User login

Secure Text Messaging in Healthcare: Latent Threats and Opportunities to Improve Patient Safety

UNINTENDED CONSEQUENCES

Over the past two decades, physicians and nurses practicing in hospital settings have faced an onslaught of challenges in communication, an area frequently cited as critical to providing safe and effective care to patients.1-3 Communication needs have increased significantly as hospitalized patients have become more acute, complex, and technology-dependent, requiring larger healthcare teams comprising subspecialists across multiple disciplines spread across increasingly larger inpatient facilities.4 During this same period, the evolution of mobile phones has led to dramatic shifts in personal communication patterns, with asynchronous text messaging replacing verbal communication.5-7

In response to both the changing communication needs of clinicians and shifting cultural conventions, healthcare systems and providers alike have viewed text messaging as a solution to these growing communication problems. In fact, an entire industry has developed around “secure” and “Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)-compliant” text messaging platforms, which we will refer to below as secure text messaging systems (STMS). These systems offer benefits over carrier-based text messaging given their focus on the healthcare environment and HIPAA compliance. However, hospitals’ rapid adoption of these systems has outpaced our abilities to surveil, recognize, and understand the unintended consequences of transitioning to STMS communication in the hospital setting where failures in communication can be catastrophic. Below, we highlight three critical areas of concern encountered at our institutions and offer five potential mitigating strategies (Table).

CRITICAL AREAS OF CONCERN

Text Messaging is a Form of Alarm Fatigue

Text messaging renders clinicians vulnerable to a unique form of alarm fatigue. The burden of alarm fatigue has been well described in the literature and applies to interruptions to workflow in the electronic medical record and sensory alerts in clinical settings.8,9 Text messaging serves as yet another interruption for healthcare providers. Without a framework to triage urgent versus nonurgent messages, a clinician can become inundated with information and miss critical messages. This can lead to delayed or incorrect responses and impede patient care. System design and implementation can also contribute to this phenomenon. For example, a text message analysis at one center identified how system and workflow design resulted in all messages to an intensive care unit team being routed to a single physician’s phone.10 This design left the singular physician at risk of information and task overload and at the mercy of endless interruptive alerts. Although this can occur with any communication system, it has been well demonstrated that adopting STMS correlates with an increased frequency of messaging, leading to an increase in interruptive alerts, which may have implications for patient safety.11 This type of systems failure is silent unless proactively identified or revealed through a retrospective review of a resulting safety event.

Text Messaging Inappropriately Replaces Critical Communications that Should Happen in Person or by Phone

Text messaging has de-emphasized interpersonal communication skills and behaviors critical for quality and safety in hospital-based care. This concern emerges alongside evidence suggesting that new generations of physician trainees have profoundly different communication habits, preferences, and skillsets based on their experience in a text-heavy, asynchronous world of communication.12 There is reason to worry that reliance on text messaging in healthcare leads to similar alterations in relationships and collaboration as it has in our broader cultural context.13 Academic medical centers in particular should attempt to mitigate the loss of profound and formative learning that occurs during face-to-face encounters between providers of different disciplines, experience levels, and specialties.

Text Messaging Increases the Risk of Communication Error

Finally, text messaging appears to be highly vulnerable to communication errors in the healthcare setting. Prior work emphasizes the importance of nonverbal communication in face-to-face and even voice-to-voice interactions, highlighting the loss of fidelity when using text-only methods to communicate.1 Furthermore, the asynchronous nature of text messaging grants little room for clarification of minor misunderstandings that often arise in text-only communication through minor alterations in punctuation or automatic spelling corrections, a frequent occurrence when using medical terminology. Although a seasoned physician may be able to piece together the issues that deserve further clarification, young residents may be more hesitant to ask clarifying questions and determine the right course of action due to clinical inexperience.

PROPOSED SOLUTIONS

Deliberate Design and Implementation

A recent systematic review identified a lack of high-quality evidence evaluating the impact of mobile technologies on communication and teamwork in hospital settings.14 This paucity of understanding renders communication via STMS in the healthcare setting uniquely vulnerable to latent safety threats unless the design and implementation of these systems are purposeful and proactive.

These concerns led us to postulate that deliberate and proactive implementation of these systems, rather than passive adoption, is needed in the healthcare environment. We propose a number of approaches and interventions that may guide institutions as they seek to implement STMS or redesign communication in the inpatient setting. At the core of these proposals lies an important tension: can implementation of STMS occur in isolation or should the arrival of these systems prompt an overhaul of an institution’s clinical communication system and culture?15

Proactive Surveillance

Surveillance is one proactive method for healthcare systems to understand where and how the implementation of STMS might lead to safety threats. From a quantitative standpoint, understanding the burden of messaging for each user across the system can reveal the clinical roles in the system that are particularly vulnerable to alert fatigue or information overload. Quality assurance monitoring of critical roles in the hospital (ie, airway emergency team, rapid response teams) could be conducted to ensure accurate directory listings at all times. Associating conversations with events, from serious safety events to near misses, could help leaders understand when and how text messaging contributes to safety events and create actionable learnings for safety learning systems.

Standardized Communication

A standardized language eliminates the burden of individuals to parse and translate each individual text message. A standardized algorithm for language, urgency, and expectations (ie, response before escalation) would help define the interaction in the clinical setting.16 Moving toward standardized, meaningful “quick messages,” one of our centers has implemented a campaign to “stick to the FACS,” where the following four standard quick messages are available for users: (1) “FYI no response needed,” (2) “ACTION needed within X min,” (3) “CONCERN can we talk or meet,” and (4) “STAT immediate response required.” These quick messages, developed with frontline stakeholders, represent the majority of requests exchanged by providers, and help standardize expectations and task prioritization.

Targeted Training

Targeted training and culture change efforts might help institutions counteract the broader impact of asynchronous messaging on communication skills and behaviors. Highlighting the contrast between clinical and casual communication with an emphasis on examples, scenarios, or role-playing has the potential to emphasize why and how clinical communication with STMS requires a careful, deliberate approach. For instance, safety culture training at one of our institutions features a scenario that illustrates the potential for miscommunication and missed connection between a nurse and a physician on the wards. The scenario gives way to discussion between participants about the shortcomings of text messaging and allows the facilitator to segue into the “dos and don’ts” of text messaging and when a phone call might be more appropriate.

Innovate

Finally, creatively harnessing the technology and data underlying these STMS may uncover methods to identify and mitigate communication errors in real time. For instance, using trigger methods to create a “ripple in the pond,” whereby a floor nurse reaching out with an urgent text automatically loops in the charge nurse of the unit. Building a chatbot or a virtual assistant functionality by leveraging user behavior patterns and natural language processing to provide text-based guidance to users might help busy clinicians connect to the key decision-makers on their team. For example, in response to an unanswered text, a virtual assistant might reach out to the waiting provider as follows: “you texted the resident 20 minutes ago and they haven’t replied, would you like to call the fellow instead?” The data-rich nature of these systems implies that they are ripe for automated solutions that can respond to behavioral- or text-based patterns to augment the existing operation and safety infrastructure.

CONCLUSION

The transition of healthcare communication systems toward STMS is already well underway. These systems, despite their flaws, are undoubtedly an improvement over legacy paging systems and, if properly implemented, offer several benefits to large healthcare systems. However, the communication needs in the healthcare setting are vastly different from the personal communication needs in everyday text messaging. As clinicians at the forefront of these transitions, we have the opportunity to critically assess the unique communication requirements in our hospital settings and help shape the way STMS are implemented in our hospitals. Pausing to deliberate about the limitations and the vulnerabilities of the current messaging systems for our acute clinical needs, including how they impact training and education, will allow us to proactively design and implement better communication systems that improve patient safety.

1. Sutcliffe KM, Lewton E, Rosenthal MM. Communication failures: an insidious contributor to medical mishaps. Acad Med. 2004;79(2):186-194. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200402000-00019.

2. Ash JS, Berg M, Coiera E. Some unintended consequences of information technology in health care: The nature of patient care information system-related errors. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2004;11(2):104-112. https://doi.org/10.1197/jamia.M1471.

3. Coiera E. When conversation is better than computation. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2000;7(3):277-286. https://doi.org/10.1136/jamia.2000.0070277.

4. Simon TD, Berry J, Feudtner C, et al. Children with complex chronic conditions in inpatient hospital settings in the United States. Pediatrics. 2010;126(4):647-655. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-3266.

5. The Nielsen Company. In U.S., SMS Text Messaging Tops Mobile Phone Calling. https://www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/article/2008/in-us-text-messaging-tops-mobile-phone-calling/. Accessed July 22, 2019.

6. The Nielsen Company. New Mobile Obsession in U.S. Teens Triple Data Usage. The Nielsen Company. Published 2011. Accessed July 22, 2019.

7. The Nielsen Company. U.S. Teen Mobile Report Calling Yesterday, Texting Today, Using Apps Tomorrow. The Nielsen Company. https://www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/article/2010/u-s-teen-mobile-report-calling-yesterday-texting-today-using-apps-tomorrow/. Accessed July 22, 2019.

8. Sendelbach S, Funk M. Alarm fatigue: a patient safety concern. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2013;24(4):378-386; quiz 387-378.

9. Paine CW, Goel VV, Ely E, et al. Systematic review of physiologic monitor alarm characteristics and pragmatic interventions to reduce alarm frequency. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(2):136-144. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2520.

10. Hagedorn PA, Kirkendall ES, Spooner SA, Mohan V. Inpatient communication networks: leveraging secure text-messaging platforms to gain insight into inpatient communication systems. Appl Clin Inform. 2019;10(3):471-478. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0039-1692401.

11. Westbrook JI, Coiera E, Dunsmuir WT, et al. The impact of interruptions on clinical task completion. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19(4):284-289. https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2009.039255.

12. Castells M. The Rise of the Network Society. 2nd ed. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010.

13. Lo V, Wu RC, Morra D, Lee L, Reeves S. The use of smartphones in general and internal medicine units: A boon or a bane to the promotion of interprofessional collaboration? J Interprof Care. 2012;26(4):276-282. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2012.663013.

14. Martin G, Khajuria A, Arora S, King D, Ashrafian H, Darzi A. The impact of mobile technology on teamwork and communication in hospitals: a systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assn. 2019;26(4):339-355. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocy175.

15. Liu X, Sutton PR, McKenna R, et al. Evaluation of secure messaging applications for a health care system: a case study. Appl Clin Inform. 2019;10(1):140-150. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0039-1678607.

16. Weigert RM, Schmitz AH, Soung PJ, Porada K, Weisgerber MC. Improving standardization of paging communication using quality improvement methodology. Pediatrics. 2019;143(4). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-1362.

UNINTENDED CONSEQUENCES

Over the past two decades, physicians and nurses practicing in hospital settings have faced an onslaught of challenges in communication, an area frequently cited as critical to providing safe and effective care to patients.1-3 Communication needs have increased significantly as hospitalized patients have become more acute, complex, and technology-dependent, requiring larger healthcare teams comprising subspecialists across multiple disciplines spread across increasingly larger inpatient facilities.4 During this same period, the evolution of mobile phones has led to dramatic shifts in personal communication patterns, with asynchronous text messaging replacing verbal communication.5-7

In response to both the changing communication needs of clinicians and shifting cultural conventions, healthcare systems and providers alike have viewed text messaging as a solution to these growing communication problems. In fact, an entire industry has developed around “secure” and “Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)-compliant” text messaging platforms, which we will refer to below as secure text messaging systems (STMS). These systems offer benefits over carrier-based text messaging given their focus on the healthcare environment and HIPAA compliance. However, hospitals’ rapid adoption of these systems has outpaced our abilities to surveil, recognize, and understand the unintended consequences of transitioning to STMS communication in the hospital setting where failures in communication can be catastrophic. Below, we highlight three critical areas of concern encountered at our institutions and offer five potential mitigating strategies (Table).

CRITICAL AREAS OF CONCERN

Text Messaging is a Form of Alarm Fatigue

Text messaging renders clinicians vulnerable to a unique form of alarm fatigue. The burden of alarm fatigue has been well described in the literature and applies to interruptions to workflow in the electronic medical record and sensory alerts in clinical settings.8,9 Text messaging serves as yet another interruption for healthcare providers. Without a framework to triage urgent versus nonurgent messages, a clinician can become inundated with information and miss critical messages. This can lead to delayed or incorrect responses and impede patient care. System design and implementation can also contribute to this phenomenon. For example, a text message analysis at one center identified how system and workflow design resulted in all messages to an intensive care unit team being routed to a single physician’s phone.10 This design left the singular physician at risk of information and task overload and at the mercy of endless interruptive alerts. Although this can occur with any communication system, it has been well demonstrated that adopting STMS correlates with an increased frequency of messaging, leading to an increase in interruptive alerts, which may have implications for patient safety.11 This type of systems failure is silent unless proactively identified or revealed through a retrospective review of a resulting safety event.

Text Messaging Inappropriately Replaces Critical Communications that Should Happen in Person or by Phone

Text messaging has de-emphasized interpersonal communication skills and behaviors critical for quality and safety in hospital-based care. This concern emerges alongside evidence suggesting that new generations of physician trainees have profoundly different communication habits, preferences, and skillsets based on their experience in a text-heavy, asynchronous world of communication.12 There is reason to worry that reliance on text messaging in healthcare leads to similar alterations in relationships and collaboration as it has in our broader cultural context.13 Academic medical centers in particular should attempt to mitigate the loss of profound and formative learning that occurs during face-to-face encounters between providers of different disciplines, experience levels, and specialties.

Text Messaging Increases the Risk of Communication Error

Finally, text messaging appears to be highly vulnerable to communication errors in the healthcare setting. Prior work emphasizes the importance of nonverbal communication in face-to-face and even voice-to-voice interactions, highlighting the loss of fidelity when using text-only methods to communicate.1 Furthermore, the asynchronous nature of text messaging grants little room for clarification of minor misunderstandings that often arise in text-only communication through minor alterations in punctuation or automatic spelling corrections, a frequent occurrence when using medical terminology. Although a seasoned physician may be able to piece together the issues that deserve further clarification, young residents may be more hesitant to ask clarifying questions and determine the right course of action due to clinical inexperience.

PROPOSED SOLUTIONS

Deliberate Design and Implementation

A recent systematic review identified a lack of high-quality evidence evaluating the impact of mobile technologies on communication and teamwork in hospital settings.14 This paucity of understanding renders communication via STMS in the healthcare setting uniquely vulnerable to latent safety threats unless the design and implementation of these systems are purposeful and proactive.

These concerns led us to postulate that deliberate and proactive implementation of these systems, rather than passive adoption, is needed in the healthcare environment. We propose a number of approaches and interventions that may guide institutions as they seek to implement STMS or redesign communication in the inpatient setting. At the core of these proposals lies an important tension: can implementation of STMS occur in isolation or should the arrival of these systems prompt an overhaul of an institution’s clinical communication system and culture?15

Proactive Surveillance

Surveillance is one proactive method for healthcare systems to understand where and how the implementation of STMS might lead to safety threats. From a quantitative standpoint, understanding the burden of messaging for each user across the system can reveal the clinical roles in the system that are particularly vulnerable to alert fatigue or information overload. Quality assurance monitoring of critical roles in the hospital (ie, airway emergency team, rapid response teams) could be conducted to ensure accurate directory listings at all times. Associating conversations with events, from serious safety events to near misses, could help leaders understand when and how text messaging contributes to safety events and create actionable learnings for safety learning systems.

Standardized Communication

A standardized language eliminates the burden of individuals to parse and translate each individual text message. A standardized algorithm for language, urgency, and expectations (ie, response before escalation) would help define the interaction in the clinical setting.16 Moving toward standardized, meaningful “quick messages,” one of our centers has implemented a campaign to “stick to the FACS,” where the following four standard quick messages are available for users: (1) “FYI no response needed,” (2) “ACTION needed within X min,” (3) “CONCERN can we talk or meet,” and (4) “STAT immediate response required.” These quick messages, developed with frontline stakeholders, represent the majority of requests exchanged by providers, and help standardize expectations and task prioritization.

Targeted Training

Targeted training and culture change efforts might help institutions counteract the broader impact of asynchronous messaging on communication skills and behaviors. Highlighting the contrast between clinical and casual communication with an emphasis on examples, scenarios, or role-playing has the potential to emphasize why and how clinical communication with STMS requires a careful, deliberate approach. For instance, safety culture training at one of our institutions features a scenario that illustrates the potential for miscommunication and missed connection between a nurse and a physician on the wards. The scenario gives way to discussion between participants about the shortcomings of text messaging and allows the facilitator to segue into the “dos and don’ts” of text messaging and when a phone call might be more appropriate.

Innovate

Finally, creatively harnessing the technology and data underlying these STMS may uncover methods to identify and mitigate communication errors in real time. For instance, using trigger methods to create a “ripple in the pond,” whereby a floor nurse reaching out with an urgent text automatically loops in the charge nurse of the unit. Building a chatbot or a virtual assistant functionality by leveraging user behavior patterns and natural language processing to provide text-based guidance to users might help busy clinicians connect to the key decision-makers on their team. For example, in response to an unanswered text, a virtual assistant might reach out to the waiting provider as follows: “you texted the resident 20 minutes ago and they haven’t replied, would you like to call the fellow instead?” The data-rich nature of these systems implies that they are ripe for automated solutions that can respond to behavioral- or text-based patterns to augment the existing operation and safety infrastructure.

CONCLUSION

The transition of healthcare communication systems toward STMS is already well underway. These systems, despite their flaws, are undoubtedly an improvement over legacy paging systems and, if properly implemented, offer several benefits to large healthcare systems. However, the communication needs in the healthcare setting are vastly different from the personal communication needs in everyday text messaging. As clinicians at the forefront of these transitions, we have the opportunity to critically assess the unique communication requirements in our hospital settings and help shape the way STMS are implemented in our hospitals. Pausing to deliberate about the limitations and the vulnerabilities of the current messaging systems for our acute clinical needs, including how they impact training and education, will allow us to proactively design and implement better communication systems that improve patient safety.

UNINTENDED CONSEQUENCES

Over the past two decades, physicians and nurses practicing in hospital settings have faced an onslaught of challenges in communication, an area frequently cited as critical to providing safe and effective care to patients.1-3 Communication needs have increased significantly as hospitalized patients have become more acute, complex, and technology-dependent, requiring larger healthcare teams comprising subspecialists across multiple disciplines spread across increasingly larger inpatient facilities.4 During this same period, the evolution of mobile phones has led to dramatic shifts in personal communication patterns, with asynchronous text messaging replacing verbal communication.5-7

In response to both the changing communication needs of clinicians and shifting cultural conventions, healthcare systems and providers alike have viewed text messaging as a solution to these growing communication problems. In fact, an entire industry has developed around “secure” and “Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)-compliant” text messaging platforms, which we will refer to below as secure text messaging systems (STMS). These systems offer benefits over carrier-based text messaging given their focus on the healthcare environment and HIPAA compliance. However, hospitals’ rapid adoption of these systems has outpaced our abilities to surveil, recognize, and understand the unintended consequences of transitioning to STMS communication in the hospital setting where failures in communication can be catastrophic. Below, we highlight three critical areas of concern encountered at our institutions and offer five potential mitigating strategies (Table).

CRITICAL AREAS OF CONCERN

Text Messaging is a Form of Alarm Fatigue

Text messaging renders clinicians vulnerable to a unique form of alarm fatigue. The burden of alarm fatigue has been well described in the literature and applies to interruptions to workflow in the electronic medical record and sensory alerts in clinical settings.8,9 Text messaging serves as yet another interruption for healthcare providers. Without a framework to triage urgent versus nonurgent messages, a clinician can become inundated with information and miss critical messages. This can lead to delayed or incorrect responses and impede patient care. System design and implementation can also contribute to this phenomenon. For example, a text message analysis at one center identified how system and workflow design resulted in all messages to an intensive care unit team being routed to a single physician’s phone.10 This design left the singular physician at risk of information and task overload and at the mercy of endless interruptive alerts. Although this can occur with any communication system, it has been well demonstrated that adopting STMS correlates with an increased frequency of messaging, leading to an increase in interruptive alerts, which may have implications for patient safety.11 This type of systems failure is silent unless proactively identified or revealed through a retrospective review of a resulting safety event.

Text Messaging Inappropriately Replaces Critical Communications that Should Happen in Person or by Phone

Text messaging has de-emphasized interpersonal communication skills and behaviors critical for quality and safety in hospital-based care. This concern emerges alongside evidence suggesting that new generations of physician trainees have profoundly different communication habits, preferences, and skillsets based on their experience in a text-heavy, asynchronous world of communication.12 There is reason to worry that reliance on text messaging in healthcare leads to similar alterations in relationships and collaboration as it has in our broader cultural context.13 Academic medical centers in particular should attempt to mitigate the loss of profound and formative learning that occurs during face-to-face encounters between providers of different disciplines, experience levels, and specialties.

Text Messaging Increases the Risk of Communication Error

Finally, text messaging appears to be highly vulnerable to communication errors in the healthcare setting. Prior work emphasizes the importance of nonverbal communication in face-to-face and even voice-to-voice interactions, highlighting the loss of fidelity when using text-only methods to communicate.1 Furthermore, the asynchronous nature of text messaging grants little room for clarification of minor misunderstandings that often arise in text-only communication through minor alterations in punctuation or automatic spelling corrections, a frequent occurrence when using medical terminology. Although a seasoned physician may be able to piece together the issues that deserve further clarification, young residents may be more hesitant to ask clarifying questions and determine the right course of action due to clinical inexperience.

PROPOSED SOLUTIONS

Deliberate Design and Implementation

A recent systematic review identified a lack of high-quality evidence evaluating the impact of mobile technologies on communication and teamwork in hospital settings.14 This paucity of understanding renders communication via STMS in the healthcare setting uniquely vulnerable to latent safety threats unless the design and implementation of these systems are purposeful and proactive.

These concerns led us to postulate that deliberate and proactive implementation of these systems, rather than passive adoption, is needed in the healthcare environment. We propose a number of approaches and interventions that may guide institutions as they seek to implement STMS or redesign communication in the inpatient setting. At the core of these proposals lies an important tension: can implementation of STMS occur in isolation or should the arrival of these systems prompt an overhaul of an institution’s clinical communication system and culture?15

Proactive Surveillance

Surveillance is one proactive method for healthcare systems to understand where and how the implementation of STMS might lead to safety threats. From a quantitative standpoint, understanding the burden of messaging for each user across the system can reveal the clinical roles in the system that are particularly vulnerable to alert fatigue or information overload. Quality assurance monitoring of critical roles in the hospital (ie, airway emergency team, rapid response teams) could be conducted to ensure accurate directory listings at all times. Associating conversations with events, from serious safety events to near misses, could help leaders understand when and how text messaging contributes to safety events and create actionable learnings for safety learning systems.

Standardized Communication

A standardized language eliminates the burden of individuals to parse and translate each individual text message. A standardized algorithm for language, urgency, and expectations (ie, response before escalation) would help define the interaction in the clinical setting.16 Moving toward standardized, meaningful “quick messages,” one of our centers has implemented a campaign to “stick to the FACS,” where the following four standard quick messages are available for users: (1) “FYI no response needed,” (2) “ACTION needed within X min,” (3) “CONCERN can we talk or meet,” and (4) “STAT immediate response required.” These quick messages, developed with frontline stakeholders, represent the majority of requests exchanged by providers, and help standardize expectations and task prioritization.

Targeted Training

Targeted training and culture change efforts might help institutions counteract the broader impact of asynchronous messaging on communication skills and behaviors. Highlighting the contrast between clinical and casual communication with an emphasis on examples, scenarios, or role-playing has the potential to emphasize why and how clinical communication with STMS requires a careful, deliberate approach. For instance, safety culture training at one of our institutions features a scenario that illustrates the potential for miscommunication and missed connection between a nurse and a physician on the wards. The scenario gives way to discussion between participants about the shortcomings of text messaging and allows the facilitator to segue into the “dos and don’ts” of text messaging and when a phone call might be more appropriate.

Innovate

Finally, creatively harnessing the technology and data underlying these STMS may uncover methods to identify and mitigate communication errors in real time. For instance, using trigger methods to create a “ripple in the pond,” whereby a floor nurse reaching out with an urgent text automatically loops in the charge nurse of the unit. Building a chatbot or a virtual assistant functionality by leveraging user behavior patterns and natural language processing to provide text-based guidance to users might help busy clinicians connect to the key decision-makers on their team. For example, in response to an unanswered text, a virtual assistant might reach out to the waiting provider as follows: “you texted the resident 20 minutes ago and they haven’t replied, would you like to call the fellow instead?” The data-rich nature of these systems implies that they are ripe for automated solutions that can respond to behavioral- or text-based patterns to augment the existing operation and safety infrastructure.

CONCLUSION

The transition of healthcare communication systems toward STMS is already well underway. These systems, despite their flaws, are undoubtedly an improvement over legacy paging systems and, if properly implemented, offer several benefits to large healthcare systems. However, the communication needs in the healthcare setting are vastly different from the personal communication needs in everyday text messaging. As clinicians at the forefront of these transitions, we have the opportunity to critically assess the unique communication requirements in our hospital settings and help shape the way STMS are implemented in our hospitals. Pausing to deliberate about the limitations and the vulnerabilities of the current messaging systems for our acute clinical needs, including how they impact training and education, will allow us to proactively design and implement better communication systems that improve patient safety.

1. Sutcliffe KM, Lewton E, Rosenthal MM. Communication failures: an insidious contributor to medical mishaps. Acad Med. 2004;79(2):186-194. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200402000-00019.

2. Ash JS, Berg M, Coiera E. Some unintended consequences of information technology in health care: The nature of patient care information system-related errors. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2004;11(2):104-112. https://doi.org/10.1197/jamia.M1471.

3. Coiera E. When conversation is better than computation. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2000;7(3):277-286. https://doi.org/10.1136/jamia.2000.0070277.

4. Simon TD, Berry J, Feudtner C, et al. Children with complex chronic conditions in inpatient hospital settings in the United States. Pediatrics. 2010;126(4):647-655. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-3266.

5. The Nielsen Company. In U.S., SMS Text Messaging Tops Mobile Phone Calling. https://www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/article/2008/in-us-text-messaging-tops-mobile-phone-calling/. Accessed July 22, 2019.

6. The Nielsen Company. New Mobile Obsession in U.S. Teens Triple Data Usage. The Nielsen Company. Published 2011. Accessed July 22, 2019.

7. The Nielsen Company. U.S. Teen Mobile Report Calling Yesterday, Texting Today, Using Apps Tomorrow. The Nielsen Company. https://www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/article/2010/u-s-teen-mobile-report-calling-yesterday-texting-today-using-apps-tomorrow/. Accessed July 22, 2019.

8. Sendelbach S, Funk M. Alarm fatigue: a patient safety concern. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2013;24(4):378-386; quiz 387-378.

9. Paine CW, Goel VV, Ely E, et al. Systematic review of physiologic monitor alarm characteristics and pragmatic interventions to reduce alarm frequency. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(2):136-144. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2520.

10. Hagedorn PA, Kirkendall ES, Spooner SA, Mohan V. Inpatient communication networks: leveraging secure text-messaging platforms to gain insight into inpatient communication systems. Appl Clin Inform. 2019;10(3):471-478. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0039-1692401.

11. Westbrook JI, Coiera E, Dunsmuir WT, et al. The impact of interruptions on clinical task completion. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19(4):284-289. https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2009.039255.

12. Castells M. The Rise of the Network Society. 2nd ed. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010.

13. Lo V, Wu RC, Morra D, Lee L, Reeves S. The use of smartphones in general and internal medicine units: A boon or a bane to the promotion of interprofessional collaboration? J Interprof Care. 2012;26(4):276-282. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2012.663013.

14. Martin G, Khajuria A, Arora S, King D, Ashrafian H, Darzi A. The impact of mobile technology on teamwork and communication in hospitals: a systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assn. 2019;26(4):339-355. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocy175.

15. Liu X, Sutton PR, McKenna R, et al. Evaluation of secure messaging applications for a health care system: a case study. Appl Clin Inform. 2019;10(1):140-150. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0039-1678607.

16. Weigert RM, Schmitz AH, Soung PJ, Porada K, Weisgerber MC. Improving standardization of paging communication using quality improvement methodology. Pediatrics. 2019;143(4). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-1362.

1. Sutcliffe KM, Lewton E, Rosenthal MM. Communication failures: an insidious contributor to medical mishaps. Acad Med. 2004;79(2):186-194. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200402000-00019.

2. Ash JS, Berg M, Coiera E. Some unintended consequences of information technology in health care: The nature of patient care information system-related errors. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2004;11(2):104-112. https://doi.org/10.1197/jamia.M1471.

3. Coiera E. When conversation is better than computation. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2000;7(3):277-286. https://doi.org/10.1136/jamia.2000.0070277.

4. Simon TD, Berry J, Feudtner C, et al. Children with complex chronic conditions in inpatient hospital settings in the United States. Pediatrics. 2010;126(4):647-655. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-3266.

5. The Nielsen Company. In U.S., SMS Text Messaging Tops Mobile Phone Calling. https://www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/article/2008/in-us-text-messaging-tops-mobile-phone-calling/. Accessed July 22, 2019.

6. The Nielsen Company. New Mobile Obsession in U.S. Teens Triple Data Usage. The Nielsen Company. Published 2011. Accessed July 22, 2019.

7. The Nielsen Company. U.S. Teen Mobile Report Calling Yesterday, Texting Today, Using Apps Tomorrow. The Nielsen Company. https://www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/article/2010/u-s-teen-mobile-report-calling-yesterday-texting-today-using-apps-tomorrow/. Accessed July 22, 2019.

8. Sendelbach S, Funk M. Alarm fatigue: a patient safety concern. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2013;24(4):378-386; quiz 387-378.

9. Paine CW, Goel VV, Ely E, et al. Systematic review of physiologic monitor alarm characteristics and pragmatic interventions to reduce alarm frequency. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(2):136-144. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2520.

10. Hagedorn PA, Kirkendall ES, Spooner SA, Mohan V. Inpatient communication networks: leveraging secure text-messaging platforms to gain insight into inpatient communication systems. Appl Clin Inform. 2019;10(3):471-478. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0039-1692401.

11. Westbrook JI, Coiera E, Dunsmuir WT, et al. The impact of interruptions on clinical task completion. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19(4):284-289. https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2009.039255.

12. Castells M. The Rise of the Network Society. 2nd ed. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010.

13. Lo V, Wu RC, Morra D, Lee L, Reeves S. The use of smartphones in general and internal medicine units: A boon or a bane to the promotion of interprofessional collaboration? J Interprof Care. 2012;26(4):276-282. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2012.663013.

14. Martin G, Khajuria A, Arora S, King D, Ashrafian H, Darzi A. The impact of mobile technology on teamwork and communication in hospitals: a systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assn. 2019;26(4):339-355. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocy175.

15. Liu X, Sutton PR, McKenna R, et al. Evaluation of secure messaging applications for a health care system: a case study. Appl Clin Inform. 2019;10(1):140-150. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0039-1678607.

16. Weigert RM, Schmitz AH, Soung PJ, Porada K, Weisgerber MC. Improving standardization of paging communication using quality improvement methodology. Pediatrics. 2019;143(4). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-1362.

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

A Qualitative Study of Increased Pediatric Reutilization After a Postdischarge Home Nurse Visit

Readmission rates are used as metrics for care quality and reimbursement, with penalties applied to hospitals with higher than expected rates1 and up to 30% of pediatric readmissions deemed potentially preventable.2 There is a paucity of information on how to prevent pediatric readmissions,3 yet pediatric hospitals are tasked with implementing interventions for readmission reduction.

The Hospital to Home Outcomes (H2O) trial was a 2-arm, randomized controlled trial in which patients discharged from hospital medicine and neuroscience services at a single institution were randomized to receive a single home visit from a registered nurse (RN) within 96 hours of discharge.4 RNs completed a structured nurse visit designed specifically for the trial. Lists of “red flags” or warning signs associated with common diagnoses were provided to assist RNs in standardizing education about when to seek additional care. The hypothesis was that the postdischarge visits would result in lower reutilization rates (unplanned readmissions, emergency department [ED] visits, and urgent care visits).5

Unexpectedly, children randomized to receive the postdischarge nurse visit had higher rates of 30-day unplanned healthcare reutilization, with children randomly assigned to the intervention demonstrating higher odds of 30-day healthcare use (OR 1.33; 95% CI 1.003-1.76).4 We sought to understand perspectives on these unanticipated findings by obtaining input from relevant stakeholders. There were 2 goals for the qualitative analysis: first, to understand possible explanations of the increased reutilization finding; second, to elicit suggestions for improving the nurse visit intervention.

METHODS

We selected an in-depth qualitative approach, using interviews and focus groups to explore underlying explanations for the increase in 30-day unplanned healthcare reutilization among those randomized to receive the postdischarge nurse visit during the H2O trial.4 Input was sought from 4 stakeholder groups—parents, primary care physicians (PCPs), hospital medicine physicians, and home care RNs—in an effort to triangulate data sources and elicit rich and diverse opinions. Approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board prior to conducting the study.

Recruitment

Parents

Because we conducted interviews approximately 1 year after the trial’s conclusion, we purposefully selected families who were enrolled in the latter portion of the H2O trial in order to enhance recall. Beginning with the last families in the study, we sequentially contacted families in reverse order. We contacted 10 families in each of 4 categories (intervention/reutilization, intervention/no reutilization, control/reutilization, control/no reutilization). A total of 3 attempts were made by telephone to contact each family. Participants received a grocery store gift card for participating in the study.

Primary Care Physicians

We conducted focus groups with a purposive sample of physicians recruited from 2 community practices and 1 hospital-owned practice.

Hospital Medicine Physicians

We conducted focus groups with a purposive sample of physicians from our Division of Hospital Medicine. There was a varying level of knowledge of the original trial; however, none of the participants were collaborators in the trial.

Home Care RNs

We conducted focus groups with a subset of RNs who were involved with trial visits. All RNs were members of the pediatric home care division associated with the hospital with specific training in caring for patients at home.

Data Collection

The study team designed question guides for each stakeholder group (Appendix 1). While questions were tailored for specific stakeholders, all guides included the following topics: benefits and challenges of nurse visits, suggestions for improving the intervention in future trials, and reactions to the trial results (once presented to participants). Only the results of the intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis were shared with stakeholders because ITT is considered the gold standard for trial analysis and allows easy understanding of the results.

A single investigator (A.L.) conducted parental interviews by telephone. Focus groups for PCPs, hospital medicine physicians, and RN groups were held at practice locations in private conference rooms and were conducted by trained moderators (S.N.S., A.L., and H.T.C.). Moderators probed responses to the open-ended questions to delve deeply into issues. The question guides were modified in an iterative fashion to include new concepts raised during interviews or focus groups. All interviews and focus groups were recorded and transcribed verbatim with all identifiable information redacted.

Data Analysis

During multiple cycles of inductive thematic analysis,6 we examined, discussed, interpreted, and organized responses to the open-ended questions,6,7 analyzing each stakeholder group separately. First, transcripts were shared with and reviewed by the entire multidisciplinary team (12 members) which included hospital medicine physicians, PCPs, home care nursing leaders, a nurse scientist, a parent representative, research coordinators, and a qualitative research methodologist. Second, team members convened to discuss overall concepts and ideas and created the preliminary coding frameworks. Third, a smaller subgroup (research coordinator [A.L]., hospital medicine physician [S.R.], parent representative [M.M.], and qualitative research methodologist [S.N.S.]), refined the unique coding framework for each stakeholder group and then independently applied codes to participant comments. This subgroup met regularly to reach consensus about the assigned codes and to further refine the codebooks. The codes were organized into major and minor themes based on recurring patterns in the data and the salience or emphasis given by participants. The subgroup’s work was reviewed and discussed on an ongoing basis by the entire multidisciplinary team. Triangulation of the data was achieved in multiple ways. The preliminary results were shared in several forums, and feedback was solicited and incorporated. Two of 4 members of the subgroup analytic team were not part of the trial planning or data collection, providing a potentially broader perspective. All coding decisions were maintained in an electronic database, and an audit trail was created to document codebook revisions.

RESULTS

A total of 33 parents participated in the interviews (intervention/readmit [8], intervention/no readmit [8], control/readmit [8], and control/no readmit [9]). Although we selected families from all 4 categories, we were not able to explore qualitative differences between these groups because of the relatively low numbers of participants. Parent data was very limited as interviews were brief and “control” parents had not received the intervention. Three focus groups were held with PCPs (7 participants in total), 2 focus groups were held with hospital medicine physicians (12 participants), and 2 focus groups were held with RNs (10 participants).

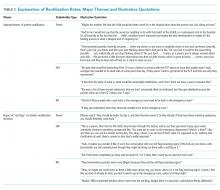

Goal 1: Explanation of Reutilization Rates

During interviews and focus groups, the results of the H2O trial were discussed, and stakeholders were asked to comment on potential explanations of the findings. 4 major themes and 5 minor themes emerged from analysis of the transcripts (summarized in Table 1).

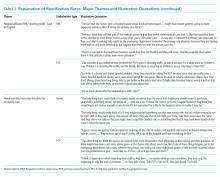

Theme 1: Appropriateness of Patient Reutilization

Hospital medicine physicians and home care RNs questioned whether the reutilization events were clinically indicated. RNs wondered whether children who reutilized the ED were also readmitted to the hospital; many perceived that if the child was ill enough to be readmitted, then the ED revisit was warranted (Table 2). Parents commented on parental decision-making and changes in clinical status of the child leading to reutilization (Table 2).

Theme 2: Impact of Red Flags/Warning Sign Instructions on Family’s Reutilization Decisions

Theme 3: Hospital-Affiliated RNs “Directing Traffic” Back to Hospital

Both physician groups were concerned that, because the study was conducted by hospital-employed nurses, families might have been more likely to reaccess care at the hospital. Thus, the connection with the hospital was strengthened in the H2O model, potentially at the expense of the connection with PCPs. Physicians hypothesized that families might “still feel part of the medical system,” so families would return to the hospital if there was a problem. PCPs emphasized that there may have been straightforward situations that could have been handled appropriately in the outpatient office (Table 2).

Theme 4: Home Visit RNs Had a Low Threshold for Escalating Care

Parents and PCPs hypothesized that RNs are more conservative and, therefore, would have had a low threshold to refer back to the hospital if there were concerns in the home. One parent commented: “I guess, nurses are just by trade accustomed to erring on the side of caution and medical intervention instead of letting time take its course. … They’re more apt to say it’s better off to go to the hospital and have everything be fine” (Table 2).

Minor Themes

Participants also explained reutilization in ways that coalesced into 5 minor themes: (1) families receiving a visit might perceive that their child was sicker; (2) patients in the control group did not reutilize enough; (3) receiving more education on a child’s illness drives reutilization; (4) provider access issues; and (5) variability of RN experience may determine whether escalated care. Supportive quotations found in Appendix 2.

We directly asked parents if they would want a nurse home visit in the future after discussing the results of the study. Almost all of the parents in the intervention group and most of the parents in the control group were in favor of receiving a visit, even knowing that patients who had received a visit were more likely to reutilize care.

Goal 2: Suggestions for Improving Intervention Design

Three major themes and 3 minor themes were related to improving the design of the intervention (Table 1).

Theme 1: Need for Improved Postdischarge Communication

All stakeholder groups highlighted postdischarge communication as an area that could be improved. Parents were frustrated with regard to attempts to connect with inpatient physicians after discharge. PCPs suggested developing pathways for the RN to connect with the primary care office as opposed to the hospital. Hospital medicine physicians discussed a lack of consensus regarding patient ownership following discharge and were uncertain about what types of postdischarge symptoms PCPs would be comfortable managing. RNs described specific situations when they had difficulty contacting a physician to escalate care (Table 3).

Theme 2: Individualizing Home Visits—One Size Does Not Fit All

All stakeholder groups also encouraged “individualization” of home visits according to patient and family characteristics, diagnosis, and both timing and severity of illness. PCPs recommended visits only for certain diagnoses. Hospital medicine physicians voiced similar sentiments as the PCPs and added that worrisome family dynamics during a hospitalization, such as a lack of engagement with the medical team, might also warrant a visit. RNs suggested visits for those families with more concerns, for example, those with young children or children recovering from an acute respiratory illness (Table 3).

Theme 3: Providing Context for and Framing of Red Flags

Physicians and nurses suggested providing more context to “red flag” instructions and education. RNs emphasized that some families seemed to benefit from the opportunity to discuss their postdischarge concerns with a medical professional. Others appreciated concrete written instructions that spelled out how to respond in certain situations (Table 3).

Minor Themes

Three minor themes were revealed regarding intervention design improvement (Table 1): (1) streamlining the discharge process; (2) improving the definition of the scope and goal of intervention; and (3) extending inpatient team expertise post discharge. Supportive quotations can be found in Appendix 3.

DISCUSSION

When stakeholders were asked about why postdischarge RN visits led to increased postdischarge urgent healthcare visits, they questioned the appropriateness of the reutilization events, wondered about the lack of context for the warning signs that nurses provided families as part of the intervention, worried that families were encouraged to return to the hospital because of the ties of the trial to the hospital, and suggested that RNs had a low threshold to refer patients back to the hospital. When asked about how to design an improved nurse visit to better support families, stakeholders emphasized improving communication, individualizing the visit, and providing context around the red-flag discussion, enabling more nuanced instructions about how to respond to specific events.

A synthesis of themes suggests that potential drivers for increased utilization rates may lie in the design and goals of the initial project. The intervention was designed to support families and enhance education after discharge, with components derived from pretrial focus groups with families after a hospital discharge.8 The intervention was not designed to divert patients from the ED nor did it enhance access to the PCP. A second trial of the intervention adapted to a phone call also failed to decrease reutilization rates.9 Both physician stakeholder groups perceived that the intervention directed traffic back to the hospital because of the intervention design. Coupled with the perception that the red flags may have changed a family’s threshold for seeking care and/or that an RN may be more apt to refer back to care, this failure to push utilization to the primary care office may explain the unexpected trial results. Despite the stakeholders’ perception of enhanced connection back to the hospital as a result of the nurse visit, in analysis of visit referral patterns, a referral was made directly back to the ED in only 4 of the 651 trial visits (Tubbs-Cooley H, Riddle SR, Gold JM, et al.; under review. Pediatric clinical and social concerns identified by home visit nurses in the immediate postdischarge period 2020).

Both H2O trials demonstrated improved recall of red flags by parents who received the intervention, which may be important given the stakeholders’ perspectives that the red flags may not have been contextualized well enough. Yet neither trial demonstrated any differences in postdischarge coping or time to return to normal routine. In interviews with parents, despite the clearly stated results of increased reutilization, intervention parents endorsed a desire for a home visit in the future, raising the possibility that our outcome measures did not capture parents’ priorities adequately.

When asked to recommend design improvements of the intervention, 2 major themes (improvement in communication and individualization of visits) were discussed by all stakeholder groups, providing actionable information to modify or create new interventions. Focus groups with clinicians suggested that communication challenges may have influenced reutilization likelihood during the postdischarge period. RNs expressed uncertainty about who to call with problems or questions at the time of a home visit. This was compounded by difficulty reaching physicians. Both hospital medicine physicians and PCPs identified system challenges including questions of patient ownership, variable PCP practice communication preferences, and difficulty in identifying a partnered staff member (on either end of the inpatient-outpatient continuum) who was familiar with a specific patient. While the communication issues raised may reflect difficulties in our local healthcare system, there is broad evidence of postdischarge communication challenges. In adults, postdischarge communication failures between home health staff and physicians are associated with an increased risk of readmission.10 The real or perceived lack of communication between inpatient and outpatient providers can add to parental confusion post discharge.11 Although there have been efforts to improve the reliability of communication across this gulf,12,13 it is not clear whether changes to discharge communication could help to avoid pediatric reutilization events.14

The theme of individualization of the home nurse visit is consistent with evidence regarding the impact of focusing the intervention on patients with specific diagnoses or demographics. In adults, reduced reutilization associated with postdischarge home nurse visits has been described in specific populations such as patients with heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.15 Impact of home nurse visits on patients within diagnosis-specific populations with certain demographics (such as advanced age) has also been described.16 In the pediatric population, readmission rates vary widely by diagnosis.17 A systematic review of interventions to reduce pediatric readmissions found increased impact of discharge interventions in specific populations (asthma, oncology, and NICU).3

Next steps may lie in interventions in targeted populations that function as part of a care continuum bridging the patient from the inpatient to the outpatient setting. A home nurse visit as part of this discharge structure may prove to have more impact on reducing reutilization. One population which accounts for a large proportion of readmissions and where there has been recent focus on discharge transition of care has been children with medical complexity.18 This group was largely excluded from the H2O trial. Postdischarge home nurse visits in this population have been found to be feasible and address many questions and problems, but the effect on readmission is less clear.19 Family priorities and preferences related to preparation for discharge, including family engagement, respect for discharge readiness, and goal of returning to normal routines, may be areas on which to focus with future interventions in this population.20 In summary, although widespread postdischarge interventions (home nurse visit4 and nurse telephone call9) have not been found to be effective, targeting interventions to specific populations by diagnosis or demographic factors may prove to be more effective in reducing pediatric reutilization.

There were several strengths to this study. This qualitative approach allowed us to elucidate potential explanations for the H2O trial results from multiple perspectives. The multidisciplinary composition of our analytic team and the use of an iterative process sparked diverse contributions in a dynamic, ongoing discussion and interpretation of our data.

This study should be considered in the context of several limitations. For families and RNs, there was a time lag between participation in the trial and participation in the qualitative study call or focus group which could lead to difficulty recalling details. Only families who received the intervention could give opinions on their experience of the nurse visit, while families in the control group were asked to hypothesize. Focus groups with hospital medicine physicians and PCPs were purposive samples, and complete demographic information of participants was not collected.

CONCLUSION

Key stakeholders reflecting on a postdischarge RN visit trial suggested multiple potential explanations for the unexpected increase in reutilization in children randomized to the intervention. Certain participants questioned whether all reutilization events were appropriate or necessary. Others expressed concerns that the H2O intervention lacked context and directed children back to the hospital instead of the PCP. Parents, PCPs, hospital medicine physicians, and RNs all suggested that future transition-focused interventions should enhance postdischarge communication, strengthen connection to the PCP, and be more effectively tailored to the needs of the individual patient and family.

Acknowledgments

Collaborators: H2O Trial Study Group: Joanne Bachus, BSN, RN, Department of Patient Services, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, Ohio; Monica L Borell, BSN, RN, Department of Patient Services, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, Ohio; Lenisa V Chang, MA, PhD; Patricia Crawford, RN, Department of Patient Services, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, Ohio; Sarah A Ferris, BA, Division of Hospital Medicine, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, Ohio; Judy A Heilman BSN, RN, Department of Patient Services, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, Ohio; Jane C Khoury, PhD, Division of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, Ohio; Karen Lawley, BSN, RN, Department of Patient Services, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, Ohio; Lynne O’Donnell, BSN, RN, Department of Patient Services, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, Ohio; Hadley S Sauers-Ford, MPH, Department of Pediatrics, UC Davis Health, Sacramento, California; Anita N Shah, DO, MPH, Division of Hospital Medicine, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, Ohio; Lauren G Solan, MD, Med, University of Rochester, Rochester, New York; Heidi J Sucharew, PhD, Division of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, Ohio; Karen P Sullivan, BSN, RN, Department of Patient Services, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, Ohio; Christine M White, MD, MAT, Division of Hospital Medicine, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, Ohio.

1. Auger KA, Simon TD, Cooperberg D, et al. Summary of STARNet: seamless transitions and (re)admissions network. Pediatrics. 2015;135(1):164-175. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-1887.

2. Toomey SL, Peltz A, Loren S, et al. Potentially preventable 30-day hospital readmissions at a Children’s Hospital. Pediatrics. 2016;138(2). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-4182.

3. Auger KA, Kenyon CC, Feudtner C, Davis MM. Pediatric hospital discharge interventions to reduce subsequent utilization: a systematic review. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(4):251-260. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2134.

4. Auger KA, Simmons JM, Tubbs-Cooley HL, et al. Postdischarge nurse home visits and reuse: the Hospital to Home Outcomes (H2O) trial. Pediatrics. 2018;142(1). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-3919.

5. Tubbs-Cooley HL, Pickler RH, Simmons JM, et al. Testing a post-discharge nurse-led transitional home visit in acute care pediatrics: the Hospital-To-Home Outcomes (H2O) study protocol. J Adv Nurs. 2016;72(4):915-925. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12882.

6. Guest G. Collecting Qualitative Data: A Field Manual for Applied Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2013.

7. Patton M. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2014.

8. Solan LG, Beck AF, Brunswick SA, et al. The family perspective on Hospital to Home Transitions: a qualitative study. Pediatrics. 2015;136(6):e1539-e1549. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-2098.

9. Auger KA, Shah SS, Tubbs-Cooley HL, et al. Effects of a 1-time nurse-led telephone call after pediatric discharge: the H2O II randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(9):e181482. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.1482.

10. Pesko MF, Gerber LM, Peng TR, Press MJ. Home health care: nurse-physician communication, patient severity, and hospital readmission. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(2):1008-1024. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12667.

11. Solan LG, Beck AF, Shardo SA, et al. Caregiver perspectives on communication during hospitalization at an academic pediatric institution: a qualitative study. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(5):304-311. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2919.

12. Zackoff MW, Graham C, Warrick D, et al. Increasing PCP and hospital medicine physician verbal communication during hospital admissions. Hosp Pediatr. 2018;8(4):220-226. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2017-0119.

13. Mussman GM, Vossmeyer MT, Brady PW, et al. Improving the reliability of verbal communication between primary care physicians and pediatric hospitalists at hospital discharge. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(9):574-580. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2392.

14. Coller RJ, Klitzner TS, Saenz AA, et al. Discharge handoff communication and pediatric readmissions. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(1):29-35. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2670.

15. Yang F, Xiong ZF, Yang C, et al. Continuity of care to prevent readmissions for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. COPD. 2017;14(2):251-261. https://doi.org/10.1080/15412555.2016.1256384.

16. Finlayson K, Chang AM, Courtney MD, et al. Transitional care interventions reduce unplanned hospital readmissions in high-risk older adults. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):956. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3771-9.

17. Berry JG, Toomey SL, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Pediatric readmission prevalence and variability across hospitals. JAMA. 2013;309(4):372-380. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.188351.

18. Coller RJ, Nelson BB, Sklansky DJ, et al. Preventing hospitalizations in children with medical complexity: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2014;134(6):e1628-e1647. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-1956.

19. Wells S, O’Neill M, Rogers J, et al. Nursing-led home visits post-hospitalization for children with medical complexity. J Pediatr Nurs. 2017;34:10-16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2017.03.003.

20. Leyenaar JK, O’Brien ER, Leslie LK, Lindenauer PK, Mangione-Smith RM. Families’ priorities regarding hospital-to-home transitions for children with medical complexity. Pediatrics. 2017;139(1). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1581.

Readmission rates are used as metrics for care quality and reimbursement, with penalties applied to hospitals with higher than expected rates1 and up to 30% of pediatric readmissions deemed potentially preventable.2 There is a paucity of information on how to prevent pediatric readmissions,3 yet pediatric hospitals are tasked with implementing interventions for readmission reduction.

The Hospital to Home Outcomes (H2O) trial was a 2-arm, randomized controlled trial in which patients discharged from hospital medicine and neuroscience services at a single institution were randomized to receive a single home visit from a registered nurse (RN) within 96 hours of discharge.4 RNs completed a structured nurse visit designed specifically for the trial. Lists of “red flags” or warning signs associated with common diagnoses were provided to assist RNs in standardizing education about when to seek additional care. The hypothesis was that the postdischarge visits would result in lower reutilization rates (unplanned readmissions, emergency department [ED] visits, and urgent care visits).5

Unexpectedly, children randomized to receive the postdischarge nurse visit had higher rates of 30-day unplanned healthcare reutilization, with children randomly assigned to the intervention demonstrating higher odds of 30-day healthcare use (OR 1.33; 95% CI 1.003-1.76).4 We sought to understand perspectives on these unanticipated findings by obtaining input from relevant stakeholders. There were 2 goals for the qualitative analysis: first, to understand possible explanations of the increased reutilization finding; second, to elicit suggestions for improving the nurse visit intervention.

METHODS

We selected an in-depth qualitative approach, using interviews and focus groups to explore underlying explanations for the increase in 30-day unplanned healthcare reutilization among those randomized to receive the postdischarge nurse visit during the H2O trial.4 Input was sought from 4 stakeholder groups—parents, primary care physicians (PCPs), hospital medicine physicians, and home care RNs—in an effort to triangulate data sources and elicit rich and diverse opinions. Approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board prior to conducting the study.

Recruitment

Parents

Because we conducted interviews approximately 1 year after the trial’s conclusion, we purposefully selected families who were enrolled in the latter portion of the H2O trial in order to enhance recall. Beginning with the last families in the study, we sequentially contacted families in reverse order. We contacted 10 families in each of 4 categories (intervention/reutilization, intervention/no reutilization, control/reutilization, control/no reutilization). A total of 3 attempts were made by telephone to contact each family. Participants received a grocery store gift card for participating in the study.

Primary Care Physicians

We conducted focus groups with a purposive sample of physicians recruited from 2 community practices and 1 hospital-owned practice.

Hospital Medicine Physicians

We conducted focus groups with a purposive sample of physicians from our Division of Hospital Medicine. There was a varying level of knowledge of the original trial; however, none of the participants were collaborators in the trial.

Home Care RNs

We conducted focus groups with a subset of RNs who were involved with trial visits. All RNs were members of the pediatric home care division associated with the hospital with specific training in caring for patients at home.

Data Collection

The study team designed question guides for each stakeholder group (Appendix 1). While questions were tailored for specific stakeholders, all guides included the following topics: benefits and challenges of nurse visits, suggestions for improving the intervention in future trials, and reactions to the trial results (once presented to participants). Only the results of the intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis were shared with stakeholders because ITT is considered the gold standard for trial analysis and allows easy understanding of the results.

A single investigator (A.L.) conducted parental interviews by telephone. Focus groups for PCPs, hospital medicine physicians, and RN groups were held at practice locations in private conference rooms and were conducted by trained moderators (S.N.S., A.L., and H.T.C.). Moderators probed responses to the open-ended questions to delve deeply into issues. The question guides were modified in an iterative fashion to include new concepts raised during interviews or focus groups. All interviews and focus groups were recorded and transcribed verbatim with all identifiable information redacted.

Data Analysis

During multiple cycles of inductive thematic analysis,6 we examined, discussed, interpreted, and organized responses to the open-ended questions,6,7 analyzing each stakeholder group separately. First, transcripts were shared with and reviewed by the entire multidisciplinary team (12 members) which included hospital medicine physicians, PCPs, home care nursing leaders, a nurse scientist, a parent representative, research coordinators, and a qualitative research methodologist. Second, team members convened to discuss overall concepts and ideas and created the preliminary coding frameworks. Third, a smaller subgroup (research coordinator [A.L]., hospital medicine physician [S.R.], parent representative [M.M.], and qualitative research methodologist [S.N.S.]), refined the unique coding framework for each stakeholder group and then independently applied codes to participant comments. This subgroup met regularly to reach consensus about the assigned codes and to further refine the codebooks. The codes were organized into major and minor themes based on recurring patterns in the data and the salience or emphasis given by participants. The subgroup’s work was reviewed and discussed on an ongoing basis by the entire multidisciplinary team. Triangulation of the data was achieved in multiple ways. The preliminary results were shared in several forums, and feedback was solicited and incorporated. Two of 4 members of the subgroup analytic team were not part of the trial planning or data collection, providing a potentially broader perspective. All coding decisions were maintained in an electronic database, and an audit trail was created to document codebook revisions.

RESULTS

A total of 33 parents participated in the interviews (intervention/readmit [8], intervention/no readmit [8], control/readmit [8], and control/no readmit [9]). Although we selected families from all 4 categories, we were not able to explore qualitative differences between these groups because of the relatively low numbers of participants. Parent data was very limited as interviews were brief and “control” parents had not received the intervention. Three focus groups were held with PCPs (7 participants in total), 2 focus groups were held with hospital medicine physicians (12 participants), and 2 focus groups were held with RNs (10 participants).

Goal 1: Explanation of Reutilization Rates

During interviews and focus groups, the results of the H2O trial were discussed, and stakeholders were asked to comment on potential explanations of the findings. 4 major themes and 5 minor themes emerged from analysis of the transcripts (summarized in Table 1).

Theme 1: Appropriateness of Patient Reutilization

Hospital medicine physicians and home care RNs questioned whether the reutilization events were clinically indicated. RNs wondered whether children who reutilized the ED were also readmitted to the hospital; many perceived that if the child was ill enough to be readmitted, then the ED revisit was warranted (Table 2). Parents commented on parental decision-making and changes in clinical status of the child leading to reutilization (Table 2).

Theme 2: Impact of Red Flags/Warning Sign Instructions on Family’s Reutilization Decisions

Theme 3: Hospital-Affiliated RNs “Directing Traffic” Back to Hospital

Both physician groups were concerned that, because the study was conducted by hospital-employed nurses, families might have been more likely to reaccess care at the hospital. Thus, the connection with the hospital was strengthened in the H2O model, potentially at the expense of the connection with PCPs. Physicians hypothesized that families might “still feel part of the medical system,” so families would return to the hospital if there was a problem. PCPs emphasized that there may have been straightforward situations that could have been handled appropriately in the outpatient office (Table 2).

Theme 4: Home Visit RNs Had a Low Threshold for Escalating Care

Parents and PCPs hypothesized that RNs are more conservative and, therefore, would have had a low threshold to refer back to the hospital if there were concerns in the home. One parent commented: “I guess, nurses are just by trade accustomed to erring on the side of caution and medical intervention instead of letting time take its course. … They’re more apt to say it’s better off to go to the hospital and have everything be fine” (Table 2).

Minor Themes

Participants also explained reutilization in ways that coalesced into 5 minor themes: (1) families receiving a visit might perceive that their child was sicker; (2) patients in the control group did not reutilize enough; (3) receiving more education on a child’s illness drives reutilization; (4) provider access issues; and (5) variability of RN experience may determine whether escalated care. Supportive quotations found in Appendix 2.

We directly asked parents if they would want a nurse home visit in the future after discussing the results of the study. Almost all of the parents in the intervention group and most of the parents in the control group were in favor of receiving a visit, even knowing that patients who had received a visit were more likely to reutilize care.

Goal 2: Suggestions for Improving Intervention Design

Three major themes and 3 minor themes were related to improving the design of the intervention (Table 1).

Theme 1: Need for Improved Postdischarge Communication

All stakeholder groups highlighted postdischarge communication as an area that could be improved. Parents were frustrated with regard to attempts to connect with inpatient physicians after discharge. PCPs suggested developing pathways for the RN to connect with the primary care office as opposed to the hospital. Hospital medicine physicians discussed a lack of consensus regarding patient ownership following discharge and were uncertain about what types of postdischarge symptoms PCPs would be comfortable managing. RNs described specific situations when they had difficulty contacting a physician to escalate care (Table 3).

Theme 2: Individualizing Home Visits—One Size Does Not Fit All

All stakeholder groups also encouraged “individualization” of home visits according to patient and family characteristics, diagnosis, and both timing and severity of illness. PCPs recommended visits only for certain diagnoses. Hospital medicine physicians voiced similar sentiments as the PCPs and added that worrisome family dynamics during a hospitalization, such as a lack of engagement with the medical team, might also warrant a visit. RNs suggested visits for those families with more concerns, for example, those with young children or children recovering from an acute respiratory illness (Table 3).

Theme 3: Providing Context for and Framing of Red Flags