User login

The CROWNing Event on Hair Loss in Women of Color: A Framework for Advocacy and Community Engagement (FACE) Survey Analysis

Hair loss is a primary reason why women with skin of color seek dermatologic care.1-3 In addition to physical disfigurement, patients with hair loss are more likely to report feelings of depression, anxiety, and low self-esteem compared to the general population.4 There is a critical gap in advocacy efforts and educational information intended for women with skin of color. The American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) has 6 main public health programs (https://www.aad.org/public/public-health) and 8 stated advocacy priorities (https://www.aad.org/member/advocacy/priorities) but none of them focus on outreach to minority communities.

Historically, hair in patients with skin of color also has been a systemic tangible target for race-based discrimination. The Create a Respectful and Open World for Natural Hair (CROWN) Act was passed to protect against discrimination based on race-based hairstyles in schools and workplaces.5 Health care providers play an important role in advocating for their patients, but studies have shown that barriers to effective advocacy include a lack of knowledge, resources, or time.6-8 Virtual advocacy events improve participants’ understanding and interest in community engagement and advocacy.6,7 With the mission to engage, educate, and empower women with skin of color and the dermatologists who treat them, the Virginia Dermatology Society hosted the virtual CROWNing Event on Hair Loss in Women of Color in July 2021. We believe that this event, as well as this column, can serve as a template to improve advocacy and educational efforts for additional topics and diseases that affect marginalized or underserved populations. Survey data were collected and analyzed to establish a baseline of awareness and understanding of hair loss in women with skin of color and to evaluate the impact of a virtual event on participants’ empowerment and familiarity with resources for this population.

Methods

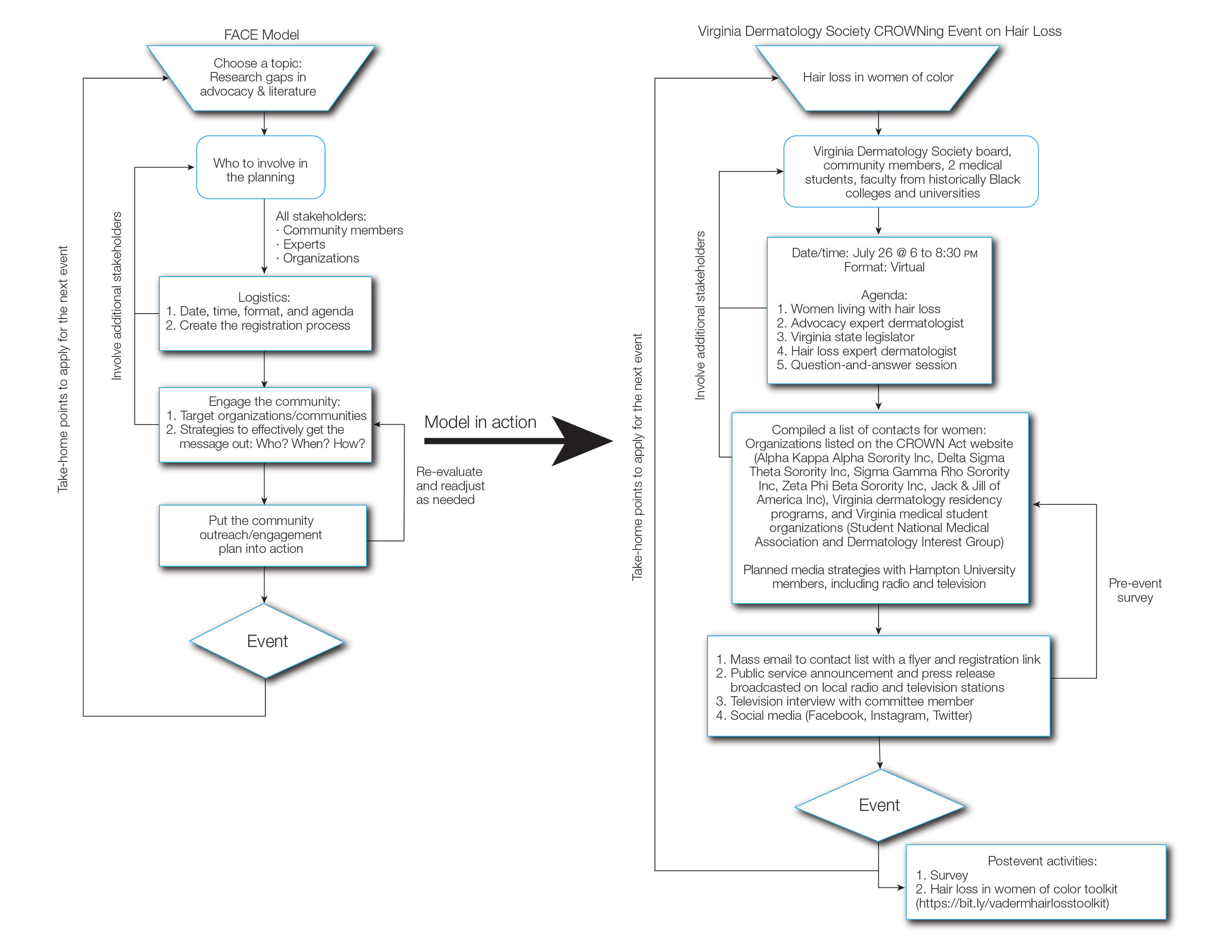

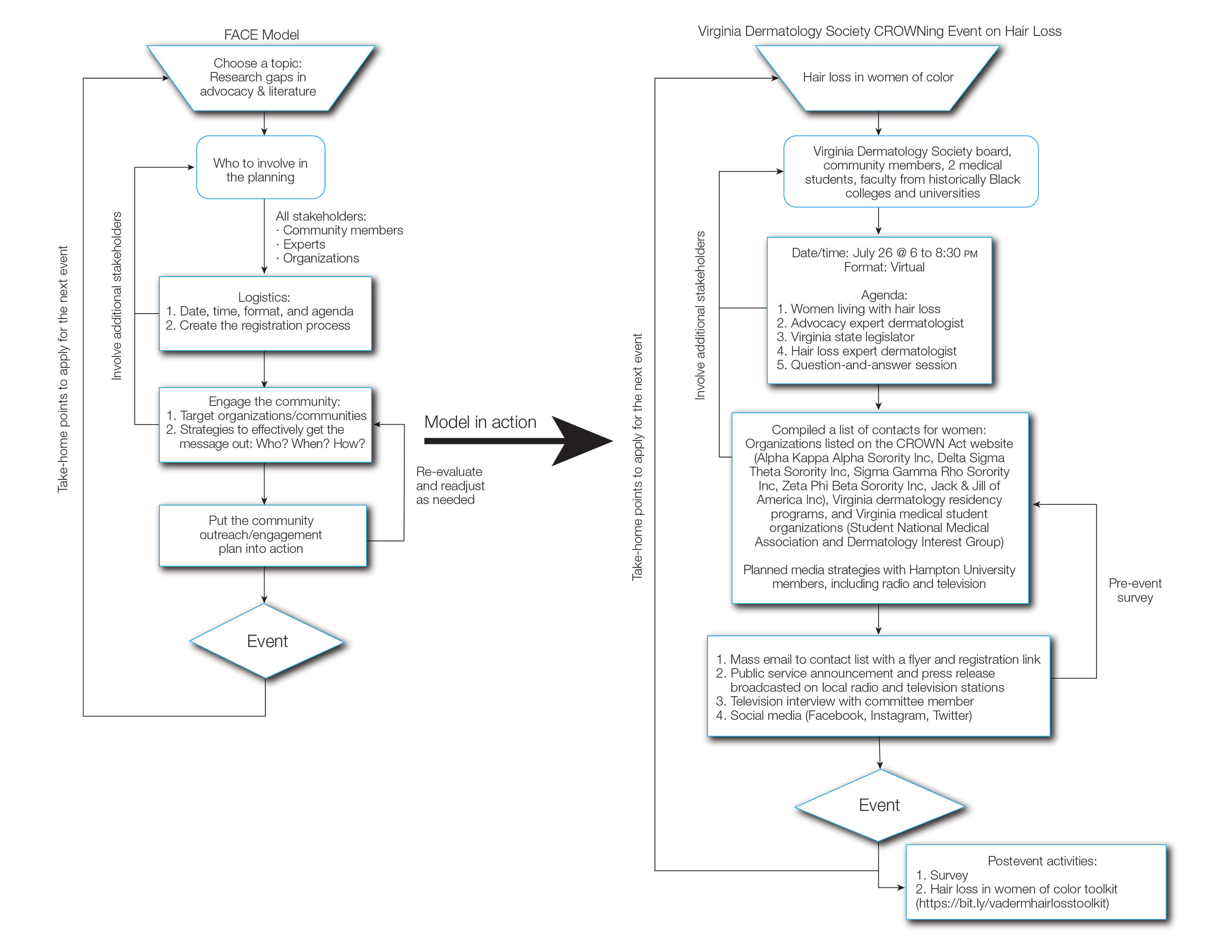

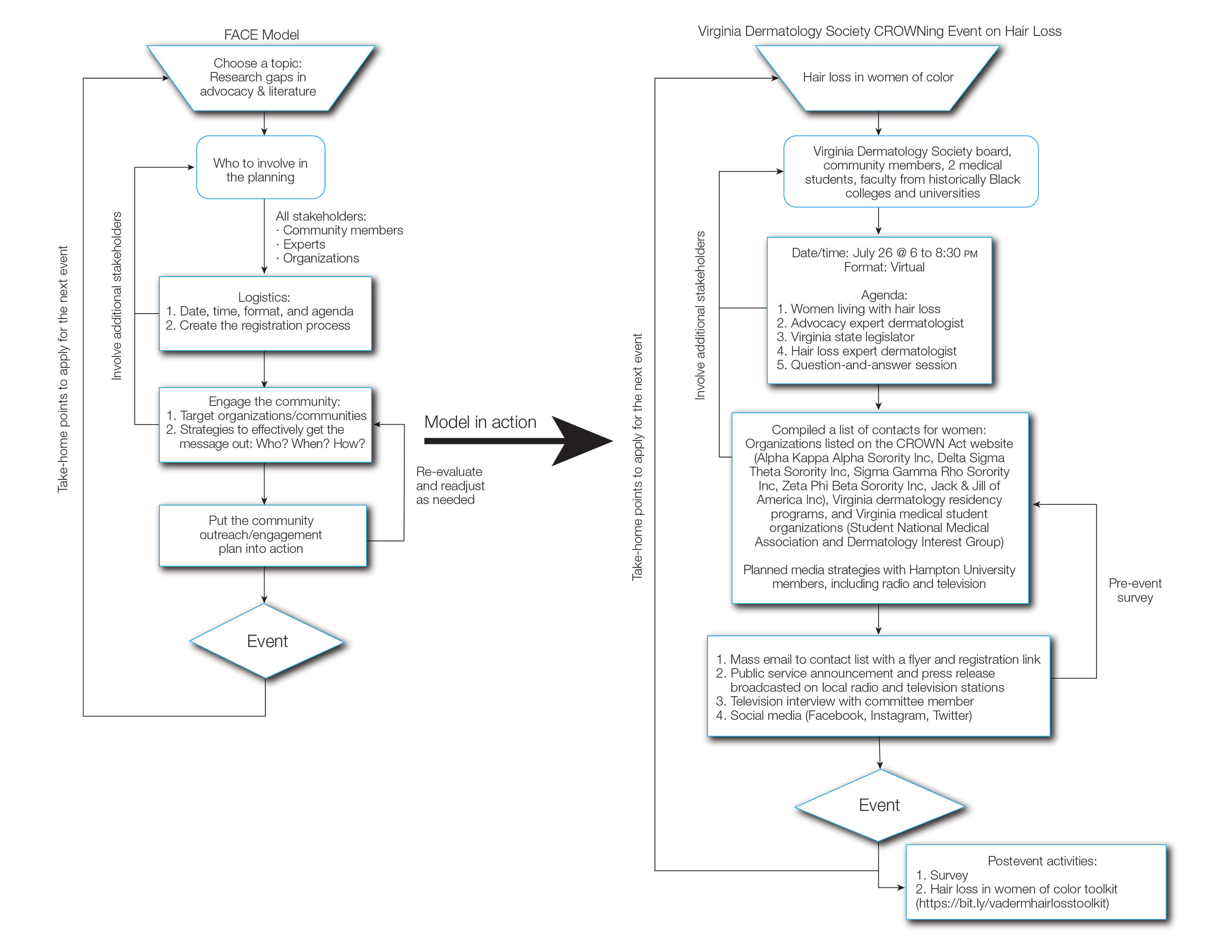

The Virginia Dermatology Society organized a virtual event focused on hair loss and practical political advocacy for women with skin of color. As members of the Virginia Dermatology Society and as part of the planning and execution of this event, the authors engaged relevant stakeholder organizations and collaborated with faculty at a local historically Black university to create a targeted, culturally sensitive communication strategy known as the Framework for Advocacy and Community Engagement (FACE) model (Figure). The agenda included presentations by 2 patients of color living with a hair loss disorder, a dermatologist with experience in advocacy, a Virginia state legislator, and a dermatologic hair loss expert, followed by a final question-and-answer session.

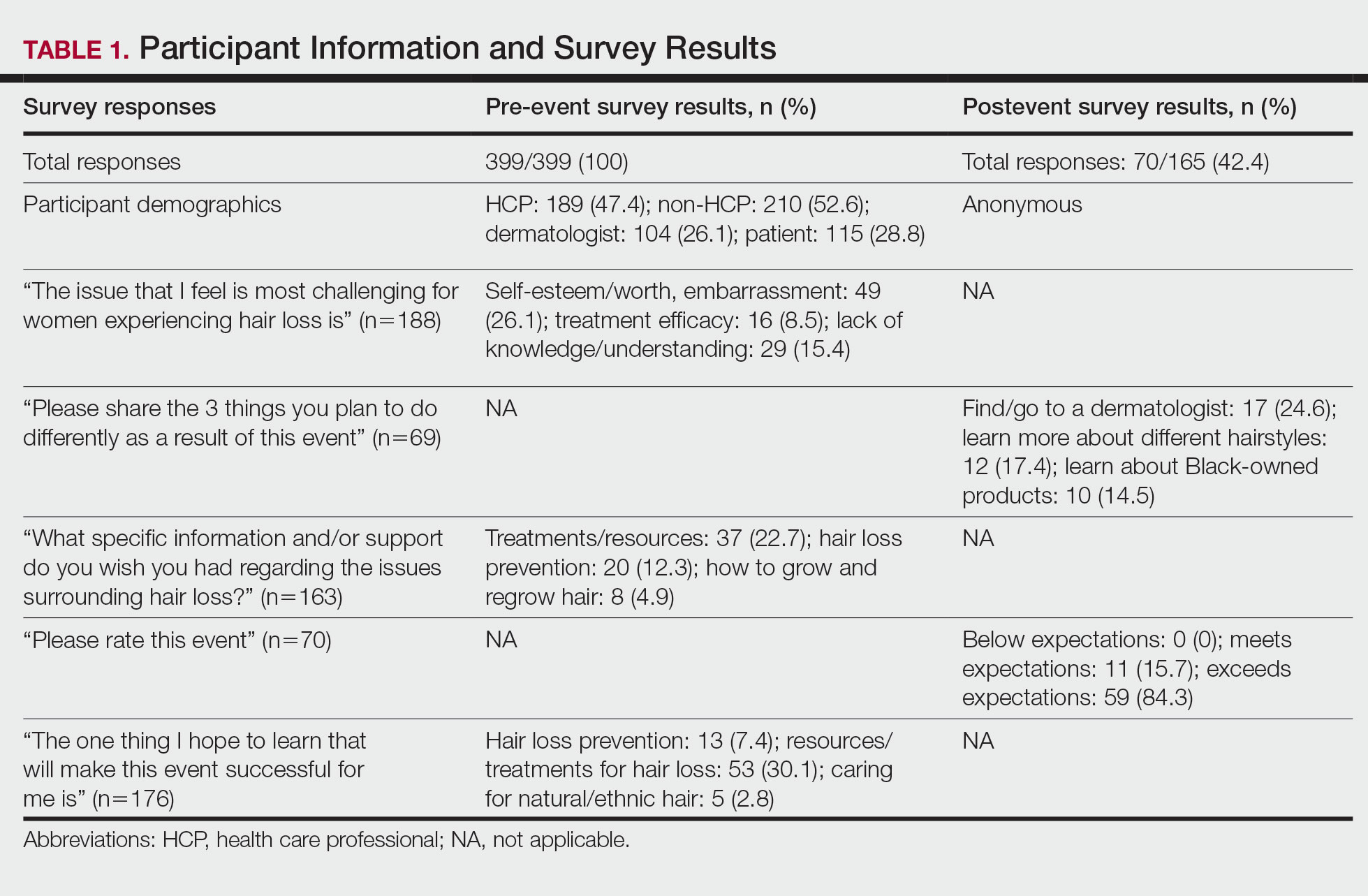

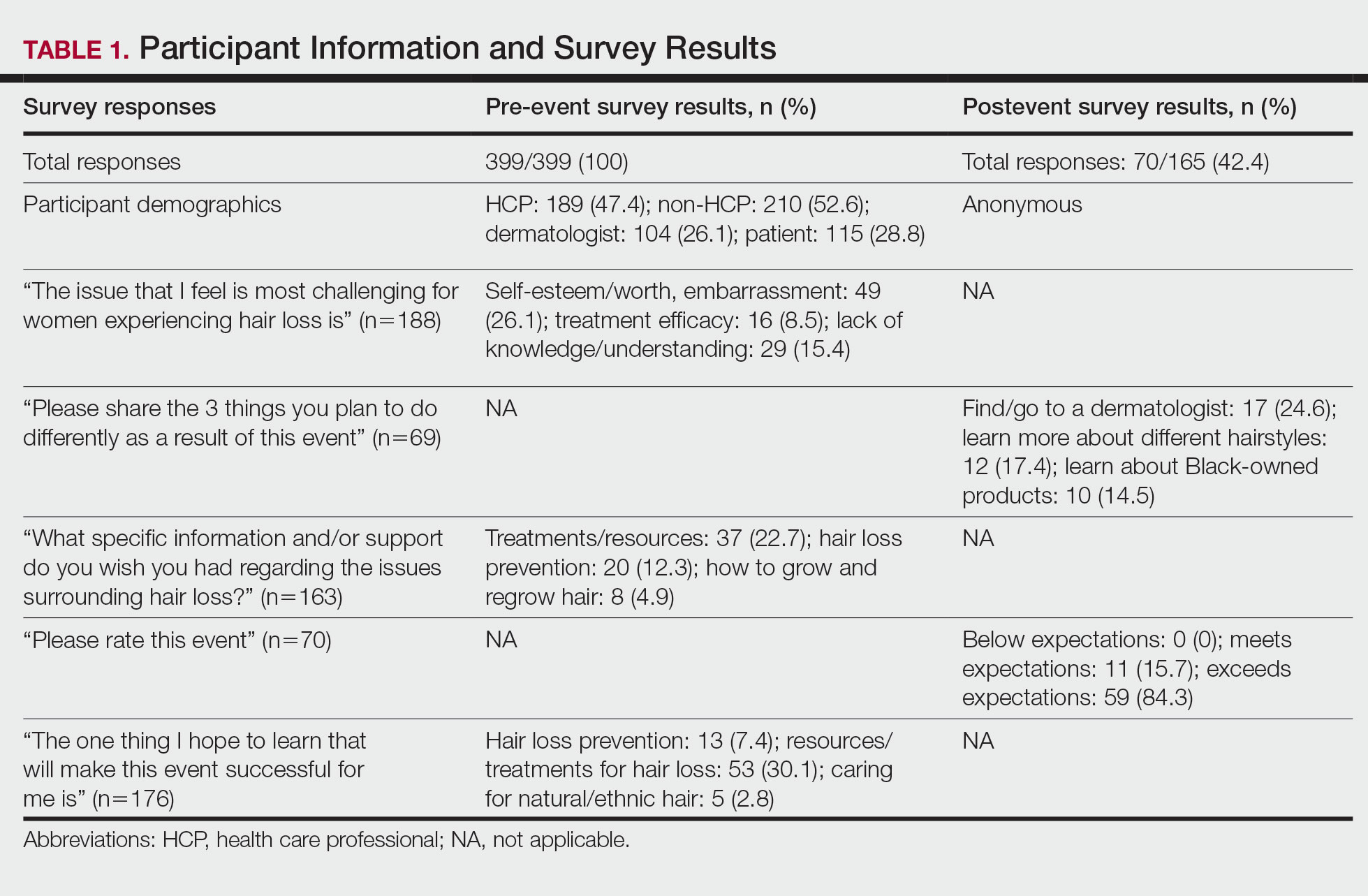

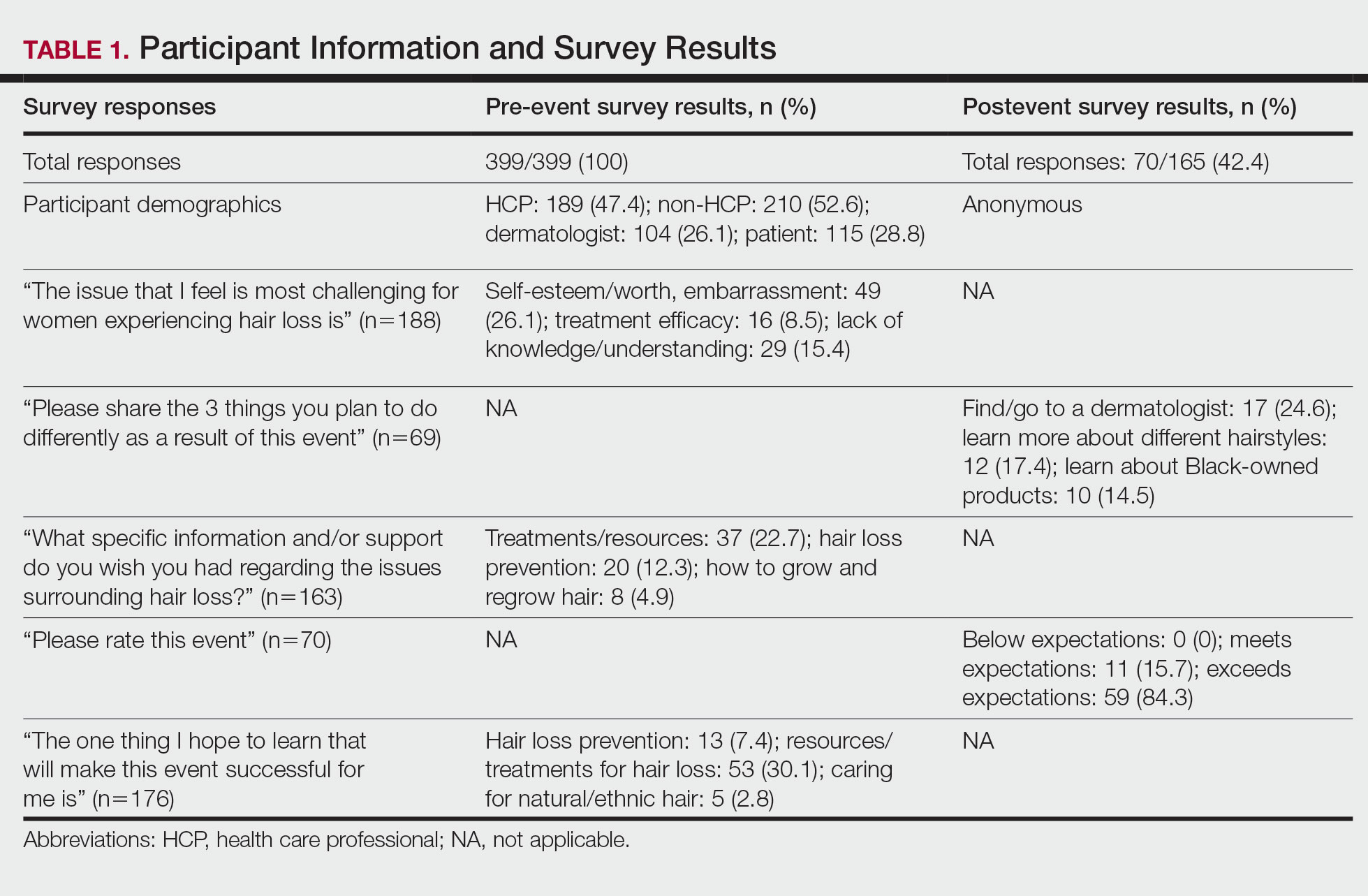

We created pre- and postevent Likert scale surveys assessing participant attitudes, knowledge, and awareness surrounding hair loss that were distributed electronically to all 399 registrants before and after the event, respectively. The responses were analyzed using a Mann-Whitney U test.

Based on preliminary pre-event survey data, we created a resource toolkit (https://bit.ly/vadermhairlosstoolkit) for distribution to both patients and physicians. The toolkit included articles about evaluating, diagnosing, and treating different types of hair loss that would be beneficial for dermatologists, as well as informational articles, online resources, and videos that would be helpful to patients.

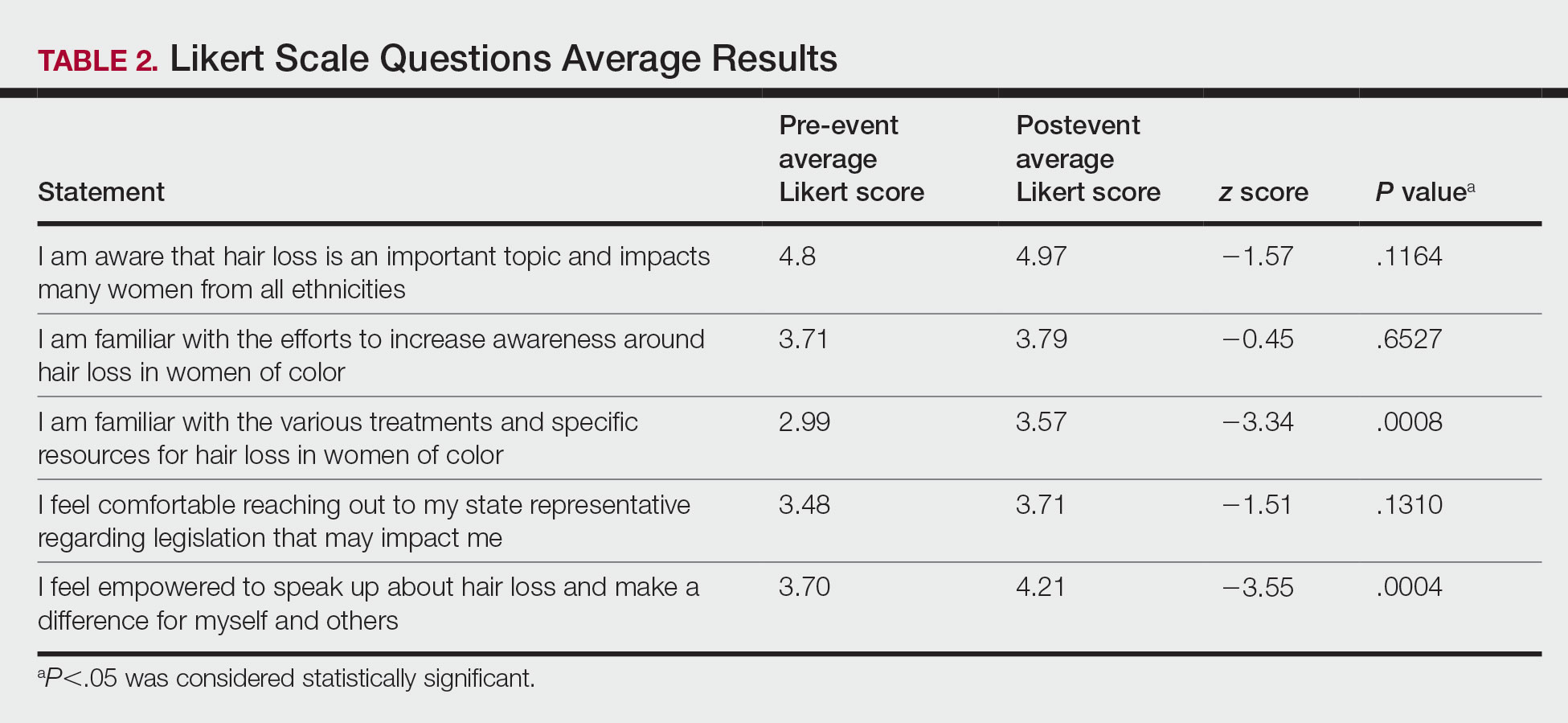

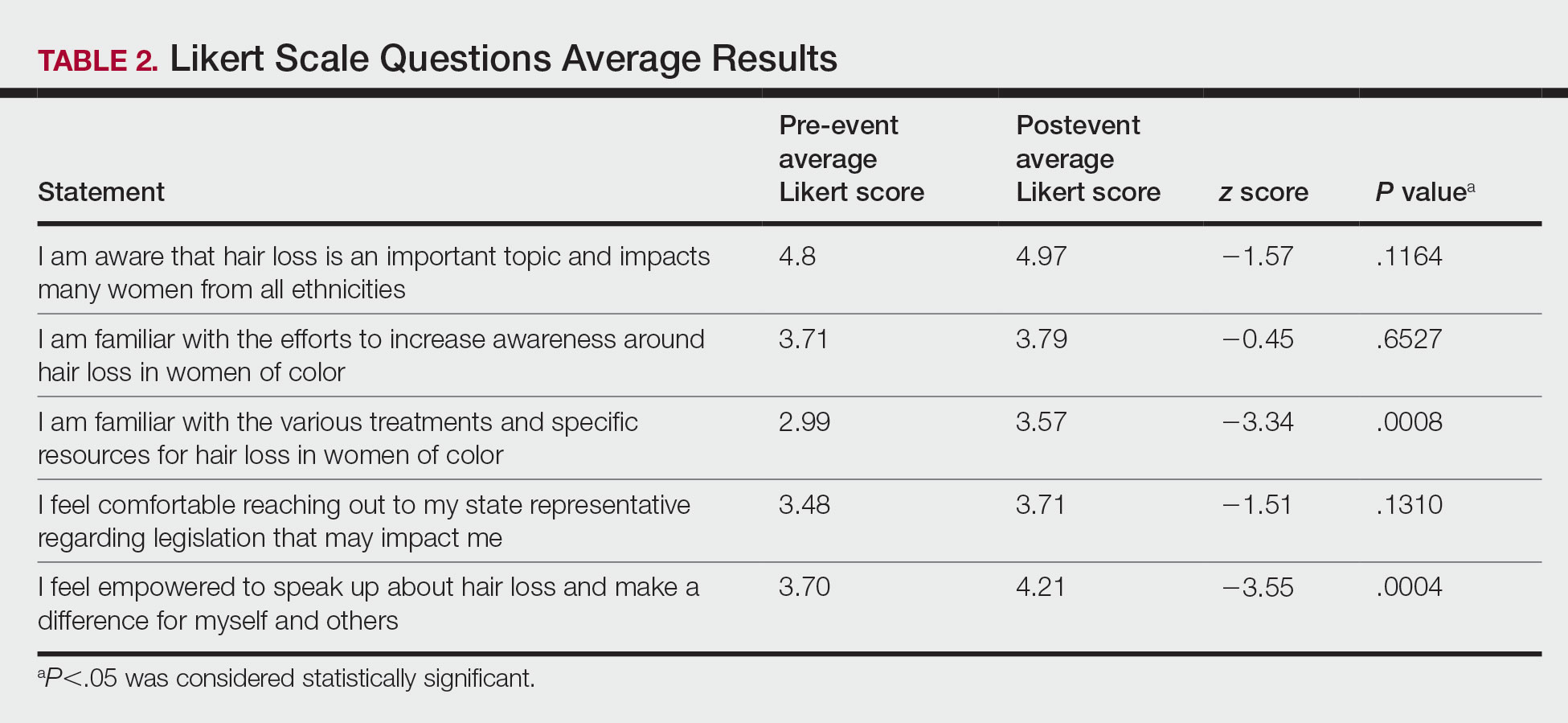

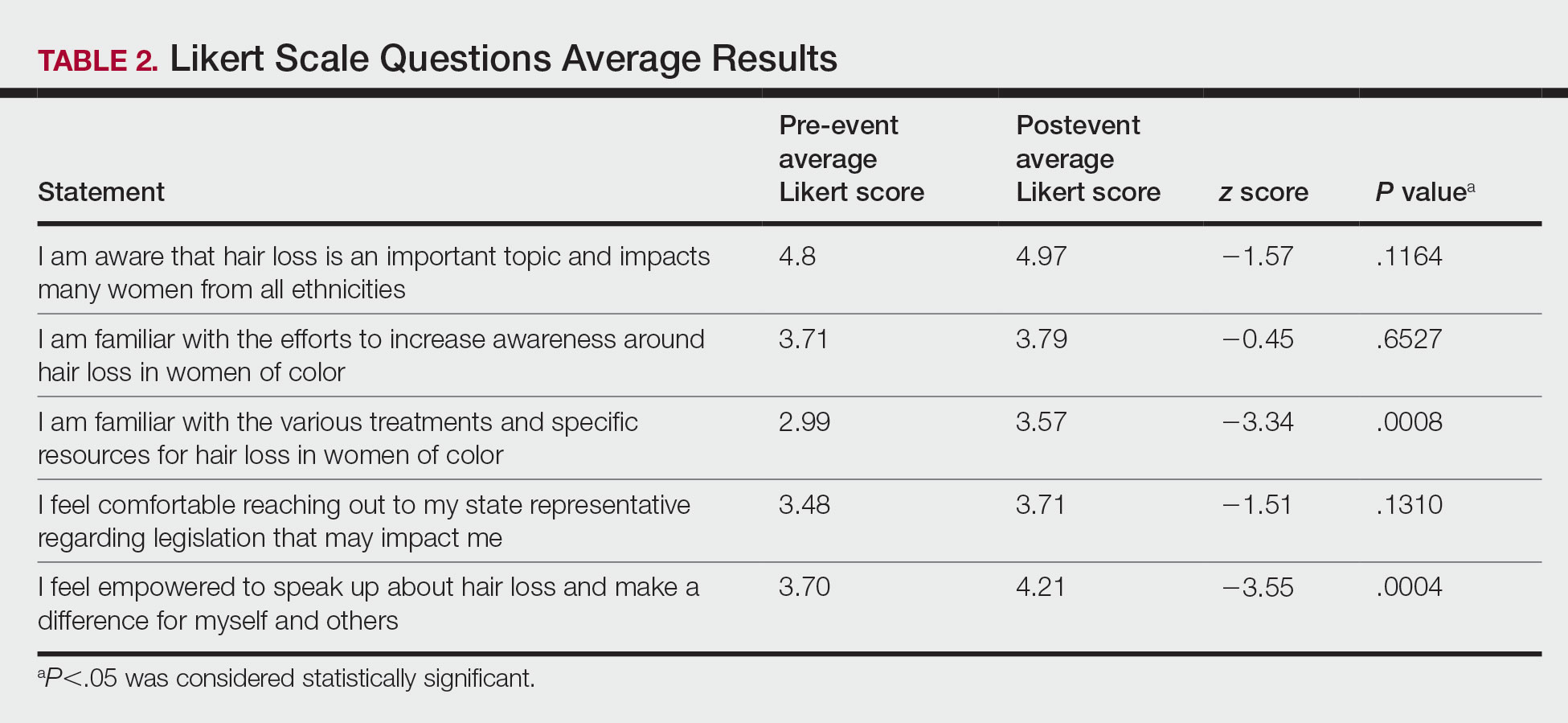

Of the 399 registrants, 165 (41.4%) attended the live virtual event. The postevent survey was completed by 70 (42.4%) participants and showed that familiarity with resources and treatments (z=−3.34, P=.0008) and feelings of empowerment (z=−3.55, P=.0004) significantly increased from before the event (Table 2). Participants indicated that the event exceeded (84.3%) or met (15.7%) their expectations.

Comment

Hair Loss Is Prevalent in Skin of Color Patients—Alopecia is the fourth most common reason women with skin of color seek care from a dermatologist, accounting for 8.3% of all visits in a study of 1412 patient visits; however, it was not among the leading 10 diagnoses made during visits for White patients.3 Traction alopecia, discoid lupus erythematosus, and central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia occur more commonly in Black women,9 many of whom do not feel their dermatologists understand hair in this population.10,11 Lack of skin of color education in medical school and dermatology residency programs has been reported and must be improved to eliminate the knowledge gaps, acquire cultural competence, and improve all aspects of care for patients with skin of color.11-14 Our survey results similarly demonstrated that only 66% of board-certified dermatologists reported being familiar with the various and specific resources and treatments for hair loss in women of color. Improved understanding of hair in patients of color is a first step in diagnosing and treating hair loss.15 Expertise of dermatologists in skin of color improves the dermatology experience of patients of color.11

Hair loss is more than a cosmetic issue, and it is essential that it is regarded as such. Patients with hair loss have an increased prevalence of depression and anxiety compared to the general population and report lower self-esteem, heightened self-consciousness, and loss of confidence.4,9 Historically, the lives of patients of color have been drastically affected by society’s perceptions of their skin color and hairstyle.16

Hair-Based Discrimination in the Workplace—To compound the problem, hair also is a common target of race-based discrimination behind the illusion of “professionalism.” Hair-based discrimination keeps people of color out of professional workplaces; for instance, women of color are more likely to be sent home due to hair appearance than White women.5 The CROWN Act, created in 2019, extends statutory protection to hair texture and protective hairstyles such as braids, locs, twists, and knots in the workplace and public schools to protect against discrimination due to race-based hairstyles. The CROWN Act provides an opportunity for dermatologists to support legislation that protects patients of color and the fundamental human right to nondiscrimination. As societal pressure for damaging hair practices such as hot combing or chemical relaxants decreases, patient outcomes will improve.5

How to Support the CROWN Act—There are various meaningful ways for dermatologists to support the CROWN act, including but not limited to signing petitions, sending letters of support to elected representatives, joining the CROWN Coalition, raising awareness and educating the public through social media, vocalizing against hair discrimination in our own workplaces and communities, and asking patients about their experiences with hair discrimination.5 In addition to advocacy, other antiracist actions suggested to improve health equity include creating curricula on racial inequity and increasing diversity in dermatology.16

There are many advocacy and public health campaigns promoted on the AAD website; however, despite the AAD’s formation of the Access to Dermatologic Care Task Force (ATDCTF) with the goal to raise awareness among dermatologists of health disparities affecting marginalized and underserved populations and to develop policies that increase access to care for these groups, there are still critical gaps in advocacy and information.13 This gap in both advocacy and understanding of hair loss conditions in women of color is one reason the CROWNing Event in July 2021 was held, and we believe this event along with this column can serve as a template for addressing additional topics and diseases that affect marginalized or underserved populations.

Dermatologists can play a vital role in advocating for skin and hair needs in all patient populations from the personal or clinical encounter level to population-level policy legislation.5,8 As experts in skin and hair, dermatologists are best prepared to assume leadership in addressing racial health inequities, educating the public, and improving awareness.5,16 Dermatologists must be able to diagnose and manage skin conditions in people of color.12 However, health advocacy should extend beyond changes to health behavior or health interventions and instead address the root causes of systemic issues that drive disparate health outcomes.6 Every dermatologist has a contribution to make; it is time for us to acknowledge that patients’ ailments neither begin nor end at the clinic door.8,16 As dermatologists, we must speak out against the racial inequities and discriminatory policies affecting the lives of patients of color.16

Although the CROWNing event should be considered successful, reflection in hindsight has allowed us to find ways to improve the impact of future events, including incorporating more lay members of the respective community in the planning process, allocating more time during the event programming for questions, and streamlining the distribution of pre-event and postevent surveys to better gauge knowledge retention among participants and gain crucial feedback for future event planning.

How to Use the FACE Model—We believe that the FACE model (Figure) can help providers engage lay members of the community with additional topics and diseases that affect marginalized and underserved populations. We recommend that future organizers engage stakeholders early during the design, planning, and implementation phases to ensure that the community’s most pressing needs are addressed. Dermatologists possess the knowledge and influence to serve as powerful advocates and champions for health equity. As physicians on the front lines of dermatologic health, we are uniquely positioned to engage and partner with patients through educational and advocacy events such as ours. Similarly, informed and empowered patients can advocate for policies and be proponents for greater research funding.5 We call on the AAD and other dermatologic organizations to expand community outreach and advocacy efforts to include underserved and underrepresented populations.

Acknowledgments—The authors would like to thank and acknowledge the faculty at Hampton University (Hampton, Virginia)—specifically Ms. B. DáVida Plummer, MA—for assistance with communication strategies, including organizing the radio and television announcements and proofreading the public service announcements. We also would like to thank other CROWNing Event Planning Committee members, including Natalia Mendoza, MD (Newport News, Virginia); Farhaad Riyaz, MD (Gainesville, Virginia); Deborah Elder, MD (Charlottesville, Virginia); and David Rowe, MD (Charlottesville, Virginia), as well as Sandra Ring, MS, CCLS, CNP (Chicago, Illinois), from the AAD and the various speakers at the event, including the 2 patients; Victoria Barbosa, MD, MPH, MBA (Chicago, Illinois); Avery LaChance, MD, MPH (Boston, Massachusetts); and Senator Lionell Spruill Sr (Chesapeake, Virginia). We acknowledge Marieke K. Jones, PhD, at the Claude Moore Health Sciences Library at the University of Virginia (Charlottesville, Virginia), for her statistical expertise.

- Davis SA, Narahari S, Feldman SR, et al. Top dermatologic conditions in patients of color: an analysis of nationally representative data. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:466-473.

- Lawson CN, Hollinger J, Sethi S, et al. Updates in the understanding and treatments of skin & hair disorders in women of color. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2017;3(suppl 1):S21-S37. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2017.02.006

- Alexis AF, Sergay AB, Taylor SC. Common dermatologic disorders in skin of color: a comparative practice survey. Cutis. 2007;80:387-394.

- Jamerson TA, Aguh C. An approach to patients with alopecia. Med Clin North Am. 2021;105:599-610. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2021.04.002

- Lee MS, Nambudiri VE. The CROWN act and dermatology: taking a stand against race-based hair discrimination. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1181-1182. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.11.065

- Tran A, Gohara M. Community engagement matters: a call for greater advocacy in dermatology. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7:189-190. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2021.01.008

- Yu Z, Moustafa D, Kwak R, et al. Engaging in advocacy during medical training: assessing the impact of a virtual COVID-19-focused state advocacy day [published online January 13, 2021]. Postgrad Med J. doi:10.1136/postgradmedj-2020-139362

- Earnest MA, Wong SL, Federico SG. Perspective: physician advocacy: what is it and how do we do it? Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2010;85:63-67. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c40d40

- Raffi J, Suresh R, Agbai O. Clinical recognition and management of alopecia in women of color. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2019;5:314-319. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2019.08.005

- Gathers RC, Mahan MG. African American women, hair care, and health barriers. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:26-29.

- Gorbatenko-Roth K, Prose N, Kundu RV, et al. Assessment of Black patients’ perception of their dermatology care. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:1129-1134. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.2063

- Ebede T, Papier A. Disparities in dermatology educational resources. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:687-690. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.10.068

- Buster KJ, Stevens EI, Elmets CA. Dermatologic health disparities. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:53-59, viii. doi:10.1016/j.det.2011.08.002

- Taylor SC. Meeting the unique dermatologic needs of black patients. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:1109-1110. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.1963

- Dlova NC, Salkey KS, Callender VD, et al. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: new insights and a call for action. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2017;18:S54-S56. doi:10.1016/j.jisp.2017.01.004

- Smith RJ, Oliver BU. Advocating for Black lives—a call to dermatologists to dismantle institutionalized racism and address racial health inequities. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:155-156. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.4392

Hair loss is a primary reason why women with skin of color seek dermatologic care.1-3 In addition to physical disfigurement, patients with hair loss are more likely to report feelings of depression, anxiety, and low self-esteem compared to the general population.4 There is a critical gap in advocacy efforts and educational information intended for women with skin of color. The American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) has 6 main public health programs (https://www.aad.org/public/public-health) and 8 stated advocacy priorities (https://www.aad.org/member/advocacy/priorities) but none of them focus on outreach to minority communities.

Historically, hair in patients with skin of color also has been a systemic tangible target for race-based discrimination. The Create a Respectful and Open World for Natural Hair (CROWN) Act was passed to protect against discrimination based on race-based hairstyles in schools and workplaces.5 Health care providers play an important role in advocating for their patients, but studies have shown that barriers to effective advocacy include a lack of knowledge, resources, or time.6-8 Virtual advocacy events improve participants’ understanding and interest in community engagement and advocacy.6,7 With the mission to engage, educate, and empower women with skin of color and the dermatologists who treat them, the Virginia Dermatology Society hosted the virtual CROWNing Event on Hair Loss in Women of Color in July 2021. We believe that this event, as well as this column, can serve as a template to improve advocacy and educational efforts for additional topics and diseases that affect marginalized or underserved populations. Survey data were collected and analyzed to establish a baseline of awareness and understanding of hair loss in women with skin of color and to evaluate the impact of a virtual event on participants’ empowerment and familiarity with resources for this population.

Methods

The Virginia Dermatology Society organized a virtual event focused on hair loss and practical political advocacy for women with skin of color. As members of the Virginia Dermatology Society and as part of the planning and execution of this event, the authors engaged relevant stakeholder organizations and collaborated with faculty at a local historically Black university to create a targeted, culturally sensitive communication strategy known as the Framework for Advocacy and Community Engagement (FACE) model (Figure). The agenda included presentations by 2 patients of color living with a hair loss disorder, a dermatologist with experience in advocacy, a Virginia state legislator, and a dermatologic hair loss expert, followed by a final question-and-answer session.

We created pre- and postevent Likert scale surveys assessing participant attitudes, knowledge, and awareness surrounding hair loss that were distributed electronically to all 399 registrants before and after the event, respectively. The responses were analyzed using a Mann-Whitney U test.

Based on preliminary pre-event survey data, we created a resource toolkit (https://bit.ly/vadermhairlosstoolkit) for distribution to both patients and physicians. The toolkit included articles about evaluating, diagnosing, and treating different types of hair loss that would be beneficial for dermatologists, as well as informational articles, online resources, and videos that would be helpful to patients.

Of the 399 registrants, 165 (41.4%) attended the live virtual event. The postevent survey was completed by 70 (42.4%) participants and showed that familiarity with resources and treatments (z=−3.34, P=.0008) and feelings of empowerment (z=−3.55, P=.0004) significantly increased from before the event (Table 2). Participants indicated that the event exceeded (84.3%) or met (15.7%) their expectations.

Comment

Hair Loss Is Prevalent in Skin of Color Patients—Alopecia is the fourth most common reason women with skin of color seek care from a dermatologist, accounting for 8.3% of all visits in a study of 1412 patient visits; however, it was not among the leading 10 diagnoses made during visits for White patients.3 Traction alopecia, discoid lupus erythematosus, and central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia occur more commonly in Black women,9 many of whom do not feel their dermatologists understand hair in this population.10,11 Lack of skin of color education in medical school and dermatology residency programs has been reported and must be improved to eliminate the knowledge gaps, acquire cultural competence, and improve all aspects of care for patients with skin of color.11-14 Our survey results similarly demonstrated that only 66% of board-certified dermatologists reported being familiar with the various and specific resources and treatments for hair loss in women of color. Improved understanding of hair in patients of color is a first step in diagnosing and treating hair loss.15 Expertise of dermatologists in skin of color improves the dermatology experience of patients of color.11

Hair loss is more than a cosmetic issue, and it is essential that it is regarded as such. Patients with hair loss have an increased prevalence of depression and anxiety compared to the general population and report lower self-esteem, heightened self-consciousness, and loss of confidence.4,9 Historically, the lives of patients of color have been drastically affected by society’s perceptions of their skin color and hairstyle.16

Hair-Based Discrimination in the Workplace—To compound the problem, hair also is a common target of race-based discrimination behind the illusion of “professionalism.” Hair-based discrimination keeps people of color out of professional workplaces; for instance, women of color are more likely to be sent home due to hair appearance than White women.5 The CROWN Act, created in 2019, extends statutory protection to hair texture and protective hairstyles such as braids, locs, twists, and knots in the workplace and public schools to protect against discrimination due to race-based hairstyles. The CROWN Act provides an opportunity for dermatologists to support legislation that protects patients of color and the fundamental human right to nondiscrimination. As societal pressure for damaging hair practices such as hot combing or chemical relaxants decreases, patient outcomes will improve.5

How to Support the CROWN Act—There are various meaningful ways for dermatologists to support the CROWN act, including but not limited to signing petitions, sending letters of support to elected representatives, joining the CROWN Coalition, raising awareness and educating the public through social media, vocalizing against hair discrimination in our own workplaces and communities, and asking patients about their experiences with hair discrimination.5 In addition to advocacy, other antiracist actions suggested to improve health equity include creating curricula on racial inequity and increasing diversity in dermatology.16

There are many advocacy and public health campaigns promoted on the AAD website; however, despite the AAD’s formation of the Access to Dermatologic Care Task Force (ATDCTF) with the goal to raise awareness among dermatologists of health disparities affecting marginalized and underserved populations and to develop policies that increase access to care for these groups, there are still critical gaps in advocacy and information.13 This gap in both advocacy and understanding of hair loss conditions in women of color is one reason the CROWNing Event in July 2021 was held, and we believe this event along with this column can serve as a template for addressing additional topics and diseases that affect marginalized or underserved populations.

Dermatologists can play a vital role in advocating for skin and hair needs in all patient populations from the personal or clinical encounter level to population-level policy legislation.5,8 As experts in skin and hair, dermatologists are best prepared to assume leadership in addressing racial health inequities, educating the public, and improving awareness.5,16 Dermatologists must be able to diagnose and manage skin conditions in people of color.12 However, health advocacy should extend beyond changes to health behavior or health interventions and instead address the root causes of systemic issues that drive disparate health outcomes.6 Every dermatologist has a contribution to make; it is time for us to acknowledge that patients’ ailments neither begin nor end at the clinic door.8,16 As dermatologists, we must speak out against the racial inequities and discriminatory policies affecting the lives of patients of color.16

Although the CROWNing event should be considered successful, reflection in hindsight has allowed us to find ways to improve the impact of future events, including incorporating more lay members of the respective community in the planning process, allocating more time during the event programming for questions, and streamlining the distribution of pre-event and postevent surveys to better gauge knowledge retention among participants and gain crucial feedback for future event planning.

How to Use the FACE Model—We believe that the FACE model (Figure) can help providers engage lay members of the community with additional topics and diseases that affect marginalized and underserved populations. We recommend that future organizers engage stakeholders early during the design, planning, and implementation phases to ensure that the community’s most pressing needs are addressed. Dermatologists possess the knowledge and influence to serve as powerful advocates and champions for health equity. As physicians on the front lines of dermatologic health, we are uniquely positioned to engage and partner with patients through educational and advocacy events such as ours. Similarly, informed and empowered patients can advocate for policies and be proponents for greater research funding.5 We call on the AAD and other dermatologic organizations to expand community outreach and advocacy efforts to include underserved and underrepresented populations.

Acknowledgments—The authors would like to thank and acknowledge the faculty at Hampton University (Hampton, Virginia)—specifically Ms. B. DáVida Plummer, MA—for assistance with communication strategies, including organizing the radio and television announcements and proofreading the public service announcements. We also would like to thank other CROWNing Event Planning Committee members, including Natalia Mendoza, MD (Newport News, Virginia); Farhaad Riyaz, MD (Gainesville, Virginia); Deborah Elder, MD (Charlottesville, Virginia); and David Rowe, MD (Charlottesville, Virginia), as well as Sandra Ring, MS, CCLS, CNP (Chicago, Illinois), from the AAD and the various speakers at the event, including the 2 patients; Victoria Barbosa, MD, MPH, MBA (Chicago, Illinois); Avery LaChance, MD, MPH (Boston, Massachusetts); and Senator Lionell Spruill Sr (Chesapeake, Virginia). We acknowledge Marieke K. Jones, PhD, at the Claude Moore Health Sciences Library at the University of Virginia (Charlottesville, Virginia), for her statistical expertise.

Hair loss is a primary reason why women with skin of color seek dermatologic care.1-3 In addition to physical disfigurement, patients with hair loss are more likely to report feelings of depression, anxiety, and low self-esteem compared to the general population.4 There is a critical gap in advocacy efforts and educational information intended for women with skin of color. The American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) has 6 main public health programs (https://www.aad.org/public/public-health) and 8 stated advocacy priorities (https://www.aad.org/member/advocacy/priorities) but none of them focus on outreach to minority communities.

Historically, hair in patients with skin of color also has been a systemic tangible target for race-based discrimination. The Create a Respectful and Open World for Natural Hair (CROWN) Act was passed to protect against discrimination based on race-based hairstyles in schools and workplaces.5 Health care providers play an important role in advocating for their patients, but studies have shown that barriers to effective advocacy include a lack of knowledge, resources, or time.6-8 Virtual advocacy events improve participants’ understanding and interest in community engagement and advocacy.6,7 With the mission to engage, educate, and empower women with skin of color and the dermatologists who treat them, the Virginia Dermatology Society hosted the virtual CROWNing Event on Hair Loss in Women of Color in July 2021. We believe that this event, as well as this column, can serve as a template to improve advocacy and educational efforts for additional topics and diseases that affect marginalized or underserved populations. Survey data were collected and analyzed to establish a baseline of awareness and understanding of hair loss in women with skin of color and to evaluate the impact of a virtual event on participants’ empowerment and familiarity with resources for this population.

Methods

The Virginia Dermatology Society organized a virtual event focused on hair loss and practical political advocacy for women with skin of color. As members of the Virginia Dermatology Society and as part of the planning and execution of this event, the authors engaged relevant stakeholder organizations and collaborated with faculty at a local historically Black university to create a targeted, culturally sensitive communication strategy known as the Framework for Advocacy and Community Engagement (FACE) model (Figure). The agenda included presentations by 2 patients of color living with a hair loss disorder, a dermatologist with experience in advocacy, a Virginia state legislator, and a dermatologic hair loss expert, followed by a final question-and-answer session.

We created pre- and postevent Likert scale surveys assessing participant attitudes, knowledge, and awareness surrounding hair loss that were distributed electronically to all 399 registrants before and after the event, respectively. The responses were analyzed using a Mann-Whitney U test.

Based on preliminary pre-event survey data, we created a resource toolkit (https://bit.ly/vadermhairlosstoolkit) for distribution to both patients and physicians. The toolkit included articles about evaluating, diagnosing, and treating different types of hair loss that would be beneficial for dermatologists, as well as informational articles, online resources, and videos that would be helpful to patients.

Of the 399 registrants, 165 (41.4%) attended the live virtual event. The postevent survey was completed by 70 (42.4%) participants and showed that familiarity with resources and treatments (z=−3.34, P=.0008) and feelings of empowerment (z=−3.55, P=.0004) significantly increased from before the event (Table 2). Participants indicated that the event exceeded (84.3%) or met (15.7%) their expectations.

Comment

Hair Loss Is Prevalent in Skin of Color Patients—Alopecia is the fourth most common reason women with skin of color seek care from a dermatologist, accounting for 8.3% of all visits in a study of 1412 patient visits; however, it was not among the leading 10 diagnoses made during visits for White patients.3 Traction alopecia, discoid lupus erythematosus, and central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia occur more commonly in Black women,9 many of whom do not feel their dermatologists understand hair in this population.10,11 Lack of skin of color education in medical school and dermatology residency programs has been reported and must be improved to eliminate the knowledge gaps, acquire cultural competence, and improve all aspects of care for patients with skin of color.11-14 Our survey results similarly demonstrated that only 66% of board-certified dermatologists reported being familiar with the various and specific resources and treatments for hair loss in women of color. Improved understanding of hair in patients of color is a first step in diagnosing and treating hair loss.15 Expertise of dermatologists in skin of color improves the dermatology experience of patients of color.11

Hair loss is more than a cosmetic issue, and it is essential that it is regarded as such. Patients with hair loss have an increased prevalence of depression and anxiety compared to the general population and report lower self-esteem, heightened self-consciousness, and loss of confidence.4,9 Historically, the lives of patients of color have been drastically affected by society’s perceptions of their skin color and hairstyle.16

Hair-Based Discrimination in the Workplace—To compound the problem, hair also is a common target of race-based discrimination behind the illusion of “professionalism.” Hair-based discrimination keeps people of color out of professional workplaces; for instance, women of color are more likely to be sent home due to hair appearance than White women.5 The CROWN Act, created in 2019, extends statutory protection to hair texture and protective hairstyles such as braids, locs, twists, and knots in the workplace and public schools to protect against discrimination due to race-based hairstyles. The CROWN Act provides an opportunity for dermatologists to support legislation that protects patients of color and the fundamental human right to nondiscrimination. As societal pressure for damaging hair practices such as hot combing or chemical relaxants decreases, patient outcomes will improve.5

How to Support the CROWN Act—There are various meaningful ways for dermatologists to support the CROWN act, including but not limited to signing petitions, sending letters of support to elected representatives, joining the CROWN Coalition, raising awareness and educating the public through social media, vocalizing against hair discrimination in our own workplaces and communities, and asking patients about their experiences with hair discrimination.5 In addition to advocacy, other antiracist actions suggested to improve health equity include creating curricula on racial inequity and increasing diversity in dermatology.16

There are many advocacy and public health campaigns promoted on the AAD website; however, despite the AAD’s formation of the Access to Dermatologic Care Task Force (ATDCTF) with the goal to raise awareness among dermatologists of health disparities affecting marginalized and underserved populations and to develop policies that increase access to care for these groups, there are still critical gaps in advocacy and information.13 This gap in both advocacy and understanding of hair loss conditions in women of color is one reason the CROWNing Event in July 2021 was held, and we believe this event along with this column can serve as a template for addressing additional topics and diseases that affect marginalized or underserved populations.

Dermatologists can play a vital role in advocating for skin and hair needs in all patient populations from the personal or clinical encounter level to population-level policy legislation.5,8 As experts in skin and hair, dermatologists are best prepared to assume leadership in addressing racial health inequities, educating the public, and improving awareness.5,16 Dermatologists must be able to diagnose and manage skin conditions in people of color.12 However, health advocacy should extend beyond changes to health behavior or health interventions and instead address the root causes of systemic issues that drive disparate health outcomes.6 Every dermatologist has a contribution to make; it is time for us to acknowledge that patients’ ailments neither begin nor end at the clinic door.8,16 As dermatologists, we must speak out against the racial inequities and discriminatory policies affecting the lives of patients of color.16

Although the CROWNing event should be considered successful, reflection in hindsight has allowed us to find ways to improve the impact of future events, including incorporating more lay members of the respective community in the planning process, allocating more time during the event programming for questions, and streamlining the distribution of pre-event and postevent surveys to better gauge knowledge retention among participants and gain crucial feedback for future event planning.

How to Use the FACE Model—We believe that the FACE model (Figure) can help providers engage lay members of the community with additional topics and diseases that affect marginalized and underserved populations. We recommend that future organizers engage stakeholders early during the design, planning, and implementation phases to ensure that the community’s most pressing needs are addressed. Dermatologists possess the knowledge and influence to serve as powerful advocates and champions for health equity. As physicians on the front lines of dermatologic health, we are uniquely positioned to engage and partner with patients through educational and advocacy events such as ours. Similarly, informed and empowered patients can advocate for policies and be proponents for greater research funding.5 We call on the AAD and other dermatologic organizations to expand community outreach and advocacy efforts to include underserved and underrepresented populations.

Acknowledgments—The authors would like to thank and acknowledge the faculty at Hampton University (Hampton, Virginia)—specifically Ms. B. DáVida Plummer, MA—for assistance with communication strategies, including organizing the radio and television announcements and proofreading the public service announcements. We also would like to thank other CROWNing Event Planning Committee members, including Natalia Mendoza, MD (Newport News, Virginia); Farhaad Riyaz, MD (Gainesville, Virginia); Deborah Elder, MD (Charlottesville, Virginia); and David Rowe, MD (Charlottesville, Virginia), as well as Sandra Ring, MS, CCLS, CNP (Chicago, Illinois), from the AAD and the various speakers at the event, including the 2 patients; Victoria Barbosa, MD, MPH, MBA (Chicago, Illinois); Avery LaChance, MD, MPH (Boston, Massachusetts); and Senator Lionell Spruill Sr (Chesapeake, Virginia). We acknowledge Marieke K. Jones, PhD, at the Claude Moore Health Sciences Library at the University of Virginia (Charlottesville, Virginia), for her statistical expertise.

- Davis SA, Narahari S, Feldman SR, et al. Top dermatologic conditions in patients of color: an analysis of nationally representative data. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:466-473.

- Lawson CN, Hollinger J, Sethi S, et al. Updates in the understanding and treatments of skin & hair disorders in women of color. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2017;3(suppl 1):S21-S37. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2017.02.006

- Alexis AF, Sergay AB, Taylor SC. Common dermatologic disorders in skin of color: a comparative practice survey. Cutis. 2007;80:387-394.

- Jamerson TA, Aguh C. An approach to patients with alopecia. Med Clin North Am. 2021;105:599-610. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2021.04.002

- Lee MS, Nambudiri VE. The CROWN act and dermatology: taking a stand against race-based hair discrimination. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1181-1182. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.11.065

- Tran A, Gohara M. Community engagement matters: a call for greater advocacy in dermatology. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7:189-190. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2021.01.008

- Yu Z, Moustafa D, Kwak R, et al. Engaging in advocacy during medical training: assessing the impact of a virtual COVID-19-focused state advocacy day [published online January 13, 2021]. Postgrad Med J. doi:10.1136/postgradmedj-2020-139362

- Earnest MA, Wong SL, Federico SG. Perspective: physician advocacy: what is it and how do we do it? Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2010;85:63-67. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c40d40

- Raffi J, Suresh R, Agbai O. Clinical recognition and management of alopecia in women of color. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2019;5:314-319. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2019.08.005

- Gathers RC, Mahan MG. African American women, hair care, and health barriers. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:26-29.

- Gorbatenko-Roth K, Prose N, Kundu RV, et al. Assessment of Black patients’ perception of their dermatology care. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:1129-1134. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.2063

- Ebede T, Papier A. Disparities in dermatology educational resources. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:687-690. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.10.068

- Buster KJ, Stevens EI, Elmets CA. Dermatologic health disparities. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:53-59, viii. doi:10.1016/j.det.2011.08.002

- Taylor SC. Meeting the unique dermatologic needs of black patients. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:1109-1110. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.1963

- Dlova NC, Salkey KS, Callender VD, et al. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: new insights and a call for action. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2017;18:S54-S56. doi:10.1016/j.jisp.2017.01.004

- Smith RJ, Oliver BU. Advocating for Black lives—a call to dermatologists to dismantle institutionalized racism and address racial health inequities. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:155-156. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.4392

- Davis SA, Narahari S, Feldman SR, et al. Top dermatologic conditions in patients of color: an analysis of nationally representative data. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:466-473.

- Lawson CN, Hollinger J, Sethi S, et al. Updates in the understanding and treatments of skin & hair disorders in women of color. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2017;3(suppl 1):S21-S37. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2017.02.006

- Alexis AF, Sergay AB, Taylor SC. Common dermatologic disorders in skin of color: a comparative practice survey. Cutis. 2007;80:387-394.

- Jamerson TA, Aguh C. An approach to patients with alopecia. Med Clin North Am. 2021;105:599-610. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2021.04.002

- Lee MS, Nambudiri VE. The CROWN act and dermatology: taking a stand against race-based hair discrimination. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1181-1182. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.11.065

- Tran A, Gohara M. Community engagement matters: a call for greater advocacy in dermatology. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7:189-190. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2021.01.008

- Yu Z, Moustafa D, Kwak R, et al. Engaging in advocacy during medical training: assessing the impact of a virtual COVID-19-focused state advocacy day [published online January 13, 2021]. Postgrad Med J. doi:10.1136/postgradmedj-2020-139362

- Earnest MA, Wong SL, Federico SG. Perspective: physician advocacy: what is it and how do we do it? Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2010;85:63-67. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c40d40

- Raffi J, Suresh R, Agbai O. Clinical recognition and management of alopecia in women of color. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2019;5:314-319. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2019.08.005

- Gathers RC, Mahan MG. African American women, hair care, and health barriers. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:26-29.

- Gorbatenko-Roth K, Prose N, Kundu RV, et al. Assessment of Black patients’ perception of their dermatology care. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:1129-1134. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.2063

- Ebede T, Papier A. Disparities in dermatology educational resources. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:687-690. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.10.068

- Buster KJ, Stevens EI, Elmets CA. Dermatologic health disparities. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:53-59, viii. doi:10.1016/j.det.2011.08.002

- Taylor SC. Meeting the unique dermatologic needs of black patients. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:1109-1110. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.1963

- Dlova NC, Salkey KS, Callender VD, et al. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: new insights and a call for action. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2017;18:S54-S56. doi:10.1016/j.jisp.2017.01.004

- Smith RJ, Oliver BU. Advocating for Black lives—a call to dermatologists to dismantle institutionalized racism and address racial health inequities. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:155-156. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.4392

Practice Points

- Hair loss is associated with low self-esteem in women with skin of color; therefore, it is important to both acknowledge the social and psychological impacts of hair loss in this population and provide educational resources and community events that address patient concerns.

- There is a deficit of dermatology advocacy efforts that address conditions affecting patients with skin of color. Highlighting this disparity is the first step to catalyzing change.

- Dermatologists are responsible for advocating for women with skin of color and for addressing the social issues that impact their quality of life.

- The Framework for Advocacy and Community Efforts (FACE) model is a template for others to use when planning community engagement and advocacy efforts.

Multiple Lesions With Recurrent Bleeding

The Diagnosis: Nevoid Basal Cell Carcinoma Syndrome

Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (NBCCS), also known as Gorlin syndrome, is a rare autosomal-dominant disorder that increases the risk for developing various carcinomas and affects multiple organ systems. Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome is estimated at 1 per 40,000 to 60,000 individuals with no sexual predilection.1,2 Pathogenesis of NBCCS occurs through molecular alterations in the dormant hedgehog signaling pathway, causing constitutive signaling activity and a loss of function in the tumor suppressor patched 1 gene, PTCH1. As a result, the inhibition of smoothened oncogenes is released, Gli proteins are activated, and the hedgehog signaling pathway is no longer quiescent.2 Additional loss of function in the suppressor of fused homolog protein, a negative regulator of the hedgehog pathway, allows for further tumor proliferation. The crucial role these genes play in the hedgehog signaling pathway and their mutation association with NBCCS allows for molecular confirmation in the diagnosis of NBCCS. Allelic losses at the PTCH1 gene site are thought to occur in approximately 70% of NBCCS patients.2

Diagnosis of NBCCS is based on genetic testing to examine pathogenic gene variants, notably in the PTCH1 gene, and identification of characteristic clinical findings.2 Diagnosis of NBCCS requires either 2 minor suggestive criteria and 1 major suggestive criterion, 2 major suggestive criteria and 1 minor suggestive criterion, or 1 major suggestive criterion with molecular confirmation. The presence of basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) before 20 years of age or an excessive numbers of BCCs, keratocystic odontogenic tumors (KOTs), palmar or plantar pitting, and first-degree relatives with NBCCS are classified as major suggestive criteria.2 Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome patients typically have BCCs that crust, ulcerate, or bleed. Minor suggestive criteria for NBCCS are rib abnormalities, skeletal malformations, macrocephaly, cleft lip or palate, and desmoplastic medulloblastoma.2-4 Suppressor of fused homolog protein mutations may increase the risk for desmoplastic medulloblastoma in NBCCS patients. Our patient had 4 of the major suggestive criteria, including a history of KOTs, multiple BCCs, first-degree relatives with NBCCS, and palmar or plantar pitting (bottom quiz image), while having 1 minor suggestive criterion of frontal bossing.

Patients with NBCCS have high phenotypic variability, as their skin carcinomas do not have the classic features of pearly surfaces or corkscrew telangiectasia that typically are associated with BCCs.1 Basal cell carcinomas in NBCCS-affected individuals usually are indistinguishable from sporadic lesions that arise in sun-exposed areas, making NBCCS difficult to diagnose. These sporadic lesions often are misdiagnosed as psoriatic or eczematous lesions, and additional subsequent examination is required. The findings of multiple papules and plaques spanning the body as well as lesions with rolled borders and ulcerated bases, indicative of BCCs, aid dermatologists in distinguishing benign lesions from those of NBCCS.1

Additional differential diagnoses are required to distinguish NBCCS from other similar inherited skin disorders that are characterized by BCCs. The presence of multiple incidental BCCs early in life remains a histopathologic clue for NBCCS diagnosis, as opposed to Rombo syndrome, in which BCCs often develop in adulthood.2,4 In addition, although both Bazex syndrome and Muir-Torre syndrome are characterized by the early onset of BCCs, the lack of skeletal abnormalities and palmar and plantar pitting distinguish these entities from NBCCS.2,4 Furthermore, though psoriasis also can present on the scalp, clinical presentation often includes well-demarcated and symmetric plaques that are erythematous and silvery, all of which were not present in our patient and typically are not seen in NBCCS.5

The recommended treatment of NBCCS is vismodegib, a specific oncogene inhibitor. This medication suppresses the hedgehog signaling pathway by inhibiting smoothened oncogenes and downstream target molecules, thereby decreasing tumor proliferation.6 In doing so, vismodegib inhibits the development of new BCCs while reducing the burden of present ones. Additionally, vismodegib appears to effectively treat KOTs. If successful, this medication may be able to suppress KOTs in patients with NBCCS and thus facilitate surgery.6 Additional hedgehog inhibitors include patidegib, sonidegib, and itraconazole. Patidegib gel 2% currently is in phase 3 clinical trials for evaluation of efficacy and safety in treatment of NBCCS. Sonidegib is approved for the treatment of locally advanced BCCs in the United States and the European Union and for both locally advanced BCCs and metastatic BCCs in Switzerland and Australia.7 Further research is needed before recommending antifungal itraconazole for NBCCS clinical use.8 Other medications for localized areas include topical application of 5-fluorouracil and imiquimod.2

- Sangehra R, Grewal P. Gorlin syndrome presentation and the importance of differential diagnosis of skin cancer: a case report. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2018;21:222-224.

- Bresler S, Padwa B, Granter S. Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (Gorlin syndrome). Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10:119-124.

- Fujii K, Miyashita T. Gorlin syndrome (nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome): update and literature review. Pediatr Int. 2014;56:667-674.

- Evans G, Farndon P. Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. GeneReviews [Internet]. University of Washington; 1993-2020.

- Kim WB, Jerome D, Yeung J. Diagnosis and management of psoriasis. Can Fam Physician. 2017;63:278-285.

- Booms P, Harth M, Sader R, et al. Vismodegib hedgehog-signaling inhibition and treatment of basal cell carcinomas as well as keratocystic odontogenic tumors in Gorlin syndrome. Ann Maxillofac Surg. 2015;5:14-19.

- Gutzmer R, Soloon J. Hedgehog pathway inhibition for the treatment of basal cell carcinoma. Target Oncol. 2019;14:253-267.

- Leavitt E, Lask G, Martin S. Sonic hedgehog pathway inhibition in the treatment of advanced basal cell carcinoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2019;20:84.

The Diagnosis: Nevoid Basal Cell Carcinoma Syndrome

Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (NBCCS), also known as Gorlin syndrome, is a rare autosomal-dominant disorder that increases the risk for developing various carcinomas and affects multiple organ systems. Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome is estimated at 1 per 40,000 to 60,000 individuals with no sexual predilection.1,2 Pathogenesis of NBCCS occurs through molecular alterations in the dormant hedgehog signaling pathway, causing constitutive signaling activity and a loss of function in the tumor suppressor patched 1 gene, PTCH1. As a result, the inhibition of smoothened oncogenes is released, Gli proteins are activated, and the hedgehog signaling pathway is no longer quiescent.2 Additional loss of function in the suppressor of fused homolog protein, a negative regulator of the hedgehog pathway, allows for further tumor proliferation. The crucial role these genes play in the hedgehog signaling pathway and their mutation association with NBCCS allows for molecular confirmation in the diagnosis of NBCCS. Allelic losses at the PTCH1 gene site are thought to occur in approximately 70% of NBCCS patients.2

Diagnosis of NBCCS is based on genetic testing to examine pathogenic gene variants, notably in the PTCH1 gene, and identification of characteristic clinical findings.2 Diagnosis of NBCCS requires either 2 minor suggestive criteria and 1 major suggestive criterion, 2 major suggestive criteria and 1 minor suggestive criterion, or 1 major suggestive criterion with molecular confirmation. The presence of basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) before 20 years of age or an excessive numbers of BCCs, keratocystic odontogenic tumors (KOTs), palmar or plantar pitting, and first-degree relatives with NBCCS are classified as major suggestive criteria.2 Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome patients typically have BCCs that crust, ulcerate, or bleed. Minor suggestive criteria for NBCCS are rib abnormalities, skeletal malformations, macrocephaly, cleft lip or palate, and desmoplastic medulloblastoma.2-4 Suppressor of fused homolog protein mutations may increase the risk for desmoplastic medulloblastoma in NBCCS patients. Our patient had 4 of the major suggestive criteria, including a history of KOTs, multiple BCCs, first-degree relatives with NBCCS, and palmar or plantar pitting (bottom quiz image), while having 1 minor suggestive criterion of frontal bossing.

Patients with NBCCS have high phenotypic variability, as their skin carcinomas do not have the classic features of pearly surfaces or corkscrew telangiectasia that typically are associated with BCCs.1 Basal cell carcinomas in NBCCS-affected individuals usually are indistinguishable from sporadic lesions that arise in sun-exposed areas, making NBCCS difficult to diagnose. These sporadic lesions often are misdiagnosed as psoriatic or eczematous lesions, and additional subsequent examination is required. The findings of multiple papules and plaques spanning the body as well as lesions with rolled borders and ulcerated bases, indicative of BCCs, aid dermatologists in distinguishing benign lesions from those of NBCCS.1

Additional differential diagnoses are required to distinguish NBCCS from other similar inherited skin disorders that are characterized by BCCs. The presence of multiple incidental BCCs early in life remains a histopathologic clue for NBCCS diagnosis, as opposed to Rombo syndrome, in which BCCs often develop in adulthood.2,4 In addition, although both Bazex syndrome and Muir-Torre syndrome are characterized by the early onset of BCCs, the lack of skeletal abnormalities and palmar and plantar pitting distinguish these entities from NBCCS.2,4 Furthermore, though psoriasis also can present on the scalp, clinical presentation often includes well-demarcated and symmetric plaques that are erythematous and silvery, all of which were not present in our patient and typically are not seen in NBCCS.5

The recommended treatment of NBCCS is vismodegib, a specific oncogene inhibitor. This medication suppresses the hedgehog signaling pathway by inhibiting smoothened oncogenes and downstream target molecules, thereby decreasing tumor proliferation.6 In doing so, vismodegib inhibits the development of new BCCs while reducing the burden of present ones. Additionally, vismodegib appears to effectively treat KOTs. If successful, this medication may be able to suppress KOTs in patients with NBCCS and thus facilitate surgery.6 Additional hedgehog inhibitors include patidegib, sonidegib, and itraconazole. Patidegib gel 2% currently is in phase 3 clinical trials for evaluation of efficacy and safety in treatment of NBCCS. Sonidegib is approved for the treatment of locally advanced BCCs in the United States and the European Union and for both locally advanced BCCs and metastatic BCCs in Switzerland and Australia.7 Further research is needed before recommending antifungal itraconazole for NBCCS clinical use.8 Other medications for localized areas include topical application of 5-fluorouracil and imiquimod.2

The Diagnosis: Nevoid Basal Cell Carcinoma Syndrome

Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (NBCCS), also known as Gorlin syndrome, is a rare autosomal-dominant disorder that increases the risk for developing various carcinomas and affects multiple organ systems. Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome is estimated at 1 per 40,000 to 60,000 individuals with no sexual predilection.1,2 Pathogenesis of NBCCS occurs through molecular alterations in the dormant hedgehog signaling pathway, causing constitutive signaling activity and a loss of function in the tumor suppressor patched 1 gene, PTCH1. As a result, the inhibition of smoothened oncogenes is released, Gli proteins are activated, and the hedgehog signaling pathway is no longer quiescent.2 Additional loss of function in the suppressor of fused homolog protein, a negative regulator of the hedgehog pathway, allows for further tumor proliferation. The crucial role these genes play in the hedgehog signaling pathway and their mutation association with NBCCS allows for molecular confirmation in the diagnosis of NBCCS. Allelic losses at the PTCH1 gene site are thought to occur in approximately 70% of NBCCS patients.2

Diagnosis of NBCCS is based on genetic testing to examine pathogenic gene variants, notably in the PTCH1 gene, and identification of characteristic clinical findings.2 Diagnosis of NBCCS requires either 2 minor suggestive criteria and 1 major suggestive criterion, 2 major suggestive criteria and 1 minor suggestive criterion, or 1 major suggestive criterion with molecular confirmation. The presence of basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) before 20 years of age or an excessive numbers of BCCs, keratocystic odontogenic tumors (KOTs), palmar or plantar pitting, and first-degree relatives with NBCCS are classified as major suggestive criteria.2 Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome patients typically have BCCs that crust, ulcerate, or bleed. Minor suggestive criteria for NBCCS are rib abnormalities, skeletal malformations, macrocephaly, cleft lip or palate, and desmoplastic medulloblastoma.2-4 Suppressor of fused homolog protein mutations may increase the risk for desmoplastic medulloblastoma in NBCCS patients. Our patient had 4 of the major suggestive criteria, including a history of KOTs, multiple BCCs, first-degree relatives with NBCCS, and palmar or plantar pitting (bottom quiz image), while having 1 minor suggestive criterion of frontal bossing.

Patients with NBCCS have high phenotypic variability, as their skin carcinomas do not have the classic features of pearly surfaces or corkscrew telangiectasia that typically are associated with BCCs.1 Basal cell carcinomas in NBCCS-affected individuals usually are indistinguishable from sporadic lesions that arise in sun-exposed areas, making NBCCS difficult to diagnose. These sporadic lesions often are misdiagnosed as psoriatic or eczematous lesions, and additional subsequent examination is required. The findings of multiple papules and plaques spanning the body as well as lesions with rolled borders and ulcerated bases, indicative of BCCs, aid dermatologists in distinguishing benign lesions from those of NBCCS.1

Additional differential diagnoses are required to distinguish NBCCS from other similar inherited skin disorders that are characterized by BCCs. The presence of multiple incidental BCCs early in life remains a histopathologic clue for NBCCS diagnosis, as opposed to Rombo syndrome, in which BCCs often develop in adulthood.2,4 In addition, although both Bazex syndrome and Muir-Torre syndrome are characterized by the early onset of BCCs, the lack of skeletal abnormalities and palmar and plantar pitting distinguish these entities from NBCCS.2,4 Furthermore, though psoriasis also can present on the scalp, clinical presentation often includes well-demarcated and symmetric plaques that are erythematous and silvery, all of which were not present in our patient and typically are not seen in NBCCS.5

The recommended treatment of NBCCS is vismodegib, a specific oncogene inhibitor. This medication suppresses the hedgehog signaling pathway by inhibiting smoothened oncogenes and downstream target molecules, thereby decreasing tumor proliferation.6 In doing so, vismodegib inhibits the development of new BCCs while reducing the burden of present ones. Additionally, vismodegib appears to effectively treat KOTs. If successful, this medication may be able to suppress KOTs in patients with NBCCS and thus facilitate surgery.6 Additional hedgehog inhibitors include patidegib, sonidegib, and itraconazole. Patidegib gel 2% currently is in phase 3 clinical trials for evaluation of efficacy and safety in treatment of NBCCS. Sonidegib is approved for the treatment of locally advanced BCCs in the United States and the European Union and for both locally advanced BCCs and metastatic BCCs in Switzerland and Australia.7 Further research is needed before recommending antifungal itraconazole for NBCCS clinical use.8 Other medications for localized areas include topical application of 5-fluorouracil and imiquimod.2

- Sangehra R, Grewal P. Gorlin syndrome presentation and the importance of differential diagnosis of skin cancer: a case report. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2018;21:222-224.

- Bresler S, Padwa B, Granter S. Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (Gorlin syndrome). Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10:119-124.

- Fujii K, Miyashita T. Gorlin syndrome (nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome): update and literature review. Pediatr Int. 2014;56:667-674.

- Evans G, Farndon P. Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. GeneReviews [Internet]. University of Washington; 1993-2020.

- Kim WB, Jerome D, Yeung J. Diagnosis and management of psoriasis. Can Fam Physician. 2017;63:278-285.

- Booms P, Harth M, Sader R, et al. Vismodegib hedgehog-signaling inhibition and treatment of basal cell carcinomas as well as keratocystic odontogenic tumors in Gorlin syndrome. Ann Maxillofac Surg. 2015;5:14-19.

- Gutzmer R, Soloon J. Hedgehog pathway inhibition for the treatment of basal cell carcinoma. Target Oncol. 2019;14:253-267.

- Leavitt E, Lask G, Martin S. Sonic hedgehog pathway inhibition in the treatment of advanced basal cell carcinoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2019;20:84.

- Sangehra R, Grewal P. Gorlin syndrome presentation and the importance of differential diagnosis of skin cancer: a case report. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2018;21:222-224.

- Bresler S, Padwa B, Granter S. Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (Gorlin syndrome). Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10:119-124.

- Fujii K, Miyashita T. Gorlin syndrome (nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome): update and literature review. Pediatr Int. 2014;56:667-674.

- Evans G, Farndon P. Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. GeneReviews [Internet]. University of Washington; 1993-2020.

- Kim WB, Jerome D, Yeung J. Diagnosis and management of psoriasis. Can Fam Physician. 2017;63:278-285.

- Booms P, Harth M, Sader R, et al. Vismodegib hedgehog-signaling inhibition and treatment of basal cell carcinomas as well as keratocystic odontogenic tumors in Gorlin syndrome. Ann Maxillofac Surg. 2015;5:14-19.

- Gutzmer R, Soloon J. Hedgehog pathway inhibition for the treatment of basal cell carcinoma. Target Oncol. 2019;14:253-267.

- Leavitt E, Lask G, Martin S. Sonic hedgehog pathway inhibition in the treatment of advanced basal cell carcinoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2019;20:84.

A 63-year-old man with frontal bossing and a history of jaw cysts presented with numerous lesions on the scalp, trunk, and legs with recurrent bleeding. Both of his siblings had similar findings. Many lesions had been present for at least 40 years. Physical examination revealed a large, irregular, atrophic, hyperpigmented plaque on the central scalp with multiple translucent hyperpigmented papules at the periphery (top). Similar papules and plaques were present at the temples, around the waist, and on the distal lower extremities, leading to surgical excision of the largest leg lesions. In addition, there were many pinpoint pits on both palms (bottom). A biopsy was submitted for review, which confirmed basal cell carcinomas on the scalp.