User login

A Crisis in Scope: Recruitment and Retention Challenges Reported by VA Gastroenterology Section Chiefs

Veterans have a high burden of digestive diseases, and gastroenterologists are needed for the diagnosis and management of these conditions.1-4 According to the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Workforce Management and Consulting (WMC) office, the physician specialties with the greatest shortages are psychiatry, primary care, and gastroenterology.5 The VHA estimates it must hire 70 new gastroenterologists annually between fiscal years 2023 and 2027 to provide timely digestive care.5

Filling these positions will be increasingly difficult as competition for gastroenterologists is fierce. A recent Merritt Hawkins review states, “Gastroenterologists were the most in-demand type of provider during the 2022 review period.”6 In 2022, the median annual salary for US gastroenterologists was reported to be $561,375.7 Currently, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has an aggregate annual pay limit of $400,000 for all federal employees and cannot compete based on salary alone.

Retention of existing VA gastroenterologists also is challenging. The WMC has reported that 21.6% of VA gastroenterologists are eligible to retire, and in 2021, 8.2% left the VA to retire or seek non-VA positions.5 While not specific to the VA, a survey of practicing gastroenterologists conducted by the American College of Gastroenterology found a 49% burnout rate among respondents.8 Factors contributing to burnout at all career stages included administrative nonclinical work and a lack of clinical support staff.8 Burnout is also linked with higher rates of medical errors, interpersonal conflicts, and patient dissatisfaction. Burnout is more common among those with an innate strong sense of purpose and responsibility for their patients, characteristics we have observed in our VA colleagues.9

As members of the Section Chief Subcommittee of the VA Gastroenterology Field Advisory Board (GI FAB), we are passionate about providing outstanding gastroenterology care to US veterans, and we are alarmed at the struggles we are observing with recruiting and retaining a qualified national gastroenterology physician workforce. As such, we set out to survey the VA gastroenterology section chief community to gain insights into recruitment and retention challenges they have faced and identify potential solutions to these problems.

Methods

The GI FAB Section Chief Subcommittee developed a survey on gastroenterologist recruitment and retention using Microsoft Forms (Appendix). A link to the survey, which included 11 questions about facility location, current vacancies, and free text responses on barriers to recruitment and retention and potential solutions, was sent via email to all gastroenterology section chiefs on the National Gastroenterology and Hepatology Program Office’s email list of section chiefs on January 31, 2023. A reminder to complete the survey was sent to all section chiefs on February 8, 2023. Survey responses were aggregated and analyzed by the authors using descriptive statistics.

Results

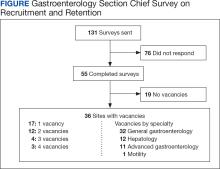

The VA gastroenterologist recruitment and retention survey was emailed to 131 gastroenterology section chiefs and completed by 55 respondents (42%) (Figure). Of the responding section chiefs, 36 (65%) reported gastroenterologist vacancies at their facilities. Seventeen respondents (47%) reported a single vacancy, 12 (33%) reported 2 vacancies, 4 (11%) reported 3 vacancies, and 3 (8%) reported 4 vacancies. Of the sites with reported vacancies, 32 (89%) reported a need for a general gastroenterologist, 12 (33%) reported a need for a hepatologist, 11 (31%) reported a need for an advanced endoscopist, 9 (25%) reported a need for a gastroenterologist with specialized expertise in inflammatory bowel diseases, and 1 (3%) reported a need for a gastrointestinal motility specialist.

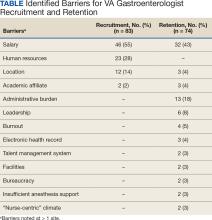

Numerous barriers to the recruitment and retention of gastroenterologists were reported. Given the large number of respondents that reported a unique barrier (ie, being the only respondents to report the barrier), a decision was made to include only barriers to recruitment and retention that were reported by at least 2 sites (Table). While there were some common themes, the reported barriers to retention differed from those to recruitment. The most reported barriers to recruitment were 46 respondents who noted salary, 23 reported human resources-related challenges, and 12 reported location. Respondents also noted various retention barriers, including 32 respondents who reported salary barriers; 13 reported administrative burden barriers, 6 reported medical center leadership, and 4 reported burnout.

Survey respondents provided multiple recommendations on how the VA can best support the recruitment and retention of gastroenterologists. The most frequent recommendations were to increase financial compensation by increasing the current aggregate salary cap to > $400,000, increasing the use of recruitment and retention incentives, and ensuring that gastroenterology is on the national Educational Debt Reduction Program (EDRP) list, which facilitates student loan repayment. It was recommended that a third-party company assist with hiring to overcome perceived issues with human resources. Additionally, there were multiple recommendations for improving administrative and clinical support. These included mandating how many support staff should be assigned to each gastroenterologist and providing best practice recommendations for support staff so that gastroenterologists can focus on physician-level work. Recommendations also included having a dedicated gastroenterology practice manager, nurse care coordinators, a colorectal cancer screening/surveillance coordinator, sufficient medical support assistants, and quality improvement personnel tracking ongoing professional practice evaluation data. Survey respondents also highlighted specific suggestions for recruiting recent graduates. These included offering a 4-day work week, as recent graduates place a premium on work-life balance, and ensuring gastroenterologists have individual offices. One respondent commented that gastroenterology fellows seeing VA gastroenterology attendings in cramped, shared offices, contrasted with private practice gastroenterologists in large private offices, may contribute to choosing private practice over joining the VA.

Discussion

Gastroenterology is currently listed by VHA WMC as 1 of the top 3 medical specialties in the VA with the most physician shortages.5 Working as a physician in the VA has long been recognized to have many benefits. First and foremost, many physicians are motivated by the VA mission to serve veterans, as this offers personal fulfillment and other intangible benefits. In addition, the VA can provide work-life balance, which is often not possible in fee-for-service settings, with patient panels and call volumes typically lower than in comparable private hospital settings. Moreover, VA physicians have outstanding teaching opportunities, as the VA is the largest supporter of medical education, with postgraduate trainees rotating through > 150 VA medical centers. Likewise, the VA offers a variety of student loan repayment programs (eg, the Specialty Education Loan Repayment Program and the EDRP). The VA offers research funding such as the Cooperative Studies Programs or program project funding, and rewards in parallel with the National Institute of Health (eg, career development awards, or merit review awards) and other grants. VA researchers have conducted many landmark studies that continue to shape the practice of gastroenterology and hepatology. From the earliest studies to demonstrate the effectiveness of screening colonoscopy, to the largest ongoing clinical trial in US history to assess the effectiveness of fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) vs screening colonoscopy.10-12 The VA has also led the field in the study of gastroesophageal reflux disease, hepatitis C treatment, and liver cancer screening.13-15 VA physicians also benefit from participation in the Federal Employee Retirement System, including its pension system.

These benefits apply to all medical specialties, making the VA a potentially appealing workplace for gastroenterologists. However, recent trends indicate that recruitment and retention of gastroenterologists is increasingly challenging, as the VA gastroenterology workforce grew by 5.0% in fiscal year (FY) 2020 and 1.8% in FY 2021. However, it was on track to end FY 2022 with a loss (-1.1%).5 It must be noted that this trend is not limited to the VA, and the National Center for Health Workforce Analysis predicts that gastroenterology will remain among the highest projected specialty shortages. Driven by increased demand for digestive health care services, more physicians nearing traditional retirement age, and substantially higher rates of burnout after the COVID-19 pandemic.16 All these factors are likely to result in an increasingly competitive market for gastroenterology, highlight the growing differences between VA and non-VA positions, and may augment the impact of differences for the individual gastroenterologist weighing employment options within and outside the VA.

The survey responses from VA gastroenterology section chiefs help identify potential impediments to the successful recruitment and retention in the specialty. Noncompetitive salary was the most significant barrier to the successful recruitment of gastroenterologists, identified by 46 of 55 respondents. According to a 2022 Medical Group Management Association report, the median annual salary for US gastroenterologists was $561,375.7 According to internal VA WMC data, the median 2022 VA gastroenterologist salary ranged between $287,976 and $346,435, depending on facility complexity level, excluding recruitment, retention, or relocation bonuses; performance pay; or cash awards. The current aggregate salary cap of $400,000 indicates that the VHA will likely be increasingly noncompetitive in the coming years unless novel pay authorizations are implemented.

Suboptimal human resources were the second most commonly cited impediment to recruiting gastroenterologists. Many section chiefs expressed frustration with the inefficient and slow administrative process of onboarding new gastroenterologists, which may take many months and not infrequently results in losing candidates to competing entities. While this issue is specific to recruitment, recurring and long-standing vacancies can increase work burdens, complicate logistics for remaining faculty, and may also negatively impact retention. One potential opportunity to improve VHA competitiveness is to streamline the administrative component of recruitment and optimize human resources support. The use of a third-party hiring company also should be considered.

Survey responses also indicated that administrative burden and insufficient support staff were significant retention challenges. Several respondents described a lack of efficient endoscopy workflow and delegation of simple administrative tasks to gastroenterologists as more likely in units without proper task distribution. Importantly, these shortcomings occur at the expense of workload-generating activities and career-enhancing opportunities.

While burnout rates among VA gastroenterologists have not been documented systematically, they likely correlate with workplace frustration and jeopardizegastroenterologist retention. Successful retention of gastroenterologists as highly trained medical professionals is more likely in workplaces that are vertically organized, efficient, and use physicians at the top of their skill level.

Conclusions

The VA offers the opportunity for a rewarding lifelong career in gastroenterology. The fulfillment of serving veterans, teaching future health care leaders, performing impactful research, and having job security is invaluable. Despite the tremendous benefits, this survey supports improving VA recruitment and retention strategies for the high-demand gastroenterology specialty. Improved salary parity is needed for workforce maintenance and recruitment, as is improved administrative and clinical support to maintain the high level of care our veterans deserve.

1. Shin A, Xu H, Imperiale TF. The prevalence, humanistic burden, and health care impact of irritable bowel syndrome among united states veterans. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;21(4):1061-1069.e1. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2022.08.005.

2. Kent KG. Prevalence of gastrointestinal disease in US military veterans under outpatient care at the veterans health administration. SAGE Open Med. 2021;9:20503121211049112. doi:10.1177/20503121211049112

3. Beste LA, Leipertz SL, Green PK, Dominitz JA, Ross D, Ioannou GN. Trends in burden of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma by underlying liver disease in US veterans, 2001-2013. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(6):1471-e18. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2015.07.056

4. Zullig LL, Sims KJ, McNeil R, et al. Cancer incidence among patients of the U.S. veterans affairs health care system: 2010 update. Mil Med. 2017;182(7):e1883-e1891. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-16-00371

5. VHA Physician Workforce Resources Blueprint. US Dept of Veterans Affairs. https://dvagov.sharepoint.com/sites/WMCPortal/WFP/Documents/Reports/VHA Physician Workforce Resources Blueprint FY 23-27.pdf [Source not verified]

6. AMN Healthcare. 2022 Review of Physician and Advanced Practitioner Recruiting Incentives. Accessed June 12, 2024. https://www1.amnhealthcare.com/l/123142/2022-07-13/q6ywxg/123142/1657737392vyuONaZZ/mha2022incentivesurgraphic.pdf

7. Medical Group Management Association. MGMA DataDive Provider Compensation Data. Accessed June 12, 2024. https://www.mgma.com/datadive/provider-compensation

8. Anderson JC, Bilal M, Burke CA, et al. Burnout among US gastroenterologists and fellows in training: identifying contributing factors and offering solutions. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2023;57(10):1063-1069. doi:10.1097/MCG.0000000000001781

9. Lacy BE, Chan JL. Physician burnout: the hidden health care crisis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16(3):311-317. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2017.06.043

10. Lieberman DA, Weiss DG, Bond JH, Ahnen DJ, Garewal H, Chejfec G. Use of colonoscopy to screen asymptomatic adults for colorectal cancer. Veterans affairs cooperative study group 380. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(3):162-168. doi:10.1056/NEJM200007203430301

11. Lieberman DA, Weiss DG; Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group 380. One-time screening for colorectal cancer with combined fecal occult-blood testing and examination of the distal colon. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(8):555-560. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa010328

12. Robertson DJ, Dominitz JA, Beed A, et al. Baseline features and reasons for nonparticipation in the colonoscopy versus fecal immunochemical test in reducing mortality from colorectal cancer (CONFIRM) study, a colorectal cancer screening trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(7):e2321730. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.21730

13. Spechler SJ, Hunter JG, Jones KM, et al. Randomized trial of medical versus surgical treatment for refractory heartburn. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(16):1513-1523. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1811424

14. Beste LA, Green PK, Berry K, Kogut MJ, Allison SK, Ioannou GN. Effectiveness of hepatitis C antiviral treatment in a USA cohort of veteran patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2017;67(1):32-39. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2017.02.027

15. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans affairs cooperative studies program (CSP). CSP #2023. Updated July 2022. Accessed June 12, 2024. https://www.vacsp.research.va.gov/CSP_2023/CSP_2023.asp

16. US Health Resources & Services Administration. Workforce projections. Accessed June 12, 2024. https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-workforce/workforce-projections

Veterans have a high burden of digestive diseases, and gastroenterologists are needed for the diagnosis and management of these conditions.1-4 According to the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Workforce Management and Consulting (WMC) office, the physician specialties with the greatest shortages are psychiatry, primary care, and gastroenterology.5 The VHA estimates it must hire 70 new gastroenterologists annually between fiscal years 2023 and 2027 to provide timely digestive care.5

Filling these positions will be increasingly difficult as competition for gastroenterologists is fierce. A recent Merritt Hawkins review states, “Gastroenterologists were the most in-demand type of provider during the 2022 review period.”6 In 2022, the median annual salary for US gastroenterologists was reported to be $561,375.7 Currently, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has an aggregate annual pay limit of $400,000 for all federal employees and cannot compete based on salary alone.

Retention of existing VA gastroenterologists also is challenging. The WMC has reported that 21.6% of VA gastroenterologists are eligible to retire, and in 2021, 8.2% left the VA to retire or seek non-VA positions.5 While not specific to the VA, a survey of practicing gastroenterologists conducted by the American College of Gastroenterology found a 49% burnout rate among respondents.8 Factors contributing to burnout at all career stages included administrative nonclinical work and a lack of clinical support staff.8 Burnout is also linked with higher rates of medical errors, interpersonal conflicts, and patient dissatisfaction. Burnout is more common among those with an innate strong sense of purpose and responsibility for their patients, characteristics we have observed in our VA colleagues.9

As members of the Section Chief Subcommittee of the VA Gastroenterology Field Advisory Board (GI FAB), we are passionate about providing outstanding gastroenterology care to US veterans, and we are alarmed at the struggles we are observing with recruiting and retaining a qualified national gastroenterology physician workforce. As such, we set out to survey the VA gastroenterology section chief community to gain insights into recruitment and retention challenges they have faced and identify potential solutions to these problems.

Methods

The GI FAB Section Chief Subcommittee developed a survey on gastroenterologist recruitment and retention using Microsoft Forms (Appendix). A link to the survey, which included 11 questions about facility location, current vacancies, and free text responses on barriers to recruitment and retention and potential solutions, was sent via email to all gastroenterology section chiefs on the National Gastroenterology and Hepatology Program Office’s email list of section chiefs on January 31, 2023. A reminder to complete the survey was sent to all section chiefs on February 8, 2023. Survey responses were aggregated and analyzed by the authors using descriptive statistics.

Results

The VA gastroenterologist recruitment and retention survey was emailed to 131 gastroenterology section chiefs and completed by 55 respondents (42%) (Figure). Of the responding section chiefs, 36 (65%) reported gastroenterologist vacancies at their facilities. Seventeen respondents (47%) reported a single vacancy, 12 (33%) reported 2 vacancies, 4 (11%) reported 3 vacancies, and 3 (8%) reported 4 vacancies. Of the sites with reported vacancies, 32 (89%) reported a need for a general gastroenterologist, 12 (33%) reported a need for a hepatologist, 11 (31%) reported a need for an advanced endoscopist, 9 (25%) reported a need for a gastroenterologist with specialized expertise in inflammatory bowel diseases, and 1 (3%) reported a need for a gastrointestinal motility specialist.

Numerous barriers to the recruitment and retention of gastroenterologists were reported. Given the large number of respondents that reported a unique barrier (ie, being the only respondents to report the barrier), a decision was made to include only barriers to recruitment and retention that were reported by at least 2 sites (Table). While there were some common themes, the reported barriers to retention differed from those to recruitment. The most reported barriers to recruitment were 46 respondents who noted salary, 23 reported human resources-related challenges, and 12 reported location. Respondents also noted various retention barriers, including 32 respondents who reported salary barriers; 13 reported administrative burden barriers, 6 reported medical center leadership, and 4 reported burnout.

Survey respondents provided multiple recommendations on how the VA can best support the recruitment and retention of gastroenterologists. The most frequent recommendations were to increase financial compensation by increasing the current aggregate salary cap to > $400,000, increasing the use of recruitment and retention incentives, and ensuring that gastroenterology is on the national Educational Debt Reduction Program (EDRP) list, which facilitates student loan repayment. It was recommended that a third-party company assist with hiring to overcome perceived issues with human resources. Additionally, there were multiple recommendations for improving administrative and clinical support. These included mandating how many support staff should be assigned to each gastroenterologist and providing best practice recommendations for support staff so that gastroenterologists can focus on physician-level work. Recommendations also included having a dedicated gastroenterology practice manager, nurse care coordinators, a colorectal cancer screening/surveillance coordinator, sufficient medical support assistants, and quality improvement personnel tracking ongoing professional practice evaluation data. Survey respondents also highlighted specific suggestions for recruiting recent graduates. These included offering a 4-day work week, as recent graduates place a premium on work-life balance, and ensuring gastroenterologists have individual offices. One respondent commented that gastroenterology fellows seeing VA gastroenterology attendings in cramped, shared offices, contrasted with private practice gastroenterologists in large private offices, may contribute to choosing private practice over joining the VA.

Discussion

Gastroenterology is currently listed by VHA WMC as 1 of the top 3 medical specialties in the VA with the most physician shortages.5 Working as a physician in the VA has long been recognized to have many benefits. First and foremost, many physicians are motivated by the VA mission to serve veterans, as this offers personal fulfillment and other intangible benefits. In addition, the VA can provide work-life balance, which is often not possible in fee-for-service settings, with patient panels and call volumes typically lower than in comparable private hospital settings. Moreover, VA physicians have outstanding teaching opportunities, as the VA is the largest supporter of medical education, with postgraduate trainees rotating through > 150 VA medical centers. Likewise, the VA offers a variety of student loan repayment programs (eg, the Specialty Education Loan Repayment Program and the EDRP). The VA offers research funding such as the Cooperative Studies Programs or program project funding, and rewards in parallel with the National Institute of Health (eg, career development awards, or merit review awards) and other grants. VA researchers have conducted many landmark studies that continue to shape the practice of gastroenterology and hepatology. From the earliest studies to demonstrate the effectiveness of screening colonoscopy, to the largest ongoing clinical trial in US history to assess the effectiveness of fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) vs screening colonoscopy.10-12 The VA has also led the field in the study of gastroesophageal reflux disease, hepatitis C treatment, and liver cancer screening.13-15 VA physicians also benefit from participation in the Federal Employee Retirement System, including its pension system.

These benefits apply to all medical specialties, making the VA a potentially appealing workplace for gastroenterologists. However, recent trends indicate that recruitment and retention of gastroenterologists is increasingly challenging, as the VA gastroenterology workforce grew by 5.0% in fiscal year (FY) 2020 and 1.8% in FY 2021. However, it was on track to end FY 2022 with a loss (-1.1%).5 It must be noted that this trend is not limited to the VA, and the National Center for Health Workforce Analysis predicts that gastroenterology will remain among the highest projected specialty shortages. Driven by increased demand for digestive health care services, more physicians nearing traditional retirement age, and substantially higher rates of burnout after the COVID-19 pandemic.16 All these factors are likely to result in an increasingly competitive market for gastroenterology, highlight the growing differences between VA and non-VA positions, and may augment the impact of differences for the individual gastroenterologist weighing employment options within and outside the VA.

The survey responses from VA gastroenterology section chiefs help identify potential impediments to the successful recruitment and retention in the specialty. Noncompetitive salary was the most significant barrier to the successful recruitment of gastroenterologists, identified by 46 of 55 respondents. According to a 2022 Medical Group Management Association report, the median annual salary for US gastroenterologists was $561,375.7 According to internal VA WMC data, the median 2022 VA gastroenterologist salary ranged between $287,976 and $346,435, depending on facility complexity level, excluding recruitment, retention, or relocation bonuses; performance pay; or cash awards. The current aggregate salary cap of $400,000 indicates that the VHA will likely be increasingly noncompetitive in the coming years unless novel pay authorizations are implemented.

Suboptimal human resources were the second most commonly cited impediment to recruiting gastroenterologists. Many section chiefs expressed frustration with the inefficient and slow administrative process of onboarding new gastroenterologists, which may take many months and not infrequently results in losing candidates to competing entities. While this issue is specific to recruitment, recurring and long-standing vacancies can increase work burdens, complicate logistics for remaining faculty, and may also negatively impact retention. One potential opportunity to improve VHA competitiveness is to streamline the administrative component of recruitment and optimize human resources support. The use of a third-party hiring company also should be considered.

Survey responses also indicated that administrative burden and insufficient support staff were significant retention challenges. Several respondents described a lack of efficient endoscopy workflow and delegation of simple administrative tasks to gastroenterologists as more likely in units without proper task distribution. Importantly, these shortcomings occur at the expense of workload-generating activities and career-enhancing opportunities.

While burnout rates among VA gastroenterologists have not been documented systematically, they likely correlate with workplace frustration and jeopardizegastroenterologist retention. Successful retention of gastroenterologists as highly trained medical professionals is more likely in workplaces that are vertically organized, efficient, and use physicians at the top of their skill level.

Conclusions

The VA offers the opportunity for a rewarding lifelong career in gastroenterology. The fulfillment of serving veterans, teaching future health care leaders, performing impactful research, and having job security is invaluable. Despite the tremendous benefits, this survey supports improving VA recruitment and retention strategies for the high-demand gastroenterology specialty. Improved salary parity is needed for workforce maintenance and recruitment, as is improved administrative and clinical support to maintain the high level of care our veterans deserve.

Veterans have a high burden of digestive diseases, and gastroenterologists are needed for the diagnosis and management of these conditions.1-4 According to the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Workforce Management and Consulting (WMC) office, the physician specialties with the greatest shortages are psychiatry, primary care, and gastroenterology.5 The VHA estimates it must hire 70 new gastroenterologists annually between fiscal years 2023 and 2027 to provide timely digestive care.5

Filling these positions will be increasingly difficult as competition for gastroenterologists is fierce. A recent Merritt Hawkins review states, “Gastroenterologists were the most in-demand type of provider during the 2022 review period.”6 In 2022, the median annual salary for US gastroenterologists was reported to be $561,375.7 Currently, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has an aggregate annual pay limit of $400,000 for all federal employees and cannot compete based on salary alone.

Retention of existing VA gastroenterologists also is challenging. The WMC has reported that 21.6% of VA gastroenterologists are eligible to retire, and in 2021, 8.2% left the VA to retire or seek non-VA positions.5 While not specific to the VA, a survey of practicing gastroenterologists conducted by the American College of Gastroenterology found a 49% burnout rate among respondents.8 Factors contributing to burnout at all career stages included administrative nonclinical work and a lack of clinical support staff.8 Burnout is also linked with higher rates of medical errors, interpersonal conflicts, and patient dissatisfaction. Burnout is more common among those with an innate strong sense of purpose and responsibility for their patients, characteristics we have observed in our VA colleagues.9

As members of the Section Chief Subcommittee of the VA Gastroenterology Field Advisory Board (GI FAB), we are passionate about providing outstanding gastroenterology care to US veterans, and we are alarmed at the struggles we are observing with recruiting and retaining a qualified national gastroenterology physician workforce. As such, we set out to survey the VA gastroenterology section chief community to gain insights into recruitment and retention challenges they have faced and identify potential solutions to these problems.

Methods

The GI FAB Section Chief Subcommittee developed a survey on gastroenterologist recruitment and retention using Microsoft Forms (Appendix). A link to the survey, which included 11 questions about facility location, current vacancies, and free text responses on barriers to recruitment and retention and potential solutions, was sent via email to all gastroenterology section chiefs on the National Gastroenterology and Hepatology Program Office’s email list of section chiefs on January 31, 2023. A reminder to complete the survey was sent to all section chiefs on February 8, 2023. Survey responses were aggregated and analyzed by the authors using descriptive statistics.

Results

The VA gastroenterologist recruitment and retention survey was emailed to 131 gastroenterology section chiefs and completed by 55 respondents (42%) (Figure). Of the responding section chiefs, 36 (65%) reported gastroenterologist vacancies at their facilities. Seventeen respondents (47%) reported a single vacancy, 12 (33%) reported 2 vacancies, 4 (11%) reported 3 vacancies, and 3 (8%) reported 4 vacancies. Of the sites with reported vacancies, 32 (89%) reported a need for a general gastroenterologist, 12 (33%) reported a need for a hepatologist, 11 (31%) reported a need for an advanced endoscopist, 9 (25%) reported a need for a gastroenterologist with specialized expertise in inflammatory bowel diseases, and 1 (3%) reported a need for a gastrointestinal motility specialist.

Numerous barriers to the recruitment and retention of gastroenterologists were reported. Given the large number of respondents that reported a unique barrier (ie, being the only respondents to report the barrier), a decision was made to include only barriers to recruitment and retention that were reported by at least 2 sites (Table). While there were some common themes, the reported barriers to retention differed from those to recruitment. The most reported barriers to recruitment were 46 respondents who noted salary, 23 reported human resources-related challenges, and 12 reported location. Respondents also noted various retention barriers, including 32 respondents who reported salary barriers; 13 reported administrative burden barriers, 6 reported medical center leadership, and 4 reported burnout.

Survey respondents provided multiple recommendations on how the VA can best support the recruitment and retention of gastroenterologists. The most frequent recommendations were to increase financial compensation by increasing the current aggregate salary cap to > $400,000, increasing the use of recruitment and retention incentives, and ensuring that gastroenterology is on the national Educational Debt Reduction Program (EDRP) list, which facilitates student loan repayment. It was recommended that a third-party company assist with hiring to overcome perceived issues with human resources. Additionally, there were multiple recommendations for improving administrative and clinical support. These included mandating how many support staff should be assigned to each gastroenterologist and providing best practice recommendations for support staff so that gastroenterologists can focus on physician-level work. Recommendations also included having a dedicated gastroenterology practice manager, nurse care coordinators, a colorectal cancer screening/surveillance coordinator, sufficient medical support assistants, and quality improvement personnel tracking ongoing professional practice evaluation data. Survey respondents also highlighted specific suggestions for recruiting recent graduates. These included offering a 4-day work week, as recent graduates place a premium on work-life balance, and ensuring gastroenterologists have individual offices. One respondent commented that gastroenterology fellows seeing VA gastroenterology attendings in cramped, shared offices, contrasted with private practice gastroenterologists in large private offices, may contribute to choosing private practice over joining the VA.

Discussion

Gastroenterology is currently listed by VHA WMC as 1 of the top 3 medical specialties in the VA with the most physician shortages.5 Working as a physician in the VA has long been recognized to have many benefits. First and foremost, many physicians are motivated by the VA mission to serve veterans, as this offers personal fulfillment and other intangible benefits. In addition, the VA can provide work-life balance, which is often not possible in fee-for-service settings, with patient panels and call volumes typically lower than in comparable private hospital settings. Moreover, VA physicians have outstanding teaching opportunities, as the VA is the largest supporter of medical education, with postgraduate trainees rotating through > 150 VA medical centers. Likewise, the VA offers a variety of student loan repayment programs (eg, the Specialty Education Loan Repayment Program and the EDRP). The VA offers research funding such as the Cooperative Studies Programs or program project funding, and rewards in parallel with the National Institute of Health (eg, career development awards, or merit review awards) and other grants. VA researchers have conducted many landmark studies that continue to shape the practice of gastroenterology and hepatology. From the earliest studies to demonstrate the effectiveness of screening colonoscopy, to the largest ongoing clinical trial in US history to assess the effectiveness of fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) vs screening colonoscopy.10-12 The VA has also led the field in the study of gastroesophageal reflux disease, hepatitis C treatment, and liver cancer screening.13-15 VA physicians also benefit from participation in the Federal Employee Retirement System, including its pension system.

These benefits apply to all medical specialties, making the VA a potentially appealing workplace for gastroenterologists. However, recent trends indicate that recruitment and retention of gastroenterologists is increasingly challenging, as the VA gastroenterology workforce grew by 5.0% in fiscal year (FY) 2020 and 1.8% in FY 2021. However, it was on track to end FY 2022 with a loss (-1.1%).5 It must be noted that this trend is not limited to the VA, and the National Center for Health Workforce Analysis predicts that gastroenterology will remain among the highest projected specialty shortages. Driven by increased demand for digestive health care services, more physicians nearing traditional retirement age, and substantially higher rates of burnout after the COVID-19 pandemic.16 All these factors are likely to result in an increasingly competitive market for gastroenterology, highlight the growing differences between VA and non-VA positions, and may augment the impact of differences for the individual gastroenterologist weighing employment options within and outside the VA.

The survey responses from VA gastroenterology section chiefs help identify potential impediments to the successful recruitment and retention in the specialty. Noncompetitive salary was the most significant barrier to the successful recruitment of gastroenterologists, identified by 46 of 55 respondents. According to a 2022 Medical Group Management Association report, the median annual salary for US gastroenterologists was $561,375.7 According to internal VA WMC data, the median 2022 VA gastroenterologist salary ranged between $287,976 and $346,435, depending on facility complexity level, excluding recruitment, retention, or relocation bonuses; performance pay; or cash awards. The current aggregate salary cap of $400,000 indicates that the VHA will likely be increasingly noncompetitive in the coming years unless novel pay authorizations are implemented.

Suboptimal human resources were the second most commonly cited impediment to recruiting gastroenterologists. Many section chiefs expressed frustration with the inefficient and slow administrative process of onboarding new gastroenterologists, which may take many months and not infrequently results in losing candidates to competing entities. While this issue is specific to recruitment, recurring and long-standing vacancies can increase work burdens, complicate logistics for remaining faculty, and may also negatively impact retention. One potential opportunity to improve VHA competitiveness is to streamline the administrative component of recruitment and optimize human resources support. The use of a third-party hiring company also should be considered.

Survey responses also indicated that administrative burden and insufficient support staff were significant retention challenges. Several respondents described a lack of efficient endoscopy workflow and delegation of simple administrative tasks to gastroenterologists as more likely in units without proper task distribution. Importantly, these shortcomings occur at the expense of workload-generating activities and career-enhancing opportunities.

While burnout rates among VA gastroenterologists have not been documented systematically, they likely correlate with workplace frustration and jeopardizegastroenterologist retention. Successful retention of gastroenterologists as highly trained medical professionals is more likely in workplaces that are vertically organized, efficient, and use physicians at the top of their skill level.

Conclusions

The VA offers the opportunity for a rewarding lifelong career in gastroenterology. The fulfillment of serving veterans, teaching future health care leaders, performing impactful research, and having job security is invaluable. Despite the tremendous benefits, this survey supports improving VA recruitment and retention strategies for the high-demand gastroenterology specialty. Improved salary parity is needed for workforce maintenance and recruitment, as is improved administrative and clinical support to maintain the high level of care our veterans deserve.

1. Shin A, Xu H, Imperiale TF. The prevalence, humanistic burden, and health care impact of irritable bowel syndrome among united states veterans. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;21(4):1061-1069.e1. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2022.08.005.

2. Kent KG. Prevalence of gastrointestinal disease in US military veterans under outpatient care at the veterans health administration. SAGE Open Med. 2021;9:20503121211049112. doi:10.1177/20503121211049112

3. Beste LA, Leipertz SL, Green PK, Dominitz JA, Ross D, Ioannou GN. Trends in burden of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma by underlying liver disease in US veterans, 2001-2013. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(6):1471-e18. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2015.07.056

4. Zullig LL, Sims KJ, McNeil R, et al. Cancer incidence among patients of the U.S. veterans affairs health care system: 2010 update. Mil Med. 2017;182(7):e1883-e1891. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-16-00371

5. VHA Physician Workforce Resources Blueprint. US Dept of Veterans Affairs. https://dvagov.sharepoint.com/sites/WMCPortal/WFP/Documents/Reports/VHA Physician Workforce Resources Blueprint FY 23-27.pdf [Source not verified]

6. AMN Healthcare. 2022 Review of Physician and Advanced Practitioner Recruiting Incentives. Accessed June 12, 2024. https://www1.amnhealthcare.com/l/123142/2022-07-13/q6ywxg/123142/1657737392vyuONaZZ/mha2022incentivesurgraphic.pdf

7. Medical Group Management Association. MGMA DataDive Provider Compensation Data. Accessed June 12, 2024. https://www.mgma.com/datadive/provider-compensation

8. Anderson JC, Bilal M, Burke CA, et al. Burnout among US gastroenterologists and fellows in training: identifying contributing factors and offering solutions. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2023;57(10):1063-1069. doi:10.1097/MCG.0000000000001781

9. Lacy BE, Chan JL. Physician burnout: the hidden health care crisis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16(3):311-317. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2017.06.043

10. Lieberman DA, Weiss DG, Bond JH, Ahnen DJ, Garewal H, Chejfec G. Use of colonoscopy to screen asymptomatic adults for colorectal cancer. Veterans affairs cooperative study group 380. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(3):162-168. doi:10.1056/NEJM200007203430301

11. Lieberman DA, Weiss DG; Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group 380. One-time screening for colorectal cancer with combined fecal occult-blood testing and examination of the distal colon. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(8):555-560. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa010328

12. Robertson DJ, Dominitz JA, Beed A, et al. Baseline features and reasons for nonparticipation in the colonoscopy versus fecal immunochemical test in reducing mortality from colorectal cancer (CONFIRM) study, a colorectal cancer screening trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(7):e2321730. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.21730

13. Spechler SJ, Hunter JG, Jones KM, et al. Randomized trial of medical versus surgical treatment for refractory heartburn. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(16):1513-1523. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1811424

14. Beste LA, Green PK, Berry K, Kogut MJ, Allison SK, Ioannou GN. Effectiveness of hepatitis C antiviral treatment in a USA cohort of veteran patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2017;67(1):32-39. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2017.02.027

15. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans affairs cooperative studies program (CSP). CSP #2023. Updated July 2022. Accessed June 12, 2024. https://www.vacsp.research.va.gov/CSP_2023/CSP_2023.asp

16. US Health Resources & Services Administration. Workforce projections. Accessed June 12, 2024. https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-workforce/workforce-projections

1. Shin A, Xu H, Imperiale TF. The prevalence, humanistic burden, and health care impact of irritable bowel syndrome among united states veterans. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;21(4):1061-1069.e1. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2022.08.005.

2. Kent KG. Prevalence of gastrointestinal disease in US military veterans under outpatient care at the veterans health administration. SAGE Open Med. 2021;9:20503121211049112. doi:10.1177/20503121211049112

3. Beste LA, Leipertz SL, Green PK, Dominitz JA, Ross D, Ioannou GN. Trends in burden of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma by underlying liver disease in US veterans, 2001-2013. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(6):1471-e18. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2015.07.056

4. Zullig LL, Sims KJ, McNeil R, et al. Cancer incidence among patients of the U.S. veterans affairs health care system: 2010 update. Mil Med. 2017;182(7):e1883-e1891. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-16-00371

5. VHA Physician Workforce Resources Blueprint. US Dept of Veterans Affairs. https://dvagov.sharepoint.com/sites/WMCPortal/WFP/Documents/Reports/VHA Physician Workforce Resources Blueprint FY 23-27.pdf [Source not verified]

6. AMN Healthcare. 2022 Review of Physician and Advanced Practitioner Recruiting Incentives. Accessed June 12, 2024. https://www1.amnhealthcare.com/l/123142/2022-07-13/q6ywxg/123142/1657737392vyuONaZZ/mha2022incentivesurgraphic.pdf

7. Medical Group Management Association. MGMA DataDive Provider Compensation Data. Accessed June 12, 2024. https://www.mgma.com/datadive/provider-compensation

8. Anderson JC, Bilal M, Burke CA, et al. Burnout among US gastroenterologists and fellows in training: identifying contributing factors and offering solutions. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2023;57(10):1063-1069. doi:10.1097/MCG.0000000000001781

9. Lacy BE, Chan JL. Physician burnout: the hidden health care crisis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16(3):311-317. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2017.06.043

10. Lieberman DA, Weiss DG, Bond JH, Ahnen DJ, Garewal H, Chejfec G. Use of colonoscopy to screen asymptomatic adults for colorectal cancer. Veterans affairs cooperative study group 380. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(3):162-168. doi:10.1056/NEJM200007203430301

11. Lieberman DA, Weiss DG; Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group 380. One-time screening for colorectal cancer with combined fecal occult-blood testing and examination of the distal colon. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(8):555-560. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa010328

12. Robertson DJ, Dominitz JA, Beed A, et al. Baseline features and reasons for nonparticipation in the colonoscopy versus fecal immunochemical test in reducing mortality from colorectal cancer (CONFIRM) study, a colorectal cancer screening trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(7):e2321730. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.21730

13. Spechler SJ, Hunter JG, Jones KM, et al. Randomized trial of medical versus surgical treatment for refractory heartburn. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(16):1513-1523. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1811424

14. Beste LA, Green PK, Berry K, Kogut MJ, Allison SK, Ioannou GN. Effectiveness of hepatitis C antiviral treatment in a USA cohort of veteran patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2017;67(1):32-39. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2017.02.027

15. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans affairs cooperative studies program (CSP). CSP #2023. Updated July 2022. Accessed June 12, 2024. https://www.vacsp.research.va.gov/CSP_2023/CSP_2023.asp

16. US Health Resources & Services Administration. Workforce projections. Accessed June 12, 2024. https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-workforce/workforce-projections

A Nationwide Survey and Needs Assessment of Colonoscopy Quality Assurance Programs

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is an important concern for the VA, and colonoscopy is one primary screening, surveillance, and diagnostic modality used. The observed reductions in CRC incidence and mortality over the past decade largely have been attributed to the widespread use of CRC screening options.1,2 Colonoscopy quality is critical to CRC prevention in veterans. However, endoscopy skills to detect and remove colorectal polyps using colonoscopy vary in practice.3-5

Quality benchmarks, linked to patient outcomes, have been established by specialty societies and proposed by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services as reportable quality metrics.6 Colonoscopy quality metrics have been shown to be associated with patient outcomes, such as the risk of developing CRC after colonoscopy. The adenoma detection rate (ADR), defined as the proportion of average-risk screening colonoscopies in which 1 or more adenomas are detected, has the strongest association to interval or “missed” CRC after screening colonoscopy and has been linked to a risk for fatal CRC despite colonoscopy.3

In a landmark study of 314,872 examinations performed by 136 gastroenterologists, the ADR ranged from 7.4% to 52.5%.3 Among patients with ADRs in the highest quintile compared with patients in the lowest, the adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) for any interval cancer was 0.52 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.39-0.69) and for fatal interval cancers was 0.38 (95% CI, 0.22-0.65).3 Another pooled analysis from 8 surveillance studies that followed more than 800 participants with adenoma(s) after a baseline colonoscopy showed 52% of incident cancers as probable missed lesions, 19% as possibly related to incomplete resection of an earlier, noninvasive lesion, and only 24% as probable new lesions.7 These interval cancers highlight the current imperfections of colonoscopy and the focus on measurement and reporting of quality indicators for colonoscopy.8-12

According to VHA Directive 1015, in December 2014, colonoscopy quality should be monitored as part of an ongoing quality assurance program.13 A recent report from the VA Office of the Inspector General (OIG) highlighted colonoscopy-quality deficiencies.14 The OIG report strongly recommended that the “Acting Under Secretary for Health require standardized documentation of quality indicators based on professional society guidelines and published literature.”14However, no currently standardized and readily available VHA resource measures, reports, and ensures colonoscopy quality.

The authors hypothesized that colonoscopy quality assurance programs vary widely across VHA sites. The objective of this survey was to assess the measurement and reporting practices for colonoscopy quality and identify both strengths and areas for improvement to facilitate implementation of quality assurance programs across the VA health care system.

Methods

The authors performed an online survey of VA sites to assess current colonoscopy quality assurance practices. The institutional review boards (IRBs) at the University of Utah and VA Salt Lake City Health Care System and University of California, San Francisco and San Francisco VA Health Care System classified the study as a quality improvement project that did not qualify for human subjects’ research requiring IRB review.

The authors iteratively developed and refined the questionnaire with a survey methodologist and 2 clinical domain experts. The National Program Director for Gastroenterology, and the National Gastroenterology Field Advisory Committee reviewed the survey content and pretested the survey instrument prior to final data collection. The National Program Office for Gastroenterology provided an e-mail list of all known VA gastroenterology section chiefs. The authors administered the final survey via e-mail, using the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap; Vanderbilt University Medical Center) platform beginning January 9, 2017.15

A follow-up reminder e-mail was sent to nonresponders after 2 weeks. After this second invitation, sites were contacted by telephone to verify that the correct contact information had been captured. Subsequently, 50 contacts were updated if e-mails bounced back or the correct contact was obtained. Points of contact received a total of 3 reminder e-mails until the final closeout of the survey on March 28, 2017; 65 of 89 (73%) of the original contacts completed the survey vs 31 of 50 (62%) of the updated contacts.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics of the responses were calculated to determine the overall proportion of VA sites measuring colonoscopy quality metrics and identification of areas in need of quality improvement. The response rate for the survey was defined as the total number of responses obtained as a proportion of the total number of points of contact. This corresponds to the American Association of Public Opinion Research’s RR1, or minimum response rate, formula.16 All categoric responses are presented as proportions. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA SE12.0 (College Station, TX).

Results

Of the 139 points of contact invited, 96 completed the survey (response rate of 69.0%), representing 93 VA facilities (of 141 possible facilities) in 44 different states. Three sites had 2 responses. Sites used various and often a combination of methods to measure quality (Table 1).

A majority of sites’ (63.5%) quality reports represented individual provider data, whereas fewer provided quality reports for physician groups (22.9%) or for the entire facility (40.6%). Provider quality information was de-identified in 43.8% of reporting sites’ quality reports and identifiable in 37.5% of reporting sites’ quality reports. A majority of sites (74.0%) reported that the local gastroenterology section chief or quality manager has access to the quality reports. Fewer sites reported providing data to individual endoscopists (44.8% for personal and peer data and 32.3% for personal data only). One site (1%) responded that quality reports were available for public access. Survey respondents also were asked to provide the estimated time (hours required per month) to collect the data for quality metrics. Of 75 respondents providing data for this question, 28 (29.2%) and 17 (17.7%), estimated between 1 to 5 and 6 to 10 hours per month, respectively. Ten sites estimated spending between 11 to 20 hours, and 7 sites estimated spending more than 20 hours per month collecting quality metrics. A total of 13 respondents (13.5%) stated uncertainty about the time burden.

As shown in the Figure, numerous quality metrics were collected across sites with more than 80% of sites collecting information on bowel preparation quality (88.5%), cecal intubation rate (87.5%), and complications (83.3%). A majority of sites also reported collecting data on appropriateness of surveillance intervals (62.5%), colonoscopy withdrawal times (62.5%), and ADRs (61.5%). Seven sites (7.3%) did not collect quality metrics.

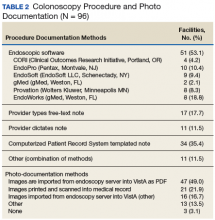

Information also was collected on colonoscopy procedure documentation to inform future efforts at standardization. A small majority (53.1%) of sites reported using endoscopic software to generate colonoscopy procedure documentation. Within these sites, 6 different types of endoscopic note writing software were used to generate procedure notes (Table 2).

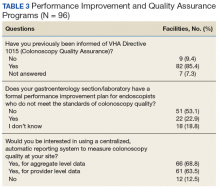

Most sites (85.4%) were aware of VHA Directive 1015 recommendations for colonoscopy quality assurance programs. A significant majority (89.5%) of respondents also indicated interest in a centralized automatic reporting system to measure and report colonoscopy quality in some form, either with aggregate data, provider data, or both (Table 3).

Discussion

This survey on colonoscopy quality assurance programs is the first assessment of the VHA’s efforts to measure and report colonoscopy quality indicators. The findings indicated that the majority of VA sites are measuring and reporting at least some measures of colonoscopy quality. However, the programs are significantly variable in terms of methods used to collect quality metrics, specific quality measures obtained, and how quality is reported.

The authors’ work is novel in that this is the first report of the status of colonoscopy quality assurance programs in a large U.S. health care system. The VA health care system is the largest integrated health system in the U.S., serving more than 9 million veterans annually. This survey’s high response rate further strengthens the findings. Specifically, the survey found that VA sites are making a strong concerted effort to measure and report colonoscopy quality. However, there is significant variability in documentation, measurement, and reporting practices. Moreover, the majority of VA sites do not have formal performance improvement plans in place for endoscopists who do not meet thresholds for colonoscopy quality.

Screening colonoscopy for CRC offers known mortality benefits to patients.1,17-19 Significant prior work has described and validated the importance of colonoscopy quality metrics, including bowel preparation quality, cecal intubation rate, and ADR and their association with interval colorectal cancer and death.20-23 Gastroenterology professional societies, including the American College of Gastroenterology and the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, have recommended and endorsed measurement and reporting of colonoscopy metrics.24 There is general agreement among endoscopists that colonoscopy quality is an important aspect of performing the procedure.

The lack of formal performance improvement programs is a key finding of this survey. Recent studies have shown that improvements in quality metrics, such as the ADR, by individual endoscopists result in reductions in interval colorectal cancer and death.25 Kahi and colleagues previously showed that providing a quarterly report card improves colonoscopy quality.26 Keswani and colleagues studied a combination of a report card and implementation of standards of practice with resultant improvement in colonoscopy quality.27 Most recently, in a large prospective cohort study of individuals who underwent a screening colonoscopy, 294 of the screening endoscopists received annual feedback and quality benchmark indicators to improve colonoscopy performance.25 The majority of the endoscopists (74.5%) increased their annual ADR category over the study period. Moreover, patients examined by endoscopists who reached or maintained the highest ADR quintile (> 24.6%) had significantly lower risk of interval CRC and death. The lack of formal performance improvement programs across the VHA is concerning but reveals a significant opportunity to improve veteran health outcomes on a large scale.

This study’s findings also highlight the intense resources necessary to measure and report colonoscopy quality. The ability to measure and report quality metrics requires having adequate documentation and data to obtain quality metrics. Administrative databases from electronic health records offer some potential for routine monitoring of quality metrics.28 However, most administrative databases, including the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW), contain administrative billing codes (ICD and CPT) linked to limited patient data, including demographics and structured medical record data. The actual data required for quality reporting of important metrics (bowel preparation quality, cecal intubation rates, and ADRs) are usually found in clinical text notes or endoscopic note documentation and not available as structured data. Due to this issue, the majority of VA sites (79.2%) are using manual chart review to collect quality metric data, resulting in widely variable estimates on time burden. A minority of sites in this study (39.6%) reported using automated endoscopic software reporting capability that can help with the time burden. However, even in the VA, an integrated health system, a wide variety of software brands, documentation practices, and photo documentation was found.

Future endoscopy budget and purchase decisions for the individual VA sites should take into account how new technology and software can more easily facilitate accurate quality reporting. A specific policy recommendation would be for the VA to consider a uniform endoscopic note writer for procedure notes. Pathology data, which is necessary for the calculation of ADR, also should be available as structured data in the CDW to more easily measure colonoscopy quality. Continuous measurement and reporting of quality also requires ongoing information technology infrastructure and quality control of the measurement process.

Limitations

This survey was a cross-section of VA sites’ points of contact regarding colonoscopy quality assurance programs, so the results are descriptive in nature. However, the instrument was carefully developed, using both subject matter and survey method expertise. The questionnaire also was refined through pretesting prior to data collection. The initial contact list was found to have errors, and the list had to be updated after launching the survey. Updated information for most of the contacts was available.

Another limitation was the inability to survey nongastroenterologist-run endoscopy centers, because many centers use surgeons or other nongastroenterology providers. The authors speculate that quality monitoring may be less likely to be present at these facilities as they may not be aware of the gastroenterology professional society recommendations. The authors did not require or insist that all questions be answered, so some data were missing from sites. However, 93.7% of respondents completed the entire survey.

Conclusion

The authors have described the status of colonoscopy quality assurance programs across the VA health care system. Many sites are making robust efforts to measure and report quality especially of process measures. However, there are significant time and manual workforce efforts required, and this work is likely associated with the variability in programs. Importantly, ADR, which is the quality metric that has been most strongly associated with risk of colon cancer mortality, is not being measured by 38% of sites.

These results reinforce a critical need for a centralized, automated quality reporting infrastructure to standardize colonoscopy quality reporting, reduce workload, and ensure veterans receive high-quality colonoscopy.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support and feedback of the National Gastroenterology Program Field Advisory Committee for survey development and testing. The authors coordinated the survey through the Salt Lake City Specialty Care Center of Innovation in partnership with the National Gastroenterology Program Office and the Quality Enhancement Research Initiative: Quality Enhancement Research Initiative, Measurement Science Program, QUE15-283. The work also was partially supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health Award UL1TR001067 and Merit Review Award 1 I01 HX001574-01A1 from the United States Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research & Development Service of the VA Office of Research and Development.

1. Brenner H, Stock C, Hoffmeister M. Effect of screening sigmoidoscopy and screening colonoscopy on colorectal cancer incidence and mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials and observational studies. BMJ. 2014;348:g2467.

2. Meester RGS, Doubeni CA, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, et al. Colorectal cancer deaths attributable to nonuse of screening in the United States. Ann Epidemiol. 2015;25(3):208-213.e1.

3. Corley DA, Jensen CD, Marks AR, et al. Adenoma detection rate and risk of colorectal cancer and death. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(26):1298-1306.

4. Meester RGS, Doubeni CA, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, et al. Variation in adenoma detection rate and the lifetime benefits and cost of colorectal cancer screening: a microsimulation model. JAMA. 2015;313(23):2349-2358.

5. Boroff ES, Gurudu SR, Hentz JG, Leighton JA, Ramirez FC. Polyp and adenoma detection rates in the proximal and distal colon. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(6):993-999.

6. Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Quality measures. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Qual ityMeasures/index.html. Updated December 19, 2017. Accessed January 17, 2018.

7. Robertson DJ, Lieberman DA, Winawer SJ, et al. Colorectal cancers soon after colonoscopy: a pooled multicohort analysis. Gut. 2014;63(6):949-956.

8. Fayad NF, Kahi CJ. Colonoscopy quality assessment. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2015;25(2):373-386.

9. de Jonge V, Sint Nicolaas J, Cahen DL, et al; SCoPE Consortium. Quality evaluation of colonoscopy reporting and colonoscopy performance in daily clinical practice. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75(1):98-106.

10. Johnson DA. Quality benchmarking for colonoscopy: how do we pick products from the shelf? Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75(1):107-109.

11. Anderson JC, Butterly LF. Colonoscopy: quality indicators. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2015;6(2):e77.

12. Kaminski MF, Regula J, Kraszewska E, et al. Quality indicators for colonoscopy and the risk of interval cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(19):1795-1803.

13. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. Colorectal cancer screening. VHA Directive 1015. Published December 30, 2014.

14. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, VA Office of the Inspector General, Office of Healthcare Inspections. Healthcare inspection: alleged access delays and surgery service concerns, VA Roseburg Healthcare System, Roseburg, Oregon. Report No.15-00506-535. https://www.va.gov/oig /pubs/VAOIG-15-00506-535.pdf. Published July 11, 2017. Accessed January 9, 2018.

15. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381.

16. The American Association for Public Opinion Research. Standard Definitions: Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys. 9th edition. http://www.aapor.org/AAPOR_Main/media/publications/Standard-Definitions20169theditionfinal.pdf. Revised 2016. Accessed January 9, 2018.

17. Kahi CJ, Imperiale TF, Juliar BE, Rex DK. Effect of screening colonoscopy on colorectal cancer incidence and mortality. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7(7):770-775.

18. Manser CN, Bachmann LM, Brunner J, Hunold F, Bauerfeind P, Marbet UA. Colonoscopy screening markedly reduces the occurrence of colon carcinomas and carcinoma-related death: a closed cohort study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76(1):110-117.

19. Nishihara R, Wu K, Lochhead P, et al. Long-term colorectal-cancer incidence and mortality after lower endoscopy. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(12):1095-1105.

20. Harewood GC, Sharma VK, de Garmo P. Impact of colonoscopy preparation quality on detection of suspected colonic neoplasia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58(1):76-79.

21. Hillyer GC, Lebwohl B, Rosenberg RM, et al. Assessing bowel preparation quality using the mean number of adenomas per colonoscopy. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2014;7(6):238-246.

22. Clark BT, Rustagi T, Laine L. What level of bowel prep quality requires early repeat colonoscopy: systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of preparation quality on adenoma detection rate. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(11):1714-1723; quiz 1724.

23. Johnson DA, Barkun AN, Cohen LB, et al; US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Optimizing adequacy of bowel cleansing for colonoscopy: recommendations from the US multi-society task force on colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2014;147(4):903-924.

24. Rex DK, Petrini JL, Baron TH, et al; ASGE/ACG Taskforce on Quality in Endoscopy. Quality indicators for colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(4):873-885.

25. Kaminski MF, Wieszczy P, Rupinski M, et al. Increased rate of adenoma detection associates with reduced risk of colorectal cancer and death. Gastroenterology. 2017;153(1):98-105.

26. Kahi CJ, Ballard D, Shah AS, Mears R, Johnson CS. Impact of a quarterly report card on colonoscopy quality measures. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2013;77(6):925-931.

27. Keswani RN, Yadlapati R, Gleason KM, et al. Physician report cards and implementing standards of practice are both significantly associated with improved screening colonoscopy quality. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(8):1134-1139.

28. Logan JR, Lieberman DA. The use of databases and registries to enhance colonoscopy quality. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2010;20(4):717-734.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is an important concern for the VA, and colonoscopy is one primary screening, surveillance, and diagnostic modality used. The observed reductions in CRC incidence and mortality over the past decade largely have been attributed to the widespread use of CRC screening options.1,2 Colonoscopy quality is critical to CRC prevention in veterans. However, endoscopy skills to detect and remove colorectal polyps using colonoscopy vary in practice.3-5

Quality benchmarks, linked to patient outcomes, have been established by specialty societies and proposed by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services as reportable quality metrics.6 Colonoscopy quality metrics have been shown to be associated with patient outcomes, such as the risk of developing CRC after colonoscopy. The adenoma detection rate (ADR), defined as the proportion of average-risk screening colonoscopies in which 1 or more adenomas are detected, has the strongest association to interval or “missed” CRC after screening colonoscopy and has been linked to a risk for fatal CRC despite colonoscopy.3

In a landmark study of 314,872 examinations performed by 136 gastroenterologists, the ADR ranged from 7.4% to 52.5%.3 Among patients with ADRs in the highest quintile compared with patients in the lowest, the adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) for any interval cancer was 0.52 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.39-0.69) and for fatal interval cancers was 0.38 (95% CI, 0.22-0.65).3 Another pooled analysis from 8 surveillance studies that followed more than 800 participants with adenoma(s) after a baseline colonoscopy showed 52% of incident cancers as probable missed lesions, 19% as possibly related to incomplete resection of an earlier, noninvasive lesion, and only 24% as probable new lesions.7 These interval cancers highlight the current imperfections of colonoscopy and the focus on measurement and reporting of quality indicators for colonoscopy.8-12

According to VHA Directive 1015, in December 2014, colonoscopy quality should be monitored as part of an ongoing quality assurance program.13 A recent report from the VA Office of the Inspector General (OIG) highlighted colonoscopy-quality deficiencies.14 The OIG report strongly recommended that the “Acting Under Secretary for Health require standardized documentation of quality indicators based on professional society guidelines and published literature.”14However, no currently standardized and readily available VHA resource measures, reports, and ensures colonoscopy quality.

The authors hypothesized that colonoscopy quality assurance programs vary widely across VHA sites. The objective of this survey was to assess the measurement and reporting practices for colonoscopy quality and identify both strengths and areas for improvement to facilitate implementation of quality assurance programs across the VA health care system.

Methods

The authors performed an online survey of VA sites to assess current colonoscopy quality assurance practices. The institutional review boards (IRBs) at the University of Utah and VA Salt Lake City Health Care System and University of California, San Francisco and San Francisco VA Health Care System classified the study as a quality improvement project that did not qualify for human subjects’ research requiring IRB review.

The authors iteratively developed and refined the questionnaire with a survey methodologist and 2 clinical domain experts. The National Program Director for Gastroenterology, and the National Gastroenterology Field Advisory Committee reviewed the survey content and pretested the survey instrument prior to final data collection. The National Program Office for Gastroenterology provided an e-mail list of all known VA gastroenterology section chiefs. The authors administered the final survey via e-mail, using the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap; Vanderbilt University Medical Center) platform beginning January 9, 2017.15

A follow-up reminder e-mail was sent to nonresponders after 2 weeks. After this second invitation, sites were contacted by telephone to verify that the correct contact information had been captured. Subsequently, 50 contacts were updated if e-mails bounced back or the correct contact was obtained. Points of contact received a total of 3 reminder e-mails until the final closeout of the survey on March 28, 2017; 65 of 89 (73%) of the original contacts completed the survey vs 31 of 50 (62%) of the updated contacts.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics of the responses were calculated to determine the overall proportion of VA sites measuring colonoscopy quality metrics and identification of areas in need of quality improvement. The response rate for the survey was defined as the total number of responses obtained as a proportion of the total number of points of contact. This corresponds to the American Association of Public Opinion Research’s RR1, or minimum response rate, formula.16 All categoric responses are presented as proportions. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA SE12.0 (College Station, TX).

Results

Of the 139 points of contact invited, 96 completed the survey (response rate of 69.0%), representing 93 VA facilities (of 141 possible facilities) in 44 different states. Three sites had 2 responses. Sites used various and often a combination of methods to measure quality (Table 1).

A majority of sites’ (63.5%) quality reports represented individual provider data, whereas fewer provided quality reports for physician groups (22.9%) or for the entire facility (40.6%). Provider quality information was de-identified in 43.8% of reporting sites’ quality reports and identifiable in 37.5% of reporting sites’ quality reports. A majority of sites (74.0%) reported that the local gastroenterology section chief or quality manager has access to the quality reports. Fewer sites reported providing data to individual endoscopists (44.8% for personal and peer data and 32.3% for personal data only). One site (1%) responded that quality reports were available for public access. Survey respondents also were asked to provide the estimated time (hours required per month) to collect the data for quality metrics. Of 75 respondents providing data for this question, 28 (29.2%) and 17 (17.7%), estimated between 1 to 5 and 6 to 10 hours per month, respectively. Ten sites estimated spending between 11 to 20 hours, and 7 sites estimated spending more than 20 hours per month collecting quality metrics. A total of 13 respondents (13.5%) stated uncertainty about the time burden.

As shown in the Figure, numerous quality metrics were collected across sites with more than 80% of sites collecting information on bowel preparation quality (88.5%), cecal intubation rate (87.5%), and complications (83.3%). A majority of sites also reported collecting data on appropriateness of surveillance intervals (62.5%), colonoscopy withdrawal times (62.5%), and ADRs (61.5%). Seven sites (7.3%) did not collect quality metrics.

Information also was collected on colonoscopy procedure documentation to inform future efforts at standardization. A small majority (53.1%) of sites reported using endoscopic software to generate colonoscopy procedure documentation. Within these sites, 6 different types of endoscopic note writing software were used to generate procedure notes (Table 2).

Most sites (85.4%) were aware of VHA Directive 1015 recommendations for colonoscopy quality assurance programs. A significant majority (89.5%) of respondents also indicated interest in a centralized automatic reporting system to measure and report colonoscopy quality in some form, either with aggregate data, provider data, or both (Table 3).

Discussion

This survey on colonoscopy quality assurance programs is the first assessment of the VHA’s efforts to measure and report colonoscopy quality indicators. The findings indicated that the majority of VA sites are measuring and reporting at least some measures of colonoscopy quality. However, the programs are significantly variable in terms of methods used to collect quality metrics, specific quality measures obtained, and how quality is reported.

The authors’ work is novel in that this is the first report of the status of colonoscopy quality assurance programs in a large U.S. health care system. The VA health care system is the largest integrated health system in the U.S., serving more than 9 million veterans annually. This survey’s high response rate further strengthens the findings. Specifically, the survey found that VA sites are making a strong concerted effort to measure and report colonoscopy quality. However, there is significant variability in documentation, measurement, and reporting practices. Moreover, the majority of VA sites do not have formal performance improvement plans in place for endoscopists who do not meet thresholds for colonoscopy quality.

Screening colonoscopy for CRC offers known mortality benefits to patients.1,17-19 Significant prior work has described and validated the importance of colonoscopy quality metrics, including bowel preparation quality, cecal intubation rate, and ADR and their association with interval colorectal cancer and death.20-23 Gastroenterology professional societies, including the American College of Gastroenterology and the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, have recommended and endorsed measurement and reporting of colonoscopy metrics.24 There is general agreement among endoscopists that colonoscopy quality is an important aspect of performing the procedure.

The lack of formal performance improvement programs is a key finding of this survey. Recent studies have shown that improvements in quality metrics, such as the ADR, by individual endoscopists result in reductions in interval colorectal cancer and death.25 Kahi and colleagues previously showed that providing a quarterly report card improves colonoscopy quality.26 Keswani and colleagues studied a combination of a report card and implementation of standards of practice with resultant improvement in colonoscopy quality.27 Most recently, in a large prospective cohort study of individuals who underwent a screening colonoscopy, 294 of the screening endoscopists received annual feedback and quality benchmark indicators to improve colonoscopy performance.25 The majority of the endoscopists (74.5%) increased their annual ADR category over the study period. Moreover, patients examined by endoscopists who reached or maintained the highest ADR quintile (> 24.6%) had significantly lower risk of interval CRC and death. The lack of formal performance improvement programs across the VHA is concerning but reveals a significant opportunity to improve veteran health outcomes on a large scale.