User login

Blood cultures contribute little to uncomplicated SSTI treatment

SAN ANTONIO – Despite mounting evidence that blood cultures don’t contribute to the care of immunocompetent children admitted to the hospital with uncomplicated skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs), they continue to be performed routinely in some hospitals, according to a study presented at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2015 meeting.

Current practice guidelines recommend against routine use of blood cultures in uncomplicated SSTIs (Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(2):e10-52).

A 2013 study of children admitted for uncomplicated SSTIs (n = 482) found no positive blood cultures in the cohort, and cultures were also associated with a significantly longer length of stay. More than half of those children, however, had received antibiotics before their blood cultures, leaving open the possibility that some negative results were the result of treatment with antibiotics (Pediatrics. 2013;132(3):454-9).

Dr. Claudette Gonzalez and her colleagues at Nicklaus Children’s Hospital, Miami, presented findings from a study that used a cohort of otherwise healthy infants and children (n = 176) admitted from the emergency department with uncomplicated SSTIs.

Dr. Gonzalez and her associates sought to strengthen the evidence against routine use of cultures by excluding children who had received antibiotics within 2 weeks of presenting to the hospital.Dr. Gonzalez noted that, despite guidelines, blood cultures remained a routine part of the workup at her hospital, with 66% of the study sample receiving cultures (n = 116). Of febrile patients, 80% received cultures; of nonfebrile patients, 59% received cultures. Patients who had a blood culture drawn were significantly more likely to have had fever (P < .01). They also were more likely to have higher white blood cell and C-reactive protein (CRP) counts (P > .05 for both), but despite this, the rate of positive blood cultures was still less than 1%.

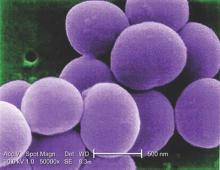

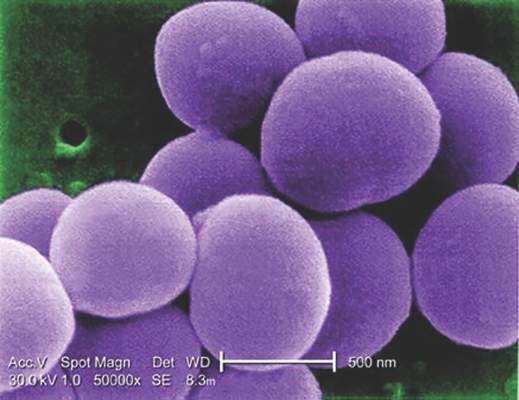

Of the 116 blood cultures drawn, 5 grew contaminants and only 1 was a true positive, for methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA).

The study, unlike most previous studies, enrolled patients younger than 1 year of age (n = 28), but Dr. Gonzalez said that “we don’t have a big enough sample to really make conclusions about that age group.” Also in contrast to some previous studies, Dr. Gonzalez and her associates did not find a statistically significant difference in length of stay between the patients who had received cultures and those that did not (mean 3.62 vs. 3.4 days, P > .05).The one patient in the study with true bacteremia was a 1.4-year-old child presenting with no fever, cellulitis of hands and feet, no lymphangitis, and a white blood count of 8.5 × 103/L and a CRP of less than 0.5 mg/dL. “The WBC count was within normal range and the CRP was not elevated, so you wouldn’t have necessarily picked this kid out to say he needs a blood culture,” Dr. Gonzalez said at the meeting, which was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the AAP Section on Hospital Medicine, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

Still, she said, the study strengthens the evidence base against use of blood cultures in this population. “For children 1 year and older I think it’s very clear,” she said. The investigators are now proceeding with an implementation study to determine whether guidance against routine blood cultures should be put into practice at their institution.

Although the initial study revealed that 66% of children with uncomplicated SSTIs were receiving cultures, preliminary unpublished results show “it’s now at about 44%,” she said, following education of residents, fellows, and ED clinicians.

In addition to communicating with the ED to reduce use of blood cultures in this population, Dr. Gonzalez said, “we’re getting guidelines plugged into our order set in the [electronic medical record], so that’s a second reminder not to draw blood cultures. And we’re measuring to see if our rates improve further.”

Dr. Gonzalez received no outside funding for her study and disclosed no conflicts of interest.

SAN ANTONIO – Despite mounting evidence that blood cultures don’t contribute to the care of immunocompetent children admitted to the hospital with uncomplicated skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs), they continue to be performed routinely in some hospitals, according to a study presented at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2015 meeting.

Current practice guidelines recommend against routine use of blood cultures in uncomplicated SSTIs (Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(2):e10-52).

A 2013 study of children admitted for uncomplicated SSTIs (n = 482) found no positive blood cultures in the cohort, and cultures were also associated with a significantly longer length of stay. More than half of those children, however, had received antibiotics before their blood cultures, leaving open the possibility that some negative results were the result of treatment with antibiotics (Pediatrics. 2013;132(3):454-9).

Dr. Claudette Gonzalez and her colleagues at Nicklaus Children’s Hospital, Miami, presented findings from a study that used a cohort of otherwise healthy infants and children (n = 176) admitted from the emergency department with uncomplicated SSTIs.

Dr. Gonzalez and her associates sought to strengthen the evidence against routine use of cultures by excluding children who had received antibiotics within 2 weeks of presenting to the hospital.Dr. Gonzalez noted that, despite guidelines, blood cultures remained a routine part of the workup at her hospital, with 66% of the study sample receiving cultures (n = 116). Of febrile patients, 80% received cultures; of nonfebrile patients, 59% received cultures. Patients who had a blood culture drawn were significantly more likely to have had fever (P < .01). They also were more likely to have higher white blood cell and C-reactive protein (CRP) counts (P > .05 for both), but despite this, the rate of positive blood cultures was still less than 1%.

Of the 116 blood cultures drawn, 5 grew contaminants and only 1 was a true positive, for methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA).

The study, unlike most previous studies, enrolled patients younger than 1 year of age (n = 28), but Dr. Gonzalez said that “we don’t have a big enough sample to really make conclusions about that age group.” Also in contrast to some previous studies, Dr. Gonzalez and her associates did not find a statistically significant difference in length of stay between the patients who had received cultures and those that did not (mean 3.62 vs. 3.4 days, P > .05).The one patient in the study with true bacteremia was a 1.4-year-old child presenting with no fever, cellulitis of hands and feet, no lymphangitis, and a white blood count of 8.5 × 103/L and a CRP of less than 0.5 mg/dL. “The WBC count was within normal range and the CRP was not elevated, so you wouldn’t have necessarily picked this kid out to say he needs a blood culture,” Dr. Gonzalez said at the meeting, which was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the AAP Section on Hospital Medicine, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

Still, she said, the study strengthens the evidence base against use of blood cultures in this population. “For children 1 year and older I think it’s very clear,” she said. The investigators are now proceeding with an implementation study to determine whether guidance against routine blood cultures should be put into practice at their institution.

Although the initial study revealed that 66% of children with uncomplicated SSTIs were receiving cultures, preliminary unpublished results show “it’s now at about 44%,” she said, following education of residents, fellows, and ED clinicians.

In addition to communicating with the ED to reduce use of blood cultures in this population, Dr. Gonzalez said, “we’re getting guidelines plugged into our order set in the [electronic medical record], so that’s a second reminder not to draw blood cultures. And we’re measuring to see if our rates improve further.”

Dr. Gonzalez received no outside funding for her study and disclosed no conflicts of interest.

SAN ANTONIO – Despite mounting evidence that blood cultures don’t contribute to the care of immunocompetent children admitted to the hospital with uncomplicated skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs), they continue to be performed routinely in some hospitals, according to a study presented at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2015 meeting.

Current practice guidelines recommend against routine use of blood cultures in uncomplicated SSTIs (Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(2):e10-52).

A 2013 study of children admitted for uncomplicated SSTIs (n = 482) found no positive blood cultures in the cohort, and cultures were also associated with a significantly longer length of stay. More than half of those children, however, had received antibiotics before their blood cultures, leaving open the possibility that some negative results were the result of treatment with antibiotics (Pediatrics. 2013;132(3):454-9).

Dr. Claudette Gonzalez and her colleagues at Nicklaus Children’s Hospital, Miami, presented findings from a study that used a cohort of otherwise healthy infants and children (n = 176) admitted from the emergency department with uncomplicated SSTIs.

Dr. Gonzalez and her associates sought to strengthen the evidence against routine use of cultures by excluding children who had received antibiotics within 2 weeks of presenting to the hospital.Dr. Gonzalez noted that, despite guidelines, blood cultures remained a routine part of the workup at her hospital, with 66% of the study sample receiving cultures (n = 116). Of febrile patients, 80% received cultures; of nonfebrile patients, 59% received cultures. Patients who had a blood culture drawn were significantly more likely to have had fever (P < .01). They also were more likely to have higher white blood cell and C-reactive protein (CRP) counts (P > .05 for both), but despite this, the rate of positive blood cultures was still less than 1%.

Of the 116 blood cultures drawn, 5 grew contaminants and only 1 was a true positive, for methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA).

The study, unlike most previous studies, enrolled patients younger than 1 year of age (n = 28), but Dr. Gonzalez said that “we don’t have a big enough sample to really make conclusions about that age group.” Also in contrast to some previous studies, Dr. Gonzalez and her associates did not find a statistically significant difference in length of stay between the patients who had received cultures and those that did not (mean 3.62 vs. 3.4 days, P > .05).The one patient in the study with true bacteremia was a 1.4-year-old child presenting with no fever, cellulitis of hands and feet, no lymphangitis, and a white blood count of 8.5 × 103/L and a CRP of less than 0.5 mg/dL. “The WBC count was within normal range and the CRP was not elevated, so you wouldn’t have necessarily picked this kid out to say he needs a blood culture,” Dr. Gonzalez said at the meeting, which was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the AAP Section on Hospital Medicine, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

Still, she said, the study strengthens the evidence base against use of blood cultures in this population. “For children 1 year and older I think it’s very clear,” she said. The investigators are now proceeding with an implementation study to determine whether guidance against routine blood cultures should be put into practice at their institution.

Although the initial study revealed that 66% of children with uncomplicated SSTIs were receiving cultures, preliminary unpublished results show “it’s now at about 44%,” she said, following education of residents, fellows, and ED clinicians.

In addition to communicating with the ED to reduce use of blood cultures in this population, Dr. Gonzalez said, “we’re getting guidelines plugged into our order set in the [electronic medical record], so that’s a second reminder not to draw blood cultures. And we’re measuring to see if our rates improve further.”

Dr. Gonzalez received no outside funding for her study and disclosed no conflicts of interest.

AT PEDIATRIC HOSPITAL MEDICINE 2015

Key clinical point: Blood cultures reveal little evidence of bacteremia in children with uncomplicated SSTIs, even children not previously treated with antibiotics.

Major finding: Fewer than 1% of children presenting to the ED with uncomplicated SSTIs have evidence of bacteremia.

Data source: Single-site observational study of 176 children presenting to an urban ED with uncomplicated SSTIs and/or fever; none received prior antibiotics, 66% received blood cultures.

Disclosures: Dr. Gonzalez received no outside funding for her study and disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Hypertonic saline linked to modest drop in length of stay for bronchiolitis

SAN ANTONIO – Nebulized hypertonic saline has emerged as a promising, low-risk, and low-cost treatment option for bronchiolitis, a disease for which few options exist.

Still, the evidence for hypertonic saline remains inconsistent, with many studies failing to show a clear benefit in clinical scores or length of stay compared with normal saline in children hospitalized for bronchiolitis. Supportive care remains the recommended approach for this patient group.

A 2013 Cochrane review of trials comparing normal saline 0.9% with hypertonic saline 3% suggested that hypertonic saline reduced mean hospital length of stay by 1.3 days in children with bronchiolitis as well as improved clinical severity scores. But more recent negative trials have called the Cochrane findings into question.

At the Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting, Dr. Corinne G. Brooks of the Children’s Hospital at Dartmouth-Hitchcock in Lebanon, N.H., presented an updated evaluation of the Cochrane findings as well as several newer studies, which found that study heterogeneity was excessively high, though resolved by accounting for culturally expected length of stay, which varied from 2 to 7 days across studies.

Studies conducted in countries where average length of stay for bronchiolitis in the placebo arm is longer than 3 days reported a greater benefit than did those in countries like the United States, in which stays typically average fewer than 3 days. Because hospital length of stay should be correlated with severity of illness, Dr. Brooks also evaluated respiratory scores available in each study and found that higher scores also correlated with the utility of hypertonic saline.

The two Chinese studies included in the review had particularly long lengths of stay and were conducted in a city with poor air quality, and in which about 70% of patients were on systemic corticosteroids at baseline. “So there’s some question as to whether they were even measuring the same disease process,” Dr. Brooks told the conference.

Dr. Brooks and her colleagues reevaluated the Cochrane data both with and without the two outlying studies from China, and incorporated results from three additional studies not included in the Cochrane review.

Modeling cumulative results using a length of stay typical in the United States, the benefit from hypertonic saline was a reduction of 0.31 days, or 31 days/100 patients.

Dr. Brooks noted that the current data are consistent with two possibilities, that the longer a patient is treated with hypertonic saline, the better it works or that “perhaps hypertonic saline works better for sicker patients – we don’t know yet.” She acknowledged several limitations of the meta-analysis, including that patient age, additional medications, day of illness at admission, and frequency of treatment could not be correlated.

The existing data “do not support rejecting hypertonic saline for all patients or giving it to all populations,” Dr. Brooks told the conference, noting that “there are good physiologic reasons to believe hypertonic saline might have an impact based on its benefits to other respiratory populations such as cystic fibrosis – and it’s particularly appealing because of its low risk and low cost.”

However, she said, “if we’re going to use this intervention intelligently, we need to find where there is and where there isn’t a benefit.”

Dr. Brooks concluded that hypertonic saline might be worth considering for patients with an expected stay of longer than 3 days or for those with baseline clinical scores higher than average. Her study received no outside funding, and she disclosed no conflicts of interest.

SAN ANTONIO – Nebulized hypertonic saline has emerged as a promising, low-risk, and low-cost treatment option for bronchiolitis, a disease for which few options exist.

Still, the evidence for hypertonic saline remains inconsistent, with many studies failing to show a clear benefit in clinical scores or length of stay compared with normal saline in children hospitalized for bronchiolitis. Supportive care remains the recommended approach for this patient group.

A 2013 Cochrane review of trials comparing normal saline 0.9% with hypertonic saline 3% suggested that hypertonic saline reduced mean hospital length of stay by 1.3 days in children with bronchiolitis as well as improved clinical severity scores. But more recent negative trials have called the Cochrane findings into question.

At the Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting, Dr. Corinne G. Brooks of the Children’s Hospital at Dartmouth-Hitchcock in Lebanon, N.H., presented an updated evaluation of the Cochrane findings as well as several newer studies, which found that study heterogeneity was excessively high, though resolved by accounting for culturally expected length of stay, which varied from 2 to 7 days across studies.

Studies conducted in countries where average length of stay for bronchiolitis in the placebo arm is longer than 3 days reported a greater benefit than did those in countries like the United States, in which stays typically average fewer than 3 days. Because hospital length of stay should be correlated with severity of illness, Dr. Brooks also evaluated respiratory scores available in each study and found that higher scores also correlated with the utility of hypertonic saline.

The two Chinese studies included in the review had particularly long lengths of stay and were conducted in a city with poor air quality, and in which about 70% of patients were on systemic corticosteroids at baseline. “So there’s some question as to whether they were even measuring the same disease process,” Dr. Brooks told the conference.

Dr. Brooks and her colleagues reevaluated the Cochrane data both with and without the two outlying studies from China, and incorporated results from three additional studies not included in the Cochrane review.

Modeling cumulative results using a length of stay typical in the United States, the benefit from hypertonic saline was a reduction of 0.31 days, or 31 days/100 patients.

Dr. Brooks noted that the current data are consistent with two possibilities, that the longer a patient is treated with hypertonic saline, the better it works or that “perhaps hypertonic saline works better for sicker patients – we don’t know yet.” She acknowledged several limitations of the meta-analysis, including that patient age, additional medications, day of illness at admission, and frequency of treatment could not be correlated.

The existing data “do not support rejecting hypertonic saline for all patients or giving it to all populations,” Dr. Brooks told the conference, noting that “there are good physiologic reasons to believe hypertonic saline might have an impact based on its benefits to other respiratory populations such as cystic fibrosis – and it’s particularly appealing because of its low risk and low cost.”

However, she said, “if we’re going to use this intervention intelligently, we need to find where there is and where there isn’t a benefit.”

Dr. Brooks concluded that hypertonic saline might be worth considering for patients with an expected stay of longer than 3 days or for those with baseline clinical scores higher than average. Her study received no outside funding, and she disclosed no conflicts of interest.

SAN ANTONIO – Nebulized hypertonic saline has emerged as a promising, low-risk, and low-cost treatment option for bronchiolitis, a disease for which few options exist.

Still, the evidence for hypertonic saline remains inconsistent, with many studies failing to show a clear benefit in clinical scores or length of stay compared with normal saline in children hospitalized for bronchiolitis. Supportive care remains the recommended approach for this patient group.

A 2013 Cochrane review of trials comparing normal saline 0.9% with hypertonic saline 3% suggested that hypertonic saline reduced mean hospital length of stay by 1.3 days in children with bronchiolitis as well as improved clinical severity scores. But more recent negative trials have called the Cochrane findings into question.

At the Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting, Dr. Corinne G. Brooks of the Children’s Hospital at Dartmouth-Hitchcock in Lebanon, N.H., presented an updated evaluation of the Cochrane findings as well as several newer studies, which found that study heterogeneity was excessively high, though resolved by accounting for culturally expected length of stay, which varied from 2 to 7 days across studies.

Studies conducted in countries where average length of stay for bronchiolitis in the placebo arm is longer than 3 days reported a greater benefit than did those in countries like the United States, in which stays typically average fewer than 3 days. Because hospital length of stay should be correlated with severity of illness, Dr. Brooks also evaluated respiratory scores available in each study and found that higher scores also correlated with the utility of hypertonic saline.

The two Chinese studies included in the review had particularly long lengths of stay and were conducted in a city with poor air quality, and in which about 70% of patients were on systemic corticosteroids at baseline. “So there’s some question as to whether they were even measuring the same disease process,” Dr. Brooks told the conference.

Dr. Brooks and her colleagues reevaluated the Cochrane data both with and without the two outlying studies from China, and incorporated results from three additional studies not included in the Cochrane review.

Modeling cumulative results using a length of stay typical in the United States, the benefit from hypertonic saline was a reduction of 0.31 days, or 31 days/100 patients.

Dr. Brooks noted that the current data are consistent with two possibilities, that the longer a patient is treated with hypertonic saline, the better it works or that “perhaps hypertonic saline works better for sicker patients – we don’t know yet.” She acknowledged several limitations of the meta-analysis, including that patient age, additional medications, day of illness at admission, and frequency of treatment could not be correlated.

The existing data “do not support rejecting hypertonic saline for all patients or giving it to all populations,” Dr. Brooks told the conference, noting that “there are good physiologic reasons to believe hypertonic saline might have an impact based on its benefits to other respiratory populations such as cystic fibrosis – and it’s particularly appealing because of its low risk and low cost.”

However, she said, “if we’re going to use this intervention intelligently, we need to find where there is and where there isn’t a benefit.”

Dr. Brooks concluded that hypertonic saline might be worth considering for patients with an expected stay of longer than 3 days or for those with baseline clinical scores higher than average. Her study received no outside funding, and she disclosed no conflicts of interest.

AT THE PEDIATRIC HOSPITAL MEDICINE 2015 MEETING

Key clinical point: Use of nebulized hypertonic saline shortens hospital length of stay modestly in pediatric patients with bronchiolitis.

Major finding: Compared with normal saline, hypertonic saline reduced stays by 31 days per 100 patients, presuming a short length of stay of 3 days.

Data source: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing normal saline 0.9% with hypertonic saline 3% in children with bronchiolitis; outlier results from two studies were excluded for exceptionally long lengths of stay.

Disclosures: Dr. Brooks disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Targeting gut microbiome boosted metformin tolerance

Boston – A purified food supplement designed to alter gut bacterial composition improved both metformin tolerance and fasting glucose levels among people with type 2 diabetes, according to results from a small randomized study presented at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

Research into how diabetes affects and is affected by the gut microbiome is still in its infancy. However, compared with nondiabetics, people with type 2 diabetes have been shown to have microbiomes richer in certain types of bacteria than others, and these altered bacterial profiles may be linked to changes in insulin sensitivity, glucose regulation, and methane production.

Mark L Heiman, Ph.D., of MicroBiome Therapeutics in New Orleans, designed the intervention, a powder comprising three purified food ingredients: inulin from agave, beta-glucan from oatmeal, and polyphenols derived from blueberry skins. These were hypothesized to alter gut microbial composition by stimulating blooms of microbes that can generate short-chain fatty acids, displacing some bacteria-producing lactic acid; increase viscosity in the colon (allowing for sequestering of bile acids); and combat oxidative stress and methane production.

Though first investigated as a monotherapy for use in people with prediabetes, the so-called gut microbiome modulator NM504 was found incidentally to improve metformin tolerance in people with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes (Benef. Microbes 2014;5:29-32), and researchers hypothesized that metformin likely interacts with microbiota in the colon, resulting in an abundance of lactate-producing bacteria. Lactic acid production in the colon, exacerbated by starch or sugar consumption, is a known contributor to adverse GI side effects in people taking metformin.

Dr. Heiman presented results from a randomized, placebo-controlled, single-center crossover study in 10 people with type 2 diabetes (8 female) with difficulty tolerating metformin due to GI symptoms or who had discontinued previous therapy because of these symptoms (J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2015;9:808-14).

Subjects were randomly assigned metformin (500 mg twice daily in the first week titrated to three times daily in the second week) alongside the experimental product or placebo. They were asked to record their glucose and adverse GI symptoms (including stool consistency, urgency to evacuate, bloating sensation, and flatulence) every day; metformin tolerance was measured by these symptoms using a scoring system previously validated in patients with irritable bowel syndrome.

After 2 weeks of treatment and a washout period of 2 weeks with no treatment, subjects’ initial treatment assignments were reversed for an additional 2 weeks, and outcomes were recorded.

The combination of metformin and NM504 resulted in improved tolerance score of metformin, compared with placebo (6.78 ± 0.65 [mean ± standard error of the mean] vs. 4.45 ± 0.69, P = .0006). Mean fasting glucose levels were significantly lower with the metformin/NM504 combination (121.3 ± 7.8 mg/dL) than with metformin-placebo (151.9 ± 7.8 mg/dL), (P < .02).

It is unclear whether the improved glucose was a result of improved availability of metformin or an independent effect of the intervention. Last year Dr. Heiman presented results from a previous study of 28 adults with prediabetes randomized to NM504 monotherapy or placebo who saw significantly lower blood sugar levels at 120 and 180 minutes after a glucose challenge, compared with patients taking placebo. This was presented at the International Congress of Endocrinology’s annual meeting (ICE-Endo) 2014 meeting in Chicago; Dr. Heiman noted that the results are awaiting review and perhaps publication.

Dr. Heiman commented that the glucose-regulating effect seen in the metformin study “appeared somewhat durable, even after the 2-week washout period” among subjects switching from intervention to placebo; however, further studies would be needed to determine its effect on insulin sensitivity. Fecal microbial composition was not investigated before and after treatment.

Dr. Daniel Hsia of Pennington Biomedical Research Center, in Baton Rouge, La., a study coauthor, said in an interview that although larger trials would be needed to validate the results and better understand the activity of the intervention in the gut, the findings were “promising” for a proof-of-concept study.

“At this point, we’re not going to start using this in every single diabetes patient on metformin, but it’s very encouraging that you could potentially make it more accessible. Metformin is a very good agent with one of the longest histories. It’s cheap, it can be used in combination with a lot of other medications, but a certain percentage of people will have to stop metformin altogether due to side effects.” Metformin is also approved for children with type 2 diabetes as young as 10 years, he pointed out. “The fact that [NM504] is food and you could add this to the regimen makes it very appealing” for use in adolescent patients, he said.

Dr. Heiman, a former obesity researcher at Eli Lilly, said that interventions to manipulate gut microbiota were worthy of deeper investigation. “In the past we were content to say ‘you’ve got bacteria to help you digest food’ – but little was known about what they do, whether they convert sugars to short-chain fatty acids, whether they might send out signals that may, for example, make you crave sugar. The exciting things is learning what all the signals are, and how they communicate with the body,” he said.

MicroBiome Therapeutics, owner of a patent on the investigational product, sponsored the study. Dr Heiman is an employee of MicroBiome Therapeutics, and another coauthor disclosed funding from the company. Dr. Hsia and three other coauthors reported no conflicts of interest.

Boston – A purified food supplement designed to alter gut bacterial composition improved both metformin tolerance and fasting glucose levels among people with type 2 diabetes, according to results from a small randomized study presented at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

Research into how diabetes affects and is affected by the gut microbiome is still in its infancy. However, compared with nondiabetics, people with type 2 diabetes have been shown to have microbiomes richer in certain types of bacteria than others, and these altered bacterial profiles may be linked to changes in insulin sensitivity, glucose regulation, and methane production.

Mark L Heiman, Ph.D., of MicroBiome Therapeutics in New Orleans, designed the intervention, a powder comprising three purified food ingredients: inulin from agave, beta-glucan from oatmeal, and polyphenols derived from blueberry skins. These were hypothesized to alter gut microbial composition by stimulating blooms of microbes that can generate short-chain fatty acids, displacing some bacteria-producing lactic acid; increase viscosity in the colon (allowing for sequestering of bile acids); and combat oxidative stress and methane production.

Though first investigated as a monotherapy for use in people with prediabetes, the so-called gut microbiome modulator NM504 was found incidentally to improve metformin tolerance in people with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes (Benef. Microbes 2014;5:29-32), and researchers hypothesized that metformin likely interacts with microbiota in the colon, resulting in an abundance of lactate-producing bacteria. Lactic acid production in the colon, exacerbated by starch or sugar consumption, is a known contributor to adverse GI side effects in people taking metformin.

Dr. Heiman presented results from a randomized, placebo-controlled, single-center crossover study in 10 people with type 2 diabetes (8 female) with difficulty tolerating metformin due to GI symptoms or who had discontinued previous therapy because of these symptoms (J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2015;9:808-14).

Subjects were randomly assigned metformin (500 mg twice daily in the first week titrated to three times daily in the second week) alongside the experimental product or placebo. They were asked to record their glucose and adverse GI symptoms (including stool consistency, urgency to evacuate, bloating sensation, and flatulence) every day; metformin tolerance was measured by these symptoms using a scoring system previously validated in patients with irritable bowel syndrome.

After 2 weeks of treatment and a washout period of 2 weeks with no treatment, subjects’ initial treatment assignments were reversed for an additional 2 weeks, and outcomes were recorded.

The combination of metformin and NM504 resulted in improved tolerance score of metformin, compared with placebo (6.78 ± 0.65 [mean ± standard error of the mean] vs. 4.45 ± 0.69, P = .0006). Mean fasting glucose levels were significantly lower with the metformin/NM504 combination (121.3 ± 7.8 mg/dL) than with metformin-placebo (151.9 ± 7.8 mg/dL), (P < .02).

It is unclear whether the improved glucose was a result of improved availability of metformin or an independent effect of the intervention. Last year Dr. Heiman presented results from a previous study of 28 adults with prediabetes randomized to NM504 monotherapy or placebo who saw significantly lower blood sugar levels at 120 and 180 minutes after a glucose challenge, compared with patients taking placebo. This was presented at the International Congress of Endocrinology’s annual meeting (ICE-Endo) 2014 meeting in Chicago; Dr. Heiman noted that the results are awaiting review and perhaps publication.

Dr. Heiman commented that the glucose-regulating effect seen in the metformin study “appeared somewhat durable, even after the 2-week washout period” among subjects switching from intervention to placebo; however, further studies would be needed to determine its effect on insulin sensitivity. Fecal microbial composition was not investigated before and after treatment.

Dr. Daniel Hsia of Pennington Biomedical Research Center, in Baton Rouge, La., a study coauthor, said in an interview that although larger trials would be needed to validate the results and better understand the activity of the intervention in the gut, the findings were “promising” for a proof-of-concept study.

“At this point, we’re not going to start using this in every single diabetes patient on metformin, but it’s very encouraging that you could potentially make it more accessible. Metformin is a very good agent with one of the longest histories. It’s cheap, it can be used in combination with a lot of other medications, but a certain percentage of people will have to stop metformin altogether due to side effects.” Metformin is also approved for children with type 2 diabetes as young as 10 years, he pointed out. “The fact that [NM504] is food and you could add this to the regimen makes it very appealing” for use in adolescent patients, he said.

Dr. Heiman, a former obesity researcher at Eli Lilly, said that interventions to manipulate gut microbiota were worthy of deeper investigation. “In the past we were content to say ‘you’ve got bacteria to help you digest food’ – but little was known about what they do, whether they convert sugars to short-chain fatty acids, whether they might send out signals that may, for example, make you crave sugar. The exciting things is learning what all the signals are, and how they communicate with the body,” he said.

MicroBiome Therapeutics, owner of a patent on the investigational product, sponsored the study. Dr Heiman is an employee of MicroBiome Therapeutics, and another coauthor disclosed funding from the company. Dr. Hsia and three other coauthors reported no conflicts of interest.

Boston – A purified food supplement designed to alter gut bacterial composition improved both metformin tolerance and fasting glucose levels among people with type 2 diabetes, according to results from a small randomized study presented at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

Research into how diabetes affects and is affected by the gut microbiome is still in its infancy. However, compared with nondiabetics, people with type 2 diabetes have been shown to have microbiomes richer in certain types of bacteria than others, and these altered bacterial profiles may be linked to changes in insulin sensitivity, glucose regulation, and methane production.

Mark L Heiman, Ph.D., of MicroBiome Therapeutics in New Orleans, designed the intervention, a powder comprising three purified food ingredients: inulin from agave, beta-glucan from oatmeal, and polyphenols derived from blueberry skins. These were hypothesized to alter gut microbial composition by stimulating blooms of microbes that can generate short-chain fatty acids, displacing some bacteria-producing lactic acid; increase viscosity in the colon (allowing for sequestering of bile acids); and combat oxidative stress and methane production.

Though first investigated as a monotherapy for use in people with prediabetes, the so-called gut microbiome modulator NM504 was found incidentally to improve metformin tolerance in people with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes (Benef. Microbes 2014;5:29-32), and researchers hypothesized that metformin likely interacts with microbiota in the colon, resulting in an abundance of lactate-producing bacteria. Lactic acid production in the colon, exacerbated by starch or sugar consumption, is a known contributor to adverse GI side effects in people taking metformin.

Dr. Heiman presented results from a randomized, placebo-controlled, single-center crossover study in 10 people with type 2 diabetes (8 female) with difficulty tolerating metformin due to GI symptoms or who had discontinued previous therapy because of these symptoms (J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2015;9:808-14).

Subjects were randomly assigned metformin (500 mg twice daily in the first week titrated to three times daily in the second week) alongside the experimental product or placebo. They were asked to record their glucose and adverse GI symptoms (including stool consistency, urgency to evacuate, bloating sensation, and flatulence) every day; metformin tolerance was measured by these symptoms using a scoring system previously validated in patients with irritable bowel syndrome.

After 2 weeks of treatment and a washout period of 2 weeks with no treatment, subjects’ initial treatment assignments were reversed for an additional 2 weeks, and outcomes were recorded.

The combination of metformin and NM504 resulted in improved tolerance score of metformin, compared with placebo (6.78 ± 0.65 [mean ± standard error of the mean] vs. 4.45 ± 0.69, P = .0006). Mean fasting glucose levels were significantly lower with the metformin/NM504 combination (121.3 ± 7.8 mg/dL) than with metformin-placebo (151.9 ± 7.8 mg/dL), (P < .02).

It is unclear whether the improved glucose was a result of improved availability of metformin or an independent effect of the intervention. Last year Dr. Heiman presented results from a previous study of 28 adults with prediabetes randomized to NM504 monotherapy or placebo who saw significantly lower blood sugar levels at 120 and 180 minutes after a glucose challenge, compared with patients taking placebo. This was presented at the International Congress of Endocrinology’s annual meeting (ICE-Endo) 2014 meeting in Chicago; Dr. Heiman noted that the results are awaiting review and perhaps publication.

Dr. Heiman commented that the glucose-regulating effect seen in the metformin study “appeared somewhat durable, even after the 2-week washout period” among subjects switching from intervention to placebo; however, further studies would be needed to determine its effect on insulin sensitivity. Fecal microbial composition was not investigated before and after treatment.

Dr. Daniel Hsia of Pennington Biomedical Research Center, in Baton Rouge, La., a study coauthor, said in an interview that although larger trials would be needed to validate the results and better understand the activity of the intervention in the gut, the findings were “promising” for a proof-of-concept study.

“At this point, we’re not going to start using this in every single diabetes patient on metformin, but it’s very encouraging that you could potentially make it more accessible. Metformin is a very good agent with one of the longest histories. It’s cheap, it can be used in combination with a lot of other medications, but a certain percentage of people will have to stop metformin altogether due to side effects.” Metformin is also approved for children with type 2 diabetes as young as 10 years, he pointed out. “The fact that [NM504] is food and you could add this to the regimen makes it very appealing” for use in adolescent patients, he said.

Dr. Heiman, a former obesity researcher at Eli Lilly, said that interventions to manipulate gut microbiota were worthy of deeper investigation. “In the past we were content to say ‘you’ve got bacteria to help you digest food’ – but little was known about what they do, whether they convert sugars to short-chain fatty acids, whether they might send out signals that may, for example, make you crave sugar. The exciting things is learning what all the signals are, and how they communicate with the body,” he said.

MicroBiome Therapeutics, owner of a patent on the investigational product, sponsored the study. Dr Heiman is an employee of MicroBiome Therapeutics, and another coauthor disclosed funding from the company. Dr. Hsia and three other coauthors reported no conflicts of interest.

AT THE ADA ANNUAL SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: NM504, a food-derived product intended to stimulate gut production of beneficial bacteria, improved tolerance to metformin in people with type 2 diabetes.

Major finding: Patients previously reporting discontinuation of metformin therapy were significantly more tolerant to metformin (P = .0006) when randomized to an experimental agent hypothesized to alter gut microbial composition.

Data source: A small (n = 10) randomized trial in an academic clinical setting; patients were randomized 1:1 to receive an escalating dose of metformin plus placebo or NM504 for 2 weeks. After 2-week interruption, treatment assignments were switched for all patients.

Disclosures: The manufacturer sponsored the study of the proprietary investigational product. The lead investigator is a company employee and one of the coauthors disclosed a financial relationship.

NSAID monotherapy as effective as combinations for low back pain

SAN DIEGO – Patients presenting to emergency departments with acute low back pain who were treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug monotherapy did as well as those who received an NSAID combined with an opioid or muscle relaxant, though combination therapies are far more commonly prescribed in the ED.

At the annual meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine, Dr. Benjamin W. Friedman of Montefiore Medical Center in New York presented results from a trial of 323 adult patients aged 64 and younger at Montefiore’s emergency department who had acute low back pain not related to trauma, and functional impairment.

Patients were evaluated at baseline using the Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ), and randomized to receive naproxen sodium 500 mg along with placebo tablets (n = 107), cyclobenzaprine 5 mg (n = 108), or oxycodone 5 mg/acetaminophen 325 mg (n = 108) for low back pain. Patients and clinicians were blinded to treatment assignment.

Subjects were advised to take naproxen sodium along with 1 or 2 tablets of the study drug, every 8 hours as needed. They were followed up by telephone 1 week later and again at 3 months, with 92% followed up at 3 months.

At 1 week after the ED visit, there were no clinically or statistically significant differences seen among the treatment groups in improvements measured by RMDQ scores, with placebo subjects showing a mean improvement of 9.6% (98% CI, 7.7-11.5); cyclobenzaprine subjects, 10.1 (98% CI, 7.9-12.3); and oxycodone/acetaminophen subjects, 10.9 (98% CI, 8.9-13.0). At 3 months, functional and pain outcomes did not differ significantly among the groups.

Adverse events were lowest in the placebo group, with 21% of patients reporting at least one after the first week, compared with 34% for cyclobenzaprine and 40% for oxycodone; the most commonly reported effects were drowsiness, dizziness, and gastric symptoms. “This works out to a number needed to harm for cyclobenzaprine of eight, and for Percocet [oxycodone/acetaminophen] of five,” compared with placebo, Dr. Friedman told the conference.

However, he noted, of the patients who adhered to the study medications – that is, who took them more than once – only 30% of those on oxycodone reported moderate or severe back pain at 1 week, compared with 48% of patients taking placebo, a statistically significant difference, though overall RMDQ improvement did not differ among the groups.

“Giving [oxycodone] to all your patients with lower back pain is a strategy that’s not going to work,” he said. “But if you limit it to patients who really need it and are likely to adhere to it, that’s a population who might see a benefit. Just remember, the number to harm needed is five. Don’t prescribe this medication lightly.”

Dr. Friedman said that low back pain complaints account for 2.4% of all ED visits in the United States, or 2.7 million visits annually, and that more than half of ED prescriptions for low back pain comprise combinations of two of the drug classes, with 16% of prescriptions combining all three.

Dr. Friedman’s study was internally funded and neither he nor his coinvestigators disclosed conflicts of interest.

SAN DIEGO – Patients presenting to emergency departments with acute low back pain who were treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug monotherapy did as well as those who received an NSAID combined with an opioid or muscle relaxant, though combination therapies are far more commonly prescribed in the ED.

At the annual meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine, Dr. Benjamin W. Friedman of Montefiore Medical Center in New York presented results from a trial of 323 adult patients aged 64 and younger at Montefiore’s emergency department who had acute low back pain not related to trauma, and functional impairment.

Patients were evaluated at baseline using the Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ), and randomized to receive naproxen sodium 500 mg along with placebo tablets (n = 107), cyclobenzaprine 5 mg (n = 108), or oxycodone 5 mg/acetaminophen 325 mg (n = 108) for low back pain. Patients and clinicians were blinded to treatment assignment.

Subjects were advised to take naproxen sodium along with 1 or 2 tablets of the study drug, every 8 hours as needed. They were followed up by telephone 1 week later and again at 3 months, with 92% followed up at 3 months.

At 1 week after the ED visit, there were no clinically or statistically significant differences seen among the treatment groups in improvements measured by RMDQ scores, with placebo subjects showing a mean improvement of 9.6% (98% CI, 7.7-11.5); cyclobenzaprine subjects, 10.1 (98% CI, 7.9-12.3); and oxycodone/acetaminophen subjects, 10.9 (98% CI, 8.9-13.0). At 3 months, functional and pain outcomes did not differ significantly among the groups.

Adverse events were lowest in the placebo group, with 21% of patients reporting at least one after the first week, compared with 34% for cyclobenzaprine and 40% for oxycodone; the most commonly reported effects were drowsiness, dizziness, and gastric symptoms. “This works out to a number needed to harm for cyclobenzaprine of eight, and for Percocet [oxycodone/acetaminophen] of five,” compared with placebo, Dr. Friedman told the conference.

However, he noted, of the patients who adhered to the study medications – that is, who took them more than once – only 30% of those on oxycodone reported moderate or severe back pain at 1 week, compared with 48% of patients taking placebo, a statistically significant difference, though overall RMDQ improvement did not differ among the groups.

“Giving [oxycodone] to all your patients with lower back pain is a strategy that’s not going to work,” he said. “But if you limit it to patients who really need it and are likely to adhere to it, that’s a population who might see a benefit. Just remember, the number to harm needed is five. Don’t prescribe this medication lightly.”

Dr. Friedman said that low back pain complaints account for 2.4% of all ED visits in the United States, or 2.7 million visits annually, and that more than half of ED prescriptions for low back pain comprise combinations of two of the drug classes, with 16% of prescriptions combining all three.

Dr. Friedman’s study was internally funded and neither he nor his coinvestigators disclosed conflicts of interest.

SAN DIEGO – Patients presenting to emergency departments with acute low back pain who were treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug monotherapy did as well as those who received an NSAID combined with an opioid or muscle relaxant, though combination therapies are far more commonly prescribed in the ED.

At the annual meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine, Dr. Benjamin W. Friedman of Montefiore Medical Center in New York presented results from a trial of 323 adult patients aged 64 and younger at Montefiore’s emergency department who had acute low back pain not related to trauma, and functional impairment.

Patients were evaluated at baseline using the Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ), and randomized to receive naproxen sodium 500 mg along with placebo tablets (n = 107), cyclobenzaprine 5 mg (n = 108), or oxycodone 5 mg/acetaminophen 325 mg (n = 108) for low back pain. Patients and clinicians were blinded to treatment assignment.

Subjects were advised to take naproxen sodium along with 1 or 2 tablets of the study drug, every 8 hours as needed. They were followed up by telephone 1 week later and again at 3 months, with 92% followed up at 3 months.

At 1 week after the ED visit, there were no clinically or statistically significant differences seen among the treatment groups in improvements measured by RMDQ scores, with placebo subjects showing a mean improvement of 9.6% (98% CI, 7.7-11.5); cyclobenzaprine subjects, 10.1 (98% CI, 7.9-12.3); and oxycodone/acetaminophen subjects, 10.9 (98% CI, 8.9-13.0). At 3 months, functional and pain outcomes did not differ significantly among the groups.

Adverse events were lowest in the placebo group, with 21% of patients reporting at least one after the first week, compared with 34% for cyclobenzaprine and 40% for oxycodone; the most commonly reported effects were drowsiness, dizziness, and gastric symptoms. “This works out to a number needed to harm for cyclobenzaprine of eight, and for Percocet [oxycodone/acetaminophen] of five,” compared with placebo, Dr. Friedman told the conference.

However, he noted, of the patients who adhered to the study medications – that is, who took them more than once – only 30% of those on oxycodone reported moderate or severe back pain at 1 week, compared with 48% of patients taking placebo, a statistically significant difference, though overall RMDQ improvement did not differ among the groups.

“Giving [oxycodone] to all your patients with lower back pain is a strategy that’s not going to work,” he said. “But if you limit it to patients who really need it and are likely to adhere to it, that’s a population who might see a benefit. Just remember, the number to harm needed is five. Don’t prescribe this medication lightly.”

Dr. Friedman said that low back pain complaints account for 2.4% of all ED visits in the United States, or 2.7 million visits annually, and that more than half of ED prescriptions for low back pain comprise combinations of two of the drug classes, with 16% of prescriptions combining all three.

Dr. Friedman’s study was internally funded and neither he nor his coinvestigators disclosed conflicts of interest.

AT SAEM 2015

Key clinical point: Patients prescribed naproxen sodium for low back pain at the emergency department had functional and pain scores similar to those of patients on combination therapies

Major finding: No statistically significant differences in disability scores were seen among patients treated with the NSAID, or the NSAID in combination with oxycodone or cyclobenzaprine at 1 week.

Data source: A study of 323 patients randomized 1:1:1 to naproxen sodium plus placebo, oxycodone, or cyclobenzaprine in an urban hospital ED.

Disclosures: Dr. Friedman’s study was internally funded and neither he nor his coinvestigators disclosed conflicts of interest.

Liraglutide shrank epicardial fat 42% in type 2 diabetes

BOSTON – Liraglutide in combination with metformin reduced epicardial adipose tissue by nearly half within 6 months of treatment in people with type 2 diabetes, an effect independent of either body weight loss or glycemic control, according to a new study.

Epicardial adipose tissue (EAT) is the fat depot around the heart. While EAT has many cardioprotective properties, increased or excess EAT – seen more frequently in people with type 2 diabetes – has been linked to coronary artery disease, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, insulin resistance, and liver disease, according to a review by Gianluca Iacobellis, M.D., Ph.D., professor of clinical medicine in the division of endocrinology, diabetes and metabolism at the University of Miami (Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2015;11: 363-71).

More than a decade ago, Dr. Iacobellis proposed and validated ultrasound measurement of EAT thickness as marker of visceral fat and a therapeutic target (J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003;88: 5163-8).

At the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association, Dr. Iacobellis presented preliminary findings from a case-control study in 35 patients with type 2 diabetes with body mass indexes greater than 27 kg/m2 and hemoglobin A1c levels no greater than 8% on metformin monotherapy.

Patients were randomized to remain on metformin or metformin plus the glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) analogue liraglutide subcutaneously up to 1.8 mg once daily for 6 months. EAT thickness was measured by ultrasound at baseline, 3 months, and 6 months, along with HbA1c and BMI measures. In the liraglutide group (20 patients), EAT decreased significantly from 10.2 mm to 6.9 mm and 5.8 mm (P < 0.001) after 3 months and 6 months, respectively, for a 42% reduction at 6 months. The metformin-only group (15 patients) saw no reduction in EAT.

The EAT reduction seen in the intervention group was much greater than, and independent of, reductions in body weight or HbA1c. Average BMI fell from 33 kg/m2 at baseline to 31.8 kg/m2 and 31.7 kg/m2 at 3 months and 6 months, respectively, while HbA1c declined 18% among patients on liraglutide.

The findings have important clinical and research implications, Dr. Iacobellis said in an interview. “Emerging evidence is pointing out that EAT as measured with reliable, safe, and cheap ultrasound can be a therapeutic target for medications directly or indirectly targeting the adipose tissue,” he said. And EAT can be measured in clinical settings, he added.

Moreover, there is a strong likelihood that further studies will show cardiovascular benefit associated with reductions in EAT, Dr. Iacobellis predicted.

“There is a direct cross-talk between the cardiac fat and the heart,” he said. “If you target the fat, if you’re able to modulate or to reduce the adipose tissue of the heart, you can directly modulate the myocardium and improve cardiovascular performance.”

Dr. Iacobellis’ study on liraglutide is ongoing, and the investigators are examining the effects of other classes of drugs, including the sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SLGT-2) inhibitors, on EAT in people with type 2 diabetes. Dr. Iacobellis said he did not know whether to consider the EAT reduction a likely class effect of GLP-1 analogue medications. It is biologically plausible, he added, because human adipose tissues express GLP-1 receptors.

Other studies are showing that exenatide may have some beneficial cardiovascular effect in patients with coronary artery disease, he said. “However, liraglutide seems to be the most effective in targeting the adipose tissue. There may be a class effect, but one drug could have a more prominent effect compared to others.”

It is possible that liraglutide’s metabolic and weight-loss benefits are in some way mediated by its effect on EAT and other visceral fat depots, Dr. Iacobellis observed, although further research will be needed to show that.

“We know that people lose weight on liraglutide, and we know they have an improvement in glucose control. But what we don’t know is whether the metabolic improvement is actually driven by an effect of the medication on the organ-specific fat depot,” he said.

Novo Nordisk and the University of Miami sponsored the study. Neither Dr. Iacobellis nor his coauthors disclosed conflicts of interest.

BOSTON – Liraglutide in combination with metformin reduced epicardial adipose tissue by nearly half within 6 months of treatment in people with type 2 diabetes, an effect independent of either body weight loss or glycemic control, according to a new study.

Epicardial adipose tissue (EAT) is the fat depot around the heart. While EAT has many cardioprotective properties, increased or excess EAT – seen more frequently in people with type 2 diabetes – has been linked to coronary artery disease, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, insulin resistance, and liver disease, according to a review by Gianluca Iacobellis, M.D., Ph.D., professor of clinical medicine in the division of endocrinology, diabetes and metabolism at the University of Miami (Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2015;11: 363-71).

More than a decade ago, Dr. Iacobellis proposed and validated ultrasound measurement of EAT thickness as marker of visceral fat and a therapeutic target (J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003;88: 5163-8).

At the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association, Dr. Iacobellis presented preliminary findings from a case-control study in 35 patients with type 2 diabetes with body mass indexes greater than 27 kg/m2 and hemoglobin A1c levels no greater than 8% on metformin monotherapy.

Patients were randomized to remain on metformin or metformin plus the glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) analogue liraglutide subcutaneously up to 1.8 mg once daily for 6 months. EAT thickness was measured by ultrasound at baseline, 3 months, and 6 months, along with HbA1c and BMI measures. In the liraglutide group (20 patients), EAT decreased significantly from 10.2 mm to 6.9 mm and 5.8 mm (P < 0.001) after 3 months and 6 months, respectively, for a 42% reduction at 6 months. The metformin-only group (15 patients) saw no reduction in EAT.

The EAT reduction seen in the intervention group was much greater than, and independent of, reductions in body weight or HbA1c. Average BMI fell from 33 kg/m2 at baseline to 31.8 kg/m2 and 31.7 kg/m2 at 3 months and 6 months, respectively, while HbA1c declined 18% among patients on liraglutide.

The findings have important clinical and research implications, Dr. Iacobellis said in an interview. “Emerging evidence is pointing out that EAT as measured with reliable, safe, and cheap ultrasound can be a therapeutic target for medications directly or indirectly targeting the adipose tissue,” he said. And EAT can be measured in clinical settings, he added.

Moreover, there is a strong likelihood that further studies will show cardiovascular benefit associated with reductions in EAT, Dr. Iacobellis predicted.

“There is a direct cross-talk between the cardiac fat and the heart,” he said. “If you target the fat, if you’re able to modulate or to reduce the adipose tissue of the heart, you can directly modulate the myocardium and improve cardiovascular performance.”

Dr. Iacobellis’ study on liraglutide is ongoing, and the investigators are examining the effects of other classes of drugs, including the sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SLGT-2) inhibitors, on EAT in people with type 2 diabetes. Dr. Iacobellis said he did not know whether to consider the EAT reduction a likely class effect of GLP-1 analogue medications. It is biologically plausible, he added, because human adipose tissues express GLP-1 receptors.

Other studies are showing that exenatide may have some beneficial cardiovascular effect in patients with coronary artery disease, he said. “However, liraglutide seems to be the most effective in targeting the adipose tissue. There may be a class effect, but one drug could have a more prominent effect compared to others.”

It is possible that liraglutide’s metabolic and weight-loss benefits are in some way mediated by its effect on EAT and other visceral fat depots, Dr. Iacobellis observed, although further research will be needed to show that.

“We know that people lose weight on liraglutide, and we know they have an improvement in glucose control. But what we don’t know is whether the metabolic improvement is actually driven by an effect of the medication on the organ-specific fat depot,” he said.

Novo Nordisk and the University of Miami sponsored the study. Neither Dr. Iacobellis nor his coauthors disclosed conflicts of interest.

BOSTON – Liraglutide in combination with metformin reduced epicardial adipose tissue by nearly half within 6 months of treatment in people with type 2 diabetes, an effect independent of either body weight loss or glycemic control, according to a new study.

Epicardial adipose tissue (EAT) is the fat depot around the heart. While EAT has many cardioprotective properties, increased or excess EAT – seen more frequently in people with type 2 diabetes – has been linked to coronary artery disease, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, insulin resistance, and liver disease, according to a review by Gianluca Iacobellis, M.D., Ph.D., professor of clinical medicine in the division of endocrinology, diabetes and metabolism at the University of Miami (Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2015;11: 363-71).

More than a decade ago, Dr. Iacobellis proposed and validated ultrasound measurement of EAT thickness as marker of visceral fat and a therapeutic target (J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003;88: 5163-8).

At the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association, Dr. Iacobellis presented preliminary findings from a case-control study in 35 patients with type 2 diabetes with body mass indexes greater than 27 kg/m2 and hemoglobin A1c levels no greater than 8% on metformin monotherapy.

Patients were randomized to remain on metformin or metformin plus the glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) analogue liraglutide subcutaneously up to 1.8 mg once daily for 6 months. EAT thickness was measured by ultrasound at baseline, 3 months, and 6 months, along with HbA1c and BMI measures. In the liraglutide group (20 patients), EAT decreased significantly from 10.2 mm to 6.9 mm and 5.8 mm (P < 0.001) after 3 months and 6 months, respectively, for a 42% reduction at 6 months. The metformin-only group (15 patients) saw no reduction in EAT.

The EAT reduction seen in the intervention group was much greater than, and independent of, reductions in body weight or HbA1c. Average BMI fell from 33 kg/m2 at baseline to 31.8 kg/m2 and 31.7 kg/m2 at 3 months and 6 months, respectively, while HbA1c declined 18% among patients on liraglutide.

The findings have important clinical and research implications, Dr. Iacobellis said in an interview. “Emerging evidence is pointing out that EAT as measured with reliable, safe, and cheap ultrasound can be a therapeutic target for medications directly or indirectly targeting the adipose tissue,” he said. And EAT can be measured in clinical settings, he added.

Moreover, there is a strong likelihood that further studies will show cardiovascular benefit associated with reductions in EAT, Dr. Iacobellis predicted.

“There is a direct cross-talk between the cardiac fat and the heart,” he said. “If you target the fat, if you’re able to modulate or to reduce the adipose tissue of the heart, you can directly modulate the myocardium and improve cardiovascular performance.”

Dr. Iacobellis’ study on liraglutide is ongoing, and the investigators are examining the effects of other classes of drugs, including the sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SLGT-2) inhibitors, on EAT in people with type 2 diabetes. Dr. Iacobellis said he did not know whether to consider the EAT reduction a likely class effect of GLP-1 analogue medications. It is biologically plausible, he added, because human adipose tissues express GLP-1 receptors.

Other studies are showing that exenatide may have some beneficial cardiovascular effect in patients with coronary artery disease, he said. “However, liraglutide seems to be the most effective in targeting the adipose tissue. There may be a class effect, but one drug could have a more prominent effect compared to others.”

It is possible that liraglutide’s metabolic and weight-loss benefits are in some way mediated by its effect on EAT and other visceral fat depots, Dr. Iacobellis observed, although further research will be needed to show that.

“We know that people lose weight on liraglutide, and we know they have an improvement in glucose control. But what we don’t know is whether the metabolic improvement is actually driven by an effect of the medication on the organ-specific fat depot,” he said.

Novo Nordisk and the University of Miami sponsored the study. Neither Dr. Iacobellis nor his coauthors disclosed conflicts of interest.

AT THE ADA ANNUAL SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: Liraglutide, a GLP-1 analogue used to promote glycemic control in people with type 2 diabetes, shrank epicardial adipose tissue by 42% in 6 months in patients with type 2 diabetes.

Major finding: In 20 patients on liraglutide and metformin, EAT decreased from 10.2 mm to 6.9 mm and 5.8 mm (P < 0.001) after 3 months and 6 months, respectively, for a 42% reduction at 6 months. A metformin-only group of 15 patients saw no reduction in EAT.

Data source: A case-control study of 35 patients randomized to liraglutide and metformin or metformin only and followed up at 3 months and 6 months for BMI, HbA1c, and ultrasound EAT thickness.

Disclosures: Novo Nordisk and the University of Miami sponsored the study. Neither Dr. Iacobellis nor his coauthors disclosed conflicts of interest.

ADA: Alefacept slows progress of type 1 diabetes 15 months post-treatment

BOSTON– Alefacept, an immunosuppressive biologic drug approved to treat psoriasis but later withdrawn by its manufacturer, appears to stem the progression of new-onset type 1 diabetes more than a year after therapy is stopped.

In type 1 diabetes, pancreatic beta cells are destroyed by autoreactive effector T cells, which alefacept targets as one of its mechanisms of action.

“What we think is happening – the most likely conservative hypothesis – is that we’ve rescued beta cells that were traumatized but not killed,” resulting in some restoration of beta-cell function and endogenous insulin secretion, said Dr. Gerald Nepom, director of Benaroya Research Institute at Virginia Mason in Seattle.

At the 75th annual sessions of the American Diabetes association, Dr. Mario Ehlers, another researcher involved with the study, presented 24-month results from T1DAL (Targeting of memory T cells with alefacept in new onset type 1 diabetes).

The study randomized 49 people aged 12-35 years who had been diagnosed with type 1 diabetes within the previous 100 days to treatment with weekly injections of alefacept (n = 33) or placebo (n = 16). Active treatment occurred over two 12-week periods, with the last treatment administered 36 weeks into the study.

In 2013, the T1DAL investigators published their results from 12 months (about 4 months after treatment was stopped). They found that alefacept did not bring about statistically significant differences over placebo in insulin production 2 hours after a meal (measured as mean C-peptide secretion area under curve), but at 4 hours, the differences reached statistical significance (Lancet 2013;1:284-94). In addition, insulin use and hypoglycemic events were found to be significantly reduced in the treatment arm.

New results from 24 months’ follow-up of the T1DAL cohort showed a more impressive effect.

At 15 months after cessation of therapy, the 2-hour postprandial mean C-peptide AUC was significantly greater in the treatment group (P = .002) than the placebo group, as was the 4-hour measure (P = .015). Insulin requirements remained significantly lower (P = .002) and rates of major hypoglycemic events were reduced by about half (P < .001) among subjects who had received alefacept.

Dr. Nepom stressed that while these results were “spectacular” for patients who responded, only about one-third of the treatment arm showed higher C peptide at 24 months than at baseline. “So while there was sustained and significant benefit, it was not in everybody,” he said.

“There’s a responder and a nonresponder situation here, and we’re continuing to evaluate all kinds of biologic biomarkers to try and understand the differences between patients who improved in the second year and those who didn’t.”

Investigators will continue following up the T1DAL patients who responded for as long as patients consent, without further medication, to see how durable the effect is, Dr. Nepom said.

An optimal clinical treatment protocol with alefacept needs to be investigated in a separate trial, he said. Currently, the focus is on adding an immunomodulatory drug after induction treatment with alefacept in the hope that this prolongs the “honeymoon period” seen in the T1DAL responders, and/or extends the benefit to more than just a third of patients.

“Durable clinical responses are likely to require therapies that address more than a single immunological pathway, such as a sequential combination of treatments that first interrupt ongoing disease and secondly restore normal function,” Dr. Nepom said.

Like T1DAL, the new trial will be conducted under the Immune Tolerance Network, a publicly funded research consortium headed by Dr. Nepom that makes all its trial data available to the public. The results from T1DAL will be also published this year in the Journal of Clinical Investigation.

Alefacept (Amevive, Astellas Pharma) was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2003 to treat moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis in adults. In 2011, its manufacturer withdrew it from the market, citing business reasons. “We are actively working with interested parties to fix that situation,” Dr. Nepom said.

The Immune Tolerance Network is also investigating whether tocilizumab (Actemra, Genentech), an antibody that targets the interleukin-6 receptor, can slow disease progression and help maintain insulin production in people with new-onset T1D.

The Immune Tolerance Network is funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Dr. Nepom disclosed financial support from Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, and Pfizer, and research support from Astellas and Bayer. A T1DAL coauthor and former lead investigator, Mark Rigby, recently joined Janssen pharmaceuticals as an employee. Dr. Ehlers disclosed no conflicts of interest.

BOSTON– Alefacept, an immunosuppressive biologic drug approved to treat psoriasis but later withdrawn by its manufacturer, appears to stem the progression of new-onset type 1 diabetes more than a year after therapy is stopped.

In type 1 diabetes, pancreatic beta cells are destroyed by autoreactive effector T cells, which alefacept targets as one of its mechanisms of action.

“What we think is happening – the most likely conservative hypothesis – is that we’ve rescued beta cells that were traumatized but not killed,” resulting in some restoration of beta-cell function and endogenous insulin secretion, said Dr. Gerald Nepom, director of Benaroya Research Institute at Virginia Mason in Seattle.

At the 75th annual sessions of the American Diabetes association, Dr. Mario Ehlers, another researcher involved with the study, presented 24-month results from T1DAL (Targeting of memory T cells with alefacept in new onset type 1 diabetes).

The study randomized 49 people aged 12-35 years who had been diagnosed with type 1 diabetes within the previous 100 days to treatment with weekly injections of alefacept (n = 33) or placebo (n = 16). Active treatment occurred over two 12-week periods, with the last treatment administered 36 weeks into the study.

In 2013, the T1DAL investigators published their results from 12 months (about 4 months after treatment was stopped). They found that alefacept did not bring about statistically significant differences over placebo in insulin production 2 hours after a meal (measured as mean C-peptide secretion area under curve), but at 4 hours, the differences reached statistical significance (Lancet 2013;1:284-94). In addition, insulin use and hypoglycemic events were found to be significantly reduced in the treatment arm.

New results from 24 months’ follow-up of the T1DAL cohort showed a more impressive effect.

At 15 months after cessation of therapy, the 2-hour postprandial mean C-peptide AUC was significantly greater in the treatment group (P = .002) than the placebo group, as was the 4-hour measure (P = .015). Insulin requirements remained significantly lower (P = .002) and rates of major hypoglycemic events were reduced by about half (P < .001) among subjects who had received alefacept.

Dr. Nepom stressed that while these results were “spectacular” for patients who responded, only about one-third of the treatment arm showed higher C peptide at 24 months than at baseline. “So while there was sustained and significant benefit, it was not in everybody,” he said.

“There’s a responder and a nonresponder situation here, and we’re continuing to evaluate all kinds of biologic biomarkers to try and understand the differences between patients who improved in the second year and those who didn’t.”

Investigators will continue following up the T1DAL patients who responded for as long as patients consent, without further medication, to see how durable the effect is, Dr. Nepom said.

An optimal clinical treatment protocol with alefacept needs to be investigated in a separate trial, he said. Currently, the focus is on adding an immunomodulatory drug after induction treatment with alefacept in the hope that this prolongs the “honeymoon period” seen in the T1DAL responders, and/or extends the benefit to more than just a third of patients.

“Durable clinical responses are likely to require therapies that address more than a single immunological pathway, such as a sequential combination of treatments that first interrupt ongoing disease and secondly restore normal function,” Dr. Nepom said.

Like T1DAL, the new trial will be conducted under the Immune Tolerance Network, a publicly funded research consortium headed by Dr. Nepom that makes all its trial data available to the public. The results from T1DAL will be also published this year in the Journal of Clinical Investigation.

Alefacept (Amevive, Astellas Pharma) was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2003 to treat moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis in adults. In 2011, its manufacturer withdrew it from the market, citing business reasons. “We are actively working with interested parties to fix that situation,” Dr. Nepom said.

The Immune Tolerance Network is also investigating whether tocilizumab (Actemra, Genentech), an antibody that targets the interleukin-6 receptor, can slow disease progression and help maintain insulin production in people with new-onset T1D.

The Immune Tolerance Network is funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Dr. Nepom disclosed financial support from Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, and Pfizer, and research support from Astellas and Bayer. A T1DAL coauthor and former lead investigator, Mark Rigby, recently joined Janssen pharmaceuticals as an employee. Dr. Ehlers disclosed no conflicts of interest.

BOSTON– Alefacept, an immunosuppressive biologic drug approved to treat psoriasis but later withdrawn by its manufacturer, appears to stem the progression of new-onset type 1 diabetes more than a year after therapy is stopped.

In type 1 diabetes, pancreatic beta cells are destroyed by autoreactive effector T cells, which alefacept targets as one of its mechanisms of action.

“What we think is happening – the most likely conservative hypothesis – is that we’ve rescued beta cells that were traumatized but not killed,” resulting in some restoration of beta-cell function and endogenous insulin secretion, said Dr. Gerald Nepom, director of Benaroya Research Institute at Virginia Mason in Seattle.

At the 75th annual sessions of the American Diabetes association, Dr. Mario Ehlers, another researcher involved with the study, presented 24-month results from T1DAL (Targeting of memory T cells with alefacept in new onset type 1 diabetes).

The study randomized 49 people aged 12-35 years who had been diagnosed with type 1 diabetes within the previous 100 days to treatment with weekly injections of alefacept (n = 33) or placebo (n = 16). Active treatment occurred over two 12-week periods, with the last treatment administered 36 weeks into the study.