User login

How to identify balance disorders and reduce fall risk

CASE Mr. J, a 75-year-old man, presents to your family practice reporting that he feels increasingly unsteady and slow while walking. He fell twice last year, without resulting injury. He now worries about tripping while walking around the house and relies on his spouse to run errands.

Clearly, Mr. J is experiencing a problem with balance. What management approach should you undertake to prevent him from falling?

Balance disorders are common in older people and drastically hinder quality of life.1-4 Patients often describe imbalance as vague symptoms: dizziness, unsteadiness, faintness, spinning sensations.5,6 Importantly, balance disorders disrupt normal gait and contribute to falls that are a major cause of disability and morbidity in older people. Almost 30% of people older than 65 years report 1 or more falls annually.7 Factors that increase the risk of falls include impaired mobility, previously reported falls, reduced psychological functioning, chronic medical conditions, and polypharmacy.7,8

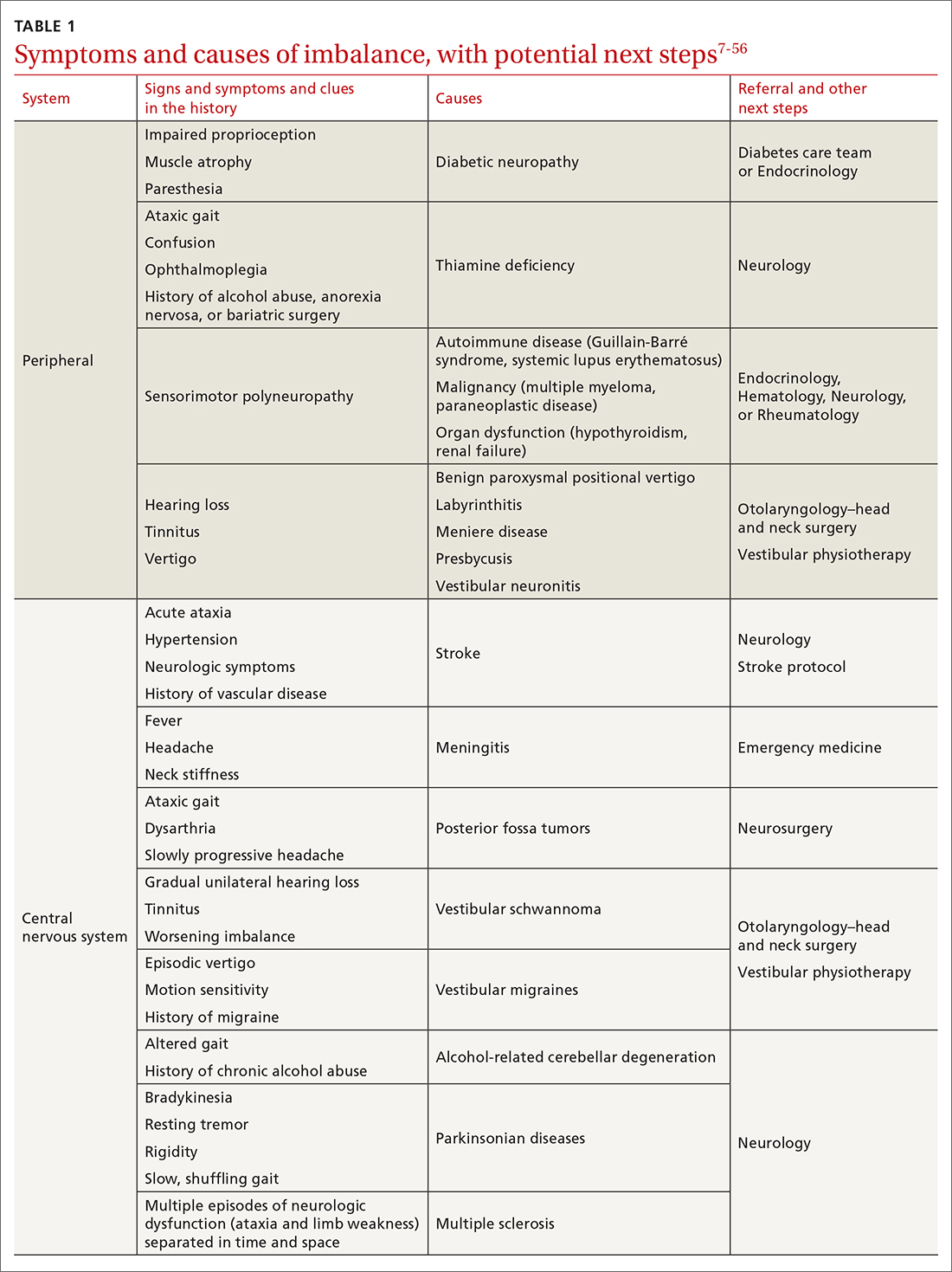

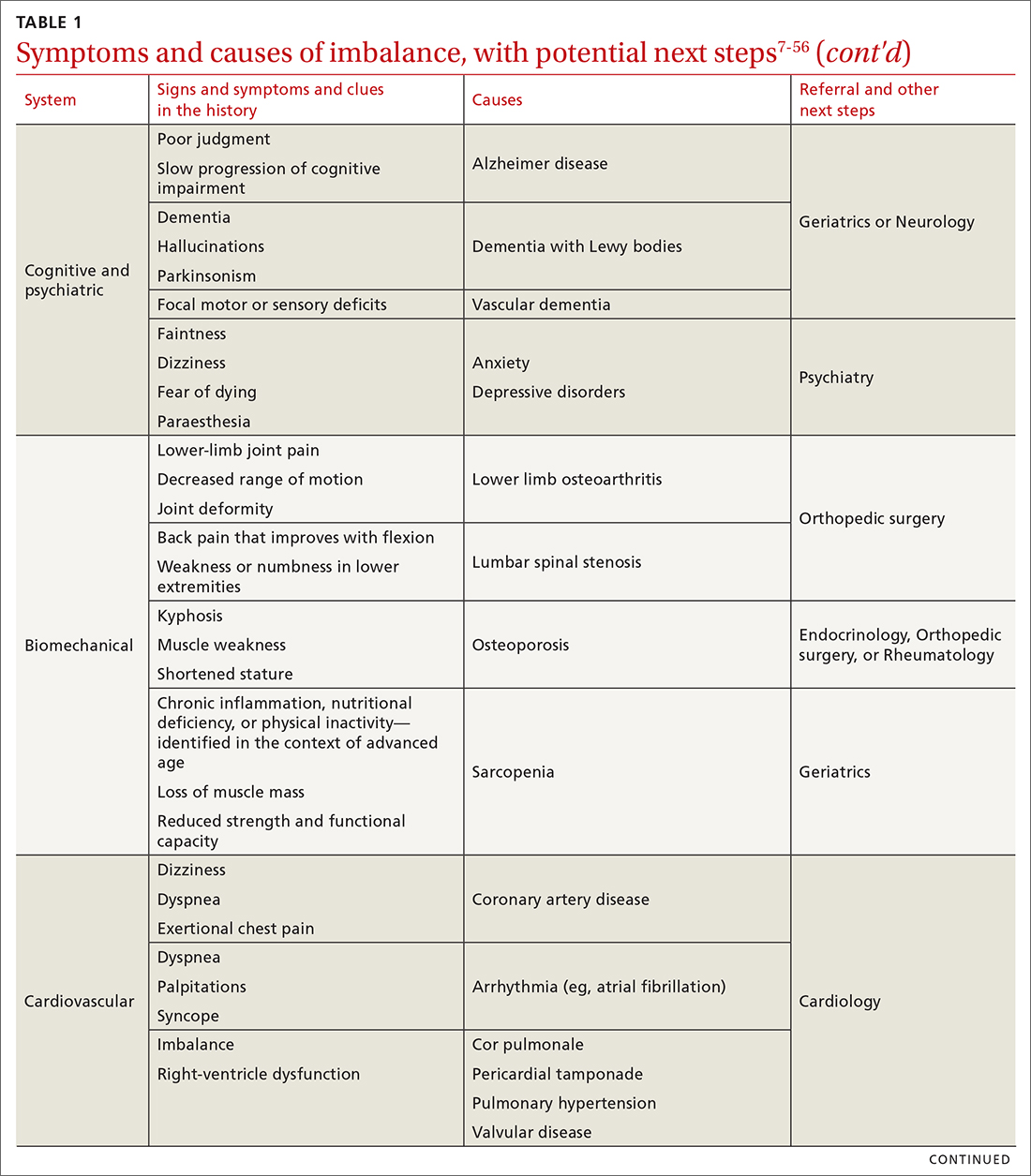

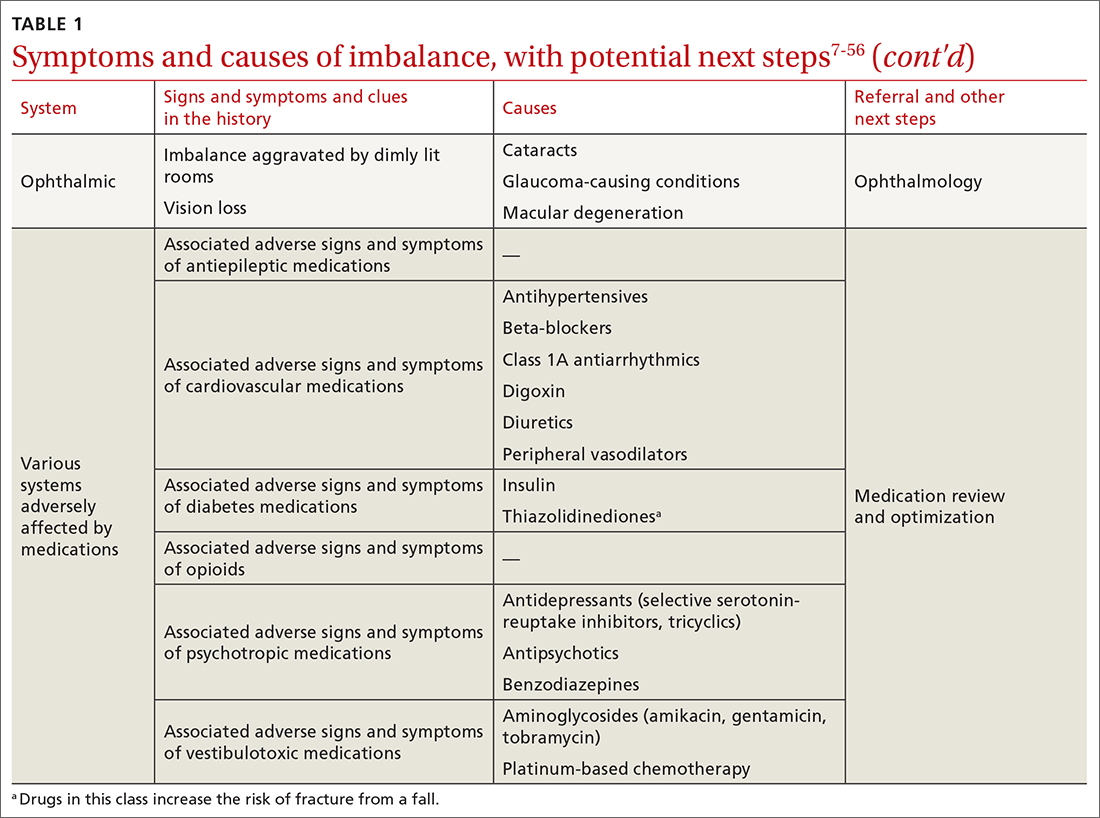

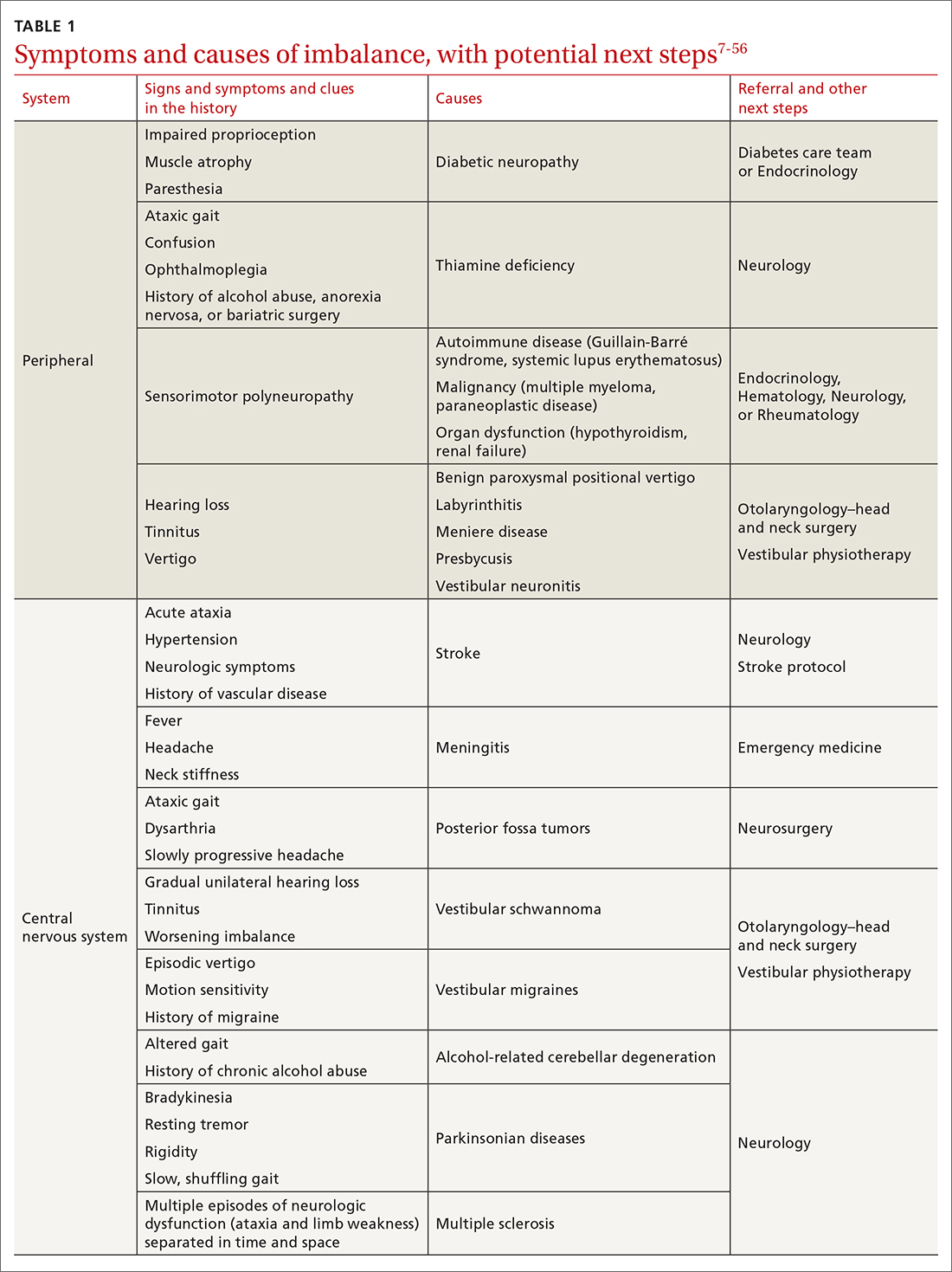

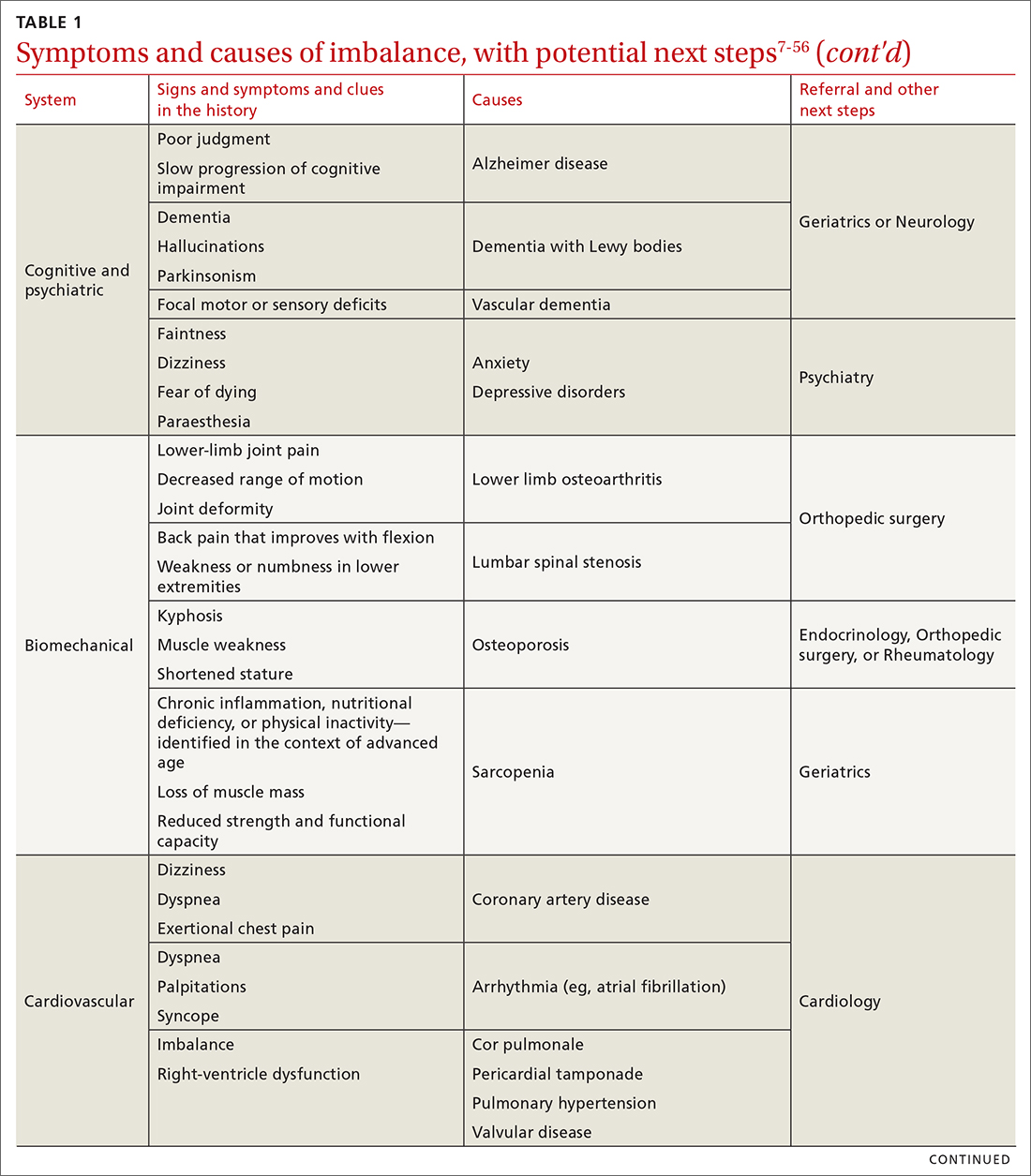

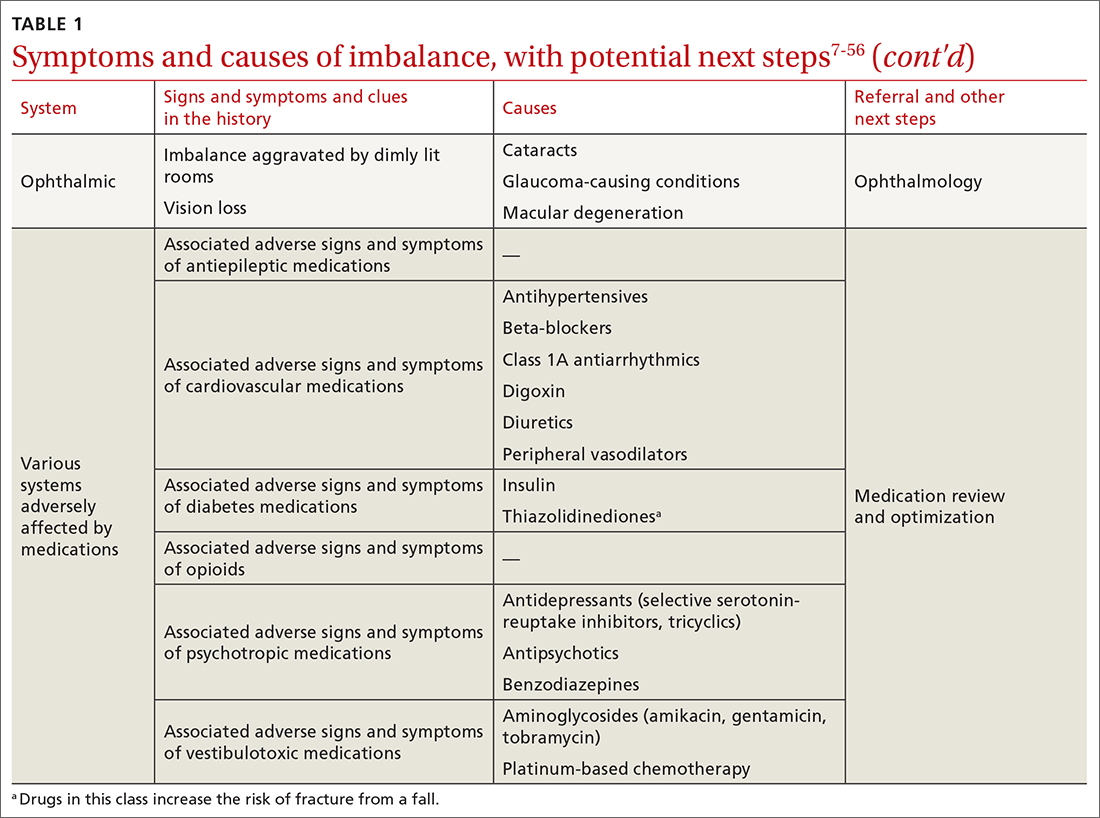

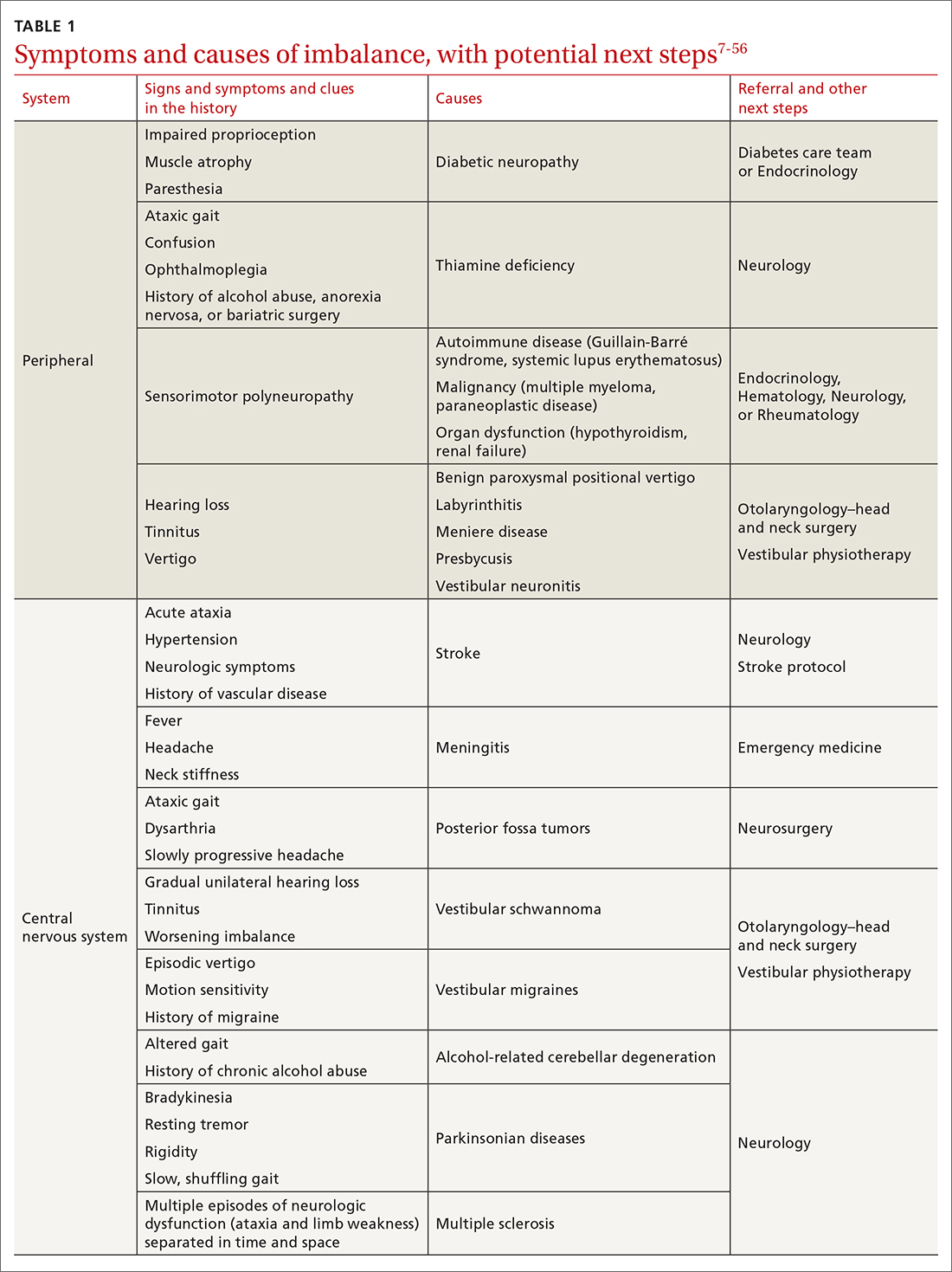

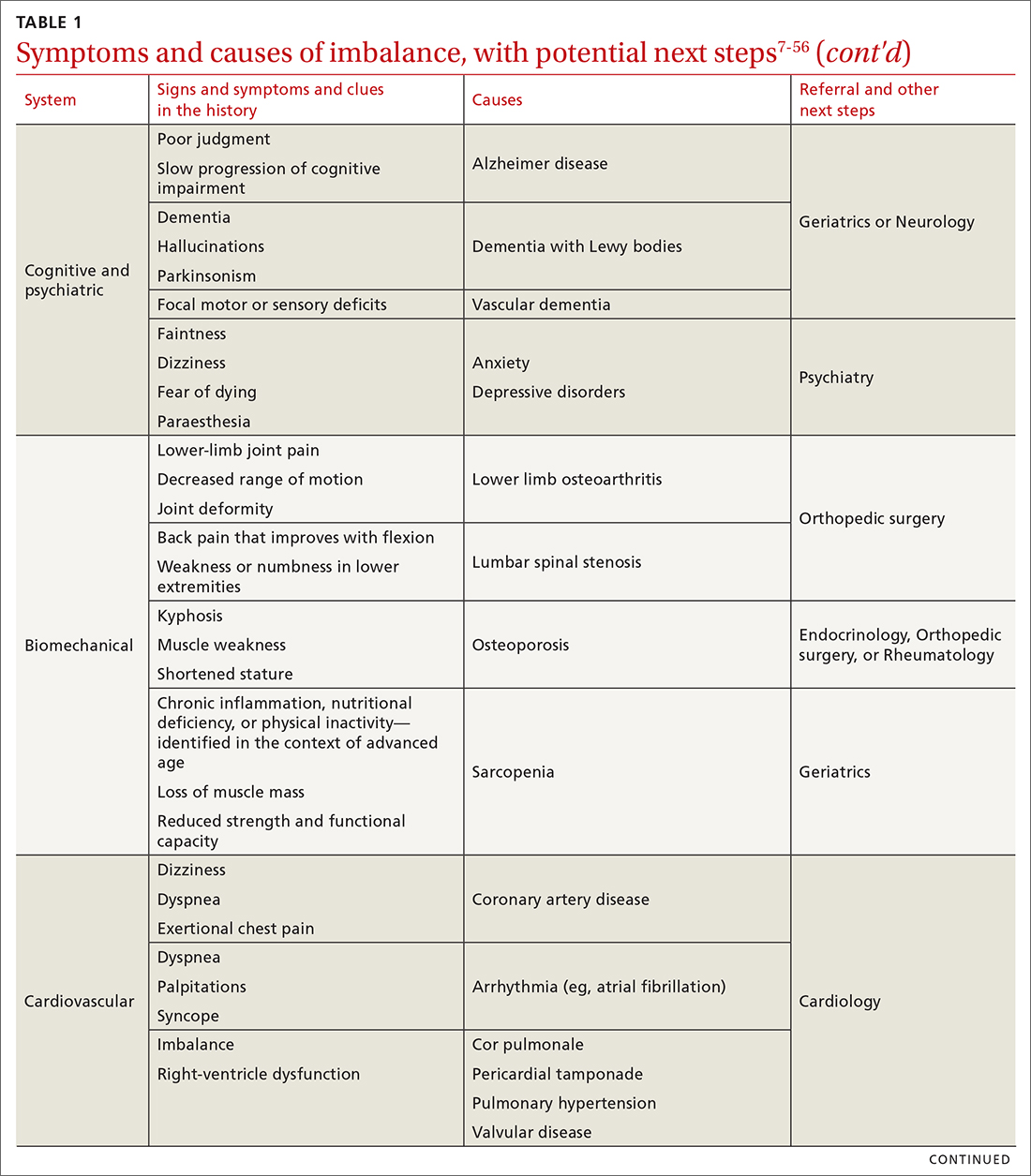

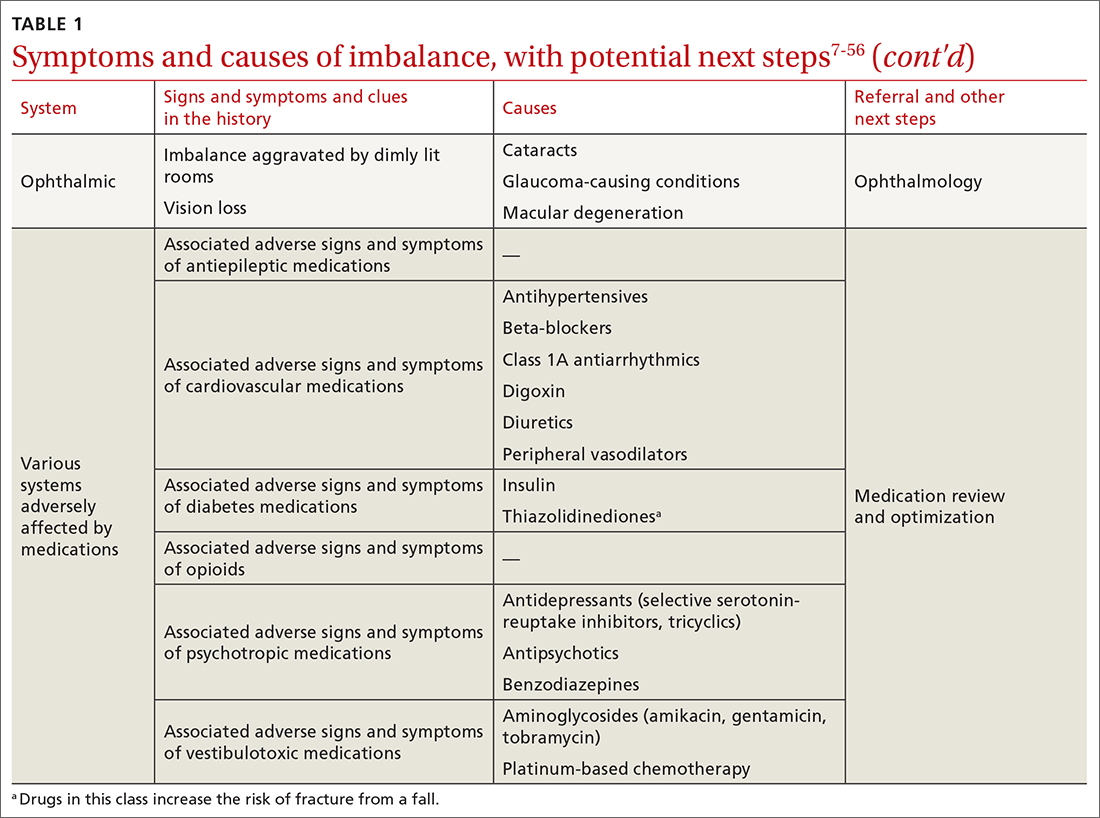

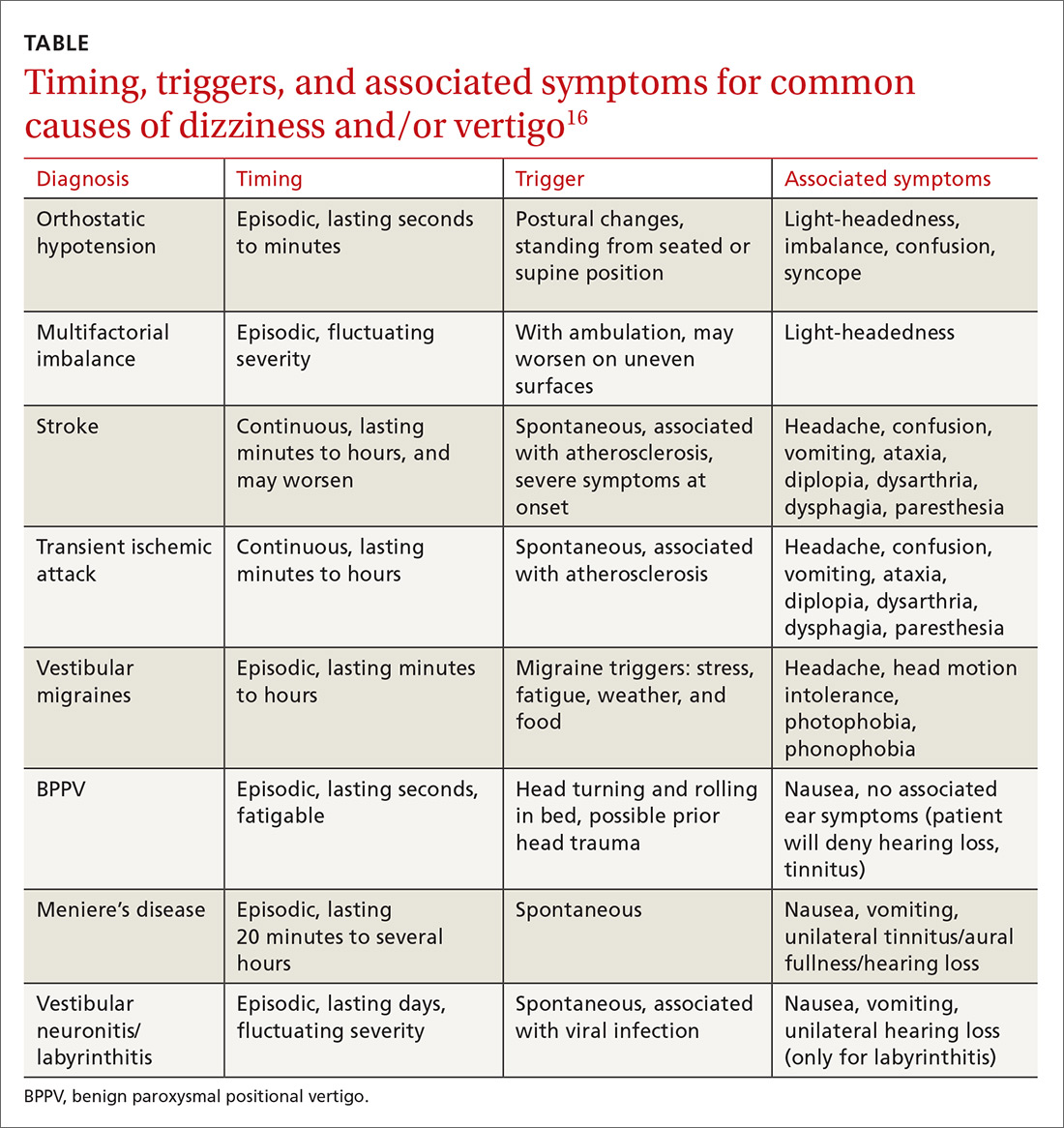

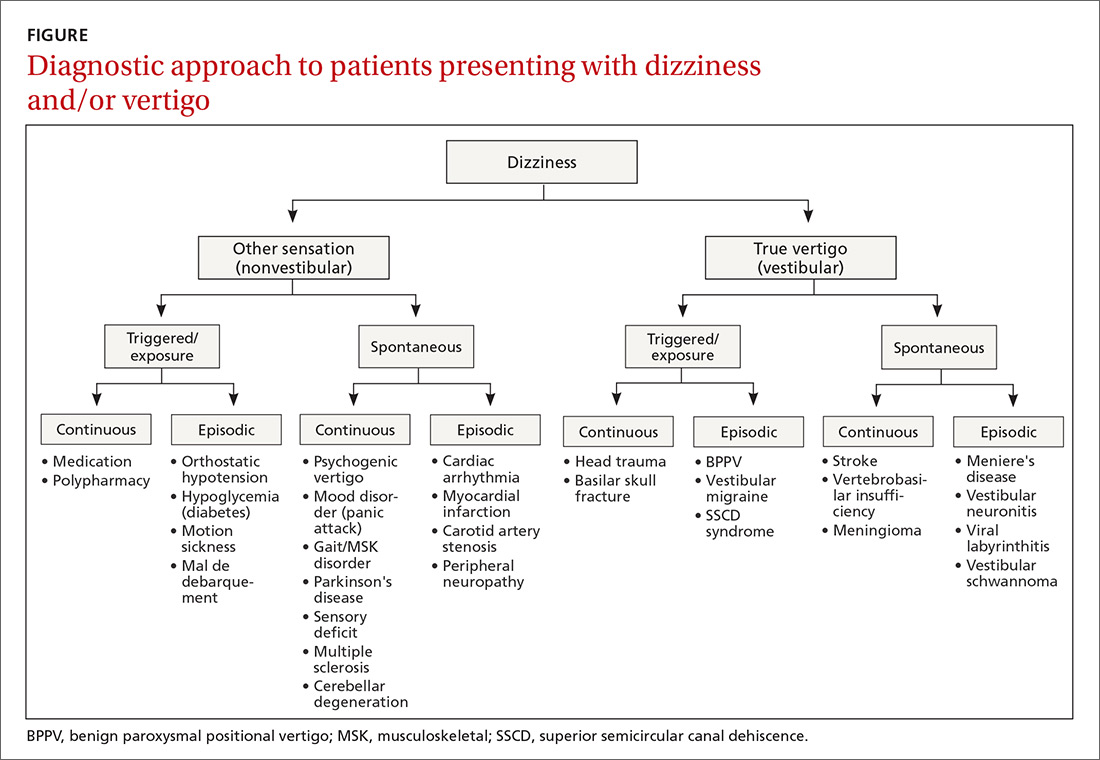

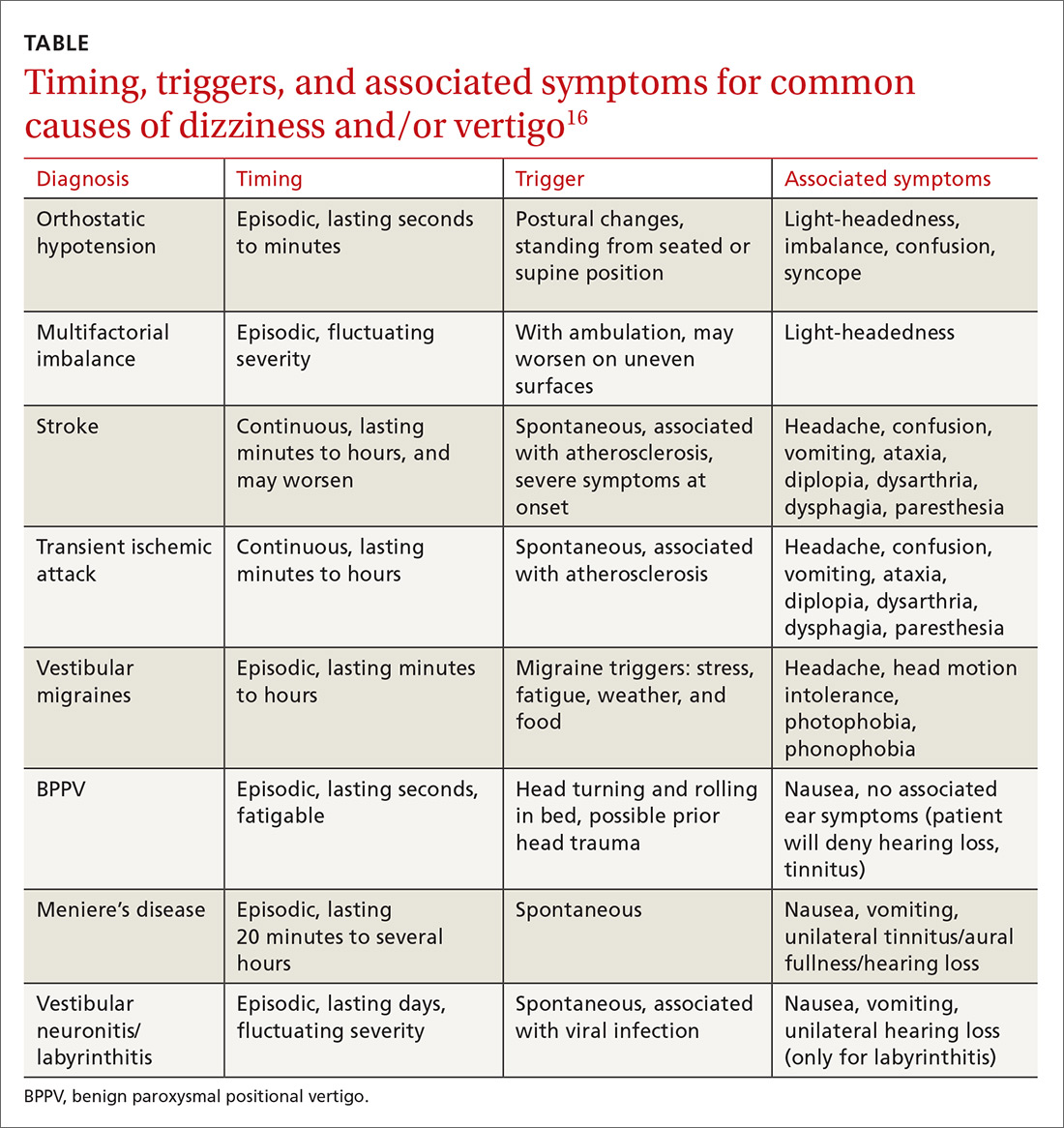

The cause of any single case of imbalance is often multifactorial, resulting from dysfunction of multiple body systems (TABLE 17-56); in our clinical experience, most patients with imbalance and who are at risk of falls do not have a detectable deficit of the vestibular system. These alterations in function arise in 3 key systems—vision, proprioception, and vestibular function—which signal to, and are incorporated by, the cerebellum to mediate balance. Cognitive and neurologic decline are also factors in imbalance.

Considering that 20% of falls result in serious injury in older populations, it is important to identify balance disorders and implement preventive strategies to mitigate harmful consequences of falls on patients’ health and independence.7,57 In this article, we answer the question that the case presentation raises about the proper management approach to imbalance in family practice, including assessment of risk and rehabilitation strategies to reduce the risk of falls. Our insights and recommendations are based on our clinical experience and a review of the medical literature from the past 40 years.

CASE Mr. J has a history of hypertension, age-related hearing loss, and osteoarthritis of the knees; he has not had surgery for the arthritis. His medications are antihypertensives and extra-strength acetaminophen for knee pain.

Making the diagnosis of a balance disorder

History

A thorough clinical history, often including a collateral history from caregivers, narrows the differential diagnosis. Information regarding onset, duration, timing, character, and previous episodes of imbalance is essential. Symptoms of imbalance are often challenging for the patient to describe: They might use terms such as vertigo or dizziness, when, in fact, on further questioning, they are describing balance difficulties. Inquiry into (1) their use of assistive walking devices and (2) development or exacerbation of neurologic, musculoskeletal, auditory, visual, and mood symptoms is necessary. Note the current level of their mobility, episodes of pain or fatigue, previous falls and associated injuries, fear of falling, balance confidence, and sensations that precede falls.58

Continue to: The medical and surgical histories

The medical and surgical histories are key pieces of information. The history of smoking, alcohol habits, and substance use is relevant.

A robust medication history is essential to evaluate a patient’s risk of falling. Polypharmacy—typically, defined as taking 4 or more medications—has been repeatedly associated with a heightened risk of falls.53,59-61 Moreover, a dose-dependent association between polypharmacy and hospitalization following falls has been identified, and demonstrates that taking 10 or more medications greatly increases the risk of hospitalization.59 Studies of polypharmacy cement the importance of inquiring about medication use when assessing imbalance, particularly in older patients.

Physical examination

A focused and detailed physical examination provides insight into systems that should be investigated:

- Obtain vital signs, including orthostatic vitals to test for orthostatic hypotension62; keep in mind that symptoms of orthostatic dizziness can occur without orthostatic hypotension.

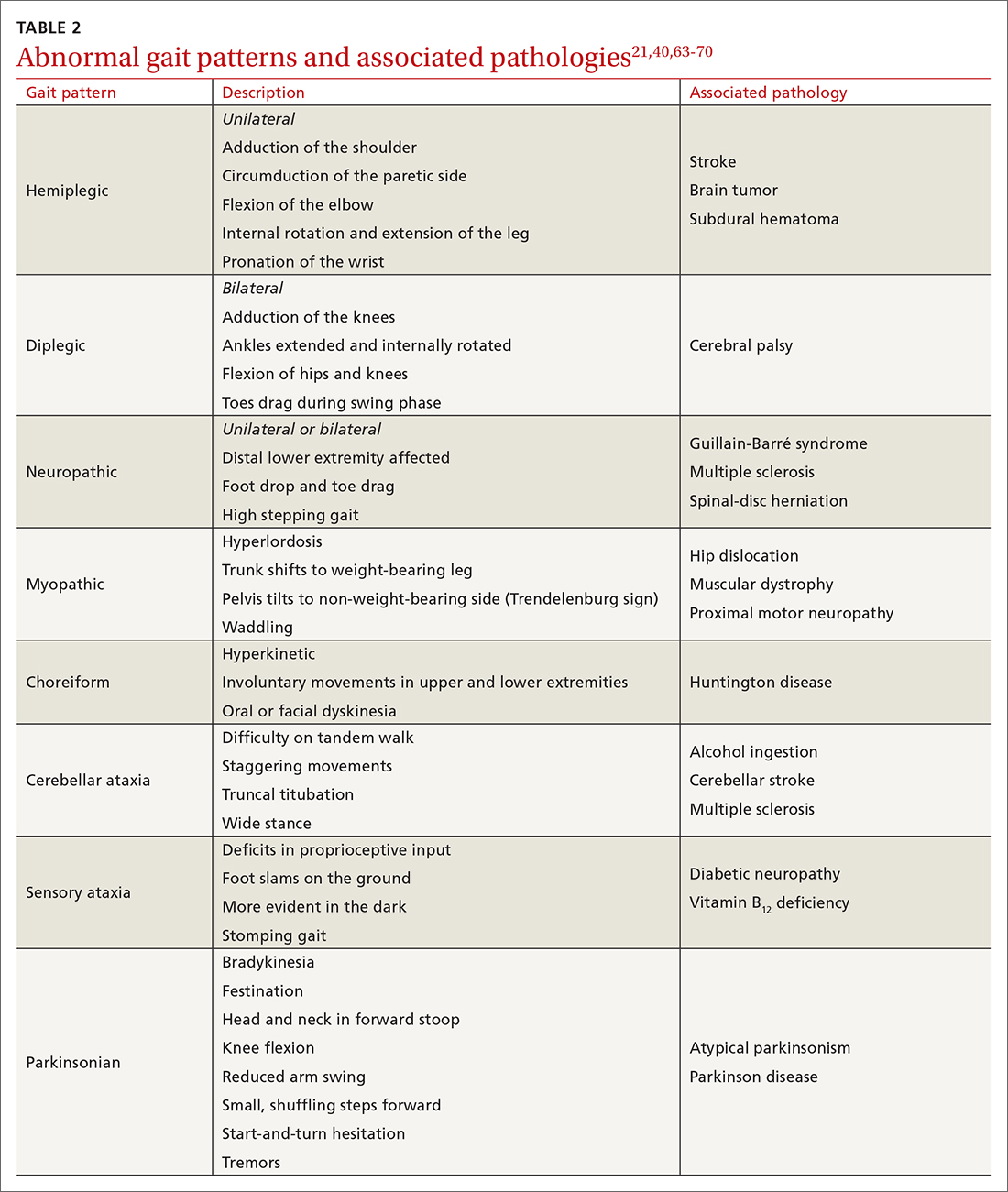

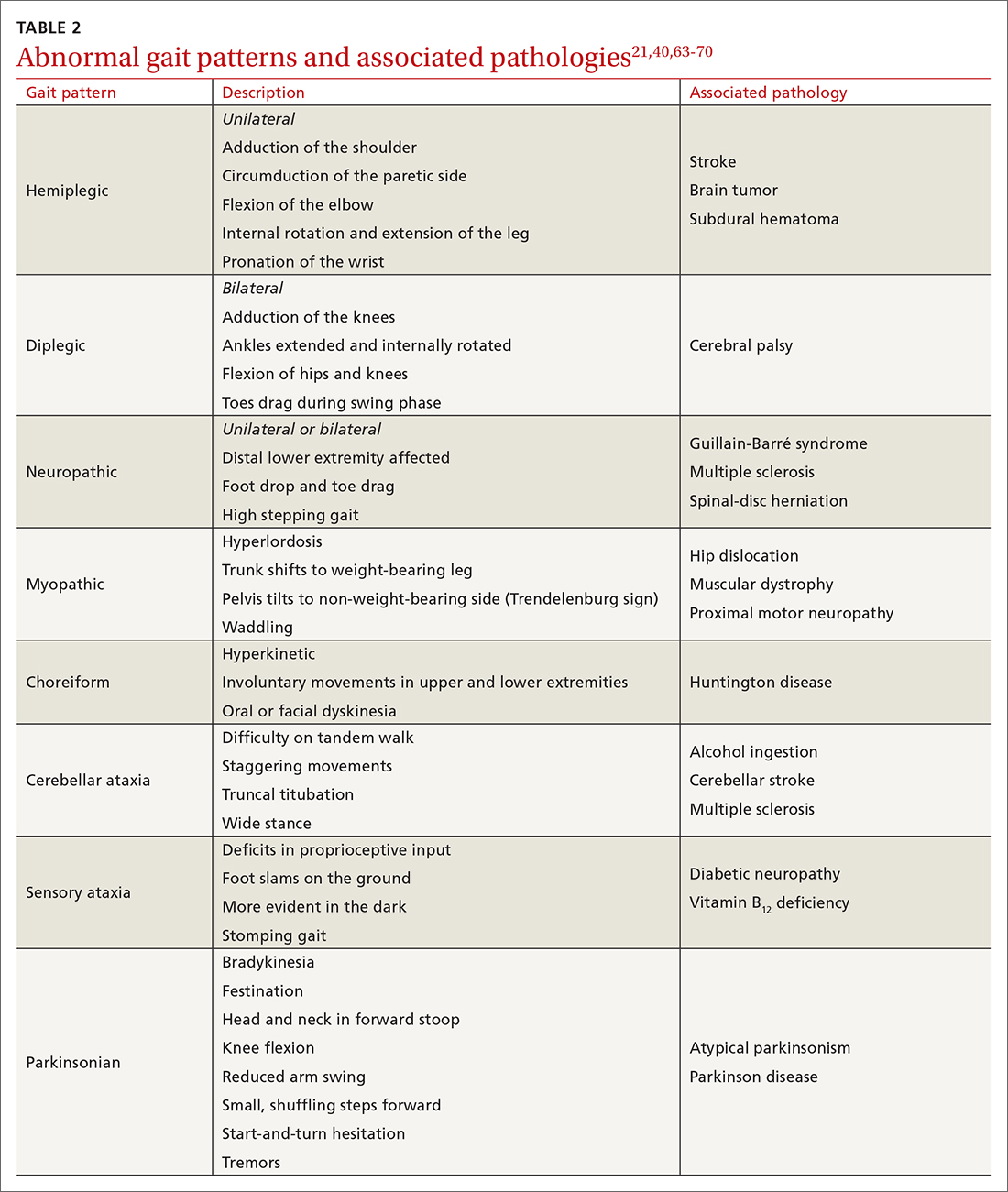

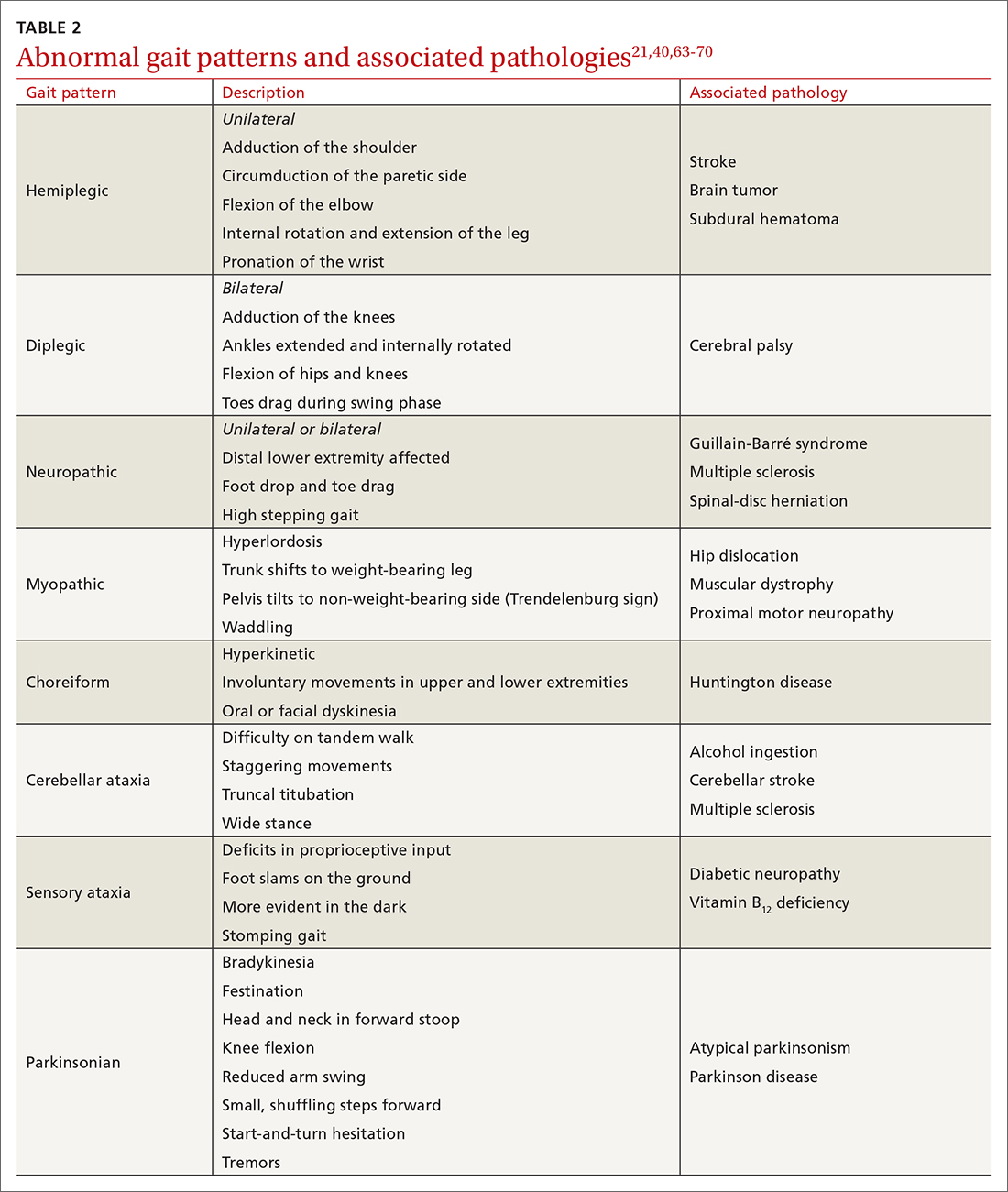

- Examine gait, which can distinguish between causes of imbalance (TABLE 2).21,40,63-70

- Perform a cardiac examination.

- Assess visual acuity and visual fields; test for nystagmus and identify any optic-nerve and retinal abnormalities.

- Evaluate lower-limb sensation, proprioception, and motor function.

- Evaluate suspected vestibular dysfunction, including dysfunction with positional testing (the Dix-Hallpike maneuver71). The patient is taken from sitting to supine while the head is rotated 45° to the tested side by the examiner. As the patient moves into a supine position, the neck is extended 30° off the table and held for at least 30 seconds. The maneuver is positive if torsional nystagmus is noted while the head is held rotated during neck extension. The maneuver is negative if the patient reports dizziness, vertigo, unsteadiness, or “pressure in the head.” Torsional nystagmus must be present to confirm a diagnosis of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo.

- If you suspect a central nervous system cause of imbalance, assess the cranial nerves, coordination, strength, and, of course, balance.

CASE

Mr. J’s physical examination showed normal vital signs without significant postural changes in blood pressure. Gait analysis revealed a slowed gait, with reduced range of motion in both knees over the entire gait cycle. Audiometry revealed symmetric moderate sensorineural hearing loss characteristic of presbycusis.

Diagnostic investigations

Consider focused investigations into imbalance based on the history and physical examination. We discourage overly broad testing and imaging; in primary care, cost and limited access to technology can bar robust investigations into causes of imbalance. However, identification of acute pathologies should prompt immediate referral to the emergency department. Furthermore, specific symptoms (TABLE 17-56) should prompt referral to specialists for assessment.

Continue to: In the emergency department...

In the emergency department and academic hospitals, key investigations can identify causes of imbalance:

- Electrocardiography and Holter monitoring test for cardiac arrhythmias.

- Echocardiography identifies structural abnormalities.

- Radiography and computed tomography are useful for detecting musculoskeletal abnormalities.

- Bone densitometry can identify osteoporosis.

- Head and spinal cord magnetic resonance imaging can be used to identify lesions of the central nervous system.

- Computed tomographic angiography of the head and neck is useful for identifying stroke, cerebral atrophy, and stenotic lesions of the carotid and vertebral arteries.

- Nerve conduction studies and levels of serum vitamin B12, hemoglobin A1C, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and random cortisol can uncover causes of peripheral neuropathy.

- Bedside cognitive screening tests can be used to measure cognitive decline.72

- Suspicion of vestibular disease requires audiometry and vestibular testing, including videonystagmography, head impulse testing, and vestibular evoked myogenic potentials.

In many cases of imbalance, no specific underlying correctable cause is discovered.

Management of imbalance

Pharmacotherapy

Targeted pharmacotherapy can be utilized in select clinical scenarios:

- Medical treatment of peripheral neuropathy should target the underlying condition.

- Cognitive behavioral therapy and antidepressants are useful for treating anxiety and depressive disorders.73

- Musculoskeletal pain can be managed with acetaminophen and topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), using a short course of an oral NSAID when needed.74

- Cardiovascular disease management might include any of several classes of pharmacotherapy, including antiplatelet and lipid-lowering medications, antiarrhythmic drugs, and antihypertensive agents.

- Acute episodes of vertigo due to vestibular neuritis or labyrinthitis can be managed with an antiemetic.46

Surgical treatment

Surgery is infrequently considered for patients with imbalance. Examples of indications include microsurgical resection of vestibular schwannoma, resection of central nervous system tumors, lens replacement surgery for cataract, surgical management of severe spinal fracture, and hip or knee arthroplasty in select patients.

Tools for assessing the risk of falls

Scoring systems called falls risk assessment tools, or FRAT, have been developed to gauge a patient’s risk of falling. The various FRATs differ in specificity and sensitivity for predicting the risk of falls, and are typically designed for specific clinical environments, such as hospital inpatient care or long-term care facilities. Specifically, FRATs attempt to classify risk using sets of risk factors known to be associated with falls.

Continue to: Research abounds into...

Research abounds into the validity of commonly used FRATs across institutions, patient populations, and clinical environments:

The Johns Hopkins FRATa determines risk using metrics such as age, fall history, incontinence, cognition, mobility, and medications75; it is predominantly used for assessment in hospital inpatient units. This tool has been validated repeatedly.76,77

Peninsula Health FRATb stratifies patients in subacute and residential aged-care settings, based on risk factors that include recent falls, medications, psychological status, and cognition.78

FRAT-upc is a web-based tool that generates falls risk using risk factors that users input. This tool has been studied in the context of patients older than 65 years living in the community.79

Although FRATs are reasonably useful for predicting falls, their utility varies by patient population and clinical context. Moreover, it has been suggested that FRATs neglect environmental and personal factors when assessing risk by focusing primarily on bodily factors.80 Implementing a FRAT requires extensive consideration of the target population and should be accompanied by clinical judgment that is grounded in an individual patient’s circumstances.81

Continue to: Preventing falls in primary care

Preventing falls in primary care

An approach to preventing falls includes the development of individualized programs that account for frailty, a syndrome of physiologic decline associated with aging. Because frailty leads to diminished balance and mobility, a patient’s frailty index—determined using the 5 frailty phenotype criteria (exhaustion, weight loss, low physical activity, weakness, slowness)82 or the Canadian Study of Health and Aging Clinical Frailty Scale83—is a useful tool for predicting falls risk and readmission for falls following trauma-related injury. Prevention of falls in communities is critical for reducing mortality and allowing older people to maintain their independence and quality of life.

Exercise. In some areas, exercise and falls prevention programs are accessible to seniors.84 Community exercise programs that focus on balance retraining and muscle strengthening can reduce the risk of falls.73,85 The Choosing Wisely initiative of the ABIM [American Board of Internal Medicine] Foundation recommends that exercise programs be designed around an accurate functional baseline of the patient to avoid underdosed strength training.54

Multifactorial risk assessment in high-risk patients can reduce the rate of falls. Such an assessment includes examination of orthostatic blood pressure, vision and hearing, bone health, gait, activities of daily living, cognition, and environmental hazards, and enables provision of necessary interventions.73,86 Hearing amplification, specifically, correlates with enhanced postural control, slowed cognitive decline, and a reduced likelihood of falls.87-93 The mechanism behind improved balance performance might be reduced cognitive load through supporting a patient’s listening needs.88-90

Pharmacotherapy. Optimizing medications and performing a complete medication review before prescribing new medications is highly recommended to avoid unnecessary polypharmacy7,8,18,53-56 (TABLE 17-56).

Management of comorbidities associated with a higher risk of falls, including arthritis, cancer, stroke, diabetes, depression, kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cognitive impairment, hypertension, and atrial fibrillation, is essential.94-96

Continue to: Home safety interventions

Home safety interventions, through occupational therapy, are important. These include removing unsafe mats and step-overs and installing nonslip strips on stairs, double-sided tape under mats, and handrails.73-97

Screening for risk of falls. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that (1) all patients older than 65 years and (2) any patient presenting with an acute fall undergo screening for their risk of falls.98 When a patient is identified as at risk of falling, you can, when appropriate, assess modifiable risk factors and facilitate interventions.98 This strategy is supported by a 2018 statement from the US Preventive Services Task Force99 that recommends identifying high-risk patients who have:

- a history of falling

- a balance disturbance that causes a deficit of mobility or function

- poor performance on clinical tests, such as the 3-meter Timed Up and Go (TUG) assessment (www.cdc.gov/steadi/pdf/TUG_test-print.pdf).

An increased risk of falls should prompt you to refer the patient to community programs and physiotherapy in accordance with the individual’s personal goals99; a balance and vestibular physiotherapist is ideally positioned to accurately assess and manage patients at risk of falls. Specifically, the Task Force identified exercise programs and multifactorial interventions as being beneficial in preventing falls in high-risk older people.99

Balance assessment and rehabilitation in specialty centers

An individualized rehabilitation program aims to restore safe mobility by testing and addressing specific balance deficits, improving functional balance, and increasing balance confidence. Collaboration with colleagues from physiotherapy and occupational therapy aids in tailoring individualized programs.

Many tests are available to assess balance, determine the risk of falls, and guide rehabilitation:

- The timed 10-meter walk testd and the TUG test are simple assessments that measure functional mobility; both have normalized values for the risk of falls. A TUG time of ≥ 12 seconds suggests a high risk of falls.

- The 30-second chair stande evaluates functional lower-extremity strength in older patients. The test can indicate if lower-extremity strength is contributing to a patient’s imbalance.

- The modified clinical test of sensory interaction in balancef is a static balance test that measures the integrity of sensory inputs. The test can suggest if 1 or more sensory systems are compromised.

- The mini balance evaluation systems testg is similar: It can differentiate balance deficits by underlying system and allows individualization of a rehabilitation program.

- The functional gait assessmenth is a modification of the dynamic gait index that assesses postural stability during everyday dynamic activities, including tasks such as walking with head turns and pivots.

- The Berg Balance Scalei continues to be used extensively to assess balance.

Continue to: The mini balance evaluation systems test...

The mini balance evaluation systems test, functional gait index, and Berg Balance Scale all have normative age-graded values to predict fall risk.

CASE

Mr. J was referred for balance assessment and to a rehabilitation program. He underwent balance physiotherapy, including multifactorial balance assessment, joined a community exercise program, was fitted with hearing aids, and had his home environment optimized by an occupational therapist. (See examples of “home safety interventions” under “Preventing falls in primary care.”)

3 months later. Mr. J says he feels stronger on his feet. His knee pain has eased, and he is more confident walking around his home. He continues to engage in exercise programs and is comfortable running errands with his spouse.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jason A. Beyea, MD, PhD, FRCSC, Division of OtolaryngologyHead and Neck Surgery, Queen’s University, 144 Brock Street, Kingston, Ontario, Canada, K7L 5G2; [email protected]

a www.hopkinsmedicine.org/institute_nursing/models_tools/jhfrat_acute%20care%20original_6_22_17.pdf

c www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4376110/figure/figure14/?report=objectonly

e www.cdc.gov/steadi/pdf/STEADI-Assessment-30Sec-508.pdf

f www.mdapp.co/mctsib-modified-clinical-test-of-sensory-interaction-in-balance-calculator-404/

g www.sralab.org/sites/default/files/2017-07/MiniBEST_revised_final_3_8_13.pdf

1. Larocca NG. Impact of walking impairment in multiple sclerosis: perspectives of patients and care partners. Patient. 2011;4:189-201. doi: 10.2165/11591150-000000000-00000

2. TB, ZF, ES, et al. The relationship of balance disorders with falling, the effect of health problems, and social life on postural balance in the elderly living in a district in Turkey. Geriatrics (Basel). 2019;4:37. doi: 10.3390/geriatrics4020037

3. R, Sixt E, Landahl S, et al. Prevalence of dizziness and vertigo in an urban elderly population. J Vestib Res. 2004;14:47-52.

4. Sturnieks DL, St George R, Lord SR. Balance disorders in the elderly. Neurophysiol Clin. 2008;38:467-478. doi: 10.1016/j.neucli.2008.09.001

5. Boult C, Murphy J, Sloane P, et al. The relation of dizziness to functional decline. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39:858-861. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb04451.x

6. Lin HW, Bhattacharyya N. Balance disorders in the elderly: epidemiology and functional impact. Laryngoscope. 2012;122:1858-1861. doi: 10.1002/lary.23376

7. Jia H, Lubetkin EI, DeMichele K, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and burden of disease for falls and balance or walking problems among older adults in the U.S. Prev Med. 2019;126:105737. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.05.025

8. Al-Momani M, Al-Momani F, Alghadir AH, et al. Factors related to gait and balance deficits in older adults. Clin Interv Aging. 2016;11:1043-1049. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S112282

9. Agrawal Y, Ward BK, Minor LB. Vestibular dysfunction: prevalence, impact and need for targeted treatment. J Vestib Res. 2013;23:113-117. doi: 10.3233/VES-130498

10. Altinsoy B, Erboy F, Tanriverdi H, et al. Syncope as a presentation of acute pulmonary embolism. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2016;12:1023-1028. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S105722

11. Belvederi Murri M, Triolo F, Coni A, et al. Instrumental assessment of balance and gait in depression: a systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2020;284:112687. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112687

12. Bhattacharyya N, Gubbels SP, Schwartz SR, et al. Clinical practice guideline: benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (update). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;156(suppl 3):S1-S47. doi: 10.1177/0194599816689667

13. S, Schwarm S, Grevenrath P, et al. Prevalence, aetiologies and prognosis of the symptom dizziness in primary care - a systematic review. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19:33. doi: 10.1186/s12875-017-0695-0

14. Brouwer MC, Tunkel AR, van de Beek D. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and antimicrobial treatment of acute bacterial meningitis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:467-492. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00070-09

15. Chad DA. Lumbar spinal stenosis. Neurol Clin. 2007;25:407-418. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2007.01.003

16. Conrad BP, Shokat MS, Abbasi AZ, et al. Associations of self-report measures with gait, range of motion and proprioception in patients with lumbar spinal stenosis. Gait Posture. 2013;38:987-992. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2013.05.010

17. de Luna RA, Mihailovic A, Nguyen AM, et al. The association of glaucomatous visual field loss and balance. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2017;6:8. doi: 10.1167/tvst.6.3.8

18. DiSogra RM. Common aminoglycosides and platinum-based ototoxic drugs: cochlear/vestibular side effects and incidence. Semin Hear. 2019;40:104-107. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1684040

19. Ebersbach G, Moreau C, Gandor F, et al. Clinical syndromes: parkinsonian gait. Mov Disord. 2013;28:1552-1559. doi: 10.1002/mds.25675

20. Evans WJ. Skeletal muscle loss: cachexia, sarcopenia, and inactivity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:1123S-1127S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.28608A

21. Filli L, Sutter T, Easthope CS, et al. Profiling walking dysfunction in multiple sclerosis: characterisation, classification and progression over time. Sci Rep. 2018;8:4984. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-22676-0

22. Fritz NE, Kegelmeyer DA, Kloos AD, et al. Motor performance differentiates individuals with Lewy body dementia, Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease. Gait Posture. 2016;50:1-7. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2016.08.009

23. Furman JM, Jacob RG. A clinical taxonomy of dizziness and anxiety in the otoneurological setting. J Anxiety Disord. 2001;15:9-26. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(00)00040-2

24. Furman JM, Marcus DA, Balaban CD. Vestibular migraine: clinical aspects and pathophysiology. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:706-715. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70107-8

25. Gerson LW, Jarjoura D, McCord G. Risk of imbalance in elderly people with impaired hearing or vision. Age Ageing. 1989;18:31-34. doi: 10.1093/ageing/18.1.31

26. Goudakos JK, Markou KD, Franco-Vidal V, et al. Corticosteroids in the treatment of vestibular neuritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Otol Neurotol. 2010;31:183-189. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3181ca843d

27. Green AD, CS, Bastian L, et al. Does this woman have osteoporosis? JAMA. 2004;292:2890-2900. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.23.2890

28. Hallemans A, Ortibus E, Meire F, et al. Low vision affects dynamic stability of gait. Gait Posture. 2010;32:547-551. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2010.07.018

29. Handelsman JA. Vestibulotoxicity: strategies for clinical diagnosis and rehabilitation. Int J Audiol. 2018;57(suppl 4):S99-S107. doi: 10.1080/14992027.2018.1468092

30. Head VA, Wakerley BR. Guillain-Barré syndrome in general practice: clinical features suggestive of early diagnosis. Br J Gen Pract. 2016;66:218-219. doi: 10.3399/bjgp16X684733

31. Helbostad JL, Vereijken B, Hesseberg K, et al. Altered vision destabilizes gait in older persons. Gait Posture. 2009;30:233-238. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2009.05.004

32. Hsu W-L, Chen C-Y, Tsauo J-Y, et al. Balance control in elderly people with osteoporosis. J Formos Med Assoc. 2014;113:334-339. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2014.02.006

33. Kim H-S, Yun DH, Yoo SD, et al. Balance control and knee osteoarthritis severity. Ann Rehabil Med. 2011;35:701-709. doi: 10.5535/arm.2011.35.5.701

34. Li L, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, et al. Hearing loss and gait speed among older adults in the United States. Gait Posture. 2013;38:25-29.

35. McKeith IG, Boeve BF, Dickson DW, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: fourth consensus report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2017;89:88-100. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004058

36. Milner KA, Funk M, Richards S, et al. Gender differences in symptom presentation associated with coronary heart disease. Am J Cardiol. 1999;84:396-399. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)00322-7

37. Paillard T, F, Bru N, et al. The impact of time of day on the gait and balance control of Alzheimer’s patients. Chronobiol Int. 2016;33:161-168. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2015.1124885

38. Paldor I, Chen AS, Kaye AH. Growth rate of vestibular schwannoma. J Clin Neurosci. 2016;32:1-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2016.05.003

39. Picorelli AMA, Hatton AL, Gane EM, et al. Balance performance in older adults with hip osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Gait Posture. 2018;65:89-99. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2018.07.001

40. Raccagni C, Nonnekes J, Bloem BR, et al. Gait and postural disorders in parkinsonism: a clinical approach. J Neurol. 2020;267:3169-3176. doi: 10.1007/s00415-019-09382-1

41. Shanmugarajah PD, Hoggard N, Currie S, et al. Alcohol-related cerebellar degeneration: not all down to toxicity? Cerebellum Ataxias. 2016;3:17. doi: 10.1186/s40673-016-0055-1

42. Shih RY, Smirniotopoulos JG. Posterior fossa tumors in adult patients. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2016;26:493-510. doi: 10.1016/j.nic.2016.06.003

43. Smith EE. Clinical presentations and epidemiology of vascular dementia. Clin Sci (Lond). 2017;131:1059-1068. doi: 10.1042/CS20160607

44. Streur M, Ratcliffe SJ, Ball J, et al. Symptom clusters in adults with chronic atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2017;32:296-303. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0000000000000344

45. Strupp M, M, JA. Peripheral vestibular disorders: an update. Curr Opin Neurol. 2019;32:165-173. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000649

46. Thompson TL, Amedee R. Vertigo: a review of common peripheral and central vestibular disorders. Ochsner J. 2009;9:20-26.

47. Timar B, Timar R, L, et al. The impact of diabetic neuropathy on balance and on the risk of falls in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0154654. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154654

48. Walls R, Hockberger R, Gausche-Hill M. Peripheral nerve disorders. In: Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice. 9th ed. Elsevier, Inc; 2018:1307-1320.

49. Watson JC, Dyck PJB. Peripheral neuropathy: a practical approach to diagnosis and symptom management. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90:940-951. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.05.004

50. Whitfield KC, Bourassa MW, Adamolekun B, et al. Thiamine deficiency disorders: diagnosis, prevalence, and a roadmap for global control programs. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2018;1430:3-43. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13919

51. Wu V, Sykes EA, Beyea MM, et al. Approach to Meniere disease management. Can Fam Physician. 2019;65:463-467.

52. Yew KS, Cheng EM. Diagnosis of acute stroke. Am Fam Physician. 2015;91:528-536.

53. Seppala LJ, van de Glind EMM, Daams JG, et al; . Fall-risk-increasing drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis: III. Others. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018;19:372.e1-372.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2017.12.099

54. ABIM Foundation. Choosing wisely. Choosing Wisely website. 2021. Accessed November 11. 2021. www.choosingwisely.org/

55. Berlie HD, Garwood CL. Diabetes medications related to an increased risk of falls and fall-related morbidity in the elderly. Ann Pharmacother. 2010;44:712-717. doi: 10.1345/aph.1M551

56. Hartikainen S, E, Louhivuori K. Medication as a risk factor for falls: critical systematic review. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62:1172-1181. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.10.1172

57. Khanuja K, Joki J, Bachmann G, et al. Gait and balance in the aging population: Fall prevention using innovation and technology. Maturitas. 2018;110:51-56. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2018.01.021

58. Salzman B. Gait and balance disorders in older adults. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82:61-68.

59. Zaninotto P, Huang YT, Di Gessa G, et al. Polypharmacy is a risk factor for hospital admission due to a fall: evidence from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1804. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09920-x

60. Morin L, Calderon A, Welmer AK, et al. Polypharmacy and injurious falls in older adults: a nationwide nested case-control study. Clin Epidemiol. 2019;11:483-493. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S201614

61. Dhalwani NN, Fahami R, Sathanapally H, et al. Association between polypharmacy and falls in older adults: a longitudinal study from England. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e016358. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016358

62. Arnold AC, Raj SR. Orthostatic hypotension: a practical approach to investigation and management. Can J Cardiol. 2017;33:1725-1728. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2017.05.007

63. Alexander NB. Differential diagnosis of gait disorders in older adults. Clin Geriatr Med. 1996;12:689-703.

64. Baker JM. Gait disorders. Am J Med. 2018;131:602-607. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.11.051

65. Cameron MH, Wagner JM. Gait abnormalities in multiple sclerosis: pathogenesis, evaluation, and advances in treatment. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2011;11:507-515. doi: 10.1007/s11910-011-0214-y

66. Chen C-L, Chen H-C, Tang SF-T, et al. Gait performance with compensatory adaptations in stroke patients with different degrees of motor recovery. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;82:925-935. doi: 10.1097/01.PHM.0000098040.13355.B5

67. Marsden J, Harris C. Cerebellar ataxia: pathophysiology and rehabilitation. Clin Rehabil. 2011;25:195-216. doi: 10.1177/0269215510382495

68. Mirek E, Filip M, W, et al. Three-dimensional trunk and lower limbs characteristics during gait in patients with Huntington’s disease. Front Neurosci. 2017;11:566. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2017.00566

69. Paramanandam V, Lizarraga KJ, Soh D, et al. Unusual gait disorders: a phenomenological approach and classification. Expert Rev Neurother. 2019;19:119-132. doi: 10.1080/14737175.2019.1562337

70. Sahyouni R, Goshtasbi K, Mahmoodi A, et al. Chronic subdural hematoma: a historical and clinical perspective. World Neurosurg. 2017;108:948-953. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.09.064

71. Talmud JD, Coffey R, Edemekong PF. Dix Hallpike maneuver. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing Updated September 5, 2021. Accessed December 6, 2021. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459307/

72. Molnar FJ, Benjamin S, Hawkins SA, et al. One size does not fit all: choosing practical cognitive screening tools for your practice. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68:2207-2213. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16713

73. Gillespie LD, Robertson MC, Gillespie WJ, et al. Interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012:CD007146. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007146.pub3

74. Wongrakpanich S, Wongrakpanich A, Melhado K, Rangaswami J. A comprehensive review of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use in the elderly. Aging Dis. 2018;9:143-150. doi: 10.14336/AD.2017.0306

75. Poe SS, Cvach M, Dawson PB, Straus H, Hill EE. The Johns Hopkins Fall Risk Assessment Tool: postimplementation evaluation. J Nurs Care Qual. 2007;22:293-298. doi: 10.1097/01.NCQ.0000290408.74027.39

76. Poe SS, Dawson PB, Cvach M, et al. The Johns Hopkins Fall Risk Assessment Tool: a study of reliability and validity. J Nurs Care Qual. 2018;33:10-19. doi: 10.1097/NCQ.0000000000000301

77. Klinkenberg WD, Potter P. Validity of the Johns Hopkins Fall Risk Assessment Tool for predicting falls on inpatient medicine services. J Nurs Care Qual. 2017;32:108-113. doi: 10.1097/NCQ.0000000000000210

78. Stapleton C, Hough P, Oldmeadow L, et al. Four-item fall risk screening tool for subacute and residential aged care: the first step in fall prevention. Australas J Ageing. 2009;28:139-143. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6612.2009.00375.x

79. Cattelani L, Palumbo P, Palmerini L, et al. FRAT-up, a Web-based fall-risk assessment tool for elderly people living in the community. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17:e41. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4064

80. De Clercq H, Naudé A, Bornman J. Factors included in adult fall risk assessment tools (FRATs): a systematic review. Ageing Soc. 2020;41:2558-2582. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X2000046X

81. Yap G, Melder A. Accuracy of validated falls risk assessment tools and clinical judgement. Centre for Clinical Effectiveness, Monash Innovation and Quality. Monash Health. February 5, 2020. Accessed November 11, 2021. https://monashhealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Rapid-Review_Falls-risk-tools-FINAL.pdf

82. Chittrakul J, Siviroj P, Sungkarat S, et al. Physical frailty and fall risk in community-dwelling older adults: a cross-sectional study. J Aging Res. 2020;2020:3964973. doi: 10.1155/2020/3964973

83. Hatcher VH, Galet C, Lilienthal M, et al. Association of clinical frailty scores with hospital readmission for falls after index admission for trauma-related injury. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e1912409. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.12409

84. Exercise and fall prevention programs. Government of Ontario Ministry of Health. Updated April 9, 2019. Accessed November 11. 2021. www.ontario.ca/page/exercise-and-falls-prevention-programs

85. Sherrington C, Fairhall NJ, Wallbank GK, et al. Exercise for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;1:CD012424. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012424.pub2

86. Hopewell S, Copsey B, Nicolson P, et al. Multifactorial interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 41 trials and almost 20 000 participants. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54:1340-1350. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2019-100732

87. Jafari Z, Kolb BE, Mohajerani MH. Age-related hearing loss and tinnitus, dementia risk, and auditory amplification outcomes. Ageing Res Rev. 2019;56:100963. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2019.100963

88. Griffiths TD, Lad M, Kumar S, et al. How can hearing loss cause dementia? Neuron. 2020;108:401-412. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2020.08.003

89. Martini A, Castiglione A, Bovo R, et al. Aging, cognitive load, dementia and hearing loss. Audiol Neurootol. 2014;19(suppl 1):2-5. doi: 10.1159/000371593

90. Vitkovic J, Le C, Lee S-L, et al. The contribution of hearing and hearing loss to balance control. Audiol Neurootol. 2016;21:195-202. doi: 10.1159/000445100

91. Maheu M, Behtani L, Nooristani M, et al. Vestibular function modulates the benefit of hearing aids in people with hearing loss during static postural control. Ear Hear. 2019;40:1418-1424. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000720

92. Negahban H, Bavarsad Cheshmeh Ali M, Nassadj G. Effect of hearing aids on static balance function in elderly with hearing loss. Gait Posture. 2017;58:126-129. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2017.07.112

93. Mahmoudi E, Basu T, Langa K, et al. Can hearing aids delay time to diagnosis of dementia, depression, or falls in older adults? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67:2362-2369. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16109

94. Paliwal Y, Slattum PW, Ratliff SM. Chronic health conditions as a risk factor for falls among the community-dwelling US older adults: a zero-inflated regression modeling approach. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:5146378. doi: 10.1155/2017/5146378

95. Deandrea S, Lucenteforte E, Bravi F, et al. Risk factors for falls in community-dwelling older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiology. 2010;21:658-668. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181e89905

96. Ambrose AF, Paul G, Hausdorff JM. Risk factors for falls among older adults: a review of the literature. Maturitas. 2013;75:51-61. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2013.02.009

97. Stevens M, Holman CD, Bennett N. Preventing falls in older people: impact of an intervention to reduce environmental hazards in the home. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:1442-1447. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.4911235.x

98. Clinical resources. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention STEADI-Older Adult Fall Prevention website. 2020. Accessed November 12, 2021. www.cdc.gov/steadi/materials.html

99. ; Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Owens DK, et al. Interventions to prevent falls in community-dwelling older adults: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;319:1696-1704. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.3097

CASE Mr. J, a 75-year-old man, presents to your family practice reporting that he feels increasingly unsteady and slow while walking. He fell twice last year, without resulting injury. He now worries about tripping while walking around the house and relies on his spouse to run errands.

Clearly, Mr. J is experiencing a problem with balance. What management approach should you undertake to prevent him from falling?

Balance disorders are common in older people and drastically hinder quality of life.1-4 Patients often describe imbalance as vague symptoms: dizziness, unsteadiness, faintness, spinning sensations.5,6 Importantly, balance disorders disrupt normal gait and contribute to falls that are a major cause of disability and morbidity in older people. Almost 30% of people older than 65 years report 1 or more falls annually.7 Factors that increase the risk of falls include impaired mobility, previously reported falls, reduced psychological functioning, chronic medical conditions, and polypharmacy.7,8

The cause of any single case of imbalance is often multifactorial, resulting from dysfunction of multiple body systems (TABLE 17-56); in our clinical experience, most patients with imbalance and who are at risk of falls do not have a detectable deficit of the vestibular system. These alterations in function arise in 3 key systems—vision, proprioception, and vestibular function—which signal to, and are incorporated by, the cerebellum to mediate balance. Cognitive and neurologic decline are also factors in imbalance.

Considering that 20% of falls result in serious injury in older populations, it is important to identify balance disorders and implement preventive strategies to mitigate harmful consequences of falls on patients’ health and independence.7,57 In this article, we answer the question that the case presentation raises about the proper management approach to imbalance in family practice, including assessment of risk and rehabilitation strategies to reduce the risk of falls. Our insights and recommendations are based on our clinical experience and a review of the medical literature from the past 40 years.

CASE Mr. J has a history of hypertension, age-related hearing loss, and osteoarthritis of the knees; he has not had surgery for the arthritis. His medications are antihypertensives and extra-strength acetaminophen for knee pain.

Making the diagnosis of a balance disorder

History

A thorough clinical history, often including a collateral history from caregivers, narrows the differential diagnosis. Information regarding onset, duration, timing, character, and previous episodes of imbalance is essential. Symptoms of imbalance are often challenging for the patient to describe: They might use terms such as vertigo or dizziness, when, in fact, on further questioning, they are describing balance difficulties. Inquiry into (1) their use of assistive walking devices and (2) development or exacerbation of neurologic, musculoskeletal, auditory, visual, and mood symptoms is necessary. Note the current level of their mobility, episodes of pain or fatigue, previous falls and associated injuries, fear of falling, balance confidence, and sensations that precede falls.58

Continue to: The medical and surgical histories

The medical and surgical histories are key pieces of information. The history of smoking, alcohol habits, and substance use is relevant.

A robust medication history is essential to evaluate a patient’s risk of falling. Polypharmacy—typically, defined as taking 4 or more medications—has been repeatedly associated with a heightened risk of falls.53,59-61 Moreover, a dose-dependent association between polypharmacy and hospitalization following falls has been identified, and demonstrates that taking 10 or more medications greatly increases the risk of hospitalization.59 Studies of polypharmacy cement the importance of inquiring about medication use when assessing imbalance, particularly in older patients.

Physical examination

A focused and detailed physical examination provides insight into systems that should be investigated:

- Obtain vital signs, including orthostatic vitals to test for orthostatic hypotension62; keep in mind that symptoms of orthostatic dizziness can occur without orthostatic hypotension.

- Examine gait, which can distinguish between causes of imbalance (TABLE 2).21,40,63-70

- Perform a cardiac examination.

- Assess visual acuity and visual fields; test for nystagmus and identify any optic-nerve and retinal abnormalities.

- Evaluate lower-limb sensation, proprioception, and motor function.

- Evaluate suspected vestibular dysfunction, including dysfunction with positional testing (the Dix-Hallpike maneuver71). The patient is taken from sitting to supine while the head is rotated 45° to the tested side by the examiner. As the patient moves into a supine position, the neck is extended 30° off the table and held for at least 30 seconds. The maneuver is positive if torsional nystagmus is noted while the head is held rotated during neck extension. The maneuver is negative if the patient reports dizziness, vertigo, unsteadiness, or “pressure in the head.” Torsional nystagmus must be present to confirm a diagnosis of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo.

- If you suspect a central nervous system cause of imbalance, assess the cranial nerves, coordination, strength, and, of course, balance.

CASE

Mr. J’s physical examination showed normal vital signs without significant postural changes in blood pressure. Gait analysis revealed a slowed gait, with reduced range of motion in both knees over the entire gait cycle. Audiometry revealed symmetric moderate sensorineural hearing loss characteristic of presbycusis.

Diagnostic investigations

Consider focused investigations into imbalance based on the history and physical examination. We discourage overly broad testing and imaging; in primary care, cost and limited access to technology can bar robust investigations into causes of imbalance. However, identification of acute pathologies should prompt immediate referral to the emergency department. Furthermore, specific symptoms (TABLE 17-56) should prompt referral to specialists for assessment.

Continue to: In the emergency department...

In the emergency department and academic hospitals, key investigations can identify causes of imbalance:

- Electrocardiography and Holter monitoring test for cardiac arrhythmias.

- Echocardiography identifies structural abnormalities.

- Radiography and computed tomography are useful for detecting musculoskeletal abnormalities.

- Bone densitometry can identify osteoporosis.

- Head and spinal cord magnetic resonance imaging can be used to identify lesions of the central nervous system.

- Computed tomographic angiography of the head and neck is useful for identifying stroke, cerebral atrophy, and stenotic lesions of the carotid and vertebral arteries.

- Nerve conduction studies and levels of serum vitamin B12, hemoglobin A1C, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and random cortisol can uncover causes of peripheral neuropathy.

- Bedside cognitive screening tests can be used to measure cognitive decline.72

- Suspicion of vestibular disease requires audiometry and vestibular testing, including videonystagmography, head impulse testing, and vestibular evoked myogenic potentials.

In many cases of imbalance, no specific underlying correctable cause is discovered.

Management of imbalance

Pharmacotherapy

Targeted pharmacotherapy can be utilized in select clinical scenarios:

- Medical treatment of peripheral neuropathy should target the underlying condition.

- Cognitive behavioral therapy and antidepressants are useful for treating anxiety and depressive disorders.73

- Musculoskeletal pain can be managed with acetaminophen and topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), using a short course of an oral NSAID when needed.74

- Cardiovascular disease management might include any of several classes of pharmacotherapy, including antiplatelet and lipid-lowering medications, antiarrhythmic drugs, and antihypertensive agents.

- Acute episodes of vertigo due to vestibular neuritis or labyrinthitis can be managed with an antiemetic.46

Surgical treatment

Surgery is infrequently considered for patients with imbalance. Examples of indications include microsurgical resection of vestibular schwannoma, resection of central nervous system tumors, lens replacement surgery for cataract, surgical management of severe spinal fracture, and hip or knee arthroplasty in select patients.

Tools for assessing the risk of falls

Scoring systems called falls risk assessment tools, or FRAT, have been developed to gauge a patient’s risk of falling. The various FRATs differ in specificity and sensitivity for predicting the risk of falls, and are typically designed for specific clinical environments, such as hospital inpatient care or long-term care facilities. Specifically, FRATs attempt to classify risk using sets of risk factors known to be associated with falls.

Continue to: Research abounds into...

Research abounds into the validity of commonly used FRATs across institutions, patient populations, and clinical environments:

The Johns Hopkins FRATa determines risk using metrics such as age, fall history, incontinence, cognition, mobility, and medications75; it is predominantly used for assessment in hospital inpatient units. This tool has been validated repeatedly.76,77

Peninsula Health FRATb stratifies patients in subacute and residential aged-care settings, based on risk factors that include recent falls, medications, psychological status, and cognition.78

FRAT-upc is a web-based tool that generates falls risk using risk factors that users input. This tool has been studied in the context of patients older than 65 years living in the community.79

Although FRATs are reasonably useful for predicting falls, their utility varies by patient population and clinical context. Moreover, it has been suggested that FRATs neglect environmental and personal factors when assessing risk by focusing primarily on bodily factors.80 Implementing a FRAT requires extensive consideration of the target population and should be accompanied by clinical judgment that is grounded in an individual patient’s circumstances.81

Continue to: Preventing falls in primary care

Preventing falls in primary care

An approach to preventing falls includes the development of individualized programs that account for frailty, a syndrome of physiologic decline associated with aging. Because frailty leads to diminished balance and mobility, a patient’s frailty index—determined using the 5 frailty phenotype criteria (exhaustion, weight loss, low physical activity, weakness, slowness)82 or the Canadian Study of Health and Aging Clinical Frailty Scale83—is a useful tool for predicting falls risk and readmission for falls following trauma-related injury. Prevention of falls in communities is critical for reducing mortality and allowing older people to maintain their independence and quality of life.

Exercise. In some areas, exercise and falls prevention programs are accessible to seniors.84 Community exercise programs that focus on balance retraining and muscle strengthening can reduce the risk of falls.73,85 The Choosing Wisely initiative of the ABIM [American Board of Internal Medicine] Foundation recommends that exercise programs be designed around an accurate functional baseline of the patient to avoid underdosed strength training.54

Multifactorial risk assessment in high-risk patients can reduce the rate of falls. Such an assessment includes examination of orthostatic blood pressure, vision and hearing, bone health, gait, activities of daily living, cognition, and environmental hazards, and enables provision of necessary interventions.73,86 Hearing amplification, specifically, correlates with enhanced postural control, slowed cognitive decline, and a reduced likelihood of falls.87-93 The mechanism behind improved balance performance might be reduced cognitive load through supporting a patient’s listening needs.88-90

Pharmacotherapy. Optimizing medications and performing a complete medication review before prescribing new medications is highly recommended to avoid unnecessary polypharmacy7,8,18,53-56 (TABLE 17-56).

Management of comorbidities associated with a higher risk of falls, including arthritis, cancer, stroke, diabetes, depression, kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cognitive impairment, hypertension, and atrial fibrillation, is essential.94-96

Continue to: Home safety interventions

Home safety interventions, through occupational therapy, are important. These include removing unsafe mats and step-overs and installing nonslip strips on stairs, double-sided tape under mats, and handrails.73-97

Screening for risk of falls. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that (1) all patients older than 65 years and (2) any patient presenting with an acute fall undergo screening for their risk of falls.98 When a patient is identified as at risk of falling, you can, when appropriate, assess modifiable risk factors and facilitate interventions.98 This strategy is supported by a 2018 statement from the US Preventive Services Task Force99 that recommends identifying high-risk patients who have:

- a history of falling

- a balance disturbance that causes a deficit of mobility or function

- poor performance on clinical tests, such as the 3-meter Timed Up and Go (TUG) assessment (www.cdc.gov/steadi/pdf/TUG_test-print.pdf).

An increased risk of falls should prompt you to refer the patient to community programs and physiotherapy in accordance with the individual’s personal goals99; a balance and vestibular physiotherapist is ideally positioned to accurately assess and manage patients at risk of falls. Specifically, the Task Force identified exercise programs and multifactorial interventions as being beneficial in preventing falls in high-risk older people.99

Balance assessment and rehabilitation in specialty centers

An individualized rehabilitation program aims to restore safe mobility by testing and addressing specific balance deficits, improving functional balance, and increasing balance confidence. Collaboration with colleagues from physiotherapy and occupational therapy aids in tailoring individualized programs.

Many tests are available to assess balance, determine the risk of falls, and guide rehabilitation:

- The timed 10-meter walk testd and the TUG test are simple assessments that measure functional mobility; both have normalized values for the risk of falls. A TUG time of ≥ 12 seconds suggests a high risk of falls.

- The 30-second chair stande evaluates functional lower-extremity strength in older patients. The test can indicate if lower-extremity strength is contributing to a patient’s imbalance.

- The modified clinical test of sensory interaction in balancef is a static balance test that measures the integrity of sensory inputs. The test can suggest if 1 or more sensory systems are compromised.

- The mini balance evaluation systems testg is similar: It can differentiate balance deficits by underlying system and allows individualization of a rehabilitation program.

- The functional gait assessmenth is a modification of the dynamic gait index that assesses postural stability during everyday dynamic activities, including tasks such as walking with head turns and pivots.

- The Berg Balance Scalei continues to be used extensively to assess balance.

Continue to: The mini balance evaluation systems test...

The mini balance evaluation systems test, functional gait index, and Berg Balance Scale all have normative age-graded values to predict fall risk.

CASE

Mr. J was referred for balance assessment and to a rehabilitation program. He underwent balance physiotherapy, including multifactorial balance assessment, joined a community exercise program, was fitted with hearing aids, and had his home environment optimized by an occupational therapist. (See examples of “home safety interventions” under “Preventing falls in primary care.”)

3 months later. Mr. J says he feels stronger on his feet. His knee pain has eased, and he is more confident walking around his home. He continues to engage in exercise programs and is comfortable running errands with his spouse.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jason A. Beyea, MD, PhD, FRCSC, Division of OtolaryngologyHead and Neck Surgery, Queen’s University, 144 Brock Street, Kingston, Ontario, Canada, K7L 5G2; [email protected]

a www.hopkinsmedicine.org/institute_nursing/models_tools/jhfrat_acute%20care%20original_6_22_17.pdf

c www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4376110/figure/figure14/?report=objectonly

e www.cdc.gov/steadi/pdf/STEADI-Assessment-30Sec-508.pdf

f www.mdapp.co/mctsib-modified-clinical-test-of-sensory-interaction-in-balance-calculator-404/

g www.sralab.org/sites/default/files/2017-07/MiniBEST_revised_final_3_8_13.pdf

CASE Mr. J, a 75-year-old man, presents to your family practice reporting that he feels increasingly unsteady and slow while walking. He fell twice last year, without resulting injury. He now worries about tripping while walking around the house and relies on his spouse to run errands.

Clearly, Mr. J is experiencing a problem with balance. What management approach should you undertake to prevent him from falling?

Balance disorders are common in older people and drastically hinder quality of life.1-4 Patients often describe imbalance as vague symptoms: dizziness, unsteadiness, faintness, spinning sensations.5,6 Importantly, balance disorders disrupt normal gait and contribute to falls that are a major cause of disability and morbidity in older people. Almost 30% of people older than 65 years report 1 or more falls annually.7 Factors that increase the risk of falls include impaired mobility, previously reported falls, reduced psychological functioning, chronic medical conditions, and polypharmacy.7,8

The cause of any single case of imbalance is often multifactorial, resulting from dysfunction of multiple body systems (TABLE 17-56); in our clinical experience, most patients with imbalance and who are at risk of falls do not have a detectable deficit of the vestibular system. These alterations in function arise in 3 key systems—vision, proprioception, and vestibular function—which signal to, and are incorporated by, the cerebellum to mediate balance. Cognitive and neurologic decline are also factors in imbalance.

Considering that 20% of falls result in serious injury in older populations, it is important to identify balance disorders and implement preventive strategies to mitigate harmful consequences of falls on patients’ health and independence.7,57 In this article, we answer the question that the case presentation raises about the proper management approach to imbalance in family practice, including assessment of risk and rehabilitation strategies to reduce the risk of falls. Our insights and recommendations are based on our clinical experience and a review of the medical literature from the past 40 years.

CASE Mr. J has a history of hypertension, age-related hearing loss, and osteoarthritis of the knees; he has not had surgery for the arthritis. His medications are antihypertensives and extra-strength acetaminophen for knee pain.

Making the diagnosis of a balance disorder

History

A thorough clinical history, often including a collateral history from caregivers, narrows the differential diagnosis. Information regarding onset, duration, timing, character, and previous episodes of imbalance is essential. Symptoms of imbalance are often challenging for the patient to describe: They might use terms such as vertigo or dizziness, when, in fact, on further questioning, they are describing balance difficulties. Inquiry into (1) their use of assistive walking devices and (2) development or exacerbation of neurologic, musculoskeletal, auditory, visual, and mood symptoms is necessary. Note the current level of their mobility, episodes of pain or fatigue, previous falls and associated injuries, fear of falling, balance confidence, and sensations that precede falls.58

Continue to: The medical and surgical histories

The medical and surgical histories are key pieces of information. The history of smoking, alcohol habits, and substance use is relevant.

A robust medication history is essential to evaluate a patient’s risk of falling. Polypharmacy—typically, defined as taking 4 or more medications—has been repeatedly associated with a heightened risk of falls.53,59-61 Moreover, a dose-dependent association between polypharmacy and hospitalization following falls has been identified, and demonstrates that taking 10 or more medications greatly increases the risk of hospitalization.59 Studies of polypharmacy cement the importance of inquiring about medication use when assessing imbalance, particularly in older patients.

Physical examination

A focused and detailed physical examination provides insight into systems that should be investigated:

- Obtain vital signs, including orthostatic vitals to test for orthostatic hypotension62; keep in mind that symptoms of orthostatic dizziness can occur without orthostatic hypotension.

- Examine gait, which can distinguish between causes of imbalance (TABLE 2).21,40,63-70

- Perform a cardiac examination.

- Assess visual acuity and visual fields; test for nystagmus and identify any optic-nerve and retinal abnormalities.

- Evaluate lower-limb sensation, proprioception, and motor function.

- Evaluate suspected vestibular dysfunction, including dysfunction with positional testing (the Dix-Hallpike maneuver71). The patient is taken from sitting to supine while the head is rotated 45° to the tested side by the examiner. As the patient moves into a supine position, the neck is extended 30° off the table and held for at least 30 seconds. The maneuver is positive if torsional nystagmus is noted while the head is held rotated during neck extension. The maneuver is negative if the patient reports dizziness, vertigo, unsteadiness, or “pressure in the head.” Torsional nystagmus must be present to confirm a diagnosis of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo.

- If you suspect a central nervous system cause of imbalance, assess the cranial nerves, coordination, strength, and, of course, balance.

CASE

Mr. J’s physical examination showed normal vital signs without significant postural changes in blood pressure. Gait analysis revealed a slowed gait, with reduced range of motion in both knees over the entire gait cycle. Audiometry revealed symmetric moderate sensorineural hearing loss characteristic of presbycusis.

Diagnostic investigations

Consider focused investigations into imbalance based on the history and physical examination. We discourage overly broad testing and imaging; in primary care, cost and limited access to technology can bar robust investigations into causes of imbalance. However, identification of acute pathologies should prompt immediate referral to the emergency department. Furthermore, specific symptoms (TABLE 17-56) should prompt referral to specialists for assessment.

Continue to: In the emergency department...

In the emergency department and academic hospitals, key investigations can identify causes of imbalance:

- Electrocardiography and Holter monitoring test for cardiac arrhythmias.

- Echocardiography identifies structural abnormalities.

- Radiography and computed tomography are useful for detecting musculoskeletal abnormalities.

- Bone densitometry can identify osteoporosis.

- Head and spinal cord magnetic resonance imaging can be used to identify lesions of the central nervous system.

- Computed tomographic angiography of the head and neck is useful for identifying stroke, cerebral atrophy, and stenotic lesions of the carotid and vertebral arteries.

- Nerve conduction studies and levels of serum vitamin B12, hemoglobin A1C, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and random cortisol can uncover causes of peripheral neuropathy.

- Bedside cognitive screening tests can be used to measure cognitive decline.72

- Suspicion of vestibular disease requires audiometry and vestibular testing, including videonystagmography, head impulse testing, and vestibular evoked myogenic potentials.

In many cases of imbalance, no specific underlying correctable cause is discovered.

Management of imbalance

Pharmacotherapy

Targeted pharmacotherapy can be utilized in select clinical scenarios:

- Medical treatment of peripheral neuropathy should target the underlying condition.

- Cognitive behavioral therapy and antidepressants are useful for treating anxiety and depressive disorders.73

- Musculoskeletal pain can be managed with acetaminophen and topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), using a short course of an oral NSAID when needed.74

- Cardiovascular disease management might include any of several classes of pharmacotherapy, including antiplatelet and lipid-lowering medications, antiarrhythmic drugs, and antihypertensive agents.

- Acute episodes of vertigo due to vestibular neuritis or labyrinthitis can be managed with an antiemetic.46

Surgical treatment

Surgery is infrequently considered for patients with imbalance. Examples of indications include microsurgical resection of vestibular schwannoma, resection of central nervous system tumors, lens replacement surgery for cataract, surgical management of severe spinal fracture, and hip or knee arthroplasty in select patients.

Tools for assessing the risk of falls

Scoring systems called falls risk assessment tools, or FRAT, have been developed to gauge a patient’s risk of falling. The various FRATs differ in specificity and sensitivity for predicting the risk of falls, and are typically designed for specific clinical environments, such as hospital inpatient care or long-term care facilities. Specifically, FRATs attempt to classify risk using sets of risk factors known to be associated with falls.

Continue to: Research abounds into...

Research abounds into the validity of commonly used FRATs across institutions, patient populations, and clinical environments:

The Johns Hopkins FRATa determines risk using metrics such as age, fall history, incontinence, cognition, mobility, and medications75; it is predominantly used for assessment in hospital inpatient units. This tool has been validated repeatedly.76,77

Peninsula Health FRATb stratifies patients in subacute and residential aged-care settings, based on risk factors that include recent falls, medications, psychological status, and cognition.78

FRAT-upc is a web-based tool that generates falls risk using risk factors that users input. This tool has been studied in the context of patients older than 65 years living in the community.79

Although FRATs are reasonably useful for predicting falls, their utility varies by patient population and clinical context. Moreover, it has been suggested that FRATs neglect environmental and personal factors when assessing risk by focusing primarily on bodily factors.80 Implementing a FRAT requires extensive consideration of the target population and should be accompanied by clinical judgment that is grounded in an individual patient’s circumstances.81

Continue to: Preventing falls in primary care

Preventing falls in primary care

An approach to preventing falls includes the development of individualized programs that account for frailty, a syndrome of physiologic decline associated with aging. Because frailty leads to diminished balance and mobility, a patient’s frailty index—determined using the 5 frailty phenotype criteria (exhaustion, weight loss, low physical activity, weakness, slowness)82 or the Canadian Study of Health and Aging Clinical Frailty Scale83—is a useful tool for predicting falls risk and readmission for falls following trauma-related injury. Prevention of falls in communities is critical for reducing mortality and allowing older people to maintain their independence and quality of life.

Exercise. In some areas, exercise and falls prevention programs are accessible to seniors.84 Community exercise programs that focus on balance retraining and muscle strengthening can reduce the risk of falls.73,85 The Choosing Wisely initiative of the ABIM [American Board of Internal Medicine] Foundation recommends that exercise programs be designed around an accurate functional baseline of the patient to avoid underdosed strength training.54

Multifactorial risk assessment in high-risk patients can reduce the rate of falls. Such an assessment includes examination of orthostatic blood pressure, vision and hearing, bone health, gait, activities of daily living, cognition, and environmental hazards, and enables provision of necessary interventions.73,86 Hearing amplification, specifically, correlates with enhanced postural control, slowed cognitive decline, and a reduced likelihood of falls.87-93 The mechanism behind improved balance performance might be reduced cognitive load through supporting a patient’s listening needs.88-90

Pharmacotherapy. Optimizing medications and performing a complete medication review before prescribing new medications is highly recommended to avoid unnecessary polypharmacy7,8,18,53-56 (TABLE 17-56).

Management of comorbidities associated with a higher risk of falls, including arthritis, cancer, stroke, diabetes, depression, kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cognitive impairment, hypertension, and atrial fibrillation, is essential.94-96

Continue to: Home safety interventions

Home safety interventions, through occupational therapy, are important. These include removing unsafe mats and step-overs and installing nonslip strips on stairs, double-sided tape under mats, and handrails.73-97

Screening for risk of falls. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that (1) all patients older than 65 years and (2) any patient presenting with an acute fall undergo screening for their risk of falls.98 When a patient is identified as at risk of falling, you can, when appropriate, assess modifiable risk factors and facilitate interventions.98 This strategy is supported by a 2018 statement from the US Preventive Services Task Force99 that recommends identifying high-risk patients who have:

- a history of falling

- a balance disturbance that causes a deficit of mobility or function

- poor performance on clinical tests, such as the 3-meter Timed Up and Go (TUG) assessment (www.cdc.gov/steadi/pdf/TUG_test-print.pdf).

An increased risk of falls should prompt you to refer the patient to community programs and physiotherapy in accordance with the individual’s personal goals99; a balance and vestibular physiotherapist is ideally positioned to accurately assess and manage patients at risk of falls. Specifically, the Task Force identified exercise programs and multifactorial interventions as being beneficial in preventing falls in high-risk older people.99

Balance assessment and rehabilitation in specialty centers

An individualized rehabilitation program aims to restore safe mobility by testing and addressing specific balance deficits, improving functional balance, and increasing balance confidence. Collaboration with colleagues from physiotherapy and occupational therapy aids in tailoring individualized programs.

Many tests are available to assess balance, determine the risk of falls, and guide rehabilitation:

- The timed 10-meter walk testd and the TUG test are simple assessments that measure functional mobility; both have normalized values for the risk of falls. A TUG time of ≥ 12 seconds suggests a high risk of falls.

- The 30-second chair stande evaluates functional lower-extremity strength in older patients. The test can indicate if lower-extremity strength is contributing to a patient’s imbalance.

- The modified clinical test of sensory interaction in balancef is a static balance test that measures the integrity of sensory inputs. The test can suggest if 1 or more sensory systems are compromised.

- The mini balance evaluation systems testg is similar: It can differentiate balance deficits by underlying system and allows individualization of a rehabilitation program.

- The functional gait assessmenth is a modification of the dynamic gait index that assesses postural stability during everyday dynamic activities, including tasks such as walking with head turns and pivots.

- The Berg Balance Scalei continues to be used extensively to assess balance.

Continue to: The mini balance evaluation systems test...

The mini balance evaluation systems test, functional gait index, and Berg Balance Scale all have normative age-graded values to predict fall risk.

CASE

Mr. J was referred for balance assessment and to a rehabilitation program. He underwent balance physiotherapy, including multifactorial balance assessment, joined a community exercise program, was fitted with hearing aids, and had his home environment optimized by an occupational therapist. (See examples of “home safety interventions” under “Preventing falls in primary care.”)

3 months later. Mr. J says he feels stronger on his feet. His knee pain has eased, and he is more confident walking around his home. He continues to engage in exercise programs and is comfortable running errands with his spouse.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jason A. Beyea, MD, PhD, FRCSC, Division of OtolaryngologyHead and Neck Surgery, Queen’s University, 144 Brock Street, Kingston, Ontario, Canada, K7L 5G2; [email protected]

a www.hopkinsmedicine.org/institute_nursing/models_tools/jhfrat_acute%20care%20original_6_22_17.pdf

c www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4376110/figure/figure14/?report=objectonly

e www.cdc.gov/steadi/pdf/STEADI-Assessment-30Sec-508.pdf

f www.mdapp.co/mctsib-modified-clinical-test-of-sensory-interaction-in-balance-calculator-404/

g www.sralab.org/sites/default/files/2017-07/MiniBEST_revised_final_3_8_13.pdf

1. Larocca NG. Impact of walking impairment in multiple sclerosis: perspectives of patients and care partners. Patient. 2011;4:189-201. doi: 10.2165/11591150-000000000-00000

2. TB, ZF, ES, et al. The relationship of balance disorders with falling, the effect of health problems, and social life on postural balance in the elderly living in a district in Turkey. Geriatrics (Basel). 2019;4:37. doi: 10.3390/geriatrics4020037

3. R, Sixt E, Landahl S, et al. Prevalence of dizziness and vertigo in an urban elderly population. J Vestib Res. 2004;14:47-52.

4. Sturnieks DL, St George R, Lord SR. Balance disorders in the elderly. Neurophysiol Clin. 2008;38:467-478. doi: 10.1016/j.neucli.2008.09.001

5. Boult C, Murphy J, Sloane P, et al. The relation of dizziness to functional decline. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39:858-861. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb04451.x

6. Lin HW, Bhattacharyya N. Balance disorders in the elderly: epidemiology and functional impact. Laryngoscope. 2012;122:1858-1861. doi: 10.1002/lary.23376

7. Jia H, Lubetkin EI, DeMichele K, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and burden of disease for falls and balance or walking problems among older adults in the U.S. Prev Med. 2019;126:105737. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.05.025

8. Al-Momani M, Al-Momani F, Alghadir AH, et al. Factors related to gait and balance deficits in older adults. Clin Interv Aging. 2016;11:1043-1049. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S112282

9. Agrawal Y, Ward BK, Minor LB. Vestibular dysfunction: prevalence, impact and need for targeted treatment. J Vestib Res. 2013;23:113-117. doi: 10.3233/VES-130498

10. Altinsoy B, Erboy F, Tanriverdi H, et al. Syncope as a presentation of acute pulmonary embolism. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2016;12:1023-1028. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S105722

11. Belvederi Murri M, Triolo F, Coni A, et al. Instrumental assessment of balance and gait in depression: a systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2020;284:112687. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112687

12. Bhattacharyya N, Gubbels SP, Schwartz SR, et al. Clinical practice guideline: benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (update). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;156(suppl 3):S1-S47. doi: 10.1177/0194599816689667

13. S, Schwarm S, Grevenrath P, et al. Prevalence, aetiologies and prognosis of the symptom dizziness in primary care - a systematic review. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19:33. doi: 10.1186/s12875-017-0695-0

14. Brouwer MC, Tunkel AR, van de Beek D. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and antimicrobial treatment of acute bacterial meningitis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:467-492. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00070-09

15. Chad DA. Lumbar spinal stenosis. Neurol Clin. 2007;25:407-418. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2007.01.003

16. Conrad BP, Shokat MS, Abbasi AZ, et al. Associations of self-report measures with gait, range of motion and proprioception in patients with lumbar spinal stenosis. Gait Posture. 2013;38:987-992. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2013.05.010

17. de Luna RA, Mihailovic A, Nguyen AM, et al. The association of glaucomatous visual field loss and balance. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2017;6:8. doi: 10.1167/tvst.6.3.8

18. DiSogra RM. Common aminoglycosides and platinum-based ototoxic drugs: cochlear/vestibular side effects and incidence. Semin Hear. 2019;40:104-107. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1684040

19. Ebersbach G, Moreau C, Gandor F, et al. Clinical syndromes: parkinsonian gait. Mov Disord. 2013;28:1552-1559. doi: 10.1002/mds.25675

20. Evans WJ. Skeletal muscle loss: cachexia, sarcopenia, and inactivity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:1123S-1127S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.28608A

21. Filli L, Sutter T, Easthope CS, et al. Profiling walking dysfunction in multiple sclerosis: characterisation, classification and progression over time. Sci Rep. 2018;8:4984. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-22676-0

22. Fritz NE, Kegelmeyer DA, Kloos AD, et al. Motor performance differentiates individuals with Lewy body dementia, Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease. Gait Posture. 2016;50:1-7. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2016.08.009

23. Furman JM, Jacob RG. A clinical taxonomy of dizziness and anxiety in the otoneurological setting. J Anxiety Disord. 2001;15:9-26. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(00)00040-2

24. Furman JM, Marcus DA, Balaban CD. Vestibular migraine: clinical aspects and pathophysiology. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:706-715. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70107-8

25. Gerson LW, Jarjoura D, McCord G. Risk of imbalance in elderly people with impaired hearing or vision. Age Ageing. 1989;18:31-34. doi: 10.1093/ageing/18.1.31

26. Goudakos JK, Markou KD, Franco-Vidal V, et al. Corticosteroids in the treatment of vestibular neuritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Otol Neurotol. 2010;31:183-189. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3181ca843d

27. Green AD, CS, Bastian L, et al. Does this woman have osteoporosis? JAMA. 2004;292:2890-2900. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.23.2890

28. Hallemans A, Ortibus E, Meire F, et al. Low vision affects dynamic stability of gait. Gait Posture. 2010;32:547-551. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2010.07.018

29. Handelsman JA. Vestibulotoxicity: strategies for clinical diagnosis and rehabilitation. Int J Audiol. 2018;57(suppl 4):S99-S107. doi: 10.1080/14992027.2018.1468092

30. Head VA, Wakerley BR. Guillain-Barré syndrome in general practice: clinical features suggestive of early diagnosis. Br J Gen Pract. 2016;66:218-219. doi: 10.3399/bjgp16X684733

31. Helbostad JL, Vereijken B, Hesseberg K, et al. Altered vision destabilizes gait in older persons. Gait Posture. 2009;30:233-238. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2009.05.004

32. Hsu W-L, Chen C-Y, Tsauo J-Y, et al. Balance control in elderly people with osteoporosis. J Formos Med Assoc. 2014;113:334-339. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2014.02.006

33. Kim H-S, Yun DH, Yoo SD, et al. Balance control and knee osteoarthritis severity. Ann Rehabil Med. 2011;35:701-709. doi: 10.5535/arm.2011.35.5.701

34. Li L, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, et al. Hearing loss and gait speed among older adults in the United States. Gait Posture. 2013;38:25-29.

35. McKeith IG, Boeve BF, Dickson DW, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: fourth consensus report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2017;89:88-100. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004058

36. Milner KA, Funk M, Richards S, et al. Gender differences in symptom presentation associated with coronary heart disease. Am J Cardiol. 1999;84:396-399. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)00322-7

37. Paillard T, F, Bru N, et al. The impact of time of day on the gait and balance control of Alzheimer’s patients. Chronobiol Int. 2016;33:161-168. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2015.1124885

38. Paldor I, Chen AS, Kaye AH. Growth rate of vestibular schwannoma. J Clin Neurosci. 2016;32:1-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2016.05.003

39. Picorelli AMA, Hatton AL, Gane EM, et al. Balance performance in older adults with hip osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Gait Posture. 2018;65:89-99. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2018.07.001

40. Raccagni C, Nonnekes J, Bloem BR, et al. Gait and postural disorders in parkinsonism: a clinical approach. J Neurol. 2020;267:3169-3176. doi: 10.1007/s00415-019-09382-1

41. Shanmugarajah PD, Hoggard N, Currie S, et al. Alcohol-related cerebellar degeneration: not all down to toxicity? Cerebellum Ataxias. 2016;3:17. doi: 10.1186/s40673-016-0055-1

42. Shih RY, Smirniotopoulos JG. Posterior fossa tumors in adult patients. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2016;26:493-510. doi: 10.1016/j.nic.2016.06.003

43. Smith EE. Clinical presentations and epidemiology of vascular dementia. Clin Sci (Lond). 2017;131:1059-1068. doi: 10.1042/CS20160607

44. Streur M, Ratcliffe SJ, Ball J, et al. Symptom clusters in adults with chronic atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2017;32:296-303. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0000000000000344

45. Strupp M, M, JA. Peripheral vestibular disorders: an update. Curr Opin Neurol. 2019;32:165-173. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000649

46. Thompson TL, Amedee R. Vertigo: a review of common peripheral and central vestibular disorders. Ochsner J. 2009;9:20-26.

47. Timar B, Timar R, L, et al. The impact of diabetic neuropathy on balance and on the risk of falls in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0154654. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154654

48. Walls R, Hockberger R, Gausche-Hill M. Peripheral nerve disorders. In: Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice. 9th ed. Elsevier, Inc; 2018:1307-1320.

49. Watson JC, Dyck PJB. Peripheral neuropathy: a practical approach to diagnosis and symptom management. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90:940-951. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.05.004

50. Whitfield KC, Bourassa MW, Adamolekun B, et al. Thiamine deficiency disorders: diagnosis, prevalence, and a roadmap for global control programs. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2018;1430:3-43. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13919