User login

Hospitalization driving bariatric surgery cost differences

Medicare payments to hospitals for bariatric operations varied by nearly $2,000 per episode of care, mostly because of differences in costs incurred in the initial – or index – hospitalization.

The findings, published online Sept. 16 in JAMA Surgery, offer hospitals a guide to where cost variation is highest (doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2015.2394) for these procedures.

Knowing where costs vary the most is particularly important if hospitals opt to accept bundled Medicare payments for bariatric procedures, which are a proposed addition to 48 other episodes of care that can currently be reimbursed in this way. Under bundled care payment programs, hospitals receive a single payment for all services related to a surgery or other episode of care, thereby accepting more risk when inefficiencies occur.

For their research, Dr. Tyler R. Grenda and his colleagues at University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Center for Healthcare Outcomes and Policy, looked at claims data for 24,647 patients receiving bariatric procedures at 463 hospitals during 2011-2012.

Operations included laparoscopic gastric banding, laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, and open Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, with fewer than 5% of patients receiving other interventions. Mean total payments varied from $11,086 to $13,073 per episode of care, defined as index hospitalization through 30 days postdischarge, for a 16.5% difference between the lowest and highest hospital quartiles.

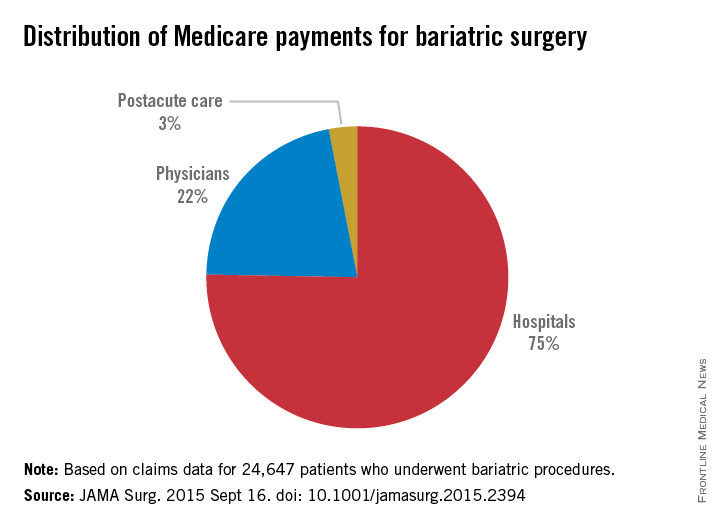

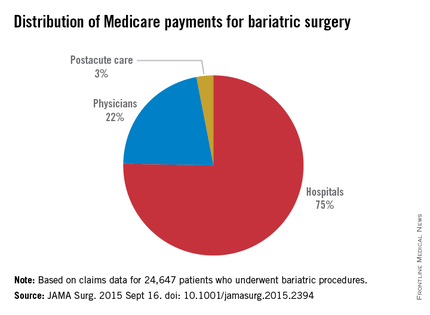

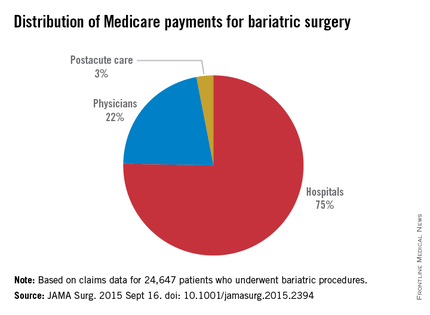

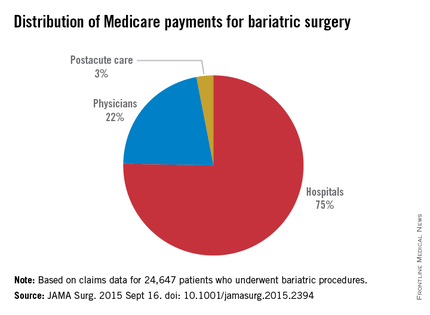

The index hospitalization was responsible for the largest portion of total payments (75%), seen in the study, followed by physician services (21%) and postacute care services (2.8%).

The large share of costs incurred during the index hospitalization was “likely owing to inpatient complications that drive [diagnosis-related group] up-coding,” the authors wrote, noting that DRG with complications result in higher Medicare payments.

Dr. Grenda and his colleagues concluded that bariatric surgery “appears to have a distinct pattern of hospital cost variation” unlike that seen in other procedures that have been studied to identify drivers of cost differences. “This difference in the pattern of variation emphasizes the importance of understanding cost variation specific to each procedure,” they wrote.

For example, a study that looked at hip fracture repair found that postacute care accounted for a large portion of variation in payments, while less variation was seen for the index hospitalization (Health Serv Res. 2010;45[6, pt 1]:1783-95).

In the current policy environment, in which bundled payments are seen as a way to shift cost accountability to hospitals, “a detailed understanding of variation in the costs for bariatric surgery will be essential for hospitals to identify areas of risk and opportunities for improvement,” the researchers wrote in their analysis.

Dr. Grenda and his colleagues’ research was funded by Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. One coauthor and the supervisor of the study, Dr. Justin Dimnick, disclosed a financial relationship with ArborMetrix, a health care analytics firm not involved with the study; he is also an editor of JAMA Surgery, which published the study.

Medicare payments to hospitals for bariatric operations varied by nearly $2,000 per episode of care, mostly because of differences in costs incurred in the initial – or index – hospitalization.

The findings, published online Sept. 16 in JAMA Surgery, offer hospitals a guide to where cost variation is highest (doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2015.2394) for these procedures.

Knowing where costs vary the most is particularly important if hospitals opt to accept bundled Medicare payments for bariatric procedures, which are a proposed addition to 48 other episodes of care that can currently be reimbursed in this way. Under bundled care payment programs, hospitals receive a single payment for all services related to a surgery or other episode of care, thereby accepting more risk when inefficiencies occur.

For their research, Dr. Tyler R. Grenda and his colleagues at University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Center for Healthcare Outcomes and Policy, looked at claims data for 24,647 patients receiving bariatric procedures at 463 hospitals during 2011-2012.

Operations included laparoscopic gastric banding, laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, and open Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, with fewer than 5% of patients receiving other interventions. Mean total payments varied from $11,086 to $13,073 per episode of care, defined as index hospitalization through 30 days postdischarge, for a 16.5% difference between the lowest and highest hospital quartiles.

The index hospitalization was responsible for the largest portion of total payments (75%), seen in the study, followed by physician services (21%) and postacute care services (2.8%).

The large share of costs incurred during the index hospitalization was “likely owing to inpatient complications that drive [diagnosis-related group] up-coding,” the authors wrote, noting that DRG with complications result in higher Medicare payments.

Dr. Grenda and his colleagues concluded that bariatric surgery “appears to have a distinct pattern of hospital cost variation” unlike that seen in other procedures that have been studied to identify drivers of cost differences. “This difference in the pattern of variation emphasizes the importance of understanding cost variation specific to each procedure,” they wrote.

For example, a study that looked at hip fracture repair found that postacute care accounted for a large portion of variation in payments, while less variation was seen for the index hospitalization (Health Serv Res. 2010;45[6, pt 1]:1783-95).

In the current policy environment, in which bundled payments are seen as a way to shift cost accountability to hospitals, “a detailed understanding of variation in the costs for bariatric surgery will be essential for hospitals to identify areas of risk and opportunities for improvement,” the researchers wrote in their analysis.

Dr. Grenda and his colleagues’ research was funded by Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. One coauthor and the supervisor of the study, Dr. Justin Dimnick, disclosed a financial relationship with ArborMetrix, a health care analytics firm not involved with the study; he is also an editor of JAMA Surgery, which published the study.

Medicare payments to hospitals for bariatric operations varied by nearly $2,000 per episode of care, mostly because of differences in costs incurred in the initial – or index – hospitalization.

The findings, published online Sept. 16 in JAMA Surgery, offer hospitals a guide to where cost variation is highest (doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2015.2394) for these procedures.

Knowing where costs vary the most is particularly important if hospitals opt to accept bundled Medicare payments for bariatric procedures, which are a proposed addition to 48 other episodes of care that can currently be reimbursed in this way. Under bundled care payment programs, hospitals receive a single payment for all services related to a surgery or other episode of care, thereby accepting more risk when inefficiencies occur.

For their research, Dr. Tyler R. Grenda and his colleagues at University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Center for Healthcare Outcomes and Policy, looked at claims data for 24,647 patients receiving bariatric procedures at 463 hospitals during 2011-2012.

Operations included laparoscopic gastric banding, laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, and open Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, with fewer than 5% of patients receiving other interventions. Mean total payments varied from $11,086 to $13,073 per episode of care, defined as index hospitalization through 30 days postdischarge, for a 16.5% difference between the lowest and highest hospital quartiles.

The index hospitalization was responsible for the largest portion of total payments (75%), seen in the study, followed by physician services (21%) and postacute care services (2.8%).

The large share of costs incurred during the index hospitalization was “likely owing to inpatient complications that drive [diagnosis-related group] up-coding,” the authors wrote, noting that DRG with complications result in higher Medicare payments.

Dr. Grenda and his colleagues concluded that bariatric surgery “appears to have a distinct pattern of hospital cost variation” unlike that seen in other procedures that have been studied to identify drivers of cost differences. “This difference in the pattern of variation emphasizes the importance of understanding cost variation specific to each procedure,” they wrote.

For example, a study that looked at hip fracture repair found that postacute care accounted for a large portion of variation in payments, while less variation was seen for the index hospitalization (Health Serv Res. 2010;45[6, pt 1]:1783-95).

In the current policy environment, in which bundled payments are seen as a way to shift cost accountability to hospitals, “a detailed understanding of variation in the costs for bariatric surgery will be essential for hospitals to identify areas of risk and opportunities for improvement,” the researchers wrote in their analysis.

Dr. Grenda and his colleagues’ research was funded by Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. One coauthor and the supervisor of the study, Dr. Justin Dimnick, disclosed a financial relationship with ArborMetrix, a health care analytics firm not involved with the study; he is also an editor of JAMA Surgery, which published the study.

FROM JAMA SURGERY

Key clinical point: Initial hospitalization costs account for the lion’s share of cost variation for bariatric operations covered under Medicare.

Major finding: Mean total costs varied from $11,086 to about $13,073 per care episode, a 16.5% difference between the lowest- and highest-quartile hospitals; index hospitalizations accounted for 75% of payments, with less spent on physician fees and aftercare.

Data source: Medicare claims data for nearly 25,000 bariatric procedures performed at U.S. hospitals during 2011-2012.

Disclosures: Study was sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; one coauthor disclosed financial relationship with a health analytics firm and journal editorship.

Silicosis seen in nearly all denim sandblasters

In a study of young men who had worked as denim sandblasters, nearly all developed silicosis, while most had evidence of radiographic progression and/or significant lung function loss more than 4 years after their exposure to silica dust had ended.

The findings, published in the September issue of CHEST, derive from a study of 145 former sandblasters first identified in Turkey in 2007. At that time all had already ended their work as sandblasters at various facilities at least 10 months prior, and some had worked as little as a month. Mean age in the cohort was under 24 years in 2007, and first exposures occurred before a mean 18 years of age (CHEST 2015;148[3]:647-54).

In 2011, Dr. Metin Akgun and colleagues at Atatürk University in Erzurum, Turkey, revisited this cohort for follow-up and found that nine of the subjects had died. The researchers identified 83 of the surviving subjects and were able to conduct chest radiographs and spirometry on 74.

Dr. Akgun and colleagues sought to determine whether the silicosis cases, based on the International Labor Organization definitions of silicosis, had increased beyond the 53% seen in 2007, and measured pulmonary function loss and radiographic progression 4 years later.

The researchers found evidence of significant (more than 12%) pulmonary function loss in 66% of the follow-up cohort, and radiographic progression in 82%. Silicosis was found in all but one subject. Mean total length of exposure to silicone dust was about 3.5 years for this group, though no subject had been exposed after 2007.

Of the 74 living sandblasters available for reexamination, the prevalence of silicosis increased from 55.4% to 95.9%.

The findings, Dr. Akgun and colleagues wrote, confirmed that silicosis could develop without further exposure to silica dust after a course of work in denim sandblasting.

Younger age and younger age at first exposure were significantly associated with radiographic progression, the researchers found. Progression, pulmonary function loss, and mortality were associated with having worked as a foreman and with sleeping at the workplace, both indicative of higher exposure.

The nine subjects who died between 2007 and 2011 were more likely to have worked in more factories, to have been younger when first exposed, and never to have smoked.

Although Turkey banned silica sandblasting of denim jeans in 2009 in response to silicosis concerns, “the occupational health consequences are global as long as sandblasted jeans are sold, because production has shifted to other countries, including Bangladesh,” the researchers wrote in their analysis, recommending that clothing manufacturers “clarify their policies on purchasing sandblasted denim in light of the mortality and morbidity from silicosis associated with this process in the global supply chain.”

Dr. Akgun and colleagues noted that their study was limited by their inability to recruit the remaining 62 workers they had first seen in 2007, of whom a higher percentage were foremen. This reduced their ability to evaluate in more detail the differences in outcomes by exposure level.

Also, they noted, tuberculosis tests and sputum cultures were not performed at follow-up, leading to the possibility that mycobacterial infection may have affected disease progression in some subjects.

The authors disclosed that hey had no outside funding or conflicts of interest related to their findings.

In a study of young men who had worked as denim sandblasters, nearly all developed silicosis, while most had evidence of radiographic progression and/or significant lung function loss more than 4 years after their exposure to silica dust had ended.

The findings, published in the September issue of CHEST, derive from a study of 145 former sandblasters first identified in Turkey in 2007. At that time all had already ended their work as sandblasters at various facilities at least 10 months prior, and some had worked as little as a month. Mean age in the cohort was under 24 years in 2007, and first exposures occurred before a mean 18 years of age (CHEST 2015;148[3]:647-54).

In 2011, Dr. Metin Akgun and colleagues at Atatürk University in Erzurum, Turkey, revisited this cohort for follow-up and found that nine of the subjects had died. The researchers identified 83 of the surviving subjects and were able to conduct chest radiographs and spirometry on 74.

Dr. Akgun and colleagues sought to determine whether the silicosis cases, based on the International Labor Organization definitions of silicosis, had increased beyond the 53% seen in 2007, and measured pulmonary function loss and radiographic progression 4 years later.

The researchers found evidence of significant (more than 12%) pulmonary function loss in 66% of the follow-up cohort, and radiographic progression in 82%. Silicosis was found in all but one subject. Mean total length of exposure to silicone dust was about 3.5 years for this group, though no subject had been exposed after 2007.

Of the 74 living sandblasters available for reexamination, the prevalence of silicosis increased from 55.4% to 95.9%.

The findings, Dr. Akgun and colleagues wrote, confirmed that silicosis could develop without further exposure to silica dust after a course of work in denim sandblasting.

Younger age and younger age at first exposure were significantly associated with radiographic progression, the researchers found. Progression, pulmonary function loss, and mortality were associated with having worked as a foreman and with sleeping at the workplace, both indicative of higher exposure.

The nine subjects who died between 2007 and 2011 were more likely to have worked in more factories, to have been younger when first exposed, and never to have smoked.

Although Turkey banned silica sandblasting of denim jeans in 2009 in response to silicosis concerns, “the occupational health consequences are global as long as sandblasted jeans are sold, because production has shifted to other countries, including Bangladesh,” the researchers wrote in their analysis, recommending that clothing manufacturers “clarify their policies on purchasing sandblasted denim in light of the mortality and morbidity from silicosis associated with this process in the global supply chain.”

Dr. Akgun and colleagues noted that their study was limited by their inability to recruit the remaining 62 workers they had first seen in 2007, of whom a higher percentage were foremen. This reduced their ability to evaluate in more detail the differences in outcomes by exposure level.

Also, they noted, tuberculosis tests and sputum cultures were not performed at follow-up, leading to the possibility that mycobacterial infection may have affected disease progression in some subjects.

The authors disclosed that hey had no outside funding or conflicts of interest related to their findings.

In a study of young men who had worked as denim sandblasters, nearly all developed silicosis, while most had evidence of radiographic progression and/or significant lung function loss more than 4 years after their exposure to silica dust had ended.

The findings, published in the September issue of CHEST, derive from a study of 145 former sandblasters first identified in Turkey in 2007. At that time all had already ended their work as sandblasters at various facilities at least 10 months prior, and some had worked as little as a month. Mean age in the cohort was under 24 years in 2007, and first exposures occurred before a mean 18 years of age (CHEST 2015;148[3]:647-54).

In 2011, Dr. Metin Akgun and colleagues at Atatürk University in Erzurum, Turkey, revisited this cohort for follow-up and found that nine of the subjects had died. The researchers identified 83 of the surviving subjects and were able to conduct chest radiographs and spirometry on 74.

Dr. Akgun and colleagues sought to determine whether the silicosis cases, based on the International Labor Organization definitions of silicosis, had increased beyond the 53% seen in 2007, and measured pulmonary function loss and radiographic progression 4 years later.

The researchers found evidence of significant (more than 12%) pulmonary function loss in 66% of the follow-up cohort, and radiographic progression in 82%. Silicosis was found in all but one subject. Mean total length of exposure to silicone dust was about 3.5 years for this group, though no subject had been exposed after 2007.

Of the 74 living sandblasters available for reexamination, the prevalence of silicosis increased from 55.4% to 95.9%.

The findings, Dr. Akgun and colleagues wrote, confirmed that silicosis could develop without further exposure to silica dust after a course of work in denim sandblasting.

Younger age and younger age at first exposure were significantly associated with radiographic progression, the researchers found. Progression, pulmonary function loss, and mortality were associated with having worked as a foreman and with sleeping at the workplace, both indicative of higher exposure.

The nine subjects who died between 2007 and 2011 were more likely to have worked in more factories, to have been younger when first exposed, and never to have smoked.

Although Turkey banned silica sandblasting of denim jeans in 2009 in response to silicosis concerns, “the occupational health consequences are global as long as sandblasted jeans are sold, because production has shifted to other countries, including Bangladesh,” the researchers wrote in their analysis, recommending that clothing manufacturers “clarify their policies on purchasing sandblasted denim in light of the mortality and morbidity from silicosis associated with this process in the global supply chain.”

Dr. Akgun and colleagues noted that their study was limited by their inability to recruit the remaining 62 workers they had first seen in 2007, of whom a higher percentage were foremen. This reduced their ability to evaluate in more detail the differences in outcomes by exposure level.

Also, they noted, tuberculosis tests and sputum cultures were not performed at follow-up, leading to the possibility that mycobacterial infection may have affected disease progression in some subjects.

The authors disclosed that hey had no outside funding or conflicts of interest related to their findings.

FROM CHEST

Key clinical point: At 4 years post exposure to silica dust, nearly all men who formerly worked sandblasting denim in textile factories developed silicosis.

Major finding: Prevalence of silicosis increased from 55.4% to 95.9% between 2007 and 2011, while radiographic progression was seen in 82% of subjects at follow-up, and pulmonary function loss in 66%.

Data source: Observational cohort of 145 Turkish men first recruited in 2007 and screened for silicosis, with 74 followed up clinically in 2011.

Disclosures: Study was funded by investigator institutions in Turkey. The researchers reported having no conflicts.

Hospitalizations drive 10-year COPD cost rise

The cost burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease increased significantly between 2000 and 2010 in British Columbia, according to results from a Canadian cohort study.

Hospitalization – and the fact that more COPD patients were diagnosed in the hospital rather than in community settings – appeared to be the primary driver of excess costs in COPD patients, which were about $5,452 more per patient-year than for a matched comparison cohort of people without COPD. (Note: All dollar amounts are in Canadian dollars, which were valued at 95% of the U.S. dollar in 2010).

Excess costs related to COPD increased by $296 per person year (P less than .01) over the course of the study, with hospital costs accounting for the great majority, increasing by $258 per person-year (P less than .01).

Inpatient costs accounted for more than half (57%) of total excess COPD-related costs recorded, with more than 40% of people in the COPD cohort diagnosed after hospital admission.

The study authors, led by Amir Khakban, M.Sc, of the University of British Colombia in Vancouver, suggested that low rates of spirometry use and limited awareness of COPD among community practitioners were the key factors leading to more hospitalizations over the course of a decade, and consequently to higher costs.

For their research, published in the September issue of CHEST (2015;148[3]:640-46), Mr. Khakban and colleagues used health care billing records from 153,570 COPD patients in British Columbia along with 246,801 age- and sex-matched controls identified in the same government database. Mean age at entry was 66.9 years for both cohorts, and slightly under half of the patients were women.

COPD is a known contributor to high medical costs, due to disease exacerbations that require hospitalization, and has long been recognized in Canada and elsewhere as a leading cause of hospitalization (Respir Med. 2003;97[suppl C]:S23-S31). However, Mr. Khakban and colleagues’ study showed a rapid cost increase over a 10-year period, with costs 38% higher in 2010 than in 2001.

Compared with hospital-related costs (at 57%), outpatient, medication, and community care costs accounted for 16%, 22%, and 5%, respectively, of the excess costs seen among COPD patients in the study.

“Despite improvements, current disease management and care standards seem to be far from optimal and are not likely making any major impact,” the investigators wrote in their analysis. “This is especially evident in the high and growing rate of hospitalization as a major determinant of the burden of COPD.”

Mr. Khakban and colleagues noted that their findings likely represent an underestimate of the true cost burden of COPD, as reliance on narrow definitions from medical billing records means many cases were likely to have been missed. Also, they noted, the database used did not capture information on lung function or smoking, so costs could not be further analyzed according to disease severity or smoking status.

“In addition, not all components of direct costs are captured in the administrative health data. For example, costs of nonprescription medication or devices, and costs of complementary and alternative care are not captured in our results.”

The study was funded by the Institute for Heart + Lung Health, Genome Canada, St. Paul’s Hospital Foundation, PROOF Centre, the National Sanitarium Association, and the Canadian Respiratory Research Network. One coauthor, Carlo Marra, Pharm.D., disclosed financial relationships with GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer and Abbvie.

The cost burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease increased significantly between 2000 and 2010 in British Columbia, according to results from a Canadian cohort study.

Hospitalization – and the fact that more COPD patients were diagnosed in the hospital rather than in community settings – appeared to be the primary driver of excess costs in COPD patients, which were about $5,452 more per patient-year than for a matched comparison cohort of people without COPD. (Note: All dollar amounts are in Canadian dollars, which were valued at 95% of the U.S. dollar in 2010).

Excess costs related to COPD increased by $296 per person year (P less than .01) over the course of the study, with hospital costs accounting for the great majority, increasing by $258 per person-year (P less than .01).

Inpatient costs accounted for more than half (57%) of total excess COPD-related costs recorded, with more than 40% of people in the COPD cohort diagnosed after hospital admission.

The study authors, led by Amir Khakban, M.Sc, of the University of British Colombia in Vancouver, suggested that low rates of spirometry use and limited awareness of COPD among community practitioners were the key factors leading to more hospitalizations over the course of a decade, and consequently to higher costs.

For their research, published in the September issue of CHEST (2015;148[3]:640-46), Mr. Khakban and colleagues used health care billing records from 153,570 COPD patients in British Columbia along with 246,801 age- and sex-matched controls identified in the same government database. Mean age at entry was 66.9 years for both cohorts, and slightly under half of the patients were women.

COPD is a known contributor to high medical costs, due to disease exacerbations that require hospitalization, and has long been recognized in Canada and elsewhere as a leading cause of hospitalization (Respir Med. 2003;97[suppl C]:S23-S31). However, Mr. Khakban and colleagues’ study showed a rapid cost increase over a 10-year period, with costs 38% higher in 2010 than in 2001.

Compared with hospital-related costs (at 57%), outpatient, medication, and community care costs accounted for 16%, 22%, and 5%, respectively, of the excess costs seen among COPD patients in the study.

“Despite improvements, current disease management and care standards seem to be far from optimal and are not likely making any major impact,” the investigators wrote in their analysis. “This is especially evident in the high and growing rate of hospitalization as a major determinant of the burden of COPD.”

Mr. Khakban and colleagues noted that their findings likely represent an underestimate of the true cost burden of COPD, as reliance on narrow definitions from medical billing records means many cases were likely to have been missed. Also, they noted, the database used did not capture information on lung function or smoking, so costs could not be further analyzed according to disease severity or smoking status.

“In addition, not all components of direct costs are captured in the administrative health data. For example, costs of nonprescription medication or devices, and costs of complementary and alternative care are not captured in our results.”

The study was funded by the Institute for Heart + Lung Health, Genome Canada, St. Paul’s Hospital Foundation, PROOF Centre, the National Sanitarium Association, and the Canadian Respiratory Research Network. One coauthor, Carlo Marra, Pharm.D., disclosed financial relationships with GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer and Abbvie.

The cost burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease increased significantly between 2000 and 2010 in British Columbia, according to results from a Canadian cohort study.

Hospitalization – and the fact that more COPD patients were diagnosed in the hospital rather than in community settings – appeared to be the primary driver of excess costs in COPD patients, which were about $5,452 more per patient-year than for a matched comparison cohort of people without COPD. (Note: All dollar amounts are in Canadian dollars, which were valued at 95% of the U.S. dollar in 2010).

Excess costs related to COPD increased by $296 per person year (P less than .01) over the course of the study, with hospital costs accounting for the great majority, increasing by $258 per person-year (P less than .01).

Inpatient costs accounted for more than half (57%) of total excess COPD-related costs recorded, with more than 40% of people in the COPD cohort diagnosed after hospital admission.

The study authors, led by Amir Khakban, M.Sc, of the University of British Colombia in Vancouver, suggested that low rates of spirometry use and limited awareness of COPD among community practitioners were the key factors leading to more hospitalizations over the course of a decade, and consequently to higher costs.

For their research, published in the September issue of CHEST (2015;148[3]:640-46), Mr. Khakban and colleagues used health care billing records from 153,570 COPD patients in British Columbia along with 246,801 age- and sex-matched controls identified in the same government database. Mean age at entry was 66.9 years for both cohorts, and slightly under half of the patients were women.

COPD is a known contributor to high medical costs, due to disease exacerbations that require hospitalization, and has long been recognized in Canada and elsewhere as a leading cause of hospitalization (Respir Med. 2003;97[suppl C]:S23-S31). However, Mr. Khakban and colleagues’ study showed a rapid cost increase over a 10-year period, with costs 38% higher in 2010 than in 2001.

Compared with hospital-related costs (at 57%), outpatient, medication, and community care costs accounted for 16%, 22%, and 5%, respectively, of the excess costs seen among COPD patients in the study.

“Despite improvements, current disease management and care standards seem to be far from optimal and are not likely making any major impact,” the investigators wrote in their analysis. “This is especially evident in the high and growing rate of hospitalization as a major determinant of the burden of COPD.”

Mr. Khakban and colleagues noted that their findings likely represent an underestimate of the true cost burden of COPD, as reliance on narrow definitions from medical billing records means many cases were likely to have been missed. Also, they noted, the database used did not capture information on lung function or smoking, so costs could not be further analyzed according to disease severity or smoking status.

“In addition, not all components of direct costs are captured in the administrative health data. For example, costs of nonprescription medication or devices, and costs of complementary and alternative care are not captured in our results.”

The study was funded by the Institute for Heart + Lung Health, Genome Canada, St. Paul’s Hospital Foundation, PROOF Centre, the National Sanitarium Association, and the Canadian Respiratory Research Network. One coauthor, Carlo Marra, Pharm.D., disclosed financial relationships with GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer and Abbvie.

FROM CHEST

Key clinical point: Hospitalizations appeared to drive a 10-year increase in costs for COPD patients in British Columbia, Canada

Major finding: COPD patients saw $5,452 in excess costs per patient-year compared with non-COPD patients of like age and sex; 57% of this excess was a result of inpatient care.

Data source: Cohort study comparing medical billing records from more than 150,000 COPD patients from a British Columbia database against about 250,000 non-COPD patients identified in same database.

Disclosures: Study was sponsored by investigator institutions, the Institute for Heart + Lung Health, the National Sanitarium Association, and the Canadian Respiratory Research Network; one coauthor disclosed financial relationships with pharmaceutical firms.

SAMHSA: Adult marijuana use on the rise

More than one-tenth of Americans were current users of illicit drugs in 2014, and drug use among adults – marijuana in particular – was on the rise.

An estimated 27 million people, or 10.2% of Americans, used an illicit drug within the previous month, according to the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), released Sept. 10 by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA).

About 22 million of those people used marijuana within the previous month, and 4.3 million took prescription pain relievers for nonmedical purposes.

Some 8.4% of Americans aged 12 and older reported current marijuana use, an increase from previous survey years, and 1.6% reported current nonmedical use of pain drugs, a trend that has remained fairly steady, according to the survey.

A significant uptick in nonmedical use of marijuana was seen among adults aged 26 and older, Kana Enomoto, SAMHSA’s acting administrator, said at a Sept. 10 news conference.

Some 6.6% of these adults, or about 13.5 million people, reported being users of marijuana last year, compared with 5.6% in 2013 (P less than .5). Steady increases in marijuana use in this age group have been noted for about a decade.

Heroin use also was higher than in previous years, with an estimated 435,000 users in the United States in 2014, a statistically significant jump from 0.1% of the population aged 12 and older in 2013 to 0.2% last year, with most of the increase driven by people 26 and older.

An estimated 1.5 million Americans, or 0.6% of the population aged 12 and older, were current users of cocaine, including some 354,000 current users of crack cocaine. Cocaine use was similar to patterns seen in recent years.

Overall, current illicit drug use trends appeared to be holding steady or declining in younger age groups, but the increases in adult use are “concerning,” particularly for heroin, said Ms. Enomoto.

Recent declines in alcohol and tobacco use among young people appeared to be holding up. Among adolescents aged 12-17, 4.9% had smoked cigarettes in the previous month, down from 5.6% in 2013 and 6.6% in 2012.

Alcohol use and use patterns among young people were little changed from 2013, and overall incidence of substance use disorders hovered at 8.1% for 2014 among people 12 and older.

The incidence of mental health disorders, including any mental illness and serious mental illness (18.1% and 4.1% of adults over 18, respectively), remained little changed from recent years. Co-occurring mental illness and substance use disorders were at 3.3% of all adults, similar to rates seen since 2006.

The NSDUH data were collected through face-to-face interviews with nearly 68,000 Americans in 2014.

More than one-tenth of Americans were current users of illicit drugs in 2014, and drug use among adults – marijuana in particular – was on the rise.

An estimated 27 million people, or 10.2% of Americans, used an illicit drug within the previous month, according to the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), released Sept. 10 by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA).

About 22 million of those people used marijuana within the previous month, and 4.3 million took prescription pain relievers for nonmedical purposes.

Some 8.4% of Americans aged 12 and older reported current marijuana use, an increase from previous survey years, and 1.6% reported current nonmedical use of pain drugs, a trend that has remained fairly steady, according to the survey.

A significant uptick in nonmedical use of marijuana was seen among adults aged 26 and older, Kana Enomoto, SAMHSA’s acting administrator, said at a Sept. 10 news conference.

Some 6.6% of these adults, or about 13.5 million people, reported being users of marijuana last year, compared with 5.6% in 2013 (P less than .5). Steady increases in marijuana use in this age group have been noted for about a decade.

Heroin use also was higher than in previous years, with an estimated 435,000 users in the United States in 2014, a statistically significant jump from 0.1% of the population aged 12 and older in 2013 to 0.2% last year, with most of the increase driven by people 26 and older.

An estimated 1.5 million Americans, or 0.6% of the population aged 12 and older, were current users of cocaine, including some 354,000 current users of crack cocaine. Cocaine use was similar to patterns seen in recent years.

Overall, current illicit drug use trends appeared to be holding steady or declining in younger age groups, but the increases in adult use are “concerning,” particularly for heroin, said Ms. Enomoto.

Recent declines in alcohol and tobacco use among young people appeared to be holding up. Among adolescents aged 12-17, 4.9% had smoked cigarettes in the previous month, down from 5.6% in 2013 and 6.6% in 2012.

Alcohol use and use patterns among young people were little changed from 2013, and overall incidence of substance use disorders hovered at 8.1% for 2014 among people 12 and older.

The incidence of mental health disorders, including any mental illness and serious mental illness (18.1% and 4.1% of adults over 18, respectively), remained little changed from recent years. Co-occurring mental illness and substance use disorders were at 3.3% of all adults, similar to rates seen since 2006.

The NSDUH data were collected through face-to-face interviews with nearly 68,000 Americans in 2014.

More than one-tenth of Americans were current users of illicit drugs in 2014, and drug use among adults – marijuana in particular – was on the rise.

An estimated 27 million people, or 10.2% of Americans, used an illicit drug within the previous month, according to the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), released Sept. 10 by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA).

About 22 million of those people used marijuana within the previous month, and 4.3 million took prescription pain relievers for nonmedical purposes.

Some 8.4% of Americans aged 12 and older reported current marijuana use, an increase from previous survey years, and 1.6% reported current nonmedical use of pain drugs, a trend that has remained fairly steady, according to the survey.

A significant uptick in nonmedical use of marijuana was seen among adults aged 26 and older, Kana Enomoto, SAMHSA’s acting administrator, said at a Sept. 10 news conference.

Some 6.6% of these adults, or about 13.5 million people, reported being users of marijuana last year, compared with 5.6% in 2013 (P less than .5). Steady increases in marijuana use in this age group have been noted for about a decade.

Heroin use also was higher than in previous years, with an estimated 435,000 users in the United States in 2014, a statistically significant jump from 0.1% of the population aged 12 and older in 2013 to 0.2% last year, with most of the increase driven by people 26 and older.

An estimated 1.5 million Americans, or 0.6% of the population aged 12 and older, were current users of cocaine, including some 354,000 current users of crack cocaine. Cocaine use was similar to patterns seen in recent years.

Overall, current illicit drug use trends appeared to be holding steady or declining in younger age groups, but the increases in adult use are “concerning,” particularly for heroin, said Ms. Enomoto.

Recent declines in alcohol and tobacco use among young people appeared to be holding up. Among adolescents aged 12-17, 4.9% had smoked cigarettes in the previous month, down from 5.6% in 2013 and 6.6% in 2012.

Alcohol use and use patterns among young people were little changed from 2013, and overall incidence of substance use disorders hovered at 8.1% for 2014 among people 12 and older.

The incidence of mental health disorders, including any mental illness and serious mental illness (18.1% and 4.1% of adults over 18, respectively), remained little changed from recent years. Co-occurring mental illness and substance use disorders were at 3.3% of all adults, similar to rates seen since 2006.

The NSDUH data were collected through face-to-face interviews with nearly 68,000 Americans in 2014.

Higher Risk for Arrhythmia in Psoriasis Patients

Patients with psoriasis are at increased risk of arrhythmia, with the risk even greater for younger patients and those with psoriatic arthritis, according to a population-based cohort study conducted in Taiwan.

Dr. Hsien-Yi Chiu of National Taiwan University and Wei-Lun Chang of National Yang-Ming University, both in Taipei, and their colleagues, looked at records from 40,637 patients diagnosed with psoriasis and 162,548 age- and sex-matched controls without psoriasis, over a mean follow-up of about 6 years, for the incidence of arrhythmias over a mean of 6 years.

In an article published in the September issue of the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, the investigators reported that those patients with psoriasis were at a significantly higher risk of developing arrhythmia, independent of traditional cardiovascular risk factors (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.34; 95% confidence interval, 1.29-1.39). Increased risk for patients with mild disease (aHR,1.35; 95% CI, 1.30-1.41) was comparable to that of patients with severe disease (aHR, 1.25; 95% CI 1.12-1.39) and more pronounced in the subgroup of patients with psoriatic arthritis (aHR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.22-1.74). Younger patients, between aged 20 and 39 years, were at a higher risk (aHR, 1.39; 95% CI, 1.26-1.54) than older patients in the cohort (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015 Sep;73:429-38).

Although previous studies have shown severe psoriasis to be associated with a nearly 60% increase in cardiovascular morbidity and mortality beyond traditional risk factors, less is known about arrhythmias specifically. “Inflammation may contribute to the alteration of cardiomyocyte electrophysiology, such as dysregulation of ion channel function, leading to increased risk of arrhythmia,” the investigators wrote.

The authors noted that limitations of their study were the potential surveillance bias for psoriasis patients due to increased hospital visits, and the fact that alcohol and tobacco use was not captured in the patient data. Treatment with systemic therapies may lower cardiovascular risk in psoriasis patients, they added, which may have explained why the arrhythmia risk among patients with severe disease was similar to those with mild disease.

The findings indicate “that psoriasis can be added to future risk-stratification scores for arrhythmia,” the investigators wrote, adding that patients with psoriasis, “especially young patients and those with PsA [psoriatic arthritis] , should be more closely screened for various types of arrhythmia,” with the hope of earlier intervention leading to reduction of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

Patients with psoriasis are at increased risk of arrhythmia, with the risk even greater for younger patients and those with psoriatic arthritis, according to a population-based cohort study conducted in Taiwan.

Dr. Hsien-Yi Chiu of National Taiwan University and Wei-Lun Chang of National Yang-Ming University, both in Taipei, and their colleagues, looked at records from 40,637 patients diagnosed with psoriasis and 162,548 age- and sex-matched controls without psoriasis, over a mean follow-up of about 6 years, for the incidence of arrhythmias over a mean of 6 years.

In an article published in the September issue of the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, the investigators reported that those patients with psoriasis were at a significantly higher risk of developing arrhythmia, independent of traditional cardiovascular risk factors (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.34; 95% confidence interval, 1.29-1.39). Increased risk for patients with mild disease (aHR,1.35; 95% CI, 1.30-1.41) was comparable to that of patients with severe disease (aHR, 1.25; 95% CI 1.12-1.39) and more pronounced in the subgroup of patients with psoriatic arthritis (aHR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.22-1.74). Younger patients, between aged 20 and 39 years, were at a higher risk (aHR, 1.39; 95% CI, 1.26-1.54) than older patients in the cohort (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015 Sep;73:429-38).

Although previous studies have shown severe psoriasis to be associated with a nearly 60% increase in cardiovascular morbidity and mortality beyond traditional risk factors, less is known about arrhythmias specifically. “Inflammation may contribute to the alteration of cardiomyocyte electrophysiology, such as dysregulation of ion channel function, leading to increased risk of arrhythmia,” the investigators wrote.

The authors noted that limitations of their study were the potential surveillance bias for psoriasis patients due to increased hospital visits, and the fact that alcohol and tobacco use was not captured in the patient data. Treatment with systemic therapies may lower cardiovascular risk in psoriasis patients, they added, which may have explained why the arrhythmia risk among patients with severe disease was similar to those with mild disease.

The findings indicate “that psoriasis can be added to future risk-stratification scores for arrhythmia,” the investigators wrote, adding that patients with psoriasis, “especially young patients and those with PsA [psoriatic arthritis] , should be more closely screened for various types of arrhythmia,” with the hope of earlier intervention leading to reduction of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

Patients with psoriasis are at increased risk of arrhythmia, with the risk even greater for younger patients and those with psoriatic arthritis, according to a population-based cohort study conducted in Taiwan.

Dr. Hsien-Yi Chiu of National Taiwan University and Wei-Lun Chang of National Yang-Ming University, both in Taipei, and their colleagues, looked at records from 40,637 patients diagnosed with psoriasis and 162,548 age- and sex-matched controls without psoriasis, over a mean follow-up of about 6 years, for the incidence of arrhythmias over a mean of 6 years.

In an article published in the September issue of the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, the investigators reported that those patients with psoriasis were at a significantly higher risk of developing arrhythmia, independent of traditional cardiovascular risk factors (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.34; 95% confidence interval, 1.29-1.39). Increased risk for patients with mild disease (aHR,1.35; 95% CI, 1.30-1.41) was comparable to that of patients with severe disease (aHR, 1.25; 95% CI 1.12-1.39) and more pronounced in the subgroup of patients with psoriatic arthritis (aHR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.22-1.74). Younger patients, between aged 20 and 39 years, were at a higher risk (aHR, 1.39; 95% CI, 1.26-1.54) than older patients in the cohort (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015 Sep;73:429-38).

Although previous studies have shown severe psoriasis to be associated with a nearly 60% increase in cardiovascular morbidity and mortality beyond traditional risk factors, less is known about arrhythmias specifically. “Inflammation may contribute to the alteration of cardiomyocyte electrophysiology, such as dysregulation of ion channel function, leading to increased risk of arrhythmia,” the investigators wrote.

The authors noted that limitations of their study were the potential surveillance bias for psoriasis patients due to increased hospital visits, and the fact that alcohol and tobacco use was not captured in the patient data. Treatment with systemic therapies may lower cardiovascular risk in psoriasis patients, they added, which may have explained why the arrhythmia risk among patients with severe disease was similar to those with mild disease.

The findings indicate “that psoriasis can be added to future risk-stratification scores for arrhythmia,” the investigators wrote, adding that patients with psoriasis, “especially young patients and those with PsA [psoriatic arthritis] , should be more closely screened for various types of arrhythmia,” with the hope of earlier intervention leading to reduction of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY

Higher risk of arrhythmia in psoriasis patients

Patients with psoriasis are at increased risk of arrhythmia, with the risk even greater for younger patients and those with psoriatic arthritis, according to a population-based cohort study conducted in Taiwan.

Dr. Hsien-Yi Chiu of National Taiwan University and Wei-Lun Chang of National Yang-Ming University, both in Taipei, and their colleagues, looked at records from 40,637 patients diagnosed with psoriasis and 162,548 age- and sex-matched controls without psoriasis, over a mean follow-up of about 6 years, for the incidence of arrhythmias over a mean of 6 years.

In an article published in the September issue of the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, the investigators reported that those patients with psoriasis were at a significantly higher risk of developing arrhythmia, independent of traditional cardiovascular risk factors (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.34; 95% confidence interval, 1.29-1.39). Increased risk for patients with mild disease (aHR,1.35; 95% CI, 1.30-1.41) was comparable to that of patients with severe disease (aHR, 1.25; 95% CI 1.12-1.39) and more pronounced in the subgroup of patients with psoriatic arthritis (aHR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.22-1.74). Younger patients, between aged 20 and 39 years, were at a higher risk (aHR, 1.39; 95% CI, 1.26-1.54) than older patients in the cohort (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015 Sep;73:429-38).

Although previous studies have shown severe psoriasis to be associated with a nearly 60% increase in cardiovascular morbidity and mortality beyond traditional risk factors, less is known about arrhythmias specifically. “Inflammation may contribute to the alteration of cardiomyocyte electrophysiology, such as dysregulation of ion channel function, leading to increased risk of arrhythmia,” the investigators wrote.

The authors noted that limitations of their study were the potential surveillance bias for psoriasis patients due to increased hospital visits, and the fact that alcohol and tobacco use was not captured in the patient data. Treatment with systemic therapies may lower cardiovascular risk in psoriasis patients, they added, which may have explained why the arrhythmia risk among patients with severe disease was similar to those with mild disease.

The findings indicate “that psoriasis can be added to future risk-stratification scores for arrhythmia,” the investigators wrote, adding that patients with psoriasis, “especially young patients and those with PsA [psoriatic arthritis] , should be more closely screened for various types of arrhythmia,” with the hope of earlier intervention leading to reduction of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

Patients with psoriasis are at increased risk of arrhythmia, with the risk even greater for younger patients and those with psoriatic arthritis, according to a population-based cohort study conducted in Taiwan.

Dr. Hsien-Yi Chiu of National Taiwan University and Wei-Lun Chang of National Yang-Ming University, both in Taipei, and their colleagues, looked at records from 40,637 patients diagnosed with psoriasis and 162,548 age- and sex-matched controls without psoriasis, over a mean follow-up of about 6 years, for the incidence of arrhythmias over a mean of 6 years.

In an article published in the September issue of the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, the investigators reported that those patients with psoriasis were at a significantly higher risk of developing arrhythmia, independent of traditional cardiovascular risk factors (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.34; 95% confidence interval, 1.29-1.39). Increased risk for patients with mild disease (aHR,1.35; 95% CI, 1.30-1.41) was comparable to that of patients with severe disease (aHR, 1.25; 95% CI 1.12-1.39) and more pronounced in the subgroup of patients with psoriatic arthritis (aHR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.22-1.74). Younger patients, between aged 20 and 39 years, were at a higher risk (aHR, 1.39; 95% CI, 1.26-1.54) than older patients in the cohort (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015 Sep;73:429-38).

Although previous studies have shown severe psoriasis to be associated with a nearly 60% increase in cardiovascular morbidity and mortality beyond traditional risk factors, less is known about arrhythmias specifically. “Inflammation may contribute to the alteration of cardiomyocyte electrophysiology, such as dysregulation of ion channel function, leading to increased risk of arrhythmia,” the investigators wrote.

The authors noted that limitations of their study were the potential surveillance bias for psoriasis patients due to increased hospital visits, and the fact that alcohol and tobacco use was not captured in the patient data. Treatment with systemic therapies may lower cardiovascular risk in psoriasis patients, they added, which may have explained why the arrhythmia risk among patients with severe disease was similar to those with mild disease.

The findings indicate “that psoriasis can be added to future risk-stratification scores for arrhythmia,” the investigators wrote, adding that patients with psoriasis, “especially young patients and those with PsA [psoriatic arthritis] , should be more closely screened for various types of arrhythmia,” with the hope of earlier intervention leading to reduction of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

Patients with psoriasis are at increased risk of arrhythmia, with the risk even greater for younger patients and those with psoriatic arthritis, according to a population-based cohort study conducted in Taiwan.

Dr. Hsien-Yi Chiu of National Taiwan University and Wei-Lun Chang of National Yang-Ming University, both in Taipei, and their colleagues, looked at records from 40,637 patients diagnosed with psoriasis and 162,548 age- and sex-matched controls without psoriasis, over a mean follow-up of about 6 years, for the incidence of arrhythmias over a mean of 6 years.

In an article published in the September issue of the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, the investigators reported that those patients with psoriasis were at a significantly higher risk of developing arrhythmia, independent of traditional cardiovascular risk factors (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.34; 95% confidence interval, 1.29-1.39). Increased risk for patients with mild disease (aHR,1.35; 95% CI, 1.30-1.41) was comparable to that of patients with severe disease (aHR, 1.25; 95% CI 1.12-1.39) and more pronounced in the subgroup of patients with psoriatic arthritis (aHR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.22-1.74). Younger patients, between aged 20 and 39 years, were at a higher risk (aHR, 1.39; 95% CI, 1.26-1.54) than older patients in the cohort (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015 Sep;73:429-38).

Although previous studies have shown severe psoriasis to be associated with a nearly 60% increase in cardiovascular morbidity and mortality beyond traditional risk factors, less is known about arrhythmias specifically. “Inflammation may contribute to the alteration of cardiomyocyte electrophysiology, such as dysregulation of ion channel function, leading to increased risk of arrhythmia,” the investigators wrote.

The authors noted that limitations of their study were the potential surveillance bias for psoriasis patients due to increased hospital visits, and the fact that alcohol and tobacco use was not captured in the patient data. Treatment with systemic therapies may lower cardiovascular risk in psoriasis patients, they added, which may have explained why the arrhythmia risk among patients with severe disease was similar to those with mild disease.

The findings indicate “that psoriasis can be added to future risk-stratification scores for arrhythmia,” the investigators wrote, adding that patients with psoriasis, “especially young patients and those with PsA [psoriatic arthritis] , should be more closely screened for various types of arrhythmia,” with the hope of earlier intervention leading to reduction of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Patients with psoriasis are at an increased risk of developing arrhythmias compared to those without psoriasis.

Major finding: After researchers adjusted for medical history and medication use, patients with psoriasis were at increased risk of overall arrhythmia (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.34; 95% confidence interval, 1.29-1.39).

Data source: A retrospective cohort study using data from almost 41,000 psoriasis patients identified from the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database, and almost 163,000 age and sex-matched cohorts from the same database

Disclosures: Study was institutionally funded. Dr. Chiu, Ms. Chang, and three other authors had no disclosures; one author disclosed having conducted clinical trials, or having received honoraria from several companies, including Pfizer and Novartis, and having received speaking fees from AbbVie.

More alarms mean slower response in PICU, pediatric wards

SAN ANTONIO – Alarm fatigue, the desensitization that can occur when clinicians are exposed to an excessive number of nonactionable clinical alarms, is an urgent concern for pediatric hospitalists, who are studying the phenomenon in both intensive care and ward settings, according to Dr. Christopher P. Bonafide.

This year the ECRI Institute named alarm fatigue the top health technology hazard of 2015. And a Joint Commission national patient safety goal, issued in 2014, demands that hospitals begin implementing alarm system management strategies by January 2016 to combat fatigue and other potential downstream consequences of being overwhelmed with alarms.

At the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2015 meeting, Dr. Bonafide discussed ongoing work at his institution, the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, to pinpoint how and why alarm fatigue might be occurring there.

Dr. Bonafide and his colleagues evaluated data from in-room video cameras, bedside cardiorespiratory and pulse-oximetry monitors, and text messages communicating monitor alerts to nurses. They examined whether an alert was valid (consistent with the patient’s actual physiologic state) and actionable (meriting intervention or consultation), as well as how long it took nurses to respond.

The study was conducted during day shifts. Using data from about 5,000 alarms, and 210 hours of video from both the pediatric ward and the pediatric intensive care unit, the investigators found that 76% of alarms in the PICU were valid, and 13% were actionable. In the pediatric ward, 41% of alarms were valid, and only 1% were actionable.

Exposure to more nonactionable alarms was significantly correlated with longer response times to the patient’s bedside, Dr. Bonafide and his colleagues found. Overall, it took nurses exposed to more than 80 nonactionable alarms in the previous 2-hour period more than twice as long to respond to alarms than if they’d been exposed to 29 or fewer alarms in the preceding 2 hours (P less than .01).

“We think alarm fatigue is the most likely explanation for these findings,” Dr. Bonafide said at the meeting, sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the AAP Section on Hospital Medicine, and the Academic Pediatric Association. He noted that a larger study was underway to look more closely at other variables, such as the patient’s acuity and the nurse’s full patient load.

In an interview, Dr. Bonafide called bedside systems such as pulse oximetry and heart rate monitoring “some of the most powerful tools we have” to detect deterioration in the hospital. But a high signal-to-noise ratio can make them “essentially useless,” he said. “They fade into the background.”

Improving alarm systems “is about making alarms less of an every-minute occurrence by improving that signal-to-noise ratio so that when that alarm buzzes, it is a good decision to interrupt what you’re doing and check on the patient to figure out what’s going on,” he said.

Some of the possible solutions to keep alarms rarer include establishing more precise heart rate and respiratory norms for pediatric patients, and adjusting the thresholds for monitoring. “We would love it if for every patient, when that alarm goes off it’s already set to a point where it’s actionable,” he said.

While Dr. Bonafide has focused on measuring and understanding alarm fatigue to date, he said he and his team are “incredibly excited to begin focusing on what we can actually do to reduce nonactionable alarms and improve outcomes for patients.”

To address this, the investigators are conducting a cluster-randomized trial evaluating a data-driven dashboard that helps physicians and nurses identify alarm hot spots, and guides them through the best ways to intervene and reduce alarms.

What’s still lacking in the hospitalist community, Dr. Bonafide said, is “consensus around what is actionable.” This will require hospitalists to meet and talk about consensus guidelines on what constitutes an actionable pulse-oximetry or heart rate alarm, when it is appropriate to intervene, and when it is absolutely necessary to intervene.

Dr. Bonafide said he plans to begin developing a protocol for this work with collaborators from Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital, Stanford, Calif.

“This has the potential to really help inform decision making on thousands of patients per day across the United States,” he said.

Dr. Bonafide’s study was funded by a grant from the Pennsylvania Department of Public Health Commonwealth Universal Research Enhancement Program. His team has received funding from the National Institutes of Health, the Academic Pediatric Association, and the Society of Hospital Medicine. He declared no conflicts of interest.

SAN ANTONIO – Alarm fatigue, the desensitization that can occur when clinicians are exposed to an excessive number of nonactionable clinical alarms, is an urgent concern for pediatric hospitalists, who are studying the phenomenon in both intensive care and ward settings, according to Dr. Christopher P. Bonafide.

This year the ECRI Institute named alarm fatigue the top health technology hazard of 2015. And a Joint Commission national patient safety goal, issued in 2014, demands that hospitals begin implementing alarm system management strategies by January 2016 to combat fatigue and other potential downstream consequences of being overwhelmed with alarms.

At the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2015 meeting, Dr. Bonafide discussed ongoing work at his institution, the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, to pinpoint how and why alarm fatigue might be occurring there.

Dr. Bonafide and his colleagues evaluated data from in-room video cameras, bedside cardiorespiratory and pulse-oximetry monitors, and text messages communicating monitor alerts to nurses. They examined whether an alert was valid (consistent with the patient’s actual physiologic state) and actionable (meriting intervention or consultation), as well as how long it took nurses to respond.

The study was conducted during day shifts. Using data from about 5,000 alarms, and 210 hours of video from both the pediatric ward and the pediatric intensive care unit, the investigators found that 76% of alarms in the PICU were valid, and 13% were actionable. In the pediatric ward, 41% of alarms were valid, and only 1% were actionable.

Exposure to more nonactionable alarms was significantly correlated with longer response times to the patient’s bedside, Dr. Bonafide and his colleagues found. Overall, it took nurses exposed to more than 80 nonactionable alarms in the previous 2-hour period more than twice as long to respond to alarms than if they’d been exposed to 29 or fewer alarms in the preceding 2 hours (P less than .01).

“We think alarm fatigue is the most likely explanation for these findings,” Dr. Bonafide said at the meeting, sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the AAP Section on Hospital Medicine, and the Academic Pediatric Association. He noted that a larger study was underway to look more closely at other variables, such as the patient’s acuity and the nurse’s full patient load.

In an interview, Dr. Bonafide called bedside systems such as pulse oximetry and heart rate monitoring “some of the most powerful tools we have” to detect deterioration in the hospital. But a high signal-to-noise ratio can make them “essentially useless,” he said. “They fade into the background.”

Improving alarm systems “is about making alarms less of an every-minute occurrence by improving that signal-to-noise ratio so that when that alarm buzzes, it is a good decision to interrupt what you’re doing and check on the patient to figure out what’s going on,” he said.

Some of the possible solutions to keep alarms rarer include establishing more precise heart rate and respiratory norms for pediatric patients, and adjusting the thresholds for monitoring. “We would love it if for every patient, when that alarm goes off it’s already set to a point where it’s actionable,” he said.

While Dr. Bonafide has focused on measuring and understanding alarm fatigue to date, he said he and his team are “incredibly excited to begin focusing on what we can actually do to reduce nonactionable alarms and improve outcomes for patients.”

To address this, the investigators are conducting a cluster-randomized trial evaluating a data-driven dashboard that helps physicians and nurses identify alarm hot spots, and guides them through the best ways to intervene and reduce alarms.

What’s still lacking in the hospitalist community, Dr. Bonafide said, is “consensus around what is actionable.” This will require hospitalists to meet and talk about consensus guidelines on what constitutes an actionable pulse-oximetry or heart rate alarm, when it is appropriate to intervene, and when it is absolutely necessary to intervene.

Dr. Bonafide said he plans to begin developing a protocol for this work with collaborators from Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital, Stanford, Calif.

“This has the potential to really help inform decision making on thousands of patients per day across the United States,” he said.

Dr. Bonafide’s study was funded by a grant from the Pennsylvania Department of Public Health Commonwealth Universal Research Enhancement Program. His team has received funding from the National Institutes of Health, the Academic Pediatric Association, and the Society of Hospital Medicine. He declared no conflicts of interest.

SAN ANTONIO – Alarm fatigue, the desensitization that can occur when clinicians are exposed to an excessive number of nonactionable clinical alarms, is an urgent concern for pediatric hospitalists, who are studying the phenomenon in both intensive care and ward settings, according to Dr. Christopher P. Bonafide.

This year the ECRI Institute named alarm fatigue the top health technology hazard of 2015. And a Joint Commission national patient safety goal, issued in 2014, demands that hospitals begin implementing alarm system management strategies by January 2016 to combat fatigue and other potential downstream consequences of being overwhelmed with alarms.

At the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2015 meeting, Dr. Bonafide discussed ongoing work at his institution, the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, to pinpoint how and why alarm fatigue might be occurring there.

Dr. Bonafide and his colleagues evaluated data from in-room video cameras, bedside cardiorespiratory and pulse-oximetry monitors, and text messages communicating monitor alerts to nurses. They examined whether an alert was valid (consistent with the patient’s actual physiologic state) and actionable (meriting intervention or consultation), as well as how long it took nurses to respond.

The study was conducted during day shifts. Using data from about 5,000 alarms, and 210 hours of video from both the pediatric ward and the pediatric intensive care unit, the investigators found that 76% of alarms in the PICU were valid, and 13% were actionable. In the pediatric ward, 41% of alarms were valid, and only 1% were actionable.

Exposure to more nonactionable alarms was significantly correlated with longer response times to the patient’s bedside, Dr. Bonafide and his colleagues found. Overall, it took nurses exposed to more than 80 nonactionable alarms in the previous 2-hour period more than twice as long to respond to alarms than if they’d been exposed to 29 or fewer alarms in the preceding 2 hours (P less than .01).

“We think alarm fatigue is the most likely explanation for these findings,” Dr. Bonafide said at the meeting, sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the AAP Section on Hospital Medicine, and the Academic Pediatric Association. He noted that a larger study was underway to look more closely at other variables, such as the patient’s acuity and the nurse’s full patient load.

In an interview, Dr. Bonafide called bedside systems such as pulse oximetry and heart rate monitoring “some of the most powerful tools we have” to detect deterioration in the hospital. But a high signal-to-noise ratio can make them “essentially useless,” he said. “They fade into the background.”

Improving alarm systems “is about making alarms less of an every-minute occurrence by improving that signal-to-noise ratio so that when that alarm buzzes, it is a good decision to interrupt what you’re doing and check on the patient to figure out what’s going on,” he said.

Some of the possible solutions to keep alarms rarer include establishing more precise heart rate and respiratory norms for pediatric patients, and adjusting the thresholds for monitoring. “We would love it if for every patient, when that alarm goes off it’s already set to a point where it’s actionable,” he said.

While Dr. Bonafide has focused on measuring and understanding alarm fatigue to date, he said he and his team are “incredibly excited to begin focusing on what we can actually do to reduce nonactionable alarms and improve outcomes for patients.”

To address this, the investigators are conducting a cluster-randomized trial evaluating a data-driven dashboard that helps physicians and nurses identify alarm hot spots, and guides them through the best ways to intervene and reduce alarms.

What’s still lacking in the hospitalist community, Dr. Bonafide said, is “consensus around what is actionable.” This will require hospitalists to meet and talk about consensus guidelines on what constitutes an actionable pulse-oximetry or heart rate alarm, when it is appropriate to intervene, and when it is absolutely necessary to intervene.

Dr. Bonafide said he plans to begin developing a protocol for this work with collaborators from Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital, Stanford, Calif.

“This has the potential to really help inform decision making on thousands of patients per day across the United States,” he said.

Dr. Bonafide’s study was funded by a grant from the Pennsylvania Department of Public Health Commonwealth Universal Research Enhancement Program. His team has received funding from the National Institutes of Health, the Academic Pediatric Association, and the Society of Hospital Medicine. He declared no conflicts of interest.

AT PEDIATRIC HOSPITAL MEDICINE 2015

Key clinical point: Nurses’ exposure to more nonactionable pediatric alarms was found to be correlated with significantly slower response time to the patient’s bedside as their shift progressed.

Major finding: Nurses exposed to 80+ nonactionable alarms in the previous 2 hours took more than twice as long to respond to alarms as did nurses exposed to 29 or fewer alarms in the previous 2 hours (P less than .01).

Data source: 210 hours’ video and 4,962 time-stamped bedside monitor alarms on the pediatric ward and PICU at one children’s hospital; study conducted more than 120 hours in PICU and 120 hours on the ward.

Disclosures: Dr. Bonafide’s study was funded by a grant from the Pennsylvania Department of Public Health Commonwealth Universal Research Enhancement Program. His team has received funding from the National Institutes of Health, the Academic Pediatric Association, and the Society of Hospital Medicine. He declared no conflicts of interest.

S. aureus seen in 1% of pediatric CAP cases

SAN ANTONIO – Current guidelines on community-acquired pneumonia recommend penicillin, amoxicillin, or ampicillin as first-line treatment in children with CAP.

However, a small minority will have Staphylococcus aureus infections not treatable with these antibiotics, raising some concern about how many of these cases might be missed.

At the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2015 meeting, Dr. Meghan E. Hofto of Children’s of Alabama at the University of Alabama, Birmingham, presented research from a study of 554 patients admitted to the hospital with community acquired pneumonia, including 78 patients with complicated pneumonia.

Seven patients in the cohort (1.3%) had S. aureus infections, Dr. Hofto and her colleagues found. Of those, six were recorded as having complicated pneumonia, characterized by pleural effusion or cavitation.

Six patients with S. aureus had been started on antibiotics in other health care settings prior to admission (amoxicillin n = 4, multiple agents n = 2). One patient positive for flu was first treated with oseltamavir only. However, all staph patients once admitted were started on vancomycin, which is effective against S. aureus, within 24 hours. Five were diagnosed by pleural fluid culture; one case was identified by clinical presentation, and another by sputum culture, Dr. Hofto said at the meeting, sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the AAP Section on Hospital Medicine, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

The S. aureus patients were younger than the cohort as a whole (median 18 months vs. 40.5 months). Length of stay was significantly longer for these patients, compared with the rest of the cohort (median 10 vs. 2 days, P less than .01), and S. aureus patients had significantly higher incidence of anemia (P less than .01), a finding that Dr. Hofto said was striking.

Within 24 hours of presentation, six out the seven staph cases had anemia, she said, while of all the 78 patients with complicated disease, 12 had anemia. Community acquired S. aureus pneumonia has been linked in other studies to severe leukopenia, Dr. Hofto noted (BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:359) and (Paediatric Respiratory Reviews 2011 Sept;12:182-9).In an interview, Dr. Hofto said the findings supported current guidance in favor of first-line penicillin, amoxicillin, or ampicillin. “Part of what we’re looking at with guideline adherence is the barriers to treating with empiric narrow spectrum antibiotics – and obviously, one of the things people are concerned about is that are we going to miss something,” she said.

“I think we can pretty confidently say that if it’s uncomplicated CAP – if there’s no pleural effusion, no necrosis, no cavitation – you can treat with narrow spectrum, and the likelihood of it being staph is slim to none.”

If within 48 hours, patients are not responding to the first-line treatment, “you should start thinking about other causes,” Dr. Hofto said, noting that her review found all staph aureus patients were started on antibiotics effective against S. aureus – mostly vancomycin and ceftriaxone – within 24 hours of presentation.

Dr. Hofto noted as a limitation of her study, which used retrospective chart reviews of more than 3,400 children hospitalized for suspected pneumonia over a 3-year period, that additional S. aureus cases could have been missed because of a lack of proper coding or microbial confirmation. Another limitation was the single-site design and the relatively small number of S. aureus cases.

Dr. Hofto said she is conducting a more in-depth chart review ensure that no further cases of S. aureus CAP were missed in her sample.

The study received no outside funding, and Dr. Hofto disclosed no conflicts of interest.

SAN ANTONIO – Current guidelines on community-acquired pneumonia recommend penicillin, amoxicillin, or ampicillin as first-line treatment in children with CAP.

However, a small minority will have Staphylococcus aureus infections not treatable with these antibiotics, raising some concern about how many of these cases might be missed.

At the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2015 meeting, Dr. Meghan E. Hofto of Children’s of Alabama at the University of Alabama, Birmingham, presented research from a study of 554 patients admitted to the hospital with community acquired pneumonia, including 78 patients with complicated pneumonia.

Seven patients in the cohort (1.3%) had S. aureus infections, Dr. Hofto and her colleagues found. Of those, six were recorded as having complicated pneumonia, characterized by pleural effusion or cavitation.