User login

Eruptive Vellus Hair Cysts in Identical Triplets With Dermoscopic Findings

Case Report

Four-year-old identical triplet girls with numerous asymptomatic scattered papules on the chest of 4 months’ duration were referred to a dermatologist by their pediatrician for molluscum contagiosum. The patients’ father reported that there was no history of trauma, irritation, or manipulation to the affected area. Their medical history was notable for prematurity at 32 weeks’ gestation and congenital dermal melanocytosis. Family history was notable for their father having acne and similar papules on the chest during adolescence that resolved with isotretinoin therapy.

On physical examination there were multiple smooth, hyperpigmented to erythematous, comedonal, 1- to 2-mm papules dispersed on the anterior central chest of all 3 patients (Figure 1). Clinically, these lesions were fairly indistinguishable from other common dermatologic conditions such as acne or milia. Dermoscopic examination revealed homogenous yellow-white areas surrounded by light brown to erythematous halos (Figure 2). Histopathologic examination was not performed given the benign clinical diagnosis and avoidance of biopsy in pediatric populations. Based on dermoscopic features and history, a diagnosis of eruptive vellus hair cysts (EVHCs) in identical triplets was made.

Comment

Pathogenesis

Eruptive vellus hair cysts, first introduced by Esterly et al1 in 1977, are uncommon benign lesions presumed to be caused by an abnormal development of the infundibular portion of the hair follicle.2 They are usually 1- to 3-mm, reddish brown, monomorphous papules overlapping with pilosebaceous and apocrine units.3 Although the lesions typically are located on the chest and extremities, they may occur on the face, abdomen, axillae, buttocks, or genital area.1,3 The inheritance of EVHCs is unclear. The majority of reported cases are sporadic; however, the literature mentions 19 families affected by autosomal-dominant EVHCs based on phylogeny.3 In 2015, EVHCs were reported in identical twins, further supporting the case for a genetic mutation.4 We augment this autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern by presenting a case of identical triplets with EVHCs. The patients’ father reported similar lesions in childhood, further underscoring a genetic basis.

The pathogenesis of EVHC is uncertain, with 2 main theories. Some propose retention of vellus hair and keratin in a cavity formed by an abnormal vellus hair follicle causing infundibular occlusion. Others consider the growth of benign follicular hamartomas that differentiate to become vellus hairs.1

Clinical Presentation

The sporadic form of EVHCs is noted to be more common and clinically presents later, with an average age at onset of 16 years and an average age at diagnosis of 24 years.3 The sporadic form occurs without trauma or manipulation as a precursor. Less commonly, lesions present at birth or in early infancy and may show an autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern with a similar distribution across relatives.3

Other variants of EVHCs have been described. Late-onset EVHC usually occurs at 35 years or older (average age, 57 years), with a female to male predominance of 2.5 to 1.3 This late onset may be attributed to proliferation of ductal follicular keratinocytes or loss of perifollicular elastic fibers exacerbated by exogenous factors such as manipulation, UV rays, or trauma.5

For unilesional EVHC, the average age at diagnosis is 27 years.3 Some of these lesions may be pedunculated and greater than 8 mm. There is a female to male predominance of 2 to 1. Eruptive vellus hair cysts with steatocystoma multiplex can be seen with an average age at onset of 19 years and a female to male predominance of 0.2 to 1. There may be a family history of this subset, as reported in 3 patients with this pattern.3

Diagnosis

The recommended workup for EVHCs varies by patient and age. Eruptive vellus hair cysts present an opportunity to utilize noninvasive diagnostic procedures, especially for the pediatric population, to avoid scarring and pain from manipulation or biopsies. Although many practitioners may comfortably diagnose EVHCs clinically, 6 cases were misdiagnosed as steatocystoma multiplex, keratosis pilaris, or milia prior to histopathology revealing vellus hair cysts.6

Dermoscopy presents as a useful diagnostic aid. Eruptive vellus hair cysts exhibit light yellow homogenous circular structures with a maroon or erythematous halo.2,7 A central gray-blue color point may be seen due to melanin in the pigmented hair shaft.7 A dermoscopy review of EVHCs reported radiating capillaries.2 Occasionally, nonfollicular homogenous blue pigmentation may be seen due to a connection to atrophic hair follicles in the mid dermis and no normal hair follicle around the cysts.8 In comparison, dermoscopic characteristics of molluscum contagiosum demonstrated a polylobular, white-yellow, amorphous structure at the center with a hardened central umbilicated core and a crown of hairpin vessels at the periphery. Additionally, comedonal acne, commonly mistaken for EVHCs, reveals a brown-yellow hard central plug with sparse inflammation under dermoscopy.2 Thus, differentiation of these entities with dermoscopy should be highly prioritized to better aid in the diagnosis of pediatric dermatologic conditions using painless noninvasive techniques.

Treatment

The main indication for treatment of EVHCs is cosmetic concern. Twenty-five percent of EVHCs spontaneously resolve with transepidermal hair elimination or a granulomatous reaction.4,5 A case report of 4 siblings with congenital EVHCs also described a mother with similar lesions that resolved spontaneously in early adulthood,3 as our patients’ father also noted. Treatment modalities including topical keratolytic agents such as urea 10%, retinoic acid 0.05%, tazarotene cream 0.1%, and lactic acid 12%; incision and drainage; CO2 laser; or erbium-doped YAG laser ablation have been tried with minimal improvement.9 Of note, tazarotene cream 0.1% has demonstrated better results than both erbium-doped YAG laser and drainage and incision of EVHCs.4 Additionally, another report evidenced partial improvement with calcipotriene within 2 months with some lesions completely resolved and others flattened, which may be attributed to the antiproliferative and prodifferentiating effects on the ductal follicular keratinocytes by calcipotriene.5 Lastly, an additional study indicated that isotretinoin and vitamin A derivatives were ineffective for clearing EVHCs.10

Conclusion

We presented 3 identical triplets with the classic pediatric onset and dermoscopic findings of EVHCs on the trunk. Although the definitive diagnosis of EVHCs relies on histopathology, we argue that their unique dermoscopic findings combined with a thorough clinical examination is sufficient to recognize this benign condition and avoid painful procedures in the pediatric population.

- Esterly NB, Fretzin DF, Pinkus H. Eruptive vellus hair cysts. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:500-503.

- Alfaro-Castellón P, Mejía-Rodríguez SA, Valencia-Herrera A, et al. Dermoscopy distinction of eruptive vellus hair cysts with molluscum contagiosum and acne lesions. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:772-773.

- Torchia D, Vega J, Schachner LA. Eruptive vellus hair cysts: a systematic review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13:19-28.

- Pauline G, Alain H, Jean-Jaques R, et al. Eruptive vellus hair cysts: an original case occurring in twins [published online July 11, 2014]. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:E209-E212.

- Erkek E, Kurtipek GS, Duman D, et al. Eruptive vellus hair cysts: report of a pediatric case with partial response to calcipotriene therapy. Cutis. 2009;84:295-298.

- Shi G, Zhou Y, Cai YX, et al. Clinicopathological features and expression of four keratins (K10, K14, K17 and K19) in six cases of eruptive vellus hair cysts. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2014;39:496-499.

- Panchaprateep R, Tanus A, Tosti A. Clinical, dermoscopic, and histopathologic features of body hair disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:890-900.

- Takada S, Togawa Y, Wakabayashii S, et al. Dermoscopic findings in eruptive vellus hair cysts: a case report. Austin J Dermatol. 2014;1:1004.

- Khatu S, Vasani R, Amin S. Eruptive vellus hair cyst presenting as asymptomatic follicular papules on extremities. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2013;4:213-215.

- Urbina-Gonzalez F, Aguilar-Martinez A, Cristobal-Gil M, et al. The treatment of eruptive vellus hair cysts with isotretinoin. Br J Dermatol. 1987;116:465-466.

Case Report

Four-year-old identical triplet girls with numerous asymptomatic scattered papules on the chest of 4 months’ duration were referred to a dermatologist by their pediatrician for molluscum contagiosum. The patients’ father reported that there was no history of trauma, irritation, or manipulation to the affected area. Their medical history was notable for prematurity at 32 weeks’ gestation and congenital dermal melanocytosis. Family history was notable for their father having acne and similar papules on the chest during adolescence that resolved with isotretinoin therapy.

On physical examination there were multiple smooth, hyperpigmented to erythematous, comedonal, 1- to 2-mm papules dispersed on the anterior central chest of all 3 patients (Figure 1). Clinically, these lesions were fairly indistinguishable from other common dermatologic conditions such as acne or milia. Dermoscopic examination revealed homogenous yellow-white areas surrounded by light brown to erythematous halos (Figure 2). Histopathologic examination was not performed given the benign clinical diagnosis and avoidance of biopsy in pediatric populations. Based on dermoscopic features and history, a diagnosis of eruptive vellus hair cysts (EVHCs) in identical triplets was made.

Comment

Pathogenesis

Eruptive vellus hair cysts, first introduced by Esterly et al1 in 1977, are uncommon benign lesions presumed to be caused by an abnormal development of the infundibular portion of the hair follicle.2 They are usually 1- to 3-mm, reddish brown, monomorphous papules overlapping with pilosebaceous and apocrine units.3 Although the lesions typically are located on the chest and extremities, they may occur on the face, abdomen, axillae, buttocks, or genital area.1,3 The inheritance of EVHCs is unclear. The majority of reported cases are sporadic; however, the literature mentions 19 families affected by autosomal-dominant EVHCs based on phylogeny.3 In 2015, EVHCs were reported in identical twins, further supporting the case for a genetic mutation.4 We augment this autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern by presenting a case of identical triplets with EVHCs. The patients’ father reported similar lesions in childhood, further underscoring a genetic basis.

The pathogenesis of EVHC is uncertain, with 2 main theories. Some propose retention of vellus hair and keratin in a cavity formed by an abnormal vellus hair follicle causing infundibular occlusion. Others consider the growth of benign follicular hamartomas that differentiate to become vellus hairs.1

Clinical Presentation

The sporadic form of EVHCs is noted to be more common and clinically presents later, with an average age at onset of 16 years and an average age at diagnosis of 24 years.3 The sporadic form occurs without trauma or manipulation as a precursor. Less commonly, lesions present at birth or in early infancy and may show an autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern with a similar distribution across relatives.3

Other variants of EVHCs have been described. Late-onset EVHC usually occurs at 35 years or older (average age, 57 years), with a female to male predominance of 2.5 to 1.3 This late onset may be attributed to proliferation of ductal follicular keratinocytes or loss of perifollicular elastic fibers exacerbated by exogenous factors such as manipulation, UV rays, or trauma.5

For unilesional EVHC, the average age at diagnosis is 27 years.3 Some of these lesions may be pedunculated and greater than 8 mm. There is a female to male predominance of 2 to 1. Eruptive vellus hair cysts with steatocystoma multiplex can be seen with an average age at onset of 19 years and a female to male predominance of 0.2 to 1. There may be a family history of this subset, as reported in 3 patients with this pattern.3

Diagnosis

The recommended workup for EVHCs varies by patient and age. Eruptive vellus hair cysts present an opportunity to utilize noninvasive diagnostic procedures, especially for the pediatric population, to avoid scarring and pain from manipulation or biopsies. Although many practitioners may comfortably diagnose EVHCs clinically, 6 cases were misdiagnosed as steatocystoma multiplex, keratosis pilaris, or milia prior to histopathology revealing vellus hair cysts.6

Dermoscopy presents as a useful diagnostic aid. Eruptive vellus hair cysts exhibit light yellow homogenous circular structures with a maroon or erythematous halo.2,7 A central gray-blue color point may be seen due to melanin in the pigmented hair shaft.7 A dermoscopy review of EVHCs reported radiating capillaries.2 Occasionally, nonfollicular homogenous blue pigmentation may be seen due to a connection to atrophic hair follicles in the mid dermis and no normal hair follicle around the cysts.8 In comparison, dermoscopic characteristics of molluscum contagiosum demonstrated a polylobular, white-yellow, amorphous structure at the center with a hardened central umbilicated core and a crown of hairpin vessels at the periphery. Additionally, comedonal acne, commonly mistaken for EVHCs, reveals a brown-yellow hard central plug with sparse inflammation under dermoscopy.2 Thus, differentiation of these entities with dermoscopy should be highly prioritized to better aid in the diagnosis of pediatric dermatologic conditions using painless noninvasive techniques.

Treatment

The main indication for treatment of EVHCs is cosmetic concern. Twenty-five percent of EVHCs spontaneously resolve with transepidermal hair elimination or a granulomatous reaction.4,5 A case report of 4 siblings with congenital EVHCs also described a mother with similar lesions that resolved spontaneously in early adulthood,3 as our patients’ father also noted. Treatment modalities including topical keratolytic agents such as urea 10%, retinoic acid 0.05%, tazarotene cream 0.1%, and lactic acid 12%; incision and drainage; CO2 laser; or erbium-doped YAG laser ablation have been tried with minimal improvement.9 Of note, tazarotene cream 0.1% has demonstrated better results than both erbium-doped YAG laser and drainage and incision of EVHCs.4 Additionally, another report evidenced partial improvement with calcipotriene within 2 months with some lesions completely resolved and others flattened, which may be attributed to the antiproliferative and prodifferentiating effects on the ductal follicular keratinocytes by calcipotriene.5 Lastly, an additional study indicated that isotretinoin and vitamin A derivatives were ineffective for clearing EVHCs.10

Conclusion

We presented 3 identical triplets with the classic pediatric onset and dermoscopic findings of EVHCs on the trunk. Although the definitive diagnosis of EVHCs relies on histopathology, we argue that their unique dermoscopic findings combined with a thorough clinical examination is sufficient to recognize this benign condition and avoid painful procedures in the pediatric population.

Case Report

Four-year-old identical triplet girls with numerous asymptomatic scattered papules on the chest of 4 months’ duration were referred to a dermatologist by their pediatrician for molluscum contagiosum. The patients’ father reported that there was no history of trauma, irritation, or manipulation to the affected area. Their medical history was notable for prematurity at 32 weeks’ gestation and congenital dermal melanocytosis. Family history was notable for their father having acne and similar papules on the chest during adolescence that resolved with isotretinoin therapy.

On physical examination there were multiple smooth, hyperpigmented to erythematous, comedonal, 1- to 2-mm papules dispersed on the anterior central chest of all 3 patients (Figure 1). Clinically, these lesions were fairly indistinguishable from other common dermatologic conditions such as acne or milia. Dermoscopic examination revealed homogenous yellow-white areas surrounded by light brown to erythematous halos (Figure 2). Histopathologic examination was not performed given the benign clinical diagnosis and avoidance of biopsy in pediatric populations. Based on dermoscopic features and history, a diagnosis of eruptive vellus hair cysts (EVHCs) in identical triplets was made.

Comment

Pathogenesis

Eruptive vellus hair cysts, first introduced by Esterly et al1 in 1977, are uncommon benign lesions presumed to be caused by an abnormal development of the infundibular portion of the hair follicle.2 They are usually 1- to 3-mm, reddish brown, monomorphous papules overlapping with pilosebaceous and apocrine units.3 Although the lesions typically are located on the chest and extremities, they may occur on the face, abdomen, axillae, buttocks, or genital area.1,3 The inheritance of EVHCs is unclear. The majority of reported cases are sporadic; however, the literature mentions 19 families affected by autosomal-dominant EVHCs based on phylogeny.3 In 2015, EVHCs were reported in identical twins, further supporting the case for a genetic mutation.4 We augment this autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern by presenting a case of identical triplets with EVHCs. The patients’ father reported similar lesions in childhood, further underscoring a genetic basis.

The pathogenesis of EVHC is uncertain, with 2 main theories. Some propose retention of vellus hair and keratin in a cavity formed by an abnormal vellus hair follicle causing infundibular occlusion. Others consider the growth of benign follicular hamartomas that differentiate to become vellus hairs.1

Clinical Presentation

The sporadic form of EVHCs is noted to be more common and clinically presents later, with an average age at onset of 16 years and an average age at diagnosis of 24 years.3 The sporadic form occurs without trauma or manipulation as a precursor. Less commonly, lesions present at birth or in early infancy and may show an autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern with a similar distribution across relatives.3

Other variants of EVHCs have been described. Late-onset EVHC usually occurs at 35 years or older (average age, 57 years), with a female to male predominance of 2.5 to 1.3 This late onset may be attributed to proliferation of ductal follicular keratinocytes or loss of perifollicular elastic fibers exacerbated by exogenous factors such as manipulation, UV rays, or trauma.5

For unilesional EVHC, the average age at diagnosis is 27 years.3 Some of these lesions may be pedunculated and greater than 8 mm. There is a female to male predominance of 2 to 1. Eruptive vellus hair cysts with steatocystoma multiplex can be seen with an average age at onset of 19 years and a female to male predominance of 0.2 to 1. There may be a family history of this subset, as reported in 3 patients with this pattern.3

Diagnosis

The recommended workup for EVHCs varies by patient and age. Eruptive vellus hair cysts present an opportunity to utilize noninvasive diagnostic procedures, especially for the pediatric population, to avoid scarring and pain from manipulation or biopsies. Although many practitioners may comfortably diagnose EVHCs clinically, 6 cases were misdiagnosed as steatocystoma multiplex, keratosis pilaris, or milia prior to histopathology revealing vellus hair cysts.6

Dermoscopy presents as a useful diagnostic aid. Eruptive vellus hair cysts exhibit light yellow homogenous circular structures with a maroon or erythematous halo.2,7 A central gray-blue color point may be seen due to melanin in the pigmented hair shaft.7 A dermoscopy review of EVHCs reported radiating capillaries.2 Occasionally, nonfollicular homogenous blue pigmentation may be seen due to a connection to atrophic hair follicles in the mid dermis and no normal hair follicle around the cysts.8 In comparison, dermoscopic characteristics of molluscum contagiosum demonstrated a polylobular, white-yellow, amorphous structure at the center with a hardened central umbilicated core and a crown of hairpin vessels at the periphery. Additionally, comedonal acne, commonly mistaken for EVHCs, reveals a brown-yellow hard central plug with sparse inflammation under dermoscopy.2 Thus, differentiation of these entities with dermoscopy should be highly prioritized to better aid in the diagnosis of pediatric dermatologic conditions using painless noninvasive techniques.

Treatment

The main indication for treatment of EVHCs is cosmetic concern. Twenty-five percent of EVHCs spontaneously resolve with transepidermal hair elimination or a granulomatous reaction.4,5 A case report of 4 siblings with congenital EVHCs also described a mother with similar lesions that resolved spontaneously in early adulthood,3 as our patients’ father also noted. Treatment modalities including topical keratolytic agents such as urea 10%, retinoic acid 0.05%, tazarotene cream 0.1%, and lactic acid 12%; incision and drainage; CO2 laser; or erbium-doped YAG laser ablation have been tried with minimal improvement.9 Of note, tazarotene cream 0.1% has demonstrated better results than both erbium-doped YAG laser and drainage and incision of EVHCs.4 Additionally, another report evidenced partial improvement with calcipotriene within 2 months with some lesions completely resolved and others flattened, which may be attributed to the antiproliferative and prodifferentiating effects on the ductal follicular keratinocytes by calcipotriene.5 Lastly, an additional study indicated that isotretinoin and vitamin A derivatives were ineffective for clearing EVHCs.10

Conclusion

We presented 3 identical triplets with the classic pediatric onset and dermoscopic findings of EVHCs on the trunk. Although the definitive diagnosis of EVHCs relies on histopathology, we argue that their unique dermoscopic findings combined with a thorough clinical examination is sufficient to recognize this benign condition and avoid painful procedures in the pediatric population.

- Esterly NB, Fretzin DF, Pinkus H. Eruptive vellus hair cysts. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:500-503.

- Alfaro-Castellón P, Mejía-Rodríguez SA, Valencia-Herrera A, et al. Dermoscopy distinction of eruptive vellus hair cysts with molluscum contagiosum and acne lesions. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:772-773.

- Torchia D, Vega J, Schachner LA. Eruptive vellus hair cysts: a systematic review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13:19-28.

- Pauline G, Alain H, Jean-Jaques R, et al. Eruptive vellus hair cysts: an original case occurring in twins [published online July 11, 2014]. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:E209-E212.

- Erkek E, Kurtipek GS, Duman D, et al. Eruptive vellus hair cysts: report of a pediatric case with partial response to calcipotriene therapy. Cutis. 2009;84:295-298.

- Shi G, Zhou Y, Cai YX, et al. Clinicopathological features and expression of four keratins (K10, K14, K17 and K19) in six cases of eruptive vellus hair cysts. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2014;39:496-499.

- Panchaprateep R, Tanus A, Tosti A. Clinical, dermoscopic, and histopathologic features of body hair disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:890-900.

- Takada S, Togawa Y, Wakabayashii S, et al. Dermoscopic findings in eruptive vellus hair cysts: a case report. Austin J Dermatol. 2014;1:1004.

- Khatu S, Vasani R, Amin S. Eruptive vellus hair cyst presenting as asymptomatic follicular papules on extremities. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2013;4:213-215.

- Urbina-Gonzalez F, Aguilar-Martinez A, Cristobal-Gil M, et al. The treatment of eruptive vellus hair cysts with isotretinoin. Br J Dermatol. 1987;116:465-466.

- Esterly NB, Fretzin DF, Pinkus H. Eruptive vellus hair cysts. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:500-503.

- Alfaro-Castellón P, Mejía-Rodríguez SA, Valencia-Herrera A, et al. Dermoscopy distinction of eruptive vellus hair cysts with molluscum contagiosum and acne lesions. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:772-773.

- Torchia D, Vega J, Schachner LA. Eruptive vellus hair cysts: a systematic review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13:19-28.

- Pauline G, Alain H, Jean-Jaques R, et al. Eruptive vellus hair cysts: an original case occurring in twins [published online July 11, 2014]. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:E209-E212.

- Erkek E, Kurtipek GS, Duman D, et al. Eruptive vellus hair cysts: report of a pediatric case with partial response to calcipotriene therapy. Cutis. 2009;84:295-298.

- Shi G, Zhou Y, Cai YX, et al. Clinicopathological features and expression of four keratins (K10, K14, K17 and K19) in six cases of eruptive vellus hair cysts. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2014;39:496-499.

- Panchaprateep R, Tanus A, Tosti A. Clinical, dermoscopic, and histopathologic features of body hair disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:890-900.

- Takada S, Togawa Y, Wakabayashii S, et al. Dermoscopic findings in eruptive vellus hair cysts: a case report. Austin J Dermatol. 2014;1:1004.

- Khatu S, Vasani R, Amin S. Eruptive vellus hair cyst presenting as asymptomatic follicular papules on extremities. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2013;4:213-215.

- Urbina-Gonzalez F, Aguilar-Martinez A, Cristobal-Gil M, et al. The treatment of eruptive vellus hair cysts with isotretinoin. Br J Dermatol. 1987;116:465-466.

Practice Points

- Eruptive vellus hair cysts (EVHCs) are 1- to 3-mm round, dome-shaped, flesh-colored, asymptomatic, benign papules typically occurring on the chest and extremities.

- Pathogenesis and inheritance are unclear. Although the majority of EVHC cases are sporadic, the strong influence of genes is indicated by numerous reports of families in whom 2 or more members were affected.

- Dermoscopy is a noninvasive diagnostic procedure that should be utilized to diagnose EVHCs in the pediatric population; specifically, EVHCs exhibit light yellow, homogenous, circular structures with a maroon or erythematous halo.

- The main indication for treatment of EVHCs is cosmetic concern; however, one-quarter of cases may resolve spontaneously.

Successful Treatment of Ota Nevus With the 532-nm Solid-State Picosecond Laser

Ota nevus is a dermal melanocytosis that is typically characterized by blue, gray, or brown pigmented patches in the periorbital region.1 The condition has a prevalence of 0.04% in a Philadelphia study of 6915 patients and is most notable in patients with skin of color, affecting up to 0.6% of Asians,2 0.038% of white individuals, and 0.014% of black individuals.3,4 The appearance of an Ota nevus often imparts a negative psychosocial impact on the patient, prompting requests for treatment and/or removal.5 Laser treatment of Ota nevi must be carefully implemented, especially in Fitzpatrick skin types IV through VI. Although 532- and 755-nm Q-switched nanosecond lasers have been used to treat Ota nevi,5,6 typically only moderate improvement is seen; further treatment at higher fluences will only increase the risk for dyspigmentation and scarring.6

We report a case of successful treatment of an Ota nevus following 2 treatment sessions with the 532-nm solid-state picosecond laser, which is a novel application in patients with skin of color (Fitzpatrick skin types IV-VI). The Q-switched nanosecond laser has been shown to be moderately effective at treating Ota nevi.6

Case Report

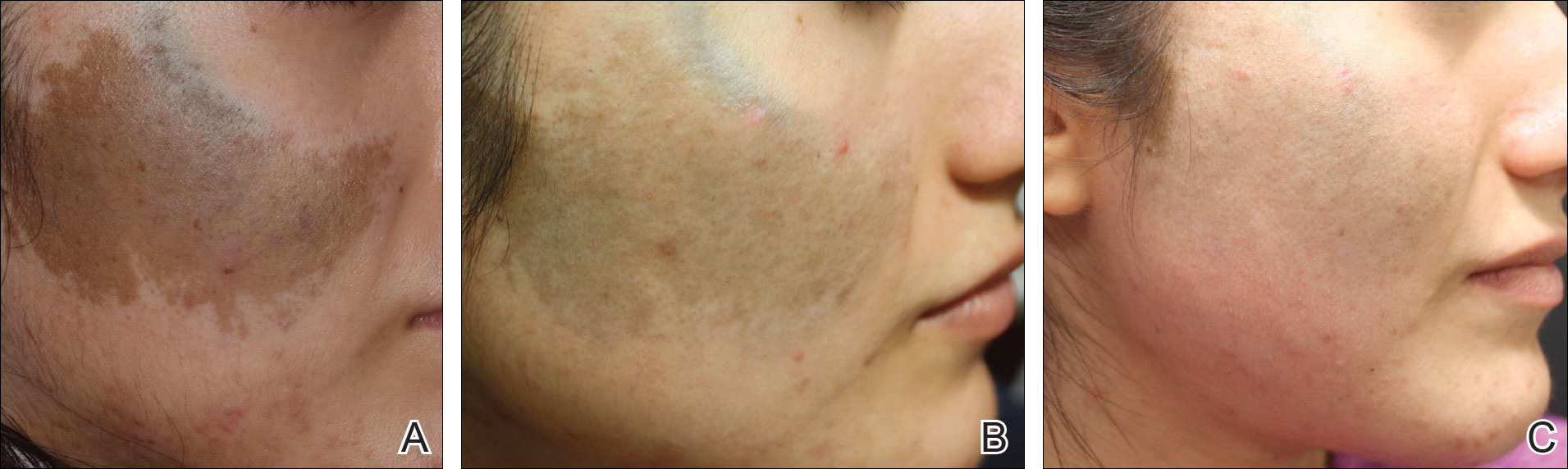

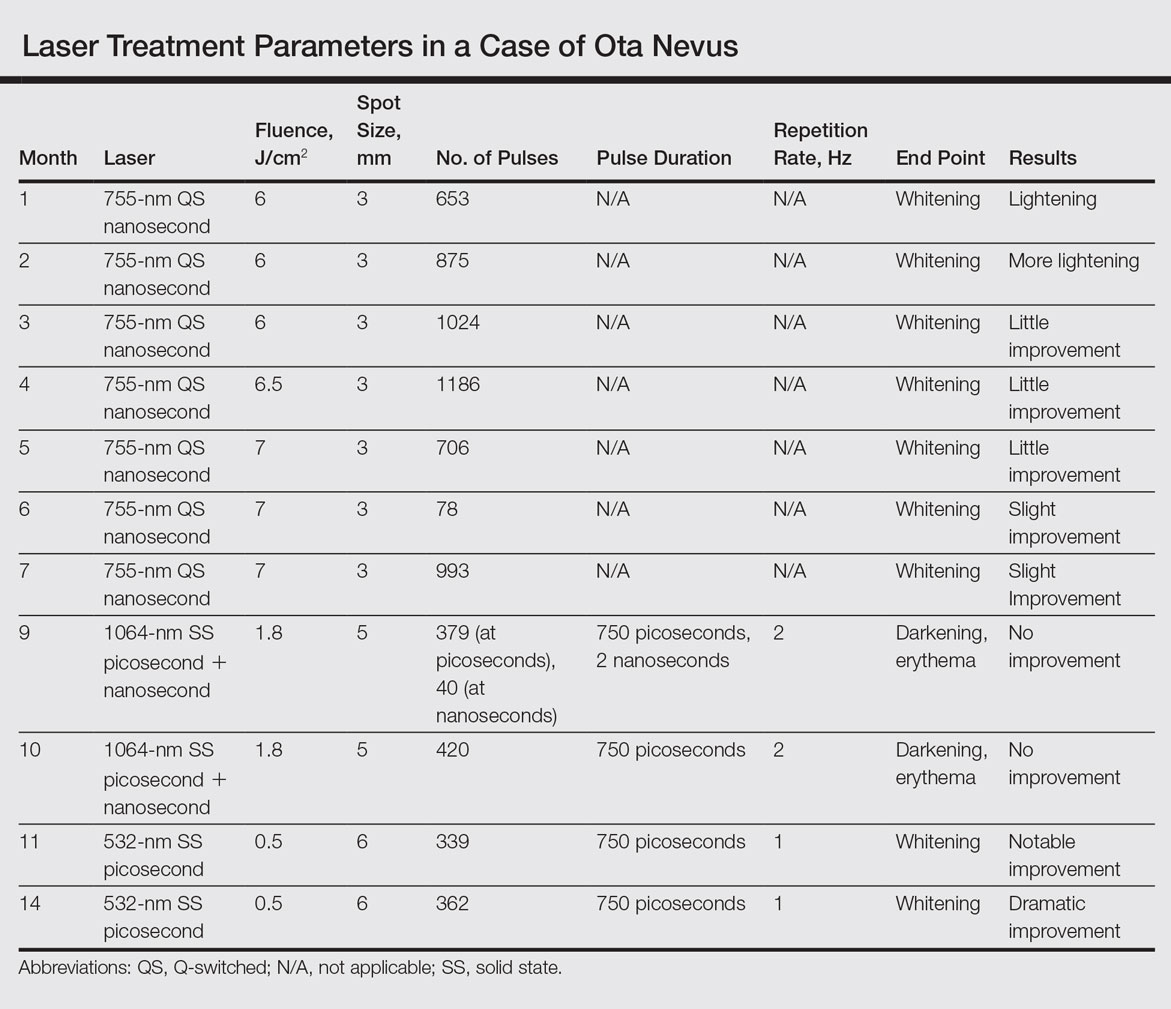

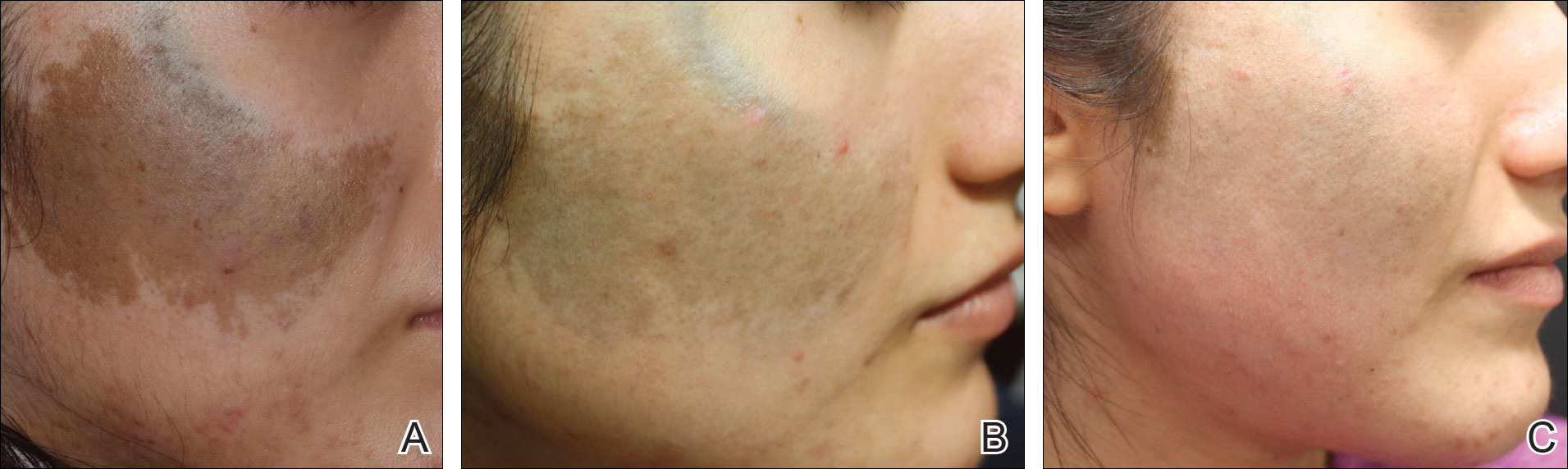

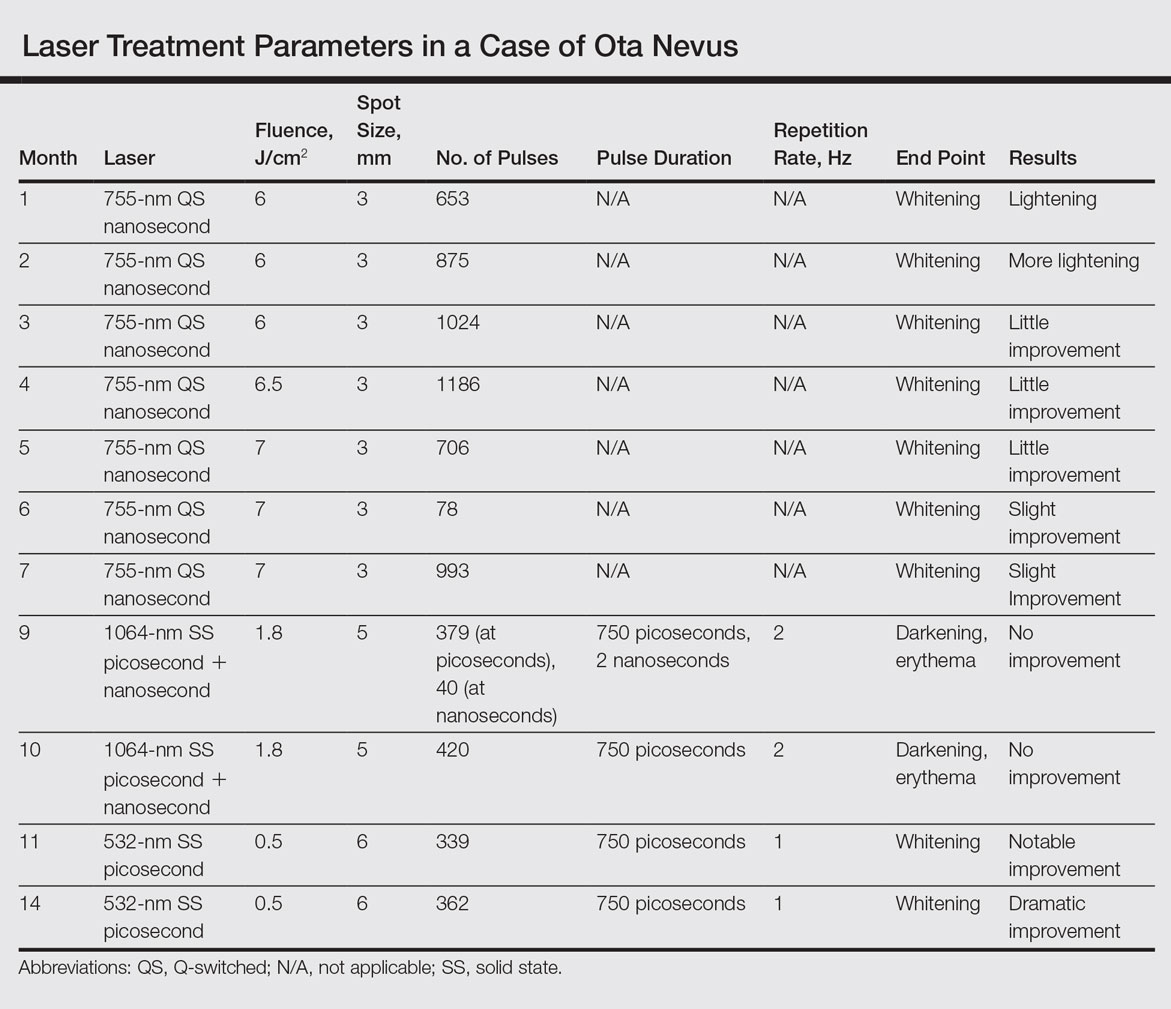

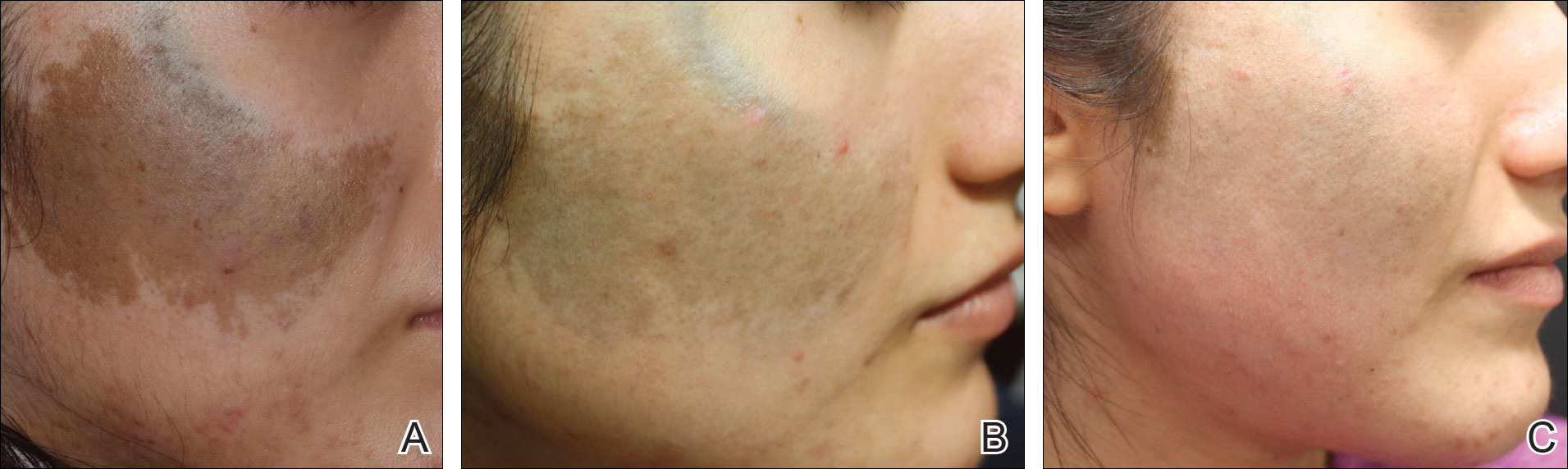

An 18-year-old woman with Fitzpatrick skin type IV presented for cosmetic removal of an 8×5-cm dark brown-blue patch on the right temple and malar and buccal cheek present since birth that had failed to respond to an unknown laser treatment that was administered outside of the United States (Figure, A). To ascertain the diagnosis, a biopsy was performed, showing histology consistent with Ota nevus. Initially, the 755-nm Q-switched nanosecond laser was recommended for treatment. Over the course of 7 months (1 treatment session per month [Table]), the patient saw improvement but not to the desired extent. The patient then underwent 2 treatments at 4-week intervals with the 1064-nm solid-state picosecond and nanosecond lasers; however, no improvement was seen following these 2 sessions (Table).

The next month the patient received treatment with a novel 532-nm solid-state picosecond laser using the following parameters: fluence, 0.5 J/cm2; spot size, 6 mm; repetition rate, 1 Hz; pulse duration, 750 picoseconds; 339 pulses. The end point was whitening. A remarkable clinical response was demonstrated 6 weeks later (Figure, B). A second treatment with the 532-nm solid-state picosecond laser was then performed at 14 months. On a return visit 2 months after the second treatment, the patient showed dramatic improvement, almost to the degree of complete resolution (Figure, C).

Comment

Pigmentation disorders are more common in patients with skin of color, and those affected may experience psychological effects secondary to these dermatoses, prompting requests for treatment and/or removal.7 Although the 532- and 755-nm Q-switched nanosecond lasers have been used to treat Ota nevi,3 the challenge remains for patients with skin of color, as these lasers work through photothermolysis, which generates heat and may cause thermal damage by targeting melanin. Because more melanin is present in skin of color patients, the threshold for too much heat is lower and these patients are at a higher risk for adverse events such as scarring and hyperpigmentation.6,8

By delivering energy in shorter pulses, the novel 532-nm solid-state picosecond laser shows greater fragmentation of melanosomes into melanin particles that are eventually phagocytosed.8 In our patient, dramatic improvement was noted after only 2 treatments, as evidenced by other picosecond treatments on Ota nevi,6,8 suggesting that fewer treatments are necessary when using the 532-nm solid-state picosecond laser for Ota nevi.

Although the 532-nm solid-state picosecond laser was cleared by the US Food and Drug Administration for tattoo removal, this laser shows potential use in other pigmentary disorders, particularly in patients with skin of color, as demonstrated in our case. With continued understanding through further studies, this picosecond laser with a shorter pulse duration may prove to be a safer and more effective alternative to the Q-switched nanosecond laser.

Conclusion

As shown in our case, the 532-nm solid-state picosecond laser appears to be a safe and effective modality for treating Ota nevi. This case demonstrates the potential utility of this laser in patients desiring more complete clearing, as it removes pigment more rapidly with lower risk for serious adverse effects. The 9th Cosmetic Surgery Forum will be held November 29-December 2, 2017, in Las Vegas, Nevada. Get more information at www.cosmeticsurgeryforum.com.

- Kim JY, Lee HG, Kim MJ, et al. The efficacy and safety of episcleral pigmentation removal from pig eyes: using a 532-nm quality-switched Nd: YAG laser. Cornea. 2012;31:1449-1454.

- Watanabe S, Takahashi H. Treatment of nevus of Ota with the Q-switched ruby laser. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1745-1750.

- Yates B, Que SK, D'Souza L, et al. Laser treatment of periocular skin conditions. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:197-206.

- Gonder JR, Ezell PC, Shields JA, et al. Ocular melanocytosis. a study to determine the prevalence rate of ocular melanocytosis. Ophthalmology. 1982;89:950-952.

- Chesnut C, Diehl J, Lask G. Treatment of nevus of Ota with a picosecond 755-nm alexandrite laser. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:508-510.

- Moreno-Arias GA, Camps-Fresneda A. Treatment of nevus of Ota with the Q-switched alexandrite laser. Lasers Surg Med. 2001;28:451-455.

- Manuskiatti W, Eimpunth S, Wanitphakdeedecha R. Effect of cold air cooling on the incidence of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation after Q-switched Nd:YAG laser treatment of acquired bilateral nevus of Ota like macules. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:1139-1143.

- Levin MK, Ng E, Bae YS, et al. Treatment of pigmentary disorders in patients with skin of color with a novel 755 nm picosecond, Q-switched ruby, and Q-switched Nd:YAG nanosecond lasers: a retrospective photographic review. Lasers Surg Med. 2016;48:181-187.

Ota nevus is a dermal melanocytosis that is typically characterized by blue, gray, or brown pigmented patches in the periorbital region.1 The condition has a prevalence of 0.04% in a Philadelphia study of 6915 patients and is most notable in patients with skin of color, affecting up to 0.6% of Asians,2 0.038% of white individuals, and 0.014% of black individuals.3,4 The appearance of an Ota nevus often imparts a negative psychosocial impact on the patient, prompting requests for treatment and/or removal.5 Laser treatment of Ota nevi must be carefully implemented, especially in Fitzpatrick skin types IV through VI. Although 532- and 755-nm Q-switched nanosecond lasers have been used to treat Ota nevi,5,6 typically only moderate improvement is seen; further treatment at higher fluences will only increase the risk for dyspigmentation and scarring.6

We report a case of successful treatment of an Ota nevus following 2 treatment sessions with the 532-nm solid-state picosecond laser, which is a novel application in patients with skin of color (Fitzpatrick skin types IV-VI). The Q-switched nanosecond laser has been shown to be moderately effective at treating Ota nevi.6

Case Report

An 18-year-old woman with Fitzpatrick skin type IV presented for cosmetic removal of an 8×5-cm dark brown-blue patch on the right temple and malar and buccal cheek present since birth that had failed to respond to an unknown laser treatment that was administered outside of the United States (Figure, A). To ascertain the diagnosis, a biopsy was performed, showing histology consistent with Ota nevus. Initially, the 755-nm Q-switched nanosecond laser was recommended for treatment. Over the course of 7 months (1 treatment session per month [Table]), the patient saw improvement but not to the desired extent. The patient then underwent 2 treatments at 4-week intervals with the 1064-nm solid-state picosecond and nanosecond lasers; however, no improvement was seen following these 2 sessions (Table).

The next month the patient received treatment with a novel 532-nm solid-state picosecond laser using the following parameters: fluence, 0.5 J/cm2; spot size, 6 mm; repetition rate, 1 Hz; pulse duration, 750 picoseconds; 339 pulses. The end point was whitening. A remarkable clinical response was demonstrated 6 weeks later (Figure, B). A second treatment with the 532-nm solid-state picosecond laser was then performed at 14 months. On a return visit 2 months after the second treatment, the patient showed dramatic improvement, almost to the degree of complete resolution (Figure, C).

Comment

Pigmentation disorders are more common in patients with skin of color, and those affected may experience psychological effects secondary to these dermatoses, prompting requests for treatment and/or removal.7 Although the 532- and 755-nm Q-switched nanosecond lasers have been used to treat Ota nevi,3 the challenge remains for patients with skin of color, as these lasers work through photothermolysis, which generates heat and may cause thermal damage by targeting melanin. Because more melanin is present in skin of color patients, the threshold for too much heat is lower and these patients are at a higher risk for adverse events such as scarring and hyperpigmentation.6,8

By delivering energy in shorter pulses, the novel 532-nm solid-state picosecond laser shows greater fragmentation of melanosomes into melanin particles that are eventually phagocytosed.8 In our patient, dramatic improvement was noted after only 2 treatments, as evidenced by other picosecond treatments on Ota nevi,6,8 suggesting that fewer treatments are necessary when using the 532-nm solid-state picosecond laser for Ota nevi.

Although the 532-nm solid-state picosecond laser was cleared by the US Food and Drug Administration for tattoo removal, this laser shows potential use in other pigmentary disorders, particularly in patients with skin of color, as demonstrated in our case. With continued understanding through further studies, this picosecond laser with a shorter pulse duration may prove to be a safer and more effective alternative to the Q-switched nanosecond laser.

Conclusion

As shown in our case, the 532-nm solid-state picosecond laser appears to be a safe and effective modality for treating Ota nevi. This case demonstrates the potential utility of this laser in patients desiring more complete clearing, as it removes pigment more rapidly with lower risk for serious adverse effects. The 9th Cosmetic Surgery Forum will be held November 29-December 2, 2017, in Las Vegas, Nevada. Get more information at www.cosmeticsurgeryforum.com.

Ota nevus is a dermal melanocytosis that is typically characterized by blue, gray, or brown pigmented patches in the periorbital region.1 The condition has a prevalence of 0.04% in a Philadelphia study of 6915 patients and is most notable in patients with skin of color, affecting up to 0.6% of Asians,2 0.038% of white individuals, and 0.014% of black individuals.3,4 The appearance of an Ota nevus often imparts a negative psychosocial impact on the patient, prompting requests for treatment and/or removal.5 Laser treatment of Ota nevi must be carefully implemented, especially in Fitzpatrick skin types IV through VI. Although 532- and 755-nm Q-switched nanosecond lasers have been used to treat Ota nevi,5,6 typically only moderate improvement is seen; further treatment at higher fluences will only increase the risk for dyspigmentation and scarring.6

We report a case of successful treatment of an Ota nevus following 2 treatment sessions with the 532-nm solid-state picosecond laser, which is a novel application in patients with skin of color (Fitzpatrick skin types IV-VI). The Q-switched nanosecond laser has been shown to be moderately effective at treating Ota nevi.6

Case Report

An 18-year-old woman with Fitzpatrick skin type IV presented for cosmetic removal of an 8×5-cm dark brown-blue patch on the right temple and malar and buccal cheek present since birth that had failed to respond to an unknown laser treatment that was administered outside of the United States (Figure, A). To ascertain the diagnosis, a biopsy was performed, showing histology consistent with Ota nevus. Initially, the 755-nm Q-switched nanosecond laser was recommended for treatment. Over the course of 7 months (1 treatment session per month [Table]), the patient saw improvement but not to the desired extent. The patient then underwent 2 treatments at 4-week intervals with the 1064-nm solid-state picosecond and nanosecond lasers; however, no improvement was seen following these 2 sessions (Table).

The next month the patient received treatment with a novel 532-nm solid-state picosecond laser using the following parameters: fluence, 0.5 J/cm2; spot size, 6 mm; repetition rate, 1 Hz; pulse duration, 750 picoseconds; 339 pulses. The end point was whitening. A remarkable clinical response was demonstrated 6 weeks later (Figure, B). A second treatment with the 532-nm solid-state picosecond laser was then performed at 14 months. On a return visit 2 months after the second treatment, the patient showed dramatic improvement, almost to the degree of complete resolution (Figure, C).

Comment

Pigmentation disorders are more common in patients with skin of color, and those affected may experience psychological effects secondary to these dermatoses, prompting requests for treatment and/or removal.7 Although the 532- and 755-nm Q-switched nanosecond lasers have been used to treat Ota nevi,3 the challenge remains for patients with skin of color, as these lasers work through photothermolysis, which generates heat and may cause thermal damage by targeting melanin. Because more melanin is present in skin of color patients, the threshold for too much heat is lower and these patients are at a higher risk for adverse events such as scarring and hyperpigmentation.6,8

By delivering energy in shorter pulses, the novel 532-nm solid-state picosecond laser shows greater fragmentation of melanosomes into melanin particles that are eventually phagocytosed.8 In our patient, dramatic improvement was noted after only 2 treatments, as evidenced by other picosecond treatments on Ota nevi,6,8 suggesting that fewer treatments are necessary when using the 532-nm solid-state picosecond laser for Ota nevi.

Although the 532-nm solid-state picosecond laser was cleared by the US Food and Drug Administration for tattoo removal, this laser shows potential use in other pigmentary disorders, particularly in patients with skin of color, as demonstrated in our case. With continued understanding through further studies, this picosecond laser with a shorter pulse duration may prove to be a safer and more effective alternative to the Q-switched nanosecond laser.

Conclusion

As shown in our case, the 532-nm solid-state picosecond laser appears to be a safe and effective modality for treating Ota nevi. This case demonstrates the potential utility of this laser in patients desiring more complete clearing, as it removes pigment more rapidly with lower risk for serious adverse effects. The 9th Cosmetic Surgery Forum will be held November 29-December 2, 2017, in Las Vegas, Nevada. Get more information at www.cosmeticsurgeryforum.com.

- Kim JY, Lee HG, Kim MJ, et al. The efficacy and safety of episcleral pigmentation removal from pig eyes: using a 532-nm quality-switched Nd: YAG laser. Cornea. 2012;31:1449-1454.

- Watanabe S, Takahashi H. Treatment of nevus of Ota with the Q-switched ruby laser. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1745-1750.

- Yates B, Que SK, D'Souza L, et al. Laser treatment of periocular skin conditions. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:197-206.

- Gonder JR, Ezell PC, Shields JA, et al. Ocular melanocytosis. a study to determine the prevalence rate of ocular melanocytosis. Ophthalmology. 1982;89:950-952.

- Chesnut C, Diehl J, Lask G. Treatment of nevus of Ota with a picosecond 755-nm alexandrite laser. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:508-510.

- Moreno-Arias GA, Camps-Fresneda A. Treatment of nevus of Ota with the Q-switched alexandrite laser. Lasers Surg Med. 2001;28:451-455.

- Manuskiatti W, Eimpunth S, Wanitphakdeedecha R. Effect of cold air cooling on the incidence of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation after Q-switched Nd:YAG laser treatment of acquired bilateral nevus of Ota like macules. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:1139-1143.

- Levin MK, Ng E, Bae YS, et al. Treatment of pigmentary disorders in patients with skin of color with a novel 755 nm picosecond, Q-switched ruby, and Q-switched Nd:YAG nanosecond lasers: a retrospective photographic review. Lasers Surg Med. 2016;48:181-187.

- Kim JY, Lee HG, Kim MJ, et al. The efficacy and safety of episcleral pigmentation removal from pig eyes: using a 532-nm quality-switched Nd: YAG laser. Cornea. 2012;31:1449-1454.

- Watanabe S, Takahashi H. Treatment of nevus of Ota with the Q-switched ruby laser. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1745-1750.

- Yates B, Que SK, D'Souza L, et al. Laser treatment of periocular skin conditions. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:197-206.

- Gonder JR, Ezell PC, Shields JA, et al. Ocular melanocytosis. a study to determine the prevalence rate of ocular melanocytosis. Ophthalmology. 1982;89:950-952.

- Chesnut C, Diehl J, Lask G. Treatment of nevus of Ota with a picosecond 755-nm alexandrite laser. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:508-510.

- Moreno-Arias GA, Camps-Fresneda A. Treatment of nevus of Ota with the Q-switched alexandrite laser. Lasers Surg Med. 2001;28:451-455.

- Manuskiatti W, Eimpunth S, Wanitphakdeedecha R. Effect of cold air cooling on the incidence of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation after Q-switched Nd:YAG laser treatment of acquired bilateral nevus of Ota like macules. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:1139-1143.

- Levin MK, Ng E, Bae YS, et al. Treatment of pigmentary disorders in patients with skin of color with a novel 755 nm picosecond, Q-switched ruby, and Q-switched Nd:YAG nanosecond lasers: a retrospective photographic review. Lasers Surg Med. 2016;48:181-187.

Resident Pearl

The Q-switched 532-nm picosecond laser delivers energy in short pulses, creating fragmentation of melanosomes into melanin particles that eventually become phagocytosed. This process may be safer for patients with Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI, as it decreases the risk for dyschromia and scarring.