User login

Top Qualifications Hospitalist Leaders Seek in Candidates: Results from a National Survey

Hospital Medicine (HM) is medicine’s fastest growing specialty.1 Rapid expansion of the field has been met with rising interest by young physicians, many of whom are first-time job seekers and may desire information on best practices for applying and interviewing in HM.2-4 However, no prior work has examined HM-specific candidate qualifications and qualities that may be most valued in the hiring process.

As members of the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) Physicians in Training Committee, a group charged with “prepar[ing] trainees and early career hospitalists in their transition into hospital medicine,” we aimed to fill this knowledge gap around the HM-specific hiring process.

METHODS

Survey Instrument

The authors developed the survey based on expertise as HM interviewers (JAD, AH, CD, EE, BK, DS, and SM) and local and national interview workshop leaders (JAD, CD, BK, SM). The questionnaire focused on objective applicant qualifications, qualities and attributes displayed during interviews (Appendix 1). Content, length, and reliability of physician understanding were assessed via feedback from local HM group leaders.

Respondents were asked to provide nonidentifying demographics and their role in their HM group’s hiring process. If they reported no role, the survey was terminated. Subsequent standardized HM group demographic questions were adapted from the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) State of Hospital Medicine Report.5

Survey questions were multiple choice, ranking and free-response aimed at understanding how respondents assess HM candidate attributes, skills, and behavior. For ranking questions, answer choice order was randomized to reduce answer order-based bias. One free-response question asked the respondent to provide a unique interview question they use that “reveals the most about a hospitalist candidate.” Responses were then individually inserted into the list of choices for a subsequent ranking question regarding the most important qualities a candidate must demonstrate.

Respondents were asked four open-ended questions designed to understand the approach to candidate assessment: (1) use of unique interview questions (as above); (2) identification of “red flags” during interviews; (3) distinctions between assessment of long-term (LT) career hospitalist candidates versus short-term (ST) candidates (eg, those seeking positions prior to fellowship); and (4) key qualifications of ST candidates.

Survey Administration

Survey recipients were identified via SHM administrative rosters. Surveys were distributed electronically via SHM to all current nontrainee physician members who reported a United States mailing address. The survey was determined to not constitute human subjects research by the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Committee on Clinical Investigations.

Data Analysis

Multiple-choice responses were analyzed descriptively. For ranking-type questions, answers were weighted based on ranking order.

Responses to all open-ended survey questions were analyzed using thematic analysis. We used an iterative process to develop and refine codes identifying key concepts that emerged from the data. Three authors independently coded survey responses. As a group, research team members established the coding framework and resolved discrepancies via discussion to achieve consensus.

RESULTS

Survey links were sent to 8,398 e-mail addresses, of which 7,306 were undeliverable or unopened, leaving 1,092 total eligible respondents. Of these, 347 (31.8%) responded.

A total of 236 respondents reported having a formal role in HM hiring. Of these roles, 79.0% were one-on-one interviewers, 49.6% group interviewers, 45.5% telephone/videoconference interviewers, 41.5% participated on a selection committee, and 32.1% identified as the ultimate decision-maker. Regarding graduate medical education teaching status, 42.0% of respondents identified their primary workplace as a community/affiliated teaching hospital, 33.05% as a university-based teaching hospital, and 23.0% as a nonteaching hospital. Additional characteristics are reported in Appendix 2.

Quantitative Analysis

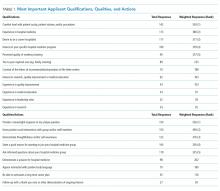

Respondents ranked the top five qualifications of HM candidates and the top five qualities a candidate should demonstrate on the interview day to be considered for hiring (Table 1).

When asked to rate agreement with the statement “I evaluate and consider all hospital medicine candidates similarly, regardless of whether they articulate an interest in hospital medicine as a long-term career or as a short-term position before fellowship,” 99 (57.23%) respondents disagreed.

Qualitative Analysis

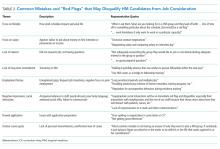

Thematic analysis of responses to open-ended survey questions identified several “red flag” themes (Table 2). Negative interactions with current providers or staff were commonly noted. Additional red flags were a lack of knowledge or interest in the specific HM group, an inability to articulate career goals, or abnormalities in employment history or application materials. Respondents identified an overly strong focus on lifestyle or salary as factors that might limit a candidate’s chance of advancing in the hiring process.

Responses to free-text questions additionally highlighted preferred questioning techniques and approaches to HM candidate assessment (Appendix 3). Many interview questions addressed candidate interest in a particular HM program and candidate responses to challenging scenarios they had encountered. Other questions explored career development. Respondents wanted LT candidates to have specific HM career goals, while they expected ST candidates to demonstrate commitment to and appreciation of HM as a discipline.

Some respondents described their approach to candidate assessment in terms of investment and risk. LT candidates were often viewed as investments in stability and performance; they were evaluated on current abilities and future potential as related to group-specific goals. Some respondents viewed hiring ST candidates as more risky given concerns that they might be less engaged or integrated with the group. Others viewed the hiring of LT candidates as comparably more risky, relating the longer time commitment to the potential for higher impact on the group and patient care. Accordingly, these respondents viewed ST candidate hiring as less risky, estimating their shorter time commitment as having less of a positive or negative impact, with the benefit of addressing urgent staffing issues or unfilled less desirable positions. One respondent summarized: “If they plan to be a career candidate, I care more about them as people and future coworkers. Short term folks are great if we are in a pinch and can deal with personality issues for a short period of time.”

Respondents also described how valued candidate qualities could help mitigate the risk inherent in hiring, especially for ST hires. Strong interpersonal and teamwork skills were highlighted, as well as a demonstrated record of clinical excellence, evidenced by strong training backgrounds and superlative references. A key factor aiding in ST hiring decisions was prior knowledge of the candidate, such as residents or moonlighters previously working in the respondent’s institution. This allowed for familiarity with the candidate’s clinical acumen as well as perceived ease of onboarding and knowledge of the system.

DISCUSSION

We present the results of a national survey of hospitalists identifying candidate attributes, skills, and behaviors viewed most favorably by those involved in the HM hiring process. To our knowledge, this is the first research to be published on the topic of evaluating HM candidates.

Survey respondents identified demonstrable HM candidate clinical skills and experience as highly important, consistent with prior research identifying clinical skills as being among those that hospitalists most value.6 Based on these responses, job seekers should be prepared to discuss objective measures of clinical experience when appropriate, such as number of cases seen or procedures performed. HM groups may accordingly consider the use of hiring rubrics or scoring systems to standardize these measures and reduce bias.

Respondents also highly valued more subjective assessments of HM applicants’ candidacy. The most highly ranked action item was a candidate’s ability to meaningfully respond to a respondent’s customized interview question. There was also a preference for candidates who were knowledgeable about and interested in the specifics of a particular HM group. The high value placed on these elements may suggest the need for formalized coaching or interview preparation for HM candidates. Similarly, interviewer emphasis on customized questions may also highlight an opportunity for HM groups to internally standardize how to best approach subjective components of the interview.

Our heterogeneous findings on the distinctions between ST and LT candidate hiring practices support the need for additional research on the ST HM job market. Until then, our findings reinforce the importance of applicant transparency about ST versus LT career goals. Although many programs may prefer LT candidates over ST candidates, our results suggest ST candidates may benefit from targeting groups with ST needs and using the application process as an opportunity to highlight certain mitigating strengths.

Our study has limitations. While our population included diverse national representation, the response rate and demographics of our respondents may limit generalizability beyond our study population. Respondents represented multiple perspectives within the HM hiring process and were not limited to those making the final hiring decisions. For questions with prespecified multiple-choice answers, answer choices may have influenced participant responses. Our conclusions are based on the reported preferences of those involved in the HM hiring process and not actual hiring behavior. Future research should attempt to identify factors (eg, region, graduate medical education status, practice setting type) that may be responsible for some of the heterogeneous themes we observed in our analysis.

Our research represents introductory work into the previously unpublished topic of HM-specific hiring practices. These findings may provide relevant insight for trainees considering careers in HM, hospitalists reentering the job market, and those involved in career advising, professional development and the HM hiring process.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge current and former members of SHM’s Physicians in Training Committee whose feedback and leadership helped to inspire this project, as well as those students, residents, and hospitalists who have participated in our Hospital Medicine Annual Meeting interview workshop.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

1. Wachter RM, Goldman L. Zero to 50,000-The 20th anniversary of the hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(11):1009-1011. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1607958.

2. Leyenaar JK, Frintner MP. Graduating pediatric residents entering the hospital medicine workforce, 2006-2015. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(2):200-207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2017.05.001.

3. Ratelle JT, Dupras DM, Alguire P, Masters P, Weissman A, West CP. Hospitalist career decisions among internal medicine residents. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(7):1026-1030. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2811-3.

4. Sweigart JR, Tad-Y D, Kneeland P, Williams MV, Glasheen JJ. Hospital medicine resident training tracks: developing the hospital medicine pipeline. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(3):173-176. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2703.

5. 2016 State of Hospital Medicine Report. 2016. https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/practice-management/shms-state-of-hospital-medicine/. Accessed 7/1/2017.

6. Plauth WH, 3rd, Pantilat SZ, Wachter RM, Fenton CL. Hospitalists’ perceptions of their residency training needs: results of a national survey. Am J Emerg Med. 2001;111(3):247-254. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9343(01)00837-3.

Hospital Medicine (HM) is medicine’s fastest growing specialty.1 Rapid expansion of the field has been met with rising interest by young physicians, many of whom are first-time job seekers and may desire information on best practices for applying and interviewing in HM.2-4 However, no prior work has examined HM-specific candidate qualifications and qualities that may be most valued in the hiring process.

As members of the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) Physicians in Training Committee, a group charged with “prepar[ing] trainees and early career hospitalists in their transition into hospital medicine,” we aimed to fill this knowledge gap around the HM-specific hiring process.

METHODS

Survey Instrument

The authors developed the survey based on expertise as HM interviewers (JAD, AH, CD, EE, BK, DS, and SM) and local and national interview workshop leaders (JAD, CD, BK, SM). The questionnaire focused on objective applicant qualifications, qualities and attributes displayed during interviews (Appendix 1). Content, length, and reliability of physician understanding were assessed via feedback from local HM group leaders.

Respondents were asked to provide nonidentifying demographics and their role in their HM group’s hiring process. If they reported no role, the survey was terminated. Subsequent standardized HM group demographic questions were adapted from the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) State of Hospital Medicine Report.5

Survey questions were multiple choice, ranking and free-response aimed at understanding how respondents assess HM candidate attributes, skills, and behavior. For ranking questions, answer choice order was randomized to reduce answer order-based bias. One free-response question asked the respondent to provide a unique interview question they use that “reveals the most about a hospitalist candidate.” Responses were then individually inserted into the list of choices for a subsequent ranking question regarding the most important qualities a candidate must demonstrate.

Respondents were asked four open-ended questions designed to understand the approach to candidate assessment: (1) use of unique interview questions (as above); (2) identification of “red flags” during interviews; (3) distinctions between assessment of long-term (LT) career hospitalist candidates versus short-term (ST) candidates (eg, those seeking positions prior to fellowship); and (4) key qualifications of ST candidates.

Survey Administration

Survey recipients were identified via SHM administrative rosters. Surveys were distributed electronically via SHM to all current nontrainee physician members who reported a United States mailing address. The survey was determined to not constitute human subjects research by the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Committee on Clinical Investigations.

Data Analysis

Multiple-choice responses were analyzed descriptively. For ranking-type questions, answers were weighted based on ranking order.

Responses to all open-ended survey questions were analyzed using thematic analysis. We used an iterative process to develop and refine codes identifying key concepts that emerged from the data. Three authors independently coded survey responses. As a group, research team members established the coding framework and resolved discrepancies via discussion to achieve consensus.

RESULTS

Survey links were sent to 8,398 e-mail addresses, of which 7,306 were undeliverable or unopened, leaving 1,092 total eligible respondents. Of these, 347 (31.8%) responded.

A total of 236 respondents reported having a formal role in HM hiring. Of these roles, 79.0% were one-on-one interviewers, 49.6% group interviewers, 45.5% telephone/videoconference interviewers, 41.5% participated on a selection committee, and 32.1% identified as the ultimate decision-maker. Regarding graduate medical education teaching status, 42.0% of respondents identified their primary workplace as a community/affiliated teaching hospital, 33.05% as a university-based teaching hospital, and 23.0% as a nonteaching hospital. Additional characteristics are reported in Appendix 2.

Quantitative Analysis

Respondents ranked the top five qualifications of HM candidates and the top five qualities a candidate should demonstrate on the interview day to be considered for hiring (Table 1).

When asked to rate agreement with the statement “I evaluate and consider all hospital medicine candidates similarly, regardless of whether they articulate an interest in hospital medicine as a long-term career or as a short-term position before fellowship,” 99 (57.23%) respondents disagreed.

Qualitative Analysis

Thematic analysis of responses to open-ended survey questions identified several “red flag” themes (Table 2). Negative interactions with current providers or staff were commonly noted. Additional red flags were a lack of knowledge or interest in the specific HM group, an inability to articulate career goals, or abnormalities in employment history or application materials. Respondents identified an overly strong focus on lifestyle or salary as factors that might limit a candidate’s chance of advancing in the hiring process.

Responses to free-text questions additionally highlighted preferred questioning techniques and approaches to HM candidate assessment (Appendix 3). Many interview questions addressed candidate interest in a particular HM program and candidate responses to challenging scenarios they had encountered. Other questions explored career development. Respondents wanted LT candidates to have specific HM career goals, while they expected ST candidates to demonstrate commitment to and appreciation of HM as a discipline.

Some respondents described their approach to candidate assessment in terms of investment and risk. LT candidates were often viewed as investments in stability and performance; they were evaluated on current abilities and future potential as related to group-specific goals. Some respondents viewed hiring ST candidates as more risky given concerns that they might be less engaged or integrated with the group. Others viewed the hiring of LT candidates as comparably more risky, relating the longer time commitment to the potential for higher impact on the group and patient care. Accordingly, these respondents viewed ST candidate hiring as less risky, estimating their shorter time commitment as having less of a positive or negative impact, with the benefit of addressing urgent staffing issues or unfilled less desirable positions. One respondent summarized: “If they plan to be a career candidate, I care more about them as people and future coworkers. Short term folks are great if we are in a pinch and can deal with personality issues for a short period of time.”

Respondents also described how valued candidate qualities could help mitigate the risk inherent in hiring, especially for ST hires. Strong interpersonal and teamwork skills were highlighted, as well as a demonstrated record of clinical excellence, evidenced by strong training backgrounds and superlative references. A key factor aiding in ST hiring decisions was prior knowledge of the candidate, such as residents or moonlighters previously working in the respondent’s institution. This allowed for familiarity with the candidate’s clinical acumen as well as perceived ease of onboarding and knowledge of the system.

DISCUSSION

We present the results of a national survey of hospitalists identifying candidate attributes, skills, and behaviors viewed most favorably by those involved in the HM hiring process. To our knowledge, this is the first research to be published on the topic of evaluating HM candidates.

Survey respondents identified demonstrable HM candidate clinical skills and experience as highly important, consistent with prior research identifying clinical skills as being among those that hospitalists most value.6 Based on these responses, job seekers should be prepared to discuss objective measures of clinical experience when appropriate, such as number of cases seen or procedures performed. HM groups may accordingly consider the use of hiring rubrics or scoring systems to standardize these measures and reduce bias.

Respondents also highly valued more subjective assessments of HM applicants’ candidacy. The most highly ranked action item was a candidate’s ability to meaningfully respond to a respondent’s customized interview question. There was also a preference for candidates who were knowledgeable about and interested in the specifics of a particular HM group. The high value placed on these elements may suggest the need for formalized coaching or interview preparation for HM candidates. Similarly, interviewer emphasis on customized questions may also highlight an opportunity for HM groups to internally standardize how to best approach subjective components of the interview.

Our heterogeneous findings on the distinctions between ST and LT candidate hiring practices support the need for additional research on the ST HM job market. Until then, our findings reinforce the importance of applicant transparency about ST versus LT career goals. Although many programs may prefer LT candidates over ST candidates, our results suggest ST candidates may benefit from targeting groups with ST needs and using the application process as an opportunity to highlight certain mitigating strengths.

Our study has limitations. While our population included diverse national representation, the response rate and demographics of our respondents may limit generalizability beyond our study population. Respondents represented multiple perspectives within the HM hiring process and were not limited to those making the final hiring decisions. For questions with prespecified multiple-choice answers, answer choices may have influenced participant responses. Our conclusions are based on the reported preferences of those involved in the HM hiring process and not actual hiring behavior. Future research should attempt to identify factors (eg, region, graduate medical education status, practice setting type) that may be responsible for some of the heterogeneous themes we observed in our analysis.

Our research represents introductory work into the previously unpublished topic of HM-specific hiring practices. These findings may provide relevant insight for trainees considering careers in HM, hospitalists reentering the job market, and those involved in career advising, professional development and the HM hiring process.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge current and former members of SHM’s Physicians in Training Committee whose feedback and leadership helped to inspire this project, as well as those students, residents, and hospitalists who have participated in our Hospital Medicine Annual Meeting interview workshop.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Hospital Medicine (HM) is medicine’s fastest growing specialty.1 Rapid expansion of the field has been met with rising interest by young physicians, many of whom are first-time job seekers and may desire information on best practices for applying and interviewing in HM.2-4 However, no prior work has examined HM-specific candidate qualifications and qualities that may be most valued in the hiring process.

As members of the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) Physicians in Training Committee, a group charged with “prepar[ing] trainees and early career hospitalists in their transition into hospital medicine,” we aimed to fill this knowledge gap around the HM-specific hiring process.

METHODS

Survey Instrument

The authors developed the survey based on expertise as HM interviewers (JAD, AH, CD, EE, BK, DS, and SM) and local and national interview workshop leaders (JAD, CD, BK, SM). The questionnaire focused on objective applicant qualifications, qualities and attributes displayed during interviews (Appendix 1). Content, length, and reliability of physician understanding were assessed via feedback from local HM group leaders.

Respondents were asked to provide nonidentifying demographics and their role in their HM group’s hiring process. If they reported no role, the survey was terminated. Subsequent standardized HM group demographic questions were adapted from the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) State of Hospital Medicine Report.5

Survey questions were multiple choice, ranking and free-response aimed at understanding how respondents assess HM candidate attributes, skills, and behavior. For ranking questions, answer choice order was randomized to reduce answer order-based bias. One free-response question asked the respondent to provide a unique interview question they use that “reveals the most about a hospitalist candidate.” Responses were then individually inserted into the list of choices for a subsequent ranking question regarding the most important qualities a candidate must demonstrate.

Respondents were asked four open-ended questions designed to understand the approach to candidate assessment: (1) use of unique interview questions (as above); (2) identification of “red flags” during interviews; (3) distinctions between assessment of long-term (LT) career hospitalist candidates versus short-term (ST) candidates (eg, those seeking positions prior to fellowship); and (4) key qualifications of ST candidates.

Survey Administration

Survey recipients were identified via SHM administrative rosters. Surveys were distributed electronically via SHM to all current nontrainee physician members who reported a United States mailing address. The survey was determined to not constitute human subjects research by the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Committee on Clinical Investigations.

Data Analysis

Multiple-choice responses were analyzed descriptively. For ranking-type questions, answers were weighted based on ranking order.

Responses to all open-ended survey questions were analyzed using thematic analysis. We used an iterative process to develop and refine codes identifying key concepts that emerged from the data. Three authors independently coded survey responses. As a group, research team members established the coding framework and resolved discrepancies via discussion to achieve consensus.

RESULTS

Survey links were sent to 8,398 e-mail addresses, of which 7,306 were undeliverable or unopened, leaving 1,092 total eligible respondents. Of these, 347 (31.8%) responded.

A total of 236 respondents reported having a formal role in HM hiring. Of these roles, 79.0% were one-on-one interviewers, 49.6% group interviewers, 45.5% telephone/videoconference interviewers, 41.5% participated on a selection committee, and 32.1% identified as the ultimate decision-maker. Regarding graduate medical education teaching status, 42.0% of respondents identified their primary workplace as a community/affiliated teaching hospital, 33.05% as a university-based teaching hospital, and 23.0% as a nonteaching hospital. Additional characteristics are reported in Appendix 2.

Quantitative Analysis

Respondents ranked the top five qualifications of HM candidates and the top five qualities a candidate should demonstrate on the interview day to be considered for hiring (Table 1).

When asked to rate agreement with the statement “I evaluate and consider all hospital medicine candidates similarly, regardless of whether they articulate an interest in hospital medicine as a long-term career or as a short-term position before fellowship,” 99 (57.23%) respondents disagreed.

Qualitative Analysis

Thematic analysis of responses to open-ended survey questions identified several “red flag” themes (Table 2). Negative interactions with current providers or staff were commonly noted. Additional red flags were a lack of knowledge or interest in the specific HM group, an inability to articulate career goals, or abnormalities in employment history or application materials. Respondents identified an overly strong focus on lifestyle or salary as factors that might limit a candidate’s chance of advancing in the hiring process.

Responses to free-text questions additionally highlighted preferred questioning techniques and approaches to HM candidate assessment (Appendix 3). Many interview questions addressed candidate interest in a particular HM program and candidate responses to challenging scenarios they had encountered. Other questions explored career development. Respondents wanted LT candidates to have specific HM career goals, while they expected ST candidates to demonstrate commitment to and appreciation of HM as a discipline.

Some respondents described their approach to candidate assessment in terms of investment and risk. LT candidates were often viewed as investments in stability and performance; they were evaluated on current abilities and future potential as related to group-specific goals. Some respondents viewed hiring ST candidates as more risky given concerns that they might be less engaged or integrated with the group. Others viewed the hiring of LT candidates as comparably more risky, relating the longer time commitment to the potential for higher impact on the group and patient care. Accordingly, these respondents viewed ST candidate hiring as less risky, estimating their shorter time commitment as having less of a positive or negative impact, with the benefit of addressing urgent staffing issues or unfilled less desirable positions. One respondent summarized: “If they plan to be a career candidate, I care more about them as people and future coworkers. Short term folks are great if we are in a pinch and can deal with personality issues for a short period of time.”

Respondents also described how valued candidate qualities could help mitigate the risk inherent in hiring, especially for ST hires. Strong interpersonal and teamwork skills were highlighted, as well as a demonstrated record of clinical excellence, evidenced by strong training backgrounds and superlative references. A key factor aiding in ST hiring decisions was prior knowledge of the candidate, such as residents or moonlighters previously working in the respondent’s institution. This allowed for familiarity with the candidate’s clinical acumen as well as perceived ease of onboarding and knowledge of the system.

DISCUSSION

We present the results of a national survey of hospitalists identifying candidate attributes, skills, and behaviors viewed most favorably by those involved in the HM hiring process. To our knowledge, this is the first research to be published on the topic of evaluating HM candidates.

Survey respondents identified demonstrable HM candidate clinical skills and experience as highly important, consistent with prior research identifying clinical skills as being among those that hospitalists most value.6 Based on these responses, job seekers should be prepared to discuss objective measures of clinical experience when appropriate, such as number of cases seen or procedures performed. HM groups may accordingly consider the use of hiring rubrics or scoring systems to standardize these measures and reduce bias.

Respondents also highly valued more subjective assessments of HM applicants’ candidacy. The most highly ranked action item was a candidate’s ability to meaningfully respond to a respondent’s customized interview question. There was also a preference for candidates who were knowledgeable about and interested in the specifics of a particular HM group. The high value placed on these elements may suggest the need for formalized coaching or interview preparation for HM candidates. Similarly, interviewer emphasis on customized questions may also highlight an opportunity for HM groups to internally standardize how to best approach subjective components of the interview.

Our heterogeneous findings on the distinctions between ST and LT candidate hiring practices support the need for additional research on the ST HM job market. Until then, our findings reinforce the importance of applicant transparency about ST versus LT career goals. Although many programs may prefer LT candidates over ST candidates, our results suggest ST candidates may benefit from targeting groups with ST needs and using the application process as an opportunity to highlight certain mitigating strengths.

Our study has limitations. While our population included diverse national representation, the response rate and demographics of our respondents may limit generalizability beyond our study population. Respondents represented multiple perspectives within the HM hiring process and were not limited to those making the final hiring decisions. For questions with prespecified multiple-choice answers, answer choices may have influenced participant responses. Our conclusions are based on the reported preferences of those involved in the HM hiring process and not actual hiring behavior. Future research should attempt to identify factors (eg, region, graduate medical education status, practice setting type) that may be responsible for some of the heterogeneous themes we observed in our analysis.

Our research represents introductory work into the previously unpublished topic of HM-specific hiring practices. These findings may provide relevant insight for trainees considering careers in HM, hospitalists reentering the job market, and those involved in career advising, professional development and the HM hiring process.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge current and former members of SHM’s Physicians in Training Committee whose feedback and leadership helped to inspire this project, as well as those students, residents, and hospitalists who have participated in our Hospital Medicine Annual Meeting interview workshop.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

1. Wachter RM, Goldman L. Zero to 50,000-The 20th anniversary of the hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(11):1009-1011. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1607958.

2. Leyenaar JK, Frintner MP. Graduating pediatric residents entering the hospital medicine workforce, 2006-2015. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(2):200-207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2017.05.001.

3. Ratelle JT, Dupras DM, Alguire P, Masters P, Weissman A, West CP. Hospitalist career decisions among internal medicine residents. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(7):1026-1030. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2811-3.

4. Sweigart JR, Tad-Y D, Kneeland P, Williams MV, Glasheen JJ. Hospital medicine resident training tracks: developing the hospital medicine pipeline. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(3):173-176. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2703.

5. 2016 State of Hospital Medicine Report. 2016. https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/practice-management/shms-state-of-hospital-medicine/. Accessed 7/1/2017.

6. Plauth WH, 3rd, Pantilat SZ, Wachter RM, Fenton CL. Hospitalists’ perceptions of their residency training needs: results of a national survey. Am J Emerg Med. 2001;111(3):247-254. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9343(01)00837-3.

1. Wachter RM, Goldman L. Zero to 50,000-The 20th anniversary of the hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(11):1009-1011. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1607958.

2. Leyenaar JK, Frintner MP. Graduating pediatric residents entering the hospital medicine workforce, 2006-2015. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(2):200-207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2017.05.001.

3. Ratelle JT, Dupras DM, Alguire P, Masters P, Weissman A, West CP. Hospitalist career decisions among internal medicine residents. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(7):1026-1030. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2811-3.

4. Sweigart JR, Tad-Y D, Kneeland P, Williams MV, Glasheen JJ. Hospital medicine resident training tracks: developing the hospital medicine pipeline. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(3):173-176. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2703.

5. 2016 State of Hospital Medicine Report. 2016. https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/practice-management/shms-state-of-hospital-medicine/. Accessed 7/1/2017.

6. Plauth WH, 3rd, Pantilat SZ, Wachter RM, Fenton CL. Hospitalists’ perceptions of their residency training needs: results of a national survey. Am J Emerg Med. 2001;111(3):247-254. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9343(01)00837-3.

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

Perceived safety and value of inpatient “very important person” services

Recent publications in the medical literature and lay press have stirred controversy regarding the use of inpatient ‘very important person’ (VIP) services.1-3 The term “VIP services” often refers to select conveniences offered in addition to the assumed basic level of care and services provided by a hospital. Examples include additional space, enhanced facilities, specific comforts, or personal support. In some instances, these amenities may only be provided to patients who have close financial, social, or professional relationships with the hospital.

How VIP patients interact with their health system to obtain VIP services has raised unique concerns. Some have speculated that the presence of a VIP patient may be disruptive to the care of non-VIP patients, while others have cautioned physicians about potential dangers to the VIP patients themselves.4-6 Despite much being written on the topics of VIP patients and services in both the lay and academic press, our literature review identified only 1 study on the topic, which cataloged the preferential treatment of VIP patients in the emergency department.6 We are unaware of any investigations of VIP-service use in the inpatient setting. Through a multisite survey of hospital medicine physicians, we assessed physician viewpoints and behavior regarding VIP services.

METHODS

The Hospital Medicine Reengineering Network (HOMERuN) is a nation-wide learning organization focused on measuring and improving the outcomes of hospitalized patients.7 We surveyed hospitalists from 8 HOMERuN hospitals (Appendix 1). The survey instrument contained 4 sections: nonidentifying respondent demographics, local use of VIP services, reported physician perceptions of VIP services, and case-based assessments (Appendix 2). Survey questions and individual cases were developed by study authors and based on real scenarios and concerns provided by front-line clinical providers. Content, length, and reliability of physician understanding were assessed by a 5-person focus group consisting of physicians not included in the survey population.

Subjects were identified via administrative rosters from each HOMERuN site. Surveys were administered via SurveyMonkey, and results were analyzed descriptively. Populations were compared via the Fisher exact test. “VIP services” were defined as conveniences provided in addition to the assumed basic level of care and services (eg, private or luxury-style rooms, access to a special menu, better views, dedicated personal care attendants, hospital liaisons). VIP patients were defined as those patients receiving VIP services. A hospital was identified as providing VIP services if 50% or more of respondents from that site reported the presence of VIP services.

RESULTS

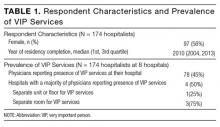

Of 366 hospitalists contacted, 160 completed the survey (44%). Respondent characteristics and reported prevalence of VIP services are demonstrated in Table 1. In total, 78 respondents (45%) reported the presence of VIP services at their hospital. Of the 8 sites surveyed, a majority of physicians at 4 sites (50%) reported presence of VIP services.

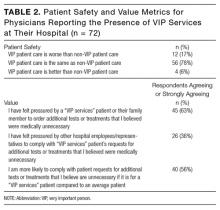

Of respondents reporting the presence of VIP services at their hospital, a majority felt that, from a patient safety perspective, the care received by VIP patients was the same as care received by non-VIP patients (Table 2). A majority reported they had felt pressured by a VIP patient or a family member to order additional tests or treatments that the physician believed were medically unnecessary and that they would be more likely to comply with VIP patient’s requests for tests or treatments they felt were unnecessary. More than one-third (36%) felt pressured by other hospital employees or representatives to comply with VIP services patient’s requests for additional tests or treatments that the physicians believed were medically unnecessary.

When presented the case of a VIP patient with community-acquired pneumonia who is clinically stable for discharge but expressing concerns about leaving the hospital, 61 (38%) respondents reported they would not discharge this patient home: 39 of 70 (55.7%) who reported the presence of VIP services at their hospital, and 22 of 91 (24.2%) who reported the absence of VIP services (P < 0.001). Of those who reported they would not discharge this patient home, 37 (61%) reported the reason for this related to the patient’s connection to the Board of Trustees; 48 (79%) reported the reason for this related to the patient’s concerns; 9 (15%) reported the reason for this related to their own concerns regarding medical details of the patient’s case (respondents could select more than 1 reason).

When presented the case of a VIP patient with acute pulmonary embolism who is medically ready for discharge with primary care physician-approved anticoagulation and discharge plans but for whom their family requests additional consultations and inpatient hypercoagulable workup, 33 (21%) respondents reported they would order additional testing and specialist consultation: 17 of 69 (24.6%) who reported the presence of VIP services their hospital, and 16 of 91 (17.6%) who reported the absence of VIP services (P = 0.33). Of those who reported they would order additional testing and specialist consultation, 14 (42%) reported the reason for this related to the family’s financial connections to the hospital; 30 (91%) reported the reason for this related to the family’s concerns; 3 (9%) reported the reason for this related to their own concerns about the medical details of the patient’s case (respondents could select more than 1 reason).

DISCUSSION

In our study, a majority of physicians who reported the presence of VIP services at their hospital felt pressured by VIP patients or their family members to perform unnecessary testing or treatment. While this study was not designed to quantify the burden of unnecessary care for VIP patients, our results have implications for individual patients and public health, including potential effects on resource availability, the identification of clinically irrelevant incidental findings, and short- and long-term medical complications of procedures, testing and radiation exposure.

Prior publications have advocated that physicians and hospitals should not allow VIP status to influence management decisions.3,5 We found that more than one-third of physicians who reported the presence of VIP services at their hospital also reported receiving pressure from hospital representatives to provide care to VIP patients that was not medically indicated. These findings highlight an example of the tension faced by physicians who are caught between patient requests and the delivery of value-based care. This potential conflict may be amplified particularly for those patients with close financial, social, or professional ties to the hospitals (and physicians) providing their care. These results suggest the need for physicians, administrators, and patients to work together to address the potential blurring of ethical boundaries created by VIP relationships. Prevention of harm and avoidance of placing physicians in morally distressing situations are common goals for all involved parties.

Efforts to reduce unnecessary care have predominantly focused on structural and knowledge-based drivers.4,8,9 Our results highlight the presence of additional forces. A majority of physician respondents who reported the presence of VIP services at their hospital also reported that they would be more likely to comply with requests for unnecessary care for a VIP patient as compared to a non-VIP patient. Furthermore, in case-based questions about the requests of a VIP patient and their family for additional unnecessary care, a significant portion of physicians who reported they would comply with these requests listed the VIP status of the patient or family as a factor underlying this decision. Only a minority of physicians reported their decision to provide additional care was the result of their own medically-based concerns. Because these cases were hypothetical and we did not include comparator cases involving non-VIP patients, it remains uncertain whether the observed perceptions accurately reflect real-world differences in the care of VIP and non-VIP patients. Nonetheless, our findings emphasize the importance of better understanding the social drivers of overuse and physician communication strategies related to medically inappropriate tests.10,11

Demand for unnecessary testing may be driven by the mentality that “more is better.”12 Contrary to this belief, provision of unnecessary care can increase the risk of patient harm.13 Despite physician respondents reporting that VIP patients requested and/or received additional unnecessary care, a majority of respondents felt that patient safety for VIP patients was equivalent to that for non-VIP patients. As we assessed only physician perceptions of safety, which may not necessarily correlate with actual safety, further research in this area is needed.

Our study was limited by several factors. While our study population included hospitalists from 8 geographically broad hospitals, including university, safety net, and community hospitals, study responses may not be reflective of nationwide trends. Our response rate may limit our ability to generalize conclusions beyond respondents. Second, our study captured physician perceptions of behavior and safety rather than actually measuring practice and outcomes. Studies comparing physician practice patterns and outcomes between VIP and non-VIP patients would be informative. Additionally, despite our inclusive survey design process, our survey was not validated, and it is possible that our questions were not interpreted as intended. Lastly, despite the anonymous nature of our survey, physicians may have felt compelled to respond in a particular way due to conflicting professional, financial, or social factors.

Our findings provide initial insight into how care for the VIP patient may present unique challenges for physicians, hospitals, and society by systematizing care inequities, as well as potentially incentivizing low-value care practices. Whether these imbalances produce clinical harms or benefits remains worthy of future studies.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

1. Bernstein N. Chefs, butlers, marble baths: Hospitals vie for the affluent. New York Times. January 21, 2012. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/22/nyregion/chefs-butlers-and-marble-baths-not-your-average-hospital-room.html. Accessed February 1, 2017.

2. Kennedy DW, Kagan SH, Abramson KB, Boberick C, Kaiser LR. Academic medicine amenities unit: developing a model to integrate academic medical care with luxury hotel services. Acad Med. 2009;84(2):185-191. PubMed

3. Alfandre D, Clever S, Farber NJ, Hughes MT, Redstone P, Lehmann LS. Caring for ‘very important patients’--ethical dilemmas and suggestions for practical management. Am J Med. 2016;129(2):143-147. PubMed

4. Bulger J, Nickel W, Messler J, et al. Choosing wisely in adult hospital medicine: five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):486-492. PubMed

5. Martin A, Bostic JQ, Pruett K. The V.I.P.: hazard and promise in treating “special” patients. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43(3):366-369. PubMed

6. Smally AJ, Carroll B, Carius M, Tilden F, Werdmann M. Treatment of VIPs. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58(4):397-398. PubMed

7. Auerbach AD, Patel MS, Metlay JP, et al. The hospital medicine reengineering network (HOMERuN): a learning organization focused on improving hospital care. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):415-420. PubMed

8. Caverly TJ, Combs BP, Moriates C, Shah N, Grady D. Too much medicine happens too often: the teachable moment and a call for manuscripts from clinical trainees. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(1):8-9. PubMed

9. Schwartz AL, Chernew ME, Landon BE, McWilliams JM. Changes in low-value services in year 1 of the Medicare pioneer accountable care organization program. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(11):1815-1825. PubMed

10. Paterniti DA, Fancher TL, Cipri CS, Timmermans S, Heritage J, Kravitz RL. Getting to “no”: strategies primary care physicians use to deny patient requests. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(4):381-388. PubMed

11. Veroff D, Marr A, Wennberg DE. Enhanced support for shared decision making reduced costs of care for patients with preference-sensitive conditions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(2):285-293. PubMed

12. Korenstein D. Patient perception of benefits and harms: the Achilles heel of high-value care. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(2):287-288. PubMed

13. Moynihan R, Doust J, Henry D. Preventing overdiagnosis: how to stop harming the healthy. BMJ. 2012;344:e3502. PubMed

Recent publications in the medical literature and lay press have stirred controversy regarding the use of inpatient ‘very important person’ (VIP) services.1-3 The term “VIP services” often refers to select conveniences offered in addition to the assumed basic level of care and services provided by a hospital. Examples include additional space, enhanced facilities, specific comforts, or personal support. In some instances, these amenities may only be provided to patients who have close financial, social, or professional relationships with the hospital.

How VIP patients interact with their health system to obtain VIP services has raised unique concerns. Some have speculated that the presence of a VIP patient may be disruptive to the care of non-VIP patients, while others have cautioned physicians about potential dangers to the VIP patients themselves.4-6 Despite much being written on the topics of VIP patients and services in both the lay and academic press, our literature review identified only 1 study on the topic, which cataloged the preferential treatment of VIP patients in the emergency department.6 We are unaware of any investigations of VIP-service use in the inpatient setting. Through a multisite survey of hospital medicine physicians, we assessed physician viewpoints and behavior regarding VIP services.

METHODS

The Hospital Medicine Reengineering Network (HOMERuN) is a nation-wide learning organization focused on measuring and improving the outcomes of hospitalized patients.7 We surveyed hospitalists from 8 HOMERuN hospitals (Appendix 1). The survey instrument contained 4 sections: nonidentifying respondent demographics, local use of VIP services, reported physician perceptions of VIP services, and case-based assessments (Appendix 2). Survey questions and individual cases were developed by study authors and based on real scenarios and concerns provided by front-line clinical providers. Content, length, and reliability of physician understanding were assessed by a 5-person focus group consisting of physicians not included in the survey population.

Subjects were identified via administrative rosters from each HOMERuN site. Surveys were administered via SurveyMonkey, and results were analyzed descriptively. Populations were compared via the Fisher exact test. “VIP services” were defined as conveniences provided in addition to the assumed basic level of care and services (eg, private or luxury-style rooms, access to a special menu, better views, dedicated personal care attendants, hospital liaisons). VIP patients were defined as those patients receiving VIP services. A hospital was identified as providing VIP services if 50% or more of respondents from that site reported the presence of VIP services.

RESULTS

Of 366 hospitalists contacted, 160 completed the survey (44%). Respondent characteristics and reported prevalence of VIP services are demonstrated in Table 1. In total, 78 respondents (45%) reported the presence of VIP services at their hospital. Of the 8 sites surveyed, a majority of physicians at 4 sites (50%) reported presence of VIP services.

Of respondents reporting the presence of VIP services at their hospital, a majority felt that, from a patient safety perspective, the care received by VIP patients was the same as care received by non-VIP patients (Table 2). A majority reported they had felt pressured by a VIP patient or a family member to order additional tests or treatments that the physician believed were medically unnecessary and that they would be more likely to comply with VIP patient’s requests for tests or treatments they felt were unnecessary. More than one-third (36%) felt pressured by other hospital employees or representatives to comply with VIP services patient’s requests for additional tests or treatments that the physicians believed were medically unnecessary.

When presented the case of a VIP patient with community-acquired pneumonia who is clinically stable for discharge but expressing concerns about leaving the hospital, 61 (38%) respondents reported they would not discharge this patient home: 39 of 70 (55.7%) who reported the presence of VIP services at their hospital, and 22 of 91 (24.2%) who reported the absence of VIP services (P < 0.001). Of those who reported they would not discharge this patient home, 37 (61%) reported the reason for this related to the patient’s connection to the Board of Trustees; 48 (79%) reported the reason for this related to the patient’s concerns; 9 (15%) reported the reason for this related to their own concerns regarding medical details of the patient’s case (respondents could select more than 1 reason).

When presented the case of a VIP patient with acute pulmonary embolism who is medically ready for discharge with primary care physician-approved anticoagulation and discharge plans but for whom their family requests additional consultations and inpatient hypercoagulable workup, 33 (21%) respondents reported they would order additional testing and specialist consultation: 17 of 69 (24.6%) who reported the presence of VIP services their hospital, and 16 of 91 (17.6%) who reported the absence of VIP services (P = 0.33). Of those who reported they would order additional testing and specialist consultation, 14 (42%) reported the reason for this related to the family’s financial connections to the hospital; 30 (91%) reported the reason for this related to the family’s concerns; 3 (9%) reported the reason for this related to their own concerns about the medical details of the patient’s case (respondents could select more than 1 reason).

DISCUSSION

In our study, a majority of physicians who reported the presence of VIP services at their hospital felt pressured by VIP patients or their family members to perform unnecessary testing or treatment. While this study was not designed to quantify the burden of unnecessary care for VIP patients, our results have implications for individual patients and public health, including potential effects on resource availability, the identification of clinically irrelevant incidental findings, and short- and long-term medical complications of procedures, testing and radiation exposure.

Prior publications have advocated that physicians and hospitals should not allow VIP status to influence management decisions.3,5 We found that more than one-third of physicians who reported the presence of VIP services at their hospital also reported receiving pressure from hospital representatives to provide care to VIP patients that was not medically indicated. These findings highlight an example of the tension faced by physicians who are caught between patient requests and the delivery of value-based care. This potential conflict may be amplified particularly for those patients with close financial, social, or professional ties to the hospitals (and physicians) providing their care. These results suggest the need for physicians, administrators, and patients to work together to address the potential blurring of ethical boundaries created by VIP relationships. Prevention of harm and avoidance of placing physicians in morally distressing situations are common goals for all involved parties.

Efforts to reduce unnecessary care have predominantly focused on structural and knowledge-based drivers.4,8,9 Our results highlight the presence of additional forces. A majority of physician respondents who reported the presence of VIP services at their hospital also reported that they would be more likely to comply with requests for unnecessary care for a VIP patient as compared to a non-VIP patient. Furthermore, in case-based questions about the requests of a VIP patient and their family for additional unnecessary care, a significant portion of physicians who reported they would comply with these requests listed the VIP status of the patient or family as a factor underlying this decision. Only a minority of physicians reported their decision to provide additional care was the result of their own medically-based concerns. Because these cases were hypothetical and we did not include comparator cases involving non-VIP patients, it remains uncertain whether the observed perceptions accurately reflect real-world differences in the care of VIP and non-VIP patients. Nonetheless, our findings emphasize the importance of better understanding the social drivers of overuse and physician communication strategies related to medically inappropriate tests.10,11

Demand for unnecessary testing may be driven by the mentality that “more is better.”12 Contrary to this belief, provision of unnecessary care can increase the risk of patient harm.13 Despite physician respondents reporting that VIP patients requested and/or received additional unnecessary care, a majority of respondents felt that patient safety for VIP patients was equivalent to that for non-VIP patients. As we assessed only physician perceptions of safety, which may not necessarily correlate with actual safety, further research in this area is needed.

Our study was limited by several factors. While our study population included hospitalists from 8 geographically broad hospitals, including university, safety net, and community hospitals, study responses may not be reflective of nationwide trends. Our response rate may limit our ability to generalize conclusions beyond respondents. Second, our study captured physician perceptions of behavior and safety rather than actually measuring practice and outcomes. Studies comparing physician practice patterns and outcomes between VIP and non-VIP patients would be informative. Additionally, despite our inclusive survey design process, our survey was not validated, and it is possible that our questions were not interpreted as intended. Lastly, despite the anonymous nature of our survey, physicians may have felt compelled to respond in a particular way due to conflicting professional, financial, or social factors.

Our findings provide initial insight into how care for the VIP patient may present unique challenges for physicians, hospitals, and society by systematizing care inequities, as well as potentially incentivizing low-value care practices. Whether these imbalances produce clinical harms or benefits remains worthy of future studies.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

Recent publications in the medical literature and lay press have stirred controversy regarding the use of inpatient ‘very important person’ (VIP) services.1-3 The term “VIP services” often refers to select conveniences offered in addition to the assumed basic level of care and services provided by a hospital. Examples include additional space, enhanced facilities, specific comforts, or personal support. In some instances, these amenities may only be provided to patients who have close financial, social, or professional relationships with the hospital.

How VIP patients interact with their health system to obtain VIP services has raised unique concerns. Some have speculated that the presence of a VIP patient may be disruptive to the care of non-VIP patients, while others have cautioned physicians about potential dangers to the VIP patients themselves.4-6 Despite much being written on the topics of VIP patients and services in both the lay and academic press, our literature review identified only 1 study on the topic, which cataloged the preferential treatment of VIP patients in the emergency department.6 We are unaware of any investigations of VIP-service use in the inpatient setting. Through a multisite survey of hospital medicine physicians, we assessed physician viewpoints and behavior regarding VIP services.

METHODS

The Hospital Medicine Reengineering Network (HOMERuN) is a nation-wide learning organization focused on measuring and improving the outcomes of hospitalized patients.7 We surveyed hospitalists from 8 HOMERuN hospitals (Appendix 1). The survey instrument contained 4 sections: nonidentifying respondent demographics, local use of VIP services, reported physician perceptions of VIP services, and case-based assessments (Appendix 2). Survey questions and individual cases were developed by study authors and based on real scenarios and concerns provided by front-line clinical providers. Content, length, and reliability of physician understanding were assessed by a 5-person focus group consisting of physicians not included in the survey population.

Subjects were identified via administrative rosters from each HOMERuN site. Surveys were administered via SurveyMonkey, and results were analyzed descriptively. Populations were compared via the Fisher exact test. “VIP services” were defined as conveniences provided in addition to the assumed basic level of care and services (eg, private or luxury-style rooms, access to a special menu, better views, dedicated personal care attendants, hospital liaisons). VIP patients were defined as those patients receiving VIP services. A hospital was identified as providing VIP services if 50% or more of respondents from that site reported the presence of VIP services.

RESULTS

Of 366 hospitalists contacted, 160 completed the survey (44%). Respondent characteristics and reported prevalence of VIP services are demonstrated in Table 1. In total, 78 respondents (45%) reported the presence of VIP services at their hospital. Of the 8 sites surveyed, a majority of physicians at 4 sites (50%) reported presence of VIP services.

Of respondents reporting the presence of VIP services at their hospital, a majority felt that, from a patient safety perspective, the care received by VIP patients was the same as care received by non-VIP patients (Table 2). A majority reported they had felt pressured by a VIP patient or a family member to order additional tests or treatments that the physician believed were medically unnecessary and that they would be more likely to comply with VIP patient’s requests for tests or treatments they felt were unnecessary. More than one-third (36%) felt pressured by other hospital employees or representatives to comply with VIP services patient’s requests for additional tests or treatments that the physicians believed were medically unnecessary.

When presented the case of a VIP patient with community-acquired pneumonia who is clinically stable for discharge but expressing concerns about leaving the hospital, 61 (38%) respondents reported they would not discharge this patient home: 39 of 70 (55.7%) who reported the presence of VIP services at their hospital, and 22 of 91 (24.2%) who reported the absence of VIP services (P < 0.001). Of those who reported they would not discharge this patient home, 37 (61%) reported the reason for this related to the patient’s connection to the Board of Trustees; 48 (79%) reported the reason for this related to the patient’s concerns; 9 (15%) reported the reason for this related to their own concerns regarding medical details of the patient’s case (respondents could select more than 1 reason).

When presented the case of a VIP patient with acute pulmonary embolism who is medically ready for discharge with primary care physician-approved anticoagulation and discharge plans but for whom their family requests additional consultations and inpatient hypercoagulable workup, 33 (21%) respondents reported they would order additional testing and specialist consultation: 17 of 69 (24.6%) who reported the presence of VIP services their hospital, and 16 of 91 (17.6%) who reported the absence of VIP services (P = 0.33). Of those who reported they would order additional testing and specialist consultation, 14 (42%) reported the reason for this related to the family’s financial connections to the hospital; 30 (91%) reported the reason for this related to the family’s concerns; 3 (9%) reported the reason for this related to their own concerns about the medical details of the patient’s case (respondents could select more than 1 reason).

DISCUSSION

In our study, a majority of physicians who reported the presence of VIP services at their hospital felt pressured by VIP patients or their family members to perform unnecessary testing or treatment. While this study was not designed to quantify the burden of unnecessary care for VIP patients, our results have implications for individual patients and public health, including potential effects on resource availability, the identification of clinically irrelevant incidental findings, and short- and long-term medical complications of procedures, testing and radiation exposure.

Prior publications have advocated that physicians and hospitals should not allow VIP status to influence management decisions.3,5 We found that more than one-third of physicians who reported the presence of VIP services at their hospital also reported receiving pressure from hospital representatives to provide care to VIP patients that was not medically indicated. These findings highlight an example of the tension faced by physicians who are caught between patient requests and the delivery of value-based care. This potential conflict may be amplified particularly for those patients with close financial, social, or professional ties to the hospitals (and physicians) providing their care. These results suggest the need for physicians, administrators, and patients to work together to address the potential blurring of ethical boundaries created by VIP relationships. Prevention of harm and avoidance of placing physicians in morally distressing situations are common goals for all involved parties.

Efforts to reduce unnecessary care have predominantly focused on structural and knowledge-based drivers.4,8,9 Our results highlight the presence of additional forces. A majority of physician respondents who reported the presence of VIP services at their hospital also reported that they would be more likely to comply with requests for unnecessary care for a VIP patient as compared to a non-VIP patient. Furthermore, in case-based questions about the requests of a VIP patient and their family for additional unnecessary care, a significant portion of physicians who reported they would comply with these requests listed the VIP status of the patient or family as a factor underlying this decision. Only a minority of physicians reported their decision to provide additional care was the result of their own medically-based concerns. Because these cases were hypothetical and we did not include comparator cases involving non-VIP patients, it remains uncertain whether the observed perceptions accurately reflect real-world differences in the care of VIP and non-VIP patients. Nonetheless, our findings emphasize the importance of better understanding the social drivers of overuse and physician communication strategies related to medically inappropriate tests.10,11

Demand for unnecessary testing may be driven by the mentality that “more is better.”12 Contrary to this belief, provision of unnecessary care can increase the risk of patient harm.13 Despite physician respondents reporting that VIP patients requested and/or received additional unnecessary care, a majority of respondents felt that patient safety for VIP patients was equivalent to that for non-VIP patients. As we assessed only physician perceptions of safety, which may not necessarily correlate with actual safety, further research in this area is needed.

Our study was limited by several factors. While our study population included hospitalists from 8 geographically broad hospitals, including university, safety net, and community hospitals, study responses may not be reflective of nationwide trends. Our response rate may limit our ability to generalize conclusions beyond respondents. Second, our study captured physician perceptions of behavior and safety rather than actually measuring practice and outcomes. Studies comparing physician practice patterns and outcomes between VIP and non-VIP patients would be informative. Additionally, despite our inclusive survey design process, our survey was not validated, and it is possible that our questions were not interpreted as intended. Lastly, despite the anonymous nature of our survey, physicians may have felt compelled to respond in a particular way due to conflicting professional, financial, or social factors.

Our findings provide initial insight into how care for the VIP patient may present unique challenges for physicians, hospitals, and society by systematizing care inequities, as well as potentially incentivizing low-value care practices. Whether these imbalances produce clinical harms or benefits remains worthy of future studies.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

1. Bernstein N. Chefs, butlers, marble baths: Hospitals vie for the affluent. New York Times. January 21, 2012. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/22/nyregion/chefs-butlers-and-marble-baths-not-your-average-hospital-room.html. Accessed February 1, 2017.

2. Kennedy DW, Kagan SH, Abramson KB, Boberick C, Kaiser LR. Academic medicine amenities unit: developing a model to integrate academic medical care with luxury hotel services. Acad Med. 2009;84(2):185-191. PubMed

3. Alfandre D, Clever S, Farber NJ, Hughes MT, Redstone P, Lehmann LS. Caring for ‘very important patients’--ethical dilemmas and suggestions for practical management. Am J Med. 2016;129(2):143-147. PubMed

4. Bulger J, Nickel W, Messler J, et al. Choosing wisely in adult hospital medicine: five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):486-492. PubMed

5. Martin A, Bostic JQ, Pruett K. The V.I.P.: hazard and promise in treating “special” patients. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43(3):366-369. PubMed

6. Smally AJ, Carroll B, Carius M, Tilden F, Werdmann M. Treatment of VIPs. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58(4):397-398. PubMed

7. Auerbach AD, Patel MS, Metlay JP, et al. The hospital medicine reengineering network (HOMERuN): a learning organization focused on improving hospital care. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):415-420. PubMed

8. Caverly TJ, Combs BP, Moriates C, Shah N, Grady D. Too much medicine happens too often: the teachable moment and a call for manuscripts from clinical trainees. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(1):8-9. PubMed

9. Schwartz AL, Chernew ME, Landon BE, McWilliams JM. Changes in low-value services in year 1 of the Medicare pioneer accountable care organization program. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(11):1815-1825. PubMed

10. Paterniti DA, Fancher TL, Cipri CS, Timmermans S, Heritage J, Kravitz RL. Getting to “no”: strategies primary care physicians use to deny patient requests. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(4):381-388. PubMed

11. Veroff D, Marr A, Wennberg DE. Enhanced support for shared decision making reduced costs of care for patients with preference-sensitive conditions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(2):285-293. PubMed

12. Korenstein D. Patient perception of benefits and harms: the Achilles heel of high-value care. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(2):287-288. PubMed

13. Moynihan R, Doust J, Henry D. Preventing overdiagnosis: how to stop harming the healthy. BMJ. 2012;344:e3502. PubMed

1. Bernstein N. Chefs, butlers, marble baths: Hospitals vie for the affluent. New York Times. January 21, 2012. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/22/nyregion/chefs-butlers-and-marble-baths-not-your-average-hospital-room.html. Accessed February 1, 2017.

2. Kennedy DW, Kagan SH, Abramson KB, Boberick C, Kaiser LR. Academic medicine amenities unit: developing a model to integrate academic medical care with luxury hotel services. Acad Med. 2009;84(2):185-191. PubMed

3. Alfandre D, Clever S, Farber NJ, Hughes MT, Redstone P, Lehmann LS. Caring for ‘very important patients’--ethical dilemmas and suggestions for practical management. Am J Med. 2016;129(2):143-147. PubMed

4. Bulger J, Nickel W, Messler J, et al. Choosing wisely in adult hospital medicine: five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):486-492. PubMed

5. Martin A, Bostic JQ, Pruett K. The V.I.P.: hazard and promise in treating “special” patients. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43(3):366-369. PubMed

6. Smally AJ, Carroll B, Carius M, Tilden F, Werdmann M. Treatment of VIPs. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58(4):397-398. PubMed

7. Auerbach AD, Patel MS, Metlay JP, et al. The hospital medicine reengineering network (HOMERuN): a learning organization focused on improving hospital care. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):415-420. PubMed

8. Caverly TJ, Combs BP, Moriates C, Shah N, Grady D. Too much medicine happens too often: the teachable moment and a call for manuscripts from clinical trainees. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(1):8-9. PubMed

9. Schwartz AL, Chernew ME, Landon BE, McWilliams JM. Changes in low-value services in year 1 of the Medicare pioneer accountable care organization program. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(11):1815-1825. PubMed

10. Paterniti DA, Fancher TL, Cipri CS, Timmermans S, Heritage J, Kravitz RL. Getting to “no”: strategies primary care physicians use to deny patient requests. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(4):381-388. PubMed

11. Veroff D, Marr A, Wennberg DE. Enhanced support for shared decision making reduced costs of care for patients with preference-sensitive conditions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(2):285-293. PubMed

12. Korenstein D. Patient perception of benefits and harms: the Achilles heel of high-value care. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(2):287-288. PubMed

13. Moynihan R, Doust J, Henry D. Preventing overdiagnosis: how to stop harming the healthy. BMJ. 2012;344:e3502. PubMed

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

Short-Course Antimicrobial Therapy Outcomes for Intra-Abdominal Infection

Clinical question: Does a short, fixed duration of antibiotic therapy for complicated intra-abdominal infections lead to equivalent outcomes and less antibiotic exposure than the traditional approach?

Background: Published guidelines recommend appropriate antimicrobial agents for intra-abdominal infections, but the optimal duration of therapy remains unclear. Most practitioners continue to treat for 10–14 days and until all physiologic evidence of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) has resolved. More recently, small studies have suggested that a shorter course may lead to equivalent outcomes with decreased antibiotic exposure.

Study design: Open-label, multicenter, randomized control trial.

Setting: Twenty-three sites throughout the U.S. and Canada.

Synopsis: In the short-course group, 257 patients were randomized to receive antimicrobial therapy for four full days after their index source-control procedure; 260 patients in the control group received antimicrobial therapy until two days after resolution of the physiological abnormalities related to SIRS. The median duration of therapy was 4.0 days (interquartile range [IQR] 4.0–5.0) for the experimental group and 8.0 days (IQR 5.0–10.0) in the control group (95% CI, -4.7 to -3.3; P<0.001).

There was no significant difference in surgical site infection, recurrent intra-abdominal infection, or death between the experimental and control groups (21.8% vs. 22.3%, 95% CI, -7.0 to 8.0; P=0.92). In the experimental group, 47 patients did not adhere to the protocol, and all of those patients received a longer antimicrobial treatment course than specified in the protocol.

This trial excluded patients without adequate source control and included a small number of immunocompromised hosts. The rate of nonadherence to the protocol was high, at 18% of patients in the experimental group. The calculated sample size to assert equivalence between groups was not achieved, although the results are suggestive of equivalence.

Bottom line: A shorter course of antimicrobial therapy for complicated intra-abdominal infections might lead to equivalent outcomes with less antibiotic exposure compared with current practice; however, it is challenging for providers to stop antimicrobial therapy while patients continue to show physiologic evidence of SIRS.

Citation: Sawyer RG, Claridge JA, Nathens AB, et al. Trial of short-course antimicrobial therapy for intraabdominal infection. NEJM. 2015;372(21):1996–2005.

Visit our website for more reviews of HM-focused research.

Clinical question: Does a short, fixed duration of antibiotic therapy for complicated intra-abdominal infections lead to equivalent outcomes and less antibiotic exposure than the traditional approach?

Background: Published guidelines recommend appropriate antimicrobial agents for intra-abdominal infections, but the optimal duration of therapy remains unclear. Most practitioners continue to treat for 10–14 days and until all physiologic evidence of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) has resolved. More recently, small studies have suggested that a shorter course may lead to equivalent outcomes with decreased antibiotic exposure.

Study design: Open-label, multicenter, randomized control trial.

Setting: Twenty-three sites throughout the U.S. and Canada.

Synopsis: In the short-course group, 257 patients were randomized to receive antimicrobial therapy for four full days after their index source-control procedure; 260 patients in the control group received antimicrobial therapy until two days after resolution of the physiological abnormalities related to SIRS. The median duration of therapy was 4.0 days (interquartile range [IQR] 4.0–5.0) for the experimental group and 8.0 days (IQR 5.0–10.0) in the control group (95% CI, -4.7 to -3.3; P<0.001).