User login

A Crisis in Scope: Recruitment and Retention Challenges Reported by VA Gastroenterology Section Chiefs

Veterans have a high burden of digestive diseases, and gastroenterologists are needed for the diagnosis and management of these conditions.1-4 According to the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Workforce Management and Consulting (WMC) office, the physician specialties with the greatest shortages are psychiatry, primary care, and gastroenterology.5 The VHA estimates it must hire 70 new gastroenterologists annually between fiscal years 2023 and 2027 to provide timely digestive care.5

Filling these positions will be increasingly difficult as competition for gastroenterologists is fierce. A recent Merritt Hawkins review states, “Gastroenterologists were the most in-demand type of provider during the 2022 review period.”6 In 2022, the median annual salary for US gastroenterologists was reported to be $561,375.7 Currently, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has an aggregate annual pay limit of $400,000 for all federal employees and cannot compete based on salary alone.

Retention of existing VA gastroenterologists also is challenging. The WMC has reported that 21.6% of VA gastroenterologists are eligible to retire, and in 2021, 8.2% left the VA to retire or seek non-VA positions.5 While not specific to the VA, a survey of practicing gastroenterologists conducted by the American College of Gastroenterology found a 49% burnout rate among respondents.8 Factors contributing to burnout at all career stages included administrative nonclinical work and a lack of clinical support staff.8 Burnout is also linked with higher rates of medical errors, interpersonal conflicts, and patient dissatisfaction. Burnout is more common among those with an innate strong sense of purpose and responsibility for their patients, characteristics we have observed in our VA colleagues.9

As members of the Section Chief Subcommittee of the VA Gastroenterology Field Advisory Board (GI FAB), we are passionate about providing outstanding gastroenterology care to US veterans, and we are alarmed at the struggles we are observing with recruiting and retaining a qualified national gastroenterology physician workforce. As such, we set out to survey the VA gastroenterology section chief community to gain insights into recruitment and retention challenges they have faced and identify potential solutions to these problems.

Methods

The GI FAB Section Chief Subcommittee developed a survey on gastroenterologist recruitment and retention using Microsoft Forms (Appendix). A link to the survey, which included 11 questions about facility location, current vacancies, and free text responses on barriers to recruitment and retention and potential solutions, was sent via email to all gastroenterology section chiefs on the National Gastroenterology and Hepatology Program Office’s email list of section chiefs on January 31, 2023. A reminder to complete the survey was sent to all section chiefs on February 8, 2023. Survey responses were aggregated and analyzed by the authors using descriptive statistics.

Results

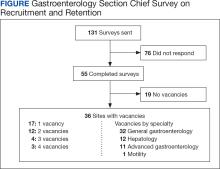

The VA gastroenterologist recruitment and retention survey was emailed to 131 gastroenterology section chiefs and completed by 55 respondents (42%) (Figure). Of the responding section chiefs, 36 (65%) reported gastroenterologist vacancies at their facilities. Seventeen respondents (47%) reported a single vacancy, 12 (33%) reported 2 vacancies, 4 (11%) reported 3 vacancies, and 3 (8%) reported 4 vacancies. Of the sites with reported vacancies, 32 (89%) reported a need for a general gastroenterologist, 12 (33%) reported a need for a hepatologist, 11 (31%) reported a need for an advanced endoscopist, 9 (25%) reported a need for a gastroenterologist with specialized expertise in inflammatory bowel diseases, and 1 (3%) reported a need for a gastrointestinal motility specialist.

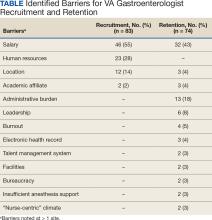

Numerous barriers to the recruitment and retention of gastroenterologists were reported. Given the large number of respondents that reported a unique barrier (ie, being the only respondents to report the barrier), a decision was made to include only barriers to recruitment and retention that were reported by at least 2 sites (Table). While there were some common themes, the reported barriers to retention differed from those to recruitment. The most reported barriers to recruitment were 46 respondents who noted salary, 23 reported human resources-related challenges, and 12 reported location. Respondents also noted various retention barriers, including 32 respondents who reported salary barriers; 13 reported administrative burden barriers, 6 reported medical center leadership, and 4 reported burnout.

Survey respondents provided multiple recommendations on how the VA can best support the recruitment and retention of gastroenterologists. The most frequent recommendations were to increase financial compensation by increasing the current aggregate salary cap to > $400,000, increasing the use of recruitment and retention incentives, and ensuring that gastroenterology is on the national Educational Debt Reduction Program (EDRP) list, which facilitates student loan repayment. It was recommended that a third-party company assist with hiring to overcome perceived issues with human resources. Additionally, there were multiple recommendations for improving administrative and clinical support. These included mandating how many support staff should be assigned to each gastroenterologist and providing best practice recommendations for support staff so that gastroenterologists can focus on physician-level work. Recommendations also included having a dedicated gastroenterology practice manager, nurse care coordinators, a colorectal cancer screening/surveillance coordinator, sufficient medical support assistants, and quality improvement personnel tracking ongoing professional practice evaluation data. Survey respondents also highlighted specific suggestions for recruiting recent graduates. These included offering a 4-day work week, as recent graduates place a premium on work-life balance, and ensuring gastroenterologists have individual offices. One respondent commented that gastroenterology fellows seeing VA gastroenterology attendings in cramped, shared offices, contrasted with private practice gastroenterologists in large private offices, may contribute to choosing private practice over joining the VA.

Discussion

Gastroenterology is currently listed by VHA WMC as 1 of the top 3 medical specialties in the VA with the most physician shortages.5 Working as a physician in the VA has long been recognized to have many benefits. First and foremost, many physicians are motivated by the VA mission to serve veterans, as this offers personal fulfillment and other intangible benefits. In addition, the VA can provide work-life balance, which is often not possible in fee-for-service settings, with patient panels and call volumes typically lower than in comparable private hospital settings. Moreover, VA physicians have outstanding teaching opportunities, as the VA is the largest supporter of medical education, with postgraduate trainees rotating through > 150 VA medical centers. Likewise, the VA offers a variety of student loan repayment programs (eg, the Specialty Education Loan Repayment Program and the EDRP). The VA offers research funding such as the Cooperative Studies Programs or program project funding, and rewards in parallel with the National Institute of Health (eg, career development awards, or merit review awards) and other grants. VA researchers have conducted many landmark studies that continue to shape the practice of gastroenterology and hepatology. From the earliest studies to demonstrate the effectiveness of screening colonoscopy, to the largest ongoing clinical trial in US history to assess the effectiveness of fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) vs screening colonoscopy.10-12 The VA has also led the field in the study of gastroesophageal reflux disease, hepatitis C treatment, and liver cancer screening.13-15 VA physicians also benefit from participation in the Federal Employee Retirement System, including its pension system.

These benefits apply to all medical specialties, making the VA a potentially appealing workplace for gastroenterologists. However, recent trends indicate that recruitment and retention of gastroenterologists is increasingly challenging, as the VA gastroenterology workforce grew by 5.0% in fiscal year (FY) 2020 and 1.8% in FY 2021. However, it was on track to end FY 2022 with a loss (-1.1%).5 It must be noted that this trend is not limited to the VA, and the National Center for Health Workforce Analysis predicts that gastroenterology will remain among the highest projected specialty shortages. Driven by increased demand for digestive health care services, more physicians nearing traditional retirement age, and substantially higher rates of burnout after the COVID-19 pandemic.16 All these factors are likely to result in an increasingly competitive market for gastroenterology, highlight the growing differences between VA and non-VA positions, and may augment the impact of differences for the individual gastroenterologist weighing employment options within and outside the VA.

The survey responses from VA gastroenterology section chiefs help identify potential impediments to the successful recruitment and retention in the specialty. Noncompetitive salary was the most significant barrier to the successful recruitment of gastroenterologists, identified by 46 of 55 respondents. According to a 2022 Medical Group Management Association report, the median annual salary for US gastroenterologists was $561,375.7 According to internal VA WMC data, the median 2022 VA gastroenterologist salary ranged between $287,976 and $346,435, depending on facility complexity level, excluding recruitment, retention, or relocation bonuses; performance pay; or cash awards. The current aggregate salary cap of $400,000 indicates that the VHA will likely be increasingly noncompetitive in the coming years unless novel pay authorizations are implemented.

Suboptimal human resources were the second most commonly cited impediment to recruiting gastroenterologists. Many section chiefs expressed frustration with the inefficient and slow administrative process of onboarding new gastroenterologists, which may take many months and not infrequently results in losing candidates to competing entities. While this issue is specific to recruitment, recurring and long-standing vacancies can increase work burdens, complicate logistics for remaining faculty, and may also negatively impact retention. One potential opportunity to improve VHA competitiveness is to streamline the administrative component of recruitment and optimize human resources support. The use of a third-party hiring company also should be considered.

Survey responses also indicated that administrative burden and insufficient support staff were significant retention challenges. Several respondents described a lack of efficient endoscopy workflow and delegation of simple administrative tasks to gastroenterologists as more likely in units without proper task distribution. Importantly, these shortcomings occur at the expense of workload-generating activities and career-enhancing opportunities.

While burnout rates among VA gastroenterologists have not been documented systematically, they likely correlate with workplace frustration and jeopardizegastroenterologist retention. Successful retention of gastroenterologists as highly trained medical professionals is more likely in workplaces that are vertically organized, efficient, and use physicians at the top of their skill level.

Conclusions

The VA offers the opportunity for a rewarding lifelong career in gastroenterology. The fulfillment of serving veterans, teaching future health care leaders, performing impactful research, and having job security is invaluable. Despite the tremendous benefits, this survey supports improving VA recruitment and retention strategies for the high-demand gastroenterology specialty. Improved salary parity is needed for workforce maintenance and recruitment, as is improved administrative and clinical support to maintain the high level of care our veterans deserve.

1. Shin A, Xu H, Imperiale TF. The prevalence, humanistic burden, and health care impact of irritable bowel syndrome among united states veterans. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;21(4):1061-1069.e1. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2022.08.005.

2. Kent KG. Prevalence of gastrointestinal disease in US military veterans under outpatient care at the veterans health administration. SAGE Open Med. 2021;9:20503121211049112. doi:10.1177/20503121211049112

3. Beste LA, Leipertz SL, Green PK, Dominitz JA, Ross D, Ioannou GN. Trends in burden of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma by underlying liver disease in US veterans, 2001-2013. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(6):1471-e18. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2015.07.056

4. Zullig LL, Sims KJ, McNeil R, et al. Cancer incidence among patients of the U.S. veterans affairs health care system: 2010 update. Mil Med. 2017;182(7):e1883-e1891. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-16-00371

5. VHA Physician Workforce Resources Blueprint. US Dept of Veterans Affairs. https://dvagov.sharepoint.com/sites/WMCPortal/WFP/Documents/Reports/VHA Physician Workforce Resources Blueprint FY 23-27.pdf [Source not verified]

6. AMN Healthcare. 2022 Review of Physician and Advanced Practitioner Recruiting Incentives. Accessed June 12, 2024. https://www1.amnhealthcare.com/l/123142/2022-07-13/q6ywxg/123142/1657737392vyuONaZZ/mha2022incentivesurgraphic.pdf

7. Medical Group Management Association. MGMA DataDive Provider Compensation Data. Accessed June 12, 2024. https://www.mgma.com/datadive/provider-compensation

8. Anderson JC, Bilal M, Burke CA, et al. Burnout among US gastroenterologists and fellows in training: identifying contributing factors and offering solutions. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2023;57(10):1063-1069. doi:10.1097/MCG.0000000000001781

9. Lacy BE, Chan JL. Physician burnout: the hidden health care crisis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16(3):311-317. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2017.06.043

10. Lieberman DA, Weiss DG, Bond JH, Ahnen DJ, Garewal H, Chejfec G. Use of colonoscopy to screen asymptomatic adults for colorectal cancer. Veterans affairs cooperative study group 380. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(3):162-168. doi:10.1056/NEJM200007203430301

11. Lieberman DA, Weiss DG; Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group 380. One-time screening for colorectal cancer with combined fecal occult-blood testing and examination of the distal colon. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(8):555-560. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa010328

12. Robertson DJ, Dominitz JA, Beed A, et al. Baseline features and reasons for nonparticipation in the colonoscopy versus fecal immunochemical test in reducing mortality from colorectal cancer (CONFIRM) study, a colorectal cancer screening trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(7):e2321730. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.21730

13. Spechler SJ, Hunter JG, Jones KM, et al. Randomized trial of medical versus surgical treatment for refractory heartburn. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(16):1513-1523. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1811424

14. Beste LA, Green PK, Berry K, Kogut MJ, Allison SK, Ioannou GN. Effectiveness of hepatitis C antiviral treatment in a USA cohort of veteran patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2017;67(1):32-39. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2017.02.027

15. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans affairs cooperative studies program (CSP). CSP #2023. Updated July 2022. Accessed June 12, 2024. https://www.vacsp.research.va.gov/CSP_2023/CSP_2023.asp

16. US Health Resources & Services Administration. Workforce projections. Accessed June 12, 2024. https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-workforce/workforce-projections

Veterans have a high burden of digestive diseases, and gastroenterologists are needed for the diagnosis and management of these conditions.1-4 According to the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Workforce Management and Consulting (WMC) office, the physician specialties with the greatest shortages are psychiatry, primary care, and gastroenterology.5 The VHA estimates it must hire 70 new gastroenterologists annually between fiscal years 2023 and 2027 to provide timely digestive care.5

Filling these positions will be increasingly difficult as competition for gastroenterologists is fierce. A recent Merritt Hawkins review states, “Gastroenterologists were the most in-demand type of provider during the 2022 review period.”6 In 2022, the median annual salary for US gastroenterologists was reported to be $561,375.7 Currently, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has an aggregate annual pay limit of $400,000 for all federal employees and cannot compete based on salary alone.

Retention of existing VA gastroenterologists also is challenging. The WMC has reported that 21.6% of VA gastroenterologists are eligible to retire, and in 2021, 8.2% left the VA to retire or seek non-VA positions.5 While not specific to the VA, a survey of practicing gastroenterologists conducted by the American College of Gastroenterology found a 49% burnout rate among respondents.8 Factors contributing to burnout at all career stages included administrative nonclinical work and a lack of clinical support staff.8 Burnout is also linked with higher rates of medical errors, interpersonal conflicts, and patient dissatisfaction. Burnout is more common among those with an innate strong sense of purpose and responsibility for their patients, characteristics we have observed in our VA colleagues.9

As members of the Section Chief Subcommittee of the VA Gastroenterology Field Advisory Board (GI FAB), we are passionate about providing outstanding gastroenterology care to US veterans, and we are alarmed at the struggles we are observing with recruiting and retaining a qualified national gastroenterology physician workforce. As such, we set out to survey the VA gastroenterology section chief community to gain insights into recruitment and retention challenges they have faced and identify potential solutions to these problems.

Methods

The GI FAB Section Chief Subcommittee developed a survey on gastroenterologist recruitment and retention using Microsoft Forms (Appendix). A link to the survey, which included 11 questions about facility location, current vacancies, and free text responses on barriers to recruitment and retention and potential solutions, was sent via email to all gastroenterology section chiefs on the National Gastroenterology and Hepatology Program Office’s email list of section chiefs on January 31, 2023. A reminder to complete the survey was sent to all section chiefs on February 8, 2023. Survey responses were aggregated and analyzed by the authors using descriptive statistics.

Results

The VA gastroenterologist recruitment and retention survey was emailed to 131 gastroenterology section chiefs and completed by 55 respondents (42%) (Figure). Of the responding section chiefs, 36 (65%) reported gastroenterologist vacancies at their facilities. Seventeen respondents (47%) reported a single vacancy, 12 (33%) reported 2 vacancies, 4 (11%) reported 3 vacancies, and 3 (8%) reported 4 vacancies. Of the sites with reported vacancies, 32 (89%) reported a need for a general gastroenterologist, 12 (33%) reported a need for a hepatologist, 11 (31%) reported a need for an advanced endoscopist, 9 (25%) reported a need for a gastroenterologist with specialized expertise in inflammatory bowel diseases, and 1 (3%) reported a need for a gastrointestinal motility specialist.

Numerous barriers to the recruitment and retention of gastroenterologists were reported. Given the large number of respondents that reported a unique barrier (ie, being the only respondents to report the barrier), a decision was made to include only barriers to recruitment and retention that were reported by at least 2 sites (Table). While there were some common themes, the reported barriers to retention differed from those to recruitment. The most reported barriers to recruitment were 46 respondents who noted salary, 23 reported human resources-related challenges, and 12 reported location. Respondents also noted various retention barriers, including 32 respondents who reported salary barriers; 13 reported administrative burden barriers, 6 reported medical center leadership, and 4 reported burnout.

Survey respondents provided multiple recommendations on how the VA can best support the recruitment and retention of gastroenterologists. The most frequent recommendations were to increase financial compensation by increasing the current aggregate salary cap to > $400,000, increasing the use of recruitment and retention incentives, and ensuring that gastroenterology is on the national Educational Debt Reduction Program (EDRP) list, which facilitates student loan repayment. It was recommended that a third-party company assist with hiring to overcome perceived issues with human resources. Additionally, there were multiple recommendations for improving administrative and clinical support. These included mandating how many support staff should be assigned to each gastroenterologist and providing best practice recommendations for support staff so that gastroenterologists can focus on physician-level work. Recommendations also included having a dedicated gastroenterology practice manager, nurse care coordinators, a colorectal cancer screening/surveillance coordinator, sufficient medical support assistants, and quality improvement personnel tracking ongoing professional practice evaluation data. Survey respondents also highlighted specific suggestions for recruiting recent graduates. These included offering a 4-day work week, as recent graduates place a premium on work-life balance, and ensuring gastroenterologists have individual offices. One respondent commented that gastroenterology fellows seeing VA gastroenterology attendings in cramped, shared offices, contrasted with private practice gastroenterologists in large private offices, may contribute to choosing private practice over joining the VA.

Discussion

Gastroenterology is currently listed by VHA WMC as 1 of the top 3 medical specialties in the VA with the most physician shortages.5 Working as a physician in the VA has long been recognized to have many benefits. First and foremost, many physicians are motivated by the VA mission to serve veterans, as this offers personal fulfillment and other intangible benefits. In addition, the VA can provide work-life balance, which is often not possible in fee-for-service settings, with patient panels and call volumes typically lower than in comparable private hospital settings. Moreover, VA physicians have outstanding teaching opportunities, as the VA is the largest supporter of medical education, with postgraduate trainees rotating through > 150 VA medical centers. Likewise, the VA offers a variety of student loan repayment programs (eg, the Specialty Education Loan Repayment Program and the EDRP). The VA offers research funding such as the Cooperative Studies Programs or program project funding, and rewards in parallel with the National Institute of Health (eg, career development awards, or merit review awards) and other grants. VA researchers have conducted many landmark studies that continue to shape the practice of gastroenterology and hepatology. From the earliest studies to demonstrate the effectiveness of screening colonoscopy, to the largest ongoing clinical trial in US history to assess the effectiveness of fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) vs screening colonoscopy.10-12 The VA has also led the field in the study of gastroesophageal reflux disease, hepatitis C treatment, and liver cancer screening.13-15 VA physicians also benefit from participation in the Federal Employee Retirement System, including its pension system.

These benefits apply to all medical specialties, making the VA a potentially appealing workplace for gastroenterologists. However, recent trends indicate that recruitment and retention of gastroenterologists is increasingly challenging, as the VA gastroenterology workforce grew by 5.0% in fiscal year (FY) 2020 and 1.8% in FY 2021. However, it was on track to end FY 2022 with a loss (-1.1%).5 It must be noted that this trend is not limited to the VA, and the National Center for Health Workforce Analysis predicts that gastroenterology will remain among the highest projected specialty shortages. Driven by increased demand for digestive health care services, more physicians nearing traditional retirement age, and substantially higher rates of burnout after the COVID-19 pandemic.16 All these factors are likely to result in an increasingly competitive market for gastroenterology, highlight the growing differences between VA and non-VA positions, and may augment the impact of differences for the individual gastroenterologist weighing employment options within and outside the VA.

The survey responses from VA gastroenterology section chiefs help identify potential impediments to the successful recruitment and retention in the specialty. Noncompetitive salary was the most significant barrier to the successful recruitment of gastroenterologists, identified by 46 of 55 respondents. According to a 2022 Medical Group Management Association report, the median annual salary for US gastroenterologists was $561,375.7 According to internal VA WMC data, the median 2022 VA gastroenterologist salary ranged between $287,976 and $346,435, depending on facility complexity level, excluding recruitment, retention, or relocation bonuses; performance pay; or cash awards. The current aggregate salary cap of $400,000 indicates that the VHA will likely be increasingly noncompetitive in the coming years unless novel pay authorizations are implemented.

Suboptimal human resources were the second most commonly cited impediment to recruiting gastroenterologists. Many section chiefs expressed frustration with the inefficient and slow administrative process of onboarding new gastroenterologists, which may take many months and not infrequently results in losing candidates to competing entities. While this issue is specific to recruitment, recurring and long-standing vacancies can increase work burdens, complicate logistics for remaining faculty, and may also negatively impact retention. One potential opportunity to improve VHA competitiveness is to streamline the administrative component of recruitment and optimize human resources support. The use of a third-party hiring company also should be considered.

Survey responses also indicated that administrative burden and insufficient support staff were significant retention challenges. Several respondents described a lack of efficient endoscopy workflow and delegation of simple administrative tasks to gastroenterologists as more likely in units without proper task distribution. Importantly, these shortcomings occur at the expense of workload-generating activities and career-enhancing opportunities.

While burnout rates among VA gastroenterologists have not been documented systematically, they likely correlate with workplace frustration and jeopardizegastroenterologist retention. Successful retention of gastroenterologists as highly trained medical professionals is more likely in workplaces that are vertically organized, efficient, and use physicians at the top of their skill level.

Conclusions

The VA offers the opportunity for a rewarding lifelong career in gastroenterology. The fulfillment of serving veterans, teaching future health care leaders, performing impactful research, and having job security is invaluable. Despite the tremendous benefits, this survey supports improving VA recruitment and retention strategies for the high-demand gastroenterology specialty. Improved salary parity is needed for workforce maintenance and recruitment, as is improved administrative and clinical support to maintain the high level of care our veterans deserve.

Veterans have a high burden of digestive diseases, and gastroenterologists are needed for the diagnosis and management of these conditions.1-4 According to the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Workforce Management and Consulting (WMC) office, the physician specialties with the greatest shortages are psychiatry, primary care, and gastroenterology.5 The VHA estimates it must hire 70 new gastroenterologists annually between fiscal years 2023 and 2027 to provide timely digestive care.5

Filling these positions will be increasingly difficult as competition for gastroenterologists is fierce. A recent Merritt Hawkins review states, “Gastroenterologists were the most in-demand type of provider during the 2022 review period.”6 In 2022, the median annual salary for US gastroenterologists was reported to be $561,375.7 Currently, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has an aggregate annual pay limit of $400,000 for all federal employees and cannot compete based on salary alone.

Retention of existing VA gastroenterologists also is challenging. The WMC has reported that 21.6% of VA gastroenterologists are eligible to retire, and in 2021, 8.2% left the VA to retire or seek non-VA positions.5 While not specific to the VA, a survey of practicing gastroenterologists conducted by the American College of Gastroenterology found a 49% burnout rate among respondents.8 Factors contributing to burnout at all career stages included administrative nonclinical work and a lack of clinical support staff.8 Burnout is also linked with higher rates of medical errors, interpersonal conflicts, and patient dissatisfaction. Burnout is more common among those with an innate strong sense of purpose and responsibility for their patients, characteristics we have observed in our VA colleagues.9

As members of the Section Chief Subcommittee of the VA Gastroenterology Field Advisory Board (GI FAB), we are passionate about providing outstanding gastroenterology care to US veterans, and we are alarmed at the struggles we are observing with recruiting and retaining a qualified national gastroenterology physician workforce. As such, we set out to survey the VA gastroenterology section chief community to gain insights into recruitment and retention challenges they have faced and identify potential solutions to these problems.

Methods

The GI FAB Section Chief Subcommittee developed a survey on gastroenterologist recruitment and retention using Microsoft Forms (Appendix). A link to the survey, which included 11 questions about facility location, current vacancies, and free text responses on barriers to recruitment and retention and potential solutions, was sent via email to all gastroenterology section chiefs on the National Gastroenterology and Hepatology Program Office’s email list of section chiefs on January 31, 2023. A reminder to complete the survey was sent to all section chiefs on February 8, 2023. Survey responses were aggregated and analyzed by the authors using descriptive statistics.

Results

The VA gastroenterologist recruitment and retention survey was emailed to 131 gastroenterology section chiefs and completed by 55 respondents (42%) (Figure). Of the responding section chiefs, 36 (65%) reported gastroenterologist vacancies at their facilities. Seventeen respondents (47%) reported a single vacancy, 12 (33%) reported 2 vacancies, 4 (11%) reported 3 vacancies, and 3 (8%) reported 4 vacancies. Of the sites with reported vacancies, 32 (89%) reported a need for a general gastroenterologist, 12 (33%) reported a need for a hepatologist, 11 (31%) reported a need for an advanced endoscopist, 9 (25%) reported a need for a gastroenterologist with specialized expertise in inflammatory bowel diseases, and 1 (3%) reported a need for a gastrointestinal motility specialist.

Numerous barriers to the recruitment and retention of gastroenterologists were reported. Given the large number of respondents that reported a unique barrier (ie, being the only respondents to report the barrier), a decision was made to include only barriers to recruitment and retention that were reported by at least 2 sites (Table). While there were some common themes, the reported barriers to retention differed from those to recruitment. The most reported barriers to recruitment were 46 respondents who noted salary, 23 reported human resources-related challenges, and 12 reported location. Respondents also noted various retention barriers, including 32 respondents who reported salary barriers; 13 reported administrative burden barriers, 6 reported medical center leadership, and 4 reported burnout.

Survey respondents provided multiple recommendations on how the VA can best support the recruitment and retention of gastroenterologists. The most frequent recommendations were to increase financial compensation by increasing the current aggregate salary cap to > $400,000, increasing the use of recruitment and retention incentives, and ensuring that gastroenterology is on the national Educational Debt Reduction Program (EDRP) list, which facilitates student loan repayment. It was recommended that a third-party company assist with hiring to overcome perceived issues with human resources. Additionally, there were multiple recommendations for improving administrative and clinical support. These included mandating how many support staff should be assigned to each gastroenterologist and providing best practice recommendations for support staff so that gastroenterologists can focus on physician-level work. Recommendations also included having a dedicated gastroenterology practice manager, nurse care coordinators, a colorectal cancer screening/surveillance coordinator, sufficient medical support assistants, and quality improvement personnel tracking ongoing professional practice evaluation data. Survey respondents also highlighted specific suggestions for recruiting recent graduates. These included offering a 4-day work week, as recent graduates place a premium on work-life balance, and ensuring gastroenterologists have individual offices. One respondent commented that gastroenterology fellows seeing VA gastroenterology attendings in cramped, shared offices, contrasted with private practice gastroenterologists in large private offices, may contribute to choosing private practice over joining the VA.

Discussion

Gastroenterology is currently listed by VHA WMC as 1 of the top 3 medical specialties in the VA with the most physician shortages.5 Working as a physician in the VA has long been recognized to have many benefits. First and foremost, many physicians are motivated by the VA mission to serve veterans, as this offers personal fulfillment and other intangible benefits. In addition, the VA can provide work-life balance, which is often not possible in fee-for-service settings, with patient panels and call volumes typically lower than in comparable private hospital settings. Moreover, VA physicians have outstanding teaching opportunities, as the VA is the largest supporter of medical education, with postgraduate trainees rotating through > 150 VA medical centers. Likewise, the VA offers a variety of student loan repayment programs (eg, the Specialty Education Loan Repayment Program and the EDRP). The VA offers research funding such as the Cooperative Studies Programs or program project funding, and rewards in parallel with the National Institute of Health (eg, career development awards, or merit review awards) and other grants. VA researchers have conducted many landmark studies that continue to shape the practice of gastroenterology and hepatology. From the earliest studies to demonstrate the effectiveness of screening colonoscopy, to the largest ongoing clinical trial in US history to assess the effectiveness of fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) vs screening colonoscopy.10-12 The VA has also led the field in the study of gastroesophageal reflux disease, hepatitis C treatment, and liver cancer screening.13-15 VA physicians also benefit from participation in the Federal Employee Retirement System, including its pension system.

These benefits apply to all medical specialties, making the VA a potentially appealing workplace for gastroenterologists. However, recent trends indicate that recruitment and retention of gastroenterologists is increasingly challenging, as the VA gastroenterology workforce grew by 5.0% in fiscal year (FY) 2020 and 1.8% in FY 2021. However, it was on track to end FY 2022 with a loss (-1.1%).5 It must be noted that this trend is not limited to the VA, and the National Center for Health Workforce Analysis predicts that gastroenterology will remain among the highest projected specialty shortages. Driven by increased demand for digestive health care services, more physicians nearing traditional retirement age, and substantially higher rates of burnout after the COVID-19 pandemic.16 All these factors are likely to result in an increasingly competitive market for gastroenterology, highlight the growing differences between VA and non-VA positions, and may augment the impact of differences for the individual gastroenterologist weighing employment options within and outside the VA.

The survey responses from VA gastroenterology section chiefs help identify potential impediments to the successful recruitment and retention in the specialty. Noncompetitive salary was the most significant barrier to the successful recruitment of gastroenterologists, identified by 46 of 55 respondents. According to a 2022 Medical Group Management Association report, the median annual salary for US gastroenterologists was $561,375.7 According to internal VA WMC data, the median 2022 VA gastroenterologist salary ranged between $287,976 and $346,435, depending on facility complexity level, excluding recruitment, retention, or relocation bonuses; performance pay; or cash awards. The current aggregate salary cap of $400,000 indicates that the VHA will likely be increasingly noncompetitive in the coming years unless novel pay authorizations are implemented.

Suboptimal human resources were the second most commonly cited impediment to recruiting gastroenterologists. Many section chiefs expressed frustration with the inefficient and slow administrative process of onboarding new gastroenterologists, which may take many months and not infrequently results in losing candidates to competing entities. While this issue is specific to recruitment, recurring and long-standing vacancies can increase work burdens, complicate logistics for remaining faculty, and may also negatively impact retention. One potential opportunity to improve VHA competitiveness is to streamline the administrative component of recruitment and optimize human resources support. The use of a third-party hiring company also should be considered.

Survey responses also indicated that administrative burden and insufficient support staff were significant retention challenges. Several respondents described a lack of efficient endoscopy workflow and delegation of simple administrative tasks to gastroenterologists as more likely in units without proper task distribution. Importantly, these shortcomings occur at the expense of workload-generating activities and career-enhancing opportunities.

While burnout rates among VA gastroenterologists have not been documented systematically, they likely correlate with workplace frustration and jeopardizegastroenterologist retention. Successful retention of gastroenterologists as highly trained medical professionals is more likely in workplaces that are vertically organized, efficient, and use physicians at the top of their skill level.

Conclusions

The VA offers the opportunity for a rewarding lifelong career in gastroenterology. The fulfillment of serving veterans, teaching future health care leaders, performing impactful research, and having job security is invaluable. Despite the tremendous benefits, this survey supports improving VA recruitment and retention strategies for the high-demand gastroenterology specialty. Improved salary parity is needed for workforce maintenance and recruitment, as is improved administrative and clinical support to maintain the high level of care our veterans deserve.

1. Shin A, Xu H, Imperiale TF. The prevalence, humanistic burden, and health care impact of irritable bowel syndrome among united states veterans. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;21(4):1061-1069.e1. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2022.08.005.

2. Kent KG. Prevalence of gastrointestinal disease in US military veterans under outpatient care at the veterans health administration. SAGE Open Med. 2021;9:20503121211049112. doi:10.1177/20503121211049112

3. Beste LA, Leipertz SL, Green PK, Dominitz JA, Ross D, Ioannou GN. Trends in burden of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma by underlying liver disease in US veterans, 2001-2013. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(6):1471-e18. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2015.07.056

4. Zullig LL, Sims KJ, McNeil R, et al. Cancer incidence among patients of the U.S. veterans affairs health care system: 2010 update. Mil Med. 2017;182(7):e1883-e1891. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-16-00371

5. VHA Physician Workforce Resources Blueprint. US Dept of Veterans Affairs. https://dvagov.sharepoint.com/sites/WMCPortal/WFP/Documents/Reports/VHA Physician Workforce Resources Blueprint FY 23-27.pdf [Source not verified]

6. AMN Healthcare. 2022 Review of Physician and Advanced Practitioner Recruiting Incentives. Accessed June 12, 2024. https://www1.amnhealthcare.com/l/123142/2022-07-13/q6ywxg/123142/1657737392vyuONaZZ/mha2022incentivesurgraphic.pdf

7. Medical Group Management Association. MGMA DataDive Provider Compensation Data. Accessed June 12, 2024. https://www.mgma.com/datadive/provider-compensation

8. Anderson JC, Bilal M, Burke CA, et al. Burnout among US gastroenterologists and fellows in training: identifying contributing factors and offering solutions. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2023;57(10):1063-1069. doi:10.1097/MCG.0000000000001781

9. Lacy BE, Chan JL. Physician burnout: the hidden health care crisis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16(3):311-317. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2017.06.043

10. Lieberman DA, Weiss DG, Bond JH, Ahnen DJ, Garewal H, Chejfec G. Use of colonoscopy to screen asymptomatic adults for colorectal cancer. Veterans affairs cooperative study group 380. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(3):162-168. doi:10.1056/NEJM200007203430301

11. Lieberman DA, Weiss DG; Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group 380. One-time screening for colorectal cancer with combined fecal occult-blood testing and examination of the distal colon. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(8):555-560. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa010328

12. Robertson DJ, Dominitz JA, Beed A, et al. Baseline features and reasons for nonparticipation in the colonoscopy versus fecal immunochemical test in reducing mortality from colorectal cancer (CONFIRM) study, a colorectal cancer screening trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(7):e2321730. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.21730

13. Spechler SJ, Hunter JG, Jones KM, et al. Randomized trial of medical versus surgical treatment for refractory heartburn. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(16):1513-1523. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1811424

14. Beste LA, Green PK, Berry K, Kogut MJ, Allison SK, Ioannou GN. Effectiveness of hepatitis C antiviral treatment in a USA cohort of veteran patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2017;67(1):32-39. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2017.02.027

15. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans affairs cooperative studies program (CSP). CSP #2023. Updated July 2022. Accessed June 12, 2024. https://www.vacsp.research.va.gov/CSP_2023/CSP_2023.asp

16. US Health Resources & Services Administration. Workforce projections. Accessed June 12, 2024. https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-workforce/workforce-projections

1. Shin A, Xu H, Imperiale TF. The prevalence, humanistic burden, and health care impact of irritable bowel syndrome among united states veterans. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;21(4):1061-1069.e1. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2022.08.005.

2. Kent KG. Prevalence of gastrointestinal disease in US military veterans under outpatient care at the veterans health administration. SAGE Open Med. 2021;9:20503121211049112. doi:10.1177/20503121211049112

3. Beste LA, Leipertz SL, Green PK, Dominitz JA, Ross D, Ioannou GN. Trends in burden of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma by underlying liver disease in US veterans, 2001-2013. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(6):1471-e18. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2015.07.056

4. Zullig LL, Sims KJ, McNeil R, et al. Cancer incidence among patients of the U.S. veterans affairs health care system: 2010 update. Mil Med. 2017;182(7):e1883-e1891. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-16-00371

5. VHA Physician Workforce Resources Blueprint. US Dept of Veterans Affairs. https://dvagov.sharepoint.com/sites/WMCPortal/WFP/Documents/Reports/VHA Physician Workforce Resources Blueprint FY 23-27.pdf [Source not verified]

6. AMN Healthcare. 2022 Review of Physician and Advanced Practitioner Recruiting Incentives. Accessed June 12, 2024. https://www1.amnhealthcare.com/l/123142/2022-07-13/q6ywxg/123142/1657737392vyuONaZZ/mha2022incentivesurgraphic.pdf

7. Medical Group Management Association. MGMA DataDive Provider Compensation Data. Accessed June 12, 2024. https://www.mgma.com/datadive/provider-compensation

8. Anderson JC, Bilal M, Burke CA, et al. Burnout among US gastroenterologists and fellows in training: identifying contributing factors and offering solutions. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2023;57(10):1063-1069. doi:10.1097/MCG.0000000000001781

9. Lacy BE, Chan JL. Physician burnout: the hidden health care crisis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16(3):311-317. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2017.06.043

10. Lieberman DA, Weiss DG, Bond JH, Ahnen DJ, Garewal H, Chejfec G. Use of colonoscopy to screen asymptomatic adults for colorectal cancer. Veterans affairs cooperative study group 380. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(3):162-168. doi:10.1056/NEJM200007203430301

11. Lieberman DA, Weiss DG; Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group 380. One-time screening for colorectal cancer with combined fecal occult-blood testing and examination of the distal colon. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(8):555-560. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa010328

12. Robertson DJ, Dominitz JA, Beed A, et al. Baseline features and reasons for nonparticipation in the colonoscopy versus fecal immunochemical test in reducing mortality from colorectal cancer (CONFIRM) study, a colorectal cancer screening trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(7):e2321730. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.21730

13. Spechler SJ, Hunter JG, Jones KM, et al. Randomized trial of medical versus surgical treatment for refractory heartburn. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(16):1513-1523. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1811424

14. Beste LA, Green PK, Berry K, Kogut MJ, Allison SK, Ioannou GN. Effectiveness of hepatitis C antiviral treatment in a USA cohort of veteran patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2017;67(1):32-39. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2017.02.027

15. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans affairs cooperative studies program (CSP). CSP #2023. Updated July 2022. Accessed June 12, 2024. https://www.vacsp.research.va.gov/CSP_2023/CSP_2023.asp

16. US Health Resources & Services Administration. Workforce projections. Accessed June 12, 2024. https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-workforce/workforce-projections

Implementation of a population-based cirrhosis identification and management system

Cirrhosis-related morbidity and mortality is potentially preventable. Antiviral treatment in patients with cirrhosis-related to hepatitis C virus (HCV) or hepatitis B virus can prevent complications.1-3 Beta-blockers and endoscopic treatments of esophageal varices are effective in primary prophylaxis of variceal hemorrhage.4 Surveillance for hepatocellular cancer is associated with increased detection of early-stage cancer and improved survival.5 However, many patients with cirrhosis are either not diagnosed in a primary care setting, or even when diagnosed, not seen or referred to specialty clinics to receive disease-specific care,6 and thus remain at high risk for complications.

Our goal was to implement a population-based cirrhosis identification and management system (P-CIMS) to allow identification of all patients with potential cirrhosis in the health care system and to facilitate their linkage to specialty liver care. We describe the implementation of P-CIMS at a large Veterans Health Administration (VHA) hospital and present initial results about its impact on patient care.

P-CIMS Intervention

P-CIMS is a multicomponent intervention that includes a secure web-based tracking system, standardized communication templates, and care coordination protocols.

Web-based tracking system

An interdisciplinary team of clinicians, programmers, and informatics experts developed the P-CIMS software program by extending an existing comprehensive care tracking system.7 The P-CIMS program (referred to as cirrhosis tracker) extracts information from VHA’s national corporate data warehouse. VHA corporate data warehouse includes diagnosis codes, laboratory test results, vital status, and pharmacy data for each encounter in the VA since October 1999. We designed the cirrhosis tracker program to identify patients who had outpatient or inpatient encounters in the last 3 years with either at least 1 cirrhosis diagnosis (defined as any instance of previously validated International Classification of Diseases-9 and -10 codes)8; or possible cirrhosis (defined as either aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index greater than 2.0 or Fibrosis-4 above 3.24 in patients with active HCV infection9 [defined based on positive HCV RNA or genotype test results]).

The user interface of the cirrhosis tracker is designed for easy patient lookup with live links to patient information extracted from the corporate data warehouse (recent laboratory test results, recent imaging studies, and appointments). The tracker also includes free-text fields that store follow-up information and alerting functions that remind the end user when to follow up with a patient. Supplementary Figure 1 shows screen-shots from the program.

We refined the program through an iterative process to ensure accuracy and completeness of data. Each data element (e.g., cirrhosis diagnosis, laboratory tests, clinic appointments) was validated using the full electronic medical record as the reference standard; this process occurred over a period of 9 months. The program can run to update patient data on a daily basis.

Standardized communication templates and care coordination protocols

Our interdisciplinary team created chart review note templates for use in the VHA electronic medical record to verify diagnosis of cirrhosis and to facilitate accurate communication with primary care providers (PCPs) and other specialty clinicians. We also designed standard patient letters to communicate the recommendations with patients. We established protocols for initial clinical reviews, patient outreach, scheduling, and follow-ups. These care coordination protocols were modified in an iterative manner during the implementation phase of P-CIMS.

Setting and patients

Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center (MEDVAMC) in Houston provides care to more than 111,000 veterans, including more than 3,800 patients with cirrhosis. At the time of P-CIMS implementation, there were three hepatologists and four advanced practice providers (APP) who provided liver-related care at the MEDVAMC.

The primary goal of the initial phase of implementation was to link patients with cirrhosis to regular liver-related care. Thus, the sample was limited to patients who did not have ongoing specialty care (i.e., no liver clinic visits in the last 6 months, including patients who were never seen in liver clinics).

Implementation strategy

We used implementation facilitation (IF), an evidence-based strategy, to implement P-CIMS.10 The IF team included facilitators (F.K., D.S.), local champions (S.M., K.H.), and technical support personnel (e.g., tracker programmers). Core components of IF were leadership engagement, creation of and regular engagement with a local stakeholder group of clinicians, educational outreach to clinicians and support staff, and problem solving. The IF activities took part in two phases: preimplementation and implementation.

Preimplementation phase

We interviewed key stakeholders to identify facilitators and barriers to P-CIMS implementation. One of the implementation facilitators (F.K.) obtained facility and clinical section’s leadership support, engaged key stakeholders, and devised a local implementation plan. Stakeholders included leadership in several disciplines: hepatology, infectious diseases, and primary care. We developed a map of clinical workflow processes to describe optimal integration of P-CIMS into existing workflow (Supplementary Figure 2).

Implementation phase

The facilitators met regularly (biweekly for the first year) with the stakeholder group including local champions and clinical staff. One of the facilitators (D.S.) served as the liaison between the P-CIMS team (F.K., A.M., R.M., T.T.) and the clinic staff to ensure that no patients were getting missed and to follow through on patient referrals to care. The programmers troubleshot technical issues that arose, and both facilitators worked with clinical staff to modify workflow as needed. At the start of IF, the facilitator conducted an initial round of trainings through in-person training or with the use of screen-sharing software. The impact of P-CIMS on patient care was tracked and feedback was provided to clinical staff on a quarterly basis.

Implementation results: Linkage to liver specialty care

P-CIMS was successfully implemented at the MEDVAMC. Patient data were first extracted in October 2015 with five updates through March 2017. In total, four APP, one MD, and the facilitator used the cirrhosis tracker on a regular basis. The clinical team (APP) conducted the initial review, triage, and outreach. It took on average 7 minutes (range, 2–20 minutes) for the initial review and outreach. The APPs entered each follow-up reminder in the tracker. For example, if they negotiated a liver clinic appointment with the patient, then they entered a reminder to follow up with the date by which this step (patient seen in liver clinic) should be completed. The tracker has a built-in alerting function. The implementation team was notified (via the tracker) when these tasks were due to ensure timely receipt of recommended care processes.

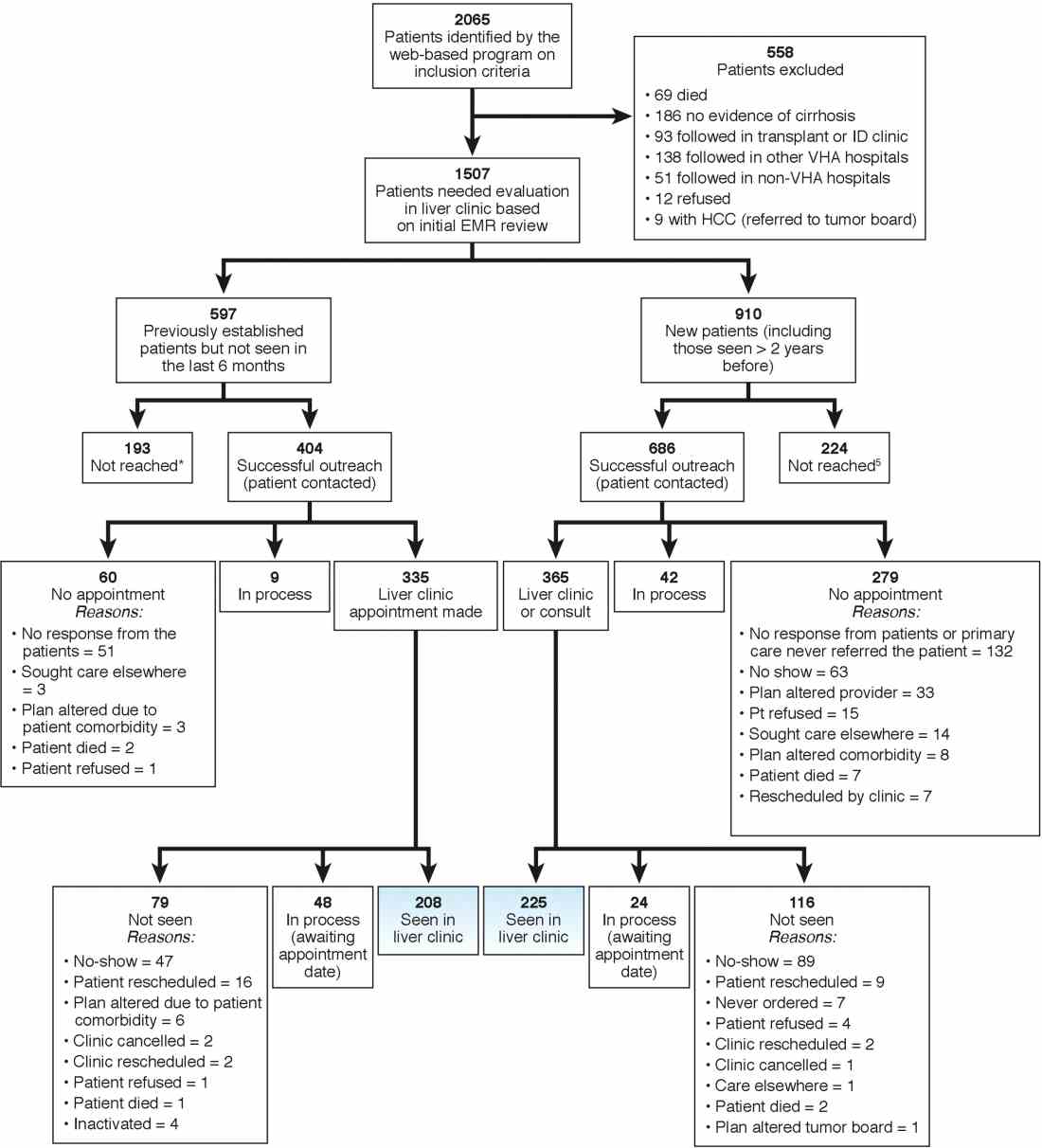

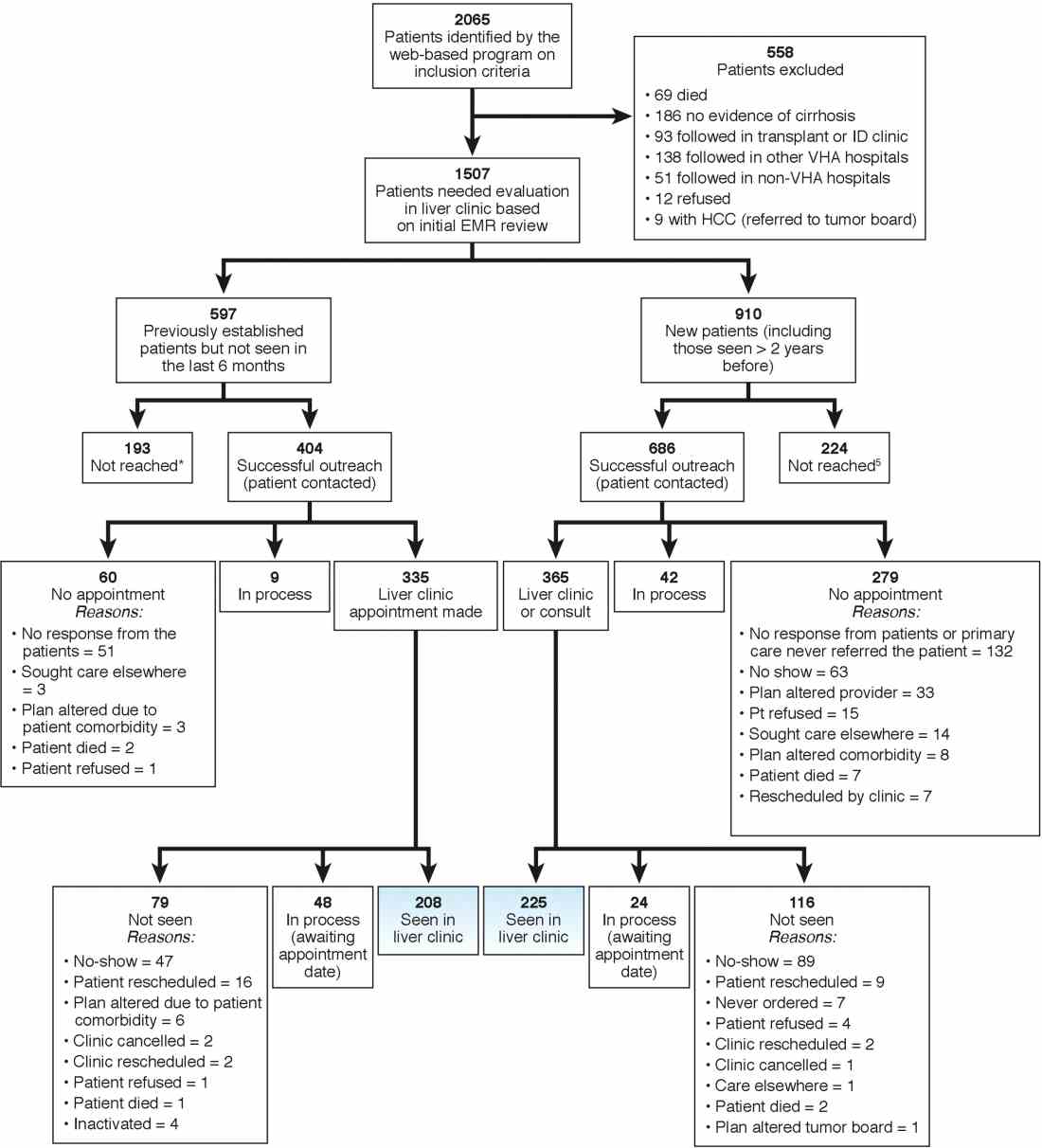

We identified 2,065 patients who met the case definition of cirrhosis (diagnosed and potentially undiagnosed) and were not in regular liver care. Based on initial review, 1,507 patients had an indication to be seen in the liver clinic. Among the remaining 558, the most common reasons for not requiring liver clinic follow-up were: being seen in other facilities (138 in other VHA and 51 in outside hospitals), followed in other specialty clinics (e.g., liver transplant or infectious disease, n = 93), or absence of cirrhosis based on initial review (n = 165) (see Figure 1 for other reasons).

We used two different strategies to reach out to the patients. Of the 1,507 patients, 597 were previously seen in the liver clinics but were lost to follow-up. These patients were contacted directly by the liver clinic staff. The other 910 patients with cirrhosis (of 1,507) had never been seen in the ambulatory liver clinics (n = 559) or were seen more than 2 years before the implementation of cirrhosis tracker (n = 351). These patients were reached through their PCPs. We used standard electronic medical record templates to request PCP’s assistance in reviewing patients' records and submitting a liver consultation after they discussed the need for liver evaluation with the patient.

Of the 597 patients who were previously seen but lost to follow-up, we successfully contacted 404 (67.7%) patients via telephone and/or letters (for the latter, success was defined when patients called back); of these 335 (82.9%) patients had clinic appointments scheduled. In total, 208 (51.5% of 404; 34.8% of 597) patients were subsequently seen in the liver clinics during a median of 12-month follow-up. As shown in Figure 1, the most common reasons for inability to successfully link patients to the clinic were at the patient level, including no show, cancellation, and noninterest in seeking liver care. It took on average 1.5 attempts (range, 1–4) to link 214 patients to the liver clinic.

Of the other 910 patients with cirrhosis, 686 (75.4%) were successfully contacted; and of these 365 (53.2%) patients had liver clinic appointments scheduled. In total, 225 (61.7% of 365; 24.7% of 910) patients were seen in the liver clinics during a median of 12-month follow-up. The reasons underlying inability to link patients to liver specialty clinics are listed in Figure 1 and included shortfalls at the PCP and the patient levels. It took on average 2.4 attempts (range, 1–5) to link 225 patients to the liver clinic.

A total of 124 patients were initiated on direct-acting antiviral agents for HCV treatment and 18 new hepatocellular carcinoma cases were diagnosed as part of P-CIMS.

Discussion and future directions

We learned several lessons during this initiative. First, it was critical to allow time to iteratively revise the cirrhosis tracker program, with input from key stakeholders, including clinician end users. For example, based on feedback, the program was modified to exclude patients who had died or those who were seeking primary care at other VHA facilities. Second, merely having a program that accurately identifies patients with cirrhosis is not the same as knowing how to get organizations and providers to use it. We found that it was critical to involve local leadership and key stakeholders in the preimplementation phase to foster active ownership of P-CIMS and to encourage the rise of natural champions. Additionally, we focused on integrating P-CIMS in the existing workflow. We also had to be cognizant of the needs of patients, such as potential problems with communication relating to notification and appointments for evaluation. Third, several elements at the facility level played a key role in the successful implementation of P-CIMS, including the culture of the facility (commitment to quality improvement); leadership engagement; and perceived need for and relative priority of identifying and managing patients with cirrhosis, especially those with chronic HCV. We also had strong buy-in from the VHA National Program Office tasked with improving care for those with liver disease, which provided support for development of the cirrhosis tracker.

Overall, our early results show that about 30% of patients with cirrhosis without ongoing linkage to liver care were seen in the liver specialty clinics because of P-CIMS. This proportion should be interpreted in the context of the patient population and setting. Cirrhosis disproportionately affects vulnerable patients, including those who are impoverished, homeless, and with drug- and alcohol-related problems; a complex population who often have difficulty staying in care. Most patients in our sample had no linkage with specialty care. It is plausible that some patients with cirrhosis would have been seen in the liver clinics, regardless of P-CIMS. However, we expect this proportion would have been substantially lower than the 30% observed with P-CIMS.

We found several barriers to successful linkage and identified possible solutions. Our results suggest that a direct outreach to patients (without going through PCP) may result in fewer failures to linkage. In total, about 35% of patients who were contacted directly by the liver clinic met the endpoint compared with about 25% of patients who were contacted via their PCP. Future iterations of P-CIMS will rely on direct outreach for most patients. We also found that many patients were unable to keep scheduled appointments; some of this was because of inability to come on specific days and times. Open-access clinics may be one way to accommodate these high-risk patients. Although a full cost-effectiveness analysis is beyond the scope of this report, annual cost of maintaining P-CIMS was less than $100,000 (facilitator and programming support), which is equivalent to antiviral treatment cost of four to five HCV patients, suggesting that P-CIMS (with ability to reach out to hundreds of patients) may indeed be cost effective (if not cost saving).

In summary, we built and successfully implemented a population-based health management system with a structured care coordination strategy to facilitate identification and linkage to care of patients with cirrhosis. Our initial results suggest modest success in managing a complex population who often have difficulty staying in care. The next steps include comparing the rates of linkage to specialty care with rates in comparable facilities that did not use the tracker; broadening the scope to ensure patients are retained in care and receive guideline-concordant care over time. We will share these results in a subsequent manuscript. To our knowledge, cirrhosis tracker is the first informatics tool that leverages data from the electronic medical records with other tools and strategies to improve quality of cirrhosis care. We believe that the lessons that we learned can also help inform efforts to design programs that encourage use of administrative data–based risk screeners to identify patients with other chronic conditions who are at risk for suboptimal outcomes.

References

1. Backus LI, Boothroyd DB, Phillips BR, et al. A sustained virologic response reduces risk of all-cause mortality in patients with hepatitis C. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:509-16.

2. Kanwal F, Kramer J, Asch SM, et al. Risk of hepatocellular cancer in HCV patients treated with direct-acting antiviral agents. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:996-1005.

3. Liaw YF, Sung JJ, Chow WC, et al. Lamivudine for patients with chronic hepatitis B and advanced liver disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1521-31.

4. Gluud LL, Klingenberg S, Nikolova D, et al. Banding ligation versus beta-blockers as primary prophylaxis in esophageal varices: systematic review of randomized trials. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2842-8.

5. Singal AG, Mittal S, Yerokun OA, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma screening associated with early tumor detection and improved survival among patients with cirrhosis in the US. Am J Med. 2017;130:1099-106.

6. Kanwal F, Volk M, Singal A, et al. Improving quality of health care for patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:1204-7.

7. Taddei T, Hunnibell L, DeLorenzo A, et al. EMR-linked cancer tracker facilitates lung and liver cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:77.

8. Kramer JR, Davila JA, Miller ED, et al. The validity of viral hepatitis and chronic liver disease diagnoses in Veterans Affairs administrative databases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:274-82.

9. Chou R, Wasson N. Blood tests to diagnose fibrosis or cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:807-20.

10. Kirchner JE, Ritchie MJ, Pitcock JA, et al. Outcomes of a partnered facilitation strategy to implement primary care-mental health. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29:904-12.

Dr. Kanwal is professor of medicine, chief of gastroenterology and hepatology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston Veterans Affairs HSR&D Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center; Dr. Mapakshi is a fellow in gastroenterology and hepatology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston Veterans Affairs HSR&D Centerof Excellence, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center; Ms. Smith is project manager at Houston Veterans Affairs HSR&D Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center; Dr. Taddei is director of the HCC Initiative, VA Connecticut Healthcare System, associate professor of medicine, digestive diseases, Yale University School of Medicine, director, liver cancer team, Smilow Cancer Hospital at Yale New Haven Hospital; Dr. Hussain is assistant professor, Baylor College of Medicine, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center; Ms. Madu is in gastroenterology and hepatology, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center; Ms. Duong is in gastroenterology and hepatology, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center; Dr. White is assistant professor of medicine, health services research, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston Veterans Affairs HSR&D Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center; Ms. Cao is a statistical analyst at Houston Veterans Affairs HSR&D Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center; Ms. Mehta is in Health Services Research at the VA Connecticut Healthcare System, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven; Dr. El-Serag is Chairman and Professor Margaret M. and Albert B. Alkek, department of medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston; Dr. Asch is chief of health service research, director of HSR&D Center for Innovation to Implementation, VA Palo Alto Health Care System , Palo Alto, Calif., professor of medicine, primary care and population health, Stanford, Calif.; Dr. Midboe is co-implementation research coordinator, HIV/Hepatitis QUERI, director VA patient safety center of inquiry, HSR&D Center for Innovation to Implementation, VA Palo Alto Health Care System, Palo Alto, Calif. The authors disclose no conflicts. This material is based on work supported by Department of Veterans Affairs, QUERI Program, QUE 15-284, VA HIV, Hepatitis C, and Related Conditions Program, and VA National Center for Patient Safety. The work is also supported in part by the Veterans Administration Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness and Safety (CIN 13-413); Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center, Houston, Tex.; and the Center for Gastrointestinal Development, Infection and Injury (NIDDK P30 DK 56338).

Cirrhosis-related morbidity and mortality is potentially preventable. Antiviral treatment in patients with cirrhosis-related to hepatitis C virus (HCV) or hepatitis B virus can prevent complications.1-3 Beta-blockers and endoscopic treatments of esophageal varices are effective in primary prophylaxis of variceal hemorrhage.4 Surveillance for hepatocellular cancer is associated with increased detection of early-stage cancer and improved survival.5 However, many patients with cirrhosis are either not diagnosed in a primary care setting, or even when diagnosed, not seen or referred to specialty clinics to receive disease-specific care,6 and thus remain at high risk for complications.

Our goal was to implement a population-based cirrhosis identification and management system (P-CIMS) to allow identification of all patients with potential cirrhosis in the health care system and to facilitate their linkage to specialty liver care. We describe the implementation of P-CIMS at a large Veterans Health Administration (VHA) hospital and present initial results about its impact on patient care.

P-CIMS Intervention

P-CIMS is a multicomponent intervention that includes a secure web-based tracking system, standardized communication templates, and care coordination protocols.

Web-based tracking system

An interdisciplinary team of clinicians, programmers, and informatics experts developed the P-CIMS software program by extending an existing comprehensive care tracking system.7 The P-CIMS program (referred to as cirrhosis tracker) extracts information from VHA’s national corporate data warehouse. VHA corporate data warehouse includes diagnosis codes, laboratory test results, vital status, and pharmacy data for each encounter in the VA since October 1999. We designed the cirrhosis tracker program to identify patients who had outpatient or inpatient encounters in the last 3 years with either at least 1 cirrhosis diagnosis (defined as any instance of previously validated International Classification of Diseases-9 and -10 codes)8; or possible cirrhosis (defined as either aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index greater than 2.0 or Fibrosis-4 above 3.24 in patients with active HCV infection9 [defined based on positive HCV RNA or genotype test results]).

The user interface of the cirrhosis tracker is designed for easy patient lookup with live links to patient information extracted from the corporate data warehouse (recent laboratory test results, recent imaging studies, and appointments). The tracker also includes free-text fields that store follow-up information and alerting functions that remind the end user when to follow up with a patient. Supplementary Figure 1 shows screen-shots from the program.

We refined the program through an iterative process to ensure accuracy and completeness of data. Each data element (e.g., cirrhosis diagnosis, laboratory tests, clinic appointments) was validated using the full electronic medical record as the reference standard; this process occurred over a period of 9 months. The program can run to update patient data on a daily basis.

Standardized communication templates and care coordination protocols

Our interdisciplinary team created chart review note templates for use in the VHA electronic medical record to verify diagnosis of cirrhosis and to facilitate accurate communication with primary care providers (PCPs) and other specialty clinicians. We also designed standard patient letters to communicate the recommendations with patients. We established protocols for initial clinical reviews, patient outreach, scheduling, and follow-ups. These care coordination protocols were modified in an iterative manner during the implementation phase of P-CIMS.

Setting and patients

Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center (MEDVAMC) in Houston provides care to more than 111,000 veterans, including more than 3,800 patients with cirrhosis. At the time of P-CIMS implementation, there were three hepatologists and four advanced practice providers (APP) who provided liver-related care at the MEDVAMC.

The primary goal of the initial phase of implementation was to link patients with cirrhosis to regular liver-related care. Thus, the sample was limited to patients who did not have ongoing specialty care (i.e., no liver clinic visits in the last 6 months, including patients who were never seen in liver clinics).

Implementation strategy

We used implementation facilitation (IF), an evidence-based strategy, to implement P-CIMS.10 The IF team included facilitators (F.K., D.S.), local champions (S.M., K.H.), and technical support personnel (e.g., tracker programmers). Core components of IF were leadership engagement, creation of and regular engagement with a local stakeholder group of clinicians, educational outreach to clinicians and support staff, and problem solving. The IF activities took part in two phases: preimplementation and implementation.

Preimplementation phase

We interviewed key stakeholders to identify facilitators and barriers to P-CIMS implementation. One of the implementation facilitators (F.K.) obtained facility and clinical section’s leadership support, engaged key stakeholders, and devised a local implementation plan. Stakeholders included leadership in several disciplines: hepatology, infectious diseases, and primary care. We developed a map of clinical workflow processes to describe optimal integration of P-CIMS into existing workflow (Supplementary Figure 2).

Implementation phase

The facilitators met regularly (biweekly for the first year) with the stakeholder group including local champions and clinical staff. One of the facilitators (D.S.) served as the liaison between the P-CIMS team (F.K., A.M., R.M., T.T.) and the clinic staff to ensure that no patients were getting missed and to follow through on patient referrals to care. The programmers troubleshot technical issues that arose, and both facilitators worked with clinical staff to modify workflow as needed. At the start of IF, the facilitator conducted an initial round of trainings through in-person training or with the use of screen-sharing software. The impact of P-CIMS on patient care was tracked and feedback was provided to clinical staff on a quarterly basis.

Implementation results: Linkage to liver specialty care

P-CIMS was successfully implemented at the MEDVAMC. Patient data were first extracted in October 2015 with five updates through March 2017. In total, four APP, one MD, and the facilitator used the cirrhosis tracker on a regular basis. The clinical team (APP) conducted the initial review, triage, and outreach. It took on average 7 minutes (range, 2–20 minutes) for the initial review and outreach. The APPs entered each follow-up reminder in the tracker. For example, if they negotiated a liver clinic appointment with the patient, then they entered a reminder to follow up with the date by which this step (patient seen in liver clinic) should be completed. The tracker has a built-in alerting function. The implementation team was notified (via the tracker) when these tasks were due to ensure timely receipt of recommended care processes.

We identified 2,065 patients who met the case definition of cirrhosis (diagnosed and potentially undiagnosed) and were not in regular liver care. Based on initial review, 1,507 patients had an indication to be seen in the liver clinic. Among the remaining 558, the most common reasons for not requiring liver clinic follow-up were: being seen in other facilities (138 in other VHA and 51 in outside hospitals), followed in other specialty clinics (e.g., liver transplant or infectious disease, n = 93), or absence of cirrhosis based on initial review (n = 165) (see Figure 1 for other reasons).

We used two different strategies to reach out to the patients. Of the 1,507 patients, 597 were previously seen in the liver clinics but were lost to follow-up. These patients were contacted directly by the liver clinic staff. The other 910 patients with cirrhosis (of 1,507) had never been seen in the ambulatory liver clinics (n = 559) or were seen more than 2 years before the implementation of cirrhosis tracker (n = 351). These patients were reached through their PCPs. We used standard electronic medical record templates to request PCP’s assistance in reviewing patients' records and submitting a liver consultation after they discussed the need for liver evaluation with the patient.

Of the 597 patients who were previously seen but lost to follow-up, we successfully contacted 404 (67.7%) patients via telephone and/or letters (for the latter, success was defined when patients called back); of these 335 (82.9%) patients had clinic appointments scheduled. In total, 208 (51.5% of 404; 34.8% of 597) patients were subsequently seen in the liver clinics during a median of 12-month follow-up. As shown in Figure 1, the most common reasons for inability to successfully link patients to the clinic were at the patient level, including no show, cancellation, and noninterest in seeking liver care. It took on average 1.5 attempts (range, 1–4) to link 214 patients to the liver clinic.

Of the other 910 patients with cirrhosis, 686 (75.4%) were successfully contacted; and of these 365 (53.2%) patients had liver clinic appointments scheduled. In total, 225 (61.7% of 365; 24.7% of 910) patients were seen in the liver clinics during a median of 12-month follow-up. The reasons underlying inability to link patients to liver specialty clinics are listed in Figure 1 and included shortfalls at the PCP and the patient levels. It took on average 2.4 attempts (range, 1–5) to link 225 patients to the liver clinic.

A total of 124 patients were initiated on direct-acting antiviral agents for HCV treatment and 18 new hepatocellular carcinoma cases were diagnosed as part of P-CIMS.

Discussion and future directions

We learned several lessons during this initiative. First, it was critical to allow time to iteratively revise the cirrhosis tracker program, with input from key stakeholders, including clinician end users. For example, based on feedback, the program was modified to exclude patients who had died or those who were seeking primary care at other VHA facilities. Second, merely having a program that accurately identifies patients with cirrhosis is not the same as knowing how to get organizations and providers to use it. We found that it was critical to involve local leadership and key stakeholders in the preimplementation phase to foster active ownership of P-CIMS and to encourage the rise of natural champions. Additionally, we focused on integrating P-CIMS in the existing workflow. We also had to be cognizant of the needs of patients, such as potential problems with communication relating to notification and appointments for evaluation. Third, several elements at the facility level played a key role in the successful implementation of P-CIMS, including the culture of the facility (commitment to quality improvement); leadership engagement; and perceived need for and relative priority of identifying and managing patients with cirrhosis, especially those with chronic HCV. We also had strong buy-in from the VHA National Program Office tasked with improving care for those with liver disease, which provided support for development of the cirrhosis tracker.

Overall, our early results show that about 30% of patients with cirrhosis without ongoing linkage to liver care were seen in the liver specialty clinics because of P-CIMS. This proportion should be interpreted in the context of the patient population and setting. Cirrhosis disproportionately affects vulnerable patients, including those who are impoverished, homeless, and with drug- and alcohol-related problems; a complex population who often have difficulty staying in care. Most patients in our sample had no linkage with specialty care. It is plausible that some patients with cirrhosis would have been seen in the liver clinics, regardless of P-CIMS. However, we expect this proportion would have been substantially lower than the 30% observed with P-CIMS.