic condition with an identical clinical and histological presentation known as fogo selvagem.1

The pathogenesis of pemphigus foliaceous is characterized by IgG autoantibodies against Dsg-1, a transmembrane glycoprotein involved in the cellular adhesion of keratinocytes, which is preferentially expressed in the superficial epidermis.2-7 Dysfunction of Dsg-1 results in the separation of superficial epidermal cells, resulting in intraepidermal blisters.2,7 In contrast to pemphigus vulgaris, there typically is a lack of oral mucosal involvement due to compensation by Dsg-3 in the mucosa.4 Potential triggers for pemphigus foliaceous include exposure to UV radiation; radiotherapy; pregnancy; physiologic stress; and drugs, most commonly captopril, penicillamine, and thiols.8

Pemphigus foliaceous lesions clinically appear as eroded and crusted lesions on an erythematous base, commonly in a seborrheic distribution on the face, scalp, and trunk with sparing of the oral mucosa,2,6 but lesions can progress to a widespread and more severe exfoliative dermatitis.7 Lesions also can appear as psoriasiform plaques and often are initially misdiagnosed as psoriasis, particularly in patients with skin of color.9,10

Diagnosis of pemphigus foliaceous typically is made using a combination of histology as well as both direct and indirect immunofluorescence. Histologically, pemphigus foliaceus presents with subcorneal acantholysis, which is most prominent in the granular layer and occasionally the presence of neutrophils and eosinophils in the blister cavity.7 Direct immunofluorescence demonstrates netlike intercellular IgG and C3 in the upper portion of the epidermis.11 Indirect immunofluorescence can help detect circulating IgG antibodies to Dsg-1, with guinea pig esophagus being the ideal substrate.11,12

First-line treatment of pemphigus foliaceus consists of systemic glucocorticoid therapy, often administered with azathioprine, methotrexate, or mycophenolate mofetil.2,6,13 Although first-line treatment is effective in 60% to 80% of patients,2 relapsing cases can be treated with cyclophosphamide, intravenous immunoglobulin, immunoadsorption, plasmapheresis, or rituximab.2

Rituximab is a chimeric monoclonal antibody targeting CD20+ B cells, leading to decreased antibody production, which has been shown to be effective in treating severe and refractory cases of pemphigus foliaceus.6,13Rituximab with short-course prednisone has been found to be more effective in achieving complete remission at 24 months than prednisone alone.14 In patients with contraindications to systemic glucocorticoid therapy, rituximab has been shown as an effective first-line therapy.15 One-quarter of patients treated with rituximab relapsed within 2 years of treatment6 (average time to relapse, 6–26 months).16 High-dose rituximab regimens, along with a higher number of rituximab treatment cycles, have been shown to prolong time to relapse.6 Further, higher baseline levels of Dsg-1 antibody have been correlated to earlier relapse and can be used following rituximab therapy to monitor disease progression.6,16

The differential diagnosis for pemphigus foliaceous includes disseminated blastomycosis, hypertrophic lupus erythematosus, sebopsoriasis, and secondary syphilis. Disseminated blastomycosis presents with cutaneous manifestations such as nodules, papules, or pustules evolving over weeks to months into ulcers with subsequent scarring.17 Hypertrophic lupus erythematosus presents with papules and nodules with associated keratotic scaling on the face, palms, and extensor surfaces of the limbs.18 Sebopsoriasis is characterized by well-defined lesions with an overlying scale distributed on the scalp, face, and chest.19 Secondary syphilis presents as early hyperpigmented macules transitioning to acral papulosquamous lesions involving the palms and soles.20

The Diagnosis: Pemphigus Foliaceous

Laboratory workup including a complete blood cell count with differential, comprehensive metabolic panel, antinuclear antibodies, Sjögren syndrome A and B antibodies, hepatitis profile, rapid plasma reagin, HIV screen, aldolase, anti–Jo-1, T-Spot TB test (Quest Diagnostics), and tissue cultures was unremarkable. Two 4-mm punch biopsies were obtained from the left cheek and upper back, both of which demonstrated intragranular acantholysis suggestive of pemphigus foliaceous (Figure 1A). A subsequent punch biopsy from the right lower abdomen sent for direct immunofluorescence demonstrated netlike positivity of IgG and C3 in the upper epidermis (Figure 1B), and serum sent for indirect immunofluorescence demonstrated intercellular IgG antibodies to desmoglein (Dsg) 1 on monkey esophagus and positive Dsg-1 antibodies on enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, confirming the diagnosis.

The patient was started on a 60-mg prednisone taper as well as dapsone 50 mg daily; the dapsone was titrated up to 100 mg daily. After tapering down to 10 mg daily of prednisone over 2 months and continuing dapsone with minimal improvement, he was given 2 infusions of rituximab 1000 mg 2 weeks apart. The scalp plaque was dramatically improved at 3-month follow-up (Figure 2), with partial improvement of the cheek plaques (Figure 3). Dapsone was increased to 150 mg daily, and he was encouraged to use triamcinolone acetonide ointment 0.1% twice daily, which led to further improvement.

Pemphigus foliaceus is an autoimmune blistering disease that most commonly occurs in middle-aged adults. It generally is less common than pemphigus vulgaris, except in Finland, Tunisia, and Brazil, where there is an endemic condition with an identical clinical and histological presentation known as fogo selvagem.1

The pathogenesis of pemphigus foliaceous is characterized by IgG autoantibodies against Dsg-1, a transmembrane glycoprotein involved in the cellular adhesion of keratinocytes, which is preferentially expressed in the superficial epidermis.2-7 Dysfunction of Dsg-1 results in the separation of superficial epidermal cells, resulting in intraepidermal blisters.2,7 In contrast to pemphigus vulgaris, there typically is a lack of oral mucosal involvement due to compensation by Dsg-3 in the mucosa.4 Potential triggers for pemphigus foliaceous include exposure to UV radiation; radiotherapy; pregnancy; physiologic stress; and drugs, most commonly captopril, penicillamine, and thiols.8

Pemphigus foliaceous lesions clinically appear as eroded and crusted lesions on an erythematous base, commonly in a seborrheic distribution on the face, scalp, and trunk with sparing of the oral mucosa,2,6 but lesions can progress to a widespread and more severe exfoliative dermatitis.7 Lesions also can appear as psoriasiform plaques and often are initially misdiagnosed as psoriasis, particularly in patients with skin of color.9,10

Diagnosis of pemphigus foliaceous typically is made using a combination of histology as well as both direct and indirect immunofluorescence. Histologically, pemphigus foliaceus presents with subcorneal acantholysis, which is most prominent in the granular layer and occasionally the presence of neutrophils and eosinophils in the blister cavity.7 Direct immunofluorescence demonstrates netlike intercellular IgG and C3 in the upper portion of the epidermis.11 Indirect immunofluorescence can help detect circulating IgG antibodies to Dsg-1, with guinea pig esophagus being the ideal substrate.11,12

First-line treatment of pemphigus foliaceus consists of systemic glucocorticoid therapy, often administered with azathioprine, methotrexate, or mycophenolate mofetil.2,6,13 Although first-line treatment is effective in 60% to 80% of patients,2 relapsing cases can be treated with cyclophosphamide, intravenous immunoglobulin, immunoadsorption, plasmapheresis, or rituximab.2

Rituximab is a chimeric monoclonal antibody targeting CD20+ B cells, leading to decreased antibody production, which has been shown to be effective in treating severe and refractory cases of pemphigus foliaceus.6,13Rituximab with short-course prednisone has been found to be more effective in achieving complete remission at 24 months than prednisone alone.14 In patients with contraindications to systemic glucocorticoid therapy, rituximab has been shown as an effective first-line therapy.15 One-quarter of patients treated with rituximab relapsed within 2 years of treatment6 (average time to relapse, 6–26 months).16 High-dose rituximab regimens, along with a higher number of rituximab treatment cycles, have been shown to prolong time to relapse.6 Further, higher baseline levels of Dsg-1 antibody have been correlated to earlier relapse and can be used following rituximab therapy to monitor disease progression.6,16

The differential diagnosis for pemphigus foliaceous includes disseminated blastomycosis, hypertrophic lupus erythematosus, sebopsoriasis, and secondary syphilis. Disseminated blastomycosis presents with cutaneous manifestations such as nodules, papules, or pustules evolving over weeks to months into ulcers with subsequent scarring.17 Hypertrophic lupus erythematosus presents with papules and nodules with associated keratotic scaling on the face, palms, and extensor surfaces of the limbs.18 Sebopsoriasis is characterized by well-defined lesions with an overlying scale distributed on the scalp, face, and chest.19 Secondary syphilis presents as early hyperpigmented macules transitioning to acral papulosquamous lesions involving the palms and soles.20

- Hans-Filho G, Aoki V, Hans Bittner NR, et al. Fogo selvagem: endemic pemphigus foliaceus. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:638-650.

- Jenson KK, Burr DM, Edwards BC. Case report: reatment of refractory pemphigus foliaceus with rituximab. Practical Dermatology. February 2016:33-36. Accessed August 27, 2021. https://practicaldermatology.com/articles/2016-feb/case-report -treatment-of-refractory-pemphigus-foliaceus-with-rituximab -financial-matters-aad-asds-resources

- Amagai M, Hashimoto T, Green KJ, et al. Antigen-specific immunoadsorption of pathogenic autoantibodies in pemphigus foliaceus. J Invest Dermatol. 1995;104:895-901.

- Mahoney MG, Wang Z, Rothenberger K, et al. Explanations for the clinical and microscopic localization of lesions in pemphigus foliaceus and vulgaris. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:461-468.

- Oktarina DAM, Sokol E, Kramer D, et al. Endocytosis of IgG, desmoglein 1, and plakoglobin in pemphigus foliaceus patient skin. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1-12.

- Kraft M, Worm M. Pemphigus foliaceus-repeated treatment with rituximab 7 years after initial response: a case report. Front Med. 2018;5:315.

- Hale EK. Pemphigus foliaceous. Dermatol Online J. 2002;8:9.

- Tavakolpour S. Pemphigus trigger factors: special focus on pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus. Arch Dermatol Res. 2018;310:95-106.

- A boobaker J, Morar N, Ramdial PK, et al. Pemphigus in South Africa. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:115-119.

- Austin E, Millsop JW, Ely H, et al. Psoriasiform pemphigus foliaceus in an African American female: an important clinical manifestation. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:471.

- Arbache ST, Nogueira TG, Delgado L, et al. Immunofluorescence testing in the diagnosis of autoimmune blistering diseases: overview of 10-year experience. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:885-889.

- Sabolinski ML, Beutner EH, Krasny S, et al. Substrate specificity of antiepithelial antibodies of pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus sera in immunofluorescence tests on monkey and guinea pig esophagus sections. J Invest Dermatol. 1987;88:545-549.

- Palacios-Álvarez I, Riquelme-McLoughlin C, Curto-Barredo L, et al. Rituximab treatment of pemphigus foliaceus: a retrospective study of 12 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:484-486.

- Murrell DF, Sprecher E. Rituximab and short-course prednisone as the new gold standard for new-onset pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:1143-1144.

- Gregoriou S, Efthymiou O, Stefanaki C, et al. Management of pemphigus vulgaris: challenges and solutions. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2015;8:521-527.

- Saleh MA. A prospective study comparing patients with early and late relapsing pemphigus treated with rituximab. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:97-103.

- Castillo CG, Kauffman CA, Miceli MH. Blastomycosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2016;30:247-264.

- Herzum A, Gasparini G, Emanuele C, et al. Atypical and rare forms of cutaneous lupus erythematosus: the importance of the diagnosis for the best management of patients. Dermatology. 2013;1-10.

- Tull TJ, Noy M, Bunker CB, et al. Sebopsoriasis in patients with HIV: a case series of 20 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2016; 173:813-815.

- Balagula Y, Mattei P, Wisco OJ, et al. The great imitator revised: the spectrum of atypical cutaneous manifestations of secondary syphilis. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1434-1441.

- Hans-Filho G, Aoki V, Hans Bittner NR, et al. Fogo selvagem: endemic pemphigus foliaceus. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:638-650.

- Jenson KK, Burr DM, Edwards BC. Case report: reatment of refractory pemphigus foliaceus with rituximab. Practical Dermatology. February 2016:33-36. Accessed August 27, 2021. https://practicaldermatology.com/articles/2016-feb/case-report -treatment-of-refractory-pemphigus-foliaceus-with-rituximab -financial-matters-aad-asds-resources

- Amagai M, Hashimoto T, Green KJ, et al. Antigen-specific immunoadsorption of pathogenic autoantibodies in pemphigus foliaceus. J Invest Dermatol. 1995;104:895-901.

- Mahoney MG, Wang Z, Rothenberger K, et al. Explanations for the clinical and microscopic localization of lesions in pemphigus foliaceus and vulgaris. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:461-468.

- Oktarina DAM, Sokol E, Kramer D, et al. Endocytosis of IgG, desmoglein 1, and plakoglobin in pemphigus foliaceus patient skin. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1-12.

- Kraft M, Worm M. Pemphigus foliaceus-repeated treatment with rituximab 7 years after initial response: a case report. Front Med. 2018;5:315.

- Hale EK. Pemphigus foliaceous. Dermatol Online J. 2002;8:9.

- Tavakolpour S. Pemphigus trigger factors: special focus on pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus. Arch Dermatol Res. 2018;310:95-106.

- A boobaker J, Morar N, Ramdial PK, et al. Pemphigus in South Africa. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:115-119.

- Austin E, Millsop JW, Ely H, et al. Psoriasiform pemphigus foliaceus in an African American female: an important clinical manifestation. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:471.

- Arbache ST, Nogueira TG, Delgado L, et al. Immunofluorescence testing in the diagnosis of autoimmune blistering diseases: overview of 10-year experience. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:885-889.

- Sabolinski ML, Beutner EH, Krasny S, et al. Substrate specificity of antiepithelial antibodies of pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus sera in immunofluorescence tests on monkey and guinea pig esophagus sections. J Invest Dermatol. 1987;88:545-549.

- Palacios-Álvarez I, Riquelme-McLoughlin C, Curto-Barredo L, et al. Rituximab treatment of pemphigus foliaceus: a retrospective study of 12 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:484-486.

- Murrell DF, Sprecher E. Rituximab and short-course prednisone as the new gold standard for new-onset pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:1143-1144.

- Gregoriou S, Efthymiou O, Stefanaki C, et al. Management of pemphigus vulgaris: challenges and solutions. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2015;8:521-527.

- Saleh MA. A prospective study comparing patients with early and late relapsing pemphigus treated with rituximab. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:97-103.

- Castillo CG, Kauffman CA, Miceli MH. Blastomycosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2016;30:247-264.

- Herzum A, Gasparini G, Emanuele C, et al. Atypical and rare forms of cutaneous lupus erythematosus: the importance of the diagnosis for the best management of patients. Dermatology. 2013;1-10.

- Tull TJ, Noy M, Bunker CB, et al. Sebopsoriasis in patients with HIV: a case series of 20 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2016; 173:813-815.

- Balagula Y, Mattei P, Wisco OJ, et al. The great imitator revised: the spectrum of atypical cutaneous manifestations of secondary syphilis. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1434-1441.

A 40-year-old Black man presented for evaluation of a thick plaque throughout the scalp (top), scaly plaques on the cheeks (bottom), and a spreading rash on the trunk that had progressed over the last few months. He had no relevant medical history, took no medications, and was in a monogamous relationship with a female partner. He previously saw an outside dermatologist who gave him triamcinolone cream, which was mildly helpful. Physical examination revealed a thick verrucous plaque throughout the scalp extending onto the forehead; thick plaques on the cheeks; and numerous, thinly eroded lesions on the trunk. Biopsies and a laboratory workup were performed.

Widespread Purple Plaques

The Diagnosis: Kaposi Sarcoma

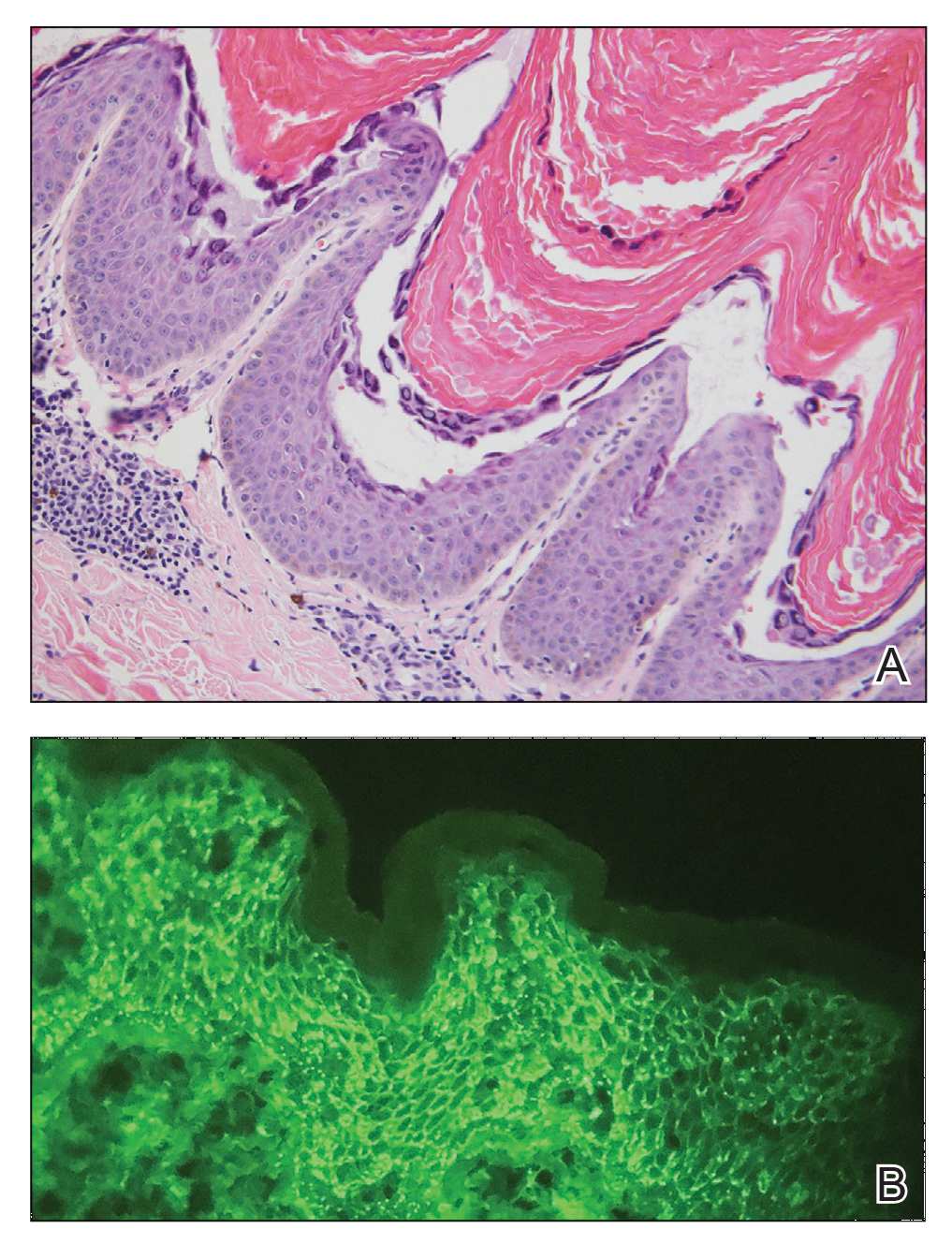

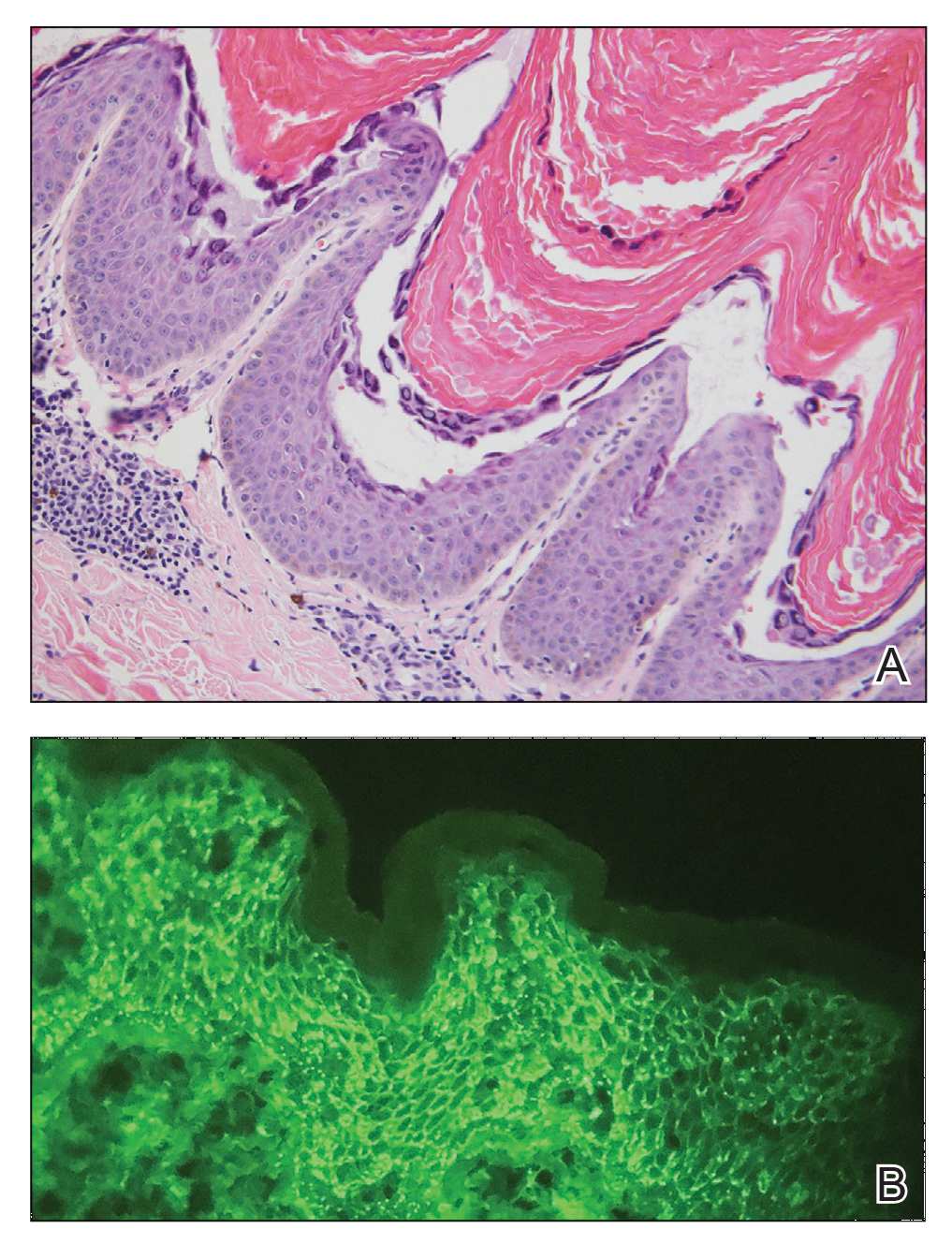

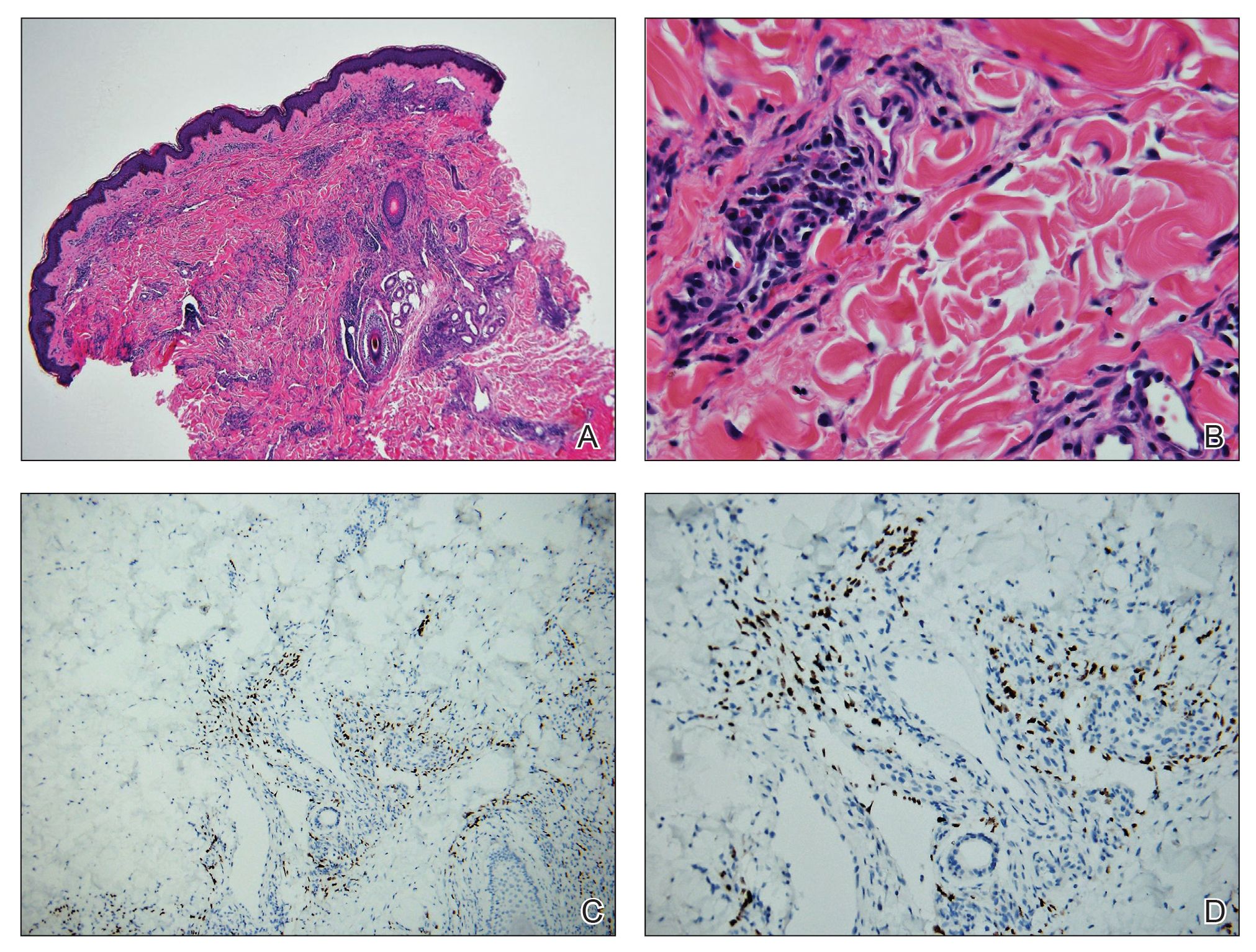

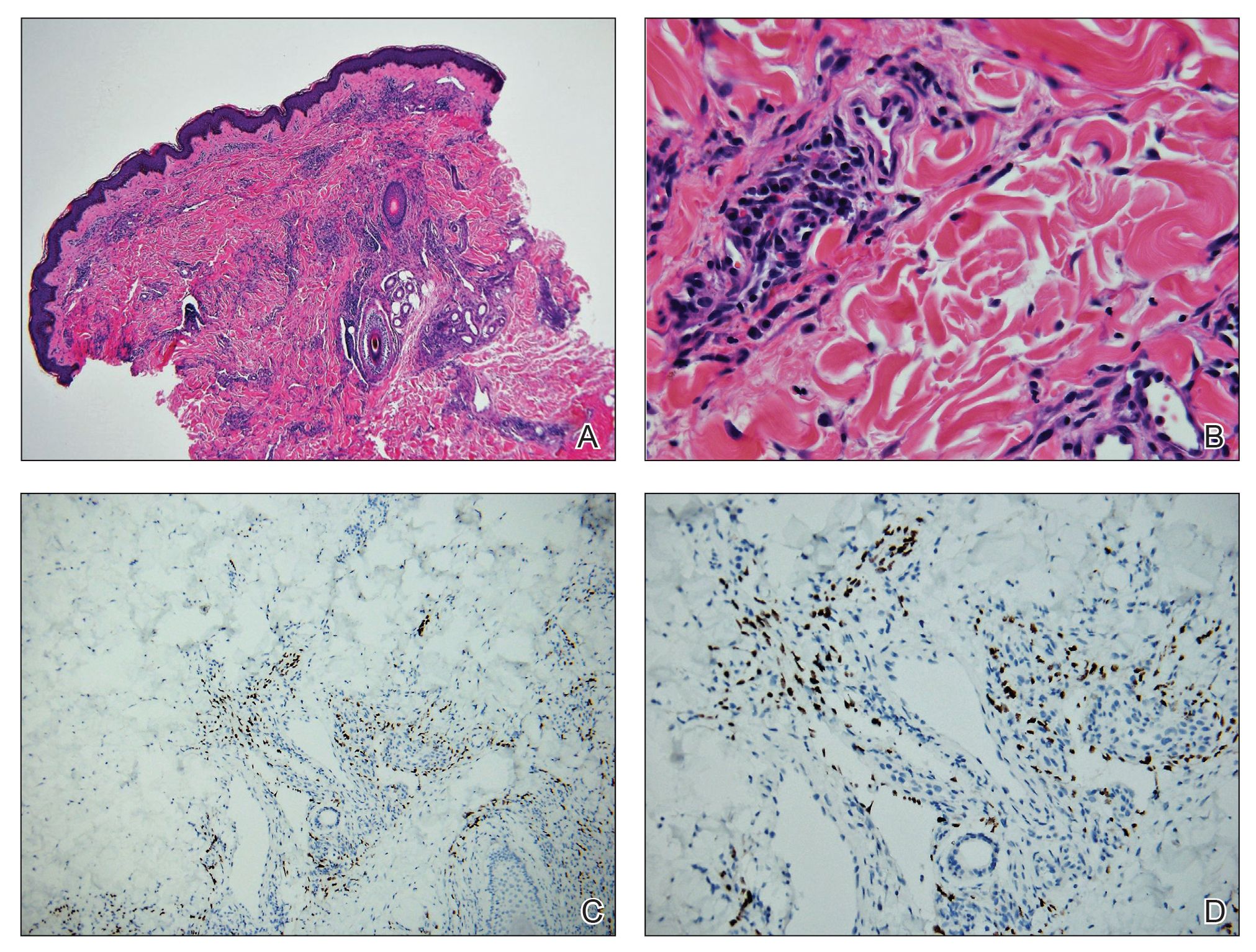

On initial presentation, the differential diagnosis included secondary syphilis, Kaposi sarcoma (KS), lichen planus pigmentosus, sarcoidosis, and psoriasis. A laboratory workup was ordered, which included complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, antinuclear antibodies, anti-Ro/Sjögren syndrome antigen A and anti-La/Sjögren syndrome antigen B autoantibodies, angiotensin-converting enzyme, rapid plasma reagin, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antibodies. A 4-mm punch biopsy of the rash also was performed from the right upper back. Histology revealed a vascular proliferation that was diffusely positive for human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8)(Figure 1). The patient was informed of the diagnosis, at which time he revealed he had a history of homosexual relationships, with his last sexual contact being more than 1 year prior to presentation. The laboratory workup confirmed a diagnosis of HIV, and the remainder of the tests were unremarkable.

He was referred to our university's HIV clinic where he was started on highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). His facial swelling worsened, leading to hospital admission. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis showed diffuse lymphadenopathy and lung nodules concerning for visceral involvement of KS. Hematology and oncology was consulted for further evaluation, and he was treated with 6 cycles of doxorubicin 20 mg/m2, which led to resolution of the lung nodules on CT and improvement of the rash burden. He was then started on alitretinoin gel 0.1% twice daily, which led to continued slow improvement (Figure 2).

Kaposi sarcoma is a vascular neoplasm that occurs from infection with HHV-8. It typically presents as painless, reddish to violaceous macules or patches involving the skin and mucosa that often progress to plaques or nodules with possible visceral involvement. Kaposi sarcoma is classified into 4 subtypes based on epidemiology and clinical presentation: classic, endemic, iatrogenic, and AIDS associated.1,2

Classic KS primarily affects elderly males of Mediterranean or Eastern European descent, with a mean age of 64.1 years and a male to female ratio of 3 to 1. It has an indolent course and a strong predilection for the skin of the lower extremities. The endemic form occurs mainly in Africa and has a more aggressive course, especially the lymphadenopathic type that affects children younger than 10 years.3 Iatrogenic KS develops in immunosuppressed patients, such as transplant recipients, and may regress if the immunosuppressive agent is stopped.1 Kaposi sarcoma is an AIDS-defining illness and is the most common malignancy in AIDS patients. It is strongly associated with a low CD4 count, which accounts for the notable decline in its incidence after the widespread introduction of HAART.1 Among HIV patients, KS has the highest incidence in men who have sex with men. This population has a higher seroprevalence of HHV-8, which suggests possible sexual transmission of HHV-8. AIDS-associated KS most commonly involves the lower extremities, face, and oral mucosa. It may have visceral involvement, particularly of the gastrointestinal and respiratory systems, which carries a poor prognosis.4,5

Approximately 40% of patients presenting with KS have gastrointestinal tract involvement.6 Of these patients, up to 80% are asymptomatic, with diagnosis usually being made on endoscopy.7 In contrast, pulmonary KS is less common and typically is symptomatic. It can involve the lung parenchyma, airways, or pleura and is diagnosed by chest radiography or CT scans. Glucocorticoid therapy is a known trigger for pulmonary KS exacerbation.8

All 4 subtypes share the same histopathologic findings consisting of spindled endothelial cell proliferation, inflammation, and angiogenesis. Immunohistochemistry reveals tumor cells that are CD34 and CD31 positive but are factor VIII negative. Staining for HHV-8 antigen is used to confirm the diagnosis. The inflammatory infiltrate predominantly is lymphocytic with scattered plasma cells.9

The laboratory results and histopathologic findings clearly indicated a diagnosis of KS in our patient. Other entities in the clinical differential would have shown notably different histopathologic findings and laboratory results. Lichen planus pigmentosus displays a lichenoid infiltrate and pigment dropout on histology. Histologic findings of psoriasis include psoriasiform acanthosis, dilated vessels in the dermal papillae, thinning of suprapapillary plates, and neutrophilic microabscesses. Sarcoidosis would demonstrate naked granulomas on histopathology. Syphilis displays variable but often psoriasiform or lichenoid findings on histology, and a positive rapid plasma reagin also would be noted.

First-line treatment of AIDS-related KS is HAART. For patients with severe and rapidly progressive KS or with visceral involvement, cytotoxic chemotherapy with doxorubicin or taxanes often is required. Additional therapies include radiotherapy, topical alitretinoin, and cryotherapy.1,10

- Schneider JW, Dittmer DP. Diagnosis and treatment of Kaposi sarcoma. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:529-539.

- Schwartz RA, Micali G, Nasca MR, et al. Kaposi sarcoma: a continuing conundrum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:179-206; quiz 207-208.

- Mohanna S, Maco V, Bravo F, et al. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of classic Kaposi’s sarcoma, seroprevalence, and variants of human herpesvirus 8 in South America: a critical review of an old disease. Int J Infect Dis. 2005;9:239-250.

- Beral V, Peterman TA, Berkelman RL, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma among persons with AIDS: a sexually transmitted infection? Lancet. 1990;335:123-128.

- Smith NA, Sabin CA, Gopal R, et al. Serologic evidence of human herpesvirus 8 transmission by homosexual but not heterosexual sex. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:600-606.

- Arora M, Goldberg EM. Kaposi sarcoma involving the gastrointestinal tract. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2010;6:459-462.

- Parente F, Cernuschi M, Orlando G, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma and AIDS: frequency of gastrointestinal involvement and its effect on survival. a prospective study in a heterogeneous population. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1991;26:1007-1012.

- Gasparetto TD, Marchiori E, Lourenco S, et al. Pulmonary involvement in Kaposi sarcoma: correlation between imaging and pathology. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2009;4:18.

- Radu O, Pantanowitz L. Kaposi sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:289-294.

- Regnier-Rosencher E, Guillot B, Dupin N. Treatments for classic Kaposi sarcoma: a systematic review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:313-331.

The Diagnosis: Kaposi Sarcoma

On initial presentation, the differential diagnosis included secondary syphilis, Kaposi sarcoma (KS), lichen planus pigmentosus, sarcoidosis, and psoriasis. A laboratory workup was ordered, which included complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, antinuclear antibodies, anti-Ro/Sjögren syndrome antigen A and anti-La/Sjögren syndrome antigen B autoantibodies, angiotensin-converting enzyme, rapid plasma reagin, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antibodies. A 4-mm punch biopsy of the rash also was performed from the right upper back. Histology revealed a vascular proliferation that was diffusely positive for human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8)(Figure 1). The patient was informed of the diagnosis, at which time he revealed he had a history of homosexual relationships, with his last sexual contact being more than 1 year prior to presentation. The laboratory workup confirmed a diagnosis of HIV, and the remainder of the tests were unremarkable.

He was referred to our university's HIV clinic where he was started on highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). His facial swelling worsened, leading to hospital admission. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis showed diffuse lymphadenopathy and lung nodules concerning for visceral involvement of KS. Hematology and oncology was consulted for further evaluation, and he was treated with 6 cycles of doxorubicin 20 mg/m2, which led to resolution of the lung nodules on CT and improvement of the rash burden. He was then started on alitretinoin gel 0.1% twice daily, which led to continued slow improvement (Figure 2).

Kaposi sarcoma is a vascular neoplasm that occurs from infection with HHV-8. It typically presents as painless, reddish to violaceous macules or patches involving the skin and mucosa that often progress to plaques or nodules with possible visceral involvement. Kaposi sarcoma is classified into 4 subtypes based on epidemiology and clinical presentation: classic, endemic, iatrogenic, and AIDS associated.1,2

Classic KS primarily affects elderly males of Mediterranean or Eastern European descent, with a mean age of 64.1 years and a male to female ratio of 3 to 1. It has an indolent course and a strong predilection for the skin of the lower extremities. The endemic form occurs mainly in Africa and has a more aggressive course, especially the lymphadenopathic type that affects children younger than 10 years.3 Iatrogenic KS develops in immunosuppressed patients, such as transplant recipients, and may regress if the immunosuppressive agent is stopped.1 Kaposi sarcoma is an AIDS-defining illness and is the most common malignancy in AIDS patients. It is strongly associated with a low CD4 count, which accounts for the notable decline in its incidence after the widespread introduction of HAART.1 Among HIV patients, KS has the highest incidence in men who have sex with men. This population has a higher seroprevalence of HHV-8, which suggests possible sexual transmission of HHV-8. AIDS-associated KS most commonly involves the lower extremities, face, and oral mucosa. It may have visceral involvement, particularly of the gastrointestinal and respiratory systems, which carries a poor prognosis.4,5

Approximately 40% of patients presenting with KS have gastrointestinal tract involvement.6 Of these patients, up to 80% are asymptomatic, with diagnosis usually being made on endoscopy.7 In contrast, pulmonary KS is less common and typically is symptomatic. It can involve the lung parenchyma, airways, or pleura and is diagnosed by chest radiography or CT scans. Glucocorticoid therapy is a known trigger for pulmonary KS exacerbation.8

All 4 subtypes share the same histopathologic findings consisting of spindled endothelial cell proliferation, inflammation, and angiogenesis. Immunohistochemistry reveals tumor cells that are CD34 and CD31 positive but are factor VIII negative. Staining for HHV-8 antigen is used to confirm the diagnosis. The inflammatory infiltrate predominantly is lymphocytic with scattered plasma cells.9

The laboratory results and histopathologic findings clearly indicated a diagnosis of KS in our patient. Other entities in the clinical differential would have shown notably different histopathologic findings and laboratory results. Lichen planus pigmentosus displays a lichenoid infiltrate and pigment dropout on histology. Histologic findings of psoriasis include psoriasiform acanthosis, dilated vessels in the dermal papillae, thinning of suprapapillary plates, and neutrophilic microabscesses. Sarcoidosis would demonstrate naked granulomas on histopathology. Syphilis displays variable but often psoriasiform or lichenoid findings on histology, and a positive rapid plasma reagin also would be noted.

First-line treatment of AIDS-related KS is HAART. For patients with severe and rapidly progressive KS or with visceral involvement, cytotoxic chemotherapy with doxorubicin or taxanes often is required. Additional therapies include radiotherapy, topical alitretinoin, and cryotherapy.1,10

The Diagnosis: Kaposi Sarcoma

On initial presentation, the differential diagnosis included secondary syphilis, Kaposi sarcoma (KS), lichen planus pigmentosus, sarcoidosis, and psoriasis. A laboratory workup was ordered, which included complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, antinuclear antibodies, anti-Ro/Sjögren syndrome antigen A and anti-La/Sjögren syndrome antigen B autoantibodies, angiotensin-converting enzyme, rapid plasma reagin, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antibodies. A 4-mm punch biopsy of the rash also was performed from the right upper back. Histology revealed a vascular proliferation that was diffusely positive for human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8)(Figure 1). The patient was informed of the diagnosis, at which time he revealed he had a history of homosexual relationships, with his last sexual contact being more than 1 year prior to presentation. The laboratory workup confirmed a diagnosis of HIV, and the remainder of the tests were unremarkable.

He was referred to our university's HIV clinic where he was started on highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). His facial swelling worsened, leading to hospital admission. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis showed diffuse lymphadenopathy and lung nodules concerning for visceral involvement of KS. Hematology and oncology was consulted for further evaluation, and he was treated with 6 cycles of doxorubicin 20 mg/m2, which led to resolution of the lung nodules on CT and improvement of the rash burden. He was then started on alitretinoin gel 0.1% twice daily, which led to continued slow improvement (Figure 2).

Kaposi sarcoma is a vascular neoplasm that occurs from infection with HHV-8. It typically presents as painless, reddish to violaceous macules or patches involving the skin and mucosa that often progress to plaques or nodules with possible visceral involvement. Kaposi sarcoma is classified into 4 subtypes based on epidemiology and clinical presentation: classic, endemic, iatrogenic, and AIDS associated.1,2

Classic KS primarily affects elderly males of Mediterranean or Eastern European descent, with a mean age of 64.1 years and a male to female ratio of 3 to 1. It has an indolent course and a strong predilection for the skin of the lower extremities. The endemic form occurs mainly in Africa and has a more aggressive course, especially the lymphadenopathic type that affects children younger than 10 years.3 Iatrogenic KS develops in immunosuppressed patients, such as transplant recipients, and may regress if the immunosuppressive agent is stopped.1 Kaposi sarcoma is an AIDS-defining illness and is the most common malignancy in AIDS patients. It is strongly associated with a low CD4 count, which accounts for the notable decline in its incidence after the widespread introduction of HAART.1 Among HIV patients, KS has the highest incidence in men who have sex with men. This population has a higher seroprevalence of HHV-8, which suggests possible sexual transmission of HHV-8. AIDS-associated KS most commonly involves the lower extremities, face, and oral mucosa. It may have visceral involvement, particularly of the gastrointestinal and respiratory systems, which carries a poor prognosis.4,5

Approximately 40% of patients presenting with KS have gastrointestinal tract involvement.6 Of these patients, up to 80% are asymptomatic, with diagnosis usually being made on endoscopy.7 In contrast, pulmonary KS is less common and typically is symptomatic. It can involve the lung parenchyma, airways, or pleura and is diagnosed by chest radiography or CT scans. Glucocorticoid therapy is a known trigger for pulmonary KS exacerbation.8

All 4 subtypes share the same histopathologic findings consisting of spindled endothelial cell proliferation, inflammation, and angiogenesis. Immunohistochemistry reveals tumor cells that are CD34 and CD31 positive but are factor VIII negative. Staining for HHV-8 antigen is used to confirm the diagnosis. The inflammatory infiltrate predominantly is lymphocytic with scattered plasma cells.9

The laboratory results and histopathologic findings clearly indicated a diagnosis of KS in our patient. Other entities in the clinical differential would have shown notably different histopathologic findings and laboratory results. Lichen planus pigmentosus displays a lichenoid infiltrate and pigment dropout on histology. Histologic findings of psoriasis include psoriasiform acanthosis, dilated vessels in the dermal papillae, thinning of suprapapillary plates, and neutrophilic microabscesses. Sarcoidosis would demonstrate naked granulomas on histopathology. Syphilis displays variable but often psoriasiform or lichenoid findings on histology, and a positive rapid plasma reagin also would be noted.

First-line treatment of AIDS-related KS is HAART. For patients with severe and rapidly progressive KS or with visceral involvement, cytotoxic chemotherapy with doxorubicin or taxanes often is required. Additional therapies include radiotherapy, topical alitretinoin, and cryotherapy.1,10

- Schneider JW, Dittmer DP. Diagnosis and treatment of Kaposi sarcoma. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:529-539.

- Schwartz RA, Micali G, Nasca MR, et al. Kaposi sarcoma: a continuing conundrum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:179-206; quiz 207-208.

- Mohanna S, Maco V, Bravo F, et al. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of classic Kaposi’s sarcoma, seroprevalence, and variants of human herpesvirus 8 in South America: a critical review of an old disease. Int J Infect Dis. 2005;9:239-250.

- Beral V, Peterman TA, Berkelman RL, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma among persons with AIDS: a sexually transmitted infection? Lancet. 1990;335:123-128.

- Smith NA, Sabin CA, Gopal R, et al. Serologic evidence of human herpesvirus 8 transmission by homosexual but not heterosexual sex. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:600-606.

- Arora M, Goldberg EM. Kaposi sarcoma involving the gastrointestinal tract. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2010;6:459-462.

- Parente F, Cernuschi M, Orlando G, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma and AIDS: frequency of gastrointestinal involvement and its effect on survival. a prospective study in a heterogeneous population. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1991;26:1007-1012.

- Gasparetto TD, Marchiori E, Lourenco S, et al. Pulmonary involvement in Kaposi sarcoma: correlation between imaging and pathology. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2009;4:18.

- Radu O, Pantanowitz L. Kaposi sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:289-294.

- Regnier-Rosencher E, Guillot B, Dupin N. Treatments for classic Kaposi sarcoma: a systematic review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:313-331.

- Schneider JW, Dittmer DP. Diagnosis and treatment of Kaposi sarcoma. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:529-539.

- Schwartz RA, Micali G, Nasca MR, et al. Kaposi sarcoma: a continuing conundrum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:179-206; quiz 207-208.

- Mohanna S, Maco V, Bravo F, et al. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of classic Kaposi’s sarcoma, seroprevalence, and variants of human herpesvirus 8 in South America: a critical review of an old disease. Int J Infect Dis. 2005;9:239-250.

- Beral V, Peterman TA, Berkelman RL, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma among persons with AIDS: a sexually transmitted infection? Lancet. 1990;335:123-128.

- Smith NA, Sabin CA, Gopal R, et al. Serologic evidence of human herpesvirus 8 transmission by homosexual but not heterosexual sex. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:600-606.

- Arora M, Goldberg EM. Kaposi sarcoma involving the gastrointestinal tract. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2010;6:459-462.

- Parente F, Cernuschi M, Orlando G, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma and AIDS: frequency of gastrointestinal involvement and its effect on survival. a prospective study in a heterogeneous population. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1991;26:1007-1012.

- Gasparetto TD, Marchiori E, Lourenco S, et al. Pulmonary involvement in Kaposi sarcoma: correlation between imaging and pathology. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2009;4:18.

- Radu O, Pantanowitz L. Kaposi sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:289-294.

- Regnier-Rosencher E, Guillot B, Dupin N. Treatments for classic Kaposi sarcoma: a systematic review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:313-331.

A 24-year-old Black man presented for evaluation of an asymptomatic rash on the face, chest, back, and arms that had been progressively spreading over the course of 3 months. He had some swelling of the lips prior to the onset of the rash and was prescribed prednisone 10 mg daily by an outside physician. He had no known medical problems and was taking no medications. Physical examination revealed numerous violaceous plaques scattered symmetrically on the trunk, arms, legs, and face. His family history was negative for autoimmune disease, and a review of systems was unremarkable. He denied any recent sexual contacts.