User login

How ObGyns can best work with radiologists to optimize screening for patients with dense breasts

If your ObGyn practices are anything like ours, every time there is news coverage of a study regarding mammography or about efforts to pass a breast density inform law, your phone rings with patient calls. In fact, every density inform law enacted in the United States, except for in Illinois, directs patients to their referring provider—generally their ObGyn—to discuss the screening and risk implications of dense breast tissue.

The steady increased awareness of breast density means that we, as ObGyns and other primary care providers (PCPs), have additional responsibilities in managing the breast health of our patients. This includes guiding discussions with patients about what breast density means and whether supplemental screening beyond mammography might be beneficial.

As members of the Medical Advisory Board for DenseBreast-info.org (an online educational resource dedicated to providing breast density information to patients and health care professionals), we are aware of the growing body of evidence demonstrating improved detection of early breast cancer using supplemental screening in dense breasts. However, we know that there is confusion among clinicians about how and when to facilitate tailored screening for women with dense breasts or other breast cancer risk factors. Here we answer 6 questions focusing on how to navigate patient discussions around the topic and the best way to collaborate with radiologists to improve breast care for patients.

Play an active role

1. What role should ObGyns and PCPs play in women’s breast health?

Elizabeth Etkin-Kramer, MD: I am a firm believer that ObGyns and all women’s health providers should be able to assess their patients’ risk of breast cancer and explain the process for managing this risk with their patients. This explanation includes the clinical implications of breast density and when supplemental screening should be employed. It is also important for providers to know when to offer genetic testing and when a patient’s personal or family history indicates supplemental screening with breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

DaCarla M. Albright, MD: I absolutely agree that PCPs, ObGyns, and family practitioners should spend the time to be educated about breast density and supplemental screening options. While the exact role providers play in managing patients’ breast health may vary depending on the practice type or location, the need for knowledge and comfort when talking with patients to help them make informed decisions is critical. Breast health and screening, including the importance of breast density, happen to be a particular interest of mine. I have participated in educational webinars, invited lectures, and breast cancer awareness media events on this topic in the past.

Continue to: Join forces with imaging centers...

Join forces with imaging centers

2. How can ObGyns and radiologists collaborate most effectively to use screening results to personalize breast care for patients?

Dr. Etkin-Kramer: It is important to have a close relationship with the radiologists that read our patients’ mammograms. We need to be able to easily contact the radiologist and quickly get clarification on a patient’s report or discuss next steps. Imaging centers should consider running outreach programs to educate their referring providers on how to risk assess, with this assessment inclusive of breast density. Dinner lectures or grand round meetings are effective to facilitate communication between the radiology community and the ObGyn community. Finally, as we all know, supplemental screening is often subject to copays and deductibles per insurance coverage. If advocacy groups, who are working to eliminate these types of costs, cannot get insurers to waive these payments, we need a less expensive self-pay option.

Dr. Albright: I definitely have and encourage an open line of communication between my practice and breast radiology, as well as our breast surgeons and cancer center to set up consultations as needed. We also invite our radiologists as guests to monthly practice meetings or grand rounds within our department to further improve access and open communication, as this environment is one in which greater provider education on density and adjunctive screening can be achieved.

Know when to refer a high-risk patient

3. Most ObGyns routinely collect family history and perform formal risk assessment. What do you need to know about referring patients to a high-risk program?

Dr. Etkin-Kramer: It is important as ObGyns to be knowledgeable about breast and ovarian cancer risk assessment and genetic testing for cancer susceptibility genes. Our patients expect that of us. I am comfortable doing risk assessment in my office, but I sometimes refer to other specialists in the community if the patient needs additional counseling. For risk assessment, I look at family and personal history, breast density, and other factors that might lead me to believe the patient might carry a hereditary cancer susceptibility gene, including Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry.1 When indicated, I check lifetime as well as short-term (5- to 10-year) risk, usually using Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC) or Tyrer-Cuzick/International Breast Cancer Intervention Study (IBIS) models, as these include breast density.

I discuss risk-reducing medications. The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends these agents if my patient’s 5-year risk of breast cancer is 1.67% or greater, and I strongly recommend chemoprevention when the patient’s 5-year BCSC risk exceeds 3%, provided likely benefits exceed risks.2,3 I discuss adding screening breast MRI if lifetime risk by Tyrer-Cuzick exceeds 20%. (Note that Gail and BCSC models are not recommended to be used to determine risk for purposes of supplemental screening with MRI as they do not consider paternal family history nor age of relatives at diagnosis.)

Dr. Albright: ObGyns should be able to ascertain a pertinent history and identify patients at risk for breast cancer based on their personal history, family history, and breast imaging/biopsy history, if relevant. We also need to improve our discussions of supplemental screening for patients who have heterogeneously dense or extremely dense breast tissue. I sense that some ObGyns may rely heavily on the radiologist to suggest supplemental screening, but patients actually look to ObGyns as their providers to have this knowledge and give them direction.

Since I practice at a large academic medical center, I have the opportunity to refer patients to our Breast Cancer Genetics Program because I may be limited on time for counseling in the office and do not want to miss salient details. With all of the information I have ascertained about the patient, I am able to determine and encourage appropriate screening and assure insurance coverage for adjunctive breast MRI when appropriate.

Continue to: Consider how you order patients’ screening to reduce barriers and cost...

Consider how you order patients’ screening to reduce barriers and cost

4. How would you suggest reducing barriers when referring patients for supplemental screening, such as MRI for high-risk women or ultrasound for those with dense breasts? Would you prefer it if such screening could be performed without additional script/referral? How does insurance coverage factor in?

Dr. Etkin-Kramer: I would love for a screening mammogram with possible ultrasound, on one script, to be the norm. One of the centers that I work with accepts a script written this way. Further, when a patient receives screening at a freestanding facility as opposed to a hospital, the fee for the supplemental screening may be lower because they do not add on a facility fee.

Dr. Albright: We have an order in our electronic health record that allows for screening mammography but adds on diagnostic mammography/bilateral ultrasonography, if indicated by imaging. I am mostly ordering that option now for all of my screening patients; rarely have I had issues with insurance accepting that script. As for when ordering an MRI, I always try to ensure that I have done the patient’s personal risk assessment and included that lifetime breast cancer risk on the order. If the risk is 20% or higher, I typically do not have any insurance coverage issues. If I am ordering MRI as supplemental screening, I typically order the “Fast MRI” protocol that our center offers. This order incurs a $299 out-of-pocket cost for the patient. Any patient with heterogeneously or extremely dense breasts on mammography should have this option, but it requires patient education, discussion with the provider, and an additional cost. I definitely think that insurers need to consider covering supplemental screening, since breast density is reportable in a majority of the US states and will soon be the national standard.

Pearls for guiding patients

5. How do you discuss breast density and the need for supplemental screening with your patients?

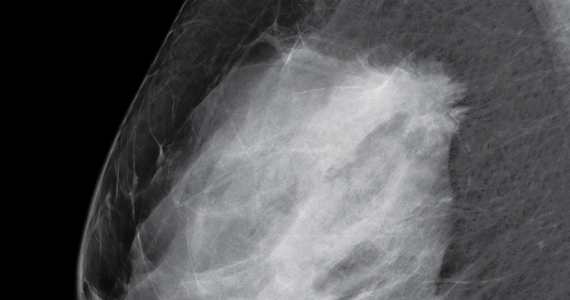

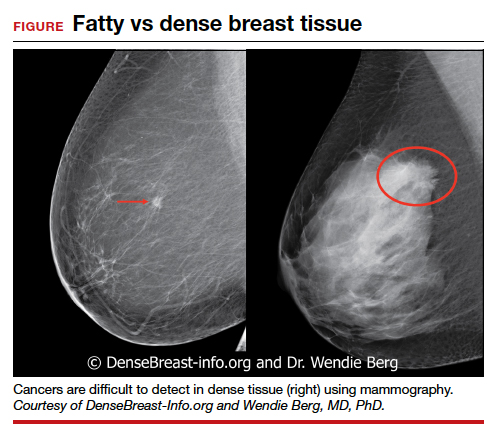

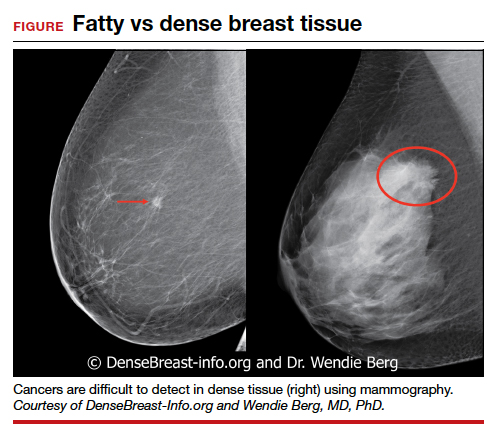

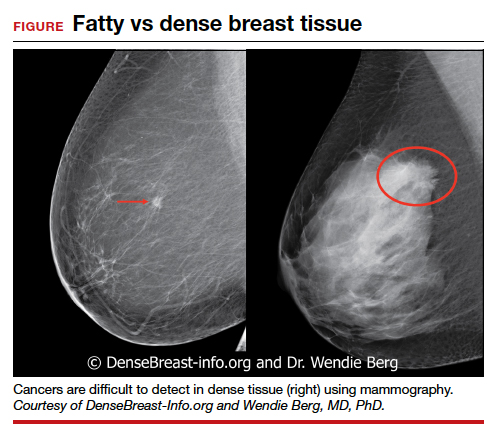

Dr. Etkin-Kramer: I strongly feel that my patients need to know when a screening test has limited ability to do its job. This is the case with dense breasts. Visuals help; when discussing breast density, I like the images supplied by DenseBreast-info.org (FIGURE). I explain the two implications of dense tissue:

- First, dense tissue makes it harder to visualize cancers in the breast—the denser the breasts, the less likely the radiologist can pick up a cancer, so mammographic sensitivity for extremely dense breasts can be as low as 25% to 50%.

- Second, high breast density adds to the risk of developing breast cancer. I explain that supplemental screening will pick up additional cancers in women with dense breasts. For example, breast ultrasound will pick up about 2-3/1000 additional breast cancers per year and MRI or molecular breast imaging (MBI) will pick up much more, perhaps 10/1000.

MRI is more invasive than an ultrasound and uses gadolinium, and MBI has more radiation. Supplemental screening is not endorsed by ACOG’s most recent Committee Opinion from 2017; 4 however, patients may choose to have it done. This is where shared-decision making is important.

I strongly recommend that all women’s health care providers complete the CME course on the DenseBreast-info.org website. “ Breast Density: Why It Matters ” is a certified educational program for referring physicians that helps health care professionals learn about breast density, its associated risks, and how best to guide patients regarding breast cancer screening.

Continue to: Dr. Albright...

Dr. Albright: When I discuss breast density, I make sure that patients understand that their mammogram determines the density of their breast tissue. I review that in the higher density categories (heterogeneously dense or extremely dense), there is a higher risk of missing cancer, and that these categories are also associated with a higher risk of breast cancer. I also discuss the potential need for supplemental screening, for which my institution primarily offers Fast MRI. However, we can offer breast ultrasonography instead as an option, especially for those concerned about gadolinium exposure. Our center offers either of these supplemental screenings at a cost of $299. I also review the lack of coverage for supplemental screening by some insurance carriers, as both providers and patients may need to advocate for insurer coverage of adjunct studies.

Educational resources

6. What reference materials, illustrations, or other tools do you use to educate your patients?

Dr. Etkin-Kramer: I frequently use handouts printed from the DenseBreast-info.org website, and there is now a brand new patient fact sheet that I have just started using. I also have an example of breast density categories from fatty replaced to extremely dense on my computer, and I am putting it on a new smart board.

Dr. Albright: The extensive resources available at DenseBreast-info.org can improve both patient and provider knowledge of these important issues, so I suggest patients visit that website, and I use many of the images and visuals to help explain breast density. I even use the materials from the website for educating my resident trainees on breast health and screening. ●

Nearly 16,000 children (up to age 19 years) face cancer-related treatment every year.1 For girls and young women, undergoing chest radiotherapy puts them at higher risk for secondary breast cancer. In fact, they have a 30% chance of developing such cancer by age 50—a risk that is similar to women with a BRCA1 mutation.2 Therefore, current recommendations for breast cancer screening among those who have undergone childhood chest radiation (≥20 Gy) are to begin annual mammography, with adjunct magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), at age 25 years (or 8 years after chest radiotherapy).3

To determine the benefits and risks of these recommendations, as well as of similar strategies, Yeh and colleagues performed simulation modeling using data from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study and two CISNET (Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network) models.4 For their study they targeted a cohort of female childhood cancer survivors having undergone chest radiotherapy and evaluated breast cancer screening with the following strategies:

- mammography plus MRI, starting at ages 25, 30, or 35 years and continuing to age 74

- MRI alone, starting at ages 25, 30, or 35 years and continuing to age 74.

They found that both strategies reduced the risk of breast cancer in the targeted cohort but that screening beginning at the earliest ages prevented most deaths. No screening at all was associated with a 10% to 11% lifetime risk of breast cancer, but mammography plus MRI beginning at age 25 reduced that risk by 56% to 71% depending on the model. Screening with MRI alone reduced mortality risk by 56% to 62%. When considering cost per quality adjusted life-year gained, the researchers found that screening beginning at age 30 to be the most cost-effective.4

Yeh and colleagues addressed concerns with mammography and radiation. Although they said the associated amount of radiation exposure is small, the use of mammography in women younger than age 30 is controversial—and not recommended by the American Cancer Society or the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.5,6

Bottom line. Yeh and colleagues conclude that MRI screening, with or without mammography, beginning between the ages of 25 and 30 should be emphasized in screening guidelines. They note the importance of insurance coverage for MRI in those at risk for breast cancer due to childhood radiation exposure.4

References

- National Cancer Institute. How common is cancer in children? https://www.cancer.gov/types/childhood-cancers/child-adolescentcancers-fact-sheet#how-common-is-cancer-in-children. Accessed September 25, 2020.

- Moskowitz CS, Chou JF, Wolden SL, et al. Breast cancer after chest radiation therapy for childhood cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2217- 2223.

- Children’s Oncology Group. Long-term follow-up guidelines for survivors of childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancers. http:// www.survivorshipguidelines.org/pdf/2018/COG_LTFU_Guidelines_v5.pdf. Accessed September 25, 2020.

- Yeh JM, Lowry KP, Schechter CB, et al. Clinical benefits, harms, and cost-effectiveness of breast cancer screening for survivors of childhood cancer treated with chest radiation. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173:331-341.

- Saslow D, Boetes C, Burke W, et al; American Cancer Society Breast Cancer Advisory Group. American Cancer Society guidelines for breast screening with MRI as an adjunct to mammography. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:75-89.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Breast cancer screening and diagnosis version 1.2019. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx. Accessed September 25, 2020.

- Bharucha PP, Chiu KE, Francois FM, et al. Genetic testing and screening recommendations for patients with hereditary breast cancer. RadioGraphics. 2020;40:913-936.

- Freedman AN, Yu B, Gail MH, et al. Benefit/risk assessment for breast cancer chemoprevention with raloxifene or tamoxifen for women age 50 years or older. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2327-2333.

- Pruthi S, Heisey RE, Bevers TB. Chemoprevention for breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:3230-3235.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee opinion no. 625: management of women with dense breasts diagnosed by mammography [published correction appears in Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:166]. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(3):750-751.

If your ObGyn practices are anything like ours, every time there is news coverage of a study regarding mammography or about efforts to pass a breast density inform law, your phone rings with patient calls. In fact, every density inform law enacted in the United States, except for in Illinois, directs patients to their referring provider—generally their ObGyn—to discuss the screening and risk implications of dense breast tissue.

The steady increased awareness of breast density means that we, as ObGyns and other primary care providers (PCPs), have additional responsibilities in managing the breast health of our patients. This includes guiding discussions with patients about what breast density means and whether supplemental screening beyond mammography might be beneficial.

As members of the Medical Advisory Board for DenseBreast-info.org (an online educational resource dedicated to providing breast density information to patients and health care professionals), we are aware of the growing body of evidence demonstrating improved detection of early breast cancer using supplemental screening in dense breasts. However, we know that there is confusion among clinicians about how and when to facilitate tailored screening for women with dense breasts or other breast cancer risk factors. Here we answer 6 questions focusing on how to navigate patient discussions around the topic and the best way to collaborate with radiologists to improve breast care for patients.

Play an active role

1. What role should ObGyns and PCPs play in women’s breast health?

Elizabeth Etkin-Kramer, MD: I am a firm believer that ObGyns and all women’s health providers should be able to assess their patients’ risk of breast cancer and explain the process for managing this risk with their patients. This explanation includes the clinical implications of breast density and when supplemental screening should be employed. It is also important for providers to know when to offer genetic testing and when a patient’s personal or family history indicates supplemental screening with breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

DaCarla M. Albright, MD: I absolutely agree that PCPs, ObGyns, and family practitioners should spend the time to be educated about breast density and supplemental screening options. While the exact role providers play in managing patients’ breast health may vary depending on the practice type or location, the need for knowledge and comfort when talking with patients to help them make informed decisions is critical. Breast health and screening, including the importance of breast density, happen to be a particular interest of mine. I have participated in educational webinars, invited lectures, and breast cancer awareness media events on this topic in the past.

Continue to: Join forces with imaging centers...

Join forces with imaging centers

2. How can ObGyns and radiologists collaborate most effectively to use screening results to personalize breast care for patients?

Dr. Etkin-Kramer: It is important to have a close relationship with the radiologists that read our patients’ mammograms. We need to be able to easily contact the radiologist and quickly get clarification on a patient’s report or discuss next steps. Imaging centers should consider running outreach programs to educate their referring providers on how to risk assess, with this assessment inclusive of breast density. Dinner lectures or grand round meetings are effective to facilitate communication between the radiology community and the ObGyn community. Finally, as we all know, supplemental screening is often subject to copays and deductibles per insurance coverage. If advocacy groups, who are working to eliminate these types of costs, cannot get insurers to waive these payments, we need a less expensive self-pay option.

Dr. Albright: I definitely have and encourage an open line of communication between my practice and breast radiology, as well as our breast surgeons and cancer center to set up consultations as needed. We also invite our radiologists as guests to monthly practice meetings or grand rounds within our department to further improve access and open communication, as this environment is one in which greater provider education on density and adjunctive screening can be achieved.

Know when to refer a high-risk patient

3. Most ObGyns routinely collect family history and perform formal risk assessment. What do you need to know about referring patients to a high-risk program?

Dr. Etkin-Kramer: It is important as ObGyns to be knowledgeable about breast and ovarian cancer risk assessment and genetic testing for cancer susceptibility genes. Our patients expect that of us. I am comfortable doing risk assessment in my office, but I sometimes refer to other specialists in the community if the patient needs additional counseling. For risk assessment, I look at family and personal history, breast density, and other factors that might lead me to believe the patient might carry a hereditary cancer susceptibility gene, including Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry.1 When indicated, I check lifetime as well as short-term (5- to 10-year) risk, usually using Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC) or Tyrer-Cuzick/International Breast Cancer Intervention Study (IBIS) models, as these include breast density.

I discuss risk-reducing medications. The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends these agents if my patient’s 5-year risk of breast cancer is 1.67% or greater, and I strongly recommend chemoprevention when the patient’s 5-year BCSC risk exceeds 3%, provided likely benefits exceed risks.2,3 I discuss adding screening breast MRI if lifetime risk by Tyrer-Cuzick exceeds 20%. (Note that Gail and BCSC models are not recommended to be used to determine risk for purposes of supplemental screening with MRI as they do not consider paternal family history nor age of relatives at diagnosis.)

Dr. Albright: ObGyns should be able to ascertain a pertinent history and identify patients at risk for breast cancer based on their personal history, family history, and breast imaging/biopsy history, if relevant. We also need to improve our discussions of supplemental screening for patients who have heterogeneously dense or extremely dense breast tissue. I sense that some ObGyns may rely heavily on the radiologist to suggest supplemental screening, but patients actually look to ObGyns as their providers to have this knowledge and give them direction.

Since I practice at a large academic medical center, I have the opportunity to refer patients to our Breast Cancer Genetics Program because I may be limited on time for counseling in the office and do not want to miss salient details. With all of the information I have ascertained about the patient, I am able to determine and encourage appropriate screening and assure insurance coverage for adjunctive breast MRI when appropriate.

Continue to: Consider how you order patients’ screening to reduce barriers and cost...

Consider how you order patients’ screening to reduce barriers and cost

4. How would you suggest reducing barriers when referring patients for supplemental screening, such as MRI for high-risk women or ultrasound for those with dense breasts? Would you prefer it if such screening could be performed without additional script/referral? How does insurance coverage factor in?

Dr. Etkin-Kramer: I would love for a screening mammogram with possible ultrasound, on one script, to be the norm. One of the centers that I work with accepts a script written this way. Further, when a patient receives screening at a freestanding facility as opposed to a hospital, the fee for the supplemental screening may be lower because they do not add on a facility fee.

Dr. Albright: We have an order in our electronic health record that allows for screening mammography but adds on diagnostic mammography/bilateral ultrasonography, if indicated by imaging. I am mostly ordering that option now for all of my screening patients; rarely have I had issues with insurance accepting that script. As for when ordering an MRI, I always try to ensure that I have done the patient’s personal risk assessment and included that lifetime breast cancer risk on the order. If the risk is 20% or higher, I typically do not have any insurance coverage issues. If I am ordering MRI as supplemental screening, I typically order the “Fast MRI” protocol that our center offers. This order incurs a $299 out-of-pocket cost for the patient. Any patient with heterogeneously or extremely dense breasts on mammography should have this option, but it requires patient education, discussion with the provider, and an additional cost. I definitely think that insurers need to consider covering supplemental screening, since breast density is reportable in a majority of the US states and will soon be the national standard.

Pearls for guiding patients

5. How do you discuss breast density and the need for supplemental screening with your patients?

Dr. Etkin-Kramer: I strongly feel that my patients need to know when a screening test has limited ability to do its job. This is the case with dense breasts. Visuals help; when discussing breast density, I like the images supplied by DenseBreast-info.org (FIGURE). I explain the two implications of dense tissue:

- First, dense tissue makes it harder to visualize cancers in the breast—the denser the breasts, the less likely the radiologist can pick up a cancer, so mammographic sensitivity for extremely dense breasts can be as low as 25% to 50%.

- Second, high breast density adds to the risk of developing breast cancer. I explain that supplemental screening will pick up additional cancers in women with dense breasts. For example, breast ultrasound will pick up about 2-3/1000 additional breast cancers per year and MRI or molecular breast imaging (MBI) will pick up much more, perhaps 10/1000.

MRI is more invasive than an ultrasound and uses gadolinium, and MBI has more radiation. Supplemental screening is not endorsed by ACOG’s most recent Committee Opinion from 2017; 4 however, patients may choose to have it done. This is where shared-decision making is important.

I strongly recommend that all women’s health care providers complete the CME course on the DenseBreast-info.org website. “ Breast Density: Why It Matters ” is a certified educational program for referring physicians that helps health care professionals learn about breast density, its associated risks, and how best to guide patients regarding breast cancer screening.

Continue to: Dr. Albright...

Dr. Albright: When I discuss breast density, I make sure that patients understand that their mammogram determines the density of their breast tissue. I review that in the higher density categories (heterogeneously dense or extremely dense), there is a higher risk of missing cancer, and that these categories are also associated with a higher risk of breast cancer. I also discuss the potential need for supplemental screening, for which my institution primarily offers Fast MRI. However, we can offer breast ultrasonography instead as an option, especially for those concerned about gadolinium exposure. Our center offers either of these supplemental screenings at a cost of $299. I also review the lack of coverage for supplemental screening by some insurance carriers, as both providers and patients may need to advocate for insurer coverage of adjunct studies.

Educational resources

6. What reference materials, illustrations, or other tools do you use to educate your patients?

Dr. Etkin-Kramer: I frequently use handouts printed from the DenseBreast-info.org website, and there is now a brand new patient fact sheet that I have just started using. I also have an example of breast density categories from fatty replaced to extremely dense on my computer, and I am putting it on a new smart board.

Dr. Albright: The extensive resources available at DenseBreast-info.org can improve both patient and provider knowledge of these important issues, so I suggest patients visit that website, and I use many of the images and visuals to help explain breast density. I even use the materials from the website for educating my resident trainees on breast health and screening. ●

Nearly 16,000 children (up to age 19 years) face cancer-related treatment every year.1 For girls and young women, undergoing chest radiotherapy puts them at higher risk for secondary breast cancer. In fact, they have a 30% chance of developing such cancer by age 50—a risk that is similar to women with a BRCA1 mutation.2 Therefore, current recommendations for breast cancer screening among those who have undergone childhood chest radiation (≥20 Gy) are to begin annual mammography, with adjunct magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), at age 25 years (or 8 years after chest radiotherapy).3

To determine the benefits and risks of these recommendations, as well as of similar strategies, Yeh and colleagues performed simulation modeling using data from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study and two CISNET (Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network) models.4 For their study they targeted a cohort of female childhood cancer survivors having undergone chest radiotherapy and evaluated breast cancer screening with the following strategies:

- mammography plus MRI, starting at ages 25, 30, or 35 years and continuing to age 74

- MRI alone, starting at ages 25, 30, or 35 years and continuing to age 74.

They found that both strategies reduced the risk of breast cancer in the targeted cohort but that screening beginning at the earliest ages prevented most deaths. No screening at all was associated with a 10% to 11% lifetime risk of breast cancer, but mammography plus MRI beginning at age 25 reduced that risk by 56% to 71% depending on the model. Screening with MRI alone reduced mortality risk by 56% to 62%. When considering cost per quality adjusted life-year gained, the researchers found that screening beginning at age 30 to be the most cost-effective.4

Yeh and colleagues addressed concerns with mammography and radiation. Although they said the associated amount of radiation exposure is small, the use of mammography in women younger than age 30 is controversial—and not recommended by the American Cancer Society or the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.5,6

Bottom line. Yeh and colleagues conclude that MRI screening, with or without mammography, beginning between the ages of 25 and 30 should be emphasized in screening guidelines. They note the importance of insurance coverage for MRI in those at risk for breast cancer due to childhood radiation exposure.4

References

- National Cancer Institute. How common is cancer in children? https://www.cancer.gov/types/childhood-cancers/child-adolescentcancers-fact-sheet#how-common-is-cancer-in-children. Accessed September 25, 2020.

- Moskowitz CS, Chou JF, Wolden SL, et al. Breast cancer after chest radiation therapy for childhood cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2217- 2223.

- Children’s Oncology Group. Long-term follow-up guidelines for survivors of childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancers. http:// www.survivorshipguidelines.org/pdf/2018/COG_LTFU_Guidelines_v5.pdf. Accessed September 25, 2020.

- Yeh JM, Lowry KP, Schechter CB, et al. Clinical benefits, harms, and cost-effectiveness of breast cancer screening for survivors of childhood cancer treated with chest radiation. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173:331-341.

- Saslow D, Boetes C, Burke W, et al; American Cancer Society Breast Cancer Advisory Group. American Cancer Society guidelines for breast screening with MRI as an adjunct to mammography. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:75-89.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Breast cancer screening and diagnosis version 1.2019. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx. Accessed September 25, 2020.

If your ObGyn practices are anything like ours, every time there is news coverage of a study regarding mammography or about efforts to pass a breast density inform law, your phone rings with patient calls. In fact, every density inform law enacted in the United States, except for in Illinois, directs patients to their referring provider—generally their ObGyn—to discuss the screening and risk implications of dense breast tissue.

The steady increased awareness of breast density means that we, as ObGyns and other primary care providers (PCPs), have additional responsibilities in managing the breast health of our patients. This includes guiding discussions with patients about what breast density means and whether supplemental screening beyond mammography might be beneficial.

As members of the Medical Advisory Board for DenseBreast-info.org (an online educational resource dedicated to providing breast density information to patients and health care professionals), we are aware of the growing body of evidence demonstrating improved detection of early breast cancer using supplemental screening in dense breasts. However, we know that there is confusion among clinicians about how and when to facilitate tailored screening for women with dense breasts or other breast cancer risk factors. Here we answer 6 questions focusing on how to navigate patient discussions around the topic and the best way to collaborate with radiologists to improve breast care for patients.

Play an active role

1. What role should ObGyns and PCPs play in women’s breast health?

Elizabeth Etkin-Kramer, MD: I am a firm believer that ObGyns and all women’s health providers should be able to assess their patients’ risk of breast cancer and explain the process for managing this risk with their patients. This explanation includes the clinical implications of breast density and when supplemental screening should be employed. It is also important for providers to know when to offer genetic testing and when a patient’s personal or family history indicates supplemental screening with breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

DaCarla M. Albright, MD: I absolutely agree that PCPs, ObGyns, and family practitioners should spend the time to be educated about breast density and supplemental screening options. While the exact role providers play in managing patients’ breast health may vary depending on the practice type or location, the need for knowledge and comfort when talking with patients to help them make informed decisions is critical. Breast health and screening, including the importance of breast density, happen to be a particular interest of mine. I have participated in educational webinars, invited lectures, and breast cancer awareness media events on this topic in the past.

Continue to: Join forces with imaging centers...

Join forces with imaging centers

2. How can ObGyns and radiologists collaborate most effectively to use screening results to personalize breast care for patients?

Dr. Etkin-Kramer: It is important to have a close relationship with the radiologists that read our patients’ mammograms. We need to be able to easily contact the radiologist and quickly get clarification on a patient’s report or discuss next steps. Imaging centers should consider running outreach programs to educate their referring providers on how to risk assess, with this assessment inclusive of breast density. Dinner lectures or grand round meetings are effective to facilitate communication between the radiology community and the ObGyn community. Finally, as we all know, supplemental screening is often subject to copays and deductibles per insurance coverage. If advocacy groups, who are working to eliminate these types of costs, cannot get insurers to waive these payments, we need a less expensive self-pay option.

Dr. Albright: I definitely have and encourage an open line of communication between my practice and breast radiology, as well as our breast surgeons and cancer center to set up consultations as needed. We also invite our radiologists as guests to monthly practice meetings or grand rounds within our department to further improve access and open communication, as this environment is one in which greater provider education on density and adjunctive screening can be achieved.

Know when to refer a high-risk patient

3. Most ObGyns routinely collect family history and perform formal risk assessment. What do you need to know about referring patients to a high-risk program?

Dr. Etkin-Kramer: It is important as ObGyns to be knowledgeable about breast and ovarian cancer risk assessment and genetic testing for cancer susceptibility genes. Our patients expect that of us. I am comfortable doing risk assessment in my office, but I sometimes refer to other specialists in the community if the patient needs additional counseling. For risk assessment, I look at family and personal history, breast density, and other factors that might lead me to believe the patient might carry a hereditary cancer susceptibility gene, including Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry.1 When indicated, I check lifetime as well as short-term (5- to 10-year) risk, usually using Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC) or Tyrer-Cuzick/International Breast Cancer Intervention Study (IBIS) models, as these include breast density.

I discuss risk-reducing medications. The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends these agents if my patient’s 5-year risk of breast cancer is 1.67% or greater, and I strongly recommend chemoprevention when the patient’s 5-year BCSC risk exceeds 3%, provided likely benefits exceed risks.2,3 I discuss adding screening breast MRI if lifetime risk by Tyrer-Cuzick exceeds 20%. (Note that Gail and BCSC models are not recommended to be used to determine risk for purposes of supplemental screening with MRI as they do not consider paternal family history nor age of relatives at diagnosis.)

Dr. Albright: ObGyns should be able to ascertain a pertinent history and identify patients at risk for breast cancer based on their personal history, family history, and breast imaging/biopsy history, if relevant. We also need to improve our discussions of supplemental screening for patients who have heterogeneously dense or extremely dense breast tissue. I sense that some ObGyns may rely heavily on the radiologist to suggest supplemental screening, but patients actually look to ObGyns as their providers to have this knowledge and give them direction.

Since I practice at a large academic medical center, I have the opportunity to refer patients to our Breast Cancer Genetics Program because I may be limited on time for counseling in the office and do not want to miss salient details. With all of the information I have ascertained about the patient, I am able to determine and encourage appropriate screening and assure insurance coverage for adjunctive breast MRI when appropriate.

Continue to: Consider how you order patients’ screening to reduce barriers and cost...

Consider how you order patients’ screening to reduce barriers and cost

4. How would you suggest reducing barriers when referring patients for supplemental screening, such as MRI for high-risk women or ultrasound for those with dense breasts? Would you prefer it if such screening could be performed without additional script/referral? How does insurance coverage factor in?

Dr. Etkin-Kramer: I would love for a screening mammogram with possible ultrasound, on one script, to be the norm. One of the centers that I work with accepts a script written this way. Further, when a patient receives screening at a freestanding facility as opposed to a hospital, the fee for the supplemental screening may be lower because they do not add on a facility fee.

Dr. Albright: We have an order in our electronic health record that allows for screening mammography but adds on diagnostic mammography/bilateral ultrasonography, if indicated by imaging. I am mostly ordering that option now for all of my screening patients; rarely have I had issues with insurance accepting that script. As for when ordering an MRI, I always try to ensure that I have done the patient’s personal risk assessment and included that lifetime breast cancer risk on the order. If the risk is 20% or higher, I typically do not have any insurance coverage issues. If I am ordering MRI as supplemental screening, I typically order the “Fast MRI” protocol that our center offers. This order incurs a $299 out-of-pocket cost for the patient. Any patient with heterogeneously or extremely dense breasts on mammography should have this option, but it requires patient education, discussion with the provider, and an additional cost. I definitely think that insurers need to consider covering supplemental screening, since breast density is reportable in a majority of the US states and will soon be the national standard.

Pearls for guiding patients

5. How do you discuss breast density and the need for supplemental screening with your patients?

Dr. Etkin-Kramer: I strongly feel that my patients need to know when a screening test has limited ability to do its job. This is the case with dense breasts. Visuals help; when discussing breast density, I like the images supplied by DenseBreast-info.org (FIGURE). I explain the two implications of dense tissue:

- First, dense tissue makes it harder to visualize cancers in the breast—the denser the breasts, the less likely the radiologist can pick up a cancer, so mammographic sensitivity for extremely dense breasts can be as low as 25% to 50%.

- Second, high breast density adds to the risk of developing breast cancer. I explain that supplemental screening will pick up additional cancers in women with dense breasts. For example, breast ultrasound will pick up about 2-3/1000 additional breast cancers per year and MRI or molecular breast imaging (MBI) will pick up much more, perhaps 10/1000.

MRI is more invasive than an ultrasound and uses gadolinium, and MBI has more radiation. Supplemental screening is not endorsed by ACOG’s most recent Committee Opinion from 2017; 4 however, patients may choose to have it done. This is where shared-decision making is important.

I strongly recommend that all women’s health care providers complete the CME course on the DenseBreast-info.org website. “ Breast Density: Why It Matters ” is a certified educational program for referring physicians that helps health care professionals learn about breast density, its associated risks, and how best to guide patients regarding breast cancer screening.

Continue to: Dr. Albright...

Dr. Albright: When I discuss breast density, I make sure that patients understand that their mammogram determines the density of their breast tissue. I review that in the higher density categories (heterogeneously dense or extremely dense), there is a higher risk of missing cancer, and that these categories are also associated with a higher risk of breast cancer. I also discuss the potential need for supplemental screening, for which my institution primarily offers Fast MRI. However, we can offer breast ultrasonography instead as an option, especially for those concerned about gadolinium exposure. Our center offers either of these supplemental screenings at a cost of $299. I also review the lack of coverage for supplemental screening by some insurance carriers, as both providers and patients may need to advocate for insurer coverage of adjunct studies.

Educational resources

6. What reference materials, illustrations, or other tools do you use to educate your patients?

Dr. Etkin-Kramer: I frequently use handouts printed from the DenseBreast-info.org website, and there is now a brand new patient fact sheet that I have just started using. I also have an example of breast density categories from fatty replaced to extremely dense on my computer, and I am putting it on a new smart board.

Dr. Albright: The extensive resources available at DenseBreast-info.org can improve both patient and provider knowledge of these important issues, so I suggest patients visit that website, and I use many of the images and visuals to help explain breast density. I even use the materials from the website for educating my resident trainees on breast health and screening. ●

Nearly 16,000 children (up to age 19 years) face cancer-related treatment every year.1 For girls and young women, undergoing chest radiotherapy puts them at higher risk for secondary breast cancer. In fact, they have a 30% chance of developing such cancer by age 50—a risk that is similar to women with a BRCA1 mutation.2 Therefore, current recommendations for breast cancer screening among those who have undergone childhood chest radiation (≥20 Gy) are to begin annual mammography, with adjunct magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), at age 25 years (or 8 years after chest radiotherapy).3

To determine the benefits and risks of these recommendations, as well as of similar strategies, Yeh and colleagues performed simulation modeling using data from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study and two CISNET (Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network) models.4 For their study they targeted a cohort of female childhood cancer survivors having undergone chest radiotherapy and evaluated breast cancer screening with the following strategies:

- mammography plus MRI, starting at ages 25, 30, or 35 years and continuing to age 74

- MRI alone, starting at ages 25, 30, or 35 years and continuing to age 74.

They found that both strategies reduced the risk of breast cancer in the targeted cohort but that screening beginning at the earliest ages prevented most deaths. No screening at all was associated with a 10% to 11% lifetime risk of breast cancer, but mammography plus MRI beginning at age 25 reduced that risk by 56% to 71% depending on the model. Screening with MRI alone reduced mortality risk by 56% to 62%. When considering cost per quality adjusted life-year gained, the researchers found that screening beginning at age 30 to be the most cost-effective.4

Yeh and colleagues addressed concerns with mammography and radiation. Although they said the associated amount of radiation exposure is small, the use of mammography in women younger than age 30 is controversial—and not recommended by the American Cancer Society or the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.5,6

Bottom line. Yeh and colleagues conclude that MRI screening, with or without mammography, beginning between the ages of 25 and 30 should be emphasized in screening guidelines. They note the importance of insurance coverage for MRI in those at risk for breast cancer due to childhood radiation exposure.4

References

- National Cancer Institute. How common is cancer in children? https://www.cancer.gov/types/childhood-cancers/child-adolescentcancers-fact-sheet#how-common-is-cancer-in-children. Accessed September 25, 2020.

- Moskowitz CS, Chou JF, Wolden SL, et al. Breast cancer after chest radiation therapy for childhood cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2217- 2223.

- Children’s Oncology Group. Long-term follow-up guidelines for survivors of childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancers. http:// www.survivorshipguidelines.org/pdf/2018/COG_LTFU_Guidelines_v5.pdf. Accessed September 25, 2020.

- Yeh JM, Lowry KP, Schechter CB, et al. Clinical benefits, harms, and cost-effectiveness of breast cancer screening for survivors of childhood cancer treated with chest radiation. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173:331-341.

- Saslow D, Boetes C, Burke W, et al; American Cancer Society Breast Cancer Advisory Group. American Cancer Society guidelines for breast screening with MRI as an adjunct to mammography. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:75-89.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Breast cancer screening and diagnosis version 1.2019. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx. Accessed September 25, 2020.

- Bharucha PP, Chiu KE, Francois FM, et al. Genetic testing and screening recommendations for patients with hereditary breast cancer. RadioGraphics. 2020;40:913-936.

- Freedman AN, Yu B, Gail MH, et al. Benefit/risk assessment for breast cancer chemoprevention with raloxifene or tamoxifen for women age 50 years or older. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2327-2333.

- Pruthi S, Heisey RE, Bevers TB. Chemoprevention for breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:3230-3235.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee opinion no. 625: management of women with dense breasts diagnosed by mammography [published correction appears in Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:166]. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(3):750-751.

- Bharucha PP, Chiu KE, Francois FM, et al. Genetic testing and screening recommendations for patients with hereditary breast cancer. RadioGraphics. 2020;40:913-936.

- Freedman AN, Yu B, Gail MH, et al. Benefit/risk assessment for breast cancer chemoprevention with raloxifene or tamoxifen for women age 50 years or older. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2327-2333.

- Pruthi S, Heisey RE, Bevers TB. Chemoprevention for breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:3230-3235.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee opinion no. 625: management of women with dense breasts diagnosed by mammography [published correction appears in Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:166]. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(3):750-751.

DenseBreast-info.org: What this resource can offer you, and your patients

Read the article Get smart about dense breasts by Wendie Berg, MD, PhD, JoAnn Pushkin, and Cindy Henke-Sarmento (October 2015)

Read the article Get smart about dense breasts by Wendie Berg, MD, PhD, JoAnn Pushkin, and Cindy Henke-Sarmento (October 2015)

Read the article Get smart about dense breasts by Wendie Berg, MD, PhD, JoAnn Pushkin, and Cindy Henke-Sarmento (October 2015)

Access DenseBreast-info.org

Get smart about dense breasts

It’s a movement that shows no signs of abating. Women in 24 states, encompassing 67% of American women, now receive some level of notification after their mammogram about breast density. Individual patient advocates continue to push for notification, and states are likely to continue to draft bills. On the national level, a federal standard is being pursued through both federal legislation and federal regulation. Clinicians practicing in states with an “inform” law, either already in effect or imminent, will be tasked with engaging in new patient conversations arising from density notification. Are you ready to answer your patients’ questions?

Navigating inconsistent data and expert comments about density and discerning which patients may benefit from additional screening can create challenges in addressing a patient’s questions about the implications of her dense tissue. If you feel less than equipped to address these issues, you are not alone. A recent survey of clinicians, con- ducted after California’s breast density notification law went into effect, showed that only 6% were comfortable answering patients’ questions relating to breast density. Seventy-five percent of respondents indicated they wanted more education on the topic.1

For women having mammography, dense breast tissue is most important because it can mask detection of cancers, and women may want to have additional screening beyond mammography. Women with dense breasts are also at increased risk for developing breast cancer. For clinicians who are on the front lines of care for women undergoing screening, the most important action items are:

- identifying who needs more screening

- weighing the risks and benefits of such additional screening.

To assist you in informing patient discussions, in this article we answer some of the most frequently asked questions of ObGyns.

Which breasts are considered dense?

The American College of Radiology recommends that density be reported in 1 of 4 categories depending on the relative amounts of fat and fibroglandular tissue2:

- almost entirely fatty—on mammography most of the tissue appears dark gray while small amounts of dense (or fibroglandular) tissue display as light gray or white.

- scattered fibroglandular density—scattered areas of dense tissue mixed with fat. Even in breasts with scattered areas of breast tissue, cancers sometimes can be missed when they resemble areas of normal tissue or are within an area of denser tissue.

- heterogeneously dense—there are large portions of the breast where dense tissue could hide masses.

- extremely dense—most of the breast appears to consist of dense tissue, creating a “white out” situation and making it extremely difficult to see through.

Breasts that are either heterogeneously dense or extremely dense are considered “dense.” About 40% of women older than age 40 have dense breasts.3

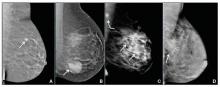

Case study: Imaging of a cancerous breast mass in a 48-year-old woman with dense breasts

This patient has heterogeneously dense breast tissue. Standard 2D mediolateral oblique (MLO) digital mammogram (A) and MLO tomosynthesis 1-mm slice (B) reveal subtle possible distortion (arrow) in the upper right breast. On tomosynthesis, the distortion is better seen, as is the underlying irregular mass (red circle).

Ultrasound (US) directed to the mass (C) shows an irregular hypoechoic (dark gray) mass (marked by calipers), compatible with cancer. US-guided core needle biopsy revealed grade 2 invasive ductal cancer with associated ductal carcinoma in situ.

Axial magnetic resonance imaging of the right breast obtained after contrast injection, and after computer subtraction of nonenhanced image (D), shows irregular spiculated enhancing (white) mass (arrow) due to the known carcinoma.

Images: Courtesy Wendie Berg, MD, PhD

Who needs more screening?

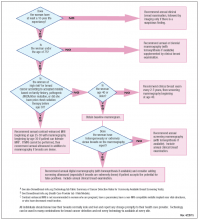

The FIGURE is a screening decision support tool representing the consensus opinion of several medical experts based on the best available scientific evidence to optimize breast cancer detection.

Do dense breasts affect the risk of developing breast cancer?

Yes. Dense breasts are a risk factor for breast cancer. According to the American Cancer Society’s Breast Cancer Facts & Figures 2013−2014, “The risk of breast cancer in-creases with increasing breast density; women with very high breast density have a 4- to 6-fold increased risk of breast cancer compared to women with the least dense breasts.”4,5

There are several reasons that dense tissue increases risk. First, the glands tend to be made up of relatively actively dividing cells that can mutate and become cancerous (the more glandular tissue present, the greater the risk). Second, the local environment around the glands may produce certain growth hormones that stimulate cells to divide, and this seems to occur more in fibrous tissue than in fatty tissue.

Most women have breast density somewhere in the middle range, with their risk for breast cancer falling in between those with extremely dense breasts and those with fatty breasts.6 The risk for developing breast cancer is influenced by a combination of many different factors, including age, family history of cancer (particularly breast or ovarian cancer), and prior atypical breast biopsies. There currently is no reliable way to fully account for the interplay of breast density, family history, prior biopsy results, and other factors in determining overall risk. Importantly, more than half of all women who develop breast cancer have no known risk factors other than being female and aging.

Is your medical support staff “density ready?”

We’re all familiar with the adage that a picture is worth a thousand words. While the medical support personnel in your office are likely quite familiar with imaging reports and the terminology used in describing dense breasts, they may be quite unfamiliar with what a fatty versus dense breast actually looks like on a mammogram, and how cancer may display in each. Illustrated examples, as seen here, are useful for reference.

In the fatty breast (A), a small cancer (arrow) is seen easily. In a breast categorized as scattered fibroglandular density (B), a large cancer is easily seen (arrow) in the relatively fatty portion of the breast, though a small cancer could have been hidden in areas with normal glandular tissue.

In a breast categorized as heterogeneously dense (C), a 4-cm (about 1.5-inch) cancer (arrows) is hidden by the dense breast tissue. This cancer also has spread to a lymph node under the arm (curved arrow).

In an extremely dense breast (D), a cancer is seen because part of it is located in the back of the breast where there is a small amount of dark fat making it easier to see (arrow and triangle marker indicating lump). If this cancer had been located near the nipple and completely surrounded by white (dense) tissue, it probably would not have been seen on mammography.

Image: Courtesy of Dr. Regina Hooley and DenseBreast-info.org

Are screening mammography outcomes different for women with dense versus fatty breasts?

Yes. Cancer is more likely to be clinically detected in the interval between mammography screens (defined as interval cancer) in women with dense breasts. Such interval cancers tend to be more aggressive and have worse outcomes. Compared with those in fatty breasts, cancers found in dense breasts more often7:

- are locally advanced (stage IIb and III)

- are multifocal or multicentric

- require a mastectomy (rather than a lumpectomy).

Does supplemental screening beyond mammography save lives?

Mammography is the only imaging screening modality that has been studied by multiple randomized controlled trials with mortality as an endpoint. Across those trials, mammography has been shown to reduce deaths due to breast cancer. The randomized trials that show a benefit from mammography are those in which mammography increased detection of invasive breast cancers before they spread to lymph nodes.8

No randomized controlled trial has yet been reported on any other imaging screening modality, but it is expected that other screening tests that increase detection of node-negative invasive breast cancers beyond mammography should further reduce breast cancer mortality.

Proving the mortality benefit of any supplemental screening modality would require a very large, very expensive randomized controlled trial with 15 to 20 years of follow-up. Given the speed of technologic developments, any results likely would be obsolete by the trial’s conclusion. What we do know is that women at high risk for breast cancer who undergo annual magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) screening are less likely to have advanced breast cancer than their counterparts who were not screened with MRI.9

We also know that average-risk women who are screened with ultrasonography in addition to mammography are unlikely to have palpable cancer in the interval between screens,10,11 with the rates of such interval cancers similar to women with fatty breasts screened only with mammography. The cancers found only on MRI or ultrasound are mostly small invasive cancers (average size, approximately 1 cm) that are mostly node negative.12,13 MRI also finds some ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS).

These results suggest that there is a benefit to finding additional cancers with supplemental screening, though it is certainly possible that, as with mammography, some of the cancers found with supplemental screening are slow growing and may never have caused a woman harm even if left untreated.

Dense breasts: Medically sourced resources

Educational Web site

DenseBreast-info.org. This site is a collaborative, multidisciplinary educational resource. It features content for both patients and health care providers with separate data streams for each and includes:

a comprehensive list of FAQs; screening flow charts; a Patient Risk Checklist; an explanation of risks, risk assessment, and links to risk assessment tools; an illustrated round-up of technologies commonly used in screening; and state-by-state legislative analysis of density inform laws across the country.

State-specific Web sites

BreastDensity.info. This site was created by the California Breast Density Information Group (CBDIG), a working group of breast radiologists and breast cancer risk specialists. The content is primarily for health care providers and features screening scenarios as well as FAQs about breast density, breast cancer risk, and the breast density notification law in California.

MIdensebreasts.org. This is a Web-based education resource created for primary care providers by the University of Michigan Health System and the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services. It includes continuing medical education credit.

Medical society materials

American Cancer Society offers Breast Density and Your Mammogram Report for patients: http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@editorial/documents/document/acspc-039989.pdf

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ 2015 Density Policy statement is available online: http://www.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Gynecologic-Practice/Management-of-Women-With-Dense-Breasts-Diagnosed-by-Mammography

American College of Radiology patient brochure details basic information about breast density and can be customized with your center’s information: http://www.acr.org/News-Publications/~/media/180321AF51AF4EA38FEC091461F5B695.pdf

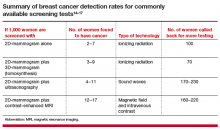

What additional screening tests are available after a 2D mammogram for a woman with dense breasts?

Depending on the patient’s age, risk level, and breast density, additional screening tools—such as tomosynthesis (also known as 3D mammography), ultrasonography, or MRI—may be recommended in addition to mammography. Indeed, in some centers, tomosynthesis is performed alone and the radiologist also reviews computer-generated 2D mammograms.

The addition of another imaging tool after a mammogram will find more cancers than mammography alone (TABLE).14−17 Women at high risk for breast cancer, such as those with pathogenic BRCA mutations, and those who were treated with radiation therapy to their chest (typically for Hodgkin disease) before age 30 and at least 8 years earlier, should be referred for annual MRI in addition to mammography (see Screening Decision Support Tool FIGURE above). If tomosynthesis is performed, the added benefit of ultrasound will be lower; further study on the actual benefit of supplemental ultrasound screening after 3D mammography is needed.

Will insurance cover supplemental screening beyond mammography?

The answer depends on the type of screening, the patient’s insurance and risk factors, the state in which you practice, and whether or not a law is in effect requiring insurance coverage for additional screening. In Illinois, for example, a woman with dense breasts can receive a screening ultrasound without a copay or deductible if it is ordered by a physician. In Connecticut, an ultrasound copay for screening dense breasts cannot exceed $20. Generally, in other states, an ultrasound will be covered if ordered by a physician, but it is subject to the copay and deductible of an individual health plan. In New Jersey, insurance coverage is provided for additional testing if a woman has extremely dense breasts.

Regardless of state, an MRI generally will be covered by insurance (subject to copay and deductible) if the patient meets high-risk criteria. In Michigan, at least one insurance company will cover a screening MRI for normal-risk women with dense breasts at a cost that matches the copay and deductible of a screening mammogram. It is important for patients to check with their insurance carrier prior to having an MRI.

Should women with dense breasts still have mammography screening?

Yes. Mammography is the first step in screening for most women (except for those who are pregnant or breastfeeding, in which case ultrasound can be performed but is usually deferred until several months after the patient is no longer pregnant or breastfeeding). While additional screening may be recommended for women with dense breasts, and for women at high risk for developing breast cancer, there are still some cancers and precancerous changes that will show on a mammogram better than on ultrasound or MRI. Wherever possible, women with dense breasts should have digital mammography rather than film mammography, due to slightly improved cancer detection using digital mammography.18

Does tomosynthesis solve the problem of screening dense breasts?

Tomosynthesis (3D mammography) slightly improves detection of cancers compared with standard digital mammography, but some cancers will remain hidden by overlapping dense tissue. We do not yet know the benefit of annual screening tomosynthesis. Without question, women at high risk for breast cancer still should have MRI if they are able to tolerate it, even if they have had tomosynthesis.

If a patient with dense breasts undergoes screening tomosynthesis, will she also need a screening ultrasound?

Preliminary studies not yet published suggest that, for women with dense breasts, ultrasound does find another 2 to 3 invasive cancers per 1,000 women screened that are not found on tomosynthesis, but further study of this issue is needed.

If recommended for additional screening with ultrasound or MRI, will a patient need that screening every year?

Usually, yes, though age and other medical conditions will change a patient’s personal risk and benefit considerations. Therefore, screening recommendations may change from one year to the next. With technology advancements and evolving guidelines, additional screening recommendations will change in the future.

Prepare yourself and your patients will benefit

The foundation of a successful screening program involves buy-in from both patient and clinician. Patients confused as to what their density notification means may have little understanding as to what next steps should be considered. To allay confusion, your patient will be best served by being provided understandable and actionable information. Advanced preparation for these conversations about the implications of dense tissue will make for more effective patient engagement.

Acknowledgment

Much of the material within this article has been sourced from the educational Web site DenseBreast-info.org. For comprehensive lists of both patient and health care provider frequently asked questions, visit http://www.DenseBreast-info.org.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Khong KA, Hargreaves J, Aminololama-Shakeri S, Lindfors KK. Impact of the California breast density law on primary care physicians. J Am Coll Radiol. 2015;12(3):256–260.

- Sickles EA, D’Orsi CJ, Bassett LW, et al. ACR BI-RADS Mammography. In: ACR BI-RADS Atlas, Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System. Reston, VA: American College of Radiology; 2013.

- Sprague BL, Gangnon RE, Burt V, et al. Prevalence of mammographically dense breasts in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(10).

- American Cancer Society. Breast Cancer Facts & Figures 2013–2014. http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@research/documents/document/acspc-042725.pdf. Published 2013. Accessed September 15, 2015.

- Harvey JA, Bovbjerg VE. Quantitative assessment of mammographic breast density: relationship with breast cancer risk. Radiology. 2004;230(1):29–41.

- Kerlikowske K, Cook AJ, Buist DS, et al. Breast cancer risk by breast density, menopause, and postmenopausal hormone therapy use. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(24):3830–3837.

- Arora N, King TA, Jacks LM, et al. Impact of breast density on the presenting features of malignancy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17(suppl 3):211–218.

- Smith RA, Duffy SW, Gabe R, Tabar L, Yen AM, Chen TH. The randomized trials of breast cancer screening: what have we learned? Radiol Clin North Am. 2004;42(5):793–806, v.

- Warner E, Hill K, Causer P, et al. Prospective study of breast cancer incidence in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation under surveillance with and without magnetic resonance imaging. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(13):1664–1669.

- Corsetti V, Houssami N, Ghirardi M, et al. Evidence of the effect of adjunct ultrasound screening in women with mammography-negative dense breasts: interval breast cancers at 1 year follow-up. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47(7): 1021–1026.

- Berg WA, Zhang Z, Lehrer D, et al. Detection of breast cancer with addition of annual screening ultrasound or a single screening MRI to mammography in women with elevated breast cancer risk. JAMA. 2012;307(13):1394–1404.

- Berg WA. Tailored supplemental screening for breast cancer: what now and what next? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192(2):390–399.

- Brem RF, Lenihan MJ, Lieberman J, Torrente J. Screening breast ultrasound: past, present, and future. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2015;204(2):234–240.

- Hooley R. Tomosynthesis. In: Berg WA, Yang WT, eds. Diagnostic Imaging: Breast. 2nd ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Amirsys; 2014:2–19.

- Friedewald SM, Rafferty EA, Rose SL, et al. Breast cancer screening using tomosynthesis in combination with digital mammography. JAMA. 2014;311(24):2499–2507.

- Berg WA. Screening Ultrasound. In: Berg WA, Yang WT, eds. Diagnostic Imaging: Breast. 2nd ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Amirsys; 2014:9–43.

- Berg WA. Screening MRI. In: Berg WA, Yang WT, eds. Diagnostic Imaging: Breast. 2nd ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Amirsys; 2014:9–49.

- Hooley R. Tomosynthesis. In: Berg WA, Yang WT, eds.Berg WA. Screening Ultrasound. In: Berg WA, Yang WT, eds.Berg WA. Screening MRI. In: Berg WA, Yang WT, eds.Pisano ED, Gatsonis C, Hendrick E, et al. Diagnostic performance of digital versus film mammography for breast-cancer screening. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(17):1773–1783.

It’s a movement that shows no signs of abating. Women in 24 states, encompassing 67% of American women, now receive some level of notification after their mammogram about breast density. Individual patient advocates continue to push for notification, and states are likely to continue to draft bills. On the national level, a federal standard is being pursued through both federal legislation and federal regulation. Clinicians practicing in states with an “inform” law, either already in effect or imminent, will be tasked with engaging in new patient conversations arising from density notification. Are you ready to answer your patients’ questions?

Navigating inconsistent data and expert comments about density and discerning which patients may benefit from additional screening can create challenges in addressing a patient’s questions about the implications of her dense tissue. If you feel less than equipped to address these issues, you are not alone. A recent survey of clinicians, con- ducted after California’s breast density notification law went into effect, showed that only 6% were comfortable answering patients’ questions relating to breast density. Seventy-five percent of respondents indicated they wanted more education on the topic.1

For women having mammography, dense breast tissue is most important because it can mask detection of cancers, and women may want to have additional screening beyond mammography. Women with dense breasts are also at increased risk for developing breast cancer. For clinicians who are on the front lines of care for women undergoing screening, the most important action items are:

- identifying who needs more screening

- weighing the risks and benefits of such additional screening.

To assist you in informing patient discussions, in this article we answer some of the most frequently asked questions of ObGyns.

Which breasts are considered dense?

The American College of Radiology recommends that density be reported in 1 of 4 categories depending on the relative amounts of fat and fibroglandular tissue2:

- almost entirely fatty—on mammography most of the tissue appears dark gray while small amounts of dense (or fibroglandular) tissue display as light gray or white.

- scattered fibroglandular density—scattered areas of dense tissue mixed with fat. Even in breasts with scattered areas of breast tissue, cancers sometimes can be missed when they resemble areas of normal tissue or are within an area of denser tissue.

- heterogeneously dense—there are large portions of the breast where dense tissue could hide masses.

- extremely dense—most of the breast appears to consist of dense tissue, creating a “white out” situation and making it extremely difficult to see through.

Breasts that are either heterogeneously dense or extremely dense are considered “dense.” About 40% of women older than age 40 have dense breasts.3

Case study: Imaging of a cancerous breast mass in a 48-year-old woman with dense breasts

This patient has heterogeneously dense breast tissue. Standard 2D mediolateral oblique (MLO) digital mammogram (A) and MLO tomosynthesis 1-mm slice (B) reveal subtle possible distortion (arrow) in the upper right breast. On tomosynthesis, the distortion is better seen, as is the underlying irregular mass (red circle).

Ultrasound (US) directed to the mass (C) shows an irregular hypoechoic (dark gray) mass (marked by calipers), compatible with cancer. US-guided core needle biopsy revealed grade 2 invasive ductal cancer with associated ductal carcinoma in situ.

Axial magnetic resonance imaging of the right breast obtained after contrast injection, and after computer subtraction of nonenhanced image (D), shows irregular spiculated enhancing (white) mass (arrow) due to the known carcinoma.

Images: Courtesy Wendie Berg, MD, PhD

Who needs more screening?

The FIGURE is a screening decision support tool representing the consensus opinion of several medical experts based on the best available scientific evidence to optimize breast cancer detection.

Do dense breasts affect the risk of developing breast cancer?

Yes. Dense breasts are a risk factor for breast cancer. According to the American Cancer Society’s Breast Cancer Facts & Figures 2013−2014, “The risk of breast cancer in-creases with increasing breast density; women with very high breast density have a 4- to 6-fold increased risk of breast cancer compared to women with the least dense breasts.”4,5

There are several reasons that dense tissue increases risk. First, the glands tend to be made up of relatively actively dividing cells that can mutate and become cancerous (the more glandular tissue present, the greater the risk). Second, the local environment around the glands may produce certain growth hormones that stimulate cells to divide, and this seems to occur more in fibrous tissue than in fatty tissue.

Most women have breast density somewhere in the middle range, with their risk for breast cancer falling in between those with extremely dense breasts and those with fatty breasts.6 The risk for developing breast cancer is influenced by a combination of many different factors, including age, family history of cancer (particularly breast or ovarian cancer), and prior atypical breast biopsies. There currently is no reliable way to fully account for the interplay of breast density, family history, prior biopsy results, and other factors in determining overall risk. Importantly, more than half of all women who develop breast cancer have no known risk factors other than being female and aging.

Is your medical support staff “density ready?”

We’re all familiar with the adage that a picture is worth a thousand words. While the medical support personnel in your office are likely quite familiar with imaging reports and the terminology used in describing dense breasts, they may be quite unfamiliar with what a fatty versus dense breast actually looks like on a mammogram, and how cancer may display in each. Illustrated examples, as seen here, are useful for reference.

In the fatty breast (A), a small cancer (arrow) is seen easily. In a breast categorized as scattered fibroglandular density (B), a large cancer is easily seen (arrow) in the relatively fatty portion of the breast, though a small cancer could have been hidden in areas with normal glandular tissue.

In a breast categorized as heterogeneously dense (C), a 4-cm (about 1.5-inch) cancer (arrows) is hidden by the dense breast tissue. This cancer also has spread to a lymph node under the arm (curved arrow).

In an extremely dense breast (D), a cancer is seen because part of it is located in the back of the breast where there is a small amount of dark fat making it easier to see (arrow and triangle marker indicating lump). If this cancer had been located near the nipple and completely surrounded by white (dense) tissue, it probably would not have been seen on mammography.

Image: Courtesy of Dr. Regina Hooley and DenseBreast-info.org

Are screening mammography outcomes different for women with dense versus fatty breasts?

Yes. Cancer is more likely to be clinically detected in the interval between mammography screens (defined as interval cancer) in women with dense breasts. Such interval cancers tend to be more aggressive and have worse outcomes. Compared with those in fatty breasts, cancers found in dense breasts more often7:

- are locally advanced (stage IIb and III)

- are multifocal or multicentric

- require a mastectomy (rather than a lumpectomy).

Does supplemental screening beyond mammography save lives?

Mammography is the only imaging screening modality that has been studied by multiple randomized controlled trials with mortality as an endpoint. Across those trials, mammography has been shown to reduce deaths due to breast cancer. The randomized trials that show a benefit from mammography are those in which mammography increased detection of invasive breast cancers before they spread to lymph nodes.8