User login

Cat Scratch Disease Presenting With Concurrent Pityriasis Rosea in a 10-Year-Old Girl

To the Editor:

Cat scratch disease (CSD) is caused by Bartonella henselae and Bartonella clarridgeiae bacteria transferred from cats to humans that results in an inflamed inoculation site and tender lymphadenopathy. Pityriasis rosea (PR) and PR-like eruptions are self-limited, acute exanthems that have been associated with infections, vaccinations, and medications. We report a case of PR occurring in a 10-year-old girl with CSD, which may suggest an association between the 2 diseases.

A 10-year-old girl who was otherwise healthy presented in the winter with a rash of 5 days’ duration. Fourteen days prior to the rash, the patient reported being scratched by a new kitten and noted a pinpoint “puncture” on the left forearm that developed into a red papule over the following week. Seven days after the cat scratch, the patient experienced pain and swelling in the left axilla. Approximately 1 week after the onset of lymphadenopathy, the patient developed an asymptomatic rash that started with a large spot on the left chest, followed by smaller spots appearing over the next 2 days and spreading to the rest of the trunk. Four days after the rash onset, the patient experienced a mild headache, low-grade subjective fever, and chills. She denied any recent travel, bug bites, sore throat, and diarrhea. She was up-to-date on all vaccinations and had not received any vaccines preceding the symptoms. Physical examination revealed a 2-cm pink, scaly, thin plaque with a collarette of scale on the left upper chest (herald patch), along with multiple thin pink papules and small plaques with central scale on the trunk (Figure 1). A pustule with adjacent linear erosion was present on the left ventral forearm (Figure 2). The patient had a tender subcutaneous nodule in the left axilla as well as bilateral anterior and posterior cervical-chain subcutaneous tender nodules. There was no involvement of the palms, soles, or mucosae.

The patient was empirically treated for CSD with azithromycin (200 mg/5 mL), 404 mg on day 1 followed by 202 mg daily for 4 days. The rash was treated with hydrocortisone cream 2.5% twice daily for 2 weeks. A wound culture of the pustule on the left forearm was negative for neutrophils and organisms. Antibody serologies obtained 4 weeks after presentation were notable for an elevated B henselae IgG titer of 1:640, confirming the diagnosis of CSD. Following treatment with azithromycin and hydrocortisone, all of the patient’s symptoms resolved after 1 to 2 weeks.

Cat scratch disease is a zoonotic infection caused by the bacteria B henselae and the more recently described pathogen B clarridgeiae. Cat fleas spread these bacteria among cats, which subsequently inoculate the bacteria into humans through bites and scratches. The incidence of CSD in the United States is estimated to be 4.5 to 9.3 per 100,000 individuals in the outpatient setting and 0.19 to 0.86 per 100,000 individuals in the inpatient setting.1 Geographic variance can occur based on flea populations, resulting in higher incidence in warm humid climates and lower incidence in mountainous arid climates. The incidence of CSD in the pediatric population is highest in children aged 5 to 9 years. A national representative survey (N=3011) from 2017 revealed that 37.2% of primary care providers had diagnosed CSD in the prior year.1

Classic CSD presents as an erythematous papule at the inoculation site lasting days to weeks, with progression to tender lymphadenopathy lasting weeks to months. Fever, malaise, and chills also can be seen. Atypical CSD occurs in up to 24% of cases in immunocompetent patients.1 Atypical and systemic presentations are varied and can include fever of unknown origin, neuroretinitis, uveitis, retinal vessel occlusion, encephalitis, hepatosplenic lesions, Parinaud oculoglandular syndrome, osteomyelitis, and endocarditis.1,2 Atypical dermatologic presentations of CSD include maculopapular rash in 7% of cases and erythema nodosum in 2.5% of cases, as well as rare reports of cutaneous vasculitis, urticaria, immune thrombocytopenic purpura, and papuloedematous eruption.3 Treatment guidelines for CSD vary widely depending on the clinical presentation as well as the immunocompetence of the infected individual. Our patient had limited regional lymphadenopathy with no signs of dissemination or neurologic involvement and was successfully treated with a 5-day course of oral azithromycin (weight based, 10 mg/kg). More extensive disease such as hepatosplenic or neurologic CSD may require multiple antibiotics for up to 6 weeks. Alternative or additional antibiotics used for CSD include rifampin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, ciprofloxacin, doxycycline, gentamicin, and clarithromycin. Opinions vary as to whether all patients or just those with complicated infections warrant antibiotic therapy.4-6

Pityriasis rosea is a self-limited acute exanthematous disease that is classically associated with a systemic reactivation of human herpesvirus (HHV) 6 and/or HHV-7. The incidence of PR is estimated to be 480 per 100,000 dermatologic patients. It is slightly more common in females and occurs most often in patients aged 10 to 35 years.7 Clinically, PR appears with the abrupt onset of a single erythematous scaly patch (termed the herald patch), followed by a secondary eruption of smaller erythematous scaly macules and patches along the trunk’s cleavage lines. The secondary eruption on the back is sometimes termed a Christmas or fir tree pattern.7,8

In addition to the classic presentation of PR, there have been reports of numerous atypical clinical presentations. The herald patch, which classically presents on the trunk, also has been reported to present on the extremities; PR of the extremities is defined by lesions that appear as large scaly plaques on the extremities only. Inverse PR presents with lesions occurring in flexural areas and acral surfaces but not on the trunk. There also is an acral PR variant in which lesions appear only on the palms, wrists, and soles. Purpuric or hemorrhagic PR has been described and presents with purpura and petechiae with or without collarettes of scale in diffuse locations, including the palate. Oral PR presents more commonly in patients of color as erosions, ulcers, hemorrhagic lesions, bullae, or geographic tongue. Erythema multiforme–like PR appears with targetoid lesions on the trunk, face, neck, and arms without a history of herpes simplex virus infection. A large pear-shaped herald patch has been reported and characterizes the gigantea PR of Darier variant. Irritated PR occurs with typical PR findings, but afflicted patients report severe pain and burning with diaphoresis. Relapsing PR can occur within 1 year of a prior episode of PR and presents without a herald patch. Persistent PR is defined by PR lasting more than 3 months, and most reported cases have included oral lesions. Finally, other PR variants that have been described include urticarial, papular, follicular, vesicular, and hypopigmented types.7-9

Furthermore, there have been reports of multiple atypical presentations occurring simultaneously in the same patient.10 Although PR classically has been associated with HHV-6 and/or HHV-7 reactivation, it has been reported with a few other clinical situations and conditions. Pityriasislike eruption specifically refers to an exanthem secondary to drugs or vaccination that resembles PR but shows clinical differences, including diffuse and confluent dusky-red macules and/or plaques with or without desquamation on the trunk, extremities, and face. Drugs that have been implicated as triggers include ACE inhibitors, gold, isotretinoin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, omeprazole, terbinafine, and tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Smallpox, tuberculosis, poliomyelitis, influenza, diphtheria, tetanus, hepatitis B virus, pneumococcus, papillomavirus, yellow fever, and pertussis vaccinations also have been associated with PR.7,11,12 Additionally, PR has been reported to occur with active systemic infections, specifically H1N1 influenza, though it is rare.13 Because of its self-limited course, treatment of PR most often involves only reassurance. Topical corticosteroids may be appropriate for pruritus.7,8

Pediatric health care providers including dermatologists should be familiar with both CSD and PR because they are common diseases that more often are encountered in the pediatric population. We present a unique case of CSD presenting with concurrent PR, which highlights a potential new etiology for PR and a rare cutaneous manifestation of CSD. Further investigation into a possible relationship between CSD and PR may be warranted. Patients with any signs and symptoms of fever, tender lymphadenopathy, worsening rash, or exposure to cats warrant a thorough history and physical examination to ensure that neither entity is overlooked.

- Nelson CA, Moore AR, Perea AE, et al. Cat scratch disease: U.S. clinicians’ experience and knowledge [published online July 14, 2017]. Zoonoses Public Health. 2018;65:67-73. doi:10.1111/zph.12368

- Habot-Wilner Z, Trivizki O, Goldstein M, et al. Cat-scratch disease: ocular manifestations and treatment outcome. Acta Ophthalmol. 2018;96:E524-E532. doi:10.1111/aos.13684

- Schattner A, Uliel L, Dubin I. The cat did it: erythema nodosum and additional atypical presentations of Bartonella henselae infection in immunocompetent hosts [published online February 16, 2018]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2017-222511

- Shorbatli L, Koranyi K, Nahata M. Effectiveness of antibiotic therapy in pediatric patients with cat scratch disease. Int J Clin Pharm. 2018;40:1458-1461. doi: 10.1007/s11096-018-0746-1

- Bass JW, Freitas BC, Freitas AD, et al. Prospective randomized double blind placebo-controlled evaluation of azithromycin for treatment of cat-scratch disease. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998;17:447-452. doi:10.1097/00006454-199806000-00002

- Spach DH, Kaplan SL. Treatment of cat scratch disease. UpToDate. Updated December 9, 2021. Accessed September 12, 2023. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-cat-scratch-disease

- Drago F, Ciccarese G, Rebora A, et al. Pityriasis rosea: a comprehensive classification. Dermatology. 2016;232:431-437. doi:10.1159/000445375

- Urbina F, Das A, Sudy E. Clinical variants of pityriasis rosea. World J Clin Cases. 2017;5:203-211. doi:10.12998/wjcc.v5.i6.203

- Alzahrani NA, Al Jasser MI. Geographic tonguelike presentation in a child with pityriasis rosea: case report and review of oral manifestations of pityriasis rosea. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:E124-E127. doi:10.1111/pde.13417

- Sinha S, Sardana K, Garg V. Coexistence of two atypical variants of pityriasis rosea: a case report and review of literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:538-540. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01549.x

- Drago F, Ciccarese G, Parodi A. Pityriasis rosea and pityriasis rosea-like eruptions: how to distinguish them? JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:800-801. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2018.04.002

- Drago F, Ciccarese G, Javor S, et al. Vaccine-induced pityriasis rosea and pityriasis rosea-like eruptions: a review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:544-545. doi:10.1111/jdv.12942

- Mubki TF, Bin Dayel SA, Kadry R. A case of pityriasis rosea concurrent with the novel influenza A (H1N1) infection. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:341-342. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2010.01090.x

To the Editor:

Cat scratch disease (CSD) is caused by Bartonella henselae and Bartonella clarridgeiae bacteria transferred from cats to humans that results in an inflamed inoculation site and tender lymphadenopathy. Pityriasis rosea (PR) and PR-like eruptions are self-limited, acute exanthems that have been associated with infections, vaccinations, and medications. We report a case of PR occurring in a 10-year-old girl with CSD, which may suggest an association between the 2 diseases.

A 10-year-old girl who was otherwise healthy presented in the winter with a rash of 5 days’ duration. Fourteen days prior to the rash, the patient reported being scratched by a new kitten and noted a pinpoint “puncture” on the left forearm that developed into a red papule over the following week. Seven days after the cat scratch, the patient experienced pain and swelling in the left axilla. Approximately 1 week after the onset of lymphadenopathy, the patient developed an asymptomatic rash that started with a large spot on the left chest, followed by smaller spots appearing over the next 2 days and spreading to the rest of the trunk. Four days after the rash onset, the patient experienced a mild headache, low-grade subjective fever, and chills. She denied any recent travel, bug bites, sore throat, and diarrhea. She was up-to-date on all vaccinations and had not received any vaccines preceding the symptoms. Physical examination revealed a 2-cm pink, scaly, thin plaque with a collarette of scale on the left upper chest (herald patch), along with multiple thin pink papules and small plaques with central scale on the trunk (Figure 1). A pustule with adjacent linear erosion was present on the left ventral forearm (Figure 2). The patient had a tender subcutaneous nodule in the left axilla as well as bilateral anterior and posterior cervical-chain subcutaneous tender nodules. There was no involvement of the palms, soles, or mucosae.

The patient was empirically treated for CSD with azithromycin (200 mg/5 mL), 404 mg on day 1 followed by 202 mg daily for 4 days. The rash was treated with hydrocortisone cream 2.5% twice daily for 2 weeks. A wound culture of the pustule on the left forearm was negative for neutrophils and organisms. Antibody serologies obtained 4 weeks after presentation were notable for an elevated B henselae IgG titer of 1:640, confirming the diagnosis of CSD. Following treatment with azithromycin and hydrocortisone, all of the patient’s symptoms resolved after 1 to 2 weeks.

Cat scratch disease is a zoonotic infection caused by the bacteria B henselae and the more recently described pathogen B clarridgeiae. Cat fleas spread these bacteria among cats, which subsequently inoculate the bacteria into humans through bites and scratches. The incidence of CSD in the United States is estimated to be 4.5 to 9.3 per 100,000 individuals in the outpatient setting and 0.19 to 0.86 per 100,000 individuals in the inpatient setting.1 Geographic variance can occur based on flea populations, resulting in higher incidence in warm humid climates and lower incidence in mountainous arid climates. The incidence of CSD in the pediatric population is highest in children aged 5 to 9 years. A national representative survey (N=3011) from 2017 revealed that 37.2% of primary care providers had diagnosed CSD in the prior year.1

Classic CSD presents as an erythematous papule at the inoculation site lasting days to weeks, with progression to tender lymphadenopathy lasting weeks to months. Fever, malaise, and chills also can be seen. Atypical CSD occurs in up to 24% of cases in immunocompetent patients.1 Atypical and systemic presentations are varied and can include fever of unknown origin, neuroretinitis, uveitis, retinal vessel occlusion, encephalitis, hepatosplenic lesions, Parinaud oculoglandular syndrome, osteomyelitis, and endocarditis.1,2 Atypical dermatologic presentations of CSD include maculopapular rash in 7% of cases and erythema nodosum in 2.5% of cases, as well as rare reports of cutaneous vasculitis, urticaria, immune thrombocytopenic purpura, and papuloedematous eruption.3 Treatment guidelines for CSD vary widely depending on the clinical presentation as well as the immunocompetence of the infected individual. Our patient had limited regional lymphadenopathy with no signs of dissemination or neurologic involvement and was successfully treated with a 5-day course of oral azithromycin (weight based, 10 mg/kg). More extensive disease such as hepatosplenic or neurologic CSD may require multiple antibiotics for up to 6 weeks. Alternative or additional antibiotics used for CSD include rifampin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, ciprofloxacin, doxycycline, gentamicin, and clarithromycin. Opinions vary as to whether all patients or just those with complicated infections warrant antibiotic therapy.4-6

Pityriasis rosea is a self-limited acute exanthematous disease that is classically associated with a systemic reactivation of human herpesvirus (HHV) 6 and/or HHV-7. The incidence of PR is estimated to be 480 per 100,000 dermatologic patients. It is slightly more common in females and occurs most often in patients aged 10 to 35 years.7 Clinically, PR appears with the abrupt onset of a single erythematous scaly patch (termed the herald patch), followed by a secondary eruption of smaller erythematous scaly macules and patches along the trunk’s cleavage lines. The secondary eruption on the back is sometimes termed a Christmas or fir tree pattern.7,8

In addition to the classic presentation of PR, there have been reports of numerous atypical clinical presentations. The herald patch, which classically presents on the trunk, also has been reported to present on the extremities; PR of the extremities is defined by lesions that appear as large scaly plaques on the extremities only. Inverse PR presents with lesions occurring in flexural areas and acral surfaces but not on the trunk. There also is an acral PR variant in which lesions appear only on the palms, wrists, and soles. Purpuric or hemorrhagic PR has been described and presents with purpura and petechiae with or without collarettes of scale in diffuse locations, including the palate. Oral PR presents more commonly in patients of color as erosions, ulcers, hemorrhagic lesions, bullae, or geographic tongue. Erythema multiforme–like PR appears with targetoid lesions on the trunk, face, neck, and arms without a history of herpes simplex virus infection. A large pear-shaped herald patch has been reported and characterizes the gigantea PR of Darier variant. Irritated PR occurs with typical PR findings, but afflicted patients report severe pain and burning with diaphoresis. Relapsing PR can occur within 1 year of a prior episode of PR and presents without a herald patch. Persistent PR is defined by PR lasting more than 3 months, and most reported cases have included oral lesions. Finally, other PR variants that have been described include urticarial, papular, follicular, vesicular, and hypopigmented types.7-9

Furthermore, there have been reports of multiple atypical presentations occurring simultaneously in the same patient.10 Although PR classically has been associated with HHV-6 and/or HHV-7 reactivation, it has been reported with a few other clinical situations and conditions. Pityriasislike eruption specifically refers to an exanthem secondary to drugs or vaccination that resembles PR but shows clinical differences, including diffuse and confluent dusky-red macules and/or plaques with or without desquamation on the trunk, extremities, and face. Drugs that have been implicated as triggers include ACE inhibitors, gold, isotretinoin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, omeprazole, terbinafine, and tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Smallpox, tuberculosis, poliomyelitis, influenza, diphtheria, tetanus, hepatitis B virus, pneumococcus, papillomavirus, yellow fever, and pertussis vaccinations also have been associated with PR.7,11,12 Additionally, PR has been reported to occur with active systemic infections, specifically H1N1 influenza, though it is rare.13 Because of its self-limited course, treatment of PR most often involves only reassurance. Topical corticosteroids may be appropriate for pruritus.7,8

Pediatric health care providers including dermatologists should be familiar with both CSD and PR because they are common diseases that more often are encountered in the pediatric population. We present a unique case of CSD presenting with concurrent PR, which highlights a potential new etiology for PR and a rare cutaneous manifestation of CSD. Further investigation into a possible relationship between CSD and PR may be warranted. Patients with any signs and symptoms of fever, tender lymphadenopathy, worsening rash, or exposure to cats warrant a thorough history and physical examination to ensure that neither entity is overlooked.

To the Editor:

Cat scratch disease (CSD) is caused by Bartonella henselae and Bartonella clarridgeiae bacteria transferred from cats to humans that results in an inflamed inoculation site and tender lymphadenopathy. Pityriasis rosea (PR) and PR-like eruptions are self-limited, acute exanthems that have been associated with infections, vaccinations, and medications. We report a case of PR occurring in a 10-year-old girl with CSD, which may suggest an association between the 2 diseases.

A 10-year-old girl who was otherwise healthy presented in the winter with a rash of 5 days’ duration. Fourteen days prior to the rash, the patient reported being scratched by a new kitten and noted a pinpoint “puncture” on the left forearm that developed into a red papule over the following week. Seven days after the cat scratch, the patient experienced pain and swelling in the left axilla. Approximately 1 week after the onset of lymphadenopathy, the patient developed an asymptomatic rash that started with a large spot on the left chest, followed by smaller spots appearing over the next 2 days and spreading to the rest of the trunk. Four days after the rash onset, the patient experienced a mild headache, low-grade subjective fever, and chills. She denied any recent travel, bug bites, sore throat, and diarrhea. She was up-to-date on all vaccinations and had not received any vaccines preceding the symptoms. Physical examination revealed a 2-cm pink, scaly, thin plaque with a collarette of scale on the left upper chest (herald patch), along with multiple thin pink papules and small plaques with central scale on the trunk (Figure 1). A pustule with adjacent linear erosion was present on the left ventral forearm (Figure 2). The patient had a tender subcutaneous nodule in the left axilla as well as bilateral anterior and posterior cervical-chain subcutaneous tender nodules. There was no involvement of the palms, soles, or mucosae.

The patient was empirically treated for CSD with azithromycin (200 mg/5 mL), 404 mg on day 1 followed by 202 mg daily for 4 days. The rash was treated with hydrocortisone cream 2.5% twice daily for 2 weeks. A wound culture of the pustule on the left forearm was negative for neutrophils and organisms. Antibody serologies obtained 4 weeks after presentation were notable for an elevated B henselae IgG titer of 1:640, confirming the diagnosis of CSD. Following treatment with azithromycin and hydrocortisone, all of the patient’s symptoms resolved after 1 to 2 weeks.

Cat scratch disease is a zoonotic infection caused by the bacteria B henselae and the more recently described pathogen B clarridgeiae. Cat fleas spread these bacteria among cats, which subsequently inoculate the bacteria into humans through bites and scratches. The incidence of CSD in the United States is estimated to be 4.5 to 9.3 per 100,000 individuals in the outpatient setting and 0.19 to 0.86 per 100,000 individuals in the inpatient setting.1 Geographic variance can occur based on flea populations, resulting in higher incidence in warm humid climates and lower incidence in mountainous arid climates. The incidence of CSD in the pediatric population is highest in children aged 5 to 9 years. A national representative survey (N=3011) from 2017 revealed that 37.2% of primary care providers had diagnosed CSD in the prior year.1

Classic CSD presents as an erythematous papule at the inoculation site lasting days to weeks, with progression to tender lymphadenopathy lasting weeks to months. Fever, malaise, and chills also can be seen. Atypical CSD occurs in up to 24% of cases in immunocompetent patients.1 Atypical and systemic presentations are varied and can include fever of unknown origin, neuroretinitis, uveitis, retinal vessel occlusion, encephalitis, hepatosplenic lesions, Parinaud oculoglandular syndrome, osteomyelitis, and endocarditis.1,2 Atypical dermatologic presentations of CSD include maculopapular rash in 7% of cases and erythema nodosum in 2.5% of cases, as well as rare reports of cutaneous vasculitis, urticaria, immune thrombocytopenic purpura, and papuloedematous eruption.3 Treatment guidelines for CSD vary widely depending on the clinical presentation as well as the immunocompetence of the infected individual. Our patient had limited regional lymphadenopathy with no signs of dissemination or neurologic involvement and was successfully treated with a 5-day course of oral azithromycin (weight based, 10 mg/kg). More extensive disease such as hepatosplenic or neurologic CSD may require multiple antibiotics for up to 6 weeks. Alternative or additional antibiotics used for CSD include rifampin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, ciprofloxacin, doxycycline, gentamicin, and clarithromycin. Opinions vary as to whether all patients or just those with complicated infections warrant antibiotic therapy.4-6

Pityriasis rosea is a self-limited acute exanthematous disease that is classically associated with a systemic reactivation of human herpesvirus (HHV) 6 and/or HHV-7. The incidence of PR is estimated to be 480 per 100,000 dermatologic patients. It is slightly more common in females and occurs most often in patients aged 10 to 35 years.7 Clinically, PR appears with the abrupt onset of a single erythematous scaly patch (termed the herald patch), followed by a secondary eruption of smaller erythematous scaly macules and patches along the trunk’s cleavage lines. The secondary eruption on the back is sometimes termed a Christmas or fir tree pattern.7,8

In addition to the classic presentation of PR, there have been reports of numerous atypical clinical presentations. The herald patch, which classically presents on the trunk, also has been reported to present on the extremities; PR of the extremities is defined by lesions that appear as large scaly plaques on the extremities only. Inverse PR presents with lesions occurring in flexural areas and acral surfaces but not on the trunk. There also is an acral PR variant in which lesions appear only on the palms, wrists, and soles. Purpuric or hemorrhagic PR has been described and presents with purpura and petechiae with or without collarettes of scale in diffuse locations, including the palate. Oral PR presents more commonly in patients of color as erosions, ulcers, hemorrhagic lesions, bullae, or geographic tongue. Erythema multiforme–like PR appears with targetoid lesions on the trunk, face, neck, and arms without a history of herpes simplex virus infection. A large pear-shaped herald patch has been reported and characterizes the gigantea PR of Darier variant. Irritated PR occurs with typical PR findings, but afflicted patients report severe pain and burning with diaphoresis. Relapsing PR can occur within 1 year of a prior episode of PR and presents without a herald patch. Persistent PR is defined by PR lasting more than 3 months, and most reported cases have included oral lesions. Finally, other PR variants that have been described include urticarial, papular, follicular, vesicular, and hypopigmented types.7-9

Furthermore, there have been reports of multiple atypical presentations occurring simultaneously in the same patient.10 Although PR classically has been associated with HHV-6 and/or HHV-7 reactivation, it has been reported with a few other clinical situations and conditions. Pityriasislike eruption specifically refers to an exanthem secondary to drugs or vaccination that resembles PR but shows clinical differences, including diffuse and confluent dusky-red macules and/or plaques with or without desquamation on the trunk, extremities, and face. Drugs that have been implicated as triggers include ACE inhibitors, gold, isotretinoin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, omeprazole, terbinafine, and tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Smallpox, tuberculosis, poliomyelitis, influenza, diphtheria, tetanus, hepatitis B virus, pneumococcus, papillomavirus, yellow fever, and pertussis vaccinations also have been associated with PR.7,11,12 Additionally, PR has been reported to occur with active systemic infections, specifically H1N1 influenza, though it is rare.13 Because of its self-limited course, treatment of PR most often involves only reassurance. Topical corticosteroids may be appropriate for pruritus.7,8

Pediatric health care providers including dermatologists should be familiar with both CSD and PR because they are common diseases that more often are encountered in the pediatric population. We present a unique case of CSD presenting with concurrent PR, which highlights a potential new etiology for PR and a rare cutaneous manifestation of CSD. Further investigation into a possible relationship between CSD and PR may be warranted. Patients with any signs and symptoms of fever, tender lymphadenopathy, worsening rash, or exposure to cats warrant a thorough history and physical examination to ensure that neither entity is overlooked.

- Nelson CA, Moore AR, Perea AE, et al. Cat scratch disease: U.S. clinicians’ experience and knowledge [published online July 14, 2017]. Zoonoses Public Health. 2018;65:67-73. doi:10.1111/zph.12368

- Habot-Wilner Z, Trivizki O, Goldstein M, et al. Cat-scratch disease: ocular manifestations and treatment outcome. Acta Ophthalmol. 2018;96:E524-E532. doi:10.1111/aos.13684

- Schattner A, Uliel L, Dubin I. The cat did it: erythema nodosum and additional atypical presentations of Bartonella henselae infection in immunocompetent hosts [published online February 16, 2018]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2017-222511

- Shorbatli L, Koranyi K, Nahata M. Effectiveness of antibiotic therapy in pediatric patients with cat scratch disease. Int J Clin Pharm. 2018;40:1458-1461. doi: 10.1007/s11096-018-0746-1

- Bass JW, Freitas BC, Freitas AD, et al. Prospective randomized double blind placebo-controlled evaluation of azithromycin for treatment of cat-scratch disease. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998;17:447-452. doi:10.1097/00006454-199806000-00002

- Spach DH, Kaplan SL. Treatment of cat scratch disease. UpToDate. Updated December 9, 2021. Accessed September 12, 2023. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-cat-scratch-disease

- Drago F, Ciccarese G, Rebora A, et al. Pityriasis rosea: a comprehensive classification. Dermatology. 2016;232:431-437. doi:10.1159/000445375

- Urbina F, Das A, Sudy E. Clinical variants of pityriasis rosea. World J Clin Cases. 2017;5:203-211. doi:10.12998/wjcc.v5.i6.203

- Alzahrani NA, Al Jasser MI. Geographic tonguelike presentation in a child with pityriasis rosea: case report and review of oral manifestations of pityriasis rosea. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:E124-E127. doi:10.1111/pde.13417

- Sinha S, Sardana K, Garg V. Coexistence of two atypical variants of pityriasis rosea: a case report and review of literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:538-540. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01549.x

- Drago F, Ciccarese G, Parodi A. Pityriasis rosea and pityriasis rosea-like eruptions: how to distinguish them? JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:800-801. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2018.04.002

- Drago F, Ciccarese G, Javor S, et al. Vaccine-induced pityriasis rosea and pityriasis rosea-like eruptions: a review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:544-545. doi:10.1111/jdv.12942

- Mubki TF, Bin Dayel SA, Kadry R. A case of pityriasis rosea concurrent with the novel influenza A (H1N1) infection. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:341-342. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2010.01090.x

- Nelson CA, Moore AR, Perea AE, et al. Cat scratch disease: U.S. clinicians’ experience and knowledge [published online July 14, 2017]. Zoonoses Public Health. 2018;65:67-73. doi:10.1111/zph.12368

- Habot-Wilner Z, Trivizki O, Goldstein M, et al. Cat-scratch disease: ocular manifestations and treatment outcome. Acta Ophthalmol. 2018;96:E524-E532. doi:10.1111/aos.13684

- Schattner A, Uliel L, Dubin I. The cat did it: erythema nodosum and additional atypical presentations of Bartonella henselae infection in immunocompetent hosts [published online February 16, 2018]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2017-222511

- Shorbatli L, Koranyi K, Nahata M. Effectiveness of antibiotic therapy in pediatric patients with cat scratch disease. Int J Clin Pharm. 2018;40:1458-1461. doi: 10.1007/s11096-018-0746-1

- Bass JW, Freitas BC, Freitas AD, et al. Prospective randomized double blind placebo-controlled evaluation of azithromycin for treatment of cat-scratch disease. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998;17:447-452. doi:10.1097/00006454-199806000-00002

- Spach DH, Kaplan SL. Treatment of cat scratch disease. UpToDate. Updated December 9, 2021. Accessed September 12, 2023. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-cat-scratch-disease

- Drago F, Ciccarese G, Rebora A, et al. Pityriasis rosea: a comprehensive classification. Dermatology. 2016;232:431-437. doi:10.1159/000445375

- Urbina F, Das A, Sudy E. Clinical variants of pityriasis rosea. World J Clin Cases. 2017;5:203-211. doi:10.12998/wjcc.v5.i6.203

- Alzahrani NA, Al Jasser MI. Geographic tonguelike presentation in a child with pityriasis rosea: case report and review of oral manifestations of pityriasis rosea. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:E124-E127. doi:10.1111/pde.13417

- Sinha S, Sardana K, Garg V. Coexistence of two atypical variants of pityriasis rosea: a case report and review of literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:538-540. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01549.x

- Drago F, Ciccarese G, Parodi A. Pityriasis rosea and pityriasis rosea-like eruptions: how to distinguish them? JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:800-801. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2018.04.002

- Drago F, Ciccarese G, Javor S, et al. Vaccine-induced pityriasis rosea and pityriasis rosea-like eruptions: a review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:544-545. doi:10.1111/jdv.12942

- Mubki TF, Bin Dayel SA, Kadry R. A case of pityriasis rosea concurrent with the novel influenza A (H1N1) infection. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:341-342. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2010.01090.x

Practice Points

- Dermatologists should familiarize themselves with the physical examination findings of cat scratch disease.

- There are numerous clinical variants and triggers of pityriasis rosea (PR).

- There may be a new infectious trigger for PR, and exposure to cats prior to a classic PR eruption should raise one’s suspicion as a possible cause.

Acroangiodermatitis of Mali and Stewart-Bluefarb Syndrome

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 56-year-old white man with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, sleep apnea, bilateral knee replacement, and cataract removal presented to the emergency department with a worsening rash on the left posterior medial leg of 6 months’ duration. He reported associated redness and tenderness with the plaques as well as increased swelling and firmness of the leg. He was admitted to the hospital where the infectious disease team treated him with cefazolin for presumed cellulitis. His condition did not improve, and another course of cefazolin was started in addition to oral fluconazole and clotrimazole–betamethasone dipropionate lotion for a possible fungal cause. Again, treatment provided no improvement.

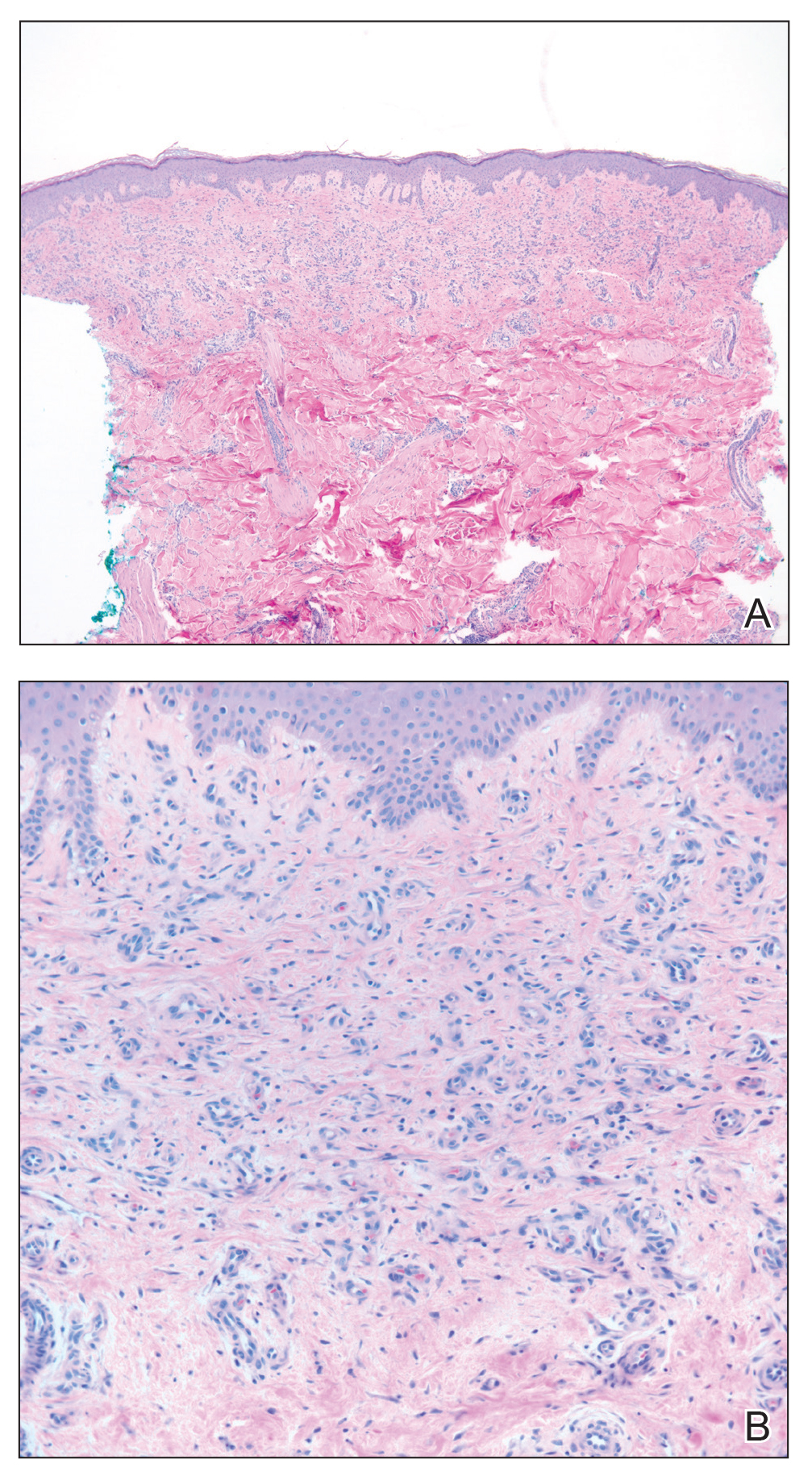

He was then evaluated by dermatology. On physical examination, the patient had edema, warmth, and induration of the left lower leg. There also was an annular and serpiginous indurated plaque with minimal scale on the left lower leg (Figure 1). A firm, dark red to purple plaque on the left medial thigh with mild scale was present. There also was scaling of the right plantar foot.

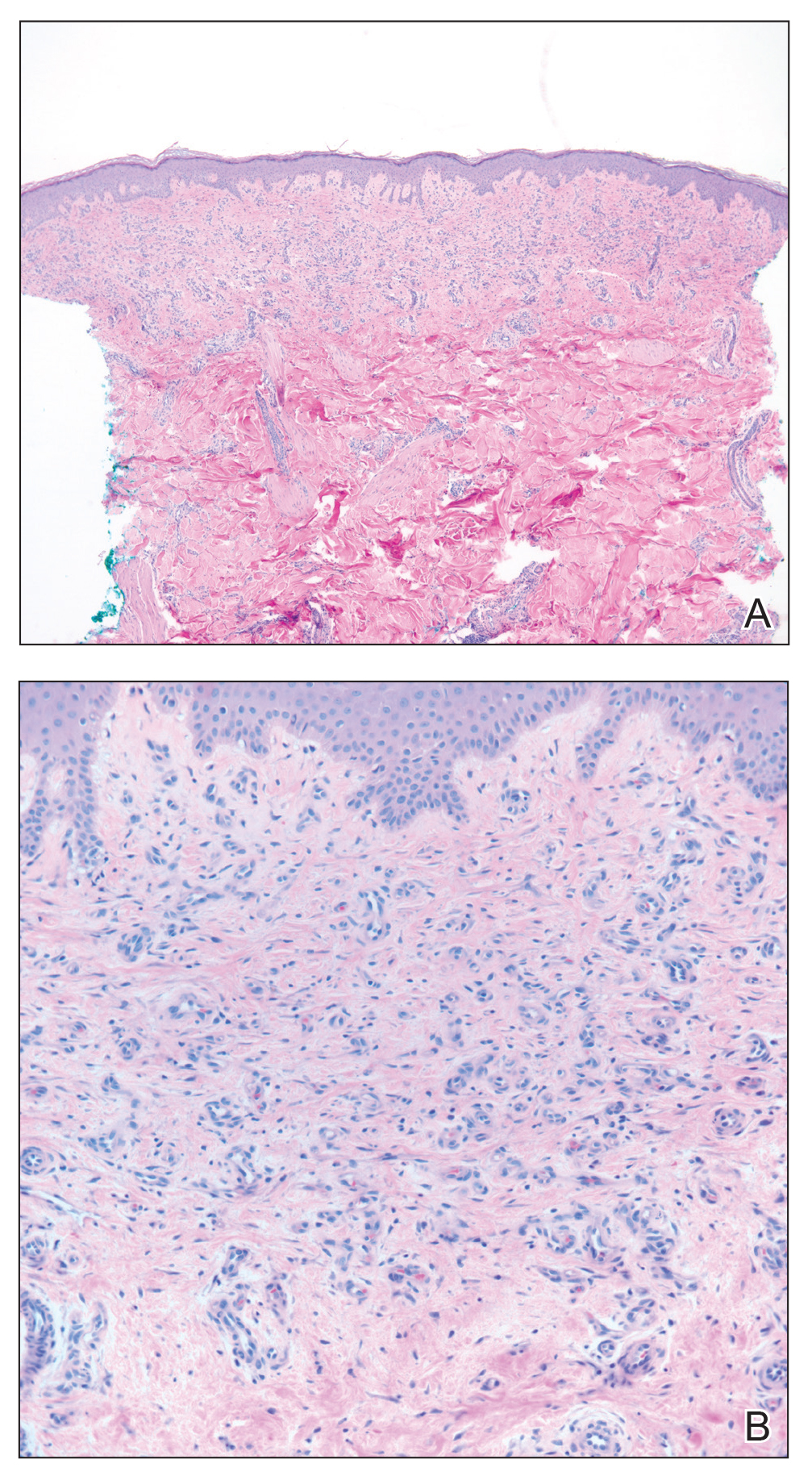

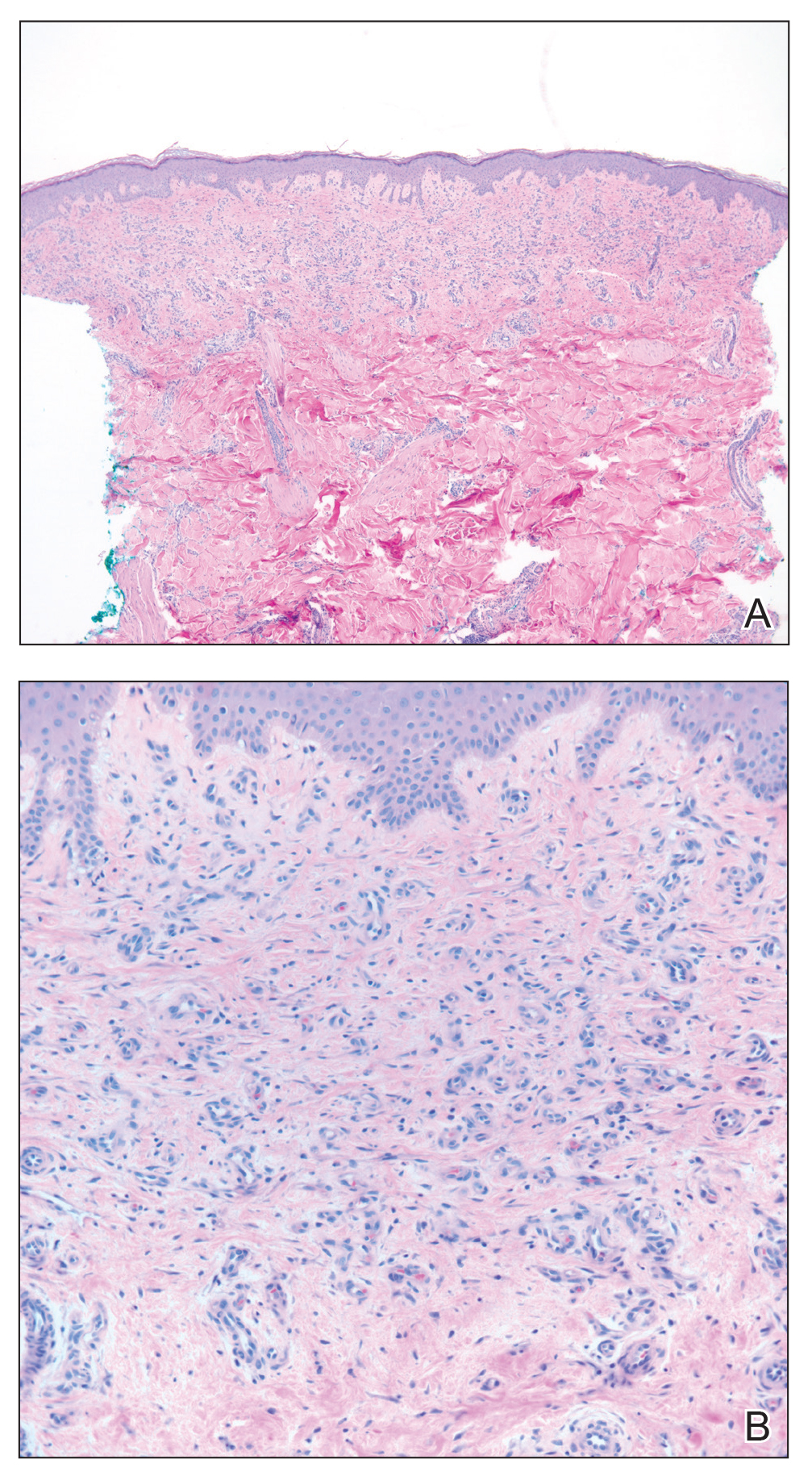

Skin biopsy revealed a dermal capillary proliferation with a scattering of inflammatory cells including eosinophils as well as dermal fibrosis (Figure 2). Periodic acid–Schiff and human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) immunostains were negative. Considering the degree and depth of vascular proliferation, Mali-type acroangiodermatitis (AAD) was the favored diagnosis.

Patient 2

A 72-year-old white man presented with a firm asymptomatic growth on the left dorsal forearm of 3 months’ duration. It was located near the site of a prior squamous cell carcinoma that was excised 1 year prior to presentation. The patient had no treatment or biopsy of the presenting lesion. His medical and surgical history included polycystic kidney disease and renal transplantation 4 years prior to presentation. He also had an arteriovenous fistula of the left arm. His other chronic diseases included chronic obstructive lung disease, congestive heart failure, hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and obstructive sleep apnea.

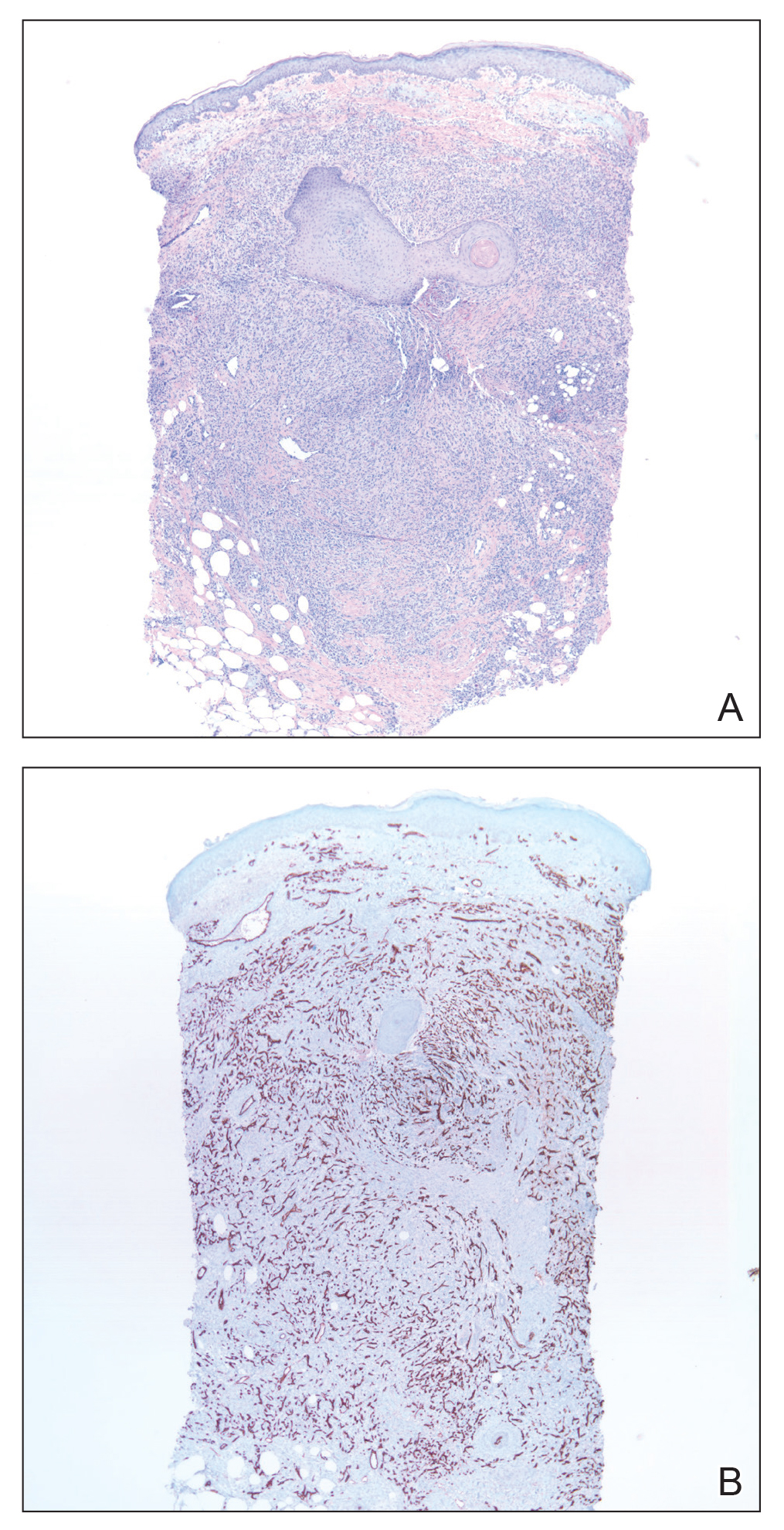

On physical examination, the patient had a 1-cm violaceous nodule on the extensor surface of the left mid forearm. An arteriovenous fistula was present proximal to the lesion on the left arm (Figure 3).

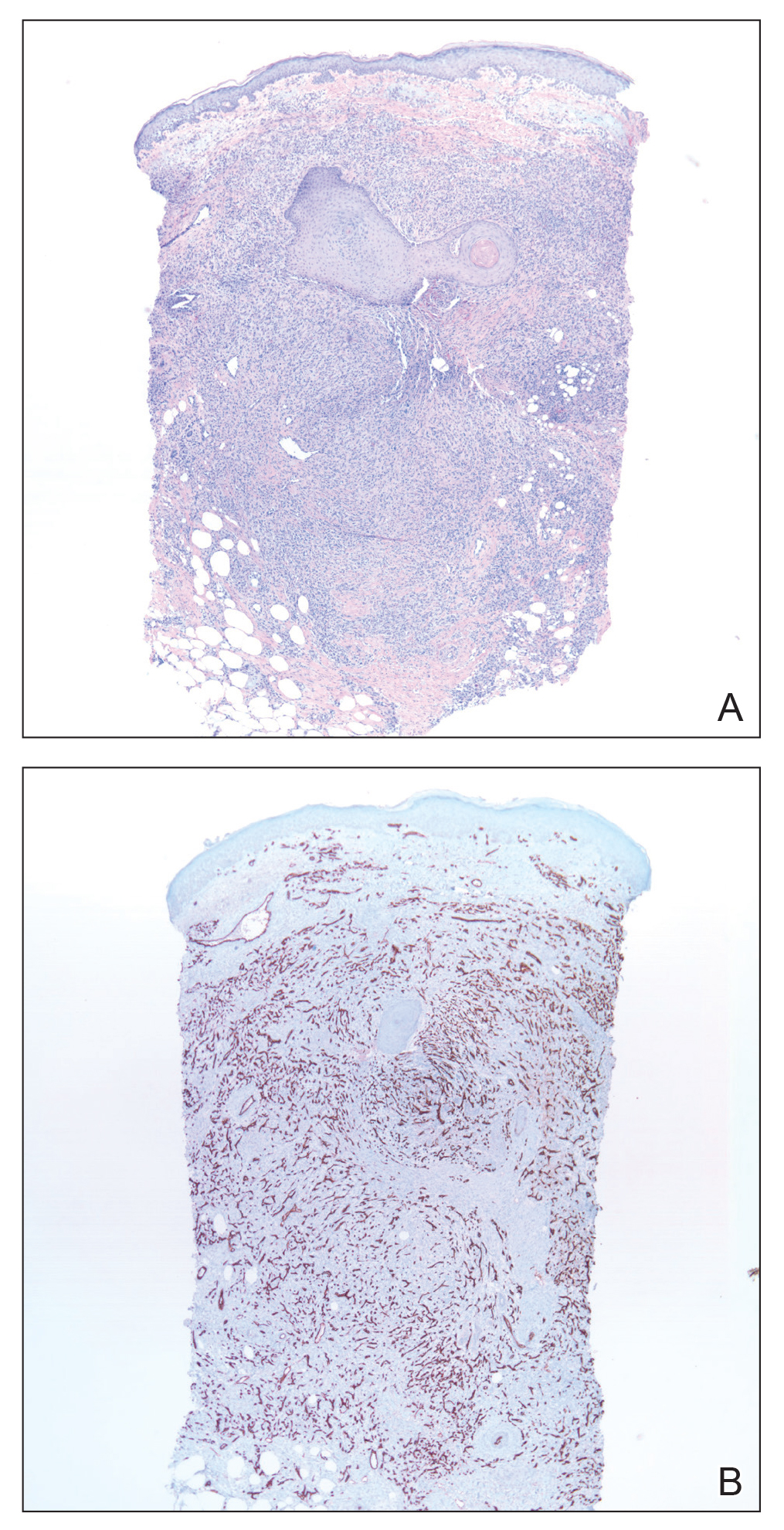

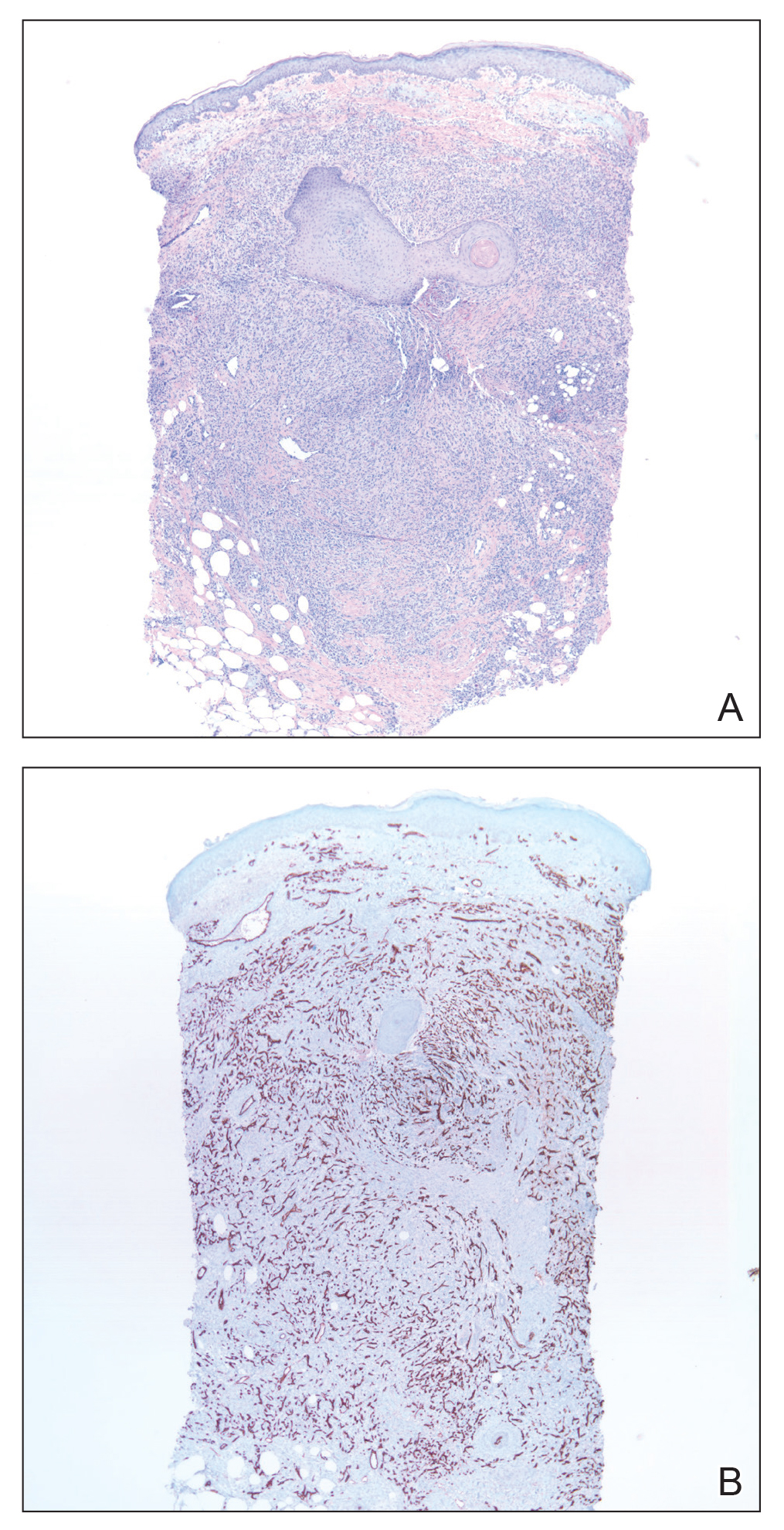

Skin biopsy revealed a tightly packed proliferation of small vascular channels that tested negative for HHV-8, tumor protein p63, and cytokeratin 5/6. Erythrocytes were noted in the lumen of some of these vessels. Neutrophils were scattered and clustered throughout the specimen (Figure 4A). Blood vessels were highlighted with CD34 (Figure 4B). Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain was negative for infectious agents. These findings favored AAD secondary to an arteriovenous malformation, consistent with Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome (SBS).

Comment

Presentation of AAD

Acroangiodermatitis is a rare chronic inflammatory skin process involving a reactive proliferation of capillaries and fibrosis of the skin that resembles Kaposi sarcoma both clinically and histopathologically. The condition has been reported in patients with chronic venous insufficiency,1 congenital arteriovenous malformation,2 acquired iatrogenic arteriovenous fistula,3 paralyzed extremity,4 suction socket lower limb prosthesis (amputees),5 and minor trauma.6-8 The lesions of AAD tend to be circumscribed, slowly evolving, red-violaceous (or brown or dusky) macules, papules, or plaques that may become verrucous or develop into painful ulcerations. They generally occur on the distal dorsal aspects of the lower legs and feet.110

Variants of AAD

Mali et al9 first reported cutaneous manifestations resembling Kaposi sarcoma in 18 patients with chronic venous insufficiency in 1965. Two years later, Bluefarb and Adams10 described kaposiform skin lesions in one patient with a congenital arteriovenous malformation without chronic venous insufficiency. It was not until 1974, however, that Earhart et al11 proposed the term pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma.10,11 Based on these findings, AAD is described as 2 variants: Mali type and SBS.

Mali-type AAD is more common and typically occurs in elderly men. It classically presents bilaterally on the lower extremities in association with severe chronic venous insufficiency.5 Skin lesions usually occur on the medial aspect of the lower legs (as in patient 1), dorsum of the heel, hallux, or second toe.12

The etiology of Mali-type AAD is poorly understood. The leading theory is that the condition involves reduced perfusion due to chronic edema, resulting in neovascularization, fibroblast proliferation, hypertrophy, and inflammatory skin changes. When AAD occurs in the setting of a suction socket prosthesis, the negative pressure of the stump-socket environment is thought to alter local circulation, leading to proliferation of small blood vessels.5,13

Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome usually involves a single extremity in young adults with congenital arteriovenous malformations, amputees, and individuals with hemiplegia or iatrogenic arteriovenous fistulae (as in patient 2).1 It was once thought to occur secondary to Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber syndrome; however, SBS rarely is accompanied by limb hypertrophy.9 Pathogenesis is thought to involve an angiogenic response to a high perfusion rate and high oxygen saturation, which leads to fibroblast proliferation and reactive endothelial hyperplasia.1,14

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

Prompt identification of an underlying arteriovenous anomaly is critical, given the sequelae of high-flow shunts, which may result in skin ulceration, limb length discrepancy, cortical thinning of bone with regional osteoporosis, and congestive heart failure.1,5 Duplex ultrasonography is the first-line diagnostic modality because it is noninvasive and widely available. The key doppler feature of an arteriovenous malformation is low resistance and high diastolic pulsatile flow,1 which should be confirmed with magnetic resonance angiography or computed tomography angiography if present on ultrasonography.

The differential diagnosis of AAD includes Kaposi sarcoma, reactive angioendotheliomatosis, diffuse dermal angiomatosis, intravascular histiocytosis, glomeruloid angioendotheliomatosis, and angiopericytomatosis.15,16 These entities present as multiple erythematous, violaceous, purpuric patches and plaques generally on the extremities but can have a widely varied distribution. Some lesions evolve to necrosis or ulceration. Histopathologic analysis is useful to differentiate these entities.

Histopathology

The histopathologic features of AAD can be nonspecific; clinicopathologic correlation often is necessary to establish the diagnosis. Features include a proliferation of small thick-walled vessels, often in a lobular arrangement, in an edematous papillary dermis. Small thrombi may be observed. There may be increased fibroblasts; plump endothelial cells; a superficial mixed infiltrate comprised of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and eosinophils; and deposition of hemosiderin.2,5 These characteristics overlap with features of Kaposi sarcoma; AAD, however, lacks slitlike vascular spaces, perivascular CD34+ expression, and nuclear atypia. A negative HHV-8 stain will assist in ruling out Kaposi sarcoma.1,17

Management

Treatment reports are anecdotal. The goal is to correct underlying venous hypertension. Conservative measures with compression garments, intermittent pneumatic compression, and limb elevation are first line.18 Oral antibiotics and local wound care with topical emollients and corticosteroids have been shown to be effective treatments.19-21

Oral erythromycin 500 mg 4 times daily for 3 weeks and clobetasol propionate cream 0.05% healed a lower extremity ulcer in a patient with Mali-type AAD.21 In another patient, conservative treatment of Mali-type AAD failed, but rapid improvement of 2 lower extremity ulcers resulted after 3 weeks of oral dapsone 50 mg twice daily.22

Conclusion

Acroangiodermatitis is a rare entity that is characterized by erythematous violaceous papules and plaques of the extremities, commonly in the setting of chronic venous insufficiency or an arteriovenous shunt. Histopathologic analysis shows proliferation of capillaries with fibrosis, extravasation of erythrocytes, and deposition of hemosiderin without the spindle cells and slitlike vascular spaces characteristic of Kaposi sarcoma. Detection of an underlying arteriovenous malformation is essential, as the disease can have local and systemic consequences, such as skin ulceration and congestive heart failure.1 Treatment options are conservative, directed toward local wound care, compression, and management of complications, such as ulceration and infection, as well as obliterating any underlying arteriovenous malformation.

- Parsi K, O’Connor AA, Bester L. Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome: report of five cases and a review of literature. Phlebology. 2015;30:505-514.

- Larralde M, Gonzalez V, Marietti R, et al. Pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma with arteriovenous malformation. Pediatr Dermatol. 2001;18:325-327.

- Nakanishi G, Tachibana T, Soga H, et al. Pseudo-Kaposi’s sarcoma of the hand associated with acquired iatrogenic arteriovenous fistula. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:415-416.

- Landthaler M, Langehenke H, Holzmann H, et al. Mali’s acroangiodermatitis (pseudo-Kaposi) in paralyzed legs. Hautarzt. 1988;39:304-307.

- Trindade F, Requena L. Pseudo-Kaposi’s sarcoma because of suction socket lower limb prosthesis. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:482-485.

- Yu-Lu W, Tao Q, Hong-Zhong J, et al. Non-tender pedal plaques and nodules: pseudo-Kaposi’s sarcoma (Stewart-Bluefarb type) induced by trauma. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2015;13:927-930.

- Del-Río E, Aguilar A, Ambrojo P, et al. Pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma induced by minor trauma in a patient with Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1993;18:151-153.

- Archie M, Khademi S, Aungst D, et al. A rare case of acroangiodermatitis associated with a congenital arteriovenous malformation (Stewart-Bluefarb Syndrome) in a young veteran: case report and review of the literature. Ann Vasc Surg. 2015;29:1448.e5-1448.e10.

- Mali JW, Kuiper JP, Hamers AA. Acro-angiodermatitis of the foot. Arch Dermatol. 1965;92:515-518.

- Bluefarb SM, Adams LA. Arteriovenous malformation with angiodermatitis. stasis dermatitis simulating Kaposi’s disease. Arch Dermatol. 1967;96:176-181.

- Earhart RN, Aeling JA, Nuss DD, et al. Pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma. A patient with arteriovenous malformation and skin lesions simulating Kaposi sarcoma. Arch Dermatol. 1974;110:907-910.

- Lugovic´ L, Pusic´ J, Situm M, et al. Acroangiodermatitis (pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma): three case reports. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2007;15:152-157.

- Horiguchi Y, Takahashi K, Tanizaki H, et al. Case of bilateral acroangiodermatitis due to symmetrical arteriovenous fistulas of the soles. J Dermatol. 2015;42:989-991.

- Dog˘an S, Boztepe G, Karaduman A. Pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma: a challenging vascular phenomenon. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:22.

- Mazloom SE, Stallings A, Kyei A. Differentiating intralymphatic histiocytosis, intravascular histiocytosis, and subtypes of reactive angioendotheliomatosis: review of clinical and histologic features of all cases reported to date. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:33-39.

- Rongioletti F, Rebora A. Cutaneous reactive angiomatoses: patterns and classification of reactive vascular proliferation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:887-896.

- Kanitakis J, Narvaez D, Claudy A. Expression of the CD34 antigen distinguishes Kaposi’s sarcoma from pseudo-Kaposi’s sarcoma (acroangiodermatitis). Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:44-46.

- Pires A, Depairon M, Ricci C, et al. Effect of compression therapy on a pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma. Dermatology. 1999;198:439-441.

- Hayek S, Atiyeh B, Zgheib E. Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome: review of the literature and case report of chronic ulcer treatment with heparan sulphate (Cacipliq20®). Int Wound J. 2015;12:169-172.

- Varyani N, Thukral A, Kumar N, et al. Nonhealing ulcer: acroangiodermatitis of Mali. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2011;2011:909383.

- Mehta AA, Pereira RR, Nayak C, et al. Acroangiodermatitis of Mali: a rare vascular phenomenon. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:553-556.

- Rashkovsky I, Gilead L, Schamroth J, et al. Acro-angiodermatitis: review of the literature and report of a case. Acta Derm Venereol. 1995;75:475-478.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 56-year-old white man with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, sleep apnea, bilateral knee replacement, and cataract removal presented to the emergency department with a worsening rash on the left posterior medial leg of 6 months’ duration. He reported associated redness and tenderness with the plaques as well as increased swelling and firmness of the leg. He was admitted to the hospital where the infectious disease team treated him with cefazolin for presumed cellulitis. His condition did not improve, and another course of cefazolin was started in addition to oral fluconazole and clotrimazole–betamethasone dipropionate lotion for a possible fungal cause. Again, treatment provided no improvement.

He was then evaluated by dermatology. On physical examination, the patient had edema, warmth, and induration of the left lower leg. There also was an annular and serpiginous indurated plaque with minimal scale on the left lower leg (Figure 1). A firm, dark red to purple plaque on the left medial thigh with mild scale was present. There also was scaling of the right plantar foot.

Skin biopsy revealed a dermal capillary proliferation with a scattering of inflammatory cells including eosinophils as well as dermal fibrosis (Figure 2). Periodic acid–Schiff and human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) immunostains were negative. Considering the degree and depth of vascular proliferation, Mali-type acroangiodermatitis (AAD) was the favored diagnosis.

Patient 2

A 72-year-old white man presented with a firm asymptomatic growth on the left dorsal forearm of 3 months’ duration. It was located near the site of a prior squamous cell carcinoma that was excised 1 year prior to presentation. The patient had no treatment or biopsy of the presenting lesion. His medical and surgical history included polycystic kidney disease and renal transplantation 4 years prior to presentation. He also had an arteriovenous fistula of the left arm. His other chronic diseases included chronic obstructive lung disease, congestive heart failure, hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and obstructive sleep apnea.

On physical examination, the patient had a 1-cm violaceous nodule on the extensor surface of the left mid forearm. An arteriovenous fistula was present proximal to the lesion on the left arm (Figure 3).

Skin biopsy revealed a tightly packed proliferation of small vascular channels that tested negative for HHV-8, tumor protein p63, and cytokeratin 5/6. Erythrocytes were noted in the lumen of some of these vessels. Neutrophils were scattered and clustered throughout the specimen (Figure 4A). Blood vessels were highlighted with CD34 (Figure 4B). Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain was negative for infectious agents. These findings favored AAD secondary to an arteriovenous malformation, consistent with Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome (SBS).

Comment

Presentation of AAD

Acroangiodermatitis is a rare chronic inflammatory skin process involving a reactive proliferation of capillaries and fibrosis of the skin that resembles Kaposi sarcoma both clinically and histopathologically. The condition has been reported in patients with chronic venous insufficiency,1 congenital arteriovenous malformation,2 acquired iatrogenic arteriovenous fistula,3 paralyzed extremity,4 suction socket lower limb prosthesis (amputees),5 and minor trauma.6-8 The lesions of AAD tend to be circumscribed, slowly evolving, red-violaceous (or brown or dusky) macules, papules, or plaques that may become verrucous or develop into painful ulcerations. They generally occur on the distal dorsal aspects of the lower legs and feet.110

Variants of AAD

Mali et al9 first reported cutaneous manifestations resembling Kaposi sarcoma in 18 patients with chronic venous insufficiency in 1965. Two years later, Bluefarb and Adams10 described kaposiform skin lesions in one patient with a congenital arteriovenous malformation without chronic venous insufficiency. It was not until 1974, however, that Earhart et al11 proposed the term pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma.10,11 Based on these findings, AAD is described as 2 variants: Mali type and SBS.

Mali-type AAD is more common and typically occurs in elderly men. It classically presents bilaterally on the lower extremities in association with severe chronic venous insufficiency.5 Skin lesions usually occur on the medial aspect of the lower legs (as in patient 1), dorsum of the heel, hallux, or second toe.12

The etiology of Mali-type AAD is poorly understood. The leading theory is that the condition involves reduced perfusion due to chronic edema, resulting in neovascularization, fibroblast proliferation, hypertrophy, and inflammatory skin changes. When AAD occurs in the setting of a suction socket prosthesis, the negative pressure of the stump-socket environment is thought to alter local circulation, leading to proliferation of small blood vessels.5,13

Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome usually involves a single extremity in young adults with congenital arteriovenous malformations, amputees, and individuals with hemiplegia or iatrogenic arteriovenous fistulae (as in patient 2).1 It was once thought to occur secondary to Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber syndrome; however, SBS rarely is accompanied by limb hypertrophy.9 Pathogenesis is thought to involve an angiogenic response to a high perfusion rate and high oxygen saturation, which leads to fibroblast proliferation and reactive endothelial hyperplasia.1,14

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

Prompt identification of an underlying arteriovenous anomaly is critical, given the sequelae of high-flow shunts, which may result in skin ulceration, limb length discrepancy, cortical thinning of bone with regional osteoporosis, and congestive heart failure.1,5 Duplex ultrasonography is the first-line diagnostic modality because it is noninvasive and widely available. The key doppler feature of an arteriovenous malformation is low resistance and high diastolic pulsatile flow,1 which should be confirmed with magnetic resonance angiography or computed tomography angiography if present on ultrasonography.

The differential diagnosis of AAD includes Kaposi sarcoma, reactive angioendotheliomatosis, diffuse dermal angiomatosis, intravascular histiocytosis, glomeruloid angioendotheliomatosis, and angiopericytomatosis.15,16 These entities present as multiple erythematous, violaceous, purpuric patches and plaques generally on the extremities but can have a widely varied distribution. Some lesions evolve to necrosis or ulceration. Histopathologic analysis is useful to differentiate these entities.

Histopathology

The histopathologic features of AAD can be nonspecific; clinicopathologic correlation often is necessary to establish the diagnosis. Features include a proliferation of small thick-walled vessels, often in a lobular arrangement, in an edematous papillary dermis. Small thrombi may be observed. There may be increased fibroblasts; plump endothelial cells; a superficial mixed infiltrate comprised of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and eosinophils; and deposition of hemosiderin.2,5 These characteristics overlap with features of Kaposi sarcoma; AAD, however, lacks slitlike vascular spaces, perivascular CD34+ expression, and nuclear atypia. A negative HHV-8 stain will assist in ruling out Kaposi sarcoma.1,17

Management

Treatment reports are anecdotal. The goal is to correct underlying venous hypertension. Conservative measures with compression garments, intermittent pneumatic compression, and limb elevation are first line.18 Oral antibiotics and local wound care with topical emollients and corticosteroids have been shown to be effective treatments.19-21

Oral erythromycin 500 mg 4 times daily for 3 weeks and clobetasol propionate cream 0.05% healed a lower extremity ulcer in a patient with Mali-type AAD.21 In another patient, conservative treatment of Mali-type AAD failed, but rapid improvement of 2 lower extremity ulcers resulted after 3 weeks of oral dapsone 50 mg twice daily.22

Conclusion

Acroangiodermatitis is a rare entity that is characterized by erythematous violaceous papules and plaques of the extremities, commonly in the setting of chronic venous insufficiency or an arteriovenous shunt. Histopathologic analysis shows proliferation of capillaries with fibrosis, extravasation of erythrocytes, and deposition of hemosiderin without the spindle cells and slitlike vascular spaces characteristic of Kaposi sarcoma. Detection of an underlying arteriovenous malformation is essential, as the disease can have local and systemic consequences, such as skin ulceration and congestive heart failure.1 Treatment options are conservative, directed toward local wound care, compression, and management of complications, such as ulceration and infection, as well as obliterating any underlying arteriovenous malformation.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 56-year-old white man with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, sleep apnea, bilateral knee replacement, and cataract removal presented to the emergency department with a worsening rash on the left posterior medial leg of 6 months’ duration. He reported associated redness and tenderness with the plaques as well as increased swelling and firmness of the leg. He was admitted to the hospital where the infectious disease team treated him with cefazolin for presumed cellulitis. His condition did not improve, and another course of cefazolin was started in addition to oral fluconazole and clotrimazole–betamethasone dipropionate lotion for a possible fungal cause. Again, treatment provided no improvement.

He was then evaluated by dermatology. On physical examination, the patient had edema, warmth, and induration of the left lower leg. There also was an annular and serpiginous indurated plaque with minimal scale on the left lower leg (Figure 1). A firm, dark red to purple plaque on the left medial thigh with mild scale was present. There also was scaling of the right plantar foot.

Skin biopsy revealed a dermal capillary proliferation with a scattering of inflammatory cells including eosinophils as well as dermal fibrosis (Figure 2). Periodic acid–Schiff and human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) immunostains were negative. Considering the degree and depth of vascular proliferation, Mali-type acroangiodermatitis (AAD) was the favored diagnosis.

Patient 2

A 72-year-old white man presented with a firm asymptomatic growth on the left dorsal forearm of 3 months’ duration. It was located near the site of a prior squamous cell carcinoma that was excised 1 year prior to presentation. The patient had no treatment or biopsy of the presenting lesion. His medical and surgical history included polycystic kidney disease and renal transplantation 4 years prior to presentation. He also had an arteriovenous fistula of the left arm. His other chronic diseases included chronic obstructive lung disease, congestive heart failure, hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and obstructive sleep apnea.

On physical examination, the patient had a 1-cm violaceous nodule on the extensor surface of the left mid forearm. An arteriovenous fistula was present proximal to the lesion on the left arm (Figure 3).

Skin biopsy revealed a tightly packed proliferation of small vascular channels that tested negative for HHV-8, tumor protein p63, and cytokeratin 5/6. Erythrocytes were noted in the lumen of some of these vessels. Neutrophils were scattered and clustered throughout the specimen (Figure 4A). Blood vessels were highlighted with CD34 (Figure 4B). Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain was negative for infectious agents. These findings favored AAD secondary to an arteriovenous malformation, consistent with Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome (SBS).

Comment

Presentation of AAD

Acroangiodermatitis is a rare chronic inflammatory skin process involving a reactive proliferation of capillaries and fibrosis of the skin that resembles Kaposi sarcoma both clinically and histopathologically. The condition has been reported in patients with chronic venous insufficiency,1 congenital arteriovenous malformation,2 acquired iatrogenic arteriovenous fistula,3 paralyzed extremity,4 suction socket lower limb prosthesis (amputees),5 and minor trauma.6-8 The lesions of AAD tend to be circumscribed, slowly evolving, red-violaceous (or brown or dusky) macules, papules, or plaques that may become verrucous or develop into painful ulcerations. They generally occur on the distal dorsal aspects of the lower legs and feet.110

Variants of AAD

Mali et al9 first reported cutaneous manifestations resembling Kaposi sarcoma in 18 patients with chronic venous insufficiency in 1965. Two years later, Bluefarb and Adams10 described kaposiform skin lesions in one patient with a congenital arteriovenous malformation without chronic venous insufficiency. It was not until 1974, however, that Earhart et al11 proposed the term pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma.10,11 Based on these findings, AAD is described as 2 variants: Mali type and SBS.

Mali-type AAD is more common and typically occurs in elderly men. It classically presents bilaterally on the lower extremities in association with severe chronic venous insufficiency.5 Skin lesions usually occur on the medial aspect of the lower legs (as in patient 1), dorsum of the heel, hallux, or second toe.12

The etiology of Mali-type AAD is poorly understood. The leading theory is that the condition involves reduced perfusion due to chronic edema, resulting in neovascularization, fibroblast proliferation, hypertrophy, and inflammatory skin changes. When AAD occurs in the setting of a suction socket prosthesis, the negative pressure of the stump-socket environment is thought to alter local circulation, leading to proliferation of small blood vessels.5,13

Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome usually involves a single extremity in young adults with congenital arteriovenous malformations, amputees, and individuals with hemiplegia or iatrogenic arteriovenous fistulae (as in patient 2).1 It was once thought to occur secondary to Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber syndrome; however, SBS rarely is accompanied by limb hypertrophy.9 Pathogenesis is thought to involve an angiogenic response to a high perfusion rate and high oxygen saturation, which leads to fibroblast proliferation and reactive endothelial hyperplasia.1,14

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

Prompt identification of an underlying arteriovenous anomaly is critical, given the sequelae of high-flow shunts, which may result in skin ulceration, limb length discrepancy, cortical thinning of bone with regional osteoporosis, and congestive heart failure.1,5 Duplex ultrasonography is the first-line diagnostic modality because it is noninvasive and widely available. The key doppler feature of an arteriovenous malformation is low resistance and high diastolic pulsatile flow,1 which should be confirmed with magnetic resonance angiography or computed tomography angiography if present on ultrasonography.

The differential diagnosis of AAD includes Kaposi sarcoma, reactive angioendotheliomatosis, diffuse dermal angiomatosis, intravascular histiocytosis, glomeruloid angioendotheliomatosis, and angiopericytomatosis.15,16 These entities present as multiple erythematous, violaceous, purpuric patches and plaques generally on the extremities but can have a widely varied distribution. Some lesions evolve to necrosis or ulceration. Histopathologic analysis is useful to differentiate these entities.

Histopathology

The histopathologic features of AAD can be nonspecific; clinicopathologic correlation often is necessary to establish the diagnosis. Features include a proliferation of small thick-walled vessels, often in a lobular arrangement, in an edematous papillary dermis. Small thrombi may be observed. There may be increased fibroblasts; plump endothelial cells; a superficial mixed infiltrate comprised of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and eosinophils; and deposition of hemosiderin.2,5 These characteristics overlap with features of Kaposi sarcoma; AAD, however, lacks slitlike vascular spaces, perivascular CD34+ expression, and nuclear atypia. A negative HHV-8 stain will assist in ruling out Kaposi sarcoma.1,17

Management

Treatment reports are anecdotal. The goal is to correct underlying venous hypertension. Conservative measures with compression garments, intermittent pneumatic compression, and limb elevation are first line.18 Oral antibiotics and local wound care with topical emollients and corticosteroids have been shown to be effective treatments.19-21

Oral erythromycin 500 mg 4 times daily for 3 weeks and clobetasol propionate cream 0.05% healed a lower extremity ulcer in a patient with Mali-type AAD.21 In another patient, conservative treatment of Mali-type AAD failed, but rapid improvement of 2 lower extremity ulcers resulted after 3 weeks of oral dapsone 50 mg twice daily.22

Conclusion

Acroangiodermatitis is a rare entity that is characterized by erythematous violaceous papules and plaques of the extremities, commonly in the setting of chronic venous insufficiency or an arteriovenous shunt. Histopathologic analysis shows proliferation of capillaries with fibrosis, extravasation of erythrocytes, and deposition of hemosiderin without the spindle cells and slitlike vascular spaces characteristic of Kaposi sarcoma. Detection of an underlying arteriovenous malformation is essential, as the disease can have local and systemic consequences, such as skin ulceration and congestive heart failure.1 Treatment options are conservative, directed toward local wound care, compression, and management of complications, such as ulceration and infection, as well as obliterating any underlying arteriovenous malformation.

- Parsi K, O’Connor AA, Bester L. Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome: report of five cases and a review of literature. Phlebology. 2015;30:505-514.

- Larralde M, Gonzalez V, Marietti R, et al. Pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma with arteriovenous malformation. Pediatr Dermatol. 2001;18:325-327.

- Nakanishi G, Tachibana T, Soga H, et al. Pseudo-Kaposi’s sarcoma of the hand associated with acquired iatrogenic arteriovenous fistula. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:415-416.

- Landthaler M, Langehenke H, Holzmann H, et al. Mali’s acroangiodermatitis (pseudo-Kaposi) in paralyzed legs. Hautarzt. 1988;39:304-307.

- Trindade F, Requena L. Pseudo-Kaposi’s sarcoma because of suction socket lower limb prosthesis. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:482-485.

- Yu-Lu W, Tao Q, Hong-Zhong J, et al. Non-tender pedal plaques and nodules: pseudo-Kaposi’s sarcoma (Stewart-Bluefarb type) induced by trauma. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2015;13:927-930.

- Del-Río E, Aguilar A, Ambrojo P, et al. Pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma induced by minor trauma in a patient with Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1993;18:151-153.

- Archie M, Khademi S, Aungst D, et al. A rare case of acroangiodermatitis associated with a congenital arteriovenous malformation (Stewart-Bluefarb Syndrome) in a young veteran: case report and review of the literature. Ann Vasc Surg. 2015;29:1448.e5-1448.e10.

- Mali JW, Kuiper JP, Hamers AA. Acro-angiodermatitis of the foot. Arch Dermatol. 1965;92:515-518.

- Bluefarb SM, Adams LA. Arteriovenous malformation with angiodermatitis. stasis dermatitis simulating Kaposi’s disease. Arch Dermatol. 1967;96:176-181.

- Earhart RN, Aeling JA, Nuss DD, et al. Pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma. A patient with arteriovenous malformation and skin lesions simulating Kaposi sarcoma. Arch Dermatol. 1974;110:907-910.

- Lugovic´ L, Pusic´ J, Situm M, et al. Acroangiodermatitis (pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma): three case reports. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2007;15:152-157.

- Horiguchi Y, Takahashi K, Tanizaki H, et al. Case of bilateral acroangiodermatitis due to symmetrical arteriovenous fistulas of the soles. J Dermatol. 2015;42:989-991.

- Dog˘an S, Boztepe G, Karaduman A. Pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma: a challenging vascular phenomenon. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:22.

- Mazloom SE, Stallings A, Kyei A. Differentiating intralymphatic histiocytosis, intravascular histiocytosis, and subtypes of reactive angioendotheliomatosis: review of clinical and histologic features of all cases reported to date. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:33-39.

- Rongioletti F, Rebora A. Cutaneous reactive angiomatoses: patterns and classification of reactive vascular proliferation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:887-896.

- Kanitakis J, Narvaez D, Claudy A. Expression of the CD34 antigen distinguishes Kaposi’s sarcoma from pseudo-Kaposi’s sarcoma (acroangiodermatitis). Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:44-46.

- Pires A, Depairon M, Ricci C, et al. Effect of compression therapy on a pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma. Dermatology. 1999;198:439-441.

- Hayek S, Atiyeh B, Zgheib E. Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome: review of the literature and case report of chronic ulcer treatment with heparan sulphate (Cacipliq20®). Int Wound J. 2015;12:169-172.

- Varyani N, Thukral A, Kumar N, et al. Nonhealing ulcer: acroangiodermatitis of Mali. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2011;2011:909383.

- Mehta AA, Pereira RR, Nayak C, et al. Acroangiodermatitis of Mali: a rare vascular phenomenon. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:553-556.

- Rashkovsky I, Gilead L, Schamroth J, et al. Acro-angiodermatitis: review of the literature and report of a case. Acta Derm Venereol. 1995;75:475-478.

- Parsi K, O’Connor AA, Bester L. Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome: report of five cases and a review of literature. Phlebology. 2015;30:505-514.

- Larralde M, Gonzalez V, Marietti R, et al. Pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma with arteriovenous malformation. Pediatr Dermatol. 2001;18:325-327.

- Nakanishi G, Tachibana T, Soga H, et al. Pseudo-Kaposi’s sarcoma of the hand associated with acquired iatrogenic arteriovenous fistula. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:415-416.

- Landthaler M, Langehenke H, Holzmann H, et al. Mali’s acroangiodermatitis (pseudo-Kaposi) in paralyzed legs. Hautarzt. 1988;39:304-307.

- Trindade F, Requena L. Pseudo-Kaposi’s sarcoma because of suction socket lower limb prosthesis. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:482-485.

- Yu-Lu W, Tao Q, Hong-Zhong J, et al. Non-tender pedal plaques and nodules: pseudo-Kaposi’s sarcoma (Stewart-Bluefarb type) induced by trauma. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2015;13:927-930.

- Del-Río E, Aguilar A, Ambrojo P, et al. Pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma induced by minor trauma in a patient with Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1993;18:151-153.

- Archie M, Khademi S, Aungst D, et al. A rare case of acroangiodermatitis associated with a congenital arteriovenous malformation (Stewart-Bluefarb Syndrome) in a young veteran: case report and review of the literature. Ann Vasc Surg. 2015;29:1448.e5-1448.e10.

- Mali JW, Kuiper JP, Hamers AA. Acro-angiodermatitis of the foot. Arch Dermatol. 1965;92:515-518.

- Bluefarb SM, Adams LA. Arteriovenous malformation with angiodermatitis. stasis dermatitis simulating Kaposi’s disease. Arch Dermatol. 1967;96:176-181.

- Earhart RN, Aeling JA, Nuss DD, et al. Pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma. A patient with arteriovenous malformation and skin lesions simulating Kaposi sarcoma. Arch Dermatol. 1974;110:907-910.

- Lugovic´ L, Pusic´ J, Situm M, et al. Acroangiodermatitis (pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma): three case reports. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2007;15:152-157.

- Horiguchi Y, Takahashi K, Tanizaki H, et al. Case of bilateral acroangiodermatitis due to symmetrical arteriovenous fistulas of the soles. J Dermatol. 2015;42:989-991.

- Dog˘an S, Boztepe G, Karaduman A. Pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma: a challenging vascular phenomenon. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:22.

- Mazloom SE, Stallings A, Kyei A. Differentiating intralymphatic histiocytosis, intravascular histiocytosis, and subtypes of reactive angioendotheliomatosis: review of clinical and histologic features of all cases reported to date. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:33-39.

- Rongioletti F, Rebora A. Cutaneous reactive angiomatoses: patterns and classification of reactive vascular proliferation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:887-896.

- Kanitakis J, Narvaez D, Claudy A. Expression of the CD34 antigen distinguishes Kaposi’s sarcoma from pseudo-Kaposi’s sarcoma (acroangiodermatitis). Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:44-46.

- Pires A, Depairon M, Ricci C, et al. Effect of compression therapy on a pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma. Dermatology. 1999;198:439-441.

- Hayek S, Atiyeh B, Zgheib E. Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome: review of the literature and case report of chronic ulcer treatment with heparan sulphate (Cacipliq20®). Int Wound J. 2015;12:169-172.

- Varyani N, Thukral A, Kumar N, et al. Nonhealing ulcer: acroangiodermatitis of Mali. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2011;2011:909383.

- Mehta AA, Pereira RR, Nayak C, et al. Acroangiodermatitis of Mali: a rare vascular phenomenon. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:553-556.

- Rashkovsky I, Gilead L, Schamroth J, et al. Acro-angiodermatitis: review of the literature and report of a case. Acta Derm Venereol. 1995;75:475-478.

Practice Points

- Acroangiodermatitis (AAD) may mimic Kaposi sarcoma clinically and histopathologically. A human herpesvirus 8 stain is helpful to differentiate these two entities.

- Diagnosis of AAD should prompt investigation of an underlying arteriovenous malformation, as the disease may have systemic consequences such as congestive heart failure.