User login

Blastomycosislike Pyoderma: Verrucous Hyperpigmented Plaques on the Pretibial Shins

To the Editor:

Blastomycosislike pyoderma (BLP), also commonly referred to as pyoderma vegetans, is a rare cutaneous bacterial infection that often mimics other fungal, inflammatory, or neoplastic disorders.1 It is characterized by a collection of neutrophilic abscesses with pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia that coalesce into crusted plaques.

A 15-year-old adolescent girl with a history of type 1 diabetes mellitus was admitted for diabetic ketoacidosis. The patient presented with bilateral pretibial lesions of 6 years’ duration that developed after swimming in a pool following reported trauma to the site. These pruritic plaques had grown slowly and were occasionally tender. Of note, with episodes of hyperglycemia, the lesions developed purulent drainage.

Upon admission to the hospital and subsequent dermatology consultation, physical examination revealed the right pretibial shin had a 15×5-cm, gray-brown, hyperpigmented, verrucous, tender plaque with purulent drainage and overlying crust (Figure 1). The left pretibial shin had a similar smaller lesion (Figure 2). Laboratory test results were notable for a white blood cell count of 41.84 cells/µL (reference range, 3.8–10.5 cells/µL), blood glucose level of 586 mg/dL (reference range, 70–99 mg/dL), and hemoglobin A1c of 11.7% (reference range, 4.0%–5.6%). A biopsy specimen from the right pretibial shin was stained with hematoxylin and eosin for dermatopathologic evaluation as well as sent for tissue culture. Tissue and wound cultures grew Staphylococcus aureus and group B Streptococcus with no fungal or acid-fast bacilli growth.

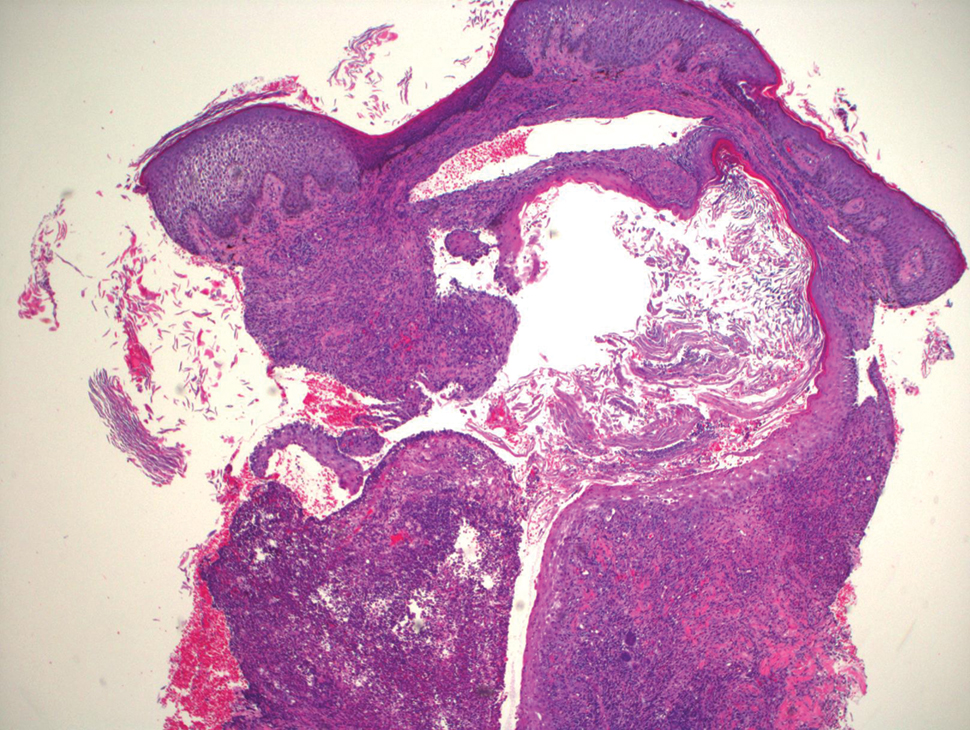

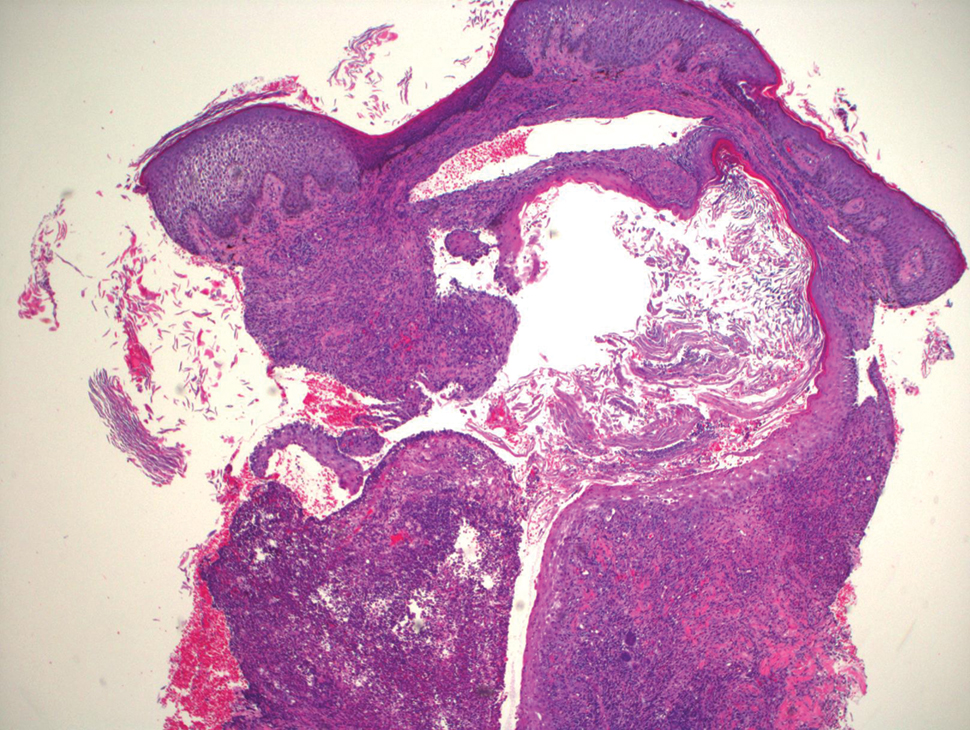

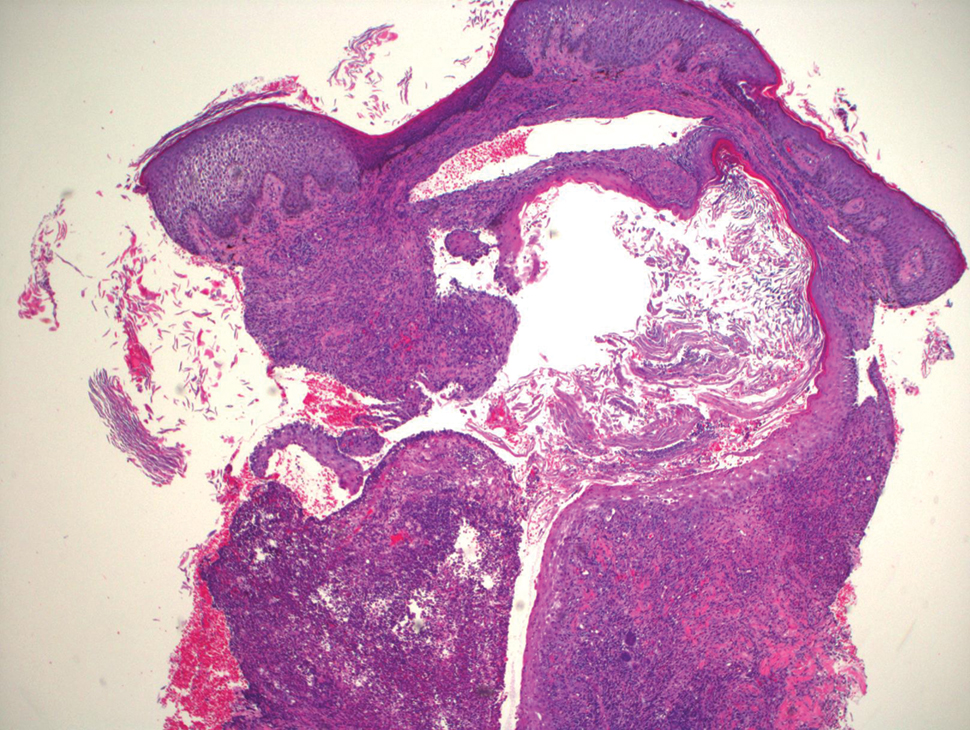

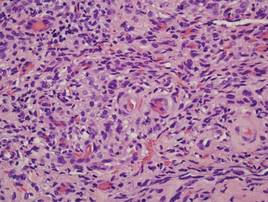

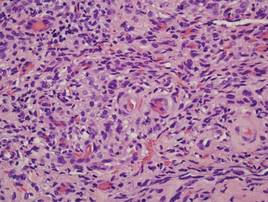

Blood cultures were negative for bacteria. Results of radiographic imaging were negative for osteomyelitis. Biopsy specimens from the right pretibial plaque showed a markedly inflamed, ruptured follicular unit with a dense dermal lympho-neutrophilic infiltrate and overlying pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia (Figure 3). Periodic acid–Schiff, Gomori methenamine-silver, acid-fast bacilli, and Giemsa stains were negative for organisms. No granules consistent with a Splendore-Hoeppli phenomenon were observed. These observations were consistent with a diagnosis of BLP.

Blastomycosislike pyoderma is a rare cutaneous bacterial infection that often mimics other fungal, inflammatory, or neoplastic disorders.1 Pediatric cases also are uncommon. Blastomycosislike pyoderma most commonly is caused by infection with S aureus or group A streptococci, but several other organisms have been implicated.2 Clinically, BLP is similar to cutaneous botryomycosis, as both are caused by similar organisms.3 However, while BLP is limited to the skin, botryomycosis may involve visceral organs.

Blastomycosislike pyoderma typically presents as verrucous, hyperkeratotic, purulent plaques with raised borders. It most commonly occurs on the face, scalp, axillae, trunk, and distal extremities. Predisposing factors include immunosuppressed states such as poor nutrition, HIV, malignancy, alcoholism, and diabetes mellitus.3,4 Hyperglycemia is thought to suppress helper T cell (TH1)–dependent immunity, which may explain why our patient’s lesions worsened with hyperglycemic episodes.5Histopathology revealed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with neutrophilic abscesses.1 The distinguishing feature between botryomycosis and BLP is the development of grains known as the Splendore-Hoeppli phenomenon in botryomycosis.6 The grains are eosinophilic and contain the causative infectious agent. The presence of these grains is consistent with botryomycosis but is not pathognomonic, as it also can be found in several bacterial, fungal, and parasitic infections.3,6

The differential diagnosis of BLP includes atypical mycobacterial infection, pyoderma gangrenosum, fungal infection, and tuberculosis verrucosa cutis.7

Although BLP is caused by bacteria, response to systemic antibiotics is variable. Other treatment modalities include dapsone, systemic and intralesional corticosteroids, retinoids, debridement, CO2 laser, and excision.6,8 Lesions typically start out localized, but it is not uncommon for them to spread to distal or vulnerable tissue, such as sites of trauma or inflammation. Our patient was started on oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and showed improvement, but she worsened with subsequent hyperglycemic episodes when antibiotics were discontinued.

1. Adis¸en E, Tezel F, Gürer MA. Pyoderma vegetans: a case for discussion. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:186-188.

2. Scuderi S, O’Brien B, Robertson I, et al. Heterogeneity of blastomycosis-like pyoderma: a selection of cases from the last 35 years. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:139-141.

3. Marschalko, M. Pyoderma vegetans: report on a case and review of data on pyoderma vegetans and cutaneous botryomycosis. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 1995;4:55-59.

4. Cerullo L, Zussman J, Young L. An unusual presentation of blastomycosislike pyoderma (pyoderma vegetans) and a review of the literature. Cutis. 2009;84:201-204.

5. Tanaka Y. Immunosuppressive mechanisms in diabetes mellitus [in Japanese]. Nihon Rinsho. 2008;66:2233-2237.

6. Hussein MR. Mucocutaneous Splendore-Hoeppli phenomenon. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:979-988.

7. Lee YS, Jung SW, Sim HS, et al. Blastomycosis-like pyoderma with good response to acitretin. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:365-368.

8. Kobraei KB, Wesson SK. Blastomycosis-like pyoderma: response to systemic retinoid therapy. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:1336-1338.

To the Editor:

Blastomycosislike pyoderma (BLP), also commonly referred to as pyoderma vegetans, is a rare cutaneous bacterial infection that often mimics other fungal, inflammatory, or neoplastic disorders.1 It is characterized by a collection of neutrophilic abscesses with pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia that coalesce into crusted plaques.

A 15-year-old adolescent girl with a history of type 1 diabetes mellitus was admitted for diabetic ketoacidosis. The patient presented with bilateral pretibial lesions of 6 years’ duration that developed after swimming in a pool following reported trauma to the site. These pruritic plaques had grown slowly and were occasionally tender. Of note, with episodes of hyperglycemia, the lesions developed purulent drainage.

Upon admission to the hospital and subsequent dermatology consultation, physical examination revealed the right pretibial shin had a 15×5-cm, gray-brown, hyperpigmented, verrucous, tender plaque with purulent drainage and overlying crust (Figure 1). The left pretibial shin had a similar smaller lesion (Figure 2). Laboratory test results were notable for a white blood cell count of 41.84 cells/µL (reference range, 3.8–10.5 cells/µL), blood glucose level of 586 mg/dL (reference range, 70–99 mg/dL), and hemoglobin A1c of 11.7% (reference range, 4.0%–5.6%). A biopsy specimen from the right pretibial shin was stained with hematoxylin and eosin for dermatopathologic evaluation as well as sent for tissue culture. Tissue and wound cultures grew Staphylococcus aureus and group B Streptococcus with no fungal or acid-fast bacilli growth.

Blood cultures were negative for bacteria. Results of radiographic imaging were negative for osteomyelitis. Biopsy specimens from the right pretibial plaque showed a markedly inflamed, ruptured follicular unit with a dense dermal lympho-neutrophilic infiltrate and overlying pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia (Figure 3). Periodic acid–Schiff, Gomori methenamine-silver, acid-fast bacilli, and Giemsa stains were negative for organisms. No granules consistent with a Splendore-Hoeppli phenomenon were observed. These observations were consistent with a diagnosis of BLP.

Blastomycosislike pyoderma is a rare cutaneous bacterial infection that often mimics other fungal, inflammatory, or neoplastic disorders.1 Pediatric cases also are uncommon. Blastomycosislike pyoderma most commonly is caused by infection with S aureus or group A streptococci, but several other organisms have been implicated.2 Clinically, BLP is similar to cutaneous botryomycosis, as both are caused by similar organisms.3 However, while BLP is limited to the skin, botryomycosis may involve visceral organs.

Blastomycosislike pyoderma typically presents as verrucous, hyperkeratotic, purulent plaques with raised borders. It most commonly occurs on the face, scalp, axillae, trunk, and distal extremities. Predisposing factors include immunosuppressed states such as poor nutrition, HIV, malignancy, alcoholism, and diabetes mellitus.3,4 Hyperglycemia is thought to suppress helper T cell (TH1)–dependent immunity, which may explain why our patient’s lesions worsened with hyperglycemic episodes.5Histopathology revealed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with neutrophilic abscesses.1 The distinguishing feature between botryomycosis and BLP is the development of grains known as the Splendore-Hoeppli phenomenon in botryomycosis.6 The grains are eosinophilic and contain the causative infectious agent. The presence of these grains is consistent with botryomycosis but is not pathognomonic, as it also can be found in several bacterial, fungal, and parasitic infections.3,6

The differential diagnosis of BLP includes atypical mycobacterial infection, pyoderma gangrenosum, fungal infection, and tuberculosis verrucosa cutis.7

Although BLP is caused by bacteria, response to systemic antibiotics is variable. Other treatment modalities include dapsone, systemic and intralesional corticosteroids, retinoids, debridement, CO2 laser, and excision.6,8 Lesions typically start out localized, but it is not uncommon for them to spread to distal or vulnerable tissue, such as sites of trauma or inflammation. Our patient was started on oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and showed improvement, but she worsened with subsequent hyperglycemic episodes when antibiotics were discontinued.

To the Editor:

Blastomycosislike pyoderma (BLP), also commonly referred to as pyoderma vegetans, is a rare cutaneous bacterial infection that often mimics other fungal, inflammatory, or neoplastic disorders.1 It is characterized by a collection of neutrophilic abscesses with pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia that coalesce into crusted plaques.

A 15-year-old adolescent girl with a history of type 1 diabetes mellitus was admitted for diabetic ketoacidosis. The patient presented with bilateral pretibial lesions of 6 years’ duration that developed after swimming in a pool following reported trauma to the site. These pruritic plaques had grown slowly and were occasionally tender. Of note, with episodes of hyperglycemia, the lesions developed purulent drainage.

Upon admission to the hospital and subsequent dermatology consultation, physical examination revealed the right pretibial shin had a 15×5-cm, gray-brown, hyperpigmented, verrucous, tender plaque with purulent drainage and overlying crust (Figure 1). The left pretibial shin had a similar smaller lesion (Figure 2). Laboratory test results were notable for a white blood cell count of 41.84 cells/µL (reference range, 3.8–10.5 cells/µL), blood glucose level of 586 mg/dL (reference range, 70–99 mg/dL), and hemoglobin A1c of 11.7% (reference range, 4.0%–5.6%). A biopsy specimen from the right pretibial shin was stained with hematoxylin and eosin for dermatopathologic evaluation as well as sent for tissue culture. Tissue and wound cultures grew Staphylococcus aureus and group B Streptococcus with no fungal or acid-fast bacilli growth.

Blood cultures were negative for bacteria. Results of radiographic imaging were negative for osteomyelitis. Biopsy specimens from the right pretibial plaque showed a markedly inflamed, ruptured follicular unit with a dense dermal lympho-neutrophilic infiltrate and overlying pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia (Figure 3). Periodic acid–Schiff, Gomori methenamine-silver, acid-fast bacilli, and Giemsa stains were negative for organisms. No granules consistent with a Splendore-Hoeppli phenomenon were observed. These observations were consistent with a diagnosis of BLP.

Blastomycosislike pyoderma is a rare cutaneous bacterial infection that often mimics other fungal, inflammatory, or neoplastic disorders.1 Pediatric cases also are uncommon. Blastomycosislike pyoderma most commonly is caused by infection with S aureus or group A streptococci, but several other organisms have been implicated.2 Clinically, BLP is similar to cutaneous botryomycosis, as both are caused by similar organisms.3 However, while BLP is limited to the skin, botryomycosis may involve visceral organs.

Blastomycosislike pyoderma typically presents as verrucous, hyperkeratotic, purulent plaques with raised borders. It most commonly occurs on the face, scalp, axillae, trunk, and distal extremities. Predisposing factors include immunosuppressed states such as poor nutrition, HIV, malignancy, alcoholism, and diabetes mellitus.3,4 Hyperglycemia is thought to suppress helper T cell (TH1)–dependent immunity, which may explain why our patient’s lesions worsened with hyperglycemic episodes.5Histopathology revealed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with neutrophilic abscesses.1 The distinguishing feature between botryomycosis and BLP is the development of grains known as the Splendore-Hoeppli phenomenon in botryomycosis.6 The grains are eosinophilic and contain the causative infectious agent. The presence of these grains is consistent with botryomycosis but is not pathognomonic, as it also can be found in several bacterial, fungal, and parasitic infections.3,6

The differential diagnosis of BLP includes atypical mycobacterial infection, pyoderma gangrenosum, fungal infection, and tuberculosis verrucosa cutis.7

Although BLP is caused by bacteria, response to systemic antibiotics is variable. Other treatment modalities include dapsone, systemic and intralesional corticosteroids, retinoids, debridement, CO2 laser, and excision.6,8 Lesions typically start out localized, but it is not uncommon for them to spread to distal or vulnerable tissue, such as sites of trauma or inflammation. Our patient was started on oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and showed improvement, but she worsened with subsequent hyperglycemic episodes when antibiotics were discontinued.

1. Adis¸en E, Tezel F, Gürer MA. Pyoderma vegetans: a case for discussion. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:186-188.

2. Scuderi S, O’Brien B, Robertson I, et al. Heterogeneity of blastomycosis-like pyoderma: a selection of cases from the last 35 years. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:139-141.

3. Marschalko, M. Pyoderma vegetans: report on a case and review of data on pyoderma vegetans and cutaneous botryomycosis. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 1995;4:55-59.

4. Cerullo L, Zussman J, Young L. An unusual presentation of blastomycosislike pyoderma (pyoderma vegetans) and a review of the literature. Cutis. 2009;84:201-204.

5. Tanaka Y. Immunosuppressive mechanisms in diabetes mellitus [in Japanese]. Nihon Rinsho. 2008;66:2233-2237.

6. Hussein MR. Mucocutaneous Splendore-Hoeppli phenomenon. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:979-988.

7. Lee YS, Jung SW, Sim HS, et al. Blastomycosis-like pyoderma with good response to acitretin. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:365-368.

8. Kobraei KB, Wesson SK. Blastomycosis-like pyoderma: response to systemic retinoid therapy. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:1336-1338.

1. Adis¸en E, Tezel F, Gürer MA. Pyoderma vegetans: a case for discussion. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:186-188.

2. Scuderi S, O’Brien B, Robertson I, et al. Heterogeneity of blastomycosis-like pyoderma: a selection of cases from the last 35 years. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:139-141.

3. Marschalko, M. Pyoderma vegetans: report on a case and review of data on pyoderma vegetans and cutaneous botryomycosis. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 1995;4:55-59.

4. Cerullo L, Zussman J, Young L. An unusual presentation of blastomycosislike pyoderma (pyoderma vegetans) and a review of the literature. Cutis. 2009;84:201-204.

5. Tanaka Y. Immunosuppressive mechanisms in diabetes mellitus [in Japanese]. Nihon Rinsho. 2008;66:2233-2237.

6. Hussein MR. Mucocutaneous Splendore-Hoeppli phenomenon. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:979-988.

7. Lee YS, Jung SW, Sim HS, et al. Blastomycosis-like pyoderma with good response to acitretin. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:365-368.

8. Kobraei KB, Wesson SK. Blastomycosis-like pyoderma: response to systemic retinoid therapy. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:1336-1338.

Practice Points

- Blastomycosislike pyoderma is a rare condition secondary to bacterial infection, but as the name suggests, it also can resemble cutaneous blastomycosis.

- Blastomycosislike pyoderma most commonly occurs in immunocompromised patients.

- The most common histologic findings include suppurative and neutrophilic inflammation with pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia.

Verrucous Kaposi Sarcoma in an HIV-Positive Man

To the Editor:

Verrucous Kaposi sarcoma (VKS) is an uncommon variant of Kaposi sarcoma (KS) that rarely is seen in clinical practice or reported in the literature. It is strongly associated with lymphedema in patients with AIDS.1 We present a case of VKS in a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–positive man with cutaneous lesions that demonstrated minimal response to treatment with efavirenz-emtricitabine-tenofovir, doxorubicin, paclitaxel, and alitretinoin.

A 48-year-old man with a history of untreated HIV presented with a persistent eruption of heavily scaled, hyperpigmented, nonindurated, thin plaques in an ichthyosiform pattern on the bilateral lower legs and ankles of 4 years’ duration (Figure 1). He also had a number of soft, compressible, cystlike plaques without much overlying epidermal change on the lower extremities. He denied any prior episodes of skin breakdown, drainage, or secondary infection. Findings from the physical examination were otherwise unremarkable.

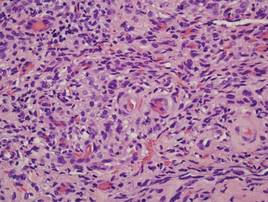

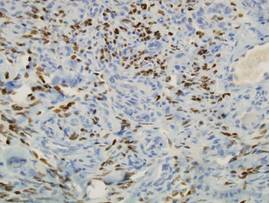

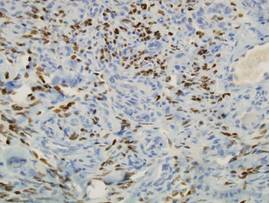

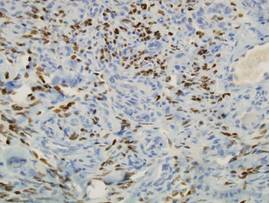

Two punch biopsies were performed on the lower legs, one from a scaly plaque and the other from a cystic area. The epidermis was hyperkeratotic and mildly hyperplastic with slitlike vascular spaces. A dense cellular proliferation of spindle-shaped cells was present in the dermis (Figure 2). Minimal cytologic atypia was noted. Immunohistochemical staining for human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) was strongly positive (Figure 3). Histologically, the cutaneous lesions were consistent with VKS.

At the current presentation, the CD4 count was 355 cells/mm3 and the viral load was 919,223 copies/mL. The CD4 count and viral load initially had been responsive to efavirenz-emtricitabine-tenofovir therapy; 17 months prior to the current presentation, the CD4 count was 692 cells/mm3 and the viral load was less than 50 copies/mL. However, the cutaneous lesions persisted despite therapy with efavirenz-emtricitabine-tenofovir, alitretinoin gel, and intralesional chemotherapeutic agents such as doxorubicin and paclitaxel.

Kaposi sarcoma, first described by Moritz Kaposi in 1872, represents a group of vascular neoplasms. Multiple subtypes have been described including classic, African endemic, transplant/AIDS associated, anaplastic, lymphedematous, hyperkeratotic/verrucous, keloidal, micronodular, pyogenic granulomalike, ecchymotic, and intravascular.1-3 Human herpesvirus 8 is associated with all clinical subtypes of KS.3 Immunohistochemical staining for HHV-8 latent nuclear antigen-1 has been shown in the literature to be highly sensitive and specific for KS and can potentially facilitate the diagnosis of KS among patients with similarly appearing dermatologic conditions, such as angiosarcoma, kaposiform hemangioendothelioma, or verrucous hemangioma.1,4 Human herpesvirus 8 infects endothelial cells and induces the proliferation of vascular spindle cells via the secretion of basic fibroblast growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor.5 Human herpesvirus 8 also can lead to lymph vessel obstruction and lymph node enlargement by infecting cells within the lymphatic system. In addition, chronic lymphedema can itself lead to verruciform epidermal hyperplasia and hyperkeratosis, which has a clinical presentation similar to VKS.1

AIDS-associated KS typically starts as 1 or more purple-red macules that rapidly progress into papules, nodules, and plaques.1 These lesions have a predilection for the head, neck, trunk, and mucous membranes. Albeit a rare presentation, VKS is strongly associated with lymphedema in patients with AIDS.1,3,5 Previously, KS was often the presenting clinical manifestation of HIV infection, but since the use of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) has become the standard of care, the incidence as well as the morbidity and mortality associated with KS has substantially decreased.1,5-7 Notably, in HIV patients who initially do not have signs or symptoms of KS, HHV-8 positivity is predictive of the development of KS within 2 to 4 years.6

In the literature, good prognostic indicators for KS include CD4 count greater than 150 cells/mm3, only cutaneous involvement, and negative B symptoms (eg, temperature >38°C, night sweats, unintentional weight loss >10% of normal body weight within 6 months).7 Kaposi sarcoma cannot be completely cured but can be appropriately managed with medical intervention. All KS subtypes are sensitive to radiation therapy; recalcitrant localized lesions can be treated with excision, cryotherapy, alitretinoin gel, laser ablation, or locally injected interferon or chemotherapeutic agents (eg, vincristine, vinblastine, actinomycin D).5,6 Liposomal anthracyclines (doxorubicin) and paclitaxel are first- and second-line agents for advanced KS, respectively.6

In HIV-associated KS, lesions frequently involute with the initiation of HAART; however, the cutaneous lesions in our patient persisted despite initiation of efavirenz-emtricitabine-tenofovir. He also was given intralesional doxorubicin andpaclitaxel as well as topical alitretinoin but did not experience complete resolution of the cutaneous lesions. It is possible that patients with VKS are recalcitrant to typical treatment modalities and therefore may require unconventional therapies to achieve maximal clearance of cutaneous lesions.

Verrucous Kaposi sarcoma is a rare presentation of KS that is infrequently seen in clinical practice or reported in the literature.3 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search term verrucous Kaposi sarcoma yielded 13 articles, one of which included a case series of 5 patients with AIDS and hyperkeratotic KS in Germany in the 1990s.5 Four of the articles were written in French, German, or Portuguese.8-11 The remainder of the articles discussed variants of KS other than VKS.

Although most patients with HIV and KS effectively respond to HAART, it may be possible that VKS is more difficult to treat. In addition, immunohistochemical staining for HHV-8, in particular HHV-8 latent nuclear antigen-1, may be useful to diagnose KS in HIV patients with uncharacteristic or indeterminate cutaneous lesions. Further research is needed to identify and delineate various efficacious therapeutic options for recalcitrant KS, particularly VKS.

Acknowledgment

We are indebted to Antoinette F. Hood, MD, Norfolk, Virginia, who digitized our patient’s histopathology slides.

1. Grayson W, Pantanowitz L. Histological variants of cutaneous Kaposi sarcoma. Diagn Pathol. 2008;3:31.

2. Amodio E, Goedert JJ, Barozzi P, et al. Differences in Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-specific and herpesvirus-non-specific immune responses in classic Kaposi sarcoma cases and matched controls in Sicily. Cancer Sci. 2011;102:1769-1773.

3. Fagone S, Cavaleri A, Camuto M, et al. Hyperkeratotic Kaposi sarcoma with leg lymphedema after prolonged corticosteroid therapy for SLE. case report and review of the literature. Minerva Med. 2001;92:177-202.

4. Cheuk W, Wong KO, Wong CS, et al. Immunostaining for human herpesvirus 8 latent nuclear antigen-1 helps distinguish Kaposi sarcoma from its mimickers. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;121:335-342.

5. Hengge UR, Stocks K, Goos M. Acquired immune deficiency syndrome-related hyperkeratotic Kaposi’s sarcoma with severe lymphedema: report of 5 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:501-505.

6. James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 2006.

7. Thomas S, Sindhu CB, Sreekumar S, et al. AIDS associated Kaposi’s Sarcoma. J Assoc Physicians India. 2011;59:387-389.

8. Mukai MM, Chaves T, Caldas L, et al. Primary Kaposi’s sarcoma of the penis [in Portuguese]. An Bras Dermatol. 2009;84:524-526.

9. Weidauer H, Tilgen W, Adler D. Kaposi’s sarcoma of the larynx [in German]. Laryngol Rhinol Otol (Stuttg). 1986;65:389-391.

10. Basset A. Clinical aspects of Kaposi’s disease [in French]. Bull Soc Pathol Exot Filiales. 1984;77(4, pt 2):529-532.

11. Wlotzke U, Hohenleutner U, Landthaler M. Dermatoses in leg amputees [in German]. Hautarzt. 1996;47:493-501.

To the Editor:

Verrucous Kaposi sarcoma (VKS) is an uncommon variant of Kaposi sarcoma (KS) that rarely is seen in clinical practice or reported in the literature. It is strongly associated with lymphedema in patients with AIDS.1 We present a case of VKS in a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–positive man with cutaneous lesions that demonstrated minimal response to treatment with efavirenz-emtricitabine-tenofovir, doxorubicin, paclitaxel, and alitretinoin.

A 48-year-old man with a history of untreated HIV presented with a persistent eruption of heavily scaled, hyperpigmented, nonindurated, thin plaques in an ichthyosiform pattern on the bilateral lower legs and ankles of 4 years’ duration (Figure 1). He also had a number of soft, compressible, cystlike plaques without much overlying epidermal change on the lower extremities. He denied any prior episodes of skin breakdown, drainage, or secondary infection. Findings from the physical examination were otherwise unremarkable.

Two punch biopsies were performed on the lower legs, one from a scaly plaque and the other from a cystic area. The epidermis was hyperkeratotic and mildly hyperplastic with slitlike vascular spaces. A dense cellular proliferation of spindle-shaped cells was present in the dermis (Figure 2). Minimal cytologic atypia was noted. Immunohistochemical staining for human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) was strongly positive (Figure 3). Histologically, the cutaneous lesions were consistent with VKS.

At the current presentation, the CD4 count was 355 cells/mm3 and the viral load was 919,223 copies/mL. The CD4 count and viral load initially had been responsive to efavirenz-emtricitabine-tenofovir therapy; 17 months prior to the current presentation, the CD4 count was 692 cells/mm3 and the viral load was less than 50 copies/mL. However, the cutaneous lesions persisted despite therapy with efavirenz-emtricitabine-tenofovir, alitretinoin gel, and intralesional chemotherapeutic agents such as doxorubicin and paclitaxel.

Kaposi sarcoma, first described by Moritz Kaposi in 1872, represents a group of vascular neoplasms. Multiple subtypes have been described including classic, African endemic, transplant/AIDS associated, anaplastic, lymphedematous, hyperkeratotic/verrucous, keloidal, micronodular, pyogenic granulomalike, ecchymotic, and intravascular.1-3 Human herpesvirus 8 is associated with all clinical subtypes of KS.3 Immunohistochemical staining for HHV-8 latent nuclear antigen-1 has been shown in the literature to be highly sensitive and specific for KS and can potentially facilitate the diagnosis of KS among patients with similarly appearing dermatologic conditions, such as angiosarcoma, kaposiform hemangioendothelioma, or verrucous hemangioma.1,4 Human herpesvirus 8 infects endothelial cells and induces the proliferation of vascular spindle cells via the secretion of basic fibroblast growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor.5 Human herpesvirus 8 also can lead to lymph vessel obstruction and lymph node enlargement by infecting cells within the lymphatic system. In addition, chronic lymphedema can itself lead to verruciform epidermal hyperplasia and hyperkeratosis, which has a clinical presentation similar to VKS.1

AIDS-associated KS typically starts as 1 or more purple-red macules that rapidly progress into papules, nodules, and plaques.1 These lesions have a predilection for the head, neck, trunk, and mucous membranes. Albeit a rare presentation, VKS is strongly associated with lymphedema in patients with AIDS.1,3,5 Previously, KS was often the presenting clinical manifestation of HIV infection, but since the use of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) has become the standard of care, the incidence as well as the morbidity and mortality associated with KS has substantially decreased.1,5-7 Notably, in HIV patients who initially do not have signs or symptoms of KS, HHV-8 positivity is predictive of the development of KS within 2 to 4 years.6

In the literature, good prognostic indicators for KS include CD4 count greater than 150 cells/mm3, only cutaneous involvement, and negative B symptoms (eg, temperature >38°C, night sweats, unintentional weight loss >10% of normal body weight within 6 months).7 Kaposi sarcoma cannot be completely cured but can be appropriately managed with medical intervention. All KS subtypes are sensitive to radiation therapy; recalcitrant localized lesions can be treated with excision, cryotherapy, alitretinoin gel, laser ablation, or locally injected interferon or chemotherapeutic agents (eg, vincristine, vinblastine, actinomycin D).5,6 Liposomal anthracyclines (doxorubicin) and paclitaxel are first- and second-line agents for advanced KS, respectively.6

In HIV-associated KS, lesions frequently involute with the initiation of HAART; however, the cutaneous lesions in our patient persisted despite initiation of efavirenz-emtricitabine-tenofovir. He also was given intralesional doxorubicin andpaclitaxel as well as topical alitretinoin but did not experience complete resolution of the cutaneous lesions. It is possible that patients with VKS are recalcitrant to typical treatment modalities and therefore may require unconventional therapies to achieve maximal clearance of cutaneous lesions.

Verrucous Kaposi sarcoma is a rare presentation of KS that is infrequently seen in clinical practice or reported in the literature.3 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search term verrucous Kaposi sarcoma yielded 13 articles, one of which included a case series of 5 patients with AIDS and hyperkeratotic KS in Germany in the 1990s.5 Four of the articles were written in French, German, or Portuguese.8-11 The remainder of the articles discussed variants of KS other than VKS.

Although most patients with HIV and KS effectively respond to HAART, it may be possible that VKS is more difficult to treat. In addition, immunohistochemical staining for HHV-8, in particular HHV-8 latent nuclear antigen-1, may be useful to diagnose KS in HIV patients with uncharacteristic or indeterminate cutaneous lesions. Further research is needed to identify and delineate various efficacious therapeutic options for recalcitrant KS, particularly VKS.

Acknowledgment

We are indebted to Antoinette F. Hood, MD, Norfolk, Virginia, who digitized our patient’s histopathology slides.

To the Editor:

Verrucous Kaposi sarcoma (VKS) is an uncommon variant of Kaposi sarcoma (KS) that rarely is seen in clinical practice or reported in the literature. It is strongly associated with lymphedema in patients with AIDS.1 We present a case of VKS in a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–positive man with cutaneous lesions that demonstrated minimal response to treatment with efavirenz-emtricitabine-tenofovir, doxorubicin, paclitaxel, and alitretinoin.

A 48-year-old man with a history of untreated HIV presented with a persistent eruption of heavily scaled, hyperpigmented, nonindurated, thin plaques in an ichthyosiform pattern on the bilateral lower legs and ankles of 4 years’ duration (Figure 1). He also had a number of soft, compressible, cystlike plaques without much overlying epidermal change on the lower extremities. He denied any prior episodes of skin breakdown, drainage, or secondary infection. Findings from the physical examination were otherwise unremarkable.

Two punch biopsies were performed on the lower legs, one from a scaly plaque and the other from a cystic area. The epidermis was hyperkeratotic and mildly hyperplastic with slitlike vascular spaces. A dense cellular proliferation of spindle-shaped cells was present in the dermis (Figure 2). Minimal cytologic atypia was noted. Immunohistochemical staining for human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) was strongly positive (Figure 3). Histologically, the cutaneous lesions were consistent with VKS.

At the current presentation, the CD4 count was 355 cells/mm3 and the viral load was 919,223 copies/mL. The CD4 count and viral load initially had been responsive to efavirenz-emtricitabine-tenofovir therapy; 17 months prior to the current presentation, the CD4 count was 692 cells/mm3 and the viral load was less than 50 copies/mL. However, the cutaneous lesions persisted despite therapy with efavirenz-emtricitabine-tenofovir, alitretinoin gel, and intralesional chemotherapeutic agents such as doxorubicin and paclitaxel.

Kaposi sarcoma, first described by Moritz Kaposi in 1872, represents a group of vascular neoplasms. Multiple subtypes have been described including classic, African endemic, transplant/AIDS associated, anaplastic, lymphedematous, hyperkeratotic/verrucous, keloidal, micronodular, pyogenic granulomalike, ecchymotic, and intravascular.1-3 Human herpesvirus 8 is associated with all clinical subtypes of KS.3 Immunohistochemical staining for HHV-8 latent nuclear antigen-1 has been shown in the literature to be highly sensitive and specific for KS and can potentially facilitate the diagnosis of KS among patients with similarly appearing dermatologic conditions, such as angiosarcoma, kaposiform hemangioendothelioma, or verrucous hemangioma.1,4 Human herpesvirus 8 infects endothelial cells and induces the proliferation of vascular spindle cells via the secretion of basic fibroblast growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor.5 Human herpesvirus 8 also can lead to lymph vessel obstruction and lymph node enlargement by infecting cells within the lymphatic system. In addition, chronic lymphedema can itself lead to verruciform epidermal hyperplasia and hyperkeratosis, which has a clinical presentation similar to VKS.1

AIDS-associated KS typically starts as 1 or more purple-red macules that rapidly progress into papules, nodules, and plaques.1 These lesions have a predilection for the head, neck, trunk, and mucous membranes. Albeit a rare presentation, VKS is strongly associated with lymphedema in patients with AIDS.1,3,5 Previously, KS was often the presenting clinical manifestation of HIV infection, but since the use of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) has become the standard of care, the incidence as well as the morbidity and mortality associated with KS has substantially decreased.1,5-7 Notably, in HIV patients who initially do not have signs or symptoms of KS, HHV-8 positivity is predictive of the development of KS within 2 to 4 years.6

In the literature, good prognostic indicators for KS include CD4 count greater than 150 cells/mm3, only cutaneous involvement, and negative B symptoms (eg, temperature >38°C, night sweats, unintentional weight loss >10% of normal body weight within 6 months).7 Kaposi sarcoma cannot be completely cured but can be appropriately managed with medical intervention. All KS subtypes are sensitive to radiation therapy; recalcitrant localized lesions can be treated with excision, cryotherapy, alitretinoin gel, laser ablation, or locally injected interferon or chemotherapeutic agents (eg, vincristine, vinblastine, actinomycin D).5,6 Liposomal anthracyclines (doxorubicin) and paclitaxel are first- and second-line agents for advanced KS, respectively.6

In HIV-associated KS, lesions frequently involute with the initiation of HAART; however, the cutaneous lesions in our patient persisted despite initiation of efavirenz-emtricitabine-tenofovir. He also was given intralesional doxorubicin andpaclitaxel as well as topical alitretinoin but did not experience complete resolution of the cutaneous lesions. It is possible that patients with VKS are recalcitrant to typical treatment modalities and therefore may require unconventional therapies to achieve maximal clearance of cutaneous lesions.

Verrucous Kaposi sarcoma is a rare presentation of KS that is infrequently seen in clinical practice or reported in the literature.3 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search term verrucous Kaposi sarcoma yielded 13 articles, one of which included a case series of 5 patients with AIDS and hyperkeratotic KS in Germany in the 1990s.5 Four of the articles were written in French, German, or Portuguese.8-11 The remainder of the articles discussed variants of KS other than VKS.

Although most patients with HIV and KS effectively respond to HAART, it may be possible that VKS is more difficult to treat. In addition, immunohistochemical staining for HHV-8, in particular HHV-8 latent nuclear antigen-1, may be useful to diagnose KS in HIV patients with uncharacteristic or indeterminate cutaneous lesions. Further research is needed to identify and delineate various efficacious therapeutic options for recalcitrant KS, particularly VKS.

Acknowledgment

We are indebted to Antoinette F. Hood, MD, Norfolk, Virginia, who digitized our patient’s histopathology slides.

1. Grayson W, Pantanowitz L. Histological variants of cutaneous Kaposi sarcoma. Diagn Pathol. 2008;3:31.

2. Amodio E, Goedert JJ, Barozzi P, et al. Differences in Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-specific and herpesvirus-non-specific immune responses in classic Kaposi sarcoma cases and matched controls in Sicily. Cancer Sci. 2011;102:1769-1773.

3. Fagone S, Cavaleri A, Camuto M, et al. Hyperkeratotic Kaposi sarcoma with leg lymphedema after prolonged corticosteroid therapy for SLE. case report and review of the literature. Minerva Med. 2001;92:177-202.

4. Cheuk W, Wong KO, Wong CS, et al. Immunostaining for human herpesvirus 8 latent nuclear antigen-1 helps distinguish Kaposi sarcoma from its mimickers. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;121:335-342.

5. Hengge UR, Stocks K, Goos M. Acquired immune deficiency syndrome-related hyperkeratotic Kaposi’s sarcoma with severe lymphedema: report of 5 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:501-505.

6. James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 2006.

7. Thomas S, Sindhu CB, Sreekumar S, et al. AIDS associated Kaposi’s Sarcoma. J Assoc Physicians India. 2011;59:387-389.

8. Mukai MM, Chaves T, Caldas L, et al. Primary Kaposi’s sarcoma of the penis [in Portuguese]. An Bras Dermatol. 2009;84:524-526.

9. Weidauer H, Tilgen W, Adler D. Kaposi’s sarcoma of the larynx [in German]. Laryngol Rhinol Otol (Stuttg). 1986;65:389-391.

10. Basset A. Clinical aspects of Kaposi’s disease [in French]. Bull Soc Pathol Exot Filiales. 1984;77(4, pt 2):529-532.

11. Wlotzke U, Hohenleutner U, Landthaler M. Dermatoses in leg amputees [in German]. Hautarzt. 1996;47:493-501.

1. Grayson W, Pantanowitz L. Histological variants of cutaneous Kaposi sarcoma. Diagn Pathol. 2008;3:31.

2. Amodio E, Goedert JJ, Barozzi P, et al. Differences in Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-specific and herpesvirus-non-specific immune responses in classic Kaposi sarcoma cases and matched controls in Sicily. Cancer Sci. 2011;102:1769-1773.

3. Fagone S, Cavaleri A, Camuto M, et al. Hyperkeratotic Kaposi sarcoma with leg lymphedema after prolonged corticosteroid therapy for SLE. case report and review of the literature. Minerva Med. 2001;92:177-202.

4. Cheuk W, Wong KO, Wong CS, et al. Immunostaining for human herpesvirus 8 latent nuclear antigen-1 helps distinguish Kaposi sarcoma from its mimickers. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;121:335-342.

5. Hengge UR, Stocks K, Goos M. Acquired immune deficiency syndrome-related hyperkeratotic Kaposi’s sarcoma with severe lymphedema: report of 5 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:501-505.

6. James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 2006.

7. Thomas S, Sindhu CB, Sreekumar S, et al. AIDS associated Kaposi’s Sarcoma. J Assoc Physicians India. 2011;59:387-389.

8. Mukai MM, Chaves T, Caldas L, et al. Primary Kaposi’s sarcoma of the penis [in Portuguese]. An Bras Dermatol. 2009;84:524-526.

9. Weidauer H, Tilgen W, Adler D. Kaposi’s sarcoma of the larynx [in German]. Laryngol Rhinol Otol (Stuttg). 1986;65:389-391.

10. Basset A. Clinical aspects of Kaposi’s disease [in French]. Bull Soc Pathol Exot Filiales. 1984;77(4, pt 2):529-532.

11. Wlotzke U, Hohenleutner U, Landthaler M. Dermatoses in leg amputees [in German]. Hautarzt. 1996;47:493-501.