User login

What is the best age to start vitamin D supplementation to prevent rickets in breastfed newborns?

It’s unclear what age is best to start vitamin D supplementation because no comparison studies exist. That said, breastfed infants who take vitamin D beginning at 3 to 5 days of life don’t develop rickets (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, randomized trial). Starting infants on vitamin D supplementation at one to 36 months of age reduces the risk of rickets (SOR: B, a controlled and a randomized controlled trial).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

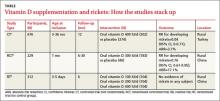

A Cochrane review of interventions for preventing rickets in children born at term found 2 studies, a controlled clinical trial and a cluster-randomized controlled trial, that included 905 breastfed infants.1 In these trials, oral vitamin D (300 or 400 IU per day) starting between one and 36 months of age reduced the risk of rickets when compared with no supplementation (TABLE). The authors concluded that it was reasonable to offer preventive measures (vitamin D or calcium) to all children 2 years or younger.

400 IU of vitamin D daily increases blood levels the most

A study done in north and south China investigated vitamin D dose by randomizing 312 infants to receive supplements of 100, 200, or 400 IU daily.2 Although no infant developed rickets, a dose of 400 IU per day achieved higher serum levels of 25-hydroxy vitamin D (25[OH]-D) than the lower doses.

In the northern location, doses of 100, 200, or 400 IU daily increased 25(OH)-D levels from 5 ng/mL at birth to an average of 12, 15, and 25 ng/mL, respectively, at 6 months. In the southern location, 25(OH)-D levels increased from 14 ng/mL at birth to 20, 22, and 25 ng/mL at 6 months for the 100, 200, and 400 IU per day doses, respectively.

Recommendations

The guidelines from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) on preventing rickets and vitamin D deficiency in infants, children, and adolescents recommends that exclusively breastfed neonates receive 400 IU of vitamin D daily, starting in the first days of life—a revision of the previous recommendation of 200 IU daily beginning at 2 months. The AAP doesn’t recommend giving vitamin D supplements to formula-fed infants because formula contains 400 IU/L of vitamin D; infants who don’t drink at least 1 liter of formula per day should receive supplementation. The AAP advocates a serum 25(OH)-D level of at least 20 ng/mL.3

The Pediatric Endocrine Society (PES) defines vitamin D deficiency as a serum 25(OH)-D level below 15 ng/mL and recommends mends maintaining the level above 20 ng/mL to prevent rickets. The PES also recommends that breastfed infants receive 400 IU of vitamin D daily starting at birth.4

1. Lerch C, Meissner T. Interventions for the prevention of nutritional rickets in term born children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD006164.

2. Specker BL, Ho ML, Oestreich A, et al. Prospective study of vitamin D supplementation and rickets in China. J Pediatr. 1992;120:733-739.

3. Wagner CL, Greer FR; American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Breastfeeding; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Nutrition. Prevention of rickets and vitamin D deficiency in infants, children, and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2008;122:1142-1152.

4. Misra M, Pacaud D, Petryk A, et al; Drug and Therapeutics Committee of the Lawson Wilkins Pediatric Endocrine Society. Vitamin D deficiency in children and its management: review of current knowledge and recommendations. Pediatrics. 2008;122:398-417.

It’s unclear what age is best to start vitamin D supplementation because no comparison studies exist. That said, breastfed infants who take vitamin D beginning at 3 to 5 days of life don’t develop rickets (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, randomized trial). Starting infants on vitamin D supplementation at one to 36 months of age reduces the risk of rickets (SOR: B, a controlled and a randomized controlled trial).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A Cochrane review of interventions for preventing rickets in children born at term found 2 studies, a controlled clinical trial and a cluster-randomized controlled trial, that included 905 breastfed infants.1 In these trials, oral vitamin D (300 or 400 IU per day) starting between one and 36 months of age reduced the risk of rickets when compared with no supplementation (TABLE). The authors concluded that it was reasonable to offer preventive measures (vitamin D or calcium) to all children 2 years or younger.

400 IU of vitamin D daily increases blood levels the most

A study done in north and south China investigated vitamin D dose by randomizing 312 infants to receive supplements of 100, 200, or 400 IU daily.2 Although no infant developed rickets, a dose of 400 IU per day achieved higher serum levels of 25-hydroxy vitamin D (25[OH]-D) than the lower doses.

In the northern location, doses of 100, 200, or 400 IU daily increased 25(OH)-D levels from 5 ng/mL at birth to an average of 12, 15, and 25 ng/mL, respectively, at 6 months. In the southern location, 25(OH)-D levels increased from 14 ng/mL at birth to 20, 22, and 25 ng/mL at 6 months for the 100, 200, and 400 IU per day doses, respectively.

Recommendations

The guidelines from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) on preventing rickets and vitamin D deficiency in infants, children, and adolescents recommends that exclusively breastfed neonates receive 400 IU of vitamin D daily, starting in the first days of life—a revision of the previous recommendation of 200 IU daily beginning at 2 months. The AAP doesn’t recommend giving vitamin D supplements to formula-fed infants because formula contains 400 IU/L of vitamin D; infants who don’t drink at least 1 liter of formula per day should receive supplementation. The AAP advocates a serum 25(OH)-D level of at least 20 ng/mL.3

The Pediatric Endocrine Society (PES) defines vitamin D deficiency as a serum 25(OH)-D level below 15 ng/mL and recommends mends maintaining the level above 20 ng/mL to prevent rickets. The PES also recommends that breastfed infants receive 400 IU of vitamin D daily starting at birth.4

It’s unclear what age is best to start vitamin D supplementation because no comparison studies exist. That said, breastfed infants who take vitamin D beginning at 3 to 5 days of life don’t develop rickets (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, randomized trial). Starting infants on vitamin D supplementation at one to 36 months of age reduces the risk of rickets (SOR: B, a controlled and a randomized controlled trial).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A Cochrane review of interventions for preventing rickets in children born at term found 2 studies, a controlled clinical trial and a cluster-randomized controlled trial, that included 905 breastfed infants.1 In these trials, oral vitamin D (300 or 400 IU per day) starting between one and 36 months of age reduced the risk of rickets when compared with no supplementation (TABLE). The authors concluded that it was reasonable to offer preventive measures (vitamin D or calcium) to all children 2 years or younger.

400 IU of vitamin D daily increases blood levels the most

A study done in north and south China investigated vitamin D dose by randomizing 312 infants to receive supplements of 100, 200, or 400 IU daily.2 Although no infant developed rickets, a dose of 400 IU per day achieved higher serum levels of 25-hydroxy vitamin D (25[OH]-D) than the lower doses.

In the northern location, doses of 100, 200, or 400 IU daily increased 25(OH)-D levels from 5 ng/mL at birth to an average of 12, 15, and 25 ng/mL, respectively, at 6 months. In the southern location, 25(OH)-D levels increased from 14 ng/mL at birth to 20, 22, and 25 ng/mL at 6 months for the 100, 200, and 400 IU per day doses, respectively.

Recommendations

The guidelines from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) on preventing rickets and vitamin D deficiency in infants, children, and adolescents recommends that exclusively breastfed neonates receive 400 IU of vitamin D daily, starting in the first days of life—a revision of the previous recommendation of 200 IU daily beginning at 2 months. The AAP doesn’t recommend giving vitamin D supplements to formula-fed infants because formula contains 400 IU/L of vitamin D; infants who don’t drink at least 1 liter of formula per day should receive supplementation. The AAP advocates a serum 25(OH)-D level of at least 20 ng/mL.3

The Pediatric Endocrine Society (PES) defines vitamin D deficiency as a serum 25(OH)-D level below 15 ng/mL and recommends mends maintaining the level above 20 ng/mL to prevent rickets. The PES also recommends that breastfed infants receive 400 IU of vitamin D daily starting at birth.4

1. Lerch C, Meissner T. Interventions for the prevention of nutritional rickets in term born children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD006164.

2. Specker BL, Ho ML, Oestreich A, et al. Prospective study of vitamin D supplementation and rickets in China. J Pediatr. 1992;120:733-739.

3. Wagner CL, Greer FR; American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Breastfeeding; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Nutrition. Prevention of rickets and vitamin D deficiency in infants, children, and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2008;122:1142-1152.

4. Misra M, Pacaud D, Petryk A, et al; Drug and Therapeutics Committee of the Lawson Wilkins Pediatric Endocrine Society. Vitamin D deficiency in children and its management: review of current knowledge and recommendations. Pediatrics. 2008;122:398-417.

1. Lerch C, Meissner T. Interventions for the prevention of nutritional rickets in term born children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD006164.

2. Specker BL, Ho ML, Oestreich A, et al. Prospective study of vitamin D supplementation and rickets in China. J Pediatr. 1992;120:733-739.

3. Wagner CL, Greer FR; American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Breastfeeding; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Nutrition. Prevention of rickets and vitamin D deficiency in infants, children, and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2008;122:1142-1152.

4. Misra M, Pacaud D, Petryk A, et al; Drug and Therapeutics Committee of the Lawson Wilkins Pediatric Endocrine Society. Vitamin D deficiency in children and its management: review of current knowledge and recommendations. Pediatrics. 2008;122:398-417.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

Does the age you introduce food to an infant affect allergies later?

Yes. In children at high risk for atopy (those with a family history of allergy, asthma, or eczema in at least 1 first-degree relative), breastfeeding or giving hydrolyzed protein formula during the first 4 to 6 months reduces the risk of atopy in the first year of life, when compared with introducing cow’s milk or soy formula (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, based on a systematic review that included only 2 double-blinded randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

There is inconsistent evidence to show that early introduction of solid food increases the incidence of atopic disease (SOR: B, systematic review of inconsistent studies).

Begin talking about infant feeding during the first postnatal visit

Mary M. Stephens, MD, MPH

East Tennessee State University, Johnson City

Having found a surprising number of children on cereal or other solids at the 2-month visit, I make it a practice to begin talking about infant feeding during the first postnatal visit. I encourage parents to wait until at least 4 months (but not more than 6 months) to start cereal, and to wait 3 to 4 days between introducing any new foods to make sure the child does not have an adverse reaction.

I generally tell all parents to keep their child on breast milk or formula and avoid whole milk until age 1, although small amounts of cheese and yogurt are fine. Additionally, I recommend avoiding citrus, honey, and eggs until age 1 and peanut butter until age 2 or 3.

For the child at high risk of atopy, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommendation to wait to introduce solid foods until 6 months of age and to wait to introduce peanuts and fish until 3 years of age seems reasonable, although I’d let parents know that they could try these foods earlier if they wanted since there is no definite evidence that those changes will make a difference.

Although I’ve never recommended hydrolyzed protein formula for children at high risk of atopy, it is an option for discussion. practical considerations to bring up in the discussion are the higher cost of these formulas and the palatability. Children receiving their formula through Women, Infant and Children (WIC) programs will need a prescription that includes the indication for the formula.

Evidence summary

Systematic reviews analyzing the modification of early feeding practices to prevent atopic disease have all been limited by a paucity of double-blinded RCTs of sufficient duration.1-3

Breastfeeding, hydrolyzed formulas confer lowest atopy risk

Breastfeeding and the use of hydrolyzed protein formulas confer the lowest risk of atopy in high-risk children when compared with cow’s milk or soy-based formulas.1,3 The relative risk for wheeze or asthma in the first year of life was 0.4 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.19–0.85) for children fed hydrolyzed protein formulas when compared with cow’s milk.1 Studies have not found a significant difference among these forms of milk for infants without a strong family history of atopic disease.3

Delaying solid food may reduce allergies

There is speculation that introducing certain solid foods early increases the risk of allergies to these foods, as well as causing generalized atopic symptoms. Few studies have examined this, and no systematic reviews focus on atopic disease.4

A cohort study (n=1265) comparing children who had been given 4 or more types of solid food before 4 months of age with those whose caregivers delayed solid foods showed an increased incidence of eczema by 10 years of age (relative risk=2.35; P<.05) in the early feeding group.5

However, a prospective interventional cohort study using a retrospective cohort as a control (n=375) compared children who had strictly avoided fish and citrus products until 1 year of age with those who had an unrestricted diet. There was no difference in the frequency of allergy to these foods as quantified by history and positive challenge test, although the authors did not include a statistical analysis of their results.6

Another study randomized 165 high-risk children into groups with standard feeding practices or an allergy prophylaxis regimen, which included avoidance of milk protein until age 1 year, eggs until 2 years, and fish and peanuts until 3 years. Although prophylaxis decreased the prevalence of atopic disorders at 1 year, there was no difference in any atopic disease between the 2 groups at age 7.7

Recommendations from others

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that for high-risk infants, solid foods should not be introduced into the diet until 6 months of age, with dairy products delayed until 1 year, eggs until 2 years, and peanuts, tree nuts, and fish until 3 years of age.8

1. Ram FS, Ducharme FM, Scarlett J. Cow’s milk protein avoidance and development of childhood wheeze in children with a family history of atopy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002;(3):CD003795.-

2. Smethurst D, Macfarlane S. Atopic eczema (web archive): prolonged breast feeding in predisposed infants. Clinical Evidence 2002;(8):1664-1682.

3. Osborn DA, Sinn J. Formulas containing hydrolysed protein for prevention of allergy and food intolerance in infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;(4):CD003664.-

4. Lanigan JA, Bishop J, Kimber AC, Morgan J. Systematic review concerning the age of introduction of complementary foods to the healthy full-term infant. Eur J Clin Nutr 2001;55:309-320.

5. Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Shannon FT. Early solid feeding and recurrent childhood eczema: a 10-year longitudinal study. Pediatrics 1990;86:541-546.

6. Saarinen UM, Kajosaari M. Does dietary elimination in infancy prevent or only postpone a food allergy? A study of fish and citrus allergy in 375 children. Lancet 1980;1:166-167.

7. Zeiger RS, Heller S. The development and prediction of atopy in high-risk children: follow-up at age seven years in a prospective randomized study of combined maternal and infant food allergen avoidance. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1995;95:1179-1190.

8. American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Nutrition. Hypoallergenic infant formulas. Pediatrics 2000;106:346-349.

Yes. In children at high risk for atopy (those with a family history of allergy, asthma, or eczema in at least 1 first-degree relative), breastfeeding or giving hydrolyzed protein formula during the first 4 to 6 months reduces the risk of atopy in the first year of life, when compared with introducing cow’s milk or soy formula (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, based on a systematic review that included only 2 double-blinded randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

There is inconsistent evidence to show that early introduction of solid food increases the incidence of atopic disease (SOR: B, systematic review of inconsistent studies).

Begin talking about infant feeding during the first postnatal visit

Mary M. Stephens, MD, MPH

East Tennessee State University, Johnson City

Having found a surprising number of children on cereal or other solids at the 2-month visit, I make it a practice to begin talking about infant feeding during the first postnatal visit. I encourage parents to wait until at least 4 months (but not more than 6 months) to start cereal, and to wait 3 to 4 days between introducing any new foods to make sure the child does not have an adverse reaction.

I generally tell all parents to keep their child on breast milk or formula and avoid whole milk until age 1, although small amounts of cheese and yogurt are fine. Additionally, I recommend avoiding citrus, honey, and eggs until age 1 and peanut butter until age 2 or 3.

For the child at high risk of atopy, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommendation to wait to introduce solid foods until 6 months of age and to wait to introduce peanuts and fish until 3 years of age seems reasonable, although I’d let parents know that they could try these foods earlier if they wanted since there is no definite evidence that those changes will make a difference.

Although I’ve never recommended hydrolyzed protein formula for children at high risk of atopy, it is an option for discussion. practical considerations to bring up in the discussion are the higher cost of these formulas and the palatability. Children receiving their formula through Women, Infant and Children (WIC) programs will need a prescription that includes the indication for the formula.

Evidence summary

Systematic reviews analyzing the modification of early feeding practices to prevent atopic disease have all been limited by a paucity of double-blinded RCTs of sufficient duration.1-3

Breastfeeding, hydrolyzed formulas confer lowest atopy risk

Breastfeeding and the use of hydrolyzed protein formulas confer the lowest risk of atopy in high-risk children when compared with cow’s milk or soy-based formulas.1,3 The relative risk for wheeze or asthma in the first year of life was 0.4 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.19–0.85) for children fed hydrolyzed protein formulas when compared with cow’s milk.1 Studies have not found a significant difference among these forms of milk for infants without a strong family history of atopic disease.3

Delaying solid food may reduce allergies

There is speculation that introducing certain solid foods early increases the risk of allergies to these foods, as well as causing generalized atopic symptoms. Few studies have examined this, and no systematic reviews focus on atopic disease.4

A cohort study (n=1265) comparing children who had been given 4 or more types of solid food before 4 months of age with those whose caregivers delayed solid foods showed an increased incidence of eczema by 10 years of age (relative risk=2.35; P<.05) in the early feeding group.5

However, a prospective interventional cohort study using a retrospective cohort as a control (n=375) compared children who had strictly avoided fish and citrus products until 1 year of age with those who had an unrestricted diet. There was no difference in the frequency of allergy to these foods as quantified by history and positive challenge test, although the authors did not include a statistical analysis of their results.6

Another study randomized 165 high-risk children into groups with standard feeding practices or an allergy prophylaxis regimen, which included avoidance of milk protein until age 1 year, eggs until 2 years, and fish and peanuts until 3 years. Although prophylaxis decreased the prevalence of atopic disorders at 1 year, there was no difference in any atopic disease between the 2 groups at age 7.7

Recommendations from others

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that for high-risk infants, solid foods should not be introduced into the diet until 6 months of age, with dairy products delayed until 1 year, eggs until 2 years, and peanuts, tree nuts, and fish until 3 years of age.8

Yes. In children at high risk for atopy (those with a family history of allergy, asthma, or eczema in at least 1 first-degree relative), breastfeeding or giving hydrolyzed protein formula during the first 4 to 6 months reduces the risk of atopy in the first year of life, when compared with introducing cow’s milk or soy formula (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, based on a systematic review that included only 2 double-blinded randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

There is inconsistent evidence to show that early introduction of solid food increases the incidence of atopic disease (SOR: B, systematic review of inconsistent studies).

Begin talking about infant feeding during the first postnatal visit

Mary M. Stephens, MD, MPH

East Tennessee State University, Johnson City

Having found a surprising number of children on cereal or other solids at the 2-month visit, I make it a practice to begin talking about infant feeding during the first postnatal visit. I encourage parents to wait until at least 4 months (but not more than 6 months) to start cereal, and to wait 3 to 4 days between introducing any new foods to make sure the child does not have an adverse reaction.

I generally tell all parents to keep their child on breast milk or formula and avoid whole milk until age 1, although small amounts of cheese and yogurt are fine. Additionally, I recommend avoiding citrus, honey, and eggs until age 1 and peanut butter until age 2 or 3.

For the child at high risk of atopy, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommendation to wait to introduce solid foods until 6 months of age and to wait to introduce peanuts and fish until 3 years of age seems reasonable, although I’d let parents know that they could try these foods earlier if they wanted since there is no definite evidence that those changes will make a difference.

Although I’ve never recommended hydrolyzed protein formula for children at high risk of atopy, it is an option for discussion. practical considerations to bring up in the discussion are the higher cost of these formulas and the palatability. Children receiving their formula through Women, Infant and Children (WIC) programs will need a prescription that includes the indication for the formula.

Evidence summary

Systematic reviews analyzing the modification of early feeding practices to prevent atopic disease have all been limited by a paucity of double-blinded RCTs of sufficient duration.1-3

Breastfeeding, hydrolyzed formulas confer lowest atopy risk

Breastfeeding and the use of hydrolyzed protein formulas confer the lowest risk of atopy in high-risk children when compared with cow’s milk or soy-based formulas.1,3 The relative risk for wheeze or asthma in the first year of life was 0.4 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.19–0.85) for children fed hydrolyzed protein formulas when compared with cow’s milk.1 Studies have not found a significant difference among these forms of milk for infants without a strong family history of atopic disease.3

Delaying solid food may reduce allergies

There is speculation that introducing certain solid foods early increases the risk of allergies to these foods, as well as causing generalized atopic symptoms. Few studies have examined this, and no systematic reviews focus on atopic disease.4

A cohort study (n=1265) comparing children who had been given 4 or more types of solid food before 4 months of age with those whose caregivers delayed solid foods showed an increased incidence of eczema by 10 years of age (relative risk=2.35; P<.05) in the early feeding group.5

However, a prospective interventional cohort study using a retrospective cohort as a control (n=375) compared children who had strictly avoided fish and citrus products until 1 year of age with those who had an unrestricted diet. There was no difference in the frequency of allergy to these foods as quantified by history and positive challenge test, although the authors did not include a statistical analysis of their results.6

Another study randomized 165 high-risk children into groups with standard feeding practices or an allergy prophylaxis regimen, which included avoidance of milk protein until age 1 year, eggs until 2 years, and fish and peanuts until 3 years. Although prophylaxis decreased the prevalence of atopic disorders at 1 year, there was no difference in any atopic disease between the 2 groups at age 7.7

Recommendations from others

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that for high-risk infants, solid foods should not be introduced into the diet until 6 months of age, with dairy products delayed until 1 year, eggs until 2 years, and peanuts, tree nuts, and fish until 3 years of age.8

1. Ram FS, Ducharme FM, Scarlett J. Cow’s milk protein avoidance and development of childhood wheeze in children with a family history of atopy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002;(3):CD003795.-

2. Smethurst D, Macfarlane S. Atopic eczema (web archive): prolonged breast feeding in predisposed infants. Clinical Evidence 2002;(8):1664-1682.

3. Osborn DA, Sinn J. Formulas containing hydrolysed protein for prevention of allergy and food intolerance in infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;(4):CD003664.-

4. Lanigan JA, Bishop J, Kimber AC, Morgan J. Systematic review concerning the age of introduction of complementary foods to the healthy full-term infant. Eur J Clin Nutr 2001;55:309-320.

5. Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Shannon FT. Early solid feeding and recurrent childhood eczema: a 10-year longitudinal study. Pediatrics 1990;86:541-546.

6. Saarinen UM, Kajosaari M. Does dietary elimination in infancy prevent or only postpone a food allergy? A study of fish and citrus allergy in 375 children. Lancet 1980;1:166-167.

7. Zeiger RS, Heller S. The development and prediction of atopy in high-risk children: follow-up at age seven years in a prospective randomized study of combined maternal and infant food allergen avoidance. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1995;95:1179-1190.

8. American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Nutrition. Hypoallergenic infant formulas. Pediatrics 2000;106:346-349.

1. Ram FS, Ducharme FM, Scarlett J. Cow’s milk protein avoidance and development of childhood wheeze in children with a family history of atopy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002;(3):CD003795.-

2. Smethurst D, Macfarlane S. Atopic eczema (web archive): prolonged breast feeding in predisposed infants. Clinical Evidence 2002;(8):1664-1682.

3. Osborn DA, Sinn J. Formulas containing hydrolysed protein for prevention of allergy and food intolerance in infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;(4):CD003664.-

4. Lanigan JA, Bishop J, Kimber AC, Morgan J. Systematic review concerning the age of introduction of complementary foods to the healthy full-term infant. Eur J Clin Nutr 2001;55:309-320.

5. Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Shannon FT. Early solid feeding and recurrent childhood eczema: a 10-year longitudinal study. Pediatrics 1990;86:541-546.

6. Saarinen UM, Kajosaari M. Does dietary elimination in infancy prevent or only postpone a food allergy? A study of fish and citrus allergy in 375 children. Lancet 1980;1:166-167.

7. Zeiger RS, Heller S. The development and prediction of atopy in high-risk children: follow-up at age seven years in a prospective randomized study of combined maternal and infant food allergen avoidance. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1995;95:1179-1190.

8. American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Nutrition. Hypoallergenic infant formulas. Pediatrics 2000;106:346-349.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

What is the best approach for patients with ASCUS detected on Pap smear?

DNA testing for human papillomavirus (HPV), especially if the sample can be obtained at the same time as the Papanicolaou (Pap) smear, can guide the management of women whose test result shows atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS). Those who test positive for high-risk types of HPV should be referred for colposcopy (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B), and those with a negative test result may resume regular Pap testing in 12 months (SOR: B). If HPV testing is unavailable, an alternative strategy is to repeat the Pap smear at 4- to 6-month intervals. After 2 negative Pap smears are obtained, usual screening may resume. But if either of the repeat Pap smears results in ASCUS or worse, the woman should be referred for colposcopy (SOR: B).

Evidence summary

Although only 5% to 10% of women with the result of ASCUS on a Pap smear have a high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL), estimates suggest that more than one third of these lesions are identified during follow-up to ASCUS Pap smears.1

The recent ASCUS-LSIL Triage Study (ALTS), a multicenter randomized trial, directly addressed the appropriate evaluation of ASCUS.2 The trial compared 3 management strategies for ASCUS Pap smears: reflex HPV-DNA testing (the initial Pap sample is tested for HPV only if the results are ASCUS), immediate referral for colposcopy, and repeat Pap smears. Reflex HPV testing had a sensitivity of 96% for detecting HSIL and a negative predictive value of 98%. The 44% of women with ASCUS who tested negative for high-risk HPV were able to avoid colposcopy. A single repeat Pap smear within 4 to 6 months, with referral for colposcopy if abnormal, had a sensitivity of 85% (sensitivity might be expected to improve with a second repeat test) and a similar colposcopy referral rate.2

A cost-effectiveness analysis that modeled data from the trial found that reflex HPV testing was most cost-effective.3 For women aged 29 years or older, HPV testing resulted in a much lower colposcopy referral rate, 31% vs 65% for younger women, without sacrificing sensitivity.4

Recommendations from others

Evidenced-based guidelines were developed at a consensus conference sponsored by the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology in September 2001.5 Recommendations were also made for women with ASCUS in special circumstances. Pregnant women should be managed the same way as nonpregnant women; immunosuppressed women should be referred for colposcopy; and postmenopausal women, who are at a lower risk for HSIL, may try a 3- to 6-week course of intravaginal estrogen followed by repeat Pap smears 1 week after estrogen treatment and again 4 to 6 months later.

If either repeat test is reported as ASCUS or greater, the woman should be referred for colposcopy. Any woman with a Pap smear reported as ASCH (atypical squamous cells, cannot exclude HSIL) should be referred for colposcopy.5

The US Preventive Services Task Force recently concluded that evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against the routine use of HPV testing as a primary screening test for cervical cancer, but they did not address the management of abnormal Pap smears.6

Thin-prep Pap smears can make workup of ASCUS easier for physician and patient

John Hill, MD

University of Colorado Health Sciences Center, Denver

The management of ASCUS Pap smears has often confused primary care doctors. This is confounded by the fact that it is often a challenge to ensure that patients follow our recommendations. How could we blame them—after all, who wants to undergo 4 Pap smears instead of 1? The advent of thin-prep Pap smears, with reflex HPV testing on the same specimen, has simplified our lives. By obtaining routine thin-prep Pap smears and then reflex HPV testing for only high-risk HPV types, fewer Pap smears and colposcopic exams are needed, without reducing the detection of HSIL. Best of all, fewer women are overtreated or lost to follow-up.

1. Manos MM, Kinney WK, Hurley LB, et al. Identifying women with cervical neoplasia: using human papillomavirus DNA testing for equivocal Papanicolaou results. JAMA 1999;281:1605-1610.

2. Solomon D, Schiffman M, Tarone R; ALTS Study Group. Comparison of three management strategies for patients with atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance: baseline results from a randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 2001;93:293-299.

3. Kim JJ, Wright TC, Goldie SJ. Cost-effectiveness of alternative triage strategies for atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance. JAMA 2002;287:2382-2390.

4. Schiffman M, Solomon D. Findings to date from the ASCUS-LSIL Triage Study (ALTS). Arch Pathol Lab Med 2003;127:946-949.

5. Wright TC, Jr, Cox JT, Massad LS, Twiggs LB. Wilkinson. EJ; ASCCP-Sponsored Consensus Conference. 2001 Consensus guidelines for the management of women with cervical cytological abnormalities. JAMA 2002;287:2120-2129.

6. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for cervical cancer: recommendations and rationale. AHRQ Publication No. 03-515A. January 2003. Rockville, Md: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Available at: www.ahcpr.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspscerv.htm. Accessed on January 27, 2004.

DNA testing for human papillomavirus (HPV), especially if the sample can be obtained at the same time as the Papanicolaou (Pap) smear, can guide the management of women whose test result shows atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS). Those who test positive for high-risk types of HPV should be referred for colposcopy (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B), and those with a negative test result may resume regular Pap testing in 12 months (SOR: B). If HPV testing is unavailable, an alternative strategy is to repeat the Pap smear at 4- to 6-month intervals. After 2 negative Pap smears are obtained, usual screening may resume. But if either of the repeat Pap smears results in ASCUS or worse, the woman should be referred for colposcopy (SOR: B).

Evidence summary

Although only 5% to 10% of women with the result of ASCUS on a Pap smear have a high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL), estimates suggest that more than one third of these lesions are identified during follow-up to ASCUS Pap smears.1

The recent ASCUS-LSIL Triage Study (ALTS), a multicenter randomized trial, directly addressed the appropriate evaluation of ASCUS.2 The trial compared 3 management strategies for ASCUS Pap smears: reflex HPV-DNA testing (the initial Pap sample is tested for HPV only if the results are ASCUS), immediate referral for colposcopy, and repeat Pap smears. Reflex HPV testing had a sensitivity of 96% for detecting HSIL and a negative predictive value of 98%. The 44% of women with ASCUS who tested negative for high-risk HPV were able to avoid colposcopy. A single repeat Pap smear within 4 to 6 months, with referral for colposcopy if abnormal, had a sensitivity of 85% (sensitivity might be expected to improve with a second repeat test) and a similar colposcopy referral rate.2

A cost-effectiveness analysis that modeled data from the trial found that reflex HPV testing was most cost-effective.3 For women aged 29 years or older, HPV testing resulted in a much lower colposcopy referral rate, 31% vs 65% for younger women, without sacrificing sensitivity.4

Recommendations from others

Evidenced-based guidelines were developed at a consensus conference sponsored by the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology in September 2001.5 Recommendations were also made for women with ASCUS in special circumstances. Pregnant women should be managed the same way as nonpregnant women; immunosuppressed women should be referred for colposcopy; and postmenopausal women, who are at a lower risk for HSIL, may try a 3- to 6-week course of intravaginal estrogen followed by repeat Pap smears 1 week after estrogen treatment and again 4 to 6 months later.

If either repeat test is reported as ASCUS or greater, the woman should be referred for colposcopy. Any woman with a Pap smear reported as ASCH (atypical squamous cells, cannot exclude HSIL) should be referred for colposcopy.5

The US Preventive Services Task Force recently concluded that evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against the routine use of HPV testing as a primary screening test for cervical cancer, but they did not address the management of abnormal Pap smears.6

Thin-prep Pap smears can make workup of ASCUS easier for physician and patient

John Hill, MD

University of Colorado Health Sciences Center, Denver

The management of ASCUS Pap smears has often confused primary care doctors. This is confounded by the fact that it is often a challenge to ensure that patients follow our recommendations. How could we blame them—after all, who wants to undergo 4 Pap smears instead of 1? The advent of thin-prep Pap smears, with reflex HPV testing on the same specimen, has simplified our lives. By obtaining routine thin-prep Pap smears and then reflex HPV testing for only high-risk HPV types, fewer Pap smears and colposcopic exams are needed, without reducing the detection of HSIL. Best of all, fewer women are overtreated or lost to follow-up.

DNA testing for human papillomavirus (HPV), especially if the sample can be obtained at the same time as the Papanicolaou (Pap) smear, can guide the management of women whose test result shows atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS). Those who test positive for high-risk types of HPV should be referred for colposcopy (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B), and those with a negative test result may resume regular Pap testing in 12 months (SOR: B). If HPV testing is unavailable, an alternative strategy is to repeat the Pap smear at 4- to 6-month intervals. After 2 negative Pap smears are obtained, usual screening may resume. But if either of the repeat Pap smears results in ASCUS or worse, the woman should be referred for colposcopy (SOR: B).

Evidence summary

Although only 5% to 10% of women with the result of ASCUS on a Pap smear have a high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL), estimates suggest that more than one third of these lesions are identified during follow-up to ASCUS Pap smears.1

The recent ASCUS-LSIL Triage Study (ALTS), a multicenter randomized trial, directly addressed the appropriate evaluation of ASCUS.2 The trial compared 3 management strategies for ASCUS Pap smears: reflex HPV-DNA testing (the initial Pap sample is tested for HPV only if the results are ASCUS), immediate referral for colposcopy, and repeat Pap smears. Reflex HPV testing had a sensitivity of 96% for detecting HSIL and a negative predictive value of 98%. The 44% of women with ASCUS who tested negative for high-risk HPV were able to avoid colposcopy. A single repeat Pap smear within 4 to 6 months, with referral for colposcopy if abnormal, had a sensitivity of 85% (sensitivity might be expected to improve with a second repeat test) and a similar colposcopy referral rate.2

A cost-effectiveness analysis that modeled data from the trial found that reflex HPV testing was most cost-effective.3 For women aged 29 years or older, HPV testing resulted in a much lower colposcopy referral rate, 31% vs 65% for younger women, without sacrificing sensitivity.4

Recommendations from others

Evidenced-based guidelines were developed at a consensus conference sponsored by the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology in September 2001.5 Recommendations were also made for women with ASCUS in special circumstances. Pregnant women should be managed the same way as nonpregnant women; immunosuppressed women should be referred for colposcopy; and postmenopausal women, who are at a lower risk for HSIL, may try a 3- to 6-week course of intravaginal estrogen followed by repeat Pap smears 1 week after estrogen treatment and again 4 to 6 months later.

If either repeat test is reported as ASCUS or greater, the woman should be referred for colposcopy. Any woman with a Pap smear reported as ASCH (atypical squamous cells, cannot exclude HSIL) should be referred for colposcopy.5

The US Preventive Services Task Force recently concluded that evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against the routine use of HPV testing as a primary screening test for cervical cancer, but they did not address the management of abnormal Pap smears.6

Thin-prep Pap smears can make workup of ASCUS easier for physician and patient

John Hill, MD

University of Colorado Health Sciences Center, Denver

The management of ASCUS Pap smears has often confused primary care doctors. This is confounded by the fact that it is often a challenge to ensure that patients follow our recommendations. How could we blame them—after all, who wants to undergo 4 Pap smears instead of 1? The advent of thin-prep Pap smears, with reflex HPV testing on the same specimen, has simplified our lives. By obtaining routine thin-prep Pap smears and then reflex HPV testing for only high-risk HPV types, fewer Pap smears and colposcopic exams are needed, without reducing the detection of HSIL. Best of all, fewer women are overtreated or lost to follow-up.

1. Manos MM, Kinney WK, Hurley LB, et al. Identifying women with cervical neoplasia: using human papillomavirus DNA testing for equivocal Papanicolaou results. JAMA 1999;281:1605-1610.

2. Solomon D, Schiffman M, Tarone R; ALTS Study Group. Comparison of three management strategies for patients with atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance: baseline results from a randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 2001;93:293-299.

3. Kim JJ, Wright TC, Goldie SJ. Cost-effectiveness of alternative triage strategies for atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance. JAMA 2002;287:2382-2390.

4. Schiffman M, Solomon D. Findings to date from the ASCUS-LSIL Triage Study (ALTS). Arch Pathol Lab Med 2003;127:946-949.

5. Wright TC, Jr, Cox JT, Massad LS, Twiggs LB. Wilkinson. EJ; ASCCP-Sponsored Consensus Conference. 2001 Consensus guidelines for the management of women with cervical cytological abnormalities. JAMA 2002;287:2120-2129.

6. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for cervical cancer: recommendations and rationale. AHRQ Publication No. 03-515A. January 2003. Rockville, Md: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Available at: www.ahcpr.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspscerv.htm. Accessed on January 27, 2004.

1. Manos MM, Kinney WK, Hurley LB, et al. Identifying women with cervical neoplasia: using human papillomavirus DNA testing for equivocal Papanicolaou results. JAMA 1999;281:1605-1610.

2. Solomon D, Schiffman M, Tarone R; ALTS Study Group. Comparison of three management strategies for patients with atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance: baseline results from a randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 2001;93:293-299.

3. Kim JJ, Wright TC, Goldie SJ. Cost-effectiveness of alternative triage strategies for atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance. JAMA 2002;287:2382-2390.

4. Schiffman M, Solomon D. Findings to date from the ASCUS-LSIL Triage Study (ALTS). Arch Pathol Lab Med 2003;127:946-949.

5. Wright TC, Jr, Cox JT, Massad LS, Twiggs LB. Wilkinson. EJ; ASCCP-Sponsored Consensus Conference. 2001 Consensus guidelines for the management of women with cervical cytological abnormalities. JAMA 2002;287:2120-2129.

6. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for cervical cancer: recommendations and rationale. AHRQ Publication No. 03-515A. January 2003. Rockville, Md: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Available at: www.ahcpr.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspscerv.htm. Accessed on January 27, 2004.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

Is ticlopidine more effective than aspirin in preventing adverse cardiovascular events after myocardial infarction (MI)?

BACKGROUND: Guidelines for management of patients after acute myocardial infarction (AMI) recommend daily aspirin therapy.1 Although ticlopidine reduces the incidence of vascular death, MI, and stroke among people with atherosclerotic disease,2 it has not been compared directly with aspirin in the post-AMI period. This study compares the efficacy and safety of aspirin and ticlopidine in survivors of AMI treated with a thrombolytic agent.

POPULATION STUDIED: This multicenter trial enrolled 1470 patients recruited at the time of discharge from the hospital after receiving successful treatment for AMI with a thrombolytic agent. Patients were not included if they required anticoagulation with warfarin, were scheduled for major surgery, had uncontrolled hypertension, or had severe comorbidity likely to limit their life expectancy. The 2 groups were similar with regard to major coronary artery disease risk factors (eg, hypertension, diabetes, smoking) as well as characteristics and management of the incident MI (eg, infarct location, ejection fraction, medications at discharge).

STUDY DESIGN AND VALIDITY: This was a randomized double-blinded multicenter trial. The patients were randomized at hospital discharge to receive either aspirin (80 mg twice daily) or ticlopidine (250 mg twice daily). Clinical follow-up was at 45 days, 3 months, and 6 months after enrollment. During these visits, compliance was assessed and information was collected on outcome endpoints, adverse reactions, and concomitant medications. An intention-to-treat analysis was performed, and patients were followed up for 6 months regardless of whether they were still taking the study drug. The study was large enough to detect a 5% difference in primary endpoints with 95% power. The main limitations in this study were the short follow-up period (6 months) and the relatively low event rate (10%). Compliance and follow-up appear to be good.

OUTCOMES MEASURED: The primary endpoint was the first occurrence of any of the following during the 6 month follow-up: fatal and nonfatal MI, fatal and nonfatal stroke, angina with objective evidence of myocardial ischemia, vascular death, or death due to any cause. The study was not large enough to detect differences for specific endpoints, only in the total frequency of endpoints.

RESULTS: At the end of the 6-month follow-up, equal numbers of patients experienced at least 1 primary endpoint (8.0% in each group). Fewer patients taking ticlopidine suffered a repeat nonfatal MI: 8 in the ticlopidine group versus 18 in the aspirin group (1.1% vs 2.4%; P=.049). There were no differences between the groups in frequencies of cardiovascular death, nonvascular death, nonfatal stroke, and documented angina. Seventy-two patients taking aspirin and 90 patients taking ticlopidine reported at least 1 drug-related adverse effect (9.8% vs 12.3%). Serious adverse effects occurred in 11 patients taking aspirin and 18 taking ticlopidine (1.5% vs 2.4%). Thirty-five patients in the aspirin group and 53 in the ticlopidine group stopped treatment because of adverse events. Gastrointestinal symptoms were the most common adverse reactions in both study groups.

This study shows that ticlopidine is as effective as, though no better than, aspirin in preventing a patient-oriented combined outcome of nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke, angina, or death. Although the numbers were small, there was a significantly lower rate of nonfatal reinfarction in the ticlopidine group. The conclusions apply to a patient population of relatively healthy adults who have experienced an AMI and are treated with thrombolysis only. Ticlopidine and aspirin were equally well tolerated with similar side effect profiles. Given the cost of treating with ticlopidine ($1 to $2 per day), aspirin ($0.01 per day) remains the treatment of choice for antiplatelet aggregation therapy in the post-MI period.

BACKGROUND: Guidelines for management of patients after acute myocardial infarction (AMI) recommend daily aspirin therapy.1 Although ticlopidine reduces the incidence of vascular death, MI, and stroke among people with atherosclerotic disease,2 it has not been compared directly with aspirin in the post-AMI period. This study compares the efficacy and safety of aspirin and ticlopidine in survivors of AMI treated with a thrombolytic agent.

POPULATION STUDIED: This multicenter trial enrolled 1470 patients recruited at the time of discharge from the hospital after receiving successful treatment for AMI with a thrombolytic agent. Patients were not included if they required anticoagulation with warfarin, were scheduled for major surgery, had uncontrolled hypertension, or had severe comorbidity likely to limit their life expectancy. The 2 groups were similar with regard to major coronary artery disease risk factors (eg, hypertension, diabetes, smoking) as well as characteristics and management of the incident MI (eg, infarct location, ejection fraction, medications at discharge).

STUDY DESIGN AND VALIDITY: This was a randomized double-blinded multicenter trial. The patients were randomized at hospital discharge to receive either aspirin (80 mg twice daily) or ticlopidine (250 mg twice daily). Clinical follow-up was at 45 days, 3 months, and 6 months after enrollment. During these visits, compliance was assessed and information was collected on outcome endpoints, adverse reactions, and concomitant medications. An intention-to-treat analysis was performed, and patients were followed up for 6 months regardless of whether they were still taking the study drug. The study was large enough to detect a 5% difference in primary endpoints with 95% power. The main limitations in this study were the short follow-up period (6 months) and the relatively low event rate (10%). Compliance and follow-up appear to be good.

OUTCOMES MEASURED: The primary endpoint was the first occurrence of any of the following during the 6 month follow-up: fatal and nonfatal MI, fatal and nonfatal stroke, angina with objective evidence of myocardial ischemia, vascular death, or death due to any cause. The study was not large enough to detect differences for specific endpoints, only in the total frequency of endpoints.

RESULTS: At the end of the 6-month follow-up, equal numbers of patients experienced at least 1 primary endpoint (8.0% in each group). Fewer patients taking ticlopidine suffered a repeat nonfatal MI: 8 in the ticlopidine group versus 18 in the aspirin group (1.1% vs 2.4%; P=.049). There were no differences between the groups in frequencies of cardiovascular death, nonvascular death, nonfatal stroke, and documented angina. Seventy-two patients taking aspirin and 90 patients taking ticlopidine reported at least 1 drug-related adverse effect (9.8% vs 12.3%). Serious adverse effects occurred in 11 patients taking aspirin and 18 taking ticlopidine (1.5% vs 2.4%). Thirty-five patients in the aspirin group and 53 in the ticlopidine group stopped treatment because of adverse events. Gastrointestinal symptoms were the most common adverse reactions in both study groups.

This study shows that ticlopidine is as effective as, though no better than, aspirin in preventing a patient-oriented combined outcome of nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke, angina, or death. Although the numbers were small, there was a significantly lower rate of nonfatal reinfarction in the ticlopidine group. The conclusions apply to a patient population of relatively healthy adults who have experienced an AMI and are treated with thrombolysis only. Ticlopidine and aspirin were equally well tolerated with similar side effect profiles. Given the cost of treating with ticlopidine ($1 to $2 per day), aspirin ($0.01 per day) remains the treatment of choice for antiplatelet aggregation therapy in the post-MI period.

BACKGROUND: Guidelines for management of patients after acute myocardial infarction (AMI) recommend daily aspirin therapy.1 Although ticlopidine reduces the incidence of vascular death, MI, and stroke among people with atherosclerotic disease,2 it has not been compared directly with aspirin in the post-AMI period. This study compares the efficacy and safety of aspirin and ticlopidine in survivors of AMI treated with a thrombolytic agent.

POPULATION STUDIED: This multicenter trial enrolled 1470 patients recruited at the time of discharge from the hospital after receiving successful treatment for AMI with a thrombolytic agent. Patients were not included if they required anticoagulation with warfarin, were scheduled for major surgery, had uncontrolled hypertension, or had severe comorbidity likely to limit their life expectancy. The 2 groups were similar with regard to major coronary artery disease risk factors (eg, hypertension, diabetes, smoking) as well as characteristics and management of the incident MI (eg, infarct location, ejection fraction, medications at discharge).

STUDY DESIGN AND VALIDITY: This was a randomized double-blinded multicenter trial. The patients were randomized at hospital discharge to receive either aspirin (80 mg twice daily) or ticlopidine (250 mg twice daily). Clinical follow-up was at 45 days, 3 months, and 6 months after enrollment. During these visits, compliance was assessed and information was collected on outcome endpoints, adverse reactions, and concomitant medications. An intention-to-treat analysis was performed, and patients were followed up for 6 months regardless of whether they were still taking the study drug. The study was large enough to detect a 5% difference in primary endpoints with 95% power. The main limitations in this study were the short follow-up period (6 months) and the relatively low event rate (10%). Compliance and follow-up appear to be good.

OUTCOMES MEASURED: The primary endpoint was the first occurrence of any of the following during the 6 month follow-up: fatal and nonfatal MI, fatal and nonfatal stroke, angina with objective evidence of myocardial ischemia, vascular death, or death due to any cause. The study was not large enough to detect differences for specific endpoints, only in the total frequency of endpoints.

RESULTS: At the end of the 6-month follow-up, equal numbers of patients experienced at least 1 primary endpoint (8.0% in each group). Fewer patients taking ticlopidine suffered a repeat nonfatal MI: 8 in the ticlopidine group versus 18 in the aspirin group (1.1% vs 2.4%; P=.049). There were no differences between the groups in frequencies of cardiovascular death, nonvascular death, nonfatal stroke, and documented angina. Seventy-two patients taking aspirin and 90 patients taking ticlopidine reported at least 1 drug-related adverse effect (9.8% vs 12.3%). Serious adverse effects occurred in 11 patients taking aspirin and 18 taking ticlopidine (1.5% vs 2.4%). Thirty-five patients in the aspirin group and 53 in the ticlopidine group stopped treatment because of adverse events. Gastrointestinal symptoms were the most common adverse reactions in both study groups.

This study shows that ticlopidine is as effective as, though no better than, aspirin in preventing a patient-oriented combined outcome of nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke, angina, or death. Although the numbers were small, there was a significantly lower rate of nonfatal reinfarction in the ticlopidine group. The conclusions apply to a patient population of relatively healthy adults who have experienced an AMI and are treated with thrombolysis only. Ticlopidine and aspirin were equally well tolerated with similar side effect profiles. Given the cost of treating with ticlopidine ($1 to $2 per day), aspirin ($0.01 per day) remains the treatment of choice for antiplatelet aggregation therapy in the post-MI period.

Enoxaparin for the Prevention of VT in Acutely Ill Patients

CLINICAL QUESTION: Is enoxaparin safe and effective for preventing venous thromboembolism (VT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) in hospitalized moderately ill nonsurgical patients?

BACKGROUND: Patients hospitalized for congestive heart failure, respiratory distress, or infection are at increased risk for venous thromboembolism (VT). Enoxaparin is effective as prophylaxis for VT in certain groups of surgical, cardiac, and stroke patients.1 The authors of this study compared this drug in 2 different doses with placebo for the prophylaxis of VT in hospitalized medical patients.

POPULATION STUDIED: A total of 1102 patients older than 40 years from 60 centers in 9 countries were enrolled. The patients were expected to be hospitalized for at least 6 days but immobilized for not more than 3 days. Most patients were considered moderately ill and were hospitalized for congestive heart failure, respiratory failure without intubation, or infection without sepsis. Patients were excluded if they had indications for anticoagulation or if they had contraindications to anticoagulation or venography.

STUDY DESIGN AND VALIDITY: This is a randomized double-blind trial comparing placebo with 20 mg and 40 mg of enoxaparin given subcutaneously once daily. All patients were screened for deep venous thromboembolism (DVT) between days 6 and 14 with a venogram or venous ultrasound study. Patients were screened earlier if they were symptomatic for DVT or PE. Images were independently reviewed by a group of radiologists unaware of treatment assignments. Risk factors for VT or PE, the degree of illness, and the duration of hospitalization were not analyzed to determine if placebo and enoxaparin groups were statistically similar. In addition, the actual number of days of prophylaxis and the incidence of chronic anticoagulation treatment were not reported.

OUTCOMES MEASURED: The primary outcomes were the rates of DVT (symptomatic and asymptomatic) and PE (fatal and nonfatal) by day 14 as confirmed by imaging or venography. Secondary outcomes included the same results by day 110 as determined by phone follow-up (60% of patients) or visit. The rates of adverse events, such as hemorrhage and thrombocytopenia, were also reported.

RESULTS: There were 6 symptomatic DVTs, 94 asymptomatic DVTs, and 4 nonfatal PEs in the study population by day 14. The 40-mg enoxaparin group had a significantly lower overall rate of VT than the placebo group (5.5% vs 14.9%; relative risk [RR] = 0.37; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.22-0.63; number needed to treat [NNT] = 11) as well as a lower incidence of proximal DVT (1.7% vs 4.9%, P= .04; NNT = 33). However, there was no significant decrease in the rate of symptomatic DVT (0.3%, 0.7%) or PE (0%, 1.0%). Results were similar at day 110 with a significantly lower overall rate of VT (7% vs 17.1%; RR = 0.41; 95% CI, 0.25-0.68) and a decrease in the rate of proximal DVT (2.2% vs 6.5%, P = .02). There was no significant decrease in the rates of symptomatic DVT (1.1% vs 1.5%) or PE (0% vs 1.2%). There was also no statistically significant difference between the 20-mg enoxaparin and placebo groups for any outcome at days 14 or 110 of follow-up. Of the 4 fatal PEs, 2 occurred in the 40-mg enoxaparin group 2 months after the end of treatment. By day 110, there was no significant difference between the 40-mg enoxaparin and placebo groups for the rate of death from any cause, and the rate of major hemorrhage and thrombocytopenia.

This study reminds us that nonsurgical moderately ill hospitalized patients are at increased risk for VT and may benefit from prophylaxis. Enoxaparin 40 mg daily reduced asymptomatic VT without a statistically significant reduction in symptomatic lower extremity VT, PE, or mortality at 2 weeks and 3 months. Enoxaparin 20 mg daily was no different from placebo. Although enoxaparin 40 mg daily appears to be safe, its benefit as a VT prophylaxis depends on the undetermined clinical significance of preventing asymptomatic lower extremity VT. The fact that fatal PEs occurred after termination of the study treatment indiactes a need to establish an appropriate duration of VT prophylaxis.

CLINICAL QUESTION: Is enoxaparin safe and effective for preventing venous thromboembolism (VT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) in hospitalized moderately ill nonsurgical patients?

BACKGROUND: Patients hospitalized for congestive heart failure, respiratory distress, or infection are at increased risk for venous thromboembolism (VT). Enoxaparin is effective as prophylaxis for VT in certain groups of surgical, cardiac, and stroke patients.1 The authors of this study compared this drug in 2 different doses with placebo for the prophylaxis of VT in hospitalized medical patients.

POPULATION STUDIED: A total of 1102 patients older than 40 years from 60 centers in 9 countries were enrolled. The patients were expected to be hospitalized for at least 6 days but immobilized for not more than 3 days. Most patients were considered moderately ill and were hospitalized for congestive heart failure, respiratory failure without intubation, or infection without sepsis. Patients were excluded if they had indications for anticoagulation or if they had contraindications to anticoagulation or venography.

STUDY DESIGN AND VALIDITY: This is a randomized double-blind trial comparing placebo with 20 mg and 40 mg of enoxaparin given subcutaneously once daily. All patients were screened for deep venous thromboembolism (DVT) between days 6 and 14 with a venogram or venous ultrasound study. Patients were screened earlier if they were symptomatic for DVT or PE. Images were independently reviewed by a group of radiologists unaware of treatment assignments. Risk factors for VT or PE, the degree of illness, and the duration of hospitalization were not analyzed to determine if placebo and enoxaparin groups were statistically similar. In addition, the actual number of days of prophylaxis and the incidence of chronic anticoagulation treatment were not reported.

OUTCOMES MEASURED: The primary outcomes were the rates of DVT (symptomatic and asymptomatic) and PE (fatal and nonfatal) by day 14 as confirmed by imaging or venography. Secondary outcomes included the same results by day 110 as determined by phone follow-up (60% of patients) or visit. The rates of adverse events, such as hemorrhage and thrombocytopenia, were also reported.

RESULTS: There were 6 symptomatic DVTs, 94 asymptomatic DVTs, and 4 nonfatal PEs in the study population by day 14. The 40-mg enoxaparin group had a significantly lower overall rate of VT than the placebo group (5.5% vs 14.9%; relative risk [RR] = 0.37; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.22-0.63; number needed to treat [NNT] = 11) as well as a lower incidence of proximal DVT (1.7% vs 4.9%, P= .04; NNT = 33). However, there was no significant decrease in the rate of symptomatic DVT (0.3%, 0.7%) or PE (0%, 1.0%). Results were similar at day 110 with a significantly lower overall rate of VT (7% vs 17.1%; RR = 0.41; 95% CI, 0.25-0.68) and a decrease in the rate of proximal DVT (2.2% vs 6.5%, P = .02). There was no significant decrease in the rates of symptomatic DVT (1.1% vs 1.5%) or PE (0% vs 1.2%). There was also no statistically significant difference between the 20-mg enoxaparin and placebo groups for any outcome at days 14 or 110 of follow-up. Of the 4 fatal PEs, 2 occurred in the 40-mg enoxaparin group 2 months after the end of treatment. By day 110, there was no significant difference between the 40-mg enoxaparin and placebo groups for the rate of death from any cause, and the rate of major hemorrhage and thrombocytopenia.

This study reminds us that nonsurgical moderately ill hospitalized patients are at increased risk for VT and may benefit from prophylaxis. Enoxaparin 40 mg daily reduced asymptomatic VT without a statistically significant reduction in symptomatic lower extremity VT, PE, or mortality at 2 weeks and 3 months. Enoxaparin 20 mg daily was no different from placebo. Although enoxaparin 40 mg daily appears to be safe, its benefit as a VT prophylaxis depends on the undetermined clinical significance of preventing asymptomatic lower extremity VT. The fact that fatal PEs occurred after termination of the study treatment indiactes a need to establish an appropriate duration of VT prophylaxis.

CLINICAL QUESTION: Is enoxaparin safe and effective for preventing venous thromboembolism (VT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) in hospitalized moderately ill nonsurgical patients?

BACKGROUND: Patients hospitalized for congestive heart failure, respiratory distress, or infection are at increased risk for venous thromboembolism (VT). Enoxaparin is effective as prophylaxis for VT in certain groups of surgical, cardiac, and stroke patients.1 The authors of this study compared this drug in 2 different doses with placebo for the prophylaxis of VT in hospitalized medical patients.

POPULATION STUDIED: A total of 1102 patients older than 40 years from 60 centers in 9 countries were enrolled. The patients were expected to be hospitalized for at least 6 days but immobilized for not more than 3 days. Most patients were considered moderately ill and were hospitalized for congestive heart failure, respiratory failure without intubation, or infection without sepsis. Patients were excluded if they had indications for anticoagulation or if they had contraindications to anticoagulation or venography.

STUDY DESIGN AND VALIDITY: This is a randomized double-blind trial comparing placebo with 20 mg and 40 mg of enoxaparin given subcutaneously once daily. All patients were screened for deep venous thromboembolism (DVT) between days 6 and 14 with a venogram or venous ultrasound study. Patients were screened earlier if they were symptomatic for DVT or PE. Images were independently reviewed by a group of radiologists unaware of treatment assignments. Risk factors for VT or PE, the degree of illness, and the duration of hospitalization were not analyzed to determine if placebo and enoxaparin groups were statistically similar. In addition, the actual number of days of prophylaxis and the incidence of chronic anticoagulation treatment were not reported.

OUTCOMES MEASURED: The primary outcomes were the rates of DVT (symptomatic and asymptomatic) and PE (fatal and nonfatal) by day 14 as confirmed by imaging or venography. Secondary outcomes included the same results by day 110 as determined by phone follow-up (60% of patients) or visit. The rates of adverse events, such as hemorrhage and thrombocytopenia, were also reported.

RESULTS: There were 6 symptomatic DVTs, 94 asymptomatic DVTs, and 4 nonfatal PEs in the study population by day 14. The 40-mg enoxaparin group had a significantly lower overall rate of VT than the placebo group (5.5% vs 14.9%; relative risk [RR] = 0.37; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.22-0.63; number needed to treat [NNT] = 11) as well as a lower incidence of proximal DVT (1.7% vs 4.9%, P= .04; NNT = 33). However, there was no significant decrease in the rate of symptomatic DVT (0.3%, 0.7%) or PE (0%, 1.0%). Results were similar at day 110 with a significantly lower overall rate of VT (7% vs 17.1%; RR = 0.41; 95% CI, 0.25-0.68) and a decrease in the rate of proximal DVT (2.2% vs 6.5%, P = .02). There was no significant decrease in the rates of symptomatic DVT (1.1% vs 1.5%) or PE (0% vs 1.2%). There was also no statistically significant difference between the 20-mg enoxaparin and placebo groups for any outcome at days 14 or 110 of follow-up. Of the 4 fatal PEs, 2 occurred in the 40-mg enoxaparin group 2 months after the end of treatment. By day 110, there was no significant difference between the 40-mg enoxaparin and placebo groups for the rate of death from any cause, and the rate of major hemorrhage and thrombocytopenia.

This study reminds us that nonsurgical moderately ill hospitalized patients are at increased risk for VT and may benefit from prophylaxis. Enoxaparin 40 mg daily reduced asymptomatic VT without a statistically significant reduction in symptomatic lower extremity VT, PE, or mortality at 2 weeks and 3 months. Enoxaparin 20 mg daily was no different from placebo. Although enoxaparin 40 mg daily appears to be safe, its benefit as a VT prophylaxis depends on the undetermined clinical significance of preventing asymptomatic lower extremity VT. The fact that fatal PEs occurred after termination of the study treatment indiactes a need to establish an appropriate duration of VT prophylaxis.