User login

Papulonodules on the Ankle in a Patient with Lung Cancer

Papulonodules on the Ankle in a Patient with Lung Cancer

THE DIAGNOSIS: Pembrolizumab-Induced Eruptive Squamous Proliferation

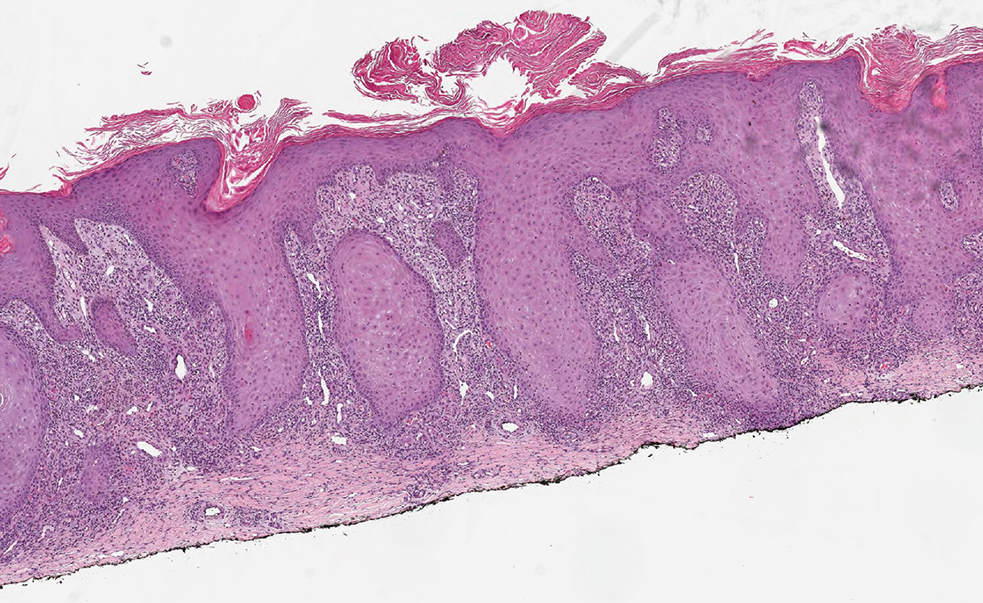

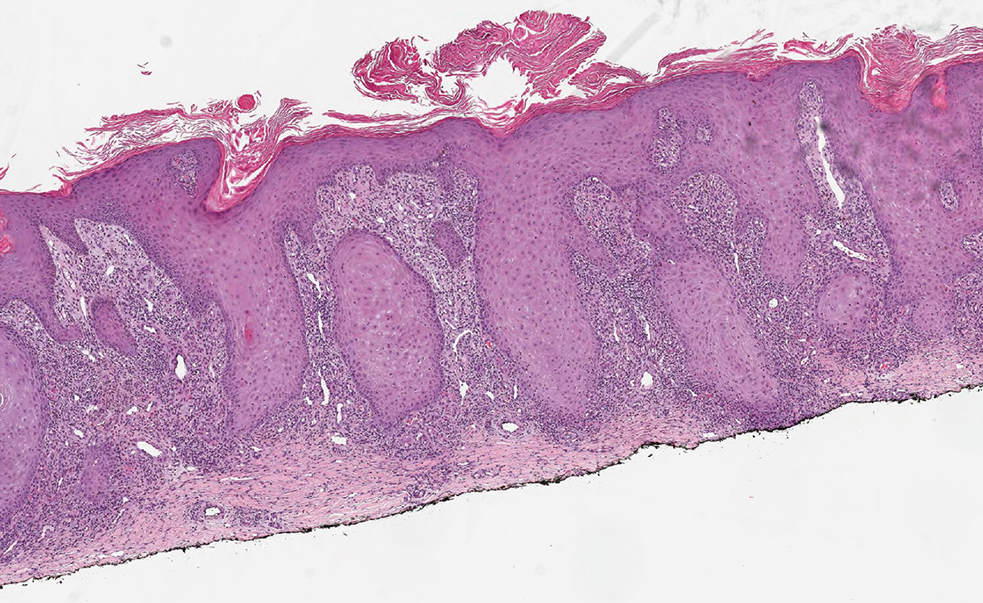

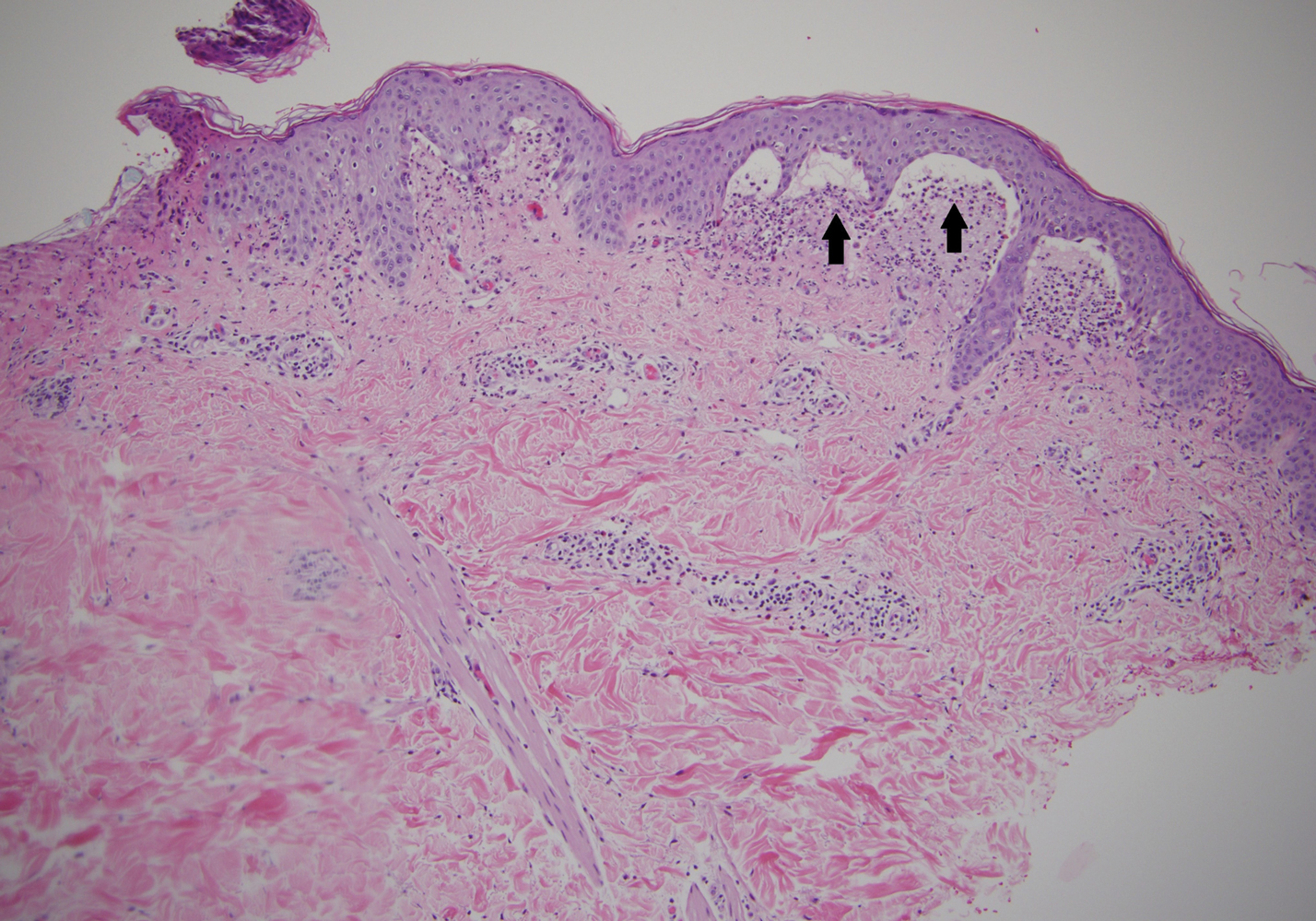

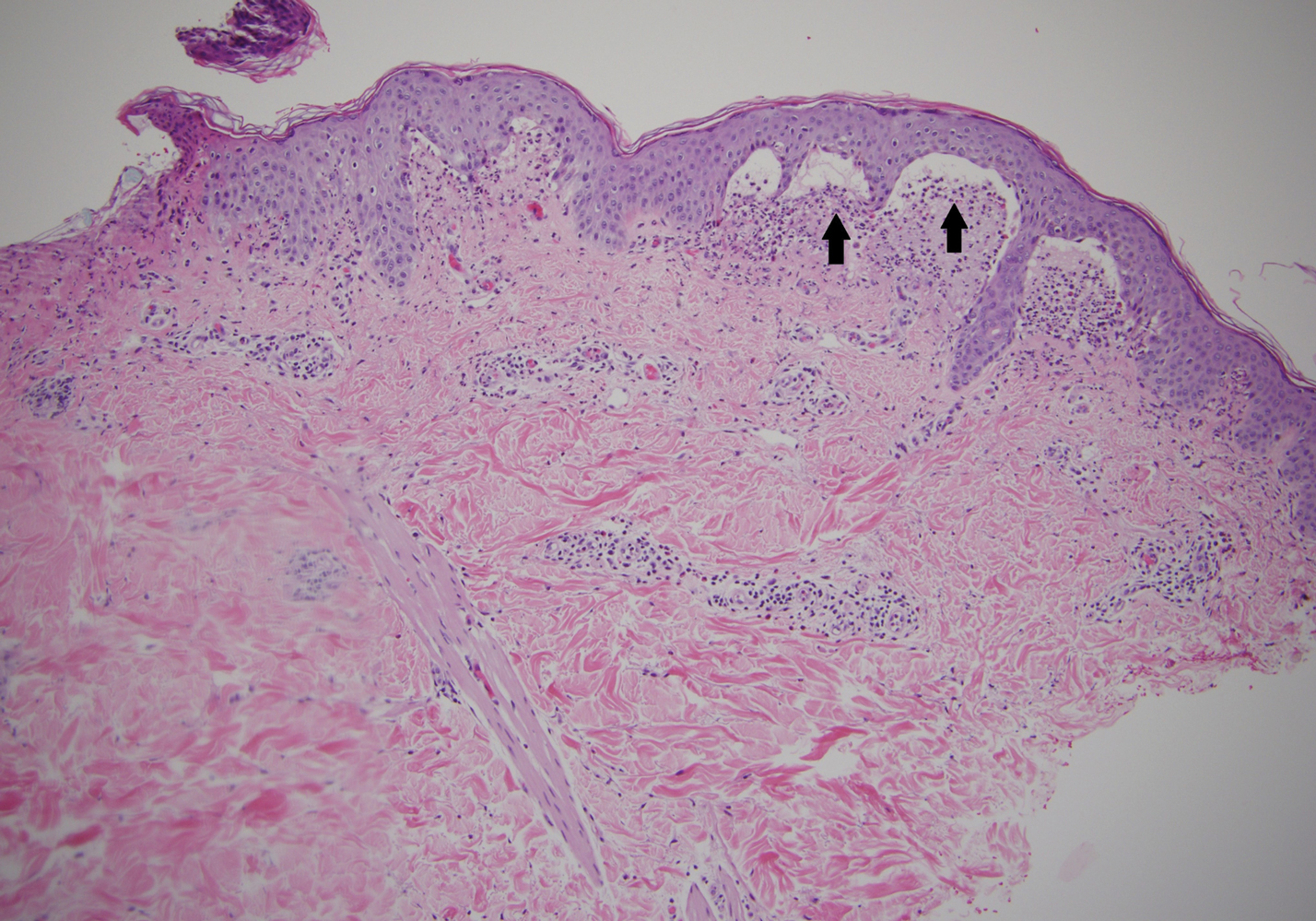

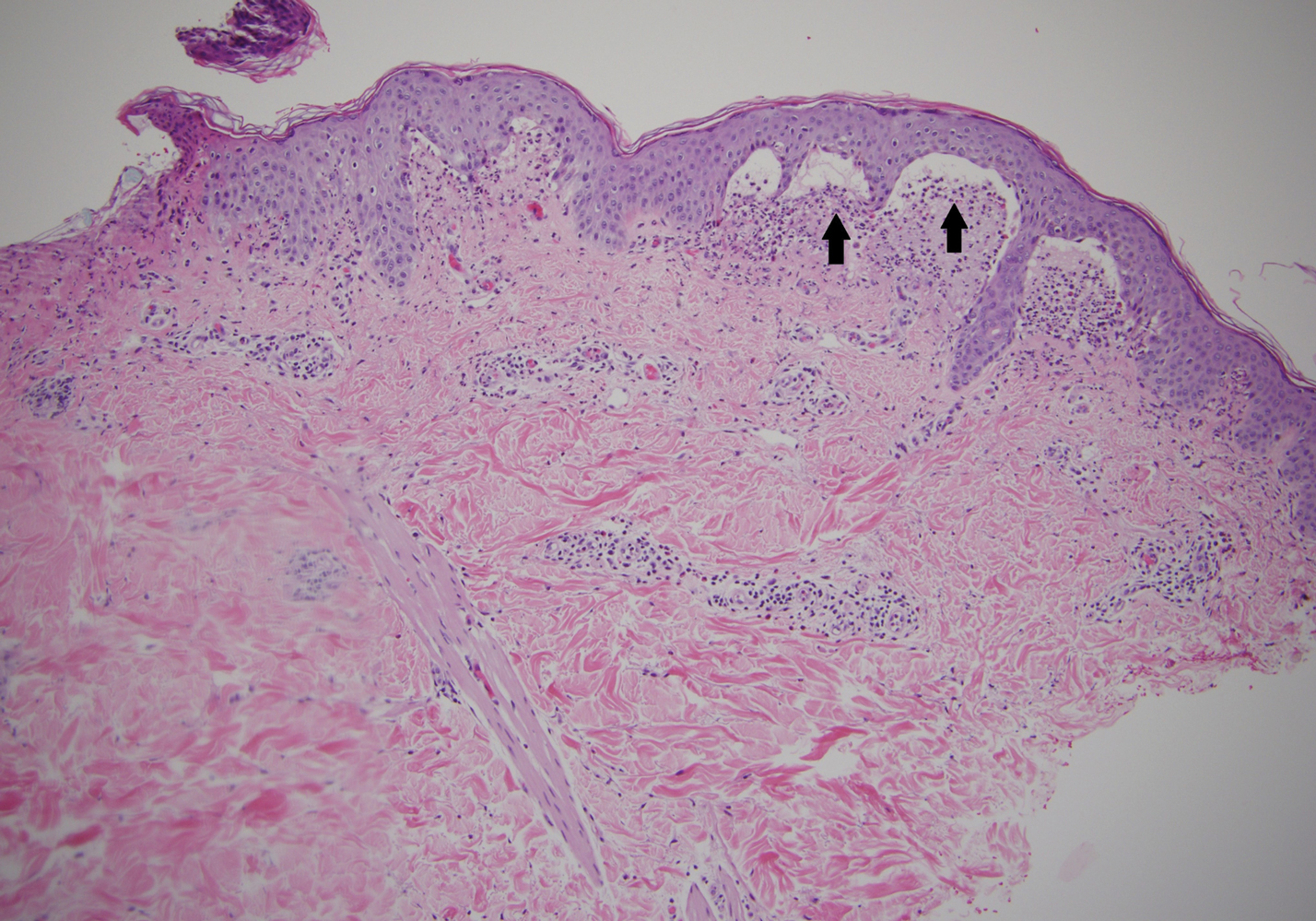

Histopathology showed a broad squamous proliferation with acanthosis of the epidermis. Large glassy keratinocytes were seen with scattered necrotic keratinocytes (Figure), and a dense lichenoid band of inflammation was present subjacent to the proliferation. Notably, no hypergranulosis, remarkable keratinocyte atypia, or increased mitotic figures were seen. Based on the patient’s medical history and biopsy results, a diagnosis of pembrolizumab-induced eruptive squamous proliferation was made. The diagnosis was supported by a growing body of evidence of this type of reaction in patients taking programmed death 1 (PD-1) inhibitors.1,2 Conservative treatment with clobetasol ointment 0.05% was initiated with complete resolution of the lesions at the 2-month follow-up appointment. Other common treatments include topical steroids, injected corticosteroids, or cryosurgery to locally control the inflammation and atypical proliferation of cells.3

Pembrolizumab is a humanized IgG4 monoclonal antibody targeting the PD-1 receptor that has been utilized for its antitumor activity against various cancers, including unresectable and metastatic melanoma, head and neck cancers, and non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).1,4,5 While this drug has extended the lives of many patients with cancer, there are adverse reactions associated with PD-1 inhibitors (eg, pembrolizumab, nivolumab). Skin toxicity to PD-1 inhibitors is the one of most common immune-mediated reactions worldwide, occurring in approximately 30% of patients.6,7 Reactions can occur while a patient is taking the inciting drug and can continue up to 2 months after treatment discontinuation.8 Skin reactions associated with PD-1 inhibitors vary from lichenoid reactions and vitiligolike patches to psoriasis or eczema flares and are organized into 4 categories: inflammatory, immunobullous, alteration of keratinocytes, and alteration of melanocytes.9 Our patient demonstrated alteration of keratinocytes, which is characterized by overlapping features of hypertrophic lichen planus and early keratoacanthoma.

The differential diagnoses for pembrolizumab-induced eruptive squamous proliferation include squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), psoriasis, hypertrophic lichen planus, and cutaneous metastasis of NSCLC. Hypertrophic lupus erythematosus also is a well-documented reaction to use of immune-checkpoint inhibitors.10 Direct immunofluorescence could have helped differentiate hypertrophic lupus erythematosus from an eruptive squamous proliferation in our patient; however, due to her response to treatment, no additional workup was done.

Squamous cell carcinoma, which is the most common type of skin cancer in Black patients in the United States,11 has been shown to manifest after a PD-1 inhibitor is taken.12 Although it typically has a more chronic persistent course, the clinical appearance of SCC can be similar to the findings seen in our patient. Histologically, SCC may demonstrate necrosis, but the atypical proliferations will invade the dermis—a feature not seen in our patient’s histopathology.13

Lichen planus (LP) is an eruptive immune reaction of violaceous polygonal papules and plaques commonly seen on the ankles14 that has been shown to be an adverse effect of pembrolizumab.15 There are several subtypes of LP including hypertrophic versions, which can appear clinically similar to the findings seen in our patient. On dermoscopy, the classic finding of white lines, known as Wickham striae, is seen in all subtypes and can help diagnose this pathologic process. Under the microscope, LP can manifest with hyperkeratosis without parakeratosis, irregular thickening of the stratum granulosum, sawtooth rete ridges, and destruction of the basal layer.14

Psoriasis also has been shown to be exacerbated by anti–PD-1 therapy, although the majority of patients diagnosed with PD-1–induced psoriasis have a personal or family history of the disease.6 Clinically, psoriasis can have a hyperpigmented or violaceous appearance in patients with skin of color.16 The histopathology of psoriasis typically reveals confluent parakeratosis, neutrophils in the stratum corneum, regular acanthosis, thinning of the suprapapillary plates, and vessels in the dermal papillae.17

Although cutaneous metastasis of NSCLC may appear clinically similar to the current case, it is one of the rarer organ sites of metastasis for lung cancer.18 In our patient, biopsy quickly ruled out this diagnosis. If it had been a site of metastasis, histopathology would have shown a dermal-based proliferation of dysplastic cells without epidermal connection.19

It is important for dermatologists to recognize eruptive squamous proliferations associated with pembrolizumab, as they often respond to conservative treatment and typically do not require dose reduction or discontinuation of the inciting drug.

- Freshwater T, Kondic A, Ahamadi M, et al. Evaluation of dosing strategy for pembrolizumab for oncology indications. J Immunother Cancer. 2017;5:43. doi:10.1186/s40425-017-0242-5

- Preti BTB, Pencz A, Cowger JJM, et al. Skin deep: a fascinating case report of immunotherapy-triggered, treatment-refractory autoimmune lichen planus and keratoacanthoma. Case Rep Oncol. 2021;14: 1189-1193. doi:10.1159/000518313

- Fradet M, Sibaud V, Tournier E, et al. Multiple keratoacanthoma-like lesions in a patient treated with pembrolizumab. Acta Derm Venereol. 2019;99:1301-1302. doi:10.2340/00015555-3301

- Flynn JP, Gerriets V. Pembrolizumab. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Updated June 26, 2023. Accessed April 2, 2025.

- Antonov NK, Nair KG, Halasz CL. Transient eruptive keratoacanthomas associated with Nivolumab. JAAD Case Rep. 2019;5:342-345. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.01.025

- Voudouri D, Nikolaou V, Laschos K, et al. Anti-Pd1/Pdl1 induced psoriasis. Curr Probl Cancer. 2017;41:407-412. doi:10.1016 /j.currproblcancer.2017.10.003

- Belum VR, Benhuri B, Postow MA, et al. Characterisation and management of dermatologic adverse events to agents targeting the PD-1 receptor. Eur J Cancer. 2016;60:12-25. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2016.02.010

- Coscarart A, Martel J, Lee MP, et al. Pembrolizumab-induced pseudoepitheliomatous eruption consistent with hypertrophic lichen planus. J Cutan Pathol. 2020;47:275-279. doi:10.1111/cup.13587

- Curry JL, Tetzlaff MT, Nagarajan P, et al. Diverse types of dermatologic toxicities from immune checkpoint blockade therapy. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:158-176. doi:10.1111/cup.12858

- Vitzthum von Eckstaedt H, Singh A, Reid P, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors and lupus erythematosus. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2024;2:15;17. doi:10.3390/ph17020252

- Halder RM, Bridgeman-Shah S. Skin cancer in African Americans. Cancer. 1995;75:667-673.

- Vu M, Chapman S, Lenz B, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma or squamous proliferation associated with nivolumab treatment for metastatic melanoma. Dermatol Online J. 2022;6:28. doi:10.5070/d328357786

- Howell JY, Ramsey ML. Squamous cell skin cancer. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Updated July 2, 2024. Accessed April 2, 2025.

- Arnold DL, Krishnamurthy K. Lichen planus. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Updated October 29, 2024. Accessed April 2, 2025.

- Yamashita A, Akasaka E, Nakano H, et al. Pembrolizumab-induced lichen planus on the scalp of a patient with non-small-cell lung carcinoma. Case Rep Dermatol. 2021;13:487-491. doi:10.1159/000519486

- Alexis AF, Blackcloud P. Psoriasis in skin of color: epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation, and treatment nuances. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:16-24.

- Murphy M, Kerr P, Grant-Kels JM. The histopathologic spectrum of psoriasis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:524-528. doi:10.1016 /j.clindermatol.2007.08.005.

- Hidaka T, Ishii Y, Kitamura S. Clinical features of skin metastasis from lung cancer. Intern Med. 1996;35:459-462. doi:10.2169 /internalmedicine.35.459.

- Sariya D, Ruth K, Adams-McDonnell R, et al. Clinicopathologic correlation of cutaneous metastases: experience from a cancer center. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:613–620. doi:10.1001/archderm.143.5.613

THE DIAGNOSIS: Pembrolizumab-Induced Eruptive Squamous Proliferation

Histopathology showed a broad squamous proliferation with acanthosis of the epidermis. Large glassy keratinocytes were seen with scattered necrotic keratinocytes (Figure), and a dense lichenoid band of inflammation was present subjacent to the proliferation. Notably, no hypergranulosis, remarkable keratinocyte atypia, or increased mitotic figures were seen. Based on the patient’s medical history and biopsy results, a diagnosis of pembrolizumab-induced eruptive squamous proliferation was made. The diagnosis was supported by a growing body of evidence of this type of reaction in patients taking programmed death 1 (PD-1) inhibitors.1,2 Conservative treatment with clobetasol ointment 0.05% was initiated with complete resolution of the lesions at the 2-month follow-up appointment. Other common treatments include topical steroids, injected corticosteroids, or cryosurgery to locally control the inflammation and atypical proliferation of cells.3

Pembrolizumab is a humanized IgG4 monoclonal antibody targeting the PD-1 receptor that has been utilized for its antitumor activity against various cancers, including unresectable and metastatic melanoma, head and neck cancers, and non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).1,4,5 While this drug has extended the lives of many patients with cancer, there are adverse reactions associated with PD-1 inhibitors (eg, pembrolizumab, nivolumab). Skin toxicity to PD-1 inhibitors is the one of most common immune-mediated reactions worldwide, occurring in approximately 30% of patients.6,7 Reactions can occur while a patient is taking the inciting drug and can continue up to 2 months after treatment discontinuation.8 Skin reactions associated with PD-1 inhibitors vary from lichenoid reactions and vitiligolike patches to psoriasis or eczema flares and are organized into 4 categories: inflammatory, immunobullous, alteration of keratinocytes, and alteration of melanocytes.9 Our patient demonstrated alteration of keratinocytes, which is characterized by overlapping features of hypertrophic lichen planus and early keratoacanthoma.

The differential diagnoses for pembrolizumab-induced eruptive squamous proliferation include squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), psoriasis, hypertrophic lichen planus, and cutaneous metastasis of NSCLC. Hypertrophic lupus erythematosus also is a well-documented reaction to use of immune-checkpoint inhibitors.10 Direct immunofluorescence could have helped differentiate hypertrophic lupus erythematosus from an eruptive squamous proliferation in our patient; however, due to her response to treatment, no additional workup was done.

Squamous cell carcinoma, which is the most common type of skin cancer in Black patients in the United States,11 has been shown to manifest after a PD-1 inhibitor is taken.12 Although it typically has a more chronic persistent course, the clinical appearance of SCC can be similar to the findings seen in our patient. Histologically, SCC may demonstrate necrosis, but the atypical proliferations will invade the dermis—a feature not seen in our patient’s histopathology.13

Lichen planus (LP) is an eruptive immune reaction of violaceous polygonal papules and plaques commonly seen on the ankles14 that has been shown to be an adverse effect of pembrolizumab.15 There are several subtypes of LP including hypertrophic versions, which can appear clinically similar to the findings seen in our patient. On dermoscopy, the classic finding of white lines, known as Wickham striae, is seen in all subtypes and can help diagnose this pathologic process. Under the microscope, LP can manifest with hyperkeratosis without parakeratosis, irregular thickening of the stratum granulosum, sawtooth rete ridges, and destruction of the basal layer.14

Psoriasis also has been shown to be exacerbated by anti–PD-1 therapy, although the majority of patients diagnosed with PD-1–induced psoriasis have a personal or family history of the disease.6 Clinically, psoriasis can have a hyperpigmented or violaceous appearance in patients with skin of color.16 The histopathology of psoriasis typically reveals confluent parakeratosis, neutrophils in the stratum corneum, regular acanthosis, thinning of the suprapapillary plates, and vessels in the dermal papillae.17

Although cutaneous metastasis of NSCLC may appear clinically similar to the current case, it is one of the rarer organ sites of metastasis for lung cancer.18 In our patient, biopsy quickly ruled out this diagnosis. If it had been a site of metastasis, histopathology would have shown a dermal-based proliferation of dysplastic cells without epidermal connection.19

It is important for dermatologists to recognize eruptive squamous proliferations associated with pembrolizumab, as they often respond to conservative treatment and typically do not require dose reduction or discontinuation of the inciting drug.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Pembrolizumab-Induced Eruptive Squamous Proliferation

Histopathology showed a broad squamous proliferation with acanthosis of the epidermis. Large glassy keratinocytes were seen with scattered necrotic keratinocytes (Figure), and a dense lichenoid band of inflammation was present subjacent to the proliferation. Notably, no hypergranulosis, remarkable keratinocyte atypia, or increased mitotic figures were seen. Based on the patient’s medical history and biopsy results, a diagnosis of pembrolizumab-induced eruptive squamous proliferation was made. The diagnosis was supported by a growing body of evidence of this type of reaction in patients taking programmed death 1 (PD-1) inhibitors.1,2 Conservative treatment with clobetasol ointment 0.05% was initiated with complete resolution of the lesions at the 2-month follow-up appointment. Other common treatments include topical steroids, injected corticosteroids, or cryosurgery to locally control the inflammation and atypical proliferation of cells.3

Pembrolizumab is a humanized IgG4 monoclonal antibody targeting the PD-1 receptor that has been utilized for its antitumor activity against various cancers, including unresectable and metastatic melanoma, head and neck cancers, and non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).1,4,5 While this drug has extended the lives of many patients with cancer, there are adverse reactions associated with PD-1 inhibitors (eg, pembrolizumab, nivolumab). Skin toxicity to PD-1 inhibitors is the one of most common immune-mediated reactions worldwide, occurring in approximately 30% of patients.6,7 Reactions can occur while a patient is taking the inciting drug and can continue up to 2 months after treatment discontinuation.8 Skin reactions associated with PD-1 inhibitors vary from lichenoid reactions and vitiligolike patches to psoriasis or eczema flares and are organized into 4 categories: inflammatory, immunobullous, alteration of keratinocytes, and alteration of melanocytes.9 Our patient demonstrated alteration of keratinocytes, which is characterized by overlapping features of hypertrophic lichen planus and early keratoacanthoma.

The differential diagnoses for pembrolizumab-induced eruptive squamous proliferation include squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), psoriasis, hypertrophic lichen planus, and cutaneous metastasis of NSCLC. Hypertrophic lupus erythematosus also is a well-documented reaction to use of immune-checkpoint inhibitors.10 Direct immunofluorescence could have helped differentiate hypertrophic lupus erythematosus from an eruptive squamous proliferation in our patient; however, due to her response to treatment, no additional workup was done.

Squamous cell carcinoma, which is the most common type of skin cancer in Black patients in the United States,11 has been shown to manifest after a PD-1 inhibitor is taken.12 Although it typically has a more chronic persistent course, the clinical appearance of SCC can be similar to the findings seen in our patient. Histologically, SCC may demonstrate necrosis, but the atypical proliferations will invade the dermis—a feature not seen in our patient’s histopathology.13

Lichen planus (LP) is an eruptive immune reaction of violaceous polygonal papules and plaques commonly seen on the ankles14 that has been shown to be an adverse effect of pembrolizumab.15 There are several subtypes of LP including hypertrophic versions, which can appear clinically similar to the findings seen in our patient. On dermoscopy, the classic finding of white lines, known as Wickham striae, is seen in all subtypes and can help diagnose this pathologic process. Under the microscope, LP can manifest with hyperkeratosis without parakeratosis, irregular thickening of the stratum granulosum, sawtooth rete ridges, and destruction of the basal layer.14

Psoriasis also has been shown to be exacerbated by anti–PD-1 therapy, although the majority of patients diagnosed with PD-1–induced psoriasis have a personal or family history of the disease.6 Clinically, psoriasis can have a hyperpigmented or violaceous appearance in patients with skin of color.16 The histopathology of psoriasis typically reveals confluent parakeratosis, neutrophils in the stratum corneum, regular acanthosis, thinning of the suprapapillary plates, and vessels in the dermal papillae.17

Although cutaneous metastasis of NSCLC may appear clinically similar to the current case, it is one of the rarer organ sites of metastasis for lung cancer.18 In our patient, biopsy quickly ruled out this diagnosis. If it had been a site of metastasis, histopathology would have shown a dermal-based proliferation of dysplastic cells without epidermal connection.19

It is important for dermatologists to recognize eruptive squamous proliferations associated with pembrolizumab, as they often respond to conservative treatment and typically do not require dose reduction or discontinuation of the inciting drug.

- Freshwater T, Kondic A, Ahamadi M, et al. Evaluation of dosing strategy for pembrolizumab for oncology indications. J Immunother Cancer. 2017;5:43. doi:10.1186/s40425-017-0242-5

- Preti BTB, Pencz A, Cowger JJM, et al. Skin deep: a fascinating case report of immunotherapy-triggered, treatment-refractory autoimmune lichen planus and keratoacanthoma. Case Rep Oncol. 2021;14: 1189-1193. doi:10.1159/000518313

- Fradet M, Sibaud V, Tournier E, et al. Multiple keratoacanthoma-like lesions in a patient treated with pembrolizumab. Acta Derm Venereol. 2019;99:1301-1302. doi:10.2340/00015555-3301

- Flynn JP, Gerriets V. Pembrolizumab. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Updated June 26, 2023. Accessed April 2, 2025.

- Antonov NK, Nair KG, Halasz CL. Transient eruptive keratoacanthomas associated with Nivolumab. JAAD Case Rep. 2019;5:342-345. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.01.025

- Voudouri D, Nikolaou V, Laschos K, et al. Anti-Pd1/Pdl1 induced psoriasis. Curr Probl Cancer. 2017;41:407-412. doi:10.1016 /j.currproblcancer.2017.10.003

- Belum VR, Benhuri B, Postow MA, et al. Characterisation and management of dermatologic adverse events to agents targeting the PD-1 receptor. Eur J Cancer. 2016;60:12-25. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2016.02.010

- Coscarart A, Martel J, Lee MP, et al. Pembrolizumab-induced pseudoepitheliomatous eruption consistent with hypertrophic lichen planus. J Cutan Pathol. 2020;47:275-279. doi:10.1111/cup.13587

- Curry JL, Tetzlaff MT, Nagarajan P, et al. Diverse types of dermatologic toxicities from immune checkpoint blockade therapy. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:158-176. doi:10.1111/cup.12858

- Vitzthum von Eckstaedt H, Singh A, Reid P, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors and lupus erythematosus. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2024;2:15;17. doi:10.3390/ph17020252

- Halder RM, Bridgeman-Shah S. Skin cancer in African Americans. Cancer. 1995;75:667-673.

- Vu M, Chapman S, Lenz B, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma or squamous proliferation associated with nivolumab treatment for metastatic melanoma. Dermatol Online J. 2022;6:28. doi:10.5070/d328357786

- Howell JY, Ramsey ML. Squamous cell skin cancer. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Updated July 2, 2024. Accessed April 2, 2025.

- Arnold DL, Krishnamurthy K. Lichen planus. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Updated October 29, 2024. Accessed April 2, 2025.

- Yamashita A, Akasaka E, Nakano H, et al. Pembrolizumab-induced lichen planus on the scalp of a patient with non-small-cell lung carcinoma. Case Rep Dermatol. 2021;13:487-491. doi:10.1159/000519486

- Alexis AF, Blackcloud P. Psoriasis in skin of color: epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation, and treatment nuances. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:16-24.

- Murphy M, Kerr P, Grant-Kels JM. The histopathologic spectrum of psoriasis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:524-528. doi:10.1016 /j.clindermatol.2007.08.005.

- Hidaka T, Ishii Y, Kitamura S. Clinical features of skin metastasis from lung cancer. Intern Med. 1996;35:459-462. doi:10.2169 /internalmedicine.35.459.

- Sariya D, Ruth K, Adams-McDonnell R, et al. Clinicopathologic correlation of cutaneous metastases: experience from a cancer center. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:613–620. doi:10.1001/archderm.143.5.613

- Freshwater T, Kondic A, Ahamadi M, et al. Evaluation of dosing strategy for pembrolizumab for oncology indications. J Immunother Cancer. 2017;5:43. doi:10.1186/s40425-017-0242-5

- Preti BTB, Pencz A, Cowger JJM, et al. Skin deep: a fascinating case report of immunotherapy-triggered, treatment-refractory autoimmune lichen planus and keratoacanthoma. Case Rep Oncol. 2021;14: 1189-1193. doi:10.1159/000518313

- Fradet M, Sibaud V, Tournier E, et al. Multiple keratoacanthoma-like lesions in a patient treated with pembrolizumab. Acta Derm Venereol. 2019;99:1301-1302. doi:10.2340/00015555-3301

- Flynn JP, Gerriets V. Pembrolizumab. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Updated June 26, 2023. Accessed April 2, 2025.

- Antonov NK, Nair KG, Halasz CL. Transient eruptive keratoacanthomas associated with Nivolumab. JAAD Case Rep. 2019;5:342-345. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.01.025

- Voudouri D, Nikolaou V, Laschos K, et al. Anti-Pd1/Pdl1 induced psoriasis. Curr Probl Cancer. 2017;41:407-412. doi:10.1016 /j.currproblcancer.2017.10.003

- Belum VR, Benhuri B, Postow MA, et al. Characterisation and management of dermatologic adverse events to agents targeting the PD-1 receptor. Eur J Cancer. 2016;60:12-25. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2016.02.010

- Coscarart A, Martel J, Lee MP, et al. Pembrolizumab-induced pseudoepitheliomatous eruption consistent with hypertrophic lichen planus. J Cutan Pathol. 2020;47:275-279. doi:10.1111/cup.13587

- Curry JL, Tetzlaff MT, Nagarajan P, et al. Diverse types of dermatologic toxicities from immune checkpoint blockade therapy. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:158-176. doi:10.1111/cup.12858

- Vitzthum von Eckstaedt H, Singh A, Reid P, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors and lupus erythematosus. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2024;2:15;17. doi:10.3390/ph17020252

- Halder RM, Bridgeman-Shah S. Skin cancer in African Americans. Cancer. 1995;75:667-673.

- Vu M, Chapman S, Lenz B, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma or squamous proliferation associated with nivolumab treatment for metastatic melanoma. Dermatol Online J. 2022;6:28. doi:10.5070/d328357786

- Howell JY, Ramsey ML. Squamous cell skin cancer. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Updated July 2, 2024. Accessed April 2, 2025.

- Arnold DL, Krishnamurthy K. Lichen planus. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Updated October 29, 2024. Accessed April 2, 2025.

- Yamashita A, Akasaka E, Nakano H, et al. Pembrolizumab-induced lichen planus on the scalp of a patient with non-small-cell lung carcinoma. Case Rep Dermatol. 2021;13:487-491. doi:10.1159/000519486

- Alexis AF, Blackcloud P. Psoriasis in skin of color: epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation, and treatment nuances. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:16-24.

- Murphy M, Kerr P, Grant-Kels JM. The histopathologic spectrum of psoriasis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:524-528. doi:10.1016 /j.clindermatol.2007.08.005.

- Hidaka T, Ishii Y, Kitamura S. Clinical features of skin metastasis from lung cancer. Intern Med. 1996;35:459-462. doi:10.2169 /internalmedicine.35.459.

- Sariya D, Ruth K, Adams-McDonnell R, et al. Clinicopathologic correlation of cutaneous metastases: experience from a cancer center. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:613–620. doi:10.1001/archderm.143.5.613

Papulonodules on the Ankle in a Patient with Lung Cancer

Papulonodules on the Ankle in a Patient with Lung Cancer

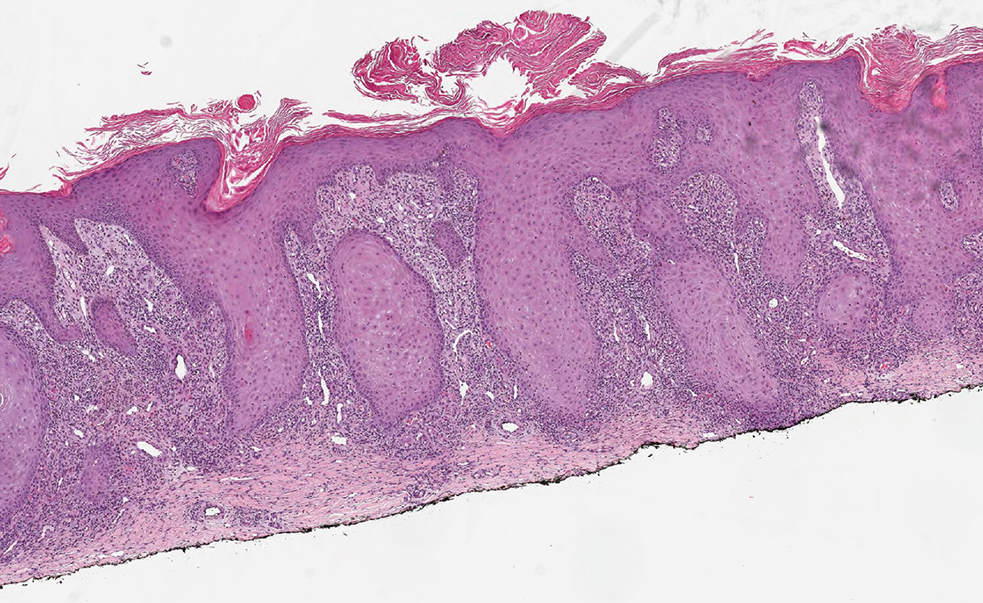

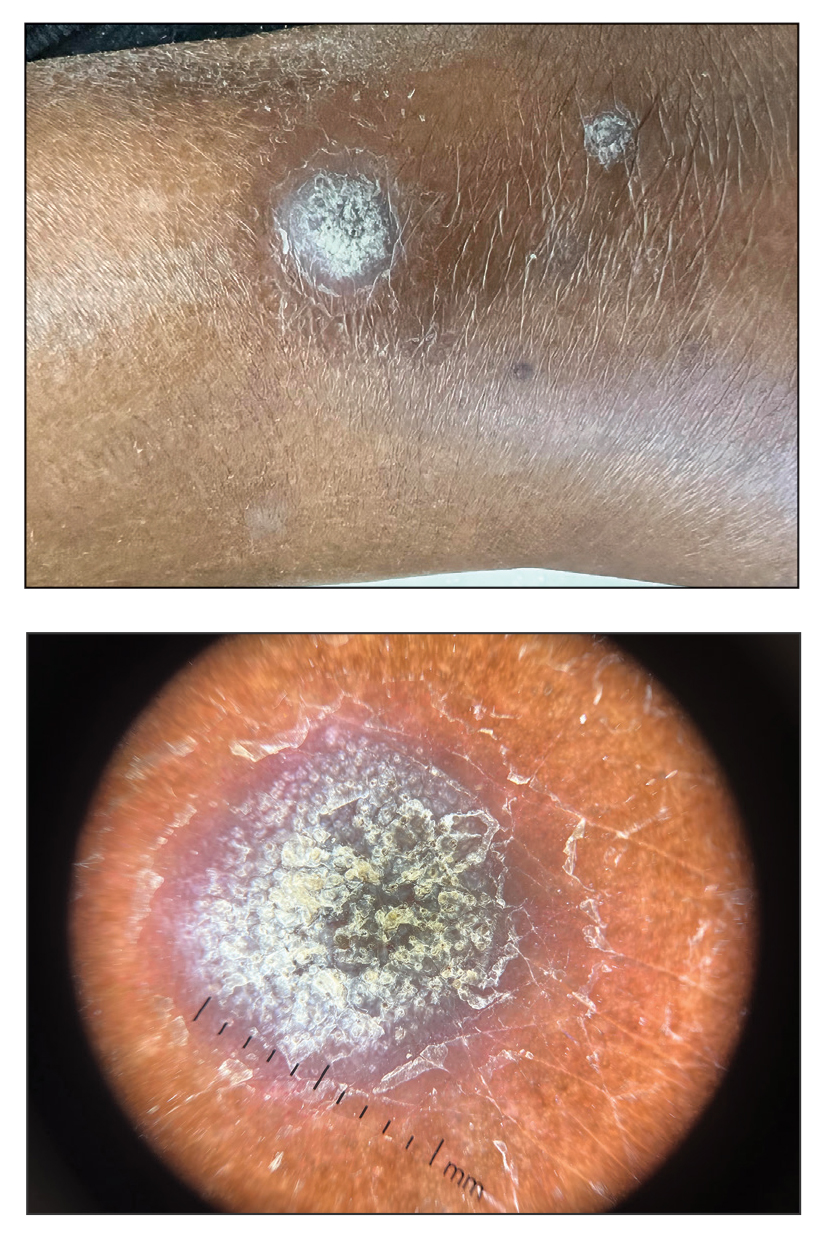

A 75-year-old woman presented to the dermatology department with well-circumscribed, round, hyperkeratotic papulonodules on the ankle of 3 months’ duration (top). The papulonodules also were evaluated by dermoscopy, which highlighted in greater detail the hyperkeratosis seen grossly (bottom). The patient had a history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and metastatic lung cancer and had been taking pembrolizumab for the past 2 years. The lesions initially appeared on the medial right foot and slowly spread proximally. Most of the lesions resolved spontaneously except for 2 on the right ankle. At the current presentation, one lesion was slightly tender to palpation, but both were otherwise asymptomatic. A lesion was biopsied and sent for dermatopathologic evaluation.

Persistent Pruritic Papules on the Buttocks

The Diagnosis: Dermatitis Herpetiformis

Dermatitis herpetiformis (DH), also known as Duhring disease, is a rare autoimmune disease. It is the cutaneous manifestation of gluten sensitivity with antibodies targeting epidermal transglutaminase.1 Symptoms of DH generally arise in the fourth decade of life, and children are less commonly affected,2 though the diagnosis should be considered at any age, as our patient was aged 19 years at the time of presentation. Dermatitis herpetiformis predominantly affects white individuals of Northern European heritage, and males more often are affected than females.2 There is a strong association with HLA-B8, HLA-DR3, and HLA-DQw2.3 It also is associated with other autoimmune disorders, including autoimmune thyroid disease, type 1 diabetes mellitus, and pernicious anemia.2

Clinically, DH is characterized by groups of intensely pruritic papulovesicles that are symmetrically located on the extensor surfaces of the upper and lower extremities, scalp, nuchal area, back, and buttocks (quiz image). Less often, the groin also may be involved, as it was in our patient (Figure 1).4 Lesions can be papulovesicular or bullous, though they often are excoriated, and primary lesions may be difficult to identify.2 The disease may have spontaneous remissions with frequent relapses. Most patients with DH have an asymptomatic gluten-sensitive enteropathy.3

A punch biopsy of a representative nonexcoriated lesion from our patient showed the characteristic collections of neutrophils and fibrin at the tips of dermal papillae on hematoxylin and eosin staining (Figure 2). These findings are suggestive of DH.1 However, other bullous diseases, such as linear IgA dermatosis and epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, may have similar appearance on histology.1 Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) of perilesional skin is the gold standard for diagnosing DH, with a sensitivity and specificity close to 100%.1 Deposits of IgA generally are concentrated in previously involved skin or noninflamed perilesional skin; DIF of erythematous or lesional skin may be false negative.5 In our patient, DIF of perilesional uninvolved skin showed granular deposits of IgA at the dermoepidermal junction with accentuation in the dermal papillae (Figure 3), further suggestive of the diagnosis of DH.6

Patients with DH frequently will have specific IgA antibodies including anti-tissue transglutaminase (tTG), anti-epidermal transglutaminase, antiendomysial antibodies, and anti-synthetic deamidated gliadin peptides.1 Only some of these tests are widely available, and the anti-tTG enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay is the least expensive and easiest to perform. A positive anti-tTG antibody test has a sensitivity ranging from 47% to 95% and a specificity greater than 90%.1 Our patient tested positive for anti-tTG and anti-deamidated synthetic gliadin-derived peptides. A diagnostic algorithm based on current evidence suggests that in patients with clinical evidence of DH, typical DIF findings combined with positive anti-tTG antibodies confirms the diagnosis of DH, as was seen in our patient.1,7 In situations where histopathology and/or antibody testing are inconclusive, additional testing to include HLA antigen typing, duodenal biopsy, and supplemental skin biopsies may be performed to help confirm or exclude a diagnosis of DH. It is unnecessary to perform a duodenal biopsy in patients with a confirmed diagnosis of DH, as DH is considered the specific cutaneous manifestation of celiac disease, and the diagnosis of DH is a diagnosis of celiac disease.1

Although pruritic papules may be found in several conditions, clinical, histopathologic, and DIF findings can help to confirm the diagnosis. Allergic contact dermatitis is a type IV hypersensitivity reaction causing eruptions of varying morphology, generally manifesting as pruritic scaly plaques that can occur anywhere on the body exposed to the offending allergen. Key histopathologic features of allergic contact dermatitis are eosinophilic spongiosis and exocytosis of eosinophils and lymphocytes.8 Papular urticaria is a hypersensitivity disorder to insect bites that consists of pruritic papules on exposed areas of skin, typically in children younger than 10 years. Genital and axillary areas usually are spared. The diagnosis is clinical.9 Recurrent herpes simplex virus infection is a short-lived outbreak that generally improves within 10 days. Herpes simplex virus infections usually are comprised of small vesicular or ulcerative lesions. Tzanck smear, skin biopsy, direct fluorescent antibody, viral culture, and polymerase chain reaction are diagnostic methods for herpes simplex virus.10 Scabies lesions typically are pruritic, erythematous, often excoriated papules and burrows located most commonly in the webs of fingers, wrists, axillae, areolae, waist, and genitalia. Diagnosis can be confirmed with scabies preparation (skin scraping showing mites, eggs, or feces), dermoscopy showing mites and burrows in vivo, or biopsy.11

First-line treatment in patients with DH and celiac disease is a strict gluten-free diet (GFD).1 A GFD will resolve the cutaneous and gastrointestinal manifestations and is the only thing that will reduce the risk for lymphoma and other diseases associated with gluten-induced enteropathy.1,2 A GFD alone will provide symptomatic relief over several months; dapsone and sulfapyridine can provide rapid relief of the pruritus and skin manifestations and usually can be weaned or discontinued after several months of following a strict GFD.12 Patients on sulfone therapy require regular follow-up and monitoring due to the risk for hemolytic anemia and other adverse effects as well as to determine the appropriate time to discontinue the medication.12 Although some patients are able to tolerate reintroduction of gluten into their diets after a period of remission, most will experience recurrent dermatologic manifestations if they continue to consume gluten.3

Because of our patient's impending move out of the area, no oral medications were started, and he was instructed to follow a GFD and seek medical care at his new location. The patient was contacted 6 months later and reported resolution of all skin lesions with just a GFD. The patient continued to follow-up with a dermatologist and gastroenterologist at his new location.

- Antiga E, Caproni M. The diagnosis and treatment of dermatitis herpetiformis. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2015;8:257-265.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatitis herpetiformis and linear IgA bullous dermatosis. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L. Dermatology. Vol 1. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017:527-537.

- James WD, Elston DM, Treat JR, et al. Chronic blistering dermatoses. In: James WD, Elston DM, Treat JR, et al, eds. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 13th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:453-474.

- Bolotin D, Petronic-Rosic V. Dermatitis herpetiformis. part 1. epidemiology, pathogenesis, and clinical presentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1017-1024.

- Zone JJ, Meyer LJ, Petersen MJ. Deposition of granular IgA relative to clinical lesions in dermatitis herpetiformis. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:912-918.

- Lever WF, Elder DE. Lever's Histopathology of the Skin. Vol 1. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott; 2009.

- Hull C. Dermatitis herpetiformis. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/dermatitis-herpetiformis. Published October 14, 2016. Updated September 25, 2019. Accessed December 10, 2019.

Yiannias J. Clinical features and diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-features-and-diagnosis-of-allergic-contact-dermatitissearch=allergic%20contact%20dermatitis&source=search_result&selectedTitle=2~150

&usage_type=default&display_rank=2#H27385290. Updated May 17, 2019. Accessed December 11, 2019.Goddard J, Stewart PH. Insect and other arthropod bites. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/insect-and-other-arthropod-bites?search=papular%2urticaria§ionRank=1&usage_type=default&anchor=H4&source=machineLearning&selectedTitle=1~24&display_rank=1#

H4. Updated October 31, 2019. Accessed December 11, 2019.Christine J, Wald A. Epidemiology, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis of herpes simplex virus type 1 infection. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/epidemiology-clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis-of-herpes-simplex-virus-type-1-infection?search=herpes%20simplex&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~150&usage_type=default&display_rank=1. Updated July 23, 2019. Accessed December 11, 2019.

- Goldstein B, Goldstein A. Scabies: epidemiology, clinical features, and diagnosis. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/scabies-epidemiology-clinical-features-and-diagnosis?search=scabies&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~92&usagetype=default&display_rank=1. Updated August 2, 2019. Accessed December 11, 2019.

- Bolotin D, Petronic-Rosic V. Dermatitis herpetiformis. part 2. diagnosis, management, and prognosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1027-1033.

The Diagnosis: Dermatitis Herpetiformis

Dermatitis herpetiformis (DH), also known as Duhring disease, is a rare autoimmune disease. It is the cutaneous manifestation of gluten sensitivity with antibodies targeting epidermal transglutaminase.1 Symptoms of DH generally arise in the fourth decade of life, and children are less commonly affected,2 though the diagnosis should be considered at any age, as our patient was aged 19 years at the time of presentation. Dermatitis herpetiformis predominantly affects white individuals of Northern European heritage, and males more often are affected than females.2 There is a strong association with HLA-B8, HLA-DR3, and HLA-DQw2.3 It also is associated with other autoimmune disorders, including autoimmune thyroid disease, type 1 diabetes mellitus, and pernicious anemia.2

Clinically, DH is characterized by groups of intensely pruritic papulovesicles that are symmetrically located on the extensor surfaces of the upper and lower extremities, scalp, nuchal area, back, and buttocks (quiz image). Less often, the groin also may be involved, as it was in our patient (Figure 1).4 Lesions can be papulovesicular or bullous, though they often are excoriated, and primary lesions may be difficult to identify.2 The disease may have spontaneous remissions with frequent relapses. Most patients with DH have an asymptomatic gluten-sensitive enteropathy.3

A punch biopsy of a representative nonexcoriated lesion from our patient showed the characteristic collections of neutrophils and fibrin at the tips of dermal papillae on hematoxylin and eosin staining (Figure 2). These findings are suggestive of DH.1 However, other bullous diseases, such as linear IgA dermatosis and epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, may have similar appearance on histology.1 Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) of perilesional skin is the gold standard for diagnosing DH, with a sensitivity and specificity close to 100%.1 Deposits of IgA generally are concentrated in previously involved skin or noninflamed perilesional skin; DIF of erythematous or lesional skin may be false negative.5 In our patient, DIF of perilesional uninvolved skin showed granular deposits of IgA at the dermoepidermal junction with accentuation in the dermal papillae (Figure 3), further suggestive of the diagnosis of DH.6

Patients with DH frequently will have specific IgA antibodies including anti-tissue transglutaminase (tTG), anti-epidermal transglutaminase, antiendomysial antibodies, and anti-synthetic deamidated gliadin peptides.1 Only some of these tests are widely available, and the anti-tTG enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay is the least expensive and easiest to perform. A positive anti-tTG antibody test has a sensitivity ranging from 47% to 95% and a specificity greater than 90%.1 Our patient tested positive for anti-tTG and anti-deamidated synthetic gliadin-derived peptides. A diagnostic algorithm based on current evidence suggests that in patients with clinical evidence of DH, typical DIF findings combined with positive anti-tTG antibodies confirms the diagnosis of DH, as was seen in our patient.1,7 In situations where histopathology and/or antibody testing are inconclusive, additional testing to include HLA antigen typing, duodenal biopsy, and supplemental skin biopsies may be performed to help confirm or exclude a diagnosis of DH. It is unnecessary to perform a duodenal biopsy in patients with a confirmed diagnosis of DH, as DH is considered the specific cutaneous manifestation of celiac disease, and the diagnosis of DH is a diagnosis of celiac disease.1

Although pruritic papules may be found in several conditions, clinical, histopathologic, and DIF findings can help to confirm the diagnosis. Allergic contact dermatitis is a type IV hypersensitivity reaction causing eruptions of varying morphology, generally manifesting as pruritic scaly plaques that can occur anywhere on the body exposed to the offending allergen. Key histopathologic features of allergic contact dermatitis are eosinophilic spongiosis and exocytosis of eosinophils and lymphocytes.8 Papular urticaria is a hypersensitivity disorder to insect bites that consists of pruritic papules on exposed areas of skin, typically in children younger than 10 years. Genital and axillary areas usually are spared. The diagnosis is clinical.9 Recurrent herpes simplex virus infection is a short-lived outbreak that generally improves within 10 days. Herpes simplex virus infections usually are comprised of small vesicular or ulcerative lesions. Tzanck smear, skin biopsy, direct fluorescent antibody, viral culture, and polymerase chain reaction are diagnostic methods for herpes simplex virus.10 Scabies lesions typically are pruritic, erythematous, often excoriated papules and burrows located most commonly in the webs of fingers, wrists, axillae, areolae, waist, and genitalia. Diagnosis can be confirmed with scabies preparation (skin scraping showing mites, eggs, or feces), dermoscopy showing mites and burrows in vivo, or biopsy.11

First-line treatment in patients with DH and celiac disease is a strict gluten-free diet (GFD).1 A GFD will resolve the cutaneous and gastrointestinal manifestations and is the only thing that will reduce the risk for lymphoma and other diseases associated with gluten-induced enteropathy.1,2 A GFD alone will provide symptomatic relief over several months; dapsone and sulfapyridine can provide rapid relief of the pruritus and skin manifestations and usually can be weaned or discontinued after several months of following a strict GFD.12 Patients on sulfone therapy require regular follow-up and monitoring due to the risk for hemolytic anemia and other adverse effects as well as to determine the appropriate time to discontinue the medication.12 Although some patients are able to tolerate reintroduction of gluten into their diets after a period of remission, most will experience recurrent dermatologic manifestations if they continue to consume gluten.3

Because of our patient's impending move out of the area, no oral medications were started, and he was instructed to follow a GFD and seek medical care at his new location. The patient was contacted 6 months later and reported resolution of all skin lesions with just a GFD. The patient continued to follow-up with a dermatologist and gastroenterologist at his new location.

The Diagnosis: Dermatitis Herpetiformis

Dermatitis herpetiformis (DH), also known as Duhring disease, is a rare autoimmune disease. It is the cutaneous manifestation of gluten sensitivity with antibodies targeting epidermal transglutaminase.1 Symptoms of DH generally arise in the fourth decade of life, and children are less commonly affected,2 though the diagnosis should be considered at any age, as our patient was aged 19 years at the time of presentation. Dermatitis herpetiformis predominantly affects white individuals of Northern European heritage, and males more often are affected than females.2 There is a strong association with HLA-B8, HLA-DR3, and HLA-DQw2.3 It also is associated with other autoimmune disorders, including autoimmune thyroid disease, type 1 diabetes mellitus, and pernicious anemia.2

Clinically, DH is characterized by groups of intensely pruritic papulovesicles that are symmetrically located on the extensor surfaces of the upper and lower extremities, scalp, nuchal area, back, and buttocks (quiz image). Less often, the groin also may be involved, as it was in our patient (Figure 1).4 Lesions can be papulovesicular or bullous, though they often are excoriated, and primary lesions may be difficult to identify.2 The disease may have spontaneous remissions with frequent relapses. Most patients with DH have an asymptomatic gluten-sensitive enteropathy.3

A punch biopsy of a representative nonexcoriated lesion from our patient showed the characteristic collections of neutrophils and fibrin at the tips of dermal papillae on hematoxylin and eosin staining (Figure 2). These findings are suggestive of DH.1 However, other bullous diseases, such as linear IgA dermatosis and epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, may have similar appearance on histology.1 Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) of perilesional skin is the gold standard for diagnosing DH, with a sensitivity and specificity close to 100%.1 Deposits of IgA generally are concentrated in previously involved skin or noninflamed perilesional skin; DIF of erythematous or lesional skin may be false negative.5 In our patient, DIF of perilesional uninvolved skin showed granular deposits of IgA at the dermoepidermal junction with accentuation in the dermal papillae (Figure 3), further suggestive of the diagnosis of DH.6

Patients with DH frequently will have specific IgA antibodies including anti-tissue transglutaminase (tTG), anti-epidermal transglutaminase, antiendomysial antibodies, and anti-synthetic deamidated gliadin peptides.1 Only some of these tests are widely available, and the anti-tTG enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay is the least expensive and easiest to perform. A positive anti-tTG antibody test has a sensitivity ranging from 47% to 95% and a specificity greater than 90%.1 Our patient tested positive for anti-tTG and anti-deamidated synthetic gliadin-derived peptides. A diagnostic algorithm based on current evidence suggests that in patients with clinical evidence of DH, typical DIF findings combined with positive anti-tTG antibodies confirms the diagnosis of DH, as was seen in our patient.1,7 In situations where histopathology and/or antibody testing are inconclusive, additional testing to include HLA antigen typing, duodenal biopsy, and supplemental skin biopsies may be performed to help confirm or exclude a diagnosis of DH. It is unnecessary to perform a duodenal biopsy in patients with a confirmed diagnosis of DH, as DH is considered the specific cutaneous manifestation of celiac disease, and the diagnosis of DH is a diagnosis of celiac disease.1

Although pruritic papules may be found in several conditions, clinical, histopathologic, and DIF findings can help to confirm the diagnosis. Allergic contact dermatitis is a type IV hypersensitivity reaction causing eruptions of varying morphology, generally manifesting as pruritic scaly plaques that can occur anywhere on the body exposed to the offending allergen. Key histopathologic features of allergic contact dermatitis are eosinophilic spongiosis and exocytosis of eosinophils and lymphocytes.8 Papular urticaria is a hypersensitivity disorder to insect bites that consists of pruritic papules on exposed areas of skin, typically in children younger than 10 years. Genital and axillary areas usually are spared. The diagnosis is clinical.9 Recurrent herpes simplex virus infection is a short-lived outbreak that generally improves within 10 days. Herpes simplex virus infections usually are comprised of small vesicular or ulcerative lesions. Tzanck smear, skin biopsy, direct fluorescent antibody, viral culture, and polymerase chain reaction are diagnostic methods for herpes simplex virus.10 Scabies lesions typically are pruritic, erythematous, often excoriated papules and burrows located most commonly in the webs of fingers, wrists, axillae, areolae, waist, and genitalia. Diagnosis can be confirmed with scabies preparation (skin scraping showing mites, eggs, or feces), dermoscopy showing mites and burrows in vivo, or biopsy.11

First-line treatment in patients with DH and celiac disease is a strict gluten-free diet (GFD).1 A GFD will resolve the cutaneous and gastrointestinal manifestations and is the only thing that will reduce the risk for lymphoma and other diseases associated with gluten-induced enteropathy.1,2 A GFD alone will provide symptomatic relief over several months; dapsone and sulfapyridine can provide rapid relief of the pruritus and skin manifestations and usually can be weaned or discontinued after several months of following a strict GFD.12 Patients on sulfone therapy require regular follow-up and monitoring due to the risk for hemolytic anemia and other adverse effects as well as to determine the appropriate time to discontinue the medication.12 Although some patients are able to tolerate reintroduction of gluten into their diets after a period of remission, most will experience recurrent dermatologic manifestations if they continue to consume gluten.3

Because of our patient's impending move out of the area, no oral medications were started, and he was instructed to follow a GFD and seek medical care at his new location. The patient was contacted 6 months later and reported resolution of all skin lesions with just a GFD. The patient continued to follow-up with a dermatologist and gastroenterologist at his new location.

- Antiga E, Caproni M. The diagnosis and treatment of dermatitis herpetiformis. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2015;8:257-265.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatitis herpetiformis and linear IgA bullous dermatosis. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L. Dermatology. Vol 1. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017:527-537.

- James WD, Elston DM, Treat JR, et al. Chronic blistering dermatoses. In: James WD, Elston DM, Treat JR, et al, eds. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 13th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:453-474.

- Bolotin D, Petronic-Rosic V. Dermatitis herpetiformis. part 1. epidemiology, pathogenesis, and clinical presentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1017-1024.

- Zone JJ, Meyer LJ, Petersen MJ. Deposition of granular IgA relative to clinical lesions in dermatitis herpetiformis. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:912-918.

- Lever WF, Elder DE. Lever's Histopathology of the Skin. Vol 1. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott; 2009.

- Hull C. Dermatitis herpetiformis. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/dermatitis-herpetiformis. Published October 14, 2016. Updated September 25, 2019. Accessed December 10, 2019.

Yiannias J. Clinical features and diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-features-and-diagnosis-of-allergic-contact-dermatitissearch=allergic%20contact%20dermatitis&source=search_result&selectedTitle=2~150

&usage_type=default&display_rank=2#H27385290. Updated May 17, 2019. Accessed December 11, 2019.Goddard J, Stewart PH. Insect and other arthropod bites. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/insect-and-other-arthropod-bites?search=papular%2urticaria§ionRank=1&usage_type=default&anchor=H4&source=machineLearning&selectedTitle=1~24&display_rank=1#

H4. Updated October 31, 2019. Accessed December 11, 2019.Christine J, Wald A. Epidemiology, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis of herpes simplex virus type 1 infection. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/epidemiology-clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis-of-herpes-simplex-virus-type-1-infection?search=herpes%20simplex&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~150&usage_type=default&display_rank=1. Updated July 23, 2019. Accessed December 11, 2019.

- Goldstein B, Goldstein A. Scabies: epidemiology, clinical features, and diagnosis. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/scabies-epidemiology-clinical-features-and-diagnosis?search=scabies&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~92&usagetype=default&display_rank=1. Updated August 2, 2019. Accessed December 11, 2019.

- Bolotin D, Petronic-Rosic V. Dermatitis herpetiformis. part 2. diagnosis, management, and prognosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1027-1033.

- Antiga E, Caproni M. The diagnosis and treatment of dermatitis herpetiformis. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2015;8:257-265.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatitis herpetiformis and linear IgA bullous dermatosis. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L. Dermatology. Vol 1. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017:527-537.

- James WD, Elston DM, Treat JR, et al. Chronic blistering dermatoses. In: James WD, Elston DM, Treat JR, et al, eds. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 13th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:453-474.

- Bolotin D, Petronic-Rosic V. Dermatitis herpetiformis. part 1. epidemiology, pathogenesis, and clinical presentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1017-1024.

- Zone JJ, Meyer LJ, Petersen MJ. Deposition of granular IgA relative to clinical lesions in dermatitis herpetiformis. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:912-918.

- Lever WF, Elder DE. Lever's Histopathology of the Skin. Vol 1. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott; 2009.

- Hull C. Dermatitis herpetiformis. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/dermatitis-herpetiformis. Published October 14, 2016. Updated September 25, 2019. Accessed December 10, 2019.

Yiannias J. Clinical features and diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-features-and-diagnosis-of-allergic-contact-dermatitissearch=allergic%20contact%20dermatitis&source=search_result&selectedTitle=2~150

&usage_type=default&display_rank=2#H27385290. Updated May 17, 2019. Accessed December 11, 2019.Goddard J, Stewart PH. Insect and other arthropod bites. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/insect-and-other-arthropod-bites?search=papular%2urticaria§ionRank=1&usage_type=default&anchor=H4&source=machineLearning&selectedTitle=1~24&display_rank=1#

H4. Updated October 31, 2019. Accessed December 11, 2019.Christine J, Wald A. Epidemiology, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis of herpes simplex virus type 1 infection. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/epidemiology-clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis-of-herpes-simplex-virus-type-1-infection?search=herpes%20simplex&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~150&usage_type=default&display_rank=1. Updated July 23, 2019. Accessed December 11, 2019.

- Goldstein B, Goldstein A. Scabies: epidemiology, clinical features, and diagnosis. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/scabies-epidemiology-clinical-features-and-diagnosis?search=scabies&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~92&usagetype=default&display_rank=1. Updated August 2, 2019. Accessed December 11, 2019.

- Bolotin D, Petronic-Rosic V. Dermatitis herpetiformis. part 2. diagnosis, management, and prognosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1027-1033.

A 19-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with intermittent pruritic lesions that began on the bilateral buttocks when he was living in Reserve Officers' Training Corps dormitories several months prior. The eruption then spread to involve the penis, suprapubic area, periumbilical area, and flanks. The patient attempted to treat the lesions with topical antifungals prior to evaluation in the emergency department where he was treated with permethrin 5% on 2 separate occasions without any improvement. A medical history was normal, and he denied recent travel, animal contacts, or new medications. Physical examination revealed several 2- to 4-mm erythematous papules and superficial erosions with an ill-defined erythematous background most notable on the penis, suprapubic area, periumbilical area, flanks, and buttocks.